レスリー・ホワイト

Leslie Alvin White, 1900-1975

☆ レスリー・アルヴィン・ホワイト(Leslie Alvin White、1900 年1月19日、コロラド州サリダ - 1975年3月31日、カリフォルニア州ローンパイン)は、文化進化論、社会文化進化論、特に新進化論を提唱し、ミシガン大学アナーバー校に人類学科を創 設したことで知られるアメリカの人類学者である。ホワイトはアメリカ人類学会の会長(1964年)を務めた。

| Leslie Alvin White

(January 19, 1900, Salida, Colorado – March 31, 1975, Lone Pine,

California) was an American anthropologist known for his advocacy of

the theories on cultural evolution, sociocultural evolution, and

especially neoevolutionism, and for his role in creating the department

of anthropology at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor.[1] White was

president of the American Anthropological Association (1964).[2] |

レ

スリー・アルヴィン・ホワイト(Leslie Alvin White、1900年1月19日、コロラド州サリダ -

1975年3月31日、カリフォルニア州ローンパイン)は、文化進化論、社会文化進化論、特に新進化論を提唱し、ミシガン大学アナーバー校に人類学科を創

設したことで知られるアメリカの人類学者である[1]。ホワイトはアメリカ人類学会の会長(1964年)を務めた[2]。 |

| Early years White lived first in Kansas and then Louisiana.[citation needed] He volunteered to fight in World War I, serving in the US Navy before enrolling at Louisiana State University in 1919. In 1921, he transferred to Columbia University, where he studied psychology, receiving a B.A. in 1923 and a M.A. in 1924. His Ph.D. in Anthropology and Sociology came from the University of Chicago(1925). White studied at Columbia, where Franz Boas had lectured, however he supported cultural evolution as defined by writers such as Lewis. H Morgan and Edward Tylor. White's interests were diverse, and he took classes in several other disciplines, including philosophy at UCLA, and clinical psychiatry, before discovering anthropology via Alexander Goldenweiser courses at the New School for Social Research. White also spent a few weeks with the Menominee and Winnebago in Wisconsin during his Ph.D. His thesis proposal was a library thesis, which foreshadowed his later theoretical work. He conducted fieldwork at Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico. In 1927 White began teaching at the University at Buffalo. |

初期 1919年にルイジアナ州立大学に入学する前に、第一次世界大戦に志願してアメリカ海軍に従軍。1921年にコロンビア大学に編入し、心理学を学び、1923年に学士号、1924年に修士号を取得。シカゴ大学で人類学と社会学の博士号を取得(1925年)。 ホワイトは、フランツ・ボースが講義をしていたコロンビア大学で学んだが、ルイス・H・モーガンやエドワード・タイラーのような作家が定義した文化進化を 支持した。H・モーガンやエドワード・タイラーのような作家が定義した文化進化を支持した。ホワイトの興味は多岐にわたり、UCLAで哲学、臨床精神医学 など他の学問分野の授業を受けた後、ニュー・スクール・フォー・ソーシャル・リサーチのアレクサンダー・ゴールデンワイザーの講座を通じて人類学に出会っ た。ホワイトは博士号取得中、ウィスコンシン州のメノミニー族とウィネベーゴ族に数週間滞在した。彼はニューメキシコのアコマ・プエブロでフィールドワー クを行った。 1927年、バッファロー大学で教鞭をとる。 |

| Buffalo transition Teaching at University of Buffalo marked a turning point in White's thinking. It was here that he developed a worldview—anthropological, political, ethical—that he would hold to and advocate until his death. White developed an interest in Marxism In 1929, he visited the Soviet Union and on his return joined the Socialist Labor Party, writing articles under the pseudonym "John Steel" for their newspaper.[3] White went to Michigan when he was hired to replace Julian Steward, who departed Ann Arbor in 1930. Although the university was home to a museum with a long history of involvement in matters anthropological, White was the only professor in the anthropology department itself. He remained here for the rest of his active career. In 1932, he headed a field school in the southwest which was attended by Fred Eggan, Mischa Titiev, and others. White brought Titiev, his student and a Russian immigrant, to Michigan as a second professor in 1936. However, during the Second World War, Titiev took part in the war effort by studying Japan. Perhaps this upset the socialist White. In any case by war's end White had broken with Titiev, who would go on to found the East Asian Studies Program, and the two were hardly even on speaking terms. No other faculty members were hired until after the war, when scholars like Richard K. Beardsley joined the department. Most would fall on one side or the other of the split between White and Titiev. As a professor in Ann Arbor, White trained students such as Robert Carneiro, Beth Dillingham, and Gertrude Dole who carried on White's program in its orthodox form, while other scholars such as Eric Wolf, Arthur Jelinek, Elman Service, and Marshall Sahlins and Napoleon Chagnon drew on their time with White to elaborate their own forms of anthropology. |

