カンカナエイ

Kankanaey people

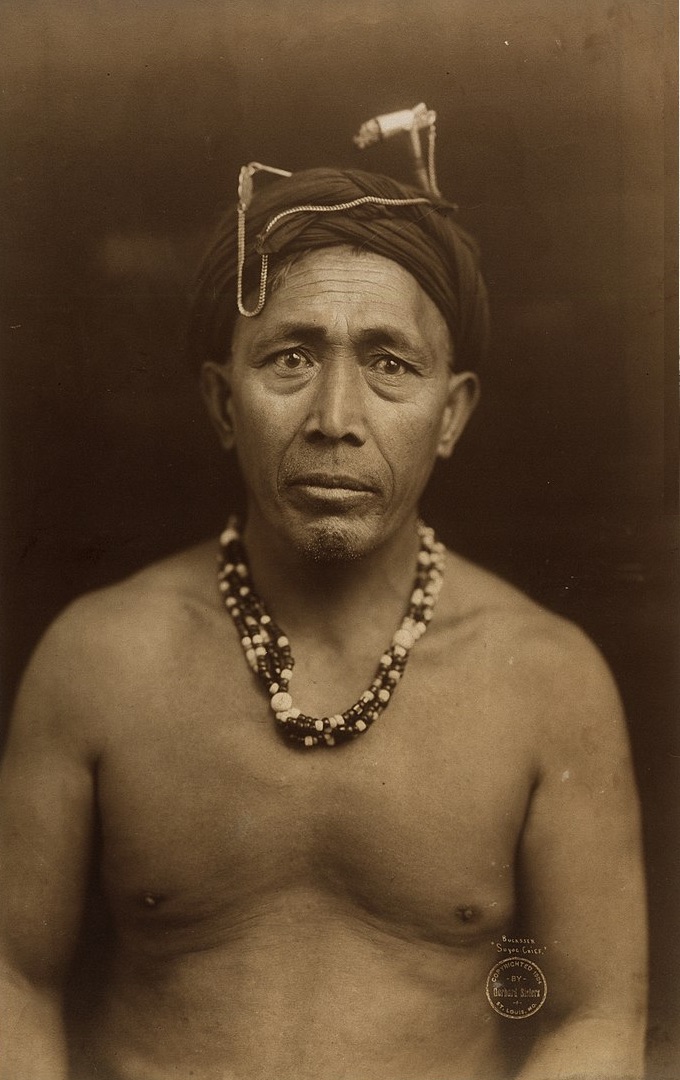

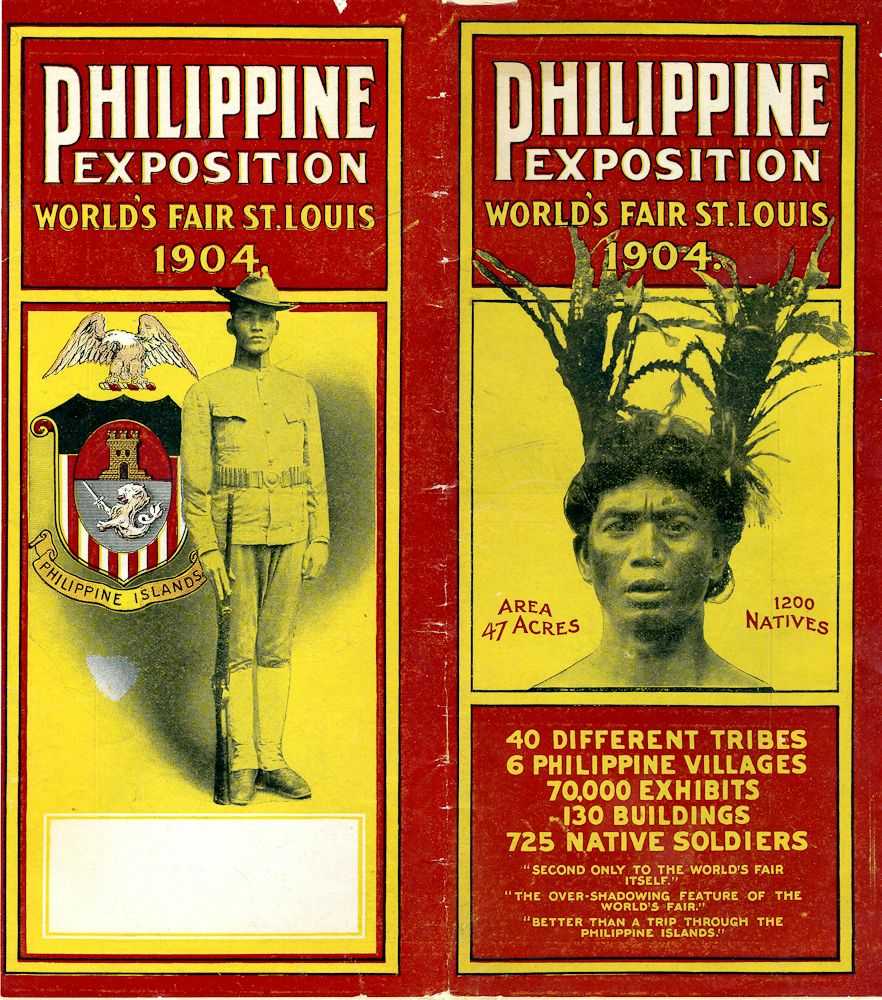

"Suyoc"

