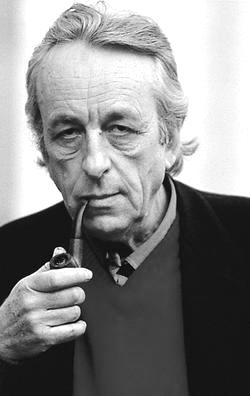

ルイ・アルチュセール

Louis Pierre

Althusser, 1918-1990

☆

ルイ・ピエール・アルチュセール(英国: 英国: /ˌæltʊ, 米国: /ˈɛər/: /1918年10月16日 -

1990年10月22日)アルジェリア生まれのフランスのマルクス主義哲学者で、パリの高等師範学校で学び、最終的に哲学教授となった。

アルチュセールは、フランス共産党(Parti communiste

français、PCF)の長年の党員であり、時には強い批判者でもあった。彼の主張と論文は、マルクス主義の理論的基盤を攻撃している脅威と対立して

いた。その中には、マルクス主義理論における経験主義の影響、ヨーロッパの共産党の分裂として現れた人文主義的・改革主義的社会主義志向、さらにはカル

ト・オブ・パーソナリティやイデオロギーの問題も含まれていた。アルチュセールは一般に構造マルクス主義者と呼ばれるが、フランス構造主義の他の学派との

関係は単純なものではなく、構造主義の多くの側面に批判的であった。

アルチュセールの生涯は、激しい精神疾患の時期が特徴的であった。1980年には、妻で社会学者のエレーヌ・リトマンの首を絞めて殺害。彼は心神喪失によ

り裁判を受ける資格がないと宣告され、精神病院に3年間収容された。1990年に死去。

| Louis Pierre

Althusser

(UK: /ˌæltʊˈsɛər/, US: /ˌɑːltuːˈsɛər/;[9] French: [altysɛʁ]; 16 October

1918 – 22 October 1990) was an Algerian-born French Marxist philosopher

who studied at the École normale supérieure in Paris, where he

eventually became Professor of Philosophy. Althusser was a long-time member and sometimes a strong critic of the French Communist Party (Parti communiste français, PCF). His arguments and theses were set against the threats that he saw attacking the theoretical foundations of Marxism. These included both the influence of empiricism on Marxist theory, and humanist and reformist socialist orientations which manifested as divisions in the European communist parties, as well as the problem of the cult of personality and of ideology. Althusser is commonly referred to as a structural Marxist, although his relationship to other schools of French structuralism is not a simple affiliation and he was critical of many aspects of structuralism. Althusser's life was marked by periods of intense mental illness. In 1980, he killed his wife, the sociologist Hélène Rytmann, by strangling her. He was declared unfit to stand trial due to insanity and committed to a psychiatric hospital for three years. He did little further academic work, dying in 1990. |

ルイ・ピエール・アルチュセール(英国: 英国: /ˌæltʊ,

米国: /ˈɛər/: /1918年10月16日 -

1990年10月22日)アルジェリア生まれのフランスのマルクス主義哲学者で、パリの高等師範学校で学び、最終的に哲学教授となった。 アルチュセールは、フランス共産党(Parti communiste français、PCF)の長年の党員であり、時には強い批判者でもあった。彼の主張と論文は、マルクス主義の理論的基盤を攻撃している脅威と対立して いた。その中には、マルクス主義理論における経験主義の影響、ヨーロッパの共産党の分裂として現れた人文主義的・改革主義的社会主義志向、さらにはカル ト・オブ・パーソナリティやイデオロギーの問題も含まれていた。アルチュセールは一般に構造マルクス主義者と呼ばれるが、フランス構造主義の他の学派との 関係は単純なものではなく、構造主義の多くの側面に批判的であった。 アルチュセールの生涯は、激しい精神疾患の時期が特徴的であった。1980年には、妻で社会学者のエレーヌ・リトマンの首を絞めて殺害。彼は心神喪失によ り裁判を受ける資格がないと宣告され、精神病院に3年間収容された。1990年に死去。 |

