嫉妬

Jealousy

☆嫉妬(Jealousy)

とは一般的に、所有物や安全の相対的な不足に対する不安や恐れ、懸念といった思考や感情を指す。

嫉妬は、怒り、恨み、無力感、無力感、嫌悪感といった一つ以上の感情から成り立つことがある。本来の意味では、嫉妬は羨望とは異なるが、英語ではこの二つ

の用語は一般に同義語となり、嫉妬は現在では羨望のみに用いられていた定義も取り込んでいる。これらの二つの感情は、同じ状況で現れがちであるため、しば

しば混同される。[1]

嫉妬は人間関係における典型的な経験であり、生後5ヶ月の乳児にも観察されている。[2][3][4][5]

一部の研究者は、嫉妬はあらゆる文化に見られ普遍的特性だと主張する。[6][7][8]

しかし他方では、嫉妬は文化固有の感情だとする見解もある。[9]

嫉妬は疑念型と反応型の二種類に分けられ[10]、しばしば一連の強い感情として強化され、普遍的人間経験として構築される。心理学者は嫉妬の根底にある

プロセスを研究するため複数のモデルを提案し、嫉妬を引き起こす要因を特定してきた[11]。社会学者は、嫉妬の引き金となる要素や社会的に許容される嫉

妬の表現を決定する上で、文化的信念や価値観が重要な役割を果たすことを実証している。[12]

生物学者は、嫉妬の表現に無意識に影響を与える可能性のある要因を特定している。[13]

歴史を通じて、芸術家たちも絵画、映画、歌、演劇、詩、書籍において嫉妬のテーマを探求してきた。また神学者たちは、それぞれの信仰の聖典に基づいて嫉妬

に関する宗教的見解を示してきた。

| Jealousy generally

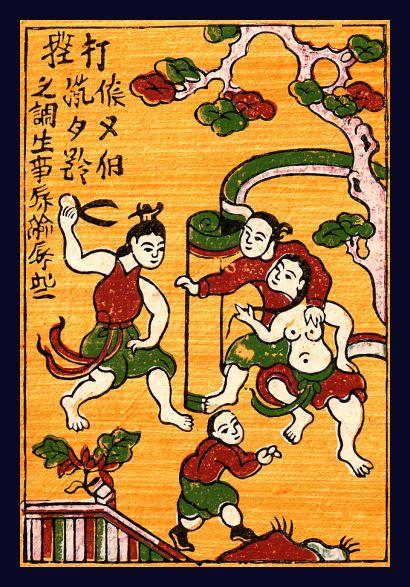

refers to the thoughts or feelings of insecurity, fear, and concern

over a relative lack of possessions or safety. Jealousy can consist of one or more emotions such as anger, resentment, inadequacy, helplessness or disgust. In its original meaning, jealousy is distinct from envy, though the two terms have popularly become synonymous in the English language, with jealousy now also taking on the definition originally used for envy alone. These two emotions are often confused with each other, since they tend to appear in the same situation.[1]  A jealousy scene shown on the Dong Ho painting of Vietnam Jealousy is a typical experience in human relationships, and it has been observed in infants as young as five months.[2][3][4][5] Some researchers claim that jealousy is seen in all cultures and is a universal trait.[6][7][8] However, others claim jealousy is a culture-specific emotion.[9] Jealousy can either be suspicious or reactive,[10] and it is often reinforced as a series of particularly strong emotions and constructed as a universal human experience. Psychologists have proposed several models to study the processes underlying jealousy and have identified factors that result in jealousy.[11] Sociologists have demonstrated that cultural beliefs and values play an important role in determining what triggers jealousy and what constitutes socially acceptable expressions of jealousy.[12] Biologists have identified factors that may unconsciously influence the expression of jealousy.[13] Throughout history, artists have also explored the theme of jealousy in paintings, films, songs, plays, poems, and books, and theologians have offered religious views of jealousy based on the scriptures of their respective faiths. |

嫉妬とは一般的に、所有物や安全の相対的な不足に対する不安や恐れ、懸

念といった思考や感情を指す。 嫉妬は、怒り、恨み、無力感、無力感、嫌悪感といった一つ以上の感情から成り立つことがある。本来の意味では、嫉妬は羨望とは異なるが、英語ではこの二つ の用語は一般に同義語となり、嫉妬は現在では羨望のみに用いられていた定義も取り込んでいる。これらの二つの感情は、同じ状況で現れがちであるため、しば しば混同される。[1]  ベトナムのドンホ絵画に描かれた嫉妬の場面 嫉妬は人間関係における典型的な経験であり、生後5ヶ月の乳児にも観察されている。[2][3][4][5] 一部の研究者は、嫉妬はあらゆる文化に見られ普遍的特性だと主張する。[6][7][8] しかし他方では、嫉妬は文化固有の感情だとする見解もある。[9] 嫉妬は疑念型と反応型の二種類に分けられ[10]、しばしば一連の強い感情として強化され、普遍的人間経験として構築される。心理学者は嫉妬の根底にある プロセスを研究するため複数のモデルを提案し、嫉妬を引き起こす要因を特定してきた[11]。社会学者は、嫉妬の引き金となる要素や社会的に許容される嫉 妬の表現を決定する上で、文化的信念や価値観が重要な役割を果たすことを実証している。[12] 生物学者は、嫉妬の表現に無意識に影響を与える可能性のある要因を特定している。[13] 歴史を通じて、芸術家たちも絵画、映画、歌、演劇、詩、書籍において嫉妬のテーマを探求してきた。また神学者たちは、それぞれの信仰の聖典に基づいて嫉妬 に関する宗教的見解を示してきた。 |

| Etymology The word stems from the French jalousie, formed from jaloux (jealous), and further from Low Latin zelosus (full of zeal), in turn from the Greek word ζῆλος (zēlos), sometimes "jealousy", but more often in a positive sense "emulation, ardour, zeal"[14][15] (with a root connoting "to boil, ferment"; or "yeast").[citation needed] The "biblical language" zeal would be known as "tolerating no unfaithfulness" while in middle English zealous is good.[16] One origin word gelus meant "possessive and suspicious" the word then turned into jelus.[16] Since William Shakespeare's use of terms like "green-eyed monster",[17] the color green has been associated with jealousy and envy, from which the expression "green with envy", is derived. |

語源 この言葉はフランス語のjalousieに由来する。これはjaloux(嫉妬深い)から派生し、さらに低ラテン語のzelosus(熱意に満ちた)に遡 る。これはギリシャ語のζῆλος(ゼーロス)に由来し、時に「嫉妬」を意味するが、より頻繁に「模倣、熱意、熱心さ」といった肯定的な意味で用いられた [14] [15](「沸騰する、発酵する」あるいは「酵母」を意味する語源を持つ)。[出典必要]「聖書的表現」としての熱意は「不誠実を許さない」と解釈される 一方、中英語では熱心であることが良いとされる。[16] 語源の一つであるgelusは「独占的で疑い深い」を意味し、後にjelusへと変化した。[16] ウィリアム・シェイクスピアが「緑の目の怪物」[17]といった表現を用いて以来、緑色は嫉妬や羨望と結びつけられるようになり、そこから「羨望で緑色になる」という表現が生まれた。 |

