ジャン=バティスト・ド・ラマルク

Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck, 1744-1829

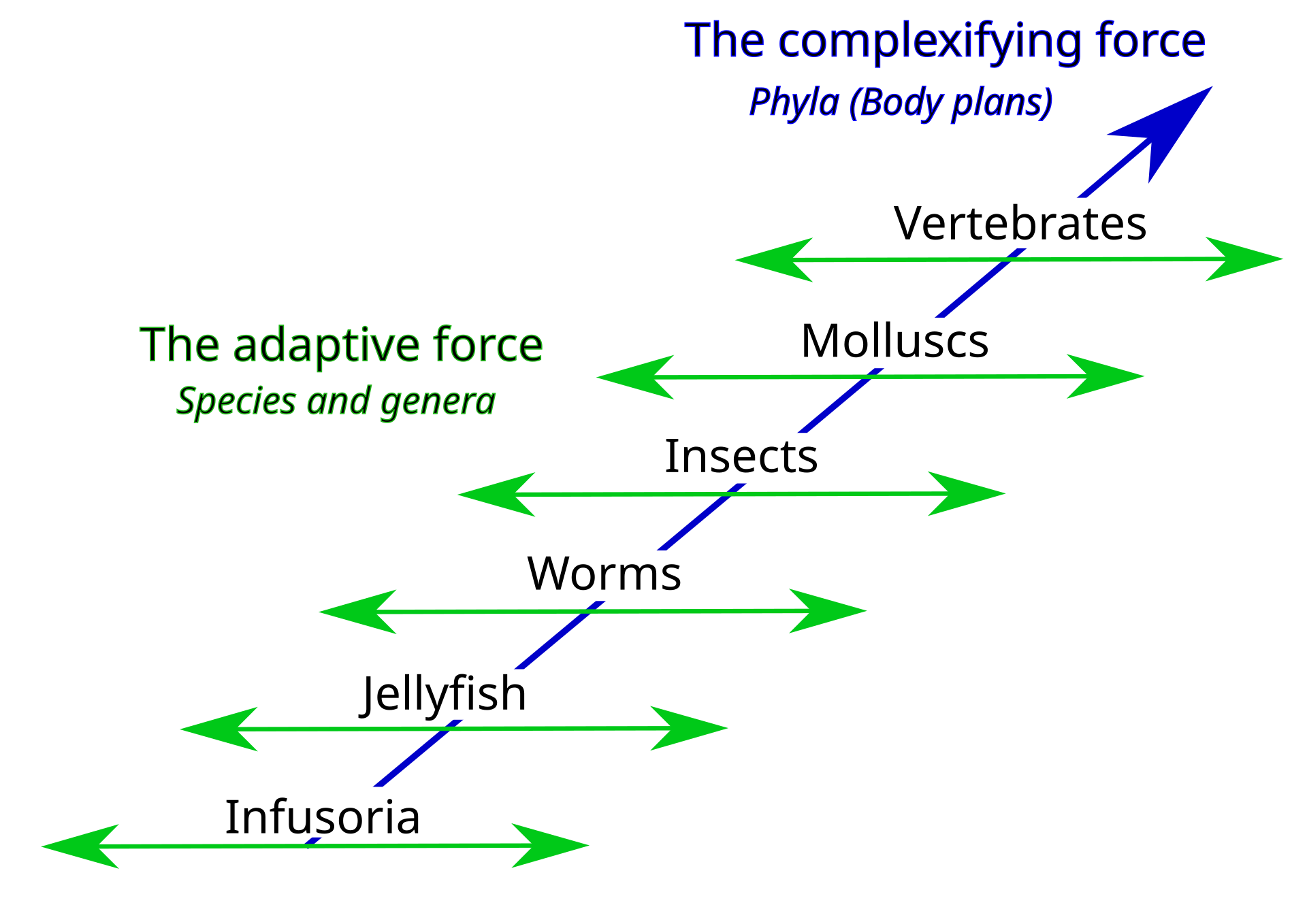

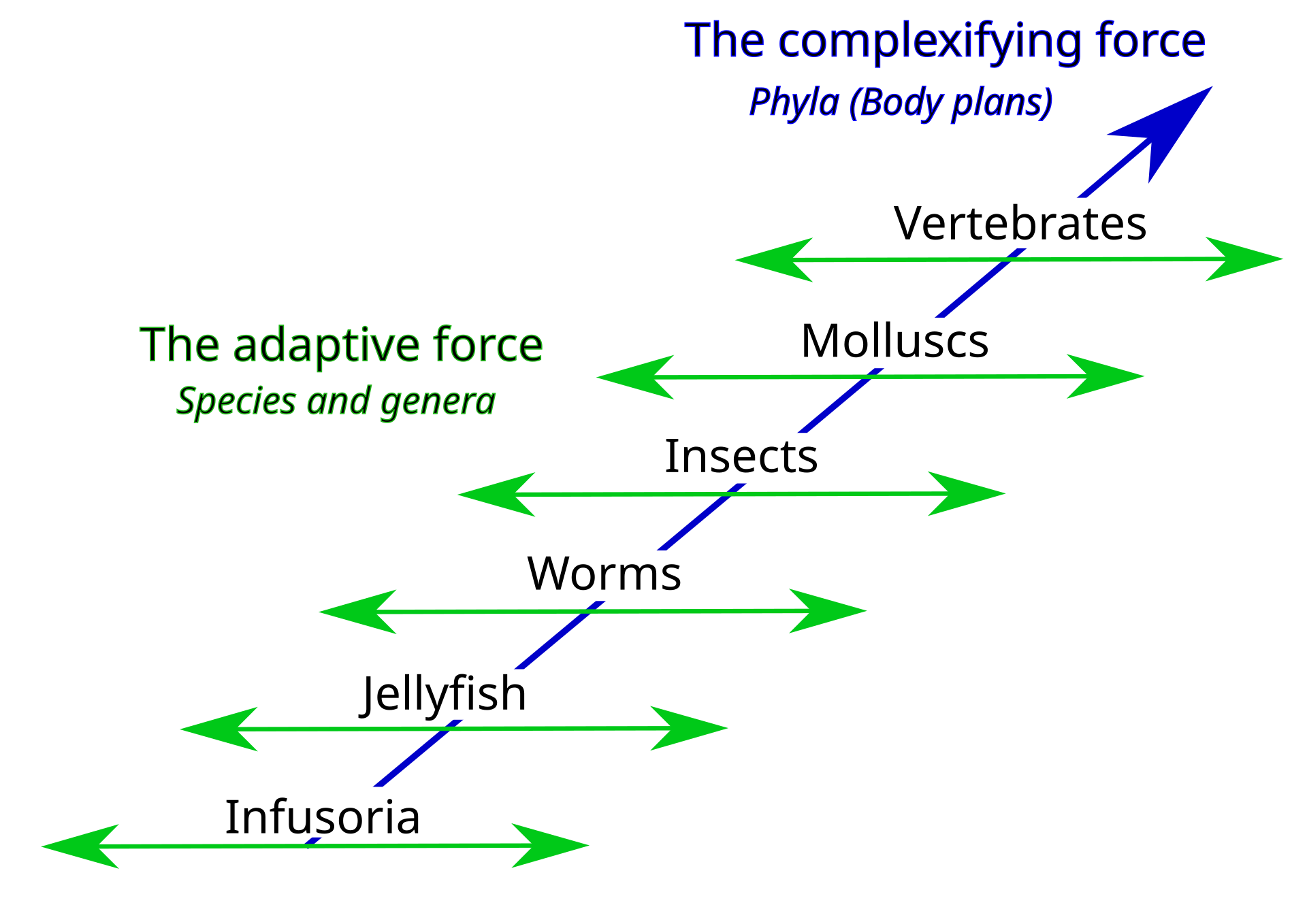

☆ ジャン=バティスト・ピエール・アントワーヌ・ド・ラマルク(1744年8月1日 - 1829年12月18日)は、しばしば単にラマルク(/ləˈmɑːrk/、[1]フランス語: [ʒɑ̃batist lamaʁk][2])として知られる、フランスの博物学者、生物学者、学者、軍人である。彼は、生物の進化は自然法則に従って起こり進行するという考え の初期の提唱者であった。 ラマルクはプロイセンとの七年戦争に従軍し、戦場での勇敢さにより勲章を授与された。モナコに赴任したラマルクは自然史に興味を抱くようになり、医学を学 ぶことを決意した。 ラマルクは植物学に特に興味を抱くようになり、後に3巻本『フランスの植物誌』(1778年)を出版した後、1779年にフランス科学アカデミーの会員と なった。ラマルクはパリ植物園に関わるようになり、1788年には植物学の教授に任命された。1793年にフランス国民議会が国立自然史博物館を設立する と、ラマルクは動物学の教授となった。 1801年には、無脊椎動物の分類に関する主要な著作『Système des animaux sans vertèbres』を出版した。この用語は彼が作った造語である。[6] 1802年の著作では、彼は「生物学」という用語を現代的な意味で初めて使用した人物の一人となった。[7][注釈 1] ラマルクは無脊椎動物学の第一人者として研究を続けた。少なくとも軟体動物学においては、分類学者として高い評価を受けている。 現代では一般的に、ラマルクは1809年の著書『動物学哲学』で述べた獲得形質遺伝説(ラマルク説、不正確に彼にちなんで名付けられた)やソフト・インヘ リタンス、使用/不使用説で記憶されている。しかし、ソフト・インヘリタンスの考え方は彼よりずっと以前から存在しており、彼の進化論のほんの一部を構成 するものであった。ラマルクの進化論への貢献は、生物進化に関する最初の真にまとまった理論[9]であり、錬金術の複雑化の力が生物を複雑性の階段を上ら せ、2番目の環境力が生物をその特性の使用と不使用を通じてその地域の環境に適応させ、他の生物と差別化するというものであった。科学者たちは、世代間エ ピジェネティクス分野の進歩がラマルクの主張の正しさをある程度証明するものであるかどうかについて議論している。[11]

| Jean-Baptiste Pierre

Antoine de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck (1 August 1744 – 18 December

1829), often known simply as Lamarck (/ləˈmɑːrk/;[1] French: [ʒɑ̃batist

lamaʁk][2]), was a French naturalist, biologist, academic, and soldier.

