滑空弾薬ドローン

Loitering munition

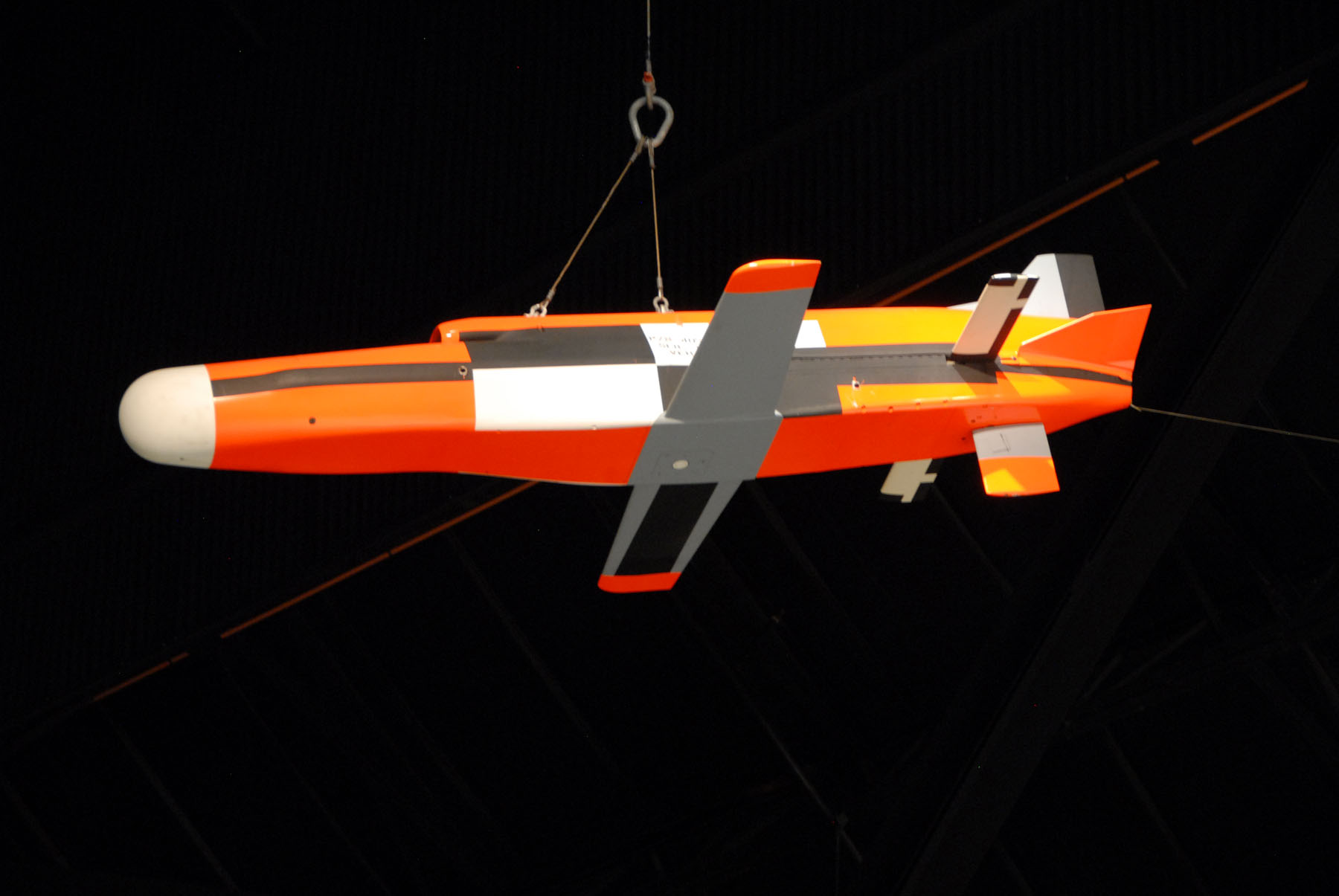

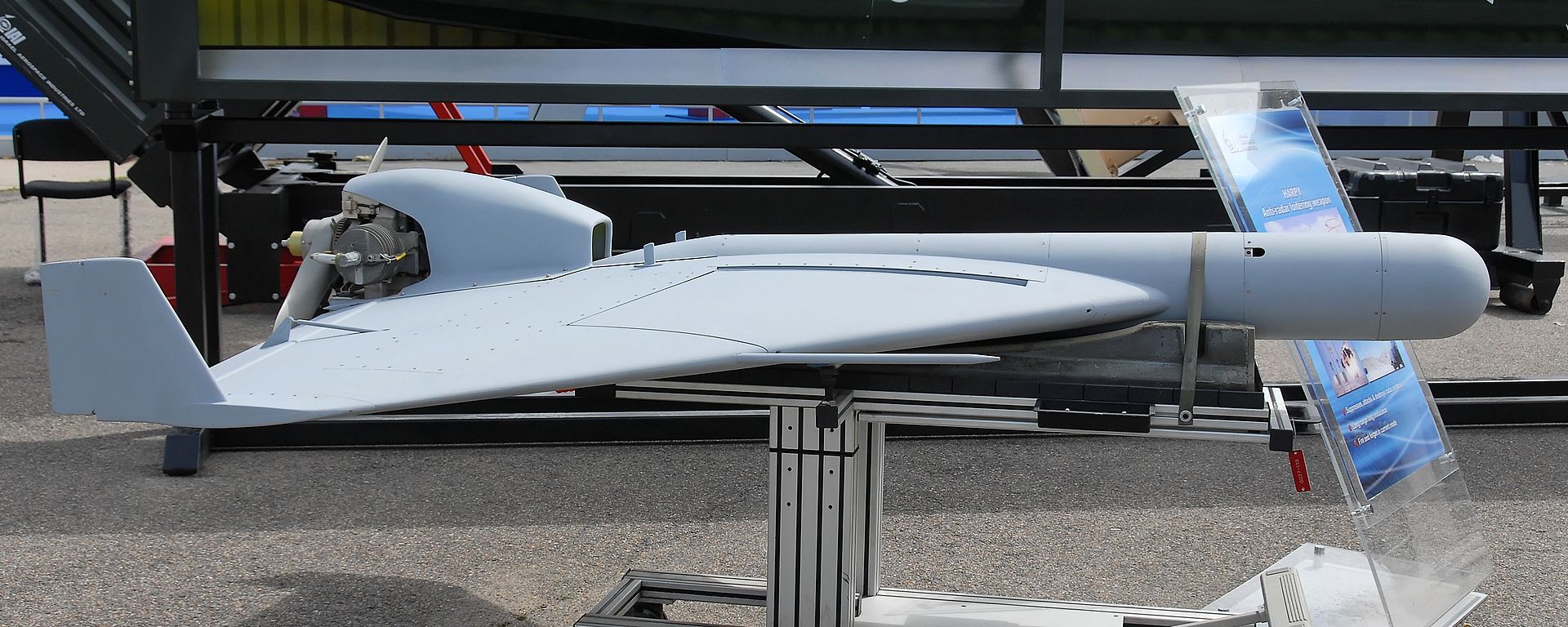

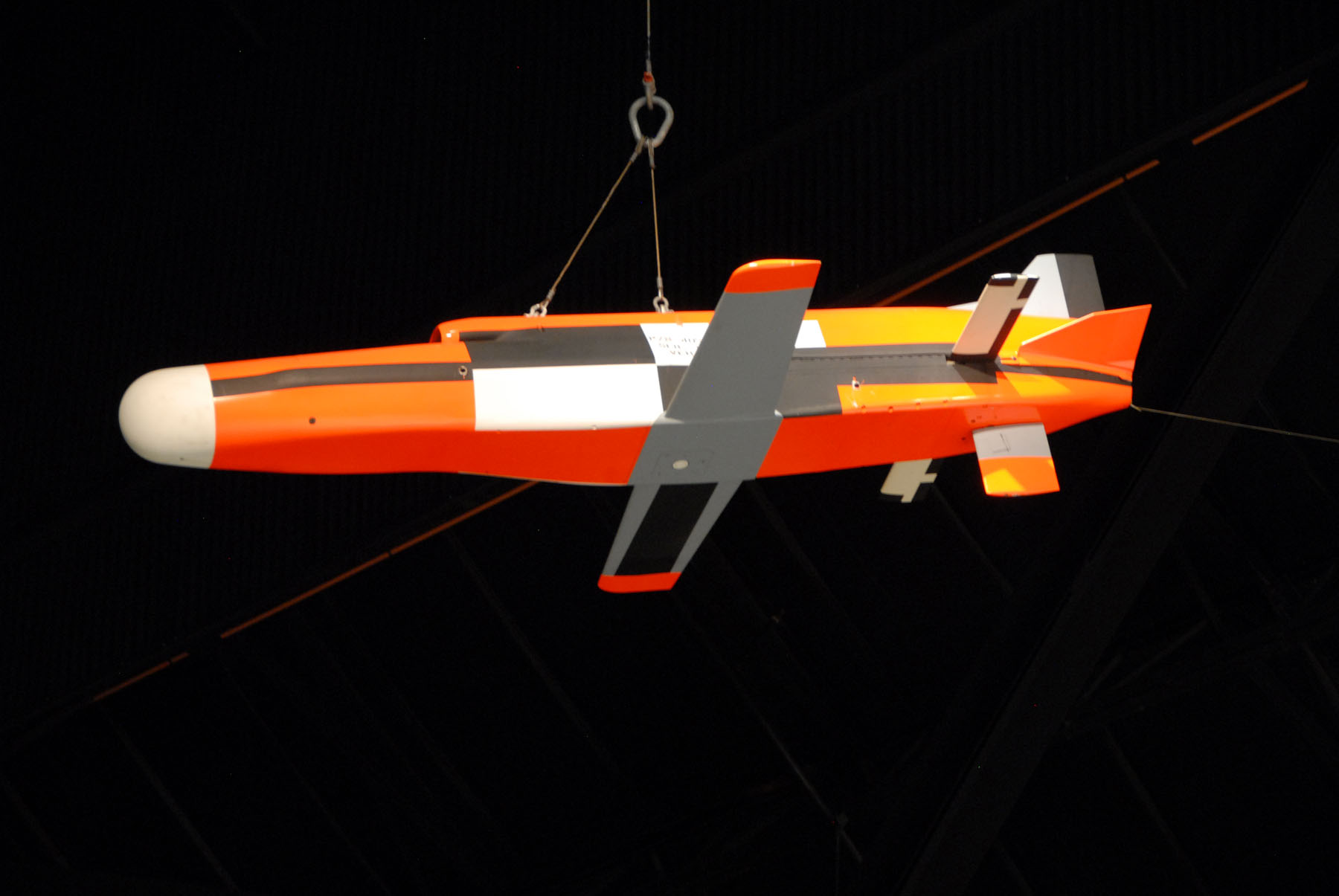

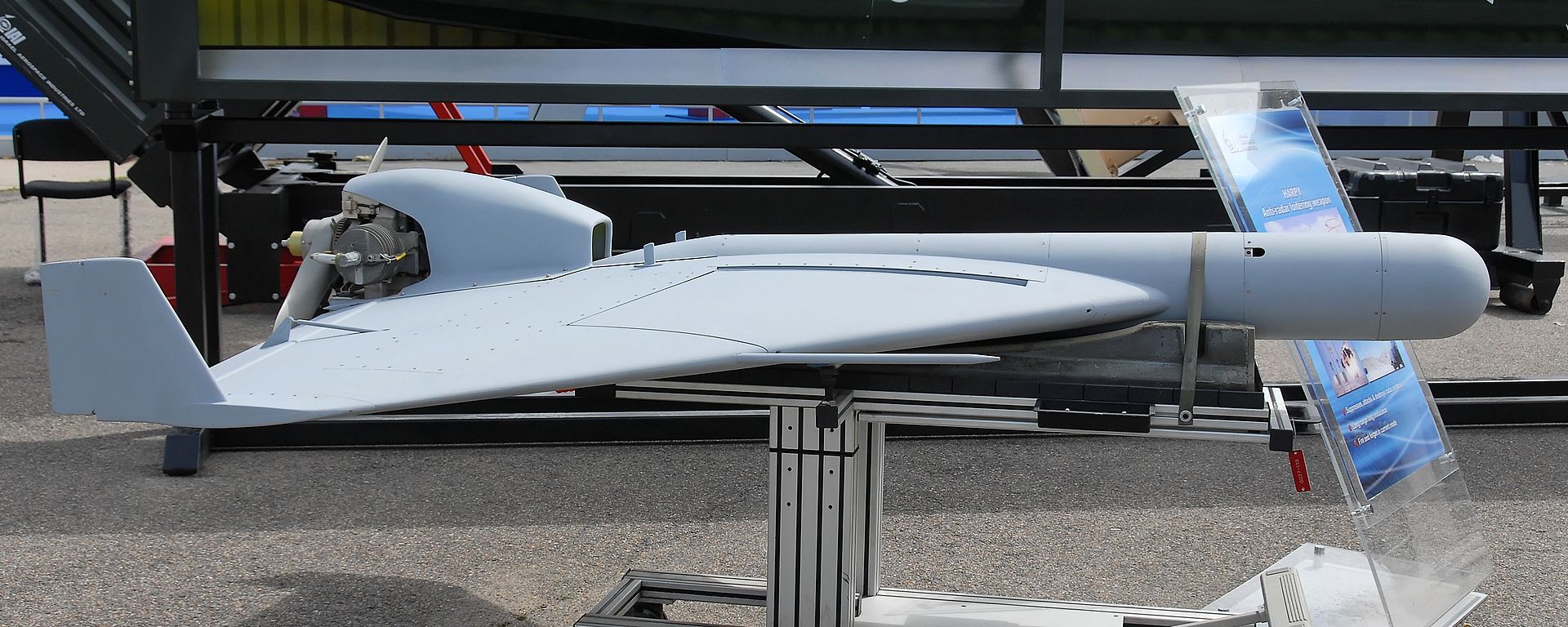

IAI Harop, a loitering munition optimized for the Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses (SEAD) role

☆ 特攻ドローン、神風ドローン、または爆発ドローンとも呼ばれる滞空弾薬ドローンは、弾頭を内蔵した空中兵器の一種であり、通常、目標が発見されるまで目標地域周辺を滞空し、その 後、目標に衝突して攻撃するように設計されている。また、飛行中に攻撃を変更したり、中止したりすることができるため、より選択的な照準が可能である

| A loitering

munition, also known as a suicide drone,[1][2][3][4] kamikaze

drone,[5][6][7] or exploding drone,[8] is a kind of aerial weapon with

a built-in warhead that is typically designed to loiter around a target

area until a target is located, then attack the target by crashing into

it.[9][10][11] Loitering munitions enable faster reaction times against

