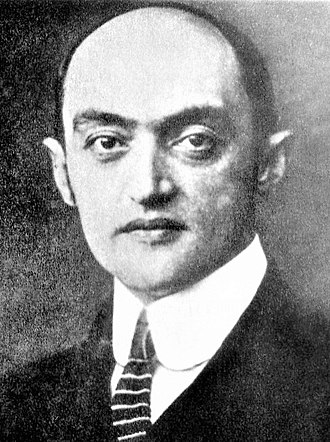

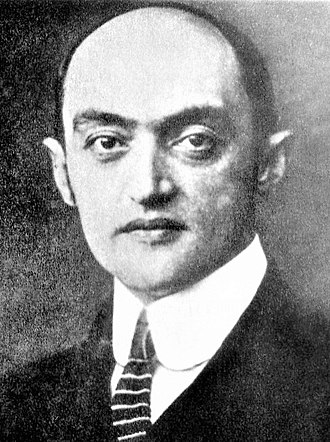

ジョセフ・アロイス・シュンペーター

Joseph Alois Schumpeter,

1883-1950

☆ ヨーゼフ(英語読みではジョゼフまたはジョセフ)・アロイス・シュンペーター(Joseph Alois Schumpeter、ドイツ語: [ˈʃˈɐ、1883年2月8日 - 1950年1月8日)[3]はオーストリアの政治経済学者。1919年にオーストリアの大蔵大臣を短期間務めた。1932年にアメリカに移住し、ハーバー ド大学教授に就任していた。シュンペーターは20世紀初頭に最も影響力のあった経済学者の一人であり、ヴェルナー・ソンバートによって作られた「創造的破 壊」という言葉を広めたことで著名である(→「イノベーション」)。

★ シュンペーターの英語で最も人気のある著書は、おそらく『資本主義、社会主義、民主主義』であろう。資本主義が崩壊し、社会主義に取って代わられるという 点ではカール・マルクスと同意見であるが、シュンペーターはこれが実現する別の方法を予測している。マルクスが、資本主義は暴力的なプロレタリア革命に よって打倒されると予言し、実際に資本主義の最も弱い国々でそれが起こったのに対し、シュンペーターは、資本主義は徐々に弱体化し、最終的には崩壊すると 考えた。具体的には、資本主義の成功はコーポラティズムをもたらし、特に知識人の間では資本主義に敵対する価値観が生まれるとした。

| Joseph Alois

Schumpeter (German: [ˈʃʊmpeːtɐ]; February 8, 1883 – January 8, 1950)[3]

was an Austrian political economist. He served briefly as Finance

Minister of Austria in 1919. In 1932, he emigrated to the United States

to become a professor at Harvard University, where he remained until

the end of his career, and in 1939 obtained American citizenship. Schumpeter was one of the most influential economists of the early 20th century and popularized the term "creative destruction", which was coined by Werner Sombart.[4][5][6] |

ヨーゼフ・アロイス・シュンペーター(Joseph Alois

Schumpeter、ドイツ語: [ˈʃˈɐ、1883年2月8日 -

1950年1月8日)[3]はオーストリアの政治経済学者。1919年にオーストリアの大蔵大臣を短期間務めた。1932年にアメリカに移住し、ハーバー

ド大学教授に就任。 シュンペーターは20世紀初頭に最も影響力のあった経済学者の一人であり、ヴェルナー・ソンバートによって作られた「創造的破壊」という言葉を広めた [4][5][6]。 |

| Early life and education Schumpeter was born in Triesch, Habsburg Moravia (now Třešť in the Czech Republic, then part of Austria-Hungary) in 1883 to German-speaking Catholic parents. Both of his grandmothers were Czech.[7] Schumpeter did not acknowledge his Czech ancestry; he considered himself an ethnic German.[7] His father owned a factory, but he died when Joseph was only four years old.[8] In 1893, Joseph and his mother moved to Vienna.[9] Schumpeter was a loyal supporter of Franz Joseph I of Austria.[7] After attending school at the Theresianum, Schumpeter began his career studying law at the University of Vienna under the Austrian capital theorist Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, taking his PhD in 1906. In 1909, after some study trips, he became a professor of economics and government at the University of Czernowitz in modern-day Ukraine. In 1911, he joined the University of Graz, where he remained until World War I. In 1918, Schumpeter was a member of the Socialization Commission established by the Council of the People's Deputies in Germany. In March 1919, he was invited to take office as Minister of Finance in the Republic of German-Austria. He proposed a capital levy as a way to tackle the war debt and opposed the socialization of the Alpine Mountain plant.[10] In 1921, he became president of the private Biedermann Bank. He was also a board member at the Kaufmann Bank. Problems at those banks left Schumpeter in debt. His resignation was a condition of the takeover of the Biedermann Bank in September 1924.[11] From 1925 until 1932, Schumpeter held a chair at the University of Bonn, Germany. He lectured at Harvard in 1927–1928 and 1930. In 1931, he was a visiting professor at The Tokyo College of Commerce. In 1932, Schumpeter moved to the United States and soon began what would become extensive efforts to help central European economist colleagues displaced by Nazism.[12] Schumpeter also became known for his opposition to Marxism and socialism that he thought would lead to dictatorship, and even criticized President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal.[13] In 1939, Schumpeter became a US citizen. At the beginning of World War II, the FBI investigated him and his wife, Elizabeth Boody (a prominent scholar of Japanese economics) for pro-Nazi leanings, but found no evidence of Nazi sympathies.[14][15] At Harvard, Schumpeter was considered a memorable character, erudite, and even showy in the classroom. He became known for his heavy teaching load and his personal and painstaking interest in his students. He served as the faculty advisor of the Graduate Economics Club and organized private seminars and discussion groups.[16] Some colleagues thought his views were outdated by Keynesianism which was fashionable; others resented his criticisms, particularly of their failure to offer an assistant professorship to Paul Samuelson, but recanted when they thought him likely to accept a position at Yale University.[17] This period of his life was characterized by hard work and comparatively little recognition of his massive 2-volume book Business Cycles. However, Schumpeter persevered, and in 1942 published what became the most popular of all his works, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, reprinted many times and in many languages in the following decades, as well as cited thousands of times.[18] |

生い立ちと教育 シュンペーターは1883年、ハプスブルク家のモラヴィア地方トリシュ(現在のチェコ共和国、当時はオーストリア=ハンガリーの一部であった)で、ドイツ 語を話すカトリック教徒の両親のもとに生まれた。父親は工場を経営していたが、ヨーゼフがわずか4歳のときに死去。1893年、ヨーゼフと母親はウィーン に移り住んだ[9]。 テレジアナムの学校に通った後、シュンペーターはウィーン大学でオーストリアの資本論者オイゲン・フォン・ベーム=バヴェルクの下で法律を学び、1906 年に博士号を取得した。1909年、数回の留学を経て、現在のウクライナにあるツェルノヴィッツ大学で経済学と行政学の教授となる。1911年にはグラー ツ大学に移り、第一次世界大戦まで在籍した。 1918年、シュンペーターはドイツ人民代議員会が設置した社会化委員会の委員となる。1919年3月、ドイツ・オーストリア共和国の大蔵大臣に招かれ る。1921年、私立ビーダーマン銀行の頭取に就任。彼はまたカウフマン銀行の取締役でもあった。これらの銀行で問題が発生し、シュンペーターは負債を抱 えることになる。彼の辞任は1924年9月のビーダーマン銀行買収の条件であった[11]。 1925年から1932年まで、シュンペーターはドイツのボン大学で教鞭をとる。1927年から1928年と1930年にはハーバード大学で講義。 1931年には東京商科大学の客員教授を務めた。1932年、シュンペーターは渡米し、すぐにナチズムによって追放された中央ヨーロッパの経済学者たちを 支援するための大規模な活動を始める。第二次世界大戦が始まると、FBIは彼と彼の妻であるエリザベス・ブーディ(著名な日本経済学者)を親ナチス派とし て調査したが、ナチスシンパの証拠は見つからなかった[14][15]。 ハーバード大学では、シュンペーターは印象的な人物で、博学であり、教室では目立ちたがり屋とさえ思われていた。授業量が多く、個人的で丹念な学生への関 心で知られるようになった。シュンペーターの同僚には、彼の見解が流行のケインズ主義によって時代遅れになっていると考える者もいた[16]。また、彼の 批判、特にポール・サミュエルソンに助教授職を与えられなかったことに憤慨する者もいたが、彼がイェール大学で職を得る可能性が高いと考えられると、撤回 した[17]。しかし、シュンペーターは耐え抜き、1942年に彼の著作の中で最も人気となった『資本主義、社会主義、民主主義』を出版し、その後数十年 の間に何度も何カ国語でも再版され、何千回も引用された[18]。 |

