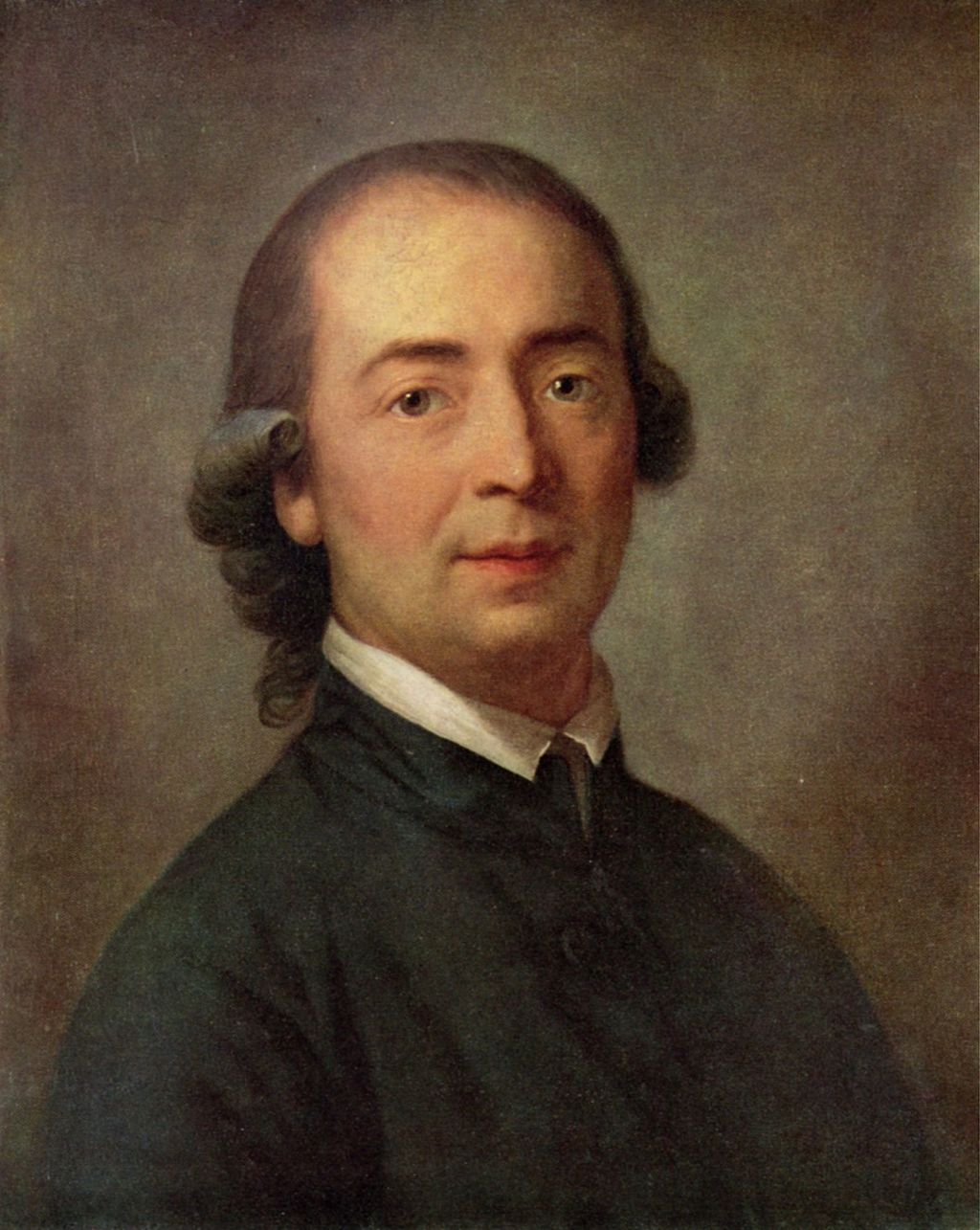

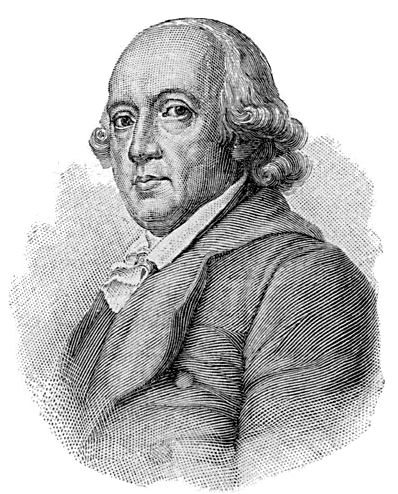

ヨハン・ゴットフリート・ヘルダー

Johann

Gottfried von Herder,1744-1803

ヨハン・ゴットフリート(1802年以降はフォン)・ヘルダー(1744年8月25日から 1803年12月18日(59歳)は、ドイツの哲学者、神学者、詩人、文芸評論家。啓蒙主義、シュトゥルム・ウント・ドラング、ワイマール古典主義に関わ る。ロマン派の哲学者、詩人であり、真 のドイツ文化は庶民(das Volk)の中から発見されるべきであると主張した。また、民俗(フォルクス)の 真の精神(der Volksgeist)を普及させるのは、民謡、民衆詩、民衆舞踊であると述べた。

| JJohann

Gottfried von Herder (/ˈhɜːrdər/ HUR-dər, German: [ˈjoːhan ˈɡɔtfʁiːt

ˈhɛʁdɐ];[26][27][28] 25 August 1744 – 18 December 1803) was a German

philosopher, theologian, poet, and literary critic. He is associated

with the Enlightenment, Sturm und Drang, and Weimar Classicism. He was

a Romantic philosopher and poet who argued that true German culture was

to be discovered among the common people (das Volk). He also stated

that it was through folk songs, folk poetry, and folk dances that the

true spirit of the nation (der Volksgeist) was popularized. |

ヨ

ハン・ゴットフリート・フォン・ヘルダー(Johann Gottfried von Herder、/ˈh↪Llər/ HUR-dər、ドイツ語:

