法あるいは法律

Law

☆法[Law]と

は、行動を規制するために社会的または政府機関によって制定され、執行可能な規則の集合体である[1]。その正確な定義は長年の議論の的となっている

[2][3][4]。法は科学として[5][6]、あるいは正義の技芸として[7][8][9]、様々な形で説明されてきた。国家が強制する法は、立法府

による制定で成文法となり、行政府による布告や規則で制定され、判例法地域では裁判官の判決で判例を形成する。独裁者は自らの領域内でこれらの機能を行使

し得る。法そのものの制定は、成文または不文の憲法と、そこに規定された権利に影響される。法は様々な形で政治、経済、歴史、社会を形成し、人々の関係に

おける仲介役も果たす。

法体系は管轄区域によって異なり、その差異は比較法学で分析される。大陸法系では、立法府やその他の中央機関が法を成文化し統合する。コモン・ロー系で

は、判例を通じて裁判官が拘束力のある判例法を作り出すことがある[10]が、場合によっては上級裁判所や立法府によって覆されることもある[11]。宗

教法は一部の宗教共同体や国家で使用されており、歴史的に世俗法に影響を与えてきた。[12][13][14][15][16]

法の範囲は二つの領域に分けられる。公法は政府と社会に関わるもので、憲法、行政法、刑法を含む。一方、私法は契約、財産、不法行為、商法などの分野にお

ける当事者間の法的紛争を扱う[17]。この区別は、特に独立した行政裁判所制度を持つ大陸法国家でより明確である。[18][19]

これに対し、コモン・ロー法域では公法と私法の区別はそれほど明確ではない。[20][21]

法は、法史学[22]、法哲学[23]、経済分析[24]、社会学[25]といった学術的探究の源泉を提供する。法はまた、平等、公平性、正義に関する重

要かつ複雑な問題を提起する。[26][27]

| Law is a set of

rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental

institutions to regulate behavior,[1] with its precise definition a

matter of longstanding debate.[2][3][4] It has been variously described

as a science[5][6] and as the art of justice.[7][8][9] State-enforced

laws can be made by a legislature, resulting in statutes; by the

executive through decrees and regulations; or by judges' decisions,

which form precedent in common law jurisdictions. An autocrat may

exercise those functions within their realm. The creation of laws

themselves may be influenced by a constitution, written or tacit, and

the rights encoded therein. The law shapes politics, economics, history

and society in various ways and also serves as a mediator of relations

between people. Legal systems vary between jurisdictions, with their differences analysed in comparative law. In civil law jurisdictions, a legislature or other central body codifies and consolidates the law. In common law systems, judges may make binding case law through precedent,[10] although on occasion this may be overturned by a higher court or the legislature.[11] Religious law is in use in some religious communities and states, and has historically influenced secular law.[12][13][14][15][16] The scope of law can be divided into two domains: public law concerns government and society, including constitutional law, administrative law, and criminal law; while private law deals with legal disputes between parties in areas such as contracts, property, torts, delicts and commercial law.[17] This distinction is stronger in civil law countries, particularly those with a separate system of administrative courts;[18][19] by contrast, the public-private law divide is less pronounced in common law jurisdictions.[20][21] Law provides a source of scholarly inquiry into legal history,[22] philosophy,[23] economic analysis[24] and sociology.[25] Law also raises important and complex issues concerning equality, fairness, and justice.[26][27] |

法[Law]とは、行動を規制するために社会的または政府機関によって制定され、

執行可能な規則の集合体である[1]。その正確な定義は長年の議論の的となっている[2][3][4]。法は科学として[5][6]、あるいは正義の技芸

として[7][8][9]、様々な形で説明されてきた。国家が強制する法は、立法府による制定で成文法となり、行政府による布告や規則で制定され、判例法

地域では裁判官の判決で判例を形成する。独裁者は自らの領域内でこれらの機能を行使し得る。法そのものの制定は、成文または不文の憲法と、そこに規定され

た権利に影響される。法は様々な形で政治、経済、歴史、社会を形成し、人々の関係における仲介役も果たす。 法体系は管轄区域によって異なり、その差異は比較法学で分析される。大陸法系では、立法府やその他の中央機関が法を成文化し統合する。コモン・ロー系で は、判例を通じて裁判官が拘束力のある判例法を作り出すことがある[10]が、場合によっては上級裁判所や立法府によって覆されることもある[11]。宗 教法は一部の宗教共同体や国家で使用されており、歴史的に世俗法に影響を与えてきた。[12][13][14][15][16] 法の範囲は二つの領域に分けられる。公法は政府と社会に関わるもので、憲法、行政法、刑法を含む。一方、私法は契約、財産、不法行為、商法などの分野にお ける当事者間の法的紛争を扱う[17]。この区別は、特に独立した行政裁判所制度を持つ大陸法国家でより明確である。[18][19] これに対し、コモン・ロー法域では公法と私法の区別はそれほど明確ではない。[20][21] 法は、法史学[22]、法哲学[23]、経済分析[24]、社会学[25]といった学術的探究の源泉を提供する。法はまた、平等、公平性、正義に関する重 要かつ複雑な問題を提起する。[26][27] |

| Etymology The word law, attested in Old English as lagu, comes from the Old Norse word lǫg. The singular form lag meant 'something laid or fixed' while its plural meant 'law'.[28] |

語源 「law」という言葉は、古英語で「lagu」と記録されているが、これは古ノルド語の「lǫg」に由来する。単数形の「lag」は「定められたもの」を意味し、複数形は「法」を意味した。[28] |

| Philosophy of law Main articles: Jurisprudence and Philosophy of law But what, after all, is a law? [...] When I say that the object of laws is always general, I mean that law considers subjects en masse and actions in the abstract, and never a particular person or action. [...] On this view, we at once see that it can no longer be asked whose business it is to make laws, since they are acts of the general will; nor whether the prince is above the law, since he is a member of the State; nor whether the law can be unjust, since no one is unjust to himself; nor how we can be both free and subject to the laws, since they are but registers of our wills. ----- Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract, II, 6.[29] The philosophy of law is commonly known as jurisprudence. Normative jurisprudence asks "what should law be?", while analytic jurisprudence asks "what is law?" |

法の哲学 主な記事: 法学と法の哲学 しかし結局のところ、法とは何か? [...] 法の対象が常に一般的であると言うとき、法は対象を集団として、行為を抽象的に扱い、決して特定の個人や行為を対象としないという意味だ。[...] この見解によれば、法律は一般意志の行為である以上、誰が法律を作るべきかという問いはもはや意味をなさなくなる。また君主が法律の上に立つかどうかも問 えない。君主も国家の一員だからだ。法律が不正である可能性も論じられない。誰も自分自身に対して不正を働くことはないからだ。さらに我々が自由でありな がら法律に従うことができる理由も説明できない。法律は我々の意志を記録したに過ぎないのだから。 ——ジャン=ジャック・ルソー『社会契約論』第二篇第六章[29] 法の哲学は一般に法学として知られる。規範的法学は「法はどうあるべきか」を問い、分析的法学は「法とは何か」を問う。 |

| Analytical jurisprudence Main article: Analytical jurisprudence There have been several attempts to produce "a universally acceptable definition of law". In 1972, Baron Hampstead suggested that no such definition could be produced.[30] McCoubrey and White said that the question "what is law?" has no simple answer.[31] Glanville Williams said that the meaning of the word "law" depends on the context in which that word is used. He said that, for example, "early customary law" and "municipal law" were contexts where the word "law" had two different and irreconcilable meanings.[32] Thurman Arnold said that it is obvious that it is impossible to define the word "law" and that it is also equally obvious that the struggle to define that word should not ever be abandoned.[33] It is possible to take the view that there is no need to define the word "law" (e.g. "let's forget about generalities and get down to cases").[34] One definition is that law is a system of rules and guidelines which are enforced through social institutions to govern behaviour.[1] In The Concept of Law, H. L. A. Hart argued that law is a "system of rules";[35] John Austin said law was "the command of a sovereign, backed by the threat of a sanction";[36] Ronald Dworkin describes law as an "interpretive concept" to achieve justice in his text titled Law's Empire;[37] and Joseph Raz argues law is an "authority" to mediate people's interests.[38] Oliver Wendell Holmes defined law as "the prophecies of what the courts will do in fact, and nothing more pretentious."[39] In his Treatise on Law, Thomas Aquinas argues that law is a rational ordering of things, which concern the common good, that is promulgated by whoever is charged with the care of the community.[40] This definition has both positivist and naturalist elements.[41] |

分析法学 詳細な記事: 分析法学 「普遍的に受け入れられる法の定義」を確立しようとする試みは幾度か行われてきた。1972年、ハンプステッド男爵は、そのような定義は不可能だと示唆し た[30]。マックーブリーとホワイトは、「法とは何か」という問いに単純な答えはないと述べた。[31] グランヴィル・ウィリアムズは、「法」という言葉の意味はその使用文脈に依存すると述べた。例えば「初期の慣習法」と「国内法」という文脈では、「法」と いう言葉が二つの異なる調和不能な意味を持つと指摘した。サーマン・アーノルドは、「法」という言葉を定義することは明らかに不可能であり、同時にその定 義への取り組みを決して放棄すべきでないことも同様に明らかだと述べた。[33]「法」という言葉を定義する必要はないという見方(例えば「一般論は忘れ て具体例に目を向けよう」)を取ることも可能である。[34] 一つの定義として、法とは行動を統制するために社会制度を通じて執行される規則と指針の体系である[1]。『法の概念』においてH. L. A. ハートは法は「規則体系」であると論じた[35]。ジョン・オースティンは法とは「制裁の脅威に裏打ちされた主権者の命令」であると述べた。[36] ロナルド・ドワークンは『法の帝国』において、法を正義を達成するための「解釈的概念」と描写している。[37] ジョセフ・ラズは、法を人々の利益を調整する「権威」と論じている。[38] オリバー・ウェンデル・ホームズは法を「裁判所が実際に取る行動を予言するものであり、それ以上の大げさなものではない」と定義した。[39] トマス・アクィナスは『法論』において、法とは共同体の利益に関わる事柄を合理的に秩序づけるものであり、共同体の管理を任された者が公布するものだと論 じている[40]。この定義には実証主義的要素と自然主義的要素の両方が含まれている[41]。 |

| Connection to morality and justice See also: Rule according to higher law Definitions of law often raise the question of the extent to which law incorporates morality.[42] John Austin's utilitarian answer was that law is "commands, backed by threat of sanctions, from a sovereign, to whom people have a habit of obedience".[36] Natural lawyers, on the other hand, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, argue that law reflects essentially moral and unchangeable laws of nature. The concept of "natural law" emerged in ancient Greek philosophy concurrently and in connection with the notion of justice, and re-entered the mainstream of Western culture through the writings of Thomas Aquinas, notably his Treatise on Law. Hugo Grotius, the founder of a purely rationalistic system of natural law, argued that law arises from both a social impulse—as Aristotle had indicated—and reason.[43] Immanuel Kant believed a moral imperative requires laws "be chosen as though they should hold as universal laws of nature".[44] Jeremy Bentham and his student Austin, following David Hume, believed that this conflated the "is" and what "ought to be" problem. Bentham and Austin argued for law's positivism; that real law is entirely separate from "morality".[45] Kant was also criticised by Friedrich Nietzsche, who rejected the principle of equality, and believed that law emanates from the will to power, and cannot be labeled as "moral" or "immoral".[46][47][48] In 1934, the Austrian philosopher Hans Kelsen continued the positivist tradition in his book the Pure Theory of Law.[49] Kelsen believed that although law is separate from morality, it is endowed with "normativity", meaning we ought to obey it. While laws are positive "is" statements (e.g. the fine for reversing on a highway is €500); law tells us what we "should" do. Thus, each legal system can be hypothesised to have a 'basic norm' (German: Grundnorm) instructing us to obey. Kelsen's major opponent, Carl Schmitt, rejected both positivism and the idea of the rule of law because he did not accept the primacy of abstract normative principles over concrete political positions and decisions.[50] Therefore, Schmitt advocated a jurisprudence of the exception (state of emergency), which denied that legal norms could encompass all of the political experience.[51] Later in the 20th century, H. L. A. Hart attacked Austin for his simplifications and Kelsen for his fiction in The Concept of Law.[52] Hart argued law is a system of rules, divided into primary (rules of conduct) and secondary ones (rules addressed to officials to administer primary rules). Secondary rules are further divided into rules of adjudication (to resolve legal disputes), rules of change (allowing laws to be varied) and the rule of recognition (allowing laws to be identified as valid). Two of Hart's students continued the debate: In his book Law's Empire, Ronald Dworkin attacked Hart and the positivists for their refusal to treat law as a moral issue. Dworkin argues that law is an "interpretive concept"[37] that requires judges to find the best fitting and most just solution to a legal dispute, given their Anglo-American constitutional traditions. Joseph Raz, on the other hand, defended the positivist outlook and criticised Hart's "soft social thesis" approach in The Authority of Law.[38] Raz argues that law is authority, identifiable purely through social sources and without reference to moral reasoning. In his view, any categorisation of rules beyond their role as authoritative instruments in mediation is best left to sociology, rather than jurisprudence.[53] |

道徳と正義との関連性 関連項目: 高次の法に基づく統治 法の定義は、法が道徳をどの程度包含するかという問題をしばしば提起する。[42] ジョン・オースティンの功利主義的回答は、法とは「制裁の脅威を背景とした、人々が従順の習慣を持つ主権者からの命令」であるというものだった。[36] 一方、ジャン=ジャック・ルソーのような自然法学者は、法は本質的に道徳的で不変の自然法を反映すると主張する。「自然法」の概念は古代ギリシャ哲学にお いて正義の概念と同時期に、またそれに関連して出現し、トマス・アクィナスの著作、特に『法論』を通じて西洋文化の主流に再登場した。 純粋に合理主義的な自然法体系の創始者であるウーゴ・グロティウスは、アリストテレスが示唆したように、法は社会的衝動と理性の両方から生じるものだと主 張した。[43] イマヌエル・カントは、道徳的義務は「普遍的な自然法則として成立すべきものとして選ばれるべき」法を求めるものだと考えた。[44] ジェレミー・ベンサムとその弟子オースティンは、デイヴィッド・ヒュームに倣い、これは「あるべき姿」と「あるがままの姿」の問題を混同していると考え た。ベンサムとオースティンは法の実証主義を主張した。つまり現実の法は「道徳」とは完全に分離しているというのだ[45]。カントはフリードリヒ・ニー チェからも批判を受けた。ニーチェは平等原理を拒否し、法は権力意志から発するものであり、「道徳的」あるいは「非道徳的」とレッテルを貼ることはできな いと考えた[46][47]。[48] 1934年、オーストリアの哲学者ハンス・ケルゼンは著書『法の純粋理論』で実証主義の伝統を継承した。[49] ケルゼンは、法は道徳とは別物だが「規範性」を備えていると考えた。つまり我々は法に従うべきだという意味だ。法律は実在論的な「ある」の表明である (例:高速道路での逆走罰金は500ユーロ)。法は我々に「すべき」ことを指示する。したがって、あらゆる法体系には従うよう命じる『基本規範』(ドイツ 語:Grundnorm)が仮定できる。ケルゼンの主要な対抗者カール・シュミットは、抽象的な規範原理が具体的な政治的立場や決定に優先することを認め なかったため、実証主義と法の支配の思想の両方を拒否した。[50] したがってシュミットは、例外(非常事態)の法理学を提唱し、法的規範が政治的経験の全てを包含し得るとする考えを否定した。[51] 20世紀後半、H. L. A. ハートは『法の概念』において、オースティンの単純化とケルゼンの虚構を批判した。[52] ハートは、法は規則体系であり、一次規則(行動規範)と二次規則(一次規則を運用する官吏向けの規則)に分けられると論じた。二次規則はさらに、裁判規則 (法的紛争を解決する)、変更規則(法の変更を可能にする)、承認規則(法の有効性を認定する)に分類される。ハート門下の二人の研究者が論争を引き継い だ。ロナルド・ドワークンは『法の帝国』において、ハートと実証主義者たちが法を道徳的問題として扱わない姿勢を批判した。ドワークンは法が「解釈的概 念」[37]であり、英米の憲政伝統を踏まえ、裁判官が法的紛争に対し最適かつ最も公正な解決策を見出すことを要求すると主張する。一方、ジョセフ・ラズ は『法の権威』において実証主義的見解を擁護し、ハートの「軟弱な社会論」的アプローチを批判した。ラズは法とは権威であり、道徳的推論を参照することな く純粋に社会的源泉を通じて識別可能だと主張する。彼の見解では、調停における権威的手段としての役割を超えた規則の分類は、法学ではなく社会学に委ねる のが最善である。 |

