ジョン・ケージ

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992)

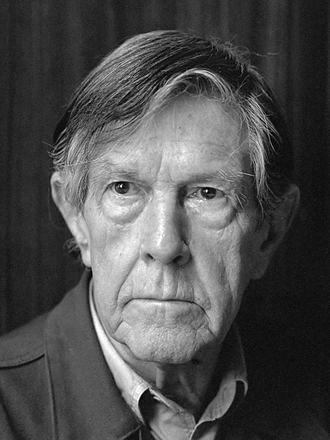

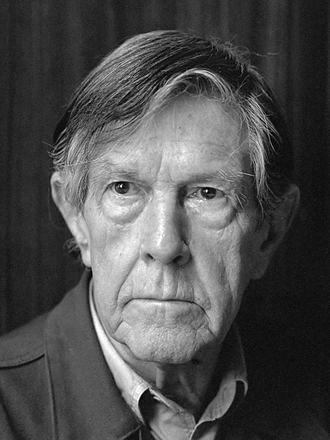

John Cage in 1988

Failing to fetch me me at first keep encouraged, Missing me one place search another, I stop some where waiting for you - Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass.

☆ ジョン・ミルトン・ケイジ・ジュニア(1912年9月5日 - 1992年8月12日)は、アメリカの作曲家、音楽理論家。音楽における不確定性、電子音響音楽、楽器の非標準的使用の先駆者であり、戦後アヴァンギャル ドを代表する人物の一人。批評家たちは彼を20世紀で最も影響力のある作曲家のひとりとして称賛している。彼はまた、主に振付家 マース・カニングハムとの関わりを通して、モダンダンスの発展にも貢献した。 ケージの師には、ヘンリー・カウエル(1933年)やアーノルド・シェーンバーグ(1933-35年)がおり、いずれも音楽における急進的な革新で知られ ているが、ケージの主な影響は様々な東アジアや南アジアの文化にあった。1940年代後半、インド哲学と禅宗の研究を通じて、ケージはアレアトール音楽、 つまり偶然に支配された音楽という考えに至り、1951年から作曲を始めた[7]。 [1957年の講義『実験音楽』において、彼は音楽を「無目的な遊び」であり、「混沌から秩序をもたらそうとする試みでもなく、創造における改善を提案す るものでもなく、単に我々が生きている人生そのものに目覚めるための方法」であると述べている[9]。 ケージの最もよく知られた作品は、1952年に作曲された「4′33″」で、意図的な音のない状態で演奏される作品である。作曲の内容は、演奏中に聴衆が 聴く環境の音であることを意図している。この作品は、ミュージシャンシップと音楽的経験に関する仮定された定義への挑戦であり、音楽学と 芸術とパフォーマンスのより広い美学の両方で人気があり、論争の的となった。ケージはまた、プリペアド・ピアノ(弦やハンマーの間や上に置かれた物によっ て音が変化するピアノ)のパイオニアでもあり、そのために数多くのダンス関連作品と数曲のコンサート作品を書いた。これらには『ソナタと間奏曲』 (1946-48年)などがある。

| John Milton Cage Jr.

(September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer and

music theorist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic

music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the

leading figures of the post-war avant-garde. Critics have lauded him as

one of the most influential composers of the 20th century.[1][2][3][4]

He was also instrumental in the development of modern dance, mostly

through his association with choreographer Merce Cunningham, who was

also Cage's romantic partner for most of their lives.[5][6] Cage's teachers included Henry Cowell (1933) and Arnold Schoenberg (1933–35), both known for their radical innovations in music, but Cage's major influences lay in various East and South Asian cultures. Through his studies of Indian philosophy and Zen Buddhism in the late 1940s, Cage came to the idea of aleatoric or chance-controlled music, which he started composing in 1951.[7] The I Ching, an ancient Chinese classic text and decision-making tool, became Cage's standard composition tool for the rest of his life.[8] In a 1957 lecture, Experimental Music, he described music as "a purposeless play" which is "an affirmation of life – not an attempt to bring order out of chaos nor to suggest improvements in creation, but simply a way of waking up to the very life we're living".[9] Cage's best known work is the 1952 composition 4′33″, a piece performed in the absence of deliberate sound; musicians who present the work do nothing but be present for the duration specified by the title. The content of the composition is intended to be the sounds of the environment heard by the audience during performance.[10][11] The work's challenge to assumed definitions about musicianship and musical experience made it a popular and controversial topic both in musicology and the broader aesthetics of art and performance. Cage was also a pioneer of the prepared piano (a piano with its sound altered by objects placed between or on its strings or hammers), for which he wrote numerous dance-related works and a few concert pieces. These include Sonatas and Interludes (1946–48).[12] |

ジョン・ミルトン・ケイジ・ジュニア(1912年9月5日 -

1992年8月12日)は、アメリカの作曲家、音楽理論家。音楽における不確定性、電子音響音楽、楽器の非標準的使用の先駆者であり、戦後アヴァンギャル

ドを代表する人物の一人。批評家たちは彼を20世紀で最も影響力のある作曲家のひとりとして称賛している[1][2][3][4]。彼はまた、主に振付家

マース・カニングハムとの関わりを通して、モダンダンスの発展にも貢献した。 ケージの師には、ヘンリー・カウエル(1933年)やアーノルド・シェーンバーグ(1933-35年)がおり、いずれも音楽における急進的な革新で知られ ているが、ケージの主な影響は様々な東アジアや南アジアの文化にあった。1940年代後半、インド哲学と禅宗の研究を通じて、ケージはアレアトール音楽、 つまり偶然に支配された音楽という考えに至り、1951年から作曲を始めた[7]。 [1957年の講義『実験音楽』において、彼は音楽を「無目的な遊び」であり、「混沌から秩序をもたらそうとする試みでもなく、創造における改善を提案す るものでもなく、単に我々が生きている人生そのものに目覚めるための方法」であると述べている[9]。 ケージの最もよく知られた作品は、1952年に作曲された「4′33″」で、意図的な音のない状態で演奏される作品である。作曲の内容は、演奏中に聴衆が 聴く環境の音であることを意図している[10][11]。この作品は、ミュージシャンシップと音楽的経験に関する仮定された定義への挑戦であり、音楽学と 芸術とパフォーマンスのより広い美学の両方で人気があり、論争の的となった。ケージはまた、プリペアド・ピアノ(弦やハンマーの間や上に置かれた物によっ て音が変化するピアノ)のパイオニアでもあり、そのために数多くのダンス関連作品と数曲のコンサート作品を書いた。これらには『ソナタと間奏曲』 (1946-48年)などがある[12]。 |

| Life 1912–1931: early years Cage was born September 5, 1912, at Good Samaritan Hospital in downtown Los Angeles.[13] His father, John Milton Cage Sr. (1886–1964), was an inventor, and his mother, Lucretia ("Crete") Harvey (1881–1968), worked intermittently as a journalist for the Los Angeles Times.[14] The family's roots were deeply American: in a 1976 interview, Cage mentioned that George Washington was assisted by an ancestor named John Cage in the task of surveying the Colony of Virginia.[15] Cage described his mother as a woman with "a sense of society" who was "never happy",[16] while his father is perhaps best characterized by his inventions: sometimes idealistic, such as a diesel-fueled submarine that gave off exhaust bubbles, the senior Cage being uninterested in an undetectable submarine;[14] others revolutionary and against the scientific norms, such as the "electrostatic field theory" of the universe.[a] John Cage Sr. taught his son that "if someone says 'can't' that shows you what to do." In 1944–45 Cage wrote two small character pieces dedicated to his parents: Crete and Dad. The latter is a short lively piece that ends abruptly, while "Crete" is a slightly longer, mostly melodic contrapuntal work.[17] Cage's first experiences with music were from private piano teachers in the Greater Los Angeles area and several relatives, particularly his aunt Phoebe Harvey James who introduced him to the piano music of the 19th century. He received first piano lessons when he was in the fourth grade at school, but although he liked music, he expressed more interest in sight reading than in developing virtuoso piano technique, and apparently was not thinking of composition.[18] During high school, one of his music teachers was Fannie Charles Dillon.[19] By 1928, though, Cage was convinced that he wanted to be a writer. He graduated that year from Los Angeles High School as a valedictorian,[20] having also in the spring given a prize-winning speech at the Hollywood Bowl proposing a day of quiet for all Americans. By being "hushed and silent," he said, "we should have the opportunity to hear what other people think," anticipating 4′33″ by more than thirty years.[21] Cage enrolled at Pomona College in Claremont as a theology major in 1928. Often crossing disciplines again, though, he encountered at Pomona the work of artist Marcel Duchamp via Professor José Pijoan, of writer James Joyce via Don Sample, of philosopher Ananda Coomaraswamy and of Henry Cowell.[19] In 1930 he dropped out, having come to believe that "college was of no use to a writer"[22] after an incident described in the 1991 autobiographical statement: I was shocked at college to see one hundred of my classmates in the library all reading copies of the same book. Instead of doing as they did, I went into the stacks and read the first book written by an author whose name began with Z. I received the highest grade in the class. That convinced me that the institution was not being run correctly. I left.[16] Cage persuaded his parents that a trip to Europe would be more beneficial to a future writer than college studies.[23] He subsequently hitchhiked to Galveston and sailed to Le Havre, where he took a train to Paris.[24] Cage stayed in Europe for some 18 months, trying his hand at various forms of art. First, he studied Gothic and Greek architecture, but decided he was not interested enough in architecture to dedicate his life to it.[22] He then took up painting, poetry and music. It was in Europe that, encouraged by his teacher Lazare Lévy,[25] he first heard the music of contemporary composers (such as Igor Stravinsky and Paul Hindemith) and finally got to know the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, which he had not experienced before. After several months in Paris, Cage's enthusiasm for America was revived after he read Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass – he wanted to return immediately, but his parents, with whom he regularly exchanged letters during the entire trip, persuaded him to stay in Europe for a little longer and explore the continent.[26] Cage started traveling, visiting various places in France, Germany, and Spain, as well as Capri and, most importantly, Majorca, where he started composing.[27] His first compositions were created using dense mathematical formulas, but Cage was displeased with the results and left the finished pieces behind when he left.[28] Cage's association with theater also started in Europe: during a walk in Seville he witnessed, in his own words, "the multiplicity of simultaneous visual and audible events all going together in one's experience and producing enjoyment."[29] 1931–1936: apprenticeship Cage returned to the United States in 1931.[28] He went to Santa Monica, California, where he made a living partly by giving small, private lectures on contemporary art. He got to know various important figures of the Southern California art world, such as Richard Buhlig (who became his first composition teacher)[30] and arts patron Galka Scheyer.[22] By 1933, Cage decided to concentrate on music rather than painting. "The people who heard my music had better things to say about it than the people who looked at my paintings had to say about my paintings", Cage later explained.[22] In 1933 he sent some of his compositions to Henry Cowell; the reply was a "rather vague letter",[31] in which Cowell suggested that Cage study with Arnold Schoenberg—Cage's musical ideas at the time included composition based on a 25-tone row, somewhat similar to Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique.[32] Cowell also advised that, before approaching Schoenberg, Cage should take some preliminary lessons, and recommended Adolph Weiss, a former Schoenberg pupil.[33] Following Cowell's advice, Cage travelled to New York City in 1933 and started studying with Weiss as well as taking lessons from Cowell himself at The New School.[30] He supported himself financially by taking up a job washing walls at a YWCA (World Young Women's Christian Association) in Brooklyn.[34] Cage's routine during that period was apparently very tiring, with just four hours of sleep on most nights, and four hours of composition every day starting at 4 am.[34][35] Several months later, still in 1933, Cage became sufficiently good at composition to approach Schoenberg.[b] He could not afford Schoenberg's price, and when he mentioned it, the older composer asked whether Cage would devote his life to music. After Cage replied that he would, Schoenberg offered to tutor him free of charge.[36] Cage studied with Schoenberg in California: first at University of Southern California and then at University of California, Los Angeles, as well as privately.[30] The older composer became one of the biggest influences on Cage, who "literally worshipped him",[37] particularly as an example of how to live one's life being a composer.[35] The vow Cage gave, to dedicate his life to music, was apparently still important some 40 years later, when Cage "had no need for it [i.e. writing music]", he continued composing partly because of the promise he gave.[38] Schoenberg's methods and their influence on Cage are well documented by Cage himself in various lectures and writings. Particularly well-known is the conversation mentioned in the 1958 lecture Indeterminacy: After I had been studying with him for two years, Schoenberg said, "In order to write music, you must have a feeling for harmony." I explained to him that I had no feeling for harmony. He then said that I would always encounter an obstacle, that it would be as though I came to a wall through which I could not pass. I said, "In that case I will devote my life to beating my head against that wall."[39] Cage studied with Schoenberg for two years, but although he admired his teacher, he decided to leave after Schoenberg told the assembled students that he was trying to make it impossible for them to write music. Much later, Cage recounted the incident: "... When he said that, I revolted, not against him, but against what he had said. I determined then and there, more than ever before, to write music."[37] Although Schoenberg was not impressed with Cage's compositional abilities during these two years, in a later interview, where he initially said that none of his American pupils were interesting, he further stated in reference to Cage: "There was one ... of course he's not a composer, but he's an inventor—of genius."[37] Cage would later adopt the "inventor" moniker and deny that he was in fact a composer.[40] At some point in 1934–35, during his studies with Schoenberg, Cage was working at his mother's arts and crafts shop, where he met artist Xenia Andreyevna Kashevaroff. She was an Alaskan-born daughter of a Russian priest; her work encompassed fine bookbinding, sculpture and collage. Although Cage was involved in relationships with Don Sample and with architect Rudolph Schindler's wife Pauline[19] when he met Xenia, he fell in love immediately. Cage and Kashevaroff were married in the desert at Yuma, Arizona, on June 7, 1935.[41] |

