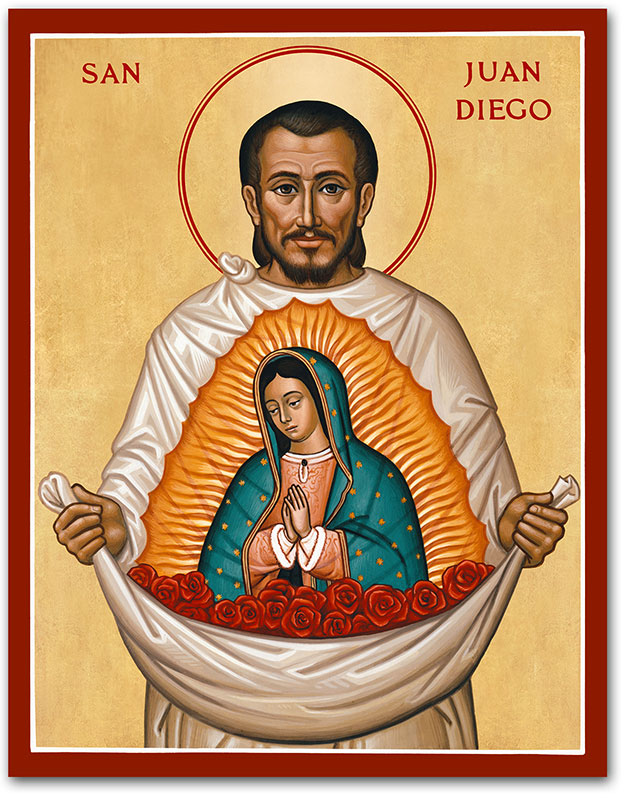

ファン・ディエゴ

Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin, 1474-1548

☆フアン・ディエゴ・クアウテラトアツィン(Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin)、 通称フアン・ディエゴ(スペイン語発音:[ˌxwanˈdjeɣo]、1474年~1548年)は、ナワ族の農民であり、マリアの幻視者であった。彼は 1531年12月に4回、グアダルペの聖母マリアの幻視を授かったと言われている。3回はテペヤックの丘で、4回目は当時メキシコ司教であったドン・フア ン・デ・スマラガの前でだった。テペヤックのふもとにあるグアダルペ聖母大聖堂には、伝統的にフアン・ディエゴのものと言われているマント(ティルマフト リ)が保管されており、聖母マリアの像が奇跡的にそのマントに刻印されたことで、その出現の真実性が証明されたと言われている。 フエイ・トラマウィソルティカなどの口頭および書面による植民地時代の資料に記されているフアン・ディエゴの幻視と奇跡的なイメージの伝達は、合わせてグ アダルペの出来事(スペイン語:el acontecimiento Guadalupano)として知られ、グアダルペの聖母への崇敬の基盤となっている。この崇敬はメキシコ全土に広がり、スペイン語圏のアメリカ大陸全体 に浸透し、さらにその範囲を広げている[b]。その結果、グアダルペの聖母大聖堂は、今や世界有数のキリスト教巡礼地となっており、2010年には 2200万人の訪問者を受け入れた。フアン・ディエゴはアメリカ大陸で生まれた最初のカトリックの聖人である。1990年に列福され、2002年に教皇ヨ ハネ・パウロ2世によって列聖された。教皇は両式典に出席するため、メキシコシティを訪れた。

| Juan Diego

Cuauhtlatoatzin,[a] also known simply as Juan Diego (Spanish

pronunciation: [ˌxwanˈdjeɣo]; 1474–1548), was a Nahua peasant and

Marian visionary. He is said to have been granted apparitions of Our

Lady of Guadalupe on four occasions in December 1531: three at the hill

of Tepeyac and a fourth before don Juan de Zumárraga, then bishop of

Mexico. The Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, located at the foot of

Tepeyac, houses the cloak (tilmahtli) that is traditionally said to be

Juan Diego's, and upon which the image of the Virgin is said to have

been miraculously impressed as proof of the authenticity of the

apparitions. Juan Diego's visions and the imparting of the miraculous image, as recounted in oral and written colonial sources such as the Huei tlamahuiçoltica, are together known as the Guadalupe event (Spanish: el acontecimiento Guadalupano), and are the basis of the veneration of Our Lady of Guadalupe. This veneration is ubiquitous in Mexico, prevalent throughout the Spanish-speaking Americas, and increasingly widespread beyond.[b] As a result, the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe is now one of the world's major Christian pilgrimage destinations, receiving 22 million visitors in 2010.[4][c] Juan Diego is the first Catholic saint indigenous to the Americas.[d] He was beatified in 1990 and canonized in 2002[8] by Pope John Paul II, who on both occasions traveled to Mexico City to preside over the ceremonies. |

フアン・ディエゴ・クアウテラトアツィン(Juan Diego

Cuauhtlatoatzin)[a]、通称フアン・ディエゴ(スペイン語発音:[ˌxwanˈdjeɣo]、1474年~1548年)は、ナワ族の農

民であり、マリアの幻視者であった。彼は1531年12月に4回、グアダルペの聖母マリアの幻視を授かったと言われている。3回はテペヤックの丘で、4回

目は当時メキシコ司教であったドン・フアン・デ・スマラガの前でだった。テペヤックのふもとにあるグアダルペ聖母大聖堂には、伝統的にフアン・ディエゴの

ものと言われているマント(ティルマフトリ)が保管されており、聖母マリアの像が奇跡的にそのマントに刻印されたことで、その出現の真実性が証明されたと

言われている。 フエイ・トラマウィソルティカなどの口頭および書面による植民地時代の資料に記されているフアン・ディエゴの幻視と奇跡的なイメージの伝達は、合わせてグ アダルペの出来事(スペイン語:el acontecimiento Guadalupano)として知られ、グアダルペの聖母への崇敬の基盤となっている。この崇敬はメキシコ全土に広がり、スペイン語圏のアメリカ大陸全体 に浸透し、さらにその範囲を広げている[b]。その結果、グアダルペの聖母大聖堂は、今や世界有数のキリスト教巡礼地となっており、2010年には 2200万人の訪問者を受け入れた[ 4][c] フアン・ディエゴはアメリカ大陸で生まれた最初のカトリックの聖人である[d]。1990年に列福され、2002年に[8]教皇ヨハネ・パウロ2世によっ て列聖された。教皇は両式典に出席するため、メキシコシティを訪れた。 |

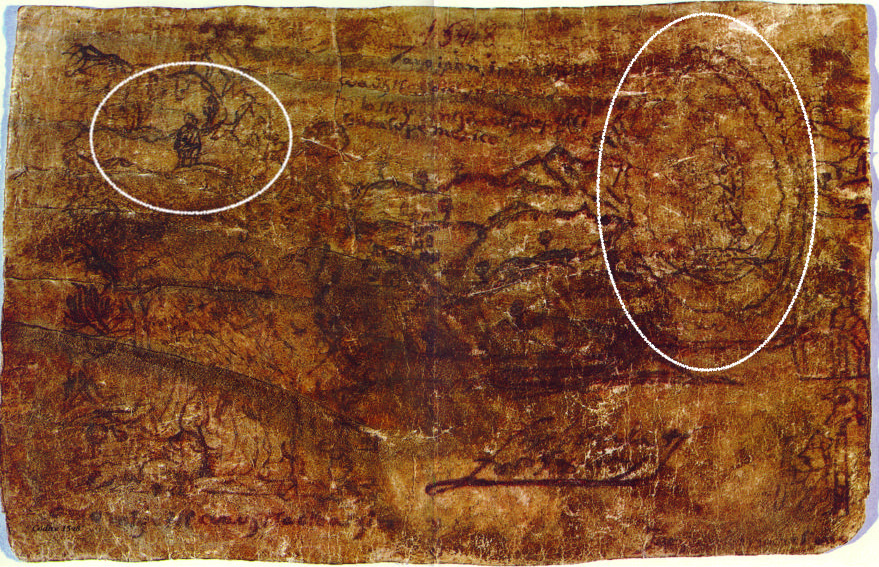

Biography At the foot of the Tepeyac Hill According to major sources, Juan Diego was born in 1474 in Cuauhtitlan,[e] and at the time of the apparitions he lived there or in Tolpetlac.[f] Although not destitute, he was neither rich nor influential.[g] His religious fervor, his artlessness, his respectful but gracious demeanour towards the Virgin Mary and the initially skeptical Bishop Juan de Zumárraga, as well as his devotion to his sick uncle and, subsequently, to the Virgin at her shrine – all of which are central to the tradition – are among his defining characteristics and testify to the sanctity of life which is the indispensable criterion for canonization.[h] He and his wife, María Lucía, were among the first to be baptized after the arrival of the main group of twelve Franciscan missionaries in Mexico in 1524.[i] His wife died two years before the apparitions, although one source (Luis Becerra Tanco, possibly through inadvertence) claims she died two years after them.[j] There is no firm tradition as to their marital relations. It is variously reported (a) that after their baptism he and his wife were inspired by a sermon on chastity to live celibately; alternatively (b) that they lived celibately throughout their marriage; and in the further alternative (c) that both of them lived and died as virgins.[k] Alternatives (a) and (b) may not necessarily conflict with other reports that Juan Diego (possibly by another wife) had a son.[9] Intrinsic to the narrative is Juan Diego's uncle, Juan Bernardino; but beyond him, María Lucía, and Juan Diego's putative son, no other family members are mentioned in the tradition. At least two 18th-century nuns claimed to be descended from Juan Diego.[10] After the apparitions, Juan Diego was permitted to live next to the hermitage erected at the foot of the hill of Tepeyac,[l] and he dedicated the rest of his life to serving the Virgin Mary at the shrine erected in accordance with her wishes. The date of death (in his 74th year) is given as 1548.[12] Main sources The earliest notices of an apparition of the Virgin Mary at Tepeyac to an indigenous man are to be found in various annals which are regarded by Dr. Miguel León-Portilla, one of the leading Mexican scholars in this field, as demonstrating "that effectively many people were already flocking to the chapel of Tepeyac long before 1556, and that the tradition of Juan Diego and the apparitions of Tonantzin (Guadalupe) had already spread."[13] Others (including leading Nahuatl and Guadalupe scholars in the USA) go only as far as saying that such notices "are few, brief, ambiguous and themselves posterior by many years".[14][m] If correctly dated to the 16th century, the Codex Escalada – which portrays one of the apparitions and states that Juan Diego (identified by his indigenous name) died "worthily" in 1548 – must be accounted among the earliest and clearest of such notices.  Juan Diego by Miguel Cabrera After the annals, a number of publications arose:[16] 1. Sánchez (1648) has a few scattered sentences noting Juan Diego's uneventful life at the hermitage in the sixteen years from the apparitions to his death. 2. The Huei tlamahuiçoltica (1649), at the start of the Nican Mopohua and at the end of the section known as the Nican Mopectana, there is some information concerning Juan Diego's life before and after the apparitions, giving many instances of his sanctity of life.[17] 3. Becerra Tanco (1666 and 1675). Juan Diego's town of origin, place of residence at the date of the apparitions, and the name of his wife are given at pages 1 and 2 of the 6th (Mexican) edition. His heroic virtues are eulogized at pages 40 to 42. Other biographical information about Juan Diego (with dates of his birth and death, of his wife's death, and of their baptism) is set out on page 50. On page 49 is the remark that Juan Diego and his wife remained chaste – at the least after their baptism – having been impressed by a sermon on chastity said to have been preached by Fray Toribio de Benevente (popularly known as Motolinía). 4. Slight and fragmented notices appear in the hearsay testimony (1666) of seven of the indigenous witnesses (Marcos Pacheco, Gabriel Xuárez, Andrés Juan, Juana de la Concepción, Pablo Xuárez, Martín de San Luis, and Catarina Mónica) collected with other testimonies in the Informaciones Jurídicas de 1666.[n] 5. Chapter 18 of Francisco de la Florencia's Estrella de el norte de México (1688) contains the first systematic account of Juan Diego's life, with attention given to some divergent strands in the tradition.[o] |

伝記 テペヤック丘のふもと 主要な情報源によると、フアン・ディエゴは1474年にクアウティトランで生まれ[e]、聖母マリアの出現時にはクアウティトランかトルペトラクに住んで いた[f]。彼は貧しいわけではなかったが、裕福でも有力でもなかった[g]。彼の宗教的熱意、素朴さ、聖母マリアと当初懐疑的だったフアン・デ・スマラ ガ司教に対する敬意に満ちた態度、病に苦しむ叔父への献身、そして聖母マリアの聖堂への献身は、いずれもこの伝承の中心をなすものであり、彼の特徴であ り、列聖に不可欠な基準である生命の聖性を証明するものである[h]。彼と彼の妻マリア・ルシア 聖母マリアと、当初は懐疑的だったフアン・デ・スマラガ司教に対する彼の敬虔な態度、病に苦しむ叔父への献身、そしてその後、聖母マリアの聖堂への献身な ど、伝承の中心となるこれらの特徴は、彼の特徴的な性格を表しており、列聖に不可欠な基準である生命の尊厳を証明している[h]。彼と彼の妻マリア・ルシ ア 、1524年にメキシコにやってきた12人のフランシスコ会宣教師の主要グループ到着後、最初に洗礼を受けた人々のうちの1組であった[i]。彼の妻は、 聖母の出現の2年前に亡くなったが、ある情報源(ルイス・ベセラ・タンコ、おそらく不注意によるものと思われる)によると、彼女は聖母の出現の2年後に亡 くなった[j]。彼らの夫婦関係については確かな伝統はない。洗礼を受けた後、夫妻は貞操に関する説教に感銘を受け、生涯独身で過ごすようになったという 説(a)と、結婚期間中ずっと独身で過ごしたという説(b)、さらに、夫妻とも処女として生涯を終えたという説(c)がある[k]。 )と(b)は、フアン・ディエゴが(おそらく別の妻との間に)息子をもうけたとする他の報告と必ずしも矛盾するわけではない[9]。この物語に欠かせない のはフアン・ディエゴの叔父フアン・ベルナルディーノであるが、彼とマリア・ルシア、そしてフアン・ディエゴの推定上の息子以外には、この伝承には家族に ついて言及されていない。少なくとも2人の18世紀の修道女が、フアン・ディエゴの子孫であると主張した[10]。出現の後、フアン・ディエゴはテペヤッ クの丘のふもとにつくられた隠者の庵の隣に住むことが許され[l]、その後は生涯を聖母マリアの願いに従って建てられた聖堂でマリアに仕えることに捧げ た。彼の死(74歳)の年は1548年とされている[12]。 主な情報源 先住民に対するテペヤックの聖母マリアの出現に関する最も古い記録は、この分野におけるメキシコを代表する学者ミゲル・レオン=ポルティージャ博士が、 「1556年よりもずっと前から、すでに多くの人々がテペヤックの礼拝堂に集まっていたこと、そしてフアン・ディエゴとトンアンツィン(グアダルペ)の幻 影の伝説がすでに広まっていたことを示している」[13]。一方、他の人々(米国の主要なナワトル語およびグアダルペ研究家を含む)は、そのような記録は 「数が少ない 、簡潔で曖昧であり、それ自体何年も後付けである」[14][m]。エスカラダ写本が16世紀に正確に作成されたとすれば、その写本には出現の1つを描写 し、フアン・ディエゴ(先住民の名前で特定されている)が1548年に「立派に」亡くなったと記されている。  ミゲル・カブレラ作のフアン・ディエゴ 年代記の発表後、多くの出版物が発行された:[16] 1.サンチェス(1648年)は、出現から彼の死までの16年間、隠遁生活を送ったフアン・ディエゴの平穏な生活を数行にわたって記している。 2. 『Huei tlamahuiçoltica』(1649年)では、『Nican Mopohua』の冒頭と『Nican Mopectana』として知られる章の終わりに、出現の前後におけるフアン・ディエゴの人生に関するいくつかの情報が記載されており、彼の神聖な生き方 について多くの例が挙げられている[17]。 3. Becerra Tanco』(1666年および1675年)。フアン・ディエゴの出身地、出現当時の居住地、妻の名前は、第6版(メキシコ版)の1ページ目と2ページ目 に記載されている。彼の英雄的美徳は40ページから42ページにかけて称賛されている。フアン・ディエゴに関するその他の伝記的情報(彼の生没年、妻の死 没年、洗礼日)は50ページに記載されている。49ページには、フアン・ディエゴと彼の妻は少なくとも洗礼後は貞操を守り続けた、という記述がある。これ は、トーリビオ・デ・ベネベント(通称モトリニア)神父が説いたとされる貞操についての説教に感銘を受けたためである。 4. 1666年の『Informaciones Jurídicas』に掲載された他の証言とともに収集された、先住民の目撃者7人(マルコス・パチェコ、ガブリエル・スアレス、アンドレス・フアン、フ アナ・デ・ラ・コンセプシオン、パブロ・スアレス、マルティン・デ・サン・ルイス、カタリナ・モニカ)による伝聞証言(1666年)には、断片的かつわず かな記述がある[n]。 5. フランシスコ・デ・ラ・フロレンシア著『メキシコ北部の星』(1688年)の第18章には、伝承の異なる部分にも注目しながら、フアン・ディエゴの人生について初めて体系的に記述されている。 |