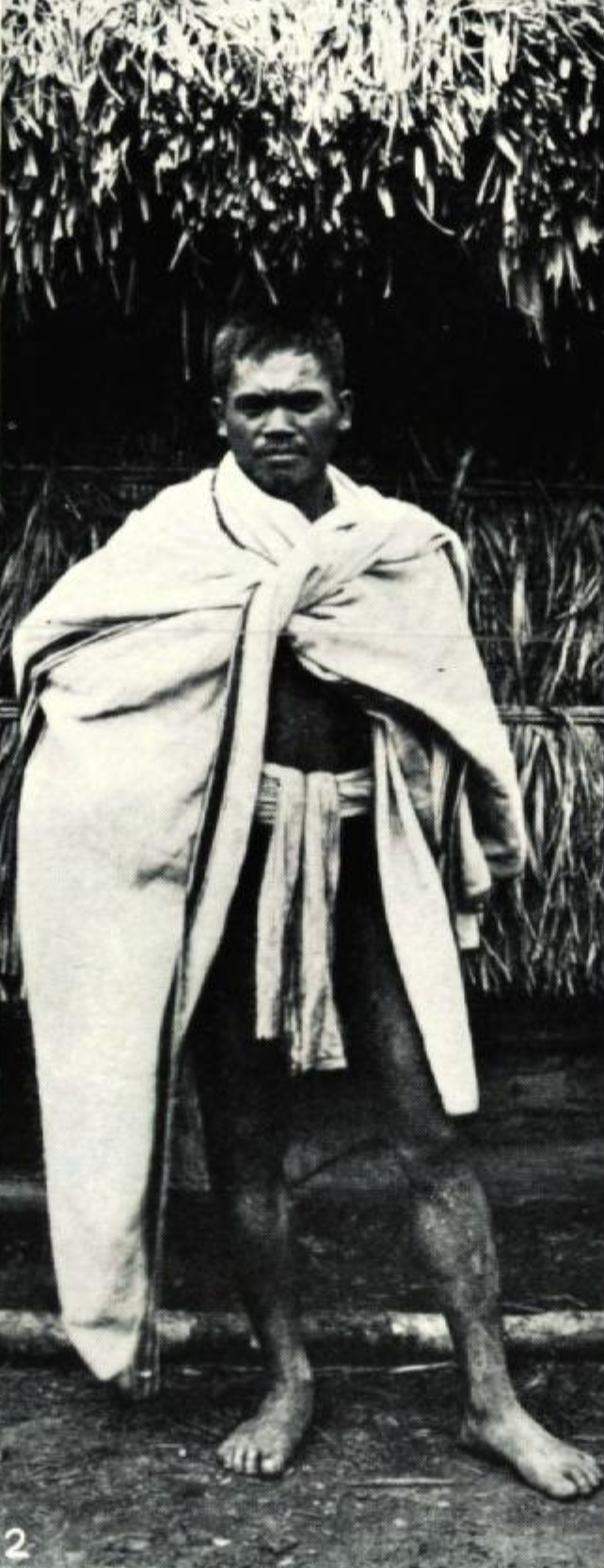

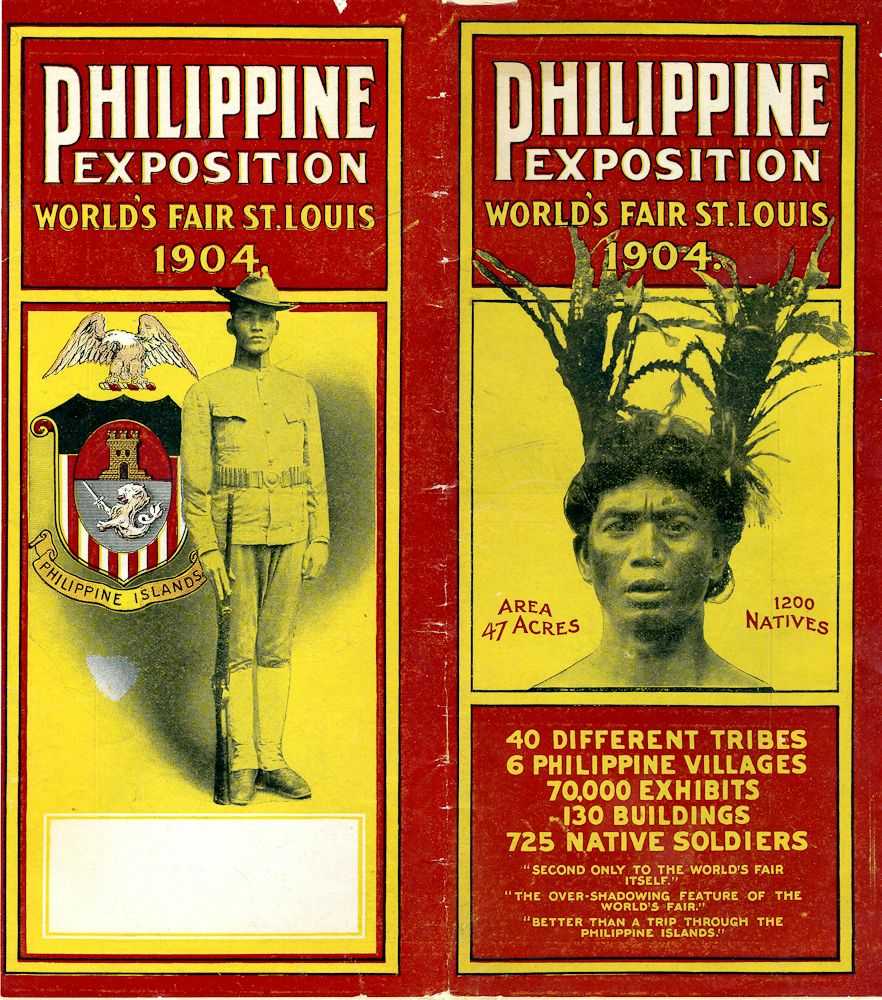

is a town in the Benguet region. This man is Benguet (Kankanaey

subtribe) Title: Bucassen, Suyoc Chief. (Taken during the 1904 World's

Fair)- 1904年セントルイス万博(Louisiana

Purchase Exposition, Expo 1904).

☆カンカナエイ(カンカナエイ語: i-Kankanaëy [ʔi̞ k̠ʌn.k̠ʌˈnʌɨi̯])は、フィリピン・ルソン島北部に住む先住民である。彼らはコルディリェラ地方の先住民集団であるイゴロット族の一部を成 す。

| The Kankanaey people (Kankanaey: i-Kankanaëy [ʔi̞ k̠ʌn.k̠ʌˈnʌɨi̯]) are an indigenous peoples of northern Luzon, Philippines. They are part of the collective group of indigenous peoples in the Cordillera known as the Igorot people. | カンカナエイ(カンカナエイ語: i-Kankanaëy [ʔi̞

k̠ʌn.k̠ʌˈnʌɨi̯])は、フィリピン・ルソン島北部に住む先住民である。彼らはコルディリェラ地方の先住民集団であるイゴロット族の一部を成

す。 |

Demographics A map of where the Kankanaey language is spoken and where the Kankanaey people live. The Kankanaey live in western Mountain Province, northern Benguet, northeastern La Union and southeastern Ilocos Sur.[2] The Kankanaey of the western Mountain Province are sometimes identified as Applai or Aplai. Because of the differences in culture from the Kankanaey of Benguet, the "Applai" have been accredited as a separate tribe.[3] Few Kankanaey can be found in some areas in of the Philippines. They form a minority in the Visayas, especially in Cebu, Iloilo and Negros provinces. They can also be found as a minority in Mindanao, particularly in the provinces of Sultan Kudarat in Soccsksargen and Lanao del Norte in Northern Mindanao.[4][5] The 2010 Philippines census counted 362,833 self-identifying Kankanaey and 67,763 self-identifying Applai.[6] |

人口統計 カンカナエイ語が話され、カンカナエイ人民が居住する地域の地図。 カンカナエイ人民は、マウンテン州西部、ベンゲット州北部、ラ・ウニオン州北東部、イロコス・スル州南東部に居住している。[2] マウンテン州西部のカンカナエイ族は、アプライ族またはアプライ族と呼ばれることもある。ベンゲット州のカンカナエイ族とは文化が異なるため、「アプライ 族」は別の部族として認められている。[3] フィリピン国内のいくつかの地域に少数のカンカナエイ族が存在する。彼らはビサヤ地方、特にセブ州、イロイロ州、ネグロス州で少数派を形成している。また ミンダナオ島でも少数派として確認され、特にソックスサルゲン地方のスルタン・クダラット州や北ミンダナオのラナオ・デル・ノルテ州に分布している。 [4][5] 2010年のフィリピン国勢調査では、自らをカンカナエイと認識する者が362,833人、アプライと認識する者が67,763人確認された。[6] |

| Prehistory Recent DNA studies show that the Kankanaey along with the Atayal people of Taiwan, were most probably among the original ancestors of the Lapita people and modern Polynesians.[7][8][9] They might even reflect a better genetic match to the original Austronesian mariners than the aboriginal Taiwanese, as the latter were influenced by more recent migrations to Taiwan, whereas the Kankanaey are thought to have remained an isolated relict population.[10] |

先史時代 最近のDNA研究によれば、カンカナエイ族は台湾のアタヤル族と共に、ラピタ文化の人々と現代ポリネシア人の祖先である可能性が高いとされる。[7] [8] [9] 彼らは台湾先住民よりも、より初期のオーストロネシア系航海者との遺伝的類似性を示す可能性がある。なぜなら台湾先住民はより近世の台湾移住の影響を受け たのに対し、カンカナエイ族は孤立した遺存集団として存続したと考えられているからだ。[10] |

| Northern Kankanaey The Northern Kankanaey or Applai live in Sagada and Besao, western Mountain province, and constitute a linguistic group. H. Otley Beyer believed they originated from a migrating group from Asia who landed on the coasts of Pangasinan before moving to Cordillera. Beyer's theory has since been discredited, and Felix Keesing speculated the people were simply evading the Spanish. Their smallest social unit is the sinba-ey, which includes the father, mother, and children. The sinba-eys make up the dap-ay/ebgan which is the ward. Their society is divided into two classes: the kadangyan (rich), who are the leaders and who inherit their power through lineage or intermarriage, and the kado (poor). They practice bilateral kinship.[11] The Northern Kankana-eys believe in many supernatural beliefs and omens, and in gods and spirits like the anito (soul of the dead) and nature spirits.[11] They also have various rituals, such as the rituals for courtship and marriage and death and burial. The courtship and marriage process of the Northern Kankana-eys starts with the man visiting the woman of his choice and singing (day-eng), or serenading her using an awiding (harp), panpipe (diw-as), or a nose flute (kalelleng). If the parents agree to their marriage, they exchange work for a day (dok-ong and ob-obbo), i.e. the man brings logs or bundled firewood as a sign of his sincerity, the woman works on the man’s father’s field with a female friend. They then undergo the preliminary marriage ritual (pasya) and exchange food. Then comes the marriage celebration itself (dawak/bayas)inclusive of the segep (which means to enter), pakde (sacrifice), betbet (butchering of pig for omens), playog/kolay (marriage ceremony proper), tebyag (merrymaking), mensupot (gift giving), sekat di tawid (giving of inheritance), and buka/inga, the end of the celebration. The married couple cannot separate once a child is born, and adultery is forbidden in their society as it is believed to bring misfortune and illness upon the adulterer.[11] The Northern Kankana-eys have rich material culture among which is the four types of houses: the two-story innagamang, binang-iyan, tinokbob and the elevated tinabla. Other buildings include the granary (agamang), male clubhouse (dap-ay or abong), and female dormitory (ebgan). Their men wear rectangular woven cloths wrapped around their waist to cover the buttocks and the groin (wanes). The women wear native woven skirts (pingay or tapis) that cover their lower body from waist to knees and is held by a thick belt (bagket).[11] Their household is sparsely furnished with only a bangkito/tokdowan, po-ok (small box for storage of rice and wine), clay pots, and sokong (carved bowl). Their baskets are made of woven rattan, bamboo or anes, and come in various shapes and sizes.[11] The Kankana-eys have three main weapons, the bolo (gamig), the axe (wasay) and the spear (balbeg), which they previously used to kill with but now serve practical purposes in their livelihood. They also developed tools for more efficient ways of doing their work like the sagad (harrow), alado (plow dragged by carabao), sinowan, plus sanggap and kagitgit for digging. They also possess Chinese jars (gosi) and copper gongs (gangsa).[11] For a living, the Northern Kankana-eys take part in barter and trade in kind, agriculture (usually on terraces), camote/sweet potato farming, slash-and-burn/swidden farming, hunting, fishing and food gathering, handicraft and other cottage industry. They have a simple political life, with the Dap-ay/abong being the center of all political, religious, and socials activities, with each dap-ay experiencing a certain degree of autonomy. The council of elders, known as the Amam-a, are a group of old, married men expert in custom law and lead in the decision-making for the village. They worship ancestors (anitos) and nature spirits.[11] |