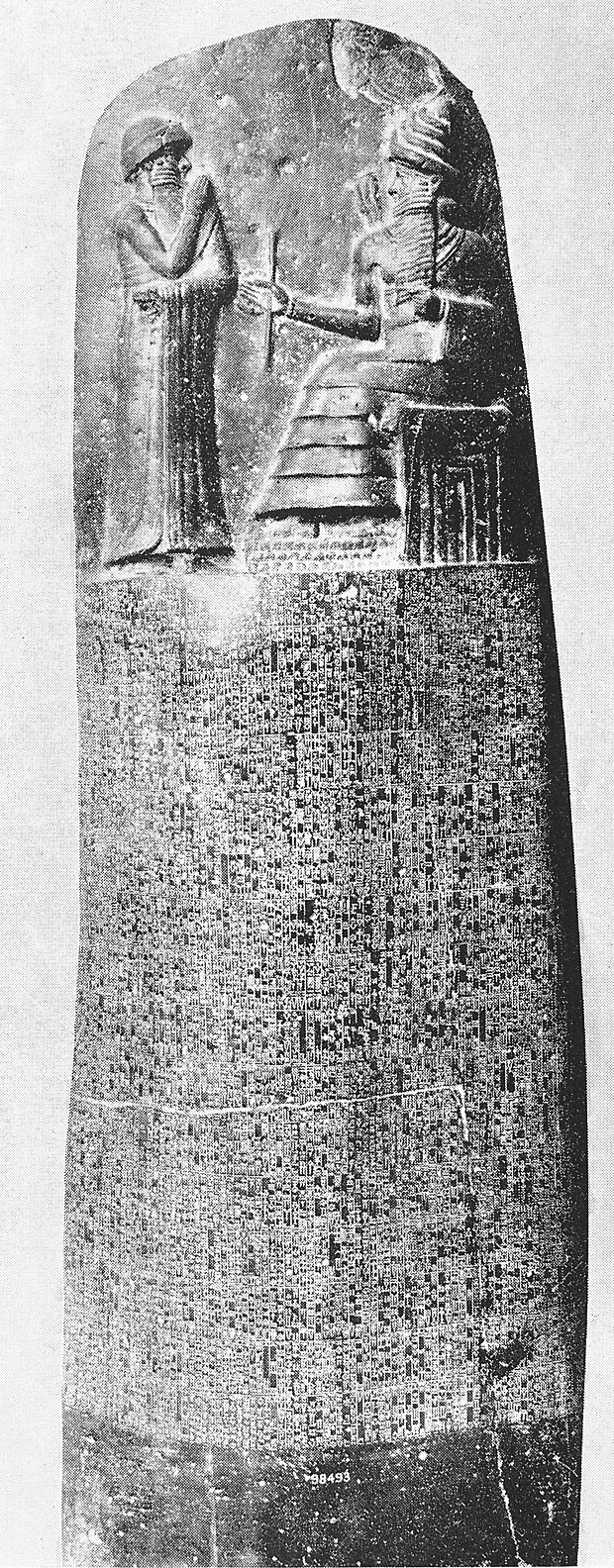

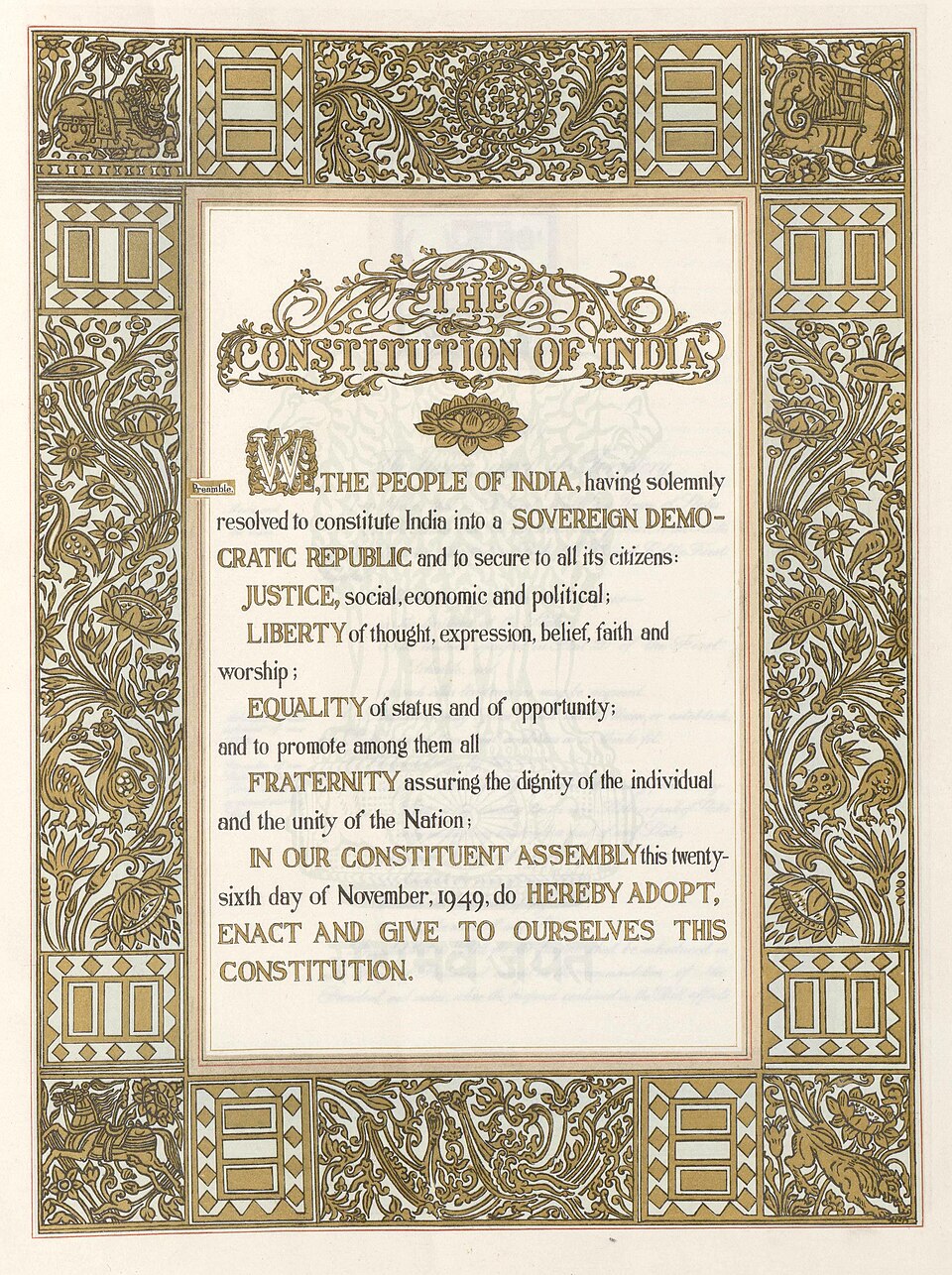

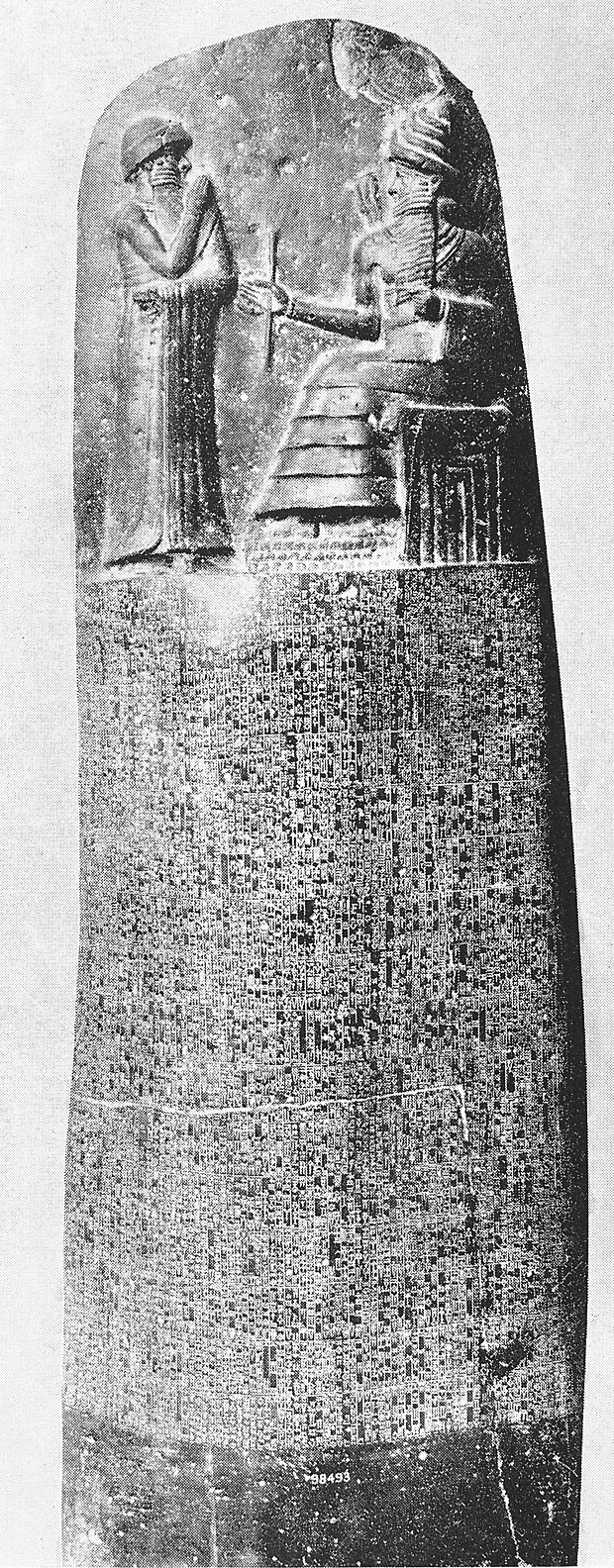

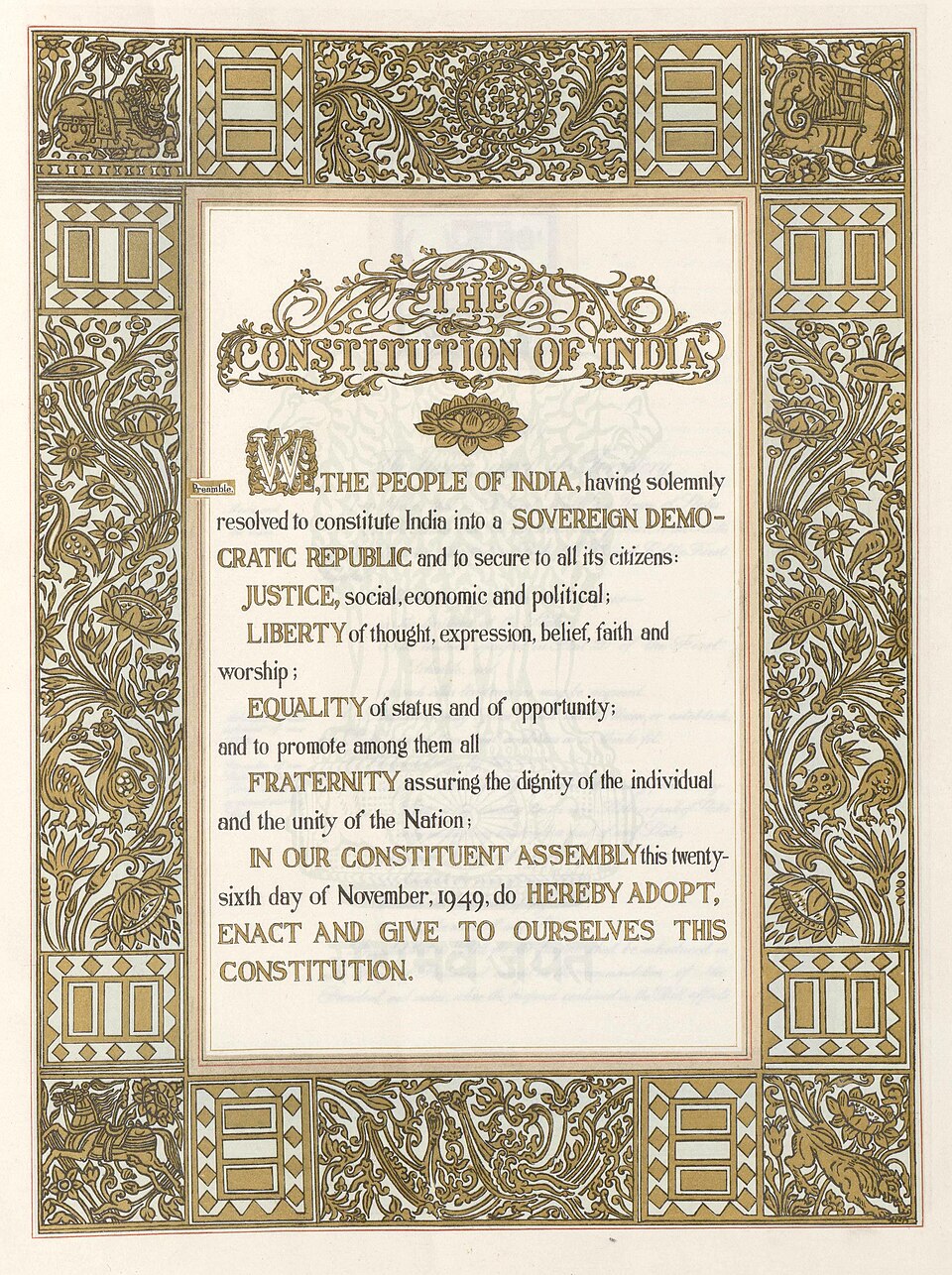

| History Main article: Legal history  A stone monument with two parts; at top, a relief depicting two figures, one standing and one seated; at bottom, cuneiform text of the Hammurabic legal code of ancient Babylon. The Code of Hammurabi is an early code of laws, from ancient Babylon. The history of law links closely to the development of civilization. Ancient Egyptian law, dating as far back as 3000 BC, was based on the concept of Ma'at and characterised by tradition, rhetorical speech, social equality and impartiality.[54][55][56] By the 22nd century BC, the ancient Sumerian ruler Ur-Nammu had formulated the first law code, which consisted of casuistic statements ("if … then ..."). Around 1760 BC, King Hammurabi further developed Babylonian law, by codifying and inscribing it in stone. Hammurabi placed several copies of his law code throughout the kingdom of Babylon as stelae, for the entire public to see; this became known as the Codex Hammurabi. The most intact copy of these stelae was discovered in the 19th century by British Assyriologists, and has since been fully transliterated and translated into various languages, including English, Italian, German, and French.[57] The Old Testament dates back to 1280 BC and takes the form of moral imperatives as recommendations for a good society. The small Greek city-state, ancient Athens, from about the 8th century BC was the first society to be based on broad inclusion of its citizenry, excluding women and enslaved people. However, Athens had no legal science or single word for "law",[58] relying instead on the three-way distinction between divine law (thémis), human decree (nómos) and custom (díkē).[59] Yet Ancient Greek law contained major constitutional innovations in the development of democracy.[60] Roman law was heavily influenced by Greek philosophy, but its detailed rules were developed by professional jurists and were highly sophisticated.[61][62] Over the centuries between the rise and decline of the Roman Empire, law was adapted to cope with the changing social situations and underwent major codification under Theodosius II and Justinian I.[a] Although codes were replaced by custom and case law during the Early Middle Ages, Roman law was rediscovered around the 11th century when medieval legal scholars began to research Roman codes and adapt their concepts to the canon law, giving birth to the jus commune. Latin legal maxims (called brocards) were compiled for guidance. In medieval England, royal courts developed a body of precedent which later became the common law. A Europe-wide Law Merchant was formed so that merchants could trade with common standards of practice rather than with the many splintered facets of local laws. The Law Merchant, a precursor to modern commercial law, emphasised the freedom to contract and alienability of property.[63] As nationalism grew in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Law Merchant was incorporated into countries' local law under new civil codes. The Napoleonic and German Codes became the most influential. In contrast to English common law, which consists of enormous tomes of case law, codes in small books are easy to export and easy for judges to apply. However, today there are signs that civil and common law are converging.[64] EU law is codified in treaties, but develops through de facto precedent laid down by the European Court of Justice.[65]  The Constitution of India, ceremonially rendered as an illustrated and calligraphed manuscript. Ancient India and China represent distinct traditions of law, and have historically had independent schools of legal theory and practice. The Arthashastra, probably compiled around 100 AD (although it contains older material), and the Manusmriti (c. 100–300 AD) were foundational treatises in India, and comprise texts considered authoritative legal guidance.[66] Manu's central philosophy was tolerance and pluralism, and was cited across Southeast Asia.[67] During the Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent, sharia was established by the Muslim sultanates and empires, most notably Mughal Empire's Fatawa-e-Alamgiri, compiled by emperor Aurangzeb and various scholars of Islam.[68][69] In India, the Hindu legal tradition, along with Islamic law, were both supplanted by common law when India became part of the British Empire.[70] Malaysia, Brunei, Singapore and Hong Kong also adopted the common law system. The Eastern Asia legal tradition reflects a unique blend of secular and religious influences.[71] Japan was the first country to begin modernising its legal system along Western lines, by importing parts of the French, but mostly the German Civil Code.[72] This partly reflected Germany's status as a rising power in the late 19th century. Similarly, traditional Chinese law gave way to westernisation towards the final years of the Qing Dynasty in the form of six private law codes based mainly on the Japanese model of German law.[73] Today Taiwanese law retains the closest affinity to the codifications from that period, because of the split between Chiang Kai-shek's nationalists, who fled there, and Mao Zedong's communists who won control of the mainland in 1949. The current legal infrastructure in the People's Republic of China was heavily influenced by Soviet Socialist law, which essentially prioritises administrative law at the expense of private law rights.[74] Due to rapid industrialisation, today China is undergoing a process of reform, at least in terms of economic, if not social and political, rights. A new contract code in 1999 represented a move away from administrative domination.[75] Furthermore, after negotiations lasting fifteen years, in 2001 China joined the World Trade Organization.[76] |

歴史 主な記事: 法の歴史  二つの部分からなる石碑。上部には、立っている人物と座っている人物を描いたレリーフ。下部には、古代バビロニアのハンムラビ法典の楔形文字が刻まれている。 ハンムラビ法典は、古代バビロニアの初期の法典である。 法の歴史は、文明の発展と密接に関連している。 紀元前3000年まで遡る古代エジプト法は、マアトの概念に基づき、伝統、修辞的演説、社会的平等、公平性を特徴とする[54][55][56]。紀元前 22世紀までに、古代シュメールの統治者ウル・ナムは最初の法典を制定した。これは事例主義的条文(「もし…ならば…」)で構成されていた。紀元前 1760年頃、ハンムラビ王はバビロニア法をさらに発展させ、成文化して石碑に刻んだ。ハンムラビは自身の法典の複写をバビロン王国全土に石碑として設置 し、国民全体が閲覧できるようにした。これがハンムラビ法典として知られるようになった。これらの石碑の中で最も完全な写本は19世紀に英国のアッシリア 学者によって発見され、その後英語、イタリア語、ドイツ語、フランス語など様々な言語へ完全な音訳と翻訳がなされた。[57] 旧約聖書は紀元前1280年に遡り、良き社会のための勧告として道徳的命令の形式を取っている。紀元前8世紀頃のギリシャの小都市国家、古代アテネは、女 性と奴隷を除き、市民を広く包含する社会として初めて成立した。しかしアテネには法学という学問も「法」を表す単一の語も存在せず[58]、代わりに神法 (テミス)、人法(ノモス)、慣習(ディケー)という三つの区別に基づいていた。[59] それでも古代ギリシャ法は民主主義の発展において主要な憲法上の革新を含んでいた。[60] ローマ法はギリシャ哲学の影響を強く受けたが、その詳細な規則は専門の法学者によって発展させられ、高度に洗練されていた。[61] [62] ローマ帝国の興亡に跨る数世紀の間、法は変化する社会状況に対応するため適応され、テオドシウス2世とユスティニアヌス1世の下で大規模な法典化が行われ た。[a] 中世初期には法典が慣習法や判例法に取って代わられたが、11世紀頃に中世の法学者たちがローマ法典を研究し、その概念を教会法に適応させることでローマ 法が再発見され、ユス・コムーネが誕生した。指針としてラテン語の法格律(ブロカールと呼ばれる)が編纂された。中世イングランドでは王室裁判所が判例法 体系を発展させ、後にコモン・ローとなった。商人たちが地方法の細分化された側面ではなく共通の実務基準で取引できるよう、ヨーロッパ全域にわたる商人法 が形成された。現代商法の前身である商人法は契約の自由と財産の譲渡可能性を強調した。[63] 18世紀から19世紀にかけてナショナリズムが高まる中、商法は新たな民法典の下で各国の国内法に組み込まれた。ナポレオン法典とドイツ法典が最も影響力 を持つようになった。膨大な判例集から成る英国のコモン・ローとは対照的に、小冊子の法典は輸出が容易で、裁判官が適用しやすかった。しかし今日、大陸法 とコモン・ローが収束しつつある兆候が見られる。[64] EU法は条約で成文化されているが、欧州司法裁判所が確立した事実上の判例を通じて発展している。[65]  インド憲法は、儀式的に図解と書道で装飾された写本として表現されている。 古代インドと中国は異なる法伝統を代表し、歴史的に独立した法理論・実践の学派を有してきた。『アルタシャストラ』(おそらく紀元100年頃に編纂された が、より古い資料を含む)と『マヌ法典』(紀元100~300年頃)はインドにおける基礎的な法典であり、権威ある法的指針とされるテキストを構成してい る。[66] マヌの中心思想は寛容と多元主義であり、東南アジア全域で引用された。[67] インド亜大陸におけるイスラム教徒の征服期には、シャリーアがイスラム教徒のスルタン国や帝国によって確立された。特にムガル帝国の『ファタワ・エ・アラ ムギル』は、皇帝アウラングゼーブと様々なイスラム学者によって編纂された。[68] [69] インドでは、ヒンドゥー法体系とイスラム法は、インドが英国帝国の一部となった際に、いずれもコモン・ローに取って代わられた。[70] マレーシア、ブルネイ、シンガポール、香港もコモン・ロー制度を採用した。東アジアの法体系は、世俗的影響と宗教的影響が独自に融合したものである。 [71] 日本は、フランス法の一部、主にドイツ民法典を導入することで、西洋式に法制度の近代化を始めた最初の国であった。[72] これは19世紀後半におけるドイツの台頭する大国の地位を部分的に反映していた。 同様に、清王朝末期には、主に日本のドイツ法モデルに基づく六つの私法典の形で、伝統的な中国法が西洋化に道を譲った。[73] 現在の台湾法は、1949 年に大陸支配権を獲得した毛沢東の共産党と、台湾に逃れた蒋介石のナショナリストとの分裂により、この時代の法典化に最も近い親和性を保っている。中華人 民共和国の現行法体系は、私法上の権利を犠牲にして行政法を本質的に優先するソビエト社会主義法の影響を強く受けている。[74] 急速な工業化により、今日の中国は少なくとも経済的権利の面では、社会的・政治的権利の面では必ずしもそうではないが、改革の過程にある。1999年の新 たな契約法は、行政支配からの脱却を示す動きであった。[75] さらに、15年に及ぶ交渉を経て、2001年に中国は世界貿易機関(WTO)に加盟した。[76] |