[ˈjojoˈɡ ˈɔtfˈˈɛʁdɐ][26][27][28]、1744年8月25日 -

1803年12月18日)は、ドイツの哲学者、神学者、詩人、文芸評論家。啓蒙主義、シュトゥルム・ウント・ドラング、ワイマール古典主義に関わる。ロマ

ン派の哲学者、詩人であり、真のドイツ文化は庶民(das Volk)の中から発見されるべきであると主張した。また、民族の真の精神(der

Volksgeist)を普及させるのは、民謡、民衆詩、民衆舞踊であると述べた。 |

| Biography Born in Mohrungen (now Morąg, Poland) in the Kingdom of Prussia, Herder grew up in a poor household, educating himself from his father's Bible and songbook. In 1762, as a youth of 17, he enrolled at the University of Königsberg, about 60 miles (100 km) north of Mohrungen, where he became a student of Immanuel Kant. At the same time, Herder became an intellectual protégé of Johann Georg Hamann, a Königsberg philosopher who disputed the claims of pure secular reason. Hamann's influence led Herder to confess to his wife later in life that "I have too little reason and too much idiosyncrasy",[28] yet Herder can justly claim to have founded a new school of German political thought. Although himself an unsociable person, Herder influenced his contemporaries greatly. One friend wrote to him in 1785, hailing his works as "inspired by God." A varied field of theorists were later to find inspiration in Herder's tantalizingly incomplete ideas. In 1764, now a clergyman, Herder went to Riga to teach. It was during this period that he produced his first major works, which were literary criticism. In 1769 Herder traveled by ship to the French port of Nantes and continued on to Paris. This resulted in both an account of his travels as well as a shift of his own self-conception as an author. By 1770 Herder went to Strasbourg, where he met the young Goethe. This event proved to be a key juncture in the history of German literature, as Goethe was inspired by Herder's literary criticism to develop his own style. This can be seen as the beginning of the "Sturm und Drang" movement. In 1771 Herder took a position as head pastor and court preacher at Bückeburg under William, Count of Schaumburg-Lippe. By the mid-1770s, Goethe was a well-known author, and used his influence at the court of Weimar to secure Herder a position as General Superintendent. Herder moved there in 1776, where his outlook shifted again towards classicism. On May 2, 1773 Herder married Maria Karoline Flachsland (1750–1809) in Darmstadt. His son Gottfried (1774–1806) was born in Bückeburg. His second son August (1776–1838) was also born in Bückeburg. His third son Wilhelm Ludwig Ernst was born 1778. His fourth son Karl Emil Adelbert (1779–1857) was born in Weimar. In 1781 his daughter Luise (1781–1860) was born, also in Weimar. His fifth son Emil Ernst Gottfried (1783–1855). In 1790 his sixth son Rinaldo Gottfried was born. Towards the end of his career, Herder endorsed the French Revolution, which earned him the enmity of many of his colleagues. At the same time, he and Goethe experienced a personal split. His unpopular attacks on Kantian philosophy were another reason for his isolation in later years.[29] In 1802 Herder was ennobled by the Elector-Prince of Bavaria, which added the prefix "von" to his last name. He died in Weimar in 1803 at age 59. |

バイオグラフィー プロイセン王国のモールンゲン(現在のポーランド、モロング)に生まれたヘルダーは、貧しい家庭に育ち、父親の聖書と歌集で独学で学んだ。1762年、 17歳の若さでモールンゲンから北へ約60マイル(100km)のケーニヒスベルク大学に入学し、イマヌエル・カントの教えを受けることになる。同時に、 ヘルダーはケーニヒスベルクの哲学者ヨハン・ゲオルク・ハーマンの知的弟子となり、純粋世俗理性の主張に異を唱えた。 ハーマンの影響により、ヘルダーは後年、妻に「私には理性がなさすぎ、特異性がありすぎる」と告白しているが[28]、ドイツ政治思想の新しい流派を確立 したと言って差し支えはないだろう。ヘルダー自身は非社交的な人間であったが、同時代の人々に大きな影響を与えた。ある友人は1785年に彼に宛てて、彼 の著作を「神の霊感によるもの」と賞賛する手紙を送っている。その後、様々な分野の理論家たちが、ヘルダーの不完全な思想にインスピレーションを得ること になる。 1764年、聖職者となったヘルダルはリガに赴き、教鞭をとるようになった。この時期、彼は文学批評を中心とした最初の主要な著作を発表した。1769 年、ヘルダーは船でフランスのナント港に渡り、さらにパリに向かった。この旅は、旅の記録であると同時に、作家としての自己認識の転換をもたらすもので あった。1770年にはストラスブールに渡り、若き日のゲーテと出会う。ゲーテはヘーダーの文芸批評に触発され、自らのスタイルを確立していったのであ る。これは「シュトゥルム・ウント・ドラング」運動の始まりといえる。1771年、ヘルダーはシャウムブルク・リッペ伯ウィリアムのもと、ビュッケブルク の主任牧師兼宮廷説教師の地位に就いた。 1770年代半ばには、ゲーテは著名な作家となり、ワイマール宮廷での影響力を利用して、ヘルダーを総監督の地位に就かせることに成功した。1776年に 移住したヘルダーは、そこで再び古典主義に傾倒していく。 1773年5月2日、ヘルダーはダルムシュタットでマリア・カロリン・フラックスラント(1750-1809)と結婚した。ビュッケブルクで長男ゴットフ リート(1774-1806)が生まれた。次男アウグスト(1776-1838)もビュッケブルクに生まれる。三男のヴィルヘルム・ルートヴィヒ・エルン ストは、1778年に生まれた。四男のカール・エミル・アデルベルト(1779-1857)はワイマールに生まれた。1781年には娘のルイーゼ (1781-1860)が生まれ、これもワイマールにあった。五男エミール・エルンスト・ゴットフリート(1783-1855)。1790年、六男のリナ ルド・ゴットフリートが生まれる。 ヘルダーは、晩年、フランス革命を支持し、多くの同僚から恨まれることになる。同時に、ゲーテとの間に個人的な亀裂が生じた。カント哲学に対する彼の不人 気な攻撃は、後年彼が孤立するもう一つの理由であった[29]。 1802年、ヘルダーはバイエルン選帝侯によって名誉を与えられ、姓に「フォン」という接頭辞が付けられた。1803年、ワイマールで59歳で死去。 |