hidden targets that emerge for short periods without placing high-value

platforms near the target area and also allow more selective targeting

as the attack can be changed mid-flight or aborted. Loitering munitions fit in the niche between cruise missiles and unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs or combat drones), sharing characteristics with both. They differ from cruise missiles in that they are designed to loiter for a relatively long time around the target area, and from UCAVs in that a loitering munition is intended to be expended in an attack and has a built-in warhead. As such, they can also be considered a nontraditional ranged weapon.  An Iranian HESA Shahed 136 long range loitering munition Loitering weapons first emerged in the 1980s for use in the Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses (SEAD) role against surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) and were deployed in that role with a number of military forces in the 1990s. Starting in the 2000s, loitering weapons were developed for additional roles ranging from relatively long-range strikes and fire support down to tactical, very short range battlefield systems that fit in a backpack. |

特攻ドローン、[1][2][3][4]神風ドローン、[5][6]

[7]または爆発ドローン[8]とも呼ばれる滞空弾薬は、弾頭を内蔵した空中兵器の一種であり、通常、目標が発見されるまで目標地域周辺を滞空し、その

後、目標に衝突して攻撃するように設計されている。また、飛行中に攻撃を変更したり、中止したりすることができるため、より選択的な照準が可能である。 ロイテリング弾薬は、巡航ミサイルと無人戦闘機(UCAVまたは戦闘ドローン)の間のニッチに位置し、両者と特徴を共有している。巡航ミサイルとの違い は、目標地域の周囲を比較的長い時間うろつく(それゆえ徘徊型兵器ともいわれる)ように設計されている点であり、UCAVとの違いは、ロイタリング弾薬が攻撃で使用されることを意図してお り、弾頭を内蔵している点である。そのため、非伝統的な射撃武器ともいえる。  イランのHESAシャヘド136長距離滞空弾 ロイタリング兵器は1980年代に地対空ミサイル(SAM)に対する敵防空(SEAD)制圧の役割で初めて登場し、1990年代には多くの軍でその役割で 配備された。2000年代に入ってからは、比較的長距離の攻撃や火力支援から、バックパックに収まる戦術的な超短距離戦場システムまで、さらなる役割のた めにロイテリング兵器が開発された。 |

