侍女たち

Las Meninas, 1656, por

Diego Velázquez

☆

『ラス・メニーナス』(スペイン語で「侍女たち」を意味し、発音は[las

meˈninas])は、1656年に制作された絵画である。マドリードのプラド美術館に所蔵され、スペインとポルトガルのフェリペ4世の宮廷画家であ

り、スペイン黄金時代の代表的な画家ディエゴ・ベラスケスの作品である。この作品は、その複雑で謎めいた構図が現実と幻想について疑問を投げかけ、鑑賞者

と描かれた人物たちの間に不確かな関係を生み出すことから、西洋絵画の中で最も広く分析されている作品の一つとなっている。

美術史家の F. J. サンチェス・カントンは、この絵はフェリペ 4

世の治世下のマドリード王宮アルカサルの一室を描いたものであり、スペイン宮廷で特定できる人物たちが、まるでスナップショットのように特定の瞬間を捉え

て描かれていると分析している。人物たちの中には、キャンバスから観客の方を向いている者もいれば、互いに交流している者もいる。5歳のインファンタ・マ

ルガリータ・テレサは、侍女、付き添い、ボディーガード、2人の小人、そして犬に囲まれている。そのすぐ後ろには、ベラスケスが大きなキャンバスに向かっ

て作業している姿が描かれている。ベラスケスは、絵画の空間を越えて、この絵を見る者が立つであろう場所の方を向いている。[3]

背景には鏡が置かれ、国王と王妃の上半身を映している。彼らは鑑賞者と同様に絵画空間の外側に配置されているように見えるが、一部の学者はこの像がベラス

ケスが制作中の絵画に映った反射像であると推測している。

『ラス・メニーナス』は西洋美術史上最も重要な絵画の一つとして長年認識されてきた。バロック画家ルカーチ・ジョルダーノはこれを「絵画の神学」と評し

[4]、1827年には王立美術アカデミー会長サー・トーマス・ローレンスが後任のデイヴィッド・ウィルキーへの書簡で「芸術の真の哲学」と称した。

[5]

近年では、ベラスケスの「最高傑作であり、絵画が達成し得るものを高度に自覚的かつ計算された形で示した作品であり、おそらくイーゼル絵画の可能性につい

てなされた最も鋭い考察である」と評されている。[6]

| Las Meninas (Spanish

for 'The Ladies-in-waiting'[a] pronounced [las meˈninas]) is a 1656

painting in the Museo del Prado in Madrid, by Diego Velázquez, the

leading artist in the court of King Philip IV of Spain and Portugal,

and of the Spanish Golden Age. It has become one of the most widely

analyzed works in Western painting for the way its complex and

enigmatic composition raises questions about reality and illusion, and

for the uncertain relationship it creates between the viewer and the

figures depicted. The painting is believed by the art historian F. J. Sánchez Cantón to depict a room in the Royal Alcazar of Madrid during the reign of Philip IV, and presents several figures, most identifiable from the Spanish court, captured in a particular moment as if in a snapshot.[b][2] Some of the figures look out of the canvas towards the viewer, while others interact among themselves. The five-year-old Infanta Margaret Theresa is surrounded by her entourage of maids of honour, chaperone, bodyguard, two little people and a dog. Just behind them, Velázquez portrays himself working at a large canvas. Velázquez looks outwards beyond the pictorial space to where a viewer of the painting would stand.[3] In the background there is a mirror that reflects the upper bodies of the king and queen. They appear to be placed outside the picture space in a position similar to that of the viewer, although some scholars have speculated that their image is a reflection from the painting Velázquez is shown working on. Las Meninas has long been recognised as one of the most important paintings in the history of Western art. The Baroque painter Luca Giordano said that it represents the "theology of painting",[4] and in 1827 the president of the Royal Academy of Arts Sir Thomas Lawrence described the work in a letter to his successor David Wilkie as "the true philosophy of the art".[5] More recently, it has been described as Velázquez's "supreme achievement, a highly self-conscious, calculated demonstration of what painting could achieve, and perhaps the most searching comment ever made on the possibilities of the easel painting".[6] |

『ラス・メニーナス』(スペイン語で「侍女たち」を意味し、発音は

[las

meˈninas])は、1656年に制作された絵画である。マドリードのプラド美術館に所蔵され、スペインとポルトガルのフェリペ4世の宮廷画家であ

り、スペイン黄金時代の代表的な画家ディエゴ・ベラスケスの作品である。この作品は、その複雑で謎めいた構図が現実と幻想について疑問を投げかけ、鑑賞者

と描かれた人物たちの間に不確かな関係を生み出すことから、西洋絵画の中で最も広く分析されている作品の一つとなっている。 美術史家の F. J. サンチェス・カントンは、この絵はフェリペ 4 世の治世下のマドリード王宮アルカサルの一室を描いたものであり、スペイン宮廷で特定できる人物たちが、まるでスナップショットのように特定の瞬間を捉え て描かれていると分析している。人物たちの中には、キャンバスから観客の方を向いている者もいれば、互いに交流している者もいる。5歳のインファンタ・マ ルガリータ・テレサは、侍女、付き添い、ボディーガード、2人の小人、そして犬に囲まれている。そのすぐ後ろには、ベラスケスが大きなキャンバスに向かっ て作業している姿が描かれている。ベラスケスは、絵画の空間を越えて、この絵を見る者が立つであろう場所の方を向いている。[3] 背景には鏡が置かれ、国王と王妃の上半身を映している。彼らは鑑賞者と同様に絵画空間の外側に配置されているように見えるが、一部の学者はこの像がベラス ケスが制作中の絵画に映った反射像であると推測している。 『ラス・メニーナス』は西洋美術史上最も重要な絵画の一つとして長年認識されてきた。バロック画家ルカーチ・ジョルダーノはこれを「絵画の神学」と評し [4]、1827年には王立美術アカデミー会長サー・トーマス・ローレンスが後任のデイヴィッド・ウィルキーへの書簡で「芸術の真の哲学」と称した。 [5] 近年では、ベラスケスの「最高傑作であり、絵画が達成し得るものを高度に自覚的かつ計算された形で示した作品であり、おそらくイーゼル絵画の可能性につい てなされた最も鋭い考察である」と評されている。[6] |

| Background Court of Philip IV  The Infanta Margaret Theresa (1651–1673), in mourning dress for her father in 1666, by del Mazo. The background figures include her young brother Charles II and the dwarf Maria Bárbola, also in Las Meninas. She left Spain for her marriage in Vienna the same year.[7] In 17th-century Spain, painters rarely enjoyed high social status. Painting was regarded as a craft, not an art such as poetry or music.[8] Nonetheless, Velázquez worked his way up through the ranks of the court of Philip IV, and in February 1651 was appointed palace chamberlain (aposentador mayor del palacio). The post brought him status and material reward, but its duties made heavy demands on his time. During the remaining eight years of his life, he painted only a few works, mostly portraits of the royal family.[9] When he painted Las Meninas, he had been with the royal household for 33 years. Philip IV's first wife, Elizabeth of France, died in 1644, and their only son, Balthasar Charles, died two years later. Lacking an heir, Philip married Mariana of Austria in 1649,[c] and Margaret Theresa (1651–1673) was their first child, and their only one at the time of the painting. Subsequently, she had a short-lived brother Philip Prospero (1657–1661), and then Charles (1661–1700) arrived, who succeeded to the throne as Charles II at the age of three. Velázquez painted portraits of Mariana and her children,[9] and although Philip himself resisted being portrayed in his old age he did allow Velázquez to include him in Las Meninas. In the early 1650s he gave Velázquez the Pieza Principal (main room) of the late Balthasar Charles's living quarters, by then serving as the palace museum, to use as his studio, where Las Meninas is set. Philip had his own chair in the studio and would often sit and watch Velázquez at work. Although constrained by rigid etiquette, the art-loving king seems to have had a close relationship with the painter. After Velázquez's death, Philip wrote "I am crushed" in the margin of a memorandum on the choice of his successor.[11][12] During the 1640s and 1650s, Velázquez served as both court painter and curator of Philip IV's expanding collection of European art. He seems to have been given an unusual degree of freedom in the role. He supervised the decoration and interior design of the rooms holding the most valued paintings, adding mirrors, statues and tapestries. He was also responsible for the sourcing, attribution, hanging and inventory of many of the Spanish king's paintings. By the early 1650s, Velázquez was widely respected in Spain as a connoisseur. Much of the collection of the Prado today—including works by Titian, Raphael, and Rubens—were acquired and assembled under Velázquez's curatorship.[13] |

背景 フェリペ4世の宮廷  1666年、父の喪服を着たインファンタ・マルガリータ・テレサ(1651–1673)。デル・マソ作。背景の人物には弟カルロス2世と小人マリア・バルボラが含まれる。彼女も『ラス・メニーナス』に登場する。同年、結婚のためスペインを離れウィーンへ向かった。[7] 17世紀のスペインでは、画家が社会的地位を享受することは稀だった。絵画は詩や音楽のような芸術ではなく、工芸と見なされていた。[8] それにもかかわらず、ベラスケスはフェリペ4世の宮廷で地位を上げていき、1651年2月には宮廷侍従長(アポセンタドール・マヨール・デル・パラシオ) に任命された。この職は彼に地位と物質的報酬をもたらしたが、その職務は彼の時間を大きく奪った。残りの8年間、彼が描いた作品はわずかであり、そのほと んどが王族の肖像画であった[9]。『ラス・メニーナス』を描いた時、彼は王室に仕えて33年が経過していた。 フェリペ4世の最初の妻、フランス王女エリザベスは1644年に死去し、唯一の息子バルタサール・カルロスも2年後に亡くなった。後継者を失ったフェリペ は1649年にオーストリアのマリアナと再婚した。最初の子供マルガリータ・テレサ(1651-1673)は、この絵が描かれた時点では唯一の子供であっ た。その後、彼女は短命の弟フェリペ・プロスペロ(1657–1661)を産み、続いてカルロス(1661–1700)が誕生した。彼は3歳で王位を継承 し、カルロス2世となった。ベラスケスはマリアナと子供たちの肖像画を描いた。フェリペ自身は老齢での肖像画制作を拒んだが、『ラス・メニーナス』への自 身の描写は許可した。1650年代初頭、フェリペは故バルタサール・カルロス王の居室だった「主室」(当時は宮殿博物館として使用)をベラスケスのアトリ エとして提供した。この部屋が『ラス・メニーナス』の舞台である。フェリペはアトリエに専用の椅子を置き、しばしば座ってベラスケスの作業を見守った。厳 格な礼儀作法に縛られながらも、芸術を愛する王は画家と親密な関係を築いていたようだ。ベラスケスの死後、フェリペは後継者選定に関する覚書の余白に「私 は打ちのめされた」と記している[11][12]。 1640年代から1650年代にかけて、ベラスケスは宮廷画家であると同時に、フェリペ4世が拡大を続けるヨーロッパ美術コレクションのキュレーターも務 めた。この役割において、彼は並外れた自由を与えられていたようだ。最も貴重な絵画が収蔵される部屋の装飾や内装を監督し、鏡や彫像、タペストリーを追加 した。またスペイン王の絵画の多くについて、調達、作者の特定、展示、目録作成も担当した。1650年代初頭までに、ベラスケスはスペインにおいて鑑定家 として広く尊敬される存在となっていた。今日のプラド美術館のコレクションの大部分——ティツィアーノ、ラファエロ、ルーベンスの作品を含む——は、ベラ スケスのキュレーター職の下で収集・編成されたものである。[13] |

