ジュール・デュモン・デュルヴィル

Jules Dumont d'Urville, 1790-1842

☆ ジュール・セバスティアン・セザール・デュモン・デュルヴィル(フランス語発音: [ʒyl dymɔ̃ dyʁvil]、1790年5月23日 - 1842年5月8日)は、南太平洋、西太平洋、オーストラリア、ニュージーランド、南極大陸を探検したフランスの探検家であり海軍士官であった。植物学者 および地図製作者として、彼はいくつかの海藻、植物、低木、およびニュージーランドのデュルビル島などの地名に自身の名を残している。

| Jules

Sébastien César Dumont d'Urville (French pronunciation: [ʒyl dymɔ̃

dyʁvil]; 23 May 1790 – 8 May 1842) was a French explorer and naval

officer who explored the south and western Pacific, Australia, New

Zealand, and Antarctica. As a botanist and cartographer, he gave his

name to several seaweeds, plants and shrubs, and places such as

d'Urville Island in New Zealand. |

ジュー

ル・セバスティアン・セザール・デュモン・デュルヴィル(フランス語発音: [ʒyl dymɔ̃ dyʁvil]、1790年5月23日 -

1842年5月8日)は、南太平洋、西太平洋、オーストラリア、ニュージーランド、南極大陸を探検したフランスの探検家であり海軍士官であった。植物学者

および地図製作者として、彼はいくつかの海藻、植物、低木、およびニュージーランドのデュルビル島などの地名に自身の名を残している。 |

| Dumont

was born at Condé-sur-Noireau in Lower Normandy.[1] His father, Gabriel

Charles François Dumont, sieur d'Urville (1728–1796), Bailiff of

Condé-sur-Noireau, was, like his ancestors, responsible to the court of

Condé. His mother Jeanne Françoise Victoire Julie (1754–1832) came from Croisilles, Calvados, and was a rigid and formal woman from an ancient family of the rural nobility of Lower Normandy. The child was weak and often sickly. After the death of his father when he was six, his mother's brother, the Abbot of Croisilles, played the part of his father and from 1798 took charge of his education. The Abbot taught him Latin, Greek, rhetoric and philosophy. From 1804 Dumont studied at the lycée Impérial in Caen. In the library of Caen, he read the Encyclopédistes and the reports of travel of Bougainville, Cook and Anson, and he became passionate about these matters. At the age of 17 years he failed the physical tests of the entrance exam to the École polytechnique and he therefore decided to enlist in the navy.[note 1] |

デュモンは、ノルマンディーの下部のコンデ・シュル・ノワローで生まれた。[1] 父親のガブリエル・シャルル・フランソワ・デュモン・シュール・ウルヴィル(1728年-1796年)は、コンデ・シュル・ノワローの代官であり、先祖と同様にコンデ宮廷に仕えていた。 彼の母、ジャンヌ・フランソワーズ・ヴィクトワール・ジュリー(1754年~1832年)は、カルヴァドス県のクロワジィユ出身で、下ノルマンディーの田舎の貴族の家系の厳格で形式的な女性であった。子供は体が弱く、病気がちであった。 6歳の時に父を亡くした後は、母の兄弟であるクロワジルの修道院長が父親代わりとなり、1798年からは彼自身の教育も担当した。修道院長は彼にラテン語、ギリシャ語、修辞学、哲学を教えた。1804年からは、デュモンはカーンのリセ・インペリアルで学んだ。 カーンの図書館で、彼は百科全書派の著作やブーガンヴィル、クック、アンソンの旅行記を読み、これらの事柄に熱中するようになった。 17歳のとき、彼はエコール・ポリテクニークの入学試験の身体検査に落ちたため、海軍に入隊することを決意した。[注1] |

| In

1807, Dumont was admitted to the École navale at Brest where he

presented himself as a timid young man, very serious and studious,

little interested in amusements and much more interested in studies

than in military matters. In 1808, he obtained the grade of first-class

candidate.[2] At the time the neglected French navy was of a much lower quality than Napoleon's Grande Armée, and its ships were blockaded in their ports by the absolute domination of the British Royal Navy. Dumont was confined to land like his colleagues and spent the first years in the navy studying foreign languages. In 1812, after having been promoted to ensign and finding himself bored with port life and disapproving of the dissolute behaviour of the other young officers, he asked to be transferred to Toulon on board the Suffren; but this ship was also blockaded in port. During this period, Dumont built on his already substantial cultural knowledge. He already spoke, in addition to Latin and Greek, English, German, Italian, Russian, Chinese and Hebrew. During his later travels in the Pacific, thanks to his prodigious memory, he would acquire some knowledge of an immense number of dialects of Polynesia and Melanesia. Meanwhile, ashore at Toulon, he learnt about botany and entomology in long excursions in the hills of Provence and he studied in the nearby naval observatory. Finally in 1814, when Napoleon had been exiled to Elba, Dumont undertook his first short navigation of the Mediterranean Sea. In 1815, he married Adèle Pepin, daughter of a clockmaker from Toulon.[3] who was openly disliked by Dumont's mother, who thought her inappropriate for her son and refused to meet her.[4] |

1807年、デュモンはブレストの海軍兵学校に入学を許可され、そこで彼は臆病な若者として自己紹介し、非常に真面目で勉強熱心であり、娯楽にはほとんど興味がなく、軍事よりも学問にずっと興味を持っていると述べた。1808年、彼は一等候補生の等級を取得した。 当時、顧みられないフランス海軍はナポレオンの大陸軍よりもはるかに質が悪く、その船はイギリス海軍の絶対的な支配により港で封鎖されていた。デュモンは同僚と同様に陸に閉じ込められ、海軍での最初の数年間は外国語の学習に費やした。 1812年、少尉に昇進したものの、港での生活に退屈し、他の若い士官たちの放蕩ぶりを好ましく思わなかった彼は、スフレに乗船してトゥーロンに転属を希望したが、この船も港で封鎖されていた。 この期間、デュモンはすでに豊富な文化知識をさらに深めた。ラテン語とギリシャ語に加え、英語、ドイツ語、イタリア語、ロシア語、中国語、ヘブライ語をす でに話していた。その後、太平洋を旅した際には、驚異的な記憶力のおかげで、ポリネシアやメラネシアの膨大な数の方言の知識を習得した。一方、トゥーロン に上陸した際には、プロヴァンスの丘陵地帯を長時間散策しながら植物学や昆虫学を学び、近くの海軍天文台で研究を行った。 そして1814年、ついにナポレオンがエルバ島に追放されたとき、デュモンは初めて地中海での短期間の航海を行った。1815年、彼はトゥーロンの時計職 人の娘アデル・ペパンと結婚した。[3] 彼女のことは、デュモンの母親が公然と嫌っており、息子にはふさわしくないと、彼女に会うことを拒否していた。[4] |