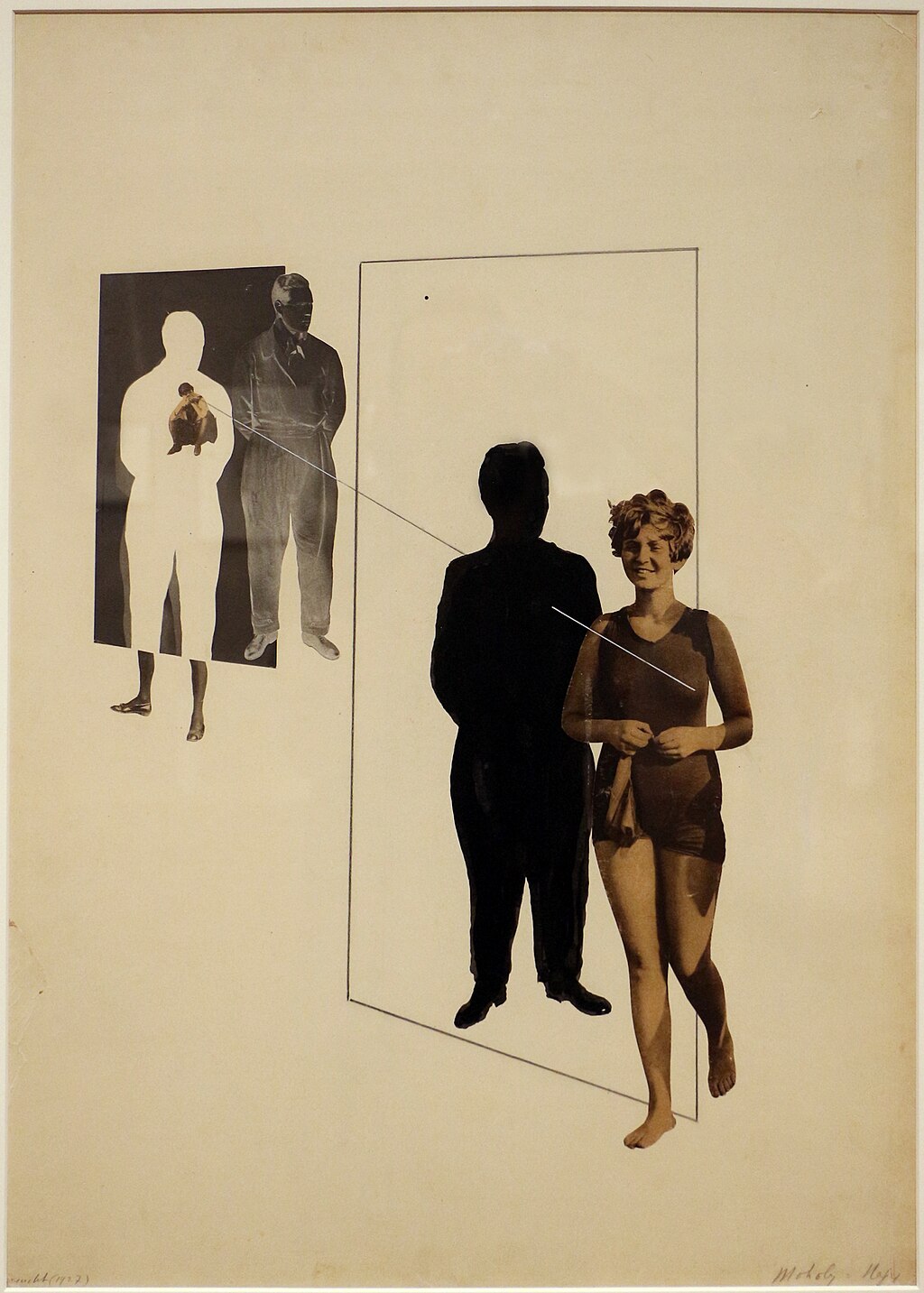

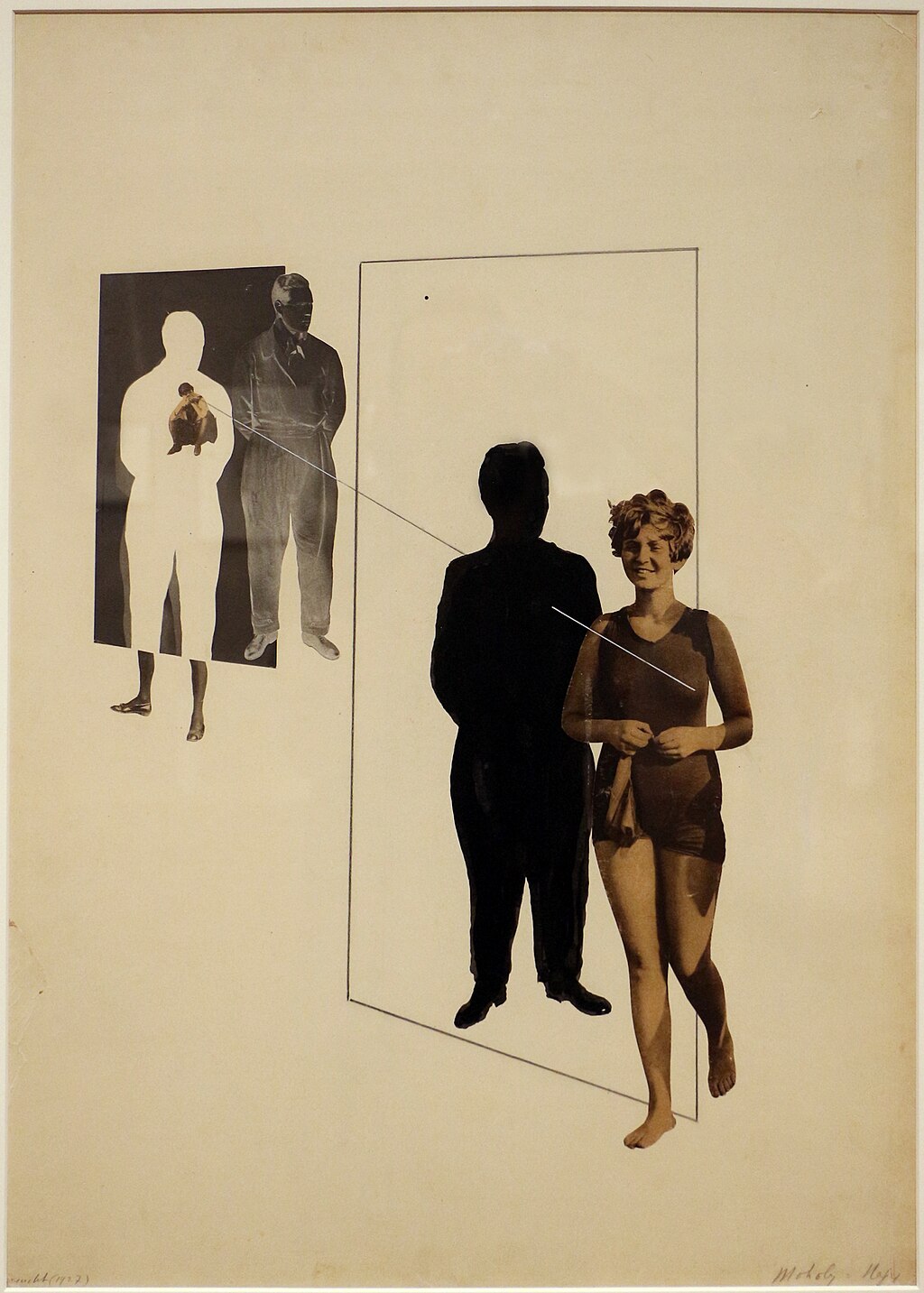

| Theories Scientific examples  Jealousy (1927), László Moholy-Nagy People do not express jealousy through a single emotion or a single behavior.[18][19][20] They instead express jealousy through diverse emotions and behaviors, which makes it difficult to form a scientific definition of jealousy. Scientists instead define it in their own words, as illustrated by the following examples: "Romantic jealousy is here defined as a complex of thoughts, feelings, and actions which follow threats to self-esteem and/or threats to the existence or quality of the relationship, when those threats are generated by the perception of potential attraction between one's partner and a (perhaps imaginary) rival."[21] "Jealousy, then, is any aversive reaction that occurs as the result of a partner's extradyadic relationship that is considered likely to occur."[22] "Jealousy is conceptualized as a cognitive, emotional, and behavioral response to a relationship threat. In the case of sexual jealousy, this threat emanates from knowing or suspecting that one's partner has had (or desires to have) sexual activity with a third party. In the case of emotional jealousy, an individual feels threatened by her or his partner's emotional involvement with and/or love for a third party."[23] "Jealousy is defined as a defensive reaction to a perceived threat to a valued relationship, arising from a situation in which the partner's involvement with an activity and/or another person is contrary to the jealous person's definition of their relationship."[24] "Jealousy is triggered by the threat of separation from, or loss of, a romantic partner, when that threat is attributed to the possibility of the partner's romantic interest in another person."[25] These definitions of jealousy share two basic themes. First, all the definitions imply a triad composed of a jealous individual, a partner, and a perception of a third party or rival. Second, all the definitions describe jealousy as a reaction to a perceived threat to the relationship between two people, or a dyad. Jealous reactions typically involve aversive emotions and/or behaviors that are assumed to be protective for their attachment relationships. These themes form the essential meaning of jealousy in most scientific studies. |