He was an early proponent of the idea that biological evolution

occurred and proceeded in accordance with natural laws.[3] Lamarck fought in the Seven Years' War against Prussia, and was awarded a commission for bravery on the battlefield.[4] Posted to Monaco, Lamarck became interested in natural history and resolved to study medicine.[5] He retired from the army after being injured in 1766, and returned to his medical studies.[5] Lamarck developed a particular interest in botany, and later, after he published the three-volume work Flore françoise (1778), he gained membership of the French Academy of Sciences in 1779. Lamarck became involved in the Jardin des Plantes and was appointed to the Chair of Botany in 1788. When the French National Assembly founded the Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle in 1793, Lamarck became a professor of zoology. In 1801, he published Système des animaux sans vertèbres, a major work on the classification of invertebrates, a term which he coined.[6] In an 1802 publication, he became one of the first to use the term "biology" in its modern sense.[7][Note 1] Lamarck continued his work as a premier authority on invertebrate zoology. He is remembered, at least in malacology, as a taxonomist of considerable stature. The modern era generally remembers Lamarck for a theory of inheritance of acquired characteristics, called Lamarckism (inaccurately named after him), soft inheritance, or use/disuse theory,[8] which he described in his 1809 Philosophie zoologique. However, the idea of soft inheritance long antedates him, formed only a small element of his theory of evolution, and was in his time accepted by many natural historians. Lamarck's contribution to evolutionary theory consisted of the first truly cohesive theory of biological evolution,[9] in which an alchemical complexifying force drove organisms up a ladder of complexity, and a second environmental force adapted them to local environments through use and disuse of characteristics, differentiating them from other organisms.[10] Scientists have debated whether advances in the field of transgenerational epigenetics mean that Lamarck was to an extent correct, or not.[11] |

ジャン=バティスト・ピエール・アントワーヌ・ド・ラマルク(1744

年8月1日 - 1829年12月18日)は、しばしば単にラマルク(/ləˈmɑːrk/、[1]フランス語: [ʒɑ̃batist

lamaʁk][2])として知られる、フランスの博物学者、生物学者、学者、軍人である。彼は、生物の進化は自然法則に従って起こり進行するという考え

の初期の提唱者であった。 ラマルクはプロイセンとの七年戦争に従軍し、戦場での勇敢さにより勲章を授与された。モナコに赴任したラマルクは自然史に興味を抱くようになり、医学を学 ぶことを決意した。 ラマルクは植物学に特に興味を抱くようになり、後に3巻本『フランスの植物誌』(1778年)を出版した後、1779年にフランス科学アカデミーの会員と なった。ラマルクはパリ植物園に関わるようになり、1788年には植物学の教授に任命された。1793年にフランス国民議会が国立自然史博物館を設立する と、ラマルクは動物学の教授となった。 1801年には、無脊椎動物の分類に関する主要な著作『Système des animaux sans vertèbres』を出版した。この用語は彼が作った造語である。[6] 1802年の著作では、彼は「生物学」という用語を現代的な意味で初めて使用した人物の一人となった。[7][注釈 1] ラマルクは無脊椎動物学の第一人者として研究を続けた。少なくとも軟体動物学においては、分類学者として高い評価を受けている。 現代では一般的に、ラマルクは1809年の著書『動物学哲学』で述べた獲得形質遺伝説(ラマルク説、不正確に彼にちなんで名付けられた)やソフト・インヘ リタンス、使用/不使用説で記憶されている。しかし、ソフト・インヘリタンスの考え方は彼よりずっと以前から存在しており、彼の進化論のほんの一部を構成 するものであった。ラマルクの進化論への貢献は、生物進化に関する最初の真にまとまった理論[9]であり、錬金術の複雑化の力が生物を複雑性の階段を上ら せ、2番目の環境力が生物をその特性の使用と不使用を通じてその地域の環境に適応させ、他の生物と差別化するというものであった。科学者たちは、世代間エ ピジェネティクス分野の進歩がラマルクの主張の正しさをある程度証明するものであるかどうかについて議論している。[11] |

| Biography Jean-Baptiste Lamarck was born in Bazentin, Picardy, northern France,[5] as the 11th child in an impoverished aristocratic family.[Note 2] Male members of the Lamarck family had traditionally served in the French army. Lamarck's eldest brother was killed in combat at the Siege of Bergen op Zoom, and two other brothers were still in service when Lamarck was in his teenaged years. Yielding to the wishes of his father, Lamarck enrolled in a Jesuit college in Amiens in the late 1750s.[5] After his father died in 1760, Lamarck bought himself a horse, and rode across the country to join the French army, which was in Germany at the time. Lamarck showed great physical courage on the battlefield in the Seven Years' War with Prussia, and he was even nominated for the lieutenancy.[5] Lamarck's company was left exposed to the direct artillery fire of their enemies, and was quickly reduced to just 14 men—with no officers. One of the men suggested that the puny, 17-year-old volunteer should assume command and order a withdrawal from the field; although Lamarck accepted command, he insisted they remain where they had been posted until relieved. When their colonel reached the remains of their company, this display of courage and loyalty impressed him so much that Lamarck was promoted to officer on the spot. However, when one of his comrades playfully lifted him by the head, he sustained an inflammation in the lymphatic glands of the neck, and he was sent to Paris to receive treatment.[5] He was awarded a commission and settled at his post in Monaco. There, he encountered Traité des plantes usuelles, a botany book by James Francis Chomel.[5] With a reduced pension of only 400 francs a year, Lamarck resolved to pursue a profession. He attempted to study medicine, and supported himself by working in a bank office.[5] Lamarck studied medicine for four years, but gave it up under his elder brother's persuasion. He was interested in botany, especially after his visits to the Jardin du Roi, and he became a student under Bernard de Jussieu, a notable French naturalist.[5] Under Jussieu, Lamarck spent 10 years studying French flora. In 1776, he wrote his first scientific essay—a chemical treatise.[12] After his studies, in 1778, he published some of his observations and results in a three-volume work, entitled Flore française. Lamarck's work was respected by many scholars, and it launched him into prominence in French science. On 8 August 1778, Lamarck married Marie Anne Rosalie Delaporte.[13] Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, one of the top French scientists of the day, mentored Lamarck, and helped him gain membership to the French Academy of Sciences in 1779 and a commission as a royal botanist in 1781, in which he traveled to foreign botanical gardens and museums.[14] Lamarck's first son, André, was born on 22 April 1781, and he made his colleague André Thouin the child's godfather. In his two years of travel, Lamarck collected rare plants that were not available in the Royal Garden, and also other objects of natural history, such as minerals and ores, that were not found in French museums. On 7 January 1786, his second son, Antoine, was born, and Lamarck chose Antoine Laurent de Jussieu, Bernard de Jussieu's nephew, as the boy's godfather.[15] On 21 April the following year, Charles René, Lamarck's third son, was born. René Louiche Desfontaines, a professor of botany at the Royal Garden, was the boy's godfather, and Lamarck's elder sister, Marie Charlotte Pelagie De Monet, was the godmother.[15] In 1788, Buffon's successor at the position of Intendant of the Royal Garden, Charles-Claude Flahaut de la Billaderie, comte d'Angiviller, created a position for Lamarck, with a yearly salary of 1,000 francs, as the keeper of the herbarium of the Royal Garden.[5] In 1790, at the height of the French Revolution, Lamarck changed the name of the Royal Garden from Jardin du Roi to Jardin des Plantes, a name that did not imply such a close association with King Louis XVI.[16] Lamarck had worked as the keeper of the herbarium for five years before he was appointed curator and professor of invertebrate zoology at the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle in 1793.[5] During his time at the herbarium, Lamarck's wife gave birth to three more children before dying on 27 September 1792. With the official title of "Professeur d'Histoire naturelle des Insectes et des Vers", Lamarck received a salary of nearly 2,500 francs per year.[17] The following year, on 9 October, he married Charlotte Reverdy, who was 30 years his junior.[15] On 26 September 1794 Lamarck was appointed to serve as secretary of the assembly of professors for the museum for a period of one year. In 1797, Charlotte died, and he married Julie Mallet the following year; she died in 1819.[15] In his first six years as professor, Lamarck published only one paper, in 1798, on the influence of the moon on the Earth's atmosphere.[5] Lamarck began as an essentialist who believed species were unchanging; however, after working on the molluscs of the Paris Basin, he grew convinced that transmutation or change in the nature of a species occurred over time.[5] He set out to develop an explanation, and on 11 May 1800 (the 21st day of Floreal, Year VIII, in the revolutionary timescale used in France at the time), he presented a lecture at the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle in which he first outlined his newly developing ideas about evolution. |

