John Gabriel Stedman 1744 – 7 March 1797

★ジョン・ ガブリエル・ステッドマン(1744年 - 1797年3月7日)はオランダ生まれのスコットランドの軍人であり、『スリナムの反乱した黒人に対する5年間の遠征記』(1796年)の著者として知ら れる作家である。この物語は、1773年から1777年にかけてスリナムで経験したことを綴ったもので、彼はオランダ軍の兵士として、逃亡奴隷の集団と戦 う現地部隊を支援するために派遣された[1]。この『語り』は当時のベストセラーとなり、奴隷制度や植民地主義の他の側面を直接描写することで、設立間も ない奴隷廃止運動において重要なツールとなった。ステッドマンの個人的な日記と比較すると、出版された『ナラティヴ』は、スリナムでのステッドマンの日々 を、衛生的に、ロマンチックに描いたものである。

★ クレジット:ジョン・ガブリエル・ステッドマン(→白人種は自らの足で自立で き ない)

| ★John Gabriel

Stedman (1744 – 7 March 1797) was a Dutch-born Scottish soldier and

writer best known for writing The Narrative of a Five Years Expedition

against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam (1796). This narrative covers

describes his experience in Suriname between 1773 and 1777, where he

was a soldier in the Dutch military deployed to assist local troops

fighting against groups of escaped slaves.[1] He first recorded his

experiences in a personal diary that he later rewrote and expanded into

the Narrative. The Narrative was a bestseller of the time and, with its

firsthand depictions of slavery and other aspects of colonialism,

became an important tool in the fledgling abolitionist movement. When

compared with Stedman's personal diary, his published Narrative is a

sanitized and romanticized version of Stedman's time in Surinam. |

ジョン・

ガブリエル・ステッドマン(1744年 -

1797年3月7日)はオランダ生まれのスコットランドの軍人であり、『スリナムの反乱した黒人に対する5年間の遠征記』(1796年)の著者として知ら

れる作家である。この物語は、1773年から1777年にかけてスリナムで経験したことを綴ったもので、彼はオランダ軍の兵士として、逃亡奴隷の集団と戦

う現地部隊を支援するために派遣された[1]。この『語り』は当時のベストセラーとなり、奴隷制度や植民地主義の他の側面を直接描写することで、設立間も

ない奴隷廃止運動において重要なツールとなった。ステッドマンの個人的な日記と比較すると、出版された『ナラティヴ』は、スリナムでのステッドマンの日々

を、衛生的に、ロマンチックに描いたものである。 |

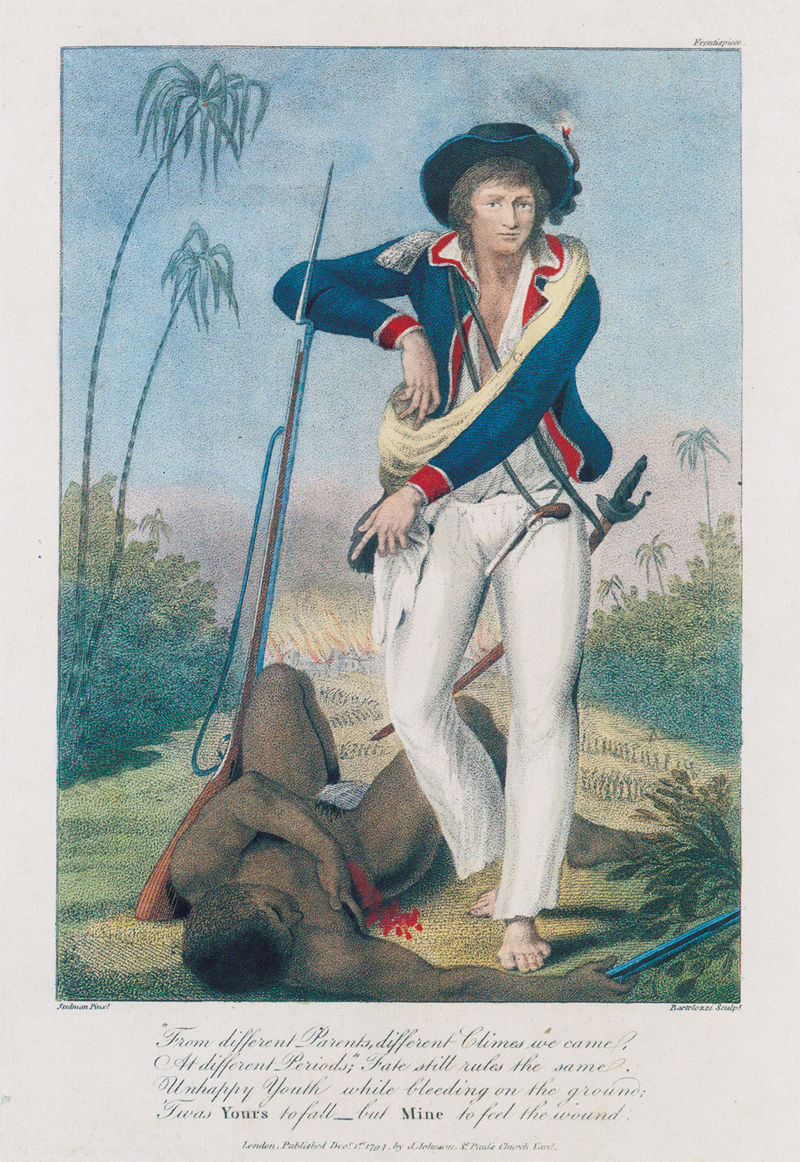

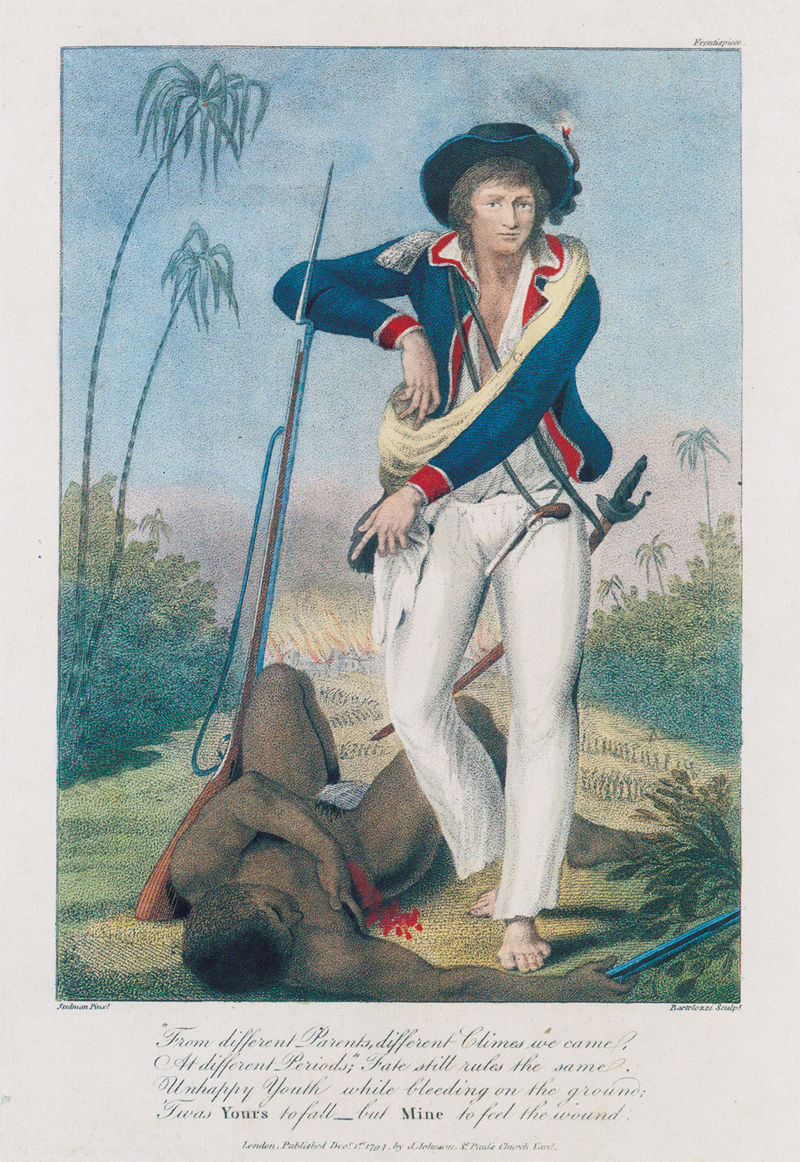

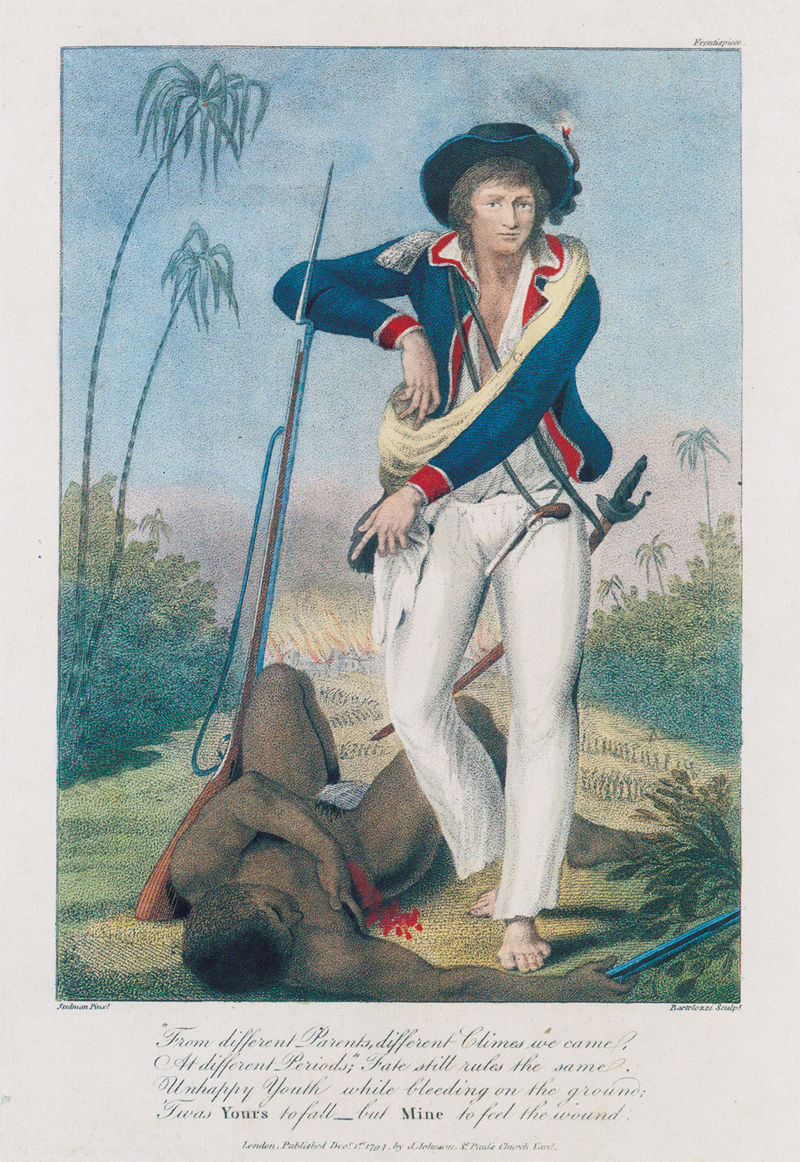

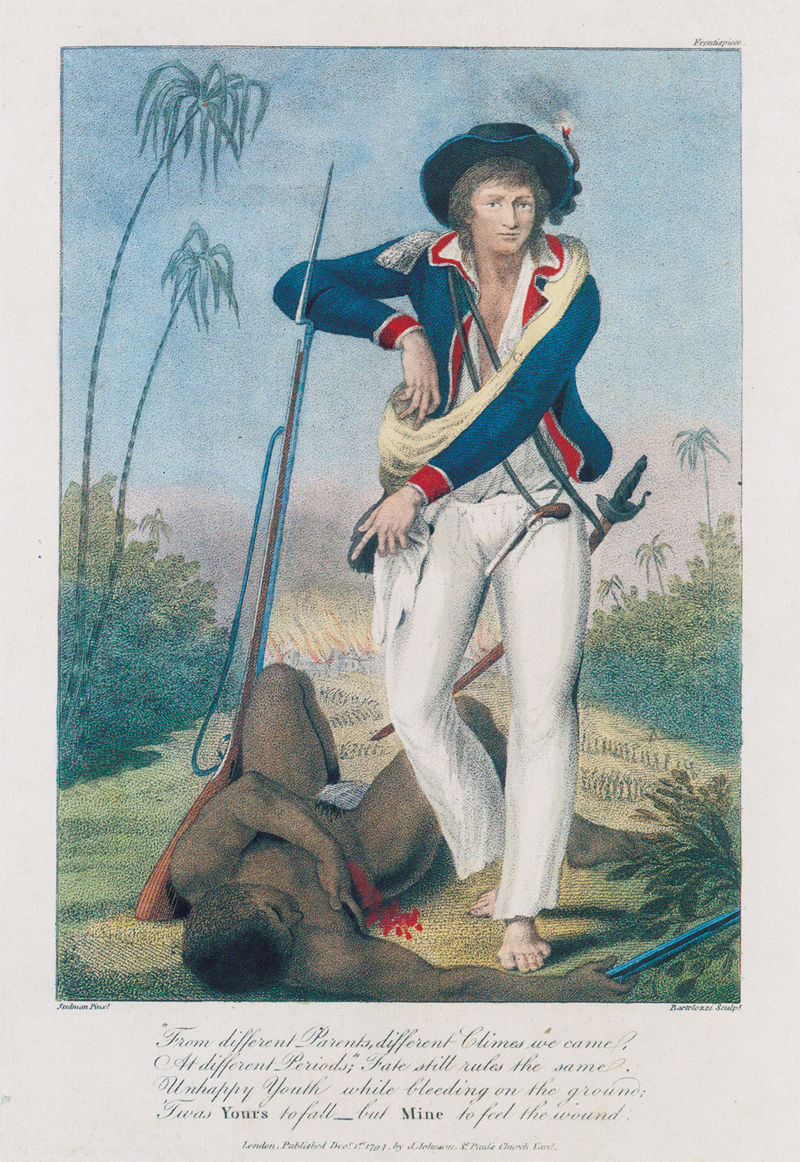

| Early life Stedman was born in 1744 in Dendermonde, then in the Austrian Netherlands, to Robert Stedman, a Scotsman and officer in the Dutch Republic's Scots Brigade, and his Franco-Dutch wife, Antoinetta Christina van Ceulen. He lived most of his childhood in the Dutch Republic with his parents, but also spent time with his uncle in Scotland. Stedman described his childhood as being "chock-full of misadventures and abrasive encounters of every description".[2] Military career Stedman's military career began at the age of 16. His first commanded rank was ensign, under which he defended various Low Country outposts in the employment of the Dutch Stadthouder. His rank was later elevated to lieutenant.[3] In 1771, Stedman reenlisted because of overwhelming debt after the death of his father.[3] Stedman left the Dutch Republic on 24 December 1772, after responding to a call for volunteers to serve in the West Indies. He was given the rank of Captain by way of a brevet, a temporary and honorary authorization for an officer to hold a higher rank.[3] His corps comprised 800 volunteers to be sent to Surinam aboard the frigate Zeelust to assist local troops fighting against marauding bands of escaped slaves, known as Maroons, in the eastern region of the colony. The corps, which was trained for the battlefields of Europe, was unprepared for battle against the unfamiliar guerrilla tactics of its opponents.[3] After arriving in the colony, Stedman received orders from Colonel Fourgeoud, commander of the newly arrived troops. Fourgeoud was known for dining on gourmet meats, wine and other delicacies while his troops survived on meager and often spoiled rations.[4] He treated Stedman cruelly, inventing tasks for him to complete and taking away his ammunition. Stedman believed that Fourgeoud neglected his duties as an officer, ignoring the well-being of his troops, and that he only retained his title through monetary bribes.