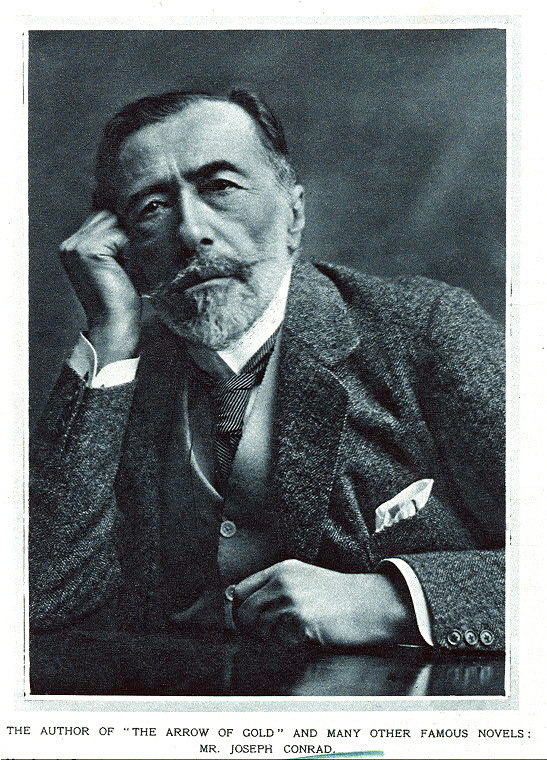

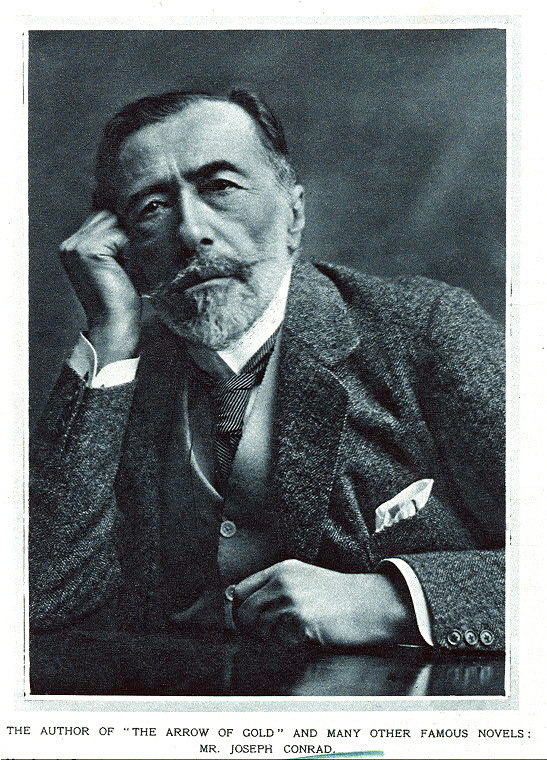

ジョセフ・コンラッド

Joseph Conrad, 1857-1924

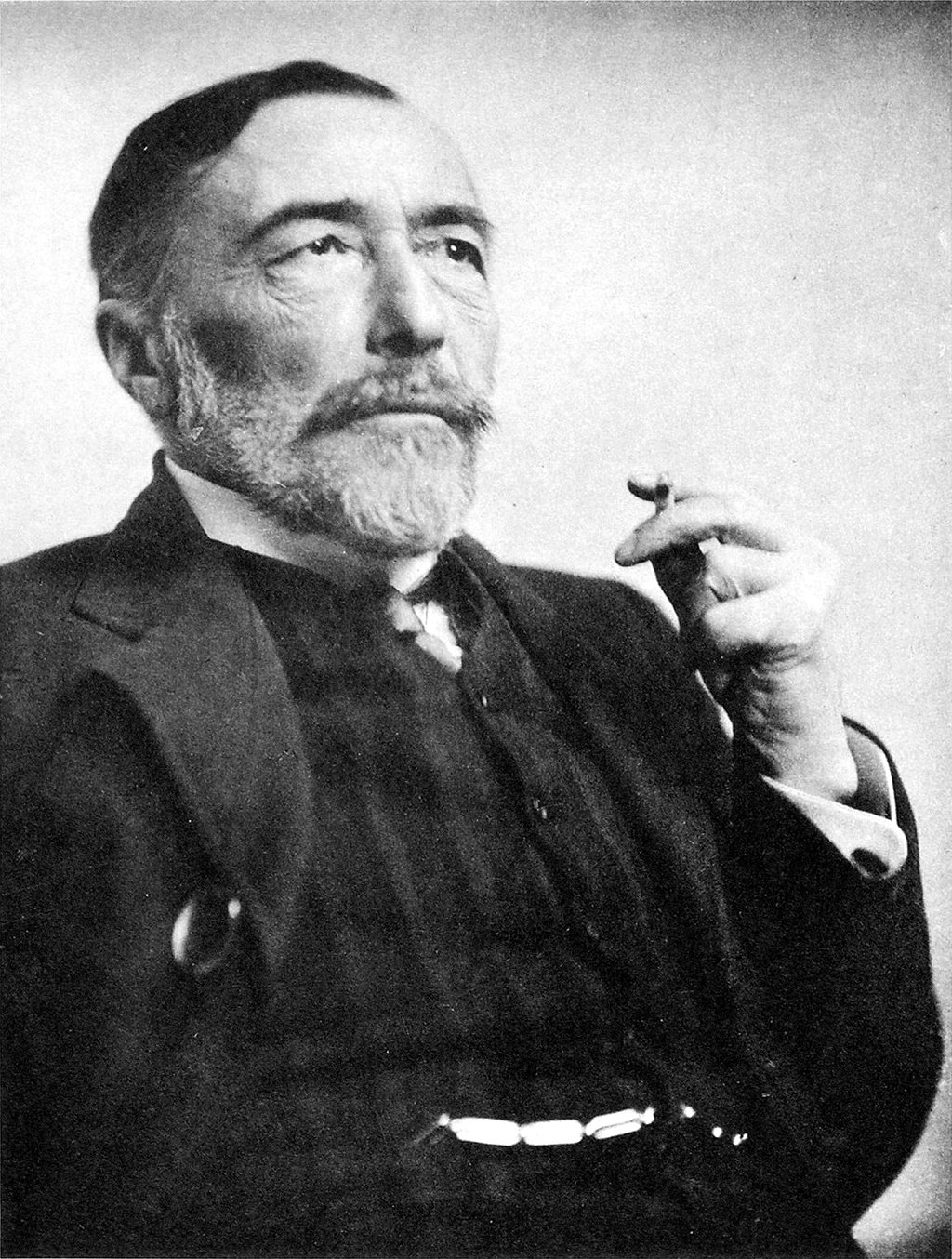

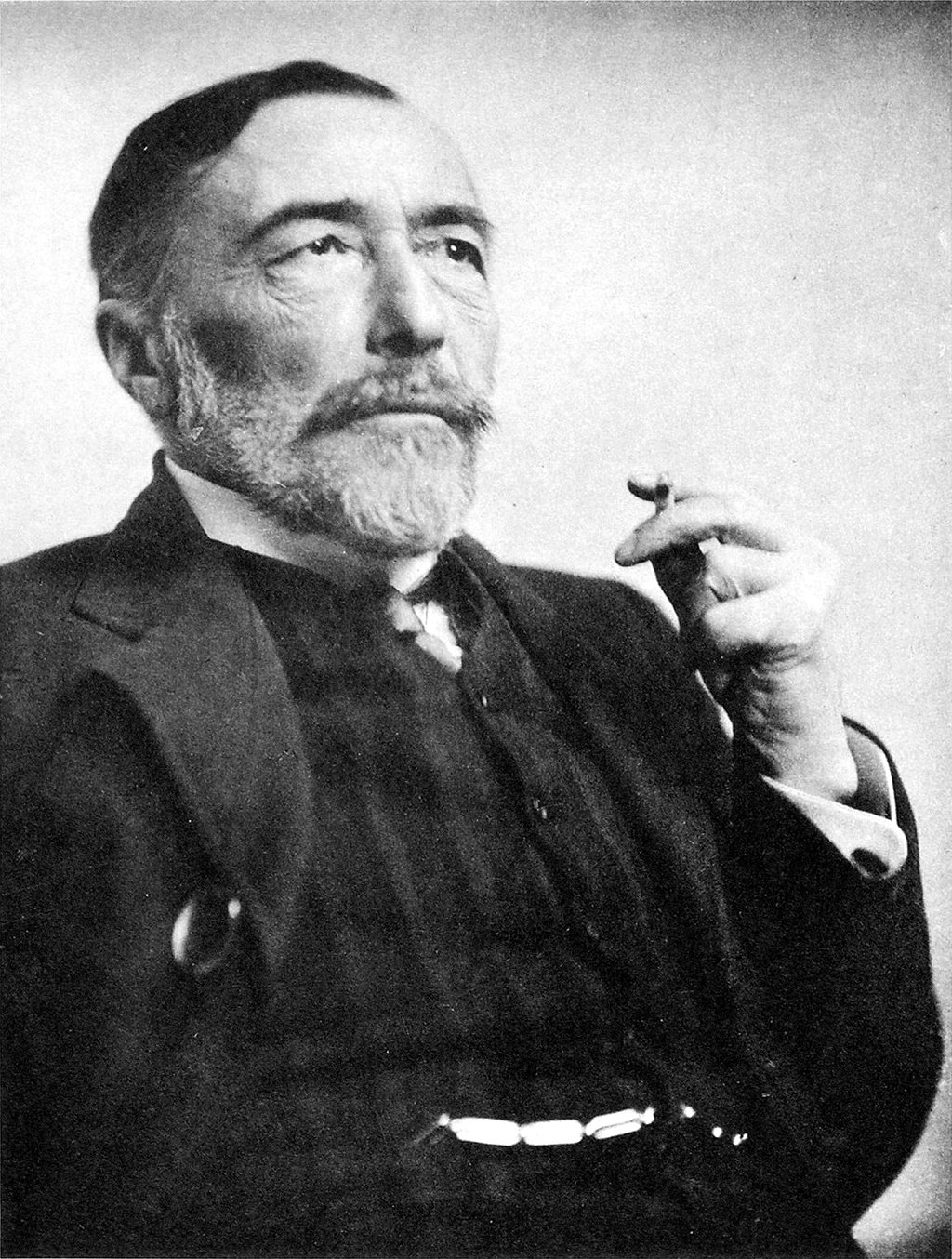

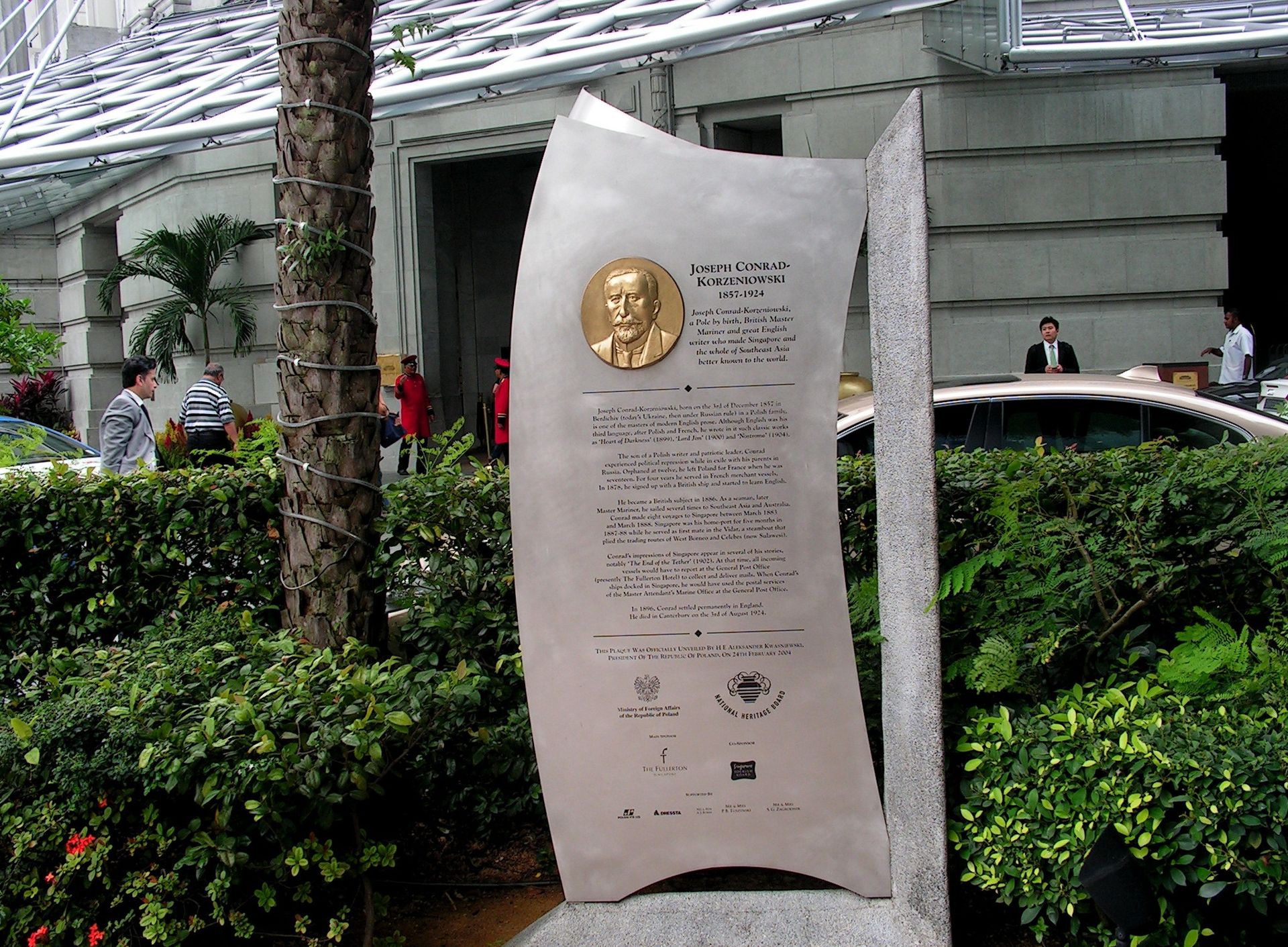

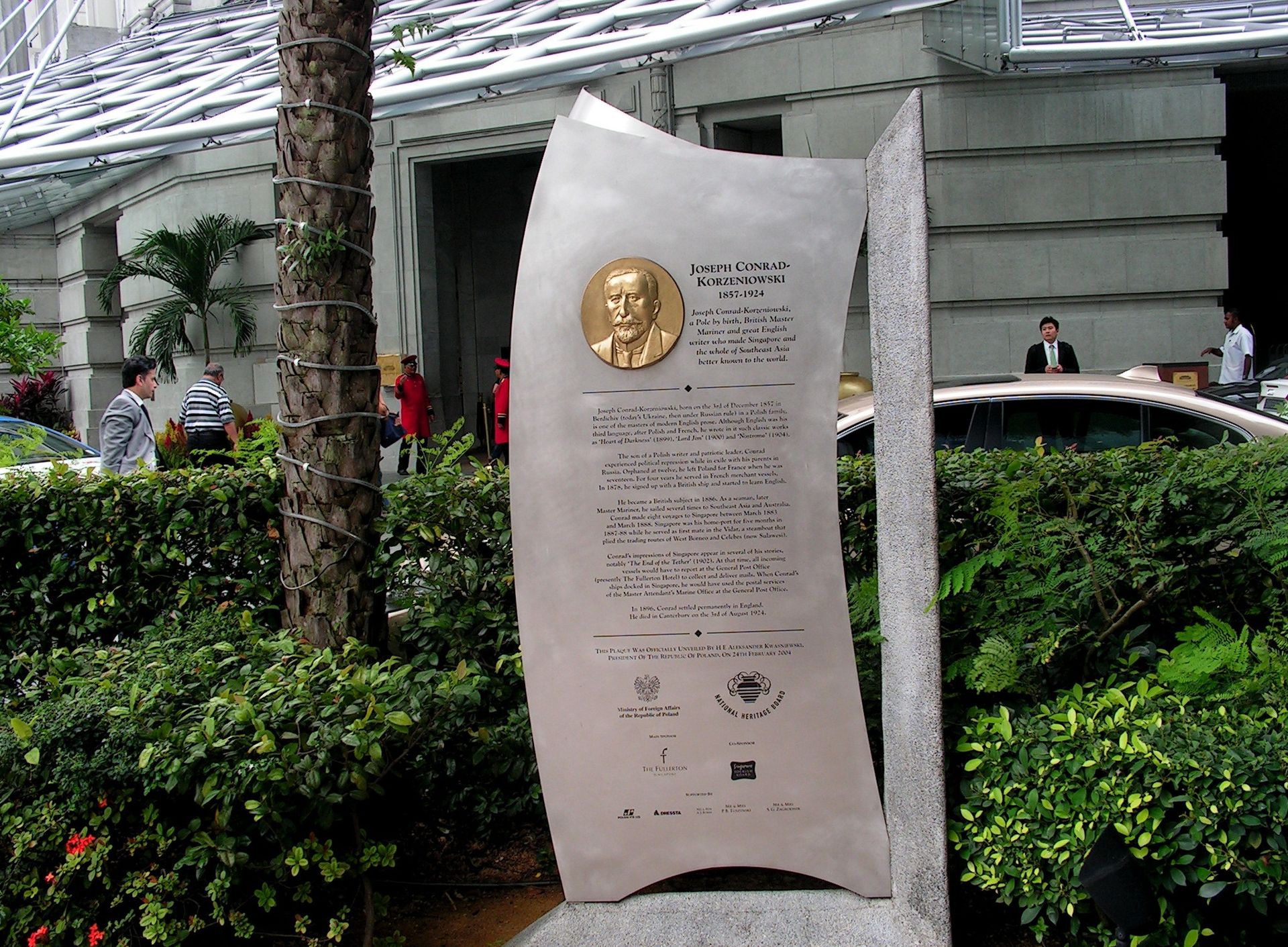

☆ ジョゼフ・コンラッド(Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski、 ポーランド生まれ: [ˈjuzɛ tɔdɔr kɔɛˈɔkɔnrat kɔɛˈɲɔfskʲi]; 1857年12月3日 - 1924年8月3日)はポーランド系イギリス人の小説家、物語作家である。彼は英語における最も偉大な作家の一人と見なされており、20代まで英語を流暢 に話せなかったが、非英語的な感覚を英文学に持ち込んだ散文の名手となった。彼は小説や物語を書いたが、その多くは航海を舞台にしたもので、無関心で不可 解で非道徳的な世界と見なした中での人間の個性の危機を描いている。 コンラッドは、ある人からは文学的印象派、他の人からは初期モダニストとみなされているが、彼の作品には19世紀のリアリズムの要素も含まれている。多く の劇映画が彼の作品から脚色され、影響を受けている。多くの作家や批評家が、20世紀の最初の20年間に書かれた彼のフィクション作品は、後の世界の出来 事を先取りしていたようだとコメントしている。 大英帝国の絶頂期に近い時期に執筆したコンラッドは、祖国ポーランドの国民的経験、ほぼ全生涯を通じて3つの占領帝国の間で小分けにされていた、フランス とイギリスの商船隊での自身の経験をもとに、帝国主義や植民地主義を含むヨーロッパ支配の世界の側面を反映し、人間の心理を深く探求する短編や小説を創作 した。

| Joseph Conrad (born

Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, Polish: [ˈjuzɛf tɛˈɔdɔr ˈkɔnrat

kɔʐɛˈɲɔfskʲi] ⓘ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Polish-British

novelist and story writer.[2][note 1] He is regarded as one of the

greatest writers in the English language and although he did not speak

English fluently until his twenties, he became a master prose stylist

who brought a non-English sensibility into English literature.[note 2]

He wrote novels and stories, many in nautical settings that depict

crises of human individuality in the midst of what he saw as an