| Biography Early life: 1918–1948 Althusser was born in French Algeria in the town of Birmendreïs, near Algiers, to a pied-noir petit-bourgeois family from Alsace, France. His father, Charles-Joseph Althusser, was a lieutenant in the French army and a bank clerk, while his mother, Lucienne Marthe Berger, a devout Roman Catholic, worked as a schoolteacher.[10] According to his own memoirs, his Algerian childhood was prosperous; historian Martin Jay said that Althusser, along with Albert Camus and Jacques Derrida, was "a product of the French colonial culture in Northern Africa."[11] In 1930, his family moved to the French city of Marseille as his father was to be the director of the Compagnie Algérienne (Algerian Banking Company) branch in the city.[12] Althusser spent the rest of his childhood there, excelling in his studies at the Lycée Saint-Charles [fr] and joining a scout group.[10] A second displacement occurred in 1936 when Althusser settled in Lyon as a student at the Lycée du Parc. Later he was accepted by the highly regarded higher-education establishment (grande école) École Normale Supérieure (ENS) in Paris.[13] At the Lycée du Parc, Althusser was influenced by Catholic professors,[b] joined the Catholic youth movement Jeunesse Étudiante Chrétienne,[14] and wanted to be a Trappist.[15] His interest in Catholicism coexisted with his communist ideology,[14] and some critics argued that his early Catholic introduction affected the way he interpreted Karl Marx.[16] The Lycée du Parc, where Althusser studied for two years and was influenced by Catholic professors After a two-year period of preparation (Khâgne) under Jean Guitton at the Lycée du Parc, Althusser was admitted into the ENS in July 1939.[17] But his attendance was deferred by many years because he was drafted into the French Army in September of that year in the run-up to World War II and, like most French soldiers following the Fall of France, was captured by the Germans. Seized in Vannes in June 1940, he was held in a prisoner-of-war camp in Schleswig-Holstein, in Northern Germany, for the five remaining years of the war.[18] In the camp, he was at first drafted to hard labour but ultimately reassigned to work in the infirmary after falling ill. This second occupation allowed him to read philosophy and literature.[19] In his memoirs, Althusser described the experiences of solidarity, political action, and community in the camp as the moment he first understood the idea of communism.[14] Althusser recalled: "It was in prison camp that I first heard Marxism discussed by a Parisian lawyer in transit—and that I actually met a communist".[20] His experience in the camp also affected his lifelong bouts of mental instability, reflected in constant depression that lasted until the end of life.[10] Psychoanalyst Élisabeth Roudinesco has argued that the absurd war experience was essential for Althusser's philosophical thought.[20] Althusser resumed his studies at the ENS in 1945 to prepare himself for the agrégation, an exam to teach philosophy in secondary schools.[14] In 1946, Althusser met sociologist Hélène Rytmann,[c] a Jewish former French Resistance member with whom he was in a relationship until he killed her by strangulation in 1980.[25] That same year, he started a close friendly relationship with Jacques Martin, a translator of G. W. F. Hegel and Herman Hesse. Martin, to whom Althusser dedicated his first book, would later commit suicide.[13] Martin was influential on Althusser's interest on reading the bibliography of Jean Cavaillès, Georges Canguilhem and Hegel.[26] Although Althusser remained a Catholic, he became more associated with left-wing groups, joining the "worker priests" movement[27] and embracing a synthesis of Christian and Marxist thought.[14] This combination may have led him to adopt German Idealism and Hegelian thought,[14] as did Martin's influence and a renewed interest in Hegel in the 1930s and 1940s in France.[28] In consonance, Althusser's master thesis to obtain his diplôme d'études supèrieures was "On Content in the Thought of G. W. F. Hegel" ("Du contenu dans la pensée de G. W. F. Hegel", 1947).[29] Based on The Phenomenology of Spirit, and under Gaston Bachelard's supervision, Althusser wrote a dissertation on how Marx's philosophy refused to withdraw from the Hegelian master–slave dialectic.[30] According to the researcher Gregory Elliott, Althusser was a Hegelian at that time but only for a short period.[31] Academic life and Communist Party affiliation: 1948–1959 The main entrance to the École Normale Supérieure on Rue d'Ulm, where Althusser established himself as well-known intellectual In 1948, he was approved to teach in secondary schools but instead made a tutor at the ENS to help students prepare for their own agrégation.[29] His performance on the exam—he was the best ranked on the writing part and second on the oral module—guaranteed this change on his occupation.[14] He was responsible for offering special courses and tutorials on particular topics and on particular figures from the history of philosophy.[14] In 1954, he became secrétaire de l'école litteraire (secretary of the literary school), assuming responsibilities for management and direction of the school.[14] Althusser was deeply influential at the ENS because of the lectures and conferences he organized with participation of leading French philosophers such as Gilles Deleuze and Jacques Lacan.[32] He also influenced a generation of French philosophers and French philosophy in general[14]—among his students were Derrida, Pierre Bourdieu, Michel Foucault, and Michel Serres.[33] In total, Althusser spent 35 years in the ENS, working there until November 1980.[34] Parallel to his academic life, Althusser joined the French Communist Party (Parti communiste français, PCF) in October 1948. In the early postwar years, the PCF was one of the most influential political forces and many French intellectuals joined it. Althusser himself declared, "Communism was in the air in 1945, after the German defeat, the victory at Stalingrad, and the hopes and lessons of the Resistance."[35] Althusser was primarily active on the "Peace Movement" section and kept for a few years his Catholic beliefs;[35] in 1949, he published in the L'Évangile captif (The captive gospel), the tenth book of the Jeunesse de l'Église (the youth wing of Church), an article on the historic situation of Catholicism in response to the question: "Is the good news preached to the men today?"[27] In it, he wrote about the relationship between the Catholic Church and the labour movement, advocating at the same time for social emancipation and the Church "religious reconquest".[30] There was mutual hostility between these two organizations—in the early 1950s, the Vatican prohibited Catholics from membership in the worker priests and left-wing movements—and it certainly affected Althusser since he firmly believed in this combination.[35] Initially afraid of joining the party because of ENS's opposition to communists, Althusser did so when he was made a tutor—when membership became less likely to affect his employment—and he even created at ENA the Cercle Politzer, a Marxist study group. Althusser also introduced colleagues and students to the party and worked closely with the communist cell of the ENS. But his professionalism made him avoid Marxism and Communism in his classes; instead, he helped students depending on the demands of their agrégation.[14] In the early 1950s, Althusser distanced himself from his youthful political and philosophical ideals[32] and from Hegel, whose teachings he considered a "bourgeois" philosophy.[30] Starting from 1948, he studied history of philosophy and gave lectures on it; the first was about Plato in 1949.[36] In 1949–1950, he gave a lecture about René Descartes,[d] and wrote a thesis titled "Politics and Philosophy in the Eighteenth Century" and a small study on Jean-Jacques Rousseau's "Second Discourse". He presented the thesis to Jean Hyppolite and Vladimir Jankélévitch in 1950 but it was rejected.[33] These studies were nonetheless valuable because Althusser later used them to write his book about Montesquieu's philosophy and an essay on Rousseau's The Social Contract.[38] Indeed, his first and the only book-length study published during his lifetime was Montesquieu, la politique et l'histoire ("Montesquieu: Politics and History") in 1959.[39] He also lectured on Rousseau from 1950 to 1955,[40] and changed his focus to philosophy of history, also studying Voltaire, Condorcet, and Helvétius, which resulted in a 1955–1956 lecture on "Les problèmes de la philosophie de l'histoire".[41] This course along with others on Machiavelli (1962), 17th- and 18th-century political philosophy (1965–1966), Locke (1971), and Hobbes (1971–1972) were later edited and released as a book by François Matheron in 2006.[42] From 1953 to 1960, Althusser basically did not publish on Marxist themes, which in turn gave him time to focus on his teaching activities and establish himself as a reputable philosopher and researcher.[43] Major works, For Marx and Reading Capital: 1960–1968 Althusser resumed his Marxist-related publications in 1960 as he translated, edited, and published a collection directed by Hyppolite about Ludwig Feuerbach's works.[32] The objective of this endeavour was to identify Feuerbach's influence on Marx's early writings, contrasting it with the absence of his thought on Marx's mature works.[14] This work spurred him to write "On the Young Marx: Theoretical Questions" ("Sur le jeune Marx – Questions de théorie", 1961).[14] Published in the journal La Pensée, it was the first in a series of articles about Marx that were later collected in his most famous book For Marx.[27] He inflamed the French debate on Marx and Marxist philosophy, and gained a considerable number of supporters.[14] Inspired by this recognition, he started to publish more articles on Marxist thought; in 1964, Althusser published an article titled "Freud and Lacan" in the journal La Nouvelle Critique, which greatly influenced the Freudo-Marxism thought.[27] At the same time, he invited Lacan to a lecture on Baruch Spinoza and the fundamental concepts of psychoanalysis.[27] The impact of the articles led Althusser to change his teaching style at the ENS,[14] and he started to minister a series of seminars on the following topics: "On the Young Marx" (1961–1962), "The Origins of Structuralism" (1962–1963; it versed[clarification needed] on Foucault's History of Madness, which Althusser highly appreciated[44]), "Lacan and Psychoanalysis" (1963–1964), and Reading Capital (1964–1965).[27] These seminars aimed for a "return to Marx" and were attended by a new generation of students.