[4] Regarding Fourgeoud's poor leadership, Stedman was uncompromising: "I solemnly declare to have still omitted many other calamities that we suffered".[5] On 10 August 1775, shortly after falling ill in Surinam, Stedman wrote Colonel Fourgeoud a letter requesting both a furlough to regain health and six months' military pay that was owed him. Fourgeoud refused his request twice, although he granted similar requests to other officers. Stedman later wrote, "This so incensed me that I not only wished him in Hell, but myself also, to have the satisfaction of seeing him burn".[6] In addition to the 800 European soldiers, Stedman fought alongside the newly formed Free Negro Corps (FNC). The FNC, Black slaves purchased from their enslavers, were promised their freedom, a house with a garden plot and combat pay for service in action against the maroons.[7] The FNC originally numbered 116 men, but 190 more were purchased and incorporated into the unit after the original group displayed courage and perseverance in action.[7] Stedman served in seven campaigns in the forests of Surinam, each averaging three months.[8] He only engaged in one battle, which took place in 1774 and concluded with the capture of the village of Gado Saby. A portrayal of this battle can be seen in the frontispiece of Stedman's Narrative, which depicts Stedman standing over a dead slave in the foreground and a village burning in the distance.[9] Throughout these campaigns, ambushes occurred frequently and disease spread rapidly, resulting in an enormous loss of troops. These losses were so great that 830 additional European troops were sent from the Dutch Republic in 1775 to supplement the original 800.[9] The campaigns were riddled with sickness, anger, fatigue, and death. Stedman observed the horrors of battle and the cat-and-mouse antics of both sides that resulted in merely pushing the battle across Surinam instead of quelling it.[9]  John Gabriel Stedman stands over a slave after the capture of Gado Saby, a village of Maroons in Surinam, from the frontispiece of his Narrative |

生い立ち ステッドマンは1744年、当時オーストリア領オランダのデンダーモンドで、スコットランド人でオランダ共和国スコットランド旅団の将校だったロバート・ ステッドマンと、その妻で仏蘭西人のアントワネッタ・クリスティーナ・ファン・セウレンの間に生まれた。幼少期のほとんどを両親とともにオランダ共和国で 過ごしたが、スコットランドの叔父とも過ごした。ステッドマンは彼の幼少期を「不運な出来事とあらゆる種類の擦れ違う出会いがぎっしり詰まっていた」と 語っている[2]。 軍歴 ステッドマンの軍歴は16歳で始まった。最初に指揮を執った階級は少尉で、オランダのスタッドホウダーに雇われ、ローカントリーのさまざまな前哨基地を防 衛した。1771年、ステッドマンは父親の死後、多額の借金のために再入隊した[3]。 1772年12月24日、ステッドマンは西インド諸島での志願兵募集に応じ、オランダ共和国を離れた。彼の軍団は800人の志願兵で構成され、フリゲート 艦ゼーラスト号でスリナムへ派遣され、植民地東部でマルーンと呼ばれる逃亡奴隷の襲撃と戦う現地部隊を支援した。ヨーロッパの戦場を想定して訓練された軍 団は、相手の不慣れなゲリラ戦術を相手に戦う準備ができていなかった[3]。 植民地に到着したステッドマンは、新しく到着した部隊の指揮官であるフォルジュー大佐から命令を受けた。彼はステッドマンに残酷な仕打ちをし、彼に任務を 課し、弾薬を取り上げた。ステッドマンは、フルゴーは将校としての義務を怠り、部隊の幸福を無視し、金銭的な賄賂によってのみその地位を維持していると考 えていた[4]: 「私は、我々が被った他の多くの災難をまだ省いていたことを厳粛に宣言する」[5]。 1775年8月10日、スリナムで病に倒れた直後、ステッドマンは健康を回復するための一時休暇と、彼に支払われていた6ヶ月分の軍人給与の両方を要求す る手紙をフォルグー大佐に書いた。フォルジュードは他の将校に同様の要求を出したにもかかわらず、2度にわたって彼の要求を拒否した。ステッドマンは後 に、「このことは私を非常に憤慨させたので、私は彼を地獄に落とすことを願っただけでなく、私自身もまた、彼が焼かれるのを見て満足することを願った」と 書いている[6]。 800人のヨーロッパ兵に加え、ステッドマンは新しく結成された自由黒人部隊(FNC)とともに戦った。FNCは奴隷商人から買い取った黒人奴隷で、自由 と庭付き一軒家、そして対マルーンの戦功に対する戦闘報酬が約束されていた[7]。FNCは当初116人だったが、当初の集団が勇気と忍耐力を発揮したた め、さらに190人が買い取られ、部隊に編入された[7]。 ステッドマンはスリナムの森で7回の作戦に従軍し、それぞれの作戦期間は平均3ヶ月であった[8]。この戦いの描写は『ステッドマンの物語』の扉絵に見る ことができ、手前で奴隷の死体の上に立つステッドマンと、遠くで燃える村が描かれている[9]。 これらのキャンペーンを通じて、待ち伏せが頻繁に発生し、病気が急速に蔓延し、その結果、莫大な兵力が失われた。これらの損失は非常に大きく、1775年 には当初の800人を補うためにオランダ共和国から830人のヨーロッパ人部隊が追加派遣された[9]。ステッドマンは、戦闘の惨状と、スリナム全域で戦 闘を鎮圧するのではなく、単に戦闘を押し進める結果となった両軍の駆け引きを観察した[9]。  スリナムのマルーン人の村、ガド・サビー捕獲後、奴隷の上に立つジョン・ガブリエル・ステッドマン(『Narrative』の扉絵より |

