カール・クラウス

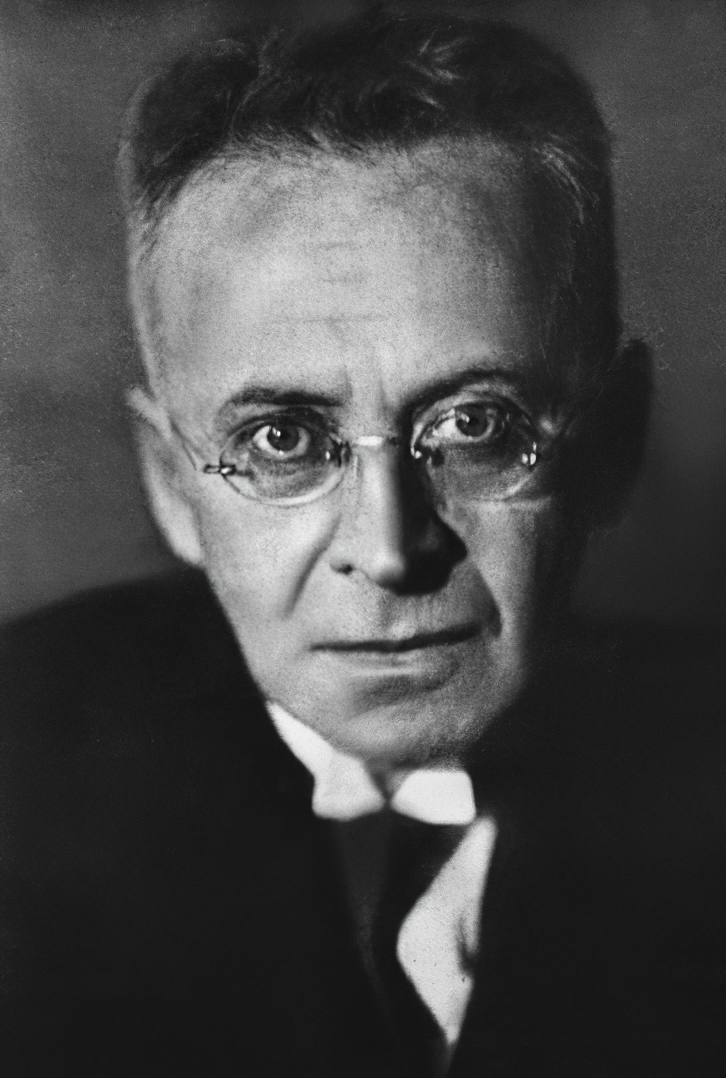

Karl Kraus, 1874-1936

Karl

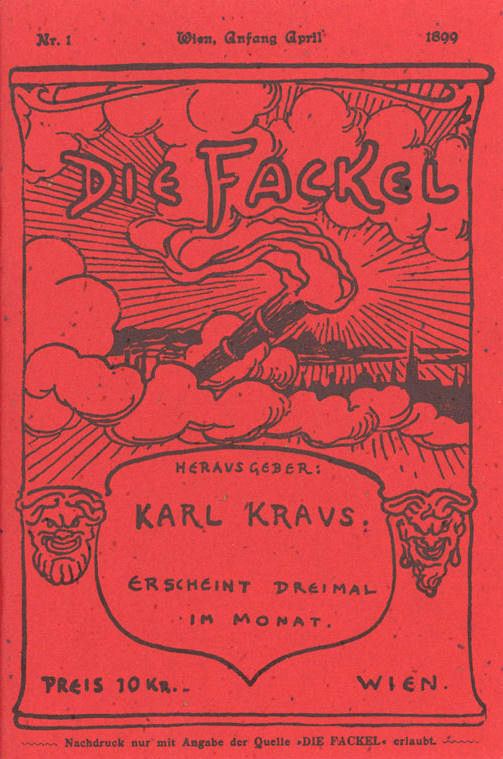

Kraus (28 April 1874 – 12 June 1936); First issue of Die Fackel, 1899.

☆

げんちゃんはこちら(genchan_tetsu.html)

【翻訳用】海豚ワイドモダン(00-Grid-modern.html)

(★ワイドモダンgenD.png)

