ルイ=フェルディナン・セリーヌ

Louis-Ferdinand Céline, 1894-

☆

ルイ・フェルディナン・オーギュスト・デストゥッシュ(Louis Ferdinand Auguste Destouches、1894年5月27日

- 1961年7月1日)は、ルイ=フェルディナン・セリーヌ(Louis-Ferdinand

Céline)というペンネームでよく知られている(英語読みではルイ・フェルディナン・セリーヌ、フランス語発音ではルイ・フェルディナン・セラン)。

フランスの小説家、論客、医師である。処女作『夜の底への旅』(1932年)でルノー賞を受賞したが、人間の悲観的な本質を描いたことや、労働者階級の話

し方を基にした文体が論争を呼んだ。

。その後、1936年の『分割払いでの死』、1944年の『ギニョールの群れ』、1957年の『城から城へ』などの小説で、セリーヌはさらに革新的で独特

な文学スタイルを展開した。モーリス・ナドーは、「英語に対してジョイスが成し遂げたことを...フランス語に対してシュールレアリストたちが試みたこと

を、セリーヌは難なく、しかも大規模に成し遂げた」と書いている。

1937年以降、セリーヌは反ユダヤ主義的な論争的作品を次々と発表し、ナチス・ドイツとの軍事同盟を提唱した。

ドイツによるフランス占領中も公然と反ユダヤ主義的な見解を支持し続け、1944年に連合軍がノルマンディーに上陸すると、ドイツに逃亡し、その後デン

マークに渡り、亡命生活を送った。

1951年にフランス裁判所により協力者として有罪判決を受けたが、まもなく軍事法廷により恩赦された。フランスに戻った彼は、医師と作家としてのキャリ

アを再開した。

セリーヌは20世紀フランスを代表する小説家の一人と広く考えられており、彼の小説は後世の作家たちに絶大な影響を与えている。しかし、彼の反ユダヤ主義

と第二次世界大戦中の活動により、フランスでは今も物議を醸す人物である。[3][4]

| Louis

Ferdinand Auguste Destouches (27 May 1894 – 1 July 1961), better known

by the pen name Louis-Ferdinand Céline (/seɪˈliːn/ say-LEEN; French:

[lwi fɛʁdinɑ̃ selin] ⓘ), was a French novelist, polemicist, and

physician. His first novel Journey to the End of the Night (1932) won

the Prix Renaudot but divided critics due to the author's pessimistic

depiction of the human condition and his writing style based on

working-class speech.[1] In subsequent novels such as Death on the

Installment Plan (1936), Guignol's Band (1944) and Castle to Castle

(1957), Céline further developed an innovative and distinctive literary

style. Maurice Nadeau wrote: "What Joyce did for the English

language...what the surrealists attempted to do for the French

language, Céline achieved effortlessly and on a vast scale."[2] From 1937 Céline wrote a series of antisemitic polemical works in which he advocated a military alliance with Nazi Germany. He continued to publicly espouse antisemitic views during the German occupation of France, and after the Allied landing in Normandy in 1944, he fled to Germany and then Denmark where he lived in exile. He was convicted of collaboration by a French court in 1951 but was pardoned by a military tribunal soon after. He returned to France where he resumed his careers as a doctor and author. Céline is widely considered to be one of the greatest French novelists of the 20th century and his novels have had an enduring influence on later authors. However, he remains a controversial figure in France due to his antisemitism and activities during the Second World War.[3][4] |

ルイ・フェルディナン・オーギュスト・デストゥッシュ(Louis

Ferdinand Auguste Destouches、1894年5月27日 -

1961年7月1日)は、ルイ=フェルディナン・セリーヌ(Louis-Ferdinand

Céline)というペンネームでよく知られている(英語読みではルイ・フェルディナン・セリーヌ、フランス語発音ではルイ・フェルディナン・セラン)。

フランスの小説家、論客、医師である。処女作『夜の底への旅』(1932年)でルノー賞を受賞したが、人間の悲観的な本質を描いたことや、労働者階級の話

し方を基にした文体が論争を呼んだ。

。その後、1936年の『分割払いでの死』、1944年の『ギニョールの群れ』、1957年の『城から城へ』などの小説で、セリーヌはさらに革新的で独特

な文学スタイルを展開した。モーリス・ナドーは、「英語に対してジョイスが成し遂げたことを...フランス語に対してシュールレアリストたちが試みたこと

を、セリーヌは難なく、しかも大規模に成し遂げた」と書いている。 1937年以降、セリーヌは反ユダヤ主義的な論争的作品を次々と発表し、ナチス・ドイツとの軍事同盟を提唱した。 ドイツによるフランス占領中も公然と反ユダヤ主義的な見解を支持し続け、1944年に連合軍がノルマンディーに上陸すると、ドイツに逃亡し、その後デン マークに渡り、亡命生活を送った。 1951年にフランス裁判所により協力者として有罪判決を受けたが、まもなく軍事法廷により恩赦された。フランスに戻った彼は、医師と作家としてのキャリ アを再開した。 セリーヌは20世紀フランスを代表する小説家の一人と広く考えられており、彼の小説は後世の作家たちに絶大な影響を与えている。しかし、彼の反ユダヤ主義 と第二次世界大戦中の活動により、フランスでは今も物議を醸す人物である。[3][4] |

| Biography Early life The only child of Fernand Destouches and Marguerite-Louise-Céline Guilloux, he was born Louis Ferdinand Auguste Destouches in 1894 at Courbevoie, just outside Paris in the Seine département (now Hauts-de-Seine). The family came originally from Normandy on his father's side and Brittany on his mother's side. His father was a middle manager in an insurance company and his mother owned a boutique where she sold antique lace.[5][6] In 1905, he was awarded his Certificat d'études, after which he worked as an apprentice and messenger boy in various trades.[6] Between 1908 and 1910, his parents sent him to Germany and England for a year in each country in order to acquire foreign languages for future employment.[6] From the time he left school until the age of eighteen Céline worked in various jobs, leaving or losing them after only short periods of time. He worked for silk sellers and jewellers, first, at eleven, as an errand boy, and later as a salesperson for a local goldsmith. Although he was no longer being formally educated, he bought schoolbooks with the money he earned, and studied by himself. It was around this time that Céline vaguely thought of becoming a doctor.[7] World War I and Africa In 1912, Céline volunteered for the French army (in what he described as an act of rebellion against his parents)[8] and began a three-year enlistment in the 12th Cuirassier Regiment stationed in Rambouillet.[6] At first he was unhappy with military life, and considered deserting. However, he adapted, and eventually attained the rank of sergeant.[9] The beginning of the First World War brought action to Céline's unit. On 25 October 1914, he volunteered to deliver a message, when others were reluctant to do so because of heavy German fire. Near Ypres, during his attempt to deliver the message, he was wounded in his right arm. (Although he was not wounded in the head, as he later claimed, he did suffer severe headaches and tinnitus for the rest of his life.)[10][11] For his bravery, he was awarded the médaille militaire in November, and appeared one year later in the weekly l'Illustré National (November 1915).[6] He later wrote that his wartime experience left him with "a profound disgust for all that is bellicose."[12] In March 1915, he was sent to London to work in the French passport office. He spent his nights visiting music halls and the haunts of the London underworld, and claimed to have met Mata Hari.[13] He later drew on his experiences in the city for his novel Guignol's Band (1944). In September, he was declared unfit for military duty and was discharged from the army. Before returning to France, he married Suzanne Nebout, a French dancer, but the marriage wasn't registered with the French Consulate and they soon separated.[14] In 1916, Céline went to French-administered Cameroon as an employee of the Forestry Company of Sangha-Oubangui. He worked as an overseer on a plantation and a trading post, and ran a pharmacy for the local inhabitants, procuring essential medical supplies from his parents in France. He left Africa in April 1917 due to ill health. His experiences in Africa left him with a distaste for colonialism and an increasing passion for medicine as a vocation.[15] |

