キャサリン・ダンハム

Katherine Mary Dunham, 1909-2006

☆ キャサリン・メアリー・ダンハム(1909年6月22日 - 2006年5月21日)[1] は、アフリカ系アメリカ人のダンサー、振付家、人類学者、社会活動家だった。ダンハムは20世紀で最も成功したダンサーの一人であり、長年にわたり自身の ダンスカンパニーを率いた。彼女は「黒人ダンスの母」とも呼ばれている[2]。 シカゴ大学在学中、ダンハムはダンサーとして活動し、ダンススクールを運営しながら、人類学の学士号を早期に取得した。大学院の学術奨学金を受けて、カリ ブ海地域へアフリカ人ディアスポラ、民族誌、現地のダンスを研究。大学院に戻り、人類学部に修士論文を提出したが、自分の天職はパフォーマンスと振付にあ ると気づき、その他の要件は満たさなかった。 1940年代から1950年代のキャリアの頂点期、ダンハムはヨーロッパとラテンアメリカで広く知られ、アメリカ合衆国でも人気を博した。ワシントン・ポ ストは彼女を「ダンサーのカサリン・ザ・グレート」と称した。彼女はほぼ30年間、当時唯一の自給自足型アメリカ黒人ダンス団である「カサリン・ダンハ ム・ダンス・カンパニー」を運営した。長いキャリアを通じて、彼女は90を超える個々のダンスを振付した。[3] ダンハムはアフリカ系アメリカ人モダンダンスの革新者であり、ダンス人類学(エトノコレオロジー)の分野でもリーダー的存在だった。また、自身のダンス作 品を支えるための動きのメソッド「ダンハム・テクニック」を開発した。[4]

| Katherine Mary

Dunham (June 22, 1909 – May 21, 2006)[1] was an African American

dancer, choreographer, anthropologist, and social activist. Dunham had

one of the most successful dance careers of the 20th century and

directed her own dance company for many years. She has been called the

"matriarch and queen mother of black dance."[2] While a student at the University of Chicago, Dunham also performed as a dancer, ran a dance school and earned an early bachelor's degree in anthropology. Receiving a postgraduate academic fellowship, she went to the Caribbean to study the African diaspora, ethnography and local dance. She returned to graduate school and submitted a master's thesis to the anthropology faculty. She did not complete the other requirements for that degree, however, as she realized that her professional calling was performance and choreography. At the height of her career in the 1940s and 1950s, Dunham was renowned throughout Europe and Latin America and was widely popular in the United States. The Washington Post called her "dancer Katherine the Great." For almost 30 years she maintained the Katherine Dunham Dance Company, the only self-supported American black dance troupe at that time. Over her long career, she choreographed more than ninety individual dances.[3] Dunham was an innovator in African-American modern dance as well as a leader in the field of dance anthropology, or ethnochoreology. She also developed the Dunham Technique, a method of movement to support her dance works.[4] |

キャサリン・メアリー・ダンハム(1909年6月22日 -

2006年5月21日)[1]

は、アフリカ系アメリカ人のダンサー、振付家、人類学者、社会活動家だった。ダンハムは20世紀で最も成功したダンサーの一人であり、長年にわたり自身の

ダンスカンパニーを率いた。彼女は「黒人ダンスの母」とも呼ばれている[2]。 シカゴ大学在学中、ダンハムはダンサーとして活動し、ダンススクールを運営しながら、人類学の学士号を早期に取得した。大学院の学術奨学金を受けて、カリ ブ海地域へアフリカ人ディアスポラ、民族誌、現地のダンスを研究。大学院に戻り、人類学部に修士論文を提出したが、自分の天職はパフォーマンスと振付にあ ると気づき、その他の要件は満たさなかった。 1940年代から1950年代のキャリアの頂点期、ダンハムはヨーロッパとラテンアメリカで広く知られ、アメリカ合衆国でも人気を博した。ワシントン・ポ ストは彼女を「ダンサーのカサリン・ザ・グレート」と称した。彼女はほぼ30年間、当時唯一の自給自足型アメリカ黒人ダンス団である「カサリン・ダンハ ム・ダンス・カンパニー」を運営した。長いキャリアを通じて、彼女は90を超える個々のダンスを振付した。[3] ダンハムはアフリカ系アメリカ人モダンダンスの革新者であり、ダンス人類学(エトノコレオロジー)の分野でもリーダー的存在だった。また、自身のダンス作 品を支えるための動きのメソッド「ダンハム・テクニック」を開発した。[4] |

| Early life Katherine Mary Dunham was born on the 22 of June in 1909 in a Chicago hospital. Her father, Albert Millard Dunham, was a descendant of slaves from West Africa and Madagascar. Her mother, Fanny June Dunham, who, according to Dunham's memoir, possessed Indian, French Canadian, English, and probably African ancestry, died when Dunham was four years old.[5] She had an older brother, Albert Jr., with whom she had a close relationship.[6] After her mother died, her father left the children with their aunt Lulu on Chicago's South Side. At the time, the South Side of Chicago was experiencing the effects of the Great Migration where Black southerners attempted to escape the Jim Crow South and poverty.[5] Along with the Great Migration, came White flight and her aunt Lulu's business suffered and ultimately closed as a result. This led to a custody battle over Katherine and her brother, brought on by their maternal relatives. This meant neither of the children was able to settle into a home for a few years. However, after her father remarried, Albert Sr. and his new wife, Annette Poindexter Dunham, took in Katherine and her brother.[7] The family moved to a predominantly white neighborhood in Joliet, Illinois. There, her father ran a dry-cleaning business.[8] Dunham became interested in both writing and dance at a young age. In 1921, a short story she wrote when she was 12 years old, called "Come Back to Arizona", was published in volume 2 of The Brownies' Book. She graduated from Joliet Central High School in 1928, where she played baseball, tennis, basketball, and track; served as vice-president of the French Club, and was on the yearbook staff.[9] In high school she joined the Terpsichorean Club and began to learn a kind of modern dance based on the ideas of Europeans [Émile Jaques-Dalcroze] and [Rudolf von Laban].[6] At the age of 15, she organized "The Blue Moon Café", a fundraising cabaret to raise money for Brown's Methodist Church in Joliet, where she gave her first public performance.[6][10] While still a high school student, she opened a private dance school for young black children.[10] |

幼少期 キャサリン・メアリー・ダンハムは、1909年6月22日にシカゴの病院で生まれた。父親のアルバート・ミラード・ダンハムは、西アフリカとマダガスカル 出身の奴隷の子孫だった。彼女の母親、ファニー・ジューン・ダナムは、ダナムの回顧録によると、インディアン、フランス系カナダ人、イギリス人、そしてお そらくアフリカ系の祖先を持つ人物だったが、ダナムが4歳のときに亡くなった[5]。彼女には、親しい関係にあった兄、アルバート・ジュニアがいた [6]。母親が亡くなった後、父親は子供たちをシカゴのサウスサイドに住む叔母のルルに預けた。当時、シカゴのサウスサイドは、ジム・クロウ法下の南部か ら貧困を逃れるための「グレート・マイグレーション」の影響を受けていた。[5] グレート・マイグレーションと共に白人の流出が起こり、ルルのビジネスは苦境に陥り、最終的に閉鎖された。これにより、キャサリンと兄の親権を巡る争い が、母方の親族によって起こされた。これにより、子どもたちは数年間、安定した住居を得ることができなかった。しかし、父親が再婚した後、アルバート・シ ニアと新しい妻アンネット・ポインデクスター・ダンハムがキャサリンと弟を引き取った。[7] 家族はイリノイ州ジョリエットの主に白人居住区に移り住んだ。そこで父親はドライクリーニング店を経営していた。[8] ダンハムは幼少期から執筆とダンスに興味を持った。1921年、12歳の時に書いた短編小説「Come Back to Arizona」が『The Brownies' Book』の第2巻に発表された。 彼女は1928年にジョリエット中央高校を卒業し、野球、テニス、バスケットボール、陸上競技部に所属し、フランス語クラブの副会長を務め、年鑑編集委員 も務めた。[9] 高校時代、彼女はテルプシコレアン・クラブに入会し、ヨーロッパの思想家[エミール・ジャック・ダルクロゼ]と[ルドルフ・フォン・ラバン]の思想に基づ いた現代舞踊を学び始めた。[6] 15歳のとき、ジョリエットにあるブラウンズ・メソジスト教会の資金調達のためのキャバレー「ブルー・ムーン・カフェ」を企画し、そこで初めて人前でパ フォーマンスを行った。[6][10] 高校生ながら、黒人の子供たちのための私立のダンススクールを開校した。[10] |

| Academia and anthropology After completing her studies at Joliet Junior College in 1928, Dunham moved to Chicago to join her brother, Albert, at the University of Chicago.[11] During her time in Chicago, Dunham enjoyed holding social gatherings and inviting visitors to her apartment. Such visitors included ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax, novelist and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston, Robert Redfield, Bronisław Malinowski, A.R. Radcliffe-Brown, Fred Eggan, and many others that she met in and around the University of Chicago.[12] After noticing that Katherine enjoyed working and socializing with people, her brother suggested that she study Anthropology.[13] University of Chicago's anthropology department was fairly new and the students were still encouraged to learn aspects of sociology, distinguishing it from other anthropology departments in the US that focused almost exclusively on non-Western peoples.[13] The Anthropology department at Chicago in the 1930s and 40s has been described as holistic, interdisciplinary, with a philosophy of liberal humanism, and principles of racial equality and cultural relativity.[13] Dunham officially joined the department in 1929 as an anthropology major,[13] while studying dances of the African diaspora. As a student, she studied under anthropologists such as A.R. Radcliffe-Brown, Edward Sapir, Melville Herskovits, Lloyd Warner and Bronisław Malinowski.[13] Under their tutelage, she showed great promise in her ethnographic studies of dance.[14] Redfield, Herskovits, and Sapir's contributions to cultural anthropology, exposed Dunham to topics and ideas that inspired her creatively and professionally.[14] For example, she was highly influenced both by Sapir's viewpoint on culture being made up of rituals, beliefs, customs and artforms, and by Herkovits' and Redfield's studies highlighting links between African and African American cultural expression.[15] It was in a lecture by Redfield that she learned about the relationship between dance and culture, pointing out that Black Americans had retained much of their African heritage in dances.[15] Dunham's relationship with Redfield in particular was highly influential. She wrote that he "opened the floodgates of anthropology" for her.[15] He showed her the connection between dance and social life giving her the momentum to explore a new area of anthropology, which she later termed "Dance Anthropology".[15] Katherine Dunham received her Bachelor’s, Master’s, and Doctoral degrees in anthropology from the University of Chicago, and later did an extensive anthropological study, particularly in the Caribbean. In 1935, Dunham was awarded travel fellowships from the Julius Rosenwald and Guggenheim foundations to conduct ethnographic fieldwork in Haiti, Jamaica, Martinique, and Trinidad studying the dance forms of the Caribbean. One example of this was studying how dance manifests within Haitian Vodou. Dunham also received a grant to work with Professor Melville Herskovits of Northwestern University, whose ideas about retention of African culture among African Americans served as a base for her research in the Caribbean.[16] After her research tour of the Caribbean in 1935, Dunham returned to Chicago in the late spring of 1936. In August she was awarded a bachelor's degree, a Ph.B., bachelor of philosophy, with her principal area of study being social anthropology.[17] She was one of the first African-American women to attend this college and to earn these degrees.[4] In 1938, using materials collected ethnographic fieldwork, Dunham submitted a thesis, The Dances of Haiti: A Study of Their Material Aspect, Organization, Form, and Function,.[18] to the Department of Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master's degree. However, fully aware of her passion for both dance performance, as well as anthropological research, she felt she had to choose between the two. Although Dunham was offered another grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to pursue her academic studies, she chose dance. She did this for many reasons. However, one key reason was that she knew she would be able to reach a broader public through dance, as opposed to the inaccessible institutions of academia. Never completing her required coursework for her graduate degree, she departed for Broadway and Hollywood.[8] Despite her choosing dance, Dunham often voiced recognition of her debt to the discipline: "without [anthropology] I don't know what I would have done….In anthropology, I learned how to feel about myself in relation to other people…. You can't learn about dances until you learn about people. In my mind, it's the most fascinating thing in the world to learn".[19] |