理論 科学的実例  『嫉妬』(1927年)、ラースロー・モホリ=ナジ 人は嫉妬を単一の感情や行動で表現しない[18][19][20]。むしろ多様な感情や行動を通じて嫉妬を表現するため、嫉妬の科学的定義を確立するのは困難である。科学者たちは代わりに、以下の例が示すように、独自の言葉でそれを定義する: 「恋愛における嫉妬とは、自己評価への脅威や関係の存在・質への脅威が生じた際に生じる思考・感情・行動の複合体と定義される。これらの脅威は、パート ナーと(おそらく想像上の)ライバルとの間に潜在的な魅力が存在するとの認識によって引き起こされるものである。」[21] 「嫉妬とは、パートナーが関係外の人間と関係を持つ可能性が高いと認識された結果生じる、あらゆる嫌悪反応である」[22] 「嫉妬は、関係への脅威に対する認知的・感情的・行動的反応として概念化される。性的嫉妬の場合、この脅威は、パートナーが第三者と性的行為を行った(ま たは行いたいと望んでいる)ことを知ったり疑ったりすることから生じる。感情的な嫉妬の場合、個人はパートナーが第三者に対して抱く感情的関与や愛情に よって脅威を感じる。」[23] 「嫉妬とは、パートナーの活動や他者への関与が、嫉妬する者の関係定義に反する状況から生じる、価値ある関係への脅威に対する防御的反応と定義される。」[24] 「嫉妬は、恋愛対象となるパートナーとの分離や喪失の脅威によって引き起こされる。その脅威は、パートナーが他の人物に恋愛感情を抱く可能性に起因すると見なされる場合である。」[25] これらの嫉妬の定義には二つの基本テーマが共通している。第一に、全ての定義が嫉妬を抱く個人、パートナー、そして第三者またはライバルの存在という認識 からなる三者関係を暗示している。第二に、いずれの定義も嫉妬を、二人の人間(二者関係)の絆に対する脅威の認識への反応として描いている。嫉妬反応には 通常、回避感情や行動が伴い、これらは愛着関係を守るための防御的行動と見なされる。これらのテーマが、大半の科学的研究における嫉妬の本質的な意味を形 成している。 |

| Comparison with envy Popular culture uses the word jealousy as a synonym for envy. Many dictionary definitions include a reference to envy or envious feelings. In fact, the overlapping use of jealousy and envy has a long history. The terms are used indiscriminately in such popular 'feel-good' books as Nancy Friday's Jealousy, where the expression 'jealousy' applies to a broad range of passions, from envy to lust and greed. While this kind of usage blurs the boundaries between categories that are intellectually valuable and psychologically justifiable, such confusion is understandable in that historical explorations of the term indicate that these boundaries have long posed problems. Margot Grzywacz's fascinating etymological survey of the word in Romance and Germanic languages[26] asserts, indeed, that the concept was one of those that proved to be the most difficult to express in language and was therefore among the last to find an unambiguous term. Classical Latin used invidia, without strictly differentiating between envy and jealousy. It was not until the postclassical era that Latin borrowed the late and poetic Greek word zelotypia and the associated adjective zelosus. It is from this adjective that are derived French jaloux, Provençal gelos, Italian geloso, Spanish celoso, and Portuguese cioso.[27] Perhaps the overlapping use of jealousy and envy occurs because people can experience both at the same time. A person may envy the characteristics or possessions of someone who also happens to be a romantic rival.[28] In fact, one may even interpret romantic jealousy as a form of envy.[29] A jealous person may envy the affection that their partner gives to a rival – affection the jealous person feels entitled to themselves. People often use the word jealousy as a broad label that applies to both experiences of jealousy and experiences of envy.[30] Although popular culture often uses jealousy and envy as synonyms, modern philosophers and psychologists have argued for conceptual distinctions between jealousy and envy. For example, philosopher John Rawls[31] distinguishes between jealousy and envy on the ground that jealousy involves the wish to keep what one has, and envy the wish to get what one does not have. Thus, a child is jealous of her parents' attention to a sibling, but envious of her friend's new bicycle. Psychologists Laura Guerrero and Peter Andersen have proposed the same distinction.[32] They claim the jealous person "perceives that he or she possesses a valued relationship, but is in danger of losing it or at least of having it altered in an undesirable manner," whereas the envious person "does not possess a valued commodity, but wishes to possess it." Gerrod Parrott draws attention to the distinct thoughts and feelings that occur in jealousy and envy.[33][34] The common experience of jealousy for many people may involve: Fear of loss Suspicion of or anger about a perceived betrayal Low self-esteem and sadness over perceived loss Uncertainty and loneliness Fear of losing an important person to another Distrust The experience of envy involves: Feelings of inferiority Longing Resentment of circumstances Ill will towards envied person often accompanied by guilt about these feelings Motivation to improve Desire to possess the attractive rival's qualities Disapproval of feelings Sadness towards other's accomplishments Parrott acknowledges that people can experience envy and jealousy at the same time. Feelings of envy about a rival can even intensify the experience of jealousy.[35] Still, the differences between envy and jealousy in terms of thoughts and feelings justify their distinction in philosophy and science. |

羨望との比較 ポピュラー・カルチャーでは、嫉妬という言葉が羨望の同義語として使われる。多くの辞書の定義には、羨望や羨望的な感情への言及が含まれている。実際、嫉妬と羨望の混同された使用には長い歴史がある。 ナンシー・フライデーの『嫉妬』のような大衆向けの「気分が良くなる」本では、これらの用語が無差別に使われている。そこでは「嫉妬」という表現が、羨望 から欲望や貪欲に至る幅広い情熱を指す。この種の用法は、知的価値があり心理的に正当化される範疇の境界線を曖昧にするが、この用語の歴史的考察が示すよ うに、こうした境界線は長年問題となってきたため、このような混乱は理解できる。マルゴット・グリワッツによるロマンス語とゲルマン語におけるこの語の興 味深い語源調査[26]は、この概念が言語で表現するのが最も困難な概念の一つであり、したがって明確な用語が確立されるのが最も遅れた概念の一つであっ たと主張している。古典ラテン語ではinvidiaを用い、羨望と嫉妬を厳密に区別しなかった。後古典期になって初めて、ラテン語は後期・詩的ギリシャ語 のzelotypiaと関連形容詞zelosusを借用した。この形容詞から派生したのが、フランス語のjaloux、プロヴァンス語のgelos、イタ リア語のgeloso、スペイン語のceloso、ポルトガル語のciosoである。[27] 嫉妬と羨望の用法が重なるのは、人が両方を同時に経験し得るからかもしれない。人は、たまたま恋愛上のライバルでもある相手の特性や所有物を羨むことがあ る。[28] 実際、恋愛上の嫉妬を羨望の一形態と解釈することさえ可能だ。[29] 嫉妬深い人格は、パートナーがライバルに注ぐ愛情を羨むかもしれない——その愛情こそが、嫉妬深い人格が自分こそが当然受けるべきだと感じるものだから だ。人々はしばしば「嫉妬」という言葉を、嫉妬の経験と羨望の経験の両方に適用される広範なラベルとして使う。[30] ポピュラー・カルチャーでは嫉妬と羨望が同義語として使われることが多いが、現代の哲学者や心理学者は両者の概念的区別を主張している。例えば哲学者ジョ ン・ロールズ[31]は、嫉妬が「既に持っているものを守りたいという願望」であるのに対し、羨望は「持っていないものを得たいという願望」である点で両 者を区別する。したがって、子供は兄弟への親の関心に嫉妬するが、友人の新しい自転車には羨望を抱く。心理学者ローラ・ゲレロとピーター・アンデルセンも 同様の区別を提案している。[32] 彼らは、嫉妬する人格は「自分が価値ある関係を所有しているが、それを失う危険、あるいは少なくとも望ましくない形で変化する危険にさらされていると認識 する」のに対し、羨望する人格は「価値あるものを所有していないが、それを所有したいと願う」と主張する。ジェロッド・パロットは、嫉妬と羨望で生じる異 なる思考や感情に注目している。[33][34] 多くの人々にとって嫉妬の一般的な経験には以下が含まれる: 喪失への恐怖 裏切りへの疑念や怒り 喪失感に伴う低い自尊心と悲しみ 不安と孤独感 大切な人格を他者に奪われる恐れ 不信感 羨望の経験には以下が含まれる: 劣等感 渇望 状況への憤り 羨望の対象への悪意(しばしばその感情への罪悪感を伴う) 向上心 魅力的なライバルの資質を所有したい欲求 感情への否定 他人の成果に対する悲しみ パロットは、人々が羨望と嫉妬を同時に経験し得ると認めている。ライバルに対する羨望の感情は、嫉妬の体験をさらに強めることさえある。[35] それでもなお、思考や感情における羨望と嫉妬の異なる点は、哲学や科学における両者の区別を正当化するものである。 |

