Loyalty is a

devotion to a country, philosophy, group, or person.[1] Philosophers

disagree on what can be an object of loyalty, as some argue that

loyalty is strictly interpersonal and only another human being can be

the object of loyalty. The definition of loyalty in law and political

science is the fidelity of an individual to a nation, either one's

nation of birth, or one's declared home nation by oath (naturalization).

|

忠誠とは、国、哲学、集団、または個人に対する献身である[1]。何が

忠誠の対象になり得るかについては哲学者の間でも意見が分かれており、忠誠は厳密には対人的なものであり、忠誠の対象になり得るのは他の人間だけであると

主張する者もいる。法律学や政治学における忠誠の定義は、個人が国家(出生国、または宣誓によって宣言された母国(帰化))に忠誠を誓うことである。

|

Historical concepts

Western world

Further information: Semper fidelis, In Treue fest, Fidelity, and

Tryggvi

Classical tragedy is often based on a conflict arising from dual

loyalty. Euthyphro, one of Plato's early dialogues, is based on the

ethical dilemma arising from Euthyphro intending to lay manslaughter

charges against his own father, who had caused the death of a slave

through negligence.

In the Gospel of Matthew 6:24, Jesus states, "No one can serve two

masters; for a slave will either hate the one and love the other, or be

devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and

wealth". This relates to the authority of a master over his servants

(as per Ephesians 6:5), who, according to Biblical law, owe undivided

loyalty to their master (as per Leviticus 25:44–46).[2] On the other

hand, the "Render unto Caesar" of the synoptic gospels acknowledges the

possibility of distinct loyalties (secular and religious) without

conflict, but if loyalty to man conflicts with loyalty to God, the

latter takes precedence.[3]

The Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition defines loyalty as

"allegiance to the sovereign or established government of one's

country" and also "personal devotion and reverence to the sovereign and

royal family". It traces the word "loyalty" to the 15th century, noting

that then it primarily referred to fidelity in service, in love, or to

an oath that one has made. The meaning that the Britannica gives as

primary, it attributes to a shift during the 16th century, noting that

the origin of the word is in the Old French loialte, that is in turn

rooted in the Latin lex, meaning "law". One who is loyal, in the feudal

sense of fealty, is one who is lawful (as opposed to an outlaw), who

has full legal rights as a consequence of faithful allegiance to a

feudal lord. Hence the 1911 Britannica derived its (early 20th century)

primary meaning of loyalty to a monarch.[4][5]

East Asia

"Loyalty" is the most important and frequently emphasized virtue in

Bushido. In combination with six other virtues, which are Righteousness

(義 gi), Courage (勇 yū), Benevolence, (仁 jin), Respect (礼 rei),

Sincerity (誠 makoto), and Honour (名誉 meiyo), it formed the Bushido

code: "It is somehow implanted in their chromosomal makeup to be

loyal".[6]

