言語学

Linguistics

☆

言語学(Linguistics)

は、言語を科学的に研究する学問である。[1][2][3]

言語分析の分野には、構文(文の構造を規定する規則)、意味論(意味)、形態論(単語の構造)、音声学(音声や手話における同等のジェスチャー)、音韻論

(特定の言語の抽象的な音声体系、および手話の類似の体系)、語用論(使用文脈が意味にどのように寄与するか)があります。[4]

生物言語学(言語の生物学的変数と進化の研究)や心理言語学(人間の言語における心理的要因の研究)などのサブディシプリンは、これらの分野の境界を橋渡

ししている。[5]

言語学は、理論的応用と実践的応用の両方にまたがる多くの分野とサブ分野を含む。[6]

理論言語学は、言語の普遍的かつ基本的な性質を理解し、それを記述するための一般的な理論的枠組みの開発に関心がある。応用言語学は、言語の研究による科

学的知見を、言語教育やリテラシーの向上方法の開発などの実践的な目的に活用することを目指している。

言語学的特徴は、さまざまな観点から研究することができる。同期的(特定の時点における言語の構造を記述する)または通時的(言語の時間の経過に伴う歴史

的発展を通じて)、単一言語話者または多言語話者、子どもまたは成人、学習過程または習得過程、抽象的対象または認知構造、書かれたテキストまたは口頭で

の発話誘発、そして最終的に機械的なデータ収集または実践的なフィールドワークを通じて。[7]

言語学は、その一部がより質的かつ全体的なアプローチを採用する文献学の分野から生まれた。[8]

現代では、文献学と言語学は、関連分野、サブディシプリン、または言語研究の独立した分野としてさまざまに記述されているが、概して言語学は包括的な用語

と見なすことができる。[9] 言語学は、言語哲学、スタイル論、修辞学、記号論、辞書学、翻訳とも関連している。

| Linguistics

is the

scientific study of language.[1][2][3] The areas of linguistic analysis

are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics

(meaning), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (speech sounds

and equivalent gestures in sign languages), phonology (the abstract

sound system of a particular language, and analogous systems of sign

languages), and pragmatics (how the context of use contributes to

meaning).[4] Subdisciplines such as biolinguistics (the study of the

biological variables and evolution of language) and psycholinguistics

(the study of psychological factors in human language) bridge many of

these divisions.[5] Linguistics encompasses many branches and subfields that span both theoretical and practical applications.[6] Theoretical linguistics is concerned with understanding the universal and fundamental nature of language and developing a general theoretical framework for describing it. Applied linguistics seeks to utilize the scientific findings of the study of language for practical purposes, such as developing methods of improving language education and literacy. Linguistic features may be studied through a variety of perspectives: synchronically (by describing the structure of a language at a specific point in time) or diachronically (through the historical development of a language over a period of time), in monolinguals or in multilinguals, among children or among adults, in terms of how it is being learnt or how it was acquired, as abstract objects or as cognitive structures, through written texts or through oral elicitation, and finally through mechanical data collection or practical fieldwork.[7] Linguistics emerged from the field of philology, of which some branches are more qualitative and holistic in approach.[8] Today, philology and linguistics are variably described as related fields, subdisciplines, or separate fields of language study but, by and large, linguistics can be seen as an umbrella term.[9] Linguistics is also related to the philosophy of language, stylistics, rhetoric, semiotics, lexicography, and translation. |

言語学は、言語を科学的に研究する学問である。[1][2][3]

言語分析の分野には、構文(文の構造を規定する規則)、意味論(意味)、形態論(単語の構造)、音声学(音声や手話における同等のジェスチャー)、音韻論

(特定の言語の抽象的な音声体系、および手話の類似の体系)、語用論(使用文脈が意味にどのように寄与するか)があります。[4]

生物言語学(言語の生物学的変数と進化の研究)や心理言語学(人間の言語における心理的要因の研究)などのサブディシプリンは、これらの分野の境界を橋渡

ししている。[5] 言語学は、理論的応用と実践的応用の両方にまたがる多くの分野とサブ分野を含む。[6] 理論言語学は、言語の普遍的かつ基本的な性質を理解し、それを記述するための一般的な理論的枠組みの開発に関心がある。応用言語学は、言語の研究による科 学的知見を、言語教育やリテラシーの向上方法の開発などの実践的な目的に活用することを目指している。 言語学的特徴は、さまざまな観点から研究することができる。同期的(特定の時点における言語の構造を記述する)または通時的(言語の時間の経過に伴う歴史 的発展を通じて)、単一言語話者または多言語話者、子どもまたは成人、学習過程または習得過程、抽象的対象または認知構造、書かれたテキストまたは口頭で の発話誘発、そして最終的に機械的なデータ収集または実践的なフィールドワークを通じて。[7] 言語学は、その一部がより質的かつ全体的なアプローチを採用する文献学の分野から生まれた。[8] 現代では、文献学と言語学は、関連分野、サブディシプリン、または言語研究の独立した分野としてさまざまに記述されているが、概して言語学は包括的な用語 と見なすことができる。[9] 言語学は、言語哲学、スタイル論、修辞学、記号論、辞書学、翻訳とも関連している。 |

