啓蒙あるいは啓蒙思想

Lumières and/or Vordenker der

Aufklärung

☆ 【啓蒙という思想】リュミエール/ルミエール(英語では The Lights。つまり「光」)は、17世紀後半に始まった文化、哲学、文学、知的運動で、西ヨーロッパで生まれ、ヨーロッパ全土に広がった。バルーク・ス ピノザ、デイ ヴィッド・ヒューム、ジョン・ロック、エドワード・ギボン、ヴォルテール、ジャン=ジャック・ルソー、ドゥニ・ディドロ、ピエール・バイル、アイザック・ ニュートンなどの哲学者が含まれる。この運動は、ガリレオ・ガリレイのような人々を擁したイタリア・ルネサンスから直接生じた南ヨーロッパの科学革命の影 響を受けている。やがてこの言葉は、英語で「啓蒙の時代」(Siècle des Lumières)を意味するようになった(→カント「啓蒙とはなにか?」)。

★ 【啓 蒙時代】啓蒙時代(Age of Enlightenment ,理性時代とも呼ばれる)は、ヨーロッパと西洋文明の歴史における一時期である。この時代には、啓蒙主義という [b] 知的[6]かつ文化的[6]な運動が隆盛を極めた。17世紀後半[6]に西ヨーロッパ[7]で始まり、18世紀に頂点を迎えた。その思想はヨーロッパ [7]全域に広がり、アメリカ大陸やオセアニアの植民地にも及んだ。[8][9][10] 理性、経験的証拠、科学的方法を重視する特徴を持ち、啓蒙主義は個人の自由、宗教的寛容、進歩、自然権の理念を推進した。その思想家たちは立憲政府、政教 分離、社会・政治改革への合理的原則の適用を提唱した。[11][12] [13] 啓蒙思想は、16世紀から17世紀にかけての科学革命を基盤として発展した。ガリレオ・ガリレイ、ヨハネス・ケプラー、フランシス・ベーコン、ピエール・ ガッサンディ、クリスティアン・ホイヘンス、アイザック・ニュートンらによる科学的探究の新手法が確立されたこの革命が、その礎となったのである。哲学的 基盤はルネ・デカルト、トマス・ホッブズ、バルーフ・スピノザ、ジョン・ロックらによって築かれた。彼らの理性、自然権、経験的知識に関する思想は啓蒙思 想の中核となった。啓蒙主義の始まりを特定する時期としては、1637年にデカルトが『方法序説』を出版したことが挙げられる。この著作では、確固たる根 拠がない限りあらゆるものを体系的に疑う方法論が示され、有名な「我思う、故に我あり(Cogito, ergo sum)」という命題が提示された。また、ニュートンの『プリンキピア・マテマティカ』(1687年)の出版を科学革命の頂点かつ啓蒙主義の始まりとする 見解もある[14][15][16]。ヨーロッパの歴史家たちは伝統的に、その始まりを1715年のフランス国王ルイ14世の死、終わりを1789年のフ ランス革命勃発と定めてきた。現在では多くの歴史家が啓蒙主義の終焉を19世紀の始まりと位置付け、最も新しい提案では1804年のイマヌエル・カントの 死をその年としている。[17](→「啓蒙の時代」)