北カンカナエイ族 北カンカナエイ族、あるいはアプライ族は、マウンテン州西部のサガダとベサオに居住し、一つの言語集団を構成している。H・オトリー・ベイヤーは、彼らが アジアからの移住集団に起源を持ち、パンガシナン州沿岸に上陸した後、コルディリェラ地方へ移動したと考えた。ベイヤーの説はその後否定され、フェリック ス・キーシングは、彼らが単にスペイン人を避けていたに過ぎないと推測した。彼らの最小社会単位はシンバエイであり、父、母、子供を含む。シンバエイはダ パエ/エブガン(区画)を構成する。社会は二つの階級に分かれる:カダンヤン(富裕層)は指導者であり、血統や婚姻を通じて権力を継承する。カド(貧困 層)はそれに対立する。彼らは両系氏族制度を実践する。[11] 北カンカナエイ族は多くの超自然的な信仰や前兆、アニト(死者の魂)や精霊といった神々や霊を信じている。[11] また求婚・結婚や死・埋葬に関する儀式など様々な儀礼を持つ。北部カンカナエ族の求婚・結婚過程は、男性が選んだ女性を訪ねて歌(デイ・エン)を捧げるこ と、あるいはアウィディン(ハープ)、パンパイプ(ディウ・アス)、鼻笛(カレレン)を用いたセレナーデで始まる。両親が結婚を承諾すると、一日労働の交 換(ドク・オングとオブ・オボ)が行われる。つまり、男性は誠意の証として丸太や束ねた薪を持ち込み、女性は女性の友人と共に男性の父親の畑で働く。その 後、予備的な結婚儀礼(パシャ)を行い、食物を交換する。続いて本婚宴(ダワク/バヤス)が行われる。これにはセゲプ(参入)、パクデ(生贄)、ベット ベット(吉兆のための豚屠殺)、プラヨグ/コラヤ(本婚礼)、 テビャグ(宴)、メンシュポット(贈答)、セカット・ディ・タウィド(相続財産の分配)、そして祝宴の締めくくりであるブカ/インガで構成される。子供が 生まれた後は夫婦が別れることは許されず、不倫は不幸や病をもたらすと信じられているため、彼らの社会では禁じられている。[11] 北カンカナエ族は豊かな物質文化を持ち、その中には四種類の家屋がある。二階建てのイナガマン、ビナンギヤン、ティノクボブ、そして高床式のティンブラ だ。その他の建物には穀物倉庫(アガマン)、男性集会所(ダプアイまたはアボン)、女性用共同寝室(エブガン)がある。男性は腰に巻いた長方形の織物(ワ ネス)で臀部と股間を覆う。女性は腰から膝までを覆う土着の織物スカート(ピンガイまたはタピス)を厚い帯(バグケット)で留めて着用する。[11] 彼らの家屋は簡素で、家具はバンキト/トクドワン(腰掛け)、ポオク(米や酒を貯蔵する小箱)、土鍋、ソコン(彫刻が施された椀)のみである。籠は籐、竹、アネスを編んで作られ、様々な形や大きさがある。[11] カンカナエ族は主に三種の武器を持つ。ボロ(ガミグ)、斧(ワサイ)、槍(バルベグ)である。これらはかつて殺傷用だったが、現在では生計のための実用具 となっている。また作業効率化のための道具も開発した。サガド(鋤)、アラド(水牛で引く鋤)、シノワン、さらに掘削用のサンガップとカギットギットなど である。中国製の壺(ゴシ)や銅製のゴング(ガンサ)も所有している。[11] 北カンカナエイ族の生計手段は、物々交換や現物取引、農業(主に段々畑)、サツマイモ栽培、焼畑農業、狩猟、漁労、採集、手工芸品製作、その他の家内工業 である。彼らの政治生活は単純で、ダパイ/アボンが全ての政治的・宗教的・社会的活動の中心であり、各ダパイはある程度の自治権を持つ。長老評議会である アママは、慣習法に精通した年配の既婚男性からなり、村の意思決定を主導する。彼らは祖先(アニトス)と自然の精霊を崇拝している。[11] |