| In the Aegean Sea In 1819, Dumont d'Urville sailed on board Chevrette, under the command of Captain Gauttier-Duparc, to carry out a hydrographic survey of the islands of the Greek archipelago. During a pause near the island of Milos, the local French representative brought to Dumont's attention the rediscovery of a marble statue a few days before (8 April 1820) by a local peasant. The statue, now known as the Venus de Milo, dates from around the year 130 BC. Dumont recognised its value and would have acquired it immediately, but the ship's commander pointed out that there was not enough space on board for an object of its size. Moreover, the expedition was likely to proceed through stormy seas that could damage it. Dumont then wrote to the French ambassador to Constantinople about its discovery.[note 2] Chevrette arrived in Constantinople on 22 April and Dumont succeeded in convincing the ambassador to acquire the statue. Meanwhile, the peasant had sold the statue to a priest, Macario Verghis, who wished to present it as a gift to an interpreter for the Sultan in Constantinople. The French ambassador's representative arrived just as the statue was being loaded aboard a ship bound for Constantinople and persuaded the island's primates (chief citizens) to annul the sale and honour the first offer. This earned Dumont the title of Chevalier (knight) of the Légion d'honneur, the attention of the French Academy of Sciences and promotion to lieutenant; and France gained a new, magnificent statue for the Louvre in Paris.[note 3] |

エーゲ海にて 1819年、デュモン・デュルヴィルは、ゴーティエ・デュパルク船長の指揮の下、ギリシャ群島の島々における水路調査を行うため、シェヴレット号に乗船し た。ミロス島付近で一時停泊していた際、現地のフランス人代表が、数日前(1820年4月8日)に地元の農民が大理石の彫像を再発見したことをデュモンに 伝えた。現在「ミロのヴィーナス」として知られるこの彫像は、紀元前130年頃のものとされている。 デュモンはその価値を認め、すぐにでも入手しようとしたが、船長は、その大きさの品物を船内に保管する十分なスペースがないことを指摘した。さらに、遠征 隊は荒海を進む可能性が高く、その場合、像が損傷する恐れがあった。そこでデュモンは、コンスタンティノープル駐在のフランス大使に発見の旨を報告した。 [注2] シェヴレットは4月22日にコンスタンティノープルに到着し、デュモンは大使を説得して像の入手に成功した。 一方、農民は像をマカリオ・ヴェルギス神父に売却していた。神父はコンスタンティノープルのスルタンの通訳者に像を贈りたいと考えていた。フランス大使の 代理人が像がコンスタンティノープル行きの船に積み込まれる寸前に到着し、島の有力者たちに売却を取り消して最初の申し出を受け入れるよう説得した。これ により、デュモンはレジオンドヌール勲章のシュヴァリエ(騎士)の称号を授与され、フランス科学アカデミーの注目を集め、中尉に昇進した。そして、フラン スはパリのルーヴル美術館に新たな素晴らしい像を手に入れた。[注3] |

| Voyage of Coquille On his return from the voyage of Chevrette, Dumont was sent to the naval archive, where he encountered Lieutenant Louis-Isidore Duperrey, a past acquaintance. The two began to plan an expedition of exploration in the Pacific,[note 4] an area out of which France had been forced during the Napoleonic Wars. France considered it might be able to regain some of its losses by taking over part of New South Wales. On 11 August 1822, the ship Coquille sailed from Toulon with the objective of collecting as much scientific and strategic information as possible on the area to which it was dispatched. Duperrey was named Commander of the expedition because he was four years older than Dumont. Dumont discovered the Adélie penguin, which is named after his wife.[5] René-Primevère Lesson travelled on Coquille as a naval doctor and naturalist. On the return to France in March 1825, Lesson and Dumont brought an imposing collection of animals and plants collected on the Falkland Islands, on the coasts of Chile and Peru, in the archipelagos of the Pacific and New Zealand, New Guinea, and Australia. Dumont was now 35 and in poor health. On board Coquille, he had behaved as a competent official, but disinclined to military discipline and subordination. On the return to France, Duperrey and Dumont were promoted to commander.[6] Collection On Coquille, Dumont tried to reconcile his responsibilities as second in command with his need to carry out scientific work. He was in charge of carrying out research in the fields of botany and entomology. La Coquille brought back to France specimens of more than 3,000 species of plants, 400 of which were previously unknown, enriching moreover the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle in Paris with more than 1,200 specimens of insects, covering 1,100 insect species (including 300 previously unknown species). The scientists Georges Cuvier and François Arago analysed the results of his searches and praised Dumont.[citation needed] As a botanist and cartographer, Dumont d'Urville left his mark on New Zealand. He gave his name to the genus of seaweeds Durvillaea, which includes southern bull-kelp; the seaweed Grateloupia urvilleana; the species of grass tree Dracophyllum urvilleanum; the shrub Hebe urvilleana and the buttercup Ranunculus urvilleanus.[7] |

コキーユ号の航海 シュベレット号の航海から戻った後、デュモンは海軍の記録保管所に送られ、そこで以前からの知り合いであるルイ=イシドール・デュペレ中尉と再会した。 2人は、ナポレオン戦争中にフランスが割譲を余儀なくされた太平洋地域[注釈4]での探検遠征を計画し始めた。フランスは、ニューサウスウェールズの一部 を占領することで、その損失の一部を取り戻せるかもしれないと考えていた。1822年8月11日、トゥーロンから出航したコキーユ号は、派遣先の地域につ いて可能な限りの科学的・戦略的情報を収集することを目的としていた。デュペレはデュモンより4歳年上だったため、遠征隊の指揮官に任命された。デュモン は、妻の名にちなんで名付けられたアデリーペンギンを発見した。 ルネ=プリムヴェール・レソンは、コクイル号に海軍軍医および博物学者として同行した。1825年3月のフランス帰国時、レソンとデュモンはフォークラン ド諸島、チリおよびペルーの沿岸、太平洋諸島、ニュージーランド、ニューギニア、オーストラリアで収集した動物および植物の素晴らしいコレクションを持ち 帰った。デュモンは35歳になり、健康状態は芳しくなかった。コクイル号では有能な役人としてふるまっていたが、軍規や服従には消極的だった。フランスへ の帰還後、デュペレとデュモンは大佐に昇進した。[6] 収集 コクイル号では、デュモンは副官としての責任と科学的調査の遂行という自身のニーズの折り合いをつけようとしていた。彼は植物学と昆虫学の分野における調 査の実施を担当していた。ラ・コキユは、3,000種以上の植物標本(そのうち400種は未知の種であった)をフランスに持ち帰り、さらにパリ国立自然史 博物館に1,100種(うち300種は未知の種)の昆虫を含む1,200種以上の昆虫標本を寄贈した。科学者のジョルジュ・キュヴィエとフランソワ・アラ ゴは、デュモンの探検の結果を分析し、デュモンを称賛した。 植物学者および地図製作者として、デュモン・デュルヴィルはニュージーランドに足跡を残した。彼は、ミカヅキモ科の海藻であるDurvillaea属に自 身の名を残し、この属には、ミカヅキモ、Grateloupia urvilleana、ドラコフィリウム・ウルヴィリアナム、ヘベ・ウルヴィリアナ、キンポウゲ属のRanunculus urvilleanusなどが含まれる。 |