| Works and ideas In 1772 Herder published Treatise on the Origin of Language and went further in this promotion of language than his earlier injunction to "spew out the ugly slime of the Seine. Speak German, O You German". Herder now had established the foundations of comparative philology within the new currents of political outlook. Throughout this period, he continued to elaborate his own unique theory of aesthetics in works such as the above, while Goethe produced works like The Sorrows of Young Werther – the Sturm und Drang movement was born. Herder wrote an important essay on Shakespeare and Auszug aus einem Briefwechsel über Ossian und die Lieder alter Völker (Extract from a correspondence about Ossian and the Songs of Ancient Peoples) published in 1773 in a manifesto along with contributions by Goethe and Justus Möser. Herder wrote that "A poet is the creator of the nation around him, he gives them a world to see and has their souls in his hand to lead them to that world." To him such poetry had its greatest purity and power in nations before they became civilised, as shown in the Old Testament, the Edda, and Homer, and he tried to find such virtues in ancient German folk songs and Norse poetry and mythology. Herder - most pronouncedly after Georg Forster's 1791 translation of the Sanskrit play Shakuntala - was influenced by the religious imagery of Hinduism and Indian literature, which he saw in a positive light, writing several essays on the topic and the preface to the 1803 edition of Shakuntala.[30][31] After becoming General Superintendent in 1776, Herder's philosophy shifted again towards classicism, and he produced works such as his unfinished Outline of a Philosophical History of Humanity which largely originated the school of historical thought. Herder's philosophy was of a deeply subjective turn, stressing influence by physical and historical circumstance upon human development, stressing that "one must go into the age, into the region, into the whole history, and feel one's way into everything". The historian should be the "regenerated contemporary" of the past, and history a science as "instrument of the most genuine patriotic spirit". Herder gave Germans new pride in their origins, modifying that dominance of regard allotted to Greek art (Greek revival) extolled among others by Johann Joachim Winckelmann and Gotthold Ephraim Lessing. He remarked that he would have wished to be born in the Middle Ages and mused whether "the times of the Swabian emperors" did not "deserve to be set forth in their true light in accordance with the German mode of thought?". Herder equated the German with the Gothic and favoured Dürer and everything Gothic. As with the sphere of art, equally he proclaimed a national message within the sphere of language. He topped the line of German authors emanating from Martin Opitz, who had written his Aristarchus, sive de contemptu linguae Teutonicae in Latin in 1617, urging Germans to glory in their hitherto despised language. Herder's extensive collections of folk-poetry began a great craze in Germany for that neglected topic. |

作品と思想 1772年、ヘルダーは『言語起源論』を出版し、「セーヌ川の醜い泥を吐き出せ」という以前の彼の命令よりもさらに踏み込んで、言語の普及に努めた。ドイ ツ語を話せ、ドイツ人よ」。ヘルダーは、政治的展望の新しい流れの中で、比較言語学の基礎を確立したのである。 この間、彼は上記のような独自の美学論を展開し、ゲーテは『若きウェルテルの悩み』などの作品を発表し、「シュトルム・ウント・ドランク」運動が生まれ た。 ヘルダーはシェイクスピアに関する重要なエッセイを書き、1773年にゲーテやユストゥス・メーザーが寄稿したマニフェスト『Auszug aus einem Briefwechsel über Ossian und die Lieder alter Völker(オシアンと古代の民の歌についての手紙からの抜粋)』を出版している。ヘルダーは、「詩人は周囲の国民の創造者であり、彼らに見るべき世界 を与え、彼らの魂をその世界へと導くために手に持っている」と書いている。旧約聖書、エッダ、ホメロスに見られるように、文明化する前の国々において、詩 は最も純粋で力強いものであり、彼は古代ドイツの民謡や北欧の詩や神話にそうした美徳を見出そうとしたのである。ヘルダーは-ゲオルク・フォースターが 1791年にサンスクリット劇『シャクンタラ』を翻訳して以降、最も顕著に-ヒンドゥー教やインド文学の宗教的イメージに影響を受け、それを肯定的に捉 え、このテーマに関するいくつかのエッセイや1803年版『シャクンタラ』の序文を執筆している[30][31]。 1776年に総監督に就任した後、ヘルダーの哲学は再び古典主義へとシフトし、歴史思想の学派をほぼ創始した『哲学的人類史の概要』(未完)などの著作を 生み出した。ヘルダーは、「時代、地域、歴史全体に入り込み、すべてを感じ取らなければならない」と主張し、物理的、歴史的環境による人間の発展への影響 を強調した、きわめて主観的な思想を持っていた。歴史家は過去の「再生された現代人」であるべきであり、歴史は「最も純粋な愛国心の道具」としての科学で ある。 ヘルダーは、ヨハン・ヨアヒム・ヴィンケルマンやゴットホルト・エフライム・レッシングが称賛したギリシャ美術の優位性(ギリシャ復興)を修正し、ドイツ 人に自分たちの起源に対する新しいプライドを与えた。彼は中世に生まれたかったと述べ、「シュヴァーベン皇帝の時代」は「ドイツ的な思考様式に則って、そ の真の光を示すに値しないのではないか」と考察している。ヘルダーはドイツをゴシックと同一視し、デューラーやゴシック的なものを好んでいた。芸術の分野 と同様に、彼は言語の分野でも国家的なメッセージを発した。1617年にラテン語で『アリスタルコス』(Aristarchus, sive de contemptu linguae Teutonicae)を書き、ドイツ人にこれまで軽蔑されてきた言語に栄光を見出すよう促したマルティン・オピッツから続くドイツ人作家の筆頭格であ る。ヘルダーが収集した民衆詩の膨大なコレクションは、ドイツでこの無視されていたテーマに対する大きな熱狂の始まりとなった。 |