indifferent, inscrutable and amoral world.[note 3] Conrad is considered a literary impressionist by some and an early modernist by others,[note 4] though his works also contain elements of 19th-century realism.[9] His narrative style and anti-heroic characters, as in Lord Jim, for example,[10] have influenced numerous authors. Many dramatic films have been adapted from and inspired by his works. Numerous writers and critics have commented that his fictional works, written largely in the first two decades of the 20th century, seem to have anticipated later world events.[note 5] Writing near the peak of the British Empire, Conrad drew on the national experiences of his native Poland—during nearly all his life, parceled out among three occupying empires[16][note 6]—and on his own experiences in the French and British merchant navies, to create short stories and novels that reflect aspects of a European-dominated world—including imperialism and colonialism—and that profoundly explore the human psyche.[18] |

ジョゼフ・コンラッド(Józef Teodor Konrad

Korzeniowski、ポーランド生まれ: [ˈjuzɛ tɔdɔr kɔɛˈɔkɔnrat kɔɛˈɲɔfskʲi] ⓘ;

1857年12月3日 - 1924年8月3日)はポーランド系イギリス人の小説家、物語作家である。 [2][注釈

1]彼は英語における最も偉大な作家の一人と見なされており、20代まで英語を流暢に話せなかったが、非英語的な感覚を英文学に持ち込んだ散文の名手と

なった。 [注2]

彼は小説や物語を書いたが、その多くは航海を舞台にしたもので、無関心で不可解で非道徳的な世界と見なした中での人間の個性の危機を描いている[注3]。 コンラッドは、ある人からは文学的印象派、他の人からは初期モダニストとみなされているが[注釈 4]、彼の作品には19世紀のリアリズムの要素も含まれている。多くの劇映画が彼の作品から脚色され、影響を受けている。多くの作家や批評家が、20世紀 の最初の20年間に書かれた彼のフィクション作品は、後の世界の出来事を先取りしていたようだとコメントしている[注釈 5]。 大英帝国の絶頂期に近い時期に執筆したコンラッドは、祖国ポーランドの国民的経験-ほぼ全生涯を通じて3つの占領帝国の間で小分けにされていた[16] [注釈 6]-と、フランスとイギリスの商船隊での自身の経験をもとに、帝国主義や植民地主義を含むヨーロッパ支配の世界の側面を反映し、人間の心理を深く探求す る短編や小説を創作した[18]。 |