|

歴史的概念

西洋世界

さらに詳しい情報 ゼンパー・フィデリス、イン・トリュー・フェスト、フィデリティ、トリュグヴィ

古典悲劇はしばしば、二重の忠誠から生じる葛藤に基づいている。プラトンの初期の対話篇のひとつである『エウテイフロ』は、過失によって奴隷を死なせた自

分の父親を過失致死罪で告発しようとしたエウテイフロから生じる倫理的ジレンマに基づいている。

マタイによる福音書6章24節で、イエスはこう述べている。「だれも二人の主人に仕えることはできない。神と富とに仕えることはできない」。これは、聖書

の掟によれば、主人に対して分け隔てなく忠誠を誓う(レビ記25:44-46)使用人(エペソ6:5)に対する主人の権威に関するものである[2]。一

方、共観福音書の「カイザルに帰せよ」は、対立することなく(世俗的な忠誠と宗教的な忠誠)異なる忠誠の可能性を認めているが、人間に対する忠誠と神に対

する忠誠が対立する場合は、後者が優先される[3]。

ブリタニカ百科事典第11版では、忠誠を「国の主権者や既成政府に対する忠誠」と定義しており、また「君主や王室に対する個人的な献身と敬愛」とも定義し

ている。忠誠」という言葉は15世紀までさかのぼり、当時は主に奉仕や恋愛における忠誠、あるいは自分の立てた誓いに対する忠誠を指していたと指摘してい

る。ブリタニカが第一義とする意味は、16世紀に変化したもので、語源は古フランス語のloialteにあり、その語源はラテン語のlex(「法」を意味

する)にあると指摘している。封建的な意味での忠誠心とは、(無法者とは対照的に)合法的な者のことであり、封建領主に忠実に忠誠を誓った結果として、完

全な法的権利を有する者のことである。それゆえ、1911年のブリタニカは(20世紀初頭の)君主への忠誠という主要な意味を導き出した[4][5]。

東アジア

「忠誠」は武士道において最も重要かつ頻繁に強調される徳目である。義」、「勇」、「仁」、「礼」、「誠」、「名誉」の6つの徳と組み合わさって武士道を

形成している: 「忠誠を尽くすことは、彼らの染色体構造に何らかの形で組み込まれている」[6]。

|

Modern concepts

Josiah Royce presented a different definition of the concept in his

1908 book The Philosophy of Loyalty.[7] According to Royce, loyalty is

a virtue, indeed a primary virtue, "the heart of all the virtues, the

central duty amongst all the duties". Royce presents loyalty, which he

defines at length, as the basic moral principle from which all other

principles can be derived.[8] The short definition that he gives of the

idea is that loyalty is "the willing and practical and thoroughgoing

devotion of a person to a cause".[9][8][10] Loyalty is thoroughgoing in

that it is not merely a casual interest but a wholehearted commitment

to a cause.[11]

Royce's view of loyalty was challenged by John Ladd, professor of

philosophy at Brown University, in the article on "Loyalty" in the

first edition of the Macmillan Encyclopedia of Philosophy (1967). Ladd

observed that by that time the subject had received "scant attention in

philosophical literature". This he attributed to "odious" associations

that the subject had with nationalism, including Nazism, and with the

metaphysics of idealism, which he characterized as "obsolete". However,

he argued that such associations were faulty and that the notion of

loyalty is "an essential ingredient in any civilized and humane system

of morals".[12]

Anthony Ralls observes that Ladd's article is that Encyclopaedia's only

article on a virtue, .[13] Ladd asserts that, contrary to Royce, causes

to which one is loyal are interpersonal, not impersonal or

suprapersonal.[14] He states that Royce's view has "the ethical defect

of postulating duties over and above our individual duties to men and

groups of men. The individual is submerged and lost in this superperson

for its tends to dissolve our specific duties to others into

'superhuman' good". Ronald F. Duska, the Lamont Post Chair of Ethics

and the Professions at The American College, extends Ladd's objection,

saying that it is a perversion of ethics and virtue for one's self-will

to be identified with anything, as Royce would have it.[15] Even if one

were identifying one's self-will with God, to be worthy of such loyalty

God would have to be the summum bonum, the perfect manifestation of

good.

Ladd himself characterizes loyalty as interpersonal, i.e., a

relationship between a lord and vassal, parent and child, or two good

friends. Duska states that this characterization leads to a problem

that Ladd overlooks. Loyalty may certainly be between two persons, but

it may also be from a person to a group of people. Examples of this,

which are unequivocally considered to be instances of loyalty, are

loyalty by a person to his or her family, to a team that he or she is a

member or fan of, or to his or her country. The problem is that it then

becomes unclear whether there is a strict interpersonal relationship

involved, and whether Ladd's contention that loyalty is

interpersonal—not suprapersonal—is an adequate description.[15] Ladd

considers loyalty from two perspectives: its proper object and its

moral value.[12]

John Kleinig, professor of philosophy at City University of New York,

observes that over the years the idea has been treated by writers from

Aeschylus through John Galsworthy to Joseph Conrad, by psychologists,

psychiatrists, sociologists, scholars of religion, political

economists, scholars of business and marketing, and—most

particularly—by political theorists, who deal with it in terms of

loyalty oaths and patriotism. As a philosophical concept, loyalty was

largely untreated by philosophers until the work of Josiah Royce, the

"grand exception" in Kleinig's words.[9] Kleinig observes that from the

1980s onwards, the subject gained attention, with philosophers

variously relating it to professional ethics, whistleblowing,

friendship, and virtue theory.[9] Additional aspects enumerated by

Kleinig include the exclusionary nature of loyalty and its subjects.[9]

The proper object of loyalty

Ladd and others, including Milton R. Konvitz[16] and Marcia W.

Baron,[14] disagree about the proper object of loyalty—what it is

possible to be loyal to. Ladd considers loyalty to be interpersonal:

the object of loyalty is always a person. In the Encyclopaedia of the

History of Ideas, Konvitz states that the objects of loyalty encompass

principles, causes, ideas, ideals, religions, ideologies, nations,

governments, parties, leaders, families, friends, regions, racial

groups, and "anyone or anything to which one's heart can become

attached or devoted".[16]: 108 Baron agrees with Ladd, inasmuch as

loyalty is "to certain people or to a group of people, not loyalty to

an ideal or cause".[14] She argues in her monograph, The Moral Status

of Loyalty, that "[w]hen we speak of causes (or ideals) we are more apt

to say that people are committed to them or devoted to them than that

they are loyal to them".[14] Kleinig agrees with Baron, noting that a

person's earliest and strongest loyalties are almost always to people,

and that only later do people arrive at abstract notions like values,

causes, and ideals. He disagrees, however, with the notion that

loyalties are restricted solely to personal attachments, considering it

"incorrect (as a matter of logic)".[17]

