自由主義・リベラリズム

Liberalism

☆

リベラリズムは、個人の権利、自由、統治される者の同意、政治的平等、私有財産の権利、法の下の平等を基盤とする政治的・道徳的哲学である。[1][2]

リベラル派は、これらの原則に対する理解によって、多様な、そしてしばしば相互に矛盾する見解を支持するが、一般的に私有財産、市場経済、

個人の権利(市民権や人権を含む)、自由民主主義、世俗主義、法の支配、経済的・政治的自由、言論の自由、報道の自由、集会の自由、信教の自由などを支持

する。[3] リベラリズムは、近代史における支配的なイデオロギーとして頻繁に引用される。[4][5]: 11

リベラリズムは啓蒙時代に明確な運動となり、西洋の哲学者や経済学者の間で人気を博した。自由主義は、世襲特権、国教、絶対王政、王の神聖な権利、伝統的

保守主義といった規範を、代表民主制、法の支配、法の下の平等に置き換えることを目指した。自由主義者はまた、重商主義政策、王家の独占、その他の貿易障

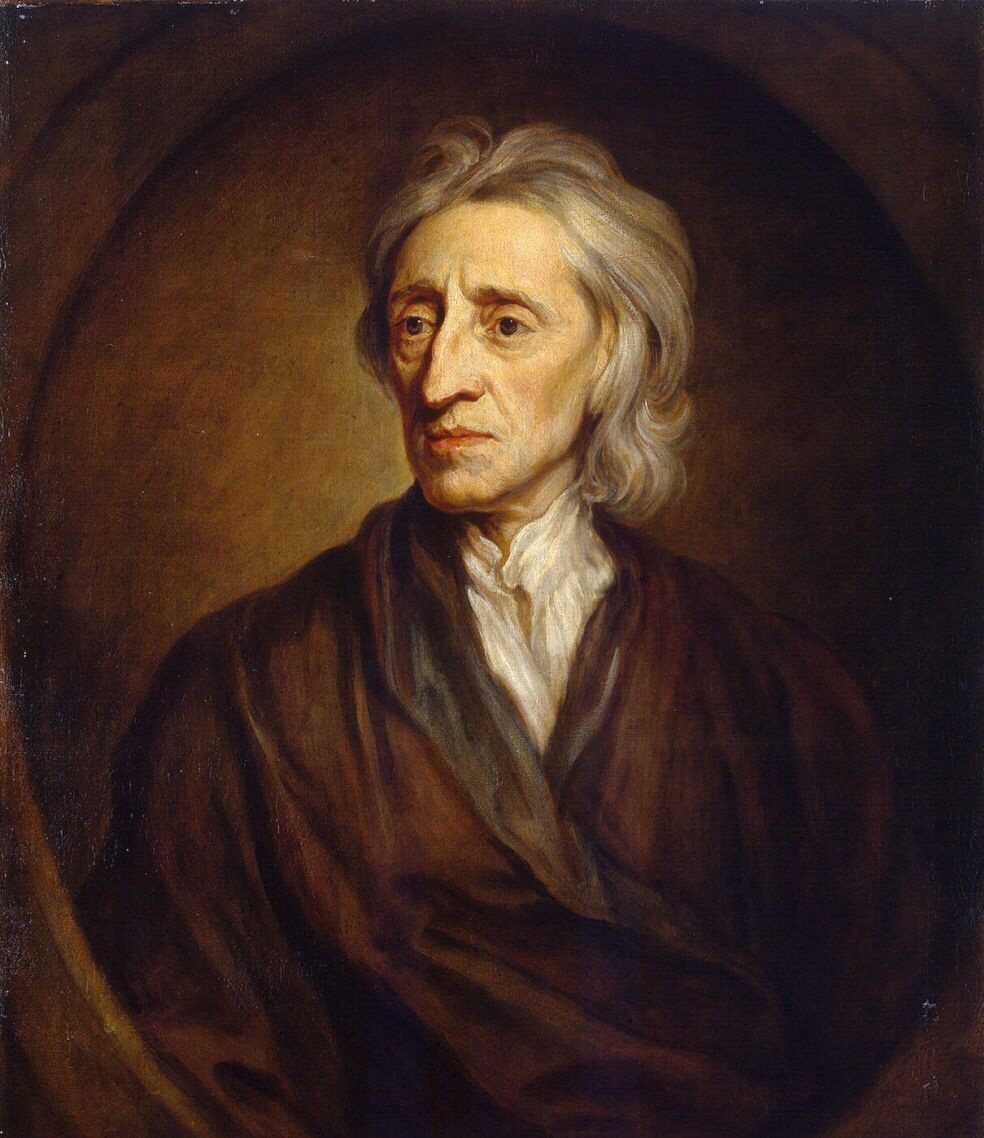

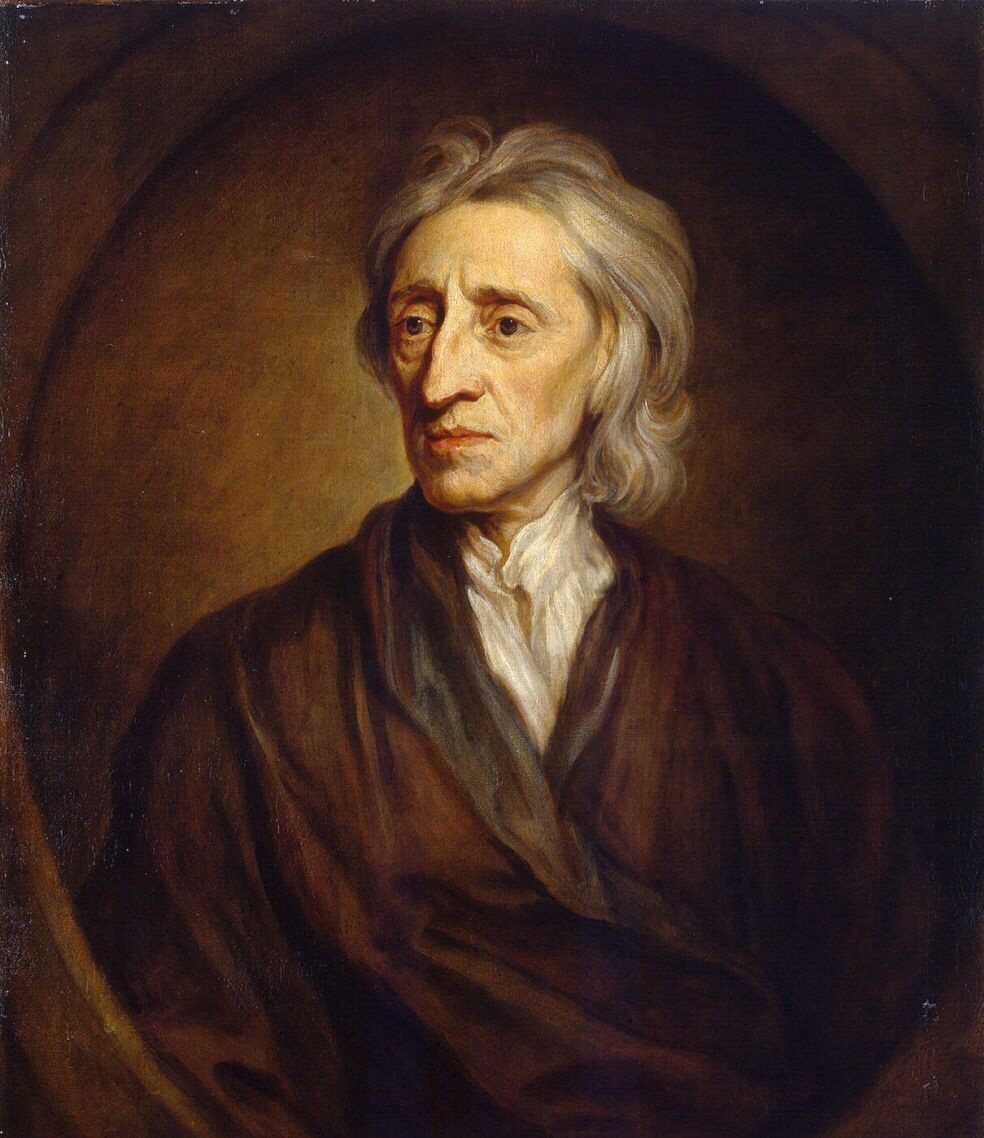

壁を廃止し、その代わりに自由貿易と市場化を推進した。哲学者ジョン・ロックは、社会契約に基づく独自の伝統として自由主義を創始した人物としてしばしば

評価されている。ロックは、 各人は生命、自由、財産に対する自然権を有しており、政府はこれらの権利を侵害してはならないと主張した。[7]

英国のリベラルな伝統は民主主義の拡大を強調する一方で、フランスのリベラリズムは権威主義の拒絶を強調し、国民形成と結びついている。[8]

☆1688

年のイギリスの名誉革命、1776年のアメリカ独立革命、1789年のフランス革命の指導者たちは、自由主義の哲学を王権の武力による転覆を正当化するた

めに利用した。19世紀には、ヨーロッパや南アメリカで自由主義政府が樹立され、アメリカでは共和制とともに定着した。[10]

ヴィクトリア朝時代のイギリスでは、政治体制を批判するために用いられ、科学と理性を人々のために訴えた。[ 11]

19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけて、オスマン帝国および中東における自由主義は、タンズィマートやアル=ナフダなどの改革期や、立憲主義、ナショナリズ

ム、世俗主義の台頭に影響を与えた。これらの変化は、他の要因とともに、今日まで続くイスラム教内部の危機感を醸成し、イスラム復興主義につながった。

1920年以前には、自由主義の主なイデオロギー上の対立者は共産主義、保守主義、社会主義であったが[12]、その後、自由主義はファシズムやマルク

ス・レーニン主義を新たな対立勢力として、大きなイデオロギー上の挑戦に直面することとなった。20世紀の間、自由主義の思想はさらに広まり、特に西ヨー

ロッパでは、自由民主主義が両世界大戦[13]および冷戦[14][15]の勝者となった。

☆ リベラル派は、言論の自由や結社の自由、独立した司法、陪審制による公開裁判、貴族特権の廃止など、重要な個人の自由を尊重する立憲秩序を求め、確立し た。[6] 近代リベラル思想と 市民権の拡大の必要性から強い影響を受けた。[16] リベラル派は市民権の拡大を推進する中で、男女平等や人種平等を提唱し、20世紀の世界的な市民権運動は、両方の目標に向けていくつかの目的を達成した。 リベラル派が受け入れたその他の目標には、普通選挙権や教育への普遍的なアクセスなどが含まれる。ヨーロッパや北米では、社会自由主義(米国では単に自由 主義と呼ばれることが多い)の確立が、福祉国家の拡大における重要な要素となった。[17] 今日、リベラル政党は世界中で引き続き権力と影響力を振るっている。現代社会の基本的な要素にはリベラルのルーツがある。初期のリベラリズムの波は、立憲 政治と議会権限を拡大しながら、経済的個人主義を広めた。[6]

| Liberalism is a

political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual,

liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, right to private

property and equality before the law.[1][2] Liberals espouse various

and often mutually warring views depending on their understanding of

these principles but generally support private property, market

economies, individual rights (including civil rights and human rights),

liberal democracy, secularism, rule of law, economic and political

freedom, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly,

and freedom of religion.[3] Liberalism is frequently cited as the

dominant ideology of modern history.[4][5]: 11 Liberalism became a distinct movement in the Age of Enlightenment, gaining popularity among Western philosophers and economists. Liberalism sought to replace the norms of hereditary privilege, state religion, absolute monarchy, the divine right of kings and traditional conservatism with representative democracy, rule of law, and equality under the law. Liberals also ended mercantilist policies, royal monopolies, and other trade barriers, instead promoting free trade and marketization.[6] Philosopher John Locke is often credited with founding liberalism as a distinct tradition based on the social contract, arguing that each man has a natural right to life, liberty and property, and governments must not violate these rights.[7] While the British liberal tradition has emphasized expanding democracy, French liberalism has emphasized rejecting authoritarianism and is linked to nation-building.[8] Leaders in the British Glorious Revolution of 1688,[9] the American Revolution of 1776, and the French Revolution of 1789 used liberal philosophy to justify the armed overthrow of royal sovereignty. The 19th century saw liberal governments established in Europe and South America, and it was well-established alongside republicanism in the United States.[10] In Victorian Britain, it was used to critique the political establishment, appealing to science and reason on behalf of the people.[11] During the 19th and early 20th centuries, liberalism in the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East influenced periods of reform, such as the Tanzimat and Al-Nahda, and the rise of constitutionalism, nationalism, and secularism. These changes, along with other factors, helped to create a sense of crisis within Islam, which continues to this day, leading to Islamic revivalism. Before 1920, the main ideological opponents of liberalism were communism, conservatism, and socialism;[12] liberalism then faced major ideological challenges from fascism and Marxism–Leninism as new opponents. During the 20th century, liberal ideas spread even further, especially in Western Europe, as liberal democracies found themselves as the winners in both world wars[13] and the Cold War.[14][15] Liberals sought and established a constitutional order that prized important individual freedoms, such as freedom of speech and freedom of association; an independent judiciary and public trial by jury; and the abolition of aristocratic privileges.[6] Later waves of modern liberal thought and struggle were strongly influenced by the need to expand civil rights.[16] Liberals have advocated gender and racial equality in their drive to promote civil rights, and global civil rights movements in the 20th century achieved several objectives towards both goals. Other goals often accepted by liberals include universal suffrage and universal access to education. In Europe and North America, the establishment of social liberalism (often called simply liberalism in the United States) became a key component in expanding the welfare state.[17] Today, liberal parties continue to wield power and influence throughout the world. The fundamental elements of contemporary society have liberal roots. The early waves of liberalism popularised economic individualism while expanding constitutional government and parliamentary authority.[6] |