★啓蒙主義の特徴:1)人文科学(ユマニズム)を目標とする、2)個人の自由とデモクラシーを基調とする、3)理性による宗教改革の精神性(→エラスムス)をもつ。

☆

【啓蒙思想家】啓蒙思想の先駆者[Vordenker

der Aufklärung](フランス語(les)philosophes des Lumières、英語 Enlightenment

figures、オランダ語

Verlichtingsdenkers)、略して啓蒙思想家とは、啓蒙時代におけるヨーロッパおよび北米の精神史上の人物を指し、理性によって思考を偏

見や迷信から解放しようとした人々である。彼らは、技術的、文化的、政治的進歩の基盤として科学と教育の発展に努め、自由な市民は、憲法と法律にのみ拘束

され、自立的に思考することで、自分の人生を自分で決定できるとの見解を確立した。啓蒙思想の先駆者たちが皆、この広範な文化と歴史に対する楽観主義を共

有していたわけではない。

啓蒙主義の画期的な主要著作は、デニス・ディドロとジャン=バティスト・ル・ロンド・ダルランベールが編集した百科事典だ。多くの啓蒙思想家(そのほとん

どは百科事典編集者)の基本的な考え方は、理性によって真実を明らかにし、美徳を促進することができるというものであった。

啓蒙思想の初期段階では、政治権力と宗教の分離(世俗化)と、個々の支配者を中心とした強力な中央集権化(絶対主義)が進んだ。その後、民衆はこの権力か

ら解放されようとした。その結果、共和制や立憲君主制といった、より民主的な国家観への動きが生まれた。憲法では、市民権と人権が保証されるべきだ。啓蒙

絶対主義の支配者たちは、自らも啓蒙思想の一部に共感し、多くの迫害された人々に一時的な亡命の権利を与え、出版の機会を提供した。

ほとんどの啓蒙思想家の考えは、古代およびルネサンスの哲学に根ざしている一方、それ以前のスコラ哲学の伝統や中世およびキリスト教の哲学は、全体として

批判的に見られ、軽視された。啓蒙思想家たちの自然科学および人文科学における立場は、決して統一されたものではなく、その影響は現在まで続いている。現

代科学のカテゴリーと方法論は、その大部分が啓蒙思想家たちの先駆的な研究から生まれている。

フランスでは、ヴォルテールが最も重要な啓蒙思想家とよく見なされ(「ヴォルテールの世紀」と表現される)、一方、アングロサクソン圏では、デイヴィッ

ド・ヒュームが最大の啓蒙思想家とよく見なされている。ドイツ語圏では、イマヌエル・カントの卓越した役割が指摘されている。啓蒙思想の主役たちは、この

運動を限られた期間のものとは見なさず、人間とその責任を中核とする無限の時代の始まりと捉えていた。啓蒙思想家の概念は、当初から厳しい批判にさらされ

ていた。

| Als Vordenker

der

Aufklärung (französisch (les) philosophes des Lumières, englisch

Enlightenment figures, niederländisch Verlichtingsdenkers), auch kurz

Aufklärer, werden Personen der europäischen und nordamerikanischen

Geistesgeschichte im Zeitalter der Aufklärung bezeichnet, die das

Denken mit den Mitteln der Vernunft von Vorurteilen und Aberglauben zu

befreien suchten. Sie bemühten sich um die Entwicklung von Wissenschaft

und Bildung als Basis eines technischen, kulturellen und politischen

Fortschritts und begründeten ihre Auffassung, der freie Bürger könne,

eigenständig denkend, nur an Verfassung und Recht gebunden, sein Leben

selbst bestimmen. Nicht alle Vordenker der Aufklärung teilten diesen

verbreiteten Kultur- und Geschichtsoptimismus. Das epochale Hauptwerk der Aufklärung ist die Enzyklopädie, herausgegeben von Denis Diderot und Jean-Baptiste le Rond d’Alembert. Der Grundgedanke vieler Aufklärer – darunter der meisten Enzyklopädisten – besagte, dass die Vernunft im Stande sei, die Wahrheit ans Licht zu bringen und Tugenden zu fördern. In einer Vor- oder Frühphase der Aufklärung vollzogen sich eine Loslösung der politischen Macht von der Religion (Säkularisierung) und eine starke Zentralisierung um einzelne Herrscherpersönlichkeiten (Absolutismus). In der weiteren Entwicklung versuchten sich die Untertanen von dieser Macht zu emanzipieren. Daraus ergab sich eine Bewegung entweder zu einer eher demokratischen Staatsauffassung in einer Republik oder in einer konstitutionellen Monarchie. In einer Verfassung sollten Bürger- und Menschenrechte garantiert werden. Die Herrscher des aufgeklärten Absolutismus, die selbst mit einigen Gedanken der Aufklärung sympathisierten, gewährten zahlreichen Verfolgten zeitweise Asyl und boten ihnen Publikationsmöglichkeiten. Die Ideen der meisten Aufklärer sind in der Philosophie der Antike und der Renaissance verwurzelt, während die vorangehende scholastische Tradition und mittelalterliche bzw. christliche Philosophie insgesamt kritisch gesehen und abgewertet wurden. Die natur- und geisteswissenschaftlichen Positionen der Aufklärer waren durchaus nicht einheitlich und wirken bis in die Gegenwart. Die Kategorien und Methodik der modernen Wissenschaft ergeben sich zu einem großen Teil aus Vorarbeiten der Aufklärer. Während in Frankreich häufig Voltaire als der bedeutendste Aufklärer gesehen wird – man spricht vom Jahrhundert Voltaires –, wird im angelsächsischen Raum oft David Hume als der größte Aufklärer betrachtet. Im deutschen Sprachgebiet wird auf die herausragende Rolle Immanuel Kants verwiesen. Die Protagonisten der Aufklärung sahen diese Bewegung nicht als einen begrenzten Zeitabschnitt, sondern als Beginn einer grenzenlosen Ära, die den Menschen und seine Verantwortung in den Mittelpunkt stellt. Von Anfang an gab es scharfe Kritik an den Konzepten der Aufklärer. |

啓蒙思想の先駆者(フランス語(les)philosophes

des Lumières、英語 Enlightenment figures、オランダ語

Verlichtingsdenkers)、略して啓蒙思想家とは、啓蒙時代におけるヨーロッパおよび北米の精神史上の人物を指し、理性によって思考を偏

見や迷信から解放しようとした人々である。彼らは、技術的、文化的、政治的進歩の基盤として科学と教育の発展に努め、自由な市民は、憲法と法律にのみ拘束

され、自立的に思考することで、自分の人生を自分で決定できるとの見解を確立した。啓蒙思想の先駆者たちが皆、この広範な文化と歴史に対する楽観主義を共

有していたわけではない。 啓蒙主義の画期的な主要著作は、デニス・ディドロとジャン=バティスト・ル・ロンド・ダルランベールが編集した百科事典だ。多くの啓蒙思想家(そのほとん どは百科事典編集者)の基本的な考え方は、理性によって真実を明らかにし、美徳を促進することができるというものであった。 啓蒙思想の初期段階では、政治権力と宗教の分離(世俗化)と、個々の支配者を中心とした強力な中央集権化(絶対主義)が進んだ。その後、民衆はこの権力か ら解放されようとした。その結果、共和制や立憲君主制といった、より民主的な国家観への動きが生まれた。憲法では、市民権と人権が保証されるべきだ。啓蒙 絶対主義の支配者たちは、自らも啓蒙思想の一部に共感し、多くの迫害された人々に一時的な亡命の権利を与え、出版の機会を提供した。 ほとんどの啓蒙思想家の考えは、古代およびルネサンスの哲学に根ざしている一方、それ以前のスコラ哲学の伝統や中世およびキリスト教の哲学は、全体として 批判的に見られ、軽視された。啓蒙思想家たちの自然科学および人文科学における立場は、決して統一されたものではなく、その影響は現在まで続いている。現 代科学のカテゴリーと方法論は、その大部分が啓蒙思想家たちの先駆的な研究から生まれている。 フランスでは、ヴォルテールが最も重要な啓蒙思想家とよく見なされ(「ヴォルテールの世紀」と表現される)、一方、アングロサクソン圏では、デイヴィッ ド・ヒュームが最大の啓蒙思想家とよく見なされている。ドイツ語圏では、イマヌエル・カントの卓越した役割が指摘されている。啓蒙思想の主役たちは、この 運動を限られた期間のものとは見なさず、人間とその責任を中核とする無限の時代の始まりと捉えていた。啓蒙思想家の概念は、当初から厳しい批判にさらされ ていた。 |