Loyalty to people and abstract notions such as causes or ideals is

considered an evolutionary tactic, as there is a greater chance of

survival and procreation if animals belong to loyal packs.[18][better

source needed]

Immanuel Kant constructed the basis for an ethical law via the concept

of duty.[19] Kant began his ethical theory by arguing that the only

virtue that can be unqualifiedly good is a good will. No other virtue

has this status because every other virtue can be used to achieve

immoral ends (for example, the virtue of loyalty is not good if one is

loyal to an evil person). The good will is unique in that it is always

good and maintains its moral value even when it fails to achieve its

moral intentions.[20] Kant regarded the good will as a single moral

principle that freely chooses to use the other virtues for moral

ends.[21]

Multiplicity, disloyalty, and whether loyalty is exclusionary

Stephen Nathanson, professor of philosophy at Northeastern University,

states that loyalty can be either exclusionary or non-exclusionary; and

can be single or multiple. Exclusionary loyalty excludes loyalties to

other people or groups; whereas non-exclusionary loyalty does not.

People may have single loyalties, to just one person, group, or thing,

or multiple loyalties to multiple objects. Multiple loyalties can

constitute a disloyalty to an object if one of those loyalties is

exclusionary, excluding one of the others. However, Nathanson observes,

this is a special case. In the general case, the existence of multiple

loyalties does not cause a disloyalty. One can, for example, be loyal

to one's friends, or one's family, and still, without contradiction, be

loyal to one's religion, or profession.[22]

Other dimensions

In addition to number and exclusion as just outlined, Nathanson

enumerates five other "dimensions" that loyalty can vary along: basis,

strength, scope, legitimacy, and attitude:[22]

basis

Loyalties may be constructed on the basis of unalterable facts that

constitute a personal connection between the subject and the object of

the loyalty, such as biological ties or place of birth (a notion of

natural allegiance propounded by Socrates in his political theory).

Alternatively, they may be constructed from personal choice and

evaluation of criteria with a full degree of freedom. The degree of

control that one has is not necessarily simple; Nathanson points out

that whilst one has no choice as to one's parents or relatives, one can

choose to desert them.[22]

strength

Loyalties can range from supreme loyalties, that override all other

considerations, to merely presumptive loyalties, that affect one's

presumptions, providing but one motivation for action that is weighed

against other motivations. Nathanson observes that strength of loyalty

is often interrelated with basis. "Blood is thicker than water" is an

aphorism that explains that loyalties that have biological ties as

their bases are generally stronger.[22]

scope

Loyalties with limited scope require few actions of the subject;

loyalties with broad or even unlimited scopes require many actions, or

indeed to do whatever may be necessary in support of the loyalty.

Loyalty to one's job, for example, may require no more action than

simple punctuality and performance of the tasks that the job requires.

Loyalty to a family member can, in contrast, have a very broad effect

upon one's actions, requiring considerable personal sacrifice. Extreme

patriotic loyalty may impose an unlimited scope of duties. Scope

encompasses an element of constraint. Where two or more loyalties

conflict, their scopes determine what weight to give to the alternative

courses of action required by each loyalty.[22]

legitimacy

This is of particular relevance to the conflicts among multiple

loyalties. People with one loyalty can hold that another, conflicting,

loyalty is either legitimate or illegitimate. In the extreme view, one

that Nathanson ascribes to religious extremists and xenophobes for

examples, all loyalties bar one's own are considered illegitimate. The

xenophobe does not regard the loyalties of foreigners to their

countries as legitimate while the religious extremist does not

acknowledge the legitimacy of other religions. At the other end of the

spectrum, past the middle ground of considering some loyalties as

legitimate and others not, according to cases, or plain and simple

indifference to other people's loyalties, is the positive regard of

other people's loyalties.[22]

attitude

The subjects of the loyalties have attitudes towards other people (note

that this dimension of loyalty concerns the subjects of the loyalty,

whereas legitimacy, above, concerns the loyalties themselves). People

may have one of a range of possible attitudes towards others who do not

share their loyalties, with hate and disdain at one end, indifference

in the middle, and concern and positive feeling at the other.[22]

|

現代の概念

ジョサイア・ロイスは1908年の著書『忠誠の哲学』(The Philosophy of

Loyalty)において、この概念について異なる定義を提示している[7]。ロイスによれば、忠誠は徳であり、まさに第一の徳であり、「あらゆる徳の中

心であり、あらゆる義務の中でも中心的な義務」である。ロイスは忠誠を、他のすべての原則がそこから導き出される基本的な道徳的原則であるとし、それを詳

細に定義している[8]。ロイスが忠誠という考え方に与えている短い定義は、忠誠とは「ある大義に対する、人の自発的かつ実践的で徹底的な献身」であると

いうものである[9][8][10]。

ロイスの忠誠観は、ブラウン大学の哲学教授であるジョン・ラッドによって、『マクミラン哲学百科事典』の初版(1967年)に掲載された「忠誠心」の記事

の中で異議を唱えられた。ラッドは、その時点までにこのテーマが「哲学文献の中でほとんど注目されていなかった」ことを指摘した。これは、このテーマがナ

チズムを含むナショナリズムや観念論の形而上学と「忌まわしい」結びつきを持ち、「時代遅れ」であるとしたためである。しかし彼は、そのような連想は誤り

であり、忠誠心という概念は「文明的で人道的な道徳体系に不可欠な要素」であると主張した[12]。

アンソニー・ラッズは、ラッドの論文は百科事典で唯一の徳に関する論文であると述べている。 13]