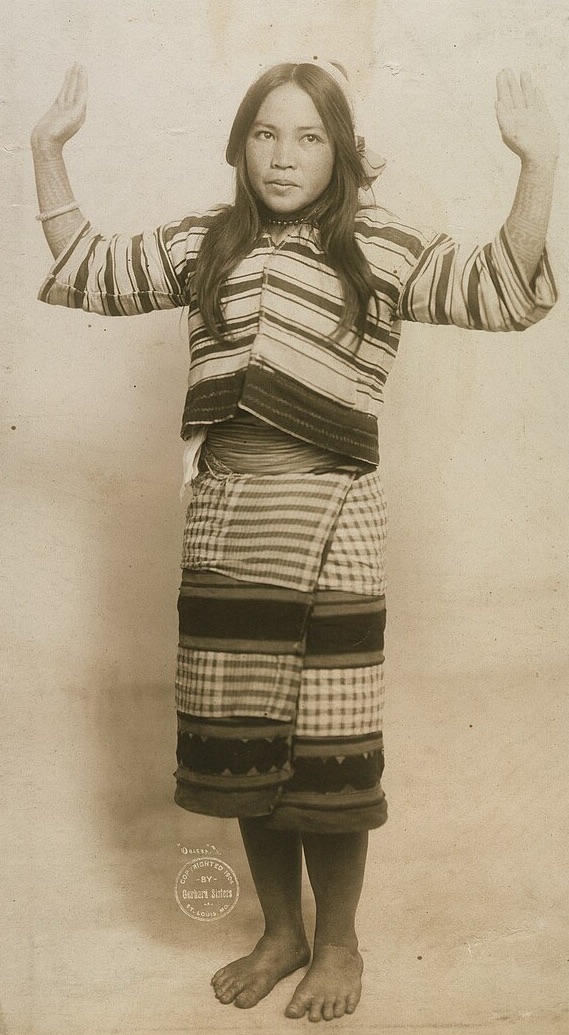

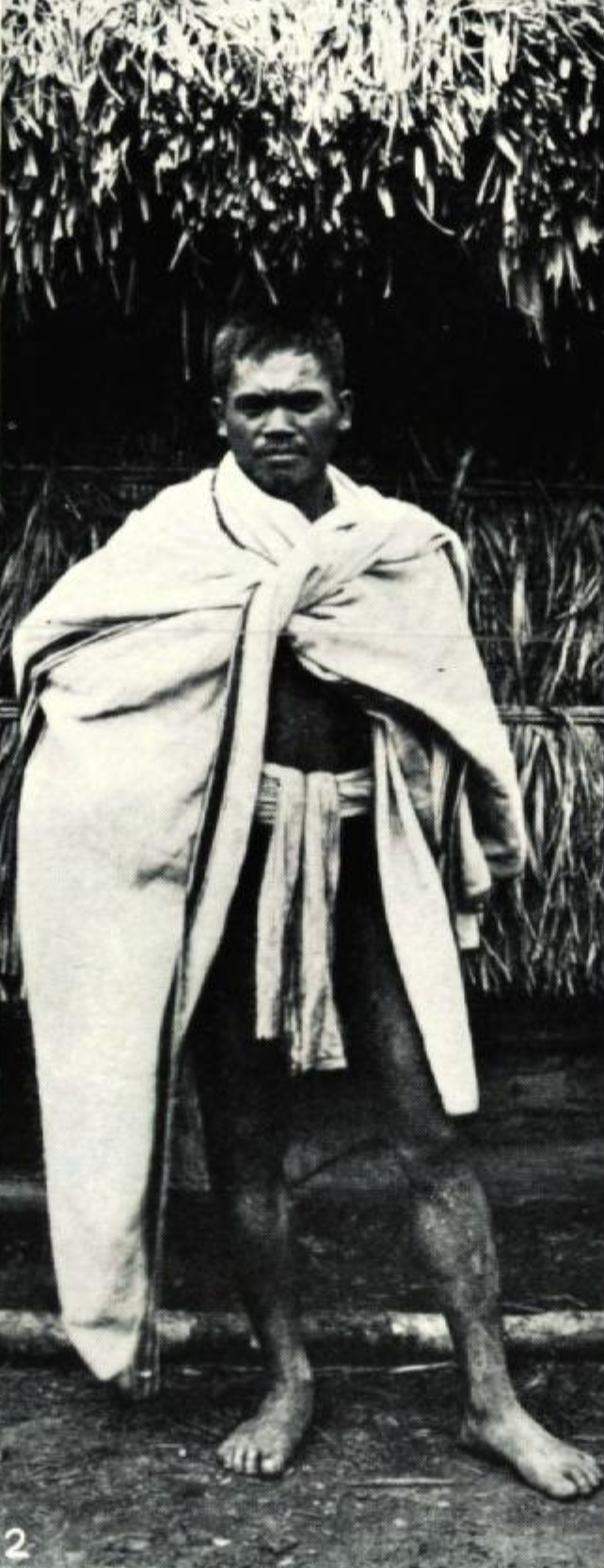

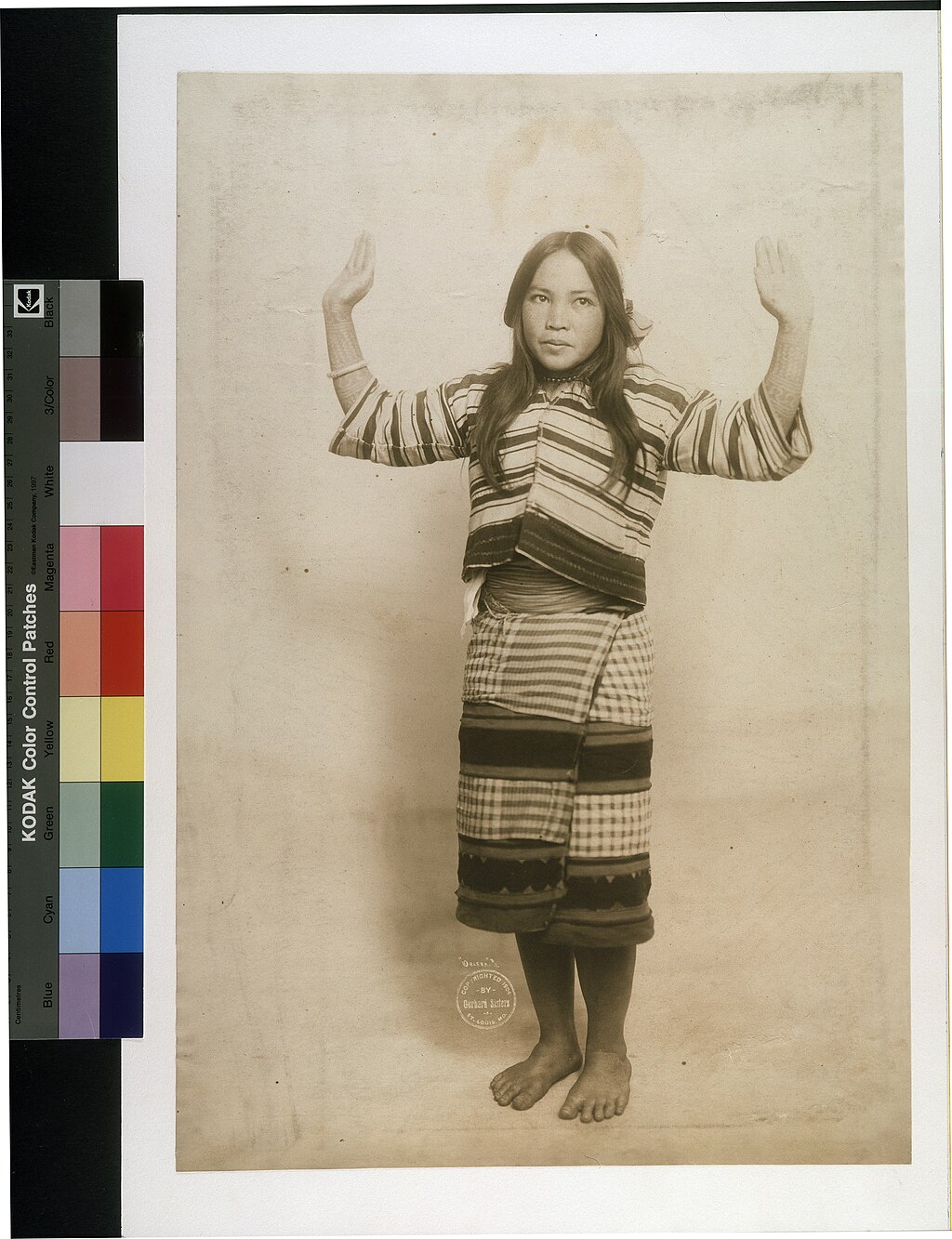

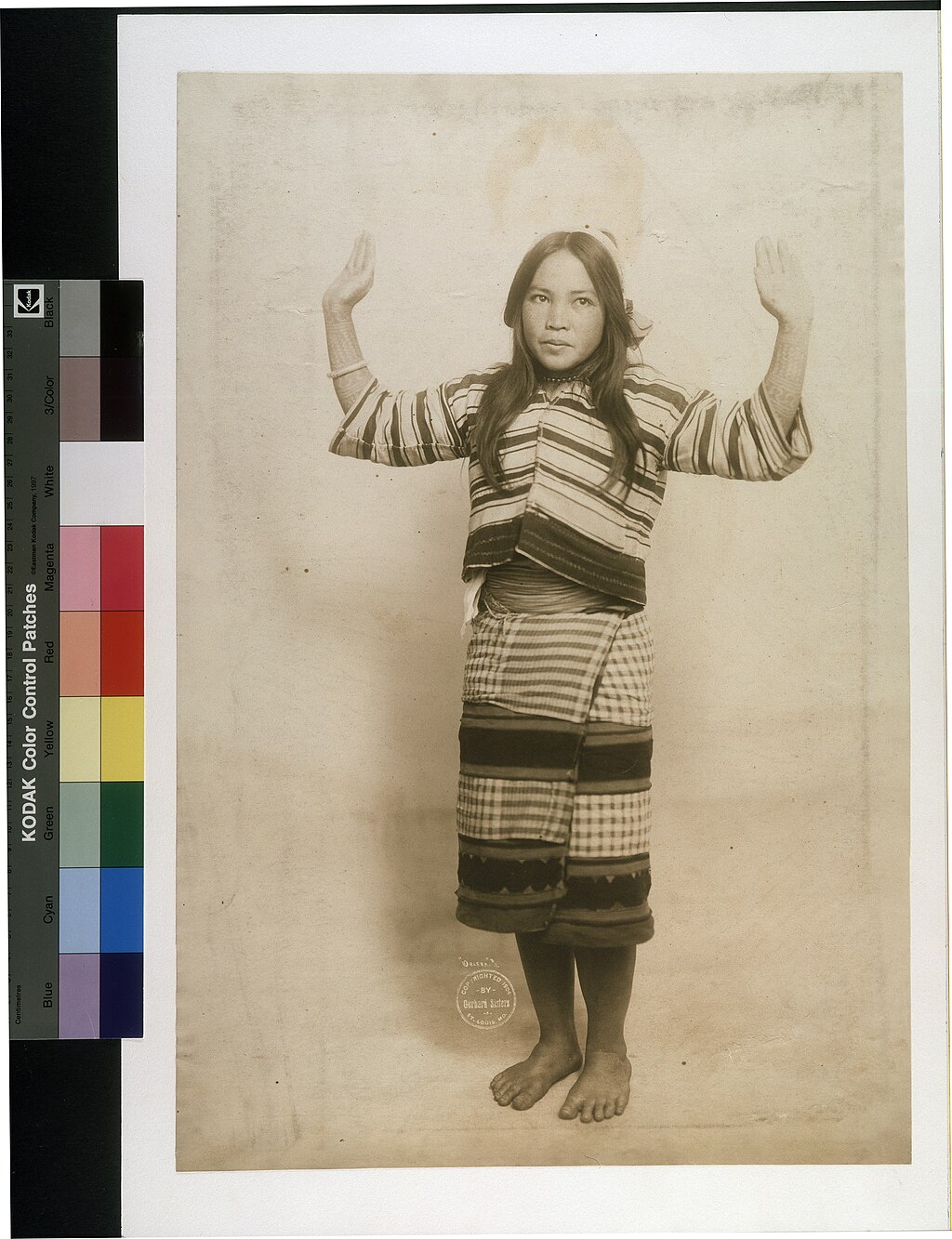

Southern Kankanaey A Kankanaey man from Irisan, Baguio, in typical attire. Note the large blanket worn over the shoulders (c. 1906) The Southern Kankanaey are one of the ethnolinguistic groups in the Cordillera. They live in the mountainous regions of Mountain Province and Benguet, more specifically in the municipalities of Tadian, Bauko, Sabangan, Bakun, Kibungan, Buguias and Mankayan.They are predominantly a nuclear family type (sinbe-ey,buma-ey, or sinpangabong), which are either patri-local or matri-local due to their bilateral kinship, composed of the husband, wife and their children. The kinship group of the Southern Kankana-eys consists of his descent group and, once he is married, his affinal kinsmen. Their society is divided into two social classes based primarily on the ownership of land: The rich (baknang) and the poor (abiteg or kodo). The baknang are the primary landowners to whom the abiteg render their services to. The Mankayan Kankana-eys, however, has no clear distinction between the baknang and the abiteg and all have equal access to resources such as the copper and gold mines.[12] Contrary to popular belief, the Southern Kankana-eys do not worship idols and images. The carved images in their homes only serve decorative purposes. They believe in the existence of deities, the highest among which is Adikaila of the Skyworld whom they believe created all things. Next in the hierarchy is the Kabunyan, who are the gods and goddesses of the Skyworld, including their teachers Lumawig and Kabigat. They also believe in the spirits of ancestors (ap-apo or kakkading), and the earth spirits they call anito. They are very superstitious and believe that performing rituals and ceremonies help deter misfortunes and calamities. Some of these rituals are pedit (to bring good luck to newlyweds), pasang (cure sterility and sleeping sickness, particularly drowsiness) and pakde (cleanse community from death-causing evil spirits).[12]   Tugmena, a Kankanaey girl from Suyoc, Mankayan, Benguet, in the Department of Anthropology at the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair The Southern Kankana-eys have a long process for courtship and marriage which starts when the man makes his intentions of marrying the woman known to her. Next is the sabangan, when the couple makes their wish to marry known to their family. The man offers firewood to the father of the woman, while the woman offers firewood to the man’s father. The parents then talk about the terms of the marriage, including the bride price to be paid by the man’s family. On the day of the marriage, the relatives of both parties offer gifts to the couple, and a pig is butchered to have its bile inspected for omens which would show if they should go on with the wedding. The wedding day for the Southern Kankana-eys is an occasion for merrymaking and usually lasts until the next day. Though married, the bride and groom are not allowed to consummate their marriage and must remain separated until such a time that they move to their own separate home.[12] The Southern Kankana-eys have different types of houses among which are binang-iyan (box-like compartment on 4 posts 5 feet high), apa or inalpa (a temporary shelter smaller than bingang-iyan), inalteb (has a gabled roof and shorter eaves allowing for the installation of windows and other opening at the side), allao (a temporary built in the fields), at-ato or dap-ay (a clubhouse or dormitory for men, with a long, low gable-roofed structure with only a single door for entrance and exit), and ebgang or olog (equivalent to the at-ato, but for women). Men traditionally wear a loincloth (wanes) around the waist and between the legs which is tightened at the back. Both ends hang loose at the front and back to provide additional cover. Men also wear a woven blanket for an upper garment and sometimes a headband, usually colored red like the wanes. The women, on the other hand, wear a tapis, a skirt wrapped around to cover from the waist to the knees held together by a belt (bagket) or tucked in the upper edges usually color white with occasional dark blue color. As adornments, both men and women wear bead leglets, copper or shell earrings, and beads of copper coin. They also sport tattoos which serve as body ornaments and "garments".