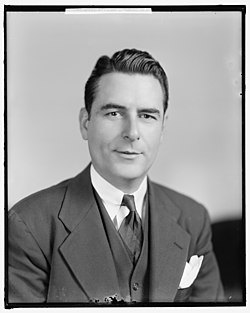

ジョン・エミル・ピュリフォイ

John Emil Peurifoy,

1907-1955

☆ジョ

ン・エミール・ピュリフォイ(1907年8月9日 -

1955年8月12日)は、冷戦初期のアメリカの外交官であり大使であった。ギリシャ、タイ、グアテマラの大使を務めた。後者の国では、1954年にハコ

ボ・アルベンスの民主政府を打倒したクーデターの際、在任中だった。

| John Emil Peurifoy

(August 9, 1907 – August 12, 1955) was an American diplomat and

ambassador in the early years of the Cold War. He served as ambassador

to Greece, Thailand, and Guatemala. In this latter country, he was

serving during the 1954 coup that overthrew the democratic government

of Jacobo Arbenz. |

ジョ

ン・エミール・ピュリフォイ(1907年8月9日 -

1955年8月12日)は、冷戦初期のアメリカの外交官であり大使であった。ギリシャ、タイ、グアテマラの大使を務めた。後者の国では、1954年にハコ

ボ・アルベンスの民主政府を打倒したクーデターの際、在任中だった。 |

| Background Peurifoy was born in Walterboro, South Carolina, on August 9, 1907.[1] His family of lawyers and jurists traced their New World ancestry to 1619, two years before the arrival of the Mayflower.[1] His mother Emily Wright died when he was six, and his father John H. Peurifoy died in December 1926.[2][3] When he graduated from high school in 1926, the yearbook recorded his ambition to be President of the United States.[1] Peurifoy received an appointment to West Point in 1926. He withdrew from the military academy after two years because of pneumonia.[1] |

背景 ピュリフォイは1907年8月9日、サウスカロライナ州ウォルターボロで生まれた。[1] 弁護士や法学者からなる彼の家系は、メイフラワー号到着の2年前である1619年に遡る。[1] 母エミリー・ライトは彼が6歳の時に亡くなり、父ジョン・H・ピュリフォイは1926年12月に死去した。[2] [3] 1926年に高校を卒業した際、卒業アルバムにはアメリカ合衆国大統領になるという彼の志が記されていた。[1] ピュリフォイは1926年にウェストポイント陸軍士官学校への入学許可を得た。しかし肺炎のため、2年後に同校を退学した。[1] |

| Career He worked for a time in New York City as a restaurant cashier and then as a Wall Street clerk.[3] He went to Washington, D.C., in April 1935 in the hopes of working for the State Department. He operated an elevator for the House of Representatives–a patronage job he got through South Carolina Congressman "Cotton Ed" Smith–and worked for the Treasury Department.[1][3] He attended night school at American University and George Washington University.[1] Peurifoy married Betty Jane Cox, a former Oklahoma schoolteacher, in 1936.[1][3] When he lost his job at Treasury, he and his wife both worked at Woodward & Lothrop department store.[3] Peurifoy identified himself as a political liberal and was a lifelong Democrat, because, he said, "You're born that way in South Carolina. It's almost like your religion."[3] |

経歴 彼はニューヨーク市でレストランのレジ係として働き、その後ウォール街の事務員として働いた。[3] 1935年4月、国務省で働くことを望んでワシントンD.C.へ移った。彼は下院議事堂のエレベーター操作員として働いた——これはサウスカロライナ州選 出の「コットン・エド」・スミス下院議員を通じて得た縁故採用の仕事だった——また財務省でも働いた。[1][3] アメリカン大学とジョージ・ワシントン大学の夜間部で学んだ。[1] ピュリフォイは1936年、元オクラホマ州の教師ベティ・ジェーン・コックスと結婚した。[1][3] 財務省を解雇された後、夫妻は共にウッドワード・アンド・ロスロップ百貨店で働いた。[3] ピュリフォイは自らを政治的リベラルと位置づけ、生涯民主党員であった。その理由について彼は「サウスカロライナでは生まれながらにしてそうなる。宗教のようなものだ」と語っている。[3] |