生涯 1912-1931年:幼少期 ケージは1912年9月5日、ロサンゼルスのダウンタウンにあるグッド・サマリタン病院で生まれた[13]。父ジョン・ミルトン・ケージ・シニア (1886-1964)は発明家であり、母ルクレチア(「クレタ」)・ハーヴェイ(1881-1968)はロサンゼルス・タイムズ紙のジャーナリストとし て断続的に働いていた。 [1976年のインタビューでケージは、ジョージ・ワシントンがヴァージニア植民地の測量をする際に、ジョン・ケージという先祖に助けられたことを語って いる。 [15]ケージは母親を「決して幸福ではなかった」「社会的な感覚」を持った女性であると評しており[16]、一方父親の発明はおそらく彼の発明によって 最もよく特徴付けられる。 [ジョン・ケージは息子に、「もし誰かが "できない "と言ったら、それは何をすべきかを示しているのだ」と教えた。1944年から45年にかけて、ケージは両親に捧げる2つの小品を書いた: クレタ」と「パパ」である。後者は短い生き生きとした曲で突然終わるが、「クレタ」はやや長く、ほとんどが旋律的な対位法的作品である[17]。 ケージが初めて音楽に触れたのは、グレーター・ロサンゼルス地域の個人的なピアノの先生と、何人かの親戚、特に叔母のフィービー・ハーヴェイ・ジェイムズ から19世紀のピアノ音楽を教わった時だった。小学校4年生のときに初めてピアノのレッスンを受けたが、音楽は好きだったものの、ヴィルトゥオーゾ的なピ アノのテクニックを身につけることよりも読譜に興味を示し、作曲は考えていなかったようだ[18]。高校時代、音楽の教師のひとりにファニー・チャール ズ・ディロンがいた[19]。その年、ロサンゼルスの高校を卒業生総代として卒業し[20]、春にはハリウッド・ボウルで受賞スピーチを行った。緘黙と沈 黙」することで、「他人の考えを聞く機会を持つべきだ」と彼は語り、30年以上も前に "4′33″を先取りしていた[21]。 ケージは1928年、クレアモントにあるポモナ・カレッジに神学専攻として入学。1930年、彼は1991年の自伝的文章に書かれたある出来事をきっかけに、「大学は作家にとって何の役にも立たない」[22]と考えるようになり、中退した: 大学で、100人の同級生が図書館で同じ本を読んでいるのを見てショックを受けた。私は彼らのようにする代わりに書庫に入り、Zで始まる名前の作家が書いた最初の本を読んだ。それで私は、この教育機関は正しく運営されていないと確信した。私はここを去りました」[16]。 その後、ヒッチハイクでガルベストンまで行き、ル・アーヴルまで船で行き、そこから列車でパリに向かった[24]。まずゴシック建築とギリシア建築を学ん だが、建築に人生を捧げるほどの興味はないと判断し、絵画、詩、音楽を始めた[22]。師であるラザール・レヴィの勧めもあり[25]、ヨーロッパで初め て現代作曲家(イーゴリ・ストラヴィンスキーやパウル・ヒンデミットなど)の音楽を聴き、ついにはそれまで体験したことのなかったヨハン・セバスティア ン・バッハの音楽を知ることになる。 パリでの数ヵ月後、ケージはウォルト・ホイットマンの『草の葉』を読んでアメリカへの熱意を取り戻し、すぐに帰国したいと思ったが、旅行中定期的に手紙の やりとりをしていた両親から、もう少しヨーロッパに滞在して大陸を探検するよう説得された[26]。 ケージは旅行を始め、フランス、ドイツ、スペインのさまざまな場所やカプリ島、そして最も重要なマヨルカ島を訪れ、そこで作曲を始めた。 [彼の最初の作曲は、緻密な数式を使用して作成されたが、ケージはその結果に不満を持ち、出発するときに完成した作品を残していった[28]。 1931-1936年:見習い時代 ケージは1931年にアメリカに戻り[28]、カリフォルニア州サンタモニカで、現代美術に関する小規模な個人講義を行うことで生計を立てていた。 1933年、ケージは絵画よりも音楽に専念することを決意する。「1933年、彼はヘンリー・カウエルにいくつかの作品を送ったが、その返事は「かなり曖 昧な手紙」であり[31]、その中でカウエルはケージにアーノルド・シェーンベルクに師事することを勧めた。 [カウエルはまた、シェーンベルクに近づく前に、ケージは予備レッスンを受けるべきだとアドバイスし、シェーンベルクの元教え子であるアドルフ・ワイスを 推薦した[33]。 コーウェルの助言に従い、ケージは1933年にニューヨークに渡り、ワイスに師事するとともに、ニュー・スクールでコーウェル自身からレッスンを受け始め た[30]。 [34]その時期のケージの日課は非常に疲れるものだったらしく、ほとんど夜は4時間しか眠れず、毎日午前4時から4時間作曲をするというものだった [34][35]。数ヶ月後、まだ1933年であったが、ケージはシェーンベルクにアプローチするほど作曲がうまくなった[b]。ケージがそうすると答え ると、シェーンベルクは無料で家庭教師をすると申し出た[36]。 ケージはカリフォルニアでシェーンベルクに師事し、最初は南カリフォルニア大学、次いでカリフォルニア大学ロサンゼルス校で、また個人的にも学んだ [30]。この年配の作曲家はケージに最も大きな影響を与えた人物のひとりとなり、彼は「文字通り彼を崇拝した」[37]。 [35]生涯を音楽に捧げるというケージの誓いは、それから40年後、ケージが「音楽(つまり作曲)を必要としなくなった」ときでもなお重要であったらし い。特によく知られているのは、1958年の講義『不確定性』で言及された会話である: 私がシェーンベルクに2年間師事した後、シェーンベルクは "音楽を書くためには、和声に対する感覚を持たなければならない "と言った。私は彼に、和声に対する感覚など持っていないと説明した。するとシェーンベルクは、私はいつも障害にぶつかり、通り抜けられない壁に突き当た るようなものだと言った。それならば、私はその壁に頭を打ち付けることに生涯を捧げよう」と言った[39]。 ケージはシェーンベルクに2年間師事したが、師を尊敬していたにもかかわらず、シェーンベルクが集まった学生たちに「彼は音楽を書くことを不可能にしよう としている」と言ったため、シェーンベルクはその場を去ることにした。ずっと後になって、ケージはこの出来事をこう語っている: 「彼がそう言ったとき、私は反旗を翻した。彼に対してではなく、彼が言ったことに対してだ。シェーンベルクはこの2年間、ケージの作曲能力に感心していな かったが、後のインタビューで、彼は当初、アメリカ人の弟子は誰も面白くなかったと語っていたが、さらにケージについて「一人いた......もちろん彼 は作曲家ではないが、天才的な発明家だ」と述べている。 シェーンベルクに師事していた1934年から35年のある時期、ケージは母親が経営する美術工芸品店で働き、そこで芸術家のゼニア・アンドレーエフナ・カ シェヴァロフと出会う。彼女はアラスカ生まれのロシア人神父の娘で、装丁、彫刻、コラージュなどの作品を手がけていた。ケージはドン・サンプルや建築家ル ドルフ・シンドラーの妻ポーリーン[19]と交際していたが、ゼニアと出会ってすぐに恋に落ちた。ケージとカシェバロフは1935年6月7日、アリゾナ州 ユマの砂漠で結婚した[41]。 |

| 1937–1949: modern dance and Eastern influences See also: Works for prepared piano by John Cage The newly married couple first lived with Cage's parents in Pacific Palisades, then moved to Hollywood.[42] During 1936–38 Cage changed numerous jobs, including one that started his lifelong association with modern dance: dance accompanist at the University of California, Los Angeles. He produced music for choreographies and at one point taught a course on "Musical Accompaniments for Rhythmic Expression" at UCLA, with his aunt Phoebe.[43] It was during that time that Cage first started experimenting with unorthodox instruments, such as household items, metal sheets, and so on. This was inspired by Oskar Fischinger, who told Cage that "everything in the world has a spirit that can be released through its sound." Although Cage did not share the idea of spirits, these words inspired him to begin exploring the sounds produced by hitting various non-musical objects.[43][44] In 1938, on Cowell's recommendation, Cage drove to San Francisco to find employment and to seek out fellow Cowell student and composer Lou Harrison. According to Cowell, the two composers had a shared interest in percussion and dance and would likely hit it off if introduced to one another. Indeed, the two immediately established a strong bond upon meeting and began a working relationship that continued for several years. Harrison soon helped Cage to secure a faculty member position at Mills College, teaching the same program as at UCLA, and collaborating with choreographer Marian van Tuyl. Several famous dance groups were present, and Cage's interest in modern dance grew further.[43] After several months he left and moved to Seattle, Washington, where he found work as composer and accompanist for choreographer Bonnie Bird at the Cornish College of the Arts. The Cornish School years proved to be a particularly important period in Cage's life. Aside from teaching and working as accompanist, Cage organized a percussion ensemble that toured the West Coast and brought the composer his first fame. His reputation was enhanced further with the invention of the prepared piano—a piano which has had its sound altered by objects placed on, beneath or between the strings—in 1940. This concept was originally intended for a performance staged in a room too small to include a full percussion ensemble. It was also at the Cornish School that Cage met several people who became lifelong friends, such as painter Mark Tobey and dancer Merce Cunningham. The latter was to become Cage's lifelong romantic partner and artistic collaborator. Cage left Seattle in the summer of 1941 after the painter László Moholy-Nagy invited him to teach at the Chicago School of Design (what later became the IIT Institute of Design). The composer accepted partly because he hoped to find opportunities in Chicago, that were not available in Seattle, to organize a center for experimental music. These opportunities did not materialize. Cage taught at the Chicago School of Design and worked as accompanist and composer at the University of Chicago. At one point, his reputation as percussion composer landed him a commission from the Columbia Broadcasting System to compose a soundtrack for a radio play by Kenneth Patchen. The result, The City Wears a Slouch Hat, was received well, and Cage deduced that more important commissions would follow. Hoping to find these, he left Chicago for New York City in the spring of 1942. In New York, the Cages first stayed with painter Max Ernst and Peggy Guggenheim. Through them, Cage met important artists such as Piet Mondrian, André Breton, Jackson Pollock, and Marcel Duchamp, and many others. Guggenheim was very supportive: the Cages could stay with her and Ernst for any length of time, and she offered to organize a concert of Cage's music at the opening of her gallery, which included paying for transportation of Cage's percussion instruments from Chicago. After she learned that Cage secured another concert, at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Guggenheim withdrew all support, and, even after the ultimately successful MoMA concert, Cage was left homeless, unemployed and penniless. The commissions he hoped for did not happen. He and Xenia spent the summer of 1942 with dancer Jean Erdman and her husband Joseph Campbell. Without the percussion instruments, Cage again turned to prepared piano, producing a substantial body of works for performances by various choreographers, including Merce Cunningham, who had moved to New York City several years earlier. Cage and Cunningham eventually became romantically involved, and Cage's marriage, already breaking up during the early 1940s, ended in divorce in 1945. Cunningham remained Cage's partner for the rest of his life. Cage also countered the lack of percussion instruments by writing, on one occasion, for voice and closed piano: the resulting piece, The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs (1942), quickly became popular and was performed by the celebrated duo of Cathy Berberian and Luciano Berio.[45] In 1944, he appeared in Maya Deren's At Land, a 15-minute silent experimental film. Like his personal life, Cage's artistic life went through a crisis in mid-1940s. The composer was experiencing a growing disillusionment with the idea of music as means of communication: the public rarely accepted his work, and Cage himself, too, had trouble understanding the music of his colleagues. In early 1946 Cage agreed to tutor Gita Sarabhai, an Indian musician who came to the US to study Western music. In return, he asked her to teach him about Indian music and philosophy.[46] Cage also attended, in late 1940s and early 1950s, D. T. Suzuki's lectures on Zen Buddhism,[47] and read further the works of Coomaraswamy.[30] The first fruits of these studies were works inspired by Indian concepts: Sonatas and Interludes for prepared piano, String Quartet in Four Parts, and others. Cage accepted the goal of music as explained to him by Sarabhai: "to sober and quiet the mind, thus rendering it susceptible to divine influences".[48] Early in 1946, his former teacher Richard Buhlig arranged for Cage to meet Berlin-born pianist Grete Sultan, who had escaped from Nazi persecution to New York in 1941.[49] They became close, lifelong friends, and Cage later dedicated part of his Music for Piano and his monumental piano cycle Etudes Australes to her. |