学界と人類学 1928年にジョリエット・ジュニア・カレッジを卒業後、ダンハムはシカゴに移り、シカゴ大学に通う兄アルバートの元へ引っ越した[11]。 シカゴ滞在期間中、ダンハムは社交会を開き、自分のアパートに客を招くことを楽しんだ。その中には、民族音楽学者のアラン・ロマックス、小説家であり人類 学者のゾラ・ニール・ハーストン、ロバート・レッドフィールド、ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキー、A.R. ラドクリフ・ブラウン、フレッド・エガンなど、シカゴ大学やその周辺で出会った多くの人々がいました[12]。キャサリンが仕事や人々と交流することを楽 しんでいることに気づいた兄は、彼女に人類学を勉強するよう勧めました。[13] シカゴ大学の人類学部は設立して間もなく、学生たちは社会学のさまざまな側面を学ぶことが奨励されていた。これは、非西洋の民族にほぼ専ら焦点を当ててい た他の米国の人類学部とは異なっていた。[13] 1930 年代から 40 年代のシカゴの人類学部は、総合的、学際的であり、自由人道主義の哲学と人種平等および文化相対主義の原則を掲げていたと評されている。[13] ダンハムは、アフリカのディアスポラ(移民社会)の舞踊を研究しながら、1929年に人類学専攻として正式に同学科に入学した[13]。学生時代、彼女は A.R. ラドクリフ・ブラウン、エドワード・サピア、メルヴィル・ハースコヴィッツ、ロイド・ワーナー、ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキーなどの人類学者から指導を受 けた[13]。彼らの指導の下、彼女は舞踊の民族誌的研究で大きな才能を発揮した。[14] レッドフィールド、ハースコヴィッツ、サピアの文化人類学への貢献により、ダンハムは、彼女の創造力や職業意識を刺激するトピックやアイデアに触れること ができた。[14] 例えば、彼女は、文化は儀式、信念、慣習、芸術形式で構成されるというサピアの見解、およびアフリカとアフリカ系アメリカ人の文化表現の関連性を強調した ハースコヴィッツとレッドフィールドの研究の両方に大きな影響を受けた。[15] レッドフィールドの講演で、彼女はダンスと文化の関係について学び、アフリカ系アメリカ人はダンスにアフリカの伝統の多くを残している、と指摘した。 [15] 特に、ダンハムとレッドフィールドの関係は、彼女に大きな影響を与えた。彼女は、彼が「人類学の扉を開いた」と書いている。[15] 彼はダンスと社会生活のつながりを示し、彼女に人類学の新たな分野を探求する勢いを与えた。彼女は後にこの分野を「ダンス人類学」と名付けた。[15] キャサリン・ダンハムは、シカゴ大学で人類学の学士号、修士号、博士号を取得し、その後、特にカリブ海地域で広範な人類学的研究を行った。 1935年、ダンハムは、ジュリアス・ローゼンウォルド財団とグッゲンハイム財団から、ハイチ、ジャマイカ、マルティニーク、トリニダードでカリブ海のダ ンス形式を研究するための民族誌学的フィールドワークを行うための旅費助成金を受けた。その一例として、ハイチのブードゥー教におけるダンスの表現を研究 したことが挙げられる。また、ダンハムは、アフリカ系アメリカ人のアフリカ文化の保持に関する考えが、彼女のカリブ海での研究の基礎となったノースウェス タン大学のメルヴィル・ハースコヴィッツ教授と共同研究を行うための助成金も受けた[16]。 1935年にカリブ海を研究旅行した後、ダンハムは1936年の春の終わりにシカゴに戻った。8 月、彼女は社会人類学を専攻して、哲学学士号(Ph.B.)を取得した[17]。彼女は、この大学に入学し、これらの学位を取得した最初のアフリカ系アメ リカ人女性の一人だった[4]。1938 年、ダンハムは、民族誌学的フィールドワークで収集した資料を用いて、論文「ハイチのダンス: A Study of Their Material Aspect, Organization, Form, and Function(ハイチのダンス:その物質的側面、組織、形態、機能に関する研究)」を人類学部に提出し、修士号取得の要件の一部を満たした。しかし、 ダンスのパフォーマンスと人類学の研究の両方に情熱を注いでいた彼女は、そのどちらかを選ばなければならないと感じた。ダンハムは、ロックフェラー財団か ら学業を続けるための別の奨学金を提示されたが、ダンスを選んだ。その理由はたくさんあった。しかし、その大きな理由のひとつは、アクセスが難しい学術機 関よりも、ダンスの方がより多くの人々に自分のことを知ってもらうことができると知っていたからだ。大学院の必要な授業を修了することなく、彼女はブロー ドウェイとハリウッドへと旅立った。 ダンスを選んだにもかかわらず、ダンハムは、人類学に対する感謝の気持ちをしばしば口にしていました。「人類学がなかったら、私は何をしていただろう…人 類学では、他の人々と自分との関わり方を学んだ。人について学ばなければ、ダンスについて学ぶことはできない。私にとって、それはこの世で最も魅力的なこ となのだ」[19] |

| Ethnographic fieldwork Her field work in the Caribbean began in Jamaica, where she lived for several months in the remote Maroon village of Accompong, deep in the mountains of Cockpit Country. (She later wrote Journey to Accompong, a book describing her experiences there.) Then she traveled to Martinique and to Trinidad and Tobago for short stays, primarily to do an investigation of Shango, the African god who was still considered an important presence in West Indian religious culture. Early in 1936, she arrived in Haiti, where she remained for several months, the first of her many extended stays in that country through her life. While in Haiti, Dunham investigated Vodun rituals and made extensive research notes, particularly on the dance movements of the participants.[20] She recorded her findings through ethnographic fieldnotes and by learning dance techniques, music and song, alongside her interlocutors.[21] This style of participant observation research was not yet common within the discipline of anthropology. However, it has now became a common practice within the discipline. She was one of the first researchers in anthropology to use her research of Afro-Haitian dance and culture for remedying racist misrepresentation of African culture in the miseducation of Black Americans. She felt it was necessary to use the knowledge she gained in her research to acknowledge that Africanist esthetics are significant to the cultural equation in American dance.[22] Years later, after extensive studies and initiations in Haiti,[21] she became a mambo in the Vodun religion.[20] She also became friends with, among others, Dumarsais Estimé, then a high-level politician, who became president of Haiti in 1949. Somewhat later, she assisted him, at considerable risk to her life, when he was persecuted for his progressive policies and sent in exile to Jamaica after a coup d'état. |

民族誌的フィールドワーク 彼女のカリブ海でのフィールドワークは、コックピット・カントリー(Cockpit Country)の奥深くにある人里離れたマローン族の村、アコンポン(Accompong)で数ヶ月間過ごしたことから始まった。(彼女は後に、その体 験を描いた『Journey to Accompong』という本を書いた。その後、彼女はマルティニーク、トリニダード・トバゴに短期滞在し、主に西インドの宗教文化において依然として重 要な存在とみなされていたアフリカの神、シャンゴについて調査を行った。1936年の初め、彼女はハイチに到着し、数ヶ月間滞在した。これは、彼女の一生 におけるハイチでの多くの長期滞在の最初のものとなった。 ハイチ滞在中、ダンハムはブードゥー教の儀式を調査し、特に参加者のダンスの動きについて広範な調査ノートを残した[20]。彼女は、対話者たちととも に、民族誌的なフィールドノートに調査結果を記録し、ダンスのテクニック、音楽、歌も学んだ[21]。この参加型観察調査のスタイルは、当時、人類学の世 界ではまだ一般的ではなかった。しかし、現在では、この分野では一般的な手法となっている。彼女は、人類学において、アフリカ系ハイチ人のダンスと文化の 研究を、アフリカ文化の誤った表現を是正し、黒人アメリカ人の教育における偏見を是正するために活用した最初の研究者の一人だった。彼女は、自分の研究で 得た知識を活用して、アフリカ文化の美学がアメリカのダンス文化において重要な役割を果たしていることを認識させる必要があると考えた[22]。数年後、 ハイチで広範な研究と修行を経て[21]、彼女はブードゥー教のマンボになった[20]。また、1949年にハイチ大統領に就任した、当時高位の政治家 だったデュマルセ・エスティメとも親交があった。その後、彼は進歩的な政策のため迫害され、クーデター後にジャマイカに追放された際、彼女は命の危険を冒 して彼を支援した。 |