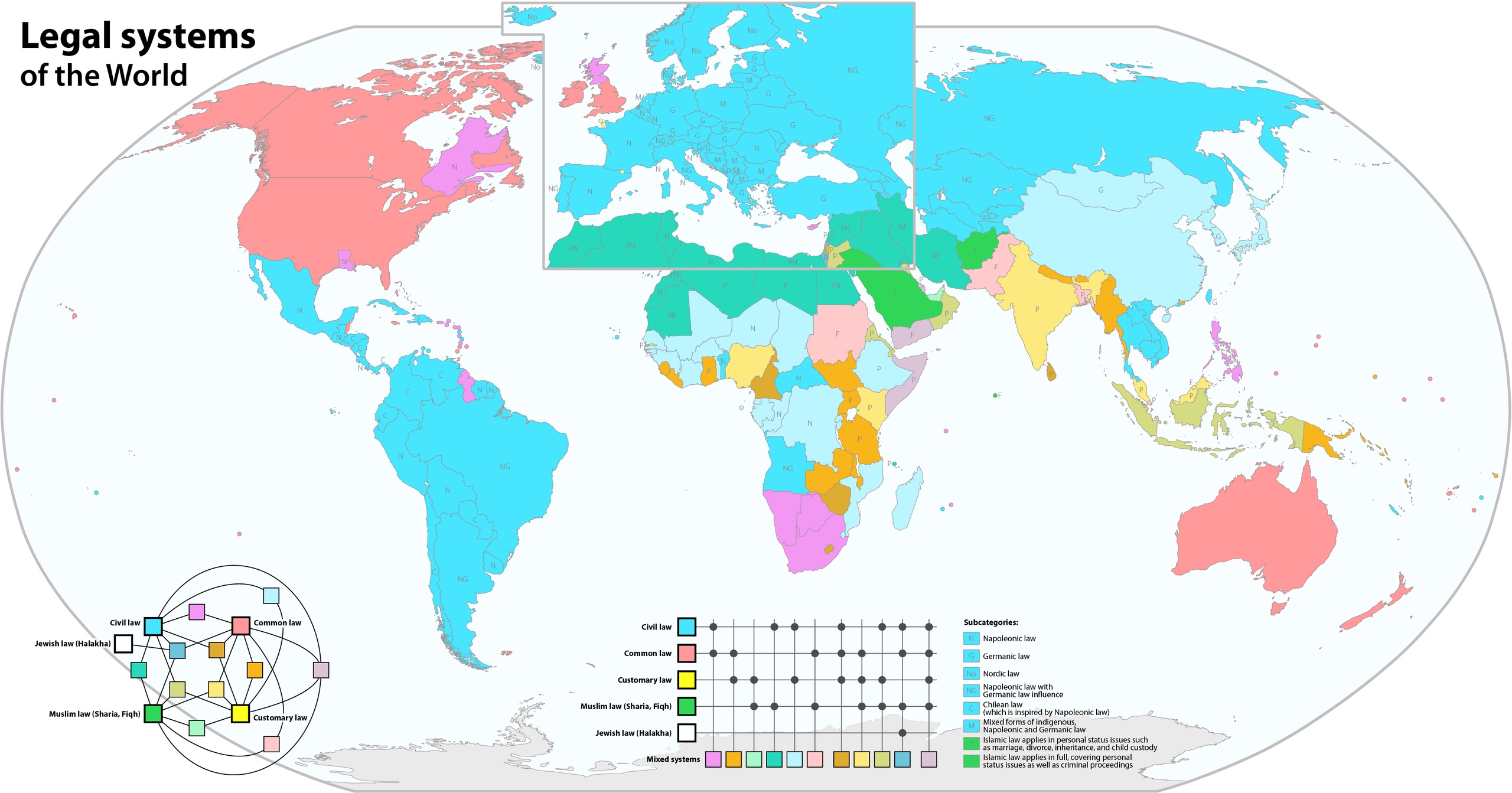

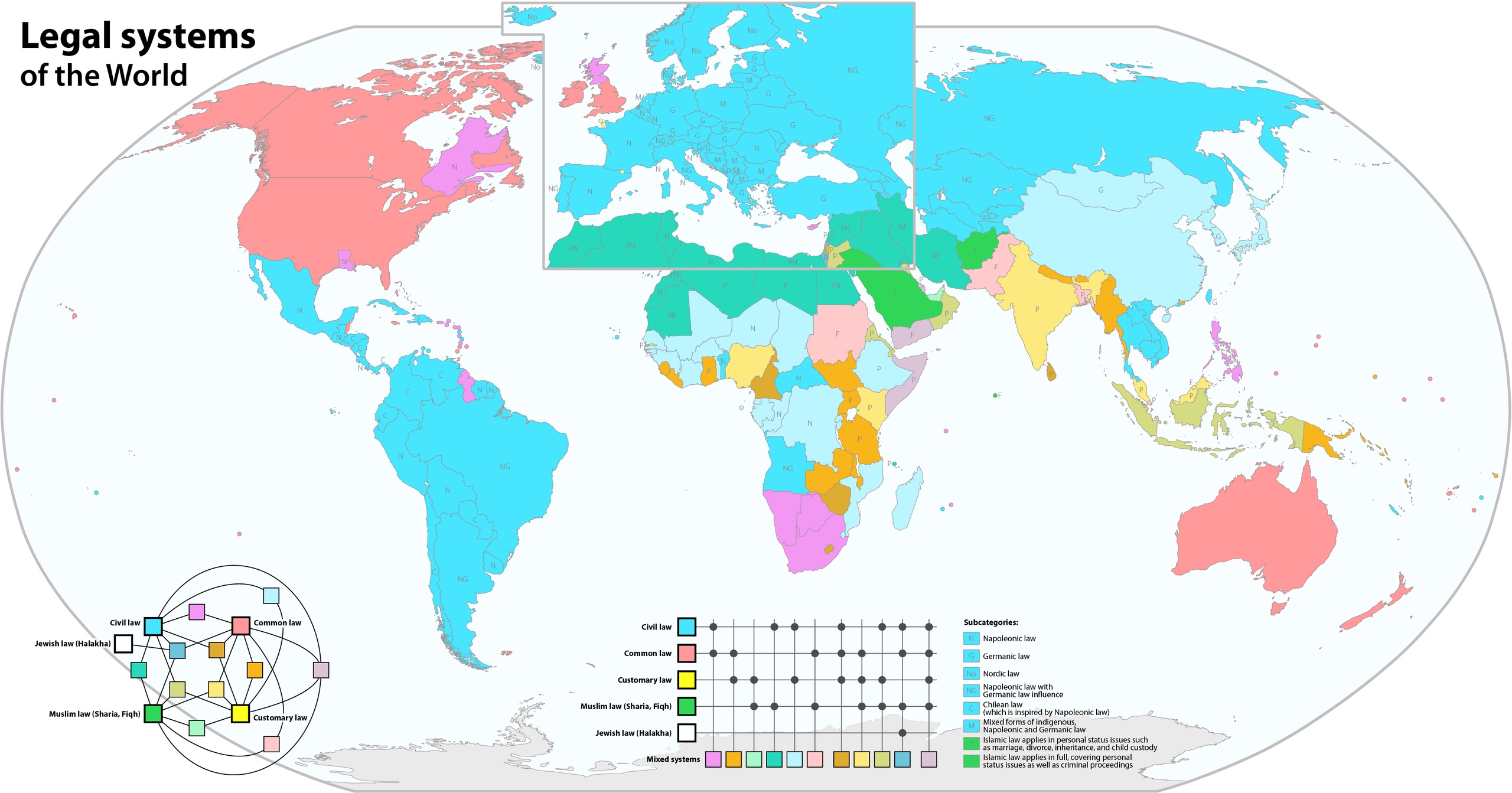

| Legal systems Main articles: Comparative law, List of national legal systems, and Comparative legal history In general, legal systems can be split between civil law and common law systems.[77] Modern scholars argue that the significance of this distinction has progressively declined. The numerous legal transplants, typical of modern law, result in the sharing of many features traditionally considered typical of either common law or civil law.[64][78] The third type of legal system is religious law, based on scriptures. The specific system that a country is ruled by is often determined by its history, connections with other countries, or its adherence to international standards. The sources that jurisdictions adopt as authoritatively binding are the defining features of any legal system.  Colour-coded map of the legal systems around the world, showing civil, common law, religious, customary and mixed legal systems.[79][additional citation(s) needed] Common law systems are shaded pink, and civil law systems are shaded blue/turquoise. |

法体系 主な記事:比較法、国家法体系一覧、比較法史 一般的に、法体系は大陸法系と英米法系に分けられる[77]。現代の学者は、この区別の重要性が次第に低下していると主張する。現代法に典型的な数多くの 法移植の結果、従来は英米法または大陸法のいずれかに典型的な特徴と考えられていた多くの要素が共有されるようになった[64]。[78] 第三の類型として、聖典に基づく宗教法が存在する。国家が採用する具体的な法体系は、その歴史、他国との繋がり、あるいは国際基準への順守度によって決定 されることが多い。管轄区域が権威ある拘束力を持つと認める法源こそが、あらゆる法体系を定義する特徴である。  世界の法体系を色分けした地図。民法体系、コモン・ロー体系、宗教法体系、慣習法体系、混血の体系を示している。[79][追加出典が必要] コモン・ロー体系はピンク色で、民法体系は青/ターコイズ色で塗り分けられている。 |

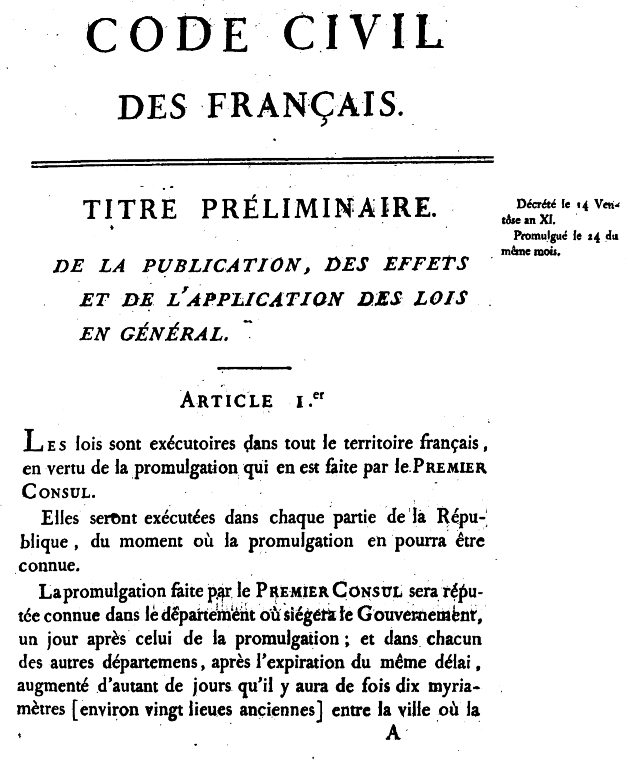

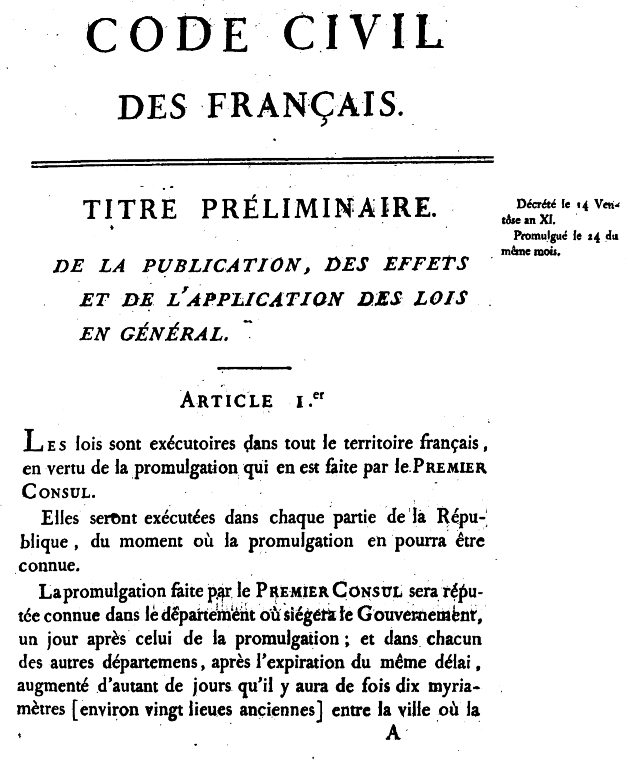

| Civil law Main article: Civil law (legal system)  First page of the 1804 edition of the Napoleonic Code Civil law is the legal system used in most countries around the world today. In civil law the sources recognised as authoritative are, primarily, legislation—especially codifications in constitutions or statutes passed by government—and custom.[b] Codifications date back millennia, with one early example being the Babylonian Codex Hammurabi. Modern civil law systems essentially derive from legal codes issued by Byzantine Emperor Justinian I in the 6th century, which were rediscovered by 11th century Italy.[80] Roman law in the days of the Roman Republic and Empire was heavily procedural, and lacked a professional legal class.[81] Instead a lay magistrate, iudex, was chosen to adjudicate. Decisions were not published in any systematic way, so any case law that developed was disguised and almost unrecognised.[82] Each case was to be decided afresh from the laws of the State, which mirrors the (theoretical) unimportance of judges' decisions for future cases in civil law systems today. From 529 to 534 AD the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I codified and consolidated Roman law up until that point, so that what remained was one-twentieth of the mass of legal texts from before.[83] This became known as the Corpus Juris Civilis. As one legal historian wrote, "Justinian consciously looked back to the golden age of Roman law and aimed to restore it to the peak it had reached three centuries before."[84] The Justinian Code remained in force in the East until the fall of the Byzantine Empire. Western Europe, meanwhile, relied on a mix of the Theodosian Code and Germanic customary law until the Justinian Code was rediscovered in the 11th century, which scholars at the University of Bologna used to interpret their own laws.[85] Civil law codifications based closely on Roman law, alongside some influences from religious laws such as canon law, continued to spread throughout Europe until the Enlightenment. Then, in the 19th century, both France, with the Code Civil, and Germany, with the Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch, modernised their legal codes. Both these codes heavily influenced not only the law systems of the countries in continental Europe but also the Japanese and Korean legal traditions.[86][87] A central doctrine in continental European legal thinking, originating in German jurisprudence, is the concept of a Rechtsstaat, meaning that everyone is subjected to the law, especially governments.[88] Today, countries that have civil law systems range from Russia and Turkey to most of Central and Latin America.[89] |