経歴 ジャン=バティスト・ラマルクは、フランス北部のピカルディ地方バゼンタンで、貧しい貴族の家庭の11番目の子供として生まれた。ラマルク家の男性は伝統 的にフランス軍に仕えていた。ラマルクの長兄はベルヘン・オプ・ゾーム包囲戦で戦死し、ラマルクが10代の頃には、他の2人の兄弟も軍務についていた。父 の希望に従い、ラマルクは1750年代後半にアミアンのイエズス会の大学に入学した。 1760年に父が亡くなると、ラマルクは馬を一頭買い、当時ドイツにいたフランス軍に入隊するためにフランス全土を馬で横断した。ラマルクはプロイセンと の七年戦争の戦場で並々ならぬ身体的な勇気を示し、中尉に推薦されるほどであった。[5] ラマルクの部隊は敵の砲撃に直接さらされ、すぐに14人(士官はいない)にまで減少した。そのうちの一人が、17歳の小柄な志願兵に指揮を任せて撤退を命 じるよう提案した。ラマルクは指揮を引き受けたものの、救援が到着するまでは配置された場所にとどまるよう主張した。 彼らの大佐が自分たちの部隊の残骸に到着したとき、この勇敢さと忠誠心を示す行動に大佐は感銘を受け、ラマルクはその場で士官に昇進した。しかし、仲間が からかって彼の頭を持ち上げたとき、首のリンパ腺に炎症を起こし、パリで治療を受けることになった。[5] 彼は任官を授与され、モナコの任地に落ち着いた。そこで彼は、ジェームズ・フランシス・ショメルの植物学書『Traité des plantes usuelles』に出会った。 年400フランに減額された年金で、ラマルクは職業に就くことを決意した。彼は医学を学ぼうとし、銀行で働いて生計を立てた。ラマルクは4年間医学を学ん だが、兄の説得によりそれを断念した。特に王立植物園を訪れた後は植物学に興味を抱くようになり、著名なフランスの博物学者ベルナール・ド・ジュシューの 弟子となった。ジュシューのもとでラマルクは10年間、フランスの植物相の研究に費やした。1776年には最初の科学論文となる化学論文を執筆した。 研究の後、1778年に彼は観察結果の一部を3巻本『Flore française』として発表した。ラマルクの研究は多くの学者から尊敬を集め、フランス科学界で頭角を現すきっかけとなった。1778年8月8日、ラ マルクはマリー・アン・ロザリー・ド・ラポルトと結婚した。[13] ジョルジュ=ルイ・ルクレール、コント・ド・ビュフォンは、当時のフランスを代表する科学者の一人であり、ラマルクの指導者となり、1779年にフランス 科学アカデミーの会員、1781年には王立植物学者に任命された。 [14] ラマルクの長男アンドレは1781年4月22日に誕生し、同僚のアンドレ・トゥアンを子供の代父とした。 2年間の旅行中、ラマルクは王立庭園にはなかった珍しい植物を集め、また、鉱物や鉱石など、フランスの博物館にはなかった自然史の標本も収集した。 1786年1月7日、彼の次男アントワーヌが誕生し、ラマルクは、ベルナール・ド・ジュシューの甥であるアントワーヌ・ローラン・ド・ジュシューを男児の 代父に選んだ。[15] 翌年4月21日には、ラマルクの三男シャルル・ルネが誕生した。王立庭園の植物学教授ルネ・ルイ・デフォンテーヌが男児の名付け親となり、ラマルクの姉マ リー・シャルロット・ペラジー・ド・モネが女児の名付け親となった。 [15] 1788年、ブッフォンの後任として王立庭園の監督官となったシャルル=クロード・フラオー・ド・ラ・ビラドリー、アンジヴィレール伯爵は、ラマルクに王 立庭園の標本庫の管理人の職を与え、年俸1,000フランの地位を与えた。 フランス革命の真っ只中の1790年、ラマルクは王立庭園の名称を「王の庭園(Jardin du Roi)」から「植物の庭園(Jardin des Plantes)」に変更した。この名称は、ルイ16世との密接な関連性を暗示するものではなかった。[16] ラマルクは、1793年に国立自然史博物館の無脊椎動物学の学芸員および教授に任命されるまでの5年間、植物標本室の管理者として働いていた。 [5] 植物標本室に勤務している間、ラマルクの妻は1792年9月27日に死去するまでにさらに3人の子供を出産した。「昆虫とミミズの自然史教授」という役職 名で、ラマルクは年間2,500フラン近い給料を受け取っていた。 [17] 翌年10月9日、30歳年下のシャルロット・レヴェルディと結婚した。[15] 1794年9月26日、ラマルクは1年間の任期で博物館教授会の書記に任命された。1797年にシャルロットが死去し、翌年ジュリー・マレと再婚した。彼 女は1819年に死去した。[15] 教授として最初の6年間、ラマルクは1798年に地球の大気に対する月の影響について1つの論文を発表したのみであった。[5] ラマルクは当初、生物は変化しないという考えを持つ本質論者であったが、パリ盆地の軟体動物を研究した後、生物の性質における変質や変化は時間をかけて起 こるという考えを強く持つようになった。 [5] 彼は説明を展開し、1800年5月11日(当時フランスで使用されていた革命暦では「フロレアル」の21日目にあたる)、国立自然史博物館で進化に関する 自身の新しい考え方を初めて概説した講義を行った。 |

Lamarck, late in life In 1801, he published Système des Animaux sans Vertèbres, a major work on the classification of invertebrates. In the work, he introduced definitions of natural groups among invertebrates. He categorized echinoderms, arachnids, crustaceans, and annelids, which he separated from the old taxon for worms known as Vermes.[16] Lamarck was the first to separate arachnids from insects in classification, and he moved crustaceans into a separate class from insects. In 1802, Lamarck published Hydrogéologie, and became one of the first to use the term biology in its modern sense.[7][18] In Hydrogéologie, Lamarck advocated a steady-state geology based on a strict uniformitarianism. He argued that global currents tended to flow from east to west, and continents eroded on their eastern borders, with the material carried across to be deposited on the western borders. Thus, the Earth's continents marched steadily westward around the globe. That year, he also published Recherches sur l'Organisation des Corps Vivants, in which he drew out his theory on evolution. He believed that all life was organized in a vertical chain, with gradation between the lowest forms and the highest forms of life, thus demonstrating a path to progressive developments in nature.[19] In his own work, Lamarck had favored the then-more traditional theory based on the classical four elements. During Lamarck's lifetime, he became controversial, attacking the more enlightened chemistry proposed by Lavoisier. He also came into conflict with the widely respected palaeontologist Georges Cuvier, who was not a supporter of evolution.[20] According to Peter J. Bowler, Cuvier "ridiculed Lamarck's theory of transformation and defended the fixity of species."[21] According to Martin J. S. Rudwick: Cuvier was clearly hostile to the materialistic overtones of current transformist theorizing, but it does not necessarily follow that he regarded species origin as supernatural; certainly he was careful to use neutral language to refer to the causes of the origins of new forms of life, and even of man.[22] Lamarck gradually turned blind; he died in Paris on 18 December 1829. When he died, his family was so poor, they had to apply to the Academie for financial assistance. Lamarck was buried in a common grave of the Montparnasse cemetery for just five years, according to the grant obtained from relatives. Later, the body was dug up along with other remains and was lost. Lamarck's books and the contents of his home were sold at auction, and his body was buried in a temporary lime pit.[23] After his death, Cuvier used the form of a eulogy to denigrate Lamarck: [Cuvier's] éloge of Lamarck is one of the most deprecatory and chillingly partisan biographies I have ever read—though he was supposedly writing respectful comments in the old tradition of de mortuis nil nisi bonum. — Gould, 1993[24] |

