イエズス会

Jesuits

☆イエズス会(ラ

テン語: Societas Iesu、略称: SJ)は、イエズス会修道会またはイエズス会士(/ˈdʒɛʒuɪts, ˈdʒɛzju-/

JEZH-oo-its, JEZ-ew-;[2] ラテン語:

Iesuitae)とも呼ばれ、[3]ローマに本部を置くカトリック教会の男子修道会である。1540年にパウロ3世の承認のもと、イグナティウス・デ・

ロヨラと6人の仲間によって創設された。今日、イエズス会は112カ国で伝道と使徒職に従事している。イエズス会士は教育、研究、文化活動に従事してい

る。また、イエズス会士は黙想会を主催し、病院や教区で奉仕活動を行い、直接的な社会事業や人道支援を後援し、エキュメニカルな対話を推進している。

イエズス会は、聖母マリアの称号である「マドンナ・デラ・ストラーダ」の庇護の下に設立され、総長によって統率されている。[4][5]

本部である一般参事会はローマにある。[6]

歴史的なイグナチオの参事会は、イエズス会の母教会であるジェズ教会に併設されたコレジオ・デル・ジェズの一部となっている。

イエズス会の会員は「永遠の貧困、貞潔、服従」を誓い、「宣教活動に関して、教皇に特別な服従を誓う」ことになっている。イエズス会員は、完全に利用可能

であり、上級者に服従することが期待されており、極端な環境での生活を要求された場合でも、世界のどこへでも行くことを命じられる。創設者のイグナティウ

スは、軍歴を持つ貴族であった。イエズス会の設立文書の冒頭には、イエズス会は「神の兵士として奉仕することを望む者[a]、特に信仰の擁護と布教、キリ

スト教の生活と教義における魂の向上のために努力する者」のために設立されたと宣言されている。[7]

そのためイエズス会士は俗に「神の兵士」[8]、「神の海兵隊員」[9]、「会社」[10]と呼ばれることもある。イエズス会は対抗宗教改革に参加し、そ

の後、第2バチカン公会議の実施にも関与した。

イエズス会の宣教師たちは16世紀から18世紀にかけて世界中に布教所を設立し、現地住民のキリスト教化に成功と失敗の両方を経験した。イエズス会はカト

リック教会内で常に論争の的となっており、世俗の政府や機関とたびたび衝突してきた。1759年以降、カトリック教会はヨーロッパのほとんどの国々および

ヨーロッパの植民地からイエズス会を追放した。1773年、教皇クレメンス14世は正式にイエズス会を解散した。1814年、教会は解散を解除した。

| The Society of Jesus

(Latin: Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuit

Order or the Jesuits (/ˈdʒɛʒuɪts, ˈdʒɛzju-/ JEZH-oo-its, JEZ-ew-;[2]

Latin: Iesuitae),[3] is a religious order of clerics regular of

pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rome.

It was founded in 1540 by Ignatius of Loyola and six companions, with

the approval of Pope Paul III. Today, the Society of Jesus is engaged

in evangelization and apostolic ministry in 112 countries. Jesuits work

in education, research, and cultural pursuits. Jesuits also conduct

retreats, minister in hospitals and parishes, sponsor direct social and

humanitarian works, and promote ecumenical dialogue. The Society of Jesus is consecrated under the patronage of Madonna della Strada, a title of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and it is led by a superior general.[4][5] The headquarters of the society, its general curia, is in Rome.[6] The historic curia of Ignatius is now part of the Collegio del Gesù attached to the Church of the Gesù, the Jesuit mother church. Members of the Society of Jesus make profession of "perpetual poverty, chastity, and obedience" and "promise a special obedience to the sovereign pontiff in regard to the missions." A Jesuit is expected to be totally available and obedient to his superiors, accepting orders to go anywhere in the world, even if required to live in extreme conditions. Ignatius, its leading founder, was a nobleman who had a military background. The opening lines of the founding document of the Society of Jesus accordingly declare that it was founded for "whoever desires to serve as a soldier of God,[a] to strive especially for the defense and propagation of the faith, and for the progress of souls in Christian life and doctrine".[7] Jesuits are thus sometimes referred to colloquially as "God's soldiers",[8] "God's marines",[9] or "the Company".[10] The Society of Jesus participated in the Counter-Reformation and, later, in the implementation of the Second Vatican Council. Jesuit missionaries established missions around the world from the 16th to the 18th century and had both successes and failures in Christianizing the native peoples. The Jesuits have always been controversial within the Catholic Church and have frequently clashed with secular governments and institutions. Beginning in 1759, the Catholic Church expelled Jesuits from most countries in Europe and from European colonies. Pope Clement XIV officially suppressed the order in 1773. In 1814, the Church lifted the suppression. |

イエズス会(ラテン語: Societas Iesu、略称:

SJ)は、イエズス会修道会またはイエズス会士(/ˈdʒɛʒuɪts, ˈdʒɛzju-/ JEZH-oo-its, JEZ-ew-;[2]

ラテン語:

Iesuitae)とも呼ばれ、[3]ローマに本部を置くカトリック教会の男子修道会である。1540年にパウロ3世の承認のもと、イグナティウス・デ・

ロヨラと6人の仲間によって創設された。今日、イエズス会は112カ国で伝道と使徒職に従事している。イエズス会士は教育、研究、文化活動に従事してい

る。また、イエズス会士は黙想会を主催し、病院や教区で奉仕活動を行い、直接的な社会事業や人道支援を後援し、エキュメニカルな対話を推進している。 イエズス会は、聖母マリアの称号である「マドンナ・デラ・ストラーダ」の庇護の下に設立され、総長によって統率されている。[4][5] 本部である一般参事会はローマにある。[6] 歴史的なイグナチオの参事会は、イエズス会の母教会であるジェズ教会に併設されたコレジオ・デル・ジェズの一部となっている。 イエズス会の会員は「永遠の貧困、貞潔、服従」を誓い、「宣教活動に関して、教皇に特別な服従を誓う」ことになっている。イエズス会員は、完全に利用可能 であり、上級者に服従することが期待されており、極端な環境での生活を要求された場合でも、世界のどこへでも行くことを命じられる。創設者のイグナティウ スは、軍歴を持つ貴族であった。イエズス会の設立文書の冒頭には、イエズス会は「神の兵士として奉仕することを望む者[a]、特に信仰の擁護と布教、キリ スト教の生活と教義における魂の向上のために努力する者」のために設立されたと宣言されている。[7] そのためイエズス会士は俗に「神の兵士」[8]、「神の海兵隊員」[9]、「会社」[10]と呼ばれることもある。イエズス会は対抗宗教改革に参加し、そ の後、第2バチカン公会議の実施にも関与した。 イエズス会の宣教師たちは16世紀から18世紀にかけて世界中に布教所を設立し、現地住民のキリスト教化に成功と失敗の両方を経験した。イエズス会はカト リック教会内で常に論争の的となっており、世俗の政府や機関とたびたび衝突してきた。1759年以降、カトリック教会はヨーロッパのほとんどの国々および ヨーロッパの植民地からイエズス会を追放した。1773年、教皇クレメンス14世は正式にイエズス会を解散した。1814年、教会は解散を解除した。 |

| History Foundation  Ignatius of Loyola Ignatius of Loyola, a Basque nobleman from the Pyrenees area of northern Spain, founded the society after discerning his spiritual vocation while recovering from a wound sustained in the Battle of Pamplona. He composed the Spiritual Exercises to help others follow the teachings of Jesus Christ. On 15 August 1534, Ignatius of Loyola (born Íñigo López de Loyola), a Spaniard from the Basque city of Loyola, and six others mostly of Castilian origin, all students at the University of Paris,[11] met in Montmartre outside Paris, in a crypt beneath the church of Saint Denis, now Saint Pierre de Montmartre, to pronounce promises of poverty, chastity, and obedience.[12] Ignatius' six companions were: Francisco Xavier from Navarre (modern Spain), Alfonso Salmeron, Diego Laínez, Nicolás Bobadilla from Castile (modern Spain), Peter Faber from Savoy, and Simão Rodrigues from Portugal.[13] The meeting has been commemorated in the Martyrium of Saint Denis, Montmartre. They called themselves the Compañía de Jesús, and also Amigos en El Señor or "Friends in the Lord", because they felt "they were placed together by Christ." The name "company" had echoes of the military (reflecting perhaps Ignatius' background as Captain in the Spanish army) as well as of discipleship (the "companions" of Jesus). The Spanish "company" would be translated into Latin as societas like in socius, a partner or comrade. From this came "Society of Jesus" (SJ) by which they would be known more widely.[14] Religious orders established in the medieval era were named after particular men: Francis of Assisi (Franciscans); Domingo de Guzmán, later canonized as Saint Dominic (Dominicans); and Augustine of Hippo (Augustinians). Ignatius of Loyola and his followers appropriated the name of Jesus for their new order, provoking resentment by other orders who considered it presumptuous. The resentment was recorded by Jesuit José de Acosta of a conversation with the Archbishop of Santo Domingo.[15] In the words of one historian: "The use of the name Jesus gave great offense. Both on the Continent and in England, it was denounced as blasphemous; petitions were sent to kings and to civil and ecclesiastical tribunals to have it changed; and even Pope Sixtus V had signed a Brief to do away with it." But nothing came of all the opposition; there were already congregations named after the Trinity and as "God's daughters".[16] In 1537, the seven travelled to Italy to seek papal approval for their order. Pope Paul III gave them a commendation, and permitted them to be ordained priests. These initial steps led to the official founding in 1540. They were ordained in Venice by the bishop of Arbe (24 June). They devoted themselves to preaching and charitable work in Italy. The Italian War of 1536–1538 renewed between Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Venice, the Pope, and the Ottoman Empire, had rendered any journey to Jerusalem impossible. Again in 1540, they presented the project to Paul III. After months of dispute, a congregation of cardinals reported favourably upon the Constitution presented, and Paul III confirmed the order through the bull Regimini militantis ecclesiae ("To the Government of the Church Militant"), on 27 September 1540. This is the founding document of the Society of Jesus as an official Catholic religious order. Ignatius was chosen as the first Superior General. Paul III's bull had limited the number of its members to sixty. This limitation was removed through the bull Exposcit debitum of Julius III in 1550.[17] In 1543, Peter Canisius entered the Company. Ignatius sent him to Messina, where he founded the first Jesuit college in Sicily. Ignatius laid out his original vision for the new order in the "Formula of the Institute of the Society of Jesus",[18] which is "the fundamental charter of the order, of which all subsequent official documents were elaborations and to which they had to conform".[19] He ensured that his formula was contained in two papal bulls signed by Pope Paul III in 1540 and by Pope Julius III in 1550.[18] The formula expressed the nature, spirituality, community life, and apostolate of the new religious order. Its famous opening statement echoed Ignatius' military background:  A fresco depicting Ignatius receiving the papal bull from Pope Paul III was created after 1743 by Johann Christoph Handke in the Church of Our Lady Of the Snow in Olomouc. Whoever desires to serve as a soldier of God beneath the banner of the Cross in our Society, which we desire to be designated by the Name of Jesus, and to serve the Lord alone and the Church, his spouse, under the Roman Pontiff, the Vicar of Christ on earth, should, after a solemn vow of perpetual chastity, poverty and obedience, keep what follows in mind. He is a member of a Society founded chiefly for this purpose: to strive especially for the defence and propagation of the faith and for the progress of souls in Christian life and doctrine, by means of public preaching, lectures and any other ministration whatsoever of the Word of God, and further by means of retreats, the education of children and unlettered persons in Christianity, and the spiritual consolation of Christ's faithful through hearing confessions and administering the other sacraments. Moreover, he should show himself ready to reconcile the estranged, compassionately assist and serve those who are in prisons or hospitals, and indeed, to perform any other works of charity, according to what will seem expedient for the glory of God and the common good.[20] |

歴史 設立  イグナチオ・デ・ロヨラ スペイン北部ピレネー山脈地方出身のバスク貴族イグナチオ・デ・ロヨラは、パンプローナの戦いで負った傷の療養中に自らの霊的使命を悟り、この会を設立した。彼は、人々がイエス・キリストの教えに従うことができるよう、『霊操』を著した。 1534年8月15日、バスク地方のロヨラ出身のスペイン人イグナチオ・デ・ロヨラ(本名イニゴ・ロペス・デ・ロヨラ)と、主にカスティーリャ出身の6人 の仲間(全員がパリの大学で学んでいた)は、パリ郊外のモンマルトルにあるサン・ドニ教会(現サン・ピエール・ド・モンマルトル)の地下聖堂で貧困、貞 操、服従の誓いを立てるために集まった。イグナチオの6人の仲間は、 ナバラ(現スペイン)出身のフランシスコ・ザビエル、アルフォンソ・サレモン、ディエゴ・ライネス、カスティーリャ(現スペイン)出身のニコラス・ボバ ディージョ、サヴォイア出身のペドロ・フェイバー、ポルトガル出身のシマオ・ロドリゲスであった。[13] この会合は、モンマルトルのサン・ドニの殉教を記念して祝われている。彼らは自らを「イエズス会」と呼び、また「主の友」または「主における友」とも呼ん だ。なぜなら、「キリストによって共に置かれた」と感じていたからである。「カンパニー」という名称には、軍隊を連想させる響き(おそらくイグナティウス がスペイン軍の大尉であったことが反映されている)と、弟子であること(イエスの「仲間」)の両方の意味合いがあった。スペイン語の「カンパニー」はラテ ン語ではsocietasと訳され、socius(パートナー、仲間)と同様である。これが転じて「イエズス会」(Society of Jesus、SJ)と呼ばれるようになり、彼らは広く知られるようになった。 中世に設立された修道会は特定の人物の名にちなんで名付けられた。アッシジのフランチェスコ(フランシスコ会)、ドミンゴ・デ・グスマン(後に聖ドミニク として列聖された)(ドミニコ会)、ヒッポのアウグスティヌス(アウグスティノ会)などである。イグナティウス・ロヨラとその信奉者たちは、自分たちの新 しい修道会にイエスの名を付けたが、それは他の修道会から思い上がっているとみなされ、反感を買った。この反感は、イエズス会のホセ・デ・アコスタがサン ト・ドミンゴ大司教との会話から記録している。[15] ある歴史家の言葉を借りれば、「イエズス会の名称の使用は大きな反感を買った。大陸でもイングランドでも、それは冒涜的であるとして非難され、名称の変更 を求める嘆願書が王や民事・宗教裁判所に送られた。シクストゥス5世法王でさえ、それを廃止する旨の簡潔な文書に署名した」 しかし、こうした反対運動はすべて無駄に終わり、すでに三位一体の名を冠した集会が存在し、「神の娘たち」と呼ばれていた。[16] 1537年、7人は自分たちの修道会の教皇の承認を求めてイタリアを訪れた。教皇パウルス3世は彼らを称賛し、司祭に叙階することを許可した。こうした初期の動きが、1540年の正式な設立につながった。 彼らは6月24日にアルベの司教によりヴェネツィアで叙階された。彼らはイタリアで布教と慈善活動に専念した。1536年から1538年にかけてのイタリ ア戦争は、神聖ローマ皇帝カール5世、ヴェネツィア共和国、教皇、オスマン帝国の間で再燃し、エルサレムへの旅は不可能となった。 1540年に再び、彼らはその計画をパウルス3世に提出した。数か月にわたる論争の後、枢機卿団は提出された憲章を好意的に報告し、パウルス3世は 1540年9月27日、雄牛レギミニ・ミリタンティス・エクレジア(「闘う教会の統治」)により、その計画を承認した。これは、カトリックの正式な修道会 としてのイエズス会の設立文書である。イグナティウスは初代総長に選ばれた。パウルス3世の勅書では会員数は60人に制限されていた。この制限は、 1550年にユリウス3世が発布した勅書「Exposit debitum」によって撤廃された。 1543年、ペトロ・カニシウスがイエズス会に入会した。イグナティウスは彼をメッシーナに派遣し、そこで彼はシチリアで最初のイエズス会カレッジを創設した。 イグナティウスは「イエズス会設立の定式」において、新しい秩序に対する自身の当初の構想を明らかにした。これは「その後のすべての公式文書がその詳細を 記し、それに従うべきものとなる、その秩序の基本憲章」である。[19] 彼は、1540年にパウルス3世が、1550年にユリウス3世が署名した2つの教皇勅書に、この定式が確実に含まれるようにした。[18] 定式は、新しい宗教団体の性質、精神性、共同生活、使徒職を表現した。その有名な冒頭の文言は、イグナティウスの軍隊での経歴を反映したものである。  イグナティウスが教皇パウルス3世から教皇綬章を受け取る様子を描いたフレスコ画は、1743年以降にオロモウツの雪の聖母教会でヨハン・クリストフ・ハンドケによって描かれた。 イエスの名で呼ばれることを望む私たちの社会において、十字架の旗印のもとで神の兵士として仕え、ローマ教皇のもとで主と教会(すなわち、キリストの代理 人である教会)にのみ仕えたいと望む者は、永遠の貞操、清貧、服従を厳粛に誓った後、以下のことを心に留めておくべきである。彼は、主にこの目的のために 設立された協会の会員である。すなわち、公の説教、講義、その他神の言葉のあらゆる伝達手段によって、またさらに、隠遁生活、キリスト教における子供や文 盲の人々の教育、告白の聴聞やその他の秘跡の執行を通じてキリストの忠実な者たちの霊的な慰めを与えることによって、信仰の擁護と普及、キリスト教的生活 と教義における魂の進歩のために特に努力することである。さらに、彼は、疎遠になっている人々を和解させる用意があることを示し、慈悲深く、刑務所や病院 にいる人々を助け、奉仕し、そして、神の栄光と公共の利益のために有益であると思われる他の慈善活動を行うべきである。[20] |

Jesuits at Akbar's court in India, c. 1605 In fulfilling the mission of the "Formula of the Institute of the Society", the first Jesuits concentrated on a few key activities. First, they founded schools throughout Europe. Jesuit teachers were trained in both classical studies and theology, and their schools reflected this. These schools taught with a balance of Aristotelian methods with mathematics.[21] Second, they sent out missionaries across the globe to evangelize those peoples who had not yet heard the Gospel, founding missions in widely diverse regions such as modern-day Paraguay, Japan, Ontario, and Ethiopia. One of the original seven arrived in India already in 1541.[22] Finally, though not initially formed for the purpose, they aimed to stop Protestantism from spreading and to preserve communion with Rome and the pope. The zeal of the Jesuits overcame the movement toward Protestantism in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and southern Germany. Ignatius wrote the Jesuit Constitutions, adopted in 1553, which created a centralised organization and stressed acceptance of any mission to which the pope might call them.[23][24][25] His main principle became the unofficial Jesuit motto: Ad Maiorem Dei Gloriam ("For the greater glory of God"). This phrase is designed to reflect the idea that any work that is not evil can be meritorious for the spiritual life if it is performed with this intention, even things normally considered of little importance.[17] The Society of Jesus is classified among institutes as an order of clerks regular, that is, a body of priests organized for apostolic work, and following a religious rule. The term Jesuit (of 15th-century origin, meaning "one who used too frequently or appropriated the name of Jesus") was first applied to the society in reproach (1544–1552).[26] The term was never used by Ignatius of Loyola, but over time, members and friends of the society adopted the name with a positive meaning.[16] While the order is limited to men, Joanna of Austria, Princess of Portugal, favored the order and she is reputed to have been admitted surreptitiously under a male pseudonym.[27] |