| Career Influences The source of Schumpeter's dynamic, change-oriented, and innovation-based economics was the historical school of economics. Although his writings could be critical of that perspective, Schumpeter's work on the role of innovation and entrepreneurship can be seen as a continuation of ideas originated by the historical school, especially the work of Gustav von Schmoller and Werner Sombart.[19][20] Despite being born in Austria and having trained with many of the same economists, some argue he cannot be categorized with the Austrian School of economics without major qualifications[21] while others maintain the opposite.[22] The Austrian sociologist Rudolf Goldscheid's concept of fiscal sociology influenced Schumpeter's analysis of the tax state.[23] A 2012 paper showed that Schumpeter's writings displayed the influence of Francis Galton's work.[24] Evolutionary economics Main article: Evolutionary economics According to Christopher Freeman (2009), "the central point of his whole life work [is]: that capitalism can only be understood as an evolutionary process of continuous innovation and 'creative destruction'".[25] History of Economic Analysis Schumpeter's scholarship is apparent in his posthumous History of Economic Analysis,[26] Schumpeter thought that the greatest 18th century economist was Turgot rather than Adam Smith, and he considered Léon Walras to be the "greatest of all economists", beside whom other economists' theories were "like inadequate attempts to catch some particular aspects of Walrasian truth".[27] Schumpeter criticized John Maynard Keynes and David Ricardo for the "Ricardian vice". According to Schumpeter, both Ricardo and Keynes reasoned in terms of abstract models, where they would freeze all but a few variables. Then they could argue that one caused the other in a simple monotonic fashion. This led to the belief that one could easily deduce policy conclusions directly from a highly abstract theoretical model. In this book, Joseph Schumpeter recognized the implication of a gold monetary standard compared to a fiat monetary standard. In History of Economic Analysis, Schumpeter stated the following: "An 'automatic' gold currency is part and parcel of a laissez-faire and free-trade economy. It links every nation's money rates and price levels with the money rates and price levels of all the other nations that are 'on gold.' However, gold is extremely sensitive to government expenditure and even to attitudes or policies that do not involve expenditure directly, for example, in foreign policy, certain policies of taxation, and, in general, precisely all those policies that violate the principles of [classical] liberalism. This is the reason why gold is so unpopular now and also why it was so popular in a bourgeois era."[28] Business cycles Schumpeter's relationships with the ideas of other economists were quite complex in his most important contributions to economic analysis – the theory of business cycles and development. Following neither Walras nor Keynes, Schumpeter starts in The Theory of Economic Development[29] with a treatise of circular flow which, excluding any innovations and innovative activities, leads to a stationary state. The stationary state is, according to Schumpeter, described by Walrasian equilibrium. The hero of his story is the entrepreneur. The entrepreneur disturbs this equilibrium and is the prime cause of economic development, which proceeds in a cyclic fashion along with several time scales. In fashioning this theory connecting innovations, cycles, and development, Schumpeter kept alive the Russian Nikolai Kondratiev's ideas on 50-year cycles, Kondratiev waves. Schumpeter suggested a model in which the four main cycles, Kondratiev (54 years), Kuznets (18 years), Juglar (9 years), and Kitchin (about 4 years) can be added together to form a composite waveform. A Kondratiev wave could consist of three lower-degree Kuznets waves.[30] Each Kuznets wave could, itself, be made up of two Juglar waves. Similarly two (or three) Kitchin waves could form a higher degree Juglar wave. If each of these were in phase; more importantly, if the downward arc of each was simultaneous so that the nadir of each was coincident, it would explain disastrous slumps and consequent depressions. As far as the segmentation of the Kondratiev Wave, Schumpeter never proposed such a fixed model. He saw these cycles varying in time – although in a tight time frame by coincidence – and for each to serve a specific purpose. Proposed economic waves Cycle/wave name Period (years) Kitchin cycle (inventory, e.g. pork cycle) 3–5 Juglar cycle (fixed investment) 7–11 Kuznets swing (infrastructural investment) 15–25 Kondratiev wave (technological basis) 45–60 This box: viewtalkedit Keynesianism In Schumpeter's theory, Walrasian equilibrium is not adequate to capture the key mechanisms of economic development. Schumpeter also thought that the institution enabling the entrepreneur to buy the resources needed to realize his vision was a well-developed capitalist financial system, including a whole range of institutions for granting credit. One could divide economists among (1) those who emphasized "real" analysis and regarded money as merely a "veil" and (2) those who thought monetary institutions are important and money could be a separate driving force. Both Schumpeter and Keynes were among the latter.[31] |

