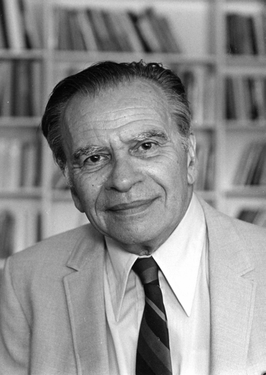

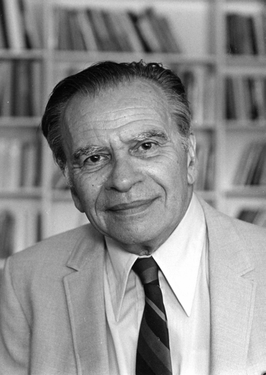

ジョセフ・グリーンバーグ

Joseph Greenberg, 1915-2001

☆

ジョセフ・ハロルド・グリーンバーグ(Joseph Harold Greenberg、1915年5月28日 - 2001年5月7日)はアメリカの言語学者で、主に言語類型論と言語の遺伝的分類に関する研究で知られる。

| Joseph Harold Greenberg

(May 28, 1915 – May 7, 2001) was an American linguist, known mainly for

his work concerning linguistic typology and the genetic classification

of languages. |

ジョセフ・ハロルド・グリーンバーグ(Joseph Harold Greenberg、1915年5月28日 - 2001年5月7日)はアメリカの言語学者で、主に言語類型論と言語の遺伝的分類に関する研究で知られる。 |

| Life Early life and education Joseph Greenberg was born on May 28, 1915, to Jewish parents in Brooklyn, New York. His first great interest was music. At the age of 14, he gave a piano concert in Steinway Hall. He continued to play the piano frequently throughout his life. After graduating from James Madison High School, he decided to pursue a scholarly career rather than a musical one. He enrolled at Columbia College in New York in 1932. During his senior year, he attended a class taught by Franz Boas concerning American Indian languages. He graduated in 1936 with a bachelor's degree. With references from Boas and Ruth Benedict, he was accepted as a graduate student by Melville J. Herskovits at Northwestern University in Chicago and graduated in 1940 with a doctorate degree. During the course of his graduate studies, Greenberg did fieldwork among the Hausa people of Nigeria, where he learned the Hausa language. The subject of his doctoral dissertation was the influence of Islam on a Hausa group that, unlike most others, had not converted to it. During 1940, he began postdoctoral studies at Yale University. These were interrupted by service in the U.S. Army Signal Corps during World War II, for which he worked as a codebreaker in North Africa and participated with the landing at Casablanca. He then served in Italy until the end of the war. Before leaving for Europe during 1943, Greenberg married Selma Berkowitz, whom he had met during his first year at Columbia University.[1] Career After the war, Greenberg taught at the University of Minnesota before returning to Columbia University in 1948 as a teacher of anthropology. While in New York, he became acquainted with Roman Jakobson and André Martinet. They introduced him to the Prague school of structuralism, which influenced his work. In 1962, Greenberg relocated to the anthropology department at Stanford University in California, where he continued working for the rest of his life. In 1965 Greenberg served as president of the African Studies Association. That same year, he was elected to the United States National Academy of Sciences.[2] He was later elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1973) and the American Philosophical Society (1975).[3][4] In 1996 he received the highest award for a scholar in Linguistics, the Gold Medal of Philology.[5] |

生涯 生い立ちと教育 ジョセフ・グリーンバーグは1915年5月28日、ニューヨークのブルックリンでユダヤ人の両親のもとに生まれた。彼が最初に興味を持ったのは音楽だった。14歳の時、スタインウェイ・ホールでピアノ・コンサートを開いた。彼は生涯を通じて頻繁にピアノを弾き続けた。 ジェームズ・マディソン高校を卒業後、音楽の道ではなく、学問の道に進むことを決意。1932年、ニューヨークのコロンビア大学に入学。4年生の時には、 フランツ・ボアズが教えるアメリカ・インディアンの言語に関するクラスに出席した。1936年に学士号を取得して卒業。ボアスとルース・ベネディクトの紹 介で、シカゴのノースウェスタン大学のメルヴィル・J・ハースコヴィッツの大学院生として受け入れられ、1940年に博士号を取得して卒業した。大学院在 学中、グリーンバーグはナイジェリアのハウサ族をフィールドワークし、そこでハウサ語を学んだ。博士論文のテーマは、他の多くの人々と違って改宗していな いハウサ族におけるイスラム教の影響であった。 1940年、彼はイェール大学で博士研究を始めた。第二次世界大戦中はアメリカ陸軍信号隊に所属し、北アフリカで暗号解読に携わり、カサブランカ上陸作戦に参加した。その後、終戦までイタリアで勤務した。 1943年にヨーロッパに出発する前に、グリーンバーグはコロンビア大学1年生のときに知り合ったセルマ・バーコウィッツと結婚した[1]。 経歴 戦後、グリーンバーグはミネソタ大学で教鞭をとった後、1948年に人類学の教師としてコロンビア大学に戻った。ニューヨーク滞在中にロマン・ヤコブソンとアンドレ・マルティネと知り合う。彼らにプラハ学派の構造主義を紹介され、彼の仕事に影響を与えた。 1962年、グリーンバーグはカリフォルニア州スタンフォード大学の人類学部に移り、そこで生涯研究を続けた。1965年にはアフリカ研究協会の会長を務 めた。同年、米国科学アカデミーの会員に選出された[2]。 その後、米国芸術科学アカデミー(1973年)、米国哲学協会(1975年)の会員に選出された[3][4]。1996年には言語学の学者として最高の賞 である言語学ゴールドメダルを受賞した[5]。 |