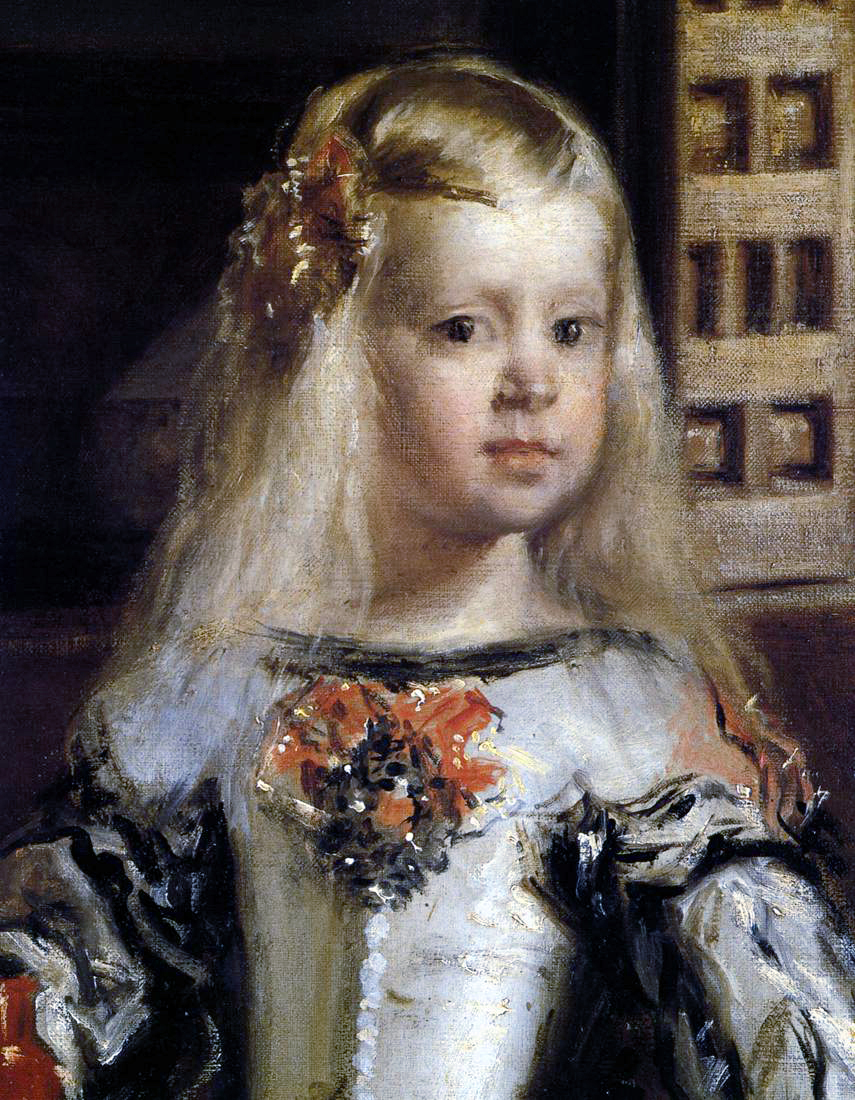

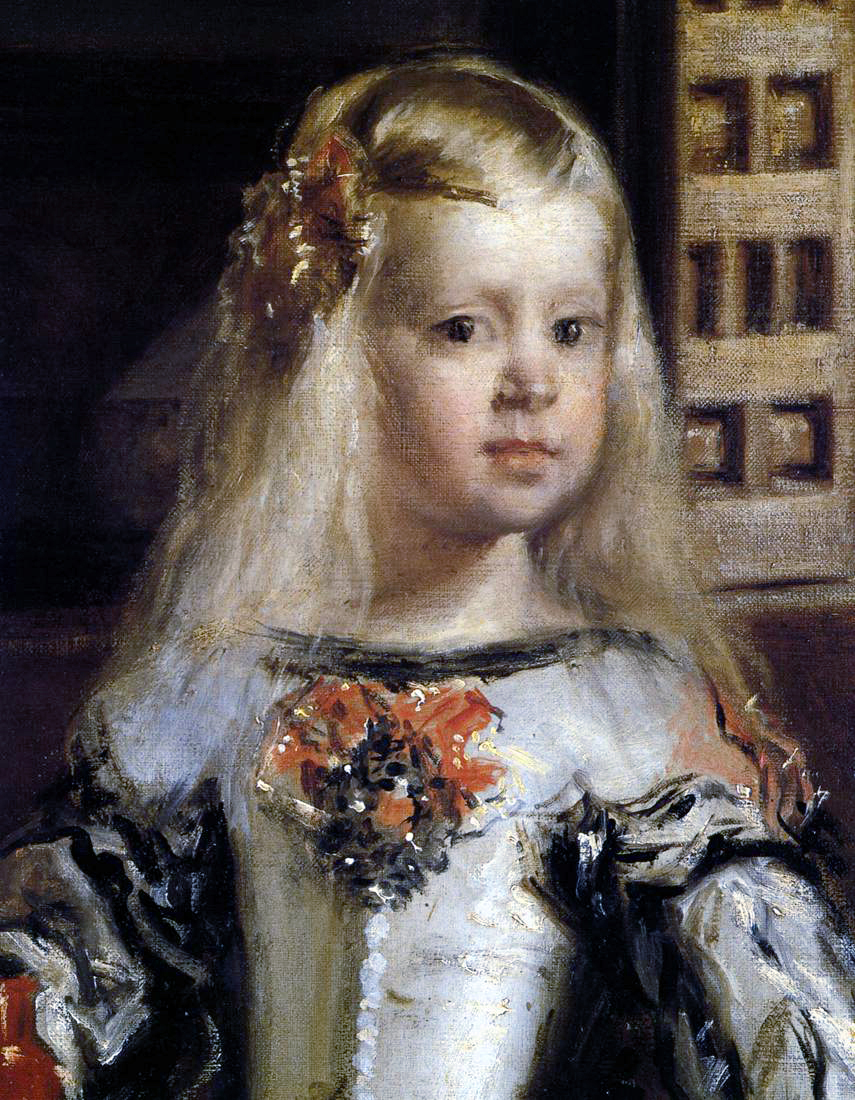

Provenance and condition Detail showing Philip IV's daughter, the Infanta Margaret Theresa. Most of her left cheek was repainted after being damaged in the fire of 1734. The painting was referred to in the earliest inventories as La Familia ("The Family").[14] Las Meninas is described in the inventory of 1666 by García de Medrano.[15] A detailed description of Las Meninas, which provides the identification of several of the figures, was published by Antonio Palomino ("the Giorgio Vasari of the Spanish Golden Age") in 1724.[3][16] Examination under infrared light reveals minor pentimenti, that is, there are traces of earlier working that the artist himself later altered. For example, at first Velázquez's own head inclined to his right rather than his left.[17] The painting has been cut down on both the left and right sides.[d] It was damaged in the 1734 fire that destroyed the Alcázar, and was restored by court painter Juan García de Miranda (1677–1749). The left cheek of the Infanta was almost completely repainted to compensate for a substantial loss of pigment.[e] After its rescue from the fire, the painting was inventoried as part of the royal collection in 1747–48, and the Infanta was misidentified as Maria Theresa, Margaret Theresa's older half-sister, an error that was repeated when the painting was inventoried at the new Madrid Royal Palace in 1772.[20] A 1794 inventory reverted to a version of the earlier title, The Family of Philip IV, which was repeated in the records of 1814. The painting entered the collection of the Museo del Prado on its foundation in 1819.[e] In 1843, the Prado catalogue listed the work for the first time as Las Meninas.[20] In recent years, the picture has suffered a loss of texture and hue. Due to exposure to pollution and crowds of visitors, the once-vivid contrasts between blue and white pigments in the costumes of the meninas have faded.[e] It was last cleaned in 1984 under the supervision of the British conservator John Brealey to remove a "yellow veil" of dust that had gathered since the previous restoration in the 19th century. The cleaning provoked, according to the art historian Federico Zeri, "furious protests, not because the picture had been damaged in any way, but because it looked different".[21][22] In addition, "[t]he Spanish press criticized Brealey at every opportunity, arguing that only someone born and raised in Spain could truly comprehend, and be allowed to handle, such an iconic piece of their culture. One day, a small riot broke out outside the room where Brealey was working".[23] However, in the opinion of the Velázquez expert José López-Rey [es], the "restoration was impeccable".[20] Due to its size, importance and value, the painting is not lent out for exhibition.[f] |

来歴と状態 フェリペ4世の娘、マルガリータ・テレサ王女の細部。1734年の火災で損傷した左頬の大部分は再塗装されている。 この絵画は初期の目録では『ラ・ファミリア』(家族)と呼ばれていた。[14] ガルシア・デ・メドラノによる1666年の目録には『ラス・メニーナス』として記載されている。[15] 『ラス・メニーナス』の詳細な解説(複数の人物の同定を含む)は、アントニオ・パロミノ(「スペイン黄金時代のジョルジョ・ヴァザーリ」)によって 1724年に発表された。[3][16] 赤外線検査により、軽微なペンティメンティ(修正痕)が確認されている。つまり、画家自身が後に修正した初期の作業痕跡が残っている。例えば、当初ベラス ケスの自身の頭部は左ではなく右を向いていた。[17] この絵画は左右両端が切り詰められている。[d] 1734年のアルカサル焼失火災で損傷を受け、宮廷画家フアン・ガルシア・デ・ミランダ(1677–1749)によって修復された。インファンタの左頬 は、色素の大幅な損失を補うためほぼ完全に塗り直されている。[e] 火災からの救出後、1747年から48年にかけて王室コレクションの一部として目録に登録された際、インファンタはマリア・テレサ(マルガリータ・テレサ の異母姉)と誤認された。この誤りは1772年に新マドリード王宮で目録作成時にも繰り返された。[20] 1794年の目録では以前の題名『フェリペ4世の家族』に戻され、1814年の記録でも同様の記載がなされた。この絵画は1819年のプラド美術館創設時 に同館の所蔵品となった。[e] 1843年、プラド美術館のカタログで初めて『ラス・メニーナス』として記載された。[20] 近年、この絵画は質感と色調の苦悩を呈している。大気汚染と多数の観覧客に晒された結果、メニーナたちの衣装に見られた青と白の鮮やかな対比は失われた。 [e] 最後の修復は1984年、英国の保存修復家ジョン・ブリーリーの監督下で行われ、19世紀の修復以降に堆積した「黄ばんだベール」状の埃を除去した。美術 史家フェデリコ・ゼリによれば、この洗浄作業は「絵画が何らかの損傷を受けたからではなく、見た目が異なるという理由で激しい抗議を引き起こした」とい う。[21][22] さらに「スペインのマスコミはあらゆる機会を利用してブレアリーを批判し、自国の文化におけるこのような象徴的な作品を真に理解し、扱うことを許されるの はスペインで生まれ育った者だけだと主張した。ある日、ブレリーが作業していた部屋の外部で小規模な暴動が発生した」[23]。しかしベラスケス研究の専 門家ホセ・ロペス=レイ[es]によれば、「修復作業は完璧であった」[20]。その大きさ、重要性、価値ゆえに、この絵画は展示のために貸し出されるこ とはない[f]。 |

| Painting materials A thorough technical investigation including a pigment analysis was conducted around 1981 in the Museo del Prado.[25] The analysis revealed the usual pigments of the Baroque period frequently used by Velázquez in his other paintings. The main pigments used for this painting were lead white, azurite (for the skirt of the kneeling menina), vermilion and red lake, ochres and carbon blacks.[26] |

絵画材料 1981年頃、プラド美術館において顔料分析を含む徹底的な技術調査が行われた[25]。分析の結果、ベラスケスが他の作品で頻繁に使用したバロック時代 の典型的な顔料が確認された。本作に使用された主な顔料は鉛白、青銅鉱(ひざまずくメニーナのスカート部分)、朱色と赤湖、黄土、そしてカーボンブラック である[26]。 |

| Description Subjects  Key to the people represented: see text Las Meninas is set in Velázquez's studio in Philip IV's alcázar palace in Madrid.[27] The high-ceilinged room is presented, in the words of Silvio Gaggi, as "a simple box that could be divided into a perspective grid with a single vanishing point".[28] In the centre of the foreground stands the Infanta Margaret Theresa (1). The five-year-old infanta, who later married Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, was at this point Philip and Mariana's only surviving child.[g] She is attended by two ladies-in-waiting, or meninas: Doña Isabel de Velasco [Wikidata] (2), who is poised to curtsy to the princess, and Doña María Agustina Sarmiento de Sotomayor [es] (3), who kneels before Margaret Theresa, offering her a drink from a red cup, or búcaro, that she holds on a golden tray.[29] To the right of the Infanta are two dwarves: the achondroplastic Austrian Mari Bárbola (4),[29] and the Italian Nicolás Pertusato [es] (5), who playfully tries to rouse a sleepy mastiff with his foot. The dog is thought to be descended from two mastiffs from Lyme Hall in Cheshire, given to Philip III in 1604 by James I of England.[h] Doña Marcela de Ulloa [es] (6), the princess's chaperone, stands behind them, dressed in mourning and talking to a bodyguard (or guardadamas) (7), Diego Ruiz Azcona.[29]  Detail showing Don José Nieto Velázquez at the door in the background of the painting To the rear and at right stands Don José Nieto Velázquez (8)—the queen's chamberlain during the 1650s, and head of the royal tapestry works—who may have been a relative of the artist. Nieto is shown standing but in pause, with his right knee bent and his feet on different steps. As the art critic Harriet Stone observes, it is uncertain whether he is "coming or going".[31] He is rendered in silhouette and appears to hold open a curtain on a short flight of stairs, with an unclear wall or space behind. Both this backlight and the open doorway reveal space behind: in the words of the art historian Analisa Leppanen, they lure "our eyes inescapably into the depths".[32] The royal couple's reflection pushes in the opposite direction, forward into the picture space. The vanishing point of the perspective is in the doorway, as can be shown by extending the line of the meeting of wall and ceiling on the right. Nieto is seen only by the king and queen, who share the viewer's point of view, and not by the figures in the foreground. In the footnotes of Joel Snyder's article, the author recognizes that Nieto is the queen's attendant and was required to be at hand to open and close doors for her. Snyder suggests that Nieto appears in the doorway so that the king and queen might depart. In the context of the painting, Snyder argues that the scene is the end of the royal couple's sitting for Velázquez and they are preparing to exit, explaining that is "why the menina to the right of the Infanta begins to curtsy".[33] Velázquez (9) is pictured to the left of the scene, looking outward past a large canvas supported by an easel.[34] On his chest is the red cross of the Order of Santiago, which he did not receive until 1659, three years after the painting was completed. According to Palomino, Philip ordered this to be added after Velázquez's death, "and some say that his Majesty himself painted it".[35] From the painter's belt hang the symbolic keys of his court offices.[36] A mirror on the back wall reflects the upper bodies and heads of two figures identified from other paintings, and by Palomino, as King Philip IV (10) and Queen Mariana (11). The most common assumption is that the reflection shows the couple in the pose they are holding for Velázquez as he paints them, while their daughter watches; and that the painting therefore shows their view of the scene.[37] |