| History First development and terminology  Northrop AGM-136 Tacit Rainbow on display at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio Initially, loitering munitions were not referred to as such but rather as 'suicide UAVs' or 'loitering missiles'. Different sources point at different projects as originating the weapon category. The failed US AGM-136 Tacit Rainbow program[12][13] or the 1980s initial Israeli Delilah variants[14][15] are mentioned by some sources.[16] The Iranian Ababil-1 was produced in the 1980s but its exact production date is unknown.[17] The Israeli IAI Harpy was produced in the late 1980s.[16]  IAI Harpy first-generation loitering munition for SEAD role Early projects did not use the "loitering munition" nomenclature, which emerged much later; they used terminology existing at the time. For instance the AGM-136 Tacit Rainbow was described in a 1988 article: the Tacit Rainbow unmanned jet aircraft being developed by Northrop to loiter on high and then swoop down on enemy radars could be called a UAV, a cruise missile, or even a standoff weapon. But it is most definitely not an RPV. — Canan, James W. "Unmanned Aerial Vehicles." Air Force Magazine (1988), page 87 Initial role in suppression of enemy air defense  Loitering Munitions HERO (UVision Air Ltd, Israel), DSEI 2019, London The response to the first generation of fixed installation surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) such as S-75 and S-125 was the development of the anti-radiation missile such as AGM-45 Shrike and other means to attack fixed SAM installations, as well as developing SEAD doctrines. The Soviet counter-response was the use of mobile SAMs such as 2K12 Kub with intermittent use of radar.[18] Thus, the SAM battery was only visible for a small period of time, during which it was also a significant threat to high-value Wild Weasel fighters. In Israel's 1982 Operation Mole Cricket 19 various means including UAVs and air-launched Samson decoys were used over suspected SAM areas to saturate enemy SAMs and to bait them to activate their radar systems, which were then attacked by anti-radiation missiles.[19][20] In the 1980s, a number of programs, such as the IAI Harpy or the AGM-136 Tacit Rainbow, integrated anti-radiation sensors into a drone or missile air frames coupled with command and control and loitering capabilities. This allowed the attacking force to place relatively cheap munitions in place over suspected SAM sites, and to attack promptly the moment the SAM battery is visible. This integrated the use of a drone as a baiting decoy with the attack role into one small and relatively cheap platform in comparison to the alternative wild weasel jet fighter.[21][22][23][24] Evolution into additional roles  XM501 US prototype capable of launching LAM (loitering attack munition) Starting in the 2000s, loitering weapons have been developed for additional roles beyond the initial SEAD role, ranging from relatively long-range strikes and fire support[25] down to tactical, very short-range battlefield use.[26][27][28][29] A documented use of loitering munitions was in the 2016 Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in which an IAI Harop was used against a bus being used as a troop transport for Armenian soldiers.[7] HESA Shahed 136 and the ZALA Lancet have been used by Russia in the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, while Ukraine has fielded loitering munitions such as the UJ-25 Skyline or the American-made AeroVironment Switchblade, which is deployed at the platoon level and fits in a backpack. During conflicts in the 2010s and 2020s, conventional armies and non-state militants alike began modifying common commercial racing drones into an FPV loitering munition by the attachment of a small explosive, so-named because of the first-person view (FPV) they provide the operator. Explosive ordnance such as an IED, grenade, mortar round or an RPG warhead are fitted to an FPV drone then deployed to aerial bomb tactical targets. FPV drones also allow direct reconnaissance during the drone's strike mission.[30][31] After the Russian invasion of Ukraine began in 2022, both Russian and Ukrainian forces were producing thousands of FPV drones every month by October 2023, many of which were donated by volunteer groups.[32] Escadrone Pegasus and the Vyriy Drone Molfar are two examples of the low-cost drones that rapidly evolved in 2022–23 during the war.[33] On 9 November 2023, Ukrainian soldiers claimed to have used a civilian-donated FPV drone to destroy a Russian Tor missile system on the Kupiansk front, showcasing the potential cost-effectiveness of fielding such munitions. A Tor missile system costs some $24 million dollars to build, which could buy 14,000 FPV drones.[34][35] |

歴史 最初の開発と用語  オハイオ州デイトンの米空軍博物館に展示されているノースロップAGM-136タシット・レインボー。 当初、ロイタリング弾はそのように呼ばれることはなく、むしろ「自爆UAV」または「ロイタリングミサイル」と呼ばれていた。異なる情報源は、この兵器カ テゴリーの起源として異なるプロジェクトを指摘している。イランのAbabil-1は1980年代に生産されたが、その正確な生産時期は不明である [17]。  IAI Harpy SEADの役割を果たす第一世代ロイタリング弾薬 初期のプロジェクトでは、かなり後になって登場した「ロイタリング弾」という命名法は使用されず、当時存在していた用語が使用された。例えば、AGM-136タシット・レインボーは1988年の記事で紹介されている: ノースロップ社が開発中の無人ジェット機「タシット・レインボー」は、上空をうろつき、敵のレーダーに急降下するもので、UAV、巡航ミサイル、あるいはスタンドオフ兵器と呼ぶこともできる。しかし、間違いなくRPVではない。 - Canan, James W. "Unmanned Aerial Vehicles". エアフォース誌(1988年)87ページ 敵の防空を制圧する初期の役割  Loitering Munitions HERO(UVision Air Ltd、イスラエル)、DSEI 2019、ロンドン S-75やS-125などの固定設置型地対空ミサイル(SAM)の第一世代への対応は、AGM-45シュライクなどの対放射ミサイルや固定SAM設置型へ の攻撃手段の開発であり、SEADドクトリンの開発であった。ソ連の対抗手段は、レーダーを断続的に使用する2K12カブのような移動式SAMの使用で あった[18]。したがって、SAM砲台はわずかな時間しか視認できず、その間は高価値のワイルド・ウィーゼル戦闘機にとっても重要な脅威であった。 1982年のイスラエルのモグラ・クリケット作戦19では、敵のSAMを飽和させ、レーダーシステムを起動させるためのおとりとして、UAVや空から発射 されたサムソンデコイを含む様々な手段が疑われるSAMエリア上空で使用され、その後、対レーダーミサイルによって攻撃された[19][20]。 1980年代には、IAI HarpyやAGM-136 Tacit Rainbowのような多くのプログラムが、コマンド・アンド・コントロールやロイタリング機能と組み合わされたドローンやミサイルのエアフレームに対放 射線センサーを統合した。これにより、攻撃部隊は比較的安価な弾薬をSAMの疑いのある場所の上空に配置し、SAMのバッテリーが見えた瞬間に速やかに攻 撃することができる。これは、囮としてのドローンの使用と攻撃の役割を1つの小型で比較的安価なプラットフォームに統合したものであり、代替となる野生の イタチのジェット戦闘機と比較したものである[21][22][23][24]。 さらなる役割への進化  LAM(ロイタリング攻撃弾)を発射可能なXM501アメリカ試作機 2000年代に入ってから、ロイタリング兵器は最初のSEADの役割を超えて、比較的長距離の攻撃や火力支援[25]から戦術的な非常に短距離の戦場での 使用[26][27][28][29]まで、追加の役割のために開発されてきた。文書化されたロイタリング弾の使用は2016年のナゴルノ・カラバフ紛争 で、IAIハロップがアルメニア兵の兵員輸送として使用されていたバスに対して使用された。 [7]HESAシャヘド136とZALAランセットは現在進行中のロシアによるウクライナ侵攻でロシアによって使用されており、ウクライナはUJ-25ス カイラインや、小隊レベルで配備されバックパックに収まるアメリカ製のエアロビロンメント・スイッチブレードなどのうろつき弾を実戦配備している。 2010年代から2020年代にかけての紛争では、従来型の軍隊も非国家武装勢力も同様に、小型の爆発物を取り付けることによって、一般的な市販のレーシ ングドローンをFPV哨戒弾に改造し始めた。IED、手榴弾、迫撃砲弾、RPG弾頭などの爆発物をFPVドローンに装着し、戦術目標を空爆する。FPVド ローンはまた、ドローンの攻撃任務中に直接偵察することも可能である[30][31]。 2022年にロシアのウクライナ侵攻が始まると、ロシア軍とウクライナ軍は2023年10月までに毎月数千機のFPVドローンを生産しており、その多くは ボランティア・グループから寄贈されたものであった[32]。 [33] 2023年11月9日、ウクライナの兵士は民間から寄贈されたFPVドローンを使用し、クピアンスク戦線でロシアのトーアミサイルシステムを破壊したと主 張し、このような弾薬を実戦配備することの潜在的な費用対効果を示した。トーアミサイルシステムの製造コストは約2400万ドルであり、14,000機の FPVドローンを購入することができる[34][35]。 |

