ルー・アンドレアス=ザロメ

Lou Andreas-Salomé, 1861-1937

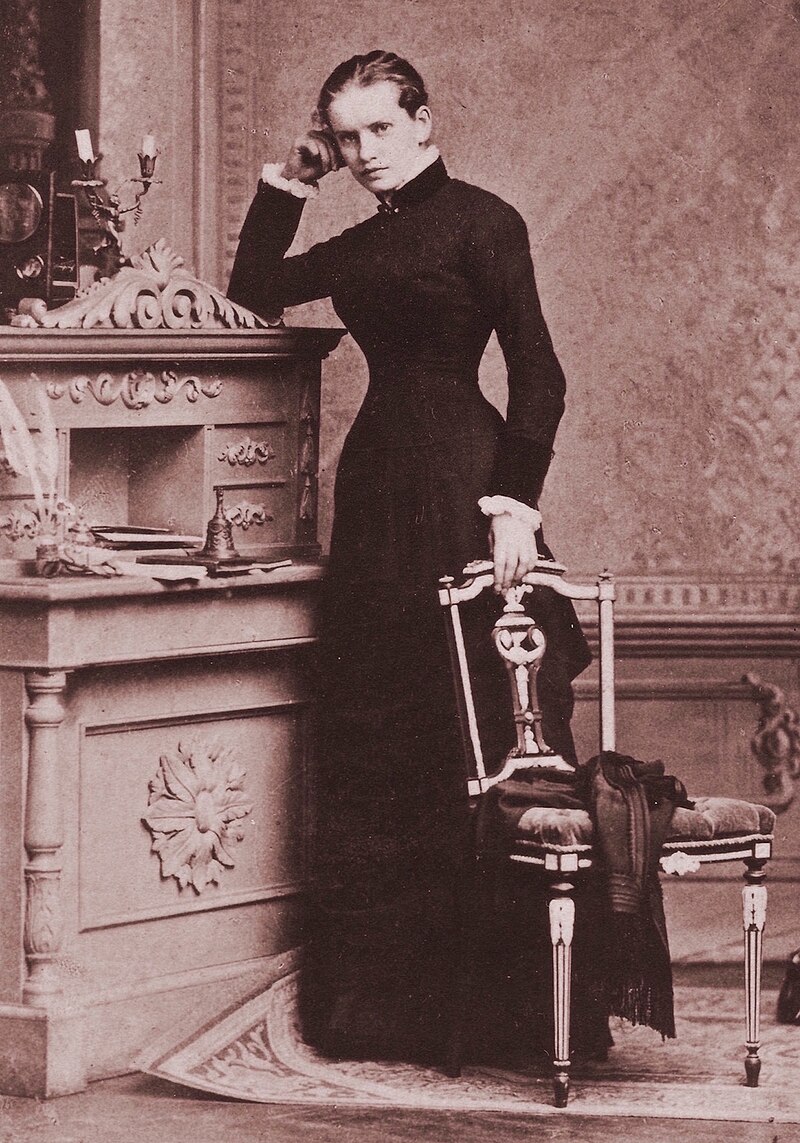

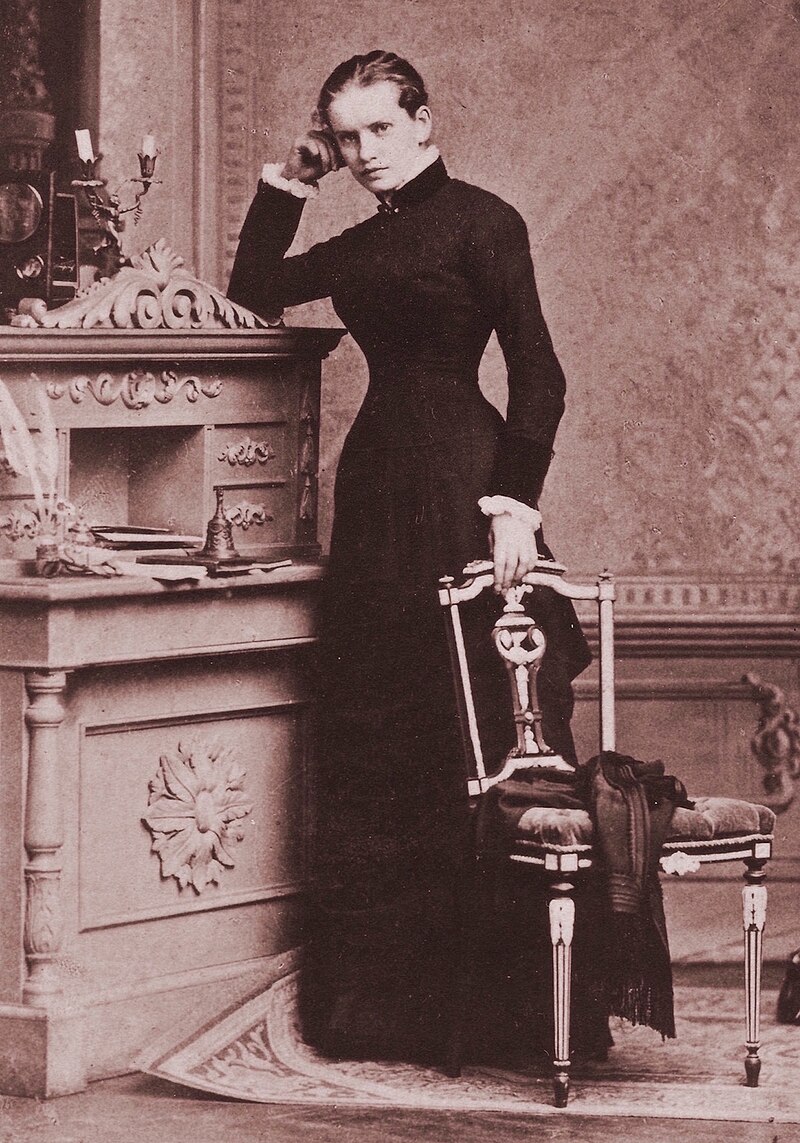

Lou Andreas-Salomé, c. 1897. Mit Blindstempel des Atelier Elvira, München

☆ ルー・アンドレアス=ザロメ、Lou Andreas-Salomé(本名:Louise von Salomé、またはLuíza Gustavovna Salomé、Lioulia von Salomé。ロシア名:Луиза Густавовна Саломе。1861年2月12日~1937年2月5日 )は、ロシア生まれの精神分析医であり、フランス・ユグノー・ドイツ系の家庭に生まれた多作の作家、語り手、随筆家であった。彼女の幅広い知的関心は、フ リードリヒ・ニーチェ、ジークムント・フロイト、ポール・レー、ライナー・マリア・リルケなど、著名な思想家たちとの交友関係につながった。