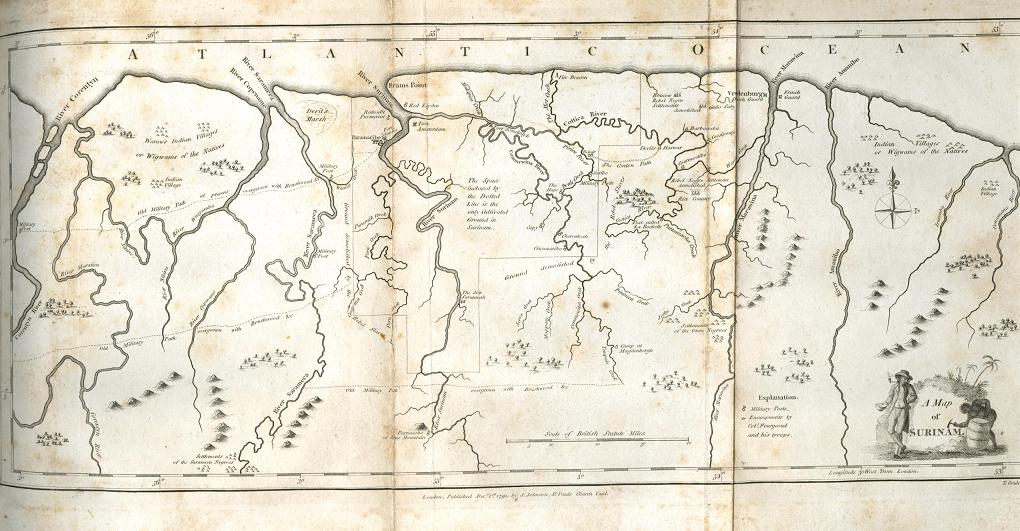

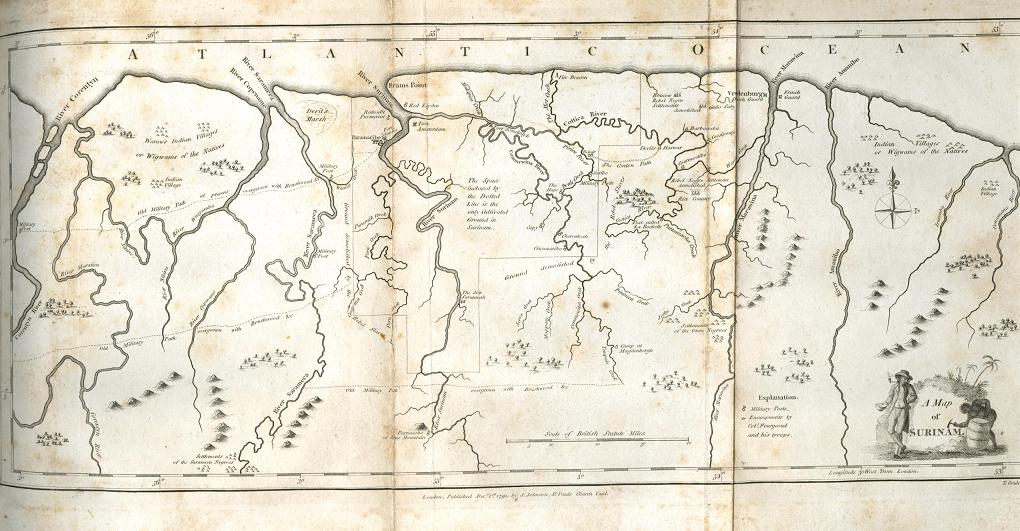

Surinam A map of Stedman's Surinam, from the original edition of Stedman's Narrative Surinam was first colonized by the governor of Barbados in the 1650s, then captured by the Dutch soon after, who quickly began to establish sugar plantations. In 1683 Surinam came under control of the Dutch West India Company. The colony developed an agricultural economy highly dependent on African slavery. Two rivers were central to the colonies: the Orinoco and the Amazon. At the time of Stedman's deployment, the Portuguese lived along the river Amazon and the Spanish along the river Orinoco. Dutch colonists were spread along the seaside and the French lived in a small settlement known as Cayenne.[10] |

スリナム ステッドマンのスリナム地図(『ステッドマンの物語』原版より) スリナムは、1650年代にバルバドス総督によって最初に植民地化され、その後すぐにオランダに占領され、すぐに砂糖プランテーションを建設し始めた。 1683年、スリナムはオランダ西インド会社の支配下に入った。植民地はアフリカ人奴隷に大きく依存した農業経済を発展させた。 オリノコ川とアマゾン川という2つの川が植民地の中心だった。ステッドマンが派遣された当時、ポルトガル人はアマゾン川沿いに、スペイン人はオリノコ川沿 いに住んでいた。オランダ人入植者は海沿いに広がり、フランス人はカイエンヌとして知られる小さな集落に住んでいた[10]。 |