民法 主な記事: 民法(法体系)  1804年版ナポレオン法典の最初のページ 民法は、今日世界中のほとんどの国で使用されている法体系である。民法において権威あるものと認められる法源は、主に立法、特に政府によって制定された憲 法や法令における成文化、そして慣習である。[b] 法典化は数千年前まで遡り、初期の例としてバビロニアのハンムラビ法典がある。現代の民法体系は本質的に、6世紀にビザンツ皇帝ユスティニアヌス1世が発 布した法典に由来し、11世紀のイタリアで再発見されたものである[80]。ローマ共和政期および帝政期のローマ法は手続き的要素が強く、専門的な法曹階 級が存在しなかった。[81] 代わりに、裁判官(iudex)と呼ばれる非専門家の裁判官が選ばれて裁定を行った。判決は体系的に公表されなかったため、判例法が発展してもそれは隠蔽 され、ほとんど認識されなかった。[82] 各事件は国家の法律に基づいて新たに裁決されるべきであり、これは現代の民法体系において裁判官の判決が将来の事件にとって(理論上)重要でないことを反 映している。西暦529年から534年にかけ、ビザンツ皇帝ユスティニアヌス1世はそれまでのローマ法を体系化・統合した。その結果、残された法典は以前 の法典総量の20分の1に縮小された[83]。これが『コーパス・ユリス・シヴィリス』として知られるようになった。ある法史家が記したように、「ユス ティニアヌスは意識的にローマ法の黄金時代を振り返り、三世紀前に達した頂点への回帰を目指した」のである。」と評している[84]。ユスティニアヌス法 典は東ローマ帝国崩壊まで東方の法体系として存続した。一方西ヨーロッパでは、11世紀にユスティニアヌス法典が再発見されるまで、テオドシウス法典とゲ ルマン慣習法の混血の体系が用いられていた。後にボローニャ大学の学者たちが自国の法解釈にこの法典を援用したのである。[85] ローマ法に強く基づき、カノン法などの宗教法の影響も受けた市民法典は、啓蒙時代までヨーロッパ全域に広がり続けた。その後19世紀、フランスは『民法 典』、ドイツは『市民法典』によって法典を近代化した。これら両法典は、大陸ヨーロッパ諸国の法体系だけでなく、日本や韓国の法伝統にも多大な影響を与え た。[86] [87] ドイツ法学に起源を持つ大陸ヨーロッパ法思想の中核的教義は、誰もが法に服する、特に政府が法に服するという「法による統治(Rechtsstaat)」 の概念である。[88] 今日、大陸法体系を採用する国々はロシアやトルコから中米・ラテンアメリカ諸国の大半に至るまで多岐にわたる。[89] |

| Common law and equity Main articles: Common law and Equity (law)  King John of England signs Magna Carta. In common law legal systems, decisions by courts are explicitly acknowledged as "law" on equal footing with legislative statutes and executive regulations. The "doctrine of precedent", or stare decisis (Latin for "to stand by decisions") means that decisions by higher courts bind lower courts to assure that similar cases reach similar results. In contrast, in civil law systems, legislative statutes are typically more detailed, and judicial decisions are shorter and less detailed because the adjudicator is only writing to decide the single case, rather than to set out reasoning that will guide future courts. Common law originated from England and has been inherited by almost every country once tied to the British Empire (except Malta, Scotland, the U.S. state of Louisiana, and the Canadian province of Quebec). In medieval England during the Norman Conquest, the law varied shire-to-shire based on disparate tribal customs. The concept of a "common law" developed during the reign of Henry II during the late 12th century, when Henry appointed judges who had the authority to create an institutionalised and unified system of law common to the country. The next major step in the evolution of the common law came when King John was forced by his barons to sign a document limiting his authority to pass laws. This "great charter" or Magna Carta of 1215 also required that the King's entourage of judges hold their courts and judgments at "a certain place" rather than dispensing autocratic justice in unpredictable places about the country.[90] A concentrated and elite group of judges acquired a dominant role in law-making under this system, and compared to its European counterparts the English judiciary became highly centralised. In 1297, for instance, while the highest court in France had fifty-one judges, the English Court of Common Pleas had five.[91] This powerful and tight-knit judiciary gave rise to a systematised process of developing common law.[92]  The Court of Chancery, London, England, early 19th century As time went on, many felt that the common law was overly systematised and inflexible, and increasing numbers of citizens petitioned the King to override the common law. On the King's behalf, the Lord Chancellor started giving judgments to do what was equitable in a case. From the time of Sir Thomas More, the first lawyer to be appointed as Lord Chancellor, a systematic body of equity grew up alongside the rigid common law, and developed its own Court of Chancery. At first, equity was often criticised as erratic.[93] Over time, courts of equity developed solid principles, especially under Lord Eldon.[94] In the 19th century in England, and in 1937 in the U.S., the two systems were merged. In developing the common law, academic writings have always played an important part, both to collect overarching principles from dispersed case law and to argue for change. William Blackstone, from around 1760, was the first scholar to collect, describe, and teach the common law.[95] But merely in describing, scholars who sought explanations and underlying structures slowly changed the way the law actually worked.[96] |

コモン・ローと衡平法 主な記事:コモン・ローと衡平法(法)  イングランドのジョン王がマグナ・カルタに署名する。 コモン・ロー法体系では、裁判所の判決は立法府の法令や行政府の規制と同等の「法」として明示的に認められる。「判例主義」、すなわち stare decisis(ラテン語で「判決を順守する」という意味)とは、高等裁判所の判決が下級裁判所に拘束力を持つことを意味し、類似の事件は類似の結果に達 することを保証する。対照的に、大陸法系では、立法上の法令は通常より詳細であり、司法判断はより簡潔で詳細度が低い。これは、裁判官が将来の裁判の指針 となるような理由付けを述べるのではなく、単一の事件を判断するために判決文を書いているためである。 コモン・ローはイギリスで生まれ、かつて大英帝国と関わりのあったほぼすべての国(マルタ、スコットランド、アメリカ合衆国ルイジアナ州、カナダケベック 州を除く)に受け継がれている。中世イングランドでは、ノーマン征服の時代、法律は、部族の慣習の違いによって、州ごとに異なっていた。「コモン・ロー」 の概念は、12 世紀後半、ヘンリー 2 世の治世中に発展した。ヘンリーは、国共通の制度化された統一的な法体系を構築する権限を持つ裁判官を任命した。コモン・ローの進化における次の大きな一 歩は、ジョン王が貴族たちに、法律を制定する権限を制限する文書への署名を強要されたときに訪れた。この「大憲章」、すなわち 1215 年のマグナ・カルタは、王の裁判官たちが、国内の予測不可能な場所で独裁的な司法を行うのではなく、「特定の場所」で法廷を開き、判決を下すことも要求し た[90]。この制度の下で、集中したエリート裁判官グループが法制定において支配的な役割を獲得し、ヨーロッパの他の国々と比べると、イギリスの司法は 高度に中央集権化された。例えば1297年、フランス最高裁が51人の判事を擁していたのに対し、イングランドの普通法裁判所はわずか5人であった [91]。この強力で結束の固い司法機構が、コモン・ロー(慣習法)を発展させる体系化されたプロセスを生み出した[92]。  大法官裁判所、ロンドン、イングランド、19世紀初頭 時が経つにつれ、コモン・ローが過度に体系化され柔軟性に欠けると感じる者が増え、国王にコモン・ローの適用除外を求める請願が相次いだ。国王の代理とし て、大法官は事件において衡平(equitable)な判断を下すようになった。トマス・モア卿(初代大法官に任命された初の法学者)の時代から、硬直し たコモン・ローと並行して衡平法(equity)の体系が形成され、独自の衡平法裁判所が発展した。当初、衡平法はしばしば不安定だと批判された [93]。時を経て、特にエルドン卿の下で衡平法裁判所は確固たる原則を確立した[94]。19世紀のイングランドと1937年のアメリカでは、両制度が 統合された。 コモン・ローの発展において、学術的著作は常に重要な役割を果たしてきた。それは、分散した判例法から包括的な原則を収集するためであり、また変化を主張 するためでもある。ウィリアム・ブラックストーンは、1760年頃からコモン・ローを収集し、記述し、教えた最初の学者であった[95]。しかし、単に記 述するだけでなく、説明や根本的な構造を求めようとした学者たちは、徐々に法律が実際に機能する方法を変化させていったのである[96]。 |

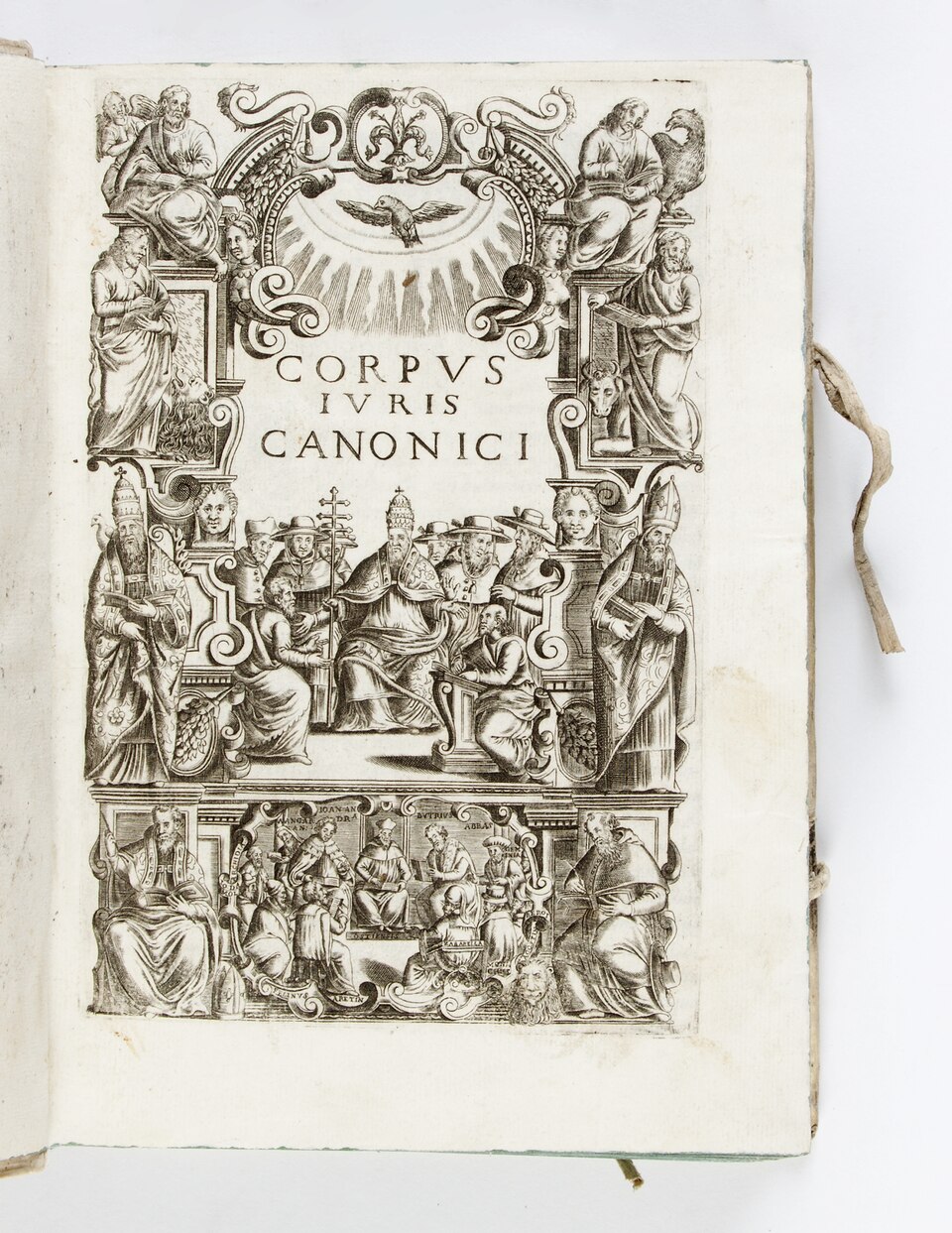

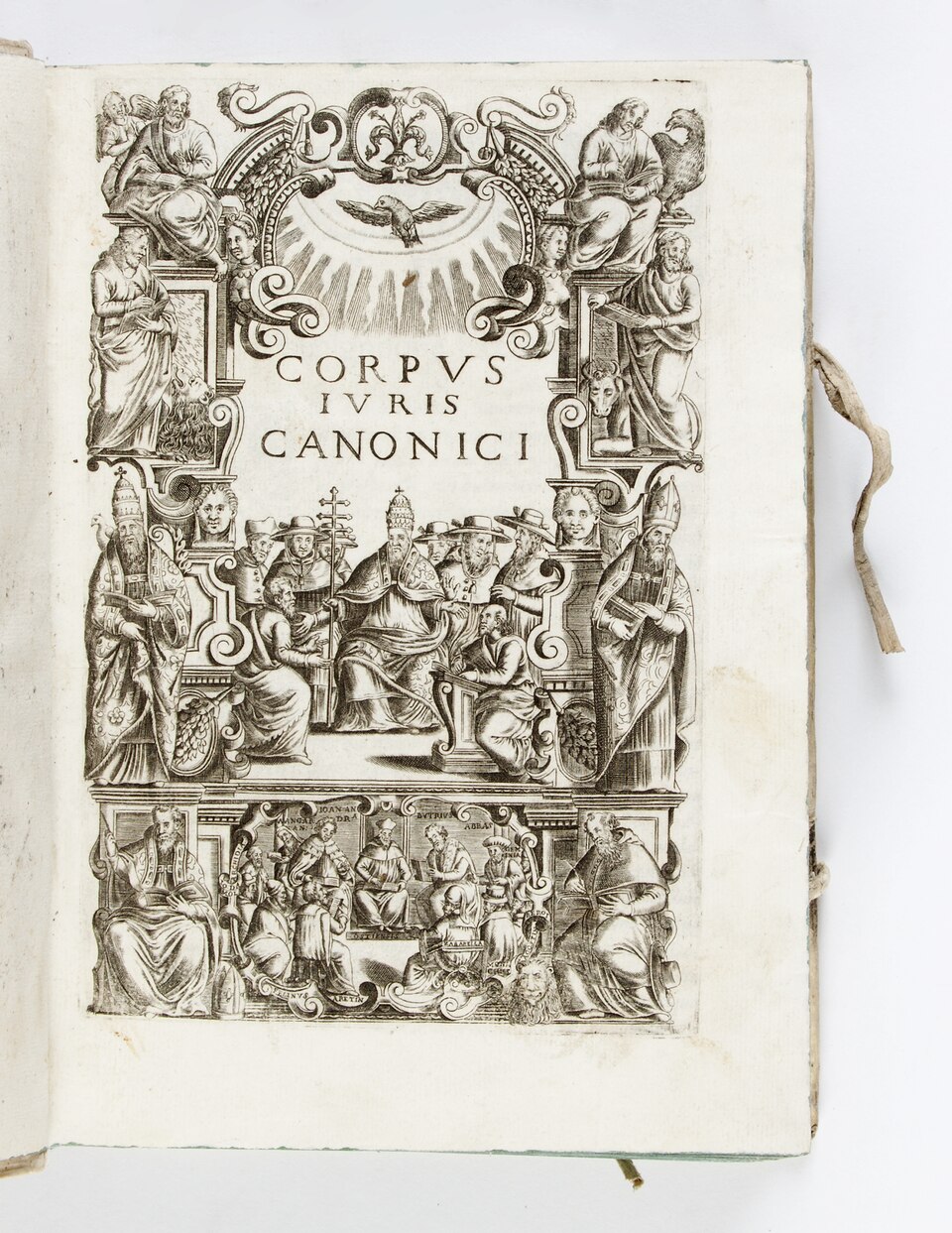

| Religious law Main article: Religious law See also: Law and religion Religious law is explicitly based on religious precepts. Examples include the Jewish Halakha and Islamic Sharia—both of which translate as the "path to follow". Christian canon law also survives in some church communities. Often the implication of religion for law is unalterability because the word of God cannot be amended or legislated against by judges or governments.[97] Nonetheless, most religious jurisdictions rely on further human elaboration to provide for thorough and detailed legal systems. For instance, the Quran has some law, and it acts as a source of further law through interpretation, Qiyas (reasoning by analogy), Ijma (consensus) and precedent.[98] This is mainly contained in a body of law and jurisprudence known as Sharia and Fiqh respectively. Another example is the Torah or Old Testament, in the Pentateuch or Five Books of Moses. This contains the basic code of Jewish law, which some Israeli communities choose to use. The Halakha is a code of Jewish law that summarizes some of the Talmud's interpretations. A number of countries are sharia jurisdictions. Israeli law allows litigants to use religious laws only if they choose. Canon law is only in use by members of the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Anglican Communion. Canon law Main article: Canon law  The Corpus Juris Canonici, the fundamental collection of canon law for over 750 years Canon law (Ancient Greek: κανών, romanized: kanon, lit. 'a straight measuring rod; a ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority, for the government of a Christian organisation or church and its members. It is the internal ecclesiastical law governing the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, and the individual national churches within the Anglican Communion.[99] The way that such church law is legislated, interpreted and at times adjudicated varies widely among these three bodies of churches. In all three traditions, a canon was originally[100] a rule adopted by a church council; these canons formed the foundation of canon law. The Catholic Church has the oldest continuously functioning legal system in the western world,[101][102] predating the evolution of modern European civil law and common law systems. The 1983 Code of Canon Law governs the Latin Church sui juris. The Eastern Catholic Churches, which developed different disciplines and practices, are governed by the Code of Canons of the Eastern Churches.[103] The canon law of the Catholic Church influenced the common law during the medieval period through its preservation of Roman law doctrine such as the presumption of innocence.[104][c] Roman Catholic canon law is a fully developed legal system, with all the necessary elements: courts, lawyers, judges, a fully articulated legal code, principles of legal interpretation, and coercive penalties, though it lacks civilly-binding force in most secular jurisdictions.[106] Sharia law Main article: Sharia Further information: Sources of Sharia Until the 18th century, Sharia law was practiced throughout the Muslim world in a non-codified form, with the Ottoman Empire's Mecelle code in the 19th century being a first attempt at codifying elements of Sharia law. Since the mid-1940s, efforts have been made, in country after country, to bring Sharia law more into line with modern conditions and conceptions.[107][108] In modern times, the legal systems of many Muslim countries draw upon both civil and common law traditions as well as Islamic law and custom. The constitutions of certain Muslim states, such as Egypt and Afghanistan, recognise Islam as the religion of the state, obliging legislature to adhere to Sharia.[109] Saudi Arabia recognises the Quran as its constitution, and is governed on the basis of Islamic law.[110] Iran has also witnessed a reiteration of Islamic law into its legal system after 1979.[111] During the last few decades, one of the fundamental features of the movement of Islamic resurgence has been the call to restore the Sharia, which has generated a vast amount of literature and affected world politics.[112] |