| language communities Herder was one of the first to argue that language contributes to shaping the frameworks and the patterns with which each linguistic community thinks and feels. For Herder, language is "the organ of thought." This has often been misinterpreted, however. Neither Herder nor the great philosopher of language, Wilhelm von Humboldt, argue that language (written or oral) determines thought. Rather, language was the appropriation of the outer world within the human mind by means of distinguishing marks (merkmale). In positing his arguments, Herder reformulated an example from works by Moses Mendelssohn and Thomas Abbt. In his conjectural narrative of human origins, Herder argued that, although language did not determine thought, the first humans perceived sheep and their bleating, or subjects and corresponding merkmale, as one and the same. That is, for these conjectured ancestors, the sheep were the bleating, and vice-versa. Hence, pre-linguistic cognition did not figure largely in Herderian conjectural narratives. Herder even moved beyond his narrative of human origins to contend that if active reflection (besonnenheit) and language persisted in human consciousness, then human impulses to signify were immanent in the pasts, presents, and futures of humanity. Avi Lifschitz subsequently reframed Herder's "the organ of thought" quotation: "Herder's equation of word and idea, of language and cognition, prompted a further attack on any attribution of the first words to the imitation of natural sounds, to the physiology of the vocal organs, or to social convention...[Herder argued] for the linguistic character of our cognition but also for the cognitive nature of human language. One could not think without language, as various Enlightenment thinkers argued, but at the same time one could not properly speak without perceiving the world in a uniquely human way...man would not be himself without language and active reflection, while language deserved its name only as a cognitive aspect of the entire human being." In response to criticism of these contentions, Herder resisted descriptions of his findings as "conjectural" pasts, casting his arguments for a dearth of pre-linguistic cognition in humans and "the problem of the origin of language as a synchronic issue rather than a diachronic one."[32] And in this sense, when Humboldt argues that all thinking is thinking in language, he is perpetuating the Herderian tradition. Herder additionally advanced select notions of myriad "authentic" conceptions of Völk and the unity of the individual and natural law, which became fodder for his self-proclaimed twentieth-century disciples. Herderian ideas continue to influence thinkers, linguists and anthropologists, and they have often been considered central to the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis and Franz Boas' coalescence of comparative linguistics and historical particularism with a neo-Kantian/Herderian four-field approach to the study of all cultures, as well as, more recently, anthropological studies by Dell Hymes. Herder's focus upon language and cultural traditions as the ties that create a "nation"[33] extended to include folklore, dance, music and art, and inspired Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm in their collection of German folk tales. Arguably, the greatest inheritor of Herder's linguistic philosophy was Wilhelm von Humboldt. Humboldt's great contribution lay in developing Herder's idea that language is "the organ of thought" into his own belief that languages were specific worldviews (Weltansichten), as Jürgen Trabant argues in the Wilhelm von Humboldt lectures on the Rouen Ethnolinguistics Project website. |

言語共同体 ヘルダーは、言語 がそれぞれの言語共同体の思考や感情の枠組みやパターンの形成に寄与していることを最初に主張した一人である。ヘルダーにとって、言語は "思考の器官 "である。しかし、これはしばしば間違って解釈されてきた。ヘルダーも偉大な言語哲学者であるヴィルヘルム・フォン・フンボルトも、言語(文字または口 頭)が思考を決定すると主張しているわけではない。むしろ、言語とは、外界を識別記号(メルクマール)により人間の心の中に充当するものであった。ヘル ダーは、メンデルスゾーンやトーマス・アプトの著作に見られるような事例をもとに、自らの主張を展開した。ヘルダーは、人間の起源について、言語が思考を 決定したわけではないが、最初の人間は羊とその鳴き声、あるいは被験者とそれに対応するメルクマールを同一のものとして認識したと推測している。つまり、 この推定された祖先にとって、羊は鳴き声であり、その逆もまた然りであった。したがって、言語以前の認知は、ヘルダーの推測の語りにはあまり登場しない。 さらにヘルダルは、人間の起源を語るにとどまらず、もし人間の意識に能動的反省(besonnenheit)と言語が存続するならば、人間の意味づけの衝 動は、人類の過去、現在、未来に内在していると主張するようになった。アヴィ・リフシッツはその後、ヘルダーの「思考の器官」の引用を再構成している。 「ヘルダーは、言葉と観念、言語と認識を同一視することで、最初の言葉を自然音の模倣、発声器官の生理学、社会的慣習に帰することに対して、さらなる攻撃 を加えた。啓蒙思想家の諸氏が主張したように、人は言語なしに考えることはできないが、同時に、人間特有の方法で世界を認識することなしには、正しく話す ことはできない。...人間は言語と能動的反省なしには自分らしくないだろうが、言語は人間全体の認識面としてのみその名に値する。"と。こうした主張に 対する批判に対して、ヘルダーは自分の発見を「思い込み」の過去とする記述に抵抗し、人間には言語以前の認知が乏しいという主張と「言語の起源という問題 を通時的な問題ではなく共時的な問題とする」[32]ことを投げかけていた。 そしてこの意味で、フンボルトがすべての思考は言語における思考であると主張するとき、彼はヘルダーの伝統を永続させているのである。ヘルダーはさらに、 無数の「本物」のフェルク概念、個人と自然法の統一という選択的な概念を進めており、それは自称20世紀の弟子たちの餌食となった。ヘルダーの思想は、思 想家、言語学者、人類学者に影響を与え続け、サピア=ウォーフ仮説やフランツ・ボースが比較言語学と歴史的特殊主義を新カント派/ヘルダーの4分野アプ ローチと統合してあらゆる文化を研究したことや、最近ではデル・ハイムズによる人類学研究の中心であると考えられている。ヘルダーは、「国家」を形成する 絆として言語と文化的伝統に着目し[33]、民俗学、舞踊、音楽、芸術を含めるようになり、ヤコブ&ヴィルヘルム・グリムがドイツの民話を収集する際にイ ンスピレーションを与えている。ヘルダーの言語哲学を最もよく受け継いだのは、ヴィルヘルム・フォン・フンボルトであろう。フンボルトの大きな功績は、言 語が「思考の器官」であるというヘルダーの考えを、言語が特定の世界観(Weltansichten)であるという彼自身の考えへと発展させたことにあ る、とユーゲン・トラバントがルーアン民族言語学プロジェクトのウェブサイトにあるヴィルヘルム・フォン・フンボルト講義の中で主張している。 |