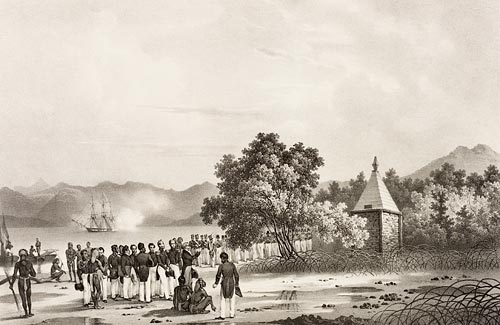

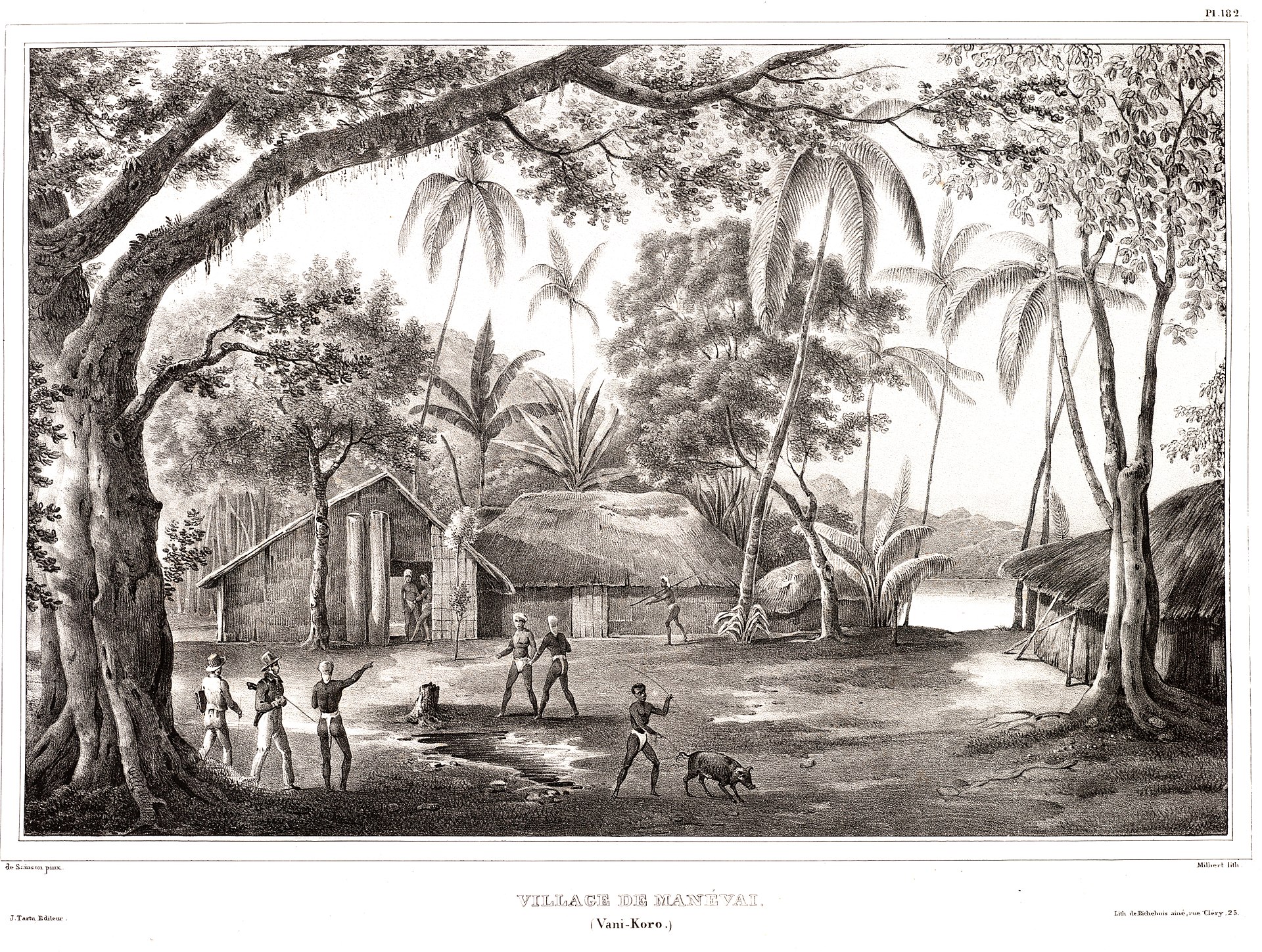

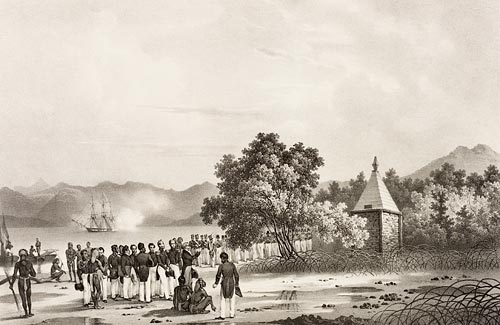

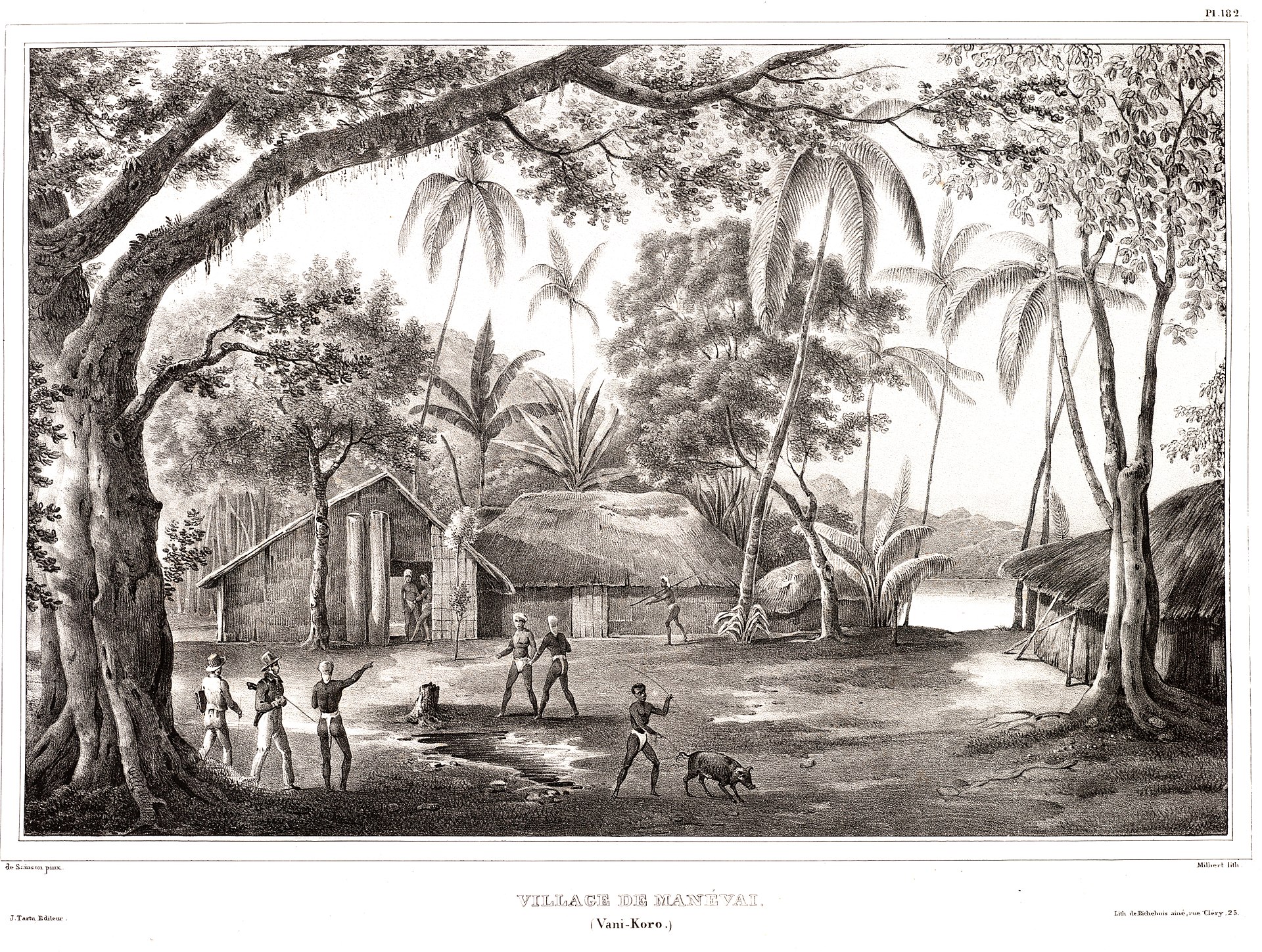

First voyage of Astrolabe Inauguration of the monument erected in honour of La Pérouse, shipwrecked and lost on the island of Vanikoro. Two months after Dumont d'Urville returned on La Coquille, he presented to the Navy Ministry a plan for a new expedition, which he hoped to command, as his relationship with Duperrey had deteriorated. The proposal was accepted and La Coquille was renamed the Astrolabe in honour of one of the ships of La Pérouse, and sailed from Toulon on 22 April 1826, towards the Pacific Ocean, for a circumnavigation of the world that was destined to last nearly three years. The new Astrolabe skirted the coast of southern Australia, carried out new relief maps of the South Island of New Zealand, including improved surveys of the Marlborough Sounds in which he navigated through the narrow and treacherous French Pass and mapped d'Urville Island, which James Cook had mapped as being part of the mainland.  Dumont d'Urville's expedition at Vanikoro. Astrolabe sailed up the east coast of the North Island, creating comprehensive coastline maps of New Zealand.[8] The ship spent six days in the Bay of Islands taking on food and water before sailing for Tonga.[8] Astrolabe visited Fiji, then Dumont executed the first relief maps of the Loyalty Islands (part of French New Caledonia) and explored the coasts of New Guinea. He identified the site of La Pérouse's shipwreck in Vanikoro (one of the Santa Cruz Islands, part of the archipelago of the Solomon Islands) and collected numerous remains of his boats. The voyage continued with the mapping of part of the Caroline Islands and the Moluccas. Astrolabe returned to Marseille on 25 March 1829, with an impressive load of hydrographical papers and collections of zoological, botanical and mineralogical reports, which were destined to strongly influence the scientific analysis of those regions. Following this expedition, he invented the terms Malaisia, Micronesia and Melanesia, distinguishing these Pacific cultures and island groups from Polynesia.  