[e][33] For Marx (a collection of works published between 1961 and 1965) and Reading Capital (in collaboration with some of his students), both published in 1965, brought international fame to Althusser.[45] Despite being criticized widely,[46] these books made Althusser a sensation in French intellectual circles[47] and one of the leading theoreticians of the PCF.[32] He supported a structuralist view of Marx's work, influenced by Cavaillès and Canguilhem,[48] affirming that Marx laid the "cornerstones" of a new science, incomparable to all non-Marxist thought, of which, from 1960 to 1966, he espoused the fundamental principles.[35] Critiques were done to Stalin's cult of personality and Althusser defended what he called "theoretical anti-humanism", as an alternative to Stalinism and the Marxist humanism—both popular at the time.[49] At mid-decade, his popularity grew to the point that it was virtually impossible to have an intellectual debate about political or ideological theoretical questions without mentioning his name.[50] Althusser's ideas were influential enough to arouse the creation of a young militants group to dispute the power within the PCF.[14] Nevertheless, the official position of the party was still Stalinist Marxism, which was criticized both from Maoist and humanist groups. Althusser was initially careful not to identify with Maoism but progressively agreed with its critique of Stalinism.[51] At the end of 1966, Althusser even published an unsigned article titled "On the Cultural Revolution", in which he considered the beginning of the Chinese Cultural Revolution as "a historical fact without precedent" and of "enormous theoretical interest".[52] Althusser mainly praised the non-bureaucratic, non-party, mass organizations in which, in his opinion, the "Marxist principles regarding the nature of the ideological' were fully applied.[53] Key events in the theoretical struggle took place in 1966. In January, there was a conference of communist philosophers in Choisy-le-Roi;[54] Althusser was absent but Roger Garaudy, the official philosopher of the party, read an indictment that opposed the "theoretical anti-humanism".[46] The controversy was the pinnacle of a long conflict between the supporters of Althusser and Garaudy. In March, in Argenteuil, the theses of Garaudy and Althusser were formally confronted by the PCF Central Committee, chaired by Louis Aragon.[46] The Party decided to keep Garaudy's position as the official one,[48] and even Lucien Sève—who was a student of Althusser at the beginning of his teaching at the ENS—supported it, becoming the closest philosopher to the PCF leadership.[46] General secretary of the party, Waldeck Rochet said that "Communism without humanism would not be Communism".[55] Even if he was not publicly censured nor expelled from the PCF, as were 600 Maoist students, the support of Garaudy resulted in a further reduction of Althusser's influence in the party.[48] Still in 1966, Althusser published in the Cahiers pour l'Analyse the article "On the 'Social Contract'" ("Sur le 'Contrat Social'"), a course about Rousseau he had given at the ENS, and "Cremonini, Painter of the Abstract" ("Cremonini, peintre de l'abstrait") about Italian painter Leonardo Cremonini.[56] In the following year, he wrote a long article titled "The Historical Task of Marxist Philosophy" ("La tâche historique de la philosophie marxiste") that was submitted to the Soviet journal Voprossi Filosofii; it was not accepted but was published a year later in a Hungarian journal.[56] In 1967–1968, Althusser and his students organized an ENS course titled "Philosophy Course for Scientists" ("Cours de philosophie pour scientifiques") that would be interrupted by May 1968 events. Some of the material of the course was reused in his 1974 book Philosophy and the Spontaneous Philosophy of the Scientists (Philosophie et philosophie spontanée des savants).[56] Another Althusser's significant work[57] from this period was "Lenin and Philosophy", a lecture first presented in February 1968 at the French Society of Philosophy [fr].[56] May 1968, Eurocommunism debates, and auto-critique: 1968–1978 During May 68, the tumultuous events of May 1968 in France, Althusser was hospitalized because of a depressive breakdown and was absent from the Latin Quarter. Many of his students participated in the events, and Régis Debray in particular became an international celebrity revolutionary.[58] Althusser's initial silence[58] was met with criticism by the protesters, who wrote on walls: "Of what use is Althusser?" ("A quoi sert Althusser?").[59] Later, Althusser was ambivalent about it; on the one hand, he was not supportive of the movement[32] and he criticized the movement as an "ideological revolt of the mass",[60] adopting the PCF official argument that an "infantile disorder" of anarchistic utopianism that had infiltrated the student movement.[61] On the other hand, he called it "the most significant event in Western history since the Resistance and the victory over Nazism" and wanted to reconcile the students and the PCF.[62] Nevertheless, the Maoist journal La Cause du peuple called him a revisionist,[60] and he was condemned by former students, mainly by Jacques Rancière.[32] After it, Althusser went through a phase of "self-criticism" that resulted in the book Essays in Self-criticism (Éléments d'autocritique, 1974) in which he revisited some of his old positions, including his support of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.[63] While Althusser was criticized in France by his former students, such as Jacques Rancière (right), his influence in Latin America grew, as exemplified by Marta Harnecker (left). In 1969, Althusser started an unfinished work[f] that was only released in 1995 as Sur la reproduction ("On the Reproduction"). However, from these early manuscripts, he developed "Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses", which was published in the journal La Pensée in 1970,[66] and became very influential on ideology discussions.[67] In the same year, Althusser wrote "Marxism and Class Struggle" ("Marxisme et lutte de classe") that would be the foreword to the book The Basic Concepts of Historical Materialism of his former student, the Chilean Marxist sociologist Marta Harnecker.[68] By this time, Althusser was very popular in Latin America: some leftist activists and intellectuals saw him almost as a new Marx, although his work has been the subject of heated debates and sharp criticism.[60] As an example of this popularity, some of his works were first translated to Spanish than into English, and others were released in book format first in Spanish and then in French.[g] At the turn from the 1960s to the 1970s, Althusser's major works were translated into English—For Marx, in 1969, and Reading Capital in 1970—disseminating his ideas among the English-speaking Marxists.[72] In the early 1970s, the PCF was, as most of European Communist parties, in a period of internal conflicts on strategic orientation that occurred against the backdrop of the emergence of Eurocommunism. In this context, Althusserian structuralist Marxism was one of the more or less defined strategic lines.[73] Althusser participated in various public events of the PCF, most notably the public debate "Communists, Intellectuals and Culture" ("Les communistes, les intellectuels et la culture") in 1973.[74] He and his supporters contested the party's leadership over its decision to abandon the notion of the "dictatorship of the proletariat" during its twenty-second congress in 1976.[75] The PCF considered that in European condition it was possible to have a peaceful transition to socialism,[76] which Althusser saw as "a new opportunistic version of Marxist Humanism".[77] In a lecture given to the Union of Communist Students in the same year, he criticized above all the form in which this decision was taken. According to Althusser—echoing his notion of "French misery" exposed on For Marx—the party demonstrated a contempt for the materialist theory when it suppressed a "scientific concept".[78] This struggle ultimately resulted in the debacle of the fraction "Union of the Left" and an open letter written by Althusser and five other intellectuals in which they asked for "a real political discussion in the PCF".[79] That same year, Althusser also published a series of articles in the newspaper Le Monde under the title of "What Must Change in the Party".[80] Published between 25 and 28 April, they were expanded and reprinted in May 1978 by François Maspero as the book Ce qui ne peut plus durer dans le parti communiste.[81] Between 1977 and 1978, Althusser mainly elaborated texts criticizing Eurocommunism and the PCF. "Marx in his Limits" ("Marx dans ses limits"), an abandoned manuscript written in 1978, argued that there was no Marxist theory of the state; it was only published in 1994 in the Écrits philosophiques et politiques I.[82] The Italian Communist newspaper Il manifesto allowed Althusser to develop new ideas on a conference held in Venice about "Power and Opposition in Post-Revolutionary Societies" in 1977.[83] His speeches resulted into the articles "The Crisis of Marxism" ("La crisi del marxismo") and "Marxism as a 'finite' theory" in which he stressed "something vital and alive can be liberated by this crisis": the perception of Marxism as a theory that originally only reflected Marx's time and then needed to be completed by a state theory.[84] The former was published as "Marxism Today" ("Marxismo oggi") in the 1978 Italian Enciclopedia Europea.[85] The latter text was included in a book published in Italy, Discutere lo Stato, and he criticized the notion of "government party" and defended the notion of a revolutionary party "out of state".[86] During the 1970s, Althusser's institutional roles at the ENS increased but he still edited and published his and other works in the series Théorie, with François Maspero.[14] Among the essays published, there was "Response to John Lewis", a 1973 reply of an English Communist's defence of Marxist Humanism.[87] Two years later, he concluded his Doctorat d'État (State doctorate) in the University of Picardie Jules Verne and acquired the right to direct research on the basis of his previously published work.[88] Some time after this recognition, Althusser married Hélène Rytmann.[14] In 1976, he compiled several of his essays written between 1964 and 1975 to publish Positions.[89] These years would be a period in which his work was very intermittent;[90] he gave a conference titled "The Transformation of Philosophy" ("La transformation de la philosophie") in two Spanish cities, first Granada and then in Madrid, in March 1976.