インドのアクバル王宮のイエズス会士、1605年頃 「ソシエダス・イェズス会定式」の使命を果たすため、最初のイエズス会士たちはいくつかの主要な活動に集中した。まず、彼らはヨーロッパ各地に学校を設立 した。イエズス会の教師たちは古典学と神学の両方で訓練を受け、彼らの学校にもそれが反映された。これらの学校では、アリストテレスの方法と数学をバラン スよく教えた。[21] 第二に、彼らは福音をまだ聞いていない人々を改宗させるために、世界中に宣教師を派遣し、現代のパラグアイ、日本、オンタリオ、エチオピアなど、広範囲に わたる地域に布教所を設立した。1541年には、最初の7人のうちの1人がすでにインドに到着していた。[22] 当初は目的としていなかったが、最終的にはプロテスタントの拡大を阻止し、ローマおよび教皇との交わりを維持することを目指した。イエズス会の熱心な活動 により、ポーランド・リトアニア共和国および南ドイツにおけるプロテスタントへの動きは阻止された。 イグナティウスは1553年に採択されたイエズス会憲章を書き、中央集権的な組織を作り、教皇が命じる任務はすべて受け入れることを強調した。[23] [24][25] 彼の主な原則は非公式のイエズス会のモットーとなった。「Ad Maiorem Dei Gloriam(神のより大きな栄光のために)」である。このフレーズは、たとえ通常は些細なものと見なされるものであっても、この意図をもって行われる のであれば、悪ではないあらゆる仕事は精神生活にとって有益となり得るという考え方を反映したものである。 イエズス会は、聖職者会として、すなわち使徒的活動のために組織された聖職者の団体として、修道会の規則に従うものとして分類されている。 イエズス会という名称(15世紀に由来し、「イエスの名を頻繁に用いたり、その名を勝手に用いたりする者」を意味する)は、1544年から1552年にか けての非難の期間に初めてこの団体に適用された。[26] この名称はイグナティウス・デ・ロヨラによって用いられたことは一度もなかったが、時が経つにつれ、この団体の会員や友人たちが肯定的な意味でこの名称を 採用するようになった。[16] この修道会は男性のみに限定されているが、ポルトガルの王女であるオーストリアのヨアンナは、この修道会を好み、男性名を偽名としてひそかに入会したとされている。[27] |

Early works Ratio Studiorum, 1598 This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The Jesuits were founded just before the Council of Trent (1545–1563) and ensuing Counter-Reformation that would introduce reforms within the Catholic Church, and so counter the Protestant Reformation throughout Catholic Europe. Ignatius and the early Jesuits did recognize, though, that the hierarchical church was in dire need of reform. Some of their greatest struggles were against corruption, venality, and spiritual lassitude within the Catholic Church. Ignatius insisted on a high level of academic preparation for the clergy in contrast to the relatively poor education of much of the clergy of his time. The Jesuit vow against "ambitioning prelacies" can be seen as an effort to counteract another problem evidenced in the preceding century. Ignatius and the Jesuits who followed him believed that the reform of the church had to begin with the conversion of an individual's heart. One of the main tools the Jesuits have used to bring about this conversion is the Ignatian retreat, called the Spiritual Exercises. During a four-week period of silence, individuals undergo a series of directed meditations on the purpose of life and contemplations on the life of Christ. They meet regularly with a spiritual director who guides their choice of exercises and helps them to develop a more discerning love for Christ. The retreat follows a "Purgative-Illuminative-Unitive" pattern in the tradition of the spirituality of John Cassian and the Desert Fathers. Ignatius' innovation was to make this style of contemplative mysticism available to all people in active life. Further, he used it as a means of rebuilding the spiritual life of the church. The Exercises became both the basis for the training of Jesuits and one of the essential ministries of the order: giving the exercises to others in what became known as "retreats". The Jesuits' contributions to the late Renaissance were significant in their roles both as a missionary order and as the first religious order to operate colleges and universities as a principal and distinct ministry.[21] By the time of Ignatius' death in 1556, the Jesuits were already operating a network of 74 colleges on three continents. A precursor to liberal education, the Jesuit plan of studies incorporated the Classical teachings of Renaissance humanism into the Scholastic structure of Catholic thought.[21] This method of teaching was important in the context of the Scientific Revolution, as these universities were open to teaching new scientific and mathematical methodology. Further, many important thinkers of the Scientific Revolution were educated by Jesuit universities.[21] In addition to the teachings of faith, the Jesuit Ratio Studiorum (1599) would standardize the study of Latin, Greek, classical literature, poetry, and philosophy as well as non-European languages, sciences, and the arts. Furthermore, Jesuit schools encouraged the study of vernacular literature and rhetoric, and thereby became important centres for the training of lawyers and public officials. The Jesuit schools played an important part in winning back to Catholicism a number of European countries which had for a time been predominantly Protestant, notably Poland and Lithuania. Today, Jesuit colleges and universities are located in over one hundred nations around the world. Under the notion that God can be encountered through created things and especially art, they encouraged the use of ceremony and decoration in Catholic ritual and devotion. Perhaps as a result of this appreciation for art, coupled with their spiritual practice of "finding God in all things", many early Jesuits distinguished themselves in the visual and performing arts as well as in music. The theater was a form of expression especially prominent in Jesuit schools.[28] Jesuit priests often acted as confessors to kings during the early modern period. They were an important force in the Counter-Reformation and in the Catholic missions, in part because their relatively loose structure (without the requirements of living and celebration of the Liturgy of Hours in common) allowed them to be flexible and meet diverse needs arising at the time.[29] |

初期の作品 『学問の比』(Ratio Studiorum)1598年 この節には検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。 出典の無い内容は疑問視されたり、削除されることがあります。 (2020年8月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) イエズス会は、カトリック教会内部の改革を導入し、カトリックのヨーロッパ全域でプロテスタントの改革に対抗する、トレント公会議(1545年-1563年)とその後の対抗宗教改革の直前に設立された。 しかし、イグナティウスと初期のイエズス会は、ヒエラルキー化された教会が改革を必要としていることを認識していた。彼らの最大の闘争のいくつかは、カト リック教会内の腐敗、堕落、精神的な倦怠感に対するものであった。イグナティウスは、当時の聖職者の多くが比較的貧しい教育しか受けていなかったのに対 し、聖職者には高度な学問的準備が必要であると主張した。イエズス会の「高位聖職者への野心」を禁ずる誓いは、前世紀に明らかになったもうひとつの問題に 対抗する努力と見なすことができる。 イグナティウスと彼に従うイエズス会士たちは、教会の改革は個人の心の改心から始めなければならないと信じていた。イエズス会がこの改心をもたらすために 用いた主な手段のひとつが、霊操と呼ばれるイグナチオ黙想会である。4週間の沈黙の期間中、参加者は人生の目的についての一連の指示瞑想とキリストの生涯 についての黙想を行う。彼らは定期的に霊的指導者と面会し、その指導者がエクササイズの選択を指導し、キリストへのより深い愛を育む手助けをする。 この黙想は、ヨハネス・カッシアヌスや砂漠の父祖たちの霊性に関する伝統に則った「浄化-啓示-一致」のパターンに従っている。イグナチオの革新は、この 瞑想的な神秘主義のスタイルを、活動的な生活を送るすべての人々に利用できるようにしたことである。さらに、彼はこれを教会の精神生活を再建する手段とし て用いた。この「鍛錬」は、イエズス会の修練の基礎となり、また、その修道会の必須の任務のひとつとなった。すなわち、この「鍛錬」を他の人々に与えるこ とであり、これは「黙想会」として知られるようになった。 イエズス会の後期ルネサンスへの貢献は、布教活動を行う修道会として、また、大学やカレッジを運営する最初の宗教団体として、重要な役割を果たした。 1556年にイグナティウスが死去した時点で、イエズス会はすでに3つの大陸に74のカレッジのネットワークを運営していた。リベラル教育の先駆けとなる イエズス会の教育計画は、ルネサンス期の人文主義の古典的教えをカトリックの学問体系に組み込んだものであった。[21] これらの大学は新しい科学や数学の方法論の教育にも門戸を開いていたため、この教育方法は科学革命の文脈において重要であった。さらに、科学革命の多くの 重要な思想家たちはイエズス会の大学で教育を受けていた。[21] イエズス会の教育方針(1599年)では、信仰の教えに加えて、ラテン語、ギリシャ語、古典文学、詩、哲学、および非ヨーロッパ言語、科学、芸術の学習を 標準化していた。さらに、イエズス会の学校では、自国文学や修辞学の研究を奨励し、それによって弁護士や公務員の養成の重要な拠点となった。 イエズス会の学校は、一時的にプロテスタントが優勢であったヨーロッパの多くの国々、特にポーランドやリトアニアをカトリックに復帰させる上で重要な役割 を果たした。今日、イエズス会の大学は世界100カ国以上に存在する。神は被造物、特に芸術を通して出会うことができるという考えに基づき、彼らはカト リックの儀式や信心における儀式や装飾の使用を奨励した。おそらく、この芸術に対する評価と「あらゆるものの中に神を見出す」という精神的な実践が結びつ いた結果、初期のイエズス会の多くのメンバーが音楽だけでなく視覚芸術や舞台芸術の分野でも頭角を現した。演劇はイエズス会の学校において特に顕著な表現 形式であった。 イエズス会の司祭は、近世初期にはしばしば王の告解司祭を務めた。彼らは対抗宗教改革やカトリック布教において重要な役割を果たしたが、その理由の一つと して、比較的緩やかな組織構造(共同生活や共同の「時祷の祭儀」の義務がなかった)により、柔軟性を持ち、当時生じていた多様なニーズに対応することがで きたことが挙げられる。[29] |

| Expansion of the order This section may be confusing or unclear to readers. Please help clarify the section. There might be a discussion about this on the talk page. (December 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  Jesuit missionary, painting from 1779 After much training and experience in theology, Jesuits went across the globe in search of converts to Christianity. Despite their dedication, they had little success in Asia, except in the Philippines. For instance, early missions in Japan resulted in the government granting the Jesuits the feudal fiefdom of Nagasaki in 1580. This was removed in 1587 due to fears over their growing influence.[30] Jesuits did, however, have much success in Latin America. Their ascendancy in societies in the Americas accelerated during the seventeenth century, wherein Jesuits created new missions in Peru, Colombia, and Bolivia; as early as 1603, there were 345 Jesuit priests in Mexico alone.[31]  Francis Xavier Francis Xavier, one of the original companions of Loyola, arrived in Goa (Portuguese India) in 1541 to carry out evangelical service in the Indies. In a 1545 letter to John III of Portugal, he requested an Inquisition to be installed in Goa to combat heresies like crypto-Judaism and crypto-Islam. Under Portuguese royal patronage, Jesuits thrived in Goa and until 1759 successfully expanded their activities to education and healthcare. In 1594 they founded the first Roman-style academic institution in the East, St. Paul Jesuit College in Macau, China. Founded by Alessandro Valignano, it had a great influence on the learning of Eastern languages (Chinese and Japanese) and culture by missionary Jesuits, becoming home to the first western sinologists such as Matteo Ricci. Jesuit efforts in Goa were interrupted by the expulsion of the Jesuits from Portuguese territories in 1759 by the powerful Marquis of Pombal, Secretary of State in Portugal.[32] The Portuguese Jesuit António de Andrade founded a mission in Western Tibet in 1624 (see also "Catholic Church in Tibet"). Two Jesuit missionaries, Johann Grueber and Albert Dorville, reached Lhasa, in Tibet, in 1661. The Italian Jesuit Ippolito Desideri established a new Jesuit mission in Lhasa and Central Tibet (1716–21) and gained an exceptional mastery of Tibetan language and culture, writing a long and very detailed account of the country and its religion as well as treatises in Tibetan that attempted to refute key Buddhist ideas and establish the truth of Catholic Christianity. |

受注の拡大 この節は、読者にとってわかりづらいかもしれません。 節の内容を明確にするため、ご協力をお願いします。 節について議論するページがあるかもしれません。 (December 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  イエズス会の宣教師、1779年からの絵画 神学に関する多くの訓練と経験を経て、イエズス会はキリスト教への改宗者を求めて世界中に広がった。彼らの献身にもかかわらず、アジアではフィリピンを除 いてほとんど成功しなかった。例えば、初期の日本での宣教は、1580年にイエズス会に長崎の封建的な封土を与えるという結果となった。これは、彼らの影 響力が拡大していることへの懸念から、1587年に撤回された。[30] しかし、イエズス会はラテンアメリカで大きな成功を収めた。 17世紀には、アメリカ大陸における彼らの影響力は加速し、イエズス会はペルー、コロンビア、ボリビアに新たな布教地を開拓した。1603年には早くも、 メキシコだけで345人のイエズス会の司祭がいた。[31]  フランシスコ・ザビエル フランシスコ・ザビエルは、ロヨラの最初の仲間であり、1541年にインドで布教活動を行うためにゴア(ポルトガル領インド)に到着した。1545年にポ ルトガルのジョアン3世に宛てた手紙の中で、彼はゴアに異端審問所を設置し、隠れユダヤ教や隠れイスラム教などの異端と戦うことを要請した。ポルトガル王 室の庇護の下、イエズス会はゴアで繁栄し、1759年までには教育や医療の分野にもその活動を拡大することに成功した。1594年には、東洋初のローマ式 学術機関であるマカオの聖ポール・イエズス会大学を設立した。アレッサンドロ・ヴァリニャーノによって設立されたこの大学は、宣教師であるイエズス会士に よる東洋の言語(中国語と日本語)や文化の学習に大きな影響を与え、マテオ・リッチのような最初の西洋の中国学者を輩出した。 1759年にポルトガル領からイエズス会が追放されたことで、イエズス会のゴアでの活動は中断された。ポルトガル国務長官で強力な権力者であったポンバル 侯爵による追放であった。 ポルトガル人イエズス会士のアントニオ・デ・アンドラーデは、1624年に西チベットに布教所を設立した(「チベットにおけるカトリック教会」も参照)。 イエズス会の宣教師であるヨハン・グルーバーとアルバート・ドルヴィルは、1661年にチベットのラサに到着した。イタリア人イエズス会員イッポリト・デ シデリはラサとチベット中央部に新たなイエズス会伝道所を設立し(1716年~1721年)、チベット語とチベット文化に卓越した知識を得た。彼はチベッ ト語で、その国と宗教に関する非常に詳細な記録を書き、また、仏教の主要な考え方を否定し、カトリック・キリスト教の真実を確立しようとする論文も執筆し た。 |

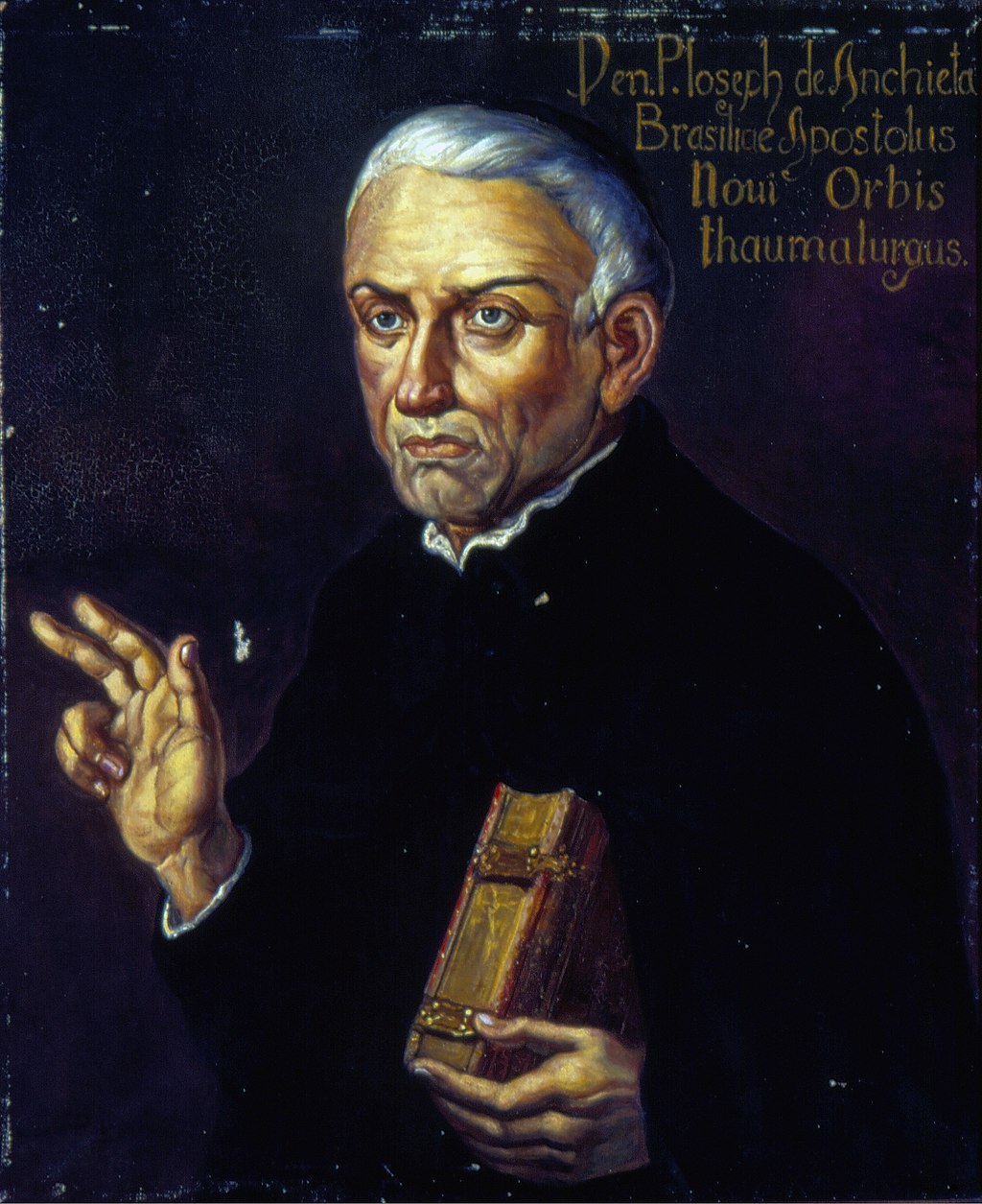

The Spanish missionary José de Anchieta was, together with Manuel da Nóbrega, the first Jesuit that Ignacio de Loyola sent to America. Jesuit missions in the Americas became controversial in Europe, especially in Spain and Portugal where they were seen as interfering with the proper colonial enterprises of the royal governments. The Jesuits were often the only force standing between the Indigenous and slavery. Together throughout South America but especially in present-day Brazil and Paraguay, they formed Indigenous Christian city-states, called "reductions". These were societies set up according to an idealized theocratic model. The efforts of Jesuits like Antonio Ruiz de Montoya to protect the natives from enslavement by Spanish and Portuguese colonizers would contribute to the call for the society's suppression. Jesuit priests such as Manuel da Nóbrega and José de Anchieta founded several towns in Brazil in the 16th century, including São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, and were very influential in the pacification, religious conversion, and education of indigenous nations. They also built schools, organized people into villages, and created a writing system for the local languages of Brazil.[31] José de Anchieta and Manuel da Nóbrega were the first Jesuits that Ignacio de Loyola sent to the Americas.[33]  Bell made in Portugal for Nanbanji Church run by Jesuits in Japan, 1576–1587 Jesuit scholars working in foreign missions were very dedicated in studying the local languages and strove to produce Latinized grammars and dictionaries. This included: Japanese (see Nippo jisho, also known as Vocabvlario da Lingoa de Iapam, "Vocabulary of the Japanese Language", a Japanese–Portuguese dictionary written 1603); Vietnamese (Portuguese missionaries created the Vietnamese alphabet,[34][35] which was later formalized by Avignon missionary Alexandre de Rhodes with his 1651 trilingual dictionary); Tupi (the main language of Brazil); and the pioneering study of Sanskrit in the West by Jean François Pons in the 1740s. Jesuit missionaries were active among indigenous peoples in New France in North America, many of them compiling dictionaries or glossaries of the First Nations and Native American languages they had learned. For instance, before his death in 1708, Jacques Gravier, vicar general of the Illinois Mission in the Mississippi River valley, compiled a Miami–Illinois–French dictionary, considered the most extensive among works of the missionaries.[36] Extensive documentation was left in the form of The Jesuit Relations, published annually from 1632 until 1673. |