| Lou

Andreas-Salomé (born either Louise von Salomé or Luíza Gustavovna

Salomé or Lioulia von Salomé, Russian: Луиза Густавовна Саломе; 12

February 1861 – 5 February 1937) was a Russian-born psychoanalyst and a

well-traveled author, narrator, and essayist from a French

Huguenot-German family.[1] Her diverse intellectual interests led to

friendships with a broad array of distinguished thinkers, including

Friedrich Nietzsche, Sigmund Freud, Paul Rée, and Rainer Maria Rilke.[2] |

Lou

Andreas-Salomé(本名:Louise von Salomé、またはLuíza Gustavovna Salomé、Lioulia

von Salomé。ロシア名:Луиза Густавовна Саломе。1861年2月12日~1937年2月5日

)は、ロシア生まれの精神分析医であり、フランス・ユグノー・ドイツ系の家庭に生まれた多作の作家、語り手、随筆家であった[1]。彼女の幅広い知的関心

は、フリードリヒ・ニーチェ、ジークムント・フロイト、ポール・レー、ライナー・マリア・リルケなど、著名な思想家たちとの交友関係につながった[2]。 |

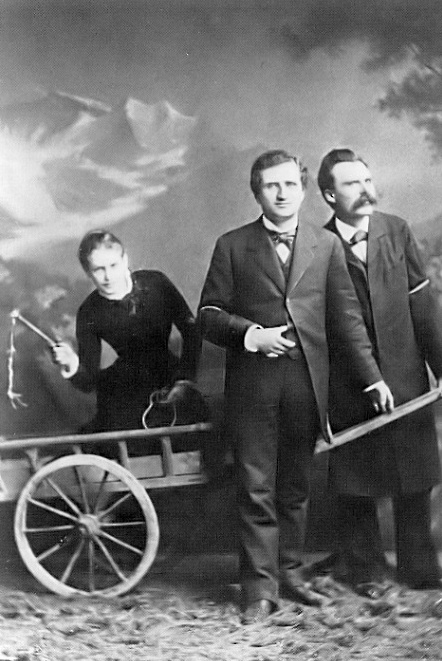

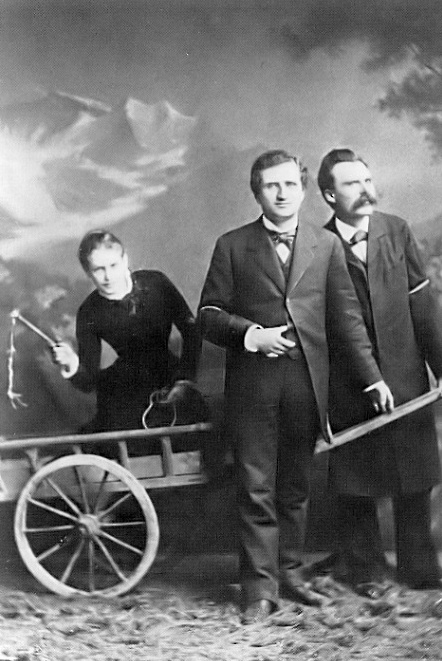

| Life Early years  Lou Salomé, circa 1880 Lou Salomé was born in St. Petersburg to Gustav Ludwig von Salomé (1807–1878), and Louise von Salomé (née Wilm) (1823–1913). Lou was their only daughter; they had five sons. Although she would later be attacked by the Nazis as a "Finnish Jew",[3] her parents were actually of French Huguenot and Northern German descent.[4] The youngest of six children, she grew up in a wealthy and well-cultured household, with all children learning Russian, German, and French; Salomé was allowed to attend her brothers' classes. Born into a strictly Protestant family, Salomé grew to resent the Reformed church and Hermann Dalton, the Orthodox Protestant pastor. She refused to be confirmed by Dalton, officially left the church at age 16, but remained interested in intellectual pursuits in the areas of philosophy, literature and religion. In fact, she was fascinated by the sermons of the Dutch pastor Hendrik Gillot, known in St. Petersburg as an opponent of Dalton's. Gillot, 25 years her senior, took her on as a student, engaging with her in the fields of theology, philosophy, world religions, and French and German literature. Together they studied innumerable authors, philosophers, theological and religious subjects, and all of this wide-ranging study laid the groundwork for her intellectual encounters with very well-known thinkers of her time. Gillot became so smitten with Salomé that he wanted to divorce his wife and marry his young student. Salomé refused, for she was not interested in marriage and sexual relations. Though disappointed and shocked by this development, she remained friends with Gillot. Following her father's death in 1879, Salomé and her mother went to Zürich so Salomé could acquire a university education as a "guest student." In her one year at the University of Zurich—one of the few schools that accepted female students—Salomé attended lectures in philosophy (logic, history of philosophy, ancient philosophy, and psychology) and theology (dogmatics). During this time, Salomé's physical health was failing due to lung disease, causing her to cough up blood. Due to this, she was instructed to heal in warmer climates, so in February 1882, Salomé and her mother went to Rome.  Left to right, Andreas-Salomé, Rée and Nietzsche (1882) Rée and Nietzsche, and later life Salomé's mother took her to Rome when Salomé was 21. At a literary salon in the city, Salomé became acquainted with the author Paul Rée. Rée proposed to her, but she instead suggested that they live and study together as 'brother and sister' along with another man for company, and thereby establish an academic commune.[5] Rée accepted the idea, and suggested that they be joined by his friend Friedrich Nietzsche. The two met Nietzsche in Rome in April 1882, and Nietzsche is believed to have instantly fallen in love with Salomé, as Rée had earlier done. Nietzsche asked Rée to propose marriage to Salomé on his behalf, which she rejected, although interested in Nietzsche as a friend.[5] Nietzsche nonetheless was content to join Rée and Salomé touring through Switzerland and Italy together, planning their commune. On 13 May, in Lucerne, when Nietzsche was alone with Salomé, he earnestly proposed marriage to her again, and she again rejected him. He was happy to continue with the plans for an academic commune.[5] After discovering the situation, Nietzsche's sister Elisabeth became determined to separate him from Salomé whom she described as an "immoral woman".[6] Nietzsche, Rée, and Salomé travelled with Salomé's mother through Italy and considered where they would set up their "Winterplan" commune. This commune was intended to be set up in an abandoned monastery, but as no suitable location was found, the plan was abandoned. After arriving in Leipzig in October 1882, the three spent a number of weeks together. However, the following month Rée and Salomé parted company with Nietzsche, leaving for Stibbe without any plans to meet again. Nietzsche soon fell into a period of mental anguish, although he continued to write to Rée, asking him, "We shall see one another from time to time, won't we?"[7] In later recriminations, Nietzsche would blame the failure in his attempts to woo Salomé both on Salomé, Rée, and on the intrigues of his sister (who had written letters to the families of Salomé and Rée to disrupt their plans for the commune). Nietzsche wrote of the affair in 1883 that he felt "genuine hatred for [his] sister."