1937-1949年:モダンダンスと東洋の影響 こちらもご参照ください: ジョン・ケージのプリペアド・ピアノのための作品 1936年から38年にかけて、ケージは数々の仕事を転々とするが、そのうちのひとつが、モダン・ダンスとの生涯の関わりの始まりとなった。彼は振付のた めの音楽を制作し、一時は叔母のフィービーとともにUCLAで「リズミックな表現のための音楽的伴奏」についての講義を担当した[43]。ケージが初め て、日用品や金属板などの異例の楽器を使った実験を始めたのはこの頃である。これは、オスカー・フィッシンガーに触発されたもので、彼はケージに、"世の 中のすべてのものには、音を通して解放できる精神がある "と語った。ケージは霊魂という考え方に共感していたわけではなかったが、この言葉に触発され、彼は様々な非音楽的な物体を叩くことによって生じる音の探 求を始めた[43][44]。 1938年、コーウェルの勧めもあり、ケイジは就職のためにサンフランシスコに向かい、同じコーウェルの教え子で作曲家のルー・ハリソンを探した。カウエ ルによれば、2人の作曲家は打楽器とダンスに共通の関心を持っており、互いに紹介し合えば意気投合するだろうとのことだった。実際、2人は出会ってすぐに 強い絆で結ばれ、数年間続く仕事上の関係が始まった。ハリソンはすぐにケージがミルズ・カレッジで教員の職を得るのを助け、UCLAと同じプログラムを教 え、振付家のマリアン・ヴァン・テュイルと共同作業を行った。数ヵ月後、彼はワシントン州シアトルに移り、コーニッシュ芸術大学で振付家ボニー・バードの 作曲家兼伴奏者として働くことになる。コーニッシュ・スクール時代は、ケージの人生において特に重要な時期であった。教職と伴奏者としての仕事の傍ら、 ケージは打楽器アンサンブルを組織し、西海岸をツアーして作曲家に最初の名声をもたらした。1940年、プリペアド・ピアノ(弦の上や下、あるいは弦と弦 の間に物を置いて音を変化させたピアノ)の発明によって、彼の名声はさらに高まった。このコンセプトはもともと、打楽器のフル・アンサンブルを入れるには 狭すぎる部屋で演奏するためのものだった。ケージが画家のマーク・トビーやダンサーのマース・カニングハムなど、生涯の友人となる何人かの人々と出会った のも、コーニッシュ・スクールでのことだった。後者のマース・カニングハムは、ケージの生涯のロマンチックなパートナーであり、芸術的なコラボレーターと なった。 1941年夏、画家のラースロー・モホリ=ナギからシカゴ・スクール・オブ・デザイン(後のIITインスティテュート・オブ・デザイン)で教えるよう誘わ れたケージは、シアトルを離れた。作曲家がこれを引き受けたのは、シアトルでは得られないような機会をシカゴで見つけ、実験音楽のためのセンターを組織す ることを望んだからでもある。こうした機会は実現しなかった。ケージはシカゴ・スクール・オブ・デザインで教鞭をとり、シカゴ大学で伴奏者兼作曲家として 働いた。ある時、打楽器作曲家としての名声が認められ、コロンビア放送からケネス・パッチェンのラジオ劇のサウンドトラックの作曲を依頼された。その結 果、『The City Wears a Slouch Hat』は好評を博し、ケージはさらに重要な依頼が続くだろうと推測した。それを期待して、1942年春、ケージはシカゴからニューヨークへ向かった。 ニューヨークでケージはまず、画家のマックス・エルンストとペギー・グッゲンハイムの家に滞在した。彼らを通じてケージは、ピエト・モンドリアン、アンド レ・ブルトン、ジャクソン・ポロック、マルセル・デュシャンなど、重要な芸術家たちと知り合った。グッゲンハイムは非常に協力的で、ケージは彼女とエルン ストのもとにいつまでも滞在することができたし、彼女はギャラリーのオープニングでケージの音楽のコンサートを企画することを申し出た。ケージが近代美術 館(MoMA)での別のコンサートを確保したことを知ったグッゲンハイムは、すべての支援を取りやめ、最終的にMoMAでのコンサートが成功した後も、 ケージはホームレス、失業者、無一文の状態に置かれた。彼が望んだコミッションは実現しなかった。彼とゼニアは1942年の夏、ダンサーのジーン・エドマ ンとその夫ジョセフ・キャンベルのもとで過ごした。打楽器を失ったケージは再びプリペアド・ピアノに転向し、数年前にニューヨークに移住していたマース・ カニングハムをはじめ、さまざまな振付家のパフォーマンスのために充実した作品を発表した。ケージとカニンガムはやがてロマンチックな関係になり、ケージ の結婚生活は1940年代初頭にすでに破綻していたが、1945年に離婚に至った。カニンガムは生涯、ケージのパートナーであり続けた。1944年には、 マヤ・デレンの15分間のサイレント実験映画『At Land』に出演。 私生活同様、ケージの芸術生活も1940年代半ばに危機を迎える。作曲家は、コミュニケーション手段としての音楽という考え方に幻滅感を募らせていた。一 般大衆が彼の作品を受け入れることはほとんどなく、ケージ自身も、同僚の音楽を理解するのに苦労していた。1946年初頭、ケージは西洋音楽を学ぶために 渡米したインド人音楽家、ギタ・サラバイの家庭教師をすることに同意した。ケージはまた、1940年代後半から1950年代前半にかけて、鈴木大拙の禅宗 に関する講義を聴講し[47]、クーマラスワミの著作を読み進めた[30]: プリペアド・ピアノのためのソナタと間奏曲、弦楽四重奏曲4部作などである。ケージは、サラバイから説明された音楽の目標を受け入れた: 「心を沈め、静めることで、神の影響を受けやすくする」[48]。 1946年初頭、恩師リヒャルト・ブーリッヒの計らいで、ケージは1941年にナチスの迫害を逃れてニューヨークに亡命したベルリン生まれのピアニスト、グレーテ・スルタンと出会う。 |

| 1950s: discovering chance After a 1949 performance at Carnegie Hall, New York, Cage received a grant from the Guggenheim Foundation, which enabled him to make a trip to Europe, where he met composers such as Olivier Messiaen and Pierre Boulez. More important was Cage's chance encounter with Morton Feldman in New York City in early 1950. Both composers attended a New York Philharmonic concert, where the orchestra performed Anton Webern's Symphony, op. 21, followed by a piece by Sergei Rachmaninoff. Cage felt so overwhelmed by Webern's piece that he left before the Rachmaninoff; and in the lobby, he met Feldman, who was leaving for the same reason.[50] The two composers quickly became friends; some time later Cage, Feldman, Earle Brown, David Tudor and Cage's pupil Christian Wolff came to be referred to as "the New York school."[51][52] In early 1951, Wolff presented Cage with a copy of the I Ching[53]—a Chinese classic text which describes a symbol system used to identify order in chance events. This version of the I Ching was the first complete English translation and had been published by Wolff's father, Kurt Wolff of Pantheon Books in 1950. The I Ching is commonly used for divination, but for Cage it became a tool to compose using chance.[54] To compose a piece of music, Cage would come up with questions to ask the I Ching; the book would then be used in much the same way as it is used for divination. For Cage, this meant "imitating nature in its manner of operation".[55][56] His lifelong interest in sound itself culminated in an approach that yielded works in which sounds were free from the composer's will: When I hear what we call music, it seems to me that someone is talking. And talking about his feelings, or about his ideas of relationships. But when I hear traffic, the sound of traffic—here on Sixth Avenue, for instance—I don't have the feeling that anyone is talking. I have the feeling that sound is acting. And I love the activity of sound ... I don't need sound to talk to me.[57] Although Cage had used chance on a few earlier occasions, most notably in the third movement of Concerto for Prepared Piano and Chamber Orchestra (1950–51),[58] the I Ching opened new possibilities in this field for him. The first results of the new approach were Imaginary Landscape No. 4 for 12 radio receivers, and Music of Changes for piano. The latter work was written for David Tudor,[59] whom Cage met through Feldman—another friendship that lasted until Cage's death.[c] Tudor premiered most of Cage's works until the early 1960s, when he stopped performing on the piano and concentrated on composing music. The I Ching became Cage's standard tool for composition: he used it in practically every work composed after 1951, and eventually settled on a computer algorithm that calculated numbers in a manner similar to throwing coins for the I Ching. Despite the fame Sonatas and Interludes earned him, and the connections he cultivated with American and European composers and musicians, Cage was quite poor. Although he still had an apartment at 326 Monroe Street (which he occupied since around 1946), his financial situation in 1951 worsened so much that while working on Music of Changes, he prepared a set of instructions for Tudor as to how to complete the piece in the event of his death.[60] Nevertheless, Cage managed to survive and maintained an active artistic life, giving lectures and performances, etc. In 1952–1953 he completed another mammoth project—the Williams Mix, a piece of tape music, which Earle Brown and Morton Feldman helped to put together.[61] Also in 1952, Cage composed the piece that became his best-known and most controversial creation: 4′33″. The score instructs the performer not to play the instrument during the entire duration of the piece—four minutes, thirty-three seconds—and is meant to be perceived as consisting of the sounds of the environment that the listeners hear while it is performed. Cage conceived "a silent piece" years earlier, but was reluctant to write it down; and indeed, the premiere (given by Tudor on August 29, 1952, at Woodstock, New York) caused an uproar in the audience.[62] The reaction to 4′33″ was just a part of the larger picture: on the whole, it was the adoption of chance procedures that had disastrous consequences for Cage's reputation. The press, which used to react favorably to earlier percussion and prepared piano music, ignored his new works, and many valuable friendships and connections were lost. Pierre Boulez, who used to promote Cage's work in Europe, was opposed to Cage's use of chance, and so were other composers who came to prominence during the 1950s, e.g. Karlheinz Stockhausen and Iannis Xenakis.[63][failed verification] During this time Cage was also teaching at the avant-garde Black Mountain College just outside Asheville, North Carolina. Cage taught at the college in the summers of 1948 and 1952 and was in residence the summer of 1953. While at Black Mountain College in 1952, he organized what has been called the first "happening" (see discussion below) in the United States, later titled Theatre Piece No. 1, a multi-layered, multi-media performance event staged the same day as Cage conceived it that "that would greatly influence 1950s and 60s artistic practices". In addition to Cage, the participants included Cunningham and Tudor.[64] From 1953 onward, Cage was busy composing music for modern dance, particularly Cunningham's dances (Cage's partner adopted chance too, out of fascination for the movement of the human body), as well as developing new methods of using chance, in a series of works he referred to as The Ten Thousand Things. In the summer of 1954 he moved out of New York and settled in Gate Hill Cooperative, a community in Stony Point, New York, where his neighbors included David Tudor, M. C. Richards, Karen Karnes, Stan VanDerBeek, and Sari Dienes. The composer's financial situation gradually improved: in late 1954 he and Tudor were able to embark on a European tour. From 1956 to 1961 Cage taught classes in experimental composition at The New School, and from 1956 to 1958 he also worked as an art director and designer of typography.[65] Among his works completed during the last years of the decade were Concert for Piano and Orchestra (1957–58), a seminal work in the history of graphic notation,[66] and Variations I (1958). 1960s: fame Cage was affiliated with Wesleyan University and collaborated with members of its Music Department from the 1950s until his death in 1992. At the university, the philosopher, poet, and professor of classics Norman O. Brown befriended Cage, an association that proved fruitful to both.[citation needed] In 1960 the composer was appointed a Fellow on the faculty of the Center for Advanced Studies (now the Center for Humanities) in the Liberal Arts and Sciences at Wesleyan,[67] where he started teaching classes in experimental music. In October 1961, Wesleyan University Press published Silence, a collection of Cage's lectures and writings on a wide variety of subjects, including the famous Lecture on Nothing that was composed using a complex time length scheme, much like some of Cage's music. Silence was Cage's first book of six but it remains his most widely read and influential.[d][30] In the early 1960s Cage began his lifelong association with C.F. Peters Corporation. Walter Hinrichsen, the president of the corporation, offered Cage an exclusive contract and instigated the publication of a catalog of Cage's works, which appeared in 1962.[65] Edition Peters soon published a large number of scores by Cage, and this, together with the publication of Silence, led to much higher prominence for the composer than ever before—one of the positive consequences of this was that in 1965 Betty Freeman set up an annual grant for living expenses for Cage, to be issued from 1965 to his death.[68] By the mid-1960s, Cage was receiving so many commissions and requests for appearances that he was unable to fulfill them. This was accompanied by a busy touring schedule; consequently Cage's compositional output from that decade was scant.[30] After the orchestral Atlas Eclipticalis (1961–62), a work based on star charts, which was fully notated, Cage gradually shifted to, in his own words, "music (not composition)." The score of 0′00″, completed in 1962, originally comprised a single sentence: "In a situation provided with maximum amplification, perform a disciplined action", and in the first performance the disciplined action was Cage writing that sentence. The score of Variations III (1962) abounds in instructions to the performers, but makes no references to music, musical instruments or sounds. Many of the Variations and other 1960s pieces were in fact "happenings", an art form established by Cage and his students in late 1950s. Cage's "Experimental Composition" classes at The New School have become legendary as an American source of Fluxus, an international network of artists, composers, and designers. The majority of his students had little or no background in music. Most were artists. They included Jackson Mac Low, Allan Kaprow, Al Hansen, George Brecht, Ben Patterson, and Dick Higgins, as well as many others Cage invited unofficially. Famous pieces that resulted from the classes include George Brecht's Time Table Music and Al Hansen's Alice Denham in 48 Seconds.[69] As set forth by Cage, happenings were theatrical events that abandon the traditional concept of stage-audience and occur without a sense of definite duration. Instead, they are left to chance. They have a minimal script, with no plot. In fact, a "happening" is so-named because it occurs in the present, attempting to arrest the concept of passing time. Cage believed that theater was the closest route to integrating art and real life. The term "happenings" was coined by Allan Kaprow, one of his students, who defined it as a genre in the late fifties. Cage met Kaprow while on a mushroom hunt with George Segal and invited him to join his class. In following these developments Cage was strongly influenced by Antonin Artaud's seminal treatise The Theatre and Its Double, and the happenings of this period can be viewed as a forerunner to the ensuing Fluxus movement. In October 1960, Mary Bauermeister's Cologne studio hosted a joint concert by Cage and the video artist Nam June Paik (Cage's friend and mentee), who in the course of his performance of Etude for Piano cut off Cage's tie and then poured a bottle of shampoo over the heads of Cage and Tudor.[70] In 1967, Cage's book A Year from Monday was first published by Wesleyan University Press. Cage's parents died during the decade: his father in 1964,[71] and his mother in 1969. Cage had their ashes scattered in Ramapo Mountains, near Stony Point, and asked for the same to be done to him after his death.[72] |