| State Department Peurifoy joined the State Department in October 1938 as a $2000 a year clerk and eight years later was earning $8000 a year as assistant to the Under Secretary of State.[1][3] During World War II, Peurifoy served as the State Department's representative on several inter-departmental committees of the Board of Economic Warfare and the War Production Board.[4] In 1945, Peurifoy managed the arrangements for Conference on International Organization in San Francisco that led to the establishment of the United Nations.[5] President Truman's Executive Order 9835 (1947) established departmental review boards to remove from government service or to deny employment to persons if "reasonable grounds exist for belief that the person involved is disloyal to the United States." In 1947, Peurifoy asked the FBI to conduct an audit of the State Department's Division of Security and Investigations, which found them "lacking in thoroughness."[6] On December 7, 1948, Peurifoy testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), as it pursued the Alger Hiss Case.[7] Secretary of State George C. Marshall appointed him Deputy Undersecretary of State for Administration in 1949, the third-ranking job in the Department, and tasked him with reorganizing the Department and handling relations with Congress.[1] His responsibilities included everything except the substance of foreign policy: the Offices of Personnel, Consular Affairs, Operating Facilities, and Management and Budget.[8] Throughout the years of Peurifoy's involvement in security and personnel issues, the Department focused on new hires rather than its established employees–the primary targets of Soviet attempts at infiltration–unless Congressional investigations prompted a review of a particular employee.[6] When Senator Joseph McCarthy charged in 1950 that Communists were working in the State Department, Peurifoy unsuccessfully challenged him to share his information.[3] However, the same year, Peurifoy told a United States Senate committee of a "homosexual underground" in the State Department and announced that 91 State Department employees had been outed and discharged.[9] His remarks along with gay-baiting comments from Senator Joseph McCarthy help ignite the so-called "Lavender scare". Peurifoy passed his foreign service examinations in 1949 and joined the Foreign Service that year.[3] |

国務省 ピュリフォイは1938年10月、年俸2000ドルの事務員として国務省に入省した。8年後には国務次官補の補佐官として年俸8000ドルを得ていた。[1][3] 第二次世界大戦中、ピュリフォイは経済戦委員会および戦時生産委員会の複数の省庁間委員会において国務省の代表を務めた。[4] 1945年、ピュリフォイはサンフランシスコ国際機関会議の運営を指揮し、これが国連創設につながった。[5]トルーマン大統領の大統領令9835号 (1947年)は、政府職員から「当該人格が米国に不忠実であると信じる合理的な根拠がある場合」に解雇または採用拒否を行う省庁審査委員会を設置した。 1947年、ピュリフォイは国務省保安調査部の監査をFBIに依頼し、同部は「徹底性に欠ける」と指摘された。[6] 1948年12月7日、ピュリフォイはアルジャー・ヒス事件を追及中の下院非米活動委員会(HUAC)で証言した。[7] ジョージ・C・マーシャル国務長官は1949 年、彼を国務次官補(行政担当)に任命した。これは国務省で三番目に位の高い職であり、省の再編と議会対応を任された。[1] 彼の責任範囲は外交政策の実質的内容を除く全てを包含した:人事局、領事局、施設局、管理予算局である. [8] ピュリフォイが安全保障と人事問題に関与した数年間、国務省は既存職員(ソ連の浸透工作の主な標的)よりも新規採用者に重点を置いていた。ただし、議会調 査によって特定の職員の再審査が必要となった場合は例外であった。[6] 1950年、ジョセフ・マッカーシー上院議員が「国務省内に共産主義者が潜伏している」と主張した際、ピュリフォイは情報開示を要求したが失敗に終わっ た。[3] しかし同年、ピュリフォイは上院委員会で国務省内に「同性愛者の地下組織」が存在すると証言し、91名の職員が暴露され解雇されたと発表した。[9] 彼の発言とジョセフ・マッカーシー上院議員の同性愛者差別的発言が相まって、いわゆる「ラベンダー・スケア(同性愛者迫害)」を煽ることとなった。 ピュリフォイは1949 年に外交官試験に合格し、同年、外交官として採用された。[3] |

| Greece In 1950, he was appointed ambassador to Greece. The Communists had already been defeated in the Greek Civil War. During his three-year tenure in Greece, to counter the possible return of the Communists, he helped strengthen the anti-Communist government, a center-right Greek government that included the Greek royal family, with whom Peurifoy had warm personal relations.[3] Due to his direct and un-diplomatic involvement in Greece's internal affairs, his name has negative connotations in Greece and a foreigner who attempts to interfere with Greece's politics is called a "Peurifoy".[10][11][12] In 1953, Peurifoy told Adlai Stevenson that the career members of the Foreign Service were "depressed" by Senator McCarthy's campaign against the State Department. He said he was "unhappy" himself and believed that McCarthy had engineered his transfer from Greece because of a dispute over "some files", though the more likely reason was his experience dealing with Communists.[13] |