キャリア 影響 シュンペーターのダイナミックで変化を志向し、イノベーションに基づく経済学の源は、経済学の歴史学派であった。彼の著作はその視点に対して批判的である 可能性もあるが、イノベーションと起業家精神の役割に関するシュンペーターの研究は、歴史学派、特にグスタフ・フォン・シュモラーとヴェルナー・ソンバー トの研究によって生み出されたアイデアの継続とみなすことができる[19][20]。オーストリアで生まれ、同じ経済学者の多くとともに訓練を受けたにも かかわらず、大きな資格なしに彼をオーストリア学派の経済学に分類することはできないと主張する者もいれば[21]、その反対を主張する者もいる [22]。 オーストリアの社会学者ルドルフ・ゴールドシャイトの財政社会学の概念は、シュンペーターの租税国家の分析に影響を与えた[23]。2012年の論文で は、シュンペーターの著作がフランシス・ガルトンの著作の影響を示していることが示されている[24]。 進化経済学 主な記事 進化経済学 クリストファー・フリーマン(2009年)によれば、「彼のライフワーク全体の中心点は、資本主義は継続的な革新と『創造的破壊』の進化過程としてしか理 解できないということである」[25]。 経済分析の歴史 シュンペーターの学識は、遺著となった『経済分析史』において明らかであり[26]、シュンペーターは、18世紀最大の経済学者はアダム・スミスよりもむ しろテュルゴーであると考え、レオン・ワラスを「すべての経済学者の中で最も偉大な人物」とみなし、他の経済学者の理論は「ワラス的真理の特定の側面を捉 えようとする不十分な試みのようなもの」であるとした[27]。シュンペーターによれば、リカルドもケインズも抽象的なモデルで推論しており、そこではい くつかの変数を除いてすべてを凍結していた。そうすれば、単純な単調変化で一方が他方を引き起こすと主張することができた。このため、高度に抽象的な理論 モデルから直接的に政策的結論を導き出すことは容易であると信じられていた。 この本の中で、ジョセフ・シュンペーターは、不換紙幣本位制と比較した金本位制の意味を認識した。経済分析の歴史』の中で、シュンペーターは次のように述 べている: 自動的な "金通貨は自由放任・自由貿易経済の一部であり、一部である。それは、すべての国の貨幣レートと物価水準を、『金を使っている』他のすべての国の貨幣レー トと物価水準と結びつけるものである。しかし、金は政府の支出や、支出を直接伴わない態度や政策、たとえば外交政策やある種の課税政策、そして一般的に は、まさに[古典的な]自由主義の原則に反するすべての政策にさえ、きわめて敏感である。これが、金が現在これほど不人気である理由であり、また、金がブ ルジョア時代にこれほど人気であった理由でもある」[28]。 景気循環 シュンペーターと他の経済学者の思想との関係は、彼の経済分析への最も重要な貢献である景気循環と発展の理論において非常に複雑であった。ワラスにもケイ ンズにも従わず、シュンペーターは『経済発展の理論』[29]において、イノベーションと革新的活動を排除して定常状態に至る循環流の論考から始めてい る。シュンペーターによれば、この定常状態はワルラス均衡によって説明される。シュンペーターの物語の主人公は企業家である。 企業家はこの均衡を乱し、経済発展の主因となる。経済発展は、いくつかの時間スケールで循環的に進行する。シュンペーターは、イノベーション、サイクル、 発展を結びつけるこの理論を構築する際、ロシアのニコライ・コンドラチエフの50年サイクル、コンドラチエフ波に関する考えを生かした。 シュンペーターは、コンドラチエフ(54年)、クズネッツ(18年)、ジュグラー(9年)、キチン(約4年)の4つの主要サイクルを足し合わせて複合波形 を形成するモデルを提案した。コンドラチエフ波は3つの低次のクズネッツ波から構成される可能性がある[30]。各クズネッツ波はそれ自体、2つのジュグ ラー波から構成される可能性がある。同様に、2つ(または3つ)のキチン波がより高次のジュグラー波を形成することもできる。さらに重要なことは、それぞ れの下降弧が同時であり、それぞれの直下点が一致するのであれば、悲惨なスランプとそれに伴う不況を説明することができる。コンドラチエフの波の区分に関 しては、シュンペーターはそのような固定的なモデルを提案したことはない。シュンペーターは、これらのサイクルが時間的に変化し、偶然の一致によってタイ トな時間枠に収まるものの、それぞれが特定の目的を果たすと考えたのである。 提案された経済の波 サイクル/波の名称 期間(年) キチン・サイクル(在庫、例えば豚肉サイクル) 3-5 ジュグラー・サイクル(固定投資) 7-11 クズネッツの波(インフラ投資) 15-25 コンドラチエフの波(技術基盤) 45-60 このボックス: viewtalkedit ケインズ主義 シュンペーターの理論では、ワルラス均衡は経済発展の重要なメカニズムを捉えるには不十分である。シュンペーターはまた、起業家がビジョンを実現するため に必要な資源を購入することを可能にする制度は、信用供与のためのあらゆる機関を含む、発達した資本主義金融システムであると考えた。経済学者は、(1) 「実物」分析を重視し、貨幣を単なる「ベール」と見なす人々、(2)貨幣制度が重要であり、貨幣は別の原動力になりうると考える人々に分けることができ る。シュンペーターもケインズも後者の一人であった[31]。 |

| Demise of capitalism This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Joseph Schumpeter" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2019) (template removal help) Schumpeter's most popular book in English is probably Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. While he agrees with Karl Marx that capitalism will collapse and be replaced by socialism, Schumpeter predicts a different way this will come about. While Marx predicted that capitalism would be overthrown by a violent proletarian revolution, which actually occurred in the least capitalist countries, Schumpeter believed that capitalism would gradually weaken itself and eventually collapse. Specifically, the success of capitalism would lead to corporatism and to values hostile to capitalism, especially among intellectuals. "Intellectuals" are a social class in a position to critique societal matters for which they are not directly responsible and to stand up for the interests of other classes. Intellectuals tend to have a negative outlook on capitalism, even while relying on it for prestige because their professions rely on antagonism toward it. The growing number of people with higher education is a great advantage of capitalism, according to Schumpeter. Yet, unemployment and a lack of fulfilling work will lead to intellectual critique, discontent, and protests. Parliaments will increasingly elect social democratic parties, and democratic majorities will vote for restrictions on entrepreneurship. Increasing workers' self-management, industrial democracy and regulatory institutions would evolve non-politically into "liberal capitalism". Thus, the intellectual and social climate needed for thriving entrepreneurship will be replaced by some form of "laborism". This will exacerbate "creative destruction" (a borrowed phrase to denote an endogenous replacement of old ways of doing things by new ways), which will ultimately undermine and destroy the capitalist structure. Schumpeter emphasizes throughout this book that he is analyzing trends, not engaging in political advocacy.[32] William Fellner, in the book Schumpeter's Vision: Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy After 40 Years, noted that Schumpeter saw any political system in which the power was fully monopolized as fascist.[33] Democratic theory In the same book, Schumpeter expounded on a theory of democracy that sought to challenge what he called the "classical doctrine". He disputed the idea that democracy was a process by which the electorate identified the common good, and politicians carried this out for them. He argued this was unrealistic, and that people's ignorance and superficiality meant that in fact they were largely manipulated by politicians, who set the agenda. Furthermore, he claimed that even if the common good was possible to find, it would still not make clear the means needed to reach its end, since citizens do not have the requisite knowledge to design government policy.[34] This made a 'rule by the people' concept both unlikely and undesirable. Instead, he advocated a minimalist model, much influenced by Max Weber, whereby democracy is the mechanism for competition between leaders, much like a market structure. Although periodic votes by the general public legitimize governments and keep them accountable, the policy program is very much seen as their own and not that of the people, and the participatory role of individuals is usually severely limited. Schumpeter defined democracy as the method by which people elect representatives in competitive elections to carry out their will.[35] This definition has been described as simple, elegant and parsimonious, making it clearer to distinguish political systems that either fulfill or fail these characteristics.[36] This minimalist definition stands in contrast to broader definitions of democracy, which may emphasize aspects such as "representation, accountability, equality, participation, justice, dignity, rationality, security, freedom".[35] Within such a minimalist definition, states which other scholars say have experienced democratic backsliding and which lack civil liberties, a free press, the rule of law and a constrained executive, would still be considered democracies.[36][37][38] For Schumpeter, the formation of a government is the endpoint of the democratic process, which means that for the purposes of his democratic theory, he has no comment on what kinds of decisions that the government can take to be a democracy.[39] Schumpeter faced pushback on his theory from other democratic theorists, such as Robert Dahl, who argued that there is more to democracy than simply the formation of government through competitive elections.[39] Schumpeter's view of democracy has been described as "elitist", as he criticizes the rationality and knowledge of voters, and expresses a preference for politicians making decisions.[40][41][42] Democracy is therefore in a sense a means to ensure circulation among elites.[41] However, studies by Natasha Piano (of the University of Chicago) emphasize that Schumpeter had substantial disdain for elites as well.[40][43] Entrepreneurship Schumpeter was probably the first scholar to theorize about entrepreneurship, and the field owed much to his contributions. His fundamental theories are often referred to[44] as Mark I and Mark II. In Mark I, Schumpeter argued that the innovation and technological change of a nation come from entrepreneurs or wild spirits. He coined the word Unternehmergeist, German for "entrepreneur-spirit", and asserted that "... the doing of new things or the doing of things that are already being done in a new way"[45] stemmed directly from the efforts of entrepreneurs. Schumpeter developed Mark II while a professor at Harvard. Many social economists and popular authors of the day argued that large businesses had a negative effect on the standard of living of ordinary people. Contrary to this prevailing opinion, Schumpeter argued that the agents that drive innovation and the economy are large companies that have the capital to invest in research and development of new products and services and to deliver them to customers more cheaply, thus raising their standard of living. In one of his seminal works, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, Schumpeter wrote: As soon as we go into details and inquire into the individual items in which progress was most conspicuous, the trail leads not to the doors of those firms that work under conditions of comparatively free competition but precisely to the door of the large concerns – which, as in the case of agricultural machinery, also account for much of the progress in the competitive sector – and a shocking suspicion dawns upon us that big business may have had more to do with creating that standard of life than with keeping it down.[46] As of 2017 Mark I and Mark II arguments are considered complementary.[44] Cycles and long wave theory Schumpeter was the most influential thinker to argue that long cycles are caused by innovation and are an incident of it. His treatise on how business cycles developed were based on Kondratiev's ideas which attributed the causes very differently. Schumpeter's treatise brought Kondratiev's ideas to the attention of English-speaking economists. Kondratiev fused important elements that Schumpeter missed. Yet, the Schumpeterian variant of the long-cycles hypothesis, stressing the initiating role of innovations, commands the widest attention today.[47] In Schumpeter's view, technological innovation is the cause of both cyclical instability and economic growth. Fluctuations in innovation cause fluctuations in investment and those cause cycles in economic growth. Schumpeter sees innovations as clustering around certain points in time periods that he refers to as "neighborhoods of equilibrium", when entrepreneurs perceive that risk and returns warrant innovative commitments. These clusters lead to long cycles by generating periods of acceleration in aggregate growth.[48] The technological view of change needs to demonstrate that changes in the rate of innovation govern changes in the rate of new investments and that the combined impact of innovation clusters takes the form of fluctuation in aggregate output or employment. The process of technological innovation involves extremely complex relations among a set of key variables: inventions, innovations, diffusion paths, and investment activities. The impact of technological innovation on aggregate output is mediated through a succession of relationships that have yet to be explored systematically in the context of the long wave. New inventions are typically primitive, their performance is usually poorer than existing technologies and the cost of their production is high. A production technology may not yet exist, as is often the case in major chemical and pharmaceutical inventions. The speed with which inventions are transformed into innovations and diffused depends on the actual and expected trajectory of performance improvement and cost reduction.[49] Innovation Schumpeter identified innovation as the critical dimension of economic change.[50] He argued that economic change revolves around innovation, entrepreneurial activities, and market power.[51] He sought to prove that innovation-originated market power can provide better results than the invisible hand and price competition.[52] He argued that technological innovation often creates temporary monopolies, allowing abnormal profits that would soon be competed away by rivals and imitators. These temporary monopolies were necessary to provide the incentive for firms to develop new products and processes.[50] Doing Business The World Bank's "Doing Business" report was influenced by Schumpeter's focus on removing impediments to creative destruction. The creation of the report is credited in part to his work. |

