リブレット

Libretto

☆

オペラ、オペレッタ、マス、オラトリオ、カンタータ、ミュージカルなどの拡張された音楽作品で使用される、または使用されることを意図したテキストをリブ

レット(イタリア語のlibrettoから。直訳すると「小冊子」)という。リブレットという用語は、ミサ曲、レクイエム、宗教的カンタータなどの主要な

典礼作品のテキスト、またはバレエのストーリーラインを指す場合にも使用される。

イタリア語のlibretto(リブレット)という単語(発音は[liˈbretto]、複数形はlibretti[liˈbretti])は、

libro(「本」)の縮小形である。フランス語の作品にはlivret、ドイツ語の作品にはTextbuch、スペイン語の作品にはlibretoとい

うように、他の言語ではlibrettoに相当する言葉が使われることもある。リブレットはあらすじやシナリオとは区別される。リブレットにはすべてのセ

リフと舞台指示が含まれるが、あらすじはあらすじで筋を要約する。一部のバレエ史家は、19世紀のパリのバレエ観客向けに販売されていた、15ページから

40ページの書籍を指してリブレットという言葉を使用している。この書籍には、バレエのストーリーが場面ごとに非常に詳細に記述されていた。

音楽作品の創作における台本作家(すなわち、台本作家)と作曲家の関係は、何世紀にもわたって変化しており、使用される情報源や執筆テクニックも変化して

きた。

現代の英語によるミュージカル作品においては、台本は作品の台本(すなわち、会話)と歌詞の両方を包含すると考えられている。

| A

libretto (From the Italian word libretto, lit. 'booklet') is the text

used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera,

operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or musical. The term libretto is

also sometimes used to refer to the text of major liturgical works,

such as the Mass, requiem and sacred cantata, or the story line of a

ballet. The Italian word libretto (pronounced [liˈbretto], plural libretti [liˈbretti]) is the diminutive of the word libro ("book"). Sometimes other-language equivalents are used for libretti in that language, livret for French works, Textbuch for German and libreto for Spanish. A libretto is distinct from a synopsis or scenario of the plot, in that the libretto contains all the words and stage directions, while a synopsis summarizes the plot. Some ballet historians also use the word libretto to refer to the 15- to 40-page books which were on sale to 19th century ballet audiences in Paris and contained a very detailed description of the ballet's story, scene by scene.[1] The relationship of the librettist (that is, the writer of a libretto) to the composer in the creation of a musical work has varied over the centuries, as have the sources and the writing techniques employed. In the context of a modern English-language musical theatre piece, the libretto is considered to encompass both the book of the work (i.e., the spoken dialogue) and the sung lyrics. |

オペラ、オペレッタ、マス、オラトリオ、カンタータ、ミュージカルなど

の拡張された音楽作品で使用される、または使用されることを意図したテキストをリブレット(イタリア語のlibrettoから。直訳すると「小冊子」)と

いう。リブレットという用語は、ミサ曲、レクイエム、宗教的カンタータなどの主要な典礼作品のテキスト、またはバレエのストーリーラインを指す場合にも使

用される。 イタリア語のlibretto(リブレット)という単語(発音は[liˈbretto]、複数形はlibretti[liˈbretti])は、 libro(「本」)の縮小形である。フランス語の作品にはlivret、ドイツ語の作品にはTextbuch、スペイン語の作品にはlibretoとい うように、他の言語ではlibrettoに相当する言葉が使われることもある。リブレットはあらすじやシナリオとは区別される。リブレットにはすべてのセ リフと舞台指示が含まれるが、あらすじはあらすじで筋を要約する。一部のバレエ史家は、19世紀のパリのバレエ観客向けに販売されていた、15ページから 40ページの書籍を指してリブレットという言葉を使用している。この書籍には、バレエのストーリーが場面ごとに非常に詳細に記述されていた。 音楽作品の創作における台本作家(すなわち、台本作家)と作曲家の関係は、何世紀にもわたって変化しており、使用される情報源や執筆テクニックも変化して きた。 現代の英語によるミュージカル作品においては、台本は作品の台本(すなわち、会話)と歌詞の両方を包含すると考えられている。 |