| Karl

Kraus (28 April 1874 – 12 June 1936)[1] was an Austrian writer and

journalist, known as a satirist, essayist, aphorist, playwright and

poet. He directed his satire at the press, German culture, and German

and Austrian politics. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in

Literature three times.[2] |

カー

ル・クラウス(1874年4月28日 -

1936年6月12日)[1]はオーストリアの作家、ジャーナリストで、風刺作家、エッセイスト、アフォリスト、劇作家、詩人として知られる。報道、ドイ

ツ文化、ドイツとオーストリアの政治を風刺した。ノーベル文学賞に3度ノミネートされた[2]。 |

| Biography Early life Kraus was born into the wealthy Jewish family of Jacob Kraus, a papermaker, and his wife Ernestine, née Kantor, in Jičín, Kingdom of Bohemia, Austria-Hungary (now the Czech Republic). The family moved to Vienna in 1877. His mother died in 1891. Kraus enrolled as a law student at the University of Vienna in 1892. Beginning in April of the same year, he began contributing to the paper Wiener Literaturzeitung, starting with a critique of Gerhart Hauptmann's The Weavers. Around that time, he unsuccessfully tried to perform as an actor in a small theater. In 1894, he changed his field of studies to philosophy and German literature. He discontinued his studies in 1896. His friendship with Peter Altenberg began about this time. Career Before 1900  First issue of Die Fackel In 1896, Kraus left university without a diploma to begin work as an actor, stage director and performer, joining the Young Vienna group, which included Peter Altenberg, Leopold Andrian, Hermann Bahr, Richard Beer-Hofmann, Arthur Schnitzler, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, and Felix Salten. In 1897, Kraus broke from this group with a biting satire, Die demolierte Literatur (Demolished Literature), and was named Vienna correspondent for the newspaper Breslauer Zeitung. One year later, as an uncompromising advocate of Jewish assimilation, he attacked the founder of modern Zionism, Theodor Herzl, with his polemic Eine Krone für Zion (A Crown for Zion). The title is a play on words, in that Krone means both "crown" and the currency of Austria-Hungary from 1892 to 1918; one Krone was the minimum donation required to participate in the Zionist Congress in Basel, and Herzl was often mocked as the "king of Zion" (König von Zion) by Viennese anti-Zionists. On 1 April 1899, Kraus renounced Judaism, and in the same year he founded his own magazine, Die Fackel (German: The Torch), which he continued to direct, publish, and write until his death, and from which he launched his attacks on hypocrisy, psychoanalysis, corruption of the Habsburg empire, nationalism of the pan-German movement, laissez-faire economic policies, and numerous other subjects. 1900–1909 In 1901 Kraus was sued by Hermann Bahr and Emmerich Bukovics, who felt they had been attacked in Die Fackel. Many lawsuits by various offended parties followed in later years. Also in 1901, Kraus found out that his publisher, Moriz Frisch, had taken over his magazine while he was absent on a months-long journey. Frisch had registered the magazine's front cover as a trademark and published the Neue Fackel (New Torch). Kraus sued and won. From that time, Die Fackel was published (without a cover page) by the printer Jahoda & Siegel. While Die Fackel at first resembled journals like Die Weltbühne, it increasingly became a magazine that was privileged in its editorial independence, thanks to Kraus's financial independence. Die Fackel printed what Kraus wanted to be printed. In its first decade, contributors included such well-known writers and artists as Peter Altenberg, Richard Dehmel, Egon Friedell, Oskar Kokoschka, Else Lasker-Schüler, Adolf Loos, Heinrich Mann, Arnold Schönberg, August Strindberg, Georg Trakl, Frank Wedekind, Franz Werfel, Houston Stewart Chamberlain and Oscar Wilde. After 1911, however, Kraus was usually the sole author. Kraus's work was published nearly exclusively in Die Fackel, of which 922 irregularly issued numbers appeared in total. Authors who were supported by Kraus include Peter Altenberg, Else Lasker-Schüler, and Georg Trakl. Die Fackel targeted corruption, journalists and brutish behaviour. Notable enemies were Maximilian Harden (in the mud of the Harden–Eulenburg affair), Moriz Benedikt (owner of the newspaper Neue Freie Presse), Alfred Kerr, Hermann Bahr, Imre Bekessy [de] and Johann Schober. In 1902, Kraus published Sittlichkeit und Kriminalität (Morality and Criminal Justice), for the first time commenting on what was to become one of his main preoccupations: he attacked the general opinion of the time that it was necessary to defend sexual morality by means of criminal justice (Der Skandal fängt an, wenn die Polizei ihm ein Ende macht, The Scandal Starts When the Police Ends It).[3] Starting in 1906, Kraus published the first of his aphorisms in Die Fackel; they were collected in 1909 in the book Sprüche und Widersprüche (Sayings and Gainsayings). In addition to his writings, Kraus gave numerous highly influential public readings during his career, put on approximately 700 one-man performances between 1892 and 1936 in which he read from the dramas of Bertolt Brecht, Gerhart Hauptmann, Johann Nestroy, Goethe, and Shakespeare, and also performed Offenbach's operettas, accompanied by piano and singing all the roles himself. Elias Canetti, who regularly attended Kraus's lectures, titled the second volume of his autobiography "Die Fackel" im Ohr ("The Torch" in the Ear) in reference to the magazine and its author. At the peak of his popularity, Kraus's lectures attracted four thousand people, and his magazine sold forty thousand copies.[4] In 1904, Kraus supported Frank Wedekind to make possible the staging in Vienna of his controversial play Pandora's Box;[5] the play told the story of a sexually enticing young dancer who rises in German society through her relationships with wealthy men but later falls into poverty and prostitution.[6] These plays' frank depiction of sexuality and violence, including lesbianism and an encounter with Jack the Ripper,[7] pushed against the boundaries of what was considered acceptable on the stage at the time. Wedekind's works are considered among the precursors of expressionism, but in 1914, when expressionist poets like Richard Dehmel began producing war propaganda, Kraus became a fierce critic of them.[4][5] In 1907, Kraus attacked his erstwhile benefactor Maximilian Harden because of his role in the Eulenburg trial in the first of his spectacular Erledigungen (Dispatches).[citation needed] 1910–1919 After 1911, Kraus was the sole author of most issues of Die Fackel. One of Kraus's most influential satirical-literary techniques was his clever wordplay with quotations. One controversy arose with the text Die Orgie, which exposed how the newspaper Neue Freie Presse was blatantly supporting Austria's Liberal Party's election campaign; the text was conceived as a guerrilla prank and sent as a fake letter to the newspaper (Die Fackel would publish it later in 1911); the enraged editor, who fell for the trick, responded by suing Kraus for "disturbing the serious business of politicians and editors".[5] After an obituary for Franz Ferdinand, who had been assassinated in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914, Die Fackel was not published for many months. In December 1914, it appeared again with an essay "In dieser großen Zeit" ("In this grand time"): "In dieser großen Zeit, die ich noch gekannt habe, wie sie so klein war; die wieder klein werden wird, wenn ihr dazu noch Zeit bleibt; … in dieser lauten Zeit, die da dröhnt von der schauerlichen Symphonie der Taten, die Berichte hervorbringen, und der Berichte, welche Taten verschulden: in dieser da mögen Sie von mir kein eigenes Wort erwarten."[8] ("In this grand time, which I used to know when it was this small; which will become small again if there is time; … in this loud time that resounds from the ghastly symphony of deeds that spawn reports, and of reports that cause deeds: in this one, you may not expect a word of my own.") In the subsequent time, Kraus wrote against the World War, and censors repeatedly confiscated or obstructed editions of Die Fackel. Kraus's masterpiece is generally considered to be the massive satirical play about the First World War, Die letzten Tage der Menschheit (The Last Days of Mankind), which combines dialogue from contemporary documents with apocalyptic fantasy and commentary by two characters called "the Grumbler" and "the Optimist". Kraus began to write the play in 1915 and first published it as a series of special Fackel issues in 1919. Its epilogue, "Die letzte Nacht" ("The last night") had already been published in 1918 as a special issue. Edward Timms has called the work a "faulted masterpiece" and a "fissured text" because the evolution of Kraus's attitude during the time of its composition (from aristocratic conservative to democratic republican) gave the text structural inconsistencies resembling a geological fault.[9] Also in 1919, Kraus published his collected war texts under the title Weltgericht (World Court of Justice). In 1920, he published the satire Literatur oder man wird doch da sehn (Literature, or You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet) as a reply to Franz Werfel's Spiegelmensch (Mirror Man), an attack against Kraus.[citation needed] 1920–1936 During January 1924, Kraus started a fight against Imre Békessy, publisher of the tabloid Die Stunde (The Hour), accusing him of extorting money from restaurant owners by threatening them with bad reviews unless they paid him. Békessy retaliated with a libel campaign against Kraus, who in turn launched an Erledigung with the catchphrase "Hinaus aus Wien mit dem Schuft!" ("Throw the scoundrel out of Vienna!"). In 1926, Békessy indeed fled Vienna to avoid arrest. Békessy achieved some later success when his novel Barabbas was the monthly selection of an American book club.[citation needed] A peak in Kraus's political commitment was his sensational attack in 1927 on the powerful Vienna police chief Johann Schober, also a former two-term chancellor, after 89 rioters were shot dead by the police during the 1927 July Revolt. Kraus produced a poster that in a single sentence requested Schober's resignation; the poster was published all over Vienna and is considered an icon of 20th-century Austrian history.[4] In 1928, the play Die Unüberwindlichen (The Insurmountables) was published. It included allusions to the fights against Békessy and Schober. During that same year, Kraus also published the records of a lawsuit Kerr had filed against him after Kraus had published Kerr's war poems in Die Fackel (Kerr, having become a pacifist, did not want his earlier enthusiasm for the war exposed). In 1932, Kraus translated Shakespeare's sonnets. Kraus supported the Social Democratic Party of Austria from at least the early 1920s,[4] and in 1934, hoping Engelbert Dollfuss could prevent Nazism from engulfing Austria, he supported Dollfuss's coup d'état, which established the Austrian fascist regime.[4] This support estranged Kraus from some of his followers. In 1933 Kraus wrote Die Dritte Walpurgisnacht (The Third Walpurgis Night), of which the first fragments appeared in Die Fackel. Kraus withheld full publication in part to protect his friends and followers hostile to Hitler who still lived in the Third Reich from Nazi reprisals, and in part because "violence is no subject for polemic."[10][11][12] This satire on Nazi ideology begins with the now-famous sentence, "Mir fällt zu Hitler nichts ein" ("Hitler brings nothing to my mind"). Lengthy extracts appear in Kraus's apologia for his silence at Hitler's coming to power, "Warum die Fackel nicht erscheint" ("Why Die Fackel is not published"), a 315-page edition of the periodical. The last issue of Die Fackel appeared in February 1936. Shortly after, he fell in a collision with a bicyclist and suffered intense headaches and loss of memory. He gave his last lecture in April, and had a severe heart attack in the Café Imperial on 10 June. He died in his apartment in Vienna on 12 June 1936, and was buried in the Zentralfriedhof cemetery in Vienna. Kraus never married, but from 1913 until his death he had a conflict-prone but close relationship with the Baroness Sidonie Nádherná von Borutín (1885–1950). Many of his works were written in Janowitz castle, Nádherný family property. Sidonie Nádherná became an important pen pal to Kraus and addressee of his books and poems.[13] In 1911 Kraus was baptized as a Catholic, but in 1923, disillusioned by the Church's support for the war, he left the Catholic Church, claiming sarcastically that he was motivated "primarily by antisemitism", i.e. indignation at Max Reinhardt's use of the Kollegienkirche in Salzburg as the venue for a theatrical performance.[14] Kraus was the subject of two books by Thomas Szasz, Karl Kraus and the Soul Doctors and Anti-Freud: Karl Kraus's Criticism of Psychoanalysis and Psychiatry, which portray Kraus as a harsh critic of Sigmund Freud and of psychoanalysis in general.[15] Other commentators, such as Edward Timms, have argued that Kraus respected Freud, though with reservations about the application of some of his theories, and that his views were far less black-and-white than Szasz suggests.[16] |