| Contributions to linguistics Linguistic typology Greenberg is considered the founder of modern linguistic typology,[6] a field that he has revitalized with his publications in the 1960s and 1970s.[7] Greenberg's reputation rests partly on his contributions to synchronic linguistics and the quest to identify linguistic universals. During the late 1950s, Greenberg began to examine languages covering a wide geographic and genetic distribution. He located a number of interesting potential universals as well as many strong cross-linguistic tendencies. In particular, Greenberg conceptualized the idea of "implicational universal", which has the form, "if a language has structure X, then it must also have structure Y." For example, X might be "mid front rounded vowels" and Y "high front rounded vowels" (for terminology see phonetics). Many scholars adopted this kind of research following Greenberg's example and it remains important in synchronic linguistics. Like Noam Chomsky, Greenberg sought to discover the universal structures on which human language is based. Unlike Chomsky, Greenberg's method was functionalist, rather than formalist. An argument to reconcile the Greenbergian and Chomskyan methods can be found in Linguistic Universals (2006), edited by Ricardo Mairal and Juana Gil. Many who are strongly opposed to Greenberg's methods of language classification (see below) acknowledge the importance of his typological work. In 1963 he published an article : "Some universals of grammar with particular reference to the order of meaningful elements". Mass comparison Main article: Mass comparison Greenberg rejected the opinion, prevalent among linguists since the mid-20th century, that comparative reconstruction was the only method to discover relationships between languages. He argued that genetic classification is methodologically prior to comparative reconstruction, or the first stage of it: one cannot engage in the comparative reconstruction of languages until one knows which languages to compare (1957:44). He also criticized the prevalent opinion that comprehensive comparisons of two languages at a time (which commonly take years to perform) could establish language families of any size. He argued that, even for 8 languages, there are already 4,140 ways to classify them into distinct families, while for 25 languages there are 4,638,590,332,229,999,353 ways (1957:44). For comparison, the Niger–Congo family is said to have some 1,500 languages. He thought language families of any size needed to be established by some scholastic means other than bilateral comparison. The theory of mass comparison is an attempt to demonstrate such means. Greenberg argued for the virtues of breadth over depth. He advocated restricting the amount of material to be compared (to basic vocabulary, morphology, and known paths of sound change) and increasing the number of languages to be compared to all the languages in a given area. This would make it possible to compare numerous languages reliably. At the same time, the process would provide a check on accidental resemblances through the sheer number of languages under review. The mathematical probability that resemblances are accidental decreases strongly with the number of languages concerned (1957:39). Greenberg used the premise that mass "borrowing" of basic vocabulary is unknown. He argued that borrowing, when it occurs, is concentrated in cultural vocabulary and clusters "in certain semantic areas", making it easy to detect (1957:39). With the goal of determining broad patterns of relationship, the idea was not to get every word right but to detect patterns. From the beginning with his theory of mass comparison, Greenberg addressed why chance resemblance and borrowing were not obstacles to its being useful. Despite that, critics consider those phenomena caused difficulties for his theory. Greenberg first termed his method "mass comparison" in an article of 1954 (reprinted in Greenberg 1955). As of 1987, he replaced the term "mass comparison" with "multilateral comparison", to emphasize its contrast with the bilateral comparisons recommended by linguistics textbooks. He believed that multilateral comparison was not in any way opposed to the comparative method, but is, on the contrary, its necessary first step (Greenberg, 1957:44). According to him, comparative reconstruction should have the status of an explanatory theory for facts already established by language classification (Greenberg, 1957:45). Most historical linguists (Campbell 2001:45) reject the use of mass comparison as a method for establishing genealogical relationships between languages. Among the most outspoken critics of mass comparison have been Lyle Campbell, Donald Ringe, William Poser, and the late R. Larry Trask. Genetic classification of languages Languages of Africa Greenberg is known widely for his development of a classification system for the languages of Africa, which he published as a series of articles in the Southwestern Journal of Anthropology from 1949 to 1954 (reprinted together as a book, The Languages of Africa, in 1955). He revised the book and published it again during 1963, followed by a nearly identical edition of 1966 (reprinted without change during 1970). A few more changes of the classification were made by Greenberg in an article during 1981. Greenberg grouped the hundreds of African languages into four families, which he dubbed Afroasiatic, Nilo-Saharan, Niger–Congo, and Khoisan. During the course of his work, Greenberg invented the term "Afroasiatic" to replace the earlier term "Hamito-Semitic", after showing that the Hamitic group, accepted widely since the 19th century, is not a valid language family. Another major feature of his work was to establish the classification of the Bantu languages, which occupy much of Central and Southern Africa, as a part of the Niger–Congo family, rather than as an independent family as many Bantuists had maintained. Greenberg's classification rested largely in evaluating competing earlier classifications. For a time, his classification was considered bold and speculative, especially the proposal of a Nilo-Saharan language family. Now, apart from Khoisan, it is generally accepted by African specialists and has been used as a basis for further work by other scholars. Greenberg's work on African languages has been criticised by Lyle Campbell and Donald Ringe, who do not believe that his classification is justified by his data and request a re-examination of his macro-phyla by "reliable methods" (Ringe 1993:104). Harold Fleming and Lionel Bender, who were sympathetic to Greenberg's classification, acknowledged that at least some of his macrofamilies (particularly the Nilo-Saharan and the Khoisan macrofamilies) are not accepted completely by most linguists and may need to be divided (Campbell 1997). Their objection was methodological: if mass comparison is not a valid method, it cannot be expected to have brought order successfully out of the confusion of African languages. By contrast, some linguists have sought to combine Greenberg's four African families into larger units. In particular, Edgar Gregersen (1972) proposed joining Niger–Congo and Nilo-Saharan into a larger family, which he termed Kongo-Saharan. Roger Blench (1995) suggests Niger–Congo is a subfamily of Nilo-Saharan. The languages of New Guinea, Tasmania, and the Andaman Islands Main article: Indo-Pacific languages During 1971 Greenberg proposed the Indo-Pacific macrofamily, which groups together the Papuan languages (a large number of language families of New Guinea and nearby islands) with the native languages of the Andaman Islands and Tasmania but excludes the Australian Aboriginal languages. Its principal feature was to reduce the manifold language families of New Guinea to a single genetic unit. This excludes the Austronesian languages, which have been established as associated with a more recent migration of people. Greenberg's subgrouping of these languages has not been accepted by the few specialists who have worked on the classification of these languages.[citation needed] However, the work of Stephen Wurm (1982) and Malcolm Ross (2005) has provided considerable evidence for his once-radical idea that these languages form a single genetic unit. Wurm stated that the lexical similarities between Great Andamanese and the West Papuan and Timor–Alor families "are quite striking and amount to virtual formal identity [...] in a number of instances." He believes this to be due to a linguistic substratum. The languages of the Americas Main article: Amerind languages Most linguists concerned with the native languages of the Americas classify them into 150 to 180 independent language families. Some believe that two language families, Eskimo–Aleut and Na-Dené, were distinct, perhaps the results of later migrations into the New World. Early on, Greenberg (1957:41, 1960) became convinced that many of the language groups considered unrelated could be classified into larger groupings. In his 1987 book Language in the Americas, while agreeing that the Eskimo–Aleut and Na-Dené groupings as distinct, he proposed that all the other Native American languages belong to a single language macro-family, which he termed Amerind. Language in the Americas has generated lively debate, but has been criticized strongly; it is rejected by most specialists of indigenous languages of the Americas and also by most historical linguists. Specialists of the individual language families have found extensive inaccuracies and errors in Greenberg's data, such as including data from non-existent languages, erroneous transcriptions of the forms compared, misinterpretations of the meanings of words used for comparison, and entirely spurious forms.[8][9][10][11][12][13] Historical linguists also reject the validity of the method of multilateral (or mass) comparison upon which the classification is based. They argue that he has not provided a convincing case that the similarities presented as evidence are due to inheritance from an earlier common ancestor rather than being explained by a combination of errors, accidental similarity, excessive semantic latitude in comparisons, borrowings, onomatopoeia, etc. However, Harvard geneticist David Reich notes that recent genetic studies have identified patterns that support Greenberg's Amerind classification: the "First American” category. "The cluster of populations that he predicted to be most closely related based on language were in fact verified by the genetic patterns in populations for which data are available.” Nevertheless, this category of "First American" people also interbred with and contributed a significant amount of genes to the ancestors of both Eskimo-Aleut and Na-Dené populations, with 60% and 90% "First American" DNA respectively constituting the genetic makeup of the two groups.[14] The languages of northern Eurasia Main article: Eurasiatic languages Later in his life, Greenberg proposed that nearly all of the language families of northern Eurasia belong to a single higher-order family, which he termed Eurasiatic. The only exception was Yeniseian, which has been related to a wider Dené–Caucasian grouping, also including Sino-Tibetan. During 2008 Edward Vajda related Yeniseian to the Na-Dené languages of North America as a Dené–Yeniseian family.[15] The Eurasiatic grouping resembles the older Nostratic groupings of Holger Pedersen and Vladislav Illich-Svitych by including Indo-European, Uralic, and Altaic. It differs by including Nivkh, Japonic, Korean, and Ainu (which the Nostraticists had excluded from comparison because they are single languages rather than language families) and in excluding Afroasiatic. At about this time, Russian Nostraticists, notably Sergei Starostin, constructed a revised version of Nostratic. It was slightly larger than Greenberg's grouping but it also excluded Afroasiatic. Recently, a consensus has been emerging among proponents of the Nostratic hypothesis. Greenberg basically agreed with the Nostratic concept, though he stressed a deep internal division between its northern 'tier' (his Eurasiatic) and a southern 'tier' (principally Afroasiatic and Dravidian). The American Nostraticist Allan Bomhard considers Eurasiatic a branch of Nostratic, alongside other branches: Afroasiatic, Elamo-Dravidian, and Kartvelian. Similarly, Georgiy Starostin (2002) arrives at a tripartite overall grouping: he considers Afroasiatic, Nostratic and Elamite to be roughly equidistant and more closely related to each other than to any other language family.[16] Sergei Starostin's school has now included Afroasiatic in a broadly defined Nostratic. They reserve the term Eurasiatic to designate the narrower subgrouping, which comprises the rest of the macrofamily. Recent proposals thus differ mainly on the precise inclusion of Dravidian and Kartvelian. Greenberg continued to work on this project after he was diagnosed with incurable pancreatic cancer and until he died during May 2001. His colleague and former student Merritt Ruhlen ensured the publication of the final volume of his Eurasiatic work (2002) after his death. |