スペイン人宣教師ホセ・デ・アンシエタは、マヌエル・ダ・ノブレガとともに、イグナチオ・デ・ロヨラがアメリカ大陸に派遣した最初のイエズス会士であった。 アメリカ大陸におけるイエズス会の布教活動はヨーロッパ、特にスペインとポルトガルで論争の的となった。 イエズス会は、先住民と奴隷制の間に立つ唯一の勢力となることが多かった。 彼らは南米全域で、特に現在のブラジルとパラグアイで協力し合い、先住民キリスト教徒の都市国家を形成した。 これらは「還俗」と呼ばれる理想的な神政モデルに従って設立された社会であった。スペインやポルトガルの植民者による先住民の奴隷化から守ろうとしたアン トニオ・ルイス・デ・モンタニャなどのイエズス会の宣教師たちの努力は、社会の弾圧を求める声に拍車をかけた。マヌエル・ダ・ノブレガやホセ・デ・アン シェッタなどのイエズス会の宣教師たちは、16世紀にブラジルにサンパウロやリオデジャネイロなどのいくつかの町を建設し、先住民の平和化、宗教改宗、教 育に多大な影響を与えた。彼らはまた学校を建設し、人々を村に組織化し、ブラジルの現地語の書き方を考案した。[31] ホセ・デ・アンシエタとマヌエル・ダ・ノブレガは、イグナチオ・デ・ロヨラがアメリカ大陸に派遣した最初のイエズス会士であった。[33]  1576年から1587年にかけて、イエズス会が日本で運営する南蛮寺のためにポルトガルで製造された鐘 海外宣教に従事するイエズス会の学者たちは、現地の言語の研究に非常に熱心に取り組み、ラテン語化された文法や辞書の作成に努めた。これには以下が含まれ る。日本語(『日葡辞書』(『Vocabvlario da Lingoa de Iapam』、『日本語の語彙』とも呼ばれる。1603年に書かれた日本語-ポルトガル語辞書)ベトナム語(ポルトガル人宣教師がベトナム文字を作成し [34][35]、その後アヴィニョン宣教師のアレクサンドル・ド・ロードが1651年に出版した3か国語辞書で正式なものとなった)トゥピ語(ブラジル の主要言語)および ジャン・フランソワ・ポンによる1740年代の西洋におけるサンスクリット語研究の先駆的な研究。 イエズス会の宣教師たちは、北米のヌーベルフランスにおける先住民の間で活動しており、その多くは、彼らが学んだファーストネーションやネイティブアメリ カンの言語の辞書や用語集を編纂していた。例えば、1708年に亡くなる前に、ミシシッピ川流域のイリノイ伝道所の代牧者であったジャック・グラヴィエ は、ミアミ族、イリノイ族、フランス語の辞書を編纂した。これは宣教師の著作の中でも最も広範なものとされている。[36] 膨大な量の文書は、『イエズス会関係』という形で残され、1632年から1673年まで毎年出版された。 |

| Britain Whereas Jesuits were active in Britain in the 16th century, due to the persecution of Catholics in the Elizabethan times, an English province was only established in 1623.[37] The first pressing issue for early Jesuits in what today is the United Kingdom was to establish places for training priests. After an English College was opened in Rome (1579), a Jesuit seminary was opened at Valladolid (1589), then one in Seville (1592), which culminated in a place of study in Louvain (1614). This was the earliest foundation of what would later be called Heythrop College. Campion Hall, founded in 1896, has been a presence within Oxford University since then. 16th and 17th-century Jesuit institutions intended to train priests were hotbeds for the persecution of Catholics in Britain, where men suspected of being Catholic priests were routinely imprisoned, tortured, and executed. Jesuits were among those killed, including the namesake of Campion Hall, as well as Brian Cansfield, Ralph Corbington, and many others. A number of them were canonized among the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales. Four Jesuit churches remain today in London alone, with three other places of worship remaining extant in England and two in Scotland.[38] |

イギリス 16世紀にはイギリスでイエズス会が活動していたが、エリザベス朝時代のカトリック迫害により、イギリス管区が設立されたのは1623年になってからだっ た。[37] 今日イギリスと呼ばれる地域における初期のイエズス会の喫緊の課題は、司祭を養成する場所を確立することであった。ローマに英語カレッジが開校(1579 年)した後、イエズス会の神学校がバリャドリッド(1589年)、セビリア(1592年)に開校し、最終的にルーヴァン(1614年)に研究施設が設立さ れた。これが後にヘイトロップ・カレッジと呼ばれることになる最も初期の設立であった。1896年に設立されたカンピオン・ホールは、それ以来オックス フォード大学内に存在している。 16世紀から17世紀にかけてのイエズス会の教育機関は、司祭の養成を目的としていたが、英国ではカトリック信者に対する迫害の温床となり、カトリックの 司祭であると疑われた男性は日常的に投獄され、拷問を受け、処刑された。イエズス会の信者の中には、キャンピオン・ホールの名前の由来となった人物をはじ め、ブライアン・カンズフィールド、ラルフ・コービントン、その他多数が殺害された。そのうちの何人かは、イングランドとウェールズの40人の殉教者の列 聖者となった。 現在でもロンドンには4つのイエズス会の教会が残っており、イングランドには3つ、スコットランドには2つの礼拝所が現存している。[38] |