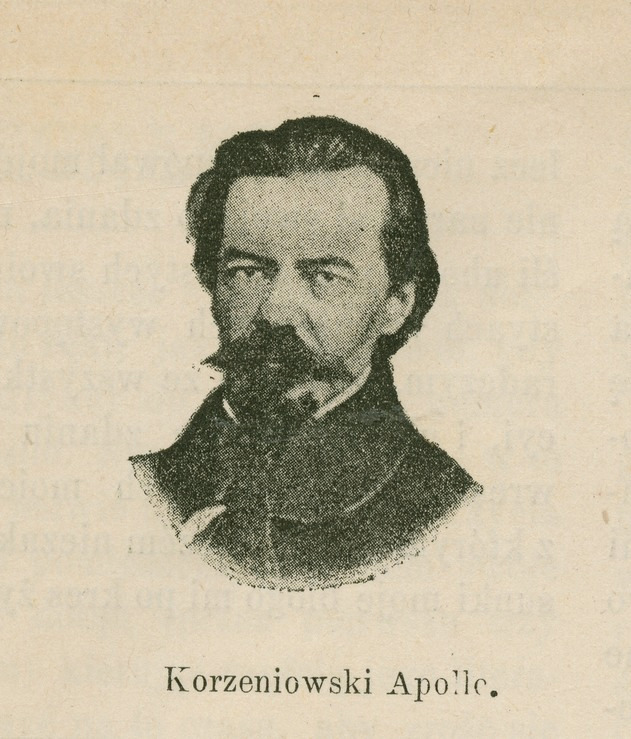

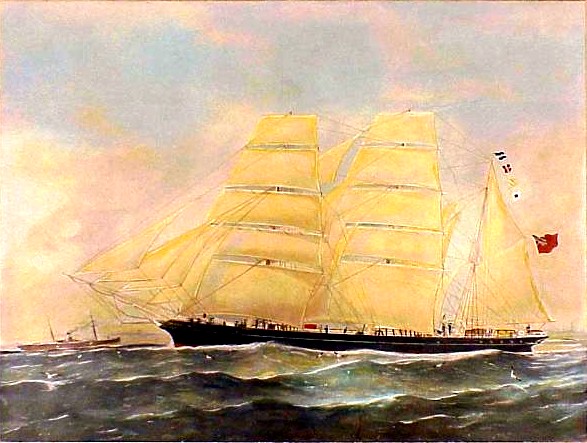

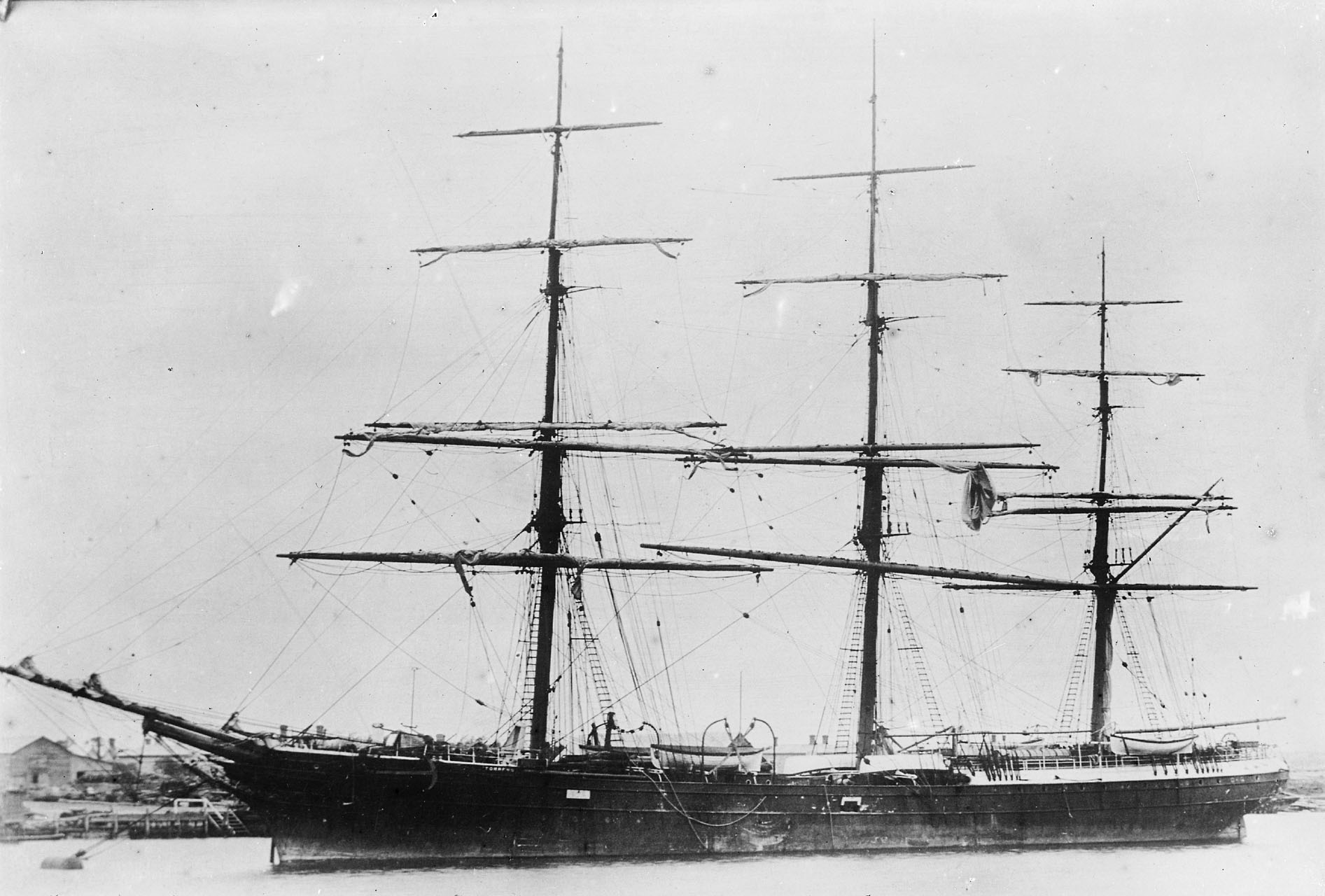

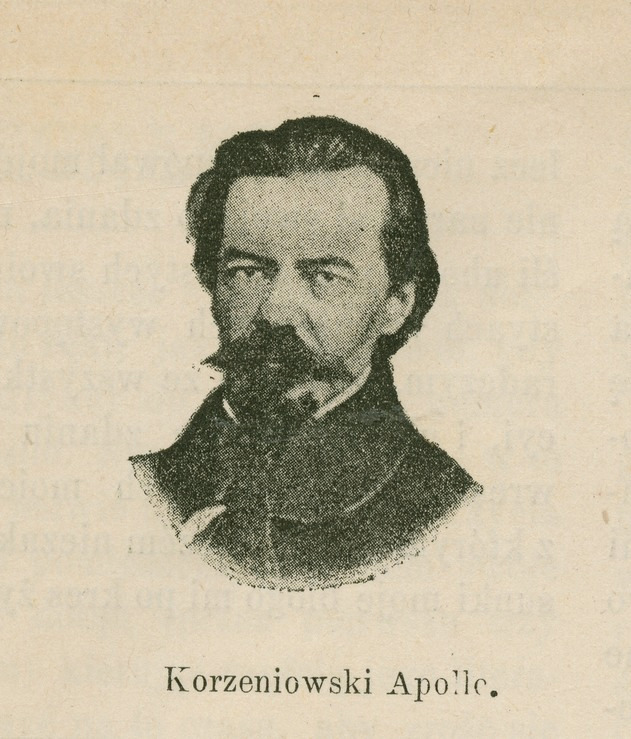

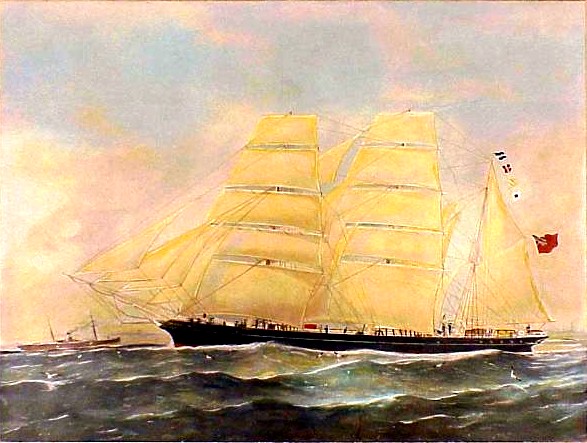

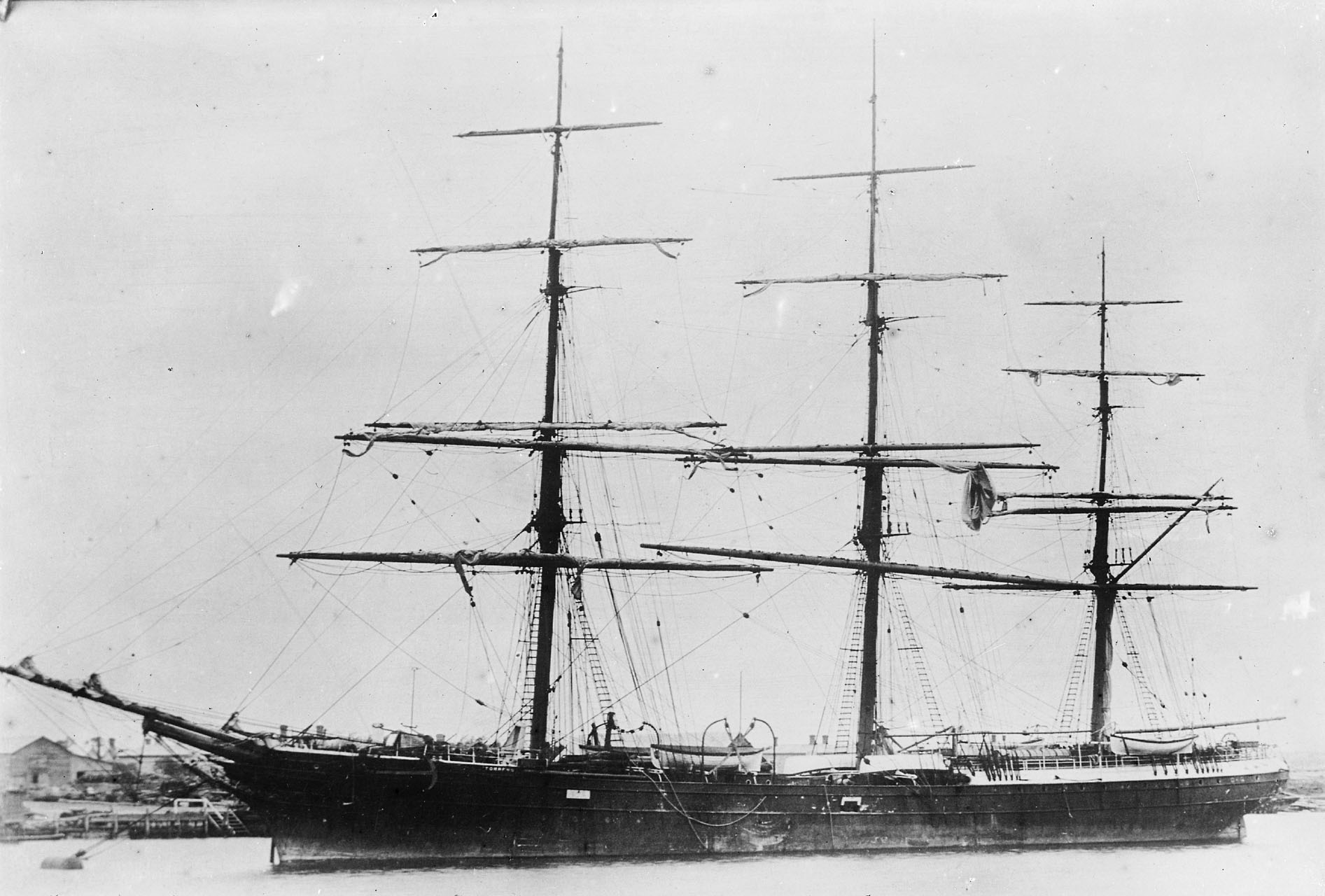

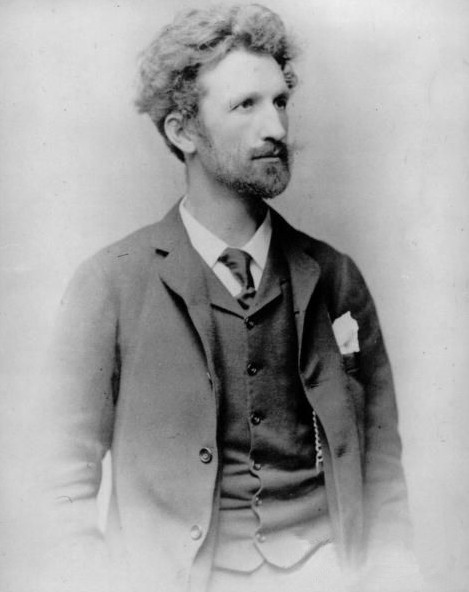

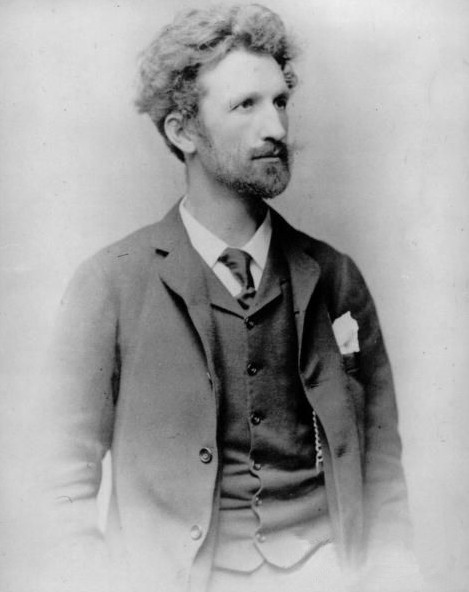

| Life Early years  Conrad's writer father, Apollo Korzeniowski Conrad was born on 3 December 1857 in Berdychiv (Polish: Berdyczów), Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire; the region had once been part of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland.[19] He was the only child of Apollo Korzeniowski—a writer, translator, political activist, and would-be revolutionary—and his wife Ewa Bobrowska. He was christened Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski after his maternal grandfather Józef, his paternal grandfather Teodor, and the heroes (both named "Konrad") of two poems by Adam Mickiewicz, Dziady and Konrad Wallenrod. His family called him "Konrad", rather than "Józef".[note 7] Though the vast majority of the surrounding area's inhabitants were Ukrainians, and the great majority of Berdychiv's residents were Jewish, almost all the countryside was owned by the Polish szlachta (nobility), to which Conrad's family belonged as bearers of the Nałęcz coat-of-arms.[22] Polish literature, particularly patriotic literature, was held in high esteem by the area's Polish population.[23] Poland had been divided among Prussia, Austria and Russia in 1795. The Korzeniowski family had played a significant role in Polish attempts to regain independence. Conrad's paternal grandfather Teodor had served under Prince Józef Poniatowski during Napoleon's Russian campaign and had formed his own cavalry squadron during the November 1830 Uprising of Poland-Lithuania against the Russian Empire.[24] Conrad's fiercely patriotic father Apollo belonged to the "Red" political faction, whose goal was to re-establish the pre-partition boundaries of Poland and that also advocated land reform and the abolition of serfdom. Conrad's subsequent refusal to follow in Apollo's footsteps, and his choice of exile over resistance, were a source of lifelong guilt for Conrad.[25][note 8]  Nowy Świat 47, Warsaw, where three-year-old Conrad lived with his parents in 1861. Because of the father's attempts at farming and his political activism, the family moved repeatedly. In May 1861 they moved to Warsaw, where Apollo joined the resistance against the Russian Empire. He was arrested and imprisoned in Pavilion X[note 9] – the dread Tenth Pavilion – of the Warsaw Citadel.[27] Conrad would write: "[I]n the courtyard of this Citadel—characteristically for our nation—my childhood memories begin."[28] On 9 May 1862 Apollo and his family were exiled to Vologda, 500 kilometres (310 mi) north of Moscow and known for its bad climate.[29] In January 1863 Apollo's sentence was commuted, and the family was sent to Chernihiv in northeast Ukraine, where conditions were much better. However, on 18 April 1865 Ewa died of tuberculosis.[30] Apollo did his best to teach Conrad at home. The boy's early reading introduced him to the two elements that later dominated his life: in Victor Hugo's Toilers of the Sea, he encountered the sphere of activity to which he would devote his youth; Shakespeare brought him into the orbit of English literature. Most of all, though, he read Polish Romantic poetry. Half a century later he explained that "The Polishness in my works comes from Mickiewicz and Słowacki. My father read [Mickiewicz's] Pan Tadeusz aloud to me and made me read it aloud.... I used to prefer [Mickiewicz's] Konrad Wallenrod [and] Grażyna. Later I preferred Słowacki. You know why Słowacki?... [He is the soul of all Poland]".[31] In the autumn of 1866, young Conrad was sent for a year-long retreat for health reasons, to Kyiv and his mother's family estate at Novofastiv [de].[32] In December 1867, Apollo took his son to the Austrian-held part of Poland, which for two years had been enjoying considerable internal freedom and a degree of self-government. After sojourns in Lwów and several smaller localities, on 20 February 1869 they moved to Kraków (until 1596 the capital of Poland), likewise in Austrian Poland. A few months later, on 23 May 1869, Apollo Korzeniowski died, leaving Conrad orphaned at the age of eleven.[33] Like Conrad's mother, Apollo had been gravely ill with tuberculosis.[34]  Tadeusz Bobrowski, Conrad's maternal uncle, mentor, and benefactor The young Conrad was placed in the care of Ewa's brother, Tadeusz Bobrowski. Conrad's poor health and his unsatisfactory schoolwork caused his uncle constant problems and no end of financial outlay. Conrad was not a good student; despite tutoring, he excelled only in geography.[35] At that time he likely received only private tutoring, as there is no evidence he attended any school regularly.[32] Since the boy's ill health was clearly of nervous origin, the physicians supposed that fresh air and physical work would harden him; his uncle hoped that well-defined duties and the rigors of work would teach him discipline. Since he showed little inclination to study, it was essential that he learn a trade; his uncle thought he could work as a sailor-cum-businessman, who would combine maritime skills with commercial activities.[36] In the autumn of 1871, thirteen-year-old Conrad announced his intention to become a sailor. He later recalled that as a child he had read (apparently in French translation) Leopold McClintock's book about his 1857–59 expeditions in the Fox, in search of Sir John Franklin's lost ships Erebus and Terror.[note 10] Conrad also recalled having read books by the American James Fenimore Cooper and the English Captain Frederick Marryat.[37] A playmate of his adolescence recalled that Conrad spun fantastic yarns, always set at sea, presented so realistically that listeners thought the action was happening before their eyes. In August 1873 Bobrowski sent fifteen-year-old Conrad to Lwów to a cousin who ran a small boarding house for boys orphaned by the 1863 Uprising; group conversation there was in French. The owner's daughter recalled: He stayed with us ten months... Intellectually he was extremely advanced but [he] disliked school routine, which he found tiring and dull; he used to say... he... planned to become a great writer.... He disliked all restrictions. At home, at school, or in the living room he would sprawl unceremoniously. He... suffer[ed] from severe headaches and nervous attacks...[38] Conrad had been at the establishment for just over a year when in September 1874, for uncertain reasons, his uncle removed him from school in Lwów and took him back to Kraków.[39] On 13 October 1874 Bobrowski sent the sixteen-year-old to Marseilles, France, for Conrad's planned merchant-marine career on French merchant ships,[36] providing him with a monthly stipend of 150 francs.[32] Though Conrad had not completed secondary school, his accomplishments included fluency in French (with a correct accent), some knowledge of Latin, German and Greek; probably a good knowledge of history, some geography, and probably already an interest in physics. He was well read, particularly in Polish Romantic literature. He belonged to the second generation in his family that had had to earn a living outside the family estates. They were born and reared partly in the milieu of the working intelligentsia, a social class that was starting to play an important role in Central and Eastern Europe.[40] He had absorbed enough of the history, culture and literature of his native land to be able eventually to develop a distinctive world view and make unique contributions to the literature of his adoptive Britain.[41] Tensions that originated in his childhood in Poland and increasing in his adulthood abroad contributed to Conrad's greatest literary achievements.[42] Zdzisław Najder, himself an emigrant from Poland, observed: Living away from one's natural environment—family, friends, social group, language—even if it results from a conscious decision, usually gives rise to... internal tensions, because it tends to make people less sure of themselves, more vulnerable, less certain of their... position and... value... The Polish szlachta and... intelligentsia were social strata in which reputation... was felt... very important... for a feeling of self-worth. Men strove... to find confirmation of their... self-regard... in the eyes of others... Such a psychological heritage forms both a spur to ambition and a source of constant stress, especially if [one has been inculcated with] the idea of [one]'s public duty...[43] Some critics have suggested that when Conrad left Poland, he wanted to break once and for all with his Polish past.[44] In refutation of this, Najder quotes from Conrad's 14 August 1883 letter to family friend Stefan Buszczyński, written nine years after Conrad had left Poland: ... I always remember what you said when I was leaving [Kraków]: "Remember"—you said—"wherever you may sail, you are sailing towards Poland!" That I have never forgotten, and never will forget![45] Merchant marine Main article: Joseph Conrad's career at sea In Marseilles Conrad had an intense social life, often stretching his budget.[32] A trace of these years can be found in the northern Corsica town of Luri, where there is a plaque to a Corsican merchant seaman, Dominique Cervoni, whom Conrad befriended. Cervoni became the inspiration for some of Conrad's characters, such as the title character of the 1904 novel Nostromo. Conrad visited Corsica with his wife in 1921, partly in search of connections with his long-dead friend and fellow merchant seaman.[46][unreliable source?]  Otago, the barque captained by Conrad in 1888 and first three months of 1889 In late 1877, Conrad's maritime career was interrupted by the refusal of the Russian consul to provide documents needed for him to continue his service. As a result, Conrad fell into debt and, in March 1878, he attempted suicide. He survived, and received further financial aid from his uncle, allowing him to resume his normal life.[32] After nearly four years in France and on French ships, Conrad joined the British merchant marine, enlisting in April 1878 (he had most likely started learning English shortly before).[32] For the next fifteen years, he served under the Red Ensign. He worked on a variety of ships as crew member (steward, apprentice, able seaman) and then as third, second and first mate, until eventually achieving captain's rank. During the 19 years from the time that Conrad had left Kraków, in October 1874, until he signed off the Adowa, in January 1894, he had worked in ships, including long periods in port, for 10 years and almost 8 months. He had spent just over 8 years at sea—9 months of it as a passenger.[47] His sole captaincy took place in 1888–89, when he commanded the barque Otago from Sydney to Mauritius.[48] During a brief call in India in 1885–86, 28-year-old Conrad sent five letters to Joseph Spiridion,[note 11] a Pole eight years his senior whom he had befriended at Cardiff in June 1885, just before sailing for Singapore in the clipper ship Tilkhurst. These letters are Conrad's first preserved texts in English. His English is generally correct but stiff to the point of artificiality; many fragments suggest that his thoughts ran along the lines of Polish syntax and phraseology. More importantly, the letters show a marked change in views from those implied in his earlier correspondence of 1881–83. He had abandoned "hope for the future" and the conceit of "sailing [ever] toward Poland", and his Panslavic ideas. He was left with a painful sense of the hopelessness of the Polish question and an acceptance of England as a possible refuge. While he often adjusted his statements to accord to some extent with the views of his addressees, the theme of hopelessness concerning the prospects for Polish independence often occurs authentically in his correspondence and works before 1914.[50]  Conrad lived at 17 Gillingham Street, Pimlico, central London after returning from the Congo The year 1890 marked Conrad's first return to Poland, where he would visit his uncle and other relatives and acquaintances.[48][51] This visit took place while he was waiting to proceed to the Congo Free State, having been hired by Albert Thys, deputy director of the Société Anonyme Belge pour le Commerce du Haut-Congo.[52] Conrad's association with the Belgian company, on the Congo River, would inspire his novella, Heart of Darkness.