| In psychology Jealousy involves an entire "emotional episode" including a complex narrative. This includes the circumstances that lead up to jealousy, jealousy itself as emotion, any attempt at self regulation, subsequent actions and events, and ultimately the resolution of the episode. The narrative can originate from experienced facts, thoughts, perceptions, memories, but also imagination, guesses and assumptions. The more society and culture matter in the formation of these factors, the more jealousy can have a social and cultural origin. By contrast, jealousy can be a "cognitively impenetrable state", where education and rational belief matter very little.[36] One possible explanation of the origin of jealousy in evolutionary psychology is that the emotion evolved in order to maximize the success of our genes: it is a biologically based emotion selected to foster the certainty about the paternity of one's own offspring. A jealous behavior, in women, is directed into avoiding sexual betrayal and a consequent waste of resources and effort in taking care of someone else's offspring.[37] There are, additionally, cultural or social explanations of the origin of jealousy. According to one, the narrative from which jealousy arises can be in great part made by the imagination. Imagination is strongly affected by a person's cultural milieu. The pattern of reasoning, the way one perceives situations, depends strongly on cultural context. It has elsewhere been suggested that jealousy is in fact a secondary emotion in reaction to one's needs not being met, be those needs for attachment, attention, reassurance or any other form of care that would be otherwise expected to arise from that primary romantic relationship. While mainstream psychology considers sexual arousal through jealousy a paraphilia, some authors on sexuality have argued that jealousy in manageable dimensions can have a definite positive effect on sexual function and sexual satisfaction. Studies have also shown that jealousy sometimes heightens passion towards partners and increases the intensity of passionate sex.[38][39] Jealousy in children and teenagers has been observed more often in those with low self-esteem and can evoke aggressive reactions. One such study suggested that developing intimate friends can be followed by emotional insecurity and loneliness in some children when those intimate friends interact with others. Jealousy is linked to aggression and low self-esteem.[40] Research by Sybil Hart, PhD, at Texas Tech University indicates that children are capable of feeling and displaying jealousy at as young as six months.[41] Infants showed signs of distress when their mothers focused their attention on a lifelike doll. This research could explain why children and infants show distress when a sibling is born, creating the foundation for sibling rivalry.[42] In addition to traditional jealousy comes Obsessive Jealousy, which can be a form of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder.[43] This jealousy is characterized by obsessional jealousy and thoughts of the partner. |

心理学において 嫉妬は複雑な物語を含む「感情的なエピソード」全体を伴う。これには嫉妬に至る状況、感情としての嫉妬そのもの、自己制御の試み、その後の行動や出来事、 そして最終的にエピソードの解決が含まれる。この物語は、経験した事実、思考、知覚、記憶から生まれることもあるが、想像、推測、仮定からも生まれる。こ れらの要素の形成において社会や文化が重要であればあるほど、嫉妬は社会的・文化的起源を持つ可能性が高くなる。対照的に、嫉妬は「認知的に不可侵な状 態」となり得る。この状態では、教育や合理的な信念はほとんど意味を持たない。[36] 進化心理学における嫉妬の起源に関する一つの説明は、この感情が我々の遺伝子の成功を格律するために進化したというものである。つまり、これは生物学的に 基盤を持つ感情であり、自身の子孫の父性に関する確信を育むために選択されたのだ。女性における嫉妬行動は、性的裏切りを回避し、その結果として他人の子 孫の世話に費やす資源と労力の浪費を防ぐことを目的としている[37]。さらに、嫉妬の起源に関する文化的・社会的説明も存在する。ある説によれば、嫉妬 が生じる物語は想像力によって大部分が構築される。想像力は人格の文化的環境に強く影響される。推論のパターンや状況の捉え方は、文化的文脈に大きく依存 する。別の研究では、嫉妬は実際には二次的な感情であり、愛情や注目、安心感といった、本来なら主要な恋愛関係から得られるはずのケアが満たされないこと への反応だと示唆されている。 主流の心理学では嫉妬による性的興奮をパラフィリアと見なすが、性に関する一部の研究者は、管理可能な範囲の嫉妬が性的機能や性的満足度に明確な好影響を 与え得ると主張している。嫉妬がパートナーへの情熱を高め、情熱的な性行為の強度を増す場合もあることが研究で示されている[38][39]。 子供や十代の若者の嫉妬は、自尊心の低い者に多く見られ、攻撃的な反応を引き起こすことがある。ある研究では、親密な友人関係を築いた後、その友人が他者 と交流すると、一部の子供に感情的な不安や孤独感が生じることが示唆されている。嫉妬は攻撃性と低い自尊心と関連している[40]。テキサス工科大学のシ ビル・ハート博士の研究によれば、子供は生後6ヶ月という早い時期から嫉妬を感じ、示す能力がある。[41] 母親がリアルな人形に注意を向けると、乳児は苦痛の兆候を示した。この研究は、子どもや乳児が兄弟が生まれた時に苦痛を示す理由を説明し、兄弟間の競争の 基盤を形成する可能性がある。[42] 従来の嫉妬に加え、強迫性嫉妬症が存在する。これは強迫性障害の一形態となり得る。[43] この嫉妬は、強迫的な嫉妬とパートナーへの執着的な思考によって特徴づけられる。 |

| In sociology Main article: Social aspects of jealousy Anthropologists have claimed that jealousy varies across cultures. Cultural learning can influence the situations that trigger jealousy and the manner in which jealousy is expressed. Attitudes toward jealousy can also change within a culture over time. For example, attitudes toward jealousy changed substantially during the 1960s and 1970s in the United States. People in the United States adopted much more negative views about jealousy. As men and women became more equal it became less appropriate or acceptable to express jealousy.[citation needed] A study was done in order to cross examine jealousy among four different cultures, Ireland, Thailand, India and the United States.[44] These cultures were chosen to demonstrate differences in expression across cultures. The study posits that male-dominant cultures are more likely to express and reveal jealousy.[44] The survey found that Thais are less likely to express jealousy than the other three cultures.[44] This is because the men in these cultures are rewarded in a way for showing jealousy due to the fact that some women interpret it as love.[44] This can also be seen when watching romantic comedies when males show they are jealous of a rival or emotionally jealous women perceive it as men caring more.[44] |

社会学において 主な記事: 嫉妬の社会的側面 人類学者は、嫉妬は文化によって異なるとしている。文化的学習は、嫉妬を引き起こす状況や嫉妬の表現方法に影響を与える。嫉妬に対する態度は、同じ文化内 でも時間とともに変化する。例えば、1960年代から1970年代にかけて、アメリカでは嫉妬に対する態度が大きく変化した。アメリカの人々は嫉妬に対し てより否定的な見方をするようになった。男女がより平等になるにつれ、嫉妬を表現することは適切でなくなり、受け入れられなくなったのである。[出典が必 要] アイルランド、タイ、インド、アメリカ合衆国の4つの異なる文化圏における嫉妬を比較検証する研究が行われた[44]。これらの文化圏は、文化間における 表現の違いを示すために選ばれた。この研究は、男性優位の文化圏ほど嫉妬を表現し露わにする傾向が強いと提唱している。[44] 調査では、タイ人は他の3つの文化圏に比べて嫉妬を表現する傾向が低いことが判明した。[44] これは、これらの文化圏では男性が嫉妬を示すことで何らかの形で報われるためである。なぜなら、一部の女性は嫉妬を愛情の表れと解釈するからだ。[44] ロマンティックコメディを観ている時にも同様の傾向が見られる。男性がライバルに対して嫉妬を示す場面や、感情的に嫉妬する女性を、男性がより気にかけて いると女性が受け止める場面がそれにあたる。[44] |