ラッドは、ロイスとは反対に、人が忠誠を誓う原因は非人間的でも超人間的でもなく、対人的なものであると主張している。この超人間は、他者に対する具体的

な義務を 「超人間的な

」善へと溶解させる傾向があるため、個人はこの超人間に沈められ、失われてしまう」と述べている。アメリカン・カレッジのラモント・ポスト倫理専門職講座

のロナルド・F・ダスカは、ラッドの反論を拡大解釈し、ロイスが言うように、自己の意志を何かと同一視することは倫理と美徳の倒錯であると述べている

[15]。仮に自己の意志を神と同一視するとしても、そのような忠誠に値するためには、神がsumum

bonum、すなわち善の完全な現れでなければならない。

ラッド自身は、忠誠を対人的なもの、すなわち、領主と家臣、親と子、あるいは二人の親友の関係として特徴づけている。ダスカは、この特徴付けはラッドが見

落としている問題につながると述べる。忠誠心とは、確かに二人の人間の間にあるものかもしれないが、ある人間からある集団に向けられたものである場合もあ

る。その例としては、家族に対する忠誠心、所属チームやファンに対する忠誠心、国に対する忠誠心などが挙げられる。問題は、そこに厳密な対人関係があるの

かどうか、忠誠心は超個人的なものではなく対人的なものであるというラッドの主張が適切な記述なのかどうかが不明確になることである[15]。ラッドは忠

誠心を、その適切な対象と道徳的価値という2つの観点から考察している[12]。

ニューヨーク市立大学のジョン・クレイニグ教授(哲学)は、長年にわたり、この概念は、アイスキュロスからジョン・ガルスワージー、ジョセフ・コンラッド

に至る作家、心理学者、精神科医、社会学者、宗教学者、政治経済学者、ビジネス・マーケティング学者、そして特に政治理論家によって、忠誠の誓いや愛国心

という観点から扱われてきたと述べている。哲学的概念としての忠誠心は、クライングの言葉を借りれば「大いなる例外」であるジョサイア・ロイスの研究が始

まるまで、哲学者たちによってほとんど扱われてこなかった[9]。クライングは、1980年代以降、哲学者たちが忠誠心を職業倫理、内部告発、友情、美徳

論などと様々に関連付けることによって、このテーマが注目されるようになったと述べている[9]。

忠誠の適切な対象

ラッドと、ミルトン・R・コンヴィッツ[16]やマーシャ・W・バロン[14]を含む他の人々は、忠誠の適切な対象-何に対して忠誠を尽くすことが可能か

-について意見が分かれている。ラッドは、忠誠とは対人的なものであり、忠誠の対象は常に人であると考える。コンヴィッツは『思想史百科事典』の中で、忠

誠の対象には主義、大義、思想、理想、宗教、イデオロギー、国家、政府、政党、指導者、家族、友人、地域、人種集団、そして「自分の心が愛着を持ったり献

身したりすることのできるあらゆるもの」が含まれると述べている[16]: 108

バロンはラッドに同意し、忠誠心とは「特定の人々や人々の集団に対するものであり、理想や大義に対する忠誠心ではない」[14]と主張する。

彼女は単行本『忠誠心の道徳的地位』の中で、「大義(または理想)について語るとき、人々はそれらに忠誠を誓っているというよりも、それらに献身的である

とか、それらに傾倒しているといった方が適切である」と論じている。

[14]クライニヒはバロンに同意し、人の最も初期で最も強い忠誠心はほとんど常に人に対するものであり、人は後になって初めて価値、大義、理想といった

抽象的な概念に到達するのだと指摘する。しかし彼は、忠誠心が個人的な愛着だけに限定されるという考え方には反対で、「(論理の問題として)正しくない」

と考えている[17]。

人や大義や理想といった抽象的な概念に対する忠誠心は、動物が忠実な群れに属していた方が生存や子孫繁栄の可能性が高くなることから、進化的な戦術である

と考えられている[18][要出典]。

イマヌエル・カントは義務の概念を通じて倫理法の基礎を構築した[19]。カントは、無条件に善であることができる唯一の徳は善意であると主張することか

ら倫理論を始めた。他の美徳はすべて不道徳な目的を達成するために使用される可能性があるため(例えば、忠誠の美徳は、悪人に忠誠を誓う場合には善ではな

い)、他の美徳はこのような地位を持たない。カントは善意を、他の美徳を道徳的目的のために自由に使用することを選択する単一の道徳的原理とみなしている