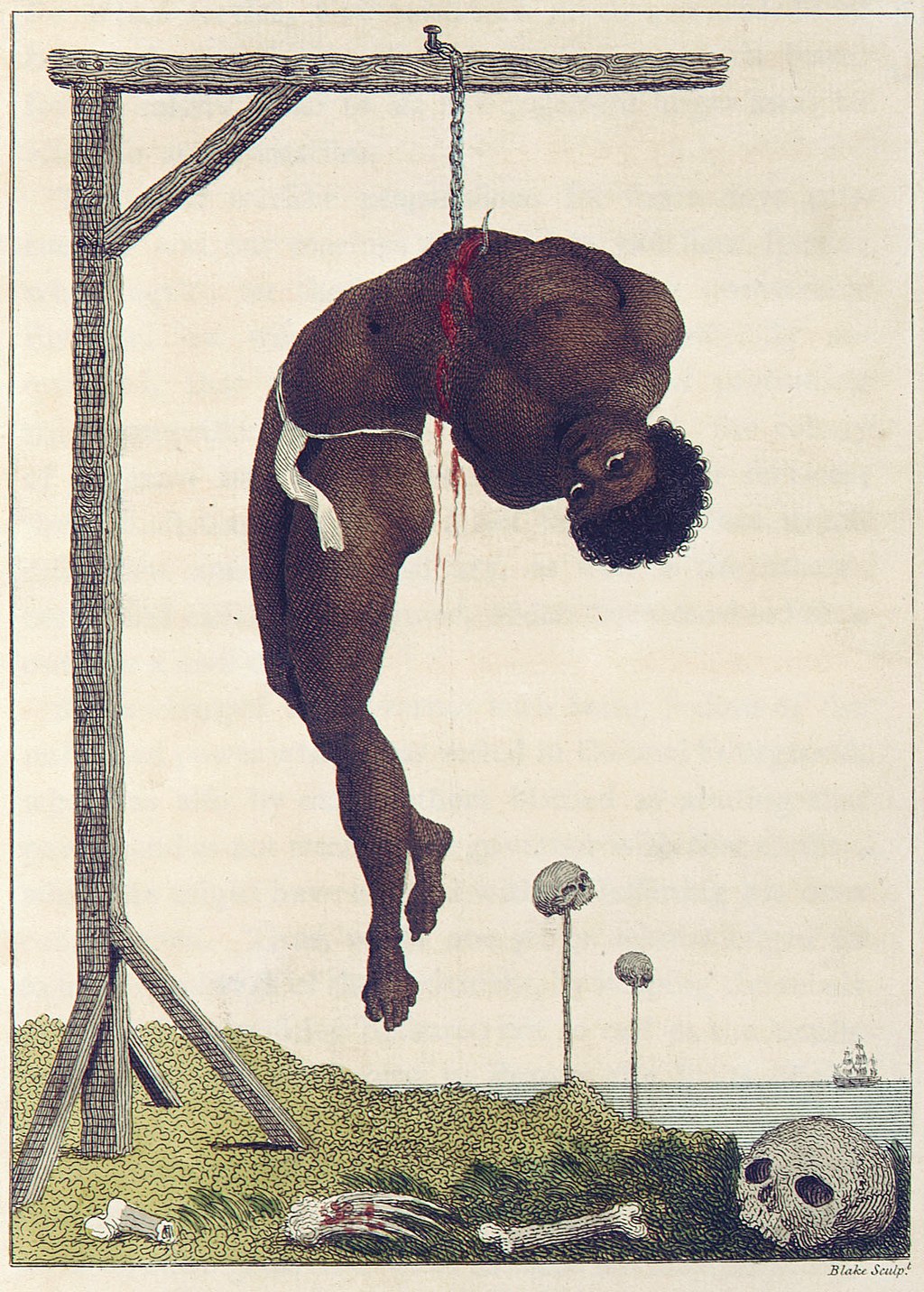

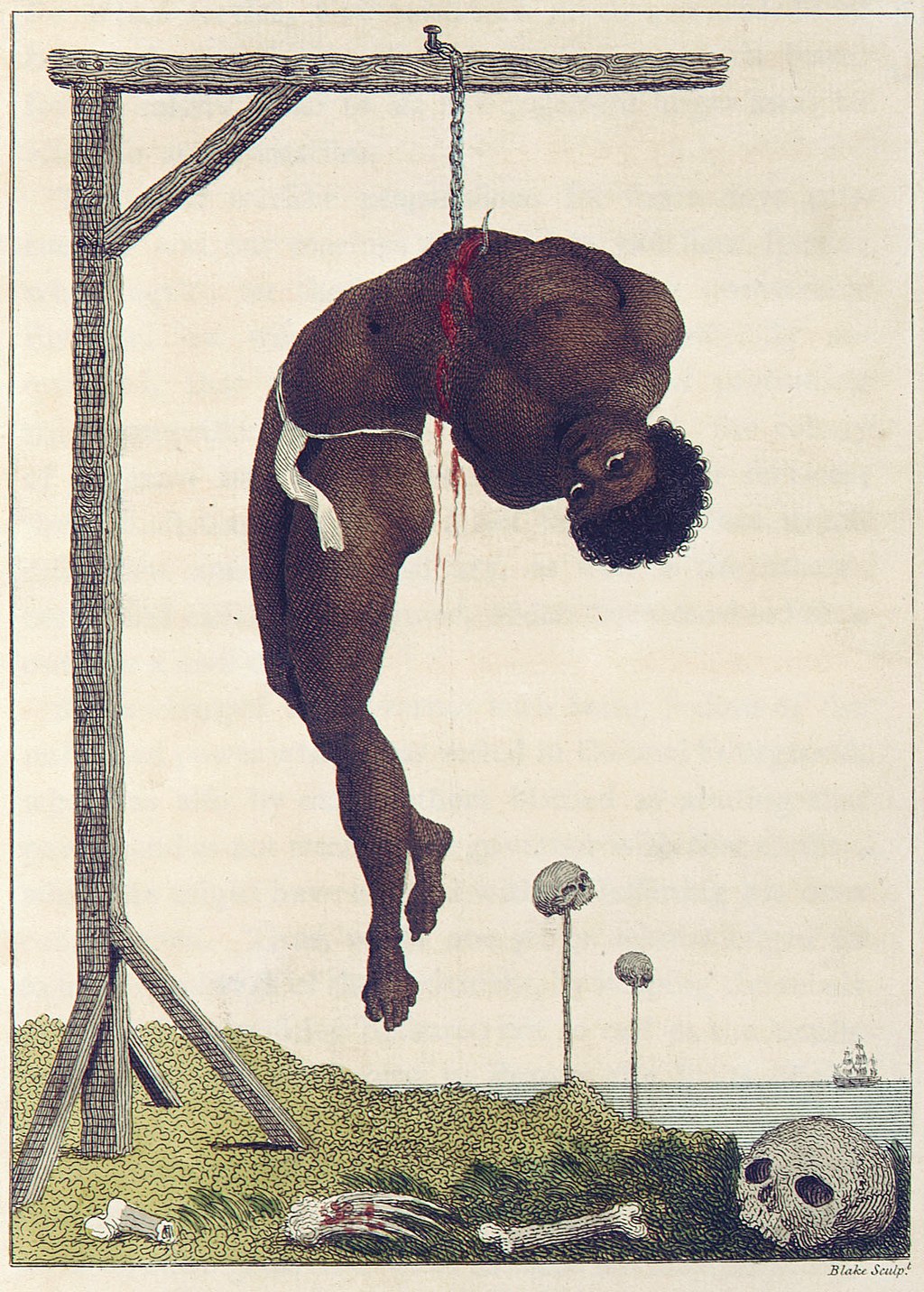

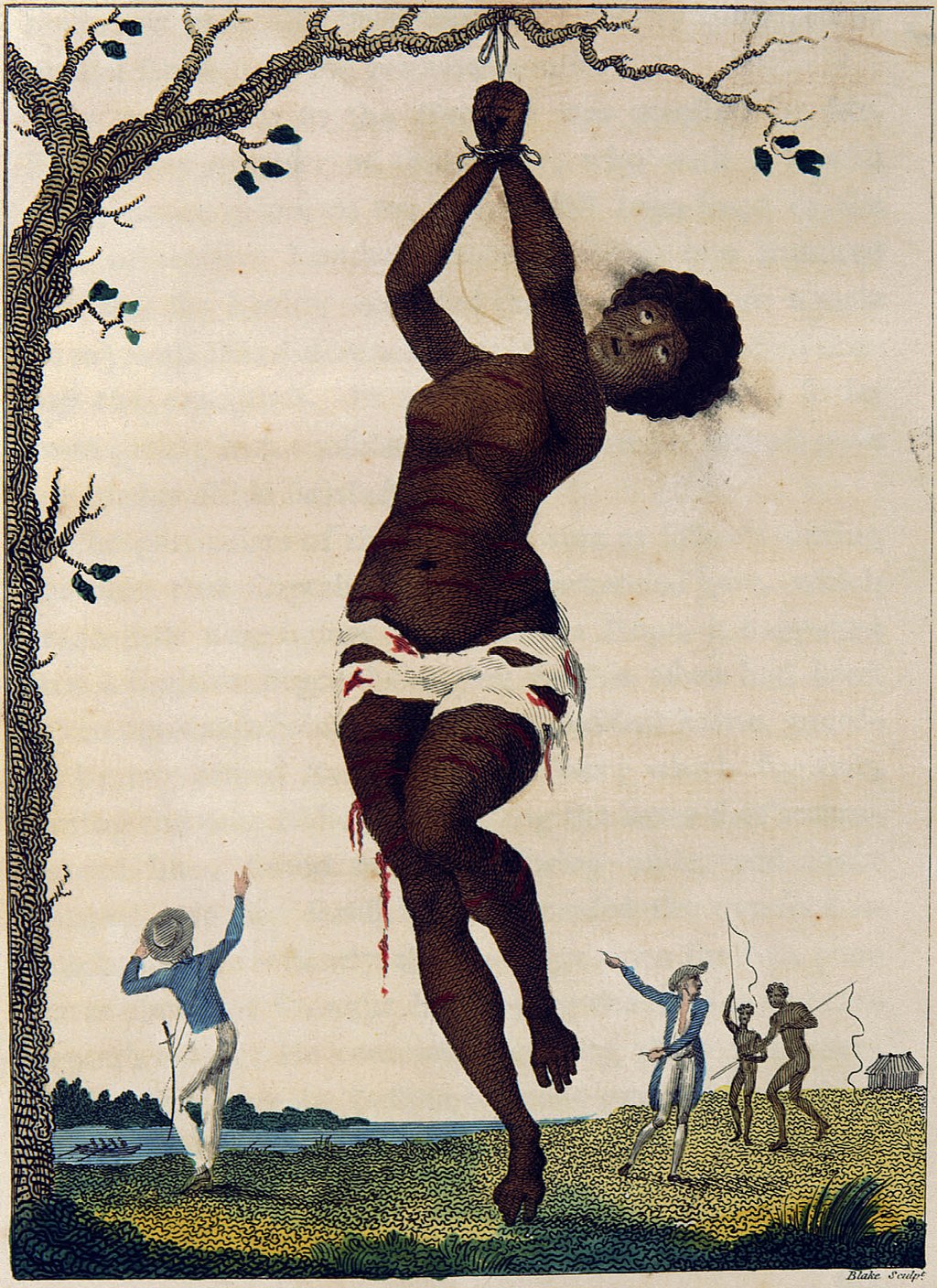

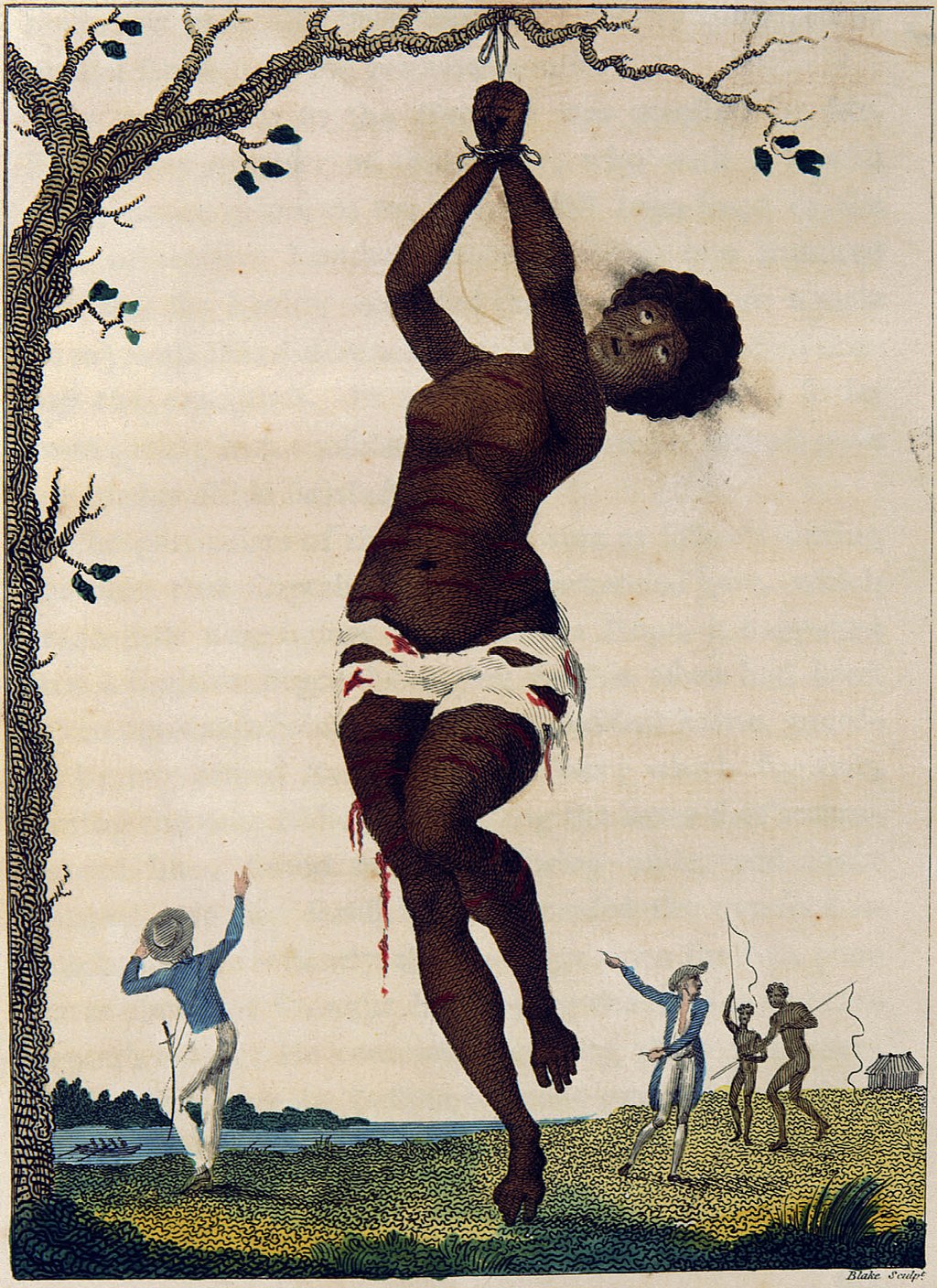

| Stedman's Narrative The Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam is an autobiographical account of Stedman's experiences in Surinam from the year 1773 through 1777. While Stedman kept a diary of his time in Surinam, which is held by the University of Minnesota Libraries, the Narrative manuscript wasn't composed until ten years after his return to Europe. In the Narrative manuscript, Stedman vividly describes the landscapes of Suriname, paying great attention to flora, fauna, and the social habits of indigenous, free and enslaved Africans, and European colonists in Suriname. His observations of life in the colony encompass the different cultures present at the time: Dutch, Scottish, native, African, Spanish, Portuguese, and French. Stedman also takes time to describe the day-to-day life in the colony. The first pages of the Narrative record Stedman's voyage to Surinam. He spends his days reading on the deck of the Boreas, attempting to avoid those sick from the turbulent sea.[11] The Boreas was accompanied by another ship the Weftellingwerf and three new frigate built transports. Stedman first arrives in Surinam on 2 February 1773. Upon his arrival in Surinam, Stedman and the troops are met by residents of the fortress Amsterdam, along the Surinam River. Here, Stedman gives his first description of the landscape of Surinam.[12] According to Stedman, the land abounded with delicious smells – lemon, orange, and shaddocks. The natives, dressed in loincloths, were somewhat shocking to Stedman at first, and he described them as "bargemen as naked as when they were born."[13] Parts of the Narrative continue to focus on descriptions of Surinam's natural environments. Stedman writes that parts of Surinam are mountainous, dry, and barren, but much of the land is ripe and fertile, enjoying a year-long growing season, with rains and a warm climate. He notes that in some parts the land is low and marshy, and crops are grown with a "flooding" method of irrigation similar to that used in ancient Egypt. Stedman also describes Surinam as having large uncultivated areas; there are immense forests, mountains (some with valuable minerals), deep marsh, swamps, and even large savanna areas. Some areas of the coast are inaccessible, with navigational obstructions such as rocks, riverbanks, quicksand, and bogs.[14] In his Narrative, Stedman writes about the contrast between the beauty of the colony and his first taste of the violence and cruelty endemic there. One of his first observations involves the torture of a nearly naked enslaved woman, chained to an iron weight. His narrative describes the woman receiving 200 lashes and carrying the weight for a month as a result of her inability to fulfill a task to which she was assigned.[11]  An Arawak woman, wearing a loincloth of woven beads, from Stedman's Narrative. Over the course of his Narrative, Stedman relays several stories regarding the state of the slaves and the horrors to which they are subjected. In one story detailed in his Narrative, involving a group sailing by boat, an enslaved mother was ordered by her mistress to hand over her crying baby. The mistress then threw the baby into the river, drowning it. The mother jumped into the river after her baby, whose body was recovered by fellow slaves. The mother later received 200 lashes for her defiant behavior. In another story, a small boy shoots himself in the head to escape flogging. In yet another, a man is completely broken on the rack and left for days to suffer until he died.[15] Publication history  Illustration of a Dutch plantation owner and slave from William Blake's illustrations of the work of Stedman's work first published in 1792-1794 Stedman's Narrative was published by Joseph Johnson, a radical figure who received criticism for the types of books he sold. In the 1790s, more than 50 percent of them were political, including Stedman's Narrative. The books he published supported the rights of slaves, Jews, women, prisoners and other oppressed peoples around the world. Johnson was an active member of the Society for Constitutional Information, an organization attempting to reform Parliament. He was condemned for the support and publication of writers who voiced liberal opinions, such as Mary Wollstonecraft, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Paine. Stedman's Narrative became a major literary success. It was translated into French, German, Dutch, Italian, and Swedish, and was eventually published in more than twenty-five different editions, including several abolitionist tracts focused on Joanna. Stedman was highly acclaimed for his insights on the slave trade and his Narrative was embraced by the abolitionist cause.[16] Paradoxically, it also became the handbook for counter-insurgency tactics in the tropics.