資本主義の終焉 このセクションの検証には追加の引用が必要です。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力ください。ソースの ないものは異議申し立てがなされ、削除される可能性があります。 出典を探す "Joseph Schumpeter" - news - newspapers - books - scholar - JSTOR (February 2019) (テンプレート削除ヘルプ) シュンペーターの英語で最も人気のある著書は、おそらく『資本主義、社会主義、民主主義』であろう。資本主義が崩壊し、社会主義に取って代わられるという 点ではカール・マルクスと同意見であるが、シュンペーターはこれが実現する別の方法を予測している。マルクスが、資本主義は暴力的なプロレタリア革命に よって打倒されると予言し、実際に資本主義の最も弱い国々でそれが起こったのに対し、シュンペーターは、資本主義は徐々に弱体化し、最終的には崩壊すると 考えた。具体的には、資本主義の成功はコーポラティズムをもたらし、特に知識人の間では資本主義に敵対する価値観が生まれるとした。 「知識人」とは、自分が直接責任を負っていない社会問題を批判し、他の階級の利益のために立ち上がる立場にある社会階級である。知識人は資本主義に対して 否定的な見方をする傾向があるが、彼らの職業は資本主義への反感に依存しているため、名声のために資本主義に依存している。シュンペーターによれば、高等 教育を受ける人々の増加は資本主義の大きな利点である。しかし、失業や充実した仕事の欠如は、知的批判や不満、抗議行動を引き起こすだろう。 議会はますます社会民主主義政党を選ぶようになり、民主的多数派は起業家精神の制限に投票するだろう。労働者の自主管理の拡大、産業民主主義、規制制度 は、非政治的に「自由資本主義」へと進化していくだろう。こうして、起業家精神の繁栄に必要な知的・社会的風土は、ある種の「労働主義」に取って代わられ るだろう。これは「創造的破壊」(古いやり方が新しいやり方によって内生的に取って代わられることを示す借用語)を悪化させ、最終的には資本主義構造を弱 体化させ、破壊することになる。 シュンペーターは本書を通じて、自分が政治的主張を行っているのではなく、傾向を分析していることを強調している[32]。 ウィリアム・フェルナーは、『シュンペーターのビジョン』という本の中で、次のように述べている: 資本主義、社会主義、そして40年後の民主主義』の中でウィリアム・フェルナーは、シュンペーターは権力が完全に独占された政治体制をファシストと見なし ていると指摘している[33]。 民主主義理論 同書でシュンペーターは、「古典的教義」と呼ばれるものに異議を唱えようとする民主主義論を展開した。シュンペーターは、民主主義とは選挙民が共通善を特 定し、政治家がそれを選挙民のために実行するというプロセスであるという考えに異議を唱えた。彼は、これは非現実的であり、人々の無知と表面的なものは、 実際には政治家によって大きく操作され、政治家がアジェンダを設定することを意味すると主張した。さらに彼は、たとえ共通善を見出すことが可能であったと しても、市民は政府の政策を設計するのに必要な知識を持っていないため、その目的を達成するために必要な手段を明確にすることはできないと主張した [34]。その代わりに、彼はマックス・ウェーバーの影響を強く受けたミニマリスト・モデルを提唱し、そこでは民主主義が市場構造のような指導者間の競争 のメカニズムとなっている。一般市民による定期的な投票が政府を正統化し、説明責任を果たさせるが、政策プログラムは国民のものではなく、彼ら自身のもの と見なされることが非常に多く、個人の参加的役割は通常厳しく制限される。 シュンペーターは民主主義を、人々が競争的な選挙で代表者を選出し、彼らの意思を実行させる方法であると定義した[35]。この定義は、シンプル、エレガ ント、かつ簡潔であると評され、これらの特徴を満たす政治体制と満たさない政治体制を区別することを明確にしている[36]。このミニマリスト的定義は、 「代表、説明責任、平等、参加、正義、尊厳、合理性、安全、自由」といった側面を強調する可能性のある、より広範な民主主義の定義とは対照的である。 [35]このようなミニマリスト的定義の中では、他の学者が民主主義の後退を経験し、市民的自由、自由な報道、法の支配、制約された行政を欠いていると言 う国家も、依然として民主主義国家とみなされることになる。 [36][37][38]シュンペーターにとって、政府の形成は民主主義プロセスの終着点であり、彼の民主主義理論の目的上、政府がどのような決定を下す ことが民主主義であるのかについて彼は何もコメントしないことを意味する[39]。 シュンペーターは、民主主義には単に競争的な選挙を通じて政府が形成される以上のものがあると主張するロバート・ダールなどの他の民主主義理論家からの彼 の理論に対する反発に直面していた[39]。 シュンペーターの民主主義観は、有権者の合理性や知識を批判し、政治家が意思決定を行うことを好むことを表明していることから、「エリート主義的」と評さ れている[40][41][42]。 したがって、民主主義はある意味でエリート間の循環を確保するための手段である[41]。 しかし、ナターシャ・ピアノ(シカゴ大学)の研究は、シュンペーターがエリートに対しても実質的な軽蔑を抱いていたことを強調している[40][43]。 企業家精神 シュンペーターはおそらく起業家精神について理論化した最初の学者であり、この分野は彼の貢献に負うところが大きい。彼の基本理論はしばしばマークIと マークIIと呼ばれる[44]。シュンペーターは、マークI において、国家の革 新と技術革新は起業家や野生の精神から生まれると主張した。彼は、ドイツ語で「企業家精神」を意味するウンターンマーガイストという言葉を 作り、「...新しいことを行うこと、あるいはすでに行われていることを新しい方法 で行うこと」[45]は、企業家の努力から直接的に生じると主張した。 シュンペーターはハーバード大学教授時代にマーク II を開発した。当時の社会経済学者や人気作家の多くは、大企業は一般庶民の生活水準に悪影響を及ぼすと主張していた。このような一般的な意見に反して、シュンペーターは、イノベーションと経済を牽引する主体は、新しい製品やサービスの研究開発に 投資し、より安く顧客に提供する資本を持つ大企業であり、その結果、顧客の生活水準が向上すると主張した。シュンペーターは、代表作のひと つである『資本主義、社会主義、民主主義』の中で、次のように書いている: 進歩が最も顕著であった個々の品目について詳細に調べるとすぐに、その足跡は比較的自由な競争条件の下で働く企業の扉ではなく、まさに大企業の扉に通じて いる--農業機械の場合のように、大企業もまた競争部門における進歩の多くを占めている--。 2017年現在、マークIとマークIIの議論は補完的であると考えられている[44]。 サイクルと長波理論 シュンペーターは、長いサイクルはイノベーションによって引き起こされ、イノベーションの付随物であると主張した最も影響力のある思想家であった。景気循 環がどのように発展するかについての彼の論考は、コンドラチエフの考えに基づくものであったが、その原因は全く異なるものであった。シュンペーターの論文 は、コンドラチエフの考えを英語圏の経済学者に注目させた。コンドラチエフは、シュンペーターが見逃した重要な要素を融合させた。シュンペーターの見解で は、技術革新は循環的不安定性と経済成長の両方の原因である。技術革新の変動が投資の変動を引き起こし、それが経済成長のサイクルを引き起こす。シュン ペーターは、起業家がリスクとリターンが革新的なコミットメントを正当化すると認識する時、技術革新は「均衡の近隣」と呼ばれる特定の時点に集中すると見 ている。こうしたクラスターは、総成長の加速期を生み出すことで、長いサイクルにつながる[48]。 変化に関する技術的な見方は、イノベーション率の変化が新規投資率の変化を支配し、イノベーショ ンクラスターの複合的な影響が総生産や雇用の変動という形で現れることを実証する必要が ある。技術革新のプロセスには、発明、イノベーション、普及経路、投資活動といった一連の重要な変数間の極めて複雑な関係が含まれる。技術革新が総生産に 与える影響は、長波の文脈ではまだ体系的に検討されていない一連の関係を通じて媒介される。新しい発明は一般的に原始的であり、その性能は既存の技術より も劣り、その生産コストは高い。主要な化学薬品や医薬品の発明によく見られるように、生産技術がまだ存在していない場合もある。発明がイノベーションに変 化し、普及するスピードは、性能向上とコスト削減の実際と予想される軌跡に依存する[49]。 イノベーション. シュンペーターは、イノベーションを経済変動の重要な次元と位置づ けた[50]。 彼は、経済変動はイノベーション、起業家的活動、 市場力を中心に展開すると主張した[51]。彼は、イノベーションに 起因する市場力が、見えざる手や価格競争よりも優れた結果をもたらすことを証明しようとした[52]。このような一時的独占は、企業が新しい製品やプロセ スを開発するインセンティブを提供するために必要であった[50]。 ビジネス 世界銀行の「Doing Business」報告書は、創造的破壊の阻害要因を取り除くことに焦点を当てたシュンペーターの影響を受けている。この報告書が作成されたのも、シュン ペーターの功績によるところが大きい。 |