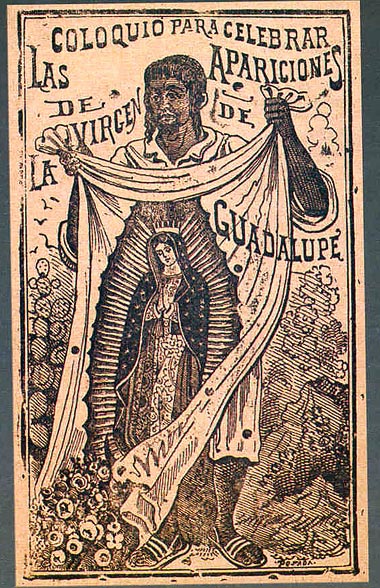

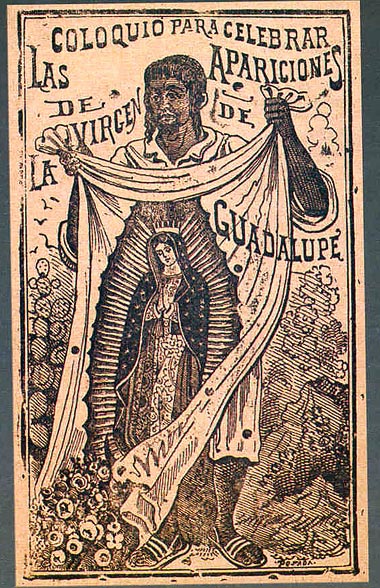

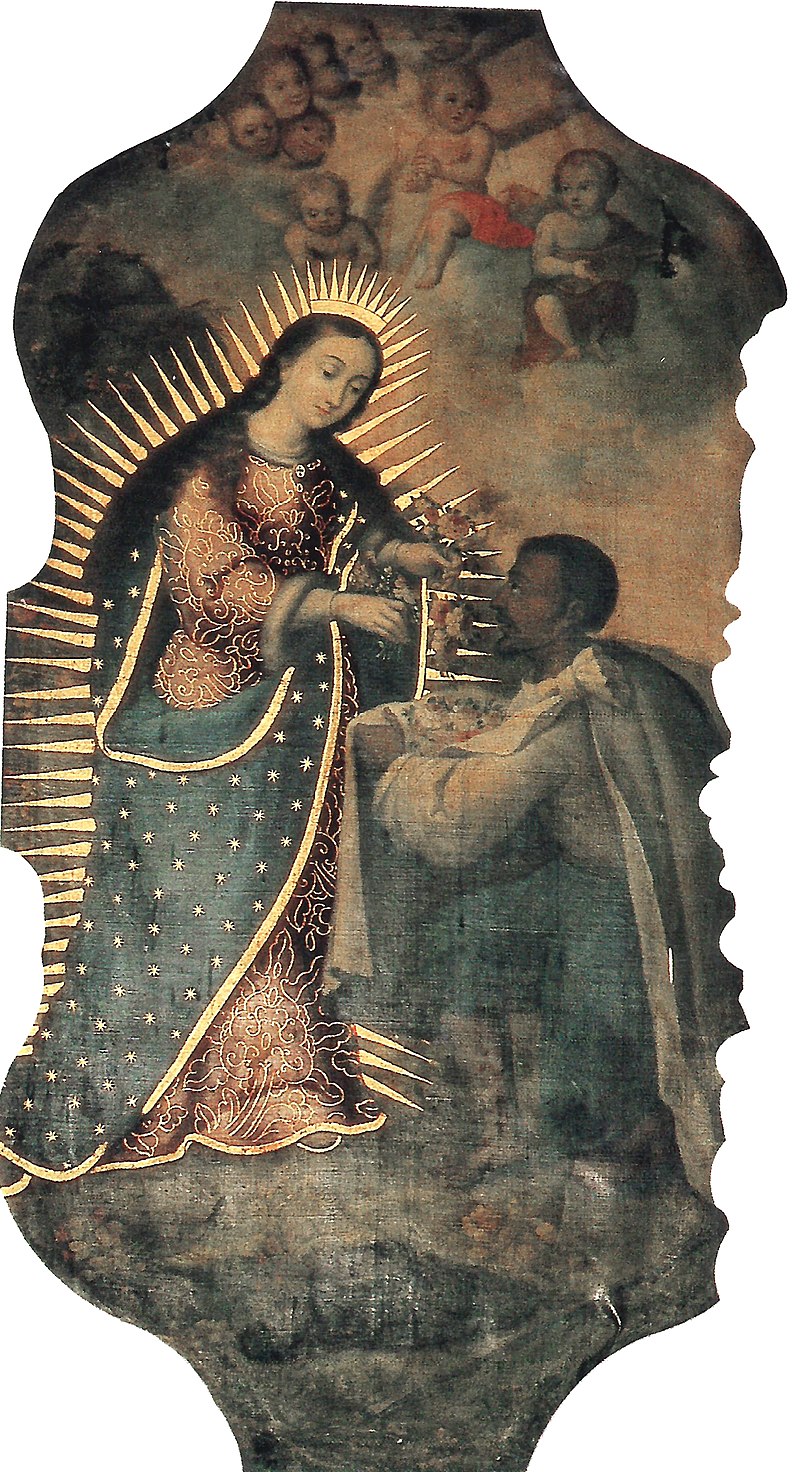

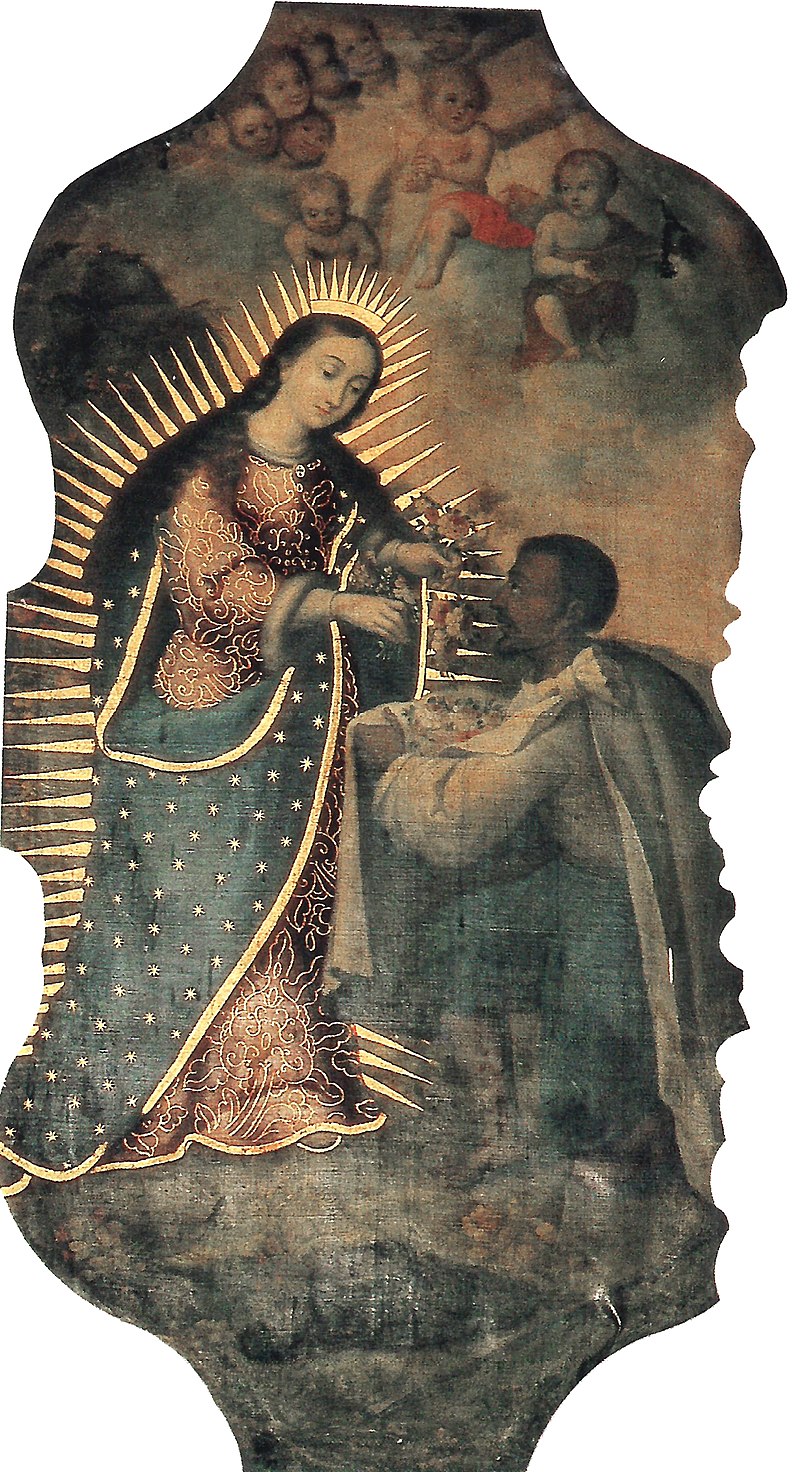

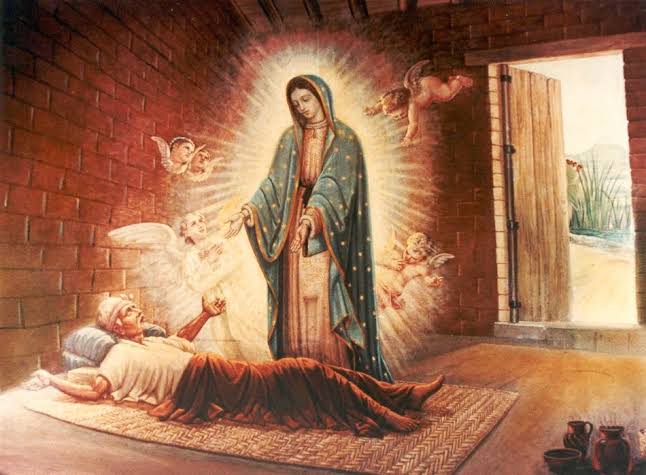

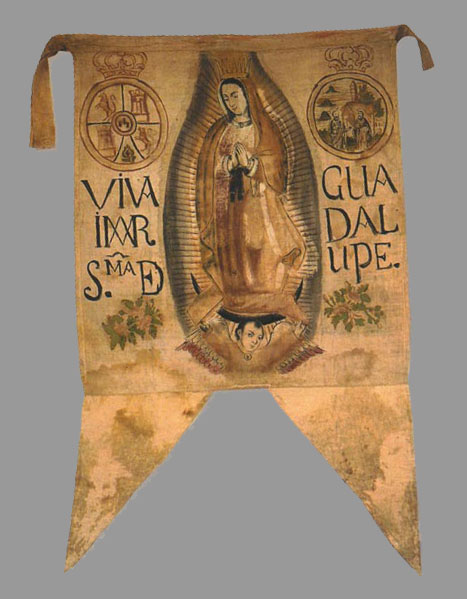

Guadalupe narrative Engraving published in the book Happiness of Mexico in 1666 and 1669 (Spain) representing Juan Diego during the appearance of the Virgin of Guadalupe The following account is based on that given in the Nican mopohua which was first published in Nahuatl in 1649 as part of a compendious work known as the Huei tlamahuiçoltica. No part of that work was available in Spanish until 1895 when, as part of the celebrations for the coronation of the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe in that year, there was published a translation of the Nican Mopohua dating from the 18th century. This translation, however, was made from an incomplete copy of the original. Nor was any part of the Huei tlamahuiçoltica republished until 1929, when a facsimile of the original was published by Primo Feliciano Velásquez together with a full translation into Spanish (including the first full translation of the Nican Mopohua), since then the Nican Mopohua, in its various translations and redactions, has supplanted all other versions as the narrative of preference.[p] The precise dates in December 1531 (as given below) were not recorded in the Nican Mopohua, but are taken from the chronology first established by Mateo de la Cruz in 1660.[20] Juan Diego, as a devout neophyte, was in the habit of regularly walking from his home to the Franciscan mission station at Tlatelolco for religious instruction and to perform his religious duties. His route passed by the hill at Tepeyac. First apparition At dawn on Wednesday December 9, 1531, while on his usual journey, he encountered the Virgin Mary who revealed herself as the ever-virgin Mother of God and instructed him to request the bishop to erect a chapel in her honour so that she might relieve the distress of all those who call on her in their need. He delivered the request, but was told by the bishop (Fray Juan Zumárraga) to come back another day after he had had time to reflect upon what Juan Diego had told him. Second apparition Later the same day: returning to Tepeyac, Juan Diego encountered the Virgin again and announced the failure of his mission, suggesting that because he was "a back-frame, a tail, a wing, a man of no importance" she would do better to recruit someone of greater standing, but she insisted that he was whom she wanted for the task. Juan Diego agreed to return to the bishop to repeat his request. This he did on the morning of Thursday December 10, when he found the bishop more compliant. The bishop asked for a sign to prove that the apparition was truly of heaven. Third apparition Juan Diego returned immediately to Tepeyac. Upon encountering the Virgin Mary, he reported the bishop's request for a sign; she conceded to provide one on the following day (December 11).[q]  Juan Diego, hoja religiosa, etching by José Guadalupe Posada, n.d. but possibly pre-1895 By Friday December 11, Juan Diego's uncle Juan Bernardino had fallen sick and Juan Diego was obliged to attend to him. In the very early hours of Saturday, December 12, Juan Bernardino's condition had deteriorated overnight. Juan Diego set out to Tlatelolco to get a priest to hear Juan Bernardino's confession and minister to him on his death-bed. Fourth apparition In order to avoid being delayed by the Virgin and embarrassed at having failed to meet her on the Monday as agreed, Juan Diego chose another route around the hill, but the Virgin intercepted him and asked where he was going; Juan Diego explained what had happened and the Virgin gently chided him for not having had recourse to her. In the words which have become the most famous phrase of the Guadalupe event and are inscribed over the main entrance to the Basilica of Guadalupe, she asked: "¿No estoy yo aquí que soy tu madre?" ("Am I not here, I who am your mother?"). She assured him that Juan Bernardino had now recovered and she told him to climb the hill and collect flowers growing there. Obeying her, Juan Diego found an abundance of flowers unseasonably in bloom on the rocky outcrop where only cactus and scrub normally grew. Using his open mantle as a sack (with the ends still tied around his neck) he returned to the Virgin; she rearranged the flowers and told him to take them to the bishop. On gaining admission to the bishop in Mexico City later that day, Juan Diego opened his mantle, the flowers poured to the floor, and the bishop saw they had left on the mantle an imprint of the Virgin's image which he immediately venerated.[r] Fifth apparition The next day Juan Diego found his uncle fully recovered, as the Virgin had assured him, and Juan Bernardino recounted that he too had seen her, at his bed-side; that she had instructed him to inform the bishop of this apparition and of his miraculous cure; and that she had told him she desired to be known under the title of Guadalupe. The bishop kept Juan Diego's mantle first in his private chapel and then in the church on public display where it attracted great attention. On December 26, 1531, a procession formed for taking the miraculous image back to Tepeyac where it was installed in a small, hastily erected chapel.[s] In the course of this procession, the first miracle was allegedly performed when an indigenous man was mortally wounded in the neck by an arrow shot by accident during some stylized martial displays executed in honour of the Virgin. In great distress, the indigenous carried him before the Virgin's image and pleaded for his life. Upon the arrow being withdrawn, the victim made a full and immediate recovery.[t] |