| 愛国主義 Herder attached exceptional importance to the concept of nationality and of patriotism – "he that has lost his patriotic spirit has lost himself and the whole worlds about himself", whilst teaching that "in a certain sense every human perfection is national". Herder carried folk theory to an extreme by maintaining that "there is only one class in the state, the Volk, (not the rabble), and the king belongs to this class as well as the peasant". Explanation that the Volk was not the rabble was a novel conception in this era, and with Herder can be seen the emergence of "the people" as the basis for the emergence of a classless but hierarchical national body. The nation, however, was individual and separate, distinguished, to Herder, by climate, education, foreign intercourse, tradition and heredity. Providence he praised for having "wonderfully separated nationalities not only by woods and mountains, seas and deserts, rivers and climates, but more particularly by languages, inclinations and characters". Herder praised the tribal outlook writing that "the savage who loves himself, his wife and child with quiet joy and glows with limited activity of his tribe as for his own life is in my opinion a more real being than that cultivated shadow who is enraptured with the shadow of the whole species", isolated since "each nationality contains its centre of happiness within itself, as a bullet the centre of gravity". With no need for comparison since "every nation bears in itself the standard of its perfection, totally independent of all comparison with that of others" for "do not nationalities differ in everything, in poetry, in appearance, in tastes, in usages, customs and languages? Must not religion which partakes of these also differ among the nationalities?" Following a trip to Ukraine, Herder wrote a prediction in his diary (Journal meiner Reise im Jahre 1769) that Slavic nations would one day be the real power in Europe, as the western Europeans would reject Christianity and rot away, while the eastern European nations would stick to their religion and their idealism, and would this way become the power in Europe. More specifically, he praised Ukraine's "beautiful skies, blithe temperament, musical talent, bountiful soil, etc. [...] someday will awaken there a cultured nation whose influence will spread [...] throughout the world." One of his related predictions was that the Hungarian nation would disappear and become assimilated by surrounding Slavic peoples; this prophecy caused considerable uproar in Hungary and is widely cited to this day.[34] |

Patriotism ヘ ルダーは、「愛国心を失った者は、自分自身と自分に関するすべての世界を失った」とし、「ある意味で、すべての人間の完成は国民的である」と説き、国民性 と愛国心の概念を非常に重要視していた。ヘルダーは、「国家にはただ一つの階級、すなわちフォルク(暴徒ではない)があり、王は農民と同様にこの階級に属 する」と主張し、民俗理論を極端に発展させた。この時代には、民衆ではなくフォルクであるという説明は斬新な発想であり、ヘルダーとともに、階級を持たな いが階層的な国家体の出現の基礎となる「民衆」の出現を見ることができる。 しかし、ヘルダーにとって国民とは、気候、教育、外国との交流、伝統、遺伝によって区別される個別的なものであった。摂理は、「森や山、海や砂漠、川や気 候だけでなく、特に言語、傾向、性格によって見事に民族を分けた」と賞賛している。ヘルダーは、「自分自身と妻と子供を静かな喜びをもって愛し、自分の人 生のために部族の限られた活動を輝かせる野蛮人は、私の考えでは、種全体の影に魅了された教養ある影よりも、より実在する存在」だと書き、「それぞれの民 族は、弾丸が重心を持つように、自らの中に幸福の中心を含んでいる」ので孤立すると賞賛している。比較の必要がないのは、「すべての国民は、その完全性の 基準を自分自身の中に持っており、他の国民との比較とはまったく無関係」だからである。「国民は、詩、外観、好み、慣習、習慣、言語のすべてにおいて異 なっているではないか。これらの要素を取り入れた宗教もまた、民族の間で異なってはいないだろうか」。 ヘルダーはウクライナ旅行の後、日記(Journal meiner Reise im Jahre 1769)に、西ヨーロッパ諸国はキリスト教を拒否して衰退し、東ヨーロッパ諸国は宗教と理想主義に固執して、いつかスラブ諸国がヨーロッパの真の権力者 となるだろうと予言している。具体的には、ウクライナの「美しい空、陽気な気質、音楽の才能、豊かな土壌など」を賞賛した。[いつの日か、そこに文化的な 国家が生まれ、その影響は世界中に広がるだろう......」と述べている。関連する予言として、ハンガリー民族は消滅し、周辺のスラブ民族に同化される というものがあり、この予言はハンガリーで大きな騒動となり、今日まで広く引用されている[34]。 |

Germany and the Enlightenment This question was

further developed by Herder's lament that Martin

Luther did not establish a national church, and his doubt whether

Germany did not buy Christianity at too high a price, that of true

nationality. Herder's patriotism bordered at times upon national

pantheism, demanding of territorial unity as "He is deserving of glory

and gratitude who seeks to promote the unity of the territories of

Germany through writings, manufacture, and institutions" and sounding

an even deeper call: This question was

further developed by Herder's lament that Martin

Luther did not establish a national church, and his doubt whether

Germany did not buy Christianity at too high a price, that of true

nationality. Herder's patriotism bordered at times upon national

pantheism, demanding of territorial unity as "He is deserving of glory

and gratitude who seeks to promote the unity of the territories of

Germany through writings, manufacture, and institutions" and sounding

an even deeper call:"But now! Again I cry, my German brethren! But now! The remains of all genuine folk-thought is rolling into the abyss of oblivion with a last and accelerated impetus. For the last century we have been ashamed of everything that concerns the fatherland." In his Ideas upon Philosophy and the History of Mankind he wrote: "Compare England with Germany: the English are Germans, and even in the latest times the Germans have led the way for the English in the greatest things." Herder, who hated absolutism and Prussian nationalism, but who was imbued with the spirit of the whole German Volk, yet as a historical theorist turned away from the ideas of the eighteenth century. Seeking to reconcile his thought with this earlier age, Herder sought to harmonize his conception of sentiment with reasoning, whereby all knowledge is implicit in the soul; the most elementary stage is the sensuous and intuitive perception which by development can become self-conscious and rational. To Herder, this development is the harmonizing of primitive and derivative truth, of experience and intelligence, feeling and reasoning. Herder is the first in a long line of Germans preoccupied with this harmony. This search is itself the key to the understanding of many German theories of the time; however Herder understood and feared the extremes to which his folk-theory could tend, and so issued specific warnings. He argued that Jews in Germany should enjoy the full rights and obligations of Germans, and that the non-Jews of the world owed a debt to Jews for centuries of abuse, and that this debt could be discharged only by actively assisting those Jews who wished to do so to regain political sovereignty in their ancient homeland of Israel.[35] Herder refused to adhere to a rigid racial theory, writing that "notwithstanding the varieties of the human form, there is but one and the same species of man throughout the whole earth". He also announced that "national glory is a deceiving seducer. When it reaches a certain height, it clasps the head with an iron band. The enclosed sees nothing in the mist but his own picture; he is susceptible to no foreign impressions." |