[7] Salomé would later (1894) write a study, Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken (Friedrich Nietzsche in his Works), of Nietzsche's personality and philosophy.[8] In 1884 Salomé became acquainted with Helene von Druskowitz, the second woman to receive a philosophy doctorate in Zurich.[citation needed] It was also rumoured that Salomé later had a romantic relationship with Sigmund Freud.[9] Marriage and relationships  Lou Andreas-Salomé and Friedrich Carl Andreas, 1886 Salomé and Rée moved to Berlin and lived together until a few years before her celibate marriage[10] to linguistics scholar Friedrich Carl Andreas. Despite her opposition to marriage and her open relationships with other men, Salomé and Andreas remained married from 1887 until his death in 1930. Salomé's co-habitation with Andreas caused the despairing Rée to fade from Salomé's life despite her assurances. Throughout her married life, she engaged in affairs and/or correspondence with the German journalist and politician Georg Ledebour, the Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke, about whom she wrote an analytical memoir,[11] and the psychoanalysts Sigmund Freud (whom she met personally in September 1911, on occasion of the 3rd Congress of Psychoanalysis held in Weimar[12]) and Victor Tausk, among others. Accounts of many of these are given in her volume Lebensrückblick. An affair with the Viennese physician Friedrich Pineles ended in an abortion and a tragic renunciation of motherhood.[13] Her relationship with Freud was still quite intellectual despite gossip about their romantic involvement. In one letter Freud commends Salomé's deep understanding of people so much that he believed she understood people better than they understood themselves. The two often exchanged letters.[14] Salomé was romantically involved with the handsome and melancholic Victor Tausk, member of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, 18 years her junior.[15] According to Anna Freud, her work Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken (Friedrich Nietzsche in his works) anticipated the psychoanalysis.[16] It was the first book about the German philosopher.[17] Anna Freud and von Salomé, who met in Vienna, had a long-time correspondence, like Sigmund Freud and von Salomé.[18] Meeting Rilke In May 1897, in Munich, she met Rilke, who had been introduced to her by Jacob Wassermann.[19] She was 36 while Rilke was only 20. She had already published with some success Im Kampf um Gott "where she exposed the problem of loss of faith (which had been her own for a long time)", several articles, and the study Jesus der Jude that Rilke had read.[19] As Philippe Jaccottet reports, Salomé wrote in Lebensrückblick: "I was your wife for years because you were the first reality, where man and body are indistinguishable from each other, an indisputable fact of life itself. I could have said literally what you told me when you confessed your love to me: Only you are real. That is how we became husband and wife even before we became friends, not by choice, but by this unfathomable marriage [...] We were brother and sister, but as in a distant past, before the marriage between brother and sister became sacrilegious."[20] In 1899 with her husband Friedrich-Carl, then again in 1900, Lou travelled to Russia, the second time with Rilke, whose first name she changed from René to Rainer.[21] She taught him Russian, to read Tolstoy (whom he would later meet) and Pushkin. She introduced him to patrons and other people in the arts, remaining Rilke's advisor, confidante, and muse throughout his adult life.[10] The romance between the poet and Salomé lasted three years, then turned into a friendship, which would continue until Rilke's death, as evidenced by their correspondence. In 1937, Freud said of Salomé's relationship with Rilke: "She was both the muse and the attentive mother of the great poet."[22] Death  Lou Andreas-Salomé's grave in Göttingen By 1930, Salomé was increasingly weak, suffered from a heart condition and diabetes, and had to be treated several times in the hospital. Her husband visited her daily during a six-week stay after a foot operation, which was arduous for the old, rather ill man, and this made them grow very close after a forty-year marriage marked by hurtful behaviour on both sides and long periods of non-communication.[23] Freud appreciated this from afar, writing: "Only what is genuinely true proves itself so long-lasting." ("So dauerhaft beweist sich doch nur das Echte.") Friedrich Carl Andreas died of cancer in 1930, and Salomé herself underwent a difficult cancer operation in 1935. At the age of 74, she ceased to work as a psychoanalyst. Salomé died of uremia in Göttingen on 5 February 1937. Her urn was laid to rest in her husband's grave in the cemetery on the Groner Landstraße in Göttingen. She is commemorated in the city by a memorial plaque outside the property where her house stood, a street named after her (Lou-Andreas-Salomé-Weg), and the name of the Lou Andreas-Salomé Institut für Psychoanalyse und Psychotherapie. A few days before her death, the Gestapo confiscated her library (according to other sources it was an SA group who destroyed the library shortly after her death). The reasons given for this confiscation were that she had been a colleague of Sigmund Freud, had practised "a Jewish science", and owned many books by Jewish authors.[24] |