| Personal life Schumpeter was married three times.[53] His first wife was Gladys Ricarde Seaver, an Englishwoman nearly 12 years his senior (married 1907, separated 1913, divorced 1925). His best man at his wedding was his friend and Austrian jurist Hans Kelsen. His second was Anna Reisinger, 20 years his junior and daughter of the concierge of the apartment where he grew up. As a divorced man, he and his bride converted to Lutheranism to marry.[54] They married in 1925, but within a year, she died in childbirth. The loss of his wife and newborn son came only weeks after Schumpeter's mother had died. Five years after arriving to the US, in 1937, at the age of 54, Schumpeter married the American economic historian Dr. Elizabeth Boody (1898–1953), who helped him popularize his work and edited what became their magnum opus, the posthumously published History of Economic Analysis.[55] Elizabeth assisted him with his research and English writing until his death.[56] Schumpeter claimed that he had set himself three goals in life: to be the greatest economist in the world, to be the best horseman in all of Austria, and the greatest lover in all of Vienna. He said he had reached two of his goals, but he never said which two,[57][58] although he is reported to have said that there were too many fine horsemen in Austria for him to succeed in all his aspirations.[59][60] Later life and death Schumpeter died in his home in Taconic, Connecticut, at the age of 66, on the night of January 7, 1950.[61] |

私生活 シュンペーターは3度結婚している[53]。最初の妻は12歳近く年上のイギリス人女性グラディス・リカード・シーヴァー(1907年結婚、1913年別 居、1925年離婚)。結婚式のベストマンは友人でオーストリアの法学者ハンス・ケルゼンだった。2人目は20歳年下のアンナ・ライジンガーで、彼が育っ たアパートのコンシェルジュの娘だった。1925年に結婚したが、1年も経たないうちに彼女は出産で亡くなった。妻と生まれたばかりの息子を失ったのは、 シュンペーターの母親が亡くなったわずか数週間後のことだった。アメリカに渡って5年後の1937年、54歳のとき、シュンペーターはアメリカの経済史家 エリザベス・ブーディ博士(1898-1953)と結婚し、彼女はシュンペーターの研究を世に広める手助けをし、死後に出版された彼らの大著となった『経 済分析史』を編集した[55]。 シュンペーターは、世界最高の経済学者になること、オーストリア一の馬術家になること、そしてウィーン一の恋人になることである。彼はそのうちの2つの目 標を達成したと語ったが、どの2つかは明言しなかった[57][58]。ただし、彼がすべての願望を成功させるためにはオーストリアには優秀な騎手が多す ぎると語ったと伝えられている[59][60]。 その後の人生と死 シュンペーターは1950年1月7日の夜、コネチカット州タコニックの自宅で66歳の生涯を閉じた[61]。 |

| Legacy For some time after his death, Schumpeter's views were most influential among various heterodox economists, especially Europeans, who were interested in industrial organization, evolutionary theory, and economic development, and who tended to be on the other end of the political spectrum from Schumpeter and were also often influenced by Keynes, Karl Marx, and Thorstein Veblen. Robert Heilbroner was one of Schumpeter's most renowned pupils, who wrote extensively about him in The Worldly Philosophers. In the journal Monthly Review, John Bellamy Foster wrote of that journal's founder Paul Sweezy, one of the leading Marxist economists in the United States and a graduate assistant of Schumpeter's at Harvard, that Schumpeter "played a formative role in his development as a thinker".[62] Other outstanding students of Schumpeter's include the economists Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen and Hyman Minsky and John Kenneth Galbraith and former chairman of the Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan.[63] Future Nobel Laureate Robert Solow was his student at Harvard, and he expanded on Schumpeter's theory.[64] Today, Schumpeter has a following outside standard textbook economics, in areas such as economic policy, management studies, industrial policy, and the study of innovation. Schumpeter was probably the first scholar to develop theories about entrepreneurship. For instance, the European Union's innovation program, and its main development plan, the Lisbon Strategy, are influenced by Schumpeter. The International Joseph A. Schumpeter Society awards the Schumpeter Prize. The Schumpeter School of Business and Economics opened in October 2008 at the University of Wuppertal, Germany. According to University President Professor Lambert T. Koch, "Schumpeter will not only be the name of the Faculty of Management and Economics, but this is also a research and teaching programme related to Joseph A. Schumpeter."[65] On September 17, 2009, The Economist inaugurated a column on business and management named "Schumpeter".[66] The publication has a history of naming columns after significant figures or symbols in the covered field, including naming its British affairs column after former editor Walter Bagehot and its European affairs column after Charlemagne. The initial Schumpeter column praised him as a "champion of innovation and entrepreneurship" whose writing showed an understanding of the benefits and dangers of business that proved to be far ahead of its time.[66] Schumpeter's thoughts inspired the economic theory of Adam Przeworski.[67] |