バッファローでの転機 バッファロー大学で教鞭をとったことが、ホワイトの考え方の転機となった。ここで彼は、人類学的、政治的、倫理的な世界観を確立した。1929年にソビエ ト連邦を訪問したホワイトは、帰国後に社会主義労働党に入党し、「ジョン・スティール」というペンネームで同党の新聞に記事を寄稿した[3]。 ホワイトは、1930年にアナーバーを去ったジュリアン・スチュワードの後任として雇われ、ミシガン大学へ。ミシガン大学には人類学に関する長い歴史を持 つ博物館があったが、人類学部で教授を務めたのはホワイトただ一人であった。彼は現役時代の残りのキャリアをここで過ごした。1932年、彼は南西部での フィールド・スクールを主宰し、フレッド・エガンやミッシャ・ティチエフらが参加した。 ホワイトは1936年、教え子でロシア移民のティティエフを第二教授としてミシガンに呼び寄せた。しかし、第二次世界大戦中、ティチエフは日本を研究する ことで戦争に参加した。おそらく、このことが社会主義者のホワイトを怒らせたのだろう。いずれにせよ、終戦までにホワイトは、後に東アジア研究プログラム を創設することになるティティエフと決裂し、2人はほとんど口もきかなかった。戦後、リチャード・K・ビアズリーのような学者が加わるまで、他の教員は採 用されなかった。ほとんどの教員が、ホワイトとティティエフの分裂のどちらか一方に属することになる。 アナーバーの教授として、ホワイトはロバート・カルネイロ、ベス・ディリンハム、ガートルード・ドールといった学生を育て、彼らはホワイトのプログラムを 正統的な形で継承した。一方、エリック・ウルフ、アーサー・イェリネク、エルマン・サービス、マーシャル・サーリンズ、ナポレオン・チャグノンといった学 者たちは、ホワイトとの時間を活かして、独自の人類学の形式を精緻化した。 |