晩年のラマルク 1801年、彼は無脊椎動物の分類に関する主要な著作『無脊椎動物の体系』を出版した。この著作の中で、彼は無脊椎動物の自然分類群の定義を導入した。彼 は棘皮動物、クモ形類、甲殻類、環形動物を分類し、それらを「Vermes」として知られる古い分類群である線形動物から分離した。[16] ラマルクは分類学においてクモ形類を昆虫から初めて分離し、甲殻類を昆虫とは別の綱に移動させた。 1802年、ラマルクは『Hydrogéologie』を出版し、生物学という用語を現代的な意味で初めて使用した人物の一人となった。[7][18] 『Hydrogéologie』において、ラマルクは厳格な斉一説に基づく定常地質学を提唱した。彼は、地球の海流は東から西に向かって流れる傾向があ り、大陸は東の境界で浸食され、その物質は西の境界に運ばれて堆積すると主張した。したがって、地球上の大陸は地球を巡りながら着実に西へと移動してい る。 その年、彼は『生物体の組織に関する研究』も発表し、進化論の理論を展開した。彼は、すべての生命は垂直的な連鎖で組織されており、最も低い生命体から最も高い生命体へと段階的に変化していると信じていた。これにより、自然界における進歩的な発展の道筋が示された。 ラマルクは自身の研究において、古典的な4元素に基づくより伝統的な理論を支持していた。ラマルクの存命中、彼は論争の的となり、ラヴワジェが提唱したよ り進歩的な化学理論を攻撃した。また、広く尊敬を集めていた古生物学者ジョルジュ・キュヴィエとも対立した。キュヴィエは進化論の支持者ではなかった。 ピーター・J・ボウラーによると、キュヴィエは「ラマルクの変成説を嘲笑し、種の固定性を擁護した」という。 キュヴィエは、当時の変成説理論の唯物論的な含みを明確に敵対視していたが、種の起源を必ずしも超自然的とみなしていたわけではない。確かに、彼は新しい生命形態の起源の原因について、また人間でさえも、ニュートラルな表現を用いるよう慎重を期していた。 ラマルクは徐々に視力を失い、1829年12月18日にパリで死去した。彼の家族は貧困にあえいでおり、アカデミーに経済的支援を申請しなければならな かった。ラマルクは親族からの補助金により、モンパルナス墓地の共同墓にわずか5年間埋葬された。その後、他の遺体とともに掘り起こされた遺体は行方不明 となった。ラマルクの書籍や自宅の所有物は競売にかけられ、遺体は一時的に石灰採掘場に埋められた。[23] 彼の死後、キュヴィエは賛辞の形式を用いてラマルクを中傷した。 キュヴィエによるラマルクの賛辞は、私がこれまでに読んだ中で最も非難的で、ぞっとするほど党派的な伝記のひとつである。ただし、彼は昔ながらの「死者に就いては善きこと以外語るべからず」という伝統に従って、敬意を表するコメントを書いていたはずである。 — グールド、1993年[24] |

| Lamarckian evolution Further information: Lamarckism § Lamarck's evolutionary framework While he was working on Hydrogéologie (1802), Lamarck had the idea to apply the principle of erosion to biology. This led him to the basic principle of evolution, which saw the fluids in organs inheriting more complex forms and functions, thus passing on these traits to the organism's descendants.[12] This was a reversal from Lamarck's previous view, published in his Memoirs of Physics and Natural History (1797), in which he briefly refers to the immutability of species.[25] Lamarck stressed two main themes in his biological work (neither of them to do with soft inheritance). The first was that the environment gives rise to changes in animals. He cited examples of blindness in moles, the presence of teeth in mammals and the absence of teeth in birds as evidence of this principle. The second principle was that life was structured in an orderly manner and that many different parts of all bodies make possible the organic movements of animals.[19] Although he was not the first thinker to advocate organic evolution, he was the first to develop a truly coherent evolutionary theory.[10] He outlined his theories regarding evolution first in his Floreal lecture of 1800, and then in three later published works: Recherches sur l'organisation des corps vivants, 1802. Philosophie zoologique, 1809. Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres, (in seven volumes, 1815–22). Lamarck employed several mechanisms as drivers of evolution, drawn from the common knowledge of his day and from his own belief in the chemistry before Lavoisier. He used these mechanisms to explain the two forces he saw as constituting evolution: force driving animals from simple to complex forms and a force adapting animals to their local environments and differentiating them from each other. He believed that these forces must be explained as a necessary consequence of basic physical principles, favoring a materialistic attitude toward biology. |

ラマルク進化論 詳細情報:ラマルク主義 § ラマルクの進化論的枠組み Hydrogéologie(1802年)の執筆中に、ラマルクは生物に侵食の原理を適用するという考えを持った。これにより、彼は進化の基本原理にたど り着いた。すなわち、器官内の体液がより複雑な形態と機能を受け継ぎ、それらの形質が生物の子孫へと受け継がれていくというものである。[12] これは、種の不変性について簡単に言及した『物理学と自然史の回想録』(1797年)で発表されたラマルクの以前の見解とは逆転するものであった。 [25] ラマルクは生物学的研究において、主に2つのテーマを強調した(いずれも「柔らかい遺伝」とは関係がない)。1つ目は、環境が動物に変化をもたらすという ものだった。彼は、モグラの盲目、哺乳類の歯の存在、鳥類の歯の欠如を、この原理の証拠として挙げた。2つ目の原理は、生命は秩序ある方法で構成されてお り、すべての生物の多くの異なる部分が、動物の有機的な動きを可能にしているというものだった。 有機的進化を唱えた最初の思想家ではなかったが、彼は真に首尾一貫した進化論を初めて展開した人物であった。彼は1800年の「フロレアル講義」で進化に関する自身の理論の概要を説明し、その後、次の3つの著作でさらに詳しく説明した。 『生物体の組織に関する研究』(Recherches sur l'organisation des corps vivants)1802年。 『動物哲学』(Philosophie zoologique)1809年。 無脊椎動物の自然史(全7巻、1815年~1822年) ラマルクは、進化の原動力として、当時の一般的な知識やラヴワジェ以前の化学に対する自身の信念から導き出されたいくつかのメカニズムを採用した。彼はこ れらのメカニズムを用いて、進化を構成すると考えた2つの力を説明した。すなわち、単純な形態から複雑な形態へと動物が進化させる力と、動物がその地域の 環境に適応し、互いに差異化する力である。彼は、これらの力は基本的な物理原理の必然的な帰結として説明されなければならないと考え、生物学に対して唯物 論的な態度を好んだ。 |

| Le pouvoir de la vie: The complexifying force Further information: Orthogenesis  Lamarck's two-factor theory involves 1) a complexifying force that drives animal body plans towards higher levels (orthogenesis) creating a ladder of phyla, and 2) an adaptive force that causes animals with a given body plan to adapt to circumstances (use and disuse, inheritance of acquired characteristics), creating a diversity of species and genera. Popular views of Lamarckism consider only an aspect of the adaptive force.[26] Lamarck referred to a tendency for organisms to become more complex, moving "up" a ladder of progress. He referred to this phenomenon as Le pouvoir de la vie or la force qui tend sans cesse à composer l'organisation (The force that perpetually tends to make order). Lamarck believed in the ongoing spontaneous generation of simple living organisms through action on physical matter by a material life force.[27][26] Lamarck ran against the modern chemistry promoted by Lavoisier (whose ideas he regarded with disdain), preferring to embrace a more traditional alchemical view of the elements as influenced primarily by earth, air, fire, and water. He asserted that once living organisms form, the movements of fluids in living organisms naturally drove them to evolve toward ever greater levels of complexity:[27] The rapid motion of fluids will etch canals between delicate tissues. Soon their flow will begin to vary, leading to the emergence of distinct organs. The fluids themselves, now more elaborate, will become more complex, engendering a greater variety of secretions and substances composing the organs. — Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertebres, 1815 He argued that organisms thus moved from simple to complex in a steady, predictable way based on the fundamental physical principles of alchemy. In this view, simple organisms never disappeared because they were constantly being created by spontaneous generation in what has been described as a "steady-state biology". Lamarck saw spontaneous generation as being ongoing, with the simple organisms thus created being transmuted over time becoming more complex. He is sometimes regarded as believing in a teleological (goal-oriented) process where organisms became more perfect as they evolved, though as a materialist, he emphasized that these forces must originate necessarily from underlying physical principles. According to the paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn, "Lamarck denied, absolutely, the existence of any 'perfecting tendency' in nature, and regarded evolution as the final necessary effect of surrounding conditions on life."[28] Charles Coulston Gillispie, a historian of science, has written "life is a purely physical phenomenon in Lamarck", and argued that Lamarck's views should not be confused with the vitalist school of thought.[29] |