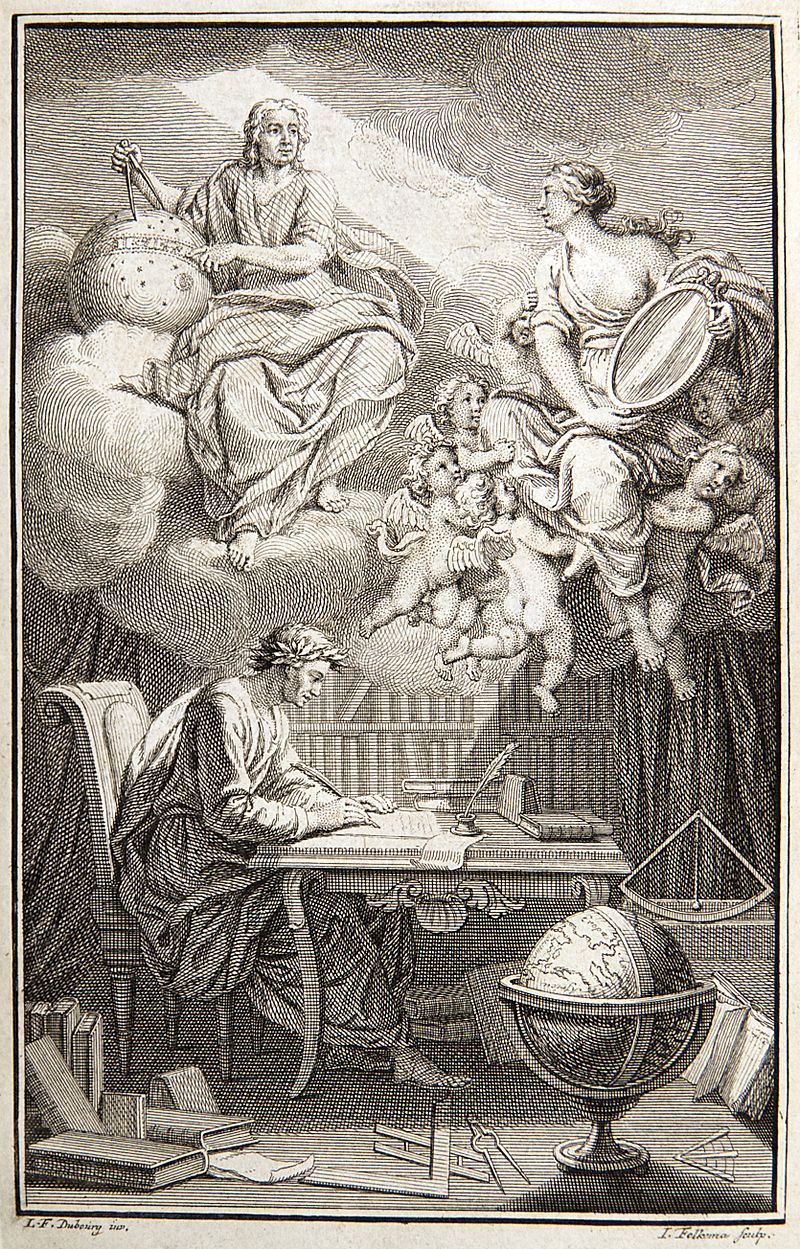

| Überblick Das aufgeklärte Denken wurde von zwei Strömungen der Philosophie der Neuzeit geprägt: dem Rationalismus, besonders vertreten durch René Descartes, und dem englischen Empirismus; hervorzuheben ist hier John Locke, unter dessen Einfluss die amerikanischen Verfassungsgrundsätze entstanden. Einerseits verbreitete sich die Überzeugung der Empiristen, dass Erkenntnis aus Sinneswahrnehmungen herrühre (Sensualismus), andererseits wuchs die Hochschätzung der im Verstand gegründeten Denkfähigkeit und Urteilskraft. Zahlreiche Wandlungen bestimmten die Epoche: Freiheit statt Absolutismus, rechtliche Gleichheit anstelle einer Ständeordnung, wissenschaftliche Erkenntnisse und Toleranz sollten Vorurteile überwinden und an die Stelle herkömmlicher Dogmen treten. Die Mehrzahl, besonders der französischen Aufklärer, war davon überzeugt, dass der Mensch von Natur aus gut ist und lediglich der Erziehung bedarf, um tugendhaft, friedlich und glücklich zu leben. Auch die Entwicklung der Menschheit betrachteten Vordenker der Aufklärung mit einem Kultur- und Geschichtsoptimismus. Das logische und unabhängige Denken der Rationalisten war zunächst auf eine Stärkung des Staates ausgerichtet und hatte religionskritische Züge, die vorderhand auf eine Stärkung der weltlichen gegenüber den geistlichen Machthabern gerichtet waren. Bald bezog sich das kritische Urteil jedoch auch auf die weltlichen Herrscher. Zweifel an Religion und Absolutismus verbreiteten sich schnell. Der deutsche Schriftsteller und Mathematiker Georg Christoph Lichtenberg verlangte in seinen Aphorismen[1] sogar: „Zweifle an allem wenigstens einmal, und wäre es auch der Satz zwei mal zwei ist vier“. Teile der Aristokratie und der niederen Geistlichkeit wie die Abbés in Frankreich begrüßten ebenso wie eine Elite des Dritten Standes die Schwächung ihrer rechtmäßigen Herren. Rivalitäten innerhalb des europäischen Adels und des Klerus verhinderten eine Unterdrückung dieser Bestrebungen. Durch ökonomische Veränderungen wie die Entwicklung des Manufakturwesens, die das Bürgertum zur wirtschaftlich bedeutendsten Schicht machten, erlangte dieser Stand ein neues Selbstbewusstsein und Selbstwertgefühl.  Kunstwerk: Akademie der Wissenschaften nach antikem Vorbild, 1698 Im Vergleich zur Epoche des Barock fand ein grundsätzliches Umdenken bezüglich Vanitas und Jenseitsbezogenheit statt. Die Konzentration auf ein Leben nach dem Tod wandelte sich in eine starke Diesseitsbezogenheit. Auch die Ethik beruhte nicht mehr zwingend auf theologischen oder anderen Vorbedingungen. Bildung bekam einen höheren Stellenwert, und die Zugänglichkeit von Information, die traditionell an gesellschaftliche Privilegien gebunden war, wurde zum Zankapfel, was seit der Mitte des 18. Jahrhunderts im mehrmals verbotenen Projekt einer Enzyklopädie allen Wissens gipfelte. Mit der Aufklärung gingen ein immenser naturwissenschaftlicher und technischer Erkenntnisfortschritt und überdies eine rasante Entwicklung von Literatur, Kunst und Musik sowie der Philosophie und der Politischen Theorie einher. Die adligen Wunderkammern begannen zu Museen im modernen Sinne zu werden. Das Misstrauen gegenüber Luxus und Sensationshunger wich mit ihrer zunehmenden Verfügbarkeit. Beschäftigung mit Literatur, Kunst und Wissenschaft sollte einem (zunächst wohlhabenden) Bürgertum ermöglicht werden und wurde zur Tugend erklärt. Philosophie, die sich mehr und mehr ausdifferenzierte, Mathematik, Naturkunde und Technik erlebten eine Blütezeit, auf deren Ergebnissen viele der heutigen Einzelwissenschaften beruhen. Jean-Baptiste le Rond d’Alembert bezeichnete seine Zeit als „Jahrhundert der Wissenschaft“.[2] Die letzten Universalgelehrten lebten in der frühen Aufklärungszeit. Eine weitere Forderung war die nach Toleranz. Die christlich geprägten gebildeten Europäer lernten andere Weltreligionen und Hochkulturen erst während der Aufklärung kennen. Dieses neu erlangte Wissen erweiterte den Horizont, trug zur Akzeptanz anderer Denkmodelle bei oder ließ den „edlen Wilden“ gar zum Vorbild werden, wie es sich in zahlreichen Kommentaren zu Reiseberichten spiegelt, die von Jean-Jacques Rousseaus Abhandlung über den Ursprung und die Grundlagen der Ungleichheit unter den Menschen (1755) inspiriert waren. Gleichzeitig verschrieben sich die Aufklärer dem Kampf gegen Aberglaube und Mystizismus. Gegen der Vernunft widersprechende Religiosität wurde mit scharfer Polemik zu Felde gezogen. |

