典礼音楽

Liturgical music

Church

singing, Tacuinum Sanitatis Casanatensis (14th century)

☆ 注意書き:この記事の例や視点は主にカトリック教会(およびキリスト教会)に関するものであり、他の宗派についてはほとんど、あるいはまったく論じていない(→「宗教音楽」)。さらに、カトリック 教会についても、歴史的な背景を十分に説明しておらず、第二バチカン公会議以降の音楽のみに焦点を当てているように見える。また、この主題に関する世界的 な見解を表しているわけではない。この記事は、必要に応じて、記事を改善したり、トークページで議論したり、新しい記事を作成したりすることができる。 (2021年10月)(この記事のメッセージの削除方法とタイミングについて学ぶ)

| Liturgical music

originated as a part of religious ceremony, and includes a number of

traditions, both ancient and modern. Liturgical music is well known as

a part of Catholic Mass, the Anglican Holy Communion service (or

Eucharist) and Evensong, the Lutheran Divine Service, the Orthodox

liturgy, and other Christian services, including the Divine Office. The qualities that create the distinctive character of liturgical music are based on the notion that liturgical music is conceived and composed according to the norms and needs of the various historic liturgies of particular denominations. |

典礼音楽は宗教儀式の一部として生まれ、古代から現代に至るまで、数多

くの伝統を含んでいる。典礼音楽は、カトリックのミサ、聖公会(または聖餐式)の聖餐式、エヴァンソンク、ルーテルの神聖なサービス、正教会の典礼、そし

て神聖なオフィスを含むその他のキリスト教のサービスとしてよく知られている。 典礼音楽の独特な特徴を生み出す要素は、特定の宗派におけるさまざまな歴史的典礼の規範やニーズに従って、典礼音楽が構想され作曲されるという考えに基づ いている。 |

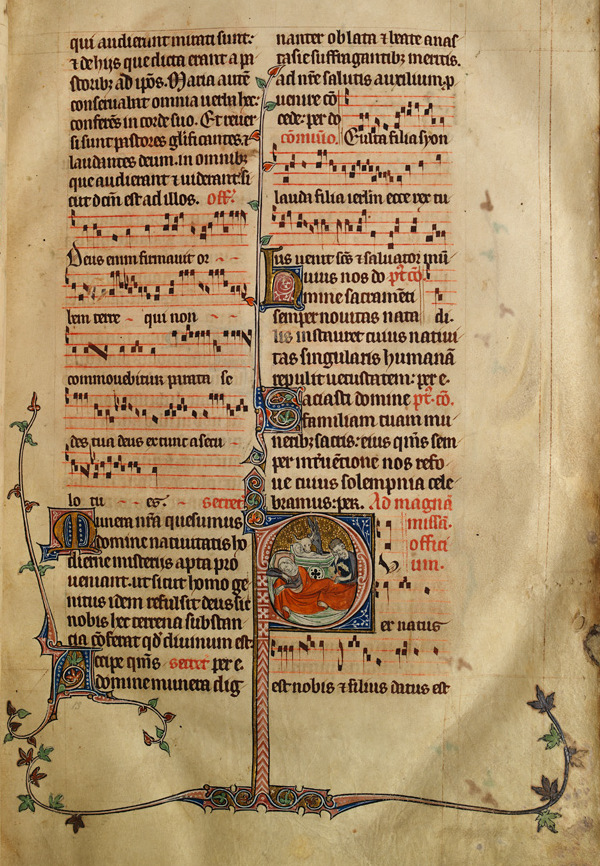

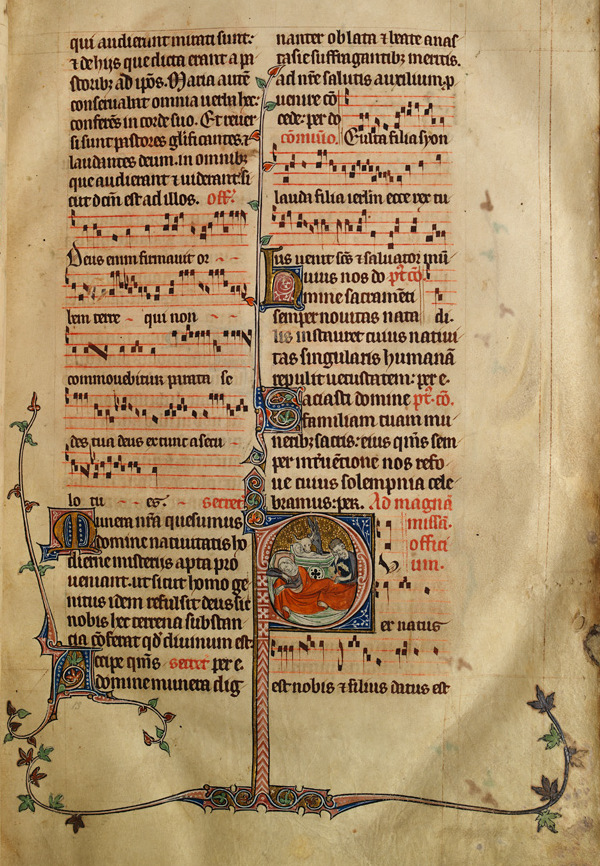

Roman Catholic church music Musical notation in a 14th-century English Missal The interest taken by the Catholic Church in music is shown not only by practitioners, but also by numerous enactments and regulations calculated to foster music worthy of Divine service.[1] Contemporary Catholic official church policy is expressed in the documents of the Second Vatican Council Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy promulgated by Pope Paul VI on December 4, 1963 (items 112–121); and most particularly Musicam sacram, the Instruction on Music In The Liturgy from the Sacred Congregation for Rites, on March 5, 1967. While there have been historic disputes within the church where elaborate music has been under criticism, there are many period works by Orlandus de Lassus, Allegri, Vittoria, where the most elaborate means of expression are employed in liturgical music, but which, nevertheless, are spontaneous outpourings of adoring hearts (cf. contrapuntal or polyphonic music). Besides plain chant and the polyphonic style, the Catholic Church also permits homophonic or figured compositions with or without instrumental accompaniment, written either in ecclesiastical modes, or the modern major or minor keys. Gregorian chant is warmly recommended by the Catholic Church, as both polyphonic music and modern unison music for the assembly.[1] Prior to the Second Vatican Council, according to the motu proprio of Pius X (November 22, 1903), the following were the general guiding principles of the Church: "Sacred music should possess, in the highest degree, the qualities proper to the liturgy, or more precisely, sanctity and purity of form from which its other character of universality spontaneously springs. It must be holy, and must therefore exclude all profanity, not only from itself but also from the manner in which it is presented by those who execute it. It must be true art, for otherwise it cannot exercise on the minds of the hearers that influence which the Church meditates when she welcomes into her liturgy the art of music. But it must also be universal, in the sense that, while every nation is permitted to admit into its ecclesiastical compositions those special forms which may be said to constitute its native music, still these forms must be subordinated in such a manner to the general characteristics of sacred music, that no one of any nation may receive an impression other than good on hearing them."[1] This was expanded upon by Pope Pius XII in his motu proprio Musicae sacrae.[2] In 1963, the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy (Sacrosanctum Concilium) of the Second Vatican Council directed that "bishops and other pastors of souls must be at pains to ensure that, whenever the sacred action is to be celebrated with song, the whole body of the faithful may be able to contribute that active participation which is rightly theirs, as laid down in Art. 28 and 30", which articles say: "To promote active participation, the people should be encouraged to take part by means of acclamations, responses, psalmody, antiphons, and songs".[3] Full and active participation of the people is a recurring theme in the Vatican II document.[4] To achieve this fulsome congregational participation, great restraint in introducing new hymns has proven most helpful.[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liturgical_music |

ローマ・カトリック教会音楽 14世紀の英国の?ミサ典書における楽譜 カトリック教会が音楽に寄せる関心は、実践者だけでなく、神聖な奉仕にふさわしい音楽を育成するための数多くの制定法や規則にも示されている。[1] 現代のカトリック教会の公式方針は、第2バチカン公会議文書『サクロサンクトム・コンシリアム』、 1963年12月4日にパウロ6世が公布した『聖なる典礼に関する憲法』(項目112~121)であり、特に1967年3月5日に儀式省から公布された 『典礼における音楽に関する教令』『ムシカム・サクラム』である。 教会内では、複雑な音楽が批判の対象となる歴史的な論争が繰り広げられてきたが、オルランド・デ・ラッスス、アレグリ、ヴィットーリアなどの時代物の作品 には、典礼音楽の中で最も複雑な表現手段が用いられているが、それにもかかわらず、敬虔な心からの自然なほとばしりであるものも多い(対位法音楽や多声音 楽を参照)。単純な聖歌やポリフォニー様式の他に、カトリック教会は、器楽伴奏付きまたは器楽伴奏なしのホモフォニーまたは数字付き作曲、教会旋法または 現代のメジャーまたはマイナーキーでの作曲も許可している。グレゴリオ聖歌は、ポリフォニー音楽と現代のユニゾン音楽の両方として、集会のためにカトリッ ク教会によって推奨されている。[1] 第2バチカン公会議に先立ち、ピウス10世のモツプロプリオ(1903年11月22日)によると、教会の一般的な指針は以下の通りであった。「聖なる音楽 は、典礼にふさわしい資質を最高度に備えているべきであり、より正確に言えば、その普遍性という他の特性が自然に生じる、形式の神聖さと純粋さである。そ れは神聖でなければならず、したがって、それ自体からだけでなく、それを演奏する人々によって表現される方法からも、あらゆる俗悪なものを排除しなければ ならない。それは真の芸術でなければならず、そうでなければ、教会が音楽という芸術を典礼に取り入れる際に意図しているような影響を、聴衆の心に及ぼすこ とはできない。しかし、普遍的であることも必要である。つまり、それぞれの国民が自国の音楽を構成するといえるような特別な形式を教会の作曲に認めること は許されるが、それらの形式は、聖なる音楽の一般的な特徴に従属するものでなければならず、どの国民もそれらを聴いて良い印象以外を受けないようにしなけ ればならない。」[1] これは、教皇ピウス12世のモトゥス・プロプリオ『聖なる音楽』でさらに詳しく述べられている。[2] 1963年、第2バチカン公会議の『聖なる典礼に関する憲章(Sacrosanctum Concilium)』では、「司教やその他の魂の牧者は、神聖な行為が歌によって祝われる場合には、常に、信仰を持つ人々の全体が、第28条と第30条 に定められているように、彼らにふさわしい積極的な参加ができるようにしなければならない」と指示している。これらの条項には次のように記載されている。 「積極的な参加を促すため、人々は、喝采、応答、詩編、応答歌、歌などの手段によって参加することが奨励されるべきである」[3]。バチカン2世文書で は、人々の完全かつ積極的な参加が繰り返しテーマとなっている。[4] この豊かな信徒参加を実現するためには、新しい賛美歌の導入を慎重に行うことが最も有益であることが証明されている。[5] |