Romantic jealousy Romantic jealousy can appear when we perceive attention between a romantic interest and a third person. Romantic jealousy arises as a result of romantic interest. It is defined as “a complex of thoughts, feelings, and actions that follow threats to self-esteem and/or threats to the existence or quality of the relationship when those threats are generated by the perception of a real or potential romantic attraction between one's partner and a (perhaps imaginary) rival.”[45] Different from sexual jealousy, romantic jealousy is triggered by threats to self and relationship (rather than sexual interest in another person). Factors, such as feelings of inadequacy as a partner, sexual exclusivity, and having put relatively more effort into the relationship, are positively correlated to relationship jealousy in both genders. |

恋愛的な嫉妬 恋愛的な嫉妬は、恋愛対象と第三人格の間に注意が向けられていると認識した時に生じることがある。 恋愛的嫉妬は、恋愛対象の存在によって生じる。 これは「自己評価への脅威、あるいは関係の存在や質への脅威が生じた際に続く思考・感情・行動の複合体」と定義される。その脅威は、パートナーと(おそら く想像上の)ライバルとの間に、現実的または潜在的な恋愛的魅力が存在すると認識されたことで生じる。[45] 性的嫉妬と異なる、恋愛的嫉妬は(他人格への性的関心ではなく)自己と関係性への脅威によって引き起こされる。パートナーとしての不十分感、性的排他性、 関係性への相対的な努力の多さといった要因は、男女ともに恋愛的嫉妬と正の相関関係にある。 |

| Communicative responses As romantic jealousy is a complicated reaction that has multiple components, i.e., thoughts, feelings, and actions, one aspect of romantic jealousy that is under study is communicative responses. Communicative responses serve three critical functions in a romantic relationship, i.e., reducing uncertainty, maintaining or repairing relationship, and restoring self-esteem.[46] If done properly, communicative responses can lead to more satisfying relationships after experiencing romantic jealousy.[47][48] There are two subsets of communicative responses: interactive responses and general behavior responses. Interactive responses is face-to-face and partner-directed while general behavior responses may not occur interactively.[46] Guerrero and colleagues further categorize multiple types of communicative responses of romantic jealousy. Interactive responses can be broken down to six types falling in different places on continua of threat and directness: Avoidance/Denial (low threat and low directness). Example: becoming silent; pretending nothing is wrong. Integrative Communication (low threat and high directness). Example: explaining feelings; calmly questioning partner. Active Distancing (medium threat and medium directness). Example: decreasing affection. Negative Affect Expression (medium threat and medium directness). Example: venting frustration; crying or sulking. Distributive Communication (high threat and high directness). Example: acting rude; making hurtful or abrasive comments. Violent Communication/Threats (high threat and high directness). Example: using physical force. Guerrero and colleagues have also proposed five general behavior responses. The five sub-types differ in whether a response is 1) directed at partner or rival(s), 2) directed at discovery or repair, and 3) positively or negatively valenced: Surveillance/ Restriction (rival-targeted, discovery-oriented, commonly negatively valenced). Example: observing rival; trying to restrict contact with partner. Rival Contacts (rival-targeted, discovery-oriented/repair-oriented, commonly negatively valenced). Example: confronting rival. Manipulation Attempts (partner-targeted, repair-oriented, negatively valenced). Example: tricking partner to test loyalty; trying to make partner feel guilty. Compensatory Restoration (partner-targeted, repair-oriented, commonly positively valenced). Example: sending flowers to partner. Violent Behavior (-, -, negatively valenced). Example: slamming doors. While some of these communicative responses are destructive and aggressive, e.g., distributive communication and active distancing, some individuals respond to jealousy in a more constructive way.[49] Integrative communication, compensatory restoration, and negative affect expression have been shown to lead to positive relation outcomes.[50] One factor that affects the type of communicative responses elicited in an individual is emotions. Jealousy anger is associated with more aggressive communicative response while irritation tends to lead to more constructive communicative behaviors. Researchers also believe that when jealousy is experienced it can be caused by differences in understanding the commitment level of the couple, rather than directly being caused by biology alone. The research identified that if a person valued long-term relationships more than being sexually exclusive, those individuals were more likely to demonstrate jealousy over emotional rather than physical infidelity.[51] Through a study conducted in three Spanish-Speaking countries, it was determined that Facebook jealousy also exists. This Facebook jealousy ultimately leads to increased relationship jealousy and study participants also displayed decreased self esteem as a result of the Facebook jealousy.[52] |

コミュニケーション的反応 恋愛における嫉妬は、思考、感情、行動といった複数の要素からなる複雑な反応である。研究対象となっている嫉妬の一側面が、コミュニケーション的反応だ。 恋愛関係において、コミュニケーション的反応は三つの重要な機能を果たす。すなわち、不確実性の軽減、関係性の維持または修復、自尊心の回復である。 [46] 適切に行われれば、コミュニケーション的反応は恋愛的嫉妬を経験した後、より満足度の高い関係へと導く可能性がある。[47][48] コミュニケーション的反応には二つのサブセットがある:相互的反応と一般的行動的反応だ。相互的反応は対面で相手に向けられるものだが、一般的行動的反応 は相互的でない形で現れることもある。[46] Guerreroらはさらに、恋愛的嫉妬のコミュニケーション的反応を複数のタイプに分類している。相互的反応は、脅威度と直接性の連続体上で異なる位置 を占める6種類に分類できる: 回避/否認(脅威度低・直接性低)。例:沈黙する;問題がないふりをする。 統合的コミュニケーション(脅威度低・直接性高)。例:感情を説明する;冷静にパートナーに問いただす。 積極的距離化(中程度の脅威と中程度の直接性)。例:愛情表現を減らす。 否定的感情表現(中程度の脅威と中程度の直接性)。例:不満をぶつける;泣いたり不機嫌になる。 分配的コミュニケーション(高脅威・高直接性)。例:無礼な態度を取る;傷つける発言や攻撃的な発言をする。 暴力的なコミュニケーション/脅迫(高脅威・高直接性)。例:物理的な力を行使する。 ゲレロらはさらに、5つの一般的な行動反応を提案している。5つのサブタイプは、反応が1) パートナーかライバルを対象とするか、2) 発見か修復を目的とするか、3) 肯定的か否定的かによって異なる: 監視/制限(ライバル対象、発見志向、一般的に否定的)。例:ライバルを観察する;パートナーとの接触を制限しようとする。 ライバル接触(ライバル対象、発見志向/修復志向、一般的に負の価値を持つ)。例:ライバルと対峙する。 操作的試み(パートナー対象、修復志向、負の価値を持つ)。例:忠誠心を試すためにパートナーを騙す;パートナーに罪悪感を抱かせようとする。 補償的修復(パートナー対象、修復志向、一般的に正の価値を持つ)。例:パートナーに花を贈る。 暴力的な行動(-, -, 負の感情を伴う)。例:ドアをバタンと閉める。 こうしたコミュニケーション反応の中には、分配的コミュニケーションや積極的距離化のように破壊的で攻撃的なものもあるが、より建設的な方法で嫉妬に対応 する個人もいる。[49] 統合的コミュニケーション、補償的修復、否定的感情表現は、良好な関係構築につながることを示している。[50] 個人が示すコミュニケーション反応の種類に影響を与える要因の一つが感情である。嫉妬に伴う怒りはより攻撃的な反応と関連し、苛立ちはより建設的な行動に つながりやすい。 研究者らはまた、嫉妬が生じる原因は生物学的な要因のみではなく、カップル間のコミットメントレベルに対する理解の相違にも起因すると考えている。研究に よれば、性的排他性よりも長期的な関係を重視する人格は、肉体的な不貞よりも感情的な不貞に対して嫉妬を示す傾向が強いことが判明した。[51] スペイン語圏3カ国で実施された研究では、フェイスブック上の嫉妬も存在することが確認された。このフェイスブック嫉妬は最終的に関係性における嫉妬を増幅させ、研究参加者はフェイスブック嫉妬の結果として自尊心の低下も示した。[52] |