経歴 幼少期 フェルナン・デストゥッシュとマルグリット=ルイーズ=セリーヌ・ギユの一人息子として、1894年にパリ郊外のセーヌ県(現オー=ド=セーヌ県)クール ブヴォアでルイ・フェルディナン・オーギュスト・デストゥッシュとして生まれた。父方の家系はノルマンディー、母方の家系はブルターニュに由来する。父親 は保険会社の中間管理職、母親はアンティークレースを売るブティックの経営者であった。[5][6] 1905年、彼はCertificat d'étudesを取得し、その後、さまざまな職業の見習いや使い走りとして働いた。[6] 1908年から1910年の間、両親は将来の就職のために外国語を習得させるため、彼を1年ずつドイツとイギリスに留学させた。[6] セリーヌは学校を離れてから18歳になるまで、さまざまな仕事に就き、短期間で辞めたり解雇されたりした。11歳で、まず使い走りとして、その後は地元の 金細工職人の店で販売員として働いた。正規の教育は受けていなかったが、稼いだお金で教科書を購入し、独学で学んだ。この頃、セリーヌは漠然と医師になる ことを考えた。[7] 第一次世界大戦とアフリカ 1912年、セリーヌはフランス軍に志願し(これは両親に対する反抗の表れであったと彼は述べている)[8]、ランブイエに駐留する第12クイラシエ連隊 に入隊した。当初は軍隊生活に不満で、脱走も考えた。しかし、彼は適応し、最終的に軍曹の地位にまで上り詰めた。[9] 第1次世界大戦の勃発により、セリーヌの部隊にも戦闘がもたらされた。1914年10月25日、ドイツ軍の激しい砲火により他の兵士たちが伝令を嫌がった 中、自ら進んで伝令を買って出た。イープル近郊で伝令を届けようとした際に、右腕に負傷した。(後に彼が主張したように、頭部に負傷はしなかったが、生涯 にわたって激しい頭痛と耳鳴りに苦しむことになった。)[10][11] その勇敢さにより、 彼は11月に軍事勲章を授与され、その1年後には『l'Illustré National』誌(1915年11月)にも登場した。[6] 彼は後に、戦時中の経験から「好戦的なものすべてに対して深い嫌悪感を抱くようになった」と書いている。[12] 1915年3月、彼はロンドンに送られ、フランス旅券局で勤務することになった。夜はミュージックホールやロンドンの裏社会のたまり場を訪れ、マタ・ハリ にも会ったと主張している。[13] 後に彼は、この都市での経験を小説『ギニョールの楽団』(1944年)に活かした。9月には軍務に適さないと宣言され、除隊となった。フランスに戻る前 に、フランス人ダンサーのスザンヌ・ネブーと結婚したが、結婚はフランス領事館に登録されず、間もなく別居した。 1916年、セリーヌはサンガ・ウバンギ森林会社の従業員として、フランスが統治するカメルーンに向かった。彼は、プランテーションと貿易会社の監督者と して働き、また地元住民のための薬局も経営し、フランスにいる両親から必要な医療用品を調達していた。健康上の理由により、1917年4月にアフリカを離 れた。アフリカでの経験により、植民地主義に対する嫌悪感を抱くようになり、天職としての医学への情熱をますます強く抱くようになった。[15] |

| Becoming a doctor (1918–1924) In March 1918, Céline was employed by the Rockefeller Foundation as part of a team travelling around Brittany delivering information sessions on tuberculosis and hygiene.[16] He met Dr Athanase Follet of the Medical Faculty of the University of Rennes, and soon became close to Follet's daughter Édith. Dr Follet encouraged him to pursue medicine and Céline studied for his baccalaureate part-time, passing his examinations in July 1919. He married Édith in August.[17] Céline enrolled in the Medical Faculty at Rennes in April 1920 and in June Édith gave birth to a daughter, Collette Destouches. In 1923 he transferred to the University of Paris and in May 1924 defended his dissertation The Life and Work of Philippe-Ignace Semmelweis (1818–1865), which has been called, "a Célinian novel in miniature".[18][19] |

医師になるまで(1918年~1924年) 1918年3月、セネはロックフェラー財団に採用され、結核と衛生に関する説明会をブルターニュ地方で行うチームの一員として活動した。[16] 彼はレンヌ大学医学部のアタナゼ・フォレ博士と出会い、すぐにフォレ博士の娘エディットと親しくなった。フォレ博士は彼に医学の道を勧めたため、セリーヌ はパートタイムでバカロレアの勉強をし、1919年7月に試験に合格した。彼は8月にエディットと結婚した。 セリーヌは1920年4月にレンヌの医学部に進学し、6月にはエディットに娘のコレット・デストゥーシュが生まれた。1923年にパリ大学に移り、 1924年5月に「フィリップ・イグナツ・ゼンメルヴェイス(1818年 - 1865年)の生涯と業績」という論文を擁護した。この論文は「セリーヌ的小説」と呼ばれている。[18][19] |

| League of Nations and medical practice (1924–1931) n June 1924 Céline joined the Health Department of the League of Nations in Geneva, leaving his wife and daughter in Rennes. His duties involved extensive travel in Europe and to Africa, Canada, the United States and Cuba. He drew on his time with the League for his play L'Église (The Church, written in 1927, but first published in 1933).[20] Édith divorced him in June 1926 and a few months later he met Elizabeth Craig, an American dancer studying in Geneva.[21] They were to remain together for the six years in which he established himself as a major author. He later wrote: "I wouldn't have amounted to anything without her."[22] He left the League of Nations in late 1927 and set up a medical practice in the working-class Paris suburb of Clichy. The practice wasn't profitable and he supplemented his income working for the nearby public clinic and a pharmaceutical company. In 1929 he gave up his private practice and moved to Montmartre with Elizabeth. However, he continued to practice at the public clinic in Clichy as well as other clinics and pharmaceutical companies. In his spare time he worked on his first novel, Voyage au bout de la nuit (Journey to the End of the Night), which was dedicated to Elizabeth, completing it in late 1931.[23] |

国際連盟と医療活動(1924-1931) 1924年6月、セリーヌは妻と娘をレンヌに残し、ジュネーヴの国際連盟保健局に入局した。 彼の任務は、ヨーロッパやアフリカ、カナダ、アメリカ、キューバへの広範囲にわたる出張を伴うものだった。 彼は、国際連盟での経験を戯曲『L'Église』(1927年に執筆、1933年に初出版)に活かした。[20] 1926年6月にエディットと離婚し、数か月後、ジュネーヴで学んでいたアメリカ人ダンサーのエリザベス・クレイグと出会った。[21] 彼が主要な作家として地位を確立するまでの6年間、2人は一緒に過ごすことになる。彼は後に「彼女がいなければ、私は何者にもなれなかっただろう」と書い ている。[22] 1927年後半に国際連盟を去り、パリの下層階級の郊外であるクリシーで診療所を開業した。診療所は利益を上げることができず、彼は近くの公立診療所や製 薬会社で働くことで収入を補った。1929年には個人開業を諦め、エリザベスとともにモンマルトルに移り住んだ。しかし、クリシーの公立診療所やその他の クリニック、製薬会社で勤務を続ける。 余暇には、エリザベスに捧げる処女作『夜の果てへの旅』(Voyage au bout de la nuit)の執筆に取り組み、1931年の終わりに完成させた。[23] |

| Writer, physician and polemicist (1932–1939) Voyage au bout de la nuit was published in October 1932 to widespread critical attention. Although Destouches sought anonymity under the pen name Céline, his identity was soon revealed by the press. The novel attracted admirers and detractors across the political spectrum, with some praising its anarchist, anticolonialist and antimilitarist themes while one critic condemned it as "the cynical, jeering confessions of a man without courage or nobility." A critic for Les Nouvelles littéraires praised the author's use of spoken, colloquial French as an "extraordinary language, the height of the natural and the artificial" while the critic for Le Populaire de Paris condemned it as mere vulgarity and obscenity.[24] The novel was the favourite for the Prix Goncourt of 1932. When the prize was awarded to Mazeline's Les Loups, the resulting scandal increased publicity for Céline's novel which sold 50,000 copies in the following two months.[25] Despite the success of Voyage, Céline saw his vocation as medicine and continued his work at the Clichy clinic and private pharmaceutical laboratories. He also began working on a novel about his childhood and youth which was to become Mort à Credit (1936) (tr Death on the Installment Plan). In June 1933 Elizabeth Craig returned permanently to America. Céline visited her in Los Angeles the following year but failed to persuade her to return.[26] Céline initially refused to take a public stance on the rise of Nazism and the increasing extreme-right political agitation in France, explaining to a friend in 1933: "I am and have always been an anarchist, I have never voted…I will never vote for anything or anybody…I don't believe in men….The Nazis loathe me as much as the socialists and the commies too."[27] Nevertheless, in 1935, British critic William Empson had written that Céline appeared to be "a man ripe for fascism".[28] Mort à credit was published in May 1936, with numerous blank spaces where passages had been removed by the publisher for fear of prosecution for obscenity. The critical response was sharply divided, with the majority of reviewers criticising it for gutter language, pessimism and contempt for humanity. The novel sold 35,000 copies up to late 1938.[29] In August Céline visited Leningrad for a month and on his return quickly wrote, and had published, an essay, Mea Culpa, in which he denounced communism and the Soviet Union.[30] In December the following year Bagatelles pour un massacre (Trifles for a Massacre) was published, a book-length racist and antisemitic polemic in which Céline advocated a military alliance with Hitler's Germany in order to save France from war and Jewish hegemony. The book won qualified support from some sections of the French far-Right and sold 75,000 copies up to the end of the war. Céline followed Bagatelles with Ecole des cadavres (School for Corpses) (November 1938) in which he developed the themes of antisemitism and a Franco-German alliance.[31] Céline was now living with Lucette Almansor, a French dancer whom he had met in 1935. They were to marry in 1943 and remain together until Céline's death. On the publication of Bagatelles, Céline quit his jobs at the Clichy clinic and the pharmaceutical laboratory and devoted himself to his writing.[32] |