生命の力:複雑化させる力 詳細情報:方向進化  ラマルクの2要因説には、1)動物がより高度なレベルに向かってその身体計画を進化させる(正進化)複雑化の力、そして2)与えられた身体計画を持つ動物 が状況に適応する(使用と不使用、獲得形質の遺伝)適応の力が含まれ、それによって種や属の多様性が生み出される。ラマルク説に対する一般的な見解では、 適応の力の一側面のみが考慮されている。 ラマルクは、生物がより複雑になる傾向、すなわち進化の階段を「上」に登る傾向について言及した。彼はこの現象を「生命の力」または「絶え間なく組織化し ようとする力」と呼んだ。ラマルクは、単純な生物が物質生命力の作用により物理的物質から自然発生し続けていると信じていた。 ラマルクは、ラヴワジェが推進した近代化学に反対し(ラヴワジェの考えを軽蔑していた)、主に土、空気、火、水の影響を受けるという、より伝統的な錬金術 的な元素観を支持した。彼は、いったん生物が形成されると、生物内の流体の動きが自然に生物をより複雑なレベルへと進化させる、と主張した。 流体の急速な動きは、繊細な組織の間に水路を刻み込む。やがて流れに変化が生じ、個々の器官が形成される。 流体自体もより複雑になり、より多様な分泌物や器官を構成する物質を生み出す。 — Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertebres, 1815 彼は、生物は錬金術の基本的な物理原理に基づいて、単純なものから複雑なものへと、着実かつ予測可能な方法で変化していくと主張した。この見解では、単純 な生物は絶え間なく自然発生によって作り出されるため、決して消滅することはない。ラマルクは自然発生は現在も進行中であり、自然発生によって作り出され た単純な生物は、時間をかけて変成し、より複雑になると考えた。彼は、生物が進化するにつれてより完全になるという目的論的(目的志向的)プロセスを信じ ていたとみなされることもあるが、唯物論者であった彼は、これらの力は必ず根本的な物理的原則から生じる必要があると強調した。古生物学者ヘンリー・フェ アフィールド・オズボーンによると、「ラマルクは、自然界における『完成傾向』の存在を完全に否定し、進化を生命に対する周囲の条件の最終的な必然的結果 とみなした」[28]。科学史家のチャールズ・カールストン・ギリスピーは、「ラマルクにおける生命とは純粋に物理的な現象である」と記し、ラマルクの見 解は生命主義の学派と混同されるべきではないと主張している[29]。 |

| L'influence des circonstances: The Adaptive Force The second component of Lamarck's theory of evolution was the adaptation of organisms to their environment. This could move organisms upward from the ladder of progress into new and distinct forms with local adaptations. It could also drive organisms into evolutionary blind alleys, where the organism became so finely adapted that no further change could occur. Lamarck argued that this adaptive force was powered by the interaction of organisms with their environment, by the use and disuse of certain characteristics. |

状況の影響:適応力 ラマルクの進化論の第二の要素は、生物が環境に適応することである。これにより、生物は局所的適応により、進化的な梯子を上り、新たな独特な形態へと変化 する可能性がある。また、生物が進化的な袋小路に入り込み、生物が非常に精巧に適応してそれ以上の変化が起こらなくなる可能性もある。ラマルクは、この適 応力は生物と環境との相互作用、特定の特性の使用と不使用によって生み出されると主張した。 |

| First law: use and disuse First Law: In every animal which has not passed the limit of its development, a more frequent and continuous use of any organ gradually strengthens, develops and enlarges that organ, and gives it a power proportional to the length of time it has been so used; while the permanent disuse of any organ imperceptibly becomes weak and deteriorates it, and progressively diminishes its functional capacity or ability to function as expected, until it finally disappears.[30] |

第一法則:使用と不使用 第一法則:発達の限界に達していないあらゆる動物において、あらゆる器官をより頻繁かつ継続的に使用すると、その器官は徐々に強化され、発達し、拡大し、 その器官がそうして使用された時間の長さに比例した力を与える。一方で、あらゆる器官を恒久的に使用しないと、徐々に弱体化し、劣化し、機能能力または期 待通りに機能する能力が徐々に低下し、最終的に消滅する。[30] |

| Second law: inheritance of acquired characteristics Main article: Inheritance of acquired characteristics Second Law: All the acquisitions or losses wrought by nature on individuals, through the influence of the environment in which their race has long been placed, and hence through the influence of the predominant use or permanent disuse of any organ; all these are preserved by reproduction to the new individuals which arise, provided that the acquired modifications are common to both sexes, or at least to the individuals which produce the young.[30] The last clause of this law introduces what is now called soft inheritance, the inheritance of acquired characteristics, or simply "Lamarckism", though it forms only a part of Lamarck's thinking.[31] However, in the field of epigenetics, evidence is growing that soft inheritance plays a part in the changing of some organisms' phenotypes; it leaves the genetic material (DNA) unaltered (thus not violating the central dogma of biology) but prevents the expression of genes,[32] such as by methylation to modify DNA transcription; this can be produced by changes in behaviour and environment. Many epigenetic changes are heritable to a degree. Thus, while DNA itself is not directly altered by the environment and behavior except through selection, the relationship of the genotype to the phenotype can be altered, even across generations, by experience within the lifetime of an individual. This has led to calls for biology to reconsider Lamarckian processes in evolution in light of modern advances in molecular biology.[33] |

第二法則:獲得形質の遺伝 詳細は「獲得形質の遺伝」を参照 第二法則:自然が個体に与えた獲得形質または喪失形質は、その個体が属する人種が長期間置かれてきた環境の影響を通じて、また、あらゆる器官の使用または 不使用の影響を通じて、すべて保存される。獲得形質が両性または少なくとも子孫を残す個体に共通している場合、これらの形質は、新たに生じる個体に再生産 を通じて保存される。 この法則の最後の条項は、現在「ソフト遺伝」と呼ばれるものを導入している。これは獲得形質の遺伝、または単に「ラマルク主義」と呼ばれるものであるが、 これはラマルクの考えの一部に過ぎない。 しかし、エピジェネティクスの分野では、ソフトインヘリタンスが一部の生物の表現型の変化に影響を及ぼしているという証拠が増えている。ソフトインヘリタ ンスは遺伝物質(DNA)を変化させない(したがって生物学の中心命題に反しない)が、DNA転写を修飾するメチル化などによって遺伝子の発現を妨げる。 これは行動や環境の変化によって引き起こされる可能性がある。多くのエピジェネティックな変化はある程度遺伝する。そのため、DNA自体は選択を除いて環 境や行動によって直接変化することはないが、個体の生涯における経験によって、世代を超えても遺伝子型と表現型の関係は変化しうる。このため、分子生物学 の現代的な進歩を踏まえて、生物学は進化におけるラマルク説のプロセスを再考すべきであるという声が高まっている。[33] |

| Religious views In his book Philosophie zoologique, Lamarck referred to God as the "sublime author of nature". Lamarck's religious views are examined in the book Lamarck, the Founder of Evolution (1901) by Alpheus Packard. According to Packard from Lamarck's writings, he may be regarded as a deist.[34] The philosopher of biology Michael Ruse described Lamarck, "as believing in God as an unmoved mover, creator of the world and its laws, who refuses to intervene miraculously in his creation."[35] Biographer James Moore described Lamarck as a "thoroughgoing deist".[36] The historian Jacques Roger has written, "Lamarck was a materialist to the extent that he did not consider it necessary to have recourse to any spiritual principle... his deism remained vague, and his idea of creation did not prevent him from believing everything in nature, including the highest forms of life, was but the result of natural processes."[37] |

宗教観 著書『動物哲学』の中で、ラマルクは神を「自然の崇高なる作者」と呼んだ。ラマルクの宗教観については、アルフィアス・パッカード著『進化論の創始者ラマ ルク』(1901年)で考察されている。パッカードによると、ラマルクの著作から、彼は自然神論者とみなされる可能性があるという。 生物学者のマイケル・ラッセはラマルクを「不動の動者、世界の創造者であり、その法則の創造者として神を信じており、その創造物に奇跡的に介入することを 拒否する」人物と評している。[35] 伝記作家のジェームズ・ムーアはラマルクを「徹底した不可知論者」と評している。[36] 歴史家のジャック・ロジャーは、「ラマルクは、精神的な原理に頼る必要はないと考える点において唯物論者であった。彼の自然神論はあいまいなままであり、 創造に関する彼の考えは、自然界におけるあらゆるもの、すなわち生命の最も高度な形態を含むものを、自然のプロセスによる結果と信じることを妨げるもので はなかった」と述べている。[37] |

Legacy Statue of Lamarck by Léon Fagel in the Jardin des Plantes, Paris Lamarck is known largely for his views on evolution, which have been dismissed in favour of developments in Darwinism. His theory of evolution only achieved fame after the publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859), which spurred critics of Darwin's new theory to fall back on Lamarckian evolution as a more well-established alternative.[38] Lamarck is usually remembered for his belief in the then commonly held theory of inheritance of acquired characteristics, and the use and disuse model by which organisms developed their characteristics. Lamarck incorporated this belief into his theory of evolution, along with other common beliefs of the time, such as spontaneous generation.[26] The inheritance of acquired characteristics (also called the theory of adaptation or soft inheritance) was rejected by August Weismann in the 1880s[Note 3] when he developed a theory of inheritance in which germ plasm (the sex cells, later redefined as DNA), remained separate and distinct from the soma (the rest of the body); thus, nothing which happens to the soma may be passed on with the germ plasm. This model allegedly underlies the modern understanding of inheritance. Lamarck constructed one of the first theoretical frameworks of organic evolution. While this theory was generally rejected during his lifetime,[39] Stephen Jay Gould argues that Lamarck was the "primary evolutionary theorist", in that his ideas, and the way in which he structured his theory, set the tone for much of the subsequent thinking in evolutionary biology, through to the present day.[40] Developments in epigenetics, the study of cellular and physiological traits that are heritable by daughter cells and not caused by changes in the DNA sequence, have caused debate about whether a "neolamarckist" view of inheritance could be correct: Lamarck was not in a position to give a molecular explanation for his theory. Eva Jablonka and Marion Lamb, for example, call themselves neolamarckists.[11][33] Reviewing the evidence, David Haig argued that any such mechanisms must themselves have evolved through natural selection.[11] Darwin allowed a role for use and disuse as an evolutionary mechanism subsidiary to natural selection, most often in respect of disuse.[Note 4] He praised Lamarck for "the eminent service of arousing attention to the probability of all change in the organic... world, being the result of law, not miraculous interposition".[42] Lamarckism is also occasionally used to describe quasi-evolutionary concepts in societal contexts, though not by Lamarck himself. For example, the memetic theory of cultural evolution is sometimes described as a form of Lamarckian inheritance of nongenetic traits. |