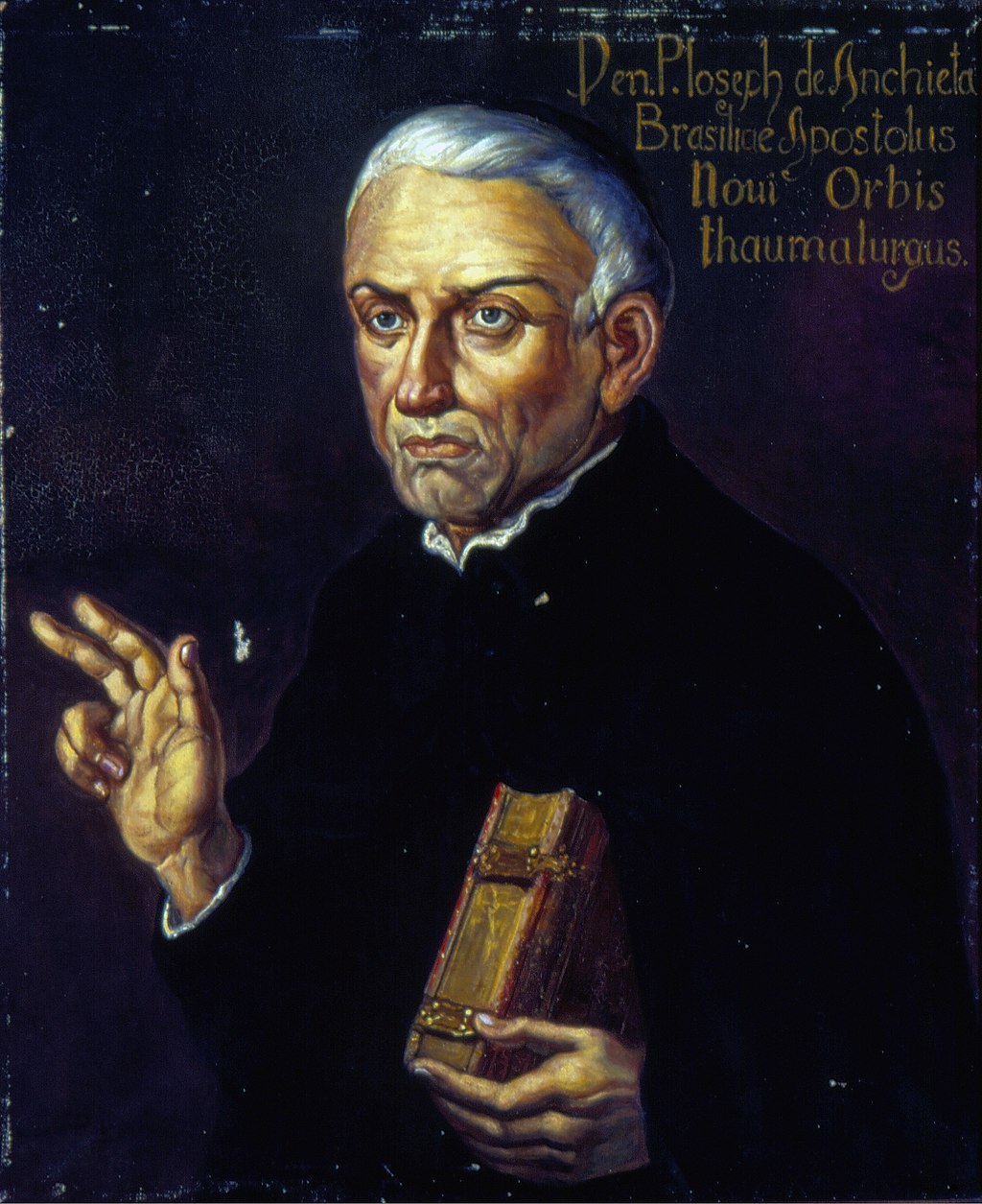

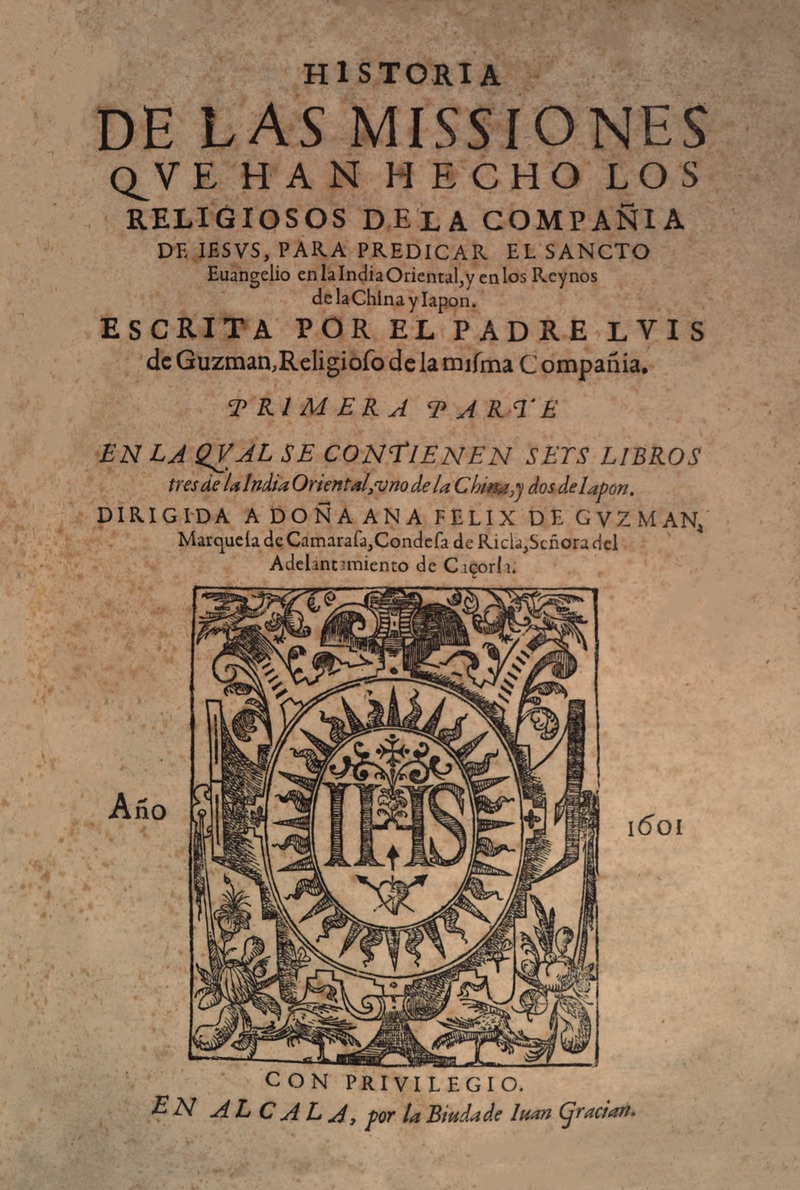

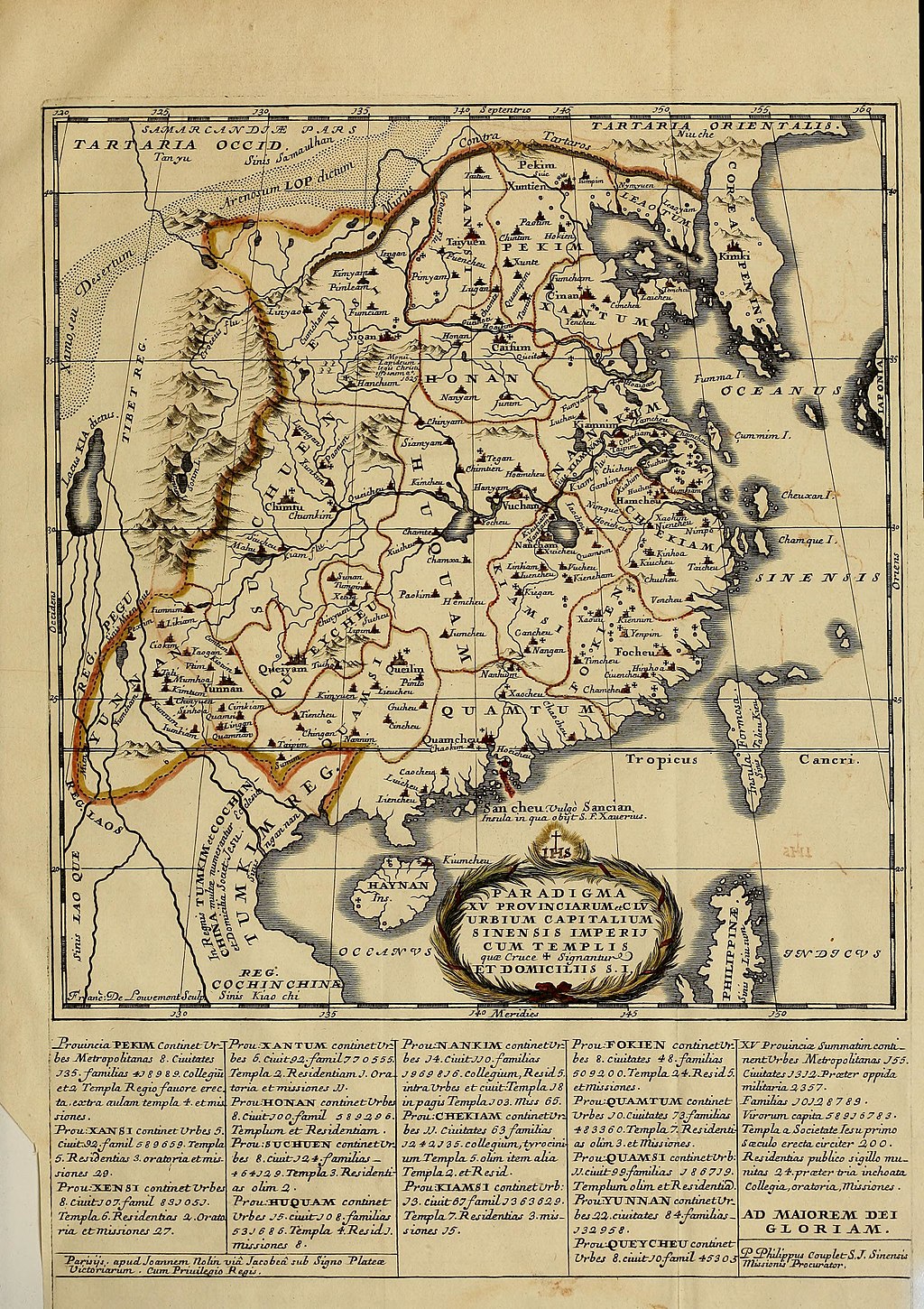

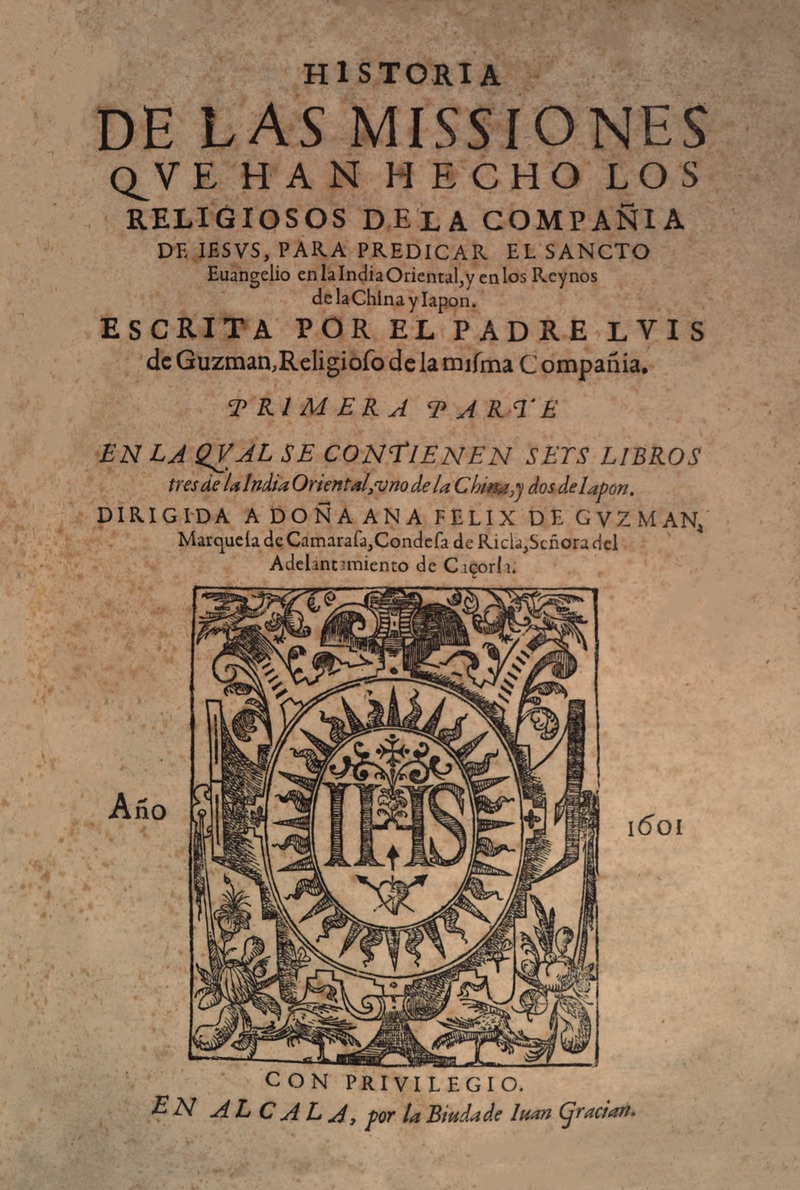

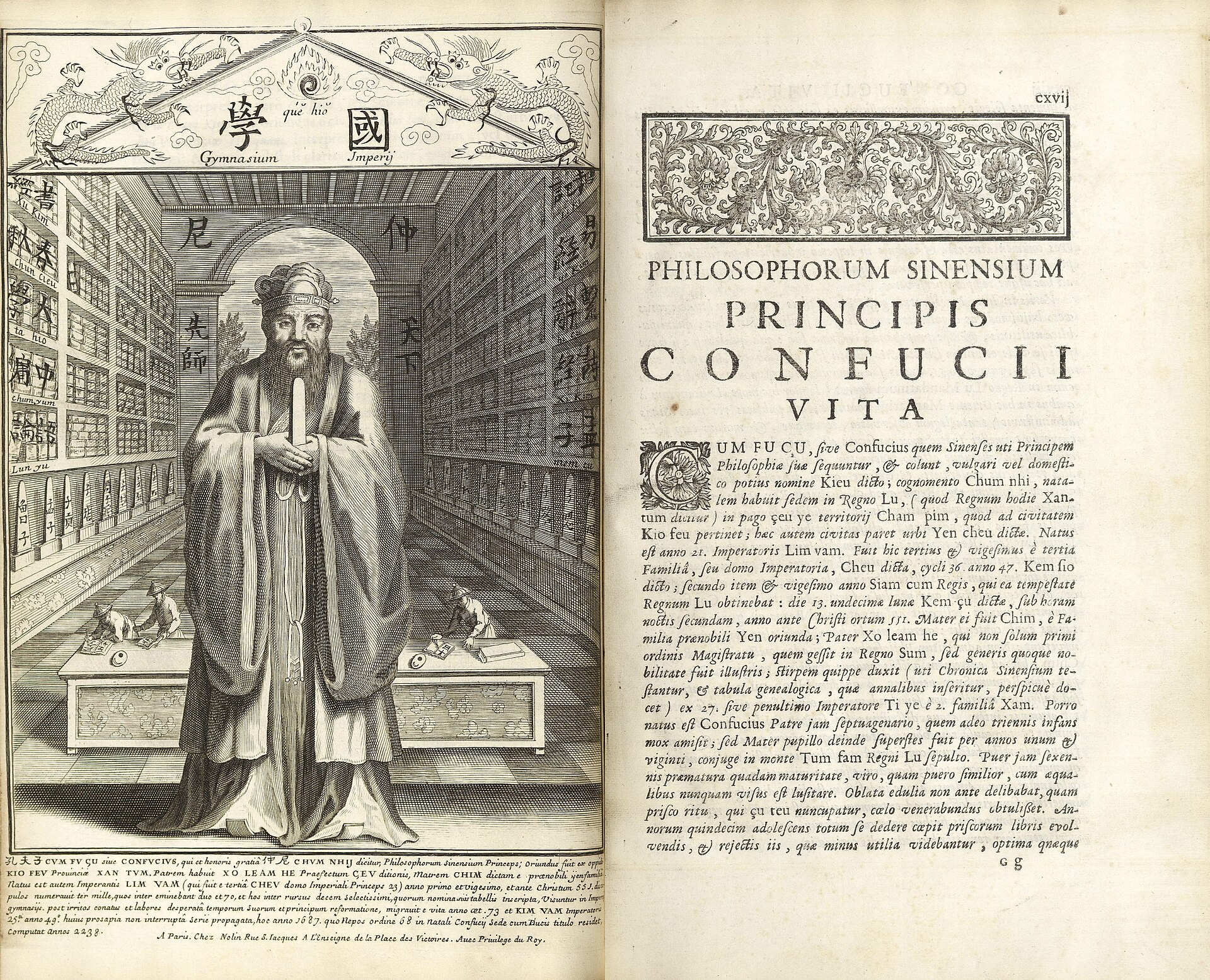

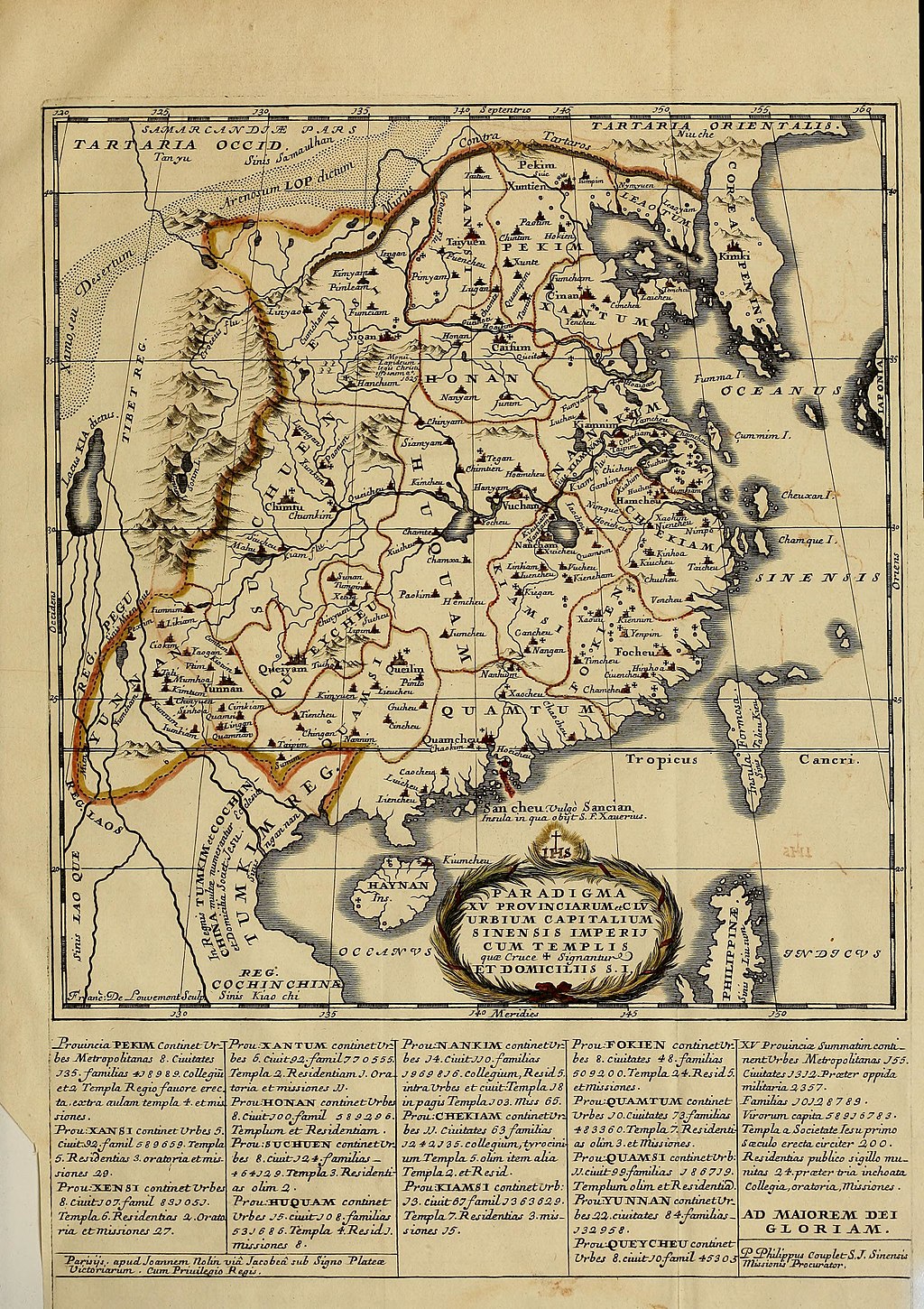

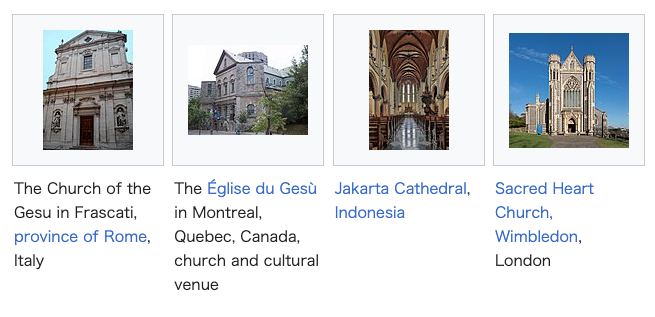

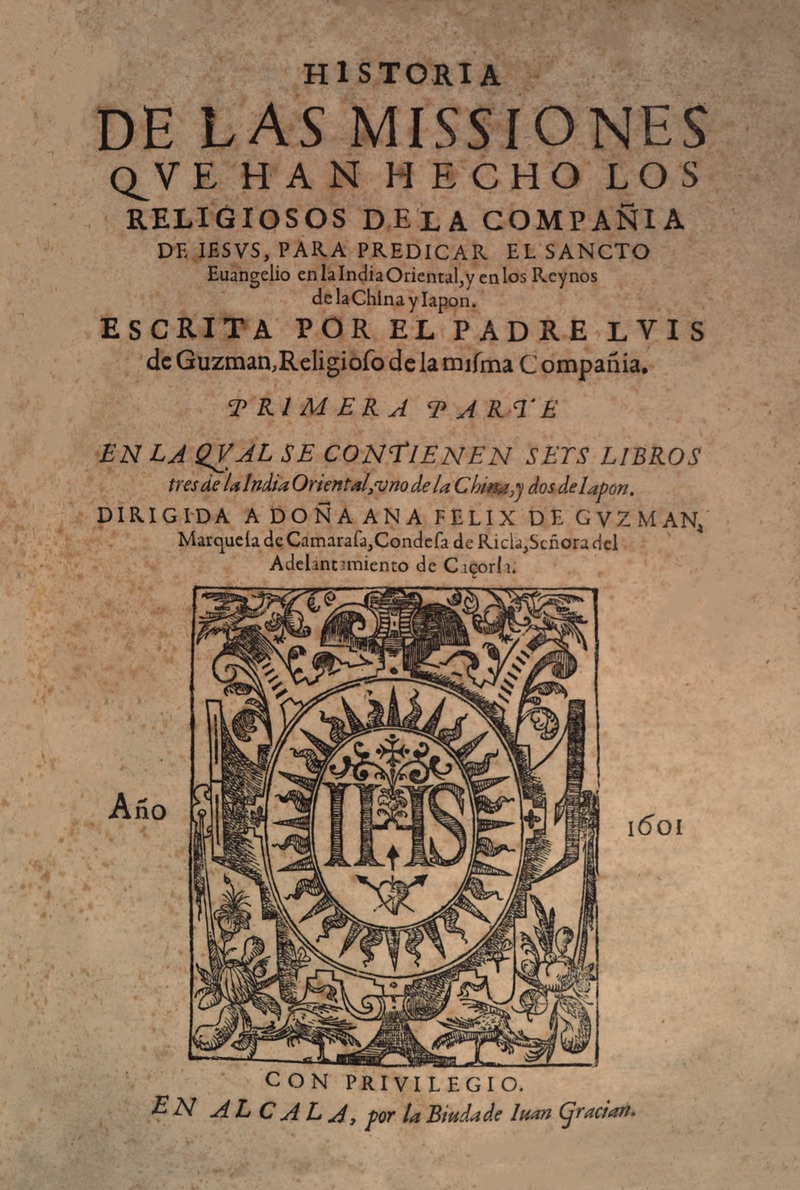

| China Main article: Jesuit missions in China  Historia de las misiones jesuitas en India, China y Japón (Luis Guzmán, 1601)  Matteo Ricci (left) and Xu Guangqi in the 1607 Chinese publication of Euclid's Elements  Confucius, Philosopher of the Chinese, or, Chinese Knowledge Explained in Latin, published by Philippe Couplet, Prospero Intorcetta, Christian Herdtrich, and François de Rougemont at Paris in 1687  A map of the 200-odd Jesuit churches and missions established across China c. 1687 The Jesuits first entered China through the Portuguese settlement on Macau, where they settled on Green Island and founded St. Paul's College. The Jesuit China missions of the 16th and 17th centuries introduced Western science and astronomy,[39] then undergoing its own revolution, to China. The scientific revolution brought by the Jesuits coincided with a time when scientific innovation had declined in China: [The Jesuits] made efforts to translate western mathematical and astronomical works into Chinese and aroused the interest of Chinese scholars in these sciences. They made very extensive astronomical observation and carried out the first modern cartographic work in China. They also learned to appreciate the scientific achievements of this ancient culture and made them known in Europe. Through their correspondence, European scientists first learned about the Chinese science and culture.[40] For over a century, Jesuits such as Michele Ruggieri, Matteo Ricci,[41] Diego de Pantoja, Philippe Couplet, Michal Boym, and François Noël refined translations and disseminated Chinese knowledge, culture, history, and philosophy to Europe. Their Latin works popularized the name "Confucius" and had considerable influence on the Deists and other Enlightenment thinkers, some of whom were intrigued by the Jesuits' attempts to reconcile Confucian morality with Catholicism.[42] Upon the arrival of the Franciscans and other monastic orders, Jesuit accommodation of Chinese culture and rituals led to the long-running Chinese Rites controversy. Despite the personal testimony of the Kangxi Emperor and many Jesuit converts that Chinese veneration of ancestors and Confucius was a nonreligious token of respect, Pope Clement XI's papal decree Cum Deus Optimus ruled that such behavior constituted impermissible forms of idolatry and superstition in 1704;[43] his legate Tournon and Bishop Charles Maigrot of Fujian, tasked with presenting this finding to the Kangxi Emperor, displayed such extreme ignorance that the emperor mandated the expulsion of Christian missionaries unable to abide by the terms of Ricci's Chinese catechism.[44][45][46][47] Tournon's summary and automatic excommunication for any violators of Clement's decree[48] – upheld by the 1715 bull Ex Illa Die – led to the swift collapse of all the missions in China;[45] the last Jesuits were finally expelled after 1721.[49] |

中国 詳細は:中国におけるイエズス会の伝道活動  インド、中国、日本におけるイエズス会宣教の歴史(ルイス・グスマン、1601年)  1607年に中国で出版された『ユークリッドの原論』のマテオ・リッチ(左)と徐光啓  1687年にパリでフィリップ・クープラン、プロスペロ・イントルチェッタ、クリスチャン・ヘルトリッヒ、フランソワ・ド・ルーモンによって出版された『中国哲学者、孔子、またはラテン語で説明された中国知識』  1687年頃に中国全土に設立されたイエズス会の教会および伝道所の地図 イエズス会は、マカオのポルトガル人居住地から中国に初めて進出し、そこで彼らは緑島に定住し、聖ポール大学を設立した。 16世紀から17世紀にかけてのイエズス会の中国布教活動は、当時革命のさなかにあった西洋の科学や天文学を中国にもたらした。イエズス会がもたらした科学革命は、中国で科学的な革新が衰退していた時期と重なっていた。 イエズス会は、西洋の数学や天文学の著作を中国語に翻訳する努力を惜しまず、中国の学者たちの関心をこれらの科学分野に引き起こした。彼らは非常に広範囲 にわたる天体観測を行い、中国で最初の近代的な地図作成作業を行った。また、彼らはこの古代文化の科学的成果を評価することを学び、それをヨーロッパに広 めた。彼らの交流を通じて、ヨーロッパの科学者たちは初めて中国の科学と文化について知ることとなった。 ミケーレ・ルジェーリ、マテオ・リッチ、ディエゴ・デ・パントーハ、フィリップ・クープリエ、ミハル・ボイム、フランソワ・ノエルといったイエズス会の宣 教師たちは、1世紀以上にわたって翻訳を推敲し、中国に関する知識、文化、歴史、哲学をヨーロッパに広めた。彼らのラテン語の著作は「孔子」の名を広め、 自然神論者や啓蒙思想家たちに大きな影響を与えた。その中には、イエズス会が儒教の道徳とカトリックを調和させようとした試みに興味を抱いた者もいた。 フランシスコ会やその他の修道会の到来により、イエズス会が中国文化や儀式に順応したことで、長期にわたる「中国礼儀」論争が引き起こされた。康熙帝や多 くのイエズス会の改宗者の証言によると、中国人による先祖崇拝や孔子崇拝は宗教とは関係のない敬意の表れであるとされたが、1704年、教皇クレメンス 11世の教皇令「Cum Deus Optimus」は、そのような行為は偶像崇拝や迷信の許されない形態であると裁定した。教皇使節のトゥルノンと福建省の司教シャルル・メグロは、この裁 定を康熙帝に伝える任務を負っていたが、彼らは極度の 無知を示したため、康熙帝はリッチの中国カテキズムの条件に従うことができないキリスト教宣教師の追放を命じた。[44][45][46][47] トゥルノンがまとめた、クレメンスの命令に違反した者に対する自動的な破門[48](1715年の雄牛Ex Illa Dieによって支持された)により、中国におけるすべての宣教は急速に崩壊した。[45] 最後のイエズス会士は、 1721年以降、最終的に追放された。[49] |