リベラリズムは、個人の権利、自由、統治される者の同意、政治的平等、

私有財産の権利、法の下の平等を基盤とする政治的・道徳的哲学である。[1][2]

リベラル派は、これらの原則に対する理解によって、多様な、そしてしばしば相互に矛盾する見解を支持するが、一般的に私有財産、市場経済、

個人の権利(市民権や人権を含む)、自由民主主義、世俗主義、法の支配、経済的・政治的自由、言論の自由、報道の自由、集会の自由、信教の自由などを支持

する。[3] リベラリズムは、近代史における支配的なイデオロギーとして頻繁に引用される。[4][5]: 11 リベラリズムは啓蒙時代に明確な運動となり、西洋の哲学者や経済学者の間で人気を博した。自由主義は、世襲特権、国教、絶対王政、王の神聖な権利、伝統的 保守主義といった規範を、代表民主制、法の支配、法の下の平等に置き換えることを目指した。自由主義者はまた、重商主義政策、王家の独占、その他の貿易障 壁を廃止し、その代わりに自由貿易と市場化を推進した。哲学者ジョン・ロックは、社会契約に基づく独自の伝統として自由主義を創始した人物としてしばしば 評価されている。ロックは、 各人は生命、自由、財産に対する自然権を有しており、政府はこれらの権利を侵害してはならないと主張した。[7] 英国のリベラルな伝統は民主主義の拡大を強調する一方で、フランスのリベラリズムは権威主義の拒絶を強調し、国民形成と結びついている。[8] 1688年のイギリスの名誉革命、1776年のアメリカ独立革命、1789年のフランス革命の指導者たちは、自由主義の哲学を王権の武力による転覆を正当 化するために利用した。19世紀には、ヨーロッパや南アメリカで自由主義政府が樹立され、アメリカでは共和制とともに定着した。[10] ヴィクトリア朝時代のイギリスでは、政治体制を批判するために用いられ、科学と理性を人々のために訴えた。[ 11] 19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけて、オスマン帝国および中東における自由主義は、タンズィマートやアル=ナフダなどの改革期や、立憲主義、ナショナリズ ム、世俗主義の台頭に影響を与えた。これらの変化は、他の要因とともに、今日まで続くイスラム教内部の危機感を醸成し、イスラム復興主義につながった。 1920年以前には、自由主義の主なイデオロギー上の対立者は共産主義、保守主義、社会主義であったが[12]、その後、自由主義はファシズムやマルク ス・レーニン主義を新たな対立勢力として、大きなイデオロギー上の挑戦に直面することとなった。20世紀の間、自由主義の思想はさらに広まり、特に西ヨー ロッパでは、自由民主主義が両世界大戦[13]および冷戦[14][15]の勝者となった。 リベラル派は、言論の自由や結社の自由、独立した司法、陪審制による公開裁判、貴族特権の廃止など、重要な個人の自由を尊重する立憲秩序を求め、確立し た。[6] 近代リベラル思想と 市民権の拡大の必要性から強い影響を受けた。[16] リベラル派は市民権の拡大を推進する中で、男女平等や人種平等を提唱し、20世紀の世界的な市民権運動は、両方の目標に向けていくつかの目的を達成した。 リベラル派が受け入れたその他の目標には、普通選挙権や教育への普遍的なアクセスなどが含まれる。ヨーロッパや北米では、社会自由主義(米国では単に自由 主義と呼ばれることが多い)の確立が、福祉国家の拡大における重要な要素となった。[17] 今日、リベラル政党は世界中で引き続き権力と影響力を振るっている。現代社会の基本的な要素にはリベラルのルーツがある。初期のリベラリズムの波は、立憲 政治と議会権限を拡大しながら、経済的個人主義を広めた。[6] |