| Anglican

church music is music that is written for Christian worship in

Anglican religious services, forming part of the liturgy. It mostly

consists of pieces written to be sung by a church choir, which may sing

a cappella or accompanied by an organ. Anglican music forms an important part of traditional worship not only in the Church of England, but also in the Scottish Episcopal Church, the Church in Wales, the Church of Ireland, the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, the Anglican Church of Canada, the Anglican Church of Australia and other Christian denominations which identify as Anglican. It can also be used at the Personal Ordinariates of the Roman Catholic Church. Forms The chief musical forms in Anglican church music are centred around the forms of worship defined in the liturgy.[1][2] Service settings Mass Setting Duration: 2 minutes and 18 seconds.2:18 The "Kyrie Eleison" from William Byrd's Mass for Four Voices Problems playing this file? See media help. Service settings are choral settings of the words of the liturgy. These include: The Ordinary of the Eucharist Sung Eucharist is a musical setting of the service of Holy Communion. Naming conventions may vary according to the churchmanship of the place of worship; in churches that tend towards a low church or broad church style of worship, the terms Eucharist or Communion are common, while in high church worship, the more Catholic term Mass may be used.[3] Musical pieces corresponding to the liturgical pattern of the Ordinary of the Mass (Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus & Benedictus, Agnus Dei) may be sung by the choir or congregation. Many English-language settings of the communion service have been written, such as those by Herbert Howells and Harold Darke; simpler settings suitable for congregational singing are also used, such as the services by John Merbecke or Martin Shaw. In high church worship, Latin Mass settings are often preferred, such as those by William Byrd.[4] Morning Service The Anglican service of morning prayer, known as Mattins, is a peculiarly Anglican service which originated in 1552 as an amalgam of the monastic offices of Matins, Lauds and Prime in Thomas Cranmer’s Second Prayer Book of Edward VI. Choral settings of the Morning Service may include the opening preces and responses (see below), the Venite, and the morning canticles of Te Deum, Benedicite, Benedictus, Jubilate and a Kyrie. Evening Service Evening Service Setting Duration: 6 minutes and 15 seconds.6:15 The Magnificat from the Evening Service in A by Stanford Evening Prayer, also known as Evensong, consists of preces and responses, Psalms, canticles, hymns and an anthem (see below). The evening canticles are the Magnificat and the Nunc Dimittis, and these texts have been set to music by many composers. Herbert Howells alone composed 20 settings of the canticles, including his Collegium Regale (1944) and St Paul's (1950) services. Like Mattins, Evensong is a service that is a distinctively Anglican service, originating in the Book of Common Prayer of 1549 as a combination of the offices of Vespers and Compline.[5] Choral Evensong is sung daily in most Church of England cathedrals, as well as in churches and cathedrals throughout the Anglican Communion. It is noted for its particular appeal to worshippers and visitors, attracting both believers and atheists with its meditative quality and cultural value.[6] A service of Choral Evensong is broadcast weekly on BBC Radio 3, a tradition begun in 1926.[7] Preces and responses Preces & responses Duration: 4 minutes and 56 seconds.4:56 The preces & responses by William Smith of Durham The Preces (or versicles) and responses are a set of prayers from the Book of Common Prayer for both Morning and Evening Prayer. They may be sung antiphonally by the priest (or a lay cantor) and choir. There are a number of popular choral settings by composers such as William Smith or Bernard Rose; alternatively, they may be sung as plainsong with a congregation. Psalms Anglican chant Duration: 3 minutes and 46 seconds.3:46 A setting of Psalm 84 by Hubert Parry Morning and Evening Prayer (and sometimes Holy Communion) include a Psalm or Psalms, chosen according to the lectionary of the day. This may be sung by the choir or congregation, either to plainsong, or to a distinctive type of chant known as Anglican chant by the choir or congregation. Anthems or motets God So Loved the World Duration: 3 minutes and 57 seconds.3:57 The popular anthem, God So Loved the World, from Stainer's Crucifixion Part-way through a service of worship, a choir may sing an anthem or motet, a standalone piece of sacred choral music, which is not part of the liturgy but is usually chosen to reflect to the liturgical theme of the day. Hymns The singing of hymns is a common feature of Anglican worship and usually includes congregational singing as well as a choir. An Introit hymn is sung at the start of a service, a Gradual hymn precedes the Gospel, an Offertory hymn is sung during the Offertory and a recessional hymn at the close of a service. Organ voluntary A piece for organ, known as a voluntary, is often played at the end of a service after the recessional hymn and dismissal. Performance A choir singing choral evensong in York Minster Almost all Anglican church music is written for choir with or without organ accompaniment. Adult singers in a cathedral choir are often referred to as lay clerks, while children may be referred to as choristers or trebles.[8] In certain places of worship, such as Winchester College in England, the more archaic spelling quirister is used.[9] An Anglican choir typically uses "SATB" voices (soprano or treble, alto or counter-tenor, tenor, and bass), though in many works some or all of these voices are divided into two for part or all of the piece; in this case the two halves of the choir (one on each side of the aisle) are traditionally named decani and cantoris which sing, respectively, Choir 1 and Choir 2 in two-choir music. There may also be soloists, usually only for part of the piece. There are also works for fewer voices, such as those written for solely men's voices or boys'/women's voices. Vestments At traditional Anglican choral services, a choir is vested, i.e. clothed in special ceremonial vestments. These are normally a cassock, a long, full-length robe which may be purple, red or black in colour, over which is worn a surplice, a knee-length white cotton robe. Normally a surplice is only worn during a service of worship, so a choir often rehearses wearing cassocks only. Younger choristers who have newly joined a choir begin to wear a surplice after an initial probationary period. Cassocks originated in the medieval period as day dress for clergy, but later came into liturgical use. Additionally, junior choristers may wear a ruff, an archaic form of dress collar, although this tradition is becoming less common. In some establishments, including the Choir of King's College, Cambridge, Eton collars are worn. Whist singing the offices, adult choir members may also wear an academic hood over their robes. In England, young choristers who have attained a certain level of proficiency with the Royal School of Church Music, an international educational organisation that promotes liturgical music, may wear an RSCM medallion.[10][11] History See also: History of the Church of England and Elizabethan Religious Settlement § Music Prior to the Reformation, music in British churches and cathedrals consisted mainly of Gregorian chant and polyphonic settings of the Latin Mass. The Anglican church did not exist as such, but the foundations of Anglican music were laid with music from the Catholic liturgy. The earliest surviving examples of European polyphony are found in the Winchester Tropers, a manuscript collection of liturgical choral music used at Winchester Cathedral, dating from the early-eleventh to mid-twelfth centuries.[12] By the time of King Henry V in the fifteenth century, the music in English cathedrals, monasteries and collegiate churches had developed a distinctive and influential style known in Western Europe as the contenance angloise, whose chief proponent was the composer John Dunstable.[13] Four members of the Westminster Abbey Choir at the Coronation of James II in 1685. In the early 1530s, the break with Rome under King Henry VIII set in motion the separation of the Church of England from the Roman Catholic Church and the Reformation in England. The Church of England's Latin liturgy was replaced with scripture and prayers in English; the Great Bible in English was authorised in 1539 and Thomas Cranmer introduced the Book of Common Prayer in 1549.[14][15] These changes were reflected in church music, and works that had previously been sung in Latin began to be replaced with new music in English. This gave rise to an era of great creativity during the Tudor period, in which composition of music for Anglican worship flourished. During the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, musicians of the Chapel Royal such as Thomas Tallis, Robert Parsons and William Byrd were called upon to demonstrate that the new Protestantism was no less splendid than the old Catholic religion.[16][17] The defining characteristic of English polyphony was one-syllable-one-note, as opposed to continental polyphony, which was melismatic (multiple notes per syllable). Latin was only permitted in Oxford/Cambridge collegiate chapels where it could be understood by the congregation. Following the events of the English Civil War and the execution of King Charles I, Puritan influences took hold in the Church of England. Anglican church music became simpler in style, and services typically focused on morning and evening prayer. During the Restoration period, musical practices of the Baroque era found their way into Anglican worship, and stringed or brass instruments sometimes accompanied choirs. In the late 17th century, the composer Henry Purcell, who served as organist of both the Chapel Royal and Westminster Abbey, wrote many choral anthems and service settings. During the Georgian era, the music of George Frideric Handel was highly significant, with his repertoire of anthems, canticles and hymns, although he never held a church post.[15] Up until the early 19th century, most Anglican church music in England was centred around the cathedrals, where trained choirs would sing choral pieces in worship. Composers wrote music to make full use of the traditional cathedral layout of a segregated chancel area and the arrangement of choir stalls into rows of Decani and Cantoris, writing antiphonal anthems.[15] A Village Choir, an 1847 painting by Thomas Webster, showing the musicians of a country parish church at that time. In parish churches, musical worship was limited to congregational singing of metrical psalms, often led by a largely untrained choir. A great quantity of simple tunes were published in the 18th and early 19th century for their use.[18] From the mid-18th century, accompaniment began to be provided by a "parish band" of instruments such as the violin, cello, clarinet, flute and bassoon.[19] These musicians would often sit in a gallery at the west end of the church, giving rise to the later term, "west gallery music".[20] The tradition of a robed choir of men and boys was virtually unknown in Anglican parish churches until the early 19th century. Around 1839, a choral revival took hold in England, partially fuelled by the Oxford Movement, which sought to revive Catholic liturgical practice in Anglican churches. Despite opposition from more Puritan-minded Anglicans, ancient practices such as intoning the versicles and responses and chanted Psalms were introduced.[21][22] The 16th century setting by John Merbecke for the Communion Service was revived in the 1840s and was almost universally adopted in parish churches.[23] Composers active around this time included Samuel Sebastian Wesley and Charles Villiers Stanford. A number of grandiose settings of the Anglican morning and evening canticles for choir and organ were composed in the late 19th and early 20th century, including settings by Thomas Attwood Walmisley, Charles Wood, Thomas Tertius Noble, Basil Harwood and George Dyson, works which remain part of the Anglican choral repertoire today. The singing of hymns was popularised within Anglicanism by the evangelical Methodist movement of the mid-18th century, but hymns, as opposed to metrical psalms, were not officially sanctioned as an integral part of Anglican Orders of Service until the early nineteenth century.[24][25] From about 1800 parish churches started to use different hymn collections in informal service like the Lock Hospital Collection[26] (1769) by Martin Madan, the Olney hymns[27] (1779) by John Newton and William Cowper and A Collection of Hymns for the Use of The People Called Methodists(Wesley 1779) (1779) by John Wesley and Charles Wesley.[24][28] In 1820, the parishioners of a church in Sheffield took their parish priest to court when he tried to introduce hymns into Sunday worship; the judgement was ambiguous, but the matter was settled in the same year by Vernon Harcourt, the Archbishop of York, who sanctioned their use at services.[29] Anglican hymnody was revitalised by the Oxford Movement and led to the publication hymnals such as Hymns Ancient and Modern (1861). The English Hymnal, edited by Percy Dearmer and Ralph Vaughan Williams, was published in 1906, and became one of the most influential hymn books ever published. It was supplanted in 1986 by the New English Hymnal.[30] The choir at Aberford, near Leeds, West Yorkshire, in the early 20th century. The acceptance of hymns in Anglican liturgy led to the adoption of the folk tradition of Christmas carol singing during the 19th century, the popularity of which was enhanced by Albert, Prince Consort teaching German carols to the royal family.[31] The Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols originated at Truro Cathedral in 1888 as a means of attracting people away from pubs on Christmas Eve; a revised version was adopted at King's College, Cambridge, first broadcast on BBC radio in 1928 and has now become an annual tradition, transmitted around the world.[32] This has done much to popularise church music, as well as published collections such as Oxford Book of Carols (1928) and Carols for Choirs. Following the early music revival of the mid-20th century, the publication of collections such as the Oxford Book of Tudor Anthems encouraged renewed interest in 17th-century composers such as Byrd and Tallis. In all but the smallest churches the congregation was until recently confined to the singing of hymns. Over the past half century or so efforts have been made to increase the role of the congregation and also to introduce more "popular" musical styles in the evangelical and charismatic leaning congregations. Not all churches can boast a full SATB choir, and a repertoire of one-, two- and three-part music is more suitable for many parish church choirs, a fact which is recognised in the current work of the Royal School of Church Music. Anglican churches also frequently draw upon the musical traditions of other Christian denominations. Works by Catholic composers such as Mozart, Lutherans such as Bach, Calvinists like Mendelssohn, and composers from other branches of Christianity are often featured. This is particularly the case in music for the Mass in Anglo-Catholic churches, much of which is taken from the work of Roman Catholic composers. Traditionally, Anglican choirs were exclusively male, due to a belief that girls' voices produced a different sound. However, recent research has shown that given the same training, the voices of girls and boys cannot be told apart, save for an interval from the C above middle C to the F above that. Salisbury Cathedral started a girls' choir in 1991 and others have since followed suit. There has been some concern that having mixed choirs in parish churches leads to fewer boys being willing to participate.[33] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anglican_church_music |