1950年代:偶然の発見 1949年にニューヨークのカーネギーホールで演奏した後、ケージはグッゲンハイム財団から助成金を得てヨーロッパを訪れ、オリヴィエ・メシアンやピエー ル・ブーレーズといった作曲家たちと知り合った。さらに重要だったのは、1950年初めにケージがニューヨークでモートン・フェルドマンと偶然出会ったこ とだ。両作曲家ともニューヨーク・フィルハーモニックのコンサートに参加し、そこでオーケストラはアントン・ウェーベルンの交響曲作品21を演奏し、続い てセルゲイ・ラフマニノフの作品を演奏した。ケージはウェーベルンの作品に圧倒され、ラフマニノフの演奏の前に退席。ロビーで、同じ理由で退席しようとし ていたフェルドマンに出会った[50]。2人の作曲家はすぐに友人となり、しばらくしてケージ、フェルドマン、アール・ブラウン、デヴィッド・チュー ダー、ケージの弟子クリスチャン・ヴォルフは「ニューヨーク派」と呼ばれるようになった[51][52]。 1951年初頭、ヴォルフはケージに『易経』[53]のコピーを贈った。この『易経』は、ウォルフの父であるクルト・ウォルフが1950年にパンテオン・ ブックスから出版したもので、初の完全な英訳版であった。易経は一般的に占いに用いられるが、ケージにとっては偶然性を利用して作曲するための道具となっ た[54]。ケージにとって、これは「自然の営みを模倣する」ことを意味した[55][56]。音そのものに対する彼の生涯の興味は、音が作曲者の意志か ら自由である作品を生み出すアプローチに結実した: 私たちが音楽と呼ぶものを聴くと、誰かが話しているように思える。そして、自分の感情や人間関係についての考えを語っている。しかし、例えばここ6番街の 交通音を聞くと、誰かが話しているという感覚はない。私は音が活動しているという感覚を持つ。私は音の活動が好きなんだ。私は音に語りかけてもらう必要は ないのです」[57]。 ケージはそれ以前にも何度か偶然性を利用していたが、特に『プリペアド・ピアノと室内オーケストラのための協奏曲』(1950-51)の第3楽章で顕著で あった[58]。この新しいアプローチの最初の成果は、12台のラジオ受信機のための《想像の風景》第4番と、ピアノのための《変化の音楽》であった。後 者の作品は、ケージがフェルドマンを通じて知り合ったデイヴィッド・チューダーのために書かれたものであり[59]、これもまたケージの死まで続いた友情 であった[c]。チューダーは1960年代初頭までケージの作品のほとんどを初演していたが、彼はピアノの演奏をやめ、作曲に専念するようになる。彼は 1951年以降に作曲されたほとんどすべての作品で易経を使用し、最終的には易経のコインを投げるのと同じような方法で数字を計算するコンピュータ・アル ゴリズムに落ち着いた。 ソナタと間奏曲』によって名声を得、アメリカやヨーロッパの作曲家や音楽家たちとのつながりを深めたにもかかわらず、ケージはかなり貧しかった。モンロー 通り326番地のアパート(1946年頃から住んでいた)にはまだ住んでいたものの、1951年には経済状況が悪化し、『変化の音楽』の制作中に、チュー ダーに自分の死後、どのように曲を完成させるかについての指示書を作成したほどであった[60]。それでもケージは何とか生き延び、講演や演奏活動など、 活発な芸術生活を維持した。 1952年から1953年にかけて、彼はもうひとつの巨大なプロジェクト、ウィリアムズ・ミックス(Williams Mix)というテープ音楽を完成させた: 4′33″. この楽譜では、4分33秒の間、演奏者は楽器を演奏しないように指示されており、演奏されている間、聴衆が聴いている環境の音から構成されていると感じら れるように意図されている。ケージは何年も前に「無音の作品」を構想していたが、それを書き留めることには消極的だった。実際、初演(1952年8月29 日、ニューヨークのウッドストックでチューダーによって行われた)は聴衆の騒動を引き起こした[62]。「4′33″」に対する反応は、より大きな絵の一 部に過ぎなかった。全体として、ケージの評判に悲惨な結果をもたらしたのは、偶然の手順を採用したことだった。以前は打楽器やプリペアド・ピアノの音楽に 好意的だったマスコミは、彼の新作を無視し、多くの貴重な友情と人脈が失われた。ヨーロッパでケージの作品を宣伝していたピエール・ブーレーズは、ケージ の偶然性の使用に反対していたし、カールハインツ・シュトックハウゼンやイアニス・クセナキスなど、1950年代に脚光を浴びるようになった他の作曲家た ちも同様だった[63][検証失敗]。 この時期、ケージはノースカロライナ州アッシュヴィル郊外にある前衛的なブラック・マウンテン・カレッジでも教鞭をとっていた。ケージは1948年と 1952年の夏に同大学で教鞭をとり、1953年の夏にはレジデンスに滞在していた。後に『シアター・ピースNo.1』と題されるこのイベントは、ケージ が構想したその日に上演され、「1950年代から60年代の芸術活動に大きな影響を与えることになる」多層的でマルチメディアなパフォーマンス・イベント であった。参加者にはケージのほか、カニンガムやチューダーも含まれていた[64]。 1953年以降、ケージはモダンダンス、特にカニンガムのダンス(ケージのパートナーも人体の動きに魅了され、偶然性を取り入れた)のための作曲に忙殺さ れ、また彼が「テン・サウザンド・シングス」と呼ぶ一連の作品の中で、偶然性を利用した新しい手法を開発した。1954年夏、彼はニューヨークを離れ、 ニューヨーク州ストーニーポイントにあるコミュニティ、ゲートヒル・コーポラティブに定住した。そこにはデイヴィッド・チューダー、M.C.リチャーズ、 カレン・カーンズ、スタン・ヴァンダービーク、サリ・ディーンズらが住んでいた。1954年後半には、チューダーとともにヨーロッパ・ツアーに出かけるこ とができた。1956年から1961年まで、ケージはニュースクールで実験的作曲のクラスを教え、1956年から1958年まではアートディレクターやタ イポグラフィのデザイナーとしても働いた。 1960年代:名声 ケージは1950年代から1992年に亡くなるまで、ウェズリアン大学に所属し、同大学の音楽学部のメンバーと共同研究を行っていた。同大学では、哲学 者、詩人、古典の教授であったノーマン・O・ブラウンがケージと親交を深め、両者にとって実りある関係となった[citation needed]。1960年、作曲家はウェズリアン大学の教養学部高等研究センター(現在の人文科学センター)の教授陣のフェローに任命され[67]、そ こで実験音楽のクラスを教え始めた。1961年10月、ウェズリアン大学出版局は、ケージの音楽の一部と同様に複雑な時間長スキームを使って作曲された有 名な『無についての講義』を含む、さまざまなテーマに関するケージの講義と著作を集めた『沈黙』を出版した。沈黙』はケージにとって最初の6冊の本であっ たが、今でも最も広く読まれ、影響力のある本である[d][30]。1960年代初頭、ケージはC.F.ピーターズ社との生涯にわたる付き合いを始めた。 同社の社長であるウォルター・ヒンリクセンはケージに独占契約を持ちかけ、1962年に出版されたケージの作品カタログの出版を扇動した[65]。 エディション・ピーターズはすぐにケージの楽譜を大量に出版し、これは『沈黙』の出版と相俟って、作曲家としてのケージの知名度をかつてないほど高めるこ とになった。これは多忙なツアー・スケジュールに伴うもので、その結果、この10年間にケージが作曲した作品はほとんどなかった[30]。1962年に完 成した《0′00″》の楽譜は、当初は一文で構成されていた: 「最大限の増幅が与えられた状況で、規律ある動作を行う」。初演では、その規律ある動作とは、ケージがその文章を書くことだった。変奏曲III』 (1962年)の楽譜には、演奏者への指示がたくさん書かれているが、音楽、楽器、音への言及はない。 変奏曲をはじめとする1960年代の作品の多くは、実は1950年代後半にケージとその弟子たちによって確立された芸術形態である「ハプニング」だった。 ニュースクールでのケージの「実験作曲」の授業は、アーティスト、作曲家、デザイナーの国際的なネットワークであるフルクサスのアメリカの源流として伝説 となっている。ケージの生徒の大半は音楽の素養がほとんどなかった。ほとんどがアーティストだった。その中には、ジャクソン・マック・ロー、アラン・カプ ロー、アル・ハンセン、ジョージ・ブレヒト、ベン・パターソン、ディック・ヒギンズなど、ケージが非公式に招いた多くのアーティストも含まれている。この クラスから生まれた有名な作品には、ジョージ・ブレヒトの『Time Table Music』やアル・ハンセンの『Alice Denham in 48 Seconds』などがある[69]。ケージが掲げたように、ハプニングとは、伝統的な舞台と観客の概念を放棄し、明確な持続時間の感覚なしに起こる演劇 的な出来事である。その代わり、ハプニングは偶然に委ねられる。筋書きのない最小限の台本しかない。実際、「ハプニング」とは、現在進行形で起こり、過ぎ ゆく時間の概念を止めようとすることから、そう名付けられた。ケージは、演劇こそが芸術と実生活を統合する最も近い道だと信じていた。ハプニング」という 言葉は、彼の弟子の一人であるアラン・カプローが50年代後半にジャンルとして定義したものである。ケージはジョージ・シーガルとキノコ狩りに出かけた際 にカプロウと出会い、彼を自分のクラスに招いた。ケージは、アントナン・アルトーの『劇場とその二重人格』から強い影響を受けており、この時期の出来事 は、その後のフルクサス運動の先駆けとして見ることができる。1960年10月、メアリー・バウエルマイスターのケルンのスタジオでは、ケージとビデオ・ アーティストのナム・ジュン・パイク(ケージの友人であり弟子)によるジョイント・コンサートが開催され、彼は『ピアノのためのエチュード』の演奏中に ケージのネクタイを切り落とし、ケージとチューダーの頭にシャンプーのボトルをかけた[70]。 1967年、ケージの著書『A Year from Monday』がウェズリアン大学出版局から初めて出版された。1964年に父、[71] 1969年に母が死去。ケージは二人の遺灰をストーニー・ポイント近くのラマポ山脈に散骨し、自分の死後も同じように散骨してくれるよう頼んだ[72]。 |