言語学への貢献 言語類型論 グリーンバーグは現代言語類型論の創始者と考えられており[6]、1960年代から1970年代にかけての出版物によって、この分野を活性化させた。グ リーンバーグの名声は、シンクロニック言語学と言語的普遍性の探求への貢献にもかかっている[7]。1950年代後半、グリーンバーグは幅広い地理的・遺 伝的分布を持つ言語を調査し始めた。彼は多くの興味深い潜在的普遍性とともに、多くの強い言語横断的傾向を発見した。 特にグリーンバーグは、"ある言語がXの構造を持つなら、Yの構造も持つに違いない "という形をとる「含意的普遍」という考え方を概念化した。例えば、Xは「中前丸母音」であり、Yは「高前丸母音」かもしれない(用語については音声学を 参照)。グリーンバーグの例にならって、多くの学者がこの種の研究を採用し、共時言語学では今でも重要な位置を占めている。 ノーム・チョムスキーと同様、グリーンバーグは人間の言語が基づいている普遍的な構造を発見しようとした。チョムスキーとは異なり、グリーンバーグの方法 は形式主義ではなく機能主義であった。グリーンバーグ的方法とチョムスキー的方法を調和させる議論は、Ricardo MairalとJuana Gilが編集した『Linguistic Universals』(2006年)に掲載されている。 グリーンバーグの言語分類法(下記参照)に強く反対する人の多くは、彼の類型論的研究の重要性を認めている。1963年、彼は論文を発表した: 「特に意味のある要素の順序に言及した文法の普遍性」。 質量比較 主な記事 質量比較 グリーンバーグは、20世紀半ばから言語学者の間で広まっていた、言語間の関係を発見する唯一の方法は比較復元であるという意見を否定した。彼は、遺伝的 分類は方法論的に比較再構築の前段階、あるいはその第一段階であり、どの言語を比較すべきかを知るまでは言語の比較再構築に取り組むことはできないと主張 した(1957:44)。 彼はまた、一度に2つの言語の包括的な比較(一般的に実施に何年もかかる)をすれば、どんな規模の言語族も確立できるという一般的な意見を批判した。彼 は、8つの言語であっても、それらを別個の語族に分類する方法はすでに4,140通りあり、25の言語では 4,638,590,332,229,999,353通りあると主張した(1957:44)。ちなみに、ニジェール・コンゴ語族にはおよそ1,500の言 語があると言われている。彼は、どのような規模の言語族であっても、二国間比較以外の何らかの学問的手段によって確立される必要があると考えていた。集団 比較論は、そのような手段を実証しようとする試みである。 グリーンバーグは、深さよりも広さの美徳を主張した。彼は、比較の対象となる言語の量を(基本的な語彙、形態素、既知の音変化の経路に)制限し、比較の対 象となる言語の数をある地域のすべての言語に増やすことを提唱した。そうすれば、多数の言語を確実に比較できるようになる。同時に、このプロセスは、比較 対象となる膨大な数の言語を通じて、偶然の類似をチェックすることにもなる。類似が偶発的である数学的確率は、関係する言語の数が増えるにつれて強く減少 する(1957:39)。 グリーンバーグは、基本語彙の大量「借用」は未知であるという前提に立った。借用が起こったとしても、それは文化的な語彙に集中し、「特定の意味領域」に 集中するため、発見が容易であると主張した(1957:39)。関係の大まかなパターンを決定することを目標に、すべての単語を正しく理解するのではな く、パターンを検出することを考えたのである。グリーンバーグは最初から大量比較の理論で、偶然の類似や借用が有用であることの障害にならない理由を取り 上げていた。にもかかわらず、批評家たちはそれらの現象が彼の理論に困難をもたらしたと考えている。 グリーンバーグは1954年の論文(Greenberg 1955に再録)で初めて自分の方法を「大量比較」と呼んだ。1987年現在、彼は言語学の教科書で推奨されている二国間比較との対比を強調するために、 「大量比較」という用語を「多国間比較」に置き換えている。彼は、多者間比較は決して比較法に対立するものではなく、逆にその必要な第一歩であると考えて いた(Greenberg, 1957:44)。彼によれば、比較による再構成は、言語分類によってすでに確立された事実に対する説明理論としての地位を持つべきであるというのである (Greenberg, 1957:45)。 ほとんどの歴史言語学者(Campbell 2001:45)は、言語間の系譜関係を確立するための方法としての大量比較の使用を否定している。集団比較を最も明確に批判しているのは、ライル・キャ ンベル、ドナルド・リンゲ、ウィリアム・ポーザー、そして故R.ラリー・トラスクである。 言語の遺伝的分類 アフリカの言語 グリーンバーグは、1949年から1954年にかけてSouthwestern Journal of Anthropology誌に一連の論文として発表したアフリカの言語の分類体系の開発で広く知られている(1955年に書籍『The Languages of Africa』として再版された)。彼はこの本を改訂し、1963年に再び出版し、1966年にはほぼ同じ版を出版した(1970年にはそのまま再版)。 1981年の論文で、グリーンバーグはさらにいくつかの分類の変更を行った。 グリーンバーグは数百のアフリカ諸語を4つの語族に分類し、アフロアシア語族、ニロ・サハラ語族、ニジェール・コンゴ語族、コイサン語族と名づけた。研究 の過程でグリーンバーグは、19世紀以来広く受け入れられてきたハミティック語族が有効な語族ではないことを示した後、それまでの「ハミト=セム語族」に 代わって「アフロアシア語族」という用語を考案した。彼の研究のもう一つの大きな特徴は、中央アフリカと南部アフリカの大部分を占めるバントゥー諸語を、 多くのバントゥー語派が主張していたような独立した語族としてではなく、ニジェール・コンゴ語族の一部として分類したことである。 グリーンバーグの分類は、競合する以前の分類を評価することに主眼を置いていた。一時期、彼の分類は大胆で推測的なものとみなされ、特にニロ=サハラ語族 という提案には注目が集まった。現在では、コイサンを除けば、この分類はアフリカの専門家の間で一般的に受け入れられており、他の学者による更なる研究の 基礎として利用されている。 グリーンバーグのアフリカ諸語に関する研究は、ライル・キャンベルとドナルド・リンゲによって批判されている。彼らは、彼の分類が彼のデータによって正当 化されるとは考えておらず、「信頼できる方法」による彼のマクロ系統の再検討を要求している(Ringe 1993:104)。