Māori men and women on board Astrolabe performing a dance, with a French officer at right. Dumont's health was by now weakened by years of a poor diet. He suffered from kidney and stomach problems and from intense attacks of gout. During the first thirteen years of their marriage, half of which passed far apart, Adélie and Jules had two sons. The first one died at a young age while his father was aboard La Coquille and the second, also called Jules, on the return of his father after four years away. Dumont d'Urville passed a short period with his family before returning to Paris, where he was promoted to captain and he was put in charge of writing the report of his travels. The five volumes were published at the expense of the French government between 1832 and 1834. During these years d'Urville, who was already a poor diplomat, became more irascible and rancorous as a result of his gout, and lost the sympathy of the naval leadership. In his report, he criticised harshly the military structures, his colleagues, the French Academy of Sciences and even the King – none of whom, in his opinion, had given the voyage of Astrolabe due acknowledgment. In 1835, Dumont was directed to return to Toulon to engage in "down to earth" work and spent two years, marked by mournful events (notably the loss of a daughter from cholera) and happy events (notably the birth of another son, Émile) but with the constant and nearly obsessive thought of a third expedition to the Pacific, analogous to James Cook's third voyage. He looked again at Astrolabe's travel notes, and found a gap in the exploration of Oceania and, in January 1837, he wrote to the Navy Ministry suggesting the opportunity for a new expedition to the Pacific. |