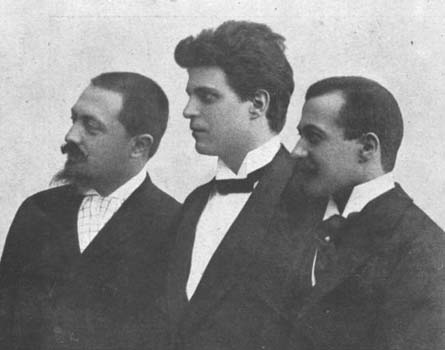

Relationship of composer and librettist The composer of Cavalleria rusticana, Pietro Mascagni, flanked by his librettists, Giovanni Targioni-Tozzetti and Guido Menasci Libretti for operas, oratorios and cantatas in the 17th and 18th centuries were generally written by someone other than the composer, often a well-known poet. Pietro Trapassi, known as Metastasio (1698–1782) was one of the most highly regarded librettists in Europe. His libretti were set many times by many different composers. Another noted 18th-century librettist was Lorenzo Da Ponte. He wrote the libretti for three of Mozart's greatest operas, and for many other composers as well. Eugène Scribe was one of the most prolific librettists of the 19th century, providing the words for works by Meyerbeer (with whom he had a lasting collaboration), Auber, Bellini, Donizetti, Rossini and Verdi. The French writers' duo Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy wrote many opera and operetta libretti for the likes of Jacques Offenbach, Jules Massenet and Georges Bizet. Arrigo Boito, who wrote libretti for, among others, Giuseppe Verdi and Amilcare Ponchielli, also composed two operas of his own. The libretto is not always written before the music. Some composers, such as Mikhail Glinka, Alexander Serov, Rimsky-Korsakov, Puccini and Mascagni wrote passages of music without text and subsequently had the librettist add words to the vocal melody lines (this has often been the case with American popular song and musicals in the 20th century, as with Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart's collaboration, although with the later team of Rodgers and Hammerstein the lyrics were generally written first, which was Rodgers' preferred modus operandi). Some composers wrote their own libretti. Richard Wagner is perhaps most famous in this regard, with his transformations of Germanic legends and events into epic subjects for his operas and music dramas. Hector Berlioz, too, wrote the libretti for two of his best-known works, La damnation de Faust and Les Troyens. Alban Berg adapted Georg Büchner's play Woyzeck for the libretto of Wozzeck.  Pages from an 1859 libretto for Ernani, with the original Italian lyrics, English translation and musical notation for one of the arias Sometimes the libretto is written in close collaboration with the composer; this can involve adaptation, as was the case with Rimsky-Korsakov and his librettist Vladimir Belsky, or an entirely original work. In the case of musicals, the music, the lyrics and the "book" (i.e., the spoken dialogue and the stage directions) may each have its own author. Thus, a musical such as Fiddler on the Roof has a composer (Jerry Bock), a lyricist (Sheldon Harnick) and the writer of the "book" (Joseph Stein). In rare cases, the composer writes everything except the dance arrangements – music, lyrics and libretto, as Lionel Bart did for Oliver!. Other matters in the process of developing a libretto parallel those of spoken dramas for stage or screen. There are the preliminary steps of selecting or suggesting a subject and developing a sketch of the action in the form of a scenario, as well as revisions that might come about when the work is in production, as with out-of-town tryouts for Broadway musicals, or changes made for a specific local audience. A famous case of the latter is Wagner's 1861 revision of the original 1845 Dresden version of his opera Tannhäuser for Paris. |