略歴 生い立ち クラウスは、オーストリア=ハンガリー(現チェコ共和国)のボヘミア王国ジチーンで、裕福なユダヤ人一家、紙漉き職人のヤコブ・クラウスとその妻エルネスティーネ(旧姓カントル)に生まれた。一家は1877年にウィーンに移住。母親は1891年に死去。 1892年、ウィーン大学の法学部に入学。同年4月からウィーン文学誌に寄稿を始め、ゲルハルト・ハウプトマンの『織工たち』の批評を発表。その頃、小劇 場で俳優として活動しようとしたが失敗。1894年、研究分野を哲学とドイツ文学に変更。1896年に学業を中断。ペーター・アルテンベルクとの交友はこ の頃から始まった。 経歴 1900年以前  Die Fackel 創刊号 ペーター・アルテンベルク、レオポルト・アンドリアン、ヘルマン・バール、リヒャルト・ベア=ホフマン、アルトゥール・シュニッツラー、フーゴ・フォン・ ホフマンスタール、フェリックス・サルテンらで結成された「ヤング・ウィーン」に参加。1897年、クラウスは痛烈な風刺小説『解体された文学』(Die demolierte Literatur)を発表してこのグループから抜け出し、ブレスラウアー・ツァイトゥング紙のウィーン特派員となった。その1年後、ユダヤ人同化の非妥 協的擁護者として、近代シオニズムの創始者テオドール・ヘルツルを『シオンのための王冠』 (Eine Krone für Zion)で攻撃した。このタイトルは言葉遊びで、クローネは「王冠」を意味し、1892年から1918年までのオーストリア=ハンガリーの通貨でもあっ た。1クローネはバーゼルのシオニスト会議に参加するために必要な最低寄付金であり、ヘルツルはしばしばウィーンの反シオニストたちから「シオンの王 (König von Zion)」と嘲笑されていた。 1899年4月1日、クラウスはユダヤ教を放棄し、同年、自身の雑誌『ディー・ファッケル』(ドイツ語:『たいまつ』)を創刊した。この雑誌は、亡くなる まで、監督、出版、執筆を続け、偽善、精神分析、ハプスブルク帝国の腐敗、汎ドイツ運動のナショナリズム、自由放任の経済政策、その他多くのテーマについ て攻撃を開始した。 1900-1909 1901年、『Die Fackel』で攻撃されたと感じたヘルマン・バールとエメリッヒ・ブコヴィッチから訴訟を起こされる。その後も、さまざまな悪意のある人々による多くの 訴訟が続いた。また1901年には、クラウスが数ヶ月の旅に出ている間に、出版社のモリッツ・フリッシュが自分の雑誌を引き継いでいたことが判明した。フ リッシュは雑誌の表紙を商標登録し、『Neue Fackel(新しい聖火)』を発行していたのだ。クラウスは訴え、勝訴した。それ以来、『Die Fackel』はヤホーダ&シーゲル社から(表紙なしで)発行されるようになった。 Die Fackel』は当初、『Die Weltbühne』のような雑誌に似ていたが、クラウスの経済的独立のおかげで、次第に編集の独立性において特権的な雑誌になっていった。Die Fackel』は、クラウスが印刷したいと望むものを印刷した。最初の10年間は、ペーター・アルテンベルク、リヒャルト・デーメル、エゴン・フリーデ ル、オスカー・ココシュカ、エルゼ・ラスカー=シューラー、アドルフ・ロース、ハインリッヒ・マン、アルノルト・シェーンベルク、アウグスト・ストリンド ベリ、ゲオルク・トラークル、フランク・ヴェーデキント、フランツ・ヴェルフェル、ヒューストン・スチュワート・チェンバレン、オスカー・ワイルドといっ た著名な作家や芸術家が寄稿した。しかし、1911年以降は通常、クラウスが単独で作者となっている。クラウスの作品はほぼ独占的にDie Fackel誌に掲載され、不定期発行で合計922冊が刊行された。クラウスの支持を受けた作家には、ペーター・アルテンベルク、エルゼ・ラスカー= シューラー、ゲオルク・トラークルらがいる。 Die Fackelは汚職、ジャーナリスト、残忍な振る舞いを標的にした。著名な敵は、マクシミリアン・ハーデン(ハーデン=オイレンブルク事件の泥沼に)、モ リッツ・ベネディクト(『ノイエ・フライ・プレス』紙のオーナー)、アルフレッド・カー、ヘルマン・バール、イムレ・ベケシー[デ]、ヨハン・ショーバー などである。 1902年、クラウスはSittlichkeit und Kriminalität (Morality and Criminalität)を出版し、後に彼の主要な関心事のひとつとなる、刑事司法によって性道徳を守る必要があるという当時の一般的な意見を初めて論 評した(Der Skandal fängt an, wenn die Polizei ihm ein Ende macht, The Scandal Starts When the Police Ends It)。 [それらは1909年に『Sprüche und Widersprüche』という本にまとめられた。 1892年から1936年までの間に、ベルトルト・ブレヒト、ゲルハルト・ハウプトマン、ヨハン・ネストロイ、ゲーテ、シェイクスピアなどの戯曲を朗読 し、オッフェンバックのオペレッタをピアノ伴奏で全役を自ら歌った。定期的にクラウスの講演会に出席していたエリアス・カネッティは、自伝の第2巻のタイ トルを、この雑誌とその著者にちなんで『耳の中の松明』(Die Fackel im Ohr)とした。人気絶頂のとき、クラウスの講演には4,000人が集まり、彼の雑誌は40,000部売れた[4]。 1904年、クラウスはフランク・ヴェーデキントを支援し、物議を醸した彼の戯曲『パンドラの箱』のウィーンでの上演を可能にした[5]。この戯曲は、裕 福な男性との関係を通じてドイツ社会で出世するが、後に貧困と売春に陥る、性的魅惑に満ちた若いダンサーの物語であった[6]。レズビアンや切り裂き ジャックとの遭遇[7]を含む、これらの戯曲の率直な性と暴力の描写は、当時舞台で許容されると考えられていた境界線を押し広げるものであった。ヴェーデ キントの作品は表現主義の先駆けのひとつとされているが、1914年、リヒャルト・デーメルのような表現主義の詩人たちが戦争プロパガンダを制作し始める と、クラウスは彼らを激しく批判するようになる[4][5]。 1907年、クラウスは、彼の壮大な『Erledigungen(ディスパッチ)』の最初の作品で、オイレンブルク裁判における彼の役割を理由に、かつての恩人マクシミリアン・ハーデンを攻撃した[要出典]。 1910-1919 1911年以降、クラウスは『Die Fackel』のほとんどの号を単独で執筆した。 クラウスの最も影響力のある風刺文学的手法のひとつは、引用を使った巧みな言葉遊びであった。この文章はゲリラ的ないたずらとして考案され、新聞社に偽の手紙として送られた(『Die Fackel(ディ・ファッケル)』は1911年の後半にこの文章を発表する)。 