遺産 レオン・ファジェル作のラマルクの像(パリ植物園 ラマルクは進化論に関する見解で広く知られているが、それはダーウィニズムの発展を支持する立場から退けられてきた。彼の進化論は、チャールズ・ダーウィ ンの『種の起源』(1859年)が出版されてからようやく有名になったが、それはダーウィンの新理論の批判者たちが、より確立された代替案としてラマルク 進化論に立ち返るきっかけとなったからである。 ラマルクは、当時一般的に信じられていた獲得形質の遺伝説と、生物がその特性を発達させる使用と不使用のモデルを信じていたことでよく知られている。ラマ ルクは、この信念を、自然発生説などの当時の一般的な信念とともに、自身の進化論に取り入れた。 [26] 獲得形質の遺伝(適応説またはソフト遺伝子説とも呼ばれる)は、1880年代にアウグスト・ワイスマンによって否定された。[注3] 彼は、生殖質(性細胞、後にDNAと再定義)が体細胞(体の残りの部分)とは別個かつ独立したままであるという遺伝の理論を展開した。したがって、体細胞 に起こったことは生殖質とともに受け継がれることはない。このモデルは、現代の遺伝に関する理解の基礎となっているとされる。 ラマルクは有機体の進化に関する最初の理論的枠組みのひとつを構築した。この理論は彼の存命中には概ね否定されていたが[39]、スティーブン・ジェイ・ グールドは、ラマルクの考え方や理論の構成方法は、進化生物学におけるその後の多くの考え方に影響を与え、現在に至るまでその基調を定めたという意味で、 ラマルクは「主要な進化論者」であったと主張している。 [40] 娘細胞に遺伝し、DNA配列の変化によって引き起こされるものではない細胞および生理学的形質を研究するエピジェネティクスの発展により、「ネオラマルキ スト」の遺伝観が正しい可能性があるという議論が巻き起こっている。ラマルクは自身の理論を分子レベルで説明できる立場にはなかった。例えば、エヴァ・ ジャブロムカとマリオン・ラムは自らをネオラマルキストと呼んでいる。[11][33] デービッド・ヘイグは証拠を検討した上で、そのようなメカニズムは自然淘汰によって進化してきたに違いないと主張した。[11] ダーウィンは、自然淘汰の補助的な進化メカニズムとして、使用と不使用の役割を認めていた。最も頻繁に言及されるのは、不使用に関するものである。[注釈 4] 彼はラマルクを「有機体におけるあらゆる変化の可能性に注目を集めた功績は高く評価されるべきである。それは、奇跡的な介入の結果ではなく、法則の結果で ある」と称賛した。[42] ラマルク主義は、ラマルク自身によるものではないが、社会的な文脈における擬似進化の概念を説明する際に使用されることもある。例えば、文化進化のミーム 理論は、遺伝形質以外の形質を継承するラマルク説の一形態として説明されることがある。 |

| Species and other taxa named by Lamarck See also: Category:Taxa named by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck During his lifetime, Lamarck named a large number of species, many of which have become synonyms. The World Register of Marine Species gives no fewer than 1,634 records.[43] The Indo-Pacific Molluscan Database gives 1,781 records.[44] Among these are some well-known families such as the ark clams (Arcidae), the sea hares (Aplysiidae), and the cockles (Cardiidae). The International Plant Names Index gives 58 records, including a number of well-known genera such as the mosquito fern (Azolla).[citation needed] |

ラマルクが命名した生物種およびその他の分類群 参照:ジャン=バティスト・ラマルクが命名した分類群 ラマルクは存命中に多数の生物種に命名したが、その多くは同義語となっている。世界海洋生物種登録簿には1,634件以上の記録がある。[43] インド太平洋軟体動物データベースには1,781件の記録がある。[44] これらのなかには、アーク貝科(Arcidae)、アメフラシ科(Aplysiidae)、ザルガイ科(Cardiidae)などのよく知られた科も含ま れる。国際植物名索引では、モ(Azolla)属など、よく知られた属を含む58件の記録が挙げられている。[要出典] |

| Species named in his honour The honeybee subspecies Apis mellifera lamarckii is named after Lamarck, as well as the bluefire jellyfish (Cyaneia lamarckii). A number of plants have also been named after him, including Amelanchier lamarckii (juneberry), Digitalis lamarckii, and Aconitum lamarckii, as well as the grass genus Lamarckia. The International Plant Names Index gives 116 records of plant species named after Lamarck.[45] Among the marine species, no fewer than 103 species or genera carry the epithet "lamarcki", "lamarckii" or "lamarckiana", but many have since become synonyms. Marine species with valid names include:[43] Acropora lamarcki Veron, 2002 Agaricia lamarcki Milne Edwards & Haime, 1851 Ascaltis lamarcki (Haeckel, 1870) Bursa lamarckii (Deshayes, 1853), a frog snail Carinaria lamarckii Blainville, 1817, a small planktonic sea snail Caligodes lamarcki Quidor, 1913 Cyanea lamarckii Péron & Lesueur 1810 Cyllene desnoyersi lamarcki Cernohorsky, 1975 Erosaria lamarckii (J. E. Gray, 1825), a cowrie Genicanthus lamarck (Lacepède, 1802), a Saltwater Angelfish. Gorgonocephalus lamarckii (Müller & Troschel, 1842) Gyroidinoides lamarckiana (d´Orbigny, 1839) Lamarckdromia Guinot & Tavares, 2003 Lamarckina Berthelin, 1881 Lobophytum lamarcki Tixier-Durivault, 1956 Marginella lamarcki Boyer, 2004, a small sea snail Megerlina lamarckiana (Davidson, 1852) Meretrix lamarckii Deshayes, 1853 Morum lamarckii (Deshayes, 1844), a small sea snail Mycetophyllia lamarckiana Milne Edwards & Haime, 1848, Neotrigonia lamarckii (Gray, 1838) Olencira lamarckii Leach, 1818 Oenothera lamarckiana Petrolisthes lamarckii (Leach, 1820) Pomatoceros lamarckii (Quatrefages, 1866) Quinqueloculina lamarckiana d´Orbigny, 1839 Raninoides lamarcki A. Milne-Edwards & Bouvier, 1923 Rhizophora x lamarckii Montr. Siphonina lamarckana Cushman, 1927 Solen lamarckii Chenu, 1843 Spondylus lamarckii Chenu, 1845, a thorny oyster Xanthias lamarckii (H. Milne Edwards, 1834) |

彼にちなんで名付けられた生物種 ミツバチの亜種であるラマルクミツバチ(学名:Apis mellifera lamarckii)や、ヒカリクラゲ(学名:Cyaneia lamarckii)は、ラマルクにちなんで名付けられた。また、アメランキア(学名:Amelanchier lamarckii)(ジューンベリー)、ジギタリス・ラマルキイ(学名:Digitalis lamarckii)、トリカブト・ラマルキイ(学名:Aconitum lamarckii)などの植物や、ラマルキア属(学名:Lamarckia)などの植物にも、彼の名が付けられている。 国際植物名指数では、ラマルクの名を冠した植物種として116の記録がある。[45] 海洋生物では、103以上の種や属が「lamarcki」、「lamarckii」、「lamarckiana」という接尾辞を冠しているが、その多くは同義語となっている。有効な名称を持つ海洋生物には以下のようなものがある。[43] Acropora lamarcki Veron, 2002 Agaricia lamarcki Milne Edwards & Haime, 1851 Ascaltis lamarcki (Haeckel, 1870) Bursa lamarckii (Deshayes, 1853)、カエルガイの一種 Carinaria lamarckii Blainville, 1817、小型の浮遊性海産巻き貝の一種 Caligodes lamarcki Quidor, 1913 Cyanea lamarckii Péron & Lesueur 1810 Cyllene desnoyersi lamarcki Cernohorsky, 1975 Erosaria lamarckii (J. E. Gray, 1825)、タカラガイの一種 Genicanthus lamarck (Lacepède, 1802)、ソルトウォーターエンジェルフィッシュ。 Gorgonocephalus lamarckii (Müller & Troschel, 1842) Gyroidinoides lamarckiana (d´Orbigny, 1839) Lamarckdromia Guinot & Tavares, 2003 Lamarckina Berthelin, 1881 Lobophytum lamarcki Tixier-Durivault, 1956 Marginella lamarcki Boyer, 2004、小さな海産巻貝 Megerlina lamarckiana (Davidson, 1852) Meretrix lamarckii Deshayes, 1853 Morum lamarckii (Deshayes, 1844)、小さな海産巻貝 Mycetophyllia lamarckiana Milne Edwards & Haime, 1848、 Neotrigonia lamarckii (Gray, 1838) Olencira lamarckii Leach, 1818 Oenothera lamarckiana Petrolisthes lamarckii (Leach, 1820) Pomatoceros lamarckii (Quatrefages, 1866) Quinqueloculina lamarckiana d´Orbigny, 1839 Raninoides lamarcki A. Milne-Edwards & Bouvier, 1923 Rhizophora x lamarckii Montr. Siphonina lamarckana Cushman, 1927 Solen lamarckii Chenu, 1843 Spondylus lamarckii Chenu, 1845、トゲのある牡蠣 Xanthias lamarckii (H. Milne Edwards, 1834) |