| Ireland See also: List of Jesuit schools in Ireland The first Jesuit school in Ireland was established at Limerick by the apostolic visitor of the Holy See, David Wolfe. Wolfe had been sent to Ireland by Pope Pius IV with the concurrence of the third Jesuit superior general, Diego Laynez.[50] He was charged with setting up grammar schools "as a remedy against the profound ignorance of the people".[51] Wolfe's mission in Ireland initially concentrated on setting the sclerotic Irish Church on a sound footing, introducing the Tridentine Reforms and finding suitable men to fill vacant sees. He established a house of religious women in Limerick known as the Menabochta ("poor women" ) and in 1565 preparations began for establishing a school at Limerick.[52] At his instigation, Richard Creagh, a priest of the Diocese of Limerick, was persuaded to accept the vacant Archdiocese of Armagh, and was consecrated at Rome in 1564. This early Limerick school, Crescent College, operated in difficult circumstances. In April 1566, William Good sent a detailed report to Rome of his activities via the Portuguese Jesuits. He informed the Jesuit superior general that he and Edmund Daniel had arrived at Limerick city two years beforehand and their situation there had been perilous. Both had arrived in the city in very bad health, but had recovered due to the kindness of the people. They established contact with Wolfe, but were only able to meet with him at night, as the English authorities were attempting to arrest the legate. Wolfe charged them initially with teaching to the boys of Limerick, with an emphasis on religious instruction, and Good translated the catechism from Latin into English for this purpose. They remained in the city for eight months, before moving to Kilmallock in December 1565 under the protection of the Earl of Desmond, where they lived in more comfort than the primitive conditions they experienced in the city. However they were unable to support themselves at Kilmallock and three months later they returned to the city in Easter 1566, and strangely set up their house in accommodation owned by the Lord Deputy of Ireland, which was conveyed to them by certain influential friends.[53] They recommenced teaching at Castle Lane, and imparting the sacraments, though their activities were restricted by the arrival of Royal Commissioners. Good reported that as he was an Englishman, English officials in the city cultivated him and he was invited to dine with them on a number of occasions, though he was warned to exercise prudence and avoid promoting the Petrine primacy and the priority of the Mass amongst the sacraments with his students and congregation, and that his sermons should emphasize obedience to secular princes if he wished to avoid arrest.[53] The number of scholars in their care was very small. An early example of a school play in Ireland is sent in one of Good's reports, which was performed on the Feast of St. John in 1566. The school was conducted in one large aula, but the students were divided into distinct classes. Good gives a highly detailed report of the curriculum taught and the top class studied the first and second parts of Johannes Despauterius's Commentarli grammatici, and read a few letters of Cicero or the dialogues of Frusius (André des Freux, SJ). The second class committed Donatus' texts in Latin to memory and read dialogues as well as works by Ēvaldus Gallus. Students in the third class learned Donatus by heart, though translated into English rather than through Latin. Young boys in the fourth class were taught to read. Progress was slow because there were too few teachers to conduct classes simultaneously.[53] In the spirit of Ignatius' Roman College founded 14 years before, no fee was requested from pupils, though as a result the two Jesuits lived in very poor conditions and were very overworked with teaching and administering the sacraments to the public. In late 1568 the Castle Lane School, in the presence of Daniel and Good, was attacked and looted by government agents sent by Sir Thomas Cusack during the pacification of Munster.[54] The political and religious climate had become more uncertain in the lead up to Pope Pius V's formal excommunication of Queen Elizabeth I, which resulted in a new wave of repression of Catholicism in England and Ireland. At the end of 1568 the Anglican Bishop of Meath, Hugh Brady, was sent to Limerick charged with a Royal Commission to seek out and expel the Jesuits. Daniel was immediately ordered to quit the city and went to Lisbon, where he resumed his studies with the Portuguese Jesuits.[54] Good moved on to Clonmel, before establishing himself at Youghal until 1577.[55] In 1571, after Wolfe had been captured and imprisoned at Dublin Castle, Daniel persuaded the Portuguese Province to agree a surety for the ransom of Wolfe, who was quickly banished on release. Daniel returned to Ireland the following year, but was immediately captured and incriminating documents were found on his person, which were taken as proof of his involvement with the rebellious cousin of the Earl of Desmond, James Fitzmaurice and a Spanish plot.[56] He was removed from Limerick, taken to Cork "just as if he were a thief or noted evildoer". After being court-martialled by the Lord President of Munster, Sir John Perrot, he was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered for treason and refused pardon in return for swearing the Act of Supremacy. His execution was carried out on 25 October 1572 and a report of it was sent by Fitzmaurice to the Jesuit Superior General in 1576, where he said that Daniel was "cruelly killed because of me".[57] With Daniel dead and Wolfe dismissed, the Irish Jesuit foundation suffered a severe setback. Good is recorded as resident at Rome by 1577 and in 1586 the seizure of Earl of Desmond's estates resulted in a new permanent Protestant plantation in Munster, making the continuation of the Limerick school impossible for a time. It was not until the early 1600s that the Jesuit mission could again re-establish itself in the city, though the Jesuits kept a low profile existence in lodgings here and there. For instance a mission led by Fr. Nicholas Leinagh re-established itself at Limerick in 1601,[58] though the Jesuit presence in the city numbered no more than 1 or 2 at a time in the years immediately following. In 1604, the Lord President of Munster, Sir Henry Brouncker - at Limerick, ordered all Jesuits from the city and Province, and offered £7 to anyone willing to betray a Jesuit priest to the authorities, and £5 for a seminarian.[59] Jesuit houses and schools throughout the province, in the years thereafter, were subject to periodic crackdown and the occasional destruction of schools, imprisonment of teachers and the levying of heavy money penalties on parents are recorded in publications of the time. In 1615-17 the Royal Visitation Books, written up by Thomas Jones, the Anglican Archbishop of Dublin, records the suppression of Jesuit schools at Waterford, Limerick and Galway.[60] Nevertheless, in spite of this occasional persecution, the Jesuits were able to exert a degree of discreet influence within the province and in Limerick. For instance in 1606, largely through their efforts, a Catholic named Christopher Holywood was elected Mayor of the city.[61] Four years earlier the resident Jesuit had raised a sum of "200 cruzados" for the purpose of founding a hospital in the city, though the project was disrupted by a severe outbreak of plague and repression by the Lord President[62] The principal activities of the order within the city at this time were devoted to preaching, administration of the sacraments and teaching. The school opened and closed intermittently in or around the area of Castle Lane, near Lahiffy's lane. During demolition work stones marked I.H.S., 1642 and 1609 were, in the 19th century, found inserted in a wall behind a tan yard near St Mary's Chapel which, according to Lenihan, were thought to mark the site of an early Jesuit school and oratory. This building, at other times, had also functioned as a dance house and candle factory.[63] For much of the 17th century, the Limerick Jesuit foundation established a more permanent and stable presence and the Jesuit Annals record a 'flourishing' school at Limerick in the 1640s.[64] During the Confederacy the Jesuits had been able to go about their business unhindered and were invited to preach publicly from the pulpit of St. Mary's Cathedral on 4 occasions. Cardinal Giovanni Rinuccini wrote to the Jesuit general in Rome praising the work of the Rector of the Limerick College, Fr. William O'Hurley, who was aided by Fr. Thomas Burke.[65] However just a few years later, during the Protectorate era, only 18 of the Jesuits resident in Ireland managed to avoid capture by the authorities. Lenihan records that the Limerick Crescent College in 1656 moved to a hut in the middle of a bog which was difficult for the authorities to find. This foundation was headed up by Fr. Nicholas Punch who was aided by Frs. Maurice Patrick, Piers Creagh and James Forde and the school attracted a large number of students from around the locality.[66] At the Restoration of Charles II, the school moved back to Castle Lane, and remained largely undisturbed for the next 40 years, until the surrender of the city to Williamite forces in 1692. In 1671, Dr. James Douley was appointed Vicar Apostolic of Limerick and during his visitation to the diocese reported to the Holy See that the Jesuits had a house and "taught schools with great fruit, instructing the youth in the articles of faith and good morals."[67] Douley also noted that this and other Catholic schools operating in the Diocese were also attended by local Protestants.[68] The Jesuit presence in Ireland, in the so-called Penal era after the Battle of the Boyne, ebbed and flowed. By 1700 they were only 6 or 7, recovering to 25 by 1750. Small Jesuit houses and schools existed at Athlone, Carrick-on-Suir, Cashel, Clonmel, Kilkenny, Waterford, New Ross, Wexford, and Drogheda, as well as Dublin and Galway. At Limerick there appears to have been a long hiatus following the defeat of the Jacobite forces and Begley states that Fr. Thomas O'Gorman was the first Jesuit to return to Limerick after the siege, arriving in 1728 and he took up residence in Jail Lane, near the Castle in the Englishtown. There he opened a school to "impart the rudiments of the classics to the better class youth of the city."[69] O'Gorman left in 1737 and was succeeded by Fr. John McGrath.[70] Next came Fr. James McMahon, who was a nephew of the Primate of Armagh, Hugh MacMahon. McMahon lived at Limerick for thirteen years until his death in 1751. In 1746 Fr Joseph Morony was sent from Bordeaux to join McMahon and the others.[71] Morony remained at the Jail Lane site teaching at what Begley states was a "high class school" until 1773 when he was ordered to close the school and oratory following the papal suppression of the Society of Jesus,[72] 208 years after its foundation by Wolfe. Morony then went to live in Dublin and worked as a secular priest. Despite the efforts of the Castle authorities and English government the Limerick school managed to survive the Protestant Reformation, the Cromwellian invasion and Williamite Wars, and subsequent Penal Laws. It was finally forced to close, not for religious or confessional reasons, but due to the political difficulties of the Jesuit Order elsewhere. Following the restoration of the Society of Jesus in 1814, the Jesuits gradually re-established a number of their schools throughout the country, starting with foundations at Kildare and Dublin. They returned to Limerick at the invitation of the Bishop of Limerick, John Ryan, in 1859 and also re-established a school at Galway in the same year. |

アイルランド 関連項目:アイルランドのイエズス会系学校一覧 アイルランド初のイエズス会系学校は、教皇庁使節のデイヴィッド・ウルフによってリムリックに設立された。ウルフは、第3代イエズス会総長ディエゴ・ライ ネス(Diego Laynez)の同意を得た上で、教皇ピウス4世によってアイルランドに派遣された。ウルフは、「国民の深刻な無知を改善する」ための文法学校の設立を命 じられた。 ウルフの当初の使命は、硬直化したアイルランド教会を健全な基盤に立て直すことに集中していた。トリエント改革を導入し、空席となっている地位にふさわし い人材を見つけることだった。彼はリムリックに「貧しい女性たち」という意味の「メナボクタ」という名の女子修道院を設立し、1565年にはリムリックに 学校を設立するための準備が始まった。 彼の勧めにより、リムリック教区の司祭リチャード・クレイグは空席となっていたアーマー大司教区の職を引き受けるよう説得され、1564年にローマで叙階された。 この初期のリムリック派、クレセント・カレッジは困難な状況下で運営されていた。1566年4月、ウィリアム・グッドはポルトガル人のイエズス会士を通じ て、ローマに自身の活動の詳細な報告を送った。彼はイエズス会の総長に、彼とエドマンド・ダニエルは2年前にリムリック市に到着したが、その時の状況は危 険なものであったと伝えた。2人とも非常に悪い保健状態で市に到着したが、市民の親切により回復した。 彼らはウルフと接触したが、英国当局が使節を逮捕しようとしていたため、彼と会うことができたのは夜だけだった。ウルフは彼らをリムリックの少年たちに宗 教教育を教えるために派遣した。グッドはその目的のために、ラテン語のカテキズムを英語に翻訳した。彼らは8か月間その都市に滞在し、1565年12月に デズモンド伯の保護のもとキルマロックに移った。そこでは、都市での原始的な環境よりも快適な生活を送ることができた。しかし、キルマーロックでは生活を 維持することができず、3か月後、1566年の復活祭にダブリンに戻った。そして、不思議なことに、アイルランド総督の所有する宿泊施設に家を構えた。こ れは、有力な友人たちによって彼らに提供されたものだった。 彼らはキャッスル・レーンで再び教え始め、秘跡を授けた。しかし、王立委員会の到着により、彼らの活動は制限されていた。グッドは、自分が英国人であるた め、市の英国人役人たちから厚遇を受け、何度も彼らとの食事に招待されたが、生徒や信者たちに対して、秘跡の中でも特に、ペトロの首位権やミサの優先性を 宣伝しないよう慎重を期すよう警告された。また、逮捕を避けたいのであれば、説教では世俗の君主への服従を強調すべきだと忠告された。 彼らが面倒を見ていた生徒の数は非常に少なかった。アイルランドにおける学校劇の初期の例は、グッドの報告書の一つに記載されており、1566年の聖ヨハ ネ祭で上演された。学校は1つの大きな講堂で行われていたが、生徒たちは明確にクラス分けされていた。グッドは、教えられていたカリキュラムについて非常 に詳細な報告をしているが、トップクラスの生徒たちはヨハネス・デスパウテリウスの『文法解説』の第1部と第2部を学び、キケロのいくつかの手紙やフルー シウスの対話を読んでいた(アンドレ・デ・フルー、イエズス会)。2番目のクラスでは、ラテン語で書かれたドナトゥス著のテキストを暗記し、対話やエヴァ ルドゥス・ガルス著の作品を読んだ。3番目のクラスの生徒は、ドナトゥスをラテン語ではなく英語に訳して暗記した。4番目のクラスの少年たちは、読み方を 教わった。同時に授業を行うには教師が少なすぎたため、進歩は遅かった。 14年前に設立されたイグナティウス・ローマ・カレッジの精神に則り、生徒からは授業料を徴収しなかったが、その結果、2人のイエズス会士は劣悪な環境で 生活し、教育や聖礼典の管理に非常に忙殺されることとなった。1568年の終わり頃、ダニエルとグッドの目の前で、ミュンスター平定中にサー・トーマス・ クーザックが派遣した政府のエージェントたちによってキャッスル・レーン・スクールが襲撃され、略奪された。[54] 教皇ピウス5世がエリザベス1世を正式に破門する前、政治と宗教の情勢はさらに不確かなものになっていた。その結果、イングランドとアイルランドではカト リックに対する弾圧の新たな波が起こった。1568年の終わりに、メースの英国国教会司教ヒュー・ブレイディがリムリックに送られ、イエズス会の追放を命 じられた。ダニエルはすぐにリムリックを去るよう命じられ、リスボンに向かい、そこでポルトガル人イエズス会士たちと共に学問を再開した。[54] グッドはクロンメルに移り、1577年までヨールに落ち着くまで過ごした。[55] 1571年、ウルフが捕らえられダブリン城に投獄された後、ダニエルはポルトガル管区にウルフの身代金を支払う保証人となるよう説得した。ウルフはすぐに 追放された。ダニエルは翌年アイルランドに戻ったが、すぐに捕らえられ、彼の人格に不利な書類が見つかった。それは、デズモンド伯爵の反逆的な従兄弟であ るジェームズ・フィッツモーリスとスペインの陰謀に関与している証拠とみなされた。彼はリムリックからコークに移送されたが、それは「まるで泥棒か悪名高 い犯罪者のように」であった。その後、ジョン・ペロット卿(Sir John Perrot)率いる軍法会議にかけられ、反逆罪により絞首刑、引きずり回し刑、四つ裂きの刑に処せられる判決が下され、大権法を誓うことによる恩赦も拒 否された。彼の処刑は1572年10月25日に行われ、フィッツモーリスが1576年にイエズス会の総長に送った報告書には、ダニエルが「私のせいで残酷 に殺された」と書かれていた。 ダニエルが死に、ウルフが解任されたことで、アイルランドのイエズス会は深刻な後退を余儀なくされた。1577年までにグッドはローマに居住していたと記 録されており、1586年にはデズモンド伯爵の領地の接収により、プロテスタントの入植地が新たに永久的に設立されたことで、リムリック派の継続は一時不 可能となった。イエズス会の宣教活動が再びこの都市で再開されるのは、1600年代初頭になってからであった。イエズス会は目立たない存在ではあったが、 あちこちに宿舎を構えていた。例えば、ニコラス・レナフ神父が率いる宣教団は1601年にリムリックに再進出したが[58]、その直後の数年間は、一度に 1人か2人しかイエズス会の宣教師がリムリックに滞在することはなかった。 1604年、マンスター総督サー・ヘンリー・ブラウンカー卿はリムリックで、市と州のイエズス会士全員に退去を命じ、イエズス会の司祭を当局に密告する者 には7ポンド、神学生には5ポンドを支払うと申し出た。[59] それ以降、州内のイエズス会の家屋や学校は定期的に弾圧の対象となり、学校の破壊や教師の投獄、また 当時の出版物には、1615年から1617年にかけて、ダブリンの英国国教会大司教トーマス・ジョーンズが記した「王立訪問記録」に、ウォーターフォー ド、リムリック、ゴールウェイのイエズス会学校の閉鎖が記録されている。[60] しかし、このような時折の迫害にもかかわらず、イエズス会はリムリック州およびリムリック市において、ある程度の影響力を及ぼすことができた。例えば 1606年には、主に彼らの努力により、クリストファー・ホーリーウッドという名のカトリック教徒が市長に選出された。[61] 4年前には、市内に病院を設立するために、居住していたイエズス会士が「200クルザード」という資金を集めたが、そのプロジェクトはペストの深刻な流行 と総督による弾圧により中断された。[62] この時期、市内の修道会の主な活動は説教、秘跡の執行、教育に専念していた。学校は、ラフィの小道近くのキャッスル・レーン周辺で断続的に開校と閉校を繰 り返した。解体作業中に、1642年と1609年と刻まれた石が、19世紀に聖マリア礼拝堂近くのタンニング工場の裏の壁から発見された。レニハンによる と、これらの石は初期のイエズス会の学校と礼拝堂の跡地を示すものと考えられていた。この建物は、それ以外の時期にはダンスホールやろうそく工場としても 機能していた。 17世紀の大半の間、リムリックのイエズス会はより恒久的で安定した存在となり、イエズス会の年代記には1640年代のリムリックの学校が「繁栄」してい たと記録されている。[64] 連合王国時代、イエズス会は妨害を受けることなく事業を展開することができ、4度にわたって聖マリア大聖堂の説教壇で公に説教を行うよう招待された。枢機 卿ジョヴァンニ・リヌッチーニは、リムリック・カレッジの学長ウィリアム・オヘア神父の働きを称賛する手紙をローマのイエズス会総長に送った。オヘア神父 はトーマス・バーク神父の支援を受けていた。[65] しかし、わずか数年後の護民官統治時代には、アイルランド在住のイエズス会士のうち当局に捕らわれずに済んだのはわずか18人であった。レニハンは、 1656年にリムリック・クレセント・カレッジが当局に見つけにくい沼地の真ん中の小屋に移転したことを記録している。この学校はニコラス・パンチ神父が 主宰し、モーリス・パトリック、ピアス・クレイグ、ジェームズ・フォーデの神父たちが支援した。この学校には地元一帯から多数の生徒が集まった。 チャールズ2世の王政復古により、学校はキャッスル・レーンに戻り、1692年にウィリアム派軍が市を占領するまで、その後40年間はほぼ平穏に過ごし た。1671年、ジェームズ・ドゥーリー博士がリムリックの使徒使徒として任命され、教区を訪問した際、イエズス会が家屋を所有し、「大きな成果を伴う学 校教育を行い、信仰の条項と良き道徳について若者たちに指導している」ことを教皇庁に報告した。[67] ドゥーリーはまた、教区で運営されているこの学校やその他のカトリック系学校には、地元のプロテスタント信者も通っていることも指摘した。[68] アイルランドにおけるイエズス会の存在は、ボインの戦い以降のいわゆる「重罪時代」には増減を繰り返していた。1700年には6つか7つにまで減少した が、1750年には25にまで回復した。アスローン、キャリック・オン・スィアー、キャッシェル、クロンメル、キルケニー、ウォーターフォード、ニュー・ ロス、ウェックスフォード、ドロヘダ、そしてダブリンやゴールウェイにも、小規模なイエズス会の家屋や学校が存在していた。リムリックでは、ジャコバイト 軍の敗北後、長い空白期間があったようである。ベグリーによると、トーマス・オゴーマン神父が、包囲戦後のリムリックに最初に帰ってきたイエズス会士であ り、1728年に到着し、イングリッシュタウンの城の近くにあるジェイル・レーンに居住した。そこで彼は「市の良家の子女に古典の初歩を教える」学校を開 いた。[69] オゴーマン神父は1737年に去り、ジョン・マクグラス神父が後任となった。[70] 次にやってきたのはジェームズ・マクマホン神父で、彼はアルマー大司教ヒュー・マクマホンの甥であった。マクマホンは1751年に亡くなるまで13年間リ ムリックに住んだ。1746年には、ジョセフ・モロニー神父がボルドーからマクマホン神父らのもとに派遣された。[71] モロニーは、ベグリーが「高級学校」と表現した学校で教鞭をとり、ウルフが設立してから208年後、イエズス会がローマ教皇庁によって解散させられたこと を受け、1773年に学校と礼拝堂の閉鎖を命じられるまで、ジェイルレーンに留まった。その後モロニーはダブリンに移り、世俗の司祭として働いた。 リムリックの学校は、キャッスル当局と英国政府の努力にもかかわらず、プロテスタント改革、クロムウェルによる侵略、ウィリアム朝戦争、その後の刑罰法を生き延びた。最終的に閉鎖に追い込まれたのは、宗教や信仰上の理由ではなく、イエズス会の政治的な困難が原因であった。 1814年にイエズス会が復活すると、キルデアとダブリンに設立した学校を皮切りに、徐々に国内各地に学校を再開設していった。1859年にはリムリック司教ジョン・ライアンの招きに応じてリムリックに戻り、同年にゴールウェイにも学校を再開設した。 |