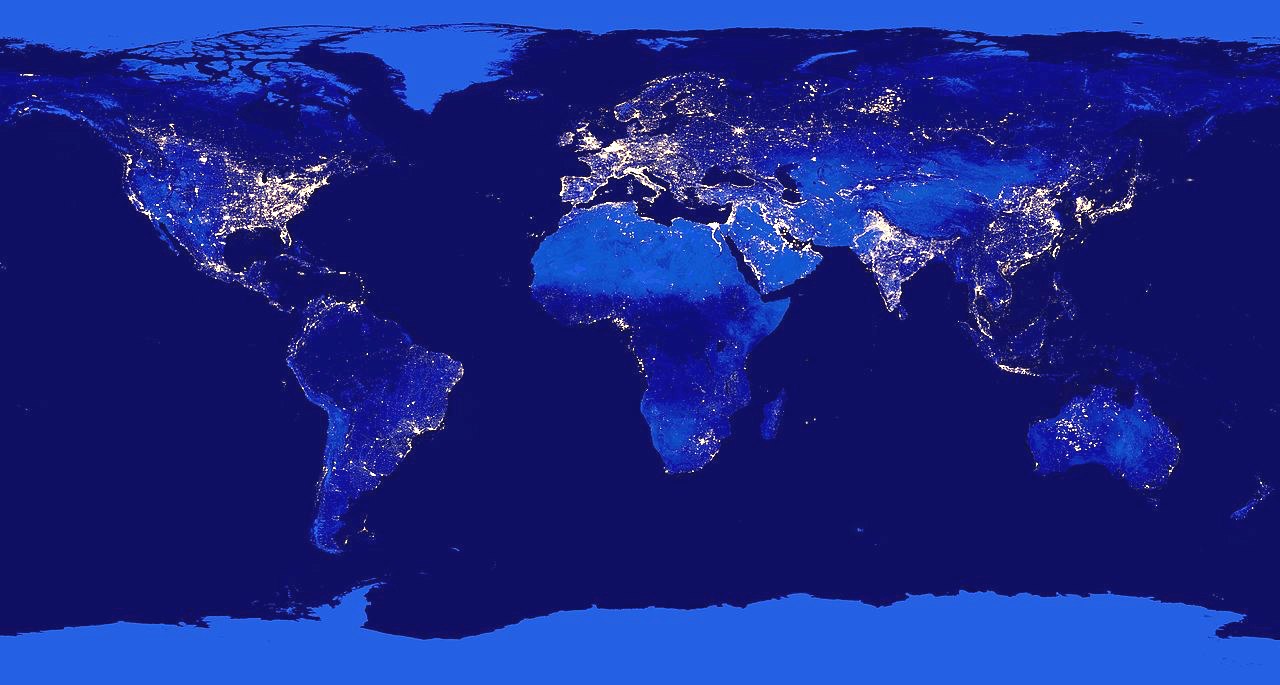

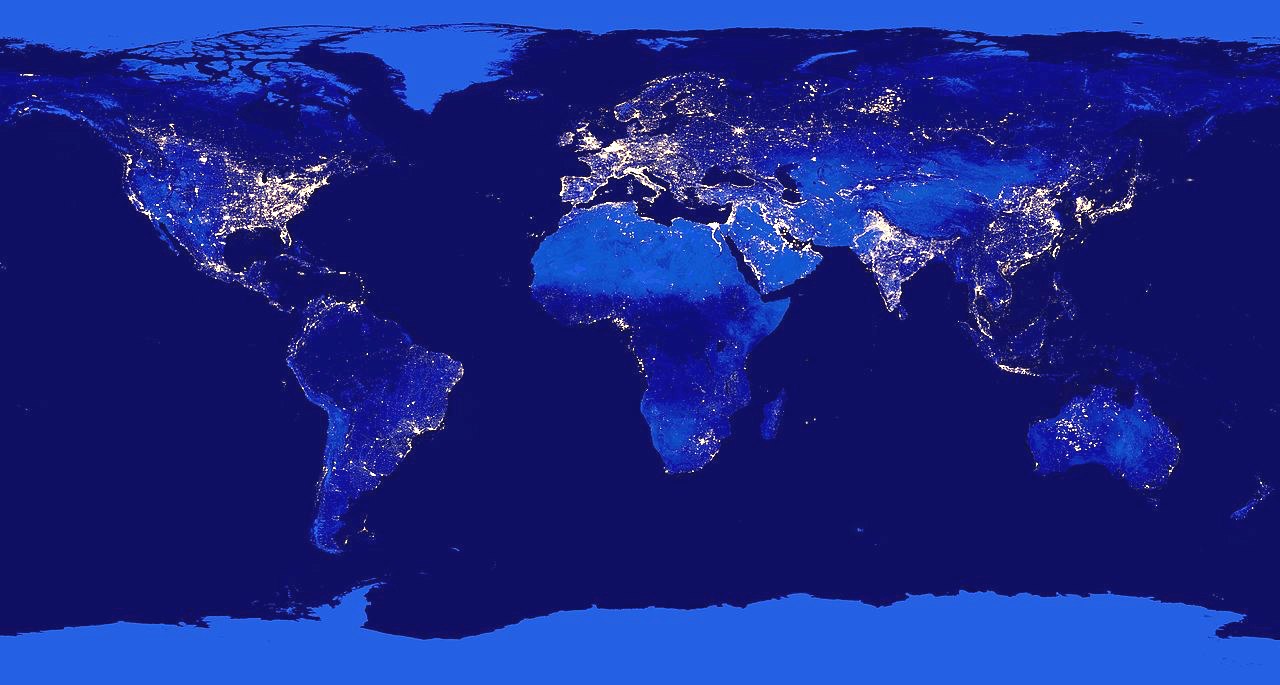

| White's anthropology Over time, White's views became framed in opposition to that of Boasians, with whom he was institutionally at odds. This could take on personal overtones: White referred to Boas's prose style as "corny" in the American Journal of Sociology. Robert Lowie, a proponent of Boas's work, referred to White's work as "a farrago of immature metaphysical notions", shaped by "the obsessive power of fanaticism [which] unconsciously warps one's vision."[4] One of White's strongest deviations from Boas's philosophy was a view of the nature of anthropology and its relation to other sciences. White understood the world to be divided into cultural, biological, and physical levels of phenomena. Such a division is a reflection of the composition of the universe and was not a heuristic device. Thus, contrary to Alfred L. Kroeber, Kluckhohn, and Edward Sapir, White saw the delineation of the object of study not as a cognitive accomplishment of the anthropologist, but as a recognition of the actually existing and delineated phenomena which comprise the world. The distinction between 'natural' and 'social' sciences was thus based not on method, but on the nature of the object of study: physicists study physical phenomena, biologists biological phenomena, and culturologists (White's term) cultural phenomena. The object of study was not delineated by the researcher's viewpoint or interest, but the method by which he approached them could be. White believed that phenomena could be explored from three different points of view: the historical, the formal-functional, and the evolutionist (or formal-temporal). The historical view was dedicated to examining the particular diachronic cultural processes, "lovingly trying to penetrate into its secrets until every feature is plain and clear." The formal-functional is essentially the synchronic approach advocated by Alfred Radcliffe-Brown and Bronisław Malinowski, attempting to discern the formal structure of a society and the functional interrelations of its components. The evolutionist approach is, like the formal approach, generalizing; but it is also diachronic, seeing particular events as general instances of larger trends. Boas claimed his science promised complex and interdependent visions of culture, but White thought that it would delegitimize anthropology if it became the dominant position, removing it from broader discourses on science. White viewed his own approach as a synthesis of historical and functional approach because it combined the diachronic scope of one with the generalizing eye for formal interrelations provided by the other. As such, it could point out "the course of cultural development in the past and its probable course in the future" a task that was anthropology's "most valuable function". This stance can be seen in his views of evolution, which are firmly rooted in the writings of Herbert Spencer, Charles Darwin, and Lewis H. Morgan. While it can be argued that White's exposition of Morgan and Spencer's was tendentious, it can be safely said that White's concepts of science and evolution were firmly rooted in their work. Advances in population biology and evolutionary theory passed White by and, unlike Steward, his conception of evolution and progress remained firmly rooted in the nineteenth century. For White, culture was a superorganic entity that was sui generis and could be explained only in terms of itself. It was composed of three levels: the technological, the social organizational, and the ideological. Each level rested on the previous one, and although they all interacted, ultimately the technological level was the determining one, what