[12] Southern Kankana-eys are economically involved in hunting and foraging (their chief livelihood), wet rice and swidden farming, fishing, animal domestication, trade, mining, weaving and pottery in their day-to-day activities to meet their needs. The leadership structure is largely based on land ownership, thus the more well-off control the community's resources. The village elders (lallakay/dakay or amam-a) who act as arbiters and jurors have the duty to settlements between conflicting members of the community, facilitate discussion among the villagers concerning the welfare of the community and lead in the observance of rituals. They also practice trial by ordeal. Native priests (mansip-ok, manbunong, and mankotom) supervise rituals, read omens, heal the sick, and remember genealogies.[12] Gold and copper mining is abundant in Mankayan. Ore veins are excavated, then crushed using a large flat stone (gai-dan). The gold is separated using a water trough (sabak and dayasan), then melted into gold cakes.[12] Musical instruments include the tubular drum (solibao), brass or copper gongs (gangsa), Jew's harp (piwpiw), nose flute (kalaleng), and a bamboo-wood guitar (agaldang).[12] There is no more pure Southern Kankana-ey culture because of culture change that modified the customs and traditions of the people. The socio-cultural changes are largely due to a combination of factors which include the change in the local government system when the Spaniards came, the introduction of Christianity, the education system that widened the perspective of the individuals of the community, and the encounters with different people and ways of life through trade and commerce.[12] |

南カンカナエイ族 バギオ市イリサン出身のカンカナエイ族男性が伝統衣装を身にまとっている。肩にかけた大きな毛布に注目(1906年頃) 南カンカナエイ族はコルディリェラ地方の民族言語集団の一つである。彼らはマウンテン州とベンゲット州の山岳地帯、具体的にはタディアン、バウコ、サバン ガン、バクン、キブンガン、ブグイアス、マンカヤンの各自治体に居住している。主に核家族型(シンベエイ、ブマエイ、またはシンパンガボン)を構成し、 夫、妻、そして子供たちで成り立つ。両系血縁に基づくため、父系居住または母系居住のいずれかである。南部カンカナエ族の親族集団は、血縁集団と、結婚後 は姻族で構成される。彼らの社会は主に土地所有に基づいて二つの階級に分かれる:富裕層(バクナン)と貧困層(アビテグまたはコド)である。バクナンは主 要な土地所有者であり、アビテグは彼らに奉仕する。しかしマンカヤン・カンカナエ族では、バクナンとアビテグの明確な区別がなく、銅や金の鉱山などの資源 へのアクセスは皆平等だ。[12] 一般的な認識とは異なり、南部カンカナエ族は偶像や像を崇拝しない。家にある彫刻像は装飾目的のみである。彼らは神々の存在を信じている。その頂点に立つ のは天空界のアディカイラであり、万物を創造したとされている。次に位階が高いのはカブニャンで、天空界の神々であり、師であるルマウィグやカビガットも 含まれる。また祖先の霊(アポポまたはカッカディン)や、アニトと呼ばれる地霊も信じている。彼らは非常に迷信深く、儀礼や祭事を行うことで災厄や不幸を 避けられると信じている。代表的な儀礼には、ペディット(新婚夫婦に幸運をもたらす)、パサン(不妊や睡眠障害、特に眠気を治す)、パクデ(死をもたらす 悪霊を共同体から祓う)などがある。[12]   1904年セントルイス万国博覧会人類学部門展示のトゥグメナ(ベンゲット州マンカヤン・スヨック出身のカンカナエイ族少女) 南カンカナエイ族の求婚と結婚には長い過程がある。まず男性が女性への結婚意思を伝える。次にサバンガンと呼ばれる儀式で、カップルが家族に結婚の意思を 表明する。男性は女性の父親に薪を贈り、女性は男性の父親に薪を贈る。その後、両親は結婚条件について話し合う。これには男性側が支払う花嫁代金も含まれ る。結婚式当日、双方の親族はカップルに贈り物を捧げ、豚を屠殺して胆汁を検査する。この検査で吉凶が占われ、結婚式を続行すべきか判断されるのだ。南カ ンカナエイ族の結婚式は祝宴の場であり、通常は翌日まで続く。結婚後も新郎新婦は婚姻を成就させてはならず、別々の家に移る時まで別居を続けねばならない [12]。 南カンカナエイ族の住居には異なる種類がある。ビンアンギヤン(高さ5フィートの4本の柱の上に箱状の区画を載せたもの)、アパまたはインアルパ(ビンア ンギヤンより小さい仮設住居)、インアルテブ(切妻屋根で軒が短く、側面に窓や開口部を設けることができる)、アラオ(野原に建てられる仮設住居)、 アタトまたはダパ(男性用クラブハウスもしくは共同寝舎。長く低い切妻屋根構造で、出入り口は単一の扉のみ)、エブガンまたはオログ(アタトに相当するが 女性用)などがある。男性は伝統的に腰と股間に巻く腰布(ワネス)を後ろで締める。両端は前後に垂れ下がり追加の覆いとなる。上着には織物のブランケット を羽織り、時に赤い頭巾を付ける。頭巾の色は腰布と同じ赤であることが多い。一方、女性はタピスと呼ばれるスカートを腰から膝まで覆うように巻き、ベルト (バグケット)で留めるか、上端を内側に折り込んで着用する。色は白が主流で、時折濃紺も見られる。装飾品として男女ともにビーズの足輪、銅製または貝殻 のイヤリング、銅貨のビーズを身につける。また、身体装飾や「衣服」として機能する刺青を施す。[12] 南カンカナエイス族は、日々の生活で狩猟採集(主な生計手段)、水稲作と焼畑農業、漁業、家畜飼育、交易、採鉱、織物、陶器製作など経済活動に従事し、必 要を満たしている。指導体制は主に土地所有権に基づいており、より裕福な者が共同体の資源を支配する。仲裁者兼陪審員として機能する村の長老(ララカイ/ ダカイまたはアマンア)は、共同体内の対立するメンバー間の和解を促し、共同体の福祉に関する村民間の議論を促進し、儀礼の執行を主導する責務を負う。彼 らはまた試練による裁判も行う。土着の司祭(マンシプ・オク、マンブノン、マンコトム)は儀礼の監督、前兆の解読、病人の治療、系譜の記憶を担う。 [12] マンカヤンでは金と銅の採掘が盛んである。鉱脈を掘り起こした後、大きな平らな石(ガイダン)で砕く。水槽(サバックとダヤサン)で金を分離し、金塊に溶解する。[12] 楽器には筒状太鼓(ソリバオ)、真鍮または銅のゴング(ガンサ)、口琴(ピウピウ)、鼻笛(カラレン)、竹と木のギター(アガルダン)がある。[12] 人々の慣習や伝統を変えた文化変化のため、純粋な南カンカナエ文化はもはや存在しない。こうした社会文化的変化は主に、スペイン人到来時の地方政府制度の 変更、キリスト教の導入、地域住民の視野を広げた教育制度、そして貿易や商業を通じた異なる人々や生活様式との接触といった要因の複合によって引き起こさ れた。[12] |