Characteristics Air-launched Delilah loitering munition, controlled by backseat WSO Loitering munitions may be as simple as an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) with attached explosives that is sent on a potential kamikaze mission, and may even be constructed with off the shelf commercial quadcopters with strapped on explosives.[36] Purpose-built munitions are more elaborate in flight and control capabilities, warhead size and design, and onboard sensors for locating targets.[37] Some loitering munitions use a human operator to locate targets whereas others, such as IAI Harop, can function autonomously searching and launching attacks without human intervention.[38][39] Another example is UVision HERO solutions – the loitering systems are operated remotely, controlled in real time by a communications system and equipped with an electro-optical camera whose images are received by the command and control station.[40][41] Some loitering munitions may return and be recovered by the operator if they are unused in an attack and have enough fuel; in particular this is characteristic of UAVs with a secondary explosive capability.[42] Other systems, such as the Delilah[14][43][11] do not have a recovery option and are self-destructed in mission aborts. |

特徴 後部座席のWSOが制御する空中発射型デライラ(Delilah) ロイタリング弾薬は、爆発物を取り付けた無人航空機(UAV)を潜在的な神風ミッションに送り込むような単純なものから、爆発物を取り付けた市販のクアッドコプターで構成されるものまである[36]。 目的別に作られた弾薬は、飛行と制御の能力、弾頭のサイズとデザイン、標的の位置を特定するための搭載センサーにおいて、より精巧になっている[37]。 [38][39]他の例として、UVision HEROソリューションがある。このうろつきシステムは遠隔操作され、通信システムによってリアルタイムで制御され、コマンド・コントロール・ステーショ ンによって画像が受信される電気光学カメラが装備されている。 特にこれは二次爆発能力を持つUAVの特徴である[42]。 デライラ[14][43][11]のような他のシステムは回収オプションを持たず、ミッションのアボートで自爆する。 |

| Countermeasures Russia uses the ZALA Lancet drones in Ukraine. Since spring 2022 Ukrainian forces have been building cages around their artillery pieces using chain link fencing, wire mesh and even wooden logs as part of the construction. One analyst told Radio Liberty that such cages were "mainly intended to disrupt Russian Lancet munitions." A picture supposedly taken from January 2023 shows the rear half of a Lancet drone that failed to detonate due to such cages. Likewise Ukrainian forces have used inflatable decoys and wooden vehicles, such as HIMARS, to confuse and deceive Lancet drones.[44][45] Ukrainian soldiers report shooting down Russian drones with sniper rifles.[46] Russian soldiers use electronic warfare to disable or misdirect Ukrainian drones and have reportedly used the Stupor anti-drone rifle, which uses an electromagnetic pulse that disrupts a drone's GPS navigation.[47] A Royal United Services Institute study in 2022 found that Russian Electronic Warfare units, in March and April 2022, knocked out or shot down 90% of Ukrainian drones that they had at the start of the war in February 2022. The main success was in jamming GPS and radio links to the drones.[48] Both Ukraine and Russia rely on electronic warfare to defeat FPV drones. Such jammers are now used on Ukrainian trenches and vehicles.[49] Russian forces have built jammers that can fit into a backpack.[50] And now pocket size jammers exist for soldiers.[51] As of June 2023 Ukraine was losing 5-10,000 drones a month, or 160 per day, according to Ukrainian soldiers. Previously they could fly their drones for kilometres, now they are lucky if they can get 500 metres in the air.[52] This has led to Russia creating wire guided FPV drones, similar to a wire-guided missile or even wire guided torpedoes. One drone captured by Ukrainian forces had "nearly seven miles (just over 10.8 kilometers)" of fibre optic cable. Such guidance would make the link between operators and FPV drone immune to jamming. It would also allow for much faster updates from the drone. However these drones would lack the manoeuvrability that wireless drones enjoy.[53] Ukraine has also responded by using autonomous drones tasking to ensure that a jammed drone can hit a target. In March 2024 footage put on social media showed a Ukrainian FPV drone being jammed just before it struck a target. Despite the loss of operator control it still managed to strike the target.[54] Russian tanks have been fitted with rooftop slat armor at the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine which could provide protection against loitering munitions in some circumstances. Some Ukrainian tanks taking part in the 2023 Ukrainian counteroffensive were also spotted using roof screens.[55][56][57] On 21 March 2024, recent footage of the submarine Tula showed that it has been fitted with a 'cope cage' to prevent drone strikes, the first ocean going asset to carry such a modification.[58] |

対策 ロシアはウクライナでZALA Lancetドローンを使用している。2022年春以来、ウクライナ軍は、チェーン・リンク・フェンス、金網、さらには木製の丸太を使って、大砲の周りに 檻を作っている。あるアナリストがラジオ・リバティーに語ったところによると、このようなケージは「主にロシアのランセット弾を妨害するためのもの」だと いう。2023年1月に撮影されたとされる写真には、このような檻のために爆発に失敗したランセット無人機の後半分が写っている。同様に、ウクライナ軍は HIMARSのようなインフレータブル・デコイや木製の車両を使用して、ランセット無人偵察機を混乱させ、欺瞞している[44][45]。 ウクライナ兵は狙撃銃でロシアの無人機を撃墜したと報告している[46]。ロシア兵は電子戦を使ってウクライナの無人機を無力化したり誤誘導したりし、無 人機のGPSナビゲーションを妨害する電磁パルスを使用するStupor対無人ライフル銃を使用したと報告されている[47]。 2022年の英国王立合同サービス研究所の調査によると、ロシアの電子戦部隊は2022年3月と4月に、2022年2月の開戦時に保有していたウクライナ の無人機の90%をノックアウトまたは撃墜した。主な成功は、無人機へのGPSと無線リンクを妨害することであった[48]。 ウクライナもロシアもFPVドローンを倒すために電子戦に依存している。そのようなジャマーは現在、ウクライナの塹壕や車両で使用されている[49]。 ロシア軍はバックパックに収まるジャマーを製造した[50]。 そして現在、兵士用のポケットサイズのジャマーが存在する[51]。 2023年6月の時点で、ウクライナは月に5~10,000機、ウクライナ兵によれば1日に160機のドローンを失っていた。以前はドローンを何キロも飛 ばすことができたが、今では空中で500メートル飛べれば幸運な方だ[52]。 このためロシアは、ワイヤー誘導ミサイルやワイヤー誘導魚雷に似たワイヤー誘導FPVドローンを開発した。ウクライナ軍が捕獲したドローンには、「約7マ イル(10.8キロメートル強)」の光ファイバーケーブルがあった。このような誘導があれば、オペレーターとFPVドローンとの間のリンクはジャミングの 影響を受けなくなる。また、ドローンからのアップデートをより速く行うことができる。しかし、これらのドローンはワイヤレスドローンが享受している操縦性 を欠いている。2024年3月、ソーシャルメディアに公開された映像は、ウクライナのFPVドローンが目標を攻撃する直前に妨害されたことを示していた。 オペレーターのコントロールが失われたにもかかわらず、ドローンは標的を攻撃することができた[54]。 ロシアの戦車は、ウクライナ侵攻の初期に屋上のスラット装甲を装備しており、状況によっては浮遊弾に対する防御を提供することができる。2023年のウク ライナ反攻作戦に参加したウクライナの戦車の中にも、ルーフスクリーンを使用しているものが目撃されている[55][56][57]。 2024年3月21日、潜水艦トゥーラの最近の映像は、ドローンによる攻撃を防ぐための「コープ・ケージ」が装備されていることを示した。 |