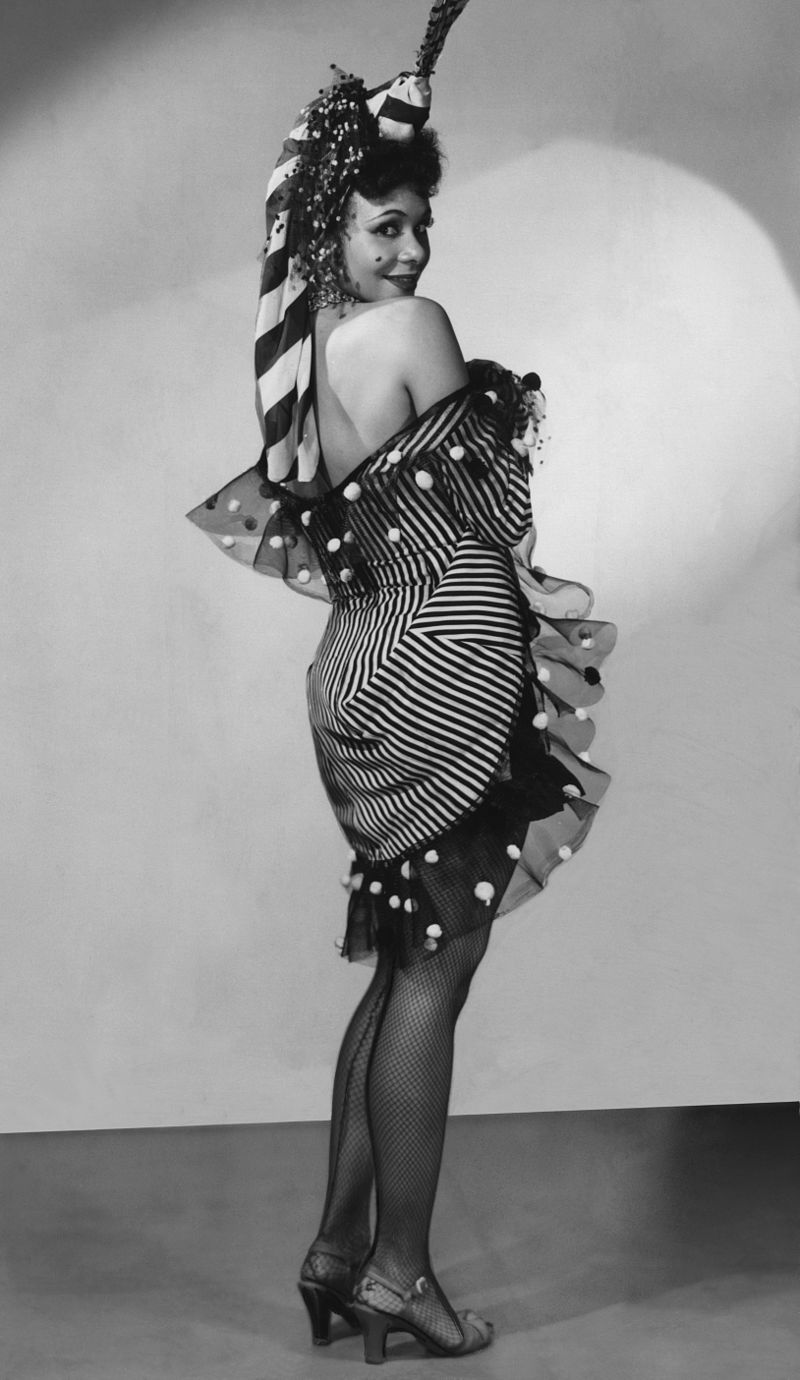

| Dancer and Choreographer From 1928 to 1938  Katherine Dunham in 1940, by Carl Van Vechten Dunham's dance career first began in Chicago when she joined the Little Theater Company of Harper Avenue. In 1928, while still an undergraduate, Dunham began to study ballet with Ludmilla Speranzeva, a Russian dancer who had settled in Chicago, after having come to the United States with the Franco-Russian vaudeville troupe Le Théâtre de la Chauve-Souris, directed by impresario Nikita Balieff. Dunham also studied ballet with Mark Turbyfill and Ruth Page, who became prima ballerina of the Chicago Opera. Additionally, she worked closely with Vera Mirova who specialized in "Oriental" dance. Through her ballet teachers, she was also exposed to Spanish, East Indian, Javanese, and Balinese dance forms.[23] In 1931, at the age of 21, Dunham formed a group called Ballets Nègres, one of the first black ballet companies in the United States. The group performed Dunham's Negro Rhapsody at the Chicago Beaux Arts Ball. After this well-received performance in 1931, the group was disbanded. Encouraged by Speranzeva to focus on modern dance instead of ballet, Dunham opened her first dance school in 1933, calling it the Negro Dance Group. It was a venue for Dunham to teach young black dancers about their African heritage. In 1934–1936, Dunham performed as a guest artist with the ballet company of the Chicago Opera. Ruth Page had written a scenario and created the choreography for William Grant Still's ballet La Guiablesse ("The Devil Woman"), based on a Martinican folk tale in Lafcadio Hearn's Two Years in the French West Indies. It opened in Chicago in 1933, with a black cast and with Page dancing the title role. The next year the production was repeated with Katherine Dunham in the lead and with students from Dunham's Negro Dance Group in the ensemble. Her dance career was interrupted in 1935 when she received funding from the Rosenwald Foundation which allowed her to travel to Jamaica, Martinique, Trinidad, and Haiti for eighteen months to explore each country's respective dance cultures. The result of this trip was Dunham's Master's thesis entitled "The Dances of Haiti". Having completed her undergraduate work at the University of Chicago and decided to pursue a performing career rather than academic studies, Dunham revived her dance ensemble. In 1937 she traveled with them to New York to take part in A Negro Dance Evening, organized by Edna Guy at the 92nd Street YMHA. The troupe performed a suite of West Indian dances in the first half of the program and a ballet entitled Tropic Death, with Talley Beatty, in the second half. Upon returning to Chicago, the company performed at the Goodman Theater and at the Abraham Lincoln Center. Dunham created Rara Tonga and Woman with a Cigar at this time, which became well known. With choreography characterized by exotic sexuality, both became signature works in the Dunham repertory. After her company performed successfully, Dunham was chosen as dance director of the Chicago Negro Theater Unit of the Federal Theatre Project. In this post, she choreographed the Chicago production of Run Li'l Chil'lun, performed at the Goodman Theater. She also created several other works of choreography, including The Emperor Jones (a response to the play by Eugene O'Neill) and Barrelhouse. At this time Dunham first became associated with designer John Pratt, whom she later married. Together, they produced the first version of her dance composition L'Ag'Ya, which premiered on January 27, 1938, as a part of the Federal Theater Project in Chicago. Based on her research in Martinique, this three-part performance integrated elements of a Martinique fighting dance into American ballet. |

ダンサー、振付家 1928年から1938年  1940年のキャサリン・ダンハム、カール・ヴァン・ヴェクテン撮影 ダンハムのダンスのキャリアは、シカゴのハーパー・アベニュー・リトル・シアター・カンパニーに入団したことから始まった。1928年、まだ大学生だった ダンハムは、興行師ニキータ・バリエフが率いるフランスとロシアの寄席劇団「Le Théâtre de la Chauve-Souris」とともにアメリカに渡った、シカゴに定住していたロシア人ダンサー、ルドミラ・スペランゼヴァにバレエを習い始めた。ダンハ ムは、マーク・タービーフィルや、シカゴ・オペラのプリマバレリーナとなったルース・ページからもバレエを学んだ。さらに、「オリエンタル」ダンスを専門 とするヴェラ・ミロヴァとも密接に協力した。バレエの教師たちを通じて、スペイン、東インド、ジャワ、バリのダンスも学んだ[23]。 1931年、21歳のときに、ダンハムは、米国で最初の黒人バレエ団のひとつである「バレエ・ネグロ」というグループを結成した。このグループは、シカ ゴ・ボザール・ボールでダンハムの「ニグロ・ラプソディ」を上演した。1931年のこの公演は好評を博したが、その後、グループは解散した。バレエではな くモダンダンスに専念するようスペランゼヴァに勧められたダンハムは、1933年に最初のダンススクール「ニグロ・ダンス・グループ」を開校した。このス クールは、ダンハムが若い黒人ダンサーたちにアフリカの伝統を教える場となった。 1934年から1936年まで、ダンハムはシカゴ・オペラバレエ団に客演アーティストとして出演した。ルース・ペイジは、ラフカディオ・ハーン『フランス 西インド諸島での2年間』に収録されたマルティニークの民話に基づくウィリアム・グラント・スティルのバレエ『ラ・ギアブレッセ』(「悪魔の女」)のシナ リオを執筆し、振付を創作した。この作品は1933年にシカゴで初演され、黒人キャストで上演され、ペイジがタイトルロールを踊った。翌年、キャサリン・ ダンハムが主演、ダンハムのニグロ・ダンス・グループの生徒たちがアンサンブルとして出演して、この作品が再演された。1935年、ローゼンウォルド財団 から資金援助を受けて、ジャマイカ、マルティニーク、トリニダード、ハイチを18ヶ月間旅し、それぞれの国のダンス文化を研究した。この旅の成果は、ダン ハムの修士論文「ハイチのダンス」となった。 シカゴ大学で学士号を取得し、学業よりも舞台の道を志したダンハムは、ダンス団を復活させた。1937年、彼女はダンス団とともにニューヨークへ旅立ち、 エドナ・ガイが92nd Street YMHAで主催した「A Negro Dance Evening」に出演した。この公演では、前半に西インドのダンスの組曲、後半にタリー・ビーティと共演したバレエ「トロピック・デス」が上演された。 シカゴに戻った後、グッドマン・シアターとエイブラハム・リンカーン・センターで公演を行った。この頃、ダンハムは「ララ・トンガ」と「葉巻を持つ女」を 創作し、これらは評判となった。エキゾチックなセクシュアリティを特徴とする振付は、ダンハムのレパートリーの代表作となった。カンパニーの成功を受け て、ダンハムは連邦劇場プロジェクト(Federal Theatre Project)のシカゴ・ニグロ・シアター・ユニット(Chicago Negro Theater Unit)のダンスディレクターに選ばれた。この職に就いて、グッドマン・シアターで上演された『Run Li『l Chil』lun』のシカゴ公演の振付を担当した。また、『The Emperor Jones』(ユージン・オニールの戯曲にインスピレーションを得た作品)や『Barrelhouse』など、他の振付作品もいくつか制作した。 この頃、ダンハムはデザイナーのジョン・プラットと知り合い、後に結婚した。2人は共同で、彼女の最初のダンス作品『L『Ag』Ya』を制作し、1938 年1月27日にシカゴの連邦劇場プロジェクトの一環として初演した。マルティニーク島での調査を基にしたこの3部構成の作品は、マルティニーク島の闘争の 舞踊の要素をアメリカのバレエに取り入れたものだった。 |

| From 1939 to the Late 1950s In 1939, Dunham's company gave additional performances in Chicago and Cincinnati and then returned to New York. Dunham had been invited to stage a new number for the popular, long-running musical revue Pins and Needles 1940, produced by the International Ladies' Garment Workers Union. As this show continued its run at the Windsor Theater, Dunham booked her own company in the theater for a Sunday performance. This concert, billed as Tropics and Le Hot Jazz, included not only her favorite partners Archie Savage and Talley Beatty, but her principal Haitian drummer, Papa Augustin. Initially scheduled for a single performance, the show was so popular that the troupe repeated it for another ten Sundays. Based on this success, the entire company was engaged for the 1940 Broadway production Cabin in the Sky, staged by George Balanchine and starring Ethel Waters. With Dunham in the sultry role of temptress Georgia Brown, the show ran for 20 weeks in New York. It next moved to the West Coast for an extended run of performances there. The show created a minor controversy in the press.  Title card for the American release of the 1943 musical film Stormy Weather. After the national tour of Cabin in the Sky, the Dunham company stayed in Los Angeles, where they appeared in the Warner Brothers short film Carnival of Rhythm (1941). The next year, after the US entered World War II, Dunham appeared in the Paramount musical film Star Spangled Rhythm (1942) in a specialty number, "Sharp as a Tack," with Eddie "Rochester" Anderson. Other movies she performed in as a dancer during this period included the Abbott and Costello comedy Pardon My Sarong (1942) and the black musical Stormy Weather (1943), which featured a stellar range of actors, musicians and dancers.[24] The company returned to New York. The company was located on the property that formerly belonged to the Isadora Duncan Dance in Caravan Hill but subsequently moved to W 43rd Street. In September 1943, under the management of the impresario Sol Hurok, her troupe opened in Tropical Review at the Martin Beck Theater. Featuring lively Latin American and Caribbean dances, plantation dances, and American social dances, the show was an immediate success. The original two-week engagement was extended by popular demand into a three-month run, after which the company embarked on an extensive tour of the United States and Canada. In Boston, then a bastion of conservatism, the show was banned in 1944 after only one performance. Although it was well received by the audience, local censors feared that the revealing costumes and provocative dances might compromise public morals. After the tour, in 1945, the Dunham company appeared in the short-lived Blue Holiday at the Belasco Theater in New York, and in the more successful Carib Song at the Adelphi Theatre. The finale to the first act of this show was Shango, a staged interpretation of a Vodun ritual, which became a permanent part of the company's repertory. In 1946, Dunham returned to Broadway for a revue entitled Bal Nègre, which received glowing notices from theater and dance critics. Early in 1947 Dunham choreographed the musical play Windy City, which premiered at the Great Northern Theater in Chicago. Later in the year she opened a cabaret show in Las Vegas, during the first year that the city became a popular entertainment as well as gambling destination. Later that year she took her troupe to Mexico, where their performances were so popular that they stayed and performed for more than two months. After Mexico, Dunham began touring in Europe, where she was an immediate sensation. In 1948, she opened A Caribbean Rhapsody, first at the Prince of Wales Theatre in London, and then took it to the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris. This was the beginning of more than 20 years during which Dunham performed with her company almost exclusively outside the United States. During these years, the Dunham company appeared in some 33 countries in Europe, North Africa, South America, Australia, and East Asia. Dunham continued to develop dozens of new productions during this period, and the company met with enthusiastic audiences in every city. Despite these successes, the company frequently ran into periods of financial difficulties, as Dunham was required to support all of the 30 to 40 dancers and musicians. Richard Buckle's memoir The Adventures of a Ballet Critic (Cresset Press, 1953) contains extended descriptions of his association with Dunham and John Pratt during her company's residency in London in 1948 with A Caribbean Rhapsody, and Buckle's collaboration with Dunham on a book about her work (Katherine Dunham: Her dancers, singers and musicians (Ballet Productions, 1949). This book was printed but never on sale due to Buckle's financial problems; the British Library holds a copy. Dunham and her company appeared in the Hollywood movie Casbah (1948) with Tony Martin, Yvonne De Carlo, and Peter Lorre, and in the Italian film Botta e Risposta, produced by Dino de Laurentiis. Also that year they appeared in the first ever, hour-long American spectacular televised by NBC, when television was first beginning to spread across America. This was followed by television spectaculars filmed in London, Buenos Aires, Toronto, Sydney, and Mexico City. In 1950, Sol Hurok presented Katherine Dunham and Her Company in a dance revue at the Broadway Theater in New York, with a program composed of some of Dunham's best works. It closed after only 38 performances. The company soon embarked on a tour of venues in South America, Europe, and North Africa. They had particular success in Denmark and France. In the mid-1950s, Dunham and her company appeared in three films: Mambo (1954), made in Italy; Die Grosse Starparade (1954), made in Germany; and Música en la Noche (1955), made in Mexico City. |