説明 主題  描かれた人びとの解説:本文参照 『ラス・メニーナス』は、マドリードのアルカサル宮殿内にあるフェリペ4世の居室、ベラスケスのアトリエを舞台としている[27]。シルヴィオ・ガッジの 言葉を借りれば、この天井の高い部屋は「単一の消失点を持つ遠近法グリッドに分割可能な単純な箱」として描かれている。[28] 前景中央にはマリア・テレサ王女(1)が立つ。後に神聖ローマ皇帝レオポルト1世と結婚するこの5歳の王女は、当時フェリペとマリアナ夫妻の唯一の生存子 であった。[g] 彼女には二人の侍女、すなわちメニーニャが付き添っている。ドニャ・イサベル・デ・ベラスコ[ウィキデータ](2)は王女に礼をする姿勢で待機し、ド ニャ・マリア・アグスティナ・サルミエント・デ・ソトマヨール[es](3)はマルガリータ・テレサの前に跪き、金色のトレイに乗せた赤い杯(ブカロ)か ら飲み物を差し出している。[29] インファンタの右側には二人の小人(ドワーフ)がいる。軟骨無形成症のオーストリア人マリ・バルボラ(4)[29]と、眠そうなマスティフ犬を足で起こそ うと戯れるイタリア人ニコラス・ペルツァート[es](5)だ。この犬は、1604年にイングランドのジェームズ1世がフェリペ3世に贈ったチェシャー州 ライム・ホールの2頭の獒犬の子孫と考えられている。[h] プリンセスの付き添い役であるドニャ・マルセラ・デ・ウジョア[es](6)が、喪服を着て彼らの後ろに立ち、護衛(またはガードアダマス)(7)である ディエゴ・ルイス・アスコナと話している。[29]  背景の扉付近に立つドン・ホセ・ニエト・ベラスケスの細部 後方右側に立つのはドン・ホセ・ニエト・ベラスケス(8)だ。1650年代の女王侍従長であり、王室タペストリー工房の責任者であった人物で、画家の親族 だった可能性がある。ニエトは立ち止まった姿勢で描かれており、右膝を曲げ、足を異なる段に置いている。美術評論家ハリエット・ストーンが指摘するよう に、彼が「入ってくるのか出ていくのか」は定かでない[31]。シルエットで描かれた彼は、短い階段のカーテンを開けているように見え、背後には不明瞭な 壁か空間が広がる。この逆光と開かれた戸口は共に背後の空間を露わにし、美術史家アナリサ・レッパネンが言うように「我々の視線を逃れようなく奥へと誘 う」のである。[32] 王室夫妻の反射像は逆に、画面空間へと押し出される。遠近法の消失点は扉口にあり、右側の壁と天井の接線延長線で示せる。ニエトは、前景の人物たちには見 えず、鑑賞者と同じ視点を持つ国王と王妃のみに認識される。ジョエル・スナイダーの論文の脚注で、著者はニエトが王妃の侍女であり、王妃のために扉を開閉 する役割を担っていたと認めている。スナイダーは、国王と王妃が退出できるよう、ニエトが戸口に現れたと示唆している。スナイダーは絵画の文脈において、 この場面は王室夫妻がベラスケスの肖像画制作を終え退出準備をしている最中だと論じ、「だからこそ王女の右側にいる侍女が礼を始めるのだ」と説明してい る。[33] ベラスケス(9)は場面の左側に描かれ、イーゼルに立てられた大きなキャンバス越しに外を見ている。[34] 彼の胸にはサンティアゴ騎士団の赤い十字章が掲げられているが、これは絵画完成から3年後の1659年に授与されたものである。パロミノによれば、フェリ ペはベラスケスの死後にこれを追加するよう命じ、「陛下自らが描いたという説もある」[35]。画家のベルトからは宮廷職務を象徴する鍵がぶら下がってい る。[36] 後壁の鏡には、他作品やパロミノの記述からフェリペ4世(10)とマリアナ王妃(11)と特定される二人の上半身と頭部が映っている。最も一般的な解釈で は、この反射像はベラスケスが二人を描いている間、娘が見守る中で彼らがとったポーズを示しており、したがってこの絵は彼らの視点から見た情景を描いてい るとされる。[37] |

Detail of the mirror hung on the back wall, showing the reflected images of Philip IV and his wife, Mariana of Austria Of the nine figures depicted, five are looking directly out at the royal couple or the viewer. Their glances, along with the king and queen's reflection, affirm the royal couple's presence outside the painted space.[31] Alternatively, art historians H. W. Janson and Joel Snyder following Antonio Palomino suggest that the image of the king and queen is a reflection from Velázquez's canvas, the front of which is obscured from the viewer.[38][39] Other writers say the canvas Velázquez is shown working on is unusually large for one of his portraits, and note that it is about the same size as Las Meninas. The painting contains the only known double portrait of the royal couple painted by the artist.[40] The point of view of the picture is approximately that of the royal couple, though this has been widely debated. Many critics suppose that the scene is viewed by the king and queen as they pose for a double portrait, while the Infanta and her companions are present only to make the process more enjoyable.[41] Ernst Gombrich suggested that the picture might have been the sitters' idea: Perhaps the princess was brought into the royal presence to relieve the boredom of the sitting and the King or the Queen remarked to Velazquez that here was a worthy subject for his brush. The words spoken by the sovereign are always treated as a command and so we may owe this masterpiece to a passing wish which only Velazquez was able to turn into reality.[42] No single theory, however, has found universal agreement.[43] Leo Steinberg suggests that the King and Queen are to the left of the viewer and the reflection in the mirror is that of the canvas, a portrait of the king and queen.[44] Clark suggests that the work comprises a scene where the ladies-in-waiting are attempting to cajole the Infanta Doña Margarita to pose with her mother and father. In his 1960 book Looking at Pictures, Clark writes: Our first feeling is of being there. We are standing just to the right of the King and Queen, whose reflections we can see in the distant mirror, looking down an austere room in the Alcázar (hung with del Mazo's copies of Rubens) and watching a familiar situation. The Infanta Doña Margarita doesn't want to pose...She is now five years old, and she has had enough. [It is] an enormous picture, so big that it stands on the floor, in which she is going to appear with her parents; and somehow the Infanta must be persuaded. Her ladies-in-waiting, known by the Portuguese name of meninas... are doing their best to cajole her, and have brought her dwarves, Maribarbola and Nicolasito, to amuse her. But in fact they alarm her almost as much as they alarm us.[45] The back wall of the room is in shadow and hung with rows of paintings, including one of a series of scenes from Ovid's Metamorphoses by Rubens, and copies, by Velázquez's son-in-law and principal assistant del Mazo, of works by Jacob Jordaens.[27] The paintings are shown in the exact positions recorded in an inventory taken around this time.[34] The wall to the right is hung with a grid of eight smaller paintings, visible mainly as frames owing to their angle from the viewer.[31] They can be identified from the inventory as more Mazo copies of paintings from the Rubens Ovid series, though only two of the subjects can be seen.[27] The paintings are recognized as representing Minerva Punishing Arachne and Apollo's Victory Over Marsyas. Both stories involve Minerva, the goddess of wisdom and patron of the arts. These two legends are both stories of mortals challenging gods and the dreadful consequences. One scholar points out that the legend dealing with two women, Minerva and Arachne, is on the same side of the mirror as the queen's reflection while the male legend, involving the god Apollo and the satyr Marsyas, is on the side of the king.[46] |

後壁に掛けられた鏡の細部。フィリップ4世とその妻マリアナ・デ・オーストリアの映し出された姿を示す。 描かれた9人の人物のうち、5人は王妃夫妻または鑑賞者の方をまっすぐ見ている。彼らの視線と、王と王妃の反射像は、王妃夫妻が絵画空間の外に存在するこ とを裏付けている。[31] 一方、美術史家のH・W・ヤンソンとジョエル・スナイダーはアントニオ・パロミーノの説に従い、王と王妃の像はベラスケスのキャンバスに映った反射であ り、その表側は鑑賞者からは見えないと主張している。[38][39] 他の研究者は、ベラスケスが制作中のキャンバスが彼の肖像画としては異常に大きく、『ラス・メニーナス』とほぼ同サイズだと指摘する。この絵画は、同画家 が描いた唯一の既知の王室夫妻の二重肖像画である。[40] 絵画の視点は王室夫妻の視点に近いが、これについては広く議論されている。多くの批評家は、この場面は二重肖像画のポーズを取る王と王妃の視点で描かれて おり、王女と侍女たちは単にその過程を楽しくするための存在だと推測している。[41] エルンスト・ゴンブリッチは、この絵はモデルたちのアイデアだったのではないかと示唆している。 おそらく、王女は、退屈な座りを和らげるために王の御前に連れてこられたのだろう。そして、王または王妃がベラスケスに、ここに彼の筆にふさわしい題材が いると指摘したのだ。君主の発言は常に命令として扱われるため、この傑作は、ベラスケスだけが実現できた、つかの間の願いに負っているのかもしれない。 [42] しかし、どの説も普遍的な合意を得ているわけではない。[43] レオ・スタインバーグは、王と王妃は鑑賞者の左側にいて、鏡に映っているのはキャンバス、つまり王と王妃の肖像画だと示唆している。[44] クラークは、この作品は、侍女たちがインファンタ・ドニャ・マルガリータに、母親と父親と一緒にポーズをとるよう説得しようとしている場面で構成されてい ると示唆している。1960年に出版された著書『Looking at Pictures』の中で、クラークは次のように述べている。 私たちの最初の印象は、その場にいるような感覚だ。私たちは、遠くの鏡に映っている王と王妃のすぐ右側に立っており、アルカサル(デル・マソのルーベンス の複製画が飾られている)の厳粛な部屋を見下ろし、見慣れた光景を見ている。インファンタ・ドニャ・マルガリータはポーズをとろうとしない... 彼女は五歳になり、もううんざりしている。巨大な絵――床に立つほど大きい――に両親と共に写るのだ。どうにかして王女を説得しなければならない。ポルト ガル語で「メニーニャス」と呼ばれる侍女たちは…彼女をなだめようと必死で、娯楽として小人のマリバルボラとニコラシトを連れてきた。だが実際、彼女たち は私たちを怖がらせるのとほぼ同じくらい、彼女自身をも怖がらせている。[45] 部屋の奥の壁は影に覆われ、絵画が列をなして掛けられている。ルーベンスによるオウィディウスの『変身物語』の一連の場面を描いた作品や、ベラスケスの娘 婿であり主要な助手であるデル・マソによるヤコブ・ヨルダーンスの作品の複製などが含まれている。[27] これらの絵画は、この頃に作成された目録に記録された正確な位置に展示されている。[34] 右側の壁には八点の小さな絵画が格子状に掛けられているが、鑑賞者からの角度の関係で主に額縁部分しか見えない。[31] 目録から、これらはルベンスのオウィディウス連作の複製であるデル・マソの作品と特定できるが、主題が確認できるのは二点のみである。[27] これらの絵画は『ミネルヴァがアラクネを罰する』と『アポロンがマルシアスに勝利する』を描いたものと認識されている。両物語とも知恵の女神であり芸術の 守護神であるミネルヴァが関わる。これらは神々に挑んだ人間たちの悲劇的な結末を描く伝説だ。ある研究者は、ミネルヴァとアラクネという二人の女性を扱っ た伝説が女王の鏡像と同じ側に、アポロンとサテュロス・マルシアスという男性伝説が王の側に配置されている点を指摘している。[46] |