遺産 シュンペーターの死後しばらくの間、シュンペーターの見解は、さまざまな異端派経済学者、特に産業組織、進化論、経済発展に関心を持ち、シュンペーターと は政治的に対極に位置し、ケインズ、カール・マルクス、ソーシュタイン・ヴェブレンからもしばしば影響を受けたヨーロッパ人の間で最も大きな影響力を持っ た。ロバート・ハイルブローナーはシュンペーターの最も有名な弟子の一人で、『世俗の哲学者たち』の中でシュンペーターについて幅広く書いている。ジョ ン・ベラミー・フォスターは『マンスリー・レビュー』誌で、同誌の創刊者であり、ハーバード大学でシュンペーターの大学院生助手を務めた米国を代表するマ ルクス主義経済学者の一人であるポール・スウィージーについて、シュンペーターは「彼の思想家としての成長に形成的な役割を果たした」と書いている [62]。 [シュンペーターの他の優れた教え子には、経済学者のニコラス・ゲオルゲスク=ローゲン、ハイマン・ミンスキー、ジョン・ケネス・ガルブレイス、連邦準備 制度理事会前議長のアラン・グリーンスパンなどがいる[63]。後のノーベル賞受賞者ロバート・ソローはハーバード大学の教え子で、シュンペーターの理論 を発展させた[64]。 今日、シュンペーターは、経済政策、経営学、産業政策、イノベーション研究などの分野で、標準的な教科書の経済学以外の分野でも支持されている。シュン ペーターはおそらく、起業家精神に関する理論を展開した最初の学者である。例えば、欧州連合のイノベーション・プログラムやその主要な開発計画であるリス ボン戦略は、シュンペーターの影響を受けている。国際ジョセフ・A・シュンペーター協会は、シュンペーター賞を授与している。 2008年10月、ドイツのヴッパタール大学にシュンペーター・スクール・オブ・ビジネス&エコノミクスが開校した。同大学学長のランバート・T・コッホ 教授によると、「シュンペーターは経営経済学部の名称であるだけでなく、これはヨーゼフ・A・シュンペーターに関連する研究・教育プログラムでもある」 [65]。 2009年9月17日、『エコノミスト』誌は、ビジネスと経営に関するコラムに「シュンペーター」と名付けた[66]。同誌は、イギリス問題コラムに元編 集者のウォルター・バゲホーの名前を、ヨーロッパ問題コラムにシャルルマーニュの名前を付けるなど、対象分野の重要人物や象徴にちなんだコラム名を付けて きた歴史がある。最初のシュンペーターのコラムでは、「イノベーションと起業家精神の擁護者」として賞賛され、その文章はビジネスの利益と危険性について の理解を示し、時代をはるかに先取りしていることが証明された[66]。 シュンペーターの考えは、アダム・プシェヴォルスキーの経済理論に影響を与えた[67]。 |

| Books Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1906). Über die mathematische Methode der theoretischen Ökonomie. Zeitschrift für Volkswirtschaft, Sozialpolitik und Verwaltung. Germany: Wien. OCLC 809174553. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1907). Das Rentenprinzip in der Verteilungslehre. Germany: Jahrbuch für Gesetzgebung, Verwaltung and Volkswirtschaft im Deutschen Reich. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1908). Das Wesen und der Hauptinhalt der theoretischen Nationalökonomie. Germany: Leipzig, Duncker & Humblot. OCLC 5455469. Translated as: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (2010). The nature and essence of economic theory. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1412811507. Translated by: Bruce A. McDaniel Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1908). Methodological Individualism. Germany. OCLC 5455469. Pdf of preface by F.A. Hayek and first eight pages. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1909). Bemerkungen über das Zurechnungsproblem. Zeitschrift für Wolkswirtschaft, Sozialpolitik und Verwaltung. Germany: Wien. OCLC 49426617. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1910). Marie Ésprit Léon Walras. Germany: Zeitschrift für Wolkswirtschaft, Sozialpolitik und Verwaltung. OCLC 64863803. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1910). Über das Wesen der Wirtschaftskrisen. Zeitschrift für Wolkswirtschaft, Sozialpolitik und Verwaltung. Germany: Wien. OCLC 64863847. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1915). Wie studiert man Sozialwissenschaft. Schriften des Sozialwissenschaftlichen Akademischen Vereins in Czernowitz, Heft II. München und Leipzig, Germany: Duncker & Humblot. OCLC 11387887. Schumpeter, Joseph A.; Opie, Redvers (1983) [1934]. The theory of economic development: an inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Books. ISBN 978-0878556984. Translated from the 1911 original German, Theorie der wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1954). Economic doctrine and method: an historical sketch. Translated by Aris, Reinhold. New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 504289265. Translated from the 1912 original German, Epochen der dogmen – und Methodengeschichte. Pdf version. Reprinted in hardback as: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (2011). Economic doctrine and method: an historical sketch. Translated by Aris, Reinhold. Whitefish Montana: Literary Licensing. ISBN 978-1258003425. Reprinted in paperback as: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (2012). Economic doctrine and method: an historical sketch. Translated by Aris, Reinhold. Mansfield Centre, Connecticut: Martino Fine Books. ISBN 978-1614273370. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1914). Das wissenschaftliche lebenswerk eugen von böhm-bawerks. Zeitschrift für Wolkswritschaft, Sozialpolitik und Verwaltung. Germany: Wien. OCLC 504214232. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1915). Vergangenheit und Zukunft der Sozialwissenschaft. Germany: München und Leipzig, Duncker & Humblot. Reprinted by the University of Michigan Library Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1918). The crisis of the tax state. OCLC 848977535. Reprinted as: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1991), "The crisis of the tax state", in Swedberg, Richard (ed.), The economics and sociology of capitalism, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, pp. 99–140, ISBN 978-0691003832 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1919). The sociology of imperialisms. Germany: Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik. Reprinted as Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1989) [1951]. Sweezy, Paul M. (ed.). Imperialism and social classes. Fairfield, New Jersey: Augustus M. Kelley. ISBN 978-0678000205. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1920). Max Weber's work. Germany: Der österreichische Volkswirt. Reprinted as: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1991), "Max Weber's work", in Swedberg, Richard (ed.), The economics and sociology of capitalism, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, pp. 220–229, ISBN 978-0691003832 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1921). Carl Menger. Zeitschrift für Wolkswritschaft, Sozialpolitik und Verwaltung. Germany: Wien. OCLC 809174610. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1927). Social classes in an ethnically homogeneous environment. Germany: Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik. OCLC 232481. Reprinted as: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1989) [1951]. Sweezy, Paul M. (ed.). Imperialism and social classes. Fairfield, New Jersey: Augustus M. Kelley. ISBN 978-0678000205. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1928). Das deutsche finanzproblem. Schriftenreihe d. dt. Volkswirt. Berlin, Germany: Dt. Volkswirt. OCLC 49426617. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1934), "Depressions: Can we learn from past experience?", in Schumpeter, Joseph A.; Chamberlin, Edward; Leontief, Wassily W.; Brown, Douglass V.; Harris, Seymour E.; Mason, Edward S.; Taylor, Overton H. (eds.), The economics of the recovery program, New York City London: McGraw-Hill, OCLC 1555914 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1934), "The nature and necessity of a price system", in Harris, Seymour E.; Bernstein, Edward M. (eds.), Economic reconstruction, New York City London: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-1258305727, OCLC 331342 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1936), "Professor Taussig on wages and capital", in Taussig, Frank W. (ed.), Explorations in economics: notes and essays contributed in honor of F.W. Taussig, New York City: McGraw-Hill, pp. 213–222, ISBN 978-0836904352 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (2006) [1939]. Business cycles: a theoretical, historical, and statistical analysis of the capitalist process. Mansfield Centre, Connecticut: Martino Publishing. ISBN 978-1578985562. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (2014) [1942]. Capitalism, socialism and democracy (2nd ed.). Floyd, Virginia: Impact Books. ISBN 978-1617208652. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1943), "Capitalism in the postwar world", in Harris, Seymour E. (ed.), Postwar economic problems, New York City London: McGraw-Hill, OCLC 730387 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1946), "The future of private enterprise in the face of modern socialistic tendencies", in Conference, Papers (ed.), The economics and sociology of capitalism (ESC) Comment sauvegarder l'entreprise privée (conference papers), Montreal: Association Professionnelle des Industriels, pp. 401–405, OCLC 796197764 See also the English translation: Henderson, David R.; Prime, Michael G. (Fall 1975). "Schumpeter on preserving private enterprise". History of Political Economy. 7 (3): 293–298. doi:10.1215/00182702-7-3-293. Schumpeter, Joseph A.; Crum, William Leonard (1946). Rudimentary mathematics for economists and statisticians. New York City London: McGraw-Hill. OCLC 1246233. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1946), "Capitalism", in Bento, William (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, Chicago: University of Chicago Schumpeter, Joseph A. (2009) [1948], "There is still time to stop inflation", in Clemence, Richard V. (ed.), Essays: on entrepreneurs, innovations, business cycles, and the evolution of capitalism, Nation's business, vol. 1, New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Books, pp. 241–252, ISBN 978-1412822749 Originally printed as: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (June 1948). "There is still time to stop inflation". The Nation's Business. United States Chamber of Commerce. 6: 33–35, 88–91. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1949), "Economic theory and entrepreneurial history", in Wohl, R. R. (ed.), Change and the entrepreneur: postulates and the patterns for entrepreneurial history, Research Center in Entrepreneurial History, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, OCLC 2030659 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1949), "The historical approach to the analysis of business cycles", in National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Conference (ed.), NBER Conference on Business Cycle Research, Chicago: University of Chicago Press Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1951). Ten great economists: from Marx to Keynes. New York Oxford: Oxford University Press. OCLC 166951. Reprinted as: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1965). Ten great economists: from Marx to Keynes. New York Oxford: Oxford University Press. OCLC 894563181. Reprinted as: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1997). Ten great economists: from Marx to Keynes. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415110785. Reprinted as: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (2003). Ten great economists: from Marx to Keynes. San Diego: Simon Publications. ISBN 978-1932512090. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1969) [1951]. Clemence, Richard V. (ed.). Essays on economic topics of J.A. Schumpeter. Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press. ISBN 978-0804605854. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1954). History of economic analysis. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0415108881. Edited from a manuscript by Elizabeth Boody Schumpeter. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1989) [1951]. Sweezy, Paul M. (ed.). Imperialism and social classes. Fairfield, New Jersey: Augustus M. Kelley. ISBN 978-0678000205. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (2014). Mann, Fritz Karl (ed.). Treatise on money [also called Money & Currency]. Translated by Alvarado, Ruben. Aalten, the Netherlands: Wordbridge Publishing. ISBN 978-9076660363. Originally printed as: Schumpeter, Joseph (1970). Das wesen des geldes. Neuauflage, Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3525131213. Reprinted in 2008. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1991). Swedberg, Richard (ed.). The economics and sociology of capitalism. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691003832. |