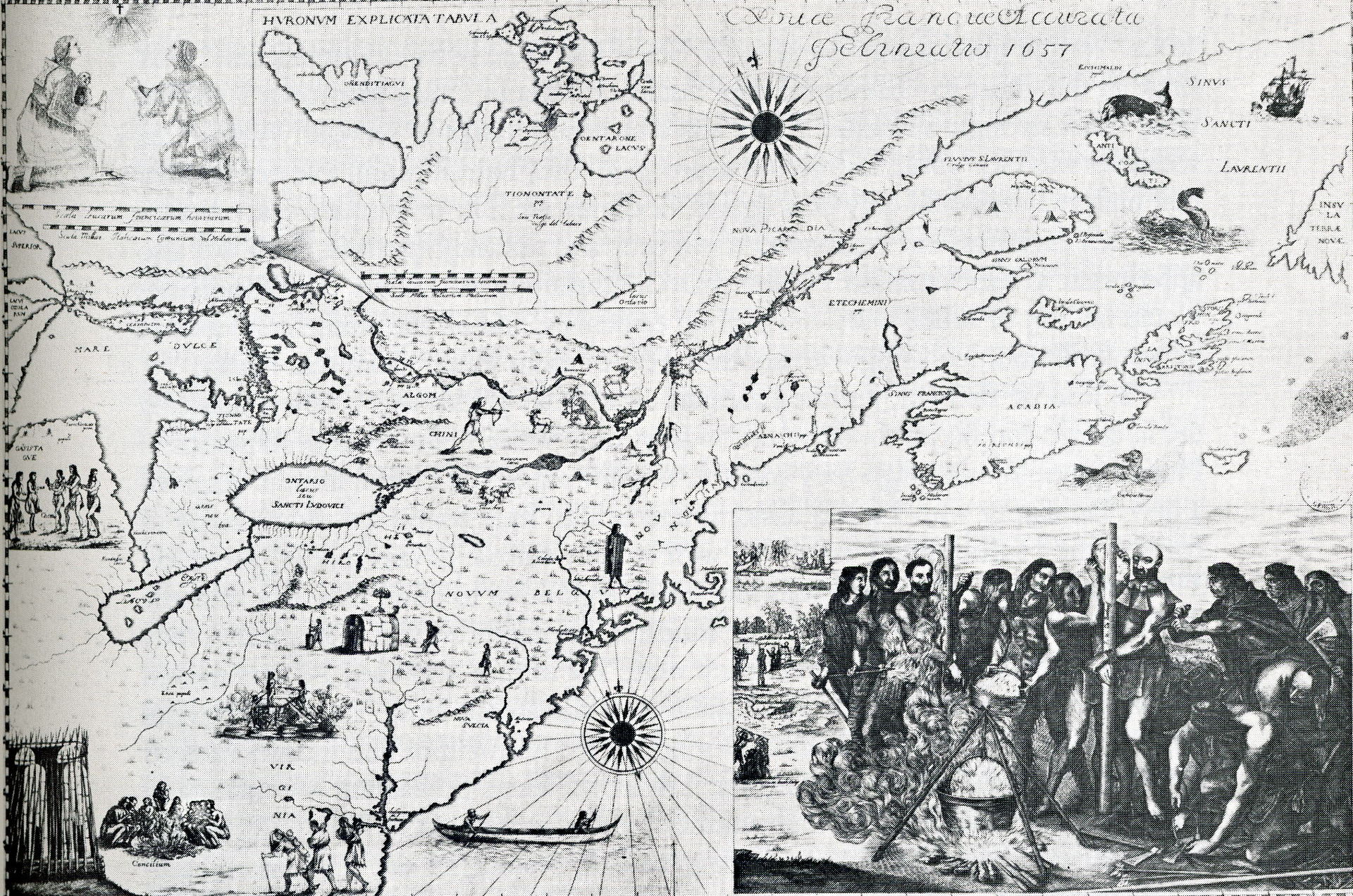

| Canada See also: Jesuit missions in North America  Bressani map of 1657 depicting the martyrdom of Jean de Brébeuf During the French colonisation of New France in the 17th century, Jesuits played an active role in North America. Samuel de Champlain established the foundations of the French colony at Québec in 1608. The native tribes that inhabited modern day Ontario, Québec, and the areas around Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay were the Montagnais, the Algonquins, and the Huron.[73] Champlain believed that these had souls to be saved, so in 1614 he obtained the Recollects, a reform branch of the Franciscans in France, to convert the native inhabitants.[74] In 1624 the French Recollects realized the magnitude of their task[75] and sent a delegate to France to invite the Society of Jesus to help with this mission. The invitation was accepted, and Jesuits Jean de Brébeuf, Énemond Massé, and Charles Lalemant arrived in Quebec in 1625.[76] Lalemant is considered to have been the first author of one of the Jesuit Relations of New France, which chronicled their evangelization during the 17th century. The Jesuits became involved in the Huron mission in 1626 and lived among the Huron peoples. Brébeuf learned the native language and created the first Huron language dictionary. Outside conflict forced the Jesuits to leave New France in 1629 when Quebec was surrendered to the English. In 1632, Quebec was returned to the French under the Treaty of Saint Germain-en-Laye and the Jesuits returned to the Huron territory.[77] After a series of epidemics of European-introduced diseases beginning in 1634, some Huron began to mistrust the Jesuits and accused them of being sorcerers casting spells from their books.[78] In 1639, Jesuit Jerome Lalemant decided that the missionaries among the Hurons needed a local residence and established Sainte-Marie near present-day Midland, Ontario, which was meant to be a replica of European society.[79] It became the Jesuit headquarters and an important part of Canadian history. Throughout most of the 1640s the Jesuits had modest success, establishing five chapels in Huronia and baptising more than one thousand Huron out of a population which may have exceeded 20,000 before the epidemics of the 1630s.[80] However, the Iroquois of New York, rivals of the Hurons, grew jealous of the Hurons' wealth and control of the fur trade system and attacked Huron villages in 1648. They killed missionaries and burned villages, and the Hurons scattered. Both de Brébeuf and Gabriel Lalemant were tortured and killed in the Iroquois raids; for this, they have been canonized as martyrs in the Catholic Church.[81] The Jesuit Paul Ragueneau burned down Sainte-Marie instead of allowing the Iroquois the satisfaction of destroying it. By late June 1649, the French and some Christian Hurons built Sainte-Marie II on Christian Island (Isle de Saint-Joseph). However, facing starvation, lack of supplies, and constant threats of Iroquois attack, the small Sainte-Marie II was abandoned in June 1650; the remaining Christian Hurons and Jesuits departed for Quebec and Ottawa.[81] As a result of the Iroquois raids and outbreak of disease, many missionaries, traders, and soldiers died.[82] Today, the Huron tribe, also known as the Wyandot, have a First Nations reserve in Quebec, Canada, and three major settlements in the United States.[83] After the collapse of the Huron nation, the Jesuits undertook the task of converting the Iroquois, something they had attempted in 1642 with little success. In 1653 the Iroquois nation had a fallout with the Dutch. They then signed a peace treaty with the French and a mission was established. The Iroquois soon turned on the French again. In 1658, the Jesuits were having little success and were under constant threat of being tortured or killed,[82] but continued their effort until 1687 when they abandoned their permanent posts in the Iroquois homeland.[84] By 1700, Jesuits turned to maintaining Quebec, Montreal, and Ottawa without establishing new posts.[85] During the Seven Years' War, Quebec was captured by the British in 1759 and New France came under British control. The British barred the immigration of more Jesuits to New France, and by 1763, only 21 Jesuits were stationed in New France. By 1773 only 11 Jesuits remained. During the same year the British crown declared that the Society of Jesus in New France was dissolved.[86] The dissolution of the order left in place substantial estates and investments, amounting to an income of approximately £5,000 a year, and the Council for the Affairs of the Province of Quebec, later succeeded by the Legislative Assembly of Quebec, assumed the task of allocating the funds to suitable recipients, chiefly schools.[87] The Jesuit mission in Quebec was re-established in 1842. There were a number of Jesuit colleges founded in the decades following; one of these colleges evolved into present-day Laval University.[88] |

カナダ 関連項目:北米におけるイエズス会の宣教活動  1657年のブレッサーニの地図には、ジャン・ド・ブレブーフの殉教が描かれている 17世紀にフランスがヌーベルフランスを植民地化していた時代、イエズス会は北米で積極的な役割を果たした。サミュエル・ド・シャンプランは1608年に ケベックのフランス植民地の基礎を築いた。現代のオンタリオ州、ケベック州、およびシムコー湖とジョージアン湾周辺の地域に居住していた先住民族は、モン タニー族、アルゴンキン族、ヒューロン族であった。[73] シャンプランは、これらの人々には救われるべき魂があると信じていたため、1614年に先住民の改宗を目的として、フランスのフランシスコ会の改革派であ るレコレクト会を獲得した。[74] 1624年、フランスのレコレクト会は 彼らの任務の重大さに気づき[75]、この任務を手助けしてもらうためにイエズス会にフランスから代表を送った。この招待は受け入れられ、イエズス会の ジャン・ド・ブレブーフ、エノモン・マッセ、シャルル・ラレマンの3名が1625年にケベックに到着した。[76] ラレマンは、17世紀における彼らの布教活動を記録した『ヌーベルフランス・イエズス会年報』の著者であると考えられている。 イエズス会は1626年にヒューロン族の布教活動に関わり、ヒューロン族の間に住み始めた。ブレブーフは先住民の言葉を学び、ヒューロン族の最初の言語辞 書を作成した。1629年、ケベックがイギリスに降伏したことにより、外部の紛争が原因でイエズス会はヌーベルフランスを去らざるを得なくなった。 1632年、サン・ジェルマン・アン・レー条約によりケベックはフランスに返還され、イエズス会はヒューロン族の領地に戻った。[77] 1634年から始まったヨーロッパから持ち込まれた病気の流行の連続の後、一部のヒューロン族はイエズス会を疑うようになり、彼らが魔術師であり、書物か ら呪文を唱えていると非難した。[78] 1639年、イエズス会のジェローム・ラレマントは、ヒューロン族の宣教師たちに現地の住居が必要だと判断し、ヨーロッパ社会の模倣となるよう、現在のオ ンタリオ州ミッドランド近郊にサント=マリーを設立した。1640年代の大半を通じて、イエズス会はささやかな成功を収め、ヒューロニアに5つの礼拝堂を 設立し、1630年代の疫病流行以前には2万人を超えていたであろう人口のうち、1000人以上のヒューロン族を洗礼した。[80] しかし、ニューヨークのイロコイ族は、ヒューロン族の富と毛皮貿易の支配に嫉妬し、1648年にヒューロン族の村を襲撃した 。宣教師を殺害し、村々を焼き払い、ヒューロン族は散り散りになった。ド・ブレブフとガブリエル・ラレマンの両名は、イロコイ族の襲撃で拷問を受け、殺害 された。このため、2人はカトリック教会で殉教者として列聖されている。 イエズス会のポール・ラゲノーは、イロコイ族に満足感を与えるためにではなく、サント=マリーを焼き払った。1649年6月下旬、フランス人と一部のキリ スト教徒のヒューロン族は、クリスチャン島(セント・ジョセフ島)にサント=マリーIIを建設した。しかし、飢餓、物資不足、そして絶え間ないイロコイ族 の攻撃の脅威に直面し、小さなサント・マリーIIは1650年6月に放棄され、残ったクリスチャン・ヒューロン族とイエズス会の宣教師たちはケベックとオ タワへと去っていった。[81] イロコイ族の襲撃と伝染病の流行により、多くの宣教師、商人、兵士が命を落とした。[82] 今日、ヒューロン族はワイアンドット族とも呼ばれ、カナダのケベック州に先住民保留地を 、カナダ、および米国に3つの主要な入植地がある。 ヒューロン族が崩壊した後、イエズス会は1642年にほとんど成功を収めることなく試みたイロコイ族の改宗を任務とした。1653年、イロコイ族はオラン ダと対立した。その後、フランスと和平条約を締結し、宣教所が設立された。イロコイ族はすぐにフランスに背を向けた。1658年には、イエズス会はほとん ど成功を収めることができず、拷問や殺害の脅威に常にさらされていたが、[82] 1687年まで活動を継続し、その年にイロコイ族の故郷における恒久的な拠点を放棄した。[84] 1700年までに、イエズス会は新たな拠点を開設することなく、ケベック、モントリオール、オタワの維持に専念するようになった。[85] 七年戦争中、1759年にケベックはイギリス軍に占領され、ヌーベルフランスはイギリスの支配下に入った。イギリスはヌーベルフランスへのイエズス会の移 住を禁止し、1763年にはヌーベルフランスに駐在するイエズス会士は21人となった。1773年にはイエズス会士は11人しか残っていなかった。同年、 英国王は、ヌーベルフランスにおけるイエズス会は解散したと宣言した。[86] 解散後も、相当な不動産や投資が残され、年間およそ5,000ポンドの収入があった。ケベック地方管区評議会(後にケベック立法議会が後を継いだ)は、主に学校への資金配分を適任者に割り当てるという任務を引き受けた。 ケベックのイエズス会伝道所は1842年に再建された。その後数十年の間に、イエズス会系の大学がいくつか設立され、そのうちの1校が現在のラヴァル大学へと発展した。[88] |

| United States Main article: Jesuits in the United States In the United States, the order is best known for its missions to the Native Americans in the early 17th century, its network of colleges and universities, and (in Europe before 1773) its politically conservative role in the Catholic Counter Reformation. The Society of Jesus, in the United States, is organized into geographic provinces, each of which being headed by a provincial superior. Today, there are four Jesuit provinces operating in the United States: the USA East, USA Central and Southern, USA Midwest, and USA West Provinces. At their height, there were ten provinces. Though there had been mergers in the past, a major reorganization of the provinces began in early 21st century, with the aim of consolidating into four provinces by 2020.[89] |

アメリカ合衆国 詳細は「アメリカ合衆国のイエズス会」を参照 アメリカ合衆国では、17世紀初頭のネイティブアメリカンへの布教活動、大学ネットワーク、および(1773年以前のヨーロッパにおける)カトリックの対抗宗教改革における政治的に保守的な役割で最もよく知られている。 アメリカ合衆国のイエズス会は、地理的な管区に組織化されており、それぞれが管区長によって統括されている。現在、米国では4つのイエズス会管区が活動し ている。すなわち、米国東部、米国中部および南部、米国中西部、米国西部の各管区である。最盛期には10の管区があった。過去にも合併はあったが、 2020年までに4つの管区に統合することを目的として、21世紀初頭に管区の大規模な再編成が開始された。[89] |

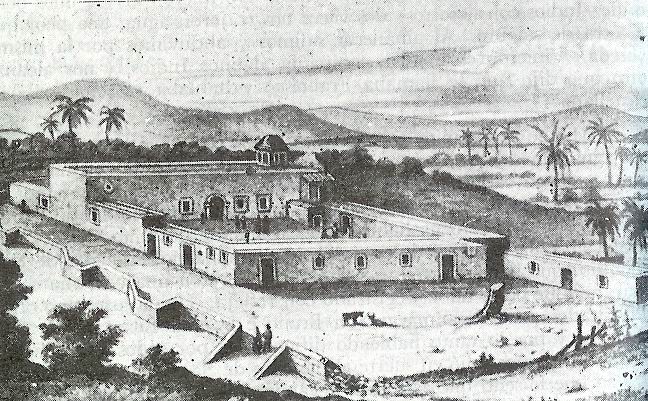

| Ecuador The Church of the Society of Jesus (Spanish: La Iglesia de la Compañía de Jesús), known colloquially as la Compañía, is a Jesuit church in Quito, Ecuador. It is among the best-known churches in Quito because of its large central nave, which is profusely decorated with gold leaf, gilded plaster and wood carvings. Inspired by two Roman Jesuit churches – the Chiesa del Gesù (1580) and the Chiesa di Sant'Ignazio di Loyola (1650) – la Compañía is one of the most significant works of Spanish Baroque architecture in South America and Quito's most ornate church. Over the 160 years of its construction, the architects of la Compañía incorporated elements of four architectural styles, although the Baroque is the most prominent. Mudéjar (Moorish) influence is seen in the geometrical figures on the pillars; the Churrigueresque characterizes much of the ornate decoration, especially in the interior walls; finally the Neoclassical style adorns the Chapel of Saint Mariana de Jesús (in early years a winery). |

エクアドル イエズス会教会(スペイン語:ラ・イグレシア・デ・ラ・コンピア・デ・ヘスス)は、俗にラ・コンピアと呼ばれ、エクアドルのキトにあるイエズス会の教会で ある。 中央の身廊が広く、金箔や金メッキの漆喰、木彫りの装飾がふんだんに施されているため、キトで最も有名な教会のひとつである。ローマのイエズス会教会であ るキエーザ・デル・ジェズ(1580年)とキエーザ・ディ・サンティグナツィオ・ディ・ロヨラ(1650年)に着想を得たラ・コンパニアは、南米における スペイン・バロック建築の最も重要な作品のひとつであり、キトで最も装飾的な教会である。 160年以上にわたる建設期間中、ラ・コンパニアの建築家たちは4つの建築様式の要素を取り入れたが、最も顕著なのはバロック様式である。ムデハル様式 (ムーア様式)の影響は柱の幾何学的な図形に見られ、シュリーゲル様式は特に内壁の装飾の多くに特徴的である。最後に、ネオクラシック様式はサンタ・マリ アナ・デ・ヘスス礼拝堂(初期はワイン醸造所)を飾っている。 |