[17] It took almost two centuries for a critical edition to be published. The unabridged critical edition, edited by Richard and Sally Price, was published in 1988. An abridged edition published in 1992 by Price and Price remains in print, as well as two editions published in 1962 and 1966 by the renowned antiquarian Stanbury Thompson. Of Thompson's 1962 and 1966 editions, Price and Price write, "Thompson's work confused as much as it elucidated. Examination of the original notebooks and papers that Thompson had used (which are now in the James Ford Bell Library at the University of Minnesota) revealed that, not only had he inserted his own commentary into that of Stedman...but he had changed dates and spellings, misread and incorrectly transcribed a large number of words".[18] A facsimile edition of the 1988 unabridged critical edition of Stedman's original 1790 manuscript, edited by Richard and Sally Price, was published in 2010 by iUniverse and in 2016 by Open Road. This latter edition remains available.  "A Negro Hung Alive by the Ribs to a Gallows," by William Blake, originally published in Stedman's Narrative Blake's illustrations Stedman's Narrative associated him with some of Europe's foremost radicals. His publisher, Johnson, was imprisoned in 1797 for printing the political writings of Gilbert Wakefield.[19] Johnson commissioned William Blake and Francesco Bartolozzi to create engravings for the Narrative. Blake engraved sixteen images for the book and delivered them in December 1792 and 1793, as well as a single plate in 1794.[20] The images depict some of the horrific atrocities against slaves that Stedman witnessed, including hanging, lashing and other forms of torture. The Blake plates are more forceful than other illustrations in the book and have the "fluidity of line" and "hallucinatory quality of his original work".[20] It is impossible to compare Stedman's sketches with the Blake plates because none of Stedman's original drawings have survived.[20] Through their collaboration, Blake and Stedman became close friends. They visited one another often,[19] and Blake later included some of his images from Stedman's Narrative in his poem "Visions of the Daughters of Albion".[20] Stedman the writer As a writer, Stedman was intrigued by Surinam, a "New World" full of complexities that were both familiar and foreign.[21] Torn between the roles of "incurable romantic"[9] and scientific observer, Stedman attempted to maintain an objective distance from this strange new world, but was drawn in by its natural beauty and what he perceived as its exoticness.[9] Stedman made a daily effort to take notes on the spot, using any material in sight that could be written on, including ammunition cartridges and bleached bone. Stedman later transcribed the notes and strung them together in a small green notebook and ten sheets of paper covered front and back with writing.[22] He intended to use these notes and journals to produce a book.[22] Stedman also made a point to write clearly and distinguish truth from hearsay. He was diligent about facts and focused primarily on firsthand accounts of events.[23] On 15 June 1778, just a year after returning to the Netherlands from Surinam, Stedman began piecing together these notes and journals into what would ultimately become his Narrative.[24] In 1787, Stedman began showing pieces of his journal to friends in an attempt to secure financial backing for the publication of the manuscript. He also attempted to gain potential subscribers in major cities throughout Europe.[9] On 8 February 1791, Stedman sent the first edition of his newly completed manuscript, along with a list of 76 subscribers, to Johnson.[9] In 1786, Stedman wrote a series of retrospective journal entries recalling the events of his life up to the age of 28. In this diary, he portrayed himself in the style and tone of such fictional characters as Tom Jones and Roderick Random.[2] He elaborated on his opposition to authority figures, which he also described during his time in Surinam, and on the sympathy he felt towards creatures and humans unnecessarily punished or tortured.[25] In these entries, Stedman tells of occasions throughout his life when he interceded on the behalf of others to alleviate suffering.[25] Stedman insisted that he did not describe the events of his life with the intention of gaining success or fortune.[26] He explained that he wrote "purely following the dictates of nature, & equally hating a made up man and a made up story."[26] The standard author abbreviation Stedman is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.[27] Discrepancies between published Narrative and personal diaries Stedman wrote his Narrative ten years after the events took place. The Narrative sometimes deviates from the diary, but Stedman was careful to provide his sources and state firsthand observations as opposed to outside accounts.[23] One of the main differences between the two works involves Stedman's representation of his relationship with Joanna. In the diary, he recounts numerous sexual encounters with enslaved women before he met Joanna, events which were removed from the Narrative. Stedman omitted a series of negotiations between himself and Joanna's mother, during which she offers to sell Joanna to him. Stedman also removes the early sexual encounters from the Narrative, and Joanna is represented as a romantic figure whom Stedman describes with sentimental and flowery language, as opposed to an enslaved girl who served his sexual and domestic needs.[28] Mary Louise Pratt refers to these changes as a "romantic transformation of a particular form of colonial sexual exploitation".[29] |