作曲家と台本作家の関係 カヴァレリア・ルスティカーナの作曲家ピエトロ・マスカーニは、台本作家のジョヴァンニ・タルジョーニ・トッツェッティとグイド・メナーシに挟まれている 17世紀と18世紀のオペラ、オラトリオ、カンタータの台本は、作曲家以外の人物によって書かれることが一般的であり、その多くは著名な詩人であった。 ピエトロ・トラパーシ(1698年~1782年)は、メタスタージオとして知られ、ヨーロッパで最も高く評価された台本作家の一人であった。彼の台本は、 多くの異なる作曲家によって何度も作曲された。18世紀の著名な台本作家には、ロレンツォ・ダ・ポンテがいた。彼はモーツァルトの最高傑作の3つのオペラ の台本を書き、その他にも多くの作曲家の作品の台本を書いた。オイゲン・スクリーブは19世紀で最も多作な台本作家の一人であり、マイヤベーア(彼とは生 涯にわたって共同作業を行った)、オーベール、ベッリーニ、ドニゼッティ、ロッシーニ、ヴェルディなどの作品の台本を提供した。フランスの作家デュオ、ア ンリ・メイヤックとルドヴィク・レヴィは、ジャック・オッフェンバック、ジュール・マスネ、ジョルジュ・ビゼーなどのために数多くのオペラやオペレッタの 台本を書いた。また、ジュゼッペ・ヴェルディやアミルカル・ポンキエッリなどの台本を書いたアリーゴ・ボーイトは、自身でも2つのオペラを作曲している。 台本は常に音楽より先に書かれるとは限らない。ミハイル・グリンカ、アレクサンドル・セローフ、リムスキー=コルサコフ、プッチーニ、マスカーニといった 作曲家は、歌詞のない楽節を書き、その後、リブレット作家にボーカルの旋律ラインに歌詞を付け加えさせた。(これは、20世紀のアメリカン・ポピュラー・ ソングやミュージカルではよく見られ、リチャード・ロジャースとロレンツ・ハートの共同作業でもそうだったが、ロジャースとハーマストンの後期のチームで は、歌詞は通常、最初に書かれていた。ロジャースの好んだ手法であった)。 自らリブレットを書いた作曲家もいる。この点で最も有名なのは、ゲルマン神話や史実をオペラや音楽劇の壮大な主題に変えたリヒャルト・ワーグナーであろ う。エクトル・ベルリオーズも、代表作である『ファウストの呪い』と『トロイの人々』のリブレットを自ら執筆している。アルバン・ベルクは、ゲオルク・ ビューヒナーの戯曲『ヴォイツェク』を『ヴォツェック』のリブレットに翻案した。  1859年の『エルナーニ』の台本ページ。イタリア語のオリジナル歌詞、英語訳、アリアの楽譜 リブレットは作曲家と緊密に協力して書かれることもある。これは、リムスキー=コルサコフと彼のリブレット作家ウラディーミル・ベルスキーの例のように、 脚色を伴う場合もあれば、まったくのオリジナル作品の場合もある。ミュージカルの場合、音楽、歌詞、そして「本」(すなわち、会話や舞台上の指示)はそれ ぞれ別の作者によることもある。したがって、『屋根の上のバイオリン弾き』のようなミュージカルには、作曲家(ジェリー・ボック)、作詞家(シェルドン・ ハーニック)、そして「ブック」の作者(ジョセフ・スタイン)がいる。稀なケースとして、作曲家がダンスアレンジメント以外のすべてを担当する場合もあ る。オリバー!』のライオネル・バートがそうであったように、音楽、歌詞、リブレットを担当する。 リブレットの制作過程では、舞台やスクリーン用の会話劇と並行して、その他の作業も行われる。主題の選択や提案、シナリオ形式での行動のスケッチの作成と いった予備的なステップがあり、また、ブロードウェイ・ミュージカルの地方公演トライアウトのように、作品が制作段階にある際に生じる可能性のある改訂 や、特定の地域観客向けに変更を加える場合もある。後者の有名な例としては、ワーグナーが1861年に、1845年のドレスデン版をパリ向けに改訂したオ ペラ『タンホイザー』がある。 |

| Literary characteristics The opera libretto from its inception (c. 1600) was written in verse, and this continued well into the 19th century, although genres of musical theatre with spoken dialogue have typically alternated verse in the musical numbers with spoken prose. Since the late 19th century some opera composers have written music to prose or free verse libretti. Much of the recitatives of George Gershwin's opera Porgy and Bess, for instance, are merely DuBose and Dorothy Heyward's play Porgy set to music as written – in prose – with the lyrics of the arias, duets, trios and choruses written in verse. The libretto of a musical, on the other hand, is almost always written in prose (except for the song lyrics). The libretto of a musical, if the musical is adapted from a play (or even a novel), may even borrow their source's original dialogue liberally – much as Oklahoma! used dialogue from Lynn Riggs's Green Grow the Lilacs, Carousel used dialogue from Ferenc Molnár's Liliom, My Fair Lady took most of its dialogue word-for-word from George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion, Man of La Mancha was adapted from the 1959 television play I, Don Quixote, which supplied most of the dialogue, and the 1954 musical version of Peter Pan used J. M. Barrie's dialogue. Even the musical Show Boat, which is greatly different from the Edna Ferber novel from which it was adapted, uses some of Ferber's original dialogue, notably during the miscegenation scene. And Lionel Bart's Oliver! uses chunks of dialogue from Charles Dickens's novel Oliver Twist, although it bills itself as a "free adaptation" of the novel. |