著書 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1906). Uber die mathematische Methode der theoretischen Ökonomie. Zeitschrift für Volkswirtschaft, Sozialpolitik und Verwaltung. ドイツ: Wien. oclc 809174553. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1907). Das Rentenprinzip in der Verteilungslehre. ドイツ: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1907). Johrbuch für Gesetzgebung, Verwaltung and Volkswirtschaft im Deutschen Reich. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1908). Das Wesen und der Hauptinhalt der theoretischen Nationalökonomie. ドイツ: Leipzig, Duncker & Humblot. OCLC 5455469. として翻訳されている: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (2010). The nature and essence of economic theory. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1412811507. ブルース・A・マクダニエル ブルース・A・マクダニエル Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1908). Methodological Individualism. ドイツ。OCLC 5455469. F.A.ハイエクによる序文と最初の8ページのPDF。 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1909). Bemerkungen über das Zurechnungsproblem. Zeitschrift für Wolkswirtschaft, Sozialpolitik und Verwaltung. ドイツ: Wien. OCLC 49426617. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1910). Marie Ésprit Léon Walras. ドイツ: Zeitschrift für Wolkswirtschaft, Sozialpolitik und Verwaltung. OCLC 64863803. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1910). Über das Wesen der Wirtschaftskrisen. Zeitschrift für Wolkswirtschaft, Sozialpolitik und Verwaltung. ドイツ: Wien. OCLC 64863847. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1915). Wie studiert man Sozialwissenschaft. Schriften des Sozialwissenschaftlichen Akademischen Vereins in Czernowitz, Heft II. Schriften des Sozialwissenschaftlichen Akademischen Vereins in Czernowitz, Heft II: Duncker & Humblot. OCLC 11387887. Schumpeter, Joseph A.; Opie, Redvers (1983) [1934]. The theory of economic development: an inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Books. ISBN 978-0878556984. 1911年のドイツ語原著『Theorie der wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung』からの翻訳。 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1954). 経済学の教義と方法:歴史的スケッチ。Aris, Reinhold訳。ニューヨーク: Oxford University Press. OCLC 504289265. 1912年のドイツ語原著『Epochen der dogmen - und Methodengeschichte』を翻訳。Pdf版。 ハードカバーで再版された: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (2011). Economic doctrine and method: an historical sketch. Aris, Reinhold訳. Whitefish Montana: Literary Licensing. ISBN 978-1258003425. ペーパーバックとして再版された: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (2012). Economic doctrine and method: an historical sketch. Aris, Reinhold訳。Mansfield Centre, Connecticut: Martino Fine Books. ISBN 978-1614273370. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1914). Das wissenschaftliche lebenswerk eugen von böhm-bawerks. Zeitschrift für Wolkswritschaft, Sozialpolitik und Verwaltung. ドイツ: Wien. oclc 504214232. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1915). Vergenheit und Zukunft der Sozialwissenschaft. ドイツ: München und Leipzig, Duncker & Humblot. ミシガン大学図書館復刻版。 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1918). 租税国家の危機 OCLC 848977535. として再版された: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1991), 「The crisis of the tax state」, in Swedberg, Richard (ed.), The economics and sociology of capitalism, Princeton, New Jersey: プリンストン大学出版局、99-140頁、ISBN 978-0691003832 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1919). The sociology of imperialisms. ドイツ: Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1989) [1951]として再版された。Sweezy, Paul M. (ed.). Imperialism and social classes. Fairfield, New Jersey: Augustus M. Kelley. ISBN 978-0678000205. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1920). Max Weber's work. ドイツ: ドイツ:Der österreichische Volkswirt. として再版された: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1991), 「Max Weber's work」, in Swedberg, Richard (ed.), The economics and sociology of capitalism, Princeton, New Jersey: プリンストン大学出版局、220-229頁、ISBN 978-0691003832 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1921). Carl Menger. Zeitschrift für Wolkswritschaft, Sozialpolitik und Verwaltung. ドイツ: Wien. oclc 809174610. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1927). 民族的に均質な環境における社会階級. ドイツ: Schumpeter (1927). Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik. OCLC 232481. として再版された: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1989) [1951]. Sweezy, Paul M. (ed.). Imperialism and social classes. Fairfield, New Jersey: Augustus M. Kelley. ISBN 978-0678000205. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1928). Das deutsche finanzproblem. Schriftenreihe d. dt. Schriftenreihe d. dt. Volkswirt. Schriftenreihe d. dt. Volkswirt: Dt. Volkswirt. Volkswirt. OCLC 49426617. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1934), "Depressions: シュンペーター, ヨーゼフ A. (1934), 「Depressions: Can we learn from past experience?」, in Schumpeter, Joseph A.; Chamberlin, Edward; Leontief, Wassily W.; Brown, Douglass V.; Harris, Seymour E.; Mason, Edward S.; Taylor, Overton H. (eds.), The economics of the recovery program, New York City London: McGraw-Hill, OCLC 1555914 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1934), 「The nature and necessity of a price system」, in Harris, Seymour E.; Bernstein, Edward M. (eds.), Economic reconstruction, New York City London: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-1258305727, OCLC 331342 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1936), 「Professor Taussig on wages and capital」, in Taussig, Frank W. (ed.), Explorations in economics: notes and essays contributed in honor of F.W. Taussig, New York City: McGraw-Hill, pp.213-222, ISBN 978-0836904352. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (2006) [1939]. Business cycles: a theoretical, historical, and statistical analysis of the capitalist process. Mansfield Centre, Connecticut: Mansfield Centre, Connecticut: Martino Publishing. ISBN 978-1578985562. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (2014) [1942]. 資本主義、社会主義、民主主義(第2版). Floyd, Virginia: Impact Books. ISBN 978-1617208652. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1943), 「Capitalism in the postwar world」, in Harris, Seymour E. (ed.), Postwar economic problems, New York City London: McGraw-Hill, OCLC 730387. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1946), 「The future of private enterprise in the face of modern socialistic tendencies」, in Conference, Papers (ed.), The economics and sociology of capitalism (ESC) Comment sauvegarder l'entreprise privée (conference papers), Montreal: Association Professionnelle des Industriels, pp. 英訳も参照のこと: Henderson, David R.; Prime, Michael G. (Fall 1975). 「Schumpeter on preserving private enterprise」. History of Political Economy. 7 (3): 293–298. doi:10.1215/00182702-7-3-293. Schumpeter, Joseph A.; Crum, William Leonard (1946). 経済学者と統計学者のための初歩的数学. New York City London: McGraw-Hill. OCLC 1246233. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1946), 「Capitalism」, in Bento, William (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, Chicago: シカゴ大学 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (2009) [1948], 「There is still time to stop inflation」, in Clemence, Richard V. (ed.), Essays: on entrepreneurs, innovations, business cycles, and the evolution of capitalism, Nation's business, vol. 1, New Brunswick, New Jersey: トランザクション・ブックス、241-252頁、ISBN 978-1412822749 原著は以下の通り: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (June 1948). 「There is still time to stop inflation」. The Nation's Business. United States Chamber of Commerce. 6: 33-35, 88-91. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1949), 「Economic theory and entrepreneurial history」, in Wohl, R. R. (ed.), Change and the entrepreneur: postulates and the patterns for entrepreneurial history, Research Center in Entrepreneurial History, Cambridge, Massachusetts: ハーバード大学出版局, OCLC 2030659 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1949), 「The historical approach to the analysis of business cycles」, in National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Conference (ed.), NBER Conference on Business Cycle Research, Chicago: シカゴ大学出版局 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1951). Ten great economists: from Marx to Keynes. New York Oxford: オックスフォード大学出版局。OCLC 166951. として再版された: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1965). Ten great economists: from Marx to Keynes. ニューヨーク オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局。OCLC 894563181. として再版された: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1997). Ten great economists: from Marx to Keynes. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415110785. として再版された: Schumpeter, Joseph A. (2003). Ten great economists: from Marx to Keynes. サンディエゴ: Simon Publications. ISBN 978-1932512090. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1969) [1951]. Clemence, Richard V. (ed.). シュンペーター経済論集. Port Washington, New York: Kennikat Press. ISBN 978-0804605854. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1954). 経済分析の歴史. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0415108881. エリザベス・ブーディー・シュンペーターの原稿から編集。 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1989) [1951]. Sweezy, Paul M. (ed.). Imperialism and social classes. Fairfield, New Jersey: Augustus M. Kelley. ISBN 978-0678000205. Schumpeter, Joseph A. (2014). Mann, Fritz Karl (ed.). Treatise on money [Money & Currencyとも呼ばれる].アルバラード、ルーベン訳。Aalten, the Netherlands: Wordbridge Publishing. ISBN 978-9076660363. 原著は以下の通り: Schumpeter, Joseph (1970). Das wesen des geldes. Neuauflage, Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3525131213. 2008年再版。 Schumpeter, Joseph A. (1991). Swedberg, Richard (ed.). The economics and sociology of capitalism. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691003832. |