聖公会の教会音楽とは、聖公会の宗教儀式におけるキリスト教の礼拝のた

めに書かれた音楽であり、典礼の一部を構成する。

主に教会の聖歌隊によって歌われるように書かれた楽曲で構成されており、アカペラで歌われることもあれば、オルガンの伴奏付きで歌われることもある。 聖公会音楽は、英国国教会だけでなく、スコットランド聖公会のほか、ウェールズ教会、アイルランド教会、米国聖公会、カナダ聖公会、オーストラリア聖公 会、および聖公会を名乗るその他のキリスト教宗派においても、伝統的な礼拝の重要な一部を構成している。また、ローマ・カトリック教会の個人管区でも使用 されている。 形式 聖公会教会音楽の主な音楽形式は、典礼で定義された礼拝形式を中心としている。[1][2] 奉神礼 ミサ曲 演奏時間:2分18秒 ウィリアム・バードの「4声のミサ曲」より「キリエ・エレイソン」 このファイルの再生に問題がありますか? メディアのヘルプをご覧ください。 奉神礼の言葉の合唱曲の設定。これには以下が含まれる。 聖餐式の通常 歌われる聖餐式は、聖餐式の音楽設定である。礼拝の名称の慣例は、礼拝の教会主義によって異なる場合がある。低教会や広教会のスタイルの礼拝を行う教会で は、EucharistやCommunionという用語が一般的であるが、高教会の礼拝では、よりカトリック的な用語であるMassが使用される場合もあ る。[3] キリエ、グローリア、クレド、サンクトゥス&ベネディクトゥス、アニュス・デイといったミサの通常文の典礼パターンに対応する楽曲は、聖歌隊また は会衆によって歌われる場合がある。聖餐式については、ハーバート・ハウエルズやハロルド・ダーケによるものなど、多くの英語の聖歌が作られている。ま た、ジョン・マーベックやマーティン・ショーによるものなど、会衆が歌うのに適したよりシンプルな聖歌も用いられている。高教会の礼拝では、ウィリアム・ バードによるものなど、ラテン語のミサ聖歌が好まれることが多い。 朝の礼拝 朝の祈りとしての聖公会式の礼拝は、マッティンズとして知られ、トマス・クランマーの『エドワード6世の第2祈祷書』における修道士の朝課(マティンズ、 ラウズ、プライム)の合併として1552年に始まった、聖公会独特の礼拝である。朝の礼拝の合唱曲には、冒頭のプレセスとレスポンス(下記参照)、 Venite、Te Deum、Benedicite、Benedictus、Jubilate、Kyrieなどの朝の聖歌が含まれる。 夕方の礼拝 夕方の礼拝の合唱曲 演奏時間:6分15秒 スタンフォード作曲の「夕方の礼拝のマグニフィカト」 夕の祈り(イブニング・サービス)は、プレセスとレスポンス、詩篇、聖歌、賛美歌、そしてアンセム(下記参照)で構成される。夕の聖歌はマグニフィカトと ヌンク・ディミティスであり、これらのテキストは多くの作曲家によって音楽がつけられている。ハーバート・ハウエルズは、コレギウム・レガル(1944 年)とセント・ポール(1950年)のサービスを含め、20曲の聖歌を作曲している。朝課と同様に、夕課もまた、1549年の『共通祈祷書』にヴェスペレ とコンプリネの儀式を組み合わせたものとして登場した、英国国教会独特の儀式である。[5] 聖歌隊による夕課は、英国国教会の大聖堂のほとんどで毎日歌われているほか、英国国教会の教会や大聖堂でも歌われている。それは、礼拝者や訪問者にとって 特に魅力的であることで知られ、その瞑想的な質と文化的価値により、信者と無神論者の両方を惹きつけている。[6] 合唱式の夕の祈りの礼拝は、1926年に始まった伝統により、BBCラジオ3で毎週放送されている。[7] プレセス・アンド・レスポンス プレセス・アンド・レスポンス 演奏時間:4分56秒 ダラムのウィリアム・スミスによるプレセス・アンド・レスポンス プレセス(またはヴェルシクル)とレスポンスは、朝と夕方の祈りのための『共通祈祷書』に収められた祈りのセットである。司祭(または平信徒の聖歌隊)と 聖歌隊が反復唱和して歌うこともある。ウィリアム・スミスやバーナード・ローズなどの作曲家による人気の高い合唱曲の設定が多数ある。また、会衆が平叙唱 で歌うこともある。 詩篇 聖歌 演奏時間:3分46秒 ヒューバート・パリーによる詩篇第84編の曲 朝と夕方の祈り(時には聖餐式)では、その日の聖書朗読箇所に従って選ばれた詩篇が歌われる。これは聖歌隊または会衆によって、定旋律または聖公会の聖歌 として知られる独特な聖歌の形式で歌われる。 アンセムまたはモテット 神は世をこれほどまでに愛された 演奏時間:3分57秒 人気の賛美歌「神は世をこれほどまでに愛された」は、スタイナー作曲の「磔刑」から 礼拝の途中で、聖歌隊が賛美歌やモテットと呼ばれる独立した聖歌を歌うことがある。これは典礼の一部ではないが、通常は当日の典礼のテーマを反映した曲が 選ばれる。 賛美歌 賛美歌の合唱は英国国教会の礼拝では一般的なもので、通常は聖歌隊だけでなく会衆による合唱も行われる。イントロイトの賛美歌は礼拝の開始時に、グラデュ アルの賛美歌は福音書の朗読の前に、オファトリオの賛美歌はオファトリオの際に、そして退場賛美歌は礼拝の終了時に歌われる。 オルガン・ヴォラティリー オルガン曲の一種で、ヴォラティリー(任意の)と呼ばれるこの曲は、しばしば退場行進の歌と解散の後、礼拝の最後に演奏される。 パフォーマンス ヨーク・ミンスターで合唱による夕の祈りを歌う聖歌隊 聖公会の教会音楽のほとんどは、オルガンの伴奏の有無に関わらず、聖歌隊のために作曲されている。 大聖堂聖歌隊の成人歌手は、しばしば「平信徒聖歌隊員(lay clerk)」と呼ばれるが、子供の場合は「少年聖歌隊員(chorister)」または「高音聖歌隊員(treble)」と呼ばれることもある。[8] イングランドのウィンチェスター・カレッジのような特定の礼拝所では、より古風な「quirister」という綴りが用いられている。[9] 聖公会の聖歌隊は通常、「SATB」の声部(ソプラノまたはトレブル、アルトまたはカウンターテナー、テノール、バス)を使用するが、多くの作品では、こ れらの声部の一部または全部が、曲の一部または全部で2つに分けられる。この場合、聖歌隊の2つのグループ(通路の両側に1つずつ)は、それぞれデカニと カントールと呼ばれ、2つの聖歌隊による音楽では、それぞれ聖歌隊1と聖歌隊2を歌う。また、通常は曲の一部のみでソロ歌手が参加することもある。男性の み、あるいは少年少女の声のみで歌われる曲など、声楽のパート数が少ない作品もある。 祭服 伝統的な英国国教会の合唱式では、聖歌隊は祭服、すなわち特別な儀式用の祭服を着用する。通常は、紫、赤、黒のいずれかの色をしたカソックと呼ばれる長い ローブで、その上に膝丈の白いコットンのローブであるスルプスを着用する。通常、スルプシスは礼拝の時のみ着用されるため、聖歌隊はカソックのみを着用し てリハーサルを行うことが多い。聖歌隊に新しく加わった若い聖歌隊員は、試用期間を経てからスルプシスを着用し始める。カソックは中世に聖職者の日常着と して誕生したが、後に典礼用としても用いられるようになった。また、年少の聖歌隊員は、襟飾りの古風な形であるラフを着用することもあるが、この伝統はあ まり一般的ではなくなりつつある。ケンブリッジ大学キングスカレッジ聖歌隊など、一部の施設ではイートンカラーが着用される。聖歌隊の成人メンバーは、聖 歌を歌う際にローブの上に学帽を着用することもある。イングランドでは、典礼音楽を推進する国際的教育機関である王立教会音楽学校で一定のレベルに達した 若い聖歌隊員は、RSCMメダリオンを着用することができる。 歴史 参照:英国国教会の歴史とエリザベス朝の宗教的和解 § 音楽 宗教改革以前、英国の教会や大聖堂における音楽は主にグレゴリオ聖歌とラテン語ミサの多声音楽で構成されていた。英国国教会はまだ存在していなかったが、 英国国教会音楽の基礎はカトリック典礼の音楽によって築かれた。ヨーロッパのポリフォニー音楽の最も古い現存する例は、ウィンチェスター大聖堂で使用され ていた典礼用合唱曲の写本集である『ウィンチェスター・トロパーズ』に見られる。これは11世紀初頭から12世紀半ばにかけての作品である。15世紀のヘ ンリー5世の時代には、英国の大聖堂、修道院、教区教会の音楽は、西ヨーロッパではコンテント・アングロワーズとして知られる独特で影響力のあるスタイル に発展していた。その主な推進者は作曲家のジョン・ダンスタブルであった。 1685年のジェームズ2世の戴冠式におけるウェストミンスター寺院聖歌隊の4人のメンバー。 1530年代初頭、ヘンリー8世王によるローマとの決別により、イングランド国教会とローマ・カトリック教会の分離とイングランドにおける宗教改革が始 まった。イングランド国教会のラテン語による典礼は、聖書と英語による祈祷に置き換えられ、1539年に英語訳の大聖書が公認され、トーマス・クランマー が1549年に『共通祈祷書』を導入した。[14][15] これらの変化は教会音楽にも反映され、それまでラテン語で歌われていた作品は、英語による新しい音楽に置き換えられていった。これにより、チューダー朝時 代には、非常に創造的な時代が到来し、英国国教会の礼拝のための音楽の作曲が盛んに行われるようになった。エリザベス1世の治世下では、トマス・タリス、 ロバート・パーソンズ、ウィリアム・バードといった王室礼拝堂楽団の音楽家たちが、新しいプロテスタントが古いカトリックの宗教に劣らない素晴らしさであ ることを証明するよう求められた。[16][17] イングランドのポリフォニーの決定的な特徴は、1音節1音であった。これは、1音節に複数の音符が用いられる大陸のポリフォニーとは対照的である。ラテン 語は、会衆が理解できるオックスフォード/ケンブリッジのカレッジ礼拝堂でのみ使用が許可されていた。 イングランド内戦とチャールズ1世の処刑の後、英国国教会にピューリタンの影響が浸透した。英国国教会の音楽はよりシンプルなスタイルとなり、礼拝は朝と 夜の祈りに重点が置かれるようになった。王政復古期には、バロック時代の音楽の慣習が英国国教会の礼拝に取り入れられ、弦楽器や金管楽器が聖歌隊に同行す ることがあった。17世紀後半には、王立礼拝堂とウェストミンスター寺院の両方のオルガニストを務めた作曲家ヘンリー・パーセルが、多くの合唱曲や礼拝曲 を作曲した。 ジョージア朝時代には、教会の役職に就くことはなかったが、ジョージ・フリードリヒ・ヘンデルの作曲した賛美歌、聖歌、讃美歌は、非常に重要な意味を持っ ていた。 19世紀初頭まで、イングランドのほとんどの英国国教会の音楽は大聖堂を中心に展開され、そこで訓練を受けた聖歌隊が礼拝で合唱曲を歌っていた。作曲家た ちは、伝統的な大聖堂のレイアウトである聖歌隊席とデカニとカントリスの聖歌隊席の配置を最大限に活用し、応答唱を書くために音楽を作曲した。 トーマス・ウェブスターによる1847年の絵画『村の聖歌隊』には、当時の田舎の教区教会の音楽家たちが描かれている。 教区教会では、音楽による礼拝は、韻律のある詩篇を会衆が歌うことに限られており、その際には、ほとんど訓練を受けていない聖歌隊が指揮を執ることが多 かった。18世紀から19世紀初頭にかけて、その用途のために、非常に多くの単純な曲が出版された。[18] 18世紀半ばからは、伴奏は「教区バンド」と呼ばれる ヴァイオリン、チェロ、クラリネット、フルート、ファゴットなどの楽器が用いられるようになった。[19] これらの音楽家たちはしばしば教会の西端にあるギャラリーに座り、後に「西ギャラリー音楽」と呼ばれるようになった。[20] 男性と少年によるローブをまとった聖歌隊の伝統は、19世紀初頭まで英国国教会の教区教会ではほとんど知られていなかった。1839年頃、英国では聖歌の 復興が起こり、英国国教会の教会でカトリックの典礼慣習を復活させようとするオックスフォード運動がその動きを後押しした。ピューリタン的な傾向の強い聖 公会からの反対にもかかわらず、詠唱と応答の節回しや詩篇の朗唱といった古代の慣習が復活した。[21][22] 16世紀にジョン・マーベックが聖餐式のために作曲した曲は1840年代に復活し、ほとんどの教区教会で採用されるようになった。[23] この時期に活躍した作曲家には、サミュエル・セバスチャン・ウェスレーやチャールズ・ヴィリエ・スタンフォードなどがいる。19世紀後半から20世紀初頭 にかけて、トーマス・アトウッド・ウォルミズリー、チャールズ・ウッド、トーマス・テルティウス・ノーブル、バジル・ハーウッド、ジョージ・ダイソンなど による、聖公会式の朝と夕方の賛美歌の壮大な合唱とオルガンのための編曲が数多く作曲された。これらの作品は、今日でも聖公会の合唱レパートリーの一部と なっている。 聖歌の合唱は、18世紀半ばの福音主義メソジスト運動によって聖公会内で広まったが、韻律詩篇とは対照的に、聖歌は19世紀初頭まで聖公会の礼拝式次第の 不可欠な一部として公式に認められていなかった。[24][25] 1800年頃から教区教会では、マーティン・マダンによる『ロック病院聖歌集』[26](1769年)や、ジョン・ニュートンとウィリアム・カウパーによ る『オルニー聖歌集』[27](1779年)、『メソジストと呼ばれる人々のための聖歌集』[28](1784年)など、非公式な礼拝でさまざまな聖歌集 が用いられるようになった。 マーティン・マダンによる『ロック病院賛美歌集』(1769年)、ジョン・ニュートンとウィリアム・カウパーによる『オルニー賛美歌集』(1779年)、 ジョン・ウェスレーとチャールズ・ウェスレーによる『メソジストと呼ばれる人々のための賛美歌集』(1779年)などである。[24][28] 1820年、 シェフィールドの教会の教区民は、日曜礼拝に賛美歌を導入しようとした教区司祭を裁判所に訴えた。判決は曖昧なものだったが、ヨーク大主教のヴァーノン・ ハーコートがその年のうちにこの問題を解決し、礼拝での賛美歌の使用を認めた。[29] 聖公会賛美歌はオックスフォード運動によって活性化され、Hymns Ancient and Modern(1861年)などの賛美歌集の出版につながった。パーシー・ディアマーとラルフ・ヴァーン・ウィリアムズが編集した『The English Hymnal』は1906年に出版され、最も影響力のある賛美歌集のひとつとなった。1986年には『New English Hymnal』に取って代わられた。[30] 20世紀初頭のウェスト・ヨークシャー州リーズ近郊のアバーフォードの聖歌隊。 聖公会の典礼で賛美歌が受け入れられたことにより、19世紀にはクリスマス・キャロルを歌うという民間伝承が取り入れられるようになった。その人気は、ア ルバート公がドイツのキャロルを王室に教えたことでさらに高まった。[31] 9つのレッスンとキャロルの祭典は、1888年にクリスマス・イブに人々をパブから引き離す手段として、トゥルーロ大聖堂で始まった 。改訂版はケンブリッジ大学のキングズ・カレッジで採用され、1928年にBBCラジオで初めて放送され、現在では毎年恒例の伝統行事となり、世界中に配 信されている。[32] これは、教会音楽の普及に大きく貢献した。また、『オックスフォード・ブック・オブ・キャロル』(1928年)や『キャロル・フォー・クワイア』などの曲 集が出版された。20世紀半ばの古楽復興に続き、『オックスフォード・ブック・オブ・チューダー・アンセムズ』などの曲集の出版により、バードやタリスと いった17世紀の作曲家への関心が再び高まった。 ごく小さな教会を除いて、最近まで会衆は賛美歌を歌うことだけに専念していた。過去半世紀ほどの間、会衆の役割を拡大し、福音派やカリスマ派の会衆ではよ り「ポピュラー」な音楽スタイルを導入する努力が重ねられてきた。すべての教会がフルのSATB合唱団を誇れるわけではなく、1部、2部、3部からなる楽 曲のレパートリーの方が多くの教区教会の聖歌隊には適している。この事実は、王立教会音楽学校の現在の活動でも認識されている。 また、英国国教会は他のキリスト教宗派の音楽的伝統も頻繁に取り入れている。カトリックの作曲家モーツァルト、ルター派のバッハ、カルヴァン派のメンデル スゾーン、その他のキリスト教宗派の作曲家の作品が頻繁に演奏される。これは特に、英国国教会とカトリック教会の音楽に顕著であり、その多くはローマ・カ トリックの作曲家の作品から採られている。 伝統的に、聖公会の聖歌隊は男性のみで構成されていた。これは、少女の歌声は異なる響きを持つという信念によるものだった。しかし、最近の研究では、同じ 訓練を受ければ、ミドルCのドからその上のファまでの音程を除いて、少女と少年の歌声は区別できないことが分かっている。ソールズベリー大聖堂は1991 年に少女合唱団を結成し、その後、他の教会も追随した。教区教会で混声合唱団を結成すると、少年の参加者が減るのではないかという懸念もあった。[33] |

| Christian

liturgy is a pattern for worship used (whether recommended or

prescribed) by a Christian congregation or denomination on a regular

basis. The term liturgy comes from Greek and means "public work".