グアダルーペの物語 1666年と1669年に『メキシコの幸福』(スペイン)で出版された版画。聖母グアダルーペの出現の際のフアン・ディエゴを描いたもの 以下の記述は、1649年にナワトル語で初めて出版された『Huei tlamahuiçoltica』という簡潔な作品の一部として発表された『Nican mopohua』に基づくものである。この作品のスペイン語訳は、1895年にグアダルーペの聖母の像の戴冠式を祝う行事の一環として、18世紀に書かれ た『ニカン・モポフア』の翻訳が出版されるまで、入手不可能であった。しかし、この翻訳は原本の不完全な写本から作成されたものであった。また、1929 年にプリモ・フェリシアーノ・ベラスケスが原本の複製を出版し、スペイン語への完全な翻訳(『ニカン・モポフア』の最初の完全な翻訳を含む)を出版するま で、『フエイ・トラマウィシオルティカ』のどの部分も再出版されなかった。それ以来、『ニカン・モポフア』は、さまざまな翻訳や編集を経て、他のすべての バージョンを凌駕する物語として好まれるようになった[p ] 1531年12月という正確な日付(下記参照)は『ニカン・モポフア』には記載されていなかったが、1660年にマテオ・デ・ラ・クルスが最初に確立した 年表から引用したものである[20]。 フアン・ディエゴは敬虔な新参者として、定期的に自宅からフランシスコ会の伝道所があるトラテロルコまで歩いて行き、宗教的な指導を受け、宗教的な義務を果たす習慣があった。彼の通る道はテペヤックの丘を通っていた。 最初の出現 1531年12月9日水曜日の夜明け、いつものように旅をしていた彼は、聖母マリアに遭遇した。聖母マリアは永遠の処女である神の母であると自らを明か し、マリアに助けを求める人々の苦しみを和らげるために、司教にマリアを称える礼拝堂を建てるよう求めるよう彼に指示した。彼はその願いを伝えたが、フア ン・ディエゴが話したことをよく考える時間が必要だと、司教(フアン・フマラガ)に言われた。 2度目の出現 同じ日の午後、テペヤックに戻ったフアン・ディエゴは再び聖母マリアに遭遇し、自分の使命が失敗に終わったことを告げ、自分は「背骨、尻尾、羽、取るに足 らない人間」なので、もっと地位の高い人物を選んだほうが良いと示唆した。しかし、聖母は彼がその任務にふさわしいと主張した。フアン・ディエゴは司教の もとに再び出向き、願いを再度伝えることに同意した。彼は12月10日(木)の朝、より協力的になった司教のもとに再び出向いた。司教は、その出現が本当 に天からのものであることを証明する印を求め、 3度目の出現 フアン・ディエゴはすぐにテペヤックに戻った。聖母マリアに遭遇したフアン・ディエゴは、司教の「印」を求める要求を報告し、マリアは翌日(12月11日)に印を与えることを承諾した[q]。  フアン・ディエゴ、宗教画、ホセ・グアダルペ・ポサダによるエッチング、年代不明だが1895年以前の可能性あり 12月11日(金)までに、フアン・ディエゴの叔父フアン・ベルナルディーノは病に倒れ、フアン・ディエゴは看病を余儀なくされた。12月12日(土)の 早朝、フアン・ベルナルディーノの容態は一晩で悪化した。フアン・ディエゴは、フアン・ベルナルディーノの告白を聞き、臨終の床で彼に奉仕する司祭を連れ てくるためにトラテロルコへと向かった。 4回目の出現 約束していた月曜日に聖母に会えずに恥をかくことを避けるため、フアン・ディエゴは丘の別のルートを選んだが、聖母に呼び止められ、どこへ行くのか尋ねら れた。フアン・ディエゴは起こったことを説明し、聖母は彼に、聖母に頼らなかったことを優しく叱責した。グアダルーペの出来事で最も有名な言葉であり、グ アダルーペ聖堂の正面入口に刻まれている言葉である。「私はここにいるではないか、あなたの母なのだから」(「Am I not here, I who am your mother?」)と彼女は言った。彼女はフアン・ベルナルディーノが回復したことを伝え、丘に登ってそこに咲く花を摘んできてほしいと彼に言った。彼女 の言うとおりにしたフアン・ディエゴは、サボテンや低木しか生えていない岩の突起に、季節外れの花が咲き乱れているのを発見した。彼はマントを袋代わりに 使い(両端は首に結んだまま)、聖母のもとに戻った。聖母は花を手に取り、司教のもとに持って行くよう彼に言った。その日のうちにメキシコシティの司教に 謁見したフアン・ディエゴはマントを開くと、花は床にこぼれ落ち、司教はマントに聖母の像の跡が残っているのを見て、すぐにそれを崇拝した。 5回目の出現 翌日、フアン・ディエゴは叔父が完全に回復したことを知った。回復していた。聖母マリアは彼にそう約束していたのだ。そして、フアン・ベルナルディーノ は、自分もベッドの側で聖母マリアを見たこと、聖母マリアは彼に、この出現と奇跡的な治癒について司教に報告するよう指示したこと、そして、聖母マリアは グアダルペの称号で知られることを望んでいると彼に告げたことを語った。司教はフアン・ディエゴのマントをまず私設礼拝堂に、次に一般公開されている教会 に保管し、人々の注目を集めた。1531年12月26日、奇跡の聖像をテペヤックに運ぶ行列が組まれ、急造の小さな礼拝堂に安置された[s]。行列の途 中、先住民が聖母マリアを称えるために行われた様式化された武術の演舞の最中に誤って放たれた矢で首に致命傷を負った際、最初の奇跡が起こったとされる。 苦しみ悶える先住民は、聖母マリア像の前に彼を運び、命乞いをした。矢が抜かれると、被害者はすぐに回復した。 |

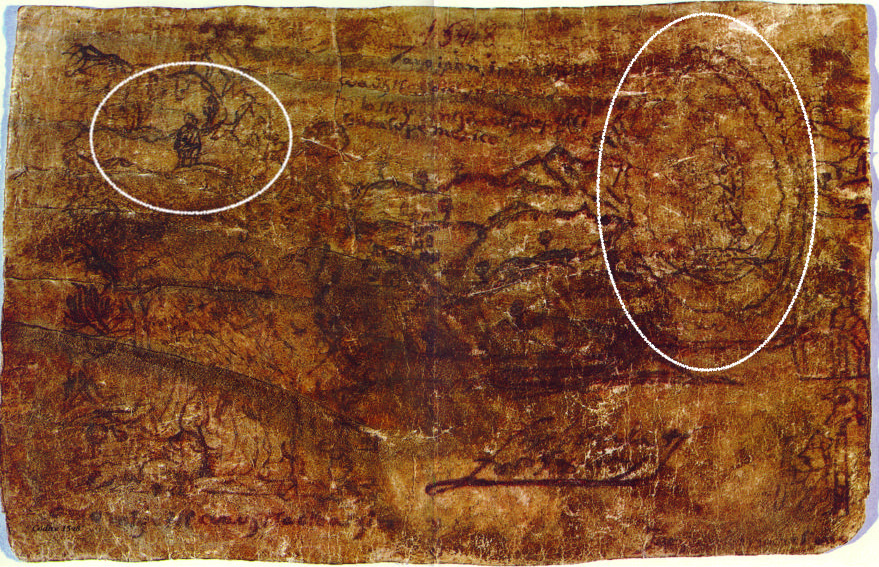

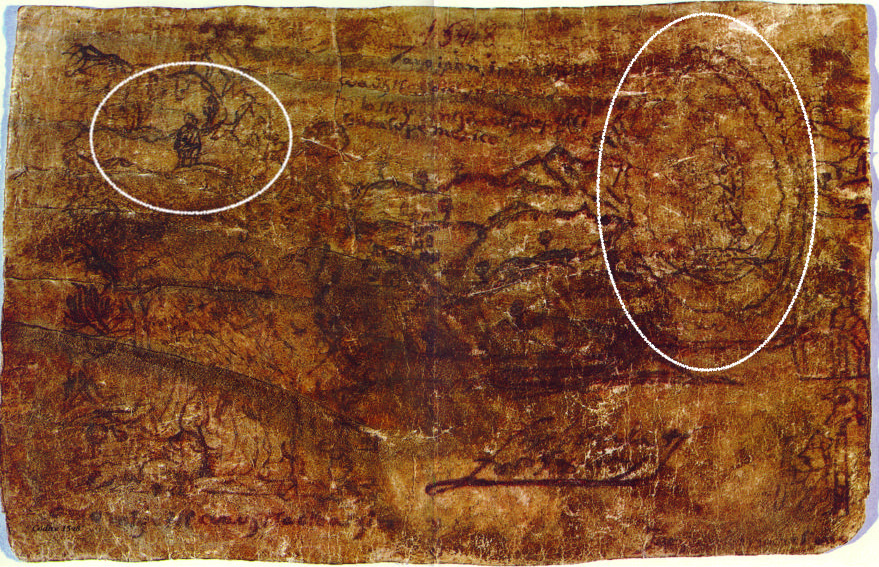

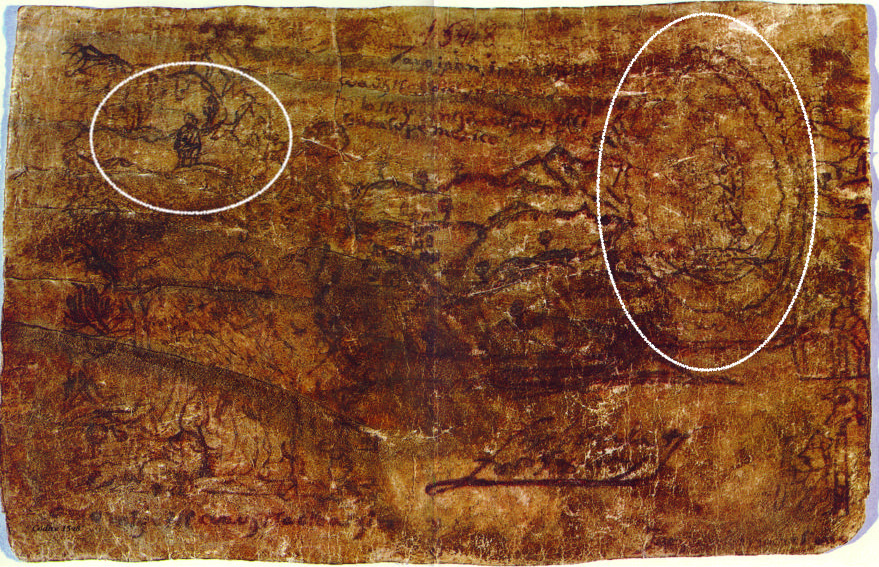

Beatification and canonization  The Codex Escalada, dated from the middle of the sixteenth century The modern movement for the canonization of Juan Diego (to be distinguished from the process for gaining official approval for the Guadalupe cult, which had begun in 1663 and was realized in 1754)[26] can be said to have arisen in earnest in 1974 during celebrations marking the five hundredth anniversary of the traditional date of his birth,[u] but it was not until January 1984 that the then Archbishop of Mexico, Cardinal Ernesto Corripio Ahumada, named a Postulator to supervise and coordinate the inquiry, and initiated the formal process for canonization.[27][v] The procedure for this first, or diocesan, stage of the canonization process had recently been reformed and simplified by order of Pope John Paul II.[28] Beatification The diocesan inquiry was formally concluded in March 1986,[29] and the decree opening the Roman stage of the process was obtained on April 7, 1986. When the decree of validity of the diocesan inquiry was given on January 9, 1987, permitting the cause to proceed, the candidate became officially "venerable". The documentation (known as the Positio or "position paper") was published in 1989, in which year all the bishops of Mexico petitioned the Holy See in support of the cause.[30] Thereafter, there was a scrutiny of the Positio by consultors expert in history (concluded in January 1990) and by consultors expert in theology (concluded in March 1990), following which the Congregation for the Causes of Saints formally approved the Positio and Pope John Paul II signed the relative decree on April 9, 1990. The process of beatification was completed in a ceremony presided over by Pope John Paul II at the Basilica of Guadalupe on May 6, 1990, when December 9 was declared as the feast day to be held annually in honor of the candidate for sainthood, thereafter known as "Blessed Juan Diego Cuauthlatoatzin".[31] In accordance with the exceptional cases provided for by Urban VIII (1625, 1634) when regulating the procedures for beatification and canonization, the requirement for an authenticating miracle prior to beatification was dispensed with, on the grounds of the antiquity of the cult.[w] Miracles Not withstanding the fact that the beatification was "equipollent",[33] the normal requirement is that at least one miracle must be attributable to the intercession of the candidate before the cause for canonization can be brought to completion. The events accepted as fulfilling this requirement occurred between May 3 and May 9, 1990, in Querétaro, Mexico (precisely during the period of the beatification) when a 20-year-old drug addict named Juan José Barragán Silva fell 10 meters (33 ft) head first from an apartment balcony onto a cement area in an apparent suicide bid. His mother Esperanza, who witnessed the fall, invoked Juan Diego to save her son who had sustained severe injuries to his spinal column, neck and cranium (including intra-cranial hemorrhage). Barragán was taken to the hospital where he went into a coma from which he suddenly emerged on May 6, 1990. A week later he was sufficiently recovered to be discharged.[x] The reputed miracle was investigated according to the usual procedure of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints: first the facts of the case (including medical records and six eye-witness testimonies including those of Barragán and his mother) were gathered in Mexico and forwarded to Rome for approval as to sufficiency, which was granted in November 1994. Next, the unanimous report of five medical consultors (as to the gravity of the injuries, the likelihood of their proving fatal, the impracticability of any medical intervention to save the patient, his complete and lasting recovery, and their inability to ascribe it to any known process of healing) was received, and approved by the Congregation in February 1998. From there the case was passed to theological consultors who examined the nexus between (i) the fall and the injuries, (ii) the mother's faith in and invocation of Blessed Juan Diego, and (iii) the recovery, inexplicable in medical terms. Their unanimous approval was signified in May 2001.[34] Finally, in September 2001, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints voted to approve the miracle, and the relative decree formally acknowledging the events as miraculous was signed by Pope John Paul II on December 20, 2001.[35] The Catholic Church considers an approved miracle to be a divinely-granted validation of the results achieved by the human process of inquiry, which constitutes a cause for canonization. Canonization  Ramon Novarro portraying Juan Diego in The Saint Who Forged a Country (1942) As not infrequently happens, the process for Diego's canonization was subject to delays and obstacles. In this case, certain interventions were initiated through unorthodox routes in early 1998 by a small group of ecclesiastics in Mexico (then or formerly attached to the Basilica of Guadalupe) pressing for a review of the sufficiency of the historical investigation.[y] This review, which not infrequently occurs in cases of equipollent beatifications,[36] was entrusted by the Congregation for the Causes of Saints (acting in concert with the Archdiocese of Mexico) to a special Historical Commission headed by the Mexican ecclesiastical historians Fidel González, Eduardo Chávez Sánchez, and José Guerrero. The results of the review were presented to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints on October 28, 1998, which unanimously approved them.[37][38][z] In the following year, the Commission's work was published in book form by González, Chávez Sánchez and Guerrero under the title Encuentro de la Virgen de Guadalupe y Juan Diego. This served, however, only to intensify the protests of those who were attempting to delay or prevent the canonization, and the arguments over the quality of the scholarship displayed by the Encuentro were conducted first in private and then in public.[aa] The main objection against the Encuentro was that it failed adequately to distinguish between the antiquity of the cult and the antiquity of the tradition of the apparitions; the argument on the other side was that every tradition has an initial oral stage where documentation will be lacking. The authenticity of the Codex Escalada and the dating of the Nican Mopohua to the 16th or 17th century have a material bearing on the duration of the oral stage.[ab] Final approbation of the decree of canonization was signified in a consistory held on February 26, 2002, at which Pope John Paul II announced that the rite of canonization would take place in Mexico at the Basilica of Guadalupe on July 31, 2002,[40] as indeed occurred.[41] |

列福と列聖  16世紀中期の『エスカラダ写本』 フアン・ディエゴの列聖を求める近代的な動き(1663年に始まり1754年に実現したグアダルーペ崇拝の公式承認を求めるプロセスとは区別される) [26]は、 1974年、彼の生誕500年を記念する祝典の際に本格的に始まったが[u]、1984年1月になってようやく、当時のメキシコ大司教エルネスト・コリピ オ・アウマダ枢機卿が調査を監督・調整する代理人(Postulator)を任命し、正式な列聖手続きを開始した[27][v]。この最初の、あるいは教 区段階の列聖手続きは、最近、教皇ヨハネ・パウロ2世の命令により改革され、簡素化されたばかりであった[28]。 列福 教区調査は1986年3月に正式に終了し[29]、ローマ段階の開始令は1986年4月7日に下された。1987年1月9日に教区調査の有効性が認めら れ、手続きを進めることが許可されると、候補者は正式に「尊敬すべき人物」となった。1989年にポジティオ(Positio)と呼ばれる文書(「立場に 関する文書」)が公表され、同年、メキシコの司教全員が教皇庁にこの聖人の列福を支持する嘆願書を提出した[30]。その後、ポジティオは、歴史に精通し た顧問団( 1990年1月に終了)、神学に精通した顧問による審査(1990年3月に終了)が行われ、その後、列聖聖人省が正式にポジティオを承認し、1990年4 月9日に教皇ヨハネ・パウロ2世が関連法令に署名した。列福のプロセスは、1990年5月6日にグアダルーペ聖堂で教皇ヨハネ・パウロ2世が主宰する式典 で完了し、12月9日が列聖候補者を称えるために毎年祝われる祝日として宣言された。以後、この人物は「福者フアン・ディエゴ・クアウトラトアツィン」と して知られるようになった[31]。ウルバヌス8世(1625年、16 34)が、列聖と聖人認定の手続きを規定した際に定めた例外的な規定に従い、列聖前の奇跡の証明要件は、その崇拝の古さを理由に免除された[w]。 奇跡 列聖が「同等の価値を持つ」[33]という事実にもかかわらず、通常の要件として、少なくとも1つの奇跡が候補者の取り成しによるものであることが証明さ れなければ、列聖の手続きを完了することはできない。この要件を満たすものとして認められた出来事は、1990年5月3日から5月9日の間、メキシコのケ レタロで起こった(正確には列福の期間中の出来事である)。20歳の薬物中毒患者、フアン・ホセ・バラガン・シルバが、アパートのバルコニーから10メー トル下のコンクリートの地面に向かって、頭から落下するという自殺未遂を起こしたのである。落下を目撃した彼の母親エスペランサは、背骨、首、頭蓋骨(頭 蓋内出血を含む)に重傷を負った息子を救うためにフアン・ディエゴに祈りを捧げた。バラガンは病院に搬送され、そこで昏睡状態に陥ったが、1990年5月 6日に突然目を覚ました。1週間後、彼は十分に回復し、退院することができた[x]。この奇跡は、聖人列聖のための聖省(Congregation for the Causes of Saints)の通常の手続きに従って調査された。まず、この事件に関する事実(医療記録、バラガンと彼の母親を含む6人の目撃証言を含む)がメキシコで 集められ、十分な証拠として承認を得るためにローマに送られた。次に、5人の医学顧問による全会一致の報告書(怪我の重大性、致命傷となる可能性、患者を 救うための医療介入の非現実性、患者の完全かつ持続的な回復、そして既知の治癒プロセスに起因するものではないという見解)が受理され、1998年2月に 聖人列福委員会により承認された。その後、この件は神学顧問団に引き継がれ、(i) 落下と負傷、(ii) 母親の聖フアン・ディエゴへの信仰と祈願、(iii) 医学的には説明のつかない回復、の関連性が検討された。2001年5月、神学顧問団は満場一致でこれを承認した[34]。そして2001年9月、列聖省は 奇跡を承認することを投票で決定し、奇跡として正式に認定する関連法令は、 2001年12月20日にヨハネ・パウロ2世によって署名された[35]。カトリック教会は、奇跡が承認されたことを、人間の探究のプロセスによって得ら れた結果を神が認めたものと見なし、列聖の理由となるとしている。 列聖  『国を造った聖人』(1942年)でフアン・ディエゴを演じたラモン・ノヴァロ しばしば起こるように、ディエゴの列聖手続きは遅れや障害に直面した。このケースでは、1998年初頭に、メキシコ(当時またはかつてグアダルーペ大聖堂 に所属していた)の聖職者からなる少人数のグループが、歴史的調査の妥当性についての再調査を要求するという、正統的ではないルートを通じた介入を開始し た[y]。同種の列福の場合にしばしば行われる[36]この調査は、列聖省(メキシコ大司教区と協力)が、メキシコの教会史家であるフィデル・ゴンサレ ス、エドゥアルド・チャベス・サンチェス、ホセ・ゲレロが率いる特別歴史委員会に委託した。 審査結果は1998年10月28日に聖人列福委員会に提出され、全会一致で承認された[37][38][z]。翌年、ゴンサレス、チャベス・サンチェス、 ゲレロが『グアダルペの聖母とファン・ディエゴの出会い』というタイトルで委員会の成果を書籍として出版した。しかし、これは、列聖を遅らせたり阻止しよ うとしている人々の抗議を激化させるだけだった。エンクエントロで提示された学術的資質の是非をめぐる議論は、まず非公開で、次に公開で行われた [aa]。エンクエントロに対する主な異論は、崇拝の古さと出現の伝統の古さを適切に区別できていないというものであった。反対側の議論は、あらゆる伝統 には、文書化が不十分な初期の口承段階があるというものだった。『エスカラダ法典』の真正性と『ニカン・モポフア』の16世紀または17世紀の年代は、口 承段階の期間に重大な影響を及ぼす[ab]。列聖令の最終承認は、2002年2月26日に開かれたコンシステリアで表明された。 2002年2月26日に開かれた会議で、教皇ヨハネ・パウロ2世は、列聖式が2002年7月31日にメキシコのグアダルーペ大聖堂で行われると発表した [40]。実際にその通りになった[41]。 |