[21]。

多重性、不誠実さ、忠誠心が排他的かどうか

ノースイースタン大学の哲学教授であるスティーブン・ネイサンソンは、忠誠は排他的か非排他的か、また単一か多重かであると述べている。排除的忠誠は他の

人々や集団への忠誠を排除するが、非排除的忠誠は排除しない。人は、ただ一人の人、グループ、物に対する単一の忠誠を持つこともあれば、複数の対象に対す

る複数の忠誠を持つこともある。複数の忠誠がある対象への不忠誠を構成するのは、その忠誠のひとつが排他的で、他の忠誠のひとつを排除している場合であ

る。しかし、これは特殊なケースだとナタンソンは指摘する。一般的なケースでは、複数の忠誠心が存在しても不忠誠を引き起こすことはない。例えば、友人や

家族に忠実であっても、矛盾なく宗教や職業に忠実であることができる[22]。

その他の次元

先ほど概説した数と排除に加えて、ナタンソンは忠誠心が変化しうる他の5つの「次元」を列挙している:根拠、強さ、範囲、正当性、態度である[22]。

基盤

忠誠は、生物学的な結びつきや出生地(ソクラテスがその政治理論の中で提唱した自然的忠誠の概念)など、主体者と忠誠の対象との間に個人的なつながりを構

成する不変の事実に基づいて構築されることがある。あるいは、完全な自由度をもった個人的な選択と基準の評価によって構築される場合もある。ナタンソン

は、自分の両親や親戚については選択の余地がない一方で、彼らを見捨てることはできると指摘している[22]。

強さ

忠誠心には、他のすべての考慮事項に優先する至高の忠誠心から、自分の推定に影響を与え、他の動機と比較検討される行動の動機の一つになるだけの推定的忠

誠心まで様々なものがある。ナタンソンは、忠誠心の強さはしばしば根拠と相互に関連していると観察している。「血は水よりも濃い」という格言は、生物学的

な結びつきを基盤とする忠誠心は一般的に強いことを説明するものである[22]。

範囲

範囲が限定された忠誠は、対象者の行動をほとんど必要としない。範囲が広い忠誠、あるいは範囲が限定されない忠誠は、多くの行動を必要とする。例えば、仕

事に対する忠誠心は、単に時間を守り、その仕事が要求する仕事をこなすこと以上の行動を必要としないかもしれない。これとは対照的に、家族への忠誠は、自

分の行動に非常に広範な影響を及ぼし、かなりの個人的犠牲を必要とすることがある。極端な愛国的忠誠心は、職務に無制限の範囲を課すかもしれない。範囲に

は制約の要素も含まれる。2つ以上の忠誠心が対立する場合、それぞれの忠誠心によって要求される代替的な行動方針にどのような重みを与えるかは、その範囲

によって決まる[22]。

正当性

これは、複数の忠誠心の対立に特に関連している。ある忠誠心を持つ人々は、対立する別の忠誠心を正当なものとも非合法なものとも考えることができる。極端

な見方では、ナタンソンは宗教的過激派や外国人嫌いを例に挙げているが、自分の忠誠心以外の忠誠心はすべて非合法と見なされる。外国人嫌いは外国人の自国

への忠誠を正当なものとみなさないし、宗教的過激派は他の宗教の正当性を認めない。スペクトルのもう一方の端には、ケースに応じて、ある忠誠を正当なもの

とみなし、他の忠誠をそうでないとみなす中間の立場を過ぎると、あるいは他人の忠誠に単純無関心になると、他人の忠誠を肯定的にみなすようになる

[22]。

態度

忠誠心の主体は、他者に対する態度を持つ(上記の正当性が忠誠心そのものに関するものであるのに対し、忠誠心のこの次元は忠誠心の主体に関するものである

ことに留意されたい)。人は、忠誠心を共有しない他者に対して、一端は憎悪や軽蔑、中間は無関心、他端は懸念や好感といった、さまざまな態度のいずれかを

とる可能性がある[22]。 |

In relation to other subjects

Patriotism

Main article: Patriotism

This section relies largely or entirely upon a single source. Relevant

discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help improve this

article by introducing citations to additional sources at this section.