人生 幼少期  1880年頃のルー・サロメ ルー・サロメは、グスタフ・ルートヴィヒ・フォン・サロメ(1807年~1878年)とルイーズ・フォン・サロメ(旧姓ウィルム)(1823年~1913 年)の間にサンクトペテルブルクで生まれた。ルーは夫妻の一人娘で、5人の息子がいた。後にナチスから「フィンランド系ユダヤ人」として攻撃されることに なるが[3]、彼女の両親は実際にはフランス・ユグノーと北ドイツ系の家系であった[4]。6人兄弟の末っ子として裕福で教養のある家庭で育った彼女は、 子供たちが皆ロシア語、ドイツ語、フランス語を学んでいた。サロメは兄たちのクラスに参加することが許されていた。 厳格なプロテスタントの家庭に生まれたサロメは、改革派教会とヘルマン・ダルトンという正統派プロテスタントの牧師を嫌うようになった。彼女はダルトンの確認式を拒否し、16歳で正式に教会を離れたが、哲学、文学、宗教といった知的探求には興味を持ち続けた。 実際、彼女はダルトンの反対者としてサンクトペテルブルクで知られていたオランダ人牧師ヘンドリック・ギロットの説教に魅了されていた。25歳年上のギヨ は彼女を弟子として迎え入れ、神学、哲学、世界宗教、フランス文学、ドイツ文学の分野を一緒に研究した。 2人は数多くの作家、哲学者、神学や宗教に関するテーマを研究し、この幅広い研究が、彼女と当時非常に著名な思想家たちとの知的交流の基盤となった。ギヨ はサロメに夢中になり、妻と離婚して若い弟子と結婚したいとまで思った。サロメは結婚や性的関係に興味がなかったため、ギヨの申し出を断った。この展開に 失望しショックを受けたものの、彼女はギヨと友人関係を維持した。 1879年に父親が死去した後、サロメと母親はチューリッヒに移り、サロメは「ゲスト学生」として大学教育を受けることができた。女性学生を受け入れてい た数少ない学校の一つであるチューリッヒ大学に1年間在籍したサロメは、哲学(論理学、哲学史、古代哲学、心理学)と神学(教義学)の講義を受講した。こ の期間、サロメは肺の病気により体調を崩し、血を吐くほど咳き込むようになった。そのため、彼女は温暖な気候で療養するように指示され、1882年2月、 サロメと母親はローマに向かった。  左から、アンドレアス・サロメ、リー、ニーチェ(1882年) リーとニーチェ、そしてその後の人生 サロメが21歳のとき、母親が彼女をローマに連れて行った。 ローマで開かれた文学サロンで、サロメは作家ポール・リーと知り合った。リーは彼女にプロポーズしたが、彼女は代わりに、もう一人の男性を仲間に加えて 「兄妹」として一緒に暮らし、勉強し、学問的な共同体を作ろう、と提案した[5]。リーはそのアイデアを受け入れ、友人のフリードリヒ・ニーチェも仲間に 加えることを提案した。二人は1882年4月にローマでニーチェと出会い、ニーチェはリーがそうであったように、たちまちサロメに恋に落ちたと考えられて いる。ニーチェはリーに、ニーチェの代理としてサロメに求婚するよう頼んだが、彼女はそれを拒否した。ただし、友人としてはニーチェに興味を持っていた。 [5] それでもニーチェは、リーとサロメがスイスとイタリアを一緒に旅行し、コミューンの計画を立てることに満足していた。5月13日、ニーチェがルツェルンで サロメと二人きりになったとき、彼は再び真剣に求婚したが、彼女は再びそれを拒否した。ニーチェは学術的なコミューンの計画を継続することに満足していた [5]。この状況を知ったニーチェの妹エリザベートは、ニーチェを「不道徳な女性」と評したサロメと別れさせる決意を固めた[6]。ニーチェ、リー、サロ メはサロメの母親とともにイタリアを旅行し、「ウィンタープラン」コミューンをどこに設立するかを検討した。このコミューンは、廃墟となった修道院に設立 される予定だったが、適当な場所が見つからなかったため、計画は中止された。 1882年10月にライプツィヒに到着した後、3人は数週間を共に過ごした。しかし、翌月にはリーとサロメがニーチェと別れて、再び会う予定もなくシュ ティーベへと去っていった。ニーチェはすぐに精神的に苦悩する時期を迎えたが、リーに手紙を書き続け、「時々会おうね」と尋ねていた[7]。後の非難の中 で、ニーチェはサロメへの求愛が失敗した理由を、サロメとリー、そして彼の妹の陰謀(ニーチェの妹は、サロメとリーの家族に手紙を書き、彼らのコミューン 計画を妨害していた)のせいにした。ニーチェは1883年にこの出来事を「妹に対して本物の憎しみを感じた」と書いている[7]。 サロメは後に(1894年)、ニーチェの人格と哲学に関する研究『フリードリヒ・ニーチェの著作』を執筆した[8]。 1884年、サロメはチューリッヒで哲学博士号を取得した2人目の女性、ヘレーネ・フォン・ドルスコヴィッツと知り合いになった[ チューリッヒで哲学博士号を取得した2人目の女性であった[出典が必要]。また、サロメは後にジークムント・フロイトと恋愛関係にあったという噂もある [9]。 結婚と人間関係  ルー・アンドレアス・サロメとフリードリヒ・カール・アンドレアス、1886年 サロメとリーはベルリンに移り住み、言語学者フリードリヒ・カール・アンドレアスとの生涯独身主義の結婚[10]の数年前まで一緒に暮らしていた。結婚に 反対し、他の男性ともオープンな関係にあったにもかかわらず、サロメとアンドレアスは1887年から1930年に彼が亡くなるまで結婚生活を続けた。 サロメとアンドレアスが同棲していたことが原因で、サロメの保証にもかかわらず、絶望したリーはサロメの人生から姿を消した。結婚生活の間、彼女はドイツ 人ジャーナリスト兼政治家のゲオルク・レーデボーア、オーストリアの詩人ライナー・マリア・リルケ(彼女は彼について分析的な回顧録を書いている [11])、精神分析医ジークムント・フロイト(彼女は1911年9月にワイマールで開催された第3回精神分析会議に出席した際にフロイトと個人的に会っ た[12])、ヴィクトル・タウスクなど、何人かの男性と不倫関係や文通をしていた。これらの多くの逸話は、彼女の著書 『Lebensrückblick』に記されている。ウィーンの医師フリードリヒ・ピネレスとの情事は、中絶と悲劇的な母性放棄で終わった[13]。フロ イトとの関係は、2人のロマンチックな関係についての噂にもかかわらず、依然として非常に知的であった。ある手紙の中で、フロイトはサロメの人に対する深 い理解を賞賛し、彼女は人々が自分自身を理解する以上に人々を理解していると信じていたほどであった。2人は頻繁に手紙を交わしていた[14]。サロメ は、ハンサムで憂鬱なヴィクトル・タウスクと恋愛関係にあった。タウスクは、18歳年下のウィーン精神分析学会会員だった[15]。 アンナ・フロイトによると、彼女の著書『フリードリヒ・ニーチェの著作』(Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken)は精神分析を予見していたという[16]。これは、ドイツの哲学者に関する最初の著書だった[17]。 ] ウィーンで出会ったアンナ・フロイトとフォン・サロメは、ジークムント・フロイトとフォン・サロメのように、長年にわたって文通をしていた[18]。 リルケとの出会い 1897年5月、ミュンヘンで、彼女はヤコブ・ヴァッサーマンに紹介されたリルケと出会った[19]。彼女は36歳、リルケは20歳だった。彼女はすでに 『神との闘い』を出版し、ある程度の成功を収めていた。この本では、(彼女自身が長い間抱えていた)信仰の喪失という問題を取り上げていた。また、いくつ かの論文や、リルケが読んだ『ユダヤ人としてのイエス』という研究も発表していた。 フィリップ・ジャコッテが『Lebensrückblick』で報告しているように、サロメはこう書いている。「私は何年もあなたの妻だった。なぜなら、 あなたは私にとって初めて現実だったからだ。男と体が区別できない、紛れもない人生の事実。あなたが私に愛を告白したとき、文字通り同じことを言えたかも しれない。あなただけが現実なのだ。それが、友人になる前から私たち夫婦となった理由だ。選択したのではなく、この計り知れない結婚によってそうなったの だ[...]。私たちは兄弟姉妹だったが、兄弟姉妹の結婚が神聖冒涜とみなされるようになる遥か昔のように。 1899年、夫フリードリヒ・カールとともに、 夫フリードリヒ・カールとともに、そして1900年には再び、ルーはロシアを訪れた。2度目の旅行にはリルケも同行し、彼女は彼のファーストネームをレネ からライナーに変えた[21]。彼女は彼にロシア語を教え、トルストイ(後に彼と出会うことになる)やプーシキンの作品を読み聞かせた。彼女は、リルケの パトロンや芸術家たちを紹介し、リルケの生涯を通じて、彼のアドバイザー、相談相手、そしてミューズであり続けた[10]。詩人とサロメのロマンスは3年 間続き、その後友情へと変わり、リルケの死まで続いた。1937年、フロイトは、サロメとリルケの関係について次のように述べた。「彼女は偉大な詩人の ミューズであり、献身的な母親でもあった」[22]。 死  ゲッティンゲンにあるルー・アンドレアス・サロメの墓 1930年までに、サロメはますます衰弱し、心臓病と糖尿病を患い、何度も入院して治療を受ける必要があった。彼女の夫は、足の手術後6週間の入院中、毎 日彼女を見舞った。高齢で病気がちだった夫にとって、それは過酷な日々だったが、このことがきっかけで、互いに傷つけ合うような言動や長期間の不仲が続い た40年間の結婚生活を経て、2人の仲は深まった[23]。フロイトはこれを遠くから見ていて、こう書いている。「本当に真実であるものだけが、それだけ 長続きするのだ。(「真実は、本当に真実であるものだけが、長続きするのだ。」)フリードリヒ・カール・アンドレアスは1930年に癌で亡くなり、サロメ 自身も1935年に困難な癌の手術を受けた。74歳で、彼女は精神分析医としての活動を停止した。 サロメは1937年2月5日、ゲッティンゲンで尿毒症により亡くなった。彼女の骨壷は、ゲッティンゲンのグローナー・ラントシュトラッセにある墓地に夫の 墓に安置された。 彼女の家は、彼女の名前が付けられた通り(Lou-Andreas-Salomé-Weg)や、Lou Andreas-Salomé Institut für Psychoanalyse und Psychotherapie(ルー・アンドレアス・サロメ精神分析・心理療法研究所)という名称で、ゲッティンゲン市内に記念されている。彼女の死の数 日前に、ゲシュタポが彼女の蔵書を没収した(他の情報源によると、彼女の死後まもなくSAグループが蔵書を破棄した)。この没収の理由は、彼女がジークム ント・フロイトの同僚であり、「ユダヤ人の科学」を実践し、ユダヤ人作家の本を多数所有していたためであった[24]。 |