| Sexual jealousy Main article: Sexual jealousy  Woman displaying jealousy while imagining her partner with another woman Sexual jealousy may be triggered when a person's partner displays sexual interest in another person.[53] The feeling of jealousy may be just as powerful if one partner suspects the other is guilty of infidelity. Fearing that their partner will experience sexual jealousy the person who has been unfaithful may lie about their actions in order to protect their partner. Experts often believe that sexual jealousy is in fact a biological imperative. It may be part of a mechanism by which humans and other animals ensure access to the best reproductive partners. It seems that male jealousy in heterosexual relationships may be influenced by their female partner's phase in her menstrual cycle. In the period around and shortly before ovulation, males are found to display more mate-retention tactics, which are linked to jealousy.[54] Furthermore, a male is more likely to employ mate-retention tactics if their partner shows more interest in other males, which is more likely to occur in the pre-ovulation phase.[55] |

性的嫉妬 主な記事:性的嫉妬  パートナーが他の女性といる姿を想像して嫉妬を示す女性 性的嫉妬は、パートナーが他の人格に対して性的関心を示した時に引き起こされることがある。[53] 嫉妬の感情は、片方の人格がもう片方が不貞を働いていると疑った場合にも同様に強くなる。不貞を働いた人格は、パートナーが性的嫉妬を抱くことを恐れ、相 手を保護するために自身の行動について嘘をつくことがある。専門家はしばしば、性的嫉妬は実際には生物学的な必然性であると考える。これは人間や他の動物 が最良の繁殖相手へのアクセスを確保するためのメカニズムの一部かもしれない。 異性愛関係における男性の嫉妬は、女性のパートナーの月経周期の段階に影響される可能性がある。排卵前後の時期、男性はより多くの配偶者維持戦術を示すこ とが確認されており、これは嫉妬と関連している[54]。さらに、パートナーが他の男性により強い関心を示す場合、男性は配偶者維持戦術を採用する可能性 が高くなる。これは排卵前期に発生する可能性が高い[55]。 |

| Contemporary views on gender-based differences According to Rebecca L. Ammon in The Osprey Journal of Ideas and Inquiry at UNF Digital Commons (2004), the Parental Investment Model based on parental investment theory posits that more women than men ratify sex differences in jealousy. In addition, more women over men consider emotional infidelity (fear of abandonment) as more distressing than sexual infidelity.[56] According to the attachment theory, sex and attachment style makes significant and unique interactive contributions to the distress experienced. Security within the relationship also heavily contributes to one's level of distress. These findings imply that psychological and cultural mechanisms regarding sex differences may play a larger role than expected. The attachment theory also claims to reveal how infants' attachment patterns are the basis for self-report measures of adult attachment. Although there are no sex differences in childhood attachment, individuals with dismissing behavior were more concerned with the sexual aspect of relationships. As a coping mechanism these individuals would report sexual infidelity as more harmful. Moreover, research shows that audit attachment styles strongly conclude with the type of infidelity that occurred. Thus psychological and cultural mechanisms are implied as unvarying differences in jealousy that play a role in sexual attachment.[57] In 1906, The American Journal of Psychology had reported that "the weight of quotable (male) authority is to the effect that women are more susceptible to jealousy". This claim was accompanied in the journal by a quote from Confucius: "The five worst maladies that afflict the female mind are indocility, discontent, slander, jealousy and naive."[58] Emotional jealousy was predicted to be nine times more responsive in females than in males. The emotional jealousy predicted in males also held turn to state that males experiencing emotional jealousy are more violent than women experiencing emotional jealousy.[59] There are distinct emotional responses to gender differences in romantic relationships. For example, due to paternity uncertainty in males, jealousy increases in males over sexual infidelity rather than emotional. According to research more women are likely to be upset by signs of resource withdraw (i.e. another female) than by sexual infidelity. A large amount of data supports this notion. However, one must consider for jealousy the life stage or experience one encounters in reference to the diverse responses to infidelity available. Research states that a componential view of jealousy consist of specific set of emotions that serve the reproductive role.[citation needed] However, research shows that men would be angry and point the blame for sexual infidelity, but women would be more hurt by emotional infidelity. Despite this fact, anger surfaces when both parties involved are responsible for some type of uncontrollable behavior, sexual conduct is not exempt. Some behavior and actions are controllable such as sexual behavior. However hurt feelings are activated by relationship deviation. No evidence is known to be sexually dimorphic in both college and adult convenience samples.[clarification needed] The Jealousy Specific Innate Model (JSIM) proved to not be innate, but may be sensitive to situational factors. As a result, it may only activate at stages. For example, it was predicted that male jealousy decreases as females reproductive values decreases.[60] A second possibility that the JSIM effect is not innate but is cultural. Differences have been highlighted in socio-economic status specific such as the divide between high school and collegiate individuals. Moreover, individuals of both genders were angrier and blamed their partners more for sexual infidelities but were more hurt by emotional infidelity. Jealousy is composed of lower-level emotional states (e.g., anger and hurt) which may be triggered by a variety of events, not by differences in individuals' life stage. Although research has recognized the importance of early childhood experiences for the development of competence in intimate relationships, early family environment is recently being examined as we age). Research on self-esteem and attachment theory suggest that individuals internalize early experiences within the family which subconsciously translates into their personal view of worth of themselves and the value of being close to other individuals, especially in an interpersonal relationship.[61] |

性別に基づく差異に関する現代的見解 UNFデジタルコモンズ『オスプレイ・ジャーナル・オブ・アイデアズ・アンド・インクワイアリー』(2004年)におけるレベッカ・L・アモンによれば、 親投資理論に基づく親投資モデルは、嫉妬における性差を認める女性が男性より多いと主張する。さらに、感情的な不貞(見捨てられる恐怖)を性的不貞より苦 痛と考える女性も男性より多い。[56] 愛着理論によれば、性別と愛着様式は、経験される苦痛に対して重要かつ独自の相互作用的貢献をする。関係性内の安全感も、個人の苦痛レベルに大きく寄与す る。これらの知見は、性差に関する心理的・文化的メカニズムが予想以上に大きな役割を果たす可能性を示唆している。愛着理論はまた、乳児期の愛着パターン が成人期の自己報告式愛着測定の基盤となることを明らかにすると主張する。幼少期の愛着に性差は認められないものの、回避的愛着を示す個体は関係の性的側 面をより重視する傾向があった。対処メカニズムとして、こうした個体は性的不貞をより有害と報告する。さらに研究によれば、監査的愛着様式は発生した不貞 の類型と強い関連性を示す。したがって、性的愛着における嫉妬の性差は、心理的・文化的メカニズムが作用していることを示唆している。[57] 1906年、『アメリカ心理学雑誌』は「引用可能な(男性)権威者の見解の大半は、女性が嫉妬に陥りやすいというものである」と報告した。この主張には、 同誌が引用した孔子の言葉が添えられていた:「女性の心を蝕む五つの最悪の病は、従順でないこと、不満、誹謗、嫉妬、そして純真さである」[58] 感情的な嫉妬は、男性よりも女性に9倍強く反応すると予測された。男性に予測される感情的な嫉妬についても、感情的な嫉妬を経験する男性は、感情的な嫉妬を経験する女性よりも暴力的であるという見解が示された。[59] 恋愛関係における性差には、明確な感情的反応の違いがある。例えば、男性における父性不確実性のため、男性は感情的な不貞よりも性的不貞に対して嫉妬が強 まる。研究によれば、多くの女性は性的不貞よりも資源の引き揚げ(つまり他の女性)の兆候に動揺する傾向がある。この見解を支持するデータは多い。ただ し、不貞に対する多様な反応を考慮する際には、嫉妬が生じる人生の段階や経験を踏まえる必要がある。研究は、嫉妬の構成要素的見解が、生殖的役割を果たす 特定の感情群から成ると述べている。[出典が必要] しかし研究によれば、男性は性的不貞に対して怒りを感じ非難する傾向がある一方、女性は感情的な不貞により傷つきやすい。この事実にもかかわらず、双方が 制御不能な行動(性的行為を含む)に関与した場合、怒りが表面化する。性的行動など制御可能な行動もあるが、関係性の逸脱によって感情的な傷つきが生じ る。大学生や成人を対象とした便宜的標本において、性差を示す証拠は確認されていない。[説明が必要] 嫉妬特異的生得モデル(JSIM)は生得ではなく、状況要因に敏感である可能性が証明された。結果として、段階的にのみ活性化されるかもしれない。例え ば、女性の生殖的価値が低下するにつれて男性の嫉妬は減少すると予測された。[60] JSIM効果が生得ではなく文化的であるという第二の可能性。社会経済的地位に特化した異なる点が強調されている。例えば、高校と大学生の間の隔たりだ。 さらに、両性とも性的不貞に対してはより怒りを感じ、パートナーを非難したが、感情的な不貞にはより傷ついた。嫉妬は低次感情状態(怒りや傷つきなど)で 構成され、個人のライフステージの違いではなく様々な出来事によって引き起こされる可能性がある。研究では、親密な関係における能力の発達に幼児期の経験 が重要であることが認識されているが、近年では加齢に伴う初期家庭環境の検証が進んでいる。自尊心と愛着理論に関する研究は、個人が家族内での初期経験を 内面化し、それが無意識のうちに自己の価値や他者(特に人間関係における)との親密さの価値に関する個人的な人格の見解へと変換されることを示唆してい る。[61] |