1914年6月28日にサラエボで暗殺されたフランツ・フェルディナントの追悼記事を掲載した後、『Die Fackel』は何カ月も発行されなかった。1914年12月、Die Fackelは "In dieser großen Zeit"(この壮大な時代に)というエッセイとともに再び掲載された: 「......この壮大な時代には、そのような小さな時代であったにもかかわらず、私はそれを知ることができなかった;しかし、そのような小さな時代で あったにもかかわらず、私はそれを知ることができなかった;このような壮大な時代には、そのような小さな時代であったにもかかわらず、私はそれを知ること ができなかった;このような壮大な時代には、そのような小さな時代であったにもかかわらず、私はそれを知ることができなかった;このような壮大な時代に は、そのような小さな時代であったにもかかわらず、私はそれを知ることができなかった。 "この壮大な時間では、それがこれほど小さかったときに私が知っていたものであり、時間があればまた小さくなるものであり、......報告を生み出す行 為と、行為を引き起こす報告の悲壮なシンフォニーから響くこの大音響の時間では、......この時間では、あなたは私自身の言葉を期待してはならない ")。その後、クラウスは世界大戦に反対する作品を執筆し、検閲当局は『Die Fackel』の出版を何度も没収したり妨害したりした。 クラウスの最高傑作は、第一次世界大戦を風刺した大作『人類最後の日』(Die letzten Tage der Menschheit)であると一般に考えられている。この作品は、現代の文書に書かれた台詞と、黙示録的な空想と、「不平主義者」と「楽観主義者」と呼 ばれる二人の登場人物による解説を組み合わせたものである。クラウスはこの戯曲を1915年に書き始め、1919年にFackelの特別号として初めて出 版した。そのエピローグである「最後の夜」は、1918年にすでに特別号として出版されていた。エドワード・ティムズはこの作品を「断層のある傑作」、 「亀裂のあるテクスト」と呼んでいるが、それはこの作品が書かれた時期のクラウスの態度の変遷(貴族的な保守主義者から民主的な共和主義者へ)が、地質学 的な断層に似た構造的な矛盾をこのテクストに与えたからである[9]。 また1919年、クラウスは『世界法廷』(Weltgericht)というタイトルで戦争に関する文章を集めた本を出版した。1920年には、クラウスを 攻撃したフランツ・ヴェルフェルの『鏡の男』(Spiegelmensch)への反論として、風刺作品『文学、あるいは君はまだ何も見ていない』 (Literatur oder man wird doch da sehn)を出版した[要出典]。 1920-1936 1924年1月、クラウスはタブロイド紙『Die Stunde』(『The Hour』)の発行人イムレ・ベケシー(Imre Békessy)との闘いを開始。ベケシーはクラウスに対する名誉毀損キャンペーンで報復し、クラウスは "Hinaus aus Wien mit dem Schuft! (この悪党をウィーンから追い出せ!)」というキャッチフレーズを掲げていた。1926年、ベケシーは逮捕を避けるため、本当にウィーンから逃亡した。 ベッケシーはその後、小説『バラバ』がアメリカのブッククラブの月刊セレクションに選ばれるなど、成功を収めた[要出典]。 クラウスの政治的コミットメントのピークは、1927年の7月革命で89人の暴徒が警察によって射殺された後、1927年に元首相のヨハン・ショーバーを 攻撃したことだった。クラウスは、一言でショーバーの辞任を要求するポスターを制作。このポスターはウィーン中に貼られ、20世紀オーストリア史の象徴と されている[4]。 1928年、戯曲『乗り越えられないもの』(Die Unüberwindlichen)が出版された。この作品には、ベッケシーとショーバーとの戦いが暗示されている。同年、クラウスは、ケールの戦争詩を 『ディ・ファッケル』誌に掲載した後、ケールがクラウスに対して起こした訴訟の記録も出版した(平和主義者となったケールは、以前の戦争への熱狂が暴露さ れることを望まなかった)。1932年、クラウスはシェイクスピアのソネットを翻訳した。 1934年、エンゲルベルト・ドルフスがナチズムがオーストリアを飲み込むのを防いでくれることを期待し、ドルフスのクーデターを支持し、オーストリアのファシスト政権を樹立した[4]。 1933年、クラウスは『第三のワルプルギスの夜(Die Dritte Walpurgisnacht)』を書き、その最初の断片が『ディ・ファッケル(Die Fackel)』に掲載された。クラウスは、まだ第三帝国に住んでいたヒトラーに敵対する友人や信奉者をナチスの報復から守るため、また「暴力は極論の対 象ではない」という理由で、完全な出版を差し控えた[10][11][12]。ナチスのイデオロギーに対するこの風刺は、今では有名な「Mir fällt zu Hitler nichts ein(ヒトラーは私の心に何ももたらさない)」という文章で始まる。ヒトラーが政権を握ったときに沈黙したことに対するクラウスの弁明書『Warum die Fackel nicht erscheint』(『Die Fackel』はなぜ出版されないのか)には、その長い抜粋が315ページにわたって掲載されている。『Die Fackel』の最終号は1936年2月に発行された。その直後、彼は自転車と衝突して倒れ、激しい頭痛と記憶喪失に見舞われた。4月に最後の講演を行 い、6月10日にカフェ・インペリアルで激しい心臓発作を起こした。1936年6月12日、ウィーンのアパートで亡くなり、ウィーンのツェントラルフリー ドホーフ墓地に埋葬された。 クラウスは一度も結婚しなかったが、1913年から亡くなるまで、男爵夫人シドニエ・ナーデルナー・フォン・ボルティン(1885~1950)と衝突を繰 り返しながらも親密な関係にあった。彼の作品の多くは、ナードニ家の財産であるヤノヴィッツ城で書かれた。シドニエ・ナーデルニーはクラウスにとって重要 なペンパルとなり、彼の著書や詩の宛先となった[13]。 1911年、クラウスはカトリックの洗礼を受けたが、1923年、教会の戦争支持に幻滅し、カトリック教会を去った。 クラウスは、トーマス・サッシュによる2冊の著書『カール・クラウスと魂の医師たち』(Karl Kraus and the Soul Doctors)と『アンチ・フロイト』(Anti-Freud)の題材となった: 15]。エドワード・ティムズのような他の論者は、クラウスはフロイトを尊敬していたが、彼の理論の一部の適用については留保しており、彼の見解はサッ シュが示唆するよりもはるかに白黒はっきりしていなかったと論じている[16]。 |