概要 啓蒙思想は、近代の哲学における二つの潮流、すなわち、ルネ・デカルトに代表される合理主義と、アメリカの憲法原則の形成に影響を与えたジョン・ロックに 代表される英国経験主義によって形作られた。一方では、認識は感覚から生じるという経験主義者の考え(感覚主義)が広まり、他方では、理性に基づく思考能 力や判断力が高く評価されるようになった。 この時代は、多くの変化によって特徴づけられた。絶対主義の代わりに自由、身分制度に代わる法的平等、科学的知見と寛容が偏見を克服し、従来の教義に取っ て代わるべきだと考えられた。大多数、特にフランスの啓蒙思想家たちは、人間は本来善良であり、徳高く、平和で幸せな生活を送るためには教育だけが必要だ と確信していた。啓蒙思想の先駆者たちは、人類の進化についても、文化と歴史に対する楽観的な見方をしてた。 合理主義者たちの論理的で独立した思考は、当初は国家の強化に向けられたものであり、宗教を批判する傾向があり、それは当面、世俗的な権力者たちに対し て、精神的権力者たちに対する強化を目的としていた。しかし、その批判的な判断はすぐに世俗的な支配者たちにも向けられるようになった。宗教や絶対主義に 対する疑念が急速に広まった。ドイツの作家であり数学者でもあるゲオルク・クリストフ・リヒテンベルクは、その格言集[1]の中で、「少なくとも一度は、 すべてに疑いを抱け。たとえそれが、2×2=4という式であっても」とさえ要求した。 フランスでは、貴族や下級聖職者(アベなど)の一部、そして第三身分のエリート層も、彼らの合法的な支配者の弱体化を歓迎した。ヨーロッパの貴族や聖職者 間の対立により、こうした動きは抑圧されることはなかった。製造業の発展などの経済の変化により、ブルジョアジーは経済的に最も重要な階層となり、新たな 自己意識と自尊心を得た。  作品:古代をモデルとした科学アカデミー、1698年 バロック時代と比較して、ヴァニタスや来世に関する考え方が根本的に変化した。死後の世界への関心は、この世への強い関心へと変化した。倫理も、もはや神 学やその他の前提条件に基づくものではない。教育はより重要視されるようになり、伝統的に社会的特権と結びついていた情報へのアクセスは争点となり、18 世紀半ばには、何度も禁止された百科事典のプロジェクトという形で、あらゆる知識の集大成として頂点に達した。啓蒙主義は、自然科学や技術における膨大な 知識の進歩、さらに文学、芸術、音楽、哲学、政治理論の急速な発展を伴った。 貴族の珍品館は、現代的な意味での博物館へと変化し始めた。贅沢やセンセーショナルな事柄に対する不信感は、それらの入手可能性が高まるにつれて薄れて いった。文学、芸術、科学への関心が(当初は富裕な)市民層にも可能となり、それは美徳と宣言された。ますます多様化していく哲学、数学、自然科学、技術 は隆盛期を迎え、その成果は今日の多くの個別科学の基礎となっている。ジャン=バティスト・ル・ロンド・ダルランベールは、その時代を「科学の世紀」と呼 んだ[2]。最後の博学者たちは、啓蒙主義の初期に生きていた。 もう一つの要求は、寛容さだった。キリスト教の影響を受けた教養のあるヨーロッパ人は、啓蒙主義の時代に初めて他の世界宗教や高度な文明について知った。 この新たに得た知識は、視野を広げ、他の思考モデルの受容に貢献し、さらには「高貴な野蛮人」を模範とさえするようになった。これは、ジャン=ジャック・ ルソーの『人間不平等起源論』(1755年)に触発された旅行記への数多くのコメントにも反映されている。同時に、啓蒙主義者たちは迷信や神秘主義との戦 いに専心した。理性と矛盾する宗教性は、鋭い論争で攻撃された。 |