ハロルド・フレミングとライオネル・ベンダーはグリーンバーグの分類に同調していたが、彼のマクロファミリーの少なくともいくつか (特にニロ・サハラ語マクロファミリーとコイサン語マクロファミリー)は、ほとんどの言語学者に完全に受け入れられておらず、分割する必要があるかもしれ ないと認めている(Campbell 1997)。彼らの反論は方法論的なもので、もし大量比較が有効な方法でないなら、アフリカ諸語の混乱から秩序をうまく導き出すことは期待できない。 対照的に、グリーンバーグの4つのアフリカ語族をより大きな単位にまとめようとする言語学者もいる。特にエドガー・グレガーセン(Edgar Gregersen, 1972)は、ニジェール・コンゴ語とニロ・サハラ語をより大きな語族に統合することを提案し、これをコンゴ・サハラ語と名付けた。Roger Blench (1995) は、ニジェール・コンゴ語はニロ・サハラ語の亜科であると提案している。 ニューギニア、タスマニア、アンダマン諸島の言語 主な記事 インド太平洋諸語 1971年、グリーンバーグはインド太平洋マクロファミリーを提唱した。このマクロファミリーは、パプア語族(ニューギニアとその近辺の島々の多数の語 族)と、アンダマン諸島とタスマニアの先住民の言語をグループ化し、オーストラリアのアボリジニの言語は除外したものである。その主な特徴は、ニューギニ アの多様な語族を単一の遺伝的単位に縮小したことである。これはオーストロネシア諸語を除外したもので、オーストロネシア諸語はより最近の人々の移動に関 連するものとして確立された。 しかし、Stephen Wurm (1982)と Malcolm Ross (2005)の研究により、これらの言語が単一の遺伝的単位を形成しているという、かつては過激だったグリーンバーグの考えにかなりの証拠が示された。ヴ ルムは、グレート・アンダマン語族と西パプア語族およびティモール・アロル語族の語彙の類似性は「非常に顕著であり、多くの場合、事実上の形式的同一性 (...)に相当する」と述べている。彼は、これは言語的な基層によるものだと考えている。 アメリカ大陸の言語 主な記事 アメリンド諸語 アメリカ大陸の言語を研究する言語学者の多くは、アメリカ大陸の言語を150から180の独立した語族に分類している。エスキモ・アリュート語とナ・デネ語の2つの語族は別個のもので、おそらく後に新大陸に移住してきた結果だとする説もある。 グリーンバーグ(1957:41, 1960)は早くから、無関係と考えられていた言語群の多くが、より大きなグループに分類できると確信していた。1987年に出版した『アメリカ大陸の言 語』(Language in the Americas)では、エスキモー・アリュート語とナ・デネ語は異なるグループであるとしながらも、それ以外のアメリカ先住民の言語はすべて、アメリン ド語と呼ばれる単一の言語マクロファミリーに属すると提唱している。 アメリカ大陸の言語は活発な議論を巻き起こしたが、強く批判されている。アメリカ大陸の先住民言語の専門家の大半はこれを否定しており、歴史言語学者の大 半もこれを否定している。個々の語族の専門家たちは、グリーンバーグのデータには、存在しない言語のデータが含まれていたり、比較された語形の転写が誤っ ていたり、比較に使われた単語の意味が誤って解釈されていたり、完全に偽の語形であったりと、広範な不正確さや誤りがあることを発見している[8][9] [10][11][12][13]。 歴史言語学者もまた、分類の根拠となっている多国間(または集団)比較の方法の妥当性を否定している。彼らは、証拠として提示された類似性が、誤り、偶然 の類似性、比較における過剰な意味的余裕、借用、オノマトペなどの組み合わせによって説明されるのではなく、以前の共通祖先からの継承によるものであると いう説得力のあるケースを提示していないと主張する。 しかし、ハーバード大学の遺伝学者デイビッド・ライヒは、最近の遺伝学的研究によって、グリーンバーグのアメリンド分類、すなわち「ファースト・アメリカ ン」を支持するパターンが確認されたと指摘している。"彼が言語に基づいて最も近縁であると予測した集団群は、データが入手可能な集団における遺伝的パ ターンによって実際に検証された。" とはいえ、この "ファースト・アメリカン "のカテゴリーに属する人々は、エスキモー・アリュートとナ・デネの両集団の祖先とも交雑し、かなりの量の遺伝子を提供しており、この2つの集団の遺伝的 構成は、それぞれ60%と90%が "ファースト・アメリカン "のDNAで占められている[14]。 ユーラシア北部の言語 主な記事 ユーラシア諸語 グリーンバーグは後年、ユーラシア大陸北部のほぼすべての語族が、ユーラシア語族と呼ばれる単一の高次の語族に属すると提唱した。ただし、イェニセア語だ けは例外で、シノ・チベット語も含む、より広いデネ=コーカサス語族に属していた。2008年、エドワード・ヴァイダはイェニセア語を北米のナ・デネ諸語 と関連づけ、デネ=イェニセア語族とした[15]。 ユーラシア語族は、インド・ヨーロッパ語族、ウラル語族、アルタイ語族を含むことで、ホルガー・ペデルセンやウラディスラフ・イリチ=スヴィティチの古い ノストラティック語族に似ている。ニブフ語、ジャポニック語、朝鮮語、アイヌ語(これらは言語族ではなく単一言語であるため、ノストラティシストたちは比 較対象から除外していた)を含み、アフロアシア語を除外している点で異なっている。この頃、セルゲイ・スタロスティンを中心とするロシアのノストラティシ ストがノストラティックの改訂版を作成した。それはグリーンバーグのグループ分けよりも若干大きかったが、アフロアシア語も除外していた。 最近、ノストラティック仮説の支持者の間でコンセンサスが生まれつつある。グリーンバーグは基本的にノストラティック仮説に同意したが、その北の「層」 (ユーラシアティック)と南の「層」(主にアフロアシアティックとドラヴィダ語)の間に深い内部分裂があることを強調した。 アメリカのノストラティック研究者アラン・ボムハードは、ユーラシア語をノストラティック語の枝とみなしている: アフラシア語、エラモ・ドラヴィダ語、カルトヴェリ語などである。同様に、Georgiy Starostin (2002)は、アフロアシア語、ノストラティック語、エラム語はほぼ等距離にあり、他のどの語族よりも互いに密接に関連していると考えている。彼らは、 マクロファミリーの残りの部分を構成する、より狭いサブグループを指定するためにユーラシア語という用語を留保している。このように、最近の提案は、主に ドラヴィダ語とカルトヴェリア語を正確に含めるかどうかで異なっている。 グリーンバーグは不治の膵臓癌と診断された後も、2001年5月に亡くなるまでこのプロジェクトに取り組み続けた。彼の同僚でありかつての教え子であったメリット・ルーレンは、彼の死後、ユーラシア語研究の最終巻(2002年)の出版を確実にした。 |