宗教法 主な記事: 宗教法 関連項目: 法と宗教 宗教法は明示的に宗教的戒律に基づいている。例としてはユダヤ教のハラハーやイスラム教のシャリーアがある。どちらも「従うべき道」と訳される。キリスト 教の教会法も一部の教会共同体で存続している。宗教が法に与える影響として、しばしば不可変性が挙げられる。神の言葉は裁判官や政府によって修正された り、それに反する法律が制定されたりすることはできないからだ。[97] とはいえ、ほとんどの宗教的法域では、徹底的かつ詳細な法体系を構築するために、さらなる人間の解釈に依存している。例えばクルアーンにはいくつかの法が 記されており、解釈、キヤース(類推による推論)、イジュマー(合意)、判例を通じて、さらなる法の源泉として機能する。[98] これは主に、それぞれシャリーアとフィクフとして知られる法体系と法学に含まれている。別の例は、モーセ五書(モーセの五書)にあるトーラー(旧約聖書) だ。これはユダヤ法の基本規範を含んでおり、一部のイスラエル共同体が使用を選択している。ハラハーは、タルムードの解釈の一部をまとめたユダヤ法の規範 である。 多くの国がシャリーア法域である。イスラエル法では、訴訟当事者が選択した場合に限り宗教法の使用を認めている。教会法はカトリック教会、東方正教会、英国国教会の構成員のみが使用している。 教会法 主な記事:教会法  コーパス・ユリス・カノニキ(Corpus Juris Canonici)は750年以上にわたり教会法の基本法典集であった 教会法(古代ギリシャ語: κανών、ローマ字表記: kanon、直訳: 『直線の測定棒;定規』)とは、キリスト教組織または教会とその構成員を統治するために、教会権威によって制定された規律と規則の体系である。カトリック 教会、東方正教会、東方正教会、および英国国教会内の個々の国家教会を統治する内部教会法である。[99] このような教会法の制定、解釈、そして時に裁定される方法は、これら三つの教会団体間で大きく異なる。三つの伝統すべてにおいて、カノンはもともと [100]教会会議で採択された規則であった。これらのカノンが教会法の基礎を形成したのである。 カトリック教会は西洋世界で最も古い継続的に機能する法体系を有している[101]。[102] これは近代ヨーロッパの市民法やコモン・ロー制度の進化に先立つものである。1983年制定の教会法典はラテン教会(sui juris)を統治する。異なる規律と慣行を発展させた東方カトリック教会は東方教会法典によって統治される。[103] カトリック教会の教会法は、無罪推定といったローマ法学説を保存したことで、中世期にコモン・ローに影響を与えた。[104][c] ローマ・カトリック教会法は、裁判所、弁護士、裁判官、完全に体系化された法典、法的解釈の原則、強制力のある罰則など、必要な要素をすべて備えた完全に発達した法体系である。ただし、ほとんどの世俗的管轄区域では民事上の拘束力を持たない。[106] シャリーア法 主な記事: シャリーア 詳細情報: シャリーアの源泉 18世紀まで、シャリーア法はイスラム世界全体で成文化されていない形で実践されていた。19世紀のオスマン帝国のメッセル法典は、シャリーア法の要素を 成文化する最初の試みであった。1940年代半ば以降、国々でシャリーア法を現代の状況や概念に適合させる努力がなされてきた。[107][108] 現代において、多くのイスラム諸国の法制度は、イスラム法や慣習に加え、大陸法とコモンローの伝統の両方を取り入れている。エジプトやアフガニスタンなど の特定のイスラム国家の憲法は、イスラム教を国教として認め、立法府にシャリーアの遵守を義務付けている。[109] サウジアラビアはクルアーンを憲法として認め、イスラム法に基づいて統治されている。[110] イランも1979年以降、法体系へのイスラム法の再導入を経験した。[111] 過去数十年におけるイスラム復興運動の根本的特徴の一つは、シャリーア回復の呼びかけであり、これは膨大な文献を生み出し、世界政治に影響を与えている。 [112] |

| Socialist law Main article: Socialist law Socialist law is the legal systems in communist states such as the former Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China.[113] Academic opinion is divided on whether it is a separate system from civil law, given major deviations based on Marxist–Leninist ideology, such as subordinating the judiciary to the executive ruling party.[113][114][115] |

社会主義法 主な記事: 社会主義法 社会主義法とは、旧ソビエト連邦や中華人民共和国などの共産主義国家における法体系を指す。[113] マルクス・レーニン主義イデオロギーに基づく重大な相違点、例えば司法を行政を掌握する与党に従属させる点などから、これが民法とは別の体系であるか否か について学説は分かれている。[113][114][115] |

| Legal methods There are distinguished methods of legal reasoning (applying the law) and methods of interpreting (construing) the law. The former are legal syllogism, which holds sway in civil law legal systems, analogy, which is present in common law legal systems, especially in the US, and argumentative theories that occur in both systems. The latter are different rules (directives) of legal interpretation such as directives of linguistic interpretation, teleological interpretation or systemic interpretation as well as more specific rules, for instance, golden rule or mischief rule. There are also many other arguments and cannons of interpretation which altogether make statutory interpretation possible. Law professor and former United States Attorney General Edward H. Levi noted that the "basic pattern of legal reasoning is reasoning by example"—that is, reasoning by comparing outcomes in cases resolving similar legal questions.[116] In a U.S. Supreme Court case regarding procedural efforts taken by a debt collection company to avoid errors, Justice Sotomayor cautioned that "legal reasoning is not a mechanical or strictly linear process".[117] Jurimetrics is the formal application of quantitative methods, especially probability and statistics, to legal questions. The use of statistical methods in court cases and law review articles has grown massively in importance in the last few decades.[118][119] |

法的方法 法的な推論(法の適用)の方法と、法の解釈(解釈)の方法には区別がある。前者は、大陸法系で主流の法的三段論法、特に米国などのコモン・ロー系に見られ る類推法、そして両法系に存在する論証理論である。後者は、言語解釈、目的論解釈、体系的解釈といった法的解釈の異なる規則(指針)や、黄金律や悪意の推 定といったより具体的な規則である。他にも多くの解釈上の論点や解釈の規範が存在し、これら全体が法令解釈を可能にしている。 法学者で元米国司法長官のエドワード・H・レヴィは、「法的推論の基本パターンは事例による推論である」と指摘した。つまり、類似の法的問題を解決した事 例の結果を比較することで推論するということだ[116]。債務回収会社が誤りを避けるために行った手続き上の努力に関する米国最高裁判所の判例におい て、ソトマイヨール判事は「法的推論は機械的あるいは厳密に直線的なプロセスではない」と警告した。[117] ジュリメトリクスとは、特に確率論や統計学といった定量的手法を法的問題に形式的に適用する学問である。裁判事例や法律評論記事における統計的手法の活用は、過去数十年でその重要性を飛躍的に高めている。[118][119] |

| Legal institutions It is a real unity of them all in one and the same person, made by covenant of every man with every man, in such manner as if every man should say to every man: I authorise and give up my right of governing myself to this man, or to this assembly of men, on this condition; that thou givest up, thy right to him, and authorise all his actions in like manner. ---- Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, XVII The main institutions of law in industrialised countries are independent courts, representative parliaments, an accountable executive, the military and police, bureaucratic organisation, the legal profession and civil society itself. John Locke, in his Two Treatises of Government, and Baron de Montesquieu in The Spirit of the Laws, advocated for a separation of powers between the political, legislature and executive bodies.[120] Their principle was that no person should be able to usurp all powers of the state, in contrast to the absolutist theory of Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan.[121] Sun Yat-sen's Five Power Constitution for the Republic of China took the separation of powers further by having two additional branches of government—a Control Yuan for auditing oversight and an Examination Yuan to manage the employment of public officials.[122] Max Weber and others reshaped thinking on the extension of state. Modern military, policing and bureaucratic power over ordinary citizens' daily lives pose special problems for accountability that earlier writers such as Locke or Montesquieu could not have foreseen. The custom and practice of the legal profession is an important part of people's access to justice, whilst civil society is a term used to refer to the social institutions, communities and partnerships that form law's political basis. |

法的制度 それは、あらゆる人間があらゆる人間と結ぶ契約によって、あたかも各人が各人にこう宣言するかのように、あらゆる人間が一体となって成し遂げる真の統一で ある。すなわち「私は自己統治の権利をこの人格、あるいはこの集団に委譲する。ただし、お前も同様に自らの権利を彼に委譲し、彼のあらゆる行為を承認する という条件付きで」と。 ——トマス・ホッブズ『リヴァイアサン』第17章 工業化国家における主要な法制度は、独立した裁判所、代表制議会、説明責任のある行政機関、軍隊と警察、官僚組織、法律専門職、そして市民社会そのもので ある。ジョン・ロックは『二つの政府論』で、モンテスキューは『法の精神』で、政治・立法・行政機関の三権分立を提唱した。[120] 彼らの原則は、トマス・ホッブズの『リヴァイアサン』の絶対主義理論とは対照的に、いかなる人格も国家の全権力を奪取してはならないというものであった。 [121] 孫文の「中華民国五権憲法」は、監査監督を行う監察院と公務員の雇用を管理する考査院という 2 つの政府機関を追加することで、三権分立をさらに推し進めた。[122] マックス・ヴェーバーらは、国家の拡張に関する考え方を再構築した。現代の軍隊、警察、官僚機構が一般市民の日常生活に対して持つ権力は、ロックやモンテ スキューなどの先人たちが予見できなかった、説明責任に関する特別な問題を引き起こしている。法律専門職の慣習と実践は、人々が司法にアクセスする上で重 要な役割を担っている。一方、市民社会とは、法の政治的基盤を形成する社会制度、コミュニティ、パートナーシップを指す用語である。 |

| Judiciary This file is an excerpt from Judiciary.[edit]  The Supreme Court Building houses the Supreme Court of the United States, the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. This section is an excerpt from Judiciary § Meaning.[edit] The judiciary is the system of courts that interprets, defends, and applies the law in the name of the state. The judiciary can also be thought of as the mechanism for the resolution of disputes. Under the doctrine of the separation of powers, the judiciary generally does not make statutory law (which is the responsibility of the legislature) or enforce law (which is the responsibility of the executive), but rather interprets, defends, and applies the law to the facts of each case. However, in some countries the judiciary does make common law. In many jurisdictions the judicial branch has the power to change laws through the process of judicial review. Courts with judicial review power may annul the laws and rules of the state when it finds them incompatible with a higher norm, such as primary legislation, the provisions of the constitution, treaties or international law. Judges constitute a critical force for judicial interpretation and constitutional review while avoiding political bias.[123] |

司法 このファイルは「司法」からの抜粋である。[編集]  最高裁判所ビルには、アメリカ合衆国連邦司法制度における最高裁判所である合衆国最高裁判所が入居している。 この節は「司法 § 意味」からの抜粋である。[編集] 司法とは、国家の名において法律を解釈し、擁護し、適用する裁判所のシステムである。司法はまた、紛争解決の仕組みとも考えられる。三権分立の原則のも と、司法は通常、成文法(立法府の責任)を制定したり、法律(行政府の責任)を執行したりはせず、各事件の事実に対して法律を解釈し、擁護し、適用する。 ただし、一部の国では司法がコモンローを制定することもある。 多くの法域では、司法府は司法審査を通じて法律を変更する権限を持つ。司法審査権を有する裁判所は、法律や規則が上位規範(基本法、憲法規定、条約、国際 法など)と矛盾すると判断した場合、それらを無効とすることができる。裁判官は、政治的偏向を避けつつ、司法解釈と憲法審査における重要な役割を担ってい る。 |

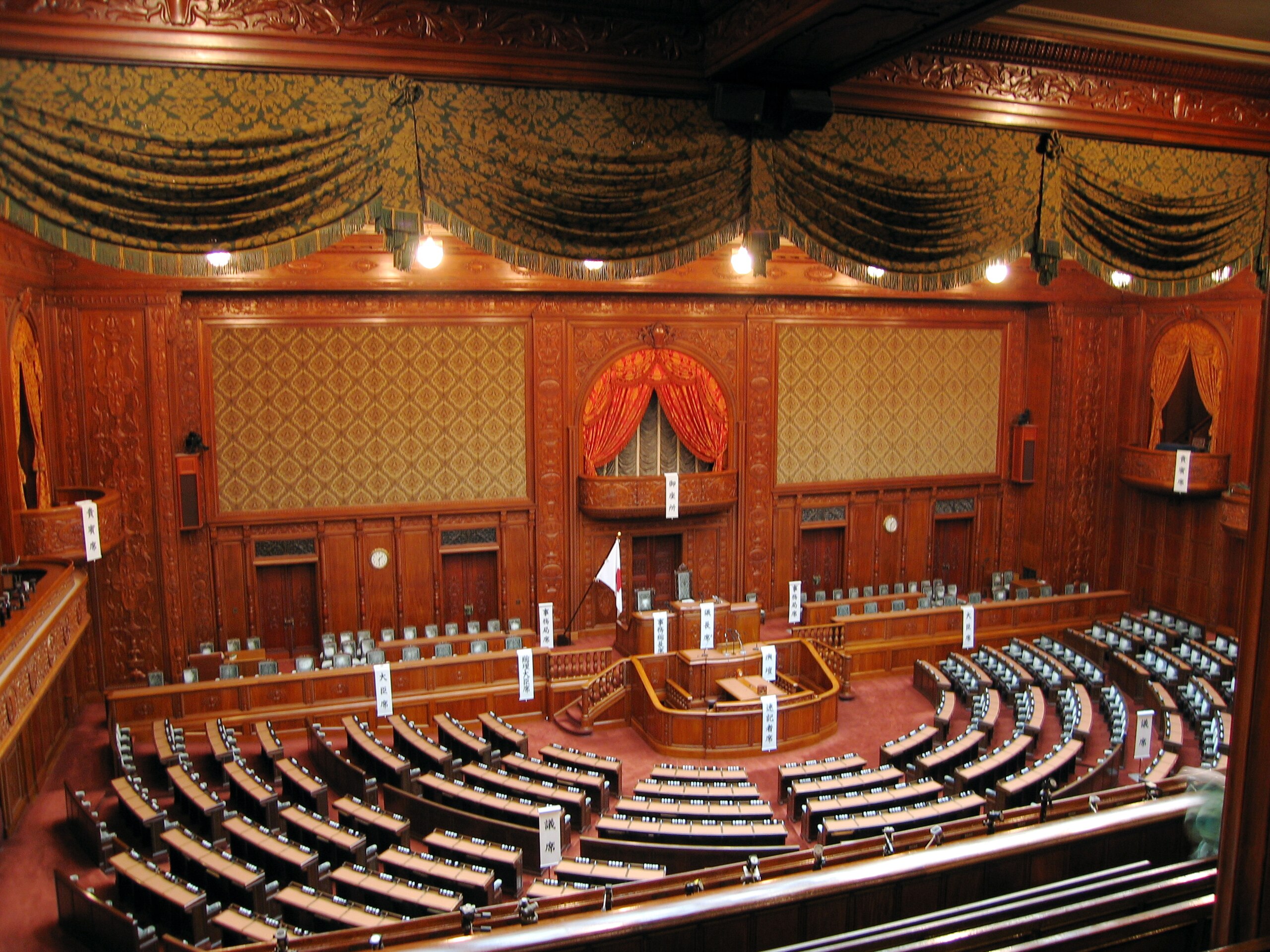

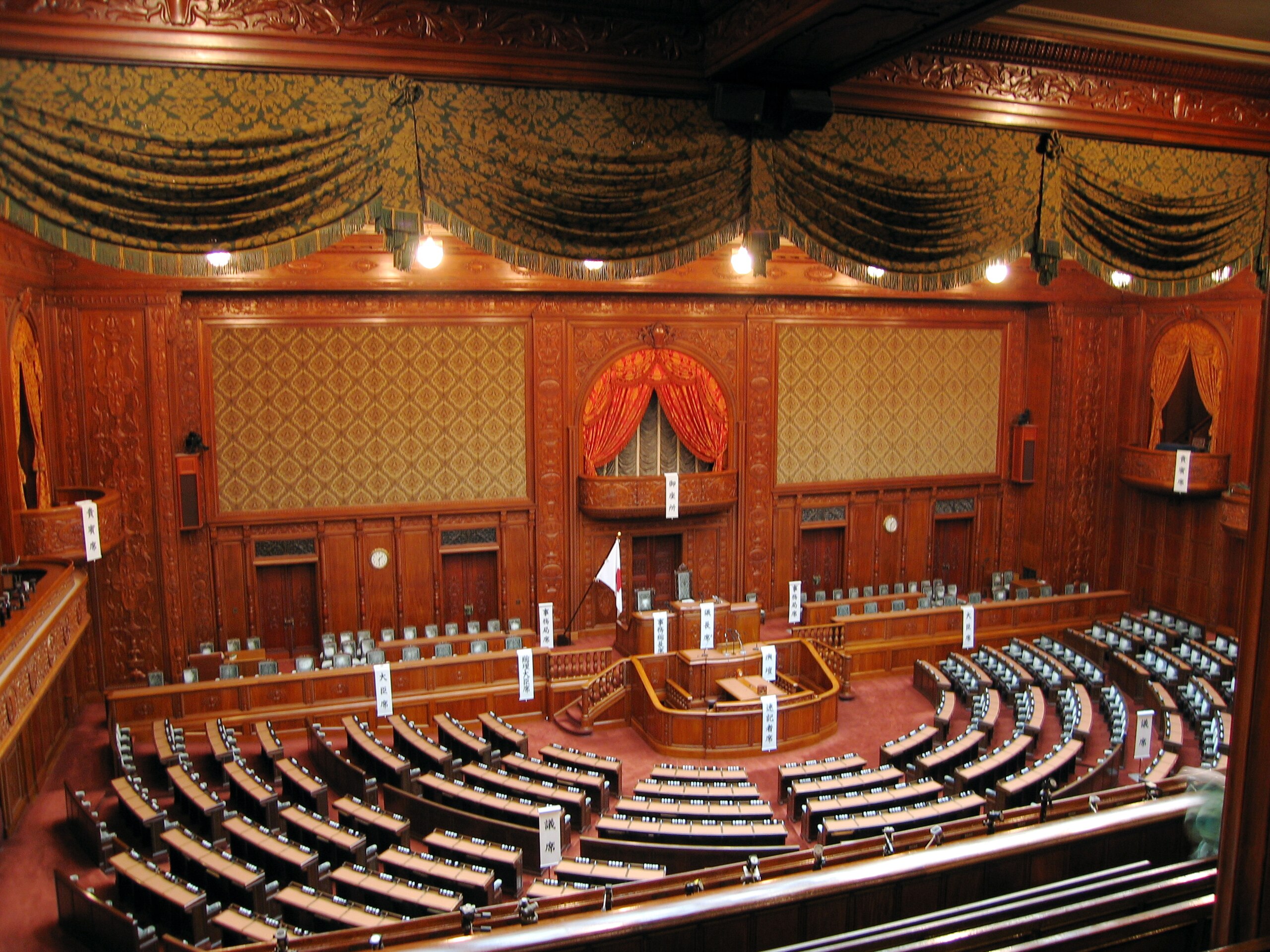

| Legislature Main article: Legislature  The Chamber of the House of Representatives, the lower house in the National Diet of Japan Prominent examples of legislatures are the Houses of Parliament in London, the Congress in Washington, D.C., the Bundestag in Berlin, the Duma in Moscow, the Parlamento Italiano in Rome and the Assemblée nationale in Paris. By the principle of representative government people vote for politicians to carry out their wishes. Although countries like Israel, Greece, Sweden and China are unicameral, most countries are bicameral, meaning they have two separately appointed legislative houses.[124] In the 'lower house' politicians are elected to represent smaller constituencies. The 'upper house' is usually elected to represent states in a federal system (as in Australia, Germany or the United States) or different voting configuration in a unitary system (as in France). In the UK the upper house is appointed by the government as a house of review. One criticism of bicameral systems with two elected chambers is that the upper and lower houses may simply mirror one another. The traditional justification of bicameralism is that an upper chamber acts as a house of review. This can minimise arbitrariness and injustice in governmental action.[124] To pass legislation, a majority of the members of a legislature must vote for a bill (proposed law) in each house. Normally there will be several readings and amendments proposed by the different political factions. If a country has an entrenched constitution, a special majority for changes to the constitution may be required, making changes to the law more difficult. A government usually leads the process, which can be formed from Members of Parliament (e.g. the UK or Germany). However, in a presidential system, the government is usually formed by an executive and his or her appointed cabinet officials (e.g. the United States or Brazil).[d] |