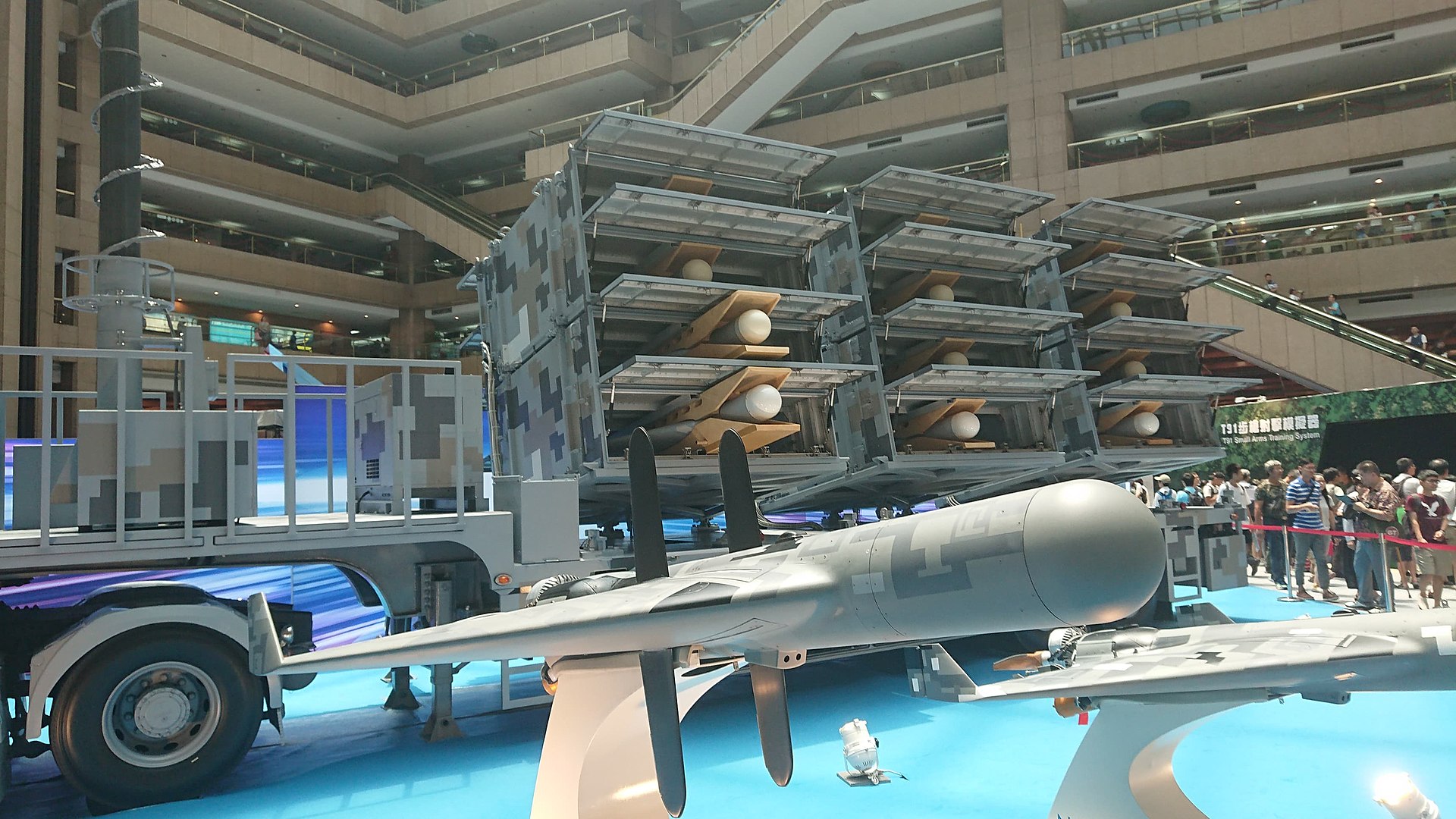

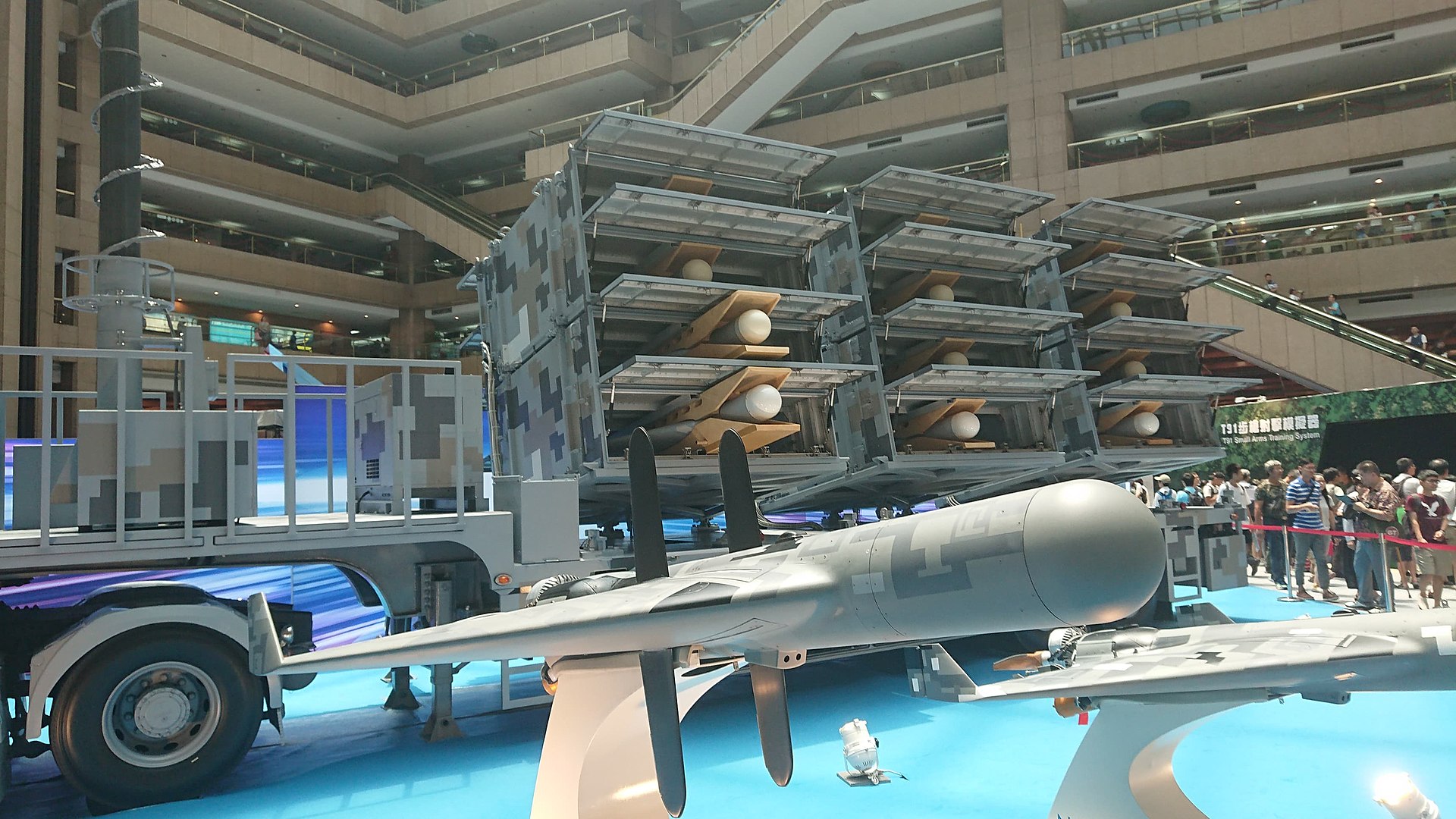

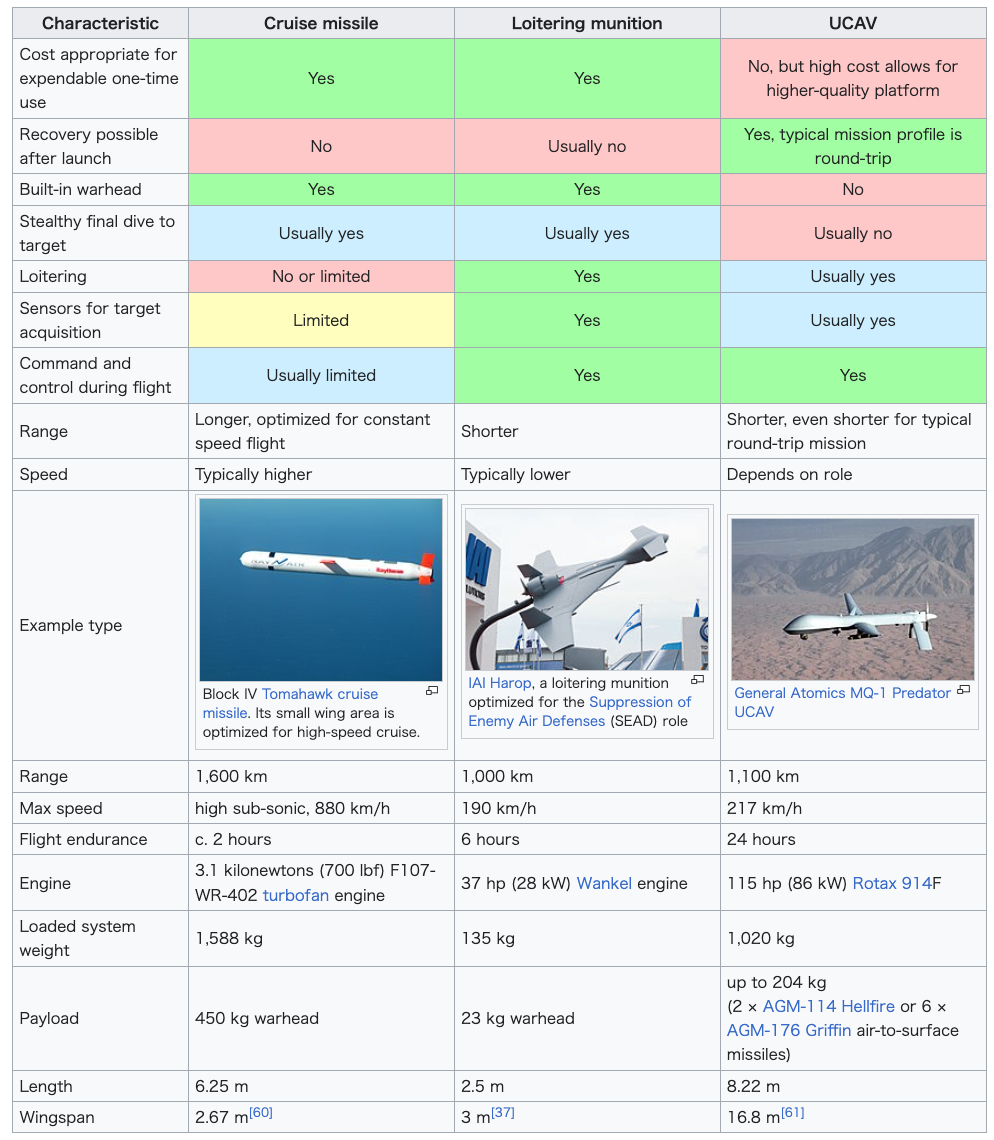

| Comparison to similar weapons Loitering munitions fit in the niche between cruise missiles and unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs).[11][59] The following table compares similar size-class cruise missiles, loitering munitions, and UCAVS:[citation needed] Whereas some cruise missiles, such as the Block IV Tomahawk, have the ability to loiter and have some sensory and remote control features,[62] their primary mission is typically strike and not target acquisition. Cruise missiles, as their name implies, are optimized for long-range flight at constant speed both in terms of propulsion systems and wings or lifting body design. They are often unable to loiter at slow fuel-efficient speeds which significantly reduces potential loiter time even when the missile has some loiter capabilities.[63] Conversely almost any UAV could be piloted to crash onto a target and most could be fitted with an improvised explosive warhead.[36] However the primary use of a UAV or UCAV would be for recoverable flight operations carrying reconnaissance equipment and/or munitions. While many UAVs are explicitly designed with loitering in mind, they are not optimized for a diving attack, often lacking forward facing cameras, lacking in control response-speed which is unneeded in regular UAV flight, and are noisy when diving, potentially providing warning to the target. UAV's, being designed as multi-use platforms, often have a unit cost that is not appropriate for regular one-time expendable mission use.