[48] During this 1890 period in the Congo, Conrad befriended Roger Casement, who was also working for Thys, operating a trading and transport station in Matadi. In 1903, as British Consul to Boma, Casement was commissioned to investigate abuses in the Congo, and later in Amazonian Peru, and was knighted in 1911 for his advocacy of human rights. Casement later became active in Irish Republicanism after leaving the British consular service.[53][note 12] Torrens: Conrad made two round trips as first mate, London to Adelaide, between November 1891 and July 1893. Conrad left Africa at the end of December 1890, arriving in Brussels by late January of the following year. He rejoined the British merchant marines, as first mate, in November.[56] When he left London on 25 October 1892 aboard the passenger clipper ship Torrens, one of the passengers was William Henry Jacques, a consumptive Cambridge University graduate who died less than a year later on 19 September 1893. According to Conrad's A Personal Record, Jacques was the first reader of the still-unfinished manuscript of Conrad's Almayer's Folly. Jacques encouraged Conrad to continue writing the novel.[57]  John Galsworthy, whom Conrad met on Torrens Conrad completed his last long-distance voyage as a seaman on 26 July 1893 when the Torrens docked at London and "J. Conrad Korzemowin"—per the certificate of discharge—debarked. When the Torrens had left Adelaide on 13 March 1893, the passengers had included two young Englishmen returning from Australia and New Zealand: 25-year-old lawyer and future novelist John Galsworthy; and Edward Lancelot Sanderson, who was going to help his father run a boys' preparatory school at Elstree. They were probably the first Englishmen and non-sailors with whom Conrad struck up a friendship and he would remain in touch with both. In one of Galsworthy's first literary attempts, The Doldrums (1895–96), the protagonist—first mate Armand—is modelled after Conrad. At Cape Town, where the Torrens remained from 17 to 19 May, Galsworthy left the ship to look at the local mines. Sanderson continued his voyage and seems to have been the first to develop closer ties with Conrad.[58] Later that year, Conrad would visit his relatives in Poland and Ukraine once again.[48][59] Writer  Conrad in 1916 (photo by Alvin Langdon Coburn) In the autumn of 1889, Conrad began writing his first novel, Almayer's Folly.[60] [T]he son of a writer, praised by his [maternal] uncle [Tadeusz Bobrowski] for the beautiful style of his letters, the man who from the very first page showed a serious, professional approach to his work, presented his start on Almayer's Folly as a casual and non-binding incident... [Y]et he must have felt a pronounced need to write. Every page right from th[e] first one testifies that writing was not something he took up for amusement or to pass time. Just the contrary: it was a serious undertaking, supported by careful, diligent reading of the masters and aimed at shaping his own attitude to art and to reality.... [W]e do not know the sources of his artistic impulses and creative gifts.[61] Conrad's later letters to literary friends show the attention that he devoted to analysis of style, to individual words and expressions, to the emotional tone of phrases, to the atmosphere created by language. In this, Conrad in his own way followed the example of Gustave Flaubert, notorious for searching days on end for le mot juste—for the right word to render the "essence of the matter." Najder opined: "[W]riting in a foreign language admits a greater temerity in tackling personally sensitive problems, for it leaves uncommitted the most spontaneous, deeper reaches of the psyche, and allows a greater distance in treating matters we would hardly dare approach in the language of our childhood. As a rule it is easier both to swear and to analyze dispassionately in an acquired language."[62] In 1894, aged 36, Conrad reluctantly gave up the sea, partly because of poor health, partly due to unavailability of ships, and partly because he had become so fascinated with writing that he had decided on a literary career. Almayer's Folly, set on the east coast of Borneo, was published in 1895. Its appearance marked his first use of the pen name "Joseph Conrad"; "Konrad" was, of course, the third of his Polish given names, but his use of it—in the anglicised version, "Conrad"—may also have been an homage to the Polish Romantic poet Adam Mickiewicz's patriotic narrative poem, Konrad Wallenrod.[63] Edward Garnett, a young publisher's reader and literary critic who would play one of the chief supporting roles in Conrad's literary career, had—like Unwin's first reader of Almayer's Folly, Wilfrid Hugh Chesson—been impressed by the manuscript, but Garnett had been "uncertain whether the English was good enough for publication." Garnett had shown the novel to his wife, Constance Garnett, later a translator of Russian literature. She had thought Conrad's foreignness a positive merit.[64] While Conrad had only limited personal acquaintance with the peoples of Maritime Southeast Asia, the region looms large in his early work. According to Najder, Conrad, the exile and wanderer, was aware of a difficulty that he confessed more than once: the lack of a common cultural background with his Anglophone readers meant he could not compete with English-language authors writing about the English-speaking world. At the same time, the choice of a non-English colonial setting freed him from an embarrassing division of loyalty: Almayer's Folly, and later "An Outpost of Progress" (1897, set in a Congo exploited by King Leopold II of Belgium) and Heart of Darkness (1899, likewise set in the Congo), contain bitter reflections on colonialism. The Malay states came theoretically under the suzerainty of the Dutch government; Conrad did not write about the area's British dependencies, which he never visited. He "was apparently intrigued by... struggles aimed at preserving national independence. The prolific and destructive richness of tropical nature and the dreariness of human life within it accorded well with the pessimistic mood of his early works."[65][note 13] Almayer's Folly, together with its successor, An Outcast of the Islands (1896), laid the foundation for Conrad's reputation as a romantic teller of exotic tales—a misunderstanding of his purpose that was to frustrate him for the rest of his career.[note 14] Almost all of Conrad's writings were first published in newspapers and magazines: influential reviews like The Fortnightly Review and the North American Review; avant-garde publications like the Savoy, New Review, and The English Review; popular short-fiction magazines like The Saturday Evening Post and Harper's Magazine; women's journals like the Pictorial Review and Romance; mass-circulation dailies like the Daily Mail and the New York Herald; and illustrated newspapers like The Illustrated London News and the Illustrated Buffalo Express.[68] He also wrote for The Outlook, an imperialist weekly magazine, between 1898 and 1906.[69][note 15] Financial success long eluded Conrad, who often requested advances from magazine and book publishers, and loans from acquaintances such as John Galsworthy.[70][note 16] Eventually a government grant ("civil list pension") of £100 per annum, awarded on 9 August 1910, somewhat relieved his financial worries,[72][note 17] and in time collectors began purchasing his manuscripts. Though his talent was early on recognised by English intellectuals, popular success eluded him until the 1913 publication of Chance, which is often considered one of his weaker novels.[48] Personal life  Time, 7 April 1923 Temperament and health Conrad was a reserved man, wary of showing emotion. He scorned sentimentality; his manner of portraying emotion in his books was full of restraint, scepticism and irony.[74] In the words of his uncle Bobrowski, as a young man Conrad was "extremely sensitive, conceited, reserved, and in addition excitable. In short [...] all the defects of the Nałęcz family."[75] Conrad suffered throughout life from ill health, physical and mental. A newspaper review of a Conrad biography suggested that the book could have been subtitled Thirty Years of Debt, Gout, Depression and Angst.[76] In 1891 he was hospitalised for several months, suffering from gout, neuralgic pains in his right arm and recurrent attacks of malaria. He also complained of swollen hands "which made writing difficult". Taking his uncle Tadeusz Bobrowski's advice, he convalesced at a spa in Switzerland.[77] Conrad had a phobia of dentistry, neglecting his teeth until they had to be extracted. In one letter he remarked that every novel he had written had cost him a tooth.[78] Conrad's physical afflictions were, if anything, less vexatious than his mental ones. In his letters he often described symptoms of depression; "the evidence", writes Najder, "is so strong that it is nearly impossible to doubt it."[79] Attempted suicide In March 1878, at the end of his Marseilles period, 20-year-old Conrad attempted suicide, by shooting himself in the chest with a revolver.[80] According to his uncle, who was summoned by a friend, Conrad had fallen into debt. Bobrowski described his subsequent "study" of his nephew in an extensive letter to Stefan Buszczyński, his own ideological opponent and a friend of Conrad's late father Apollo.[note 18] To what extent the suicide attempt had been made in earnest likely will never be known, but it is suggestive of a situational depression.[81] Romance and marriage In 1888 during a stop-over on Mauritius, in the Indian Ocean, Conrad developed a couple of romantic interests. One of these would be described in his 1910 story "A Smile of Fortune", which contains autobiographical elements (e.g., one of the characters is the same Chief Mate Burns who appears in The Shadow Line). The narrator, a young captain, flirts ambiguously and surreptitiously with Alice Jacobus, daughter of a local merchant living in a house surrounded by a magnificent rose garden. Research has confirmed that in Port Louis at the time there was a 17-year-old Alice Shaw, whose father, a shipping agent, owned the only rose garden in town.[82] More is known about Conrad's other, more open flirtation. An old friend, Captain Gabriel Renouf of the French merchant marine, introduced him to the family of his brother-in-law. Renouf's eldest sister was the wife of Louis Edward Schmidt, a senior official in the colony; with them lived two other sisters and two brothers. Though the island had been taken over in 1810 by Britain, many of the inhabitants were descendants of the original French colonists, and Conrad's excellent French and perfect manners opened all local salons to him. He became a frequent guest at the Schmidts', where he often met the Misses Renouf. A couple of days before leaving Port Louis, Conrad asked one of the Renouf brothers for the hand of his 26-year-old sister Eugenie. She was already, however, engaged to marry her pharmacist cousin. After the rebuff, Conrad did not pay a farewell visit but sent a polite letter to Gabriel Renouf, saying he would never return to Mauritius and adding that on the day of the wedding his thoughts would be with them.  Westbere House, in Canterbury, Kent, was once owned by Conrad. It is listed Grade II on the National Heritage List for England.[83] On 24 March 1896 Conrad married an Englishwoman, Jessie George.[48] The couple had two sons, Borys and John. The elder, Borys, proved a disappointment in scholarship and integrity.[84] Jessie was an unsophisticated, working-class girl, sixteen years younger than Conrad.[85] To his friends, she was an inexplicable choice of wife, and the subject of some rather disparaging and unkind remarks.[86] (See Lady Ottoline Morrell's opinion of Jessie in Impressions.) However, according to other biographers such as Frederick Karl, Jessie provided what Conrad needed, namely a "straightforward, devoted, quite competent" companion.[68] Similarly, Jones remarks that, despite whatever difficulties the marriage endured, "there can be no doubt that the relationship sustained Conrad's career as a writer", which might have been much less successful without her.[87] The couple rented a long series of successive homes, mostly in the English countryside. Conrad, who suffered frequent depressions, made great efforts to change his mood; the most important step was to move into another house. His frequent changes of home were usually signs of a search for psychological regeneration.[88] Between 1910 and 1919 Conrad's home was Capel House in Orlestone, Kent, which was rented to him by Lord and Lady Oliver. It was here that he wrote The Rescue, Victory, and The Arrow of Gold.