ギリシャ 1950年、彼はギリシャ大使に任命された。当時、ギリシャ内戦では共産主義者は既に敗北していた。ギリシャでの3年間の在任中、共産主義者の復活を防ぐ ため、彼は反共産主義政権の強化を支援した。この中道右派のギリシャ政権にはギリシャ王室も含まれており、ピュリフォイは王室と人格的に親密な関係にあっ た。[3] ギリシャの内政に直接かつ外交的配慮を欠いた形で介入したため、彼の名前はギリシャでは否定的な意味合いを持つ。ギリシャの政治に干渉しようとする外国人 は「ピュリフォイ」と呼ばれる。[10][11] [12] 1953年、ピュリフォイはアドレイ・スティーブンソンに対し、マッカーシー上院議員による国務省への攻撃に外務省のキャリア職員が「落ち込んでいる」と 伝えた。自身も「不満」であり、マッカーシーが「ある書類」をめぐる争いが原因でギリシャからの異動を画策したと信じていると述べたが、より可能性が高い 理由は共産主義者との対応経験であった。[13] |

| Guatemala In 1953, during the Eisenhower administration, Peurifoy was sent to Guatemala, the first Western Hemisphere nation to allegedly include Communists in its government.[1] The fabrications regarding the communist regime had been triggered by a year-long smear campaign instigated by the United Fruit Company UFCO, after a series of social reforms had expropriated land acquired under dubious circumstances by UFCO. The "standard" of the smear campaign had been using the social reforms in the country to accuse the regime of communism. The CIA led operation was codenamed PBSuccess. He took up his position as Ambassador there in November 1953.[1] Carlos Castillo Armas, leader of the CIA sponsored rebel forces, was already raising and arming his forces.[3] Peurifoy made clear to Guatemalan President Jacobo Arbenz that the United States cared only about removing Communists from any role in the government.[3] In June 1954, the CIA set into motion a plan to overthrow the Arbenz government. Peurifoy pressed Arbenz hard on his positions on land reform and played an active role in the coup. He then played a central role in the negotiations between Guatemala's army officers, Elfego Monzon, the head of the military junta that seized power and Carlos Castillo Armas, leader of rebel forces. Carlos Castillo Armas was later declared president of Guatemala.[1][3] His work in Greece and Guatemala earned him a reputation as "the State Department's ace troubleshooter in Communist hotspots."[1] The New York Times reported in 1954 that he contemplated running for the U.S. Presidency someday.[3] |

グアテマラ 1953年、アイゼンハワー政権下で、ピュリフォイはグアテマラに派遣された。同国民は西半球で初めて共産主義者を政府に組み込んだとされる国民である。 [1] 共産主義政権に関する捏造は、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社(UFCO)が仕掛けた1年にわたる中傷キャンペーンによって引き起こされた。UFCOが疑わしい 経緯で取得した土地が一連の社会改革によって収用された後のことである。この中傷キャンペーンの「常套手段」は、国内の社会改革を利用して政権を共産主義 と非難することだった。CIA主導の作戦はコードネーム「PBSuccess」と命名された。彼は1953年11月に同国大使として着任した[1]。 CIAが支援する反乱軍の指導者カルロス・カスティーヨ・アルマスは、既に部隊の編成と武装を進めていた[3]。ピュリフォイはグアテマラのハコボ・アル ベンス大統領に対し、米国が政府内のあらゆる立場から共産主義者を排除することのみを重視していることを明確にした。[3] 1954年6月、CIAはアルベンツ政権打倒計画を実行に移した。ピュリフォイは土地改革に関するアルベンツの立場を強く追及し、クーデターに積極的に関 与した。その後、グアテマラ軍将校、権力を掌握した軍事評議会議長エルフェゴ・モンソン、反乱軍指導者カルロス・カスティーヨ・アルマス間の交渉において 中心的な役割を果たした。カルロス・カスティーヨ・アルマスは後にグアテマラ大統領に就任した。[1][3] ギリシャとグアテマラでの活動により、彼は「共産主義のホットスポットにおける国務省のエース級トラブルシューター」との評価を得た。[1] ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙は1954年、彼が将来の米国大統領選出馬を検討していると報じた。[3] |