Within Christianity, liturgies descending from the same region,

denomination, or culture are described as ritual families. The majority of Christian denominations hold church services on the Lord's Day (with many offering Sunday morning and Sunday evening services); a number of traditions have mid-week Wednesday evening services as well.[A][3][2] In some Christian denominations, liturgies are held daily, with these including those in which the canonical hours are prayed, as well as the offering of the Eucharistic liturgies such as Mass, among other forms of worship.[4] In addition to this, many Christians attend services of worship on holy days such as Christmas, Ash Wednesday, Good Friday, Ascension Thursday, among others depending on the Christian denomination.[5] In most Christian traditions, liturgies are presided over by clergy wherever possible. History The holding of church services pertains to the observance of the Lord's Day in Christianity.[2] The Bible has a precedent for a pattern of morning and evening worship that has given rise to Sunday morning and Sunday evening services of worship held in the churches of many Christian denominations today, a "structure to help families sanctify the Lord's Day."[2] In Numbers 28:1–10 and Exodus 29:38–39, "God commanded the daily offerings in the tabernacle to be made once in the morning and then again at twilight".[2] In Psalm 92, which is a prayer concerning the observance of the Sabbath, the prophet David writes "It is good to give thanks to the Lord, to sing praises to your name, O Most High; to declare your steadfast love in the morning, and your faithfulness by night" (cf. Psalm 134:1).[2] Church father Eusebius of Caesarea thus declared: "For it is surely no small sign of God's power that throughout the whole world in the churches of God at the morning rising of the sun and at the evening hours, hymns, praises, and truly divine delights are offered to God. God's delights are indeed the hymns sent up everywhere on earth in his Church at the times of morning and evening."[2] Types Communion liturgies The Roman Rite Catholic Mass is the service in which the Eucharist is celebrated. In Latin, the corresponding word is Missa, taken from the dismissal at the end of the liturgy - Ite, Missa est, literally "Go, it is the dismissal", translated idiomatically in the current English Roman Missal as "Go forth, the Mass is ended." The Eastern Orthodox Church (Byzantine Rite) uses the term "Divine Liturgy" to denote the Eucharistic service.[6] and some Oriental Orthodox churches also use that term. The descendant churches of the Church of the East and various other Syriac Churches call their Liturgy the Holy Qurbana - Holy Offering. Anglicans variably use Holy Communion, The Lord’s Supper, the Roman Catholic term mass, or simply Holy Eucharist dependent upon churchmanship. Mass is the common term used in the Lutheran Church in Europe but more often referred to as the Divine Service, Holy Communion, or the Holy Eucharist in North American Lutheranism. Lutherans retained and utilized much of the Roman Catholic mass since the early modifications by Martin Luther. The general order of the mass and many of the various aspects remain similar between the two traditions. Latin titles for the sections, psalms, and days has been widely retained, but more recent reforms have omitted this. Recently, Lutherans have adapted much of their revised mass to coincide with the reforms and language changes brought about by post-Vatican II changes.[citation needed] Protestant traditions vary in their liturgies or "orders of worship" (as they are commonly called). Other traditions in the west often called "Mainline" have benefited from the Liturgical Movement which flowered in the mid/late 20th century. Over the course of the past several decades, these Protestant traditions have developed remarkably similar patterns of liturgy, drawing from ancient sources as the paradigm for developing proper liturgical expressions. Of great importance to these traditions has been a recovery of a unified pattern of Word and Sacrament in Lord's Day liturgy.[citation needed] Many other Protestant Christian traditions (such as the Pentecostal/Charismatics, Assembly of God, and Non-denominational churches), while often following a fixed "order of worship", tend to have liturgical practices that vary from that of the broader Christian tradition.[citation needed] Commonalities There are common elements found in most Western liturgical churches which predate the Protestant Reformation. These include:[citation needed] The Procession with the cross, followed by the other acolytes, the deacons and the priest The Invocation (beginning with the Sign of the Cross) Confession at the foot of the altar Absolution Introit, Psalms, Hymns, chants Litany Kyrie and Gloria Salutation Collect Liturgical Readings (call and response) Alleluia Verse and other responses Scripture readings at Gereja Santa, Indonesia Scripture readings, culminating in a reading from one of the Gospels. The Creed The Prayers The Lord's Prayer Commemoration of the Saints and prayers for the faithful departed. Intercessory prayers for the church and its leadership, and often, for earthly rulers. Incense Offering A division between the first half of the liturgy, open to both church members and those wanting to learn about the church, and the second half, the celebration of the Eucharist proper, open only to baptized believers in good standing with the church. The Consecration The Offertory Prayer Communion Sanctus prayer as part of the anaphora A three-fold dialogue between priest and people at the beginning of the anaphora or eucharistic prayer An anaphora, eucharistic canon, "great thanksgiving", canon or "hallowing", said by the priest in the name of all present, in order to consecrate the bread and wine as the Body and Blood of Christ. A prayer to God the Father, usually invoking the Holy Spirit, asking that the bread and wine become, or be manifested as, the body and blood of Christ. Expressions within the anaphora which indicate that sacrifice is being offered in remembrance of Christ's crucifixion. A section of the anaphora which asks that those who receive communion may be blessed thereby, and often, that they may be preserved in the faith until the end of their lives The Peace or "Passing of the Peace" Agnus Dei Benediction Divine office The term "Divine Office" describes the practice of "marking the hours of each day and sanctifying the day with prayer".[7] In the Western Catholic Church, there are multiple forms of the office. The Liturgy of the Hours is the official form of the office used throughout the Latin Church, but many other forms exist including the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the forms of the office specific to various religious orders, and the Roman Breviary which was Standard before the Second Vatican Council, to name a few.[8] There were eight such hours, corresponding to certain times of the day: Matins (sometimes called Vigil), Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline. The Second Vatican Council ordered the suppression of Prime.[9] In monasteries, Matins was generally celebrated before dawn, or sometimes over the course of a night; Lauds at the end of Matins, generally at the break of day; Prime at 6 AM; Terce at 9AM; Sext at noon; None at 3PM; Vespers at the rising of the Vespers or Evening Star (usually about 6PM); and Compline was said at the end of the day, generally right before bed time. In Anglican churches, the offices were combined into two offices: Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer, the latter sometimes known as Evensong. In more recent years, the Anglicans have added the offices of Noonday and Compline to Morning and Evening Prayer as part of the Book of Common Prayer. The Anglican Breviary, containing 8 full offices, is not the official liturgy of the Anglican Church. In Lutheranism, like Anglicanism, the offices were also combined into the two offices of Matins and Vespers (both of which are still maintained in modern Lutheran prayer books and hymnals). A common practice among Lutherans in America is to pray these offices mid-week during Advent and Lent. The office of Compline is also found in some older Lutheran worship books and more typically used in monasteries and seminaries. The Byzantine Rite maintains a daily cycle of seven non-sacramental services: Vespers (Gk. Hesperinos) at sunset commences the liturgical day Compline (Gk. Apodeipnou, "after supper") Midnight Office (Gk. mesonyktikon) Matins (Gk. Orthros), ending at dawn (in theory; in practice, the time varies greatly) The First Hour The Third and Sixth Hours The Ninth Hour The sundry Canonical Hours are, in practice, grouped together into aggregates so that there are three major times of prayer a day: Evening, Morning and Midday; for details, see Canonical hours — Aggregates. Great Vespers as it is termed in the Byzantine Rite, is an extended vespers service used on the eve of a major Feast day, or in conjunction with the divine liturgy, or certain other special occasions. In the Maronite Church's liturgies, the office is arranged so that the liturgical day begins at sundown. The first office of the day is the evening office of Ramsho, followed by the night office of Sootoro, concluding with the morning office of Safro. In the Maronite Eparchies of the United States, the approved breviary set is titled the Prayer of the Faithful.[citation needed] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_liturgy |