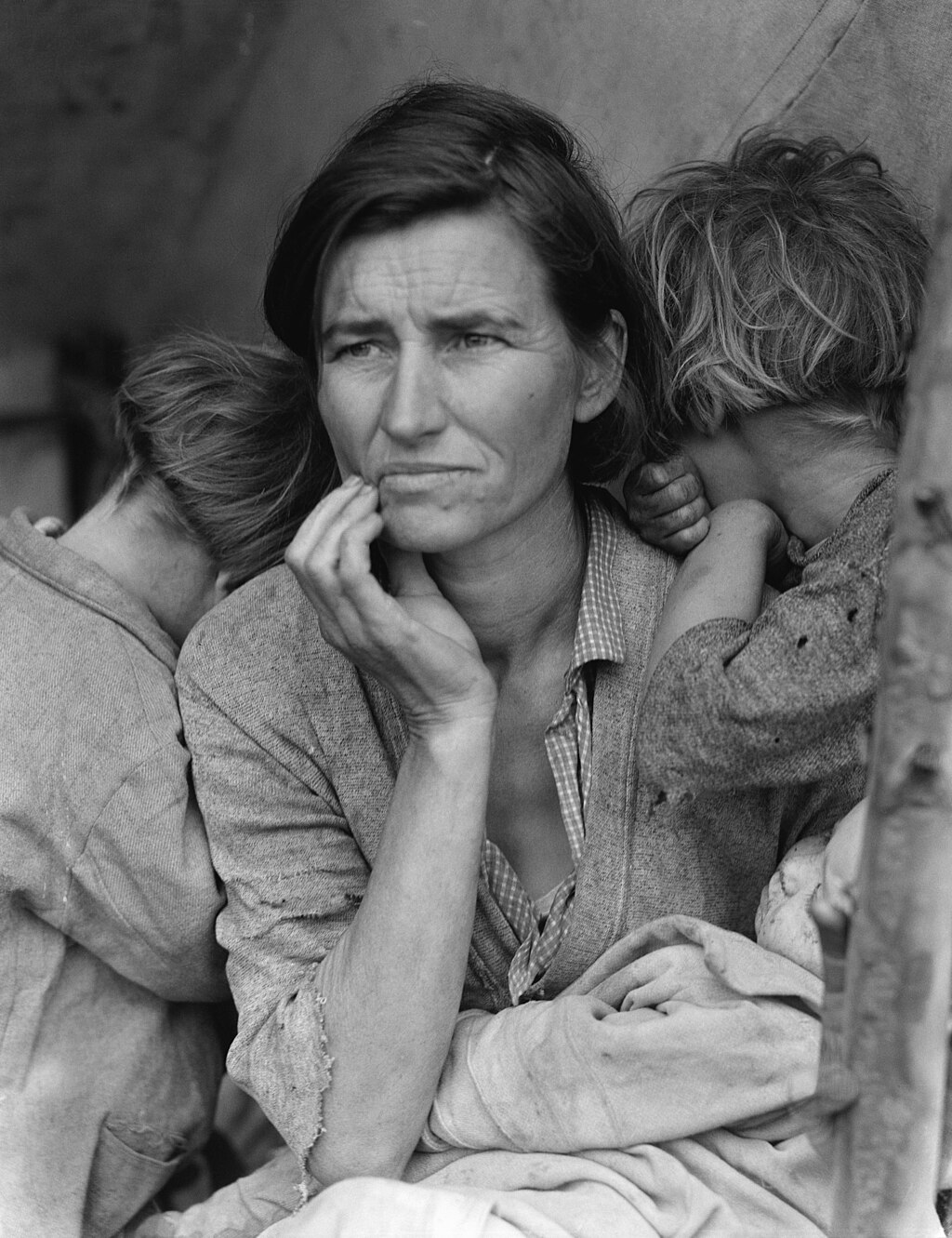

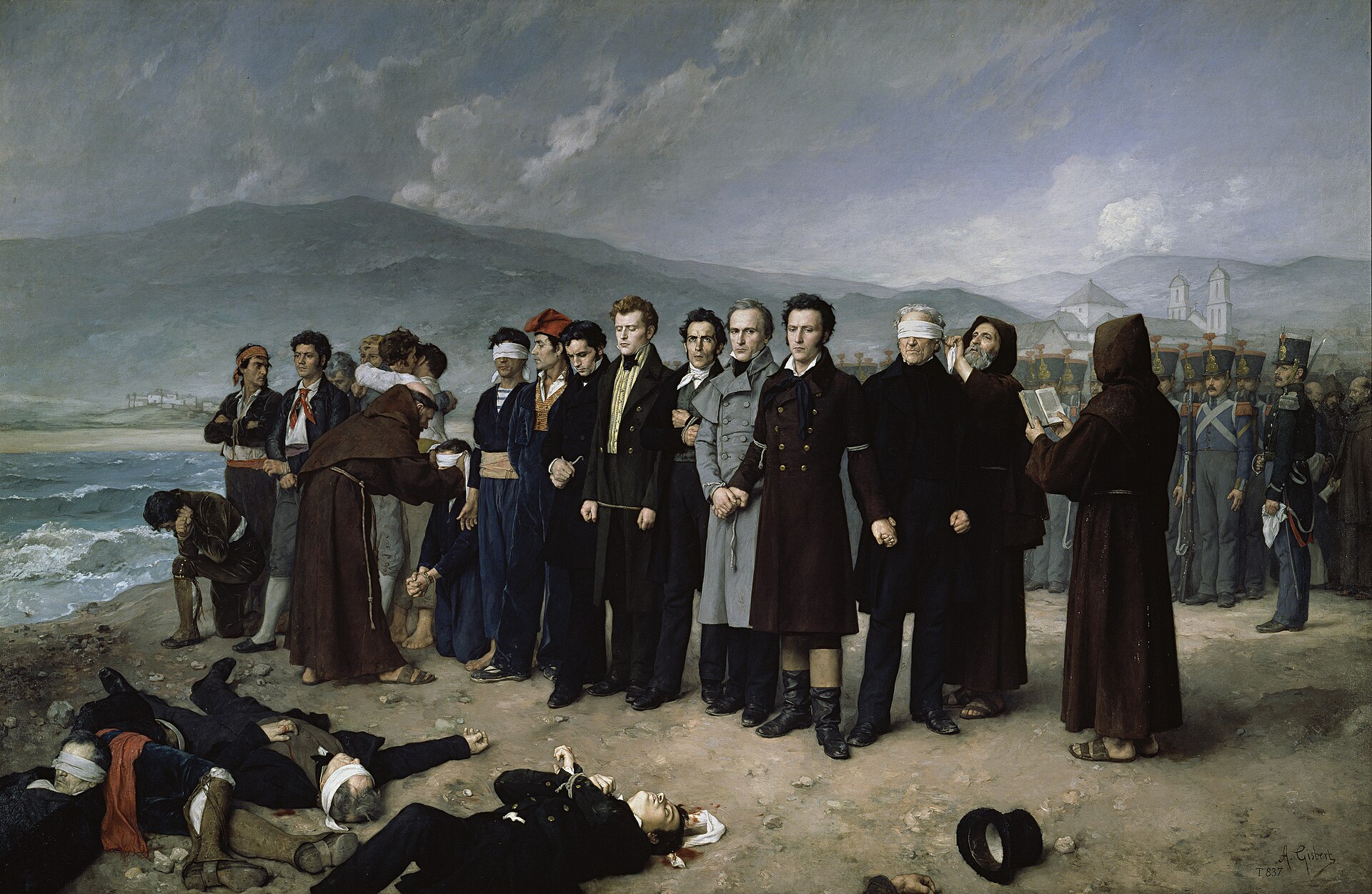

| Definitions Origins Liberal, liberty, libertarian, and libertine all trace their etymology to liber, a root from Latin that means "free".[18] One of the first recorded instances of liberal occurred in 1375 when it was used to describe the liberal arts in the context of an education desirable for a free-born man.[18] The word's early connection with the classical education of a medieval university soon gave way to a proliferation of different denotations and connotations. Liberal could refer to "free in bestowing" as early as 1387, "made without stint" in 1433, "freely permitted" in 1530, and "free from restraint"—often as a pejorative remark—in the 16th and the 17th centuries.[18] In the 16th-century Kingdom of England, liberal could have positive or negative attributes in referring to someone's generosity or indiscretion.[18] In Much Ado About Nothing, William Shakespeare wrote of "a liberal villaine" who "hath ... confest his vile encounters".[18] With the rise of the Enlightenment, the word acquired decisively more positive undertones, defined as "free from narrow prejudice" in 1781 and "free from bigotry" in 1823.[18] In 1815, the first use of liberalism appeared in English.[19] In Spain, the liberales, the first group to use the liberal label in a political context,[20] fought for decades to implement the Spanish Constitution of 1812. From 1820 to 1823, during the Trienio Liberal, King Ferdinand VII was compelled by the liberales to swear to uphold the 1812 Constitution. By the middle of the 19th century, liberal was used as a politicised term for parties and movements worldwide.[21] Yellow is the political colour most commonly associated with liberalism.[22][23][24] The United States differs from other countries in that conservatism is associated with red and liberalism with blue.[25] Modern usage and definitions In Europe and Latin America, liberalism means a moderate form of classical liberalism and includes both conservative liberalism (centre-right liberalism) and social liberalism (centre-left liberalism).[26] In North America, liberalism almost exclusively refers to social liberalism. The dominant Canadian party is the Liberal Party, and the Democratic Party is usually considered liberal in the United States.[27][28][29] In the United States, conservative liberals are usually called conservatives in a broad sense.[30][31] Social liberalism See also: Social liberalism, Welfare state, and Liberalism in the United States Over time, the meaning of liberalism began to diverge in different parts of the world. Since the 1930s, liberalism is usually used without a qualifier in the United States, to refer to social liberalism, a variety of liberalism that endorses a regulated market economy and the expansion of civil and political rights, with the common good considered as compatible with or superior to the freedom of the individual.[32] According to the Encyclopædia Britannica: "In the United States, liberalism is associated with the welfare-state policies of the New Deal programme of the Democratic administration of Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt, whereas in Europe it is more commonly associated with a commitment to limited government and laissez-faire economic policies."[33] This variety of liberalism is also known as modern liberalism to distinguish it from classical liberalism, which evolved into modern conservatism. In the United States, the two forms of liberalism comprise the two main poles of American politics, in the forms of modern American liberalism and modern American conservatism.[34] Some liberals, who call themselves classical liberals, fiscal conservatives, or libertarians, endorse fundamental liberal ideals but diverge from modern liberal thought on the grounds that economic freedom is more important than social equality.[35] Consequently, the ideas of individualism and laissez-faire economics previously associated with classical liberalism are key components of modern American conservatism and movement conservatism, and became the basis for the emerging school of modern American libertarian thought.[36][better source needed] In this American context, liberal is often used as a pejorative.[37] This political philosophy is exemplified by enactment of major social legislation and welfare programs. Two major examples in the United States are Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal policies and later Lyndon B. Johnson's Great Society, as well as other accomplishments such as the Works Progress Administration and the Social Security Act in 1935, as well as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Modern liberalism, in the United States and other major Western countries, now includes issues such as same-sex marriage, transgender rights, the abolition of capital punishment, reproductive rights and other women's rights, voting rights for all adult citizens, civil rights, environmental justice, and government protection of the right to an adequate standard of living.[38][39][40] National social services, such as equal educational opportunities, access to health care, and transportation infrastructure are intended to meet the responsibility to promote the general welfare of all citizens as established by the United States Constitution. Classical liberalism See also: Classical liberalism and Conservative liberalism Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics and civil liberties under the rule of law, with special emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, economic freedom, political freedom and freedom of speech.[41] Classical liberalism, contrary to liberal branches like social liberalism, looks more negatively on social policies, taxation and the state involvement in the lives of individuals, and it advocates deregulation.[42] Until the Great Depression and the rise of social liberalism, classical liberalism was called economic liberalism. Later, the term was applied as a retronym, to distinguish earlier 19th-century liberalism from social liberalism.[43] By modern standards, in the United States, the bare term liberalism often means social liberalism, but in Europe and Australia, the bare term liberalism often means classical liberalism.[44][45] Classical liberalism gained full flowering in the early 18th century, building on ideas dating at least as far back as the 16th century, within the Iberian, British, and Central European contexts, and it was foundational to the American Revolution and "American Project" more broadly.[46][47][48] Notable liberal individuals whose ideas contributed to classical liberalism include John Locke,[49] Jean-Baptiste Say, Thomas Malthus, and David Ricardo. It drew on classical economics, especially the economic ideas espoused by Adam Smith in Book One of The Wealth of Nations, and on a belief in natural law.[50] In contemporary times, Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, Ludwig von Mises, Thomas Sowell, George Stigler, Larry Arnhart, Ronald Coase and James M. Buchanan are seen as the most prominent advocates of classical liberalism.[51][52] However, other scholars have made reference to these contemporary thoughts as neoclassical liberalism, distinguishing them from 18th-century classical liberalism.[53][54] In the context of American politics, "classical liberalism" may be described as "fiscally conservative" and "socially liberal".[55] Despite this, classical liberals tend to reject the right's higher tolerance for economic protectionism and the left's inclination for collective group rights due to classical liberalism's central principle of individualism.[56] Additionally, in the United States, classical liberalism is considered closely tied to, or synonymous with, American libertarianism.[57][58] |

定義 起源 リベラル、自由、リバタリアン、そして放蕩者の語源はすべて、ラテン語の「自由」を意味する「liber」に遡る。[18] リベラルという語が最初に記録された例の一つは、1375年に、自由民として生まれた男性にとって望ましい教育という文脈でリベラルアーツを表現するため に使用されたものである。[18] この語が中世大学の古典的教育と早期に結びついたことで、すぐにさまざまな意味と含意の拡散が始まった。リベラルという語は、1387年には「惜しみなく 与える」、1433年には「出し惜しみしない」、1530年には「自由に許可する」、そして16世紀から17世紀にかけては「束縛のない」という意味で使 われることが多く、軽蔑的な表現として使われることもあった。 16世紀のイングランド王国では、「リベラル」という言葉は、ある人物の寛大さや無分別さを指して、肯定的な意味にも否定的な意味にも用いられた。 [18] ウィリアム・シェイクスピアは『から騒ぎ』の中で、「リベラルなヴィラン(悪女)」について、「卑しい出会いについて告白した」と書いている。[18] 啓蒙思想の台頭とともに、この言葉はより明確に肯定的な意味合いを持つようになり、1781年には「狭い偏見から自由な」もの、1823年には「偏見から 自由な」ものと定義された。[18] 1781年には「狭い偏見からの自由」、1823年には「偏狭からの自由」と定義された。[18] 1815年には、リベラリズムという言葉が初めて英語で使用された。[19] スペインでは、政治的文脈でリベラルという言葉を使用した最初のグループであるリベラレスが、1812年のスペイン憲法の施行を目指して数十年にわたって 戦った。1820年から1823年までの「自由主義の3年間」の間、フェルディナンド7世はリベラル派の圧力により、1812年の憲法を遵守することを誓 わされた。19世紀半ばには、リベラルという言葉は世界中で政党や運動を指す政治的な用語として使われるようになった。 リベラリズムと最も関連付けられる政治的な色は黄色である。[22][23][24] アメリカ合衆国では、保守主義が赤、リベラリズムが青と関連付けられている点で、他の国々とは異なっている。[25] 現代における用法と定義 ヨーロッパおよびラテンアメリカでは、リベラリズムは古典的リベラリズムの穏健な形態を意味し、保守的リベラリズム(中道右派リベラリズム)と社会リベラリズム(中道左派リベラリズム)の両方を含む。[26] 北米では、リベラリズムはほぼ社会自由主義を指す。カナダではリベラル党が支配政党であり、アメリカでは民主党が通常リベラルであると考えられている。[27][28][29] アメリカでは、保守的な自由主義者は通常、広義の保守派と呼ばれる。[30][31] 社会自由主義 関連項目:社会自由主義、福祉国家、アメリカのリベラリズム 時が経つにつれ、リベラリズムの意味は世界のさまざまな地域で乖離し始めた。1930年代以降、アメリカ合衆国では通常、修飾語を付けずにリベラリズムと いう語が使用され、社会リベラリズム、すなわち規制された市場経済と市民的・政治的権利の拡大を支持するリベラリズムの一形態を指す。 ブリタニカ百科事典によると、「米国では、リベラリズムは民主党のフランクリン・D・ルーズベルト大統領によるニューディール政策の福祉国家政策と関連付 けられているが、ヨーロッパでは、より一般的に、制限された政府と自由放任の経済政策へのコミットメントと関連付けられている」[33]。このリベラリズ ムの多様性は、古典的リベラリズムと区別するために、近代リベラリズムとも呼ばれる。古典的リベラリズムは、近代保守主義へと発展した。米国では、この2 つのリベラリズムの形態が、現代アメリカのリベラリズムと現代アメリカ保守主義という形で、米国政治の2つの主要な極を構成している。 古典的自由主義者、財政保守主義者、あるいはリバタリアンを自認する一部のリベラル派は、リベラリズムの根本的理念を支持するものの、経済的自由が社会的 平等よりも重要であるという理由で、現代のリベラル思想とは相容れない。古典的自由主義と関連付けられていた個人主義と自由放任主義の経済学は、現代のア メリカ保守主義と運動保守主義の主要な要素となり、現代のアメリカのリバタリアン思想の台頭する学派の基礎となった。[36][より良い出典が必要] このアメリカ的文脈では、リベラルはしばしば軽蔑的な意味で使用される。[37] この政治哲学は、主要な社会立法や福祉プログラムの制定によって例示される。米国における2つの主要な例としては、フランクリン・D・ルーズベルトの ニューディール政策と、その後継であるリンドン・B・ジョンソンのグレート・ソサエティ、および1935年の公共事業促進局や社会保障法、1964年の公 民権法、1965年の投票権法などの成果が挙げられる。 米国やその他の主要な西側諸国における現代のリベラリズムは、現在では、同性婚、トランスジェンダーの権利、死刑廃止、リプロダクティブ・ライツやその他 の女性の権利、成人市民の選挙権、公民権、環境正義、そして 適切な生活水準を維持する権利の保護などである。[38][39][40] 国民に対する社会サービス、例えば教育機会の均等、医療へのアクセス、交通インフラなどは、合衆国憲法によって確立された、すべての国民の福祉を促進する という責任を果たすことを目的としている。 古典的自由主義 関連項目:古典的自由主義と保守的自由主義 古典的自由主義は、自由市場と自由放任経済、法の支配に基づく市民的自由を提唱する政治的伝統であり、自由主義の一派である。特に、個人の自律性、限定さ れた政府、経済的自由、政治的自由、言論の自由を重視している。[41] 古典的自由主義は、社会自由主義のような自由主義の派閥とは対照的に、社会政策、課税、個人の生活への国家の関与に対してより否定的な見方をしており、規 制緩和を提唱している。[42] 大恐慌と社会自由主義の台頭までは、古典的自由主義は経済自由主義と呼ばれていた。その後、19世紀前半の自由主義を社会自由主義と区別するために、この 用語はレトロニムとして用いられるようになった。[43] 現代の基準では、アメリカ合衆国では「自由主義」という用語はしばしば社会自由主義を意味するが、ヨーロッパやオーストラリアでは「自由主義」という用語 はしばしば古典的自由主義を意味する。[44][45] 古典的自由主義は、少なくとも16世紀まで遡る思想を基盤として、18世紀初頭にイベリア半島、イギリス、中央ヨーロッパの文脈の中で完全に開花した。そ して、それはアメリカ独立革命と、より広義には「アメリカ計画」の基礎となった 。古典的自由主義に貢献した著名な自由主義者には、ジョン・ロック、ジャン=バティスト・セー、トマス・マルサス、デイヴィッド・リカードなどがいる。古 典派経済学、特にアダム・スミスが『国富論』第1篇で唱えた経済思想、および自然法の信念に依拠していた。[50] 現代では、フリードリヒ・ハイエク、ミルトン・フリードマン、ルートヴィヒ・フォン・ミーゼス、トーマス・ソウェル、ジョージ・スティグリッツ、ラリー・ アーナート、 ロナルド・コースやジェームズ・M・ブキャナンは古典的自由主義の最も著名な擁護者と見なされている。[51][52] しかし、他の学者たちは、これらの現代的な考え方を新古典的自由主義と呼び、18世紀の古典的自由主義と区別している。[53][54] アメリカ政治の文脈では、「古典的自由主義」は「財政的には保守的」で「社会的にリベラル」と表現されることがある。[55] にもかかわらず、古典的自由主義者は、経済保護主義に対する右派のより高い寛容さや、 古典的自由主義の中心的な原則である個人主義により、古典的自由主義者は右派の経済保護主義への高い寛容性や左派の集団的集団権への傾倒を拒絶する傾向に ある。[56] さらに、アメリカ合衆国では、古典的自由主義はアメリカのリバタリアニズムと密接に関連している、あるいは同義であると考えられている。[57][58] |