| Books Studies in African Linguistic Classification. New Haven: Compass Publishing Company. 1955. (Photo-offset reprint of the SJA articles with minor corrections.) Essays in Linguistics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1957. The Languages of Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. 1963. (Heavily revised version of Greenberg 1955. From the same publisher: second, revised edition, 1966; third edition, 1970. All three editions simultaneously published at The Hague by Mouton & Co.) Language Universals: With Special Reference to Feature Hierarchies. The Hague: Mouton & Co. 1966. (Reprinted 1980 and, with a foreword by Martin Haspelmath, 2005.) Language in the Americas. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 1987. Keith Denning; Suzanne Kemmer, eds. (1990). On Language: Selected Writings of Joseph H. Greenberg. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Indo-European and Its Closest Relatives: The Eurasiatic Language Family. Vol. 1: Grammar. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 2000. Indo-European and Its Closest Relatives: The Eurasiatic Language Family. Vol. 2: Lexicon. Stanford: Stanford University Press. 2002. William Croft, ed. (2005). Genetic Linguistics: Essays on Theory and Method. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

書籍 アフリカ言語分類の研究。ニューヘイブン:コンパス・パブリッシング・カンパニー。1955年。(SJAの記事の写真オフセット再版で、軽微な修正あり。 言語学のエッセイ。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版。1957年。 アフリカの言語。ブルーミントン:インディアナ大学出版。1963年。(グリーンバーグ著『アフリカの言語』1955年の大幅改訂版。同じ出版社より:改 訂第2版、1966年;第3版、1970年。これら3つの版はすべてハーグのMouton & Co.より同時出版された。 言語の普遍性:特に特徴の階層性について。ハーグ:Mouton & Co. 1966年。(1980年およびマーティン・ハスペルマスの序文付きで2005年に再版。) アメリカ大陸の言語。スタンフォード:スタンフォード大学出版局。1987年。 キース・デニング、スザンヌ・ケマー編。(1990年)。言語について:ジョセフ・H・グリーンバーグの論文集。カリフォルニア州スタンフォード:スタンフォード大学出版局。 インド・ヨーロッパ語族とその最も近い親戚:ユーラシア語族。第1巻:文法。スタンフォード:スタンフォード大学出版局。2000年。 印欧語とその最も近い親戚:ユーラシア語族。第2巻:語彙。スタンフォード:スタンフォード大学出版局。2002年 ウィリアム・クロフト編(2005年)。遺伝言語学:理論と方法に関する論文。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。 |

| Bibliography Blench, Roger. 1995. "Is Niger–Congo simply a branch of Nilo-Saharan?" In Fifth Nilo-Saharan Linguistics Colloquium, Nice, 24–29 August 1992: Proceedings, edited by Robert Nicolaï and Franz Rottland. Cologne: Köppe Verlag, pp. 36–49. Campbell, Lyle (1986). "Comment on Greenberg, Turner, and Zegura". Current Anthropology. 27: 488. doi:10.1086/203472. S2CID 144209907. Campbell, Lyle. 1997. American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1. Campbell, Lyle. 2001. "Beyond the comparative method." In Historical Linguistics 2001: Selected Papers from the 15th International Conference on Historical Linguistics, Melbourne, 13–17 August 2001, edited by Barry J. Blake, Kate Burridge, and Jo Taylor. Diamond, Jared. 1997. Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-03891-2. Gregersen, Edgar (1972). "Kongo-Saharan". Journal of African Languages. 11 (1): 69–89. Mairal, Ricardo and Juana Gil. 2006. Linguistic Universals. Cambridge–NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54552-5. Ringe, Donald A. (1993). "A reply to Professor Greenberg". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 137: 91–109. Ross, Malcolm. 2005. "Pronouns as a preliminary diagnostic for grouping Papuan languages." In Papuan Pasts: Cultural, Linguistic and Biological Histories of Papuan-speaking Peoples, edited by Andrew Pawley, Robert Attenborough, Robin Hide, and Jack Golson. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, pp. 15–66. Wurm, Stephen A. 1982. The Papuan Languages of Oceania. Tübingen: Gunter Narr. |