| Composition The painted surface is divided into quarters horizontally and sevenths vertically; this grid is used to organise the elaborate grouping of characters, and was a common device at the time.[47] Velázquez presents nine figures—eleven if the king and queen's reflected images are included—yet they occupy only the lower half of the canvas.[48] According to López-Rey, the painting has three focal points: the Infanta Margaret Theresa, the self-portrait and the half-length reflected images of King Philip IV and Queen Mariana. In 1960, Clark observed that the success of the composition is a result first and foremost of the accurate handling of light and shade: Each focal point involves us in a new set of relations; and to paint a complex group like the Meninas, the painter must carry in his head a single consistent scale of relations which he can apply throughout. He may use all kinds of devices to help him do this—perspective is one of them—but ultimately the truth about a complete visual impression depends on one thing, truth of tone. Drawing may be summary, colours drab, but if the relations of tone are true, the picture will hold.[47] However, the focal points are widely debated. According to Leo Steinberg the painting's orthogonals are intentionally disguised so that the picture's focal center shifts. Similar to Lopez-Rey, he describes three foci. The man in the doorway, however, is the vanishing point. More specifically, the crook of his arm is where the orthogonals of the windows and lights of the ceiling meet.[49] Depth and dimension are rendered by the use of linear perspective, by the overlapping of the layers of shapes, and in particular, as stated by Clark, through the use of tone. This compositional element operates within the picture in a number of ways. First, there is the appearance of natural light within the painted room and beyond it. The pictorial space in the midground and foreground is lit from two sources: by thin shafts of light from the open door, and by broad streams coming through the window to the right.[34] The 20th-century French philosopher and cultural critic Michel Foucault observed that the light from the window illuminates both the studio foreground and the unrepresented area in front of it, in which the king, the queen, and the viewer are presumed to be situated.[50] For José Ortega y Gasset, light divides the scene into three distinct parts, with foreground and background planes strongly illuminated, between which a darkened intermediate space includes silhouetted figures.[51] Velázquez uses this light not only to add volume and definition to each form but also to define the focal points of the painting. As the light streams from the right it brightly glints on the braid and golden hair of the female little person, who is nearest the light source. But because her face is turned from the light, and in shadow, its tonality does not make it a point of particular interest. Similarly, the light glances obliquely on the cheek of the lady-in-waiting near her, but not on her facial features. Much of her lightly coloured dress is dimmed by shadow. The Infanta, however, stands in full illumination, and with her face turned towards the light source, even though her gaze is not. Her face is framed by the pale gossamer of her hair, setting her apart from everything else in the picture. The light models the volumetric geometry of her form, defining the conic nature of a small torso bound rigidly into a corset and stiffened bodice, and the panniered skirt extending around her like an oval candy-box, casting its own deep shadow which, by its sharp contrast with the bright brocade, both emphasises and locates the small figure as the main point of attention.[52] |

構図 描かれた画面は水平方向に4分割され、垂直方向に7分割されている。このグリッドは複雑な人物配置を整理するために用いられており、当時よく使われた手法 であった[47]。ベラスケスは9人の人物を描いている(王と王妃の反射像を含めれば11人となる)が、それらはキャンバスの下半分にしか配置されていな い。[48] ロペス=レイによれば、この絵画には三つの焦点がある。マリアナ王女、自画像、そしてフィリップ4世とマリアナ王妃の半身像が映る鏡像である。1960年、クラークは構図の成功はまず何よりも光と影の正確な扱いによるものだと指摘した: それぞれの焦点が、新たな一連の関係性へと我々を引き込む。そして『メニーナス』のような複雑な集団を描くには、画家は頭の中で、作品全体に適用できる単 一で一貫した関係性の尺度を保持していなければならない。その実現のために、あらゆる手法、例えば遠近法などを用いることは可能だが、最終的には、完全な 視覚的印象の真実性は、トーンの真実性という一点に依存する。デッサンは簡略で、色彩は単調であっても、トーンの関係が真実であれば、その絵は成立するの だ。[47] しかし、焦点についてはさまざまな議論がある。レオ・スタインバーグによれば、この絵画の直交線は意図的に偽装されており、それによって絵の焦点がずれる という。ロペス・レイと同様に、彼は 3 つの焦点について述べている。しかし、戸口にいる男性が消失点である。より具体的には、彼の腕の曲がり部分が、窓と天井の照明の垂直線が交わる点である。 奥行きと次元は、線遠近法、形の層の重なり、そして特にクラークが述べているように、トーンの使用によって表現されている。この構図的要素は、絵画の中で さまざまな形で機能している。第一に、描かれた部屋とその奥に自然光が差し込む様子だ。中景と前景の絵画空間は二つの光源で照らされている。開いた扉から 差し込む細い光の筋と、右側の窓から注ぐ広い光の流れである。[34] 20世紀のフランス人哲学者・文化批評家ミシェル・フーコーは、窓からの光がアトリエの前景と、その前に描かれていない領域(王、王妃、そして鑑賞者が位 置すると想定される領域)の両方を照らしていると指摘した。[50] ホセ・オルテガ・イ・ガセットによれば、光は場面を三つの明確な部分に分割する。前景と背景の平面は強く照らされ、その中間には暗く影を落とした空間があ り、そこにシルエット状の人物が配置されている。[51] ベラスケスは、この光を用いて各形態に立体感と輪郭を与えるだけでなく、絵画の焦点も定義している。光が右側から差し込むため、光源に最も近い小人役の女 性の編み込みと金髪には明るい光が反射する。しかし彼女の顔は光源から背を向けて影になっているため、その明暗は特に注目すべき点とはならない。同様に、 彼女のそばにいる侍女の頬にも斜めに光が当たるが、顔の輪郭には当たらない。淡い色のドレスの大部分は影に覆われている。しかし王女は、視線は向いていな いものの、顔を光源に向けて完全に照らされている。彼女の顔は淡い絹のような髪に縁取られ、絵の中の他の全てから際立っている。光は彼女の体の立体的な輪 郭を浮き彫りにし、コルセットと硬いボディスに締め上げられた小さな胴体の円錐形を定義する。楕円形のキャンディ箱のように広がるパニエ付きスカートは、 鮮やかな錦織との鋭い対比によって深い影を落とし、その影自体が小さな姿を強調し、注目の主たる点として位置づけている。[52] |

Detail of Doña María de Sotomayor, showing Velázquez's free brushwork on her dress Velázquez further emphasises the Infanta by his positioning and lighting of her maids of honour, who are set opposite one another: before and behind the Infanta. The maid on the viewer's left is given a brightly lit profile, while her sleeve creates a diagonal. Her opposite figure creates a broader but less defined reflection of her attention, making a diagonal space between them, in which their charge stands protected.[i] A further internal diagonal passes through the space occupied by the Infanta. There is a similar connection between the female little person and the figure of Velázquez himself, both of whom look towards the viewer from similar angles, creating a visual tension. The face of Velázquez is dimly lit by light that is reflected, rather than direct. For this reason his features, though not as sharply defined, are more visible than those of the little person who is much nearer the light source. This appearance of a total face, full-on to the viewer, draws the attention, and its importance is marked, tonally, by the contrasting frame of dark hair, the light on the hand and brush, and the skilfully placed triangle of light on the artist's sleeve, pointing directly to the face.[53] The mirror is a perfectly defined unbroken pale rectangle within a broad black rectangle. A clear geometric shape, like a lit face, draws the attention of the viewer more than a broken geometric shape such as the door, or a shadowed or oblique face such as that of the little person in the foreground or that of the man in the background. The viewer cannot distinguish the features of the king and queen, but in the opalescent sheen of the mirror's surface, the glowing ovals are plainly turned directly to the viewer. Jonathan Miller pointed out that apart from "adding suggestive gleams at the bevelled edges, the most important way the mirror betrays its identity is by disclosing imagery whose brightness is so inconsistent with the dimness of the surrounding wall that it can only have been borrowed, by reflection, from the strongly illuminated figures of the King and Queen".[54] As the maids of honour are reflected in each other, so too do the king and queen have their doubles within the painting, in the dimly lit forms of the chaperone and guard, the two who serve and care for their daughter. The positioning of these figures sets up a pattern, one man, a couple, one man, a couple, and while the outer figures are nearer the viewer than the others, they all occupy the same horizontal band on the picture's surface.[53] Adding to the inner complexities of the picture is the male little person in the foreground, whose raised hand echoes the gesture of the figure in the background, while his playful demeanour, and distraction from the central action, are in complete contrast with it. The informality of his pose, his shadowed profile, and his dark hair all serve to make him a mirror image to the kneeling attendant of the Infanta. However, the painter has set him forward of the light streaming through the window, and so minimised the contrast of tone on this foreground figure.[53] Despite certain spatial ambiguities this is the painter's most thoroughly rendered architectural space, and the only one in which a ceiling is shown. According to López-Rey, in no other composition did Velázquez so dramatically lead the eye to areas beyond the viewer's sight: both the canvas he is seen painting, and the space beyond the frame where the king and queen stand can only be imagined.[52] The bareness of the dark ceiling, the back of Velázquez's canvas, and the strict geometry of framed paintings contrast with the animated, brilliantly lit and sumptuously painted foreground entourage.[53] Stone writes: We cannot take in all the figures of the painting in one glance. Not only do the life-size proportions of the painting preclude such an appreciation, but also the fact that the heads of the figures are turned in different directions means that our gaze is deflected. The painting communicates through images which, in order to be understood, must thus be considered in sequence, one after the other, in the context of a history that is still unfolding. It is a history that is still unframed, even in this painting composed of frames within frames.[55] According to Kahr, the composition could have been influenced by the traditional Dutch Gallery Pictures such as those by Frans Francken the Younger, Willem van Haecht, or David Teniers the Younger. Teniers' work was owned by Philip IV and would have been known by Velázquez. Like Las Meninas, they often depict formal visits by important collectors or rulers, a common occurrence, and "show a room with a series of windows dominating one side wall and paintings hung between the windows as well as on the other walls". Gallery Portraits were also used to glorify the artist as well as royalty or members of the higher classes, as may have been Velázquez's intention with this work.[56] |