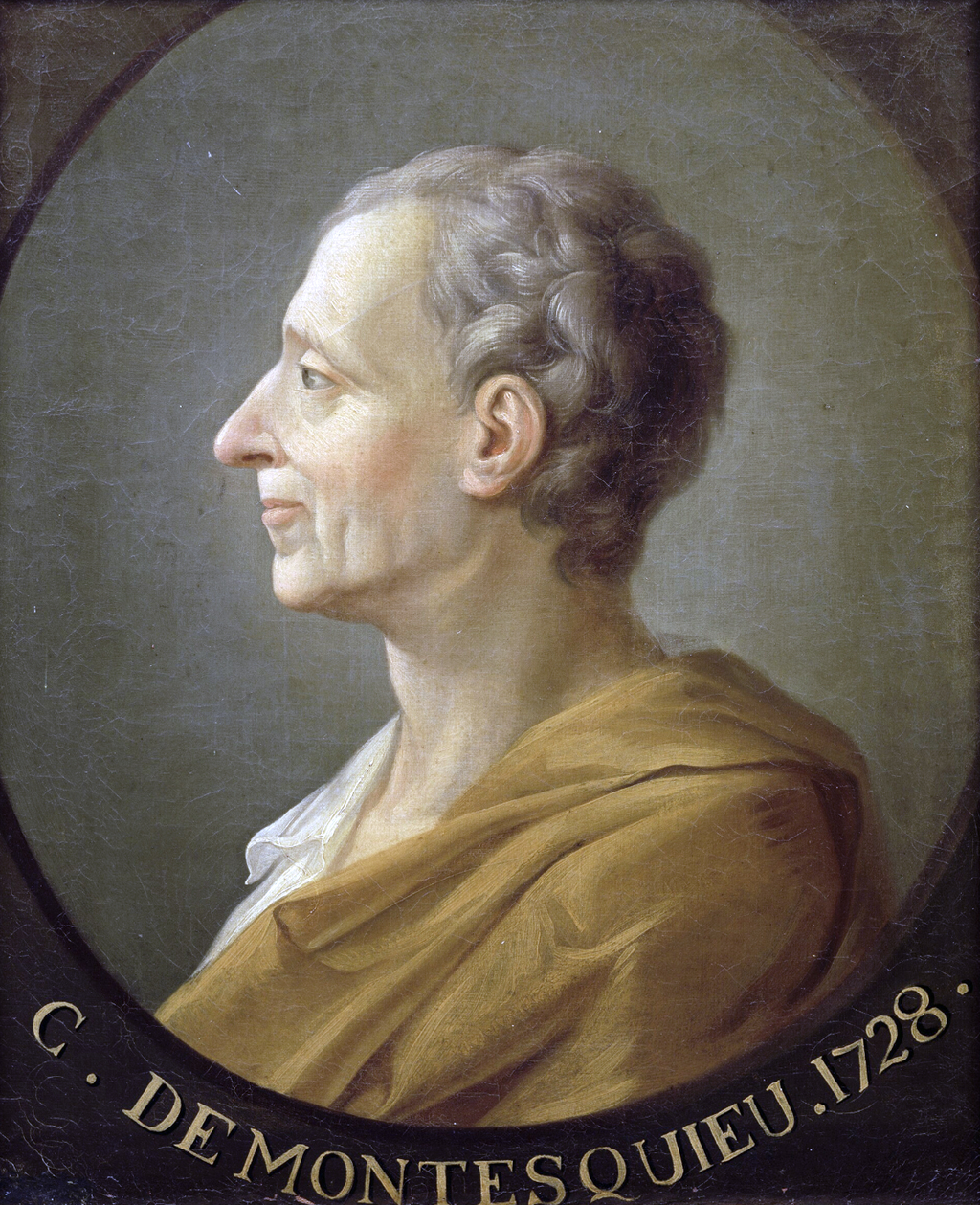

| Philosophy Liberalism—both as a political current and an intellectual tradition—is mostly a modern phenomenon that started in the 17th century, although some liberal philosophical ideas had precursors in classical antiquity and Imperial China.[59][60] The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius praised "the idea of a polity administered with regard to equal rights and equal freedom of speech, and the idea of a kingly government which respects most of all the freedom of the governed".[61] Scholars have also recognised many principles familiar to contemporary liberals in the works of several Sophists and the Funeral Oration by Pericles.[62] Liberal philosophy is the culmination of an extensive intellectual tradition that has examined and popularized some of the modern world's most important and controversial principles. Its immense scholarly output has been characterized as containing "richness and diversity", but that diversity often has meant that liberalism comes in different formulations and presents a challenge to anyone looking for a clear definition.[63] |

哲学 リベラリズムは、政治潮流としても知的伝統としても、17世紀に始まった近代的な現象であるが、リベラルな哲学思想の一部は古典古代や中国帝国にも先例が ある。[59][60] ローマ皇帝マルクス・アウレリウスは、「平等な権利と平等な言論の自由を尊重して統治される政治体制の理念、そして 統治される者の自由を何よりも尊重する王政の理念」を賞賛した。[61] 学者たちは、ソフィストのいくつかの著作やペリクレスの葬送演説にも、現代のリベラル派に馴染み深い多くの原則が認められると認識している。[62] リベラル哲学は、現代世界で最も重要かつ論争の的となるいくつかの原則を検証し、普及させてきた広範な知的伝統の集大成である。その膨大な学術的成果は 「豊かさと多様性」を含んでいると特徴づけられてきたが、その多様性はしばしばリベラリズムが異なる定式化で存在することを意味し、明確な定義を求める人 々にとって難題となっている。[63] |