| 1969–1987: new departures Cage's work from the sixties features some of his largest and most ambitious, not to mention socially utopian pieces, reflecting the mood of the era yet also his absorption of the writings of both Marshall McLuhan, on the effects of new media, and R. Buckminster Fuller, on the power of technology to promote social change. HPSCHD (1969), a gargantuan and long-running multimedia work made in collaboration with Lejaren Hiller, incorporated the mass superimposition of seven harpsichords playing chance-determined excerpts from the works of Cage, Hiller, and a potted history of canonical classics, with 52 tapes of computer-generated sounds, 6,400 slides of designs, many supplied by NASA, and shown from sixty-four slide projectors, with 40 motion-picture films. The piece was initially rendered in a five-hour performance at the University of Illinois in 1969, in which the audience arrived after the piece had begun and left before it ended, wandering freely around the auditorium in the time for which they were there.[73] Also in 1969, Cage produced the first fully notated work in years: Cheap Imitation for piano. The piece is a chance-controlled reworking of Erik Satie's Socrate, and, as both listeners and Cage himself noted, openly sympathetic to its source. Although Cage's affection for Satie's music was well-known, it was highly unusual for him to compose a personal work, one in which the composer is present. When asked about this apparent contradiction, Cage replied: "Obviously, Cheap Imitation lies outside of what may seem necessary in my work in general, and that's disturbing. I'm the first to be disturbed by it."[74] Cage's fondness for the piece resulted in a recording—a rare occurrence, since Cage disliked making recordings of his music—made in 1976. Overall, Cheap Imitation marked a major change in Cage's music: he turned again to writing fully notated works for traditional instruments, and tried out several new approaches, such as improvisation, which he previously discouraged, but was able to use in works from the 1970s, such as Child of Tree (1975). Opening bars of Cheap Imitation (1969) 0:40 Performed by the composer in 1976, shortly before he had to retire from performing Problems playing this file? See media help. Cheap Imitation became the last work Cage performed in public himself. Arthritis had troubled Cage since 1960, and by the early 1970s his hands were painfully swollen and rendered him unable to perform.[75] Nevertheless, he still played Cheap Imitation during the 1970s,[76] before finally having to give up performing. Preparing manuscripts also became difficult: before, published versions of pieces were done in Cage's calligraphic script; now, manuscripts for publication had to be completed by assistants. Matters were complicated further by David Tudor's departure from performing, which happened in the early 1970s. Tudor decided to concentrate on composition instead, and so Cage, for the first time in two decades, had to start relying on commissions from other performers, and their respective abilities. Such performers included Grete Sultan, Paul Zukofsky, Margaret Leng Tan, and many others. Aside from music, Cage continued writing books of prose and poetry (mesostics). M was first published by Wesleyan University Press in 1973. In January 1978 Cage was invited by Kathan Brown of Crown Point Press to engage in printmaking, and Cage would go on to produce series of prints every year until his death; these, together with some late watercolors, constitute the largest portion of his extant visual art. In 1979 Cage's Empty Words was first published by Wesleyan University Press. 1987–1992: final years and death See also: Number Pieces In 1987, Cage completed a piece called Two, for flute and piano, dedicated to performers Roberto Fabbriciani and Carlo Neri. The title referred to the number of performers needed; the music consisted of short notated fragments to be played at any tempo within the indicated time constraints. Cage went on to write some forty such Number Pieces, as they came to be known, one of the last being Eighty (1992, premiered in Munich on October 28, 2011), usually employing a variant of the same technique. The process of composition, in many of the later Number Pieces, was simple selection of pitch range and pitches from that range, using chance procedures;[30] the music has been linked to Cage's anarchic leanings.[77] One11 (i.e. the eleventh piece for a single performer), completed in early 1992, was Cage's first and only foray into film. Cage conceived his last musical work with Michael Bach Bachtischa: "ONE13" for violoncello with Curved Bow and three loudspeakers, which was published years later. Another new direction, also taken in 1987, was opera: Cage produced five operas, all sharing the same title Europera, in 1987–91. Europeras I and II require greater forces than III, IV and V, which are on a chamber scale. John Cage (left) and Michael Bach in Assisi, Italy, 1992 In the course of the 1980s, Cage's health worsened progressively. He suffered not only from arthritis, but also from sciatica and arteriosclerosis. He had a stroke that left the movement of his left leg restricted, and, in 1985, broke an arm. During this time, Cage pursued a macrobiotic diet.[78] Nevertheless, ever since arthritis started plaguing him, the composer was aware of his age, and, as biographer David Revill observed, "the fire which he began to incorporate in his visual work in 1985 is not only the fire he has set aside for so long—the fire of passion—but also fire as transitoriness and fragility." On August 11, 1992, while preparing evening tea for himself and Cunningham, Cage had another stroke. He was taken to St. Vincent's Hospital in Manhattan, where he died on the morning of August 12.[79] He was 79.[2] According to his wishes, Cage's body was cremated and his ashes scattered in the Ramapo Mountains, near Stony Point, New York, at the same place where he had scattered the ashes of his parents.[72] The composer's death occurred only weeks before a celebration of his 80th birthday organized in Frankfurt by composer Walter Zimmermann and musicologist Stefan Schaedler.[2] The event went ahead as planned, including a performance of the Concert for Piano and Orchestra by David Tudor and Ensemble Modern. Merce Cunningham died of natural causes in July 2009.[80] |

1969-1987年:新たな出発 ケージの60年代の作品には、社会的ユートピアはもちろんのこと、彼の最大かつ野心的な作品がいくつかあり、時代のムードを反映していると同時に、新しい メディアの効果に関するマーシャル・マクルーハンや、社会変革を促進するテクノロジーの力に関するR・バックミンスター・フラーの著作を吸収していた。レ ジャレン・ヒラーとの共同制作による巨大かつ長期にわたるマルチメディア作品『HPSCHD』(1969年)は、ケージやヒラーの作品からの偶然に決定さ れた抜粋を演奏する7台のハープシコードと、コンピューターによって生成された52本のテープ音、NASAから提供された6,400枚のデザイン・スライ ド、64台のスライド・プロジェクター、40枚の動画フィルムを大量に重ね合わせたものである。この作品は当初、1969年にイリノイ大学で行われた5時 間のパフォーマンスで上演され、観客は作品が始まってから到着し、終わる前に退場し、その時間内に講堂内を自由に歩き回った[73]。 同じく1969年、ケージは数年ぶりに完全な楽譜化された作品を制作した: ピアノのための『チープ・イミテーション』である。この曲は、エリック・サティの『ソクラテス』を偶然に制御して再構築したもので、聴衆もケージ自身もそ の出典に公然と共感していると述べている。ケージのサティの音楽に対する愛情はよく知られていたが、彼が個人的な作品、つまり作曲家が存在する作品を作曲 するのは非常に異例なことだった。この明らかな矛盾について尋ねられたケージはこう答えた: 明らかに、『チープ・イミテーション』は私の作品全般において必要と思われるものから外れている。この作品に対するケージの好意は、1976年に録音とい う珍しい事態をもたらした。彼は伝統的な楽器のための完全な記譜された作品を書くことに再び転向し、即興演奏など、以前は敬遠していたいくつかの新しいア プローチを試みたが、『Child of Tree』(1975年)のような1970年代の作品では使用することができた。 チープ・イミテーション』(1969年)の冒頭の小節 0:40 1976年、作曲者が演奏活動から引退する直前に演奏。 このファイルの再生に問題がありますか?メディアヘルプをご覧ください。 チープ・イミテーション」は、ケージが自ら人前で演奏した最後の作品となった。1960年以来、関節炎に悩まされていたケージは、1970年代初頭には手 が痛々しく腫れ上がり、演奏することができなくなっていた[75]。にもかかわらず、彼は1970年代にも《チープ・イミテーション》を演奏し[76]、 最終的には演奏を断念せざるを得なくなった。以前は、出版される作品のバージョンはケージのカリグラフィーで書かれていたが、今では出版用の原稿はアシス タントによって仕上げられなければならない。1970年代初頭に起こったデイヴィッド・チューダーの演奏活動からの離脱によって、事態はさらに複雑になっ た。チューダーは作曲に専念することを決めたため、ケージは20年ぶりに、他の演奏家とそれぞれの能力からの依頼に頼らざるを得なくなった。そのような演 奏家には、グレーテ・スルタン、ポール・ズコフスキー、マーガレット・レン・タン、その他大勢がいた。音楽以外では、ケージは散文と詩(メソスティック) の本を書き続けた。M』は1973年にウェズリアン大学出版局から初めて出版された。1978年1月、ケージはクラウン・ポイント・プレスのケイサン・ブ ラウンに版画制作に携わるよう招かれ、以後、ケージは亡くなるまで毎年版画のシリーズを制作することになる。1979年、ケージはウェズリアン大学出版局 から『Empty Words』を初めて出版した。 1987-1992年:晩年と死 関連項目 ナンバー・ピース 1987年、ケージは演奏家ロベルト・ファブリチャーニとカルロ・ネリに捧げたフルートとピアノのための作品『Two』を完成させた。このタイトルは、必 要とされる演奏者の数を意味しており、音楽は、指示された時間の制約の中で任意のテンポで演奏できるように、短い楽譜の断片で構成されていた。ケージはそ の後、このようなナンバー・ピースと呼ばれる作品を40曲ほど書き、最後の作品のひとつが『エイティ』(1992年、2011年10月28日にミュンヘン で初演)である。1992年初頭に完成した《One11》(すなわち、一人の演奏家のための11番目の作品)は、ケージにとって最初で唯一の映画作品であ る。ケージはミヒャエル・バッハ・バッハティッシャと最後の音楽作品となる《ONE13》(チェロとカーヴド・ボウと3台のスピーカーのための)を構想 し、数年後に出版された。 もうひとつの新しい方向性は、やはり1987年に打ち出されたオペラである: ケージは、1987年から91年にかけて、同じ「ユーロペラ」というタイトルの5つのオペラを制作した。ユーロペラIとIIは、室内楽規模のIII、IV、Vよりも大きな力を必要とする。 ジョン・ケージ(左)とマイケル・バッハ(1992年、イタリア、アッシジにて 1980年代に入り、ケージの健康状態は徐々に悪化していった。関節炎だけでなく、坐骨神経痛や動脈硬化にも苦しんだ。脳卒中で左足の動きが制限され、 1985年には腕を骨折した。それにもかかわらず、関節炎が彼を悩ませ始めて以来、作曲家は自分の年齢を意識していた。伝記作家のデイヴィッド・レヴィル は、「1985年に彼が視覚的な作品に取り入れ始めた炎は、彼が長い間脇に置いていた炎(情熱の炎)であるだけでなく、移り気さや脆さとしての炎でもあ る」と述べている。1992年8月11日、自分とカニンガムのために夜のお茶を用意していたとき、ケージは再び脳卒中を起こした。彼はマンハッタンのセン ト・ヴィンセント病院に運ばれ、8月12日の朝に息を引き取った[79]。 彼の遺志により、遺体は荼毘に付され、遺灰は両親の遺灰を散骨した場所と同じ、ニューヨークのストーニー・ポイントに近いラマポ山脈に散骨された [72]。作曲家ヴァルター・ツィンマーマンと音楽学者シュテファン・シェードラーによってフランクフルトで企画された彼の80歳の誕生日を祝うイベント のわずか数週間前に、作曲家の死は起こった。マース・カニングハムは2009年7月に自然死した[80]。 |