(August 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

Nathanson observes that loyalty is often directly equated to

patriotism. He states that this is a false equality; while patriots

exhibit loyalty, it is not conversely the case that all loyal persons

are patriots. He provides the example of a mercenary soldier, who

exhibits loyalty to the people or country that pays him. Nathanson

points to the difference in motivations between a loyal mercenary and a

patriot. A mercenary may well be motivated by a sense of

professionalism or a belief in the sanctity of contracts. A patriot, in

contrast, may be motivated by affection, concern, identification, and a

willingness to sacrifice.[22]

Nathanson contends that patriotic loyalty is not always a virtue. A

loyal person can, in general be relied upon, and hence people view

loyalty as virtuous. Nathanson argues that loyalty can, however, be

given to persons or causes that are unworthy. Moreover, loyalty can

lead patriots to support policies that are immoral and inhumane. Thus,

Nathanson argues, patriotic loyalty can sometimes rather be a vice than

a virtue, when its consequences exceed the boundaries of what is

otherwise morally desirable. Such loyalties, in Nathanson's view, are

erroneously unlimited in their scopes, and fail to acknowledge

boundaries of morality.[22]

Employment

Main article: Faithless servant

The faithless servant doctrine is a doctrine under the laws of a number

of states in the United States, and most notably New York State law,

pursuant to which an employee who acts unfaithfully towards his

employer must forfeit all of the compensation he received during the

period of his disloyalty.[23]

Whistleblowing

Main article: Whistleblowing

Several scholars, including Duska,[citation needed] discuss loyalty in

the context of whistleblowing. Wim Vandekerckhove of the University of

Greenwich points out that in the late 20th century saw the rise of a

notion of a bidirectional loyalty—between employees and their employer.

(Previous thinking had encompassed the idea that employees are loyal to

an employer, but not that an employer need be loyal to employees.) The

ethics of whistleblowing thus encompass a conflicting multiplicity of

loyalties, where the traditional loyalty of the employee to the

employer conflicts with the loyalty of the employee to his or her

community, which the employer's business practices may be adversely

affecting. Vandekerckhove reports that different scholars resolve the

conflict in different ways, some of which he does not find to be

satisfactory. Duska resolves the conflict by asserting that there is

really only one proper object of loyalty in such instances—the

community[citation needed]—a position that Vandekerckhove counters by

arguing that businesses are in need of employee loyalty.[5]

John Corvino, associate professor of philosophy at Wayne State

University takes a different tack, arguing that loyalty can sometimes

be a vice, not a virtue, and that "loyalty is only a virtue to the

extent that the object of loyalty is good"[citation needed] (similar to

Nathanson). Vandekerckhove calls this argument "interesting" but "too

vague" in its description of how tolerant an employee should be of an

employer's shortcomings. Vandekerckhove suggests that Duska and Corvino

combine, however, to point in a direction that makes it possible to

resolve the conflict of loyalties in the context of whistleblowing, by

clarifying the objects of those loyalties.[5]

Marketing

Main article: Loyalty business model

Businesses seek to become the objects of loyalty in order to retain

customers. Brand loyalty is a consumer's preference for a particular

brand and a commitment to repeatedly purchase that brand.[24] So-called

loyalty programs offer rewards to repeat customers in exchange for

being able to keep track of consumer preferences and buying habits.[25]

A similar concept is fan loyalty, an allegiance to and abiding interest

in a sports team, fictional character, or fictional series. Devoted

sports fans continue to remain fans even in the face of a string of

losing seasons.[26]

|

他のテーマに関連して

愛国心

主な記事 愛国心

このセクションの大部分または全体は1つの情報源に依存している。関連する議論はトークページにある。このセクションに追加ソースの引用を紹介すること

で、この記事の改善に役立ててほしい。(2023年8月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)