キリスト教の典礼は、キリスト教の集会や宗派が定期的に(推奨または規

定として)用いる礼拝のパターンである。「典礼」という用語はギリシャ語に由来し、「公共事業」を意味する。キリスト教では、同じ地域、宗派、文化に由来

する典礼は「儀式の系統」として説明される。 キリスト教の大多数の宗派は主の日曜日に礼拝を行う(日曜の朝と夕方に礼拝を行うところが多い)。また、伝統によっては水曜の夜にも礼拝を行うところもあ る。[A][3][2] キリスト教のいくつかの宗派では、典礼は毎日行われ、正規の時間帯に祈りを捧げるもの 、ミサなどの聖餐式の典礼が、その他の礼拝形態とともに祈られるものもある。[4] これに加えて、多くのキリスト教徒は、クリスマス、灰の水曜日、聖金曜日、昇天木曜日など、キリスト教の宗派によって異なる聖日にも礼拝に出席する。 [5] ほとんどのキリスト教の伝統では、可能な限り聖職者が典礼を司る。 歴史 礼拝の開催は、キリスト教における主の日(主の安息日)の遵守に関係している。[2] 聖書には朝と夜の礼拝のパターンが先例として記されており、これが今日の多くのキリスト教宗派の教会で日曜の朝と夕方に開催される礼拝の起源となってい る。「家族が主の日を聖別するための構造」である。 。」[2] 出エジプト記28章1節から10節と出エジプト記29章38節から39節では、「神は幕屋における日々の捧げものを朝と夕暮れに一度ずつ行うよう命じられ た」とある。[2] 詩篇92篇は安息日の遵守に関する祈りであり、 預言者ダビデは「主をたたえ、いと高き方の御名をほめたたえよ。朝にはあなたのいつくしみを告げ、夜にはあなたの誠実を告げよ」(詩篇134:1参照) [2]と記している。 教会の父であるエウセビオスはこう宣言した。「全世界の神の教会で、朝、太陽が昇る時と夕刻に、神への賛美歌や賛美、そして神への真の喜びが捧げられてい ることは、神の力の小さな兆候ではない。神の喜びとは、朝と夕刻に、神の教会で地球上の至る所から捧げられる賛美歌である。」[2] 種類 聖体拝領の典礼 ローマ・カトリックのミサは、聖体が祝われる儀式である。ラテン語では、ミサに対応する語はMissaであり、典礼の最後の解散の言葉「Ite, Missa est」(直訳は「行け、解散だ」)に由来する。現在の英語のローマ・ミサ典礼では、「Go forth, the Mass is ended.」(直訳は「出て行け、ミサは終わった」)と慣用的に訳されている。 東方正教会(ビザンチン典礼)では、聖体礼儀を「神聖な典礼」と呼ぶ。[6] また、一部の東方諸教会もこの用語を使用している。 東方教会の分派やその他のシリア教会は、聖体礼儀を「聖なるクルバナ(聖なる供物)」と呼ぶ。 聖公会では、聖餐式、主の晩餐、ローマ・カトリックのミサ、または単に聖体礼儀など、所属教会によってさまざまな用語が用いられている。 ミサはヨーロッパのルーテル教会で用いられている一般的な用語であるが、北米のルーテル教会では、神聖な奉仕、聖餐式、または聖体礼儀と呼ばれることが多 い。ルーテル派は、マルティン・ルターによる初期の修正以来、ローマ・カトリックのミサの多くを維持し、活用してきた。ミサの一般的な順序やさまざまな側 面の多くは、2つの伝統の間で類似している。ラテン語のタイトル、詩篇、曜日などは広く受け継がれてきたが、より最近の改革では省略されている。最近で は、ルター派は、バチカン2世以降の改革や言語の変化に合わせて、ミサの多くを改訂している。 プロテスタントの伝統は、典礼または「礼拝の順序」(一般的に呼ばれる名称)が異なる。西洋の「メインライン」と呼ばれる他の伝統は、20世紀中頃から後 半にかけて盛んになった典礼運動から恩恵を受けている。過去数十年の間に、これらのプロテスタントの伝統は、古代の典拠を適切な典礼表現を発展させるため の模範として取り入れ、驚くほど類似した典礼のパターンを発展させてきた。これらの伝統にとって非常に重要なのは、主日典礼におけるみことばと聖餐の統一 されたパターンの回復である。 多くの他のプロテスタントのキリスト教の伝統(ペンテコステ派/カリスマ派、神の集会、無宗派の教会など)は、しばしば固定的な「礼拝の順序」に従う一方 で、より広範なキリスト教の伝統とは異なる典礼の慣習を持つ傾向がある。 共通点 プロテスタントの宗教改革以前から存在する西洋の典礼教会のほとんどに共通する要素がある。これには以下が含まれる。 他の侍者、助祭、司祭に続いて十字架を掲げて行進する (十字を切ることから始まる)祈願 祭壇の足元での告白 赦免 イントロイト、詩篇、賛美歌、聖歌 連祷 キリエとグロリア 挨拶 収集 典礼の朗読(呼びかけと応答 アレルヤ詩とその他の応答 インドネシアのサンタ教会での聖書朗読 聖書朗読、福音書の朗読で最高潮に達する。 信条 祈り 主の祈り 聖人の記念と、信仰深い故人のための祈り。 教会とその指導者、そしてしばしば現世の支配者のための執り成しの祈り。 香 供物 典礼の前半部分は、教会員および教会について学びたい人々にも開かれており、後半部分は、教会と良好な関係にある洗礼を受けた信者だけが参加できる、聖餐 式そのものである。 奉献 奉納の祈り 聖餐 アナフォラの一部であるサンクタス祈り アナフォラまたは聖餐式の祈りの冒頭で、司祭と人々との間で行われる3つの対話 アナフォラ、聖餐式の聖歌、または「大感謝」、聖歌、または「聖別」は、司祭が出席者全員の名において、パンとぶどう酒をキリストの体と血として聖別する ために唱える。 父なる神への祈りであり、通常は聖霊を呼び起こし、パンとぶどう酒がキリストの体と血となる、または体と血として現れるよう求める。 キリストの磔刑を偲んで犠牲が捧げられていることを示すアナフォラ内の表現。 聖餐を受ける人々がそれによって祝福され、しばしば生涯の終わりまで信仰が保たれるようにと願うアナフォラの一部 平和または「平和の挨拶」 アニュス・デイ 祝祷 聖務 「聖務」という用語は、「1日の時を刻み、祈りによってその日を神聖なものとする」という慣習を指す。[7] 西方教会では、典礼には複数の形式がある。ラテン教会全体で用いられる公式の典礼は「時間ごとの典礼」であるが、その他にも「聖母マリアの小典礼」、特定 の修道会に特有の典礼、第2バチカン公会議以前の標準であった「ローマ式小典礼」など、多くの形式が存在する。[8] 1日には特定の時間に対応する8つの時間がある。暁の祈り(徹夜の祈りとも呼ばれる)、讃美歌、初めの祈り、第3の祈り、第6の祈り、正午の祈り、夕方の 祈り、就寝の祈り。第2バチカン公会議は初めの祈りの廃止を命じた。 修道院では、暁明け前に「暁の祈り」が、また時には夜通し行われるのが一般的であった。「暁の祈り」の終わりに「讃美歌」が歌われ、通常は夜明けに「暁の 祈り」が行われる。「暁の祈り」は午前6時、「第三の祈り」は午前9時、「六時課」は正午、「昼の祈り」は午後3時、「夕の祈り」は夕暮れ時(通常午後6 時頃)に行われ、「夕の祈り」は日没後、または夕星が昇る頃に行われる。「夕の祈り」は、通常は就寝直前に、一日の終わりに行われる。 聖公会では、これらの礼拝は朝の祈りと夕の祈りの2つに統合され、後者は時に「夕の祈り」とも呼ばれる。近年では、聖公会は「正午の祈り」と「夜の祈り」 を「朝の祈り」と「夕の祈り」に加え、「共通祈祷書」の一部としている。8つの礼拝を含む聖公会式日課は、聖公会の公式典礼ではない。 ルーテル教会でも、聖公会と同様に、これらの礼拝は「早課」と「晩課」の2つに統合された(いずれも、現代のルーテル派の祈祷書や賛美歌集では維持されて いる)。米国のルーテル派では、待降節と四旬節の間、週の半ばにこれらの礼拝を行うのが一般的である。「終課」は、一部の古いルーテル派の礼拝書にも見ら れ、修道院や神学校ではより一般的に用いられている。 ビザンチン式では、聖礼典ではない7つの礼拝が1日のサイクルとして毎日行われている。 日没時の夕課(ギリシャ語:Hesperinos)は典礼の一日を始める 就寝時課(ギリシャ語:Apodeipnou、「夕食後」) 夜中課(ギリシャ語:mesonyktikon) 暁に終わる早課(ギリシャ語:Orthros)(理論上は。実際には、時間は大幅に異なる) 第一時課 第三時課および第六時課 第九時課 さまざまな正規の時間は、実際にはまとめて3つの主要な祈りの時間帯、すなわち夕方、朝、正午となるようにグループ化されている。詳細は正規の時間 — グループを参照のこと。 ビザンチン式典礼で「大晩課」と呼ばれるものは、主要な祝祭日の前夜、あるいは神聖な典礼と併せて、またはその他の特定の特別な機会に用いられる延長され た晩課の奉仕である。 マロン典礼では、典礼日は日没から始まるように定められている。その日の最初の奉神礼は夕方のラームショー、続いて夜のソートーロ、最後に朝のサフロとな る。米国のマロン使徒座では、承認された晩課は「信仰者の祈り」というタイトルである。 |

| Contemporary

Catholic liturgical music encompasses a comprehensive variety of

styles of music for Catholic liturgy that grew both before and after

the reforms of the Second Vatican Council (Vatican II). The dominant

style in English-speaking Canada and the United States began as

Gregorian chant and folk hymns, superseded after the 1970s by a

folk-based musical genre, generally acoustic and often slow in tempo,

but that has evolved into a broad contemporary range of styles

reflective of certain aspects of age, culture, and language. There is a

marked difference between this style and those that were both common

and valued in Catholic churches before Vatican II. History Background In the early 1950s the Jesuit priest Joseph Gelineau was active in liturgical development in several movements leading toward Vatican II.[1] The new Gelineau psalmody was published in French (1953) and English (1963). Vatican II Contemporary Catholic liturgical music grew after the reforms that followed the Second Vatican Council, which called for wider use of the vernacular language in the Catholic Mass. The General Instruction of the Roman Missal states: Great importance should ... be attached to the use of singing in the celebration of the Mass, with due consideration for the culture of the people and abilities of each liturgical assembly. Although it is not always necessary (e.g. in weekday Masses) to sing all the texts that are of themselves meant to be sung, every care should be taken that singing by the ministers and the people is not absent in celebrations that occur on Sundays and on holy days of obligation.[2] It adds: All other things being equal, Gregorian chant holds pride of place because it is proper to the Roman Liturgy. Other types of sacred music, in particular polyphony, are in no way excluded, provided that they correspond to the spirit of the liturgical action and that they foster the participation of all the faithful. Since the faithful from different countries come together ever more frequently, it is fitting that they know how to sing together at least some parts of the Ordinary of the Mass in Latin, especially the Creed and the Lord's Prayer, set to the simpler melodies.[3] English Masses One of the first English language Masses was of Gregorian chant style. It was created by DePaul University graduate Dennis Fitzpatrick and entitled "Demonstration English Mass". Fitzpatrick composed and recorded it on vinyl in mid-1963. He distributed it to many of the US bishops who were returning from a break in the Second Vatican Council. The Mass was well received by many US Catholic cleric and is said to have furthered their acceptance of Sacrosanctum Concilium.[4] Mary Lou Williams, a Black Catholic composer, had completed her own Mass, Black Christ of the Andes (also known as Mary Lou's Mass) in 1962 and performed it that November at St. Francis Xavier Church in Manhattan. She recorded it in October of the next year.[5] It was based around a hymn in honor of the Peruvian saint Martin de Porres, two other short works, "Anima Christi" and "Praise the Lord".[6] The first official Mass in English in the United States was held during the 1964 National Liturgical Conference in St Louis.[7] The Communion Hymn was Clarence Rivers' "God is Love", which combined Gregorian Chant with the melodic patterns and rhythms of Negro Spirituals.[7][8] It received a 10-minute standing ovation.[9] Rivers would go on to play a major role in the Black Catholic Movement, wherein the "Gospel Mass" tradition took hold in Black Catholic parishes and introduced Black gospel music to the larger Catholic world. Other major players in this movement included Thea Bowman, James P. Lyke, George Clements, George Stallings Jr., and William "Bill" Norvel. The revision of music in the liturgy took place in March 1967, with the passage of Musicam Sacram ("Instruction on music in the liturgy"). In paragraph 46 of this document, it states that music could be played during the sacred liturgy on "instruments characteristic of a particular people." Previously the pipe organ was used for accompaniment. The use of instruments native to the culture was an important step in the multiplication of songs written to accompany the Catholic liturgy.[10] In addition to his role in creating this first English language Mass, Dennis had a large stake in F.E.L. (Friends of the English Liturgy).[11] Many of the contemporary artists who authored the folk music that was used in American Catholic Liturgy choose F.E.L. to be their publisher, as did Ray Repp, who pioneered contemporary Catholic liturgical music and authored the "First Mass for Young Americans", a suite of folk-style musical pieces designed for the Catholic liturgy. Repp gave an impetus to the development of "guitar masses".[12][13] Musical style The musical style of 21st-century Catholic music varies greatly. Much of it is composed so that choir and assembly can be accompanied by organ, piano, or guitar. More recently, due to style preferences and cost, trends show fewer and fewer parishes use the traditional pipe organ, therefore this music has generally been written for chorus with piano, guitar, and/or percussion accompaniment.[14] The vernacular Mass texts have also drawn composers who stand outside the dominant folk–popular music tradition, such as Giancarlo Menotti and Richard Proulx. Popular composers American composers of this music, with some of their most well known compositions, include:[15] Alexander Peloquin, 1918–1997. He composed the first Mass setting sung in English, and had over 150 published Masses and other pieces. Miguel del Aguila, b. 1957. Several Mass settings, Ave Maria, Salva me, Agnus Dei, Requiem Mass. Marty Haugen, b. 1950 ("Gather Us In", "Canticle of the Sun", "We Are Many Parts", many psalm settings) Michael Joncas, b. 1951 (On Eagle's Wings, "We Come to Your Feast") John Michael Talbot, b. 1954 (Songs for Worship, Vols. 1 and 2) David Haas, b. 1957 ("Blest Are They", "You Are Mine") James E. Moore Jr., 1951-2022 ("Taste and See") Clarence Rivers, 1931-2004 ("God Is Love", "Glory to God, Glory", Mass Dedicated to the Brotherhood of Man) Mary Lou Williams, 1910-1981 ("Mary Lou's Mass", "Praise the Lord", "Black Christ of the Andes") Eddie Bonnemère, 1921-1996 (""Missa Hodierna", "Help Me, Jesus") Carey Landry, b. 1945 ("Abba, Father", "Hail Mary, Gentle Woman") The Dameans, Gary Ault, Mike Balhoff, Buddy Ceaser, Gary Daigle, Darryl Ducote ("Look Beyond", "All That We Have", Remember Your Love") Dan Schutte, b. 1947 ("Here I Am, Lord", "Sing a New Song", "You Are Near") Bob Dufford, b. 1943 ("Be Not Afraid", "All the Ends of the Earth") John Foley, b. 1939 ("One Bread, One Body") Janet Mead, 1938–2022 ("Lord's Prayer") Notable composers of contemporary Catholic liturgical music from outside the US include: Irish Ian Callanan, b. 1971 ("Comfort My People", "Take and Eat, This Is My Body", "Love Is the Boat for the Journey")[16] Frenchman Lucien Deiss, 1921-2007 ("Keep in Mind") Frenchman Joseph Gelineau, 1920-2008 ("The Lord Is My Shepherd") Australian Richard Connolly, b.1927 ("Where there is charity and love") English Damian Lundy ("Sing of a Girl", "Walk in the Light") English Bernadette Farrell, b. 1957 ("Unless a Grain of Wheat", "Christ Be Our Light") English Paul Inwood, b. 1947 ("Center of my Life")[17] English Anne Quigley b. 1955 or 1956 ("There is a Longing") Filipino Eduardo Hontiveros, 1923–2008 Filipino Ryan Cayabyab, b.1954 ("Kordero Ng Diyos", "Santo", "Panginoon Maawa Ka") Spanish Cesáreo Gabaráin, 1936-1991 ("Fisher of Men", "Lord, You Have Come to the Lakeshore": Roman Catholic composer, Gold Record in Spain)[18][19] Publishers A significant percentage of American contemporary liturgical music has been published under the names of three publishers: Oregon Catholic Press (OCP), Gregorian Institute of America (GIA), and World Library Publications (WLP, the music and liturgy division of the J.S. Paluch company). Oregon Catholic Press (OCP) is a not-for-profit affiliation of the Archdiocese of Portland. Archbishop Alexander K. Sample of Portland is de facto head of OCP.[20] Archbishop Sample is the eleventh bishop of the Archdiocese of Portland and was installed on April 2, 2013. Cardinal William Levada who became Prefect for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in the Roman Curia was a former member of the board of directors.[20] Levada as Archbishop of Portland (1986–1995) led OCP during its expansive growth, and this style of music became the principal style among many English-speaking communities. Francis George, prior to becoming Archbishop of Chicago and cardinal, was also Archbishop of Portland and de facto head of OCP. OCP grew to represent approximately two-thirds of Catholic liturgical music market sales.[21] Criticism Contemporary music aims to enable the entire congregation to take part in the song, in accord with the call in Sacrosanctum Concilium for full, conscious, active participation of the congregation during the Eucharistic celebration. What its advocates call a direct and accessible style of music gives participation of the gathered community higher priority than the beauty added to the liturgy by a choir skilled in polyphony.[22] Music for worship, according to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, is to be judged by three sets of criteria – pastoral, liturgical, and musical, with the place of honor accorded to Gregorian chant and the organ. On this basis it has been argued that the adoption of the more popular musical styles is alien to the Roman Rite, and weakens the distinctiveness of Catholic worship.[22][23][24] This style contrasts with the traditional form where the congregation sings to God.[25] Musicam Sacram, a 1967 document from the Second Vatican Council said to govern the use of sacred music, states that "those instruments which are, by common opinion and use, suitable for secular music only, are to be altogether prohibited from every liturgical celebration and from popular devotions".[26] Pundit George Weigel said that "[a]n extraordinary number of trashy liturgical hymns have been written in the years since the Second Vatican Council." Weigel called "Ashes" a "prime example" of "[h]ymns that teach heresy", criticizing the lyric "We rise again from ashes to create ourselves anew" as "Pelagian drivel".[27] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liturgical_music |