ドイツと啓蒙主義 この問題は、ヘルダーがマルティン・ルター

が国民教会を設立しなかったことを嘆き、ドイツがキリスト教を真の国民性という高すぎる代価で買ったのではない

かという疑問によって、さらに発展することになる。ヘルダーは、「著作、製造、制度を通じてドイツの領土の統一を促進しようとする者は、栄光と感謝に値す

る」として領土の統一を要求し、さらに深い呼びかけを行うなど、時に国家汎神論に近い愛国心を抱いていた。 この問題は、ヘルダーがマルティン・ルター

が国民教会を設立しなかったことを嘆き、ドイツがキリスト教を真の国民性という高すぎる代価で買ったのではない

かという疑問によって、さらに発展することになる。ヘルダーは、「著作、製造、制度を通じてドイツの領土の統一を促進しようとする者は、栄光と感謝に値す

る」として領土の統一を要求し、さらに深い呼びかけを行うなど、時に国家汎神論に近い愛国心を抱いていた。しかし、今こそ!」。ドイツの同胞よ、私は再び叫ぶ。しかし、今こそ!」。すべての真の民俗思想の残骸が、最後の加速度的な推進力をもって忘却の淵へと転 がり込んでいるのだ。この一世紀、われわれは祖国にかかわるすべてのことを恥じてきた」。 彼は『哲学と人類の歴史に関する考え』の中で、「イギリスとドイツを比べてみると、イギリス人はドイツ人であり、最新の時代においても、ドイツ人はイギリ ス人のために最も偉大なことを先導してきた」と書いている。 絶対主義やプロイセン民族主義を嫌い、全ドイツ民族の精神を受け継いだヘルダーは、歴史理論家としては18世紀の思想に背を向けていた。ヘルダーは、自分 の思想をこの時代と調和させるために、情緒と理性という概念を調和させようとした。ヘルダーにとって、この発展とは、原始的な真理と派生的な真理、経験と 知性、感覚と理性を調和させることである。 ヘルダーは、この調和を探求するドイツ人の長い歴史の中で最初の人物である。この探求は、当時のドイツの多くの理論を理解する鍵である。しかし、ヘルダー は、自分の民俗理論が極端になることを理解し、それを恐れて、具体的な警告を発したのである。彼は、ドイツにいるユダヤ人はドイツ人の権利と義務を完全に 享受すべきであり、世界の非ユダヤ人は何世紀にもわたる虐待に対してユダヤ人に借りがあり、この借りは、希望するユダヤ人が古代の祖国イスラエルで政治主 権を回復するのを積極的に支援することによってのみ解消されると主張した[35]。 ヘルダーは厳格な人種論に固執せず、「人間の形態の多様性にかかわらず、地球全体に存在する人間の種類は一つで同じだ」と書いている。 また、「国家の栄光は人を欺く誘惑者である。それがある高さに達すると、鉄のバンドで頭を締め付ける。その霧の中には、自分自身の姿以外には何も見えず、 外国の印象を受けることはない。 |

| The

passage of time was to demonstrate that while many Germans were to find

influence in Herder's convictions and influence, fewer were to note his

qualifying stipulations. Herder had emphasised that his conception of the nation encouraged democracy and the free self-expression of a people's identity. He proclaimed support for the French Revolution, a position which did not endear him to royalty. He also differed with Kant's philosophy for not placing reasoning within the context of language. Herder did not think that reason itself could be criticized, as it did not exist except as the process of reasoning. This process was dependent on language.[36] He also turned away from the Sturm und Drang movement to go back to the poems of Shakespeare and Homer. To promote his concept of the Volk, he published letters and collected folk songs. These latter were published in 1773 as Voices of the Peoples in Their Songs (Stimmen der Völker in ihren Liedern). The poets Achim von Arnim and Clemens von Brentano later used Stimmen der Völker as samples for The Boy's Magic Horn (Des Knaben Wunderhorn). Herder also fostered the ideal of a person's individuality. Although he had from an early period championed the individuality of cultures – for example, in his This Too a Philosophy of History for the Formation of Humanity (1774), he also championed the individuality of persons within a culture; for example, in his On Thomas Abbt's Writings (1768) and On the Cognition and Sensation of the Human Soul (1778). In On Thomas Abbt's Writings, Herder stated that "a human soul is an individual in the realm of minds: it senses in accordance with an individual formation, and thinks in accordance with the strength of its mental organs. ... My long allegory has succeeded if it achieves the representation of the mind of a human being as an individual phenomenon, as a rarity which deserves to occupy our eyes."[37] |

時の流れは、多くのドイツ人がヘーダーの信念と影響力を見出す一方で、

彼の修飾的な規定に注目する人は少なくなっていたことを示すものだった。 ヘルダーは、自らの国家観が民主主義や国民のアイデンティティの自由な自己表現を促すものであることを強調していた。また、フランス革命への支持を表明し ていたが、これは王族にとっては好ましくない立場であった。また、カントの哲学には、理性を言語の文脈の中に位置づけないという点で異を唱えた。ヘルダー は理性そのものを批判することはできないと考えた。このプロセスは言語に依存していた[36]。彼はまたシュトルム・ウント・ドラン運動から離れ、シェイ クスピアやホメロスの詩に回帰していた。 ヴォルクの概念を広めるために、彼は手紙を出版し、民謡を収集した。後者は1773年に『Voices of the Peoples in Their Songs (Stimmen der Völker in ihren Liedern)』として刊行された。後に詩人アヒム・フォン・アルニムやクレメンス・フォン・ブレンターノが『少年の魔法の角笛』のサンプルとして 『Stimmen der Völker』を使用している。 また、ヘルダーは人の個性を大切にする思想も育んでいる。彼は早くから『これも人類形成のための歴史哲学』(1774年)で文化の個性を主張していたが、 『トーマス・アプトの著作について』(1768年)や『人間の魂の認識と感覚について』(1778年)で文化の中の人間の個性をも主張しているのである。 ヘルダーは『トーマス・アプトの著作について』の中で、「人間の魂は心の領域における個人であり、個人の形成に従って感覚し、その精神器官の強さに従って 思考する。... 私の長い寓話は、もしそれが人間の心を個々の現象として、我々の目を占めるに値する希少なものとして表現することを達成したならば、成功したことになる」 [37]。 |