[64][59]  NCSIST Chien Hsiang, an example of an expendable loitering munition The primary mission of a loitering munition is reaching the suspected target area, target acquisition during a loitering phase, followed by a self-destructive strike, and the munition is optimized in this regard in terms of characteristics (e.g. very short engine lifetime, silence in strike phase, speed of strike dive, optimization toward loitering time instead of range/speed) and unit cost (appropriate for a one-off strike mission).[65][66] |

類似兵器との比較 浮遊弾は巡航ミサイルと無人戦闘機(UCAV)の間のニッチに適合する[11][59]。 以下の表は、類似サイズクラスの巡航ミサイル、ロイタリング弾、およびUCAVSを比較したものである[要出典]。 ブロックIVトマホークのような一部の巡航ミサイルは、ロイターの能力を持ち、いくつかのセンサーや遠隔操作機能を持つが[62]、その主な任務は通常攻 撃であり、目標捕捉ではない。巡航ミサイルは、その名が示すように、推進システムと翼または揚力体の設計の両面において、一定速度での長距離飛行に最適化 されている。燃料効率の良い低速でのロイターはできないことが多く、ミサイルがある程度のロイター能力を持っている場合でも、潜在的なロイター時間が大幅 に短縮される[63]。 しかし、UAVやUCAVの主な用途は、偵察機器や弾薬を搭載した回収可能な飛行作戦であろう。多くのUAVは、徘徊を念頭に置いて明確に設計されている が、潜水攻撃には最適化されておらず、多くの場合、前方を向いたカメラがなく、通常のUAV飛行では不要な制御応答速度に欠け、潜水時には騒音が大きく、 ターゲットに警告を与える可能性がある。UAVは、多用途プラットフォームとして設計されているため、通常の1回限りの消耗品ミッションの使用には適切で ない単価を持つことが多い[64][59]。  NCSIST Chien Hsiang、消耗型ロイタリング弾薬の一例 NCSISTチエンヒャン(NCSIST Chien Hsiang)は、1回限りの攻撃ミッションに適している。 |

巡航ミサイル・滑空弾薬ドローン・無人機(無人戦闘航空移動体; UCAV)の比較 |

巡航ミサイル・滑空弾薬ドローン・無人機(無人戦闘航空移動体; UCAV)の比較 |

| Ethical and international humanitarian law concerns Main article: Lethal autonomous weapon § Ethical and legal issues Loitering munitions that are capable of making autonomous attack decisions (man out of the loop) raise moral, ethical, and international humanitarian law concerns because a human being is not involved in making the actual decision to attack and potentially kill humans, as is the case with fire-and-forget missiles in common use since the 1960s. Whereas some guided munitions may lock-on after launch or may be sensor fuzed, their flight time is typically limited and a