現代のカトリック典礼音楽は、第2バチカン公会議(バチカン2世)の改

革の前後を通じて発展した、カトリックの典礼のための幅広いスタイルの音楽を包括している。英語圏のカナダと米国で主流となっているスタイルは、グレゴリ

オ聖歌と民謡の賛美歌から始まり、1970年代以降は一般的にアコースティックでテンポの遅い、フォークをベースとした音楽ジャンルに取って代わられた。

しかし、この音楽は時代、文化、言語の特定の側面を反映した幅広い現代的なスタイルへと発展した。このスタイルと、バチカン2世以前のカトリック教会で一

般的であり、評価されていたスタイルとの間には、顕著な違いがある。 歴史 背景 1950年代初頭、イエズス会の神父ジョセフ・ゲリノーは、第2バチカン公会議につながるいくつかの運動において典礼の発展に尽力した。[1] 新しいゲリノーの詩編唱法はフランス語(1953年)と英語(1963年)で出版された。 バチカン II 現代のカトリック典礼音楽は、第二バチカン公会議後の改革を経て発展した。第二バチカン公会議では、カトリックのミサにおける現地語の使用拡大が呼びかけ られた。ローマ・ミサ典礼書総則には次のように記載されている。 ミサの式典における歌の使用には、人々の文化や式典に参加する人々の能力を十分に考慮した上で、非常に重要な意味がある。平日のミサなど、歌われることを 意図しているテキストをすべて歌う必要がない場合もあるが、日曜日や義務的祝祭日に行われる式典では、司祭や参列者による歌が欠けることのないよう、細心 の注意を払うべきである。 さらに次のように付け加えている。 他のすべての条件が同じである場合、グレゴリオ聖歌はローマ典礼にふさわしいものとして、最も重要な地位を占める。他の種類の聖歌、特にポリフォニーも、 典礼の精神にふさわしく、すべての信者の参加を促すものであれば、決して排除されるものではない。異なる国々から来た信者が集まる機会がますます増えてい るため、少なくともミサの通常唱の一部、特にシンプルなメロディにのせた「信条」と「主の祈り」を一緒に歌う方法を彼らが知っておくことは適切である。 英語によるミサ 英語によるミサの最初のもののひとつはグレゴリオ聖歌スタイルのものであった。これはデポール大学の卒業生であるデニス・フィッツパトリック氏によって作 られ、「デモンストレーション・イングリッシュ・ミサ」と名付けられた。フィッツパトリックは1963年半ばに作曲し、レコードに録音した。彼はそれを、 第2バチカン公会議の休会から戻ってきた多くの米国司教たちに配布した。このミサは多くの米国カトリック聖職者たちに好評を博し、 Sacrosanctum Conciliumの受け入れをさらに進めることになったと言われている。 黒人カトリックの作曲家メアリー・ルー・ウィリアムズは、1962年に自身のミサ曲『Black Christ of the Andes』(別名『メアリー・ルーのミサ』)を完成させ、同年11月にマンハッタンの聖フランシス・ザビエル教会で初演した。翌年10月に録音した。 [5] ペルーの聖人マルティン・デ・ポレスを称える賛美歌を中心に、「アニマ・クリスティ」と「Praise the Lord」という2つの短い作品が組み合わされている。[6] 米国で初めて公式に英語で行われたミサは、1964年のセントルイス国民典礼会議の期間中に開催された。[7] 聖餐式の賛美歌は、グレゴリオ聖歌と黒人霊歌の旋律パターンとリズムを組み合わせた、クラレンス・リバーズの「神は愛なり」であった 。[7][8] 10分間にわたるスタンディングオベーションが送られた。[9] リヴァースは、ブラック・カトリック運動において重要な役割を果たすことになる。この運動では、「ゴスペル・ミサ」の伝統がブラック・カトリックの小教区 に定着し、ブラック・ゴスペル音楽がより大きなカトリックの世界に紹介された。この運動におけるその他の主要な人物には、テア・ボーマン、ジェームズ・ P・ライク、ジョージ・クレメンツ、ジョージ・スターリングス・ジュニア、ウィリアム・「ビル」・ノーベルなどがいる。 典礼における音楽の改訂は、1967年3月に「Musicam Sacram(典礼における音楽に関する教令)」が可決されたことにより実施された。この文書の第46項では、神聖な典礼中に「特定の民族に特徴的な楽 器」を使用して音楽を演奏できることが明記されている。それまではパイプオルガンが伴奏に使われていた。その文化に固有の楽器の使用は、カトリックの典礼 に合わせた歌の作曲を増加させる上で重要な一歩であった。[10] この最初の英語ミサの作成における役割に加え、デニスはF.E.L.(Friends of the English Liturgy)に深く関わっていた。[11] アメリカのカトリックの典礼で使われるフォークミュージックの作者である現代のアーティストの多くは レイ・レップのように、現代のカトリック典礼音楽の先駆者となり、カトリック典礼用に作曲されたフォークスタイルの楽曲集「First Mass for Young Americans」の作者も、F.E.L.を出版元として選んだ。レップは「ギターミサ曲」の発展に弾みをつけた。[12][13] 音楽スタイル 21世紀のカトリック音楽の音楽スタイルは多岐にわたる。その多くは、聖歌隊や会衆がオルガン、ピアノ、ギターの伴奏で歌えるように作曲されている。最近 では、好みのスタイルやコストの問題から、伝統的なパイプオルガンを使用する小教区が減っており、この音楽は一般的に、ピアノ、ギター、打楽器の伴奏付き 合唱曲として作曲されている。 また、ミサのテキストは、支配的な民族音楽・大衆音楽の伝統の外に立つジャンカルロ・メノッティやリチャード・プルーなどの作曲家をも引きつけてきた。 人気の作曲家 この音楽のアメリカの作曲家で、最もよく知られた作品をいくつか挙げると、以下の通りである。 アレクサンダー・ペロカン(1918年 - 1997年)。英語で歌われる最初のミサ曲を作曲し、150以上のミサ曲やその他の作品を出版した。 ミゲル・デル・アギラ(1957年生まれ)。ミサ曲、アヴェ・マリア、サルヴァ・メ、アニュス・デイ、レクイエム・ミサなど。 マーティ・ハウゲン(1950年生)「ギャザー・アス・イン」、「カンティクル・オブ・ザ・サン」、「ウィー・アー・メニー・パーツ」、多数の詩篇曲 マイケル・ジョンカス(1951年生)「オン・イーグルズ・ウイングス」、「ウィー・カム・トゥ・ユア・フィースト」 ジョン・マイケル・タルボット(1954年生)「ソングス・フォー・ワーシップ、第1巻および第2巻」 デヴィッド・ハース(1957年生)、「Blest Are They」、「You Are Mine」 ジェームズ・E・ムーア・ジュニア(1951-2022)、「Taste and See」 クラレンス・リヴァーズ(1931-2004)、「God Is Love」、「Glory to God, Glory」、「Mass Dedicated to the Brotherhood of Man」 メアリー・ルー・ウィリアムズ、1910-1981年(「メアリー・ルーのミサ」、「主をたたえよ」、「アンデスの黒いキリスト」) エディ・ボネメア、1921-1996年(「ミサ・ホディエルナ」、「助けて、イエス様」) ケアリー・ランドリ、1945年生(「アバ、父よ」、「おお、おんやさしきマリア」) デイミアンズ、ゲイリー・オールト、マイク・バルホフ、バディ・シーザー、ゲイリー・ダイグル、ダリル・デュコート(「ルック・ビヨンド」、「オール・ ザット・ウィー・ハブ」、「リメンバー・ユア・ラブ」) ダン・シュッテ、1947年生(「ヒア・アイ・アム、ロード」、「シング・ア・ニュー・ソング」、「ユー・アー・ニア」) ボブ・ダフフォード、1943年生(「ビ・ノット・アフレイド」、「オール・ジ・エンズ・オブ・ジ・アース」) ジョン・フォーリー(1939年生、「一つのパン、一つの体」) ジャネット・ミード(1938年-2022年、「主の祈り」) 米国以外の現代のカトリック典礼音楽の著名な作曲家には、以下のような人物がいる。 アイルランド人イアン・カラナン(1971年生、「わが民を慰めよ」、「これは私の体である、取って食べよ」、「愛は旅の舟」)[16] フランス人ルシアン・デイス(1921-2007)(「Keep in Mind」) フランス人ジョセフ・ジェリノー(1920-2008)(「The Lord Is My Shepherd」) オーストラリア人リチャード・コノリー(1927年生)(「Where there is charity and love」) イギリス人ダミアン・ランディ(「Sing of a Girl」、「Walk in the Light」) イギリス バーナデット・ファレル(1957年生)「一粒の麦」、「キリストは我らの光」 イギリス ポール・インウッド(1947年生)「私の人生の中心」[17] イギリス アン・クイグリー(1955年または1956年生)「憧れ」 フィリピン人 エドゥアルド・ホントヴェロス(1923年 - 2008年) フィリピン人 Ryan Cayabyab, 1954年生 (「Kordero Ng Diyos」, 「Santo」, 「Panginoon Maawa Ka」) スペイン人 Cesáreo Gabaráin, 1936-1991 (「Fisher of Men」, 「Lord, You Have Come to the Lakeshore」: スペインのゴールドレコード受賞のローマ・カトリックの作曲家)[18][19] 出版社 アメリカの現代の典礼音楽のかなりの割合が、次の3つの出版社名で出版されている。オレゴン・カトリック・プレス(OCP)、グレゴリアン・インスティ テュート・オブ・アメリカ(GIA)、ワールド・ライブラリー・パブリケーションズ(WLP、J.S.パルフ社の音楽・典礼部門)。 オレゴン・カトリック・プレス(OCP)は、ポートランド大司教区の非営利団体である。ポートランド大司教アレクサンダー・K・サンプルが事実上のOCP のトップである。[20] サンプル大司教はポートランド大司教区の第11代司教であり、2013年4月2日に就任した。ローマ教皇庁の信仰教理省長官となった枢機卿ウィリアム・レ ヴァダは、かつての理事会メンバーであった。レヴァダはポートランド大司教(1986年-1995年)として、OCPが拡大成長を遂げる中、その指揮を執 り、英語圏の多くのコミュニティの間で、このスタイルの音楽が主要なスタイルとなった。シカゴ大司教および枢機卿となる前のフランシス・ジョージも、ポー トランド大司教であり、事実上OCPのトップであった。OCPはカトリック典礼音楽市場の約3分の2を占めるまでに成長した。 批判 現代の音楽は、聖体拝領の式典中に信者が十分に意識的に能動的に参加すべきであるという『サクロサンクタム・コンシリアム』の呼びかけに従い、会衆全員が 歌に参加できるようにすることを目的としている。 その支持者が「直接的で親しみやすいスタイル」と呼ぶ音楽は、多声音楽に熟練した聖歌隊が典礼に加える美よりも、集まったコミュニティの参加を優先するも のである。 米国カトリック司教協議会によると、礼拝のための音楽は、司牧、典礼、音楽の3つの基準によって判断されるべきであり、グレゴリオ聖歌とオルガンが最も尊 重されるべきである。この立場から、よりポピュラーな音楽スタイルの採用はローマ典礼にはそぐわず、カトリックの礼拝の独自性を弱めるという主張がなされ ている。[22][23][24] このスタイルは、会衆が神に歌うという伝統的な形式とは対照的である。[25] 聖楽の使用を規定する1967年の第二バチカン公会議文書 『Musicam Sacram』には、「一般的な意見と使用によって、世俗的な音楽にのみ適しているとされる楽器は、あらゆる典礼の祝典と民衆の奉献から完全に禁止され る」と記されている。識者ジョージ・ヴァイゲルは、「第二バチカン公会議以降の数年間で、非常に多くのゴミのような典礼賛美歌が作られた」と述べている。 ヴァイゲルは「灰」を「異端を教える賛美歌」の「代表的な例」と呼び、「私たちは灰から再び立ち上がり、新たに自分自身を創造する」という歌詞を「ペラギ ウス的戯言」と批判した。 |