[91] The same year he gave a lecture in Catalonia titled "Quelques questions de la crise de la théorie marxiste et du mouvement communiste international" ("Some Questions on the Crisis of Marxist Theory and the International Communist Movement") in which Althusser outlined empiricism as the main enemy of class struggle.[92] He also started a rereading of Machiavelli that would influence his later work;[93] he worked between 1975 and 1976 on "Machiavel et nous" ("Machiavelli and Us"), a draft, only published posthumously, based on a 1972 lecture,[94] and also wrote for the National Foundation of Political Science a piece titled "Machiavelli's Solitude" ("Solitude de Machiavel", 1977).[95] In Spring 1976, requested by Léon Chertok to write for the International Symposium on the Unconscious at Tbilisi, he drafted a presentation titled "The Discovery of Dr. Freud" ("La découverte du docteur Freud").[96] After sending it to Chertok and some friends, he was unsettled by the requested criticism he received by Jacques Nassif and Roudinesco, and then, by December, he wrote a new essay, "On Marx and Freud".[97] He could not attend the event in 1979 and asked Chertok to replace the texts, but Chertok published the first without his consent.[98] This would become a public "affair" in 1984 when Althusser finally noticed it by the time Chertok republished it in a book titled Dialogue franco-soviétique, sur la psychanalyse.[99] Killing of Rytmann and late years: 1978–1990 After the PCF and the left were defeated in the French legislative elections of 1978, Althusser's bouts of depression became more severe and frequent.[14] In March 1980, Althusser interrupted the dissolution session of the École Freudienne de Paris, and, "in the name of the analysts", called Lacan a "beautiful and pitiful harlequin."[95] Later, he went through a hiatal hernia-removal surgery as he had difficulties breathing while eating.[100] According to Althusser himself, the operation caused his physical and mental state to deteriorate; in particular, he developed a persecution complex and suicidal thoughts. He would recall later: I wanted not only to destroy myself physically but to wipe out all trace of my time on earth: in particular, to destroy every last one of my books and all my notes, and burn the École Normale, and also, "if possible," suppress Hélène herself while I still could.[100] After the surgery, in May, he was hospitalized for most of the summer in a Parisian clinic. His condition did not improve, but in early October he was sent home.[95] Upon returning, he wanted to get away from ENS and even proposed to buy Roudinesco's house.[100] He and Rytmann were also convinced about the "human decline", and so he tried to talk to the Pope John Paul II through his former professor Jean Guitton.[101] Most of the time, however, he and his wife spent locked in their ENS apartment.[101] In the fall of 1980, Althusser's psychiatrist René Diatkine, who by now was also treating Althusser's wife Hélène Rytmann,[102] recommended that Althusser be hospitalized, but the couple refused.[103] Before me: Hélène lying on her back, also wearing a dressing gown. ... Kneeling beside her, leaning over her body, I am engaged in massaging her neck. ... I press my two thumbs into the hollow of flesh that borders the top of the sternum, and, applying force, I slowly reach, one thumb toward the right, one thumb toward the left at an angle, the firmer area below the ears. ... Hélène's face is immobile and serene, her open eyes are fixed on the ceiling. And suddenly I am struck with terror: her eyes are interminably fixed, and above all here is the tip of her tongue lying, unusually and peacefully, between her teeth and her lips. I had certainly seen corpses before, but I had never seen the face of a strangled woman in my life. And yet I know that this is a strangled woman. What is happening? I stand up and scream: I've strangled Hélène! — Althusser, L'avenir dure longtemps[104] On 16 November 1980, Althusser strangled Rytmann in their ENS room. He himself reported the murder to the doctor in residence who contacted psychiatric institutions.[105] Even before the police arrival, the doctor and the director of ENS decided to hospitalize him in the Sainte-Anne hospital and a psychiatric examination was conducted on him.[106] Due to his mental state, Althusser was deemed to not understand the charges or the process to which he was to be submitted, so he remained at the hospital.[14] The psychiatric assessment concluded he should not be criminally charged, based on article 64 of the French Penal Code, which stated that "there is neither crime nor delict where the suspect was in a state of dementia at the time of the action".[14] The report said Althusser killed Rytmann in the course of an acute crisis of melancholy, without even realizing it, and that the "wife-murder by manual strangulation was committed without any additional violence, in the course of [an] iatrogenic hallucinatory episode complicated by melancholic depression."[107] As a result, he lost his civil rights, entrusted to a representative of the law, and he was forbidden to sign any documents.[108] In February 1981, the court ruled Althusser as having been mentally irresponsible when he committed the murder, therefore he could not be prosecuted and was not charged.[109] Nonetheless, a warrant of confinement was subsequently issued by the Paris police prefecture;[110] the Ministry of National Education mandated his retirement from the ENS;[111] and the ENS requested his family and friends to clear out his apartment.[110] In June, he was transferred to the L'Eau-Vive clinic at Soisy-sur-Seine.[112] The murder of Rytmann attracted much media attention, and there were several requests to treat Althusser as an ordinary criminal.[113] The newspaper Minute, journalist Dominique Jamet and Minister of Justice Alain Peyrefitte were among those who accused Althusser of having "privileges" because of the fact he was Communist. From this point of view, Roudinesco wrote, Althusser was three times a criminal. First, the philosopher had legitimated the current of thought judged responsible for the Gulag; second, he praised the Chinese Cultural Revolution as an alternative to both capitalism and Stalinism; and finally because he had, it was said, corrupted the elite of French youth by introducing the cult of a criminal ideology into the heart of one of the best French institutions.[107] Philosopher Pierre-André Taguieff went further on claiming Althusser taught his students to perceive crimes positively, as akin to a revolution.[114] Five years after the murder, a critique by Le Monde's Claude Sarraute would have a great impact on Althusser.[105] She compared his case to the situation of Issei Sagawa, who killed and cannibalized a woman in France, but whose psychiatric diagnosis absolved him. Sarraute criticized the fact that, when prestigious names are involved, a lot is written about them but that little is written about the victim.[23] Althusser's friends persuaded him to speak in his defense, and the philosopher wrote an autobiography in 1985.[105] He showed the result, L'avenir dure longtemps,[h] to some of his friends and considered publishing it, but he never sent it to a publisher and locked it in his desk drawer.[119] The book was only published posthumously in 1992.[120] Despite the critics, some of his friends, such as Guitton and Debray, defended Althusser, saying the murder was an act of love—as Althusser argued too.[121][failed verification] Rytmann had bouts of melancholy and self-medicated because of this.[122] Guitton said, "I sincerely think that he killed his wife out of love of her. It was a crime of mystical love".[15] Debray compared it to an altruistic suicide: "He suffocated her under a pillow to save her from the anguish that was suffocating him. A beautiful proof of love ... that one can save one's skin while sacrificing oneself for the other, only to take upon oneself all the pain of living".[15] In his autobiography, written to be the public explanation he could not provide in court,[123] Althusser stated that "she matter-of-factly asked me to kill her myself, and this word, unthinkable and intolerable in its horror, caused my whole body to tremble for a long time. It still makes me tremble ... We were living shut up in the cloister of our hell, both of us."[101] I killed a woman who was everything to me during a crisis of mental confusion, she who loved me to the point of wanting only to die because she could not continue living. And no doubt in my confusion and unconsciousness I 'did her this service,' which she did not try to prevent, but from which she died. — Althusser, L'avenir dure longtemps[124] The crime seriously tarnished Althusser's reputation.[125] As Roudinesco wrote, from 1980, he lived his life as a "specter, a dead man walking".[110] Althusser was forced to live in various public and private clinics until 1983, when he became a voluntary patient.[32] He was able to start an untitled manuscript during this time, in 1982; it was later published as "The Underground Current of the Materialism of the Encounter" ("Le courant souterrain du matérialisme de la rencontre").[81] From 1984 to 1986, he stayed at an apartment in the north of Paris,[32] where he remained confined most of his time, but he also received visits from some friends, such as philosopher and theologian Stanislas Breton, who had also been a prisoner in the German stalags;[111] from Guitton, who converted him into a "mystic monk" in Roudinesco's words;[15] and from Mexican philosopher Fernanda Navarro during six months, starting from the winter of 1984.[126] Althusser and Navarro exchanged letters until February 1987, and he also wrote a preface in July 1986 for the resulting book, Filosofía y marxismo,[126] a collection of her interviews with Althusser that was released in Mexico in 1988.[111] These interviews and correspondence were collected and published in France in 1994 as Sur la philosophie.[117] In this period he formulated his "materialism of the encounter" or "aleatory materialism", talking to Breton and Navarro about it,[127] that first appeared in Écrits philosophiques et politiques I (1994) and later in the 2006 Verso book Philosophy of the Encounter.[128] In 1987, after Althusser underwent an emergency operation because of the obstruction of the esophagus, he developed a new clinical case of depression. First brought to the Soisy-sur-Seine clinic, he was transferred to the psychiatric institution MGEN in La Verrière. There, following a pneumonia contracted during the summer, he died of a heart attack on 22 October 1990.[111] |