| Thailand Peurifoy was given a new post as U.S. ambassador to Thailand.[14] |

タイ ピュリフォイは米国駐タイ大使として新たなポストを与えられた。[14] |

| Death On August 12, 1955, while serving as ambassador in Thailand, Peurifoy and his nine-year-old son Daniel Byrd Peurifoy died when the Thunderbird he was driving collided with a truck near Hua Hin.[15] The President sent a military plane for the safe transport of their bodies back to the United States, despite questions of propriety.[14] His older son, John Clinton Peurifoy, known as Clinton, who was injured in the accident, had cerebral palsy. In 1957, Time in its "Religion" section published a story from the Peurifoys' years in Greece, when Prince Constantine told Clinton "My sister and I have been talking about you, and we have decided that you must be the favorite pupil of Jesus....In school the best pupil is always given the hardest problems to solve. God gave you the hardest problem of all, so you must be His favorite pupil." Clinton protested. Queen Frederika repeated her son's words to the Ambassador, who also objected to the sentiment.[16] A few weeks later, Time published a letter from a woman with cerebral palsy who defended Peurifoy and asked: "Why do we become mushy and impractical as well as intolerant when we speak of religion?". Another letter called the point of view taken by Time and the Queen as "fantastically puerile."[17] John Clinton died in 1959 at the age of 19.[18] Peurifoy and his sons are buried together in Arlington National Cemetery. Betty Jane Cox Peurifoy (1912–1998), the ambassador's widow, later married Arthur Chidester Steward. |

死 1955年8月12日、タイ駐在大使を務めていたピュリフォイと9歳の息子ダニエル・バード・ピュリフォイは、彼が運転するサンダーバードがホアヒン近郊 でトラックと衝突し死亡した[15]。大統領は、適切性に関する疑問があったにもかかわらず、遺体を安全に米国へ運ぶため軍用機を手配した[14]。 事故で負傷した長男ジョン・クリントン・ピュリフォイ(通称クリントン)は脳性麻痺を患っていた。1957年、『タイム』誌の「宗教」欄はピュリフォイ家 がギリシャに滞在した時期の記事を掲載した。コンスタンティノス王子がクリントンにこう語ったという。「姉と私は君のことを話していたんだ。君はきっとイ エスの最も愛する弟子に違いないと決めたよ...」 学校では、最も優秀な生徒には常に最も難しい問題が与えられる。神は君に最も難しい問題を授けた。だから君は神のお気に入りの弟子に違いない」と語った。 クリントンは抗議した。フレデリカ王妃は息子の言葉を大使に伝え、大使もこの見解に異議を唱えた[16]。数週間後、タイム誌は脳性麻痺の女性からの手紙 を掲載した。彼女はピュリフォイを擁護し「なぜ宗教について語るとき、我々は感傷的で非現実的になり、さらに不寛容になるのか?」と問いかけた。別の手紙 は、タイム誌と女王の立場を「途方もなく幼稚だ」と評した[17]。ジョン・クリントンは1959年、19歳で死去した[18]。ピュリフォイとその息子 たちはアーリントン国立墓地に共に埋葬されている。大使の未亡人ベティ・ジェーン・コックス・ピュリフォイ(1912–1998)は後にアーサー・チデス ター・スチュワートと再婚した。 |

| Legacy Based in Thailand, the John E. Peurifoy Memorial Foundation provides funds for Fulbright Scholars.[19] |