| Church music is

Christian music written for performance in church, or any musical

setting of ecclesiastical liturgy, or music set to words expressing

propositions of a sacred nature, such as a hymn. History Early Christian music The only record of communal song in the Gospels is the last meeting of the disciples before the Crucifixion.[1] Outside the Gospels, there is a reference to St. Paul encouraging the Ephesians and Colossians to use psalms, hymns and spiritual songs.[2] Later, there is a reference in Pliny the Younger who writes to the emperor Trajan (53–117) asking for advice about how to persecute the Christians in Bithynia, and describing their practice of gathering before sunrise and repeating antiphonally "a hymn to Christ, as to God". Antiphonal psalmody is the singing or musical playing of psalms by alternating groups of performers. The peculiar mirror structure of the Hebrew psalms makes it likely that the antiphonal method originated in the services of the ancient Israelites. According to the historian Socrates of Constantinople, its introduction into Christian worship was due to Ignatius of Antioch (died 107), who in a vision had seen the angels singing in alternate choirs.[3] During the first two or three centuries, Christian communities incorporated into their observances features of Greek music and the music of other cultures bordering on the eastern Mediterranean Sea.[4] As the early Church spread from Jerusalem to Asia Minor, North Africa, and Europe, it absorbed other musical influences. For example, the monasteries and churches of Syria were important in the development of psalm singing and the use of strophic devotional song, or hymns.[4] The use of instruments in early Christian music seems to have been frowned upon.[5] In the late 4th or early 5th century, St. Jerome wrote that a Christian maiden ought not even to know what a lyre or flute is like, or to what use it is put.[6] Evidence of musical roles during the 6th through 7th centuries is particularly sparse because of the cycle of invasions of Germanic tribes in the West and doctrinal and political conflict in the East as well as the consequent instability of Christian institutions in the former Roman empire.[7] The introduction of church organ music is traditionally believed to date from the time of the papacy of Pope Vitalian in the 7th century. Gregorian chant Main article: Gregorian chant  The Introit Gaudeamus omnes, scripted in square notation in the 14th–15th century Graduale Aboense, honours Henry, patron saint of Finland Gregorian chant is the main tradition of Western plainchant, a form of monophonic liturgical chant of Western Christianity that accompanied the celebration of Mass and other ritual services. This musical form originated in Monastic life, in which singing the 'Divine Service' nine times a day at the proper hours was upheld according to the Rule of Saint Benedict. Singing psalms made up a large part of the life in a monastic community, while a smaller group and soloists sang the chants. In its long history, Gregorian Chant has been subjected to many gradual changes and some reforms. It was organized, codified, and notated mainly in the Frankish lands of western and central Europe during the 12th and 13th centuries, with later additions and redactions, but the texts and many of the melodies have antecedents going back several centuries earlier. Although a 9th-century legend credits Pope Gregory the Great with having personally invented Gregorian chant by receiving the chant melodies through divine intervention of the Holy Spirit,[8] scholars now believe that the chant bearing his name arose from a later Carolingian synthesis of Roman and Gallican chant. During the following centuries, the Chant tradition was still at the heart of Church music, where it changed and acquired various accretions. Even the polyphonic music that arose from the venerable old chants in the Organa by Léonin and Pérotin in Paris (1160–1240) ended in monophonic chant and in later traditions new composition styles were practiced in juxtaposition (or co-habitation) with monophonic chant. This practice continued into the lifetime of François Couperin, whose Organ Masses were meant to be performed with alternating homophonic Chant. Although it had mostly fallen into disuse after the Baroque period, Chant experienced a revival in the 19th century in the Catholic Church and the Anglo-Catholic wing of the Anglican Communion. Mass Main article: Mass (music) The mass is a form of music that sets out the parts of the Eucharistic liturgy (chiefly belonging to the Catholic Church, the Churches of the Anglican Communion, and also the Lutheran Church) to music. Most masses are settings of the liturgy in Latin, the traditional language of the Catholic Church, but there are a significant number written in the languages of non-Catholic countries where vernacular worship has long been the norm. For example, there are many masses (often called "Communion Services") written in English for the Church of England. At a time when Christianity was competing for prominence with other religions, the music and chants were often beautiful and elaborate to attract new members to the Church.[9] Music is an integral part of mass. It accompanies various rituals acts and contributes to the totality of worship service. Music in mass is an activity that participants share with others in the celebration of Jesus Christ.[10] Masses can be a cappella, for the human voice alone, or they can be accompanied by instrumental obbligatos up to and including a full orchestra. Many masses, especially later ones, were never intended to be performed during the celebration of an actual mass. Generally, for a composition to be a full mass, it must contain the following invariable five sections, which together constitute the Ordinary of the Mass. Kyrie ("Lord have mercy") Gloria ("Glory be to God on high") Credo ("I believe in one God"), the Nicene Creed Sanctus ("Holy, Holy, Holy"), the second part of which, beginning with the word "Benedictus" ("Blessed is he"), was often sung separately after the consecration, if the setting was long. (See Benedictus for other chants beginning with that word.) Agnus Dei ("Lamb of God") This setting of the Ordinary of the Mass spawned a tradition of Mass composition to which many famous composers of the standard concert repertory made contributions, including Bach, Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven.[11] The Requiem Mass, or the Mass of the Dead,[12] is a modified version of the ordinary mass. Musical settings of the Requiem mass have a long tradition in Western music. There are many notable works in this tradition, including those by Ockeghem, Pierre de la Rue, Brumel, Jean Richafort, Pedro de Escobar, Antoine de Févin, Morales, Palestrina, Tomás Luis de Victoria, Mozart, Gossec, Cherubini, Berlioz, Brahms, Bruckner, Dvořák, Frederick Delius, Maurice Duruflé, Fauré, Liszt, Verdi, Herbert Howells, Stravinsky, Britten, György Ligeti, Penderecki, Henze, and Andrew Lloyd Webber. In a liturgical mass, there are variable other sections that may be sung, often in Gregorian chant. These sections, the "proper" of the mass, change with the day and season according to the church calendar, or according to the special circumstances of the mass. The proper of the mass is usually not set to music in a mass itself, except in the case of a Requiem Mass, but may be the subject of motets or other musical compositions. The sections of the proper of the mass include the introit, gradual, Alleluia or Tract (depending on the time of year), offertory and communion. Carols Main article: Carol (music)  Carol singers A carol is a festive song, generally religious but not necessarily connected with church worship, often having a popular character. Today the carol is represented almost exclusively by the Christmas carol, the Advent carol, and to a lesser extent by the Easter carol. The tradition of Christmas carols goes back as far as the 13th century, although carols were originally communal songs sung during celebrations like harvest tide as well as Christmas. It was only in the late 18th and 19th centuries that carols began to be sung in church, and to be specifically associated with Christmas. Traditionally, carols have often been based on medieval chord progressions, and it is this that gives them their characteristic sound. Some carols like "Personent hodie" and "Angels from the Realms of Glory" can be traced directly back to the Middle Ages, and are among the oldest musical compositions still regularly sung. Carols suffered a decline in popularity after the Reformation in the countries where Protestant churches gained prominence (although well-known Reformers like Martin Luther authored carols and encouraged their use in worship), but survived in rural communities until the revival of interest in carols in the 19th century. The first appearance in print of "God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen", "The First Noel", "I Saw Three Ships" and "Hark the Herald Angels Sing" was in Christmas Carols Ancient and Modern (1833) by William Sandys. Composers like Arthur Sullivan helped to repopularize the carol, and it is this period that gave rise to such favorites as "Good King Wenceslas" and "It Came Upon the Midnight Clear", a New England carol written by Edmund H. Sears and Richard S. Willis. Christian hymnody Further information: Hymnody of continental Europe Thomas Aquinas, in the introduction to his commentary on the Psalms, defined the Christian hymn thus: "Hymnus est laus Dei cum cantico; canticum autem exultatio mentis de aeternis habita, prorumpens in vocem." ("A hymn is the praise of God with song; a song is the exultation of the mind dwelling on eternal things, bursting forth in the voice.")[13] The earliest Christian hymns are mentioned round about the year 64 by Saint Paul in his letters. The Greek hymn, Hail Gladdening Light was mentioned by Saint Basil around 370. Latin hymns appear at around the same time, influenced by Saint Ambrose of Milan. Early Christian hymns are known as canticles and are often based on Biblical passages other than the psalms; they are still used in Catholic, Lutheran, Anglican and Methodist liturgy, examples are Te Deum and Benedicite.[14] Prudentius, a Spanish poet of the late 4th century was one of the most prolific hymn writers of the time.[15] Early Celtic hymns, associated with Saint Patrick and Saint Columba, including the still extant, Saint Patrick's Breastplate, can be traced to the 6th and 7th centuries. Catholic hymnody in the Western church introduced four-part vocal harmony as the norm, adopting major and minor keys, and came to be led by organ and choir. The Protestant Reformation resulted in two conflicting attitudes to hymns. One approach, the regulative principle of worship, favored by many Zwinglians, Calvinists among others, considered anything that was not directly authorized by the Bible to be a novel and Catholic introduction to worship, which was to be rejected. All hymns that were not direct quotations from the Bible fell into this category. Such hymns were banned, along with any form of instrumental musical accompaniment, and organs were ripped out of churches. Instead of hymns, Biblical psalms were chanted, most often without accompaniment. This was known as exclusive psalmody. Examples of this may still be found in various places, including the Churches of Christ and the "free churches" of western Scotland.  An early printing of Martin Luther's hymn "Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott" The other Reformation approach, favored by Martin Luther, produced a burst of hymn writing and congregational singing. Luther and his followers often used their hymns, or chorales, to teach tenets of the faith to worshipers. The earlier English writers tended to paraphrase biblical text, particularly Psalms; Isaac Watts followed this tradition, but is also credited as having written the first English hymn which was not a direct paraphrase of Scripture.[16] Later writers took even more freedom, some even including allegory and metaphor in their texts. Charles Wesley's hymns spread Methodist theology, not only within Methodism, but in most Protestant churches. He developed a new focus: expressing one's personal feelings in the relationship with God as well as the simple worship seen in older hymns. The Methodist Revival of the 18th century created an explosion of hymn writing in Welsh, which continued into the first half of the 19th century. African-Americans developed a rich hymnody out of the spirituals sung during times of slavery. During the Second Great Awakening in the United States, this led to the emergence of a new popular style. Fanny Crosby, Ira D. Sankey, and others produced testimonial music for evangelistic crusades. These are often designated "gospel songs" as distinct from hymns, since they generally include a refrain (or chorus) and usually (though not always) a faster tempo than the hymns. As examples of the distinction, "Amazing Grace" is a hymn (no refrain), but "How Great Thou Art" is a gospel song. During the 19th century the gospel-song genre spread rapidly in Protestantism and, to a lesser but still definite extent, in Catholicism. The gospel-song genre is unknown in the worship per se by Eastern Orthodox churches, which rely exclusively on traditional chants, and disallow instrumental accompaniment. Along with the more classical sacred music of composers ranging from Mozart to Monteverdi, the Catholic Church continued to produce many popular hymns such as Lead, Kindly Light, Silent Night, "O Sacrament Divine" and "Faith of our Fathers". Modern Many churches today use contemporary worship music which includes a range of styles often influenced by popular music. This style began in the late 1960s and became very popular during the 1970s. A distinctive form is the modern, lively black gospel style. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_music |