| List of Austrians Historical school of economics Lausanne School List of Austrian scientists The Gods of the Copybook Headings Social innovation Creative destruction Schumpeterian rent |

オーストリア人のリスト 経済学の歴史的学派 ローザンヌ学派 オーストリアの科学者一覧 コピー本の見出しの神々 社会的革新 創造的破壊 シュンペーター派のレント概念 |

| Schumpeterian

rents are earned by innovators and occur during the period of time

between the introduction of an innovation and its successful diffusion.

It is expected that successful innovations, in time, will be imitated,

but until that occurs, the innovator will earn Schumpeterian rents.

They were named after economist Joseph Schumpeter, who saw profits made

by businesses as resulting from the development of new processes which

disturb economic equilibrium, temporarily raising revenues above their

resource costs.[1] This type of profit is also called entrepreneurial

rent.[2] Schumpeterian rent is seen as a form of economic rent, although Schumpeterian rent may be seen as an incentive towards greater economic efficiency. Karl Marx In Marxian economics, the equivalent to Schumpeterian rent is the extra surplus value that is extracted from the laborer during the rise of local productivity, meaning the development of the productive forces through innovation owned by the respective capitalist, while all other enterprises are left with yet undeveloped productive forces. The result is the rise of the local rate of profit, as the respective commodity is now produced cheaper by this enterprise alone, yet can still be sold for its general market price. In Marxian theory, the earning of extra surplus value is what drives and guides the capitalist, and thus capitalism itself.[3] The value of the entrepreneurial rent and compensation for entrepreneurship Magnus Henrekson, professor of economics and president of the Research Institute of Industrial Economics (IFN) in Stockholm, wrote a paper about the value of entrepreneurial rent in 2017.[4] He wanted to show that entrepreneurship can be thoroughly analyzed by positing that entrepreneurs are searching for rates of return exceeding the risk-adjusted market rate of return. His main findings were that searching for and creating entrepreneurial rents gives rise to supernormal profits in short to medium term. But In the longer term, these rents are growing to society as cheaper and better products.[5] Entrepreneurial rents are crucial for innovation and development, which play the leading role in generating economic growth. |

シュ

ンペーター・レント(=シュンペーターの利潤・借料/借料による利潤)はイノベーターが獲得するもので、イノベーションの導入から普及が成功するまでの期

間に発生する。成功したイノベーションは、やがて模倣されることが期待されるが、それが起こるまでの間、イノベーターはシュンペーター・レ

ントから利益を得ることになる。シュンペーター・レントとは、経済学者ジョセフ・シュンペーターにちなんで命名されたもので、シュンペーターは、企業が利

益を得るのは、経済均衡を乱し、一時的に資源コスト以上の収益を上げる新しいプロセスを開発した結果であると考えた[1]。 シュンペーター・レントは経済的利潤の一形態とみなされているが、シュンペーターの利潤はより高い経済効率に向けたインセンティブとみなされることもあ る。 カール・マルクス マルクス経済学において、シュンペーター・レントに相当するものは、局所的生産性の上昇、すなわち、各資本家が所有する技術革新による生産力の発展の間 に、労働者から引き出される余剰価値である。その結果、それぞれの商品は、この企業だけによってより安く生産されるようになり、しかも一般市場価格で販売 されるようになるため、局所的利潤率が上昇する。マルクス理論では、余剰価値の獲得こそが資本家を、ひいては資本主義そのものを動かし、導くものである [3]。 企業家賃料(レント)の価値と企業家精神に対する報酬 ストックホルムの産業経済研究所(IFN)所長で経済学教授のマグヌス・ヘンレクソンは、2017年に起業家賃料の価値について論文を書いた[4]。彼の 主な発見は、起業家的レントを探し、創造することは、短期から中期にかけては超正常的な利益を生むということであった。起業家的レントは、イノベーション と発展にとって極めて重要であり、経済成長の主役となる。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Schumpeter |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