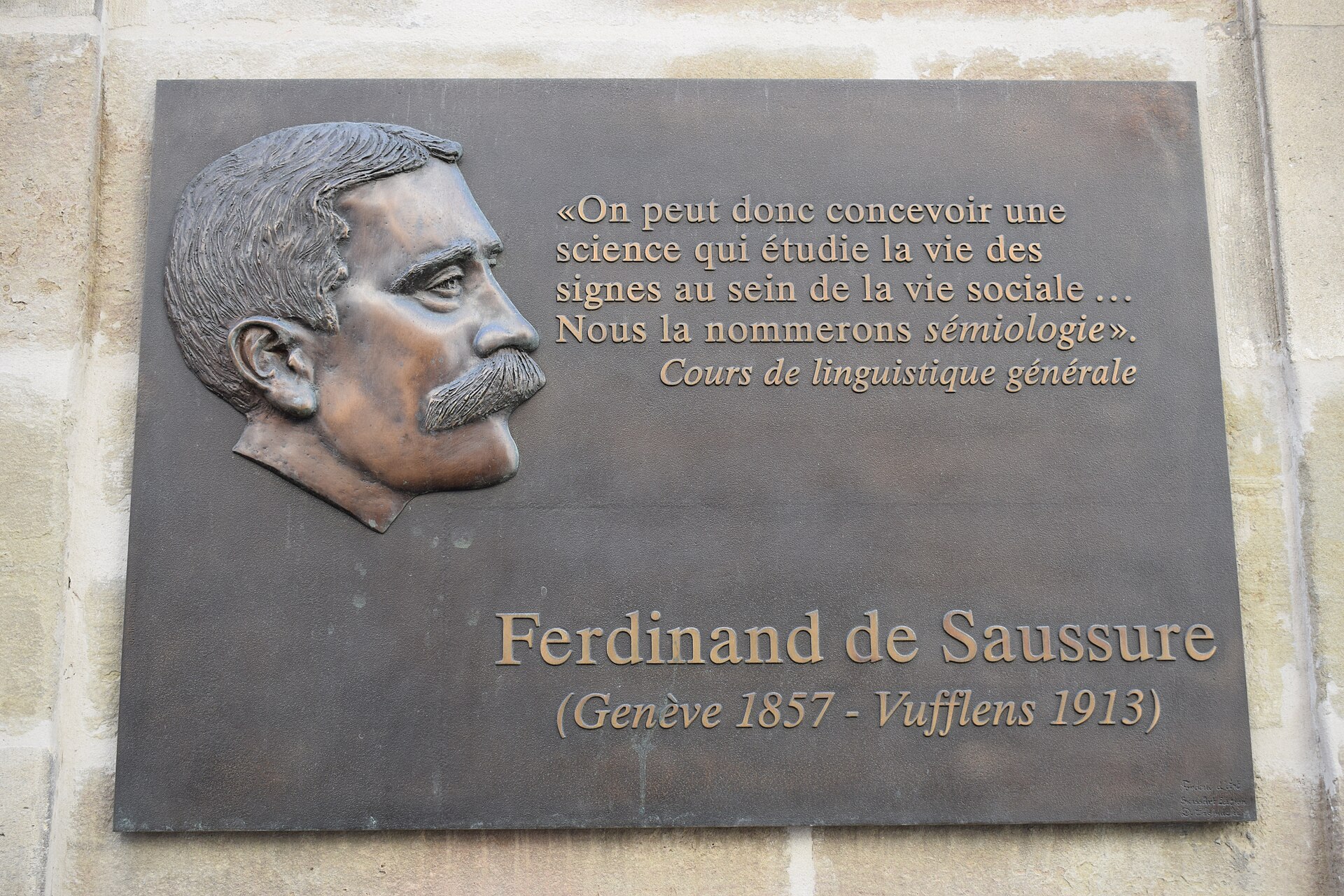

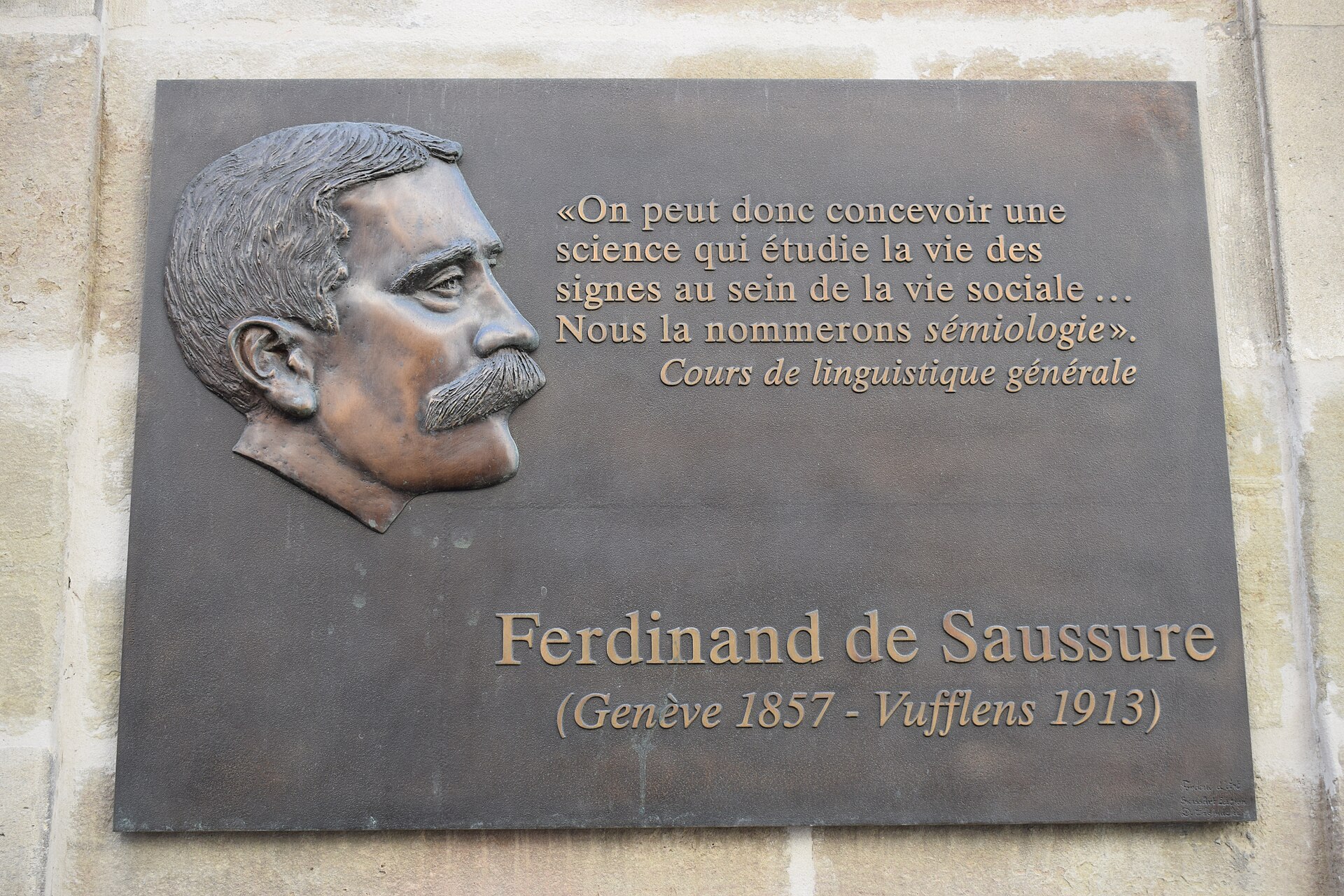

Major subdisciplines Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure is regarded as the creator of semiotics Historical linguistics Main article: Historical linguistics Historical linguistics is the study of how language changes over history, particularly with regard to a specific language or a group of languages. Western trends in historical linguistics date back to roughly the late 18th century, when the discipline grew out of philology, the study of ancient texts and oral traditions.[10] Historical linguistics emerged as one of the first few sub-disciplines in the field, and was most widely practised during the late 19th century.[11] Despite a shift in focus in the 20th century towards formalism and generative grammar, which studies the universal properties of language, historical research today still remains a significant field of linguistic inquiry. Subfields of the discipline include language change and grammaticalization. Historical linguistics studies language change either diachronically (through a comparison of different time periods in the past and present) or in a synchronic manner (by observing developments between different variations that exist within the current linguistic stage of a language).[12] At first, historical linguistics was the cornerstone of comparative linguistics, which involves a study of the relationship between different languages.[13] At that time, scholars of historical linguistics were only concerned with creating different categories of language families, and reconstructing prehistoric proto-languages by using both the comparative method and the method of internal reconstruction. Internal reconstruction is the method by which an element that contains a certain meaning is re-used in different contexts or environments where there is a variation in either sound or analogy.[13][better source needed] The reason for this had been to describe well-known Indo-European languages, many of which had detailed documentation and long written histories. Scholars of historical linguistics also studied Uralic languages, another European language family for which very little written material existed back then. After that, there also followed significant work on the corpora of other languages, such as the Austronesian languages and the Native American language families. In historical work, the uniformitarian principle is generally the underlying working hypothesis, occasionally also clearly expressed.[14] The principle was expressed early by William Dwight Whitney, who considered it imperative, a "must", of historical linguistics to "look to find the same principle operative also in the very outset of that [language] history."[15] The above approach of comparativism in linguistics is now, however, only a small part of the much broader discipline called historical linguistics. The comparative study of specific Indo-European languages is considered a highly specialized field today, while comparative research is carried out over the subsequent internal developments in a language: in particular, over the development of modern standard varieties of languages, and over the development of a language from its standardized form to its varieties.[citation needed] For instance, some scholars also tried to establish super-families, linking, for example, Indo-European, Uralic, and other language families to a hypothetical Nostratic language group.[16] While these attempts are still not widely accepted as credible methods, they provide necessary information to establish relatedness in language change. This is generally hard to find for events long ago, due to the occurrence of chance word resemblances and variations between language groups. A limit of around 10,000 years is often assumed for the functional purpose of conducting research.[17] It is also hard to date various proto-languages. Even though several methods are available, these languages can be dated only approximately.[18] In modern historical linguistics, we examine how languages change over time, focusing on the relationships between dialects within a specific period. This includes studying morphological, syntactical, and phonetic shifts. Connections between dialects in the past and present are also explored.[19] |

主要なサブ分野 スイスの言語学者フェルディナン・ド・ソシュールは、記号論の創始者とされている。 歴史言語学 主な記事:歴史言語学 歴史言語学は、特に特定の言語または言語群について、言語が歴史的にどのように変化してきたかを研究する学問だ。西洋の歴史言語学の傾向は、古代のテキス トや口頭伝承の研究である文献学からこの学問が発展した 18 世紀後半頃にさかのぼる[10]。 歴史言語学は、この分野で最初に確立されたサブ分野の一つとして登場し、19世紀後半に最も広く実践された。[11] 20世紀には、言語の普遍的性質を研究する形式主義や生成文法への焦点の移行があったが、現在も歴史的研究は言語学の重要な研究分野として残っている。こ の分野のサブ分野には、言語変化と文法化が含まれる。 歴史言語学は、言語の変化を、通時的に(過去と現在の異なる時代を比較して)または共時的に(現在の言語の段階に存在する異なるバリエーション間の発展を 観察して)研究する[12]。 当初、歴史言語学は、異なる言語間の関係を研究する比較言語学の基礎だった。[13] 当時、歴史言語学者は、言語族の異なる分類を作成し、比較法と内部再構成法を用いて先史時代の原言語を再構築することのみに関心があった。内部再構築と は、ある意味を含む要素が、音や類推に違いがある異なる文脈や環境で再利用される方法だ。[13][より良い情報源が必要] この方法は、詳細な記録と長い文字史を有するよく知られたインド・ヨーロッパ語族の言語を記述するために採用された。歴史言語学の研究者は、当時文字資料 がほとんど存在しなかったヨーロッパのもう一つの言語家族であるウラル語族の研究も行っていた。その後、オーストロネシア語族やアメリカ先住民の言語家族 など、他の言語のコーパスの研究も活発化していった。 歴史的研究では、均一性原則が一般的に基本的な作業仮説として採用されており、時折明示的に表現されることもある。[14] この原則は、ウィリアム・ドワイト・ホイットニーによって早期に提唱され、歴史言語学において「その言語の歴史の最初期においても同じ原則が作用している ことを探すこと」が不可欠な「必須の要件」であるとされた。[15] しかし、上記の言語学における比較主義的アプローチは、現在では、より広範な学問分野である歴史言語学の一部に過ぎない。特定のインド・ヨーロッパ語族の 言語の比較研究は、現在では高度に専門化された分野とみなされており、比較研究は、言語のその後の内部発展、特に、現代標準語の発展、および標準化された 形態から方言への発展について行われている。 例えば、一部の研究者は、インド・ヨーロッパ語族、ウラル語族、その他の言語族を仮説上のノストラティック言語群に結びつける超語族の確立を試みた。 [16] これらの試みは、現在も信頼できる方法として広く受け入れられていないが、言語変化における関連性を確立するための必要な情報を提供している。これは、言 語群間の偶然の単語の類似性や変異のため、過去の出来事については一般的に困難だ。研究の機能的な目的のため、約10,000年という制限がしばしば仮定 されている。[17] さまざまな原言語の年代を特定することも困難だ。いくつかの方法が存在するものの、これらの言語の年代は概算でしか特定できない。[18] 現代の歴史言語学では、特定の期間内の方言間の関係に焦点を当て、言語が時間とともにどのように変化するかについて調査している。これには、形態論的、統 語論的、音韻論的な変化の研究が含まれる。過去と現在の方言間の関連性も探求されている。[19] |

| Syntax Main article: Syntax Syntax is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, constituency,[20] agreement, the nature of crosslinguistic variation, and the relationship between form and meaning. There are numerous approaches to syntax that differ in their central assumptions and goals. |

構文(統語論) 主な記事:構文 構文とは、単語や形態素が組み合わさって、フレーズや文などのより大きな単位を形成する方法の研究だ。構文の中心的な関心事は、語順、文法関係、構成要素 [20]、一致、言語間の変動の性質、形式と意味の関係などだ。構文には、その中心的な仮定や目標が異なる、さまざまなアプローチがある。 |

| Morphology Main article: Morphology (linguistics) Morphology is the study of words, including the principles by which they are formed, and how they relate to one another within a language.[21][22] Most approaches to morphology investigate the structure of words in terms of morphemes, which are the smallest units in a language with some independent meaning. Morphemes include roots that can exist as words by themselves, but also categories such as affixes that can only appear as part of a larger word. For example, in English the root catch and the suffix -ing are both morphemes; catch may appear as its own word, or it may be combined with -ing to form the new word catching. Morphology also analyzes how words behave as parts of speech, and how they may be inflected to express grammatical categories including number, tense, and aspect. Concepts such as productivity are concerned with how speakers create words in specific contexts, which evolves over the history of a language. The discipline that deals specifically with the sound changes occurring within morphemes is morphophonology. |