| Work Salomé was a prolific writer who wrote fiction, criticism and essays on religion, philosophy, sexuality and psychology.[25] A uniform edition of her works is being published in Germany by MedienEdition Welsch.[26] She authored a "Hymn to Life" that so deeply impressed Nietzsche that he was moved to set it to music. Salomé's literary and analytical studies became such a vogue in Göttingen, where she lived late in her life, that the Gestapo waited until shortly after her death to "clean" her library of works by Jews. She was one of the first female psychoanalysts and one of the first women to write psychoanalytically on female sexuality,[27] before Helene Deutsch, for instance in her essay on the anal-erotic (1916),[28] an essay admired by Freud.[29] However, she had written about the psychology of female sexuality before she ever met Freud, in her book Die Erotik (1911). She wrote more than a dozen novels and novellas, including Im Kampf um Gott, Ruth, Rodinka, Ma, Fenitschka – eine Ausschweifung, as well as non-fiction studies such as Henrik Ibsens Frauengestalten (1892), a study of Ibsen's female characters, and a book on Nietzsche, Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken (1894). The first English translation of her novel Das Haus (1921) appeared in 2021 under the title Anneliese's House, in an annotated edition by Frank Beck and Raleigh Whitinger.[30] Salomé edited a memoir about Rilke after his death in 1926. Among her works is also her Lebensrückblick, which she wrote during her last years based on memories of her life as a free woman. In her memoirs, first published in their original German in 1951, she goes into depth about her faith and her relationships. Whoever reaches into a rosebush may seize a handful of flowers; but no matter how many one holds, it's only a small portion of the whole. Nevertheless, a handful is enough to experience the nature of the flowers. Only if we refuse to reach into the bush, because we can't possibly seize all the flowers at once, or if we spread out our handful of roses as if it were the whole of the bush itself—only then does it bloom apart from us, unknown to us, and we are left alone.[31] Salomé is said to have remarked in her last days, "I have really done nothing but work all my life, work ... why?" And in her last hours, as if talking to herself, she is reported to have said, "If I let my thoughts roam I find no one. The best, after all, is death."[32] In fiction and film Fictional accounts of Salomé's relationship with Nietzsche occur in four novels: Irvin Yalom's When Nietzsche Wept,[33] Lance Olsen's Nietzsche's Kisses, Beatriz Rivas's La hora sin diosas (The time without goddesses),[34] and William Bayer's The Luzern Photograph, in which two reenactments of the famous image of her with Nietzsche and Rée impact a murder in contemporary Oakland, California.[35] Mexican playwright Sabina Berman includes Lou Andreas-Salomé as a character in her 2000 play Feliz nuevo siglo, Doktor Freud (Freud Skating).[36] Salomé is also fictionalized in Angela von der Lippe's The Truth about Lou,[37] in Brenda Webster's Vienna Triangle,[38] in Clare Morgan's A Book for All and None,[39] in Robert Langs' two-act play Freud's Bird of Prey,[40] and in Araceli Bruch's five-act play Re-Call (written in Catalan).[41] In Liliana Cavani's movie Al di la' del bene e del male (Beyond Good and Evil) Salome is played by Dominique Sanda. In Pinchas Perry's film version of When Nietzsche Wept, Salome is played by Katheryn Winnick. Lou Salome, an opera in two acts by Giuseppe Sinopoli with libretto from Karl Dietrich Gräwe, premiered in 1981 at the Bavarian State Opera, with August Everding as General Director, staging by Götz Friedrich and set design by Andreas Reinhardt.[42] Lou Andreas-Salomé, The Audacity to be Free [de], a German-language movie directed by Cordula Kablitz-Post [de], was released in German cinemas on 30 June 2016.[43] Andreas-Salome is portrayed onscreen by Katharina Lorenz [de] and as a young woman by Liv Lisa Fries. The film was released in New York City and Los Angeles in April 2018, with a wider release to follow. |