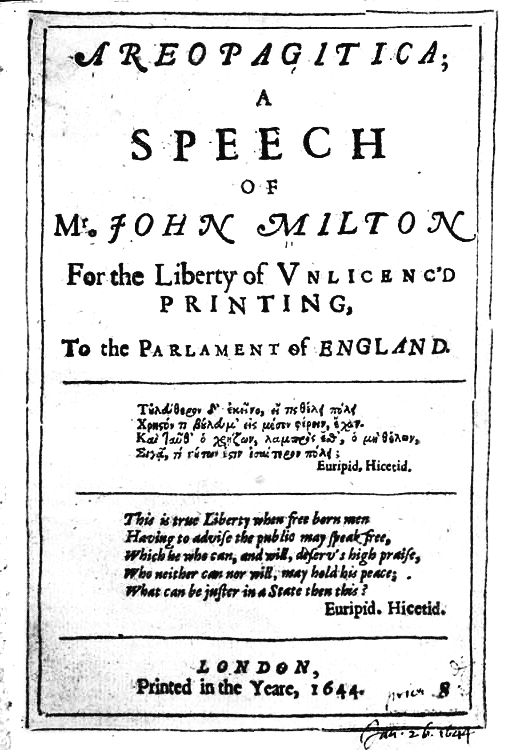

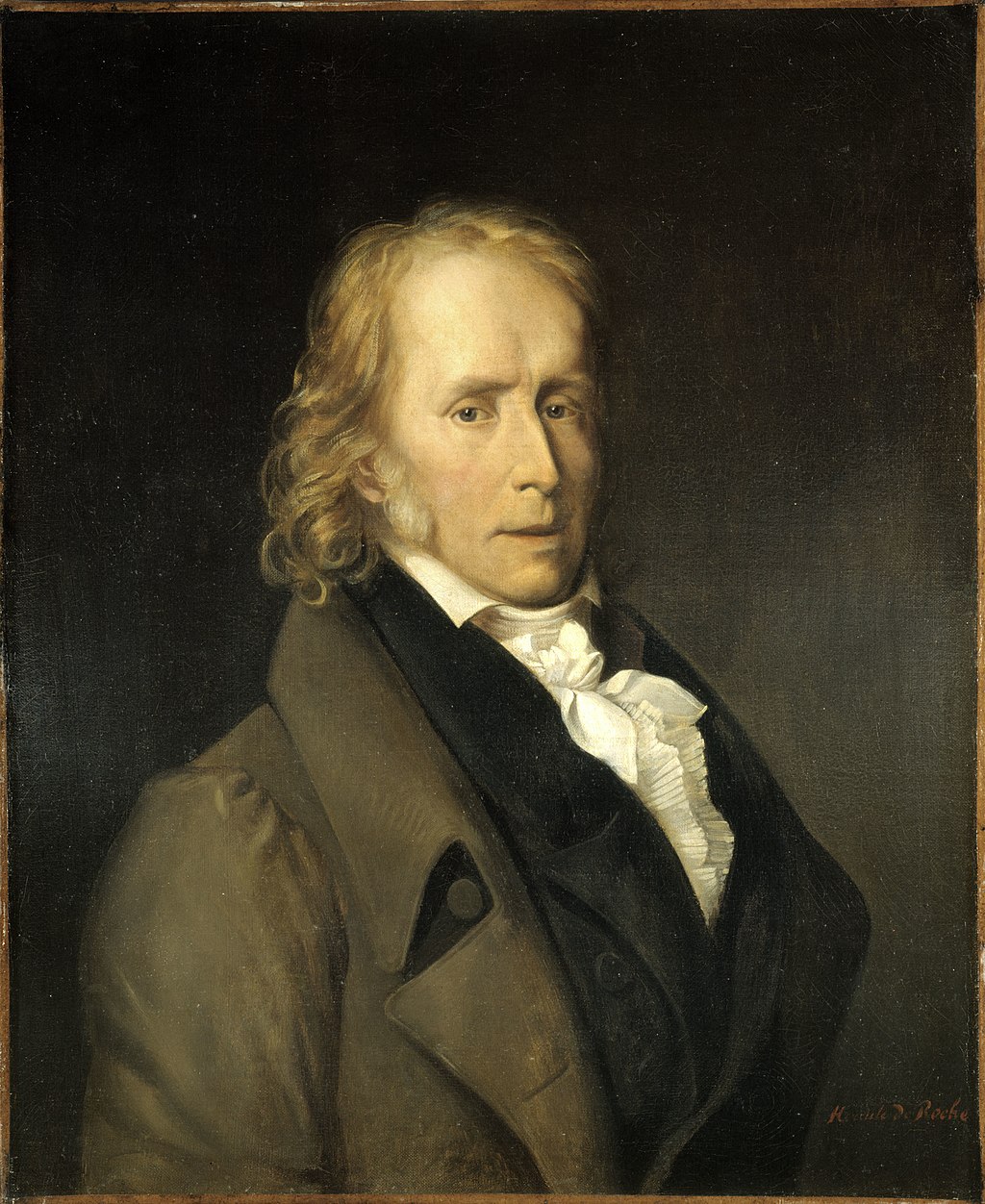

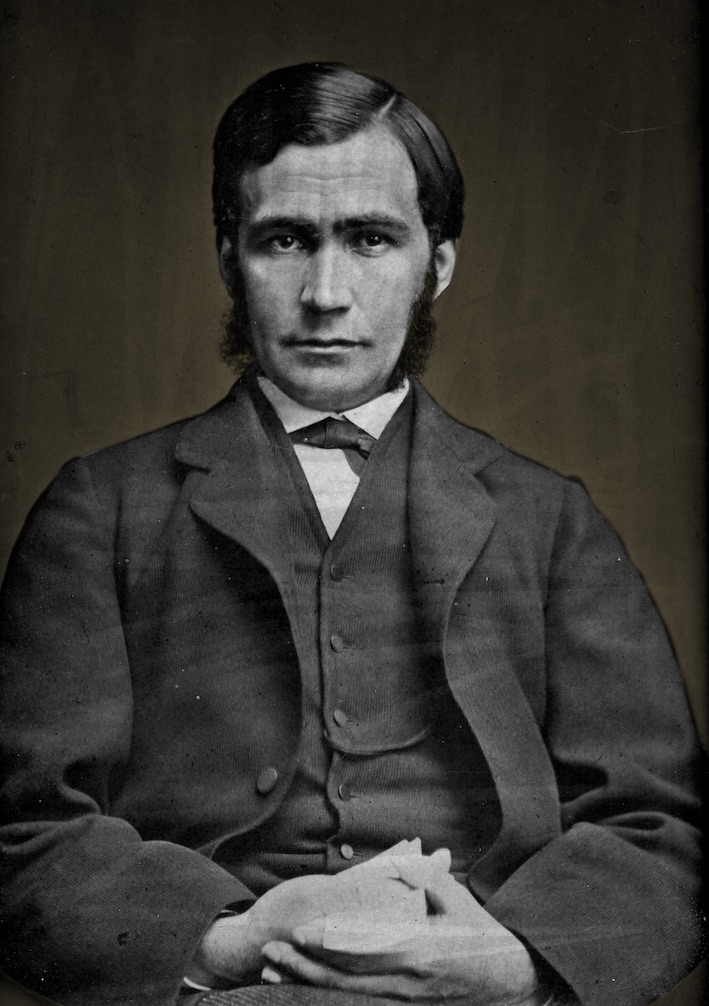

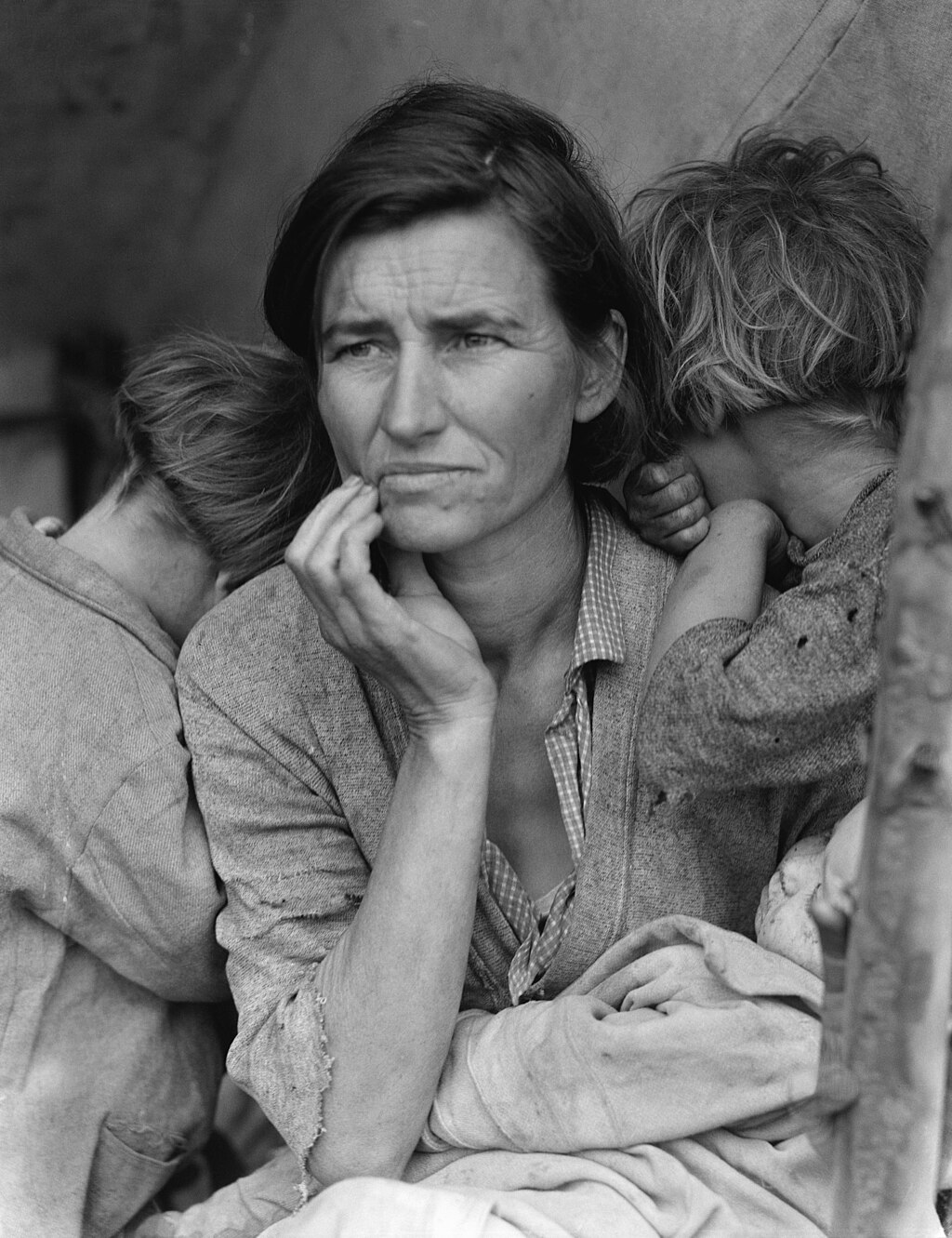

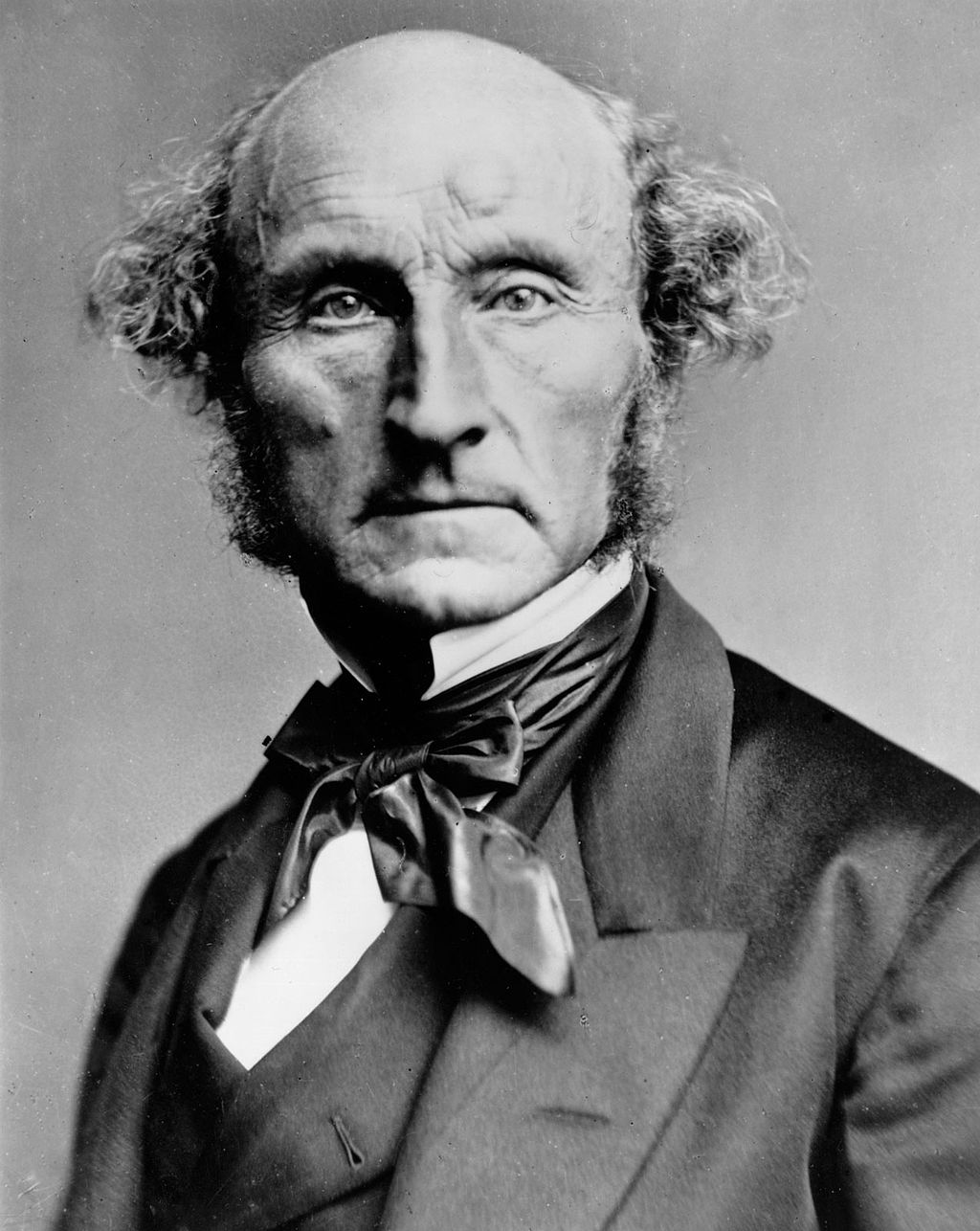

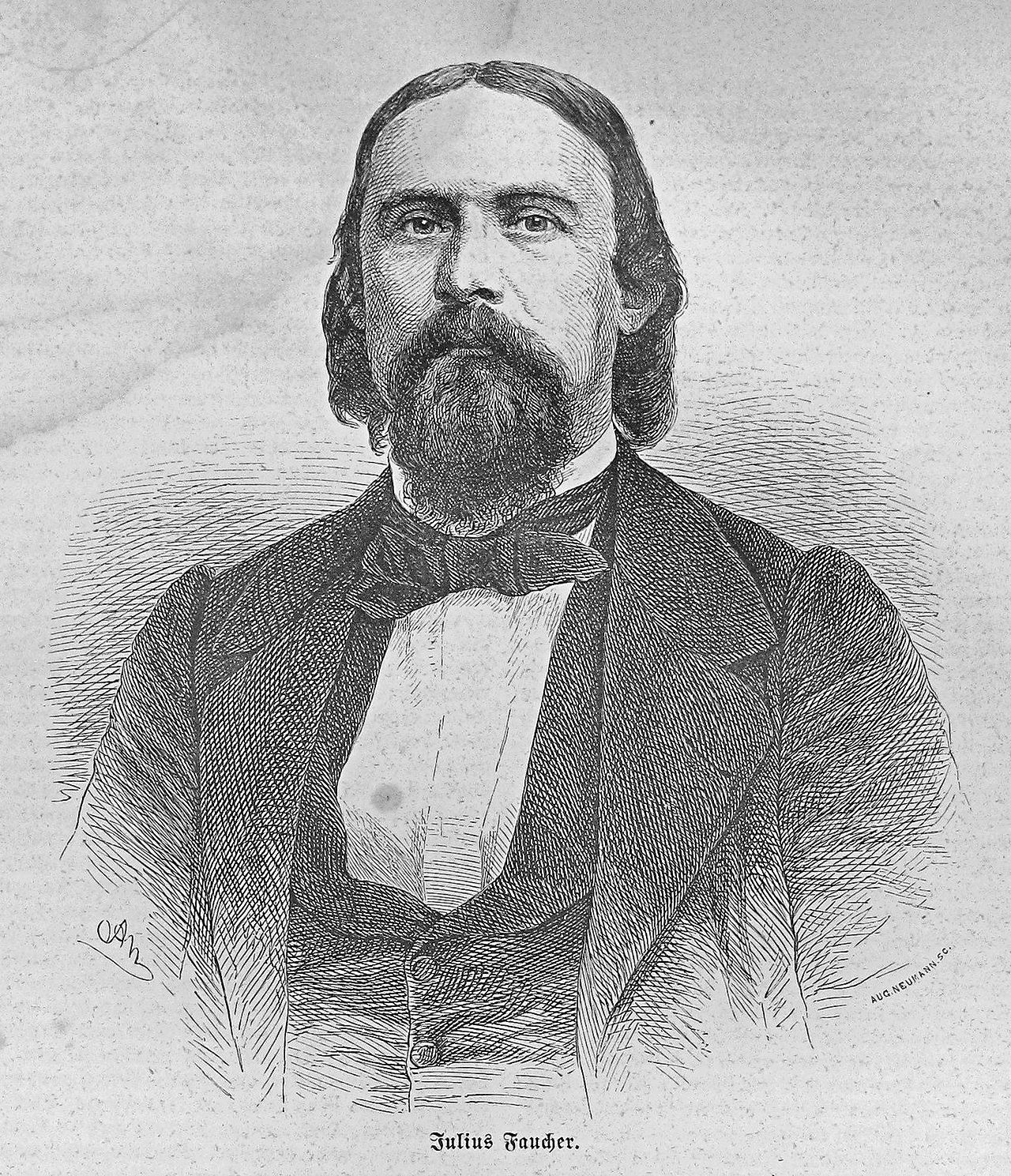

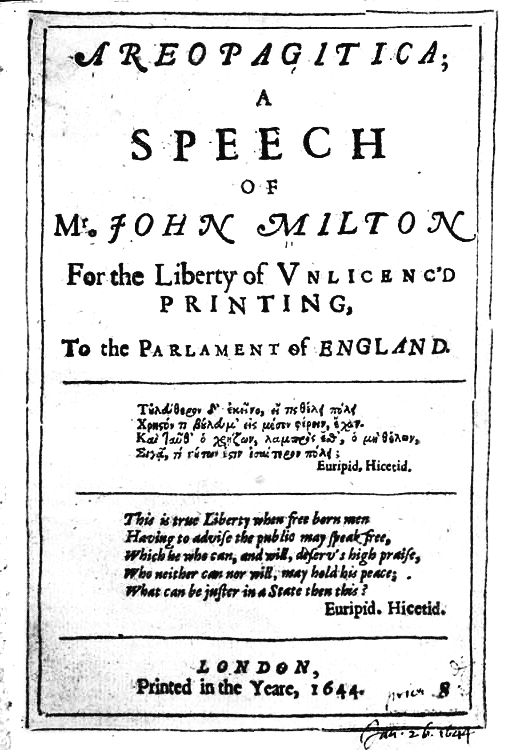

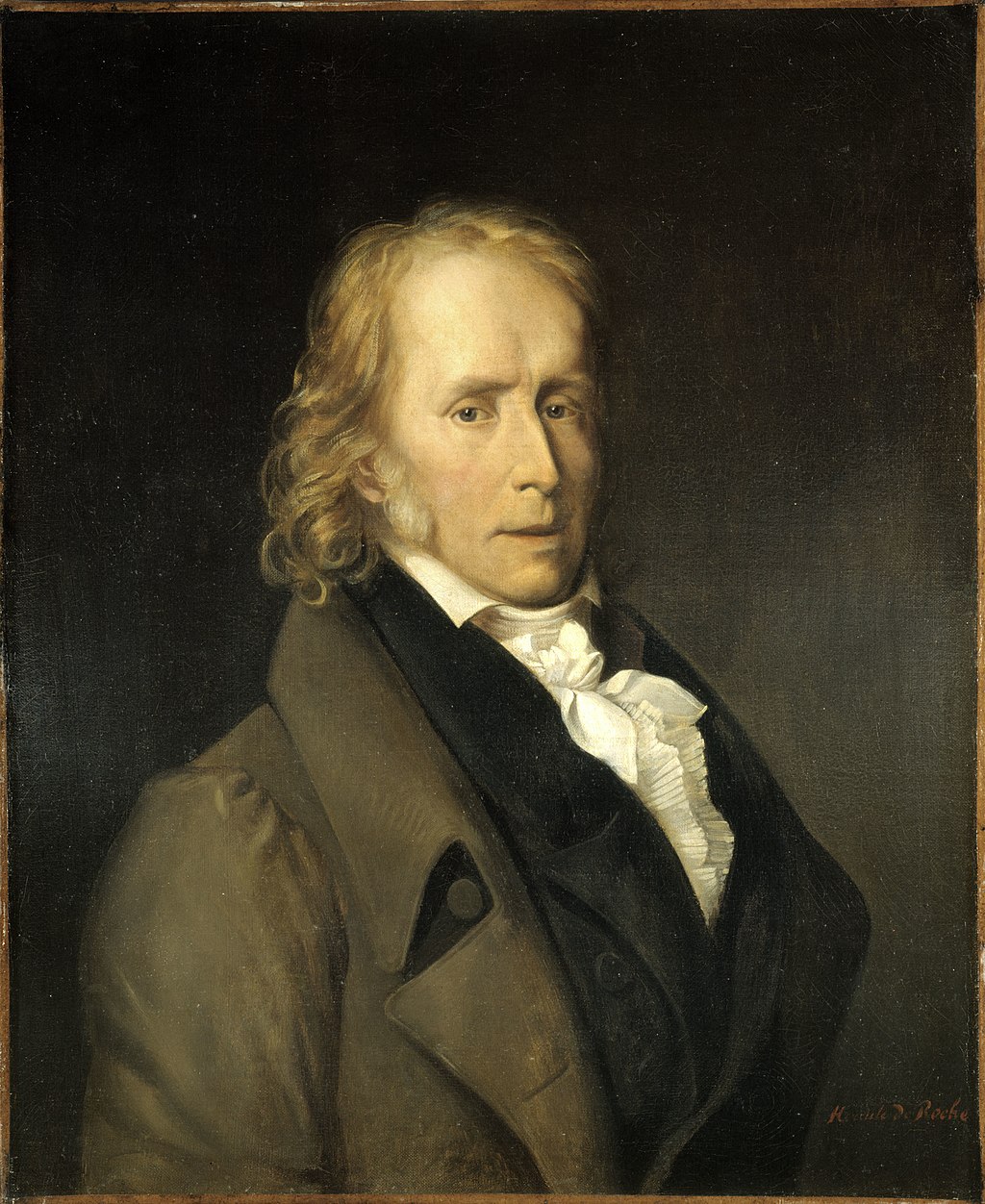

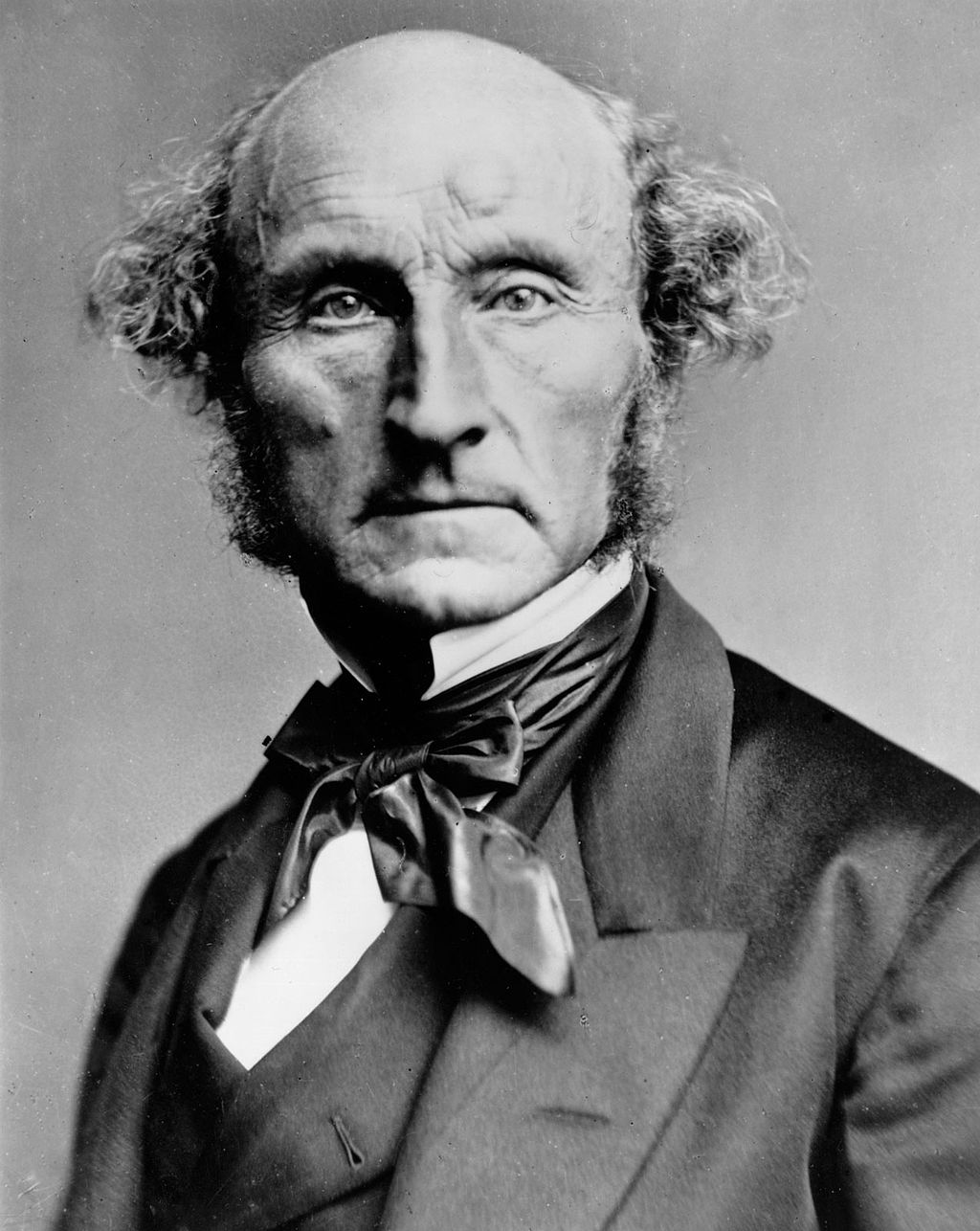

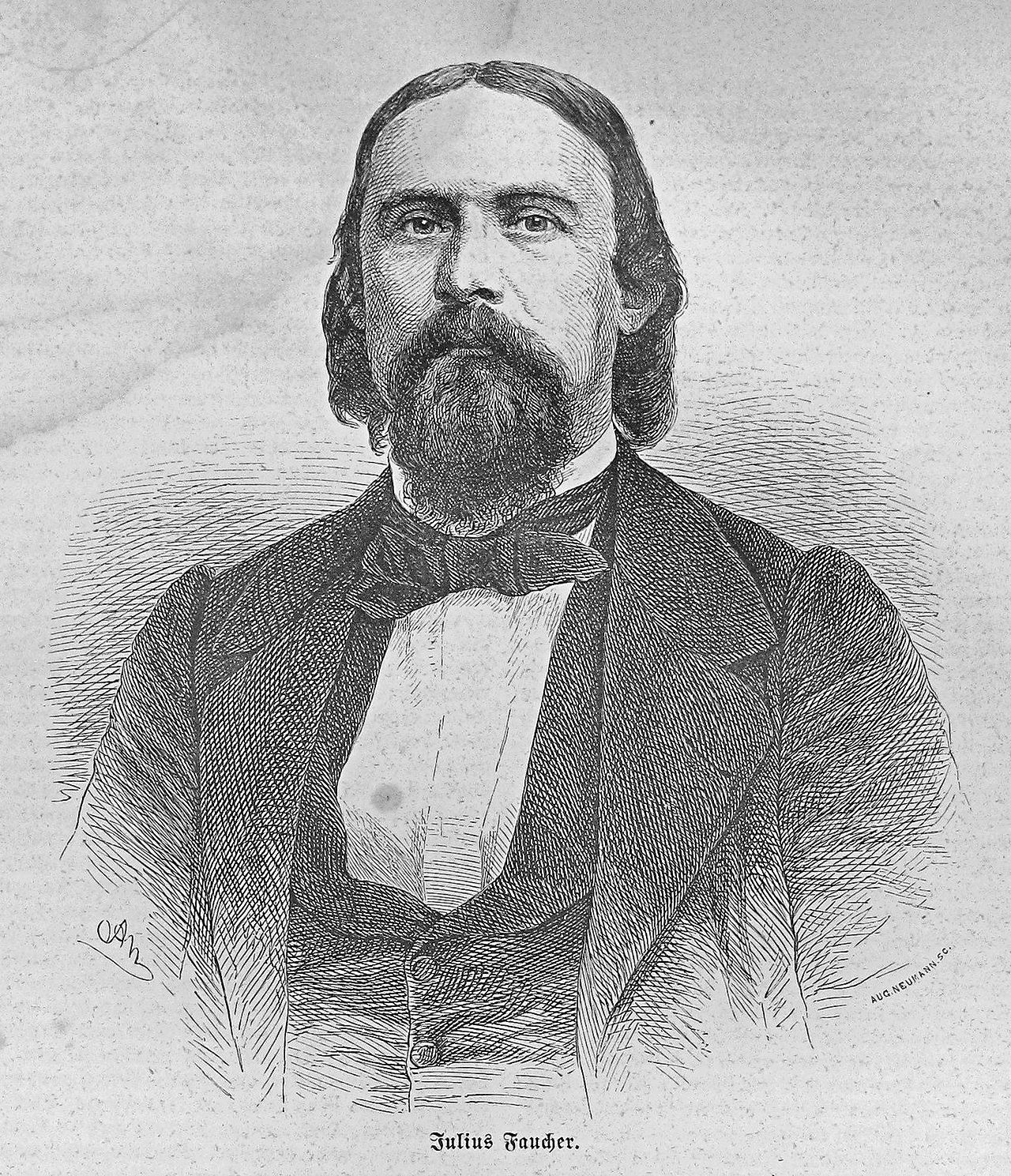

| Major themes Although all liberal doctrines possess a common heritage, scholars frequently assume that those doctrines contain "separate and often contradictory streams of thought".[63] The objectives of liberal theorists and philosophers have differed across various times, cultures and continents. The diversity of liberalism can be gleaned from the numerous qualifiers that liberal thinkers and movements have attached to the term "liberalism", including classical, egalitarian, economic, social, the welfare state, ethical, humanist, deontological, perfectionist, democratic, and institutional, to name a few.[64] Despite these variations, liberal thought does exhibit a few definite and fundamental conceptions. Political philosopher John Gray identified the common strands in liberal thought as individualist, egalitarian, meliorist and universalist. The individualist element avers the ethical primacy of the human being against the pressures of social collectivism; the egalitarian element assigns the same moral worth and status to all individuals; the meliorist element asserts that successive generations can improve their sociopolitical arrangements, and the universalist element affirms the moral unity of the human species and marginalises local cultural differences.[65] The meliorist element has been the subject of much controversy, defended by thinkers such as Immanuel Kant, who believed in human progress, while suffering criticism by thinkers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who instead believed that human attempts to improve themselves through social cooperation would fail.[66] The liberal philosophical tradition has searched for validation and justification through several intellectual projects. The moral and political suppositions of liberalism have been based on traditions such as natural rights and utilitarian theory, although sometimes liberals even request support from scientific and religious circles.[65] Through all these strands and traditions, scholars have identified the following major common facets of liberal thought: believing in equality and individual liberty supporting private property and individual rights supporting the idea of limited constitutional government recognising the importance of related values such as pluralism, toleration, autonomy, bodily integrity, and consent[67] Classical and modern See also: Age of Enlightenment John Locke and Thomas Hobbes See also: John Locke and Thomas Hobbes Enlightenment philosophers are given credit for shaping liberal ideas. These ideas were first drawn together and systematized as a distinct ideology by the English philosopher John Locke, generally regarded as the father of modern liberalism.[68][69] Thomas Hobbes attempted to determine the purpose and the justification of governing authority in post-civil war England. Employing the idea of a state of nature — a hypothetical war-like scenario prior to the state — he constructed the idea of a social contract that individuals enter into to guarantee their security and, in so doing, form the State, concluding that only an absolute sovereign would be fully able to sustain such security. Hobbes had developed the concept of the social contract, according to which individuals in the anarchic and brutal state of nature came together and voluntarily ceded some of their rights to an established state authority, which would create laws to regulate social interactions to mitigate or mediate conflicts and enforce justice. Whereas Hobbes advocated a strong monarchical commonwealth (the Leviathan), Locke developed the then-radical notion that government acquires consent from the governed, which has to be constantly present for the government to remain legitimate.[70] While adopting Hobbes's idea of a state of nature and social contract, Locke nevertheless argued that when the monarch becomes a tyrant, it violates the social contract, which protects life, liberty and property as a natural right. He concluded that the people have a right to overthrow a tyrant. By placing the security of life, liberty and property as the supreme value of law and authority, Locke formulated the basis of liberalism based on social contract theory. To these early enlightenment thinkers, securing the essential amenities of life—liberty and private property—required forming a "sovereign" authority with universal jurisdiction.[71] His influential Two Treatises (1690), the foundational text of liberal ideology, outlined his major ideas. Once humans moved out of their natural state and formed societies, Locke argued, "that which begins and actually constitutes any political society is nothing but the consent of any number of freemen capable of a majority to unite and incorporate into such a society. And this is that, and that only, which did or could give beginning to any lawful government in the world".[72]: 170 The stringent insistence that lawful government did not have a supernatural basis was a sharp break with the dominant theories of governance, which advocated the divine right of kings[73] and echoed the earlier thought of Aristotle. Dr John Zvesper described this new thinking: "In the liberal understanding, there are no citizens within the regime who can claim to rule by natural or supernatural right, without the consent of the governed".[74] Locke had other intellectual opponents besides Hobbes. In the First Treatise, Locke aimed his arguments first and foremost at one of the doyens of 17th-century English conservative philosophy: Robert Filmer. Filmer's Patriarcha (1680) argued for the divine right of kings by appealing to biblical teaching, claiming that the authority granted to Adam by God gave successors of Adam in the male line of descent a right of dominion over all other humans and creatures in the world.[75] However, Locke disagreed so thoroughly and obsessively with Filmer that the First Treatise is almost a sentence-by-sentence refutation of Patriarcha. Reinforcing his respect for consensus, Locke argued that "conjugal society is made up by a voluntary compact between men and women".[76] Locke maintained that the grant of dominion in Genesis was not to men over women, as Filmer believed, but to humans over animals.[76] Locke was not a feminist by modern standards, but the first major liberal thinker in history accomplished an equally major task on the road to making the world more pluralistic: integrating women into social theory.[76]  John Milton's Areopagitica (1644) argued for the importance of freedom of speech. Locke also originated the concept of the separation of church and state.[77] Based on the social contract principle, Locke argued that the government lacked authority in the realm of individual conscience, as this was something rational people could not cede to the government for it or others to control. For Locke, this created a natural right to the liberty of conscience, which he argued must remain protected from any government authority.[78] In his Letters Concerning Toleration, he also formulated a general defence for religious toleration. Three arguments are central: Earthly judges, the state in particular, and human beings generally, cannot dependably evaluate the truth claims of competing religious standpoints; Even if they could, enforcing a single "true religion" would not have the desired effect because belief cannot be compelled by violence; Coercing religious uniformity would lead to more social disorder than allowing diversity.[79] Locke was also influenced by the liberal ideas of Presbyterian politician and poet John Milton, who was a staunch advocate of freedom in all its forms.[80] Milton argued for disestablishment as the only effective way of achieving broad toleration. Rather than force a man's conscience, the government should recognise the persuasive force of the gospel.[81] As assistant to Oliver Cromwell, Milton also drafted a constitution of the independents (Agreement of the People; 1647) that strongly stressed the equality of all humans as a consequence of democratic tendencies.[82] In his Areopagitica, Milton provided one of the first arguments for the importance of freedom of speech—"the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties". His central argument was that the individual could use reason to distinguish right from wrong. To exercise this right, everyone must have unlimited access to the ideas of his fellow men in "a free and open encounter", which will allow good arguments to prevail. In a natural state of affairs, liberals argued, humans were driven by the instincts of survival and self-preservation, and the only way to escape from such a dangerous existence was to form a common and supreme power capable of arbitrating between competing human desires.[83] This power could be formed in the framework of a civil society that allows individuals to make a voluntary social contract with the sovereign authority, transferring their natural rights to that authority in return for the protection of life, liberty and property.[83] These early liberals often disagreed about the most appropriate form of government, but all believed that liberty was natural and its restriction needed strong justification.[83] Liberals generally believed in limited government, although several liberal philosophers decried government outright, with Thomas Paine writing, "government even in its best state is a necessary evil".[84] James Madison and Montesquieu As part of the project to limit the powers of government, liberal theorists such as James Madison and Montesquieu conceived the notion of separation of powers, a system designed to equally distribute governmental authority among the executive, legislative and judicial branches.[84] Governments had to realise, liberals maintained, that legitimate government only exists with the consent of the governed, so poor and improper governance gave the people the authority to overthrow the ruling order through all possible means, even through outright violence and revolution, if needed.[85] Contemporary liberals, heavily influenced by social liberalism, have supported limited constitutional government while advocating for state services and provisions to ensure equal rights. Modern liberals claim that formal or official guarantees of individual rights are irrelevant when individuals lack the material means to benefit from those rights and call for a greater role for government in the administration of economic affairs.[86] Early liberals also laid the groundwork for the separation of church and state. As heirs of the Enlightenment, liberals believed that any given social and political order emanated from human interactions, not from divine will.