White calls "The hero of our piece" and "the leading character of our play". The most important factor in his theory is technology: "Social systems are determined by technological systems", wrote White in his book, echoing the earlier theory of Lewis Henry Morgan. White spoke of culture as a general human phenomenon and claimed not to speak of 'cultures' in the plural. His theory, published in 1959 in The Evolution of Culture: The Development of Civilization to the Fall of Rome, rekindled the interest in social evolutionism and is counted prominently among the neoevolutionists. He believed that culture–meaning the total of all human cultural activity on the planet–was evolving. White differentiated three components of culture: technological, sociological, and ideological. He argued that it was the technological component which plays a primary role or is the primary determining factor responsible for the cultural evolution. His materialist approach is evident in the following quote: "man as an animal species, and consequently culture as a whole, is dependent upon the material, mechanical means of adjustment to the natural environment."[5] This technological component can be described as material, mechanical, physical, and chemical instruments, as well as the way people use these techniques. White's argument on the importance of technology goes as follows:[6] Technology is an attempt to solve the problems of survival. This attempt ultimately means capturing enough energy and diverting it for human needs. Societies that capture more energy and use it more efficiently have an advantage over other societies. Therefore, these different societies are more advanced in an evolutionary sense.  Composite image of the Earth at night in 2012, created by NASA and NOAA. The brightest areas of the Earth are the most urbanized, but not necessarily the most populous. Even more than 100 years after the invention of the electric light, some regions remain thinly populated and unlit. For White "the primary function of culture" and the one that determines its level of advancement is its ability to "harness and control energy." White's law states that the measure by which to judge the relative degree of evolvedness of culture was the amount of energy it could capture (energy consumption). White differentiates between five stages of human development. At first, people use the energy of their own muscles. Second, they use the energy of domesticated animals. Third, they use the energy of plants (so White refers to agricultural revolution here). Fourth, they learn to use the energy of natural resources: coal, oil, gas. Fifth, they harness nuclear energy. White introduced a formula, P = ET, where E is a measure of energy consumed per capita per year, T is the measure of efficiency in utilizing energy harnessed, and P represents the degree of cultural development in terms of product produced. In his own words: "the basic law of cultural evolution" was "culture evolves as the amount of energy harnessed per capita per year is increased, or as the efficiency of the instrumental means of putting the energy to work is increased".[6] Therefore, "we find that progress and development are effected by the improvement of the mechanical means with which energy is harnessed and put to work as well as by increasing the amounts of energy employed".[5] Although White stops short of promising that technology is the panacea for all the problems that affect mankind, like technological utopians do, his theory treats the technological factor as the most important factor in the evolution of society and is similar to ideas in the later works of Gerhard Lenski, the theory of the Kardashev scale, and some notions of technological singularity. |