| Character Karl Kraus was a subject of controversy throughout his lifetime. Marcel Reich-Ranicki called him 'vain, self-righteous and self-important'.[17] Kraus's followers saw in him an infallible authority who would do anything to help those he supported. Kraus considered posterity his ultimate audience, and reprinted Die Fackel in volume form years after it was first published.[18] A concern with language was central to Kraus's outlook, and he viewed his contemporaries' careless use of language as symptomatic of their insouciant treatment of the world. Viennese composer Ernst Krenek described meeting the writer in 1932: "At a time when people were generally decrying the Japanese bombardment of Shanghai, I met Karl Kraus struggling over one of his famous comma problems. He said something like: 'I know that everything is futile when the house is burning. But I have to do this, as long as it is at all possible; for if those who were supposed to look after commas had always made sure they were in the right place, Shanghai would not be burning'."[19] The Austrian author Stefan Zweig once called Kraus "the master of venomous ridicule" (der Meister des giftigen Spotts).[20] Up to 1930, Kraus directed his satirical writings to figures of the center and the left of the political spectrum, as he considered the flaws of the right too self-evident to be worthy of his comment.[18] Later, his responses to the Nazis included The Third Walpurgis Night. To the numerous enemies he made with the inflexibility and intensity of his partisanship, however, he was a bitter misanthrope and poor would-be (Alfred Kerr). He was accused of wallowing in hateful denunciations and Erledigungen [breakings-off].[citation needed] Along with Karl Valentin, he is considered a master of gallows humor.[21] Giorgio Agamben compared Guy Debord and Kraus for their criticism of journalists and media culture.[22] Gregor von Rezzori wrote of Kraus, "[His] life stands as an example of moral uprightness and courage which should be put before anyone who writes, in no matter what language... I had the privilege of listening to his conversation and watching his face, lit up by the pale fire of his fanatic love for the miracle of the German language and by his holy hatred for those who used it badly."[23] Kraus's work has been described as the culmination of a literary outlook. Critic Frank Field quoted the words Bertolt Brecht wrote of Kraus, on hearing of his death: "As the epoch raised its hand to end its own life, he was the hand."[24] |