| Music See also: List of compositions by John Cage Early works, rhythmic structure, and new approaches to harmony Cage's first completed pieces are currently lost. According to the composer, the earliest works were very short pieces for piano, composed using complex mathematical procedures and lacking in "sensual appeal and expressive power."[81] Cage then started producing pieces by improvising and writing down the results, until Richard Buhlig stressed to him the importance of structure. Most works from the early 1930s, such as Sonata for Clarinet (1933) and Composition for 3 Voices (1934), are highly chromatic and betray Cage's interest in counterpoint. Around the same time, the composer also developed a type of a tone row technique with 25-note rows.[82] After studies with Schoenberg, who never taught dodecaphony to his students, Cage developed another tone row technique, in which the row was split into short motives, which would then be repeated and transposed according to a set of rules. This approach was first used in Two Pieces for Piano (c. 1935), and then, with modifications, in larger works such as Metamorphosis and Five Songs (both 1938). Rhythmic proportions in Sonata III of Sonatas and Interludes for prepared piano Soon after Cage started writing percussion music and music for modern dance, he started using a technique that placed the rhythmic structure of the piece into the foreground. In Imaginary Landscape No. 1 (1939) there are four large sections of 16, 17, 18, and 19 bars, and each section is divided into four subsections, the first three of which were all 5 bars long. First Construction (in Metal) (1939) expands on the concept: there are five sections of 4, 3, 2, 3, and 4 units respectively. Each unit contains 16 bars, and is divided the same way: 4 bars, 3 bars, 2 bars, etc. Finally, the musical content of the piece is based on sixteen motives.[83] Such "nested proportions", as Cage called them, became a regular feature of his music throughout the 1940s. The technique was elevated to great complexity in later pieces such as Sonatas and Interludes for prepared piano (1946–48), in which many proportions used non-integer numbers (1¼, ¾, 1¼, ¾, 1½, and 1½ for Sonata I, for example),[84] or A Flower, a song for voice and closed piano, in which two sets of proportions are used simultaneously.[85] In late 1940s, Cage started developing further methods of breaking away with traditional harmony. For instance, in String Quartet in Four Parts (1950) Cage first composed a number of gamuts: chords with fixed instrumentation. The piece progresses from one gamut to another. In each instance the gamut was selected only based on whether it contains the note necessary for the melody, and so the rest of the notes do not form any directional harmony.[30] Concerto for prepared piano (1950–51) used a system of charts of durations, dynamics, melodies, etc., from which Cage would choose using simple geometric patterns.[30] The last movement of the concerto was a step towards using chance procedures, which Cage adopted soon afterwards.[86] Chance I Ching divination involves obtaining a hexagram by random generation (such as tossing coins), then reading the chapter associated with that hexagram. A chart system was also used (along with nested proportions) for the large piano work Music of Changes (1951), only here material would be selected from the charts by using the I Ching. All of Cage's music since 1951 was composed using chance procedures, most commonly using the I Ching. For example, works from Music for Piano were based on paper imperfections: the imperfections themselves provided pitches, coin tosses and I Ching hexagram numbers were used to determine the accidentals, clefs, and playing techniques.[87] A whole series of works was created by applying chance operations, i.e. the I Ching, to star charts: Atlas Eclipticalis (1961–62), and a series of etudes: Etudes Australes (1974–75), Freeman Etudes (1977–90), and Etudes Boreales (1978).[88] Cage's etudes are all extremely difficult to perform, a characteristic dictated by Cage's social and political views: the difficulty would ensure that "a performance would show that the impossible is not impossible"[89]—this being Cage's answer to the notion that solving the world's political and social problems is impossible.[90] Cage described himself as an anarchist, and was influenced by Henry David Thoreau.[e] Another series of works applied chance procedures to pre-existing music by other composers: Cheap Imitation (1969; based on Erik Satie), Some of "The Harmony of Maine" (1978; based on Belcher), and Hymns and Variations (1979). In these works, Cage would borrow the rhythmic structure of the originals and fill it with pitches determined through chance procedures, or just replace some of the originals' pitches.[92] Yet another series of works, the so-called Number Pieces, all completed during the last five years of the composer's life, make use of time brackets: the score consists of short fragments with indications of when to start and to end them (e.g. from anywhere between 1′15" and 1′45", and to anywhere from 2′00" to 2′30").[93] Cage's method of using the I Ching was far from simple randomization. The procedures varied from composition to composition, and were usually complex. For example, in the case of Cheap Imitation, the exact questions asked to the I Ching were these: Which of the seven modes, if we take as modes the seven scales beginning on white notes and remaining on white notes, which of those am I using? Which of the twelve possible chromatic transpositions am I using? For this phrase for which this transposition of this mode will apply, which note am I using of the seven to imitate the note that Satie wrote?[94] In another example of late music by Cage, Etudes Australes, the compositional procedure involved placing a transparent strip on the star chart, identifying the pitches from the chart, transferring them to paper, then asking the I Ching which of these pitches were to remain single, and which should become parts of aggregates (chords), and the aggregates were selected from a table of some 550 possible aggregates, compiled beforehand.[88][95] Finally, some of Cage's works, particularly those completed during the 1960s, feature instructions to the performer, rather than fully notated music. The score of Variations I (1958) presents the performer with six transparent squares, one with points of various sizes, five with five intersecting lines. The performer combines the squares and uses lines and points as a coordinate system, in which the lines are axes of various characteristics of the sounds, such as lowest frequency, simplest overtone structure, etc.[96] Some of Cage's graphic scores (e.g. Concert for Piano and Orchestra, Fontana Mix (both 1958)) present the performer with similar difficulties. Still other works from the same period consist just of text instructions. The score of 0′00″ (1962; also known as 4′33″ No. 2) consists of a single sentence: "In a situation provided with maximum amplification, perform a disciplined action." The first performance had Cage write that sentence.[97] Musicircus (1967) simply invites the performers to assemble and play together. The first Musicircus featured multiple performers and groups in a large space who were all to commence and stop playing at two particular time periods, with instructions on when to play individually or in groups within these two periods. The result was a mass superimposition of many different musics on top of one another as determined by chance distribution, producing an event with a specifically theatric feel. Many Musicircuses have subsequently been held, and continue to occur even after Cage's death. The English National Opera (ENO) became the first opera company to hold a Cage Musicircus on March 3, 2012, at the London Coliseum.[98][99] The ENO's Musicircus featured artists including Led Zeppelin bassist John Paul Jones and composer Michael Finnissy alongside ENO music director Edward Gardner, the ENO Community Choir, ENO Opera Works singers, and a collective of professional and amateur talents performing in the bars and front of house at London's Coliseum Opera House.[100] This concept of circus was to remain important to Cage throughout his life and featured strongly in such pieces as Roaratorio, an Irish circus on Finnegans Wake (1979), a many-tiered rendering in sound of both his text Writing for the Second Time Through Finnegans Wake, and traditional musical and field recordings made around Ireland. The piece was based on James Joyce's famous novel, Finnegans Wake, which was one of Cage's favorite books, and one from which he derived texts for several more of his works. Improvisation Since chance procedures were used by Cage to eliminate the composer's and the performer's likes and dislikes from music, Cage disliked the concept of improvisation, which is inevitably linked to the performer's preferences. In a number of works beginning in the 1970s, he found ways to incorporate improvisation. In Child of Tree (1975) and Branches (1976) the performers are asked to use certain species of plants as instruments, for example the cactus. The structure of the pieces is determined through the chance of their choices, as is the musical output; the performers had no knowledge of the instruments. In Inlets (1977) the performers play large water-filled conch shells – by carefully tipping the shell several times, it is possible to achieve a bubble forming inside, which produced sound. Yet, as it is impossible to predict when this would happen, the performers had to continue tipping the shells – as a result the performance was dictated by pure chance.[101] Visual art, writings, and other activities Variations III, No. 14, a 1992 print by Cage from a series of 57 Although Cage started painting in his youth, he gave it up in order to concentrate on music instead. His first mature visual project, Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel, dates from 1969. The work comprises two lithographs and a group of what Cage called plexigrams: silk screen printing on plexiglas panels. The panels and the lithographs all consist of bits and pieces of words in different typefaces, all governed by chance operations.[102] From 1978 to his death Cage worked at Crown Point Press, producing series of prints every year. The earliest project completed there was the etching Score Without Parts (1978), created from fully notated instructions, and based on various combinations of drawings by Henry David Thoreau. This was followed, the same year, by Seven Day Diary, which Cage drew with his eyes closed, but which conformed to a strict structure developed using chance operations. Finally, Thoreau's drawings informed the last works produced in 1978, Signals.[103] Between 1979 and 1982 Cage produced a number of large series of prints: Changes and Disappearances (1979–80), On the Surface (1980–82), and Déreau (1982). These were the last works in which he used engraving.[104] In 1983 he started using various unconventional materials such as cotton batting, foam, etc., and then used stones and fire (Eninka, Variations, Ryoanji, etc.) to create his visual works.[105] In 1988–1990 he produced watercolors at the Mountain Lake Workshop. The only film Cage produced was one of the Number Pieces, One11, commissioned by composer and film director Henning Lohner who worked with Cage to produce and direct the 90-minute monochrome film. It was completed only weeks before his death in 1992. One11 consists entirely of images of chance-determined play of electric light. It premiered in Cologne, Germany, on September 19, 1992, accompanied by the live performance of the orchestra piece 103. Throughout his adult life, Cage was also active as lecturer and writer. Some of his lectures were included in several books he published, the first of which was Silence: Lectures and Writings (1961). Silence included not only simple lectures, but also texts executed in experimental layouts, and works such as Lecture on Nothing (1949), which were composed in rhythmic structures. Subsequent books also featured different types of content, from lectures on music to poetry—Cage's mesostics. Cage was also an avid amateur mycologist.[106] He co-founded the New York Mycological Society with four friends,[65] and his mycology collection is presently housed by the Special Collections department of the McHenry Library at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Reception and influence Cage's pre-chance works, particularly pieces from the late 1940s such as Sonatas and Interludes, earned critical acclaim: the Sonatas were performed at Carnegie Hall in 1949. Cage's adoption of chance operations in 1951 cost him a number of friendships and led to numerous criticisms from fellow composers. Adherents of serialism such as Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen dismissed indeterminate music; Boulez, who was once on friendly terms with Cage, criticized him for "adoption of a philosophy tinged with Orientalism that masks a basic weakness in compositional technique."[107] Prominent critics of serialism, such as the Greek composer Iannis Xenakis, were similarly hostile towards Cage: for Xenakis, the adoption of chance in music was "an abuse of language and ... an abrogation of a composer's function."[108] An article by teacher and critic Michael Steinberg, Tradition and Responsibility, criticized avant-garde music in general: The rise of music that is totally without social commitment also increases the separation between composer and public, and represents still another form of departure from tradition. The cynicism with which this particular departure seems to have been made is perfectly symbolized in John Cage's account of a public lecture he had given: "Later, during the question period, I gave one of six previously prepared answers regardless of the question asked. This was a reflection of my engagement in Zen." While Mr. Cage's famous silent piece [i.e. 4′33″], or his Landscapes for a dozen radio receivers may be of little interest as music, they are of enormous importance historically as representing the complete abdication of the artist's power.[109] Cage's aesthetic position was criticized by, among others, prominent writer and critic Douglas Kahn. In his 1999 book Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts, Kahn acknowledged the influence Cage had on culture, but noted that "one of the central effects of Cage's battery of silencing techniques was a silencing of the social."[110] While much of Cage's work remains controversial,[citation needed] his influence on countless composers, artists, and writers is notable.[111] After Cage introduced chance,[clarification needed] Boulez, Stockhausen, and Xenakis remained critical, yet all adopted chance procedures in some of their works (although in a much more restricted manner); and Stockhausen's piano writing in his later Klavierstücke was influenced by Cage's Music of Changes and David Tudor.[112] Other composers who adopted chance procedures in their works included Witold Lutosławski, Mauricio Kagel, and many others.[citation needed] Music in which some of the composition and/or performance is left to chance was labelled aleatoric music—a term popularized by Pierre Boulez. Helmut Lachenmann's work was influenced by Cage's work with extended techniques.[113] Cage's rhythmic structure experiments and his interest in sound influenced a number of composers, starting at first with his close American associates Earle Brown, Morton Feldman, and Christian Wolff (and other American composers, such as La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass), and then spreading to Europe.[citation needed] For example, almost all composers of the English experimental school acknowledge his influence:[citation needed] Michael Parsons, Christopher Hobbs, John White,[114] Gavin Bryars, who studied under Cage briefly,[115] and Howard Skempton.[116] The Japanese composer Tōru Takemitsu has also cited Cage's influence.[117] Following Cage's death Simon Jeffes, founder of the Penguin Cafe Orchestra, composed a piece entitled "CAGE DEAD", using a melody based on the notes contained in the title, in the order they appear: C, A, G, E, D, E, A and D.[118] Cage's influence was also acknowledged by rock acts such as Sonic Youth (who performed some of the Number Pieces[119]) and Stereolab (who named a song after Cage[120]), composer and rock and jazz guitarist Frank Zappa,[121] and various noise music artists and bands: indeed, one writer traced the origin of noise music to 4′33″.[122] The development of electronic music was also influenced by Cage: in the mid-1970s Brian Eno's label Obscure Records released works by Cage.[123] Prepared piano, which Cage popularized, is featured heavily on Aphex Twin's 2001 album Drukqs.[124] Cage's work as musicologist helped popularize Erik Satie's music,[125][126] and his friendship with Abstract expressionist artists such as Robert Rauschenberg helped introduce his ideas into visual art. Cage's ideas also found their way into sound design: for example, Academy Award-winning sound designer Gary Rydstrom cited Cage's work as a major influence.[127] Radiohead undertook a composing and performing collaboration with Cunningham's dance troupe in 2003 because the music-group's leader Thom Yorke considered Cage one of his "all-time art heroes".[128] Centenary commemoration In 2012, amongst a wide range of American and international centennial celebrations,[129][130] an eight-day festival was held in Washington DC, with venues found notably more amongst the city's art museums and universities than performance spaces. Earlier in the centennial year, conductor Michael Tilson Thomas presented Cage's Song Books with the San Francisco Symphony at Carnegie Hall in New York.[131][132] Another celebration came, for instance, in Darmstadt, Germany, which in July 2012 renamed its central station the John Cage Railway Station during the term of its annual new-music courses.[19] At the Ruhrtriennale in Germany, Heiner Goebbels staged a production of Europeras 1 & 2 in a 36,000 sq ft converted factory and commissioned a production of Lecture on Nothing created and performed by Robert Wilson.[133] Jacaranda Music had four concerts planned in Santa Monica, California, for the centennial week.[134][135] John Cage Day was the name given to several events held during 2012 to mark the centenary of his birth. A 2012 project was curated by Juraj Kojs to celebrate the centenary of Cage's birth, titled On Silence: Homage to Cage. It consisted of 13 commissioned works created by composers from around the globe such as Kasia Glowicka, Adrian Knight and Henry Vega, each being 4 minutes and 33 seconds long in honor of Cage's famous 1952 opus, 4′33″. The program was supported by the Foundation for Emerging Technologies and Arts, Laura Kuhn and the John Cage Trust.[136] In a homage to Cage's dance work, the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company in July 2012 "performed an engrossing piece called 'Story/Time'. It was modeled on Cage's 1958 work 'Indeterminacy', in which [Cage and then Jones, respectively,] sat alone onstage, reading aloud ... series of one-minute stories [they]'d written. Dancers from Jones's company performed as [Jones] read."[128] |