1939年から1950年代後半 1939年、ダンハムのカンパニーはシカゴとシンシナティで追加公演を行い、その後ニューヨークに戻った。ダンハムは、国際婦人服労働組合が制作した、人 気のある長寿ミュージカル・レビュー「Pins and Needles 1940」の新しいナンバーの演出を依頼されていた。このショーがウィンザー・シアターで上演されている間、ダンハムは自分のカンパニーを同劇場に予約 し、日曜日の公演を行った。トロピックス・アンド・ル・ホット・ジャズと題されたこのコンサートには、彼女のお気に入りのパートナーであるアーチー・サ ヴェージとタリー・ビーティだけでなく、彼女の主なハイチ人ドラマー、パパ・オーギュスタンも参加した。当初は 1 回限りの公演だったこのショーは、大好評を博し、10 週間にわたって日曜日に上演された。 この成功を受けて、カンパニー全員が、ジョージ・バランシンが演出、エセル・ウォーターズが主演した 1940 年のブロードウェイ作品 Cabin in the Sky に起用された。ダンハムは、官能的な誘惑の女ジョージア・ブラウン役を演じ、この作品はニューヨークで 20 週間にわたって上演された。その後、西海岸に移り、長期公演が行われた。この作品は、マスコミで小さな論争を巻き起こした。  1943年のミュージカル映画『ストームイ・ウェザー』のアメリカ公開時のタイトルカード。 『キャビン・イン・ザ・スカイ』の全国ツアーの後、ダンハムのカンパニーはロサンゼルスに滞在し、ワーナー・ブラザースの短編映画『カーニバル・オブ・リ ズム』(1941年)に出演した。翌年、アメリカが第二次世界大戦に参戦した後、ダンハムはパラマウントのミュージカル映画『スター・スパングルド・リズ ム』(1942年)に出演し、エディ・ロチェスター・アンダーソンと「Sharp as a Tack」という特別ナンバーを披露した。この期間にダンマーがダンサーとして出演したその他の映画には、アボットとコステロのコメディ『パードン・マ イ・サロン』(1942年)、俳優、ミュージシャン、ダンサーの豪華な顔ぶれが共演した黒人ミュージカル『ストームイ・ウェザー』(1943年)などがあ る。 会社はニューヨークに戻った。会社は、以前はキャラバン・ヒルにあったイサドラ・ダンカン・ダンスの所有地にあったが、その後 W 43rd ストリートに移転した。1943年9月、興行師ソル・ヒューロックの経営の下、彼女の劇団はマーティン・ベック・シアターで「トロピカル・レビュー」を上 演した。活気あふれるラテンアメリカやカリブ海のダンス、プランテーションのダンス、アメリカの社交ダンスをフィーチャーしたこのショーは、即座に大成功 を収めた。当初の 2 週間の公演は、人気の高まりにより 3 ヶ月間に延長され、その後、カンパニーは米国とカナダでの大規模なツアーに出かけた。当時、保守的な風潮のあったボストンでは、1944 年に 1 回だけの公演で公演が禁止された。観客からは好評を博したが、地元の検閲当局は、露出度の高い衣装や挑発的なダンスが公序良俗を乱すことを懸念した。ツ アー終了後の 1945 年、ダンハムのカンパニーは、ニューヨークのベラスコ劇場での短命な「ブルー・ホリデー」と、より成功を収めたアデルフィ劇場での「カリブ・ソング」に出 演した。このショーの第 1 幕のフィナーレは、ブードゥー教の儀式を舞台化した「シャンゴ」で、これはカンパニーのレパートリーの定番となった。 1946年、ダンハムはブロードウェイに「バル・ネグレ」というレビューで復帰し、演劇評論家やダンス評論家から絶賛された。1947年初頭、ダンハムは ミュージカル「ウィンディ・シティ」の振付を担当し、シカゴのグレート・ノーザン・シアターで初演された。その年の後半、彼女はラスベガスでキャバレー ショーを開演した。ラスベガスがギャンブルだけでなく、エンターテイメントの町として人気を博し始めた最初の年だった。その年の後半、彼女は劇団をメキシ コに連れて行き、その公演は大変好評で、2 ヶ月以上も滞在して公演を続けた。メキシコの後、ダンハムはヨーロッパツアーを開始し、すぐに大成功を収めた。1948 年、彼女は『A Caribbean Rhapsody』をロンドンのプリンス・オブ・ウェールズ・シアターで初演し、その後、パリのシャンゼリゼ劇場でも上演した。 この年から、ダンハムは20年以上にわたり、ほぼ全公演を米国以外で行った。この間、ダンハムの劇団は、ヨーロッパ、北アフリカ、南米、オーストラリア、 東アジアの33カ国で公演を行った。ダンハムはこの期間、数十もの新作を制作し続け、カンパニーはどの都市でも熱狂的な観客の歓迎を受けた。しかし、30 人から40人のダンサーとミュージシャン全員の生活費をダンハムが負担しなければならなかったため、カンパニーはしばしば財政難に陥った。リチャード・ バックルの回顧録『The Adventures of a Ballet Critic』(Cresset Press、1953 年)には、1948 年にダンハムのカンパニーが『A Caribbean Rhapsody』を上演するためにロンドンに滞在していた間の、ダンハムやジョン・プラットとの交流、そしてダンハムの著作『Katherine Dunham: Her dancers, singers and musicians』(Ballet Productions、1949 年)の執筆にバックルが協力した経緯について詳しく記されている。この本は印刷されたが、バックルの財政難のため発売には至らなかった。英国図書館に1冊 が所蔵されている。 ダンハムと彼女のカンパニーは、トニー・マーティン、イヴォンヌ・デ・カルロ、ピーター・ローレが出演したハリウッド映画『カスバ』(1948年)や、 ディノ・デ・ラウレンティス製作のイタリア映画『ボッタ・エ・リスポスタ』に出演した。また、テレビがアメリカで普及し始めたその年、NBC が放送した、アメリカ初の 1 時間のテレビ特別番組にも出演した。その後、ロンドン、ブエノスアイレス、トロント、シドニー、メキシコシティでテレビ放映された大掛かりな番組にも出演 した。 1950年、ソル・ヒューロックは、ニューヨークのブロードウェイ・シアターで、ダンハムの最高の作品で構成されたダンス・レビュー「キャサリン・ダンハ ムと彼女のカンパニー」を上演した。この公演は38回で終了したが、カンパニーはすぐに南米、ヨーロッパ、北アフリカでのツアーに乗り出した。デンマーク とフランスで特に大きな成功を収めた。1950年代半ば、ダンハムと彼女のカンパニーは、イタリアで製作された『マンボ』(1954年)、ドイツで製作さ れた『Die Grosse Starparade』(1954年)、メキシコシティで製作された『Música en la Noche』(1955年)の3本の映画に出演した。 |

| Later career The Dunham company's international tours ended in Vienna in 1960. They were stranded without money because of bad management by their impresario. Dunham saved the day by arranging for the company to be paid to appear in a German television special, Karibische Rhythmen, after which they returned to the United States. Dunham's last appearance on Broadway was in 1962 in Bamboche!, which included a few former Dunham dancers in the cast and a contingent of dancers and drummers from the Royal Troupe of Morocco. It was not a success, closing after only eight performances. A highlight of Dunham's later career was the invitation from New York's Metropolitan Opera to stage dances for a new production of Aida, starring soprano Leontyne Price. In 1963, she became the first African American to choreograph for the Met since Hemsley Winfield set the dances for The Emperor Jones in 1933. The critics acknowledged the historical research she did on dance in ancient Egypt, but they were not appreciative of her choreography as staged for this production.[25] Subsequently, Dunham undertook various choreographic commissions at several venues in the United States and in Europe. In 1966, she served as a State Department representative for the United States to the first ever World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal. In 1967 she officially retired, after presenting a final show at the famous Apollo Theater in Harlem, New York. Even in retirement Dunham continued to choreograph: one of her major works was directing the premiere full, posthumous production Scott Joplin's opera Treemonisha in 1972, a joint production of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and the Morehouse College chorus in Atlanta, conducted by Robert Shaw.[26] This work was never produced in Joplin's lifetime, but since the 1970s, it has been successfully produced in many venues. In 1978 Dunham was featured in the PBS special, Divine Drumbeats: Katherine Dunham and Her People, narrated by James Earl Jones, as part of the Dance in America series. Alvin Ailey later produced a tribute for her in 1987–88 at Carnegie Hall with his American Dance Theater, entitled The Magic of Katherine Dunham. |

その後のキャリア ダンハム・カンパニーの国際ツアーは、1960年にウィーンで終了した。興行主の経営ミスにより、彼らは資金難に陥った。ダンハムは、ドイツのテレビ特別番組「Karibische Rhythmen」への出演料を手配し、この危機を救った。その後、彼らは米国に戻った。 ダンハムのブロードウェイでの最後の出演は、1962年の『Bamboche!』だった。この作品には、ダンハムの元ダンサー数名と、モロッコ王立舞踊団の一団がダンサーおよびドラマーとして出演した。しかし、この作品は成功を収めることはなく、8回の上演で幕を閉じた。 ダンハムの晩年のキャリアのハイライトは、ニューヨークのメトロポリタン歌劇場から、ソプラノ歌手レオニー・プライス主演の新作『アイーダ』のダンス演出 を依頼されたことだった。1963年、彼女は1933年にヘムズリー・ウィンフィールドが『皇帝ジョーンズ』のダンスを振付して以来、メトロポリタン歌劇 場で振付を手掛けた初のアフリカ系アメリカ人となった。批評家は、彼女が古代エジプトのダンスに関する歴史的研究を評価したが、この公演での振付について は好意的な評価はしなかった。[25] その後、ダンハムは、米国およびヨーロッパのさまざまな会場で、さまざまな振り付けの依頼を受けた。1966年、彼女は、セネガルのダカールで開催され た、史上初の「世界ニグロ芸術祭」に、米国国務省代表として参加した。1967年、ニューヨークのハーレムにある有名なアポロ劇場での最後の公演を経て、 彼女は正式に引退した。引退後も、ダンハムは振り付け活動を続けた。彼女の主要な作品のひとつは、1972年にアトランタ交響楽団とモアハウス大学合唱団 が共同制作、ロバート・ショーが指揮した、スコット・ジョプリンのオペラ「トレモニシャ」の死後初の上演の演出だ。[26] この作品は、ジョプリンの生涯では上演されることはなかったが、1970年代以降、多くの会場で上演され、成功を収めている。 1978年、ダンハムは、ジェームズ・アール・ジョーンズがナレーションを担当したPBSの特別番組「Divine Drumbeats: Katherine Dunham and Her People」に出演し、「Dance in America」シリーズの一部として紹介された。アルビン・エイリーは、1987年から1988年にかけて、カーネギーホールで、アメリカン・ダンス・ シアターによる「The Magic of Katherine Dunham」と題した彼女へのトリビュート公演を制作した。 |

Educator and writer Katherine Dunham 1963 In 1945, Dunham opened and directed the Katherine Dunham School of Dance and Theatre near Times Square in New York City. Her dance company was provided with rent-free studio space for three years by an admirer and patron, Lee Shubert; it had an initial enrollment of 350 students. The program included courses in dance, drama, performing arts, applied skills, humanities, cultural studies, and Caribbean research. In 1947 it was expanded and granted a charter as the Katherine Dunham School of Cultural Arts. The school was managed in Dunham's absence by Syvilla Fort, one of her dancers, and thrived for about 10 years. It was considered one of the best learning centers of its type at the time. Schools inspired by it were later opened in Stockholm, Paris, and Rome by dancers who had been trained by Dunham. Her alumni included many future celebrities, such as Eartha Kitt. As a teenager, she won a scholarship to the Dunham school and later became a dancer with the company, before beginning her successful singing career. Dunham and Kitt collaborated again in the 1970s in an Equity Production of the musical Peg, based on the Irish play, Peg O' My Heart. Dunham Company member Dana McBroom-Manno was selected as a featured artist in the show, which played on the Music Fair Circuit. Others who attended her school included James Dean, Gregory Peck, Jose Ferrer, Jennifer Jones, Shelley Winters, Sidney Poitier, Shirley MacLaine and Warren Beatty. Marlon Brando frequently dropped in to play the bongo drums, and jazz musician Charles Mingus held regular jam sessions with the drummers. Known for her many innovations, Dunham developed a dance pedagogy, later named the Dunham Technique, a style of movement and exercises based in traditional African dances, to support her choreography. This won international acclaim and is now taught as a modern dance style in many dance schools. By 1957, Dunham was under severe personal strain, which was affecting her health. She decided to live for a year in relative isolation in Kyoto, Japan, where she worked on writing memoirs of her youth. The first work, entitled A Touch of Innocence: Memoirs of Childhood, was published in 1959. A continuation based on her experiences in Haiti, Island Possessed, was published in 1969. A fictional work based on her African experiences, Kasamance: A Fantasy, was published in 1974. Throughout her career, Dunham occasionally published articles about her anthropological research (sometimes under the pseudonym of Kaye Dunn) and sometimes lectured on anthropological topics at universities and scholarly societies.[27] In 1963 Dunham was commissioned to choreograph Aida at New York's Metropolitan Opera Company, with Leontyne Price in the title role. Members of Dunham's last New York Company auditioned to become members of the Met Ballet Company. Among her dancers selected were Marcia McBroom, Dana McBroom, Jean Kelly, and Jesse Oliver. The Met Ballet Company dancers studied Dunham Technique at Dunham's 42nd Street dance studio for the entire summer leading up to the season opening of Aida. Lyndon B. Johnson was in the audience for opening night. Dunham's background as an anthropologist gave the dances of the opera a new authenticity. She was also consulted on costuming for the Egyptian and Ethiopian dress. Dana McBroom-Manno still teaches Dunham Technique in New York City and is a Master of Dunham Technique. In 1964, Dunham settled in East St. Louis, and took up the post of artist-in-residence at Southern Illinois University in nearby Edwardsville. There she was able to bring anthropologists, sociologists, educational specialists, scientists, writers, musicians, and theater people together to create a liberal arts curriculum that would be a foundation for further college work. One of her fellow professors, with whom she collaborated, was architect Buckminster Fuller. The following year, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson nominated Dunham to be technical cultural adviser—a sort of cultural ambassador—to the government of Senegal in West Africa. Her mission was to help train the Senegalese National Ballet and to assist President Leopold Senghor with arrangements for the First Pan-African World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar (1965–66). Later Dunham established a second home in Senegal, and she occasionally returned there to scout for talented African musicians and dancers. In 1967, Dunham opened the Performing Arts Training Center (PATC) in East St. Louis in an effort to use the arts to combat poverty and urban unrest. The restructuring of heavy industry had caused the loss of many working-class jobs, and unemployment was high in the city. After the 1968 riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Dunham encouraged gang members in the ghetto to come to the center to use drumming and dance to vent their frustrations. The PATC teaching staff was made up of former members of Dunham's touring company, as well as local residents. While trying to help the young people in the community, Dunham was arrested. This gained international headlines and the embarrassed local police officials quickly released her. She also continued refining and teaching the Dunham Technique to transmit that knowledge to succeeding generations of dance students. She lectured every summer until her death at annual Masters' Seminars in St. Louis, which attracted dance students from around the world. She established the Katherine Dunham Centers for Arts and Humanities in East St. Louis to preserve Haitian and African instruments and artifacts from her personal collection. In 1976, Dunham was guest artist-in-residence and lecturer for Afro-American studies at the University of California, Berkeley. A photographic exhibit honoring her achievements, entitled Kaiso! Katherine Dunham, was mounted at the Women's Center on the campus. In 1978, an anthology of writings by and about her, also entitled Kaiso! Katherine Dunham, was published in a limited, numbered edition of 130 copies by the Institute for the Study of Social Change. |