作家、医師、論客(1932年~1939年) 『夜の果てへの旅』は1932年10月に出版され、広く批評家の注目を集めた。デストゥシェスは「セリーヌ」というペンネームで匿名を希望したが、すぐに マスコミによって正体が明らかになった。この小説は政治的見解を問わず、賛同者と反対者を惹きつけた。一部では、その小説の無政府主義、反植民地主義、反 軍国主義のテーマが賞賛されたが、一方で「勇気も高潔さもない男の冷笑的で卑屈な告白」と酷評する批評家もいた。一方、『レ・ヌーヴェル・リテレール』紙 の批評家は、口語体で書かれた俗語を「並外れた言語、自然と人工の極み」と賞賛したが、『ル・ポピュレール・ド・パリ』紙の批評家は、単なる低俗さと卑猥 さだと酷評した。[24] この小説は1932年のゴンクール賞の有力候補であった。マゼリンの『狼たち』にゴンクール賞が授与されたとき、スキャンダルによってセリーヌの小説の知 名度は上がり、その2か月間で5万部が売れた。 『航海』の成功にもかかわらず、セリーヌは天職を医学に見て、クリシーの診療所と民間の製薬研究所での仕事を続けた。また、自身の子供時代と青年時代を描 いた小説の執筆にも着手し、これが後に『Mort à Credit』(1936年)(『分割払いでの死』)となる。1933年6月、エリザベス・クレイグはアメリカに永住するために帰国した。セリーヌは翌年 ロサンゼルスを訪れたが、彼女を説得して戻るようにはできなかった。 セリーヌは当初、ナチズムの台頭とフランスにおける極右政治の煽動の高まりに対して公の立場を取ることを拒否し、1933年に友人に次のように説明してい る。「私は今も昔もずっと無政府主義者であり、投票したことは一度もない。私は何に対しても、誰に対しても決して投票しない。私は人間を信じていない。ナ チスは社会主義者や共産主義者と同じくらい私を嫌っている」[27] しかし、1935年にはイギリスの批評家ウィリアム・エンプソンがセリーヌを「ファシズムに傾倒した人物」と評している[28]。 『モール・ア・クレディ』は1936年5月に出版されたが、わいせつ罪で起訴されることを恐れた出版社が削除した文章の跡が多数残されていた。批評家の反 応は大きく分かれ、大多数の批評家は下品な表現、悲観主義、人間に対する軽蔑を理由に批判した。この小説は1938年末までに3万5千部が売れた。 8月、セリーヌは1か月間レニングラードを訪問し、帰国後すぐに共産主義とソビエト連邦を非難するエッセイ『我が罪』を書き上げ、出版した。 翌年12月には『虐殺のための些事(Bagatelles pour un massacre)』が出版された。この本は、人種差別的かつ反ユダヤ主義的な論争を展開した長編小説であり、セリーヌはフランスを戦争とユダヤ人の支配 から救うためにヒトラーのドイツと軍事同盟を結ぶことを提唱した。この本は、フランスの極右の一部から一定の支持を受け、戦時中までに7万5千部が売れ た。セリーヌは『バガテル』に続いて、『死体学校』(1938年11月)で反ユダヤ主義と独仏同盟のテーマを展開した。 セリーヌは、1935年に知り合ったフランス人ダンサーのルセット・アルマンスールと同棲していた。1943年に結婚し、セリーヌの死まで一緒に暮らした。『バガテル』の出版後、セリーヌはクリシーの診療所と製薬研究所での仕事を辞め、執筆活動に専念した。 |

| 1939 to 1945 At the outbreak of war in September 1939, the draft board declared Céline 70 per cent disabled and unfit for military service. Céline gained employment as a ship's doctor on a troop transport and in January 1940 the ship accidentally rammed a British torpedo boat killing twenty British crew. In February he found a position as a doctor in a public clinic in Sartrouville, north-west of Paris. On the evacuation of Paris in June, Céline and Lucette commandeered an ambulance and evacuated an elderly woman and two newborn infants to La Rochelle. "I did the retreat myself, like many another, I chased the French army all the way from Bezons to La Rochelle, but I could never catch up."[33] Returning to Paris, Céline was appointed head doctor of the Bezons public clinic and accredited physician to the département of Seine-et-Oise.[34] He moved back to Montmartre and in February 1941 published a third polemical book Les beaux draps (A Fine Mess) in which he denounced Jews, Freemasons, the Catholic Church, the educational system and the French army. The book was later banned by the Vichy government for defaming the French military.[35] In October 1942, Céline's antisemitic books Bagatelles pour une massacre and L'école des cadavres were republished in new editions, only months after the round-up of French Jews at the Vélodrome d'Hiver.[36] Céline devoted most of his time during the occupation years to his medical work and writing a new novel, Guignol's Band, a hallucinatory reworking of his experiences in London during World War I. The novel was published in March 1944 to poor sales.[37] The French were expecting an Allied landing at any time and Céline was receiving anonymous death threats almost daily. Although he had not officially joined any collaborationist organisations, he had frequently allowed himself to be quoted in the collaborationist press expressing antisemitic views. The BBC had also named him as a collaborationist writer.[38] When the Allies landed in France in June 1944, Céline and Lucette fled to Germany, eventually staying in Sigmaringen where the Germans had created an enclave accommodating the Vichy government in exile and collaborationist militia. Using his connections with the German occupying forces, in particular with SS officer Hermann Bickler [de] who was often his guest in the apartment on Rue Girardon,[39][40] Céline obtained visas for German-occupied Denmark where he arrived in late March 1945. These events formed the basis for his post-war trilogy of novels D'un chateau l'autre (1957, tr Castle to Castle), Nord (1960, tr North) and Rigodon (1969, tr Rigadoon).[41] |

1939年から1945年 1939年9月の開戦時、徴兵委員会はセリーヌを70パーセントの障害者と認定し、兵役不適格と宣言した。セリーヌは軍隊輸送船の船医として職を得、 1940年1月、その船が誤ってイギリスの魚雷艇に衝突し、イギリス人乗組員20名が死亡した。2月には、パリ北西部のサルトゥルヴィルにある公立診療所 の医師として職を得た。6月のパリ撤退の際には、セリーヌとルセットは救急車を徴発し、老女1人と新生児2人をラ・ロシェルまで避難させた。「私も多くの 人々と同じように、ベゾンからラ・ロシェルまでフランス軍をずっと追いかけたが、結局、追いつくことはできなかった」[33] パリに戻ったセリーヌは、ベゾンの公立診療所の主任医師に任命され、セーヌ・エ・オワーズ県の認定医師となった。[34] 彼はモンマルトルに戻り、1941年2月には、ユダヤ人、フリーメイソン、カトリック教会、教育制度、フランス軍を糾弾した3冊目の論争的な著書『Les beaux draps(邦題:ファイン・メッス)』を出版した。この本は後に、フランス軍を中傷したとしてヴィシー政権により発禁処分となった。[35] 1942年10月、セリーヌの反ユダヤ主義的な著作『虐殺のための小品』と『死体たちの学校』が、ヴェロドローム・ドゥ・リヴェールでのフランス系ユダヤ 人の一斉検挙から数ヶ月しか経っていないにもかかわらず、新版として再版された。[36] セリーヌは占領期間中、ほとんどの時間を医療活動と、第一次世界大戦中のロンドンでの経験を幻覚的に再構成した新作小説『ギニョールの仲間たち』の執筆に 費やした。この小説は1944年3月に出版されたが、売れ行きは芳しくなかった。 フランス人は連合軍の上陸をいつ起こるか期待しており、セリーヌはほぼ毎日、匿名の脅迫状を受け取っていた。公式にはいかなる協力者組織にも参加していな かったが、反ユダヤ主義的な見解を表明する協力者側の新聞に、自身のコメントを引用されることを頻繁に許可していた。BBCもまた、彼を協力者側の作家と して名指ししていた。 1944年6月に連合国がフランスに上陸すると、セリーヌとリュセットはドイツに逃亡し、最終的にドイツ軍がヴィシー亡命政府と協力者民兵を受け入れる飛 び地として作ったシグマリンゲンに滞在した。ドイツ占領軍、特にSS将校ヘルマン・ビックラー(Hermann Bickler)とのつながりを利用して、ビックラーはしばしばジラルドン通りのアパートにセリーヌを招待していた[39][40]。セリーヌはドイツ占 領下のデンマークへのビザを取得し、1945年3月末に到着した。これらの出来事は、彼の戦後3部作小説『D'un chateau l'autre』(1957年、邦題『城から城へ』)、『Nord』(1960年、邦題『北』)、『Rigodon』(1969年、邦題『リガドン』)の 基盤となった。[41] |