[87] Many liberals were openly hostile to religious belief but most concentrated their opposition to the union of religious and political authority, arguing that faith could prosper independently without official sponsorship or administration by the state.[87] Beyond identifying a clear role for government in modern society, liberals have also argued over the meaning and nature of the most important principle in liberal philosophy: liberty. From the 17th century until the 19th century, liberals (from Adam Smith to John Stuart Mill) conceptualised liberty as the absence of interference from government and other individuals, claiming that all people should have the freedom to develop their unique abilities and capacities without being sabotaged by others.[88] Mill's On Liberty (1859), one of the classic texts in liberal philosophy, proclaimed, "the only freedom which deserves the name, is that of pursuing our own good in our own way".[88] Support for laissez-faire capitalism is often associated with this principle, with Friedrich Hayek arguing in The Road to Serfdom (1944) that reliance on free markets would preclude totalitarian control by the state.[89] Coppet Group and Benjamin Constant  Madame de Staël The development into maturity of modern classical in contrast to ancient liberalism took place before and soon after the French Revolution. One of the historic centres of this development was at Coppet Castle near Geneva, where the eponymous Coppet group gathered under the aegis of the exiled writer and salonnière, Madame de Staël, in the period between the establishment of Napoleon's First Empire (1804) and the Bourbon Restoration of 1814–1815.[90][91][92][93] The unprecedented concentration of European thinkers who met there was to have a considerable influence on the development of nineteenth-century liberalism and, incidentally, romanticism.[94][95][96] They included Wilhelm von Humboldt, Jean de Sismondi, Charles Victor de Bonstetten, Prosper de Barante, Henry Brougham, Lord Byron, Alphonse de Lamartine, Sir James Mackintosh, Juliette Récamier and August Wilhelm Schlegel.[97]  Benjamin Constant, a Franco-Swiss political activist and theorist Among them was also one of the first thinkers to go by the name of "liberal", the Edinburgh University-educated Swiss Protestant, Benjamin Constant, who looked to the United Kingdom rather than to ancient Rome for a practical model of freedom in a large mercantile society. He distinguished between the "Liberty of the Ancients" and the "Liberty of the Moderns".[98] The Liberty of the Ancients was a participatory republican liberty,[99] which gave the citizens the right to influence politics directly through debates and votes in the public assembly.[98] In order to support this degree of participation, citizenship was a burdensome moral obligation requiring a considerable investment of time and energy. Generally, this required a sub-group of slaves to do much of the productive work, leaving citizens free to deliberate on public affairs. Ancient Liberty was also limited to relatively small and homogenous male societies, where they could congregate in one place to transact public affairs.[98] In contrast, the Liberty of the Moderns was based on the possession of civil liberties, the rule of law, and freedom from excessive state interference. Direct participation would be limited: a necessary consequence of the size of modern states and the inevitable result of creating a mercantile society where there were no slaves, but almost everybody had to earn a living through work. Instead, the voters would elect representatives who would deliberate in Parliament on the people's behalf and would save citizens from daily political involvement.[98] The importance of Constant's writings on the liberty of the ancients and that of the "moderns" has informed the understanding of liberalism, as has his critique of the French Revolution.[100] The British philosopher and historian of ideas, Sir Isaiah Berlin, has pointed to the debt owed to Constant.[101] British liberalism Liberalism in Britain was based on core concepts such as classical economics, free trade, laissez-faire government with minimal intervention and taxation and a balanced budget. Classical liberals were committed to individualism, liberty and equal rights. Writers such as John Bright and Richard Cobden opposed aristocratic privilege and property, which they saw as an impediment to developing a class of yeoman farmers.[102]  T. H. Green, an influential liberal philosopher who established in Prolegomena to Ethics (1884) the first major foundations for what later became known as positive liberty and in a few years, his ideas became the official policy of the Liberal Party in Britain, precipitating the rise of social liberalism and the modern welfare state Beginning in the late 19th century, a new conception of liberty entered the liberal intellectual arena. This new kind of liberty became known as positive liberty to distinguish it from the prior negative version, and it was first developed by British philosopher T. H. Green. Green rejected the idea that humans were driven solely by self-interest, emphasising instead the complex circumstances involved in the evolution of our moral character.[103]: 54–55 In a very profound step for the future of modern liberalism, he also tasked society and political institutions with the enhancement of individual freedom and identity and the development of moral character, will and reason and the state to create the conditions that allow for the above, allowing genuine choice.[103]: 54–55 Foreshadowing the new liberty as the freedom to act rather than to avoid suffering from the acts of others, Green wrote the following: If it were ever reasonable to wish that the usage of words had been other than it has been ... one might be inclined to wish that the term 'freedom' had been confined to the ... power to do what one wills.[104] Rather than previous liberal conceptions viewing society as populated by selfish individuals, Green viewed society as an organic whole in which all individuals have a duty to promote the common good.[103]: 55 His ideas spread rapidly and were developed by other thinkers such as Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse and John A. Hobson. In a few years, this New Liberalism had become the essential social and political programme of the Liberal Party in Britain,[103]: 58 and it would encircle much of the world in the 20th century. In addition to examining negative and positive liberty, liberals have tried to understand the proper relationship between liberty and democracy. As they struggled to expand suffrage rights, liberals increasingly understood that people left out of the democratic decision-making process were liable to the "tyranny of the majority", a concept explained in Mill's On Liberty and Democracy in America (1835) by Alexis de Tocqueville.[105] As a response, liberals began demanding proper safeguards to thwart majorities in their attempts at suppressing the rights of minorities.[105] Besides liberty, liberals have developed several other principles important to the construction of their philosophical structure, such as equality, pluralism and tolerance. Highlighting the confusion over the first principle, Voltaire commented, "equality is at once the most natural and at times the most chimeral of things".[106] All forms of liberalism assume in some basic sense that individuals are equal.[107] In maintaining that people are naturally equal, liberals assume they all possess the same right to liberty.[108] In other words, no one is inherently entitled to enjoy the benefits of liberal society more than anyone else, and all people are equal subjects before the law.[109] Beyond this basic conception, liberal theorists diverge in their understanding of equality. American philosopher John Rawls emphasised the need to ensure equality under the law and the equal distribution of material resources that individuals required to develop their aspirations in life.[109] Libertarian thinker Robert Nozick disagreed with Rawls, championing the former version of Lockean equality.[109] To contribute to the development of liberty, liberals also have promoted concepts like pluralism and tolerance. By pluralism, liberals refer to the proliferation of opinions and beliefs that characterise a stable social order.[110] Unlike many of their competitors and predecessors, liberals do not seek conformity and homogeneity in how people think. Their efforts have been geared towards establishing a governing framework that harmonises and minimises conflicting views but still allows those views to exist and flourish.[111] For liberal philosophy, pluralism leads easily to toleration. Since individuals will hold diverging viewpoints, liberals argue, they ought to uphold and respect the right of one another to disagree.[112] From the liberal perspective, toleration was initially connected to religious toleration, with Baruch Spinoza condemning "the stupidity of religious persecution and ideological wars".[112] Toleration also played a central role in the ideas of Kant and John Stuart Mill. Both thinkers believed that society would contain different conceptions of a good ethical life and that people should be allowed to make their own choices without interference from the state or other individuals.[112] Liberal economic theory Main article: Economic liberalism  Monument to the liberals of the 19th century in Agra del Orzán neighborhood, La Coruña, Galicia, (Spain) Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, followed by the French liberal economist Jean-Baptiste Say's treatise on Political Economy published in 1803 and expanded in 1830 with practical applications, were to provide most of the ideas of economics until the publication of John Stuart Mill's Principles in 1848.[113]: 63, 68 Smith addressed the motivation for economic activity, the causes of prices and wealth distribution, and the policies the state should follow to maximise wealth.[113]: 64 Smith wrote that as long as supply, demand, prices and competition were left free of government regulation, the pursuit of material self-interest, rather than altruism, maximises society's wealth[114] through profit-driven production of goods and services. An "invisible hand" directed individuals and firms to work toward the nation's good as an unintended consequence of efforts to maximise their gain. This provided a moral justification for accumulating wealth, which some had previously viewed as sinful.[113]: 64 Smith assumed that workers could be paid as low as was necessary for their survival, which David Ricardo and Thomas Robert Malthus later transformed into the "iron law of wages".[113]: 65 His main emphasis was on the benefit of free internal and international trade, which he thought could increase wealth through specialisation in production.