略歴 生い立ち:1918-1948年 アルチュセールはフランス領アルジェリアのアルジェ近郊の町ビルマンドレイで、フランス・アルザス出身のピエ・ノワールの小市民の家庭に生まれた。父シャ ルル=ジョゼフ・アルチュセールはフランス陸軍中尉と銀行員であり、母ルシエンヌ・マルト・ベルジェは敬虔なローマ・カトリック教徒で、学校の教師として 働いていた[10]。彼自身の回想録によれば、アルジェリアでの幼少期は豊かなものであった。歴史家のマーティン・ジェイは、アルチュセールはアルベー ル・カミュやジャック・デリダとともに「北アフリカにおけるフランス植民地文化の産物」であったと述べている。 「1930年、父親がマルセイユにあるアルジェリア銀行(Compagnie Algérienne)の支店長になるため、一家はフランスのマルセイユに移り住んだ[12]。リセ・デュ・パルクでアルチュセールはカトリックの教授の 影響を受け[b]、カトリックの青年運動Jeunesse Étudiante Chrétienneに参加し[14]、トラピストを志すようになる。 [15]カトリックへの関心は共産主義思想と共存しており[14]、初期のカトリック入門がカール・マルクスの解釈方法に影響を与えたと主張する批評家も いた[16]。 アルチュセールが2年間学び、カトリックの教授の影響を受けたリセ・デュ・パルク。 リセ・デュ・パルクでジャン・ギトンの下で2年間の準備期間(Khâgne)を過ごした後、アルチュセールは1939年7月にENSに入学した[17]。 1940年6月にヴァンヌで捕らえられた彼は、ドイツ北部のシュレスヴィヒ=ホルシュタインにある捕虜収容所に、戦争の残り5年間収容された[18]。収 容所では、最初は重労働に従事させられたが、最終的に病気になったため医務室で働くことになった。アルチュセールは回顧録の中で、収容所での連帯、政治的 行動、共同体の経験が、彼が初めて共産主義の考えを理解した瞬間であったと述べている[14]: 「収容所での体験は、彼の生涯にわたる精神的な不安定さにも影響を与え、それは生涯の終わりまで続いた絶え間ない鬱状態に反映されていた。 精神分析学者のエリザベス・ルディネスコは、不条理な戦争体験がアルチュセールの哲学的思考にとって不可欠であったと論じている[20]。 1946年、アルチュセールは社会学者のエレーヌ・リトマン[c](ユダヤ人の元フランスレジスタンス)と出会い、1980年に彼女を絞殺するまで交際し ていた。マルタンはアルチュセールがジャン・カヴァイエ、ジョルジュ・カンギレム、ヘーゲルの書誌を読むことに興味を持つきっかけとなった。 [26]アルチュセールはカトリック信者のままであったが、「労働者司祭」運動[27]に参加し、キリスト教思想とマルクス主義思想の統合を受け入れるな ど、左翼団体との結びつきを強めていった[14]。 [28]これと呼応するように、アルチュセールは高等師範を取得するための修士論文は「G・W・F・ヘーゲルの思想における内容について」("Du contenu dans la pensée de G. W. F. Hegel"、1947年)であった。 [29] 『精神の現象学』に基づき、ガストン・バシュラールの指導の下、アルチュセールは、マルクスの哲学がいかにヘーゲルの主従弁証法からの離脱を拒否したかに ついて論文を書いた[30]。研究者グレゴリー・エリオットによれば、アルチュセールは当時ヘーゲル派であったが、短期間だけであった[31]。 学究生活と共産党への加盟: 1948-1959 アルチュセールが著名な知識人としての地位を確立したウルム通りにある高等師範学校の正面玄関。 1948年、アルチュセールは中等学校で教えることを認められたが、その代わりにENSのチューターとなり、学生たちのアグレガシオン(入学試験)の準備 を手伝った[29]。 [14]彼は、特定のテーマや哲学史上の特定の人物についての特別コースや個別指導を提供する責任者であった[14]。1954年、彼は secrétaire de l'école litteraire(文学部の秘書)となり、文学部の管理と指導の責任を引き受けた。 [14]アルチュセールは、ジル・ドゥルーズやジャック・ラカンといったフランスを代表する哲学者たちが参加する講義や会議を主催したことから、ENSに おいて深い影響力を有していた[32]。また、彼はフランスの哲学者の世代やフランス哲学全般[14]に影響を与えた。 学究生活と並行して、アルチュセールは1948年10月にフランス共産党に入党した。戦後初期、PCFは最も影響力のある政治勢力のひとつであり、多くの フランス人知識人がPCFに参加した。アルチュセール自身、「ドイツの敗戦、スターリングラードでの勝利、レジスタンスの希望と教訓を経て、1945年に は共産主義が宙に浮いていた」と宣言している[35]。 35]アルチュセールは主に「平和運動」のセクションで活動し、数年間はカトリックの信条を守っていた[35]。1949年、彼は『Jeunesse de l'Église(教会の青年部)』の10冊目の本である『L'Évangile captif(囚われの福音)』に、質問に対するカトリックの歴史的状況に関する論文を発表した: 「その中で、彼はカトリック教会と労働運動の関係について書いており、社会解放と教会の「宗教的レコンキスタ」を同時に提唱していた[30]。この2つの 組織の間には相互敵対関係があり、1950年代初頭、バチカンはカトリック信者が労働者司祭や左翼運動に参加することを禁止していた。 ENSが共産主義者に反対していたため、当初は入党を恐れていたアルチュセールも、入党が雇用に影響する可能性が低くなった家庭教師になったときに入党 し、ENAでマルクス主義研究グループ「セルクル・ポリッツァー」を創設した。アルチュセールはまた、同僚や学生を党に紹介し、ENSの共産主義者細胞と 密接に協力した。1950年代初頭、アルチュセールは若かりし頃の政治的・哲学的理想[32]や、ヘーゲルの教えを「ブルジョワ」哲学とみなしたことから 距離を置くようになる。 [30]1948年から哲学史を研究し、1949年にプラトンについての講義を行ったのが最初であった[36]。1949年から1950年にかけて、ル ネ・デカルトについての講義を行い[d]、「18世紀における政治と哲学」と題する論文とジャン=ジャック・ルソーの「第二談話」に関する小さな研究を書 いた。1950年にジャン・ヒポリットとウラジーミル・ジャンケレヴィッチに論文を提出したが、却下された[33]。それにもかかわらず、アルチュセール は後にモンテスキューの哲学に関する著書とルソーの『社会契約』に関するエッセイを執筆するためにこれらの研究を利用したため、これらの研究は貴重なもの であった[38]。実際、アルチュセールが存命中に出版した最初の、そして唯一の長編研究は1959年の『モンテスキュー、政治と歴史』 (Montesquieu, la politique et l'histoire)であった。 [また、1950年から1955年までルソーの講義を行い、ヴォルテール、コンドルセ、ヘルヴェティウスについても研究し、1955年から1956年にか けて「歴史哲学の問題」という講義を行った[39]。 [1953年から1960年まで、アルチュセールは基本的にマルクス主義的なテーマに関する出版を行わず、その結果、教育活動に専念する時間が与えられ、 評判の高い哲学者、研究者としての地位を確立した[43]。 主な著作『マルクスのために』と『資本論』:1960-1968年 この試みの目的は、マルクスの初期の著作におけるフォイエルバッハの影響を明らかにすることであり、マルクスの成熟した著作におけるフォイエルバッハの思 想の不在と対照をなすものであった: 雑誌『La Pensée』に掲載されたこの論文は、後に彼の最も有名な著書『マルクスのために』に収められたマルクスに関する一連の論文の最初のものであった [27]。 [1964年、アルチュセールは『ラ・ヌーヴェル・クリティーク』誌に「フロイトとラカン」と題する論文を発表し、フロイト=マルクス主義思想に大きな影 響を与えた。 [27]同時に、彼はラカンをバルーク・スピノザと精神分析の基本概念についての講義に招いた[27]。論文の影響により、アルチュセールはENSでの教 育スタイルを変更し[14]、以下のテーマで一連のセミナーを担当し始めた: 若いマルクスについて」(1961年-1962年)、「構造主義の起源」(1962年-1963年、アルチュセールが高く評価していたフーコーの『狂気の 歴史』に精通していた[clarification needed])、「ラカンと精神分析」(1963年-1964年)、「資本論を読む」(1964年-1965年)であった[27]。 広く批判されたにもかかわらず[46]、これらの書籍によってアルチュセールはフランスの知識人界でセンセーションを巻き起こし[47]、PCFを代表す る理論家の一人となった。 [32]彼はカヴァイエスとカンギレムの影響を受けたマルクスの著作の構造主義的な見方を支持し[48]、マルクスが非マルクス主義的な思想とは比較にな らない新しい科学の「礎石」を築いたと断言し、1960年から1966年までその基本原理を支持していた。 [35]スターリンのカルト的人格に対する批判が行われ、アルチュセールは、スターリニズムとマルクス主義的ヒューマニズムの代替案として、彼が「理論的 反ヒューマニズム」と呼んだものを擁護した。 [50]アルチュセールの思想は、PCF内の権力に異議を唱える若い過激派グループの創設を喚起するほど影響力があった[14]。にもかかわらず、党の公 式の立場は依然としてスターリン主義的なマルクス主義であり、毛沢東主義者からもヒューマニストからも批判されていた。1966年末、アルチュセールは 「文化大革命について」と題する無署名の論文を発表し、その中で彼は中国の文化大革命の始まりを「前例のない歴史的事実」であり、「理論的に非常に興味深 い」ものと考えていた。 [アルチュセールは主に非官僚的で非党派的な大衆組織を賞賛しており、そこでは「イデオロギーの本質に関するマルクス主義の原則」が完全に適用されている と考えていた。 理論闘争における重要な出来事は1966年に起こった。アルチュセールは欠席したが、党の公式哲学者であったロジェ・ガロディは「理論的反人間主義」に反 対する告発文を読んだ。3月、アルジャントゥイユにおいて、ルイ・アラゴンを委員長とするPCF中央委員会により、ガロディとアルチュセールの論文は正式 に対立した[46]。党はガロディの立場を公式のものとして維持することを決定し[48]、ENSで教え始めた当初アルチュセールの教え子であったリュシ アン・セーヴでさえもそれを支持し、PCF指導部に最も近い哲学者となった。 [党の書記長ワルデック・ロシェは、「ヒューマニズムのない共産主義は共産主義ではない」と述べていた。 1966年、アルチュセールは、ENSで行ったルソーについての講義「『社会契約』について」("Sur le 'Contrat Social')とイタリアの画家レオナルド・クレモニーニについての「抽象の画家クレモニーニ」("Cremonini, peintre de l'abstrait")を『カイエ・プルー・ラナリス(Cahiers pour l'Analyse)』誌に発表した[56]。 [翌年、彼は「マルクス主義哲学の歴史的課題」("La tâche historique de la philosophie marxiste")と題する長い論文を書き、ソ連の雑誌『Voprossi Filosofii』に投稿。このコースの資料の一部は1974年の著書『哲学と科学者の自発的哲学』(Philosophie et philosophie spontanée des savants)に再利用されている[56]。この時期のアルチュセールのもう一つの重要な著作[57]は、1968年2月にフランス哲学協会[fr]で 初めて発表された講義「レーニンと哲学」である[56]。 1968年5月、ユーロコミュニズム論争、自己批評:1968-1978年 1968年5月、フランスで起こった騒乱の最中、アルチュセールは鬱病のため入院し、ラテン・クオーターを不在にしていた。アルチュセールの最初の沈黙 [58]は、壁に書かれたデモ参加者たちの批判にさらされた: 「アルチュセールは何の役に立つのか?(その後、アルチュセールはそれについて両義的であった。一方では、彼はこの運動を支持しておらず[32]、「大衆 のイデオロギー的反乱」として批判し[60]、学生運動に浸透した無政府主義的ユートピア主義の「幼児的障害」であるというPCFの公式の主張を採用し た。 [61]その一方で、彼はこれを「レジスタンスとナチズムに対する勝利以来の西洋史上最も重要な出来事」と呼び、学生とPCFの和解を望んでいた。 [それにもかかわらず、毛沢東主義の雑誌『La Cause du peuple』は彼を修正主義者と呼び[60]、ジャック・ランシエールを中心とする元学生たちから非難された[32]。その後、アルチュセールは「自己 批判」の段階を経て、『自己批判のエッセイ』(Éléments d'autocritique、1974年)という本に結実した。 アルチュセールはフランスではジャック・ランシエール(右)のようなかつての教え子たちから批判されていたが、ラテンアメリカではマルタ・ハルネッカー (左)に代表されるように影響力を増していった。 1969年、アルチュセールは未完の著作[f]に着手し、1995年に『複製について』(Sur la reproduction)として発表された。同年、アルチュセールは「マルクス主義と階級闘争」("Marxisme et lutte de classe")を執筆し、それは彼の元教え子であるチリのマルクス主義社会学者マルタ・ハルネッカーの著書『史的唯物論の基本概念』の序文となる。 [この頃、アルチュセールはラテンアメリカで非常に人気があった。左翼活動家や知識人の中には、彼の著作が激しい議論や鋭い批判の対象になっているにもか かわらず、彼をほとんど新しいマルクスと見なしている者もいた[60]。この人気の一例として、彼の著作のいくつかは英語よりもまずスペイン語に翻訳さ れ、他の著作はまずスペイン語、次にフランス語の書籍として発売された。 [1960年代から1970年代への変わり目には、アルチュセールの主要な著作が英語に翻訳され、1969年には『マルクスのために』、1970年には 『資本論を読む』が翻訳され、英語圏のマルクス主義者たちの間でアルチュセールの思想が広まった[72]。 1970年代初頭、PCFはヨーロッパの共産党の多くがそうであったように、ユーロコミュニズムの出現を背景として起こった戦略的方向性に関する内部対立 の時期にあった。この文脈において、アルチュセールの構造主義的マルクス主義は、多かれ少なかれ定義された戦略路線の一つであった[73]。アルチュセー ルは、PCFの様々な公的イベントに参加し、特に1973年の公開討論会「共産主義者、知識人、文化」("Les communistes, les intellectuels et la culture")に参加した[74]。彼と彼の支持者は、1976年の第22回大会において「プロレタリアートの独裁」の概念を放棄するという党の決定 をめぐって党の指導部と争った。 [アルチュセールは、この決定を「マルクス主義ヒューマニズムの新たな日和見主義的バージョン」[77]とみなした。同年、共産主義学生同盟で行われた講 義で、彼は何よりもこの決定が取られた形式を批判した。アルチュセールによれば、マルクスのために暴露された「フランスの悲惨さ」という彼の概念を反映す るように、党は「科学的概念」を抑圧したとき、唯物論に対する侮蔑を示した[78]。この闘争は最終的に、分派「左翼連合」の破局と、アルチュセールと他 の5人の知識人が書いた「PCFにおける真の政治的議論」を求める公開書簡という結果をもたらした。 [同年、アルチュセールはまた、『ル・モンド』紙に「党内を変えなければならないもの」というタイトルの一連の記事を発表した[80]。4月25日から 28日にかけて発表されたこれらの記事は、1978年5月、フランソワ・マスペロによって『共産主義者の党内を変えなければならないもの』として増補・再 版された[81]。1978年に書かれた放棄された原稿である "Marx in his Limits" ("Marx dans ses limits")は、マルクス主義的な国家論は存在しないと主張し、1994年に『Écrits philosophiques et politiques I』として出版された[82]。 [彼のスピーチは「マルクス主義の危機」("La crisi del marxismo")と「『有限』理論としてのマルクス主義」("Marxism as a 'finite' theory")という論文に結実し、その中で彼は「この危機によって生命的で生き生きとしたものが解放されうる」こと、すなわち「マルクス主義はもとも とマルクスの時代を反映しただけの理論であり、その後国家理論によって完成される必要がある」という認識を強調した。 [後者のテキストはイタリアで出版された書籍『Discutere lo Stato』に収録され、「政府党派」の概念を批判し、「国家の外にある」革命党派の概念を擁護した[86]。 1970年代には、アルチュセールのENSにおける組織的役割は増加したが、彼はフランソワ・マスペロとともに『テオリー』シリーズを編集、出版してい た。 [87]2年後、彼はピカルディ・ジュール・ヴェルヌ大学で博士号(Doctorat d'État)を取得。 [1976年、彼は1964年から1975年の間に書かれたいくつかのエッセイをまとめ、『ポジションズ』を出版した[89]。この数年間は彼の仕事が非 常に断続的であった時期であり、[90]彼は1976年3月にスペインの2つの都市、最初はグラナダ、次にマドリードで「哲学の変容」("La transformation de la philosophie")と題された会議を開いた。 [同年、彼はカタルーニャで "Quelques questions de la crise de la thorie marxiste et du mouvement communiste international"(「マルクス主義理論の危機と国際共産主義運動に関するいくつかの質問」)と題する講演を行い、その中でアルチュセールは階 級闘争の主な敵として経験主義を概説した。 [1975年から1976年にかけて、彼は1972年の講義を基にした草稿『マキアヴェッリと私たち』("Machiavel et nous")を執筆し、死後に出版された[94]。 [1976年春、レオン・チェルトクからトビリシで開催された無意識に関する国際シンポジウムのための執筆を依頼され、「フロイト博士の発見」("The Discovery of Dr. Freud")と題するプレゼンテーションの草稿を書いた。それをチェルトクと何人かの友人に送った後、ジャック・ナシフとルディネスコから受けた批判に 動揺し、12月までに新しいエッセイ「マルクスとフロイトについて」を書いた[96]。 [1979年、彼はイベントに出席することができず、チェルトクに文章を差し替えるように頼んだが、チェルトクは彼の同意なしに最初の文章を出版した [98]。1984年、チェルトクが『Dialogue franco-soviétique, sur la psychanalyse』と題された本の中で再出版するまでにアルチュセールがようやくそれに気づいたとき、これは公の「事件」となった[99]。 リトマン殺害と晩年: 1978-1990 1980年3月、アルチュセールはエコール・フロイト・ド・パリの解散セッションを妨害し、「分析家たちの名において」ラカンを「美しく哀れなハーレクイ ン」と呼んだ[95]。 「その後、食事中に呼吸が困難になったため、食道裂孔ヘルニアの摘出手術を受けた[100]。アルチュセール本人によれば、この手術によって心身の状態が 悪化し、特に迫害コンプレックスと自殺願望が芽生えたという。彼は後にこう回想している: 特に、自分の本とノートを一冊残らず破棄し、エコール・ノルマルを焼却し、さらに「可能であれば」、エレーヌ自身をまだ抑圧できるうちに抑圧したかった [100]。 手術後の5月、彼は夏の間、パリの診療所に入院した。彼の病状は改善しなかったが、10月初旬に帰国させられた[95]。帰国後、彼はENSから離れたい と考え、ルディネスコの家を購入することを提案した[100]。彼とリトマンもまた「人間の衰退」について確信していたため、彼は元教授のジャン・ギトン を通じて教皇ヨハネ・パウロ二世と話をしようとした。 [1980年秋、アルチュセールの精神科医であったルネ・ディアトキネは、アルチュセールの妻エレーヌ・リトマンの治療にもあたっていたが[102]、ア ルチュセールの入院を勧めたが、夫妻は拒否した[103]。 エレーヌはガウンを着て仰向けに寝ていた。エレーヌの横に膝をつき、体を傾けて、私は彼女の首をマッサージしている。両手の親指を胸骨の上部にある肉のく ぼみに押し当て、力を入れながら、親指を右へ、親指を左へ、耳の下の硬い部分にゆっくりと伸ばす。エレーヌの顔は動かず穏やかで、開いた目は天井を見つめ ている。そして突然、私は恐怖に襲われた。彼女の目は延々と固定され、何よりもここに、彼女の舌の先が、珍しくも安らかに、歯と唇の間に横たわっているの だ。死体は見たことがあったが、絞殺された女性の顔は見たことがなかった。それでも、これが絞殺された女性であることはわかる。何が起こっているんだ?私 は立ち上がって叫んだ: 私はエレーヌの首を絞めたのだ! - Althusser, L'avenir dure longtemps[104]. 1980年11月16日、アルチュセールはENSの部屋でリュトマンの首を絞めた。警察が到着する前にもかかわらず、医師とENSのディレクターは彼をサ ント・アンヌ病院に入院させることを決定し、彼の精神鑑定が行われた[106]。 精神状態から、アルチュセールは罪状や提出される手続きを理解していないと判断されたため、病院にとどまった[14]。精神鑑定では、「被疑者が行為時に 認知症の状態にあった場合には、犯罪も不法行為も成立しない」とするフランス刑法第64条に基づき、刑事責任を問うべきでないと結論づけられた[15]。 [14] 報告書によれば、アルチュセールはメランコリーの急性危機の過程で、それに気づくことなくリュトマンを殺害し、「手絞めによる妻殺しは、メランコリックう つ病に複雑化した異所性の幻覚エピソードの過程で、追加的な暴力なしに行われた」[107] 。 [108]1981年2月、裁判所はアルチュセールが殺人を犯した時、精神的に無責任であったとして、起訴することはできず、起訴されなかった [109]。それにもかかわらず、その後、パリ警察によって監禁令状が発行され[110]、国民教育省はENSからの退職を命じ[111]、ENSは彼の 家族や友人にアパートの整理を要請した[110]。 リュトマンの殺害は多くのメディアの注目を集め、アルチュセールを通常の犯罪者として扱うよう何度か要求された[113]。 新聞『ミニュート』、ジャーナリストのドミニク・ジャメ、法務大臣のアラン・ペイルフィットは、アルチュセールが共産主義者であったという事実のために 「特権」を持っていると非難した人々の一人であった。ルディネスコは、アルチュセールは3度の犯罪者であると書いた。第一に、この哲学者は収容所の原因と される思想の流れを正当化したこと、第二に、彼は資本主義とスターリニズムの両方に代わるものとして中国の文化大革命を賞賛したこと、そして最後に、彼は 犯罪的なイデオロギーのカルトをフランスの最も優れた機関の中心に導入することによって、フランスの若者のエリートを堕落させたと言われたからである。 [哲学者のピエール=アンドレ・タギエフはさらに、アルチュセールは学生たちに犯罪を革命に似たものとして肯定的にとらえるよう教えていたと主張した [114]。 殺人事件から5年後、ル・モンド紙のクロード・サローテによる批評がアルチュセールに大きな影響を与えることになる[105]。アルチュセールの友人たち はアルチュセールを説得し、アルチュセールは1985年に自伝を書いた。 [105]彼はその成果である『L'avenir dure longtemps』[h]を何人かの友人に見せ、出版することも考えたが、出版社に送ることはなく、机の引き出しに閉じ込めていた[119]。 この本は死後1992年に出版された[120]。 批評家たちとは裏腹に、ギトンやドゥブレイといった友人たちの中にはアルチュセールを擁護する者もおり、殺人は愛の行為であったとアルチュセールも主張し ていた[121][検証失敗] リュトマンは憂鬱の発作を起こしており、そのために自己治療を行っていた[122] ギトンは「私は彼が妻を愛して殺したのだと心から思う。それは神秘的な愛の犯罪であった」[15]: 「彼は妻を枕の下で窒息させ、自分を窒息させる苦悩から救った。愛の美しい証明......人は相手のために自分を犠牲にしながら自分の皮膚を救うことが でき、ただ生きることの苦しみをすべて自分に背負わせることができるのだ」[15]......アルチュセールは、法廷ではできなかった公的な説明をする ために書かれた自伝[123]の中で、「彼女はあっけらかんと、自分で彼女を殺してくれと言った。今でも震えが止まらない.私たちは二人とも地獄の回廊に 閉じこもって生きていた」[101]。 私は、精神的混乱の危機の中で、私のすべてであった女性を殺した。彼女は、生き続けることができないので、ただ死にたいと思うほど私を愛していた。そし て、混乱と無意識のうちに、私は間違いなく彼女に『この奉仕をした』。 - アルチュセール『L'avenir dure longtemps』[124]。 この犯罪はアルチュセールの評判を著しく傷つけた[125]。 ルディネスコが書いているように、1980年から彼は「妖怪、死人が歩いている」ような生活を送っていた[110]。アルチュセールは1983年に自発的 な患者になるまで、様々な公立・私立の診療所での生活を余儀なくされた。 [32]彼はこの間、1982年に無題の原稿を書き始めることができた。それは後に「出会いの唯物論の地下の流れ」("Le courant souterrain du matérialisme de la rencontre")として出版された。 [1984年から1986年まで、彼はパリ北部のアパルトマンに滞在し[32]、そこでほとんどの時間を監禁されたままであったが、哲学者であり神学者で あったスタニスラス・ブルトン、ルディネスコの言葉を借りれば彼を「神秘主義的修道士」に変えたギトン、[111]、メキシコの哲学者フェルナンダ・ナ ヴァロなどの友人たちの訪問を1984年の冬から6ヶ月間受けた[15]。 [126]アルチュセールとナヴァロは1987年2月まで書簡を交換し、1988年にメキシコで発売されたアルチュセールとのインタビュー集 『Filosofía y marxismo』[126]のために1986年7月に序文を書いている[111]。 [1987年、アルチュセールは食道閉塞のために緊急手術を受けた後、うつ病の新たな臨床例を発症した。最初はソワジ・シュル・セーヌの診療所に運ばれた が、ラ・ヴェリエールの精神科病院MGENに移された。そこで、夏に肺炎を起こした後、1990年10月22日に心臓発作で死亡した[111]。 |