教育者、作家 キャサリン・ダンハム 1963年 1945年、ダンハムはニューヨークのタイムズスクエア近くにキャサリン・ダンハム・スクール・オブ・ダンス・アンド・シアターを開校し、校長を務めまし た。彼女のダンスカンパニーは、ファンでありパトロンでもあるリー・シューベルトから3年間、スタジオを無償で提供され、当初の生徒数は350人に達しま した。 プログラムには、ダンス、演劇、舞台芸術、応用技能、人文科学、文化研究、カリブ海研究などのコースがあった。1947年に拡大し、キャサリン・ダンハム 文化芸術学校として認可を受けた。ダンハムの不在中は、ダンサーの一人であるシヴィラ・フォートが学校を運営し、約 10 年間にわたって繁栄した。当時、この学校はその種の教育機関としては最高のものの一つと評価されていた。その後、ダンハムの弟子たちによって、ストックホ ルム、パリ、ローマにも同様の学校が設立された。 卒業生には、アースア・キットなど、多くの有名人が名を連ねている。10 代の頃、ダンハム・スクールに奨学金で入学し、後に同カンパニーのダンサーとなった後、歌手として成功を収めた。ダンハムとキットは、1970 年代、アイルランドの戯曲「Peg O' My Heart」を原作としたミュージカル「Peg」のエクイティ・プロダクションで再びコラボレーションを果たした。ダンハム・カンパニーのメンバーである ダナ・マクブルーム・マノが、ミュージック・フェア・サーキットで上演されたこのショーの主演アーティストに選ばれた。 彼女の学校に通った他の著名人には、ジェームズ・ディーン、グレゴリー・ペック、ホセ・フェレール、ジェニファー・ジョーンズ、シェルリー・ウィンター ズ、シドニー・ポワチエ、シャーリー・マクレーン、ウォーレン・ベイティなどがいる。マルロン・ブランドは頻繁に訪れてボンゴドラムを演奏し、ジャズ ミュージシャンのチャールズ・ミンガスはドラマーたちと定期的なジャムセッションを開催していた。多くの革新で知られるダンハムは、自分の振り付けをサ ポートするために、アフリカの伝統舞踊をベースにした動きやエクササイズからなる「ダンハム・テクニック」というダンス教育法を開発した。これは国際的に 高い評価を受け、現在では多くのダンススクールでモダンダンスのスタイルとして教えられている。 1957年、ダンハムは個人的な問題により、健康を損なうほどの深刻なストレスに陥っていた。彼女は日本・京都で1年間、比較的孤立した生活を送ることを 決意し、若き日の回想録の執筆に専念した。最初の著作『A Touch of Innocence: Memoirs of Childhood』は1959年に刊行された。ハイチでの経験を基にした続編『Island Possessed』は1969年に刊行された。アフリカの経験を基にした小説『Kasamance: A Fantasy』は1974年に出版された。ダンハムは、そのキャリアを通じて、人類学の研究に関する記事を(時にはケイ・ダンというペンネームで)時折 発表し、大学や学術団体で人類学に関する講演も行っていた。 1963年、ダンハムはニューヨークのメトロポリタン歌劇場から、レオニー・プライスを主演に迎えた『アイーダ』の振付を依頼された。ダンハムの最後の ニューヨーク・カンパニーのメンバーは、メトロポリタン・バレエ団のメンバーになるためのオーディションを受けた。その中から、マーシャ・マクブルーム、 ダナ・マクブルーム、ジャン・ケリー、ジェシー・オリバーなどが選ばれた。メトロポリタン・バレエ団のダンサーたちは、『アイーダ』のシーズン開幕までの 夏の間、ダンハムの 42 丁目のダンススタジオでダンハム・テクニックを学んだ。初演の夜、リンドン・B・ジョンソンも観客として来場した。ダンハムの人類学者としての経歴が、こ のオペラのダンスに新たな真実味を与えた。彼女は、エジプトとエチオピアの衣装のコンサルティングも担当した。ダナ・マクブルーム・マノは、現在もニュー ヨークでダンハム・テクニックを教え、ダンハム・テクニックのマスターとして活躍している。 1964 年、ダンハムはイーストセントルイスに定住し、近くのエドワーズビルにあるサザン・イリノイ大学でアーティスト・イン・レジデンスの職に就いた。そこで彼 女は、人類学者、社会学者、教育専門家、科学者、作家、音楽家、演劇関係者などを集め、大学でのさらなる研究の基礎となるリベラルアーツのカリキュラムを 作成した。彼女が協力した同僚教授の一人は、建築家のバックミンスター・フラーだった。 翌1965年、リンドン・B・ジョンソン大統領は、ダンハムを西アフリカのセネガル政府の技術文化顧問(一種の文化大使)に任命した。彼女の任務は、セネ ガル国立バレエ団の育成を支援し、レオポルド・センゴール大統領がダカールで開催する第1回パン・アフリカ・ニグロ芸術祭(1965-66)の準備を手伝 うことだった。その後、ダンハムはセネガルに第二の故郷を築き、時折そこを訪れて、才能あるアフリカのミュージシャンやダンサーを発掘した。 1967年、ダンハムは、芸術を貧困や都市の不安と闘う手段として活用しようと、イーストセントルイスにパフォーミング・アーツ・トレーニング・センター (PATC)を設立した。重工業の再編により、多くの労働者が職を失い、この都市では失業率が非常に高かった。1968年、マーティン・ルーサー・キン グ・ジュニアの暗殺に続く暴動の後、ダンハムはゲットーのギャングのメンバーたちに、センターに来てドラムやダンスで不満を発散するよう勧めた。PATC の教師陣は、ダンハムのツアーカンパニーの元メンバーと地元住民で構成されていた。コミュニティの若者たちを助けようとしたダンハムは、逮捕された。この 事件は国際的な話題となり、恥ずかしい思いをした地元警察はすぐに彼女を釈放した。彼女は、その知識を後世のダンス学生たちに伝えるため、ダンハム・テク ニックの改良と指導を続けた。彼女は、セントルイスで毎年開催されるマスターズ・セミナーで、世界中から集まるダンス学生たちに、亡くなるまで毎年夏に講 義を行った。彼女は、自分の個人コレクションであるハイチやアフリカの楽器や工芸品を保存するため、イーストセントルイスにキャサリン・ダンハム芸術人文 科学センターを設立した。 1976 年、ダンハムはカリフォルニア大学バークレー校で客員アーティスト・イン・レジデンスおよびアフリカ系アメリカ人研究講師を務めた。彼女の功績を称える写 真展「Kaiso! Katherine Dunham」が、同大学の女性センターで開催された。1978 年、彼女に関する著作や彼女自身の著作を収録したアンソロジー『Kaiso!Katherine Dunham」が、社会変化研究所から 130 部の限定版で出版された。 |

| Dunham Technique Dunham technique is a codified dance training technique developed by Katherine Dunham in the mid 20th century. Commonly grouped into the realm of modern dance techniques, Dunham is a technical dance form developed from elements of indigenous African and Afro-Caribbean dances.[28] Strongly founded in her anthropological research in the Caribbean, Dunham technique introduces rhythm as the backbone of various widely known modern dance principles including contraction and release,[29] groundedness, fall and recover,[30] counterbalance, and many more. Using some ballet vernacular, Dunham incorporates these principles into a set of class exercises she labeled as "processions". Each procession builds on the last and focuses on conditioning the body to prepare for specific exercises that come later. Video footage of Dunham technique classes show a strong emphasis on anatomical alignment, breath, and fluidity. Dancers are frequently instructed to place weight on the balls of their feet, lengthen their lumbar and cervical spines, and breathe from the abdomen and not the chest. There is also a strong emphasis on training dancers in the practices of engaging with polyrhythms by simultaneously moving their upper and lower bodies according to different rhythmic patterns. These exercises prepare the dancers for African social and spiritual dances[31] that are practiced later in the class including the Mahi,[32] Yonvalou,[33] and Congo Paillette.[34] According to Dunham, the development of her technique came out of a need for specialized dancers to support her choreographic visions and a greater yearning for technique that "said the things that [she] wanted to say."[35] Dunham explains that while she admired the narrative quality of ballet technique, she wanted to develop a movement vocabulary that captured the essence of the Afro-Caribbean dancers she worked with during her travels.[35] In a different interview, Dunham describes her technique "as a way of life,[36]" a sentiment that seems to be shared by many of her admiring students. Many of Dunham students who attended free public classes in East St. Louis Illinois speak highly about the influence of her open technique classes and artistic presence in the city.[36] Her classes are described as a safe haven for many and some of her students even attribute their success in life to the structure and artistry of her technical institution. Dunham technique is also inviting to the influence of cultural movement languages outside of dance including karate and capoeira.[36] Dunham is still taught at widely recognized dance institutions such as The American Dance Festival and The Ailey School. |

ダンハム・テクニック ダンハム・テクニックは、20 世紀半ばにキャサリン・ダンハムによって開発された、体系化されたダンスのトレーニング手法だ。一般的にモダンダンスのテクニックの分野に分類されるダン ハムは、アフリカの先住民やアフリカ系カリブ人のダンスの要素から発展した、技術的なダンス形式だ[28]。カリブ海での人類学的研究に強く根ざしたダン ハム・テクニックは、収縮と解放[29]、接地、落下と回復[30]、カウンターバランスなど、広く知られているさまざまなモダンダンスの原則の基盤とし てリズムを取り入れている。ダンハムは、バレエの用語を一部取り入れながら、これらの原則を「プロセッション」と名付けた一連のクラス演習に組み込んだ。 各プロセッションは、前のプロセッションに基づいており、後の特定の演習に備えて身体を調整することに重点を置いている。ダンハムのテクニックのクラスを 撮影したビデオ映像では、解剖学的アライメント、呼吸、流動性が強く重視されていることがわかる。ダンサーは、足指の付け根に体重をかけ、腰と首の背骨を 伸ばし、胸ではなく腹式呼吸をするよう頻繁に指示されます。また、異なるリズムパターンに合わせて上半身と下半身を同時に動かす、ポリリズムの練習も重視 されています。これらの練習は、マヒ[31]、ヨンヴァルー[32]、コンゴ・パイエット[33] など、クラスの後半で練習するアフリカの社交ダンスやスピリチュアルダンス[34] に備えるためのものです。 ダンハムによると、彼女のテクニックは、彼女の振り付けのビジョンをサポートする専門ダンサーの必要性と、「自分が表現したいことを表現できる」テクニッ クへの強い憧れから生まれたものです。ダンハムは、バレエのテクニックの物語性を賞賛する一方で、旅先で出会ったアフリカ系カリブ海のダンサーたちの本質 を捉えた動きの語彙を開発したいと思ったと説明している。別のインタビューでは、ダンハムは自分のテクニックを「生き方」と表現しており、この考えは彼女 を尊敬する多くの生徒たちも共有しているようだ。イリノイ州イーストセントルイスで開催された無料の公開クラスに参加したダンハムの生徒の多くは、彼女の オープンなテクニックのクラスと、街での芸術的な存在感が与えた影響について高く評価している[36]。彼女のクラスは多くの人々にとって安全な避難所で あると評されており、生徒の中には、彼女的技术の教育機関の構造と芸術性のおかげで人生で成功できたとさえ言う者もいる。ダンハムのテクニックは、空手や カポエイラなど、ダンス以外の文化的な動きの言語の影響も取り入れている[36]。 ダンハムは、アメリカン・ダンス・フェスティバルやエイリー・スクールなど、広く認知されているダンス機関でも今でも教えられている。 |

| Social activism The Katherine Dunham Company toured throughout North America in the mid-1940s, performing as well in the racially segregated South. Dunham refused to hold a show in one theater after finding out that the city's black residents had not been allowed to buy tickets for the performance. On another occasion, in October 1944, after getting a rousing standing ovation in Louisville, Kentucky, she told the all-white audience that she and her company would not return because "your management will not allow people like you to sit next to people like us." She expressed a hope that time and the "war for tolerance and democracy" (this was during World War II) would bring a change.[37] One historian noted that "during the course of the tour, Dunham and the troupe had recurrent problems with racial discrimination, leading her to a posture of militancy which was to characterize her subsequent career."[38] In Hollywood, Dunham refused to sign a lucrative studio contract when the producer said she would have to replace some of her darker-skinned company members. She and her company frequently had difficulties finding adequate accommodations while on tour because in many regions of the country, black Americans were not allowed to stay at hotels. While Dunham was recognized as "unofficially" representing American cultural life in her foreign tours, she was given very little assistance of any kind by the U.S. State Department. She had incurred the displeasure of departmental officials when her company performed Southland, a ballet that dramatized the lynching of a black man in the racist American South. Its premiere performance on December 9, 1950, at the Teatro Municipal in Santiago, Chile,[39][40] generated considerable public interest in the early months of 1951.[41] The State Department was dismayed by the negative view of American society that the ballet presented to foreign audiences. As a result, Dunham would later experience some diplomatic "difficulties" on her tours. The State Department regularly subsidized other less well-known groups, but it consistently refused to support her company (even when it was entertaining U.S. Army troops), although at the same time it did not hesitate to take credit for them as "unofficial artistic and cultural representatives". |