[113]: 66 He also opposed restrictive trade preferences, state grants of monopolies and employers' organisations and trade unions.[113]: 67 Government should be limited to defence, public works and the administration of justice, financed by taxes based on income.[113]: 68 Smith was one of the progenitors of the idea, which was long central to classical liberalism and has resurfaced in the globalisation literature of the later 20th and early 21st centuries, that free trade promotes peace.[115] Smith's economics was carried into practice in the 19th century with the lowering of tariffs in the 1820s, the repeal of the Poor Relief Act that had restricted the mobility of labour in 1834 and the end of the rule of the East India Company over India in 1858.[113]: 69 In his Treatise (Traité d'économie politique), Say states that any production process requires effort, knowledge and the "application" of the entrepreneur. He sees entrepreneurs as intermediaries in the production process who combine productive factors such as land, capital and labour to meet the consumers' demands. As a result, they play a central role in the economy through their coordinating function. He also highlights qualities essential for successful entrepreneurship and focuses on judgement, in that they have continued to assess market needs and the means to meet them. This requires an "unerring market sense". Say views entrepreneurial income primarily as the high revenue paid in compensation for their skills and expert knowledge. He does so by contrasting the enterprise and supply-of-capital functions, distinguishing the entrepreneur's earnings on the one hand and the remuneration of capital on the other. This differentiates his theory from that of Joseph Schumpeter, who describes entrepreneurial rent as short-term profits which compensate for high risk (Schumpeterian rent). Say himself also refers to risk and uncertainty along with innovation without analysing them in detail. Say is also credited with Say's law, or the law of markets which may be summarised as "Aggregate supply creates its own aggregate demand", and "Supply creates its own demand", or "Supply constitutes its own demand" and "Inherent in supply is the need for its own consumption". The related phrase "supply creates its own demand" was coined by John Maynard Keynes, who criticized Say's separate formulations as amounting to the same thing. Some advocates of Say's law who disagree with Keynes have claimed that Say's law can be summarized more accurately as "production precedes consumption" and that what Say is stating is that for consumption to happen, one must produce something of value so that it can be traded for money or barter for consumption later.[116][117] Say argues, "products are paid for with products" (1803, p. 153) or "a glut occurs only when too much resource is applied to making one product and not enough to another" (1803, pp. 178–179).[118] Related reasoning appears in the work of John Stuart Mill and earlier in that of his Scottish classical economist father, James Mill (1808). Mill senior restates Say's law in 1808: "production of commodities creates, and is the one and universal cause which creates a market for the commodities produced".[119] In addition to Smith's and Say's legacies, Thomas Malthus' theories of population and David Ricardo's Iron law of wages became central doctrines of classical economics.[113]: 76 Meanwhile, Jean-Baptiste Say challenged Smith's labour theory of value, believing that prices were determined by utility and also emphasised the critical role of the entrepreneur in the economy. However, neither of those observations became accepted by British economists at the time. Malthus wrote An Essay on the Principle of Population in 1798,[113]: 71–72 becoming a major influence on classical liberalism. Malthus claimed that population growth would outstrip food production because the population grew geometrically while food production grew arithmetically. As people were provided with food, they would reproduce until their growth outstripped the food supply. Nature would then provide a check to growth in the forms of vice and misery. No gains in income could prevent this, and any welfare for the poor would be self-defeating. The poor were, in fact, responsible for their problems which could have been avoided through self-restraint.[113]: 72 Several liberals, including Adam Smith and Richard Cobden, argued that the free exchange of goods between nations would lead to world peace.[120] Smith argued that as societies progressed, the spoils of war would rise, but the costs of war would rise further, making war difficult and costly for industrialised nations.[121] Cobden believed that military expenditures worsened the state's welfare and benefited a small but concentrated elite minority, combining his Little Englander beliefs with opposition to the economic restrictions of mercantilist policies. To Cobden and many classical liberals, those who advocated peace must also advocate free markets.[122] Utilitarianism was seen as a political justification for implementing economic liberalism by British governments, an idea dominating economic policy from the 1840s. Although utilitarianism prompted legislative and administrative reform, and John Stuart Mill's later writings foreshadowed the welfare state, it was mainly used as a premise for a laissez-faire approach.[123]: 32 The central concept of utilitarianism, developed by Jeremy Bentham, was that public policy should seek to provide "the greatest happiness of the greatest number". While this could be interpreted as a justification for state action to reduce poverty, it was used by classical liberals to justify inaction with the argument that the net benefit to all individuals would be higher.[113]: 76 His philosophy proved highly influential on government policy and led to increased Benthamite attempts at government social control, including Robert Peel's Metropolitan Police, prison reforms, the workhouses and asylums for the mentally ill. Keynesian economics Main article: Keynesian economics  John Maynard Keynes, one of the most influential economists of modern times and whose ideas, which are still widely felt, formalized modern liberal economic policy. During the Great Depression, the English economist John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) gave the definitive liberal response to the economic crisis. Keynes had been "brought up" as a classical liberal, but especially after World War I, became increasingly a welfare or social liberal.[124] A prolific writer, among many other works, he had begun a theoretical work examining the relationship between unemployment, money and prices back in the 1920s.[125] Keynes was deeply critical of the British government's austerity measures during the Great Depression. He believed budget deficits were a good thing, a product of recessions. He wrote: "For Government borrowing of one kind or another is nature's remedy, so to speak, for preventing business losses from being, in so severe a slump as the present one, so great as to bring production altogether to a standstill".[126] At the height of the Great Depression in 1933, Keynes published The Means to Prosperity, which contained specific policy recommendations for tackling unemployment in a global recession, chiefly counter cyclical public spending. The Means to Prosperity contains one of the first mentions of the multiplier effect.[127]  The Great Depression, with its periods of worldwide economic hardship, formed the backdrop against which the Keynesian Revolution took place (the image is Dorothea Lange's Migrant Mother depiction of destitute pea-pickers in California, taken in March 1936). Keynes's magnum opus, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, was published in 1936[128] and served as a theoretical justification for the interventionist policies Keynes favoured for tackling a recession. The General Theory challenged the earlier neo-classical economic paradigm, which had held that the market would naturally establish full employment equilibrium if it were unfettered by government interference. Classical economists believed in Say's law, which states that "supply creates its own demand" and that in a free market, workers would always be willing to lower their wages to a level where employers could profitably offer them jobs. An innovation from Keynes was the concept of price stickiness, i.e. the recognition that, in reality, workers often refuse to lower their wage demands even in cases where a classical economist might argue it is rational for them to do so. Due in part to price stickiness, it was established that the interaction of "aggregate demand" and "aggregate supply" may lead to stable unemployment equilibria, and in those cases, it is the state and not the market that economies must depend on for their salvation. The book advocated activist economic policy by the government to stimulate demand in times of high unemployment, for example, by spending on public works. In 1928, he wrote: "Let us be up and doing, using our idle resources to increase our wealth. ... With men and plants unemployed, it is ridiculous to say that we cannot afford these new developments. It is precisely with these plants and these men that we shall afford them".[126] Where the market failed to allocate resources properly, the government was required to stimulate the economy until private funds could start flowing again—a "prime the pump" kind of strategy designed to boost industrial production.[129] Liberal feminist theory Main article: Liberal feminism  Mary Wollstonecraft, widely regarded as the pioneer of liberal feminism Liberal feminism, the dominant tradition in feminist history, is an individualistic form of feminist theory that focuses on women's ability to maintain their equality through their actions and choices. Liberal feminists hope to eradicate all barriers to gender equality, claiming that the continued existence of such barriers eviscerates the individual rights and freedoms ostensibly guaranteed by a liberal social order.[130] They argue that society believes women are naturally less intellectually and physically capable than men; thus, it tends to discriminate against women in the academy, the forum and the marketplace. Liberal feminists believe that "female subordination is rooted in a set of customary and legal constraints that blocks women's entrance to and success in the so-called public world". They strive for sexual equality via political and legal reform.[131] British philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) is widely regarded as the pioneer of liberal feminism, with A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) expanding the boundaries of liberalism to include women in the political structure of liberal society.