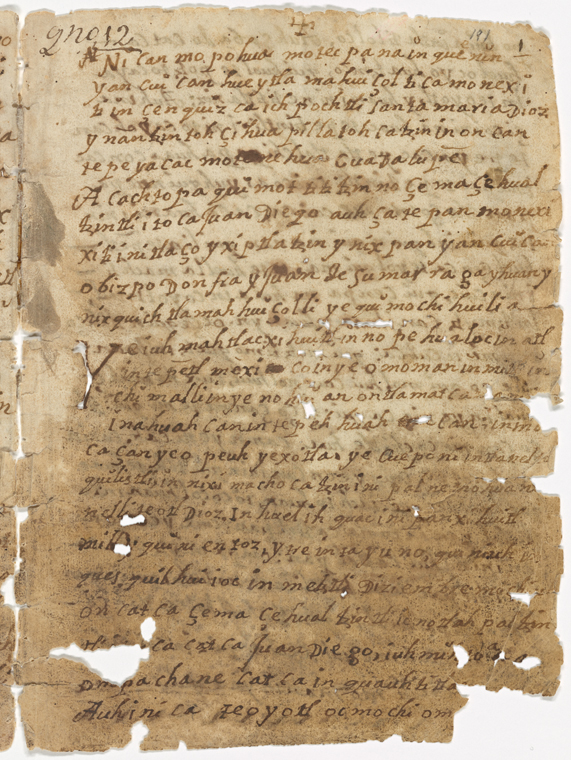

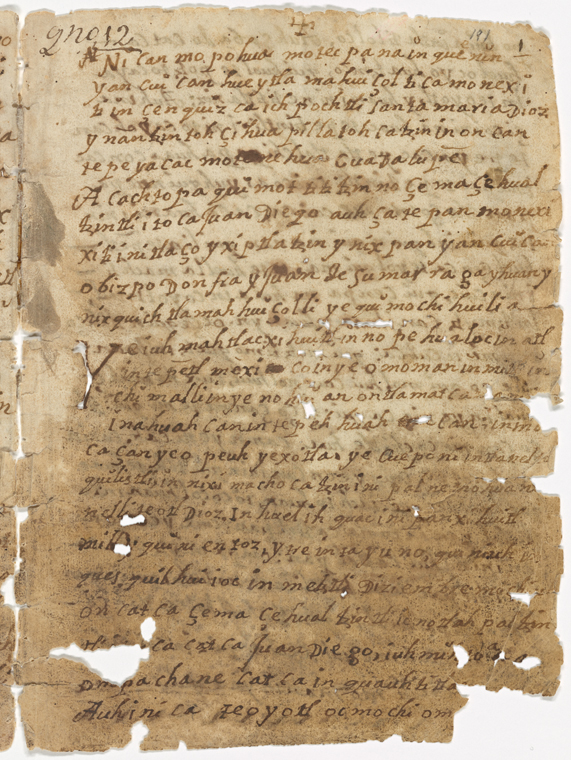

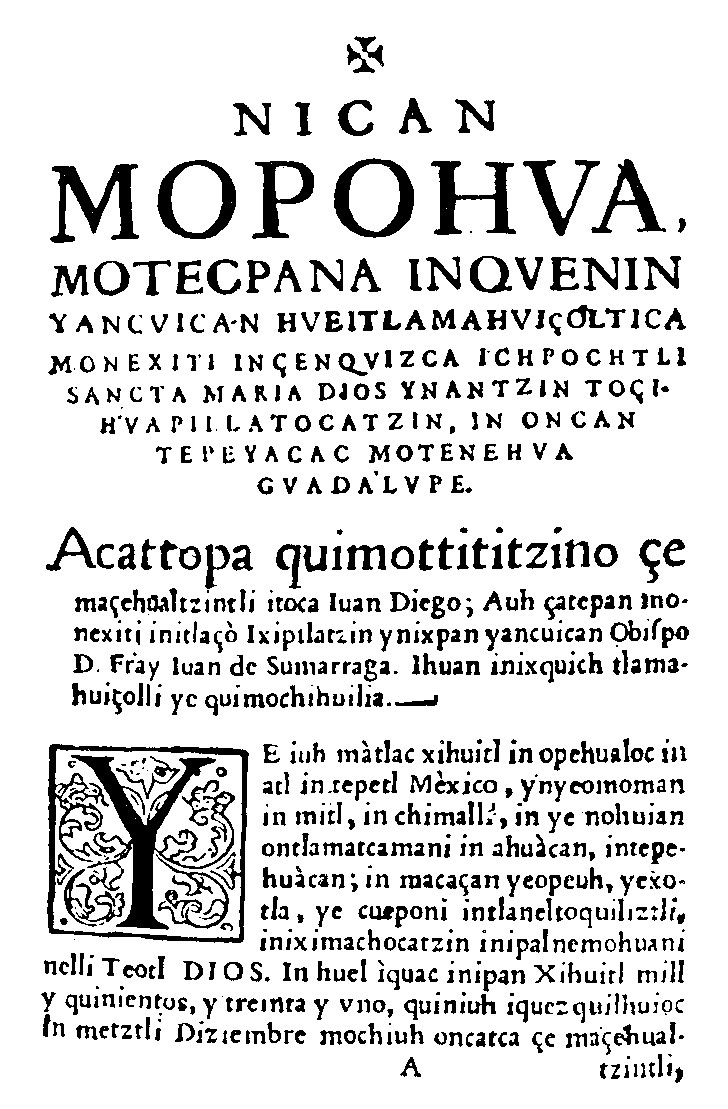

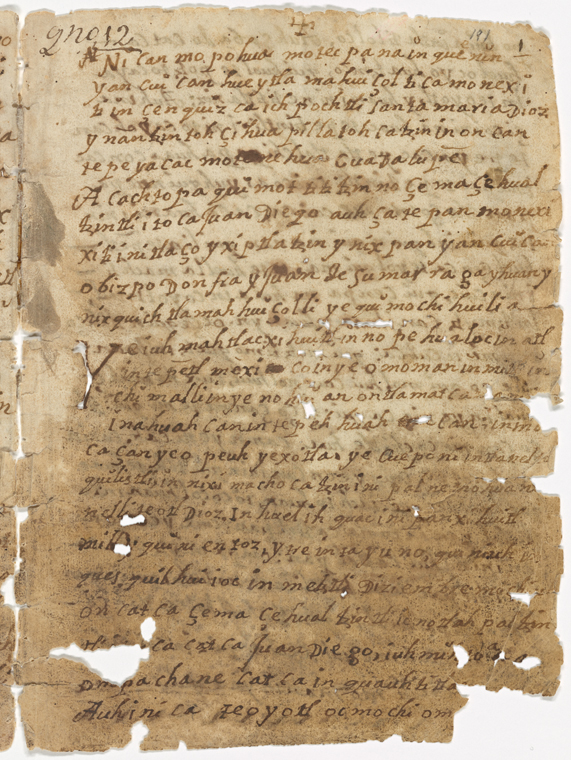

| Historicity debate This article uses texts from within a religion or faith system without referring to secondary sources that critically analyze them. Please help improve this article. (May 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The debate over the historicity of St. Juan Diego and, by extension, of the apparitions and the miraculous image, begins with a contemporary to Juan Diego, named Antonio Valeriano. Valeriano was one of the best Indian scholars at the College of Santiago de Tlatelolco at the time that Juan Diego was alive; he was proficient in Spanish as well as Latin, and a native speaker of Nahuatl. He knew Juan Diego personally [42][additional citation(s) needed] and wrote his account of the apparitions on the basis of Juan Diego's testimony.[disputed (for: Later-dated source.) – discuss] A copy of Valeriano's document was rediscovered by Jesuit Father Ernest J. Burrus in the New York Public Library.[42][43]  Copy of Huei tlamahuiçoltica preserved at the New York Library Some objections to the historicity of the Guadalupe event, grounded in the silence of the very sources which – it is argued – are those most likely to have referred to it, were raised as long ago as 1794 by Juan Bautista Muñoz and were expounded in detail by Mexican historian Joaquín García Icazbalceta in a confidential report dated 1883 commissioned by the then Archbishop of Mexico and first published in 1896. The silence of the sources is discussed in a separate section, below. The most prolific contemporary protagonist in the debate is Stafford Poole, a historian and Vincentian priest in the United States of America, who questioned the integrity and rigor of the historical investigation conducted by the Catholic Church in the interval between Juan Diego's beatification and his canonization. For a brief period in mid-1996, a vigorous debate was ignited in Mexico when it emerged that Guillermo Schulenburg, who at that time was 80 years of age, did not believe that Juan Diego was a historical person. That debate, however, was focused not so much on the weight to be accorded to the historical sources which attest to Juan Diego's existence as on the propriety of Abbot Schulenburg retaining an official position which – so it was objected – his advanced age, allegedly extravagant life-style and heterodox views disqualified him from holding. Abbot Schulenburg's resignation (announced on September 6, 1996) terminated that debate.[44] The scandal, however, re-erupted in January 2002 when the Italian journalist Andrea Tornielli published in the Italian newspaper Il Giornale a confidential letter dated December 4, 2001, which Schulenburg (among others) had sent to Cardinal Sodano, the then Secretary of State at the Vatican, reprising reservations over the historicity of Juan Diego.[45] Partly in response to these and other issues, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints (the body within the Catholic Church with oversight of the process of approving candidates for sainthood) reopened the historical phase of the investigation in 1998, and in November of that year declared itself satisfied with the results.[46] Following the canonization in 2002, the Catholic Church considers the question closed. |

歴史性に関する議論 この記事は、批判的に分析した二次資料を参照することなく、宗教または信仰体系内のテキストを使用しています。この記事の改善にご協力ください。(2018年5月) (削除方法と時期について) 聖フアン・ディエゴ、ひいては聖母マリアの出現と奇跡の像の歴史性についての議論は、フアン・ディエゴと同時代のアントニオ・バレリアーノから始まる。バ レリアーノは、フアン・ディエゴが生きていた当時、サンティアゴ・デ・トラテロルコ大学で最高のインディアン学者の一人であった。スペイン語とラテン語に 堪能で、ナワトル語を母国語としていた。彼はフアン・ディエゴと個人的に知り合い[42][追加の引用が必要]、フアン・ディエゴの証言に基づいて出現の 記述を書いた[議論の余地あり(根拠:日付の古い情報源) - 議論]。  ニューヨーク図書館に保存されているフエイ・トラマウィシコルティカの写し ニューヨーク図書館 グアダルーペの出来事の史実性に対する異論は、それについて言及した可能性が最も高いとされる情報源が沈黙していることに端を発しており、1794年には フアン・バウティスタ・ムニョスによってすでに提起されていた。1883年に当時のメキシコ大司教の依頼で作成された極秘報告書の中で、メキシコの歴史家 ホアキン・ガルシア・イカスバルセタが詳細に論じている。資料の沈黙については、以下の別項で議論する。この論争において最も活発に活動している現代の論 客は、アメリカ合衆国の歴史学者であり、ヴィンセンティアン会の司祭でもあるスタッフォード・プールである。彼は、フアン・ディエゴの列福と列聖の間の期 間にカトリック教会が行った歴史調査の完全性と厳密性を疑問視している。 1996年半ば、当時80歳だったギジェルモ・シュレンバーグ神父がフアン・ディエゴが実在の人物であるとは信じていないことが明らかになり、メキシコで は短期間ではあるが激しい論争が巻き起こった。しかし、この論争は、フアン・ディエゴの存在を証明する歴史的資料の信憑性よりも、シュレンブルク修道院長 が公職に就くことの妥当性、つまり、彼の高齢、贅沢な生活スタイル、異端的な見解により、その地位に就く資格がないという批判に焦点を当てていた。シュレ ンブルク修道院長の辞任(1996年9月6日発表)により、この論争は終結した[44]。しかし、2002年1月、イタリア人ジャーナリストのアンドレ ア・トルニエッリが、2001年12月4日付のソダーノ枢機卿(当時バチカン市国国務長官)宛ての極秘文書をイタリアの新聞「イル・ジョルナーレ」に掲載 し、このスキャンダルが再燃した。 フアン・ディエゴの歴史性に対する疑念を表明していた。 これらの問題やその他の問題への反応もあり、列聖聖人委員会(列聖候補者の承認プロセスを監督するカトリック教会内の機関)は1998年に調査の史実調査 段階を再開し、同年11月にその結果に満足していると発表した。[46] 2002年の列聖を受けて、カトリック教会はこの問題を終了したとみなしている。 |