社会活動 キャサリン・ダンハム・カンパニーは、1940年代半ばに北米をツアーし、人種差別のある南部でも公演を行った。ダンハムは、その都市の黒人住民が公演の チケットを購入することを許可されていないことを知り、ある劇場での公演を拒否した。また、1944年10月、ケンタッキー州ルイビルで熱狂的なスタン ディングオベーションを受けた後、彼女は白人だけの観客に向かって、「あなたの経営者は、あなたのような人々が私たちのような人々の隣に座ることを許さな いから、私と私のカンパニーはここには戻ってこない」と語った。彼女は、時間と「寛容と民主主義のための戦争」(これは第二次世界大戦中だった)によって 変化がもたらされることを願った[37]。ある歴史家は、「ツアー中、ダンハムと劇団は人種差別による問題を繰り返し経験し、それが彼女のその後のキャリ アを特徴づける過激な姿勢へと彼女を導いた」と記している[38]。 ハリウッドでは、プロデューサーが、肌の色が濃いカンパニーのメンバーの一部を交代させることを要求したため、ダンハムは有利なスタジオ契約への署名を拒 否した。彼女とカンパニーは、ツアー中に適切な宿泊施設を見つけるのに頻繁に困難に直面した。これは、米国の多くの地域では、アフリカ系アメリカ人はホテ ルに宿泊することが認められていなかったためだ。 ダンハムは、海外ツアーで「非公式に」アメリカの文化生活を代表する人物として認められていたが、米国国務省からはほとんど何の支援も受けなかった。彼女 のカンパニーが、人種差別的なアメリカ南部で黒人がリンチされる様子を劇化したバレエ「サウスランド」を上演したところ、国務省当局者の不興を買ってし まったのだ。1950年12月9日にチリのサンティアゴ市立劇場で行われた初演[39][40] は、1951年の初めに大きな反響を呼んだ。国務省は、このバレエが外国の観客にアメリカ社会に対する否定的な印象を与えることを懸念した。その結果、ダ ンハムはその後、ツアーでいくつかの外交上の「困難」を経験することになった。国務省は、あまり知られていない他のグループには定期的に助成金を支給して いたが、彼女のカンパニーへの支援は(米陸軍部隊の慰問公演の場合でも)一貫して拒否していた。 |

| The Afonso Arinos Law in Brazil In 1950, while visiting Brazil, Dunham and her group were refused rooms at a first-class hotel in São Paulo, the Hotel Esplanada, frequented by many American businessmen. Understanding that the fact was due to racial discrimination, she made sure the incident was publicized. The incident was widely discussed in the Brazilian press and became a hot political issue. In response, the Afonso Arinos law was passed in 1951 that made racial discrimination in publi places a felony in Brazil.[42][43][44][45][46][47] |

ブラジルのアフォンソ・アリノス法 1950年、ダンハムとその一行はブラジルを訪問中、多くのアメリカ人ビジネスマンが利用するサンパウロの一流ホテル「ホテル・エスパラーダ」に宿泊を拒 否された。この事実が人種差別によるものであると理解した彼女は、この事件を世間に公表した。この事件はブラジルのメディアで広く取り上げられ、政治的な 問題となった。これを受けて、1951年にアフォンソ・アリノス法が制定され、ブラジルで公共の場所での人種差別が犯罪とされた。[42][43] [44][45][46][47] |

| Hunger strike In 1992, at age 83, Dunham went on a highly publicized hunger strike to protest the discriminatory U.S. foreign policy against Haitian boat-people. Time reported that, "she went on a 47-day hunger strike to protest the U.S.'s forced repatriation of Haitian refugees. "My job", she said, "is to create a useful legacy."[48] During her protest, Dick Gregory led a non-stop vigil at her home, where many disparate personalities came to show their respect, such as Debbie Allen, Jonathan Demme, and Louis Farrakhan, leader of the Nation of Islam. This initiative drew international publicity to the plight of the Haitian boat-people and U.S. discrimination against them. Dunham ended her fast only after exiled Haitian president Jean-Bertrand Aristide and Jesse Jackson came to her and personally requested that she stop risking her life for this cause. In recognition of her stance, President Aristide later awarded her a medal of Haiti's highest honor. |

ハンガーストライキ 1992年、83歳のとき、ダンハムはハイチ難民に対する米国の差別的な外交政策に抗議して、大きな話題となったハンガーストライキを行った。タイム誌 は、「彼女は、ハイチ難民の強制送還に抗議して47日間のハンガーストライキを行った」と報じた。私の仕事は、有用な遺産を残すこと」と彼女は述べている [48]。彼女の抗議行動の間、ディック・グレゴリーは彼女の自宅で徹夜で徹夜祷を行い、デビー・アレン、ジョナサン・デミ、イスラム教徒団体「ネイショ ン・オブ・イスラム」の指導者ルイス・ファラカンなど、さまざまな人物が彼女への敬意を表するために訪れました。 この取り組みは、ハイチ難民の悲惨な状況と、米国による彼らに対する差別について、国際的な注目を集めた。ダンハムは、亡命中のハイチ大統領ジャン=ベル トラン・アリスティドとジェシー・ジャクソンが彼女の元を訪れ、この大義のために命を危険にさらすことをやめるよう直接懇願して初めて、ハンガーストライ キを中止した。彼女の姿勢を称え、アリスティド大統領は後に、彼女にハイチ最高の栄誉であるメダルを授与した。 |

| Personal life Dunham married Jordis McCoo, a black postal worker, in 1931, but he did not share her interests and they gradually drifted apart, finally divorcing in 1938. About that time Dunham met and began to work with John Thomas Pratt, a Canadian who had become one of America's most renowned costume and theatrical set designers. Pratt, who was white, shared Dunham's interests in African-Caribbean cultures and was happy to put his talents in her service. After he became her artistic collaborator, they became romantically involved. In the summer of 1941, after the national tour of Cabin in the Sky ended, they went to Mexico, where inter-racial marriages were less controversial than in the United States, and engaged in a commitment ceremony on 20 July, which thereafter they gave as the date of their wedding.[49] In fact, that ceremony was not recognized as a legal marriage in the United States, a point of law that would come to trouble them some years later. Katherine Dunham and John Pratt married in 1949 to adopt Marie-Christine, a French 14-month-old baby. From the beginning of their association, around 1938, Pratt designed the sets and every costume Dunham ever wore. He continued as her artistic collaborator until his death in 1986. When she was not performing, Dunham and Pratt often visited Haiti for extended stays. On one of these visits, during the late 1940s, she purchased a large property of more than seven hectares (approximately 17.3 acres) in the Carrefours suburban area of Port-au-Prince, known as Habitation Leclerc. Dunham used Habitation Leclerc as a private retreat for many years, frequently bringing members of her dance company to recuperate from the stress of touring and to work on developing new dance productions. After running it as a tourist spot, with Vodun dancing as entertainment, in the early 1960s, she sold it to a French entrepreneur in the early 1970s. In 1949, Dunham returned from international touring with her company for a brief stay in the United States, where she suffered a temporary nervous breakdown after the premature death of her beloved brother Albert. He had been a promising philosophy professor at Howard University and a protégé of Alfred North Whitehead. During this time, she developed a warm friendship with the psychologist and philosopher Erich Fromm, whom she had known in Europe. He was only one of a number of international celebrities who were Dunham's friends. In December 1951, a photo of Dunham dancing with Ismaili Muslim leader Prince Ali Khan at a private party he had hosted for her in Paris appeared in a popular magazine and fueled rumors that the two were romantically linked.[50] Both Dunham and the prince denied the suggestion. The prince was then married to actress Rita Hayworth, and Dunham was now legally married to John Pratt; a quiet ceremony in Las Vegas had taken place earlier in the year.[51] The couple had officially adopted their foster daughter, a 14-month-old girl they had found as an infant in a Roman Catholic convent nursery in Fresnes, France. Named Marie-Christine Dunham Pratt, she was their only child. Among Dunham's closest friends and colleagues was Julie Robinson, formerly a performer with the Katherine Dunham Company, and her husband, singer and later political activist Harry Belafonte. Both remained close friends of Dunham for many years, until her death. Glory Van Scott and Jean-Léon Destiné were among other former Dunham dancers who remained her lifelong friends.[52] |

私生活 ダンハムは1931年に黒人の郵便局員、ジョーディス・マックーと結婚したが、彼は彼女の興味を共有せず、2人は徐々に距離を置き、1938年に離婚し た。その頃、ダンハムは、アメリカで最も有名な衣装・舞台美術デザイナーの一人となったカナダ人、ジョン・トーマス・プラットと出会い、仕事を始めるよう になった。白人のプラットは、ダンハムと同じアフリカ・カリブ文化に興味を持ち、彼女の才能を喜んで生かそうとした。彼女の芸術的協力者となった後、2人 は恋愛関係になった。1941年の夏、全国ツアー「Cabin in the Sky」が終了した後、彼らは、人種間の結婚が米国よりもあまり問題とならなかったメキシコへ行き、7月20日に婚約式を挙げ、その日を結婚記念日と定め た[49]。実際、その式は米国では法的な結婚として認められなかったが、この法律上の問題は、数年後に2人を悩ませることになる。キャサリン・ダンハム とジョン・プラットは 1949 年に結婚し、14 ヶ月のフランス人赤ちゃん、マリー・クリスティンを養子に迎えた。2 人の付き合いが始まった 1938 年頃から、プラットはダンハムが着用するすべての衣装と舞台セットをデザインした。彼は 1986 年に亡くなるまで、彼女の芸術的な協力者として活動を続けた。 公演のない時期、ダンハムとプラットはしばしばハイチを訪れ、長期滞在していました。1940年代後半のある訪問の際、彼女はポルトープランスの郊外、カ ルフール地区に7ヘクタール(約17.3エーカー)以上の広大な土地を購入しました。ダンハムは、ハビタション・ルクレールを長年にわたり私的な隠れ家と して利用し、ダンスカンパニーのメンバーたちを頻繁に招いて、ツアーの疲れを癒やし、新しいダンス作品の制作に取り組んだ。1960年代初頭には、ブー ドゥーダンスをエンターテイメントとして提供する観光施設として運営していたが、1970年代初頭にフランスの起業家に売却した。 1949 年、ダンハムは、カンパニーとの国際ツアーから米国に一時帰国したが、最愛の兄アルバートの早すぎる死により、一時的な神経衰弱に陥った。アルバートは、 ハワード大学で有望な哲学教授であり、アルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッドの弟子だった。この間、ダンハムは、ヨーロッパで知り合った心理学者であり哲 学者であるエリック・フロムと親しい友人関係になった。フロムは、ダンハムの友人である数多くの国際的な有名人のうちの 1 人に過ぎなかった。1951年12月、ダンハムがパリでイスマイル派イスラム教徒の指導者アリ・カーン王子が主催したプライベートパーティーで踊っている 写真が人気雑誌に掲載され、2 人の恋愛説が飛び交った。[50] ダンハムと王子は、この噂を否定した。当時、王子は女優のリタ・ヘイワースと結婚しており、ダンハムはジョン・プラットと法的に結婚していた。その年の初 め、ラスベガスで静かな結婚式が挙げられていた。[51] 夫婦は、フランス・フレスヌのローマカトリックの修道院の保育所で乳児として見つけた 14 ヶ月の少女を正式に養子として迎えた。マリー・クリスティン・ダンハム・プラットと名付けられた彼女は、2 人の唯一の子供だった。 ダンハムの親しい友人や同僚には、かつてキャサリン・ダンハム・カンパニーのパフォーマーだったジュリー・ロビンソン、そして彼女の夫である歌手であり、 後に政治活動家となったハリー・ベラフォンテがいた。2人は、ダンハムが亡くなるまで長年にわたり親しい友人であり続けた。グローリー・ヴァン・スコット やジャン・レオン・デスティネも、ダンハムの生涯の友人であり続けた元ダンハム・カンパニーのダンサーたちだ。[52] |

| Death On May 21, 2006, Dunham died in her sleep from natural causes in New York City. She died at age 96.[53] |