[89] Except for several vacations in France and Italy, a 1914 vacation in his native Poland, and a 1923 visit to the United States, Conrad lived the rest of his life in England. Sojourn in Poland  In 1914 Conrad and family stayed at the Zakopane Willa Konstantynówka, operated by his cousin Aniela Zagórska, mother of his future Polish translator of the same name.[90]  Conrad's nieces Aniela Zagórska (left), Karola Zagórska; Conrad The 1914 vacation with his wife and sons in Poland, at the urging of Józef Retinger, coincided with the outbreak of World War I. On 28 July 1914, the day war broke out between Austro-Hungary and Serbia, Conrad and the Retingers arrived in Kraków (then in the Austro-Hungarian Empire), where Conrad visited childhood haunts. As the city lay only a few miles from the Russian border, there was a risk of being stranded in a battle zone. With wife Jessie and younger son John ill, Conrad decided to take refuge in the mountain resort town of Zakopane. They left Kraków on 2 August. A few days after arrival in Zakopane, they moved to the Konstantynówka pension operated by Conrad's cousin Aniela Zagórska; it had been frequented by celebrities including the statesman Józef Piłsudski and Conrad's acquaintance, the young concert pianist Artur Rubinstein.[91] Zagórska introduced Conrad to Polish writers, intellectuals, and artists who had also taken refuge in Zakopane, including novelist Stefan Żeromski and Tadeusz Nalepiński, a writer friend of anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski. Conrad aroused interest among the Poles as a famous writer and an exotic compatriot from abroad. He charmed new acquaintances, especially women. However, Marie Curie's physician sister, Bronisława Dłuska, wife of fellow physician and eminent socialist activist Kazimierz Dłuski, openly berated Conrad for having used his great talent for purposes other than bettering the future of his native land.[92][note 19] [note 20] But thirty-two-year-old Aniela Zagórska (daughter of the pension keeper), Conrad's niece who would translate his works into Polish in 1923–39, idolised him, kept him company, and provided him with books. He particularly delighted in the stories and novels of the ten-years-older, recently deceased Bolesław Prus[95][96] (who also had visited Zakopane[97]), read everything by his fellow victim of Poland's 1863 Uprising—"my beloved Prus"—that he could get his hands on, and pronounced him "better than Dickens"—a favourite English novelist of Conrad's.[98][note 21] Conrad, who was noted by his Polish acquaintances to still be fluent in his native tongue, participated in their impassioned political discussions. He declared presciently, as Józef Piłsudski had earlier in 1914 in Paris, that in the war, for Poland to regain independence, Russia must be beaten by the Central Powers (the Austro-Hungarian and German Empires), and the Central Powers must in turn be beaten by France and Britain.[100][note 22] After many travails and vicissitudes, at the beginning of November 1914 Conrad managed to bring his family back to England. On his return, he was determined to work on swaying British opinion in favour of restoring Poland's sovereignty.[102] Jessie Conrad would later write in her memoirs: "I understood my husband so much better after those months in Poland. So many characteristics that had been strange and unfathomable to me before, took, as it were, their right proportions. I understood that his temperament was that of his countrymen."[103] Politics Biographer Zdzisław Najder wrote: Conrad was passionately concerned with politics. [This] is confirmed by several of his works, starting with Almayer's Folly. [...] Nostromo revealed his concern with these matters more fully; it was, of course, a concern quite natural for someone from a country [Poland] where politics was a matter not only of everyday existence but also of life and death. Moreover, Conrad himself came from a social class that claimed exclusive responsibility for state affairs, and from a very politically active family. Norman Douglas sums it up: "Conrad was first and foremost a Pole and like many Poles a politician and moralist malgré lui [French: "in spite of himself"]. These are his fundamentals." [What made] Conrad see political problems in terms of a continuous struggle between law and violence, anarchy and order, freedom and autocracy, material interests and the noble idealism of individuals [...] was Conrad's historical awareness. His Polish experience endowed him with the perception, exceptional in the Western European literature of his time, of how winding and constantly changing were the front lines in these struggles.[104] The most extensive and ambitious political statement that Conrad ever made was his 1905 essay, "Autocracy and War", whose starting point was the Russo-Japanese War (he finished the article a month before the Battle of Tsushima Strait). The essay begins with a statement about Russia's incurable weakness and ends with warnings against Prussia, the dangerous aggressor in a future European war. For Russia he predicted a violent outburst in the near future, but Russia's lack of democratic traditions and the backwardness of her masses made it impossible for the revolution to have a salutary effect. Conrad regarded the formation of a representative government in Russia as unfeasible and foresaw a transition from autocracy to dictatorship. He saw western Europe as torn by antagonisms engendered by economic rivalry and commercial selfishness. In vain might a Russian revolution seek advice or help from a materialistic and egoistic western Europe that armed itself in preparation for wars far more brutal than those of the past.[105]  Conrad's bust by Jacob Epstein, 1924. Conrad called it "a wonderful piece of work of a somewhat monumental dignity, and yet—everybody agrees—the likeness is striking"[106] Conrad's distrust of democracy sprang from his doubts whether the propagation of democracy as an aim in itself could solve any problems. He thought that, in view of the weakness of human nature and of the "criminal" character of society, democracy offered boundless opportunities for demagogues and charlatans.[107] Conrad kept his distance from partisan politics, and never voted in British national elections.[108] He accused social democrats of his time of acting to weaken "the national sentiment, the preservation of which [was his] concern"—of attempting to dissolve national identities in an impersonal melting-pot. "I look at the future from the depth of a very black past and I find that nothing is left for me except fidelity to a cause lost, to an idea without future." It was Conrad's hopeless fidelity to the memory of Poland that prevented him from believing in the idea of "international fraternity", which he considered, under the circumstances, just a verbal exercise. He resented some socialists' talk of freedom and world brotherhood while keeping silent about his own partitioned and oppressed Poland.[107] Before that, in the early 1880s, letters to Conrad from his uncle Tadeusz[note 23] show Conrad apparently having hoped for an improvement in Poland's situation not through a liberation movement but by establishing an alliance with neighbouring Slavic nations. This had been accompanied by a faith in the Panslavic ideology—"surprising", Najder writes, "in a man who was later to emphasize his hostility towards Russia, a conviction that... Poland's [superior] civilization and... historic... traditions would [let] her play a leading role... in the Panslavic community, [and his] doubts about Poland's chances of becoming a fully sovereign nation-state."[109] Conrad's alienation from partisan politics went together with an abiding sense of the thinking man's burden imposed by his personality, as described in an 1894 letter by Conrad to a relative-by-marriage and fellow author, Marguerite Poradowska (née Gachet, and cousin of Vincent van Gogh's physician, Paul Gachet) of Brussels: We must drag the chain and ball of our personality to the end. This is the price one pays for the infernal and divine privilege of thought; so in this life it is only the chosen who are convicts—a glorious band which understands and groans but which treads the earth amidst a multitude of phantoms with maniacal gestures and idiotic grimaces. Which would you rather be: idiot or convict?[110] Conrad wrote H. G. Wells that the latter's 1901 book, Anticipations, an ambitious attempt to predict major social trends, "seems to presuppose... a sort of select circle to which you address yourself, leaving the rest of the world outside the pale. [In addition,] you do not take sufficient account of human imbecility which is cunning and perfidious."[111][note 24] In a 23 October 1922 letter to mathematician-philosopher Bertrand Russell, in response to the latter's book, The Problem of China, which advocated socialist reforms and an oligarchy of sages who would reshape Chinese society, Conrad explained his own distrust of political panaceas: I have never [found] in any man's book or... talk anything... to stand up... against my deep-seated sense of fatality governing this man-inhabited world.... The only remedy for Chinamen and for the rest of us is [a] change of hearts, but looking at the history of the last 2000 years there is not much reason to expect [it], even if man has taken to flying—a great "uplift" no doubt but no great change....[112] Leo Robson writes: Conrad... adopted a broader ironic stance—a sort of blanket incredulity, defined by a character in Under Western Eyes as the negation of all faith, devotion, and action. Through control of tone and narrative detail... Conrad exposes what he considered to be the naïveté of movements like anarchism and socialism, and the self-serving logic of such historical but "naturalized" phenomena as capitalism (piracy with good PR), rationalism (an elaborate defense against our innate irrationality), and imperialism (a grandiose front for old-school rape and pillage). To be ironic is to be awake—and alert to the prevailing "somnolence." In Nostromo... the journalist Martin Decoud... ridicul[es] the idea that people "believe themselves to be influencing the fate of the universe." (H. G. Wells recalled Conrad's astonishment that "I could take social and political issues seriously.")[113] But, writes Robson, Conrad is no moral nihilist: If irony exists to suggest that there's more to things than meets the eye, Conrad further insists that, when we pay close enough attention, the "more" can be endless. He doesn't reject what [his character] Marlow [introduced in Youth] calls "the haggard utilitarian lies of our civilisation" in favor of nothing; he rejects them in favor of "something", "some saving truth", "some exorcism against the ghost of doubt"—an intimation of a deeper order, one not easily reduced to words. Authentic, self-aware emotion—feeling that doesn't call itself "theory" or "wisdom"—becomes a kind of standard-bearer, with "impressions" or "sensations" the nearest you get to solid proof.[114] In an August 1901 letter to the editor of The New York Times Saturday Book Review, Conrad wrote: "Egoism, which is the moving force of the world, and altruism, which is its morality, these two contradictory instincts, of which one is so plain and the other so mysterious, cannot serve us unless in the incomprehensible alliance of their irreconcilable antagonism."[115][note 25] Death  Conrad's grave at Canterbury Cemetery, near Harbledown, Kent On 3 August 1924, Conrad died at his house, Oswalds, in Bishopsbourne, Kent, England, probably of a heart attack. He was interred at Canterbury Cemetery, Canterbury, under a misspelled version of his original Polish name, as "Joseph Teador Conrad Korzeniowski".[117] Inscribed on his gravestone are the lines from Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene which he had chosen as the epigraph to his last complete novel, The Rover: Sleep after toyle, port after stormie seas, Ease after warre, death after life, doth greatly please[118] Conrad's modest funeral took place amid great crowds. His old friend Edward Garnett recalled bitterly: To those who attended Conrad's funeral in Canterbury during the Cricket Festival of 1924, and drove through the crowded streets festooned with flags, there was something symbolical in England's hospitality and in the crowd's ignorance of even the existence of this great writer. A few old friends, acquaintances and pressmen stood by his grave.[117] Another old friend of Conrad's, Cunninghame Graham, wrote Garnett: "Aubry was saying to me... that had Anatole France died, all Paris would have been at his funeral."[117] Conrad's wife Jessie died twelve years later, on 6 December 1936, and was interred with him. In 1996 his grave was designated a Grade II listed structure.[119] |