[132] In her writings, such as A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Wollstonecraft commented on society's view of women and encouraged women to use their voices in making decisions separate from those previously made for them. Wollstonecraft "denied that women are, by nature, more pleasure seeking and pleasure giving than men. She reasoned that if they were confined to the same cages that trap women, men would develop the same flawed characters. What Wollstonecraft most wanted for women was personhood".[131] John Stuart Mill was also an early proponent of feminism. In his article The Subjection of Women (1861, published 1869), Mill attempted to prove that the legal subjugation of women is wrong and that it should give way to perfect equality.[133][134] He believed that both sexes should have equal rights under the law and that "until conditions of equality exist, no one can possibly assess the natural differences between women and men, distorted as they have been. What is natural to the two sexes can only be found out by allowing both to develop and use their faculties freely".[135] Mill frequently spoke of this imbalance and wondered if women were able to feel the same "genuine unselfishness" that men did in providing for their families. This unselfishness Mill advocated is the one "that motivates people to take into account the good of society as well as the good of the individual person or small family unit".[131] Like Mary Wollstonecraft, Mill compared sexual inequality to slavery, arguing that their husbands are often just as abusive as masters and that a human being controls nearly every aspect of life for another human being. In his book The Subjection of Women, Mill argues that three major parts of women's lives are hindering them: society and gender construction, education and marriage.[136] Equity feminism is a form of liberal feminism discussed since the 1980s,[137][138] specifically a kind of classically liberal or libertarian feminism.[139] Steven Pinker, an evolutionary psychologist, defines equity feminism as "a moral doctrine about equal treatment that makes no commitments regarding open empirical issues in psychology or biology".[140] Barry Kuhle asserts that equity feminism is compatible with evolutionary psychology in contrast to gender feminism.[141] Social liberal theory Main article: Social liberalism  Sismondi, who wrote the first critique of the free market from a liberal perspective in 1819 Jean Charles Léonard Simonde de Sismondi's New Principles of Political Economy (French: Nouveaux principes d'économie politique, ou de la richesse dans ses rapports avec la population) (1819) represents the first comprehensive liberal critique of early capitalism and laissez-faire economics, and his writings, which were studied by John Stuart Mill and Karl Marx among many others, had a profound influence on both liberal and socialist responses to the failures and contradictions of industrial society.[142][143][144] By the end of the 19th century, the principles of classical liberalism were being increasingly challenged by downturns in economic growth, a growing perception of the evils of poverty, unemployment and relative deprivation present within modern industrial cities, as well as the agitation of organised labour. The ideal of the self-made individual who could make his or her place in the world through hard work and talent seemed increasingly implausible. A major political reaction against the changes introduced by industrialisation and laissez-faire capitalism came from conservatives concerned about social balance, although socialism later became a more important force for change and reform. Some Victorian writers, including Charles Dickens, Thomas Carlyle and Matthew Arnold, became early influential critics of social injustice.[123]: 36–37 New liberals began to adapt the old language of liberalism to confront these difficult circumstances, which they believed could only be resolved through a broader and more interventionist conception of the state. An equal right to liberty could not be established merely by ensuring that individuals did not physically interfere with each other or by having impartially formulated and applied laws. More positive and proactive measures were required to ensure that every individual would have an equal opportunity for success.[145]  John Stuart Mill, whose On Liberty greatly influenced 19th-century liberalism John Stuart Mill contributed enormously to liberal thought by combining elements of classical liberalism with what eventually became known as the new liberalism. Mill's 1859 On Liberty addressed the nature and limits of the power that can be legitimately exercised by society over the individual.[146] He gave an impassioned defence of free speech, arguing that free discourse is a necessary condition for intellectual and social progress. Mill defined "social liberty" as protection from "the tyranny of political rulers". He introduced many different concepts of the form tyranny can take, referred to as social tyranny and tyranny of the majority. Social liberty meant limits on the ruler's power through obtaining recognition of political liberties or rights and establishing a system of "constitutional checks".[147] His definition of liberty, influenced by Joseph Priestley and Josiah Warren, was that the individual ought to be free to do as he wishes unless he harms others.[148] However, although Mill's initial economic philosophy supported free markets and argued that progressive taxation penalised those who worked harder,[149] he later altered his views toward a more socialist bent, adding chapters to his Principles of Political Economy in defence of a socialist outlook and defending some socialist causes,[150] including the radical proposal that the whole wage system be abolished in favour of a co-operative wage system. Another early liberal convert to greater government intervention was T. H. Green. Seeing the effects of alcohol, he believed that the state should foster and protect the social, political and economic environments in which individuals will have the best chance of acting according to their consciences. The state should intervene only where there is a clear, proven and strong tendency of liberty to enslave the individual.[151] Green regarded the national state as legitimate only to the extent that it upholds a system of rights and obligations most likely to foster individual self-realisation. The New Liberalism or social liberalism movement emerged in about 1900 in Britain.[152] The New Liberals, including intellectuals like L. T. Hobhouse and John A. Hobson, saw individual liberty as something achievable only under favourable social and economic circumstances.[5]: 29 In their view, the poverty, squalor and ignorance in which many people lived made it impossible for freedom and individuality to flourish. New Liberals believed these conditions could be ameliorated only through collective action coordinated by a strong, welfare-oriented, interventionist state.[153] It supports a mixed economy that includes public and private property in capital goods.[154][155] Principles that can be described as social liberal have been based upon or developed by philosophers such as John Stuart Mill, Eduard Bernstein, John Dewey, Carlo Rosselli, Norberto Bobbio and Chantal Mouffe.[156] Other important social liberal figures include Guido Calogero, Piero Gobetti, Leonard Trelawny Hobhouse and R. H. Tawney.[157] Liberal socialism has been particularly prominent in British and Italian politics.[157] Anti-state liberal theory See also: Polycentric law, Voluntaryism, Panarchy (political philosophy), Neoclassical liberalism, and Anarcho-capitalism  Gustave de Molinari  Julius Faucher Classical liberalism advocates free trade under the rule of law. In contrast, the "anti-state liberal tradition", as described by Ralph Raico, was supportive of a system where law enforcement and the courts being provided by private companies, minimizing or rejecting the role of the state. Various theorists have espoused legal philosophies similar to anarcho-capitalism. One of the first liberals to discuss the possibility of privatizing the protection of individual liberty and property was the French philosopher Jakob Mauvillon in the 18th century. Later in the 1840s, Julius Faucher and Gustave de Molinari advocated the same. In his essay The Production of Security, Molinari argued: "No government should have the right to prevent another government from going into competition with it, or to require consumers of security to come exclusively to it for this commodity". Molinari and this new type of anti-state liberal grounded their reasoning on liberal ideals and classical economics. Historian and libertarian Ralph Raico argued that what these liberal philosophers "had come up with was a form of individualist anarchism, or, as it would be called today, anarcho-capitalism or market anarchism".[158] Unlike the liberalism of Locke, which saw the state as evolving from society, the anti-state liberals saw a fundamental conflict between the voluntary interactions of people, i.e. society, and the institutions of force, i.e. the state. This society versus state idea was expressed in various ways: natural society vs artificial society, liberty vs authority, society of contract vs society of authority and industrial society vs militant society, to name a few.[159] The anti-state liberal tradition in Europe and the United States continued after Molinari in the early writings of Herbert Spencer and thinkers such as Paul Émile de Puydt and Auberon Herbert. However, the first person to use the term anarcho-capitalism was Murray Rothbard. In the mid-20th century, Rothbard synthesized elements from the Austrian School of economics, classical liberalism and 19th-century American individualist anarchists Lysander Spooner and Benjamin Tucker (while rejecting their labour theory of value and the norms they derived from it).[160] Anarcho-capitalism advocates the elimination of the state in favour of individual sovereignty, private property and free markets. Anarcho-capitalists believe that in the absence of statute (law by decree or legislation), society would improve itself through the discipline of the free market (or what its proponents describe as a "voluntary society").[161][162] In a theoretical anarcho-capitalist society, law enforcement, courts and all other security services would be operated by privately funded competitors rather than centrally through taxation. Money and other goods and services would be privately and competitively provided in an open market. Anarcho-capitalists say personal and economic activities under anarcho-capitalism would be regulated by victim-based dispute resolution organizations under tort and contract law rather than by statute through centrally determined punishment under what they describe as "political monopolies".[163] A Rothbardian anarcho-capitalist society would operate under a mutually agreed-upon libertarian "legal code which would be generally accepted, and which the courts would pledge themselves to follow".[164] Although enforcement methods vary, this pact would recognize self-ownership and the non-aggression principle (NAP). |