文学的な特徴 オペラの台本は、その誕生(1600年頃)以来、詩の形で書かれており、この傾向は19世紀まで続いた。しかし、音楽劇のジャンルでは、通常、歌の詩と会 話の散文が交互に用いられてきた。19世紀後半以降、一部のオペラ作曲家は、散文や自由詩の台本に音楽を付けている。例えば、ジョージ・ガーシュウィンの オペラ『ポーギーとベス』のレチタティーヴォの多くは、デュボースとドロシー・ヘイワードの戯曲『ポーギー』をそのまま音楽にのせたもので、アリア、デュ エット、トリオ、コーラスの歌詞は詩で書かれている。 一方、ミュージカルの台本は、歌詞を除いてはほとんどが散文で書かれている。ミュージカルの台本は、そのミュージカルが戯曲(あるいは小説)を原作とする 場合、原作の台詞をそのまま使用することさえある。オクラホマ!』はリン・リッグスの『ライラック・グリーン・グロー』、『回転木馬』はフェレンツ・モル ナールの『リリom』、『マイ・フェア・レディ』はジョージ・バーナード・ショーの『ピグマリオン』から、ほとんどの台詞をそのまま使用している。『マ ン・オブ・ラ・マンチャ』は 1959年のテレビ劇『ドン・キホーテ』から台詞のほとんどを引用し、1954年のミュージカル版『ピーターパン』ではJ. M. バリーの台詞が使用された。ミュージカル『ショー・ボート』でさえ、原作のエドナ・ファーバーの小説とは大きく異なるが、特に人種混合の場面では、ファー バーの原作の台詞がいくつか使用されている。また、ライオネル・バートの『オリバー!』では、チャールズ・ディケンズの小説『オリバー・ツイスト』の台詞 が多数使用されているが、この作品は「自由な脚色」と銘打たれている。 |

Language and translation Henry Purcell (1659–1695), whose operas were written to English libretti As the originating language of opera, Italian dominated that genre in Europe (except in France) well through the 18th century, and even into the next century in Russia, for example, when the Italian opera troupe in Saint Petersburg was challenged by the emerging native Russian repertory. Significant exceptions before 1800 can be found in Purcell's works, Handel's first operas, ballad opera and Singspiel of the 18th century, etc. Just as with literature and song, the libretto has its share of problems and challenges with translation. In the past (and even today), foreign musical stage works with spoken dialogue, especially comedies, were sometimes performed with the sung portions in the original language and the spoken dialogue in the vernacular. The effects of leaving lyrics untranslated depend on the piece. A man like Louis Durdilly[2] would translate the whole libretto, dialogues and airs, into French: Così fan tutte became Ainsi font toutes, ou la Fidélité des femmes, and instead of Ferrando singing "Un' aura amorosa" French-speaking audiences were treated to Fernand singing "Ma belle est fidèle autant qu'elle est belle".[3] Many musicals, such as the old Betty Grable – Don Ameche – Carmen Miranda vehicles, are largely unaffected, but this practice is especially misleading in translations of musicals like Show Boat, The Wizard of Oz, My Fair Lady or Carousel, in which the lyrics to the songs and the spoken text are often or always closely integrated, and the lyrics serve to further the plot.[citation needed] Availability of printed or projected translations today makes singing in the original language more practical, although one cannot discount the desire to hear a sung drama in one's own language. The Spanish words libretista (playwright, script writer or screenwriter) and libreto (script or screen play), which are used in the Hispanic TV and cinema industry, derived their meanings from the original operatic sense. |

言語と翻訳 ヘンリー・パーセル(1659年~1695年)のオペラは、英語の台本で書かれた オペラの原語としてイタリア語は18世紀までヨーロッパ(フランスを除く)でそのジャンルを支配し、ロシアではサンクトペテルブルクのイタリア人オペラ一 座が台頭しつつあったロシアのレパートリーに挑戦されたほどで、その支配は次の世紀まで続いた。1800年以前の重要な例外としては、パーセルの作品、ヘ ンデルの最初のオペラ、18世紀のバラッド・オペラやジングシュピールなどがある。 文学や歌と同様に、台本にも翻訳に伴う問題や課題がある。過去においては(そして現在でも)、外国の音楽舞台作品でセリフのあるもの、特に喜劇では、歌の 部分は原語のままで、セリフは現地語で上演されることがあった。歌詞を翻訳しないことの影響は作品によって異なる。ルイ・デュルディリのような人物[2] は、台本、セリフ、歌のすべてをフランス語に翻訳した。『コシ・ファン・トゥッテ』は『Thus are they all』または『女性の忠誠』となり、フェランドが「Un' aura amorosa」と歌う代わりに、フランス語話者の観客は「Ma belle est fidèle autant qu'elle est belle」とフェルナンドが歌うのを聴くことになった。[3] ベティ・グレイブル、ドン・アメチ、カルメン・ミランダなど、昔のミュージカル作品の多くはほとんど影響を受けていないが、ショー・ボート、オズの魔法使 い、マイ・フェア・レディ、回転木馬などのミュージカル作品の翻訳では、歌詞とセリフが密接に統合されていることが多く、また常にそうであるため、この慣 習は特に誤解を招きやすい。歌詞はストーリーをさらに盛り上げる役割を果たしている。自国語で歌われるドラマを聞きたいという欲求を否定することはできな い。 スペイン語のlibretista(劇作家、脚本家、または映画脚本家)とlibreto(台本または映画脚本)という言葉は、ヒスパニック系のテレビや映画業界で使用されているが、その意味は元々のオペラ的な感覚から派生したものである。 |