生涯 生い立ち  コンラッドの作家の父、アポロ・コルツェニウスキ コンラッドは1857年12月3日、当時ロシア帝国の一部であったウクライナのベルディチュフ(ポーランド語: Berdyczów)で生まれた[19]。作家、翻訳家、政治活動家、革命家志望であったアポロ・コルツェニヨフスキとその妻エワ・ボブロフスカの間の一 人っ子であった。洗礼名は、母方の祖父ヨゼフ、父方の祖父テオドール、そしてアダム・ミツキェヴィチの2つの詩の主人公(いずれも「コンラート」という名 前)にちなんで、ヨゼフ・テオドール・コンラート・コルツェニヨフスキと命名された。家族は彼を「ヨーゼフ」ではなく「コンラート」と呼んだ[注釈 7]。 周辺地域の住民の大多数はウクライナ人であり、ベルディチフの住民の大多数はユダヤ人であったが、ほぼすべての田園地帯はポーランドのシュラハタ(貴族) の所有地であり、コンラッドの一族はナウ・カノーラの紋章を持つ者としてこれに属していた[22]。ポーランド文学、特に愛国的な文学は、この地域のポー ランド人の間で高く評価されていた[23]。 ポーランドは1795年にプロイセン、オーストリア、ロシアに分割されていた。コルゼニウスキー家は、ポーランドの独立回復の試みにおいて重要な役割を果 たした。コンラッドの父方の祖父テオドルは、ナポレオンのロシア遠征時にヨゼフ・ポニャトフスキ公の部下として従軍し、1830年11月のロシア帝国に対 するポーランド・リトアニアの蜂起の際には自ら騎兵隊を編成した[24]。その後、コンラッドがアポロの足跡をたどることを拒否し、抵抗よりも亡命を選ん だことは、コンラッドにとって生涯の罪の意識となった[25][注 8]。  1861年、3歳のコンラッドが両親と暮らしたワルシャワのNowy Świat 47番地。 父親の農業への挑戦と政治活動のため、一家は引っ越しを繰り返した。1861年5月、一家はワルシャワに移り住み、アポロはロシア帝国に対する抵抗運動に 参加した。彼は逮捕され、ワルシャワ城塞のパヴィリオンX[注釈 9]、つまり恐るべき第10パヴィリオンに収監された[27]: 「1862年5月9日、アポロと家族はモスクワの北500キロに位置し、気候が悪いことで知られるヴォログダに流刑となった。しかし、1865年4月18 日、エワは結核で亡くなった[30]。 アポロは自宅でコンラッドを教えることに全力を尽くした。ヴィクトル・ユーゴーの『海の労働者たち』では、彼が青春時代を捧げることになる活動領域に出会 い、シェイクスピアは彼をイギリス文学の軌道に引き込んだ。シェイクスピアは彼を英文学の軌道に乗せたが、何よりも彼はポーランドのロマン派の詩を読ん だ。半世紀後、彼は次のように語っている。 「私の作品におけるポーランドらしさは、ミツキェヴィチとスウォヴァツキに由来する。父は[ミキェヴィチの]『パン・タデウシュ』を音読し、私に読ませ た......。ミツキェヴィチの)コンラート・ワレンロド(とグラジナ)を好んで読んでいた。その後、私はスウォヴァツキを好んだ。なぜスウォヴァツキ なのかわかるか?[彼は全ポーランドの魂なのだ」[31]。 1866年秋、若きコンラッドは健康上の理由から、キエフと母親の実家であるノヴォファスチフ[デ]に1年間の静養を命じられた[32]。 1867年12月、アポロは息子を連れて、2年前からかなりの自由と自治を享受していたポーランドのオーストリア領に赴いた。ルヴフやいくつかの小さな地 方での滞在を経て、1869年2月20日、同じくオーストリア領ポーランドのクラクフ(1596年までポーランドの首都)に移った。数カ月後の1869年 5月23日、アポロ・コルツェニヨフスキが亡くなり、コンラッドは11歳で孤児となった[33]。コンラッドの母同様、アポロも結核を患っていた [34]。  タデウシュ・ボブロフスキ、コンラッドの母方の叔父、指導者、恩人 幼いコンラッドは、エワの兄であるタデウシュ・ボブロフスキに預けられた。コンラッドは健康状態が悪く、学業も満足にできなかったため、叔父は常に問題を 抱え、金銭的な出費も絶えなかった。当時、コンラッドが定期的に学校に通っていた形跡がないことから、個人指導を受けていた可能性が高い[32]。コン ラッドの体調不良は明らかに神経性のものであったため、医師たちは新鮮な空気と肉体労働がコンラッドを丈夫にすると考え、叔父は明確な職務と仕事の厳しさ がコンラッドの規律を教えると期待した。叔父は、明確な職務と労働の厳しさが彼に規律を教えるだろうと期待した。彼は勉強する気がほとんどなかったため、 職業を学ぶことが不可欠だった。叔父は、彼が船乗り兼ビジネスマンとして働くことができると考え、海洋技術と商業活動を組み合わせた[36]。1871年 の秋、13歳のコンラッドは船乗りになる意思を表明した。コンラッドはまた、アメリカのジェイムズ・フェニモア・クーパーやイギリスのフレデリック・マリ ヤット船長の本も読んだと回想している[37]。青年時代の遊び仲間は、コンラッドがいつも海を舞台にしたファンタジックな物語を紡ぎ、聞き手が目の前で 起こっていると思うほどリアルに表現していたと回想している。 1873年8月、ボブロフスキは15歳のコンラッドを、1863年の蜂起で孤児となった少年たちのために小さな寄宿舎を経営していた従兄弟のもとへルヴフに送った。そこでの会話はフランス語であった: コンラッドは10ヶ月間私たちのところにいた...。知性的には非常に優れていたが、(彼は)学校の規則正しい生活が嫌いで、疲れるし退屈だと感じてい た。彼はあらゆる制約を嫌っていた。家でも、学校でも、居間でも、彼は無遠慮にのたうち回った。彼は...ひどい頭痛と神経発作に苦しんでいた... [38]。 1874年9月、コンラッドは1年余り施設にいたが、理由は定かではないが、叔父は彼をルヴフの学校から追い出し、クラクフに連れて帰った[39]。 1874年10月13日、ボブロフスキは16歳のコンラッドをフランスのマルセイユに送り、コンラッドが計画していたフランスの商船での海運業に従事させ [36]、150フランの月給を支給した[32]。コンラッドは中等学校を卒業していなかったが、フランス語に堪能であり(正しいアクセントがあった)、 ラテン語、ドイツ語、ギリシア語の知識もあった。彼は読書家で、特にポーランドのロマン派文学に造詣が深かった。彼は、一族の領地の外で生計を立てなけれ ばならなかった一族の二代目に属していた。祖国の歴史、文化、文学を十分に吸収した彼は、やがて独自の世界観を確立し、養子となったイギリスの文学に独自 の貢献をするようになる[41]。 ポーランドでの幼少期に端を発し、成人後に外国で増大した緊張が、コンラッドの最大の文学的業績に寄与した[42] : 家族、友人、社会集団、言語など、生まれ育った環境から離れて生活することは、たとえそれが意識的な決断によるものであったとしても、通常、...内的な 緊張を生む。ポーランドのスラハタや知識階級は、社会的な名声が...自己価値を感じるために...非常に重要であると...感じられる社会階層であっ た。男たちは、他人の目に映る自分の自尊心を確認しようと努力した。このような心理的遺産は、野心に拍車をかけると同時に、絶え間ないストレスの源とな る。 批評家の中には、コンラッドがポーランドを離れたとき、ポーランドの過去ときっぱりと決別したかったのだと指摘する者もいる[44]。これに対する反論と して、ナジェデルは、コンラッドがポーランドを離れた9年後に書かれた、コンラッドが家族の友人ステファン・ブシチンスキに宛てた1883年8月14日の 手紙から引用している: ... クラクフを去るときにあなたが言ったことをいつも覚えている: 「どこを航海しようとも、ポーランドに向かって航行するのだ。私はその言葉を忘れたことはないし、これからも忘れることはないだろう![45]」。 商船 主な記事 ジョセフ・コンラッドの海でのキャリア マルセイユでは、コンラッドは激しい社交生活を送り、しばしば予算を使い果たした[32]。この頃の面影はコルシカ島北部の町ルリに残っており、そこには コンラッドが親交を深めたコルシカ商船の船員ドミニク・セルヴォニの記念碑がある。セルヴォニは、1904年の小説『ノストロモ号』の主人公など、コン ラッドの登場人物のインスピレーションの源となった。1921年、コンラッドは妻とともにコルシカ島を訪れたが、その理由のひとつは、長い間死別していた 友人であり商船仲間であったセルヴォーニとのつながりを求めてのことであった[46][信頼できない情報源?]  1888年と1889年の最初の3ヶ月間、コンラッドが船長を務めたオタゴ号 1877年後半、コンラッドの海運業は、ロシア領事がコンラッドの勤務継続に必要な書類の提出を拒否したために中断された。その結果、コンラッドは借金を 抱え、1878年3月に自殺を図った。一命を取り留めたコンラッドは、叔父からさらなる経済援助を受け、普通の生活を取り戻すことができた[32]。フラ ンスで4年近くフランス船に乗った後、コンラッドはイギリス商船に入隊し、1878年4月に入隊した(その少し前から英語を学び始めていた可能性が高い) [32]。 その後15年間、彼は赤の星章の下で勤務した。乗組員(スチュワード、見習い、乗組員)、三等航海士、二等航海士、一等航海士としてさまざまな船で働き、 最終的には船長の地位に就いた。コンラッドが1874年10月にクラクフを出航してから1894年1月にアドワ号で航海を終えるまでの19年間に、長期間 の入港を含めて10年と8ヶ月近く船で働いていた。彼の唯一の船長職は1888年から89年にシドニーからモーリシャスへ向かうオタゴ号で行われた [48]。 1885年から86年にかけてインドに短期間寄港した際、28歳のコンラッドは、クリッパー船ティルクハーストでシンガポールに向かう直前の1885年6 月にカーディフで親しくなった8歳年上のポーランド人ジョセフ・スピリディオン[注釈 11]に5通の手紙を送っている。これらの手紙はコンラッドにとって初めて残された英語の文章である。彼の英語は概して正しいが、人工的なまでに堅い。多 くの断片は、彼の思考がポーランドの構文や言い回しに沿っていたことを示唆している。 さらに重要なことに、この手紙には、1881年から83年にかけての書簡に暗示されていたものとは明らかに異なる見解が示されている。彼は「未来への希 望」や「ポーランドに向かって航海する」という考え、そしてパンスラヴィア的な考えを捨てたのである。ポーランド問題の絶望を痛感し、避難先としてイギリ スを受け入れたのである。彼はしばしば宛先の意見とある程度一致するように発言を調整したが、ポーランドの独立の見通しに関する絶望感というテーマは、 1914年以前の彼の書簡や作品にしばしば忠実に現れている[50]。 コンラッドはコンゴから帰国後、ロンドン中心部ピムリコのジリンガム・ストリート17番地に住んでいた。 1890年、コンラッドは初めてポーランドに戻り、叔父をはじめとする親戚や知人を訪ねた[48][51]。この訪問は、コンラッドがコンゴ自由国に向か うのを待っている間に行われた。 [この1890年のコンゴ滞在中に、コンラッドはロジャー・ケースメントと親しくなる。彼は同じくティスの下で働き、マタディで貿易と輸送のステーション を運営していた。1903年、ボマの英国領事として、ケースメントはコンゴでの虐待、後にペルーのアマゾンでの虐待の調査を依頼され、人権擁護のため 1911年にナイトの称号を授与された。ケースメントは後に英国領事職を辞した後、アイルランド共和主義で活動するようになる[53][注釈 12]。  トーレンス コンラッドは一等航海士として、1891年11月から1893年7月にかけてロンドンからアデレードまで2往復した。 コンラッドは1890年12月末にアフリカを離れ、翌年1月下旬までにブリュッセルに到着した。1892年10月25日、客船トーレンス号でロンドンを出 航したとき、乗客のひとりにケンブリッジ大学を卒業したウィリアム・ヘンリー・ジャックがいた。コンラッドの『個人的記録』によれば、ジャックはコンラッ ドの『アルマイヤーの愚行』のまだ未完成の原稿の最初の読者だった。ジャックはコンラッドに小説の執筆を続けるよう勧めた[57]。  