死 2006年5月21日、ダンハムはニューヨーク市で眠りの中で自然死した。96歳だった。[53] |

| Legacy Anthropology Katherine Dunham predated, pioneered, and demonstrated new ways of doing and envisioning Anthropology six decades ahead of the discipline. In the 1970s, scholars of Anthropology such as Dell Hymes and William S. Willis began to discuss Anthropology's participation in scientific colonialism.[54] This wave continued throughout the 1990s with scholars publishing works (such as Decolonizing Anthropology: Moving Further in Anthropology for Liberation,[55] Decolonizing Methodologies,[56] and more recently, The Case for Letting Anthropology Burn[57]) that critique anthropology and the discipline's roles in colonial knowledge production and power structures. Much of the literature calls upon researchers to go beyond bureaucratic protocols to protect communities from harm, but rather use their research to benefit communities that they work with.[54] Six decades before this new wave of anthropological discourse began, Katherine Dunham's work demonstrated anthropology being used as a force for challenging racist and colonial ideologies.[54] After recovering crucial dance epistemologies relevant to people of the African diaspora during her ethnographic research, she applied anthropological knowledge toward developing her own dance pedagogy (Dunham Technique) that worked to reconcile with the legacy of colonization and racism and correct sociocultural injustices.[54] Her dance education, while offering cultural resources for dealing with the consequences and realities of living in a racist environment, also brought about feelings of hope and dignity for inspiring her students to contribute positively to their own communities, and spreading essential cultural and spiritual capital within the U.S.[54] Just like her colleague Zora Neale Hurston, Dunham's anthropology inspired the blurring of lines between creative disciplines and anthropology.[58] Early on into graduate school, Dunham was forced to choose between finishing her master's degree in anthropology and pursuing her career in dance. She describes this during an interview in 2002: "My problem—my strong drive at that time was to remain in this academic position that anthropology gave me, and at the same time continue with this strong drive for motion—rhythmic motion".[59] She ultimately chose to continue her career in dance without her master's degree in anthropology. A key reason for this choice was because she knew that through dance, her work would be able to be accessed by a wider array of audiences; more so than if she continued to limit her work within academia.[60] However, this decision did not keep her from engaging with and highly influencing the discipline for the rest of her life and beyond. As one of her biographers, Joyce Aschenbrenner, wrote: "anthropology became a life-way"[2] for Dunham. Her choreography and performances made use of a concept within Dance Anthropology called "research-to-performance".[2] Most of Dunham's works previewed many questions essential to anthropology's postmodern turn, such as critiquing understandings of modernity, interpretation, ethnocentrism, and cultural relativism.[61][62][63][64] During this time, in addition to Dunham, numerous Black women such as Zora Neal Hurston, Caroline Bond Day, Irene Diggs, and Erna Brodber were also working to transform the discipline into an anthropology of liberation: employing critical and creative cultural production.[54] Numerous scholars describe Dunham as pivotal to the fields of Dance Education, Applied Anthropology, Humanistic Anthropology, African Diasporic Anthropology and Liberatory Anthropology. Additionally, she was named one of the most influential African American anthropologists. She was a pioneer of Dance Anthropology, established methodologies of ethnochoreology, and her work gives essential historical context to current conversations and practices of decolonization within and outside of the discipline of anthropology.[54] Her legacy within Anthropology and Dance Anthropology continues to shine with each new day. |

遺産 人類学 キャサリン・ダンハムは、この学問分野が確立される 60 年も前に、人類学を行う新しい方法とビジョンを先駆けて示した。 1970年代、デル・ハイムズやウィリアム・S・ウィリスなどの人類学者は、科学的な植民地主義における人類学の関与について議論を始めました[54]。 この波は1990年代を通じて続き、学者たちは、人類学とこの分野における役割を批判する著作(『Decolonizing Anthropology: 解放のための人類学のさらなる進展[55]、脱植民地化の方法論[56]、そして最近では『人類学を燃やすべき理由』[57])を出版し、人類学とこの学 問が植民地主義的な知識生産と権力構造において果たした役割を批判した。多くの文献は、研究者がコミュニティを害から守るための官僚的なプロトコルを超 え、むしろ研究を共に働くコミュニティの利益に役立てるよう求めている。[54] この新しい人類学論議の波が始まる 60 年前に、キャサリン・ダンハムは、人種差別や植民地主義のイデオロギーに挑む力として人類学が活用されることを、自らの作品で実証した[54]。彼女は、 民族誌学的研究を通じて、アフリカのディアスポラの人々に重要なダンスの認識論を再発見し、その人類学的知識を、植民地化や人種主義の遺産と和解し、社会 文化的不公正を是正する、独自のダンス教育法(ダンハム・テクニック)の開発に応用した。[54] 彼女のダンス教育は、人種差別的な環境で生きる結果と現実に対処するための文化的資源を提供するとともに、生徒たちに希望と尊厳を感じさせ、自身のコミュ ニティにポジティブに貢献するよう鼓舞し、米国において不可欠な文化的・精神的資本を拡散する役割を果たした。[54] 彼女の同僚であるゾラ・ニール・ハーストンと同様、ダンハムの人類学は、創造的な分野と人類学の境界線を曖昧にするきっかけとなった[58]。大学院入学 当初、ダンハムは人類学の修士号を取得するか、ダンスのキャリアを追求するか、選択を迫られた。彼女は2002年のインタビューで次のように述べていま す:「私の問題——当時の強い動機は、人類学が与えてくれたこの学術的な立場を維持しつつ、同時にこの強い動きへの情熱——リズムのある動き——を続ける ことだった」。[59] 彼女は最終的に、人類学の修士号を取得せずにダンスのキャリアを続ける道を選択しました。この選択の主な理由は、ダンスを通じて、自分の作品がより幅広い 観客に届くことを知っていたからだった。学術界に限定して活動を続けるよりも、その可能性が高かったからだ。[60] しかし、この決断は、彼女がその後の人生において、この分野に関わり、大きな影響を与え続けることを妨げるものではなかった。彼女の伝記作家の一人、ジョ イス・アシェンブレンナーは次のように書いている。ダンハムにとって「人類学は生き方となった」[2]。彼女の振り付けやパフォーマンスは、ダンス人類学 における「リサーチ・トゥ・パフォーマンス」という概念を活用していた[2]。ダンハムの作品の多くは、現代性、解釈、民族中心主義、文化相対主義などの 理解に対する批判など、人類学のポストモダン的転換に欠かせない多くの疑問を先取りしていた。[61][62][63][64] この間、ダンハムに加え、ゾラ・ニール・ハーストン、キャロライン・ボンド・デイ、アイリーン・ディグス、エルナ・ブロドバーなど、多くの黒人女性たち が、批判的かつ創造的な文化生産を駆使して、この分野を解放の人類学へと変革するために活動していた。 多くの学者は、ダンハムをダンス教育、応用人類学、人文人類学、アフリカ・ディアスポラ人類学、解放人類学の分野において極めて重要な人物であると評して いる。さらに、彼女は最も影響力のあるアフリカ系アメリカ人人類学者の一人に選出された。彼女はダンス人類学の先駆者であり、エトノコレオロジーのメソド ロジーを確立し、その研究は人類学の分野内および外での脱植民地化に関する現在の議論と実践に不可欠な歴史的文脈を提供している。[54] 彼女の人類学とダンス人類学における遺産は、日々輝き続けている。 |

| Dance Anna Kisselgoff, a dance critic for The New York Times, called Dunham "a major pioneer in Black theatrical dance ... ahead of her time." "In introducing authentic African dance-movements to her company and audiences, Dunham—perhaps more than any other choreographer of the time—exploded the possibilities of modern dance expression." As one of her biographers, Joyce Aschenbrenner, wrote: "Today, it is safe to say, there is no American black dancer who has not been influenced by the Dunham Technique, unless he or she works entirely within a classical genre",[2] and the Dunham Technique is still taught to anyone who studies modern dance. The highly respected Dance magazine did a feature cover story on Dunham in August 2000 entitled "One-Woman Revolution". As Wendy Perron wrote, "Jazz dance, 'fusion,' and the search for our cultural identity all have their antecedents in Dunham's work as a dancer, choreographer, and anthropologist. She was the first American dancer to present indigenous forms on a concert stage, the first to sustain a black dance company.... She created and performed in works for stage, clubs, and Hollywood films; she started a school and a technique that continue to flourish; she fought unstintingly for racial justice." Scholar of the arts Harold Cruse wrote in 1964: "Her early and lifelong search for meaning and artistic values for black people, as well as for all peoples, has motivated, created opportunities for, and launched careers for generations of young black artists ... Afro-American dance was usually in the avant-garde of modern dance ... Dunham's entire career spans the period of the emergence of Afro-American dance as a serious art." Black writer Arthur Todd described her as "one of our national treasures". Regarding her impact and effect he wrote: "The rise of American Negro dance commenced ... when Katherine Dunham and her company skyrocketed into the Windsor Theater in New York, from Chicago in 1940, and made an indelible stamp on the dance world... Miss Dunham opened the doors that made possible the rapid upswing of this dance for the present generation." "What Dunham gave modern dance was a coherent lexicon of African and Caribbean styles of movement—a flexible torso and spine, articulated pelvis and isolation of the limbs, a polyrhythmic strategy of moving—which she integrated with techniques of ballet and modern dance." "Her mastery of body movement was considered 'phenomenal.' She was hailed for her smooth and fluent choreography and dominated a stage with what has been described as 'an unmitigating radiant force providing beauty with a feminine touch full of variety and nuance." Richard Buckle, ballet historian and critic, wrote: "Her company of magnificent dancers and musicians ... met with the success it has and that herself as explorer, thinker, inventor, organizer, and dancer should have reached a place in the estimation of the world, has done more than a million pamphlets could for the service of her people." "Dunham's European success led to considerable imitation of her work in European revues ... it is safe to say that the perspectives of concert-theatrical dance in Europe were profoundly affected by the performances of the Dunham troupe." While in Europe, she also influenced hat styles on the continent as well as spring fashion collections, featuring the Dunham line and Caribbean Rhapsody, and the Chiroteque Française made a bronze cast of her feet for a museum of important personalities." The Katherine Dunham Company became an incubator for many well known performers, including Archie Savage, Talley Beatty, Janet Collins, Lenwood Morris, Vanoye Aikens, Lucille Ellis, Pearl Reynolds, Camille Yarbrough, Lavinia Williams, and Tommy Gomez. Alvin Ailey, who stated that he first became interested in dance as a professional career after having seen a performance of the Katherine Dunham Company as a young teenager of 14 in Los Angeles, called the Dunham Technique "the closest thing to a unified Afro-American dance existing." For several years, Dunham's personal assistant and press promoter was Maya Deren, who later also became interested in Vodun and wrote The Divine Horseman: The Voodoo Gods of Haiti (1953). Deren is now considered to be a pioneer of independent American filmmaking. Dunham herself was quietly involved in both the Voodoo and Orisa communities of the Caribbean and the United States, in particular with the Lucumi tradition. Not only did Dunham shed light on the cultural value of black dance, but she clearly contributed to changing perceptions of blacks in America by showing society that as a black woman, she could be an intelligent scholar, a beautiful dancer, and a skilled choreographer. As Julia Foulkes pointed out, "Dunham's path to success lay in making high art in the United States from African and Caribbean sources, capitalizing on a heritage of dance within the African Diaspora, and raising perceptions of African American capabilities."[65] |