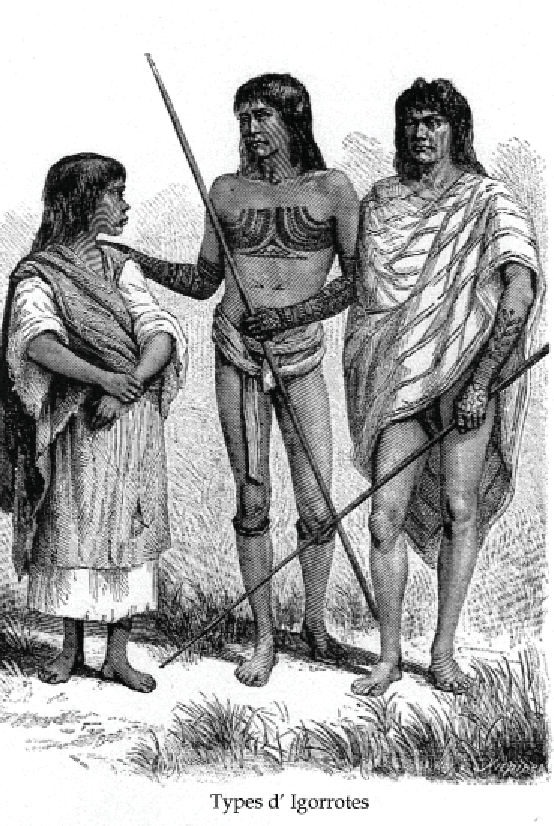

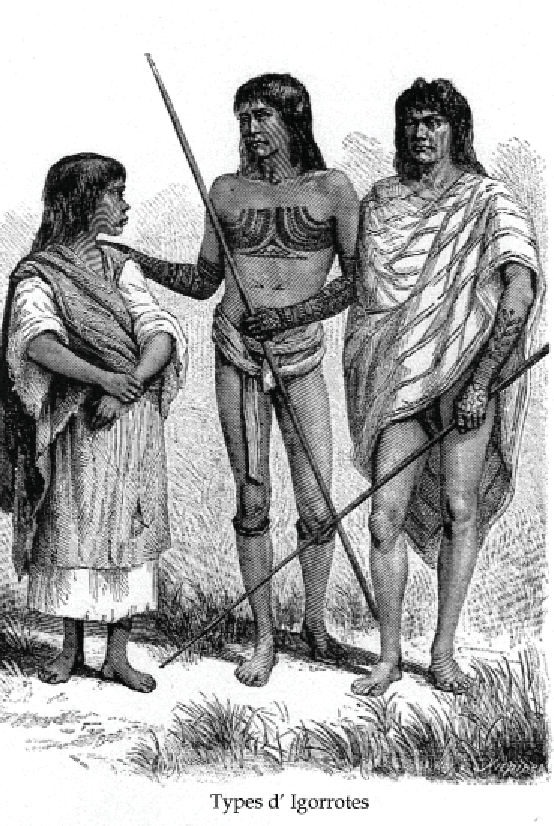

Culture Drawing of tattooed Kankanaey people in Mankayan, Benguet, by the French naturalist Antoine-Alfred Marche (1887)[13] Like most ethnic groups, the Kankanaey built sloping terraces to maximize farm space in the rugged terrain of the Cordillera Administrative Region. The Kankanaey differ in the way they dress. The soft-speaking Kankanaey women's dress has a color combination of black, white and red. The design of the upper attire is a criss-crossed style of black, white and red colors. The skirt or tapis is a combination of stripes of black, white and red. The hard-speaking Kankanaey women's dress is composed of mainly red and black with a little white styles, as for the skirt or tapis which is mostly called bakget and gateng[clarification needed]. The men wear a woven loincloth known as wanes to the Kankanaeys of Besao and Sagada. The design of the wanes may vary according to social status or municipality. The Kankanaey's major dances include tayaw, pattong and balangbang. The Tayaw is a community dance that is usually performed at weddings; it may be also danced by the Ibaloi people but has a different style. Pattong is also a community dance from Mountain Province which every municipality has its own style. Balangbang is the modern word for pattong. There are also some other dances that the Kankanaeys dance, such as the sakkuting, pinanyuan (wedding dance) and bogi-bogi (courtship dance). Kankanaey houses are built like the other Igorot houses, which reflect their social status.  Kankanaey woman posing for the tayaw dance, circa 1904, in Suyoc. |

文化 ベンゲット州マンカヤンにおける刺青を施したカンカナエイ人民の図(フランス人自然学者アントワーヌ=アルフレ・マルシュ作、1887年)[13] 他の民族と同様、カンカナエイ人民もコルディリェラ行政区の険しい地形において農地を最大化するため、傾斜した段々畑を築いた。 カンカナエイ族は服装の様式が異なる。物腰柔らかなカンカナエイ族の女性の衣装は、黒、白、赤の配色である。上着のデザインは黒、白、赤の縦横に交差した模様だ。スカートまたはタピスは黒、白、赤の縞模様を組み合わせたものである。 一方、気性の激しいカンカナエイ族の女性の衣装は、主に赤と黒を基調とし、白を少し加えたスタイルである。スカート(タピス)は主にバケトやガテンと呼ば れる。男性はベサオやサガダのカンカナエイ族に伝わるワネスと呼ばれる編み込みの腰布を身に着ける。ワネスのデザインは社会的地位や自治体によって異なる 場合がある。 カンカナエイ族の主要な舞踊には、タヤウ、パトン、バランバンがある。タヤウは結婚式で踊られる共同体の舞踊であり、イバロイの人民も踊るが様式が異な る。パトンもマウンテン州発祥の共同体舞踊で、自治体ごとに独自の様式を持つ。バランバンはパトンの現代的な呼び名だ。カンカナエイ族が踊るその他の舞踊 には、サクティン、ピナニュアン(婚礼の舞)、ボギボギ(求愛の舞)などがある。カンカナエイ族の家屋は他のイゴロット族の家と同様に、社会的地位を反映 した構造となっている。  1904年頃、スヨックでタヤウ舞踊のポーズをとるカンカナエ族の女性(氏名:オブレスカ?)。 |

| Cuisine Wet rice agriculture is the main economic activity of the Northern Kankanaey with some fields toiled twice a year while other only once due to too much water or no water at all. There are two varieties of rice called topeng which are planted in June and July and harvested in November and December, and ginolot which are planted in November and December and harvested in June and July. Northern kankana-eys also farm camote. Camote delicacies include (1) makimpit which are dried camotes, (2) boko which are camote sliced into thin pieces that could be steamed (sinalopsop) or cooked as in and sweetened with sugar (inab-abos-sang). These are good substitutes for rice that could be sliced into thin pieces and added to rice before cooking (kineykey) mixing the sweetness when the rice cooks. Squash, cucumber and other climbing vines are also planted. They also hunt and fish small fishes and eel which is a special delicacy when cooked. Crabs are also caught to make tengba, a gravy of pounded rice mixed with crabs, salted and placed in jars to age. This is common viand of every household and is eaten during childbirth.[11] Although Southern Kankanaey also engage in wet rice agriculture, the chief means of livelihood is hunting and foraging. Wild animal meat such as deer, boar, civet cats and lizards are salted and dried under the sun to preserve it. Wild roots, honey and fruits are also gathered to supplement diet. Just like their northern counterparts, there are also two varieties of rice namely kintoman and saranay or bayag. The kintoman, just as mentioned earlier, is more popularly known as red rice due to its color. On the other hand, saranay is whitish and small grained. The usual types of fish caught are eel (dagit or igat) and small river fishes as well as crabs and other crustaceans. Pigs, chickens, dogs and cattle are domesticated as additional sources of food. Dog meat is considered as a delicacy and pigs and chickens are used mainly for ceremonial activities.[12] A blood sausage known as pinuneg is eaten by the Kankanaey people.[14] |

食文化 北カンカナエイ族の主な経済活動は水稲農業だ。水が多すぎるか全くないため、年に二度耕作する田んぼもあれば、一度しか耕作しない田んぼもある。米には二 種類ある。トペンと呼ばれる品種は6月と7月に植え付け、11月と12月に収穫する。ギノロットと呼ばれる品種は11月と12月に植え付け、6月と7月に 収穫する。北部カンカナエイ族はサツマイモも栽培する。サツマイモの加工品には、(1)乾燥させたマキンピット、(2)薄切りにしたボコがある。ボコは蒸 す(シナロプソップ)か、砂糖で甘く煮る(イナバボスサン)ことができる。これらは米の代用品として優れており、薄切りにして炊飯前に加える(キネイ キー)ことで、炊き上がりに甘みが混ざる。カボチャ、キュウリ、その他のつる性植物も栽培される。また狩猟や小魚・ウナギの漁も行われ、調理すると特別な 珍味となる。カニも捕獲され、テンバ(砕いた米とカニを混ぜ塩漬けにし壺で熟成させるペースト状の調味料)の原料となる。これは各家庭の一般的な副食であ り、出産時にも食べられる[11]。 南部カンカナエイ族も水稲農業を行うが、主な生業は狩猟と採集である。鹿、猪、ジャコウネコ、トカゲなどの野生動物の肉は塩漬けにし、天日干しで保存す る。野生根菜、蜂蜜、果実も採集され食生活を補う。北部と同様に、キンタマンとサラナイ(またはバヤグ)という二種類の米が存在する。キンタマンは前述の 通り、その色から赤米として広く知られている。一方サラナイは白っぽく小粒である。主な漁獲物はウナギ(ダギットまたはイガット)、小川の魚、カニやその 他の甲殻類だ。食料源として豚、鶏、犬、牛も飼育される。犬肉は珍味とされ、豚や鶏は主に儀式用に使われる。[12] ピンネグと呼ばれる血のソーセージはカンカナエイの人民が食べる。[14] |