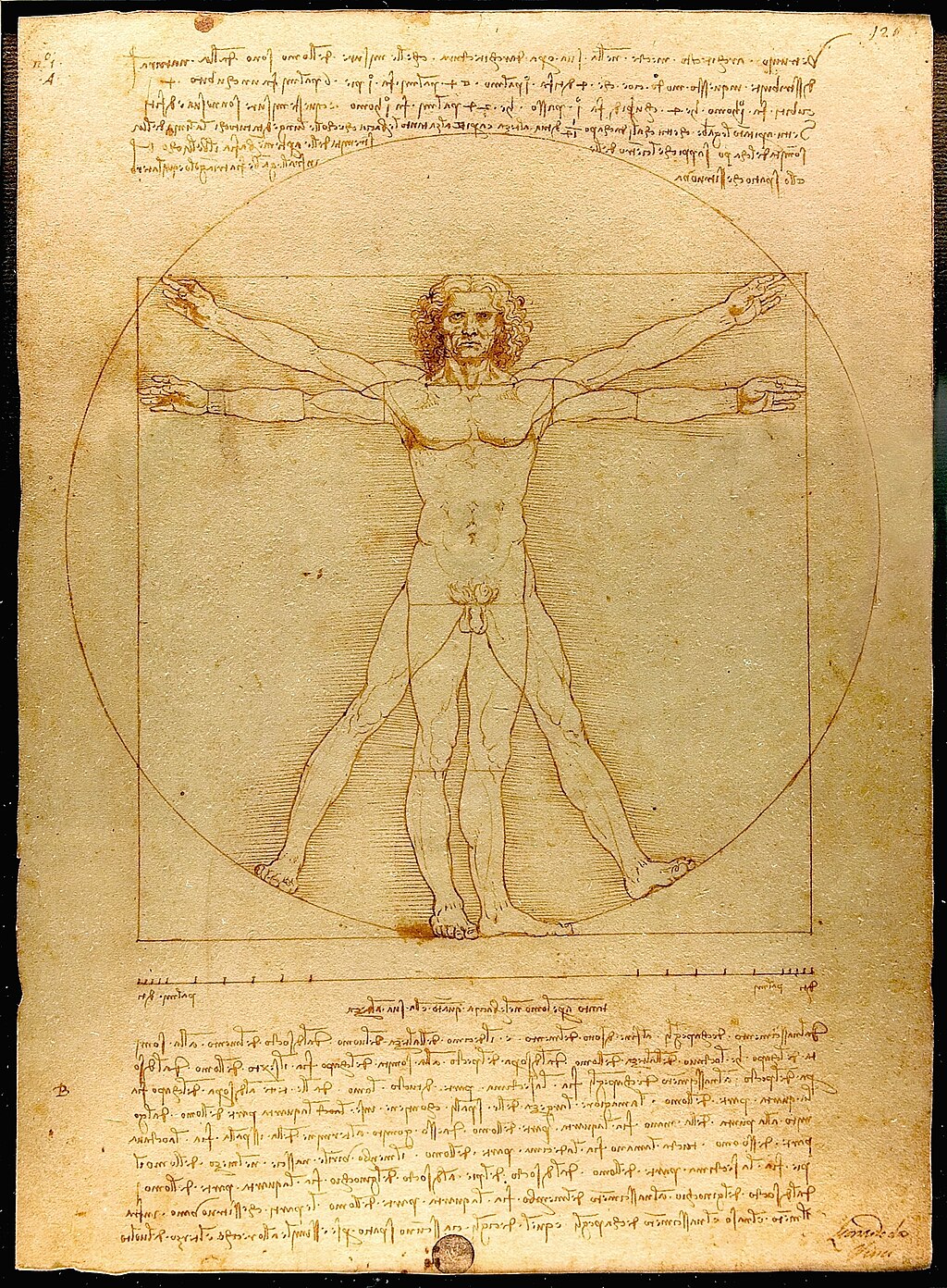

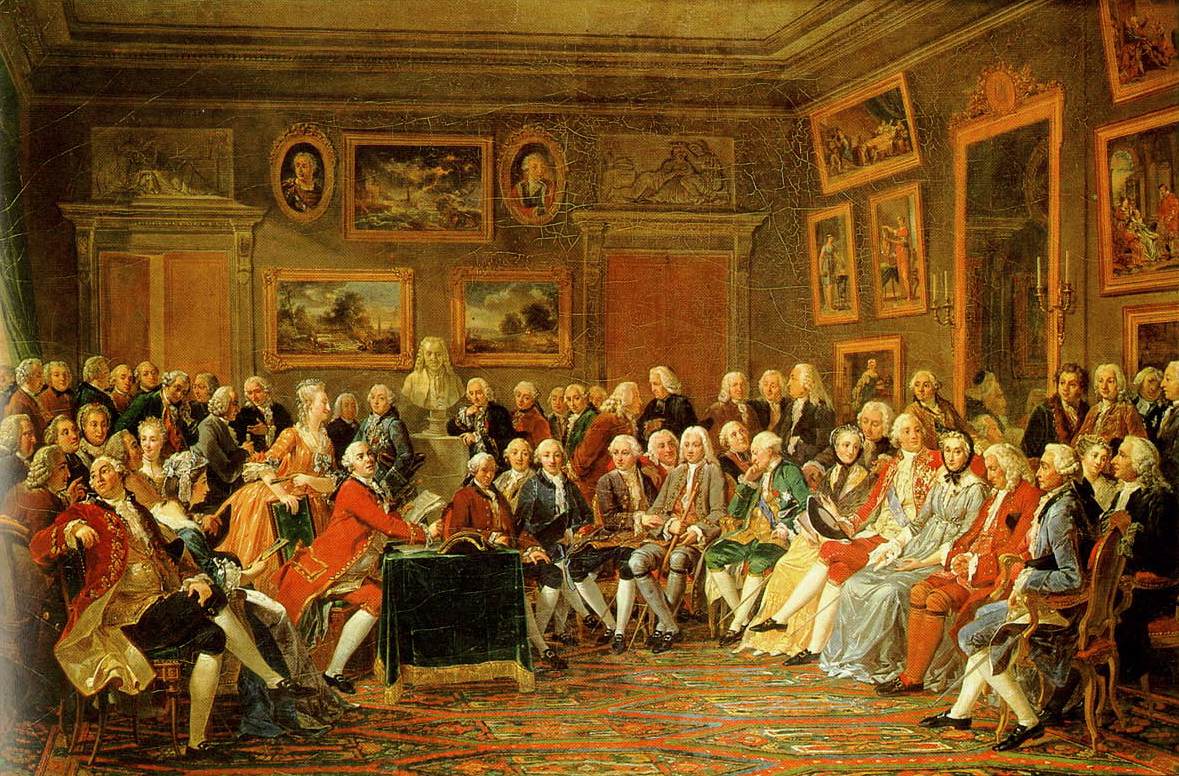

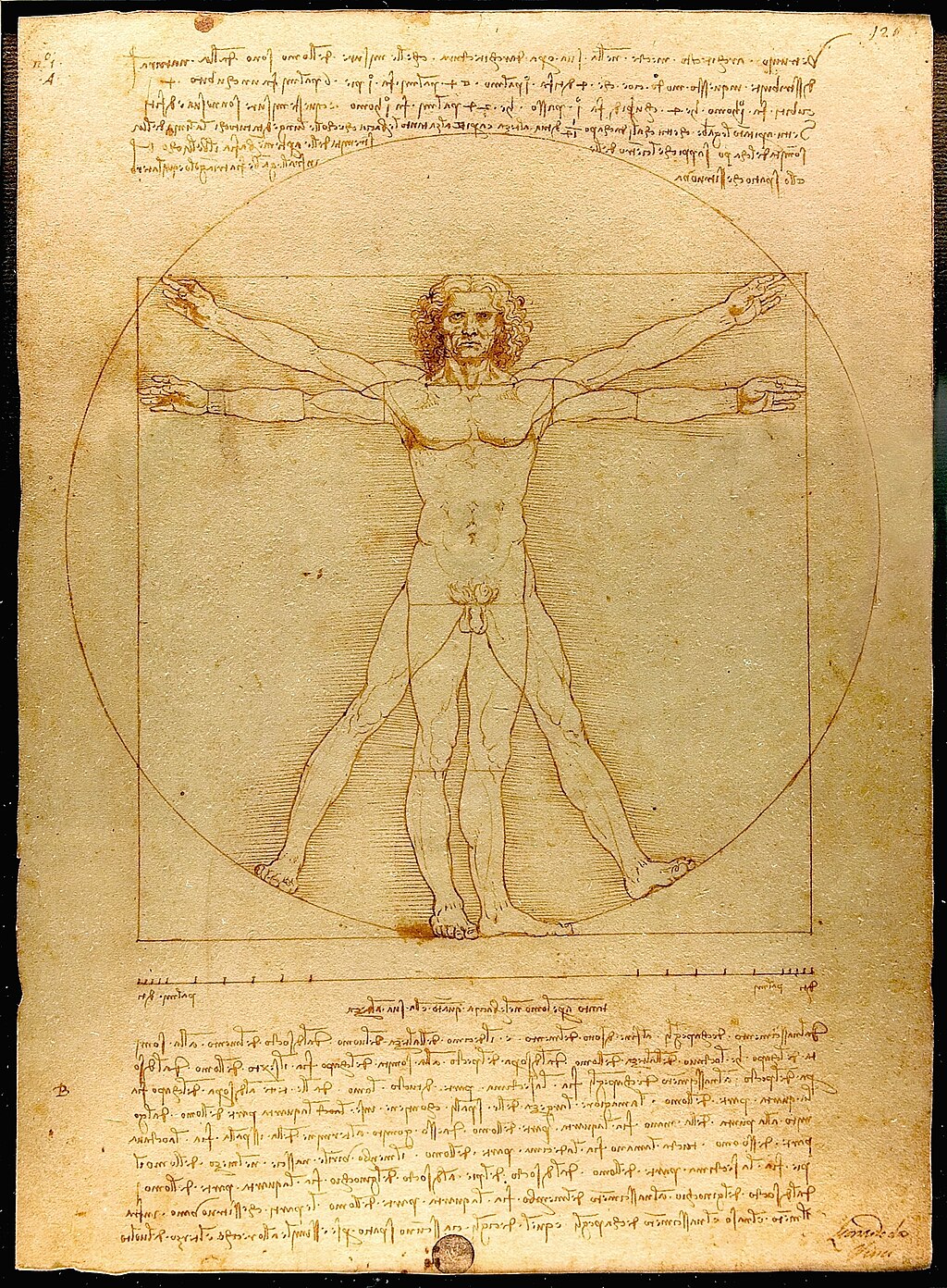

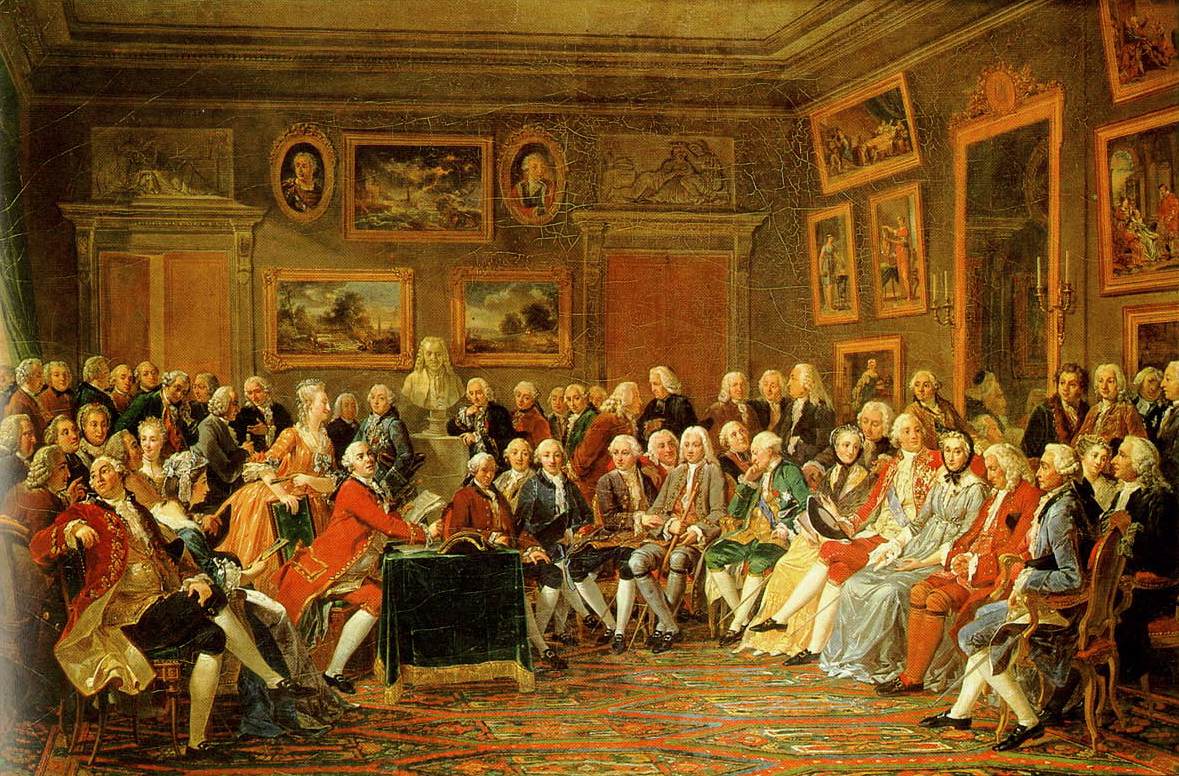

Wurzeln und Ausprägung Leonardo da Vinci (1492), Universalgelehrter der Renaissance Die moderne europäische Aufklärung, verstanden als Abkehr von einer christlich-mittelalterlichen Lebenshaltung, begann in der Renaissance, als Elemente der Antike vom Gegenbild zum Vorbild gemacht wurden. Renaissance und Reformation leiteten das Zeitalter der Aufklärung ein. Grundlegend dafür war einerseits die republikanische Regierungszeit Oliver Cromwells Mitte des 17. Jahrhunderts und 1688/89 die Glorious Revolution in England, die dort dem Absolutismus ein Ende bereitete, andererseits die Konsolidierung der französischen Staatsmacht im 17. Jahrhundert mit dem Höhepunkt absolutistischer Machtentfaltung unter Ludwig XIV.  Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, rationalistischer Universalgelehrter der Frühaufklärung Aufklärung im Sinne eines Postulats von Herrschaft der Vernunft gab es seit den großen Universalgelehrten des 17. Jahrhunderts[3] mit ihren bahnbrechenden wissenschaftlichen Forschungen: Descartes in Frankreich, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in Deutschland und Isaac Newton in England. Die geistige Aufklärung ging zunächst hauptsächlich von England und Holland aus, davon beeinflusst und radikaler ausgeprägt von Frankreich. Etwas später erfasste sie auch die Deutschen und andere Völker in Europa. Die wichtigsten Voraussetzungen für die Aufklärung waren der vorausgegangene Humanismus, die Entdeckung Amerikas und das Weltbild der frühen Neuzeit. Durch den Buchdruck wurde allmählich der Bucherwerb auch für das bürgerliche Publikum erschwinglich, wodurch ein Verlagswesen mit Zeitungsproduktion und Buchmarkt aufkam. Zudem entwickelten