| Personal life Romantic life Althusser was such a homebody that biographer William S. Lewis affirmed, "Althusser had known only home, school, and P.O.W. camp" by the time he met his future wife.[14] In contrast, when he first met Rytmann in 1946, she was a former member of the French resistance and a Communist activist. After fighting along with Jean Beaufret in the group "Service Périclès", she joined the PCF. [129] However, she was expelled from the party accused of being a double agent for the Gestapo,[130] for "Trotskyist deviation" and "crimes", which probably referred to the execution of former Nazi collaborators.[129] Although high-ranking party officials instructed him to sever relations with Rytmann,[131] Althusser tried to restore her reputation in the PCF for a long time by making inquiries into her wartime activities. Although he did not succeed in reinserting her into the party, his relationship with Rytmann nonetheless deepened during this period.[14] Their relationship "was traumatic from the outset, so Althusser claims", wrote Elliott.[132] Among the reasons were his almost total inexperience with women and the fact she was eight years older than him.[14] I had never embraced a woman, and above all I had never been embraced by a woman (at age thirty!). Desire mounted in me, we made love on the bed, it was new, exciting, exalting, and violent. When she (Hélène) had left, an abysm of anguish opened up in me, never again to close. — Althusser, L'avenir dure longtemps[133] His feelings toward her were contradictory from the very beginning; it is suggested that the strong emotional impact she caused in him led him to deep depression.[132] Roudinesco wrote that, for Althusser, Rytmann represented the opposite of himself: she had been in the Resistance while he was remote from the anti-Nazi combat; she was a Jew who carried the stamp of the Holocaust, whereas he, despite his conversion to Marxism, never escaped the formative effect of Catholicism; she suffered under Stalinism at the very moment when he was joining the party; and, in opposition to his petit-bourgeois background, her childhood was not prosperous—at the age of 13 she became the sexual abuse victim of a family doctor who, in addition, instructed her to give her terminally ill parents a dose of morphine.[129] However, this story could have been invented by Althusser, who admitted to incorporating "imagined memories" into his "traumabiography."[134][135] According to Roudinesco, she embodied for Althusser his "displaced conscience", "pitiless superego", "damned part", "black animality".[129] Althusser considered that Rytmann gave him "a world of solidarity and struggle, a world of reasoned action, ... a world of courage".[132] According to him, they performed an indispensable maternal and paternal function for one another: "She loved me as a mother loves a child ... and at the same time like a good father in that she introduced me ... to the real world, that vast arena I had never been able to enter. ... Through her desire for me she also initiated me ... into my role as a man, into my masculinity. She loved me as a woman loves a man!"[132] Roudinesco argued that Rytmann represented for him "the sublimated figure of his own hated mother to whom he remained attached all his life". In his autobiography, he wrote: "If I was dazzled by Hélène's love and the miraculous privilege of knowing her and having her in my life, I tried to give that back to her in my own way, intensely and, if I may put it this way, as a religious offering, as I had done for my mother."[136] Although Althusser was really in love with Rytmann,[14] he also had affairs with other women. Roudinesco commented that "unlike Hélène, the other women loved by Louis Althusser were generally of great physical beauty and sometimes exceptionally sensitive to intellectual dialogue".[136] She gives as an example of the latter case a woman named Claire Z., with whom he had a long relationship until he was forty-two.[137] They broke up when he met Franca Madonia, a philosopher, translator, and playwright from a well-off Italian bourgeois family from Romagna.[138] Madonia was married to Mino, whose sister Giovanna was married to the Communist painter Leonardo Cremonini. Every summer the two families gathered in a residence in the village of Bertinoro, and, according to Roudinesco, "It was in this magical setting ... that Louis Althusser fell in love with Franca, discovering through her everything he had missed in his own childhood and that he lacked in Paris: a real family, an art of living, a new manner of thinking, speaking, desiring".[139] She influenced him to appreciate modern theatre (Luigi Pirandello, Bertolt Brecht, Samuel Beckett), and, Roudinesco wrote, also on his detachment of Stalinism and "his finest texts (For Marx especially) but also his most important concepts".[140] In her company in Italy in 1961, as Elliott affirmed, was also when he "truly discovered" Machiavelli.[141] Between 1961 and 1965, they exchanged letters and telephone calls, and they also went on trips together, in which they talk about the current events, politics, and theory, as well made confidences on the happiness and unhappiness of daily life.[142] However, Madonia had an explosive reaction when Althusser tried to make her Rytmann's friend, and seek to bring Mino into their meetings.[142] They nevertheless continued to exchange letters until 1973; these were published in 1998 into an 800-page book Lettres à Franca.[143] Mental condition Althusser underwent psychiatric hospitalisations throughout his life, the first time after receiving a diagnosis of schizophrenia.[132] He suffered from bipolar disorder, and because of it he had frequent bouts of depression that started in 1938 and became regular after his five-year stay in German captivity.[144] From the 1950s onward, he was under constant medical supervision, often undergoing, in Lewis' words, "the most aggressive treatments post-war French psychiatry had to offer", which included electroconvulsive therapy, narco-analysis, and psychoanalysis.[145] Althusser did not limit himself to prescribed medications and practised self-medication.[146] The disease affected his academic productivity; in 1962, he began to write a book about Machiavelli during a depressive exacerbation but was interrupted by a three-months stay in a clinic.[105] The main psychoanalyst he attended was the anti-Lacanian René Diatkine, starting from 1964, after he had a dream about killing his own sister.[147] The sessions became more frequent in January 1965, and the real work of exploring the unconscious was launched in June.[147] Soon Althusser recognized the positive side of non-Lacanian psychoanalysis; although sometimes tried to ridicule Diatkine giving him lessons in Lacanianism, by July 1966, he considered the treatment was producing "spectacular results".[148] In 1976, Althusser estimated that he had spent fifteen of the previous thirty years in hospitals and psychiatric clinics.[149] Althusser analysed the prerequisites of his illness with the help of psychoanalysis and found them in complex relationships with his family (he devoted to this topic half of the autobiography).[150] Althusser believed that he did not have a genuine "I", which was caused by the absence of real maternal love and the fact that his father was emotionally reserved and virtually absent for his son.[151] Althusser deduced the family situation from the events before his birth, as told to him by his aunt: Lucienne Berger, his mother, was to marry his father's brother, Louis Althusser, who died in World War I near Verdun, while Charles, his father, was engaged with Lucienne's sister, Juliette.[152] Both families followed the old custom of the levirate, which obliged an older, still unmarried, brother to wed the widow of a deceased younger brother. Lucienne then married Charles, and the son was named after the deceased Louis. In Althusser's memoirs, this marriage was "madness", not so much because of the tradition itself, but because of the excessive submission, as Charles was not forced to marry Lucienne since his younger brother had not yet married her.[153] As a result, Althusser concluded, his mother did not love him, but loved the long-dead Louis.[154] The philosopher described his mother as a "castrating mother" (a term from psychoanalysis), who, under the influence of her phobias, established a strict regime of social and sexual "hygiene" for Althusser and his sister Georgette. His "feeling of fathomless solitude" could only be mitigated by communicating with his mother's parents who lived in Morvan.[155] His relationship with his mother and the desire to deserve her love, in his memoirs, largely determined his adult life and career, including his admission to the ENS and his desire to become a "well-known intellectual".[156] According to his autobiography, ENS was for Althusser a kind of refuge of intellectual "purity" from the big "dirty" world that his mother was so afraid of.[157] The facts of his autobiography have been critically evaluated by researchers. According to its own editors, L'avenir dure longtemps is "an inextricable tangle of 'facts' and 'phantasies'".[158] His friend[159] and biographer Yann Moulier-Boutang, after a careful analysis of the early period of Althusser's life, concluded that the autobiography was "a re-writing of a life through the prism of its wreckage".[160] Moulier-Boutang believed that it was Rytmann who played a key role in creating a "fatalistic" account of the history of the Althusser family, largely shaping his vision in a 1964 letter. According to Elliott, the autobiography produces primarily an impression of "destructiveness and self-destructiveness".[160] Althusser, most likely, postdated the beginning of his depression to a later period (post-war), having not mentioned earlier manifestations of the disease in school and in the concentration camp.[161] According to Moulier-Boutang, Althusser had a close psychological connection with Georgette from an early age, and although he did not often mention it in his autobiography, her "nervous illness" may have tracked his own.[162] His sister also had depression, and despite their living separately from each other for almost their entire adult lives, their depression often coincided in time.[163] Also, Althusser focused on describing family circumstances, not considering, for example, the influence of ENS on his personality.[164] Moulier-Boutang connected the depression not only with events in his personal life, but also with political disappointments.[163] |