ドニャ・マリア・デ・ソトマヨールの細部。ドレスにベラスケスの自由な筆致が表れている ベラスケスはさらに、侍女たちの配置と照明によって王女を強調している。侍女たちは互いに向き合うように配置されている――王女の前に一人、後ろに一人 だ。鑑賞者左側の侍女は明るく照らされた横顔で、その袖が斜線を描く。対峙する侍女はより広いが輪郭の曖昧な姿で、彼女の注意を反映し、二人の間に斜めの 空間を形成している。その空間に守られるように王女が立つのだ。 さらに内部対角線が、王女が占める空間を通っている。小人役の女性とベラスケス自身にも同様の関連性があり、両者とも似た角度から鑑賞者を見つめ、視覚的 な緊張感を生み出している。ベラスケスの顔は、直接光ではなく反射光でぼんやりと照らされている。このため彼の顔立ちは、光源にずっと近い小人役よりも、 輪郭ははっきりしないものの、より視認しやすい。この鑑賞者に向かって正面を向いた完全な顔の表現は視線を惹きつけ、その重要性は、対照的な黒髪のフレー ム、手と筆に当たる光、そして芸術家の袖に巧みに配置された三角形の光によって強調されている。この光の三角形は直接的に顔へと導いている。[53] 鏡は、広い黒の長方形の中に、完璧に定義された、途切れることのない淡い長方形として描かれている。明瞭な幾何学的形状は、照らされた顔のように、ドアの ような断片的な幾何学的形状や、前景の小さな人格や背景の男性のような影や斜めになった顔よりも、観る者の注意を引きつける。観る者は王と王妃の顔立ちを 識別できないが、鏡面の乳白色の輝きの中では、輝く楕円形が明らかに観る者の方を向いている。ジョナサン・ミラーは指摘している。「面取りされた縁に暗示 的な輝きを加える以外に、鏡がその正体を露わにする最も重要な方法は、周囲の壁の薄暗さとはあまりにも不釣り合いな明るさの映像を明らかにすることだ。そ れは反射によって、強く照らされた国王と王妃の姿から借り受けたものに違いない」と。[54] 侍女たちが互いに映し合っているように、王と王妃もまた絵画内に二重像を持つ。それは娘に仕え世話をする付き添いと護衛という、薄暗い光に包まれた二人の 姿だ。これらの人物の配置はパターンを形成している。一人の男、一組の夫婦、一人の男、一組の夫婦。外側の人物は他より観者に近い位置にあるが、全員が画 面上で同じ水平帯を占めている。[53] この絵の内的な複雑さをさらに増すのが、前景にいる小柄な男性だ。彼の上げた手は背景の人物の仕草を反復しているが、その遊び心のある態度と中心的な行動 からの逸脱は、それとは完全に対照をなしている。その気ままな姿勢、影に覆われた横顔、黒髪は、すべて王女の侍女と鏡像をなす要素だ。しかし画家は、窓か ら差し込む光の前方に彼を配置することで、この前景人物の明暗の対比を最小限に抑えている。[53] 空間的な曖昧さはあるものの、これは画家が最も精緻に描いた建築空間であり、天井が描かれた唯一の場面である。ロペス=レイによれば、ベラスケスがこれほ ど劇的に視線を鑑賞者の視界を超えた領域へ導いた構図は他にない。彼が描いているキャンバスも、王と王妃が立つ額縁の外側の空間も、想像に委ねられている のだ。[52] 暗い天井の無機質さ、ベラスケスのキャンバスの背面、額縁入り絵画の厳格な幾何学模様は、活気に満ち、鮮烈な光に照らされ、豪華に描かれた前景の随行者た ちと対照をなしている。[53] ストーンはこう記す: この絵画の人物像をひと目で全て把握することはできない。等身大の絵画サイズがそれを妨げるだけでなく、人物の頭部がそれぞれ異なる方向を向いているた め、視線がそらされるのだ。この絵画は、理解されるためには、まだ展開中の歴史の文脈において、順番に、一つずつ考慮されなければならないイメージを通じ て伝達する。それは、枠の中の枠で構成されたこの絵画の中にあっても、まだ枠に収められていない歴史なのだ。[55] カーによれば、この構図はフランツ・フランケン・ザ・ヤング、ウィレム・ファン・ヘーフト、あるいはダヴィッド・テニールス・ザ・ヤングといった伝統的な オランダのギャラリー絵画の影響を受けている可能性がある。テニールスの作品はフェリペ4世が所有しており、ベラスケスも知っていたはずだ。『ラス・メ ニーナス』と同様に、これらの絵画は重要な収集家や支配者による公式訪問を描いており、当時よくある光景であった。「一辺の壁を窓が占め、窓の間や他の壁 にも絵画が掛けられた部屋」を表現している。ギャラリー肖像画は、王族や上流階級と同様に、画家自身を称賛する目的でも用いられた。ベラスケスも本作で同 様の意図を持っていた可能性がある。[56] |

Mirror and reflection Detail of the mirror in van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait. Van Eyck's painting shows the pictorial space from "behind", and two further figures in front of the picture space, like those in the reflection in the mirror in Las Meninas. The spatial structure and positioning of the mirror's reflection are such that Philip IV and Mariana appear to be standing on the viewer's side of the pictorial space, facing the Infanta and her entourage. According to Janson, not only is the gathering of figures in the foreground for Philip and Mariana's benefit, but the painter's attention is concentrated on the couple, as he appears to be working on their portrait.[38] Although they can only be seen in the mirror reflection, their distant image occupies a central position in the canvas, in terms of social hierarchy as well as composition. As spectators, the viewer's position in relation to the painting is uncertain. It has been debated whether the ruling couple are standing beside the viewer or have replaced the viewer, who sees the scene through their eyes. Lending weight to the latter idea are the gazes of three of the figures—Velázquez, the Infanta, and Maribarbola—who appear to be looking directly at the viewer.[57] The mirror on the back wall indicates what is not there: the king and queen, and in the words of Harriet Stone, "the generations of spectators who assume the couple's place before the painting".[31] Writing in 1980, the critics Snyder and Cohn observed: Velázquez wanted the mirror to depend upon the useable [sic] painted canvas for its image. Why should he want that? The luminous image in the mirror appears to reflect the king and queen themselves, but it does more than just this: the mirror outdoes nature. The mirror image is only a reflection. A reflection of what? Of the real thing—of the art of Velázquez. In the presence of his divinely ordained monarchs ... Velázquez exults in his artistry and counsels Philip and Maria not to look for the revelation of their image in the natural reflection of a looking glass but rather in the penetrating vision of their master painter. In the presence of Velázquez, a mirror image is a poor imitation of the real.[58]  In the Arnolfini Portrait (1434), Jan van Eyck uses an image reflected in a mirror in a manner similar to Velázquez in Las Meninas.[17] In Las Meninas, the king and queen are supposedly "outside" the painting, yet their reflection in the back wall mirror also places them "inside" the pictorial space.[59] Snyder proposes that the painting is "a mirror of majesty" or an allusion to the mirror for princes. While it is a literal reflection of the king and queen, Snyder writes "it is the image of exemplary monarchs, a reflection of ideal character".[60] Later he focuses his attention on the princess, writing that Velázquez's portrait is "the painted equivalent of a manual for the education of the princess—a mirror of the princess".[61] The painting was likely influenced by Jan van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait, of 1434. At the time, van Eyck's painting hung in Philip's palace, and would have been familiar to Velázquez.[17][62] The Arnolfini Portrait also has a mirror positioned at the back of the pictorial space, reflecting two figures who would have the same angle of vision as does the viewer of Velázquez's painting; they are too small to identify, but it has been speculated that one may be intended as the artist himself, though he is not shown in the act of painting. According to Lucien Dällenbach: The mirror [in Las Meninas] faces the observer as in Van Eyck's painting. But here the procedure is more realistic to the degree that the "rearview" mirror in which the royal couple appears is no longer convex but flat. Whereas the reflection in the Flemish painting recomposed objects and characters within a space that is condensed and deformed by the curve of the mirror, that of Velázquez refuses to play with the laws of perspective: it projects onto the canvas the perfect double of the king and queen positioned in front of the painting.[37] |

鏡と反射 ファン・エイクの『アルノルフィーニの肖像』における鏡の細部。ファン・エイクの絵画は「背後」から見た絵画空間を描き、さらに画面空間の前方に二つの人物像を配置している。これは『ラス・メニーナス』の鏡に映る反射像の人物たちと同様である。 鏡の反射が映し出す空間構造と位置関係は、フィリップ4世とマリアナが絵画空間の鑑賞者側に立ち、インファンタとその随行者たちに向き合っているように見 える。ヤンソンによれば、前景に人物が集まっているのはフィリップとマリアナのためであるだけでなく、画家の注意が夫妻に集中していることを示している。 画家は夫妻の肖像画を描いているように見えるのだ。[38] 鏡像にしか映らないにもかかわらず、彼らの遠景像は社会的階層と構図の両面でキャンバスの中央を占めている。鑑賞者としての観者の絵画に対する位置関係は 不確かだ。統治者夫妻が観者の傍らに立っているのか、それとも観者に取って代わり、彼らの目を通して情景を見ているのかは議論の的となっている。後者の説 を裏付けるのが、ベラスケス、王女、マリバルボラの三人の視線だ。彼らは鑑賞者をまっすぐに見ているように見える。[57] 後壁の鏡は、そこに存在しないものを示している。王と王妃、そしてハリエット・ストーンの言葉を借りれば「絵画の前に立つ夫婦の立場を引き継ぐ、幾世代もの鑑賞者たち」である。[31] 1980年に批評家スナイダーとコーンはこう記している: ベラスケスは鏡の映像を、使用可能な[原文ママ]描かれたキャンバスに依存させたかった。なぜそうしたのか?鏡に映る輝かしい映像は王と王妃自身を反映し ているように見えるが、それだけではない:鏡は自然を超越する。鏡像は単なる反射に過ぎない。何を映すのか?真実の姿を――ベラスケスの芸術そのものを。 神聖なる君主たちの御前で…ベラスケスは自らの芸術的技量に誇りを抱き、フェリペとマリアにこう助言する。鏡という自然の反射に自らの姿を求めず、むしろ 巨匠画家の鋭い視線の中に真実を見出せと。ベラスケスの御前において、鏡像は真実の貧弱な模倣に過ぎないのだ。[58]  『アルノルフィーニの肖像』(1434年)において、ヤン・ファン・エイクは鏡に映る像を、ベラスケスの『ラス・メニーナス』と同様の手法で用いている。[17] 『ラス・メニーナス』では、王と王妃は本来「絵画の外」にいるはずだが、後壁の鏡に映る彼らの姿は同時に彼らを「絵画空間の内側」にも位置づけている。 [59] スナイダーは、この絵画が「威厳の鏡」あるいは君主のための鏡への言及であると提案する。王と王妃の文字通りの反射である一方で、スナイダーは「それは模 範的な君主たちの像であり、理想的な性格の反映である」と記している。[60] その後彼は王女に焦点を当て、ベラスケスの肖像画は「王女の教育のための手引書の絵画的対応物―王女の鏡である」と書いている。[61] この絵画は、1434年のヤン・ファン・エイク作『アルノルフィーニの肖像』の影響を受けている可能性が高い。当時、ファン・エイクの作品はフェリペ王の 宮殿に掛けられており、ベラスケスも目にしたはずだ。[17][62] 『アルノルフィーニの肖像』でも、絵画空間の奥に鏡が配置され、ベラスケスの絵画の鑑賞者と同じ視角を持つ二人が映っている。彼らは小さすぎて特定できな いが、一人は画家自身を意図した可能性があると推測されている。ただし、彼は絵を描いている姿は描かれていない。ルシアン・ダレンバッハによれば: 『ラス・メニーナス』の鏡はファン・エイクの絵画と同様に鑑賞者に向いている。しかしここでは手法がより現実的だ。王室夫妻が映る「後方視鏡」が凸面では なく平面になった点で。フランドル絵画の反射像が鏡の曲率によって圧縮・変形された空間内で物体や人物を再構成したのに対し、ベラスケスの反射像は遠近法 の法則を弄ぶことを拒む。絵画の前に立つ国王と王妃の完全な複製像をキャンバスに投影しているのだ。[37] |