音楽 こちらもご覧ください: ジョン・ケージ作曲リスト 初期の作品、リズム構造、和声への新しいアプローチ ケージが最初に完成させた作品は現在失われている。作曲者によると、初期の作品はピアノのための非常に短いもので、複雑な数学的手順を用いて作曲され、 「感覚的な魅力と表現力」に欠けていた[81]。その後、ケージは即興演奏とその結果を書き留めることによって作品を制作し始めたが、リチャード・ブー リッグが彼に構造の重要性を強調するまで続いた。クラリネット・ソナタ』(1933年)や『3声のためのコンポジション』(1934年)など、1930年 代前半の作品の多くは半音階的で、対位法に対するケージの関心を裏付けている。同じ頃、作曲家は25音列のトーン・ロー奏法の一種も開発した[82]。 シェーンベルクに師事したケージは、生徒にドデカフォニーを教えることはなかったが、別のトーン・ロー奏法を開発した。この奏法では、列が短い動機に分割 され、一定の規則に従って繰り返されたり移調されたりする。この手法は、まず『ピアノのための2つの小品』(1935年頃)で使われ、その後、『メタモル フォーゼ』や『5つの歌』(いずれも1938年)といった大作でも修正を加えながら使われた。 プリペアド・ピアノのためのソナタと間奏曲のソナタIIIにおけるリズムの比率 ケージが打楽器音楽やモダン・ダンスのための音楽を書き始めて間もなく、彼は曲のリズム構造を前面に押し出すテクニックを使い始めた。イマジナリーランド スケープ第1番(1939年)には、16、17、18、19小節の4つの大きなセクションがあり、各セクションは4つのサブセクションに分かれている。 First Construction (in Metal) (1939)はこのコンセプトをさらに発展させたもので、それぞれ4、3、2、3、4小節からなる5つのセクションがある。各ユニットは16小節で、同じ ように分割されている: 4小節、3小節、2小節など。最後に、曲の音楽的内容は16の動機に基づいている[83]。ケージがそう呼んだように、このような「入れ子の比率」は、 1940年代を通じて彼の音楽の常套的な特徴となった。この技法は、多くのプロポーションが非整数(例えばソナタIでは1¼、3/4、1¼、3/4、 1½、1½)を使用するプリペアド・ピアノのためのソナタと間奏曲(1946-48年)や、2組のプロポーションが同時に使用される声楽とクローズド・ピ アノのための歌曲『A Flower』[85]などの後期の作品において、非常に複雑なものへと昇華された。 1940年代後半、ケージは伝統的な和声から脱却するためのさらなる方法を開発し始めた。例えば、『4つの部分からなる弦楽四重奏曲』(1950年)で は、ケージはまず、固定された楽器編成の和音であるガムートをいくつか作曲した。曲は1つのガムットから別のガムットへと進行する。30]プリペアド・ピ アノのための協奏曲(1950-51)は、持続時間、強弱、メロディなどのチャートのシステムを使用し、ケージはそこから単純な幾何学的パターンを使用し て選択した[30]。協奏曲の最終楽章は、ケージがその後すぐに採用した偶然性の手順を使用するためのステップであった[86]。 偶然性 易経の占いは、ランダムな生成(コインを投げるなど)によって六芒星を得、その六芒星に関連する章を読む。 チャート・システムは、大作ピアノ作品『Music of Changes』(1951年)でも(入れ子のプロポーションとともに)使用されたが、ここでのみ、易経を使ってチャートから素材が選択された。1951 年以降のケージの音楽はすべて偶然の手順で作曲されており、最も一般的には易経を使用している。例えば、『ピアノのための音楽』の作品は、紙の欠点に基づ いている。欠点そのものが音程を提供し、コイントスと易経の六芒星数字が、臨時記号、音部記号、演奏技法を決定するために用いられた[87]。一連の作品 は、偶然の操作、すなわち易経を星取表に適用することによって創作された: Atlas Eclipticalis』(1961-62)、一連のエチュード: ケージのエチュードはどれも演奏するのが極めて難しいが、これはケージの社会的・政治的な見解によって規定された特徴である。 [90]ケージは自らをアナーキストと称し、ヘンリー・デイヴィッド・ソローの影響を受けていた[e]。 別の一連の作品は、他の作曲家による既存の音楽に偶然性の手順を適用したものであった: チープ・イミテーション』(1969年、エリック・サティに基づく)、『メイン州のハーモニー』の一部(1978年、ベルチャーに基づく)、『賛美歌と変 奏』(1979年)などである。これらの作品では、ケージはオリジナルのリズム構造を借りて、偶然の手続きによって決定された音程で埋め尽くしたり、オリ ジナルの音程の一部を置き換えたりしている。 [92]さらに別の一連の作品、いわゆるナンバー・ピースは、すべて作曲家の生涯の最後の5年間に完成したもので、時間括弧を利用している。スコアは、い つ開始し、いつ終了するかの指示(例えば、1′15 "から1′45 "の間のどこからでも、また2′00 "から2′30 "の間のどこからでも)がある短い断片で構成されている[93]。 ケージの易経の使用方法は、単純な無作為化とは程遠いものであった。その手順は作曲によって異なり、通常は複雑であった。例えば、『チープ・イミテーション』の場合、易経に対する正確な質問は以下のようなものだった: 白い音で始まり白い音で残る7つの音階をモードとするならば、私はそのうちのどれを使っているのか? 12の半音階移調のうち、私はどれを使っているのか? このモードのこの移調が適用されるこのフレーズに対して、サティが書いた音符を模倣するために、私は7つのうちどの音符を使っているだろうか[94]。 ケージの後期の音楽のもうひとつの例である「Etudes Australes」では、作曲の手順として、星取表の上に透明な帯を置き、星取表から音程を特定し、それを紙に移し、それから易経に、これらの音程のう ちどれを単音のままにし、どれを集合体(和音)の一部にするかを尋ね、集合体は、あらかじめ編集された約550の可能な集合体の表から選択された[88] [95]。 最後に、ケージのいくつかの作品、特に1960年代に完成した作品は、完全に楽譜化された音楽ではなく、演奏者への指示を特徴としている。変奏曲I》 (1958)の楽譜は、演奏者に6つの透明な正方形を提示する。演奏者は正方形を組み合わせ、線と点を座標系として使う。線は、最低周波数、最も単純な倍 音構造など、音のさまざまな特徴を表す軸である[96]。ケージのグラフィック・スコアのいくつか(ピアノと管弦楽のための協奏曲、フォンタナ・ミックス (ともに1958年)など)は、演奏者に同様の困難を突きつけている。さらに同時期の他の作品は、テキストの指示だけで構成されている。0′00″ (1962年、別名4′33″No.2)の楽譜は一文で構成されている: "最大限の増幅が用意された状況で、規律正しい動作を行え"。初演ではケージにこの文章を書かせた[97]。 Musicircus』(1967年)は、単純に演奏者に集まってもらい、一緒に演奏する。最初の『ムジサーカス』では、広い空間に複数のパフォーマーと グループが登場し、2つの特定の時間帯に演奏を開始し、停止する。その結果、偶然の配分によって決定されたさまざまな音楽が大量に重なり合い、独特の演劇 的雰囲気を持つイベントが生まれた。その後、多くのムジークが開催され、ケージの死後も続いている。イングリッシュ・ナショナル・オペラ(ENO)は 2012年3月3日、ロンドンのコロシアムでケージのムジサーカスを開催した最初のオペラ・カンパニーとなった[98][99]。ENOのムジサーカスで は、レッド・ツェッペリンのベーシストであるジョン・ポール・ジョーンズや作曲家のマイケル・フィニッシーのほか、ENOの音楽監督であるエドワード・ ガードナー、ENOコミュニティ合唱団、ENOオペラ・ワークスの歌手、ロンドンのコロシアム・オペラ・ハウスのバーやフロント・オブ・ハウスでパフォー マンスするプロとアマチュアの才能の集団などのアーティストが出演した[100]。 このサーカスのコンセプトは、生涯を通じてケージにとって重要であり続け、彼のテキスト『Writing for the Second Time Through Finnegans Wake』とアイルランド各地で録音された伝統的な音楽とフィールド・レコーディングの両方を音で表現した『Roaratorio, an Irish circus on Finnegans Wake』(1979年)などの作品で強くフィーチャーされた。この作品はジェイムズ・ジョイスの有名な小説『フィネガンズ・ウェイク』に基づいており、 ケージはこの本を愛読していた。 即興 ケージは、作曲家や演奏家の好き嫌いを音楽から排除するために偶然の手続きを用いていたため、演奏家の好みと必然的に結びついてしまう即興という概念を 嫌っていた。1970年代から始まる多くの作品で、彼は即興を取り入れる方法を見つけた。Child of Tree』(1975年)と『Branches』(1976年)では、演奏者は特定の種類の植物、たとえばサボテンを楽器として使うよう求められる。曲の 構成は、彼らの選択の偶然性によって決定され、音楽的なアウトプットも同様である。インレッツ』(1977年)では、演奏者たちは水を満たした大きな巻貝 を演奏している。巻貝を注意深く何度か傾けることで、内部に気泡ができ、音が出る。しかし、この現象がいつ起こるかを予測することは不可能であるため、演 奏者は貝殻を傾け続けなければならず、その結果、演奏は純粋な偶然に左右された[101]。 視覚芸術、著作、その他の活動 Variations III, No. ケージは若い頃に絵画を始めたが、音楽に集中するためにそれを断念した。彼の最初の成熟した視覚的プロジェクト『Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel』は1969年の作品である。この作品は、2枚のリトグラフと、ケージがプレキシグラムと呼ぶ、プレキシグラス・パネルにシルクスクリーン印 刷を施した作品群で構成されている。パネルとリトグラフはすべて異なる書体の言葉の断片で構成されており、そのすべてが偶然の操作に支配されている [102]。 1978年から亡くなるまで、ケージはクラウン・ポイント・プレスで働き、毎年一連の版画を制作した。そこで完成した最も初期のプロジェクトは、ヘン リー・デイヴィッド・ソローのドローイングの様々な組み合わせに基づき、完全に記譜された指示書から制作されたエッチング作品『Score Without Parts』(1978年)であった。これは同年、ケージが目を閉じて描いた『Seven Day Diary』に続くものだが、偶然の操作を使って開発された厳密な構造に準拠している。最後に、ソローのドローイングは1978年に制作された最後の作品 『Signals』に影響を与えた[103]。 1979年から1982年にかけて、ケージは多くの大規模な版画シリーズを制作した: ChangesとDisappearances』(1979-80)、『On the Surface』(1980-82)、『Déreau』(1982)。1983年からは、中綿や発泡スチロールなど様々な型破りな素材を使い始め、石や火 を使って視覚的な作品を制作するようになる(『円環花』、『変奏曲』、『龍安寺』など)[105]。