仕事 サロメは、小説、評論、宗教、哲学、性、心理学に関するエッセイを執筆した多作な作家であった[25]。彼女の作品の統一版は、ドイツでメディアエディ ション・ウェルシュ社から出版されている[26]。彼女は「生命への賛歌」を執筆し、ニーチェに深い感銘を与え、ニーチェはそれを音楽にしようとまで思っ た。サロメの文学と分析学の研究は、彼女が晩年を過ごしたゲッティンゲンで流行し、ゲシュタポは彼女の死後しばらくして、ユダヤ人の著作を「一掃」するた めに彼女の図書館を調べた。 彼女は最初の女性精神分析医の1人であり、女性の性について精神分析的に書いた最初の女性の1人であった[27]。例えば、ヘレーネ・ドゥイッチュは、肛 門のエロティシズムに関する論文(1916年)で、フロイトに賞賛された[29]。しかし、彼女はフロイトと出会う前に、著書『Die Erotik』(1911年)で女性の性心理について書いていた。 彼女は、小説や中編小説を10数冊執筆しており、その中には『Im Kampf um Gott』、『Ruth』、『Rodinka』、『Ma』、『Fenitschka – eine Ausschweifung』などがある。また、ノンフィクションの研究書としては、イプセンの女性キャラクターの研究『Henrik Ibsens Frauengestalten』(1892年)や、ニーチェに関する著書『Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken』(1894年)などがある。彼女の小説『Das Haus』(1921)の最初の英語訳は、2021年に『Anneliese's House』というタイトルで、フランク・ベックとローリー・ホワイティンガーによる注釈付き版で出版された[30]。 サロメは、リルケの死後の1926年に、リルケについての回顧録を編集した。彼女の作品には、自由人としての人生を回想して晩年に執筆した 『Lebensrückblick』もある。1951年にドイツ語で初めて出版された彼女の回顧録では、彼女の信仰と人間関係について深く掘り下げてい る。 薔薇の茂みに手を伸ばせば、一握りの花を手に入れることができる。しかし、どんなに多くの花を手にしたとしても、それは全体のごく一部でしかない。それで も、一握りの花で花の性質を知ることはできる。もし、一度にすべての花を手に入れることはできないからと、薮に手を伸ばすことを拒むか、あるいは薮全体で あるかのようにバラの花束を広げる場合のみ、バラは私たちから離れて、私たちの知らないところで咲き、私たちは孤独になる[31]。 サロメは最期の日に、「私は本当に一生、ただ働き続けてきた。なぜだろう」と語ったと言われています。そして、最期の瞬間、まるで独り言のように「考えをさまよわせても、誰もいない。結局のところ、最善なのは死だ」と言ったと伝えられている[32]。 小説と映画 ニーチェとサロメの関係を描いたフィクションは、4つの小説で登場している。アーヴィン・ヤロームの『ニーチェが泣いたとき』、[33] ランス・オルセンの『ニーチェのキス』、ベアトリス・リヴァスの『女神なき時代』、[34] ウィリアム・ベイヤーの『ルツェルン写真』である。後者の作品では、ニーチェとリーとともに写った有名な写真が再現され、現代のカリフォルニア州オークラ ンドで起こった殺人事件に影響を与える。 メキシコの劇作家サビーナ・バーマンは、2000年の戯曲『フェリス・ヌエボ・シグロ、ドクトル・フロイト(Freud Skating)』で、ルー・アンドレアス・サロメを登場人物として取り上げている[36]。 サロメは、アンジェラ・フォン・デア・リッペの『The Truth about Lou(ルーの真実)』[37]、ブレンダ・ウェブスターの『Vienna Triangle(ウィーン・トライアングル)』[38]、クレア・モーガンの『A Book for All and None(すべての人と誰でもない人のための本)[39]、ロバート・ラングスの2幕劇『Freud's Bird of Prey(フロイトの猛禽)』[40]、アラセリ・ブルックの5幕劇『Re-Call(再考)』(カタルーニャ語で書かれた作品)[41]にも登場してい る。 リリアーナ・カヴァーニ監督の映画『Al di la' del bene e del male(善と悪の彼岸)』では、ドミニク・サンダがサロメを演じている。ピンカス・ペリー監督の映画『ニーチェが泣いた時』では、サロメ役をキャサリン・ウィニックが演じている。 カール・ディートリヒ・グレーヴェの台本によるジュゼッペ・シノーポリ作曲の2幕構成のオペラ『ルー・サロメ』は、1981年にバイエルン州立歌劇場で初 演された。総監督はアウグスト・エヴァルディング、演出はゲッツ・フリードリヒ、舞台装置はアンドレアス・ラインハルトが担当した[42]。 ルー・アンドレアス・サロメ、The コルドゥラ・カブリッツ=ポスト監督によるドイツ語映画『The Audacity to be Free [de]』は、2016年6月30日にドイツの映画館で公開された[43]。アンドレアス・サロメは、カタリーナ・ローレンツ[de]が演じ、若い頃のサ ロメはリヴ・リサ・フライズが演じている。この映画は2018年4月にニューヨークとロサンゼルスで公開され、その後さらに公開地域を拡大する予定であ る。 |