形態論 主な記事:形態論 (言語学) 形態論は、単語の形成原理や、言語内で単語が互いにどのように関連しているかを研究する学問だ。[21][22] 形態論のほとんどのアプローチは、言語の中で独立した意味を持つ最小の単位である形態素の観点から単語の構造を調査している。形態素には、単独で単語とし て存在できる語根だけでなく、より大きな単語の一部としてのみ現れる接辞などのカテゴリーも含まれる。例えば、英語の語根「catch」と接尾辞「- ing」はどちらも形態素であり、「catch」は単独で単語として現れることもあれば、「-ing」と組み合わさって新しい単語「catching」を 形成することもある。形態論はまた、単語が品詞としてどのように機能するか、および単語が数、時制、相などの文法範疇を表すためにどのように変化するかに ついても分析する。生産性などの概念は、話者が特定の文脈で単語をどのように生成するかに関わり、言語の歴史とともに進化する。 形態素内で起こる音の変化を専門的に扱う学問は、形態音韻論である。 |

| Semantics and pragmatics Main articles: Semantics and Pragmatics Semantics and pragmatics are branches of linguistics concerned with meaning. These subfields have traditionally been divided according to aspects of meaning: "semantics" refers to grammatical and lexical meanings, while "pragmatics" is concerned with meaning in context. Within linguistics, the subfield of formal semantics studies the denotations of sentences and how they are composed from the meanings of their constituent expressions. Formal semantics draws heavily on philosophy of language and uses formal tools from logic and computer science. On the other hand, cognitive semantics explains linguistic meaning via aspects of general cognition, drawing on ideas from cognitive science such as prototype theory. Pragmatics focuses on phenomena such as speech acts, implicature, and talk in interaction.[23] Unlike semantics, which examines meaning that is conventional or "coded" in a given language, pragmatics studies how the transmission of meaning depends not only on the structural and linguistic knowledge (grammar, lexicon, etc.) of the speaker and listener, but also on the context of the utterance,[24] any pre-existing knowledge about those involved, the inferred intent of the speaker, and other factors.[25] |

意味論と語用論 主な記事:意味論と語用論 意味論と語用論は、意味を扱う言語学の分野です。これらの分野は伝統的に、意味の側面に応じて分類されてきました:「意味論」は文法的・語彙的な意味を扱 い、「語用論」は文脈における意味を扱います。言語学において、形式意味論は文の指称対象と、その構成要素の表現の意味から文が構成される仕組みを研究し ます。形式意味論は、言語哲学に大きく依存し、論理学やコンピュータサイエンスの形式的なツールを使用する。一方、認知意味論は、原型理論などの認知科学 の考え方を活用して、一般的な認知の側面から言語の意味を説明する。 語用論は、発話行為、含意、相互作用における会話などの現象に焦点を当てる。[23] 特定の言語で慣習的または「コード化」されている意味を考察する意味論とは異なり、語用論は、意味の伝達が、話者や聞き手の構造的・言語的知識(文法、語 彙など)だけでなく、発話の状況[24]、関係者に関する既存の知識、話者の意図の推測、その他の要因にもどのように依存するかを研究する。 |

| Phonetics and phonology Main articles: Phonetics and Phonology Phonetics and phonology are branches of linguistics concerned with sounds (or the equivalent aspects of sign languages). Phonetics is largely concerned with the physical aspects of sounds such as their articulation, acoustics, production, and perception. Phonology is concerned with the linguistic abstractions and categorizations of sounds, and it tells us what sounds are in a language, how they do and can combine into words, and explains why certain phonetic features are important to identifying a word.[26] |

音声学と音韻論 主な記事:音声学と音韻論 音声学と音韻論は、音(または手話における同等の側面)を扱う言語学の分野です。音声学は、発声、音響、生成、知覚など、音の物理的な側面を主に扱いま す。音韻論は、音の言語学的抽象化と分類を扱い、言語における音の構成要素、それらの音の組み合わせ方、および単語を形成する仕組みを説明し、特定の音声 的特徴が単語の識別において重要な理由を説明する。[26] |

| Typology This paragraph is an excerpt from Linguistic typology.[edit] Linguistic typology (or language typology) is a field of linguistics that studies and classifies languages according to their structural features to allow their comparison. Its aim is to describe and explain the structural diversity and the common properties of the world's languages.[27] Its subdisciplines include, but are not limited to phonological typology, which deals with sound features; syntactic typology, which deals with word order and form; lexical typology, which deals with language vocabulary; and theoretical typology, which aims to explain the universal tendencies.[28] |

類型論 この段落は、言語類型論からの抜粋です。[編集] 言語類型論(または言語類型学)は、言語の構造的特徴に基づいて言語を研究し分類し、その比較を可能にする言語学の分野です。その目的は、世界の言語の構 造的多様性と共通する特性を記述し説明することだ。[27] そのサブ分野には、音韻類型論(音の特徴を扱う)、構文類型論(語順や形態を扱う)、語彙類型論(言語の語彙を扱う)、および普遍的な傾向を説明すること を目的とする理論類型論などが含まれる。[28] |

| Structures This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Linguistic structures are pairings of meaning and form. Any particular pairing of meaning and form is a Saussurean linguistic sign. For instance, the meaning "cat" is represented worldwide with a wide variety of different sound patterns (in oral languages), movements of the hands and face (in sign languages), and written symbols (in written languages). Linguistic patterns have proven their importance for the knowledge engineering field especially with the ever-increasing amount of available data. Linguists focusing on structure attempt to understand the rules regarding language use that native speakers know (not always consciously). All linguistic structures can be broken down into component parts that are combined according to (sub)conscious rules, over multiple levels of analysis. For instance, consider the structure of the word "tenth" on two different levels of analysis. On the level of internal word structure (known as morphology), the word "tenth" is made up of one linguistic form indicating a number and another form indicating ordinality. The rule governing the combination of these forms ensures that the ordinality marker "th" follows the number "ten." On the level of sound structure (known as phonology), structural analysis shows that the "n" sound in "tenth" is made differently from the "n" sound in "ten" spoken alone. Although most speakers of English are consciously aware of the rules governing internal structure of the word pieces of "tenth", they are less often aware of the rule governing its sound structure. Linguists focused on structure find and analyze rules such as these, which govern how native speakers use language. |

構造 このセクションでは、出典が一切引用されていません。信頼できる出典を引用して、このセクションの改善にご協力ください。出典が明記されていない情報は、 削除される場合があります。(2019年1月) (このメッセージの削除方法と時期について) 言語構造とは、意味と形式のペアのことです。意味と形式の特定のペアは、ソシュールの言語記号です。例えば、「猫」という意味は、世界中でさまざまな音 (口頭言語)、手や顔の動き(手話)、文字(文字言語)によって表現されている。言語パターンは、利用可能なデータ量がますます増加している知識工学の分 野において、その重要性が証明されている。 構造に焦点を当てた言語学者は、ネイティブスピーカーが(必ずしも意識的にではないものの)知っている言語の使用に関する規則を理解しようとしている。す べての言語構造は、複数の分析レベルにわたって、(潜在的)意識的な規則に従って組み合わせられた構成要素に分解することができる。例えば、「10番目」 という単語の構造を 2 つの異なる分析レベルで考えてみよう。単語の内部構造(形態論)のレベルでは、「10番目」という単語は、数字を表す言語形式と序数を表す言語形式の 2 つの言語形式で構成されている。これらの形態の組み合わせを規定する規則により、序数「th」は数字「ten」の後に必ず続く。音構造(音韻論)のレベル では、構造分析により、「tenth」の「n」の音は、「ten」の「n」の音とは異なって発音されることがわかる。英語話者の大多数は、「tenth」 の単語の内部構造を支配する規則を意識的に認識していますが、その音構造を支配する規則については、意識的に認識している人は少ないです。構造に焦点を当 てた言語学者は、このような規則を発見し分析し、ネイティブスピーカーが言語を使用する方法を支配する規則を明らかにします。 |

| Grammar Grammar is a system of rules which governs the production and use of utterances in a given language. These rules apply to sound[29] as well as meaning, and include componential subsets of rules, such as those pertaining to phonology (the organization of phonetic sound systems), morphology (the formation and composition of words), and syntax (the formation and composition of phrases and sentences).[4] Modern frameworks that deal with the principles of grammar include structural and functional linguistics, and generative linguistics.[30] Sub-fields that focus on a grammatical study of language include the following: Phonetics, the study of the physical properties of speech sound production and perception, and delves into their acoustic and articulatory properties Phonology, the study of sounds as abstract elements in the speaker's mind that distinguish meaning (phonemes) Morphology, the study of morphemes, or the internal structures of words and how they can be modified Syntax, the study of how words combine to form grammatical phrases and sentences Semantics, the study of lexical and grammatical aspects of meaning[31] Pragmatics, the study of how utterances are used in communicative acts, and the role played by situational context and non-linguistic knowledge in the transmission of meaning[31] Discourse analysis, the analysis of language use in texts (spoken, written, or signed) Stylistics, the study of linguistic factors (rhetoric, diction, stress) that place a discourse in context Semiotics, the study of signs and sign processes (semiosis), indication, designation, likeness, analogy, metaphor, symbolism, signification, and communication |