立法府 主な記事: 立法府  日本の国会における下院である衆議院議場 立法府の代表的な例としては、ロンドンの議会議事堂、ワシントンD.C.の連邦議会、ベルリンの連邦議会、モスクワの国家会議、ローマのイタリア議会、パ リの国民議会が挙げられる。代議制政府の原則により、国民は自らの意思を実行させるために政治家に投票する。イスラエル、ギリシャ、スウェーデン、中国な どの国々は一院制だが、ほとんどの国は二院制であり、別々に選出された二つの立法府を持つ。[124] 「下院」では、より小さな選挙区を代表する政治家が選出される。「上院」は通常、連邦制(オーストラリア、ドイツ、アメリカ合衆国など)では州を代表する 形で、単一国家制(フランスなど)では異なる投票構成で選出される。英国では上院は政府によって任命され、審議機関としての役割を担う。二院制における二 つの選出院に対する批判の一つは、上下両院が単に互いを模倣するだけになる可能性がある点だ。二院制の伝統的な正当化根拠は、上院が審議院として機能する ことにある。これにより政府の行動における恣意性や不正を最小限に抑えられる。[124] 法案(提案された法律)を可決するには、各院で議員の過半数が賛成票を投じなければならない。通常、複数の審議段階を経て、異なる政治派閥から修正案が提 案される。国が固着憲法を有する場合、憲法改正には特別多数決が必要となり、法改正が困難になることがある。通常、政府がこのプロセスを主導する。政府は 国会議員から構成される場合がある(例:英国やドイツ)。しかし大統領制では、政府は通常、行政機関とその任命した閣僚によって構成される(例:米国やブ ラジル)。 |

| Executive Main article: Executive (government)  The G20 meetings are composed of representatives of each country's executive branch. The executive in a legal system serves as the centre of political authority of the State. In a parliamentary system, as with Britain, Italy, Germany, India, and Japan, the executive is known as the cabinet, and composed of members of the legislature. The executive is led by the head of government, whose office holds power under the confidence of the legislature. Because popular elections appoint political parties to govern, the leader of a party can change in between elections.[125] The head of state is apart from the executive, and symbolically enacts laws and acts as representative of the nation. Examples include the President of Germany (appointed by members of federal and state legislatures), the Queen of the United Kingdom (an hereditary office), and the President of Austria (elected by popular vote). The other important model is the presidential system, found in the United States and in Brazil. In presidential systems, the executive acts as both head of state and head of government, and has power to appoint an unelected cabinet. Under a presidential system, the executive branch is separate from the legislature to which it is not accountable.[125][126] Although the role of the executive varies from country to country, usually it will propose the majority of legislation, and propose government agenda. In presidential systems, the executive often has the power to veto legislation. Most executives in both systems are responsible for foreign relations, the law enforcement, and the bureaucracy. Ministers or other officials head a country's public offices, such as a foreign ministry or defence ministry. The election of a different executive is therefore capable of revolutionising an entire country's approach to government. |

行政 主な記事: 行政(政府)  G20会議は、各国の行政機関の代表者で構成される。 法制度における行政機関は、国家の政治権力の中心として機能する。英国、イタリア、ドイツ、インド、日本などの議会制国家では、行政機関は内閣と呼ばれ、 立法府の構成員で構成される。行政機関は政府の長によって率いられ、その職は立法府の信任のもとで権力を保持する。国民選挙によって政党が政権を担うた め、政党の指導者は選挙の合間に変わる可能性がある。[125] 国家元首は行政府とは別個の存在であり、象徴的に法律を公布し国民の代表として行動する。例としては、ドイツ連邦大統領(連邦及び州議会議員による任 命)、英国女王(世襲職)、オーストリア大統領(国民投票による選出)が挙げられる。もう一つの重要なモデルは、アメリカ合衆国やブラジルに見られる大統 領制である。大統領制では、行政府が国家元首と政府首班を兼任し、非選出の閣僚を任命する権限を持つ。大統領制下では、行政府は立法府から分離され、立法 府に対して責任を負わない。[125][126] 行政府の役割は国によって異なるが、通常は立法案の大半を提案し、政府の政策課題を提示する。大統領制では、行政府が立法案に拒否権を行使できる場合が多 い。両制度において、ほとんどの行政機関は外交、法執行、官僚機構を担当する。大臣やその他の官僚が外務省や国防省などの公的機関を統括する。したがっ て、異なる行政機関が選出されることで、国家全体の統治手法が根本的に変わる可能性がある。 |

| Law enforcement Main articles: Law enforcement, Police, and Military  Officers of the South African Police Service in Johannesburg, 2010 Max Weber famously argued that the state is that which controls the monopoly on the legitimate use of force.[127][128] The military and police carry out law enforcement at the request of the government or the courts. The term failed state refers to states that cannot implement or enforce policies; their police and military no longer control security and order and society moves into anarchy, the absence of government.[e] While military organisations have existed as long as government itself, the idea of a standing police force is a relatively modern concept. For example, Medieval England's system of travelling criminal courts, or assizes, used show trials and public executions to instill communities with fear to maintain control.[129] The first modern police were probably those in 17th-century Paris, in the court of Louis XIV,[130] although the Paris Prefecture of Police claim they were the world's first uniformed policemen.[131] |

法執行 主な記事:法執行、警察、軍隊  2010年、ヨハネスブルグの南アフリカ警察の警官たち マックス・ヴェーバーは、国家とは合法的な武力の行使を独占的に支配する存在であると主張したことで有名である[127][128]。軍隊と警察は、政府 や裁判所の要請に応じて法執行を行う。「失敗国家」という用語は、政策の実施や執行ができない国家を指す。その警察や軍はもはや治安や秩序を制御できず、 社会は無政府状態、つまり政府が存在しない状態に陥る。軍事組織は政府そのものと同じくらい長い歴史を持つが、常備警察という概念は比較的近代的なもので ある。例えば中世イングランドの巡回刑事裁判所(アサイズ)は、見せしめの裁判と公開処刑で地域社会に恐怖を植え付け、支配を維持した[129]。近代警 察の起源は17世紀パリ、ルイ14世の宮廷に遡るとされる[130]。ただしパリ警視庁は自らが世界初の制服警察であると主張している[131]。 |

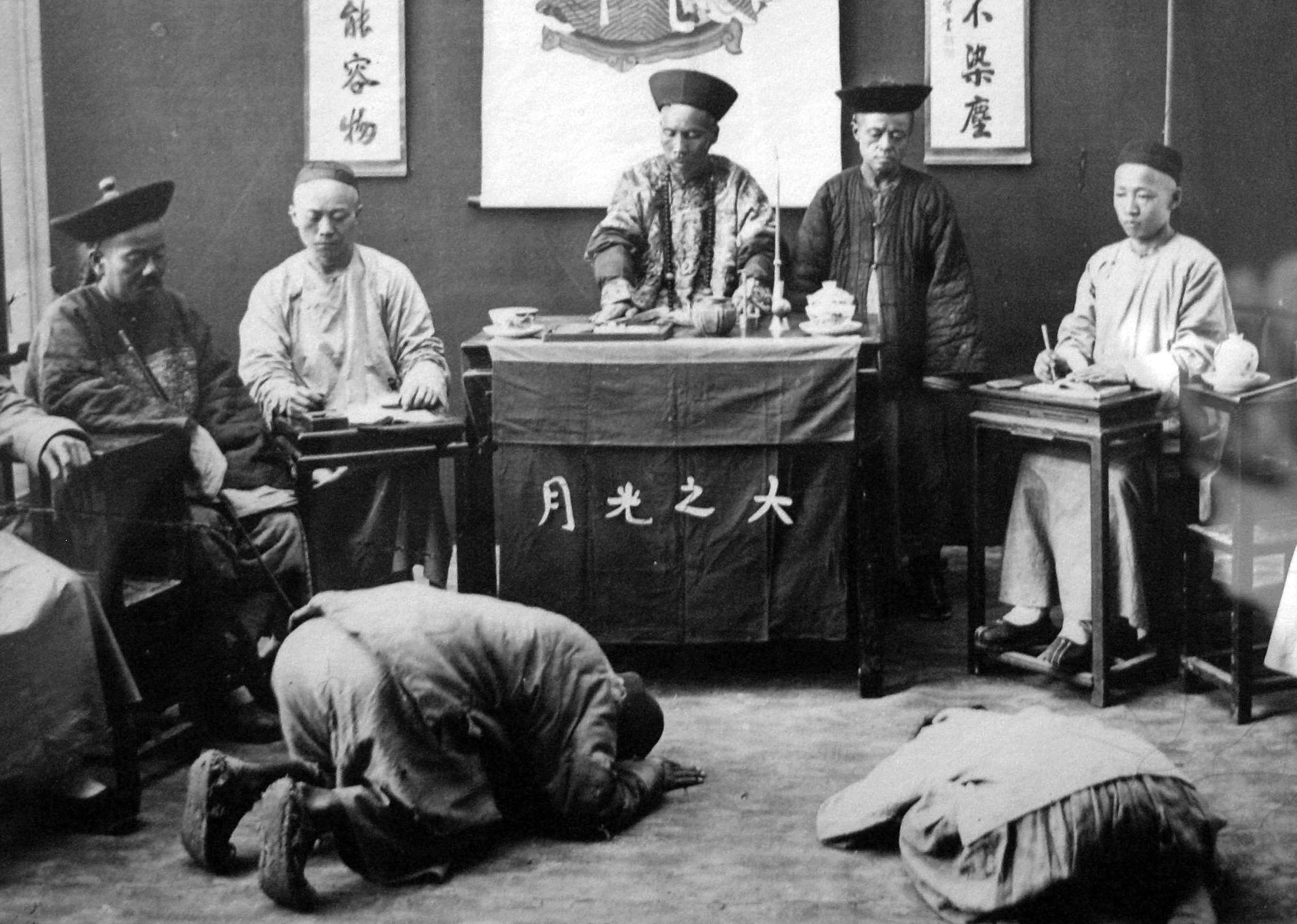

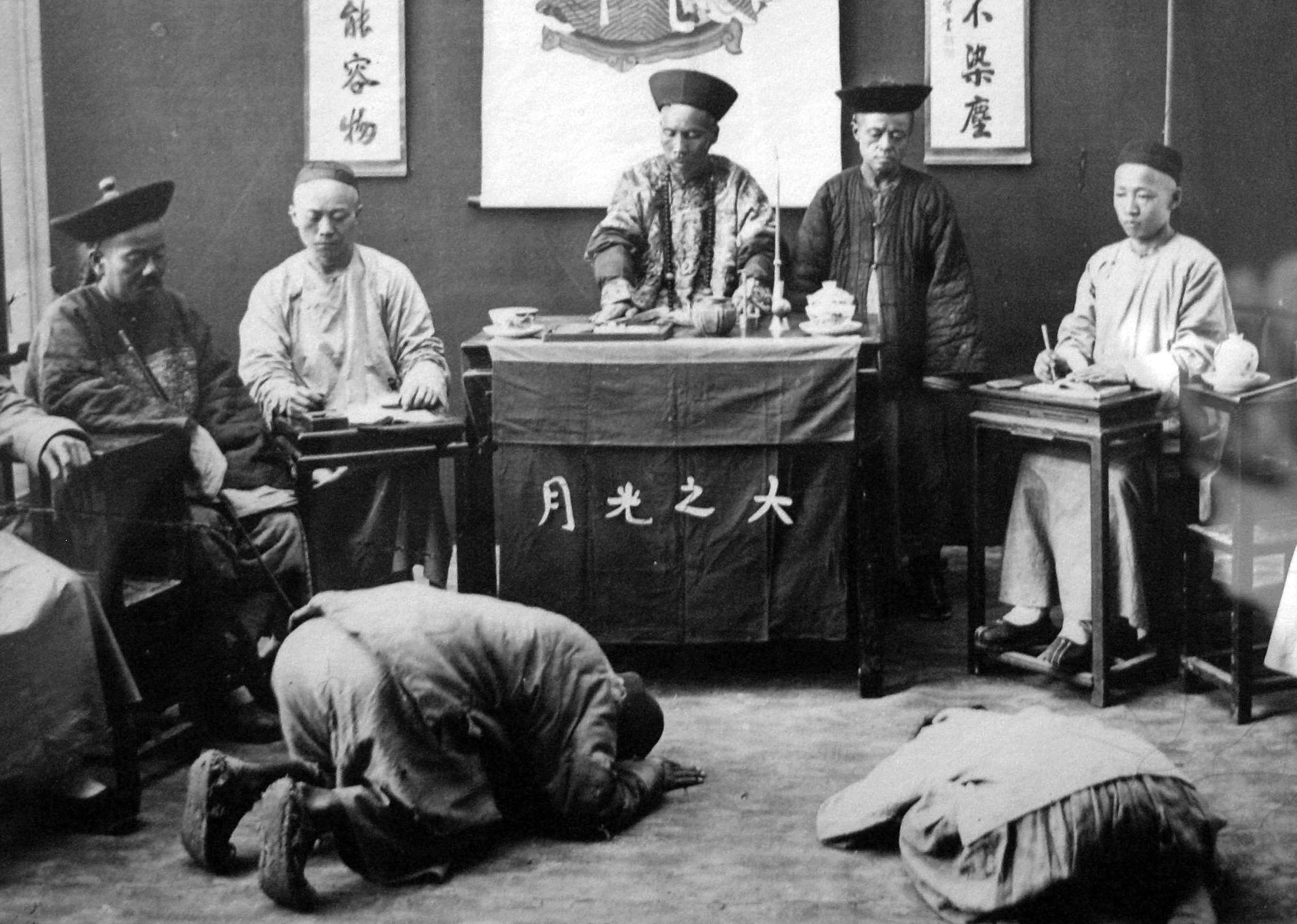

| Bureaucracy Main article: Bureaucracy  The mandarins were powerful bureaucrats in imperial China (photograph shows a Qing dynasty official with mandarin square visible). The etymology of bureaucracy derives from the French word for office (bureau) and the Ancient Greek for word power (kratos).[132][better source needed] Like the military and police, a legal system's government servants and bodies that make up its bureaucracy carry out the directives of the executive. One of the earliest references to the concept was made by Baron de Grimm, a German author who lived in France. In 1765, he wrote:  Gou Hongguo (b.1961) The real spirit of the laws in France is that bureaucracy of which the late Monsieur de Gournay used to complain so greatly; here the offices, clerks, secretaries, inspectors and intendants are not appointed to benefit the public interest, indeed the public interest appears to have been established so that offices might exist.[133] Cynicism over "officialdom" is still common, and the workings of public servants is typically contrasted to private enterprise motivated by profit.[134] In fact private companies, especially large ones, also have bureaucracies.[135] Negative perceptions of "red tape" aside, public services such as schooling, health care, policing or public transport are considered a crucial state function making public bureaucratic action the locus of government power.[135] Writing in the early 20th century, Max Weber believed that a definitive feature of a developed state had come to be its bureaucratic support.[136] Weber wrote that the typical characteristics of modern bureaucracy are that officials define its mission, the scope of work is bound by rules, and management is composed of career experts who manage top down, communicating through writing and binding public servants' discretion with rules.[137] |

官僚制 主な記事: 官僚制  官僚たちは中国帝国時代の強力な官僚であった(写真は清朝の役人で、官帽の四角い部分が確認できる)。 官僚制の語源は、フランス語で「事務所」を意味する「bureau」と、古代ギリシャ語で「権力」を意味する「kratos」に由来する[132][より 良い出典が必要]。軍隊や警察と同様に、法制度を構成する政府の役人や官僚機構は、行政機関の指示を実行する。この概念に関する最も初期の言及の一つは、 フランス在住のドイツ人作家グリム男爵によるものである。1765年、彼はこう記している:  天津市中級人民法院(地裁)で判決を受ける人権活動家の勾洪国氏(2016) フランスにおける法律の真髄は、故グルネー氏が激しく非難したあの官僚制にある。ここでは役職、事務員、書記、検査官、行政官は公共の利益のために任命されるのではない。むしろ公共の利益は、役職が存在するために設けられたように見えるのだ。[133] 「官僚機構」に対する皮肉は今でも一般的であり、公務員の仕事は、利益を追求する民間企業とは対照的に見なされることが多い。[134] 実際、民間企業、特に大企業にも官僚機構は存在する。[135] 「官僚主義」に対する否定的な見方はさておき、教育、健康、警察、公共交通などの公共サービスは、国家の重要な機能とみなされており、公共の官僚的行動は 政府権力の中心となっている。[135] 20世紀初頭に著述したマックス・ヴェーバーは、先進国家の決定的な特徴は、その官僚機構による支援にあると信じていた。[136] ヴェーバーは、現代の官僚機構の典型的な特徴は、その使命が公務員によって定義され、業務範囲が規則によって制限され、管理職はトップダウンで管理を行う キャリアの専門家で構成され、文書を通じてコミュニケーションを取り、公務員の裁量権を規則で拘束することであると記している。[137] |

| Legal profession Main article: Legal profession  Judges presiding over the Nuremberg trials at the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, Allied-occupied Germany, 1946(Presenting information on German aggression, 4 December) A corollary of the rule of law is the existence of a legal profession sufficiently autonomous to invoke the authority of the independent judiciary; the right to assistance of a barrister in a court proceeding emanates from this corollary—in England the function of barrister or advocate is distinguished from legal counselor.[138] As the European Court of Human Rights has stated, the law should be adequately accessible to everyone and people should be able to foresee how the law affects them.[139] In order to maintain professionalism, the practice of law is typically overseen by either a government or independent regulating body such as a bar association, bar council or law society. Modern lawyers achieve distinct professional identity through specified legal procedures (e.g. successfully passing a qualifying examination), are required by law to have a special qualification (a legal education earning the student a Bachelor of Laws, a Bachelor of Civil Law, or a Juris Doctor degree. Higher academic degrees may also be pursued. Examples include a Master of Laws, a Master of Legal Studies, a Bar Professional Training Course or a Doctor of Laws.), and are constituted in office by legal forms of appointment (being admitted to the bar). There are few titles of respect to signify famous lawyers, such as Esquire, to indicate barristers of greater dignity,[140][141] and Doctor of law, to indicate a person who obtained a PhD in Law. Many Muslim countries have developed similar rules about legal education and the legal profession, but some still allow lawyers with training in traditional Islamic law to practice law before personal status law courts.[142] In China and other developing countries there are not sufficient professionally trained people to staff the existing judicial systems, and, accordingly, formal standards are more relaxed.[143] Once accredited, a lawyer will often work in a law firm, in a chambers as a sole practitioner, in a government post or in a private corporation as an internal counsel. In addition a lawyer may become a legal researcher who provides on-demand legal research through a library, a commercial service or freelance work. Many people trained in law put their skills to use outside the legal field entirely.[144] Significant to the practice of law in the common law tradition is the legal research to determine the current state of the law. This usually entails exploring case-law reports, legal periodicals and legislation. Law practice also involves drafting documents such as court pleadings, persuasive briefs, contracts, or wills and trusts. Negotiation and dispute resolution skills (including ADR techniques) are also important to legal practice, depending on the field.[144] |