| Exile in Denmark (1945–1951) In November 1945 the new French government applied for Céline's extradition for collaboration, and the following month he was arrested and imprisoned at Vestre Prison by the Danish authorities pending the outcome of the application. He was released from prison in June 1947 on the condition that he would not leave Denmark. Céline's books had been withdrawn from sale in France, and he was living off a hoard of gold coins which he had hidden in Denmark before the war. In 1948 he moved to a farmhouse on the coast of the Great Belt owned by his Danish lawyer where he worked on the novels which were to become Féerie pour une autre fois (1952, tr Fable for Another Time) and Normance (1954).[42] The French authorities tried Céline in absentia for activities harmful to the national defence. He was found guilty in February 1951 and sentenced to one year in jail, a fine of 50,000 francs and confiscation of half his property. In April a French military tribunal granted him an amnesty based on his status as a disabled war veteran. In July he returned to France.[43] |

デンマークへの亡命(1945年~1951年 1945年11月、フランス新政権がセリーヌの協力者としての身柄引き渡しを申請し、翌月、デンマーク当局によって逮捕され、申請の結果が出るまでヴェス トレ刑務所に収監された。1947年6月、デンマーク国外に出ないことを条件に釈放された。セリーヌの本はフランスで販売中止となり、彼は戦前にデンマー クに隠しておいた金貨の蓄えで生活していた。1948年、彼はデンマーク人の弁護士が所有するグレートベルト海岸沿いの農家に移り住み、そこで後に 『Féerie pour une autre fois』(1952年、英題『Fable for Another Time』)と『Normance』(1954年)となる小説の執筆に取り組んだ。[42] フランス当局は、国防に有害な活動を行ったとして、セリーヌを不在のまま裁判にかけた。1951年2月、有罪判決が下され、1年の実刑、5万フランの罰 金、財産の半分を没収する判決が下された。4月、フランス軍事法廷は、戦争で障害を負った退役軍人であることを理由に恩赦を認めた。7月、彼はフランスに 戻った。[43] |