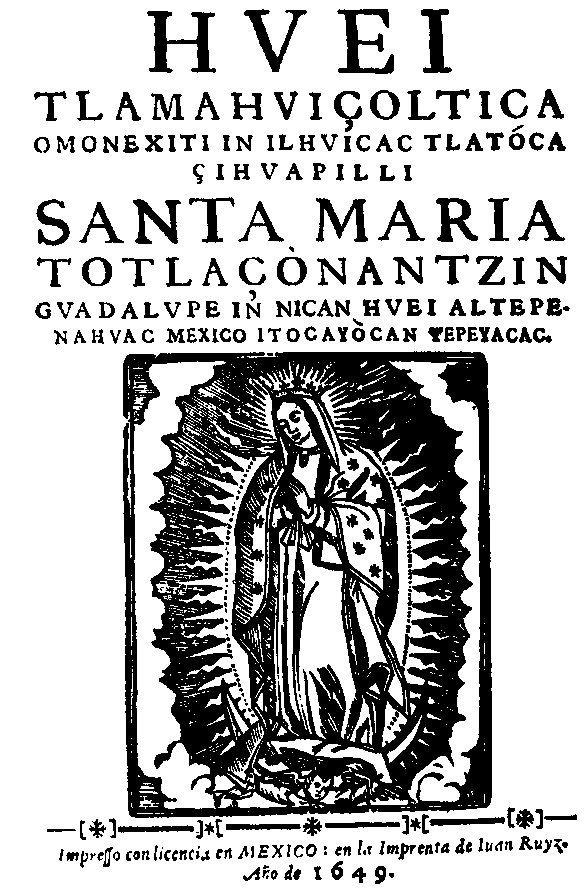

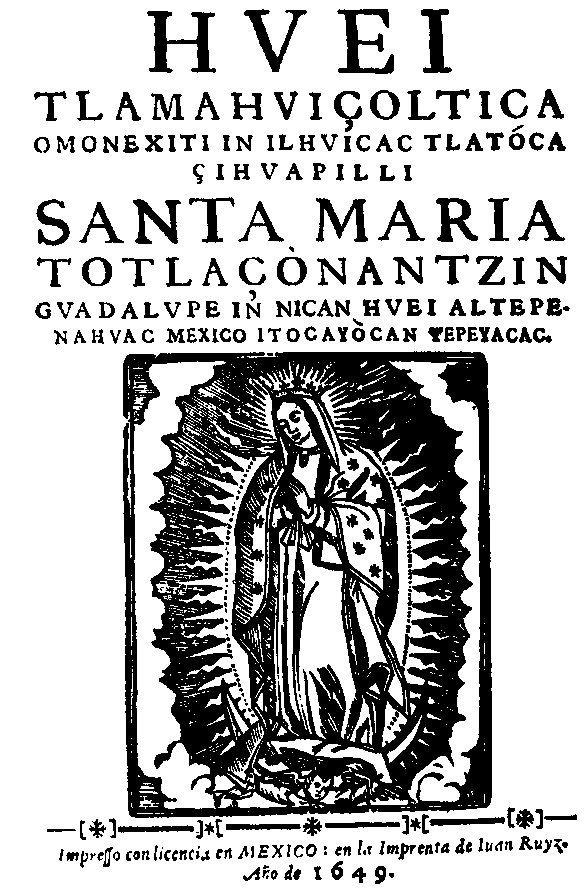

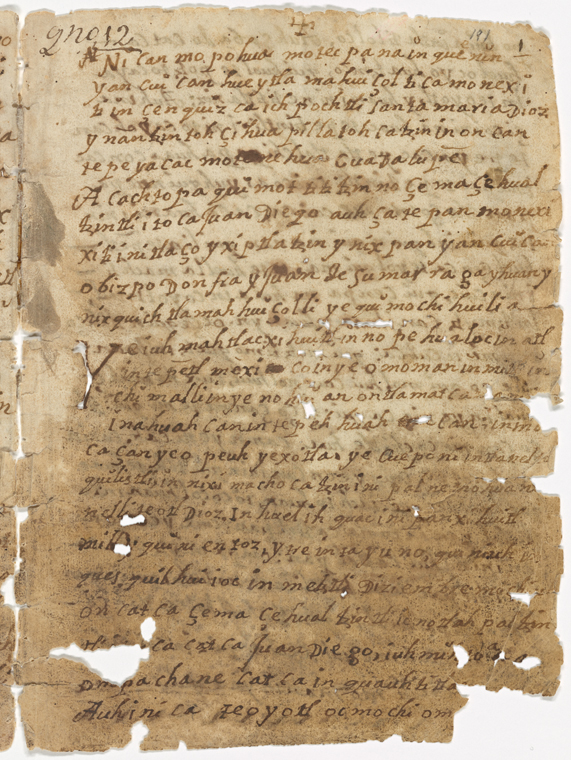

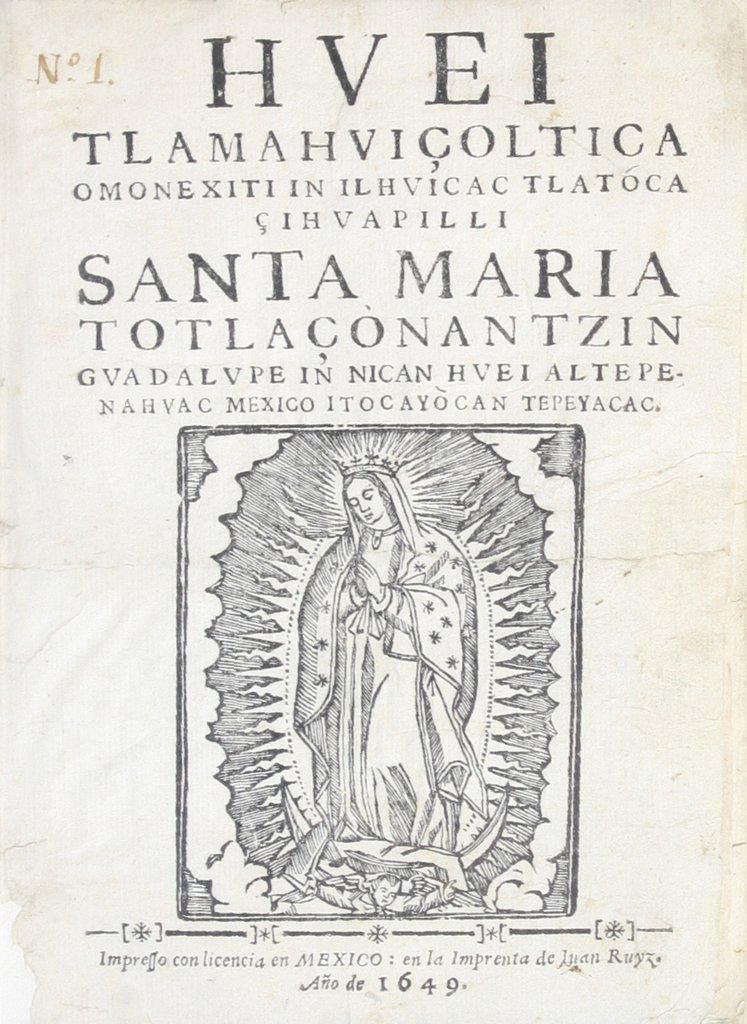

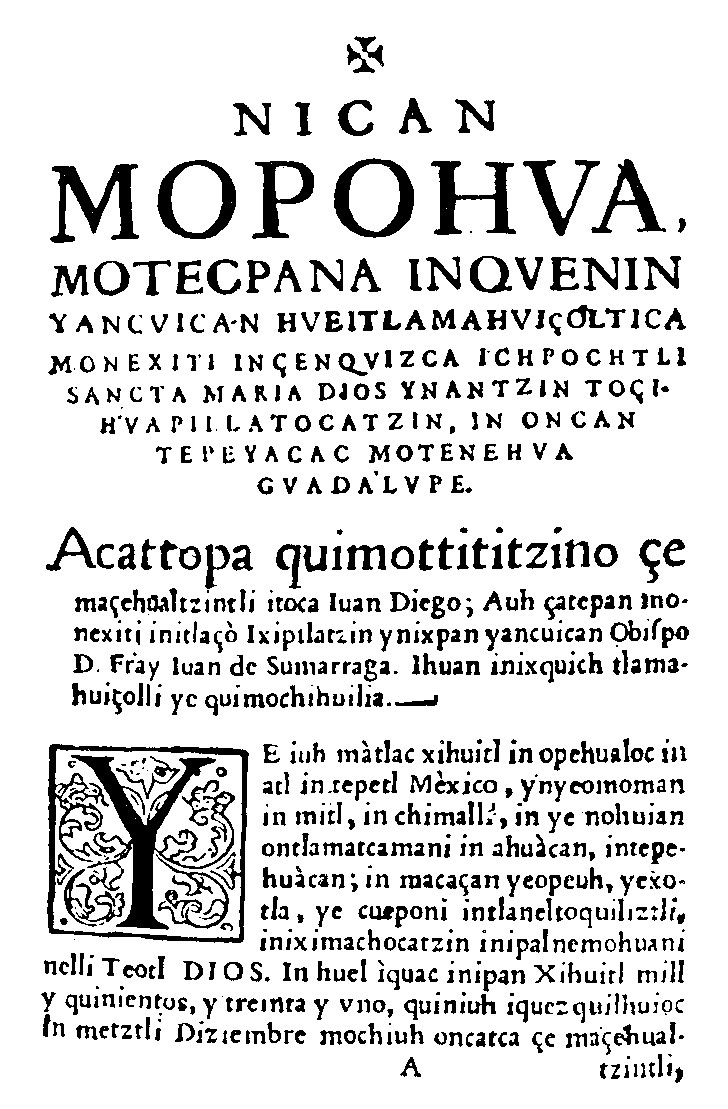

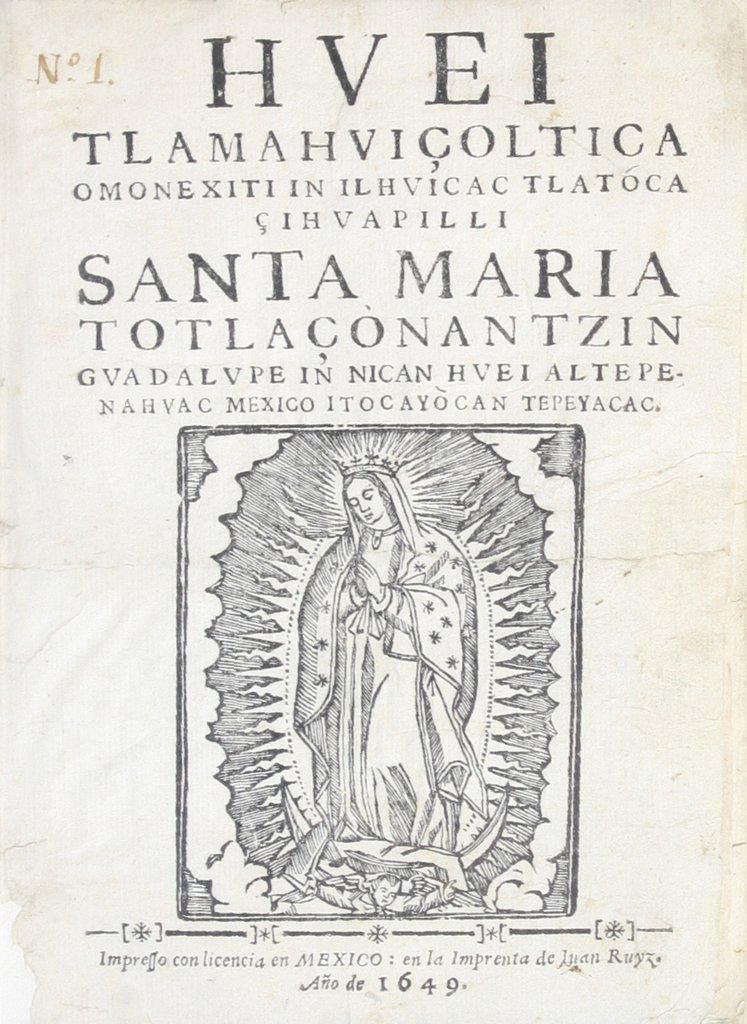

| Earliest published narrative sources for the Guadalupe event Sánchez, Imagen de la Virgen María The first written account to be published of the Guadalupe event was a theological exegesis hailing Mexico as the New Jerusalem and correlating Juan Diego with Moses at Mount Horeb and the Virgin with the mysterious Woman of the Apocalypse in chapter 12 of the Book of Revelation. Entitled Imagen de la Virgen Maria, Madre de Dios de Guadalupe, Milagrosamente aparecida en la Ciudad de México (Image of the Virgin Mary, Mother of God of Guadalupe, who miraculously appeared in the City of Mexico), it was published in Spanish in Mexico City in 1648 after a prolonged gestation.[ac] The author was a Mexican-born Spanish priest, Miguel Sánchez, who asserted in his introduction (Fundamento de la historia) that his account of the apparitions was based on documentary sources (few, and only vaguely alluded to) and on an oral tradition which he calls "antigua, uniforme y general" (ancient, consistent and widespread). The book is structured as a theological examination of the meaning of the apparitions to which is added a description of the tilma and of the sanctuary, accompanied by a description of seven miracles associated with the cult, the last of which related to a devastating inundation of Mexico City in the years 1629–1634. Although the work inspired panegyrical sermons preached in honour of the Virgin of Guadalupe between 1661 and 1766, it was not popular and was rarely reprinted.[48][49] Shorn of its devotional and scriptural matter and with a few additions, Sánchez' account was republished in 1660 by a Jesuit priest from Puebla named Mateo de la Cruz, whose book, entitled Relación de la milagrosa aparición de la Santa Virgen de Guadalupe de México ("Account of the miraculous apparition of the Holy Image of the Virgin of Guadalupe of Mexico"), was soon reprinted in Spain (1662), and served greatly to spread knowledge of the cult.[50] Nican Mopohua  The first page of the Huei tlamahuiçoltica The second-oldest published account is known by the opening words of its long title: Huei tlamahuiçoltica ("The great event"). It was published in Nahuatl by the then vicar of the hermitage at Guadalupe, Luis Lasso de la Vega, in 1649. In four places in the introduction, he announced his authorship of all or part of the text, a claim long received with varying degrees of incredulity because of the text's consummate grasp of a form of classical Nahuatl dating from the mid-16th century, the command of which Lasso de la Vega neither before nor after left any sign.[51] The complete work comprises several elements including a brief biography of Juan Diego and, most famously, a highly wrought and ceremonious account of the apparitions known from its opening words as the Nican Mopohua ("Here it is told"). Despite the variations in style and content which mark the various elements, an exclusively textual analysis by three American investigators published in 1998 provisionally (a) assigned the entire work to the same author or authors, (b) saw no good reason to strip de la Vega of the authorship role he had claimed, and (c) of the three possible explanations for the close link between Sánchez's work and the Huei tlamahuiçoltica, opted for a dependence of the latter upon the former which, however, was said to be indicated rather than proved. Whether the role to be attributed to Lasso de la Vega was creative, editorial or redactional remains an open question.[ad] Nevertheless, the broad consensus among Mexican historians (both ecclesiastical and secular) has long been, and remains, that the Nican Mopohua dates from as early as the mid-16th century and (so far as it is attributed to any author) that the likeliest hypothesis as to authorship is that Antonio Valeriano wrote it, or at least had a hand in it.[ae]The Nican Mopohua was not reprinted or translated in full into Spanish until 1929, although an incomplete translation had been published in 1895 and Becerra Tanco's 1675 account (see next entry) has close affinities with it.[55] Becerra Tanco, Felicidad de México The third work to be published was written by Luis Becerra Tanco who professed to correct some errors in the two previous accounts. Like Sánchez a Mexican-born Spanish diocesan priest, Becerra Tanco ended his career as professor of astronomy and mathematics at the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico.[56][57][58] As first published in Mexico City in 1666, Becerra Tanco's work was entitled Origen milagroso del Santuario de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe ("Miraculous origin of the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Guadalupe") and it gave an account of the apparitions mainly taken from de la Cruz' summary (see entry [1], above).[59] The text of the pamphlet was incorporated into the evidence given to a canonical inquiry conducted in 1666, the proceedings of which are known as the Informaciones Jurídicas de 1666 (see next entry). A revised and expanded edition of the pamphlet (drawing more obviously on the Nican Mopohua) was published posthumously in 1675 as Felicidad de Mexico and again in 1685 (in Seville, Spain). Republished in Mexico in 1780 and (as part of a collection of texts) republished in Spain in 1785, it became the preferred source for the apparition narrative until displaced by the Nican Mopohua which gained a new readership from the Spanish translation published by Primo Velázquez in Mexico in 1929 (becoming thereafter the narrative of choice).[60] Becerra Tanco, as Sánchez before him, confirms the absence of any documentary source for the Guadalupe event in the official diocesan records, and asserts that knowledge of it depends on the oral tradition handed on by the natives and recorded by them first in paintings and later in an alphabetized Nahuatl.[61] More precisely, Becerra Tanco claimed that before 1629 he had himself heard "cantares" (or memory songs) sung by the natives at Guadalupe celebrating the apparitions, and that he had seen among the papers of Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl (1578?–1650) (i) a mapa (or pictographic codex) which covered three centuries of native history, ending with the apparition at Tepeyac, and (ii) a manuscript book written in alphabetized Nahuatl by an Indian which described all five apparitions.[62] In a separate section entitled Testificación he names five illustrious members of the ecclesiastical and secular elite from whom he personally had received an account of the tradition – quite apart from his Indian sources (whom he does not name).[63] Informaciónes Jurídicas de 1666 The fourth in time (but not in date of publication) is the Informaciones Jurídicas de 1666 already mentioned. As its name indicates, it is a collection of sworn testimonies. These were taken down in order to support an application to Rome for liturgical recognition of the Guadalupe event. The collection includes reminiscences in the form of sworn statements by informants (many of them of advanced age, including eight Indians from Cuauhtitlán) who claimed to be transmitting accounts of the life and experiences of Juan Diego which they had received from parents, grandparents or others who had known or met him. The substance of the testimonies was reported by Florencia in chapter 13 of his work Estrella de el Norte de México (see next entry). Until very recently the only source for the text was a copy dating from 1737 of the translation made into Spanish which itself was first published in 1889.[64][65] An original copy of the translation (dated April 14, 1666) was discovered by Eduardo Chávez Sánchex in July 2001 as part of his researches in the archives of the Basilica de Guadalupe.[66] de Florencia, Estrella de el Norte de México The last to be published was Estrella de el Norte de México by Francisco de Florencia, a Jesuit priest. This was published in Mexico in 1688 and then in Barcelona and Madrid, Spain, in 1741 and 1785, respectively.[af][68] Florencia, while applauding Sánchez's theological meditations in themselves, considered that they broke the thread of the story. Accordingly, his account of the apparitions follows that of Mateo de la Cruz's abridgement.[69] Although he identified various Indian documentary sources as corroborating his account (including materials used and discussed by Becerra Tanco, as to which see the preceding entry), Florencia considered that the cult's authenticity was amply proved by the tilma itself,[70] and by what he called a "constant tradition from fathers to sons ... so firm as to be an irrefutable argument".[71] Florencia had on loan from the famous scholar and polymath Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora two such documentary sources, one of which – the antigua relación (or, old account) – he discussed in sufficient detail to reveal that it was parallel to but not identical with any of the materials in the Huei tlamahuiçoltica. So far as concerns the life of Juan Diego (and of Juan Bernardino) after the apparitions, the antigua relación reported circumstantial details which embellish rather than add to what was already known.[72] The other documentary source of Indian origin in Florencia's temporary possession was the text of a memory song said to have been composed by Don Placido, lord of Azcapotzalco, on the occasion of the solemn transfer of the Virgin's image to Tepeyac in 1531 – this he promised to insert later on in his history, but never did.[ag] |