文法 文法とは、ある言語における発話の生成と使用を支配する規則の体系である。これらの規則は音[29]だけでなく意味にも適用され、音韻論(音声システムの組 織化)、形態論(単語の形成と構成)、文法(句や文の形成と構成)など、規則の構成要素となるサブセットを含む。[4] 文法の原則を扱う現代の枠組みには、構造言語学、機能言語学、生成言語学がある。[30] 言語の文法的研究に焦点を当てたサブ分野には、以下のものがある。 音声学:発話音の生成と知覚の物理的性質を研究し、その音響的・発音的性質を深く探求する学問 音韻論:意味を区別する音の抽象的要素(音素)を研究する学問 形態論:単語の内部構造である形態素とその変化を研究する学問 文法:単語が組み合わさって文法的に正しい句や文を形成する仕組みを研究する分野 意味論:意味の語彙的・文法的側面を研究する分野[31] 語用論:発話がコミュニケーション行為においてどのように使用されるかを研究し、意味の伝達において状況的文脈や非言語的知識が果たす役割を研究する分野 [31] 談話分析、テキスト(話し言葉、書き言葉、手話)における言語の使用の分析 文体学、談話を文脈に置く言語的要因(修辞、語法、強調)の研究 記号論、記号および記号プロセス(記号作用)、指示、指定、類似、類推、隠喩、象徴、意味、コミュニケーションの研究 |

| Discourse Discourse is language as social practice (Baynham, 1995) and is a multilayered concept. As a social practice, discourse embodies different ideologies through written and spoken texts. Discourse analysis can examine or expose these ideologies. Discourse not only influences genre, which is selected based on specific contexts but also, at a micro level, shapes language as text (spoken or written) down to the phonological and lexico-grammatical levels. Grammar and discourse are linked as parts of a system.[32] A particular discourse becomes a language variety when it is used in this way for a particular purpose, and is referred to as a register.[33] There may be certain lexical additions (new words) that are brought into play because of the expertise of the community of people within a certain domain of specialization. Thus, registers and discourses distinguish themselves not only through specialized vocabulary but also, in some cases, through distinct stylistic choices. People in the medical fraternity, for example, may use some medical terminology in their communication that is specialized to the field of medicine. This is often referred to as being part of the "medical discourse", and so on. |

談話(ディスコース) 談話は、社会的実践としての言語(Baynham、1995)であり、多層的な概念です。社会的実践として、談話は、書面や口頭によるテキストを通じて、 異なるイデオロギーを体現しています。談話分析は、これらのイデオロギーを検証または明らかにすることができます。談話は、特定の文脈に基づいて選択され るジャンルに影響を与えるだけでなく、ミクロレベルでは、音韻や語彙・文法レベルに至るまで、テキスト(口頭または書面)としての言語を形作っています。 文法と談話は、システムの一部として関連している[32]。特定の談話は、特定の目的のためにこのように使用されると、言語の多様性となり、レジスターと 呼ばれる[33]。特定の専門分野におけるコミュニティの専門知識のために、特定の語彙(新しい単語)が追加される場合がある。したがって、レジスターと 談話は、専門用語だけでなく、場合によっては、明確な文体の選択によっても区別される。たとえば、医療関係者は、コミュニケーションにおいて、医療分野に 特化した医療用語を使用する場合がある。これは、多くの場合、「医療談話」の一部などと呼ばれる。 |

| Lexicon The lexicon is a catalogue of words and terms that are stored in a speaker's mind. The lexicon consists of words and bound morphemes, which are parts of words that can not stand alone, like affixes. In some analyses, compound words and certain classes of idiomatic expressions and other collocations are also considered to be part of the lexicon. Dictionaries represent attempts at listing, in alphabetical order, the lexicon of a given language; usually, however, bound morphemes are not included. Lexicography, closely linked with the domain of semantics, is the science of mapping the words into an encyclopedia or a dictionary. The creation and addition of new words (into the lexicon) is called coining or neologization,[34] and the new words are called neologisms. It is often believed that a speaker's capacity for language lies in the quantity of words stored in the lexicon. However, this is often considered a myth by linguists. The capacity for the use of language is considered by many linguists to lie primarily in the domain of grammar, and to be linked with competence, rather than with the growth of vocabulary. Even a very small lexicon is theoretically capable of producing an infinite number of sentences. Vocabulary size is relevant as a measure of comprehension. There is general consensus that reading comprehension of a written text in English requires 98% coverage, meaning that the person understands 98% of the words in the text.[35] The question of how much vocabulary is needed is therefore related to which texts or conversations need to be understood. A common estimate is 6-7,000 word families to understand a wide range of conversations and 8-9,000 word families to be able to read a wide range of written texts.[36] |

語彙(レキシコン) 語彙とは、話者の頭の中に蓄積されている単語や用語のリストのことです。語彙は、単語と、接辞のように単独では存在できない単語の一部である結合形態素で 構成されている。一部の分析では、複合語や特定の種類の慣用表現、その他のコロケーションも語彙の一部と見なされます。辞書は、特定の言語のレキシコンを アルファベット順に列挙しようとする試みである。ただし、通常は結合形態素は含まれない。語彙学は、意味論の分野と密接に関連し、単語を百科事典や辞書に 分類する科学である。新しい単語(語彙に追加されるもの)の創造と追加は、造語または新語化[34]と呼ばれ、新しい単語は新語と呼ばれる。 言語能力は、語彙に蓄積された単語の量に依存すると考えられることが多い。しかし、これは言語学者によってしばしば神話と見なされている。言語の使用能力 は、多くの言語学者によって主に文法の領域に存在し、語彙の拡大ではなく、能力と関連していると見なされている。理論上、非常に小さな語彙でも無限の文を 生成する可能性がある。 語彙の量は、理解度の尺度として重要だ。英語の文章の読解力には、その文章の 98% を理解できることが必要であるというのが一般的な見解だ。つまり、その文章に登場する単語の 98% を理解できることが必要だということだ。[35] したがって、必要な語彙の量は、理解すべき文章や会話の内容によって異なる。一般的な推定値として、幅広い会話理解には6,000~7,000の語彙群、 幅広い書かれたテキストを読むためには8,000~9,000の語彙群が必要とされている。[36] |

| Style Stylistics also involves the study of written, signed, or spoken discourse through varying speech communities, genres, and editorial or narrative formats in the mass media.[37] It involves the study and interpretation of texts for aspects of their linguistic and tonal style. Stylistic analysis entails the analysis of description of particular dialects and registers used by speech communities. Stylistic features include rhetoric,[38] diction, stress, satire, irony, dialogue, and other forms of phonetic variations. Stylistic analysis can also include the study of language in canonical works of literature, popular fiction, news, advertisements, and other forms of communication in popular culture as well. It is usually seen as a variation in communication that changes from speaker to speaker and community to community. In short, Stylistics is the interpretation of text. In the 1960s, Jacques Derrida, for instance, further distinguished between speech and writing, by proposing that written language be studied as a linguistic medium of communication in itself.[39] Palaeography is therefore the discipline that studies the evolution of written scripts (as signs and symbols) in language.[40] The formal study of language also led to the growth of fields like psycholinguistics, which explores the representation and function of language in the mind; neurolinguistics, which studies language processing in the brain; biolinguistics, which studies the biology and evolution of language; and language acquisition, which investigates how children and adults acquire the knowledge of one or more languages. |

スタイル(文体) 文体学は、さまざまな言語コミュニティ、ジャンル、およびマスメディアの編集形式や物語形式による、書面、手話、または口頭による談話の研究も扱う [37]。文体学は、言語的および音調的なスタイルの側面について、テキストの研究と解釈を行う。文体分析は、言語コミュニティで使用される特定の方言や 語調の記述の分析を伴う。スタイルの特徴には、修辞法[38]、語彙、ストレス、風刺、皮肉、対話、その他の音声的変異が含まれる。スタイル分析には、文 学の古典作品、大衆小説、ニュース、広告、その他の大衆文化におけるコミュニケーション形態における言語の研究も含まれることがある。これは通常、話者や コミュニティによって変化するコミュニケーションの変異と見なされる。要するに、スタイル論はテキストの解釈である。 1960年代には、ジャック・デリダは、書かれた言語をコミュニケーションの言語的媒体として独立して研究すべきだと提案し、言語と文字をさらに区別した [39]。そのため、古文書学は、言語における文字(記号や符号として)の進化の研究分野である。[40] 言語の形式的研究は、心理言語学(言語の心の中の表象と機能を探求する分野)、神経言語学(脳における言語処理を研究する分野)、生物言語学(言語の生物 学と進化を研究する分野)、言語獲得(子どもや大人が1つ以上の言語の知識を獲得する過程を調査する分野)などの分野の発展にもつながった。 |

| Approaches See also: Theory of language Humanistic The fundamental principle of humanistic linguistics, especially rational and logical grammar, is that language is an invention created by people. A semiotic tradition of linguistic research considers language a sign system which arises from the interaction of meaning and form.[41] The organization of linguistic levels is considered computational.[42] Linguistics is essentially seen as relating to social and cultural studies because different languages are shaped in social interaction by the speech community.[43] Frameworks representing the humanistic view of language include structural linguistics, among others.[44] Structural analysis means dissecting each linguistic level: phonetic, morphological, syntactic, and discourse, to the smallest units. These are collected into inventories (e.g. phoneme, morpheme, lexical classes, phrase types) to study their interconnectedness within a hierarchy of structures and layers.[45] Functional analysis adds to structural analysis the assignment of semantic and other functional roles that each unit may have. For example, a noun phrase may function as the subject or object of the sentence; or the agent or patient.[46] Functional linguistics, or functional grammar, is a branch of structural linguistics. In the humanistic reference, the terms structuralism and functionalism are related to their meaning in other human sciences. The difference between formal and functional structuralism lies in the way that the two approaches explain why languages have the properties they have. Functional explanation entails the idea that language is a tool for communication, or that communication is the primary function of language. Linguistic forms are consequently explained by an appeal to their functional value, or usefulness. Other structuralist approaches take the perspective that form follows from the inner mechanisms of the bilateral and multilayered language system.[47] |