| Evolution Herder has been described as a proto-evolutionary thinker by some science historians, although this has been disputed by others.[38][39][40] Concerning the history of life on earth, Herder proposed naturalistic and metaphysical (religious) ideas that are difficult to distinguish and interpret.[39] He was known for proposing a great chain of being.[40] In his book From the Greeks to Darwin, Henry Fairfield Osborn wrote that "in a general way he upholds the doctrine of the transformation of the lower and higher forms of life, of a continuous transformation from lower to higher types, and of the law of Perfectibility."[41] However, biographer Wulf Köpke disagreed, noting that "biological evolution from animals to the human species was outside of his thinking, which was still influenced by the idea of divine creation."[42] |

進化論 ヘルダーは一部の科学史家によって進化の原型となる思想家とされているが、これには異論もある[38][39][40]。 地球上の生命の歴史に関して、ヘルダーは区別と解釈が困難な自然主義と形而上学(宗教)の考えを提案していた[39] 存在の大連鎖を提案していることで知られていた[40]。 ヘンリー・フェアフィールド・オズボーンはその著書『ギリシャ人からダーウィンへ』の中で、「一般的な方法で、彼は生命の低位と高位の形態の変化、低位か ら高位への連続的な変化、および完全性の法則の教義を支持している」と書いている[41]。 しかし、伝記作家のウルフ・ケプケはこれに同意せず、「動物から人間種への生物進化は彼の思考の外にあり、それはまだ神の創造の思想に影響を受けてい た」、と指摘している[42]。 |

| Works in English Herder's Essay on Being. A Translation and Critical Approaches. Edited and translated by John K. Noyes. Rochester: Camden House 2018. Herder's early essay on metaphysics, translated with a series of critical commentaries. Song Loves the Masses: Herder on Music and Nationalism. Edited and translated by Philip Vilas Bohlman (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017). Collected writings on music, from Volkslieder to sacred song. Selected Writings on Aesthetics. Edited and translated by Gregory Moore. Princeton U.P. 2006. pp. x + 455. ISBN 978-0691115955. Edition makes many of Herder's writings on aesthetics available in English for the first time. Another Philosophy of History and Selected Political Writings, eds. Ioannis D. Evrigenis and Daniel Pellerin (Indianapolis: Hackett Pub., 2004). A translation of Auch eine Philosophie and other works. Philosophical Writings, ed. Michael N. Forster (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002). The most important philosophical works of the early Herder available in English, including an unabridged version of the Treatise on the Origin of Language and This Too a Philosophy of History for the Formation of Mankind. Sculpture: Some Observations on Shape and Form from Pygmalion's Creative Dream, ed. Jason Gaiger (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002). Herder's Plastik. Selected Early Works, eds. Ernest A. Menze and Karl Menges (University Park: The Pennsylvania State Univ. Press, 1992). Partial translation of the important text Über die neuere deutsche Litteratur. On World History, eds. Hans Adler and Ernest A. Menze (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1997). Short excerpts on history from various texts. J. G. Herder on Social & Political Culture (Cambridge Studies in the History and Theory of Politics), ed. F. M. Barnard (Cambridge University Press, 2010 (originally published in 1969)) ISBN 978-0-521-13381-4 Selected texts: 1. Journal of my voyage in the year 1769; 2. Essay on the origin of language; 3. Yet another philosophy of history; 4. Dissertation on the reciprocal influence of government and the sciences; 5. Ideas for a philosophy of the history of mankind. Herder: Philosophical Writings, ed. Desmond M. Clarke and Michael N. Forster (Cambridge University Press, 2007), ISBN 978-0-521-79088-8. Contents: Part I. General Philosophical Program: 1. How philosophy can become more universal and useful for the benefit of the people (1765); Part II. Philosophy of Language: 2. Fragments on recent German literature (1767–68); 3. Treatise on the origin of language (1772); Part III. Philosophy of Mind: 4. On Thomas Abbt's writings (1768); 5. On cognition and sensation, the two main forces of the human soul; 6. On the cognition and sensation, the two main forces of the human soul (1775); Part IV. Philosophy of History: 7. On the change of taste (1766); 8. Older critical forestlet (1767/8); 9. This too a philosophy of history for the formation of humanity (1774); Part V. Political Philosophy: 10. Letters concerning the progress of humanity (1792); 11. Letters for the advancement of humanity (1793–97). Herder on Nationality, Humanity, and History, F. M. Barnard. (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2003.) ISBN 978-0-7735-2519-1. Herder's Social and Political Thought: From Enlightenment to Nationalism, F. M. Barnard, Oxford, Publisher: Clarendon Press, 1967. ASIN B0007JTDEI. |