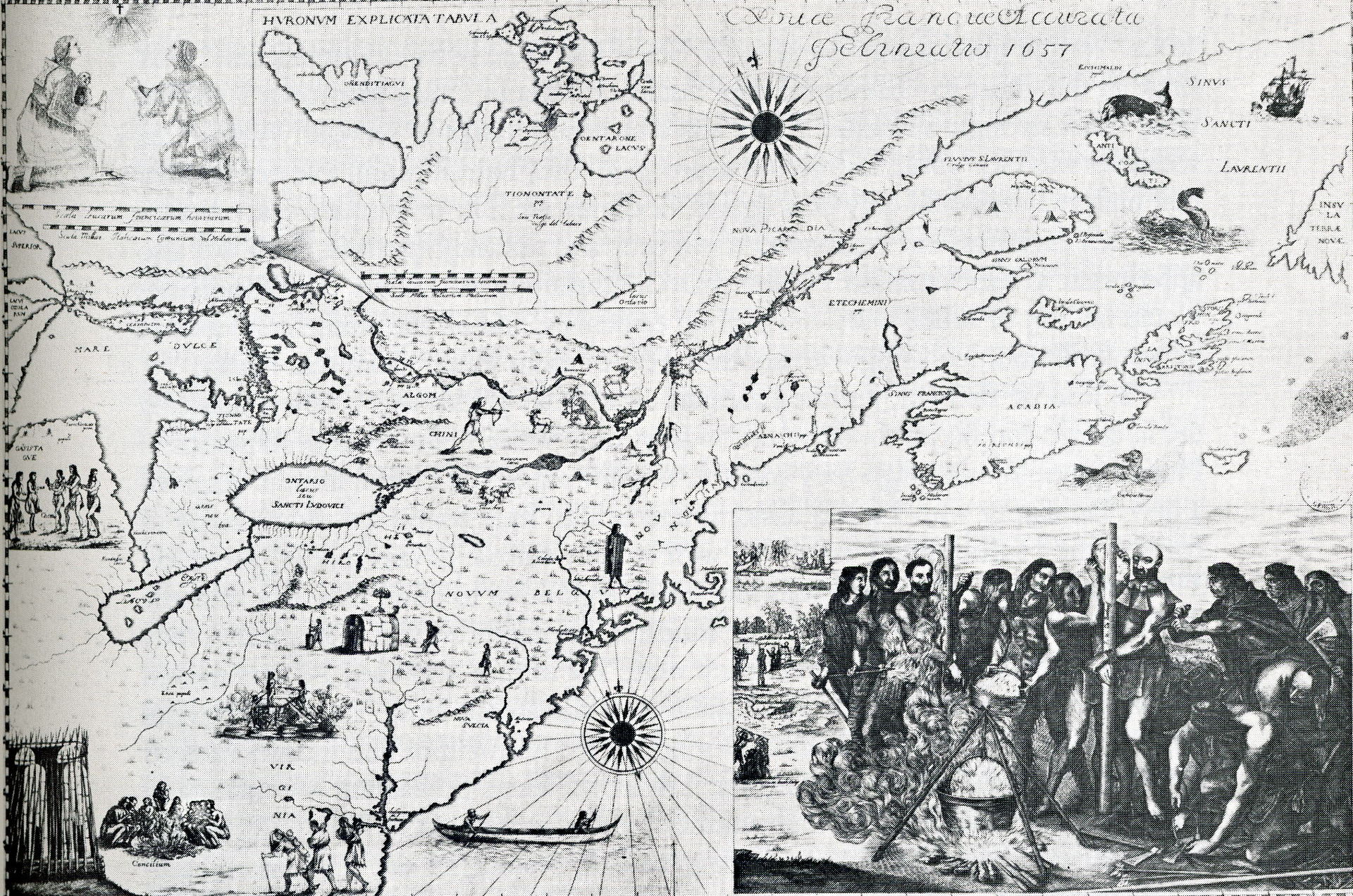

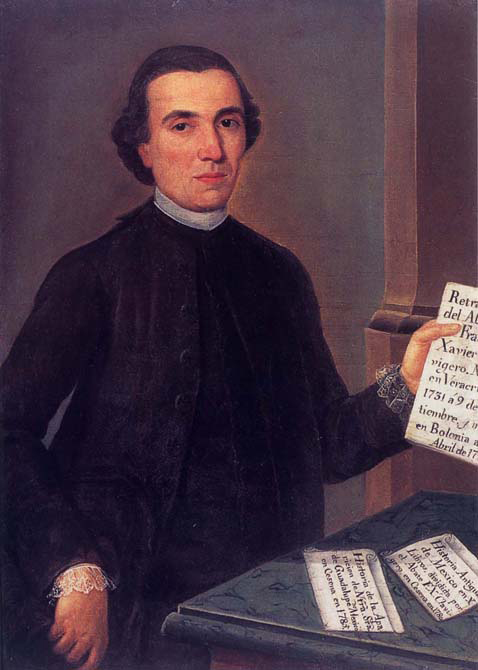

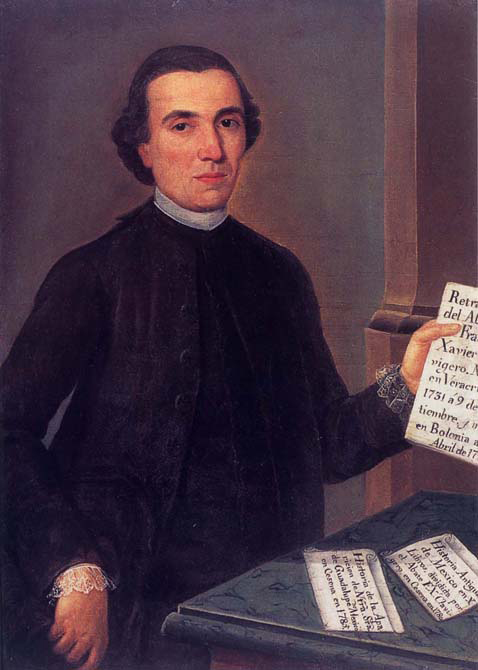

Mexico Misión de Nuestra Señora de Loreto Conchó in the 18th century, the first permanent Jesuit mission in Baja California, established by Juan María de Salvatierra in 1697  Main altar of the Jesuit colegio in Tepozotlan, now the Museo Nacional del Virreinato  Mexican-born Jesuit Francisco Clavijero (1731–1787) wrote an important history of Mexico. The Jesuits in New Spain distinguished themselves in several ways. They had high standards for acceptance to the order and many years of training. They attracted the patronage of elite families whose sons they educated in rigorous newly founded Jesuit colegios ("colleges"), including Colegio de San Pedro y San Pablo, Colegio de San Ildefonso, and the Colegio de San Francisco Javier, Tepozotlan. Those same elite families hoped that a son with a vocation to the priesthood would be accepted as a Jesuit. Jesuits were also zealous in evangelization of the indigenous, particularly on the northern frontiers. To support their colegios and members of the Society of Jesus, the Jesuits acquired landed estates that were run with the best-practices for generating income in that era. A number of these haciendas were donated by wealthy elites. The donation of a hacienda to the Jesuits was the spark igniting a conflict between 17th-century Bishop Don Juan de Palafox of Puebla and the Jesuit colegio in that city. Since the Jesuits resisted paying the tithe on their estates, this donation effectively took revenue out of the church hierarchy's pockets by removing it from the tithe rolls.[90] Many of Jesuit haciendas were huge, with Palafox asserting that just two colleges owned 300,000 head of sheep, whose wool was transformed locally in Puebla to cloth; six sugar plantations worth a million pesos and generating an income of 100,000 pesos.[90] The immense Jesuit hacienda of Santa Lucía produced pulque, the alcoholic drink made from fermented agave sap whose main consumers were the lower classes and Indigenous peoples in Spanish cities. Although most haciendas had a free work force of permanent or seasonal labourers, the Jesuit haciendas in Mexico had a significant number of enslaved people of African descent.[91] The Jesuits operated their properties as an integrated unit with the larger Jesuit order; thus revenues from haciendas funded their colegios. Jesuits did significantly expand missions to the Indigenous in the northern frontier area and a number were martyred, but the crown supported those missions.[90] Mendicant orders that had real estate were less economically integrated, so that some individual houses were wealthy while others struggled economically. The Franciscans, who were founded as an order embracing poverty, did not accumulate real estate, unlike the Augustinians and Dominicans in Mexico. The Jesuits engaged in conflict with the episcopal hierarchy over the question of payment of tithes, the ten percent tax on agriculture levied on landed estates for support of the church hierarchy from bishops and cathedral chapters to parish priests. Since the Jesuits were the largest religious order holding real estate, surpassing the Dominicans and Augustinians who had accumulated significant property, this was no small matter.[90] They argued that they were exempt, due to special pontifical privileges.[92] Bishop De Palafox took on the Jesuits over this matter and was so soundly defeated that he was recalled to Spain, where he became the bishop of the minor Diocese of Osma. As elsewhere in the Spanish empire, the Jesuits were expelled from Mexico in 1767. Their haciendas were sold off and their colegios and missions in Baja California were taken over by other orders.[93] Exiled Mexican-born Jesuit Francisco Javier Clavijero wrote an important history of Mexico while in Italy, a basis for creole patriotism. Andrés Cavo also wrote an important text on Mexican history that Carlos María de Bustamante published in the early 19th century.[94] An earlier Jesuit who wrote about the history of Mexico was Diego Luis de Motezuma (1619–99), a descendant of the Aztec monarchs of Tenochtitlan. Motezuma's Corona mexicana, o Historia de los nueve Motezumas was completed in 1696. He "aimed to show that Mexican emperors were a legitimate dynasty in the 17th-century in the European sense".[95][96] The Jesuits were allowed to return to Mexico in 1840 when General Antonio López de Santa Anna was once more president of Mexico. Their re-introduction to Mexico was "to assist in the education of the poorer classes and much of their property was restored to them".[97] |

メキシコ 18世紀のロレト・コンチョーの聖母ミッションは、1697年にフアン・マリア・デ・サルバティエラが設立した、バハ・カリフォルニア初のイエズス会の常設ミッションである  テポソトランのイエズス会コレヒオの主祭壇。現在は国立副王領博物館となっている  メキシコ生まれのイエズス会員フランシスコ・クラヴィヘロ(1731年~1787年)は、メキシコの歴史に関する重要な著作を残した。 ヌエバ・エスパーニャのイエズス会員は、いくつかの点で際立っていた。入会には高い基準が設けられ、長年の厳しい訓練が課された。彼らは、厳格なイエズス 会が新しく設立したコレヒオ(「大学」)で息子たちを教育するエリート家庭の支援を集めた。その中には、コレヒオ・デ・サン・ペドロ・イ・サン・パブロ、 コレヒオ・デ・サン・イルデフォンソ、コレヒオ・デ・サン・フランシスコ・ハビエル、テポソトランなどが含まれる。同じエリート家庭は、聖職者になること を天職とする息子たちがイエズス会に受け入れられることを望んでいた。イエズス会は、特に北部の国境地域における先住民への布教にも熱心に取り組んだ。 イエズス会の学校と会員を支援するために、イエズス会は当時としては最高の収益を生み出す方法で運営されていた広大な土地を手に入れた。これらの土地の多 くは富裕なエリート層から寄贈されたものだった。イエズス会へのハシエンダの寄付は、17世紀のプエブラのドン・ファン・デ・パラフォックス司教とイエズ ス会のコレヒオの間の対立の火種となった。イエズス会は所有地に対する什分の一税の支払いを拒否したため、この寄付は事実上、什分の一税の対象から外すこ とで教会の収入源を断つこととなった。 イエズス会のハシエンダの多くは巨大で、パラフォックスは、わずか2つのカレッジが30万頭の羊を所有しており、その羊毛はプエブラで布に加工されていた と主張している。また、6つの砂糖プランテーションは100万ペソの価値があり、10万ペソの収入を生み出していた。[90] 広大なイエズス会のハシエンダであるサンタ・ルシアは、リュウゼツランの樹液を発酵させて作るアルコール飲料であるプルケを生産していた。プルケの主な消 費者はスペインの都市の下層階級や先住民であった 。ほとんどの農園では、常勤または季節労働者の無料労働力を確保していたが、メキシコのイエズス会の農園では、アフリカ系の人々を奴隷として多数抱えてい た。 イエズス会は、その所有地をイエズス会全体と統合された単位として運営していたため、ハシエンダからの収益がコレヒオの資金となっていた。イエズス会は北 部の辺境地域における先住民への布教を大幅に拡大し、多くの殉教者を出したが、王権はこれらの布教を支援した。托鉢修道会で不動産を所有していたものは経 済的に統合されていなかったため、裕福な個人宅もあれば、経済的に苦しいところもあった。清貧を旨とする修道会として創設されたフランシスコ会は、メキシ コのアウグスティノ会やドミニコ会とは異なり、不動産を蓄積することはなかった。 イエズス会は、教会のヒエラルキーを支えるために、土地所有者に課せられた農業税である什分の一税の支払いについて、司教階層と対立した。イエズス会は、 ドミニコ会やアウグスティノ会といった多くの財産を所有する修道会を凌ぎ、最大の不動産所有者であったため、これは些細な問題ではなかった。[90] 彼らは、教皇の特別な特権により免除されるべきだと主張した。[92] デ・パラフォックス司教は、この問題でイエズス会と対立し、完膚なきまでに敗北したためスペインに召還され、オスマ小教区の司教となった。 スペイン帝国の他の地域と同様に、イエズス会は1767年にメキシコから追放された。彼らの大農園は売却され、バハ・カリフォルニアのコレヒオと伝道所は 他の修道会に引き継がれた。[93] メキシコ生まれで追放されたイエズス会のフランシスコ・ハビエル・クラビヘロは、イタリアに滞在中にメキシコの重要な歴史を書き、それがクレオール人の愛 国心の基礎となった。アンドレス・カボもまた、19世紀初頭にカルロス・マリア・デ・ブスタマンテが出版したメキシコの歴史に関する重要な文献を著した。 [94] メキシコの歴史について著述した初期のイエズス会員には、アステカのテノチティトラン王家の末裔であるディエゴ・ルイス・デ・モテスマ(1619年- 1699年)がいる。モテズマの著書『メキシコの王冠、またはモテズマ9世の歴史』は1696年に完成した。彼は「メキシコ皇帝が17世紀のヨーロッパ的 な意味での正統な王朝であったことを示すことを目的としていた」[95][96]。 イエズス会は、1840年にアントニオ・ロペス・デ・サンタ・アナ将軍が再びメキシコの大統領に就任した際に、メキシコへの再入国が許可された。彼らのメキシコへの再導入は、「貧困層の教育を支援するためであり、彼らの財産の多くは彼らに返還された」[97]。 |