アプローチ 参照:言語理論 人文科学 人文言語学、特に合理的かつ論理的な文法の根本原理は、言語は人民によって創造された発明である、というものである。言語研究の記号論的伝統では、言語は 意味と形式の相互作用から生じる記号体系とみなされる[41]。言語レベルの構成は計算可能とみなされる[42]。言語学は、異なる言語は社会言語共同体 による社会的相互作用の中で形成されるため、本質的に社会科学や文化科学に関連すると考えられている[43]。言語の人文科学的な見方を表す枠組みとして は、構造言語学などが挙げられる[44]。 構造分析とは、音声、形態、文法、談話といった各言語レベルを最小単位まで分解することを意味する。これらの単位は、構造や層の階層内での相互関係を研究 するために、一覧表(例:音素、形態素、語彙類、句の種類)にまとめられる。[45] 機能分析は、構造分析に、各単位が持つ意味やその他の機能的な役割を割り当てることを加える。例えば、名詞句は、文の主語や目的語、あるいは行為者や受動 者として機能する。[46] 機能言語学、あるいは機能文法は、構造言語学の一分野だ。人文科学の分野では、構造主義と機能主義という用語は、他の人文科学における意味と関連してい る。形式構造主義と機能構造主義の違いは、言語がなぜその特性を持っているかを説明するアプローチの違いにある。機能的説明は、言語はコミュニケーション のツールである、またはコミュニケーションが言語の主要な機能であるという考えを前提としている。言語形式は、その機能的価値または有用性に訴えることで 説明される。他の構造主義的アプローチは、形式は二層構造および多層構造の言語システムの内部メカニズムから派生するという立場を取る。[47] |

| Biological Further information: Biolinguistics and Biosemiotics Approaches such as cognitive linguistics and generative grammar study linguistic cognition with a view towards uncovering the biological underpinnings of language. In Generative Grammar, these underpinning are understood as including innate domain-specific grammatical knowledge. Thus, one of the central concerns of the approach is to discover what aspects of linguistic knowledge are innate and which are not.[48][49] Cognitive linguistics, in contrast, rejects the notion of innate grammar, and studies how the human mind creates linguistic constructions from event schemas,[50] and the impact of cognitive constraints and biases on human language.[51] In cognitive linguistics, language is approached via the senses.[52][53] A closely related approach is evolutionary linguistics[54] which includes the study of linguistic units as cultural replicators.[55][56] It is possible to study how language replicates and adapts to the mind of the individual or the speech community.[57][58] Construction grammar is a framework which applies the meme concept to the study of syntax.[59][60][61][62] The generative versus evolutionary approach are sometimes called formalism and functionalism, respectively.[63] This reference is however different from the use of the terms in human sciences.[64] |

生物学的 詳細情報:生物言語学および生物記号論 認知言語学や生成文法などのアプローチは、言語の生物学的基盤を解明することを目的として、言語認知を研究している。生成文法では、これらの基盤は、生得 的な領域特異的な文法知識を含むものと理解されている。したがって、このアプローチの中心的な関心事の一つは、言語知識のうち、生得的な側面と後天的な側 面を区別することである。[48][49] これに対し、認知言語学は先天的な文法の概念を否定し、人間の心がイベント・スキーマから言語構造をどのように生成するか[50]、および認知的制約やバ イアスが人間言語に与える影響を研究する。[51] 認知言語学では、言語は感覚を通じてアプローチされる。[52][53] 密接に関連するアプローチとして、言語単位を文化的複製子として研究する進化言語学があります。[54][55][56] 言語が個人や言語共同体の心にどのように複製され適応するかを研究することが可能です。[57][58] 構成文法は、ミームの概念を文法研究に応用する枠組みです。[59][60][61][62] 生成論的アプローチと進化論的アプローチは、それぞれ形式主義と機能主義と呼ばれることもある。[63] ただし、この用語の使用法は、人間科学における用語の使用法とは異なる。[64] |

| Methodology This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Modern linguistics is primarily descriptive.[65] Linguists describe and explain features of language without making subjective judgments on whether a particular feature or usage is "good" or "bad". This is analogous to practice in other sciences: a zoologist studies the animal kingdom without making subjective judgments on whether a particular species is "better" or "worse" than another. Prescription, on the other hand, is an attempt to promote particular linguistic usages over others, often favoring a particular dialect or "acrolect". This may have the aim of establishing a linguistic standard, which can aid communication over large geographical areas. It may also, however, be an attempt by speakers of one language or dialect to exert influence over speakers of other languages or dialects (see Linguistic imperialism). An extreme version of prescriptivism can be found among censors, who attempt to eradicate words and structures that they consider to be destructive to society. Prescription, however, may be practised appropriately in language instruction, like in ELT, where certain fundamental grammatical rules and lexical items need to be introduced to a second-language speaker who is attempting to acquire the language.[citation needed] |

方法論 このセクションには、検証のための追加の引用が必要です。信頼できる出典をこのセクションに追加して、この記事の改善にご協力ください。出典が明記されて いない内容は、削除される場合があります。(2024年2月) (このメッセージの削除方法についてはこちらをご覧ください) 現代言語学は主に記述的である[65]。言語学者は、特定の機能や使用法が「良い」か「悪い」かを主観的に判断することなく、言語の特徴を記述し、説明す る。これは他の科学の実践と類似している。動物学者は、特定の種が別の種よりも「優れている」か「劣っている」かを主観的に判断することなく、動物界を研 究する。 一方、規範主義は、特定の言語の使用法を他の使用法よりも優先し、多くの場合、特定の方言や「高語」を好む試みです。これは、広大な地域でのコミュニケー ションに役立つ言語の標準を確立することを目的としている場合があります。しかし、ある言語や方言の話し手が、他の言語や方言の話し手に影響力を行使しよ うとする試みである場合もあります(言語帝国主義を参照)。規範主義の極端な形態は、社会に破壊的だと考える言葉や構造を排除しようとする検閲者に見られ る。ただし、規範は、第二言語学習者(ELTなど)が言語を習得しようとする際に、基本的な文法規則や語彙項目を導入する必要がある場合など、言語教育に おいて適切に実践されることもある。[出典が必要] |

| Sources Most contemporary linguists work under the assumption that spoken data and signed data are more fundamental than written data. This is because Speech appears to be universal to all human beings capable of producing and perceiving it, while there have been many cultures and speech communities that lack written communication; Features appear in speech which are not always recorded in writing, including phonological rules, sound changes, and speech errors; All natural writing systems reflect a spoken language (or potentially a signed one), even with pictographic scripts like Dongba writing Naxi homophones with the same pictogram, and text in writing systems used for two languages changing to fit the spoken language being recorded; Speech evolved before human beings invented writing; Individuals learn to speak and process spoken language more easily and earlier than they do with writing. Nonetheless, linguists agree that the study of written language can be worthwhile and valuable. For research that relies on corpus linguistics and computational linguistics, written language is often much more convenient for processing large amounts of linguistic data. Large corpora of spoken language are difficult to create and hard to find, and are typically transcribed and written. In addition, linguists have turned to text-based discourse occurring in various formats of computer-mediated communication as a viable site for linguistic inquiry. The study of writing systems themselves, graphemics, is, in any case, considered a branch of linguistics. |

言語学の研究資料 現代の言語学者の多くは、発話データと手話データは、文字データよりもより基本的であるという前提に基づいて研究を行っている。これは、 発話は、それを生成し、認識することができるすべての人間にとって普遍的なものであるように見えるのに対し、文字によるコミュニケーションを持たない文化 や言語共同体も数多く存在しているからである。 発話には、音韻規則、音の変化、発話誤りなど、文字では必ずしも記録されない特徴があるからである。 すべての自然言語の文字体系は、口頭言語(または潜在的に手話言語)を反映している。例えば、ドンバ文字のような絵文字体系でも、ナシ語の同音異義語は同 じ絵文字で表され、二言語用の文字体系で書かれたテキストは、記録される口頭言語に合わせて変化する。 言語は、人間が文字を発明する前に進化した。 個人が言語を話すことや処理することは、文字を学ぶよりも容易で、早期に習得される。 それでも、言語学者たちは、書かれた言語の研究が価値あるものだと同意している。コーパス言語学や計算言語学に依存する研究では、書かれた言語は大量の言 語データを処理する際に格段に便利だ。口頭言語の大きなコーパスを作成したり見つけるのは困難で、通常は書き起こされ、文字化される。さらに、言語学者た ちは、コンピュータ媒介コミュニケーションのさまざまな形式で発生するテキストベースの会話や文脈を、言語研究の有効な対象として注目している。 文字体系そのものの研究であるグラフェミクスは、いずれにせよ言語学の一分野とされています。 |

| Analysis Before the 20th century, linguists analysed language on a diachronic plane, which was historical in focus. This meant that they would compare linguistic features and try to analyse language from the point of view of how it had changed between then and later. However, with the rise of Saussurean linguistics in the 20th century, the focus shifted to a more synchronic approach, where the study was geared towards analysis and comparison between different language variations, which existed at the same given point of time. At another level, the syntagmatic plane of linguistic analysis entails the comparison between the way words are sequenced, within the syntax of a sentence. For example, the article "the" is followed by a noun, because of the syntagmatic relation between the words. The paradigmatic plane, on the other hand, focuses on an analysis that is based on the paradigms or concepts that are embedded in a given text. In this case, words of the same type or class may be replaced in the text with each other to achieve the same conceptual understanding. |