Status Poster for La figlia di Iorio where the librettist, Gabriele D'Annunzio, is given top billing Librettists have historically received less prominent credit than the composer. In some 17th-century operas still being performed, the name of the librettist was not even recorded. As the printing of libretti for sale at performances became more common, these records often survive better than music left in manuscript. But even in late 18th century London, reviews rarely mentioned the name of the librettist, as Lorenzo Da Ponte lamented in his memoirs. By the 20th century some librettists became recognised as part of famous collaborations, as with Gilbert and Sullivan or Rodgers and Hammerstein. Today the composer (past or present) of the musical score to an opera or operetta is usually given top billing for the completed work, and the writer of the lyrics relegated to second place or a mere footnote, a notable exception being Gertrude Stein, who received top billing for Four Saints in Three Acts. Another exception was Alberto Franchetti's 1906 opera La figlia di Iorio which was a close rendering of a highly successful play by its librettist, Gabriele D'Annunzio, a celebrated Italian poet, novelist and dramatist of the day. In some cases, the operatic adaptation has become more famous than the literary text on which it was based, as with Claude Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande after a play by Maurice Maeterlinck. The question of which is more important in opera – the music or the words – has been debated over time, and forms the basis of at least two operas, Richard Strauss's Capriccio and Antonio Salieri's Prima la musica e poi le parole. |

ステータス ポスター『イオリオの娘』では、台本作家のガブリエーレ・ダンヌンツィオがトップクレジットされている 台本作家は、歴史的に作曲家よりも目立たないクレジットで紹介されてきた。現在でも上演されている17世紀のオペラの中には、台本作家の名前が記録されて いないものもある。上演時に販売される台本の印刷が一般的になるにつれ、こうした記録は、原稿として残された音楽よりもよく残っていることが多い。しか し、18世紀後半のロンドンでも、批評家が台本作家の名前に言及することはまれであったと、ロレンツォ・ダ・ポンテは回顧録で嘆いている。 20世紀になると、ギルバート&サリヴァンやロジャース&ハマースタインのように、いくつかの作品では、台本作家が有名なコラボレーションの一部として認 められるようになった。今日では、オペラやオペレッタの作曲家(過去または現在)は、完成した作品において通常、第一クレジットとしてクレジットされる。 一方、歌詞の作者は第二クレジットまたは単なる脚注に追いやられるのが一般的である。ただし、ゲルトルート・スタインは『四人の聖人』で第一クレジットと してクレジットされた。もう一つの例外は、1906年のアルベルト・フランケッティのオペラ『イオリオの娘』である。この作品は、当時著名なイタリア人詩 人、小説家、劇作家であったガブリエーレ・ダンヌンツィオによる大成功を収めた戯曲を忠実にオペラ化したものであった。オペラ化された作品が原作の文学作 品よりも有名になるケースもあり、モーリス・メーテルリンクの戯曲を原作とするクロード・ドビュッシーの『ペレアスとメリザンド』などがその例である。 オペラにおいて音楽と歌詞のどちらが重要であるかという問題は、長い間議論されてきた。そして、リヒャルト・シュトラウスの『カプリッチョ』とアントニオ・サリエリの『音楽に言葉は従う』という少なくとも2つのオペラの基盤となっている。 |