| Interpretation The elusiveness of Las Meninas, according to Dawson Carr, "suggests that art, and life, are an illusion".[63] The relationship between illusion and reality were central concerns in Spanish culture during the 17th century, figuring largely in Don Quixote, the best-known work of Spanish Baroque literature. In this respect, Calderón de la Barca's play Life is a Dream is commonly seen as the literary equivalent of Velázquez's painting: What is a life? A frenzy. What is life? A shadow, an illusion, and a sham. The greatest good is small; all life, it seems Is just a dream, and even dreams are dreams.[63]  Detail showing the red cross of the Order of Santiago painted on the breast of Velázquez. Presumably this detail was added at a later date, as the painter was admitted to the order by the king's decree on 28 November 1659.[64] Jon Manchip White notes that the painting can be seen as a résumé of the whole of Velázquez's life and career, as well as a summary of his art to that point. He placed his only confirmed self-portrait in a room in the royal palace surrounded by an assembly of royalty, courtiers, and fine objects that represent his life at court.[29] The art historian Svetlana Alpers suggests that, by portraying the artist at work in the company of royalty and nobility, Velázquez was claiming high status for both the artist and his art,[65] and in particular to propose that painting is a liberal rather than a mechanical art. This distinction was a point of controversy at the time. It would have been significant to Velázquez, since the rules of the Order of Santiago excluded those whose occupations were mechanical.[6] Kahr asserts that this was the best way for Velázquez to show that he was "neither a craftsman or a tradesman, but an official of the court". Furthermore, this was a way to prove himself worthy of acceptance by the royal family.[66] Michel Foucault devoted the opening chapter of The Order of Things (1966) to an analysis of Las Meninas. Foucault describes the painting in meticulous detail, but in a language that is "neither prescribed by, nor filtered through the various texts of art-historical investigation".[67] Foucault viewed the painting without regard to the subject matter, nor to the artist's biography, technical ability, sources and influences, social context, or relationship with his patrons. Instead he analyzes its conscious artifice, highlighting the complex network of visual relationships between painter, subject-model, and viewer: We are looking at a picture in which the painter is in turn looking out at us. A mere confrontation, eyes catching one another's glance, direct looks superimposing themselves upon one another as they cross. And yet this slender line of reciprocal visibility embraces a whole complex network of uncertainties, exchanges, and feints. The painter is turning his eyes towards us only in so far as we happen to occupy the same position as his subject.[68][69] For Foucault, Las Meninas illustrates the first signs of a new episteme, or way of thinking. It represents a midpoint between what he sees as the two "great discontinuities" in European thought, the classical and the modern: "Perhaps there exists, in this painting by Velázquez, the representation as it were of Classical representation, and the definition of the space it opens up to us ... representation, freed finally from the relation that was impeding it, can offer itself as representation in its pure form."[68][70] Now he (the painter) can be seen, caught in a moment of stillness, at the neutral centre of his oscillation. His dark torso and bright face are half-way between the visible and the invisible: emerging from the canvas beyond our view, he moves into our gaze; but when, in a moment, he makes a step to the right, removing himself from our gaze, he will be standing exactly in front of the canvas he is painting; he will enter that region where his painting, neglected for an instant, will, for him, become visible once more, free of shadow and free of reticence. As though the painter could not at the same time be seen on the picture where he is represented and also see that upon which he is representing something."[71] In his 2015 analysis, Xavier d'Hérouville brings the painting closer to its first name, namely "The Family of Philippe IV", which at the time earned it the term "theology of painting"[48] by Luca Giordano, contemporary painter of Velázquez. Through this representation, the painter would have conceptualized the divine view of his creation. When the spectator places himself in front of the canvas, in place of the King's study for which this painting was very exclusively intended, he finds himself instantly invested with the divine power, that of "seeing without being seen" the Family of Philip IV. The interface that constitutes this canvas must therefore be considered as a "one-way mirror" in which each of the protagonists of this representation looks at themselves, and behind which the monarch invests divine power, and his wife, can at leisure and in complete discretion to contemplate their life's work, their "Family", in the broadest sense of the term. Further still, this canvas can be seen not only as a summary of the state of advancement of his art at the time of painting, but also as a curriculum vitæ of Velázquez's life and career. The latter having gone so far as to represent himself in this "fresco" at three key periods of his own existence within the Court of Spain: in the background and to the left, as the King's painter, then to the right this time, at the very heart of the Family of Philip IV, alongside the governess, as valet of the King's bedroom, and finally at the back and in the center, camped on the stairs, as Aposentador or Marshal of the Palace, the supreme function he exercised as the King's best friend and confidant.[72][73] |

解釈 ドーソン・カーによれば、『ラス・メニーナス』の捉えどころなさは「芸術も人生も幻想に過ぎないことを示唆している」という。[63] 幻想と現実の関係は、17世紀スペイン文化における核心的な関心事であり、スペイン・バロック文学の最高傑作『ドン・キホーテ』に大きく描かれている。こ の点において、カルデロン・デ・ラ・バルカの戯曲『人生は夢』は、ベラスケスの絵画に文学的に相当するものとして広く認識されている: 人生とは何か? 狂乱である。人生とは何か? 影であり、幻想であり、偽りである。 最大の善は小さい。人生全体は 夢に過ぎず、夢さえもまた夢なのだ。[63]  ベラスケスの胸部に描かれたサンティアゴ騎士団の赤い十字章の詳細。この細部は後世に追加されたものと思われる。画家自身が国王の勅令により同騎士団に叙任されたのは1659年11月28日である。[64] ジョン・マンチップ・ホワイトは、この絵がベラスケスの生涯と経歴の総括であると同時に、その時点までの芸術の集大成と見なせると指摘する。彼は唯一の確 証された自画像に、宮廷での生活を象徴する王族、廷臣、精巧な品々に囲まれた王宮の部屋を描かせたのだ。[29] 美術史家のスヴェトラーナ・アルパーズは、王族や貴族に囲まれた制作中の芸術家を描くことで、ベラスケスが芸術家とその芸術の双方に高い地位を主張したと 示唆している[65]。特に絵画が機械的な芸術ではなく自由な芸術であることを提案したのだ。この区別は当時論争の的だった。サンティアゴ騎士団の規則が 機械的職業従事者を排除していたため、ベラスケスにとって重要な意味を持っていた。[6] カーは、これがベラスケスが「職人でも商人でもなく、宮廷の役人である」ことを示す最良の方法だったと主張する。さらに、これは王室に受け入れられるに値 する人物であることを証明する手段でもあった。[66] ミシェル・フーコーは『言葉と物』(1966年)の冒頭章を『ラス・メニーナス』の分析に捧げた。フーコーは絵画を細部に至るまで描写するが、その言語は 「美術史研究の諸文献によって規定されたものでも、それらを通して濾過されたものでもない」[67]。フーコーは主題や画家の経歴、技術力、出典や影響 源、社会的文脈、パトロンとの関係を一切考慮せずに絵画を鑑賞した。代わりに彼は、意識的な技巧を分析し、画家、被写体モデル、鑑賞者の間の視覚的関係の 複雑なネットワークを浮き彫りにする: 我々は、画家が我々を見つめ返している絵を見ている。単なる対峙、互いの視線が交わる瞬間、交差する視線が重なり合う。しかしこの互いの視線が交差する細 い線は、不確実性や交換、駆け引きの複雑なネットワーク全体を包含している。画家が私たちの方へ目を向けているのは、私たちがたまたま彼の被写体と同じ位 置にいる場合に限られるのだ。[68][69] フーコーにとって『ラス・メニーナス』は、新たなエピステーム(認識体系)の最初の兆候を示す。それは彼がヨーロッパ思想における二つの「大きな不連続 性」―古典と近代―の中間点として見るものだ。「おそらくこのベラスケスの絵画には、いわば古典的表象の表象と、それが我々に開く空間の定義が存在する… ついに妨げられていた関係から解放された表象は、純粋な形態としての表象として自らを提示しうるのだ」[68][70] 今や彼(画家)は、揺れ動きの中立点で静止した瞬間を捉えられている。彼の暗い胴体と明るい顔は、可視と不可視の境界線上に位置する。キャンバスの向こう から我々の視界に現れつつ、我々の視線へと入り込んでくる。しかし次の瞬間、右へ一歩踏み出して我々の視線から外れる時、彼はまさに自身が描くキャンバス の真正面に立つことになる。そこで彼は、一瞬放置された自らの絵画が、影も遠慮もなく再び見える領域に入るのだ。まるで画家は、自身が描かれた絵の中に同 時に映り込むことも、また自身が何かを描いている対象を見ることもできないかのようだ。」[71] 2015年の分析で、ザビエル・ドゥ・エルーヴィルはこの絵画をその最初の名称、すなわち「フェリペ4世の家族」に近づけた。この名称は当時、ベラスケス の同時代画家ルカーチ・ジョルダーノによって「絵画の神学」[48]という評価を得ていた。この表現を通じて、画家は自らの創造物に対する神的な視点を概 念化したのだ。鑑賞者がキャンバス前に立つとき、この絵が専ら王の書斎のために制作されたことを踏まえれば、彼は即座に神聖な力、すなわち「見られずに見 る」フィリップ4世の家族を視る力を授けられる。このキャンバスが構成するインターフェースは、従って「一方向鏡」と見なされねばならない。この表現の主 人公たちはそれぞれ鏡に映る自らを見つめ、その背後で君主は神聖な権威を付与し、王妃は完全に秘密裏に、そして気ままに、彼らの生涯の業である「家族」 ——この言葉の最も広義の意味において——を熟視することができるのだ。さらにこのキャンバスは、制作当時の芸術的到達点の総括であると同時に、ベラスケ スの生涯と経歴の履歴書とも見なせる。彼はこの「フレスコ画」に、スペイン宮廷における自身の人生の三つの重要な時期を自ら描いているのだ。背景左側では 国王の画家として、次に右側ではフェリペ4世の家族の中核に、乳母と共に国王寝室の侍従として、そして最後に後方中央の階段に陣取る姿で、宮廷長官(アポ センタードール)として描かれている。これは国王の親友かつ腹心として彼が担った最高位の職務である。[72] [73] |

Las Meninas as culmination of themes in Velázquez Diego Velázquez's Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, 1618. The smaller image may be a view to another room, a picture on the wall, or a reflection in a mirror. Many aspects of Las Meninas relate to earlier works by Velázquez in which he plays with conventions of representation. In the Rokeby Venus—his only surviving nude—the face of the subject is visible, blurred beyond any realism, in a mirror. The angle of the mirror is such that although "often described as looking at herself, [she] is more disconcertingly looking at us".[74] In the early Christ in the House of Martha and Mary of 1618,[j] Christ and his companions are seen only through a serving hatch to a room behind, according to the National Gallery (London), who are clear that this is the intention, although before restoration many art historians regarded this scene as either a painting hanging on the wall in the main scene, or a reflection in a mirror, and the debate has continued.[k][l] The dress worn in the two scenes also differs: the main scene is in contemporary dress, while the scene with Christ uses conventional iconographic biblical dress.[l] In Las Hilanderas, believed to have been painted the year after Las Meninas, two different scenes from Ovid are shown: one in contemporary dress in the foreground, and the other partly in antique dress, played before a tapestry on the back wall of a room behind the first. According to the critic Sira Dambe, "aspects of representation and power are addressed in this painting in ways closely connected with their treatment in Las Meninas".[8] In a series of portraits of the late 1630s and 1640s—all now in the Prado—Velázquez painted clowns and other members of the royal household posing as gods, heroes, and philosophers; the intention is certainly partly comic, at least for those in the know, but in a highly ambiguous way.[77] |

ベラスケスの主題の集大成としての『ラス・メニーナス』 ディエゴ・ベラスケス作『マルタとマリアの家におけるキリスト』(1618年)。小さな画像は別の部屋への眺め、壁の絵、あるいは鏡の反射かもしれない。 『ラス・メニーナス』の多くの側面は、ベラスケスが表現の慣習を弄んだ初期作品と関連している。現存する唯一の裸体画『ロケビーのヴィーナス』では、被写 体の顔が鏡に映っているが、写実性を超えたぼやけ具合だ。鏡の角度は「自身を見つめているとよく言われるが、むしろ不気味なほど我々を見つめている」よう に見える。[74] 1618年の初期作品『マルタとマリアの家におけるキリスト』[j]では、ロンドン国立美術館によれば、キリストとその一行は奥の部屋への給仕口越しにし か見えない。同館はこれが意図された表現だと明言しているが、修復前は多くの美術史家がこの場面を「主場面の壁に掛かった絵画」か「鏡の反射」と見なし、 議論は続いている。[k][l] 両場面の服装も異なる。主場面は当時の服装だが、キリストが登場する場面は聖書図像の伝統的な衣装を用いている。[l] 『糸を紡ぐ女たち』は『女官たち』の翌年に描かれたとされ、オウィディウスの二つの異なる場面が描かれている。前景には現代の衣装をまとった人物が、背景 の部屋の奥の壁にはタペストリーを背に演じている。批評家シラ・ダンベによれば、「この絵画では『女官たち』における表現と権力の扱いと密接に関連した形 で、それらの側面が扱われている」という。[8] 1630年代後半から1640年代にかけて制作された一連の肖像画(現在は全てプラド美術館所蔵)において、ベラスケスは道化師や王室関係者らを神々、英 雄、哲学者として描いている。その意図は、少なくとも事情を知る者にとっては、確かに部分的に滑稽さを伴うが、極めて曖昧な形で表現されている。[77] |