分析 20 世紀以前は、言語学者は歴史的な観点に焦点を当てた通時的な平面で言語を分析していました。つまり、言語の特徴を比較し、その言語が当時とその後でどのよ うに変化したかという観点から言語を分析しようとしていました。しかし、20 世紀にソシュール言語学が登場すると、焦点はより通時的なアプローチに移り、同じ時点に存在する異なる言語のバリエーションの分析と比較に研究が向けられ るようになった。 別のレベルでは、言語分析の統語的側面では、文の構文の中で単語が並べられる順序の比較が行われる。例えば、「the」という冠詞は、単語間の連語関係の ため、名詞に続く。一方、パラダイム的平面は、与えられたテキストに埋め込まれたパラダイムや概念に基づく分析に焦点を当てている。この場合、同じ種類や クラスの単語は、同じ概念的理解を得るために、テキスト内で互いに置き換えられる。 |

| History Main article: History of linguistics The earliest activities in the description of language have been attributed to the 6th-century-BC Indian grammarian Pāṇini[66][67] who wrote a formal description of the Sanskrit language in his Aṣṭādhyāyī.[68][69] Today, modern-day theories on grammar employ many of the principles that were laid down then.[70] Nomenclature Before the 20th century, the term philology, first attested in 1716,[71] was commonly used to refer to the study of language, which was then predominantly historical in focus.[72][73] Since Ferdinand de Saussure's insistence on the importance of synchronic analysis, however, this focus has shifted[73] and the term philology is now generally used for the "study of a language's grammar, history, and literary tradition", especially in the United States[74] (where philology has never been very popularly considered as the "science of language").[71] Although the term linguist in the sense of "a student of language" dates from 1641,[75] the term linguistics is first attested in 1847.[75] It is now the usual term in English for the scientific study of language,[76][77] though linguistic science is sometimes used. Linguistics is a multi-disciplinary field of research that combines tools from natural sciences, social sciences, formal sciences, and the humanities.[78][79][80][81] Many linguists, such as David Crystal, conceptualize the field as being primarily scientific.[82] The term linguist applies to someone who studies language or is a researcher within the field, or to someone who uses the tools of the discipline to describe and analyse specific languages.[83] |

歴史 主な記事:言語学の歴史 言語の記述における最も初期の活動は、紀元前6世紀のインディアン文法学者パニーニ[66][67]によるものとされている。彼は、サンスクリット語を正 式に記述した『アシュタディヤイ』を著した[68][69]。今日、文法に関する現代的な理論は、当時確立された原則の多くを採用している[70]。 命名 20世紀以前、言語の研究を指す用語として、1716年に初めて記録された「言語学」が一般的に用いられていた。[72][73] しかし、フェルディナン・ド・ソシュールが同期的分析の重要性を強調して以来、この焦点はシフトし[73]、現在では「言語の文法、歴史、文学伝統の研 究」を指す用語として用いられるようになった。特にアメリカ合衆国では[74](ここで「言語学」は「言語の科学」として広く認識されてこなかった)。 [71] 「言語の研究者」という意味での「言語学者」という用語は1641年に遡るが[75]、「言語学」という用語は1847年に初めて記録されている [75]。現在では、言語の科学的研究を指す英語の一般的な用語となっている[76][77]。ただし、「言語科学」という用語も時々使用される。 言語学は、自然科学、社会科学、形式科学、人文科学のツールを組み合わせた多分野にわたる研究分野だ。[78][79][80][81] デビッド・クリスタルをはじめとする多くの言語学者は、この分野を主に科学的なものとして捉えている。[82] 「言語学者」という用語は、言語を研究する人、この分野の研究者、またはこの学問のツールを用いて特定の言語を記述・分析する人を指す。[83] |

| Early grammarians Further information: Philology and Grammarian (Greco-Roman) An early formal study of language was in India with Pāṇini, the 6th century BC grammarian who formulated 3,959 rules of Sanskrit morphology. Pāṇini's systematic classification of the sounds of Sanskrit into consonants and vowels, and word classes, such as nouns and verbs, was the first known instance of its kind. In the Middle East, Sibawayh, a Persian, made a detailed description of Arabic in AD 760 in his monumental work, Al-kitab fii an-naħw (الكتاب في النحو, The Book on Grammar), the first known author to distinguish between sounds and phonemes (sounds as units of a linguistic system). Western interest in the study of languages began somewhat later than in the East,[84] but the grammarians of the classical languages did not use the same methods or reach the same conclusions as their contemporaries in the Indic world. Early interest in language in the West was a part of philosophy, not of grammatical description. The first insights into semantic theory were made by Plato in his Cratylus dialogue, where he argues that words denote concepts that are eternal and exist in the world of ideas. This work is the first to use the word etymology to describe the history of a word's meaning. Around 280 BC, one of Alexander the Great's successors founded a university (see Musaeum) in Alexandria, where a school of philologists studied the ancient texts in Greek, and taught Greek to speakers of other languages. While this school was the first to use the word "grammar" in its modern sense, Plato had used the word in its original meaning as "téchnē grammatikḗ" (Τέχνη Γραμματική), the "art of writing", which is also the title of one of the most important works of the Alexandrine school by Dionysius Thrax.[85] Throughout the Middle Ages, the study of language was subsumed under the topic of philology, the study of ancient languages and texts, practised by such educators as Roger Ascham, Wolfgang Ratke, and John Amos Comenius.[86] |

初期の文法学者 詳細情報:言語学および文法学者(ギリシャ・ローマ) 言語の初期の正式な研究は、紀元前6世紀の文法学者パニニによってインドで行われ、サンスクリット語の形態論に関する3,959の規則を定式化した。パニ ニによるサンスクリット語の音の体系的な分類(子音と母音、名詞と動詞などの品詞)は、この種の最初の例として知られている。中東では、ペルシャ人のシバ ウィーが760年に『アル=キターブ・フィー・アン=ナフ』(The Book on Grammar)という大著でアラビア語の詳細な記述を行い、音と音素(言語システムの単位としての音)を区別した最初の著者として知られている。西欧に おける言語研究への関心は東洋よりもやや遅れて始まった[84]が、古典言語の文法家は、インド・ヨーロッパ語族の世界の同時代人と同じ方法を使用した り、同じ結論に達したりしなかった。西欧における言語への初期の関心は、文法記述ではなく哲学の一部だった。意味論の最初の洞察は、プラトンの『クラテュ ロス』で述べられたもので、彼は、言葉は永遠で、観念の世界に存在する概念を表す、と主張している。この著作は、単語の意味の歴史を説明するために「語 源」という用語を初めて使用した。紀元前 280 年頃、アレクサンダー大王の後継者の 1 人がアレクサンドリアに大学(ムサエウムを参照)を設立し、そこで言語学者たちがギリシャ語の古代テキストを研究し、他の言語を話す人たちにギリシャ語を 教えた。この学校は、現代的な意味での「文法」という用語を初めて使用したが、プラトンは、この用語を本来の意味である「téchnē grammatikḗ」 (Τέχνη Γραμματική)という、ディオニュシオス・トラクスによるアレクサンドリア学派の最も重要な著作のタイトルでもある「文章の芸術」という意味で、 この単語を使用していた。[85]中世を通じて、言語の研究は、ロジャー・アシャム、ヴォルフガング・ラトケ、ヨハン・アモス・コメニウスなどの教育者に よって実践された、古代の言語やテキストの研究である文献学という分野に組み込まれていた。[86] |

| Comparative philology In the 18th century, the first use of the comparative method by William Jones sparked the rise of comparative linguistics.[87] Bloomfield attributes "the first great scientific linguistic work of the world" to Jacob Grimm, who wrote Deutsche Grammatik.[88] It was soon followed by other authors writing similar comparative studies on other language groups of Europe. The study of language was broadened from Indo-European to language in general by Wilhelm von Humboldt, of whom Bloomfield asserts:[88] This study received its foundation at the hands of the Prussian statesman and scholar Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767–1835), especially in the first volume of his work on Kavi, the literary language of Java, entitled Über die Verschiedenheit des menschlichen Sprachbaues und ihren Einfluß auf die geistige Entwickelung des Menschengeschlechts (On the Variety of the Structure of Human Language and its Influence upon the Mental Development of the Human Race). |

比較言語学 18 世紀、ウィリアム・ジョーンズが比較手法を初めて用いたことで、比較言語学が台頭した[87]。ブルームフィールドは、「世界初の偉大な科学言語学著作」 を、ドイツ語文法書『Deutsche Grammatik』を著したヤコブ・グリムに与えている[88]。その後、他の著者たちも、ヨーロッパの他の言語群について同様の比較研究を著した。言 語の研究は、インド・ヨーロッパ語族から言語一般へと拡大された。ブルームフィールドは、ヴィルヘルム・フォン・フンボルトについて次のように述べてい る。[88] この研究は、プロイセンの政治家であり学者であるヴィルヘルム・フォン・フンボルト(1767–1835)によって基礎が築かれた。特に、ジャワの文学言 語であるカヴィに関する著作『Über die Verschiedenheit des menschlichen Sprachbaues und ihren Einfluß auf die geistige Entwickelung des Menschengeschlechts(人間の言語構造の多様性とその人種の発達への影響について)』の第 1 巻で確立された。 |

| 20th-century developments There was a shift of focus from historical and comparative linguistics to synchronic analysis in early 20th century. Structural analysis was improved by Leonard Bloomfield, Louis Hjelmslev; and Zellig Harris who also developed methods of discourse analysis. Functional analysis was developed by the Prague linguistic circle and André Martinet. As sound recording devices became commonplace in the 1960s, dialectal recordings were made and archived, and the audio-lingual method provided a technological solution to foreign language learning. The 1960s also saw a new rise of comparative linguistics: the study of language universals in linguistic typology. Towards the end of the century the field of linguistics became divided into further areas of interest with the advent of language technology and digitalized corpora.[89][90][91] |

20世紀の発展 20世紀初頭、歴史言語学や比較言語学から、共時分析へと焦点が移った。構造分析は、レナード・ブルームフィールド、ルイ・ヘルムスレフ、そして談話分析 の手法も開発したゼリック・ハリスによって改良された。機能分析は、プラハ言語学派とアンドレ・マルティネによって発展した。1960年代に音声記録装置 が普及すると、方言の記録が作成されアーカイブされ、音声言語法が外国語学習の技術的解決策を提供した。1960年代には比較言語学が再興し、言語類型論 における言語の普遍性研究が進んだ。20世紀末には、言語技術とデジタル化されたコーパスの登場により、言語学の分野はさらに細分化されました。[89] [90][91] |

| Areas of research This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Linguistics" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (August 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Sociolinguistics Main article: Sociolinguistics Sociolinguistics is the study of how language is shaped by social factors. This sub-discipline focuses on the synchronic approach of linguistics, and looks at how a language in general, or a set of languages, display variation and varieties at a given point in time. The study of language variation and the different varieties of language through dialects, registers, and idiolects can be tackled through a study of style, as well as through analysis of discourse. Sociolinguists research both style and discourse in language, as well as the theoretical factors that are at play between language and society. |