コンラッドがトーレンスで出会ったジョン・ガルスワシー 1893年7月26日、トーレンス号がロンドンに停泊し、「J.コンラッド・コルゼモウィン」(除籍証明書による)が下船したとき、コンラッドは船員として最後の長距離航海を終えた。 トーレンス号が1893年3月13日にアデレードを出港したとき、乗客にはオーストラリアとニュージーランドから帰国した2人の若い英国人が含まれてい た。25歳の弁護士で後に小説家となるジョン・ガルスワージーと、父親がエルスツリーで経営する男子予備校を手伝う予定だったエドワード・ランスロット・ サンダーソンである。彼らはおそらく、コンラッドが初めて親交を結んだ英国人であり、船乗りでもなかった。ガルスワージーの最初の文学的試みのひとつであ る『The Doldrums』(1895-96)では、主人公の一等航海士アーマンドがコンラッドをモデルにしている。 トーレンス号が5月17日から19日まで滞在したケープタウンで、ガルスワージーは地元の鉱山を見るために船を離れた。サンダーソンは航海を続け、コン ラッドと親密な関係を築いた最初の人物であったようだ[58]。その年の暮れ、コンラッドはポーランドとウクライナの親戚を再び訪れることになる[48] [59]。 作家  1916年のコンラッド(アルヴィン・ラングドン・コバーン撮影) 1889年の秋、コンラッドは処女作『アルマイヤーの愚行』の執筆を始める[60]。 [母方の)叔父[タデウシュ・ボブロフスキ]からその手紙の文体の美しさを賞賛された作家の息子であり、最初のページから仕事に対する真剣でプロフェッ ショナルなアプローチを示していたコンラッドが、『アルマイヤーの愚行』の執筆を始めたのは、束縛のない気軽な出来事であった...。[彼は書く必要性を 強く感じていたに違いない。しかし、彼は書くことの必要性を強く感じていたに違いない。最初の1ページ目から、書くことが娯楽のためでも暇つぶしでもな かったことを物語っている。それどころか、それは真剣な仕事であり、巨匠たちの入念で勤勉な読書に支えられ、芸術と現実に対する彼自身の態度を形成するこ とを目的としていた......。[彼の芸術的衝動と創造的才能の源はわからない[61]。 コンラッドが後に文学仲間に宛てた手紙には、文体の分析、個々の単語や表現、フレーズの感情的なトーン、言語が作り出す雰囲気の分析に注意を払っていたこ とが示されている。この点で、コンラッドは彼なりにギュスターヴ・フローベールの例に倣った。彼は「問題の本質」を表現するのに適切な言葉、le mot justeを何日も探し続けたことで有名である。ナジダーはこう言う: 「外国語で書くということは、個人的に繊細な問題に取り組む際により大胆になれるということである。原則として、後天的に習得した言語のほうが、悪態をつくのも冷静に分析するのも容易なのである」[62]。 1894年、36歳のとき、コンラッドは不本意ながら海をあきらめたが、その理由のひとつは、健康状態が悪かったこと、船が手に入らなかったこと、そして もうひとつは、書くことに魅了され、文学の道に進むことを決意したからであった。ボルネオ東海岸を舞台にした『アルマイヤーの愚行』は1895年に出版さ れた。もちろん「コンラッド」は彼のポーランド名である「コンラッド」の3番目の名前であったが、彼が「コンラッド」というペンネームを使用したのは、 ポーランドのロマン派詩人アダム・ミキェヴィッチの愛国的な物語詩『コンラッド・ワレンロッド』へのオマージュでもあったのかもしれない[63]。 コンラッドの文学的キャリアにおいて主要な脇役の一人を演じることになる若い出版社の読者であり文芸批評家であったエドワード・ガーネットは、『アルマイ ヤーの愚行』のアンウィンの最初の読者であったウィルフリッド・ヒュー・チェソンと同様に、この原稿に感銘を受けたが、ガーネットは「出版に十分な英語か どうかは不確か」であった。ガーネットは、後にロシア文学の翻訳者となる妻のコンスタンス・ガーネットにこの小説を見せた。彼女はコンラッドが外国人であ ることを肯定的に評価していた[64]。 コンラッドが東南アジアの人々と個人的に面識があったのは限られていたが、この地域は彼の初期の作品に大きく登場する。ナジャーによれば、亡命者であり放 浪者であったコンラッドは、一度ならず告白した困難さを自覚していた。英語圏の読者と共通の文化的背景を持たないコンラッドは、英語圏の世界について書く 英語作家と競争することができなかったのである。英語圏の読者と共通の文化的背景を持たない彼は、英語圏について書く英語圏の作家と競争することはできな かった。同時に、非英語圏の植民地を舞台に選んだことで、彼は気恥ずかしい忠誠心の分裂から解放された: アルマイヤーの愚行』や、後にベルギー国王レオポルド2世に搾取されたコンゴを舞台にした『前進の前哨基地』(1897年)、同じくコンゴを舞台にした 『闇の奥』(1899年)には、植民地主義に対する辛辣な考察が含まれている。マレー諸国は理論的にはオランダ政府の宗主国であり、コンラッドは一度も訪 れたことのないこの地域のイギリス従属国については書かなかった。彼は「どうやら国民の独立を守ろうとする...闘争に興味をそそられたようだ。熱帯の自 然の多産で破壊的な豊かさと、その中での人間生活の悲惨さは、彼の初期の作品の厭世的な気分とよく一致していた」[65][注 13]。 アルマイヤーの愚行』は、その後継作である『島の追放者』(1896年)とともに、コンラッドがエキゾチックな物語のロマンチックな語り手として評価される基礎を築いた。 フォートナイトリー・レビュー』や『ノース・アメリカン・レビュー』のような影響力のある批評誌、『サヴォイ』、『ニュー・レビュー』、『イングリッ シュ・レビュー』のような前衛的な出版物、『サタデー・イブニング・ポスト』や『ハーパーズ・マガジン』のような大衆的な短編小説雑誌、『ピクトリアル・ レビュー』や『ロマンス』のような女性誌、『デイリー・メール』や『ニューヨーク・ヘラルド』のような大衆紙、『イラストレイテッド・ロンドン・ニュー ス』や『イラストレイテッド・バッファロー・エクスプレス』のような挿絵入りの新聞などである。 [また、1898年から1906年にかけて帝国主義的な週刊誌『アウトルック』にも寄稿した[69][注 15]。 1910年8月9日に支給された年額100ポンドの政府補助金(「市民リスト年金」)によって、コンラッドは経済的な心配から解放され[72][注釈 17]、やがてコレクターが彼の原稿を購入するようになった。彼の才能は早くからイギリスの知識人たちに認められていたが、1913年に『チャンス』が出 版されるまで大衆的な成功は得られなかった。 私生活  タイム』1923年4月7日号 気質と健康 コンラッドは控えめな男で、感情を表に出すことを警戒していた。叔父のボブロウスキーの言葉を借りれば、若い頃のコンラッドは「非常に繊細で、うぬぼれが強く、控えめで、おまけに興奮しやすかった。要するに[...]ナウエノーラ家の欠点をすべて備えていた」[75]。 コンラッドは生涯を通じて、肉体的にも精神的にも不健康に苦しんだ。1891年、コンラッドは痛風、右腕の神経痛、マラリアの再発に苦しみ、数ヶ月入院し た。また、手の腫れを訴え、「字を書くのが困難」であった。叔父のタデウシュ・ボブロフスキの勧めもあり、スイスの温泉で療養した[77]。コンラッドは 歯科恐怖症で、抜歯しなければならなくなるまで歯を放置していた。コンラッドの身体的な苦悩は、どちらかといえば、精神的な苦悩よりも少ないものであっ た。その証拠に」、ナジェルダーは「疑うことはほとんど不可能なほど強い」と書いている[79]。 自殺未遂 1878年3月、マルセイユ時代の終わりに、20歳のコンラッドはリボルバーで自分の胸を撃って自殺を図った[80]。友人に呼び出された叔父によると、 コンラッドは借金を抱えていた。ボブロフスキは、自身の思想的な敵対者であり、コンラッドの亡父アポロの友人であったステファン・ブシチンスキに宛てた膨 大な手紙の中で、その後の甥の「研究」について述べている[注 18] 。自殺未遂がどの程度本格的なものであったかは知る由もないが、状況的な鬱病を示唆している[81]。 ロマンスと結婚 1888年、インド洋のモーリシャスに立ち寄った際、コンラッドは2、3の恋愛感情を抱いた。そのうちのひとつが1910年に発表された「幸運の微笑み」 で描かれることになるが、この物語には自伝的要素が含まれている(例えば、登場人物のひとりは『シャドー・ライン』に登場するバーンズ航海長と同じ人物で ある)。語り手である若い船長は、立派なバラ園に囲まれた家に住む地元の商人の娘、アリス・ジャコバスと曖昧に、こっそりと浮気する。調査の結果、当時の ポートルイスには17歳のアリス・ショーがおり、その父親は海運代理店で、町で唯一のバラ園を所有していたことが確認されている[82]。 コンラッドのもう一つの、より公然の浮気についてはもっと知られている。旧友であるフランス商船のガブリエル・ルヌーフ大尉は、コンラッドを義兄の家族に 紹介した。ルヌーフの長姉は植民地の高官ルイ・エドワード・シュミットの妻で、他に2人の姉と2人の兄弟がいた。島は1810年に英国に占領されたが、住 民の多くはフランス人入植者の子孫であり、コンラッドは優れたフランス語と完璧なマナーで、地元のサロンをすべて彼に開放した。コンラッドはシュミット家 に頻繁に通うようになり、そこでルヌーフ夫人にしばしば会った。ポートルイスを去る数日前、コンラッドはルヌーフ兄弟の一人に26歳の妹ユージェニーの求 婚をした。しかし、彼女はすでに薬剤師のいとこと婚約していた。拒絶された後、コンラッドは別れの訪問はしなかったが、ガブリエル・ルヌーフに丁寧な手紙 を送り、モーリシャスには二度と戻らないと言い、結婚式の日には彼らのことを思っていると付け加えた。  ケント州カンタベリーにあるウェストベア・ハウスは、かつてコンラッドが所有していた。イングランドの国民遺産リストにグレードⅡとして登録されている[83]。 1896年3月24日、コンラッドはイギリス人女性のジェシー・ジョージと結婚した[48]。ジェシーはコンラッドより16歳も年下で、素朴な労働者階級 の少女だった[85]。コンラッドの友人たちにとって、彼女は不可解な妻選びであり、かなり軽蔑的で不親切な発言の対象だった[86](『印象』における レディ・オットリン・モレルのジェシーに対する評価を参照)。 しかし、フレデリック・カールなど他の伝記作家によれば、ジェシーはコンラッドが必要としていたもの、すなわち「素直で、献身的で、かなり有能な」伴侶を 提供した[68]。同様に、ジョーンズは、結婚生活がどのような困難に耐えたとしても、「この関係がコンラッドの作家としてのキャリアを支えたことに疑い の余地はない」と述べている。 コンラッド夫妻は、主にイギリスの田舎に、長い間、家を借り続けた。コンラッドはたびたびうつ病を患い、気分を変えるために多大な努力をした。1910年 から1919年の間、コンラッドの住まいはケント州オルストンのカペル・ハウスで、オリヴァー卿夫妻が彼に貸していた。ここで『救出』、『勝利』、『金の 矢』を執筆した[89]。 フランスとイタリアでの数回の休暇、1914年の母国ポーランドでの休暇、1923年のアメリカ訪問を除いて、コンラッドは残りの生涯をイギリスで過ごした。 ポーランド滞在  1914年、コンラッドと家族は、後に同名のポーランド人翻訳者となるアニエラ・ザゴルスカの母である従姉妹が経営するザコパネ・ウィラ・コンスタンティヌフカに滞在した[90]。  コンラッドの姪アニエラ・ザゴルスカ(左)、カロラ・ザゴルスカ;コンラッド 1914年7月28日、オーストリア=ハンガリーとセルビアの間で戦争が勃発した日、コンラッドとレッティンガー夫妻はクラクフ(当時はオーストリア=ハンガリー帝国領)に到着し、コンラッドは幼少時代に過ごした場所を訪れた。 この街はロシアとの国境からわずか数マイルしか離れていなかったため、戦闘地域に取り残される危険性があった。妻ジェシーと次男ジョンが病気だったため、 コンラッドは山岳リゾートの町ザコパネに避難することにした。彼らは8月2日にクラクフを出発した。ザコパネに到着して数日後、彼らはコンラッドのいとこ アニエラ・ザゴルスカが経営するペンション「コンスタンチヌフカ」に移った。