アストロラーベの最初の航海 バニコロ島で遭難し行方不明となったラペルーズを称える記念碑の落成式。 デュモン・デュルヴィルがラ・コキーユ号で帰還してから2か月後、デュペレとの関係が悪化したため、自ら指揮を執ることを希望し、新たな探検計画を海軍省 に提出した。この提案は受け入れられ、ラ・コキーユはラペルーズの船のひとつに敬意を表してアストロラーベと改名され、1826年4月22日にトゥーロン を出航し、3年近く続くことになる世界一周の航海のため太平洋に向けて出発した。 新しいアストロラーベ号は、南オーストラリアの海岸に沿って航行し、ニュージーランドの南島で新たな救済地図を作成した。その中には、マルボロ海峡の狭く 危険なフランス海峡を通り抜けた際の改良調査や、ジェームズ・クックが本土の一部として地図に記したデュルビル島を地図に落とし込んだものも含まれてい た。  デュモン・デュルヴィルのヴァニエコロ島での探検。 アストロラーベ号は北島の東海岸を航行し、ニュージーランドの包括的な海岸線地図を作成した。[8] 船は、トンガに向けて出航する前に、ベイ・オブ・アイランズで6日間を費やして食料と水の補給を行った。[8] アストロラーベ号はフィジーを訪れ、その後デュモンがロイヤリティ諸島(フランス領ニューカレドニアの一部)の最初の地形図を作成し、ニューギニアの海岸 を調査した。彼はバニクロ島(ソロモン諸島の一部であるサンタクルス諸島の一つ)でラペルーズの難破船の場所を特定し、多数の船の残骸を収集した。航海は カロリン諸島とモルッカ諸島の地図作成を伴って続行された。アストロラーベは、水路に関する論文や動物学、植物学、鉱物学の報告書の収集物という素晴らし い成果を携え、1829年3月25日にマルセイユに戻った。これらの地域に関する科学的分析に多大な影響を与えることとなった。この遠征の後、彼はポリネ シアと区別するために、太平洋の文化や島々をマライ群島、ミクロネシア、メラネシアと名付けた。  アストロラーベ号に乗船したマオリ族の男女がダンスを披露している。右側にフランス人将校がいる。 長年の粗食により、デュモンの健康はすでに弱っていた。腎臓と胃の不調に苦しみ、痛風の発作にも襲われていた。結婚後13年間、そのうち半分は離れ離れで 過ごしたが、アデリーとジュールには2人の息子が生まれた。最初の息子は、父親がラ・コキーユ号に乗船中、幼くして亡くなり、2人目の息子もジュールと名 付けられたが、4年間の不在を経て父親が戻った時に亡くなった。 デュモン・デュルヴィルは家族と短い期間を過ごした後、パリに戻った。そこで彼は船長に昇進し、航海の報告書の執筆を任された。5巻からなるその報告書 は、1832年から1834年の間にフランス政府の費用で出版された。この間、すでに貧しい外交官であったデュルヴィルは、痛風の影響で短気で憤りっぽく なり、海軍上層部の同情を失った。報告書の中で、彼は軍の組織、同僚、フランス科学アカデミー、さらには国王までも厳しく批判した。デュルヴィルは、アス トロラーベ号の航海を正当に評価した者は誰もいなかったと主張した。 1835年、デュモンはトゥーロンに戻り「現実的な」仕事に従事するよう命じられ、2年間を過ごした。その間には悲しい出来事(特にコレラによる娘の死) や嬉しい出来事(特に息子のエミール誕生)があったが、常に、そして執拗なほどに、ジェームズ・クックの3度目の航海にならった3度目の太平洋探検を考え ていた。彼はアストロラーベの旅行記を再調査し、オセアニアの探検に空白があることに気づき、1837年1月、海軍省に太平洋への新たな探検の機会につい て提案する手紙を書いた。 |