法律専門職 主な記事: 法律専門職  1946年、連合国占領下のドイツ、ニュルンベルクの司法宮殿でニュルンベルク裁判を主宰した裁判官たち——手前(ドイツの侵略に関する情報を提示する、12月4日) 法の支配の帰結として、独立した司法の権威を主張できるほど自律的な法律専門職の存在が求められる。法廷手続きにおける弁護士の援助を受ける権利は、この 帰結から派生するものである。イギリスでは、弁護士(barrister)または弁護人(advocate)の機能は、法律顧問(legal counselor)とは区別される。[138] 欧州人権裁判所が述べたように、法律は誰もが十分にアクセス可能であるべきであり、人々は法律が自分にどう影響するかを予測できるべきだ。[139] 専門性を維持するため、法律実務は通常、政府または弁護士会・法曹評議会・法曹協会などの独立規制機関によって監督される。現代の弁護士は、特定の法的手 続き(例:資格試験の合格)を通じて明確な職業的アイデンティティを獲得し、法律により特別な資格(法学士・民法学士・法務博士の学位を取得する法教育) を保持することが義務付けられている。より高度な学位の取得も可能である。例としては、法学修士、法律学修士、弁護士専門職養成課程修了者、法学博士など がある。また、弁護士資格は法的な任命手続き(弁護士登録)によって正式に付与される。著名な弁護士を示す敬称は少なく、例えば「エスクァイア」はより高 位の法廷弁護士を示す[140][141]、「法学博士」は法学の博士号を取得した人格を示す。 多くのイスラム諸国でも法教育と法律専門職に関する類似の規則が整備されているが、伝統的なイスラム法(シャリーア)の訓練を受けた弁護士が、個人的身分 法裁判所において法律実務を行うことを認める国もある[142]。中国やその他の発展途上国では、既存の司法制度を運営するのに十分な専門的訓練を受けた 人材が不足しており、それに応じて正式な基準はより緩和されている。[143] 弁護士資格を取得すると、法律事務所や個人事務所で働くことが多い。政府機関や民間企業で社内弁護士として勤務する場合もある。また、図書館や商業サービ ス、フリーランスとしてオンデマンドの法律調査を提供する法律研究者になることもある。法律を学んだ者の多くは、法律分野とは全く異なる分野でその技能を 活用している。[144] コモンローの伝統における法律実務で重要なのは、現行法の状態を確定するための法律調査である。これは通常、判例報告、法律雑誌、立法の調査を伴う。法律 実務には、裁判書類、説得力のある準備書面、契約書、遺言書や信託契約書などの文書作成も含まれる。交渉や紛争解決スキル(ADR技術を含む)も、分野に よっては法律実務において重要である。[144] |

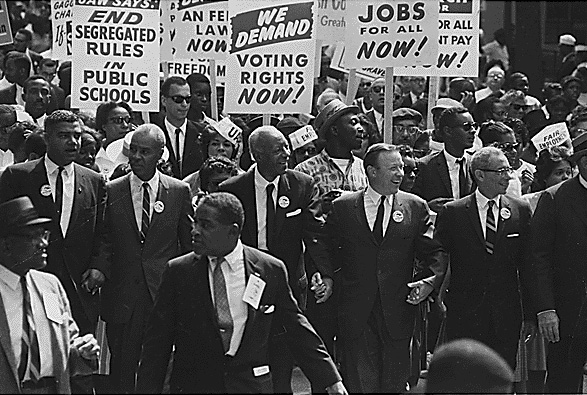

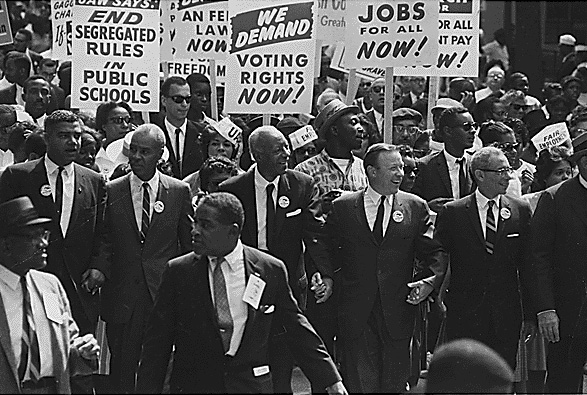

| Civil society Main article: Civil society  A march in Washington, D.C. during the American civil rights movement in 1963 The Classical republican concept of "civil society" dates back to Hobbes and Locke.[145] Locke saw civil society as people who have "a common established law and judicature to appeal to, with authority to decide controversies between them."[146] German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel distinguished the "state" from "civil society" (German: bürgerliche Gesellschaft) in Elements of the Philosophy of Right.[147][148] Hegel believed that civil society and the state were polar opposites, within the scheme of his dialectic theory of history. The modern dipole state–civil society was reproduced in the theories of Alexis de Tocqueville and Karl Marx.[149][150] In post-modern theory, civil society is necessarily a source of law, by being the basis from which people form opinions and lobby for what they believe law should be. As Australian barrister and author Geoffrey Robertson QC wrote of international law, "one of its primary modern sources is found in the responses of ordinary men and women, and of the non-governmental organizations which many of them support, to the human rights abuses they see on the television screen in their living rooms."[151] Freedom of speech, freedom of association and many other individual rights allow people to gather, discuss, criticise and hold to account their governments, from which the basis of a deliberative democracy is formed. The more people are involved with, concerned by and capable of changing how political power is exercised over their lives, the more acceptable and legitimate the law becomes to the people. The most familiar institutions of civil society include economic markets, profit-oriented firms, families, trade unions, hospitals, universities, schools, charities, debating clubs, non-governmental organisations, neighbourhoods, churches, and religious associations. There is no clear legal definition of the civil society, and of the institutions it includes. Most of the institutions and bodies who try to give a list of institutions (such as the European Economic and Social Committee) exclude the political parties.[152][153][154] |

市民社会 主な記事: 市民社会  1963年、アメリカ公民権運動中のワシントンD.C.での行進 古典的共和主義における「市民社会」の概念は、ホッブズとロックに遡る。[145]ロックは市民社会を「共通の確立された法と裁判権を持ち、相互の争いを 裁く権威に訴えることができる人々」と捉えた。[146] ドイツの哲学者ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルは『法の哲学』において「国家」と「市民社会」(ドイツ語: bürgerliche Gesellschaft)を区別した。[147][148] ヘーゲルは、彼の弁証法的歴史理論の枠組みの中で、市民社会と国家は正反対の極にあると信じていた。この現代的な二極国家・市民社会は、アレクシス・ド・ トクヴィルとカール・マルクスの理論にも再現されている[149][150]。ポストモダン理論では、市民社会は、人々が意見を形成し、法律のあるべき姿 についてロビー活動を行う基盤となることで、必然的に法の源泉となっている。オーストラリアの弁護士であり作家でもあるジェフリー・ロバートソン QC が国際法について書いたように、「その主要な現代的な源泉の一つは、普通の男女、そして彼らの多くが支援する非政府組織が、リビングルームのテレビ画面で 目にする人権侵害に対して示す反応にある」[151]。 言論の自由、結社の自由、その他多くの個人の権利は、人々が集まり、議論し、批判し、政府に説明責任を求めることを可能にし、そこから審議民主主義の基盤 が形成される。より多くの人々が、自分たちの生活に対する政治権力の行使に関与し、関心を持ち、それを変えることができるようになればなるほど、法律は人 々にとってより受け入れやすく、正当なものになる。市民社会で最もよく知られた組織には、経済市場、営利企業、家族、労働組合、病院、大学、学校、慈善団 体、討論クラブ、非政府組織、地域コミュニティ、教会、宗教団体などがある。市民社会とその構成組織について、明確な法的定義は存在しない。制度のリスト を作成しようとする機関や団体(欧州経済社会評議会など)の大半は、政党をそのリストから除外している。[152][153][154] |

| Areas of law See also: List of areas of law All legal systems deal with the same basic issues, but jurisdictions categorise and identify their legal topics in different ways. A common distinction is that between "public law" (a term related closely to the state, and including constitutional, administrative and criminal law), and "private law" (which covers contract, tort and property).[f] In civil law systems, contract and tort fall under a general law of obligations, while trusts law is dealt with under statutory regimes or international conventions. International, constitutional and administrative law, criminal law, contract, tort, property law and trusts are regarded as the "traditional core subjects",[g] although there are many further disciplines. International law Further information: Sources of international law See also: Conflict of laws, European Union law, and Public international law  Bound volumes of the American Journal of International Law at the University of Münster in Germany International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of rules, norms, legal customs and standards that states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generally do, obey in their mutual relations. In international relations, actors are simply the individuals and collective entities, such as states, international organizations, and non-state groups, which can make behavioral choices, whether lawful or unlawful. Rules are formal, typically written expectations that outline required behavior, while norms are informal, often unwritten guidelines about appropriate behavior that are shaped by custom and social practice.[155] It establishes norms for states across a broad range of domains, including war and diplomacy, economic relations, and human rights. International law differs from state-based domestic legal systems in that it operates largely through consent, since there is no universally accepted authority to enforce it upon sovereign states. States and non-state actors may choose to not abide by international law, and even to breach a treaty, but such violations, particularly of peremptory norms, can be met with disapproval by others and in some cases coercive action including diplomacy, economic sanctions, and war. The lack of a final authority in international law can also cause far reaching differences. This is partly the effect of states being able to interpret international law in a manner which they see fit. This can lead to problematic stances which can have large local effects.[156] |

法分野 関連項目: 法分野の一覧 全ての法体系は同じ基本的な問題を取り扱うが、管轄区域によって法主題の分類や識別方法は異なる。一般的な区別として、「公法」(国家と密接に関連する用 語で、憲法、行政法、刑法を含む)と「私法」(契約法、不法行為法、財産法を含む)がある。[f] 民法体系では、契約と不法行為は一般的な債務法に分類され、信託法は法令制度や国際条約で扱われる。国際法、憲法・行政法、刑法、契約法、不法行為法、財 産法、信託法は「伝統的な中核科目」と見なされるが[g]、他にも多くの分野が存在する。 国際法 詳細情報: 国際法の源泉 関連項目: 抵触法、欧州連合法、国際公法  ドイツ・ミュンスター大学所蔵の『アメリカ国際法ジャーナル』合本 国際法は、公法国際法や国家法とも呼ばれ、国家やその他の主体が相互関係において遵守する義務を感じ、一般的に遵守する規則、規範、法的慣習、基準の集合 体である。国際関係における主体とは、国家、国際機関、非国家組織など、合法・違法を問わず行動選択を行う個人や集団を指す。規則とは要求される行動を定 めた形式的(通常は文書化された)期待であり、規範とは慣習や社会的慣行によって形成される非形式的(しばしば文書化されていない)適切な行動指針である [155]。国際法は戦争・外交、経済関係、人権など広範な領域において国家間の規範を確立する。 国際法は、主権国家に対してこれを強制する普遍的に認められた権威が存在しないため、主に合意によって機能するという点で、国家ベースの国内法体系とは異 なる。国家や非国家主体は国際法に従わない選択をし、条約を破ることも可能だが、特に強行規範の違反は、他者からの非難や、場合によっては外交、経済制 裁、戦争を含む強制的措置に直面する可能性がある。国際法に最終的な権威が存在しないことは、広範な差異を生む原因にもなる。これは一部、国家が国際法を 自らの都合に合うように解釈できることに起因する。この解釈の自由は問題のある立場を生み出し、地域的に大きな影響を及ぼす可能性がある[156]。 |

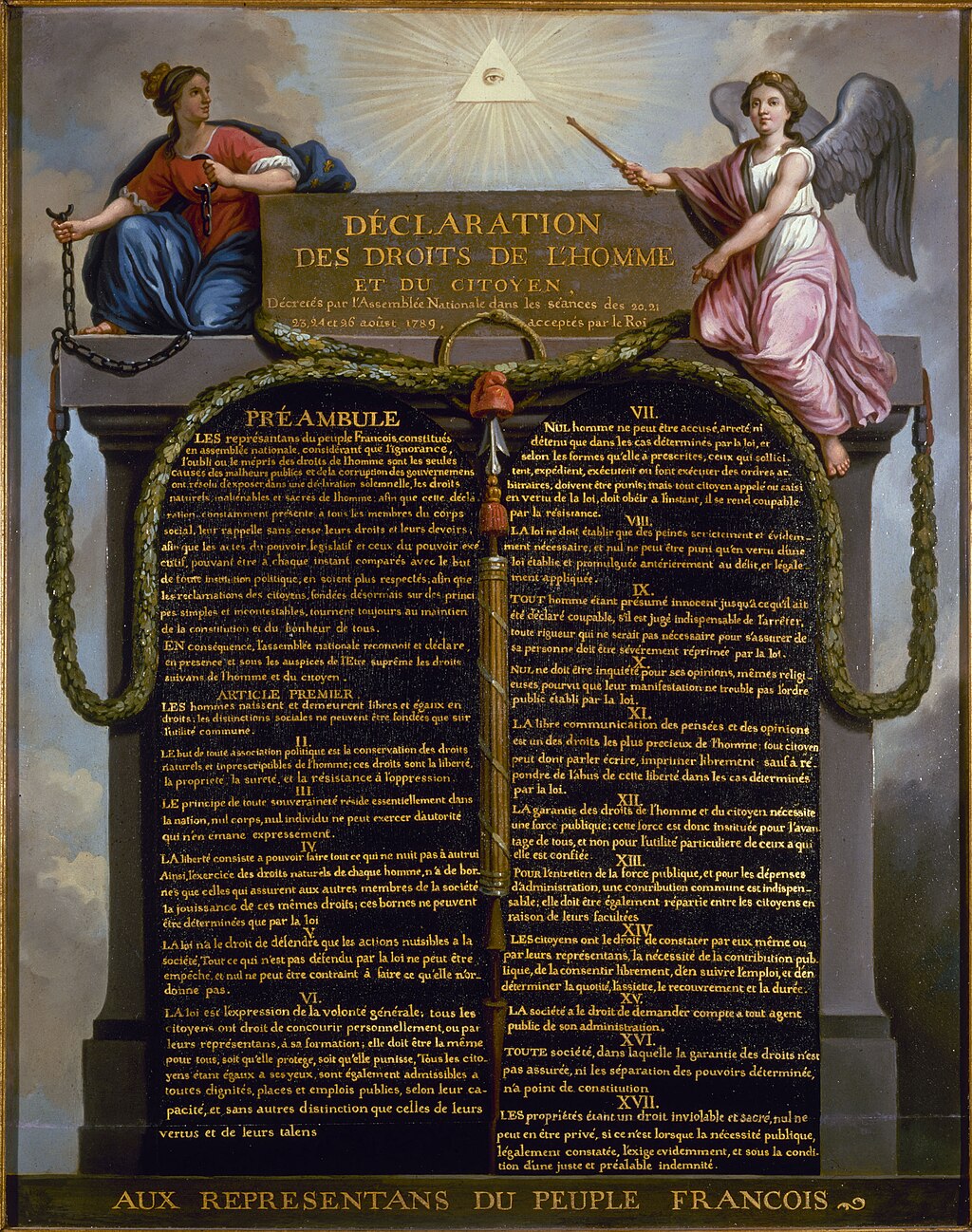

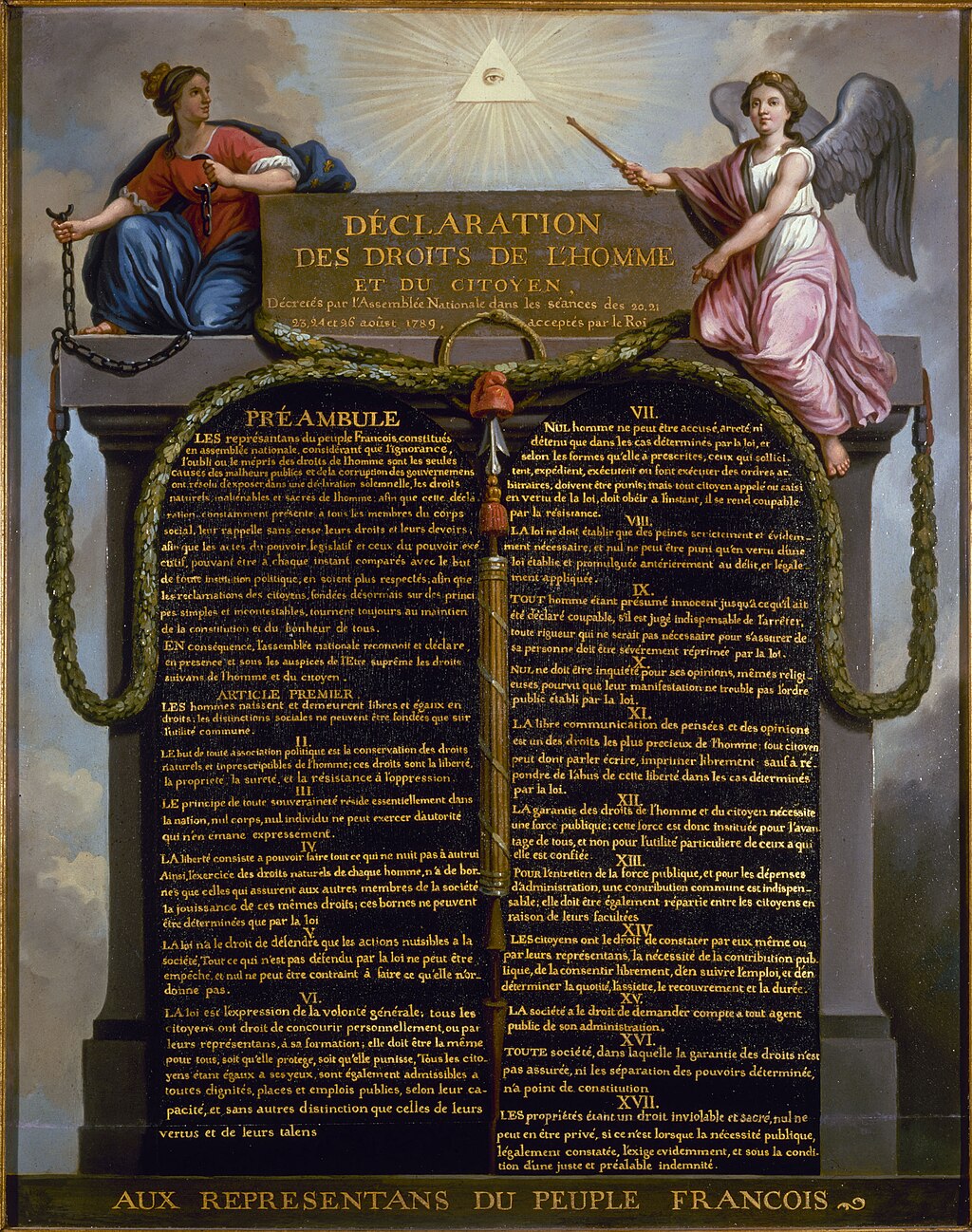

| Constitutional and administrative law Main articles: Administrative law and Constitutional law  The 1789 French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen Constitutional and administrative law govern the affairs of the state. Constitutional law concerns both the relationships between the executive, legislature and judiciary and the human rights or civil liberties of individuals against the state. Most jurisdictions, like the United States and France, have a single codified constitution with a bill of rights. A few, like the United Kingdom, have no such document. A "constitution" is simply those laws which constitute the body politic, from statute, case law and convention. The fundamental constitutional principle, inspired by John Locke, holds that the individual can do anything except that which is forbidden by law, and the state may do nothing except that which is authorised by law.[157][158] Administrative law is the chief method for people to hold state bodies to account. People (wheresoever allowed) may potentially have prerogative to legally challenge (or sue) an agency, local council, public service, or government ministry for judicial review of the offending edict (law, ordinance, policy order). Such challenge vets the ability of actionable authority under the law, and that the government entity observed required procedure. The first specialist administrative court was the Conseil d'État set up in 1799, as Napoleon assumed power in France.[159] A sub-discipline of constitutional law is election law. It along with Elections commissions, councils, or committees deal with policy and procedures facilitating elections. These rules settle disputes or enable the translation of the will of the people into functioning democracies. Election law addresses issues who is entitled to vote, voter registration, ballot access, campaign finance and party funding, redistricting, apportionment, electronic voting and voting machines, accessibility of elections, election systems and formulas, vote counting, election disputes, referendums, and issues such as electoral fraud and electoral silence. |