ナタンソンは、忠誠心がしばしば愛国心と直接的に同一視されることを観察している。愛国者は忠誠心を示すが、逆に忠誠心のある人がすべて愛国者であるわけ

ではない。彼は傭兵の例を示し、傭兵は自分に報酬を支払ってくれる国民や国に忠誠心を示すという。ナタンソンは、忠実な傭兵と愛国者の動機の違いを指摘す

る。傭兵の動機は、プロ意識であったり、契約の神聖さに対する信念であったりする。これに対して愛国者は、愛情、関心、同一化、犠牲を厭わないことなどが

動機となることがある[22]。

ナタンソンは、愛国的な忠誠心は必ずしも美徳ではないと主張する。忠実な人物は一般的に信頼されることができ、それゆえ人々は忠実さを美徳とみなす。しか

しナタンソンは、忠誠は価値のない人物や大義に与えられることもあると主張する。さらに、忠誠心は愛国者を不道徳で非人道的な政策の支持に導くこともあ

る。このように、愛国的な忠誠心は、その結果が道徳的に望ましいとされる範囲を超える場合、美徳というよりもむしろ悪徳となることがあるとナタンソンは主

張する。ナタンソンの見解では、このような忠誠心は、その範囲が誤って無制限であり、道徳の境界を認めないものである[22]。

雇用

主な記事 忠実でない使用人

忠実でない使用人(faithless servant

doctrine)とは、アメリカの多くの州法、特にニューヨーク州法に基づく教義であり、雇用主に対して不誠実な行為をした従業員は、不誠実な期間中に

受け取った報酬をすべて没収されなければならない[23]。

内部告発

主な記事 内部告発

ダスカを含む何人かの学者[要出典]は、内部告発の文脈で忠誠心について論じている。グリニッジ大学のヴィム・ヴァンデケルクホーフは、20世紀後半に従

業員と雇用主の双方向の忠誠という概念が台頭してきたことを指摘している。(それまでの考え方は、従業員は雇用主に忠誠を誓うが、雇用主は従業員に忠誠を

誓う必要はないというものだった)。従業員の雇用主に対する伝統的な忠誠心と、雇用主の事業慣行が悪影響を及ぼしている可能性のある従業員の地域社会に対

する忠誠心とが相反する場合である。ヴァンデカークホフによれば、学者によってこの対立を解決する方法はさまざまであり、そのうちのいくつかは満足できる

ものではないという。ダスカは、このような場合、忠誠の対象として適切なのは本当にただ1つ、地域社会だけであると主張することで対立を解決している[要

出典]が、ヴァンデカークホフは、企業は従業員の忠誠を必要としていると主張することでこれに反論している[5]。

ウェイン州立大学の哲学准教授であるジョン・コルヴィーノは、忠誠心は時として美徳ではなく悪徳になる可能性があり、「忠誠心は、忠誠の対象が善である限

りにおいてのみ美徳である」[要出典]と主張する(ナタンソンと同様)。ヴァンデカークホーフはこの議論を「興味深い」としながらも、従業員が雇用者の欠

点に対してどの程度寛容であるべきかについての記述が「漠然としすぎている」と評している。しかし、ヴァンデカークホフは、ダスカとコルヴィーノが組み合

わさることで、忠誠心の対象を明確にすることで、内部告発の文脈における忠誠心の対立を解決することが可能になる方向を指し示していると示唆している

[5]。

マーケティング

主な記事 ロイヤルティビジネスモデル

企業は顧客を維持するためにロイヤリティの対象になろうとする。ブランド・ロイヤルティとは、消費者が特定のブランドを好み、そのブランドを繰り返し購入

することを約束することである[24]。いわゆるロイヤルティ・プログラムは、消費者の嗜好や購買習慣を把握できる代わりに、リピーターに特典を提供する

ものである[25]。

似たような概念に、スポーツチームや架空のキャラクター、架空のシリーズに対する忠誠心や変わらぬ関心であるファン・ロイヤリティがある。熱心なスポーツ

ファンは、負けが続いてもファンであり続ける[26]。

|

In the Bible

Abraham and Isaac by Rembrandt

Attempting to serve two masters leads to "double-mindedness" (James

4:8), undermining loyalty to a cause. The Bible also speaks of loyal

ones, which would be those who follow the Bible with absolute loyalty,

as in "Precious in the eyes of God is the death of his loyal ones"

(Psalms 116:15). Most Jewish and Christian authors view the binding of

Isaac (Genesis 22), in which Abraham was called by God to offer his son

Isaac as a burnt offering, as a test of Abraham's loyalty.[27] Joseph's

faithfulness to his master Potiphar and his rejection of Potiphar's

wife's advances (Genesis 39) have also been called an example of the

virtue of loyalty.[28]: 665

|

聖書の中で

レンブラント作「アブラハムとイサク」

二人の主人に仕えようとすることは「二心」(ヤコブ4:8)につながり、大義に対する忠誠心を損なう。聖書はまた、「神の目には、その忠実な者の死は尊

い」(詩篇116:15)のように、絶対的な忠誠心を持って聖書に従う者のことを、忠実な者と呼んでいる。ユダヤ教とキリスト教の著者の多くは、アブラハ

ムが神に召されて息子イサクを燔祭として捧げたイサクの縛り(創世記22章)を、アブラハムの忠誠心の試練とみなしている[27]。ヨセフが主人ポティ

ファルに忠実で、ポティファルの妻の誘いを断ったこと(創世記39章)も、忠誠の美徳の例と呼ばれている[28]。

|

Misplaced

Main article: Misplaced loyalty

Misplaced or mistaken loyalty refers to loyalty placed in other persons

or organisations where that loyalty is not acknowledged or respected,

is betrayed, or taken advantage of. It can also mean loyalty to a

malignant or misguided cause.

Social psychology provides a partial explanation for the phenomenon in

the way "the norm of social commitment directs us to honor our

agreements... People usually stick to the deal even though it has

changed for the worse".[29] Humanists point out that "man inherits the

capacity for loyalty, but not the use to which he shall put it... may

unselfishly devote himself to what is petty or vile, as he may to what

is generous and noble".[30]