参考文献 Blench, Roger. 1995. 「ニジェール・コンゴ語は単にニロサハラ語の分岐なのか?」Robert NicolaïとFranz Rottland編『第5回ニロサハラ語学コロキアム、1992年8月24日~29日、ニース:議事録』ケルン:Köppe Verlag、36~49ページ。 キャンベル、ライル(1986年)。「グリーンバーグ、ターナー、ゼグラへのコメント」。『カレント・アンソロポロジー』27: 488. doi:10.1086/203472. S2CID 144209907. キャンベル、ライル。1997年。『アメリカインディアン諸語:ネイティブ・アメリカンの歴史言語学』。ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版。ISBN 0-19-509427-1. キャンベル、ライル。2001年。「比較方法を超えて」。バリー・J・ブレイク、ケイト・ブリッジ、ジョー・テイラー編『歴史言語学2001:第15回歴史言語学国際会議(2001年8月13日~17日、メルボルン)の論文集』所収。 ダイヤモンド、ジャレド。1997年。『銃・病原菌・鉄――1万3000年にわたる人類史の謎』。ニューヨーク:ノートン。ISBN 0-393-03891-2。 グレゴセン、エドガー(1972年)。「コンゴ・サハラ語族」。『アフリカ諸語研究』。11(1):69-89。 Mairal, Ricardo and Juana Gil. 2006. Linguistic Universals. Cambridge–NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54552-5. Ringe, Donald A. (1993). 「A reply to Professor Greenberg」. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 137: 91–109. ロス、マルコム。2005年。「パプア諸語のグループ分けのための予備診断としての代名詞」アンドリュー・ポーリー、ロバート・アッテンボロー、ロビン・ ハイド、ジャック・ゴルソン編『パプア諸語を話す人々の文化的・言語的・生物学的歴史』パシフィック・ランゲージ・シリーズ、キャンベラ、15-66ペー ジ。 Wurm, Stephen A. 1982. The Papuan Languages of Oceania. Tübingen: Gunter Narr. |

| Linguistic universal Moscow School of Comparative Linguistics Monogenesis (linguistics) Nostratic languages |

言語学的普遍 モスクワ比較言語学派 単源説(言語学 ノストラクト諸語 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Greenberg |

|

| A linguistic universal

is a pattern that occurs systematically across natural languages,

potentially true for all of them. For example, All languages have nouns

and verbs, or If a language is spoken, it has consonants and vowels.

Research in this area of linguistics is closely tied to the study of

linguistic typology, and intends to reveal generalizations across

languages, likely tied to cognition, perception, or other abilities of

the mind. The field originates from discussions influenced by Noam

Chomsky's proposal of a Universal Grammar, but

was largely pioneered by the linguist Joseph Greenberg, who derived a

set of forty-five basic universals, mostly dealing with syntax, from a

study of some thirty languages. Though there has been significant research into linguistic universals, in more recent time some linguists, including Nicolas Evans and Stephen C. Levinson, have argued against the existence of absolute linguistic universals that are shared across all languages. These linguists cite problems such as ethnocentrism amongst cognitive scientists, and thus linguists, as well as insufficient research into all of the world's languages in discussions related to linguistic universals, instead promoting these similarities as simply strong tendencies. |

言

語的普遍性とは、自然言語全体に体系的に見られるパターンであり、すべての言語に当てはまる可能性がある。例えば、すべての言語には名詞と動詞がある、あ

るいは、ある言語が話されている場合、その言語には子音と母音がある、などである。言語学のこの分野の研究は、言語類型論の研究と密接に結びついており、

言語間の一般化を明らかにすることを意図している。この分野は、ノーム・チョムスキーによる普遍文法の提案に影響された議論に端を発するが、言語学者ジョセフ・グリーンバーグが、約30の言語の研究から、主に統語論を扱う45の基本的普遍語セットを導き出したことが、その主な先駆者である。 言語的普遍性については重要な研究がなされてきたが、最近ではニコラス・エヴァンスやスティーヴン・C・レヴィンソンをはじめとする言語学者たちが、言語 的普遍性には反対であると主張している。レビンソンをはじめとする一部の言語学者は、すべての言語に共通する絶対的な言語的普遍性の存在に異議を唱えてい る。これらの言語学者は、言語的普遍性に関する議論において、認知科学者、ひいては言語学者におけるエスノセントリズム(民族中心主義)の問題や、世界中 のすべての言語に対する研究が不十分であることなどを挙げ、代わりにこれらの類似性を単なる強い傾向として宣伝している。 |

| Terminology Linguists distinguish between two kinds of universals: absolute (opposite: statistical, often called tendencies) and implicational (opposite: non-implicational). Absolute universals apply to every known language and are quite few in number; an example is All languages have pronouns. An implicational universal applies to languages with a particular feature that is always accompanied by another feature, such as If a language has trial grammatical number, it also has dual grammatical number, while non-implicational universals just state the existence (or non-existence) of one particular feature. Also in contrast to absolute universals are tendencies, statements that may not be true for all languages but nevertheless are far too common to be the result of chance.[1] They also have implicational and non-implicational forms. An example of the latter would be The vast majority of languages have nasal consonants.[2] However, most tendencies, like their universal counterparts, are implicational. For example, With overwhelmingly greater-than-chance frequency, languages with normal SOV order are postpositional. Strictly speaking, a tendency is not a kind of universal, but exceptions to most statements called universals can be found. For example, Latin is an SOV language with prepositions. Often it turns out that these exceptional languages are undergoing a shift from one type of language to another. In the case of Latin, its descendant Romance languages switched to SVO, which is a much more common order among prepositional languages. Universals may also be bidirectional or unidirectional. In a bidirectional universal two features each imply the existence of each other. For example, languages with postpositions usually have SOV order, and likewise SOV languages usually have postpositions. The implication works both ways, and thus the universal is bidirectional. By contrast, in a unidirectional universal the implication works only one way. Languages that place relative clauses before the noun they modify again usually have SOV order, so pre-nominal relative clauses imply SOV. On the other hand, SOV languages worldwide show little preference for pre-nominal relative clauses, and thus SOV implies little about the order of relative clauses. As the implication works only one way, the proposed universal is a unidirectional one. Linguistic universals in syntax are sometimes held up as evidence for universal grammar (although epistemological arguments are more common). Other explanations for linguistic universals have been proposed, for example, that linguistic universals tend to be properties of language that aid communication. If a language were to lack one of these properties, it has been argued, it would probably soon evolve into a language having that property.[3] Michael Halliday has argued for a distinction between descriptive and theoretical categories in resolving the matter of the existence of linguistic universals, a distinction he takes from J.R. Firth and Louis Hjelmslev. He argues that "theoretical categories, and their inter-relations construe an abstract model of language...; they are interlocking and mutually defining". Descriptive categories, by contrast, are those set up to describe particular languages. He argues that "When people ask about 'universals', they usually mean descriptive categories that are assumed to be found in all languages. The problem is there is no mechanism for deciding how much alike descriptive categories from different languages have to be before they are said to be 'the same thing'".[4] |