ステッドマンの物語 Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam』は、1773年から1777年までのスリナムでのステッドマンの体験を綴った自伝的物語である。ステッドマンはスリナム滞在中の日記を残 しており、それはミネソタ大学図書館に所蔵されている。物語原稿の中で、ステッドマンはスリナムの風景を生き生きと描写し、動植物や、スリナムの先住民、 自由奴隷にされたアフリカ人、ヨーロッパ人入植者の社会習慣に細心の注意を払っている。植民地での生活についての彼の観察は、当時存在したさまざまな文化 を包括している: オランダ人、スコットランド人、先住民、アフリカ人、スペイン人、ポルトガル人、フランス人。ステッドマンはまた、植民地での日々の生活についても時間を かけて描写している。 『物語』の最初のページには、ステッドマンのスリナムへの航海が記録されている。彼はボレアス号の甲板で読書に明け暮れ、荒れ狂う海から病人を避けようとし ていた[11]。ボレアス号には、もう1隻のウェフテリングヴェルフ号と3隻の新造フリゲート艦が同乗していた。ステッドマンは1773年2月2日にスリ ナムへ到着。スリナム到着後、ステッドマンと部隊はスリナム川沿いの要塞アムステルダムの住民に迎えられる。ここでステッドマンは、スリナムの風景につい て最初の描写をする。ふんどし姿の原住民はステッドマンにとって最初はやや衝撃的で、彼は彼らを「生まれたときのように裸の船乗りたち」と表現した [13]。 『物語』の一部は引き続きスリナムの自然環境の描写に焦点を当てている。ステッドマンは、スリナムの一部は山岳地帯で、乾燥し、不毛であるが、多くの土地は 熟して肥沃であり、雨が降り、温暖な気候で、1年中成長期を楽しむことができると書いている。彼は、土地が低く湿地帯になっているところもあり、作物は古 代エジプトで使われていたような「湛水」方式の灌漑で栽培されていると述べている。ステッドマンはまた、スリナムには広大な未開拓地があり、広大な森林、 山々(中には貴重な鉱物を産出するものもある)、深い沼地、湿地帯、さらには広大なサバンナ地帯があると述べている。海岸には、岩、川岸、流砂、沼地など の航行障害物があり、アクセスできない地域もある[14]。 ステッドマンは『語り』の中で、植民地の美しさと、そこで初めて味わった暴力と残酷さの対比について書いている。彼の最初の観察のひとつは、鉄の錘に鎖で つながれた、ほとんど裸の奴隷女性の拷問であった。彼の叙述によれば、その女性は200回の鞭打ちを受け、割り当てられた仕事を果たせなかった結果、1ヶ 月間重りを背負うことになった[11]。  ビーズで編まれた腰布を身につけたアラワク族の女性(ステッドマンの『語り』より)。 ステッドマンは『語り』の中で、奴隷たちの様子や彼らが受ける恐怖に関する話をいくつか紹介している。彼の『語り』に詳述されている、船で航海している一 団にまつわるある話では、奴隷にされた母親が、泣いている赤ん坊を引き渡すよう愛人に命じられた。そして愛人は赤ん坊を川に投げ入れ、溺れさせた。母親は 赤ん坊を追って川に飛び込み、その死体は奴隷仲間によって回収された。母親はその後、その反抗的な行動に対して200回の鞭打ちを受けた。別の話では、小 さな少年が鞭打ちから逃れるために自分の頭を撃ち抜いた。さらに別の話では、男が鞭打たれた棚で完全に骨折し、死ぬまで何日も放置されて苦しむというもの だった[15]。 出版の歴史  1792年から1794年にかけて出版されたウィリアム・ブレイクのステッドマンの挿絵に描かれたオランダ人農園主と奴隷の挿絵 ステッドマンの物語』は、急進的な人物であり、販売する本の種類で批判を受けたジョセフ・ジョンソンによって出版された。1790年代には、ステッドマン ズ・ナラティブを含め、その50%以上が政治的なものであった。彼が出版した本は、奴隷、ユダヤ人、女性、囚人、その他世界中の抑圧された人々の権利を支 持するものだった。ジョンソンは、議会改革を試みる組織「憲法情報協会」のメンバーとして活躍した。彼は、メアリー・ウルストンクラフト、ベンジャミン・ フランクリン、トマス・ペインなど、リベラルな意見を述べる作家を支援し、出版したことで非難された。 ステッドマンの『語り』は文学的に大成功を収めた。フランス語、ドイツ語、オランダ語、イタリア語、スウェーデン語に翻訳され、最終的にはジョアンナに焦 点を当てた奴隷廃止論者の小冊子を含む25種類以上の版が出版された。ステッドマンは奴隷貿易に関する洞察で高く評価され、彼の『語り』は奴隷廃止運動に 受け入れられた[16]。逆説的だが、この本は熱帯における対反乱戦術のハンドブックにもなった[17]。 批評版が出版されるまでには、ほぼ2世紀を要した。1988年にリチャード・プライスとサリー・プライスによって編集された無修正版が出版された。 1992年にプライスとプライスによって出版された要約版と、著名な古書研究家スタンベリー・トンプソンによって1962年と1966年に出版された2つ の版が現在も出版されている。トンプソンの1962年版と1966年版について、プライスとプライスはこう書いている。トンプソンが使っていたオリジナル のノートや書類(現在、ミネソタ大学のジェームズ・フォード・ベル図書館に所蔵されている)を調べてみると、ステッドマンの注釈に自分の注釈を挿入してい るだけでなく、日付や綴りも変えていた。 18]リチャード・プライス、サリー・プライス夫妻が編集した、ステッドマンの1790年のオリジナル原稿の1988年の未修正批評版のファクシミリ版が 2010年にiUniverse社から、2016年にオープンロード社から出版された。この後者の版は現在も入手可能である。  ウィリアム・ブレイク作 "A Negro Hung Alive by the Ribs to a Gallows", original published in Stedman's Narrative. ブレイクの挿絵 ステッドマンズ・ナラティブ』は、彼をヨーロッパ有数の急進派と結びつけた。彼の出版社ジョンソンは、ギルバート・ウェイクフィールドの政治的著作を印刷 したため、1797年に投獄された[19]。ジョンソンは、ウィリアム・ブレイクとフランチェスコ・バルトロッツィに『語り』の挿絵を依頼した。ブレイク はこの本のために16枚の絵を彫り、1792年12月と1793年に、そして1794年に1枚ずつ納品した[20]。その絵には、ステッドマンが目撃し た、絞首刑や鞭打ちなどの拷問を含む、奴隷に対する恐ろしい残虐行為のいくつかが描かれている。ステッドマンのスケッチとブレイクの版画を比較すること は、ステッドマンの原画が現存していないため不可能である[20]。彼らは頻繁にお互いを訪問し[19]、ブレイクは後にステッドマンの『語り』から得た イメージのいくつかを詩『アルビオンの娘たちの幻影』に取り入れた[20]。 作家としてのステッドマン 不治のロマンチスト」[9]と科学的観察者という役割の間で葛藤するステッドマンは、この見知らぬ新世界から客観的な距離を保とうとしたが、その自然の美 しさと異国情緒に引き込まれた[9]。 ステッドマンは毎日、弾薬のカートリッジや漂白した骨など、目に入るあらゆる材料を使って、その場でメモを取ることに努めた。ステッドマンは後にそのメモ を書き写し、小さな緑色のノートと、表も裏も文字で覆われた10枚の紙につなぎ合わせた[22]。彼はこれらのメモと日記を使って本を作るつもりだった [22]。ステッドマンはまた、明確に書くことと、伝聞と真実を区別することを心がけた。彼は事実に対して勤勉であり、主に出来事の直接の証言に重点を置 いていた[23]。 1778年6月15日、スリナムからオランダに戻ったわずか1年後、ステッドマンはこれらのメモや日記をつなぎ合わせて、最終的に『語り』となるものを書 き始めた[24]。1791年2月8日、ステッドマンは新たに完成した原稿の初版を76人の購読者リストとともにジョンソンに送った[9]。 1786年、ステッドマンは28歳までの人生の出来事を回想する一連の日記を書いた。この日記の中で、彼はトム・ジョーンズやロデリック・ランダムといっ た架空の人物のようなスタイルと口調で自分自身を描写している[2]。彼はスリナム滞在中にも描写していた権力者への反発や、不必要に罰せられたり拷問さ れたりしている生き物や人間への同情について詳しく述べている。 [25]これらのエントリの中で、ステッドマンは、彼が苦しみを軽減するために他の人のために仲裁した彼の人生を通しての機会について語っている [25]。 ステッドマンは、彼が成功や幸運を得ることを意図して自分の人生の出来事を記述していないと主張した[26]。 彼は「純粋に自然の命令に従うと、同様に作り上げられた人間と作り上げられた物語を嫌って」書いたと説明した[26]。 標準的な著者の略称であるステッドマンは、植物名を引用する際に著者としてこの人物を示すために使用される[27]。 出版された『語り』と個人的な日記の食い違い ステッドマンは出来事が起こった10年後に「語り」を書いた。ナラティヴは時々日記から逸脱しているが、ステッドマンは出典を示し、外部の証言とは対照的 に、直接の観察を述べるように注意していた[23]。2つの著作の主な違いの1つは、ジョアンナとの関係についてのステッドマンの表現である。日記では、 ジョアンナと出会う前の奴隷女性たちとの数々の性的な出会いが語られているが、この出来事は『語り』からは削除されている。ステッドマンは、ジョアンナの 母親がジョアンナを売りたいと申し出る、彼とジョアンナの間の一連の交渉を省略している。ステッドマンはまた、初期の性的出会いを『語り』から削除し、 ジョアンナは、ステッドマンが感傷的で花のような言葉で描写するロマンチックな人物として表現され、彼の性的・家庭的欲求に奉仕する奴隷の少女とは対照的 である[28]。メアリー・ルイーズ・プラットは、こうした変化を「植民地的性的搾取の特殊な形態のロマンチックな変容」と呼んでいる[29]。 |