| Bibliography Lou Andreas-Salomé's published works as cited by An Encyclopedia of Continental Women Writers.[44]: 36–38 Im Kampf um Gott, 1885. Henrik Ibsens Frau-Gestalten, 1892. Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken, 1894. Ruth, 1895, 1897. Fenitshcka. Eine Ausschweifung, 1898,1983. Menschenkinder, 1899. Aus fremder Seele, 1901. Ma, 1901. Im Zwischenland, 1902. Die Erotik, 1910. Drei Briefe an einen Knaben, 1917. Das Haus, 1919,1927. Die Stunde ohne Gott und andere Kindergeschichten, 1921. Der Teufel und seine Grossmutter, 1922. Rodinka, 1923. Rainer Maria Rilke, 1928. Mein Dank an Freud: Offener Brief an Professor Freud zu seinem 75 Geburtstag, 1931. Lebensrückblick. Grundriss einiger Lebenserinnerungen, ed. E. Pfeiffer, 1951, 1968. Rainer Maria Rilke – Lou Andreas-Salomé. Briefwechsel, ed. E. Pfeiffer, 1952. In der Schule bei Freud, ed. E. Pfeiffer, 1958. Sigmund Freud – Lou Andreas-Salomé. Briefwechsel, ed. E. Pfeiffer, 1966. Friedrich Nietzsche, Paul Rée, Lou von Salomé: Die Dokumente ihrer Begegnung, ed. E. Pfeiffer, 1970. Translations The Freud Journal of Lou Andreas-Salomé, tr. Stanley Leavy, 1964. Sigmund Freud and Lou Andreas-Salomé, Letters, tr. byu W. and E. Robson Scott, 1972. Ibsen's Heroines, ed., tr., and introd. by Siegfried Mandel, 1985. Anneliese's House, edited and translated by Frank Beck and Raleigh Whitinger. Boydell and Brewer, 2021. |