レガシー タイに拠点を置くジョン・E・ピュリフォイ記念財団は、フルブライト奨学生への資金提供を行っている。[19] |

| References 1. The New York Times: "Peurifoy's First-Name Diplomacy Succeeded in Hard Assignments," August 13, 1955, accessed April 17, 2011 2. Walter B. Edgar, ed., The South Carolina Encyclopedia (University of South Carolina Press, 2006), 718 3. The New York Times: Flora Lewis, "Ambassador Extraordinary: John Peurifoy" July 18, 1954, accessed April 17, 2011 4. Alexander Hopkins McDannald , ed., The Americana 1956 Annual: An Encyclopedia of the Events of 1955 (Americana Corporation, 1956), 585 5. Though Peurifoy is sometimes described as playing a role in the creation of the United Nations, his assignment, according to Flora Lewis of The New York Times, was "little more than a gigantic housekeeping job–to arrange for 5,600 hotel rooms, endless taxis, world-wide cable and radio facilities, committee offices and reception halls." The New York Times: Flora Lewis, "Ambassador Extraordinary: John Peurifoy" July 18, 1954, accessed April 17, 2011 6. Richard Loss, "Secretary of State Dean Acheson as Political Executive: Administrator of Personnel Security," Public Administration Review, vol. 34 (1974), 354-6 7. Hearings Regarding Communist Espionage in the United States Government – Part Two (PDF). US Government Printing Office. December 1948. pp. 1380–1381 (Robert E. Stripling), 1381–1385 (William Wheeler), 1385–1386 (Keith B. Lewis), 1386–1391 (Sumner Welles), 1391–1399 (John Peurifoy), 1399–1429 (Isaac Don Levine), 1429–1449 (Julian Wadleigh), 1449–1451 (Courtney E. Owens), 1451–1467 (Nathan L. Levine), 1467–1474 (Marion Bachrach). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 23, 2017. Retrieved 30 October 2018. 8. Dean Acheson, Present at the Creation: My Years in the State Department (NY: W.W. Norton, 1969), 255 9. Judith Adkins (2016). "These People Are Frightened to Death: Congressional Investigations and the Lavender Scare". National Archives. Retrieved January 2, 2022. 10. Bitsika, Panagiota (26 April 1998). Οι αμερικανοί πρεσβευτές στην Αθήνα [The American ambassadors in Athens]. To Vima (in Greek). Retrieved 18 March 2013. Το όνομα «Πιουριφόι» έγινε σύντομα σύμβολο για τον άθλιο και ωμό τρόπο με τον οποίο οι Αμερικανοί φέρονταν στους... υποτελείς τους. Ο βιογράφος του μάλιστα σημειώνει: «Ο Πιουριφόι εννοούσε να φέρεται προς τις ελληνικές κυβερνήσεις σαν να ήταν υποταγμένες, όπως στα πολεμικά χρόνια του 1946-49»." "The name "Peurifoy" soon became a byword for the vile and brutal way the Americans treated their... subjects. His biographer notes that: "Peurifoy intended to behave towards the Greek governments as if they were subservient, as in the war years of 1946–49"." 11. Αγωνιστική απάντηση στον σύγχρονο Πιουριφόι [Combative response to the new Peurifoy]. Rizospastis (in Greek). 26 April 1998. Retrieved 18 March 2013. ... του τοποτηρητή των αμερικανικών συμφερόντων στη χώρα μας πρέσβη, Ν. Μπερνς. Ο νέος Πιουριφόι... ["the supervisor of American interests in our country, ambassador N. Burns. The new Peurifoy..."] 12. "Δυσφορία Aθήνας για Mίλερ" [Athens expresses discontent with Miller]. Kathimerini (in Greek). 5 March 2003. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013. Eίναι καιρός να συνειδητοποιήσει ότι η εποχή Πιουριφόι δεν μπορεί ν' αναβιώσει. ["It is time he realized that the era of Peurifoy can not be revived"] 13. Blanche Wiesen Cook, The Declassified Eisenhower: A Divided Legacy (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1981), 158, 242 14. Immerman, Richard H. (1990). The CIA in Guatemala: the foreign policy of intervention. The Texas Pan American series (5. paperback print. ed.). Austin: Univ. of Texas Pr. ISBN 978-0-292-71083-2. 15. TIME: "Milestones", August 22, 1955, accessed April 17, 2011 16. TIME: "Religion: The Best Pupil," January 7, 1957, accessed April 17, 2011 17. TIME: "Letters," January 28, 1957 Archived September 29, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, accessed April 17, 2011. The story was retold by Robert Sargent Shriver, Jr. later that year. Sargent Shriver Peace Institute: "The Ancient Mystery of Guiltless Suffering," March 21, 1957 Archived August 24, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, accessed April 18, 2011 18. TIME: "Milestones," October 5, 1959, accessed April 17, 2011 19. Thailand - United States Educational Foundation: "Peurifoy Foundation: Holding TUSEF’s Hands to Help Fulbright Grantees" Archived 2011-03-16 at the Wayback Machine, accessed April 17, 2011 |