ホワイトの人類学 やがてホワイトの見解は、制度的に対立していたボアジアンの見解と対立する枠組みを持つようになった。これは個人的な意味合いも含んでいた: ホワイトは『アメリカン・ジャーナル・オブ・ソシオロジー』誌上で、ボアスの散文スタイルを「陳腐なもの」と呼んだ。ボースの著作の支持者であったロバー ト・ローウィーは、ホワイトの著作を「未熟な形而上学的観念の乱雑さ」と呼び、「無意識のうちに視野を歪めてしまう狂信の強迫的な力」[4]によって形作 られていると述べている。 ホワイトがボースの哲学から最も強く逸脱していたのは、人類学の本質と他の科学との関係についての見解であった。ホワイトは世界を文化的、生物学的、物理 的なレベルの現象に分割して理解していた。このような区分は宇宙の構成を反映したものであり、発見的な装置ではなかった。したがって、アルフレッド・L・ クルーバー、クルックホーン、エドワード・サピアとは対照的に、ホワイトは研究対象の区分を人類学者の認識的達成としてではなく、世界を構成する現実に存 在し、区切られた現象の認識として捉えていた。物理学者は物理現象を、生物学者は生物現象を、文化学者(ホワイトの用語)は文化現象を研究するのである。 物理学者は物理現象を、生物学者は生物現象を、文化学者(ホワイトの用語)は文化現象を研究するのである。研究対象は研究者の視点や関心によって規定され るのではなく、研究者がそれらにアプローチする方法によって規定されるのである。ホワイトは、現象は歴史的視点、形式的機能的視点、進化論的視点(あるい は形式的時間的視点)という3つの異なる視点から探求できると考えた。歴史的視点は、特定の通時的な文化的プロセスを検証することに専念し、"すべての特 徴が明白になるまで、その秘密に愛情を持って入り込もうとする "ものであった。形式的-機能的アプローチは、基本的にアルフレッド・ラドクリフ=ブラウンとブロニスワフ・マリノフスキーが提唱した共時的アプローチで あり、社会の形式的構造とその構成要素の機能的相互関係を見極めようとするものである。進化論的アプローチは、形式的アプローチと同様に一般化するもので あるが、通時的でもあり、特定の出来事をより大きな傾向の一般的な例として捉えるものである。 ボアスは自身の科学が複雑で相互依存的な文化像を約束すると主張したが、ホワイトは、それが支配的な立場になれば人類学を委縮させ、科学に関する広範な言 説から排除してしまうと考えた。ホワイトは、自らのアプローチを歴史的アプローチと機能的アプローチの統合とみなしていた。それは、歴史的アプローチの通 時的な範囲と、機能的アプローチの形式的な相互関係に対する一般化の目を組み合わせたものだったからである。そのため、「過去における文化的発展の過程 と、将来における文化的発展の可能性」を指摘することができ、それは人類学の「最も価値ある機能」であった。 このような姿勢は、ハーバート・スペンサー、チャールズ・ダーウィン、ルイス・H・モーガンの著作にしっかりと根を下ろした彼の進化観に見ることができ る。モーガンとスペンサーの著作に対するホワイトの解説が冗長であったという議論はあるが、ホワイトの科学と進化に関する概念は、彼らの著作にしっかりと 根ざしていたと言ってよい。集団生物学と進化論の進歩はホワイトの前を通り過ぎ、スチュワードとは異なり、彼の進化と進歩の概念は19世紀にしっかりと根 を下ろしたままであった。 ホワイトにとって、文化とは超有機的な存在であり、それ自体でしか説明できないものであった。それは技術的なもの、社会組織的なもの、そしてイデオロギー 的なものという3つのレベルで構成されていた。