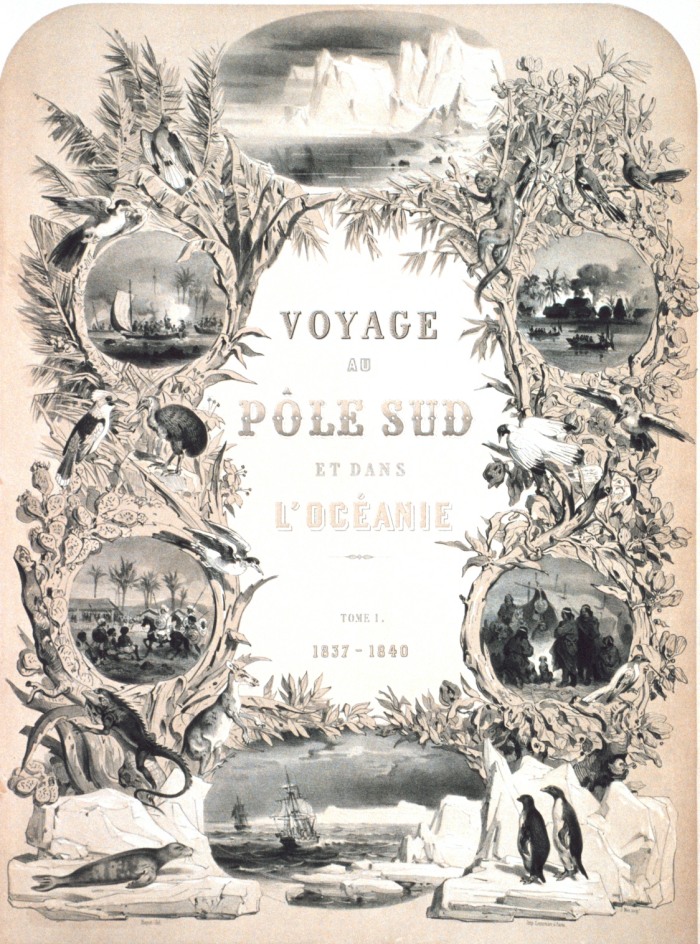

Second voyage of Astrolabe The Astrolabe and the Zelee caught in Antarctic ice, watercolour by A. Mayer. (1838) King Louis Philippe approved the plan, but he ordered that the expedition aim for the South Magnetic Pole and to claim it for France; if that was not possible, Dumont's expedition was asked to equal the most southerly latitude of 74°34'S achieved in 1823 by James Weddell. Thus France became part of the international competition for polar exploration, along with the United States and the United Kingdom.[note 5]  Second voyage of the Astrolabe Dumont was initially unhappy with the modifications made to his proposal. He had little interest in polar exploration and preferred tropical routes. But soon his vanity took over and he saw the opportunity for achieving a prestigious objective.[note 6] The two ships, Astrolabe and Zélée were prepared for the voyage at Toulon. The Astrolabe was commanded by Dumont d'Urville, and Gaston de Roquemaurel as second, and La Zélée by Charles Hector Jacquinot. [9] In the course of the preparation Dumont also went to London to acquire documentation and instrumentation, meeting the British Admiralty's oceanographer, Francis Beaufort and the President of the Royal Geographical Society, John Washington, both strong supporters of the British expeditions to the South Pole.[note 7] First contact with Antarctica  Astrolabe making water on a floe 6 February 1838 Astrolabe and Zélée sailed from Toulon on 7 September 1837, after three weeks of delay compared to Dumont's plans. His objectives were to reach the most southerly point possible at this time in the Weddell Sea; to pass through the Strait of Magellan; to travel up the coast of Chile in order to head for Oceania with the objective of inspecting the new British colonies in Western Australia; to sail to Hobart; and to sail to New Zealand to find opportunities for French whalers and to examine places where a penal colony might be established. After passing through the East Indies, the mission would have to round the Cape of Good Hope and return to France. Early in the voyage, part of the crew was involved in a drunken brawl and arrested in Tenerife. A short pause was made in Rio de Janeiro to disembark a sick official. During the first part of the voyage there were also problems of provisioning, particularly rotten meat, which affected the health of the crew. At the end of November, the ships reached the Strait of Magellan. Dumont thought there was sufficient time to explore the strait for three weeks, taking into account the precise maps drawn by Phillip Parker King in HMS Beagle between 1826 and 1830, before heading south again. In the Strait of Magellan Dummont surveyed the coast trying to find out the ruins of Ciudad Rey Don Felipe, a city founded in 1584 as part of a failed Spanish colonization attempt to control the passage through the strait.[10] An expedition report recommended that a French colony be established at the strait to support future traffic along the route.[11] The strait was eventually settled by Chile in 1843.[12] Two weeks after seeing their first iceberg, Astrolabe and Zélée found themselves entangled again in a mass of ice on 1 January 1838. The same night the pack ice prevented the ships from continuing to the south. In the next two months Dumont led increasingly desperate attempts to find a passage through the ice so that he could reach the desired latitude. For a while the ships managed to keep to an ice-free channel, but shortly afterwards they became trapped again, after a wind change. Five days of continuous work were necessary in order to open a corridor in the pack ice to free them. After reaching the South Orkney Islands, the expedition headed directly to the South Shetland Islands and the Bransfield Strait separating them from Antarctica. In spite of thick fog they located some land only sketched on the maps, which Dumont named Terre de Louis-Philippe (now called Graham Land), the Joinville Island group and Rosamel Island (now called Andersson Island).[note 8] Conditions on board had rapidly deteriorated: most of the crew had obvious symptoms of scurvy and the main decks were covered by smoke from the ships' fires and bad smells and became unbearable. At the end of February 1838, Dumont accepted that he was not able to continue further south, and he continued to doubt the actual latitude reached by Weddell. He therefore directed the two ships towards Talcahuano, in Chile, where he established a temporary hospital for the crew members affected by scurvy.[note 9] Pacific During months of exploration in the Pacific, the ship visited many islands in Polynesia. On their arrival in the Marquesas Islands, the crews found ways "to socialise" with the islanders. Dumont's moral conduct was irreproachable, but he provided a highly summarised description of some incidents of their stay in Nuku Hiva in his reports. During the voyage from the East Indies to Tasmania some of the crew were lost to tropical fevers and dysentery (14 men and 3 officials); but for Dumont the worst moment during the expedition was at Valparaíso, where he received a letter from his wife that informed him of the death of his second son from cholera. Adélie's sorrowful demand that he return home coincided with a deterioration in his health: Dumont was more and more often hit by attacks of gout and stomach pains. On 12 December 1839 the two corvettes landed at Hobart, where the sick and the dying were treated. Dumont was received by John Franklin, Governor of Tasmania and an Arctic explorer who later perished on the infamous Franklin Expedition, from whom he learned that the ships of the American expedition led by Charles Wilkes were berthed in Sydney waiting to sail south. Seeing the consistent reduction of the crews, decimated by misfortunes, Dumont expressed his intention to leave this time for the Antarctic with Astrolabe only, in order to attempt to reach the South Magnetic Pole around longitude 140°. A deeply wounded Captain Jacquinot urged the hiring of a number of replacements (generally deserters from a French whaler anchored in Hobart) and convinced him to reconsider his intentions; Astrolabe and Zelée both left Hobart on 1 January 1840. Dumont's plan was very simple: to head south, wind conditions permitting. Turning south The first days of the voyage mainly involved the crossing of twenty degrees and a westerly current; on board there were further misfortunes, including the loss of a man. Crossing the 50°S parallel, they experienced unexpected falls in the air and water temperatures. After completing the crossing of the Antarctic Convergence, on 16 January 1840, at 60°S they sighted the first iceberg and two days later the ships found themselves in the middle of a mass of ice. On 20 January[note 10] the expedition crossed the Antarctic Circle, with celebrations similar to crossing of the Equator ceremonies, and they sighted land the same afternoon.[13] The two ships slowly sailed to the West, skirting walls of ice, and on 22 January,[note 11] just before 9 in the evening, some members of the crew disembarked[14] on the north-westernmost and highest islet[15][16] of the rocky group of Dumoulin Islands,[17][18] at 500–600 m from the icy coast of the Astrolabe Glacier Tongue of the time, today about 4 km north from the glacier extremity near Cape Géodésie, and hoisted the French tricolour.[19][note 12] Dumont named the archipelago Pointe Géologie[20][21] and the land beyond, Terre Adélie[note 13] The map of the coast drawn under sail by the hydrographer Clément Adrien Vincendon-Dumoulin [fr] is remarkably accurate given the means of the time.[22] In the following days the expedition followed the coast westward then led for the first time some experiments to determine the approximate position of the South magnetic pole. They sighted the American schooner Porpoise of the United States Exploring Expedition commanded by Charles Wilkes on 30 January 1840, but failed to communicate due to a misunderstanding.[23] On 1 February, Dumont decided to turn to the north heading for Hobart, which the two ships reached 17 days later. They were present for the arrival of the two ships of James Ross's expedition to Antarctica, HMS Terror and HMS Erebus. On 25 February, the schooners sailed towards the Auckland Islands, where they carried out magnetic measurements and they left a commemorative plate of their visit (as had the commander of Porpoise previously), in which they announced the discovery of the South Magnetic Pole.[note 14] They returned via New Zealand, the Torres Strait, Timor, Réunion, Saint Helena and finally Toulon, returning on 6 November 1840, the last French expedition of exploration to sail. Return to France Frontispiece to: Voyage au pole sud et dans l'Oceanie On his return Dumont d'Urville was promoted to rear admiral and was awarded the Gold Medal of the Société de Géographie (Geographical Society of Paris), later becoming its president. He then took over the writing of the report of the expedition, Voyage au pôle Sud et dans l'Océanie sur les corvettes l'Astrolabe et la Zélée 1837–1840, which was published between 1841 and 1854 in 24 volumes, plus seven more volumes with illustrations and maps. |