ダンス ニューヨーク・タイムズのダンス評論家、アンナ・キッセルゴフは、ダンハムを「黒人演劇ダンスの主要な先駆者であり、時代を先取りしていた」と評してい る。「彼女のカンパニーと観客に、本物のアフリカのダンスの動きを紹介することで、ダンハムは、おそらく当時の他のどの振付家よりも、モダンダンスの表現 の可能性を飛躍的に広げた」と。 彼女の伝記作家の一人、ジョイス・アシェンブレンナーは、「今日、ダンハム・テクニックの影響を受けていないアメリカの黒人ダンサーは、クラシックのジャ ンルに専念している人以外にはいない」と述べています[2]。ダンハム・テクニックは、今でもモダンダンスを学ぶ人たちに教えられています。 権威ある雑誌「Dance」は、2000年8月号の表紙で、ダンハムを「One-Woman Revolution(一人の女性による革命)」と題して特集した。ウェンディ・ペロンは、「ジャズダンス、『フュージョン』、そして私たちの文化的アイ デンティティの探求は、すべてダンハムのダンサー、振付家、人類学者としての活動に端を発している。彼女は、コンサートステージで先住民の舞踊を初めて披 露したアメリカ人ダンサーであり、黒人によるダンスカンパニーを初めて維持した人物でもある。彼女は舞台、クラブ、ハリウッド映画のための作品を作り、出 演した。また、現在も繁栄を続ける学校とテクニックを創設し、人種的正義のために惜しみなく闘った」と評している。 芸術学者のハロルド・クルーズは 1964 年に、「黒人、そしてすべての人々のための意味と芸術的価値を、初期から生涯にわたって探求し続けた彼女は、何世代にもわたる若い黒人アーティストたちに 刺激を与え、機会を創出し、そのキャリアを立ち上げた... アフリカ系アメリカ人のダンスは、通常、モダンダンスの前衛的な存在だった... ダンハムのキャリアは、アフリカ系アメリカ人のダンスが本格的な芸術として登場してからその全期間に及ぶ」と書いている。 黒人作家アーサー・トッドは、彼女を「私たちの国宝の一人」と表現している。彼女の影響力と効果について、彼は次のように書いている。「アメリカ黒人ダン スの台頭は、1940年にキャサリン・ダンハムと彼女のカンパニーがシカゴからニューヨークのウィンザー・シアターに躍り出て、ダンス界に消えることのな い足跡を残したことから始まった... ダンハムさんは、現在の世代にとってこのダンスの急速な隆盛を可能にした扉を開いたのだ。ダンハムがモダンダンスにもたらしたのは、アフリカやカリブ海の 動きのスタイルを統合した一貫した語彙、つまり、柔軟な胴体と背骨、関節の明確な骨盤、手足の分離、多リズム的な動きの戦略であり、彼女はそれをバレエや モダンダンスのテクニックと融合させた。「彼女の身体の動きの mastery は『現象的』と評された。滑らかで流暢な振付で称賛され、舞台を支配する『女性的なタッチに満ちた多様性とニュアンスに富んだ美しさを放つ、抑えがたい輝 き』と形容される存在だった。」 バレエ史家であり評論家のリチャード・バックルは、「彼女の素晴らしいダンサーとミュージシャンからなるカンパニーは...その成功を収め、探求者、思想 家、発明家、組織者、そしてダンサーとしての彼女自身が世界から評価される地位に到達したことは、100万冊のパンフレットよりも、彼女の人民のために大 きな貢献をした」と書いている。 ダンハムのヨーロッパでの成功は、ヨーロッパのレビューで彼女の作品を模倣する動きを大いに引き起こした... ヨーロッパのコンサート・シアター・ダンスの視点は、ダンハムの劇団による公演によって深く影響を受けたと断言しても差し支えないだろう。 ヨーロッパ滞在中は、ダンハム・ラインやカリビアン・ラプソディなどの春コレクションで、ヨーロッパの帽子スタイルにも影響を与え、チロテック・フランセーズは、著名人の足型を博物館用にブロンズで鋳造した。 キャサリン・ダンハム・カンパニーは、アーチー・サヴェージ、タリー・ビーティ、ジャネット・コリンズ、レンウッド・モリス、ヴァノエ・エイケンス、ル シール・エリス、パール・レイノルズ、カミーユ・ヤーブロー、ラヴィニア・ウィリアムズ、トミー・ゴメスなど、多くの著名なパフォーマーの育成の場となっ た。 14 歳の頃、ロサンゼルスでキャサリン・ダンハム・カンパニーの公演を観て、プロのダンサーになることを志したアルビン・エイリーは、ダンハムのテクニックを「統一されたアフリカ系アメリカ人のダンスに最も近いもの」と評している。 ダンハムの個人秘書兼広報担当は、後にブードゥー教に興味を持ち、『The Divine Horseman: The Voodoo Gods of Haiti』(1953年)を執筆したマヤ・デレンだった。デレンは現在、アメリカのインディペンデント映画界のパイオニアとみなされている。ダンハム自 身も、カリブ海地域とアメリカ合衆国のブードゥー教およびオリシャ教のコミュニティ、特にルクミの伝統にひそかに関わっていた。 ダンハムは、黒人ダンスの文化的価値に光を当てただけでなく、黒人女性としても知的な学者であり、美しいダンサーであり、熟練の振付家であるということを 社会に示すことで、アメリカにおける黒人の認識の変化に明らかに貢献した。ジュリア・フォークスが指摘したように、「ダンハムの成功の秘訣は、アフリカと カリブ海地域の文化を源流とするハイアートをアメリカで創造し、アフリカのディアスポラ(移民社会)のダンスの伝統を活かし、アフリカ系アメリカ人の能力 に対する認識を高めたことにある」[65]。 |

| Awards and honors Over the years Katherine Dunham has received scores of special awards, including more than a dozen honorary doctorates from various American universities. In 1971 she received the Heritage Award from the National Dance Association. In 1979 at Carnegie Hall, she received the Albert Schweitzer Music Award "for a life's work dedicated to music and devoted to humanity." In 1983 she was a recipient of one of the highest artistic awards in the United States, the Kennedy Center Honors. In 1986 the American Anthropological Association gave her a Distinguished Service Award. In 1987 she received the Samuel H. Scripps American Dance Festival Award, and was also inducted into the National Museum of Dance's Mr. & Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney Hall of Fame in Saratoga Springs, New York. She also received a Candace Award from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women.[66] In 1989 she was awarded a National Medal of Arts, an honor shared by only two other University of Chicago alumni, Saul Bellow and Philip Roth. Dunham has her own star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[67] In 2000 she was named one of the first one hundred of "America's Irreplaceable Dance Treasures" by the Dance Heritage Coalition. In 2002 Molefi Kete Asante included her in his book 100 Greatest African Americans.[68] In 2004 she received a Lifetime Achievement Award from Dance Teacher magazine.[69] In 2005, she was awarded "Outstanding Leadership in Dance Research" by the Congress on Research in Dance. |

受賞歴 長年にわたり、キャサリン・ダンハムは、さまざまなアメリカの大学から 12 以上の名誉博士号を含む、数多くの特別賞を受賞している。 1971 年、彼女は全米ダンス協会からヘリテージ賞を受賞した。 1979 年、カーネギーホールで、「音楽と人類に献身した生涯の功績」により、アルバート・シュヴァイツァー音楽賞を受賞した。 1983年には、アメリカで最も権威ある芸術賞の一つであるケネディ・センター・アワードを受賞しました。 1986年には、アメリカ人類学会から功労賞を受賞しました。 1987年には、サミュエル・H・スクリップス・アメリカン・ダンス・フェスティバル賞を受賞し、ニューヨーク州サラトガスプリングスにある国立ダンス博 物館のミスター&ミセス・コーネリアス・ヴァンダービルト・ホイットニー殿堂にも殿堂入りした。また、全米黒人女性100人連合からキャンディス 賞も受賞している。 1989年には、シカゴ大学卒業生として、ソール・ベローとフィリップ・ロスに次ぐ3人目となる、全米芸術勲章を授与された。 ダンハムは、セントルイス・ウォーク・オブ・フェイムに自分の星を持っている。 2000年には、ダンス・ヘリテージ・コアルティションにより、「アメリカのかけがえのないダンスの宝」の最初の100人に選ばれた。 2002年、モレフィ・ケテ・アサンテは、自身の著書『100 Greatest African Americans』に彼女を収録した。[68] 2004年、ダンス教師誌から生涯功績賞を受賞した。[69] 2005年、ダンス研究会議から「ダンス研究における卓越したリーダーシップ」賞を受賞した。 |

| Further reading Das, Joanna Dee (2017). Katherine Dunham: dance and the African diaspora. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190264871. |

さらに詳しく読む Das, Joanna Dee (2017). Katherine Dunham: dance and the African diaspora. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190264871. |

| Sources Aschenbrenner, Joyce. Katherine Dunham: Dancing A Life. US: University of Illinois Press, 2002.[ISBN missing] Chin, Elizabeth. "Katherine Dunham's Dance as Public Anthropology." ..American Anthropologist.. 112, no. 4 (December 2010): 640–642. Katherine Dunham's Dance as Public Anthropology. Chin, Elizabeth. Katherine Dunham: Recovering an Anthropological Legacy, Choreographing Ethnographic Futures. Advanced Seminar Series. Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced research Press, 2014. Biography [ISBN missing] Cruz Banks, Ojeya. "Katherine Dunham: Decolonizing Anthropology Through African American Dance Pedagogy." Transforming Anthropology 20 (2012): 159–168. Dunham, Katherine. A Touch of Innocence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994. [ISBN missing] Dunham, Katherine. Island Possessed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994 [ISBN missing] Haskins, James, Katherine Dunham. New York: Coward, McCann, & Geoghegan, 1982. [ISBN missing] "Kaiso!: Writings by and About Katherine Dunham." Katherine Dunham on dance anthropology. Video. Katherine Dunham on dance anthropology. Katherine Dunham on her anthropological films. Video. Katherine Dunham on her anthropological films Kraut, Anthea, "Between Primitivism and Diaspora: The Dance Performances of Josephine Baker, Zora Neale Hurston, and Katherine Dunham," Theatre Journal 55 (2003): 433–450. Long, Richard A., The Black Tradition in American Dance. New York: Smithmark Publications, 1995. [ISBN missing] |

出典 Aschenbrenner, Joyce. Katherine Dunham: Dancing A Life. US: University of Illinois Press, 2002. [ISBN 欠落] Chin, Elizabeth. 「Katherine Dunham's Dance as Public Anthropology」 ..American Anthropologist.. 112, no. 4 (2010年12月): 640–642. Katherine Dunham's Dance as Public Anthropology. Chin, Elizabeth. Katherine Dunham: Recovering an Anthropological Legacy, Choreographing Ethnographic Futures. Advanced Seminar Series. Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced research Press, 2014. 伝記 [ISBN なし] クルス・バンクス、オジェヤ。「キャサリン・ダンハム:アフリカ系アメリカ人のダンス教育を通じて人類学を脱植民地化する」 Transforming Anthropology 20 (2012): 159–168. ダンハム、キャサリン。A Touch of Innocence。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局、1994年。[ISBN 欠落] ダンハム、キャサリン。Island Possessed。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局、1994年 [ISBN 欠落] ハスキンス、ジェームズ、キャサリン・ダンハム。ニューヨーク:カウアード、マッキャン、ジオヘガン、1982 年。[ISBN なし] 「Kaiso!: Writings by and About Katherine Dunham(カイソ!:キャサリン・ダンハムによる、そしてキャサリン・ダンハムに関する著作)」。 キャサリン・ダンハム、ダンス人類学について。ビデオ。キャサリン・ダンハム、ダンス人類学について。 キャサリン・ダンハム、彼女の人類学映画について。ビデオ。キャサリン・ダンハム、彼女の人類学映画について クラウト、アンシア、「プリミティヴィズムとディアスポラの間:ジョセフィン・ベイカー、ゾラ・ニール・ハーストン、キャサリン・ダンハムのダンスパフォーマンス」『シアター・ジャーナル』55(2003):433-450。 ロング、リチャード A.、『アメリカン・ダンスにおけるブラックの伝統』。ニューヨーク:スミスマーク出版、1995年。[ISBN なし] |

| The Katherine Dunham Collection and the online Katherine Dunham Collection at the Library of Congress. Guide to the Photograph Collection on Katherine Dunham. Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California. Dunham Collection – Missouri History Museum Katherine Dunham Museum Archived 2013-03-03 at the Wayback Machine in East St. Louis, Illinois |

キャサリン・ダンハム・コレクションおよび米国議会図書館のオンライン・キャサリン・ダンハム・コレクション。 キャサリン・ダンハムに関する写真コレクションのガイド。特別コレクションおよびアーカイブ、カリフォルニア大学アーバイン校図書館、カリフォルニア州アーバイン。 ダンハム・コレクション – ミズーリ歴史博物館 キャサリン・ダンハム博物館 2013年3月3日にウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ、イリノイ州イーストセントルイス |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