| Publication Libretti have been made available in several formats, some more nearly complete than others. The text – i.e., the spoken dialogue, song lyrics and stage directions, as applicable – is commonly published separately from the music (such a booklet is usually included with sound recordings of most operas). Sometimes (particularly for operas in the public domain) this format is supplemented with melodic excerpts of musical notation for important numbers. Printed scores for operas naturally contain the entire libretto, although there can exist significant differences between the score and the separately printed text. More often than not, this involves the extra repetition of words or phrases from the libretto in the actual score. For example, in the aria "Nessun dorma" from Puccini's Turandot, the final lines in the libretto are "Tramontate, stelle! All'alba, vincerò!" (Fade, you stars! At dawn, I will win!). However, in the score they are sung as "Tramontate, stelle! Tramontate, stelle! All'alba, vincerò! Vincerò! Vincerò!". Because the modern musical tends to be published in two separate but intersecting formats (i.e., the book and lyrics, with all the words, and the piano-vocal score, with all the musical material, including some spoken cues), both are needed in order to make a thorough reading of an entire show. |

出版 リブレットは、いくつかのフォーマットで入手可能となっているが、その完成度は様々である。テキスト、すなわち、台詞、歌詞、演出指示などは、音楽とは別 個に出版されるのが一般的である(このようなブックレットは、ほとんどのオペラの音源に通常添付されている)。時折(特にパブリックドメインのオペラの場 合)、このフォーマットに重要なナンバーの旋律の楽譜が追加されることもある。 オペラの印刷楽譜には当然ながら全歌詞が含まれているが、楽譜と別に印刷された歌詞には大きな相違がある場合がある。 多くの場合、実際の楽譜には歌詞やフレーズが繰り返し記載されている。 例えば、プッチーニ作曲のオペラ『トゥーランドット』のアリア「誰も寝てはならぬ」では、歌詞の最後の行は「星々よ、消え失せろ!夜明けとともに、私は勝 つ!」と歌われる。しかし、楽譜では「Tramontate, stelle! Tramontate, stelle! All'alba, vincerò! Vincerò! Vincerò!」と歌われる。 現代の音楽は、歌詞とすべての歌詞が記載された歌詞本、そして音楽素材と一部のセリフが記載されたピアノ・ボーカルスコアという、2つの別個の、しかし相互に交差する形式で出版される傾向にあるため、ショー全体を完全に理解するには両方とも必要となる。 |

| List of opera librettists |

リブレット作家リスト |

| Further reading Kennedy, Michael (2006), The Oxford Dictionary of Music, 985 pages, ISBN 0-19-861459-4 MacNutt, Richard (1992), "Libretto" in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, ed. Stanley Sadie (London) ISBN 0-333-73432-7 Neville, Don (1990). Frontier Research in Opera and Multimedia Preservation: a Project Involving the Documentation and Full Text Retrieval of the Libretti of Pietro Metastasio. London: Faculty of Music, University of Western Ontario. Without ISBN Portinari, Folco (1981). Pari siamo! Io la lingua, egli ha il pugnale. Storia del melodramma ottocentesco attraverso i suoi libretti. Torino: E.D.T. Edizioni. ISBN 88-7063-017-X. Smith, Patrick J. The Tenth Muse: a Historical Study of the Opera Libretto. First ed. New York: A.A. Knopf, 1970. xxii, 417, xvi p. + [16] p. of b&w ill. Without ISBN or SBN Warrack, John and West, Ewan (1992), The Oxford Dictionary of Opera, 782 pages, ISBN 0-19-869164-5 |

参考文献 ケネディ、マイケル著(2006年)、『オックスフォード音楽事典』、985ページ、ISBN 0-19-861459-4 マクナット、リチャード著(1992年)、『ニューグローヴ歌劇辞典』、スタンリー・サディ編、ロンドン、ISBN 0-333-73432-7 ネヴィル、ドン(1990年)。オペラとマルチメディア保存におけるフロンティア研究:ピエトロ・メタスタージオのオペラ台本のドキュメント化と全文検索を含むプロジェクト。ロンドン:ウェスタン・オンタリオ大学音楽学部。ISBNなし Portinari, Folco (1981). Pari siamo! Io la lingua, egli ha il pugnale. Storia del melodramma ottocentesco attraverso i suoi libretti. Torino: E.D.T. Edizioni. ISBN 88-7063-017-X. Smith, Patrick J. The Tenth Muse: a Historical Study of the Opera Libretto. First ed. ニューヨーク:A.A. Knopf、1970年。xxii, 417, xvi p. + [16] p. of b&w ill. ISBNまたはSBNなし Warrack, John and West, Ewan (1992), The Oxford Dictionary of Opera, 782ページ、ISBN 0-19-869164-5 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Libretto |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

cc

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