このペンションは、政治家ヨゼフ・ピウスツキやコンラッドの知人である若きコ ンサートピアニスト、アルトゥール・ルービンシュタインなどの著名人がよく利用していた[91]。 ザゴルスカは、小説家ステファン・ジェロムスキや人類学者ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキの友人であった作家タデウシュ・ナレピンスキなど、同じくザコパネに 避難していたポーランドの作家、知識人、芸術家にコンラッドを紹介した。コンラッドは有名な作家として、また外国から来た異国の同胞としてポーランド人の 関心を集めた。彼は新しい知り合い、特に女性を魅了した。 しかし、マリー・キュリーの医師の妹で、同じ医師で著名な社会主義活動家カジミエシュ・ドゥウスキの妻であるブロニスワワ・ドゥウスカは、コンラッドが自 分の偉大な才能を祖国の未来をより良くする以外の目的のために使ったことを公然と非難した[92][注 19][注 20]。 しかし、コンラッドの姪で、1923年から39年にかけてコンラッドの作品をポーランド語に翻訳することになる32歳のアニエラ・ザゴルスカ(年金管理人 の娘)は、コンラッドを慕い、付き合い、本を提供した。特に10歳年上で最近亡くなったボレスワフ・プリュス[95][96](彼もまたザコパネを訪れて いた[97])の物語や小説を喜び、1863年のポーランドの蜂起の犠牲者仲間である「私の愛するプリュス」の手に入るものはすべて読み、コンラッドが好 んだイギリスの小説家である「ディケンズよりも優れている」と評した[98][注釈 21]。 コンラッドはポーランドの知人たちから、いまだに母国語が流暢であることを指摘され、彼らの熱のこもった政治的議論に参加した。ポーランドが独立を取り戻 すためには、戦争においてロシアが中央列強(オーストリア=ハンガリー帝国とドイツ帝国)に打ち勝たなければならず、中央列強は今度はフランスとイギリス に打ち勝たなければならない[100][注釈 22]と、1914年にヨゼフ・ピウスツキがパリで先駆けて宣言したように、彼は先見の明があった。 多くの苦難と波乱を経て、1914年11月初め、コンラッドは家族をイギリスに連れて帰ることに成功した。帰国後、彼はポーランドの主権回復を支持するイギリスの世論を動かすことに尽力する決意を固めた[102]。 ジェシー・コンラッドは後に回想録にこう記している: 「ポーランドでの数ヶ月の後、私は夫のことがよくわかった。それまでは奇妙で理解不能だった多くの特徴が、いわば正しい比率を持つようになった。私は彼の気質が彼の同胞の気質であることを理解した」[103]。 政治 伝記作家のズジスワフ・ナイデルはこう書いている: コンラッドは政治に熱心だった。[このことは、『アルマイヤーの愚行』から始まるいくつかの作品によって確認できる。[それはもちろん、政治が日常生活の 問題であるだけでなく、生と死の問題でもあった国(ポーランド)出身の人物にとっては、ごく自然な関心事であった。しかも、コンラッド自身は、国家問題に 対する独占的な責任を主張する社会階級の出身であり、非常に政治活動的な家庭の出身であった。ノーマン・ダグラスはこう総括する: 「コンラッドは何よりもまずポーランド人であり、多くのポーランド人と同様、政治家であり、モラリストであった。これが彼の基本である。[コンラッドに政 治問題を、法と暴力、無政府と秩序、自由と独裁、物質的利益と個人の崇高な理想主義との間の絶え間ない闘争という観点からとらえさせたのは......コ ンラッドの歴史認識であった。彼のポーランドの経験は、当時の西欧文学のなかでも例外的に、これらの闘争の最前線がいかに曲がりくねったものであり、絶え ず変化するものであるかという認識を彼に与えた[104]。 コンラッドがこれまでに書いた中で最も広範で野心的な政治的発言は、1905年のエッセイ『独裁と戦争』であり、その出発点は日露戦争であった(彼はこの 論文を対馬海峡海戦の1ヶ月前に書き上げた)。このエッセイは、ロシアの不治の弱さについての記述で始まり、将来のヨーロッパ戦争における危険な侵略者で あるプロイセンに対する警告で終わっている。ロシアについては、近い将来に暴力的な暴発が起こると予測していたが、ロシアには民主主義の伝統がなく、大衆 も後進的であるため、革命が救済的な効果をもたらすことは不可能であった。コンラッドは、ロシアで代議制政府を樹立することは不可能だと考え、独裁政治か ら独裁政治への移行を予見した。コンラッドは、西ヨーロッパが経済的対立と商業的利己主義によって引き起こされた対立に引き裂かれていると見ていた。ロシ ア革命は、過去の戦争よりもはるかに残忍な戦争に備えて武装した、物質主義的でエゴイスティックな西ヨーロッパに助言や助けを求めても無駄かもしれない [105]。  1924年、ジェイコブ・エプスタインによるコンラッドの胸像。コンラッドはこの胸像を「いささか記念碑的な威厳のある素晴らしい作品であり、しかもその似顔絵が印象的であることは誰もが認めるところである」と評している[106]。 コンラッドの民主主義に対する不信感は、それ自体が目的である民主主義の普及が何らかの問題を解決することができるのかという疑問から生じていた。コン ラッドは、人間の本性の弱さと社会の「犯罪的」性格を考慮すると、民主主義はデマゴーグやチャラタンに無限の機会を提供すると考えた[107]。 コンラッドは、当時の社会民主主義者が「国民感情(国民感情を維持することが彼の関心事であった)」を弱めるような行動をとり、非人間的な坩堝の中で国民 のアイデンティティを溶解させようとしていることを非難した。「私は非常に黒い過去の深みから未来を見つめ、私には失われた大義への忠誠、未来のない思想 への忠誠以外、何も残されていないことに気がついた"。ポーランドの記憶に対するコンラッドの絶望的な忠誠心が、「国際友愛」という考えを信じることを妨 げたのである。彼は、自由と世界の兄弟愛について語る一方で、分割され抑圧された自国のポーランドについては沈黙を守る一部の社会主義者に憤慨していた [107]。 それ以前の1880年代初頭、叔父のタデウシュからコンラッドに宛てた手紙[注釈 23]を見ると、コンラッドはポーランドの状況の改善を解放運動ではなく、近隣のスラヴ諸国との同盟の確立によって望んでいたようである。これには、パン スラヴィック・イデオロギーへの信頼が伴っていた-「後にロシアへの敵意を強調することになる人物としては驚くべきことだが」、ナジデルはこう書いてい る。ポーランドの(優れた)文明と(歴史的な)伝統によって、ポーランドはパンスラヴ共同体の中で(主導的な)役割を果たすことができるという確信、そし てポーランドが完全に主権を持つ国民国家になる可能性についての疑念であった」[109]。 1894年、コンラッドがブリュッセルの親戚で作家仲間のマルグリット・ポラドフスカ(旧姓ガシェ、フィンセント・ファン・ゴッホの主治医ポール・ガシェのいとこ)に宛てた手紙にこう書かれている: 私たちは自分の人格という鎖と玉を最後まで引きずっていかなければならない。この世で囚人となるのは、選ばれた者たちだけである。理解し、うめき声をあげ ながらも、マニアックな身振りとバカげた笑みを浮かべながら、大勢の幻影の中で大地を踏みしめる栄光の一団である。バカと囚人、あなたはどちらになりたい だろうか? コンラッドはH.G.ウェルズに対して、1901年に刊行されたウェルズの著書『予期』は社会の大きな流れを予見しようとする野心的な試みであったが、 「世界の他の部分を埒外に置き去りにして、自分自身だけを対象とする一種の選ばれたサークルを前提にしているようだ。[加えて、狡猾で裏切り者である人間 の愚かさを十分に考慮していない」[111][注 24]。 1922年10月23日、数学者であり哲学者でもあるバートランド・ラッセルに宛てた手紙の中で、ラッセルの著書『中国の問題』(The Problem of China)に対して、社会主義改革と中国社会を再構築する聖賢の寡頭制を提唱したコンラッドは、政治的万能薬に対する自身の不信感を説明している: 私は、この人間の住む世界を支配している宿命に対する私の根深い感覚に立ち向かえるようなものを...どんな人の本や...話の中にも...見いだしたこ とはない...。中国人と私たちにとっての唯一の救済策は、[心の]変化であるが、過去2000年の歴史を見ると、人間が空を飛ぶようになったとしても、 [それを]期待する理由はあまりない-大きな「高揚」は間違いないが、大きな変化はない[112]。 レオ・ロブソンはこう書いている: コンラッドは......より広範な皮肉的スタンス、つまり『西部の瞳の下に』の登場人物によって定義された、あらゆる信仰、献身、行動の否定という、あ る種の包括的な信じられないというスタンスを採用した。口調と物語の細部をコントロールすることによって...。コンラッドは、無政府主義や社会主義と いった運動のナイーブさや、資本主義(宣伝効果のある海賊行為)、合理主義(人間の生来の非合理性に対する精巧な防衛策)、帝国主義(昔ながらの強姦と略 奪のための壮大な隠れ蓑)といった歴史的だが「自然化」された現象の利己的な論理を暴いている。皮肉であるということは、目を覚まし、蔓延する 「傾眠 」を警戒することである。ノストロモ』では...ジャーナリストのマーティン・デクーは...人々が「自分自身が宇宙の運命を左右していると信じている」 という考えを嘲笑している。(H.G.ウェルズは、コンラッドが「私は社会的、政治的問題を真剣に受け止めることができる」と驚いていたことを回想してい る)[113]。 しかしロブソンは、コンラッドは道徳的ニヒリストではないと書いている: 物事には目に映る以上のものがあることを示唆するために皮肉が存在するのだとすれば、コンラッドはさらに、十分に注意を払えば、その「以上のもの」は無限 にありうると主張する。彼は、[『若者たち』に登場する]マーローが「私たちの文明の窶れた功利主義的な嘘」と呼ぶものを、何もないものとして拒絶するの ではなく、「何か」、「救いのある真実」、「疑念の亡霊に対する悪魔祓い」、つまり言葉には容易に還元できない、より深い秩序の暗示として拒絶するのであ る。本物の、自覚的な感情-自らを「理論」とも「知恵」とも呼ばない感情-は、一種の旗手となり、「印象」や「感覚」が最も確かな証拠に近いものとなる [114]。 1901年8月、『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙の『サタデイ・ブック・レヴュー』の編集者に宛てた手紙の中で、コンラッドは次のように書いている。「世界 を動かす力であるエゴイズムと、その道徳である利他主義、この二つの矛盾した本能は、一方はとても平明であり、他方はとても神秘的であるが、その両立しが たい拮抗の不可解な同盟の中でなければ、われわれに奉仕することはできない」[115][注 25]。 死  ケント州ハーブルダウン近郊のカンタベリー墓地にあるコンラッドの墓 1924年8月3日、コンラッドはイングランド、ケント州ビショップボーンの自宅オズワルズで、おそらく心臓発作のため死去した。墓碑銘には、エドマンド・スペンサーの『フェアリー・クイーン』の一節が刻まれている: 戯れの後の眠り、嵐の海の後の港、 戦いの後の安らぎ、生の後の死は、大いに喜ばしい[118]。 コンラッドのささやかな葬儀は大群衆の中で行われた。旧友エドワード・ガーネットは苦々しげに回想している: 1924年のクリケット・フェスティバルの最中にカンタベリーで行われたコンラッドの葬儀に参列し、国旗で飾られた混雑した通りを車で通り抜けた人々に とって、イギリスのもてなしと、この偉大な作家の存在すら知らない群衆の姿には、象徴的なものがあった。数人の旧友、知人、報道関係者が彼の墓のそばに 立っていた[117]。 コンラッドのもう一人の旧友カニングヘイム・グラハムはガーネットにこう書いている:「オーブリーは私に......アナトール・フランスが死んでいたら、パリ中が彼の葬儀に参列していただろうと言っていた」[117]。 コンラッドの妻ジェシーは12年後の1936年12月6日に亡くなり、彼とともに埋葬された。 1996年、コンラッドの墓は第二級建造物に指定された[119]。 |