書誌 大陸女性作家百科事典[44]:36-38に引用されているルー・アンドレアス=サロメの出版物 神のための闘争』1885年 ヘンリック・イプセンの『フラウ=ゲシュタルテン』1892年。 フリードリヒ・ニーチェ作品集、1894年。 ルース、1895年、1897年。 フェニツカ。蕩尽』1898年、1983年。 人間の子供たち』1899年。 もうひとつの魂から、1901年。 Ma, 1901. 中間地にて、1902年。 エロティック, 1910. 少年への3通の手紙、1917年 家、1919年、1927年 神さまのいない時間、その他の童話, 1921. 悪魔とおばあさん, 1922. ロディンカ、1923年 ライナー・マリア・リルケ、1928年。 フロイトに感謝:75歳の誕生日を迎えたフロイト教授への公開書簡、1931年。 ライフ・レビュー。いくつかの回想録の概要、E. ファイファー編、1951年、1968年。 ライナー・マリア・リルケ - ルー・アンドレアス=サロメ. 1952年、E.ファイファー編。 フロイトと学校にて, E. ファイファー編, 1958. ジークムント・フロイト - ルー・アンドレアス=サロメ. E. ファイファー編、1966年。 フリードリヒ・ニーチェ、パウル・レー、ルー・フォン・サロメ:その生い立ち』E. ファイファー編、1970年。 翻訳 ルー・アンドレアス・サロメのフロイト日誌』スタンリー・リーヴィー訳、1964年。 ジークムント・フロイトとルー・アンドレアス=サロメの書簡集, byu W. and E. Robson Scott, 1972. Robson Scott, 1972. イプセンのヒロインたち』ジークフリート・マンデル編・訳・序 1985年 フランク・ベック、ローリー・ホワイティンガー編訳『アンネリーゼの家』ボイデル&ブリュワー、1972年。Boydell and Brewer, 2021. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lou_Andreas-Salom%C3%A9 |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