キャラクター カール・クラウスは生涯を通じて論争の的であった。マルセル・ライヒ=ラニツキは彼を「うぬぼれが強く、独善的で独りよがり」と呼んだ[17]。クラウスは後世の人々を究極の読者と考え、『Die Fackel』を初版から数年後に一巻の形で再版した[18]。 言語への関心はクラウスの展望の中心であり、彼は同時代の人々の無頓着な言語使用を、彼らが世界を無分別に扱っていることの徴候とみなしていた。ウィーン の作曲家エルンスト・クレネックは、1932年にクラウスに会ったときのことをこう語っている: 「日本軍の上海砲撃を非難していた頃、私はカール・クラウスに会った。彼はこう言った: 家が燃えているときは、すべてが無駄だとわかっている。しかし、私は可能な限り、これをしなければならない。もし、コンマの世話をすることになっている人 々が、コンマが常に正しい位置にあることを確認していたら、上海は燃えていなかっただろう」[19]。 オーストリアの作家シュテファン・ツヴァイクはかつてクラウスを「毒のある嘲笑の巨匠」(der Meister des giftigen Spotts)と呼んだ[20]。1930年まで、クラウスは風刺的な著作を政治スペクトルの中央と左の人物に向けた。 しかし、その党派性の融通の利かなさと激しさで作った数多くの敵にとって、彼は辛辣な人間嫌いであり、哀れな自惚れ屋(アルフレッド・カー)であった。カール・ヴァレンティンと並んで、絞首台のユーモアの名手とされている[21]。 ジョルジョ・アガンベンは、ジャーナリストやメディア文化に対する批判について、ギー・ドゥボールとクラウスを比較した[22]。 グレゴール・フォン・レッツォーリはクラウスについてこう書いている。私は彼の会話を聞き、ドイツ語の奇跡に対する狂信的な愛と、ドイツ語を悪用する者に対する聖なる憎悪の炎に照らされた彼の顔を見る機会に恵まれた」[23]。 クラウスの作品は、文学観の集大成と評されてきた。批評家のフランク・フィールドは、ベルトルト・ブレヒトがクラウスの死を聞いて書いた言葉を引用している: 「エポックが自らの生に終止符を打つために手を挙げたとき、彼はその手であった」[24]。 |