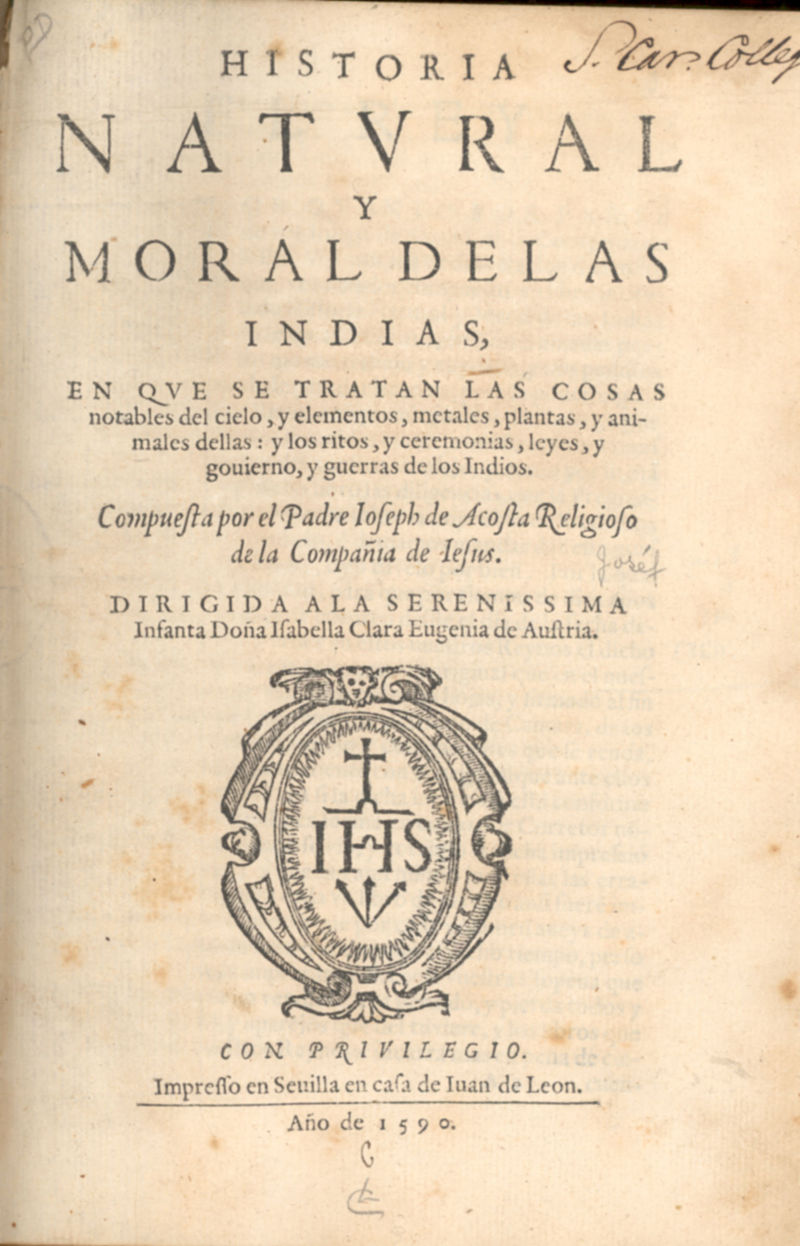

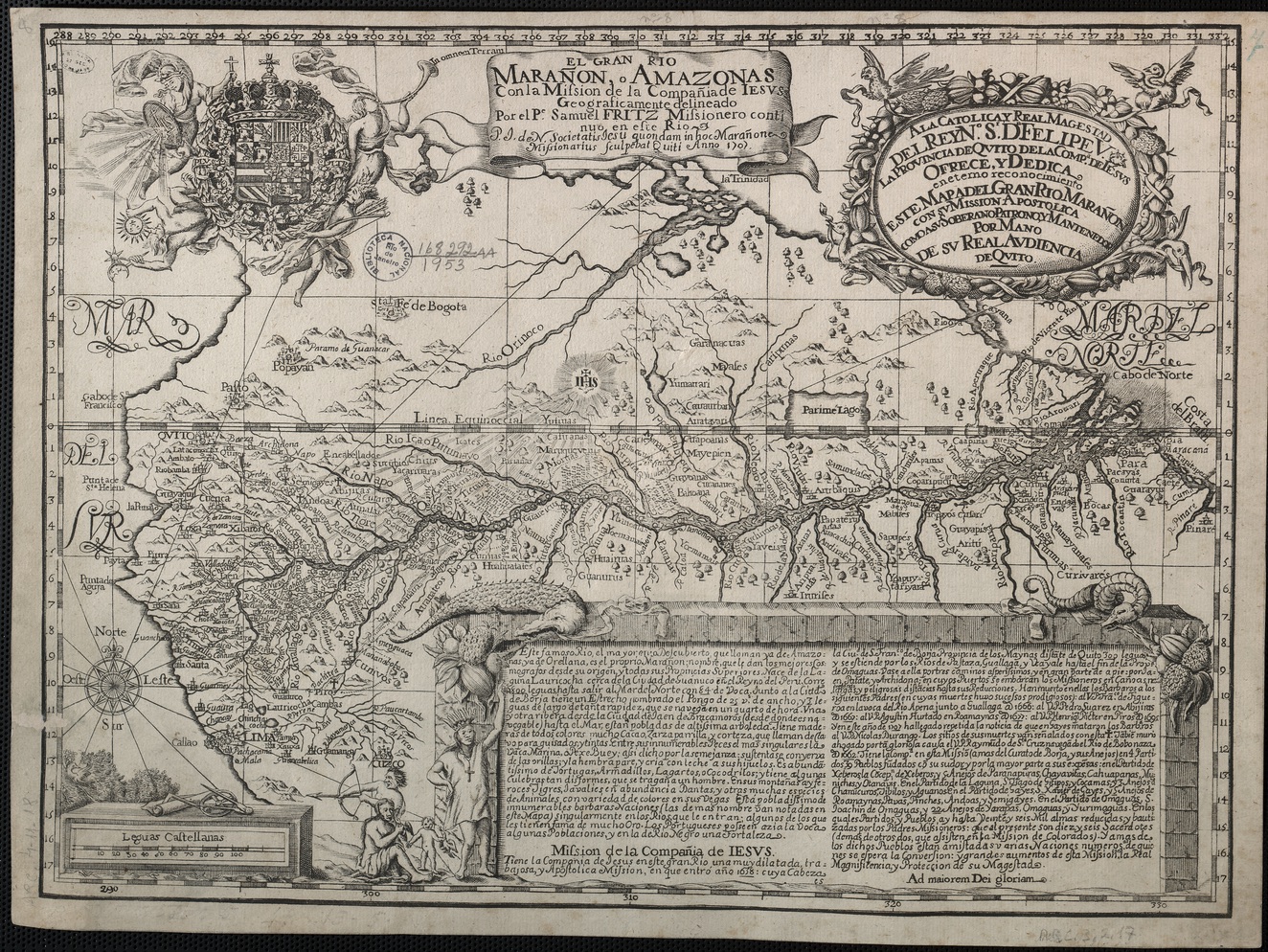

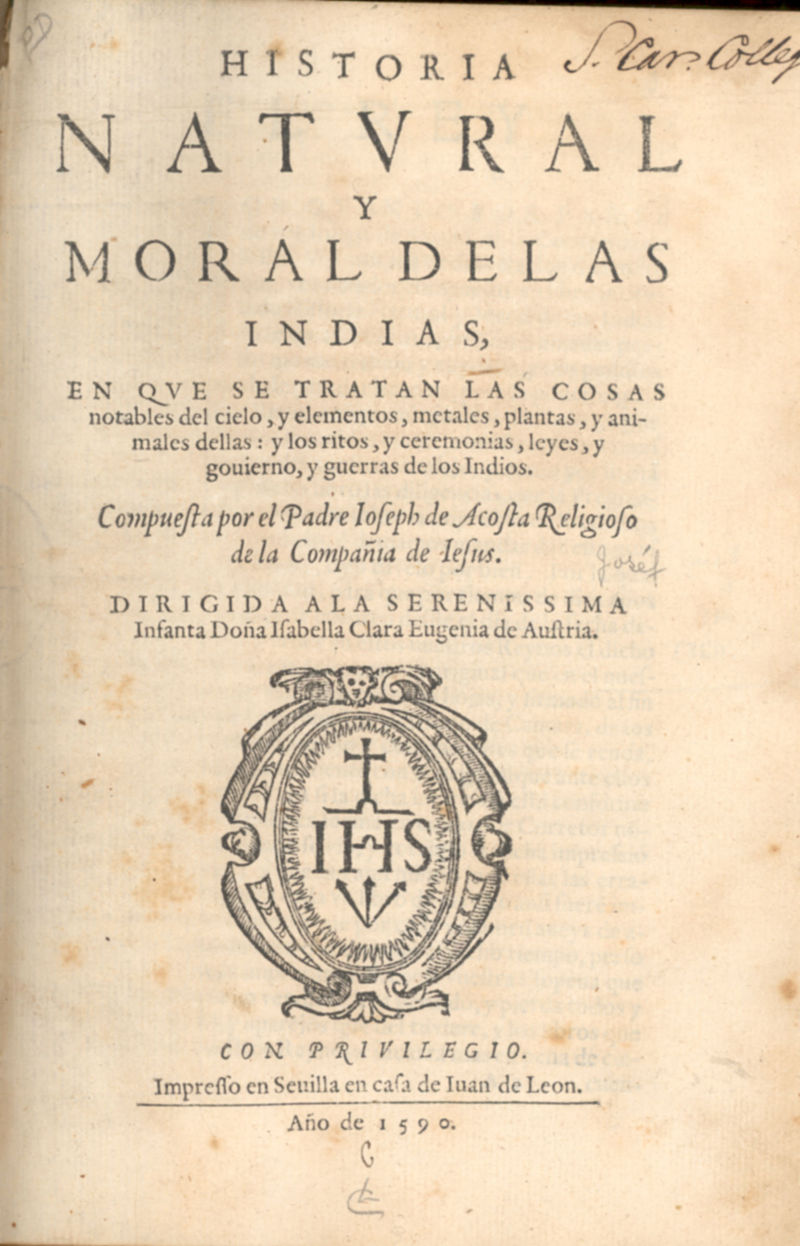

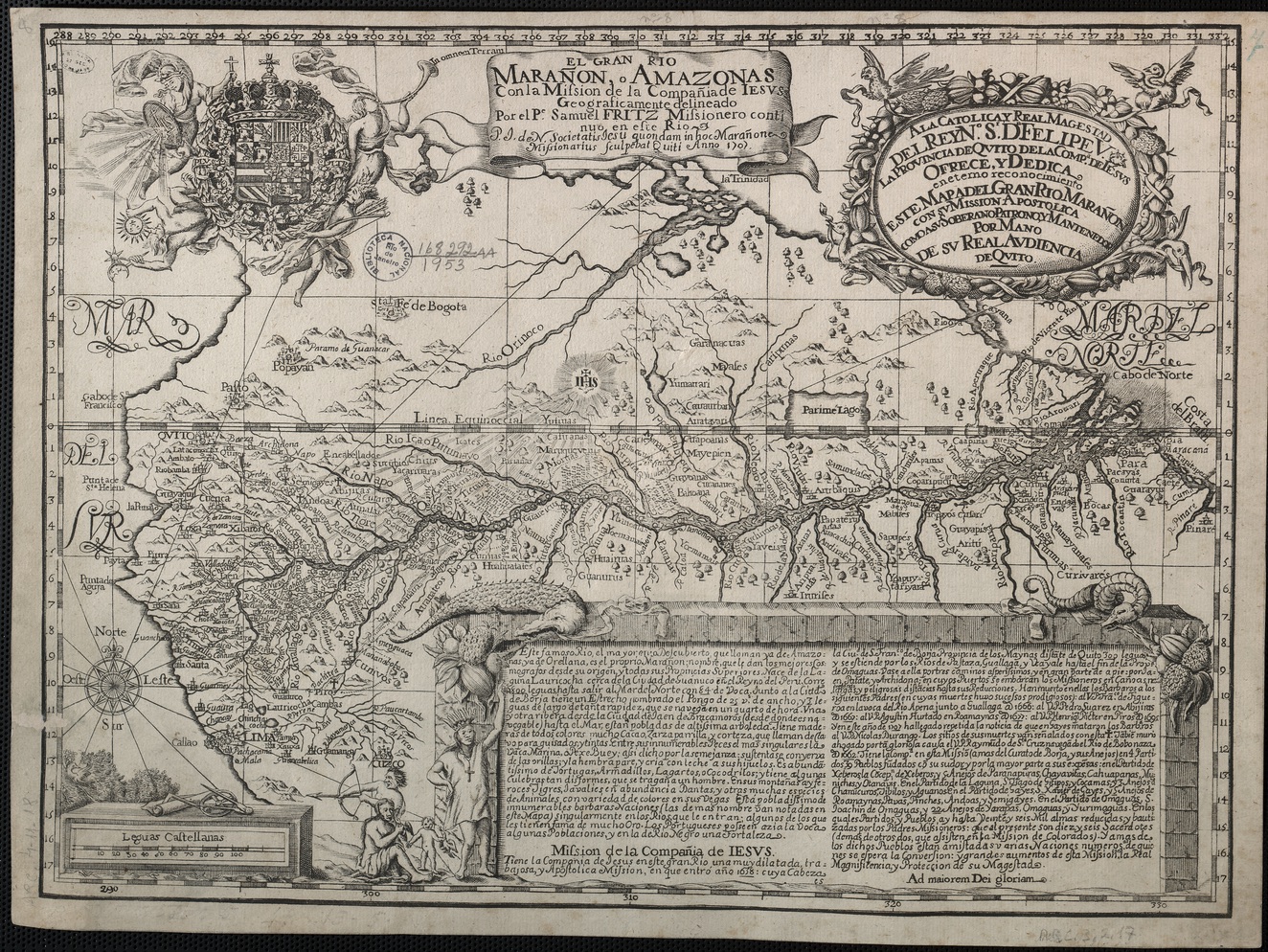

| Northern Spanish America This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  Acosta's Historia natural y moral de las Indias (1590) text on the Americas The Jesuits arrived in the Viceroyalty of Peru by 1571; it was a key area of the Spanish Empire, with not only dense indigenous populations but also huge deposits of silver at Potosí. A major figure in the first wave of Jesuits was José de Acosta (1540–1600), whose book Historia natural y moral de las Indias (1590) introduced Europeans to Spain's American empire via fluid prose and keen observation and explanation, based on 15 years in Peru and some time in New Spain (Mexico). Viceroy of Peru Don Francisco de Toledo urged the Jesuits to evangelize the Indigenous peoples of Peru, wanting to put them in charge of parishes, but Acosta adhered to the Jesuit position that they were not subject to the jurisdiction of bishops and to catechize in Indigenous parishes would bring them into conflict with the bishops. For that reason, the Jesuits in Peru focused on education of elite men rather than the indigenous populations.[98]  Peter Claver ministering to African slaves at Cartagena To minister to newly arrived African slaves, Alonso de Sandoval (1576–1651) worked at the port of Cartagena de Indias. Sandoval wrote about this ministry in De instauranda Aethiopum salute (1627),[99] describing how he and his assistant Peter Claver, later canonized, met slave transport ships in the harbour, went below decks where 300–600 slaves were chained, and gave physical aid with water, while introducing the Africans to Christianity. In his treatise, he did not condemn slavery or the ill-treatment of slaves, but sought to instruct fellow Jesuits to this ministry and describe how he catechized the slaves.[100] Rafael Ferrer was the first Jesuit of Quito to explore and found missions in the upper Amazon regions of South America from 1602 to 1610, which belonged to the Audiencia (high court) of Quito that was a part of the Viceroyalty of Peru until it was transferred to the newly created Viceroyalty of New Granada in 1717. In 1602, Ferrer began to explore the Aguarico, Napo, and Marañon rivers (Sucumbios region, in what is today Ecuador and Peru), and between 1604 and 1605 set up missions among the Cofane natives. He was martyred by an apostate native in 1610. In 1639, the Audiencia of Quito organized an expedition to renew its exploration of the Amazon river and the Quito Jesuit (Jesuita Quiteño) Cristóbal de Acuña was a part of this expedition. The expedition disembarked from the Napo river 16 February 1639 and arrived in what is today Pará, Brazil, on the banks of the Amazon river on 12 December 1639. In 1641, Acuña published in Madrid a memoir of his expedition to the Amazon river entitled Nuevo Descubrimiento del gran rio de las Amazonas, which for academics became a fundamental reference on the Amazon region. In 1637, the Jesuits Gaspar Cugia and Lucas de la Cueva from Quito began establishing the Mainas missions in territories on the banks of the Marañón River, around the Pongo de Manseriche region, close to the Spanish settlement of Borja. Between 1637 and 1652 there were 14 missions established along the Marañón River and its southern tributaries, the Huallaga and the Ucayali rivers. Jesuit de la Cueva and Raimundo de Santacruz opened up two new routes of communication with Quito, through the Pastaza and Napo rivers.  Samuel Fritz's 1707 map showing the Amazon and the Orinoco Between 1637 and 1715, Samuel Fritz founded 38 missions along the length of the Amazon river, between the Napo and Negro rivers, that were called the Omagua Missions. These missions were continually attacked by the Brazilian Bandeirantes beginning in the year 1705. In 1768, the only Omagua mission that was left was San Joaquin de Omaguas, since it had been moved to a new location on the Napo river away from the Bandeirantes. In the immense territory of Maynas, the Jesuits of Quito made contact with a number of indigenous tribes which spoke 40 different languages, and founded a total of 173 Jesuit missions encompassing 150,000 inhabitants. Because of the constant epidemics (smallpox and measles) and warfare with other tribes and the Bandeirantes, the total number of Jesuit Missions were reduced to 40 by 1744. The Jesuit missions offered the Indigenous people Christianity, iron tools, and a small degree of protection from the slavers and the colonists. In exchange, the Indigenous had to submit to Jesuit discipline and adopt, at least superficially, a lifestyle foreign to their experience. The population of the missions was only sustained by frequent expeditions into the jungle by Jesuits, soldiers, and Christian Indians to capture Indigenous people and force them to return or to settle in the missions.[101] At the time when the Jesuits were expelled from Spanish America in 1767, the Jesuits registered 36 missions run by 25 Jesuits in the Audiencia of Quito – 6 in the Napo and Aguarico Missions and 19 in the Pastaza and Iquitos Missions, with a population at 20,000 inhabitants.[102] |

スペイン領北アメリカ この節は検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分です。この記事を改善するために、この節の信頼できる情報源を追加してください。出典の 明記されていない内容は、異議を申し立てられ、削除される場合があります。 (2020年8月) (Learn how and when to remove this message)  アコスタ著『アメリカ大陸の自然と道徳史』(1590年)のテキスト イエズス会は1571年までにペルー副王領に到着した。そこはスペイン帝国の重要な地域であり、先住民の人口が密集していただけでなく、ポトシには膨大な 量の銀が埋蔵されていた。イエズス会の第一派の主要人物はホセ・デ・アコスタ(1540年-1600年)で、著書『Historia natural y moral de las Indias』(1590年)では、流麗な散文と鋭い観察と説明により、ペルーでの15年間の滞在とヌエバ・エスパーニャ(メキシコ)での滞在を基に、 ヨーロッパの人々にスペインのアメリカ帝国を紹介した。ペルー総督フランシスコ・デ・トレドは、イエズス会にペルーの先住民への布教を促し、彼らを教区の 責任者にしようとしたが、アコスタはイエズス会の立場を固守し、先住民は司教の管轄下にはなく、先住民の教区でカテキズムを行うことは司教との対立を招く ことになると考えた。そのため、ペルーのイエズス会は先住民よりもエリート男性の教育に重点を置いた。  カルタヘナでアフリカ人奴隷に奉仕するペドロ・クラヴェル 新たに到着したアフリカ人奴隷に奉仕するために、アルフォンソ・デ・サンドバル(1576年-1651年)はカルタヘナ・デ・インディアス港で働いた。サ ンドバルは、この奉仕活動について『De instauranda Aethiopum salute』(1627年)に記し、後に列聖されることになる彼の助手ペドロ・クラヴェルとともに港で奴隷輸送船に遭遇し、甲板の下に降りて 300~600人の奴隷が鎖につながれているのを見つけ、彼らに水を与えて身体的援助を行い、アフリカ人にキリスト教を紹介したことを述べている。彼の論 文では、奴隷制度や奴隷への虐待を非難することはなかったが、イエズス会の仲間たちにこの奉仕活動について教えることを求め、また、奴隷たちにどのように して信仰を教えたかを説明しようとした。 ラファエル・フェレールは、1602年から1610年にかけて、キトのイエズス会士として初めて南米アマゾン上流地域を探検し、宣教地を設立した。この地 域は、1717年に新しく設立された新グラナダ副王領に移管されるまで、ペルー副王領の一部であったキトの高等裁判所(オーディエンシア)に属していた。 1602年、フェレールはアグアリコ川、ナポ川、マラニョン川(現在のエクアドルとペルーのスクンビオス地域)の探検を開始し、1604年から1605年 にかけてはコファネ族の原住民の間で布教活動を行った。1610年、彼は背教した原住民の手で殉教した。 1639年、キトのオーディエンシアはアマゾン川の探検を再開する遠征隊を組織し、キトのイエズス会士(Jesuita Quiteño)クリストバル・デ・アキュナは、この遠征隊の一員であった。この探検隊は1639年2月16日にナポ川に上陸し、1639年12月12日 にアマゾン川のほとりにある現在のブラジル、パラー州に到着した。1641年、アクーニャはマドリードで、アマゾン川探検の回顧録『アマゾン川大発見』を 出版した。この回顧録は学術界においてアマゾン地域に関する基本文献となった。 1637年、キト出身のイエズス会士ガスパル・クギアとルーカス・デ・ラ・クエバは、スペインの入植地ボルハに近いポンゴ・デ・マンセリチェ周辺、マラ ニョン川の河岸の地域にマイナス伝道所を設立し始めた。1637年から1652年の間に、マラニョン川とその南の支流であるワラジャ川とウカヤリ川沿いに 14の伝道所が設立された。イエズス会のデ・ラ・クエバとライムンド・デ・サンタクルスは、パスタサ川とナポ川を通るキトとの新たな2つの交通ルートを開 拓した。  サミュエル・フリッツが1707年に作成したアマゾン川とオリノコ川を示す地図 1637年から1715年の間、サミュエル・フリッツはアマゾン川のナポ川とニグロ川の間の流域に38の伝道所を設立した。これらの伝道所はオマグア伝道 所と呼ばれた。これらのミッションは、1705年からブラジルのバンデイランテスに絶え間なく攻撃されていた。1768年、バンデイランテスから離れたナ ポ川の新しい場所に移転したため、残ったオマグア・ミッションはサン・ホアキン・デ・オマグアスのみとなった。 広大なマニナス領土において、キトのイエズス会は40の異なる言語を話す多数の先住民部族と接触し、15万人の住民を擁する合計173のイエズス会伝道所 を設立した。 絶え間なく発生する疫病(天然痘や麻疹)や他の部族やバンデイランテスとの戦闘により、1744年までにイエズス会伝道所の総数は40にまで減少した。イ エズス会の伝道所は先住民にキリスト教、鉄製の道具、奴隷商人や入植者からのわずかな保護を提供した。その見返りとして、先住民はイエズス会の規律に従 い、少なくとも表面的には、それまでの生活様式とは異なる生活様式を受け入れなければならなかった。宣教地の人口は、先住民を捕らえて帰還させるか、宣教 地への移住を強制するために、イエズス会士、兵士、キリスト教徒インディアンが頻繁にジャングルへ遠征することで維持されていたに過ぎなかった。 [101] 1767年にイエズス会がスペイン領アメリカから追放された当時、キトの聴罪院にはイエズス会士25名が36の宣教地を運営しており、その内訳はナポとア ガリコの宣教地が6つ、 パスタサとイキトス伝道地に19あり、人口は2万人であった。[102] |