憲法と行政法 主な記事:行政法と憲法  1789年フランス人権宣言 憲法と行政法は国家の事務を統治する。憲法は、行政・立法・司法の三権の関係と、国家に対する個人の人権または市民的自由の両方に関わる。アメリカやフラ ンスのように、権利章典を含む単一の成文憲法を持つ法域がほとんどだ。英国のように、そのような文書を持たない国も少数存在する。「憲法」とは、成文法、 判例法、慣習法から成る政体=国家を構成する法律群を指すに過ぎない。 ジョン・ロックに端を発する根本的な憲法原則は、個人が法律で禁止されていないことは何でも行える一方、国家は法律で認められたこと以外は何もできないと 定める。[157] [158] 行政法は、国民が国家機関に説明責任を求める主要な手段である。国民(それが認められる場所において)は、行政機関、地方議会、公共サービス、政府省庁を 法的に訴追(または提訴)し、問題のある法令(法律、規律、政策指令)の司法審査を求める潜在的な権利を有し得る。このような訴追は、法的根拠に基づく行 動権限の適格性と、政府機関が所定の手続きを遵守したかどうかを検証するものである。最初の専門行政裁判所は、ナポレオンがフランスで権力を掌握した 1799年に設立された国務院(Conseil d'État)である。[159] 憲法法のサブ分野として選挙法がある。選挙管理委員会、評議会、または委員会と共に、選挙を円滑に行うための政策と手続きを扱う。これらの規則は紛争を解 決し、国民の意思を機能する民主主義へと変換することを可能にする。選挙法は、投票権の帰属、有権者登録、投票用紙へのアクセス、選挙運動資金と政党資 金、選挙区再編成、議席配分、電子投票と投票機、選挙のアクセシビリティ、選挙制度と定式、開票、選挙紛争、住民投票、選挙不正や選挙沈黙といった問題な どを扱う。 |

| Criminal law Main article: Criminal law Criminal law, also known as penal law, pertains to crimes and punishment.[160] It thus regulates the definition of and penalties for offences found to have a sufficiently deleterious social impact but, in itself, makes no moral judgment on an offender nor imposes restrictions on society that physically prevent people from committing a crime in the first place.[161][162] Investigating, apprehending, charging, and trying suspected offenders is regulated by the law of criminal procedure.[163] The paradigm case of a crime lies in the proof, beyond reasonable doubt, that a person is guilty of two things. First, the accused must commit an act which is deemed by society to be criminal, or actus reus (guilty act).[164] Second, the accused must have the requisite malicious intent to do a criminal act, or mens rea (guilty mind). However, for so called "strict liability" crimes, an actus reus is enough.[165] Criminal systems of the civil law tradition distinguish between intention in the broad sense (dolus directus and dolus eventualis), and negligence. Negligence does not carry criminal responsibility unless a particular crime provides for its punishment.[166][167]  Adolf Eichmann (standing in glass booth at left) being sentenced to death at the conclusion of his 1961 trial, an example of a criminal law proceeding Examples of crimes include murder, assault, fraud and theft. In exceptional circumstances defences can apply to specific acts, such as killing in self defence, or pleading insanity. Another example is in the 19th-century English case of R v Dudley and Stephens, which tested whether a defence of "necessity" could justify murder and cannibalism to survive a shipwreck.[168] Criminal law offences are viewed as offences against not just individual victims, but the community as well.[161][162] The state, usually with the help of police, takes the lead in prosecution, which is why in common law countries cases are cited as "The People v ..." or "R (for Rex or Regina) v ...". Also, lay juries are often used to determine the guilt of defendants on points of fact: juries cannot change legal rules. Some developed countries still condone capital punishment for criminal activity, but the normal punishment for a crime will be imprisonment, fines, state supervision (such as probation), or community service. Modern criminal law has been affected considerably by the social sciences, especially with respect to sentencing, legal research, legislation, and rehabilitation.[169] On the international field, 111 countries are members of the International Criminal Court, which was established to try people for crimes against humanity.[170] |

刑法 主な記事: 刑法 刑法は、犯罪と刑罰に関する法である。[160] したがって、社会的に十分な有害な影響があると認められる犯罪の定義と罰則を規定するが、それ自体では、犯罪者に対する道徳的判断を下すことも、人々がそ もそも犯罪を犯すことを物理的に妨げるような社会への制限を課すこともない。[161][162] 容疑者の捜査、逮捕、起訴、裁判は刑事訴訟法によって規制される。[163] 犯罪の典型的な事例は、合理的な疑いを超えて、ある人格が二つの点で有罪であると証明されることに存在する。第一に、被告人は社会が犯罪とみなす行為、す なわち行為的要件(actus reus)を犯さなければならない。[164] 第二に、被告人は犯罪行為を行うための必要な悪意、すなわちmens rea(有罪の心)を有していなければならない。ただし、いわゆる「厳格責任」犯罪においては、actus reusのみで十分である。[165] 民法系の刑事制度では、広義の故意(dolus directusとdolus eventualis)と過失を区別する。過失は、特定の犯罪が処罰を規定している場合を除き、刑事責任を伴わない。[166][167]  アドルフ・アイヒマン(左側のガラスブース内に立つ)が1961年の裁判終了時に死刑判決を受ける様子。刑事法手続きの一例である 犯罪の例には殺人、暴行、詐欺、窃盗などがある。例外的な状況では、特定の行為に対して抗弁が適用される場合がある。例えば正当防衛による殺害や、心神喪 失を主張する場合などだ。別の例として、19世紀英国のR対ダドリー・アンド・スティーブンス事件がある。この事件では、難破船から生存するために殺人や 人肉食を行った行為を「必要性」の抗弁で正当化できるかどうかが争点となった[168]。 刑法上の犯罪は、個々の被害者に対するだけでなく、社会全体に対する犯罪と見なされる。[161][162] 国家は通常警察の支援を得て起訴を主導するため、コモンロー諸国では事件が「人民対...」または「R(国王または女王の略称)対...」として引用され る。また、事実認定に基づく被告の有罪無罪の判断には、しばしば一般市民からなる陪審員が用いられる。陪審員は法律の規則を変更することはできない。一部 の先進国では、犯罪行為に対する死刑を依然として容認しているが、犯罪に対する通常の刑罰は、懲役、罰金、国家による監督(保護観察など)、または社会奉 仕となる。現代の刑法は社会科学の影響を大きく受けており、特に量刑、法研究、立法、更生分野で顕著だ[169]。国際的には、人道に対する罪を裁くため に設立された国際刑事裁判所に111カ国が加盟している[170]。 |

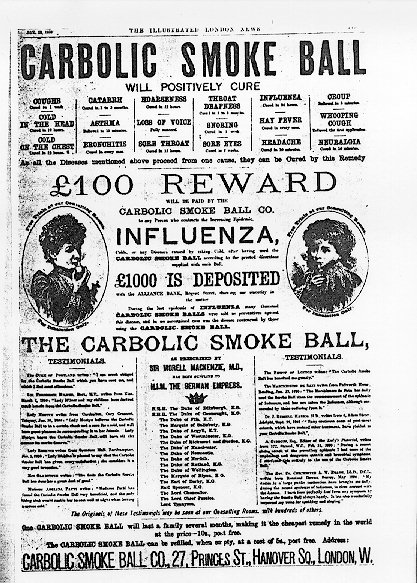

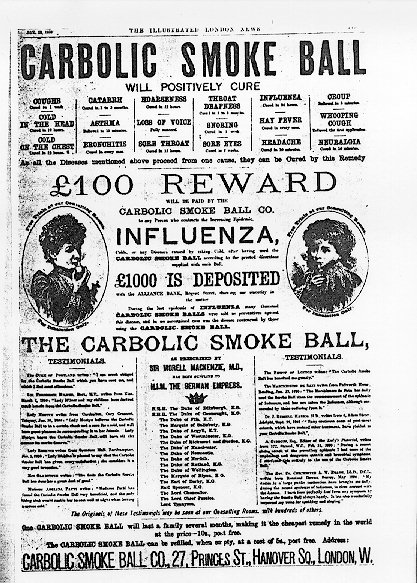

| Contract law Main article: Contract  The famous Carbolic Smoke Ball advertisement to cure influenza was held to be a unilateral contract. Contract law concerns enforceable promises, and can be summed up in the Latin phrase pacta sunt servanda (agreements must be kept).[171] In common law jurisdictions, three key elements to the creation of a contract are necessary: offer and acceptance, consideration and the intention to create legal relations. Consideration indicates the fact that all parties to a contract have exchanged something of value. Some common law systems, including Australia, are moving away from the idea of consideration as a requirement. The idea of estoppel or culpa in contrahendo, can be used to create obligations during pre-contractual negotiations.[172] Civil law jurisdictions treat contracts differently in a number of respects, with a more interventionist role for the state in both the formation and enforcement of contracts.[173] Compared to common law jurisdictions, civil law systems incorporate more mandatory terms into contracts, allow greater latitude for courts to interpret and revise contract terms and impose a stronger duty of good faith, but are also more likely to enforce penalty clauses and specific performance of contracts.[173] They also do not require consideration for a contract to be binding.[174] In France, an ordinary contract is said to form simply on the basis of a "meeting of the minds" or a "concurrence of wills". Germany has a special approach to contracts, which ties into property law. Their 'abstraction principle' (Abstraktionsprinzip) means that the personal obligation of contract forms separately from the title of property being conferred. When contracts are invalidated for some reason (e.g. a car buyer is so drunk that he lacks legal capacity to contract)[175] the contractual obligation to pay can be invalidated separately from the proprietary title of the car. Unjust enrichment law, rather than contract law, is then used to restore title to the rightful owner.[176] |

契約法 主な記事: 契約  インフルエンザ治療を謳った有名なカルボリック・スモークボールの広告は、一方的契約と見なされた。 契約法は強制力のある約束を扱い、ラテン語の格言「契約は守られねばならない(pacta sunt servanda)」に要約される。[171] 普通法圏では、契約成立には三つの要素が必要である:申し出と承諾、対価、法的関係を生じさせる意思。 対価とは、契約当事者全員が価値あるものを交換した事実を示す。オーストラリアを含む一部のコモンロー法域では、対価を要件とする考えから離脱しつつあ る。契約前の交渉段階で義務を生じさせるには、禁反言(estoppel)や契約締結上の過失(culpa in contrahendo)の概念が用いられることがある。[172] 大陸法系の法域では、契約の成立と履行の両面において国家の介入的役割がより強く、契約の扱いがいくつかの点で異なる。[173] 普通法系と比較すると、大陸法系では契約に強制条項が多く組み込まれ、裁判所が契約条項を解釈・修正する余地が大きく、信義誠実義務がより強く課される。 一方で、違約金条項や契約の特定履行の強制もより積極的に行われる傾向がある。[173] また、契約の拘束力に代価を必要としない。[174] フランスでは、通常の契約は単に「意思の合致」または「意思の競合」に基づいて成立するとされる。ドイツは契約法に財産法と連動した特殊なアプローチを取 る。その「抽象化原則」(Abstraktionsprinzip)とは、契約上の個人的義務が、付与される財産権とは別個に成立することを意味する。何 らかの理由で契約が無効となる場合(例:自動車購入者が酩酊状態で契約能力を欠く場合)[175]、支払義務という契約上の義務は、自動車の所有権とは別 個に無効とすることができる。この場合、権利を正当な所有者に回復させるために用いられるのは契約法ではなく、不当利得法である。 |

| Torts and delicts Main articles: Delict and Tort Certain civil wrongs are grouped together as torts under common law systems and delicts under civil law systems.[177] To have acted tortiously, one must have breached a duty to another person, or infringed some pre-existing legal right. A simple example might be unintentionally hitting someone with a ball.[178] Under the law of negligence, the most common form of tort, the injured party could potentially claim compensation for their injuries from the party responsible. The principles of negligence are illustrated by Donoghue v Stevenson.[h] A friend of Donoghue ordered an opaque bottle of ginger beer (intended for the consumption of Donoghue) in a café in Paisley. Having consumed half of it, Donoghue poured the remainder into a tumbler. The decomposing remains of a snail floated out. She claimed to have suffered from shock, fell ill with gastroenteritis and sued the manufacturer for carelessly allowing the drink to be contaminated. The House of Lords decided that the manufacturer was liable for Mrs Donoghue's illness. Lord Atkin took a distinctly moral approach and said: The liability for negligence [...] is no doubt based upon a general public sentiment of moral wrongdoing for which the offender must pay. [...] The rule that you are to love your neighbour becomes in law, you must not injure your neighbour; and the lawyer's question, Who is my neighbour? receives a restricted reply. You must take reasonable care to avoid acts or omissions which you can reasonably foresee would be likely to injure your neighbour.[179] This became the basis for the four principles of negligence, namely that: 1. Stevenson owed Donoghue a duty of care to provide safe drinks; 2. he breached his duty of care; 3. the harm would not have occurred but for his breach; and 4. his act was the proximate cause of her harm.[h] Another example of tort might be a neighbour making excessively loud noises with machinery on his property.[180] Under a nuisance claim the noise could be stopped. Torts can also involve intentional acts such as assault, battery or trespass. A better known tort is defamation, which occurs, for example, when a newspaper makes unsupportable allegations that damage a politician's reputation.[181] More infamous are economic torts, which form the basis of labour law in some countries by making trade unions liable for strikes,[182] when statute does not provide immunity.[i] |

不法行為とデリクト(犯罪) 主な記事: デリクトと不法行為 特定の民事上の不正行為は、コモン・ロー法体系では不法行為(tort)、大陸法体系ではデリクト(delict)として分類される。[177] 不法行為を構成するためには、他人格に対する義務に違反するか、既存の法的権利を侵害しなければならない。単純な例としては、意図せずボールで誰かを打つ ことが挙げられる[178]。不法行為の中で最も一般的な過失責任法の下では、被害者は加害者に対して負傷に対する賠償を請求できる可能性がある。過失責 任の原則はドノヒュー対スティーブンソン事件[h]によって示されている。ドノヒューの友人がペイズリーのカフェで(ドノヒューが飲むための)不透明な瓶 入りのジンジャービールを注文した。半分を飲んだ後、ドノヒューは残りをタンブラーに注いだ。すると腐敗したカタツムリの死骸が浮かび上がった。彼女は苦 悩し、胃腸炎を発症したと主張し、飲料の汚染を不注意に許したとして製造業者を訴えた。貴族院は製造業者がドノヒュー夫人の病気について責任を負うと判決 した。アトキン卿は明確に道徳的立場から次のように述べた: 過失責任は[...]間違いなく、加害者が償わねばならない道徳的過失に対する一般大衆の感情に基づいている。[...]「隣人を愛せよ」という戒めは法 において「隣人を傷つけてはならない」となる。そして弁護士の問い「誰が私の隣人か?」には限定的な答えが与えられる。あなたは、合理的に予見可能な隣人 への危害を招く行為や不作為を避けるため、合理的な注意を払わねばならない。[179] これが過失の四原則の基礎となった。すなわち: 1. スティーブンソンはドノヒューに対し、安全な飲料を提供する注意義務を負っていた。 2. 彼は注意義務に違反した。 3. 彼の違反がなければ損害は生じなかった。 4. 彼の行為は彼女の損害の直接原因であった。[h] 不法行為の別の例として、隣人が自身の敷地内で機械を過剰に騒音を発するケースが挙げられる。[180] 迷惑行為の主張により、騒音は差し止められる可能性がある。不法行為には暴行、傷害、不法侵入などの故意の行為も含まれる。よりよく知られた不法行為は名 誉毀損であり、例えば新聞が根拠のない主張をして政治家の評判を傷つけた場合に発生する。[181] さらに悪名高いのは経済的不法行為であり、これは労働法の基本を成すもので、法令が免責を定めていない場合、[182] 労働組合にストライキの責任を負わせる。[i] |

| Property law Main article: Property law  The South Sea Bubble by Edward Matthew Ward. The South Sea Bubble in 1720, one of the world's first ever speculations and crashes, led to strict regulation on share trading.[183] Property law governs ownership and possession. Real property, sometimes called 'real estate', refers to ownership of land and things attached to it.[184] Personal property, refers to everything else; movable objects, such as computers, cars, jewelry or intangible rights, such as stocks and shares. A right in rem is a right to a specific piece of property, contrasting to a right in personam which allows compensation for a loss, but not a particular thing back. Land law forms the basis for most kinds of property law, and is the most complex. It concerns mortgages, rental agreements, licences, covenants, easements and the statutory systems for land registration. Regulations on the use of personal property fall under intellectual property, company law, trusts and commercial law. A representative example of property law is the 1722 suit of Armory v Delamirie, applying English law.[185] A child was deprived of possession of the gemstones that had been set in piece of jewellery, by the businessperson entrusted to appraise the piece. The court articulated that, according to the view of property in common law jurisdictions, the person who can show the best claim to a piece of property, against any contesting party, is the owner.[186] By contrast, the classic civil law approach to property, propounded by Friedrich Carl von Savigny, is that it is a right good against the world. Obligations, like contracts and torts, are conceptualised as rights good between individuals.[187] The idea of property raises many further philosophical and political issues. Locke argued that our "lives, liberties and estates" are our property because we own our bodies and mix our labour with our surroundings.[188] |