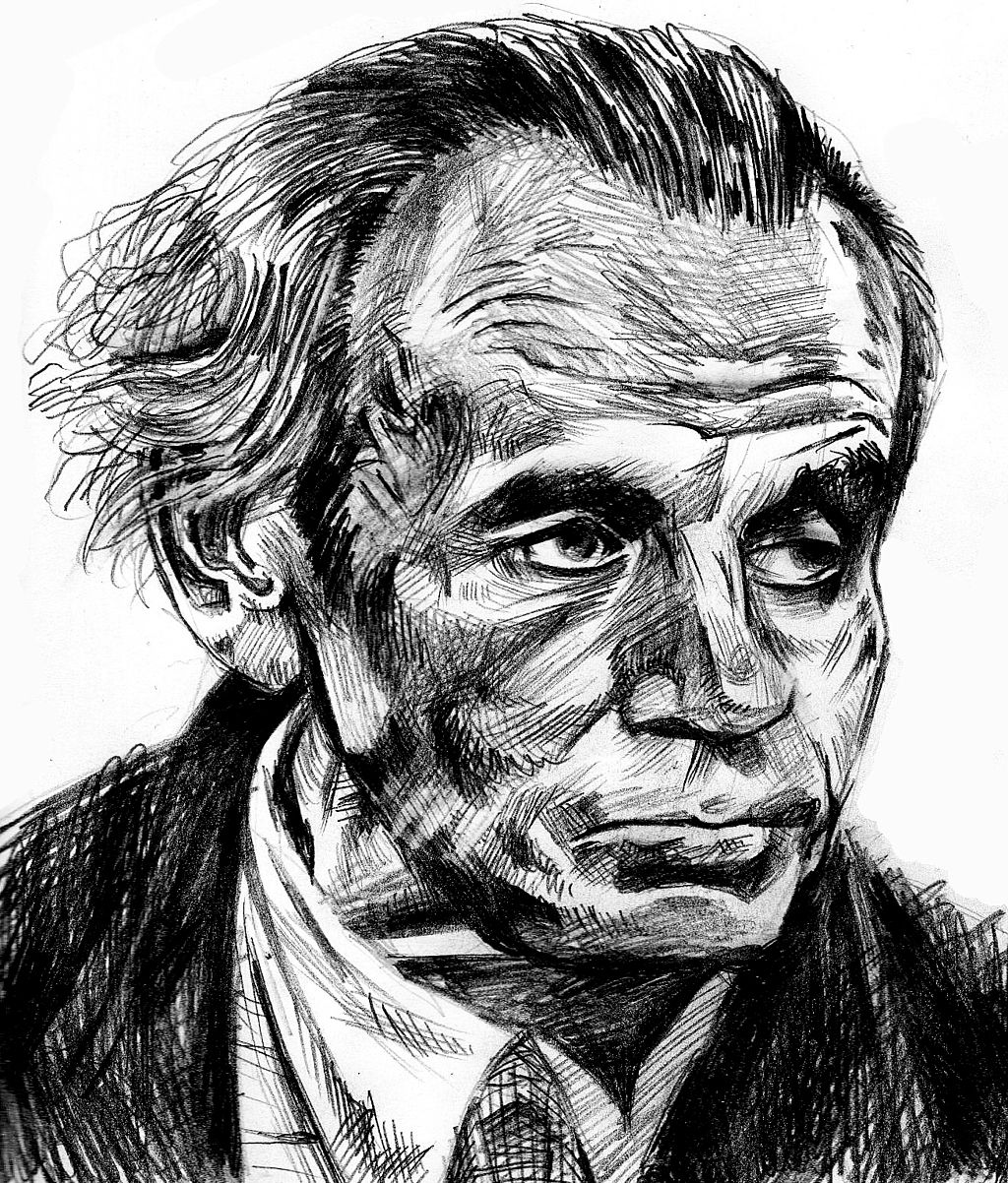

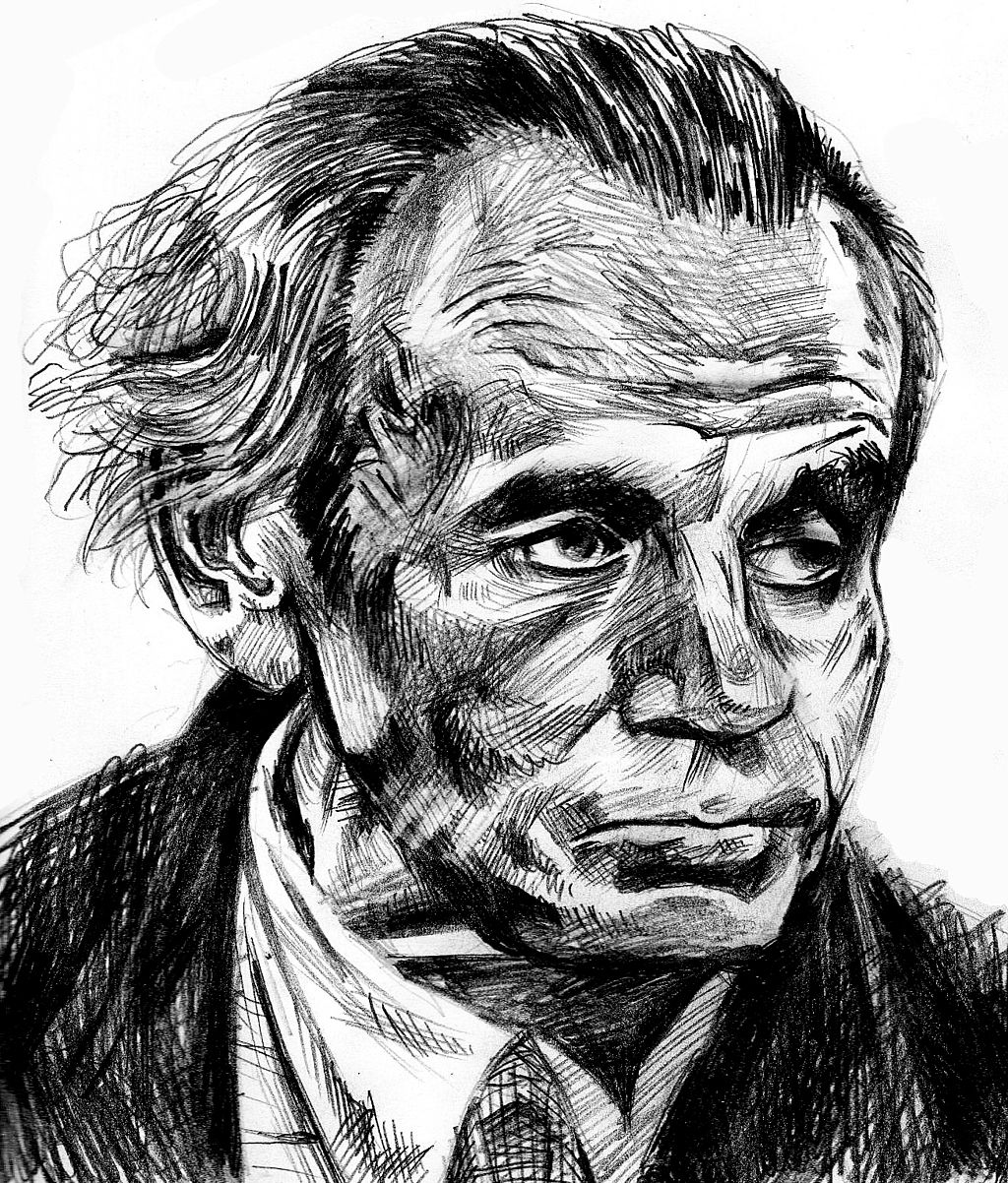

| Final years in France (1951–1961) Drawing of Louis-Ferdinand Céline Back in France, Céline signed a contract with the publisher Gallimard to republish all his novels. Céline and Lucette bought a villa in Meudon, on the southwestern outskirts of Paris, where Céline was to live for the remainder of his life. He registered as a doctor in 1953 and set up a practice in his Meudon home, while Lucette established a dance school on the top floor.[44] Céline's first post-war novels, Féerie pour une autre fois and Normance, received little critical attention and sold poorly.[45] However, his 1957 novel D'un château l'autre, a chronicle of his time in Sigmaringen, attracted considerable media and critical interest and revived the controversy over his wartime activities. The novel was a modest commercial success, selling close to 30,000 copies in its first year.[46] A sequel, Nord, was published in 1960 to generally favourable reviews. Céline completed a second draft of his final novel, Rigodon, on 30 June 1961. He died at home of a ruptured aneurysm the following day.[47] |

フランスでの晩年(1951年~1961年) フランスに戻ったセリーヌは、ガリマール出版社と、自身の小説のすべてを再出版する契約を結んだ。セリーヌとルセットは、パリ南西部郊外のムードンに別荘 を購入し、セリーヌはそこで残りの人生を過ごすことになった。1953年に医師として登録し、ムードンの自宅で診療所を開業した。一方、ルセットは最上階 にダンススクールを開設した。 セリーヌの戦後初の小説『Féerie pour une autre fois』と『Normance』は、ほとんど批評家の注目を集めることなく、売れ行きも芳しくなかった。[45] しかし、1957年の小説『D'un château l'autre』は、ジグマリンゲンでの生活を綴ったもので、メディアや批評家の関心を集め、戦時中の活動に対する論争を再燃させた。この小説は商業的に は控えめな成功を収め、初年度に3万部近くを売り上げた。[46] 続編『北』は1960年に出版され、概ね好意的な評価を受けた。セリーヌは1961年6月30日に最後の小説『リゴドン』の第二稿を完成させた。翌日、動 脈瘤の破裂により自宅で死去した。[47] |

| Antisemitism, fascism and collaboration While Céline's first two novels contained no overt antisemitism, his polemical books Bagatelles pour un massacre (Trifles for a Massacre) (1937) and L'École des cadavres (The School of Corpses) (1938) are virulently antisemitic. Céline's antisemitism was generally welcomed by the French far Right, but some, such as Brasillach, were concerned that its crudity might be counterproductive.[48] Nevertheless, biographer Frédéric Vitoux concludes that: "through the ferocity of his voice and the respect in which it was held, Céline had made himself the most popular and most resounding spokesman of pre-war antisemitism."[49] Céline's public antisemitism continued after the defeat of France in June 1940. In 1941 he published Les beaux draps (A Fine Mess) in which he lamented that: "France is Jewish and Masonic, once and for all." He also contributed over thirty letters, interviews and responses to questionnaires to the collaborationist press, including many antisemitic statements.[50] The German officer and writer Ernst Jünger stated in his Paris war diaries that Céline told him on 7 December 1941 "of his consternation, his astonishment" that the Germans did not "exterminate" the French Jews.[51][52] Some Nazis thought Céline's antisemitic pronouncements were so extreme as to be counter-productive. Bernhard Payr [de], the German superintendent of propaganda in France, considered that Céline "started from correct racial notions" but his "savage, filthy slang" and "brutal obscenities" spoiled his "good intentions" with "hysterical wailing".[53][54] Céline's attitude towards fascism was ambiguous. In 1937 and 1938 he advocated a Franco-German military alliance to save France from war and Jewish hegemony. However, Vitoux argues that Céline's main motive was a desire for peace at any cost, rather than enthusiasm for Hitler. Following the election victory of the French Popular Front in May 1936, Céline saw the socialist leader Léon Blum and the communists led by Maurice Thorez as greater threats to France than Hitler: "…I'd prefer a dozen Hitlers to one all-powerful Blum."[55] While Céline claimed he was not a fascist and never joined any fascist organisation, in December 1941 he publicly supported the formation of a single party to unite the French far right. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, he expressed his support for Jacques Doriot's Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism (LVF).[56] However, according to Merlin Thomas, Céline didn't "subscribe to any recognisable fascist ideology other than the attack on Jewry."[57] Following the war, Céline was found guilty of activities potentially harmful to national defence, due to his membership of the collaborationist Cercle Européen (which Céline denied) and his letters to collaborationist journals.[58] According to Vitoux: "Céline became a member of no committee and no administration (…). He never provided any assistance, either by report, advice, or information, to the German ambassador, let alone the Gestapo or the Central Jewish Office." Nevertheless: "Céline's writings had permanently marked French ideology, furthered and supported its antisemitism and consequently its complacency toward the Germans. That cannot be denied."[59] |