In animals

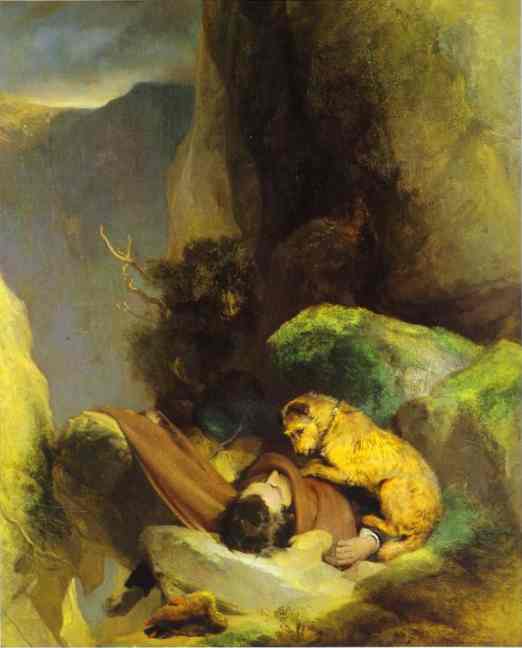

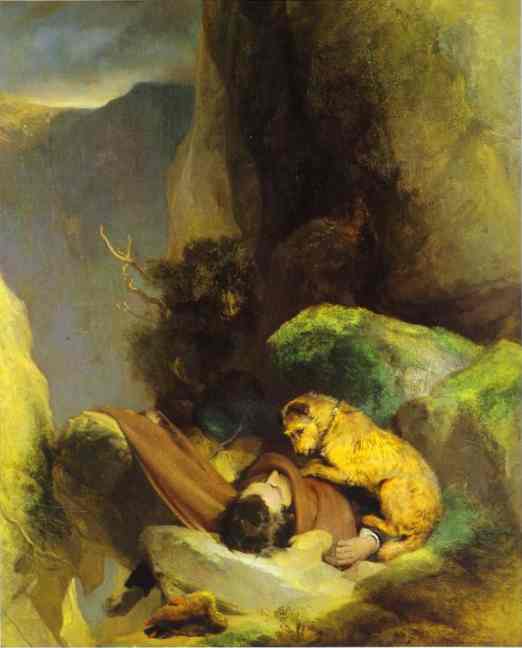

Foxie, guarding the body of her master Charles Gough, in Attachment by

Edwin Landseer, 1829

Animals as pets may display a sense of loyalty to humans. Famous cases

include Greyfriars Bobby, a Skye terrier who attended his master's

grave for fourteen years; Hachiko, a dog who returned to the place he

used to meet his master every day for nine years after his death;[31]

and Foxie, the spaniel belonging to Charles Gough, who stayed by her

dead master's side for three months on Helvellyn in the Lake District

in 1805 (although it is possible that Foxie had eaten Gough's body).[32]

In the Mahabharata, the righteous King Yudhishthira appears at the

gates of Heaven at the end of his life with a stray dog he had picked

up along the way as a companion, having previously lost his brothers

and his wife to death. The god Indra is prepared to admit him to

Heaven, but refuses to admit the dog, so Yudhishthira refuses to

abandon the dog, and prepares to turn away from the gates of Heaven.

Then the dog is revealed to be the manifestation of Dharma, the god of

righteousness and justice, and who turned out to be his deified self.

Yudhishthira enters heaven in the company of his dog, the god of

righteousness.[33][28]: 684–85 Yudhishthira is known by the epithet

Dharmaputra, the lord of righteous duty.

|

見当違い

主な記事 誤った忠誠心

誤った忠誠心とは、他の人物や組織に置かれた忠誠心が認められなかったり、尊重されなかったり、裏切られたり、利用されたりすることを指す。また、悪意や

見当違いの大義に対する忠誠を意味することもある。

社会心理学は、「社会的コミットメントの規範は、合意を尊重するよう私たちに指示する...」という方法で、この現象を部分的に説明している。人間は忠誠

の能力を受け継いでいるが、それを何に使うかは決まっていない。

動物の場合

主人チャールズ・ゴウの遺体を守るフォクシー(1829年、エドウィン・ランドシーア作『アタッチメント』より

ペットとしての動物は、人間に対して忠誠心を示すことがある。有名な例としては、主人の墓に14年間通い続けたスカイ・テリアのグレイフライアーズ・ボ

ビー、主人の死後9年間、毎日主人と会っていた場所に戻ってきた犬のハチ公[31]、1805年に湖水地方のヘルブリンで死んだ主人のそばに3ヶ月間留

まったチャールズ・ゴウのスパニエル、フォクシー(ただし、フォクシーがゴウの遺体を食べた可能性もある)などが挙げられる[32]。

『マハーバーラタ』では、正義の王ユディシュティラが、兄弟と妻を死で失った後、途中で拾った野良犬を道連れに、人生の終わりに天国の門に現れる。インド

ラ神は彼を天国に入れる用意をしていたが、犬を入れることを拒んだため、ユディシュティラは犬を捨てることを拒み、天国の門から背を向ける準備をする。す

ると、犬は正義と正義の神ダルマの現れであり、ダルマが神格化された自分であることが判明する。ユディシュティラは正義の神である犬に連れられて天国に入

る[33][28]: 684-85 ユディシュティラはダルマプトラという諡号で知られ、正義の義務の主である。

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

☆

☆