1988年から1990年にかけては、マウンテンレイ ク・ワークショップで水彩画を制作。 ケージが制作した唯一の映画は、作曲家であり映画監督でもあるヘニング・ローナーに依頼されたナンバー・ピースのひとつ『One11』で、90分のモノク ロ映画の制作と監督をケージと共に行った。この作品が完成したのは、1992年にケージが亡くなるわずか数週間前のことだった。One11』は、偶然に決 定された電光の戯れのイメージのみで構成されている。この作品は1992年9月19日にドイツのケルンで初演され、オーケストラ曲「103」の生演奏とと もに上映された。 ケージは生涯を通じて、講演や執筆活動にも積極的に取り組んだ。講演の一部は、彼が出版した数冊の本に収録されている: Lectures and Writings』(1961年)である。沈黙』には、単純な講義だけでなく、実験的なレイアウトで書かれたテキストや、『無についての講義』(1949 年)のようなリズム構造で構成された作品も含まれていた。その後の作品集でも、音楽に関するレクチャーから詩、つまりケージのメソスティックスまで、さま ざまなタイプの内容が取り上げられている。 ケージはまた、熱心なアマチュア菌類学者でもあった[106]。彼は4人の友人とニューヨーク菌類学会を共同で設立し[65]、彼の菌類学コレクションは現在、カリフォルニア大学サンタクルーズ校のマクヘンリー図書館の特別コレクション部門に収蔵されている。 受容と影響 ケージの偶然性以前の作品、特に『ソナタ集』や『間奏曲集』といった1940年代後半の作品は批評家から高い評価を得ており、『ソナタ集』は1949年に カーネギーホールで演奏された。1951年、ケージがチャンス・オペレーションを採用したことで、彼は多くの友人を失い、作曲家仲間から多くの批判を浴び ることになった。ピエール・ブーレーズやカールハインツ・シュトックハウゼンといった直列主義の信奉者たちは、不確定な音楽を否定した。かつてケージと友 好的な関係にあったブーレーズは、「作曲技法における基本的な弱点を覆い隠すオリエンタリズムを帯びた哲学を採用した」と彼を批判した[107]。 「ギリシャの作曲家イアニス・クセナキスなどの著名な批評家も同様にケージに敵意を抱いていた。クセナキスにとって、音楽における偶然性の採用は「言語の 乱用であり、......作曲家の機能の放棄」であった[108]。 教師であり批評家であるマイケル・スタインバーグの論文『伝統と責任』は、前衛音楽全般を批判している: 社会的なコミットメントをまったく持たない音楽の台頭は、作曲家と大衆の間の隔たりを増大させ、伝統からの逸脱のまた別の形を表している。この特別な出発 がなされたと思われるシニシズムは、ジョン・ケージが行った公開講座の説明に見事に象徴されている: 「その後、質問の時間に、私はあらかじめ用意された6つの答えのうちのひとつを、質問の内容に関係なく答えた。これは私の禅への取り組みを反映したもの だった。" ケージ氏の有名なサイレント作品[すなわち4′33″]や、12台のラジオ受信機のための『風景』は、音楽としてはほとんど興味がないかもしれないが、芸 術家の力の完全な放棄を表すものとして、歴史的には非常に重要である[109]。 ケージの美学的立場は、とりわけ著名な作家であり批評家であるダグラス・カーンによって批判された。1999年の著書『Noise, Water, Meat: カーンは『A History of Sound in the Arts(芸術における音の歴史)』の中で、ケージが文化に与えた影響を認めつつも、「ケージの一連の沈黙の技法の中心的な効果のひとつは、社会的なもの を沈黙させることだった」と指摘している[110]。 ケージが偶然性を導入した後、ブーレーズ、シュトックハウゼン、クセナキスは批判的であり続けたが、彼らの作品の一部には偶然性の手法が取り入れられてい る(ただし、より限定された方法で)。 [また、シュトックハウゼンの後期のクラヴィアシュテュッケのピアノ曲は、ケージの『変化の音楽』やデヴィッド・チューダーの影響を受けている。ヘルムー ト・ラッヘンマン(Helmut Lachenmann)の作品は、拡張技法を用いたケージの作品に影響を受けている[113]。 ケージのリズム構造の実験と音への興味は多くの作曲家に影響を与え、最初は彼の親しいアメリカ人仲間であるアール・ブラウン、モートン・フェルドマン、ク リスチャン・ウルフ(そしてラ・モンテ・ヤング、テリー・ライリー、スティーヴ・ライヒ、フィリップ・グラスといった他のアメリカ人作曲家たち)から始ま り、その後ヨーロッパへと広がっていった。 [例えば、マイケル・パーソンズ、クリストファー・ホッブス、ジョン・ホワイト、[114]ケージの下で短期間学んだギャヴィン・ブライヤーズ、 [115]ハワード・スケンプトンなど、イギリスの実験派の作曲家のほとんどがケージの影響を認めている[116]。 ケージの死後、ペンギン・カフェ・オーケストラの創設者であるサイモン・ジェフスは、「CAGE DEAD」と題した作品を作曲した: C、A、G、E、D、E、A、Dである[118]。 ケージの影響は、ソニック・ユース(ナンバー・ピースの一部を演奏[119])やステレオラボ(ケージの名前を曲名にした[120])などのロック・アー ティスト、作曲家でありロックとジャズのギタリストであるフランク・ザッパ[121]、そして様々なノイズ・ミュージックのアーティストやバンドも認めて いる[122]。 [ケージの広めたプリペアド・ピアノは、エイフェックス・ツインの2001年のアルバム『Drukqs』に大きくフィーチャーされている[124]。ケー ジの音楽学者としての活動は、エリック・サティの音楽の普及に貢献し[125][126]、ロバート・ラウシェンバーグのような抽象表現主義のアーティス トとの友情は、彼の考えをビジュアル・アートに導入するのに役立った。例えば、アカデミー賞を受賞した音響デザイナーのゲイリー・ライドストロームは、 ケージの作品に大きな影響を受けたと述べている[127]。レディオヘッドは2003年にカニンガムの舞踊団と作曲とパフォーマンスのコラボレーションを 行ったが、これは音楽グループのリーダーであるトム・ヨークがケージを「オールタイム・アート・ヒーロー」の一人と考えていたからである[128]。 100周年記念 2012年、ワシントンDCでは、アメリカ国内外からさまざまな100周年記念行事が行われるなか、8日間のフェスティバルが開催された[129] [130]。100周年の前年には、指揮者のマイケル・ティルソン・トーマスがニューヨークのカーネギーホールでサンフランシスコ交響楽団とケージの『ソ ング・ブックス』を上演した[131][132]。2012年7月にドイツのダルムシュタットでは、毎年開催されるニューミュージック・コースの期間中、 中央駅をジョン・ケージ鉄道駅と改名した[19]。 [19] ドイツのルールトリエンナーレでは、ハイナー・ゲッペルスが工場を改造した36,000平方フィートのスペースで『Europeras 1 & 2』を上演し、ロバート・ウィルソンに『Lecture on Nothing』の制作と演奏を依頼した[133]。 ジャカランダ・ミュージックは、生誕100周年の週にカリフォルニア州サンタモニカで4つのコンサートを計画していた[134][135] 。 ケージの生誕100周年を記念して2012年にジュライ・コイスによってキュレーションされたプロジェクト: ケージへのオマージュ』である。これは、カシア・グロヴィッカ、エイドリアン・ナイト、ヘンリー・ヴェガといった世界中の作曲家による13の委嘱作品で構 成され、ケージの有名な1952年の作品 "4′33″にちなんで、それぞれの長さは4分33秒であった。このプログラムは、Foundation for Emerging Technologies and Arts、Laura Kuhn、John Cage Trustの支援を受けた[136]。 ケージのダンス作品へのオマージュとして、ビル・T・ジョーンズ/アーニー・ゼイン・ダンス・カンパニーは2012年7月に「『Story/Time』と 呼ばれる夢中にさせる作品を上演した。これはケージの1958年の作品『Indeterminacy(不確定性)』をモデルにしたもので、(ケージと当時 のジョーンズがそれぞれ)舞台上に一人で座り、(彼らが)書いた1分間の物語を朗読するというものだった。ジョーンズのカンパニーのダンサーたちは、 [ジョーンズの]朗読に合わせてパフォーマンスを行った」[128]。 |

| Archives This list is incomplete; you can help by adding missing items. (August 2020) The archive of the John Cage Trust is held at Bard College in upstate New York.[137] The John Cage Music Manuscript Collection held by the Music Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts contains most of the composer's musical manuscripts, including sketches, worksheets, realizations, and unfinished works. The John Cage Papers are held in the Special Collections and Archives department of Wesleyan University's Olin Library in Middletown, Connecticut. They contain manuscripts, interviews, fan mail, and ephemera. Other material includes clippings, gallery and exhibition catalogs, a collection of Cage's books and serials, posters, objects, exhibition and literary announcement postcards, and brochures from conferences and other organizations The John Cage Collection at Northwestern University in Illinois contains the composer's correspondence, ephemera, and the Notations collection.[138] |

|

| An Anthology of Chance Operations List of compositions by John Cage The Organ2/ASLSP (a.k.a. As Slow as Possible) project, the longest concert ever created. The Revenge of the Dead Indians, a 1993 documentary about Cage by Henning Lohner. Works for prepared piano by John Cage |

|