| Major works 1778 Flore françoise, ou, Description succincte de toutes les plantes qui croissent naturellement en France 1st ed. 2nd ed. 1795, 3rd 1805 (de Candolle ed.) 1795 Recherches sur les causes des principaux faits physiques (in French). Vol. 1. Milano: Luigi Veladini. 1795. 1809. Philosophie zoologique, ou Exposition des considérations relatives à l'histoire naturelle des animaux..., Paris. Translated with introduction and commentary in 1914 by Hugh S. R. Elliot as Zoological Philosophy. Arguably the most comprehensive discussion of the topic of Lamarckism and more of Lamarck's views. Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste (1783–1808). Encyclopédie méthodique. Botanique. Paris: Panckoucke. (see Encyclopédie méthodique) Supplement 1810–1817 L'Illustration des genres, vol. I: 1791, vol. II: 1793, vol. III: 1800, Supplement by Poiret 1823 On invertebrate classification: 1801. Système des animaux sans vertèbres, ou tableau général des classes, des ordres et des genres de ces animaux; présentant leurs caractères essentiels et leur distribution, d'après la considération de leurs..., Paris, Detreville, VIII: 1–432. 1815–22. Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres, présentant les caractères généraux et particuliers de ces animaux..., Tome 1 (1815): 1–462; Tome 2 (1816): 1–568; Tome 3 (1816): 1–586; Tome 4 (1817): 1–603; Tome 5 (1818): 1–612; Tome 6, Pt.1 (1819): 1–343; Tome 6, Pt.2 (1822): 1–252; Tome 7 (1822): 1–711. The standard author abbreviation Lam. is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.[46] |

主要作品 1778 『フランスの植物誌、またはフランスに自生するすべての植物の簡潔な記述』初版。 第2版。1795年、第3版。1805年(ド・カンドル編)。 1795年 『物理学的諸現象の主な原因に関する研究』(フランス語)。第1巻。ミラノ:ルイジ・ベラディーニ。1795年。 1809. 『動物哲学、または動物史に関する考察の展示』、パリ。1914年にヒュー・S・R・エリオットが『動物哲学』として英訳し、序文と注釈を付した。ラマルク主義のテーマについて、おそらく最も包括的な議論であり、ラマルクの意見をより多く含んでいる。 ラマルク、ジャン=バティスト(1783年~1808年)。『方法論百科事典』。植物学。パリ:パンクー。(『方法論百科事典』を参照) 補遺 1810年~1817年 『属の図解』第1巻:1791年、第2巻:1793年、第3巻:1800年、ポアレによる補遺 1823年 無脊椎動物の分類について: 1801年。Système des animaux sans vertèbres, ou tableau général des classes, des ordres et des genres de ces animaux; presenting leurs caractères essentiels et leur distribution, d'après la considération de leurs..., Paris, Detreville, VIII: 1–432. 1815–22. 脊椎のない動物の自然史、これらの動物の一般的な特徴と特定の特徴を提示する...、第1巻(1815年):1-462、第2巻(1816年):1- 568、第3巻(1816年):1-586、第4巻(1817年):1-603、第5巻(1818年): 1–612; 第6巻第1部(1819年):1–343; 第6巻第2部(1822年):1–252; 第7巻(1822年):1–711。 標準的な著者の略称であるLam.は、植物名を引用する際に著者を表すために使用される。[46] |

| Acclimation Baldwin effect Environmental determinism Exaptation Evolution Gene-centered view of evolution Genetic assimilation Intragenomic conflict Lysenkoism Maladaptation Neutral theory of molecular evolution Phenotypic plasticity Society of the Friends of Truth Spandrel Mount Lamarck |

順応 ボールドウィン効果 環境決定論 適応進化 進化 遺伝子中心説 遺伝的同化 ゲノム内対立 リセンコ主義 不適応 分子進化の中立理論 表現型の可塑性 真理の友の会 スパンドレル ラマルク山 |

| Bibliography Bange, Raphaël; Corsi, Pietro (n.d.). "Chronologie de la vie de Jean-Baptiste Lamarck" (in French). Centre national de la recherche scientifique. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2007. Bowler, Peter (1989). Evolution : the history of an idea (Revised ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06386-0. OCLC 17841313. Bowler, Peter J. (2003). Evolution: the History of an Idea (3rd ed.). California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23693-6. Burkhardt, Richard W. Jr. (1970). "Lamarck, evolution, and the politics of science". Journal of the History of Biology. 3 (2): 275–298. doi:10.1007/bf00137355. JSTOR 4330543. PMID 11609655. S2CID 33402055. Coleman, William L. (1977). Biology in the Nineteenth Century: problems of form, function, and transformation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29293-1. Curtis, Caitlin; Millar, Craig; Lambert, David (September 2018). "The Sacred Ibis debate: The first test of evolution". PLOS Biology. 16 (9): e2005558. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2005558. PMC 6159855. PMID 30260949. Cuvier, Georges (January 1836). "Elegy of Lamarck". Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal. 20: 1–22. Damkaer, David M. (2002). The Copepodologist's Cabinet: a Biographical and Bibliographical History. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-240-5. Darwin, Charles (1861–1882). "Historical sketch". On the Origin of Species (3rd–6th ed.). London: John Murray. Darwin, Charles (2001). Appleman, Philip (ed.). Darwin: Texts, Commentary. Norton critical editions in the history of ideas (3rd ed.). Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-95849-2. Delange, Yves (1984). Lamarck, sa vie, son œuvre. Arles: Actes Sud. ISBN 978-2-903098-97-1. Dudenredaktion; Kleiner, Stefan; Knöbl, Ralf (2015) [First published 1962]. Das Aussprachewörterbuch [The Pronunciation Dictionary] (in German) (7th ed.). Berlin: Dudenverlag. ISBN 978-3-411-04067-4. Fitzpatrick, Tony (2006). "Researcher gives hard thoughts on soft inheritance: above and beyond the gene". Washington University in St. Louis. Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2011. Gillispie, Charles Coulston (1960). The Edge of Objectivity: An Essay in the History of Scientific Ideas. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02350-6. Gould, Stephen Jay (1993). "Foreword". In Jean Chandler Smith (ed.). Georges Cuvier: an annotated bibliography of his published works. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 978-1-56098-199-2. ——— (2001). The lying stones of Marrakech : penultimate reflections in natural history. Vintage. ISBN 978-0-09-928583-0. ——— (2002). The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Harvard: Belknap Harvard. ISBN 978-0-674-00613-3. Haig, David (2007). "Weismann Rules! OK? Epigenetics and the Lamarckian temptation". Biology and Philosophy. 22 (3): 415–428. doi:10.1007/s10539-006-9033-y. S2CID 16322990. Jablonka, Eva; Lamb, Marion J.; Avital, Eytan (1998). "'Lamarckian' mechanisms in darwinian evolution". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 13 (5): 206–210. doi:10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01344-5. PMID 21238269. Jablonka, Eva (2006). Evolution in Four Dimensions: Genetic, Epigenetic, Behavioral, and Symbolic Variation in the History of Life. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-60069-9. Jordanova, Ludmilla (1984). Lamarck, past master. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-287587-7. Jurmain, Robert; Lynn Kilgore; Wenda Trevathan; Russell L. Ciochon (2011). Introduction to Physical Anthropology (13th ed.). Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-111-29793-0. Lamarck, J. B. (1914). Zoological Philosophy. London. Larson, Edward J (May 2004). ""A Growing sense of progress". Evolution: The remarkable history of a Scientific Theory. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 9780679642886. Mantoy, Bernard (1968). Lamarck. Savants du monde entier. Vol. 36. Paris: Seghers. Mayr, Ernst (1964) [1859]. "Introduction". In Charles Darwin (ed.). On the Origin of Species: a Facsimile of the First Edition. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-63752-8. Mitchell, Peter Chalmers (1911). "Evolution" . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. Moore, James R. (1981). The Post-Darwinian Controversies: A Study of the Protestant Struggle to Come to Terms with Darwin in Great Britain and America 1870–1900. Cambridge University Press. Osborn, Henry Fairfield (1894). From the Greeks to Darwin. Macmillan and Company. Osborn, Henry Fairfield (1905). From the Greeks to Darwin: an outline of the development of the evolution idea (2nd ed.). New York: Macmillan. Packard, Alpheus Spring (1901). Lamarck, the founder of Evolution: his life and work with translations of his writing on organic evolution. New York: Longmans, Green. Packard, Alpheus Spring (2008) [1901]. Lamarck, The Founder of Evolution. Wildhern Press. Roger, Jacques (1986). "The Mechanist Conception of Life". In Lindberg, David C.; Numbers, Ronald L. (eds.). God and Nature: Historical Essays on the Encounter Between Christianity and Science. University of California Press. Rudwick, Martin J. S. (1998). Georges Cuvier, Fossil Bones, and Geological Catastrophes: New Translations and Interpretations of the Primary Texts. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73107-0. Ruse, Michael (1999). The Darwinian Revolution: Science Red in Tooth and Claw. University of Chicago Press. Szyfman, Léon (1982). Jean-Baptiste Lamarck et son époque. Paris: Masson. ISBN 978-2-225-76087-7. Junko A. Arai; Shaomin Li; Dean M. Hartley; Larry A. Feig (2009). "Transgenerational rescue of a genetic defect in long-term potentiation and memory formation by juvenile enrichment". The Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (5): 1496–1502. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5057-08.2009. PMC 3408235. PMID 19193896. Ross Honeywill (2008). Lamarck's Evolution: Two Centuries of Genius and Jealousy. Pier 9. ISBN 978-1-921208-60-7. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Waggoner, Ben; Speer, B. R. (2 September 1998). "Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829)". UCMP Berkeley. Retrieved 16 December 2018. Weber, A. S. (2000). Nineteenth-Century Science: An Anthology. Broadview Press. ISBN 978-1-55111-165-0. |