それぞれのレベルは前のレベルに依存しており、それらはすべて相互作用していたが、最終的には技術的なレベ ルが決定的なものであり、ホワイトが「我々の作品の主人公」「我々の劇の主役」と呼ぶものであった。彼の理論で最も重要な要素は技術である: 「社会システムは技術システムによって決定される」とホワイトは著書の中で書いており、ルイス・ヘンリー・モーガンの以前の理論に共鳴している。 ホワイトは文化を一般的な人間現象として語り、「文化」を複数形では語らないと主張した。彼の理論は1959年に『文化の進化』として発表された: 文明の発展からローマの滅亡まで』(The Development of Civilization to the Fall of Rome)で発表された彼の理論は、社会進化論への関心を再燃させ、新進進化論者の中でも重要な位置を占めている。彼は、文化とは地球上のすべての人間の 文化活動の総体を意味し、進化していると考えた。ホワイトは文化の構成要素を技術的、社会学的、思想的の3つに分類した。彼は、文化の進化に主要な役割を 果たす、あるいは主要な決定要因であるのは技術的要素であると主張した。彼の唯物論的アプローチは、次の引用に表れている: 「動物種としての人間、ひいては全体としての文化は、自然環境に適応するための物質的、機械的な手段に依存している。技術の重要性に関するホワイトの議論 は次のようなものである[6]。 技術とは、生存の問題を解決しようとする試みである。 この試みは最終的に、十分なエネルギーを獲得し、それを人間の必要性に転用することを意味する。 より多くのエネルギーを獲得し、それをより効率的に利用する社会は、他の社会よりも優位に立つ。 したがって、これらの異なる社会は、進化的な意味でより進んでいる。  NASAとNOAAが作成した2012年の夜の地球の合成画像。地球上で最も明るい地域は最も都市化しているが、必ずしも人口が多いわけではない。電灯の発明から100年以上経っても、人口が少なく明かりのない地域もある。 ホワイトにとって「文化の主要な機能」であり、その進歩のレベルを決定するものは、「エネルギーを利用し、制御する能力」である。ホワイトの法則は、文化 の相対的な進化の度合いを判断する尺度は、その文化が取り込むことのできるエネルギーの量(エネルギー消費量)であるとしている。 ホワイトは人間の発達を5段階に分けている。最初は自分の筋肉のエネルギーを使う。次に、家畜化された動物のエネルギーを使う。第三に、植物のエネルギー を利用する(ホワイトはここで農業革命を指している)。第四に、石炭、石油、ガスといった天然資源のエネルギーを利用する。第5に、原子力エネルギーを利 用する。ホワイトは数式を紹介した、 P=ET、 ここで、Eは国民一人当たりの年間エネルギー消費量、Tは利用したエネルギーの利用効率、Pは生産された製品の文化的発展の度合いを表す。彼自身の言葉を 借りれば 「文化的進化の基本法則」は、「文化は、一人当たり年間に利用されるエネルギーの量が増大するにつれて、あるいは、エネルギーを利用する道具的手段の効率 が増大するにつれて、進化する」というものであった。 [ホワイトは、技術的ユートピア主義者のように、技術が人類に影響を与えるすべての問題の万能薬であると約束することはしないが、彼の理論は、技術的要因 を社会の進化における最も重要な要因として扱っており、ゲルハルト・レンスキーの後の著作、カルダシェフ・スケールの理論、技術的特異点のいくつかの概念 における考え方に類似している。 |