英語で書かれた作品 ヘルダー著『存在についてのエッセイ』。翻訳と批評的アプローチ。ジョン・K・ノイエス編訳。ロチェスター:カムデン・ハウス 2018年。ヘルダーの初期の形而上学に関するエッセイを、一連の批評的論評とともに翻訳。 『歌は大衆を愛する:ヘルダーの音楽とナショナリズム』。フィリップ・ヴィラス・ボールマン編訳。バークレー:カリフォルニア大学出版、2017年。フォ ルクスリートから聖歌まで、音楽に関する著作集。 美学に関する著作集。編集・翻訳:グレゴリー・ムーア。プリンストン大学出版局、2006年。x + 455ページ。ISBN 978-0691115955。この版により、ヘルダーの美学に関する著作の多くが初めて英語で読めるようになった。 『もう一つの歴史哲学と政治的著作集』、編者:イオアニス・D・エヴリゲニス、ダニエル・ペレリン(インディアナポリス:ハケット出版、2004年)。 『もう一つの哲学』とその他の著作の翻訳。 『哲学的著作集』、編者:マイケル・N・フォースター(ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版、2002年)。初期ヘルダーの最も重要な哲学作品の英訳。 『言語起源論』の完全版と『これもまた哲学である 人類形成のための歴史』を含む。 彫刻:ピグマリオン創造の夢から形と様式に関するいくつかの観察、ジェイソン・ガイガー編(シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版、2002年)。ヘルダーの『プラス ティーク』。 アーネスト・A・メンゼとカール・メンゲス編(ペンシルベニア州立大学出版、1992年) 重要な文献『ドイツの近現代文学について』の抜粋翻訳。 ハンス・アドラーとアーネスト・A・メンゼ編(ニューヨーク州アーモンク、M.E. Sharpe、1997年) さまざまな文献から抜粋した歴史に関する短い文章。 J. G. ヘルダーの社会・政治文化論(ケンブリッジ政治史・理論研究)、編者 F. M. バーナード(ケンブリッジ大学出版局、2010年(初版は1969年))ISBN 978-0-521-13381-4 抜粋テキスト: 1. 1769年の航海日誌、2. 言語の起源に関する論文、3. 歴史に関するもう一つの哲学、4. 政府と科学の相互影響に関する論文、5. 人類の歴史哲学のためのアイデア。 ヘルダー:哲学的著作、編者:デズモンド・M・クラーク、マイケル・N・フォースター(ケンブリッジ大学出版局、2007年)、ISBN 978-0-521-79088-8。目次:第I部 一般的な哲学的プログラム:1. 哲学がより普遍的になり、人々の利益のために役立つには(1765年);第II部。言語哲学:2. 最近のドイツ文学に関する断章(1767年~68年);3. 言語の起源についての論文(1772年);第3部。心の哲学:4. トーマス・アッバートの著作について(1768年);5. 人間の魂の2つの主な力である認識と感覚について(1775年);第4部。歴史哲学:7. 趣味の変化について(1766年);8. 古い批評の小論(1767/8年);9. 人間性の形成のための歴史哲学(1774年);第5部 政治哲学:10. 人類の進歩に関する書簡(1792年);11. 人類の進歩のための書簡(1793-97年)。 ヘルダーの民族性、人間性、歴史について、F. M. バーナード著。(モントリオールおよびキングストン:マギル・クイーンズ大学出版、2003年)ISBN 978-0-7735-2519-1。 ヘルダーの社会・政治思想:啓蒙思想から国民主義へ、F. M. バーナード著、オックスフォード、出版社:Clarendon Press、1967年。ASIN B0007JTDEI。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Gottfried_Herder |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| Volksgeist |

フォルクスガイスト(民族の精神) |

| Volksgeist or Nationalgeist

refers to a "spirit" of an individual people (Volk), its "national

spirit" or "national character".[16] The term Nationalgeist is used in

the 1760s by Justus Möser and by Johann Gottfried Herder. The term

Nation at this time is used in the sense of natio "nation, ethnic

group, race", mostly replaced by the term Volk after 1800.[17] In the

early 19th century, the term Volksgeist was used by Friedrich Carl von

Savigny in order to express the "popular" sense of justice. Savigniy

explicitly referred to the concept of an esprit des nations used by

Voltaire.[18] and of the esprit général invoked by Montesquieu.[19] Hegel uses the term in his Lectures on the Philosophy of History. Based on the Hegelian use of the term, Wilhelm Wundt, Moritz Lazarus and Heymann Steinthal in the mid-19th-century established the field of Völkerpsychologie ("psychology of nations"). In Germany the concept of Volksgeist has developed and changed its meaning through eras and fields. The most important examples are: In the literary field, Schlegel and the Brothers Grimm; in the history of cultures, Herder; in the history of the State or political history, Hegel; in the field of law, Savigny; and in the field of psychology Wundt.[20] This means that the concept is ambiguous. Furthermore it is not limited to Romanticism as it is commonly known.[21] The concept of was also influential in American cultural anthropology. According to the historian of anthropology George W. Stocking, Jr., "… one may trace the later American anthropological idea of culture back through Bastian's Volkergedanken and the folk psychologist's Volksgeister to Wilhelm von Humboldt's Nationalcharakter – and behind that, although not without a paradoxical and portentous residue of conceptual and ideological ambiguity, to the Herderian ideal of Volksgeist."[clarification needed][year needed][page needed] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geist |

VolksgeistまたはNationalgeistは、個々の民族

(Volk)の「精神」、すなわち「国民精神」または「国民性」を指す。[16]

Nationalgeistという用語は、1760年代にユストゥス・モーザーとヨハン・ゴットフリート・ヘルダーによって使用された。この時期の

Nation(国民)という用語は、natio(ラテン語:ネイション)「国民、民族、人種」という意味で使用されていたが、1800年以降は主に

Volk(フォルク)という用語に置き換えられた。[17]

19世紀初頭には、フリードリヒ・カール・フォン・サヴィニーが正義の「大衆」的な感覚を表現するためにVolksgeist(フォルクスガイスト)とい

う用語を使用した。サヴィニーは、ヴォルテールが用いたエスプリ・デ・ナシオンの概念を明確に参照している。[18]

また、モンテスキューが呼び起こしたエスプリ・ジェネラルについても言及している。[19] ヘーゲルは『歴史哲学講義』でこの用語を使用している。ヘーゲルによるこの用語の使用に基づき、19世紀半ばにヴィルヘルム・ヴント、モーリッツ・ラザー ル、ハイマン・シュタインタルは「民族心理学」(「民族の心理学」)という分野を確立した。 ドイツでは、時代や分野によってフォルクスガイストの概念は発展し、その意味も変化してきた。最も重要な例としては、 文学の分野ではシュレーゲルとグリム兄弟、文化史ではヘルダー、国家史や政治史ではヘーゲル、法学ではサヴィニー、心理学ではヴントである。[20] つまり、この概念は曖昧であるということである。さらに、一般的に考えられているように、ロマン主義に限定されるものではない。[21] この概念は、アメリカの文化人類学にも影響を与えた。人類学者のジョージ・W・ストッキング・ジュニアによると、「... 後世のアメリカの人類学における文化の概念は、バスティアンの『民族精神』や民俗心理学者の『民族精神』を経て、ヴィルヘルム・フォン・フンボルトの『国 民性』にまで遡ることができる。そして、その背後には、概念やイデオロギーのあいまいさという逆説的で不吉な痕跡を残しつつも、ヘルダーの『民族精神』の 理想がある。[要出典][要出典][要出典] |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