反ユダヤ主義、ファシズムと協力 セリーヌの最初の2作にはあからさまな反ユダヤ主義は見られないが、彼の論争的な著作『大虐殺のための些細なこと』(1937年)と『死体の学校』 (1938年)は、激しい反ユダヤ主義に満ちている。セリーヌの反ユダヤ主義は、フランスの極右派から概ね歓迎されたが、ブラシラックのように、そのあか らさまな表現が逆効果になるのではないかと懸念する者もいた。[48] しかし、伝記作家のフレデリック・ヴィトゥーは、「セリーヌは、その声の激しさや、その声が持つ敬意によって、戦前の反ユダヤ主義の最も人気があり、最も 影響力のある代弁者となった」と結論づけている。[49] セリーヌの公の場での反ユダヤ主義は、1940年6月のフランスの敗戦後も続いた。1941年には『Les beaux draps(邦題:ファイン・メッス)』を出版し、その中で彼は次のように嘆いた。「フランスはユダヤ的であり、フリーメイソン的である。」と嘆いた。ま た、彼は30通以上の手紙やインタビュー、アンケート回答を協力者である新聞社に寄稿し、その中には多くの反ユダヤ主義的な主張が含まれていた。[50] ドイツの将校であり作家でもあるエルンスト・ユンガーは、パリ戦時日記の中で、セリーヌが1941年12月7日に 「ドイツ軍がフランス系ユダヤ人を『絶滅』しなかったことに対する彼の狼狽と驚愕」について語ったと述べている。[51][52] ナチスの中には、セリーヌの反ユダヤ主義的発言は極端すぎて逆効果であると考えた者もいた。フランスにおけるドイツの宣伝責任者ベルンハルト・パイル (Bernhard Payr)は、セリーヌは「正しい人種観から出発している」と考えたが、彼の「野蛮で卑猥な俗語」と「残忍な卑猥さ」が「善意」を「ヒステリックな叫び」 で台無しにしているとみなした。[53][54] セリーヌのファシズムに対する態度はあいまいであった。1937年と1938年には、戦争とユダヤ人の支配からフランスを救うために、フランスとドイツの 軍事同盟を提唱した。しかし、ヴィトゥーは、セリーヌの主な動機はヒトラーへの熱狂というよりも、何としても平和を望む気持ちであったと主張している。 1936年5月のフランス人民戦線の選挙勝利後、セリーヌは社会主義者のリーダーであるレオン・ブルムとモーリス・トレス率いる共産主義者たちを、ヒト ラーよりもフランスにとって大きな脅威であると見ていた。「…私は、強大な権力を持つブルム一人よりも、ヒトラーが12人いた方がましだ」[55] セリーヌは、自分はファシストではなく、ファシストの組織にも参加したことはないと主張していたが、1941年12月には、フランス極右派を統合する単一 政党の結成を公然と支持した。1941年6月にドイツがソビエト連邦に侵攻した際には、ジャック・ドリオのフランス人ボリシェヴィズム志願軍団(LVF) への支持を表明した。[56] しかし、マーリン・トーマスによると、セリーヌは「ユダヤ人に対する攻撃以外の、明確なファシストのイデオロギーを信奉していたわけではない」という。 [57] 戦後、セリーヌは、協力者であったヨーロッパ・サークル(Cercle Européen)のメンバーであったこと(セリーヌはこれを否定している)と、協力者であった雑誌に手紙を書いていたことを理由に、国民防衛に有害な活 動を行ったとして有罪判決を受けた。ヴィトゥーによると、「セリーヌは、いかなる委員会や行政機関のメンバーにもならなかった(…)。彼は、ドイツ大使に 報告、助言、情報を提供したことは一度もなく、ゲシュタポや中央ユダヤ局に提供したことは言うまでもない」 しかし、「セリーヌの著作はフランスのイデオロギーに永続的な影響を与え、反ユダヤ主義を助長し、支持し、結果としてドイツに対する満足感をもたらした。 これは否定できない」[59]。 |

| Literary themes and style Themes Céline's novels reflect a pessimistic view of the human condition in which human suffering is inevitable, death is final, and hopes for human progress and happiness are illusory. He depicts a world where there is no moral order and where the rich and powerful will always oppress the poor and weak.[60] According to Céline's biographer Patrick McCarthy, Célinian man suffers from an original sin of malicious hatred, but there is no God to redeem him. "The characteristic trait of Célinian hatred is that it is gratuitous: one does not dislike because the object of dislike has harmed one; one hates because one has to."[61] Literary critic Merlin Thomas notes that the experience of war marked Céline for life and it is a theme in all his novels except Death on the Installment Plan. In Journey to the End of the Night, Céline presents the horror and stupidity of war as an implacable force which "turns the ordinary individual into an animal intent only on survival".[62] McCarthy contends that for Céline war is "the most striking manifestation of the evil present in the human condition."[63] The individual's struggle for survival in a hostile world is a recurring theme in Céline's novels.[62] Although Célinian man can't escape his fate, according to McCarthy: "he has some control over his death. He need not be arbitrarily slaughtered in battle and he need not blind himself with divertissements. He can choose to face death, a more painful but more dignified process."[64] Merlin Thomas points out that the Célinian anti-hero also typically chooses defiance. "If you are weak, then you will derive strength from stripping those you fear of all the prestige they pretend to possess (…) [T]he attitude of defiance just outlined is an element of hope and personal salvation."[65] Thomas notes that the Célinian narrator finds some consolation in beauty and creativity. The narrator is "always touched by human physical beauty, by the contemplation of a splendidly formed human body which moves with grace." For Céline ballet and the ballerina are exemplars of artistic and human beauty.[66] McCarthy points out that Céline habitually depicts the movement of people and objects as a dance and attempts to capture the rhythms of dance and music in language. "Yet the dance is always the danse macabre and things disintegrate because death strikes them."[67] Style Céline was critical of the French "academic" literary style which privileged elegance, clarity and exactitude.[68] He advocated a new style aimed at directly conveying emotional intensity:[69] "It seemed to me that there were two ways of telling stories. The classic, normal, academic way which consists of creeping along from one incident to the next...the way cars go along in the street...and then, the other way, which means descending into the intimacy of things, into the fibre, the nerves, the feelings of things, the flesh, and going straight on to the end, to its end, in intimacy, in maintained poetic tension, in inner life, like the métro through an inner city, straight to the end...[.]" Céline was a major innovator in French literary language.[70] In his first two novels, Journey to the End of the Night and Death on the Installment Plan, Céline shocked many critics by his use of a unique language based on the spoken French of the working class, medical and nautical jargon, neologisms, obscenities, and the specialised slang of soldiers, sailors and the criminal underworld.[71][72] He also developed an idiosyncratic system of punctuation based on extensive use of ellipses and exclamation marks. Thomas sees Céline's three dots as: "almost comparable to the pointing of a psalm: they divide the text into rhythmical rather than syntactical units, permit extreme variations of pace and make possible to a great extent the hallucinatory lyricism of his style."[73] Céline called his increasingly rhythmic, syncopated writing style his "little music."[74] McCarthy writes that in Fables for Another Time: "Celine's fury drives him beyond prose and into a new tongue – part poetry and part music – to express what he has to say."[75] Céline's style evolved to reflect the themes of his novels. According to McCarthy, in Céline's final war trilogy, Castle to Castle, North and Rigadoon: "all worlds disappear into an eternal nothingness (…) the trilogy is written in short, bare phrases: language dissolves as reality does."[76] |

文学的なテーマとスタイル テーマ セリーヌの小説は、人間の苦しみは避けられず、死は最終的であり、人間的な進歩や幸福への希望は幻想であるという、人間の状態に対する悲観的な見方を反映 している。彼は、道徳的な秩序が存在せず、富裕層や権力者が常に貧困層や弱者を抑圧する世界を描いている。[60] セリーヌの伝記作家であるパトリック・マッカーシーによると、セリーヌ的な人間は悪意のある憎悪という原罪に苦しんでいるが、彼を救済する神は存在しな い。「セリーヌ的な憎悪の特徴は、それが無償であることだ。嫌悪の対象が自分を傷つけたから嫌うのではなく、嫌わなければならないから嫌うのだ」[61] 文学評論家のマーリン・トーマスは、セリーヌにとって戦争の経験は生涯にわたるものであり、『分割払いでの死』以外のすべての小説のテーマとなっていると 指摘している。『夜の底へ』において、セリーヌは戦争の恐怖と愚かさを容赦ない力として描き、「普通の人間を生存本能のみに駆られた動物へと変えてしま う」と表現している。[62] マッカーシーは、セリーヌにとって戦争とは「人間の本性に内在する悪の最も顕著な表れ」であると主張している。[63] 敵対的な世界における個人の生存のための闘いは、セリーヌの小説では繰り返し登場するテーマである。[62] セリーヌ的な男は運命から逃れることはできないが、マッカーシーによれば、「死についてはある程度コントロールできる。戦いで恣意的に殺される必要はない し、道楽に目を奪われる必要もない。死と向き合うことを選ぶこともできる。それはより苦痛を伴うが、より尊厳のあるプロセスである」[64] マーリン・トーマスは、セリーヌのアンチヒーローもまた、典型的に反抗を選ぶと指摘している。「もしあなたが弱いのであれば、あなたが恐れる人々が持つ威 信をすべて剥ぎ取ることで、強さを引き出すことができるだろう(…)今述べた反抗の姿勢は、希望と個人的な救済の要素である」[65] トマスは、セリーヌの語り手は美と創造性の中に慰めを見出すと指摘している。語り手は「常に人間の肉体的な美しさ、優雅に動く見事に形成された人間の身体 の観照に感動する」のである。セリーヌにとって、バレエとバレリーナは芸術的、人間的な美の典型である。[66] マッカーシーは、セリーヌは人々や物の動きをダンスとして描くことが常であり、ダンスや音楽のリズムを言葉で表現しようとしていると指摘している。しか し、そのダンスは常に死の舞踏であり、死が襲うことで物事は崩壊する」[67] スタイル セリーヌは、優雅さ、明瞭さ、正確さを重視するフランスの「アカデミック」な文学スタイルを批判していた。[68] 彼は、感情の激しさを直接的に伝えることを目的とした新しいスタイルを提唱していた。[69] 「物語を語るには2つの方法があるように思えた。1つは、古典的で、普通で、アカデミックな方法で、それは次から次へと事件を追っていくようなものだ。そ れは、車が通りを走るようなものだ。そしてもう1つは、物事の親密さ、繊維、神経 、感情、肉体へと降りていき、親密さ、維持された詩的な緊張感、内面的な生活の中で、最後までまっすぐ進んでいく、という方法だ。 セリーヌはフランス文学の言語に大きな革新をもたらした。[70] 処女作『夜の底へ』と『分割払いでの死』の2作において、セリーヌは労働者階級の話し言葉、医学用語、海事用語、 新語、卑語、そして兵士や船員、犯罪組織の専門用語を駆使した独特の文体で多くの批評家を驚かせた。[71][72] また、彼は省略記号や感嘆符を多用した独特の句読法を編み出した。トマスはセリーヌの3つの点を「詩篇の句読点にほぼ匹敵する」と見なし、「それらは文章 を構文上の単位ではなく、むしろリズム上の単位に分割し、極端な速度の変化を可能にし、彼のスタイルの幻覚的なリリシズムを大いに可能にする」と述べてい る。 セリーヌは、ますますリズミカルでシンコペーションを多用する彼の文体を「小さな音楽」と呼んだ。[74] マッカーシーは『Fables for Another Time』で、「セリーヌの怒りが彼を散文の域を超えさせ、詩と音楽の要素を併せ持つ新しい言語へと駆り立て、彼が言わなければならないことを表現させ た」と書いている。[75] セリーヌの文体は、小説のテーマを反映して進化していった。マッカーシーによると、セリーヌの最後の戦争三部作『城から城へ』、『北』、『リガドン』で は、「すべての世界が永遠の無へと消え去る(…)この三部作は短い、飾り気のない表現で書かれている。言語は現実がそうであるように溶解する」[76]。 |