Influence Francisco Goya's Charles IV of Spain and His Family references Las Meninas, but is less sympathetic towards its subjects.[78] In 1692, Giordano became one of the few allowed to view paintings in Philip IV's private apartments, and was greatly impressed by Las Meninas. Giordano described the work as the "theology of painting",[48] and was inspired to paint A Homage to Velázquez (National Gallery, London).[79] By the early 18th century his oeuvre was gaining international recognition, and later in the century British collectors ventured to Spain in search of acquisitions. Since the popularity of Italian art was then at its height among British connoisseurs, they concentrated on paintings that showed obvious Italian influence, largely ignoring others such as Las Meninas.[80]  John Singer Sargent, The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882, Boston Museum of Fine Arts An almost immediate influence can be seen in the two portraits by del Mazo of subjects depicted in Las Meninas, which in some ways reverse the motif of that painting. Ten years later, in 1666, Mazo painted Infanta Margaret Theresa, who was then 15 and just about to leave Madrid to marry the Holy Roman Emperor. In the background are figures in two further receding doorways, one of which was the new King Charles (Margaret Theresa's brother), and another the little person Maribarbola. A Mazo portrait of the widowed Queen Mariana again shows, through a doorway in the Alcázar, the young king with little people, possibly including Maribarbola, and attendants who offer him a drink.[81][82] Mazo's painting of The Family of the Artist also shows a composition similar to that of Las Meninas.[83]  During 1957 Pablo Picasso painted 58 recreations of Las Meninas.[84] Francisco Goya etched a print of Las Meninas in 1778,[85] and used Velázquez's painting as the model for his Charles IV of Spain and His Family. As in Las Meninas, the royal family in Goya's work is apparently visiting the artist's studio. In both paintings the artist is shown working on a canvas, of which only the rear is visible. Goya, however, replaces the atmospheric and warm perspective of Las Meninas with what Pierre Gassier calls a sense of "imminent suffocation". Goya's royal family is presented on a "stage facing the public, while in the shadow of the wings the painter, with a grim smile, points and says: 'Look at them and judge for yourself!' "[78] The 19th-century British art collector William John Bankes travelled to Spain during the Peninsular War (1808–1814) and acquired a copy of Las Meninas painted by Mazo,[86] which he believed to be an original preparatory oil sketch by Velázquez—although Velázquez did not usually paint studies. Bankes described his purchase as "the glory of my collection", noting that he had been "a long while in treaty for it and was obliged to pay a high price".[87] An appreciation for Velázquez's less Italianate paintings developed after 1819, when Ferdinand VII opened the royal collection to the public.[86] In 1879 John Singer Sargent painted a small-scale copy of Las Meninas, while his 1882 painting The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit is a homage to Velázquez's panel. The Irish artist Sir John Lavery chose Velázquez's masterpiece as the basis for his portrait The Royal Family at Buckingham Palace, 1913. George V visited Lavery's studio during the execution of the painting, and, perhaps remembering the legend that Philip IV had daubed the cross of the Knights of Santiago on the figure of Velázquez, asked Lavery if he could contribute to the portrait with his own hand. According to Lavery, "Thinking that royal blue might be an appropriate colour, I mixed it on the palette, and taking a brush he [George V] applied it to the Garter ribbon."[86] Between August and December 1957, Pablo Picasso painted a series of 58 interpretations of Las Meninas, and figures from it, which currently fill the Las Meninas room of the Museu Picasso in Barcelona, Spain.[88] Picasso did not vary the characters within the series, but largely retained the naturalness of the scene; according to the museum, his works constitute an "exhaustive study of form, rhythm, colour and movement".[84] |

影響 フランシスコ・ゴヤの『スペイン国王カルロス4世とその家族』は『ラス・メニーナス』を参照しているが、その主題に対してはより冷淡である。[78] 1692年、ジョルダーノはフェリペ4世の私室で絵画を鑑賞することを許された数少ない人物の一人となり、『ラス・メニーナス』に深く感銘を受けた。彼は この作品を「絵画の神学」と評し[48]、その影響を受けて『ベラスケスへのオマージュ』(ロンドン、ナショナル・ギャラリー所蔵)を描いた。[79] 18世紀初頭までに彼の作品は国際的な評価を得て、世紀後半には英国の収集家がスペインに赴き作品を購入した。当時英国美術愛好家の間でイタリア美術の人 気が頂点に達していたため、彼らは明らかなイタリアの影響が見られる絵画に集中し、『ラス・メニーナス』のような作品はほとんど無視した。[80]  ジョン・シンガー・サージェント『エドワード・ダーリー・ボイトの娘たち』1882年 ボストン美術館 デル・マソによる『ラス・メニーナス』の登場人物を描いた二点の肖像画には、ほぼ即座の影響が認められる。これらの作品は、ある意味で『ラス・メニーナ ス』のモチーフを逆転させている。10年後の1666年、マソは当時15歳で、神聖ローマ皇帝との結婚のためまもなくマドリードを離れる予定だったマリア ナ王女を描いた。背景にはさらに奥行きのある二つの扉口に人物が描かれている。一方は新国王カルロス(マルガリータ・テレサの兄)、もう一方は小人マリバ ルボラである。マソが描いた未亡人マリアナ女王の肖像画でも、アルカサル宮殿の扉越しに、小人たち(おそらくマリバルボラを含む)と飲み物を差し出す従者 たちに囲まれた若き国王の姿が再び描かれている。[81][82] マソの『画家の家族』も『ラス・メニーナス』と同様の構図を示している。[83]  1957年、パブロ・ピカソは『ラス・メニーナス』を58点模写した。[84] フランシスコ・ゴヤは1778年に『ラス・メニーナス』の版画を制作した[85]。またベラスケスの絵画をモデルに『スペイン国王カルロス4世とその家 族』を描いた。ゴヤの作品における王族も『ラス・メニーナス』同様、画家のアトリエを訪れているように見える。両作品とも、画家がキャンバスに描いている 様子が描かれているが、見えるのはキャンバスの背面だけだ。しかしゴヤは、『ラス・メニーナス』の温かみのある雰囲気と遠近法を、ピエール・ガシエが「差 し迫った窒息感」と呼ぶものに置き換えている。ゴヤの王族は「観客に向き合った舞台」に配置され、舞台袖の影では画家が不気味な笑みを浮かべて指さしなが ら言うのだ。「彼らを見て、お前たち自身で判断しろ!」と。[78] 19世紀の英国美術収集家ウィリアム・ジョン・バンクスは、半島戦争(1808-1814)中にスペインを訪れ、マソが描いた『ラス・メニーナス』の複製 画を入手した[86]。彼はこれをベラスケスの原画下絵油彩スケッチと信じていたが、ベラスケスは通常下絵を描かなかった。バンクスはこの購入を「我がコ レクションの栄光」と称し、「長い交渉の末、高額を支払わざるを得なかった」と記している。[87] フェルディナンド7世が王室コレクションを一般公開した1819年以降、ベラスケスのイタリア風ではない絵画に対する評価が高まった。[86] 1879年、ジョン・シンガー・サージェントは『ラス・メニーナス』の縮小複製画を描き、1882年の作品『エドワード・ダーリー・ボイトの娘たち』はベ ラスケスのパネルへのオマージュである。アイルランドの芸術家、ジョン・レイブリー卿は、1913年に描いた肖像画「バッキンガム宮殿の王室」のベースと して、ベラスケスの傑作を選んだ。ジョージ5世は、この絵の制作中にレイブリーのスタジオを訪れ、おそらくフィリップ4世がベラスケスの肖像にサンティア ゴ騎士団の十字架を塗りつけたという伝説を思い出し、レイブリーに、自分の手で肖像画に何か貢献できないかと尋ねた。レイブリーによれば、「ロイヤルブ ルーがふさわしい色だと思い、パレットでミヘ、彼は(ジョージ5世)筆を取り、ガーターリボンにそれを塗った」という。 1957年8月から12月にかけて、パブロ・ピカソは『ラス・メニーナス』とその登場人物たちを題材にした58点の連作を制作した。これらの作品は現在、 スペイン・バルセロナのピカソ美術館の「ラス・メニーナス」の部屋に展示されている。[88] ピカソは、このシリーズの中で登場人物に変化を持たせることはなく、その場面の自然さをほぼそのまま残した。同美術館によれば、彼の作品は「形、リズム、 色彩、動きに関する徹底的な研究」を構成しているという。[84] |

| Notes a. The name is sometimes given in print as Las Meniñas, but there is no word "meniña" in Spanish. The word means "girl from a noble family brought up to serve at court" (Oxford Concise Spanish Dictionary) and comes from menina (Portuguese for 'girl'). This misspelling (may be due to confusion with niña (Spanish for 'girl') b. In 1855, William Stirling wrote in Velázquez and his works: "Velázquez seems to have anticipated the discovery of Daguerre and, taking a real room and real people grouped together by chance, to have fixed them, as it were, by magic, for all time, on canvas".[1] c. Mariana of Austria was betrothed to Balthasar Charles in 1646.[10] d. There is no documentation as to the dates or reasons for the trimming. López-Rey states that the truncation is more notable on the right.[18] e. Records of 1735 show that the original frame was lost during the painting's rescue from the fire. The appraisal of 1747–48 makes reference to the painting having been "lately restored".[19] f. The work was evacuated to Geneva by the Republican Government, together with much of the Prado's collection, during the last months of the Spanish Civil War, where it hung in an exhibition of Spanish paintings in 1939.[24] g. Maria Theresa was by then queen of France as wife of Louis XIV of France. Philip Prospero, Prince of Asturias, was born the following year, but died at four, shortly before his brother Charles II was born. One daughter from this marriage, and five from Philip's first marriage, died in infancy. h. "And a couple of Lyme-hounds of singular qualities which the King and Queen in very kind manner accepted."[30] i. "The composition is anchored by the two strong diagonals that intersect at about the spot where the Infanta stands ..."[52] j. According to López-Rey, "[The Arnolfini Portrait] has little in common with Velázquez' composition, the closest and most meaningful antecedent to which is to be found within his own oeuvre in Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, painted almost forty years earlier, in Seville, before he could have seen the Arnolfini portrait in Madrid".[75] k. The restoration was in 1964, and removed earlier "clumsy repainting".[76] l. Jonathan Miller, for example, in 1998, continued to regard the inset picture as a reflection in a mirror.[74] |

注記 a. この名称は印刷物で「ラス・メニニャス」と表記されることがあるが、スペイン語に「メニニャ」という単語は存在しない。この語は「宮廷に仕えるために育て られた貴族の娘」(オックスフォード簡明スペイン語辞典)を意味し、ポルトガル語の「メニーニャ」(少女)に由来する。この誤表記は(スペイン語の「ニー ニャ」(少女)との混同による可能性がある) b. 1855年、ウィリアム・スターリングは『ベラスケスとその作品』でこう記している。「ベラスケスはダゲールの発見を予見していたかのようだ。現実の部屋と偶然集まった人々を捉え、呪術的に永遠にキャンバスに固定したのである」[1] c. オーストリアのマリアナは1646年にバルタサール・カルロスと婚約した[10] d. 切り取りの日付や理由に関する記録は存在しない。ロペス=レイは、右側の切り取りがより顕著だと述べている。[18] e. 1735年の記録によれば、火災からの救出時に元の額縁は失われた。1747-48年の鑑定書には、この絵画が「最近修復された」と記されている。[19] f. この作品はスペイン内戦末期、プラド美術館の所蔵品の大半と共に共和派政府によってジュネーブへ避難させられ、1939年のスペイン絵画展で展示された。[24] g. マリア・テレジアはこの時点でフランス国王ルイ14世の妃としてフランス王妃であった。アストゥリアス公フェリペ・プロスペロは翌年に誕生したが、弟カル ロス2世誕生直前の4歳で死去した。この結婚による娘1人と、フィリップの最初の結婚による娘5人は幼少期に亡くなった。 h. 「そして王と王妃が非常に親切に受け入れてくださった、特異な性質を持つライム猟犬2頭」[30] i. 「構図は、インファンタが立つ位置付近で交差する2本の強い対角線によって支えられている…」[52] j. ロペス=レイによれば、「『アルノルフィーニの肖像』はベラスケスの構図と共通点がほとんどない。最も近く、かつ意味のある先例は、彼がマドリードでアル ノルフィーニの肖像を見る前に、セビリアでほぼ40年前に描いた『マルタとマリアの家におけるキリスト』の中にこそ見出される」。[75] k. 1964年の修復では、以前の「不器用な上塗り」が除去された。[76] l. 例えばジョナサン・ミラーは1998年時点で、嵌め込み絵を鏡の反射像と見なす見解を堅持していた。[74] |