参考文献 Bange, Raphaël; Corsi, Pietro (n.d.). 「Chronologie de la vie de Jean-Baptiste Lamarck」 (フランス語). Centre national de la recherche scientifique. 2013年4月12日オリジナルよりアーカイブ。2007年7月10日閲覧。 Bowler, Peter (1989). Evolution : the history of an idea (Revised ed.). カリフォルニア大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-520-06386-0. OCLC 17841313. Bowler, Peter J. (2003). Evolution: the History of an Idea (3rd ed.). カリフォルニア: カリフォルニア大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-520-23693-6. Burkhardt, Richard W. Jr. (1970). 「Lamarck, evolution, and the politics of science」. Journal of the History of Biology. 3 (2): 275–298. doi:10.1007/bf00137355. JSTOR 4330543. PMID 11609655. S2CID 33402055. コールマン、ウィリアム・L. (1977年). 19世紀の生物学:形態、機能、変態の問題. ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-521-29293-1. カーティス、ケイトリン、ミラー、クレイグ、ランバート、デイビッド(2018年9月)。「聖なるトキの議論:進化の最初のテスト」。PLOS Biology。16(9):e2005558。doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.2005558。PMC 6159855。PMID 30260949。 キュヴィエ, ジョルジュ (1836年1月). 「ラマルクの哀歌」. エディンバラ新哲学ジャーナル. 20: 1–22. Damkaer, David M. (2002). 「カイアシ学者の書斎:伝記的および書誌的歴史」. フィラデルフィア: アメリカ哲学協会. ISBN 978-0-87169-240-5. ダーウィン、チャールズ(1861年-1882年)。「歴史的概観」。種の起源(第3版-第6版)。ロンドン:ジョン・マレー。 ダーウィン、チャールズ(2001年)。アップルマン、フィリップ(編)。ダーウィン:テキスト、注釈。ノートン批判版の思想史(第3版)。ノートン。ISBN 978-0-393-95849-2。 イヴ・ドランジュ著『ラマルク、その生涯とその業績』(1984年)アルル:アクトゥ・シュッド社。ISBN 978-2-903098-97-1。 Dudenredaktion; Kleiner, Stefan; Knöbl, Ralf (2015) [初版1962年]. Das Aussprachewörterbuch [The Pronunciation Dictionary] (in German) (7th ed.). Berlin: Dudenverlag. ISBN 978-3-411-04067-4. フィッツパトリック、トニー(2006年)。「研究者が柔らかい遺伝について難しい考えを述べる:遺伝子を超えて」。ワシントン大学セントルイス校。2016年1月8日アーカイブ。2011年10月8日取得。 ギリスピー、チャールズ・カールストン(1960年)。『客観性の限界:科学思想史論考』。プリンストン大学出版局. ISBN 0-691-02350-6. スティーブン・ジェイ・グールド (1993年). 「序文」. ジャン・チャンドラー・スミス編. ジョルジュ・キュヴィエ: 彼の出版物の注釈付き書誌. ワシントンD.C.: スミソニアン協会出版. ISBN 978-1-56098-199-2. ——(2001年)『マラケシュの嘘つきの石:博物学における最後の二番目の反省』ヴィンテージ社。ISBN 978-0-09-928583-0。 ——(2002年)『進化論の構造』ハーバード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-674-00613-3。 ヘイグ、デイヴィッド(2007年)。「ワイスマン則!いい? エピジェネティクスとラマルク的誘惑」。『生物学と哲学』22 (3): 415–428. doi:10.1007/s10539-006-9033-y. S2CID 16322990. Jablonka, Eva; Lamb, Marion J.; Avital, Eytan (1998). 「ダーウィン進化におけるラマルク的メカニズム」. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 13 (5): 206–210. doi:10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01344-5. PMID 21238269. Jablonka, Eva (2006). Evolution in Four Dimensions: Genetic, Epigenetic, Behavioral, and Symbolic Variation in the History of Life. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-60069-9. ヨルダノヴァ、ルドミラ(1984年)。ラマルク、過去の名人。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-287587-7。 Jurmain, Robert; Lynn Kilgore; Wenda Trevathan; Russell L. Ciochon (2011). Introduction to Physical Anthropology (13th ed.). Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-111-29793-0. ラマルク、J. B. (1914). Zoological Philosophy. London. Larson, Edward J (2004年5月). 「」A Growing sense of progress」. Evolution: The remarkable history of a Scientific Theory. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 9780679642886. Mantoy, Bernard (1968). Lamarck. Savants du monde entier. Vol. 36. Paris: Seghers. マイヤー、エルンスト(1964年)[1859年]。「序文」。チャールズ・ダーウィン(編)『種の起源:初版のファクシミリ版』ハーバード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-674-63752-8。 ミッチェル、ピーター・チャルマーズ(1911年)。「進化」。ヒュー・チゾム(編)『ブリタニカ百科事典』。第10巻(第11版)。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 ムーア、ジェームズ・R.(1981年)。『ポスト・ダーウィニズム論争:英国と米国におけるプロテスタントのダーウィン受容をめぐる論争の研究(1870年~1900年)』ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 オズボーン、ヘンリー・フェアフィールド(1894年)。『ギリシャからダーウィンまで』マクミラン社。 オズボーン、ヘンリー・フェアフィールド(1905年)。ギリシャからダーウィンまで:進化論の展開の概略(第2版)。ニューヨーク:マクミラン。 パッカード、アルフィウス・スプリング(1901年)。進化論の創始者ラマルク:有機的進化に関する彼の著作の翻訳と彼の生涯と業績。ニューヨーク:ロングマンズ、グリーン。 Packard, Alpheus Spring (2008) [1901]. Lamarck, The Founder of Evolution. Wildhern Press. Roger, Jacques (1986). 「The Mechanist Conception of Life」. In Lindberg, David C.; Numbers, Ronald L. (eds.). God and Nature: Historical Essays on the Encounter Between Christianity and Science. University of California Press. Rudwick, Martin J. S. (1998). Georges Cuvier, Fossil Bones, and Geological Catastrophes: New Translations and Interpretations of the Primary Texts. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73107-0. Ruse, Michael (1999). The Darwinian Revolution: Science Red in Tooth and Claw. University of Chicago Press. Szyfman, Léon (1982). Jean-Baptiste Lamarck et son époque. Paris: Masson. ISBN 978-2-225-76087-7. Junko A. Arai; Shaomin Li; Dean M. Hartley; Larry A. Feig (2009). 「Transgenerational rescue of a genetic defect in long-term potentiation and memory formation by juvenile enrichment」. The Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (5): 1496–1502. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5057-08.2009. PMC 3408235. PMID 19193896. ロス・ハニーウィル (2008年). 『ラマルクの進化論:2世紀にわたる天才と嫉妬』. ピア9。ISBN 978-1-921208-60-7。2009年2月1日オリジナルよりアーカイブ。 Waggoner, Ben; Speer, B. R. (1998年9月2日). 「Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829)」. UCMP Berkeley. 2018年12月16日閲覧。 Weber, A. S. (2000). Nineteenth-Century Science: An Anthology. Broadview Press. ISBN 978-1-55111-165-0. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Baptiste_Lamarck |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