グアダルーペの出来事の最も古い出版された物語的資料 サンチェス著『マリアの聖母の像 グアダルーペの出来事の最初の出版された記述は、メキシコを新しいエルサレムとして称賛し、ホレブ山でのモーゼと黙示録第12章の黙示録の神秘的な女とを 関連づける神学的な解釈であった。「グアダルペの聖母マリア、神の母マリア、奇跡的にメキシコシティに現れたマリアの像」と題されたこの本は、長い準備期 間を経て1648年にメキシコシティでスペイン語で出版された[ac]。著者はメキシコ生まれのスペイン人司祭ミゲル・サンチェスで、序文 (Fundamento de la historia)で、出現の記述は(数が少なく、曖昧にしか言及されていない)文書資料と、彼が「antigua, uniforme y general」(古代、一貫性があり、広範囲に普及している)と呼ぶ口承伝承に基づいていると主張している。この本は、聖像出現の意味を神学的に考察す る構成となっており、ティルマと聖域の説明に加え、この信仰と関連のある7つの奇跡の説明も付されている。最後の奇跡は、1629年から1634年にかけ てメキシコシティを襲った壊滅的な洪水に関するものである。この本は、1661年から1766年にかけてグアダルペの聖母マリアを称える賛美の説教の題材 となったが、人気が出ず、再版されることはほとんどなかった[48][49]。信仰や聖書の記述を削除し、いくつかの内容を追加したサンチェスの記述は、 プエブラ出身のイエズス会の司祭マテオ・デ・ラ・クルスが1660年に再出版した。彼の著書『Relación de la milagrosa aparición de la 『メキシコ・グアダルペの聖母』(「メキシコ・グアダルペの聖母の聖像の奇跡的な出現の記録」)は、まもなくスペインでも再版され(1662年)、この崇 拝に関する知識の普及に大きく貢献した[50]。 『ニカン・モポフア』  『ウエイ・トラマウィソルティカ』の最初のページ 出版された記録の中で2番目に古いものは、長いタイトルの冒頭で知られている。1649年、グアダルーペの隠遁所の当時の司祭であったルイス・ラッソ・ デ・ラ・ベガによってナワトル語で出版された。序文の4か所において、彼はこの文章のすべてまたは一部を自分が書いたと明言している。この文章は16世紀 中期の古典ナワトル語を完璧に理解しており、ラッソ・デ・ラ・ベガはその文章を完全に理解していたため、この主張は長い間、さまざまなレベルで疑いの目を 向けられてきた。ラソ・デ・ラ・ベガは、その前にも後も、その証拠を残さなかった[51]。この作品は、フアン・ディエゴの簡単な伝記や、最も有名な「ニ カン・モポフア」(「ここに語られる」)として冒頭で知られる、非常に精巧で厳粛な出現の記述など、いくつかの要素から構成されている。各要素のスタイル や内容には違いが見られるが、1998年に発表された3人のアメリカ人研究者によるテキストのみの分析では、暫定的に(a)この作品をすべて同じ著者また は著者たちが書いたものと見なし、(b)デ・ラ・ベガが主張していた著者の役割を剥奪する十分な理由はないと結論づけ、(c)サンチェスの作品とフエイ・ トラマヒュイコルティカの密接な関係について考えられる3つの説明のうち、後者が前者に依存しているとする説を採用した。ただし、これは証明されたという よりも示唆されたものであるとされている。 主張していたヒップの役割を奪う正当な理由はないと結論付け、(c) サンチェスの作品とHuei tlamahuiçolticaの密接な関係について考えられる3つの説明のうち、後者が前者に依存しているという説を採用した。ただし、これは証明され たというよりも示唆されたものであるとされている。ラッソ・デ・ラ・ベガが果たした役割が、創造的、編集的、または校正的であったかどうかは、依然として 未解決の問題である[ad]。しかし、メキシコの歴史家(教会関係者および世俗関係者)の間で広く認められているのは、ニカン・モポフアは16世紀半ばに はすでに存在していたという見解であり、 (作者として考えられるのは)アントニオ・バレリアーノが書いたか、少なくともそれに手を加えたという説が最も有力である[ae]。ニカン・モポフアは、 1895年に不完全な翻訳が出版されていたものの、1929年までスペイン語に全文が再版されたり翻訳されたりすることはなかった。 95年に不完全な翻訳が出版され、ベセラ・タンコの1675年の記述(次の項目参照)はそれに近い内容となっている[55]。 ベセラ・タンコ『メキシコの幸福』 3番目に出版された作品は、ルイス・ベセラ・タンコによって書かれたもので、彼は2つの以前の記述の誤りを訂正すると主張していた。メキシコ生まれのスペ イン人司祭サンチェスと同様、ベセラ・タンコはメキシコ王立教皇大学の天文学と数学の教授としてその生涯を終えた[56][57][58]。1666年に メキシコシティで初めて出版されたベセラ・タンコの著作は、『グアダルペの聖母聖域の奇跡的な起源』(Origen milagroso del Santuario de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe)と題され、主にデ・ラ・クルスの要約(上記の項目[1]を参照)から引用した出現の記述が掲載されていた[59]。グアダルペの聖母 の聖域の奇跡的な起源」)と題され、主にデ・ラ・クルスの要約(上記の項目[1]を参照)から引用された出現の記述が掲載されていた[59]。この小冊子 の文章は、1666年に実施された教会法上の調査の証拠として提出され、その手続きは「1666年の司法情報」(次の項目を参照)として知られている。こ のパンフレットは、ニカン・モポフアを参考にさらに改訂・拡大され、1675年に『フェリシダッド・デ・メヒコ』として死後出版された。1780年にメキ シコで再出版され、(テキスト集の一部として)1785年にスペインで再出版された後、この本は聖母マリア出現の物語の最も好まれる情報源となった。しか し、1929年にプリモ・ベラスケスがメキシコで出版したスペイン語訳により、新たな読者層を獲得した『ニカン・モポフア』にその座を奪われた(その後、 この本は最も好まれる物語となった)。 )[60] ベセラ・タンコは、サンチェス同様、グアダルペの出来事の公式教区記録に文書資料が存在しないことを確認し、その知識は先住民から口頭で伝えられ、最初に 絵画で、後にアルファベット化されたナワトル語で記録されたものによると主張している[61]。より正確には、ベセラ・タンコは、1 629年以前、彼はグアダルーペで聖母マリアの出現を祝うために先住民が歌う「カンターレス」(記憶の歌)を自ら耳にし、フェルナンド・デ・アルヴァ・イ クストリルコチル(1578年?–1650年)の書類の中に、(i) 先住民の3世紀にわたる歴史を網羅し、テペヤックの聖母マリアの出現で終わる「地図」(絵文字の写本)、 テペヤックでの出現で終わっている。また、(ii) 5つの出現のすべてについて、アルファベット表記のナワトル語で書かれた、インディアンによる手書きの原稿本も存在していた[62]。 Testificación(証言)と題された別のセクションでは、教会と世俗のエリート層から5人の著名な人物が挙げられており、その人物たちから、彼 は個人的に伝承について話を聞いた。これは、インディアンからの情報源(名前は挙げられていない)とはまったく別である[63]。 1666年の法廷情報 4番目に登場するのは(出版日は異なるが)、すでに触れた1666年の『Informaciones Jurídicas de 1666』である。その名の通り、宣誓証言を集めたものである。これらは、グアダルペの出来事を典礼としてローマに承認してもらうための申請を裏付けるた めに記録された。このコレクションには、情報提供者(その多くは高齢で、クアウティトラン出身の8人のインディアンを含む)が宣誓証言した回想録が含まれ ている。情報提供者たちは、両親や祖父母、あるいは彼を知っていたり会ったことのある人々から聞いた、フアン・ディエゴの人生や経験に関する話を伝えたと 主張している。証言の要点は、フローレンシアが著書『Estrella de el Norte de México』の第13章で報告している(次の項目参照)。ごく最近まで、このテキストの唯一の資料は、1737年にスペイン語に翻訳されたもののコピー であり、そのスペイン語訳は1889年に初めて出版されたものであった[64][65]。翻訳のオリジナルコピー(1666年4月14日付)は、 2001年7月、エドゥアルド・チャベス・サンチェスがグアダルーペ聖堂の文書館で研究していた際に、この翻訳のオリジナル(1666年4月14日付)を 発見した[66]。 フランシスコ・デ・フローレンシア著『メキシコの北の星 最後に出版されたのは、イエズス会の司祭フランシスコ・デ・フローレンシア著『メキシコの北の星』であった。これは1688年にメキシコで、1741年に スペインのバルセロナで、1785年にマドリードで出版された。[af][68] フローレンシアは、サンチェスの神学的な考察自体を称賛しながらも、それが物語の筋を壊していると考えていた。したがって、彼の霊現の記述はマテオ・デ・ ラ・クルスの要約に続くものである[69]。彼は、彼の記述を裏付けるさまざまなインディアン文献資料を特定したが(ベセラ・タンコが使用し、議論した資 料については、前の項目を参照)、フロレンシアは、その教団の信憑性はティルマ自体によって十分に証明されていると考え、また、彼が「父から子へと受け継 がれてきた...反論の余地のない確固とした伝統」と呼んだものによっても証明されていると考えた[70]。父から子へと受け継がれてきた...反論の余 地のない確固とした伝統」[71]である。フローレンシアは、著名な学者であり博識家でもあったカルロス・デ・シグエンサ・イ・ゴンゴラから、2つのその ような文献資料を借り受けていた。そのうちの1つである「アンティグア・レシオン(古い記録)」について、フローレンシアは十分な詳細を論じており、それ がフエイ・トラマウィソルトカの資料のいずれとも一致しないが、並行するものであることを明らかにしていた。出現後のフアン・ディエゴ(およびフアン・ベ ルナルディーノ)の人生に関しては、アンティーグア・レシオンは、既知の事実を補強するよりもむしろ美化する状況の詳細を報告している[72]。フローレ ンシアが一時的に所有していたもう一つのインディアン起源の文書資料は、 1531年にアスカポツァルコの領主ドン・プラシドが、聖母の像をテペヤックに移す厳粛な儀式のために作曲したとされる記憶の歌の歌詞である。彼は後にこ の歌を自身の歴史書に加えることを約束したが、結局それは実現しなかった[ag]。 |

Historicity arguments Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe (interior) The primary doubts about the historicity of Juan Diego (and the Guadalupe event itself) arise from the silence of those major sources who would be expected to have mentioned him, including, in particular, Bishop Juan de Zumárraga and the earliest ecclesiastical historians who reported the spread of the Catholic faith among the Indians in the early decades after the capture of Tenochtítlan in 1521. Despite references in near-contemporary sources which do attest a mid-16th-century Marian cult attached to a miraculous image of the Virgin at a shrine at Tepeyac under the title of Our Lady of Guadalupe, and despite the weight of oral tradition concerning Juan Diego and the apparitions (which, at the most, spans less than four generations before being reduced to writing), the fundamental objection of this silence of core 16th-century sources remains a perplexing feature of the history of the cult which has, nevertheless, continued to grow outside Mexico and the Americas. The first writer to address this problem of the silence of the sources was Francisco de Florencia in chapter 12 of his book Estrella de el norte de Mexico (see previous section). However, it was not until 1794 that the argument from silence was presented to the public in detail by someone – Juan Bautista Muñoz – who clearly did not believe in the historicity of Juan Diego or of the apparitions. Substantially the same argument was publicized in updated form at the end of the 19th and 20th centuries in reaction to renewed steps taken by the ecclesiastical authorities to defend and promote the cult through the coronation of the Virgin in 1895 and the beatification of Juan Diego in 1990.[ah][75] The silence of the sources can be examined by reference to two main periods: (i) 1531–1556 and (ii) 1556–1606 which, for convenience, may loosely be termed (i) Zumárraga's silence, and (ii) the Franciscan silence. Despite the accumulation of evidence by the start of the 17th century (including allusions to the apparitions and the miraculous origin of the image),[ai][76] the phenomenon of silence in the sources persists well into the second decade of that century, by which time the silence ceases to be prima facie evidence that there was no tradition of the Guadalupe event before the publication of the first narrative account of it in 1648. For example, Bernardo de Balbuena wrote a poem while in Mexico City in 1602 entitled La Grandeza Mexicana in which he mentions all the cults and sanctuaries of any importance in Mexico City except Guadalupe, and Antonio de Remesal published in 1620 a general history of the New World which devoted space to Zumárraga but was silent about Guadalupe.[77] Zumárraga's silence Period (i) extends from the date of the alleged apparitions down to 1556, by which date there first emerges clear evidence of a Marian cult (a) located in an already existing ermita or oratory at Tepeyac, (b) known under the name Guadalupe, (c) focussed on a painting, and (d) believed to be productive of miracles (especially miracles of healing). This first period itself divides into two unequal sub-periods either side of the year 1548 when Bishop Zumárraga died. Post-1548 The later sub-period can be summarily disposed of, for it is almost entirely accounted for by the delay between Zumárraga's death on June 3, 1548, and the arrival in Mexico of his successor, Archbishop Alonso de Montúfar, on June 23, 1554.[78][79] During this interval there was lacking not only a bishop in Mexico City (the only local source of authority over the cult of the Virgin Mary and over the cult of the saints), but also an officially approved resident at the ermita – Juan Diego having died in the same month as Zumárraga, and no resident priest having been appointed until the time of Montúfar. In the circumstances, it is not surprising that a cult at Tepeyac (whatever its nature) should have fallen into abeyance. Nor is it a matter for surprise that a cult failed to spring up around Juan Diego's tomb at this time. The tomb of the saintly fray Martín de Valencia (the leader of the twelve pioneering Franciscan priests who had arrived in New Spain in 1524) was opened for veneration many times for more than thirty years after his death in 1534 until it was found, on the last occasion, to be empty. But, dead or alive, fray Martín had failed to acquire a reputation as a miracle-worker.[80] Pre-1548 Turning to the years before Zumárraga's death, there is no known document securely dated to the period 1531 to 1548 which mentions Juan Diego, a cult to the Virgin Mary at Tepeyac, or the Guadalupe event. The lack of any contemporary evidence linking Zumárraga with the Guadalupe event is particularly noteworthy, but, of the surviving documents attributable to him, only his will can be said to be just such a document as might have been expected to mention an ermita or the cult.[aj] In this will Zumárraga left certain movable and personal items to the cathedral, to the infirmary of the monastery of St. Francis, and to the Conceptionist convent (all in Mexico City); divided his books between the library of the monastery of St Francis in Mexico City and the guesthouse of a monastery in his home-town of Durango, Spain; freed his slaves and disposed of his horses and mules; made some small bequests of corn and money; and gave substantial bequests in favour of two charitable institutions founded by him, one in Mexico City and one in Veracruz.[81] Even without any testamentary notice, Zumárraga's lack of concern for the ermita at Tepeyac is amply demonstrated by the fact that the building said to have been erected there in 1531 was, at best, a simple adobe structure, built in two weeks and not replaced until 1556 (by Archbishop Montúfar, who built another adobe structure on the same site).[ak] Among the factors which might explain a change of attitude by Zumárraga to a cult which he seemingly ignored after his return from Spain in October 1534, the most prominent is a vigorous inquisition conducted by him between 1536 and 1539 specifically to root out covert devotion among natives to pre-Christian deities. The climax of the sixteen trials in this period (involving 27 mostly high-ranking natives) was the burning at the stake of Don Carlos Ometochtli, lord of the wealthy and important city of Texcoco, in 1539 – an event so fraught with potential for social and political unrest that Zumárraga was officially reprimanded by the Council of the Indies in Spain and subsequently relieved of his inquisitorial functions (in 1543).[82] In such a climate and at such a time as that he can hardly have shown favour to a cult which had been launched without any prior investigation, had never been subjected to a canonical inquiry, and was focussed on a cult object with particular appeal to natives at a site arguably connected with popular devotion to a pre-Christian female deity. Leading Franciscans were notoriously hostile to – or at best suspicious of – Guadalupe throughout the second half of the 16th century precisely on the grounds of practices arguably syncretic or worse. This is evident in the strong reaction evinced in 1556 when Zumárraga's successor signified his official support for the cult by rebuilding the ermita, endowing the sanctuary, and establishing a priest there the previous year (see next sub-section). It is reasonable to conjecture that had Zumárraga shown any similar partiality for the cult from 1534 onwards (in itself unlikely, given his role as Inquisitor from 1535), he would have provoked a similar public rebuke.[83] The Franciscan silence The second main period during which the sources are silent extends for the half century after 1556 when the then Franciscan provincial, fray Francisco de Bustamante, publicly rebuked Archbishop Montúfar for promoting the Guadalupe cult. In this period, three Franciscan friars (among others) were writing histories of New Spain and of the peoples (and their cultures) who either submitted to or were defeated by the Spanish Conquistadores. A fourth Franciscan friar, Toribio de Benevente (known as Motolinía), who had completed his history as early as 1541, falls outside this period, but his work was primarily in the Tlaxcala-Puebla area.[al] One explanation for the Franciscans' particular antagonism to the Marian cult at Tepeyac is that (as Torquemada asserts in his Monarquía indiana, Bk.X, cap.28) it was they who had initiated it in the first place, before realising the risks involved.[85][am] In due course this attitude was gradually relaxed, but not until some time after a change in spiritual direction in New Spain attributed to a confluence of factors including (i) the passing away of the first Franciscan pioneers with their distinct brand of evangelical millennarianism compounded of the ideas of Joachim de Fiore and Desiderius Erasmus (the last to die were Motolinía in 1569 and Andrés de Olmos in 1571), (ii) the arrival of Jesuits in 1572 (founded by Ignatius Loyola and approved as a religious order in 1540), and (iii) the assertion of the supremacy of the bishops over the Franciscans and the other mendicant Orders by the Third Mexican Council of 1585, thus signalling the end of jurisdictional arguments dating from the arrival of Zumárraga in Mexico in December 1528.[87][88] Other events largely affecting society and the life of the Church in New Spain in the second half of the 16th century cannot be ignored in this context: depopulation of the indigenous through excessive forced labour and the great epidemics of 1545, 1576–1579 and 1595,[89] and the Council of Trent, summoned in response to the pressure for reform, which sat in twenty-five sessions between 1545 and 1563 and which reasserted the basic elements of the Catholic faith and confirmed the continuing validity of certain forms of popular religiosity (including the cult of the saints).[90] Conflict over an evangelical style of Catholicism promoted by Desiderius Erasmus, which Zumárraga and the Franciscan pioneers favoured, was terminated by the Catholic Church's condemnation of Erasmus' works in the 1550s. The themes of Counter-reformation Catholicism were strenuously promoted by the Jesuits, who enthusiastically took up the cult of Guadalupe in Mexico.[91][92] The basis of the Franciscans' disquiet and even hostility to Guadalupe was their fear that the evangelization of the natives had been superficial, that the indigenous had retained some of their pre-Christian beliefs, and, in the worst case, that Christian baptism was a cloak for persisting in pre-Christian devotions.[85][93][94] These concerns are to be found in what was said or written by leading Franciscans such as fray Francisco de Bustamante (involved in a dispute on this topic with Archbishop Montúfar in 1556, as mentioned above); fray Bernardino de Sahagún (whose Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España was completed in 1576/7 with an appendix on surviving superstitions in which he singles out Guadalupe as a prime focus of suspect devotions); fray Jerónimo de Mendieta (whose Historia eclesiástica indiana was written in the 1590s); and fray Juan de Torquemada who drew heavily on Mendieta's unpublished history in his own work known as the Monarquía indiana (completed in 1615 and published in Seville, Spain, that same year). There was no uniform approach to the problem and some Franciscans were less reticent than others. Bustamante publicly condemned the cult of Our Lady of Guadalupe outright precisely because it was centred on a painting (allegedly said to have been painted "yesterday" by an Indian) to which miraculous powers were attributed,[95] whereas Sahagún expressed deep reservations as to the Marian cult at Tepeyac without mentioning the cult image at all.[96][97][98] Mendieta made no reference to the Guadalupe event although he paid particular attention to Marian and other apparitions and miraculous occurrences in Book IV of his history – none of which, however, had evolved into established cults centred on a cult object. Mendieta also drew attention to the natives' subterfuge of concealing pre-Christian cult objects inside or behind Christian statues and crucifixes in order to mask the true focus of their devotion.[99] Torquemada repeated, with variations, an established idea that churches had been deliberately erected to Christian saints at certain locations (Tepeyac among them) in order to channel pre-Christian devotions towards Christian cults.[100] Significance of silence The non-reference by certain church officials of Juan Diego does not necessarily prove that he did not exist.[an] The relevance of the silence has been questioned by some, citing certain documents from the time of Zumárraga, as well as the fact that Miguel Sánchez preached a sermon in 1653 on the Immaculate Conception in which he cites chapter 12 of the Book of Revelation, but makes no mention of Guadalupe.[102] |