| Selected publications Ethnological Essays: Selected Essays of Leslie A. White. University of New Mexico Press. 1987. The Evolution of Culture: The Development of Civilization to the Fall of Rome. 1959. The Science of Culture: A study of man and civilization. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1949. The Pueblo of Santa Ana, New Mexico. American Anthropological Association Memoir 60, 1949. The Pueblo of San Felipe. American Anthropological Association Memoir No. 38, 1938. The Pueblo of Santo Domingo. American Anthropological Association Memoir 60, 1935. The Acoma Indians. Bureau of American Ethnology, 47th annual report, pp. 1–192. Smithsonian Institution, 1932. |

|

| Leslie

A. White: Evolution and Revolution in Anthropology by William Peace.

University of Nebraska Press, 2004 (the definitive biography of White). Richard Beardsley. An appraisal of Leslie A. White's scholarly influence. American Anthropologist 78:617–620, 1976. Jerry D. Moore. Leslie White: Evolution Emergent. Chapter 13 of Visions of Culture. pp. 169–180. Alta Mira, 1997. Moses, Daniel Noah (2009). The Promise of Progress: The Life and Work of Lewis Henry Morgan. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. Elman Service. Leslie Alvin White, 1900–1975. American Anthropologist 78:612–617, 1976. The Leslie White Papers - Finding guide and information about Leslie White's papers at the Bentley Historical library. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leslie_White |

|

| Leslie White (1900-1975) Leslie White, fue un antropólogo norteamericano con un gran conocimiento acerca de la evolución cultural. La construcción de su teoría fue el producto de una fuerte influencia de la teoría económica Marxista y la teoría evolucionista Darwiniana, así como del trabajo de campo que hizo en sus primeros años White estuvo estudiando inicialmente en Lousiana State University, después se traslado a Columbia University, donde recibió su licenciatura y su Master en psicología. Finalmente se trasladó a Chicago Universitydonde hizo sus estudios de doctorado en sociología. White empezó su trabajo de campo en el sur oeste de Estados Unidos con el pueblo indígena Keresan. White fue profesor en Michigan University, sus últimos años los dedicó a trabajar en el departamento de antropología en University of California, Santa Barbara. Durante toda su vida, White estuvo interesado en la evolución en general. Él sustentó fuertemente sus ideas sobre escritores del siglo XIX como Herbert Spencer, Lewis H. Morgan y Edward Taylor, adaptando muchas de sus ideas y dándoles un nuevo enfoque, así como también desarrollando un nuevo término que denominó “culturology”. Acuñó este concepto porque creyó que las culturas no podían explicarse en términos de psicología, biología o sociología. Por “culturology” entendía “El campo de la ciencia que estudia e interpreta el orden de los fenómenos en los distintos periodos de la cultura”. White estuvo interesado por el desarrollo tecnológico, especialmente en los avances y su relación con los efectos en la cultura, “la cultura avanza cuando la suma total de la energía se almacena de acuerdo al incremento per capita por año, o por la eficacia de la economía que puede controlar los recursos energéticos y su incremento, o ambos”. White creyó que la tecnología es el principal factor dentro de los sistemas culturales. White hizo muchos aportes a la antropología en el campo de investigación a través de ensayos y conferencias, pero la mayoría fueron recoplilados como su gran contribución en una serie de ensayos que llamó “la ciencia de la cultura”. https://www.liceus.com/leslie-white/ |

レスリー・ホワイト(1900-1975) レスリー・ホワイトは、文化進化に強い理解を持つアメリカの人類学者である。彼の理論構築は、マルクス主義経済理論とダーウィン進化論の強い影響と、彼が若い頃に行ったフィールドワークの成果である。 ホワイトは当初ルイジアナ州立大学で学び、その後コロンビア大学に移って心理学の学士号と修士号を取得した。最後にシカゴ大学に移り、社会学の博士課程を 修了した。ホワイトはアメリカ南西部の先住民ケレサン族とのフィールドワークを開始した。ミシガン大学で教授を務めた後、晩年はカリフォルニア大学サンタ バーバラ校の人類学部で働いた。 ホワイトは生涯を通じて進化論全般に関心を抱いていた。彼はハーバート・スペンサー、ルイス・H・モーガン、エドワード・テイラーといった19世紀の作家 を大いに参考にし、彼らのアイデアの多くを適応させ、新たな焦点を与えた。彼は、文化は心理学や生物学、社会学では説明できないと考えたからである。「文化学」とは、「文化のさまざまな時代における現象の秩序を研究し、解釈する科学の分野」という意味である。 ホワイトは、技術の発展、特に進歩と文化への影響との関係に関心を抱いていた。「文化が進歩するのは、エネルギーの総和が、一人当たりの年間増加量に応じ て蓄積されるときか、エネルギー資源とその増加を制御できる経済の効率によって、あるいはその両方によってである」。ホワイトは、技術が文化システムの主 要な要因であると考えていた。 ホワイトは、エッセイや講演を通じて研究の分野で人類学に多くの貢献をしたが、そのほとんどは、彼が「文化の科学」と呼んだ一連のエッセイに、彼の主要な貢献として集められている。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