Stedman and slavery Author William Blake's "Flagellation of a Female Samboe Slave", 1796, Stedman's attitudes toward slavery were complicated, although he witnessed many atrocities committed against slaves firsthand Stedman's attitude toward slaves and slavery has been the subject of scholarly debate. In spite of the abolitionist utility of the text, Stedman himself was far from an abolitionist. A defense of slavery runs throughout the text, emphasizing problems that would arise from sudden emancipation.[30] In fact, Stedman believed that slavery was necessary in some form to continue allowing European nations to indulge their excessive desires for commodities such as tobacco and sugar. Stedman's relationship with the slave Joanna further complicates his views toward slavery. Stedman described their relationship as one "of romantic love rather than filial servitude,"[31] although Joanna's feelings on the relationship are unknown. The Narrative is also an ethnocentric text.[30] Some critics argue that the book made Stedman seem like a much more consistent pro-slavery advocate than he intended.[32] But Stedman's attitudes toward individual slaves did not coincide with his attitude toward the institution of slavery. His sympathy for the suffering slaves, expressed throughout the book, is consistently obfuscated by his opinion about slavery as an institution, which according to Werner Sollors was "complicated, its representation strongly affected by the revisions."[32] Sexual encounters According to the editorial introduction to the Narrative, Stedman "larded his autobiographical sketch with amorous adventures."[33] For example, as a young man growing up in Holland, Stedman had concurrent affairs with his landlord's wife and her maid until the landlady became jealous and evicted both Stedman and the maid simultaneously.[33] Stedman details frequent sexual encounters with free and enslaved women of African descent in his travel diary, beginning on 9 February 1773, the night he arrived in Suriname's capital, Paramaribo.[28] 9 February is recounted with the following entry: "Our troops were disembarked at Parramaribo...I get fudled [sic] at a tavern, go to sleep at Mr. Lolkens, who was in the country, I f—k one of his negro maids".[34] The personal journal that Stedman kept (and the sexual encounters mentioned therein) varies quite a bit from his published Narrative. The image-conscious Stedman, with a wife and children back in Europe, wanted to cultivate the impression of a gentleman rather than the serial adulterer he portrays in his diaries. Stedman's Narrative removes the depersonalized sex with women of color and replaces it with more detail regarding his relationship with Joanna.[35] Price and Price summarize these changes as "While his diaries depicted a society in which depersonalized sex between European men and slave women was pervasive and routine, his 1790 manuscript transformed Suriname into the exotic setting for a deeply romantic and appropriately tragic love affair."[18] Joanna  An engraving of Joanna from the original edition of Stedman's Narrative. Stedman first mentions Joanna by name in his journal on 11 April 1773 in relation to his negotiation with her mother for the purchasing of Joanna's sexual and domestic services: "J—, her Mother, and Q— mother come to a close bargain with me, we put it of for reasons I gave them."[28][34] Stedman eventually negotiates an arrangement with Joanna's mother, which he indicates in this diary entry: "J—a comes to stay with me. I give her presents to the value of about ten Pound sterling and am perfectly happy."[34] In the 1790 manuscript edition of Stedman's travel narrative, edited and expanded on from his travel diary, he praised the physical appearance of Joanna, "bespeaking the Goodness of her heart".[36] Throughout the Narrative, Stedman praises Joanna's character. He often describes instances of what he viewed as her loyalty and devotion to him through his absences and illnesses: "She told me she had heard of my forlorn situation; and if I still entertained for her the same good opinion I had formerly expressed, her only request was that she might be permitted to wait upon me till I recovered. I gratefully accepted the offer; and by her unwearied care and attention, I had the good fortune to regain my health."[37] In the nineteenth century, abolitionists circulated Stedman and Joanna's story, most notably in Lydia Maria Child's collection The Oasis in 1834.[38] The first abridged edition of Stedman's Narrative to concentrate on Joanna's narrative was published in 1824, titled Joanna, or The Female Slave, a West Indian Tale. The anonymous compiler of the 1824 version writes in the preface that emancipation is "neither practicable or advisable" but advocates for "the abolition of cruelty".[39] In 1838, Isaac Knapp, a Boston abolitionist and printer, published Narrative of Joanna; An Emancipated Slave, of Surinam. Knapp founded the New England Anti-Slavery Society in 1832 along with William Lloyd Garrison. Knapp and Garrison also co-founded the abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator in 1831. Like Lydia Maria Child's version of Stedman and Joanna's narrative included in the abolitionist collection The Oasis in 1834, Narrative of Joanna was circulated in a distinctly American abolitionist discourse. Stedman and Joanna had a son, named Johnny. Johnny was eventually freed from slavery, but not Joanna. However, when Stedman returned to the Dutch Republic in June 1777, Joanna and their son stayed behind in Surinam. Stedman explained this by saying that Joanna refused to return with him: "She said, that if I soon returned to Europe, she must either be parted from me forever, or accompany me to a land where the inferiority of her condition must prove a great disadvantage to her benefactor and to herself; and in either of these cases, she should be most miserable."[40] Shortly after his return to the Dutch Republic, Stedman married a Dutch woman, Adriana Wierts van Coehorn, and started a family with her. According to Stanbury Thompson's edition of Stedman's journals, Joanna died in 1782, after which their son migrated to Europe to live with Stedman and was educated at Blundell's School. Johnny later served as a midshipman in the Royal Navy and died at sea near Jamaica.[41] Stedman's family in Devon Stedman's wife, Adriana, was the wealthy granddaughter of a well-known Dutch engineer. Together they settled in Tiverton, Devonshire, and had five children: Sophia Charlotte, Maria Joanna, George William, Adrian, and John Cambridge. Following the death of Joanna, Johnny joined their household. Adriana made no attempt to hide her feelings of resentment toward Johnny and Stedman often protected his son from her wrath. Stedman favored his first son and later wrote a journal almost entirely devoted to accounts of Johnny's adolescence. After Johnny's death, Stedman published a poem he wrote for his son, eulogizing their relationship.[19] The last lines are as follows: "Fly gentle shade, fly to that blest abode, There view thy mother – and adore thy God. There, O my boy!, on that celestial shore, O may we gladly meet, and part no more." Stedman's daughters were married to prosperous men of good families. His other sons joined the military. George William served as a lieutenant in the Royal Navy and died while attempting to board a Spanish ship off the coast of Cuba in 1803. Adrian fought in the First Anglo-Sikh War for which he was later honored after participating in the Battle of Aliwal against the Sikhs, and died at sea in 1849. John Cambridge served as captain of the 34th Light Infantry of the East India Company military and was killed in an attack on Rangoon in 1824.[19] |

ステッドマンと奴隷制度 作家ウィリアム・ブレイクの "Flagellation of a Female Samboe Slave", 1796, ステッドマンの奴隷制度に対する態度は複雑であった。 奴隷と奴隷制に対するステッドマンの態度は、学者たちの議論の的となってきた。本書は奴隷制度廃止論者のためのものであるにもかかわらず、ステッドマン自 身は奴隷制度廃止論者ではなかった。実際には、ステッドマンは、ヨーロッパ諸国がタバコや砂糖などの商品に対する過剰な欲望を満たすことを可能にし続ける ためには、奴隷制度が何らかの形で必要であると考えていた。 ステッドマンと奴隷ジョアンナとの関係は、奴隷制度に対する彼の見解をさらに複雑にしている。ステッドマンは二人の関係を「親孝行な隷属というよりも、む しろロマンチックな愛の関係」[31]と表現しているが、ジョアンナの心情は不明である。 また、『語り』は民族中心主義的な文章でもある[30]。この本のせいで、ステッドマンは彼が意図していたよりもずっと一貫した奴隷制擁護論者のように思 われたと主張する批評家もいる[32]。しかし、個々の奴隷に対するステッドマンの態度は、奴隷制度に対する彼の態度と一致していたわけではない。ヴェル ナー・ソラーズによれば、奴隷制度は「複雑であり、その表現は改訂によって強く影響を受けた」[32]。 性的な出会い 例えば、オランダで育った青年時代、ステッドマンは大家の妻とその女中と同時に関係を持ったが、大家は嫉妬し、ステッドマンと女中を同時に追い出した。 [33] ステッドマンは、スリナムの首都パラマリボに到着した1773年2月9日の夜から始まる旅行日記の中で、アフリカ系の自由民や奴隷の女性たちとの頻繁な性 的逢瀬について詳述している[28]: 「私たちの軍隊はパラマリボで下船した......私は居酒屋でふてくされ[sic]、田舎にいたロルケンス氏のところで寝て、私は彼の黒人のメイドの一 人とやった」[34]。 ステッドマンがつけていた個人的な日記(と、そこで言及された性的な出会い)は、出版された『語り』とはかなり異なっている。イメージに敏感なステッドマ ンは、妻子がヨーロッパにいるため、日記で描いているような連続不倫者ではなく、紳士的な印象を育みたかったのだ。ステッドマンの『語り』では、有色人種 の女性との非人格化されたセックスが削除され、ジョアンナとの関係に関するより詳細な描写に置き換えられている[35]。プライスとプライスは、これらの 変更を「彼の日記が、ヨーロッパ人男性と奴隷女性との非人格化されたセックスが蔓延し日常化している社会を描いていたのに対し、1790年の彼の手稿は、 スリナムを、深くロマンチックで適切な悲恋のためのエキゾチックな舞台へと変貌させた」と要約している[18]。 ジョアンナ  ステッドマンの『語り』の原版に掲載されたジョアンナのエングレーヴィング。 ステッドマンは1773年4月11日の日記の中で、ジョアンナの母親とジョアンナの性的・家事的サービスを購入するための交渉に関連して、初めてジョアン ナの名前を挙げている: 「J-、彼女の母、Q-母が私と親密な交渉をするようになったが、私が彼らに言った理由のために断念した」[28][34] ステッドマンは最終的にジョアンナの母親と交渉し、この日記の中でそれを示している: 「J-aは私のところに泊まりに来た。私は彼女に10ポンドほどのプレゼントを渡し、完全に満足している」[34]。ステッドマンの旅行記の1790年の 写本版では、旅行日記を編集・増補し、ジョアンナの容姿を「彼女の心の善良さを物語っている」と賞賛している[36]。 物語全体を通して、ステッドマンはジョアンナの人柄を賞賛している。彼はしばしば、彼の不在や病気を通して、彼女が自分に対する忠誠心や献身とみなした事 例を描写している: 「私が以前と同じように彼女に好意を抱いているのであれば、私が回復するまで待っていてほしいというのが彼女の唯一の願いだった。私はありがたくその申し 出を受け入れ、彼女のたゆまぬ世話と配慮によって、私は幸運にも健康を取り戻すことができた」[37]。 19世紀には、奴隷廃止論者たちがステッドマンとジョアンナの物語を流布し、特に1834年のリディア・マリア・チャイルドの作品集『オアシス』(The Oasis)に掲載された[38]。ジョアンナの物語に焦点を当てた『ステッドマンの物語』の最初の要約版は1824年に出版され、『ジョアンナ、あるい は女奴隷、西インド物語』(Joanna, or The Female Slave, a West Indian Tale)と題された。1824年版の匿名の編者は序文で、奴隷解放は「現実的でも、望ましいことでもない」としながらも、「残酷な行為の廃止」を提唱し ている[39]。1838年、ボストンの奴隷廃止論者で印刷工のアイザック・ナップが『スリナムの奴隷解放されたジョアンナの物語(Narrative of Joanna; An Emancipated Slave, of Surinam)』を出版。ナップは1832年、ウィリアム・ロイド・ギャリソンとともにニューイングランド反奴隷制協会を設立。ナップとギャリソンはま た、1831年に奴隷廃止論者の新聞『リベレーター』を共同で創刊した。リディア・マリア・チャイルド版ステッドマンとジョアンナの物語が1834年に奴 隷廃止論者たちの作品集『オアシス』に収録されたように、『ジョアンナの物語』は、アメリカ独自の奴隷廃止論的言説の中で流布された。 ステッドマンとジョアンナにはジョニーという息子がいた。ジョニーはやがて奴隷から解放されたが、ジョアンナは解放されなかった。しかし、1777年6月 にステッドマンがオランダ共和国に戻ったとき、ジョアンナと息子はスリナムに残った。ステッドマンはこのことについて、ジョアンナが一緒に戻ることを拒ん だと説明している: 「もし私がすぐにヨーロッパに戻れば、彼女は永遠に私と別れるか、あるいは、彼女の地位の劣勢が彼女の恩人と彼女自身にとって大きな不利益となるような土 地に同行しなければならず、どちらの場合でも、彼女は最も惨めな思いをしなければならないと言った」[40]。 オランダ共和国に戻った直後、ステッドマンはオランダ人女性アドリアナ・ヴィエルツ・ファン・コーホーンと結婚し、家庭を築いた。スタンブリー・トンプソ ン版のステッドマンの日記によると、ジョアンナは1782年に死去し、その後、二人の息子はステッドマンと暮らすためにヨーロッパに移住し、ブランデル ズ・スクールで教育を受けた。ジョニーは後に英国海軍の中尉として従軍し、ジャマイカ近海で戦死した[41]。 デヴォンのステッドマン一家 ステッドマンの妻アドリアナは、有名なオランダ人技師の裕福な孫娘だった。二人はデヴォンシャーのティバートンに定住し、5人の子供をもうけた: ソフィア・シャーロット、マリア・ジョアンナ、ジョージ・ウィリアム、エイドリアン、ジョン・ケンブリッジである。ジョアンナの死後、ジョニーが家庭に加 わった。アドリアナはジョニーに対する恨みの感情を隠そうとはせず、ステッドマンは彼女の怒りから息子を守ることが多かった。ステッドマンは長男を寵愛 し、のちにほとんどジョニーの思春期を綴った日記を書いた。ジョニーの死後、ステッドマンは息子のために書いた詩を発表し、二人の関係を賛美した [19]。 最後の行は以下の通り: "飛べ、優しい日陰よ、その至福の住処へ飛べ、 そこで汝の母を見よ、そして汝の神を崇めよ。 我が子よ、あの天空の岸辺へ、 汝の母を見、汝の神を崇めよ。 ステッドマンの娘たちは裕福な良家の男性と結婚した。他の息子たちは軍に入った。ジョージ・ウィリアムは英国海軍中尉として従軍し、1803年にキューバ 沖でスペイン船に乗り込もうとして戦死した。エイドリアンは第一次アングロ・シク戦争でシク教徒とのアリワルの戦いに参加し、後にその功績が称えられ、 1849年に海上で戦死した。ジョン・ケンブリッジは東インド会社軍の第34軽歩兵隊長を務め、1824年にラングーンへの攻撃で戦死した[19]。 |