用語 言語学者は2種類の普遍性を区別する:絶対的普遍性(反対語:統計的普遍性、しばしば傾向性とも呼ばれる)と含意的普遍性(反対語:非含意的普遍性)。絶 対的普遍はすべての既知の言語に適用され、その数は非常に少ない。一方、非意訳的普遍はある特定の特徴の存在(または非存在)を述べるだけです。 また絶対的普遍と対照的なのが傾向で、すべての言語に当てはまるとは限らないが、偶然の結果にしてはあまりにも一般的な記述である[1]。後者の例として は、The vast majority of languages have nasal consonants(大多数の言語には鼻子音がある)がある[2]。しかし、ほとんどの傾向は、普遍的なものと同様に、暗示的なものである。例えば、通 常の SOV 順序を持つ言語は、確率よりも圧倒的に高い頻度で後置詞的である。厳密に言えば、傾向は普遍的なものではないが、普遍的と呼ばれるほとんどの文には例外が ある。例えば、ラテン語は前置詞を持つSOV言語である。このような例外的な言語が、あるタイプの言語から別のタイプの言語へと移行しつつあることがしば しば判明する。ラテン語の場合、その子孫であるロマンス諸語は、前置詞のある言語ではより一般的な順序であるSVOに切り替わった。 普遍語には双方向性と単方向性がある。双方向普遍では、2つの特徴がそれぞれ互いの存在を暗示する。たとえば、後置詞を持つ言語は通常 SOV 順序を持ち、同様に SOV 言語は通常後置詞を持つ。暗示は双方向に働くので、普遍は双方向性を持つ。一方、一方向性普遍語では、含意は一方向にしか働かない。相対節を修飾する名詞 の前に置く言語は、通常 SOV 順序を持つため、名詞の前の相対節は SOV を意味します。一方、世界中のSOV言語は、名詞の前に相対節を置くことをあまり好まないため、SOVは相対節の順序をほとんど意味しません。暗示は一方 向にしか働かないので、提案されている普遍性は一方向的なものである。 構文における言語的普遍性は、普遍文法の証拠として取り上げられることもある(認識論的な議論の方が一般的だが)。例えば、言語的普遍性はコミュニケー ションを助ける言語の特性である傾向がある、などである。もしある言語がこのような特性の一つを欠いていたとしても、おそらくすぐにその特性を持つ言語に 進化するだろうと主張されている[3]。 マイケル・ハリデー(Michael Halliday)は、言語的普遍性の存在の問題を解決する上で、記述的カテゴリーと理論的カテゴリーの区別を主張しており、この区別はJ.R.ファース (J.R. Firth)とルイス・ヒェルムスレフ(Louis Hjelmslev)から取ったものである。理論的範疇とその相互関係は言語の抽象的なモデルを構築する。対照的に、記述的カテゴリーとは、特定の言語を 記述するために設定されたカテゴリーである。彼は「人々が『普遍的なもの』について尋ねるとき、それは通常、すべての言語に見られると想定される記述的カ テゴリーを意味する」と主張する。問題は、異なる言語の記述的カテゴリーが『同じもの』と言われる前に、どの程度似ていなければならないかを決定するメカ ニズムがないことである」[4]。 |

| Universal grammar Main article: Universal grammar Noam Chomsky's work related to the innateness hypothesis as it pertains to our ability to rapidly learn any language without formal instruction and with limited input, or what he refers to as a poverty of the stimulus, is what began research into linguistic universals. This led to his proposal for a shared underlying grammar structure for all languages, a concept he called universal grammar (UG), which he claimed must exist somewhere in the human brain prior to language acquisition. Chomsky defines UG as "the system of principles, conditions, and rules that are elements or properties of all human languages... by necessity."[5] He states that UG expresses "the essence of human language,"[5] and believes that the structure-dependent rules of UG allow humans to interpret and create an infinite number of novel grammatical sentences. Chomsky asserts that UG is the underlying connection between all languages and that the various differences between languages are all relative with respect to UG. He claims that UG is essential to our ability to learn languages, and thus uses it as evidence in a discussion of how to form a potential 'theory of learning' for how humans learn all or most of our cognitive processes throughout our lives. The discussion of Chomsky's UG, its innateness, and its connection to how humans learn language has been one of the more covered topics in linguistics studies to date. However, there is division amongst linguists between those who support Chomsky's claims of UG and those who argued against the existence of an underlying shared grammar structure that can account for all languages. |

普遍文法 主な記事 普遍文法 ノーム・チョムスキーが、正式な指導を受けず、限られた入力、あるいは彼の言う「刺激の貧困」によって、どのような言語でも迅速に学習する能力に関する生 得性仮説に関連する研究を行ったことが、言語的普遍性に関する研究の始まりである。これが、すべての言語に共通する根本的な文法構造、すなわち普遍文法 (UG)と呼ばれる概念を提唱するきっかけとなった。チョムスキーはUGを「必然的にすべての人間の言語の要素または特性である原理、条件、および規則の システム」[5]と定義し、UGは「人間の言語の本質」[5]を表現していると述べ、UGの構造に依存した規則によって、人間は無限に新しい文法文を解釈 し、作成することができると考えている。チョムスキーは、UGはすべての言語の根底にあるつながりであり、言語間のさまざまな違いはすべてUGに関する相 対的なものであると主張する。彼は、UGは人間が言語を学習する能力に不可欠であると主張し、そのため、人間が生涯を通じて認知過程のすべて、あるいは大 部分をどのように学習していくのかについて、潜在的な「学習理論」を形成する方法についての議論において、UGを証拠として用いている。チョムスキーの UG、その生得性、そして人間の言語学習方法との関連性についての議論は、これまでの言語学研究において、より多く取り上げられてきたトピックのひとつで ある。しかし、言語学者の間では、チョムスキーのUGの主張を支持する人々と、すべての言語を説明できる根本的な共有文法構造の存在に反対する人々の間で 意見が分かれている。 |

| Semantics In semantics, research into linguistic universals has taken place in a number of ways. Some linguists, starting with Gottfried Leibniz, have pursued the search for a hypothetic irreducible semantic core of all languages. A modern variant of this approach can be found in the natural semantic metalanguage of Anna Wierzbicka and associates. See, for example,[6] and[7] Other lines of research suggest cross-linguistic tendencies to use body part terms metaphorically as adpositions,[8] or tendencies to have morphologically simple words for cognitively salient concepts.[9] The human body, being a physiological universal, provides an ideal domain for research into semantic and lexical universals. In a seminal study, Cecil H. Brown (1976) proposed a number of universals in the semantics of body part terminology, including the following: in any language, there will be distinct terms for BODY, HEAD, ARM, EYES, NOSE, and MOUTH; if there is a distinct term for FOOT, there will be a distinct term for HAND; similarly, if there are terms for INDIVIDUAL TOES, then there are terms for INDIVIDUAL FINGERS. Subsequent research has shown that most of these features have to be considered cross-linguistic tendencies rather than true universals. Several languages like Tidore and Kuuk Thaayorre lack a general term meaning 'body'. On the basis of such data it has been argued that the highest level in the partonomy of body part terms would be the word for 'person'.[10] Some other examples of proposed linguistic universals in semantics include the idea that all languages possess words with the meaning '(biological) mother' and 'you (second person singular pronoun)' as well as statistical tendencies of meanings of basic color terms in relation to the number of color terms used by a respective language. For example, if a languages possesses only two terms for describing color, their respective meanings will be 'black' and 'white' (or perhaps 'dark' and 'light'). If a language possesses more than two color terms, then the additional terms will follow trends related to the focal colors, which are determined by the physiology of how we perceive color rather than linguistics. Thus, if a language possesses three color terms, the third will mean 'red', and if a language possesses four color terms, the next will mean 'yellow' or 'green'. If there are five color terms, then both 'yellow' and 'green' are added, if six, then 'blue' is added, and so on. |