歴史性に関する議論 グアダルペの聖母大聖堂(内部) フアン・ディエゴ(およびグアダルペの出来事自体)の歴史性に対する主な疑念は、フアン・ディエゴについて言及しているはずである主要な情報源が沈黙して いることから生じている。特に、1521年のテノチティトラン陥落後、最初の数十年間にインディアンへのカトリック信仰の普及について報告したフアン・ デ・スマラガ司教や初期の教会史家などが該当する。16世紀中期のマリア崇拝が、テペヤックの聖母グアダルペの聖堂にある奇跡的な聖母マリア像と結びつい ていたことを示す、ほぼ同時代の資料への言及があるにもかかわらず、また、フアン・ディエゴと聖母マリアの出現に関する口承の重要性にもかかわらず (最も長いものでも、文章化されるまでに4世代未満しか経っていない)にもかかわらず、16世紀の主要な情報源が沈黙しているという事実は、この教団の謎 めいた歴史の特徴であり続けている。この資料の沈黙の問題を最初に取り上げたのは、フランシスコ・デ・フロレンシアで、著書『メキシコ北部の星』の第12 章で述べている(前節参照)。しかし、沈黙の議論が詳細に公表されたのは、フアン・バウティスタ・ムニョスという人物によってであり、それは1794年の ことである。彼は明らかにフアン・ディエゴや聖母の出現の史実性を信じていなかった。1895年の聖母戴冠式や1990年のフアン・ディエゴの列福など、 教会の当局が聖母マリアの崇拝を擁護し推進する新たな措置を講じたことに対する反発として、19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけて、実質的に同じ論点が更新 された形で公表された。 資料の沈黙については、次の2つの主要な時期を基準に検討することができる。(i) 1531年~1556年、(ii) 1556年~1606年。便宜上、(i) スマラガの沈黙、(ii) フランシスコ会の沈黙と呼ぶことができる。17世紀初頭までに、出現や像の奇跡的な起源に関する言及を含む証拠が蓄積されたにもかかわらず[ai] [76]、資料における沈黙の現象は、1648年にグアダルペの出来事の最初の物語的記述が発表されるまで、グアダルペの出来事の伝統が存在しなかったこ とを示す明白な証拠ではなくなった。例えば、ベルナルド・デ・バルブエナは1602年にメキシコシティで『ラ・グランデサ・メヒカーナ』と題する詩を書 き、その中でメキシコシティの重要なあらゆる崇拝と聖域について言及しているが、グアダルーペについては言及していない。また、アントニオ・デ・レメサル は1620年に新世界の一般史を出版したが、その中にはズマラガについては詳しく書かれているが、グアダルーペについては何も書かれていない。 ズマラガ ズマラガの沈黙 (i) は、聖母マリアの幻影が報告された日から1556年までを指し、この年にはマリア崇拝の明確な証拠が初めて現れた。それは、(a) テペヤックの既存の礼拝堂や祈りの部屋にある、(b) グアダルーペの名で知られている、(c) 絵画に焦点を当てている、(d) 奇跡(特に癒しの奇跡)をもたらすと考えられている。この最初の時期は、1548年に司教ズマラガが死去した前後で、2つの異なるサブ期間に分けられる。 1548年以降 後者の期間は、1548年6月3日にズマラガが死去してから、後継者であるモンテファー大司教が1554年6月23日にメキシコに到着するまでの間の遅れ によってほぼ完全に説明できるため、簡単にまとめることができる[78][ 79] この期間、メキシコシティには司教(聖母マリアと聖人崇拝の唯一の地元権威)がいないだけでなく、エルミタに正式に承認された居住者もいなかった。フア ン・ディエゴはズマラガと同じ月に亡くなり、モンテファーの時代になるまで居住司祭が任命されなかったのだ。このような状況では、テペヤックの礼拝堂(そ の性質が何であれ)が休止状態に陥ったとしても驚くには当たらない。また、この時期にフアン・ディエゴの墓の周りに礼拝堂が建設されなかったとしても驚く には当たらない。聖人マルティン・デ・バレンシア(1524年に新スペインに到着した12人の先駆的フランシスコ会修道士たちのリーダー)の墓は、 1534年に彼が亡くなった後、30年以上何度も参拝のために開かれ、最後に空であることが分かった。しかし、生きているか死んでいるかにかかわらず、フ ラ・マルティンは奇跡を起こす人物としての評判を得ることはできなかった[80]。 1548年以前 ツマラガの死の前年について言えば、1531年から1548年の間に、フアン・ディエゴ、テペヤックの聖母マリア崇拝、グアダルペの出来事を言及した確実 な日付の文書は知られていない。ズマラガとグアダルーペの出来事を結びつけるような同時代の証拠がないことは特に注目に値するが、彼に帰せられる現存する 文書のうち、エルミタや崇拝について言及している可能性があると期待される文書は、彼の遺言書だけである[aj]。この遺言書で、ズマラガは、大聖堂、サ ンフランシスコ修道院の診療所、 そしてコンセプシオニスタ修道院(いずれもメキシコシティ)に遺贈し、蔵書をメキシコシティのサンフランシスコ修道院の図書館と故郷であるスペインのドゥ ランゴにある修道院のゲストハウスに分け、奴隷を解放し、馬とラバを手放し、トウモロコシと金銭を少し遺贈し、自身が設立した慈善団体2団体に多額の遺贈 を行った。そして、ベラクルスに設立された2つの慈善団体に多額の遺産を残した。同じ場所に別の土造りの建物を建てた)[ak]。1534年10月にスペ インから帰国した後、ズマラガがそれまで無視していたように見えたこの宗教に対する態度を変化させた要因として考えられるものの中で、最も顕著なのは、 1536年から1539年にかけて、特に先住民のキリスト教以前の神々に対する隠れた信仰を根絶するために、彼が主導した活発な異端審問である。この期間 に行われた16件の裁判(主に高位の人々が関与した27件)のクライマックスは、1539年にテスココの裕福で重要な都市の領主ドン・カルロス・オメトク トリが火あぶりにされたことであった。この出来事は、社会や政治の不安要素を孕む可能性があったため、スペインのインド評議会から公式に叱責されたズマラ ガは、その後 (1543年)[82]。このような時代背景の中で、事前調査も正式な調査もなされておらず、先住民の信仰の対象となっている、キリスト教以前の女神への 信仰と関連があるとされる場所に置かれている、先住民にとって特別な魅力を持つ聖像に焦点を当てたカルトを、彼が好意的に受け止めることはあり得なかっ た。16世紀後半を通じて、グアダルーペに対して敵意を抱く、あるいはせいぜい疑いの目を向けるフランシスコ会の指導者は多かった。その理由は、明らかに 折衷的、あるいはそれ以上の要素を含むとされる慣習にあった。これは、1556年にズマラガの後任者が前年にエルミタを再建し、聖域に資金を投入し、そこ に司祭を置いたことで、この教団への公式な支持を表明した際に示された強い反発からも明らかである(次の小節を参照)。1534年以降、ズマラガがカルト に対して同様の偏愛を示していたら(1535年から彼が宗教裁判官を務めていたことを考えると、それ自体が考えにくい)、同様の公の非難を招いたであろう と推測するのは妥当である[83]。 フランシスコ会の沈黙 資料が沈黙している2つ目の主な期間は、1556年以降半世紀にわたって続いた。当時のフランシスコ会管区長、フラビオ・デ・ブスタマンテが、グアダルー ペの崇拝を推奨したモンテファル大司教を公然と非難した時期である。この期間、3人のフランシスコ会の修道士(そのほか数人)が、スペインの征服者たちに 服従したか、あるいは征服者たちに敗北した人々(およびその文化)に関する、新スペインの歴史を執筆していた。1541年にすでに歴史を完成させていた、 第4のフランシスコ会修道士トリビオ・デ・ベネベント(モトリニアとして知られる)は、この期間に含まれないが、彼の作品は主にトラスカラ・プエブラ地域 を対象としていた[al]。フランシスコ会がテペヤックの聖母崇拝に特に敵対していた理由の一つとして、(トルケマーダが『Monarquía Indiana』第10巻第28章で主張しているように トルケマーダが『インディアナ君主論』第10巻第28章で主張しているように、フランシスコ会はそもそも、危険性を認識する前にそれを始めたのだという説 がある[85][am]。やがてこの姿勢は徐々に緩和されたが、それは(i)ヨアヒム・デ・フィオレとデシデリウス・エラスムスの思想を融合させた独自の 福音主義千年王国説を持つ最初のフランシスコ会の開拓者たちが相次いで死去したこと(最後に亡くなったのは1569年のモトリニアと1571年のアンドレ ス・デ・オルモス)、(ii)1572年のイエズス会の到来(イグナティウス・ロヨラが創設し、1540年に修道会として承認された)、(iii)トルケ マーダの主張など、さまざまな要因が重なった結果、ニュースペインにおける精神的な方向性が変化してからしばらく経ってからであった。ヨアヒム・デ・フィ オーレとデシデリウス・エラスムスの思想を融合させた独自の千年王国説を信奉していた最初のフランシスコ会の開拓者たちが相次いで死去したこと(最後に亡 くなったのは、1569年のモトリニヤと1571年のアンドレス・デ・オルモス)、(ii) 1572年のイエズス会の到来(イグナティウス・ロヨラによって創設され、1540年に修道会として承認された)、(iii) 1585年の第3回メキシコ公会議で、司教がフランシスコ会や他の托鉢修道会よりも優位にあることが主張されたことにより、1528年12月のズマラーガ のメキシコ到着以来続いていた管轄権をめぐる論争に終止符が打たれた[87][88]。16世紀後半にニュースペインの社会と教会の生活に大きく影響を与 えたその他の出来事として、 1545年、1576年から1579年、1595年に起こった大流行病や、過酷な強制労働による先住民の人口減少[89]、改革を求める圧力を受けて招集 されたトレント公会議(1545年から1563年にかけて25回開催された)など、16世紀後半のニュースペインにおける社会や教会の生活に大きく影響を 与えた出来事を無視することはできない。そして、カトリック信仰の基本的要素を再確認し、特定の形式の民間信仰(聖人崇拝を含む)の継続的な妥当性を確認 した[90]。デシデリウス・エラスムスが推進し、ズマラガやフランシスコ会の先駆者たちが支持した福音主義的カトリック様式をめぐる対立は、1550年 代にカトリック教会がエラスムスの著作を非難したことで終結した。対抗宗教改革のカトリックのテーマは、メキシコにおけるグアダルーペの崇拝に熱狂的に取 り組んだイエズス会によって精力的に推進された[91][92]。 フランシスコ会の不安、さらにはグアダルーペに対する敵意の根底には、先住民への布教が表面的なものであったこと、先住民がキリスト教以前の信仰の一部を 保持していること、そして最悪の場合、キリスト教の洗礼はキリスト教以前の信仰を固執するための隠れ蓑となっているのではないかという懸念があった [85][93][94]。 キリスト教以前の信仰を固執するための隠れ蓑である、という最悪のケースも想定されていた。[85][93][94] これらの懸念は、フランシスコ会の指導的立場にあったフランシスコ・デ・ブスタマンテ修道士(前述の通り、1556年にモンテファール大司教とこのテーマ で論争した)、ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグン修道士(1576年/7年に『ヌエバ・エスパーニャの事物全般史』を完成させ、付録として 彼はグアダルーペを疑わしい崇拝の主な焦点として取り上げた、生き残っている迷信に関する付録を添えて、1576年から1577年に『ヌエバ・エスパー ニャの事物全般に関する歴史』を完成させた)。また、フアン・デ・トルケマーダ修道士は、メンディエタの未発表の歴史を大いに参考にしながら、自身の著作 『インディアン王政』を執筆した(1615年に完成し、同年スペインのセビリアで出版)。この問題に対するアプローチは統一されておらず、フランシスコ会 の修道士の中には、他の人よりも口数が少ない者もいた。ブスタマンテは、奇跡的な力が宿るとされる絵画(インディアンが「昨日」描いたとされる)を中心に 展開されるグアダルペの聖母崇拝を公然と非難した[95]のに対し、サアグンはテペヤックの聖母崇拝について深い懸念を表明したが、 その聖像については一切言及していない[96][97][98]。メンディエタは、マリアやその他の出現、奇跡的な出来事に特に注意を払ったものの、グア ダルーペの出来事に一切言及しなかった。しかし、これらの出来事はいずれも、聖像を中心とした確立した崇拝へと発展することはなかった。メンディエタは、 先住民がキリスト教の像や十字架の中に、あるいはその裏側に、キリスト教以前の信仰の対象を隠して、自分たちの真の信仰の対象を隠すという策略にも注目し た[99]。トルケマーダは、教会が特定の場所(テペヤックもその一つ)に意図的に建てられたのは、キリスト教以前の信仰をキリスト教の信仰対象へと導く ためだったという定説を、バリエーションを変えて繰り返した[100]。 沈黙の重要性 フアン・ディエゴについて言及しない一部の教会関係者の発言は、必ずしも彼が実在しなかったことを証明するものではない[an]。沈黙の妥当性について は、ズマラガの時代からの特定の文書や、ミゲル・サンチェスが1653年に無原罪の御宿りを説教し、ヨハネの黙示録第12章を引用したが、グアダルペにつ いては言及しなかった事実を引用し、疑問視する者もいる[102]。 |