研究分野 このセクションには、検証のための追加の引用が必要です。信頼できる出典をこのセクションに追加して、この記事の改善にご協力ください。出典のない内容 は、削除される場合があります。 出典を探す:「言語学」 – ニュース · 新聞 · 書籍 · 学者 · JSTOR (2021年8月) (このメッセージの削除方法と時期について) 社会言語学 主な記事:社会言語学 社会言語学は、言語が社会的要因によってどのように形成されるかを研究する学問だ。この学問分野は、言語学の通時的なアプローチに焦点を当て、一般的な言 語、あるいは一連の言語が、ある特定の時点でどのように変化や多様性を示すかを考察する。方言、語調、個人語などによる言語のバリエーションや異なる言語 のバリエーションの研究は、スタイルの研究や談話分析によって取り組むことができる。社会言語学者は、言語のスタイルや談話、そして言語と社会の間で作用 する理論的要因の両方を研究している。 |

| Developmental linguistics Main article: Developmental linguistics Developmental linguistics is the study of the development of linguistic ability in individuals, particularly the acquisition of language in childhood. Some of the questions that developmental linguistics looks into are how children acquire different languages, how adults can acquire a second language, and what the process of language acquisition is.[92] |

発達言語学 主な記事:発達言語学 発達言語学は、個人における言語能力の発達、特に幼児期の言語習得を研究する学問だ。発達言語学が研究する課題としては、子供たちがどのように異なる言語 を習得するのか、大人が第二言語を習得するにはどうすればよいのか、言語習得のプロセスはどのようなものなのか、などが挙げられる。 |

| Neurolinguistics Main article: Neurolinguistics Neurolinguistics is the study of the structures in the human brain that underlie grammar and communication. Researchers are drawn to the field from a variety of backgrounds, bringing along a variety of experimental techniques as well as widely varying theoretical perspectives. Much work in neurolinguistics is informed by models in psycholinguistics and theoretical linguistics, and is focused on investigating how the brain can implement the processes that theoretical and psycholinguistics propose are necessary in producing and comprehending language. Neurolinguists study the physiological mechanisms by which the brain processes information related to language, and evaluate linguistic and psycholinguistic theories, using aphasiology, brain imaging, electrophysiology, and computer modelling. Amongst the structures of the brain involved in the mechanisms of neurolinguistics, the cerebellum which contains the highest numbers of neurons has a major role in terms of predictions required to produce language.[93] |

神経言語学 主な記事:神経言語学 神経言語学は、文法やコミュニケーションの基盤となる人間の脳の構造を研究する学問だよ。この分野には、多様な背景を持つ研究者が集まり、多様な実験手法 や理論的視点をもたらしている。神経言語学の研究の多くは、心理言語学や理論言語学のモデルを参考にしており、理論言語学や心理言語学が言語の生成と理解 に必要だと提唱するプロセスを脳がどのように実現しているかを調査することに焦点を当てている。神経言語学者は、脳が言語に関連する情報を処理する生理学 的メカニズムを研究し、失語症学、脳画像、電気生理学、コンピュータモデルを用いて、言語学と心理言語学の理論を評価する。神経言語学のメカニズムに関与 する脳の構造のうち、最も多くの神経細胞を含む小脳は、言語の生成に必要な予測において重要な役割を果たしている。[93] |

| Applied linguistics Main article: Applied linguistics Linguists are largely concerned with finding and describing the generalities and varieties both within particular languages and among all languages. Applied linguistics takes the results of those findings and "applies" them to other areas. Linguistic research is commonly applied to areas such as language education, lexicography, translation, language planning, which involves governmental policy implementation related to language use, and natural language processing. "Applied linguistics" has been argued to be something of a misnomer.[94] Applied linguists actually focus on making sense of and engineering solutions for real-world linguistic problems, and not literally "applying" existing technical knowledge from linguistics. Moreover, they commonly apply technical knowledge from multiple sources, such as sociology (e.g., conversation analysis) and anthropology. (Constructed language fits under Applied linguistics.) Today, computers are widely used in many areas of applied linguistics. Speech synthesis and speech recognition use phonetic and phonemic knowledge to provide voice interfaces to computers. Applications of computational linguistics in machine translation, computer-assisted translation, and natural language processing are areas of applied linguistics that have come to the forefront. Their influence has had an effect on theories of syntax and semantics, as modelling syntactic and semantic theories on computers constraints. Linguistic analysis is a sub-discipline of applied linguistics used by many governments to verify the claimed nationality of people seeking asylum who do not hold the necessary documentation to prove their claim.[95] This often takes the form of an interview by personnel in an immigration department. Depending on the country, this interview is conducted either in the asylum seeker's native language through an interpreter or in an international lingua franca like English.[95] Australia uses the former method, while Germany employs the latter; the Netherlands uses either method depending on the languages involved.[95] Tape recordings of the interview then undergo language analysis, which can be done either by private contractors or within a department of the government. In this analysis, linguistic features of the asylum seeker are used by analysts to make a determination about the speaker's nationality. The reported findings of the linguistic analysis can play a critical role in the government's decision on the refugee status of the asylum seeker.[95] |

応用言語学 主な記事:応用言語学 言語学者は、特定の言語内およびすべての言語間の一般性および多様性を見出し、それを記述することに主に関心がある。応用言語学は、これらの発見の結果を 他の分野に「応用」する。言語研究は、言語教育、辞書編集、翻訳、言語使用に関する政府政策の実施を含む言語計画、自然言語処理などの分野に一般的に応用 されている。「応用言語学」という用語は、やや不適切な呼称であるとの指摘がある。[94] 応用言語学者は、言語学の既存の専門知識を文字通り「応用」するのではなく、現実の言語問題の意味を理解し、解決策を設計することに焦点を当てている。さ らに、彼らは社会学(例:会話分析)や人類学など、複数の分野の専門知識を応用することが多い。(人工言語は応用言語学に含まれる。) 現在、コンピュータは応用言語学の多くの分野で広く活用されています。音声合成と音声認識は、音声インターフェースを提供するために音声学と音韻論の知識 を活用しています。機械翻訳、コンピュータ支援翻訳、自然言語処理における計算言語学の応用は、応用言語学の主要な分野として浮上しています。これらの影 響は、コンピュータ上の制約下で文法や意味論の理論をモデル化することで、文法や意味論の理論にも影響を及ぼしています。 言語分析は、必要な書類を所持していない難民申請者の国籍を検証するために、多くの政府で使用されている応用言語学のサブ分野です。[95] これは多くの場合、入国管理局の職員による面接という形で行われます。国によっては、この面接は難民申請者の母国語を通訳を介して行われるか、英語のよう な国際共通語で行われる。[95] オーストラリアは前者の方式を採用しており、ドイツは後者の方式を採用している。オランダは、関与する言語に応じてどちらの方式も採用している。[95] 面接の録音は言語分析の対象となり、これは民間業者または政府の部門内で実施される。この分析では、分析者は、難民申請者の言語的特徴を用いて、その話者 の国籍を判断する。言語分析の結果は、難民申請者の難民認定に関する政府の決定に重要な役割を果たすことがある[95]。 |

| Language documentation Language documentation combines anthropological inquiry (into the history and culture of language) with linguistic inquiry, in order to describe languages and their grammars. Lexicography involves the documentation of words that form a vocabulary. Such a documentation of a linguistic vocabulary from a particular language is usually compiled in a dictionary. Computational linguistics is concerned with the statistical or rule-based modeling of natural language from a computational perspective. Specific knowledge of language is applied by speakers during the act of translation and interpretation, as well as in language education – the teaching of a second or foreign language. Policy makers work with governments to implement new plans in education and teaching which are based on linguistic research. Since the inception of the discipline of linguistics, linguists have been concerned with describing and analysing previously undocumented languages. Starting with Franz Boas in the early 1900s, this became the main focus of American linguistics until the rise of formal linguistics in the mid-20th century. This focus on language documentation was partly motivated by a concern to document the rapidly disappearing languages of indigenous peoples. The ethnographic dimension of the Boasian approach to language description played a role in the development of disciplines such as sociolinguistics, anthropological linguistics, and linguistic anthropology, which investigate the relations between language, culture, and society. The emphasis on linguistic description and documentation has also gained prominence outside North America, with the documentation of rapidly dying indigenous languages becoming a focus in some university programs in linguistics. Language description is a work-intensive endeavour, usually requiring years of field work in the language concerned, so as to equip the linguist to write a sufficiently accurate reference grammar. Further, the task of documentation requires the linguist to collect a substantial corpus in the language in question, consisting of texts and recordings, both sound and video, which can be stored in an accessible format within open repositories, and used for further research.[96] |