意味論 意味論では、言語的普遍性の研究はさまざまな形で行われてきた。ゴットフリート・ライプニッツに始まる一部の言語学者は、すべての言語に共通する不可逆的 な意味論的中核を仮説的に追求した。このアプローチの現代的な変形は、アンナ・ヴィエルツビッカとその仲間たちの自然意味メタ言語に見られる。例えば、 [6]や[7]を参照のこと。他の研究では、体の部位の用語を形容詞として比喩的に使用する言語横断的傾向[8]や、認知的に顕著な概念に対して形態論的 に単純な単語を持つ傾向が示唆されている[9]。Cecil H. Brown (1976)は重要な研究の中で、身体部位の用語の意味論における普遍性をいくつか提案した。その後の研究により、これらの特徴のほとんどは、真の普遍性 というよりも、むしろ言語横断的な傾向と考えなければならないことが明らかになった。TidoreやKuuk Thaayorreのようないくつかの言語には、「身体」を意味する一般的な用語がない。このようなデータに基づいて、身体部位の用語のパルトノミーにお ける最上位は「人」を表す単語であろうと主張されている[10]。 意味論において提案されている言語的普遍性の他の例としては、すべての言語が「(生物学的な)母親」や「あなた(二人称単数代名詞)」を意味する単語を 持っているという考えや、それぞれの言語が使用する色彩用語の数に対する基本色彩用語の意味の統計的傾向などがある。例えば、ある言語が色を表す用語を2 つしか持たない場合、それぞれの意味は「黒」と「白」(あるいは「暗い」と「明るい」)となる。ある言語が2つ以上の色に関する用語を持つ場合、追加され る用語は焦点となる色に関連する傾向に従うことになるが、これは言語学というよりも、人間がどのように色を知覚するかという生理学によって決定される。し たがって、ある言語が3つの色彩用語を持つ場合、3つ目の色彩用語は「赤」を意味し、ある言語が4つの色彩用語を持つ場合、次の色彩用語は「黄」または 「緑」を意味する。色彩用語が5つあれば「黄」と「緑」の両方が加わり、6つあれば「青」が加わる、という具合である。 |

| Counterarguments Nicolas Evans and Stephen C. Levinson are two linguists who have written against the existence of linguistic universals, making a particular mention towards issues with Chomsky's proposal for a Universal Grammar. They argue that across the 6,000-8,000 languages spoken around the world today, there are merely strong tendencies rather than universals at best.[11] In their view, these arise primarily due to the fact that many languages are connected to one another through shared historical backgrounds or common lineage, such as group Romance languages in Europe that were all derived from ancient Latin, and therefore it can be expected that they share some core similarities. Evans and Levinson believe that linguists who have previously proposed or supported concepts associated with linguistic universals have done so "under the assumption that most languages are English-like in their structure"[11] and only after analyzing a limited range of languages. They identify ethnocentrism, the idea "that most cognitive scientists, linguists included, speak only familiar European languages, all close cousins in structure,"[11] as a possible influence towards the various issues they identify in the assertions made on linguistic universals. With regards to Chomsky's universal grammar, these linguists claim that the explanation of the structure and rules applied to UG are either false due to a lack of detail into the various constructions use when creating or interpreting a grammatical sentence, or that the theory is unfalsifiable due to the vague and oversimplified assertions made by Chomsky. Instead, Evans and Levinson highlight the vast diversity that exists amongst the many languages spoken around the world to advocate for further investigation into the many cross-linguistic variations that do exist. Their article promotes linguistic diversity by citing multiple examples of variation in how "languages can be structured at every level: phonetic, phonological, morphological, syntactic and semantic."[11] They claim that increased understanding and acceptance of linguistic diversity over the concepts of false claims of linguistic universals, better stated to them as strong tendencies, will lead to more enlightening discoveries in the studies of human cognition. |

反論 Nicolas EvansとStephen C. レビンソンは言語的普遍性の存在に反対する2人の言語学者であり、特にチョムスキーが提案した普遍文法の問題点について言及している。彼らの見解では、こ れらは主に多くの言語が歴史的背景や共通の系譜を共有することで互いに結びついているという事実に起因しており、例えばヨーロッパのロマンス諸語はすべて 古代ラテン語から派生したものであるため、核となる類似点を共有していることが予想される。EvansとLevinsonは、これまで言語学者が言語的普 遍性に関連する概念を提唱したり支持したりしてきたのは、「ほとんどの言語がその構造において英語に似ているという仮定の下」[11]で、限られた範囲の 言語を分析した後であったと考えている。彼らはエスノセントリズム(民族中心主義)、つまり「言語学者を含むほとんどの認知科学者は、構造においてすべて 近い親戚である馴染みのあるヨーロッパ言語しか話さない」という考え[11]を、言語的普遍性に関する主張の中で彼らが特定した様々な問題に対する影響の 可能性として挙げている。チョムスキーの普遍文法に関して、これらの言語学者たちは、UGに適用されている構造とルールの説明は、文法的な文章を作成した り解釈したりする際に使用される様々な構文に関する詳細が欠けているために誤っているか、あるいはチョムスキーが行った主張が曖昧で単純化しすぎているた めに、この理論は反証不可能であると主張している。その代わりに、エバンスとレヴィンソンは、世界中で話されている多くの言語の間に存在する膨大な多様性 を強調し、実際に存在する多くの言語間の差異をさらに調査することを提唱している。彼らの論文では、「言語が音声学的、音韻論的、形態論的、統語論的、意 味論的といったあらゆるレベルで構造化されうる」[11]というバリエーションに関する複数の例を挙げて、言語の多様性を促進している。彼らは、言語的普 遍性という誤った主張の概念よりも、言語の多様性に対する理解と受容を深めることが、人間の認知の研究においてより啓発的な発見につながると主張してい る。 |

| Conservativity Cultural universal Greenberg's linguistic universals Swadesh list |

保守性 文化の普遍性 グリーンバーグの言語普遍性 スワデシュ・リスト |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linguistic_universal |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