| Selected works Die demolierte Literatur [Demolished Literature] (1897) Eine Krone für Zion [A Crown for Zion] (1898) Sittlichkeit und Kriminalität [Morality and Criminal Justice] (1908) Sprüche und Widersprüche [Sayings and Contradictions] (1909) Die chinesische Mauer [The Wall of China] (1910) Pro domo et mundo [For Home and for the World] (1912) Nestroy und die Nachwelt [Nestroy and Posterity] (1913) Worte in Versen (1916–30) Die letzten Tage der Menschheit (The Last Days of Mankind) (1918) Weltgericht [The Last Judgment] (1919) Nachts [At Night] (1919) Untergang der Welt durch schwarze Magie [The End of the World Through Black Magic] (1922) Literatur (Literature) (1921) Traumstück [Dream Piece] (1922) Die letzten Tage der Menschheit: Tragödie in fünf Akten mit Vorspiel und Epilog [The Last Days of Mankind: Tragedy in Five Acts with Preamble and Epilogue] (1922) Wolkenkuckucksheim [Cloud Cuckoo Land] (1923) Traumtheater [Dream Theatre] (1924) Epigramme [Epigrams] (1927) Die Unüberwindlichen [The Insurmountables] (1928) Literatur und Lüge [Literature and Lies] (1929) Shakespeares Sonette (1933) Die Sprache [Language] (posthumous, 1937) Die dritte Walpurgisnacht [The Third Walpurgis Night] (posthumous, 1952) Some works have been re-issued in recent years: Die letzten Tage der Menschheit, Bühnenfassung des Autors, 1992 Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-22091-8 Die Sprache, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37817-1 Die chinesische Mauer, mit acht Illustrationen von Oskar Kokoschka, 1999, Insel, ISBN 3-458-19199-2 Aphorismen. Sprüche und Widersprüche. Pro domo et mundo. Nachts, 1986, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37818-X Sittlichkeit und Krimininalität, 1987, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37811-2 Dramen. Literatur, Traumstück, Die unüberwindlichen u.a., 1989, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37821-X Literatur und Lüge, 1999, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37813-9 Shakespeares Sonette, Nachdichtung, 1977, Diogenes, ISBN 3-257-20381-0 Theater der Dichtung mit Bearbeitungen von Shakespeare-Dramen, Suhrkamp 1994, ISBN 3-518-37825-2 Hüben und Drüben, 1993, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37828-7 Die Stunde des Gerichts, 1992, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37827-9 Untergang der Welt durch schwarze Magie, 1989, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37814-7 Brot und Lüge, 1991, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37826-0 Die Katastrophe der Phrasen, 1994, Suhrkamp, ISBN 3-518-37829-5 |