| In animals A study by researchers at the University of California, San Diego, replicated jealousy studies done on humans on canines. They reported, in a paper published in PLOS ONE in 2014, that a significant number of dogs exhibited jealous behaviors when their human companions paid attention to dog-like toys, compared to when their human companions paid attention to non-social objects.[62] In addition, Jealousy has been speculated to be a potential factor in incidences of aggression or emotional tension in dogs.[63][64] Mellissa Starling, an animal behavior consultant of the University of Sydney, noted that "dogs are social animals and they obey a group hierarchy. Changes in the home, like the arrival of a baby, can prompt a family pet to behave differently to what one might expect."[65] |

動物において カリフォルニア大学サンディエゴ校の研究者による研究では、人間を対象とした嫉妬の研究を犬で再現した。2014年にPLOS ONE誌に掲載された論文で、飼い主が犬型のおもちゃに注目した場合、非社会的対象に注目した場合と比較して、かなりの数の犬が嫉妬行動を示したと報告し ている。[62] さらに、嫉妬は犬の攻撃性や情緒的緊張の潜在的要因として推測されている[63][64]。シドニー大学の動物行動コンサルタント、メリッサ・スターリン グは「犬は社会性動物であり、群れの階層に従う。家庭環境の変化、例えば赤ちゃんの誕生は、家族の一員であるペットの行動を予想外のものに変える可能性が ある」と指摘している[65]。 |

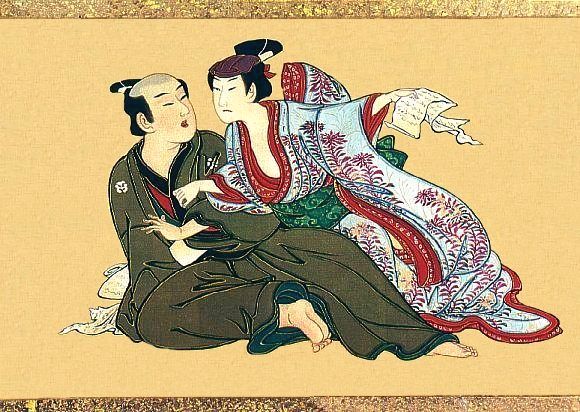

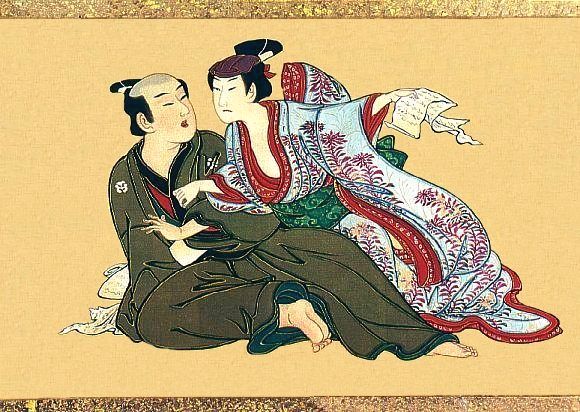

| Applications In fiction, film, and art  A painting by Miyagawa Isshō shows a young onnagata catching his older lover with a love letter from a rival, c. 1750. Artistic depictions of jealousy occur in fiction, films, and other art forms such as painting and sculpture. Jealousy is a common theme in literature, art, theatre, and film. Often, it is presented as a demonstration of particularly deep feelings of love, rather than a destructive obsession. A study done by Ferris, Smith, Greenberg, and Smith[66] looked into the way people saw dating and romantic relationships based on how many reality dating shows they watched.[67] People who spent a large amount of time watching these reality dating shows "endorsed" or supported the "dating attitudes" that would be shown on the show.[67] While the other people who do not spend time watching reality dating shows did not mirror the same ideas.[67] This means if someone watches a reality dating show that displays men and women reacting violently or aggressively towards their partner due to jealousy they can mirror that.[67] This is reflected in romantic movies as well.[67] Jessica R. Frampton conducted a study looking into romantic jealousy in movies. The study found that there were "230 instances of romantic jealousy were identified in the 51 top-grossing romantic comedies from 2002–2014"[67] Some of the films did not display romantic jealousy however, some featured many examples of romantic jealousy.[67] This was due to the fact that some of the top-grossing movies did not contain a rival or romantic competition.[67] While others such as Forgetting Sarah Marshall was said to contain "19 instances of romantic jealousy."[67] Out of the 230 instances 58% were reactive jealousy while 31% showed possessive jealousy.[67] The last 11% displayed anxious jealousy it was seen the least in all 230 cases.[67] Out of the 361 reactions to the jealousy found 53% were found to be "Destructive responses."[67] Only 19% of responses were constructive while 10% showed avoidant responses.[67] The last 18% were considered "rival focused responses" which lead to the finding that "there was a higher than expected number of rival-focused responses to possessive jealousy."[67] |

応用例 小説、映画、芸術における表現  宮川一翔の絵画には、若い女形役者が年上の恋人を、ライバルからのラブレターで捕らえる場面が描かれている。約1750年頃。 嫉妬の芸術的描写は、小説、映画、絵画や彫刻などの芸術形式に見られる。嫉妬は文学、芸術、演劇、映画における普遍的なテーマだ。多くの場合、それは破壊的な執着というよりは、特に深い愛情の表れとして描かれる。 フェリス、スミス、グリーンバーグ、スミスによる研究[66]は、リアリティ番組の視聴時間と人民の恋愛観の関係を調査した。[67] こうした番組を長時間視聴する人々は、番組内で示される「恋愛観」を「支持」または擁護する傾向があった。[67] 一方、視聴しない人々は同様の考え方を反映しなかった。[67] つまり、嫉妬からパートナーに対して暴力的・攻撃的な反応を示す男女を描いた番組を視聴すると、視聴者も同様の行動を模倣する可能性がある。[67] この傾向は恋愛映画にも見られる。[67] ジェシカ・R・フラムトンは映画における恋愛的嫉妬を調査した。その結果、「2002年から2014年にかけての興行収入上位51作品のロマンティックコ メディにおいて、230件の恋愛的嫉妬が確認された」と報告されている。[67] ただし、ロマンチックな嫉妬を描いていない作品もあれば、多くの例を扱った作品もあった。[67] これは、興行収入上位の映画の中にはライバルや恋愛競争が登場しない作品もあったためである。[67] 一方、『サラ・マーシャルを忘れる方法』のような作品は「19件のロマンチックな嫉妬の事例」を含むとされている。[67] 230件の事例のうち、58%が反応的嫉妬、31%が所有欲的嫉妬であった[67]。残り11%は不安的嫉妬を示し、全230件中で最も少ない割合だった [67]。嫉妬に対する361の反応のうち、53%が「破壊的反応」と判定された。[67] 建設的反応はわずか19%で、回避的反応は10%だった。[67] 残り18%は「ライバル指向的反応」と分類され、これにより「所有的嫉妬に対するライバル指向的反応が予想以上に多かった」という結論に至った。[67] |

| In religion Main article: Jealousy in religion Jealousy in religion examines how the scriptures and teachings of various religions deal with the topic of jealousy. Religions may be compared and contrasted on how they deal with two issues: concepts of divine jealousy, and rules about the provocation and expression of human jealousy. |