教会音楽とは、教会で演奏するために書かれたキリスト教音楽、または教

会典礼の音楽的設定、または賛美歌のような神聖な性質を持つ命題を表現する言葉に合わせた音楽のことである。 歴史 初期のキリスト教音楽 福音書以外では、聖パウロがエフェソの信徒とコロサイの信徒に詩編、賛美歌、霊的な歌を用いるように勧めている記述がある[2]。 その後、若きプリニウスがトラヤヌス帝(53-117)に宛てた手紙には、ビティニア地方のキリスト教徒を迫害する方法について助言を求める記述があり、 日の出前に集まって「キリストへの賛歌を神への賛歌として」反唱する彼らの習慣について述べている。対唱詩編曲とは、詩編を交互に演奏者が歌ったり演奏し たりすることである。ヘブライ語の詩篇には独特の鏡像構造があることから、対唱詩編は古代イスラエル人の礼拝に端を発していると考えられる。コンスタンチ ノープルの歴史家ソクラテスによれば、キリスト教礼拝への導入はアンティオキアのイグナティウス(107年没)によるもので、彼は幻視の中で天使が交互に 聖歌隊を組んで歌うのを見たという。 最初の2~3世紀、キリスト教共同体はギリシャ音楽や東地中海に接する他の文化の音楽の特徴を礼拝に取り入れた[4]。エルサレムから小アジア、北アフリ カ、ヨーロッパへと初代教会が広がるにつれて、他の音楽の影響も吸収した。例えば、シリアの修道院や教会は、詩編の歌唱や梗概的な献身的な歌、賛美歌の発 展において重要であった[4]。 4世紀後半から5世紀初頭にかけて、聖ジェロームは、キリスト教徒の乙女は竪琴やフルートがどのようなものか、またどのような用途に使われるのかさえ知る べきでないと書いている[5]。 [6世紀から7世紀にかけては、西方ではゲルマン民族の侵入、東方では教義的・政治的対立が繰り返され、旧ローマ帝国ではキリスト教の制度が不安定であっ たため、音楽の役割に関する証拠は特に乏しい[7]。教会にオルガン音楽が導入されたのは、伝統的には7世紀の教皇ヴィタリアヌスの時代と考えられてい る。 グレゴリオ聖歌 主な記事 グレゴリオ聖歌  14~15世紀のGraduale Aboenseに方形記譜法で書かれたイントロイトGaudeamus omnesは、フィンランドの守護聖人ヘンリーを称えている。 グレゴリオ聖歌は、西方平原聖歌の主要な伝統であり、西方キリスト教の単旋律典礼聖歌の一形態で、ミサやその他の儀式に伴奏された。この音楽形式は修道院 生活に端を発し、聖ベネディクトの規則に従って、1日9回、適切な時間に「神聖な礼拝」を歌うことが守られていた。詩篇を歌うことは修道院共同体の生活の 大部分を占め、聖歌は少人数のグループやソリストが歌っていた。 その長い歴史の中で、グレゴリオ聖歌は多くの段階的な変化といくつかの改革にさらされてきた。グレゴリオ聖歌は、12世紀から13世紀にかけて、主に西 ヨーロッパと中央ヨーロッパのフランク王国で組織され、成文化され、楽譜化された。9世紀の伝説では、教皇グレゴリウス大王が聖霊の介入によって聖歌の旋 律を受け取り、自らグレゴリオ聖歌を創作したとされているが[8]、現在では、教皇の名を冠した聖歌は、ローマ聖歌とガリア聖歌の後期カロリング朝時代の 統合によって生まれたと学者たちは考えている。 その後何世紀もの間、聖歌の伝統は教会音楽の中心であり続け、様々な変化を遂げ、様々な付加物を獲得していった。パリのレオナンとペロタンによるオルガナ (1160-1240年)の由緒ある古い聖歌から生まれたポリフォニックな音楽でさえも、モノフォニックな聖歌に終わり、後の伝統では、新しい作曲様式が モノフォニックな聖歌と並存(または同居)して実践された。フランソワ・クープランのオルガン・ミサ曲は、同音聖歌と交互に演奏されるよう意図されてい た。バロック時代以降、聖歌はほとんど使われなくなったが、19世紀にはカトリック教会や英国国教会のアングロ・カトリック派で復活を遂げた。 ミサ 主な記事 ミサ曲(音楽) ミサ曲は、聖体礼儀(主にカトリック教会、聖公会の諸教会、ルター派教会に属する)の各パートを音楽化したものである。ほとんどのミサ曲は、カトリック教 会の伝統的な言語であるラテン語で書かれた典礼であるが、長い間、方言による礼拝が主流であった非カトリック諸国の言語で書かれたものも相当数ある。たと えば、英国国教会のために英語で書かれたミサ曲(しばしば「聖餐式」と呼ばれる)も多い。キリスト教が他の宗教と隆盛を競っていた当時、新しい教会員を教 会に惹きつけるために、音楽や聖歌はしばしば美しく、手の込んだものだった[9]。 音楽はミサに不可欠な要素である。音楽は様々な儀式行為に付随し、礼拝の全体性に貢献する。ミサにおける音楽は、参加者がイエス・キリストを祝うために他 の人々と分かち合う活動である[10]。 ミサはアカペラで声だけで行われることもあれば、フルオーケストラを含む器楽のオブリガートを伴うこともある。多くのミサ曲、特に後世のミサ曲は、実際の ミサの祝典の中で演奏されることは意図されていなかった。 一般的に、ミサ曲として成立するためには、次の5つの部分が必ず含まれていなければならない。 キリエ(「主よ憐れみたまえ) グローリア(「高き神に栄光あれ) クレド(「私は唯一の神を信じます」)、ニカイア信条 サンクトゥス(「聖なる、聖なる、聖なる」)、その第2部は「ベネディクトゥス」(「祝福された方」)で始まるが、長い曲の場合、奉献式の後に別に歌われ ることが多かった。(この言葉で始まる他の聖歌については、ベネディクトゥスを参照のこと)。 アニュス・デイ(神の子羊) このミサ典礼曲は、バッハ、ハイドン、モーツァルト、ベートーヴェンなど、標準的なコンサート・レパートリーの多くの有名な作曲家が貢献したミサ曲の伝統 を生み出した[11]。 レクイエム・ミサ(死者のミサ)[12]は、通常のミサを修正したものである。レクイエムのミサ曲は、西洋音楽において長い伝統を持っている。オッケヘ ム、ピエール・ド・ラ・リュー、ブルーメル、ジャン・リシャフォール、ペドロ・デ・エスコバル、アントワーヌ・ド・フェヴァン、モラレス、パレストリー ナ、トマス・ルイス・デ・ヴィクトリア、モーツァルト、ゴセック、ケルビーニ、ゴセック、ケルビーニ、モーツァルトなど、多くの著名な作品がある、 ゴセック、ケルビーニ、ベルリオーズ、ブラームス、ブルックナー、ドヴォルザーク、フレデリック・デリアス、モーリス・デュルフレ、フォーレ、リスト、 ヴェルディ、ハーバート・ハウエルズ、ストラヴィンスキー、ブリテン、ギョルジー・リゲティ、ペンデレツキ、ヘンツェ、アンドリュー・ロイド・ウェバー。 典礼ミサでは、多くの場合グレゴリオ聖歌で歌われる他の様々なセクションがある。ミサの 「本編 」と呼ばれるこれらの部分は、教会暦やミサの特別な状況に応じて、日や季節によって変わる。レクイエム・ミサの場合を除き、ミサそのものが音楽化されるこ とは通常ないが、モテットやその他の楽曲の主題となることはある。ミサ曲には、導入部、緩徐部、アレルヤまたはトラクト(時期によって異なる)、オファー トリー、聖体拝領などがある。 キャロル 主な記事 キャロル(音楽)  キャロル歌手 キャロル(Carol)とは、祝祭の歌のことで、一般的には宗教的なものであるが、必ずしも教会の礼拝とは関係なく、しばしばポピュラーな性格を持つ。今 日、キャロルはクリスマス・キャロル、アドヴェント・キャロル、イースター・キャロルに代表される。 クリスマス・キャロルの伝統は13世紀にまで遡るが、キャロルはもともとクリスマスだけでなく、収穫の潮時などの祝いの時に歌われる共同体の歌だった。 キャロルが教会で歌われるようになったのは18世紀後半から19世紀にかけてのことで、特にクリスマスと結びついている。伝統的に、キャロルは中世のコー ド進行に基づいていることが多く、それがキャロルの特徴的な響きを生み出している。Personent hodie」や「Angels from the Realms of Glory」のようなキャロルのいくつかは、中世に直接遡ることができ、現在でも定期的に歌われている最も古い楽曲のひとつである。 宗教改革後、プロテスタント教会が台頭した国々ではキャロルの人気は下火になったが(マルティン・ルターのような有名な改革者たちはキャロルを作詞し、礼 拝での使用を奨励した)、19世紀にキャロルへの関心が復活するまで農村社会では存続した。God Rest Ye Merry, Gentlemen「、」The First Noel「、」I Saw Three Ships「、」Hark the Herald Angels Sing "が印刷物として初めて登場したのは、ウィリアム・サンディスの『Christmas Carols Ancient and Modern』(1833年)だった。アーサー・サリヴァンのような作曲家がキャロルの再普及に貢献し、エドマンド・H・シアーズとリチャード・S・ウィ リスによって書かれたニューイングランドのキャロルである「Good King Wenceslas」や「It Came Upon the Midnight Clear」などが生まれたのもこの時期である。 キリスト教讃美歌 さらに詳しい情報 ヨーロッパ大陸の賛美歌 トマス・アクィナスは詩篇注解の序文で、キリスト教讃美歌をこう定義している: 「讃美歌とは、神への賛歌であり、神への賛歌であり、神への賛歌である。(讃美歌は歌による神の賛美であり、歌は永遠のものに宿る心の歓喜であり、声の中 ではじける」)[13] キリスト教最古の讃美歌は、64年頃に聖パウロがその書簡の中で言及している。ギリシャ語の賛美歌「Hail Gladdening Light」は、370年頃に聖バジルが言及している。ラテン語の賛美歌は、ミラノの聖アンブローズの影響を受け、ほぼ同時期に登場する。初期キリスト教 の賛美歌はカンティクルと呼ばれ、詩篇以外の聖書の一節に基づいていることが多い。カトリック、ルーテル、英国国教会、メソジストの典礼では今でも使われ ており、その例としてテ・デウムやベネディシテが挙げられる。 [14]4世紀後半のスペインの詩人プルデンティウスは、当時最も多くの賛美歌を書いた一人であった[15]。聖パトリックと聖コロンバに関連する初期の ケルト賛美歌は、現存する『聖パトリックの胸当て』を含め、6世紀から7世紀まで遡ることができる。西方教会におけるカトリックの賛美歌は、4声のハーモ ニーを標準とし、長調と短調を採用し、オルガンと聖歌隊によって歌われるようになった。 プロテスタントの宗教改革は、賛美歌に対して2つの相反する態度をもたらした。ひとつは、多くのツヴィングリ派やカルヴァン派などが支持した礼拝規定主義 で、聖書によって直接認可されていないものは、斬新でカトリック的な礼拝への導入とみなされ、拒否された。聖書からの直接の引用でない賛美歌はすべてこの カテゴリーに入った。そのような賛美歌は、あらゆる形の器楽伴奏とともに禁止され、教会からオルガンが引き抜かれた。賛美歌の代わりに聖書の詩篇が唱えら れ、ほとんどの場合伴奏なしで歌われた。これは専属詩編と呼ばれた。その例は、キリスト教会やスコットランド西部の「自由教会」など、さまざまな場所で今 でも見られる。  マルティン・ルターの賛美歌 「Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott 」の初期の印刷物。 マルティン・ルターが好んだもう一つの宗教改革のアプローチは、賛美歌の作曲と会衆の歌唱を爆発的に増加させた。ルターとその信奉者たちは、しばしば賛美 歌(コラール)を使って礼拝者に信仰の教義を教えた。アイザック・ワッツはこの伝統に従ったが、聖句の直接的な言い換えではない最初のイギリス賛美歌を書 いたとされている。 チャールズ・ウェスレーの賛美歌は、メソジスト神学をメソジスト内だけでなく、ほとんどのプロテスタント教会に広めた。彼は、古い賛美歌に見られるような 単純な賛美だけでなく、神との関係における個人的な感情を表現するという新しい焦点を打ち出した。18世紀のメソジスト復興は、ウェールズ語による賛美歌 の爆発的な創作を生み出し、それは19世紀前半まで続いた。 アフリカ系アメリカ人は、奴隷時代に歌われた霊歌から豊かな賛美歌を発展させた。アメリカにおける第二次大覚醒の時代には、これが新しいポピュラー・スタ イルの出現につながった。ファニー・クロスビー、アイラ・D・サンキーらは、伝道十字軍のための証言音楽を制作した。これらは一般的にリフレイン(または コーラス)を含み、賛美歌よりもテンポが速いことが多いため(必ずしもそうではないが)、賛美歌とは区別して「ゴスペル・ソング」と呼ばれることが多い。 この区別の例として、「Amazing Grace」は賛美歌(リフレインはない)だが、「How Great Thou Art」はゴスペル・ソングである。19世紀、ゴスペル・ソングというジャンルはプロテスタントで急速に広まり、わずかではあるがカトリックでも広まっ た。ゴスペルソングというジャンルは、伝統的な聖歌にのみ依存し、楽器の伴奏を認めない東方正教会では、礼拝そのものでは知られていない。 モーツァルトからモンテヴェルディまでの作曲家による、より古典的な聖楽曲とともに、カトリック教会は、「導きよ、優しい光よ」、「きよしこの夜」、「神 聖なる聖餐」、「父祖の信仰」など、多くのポピュラーな賛美歌を作り続けた。 現代 今日の多くの教会では、ポピュラー音楽の影響を受けた様々なスタイルの現代賛美音楽が用いられている。このスタイルは1960年代後半に始まり、1970 年代に非常に人気が出た。特徴的な形式は、現代的で生き生きとしたブラック・ゴスペル・スタイルである。 |

| Christian music

is music that has been written to express either personal or a communal

belief regarding Christian life and faith. Common themes of Christian

music include praise, worship, penitence and lament, and its forms vary

widely around the world. Church music, hymnals, gospel and worship

music are a part of Christian media and also include contemporary

Christian music which itself supports numerous Christian styles of

music, including hip hop, rock, contemporary worship and urban

contemporary gospel. Like other forms of music the creation, performance, significance and even the definition of Christian music varies according to culture and social context. Christian music is composed and performed for many purposes, ranging from aesthetic pleasure, religious or ceremonial purposes or with a positive message as an entertainment product for the marketplace. |

キリスト教音楽とは、キリスト教の生活や信仰に関する個人的または共同

的な信念を表現するために作られた音楽のことである。キリスト教音楽に共通するテーマには、賛美、礼拝、懺悔、嘆きなどがあり、その形態は世界中で大きく

異なっている。教会音楽、賛美歌、ゴスペル、ワーシップ音楽はキリスト教メディアの一部であり、ヒップホップ、ロック、コンテンポラリー・ワーシップ、