言語の文書化 言語の文書化は、言語とその文法を記述するために、人類学的な調査(言語の歴史や文化に関する調査)と言語学的な調査を組み合わせたものです。辞書編纂 は、語彙を構成する単語を文書化することです。特定の言語の言語学的語彙をこのように文書化したものは、通常、辞書として編集されます。計算言語学は、計 算の観点から自然言語の統計的または規則に基づくモデル化を扱う。言語に関する特定の知識は、翻訳や通訳の行為、および第二言語や外国語の教育において、 話者によって適用される。政策立案者は、言語研究に基づく教育や指導の新しい計画を実施するために、政府と協力している。 言語学という学問が確立されて以来、言語学者は、これまで記録されていなかった言語の記述と分析に取り組んできた。1900年代初頭のフランツ・ボアズを 皮切りに、これは20世紀半ばに形式言語学が登場するまで、アメリカの言語学の主な研究対象となった。言語の文書化に重点が置かれたのは、急速に消滅しつ つある先住民族の言語を記録したいという思いがあったためでもある。言語記述に対するボアスのアプローチの民族誌的側面は、言語、文化、社会の関係を研究 する社会言語学、人類言語学、言語人類学などの学問分野の発展に貢献した。 言語の記述と記録の重視は、北米以外でも注目され、急速に消滅しつつある先住民の言語の記録が、一部の大学の言語学プログラムで重点課題となっている。言 語記述は、通常、対象言語に関する数年間の現地調査を要する労力のかかる作業であり、言語学者が十分な正確性を備えた参照文法を書くための基礎を築く必要 がある。さらに、記録の作業では、言語学者に対し、対象言語のテキストと音声・動画の記録からなる大規模なコーパスを収集し、オープンリポジトリ内でアク セス可能な形式で保存し、今後の研究に活用できるようにすることが求められる。[96] |

| Translation Main articles: Translation and Translation studies The sub-field of translation includes the translation of written and spoken texts across media, from digital to print and spoken. To translate literally means to transmute the meaning from one language into another. Translators are often employed by organizations such as travel agencies and governmental embassies to facilitate communication between two speakers who do not know each other's language. Translators are also employed to work within computational linguistics setups like Google Translate, which is an automated program to translate words and phrases between any two or more given languages. Translation is also conducted by publishing houses, which convert works of writing from one language to another in order to reach varied audiences. Cross-national and cross-cultural survey research studies employ translation to collect comparable data among multilingual populations.[97][98] Academic translators specialize in or are familiar with various other disciplines such as technology, science, law, economics, etc. |

翻訳 主な記事:翻訳および翻訳学 翻訳のサブ分野には、デジタルから印刷物、音声など、さまざまなメディア間の文章や音声の翻訳が含まれる。翻訳とは、ある言語の意味を別の言語に忠実に表 現することだ。翻訳者は、旅行代理店や政府大使館などの組織に雇用され、互いの言語を知らない2人の話者のコミュニケーションを円滑にする役割を果たして いる。翻訳者は、Google Translateのような計算言語学のシステムでも働いている。これは、任意の2つ以上の言語間で単語やフレーズを翻訳する自動プログラムだ。翻訳は出 版社でも行われ、作品を別の言語に翻訳して多様な読者層に届けるための作業だ。多国籍および異文化間の調査研究では、多言語を話す人々から比較可能なデー タを収集するために翻訳が活用されている。[97][98] 学術翻訳者は、技術、科学、法律、経済学など、さまざまな分野を専門としているか、あるいは精通している。 |

| Clinical linguistics Main article: Clinical linguistics Clinical linguistics is the application of linguistic theory to the field of speech-language pathology. Speech language pathologists work on corrective measures to treat communication and swallowing disorders. |

臨床言語学 主な記事:臨床言語学 臨床言語学は、言語理論を言語聴覚学の分野に応用した学問です。言語聴覚士は、コミュニケーション障害や嚥下障害の治療のための矯正措置に取り組んでいま す。 |

| Computational linguistics Main article: Computational linguistics Computational linguistics is the study of linguistic issues in a way that is "computationally responsible", i.e., taking careful note of computational consideration of algorithmic specification and computational complexity, so that the linguistic theories devised can be shown to exhibit certain desirable computational properties and their implementations. Computational linguists also work on computer language and software development. |

計算言語学 主な記事:計算言語学 計算言語学とは、アルゴリズムの仕様や計算の複雑さを慎重に考慮した「計算上責任のある」方法で言語の問題を研究する学問です。これにより、考案された言 語理論が特定の望ましい計算特性を示し、その実装が可能であることを示すことができます。計算言語学者は、コンピュータ言語やソフトウェアの開発にも取り 組んでいます。 |

| Evolutionary linguistics Main article: Evolutionary linguistics Evolutionary linguistics is a sociobiological approach to analyzing the emergence of the language faculty through human evolution, and also the application of evolutionary theory to the study of cultural evolution among different languages. It is also a study of the dispersal of various languages across the globe, through movements among ancient communities.[99] |

進化言語学 主な記事:進化言語学 進化言語学は、人間の進化を通じて言語能力の出現を分析する社会生物学的アプローチであり、また、異なる言語間の文化の進化の研究に進化論を適用する学問 でもある。また、古代のコミュニティ間の移動を通じて、さまざまな言語が世界中に拡散した過程の研究でもある。[99] |

| Forensic linguistics Main article: Forensic linguistics Forensic linguistics is the application of linguistic analysis to forensics. Forensic analysis investigates the style, language, lexical use, and other linguistic and grammatical features used in the legal context to provide evidence in courts of law. Forensic linguists have also used their expertise in the framework of criminal cases.[100][101] |

法言語学(司法言語学) 主な記事:法言語学 法言語学とは、法医学に言語分析を適用した分野です。法言語分析は、法廷で証拠として提出される文書や発言の文体、言語、語彙の使用、その他の言語的・文 法的特徴を調査します。法言語学者は、刑事事件の枠組みにおいてもその専門知識を活用しています。[100][101] |

| Articulatory phonetics – A

branch of linguistics studying how humans make sounds Articulatory synthesis – Computational techniques for speech synthesis Axiom of categoricity – Controversial tenet of linguistic theory Critical discourse analysis – Interdisciplinary approach to study discourse Cryptanalysis – Study of analyzing information systems in order to discover their hidden aspects Decipherment – Rediscovery of a language or script's meaning Global language system – Connections between language groups Hermeneutics – Theory and methodology of text interpretation Integrational linguistics – Theory of language Integrationism – Approach in the theory of communication Interlinguistics – Subfield of linguistics Language engineering – Creation of language processing systems Language geography – Study of the geographic distribution of languages Linguistic rights – Right to choose one's own language Metalinguistics – Study of relationship between language and culture Metacommunicative competence – Communication about how information is meant to be interpreted Microlinguistics – Branch of linguistics Onomastics – Study of proper names Reading – Taking in the meaning of letters or symbols Speech processing – Study of speech signals and the processing methods of these signals Stratificational linguistics – Theory of language usage and production Outline and lists Index of linguistics articles List of departments of linguistics List of summer schools of linguistics List of schools of linguistics |

発音音声学 –

人間が発音をどのように行うかを研究する言語学の一分野 発音合成 – 音声合成のための計算技術 カテゴリー性公理 – 言語理論における論争の的となっている原則 批判的談話分析 – 談話を研究するための学際的なアプローチ 暗号解読 – 情報システムの隠れた側面を発見するためにその分析を行う研究 解読 – 言語や文字の意味の再発見 グローバル言語システム – 言語群間のつながり 解釈学 – テキストの解釈に関する理論と方法論 統合言語学 – 言語の理論 統合主義 – コミュニケーション理論におけるアプローチ 対言語学 – 言語学の分野 言語工学 – 言語処理システムの作成 言語地理学 – 言語の地理的分布の研究 言語権 – 自分の言語を選択する権利 メタ言語学 – 言語と文化の関係の研究 メタコミュニケーション能力 – 情報がどのように解釈されるべきかについてのコミュニケーション ミクロ言語学 – 言語学の一分野 地名学 – 固有名詞の研究 読解 – 文字や記号の意味を理解すること 音声処理 – 音声信号とその処理方法の研究 階層言語学 – 言語の使用と生成の理論 概要と一覧 言語学記事の索引 言語学の部門一覧 言語学のサマースクール一覧 言語学の学校一覧 |

| Bibliography Akmajian, Adrian; Demers, Richard; Farmer, Ann; Harnish, Robert (2010). Linguistics: An Introduction to Language and Communication. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-51370-8. Aronoff, Mark; Rees-Miller, Janie, eds. (2000). The handbook of linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell. Bloomfield, Leonard (1983) [1914]. An Introduction to the Study of Language (New ed.). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-8047-3. Chomsky, Noam (1998). On Language. The New Press, New York. ISBN 978-1-56584-475-9. Crystal, David (1990). Linguistics. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-013531-2. Derrida, Jacques (1967). Of Grammatology. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5830-7. Hall, Christopher (2005). An Introduction to Language and Linguistics: Breaking the Language Spell. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8264-8734-6. Isac, Daniela; Charles Reiss (2013). I-language: An Introduction to Linguistics as Cognitive Science (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-966017-9. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2013. McShane, Marjorie; Nirenburg, Sergei (2021). Linguistics for the Age of AI. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262363136. |

参考文献 Akmajian, Adrian; Demers, Richard; Farmer, Ann; Harnish, Robert (2010). Linguistics: An Introduction to Language and Communication. マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-51370-8. アロノフ、マーク、リース・ミラー、ジャニー編(2000)。『言語学ハンドブック』。オックスフォード:ブラックウェル。 ブルームフィールド、レナード(1983) [1914]。『言語研究入門』(新編)。アムステルダム:ジョン・ベンジャミンズ出版。ISBN 978-90-272-8047-3。 チョムスキー、ノーム (1998)。言語について。ニューヨーク、ニュープレス。ISBN 978-1-56584-475-9。 クリスタル、デビッド (1990)。言語学。ペンギンブックス。ISBN 978-0-14-013531-2。 デリダ、ジャック (1967)。『文法学』 The Johns Hopkins University Press。ISBN 978-0-8018-5830-7。 ホール、クリストファー (2005)。『言語と言語学入門:言語の呪縛を解く』 Routledge。ISBN 978-0-8264-8734-6。 イサク、ダニエラ、チャールズ・ライス (2013)。I-language: An Introduction to Linguistics as Cognitive Science (第 2 版)。オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-966017-9。2011年7月6日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2013年5月17日に取得。 マクシェーン、マージョリー;ニレンバーグ、セルゲイ(2021)。『AI時代の言語学』。MITプレス。ISBN 9780262363136。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linguistics#Methodology |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099