宗教における嫉妬 主な記事: 宗教における嫉妬 宗教における嫉妬とは、様々な宗教の聖典や教えが嫉妬という主題をどのように扱っているかを考察するものである。宗教は、二つの問題に対する対応の仕方で比較対照されることがある。すなわち、神の嫉妬という概念と、人間の嫉妬を誘発し表現することに関する規則である。 |

| Compersion — empathizing with the joy of another. Crime of passion Delusional disorder, jealous subtype Inferiority complex Pathological jealousy Emotion Relational transgression |

共感——他人の喜びに共感すること。 激情による犯罪 妄想性障害、嫉妬型 劣等感 病的嫉妬 感情 関係性の越境 |

| Pistole, Johthan; Roberts,

Carole; Mosko, Amber (2010). "Commitment predictors: Long-distance

versus geographically close relationships". Journal of Counseling &

Development. 88 (2): 2. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00003.x. Rydell, Robert J.; McConnell, Allen R.; Bringle, Robert G. (2004). "Jealousy and commitment: Perceived threat and the effect of relationship alternatives". Personal Relationships. 11 (4): 451–468. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00092.x. Lyhda, Belcher (2009). " Different Types of Jealousy" livestrong.com Green, Melanie; Sabin, John (2006). "Gender, Socioeconomic Status, age and jealousy: Emotional responses to infidelity in a national sample". Emotion. 6 (2): 330–4. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.6.2.330. PMID 16768565. |

ピストル、ジョサン、ロバーツ、キャロル、モスコ、アンバー

(2010)。「コミットメントの予測因子:遠距離恋愛と地理的に近い恋愛の比較」。カウンセリング&開発ジャーナル。88 (2): 2.

doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00003.x。 Rydell, Robert J.; McConnell, Allen R.; Bringle, Robert G. (2004). 「嫉妬とコミットメント:知覚される脅威と関係の代替案の影響」. Personal Relationships. 11 (4): 451–468. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00092.x. Lyhda, Belcher (2009). 「嫉妬の異なるタイプ」 livestrong.com Green, Melanie; Sabin, John (2006). 「性別、社会経済的地位、年齢と嫉妬:国民サンプルにおける不貞行為への感情的反応」. Emotion. 6 (2): 330–4. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.6.2.330. PMID 16768565. |

| Further reading Peter Goldie. The Emotions, A Philosophical Exploration . Oxford University Press, 2000 W. Gerrod Parrott. Emotions in Social Psychology . Psychology Press, 2001 Jesse J. Prinz. Gut Reactions: A Perceptual Theory of Emotions. Oxford University Press, 2004 Staff, P.T. (January–February 1994), "A devastating difference", Psychology Today, Document ID 1544, archived from the original on 27 April 2006, retrieved 8 July 2006 Jealousy among the Sangha Archived 5 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine Quoting Jeremy Hayward from his book on Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche Warrior-King of Shambhala: Remembering Chögyam Trungpa Hart, S. L. & Legerstee, M. (Eds.) "Handbook of Jealousy: Theory, Research, and Multidisciplinary Approaches" . Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. Pistole, M.; Roberts, A.; Mosko, J. E. (2010). "Commitment Predictors: Long-Distance Versus Geographically Close Relationships". Journal of Counseling & Development. 88 (2): 146. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00003.x. Levy, Kenneth N., Kelly, Kristen M Feb 2010; Sex Differences in Jealousy: A Contribution From Attachment Theory Psychological Science, vol. 21: pp. 168–173 Green, M. C.; Sabini, J. (2006). "Gender, socioeconomic status, age, and jealousy: Emotional responses to infidelity in a national sample". Emotion. 6 (2): 330–334. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.6.2.330. PMID 16768565. Rauer, A. J.; Volling, B. L. (2007). "Differential parenting and sibling jealousy: Developmental correlates of young adults' romantic relationships". Personal Relationships. 14 (4): 495–511. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00168.x. PMC 2396512. PMID 19050748. Pistole, M.; Roberts, A.; Mosko, J. E. (2010). "Commitment Predictors: Long-Distance Versus Geographically Close Relationships". Journal of Counseling & Development. 88 (2): 146. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00003.x. Tagler, M. J. (2010). "Sex differences in jealousy: Comparing the influence of previous infidelity among college students and adults". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 1 (4): 353–360. doi:10.1177/1948550610374367. S2CID 143895254. Tagler, M. J.; Gentry, R. H. (2011). "Gender, jealousy, and attachment: A (more) thorough examination across measures and samples". Journal of Research in Personality. 45 (6): 697–701. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2011.08.006. |

参考文献 ピーター・ゴールディ著『感情の哲学的探求』オックスフォード大学出版局、2000年 W・ジェロッド・パロット著『社会心理学における感情』サイコロジー・プレス、2001年 ジェシー・J・プリンツ著『直感的な反応:感情の知覚理論』オックスフォード大学出版局、2004年 スタッフ、P.T.(1994年1月~2月)、「壊滅的な差異」、『サイコロジー・トゥデイ』、文書ID 1544、2006年4月27日にオリジナルからアーカイブ、2006年7月8日に取得 サンガ間の嫉妬 2009年1月5日、ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ ジェレミー・ヘイワードの著書『チョギャム・トゥルンパ・リンポチェ シャンバラの戦士王:チョギャム・トゥルンパを偲んで』から引用 ハート、S. L.、レゲルスティ、M. (編) 『嫉妬のハンドブック:理論、研究、学際的アプローチ』 . Wiley-Blackwell、2010年。 Pistole、M.、ロバーツ、A.、モスコ、J. E. (2010)。「コミットメントの予測因子:遠距離恋愛と地理的に近い恋愛」。カウンセリング&開発ジャーナル。88 (2): 146。doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00003.x. Levy, Kenneth N., Kelly, Kristen M 2010年2月; 嫉妬における性差:愛着理論からの貢献 心理科学、第21巻:168-173ページ Green, M. C.; サビーニ, J. (2006). 「性別、社会経済的地位、年齢、そして嫉妬:国民サンプルにおける不貞への感情的反応」. Emotion. 6 (2): 330–334. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.6.2.330. PMID 16768565. ラウアー、A. J.;ヴォリング、B. L. (2007). 「差別的養育と兄弟間の嫉妬:若年成人の恋愛関係の発達的相関」. Personal Relationships. 14 (4): 495–511. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00168.x. PMC 2396512. PMID 19050748. Pistole, M.; ロバーツ, A.; モスコ, J. E. (2010). 「コミットメントの予測因子:遠距離恋愛と地理的に近い恋愛の比較」。カウンセリング&開発ジャーナル。88 (2): 146. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00003.x. Tagler, M. J. (2010). 「嫉妬における性差:大学生と成人における過去の不貞行為の影響比較」. ソーシャル・サイコロジカル・アンド・人格・サイエンス. 1 (4): 353–360. doi:10.1177/1948550610374367. S2CID 143895254. Tagler, M. J.; Gentry, R. H. (2011). 「性別、嫉妬、愛着:測定法とサンプルを横断した(より)徹底的な検証」. Journal of Research in Personality. 45 (6): 697–701. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2011.08.006. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jealousy |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099