| References |

(省略) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Las_Meninas |

| Sources Alpers, Svetlana (2005). The Vexations of art: Velázquez and others. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10825-5. Beaujean, Dieter (2001). Velasquez. London: Konemann. p. 90. ISBN 978-3-8290-5865-0. Brady, Xavier (2006). Velázquez and Britain. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-1-85709-303-2. Campbell, Lorne (1998). The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Paintings. London: National Gallery Catalogues (new series). p. 180. ISBN 978-1-85709-171-7. Canaday, John (1972) [1969]. "Baroque Painters". The Lives of the Painters. New York: Norton Library. ISBN 978-0-393-00665-0. Carr, Dawson W. (2006). "Painting and Reality: The Art and Life of Velázquez". In Carr, Dawson W.; Bray, Xavier (eds.). Velázquez. London: National Gallery. ISBN 978-1-85709-303-2. Clark, Kenneth (1960). Looking at Pictures (1961 reprint ed.). New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston. LCCN 60-10106. OCLC 1036517825. ISBN 978-0-7195-0232-3 (later reprint) Dällenbach, Lucien (1977). Le récit spéculaire: Essai sur la mise en abyme. Paris: Seuil. p. 21. ISBN 978-2-0200-4556-8. Dambe, Sira (December 2006). "Enslaved sovereign: aesthetics of power in Foucault, Velázquez and Ovid". Journal of Literary Studies. 22 (3–4): 229–256. doi:10.1080/02564710608530402. S2CID 143516350. d'Hérouville, Xavier (2015). Les Ménines ou l'art conceptuel de Diego Vélasquez (in French). L'Harmattan, collection Ouverture philosophique, série Esthétique. ISBN 978-2-343-07070-4. Editorial (January 1985). "The cleaning of 'Las Meninas'". The Burlington Magazine. 127 (982). Burlington Magazine Publications Ltd: 2–3, 41. JSTOR 881920. Foucault, Michel (1996). The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 978-0679-75335-3. Gaggi, Silvio (1989). Modern/Postmodern: A Study in Twentieth-century Arts and Ideas. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-1384-3. Gassier, Pierre (1995). Goya: Biographical and Critical Study. New York: Skira. ISBN 978-0-7581-3747-0. Archived from the original on 27 February 2008. Gresle, Yvette (6 July 2007). "Foucault's 'Las Meninas' and Art-Historical Methods". Journal of Literary Studies. 22 (3–4). Taylor & Francis: 211–228. doi:10.1080/02564710608530401. S2CID 145488454. Greub, Thierry. "Der Platz Des Bildes Und der »Platz Des Königs«: Diego Velázquez’ ‘Las Meninas’ Im Sommer-Arbeitszimmer Philipps IV", Zeitschrift Für Kunstgeschichte 78, no. 3/4 (2015): 441–87. JSTOR 24857047 Harris, E (1990). Velázquez y Gran Bretana. Seville: Symposium Internacional Velázquez. p. 127. Held, Jutta; Potts, Alex (1988). "How Do the Political Effects of Pictures Come About? The Case of Picasso's Guernica". Oxford Art Journal. 11 (1). Oxford University Press: 33–39. doi:10.1093/oxartj/11.1.33. JSTOR 1360321. Honour, Hugh; Fleming, John (1982). A World History of Art. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-85669-451-3. Janson, H. W. (1977). History of Art: A Survey of the Major Visual Arts from the Dawn of History to the Present Day (2nd ed.). New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-13-389296-3. Kahr, Madlyn Millner (June 1975). "Velazquez and Las Meninas". The Art Bulletin. 57 (2). College Art Association: 225–246. doi:10.2307/3049372. JSTOR 3049372. Kubler, George (1966). "Three Remarks on the Meninas". The Art Bulletin. 48 (2): 212–214. doi:10.2307/3048367. JSTOR 3048367. Levey, Michael (1971). Painting at Court. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-8147-4950-0. López-Rey, José (1999). Velázquez: Catalogue Raisonné. Cologne: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8228-8277-1. Lowrie, Joyce (1999). "Barbey D'Aurevilly's Une Page D'Histoire: A poetics of incest". Romanic Review. 90 (2). MacLaren, Neil (1970). The Spanish School, National Gallery Catalogues. Revised by Allan Braham. London: National Gallery. ISBN 978-0-947645-46-5. McKim-Smith, G.; Andersen-Bergdoll, G.; Newman, R. (1988). Examining Velazquez. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-03615-2. Miller, Jonathan (1998). On Reflection. London: National Gallery Publications Limited. ISBN 978-0-300-07713-1. Museo del Prado (1996). Museo del Prado, Catálogo de las pinturas [Prado Museum, Catalog of paintings] (in Spanish). Madrid: Ministerio de Educación y Cultura, Madrid. ISBN 978-84-7483-410-9. Ortega y Gasset, José (1953). Velázquez. New York: Random House. p. XLVII. Palomino, Antonio (1715–1724). El museo pictorico y escala optica [The pictorial museum and optical scale] (in Spanish). Vol. 2. Madrid. Retrieved 1 September 2017. Snyder, Joel; Cohen, Ted (Winter 1980). "Reflexions on Las Meninas: Paradox Lost". Critical Inquiry. 7 (2). The University of Chicago Press: 429–447. doi:10.1086/448107. JSTOR 1343136. S2CID 161395640. Snyder, Joel (June 1985). "Las Meninas and the Mirror of Prices". Critical Inquiry. 11 (4). The University of Chicago Press: 539–572. doi:10.1086/448307. JSTOR 1343417. S2CID 162111194. Steinberg, Leo (Winter 1981). "Velázquez' Las Meninas". October. 19. The MIT Press: 45–54. doi:10.2307/778659. JSTOR 778659. Stone, Harriet (1996). The Classical Model: Literature and Knowledge in Seventeenth-Century France. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3212-5. White, Jon Manchip (1969). Diego Velázquez: Painter and Courtier. London: Hamish Hamilton Ltd. ISBN 978-0241-0-1624-4. Zeri, Federico (1990). Behind the Image, the art of reading paintings. London: Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-4348-9688-2. |

出典 アルパーズ、スヴェトラーナ(2005)。『芸術の煩わしさ:ベラスケスとその他』。ニューヘイブン:イェール大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-300-10825-5。 ボージャン、ディーター(2001)。『ベラスケス』。ロンドン:コネマン。90 ページ。ISBN 978-3-8290-5865-0。 ブレイディ、ザビエル(2006)。『ベラスケスとイギリス』。ニューヘイブン:イェール大学出版局。ISBN 978-1-85709-303-2。 キャンベル、ローン (1998)。『15 世紀のオランダ絵画』 ロンドン:ナショナル・ギャラリー・カタログ(新シリーズ)。180 ページ。ISBN 978-1-85709-171-7。 カナデイ、ジョン (1972) [1969]。『バロックの画家たち』。『画家の生涯』所収。ニューヨーク:ノートン図書館。ISBN 978-0-393-00665-0。 カー、ドーソン W. (2006)。「絵画と現実:ベラスケスの芸術と生涯」カー、ドーソン W.、ブレイ、ザビエル (編)『ベラスケス』所収。ロンドン:ナショナル・ギャラリー。ISBN 978-1-85709-303-2。 クラーク、ケネス(1960)。『絵画を見る』(1961年再版)。ニューヨーク:ホルト・ラインハート・アンド・ウィンストン。LCCN 60-10106。OCLC 1036517825。ISBN 978-0-7195-0232-3 (後刷版) ダレンバッハ、ルシアン (1977). 『鏡像的物語:アビームの技法に関する試論』. パリ: シュル. p. 21. ISBN 978-2-0200-4556-8. ダンベ、シラ(2006年12月)。「奴隷化された主権者:フーコー、ベラスケス、オウィディウスにおける権力の美学」。『文学研究ジャーナル』。22巻 3-4号:229-256頁。doi:10.1080/02564710608530402。S2CID 143516350. ド・エルーヴィル、ザヴィエ(2015年)。『メニーナス、あるいはディエゴ・ベラスケスのコンセプチュアル・アート』(フランス語)。ラルマタン社、哲学的開眼コレクション、美学シリーズ。ISBN 978-2-343-07070-4。 編集部 (1985年1月). 「『ラス・メニーナス』の修復」. 『バーリントン・マガジン』. 127 (982). バーリントン・マガジン出版: 2–3, 41. JSTOR 881920. フーコー, ミシェル (1996). 『言葉と物』. パリ: ガリマール. ISBN 978-0679-75335-3。 ガッジ、シルヴィオ(1989)。『モダン/ポストモダン:20世紀の芸術と思想の研究』。フィラデルフィア:ペンシルベニア大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8122-1384-3。 ガシエ、ピエール(1995)。『ゴヤ:伝記的・批評的研究』。ニューヨーク:スキラ。ISBN 978-0-7581-3747-0。2008年2月27日にオリジナルからアーカイブされた。 グレル、イヴェット(2007年7月6日)。「フーコーの『ラス・メニーナス』と美術史的方法論」『文学研究ジャーナル』22巻3-4号。テイラー&フラ ンシス:211-228頁。doi:10.1080/02564710608530401。S2CID 145488454。 グリュブ、ティエリー。「絵画の位置と『王の位置』:フェリペ4世の夏の書斎におけるディエゴ・ベラスケスの『ラス・メニーナス』」、『美術史雑誌』78巻3/4号(2015年):441–87頁。JSTOR 24857047 ハリス、E(1990)。『ベラスケスとグレートブリテン』セビリア:シンポジウム・インターナショナル・ベラスケス。127頁。 ヘルド、ユッタ;ポッツ、アレックス(1988)。「絵画の政治的効果はどのように生じるのか?ピカソの『ゲルニカ』の事例」『オックスフォード美術 ジャーナル』11巻1号。オックスフォード大学出版局:33–39頁。doi:10.1093/oxartj/11.1.33. JSTOR 1360321. オナー, ヒュー; フレミング, ジョン (1982). 『世界美術史』. ロンドン: マクミラン. ISBN 978-1-85669-451-3. ジャンソン, H. W. (1977). 『美術史:歴史の黎明期から現代までの主要視覚芸術概説』(第2版). ニュージャージー: プレンティス・ホール. p. 433. ISBN 978-0-13-389296-3. カー、マドリン・ミルナー(1975年6月)。「ベラスケスと『ラス・メニーナス』」。『アート・ブルティン』57巻2号。カレッジ・アート協会:225–246頁。doi:10.2307/3049372。JSTOR 3049372。 クブラー、ジョージ(1966)。「『ラス・メニーナス』に関する三つの所見」。『アート・ブルティン』。48巻2号:212–214頁。doi:10.2307/3048367。JSTOR 3048367。 レヴィー、マイケル(1971)。宮廷の絵画。ロンドン:ワイデンフェルド&ニコルソン。147頁。ISBN 978-0-8147-4950-0。 ロペス=レイ、ホセ(1999)。『ベラスケス:作品総覧』。ケルン:タッシェン。ISBN 978-3-8228-8277-1。 ローリー、ジョイス(1999)。「バルベ・ドーレヴィリの『歴史の一頁』:近親相姦の詩学」。『ロマンティック・レビュー』。90巻2号。 マクラレン、ニール(1970)。『スペイン絵画派、ナショナル・ギャラリー・カタログ』。アラン・ブラハムによる改訂。ロンドン:ナショナル・ギャラリー。ISBN 978-0-947645-46-5。 マッキム=スミス、G.;アンデルセン=バーグドル、G.;ニューマン、R.(1988)。『ベラスケスを検証する』。ニューヘイブン:イェール大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-300-03615-2。 ミラー、ジョナサン(1998)。『反射について』。ロンドン:国民美術館出版。ISBN 978-0-300-07713-1。 プラド美術館 (1996). 『プラド美術館絵画目録』 (スペイン語). マドリード:教育文化省。ISBN 978-84-7483-410-9。 オルテガ・イ・ガセット、ホセ(1953)。『ベラスケス』。ニューヨーク:ランダムハウス。p. XLVII。 パロミノ、アントニオ(1715–1724)。『絵画博物館と光学尺度』(スペイン語)。第2巻。マドリード。2017年9月1日取得。 スナイダー、ジョエル; コーエン、テッド(1980年冬)。「『ラス・メニーナス』に関する考察:失われたパラドックス」。『クリティカル・インクワイアリー』。7巻2号。シカ ゴ大学出版局:429–447頁。doi:10.1086/448107。JSTOR 1343136。S2CID 161395640。 スナイダー、ジョエル(1985年6月)。「ラス・メニーナスと価格の鏡」。クリティカル・インクワイアリー。11 (4)。シカゴ大学出版局:539–572。doi:10.1086/448307。JSTOR 1343417。S2CID 162111194。 スタインバーグ、レオ(1981年冬)。「ベラスケスの『ラス・メニーナス』」。10月。19。MITプレス:45-54。doi:10.2307/778659。JSTOR 778659。 ストーン、ハリエット (1996). 『古典的モデル:17 世紀フランスの文学と知識』. イサカ:コーネル大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-8014-3212-5. ホワイト、ジョン・マンチップ (1969)。『ディエゴ・ベラスケス:画家であり宮廷人』。ロンドン:ハミッシュ・ハミルトン社。ISBN 978-0241-0-1624-4。 ゼリ、フェデリコ (1990)。『イメージの背後、絵画を読む技術』。ロンドン:ハイネマン社。ISBN 978-0-4348-9688-2。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Las_Meninas |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099