sich sogenannte Lesegesellschaften, über die auch Bürger, die des Lesens nicht mächtig waren, an die Literatur herangeführt wurden. Gegen Ende des 17. Jahrhunderts kam Reiseliteratur in Mode. Hatte man zuvor den Europäer (und Christen) für überlegen gehalten, las man nun, dass manche Anders- oder Ungläubige sehr wohl ethische Prinzipien und eine eigene Hochkultur haben konnten. So übte die Reiseliteratur jener Tage mehr oder weniger deutliche Kritik an der europäischen Gesellschaft. In fiktiven Reiseberichten, zum Beispiel Montesquieus Persischen Briefen, in denen zwei Perser Europa besuchen, sehen die Leser ihre Welt durch die Augen der Fremden – reich an satirischen Elementen, Voltaire lässt einen Indianer den französischen Absolutismus erkunden.[4]  Salon der Madame Geoffrin In Frankreich bildeten sich im 18. Jahrhundert, vereinzelt schon im 17. Jahrhundert Literarische Salons, die meistens von gebildeten Frauen geführt wurden, so die Salons der Madame de Deffand, ihrer Nachfolgerin Julie de Lespinasse und der Madame Necker. Hier verkehrten die Erneuerer von Kultur, Wissenschaft und Politik. Dem Salon der philosophes, auch cercle d’Auteuil (Kreis von Auteuil)[5] genannt, stand Anne-Catherine de Ligniville Helvétius vor. Aufgrund der strengen Zensur im eigenen Land arbeiteten einige französische Druckereien in Amsterdam, wo auch berühmte Aufklärer Zuflucht fanden. Schriften wurden von dort nach Frankreich geschmuggelt. Das gleiche Muster zeigte sich in Österreich; viele Druckwerke erschienen in Deutschland. In den Londoner Debating Societies tauschten sich gebildete Männer erstmals 1780 über öffentliche Angelegenheiten aus. Das Zeitalter der Aufklärung war geprägt durch eine Bewegung der Säkularisierung und eine Abkehr von der absolutistischen hin zu einer demokratischen Staatsauffassung. Die englischen Aufklärer nannten sich „Free-Thinker“, ein Begriff, der auch in Frankreich (Libre Penseur) und Deutschland (Freidenker) verwendet wurde. Das liberale Konzept der Menschen- und Bürgerrechte kam auf. Es ging auf John Locke[6] zurück, der natürliche Rechte auf Leben, Freiheit, Glück und Eigentum sowie ein Widerstandsrecht gegen eine despotische Obrigkeit postulierte.[7] Die Bewegung trat für ein vernunftgemäßes, selbständiges Denken ein, lehnte Vorurteile, Fanatismus und „religiösen Aberglauben“ ab und entwickelte eine „Vernunftreligion“ mit dem Glauben an einen Gott, den sogenannten Deismus, der von manchen Aufklärern wie David Hume und Jean-Jacques Rousseau nicht auf den Verstand, sondern auf die Gefühle zurückgeführt wurde. Anhänger der Aufklärung waren tolerante Christen bzw. Juden, Deisten, Pantheisten, Agnostiker oder leiteten ihren Atheismus aus einem konsequenten Materialismus ab. Einigkeit bestand darüber, dass Wissenschaft und Bildung gefördert und verbreitet werden sollten. Die Wohlhabenden und Gebildeten, vorrangig das ökonomisch erfolgreiche Bürgertum, waren Träger der Aufklärung. Es gab aber auch zahlreiche Aristokraten als Vorläufer oder Vertreter des Aufklärungsgedankens. Manche sympathisierten mit der Bewegung und unterstützten in juristische oder finanzielle Bedrängnis geratene Aufklärer. Marie Jean Antoine Nicolas Caritat, Marquis de Condorcet ging so weit, seinen Adelstitel Markgraf abzulegen und sich fortan Nicolas de Condorcet zu nennen.[8] Große Bedeutung erlangte die Freimaurerei – entstanden im 18. Jahrhundert – mit ihren Grundpfeilern: Freiheit, Gleichheit, Brüderlichkeit, Toleranz und Humanität. Im Berliner jüdischen Bildungsbürgertum begründete 1770 der bekannte Philosoph Moses Mendelssohn die Haskala, eine Vereinigung, die sich innerhalb der Aufklärung die jüdische Emanzipation und Gleichberechtigung zum Ziel gesetzt hatte. |