参考文献 1. ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙:「ペウリフォイのファーストネーム外交は困難な任務で成功した」、1955年8月13日、2011年4月17日アクセス 2. ウォルター・B・エドガー編、『サウスカロライナ百科事典』(サウスカロライナ大学出版、2006年)、718ページ 3. ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙:フローラ・ルイス、「特命全権大使:ジョン・ピュリフォイ」、1954年7月18日、2011年4月17日アクセス 4. アレクサンダー・ホプキンズ・マクドナルド編、『アメリカナ 1956 年鑑:1955 年の出来事事典』(アメリカナ社、1956 年)、585 ページ 5. ピュリフォイは国連創設に役割を果たしたと評されることもあるが、ニューヨーク・タイムズのフローラ・ルイスによれば、彼の任務は「5,600室のホテル の部屋、無数のタクシー、世界規模のケーブルおよびラジオ設備、委員会事務所、レセプションホールの手配という、巨大な家事仕事にすぎなかった」という。 ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙:フローラ・ルイス「特命全権大使:ジョン・ピュリフォイ」1954年7月18日付、2011年4月17日閲覧 6. リチャード・ロス「政治的執行官としての国務長官ディーン・アチソン:人事保安管理者」『公共行政評論』第34巻(1974年)、354-6頁 7. 『米国政府における共産主義スパイ活動に関する公聴会-第二部』(PDF)。米国政府印刷局。1948年12月。pp. 1380–1381 (ロバート・E・ストリップリング)、1381–1385 (ウィリアム・ウィーラー)、1385–1386 (キース・B・ルイス)、1386–1391 (サムナー・ウェルズ)、1391–1399 (ジョン・ピュリフォイ)、 1399–1429頁(アイザック・ドン・レヴィン)、1429–1449頁(ジュリアン・ワドリー)、1449–1451頁(コートニー・E・オーウェ ンズ)、1451–1467頁(ネイサン・L・レヴィン)、1467–1474頁(マリオン・バックラック)。2017年1月23日にオリジナル (PDF)からアーカイブされた。2018年10月30日に取得。 8. ディーン・アチソン『創世の現場:国務省での私の年月』(ニューヨーク:W.W.ノートン、1969年)、255頁 9. ジュディス・アドキンス (2016). 「これらの人々は恐怖のどん底にいる:議会調査とラベンダー・スケア」. 国立公文書館. 2022年1月2日に閲覧. 10. ビツィカ, パナギオタ (1998年4月26日). アテネのアメリカ大使たち[The American ambassadors in Athens]. ト・ヴィマ(ギリシャ語). 2013年3月18日閲覧. 「ピウリフォイ」という名は、アメリカ人が彼らに対して取った卑劣で残酷な手法の象徴となった。彼の伝記作家はこう記している。「ピュリフォイは、 1946年から49年の戦時中のように、ギリシャ政府を従属的な存在として扱うつもりだった」 「ピュリフォイ」という名は、アメリカ人が彼らの...被支配者たちに対して取った卑劣で残忍な扱いの代名詞となった。彼の伝記作家はこう記している: 「ピュリフォイは、1946年から49年の戦時中のように、ギリシャ政府を従属的な存在として扱うことを意図していた」 11. 現代のピュリフォイへの闘争的応答 [Combative response to the new Peurifoy]. リゾスパスティス (ギリシャ語). 1998年4月26日. 2013年3月18日取得。...わが国における米国利害の監督者、N・バーンズ大使。新たなピュリフォイ... [「わが国における米国利害の監督者、N・バーンズ大使。新たなピュリフォイ...」] 12. 「アテネ、ミラーに不満」[Athens expresses discontent with Miller]。カティメリニ(ギリシャ語)。2003年3月5日。2013年4月11日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2013年3月18日取得。彼はそ ろそろ気づくべきだ、ピュリフォイの時代は復活できないと。[「彼がピウリフォイの時代は復活できないと気づく時が来た」] 13. ブランシュ・ワイゼン・クック著『機密解除されたアイゼンハワー:分断された遺産』(ニューヨーク州ガーデンシティ:ダブルデイ社、1981年)、158頁、242頁 14. リチャード・H・イマーマン著(1990年)。『グアテマラにおけるCIA:介入の外交政策』テキサス・パンアメリカン・シリーズ(第5版ペーパーバック版)。オースティン:テキサス大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-292-71083-2。 15. TIME誌「マイルストーンズ」、1955年8月22日号、2011年4月17日閲覧 16. TIME: 「宗教:最良の生徒」, 1957年1月7日, 2011年4月17日閲覧 17. TIME: 「レターズ」, 1957年1月28日, 2011年9月29日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ, 2011年4月17日閲覧。この話は同年後半にロバート・サージェント・シュライバー・ジュニアによって再語られた。サージェント・シュライバー平和研究 所:「無罪の苦悩の古代の謎」、1957年3月21日(2011年8月24日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ)、2011年4月18日閲覧 18. TIME誌「マイルストーン」、1959年10月5日、2011年4月17日閲覧 19. タイ・アメリカ教育財団「ピュリフォイ財団:フルブライト奨学生支援のためTUSEFと手を携えて」2011年3月16日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ、2011年4月17日閲覧 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Peurifoy |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099