Works in English translation The last days of mankind; a tragedy in five acts. An abridgement translated by Alexander Gode and Sue Allen Wright. New York: F. Ungar Pub. Co. 1974. ISBN 9780804424844. No Compromise: Selected Writings of Karl Kraus (1977, ed. Frederick Ungar, includes poetry, prose, and aphorisms from Die Fackel as well as correspondences and excerpts from The Last Days of Mankind.) In These Great Times: A Karl Kraus Reader (1984), ed. Harry Zohn, contains translated excerpts from Die Fackel, including poems with the original German text alongside, and a drastically abridged translation of The Last Days of Mankind. Anti-Freud: Karl Kraus' Criticism of Psychoanalysis and Psychiatry (1990) by Thomas Szasz contains Szasz's translations of several of Kraus' articles and aphorisms on psychiatry and psychoanalysis. Half Truths and One-and-a-Half Truths: selected aphorisms (1990) translated by Hary Zohn. Chicago ISBN 0-226-45268-9. Dicta and Contradicta, tr. Jonathan McVity (2001), a collection of aphorisms. The Last Days of Mankind (1999) a radio drama broadcast on BBC Three. Paul Scofield plays The Voice of God. Adapted and directed by Giles Havergal. The 3 episodes were broadcast from 6 to 13 December 1999. Work in progress. An incomplete and extensively annotated English translation by Michael Russell of The Last Days of Mankind is available at http://www.thelastdaysofmankind.org. It consists currently of Prologue, Act I, Act II and the Epilogue, slightly more than 50 percent of the original text. This is part of a project to translate a complete performable text with a focus on performable English that in some (modest) ways reflects Kraus's prose and verse in German, with an apparatus of footnotes explaining and illustrating Kraus's complex and dense references. The all-verse Epilogue is now published as a separate text, available from Amazon as a book and on Kindle. Also on this site will be a complete "working'" translation by Cordelia von Klot, provided as a tool for students and the only version of the whole play accessible online, translated into English with the useful perspective of a German speaker. The Kraus Project: Essays by Karl Kraus (2013) translated by Jonathan Franzen, with commentary and additional footnotes by Paul Reitter and Daniel Kehlmann. In These Great Times and Other Writings (2014, translated with notes by Patrick Healy, ebook only from November Editions. Collection of eleven essays, aphorisms, and the prologue and first act of The Last Days of Mankind) www.abitofpitch.com is dedicated to publishing selected writings of Karl Kraus in English translation with new translations appearing in irregular intervals. The Last Days of Mankind (2015), complete text translated by Fred Bridgham and Edward Timms. Yale University Press. The Last Days of Mankind (2016), alternate translation by Patrick Healy, November Editions Third Walpurgis Night: the Complete Text (2020), translated by Fred Bridgham. Yale University Press. |

| ・人類最期の日々 / カール・クラウス著 ; 池内紀訳, 法政大学出版局 , 2016 ・カール・クラウス : 闇にひとつ炬火あり / 池内紀 [著], 講談社 , 2015 . - (講談社学術文庫, [2331]) ・黒魔術による世界の没落 / カール・クラウス著 ; 山口裕之, 河野英二訳, 現代思潮新社 , 2008 . - (Être★エートル叢書, 18) ・言葉 / 武田昌一, 佐藤康彦, 木下康光訳, 法政大学出版局 , 1993 . - (カール・クラウス著作集 / [カール・クラウス著], 7・8) ・アフォリズム / 池内紀編訳, 法政大学出版局 , 1978 . - (カール・クラウス著作集 / [カール・クラウス著], 5) ・第三のワルプルギスの夜 / 佐藤康彦, 武田昌一, 高木久雄訳, 法政大学出版局 , 1976 . - (カール・クラウス著作集 / [カール・クラウス著], 6) ・人類最期の日々 / 池内紀訳、法政大学出版局 , 1971 . - (カール・クラウス著作集 / [カール・クラウス著], 9, 10) |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