| Pastoral significance in the Catholic Church in Mexico and beyond The evangelization of the New World Both the author of the Nican Mopectana and Miguel Sánchez explain that the Virgin's immediate purpose in appearing to Juan Diego (and to don Juan, the seer of the cult of los Remedios) was evangelical – to draw the peoples of the New World to faith in Jesus Christ:[103] In the beginning when the Christian faith had just arrived here in the land that today is called New Spain, in many ways the heavenly lady, the consummate Virgin Saint Mary, cherished, aided and defended the local people so that they might entirely give themselves and adhere to the faith. ...In order that they might invoke her fervently and trust in her fully, she saw fit to reveal herself for the first time to two [Indian] people here. The continuing importance of this theme was emphasised in the years leading up to the canonization of Juan Diego. It received further impetus in the Pastoral Letter issued by Cardinal Rivera in February 2002 on the eve of the canonization, and was asserted by John Paul II in his homily at the canonization ceremony itself when he called Juan Diego "a model of evangelization perfectly inculturated" – an allusion to the implantation of the Catholic Church within indigenous culture through the medium of the Guadalupe event.[104] Reconciling two worlds  Image of Our Lady of Guadalupe as it currently appears on the tilma In the 17th century, Miguel Sánchez interpreted the Virgin as addressing herself specifically to the indigenous people, while noting that Juan Diego himself regarded all the residents of New Spain as his spiritual heirs, the inheritors of the holy image.[105] The Virgin's own words to Juan Diego as reported by Sánchez were equivocal: she wanted a place at Tepeyac where she can show herself,[106] as a compassionate mother to you and yours, to my devotees, to those who should seek me for the relief of their necessities. By contrast, the words of the Virgin's initial message as reported in Nican Mopohua are, in terms, specific to all residents of New Spain without distinction, while including others, too:[107] I am the compassionate mother of you and of all you people here in this land, and of the other various peoples who love me, who cry out to me. The special but not exclusive favour of the Virgin to the indigenous peoples is highlighted in Lasso de la Vega's introduction:[108] You wish us your children to cry out to [you], especially the local people, the humble commoners to whom you revealed yourself. At the conclusion of the miracle cycle in the Nican Mopectana, there is a broad summary which embraces the different elements in the emergent new society, "the local people and the Spaniards [Caxtilteca] and all the different peoples who called on and followed her".[109] The role of Juan Diego as both representing and confirming the human dignity of the indigenous populations and of asserting their right to claim a place of honour in the New World is therefore embedded in the earliest narratives, nor did it thereafter become dormant awaiting rediscovery in the 20th century. Archbishop Lorenzana, in a sermon of 1770, applauded the evident fact that the Virgin signified honour to the Spaniards (by stipulating for the title "Guadalupe"), to the natives (by choosing Juan Diego), and to those of mixed race (by the colour of her face). In another place in the sermon he noted a figure of eight on the Virgin's robe and said it represented the two worlds that she was protecting (the old and the new).[110] This aim of harmonising and giving due recognition to the different cultures in Mexico rather than homogenizing them was also evident in the iconography of Guadalupe in the 18th century as well as in the celebrations attending the coronation of the image of Guadalupe in 1895 at which a place was given to 28 natives from Cuautitlán (Juan Diego's birthplace) wearing traditional costume.[111] The prominent role accorded indigenous participants in the actual canonization ceremony (not without criticism by liturgical purists) constituted one of the most striking features of those proceedings.[112] |

メキシコおよびその他の地域のカトリック教会における司牧的な意義 新世界の福音化 『ニカン・モペクタナ』の作者とミゲル・サンチェスは、聖母マリアがフアン・ディエゴ(およびロス・レメディオス教団の預言者ドン・フアン)の前に姿を現した直接的な目的は福音化、すなわち 新世界の民をイエス・キリストへの信仰へと導くためであった[103]。 キリスト教の信仰が、今日ニュー・スペインと呼ばれるこの地に初めて伝わった当初、天上の聖母マリアは、人々が完全に信仰に身を捧げ、それに従うことがで きるよう、さまざまな形で現地の人々を慈しみ、助け、守った。...人々が彼女を熱烈に呼び求め、完全に信頼できるよう、彼女はここで2人の[インディア ン]人々に初めて姿を現すことにした。 このテーマの重要性は、フアン・ディエゴの列聖に至るまで強調され続けた。2002年2月に、列聖式の前夜にリベラ枢機卿が発表した司牧書簡により、この テーマは一層強調され、列聖式典での説教で、教皇ヨハネ・パウロ2世はフアン・ディエゴを「完全に現地文化に根付いた伝道の模範」と呼び、 グアダルーペの出来事を媒介として先住民文化に根付いたカトリック教会のことを暗示している[104]。 2つの世界の和解  ティルマに描かれた現在のグアダルーペの聖母のイメージ 17世紀、ミゲル・サンチェスは聖母が先住民に特に語りかけていると解釈し、一方、フアン・ディエゴ自身は新スペインの住民全員を精神的後継者、すなわち 聖なる像の継承者たちである。[105] サンチェスが報告した、聖母マリアがフアン・ディエゴに語った言葉には曖昧さがあった。 彼女はテペヤックに、自分自身を顕現できる場所が欲しいと望んでいた。あなたとあなたの家族、私の信奉者たち、そして私を求めて必要を満たそうとする人々に、慈愛に満ちた母として。 それとは対照的に、『ニカン・モポフア』で報告されている聖母の最初のメッセージの言葉は、他の人々も含むが、ニュースペインのすべての住民に区別なく向けられたものである。 私はあなた方、そしてこの土地に住むあなた方すべて、そして私を愛し、私に助けを求める他のさまざまな民族の慈愛に満ちた母です。 先住民に対する聖母の特別な、しかし排他的な恩恵は、ラッソ・デ・ラ・ベガの序文で強調されている:[108] あなたは、私たちをあなたの子供たちとして、特に地元の民、あなたがお姿を現された謙虚な平民たちに、あなたに助けを求めて叫んでほしいと望んでいる。 『ニカン・モペクテナ』の奇跡の物語の結末には、新たに生まれた社会におけるさまざまな要素を包括する次のような概要がある。「現地の人々やスペイン人(カシュティルテカ)や、彼女を呼び求め、彼女に従ったさまざまな人々」。[1 09] 先住民の尊厳を代弁し、確認し、新世界における名誉ある地位を要求する権利を主張するというフアン・ディエゴの役割は、したがって最も古い物語に組み込ま れている。また、20世紀になって再発見されるのを待つために眠っていたわけでもない。1770年の説教でロレンサナ大司教は、聖母マリアがスペイン人 (グアダルペという称号を定めたことで)、先住民(フアン・ディエゴを選んだことで)、混血の人々(聖母の顔の色のことで)に名誉を象徴するという明白な 事実を称賛した。説教の別の箇所では、聖母の衣に描かれた数字の8に注目し、それは彼女が守っている2つの世界(古い世界と新しい世界)を表していると述 べた[110]。メキシコにおける異なる文化を同質化するのではなく調和させ、正当に評価するというこの目的は、18世紀のグアダルペの図像や、 1895年のグアダルペの聖母の像の戴冠式では、クアウティトラン(フアン・ディエゴの出身地)の28人の先住民が伝統的な衣装を着て参加し、彼らに場所 が用意された。[111]実際の列聖式で先住民参加者に与えられた重要な役割(典礼の純粋主義者からの批判もなかったわけではない)は、その手続きの最も 顕著な特徴の一つであった。[112] |

| Portal:Catholic Church/Patron Archive/December 9 |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_Diego |

★

Recuerdo de Tepeyac

| Tepeyac or the Hill of Tepeyac, historically known by the names Tepeyacac and Tepeaquilla, is located inside Gustavo A. Madero, the northernmost Alcaldía or borough of Mexico City. According to the Catholic tradition, it is the site where Saint Juan Diego met the Virgin of Guadalupe in December 1531, and received the iconic image of the Lady of Guadalupe. The Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe located there is one of the most visited Catholic shrines in the world. Spanish colonists erected a Catholic chapel at the site, Our Lady of Guadalupe, "the place of many miracles."[1]: 363 It forms part of the Sierra de Guadalupe mountain range. | テペヤック、あるいはテペヤックの丘は、歴史的にはテペヤカックやテペ

アキージャの名で知られ、メキシコシティ最北端の行政区であるグスタボ・A・マデロ区内にある。カトリックの伝承によれば、1531年12月に聖フアン・

ディエゴがグアダルーペの聖母と出会い、グアダルーペの聖母の象徴的な像を授かった場所である。そこに建つグアダルーペの聖母大聖堂は、世界で最も参拝者

の多いカトリック聖地の一つだ。スペイン人入植者たちはこの地にカトリック礼拝堂を建立した。その名は「奇跡の多い場所」を意味するグアダルーペの聖母で

ある[1]: 363 。この丘はグアダルーペ山脈の一部を成している。 |

| Pre-Columbian history Tepeyac Hill "had been a place for worshipping Aztec earth goddesses."[2] Tepeyac is believed to have been a Pre-Columbian worship site for the indigenous mother goddess Tonantzin Coatlaxopeuh ("Tonantzin" is a title of the greatest respect and "Coatlaxopeuh" is a name). |

コロンブス以前の歴史 テペヤックの丘は「アステカの地母神を祀る場所であった」[2]。テペヤックは先住民の母なる女神トナントシンの崇拝地であったと考えられている。トナントシンは「トナントシン」が最高の敬意を表す称号で、「コアトラクソペウ」が名前である。 |

| Etymology In Nahuatl, Tepeyacac is a proper noun, a combination of tepetl ("mountain"), yacatl ("nose"), and the relational word -c, ("at"). According to scholars of the Nahuatl language, "the term would generally be expected to mean 'a settlement on the ridge or brow of a hill.' Since yacatl (the nose going first) often implies antecedence, here the word may refer to the fact that the hill is the first and most prominent of a series of three."[3] |

語源 ナワトル語において、テペヤカックは固有名詞であり、「山」を意味するテペトル、「鼻」を意味するヤカトル、そして関係詞の接尾辞-c(「〜で」)が組み 合わさったものである。ナワトル語の研究者によれば、「この用語は一般的に『丘の尾根や頂上にある集落』を意味すると考えられる。ヤカトル(鼻が先に来 る)はしばしば先行性を示すため、ここではこの言葉が、その丘が三つの丘の中で最初で最も目立つことを指している可能性がある」[3]。 |

| Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe El Tepeyac National Park |

グアダルーペの聖母大聖堂 エル・テペヤック国立公園 |

| 1. Diaz, B., 1969, The Conquest of New Spain, London: Penguin Books, ISBN 0140441239 2. "National Geographic Magazine". Archived from the original on November 10, 2015. 3. Sousa, Lisa, Stafford Poole, and James Lockhart, eds. (1998). The Story of Guadalupe: Luis Laso de la Vega's Huei tlamahuicoltica of 1649. Stanford University Press. pp. 60, fn. 2 – via Google Books. |

1. ディアス, B., 1969, 『新スペイン征服史』, ロンドン: ペンギンブックス, ISBN 0140441239 2. 「ナショナルジオグラフィック誌」. 2015年11月10日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ. 3. Sousa, Lisa, Stafford Poole, and James Lockhart, eds. (1998). 『グアダルーペの物語:ルイス・ラソ・デ・ラ・ベガの1649年『ウエ・トラマウィコルティカ』』. スタンフォード大学出版局. pp. 60, fn. 2 – Google Books経由. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tepeyac |

☆グアダルーペの聖母(Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe)

| Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe,

conocida comúnmente como la Virgen de Guadalupe,[2] es una aparición

mariana de la Iglesia católica de origen mexicano, cuya imagen tiene su

principal centro de culto en la Basílica de Guadalupe, ubicada en las

faldas del cerro del Tepeyac, en el norte de la Ciudad de México. De acuerdo al relato guadalupano conocido como Nican mopohua (1556) que narra que tras la primera aparición, la Virgen ordenó a Juan Diego que se presentara ante el primer obispo de México, Juan de Zumárraga, para decirle que le erigieran un templo el cual recogió la tradición oral mexicana,[3] y lo descrito por otros documentos históricos como el códice Escalada (1548), el Nican Motecpana (1590), Nican Tlantica, el Huei Tlamahuizoltica (1649) y otros documentos, María, la madre de Jesús se apareció en cuatro ocasiones al indígena chichimeca Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin en el cerro del Tepeyac, y en una ocasión a Juan Bernardino, tío de Juan Diego. El obispo Juan de Zumárraga pidió una prueba a Juan Diego, pues era escéptico a dicha aparición. En la última aparición de la Virgen y por orden suya, Juan Diego llevó en su ayate unas rosas de Castilla que cortó en el Tepeyac y se dirigió al palacio del obispado. Al desplegar su ayate ante Juan de Zumárraga, dejó al descubierto la imagen de la Virgen María, cuyos rasgos han sido interpretados como "mestizos" a pesar de ser de piel mucho más clara que su homónima española. El parecido entre esa figura y la bordada en el entonces por todos conocido Pendón de Hernán Cortés sería la causa de que se le denominara Virgen de Guadalupe.[4] Según el Nican Mopohua, texto hagiográfico publicado en el siglo xvii,[5] las apariciones tuvieron lugar en 1531, ocurriendo la cuarta el 12 de diciembre de ese mismo año. La fuente más importante que las relata fue el mismo Juan Diego, que habría contado todo lo que había acontecido. Posteriormente esta tradición oral fue recogida en un escrito con sonido náhuatl pero con caracteres latinos; este escrito es llamado el Nican mopohua, y es atribuido al indígena Antonio Valeriano (1522-1605). Posteriormente, en 1648, es publicado el libro Imagen de la Virgen María Madre de Dios de Guadalupe por el presbítero Miguel Sánchez, contribuyendo a recopilar todo lo que se sabía en la época sobre la devoción guadalupana. Según diversos investigadores, el culto guadalupano es una de las creencias más históricamente arraigadas en el actual México y parte de su identidad,[5][6][7] y ha estado presente en el desarrollo como país desde el siglo xvi[8] incluso en sus procesos sociales más importantes como la Independencia de México, la de Reforma, la Revolución mexicana[7] y en la sociedad mexicana actual, en donde cuenta con millones de fieles, algunos de ellos profesantes como guadalupanos sin ser necesariamente parte del catolicismo.[9] Las raíces devocionales primigenias de esta imagen estarían en la Virgen de Guadalupe de Extremadura, por la cual tenían devoción los conquistadores españoles.[10] |

グアダルーペの聖母は、一般にグアダルーペの聖母として知られており、メキシコに起源を持つカトリック教会の聖母マリアの御出現である。その像は、メキシコシティ北部のテペヤック山の麓にあるグアダルーペ大聖堂を主な礼拝の中心地としている。 グアダルーペの物語「ニカン・モポワ」(1556年)によると、最初の出現の後、聖母はフアン・ディエゴに、メキシコ初代司教フアン・デ・スマラガの前に 現れて、彼女のために寺院を建立するよう伝えるよう命じた。これはメキシコの口承の伝統をまとめたものであり、 [3]、また、エスカラダ写本(1548年)、ニカン・モテクパナ(1590年)、ニカン・トランティカ、 フエイ・トラマウィゾルティカ(1649年)などの歴史的文書にも記述されている。イエスの母マリアは、チチメカ族の先住民フアン・ディエゴ・クアウトラ トアツィンにテペヤックの丘で4回、またフアン・ディエゴの叔父であるフアン・ベルナルディーノに1回、出現した。司教フアン・デ・スマラガは、その出現 を懐疑的に見ていたため、フアン・ディエゴに証拠を求めた。聖母が最後に現れたとき、彼女の指示で、フアン・ディエゴはテペヤックで摘んだカスティーリャ のバラをアヤテ(布)に包んで司教の宮殿に向かった。フアン・デ・スマラガの前でアヤテを広げると、聖母マリアの姿が現れた。その顔立ちは、スペインの聖 母よりもはるかに肌の色が明るいにもかかわらず、「メスティーソ」と解釈されている。この姿と、当時誰もが知っていたエルナン・コルテスの旗に刺繍されて いた姿との類似性が、この聖母がグアダルーペの聖母と呼ばれるようになった理由である。 17世紀に出版された聖人伝『ニカン・モポワ』によれば、[5] 聖母の出現は1531年に起こり、4回目の出現は同年12月12日だった。この出来事を伝えている最も重要な情報源は、その出来事をすべて語ったとされる フアン・ディエゴ自身だった。その後、この口承の伝統は、ナワトル語の音でラテン文字を使って書かれた文書にまとめられた。この文書は『ニカン・モポワ』 と呼ばれ、先住民のアントニオ・バレリアノ(1522-1605)によるものとされている。その後、1648年に司祭ミゲル・サンチェスによって『グアダ ルーペの聖母マリア像』という本が出版され、当時グアダルーペの信仰について知られていたことをすべてまとめることに貢献した。 さまざまな研究者によると、グアダルーペの信仰は、現在のメキシコにおいて歴史的に最も根強い信仰の一つであり、そのアイデンティティの一部である [5]。[6][7] 16世紀以来、メキシコという国の発展、さらにはメキシコ独立、改革、メキシコ革命[7] といった重要な社会的プロセス、そして現在のメキシコ社会においても存在し続けており、何百万人もの信者がいる。その中には、必ずしもカトリック教徒では ないにもかかわらず、グアダルーペの信者であると公言する者もいる。この像の信仰のルーツは、スペインの征服者たちが信仰していたエストレマドゥーラのグ アダルーペの聖母にあると考えられている。 |