human launches them at an area where enemy activity is strongly suspected, as is the case with modern fire-and-forget missiles and airstrike planning. An autonomous loitering munition, on the other hand, may be launched at an area where enemy activity is only probable, and loiter searching autonomously for targets for potentially hours following the initial launch decision, though it may be able to request final authorization for an attack from a human. The IAI Harpy and IAI Harop are frequently cited in the relevant literature as they set a precedent for an aerial system (though not necessarily a precedent when comparing to a modern naval mine) in terms of length and quality of autonomous function, in relation to a cruise missile for example.[67][68][69][70][71][72] |

倫理的および国際人道法上の懸念 主な記事 致死的自律兵器§倫理的・法的問題 自律的な攻撃決定が可能な滞空弾(人がループから外れる)は、1960年代から一般的に使用されているファイア・アンド・フォーゲット・ミサイルの場合の ように、人間が実際の攻撃決定に関与せず、人間を殺す可能性があるため、道徳的、倫理的、国際人道法上の懸念を引き起こす。誘導弾の中には、発射後にロッ クオンしたり、センサーフューズが付いたりするものもあるが、その飛行時間は通常限られており、現代のファイア・アンド・フォゲット・ミサイルや空爆計画 のように、敵の活動が強く疑われる地域に人間が発射する。一方、自律型浮遊弾薬は、敵の活動が推測される地域に発射され、最初の発射決定から数時間、自律 的に標的を探して浮遊する。IAI HarpyとIAI Haropは、例えば巡航ミサイルとの関連で、自律機能の長さと質という点で、(近代的な海軍機雷と比較する場合は必ずしも前例ではないが)航空システム の前例を作ったとして、関連文献に頻繁に引用されている[67][68][69][70][71][72]。 |

| List of users and producers |

各国の滑空弾薬ドローン装備のリスト(省略) |

| Flying bomb XM501 Non-Line-of-Sight Launch System Boeing Persistent Munition Technology Demonstrator Low Cost Autonomous Attack System Sypaq Corvo Precision Payload Delivery System Television guidance V-1 flying bomb |

フライングボム XM501見通し外発射システム ボーイング持続弾技術実証機 低コスト自律攻撃システム Sypaq Corvo 精密ペイロード運搬システム テレビ誘導 V-1飛行爆弾 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loitering_munition |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