| Final years and death Little is known about the final years of Stedman's life. The "Army List" continued to print his name until 1805, after he had been dead for eight years. On 5 July 1793, he was commissioned as a major in the second battalion of the Scots Brigade, and promoted to lieutenant-colonel on 3 May 1796. The title page of his book notes that he reached the rank of captain, via the brevet given at the start of his deployment in the West Indies. According to the Dictionary of National Biography, family tradition maintains that Stedman suffered a severe accident around 1796 which prevented him from commanding a regiment at Gibraltar. He retired to Tiverton, Devon. Instructions left by Stedman before his death requested that he be buried in the parish of Bickleigh next to self-styled gypsy king Bampfylde Moore Carew. He asked specifically to be interred at precisely midnight by torchlight. Stedman's final request was apparently not honored in full, as his grave lies in front of the vestry door, on the opposite side of the church from Carew.[42] |

晩年と死 ステッドマンの晩年についてはほとんど知られていない。陸軍名簿』には、死後8年経った1805年まで彼の名前が掲載され続けた。1793年7月5日、ス コットランド旅団第2大隊の少佐に任命され、1796年5月3日に中佐に昇進した。著書のタイトル・ページには、西インド諸島への派遣開始時に与えられた ブルベットにより大尉の階級に達したことが記されている。The Dictionary of National Biographyによると、一族の言い伝えによると、ステッドマンは1796年頃にひどい事故に見舞われ、ジブラルタルで連隊を指揮することができなく なったという。彼はデヴォンのティバートンに引退した。ステッドマンが生前に残した遺書には、自称ジプシー王バンプフィルド・ムーア・カリューの隣、ビッ クリー教区に埋葬するようにとの指示があった。彼は特に、正確には真夜中に松明を灯して埋葬してほしいと頼んだ。ステッドマンの墓は、カリューとは教会の 反対側にある牧師館のドアの前にあるため、ステッドマンの最後の要求は完全には受け入れられなかったようである[42]。 |

| Publications John Gabriel Stedman (1988). Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam: Transcribed for the First Time from the Original 1790 Manuscript. Edited by Richard Price and Sally Price. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988. John Gabriel Stedman (1963). Expedition to Surinam. Being the Narrative of a Five Years Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam in Guiana etc. Edited and abridged by Christopher Bryant. Folio Society, 1963. John Gabriel Stedman (1962). Journal of John Gabriel Stedman soldier and author. Edited by Stanbury Thompson. London, The Mitre Press, 1962. John Gabriel Stedman (1818), Viaggio al Surinam e nell'interno della Guiana ossia relazione di cinque anni di corse e di osservazioni fatte in questo interessante e poco conosciuto paese dal Capitano Stedman. Milano : Dalla tipografia di Giambattista Sonzogno, 1818. John Gabriel Stedman (1813), Narrative, of a Five Years' Expedition, Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, vol. 1 (2nd corrected ed.), London: J. Johnson & Th. Payne John Gabriel Stedman (1813), Narrative, of a Five Years' Expedition, Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, vol. 2 (2nd corrected ed.), London: J. Johnson & Th. Payne John Gabriel Stedman (1800), Capitain Johan Stedmans dagbok öfwer sina fälttåg i Surinam, jämte beskrifning om detta nybygges inwånare och öfriga märkwärdigheter. : Sammandrag. Stockholm : Tryckt i Kongl. Ordens Boktryckeriet hos Assessoren Johan Pfeiffer, År 1800. John Gabriel Stedman (1799–1800), Reize naar Surinamen, en door de binnenste gedeelten van Guiana; / door den Capitain John Gabriël Stedman. ; Met plaaten en kaarten. ; Naar het engelsch. Te Amsterdam : By Johannes Allart, 1799–1800. John Gabriel Stedman (1799), Voyage à Surinam et dans l'intérieur de la Guiane contenant La Relation de cinq Années de Courses et d'Observations faites dans cette Contrée intéressante et peu connue ; avec des Détails sur les Indiens de la Guiane et les Négres, Paris: F. Buisson John Gabriel Stedman (1797), Stedmans Nachrichten von Suriname, dem letzten Aufruhr der dortigen Negersclaven und ihrer Bezwingung in den Jahren 1772 bis 1777. Auszugsweise übersetzt von M. C. Sprengel. Halle : In der Rengerschen Buchhandlung, 1797 John Gabriel Stedman (1796), Narrative of a five years' expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam in Guiana, on the wild coast of South America from the year 1772 to 1777, elucidating the history of that country and describing its productions. Quadrupedes, Birds, Fishes, Reptiles, Trees, Shrubs, Fruits and Roots; with an account of the Indians of Guiana and negroes of Guinea., London: J. Johnson and J. Edwards John Gabriel Stedman The Study of Astronomy, adapted to the capacities of youth |

出版物 ジョン・ガブリエル・ステッドマン著(1988年)。『スリナムの反乱ニグロに対する5年間の遠征の物語:1790年のオリジナル原稿から初めて転写されたもの。リチャード・プライスとサリー・プライス編。ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学出版、1988年。 ジョン・ガブリエル・ステッドマン(1963年)。スリナム遠征。ギアナのスリナムで反乱を起こしたニグロに対する5年間の遠征の物語。クリストファー・ブライアント編集・要約。フォリオ・ソサエティ、1963年。 ジョン・ガブリエル・ステッドマン(1962年)。軍人であり作家であるジョン・ガブリエル・ステッドマンの日記。スタンバリー・トンプソン編集。ロンドン、The Mitre Press、1962年。 ジョン・ガブリエル・ステッドマン著(1818年)、『スリナムとギアナ奥地への旅、あるいは、この興味深いながらもあまり知られていない国における5年 間の探検と観察についての報告』。ミラノ:Dalla tipografia di Giambattista Sonzogno、1818年。 ジョン・ガブリエル・ステッドマン著(1813年)、『スリナムの反乱ニグロに対する5年間の遠征記』第1巻(第2版)、ロンドン:J. Johnson & Th. Payne ジョン・ガブリエル・ステッドマン著(1813年)、『スリナムの反乱ニグロに対する5年間の遠征記』第2巻(第2版)、ロンドン:J. Johnson & Th. Payne ジョン・ガブリエル・ステッドマン(1800年)、「ヨハン・ステッドマン隊長のスリナム遠征日誌、およびこの入植地の住民とその他の出来事についての説明。:要約。ストックホルム:王立騎士団の印刷所で印刷、アセッサーのヨハン・ファイファー、1800年。 ジョン・ガブリエル・ステッドマン(1799-1800)、スリナムへの旅、およびギアナ奥地探検記;/大尉ジョン・ガブリエル・ステッドマン著。図版および地図付き。英語版。アムステルダムにて:ヨハネス・アラルト著、1799-1800。 ジョン・ガブリエル・ステッドマン著『スリナムとギアナ奥地への航海』(1799年)には、この興味深い地域についてほとんど知られていない5年間の狩猟と観察の記録が収められている。また、ギアナのインディアンと黒人奴隷に関する詳細な記述もある。パリ:F.ブイソン ジョン・ガブリエル・ステッドマン著(1797年)、『ステッドマンによるスリナム通信、1772年から1777年にかけての現地の黒人奴隷の最後の反乱とその鎮圧について。抜粋翻訳、M. C. シュペングル著。ハレ:レンゲル書店、1797年 ジョン・ガブリエル・ステッドマン著(1796年)、「1772年から1777年までの5年間にわたる、ギアナのスリナムで反乱を起こしたニグロ族に対す る遠征の物語。南米の野生海岸で、その国の歴史を解明し、その生産物を記述する。四足獣、鳥類、魚類、爬虫類、樹木、低木、果実および根。ギアナのイン ディアンとギニアのニグロについての記述付き。ロンドン:J.ジョンソンおよびJ.エドワーズ ジョン・ガブリエル・ステッドマン 青少年の能力に合わせた天文学の研究 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Gabriel_Stedman |

|

リ ンク

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1997-2099

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099