私生活 ロマンチックな生活 アルチュセールは、伝記作家のウィリアム・S・ルイスが「アルチュセールは、後の妻と出会うまでに、家と学校とP.O.W.キャンプしか知らなかった」と 断言するほど、家庭的な人間だった[14]。対照的に、彼が1946年に初めてリュトマンと出会ったとき、彼女は元フランスのレジスタンスで共産主義活動 家だった。ジャン・ボーフレとともに「サービス・ペリクレ」というグループで戦った後、彼女はPCFに参加した[129]。[129]しかし、彼女はゲ シュタポの二重スパイであるとして党から追放され[130]、「トロツキストの逸脱」と「ナチスの元協力者の処刑を指すと思われる犯罪」を犯した [129]。彼は彼女を党に復帰させることに成功しなかったが、それにもかかわらず、彼とリトマンとの関係はこの期間に深まった[14]。 彼らの関係は「最初からトラウマ的なものであったとアルチュセールは主張している」とエリオットは書いている[132]。その理由の中には、女性との経験 がほとんどなかったことと、彼女が8歳年上であったことがあった[14]。 私は女性を抱いたことがなかったし、とりわけ女性に抱かれたこともなかった(30歳にもなって!)。私の中で欲望が高まり、ベッドの上で愛し合い、それは 新しく、刺激的で、高揚感があり、暴力的だった。彼女(エレーヌ)が去ったとき、私の中に苦悩の淵が広がり、二度と閉じることはなかった。 - アルチュセール『L'avenir dure longtemps』[133]。 彼女に対する彼の感情は当初から矛盾していた。彼女が彼に与えた強い感情的衝撃が彼を深い憂鬱へと導いたと示唆されている。 [132]ルディネスコは、アルチュセールにとってリュトマンは自分とは正反対の存在であったと書いている: アルチュセールがマルクス主義に改宗したにもかかわらず、カトリシズムの形成的影響から逃れることができなかったのに対して、彼女はホロコーストの刻印を 背負ったユダヤ人であった。 [129]しかし、この話はアルチュセールによって捏造された可能性があり、アルチュセールは彼の「トラウマバイオグラフィー」に「想像された記憶」を組 み込んでいることを認めている[134][135]。ルディネスコによれば、彼女はアルチュセールにとって彼の「ずれた良心」、「無情な超自我」、「呪わ れた部分」、「黒いアニマリティ」を体現していた[129]。 アルチュセールは、リュトマンが彼に「連帯と闘争の世界、理性的な行動の世界、......勇気の世界」を与えたと考えていた[132]。彼によれば、二 人は互いに欠くことのできない母性と父性の機能を果たしていた: 「母親が子供を愛するように、彼女は私を愛した......そして同時に、良き父親のように、私を現実の世界、私が足を踏み入れることのできなかった広大 な舞台へと導いてくれた。... 彼女はまた、私への欲望を通して、私を男としての役割、男らしさへと導いてくれた。女が男を愛するように、彼女は私を愛したのだ!」[132] ルディネスコは、リュトマンが彼にとって「生涯愛したままであった憎き母の昇華された姿」であったと主張した。自伝の中で彼は、「もし私がエレーヌの愛 と、彼女を知り、彼女を自分の人生に迎えるという奇跡的な特権に目がくらんだのだとしたら、私は自分なりのやり方で、強烈に、この言い方をするなら宗教的 な供え物として、母にしたように、それを彼女に返そうとした」と書いている[136]。 アルチュセールはリュトマンと本当に愛し合っていたが[14]、他の女性とも関係を持っていた。ルディネスコは「エレーヌと違って、ルイ・アルチュセール が愛した他の女性たちは概して肉体美に優れ、時には知的対話に特別に敏感であった」とコメントしている[136]、 マドニアはミノと結婚しており、その妹ジョヴァンナは共産主義者の画家レオナルド・クレモニーニと結婚していた。ルイ・アルチュセールがフランカと恋に落 ちたのは、この魔法のような環境においてであった。 [ルイジ・ピランデッロ、ベルトルト・ブレヒト、サミュエル・ベケットのような現代演劇を評価するようになり、スターリン主義から離れ、「彼の最も優れた テキスト(特にマルクスについて)だけでなく、最も重要な概念」にも影響を与えたとルディネスコは書いている。 [1961年、エリオットが断言したように、マドニアがマキャベリを「真に発見」したのは、イタリアで彼女と一緒にいたときでもあった[141]。 1961年から1965年にかけて、ふたりは手紙や電話を交換し、一緒に旅行にも出かけた。 [しかし、アルチュセールが彼女をリュトマンの友人にしようとしたとき、マドニアは爆発的な反応を示し、ミノを二人の会合に引き入れようとした [142]。それでも二人は1973年まで手紙のやり取りを続け、それらは1998年に800ページに及ぶ『Lettres à Franca』として出版された[143]。 精神状態 アルチュセールは生涯を通じて精神科に入院しており、最初の入院は精神分裂病の診断を受けた後であった[132]。双極性障害に苦しみ、そのために 1938年に始まったうつ病の発作が頻繁に起こり、5年間のドイツでの捕虜生活の後に定期的に起こるようになった。 [1950年代以降、彼は常に医学的監視下に置かれ、ルイスの言葉を借りれば「戦後フランスの精神医学が提供した最も積極的な治療法」である電気けいれん 療法、麻薬分析、精神分析などをしばしば受けた[145]。 [この病気は彼の学問的生産性に影響を与えた。1962年、彼はうつ病の増悪中にマキアヴェッリについての本を書き始めたが、3ヶ月のクリニックでの入院 によって中断された[105]。彼が通っていた主な精神分析家は、1964年から反ラカン派のルネ・ディアトキンであった。 [147]すぐにアルチュセールは、非ラカン派の精神分析の肯定的な側面を認識した。時々、ラカン主義のレッスンを与えるディアトキンを嘲笑しようとした が、1966年7月までに、彼は治療が「壮大な結果」をもたらしていると考えていた[148]。 アルチュセールは精神分析の助けを借りて自分の病気の前提条件を分析し、家族との複雑な関係の中にそれを見出した(彼は自伝の半分をこのトピックに費やし た)[150]。アルチュセールは、自分には本物の「私」がないと信じていたが、それは本当の母性愛の不在と、父親が息子に対して感情的に控えめで、事実 上不在であったことが原因であった[151]: 母ルシエンヌ・ベルジェは父の兄ルイ・アルチュセールと結婚することになっていたが、彼は第一次世界大戦でヴェルダン近郊で戦死し、父シャルルはルシエン ヌの妹ジュリエットと婚約していた。ルシエンヌはシャルルと結婚し、息子は亡くなったルイにちなんで名付けられた。アルチュセールの回想録によれば、この 結婚は「狂気」であり、伝統そのものというよりも、シャルルがルシエンヌとまだ結婚していなかったため、結婚を強制されなかったという過剰な服従のためで あった[153]。その結果、アルチュセールは、母親は彼を愛していたのではなく、長く死んだルイを愛していたのだと結論づけた。 [154]哲学者は母を「去勢する母」(精神分析の用語)と表現し、恐怖症の影響でアルチュセールと妹のジョルジェットには社会的、性的「衛生」の厳格な 体制を確立した。自伝によれば、アルチュセールにとってENSは、母が恐れていた大きな「汚れた」世界からの知的「純粋さ」の避難所のようなものであった [157]。 彼の自伝の事実は研究者によって批判的に評価されている。彼の友人[159]であり伝記作家でもあるヤン・ムーリエ=ブータンは、アルチュセールの人生の 初期を注意深く分析した後、この自伝は「残骸のプリズムを通して人生を書き直したもの」であると結論づけた[160]。 [160] ムーリエ=ブータンは、アルチュセール家の歴史について「宿命論的」な説明を作り上げる上で重要な役割を果たしたのはリュトマンであり、1964年の書簡 で彼のヴィジョンを大きく形成したと考えていた。ムーリエ=ブータンによれば、アルチュセールは幼い頃からジョルジェットと密接な心理的関係を持ってお り、自伝の中ではあまり言及しなかったが、彼女の「神経症」はアルチュセール自身の「神経症」と重なっていた可能性がある[162]。 [162]彼の妹もまたうつ病を患っており、二人は成人してからもほとんどずっと別々に暮らしていたにもかかわらず、二人のうつ病はしばしば時期的に一致 していた[163]。またアルチュセールは家族の状況を描写することに重点を置いており、例えばENSが彼の人格に与えた影響については考慮していなかっ た[164]。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099