Funerary practices Coffins stacked inside the Lumiang Cave in Sagada, Mountain Province, Philippines See also: Funeral practices and burial customs in the Philippines Hanging coffins are one of the funerary practices among the Kankanaey people of Sagada, Mountain Province. They have not been studied by archaeologists, so the exact age of the coffins is unknown, though they are believed to be centuries old. The coffins are placed underneath natural overhangs, either on natural rock shelves/crevices or on projecting beams slotted into holes dug into the cliff-side. The coffins are small because the bodies inside the coffins are in a fetal position. This is due to the belief that people should leave the world in the same position as they entered it, a tradition common throughout the various pre-colonial cultures of the Philippines. The coffins are usually carved by their eventual occupants during their lifetimes.[15] Despite their popularity, hanging coffins are not the main funerary practice of the Kankanaey. It is reserved only for distinguished or honorable leaders of the community. They must have performed acts of merit, made wise decisions, and led traditional rituals during their lifetimes. The height at which their coffins are placed reflects their social status. Most people interred in hanging coffins are the most prominent members of the amam-a, the council of male elders in the traditional dap-ay (the communal men's dormitory and civic center of the village). There is also one documented case of a woman being accorded the honor of a hanging coffin interment.[16] The more common burial custom of the Kankanaey is for coffins to be tucked into crevices or stacked on top of each other inside limestone caves. Like in hanging coffins, the location depends on the status of the deceased as well as the cause of death. All of these burial customs require specific pre-interment rituals known as the sangadil. The Kankanaey believe that interring the dead in caves or cliffs ensures that their spirits (anito) can roam around and continue to protect the living.[17] The Northern Kankana-eys honor their dead by keeping vigil and performing the rituals sangbo (offering of 2 pigs and 3 chickens), baya-o (singing of a dirge by three men), menbaya-o (elegy) and sedey (offering of pig). They finish off the burial ritual with dedeg (song of the dead), and then, the sons and grandsons carry the body to its resting place.[11] The funeral ritual of the Southern Kankana-eys lasts up to ten days, when the family honors their dead by chanting dirges and vigils and sacrificing a pig for each day of the vigil. Five days after the burial of the dead, those who participated in the burial take a bath in a river together, butcher a chicken, then offer a prayer to the soul of the dead.[12] |

葬送の慣習 フィリピン、マウンテン州サガダのルミアン洞窟内に積み上げられた棺 関連項目:フィリピンの葬儀慣習と埋葬習俗 吊り棺は、マウンテン州サガダのカンカナエイ族における葬送の慣習の一つだ。考古学者による研究が行われていないため、棺の正確な年代は不明だが、数世紀 前のものと見られている。棺は自然の張り出し部分、すなわち岩棚や岩の裂け目、あるいは崖面に掘られた穴に差し込まれた梁の上に置かれる。棺は小さい。棺 の中の遺体は胎児の姿勢をとっているからだ。これは「人民はこの世に生を受けた時と同じ姿勢で去るべきだ」という信念によるもので、フィリピンの様々な植 民地以前の文化に共通する伝統である。棺は通常、生前にその使用者自身が彫るものである。[15] 懸棺は人気があるが、カンカナエイ族の主要な葬送習俗ではない。これはコミュニティの傑出した指導者や名誉ある指導者にのみ許される。彼らは生前に功績を 挙げ、賢明な決断を下し、伝統的な儀礼を主導していなければならない。棺が設置される高さは、その人物の社会的地位を反映している。懸棺に埋葬される人民 の大半は、伝統的なダップアイ(村の共同男性宿舎兼市民センター)における男性長老評議会「アマンア」の最も著名なメンバーである。また、女性が懸棺によ る埋葬の栄誉を与えられた事例が1件記録されている。[16] カンカナエイ族のより一般的な埋葬習俗は、石灰岩の洞窟内の裂け目に棺を収めるか、あるいは積み重ねて安置するものである。吊り棺と同様に、その場所は故 人の地位や死因によって決まる。これらの埋葬習俗はいずれも、サンガディルと呼ばれる特定の埋葬前儀礼を必要とする。カンカナエイ族は、洞窟や崖に死者を 埋葬することで、その霊(アニト)が自由に動き回り、生きている者を守り続けられると信じている[17]。 北カンカナエイ族は、通夜を営み、サンボ(豚2頭と鶏3羽の供物)、バヤオ(3人の男性による哀歌の歌唱)、メンバヤオ(挽歌)、セデイ(豚の供物)と いった儀礼を執り行うことで死者を称える。埋葬の儀礼はデデグ(死者の歌)で締めくくられ、その後、息子や孫たちが遺体を安息の地へ運ぶ。[11] 南部カンカナエ族の葬儀儀礼は最大10日間続き、家族は死者を悼むために哀歌を詠み、夜通し見守り、見守りの日数に応じて豚を1頭ずつ犠牲にする。死者を 埋葬してから5日後、埋葬に参加した者たちは川で一緒に沐浴し、鶏を屠殺した後、死者の魂に祈りを捧げる。[12] |

| Tattoos Main article: Batok  A close up of traditional Kankanaey tattoos Ancient tattoos can be found among mummified remains of various Cordilleran peoples in cave and hanging coffin burials in northern Luzon, with the oldest surviving examples of which going back to the 13th century. The tattoos on the mummies are often highly individualized, covering the arms of female adults and the whole body of adult males. A 700 to 900-year-old Kankanaey mummy in particular, nicknamed "Apo Anno", had tattoos covering even the soles of the feet and the fingertips. The tattoo patterns are often also carved on the coffins containing the mummies.[18] Tattooing survived up until the mid-20th century, until modernization and conversion to Christianity finally made tattooing traditions extinct among the Kankanaey.[19][20] |

刺青 主な記事: バトック  伝統的なカンカナエイ族(首長ブカッサン・スヤック)の刺青のクローズアップ 古代の刺青は、ルソン島北部の洞窟や吊り棺の埋葬地で見つかる様々なコルディリェラ諸民族のミイラ化した遺体に見られる。現存する最古の例は13世紀まで 遡る。ミイラの刺青はしばしば非常に個性的で、成人女性の腕や成人男性の全身を覆っている。特に「アポ・アノ」の愛称で知られる700~900年前のカン カナエイ族ミイラは、足の裏や指先まで刺青が施されていた。刺青の模様は、ミイラを納めた棺にも刻まれていることが多い。[18] 刺青の習慣は20世紀半ばまで続いていたが、近代化とキリスト教への改宗により、カンカナエイ族の間ではついに消滅した。[19][20] |

| Language Main article: Kankanaey language In intonation, there is a hard- (Applai) and soft-speaking Kankanaeys. Speakers of hard Kankanaey are from Sagada, Besao and the surrounding parts or barrios of the said municipalities. They speak Kankanaey with hard intonation and they differ in some words from the soft-speaking Kankanaey. The soft-speaking Kankanaeys come from Northern and some parts of Benguet and from the municipalities of Sabangan, Tadian and Bauko in Mountain Province. In words, for example, an Applai might say otik or beteg (pig) and the soft-speaking Kankanaey may say busaang or beteg as well. The Kankanaeys may also differ in some words like egay or aga, maid or maga. The Kankanaeys also speak Ilocano. |

言語 主な記事: カンカナエイ語 イントネーションにおいて、カンカナエイ語には硬い話し方(アプライ)と柔らかい話し方がある。硬いカンカナエイ語を話す者はサガダ、ベサオ及びそれらの 自治体の周辺地域やバリオ(地区)出身である。彼らは硬いイントネーションでカンカナエイ語を話し、柔らかい話し方のカンカナエイ語とはいくつかの単語が 異なる。柔らかい話し方のカンカナエ語話者は、ベンゲット州北部及び一部地域、マウンテン州のサバンガン、タディアン、バウコ各自治体出身である。例えば 単語では、アプライは「オティック」や「ベテグ」(豚)と言うのに対し、柔らかい話し方のカンカナエ語話者は「ブサアン」や「ベテグ」と言うこともある。 カンカナエイ語は「egay」と「aga」、「maid」と「maga」のように語彙が異なる場合もある。カンカナエイ語話者はイロカノ語も話す。 |

| Religion Main article: List of Philippine mythological figures Immortals Lumawig: the supreme deity; creator of the universe and preserver of life[21] Bugan: married to Lumawig[21] Bangan: the goddess of romance; a daughter of Bugan and Lumawig[21] Obban: the goddess of reproduction; a daughter of Bugan and Lumawig[21] Kabigat: one of the deities who contact mankind through spirits called anito and their ancestral spirits[21] Balitok: one of the deities who contact mankind through spirits called anito and their ancestral spirits[21] Wigan: one of the deities who contact mankind through spirits called anito and their ancestral spirits[21] Timugan: two brothers who took their sankah (handspades) and kayabang (baskets) and dug a hole into the lower world, Aduongan; interrupted by the deity Masaken; one of the two agreed to marry one of Masaken's daughters, but they both went back to earth when the found that the people of Aduongan were cannibals[22] Masaken: ruler of the underworld who interrupted the Timugan brothers[22] |