| Legacy Céline is widely considered to be one of the major French novelists of the twentieth century.[4] According to George Steiner: "[T]wo bodies of work lead into the idiom and sensibility of twentieth-century narrative: that of Céline and that of Proust."[77] Although many writers have admired and have been influenced by Céline's fiction, McCarthy argues that he holds a unique place in modern writing due to his pessimistic vision of the human condition and idiosyncratic writing style.[78] Writers of the absurd, such as Sartre and Camus, were influenced by Céline, but didn't share his extreme pessimism or politics.[79] Alain Robbe-Grillet cites Céline as a major influence on the nouveau-roman and Günter Grass also shows a debt to Céline's writing style.[78] Patrick Modiano admires Céline as a stylist, and produced a parody of his style in his debut novel La place de l'étoile.[80] McCarthy and O'Connell include Henry Miller, William S. Burroughs, Kurt Vonnegut and others as American writers influenced by Céline.[81][82] Céline remains a controversial figure in France. In 2011, the fiftieth anniversary of Céline's death, the writer had initially appeared on an official list of 500 people and events associated with French culture which were to be celebrated nationally that year. Following protests, Frédéric Mitterrand, then French Minister of Culture and Communication, announced that Céline would be removed from the list because of his antisemitic writings.[83] In December 2017, the French government and Jewish leaders expressed concern over plans by the publisher Gallimard to republish Céline's antisemitic books.[84] In January 2018 Gallimard announced that it was suspending publication.[4] In March Gallimard clarified that it still intended to publish a critical edition of the books with scholarly introductions.[85] A collection of Céline's unpublished manuscripts including La Volonté du roi Krogold,[86] Londres, and 6,000 unpublished pages of already published works (Casse-pipe, Mort à crédit, Journey to the End of the Night), were handed over by a Libération journalist, Jean-Pierre Thibaudat, to the Nanterre police in March 2020, and revealed in August 2021. The manuscripts had been missing since Céline fled Paris in 1944.[87][88] French writer and Céline expert David Alliot maintains that it will take many years for these writings to be completely appreciated and published.[89] Writing in The Jewish Chronicle in September 2021, Oliver Kamm described Céline as a "French literary hero [who] needs to be forgotten".[90] The lost manuscripts of Céline have been described as "one of the greatest literary discoveries of the past century, but also one of the most troubling".[91] In May 2022, Céline's Guerre (War) was published by Gallimard,[92] and Londres (London) followed in October 2022.[93] The latter novel was probably written in 1934 and includes a key character who is a Jewish doctor.[94] |

レガシー セリーヌは、20世紀の主要なフランス人小説家の一人であると広く考えられている。[4] ジョージ・スタイナーによると、「2つの作品群が20世紀の物語のイディオムと感性につながっている。セリーヌの作品とプルーストの作品である」[77]。 多くの作家がセリーヌの小説に感銘を受け、影響を受けてきたが、マッカーシーは、人間の条件に対する彼の悲観的な見方と独特な文体により、セリーヌは現代 の文学において独自の地位を占めていると主張している。[78] サルトルやカミュといった不条理主義の作家たちはセリーヌの影響を受けていたが、セリーヌのような極端な悲観主義や政治的傾向は共有していなかった。 [79] アラン・ロブ=グリエはセリーヌをヌーヴォー・ロマンの主要な影響源として挙げている ヌーヴォー・ロマンに大きな影響を与えたとし、ギュンター・グラスもセリーヌの文体に影響を受けたと述べている。[78] パトリック・モディアノはセリーヌの文体を賞賛し、デビュー作『星の広場』でセリーヌの文体をパロディ化した作品を書いた。[80] マッカーシーとオコネルは、セリーヌの影響を受けたアメリカの作家として、ヘンリー・ミラー、ウィリアム・S・バロウズ、カート・ヴォネガットなどを挙げ ている。[81][82] セリーヌはフランスでは依然として物議を醸す人物である。2011年、セリーヌの没後50周年に際し、作家は当初、その年に国民的に祝われるフランス文化 に関連する500人の人物や出来事の公式リストに載っていた。抗議を受けて、当時の文化・通信大臣フレデリック・ミッテランは、セリーヌをリストから削除 すると発表した。理由は、彼の反ユダヤ的な著作のためである。 2017年12月、フランス政府とユダヤ人指導者は、ガリマール出版社がセリーヌの反ユダヤ主義的な書籍を再出版する計画について懸念を表明した。 [84] 2018年1月、ガリマールは出版を中止すると発表した。[4] 3月、ガリマールは学術的な序文を付けた批判版を出版するつもりであることを明らかにした。[85] セリーヌの未発表原稿のコレクションには、『クロゴールド王の意志』、『ロンド』、およびすでに出版された作品(『パイプを折る男』、『クレジットで死 す』、『夜の果てへの旅』)の6,000ページの未発表原稿が含まれており、2020年3月にリベラシオン紙のジャーナリスト、ジャン=ピエール・ティ ボーダがナンテール警察に引き渡し、2021年8月に公開された。原稿は、セリーヌが1944年にパリを離れて以来、行方不明となっていた。[87] [88] フランスの作家でセリーヌの専門家であるダヴィッド・アリオは、これらの著作が完全に評価され、出版されるには何年もかかるだろうと主張している。 [89] 2021年9月の『The Jewish Chronicle』誌への寄稿で、オリバー・カムは、セリーヌを「フランス文学の英雄」と表現したが、 オリバー・カムは『ザ・ジューイッシュ・クロニクル』誌に、セリーヌを「フランス文学の英雄だが、忘れ去られるべき人物」と評した。[90] セリーヌの失われた原稿は「過去100年間で最も偉大な文学的発見のひとつであると同時に、最も厄介な発見のひとつ」と評されている。[91] 2022年5月には、セリーヌの『Guerre(戦争)』がガリマール社から出版され[92]、2022年10月には『Londres(ロンドン)』が続いた[93]。後者の小説は1934年に書かれたもので、ユダヤ人の医師である重要な登場人物が登場する[94]。 |