アストロラーベの2度目の航海 アストロラーベとゼリーが南極の氷に閉じ込められる、A.メイヤーによる水彩画。(1838年) ルイ・フィリップ王は計画を承認したが、南磁極を目指し、フランス領とすること、それが不可能であれば、ジェームズ・ウェッデルが1823年に達成した南 緯74度34分に並ぶことをデュモンの探検隊に命じた。こうしてフランスは、アメリカ合衆国やイギリスとともに、極地探検における国際競争の一翼を担うこ ととなった。[注5]  アストロラーベの2度目の航海 デュモンは当初、自身の提案に施された変更に不満を抱いていた。極地探検にはほとんど興味がなく、熱帯ルートを好んでいた。しかし、すぐに彼の虚栄心が前 面に出て、彼は名高い目的を達成する機会を見出した。[注釈6] 2隻の船、アストロラーベ号とゼレー号はトゥーロンで航海の準備が整えられた。アストロラーベ号はデュモン・デュルヴィルが指揮を執り、ガストン・ド・ロ クメーユが副長を務め、ゼレー号はシャルル・エクトール・ジャクニョが指揮を執った。[9] 準備の過程で、ドゥモンはロンドンに赴き、資料や機器を入手し、英国海軍本部海洋学者のフランシス・ビューフォートや王立地理学会会長のジョン・ワシント ンと面会した。両者は、南極点への英国探検の強力な支援者であった。 南極大陸との最初の接触  アストロラーベが氷塊上で水を作る 1838年2月6日 アストロラーベとゼレーは、デュモンの計画より3週間遅れて、1837年9月7日にトゥーロンを出航した。彼の目的は、ウェッデル海で当時考えられる最南 端に到達すること、マゼラン海峡を通過すること、チリの沿岸を北上してオセアニアに向かい、西オーストラリアの新しいイギリス植民地を視察すること、ホ バートに寄港すること、ニュージーランドに赴き、フランス捕鯨船の機会を見つけ、流刑植民地を建設する場所を調査することだった。東インド諸島を通過した 後、使節団は喜望峰を回ってフランスに戻る必要があった。 航海の初期、乗組員の一部が酔っ払って乱闘を起こし、テネリフェ島で逮捕された。リオ・デ・ジャネイロで、病気の役人を下船させるために短い停泊があっ た。航海の初期には、特に腐った肉など、食料調達の問題も発生し、乗組員の健康に影響を与えた。11月末、船団はマゼラン海峡に到着した。デュモンは、 フィリップ・パーカー・キングがHMSビーグル号で1826年から1830年の間に作成した正確な地図を考慮し、南に向かう前に3週間かけて海峡を調査す る時間は十分にあると考えた。 マゼラン海峡でデュモンは、1584年にスペインが海峡の通行を支配しようとして失敗した植民地化計画の一部として建設された都市、シウダー・レイ・ド ン・フェリペの遺跡を見つけようと沿岸を調査した。[10] 探検の報告書では、将来の航路利用を支援するために、海峡にフランス植民地を建設することが推奨された。[11] 海峡は最終的に1843年にチリによって領有された。[12] 最初の氷山を目にしてから2週間後の1838年1月1日、アストロラーベとゼレーは再び大量の氷に巻き込まれた。その夜、船団は氷塊のために南へ進むこと ができなくなった。それから2か月間、デュモンは希望する緯度に到達するために氷の通路を見つけようと、ますます絶望的な試みを続けた。しばらくの間、船 団は氷のない航路を航行することができたが、風向きが変わったため、まもなく再び行き詰まってしまった。船団を解放するために、氷原に通路を開くのに5日 間の連続作業が必要だった。 南オークニー諸島に到着した後、探検隊は南シェトランド諸島と、そこから南極大陸を隔てるブランズフィールド海峡へと直行した。濃い霧にもかかわらず、彼 らは地図に大まかにしか描かれていない陸地を発見した。デュモンは、その陸地を「テール・ド・ルイ・フィリップ」(現在のグラハムランド)、ジョインヴィ ル諸島、ロザメル島(現在のアンデショーン島)と名付けた。[注8] 船内の状況は急速に悪化していた。乗組員のほとんどが壊血病の明らかな症状を示しており、船の火の煙と悪臭が主甲板を覆い、耐え難いものとなっていた。 1838年2月末、デュモンはこれ以上南へ進むことは不可能であることを認め、ウェッデルが到達した実際の緯度を疑い続けた。そのため、彼は2隻の船をチ リのタルカワノに向かわせ、壊血病に罹った乗組員のために臨時の病院を設置した。 太平洋 太平洋での数か月にわたる探検中、船はポリネシアの多くの島々を訪れた。 マルケサス諸島に到着すると、乗組員たちは島民と「交流」する方法を見つけた。 デュモンの行動は非の打ちどころがなかったが、彼はヌク・ヒバでの滞在中のいくつかの出来事について、報告書に非常に簡潔な記述をした。東インド諸島から タスマニアへの航海中、熱帯熱や赤痢で何人かの乗組員(14人の男と3人の職員)が命を落としたが、デュモンにとって探検中の最悪の瞬間はバルパライソ で、妻から次男がコレラで死亡したとの知らせを受け取った時だった。アデリーの悲しみに暮れた帰国要求は、彼の健康状態の悪化と時を同じくしていた。デュ モンはますます痛風の発作や胃痛に襲われることが多くなっていた。 1839年12月12日、2隻のコルベットはホバートに到着し、病人や瀕死の者はそこで治療を受けた。デュモンはタスマニア総督であり、後に悪名高いフラ ンクリン探検隊で命を落とした北極探検家でもあるジョン・フランクリンに迎えられた。フランクリンから、チャールズ・ウィルクス率いるアメリカ探検隊の船 がシドニーに停泊し、南に向かって出航するのを待っていることを知らされた。 不幸な出来事に遭い、乗組員が減り続けたことを受け、デュモンはアストロラーベ号のみで今度こそ南極大陸に向かい、経度140°付近の南磁極に到達しよう と試みるつもりであると表明した。ひどく傷ついたジャクノ船長は、多数の交代要員(ホバートに停泊中のフランス捕鯨船からの脱走者が一般的)を雇うことを 強く主張し、デュモンに考え直すよう説得した。アストロラーベとゼレーは1840年1月1日にホバートを出発した。デュモンの計画はいたってシンプルだっ た。風向きが許せば南に向かう。 南に向かう 航海の最初の数日間は、主に20度線と西風を横断するものであった。船内では、さらに不幸な出来事が起こり、一人の男を失った。南緯50度線を越えると、 予想外に気温と水温が低下した。1840年1月16日、南緯60度で南極収束線を越えた後、最初の氷山を発見し、2日後には船団は氷の塊の真ん中にいた。 1月20日[注釈 10]、探検隊は赤道通過の儀式に似た祝典を挙げて南極圏を越え、同日午後には陸地を発見した。 2隻の船はゆっくりと西に向かって氷の壁を避けながら航行し、1月22日[注11]の夜9時直前、乗組員の一部が 、当時アストロラーベ氷河舌部の氷の海岸から500~600mの地点にあり、現在はケープ・ジョドセシー近くの氷河の末端から北に約4kmの地点にある。 そして、フランス国旗を掲げた。この諸島を「地質学岬」(Pointe Géologie)と名付け[20][21]、その先の陸地を「アデリーランド」(Terre Adélie)と名付けた[注釈 13]。水路学者クレマン・アドリアン・ヴァンセドン=デュムラン(fr)が航海中に作成した海岸の地図は、当時の手段を考慮すると非常に正確である [22]。 その後数日間、探検隊は海岸を西に向かって進み、初めて南磁極のおおよその位置を特定するための実験を行った。彼らは1840年1月30日にチャールズ・ ウィルクスが指揮するアメリカ探検遠征隊のアメリカスクーナー船ポルポイス号を発見したが、誤解により意思疎通はできなかった。[23] 2月1日、デュモンはホバートに向かって北に向かうことを決断し、2隻の船は17日後に到着した。ジェームズ・ロスが南極大陸探検のために派遣した2隻の 船、HMSテラー号とHMSエレバス号の到着に立ち会った。 2月25日、スクーナー船はオークランド諸島に向けて出帆し、そこで磁気測定を実施し、以前にポルポワーズ号の指揮官がそうしたように、訪問の記念プレー トを残した。そのプレートには、 。彼らはニュージーランド、トレス海峡、ティモール、レユニオン、セントヘレナを経由し、最後にトゥーロンに戻り、1840年11月6日に帰還した。これ は、フランスが最後に航海した探検遠征であった。 フランスへの帰還  『南極点およびオセアニア航海』の口絵 帰国後、デュモン・デュルヴィルは少将に昇進し、パリ地理学会から金メダルを授与され、後にその会長となった。その後、彼は南極点およびオセアニアへの探 検航海に関する報告書『南極点およびオセアニアへの航海:アストロラーブ号およびゼレ号による1837年~1840年』の執筆を引き継ぎ、1841年から 1854年の間に24巻が出版され、さらに図版と地図を収録した7巻が出版された。 |