宗教 主な記事: フィリピンの神話上の人物のリスト 不滅=不死の存在 ルマウィグ:最高神。宇宙の創造主であり、生命の守護者である[21] ブガン:ルマウィグの配偶者[21] バンガン:恋愛の女神。ブガンとルマウィグの娘である[21] オッバン:生殖の女神。ブガンとルマウィグの娘である[21] カビガット:アニトと呼ばれる精霊や祖先の霊を通じて人類と接触する神々の一人である[21] バリトック:アニトと呼ばれる精霊や祖先の霊を通じて人類と接触する神々の一人である[21] ウィガン:アニトと呼ばれる精霊や祖先の霊を通じて人類と接触する神々の一人である[21] ティムガン:サンカ(手鍬)とカヤバン(籠)を持って下界アドゥオンガンへ穴を掘った二人の兄弟。神マサケンに妨げられ、一人はマサケンの娘との結婚を承諾したが、アドゥオンガンの人民が人食い族だと知ると二人とも地上へ戻った[22] マサケン:ティムガン兄弟の行動を妨げた冥界の支配者である[22] |

| Igorot people |

イゴロット人 |

| References 1. "Ethnicity in the Philippines (2020 Census of Population and Housing)". Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved July 4, 2023. 2. Fry, Howard (2006). A History of the Mountain Province (Revised ed.). Quezon City, Philippines: New Day Publishers. p. 22. ISBN 978-971-10-1161-1. On the west side (of) the Bontok people . . . the Lepanto provincial area . . . (whose) population is somewhat mixed . . . but which I think is mainly Kankanai, who also people the northern part of Benguet . . . (and) the entire valley of the river Amburayan . . . 3. Jefrernovas, V; Perez, PL (2011). "Defining indigeneity representation and the indigenous people's rights act of 1997". Identity Politics in the Public Realm: Bringing Institutions Back In. UBC Press: 91. {{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help) 4. "The Kankanaey People of the Philippines: History, Culture, Customs and Tradition [Indigenous People | Cordillera Ethnic Tribes]". 5. https://web.archive.org/web/20160424192103/http://sultankudaratprovince.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/SEP-2010_Sultan-Kudarat-Province.pdf [bare URL PDF] 6. "2010 Census of Population and Housing, Report No. 2A: Demographic and Housing Characteristics (Non-Sample Variables) - Philippines" (PDF). Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 7 October 2020. 7. Gibbons, Ann (2016-10-03). "'Game-changing' study suggests first Polynesians voyaged all the way from East Asia". www.sciencemag.org. 8. Weule, Genelle (2016-10-03). "DNA reveals earliest Pacific Islander ancestors came from Asia". ABC News - Science. 9. Skoglund, Pontus; Posth, Cosimo; Sirak, Kendra; et al. (2016). "Genomic insights into the peopling of the Southwest Pacific". Nature. 538 (7626): 510–513. Bibcode:2016Natur.538..510S. doi:10.1038/nature19844. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 5515717. PMID 27698418. 10. Mörseburg, Alexander; Pagani, Luca; Ricaut, Francois-Xavier; et al. (2016). "Multi-layered population structure in Island Southeast Asians". European Journal of Human Genetics. 24 (11): 1605–1611. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2016.60. PMC 5045871. PMID 27302840. S2CID 2682757. 11. Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "7 The Northern Kankana-eys". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 136–155. ISBN 9789711011093. 12. Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "8 The Southern Kankana-eys". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 156–175. ISBN 9789711011093. 13. Marche, Antoine-Alfred (1887). Luçon et Palaouan, six années de voyages aux Philippines. Paris: Librairie Hachette. pp. 153–155. 14. "Baguio eats: Head to this restaurant for a literal taste of blood". ABS-CBN News. Retrieved 25 March 2019. 15. Panchal, Jenny H.; Cimacio, Maria Beatriz (2016). "Culture Shock – A Study of Domestic Tourists in Sagada, Philippines" (PDF). 4th Interdisciplinary Tourism Research Conference: 334–338. 16. Comila, Felipe S. (2007). "The Disappearing Dap-ay: Coping with Change in Sagada". In Arquiza, Yasmin D. (ed.). The Road to Empowerment: Strengthening the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (PDF). Vol. 2: Nurturing the earth, nurturing life. International Labour Organization. pp. 1–16. 17. Macatulad, JB; Macatulad, Renée (5 February 2015). "The Hanging Coffins of Echo Valley, Sagada, Mountain Province". Will Fly For Food. Retrieved 29 October 2020. 18. Salvador-Amores, Analyn (2012). "The Recontextualization of Burik (Traditional Tattoos) of Kabayan Mummies in Benguet to Contemporary Practices". Humanities Diliman. 9 (1): 74–94. 19. Salvador-Amores, Analyn. "Burik: Tattoos of the Ibaloy Mummies of Benguet, North Luzon, Philippines". Ancient Ink: The Archaeology of Tattooing. University of Washington Press, Seattle, Washington: 37–55. {{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help) 20. Salvador-Amores, Analyn (June 2011). "Batok (Traditional Tattoos) in Diaspora: The Reinvention of a Globally Mediated Kalinga Identity". South East Asia Research. 19 (2): 293–318. doi:10.5367/sear.2011.0045. S2CID 146925862. 21. Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc. 22. Wilson, L. L. (1947). Apayao Life and Legends. Baugio City: Private. |

参考文献 1. 「フィリピンの民族構成(2020年国勢調査)」。フィリピン統計局。2023年7月4日閲覧。 2. フライ、ハワード(2006)。『マウンテン州の歴史』(改訂版)。フィリピン・ケソンシティ:ニューデイ出版社。22頁。ISBN 978-971-10-1161-1。西側にはボントック族が人民する…レパント州地域…(その)人口はやや混血の様相を呈しているが…主にカンカナイ族 だと考える。彼らはベンゲット州北部にも人民し…(そして)アンブラヤン川流域全体にも分布している… 3. Jefrernovas, V; Perez, PL (2011). 「先住性の定義と1997年先住民権利法」. 『公共領域におけるアイデンティティ政治:制度の再考』. UBC Press: 91. {{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help) 4. 「フィリピンのカンカナエイ人民:歴史、文化、習慣、伝統[先住民|コルディリェラ民族部族]」。 5. https://web.archive.org/web/20160424192103/http://sultankudaratprovince.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/SEP-2010_Sultan-Kudarat-Province.pdf [bare URL PDF] 6. 「2010年人口・住宅センサス、報告書第2A号:人口統計及び住宅特性(非標本変数)-フィリピン」(PDF)。フィリピン統計局。2020年10月7日閲覧。 7. ギボンズ、アン (2016-10-03). 「『画期的』研究が示す、最初のポリネシア人は東アジアから航海した可能性」. www.sciencemag.org. 8. ウィール、ジェネール (2016-10-03). 「DNAが明らかにした、最古の太平洋諸島民の祖先はアジア出身」. ABCニュース - 科学. 9. Skoglund, Pontus; Posth, Cosimo; Sirak, Kendra; et al. (2016). 「南西太平洋への移住に関するゲノム学的知見」. Nature. 538 (7626): 510–513. Bibcode:2016Natur.538..510S. doi:10.1038/nature19844。ISSN 0028-0836。PMC 5515717。PMID 27698418。 10. Mörseburg, Alexander; Pagani, Luca; Ricaut, Francois-Xavier; et al. (2016). 「東南アジア諸島の多層的な人口構造」『European Journal of Human Genetics』24 (11): 1605–1611. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2016.60. PMC 5045871. PMID 27302840. S2CID 2682757. 11. Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). 「7 北部カンカナエイス族」. 『コルディリェラ地方主要民族言語集団の民族誌』. ケソンシティ: New Day Publishers. pp. 136–155. ISBN 9789711011093. 12. Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). 「8 南部カンカナエイス族」. 『コルディリェラ地方の主要民族言語集団の民族誌』. ケソンシティ: New Day Publishers. pp. 156–175. ISBN 9789711011093. 13. マルシュ、アントワーヌ=アルフレッド(1887年)。『ルソンとパラワン、フィリピンにおける六年間の旅』。パリ:リブレリー・アシェット。pp. 153–155。 14. 「バギオの食:文字通り血の味を味わうならこのレストランへ」。ABS-CBNニュース。2019年3月25日閲覧。 15. パンチャル、ジェニー・H.;シマシオ、マリア・ベアトリス(2016)。「カルチャーショック – フィリピン・サガダにおける国内観光客の研究」(PDF)。第4回学際的観光研究会議:334–338頁。 16. コミラ、フェリペ・S.(2007)。「消えゆくダパイ:サガダにおける変化への対処」. アルキザ, ヤスミン・D. (編). 『エンパワーメントへの道:先住民権利法の強化』 (PDF). 第2巻: 大地を育み、生命を育む. 国際労働機関. pp. 1–16. 17. マカトゥラッド, JB; マカトゥラッド, ルネ (2015年2月5日). 「サガダ、マウンテン州、エコーバレーの吊るされた棺」. Will Fly For Food. 2020年10月29日閲覧. 18. サルバドール=アモレス、アナリン (2012). 「ベンゲットのカバヤンミイラのブリク(伝統的刺青)の現代的実践への再文脈化」. Humanities Diliman. 9 (1): 74–94. 19. Salvador-Amores, Analyn. 「ブリク:フィリピン北ルソン、ベンゲット州イバロイミイラの刺青」. Ancient Ink: The Archaeology of Tattooing. University of Washington Press, Seattle, Washington: 37–55. {{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (ヘルプ) 20. サルバドール=アモレス、アナリン (2011年6月). 「ディアスポラにおけるバトック(伝統的な入れ墨):グローバルに媒介されたカリンガのアイデンティティの再発明」. 『東南アジア研究』. 19 (2): 293–318. doi:10.5367/sear.2011.0045. S2CID 146925862。 21. Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc. 22. Wilson, L. L. (1947). Apayao Life and Legends. Baugio City: Private. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kankanaey_people |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099