| Works Novels and short story Journey to the End of the Night (Voyage au bout de la nuit) 1932; tr. by John H. P. Marks (1934); tr. by Manheim, Ralph (1983). New York: New Directions Publishing ISBN 0-8112-0847-8 Death on Credit (Mort à crédit), 1936; tr. by Marks, John H. P., Little, Brown and Company, Boston, 1938 – aka Death on the Installment Plan (US, 1966), tr. by Ralph Manheim Guignol's Band, 1944; tr. by Bernard Frechtman and Jack T. Nile, (1954). London: Vision Press London Bridge: Guignol's Band II (Le Pont de Londres − Guignol's band II), published posthumously in 1964; tr. by Di Bernardi, Dominic (1995). Dalkey Archive Press ISBN 1-56478-071-6 Cannon-Fodder (Casse-pipe) 1949; tr. by Kyra De Coninck and Billy Childish (1988). Hangman Fable for Another Time (Féerie pour une autre fois) 1952; tr. by Hudson, Mary (2003). Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press ISBN 0-8032-6424-0 Normance, 1954; tr. by Jones, Marlon (2009). Dalkey Archive Press ISBN 978-1-56478-525-1 (Sequel to Fable for Another Time.) Castle to Castle (D'un château l'autre) 1957; tr. by Manheim, Ralph (1968). New York: Delacorte Press North (Nord), 1960; tr. by Manheim, Ralph (1972). New York: Delacorte Press Rigadoon (Rigodon), completed in 1961 but published posthumously in 1969; tr. by Manheim, Ralph (1974). New York: Delacorte Press War (Guerre) 1934; tr. by Mandell, Charlotte (July 2024), New York: New Directions Publishing ISBN 9780811237321; tr. by Berg, Sander (October 2024), London: Alma Classics ISBN 9781847499165. Londres (London), Paris, Gallimard, 2022 (untranslated) Des vagues (Waves), short story, written in 1917, published in the fourth volume of Cahiers Céline de Gallimard in 1977 (untranslated) Other selected works Carnet du cuirassier Destouches, dans Casse-Pipe, Paris, Gallimard, 1970 (untranslated) Semmelweis (La Vie et l'œuvre de Philippe Ignace Semmelweis. [1924]), Harman, John (tr.) (2008). London: Atlas Press. ISBN 978-1-900565-47-9 Ballets without Music, without Dancers, without Anything, (Ballets sans musique, sans personne, sans rien, (1959); tr. by Thomas Christensen and Carol Christensen, Green Integer, 1999 The Church (L'Église), (written 1927, published 1933; tr. by Mark Spitzer and Simon Green, Green Integer, 2003 Mea Culpa, 1936; tr. by Robert Allerton Parker, Little, Brown and Company, Boston, 1937 Trifles for a Massacre (Bagatelles pour un massacre), 1937; translated anonymously School for Corpses (L'École des cadavres), 1938; tr. by Szandor Kuragin, 2016, Louis Ferdinand Céline – School For Corpses[95] A Fine Mess (Les Beaux Draps), 1941 (untranslated) "Reply to Charges of Treason Made by the French Department of Justice (Réponses aux accusations formulées contre moi par la justice française au titre de trahison et reproduites par la Police Judiciaire danoise au cours de mes interrogatoires, pendant mon incarcération 1945–1946 à Copenhague, 6 November 1946"; tr. by Julien Cornell, South Atlantic Quarterly 93, no. 2, 1994 Conversations with Professor Y (Entretiens avec le Professeur Y), 1955; tr. by Stanford Luce (2006). Dalkey Archive Press. ISBN 1-56478-449-5 The Selected Correspondence of Louis-Ferdinand Céline; tr. Mitch Abidor, Kilmog Press, New Zealand, 2015 Progrés, Paris, Mercure de France, 1978 (untranslated) Arletty, jeune fille dauphinoise (scénario), Pris, La Flute de Pan, 1983 (untranslated) |

作品 小説および短編 夜の果てへの旅(Voyage au bout de la nuit)1932年;ジョン・H・P・マークス訳(1934年);マンハイム、ラルフ訳(1983年)。ニューヨーク:ニュー・ディレクションズ・パブリッシング ISBN 0-8112-0847-8 『クレジットによる死』(Mort à crédit)、1936年、訳者:ジョン・H・P・マークス、出版社:リトル・ブラウン・アンド・カンパニー、ボストン、1938年 - 別名『分割払いによる死』(Death on the Installment Plan)(米国、1966年)、訳者:ラルフ・マンハイム 『ギニョールの楽団』(Guignol's Band)、1944年、訳者:バーナード・フレクトマン、ジャック・T・ナイル、(1954年)。ロンドン:ビジョン・プレス ロンドン橋:ギニョールの楽団II(Le Pont de Londres − Guignol's band II)は1964年に死後出版された。訳:ディ・ベルナルディ、ドミニク(1995年)。Dalkey Archive Press ISBN 1-56478-071-6 Cannon-Fodder (Casse-pipe) 1949; tr. by Kyra De Coninck and Billy Childish (1988). 絞首刑執行人 寓話(Féerie pour une autre fois) 1952; tr. by Hudson, Mary (2003). リンカーンとロンドン:ネブラスカ大学出版局 ISBN 0-8032-6424-0 ノーマンス、1954年;訳者:ジョーンズ、マーロン(2009年)。 ダルキー・アーカイブ・プレス ISBN 978-1-56478-525-1 (『もうひとつの寓話』の続編) 城から城へ(D'un château l'autre)1957年;訳者:マンハイム、ラルフ(1968年)。 ニューヨーク:デラコルテ・プレス 1960年、ラルフ・マンハイム訳、ニューヨーク:デルコルト・プレス リガドン(Rigadoon)1961年完成、1969年没後出版、ラルフ・マンハイム訳、ニューヨーク:デルコルト・プレス 戦争(Guerre)1934年、マンデル、シャーロット訳(2024年7月)、ニューヨーク:ニュー・ディレクションズ・パブリッシング ISBN 9780811237321、ベルク、サンダー訳(2024年10月)、ロンドン:アルマ・クラシックス ISBN 9781847499165。 ロンドン(London)、パリ、ガリマール、2022年(未翻訳) 『波』(Des vagues)という短編小説、1917年執筆、1977年『ガリマール・セリーヌ・ノート』第4巻で発表(未翻訳) その他の主な作品 『胸甲騎兵デストゥシュの日記』、パリ、ガリマール、1970年(未訳) 『センメルヴェイス』(『フィリップ・イグナツ・センメルヴェイスの生涯と業績』[1924年])、ジョン・ハーマン(訳)、2008年。ロンドン:アトラス・プレス。ISBN 978-1-900565-47-9 音楽なし、ダンサーなし、何もなしのバレエ(Ballets sans musique, sans personne, sans rien, (1959); トーマス・クリステンセンとキャロル・クリステンセン訳、グリーンインテージャー、1999年 『教会』(L'Église)(1927年執筆、1933年出版、マーク・スピッツァーとサイモン・グリーン訳、グリーン・インテージャー、2003年 『我が罪』(Mea Culpa)、1936年、ロバート・アラーソン・パーカー訳、リトル・ブラウン・アンド・カンパニー、ボストン、1937年 大虐殺のための些細なこと(Bagatelles pour un massacre)、1937年;匿名で翻訳 死体学校(L'École des cadavres)、1938年;訳者:サンドール・クラギン、2016年、ルイ・フェルディナン・セリーヌ著『死体学校』[95] A Fine Mess (Les Beaux Draps), 1941 (未翻訳) 「フランス司法省による反逆罪容疑への反論(Réponses aux accusations formulées contre moi par la justice française au titre de trahison et reproduites par la Police Judiciaire danoise au cours de mes interrogatoires, pendant 1945年から1946年にかけてコペンハーゲンで収監されていた際に受けた取り調べで、フランス司法省が私に対して反逆罪で申し立てた容疑と、ノル ウェー司法警察が再現した容疑に対する回答、1946年11月6日」; ジュリアン・コーネルによる翻訳、South Atlantic Quarterly 93, no. 2, 1994 『Y教授との対話』(Entretiens avec le Professeur Y)、1955年、スタンフォード・ルーシー訳(2006年)。Dalkey Archive Press。ISBN 1-56478-449-5 『ルイ=フェルディナン・セリーヌの選集』(The Selected Correspondence of Louis-Ferdinand Céline)、ミッチ・アビドール訳、ニュージーランドのKilmog Press、2015年 プログレ、パリ、メルキュール・ド・フランス、1978年(未翻訳) アルレッティ、若い娘のドーフィネ人(シナリオ)、プリス、ラ・フルート・ド・パン、1983年(未翻訳) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis-Ferdinand_C%C3%A9line |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