| Death and legacy On 8 May 1842, Dumont and his family boarded a train from Versailles to Paris after seeing water games celebrating the king. Near Meudon the train's locomotive derailed, the wagons rolled and the tender's coal ended up on the front of the train and caught fire. Dumont's whole family died in the flames of the first French railway disaster, generally known as the Versailles rail accident.[24] Dumont's remains were identified by Pierre-Marie Alexandre Dumoutier, a doctor on board the Astrolabe and a phrenologist.  Dumont-d'Urville's tombstone in Paris Dumont was buried in the cemetery of Montparnasse in Paris. This tragedy led to the end of the practice in France of locking passengers in their train compartments. He is the author of The New Zealanders: A story of Austral lands – likely to be the first novel written about fictional Maori characters. Later, in honour of his many valuable chartings, the D'Urville Sea off Antarctica; D'Urville Island in the Joinville Island group in Antarctica; D'Urville Wall on the David Glacier in Antarctica, Cape d'Urville, Irian Jaya, Indonesia; Mount D'Urville, Auckland Island; and D'Urville Island in New Zealand were named after him. The Dumont d'Urville Station on Antarctica is also named after him, as is the Rue Dumont d'Urville, a street near the Champs-Élysées in the 8th arrondissement of Paris, and the Lycée Dumont D'Urville in Caen. Dumont d'Urville himself named Pepin Island in New Zealand and Adélie Land in Antarctica after his wife, and Croisilles Harbour for his mother's family.[7] [note 15] A French naval transport ship employed in French Polynesia is named after him;[25] as was a 1931 sloop which served in World War II.[26] The standard author abbreviation d'Urv. is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.[27] |

死と遺産 1842年5月8日、デュモンとその家族は、国王を祝う水上ショーを見た後、ヴェルサイユからパリ行きの列車に乗った。ムードンの近くで列車の機関車が脱 線し、貨車が転がり、炭水車の石炭が列車の前面に飛び散って火災が発生した。デュモン一家全員がこのフランス初の鉄道事故(一般にはヴェルサイユ鉄道事故 として知られている)の炎の中で命を落とした。デュモンの遺体は、アストロラーブ号の医師で骨相学者のピエール=マリー・アレクサンドル・デュムティエに よって確認された。  パリにあるデュモン・デュルヴィルの墓碑 デュモンはパリのモンパルナス墓地に埋葬された。この悲劇により、フランスでは乗客を列車のコンパートメントに閉じ込めるという慣行が廃止された。 彼は『ニュージーランド人:南半球の物語』の著者であり、おそらく架空のマオリ族のキャラクターを扱った最初の小説である。その後、数々の貴重な測量に敬 意を表して、南極大陸沖のデュルビル海、南極大陸のジョインビル諸島にあるデュルビル島、南極大陸のデヴィッド氷河にあるデュルビル壁、インドネシアのイ リアンジャヤ州にあるデュルビル岬、オークランド諸島のデュルビル山、ニュージーランドのデュルビル島に、彼の名が付けられた。また、南極大陸にあるデュ モン・デュルヴィル基地、パリの8区にあるシャンゼリゼ通りの近くのデュモン・デュルヴィル通り、そしてカーンのデュモン・デュルヴィル高校も彼の名に因 んで名付けられている。 デュモン・デュルヴィル自身は、ニュージーランドのペピン島と南極大陸のアデリーランドを妻の名にちなんで命名し、また、母方の実家の村にクロワジール港と名付けた。[7][注釈 15] フランス領ポリネシアで就航しているフランス海軍の輸送船は、彼にちなんで名付けられている。[25] また、第二次世界大戦で活躍した1931年のスループ艦にも彼の名が付けられている。[26] 植物学名を引用する際にこの人物を著者として示す場合、標準的な著者略称であるd'Urv.が使用される。[27] |

| References Dunmore, John (2007). The Life of Dumont d'Urville: From Venus to Antarctica. Auckland, New Zealand: Exisle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-908988-71-6. Edward Duyker Dumont d’Urville: Explorer and Polymath, Otago University Press, Dunedin, 2014, pp. 671, ISBN 978 1 877578 70 0, University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu, 2014, ISBN 9780824851392. Guillon, Jacques (1986). Dumont d'Urville (in French). Paris: France-Empire. Gurney, Alan (2000). The race to the white continent. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 320. ISBN 0-393-05004-1. Lesson, René-Primevère Alan (1845). Notice historique sur l'amiral Dumont d'Urville (in French). Rochefort: Imprimerie de Henry Loustau. Taillemite, Étienne (2008). Les hommes qui ont fait la marine française. Paris: Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-02222-8. Vergniol, Camille (1930). Dumont d'Urville. La grande légende de la mer (in French). |

参考文献 Dunmore, John (2007). デュモン・デュルヴィルの生涯:金星から南極まで. Auckland, New Zealand: Exisle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-908988-71-6. Edward Duyker Dumont d'Urville: Explorer and Polymath, Otago University Press, Dunedin, 2014, pp.671, ISBN 978 1 877578 70 0, University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu, 2014, ISBN 9780824851392. Guillon, Jacques (1986). Dumont d'Urville (in French). Paris: France-Empire. Gurney, Alan (2000). The race to the white continent. ニューヨーク:W.W.ノートン&カンパニー。 Lesson, René-Primevère Alan (1845). Notice historique sur l'amiral Dumont d'Urville (in French). Rochefort: Imprimerie de Henry Loustau. Taillemite, Étienne (2008). Les hommes qui ot fait la marine française. Paris: Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-02222-8. Vergniol, Camille (1930). Dumont d'Urville. La grande légende de la mer (in French). |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jules_Dumont_d%27Urville |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