ルーツと特徴 レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチ(1492)、ルネサンスの博学者 キリスト教と中世の生活様式からの脱却として理解される、近代ヨーロッパの啓蒙主義は、古代の要素が対極的なイメージから模範的なイメージへと変化したル ネサンス期に始まった。ルネサンスと宗教改革は、啓蒙主義の時代を切り開いた。その基礎となったのは、17世紀半ばのオリバー・クロムウェルの共和政、 1688年から1689年にかけてのイングランドの栄光の革命(絶対主義に終止符を打った)、そして17世紀のフランス国家権力の統合と、ルイ14世によ る絶対主義の権力拡大の頂点だった。  ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツ、啓蒙初期における合理主義の博学者 理性による支配という仮説としての啓蒙は、17 世紀の偉大な博学者たち[3] による画期的な科学的研究によって始まった。フランスではデカルト、ドイツではゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツ、イギリスではアイザック・ ニュートンである。 知的啓蒙は、当初は主にイギリスとオランダで始まり、その影響を受けて、フランスでより過激な形で展開された。その後、ドイツやヨーロッパの他の国々にも 広がった。 啓蒙主義の最も重要な前提条件は、それ以前のヒューマニズム、アメリカ大陸の発見、そして近世の世界観だった。活版印刷によって、市民層も徐々に本を購入 できるようになったため、新聞の制作や書籍市場を扱う出版業界が台頭した。さらに、いわゆる読書会も発展し、読書ができない市民も文学に触れることができ るようになった。 17 世紀の終わり頃、旅行文学が流行した。それまでは、ヨーロッパ人(およびキリスト教徒)が優越的であると見なされていたが、今では、異なる信仰を持つ者や 非信者にも、倫理的原則や独自の高度な文化があることが書かれるようになった。こうして、当時の旅行文学は、多かれ少なかれ、ヨーロッパ社会を批判する内 容だった。2人のペルシャ人がヨーロッパを訪れるモンテスキューの『ペルシャの書簡』などの架空の旅行記では、読者は見知らぬ人々の目を通して自分の世界 を見る。この作品には風刺的な要素が多く、ヴォルテールは、フランス絶対主義をインディアンに探求させている。  マダム・ジェフランのサロン フランスでは、18 世紀、そして 17 世紀にも散見されるようになった文学サロンが、主に教養のある女性たちによって運営されていた。マダム・ド・デファン、その後継者であるジュリー・ド・レ スピナッセ、マダム・ネッケルなどのサロンがそれだ。ここでは、文化、科学、政治の革新者たちが交流していた。哲学者たちのサロン、別名サークル・ドー トゥイユ(オートゥイユのサークル)は、アンヌ・カトリーヌ・ド・リニヴィル・エルヴェティウスが主宰した。自国での厳しい検閲のため、一部のフランスの 印刷所は、有名な啓蒙思想家たちも避難したアムステルダムで労働していた。印刷物はそこからフランスに密輸された。オーストリアでも同様の傾向が見られ、 多くの印刷物がドイツで出版された。ロンドンの討論会では、1780年に初めて、教養のある男性たちが公共の問題について意見交換を行った。 啓蒙時代は、世俗化の動きと、絶対主義から民主主義への国家観の転換によって特徴づけられた。イギリスの啓蒙思想家たちは、自分たちを「自由思想家」と呼 んでおり、この用語はフランス(Libre Penseur)やドイツ(Freidenker)でも使用されていた。人権と市民権の自由主義的な概念が登場した。これは、生命、自由、幸福、財産に対 する自然権、および専制的な権力に対する抵抗の権利を提唱したジョン・ロック[6] に端を発している。この運動は、理性に基づく自立的な思考を提唱し、偏見、狂信、「宗教的迷信」を拒絶し、神を信じる「理性宗教」、いわゆる自然神論を発 展させた。デヴィッド・ヒュームやジャン・ジャック・ルソーなどの啓蒙思想家たちは、この自然神論を理性ではなく感情に起因するものと見なした。 啓蒙思想の支持者は、寛容なキリスト教徒やユダヤ教徒、自然神論者、汎神論者、不可知論者、あるいは一貫した唯物論から無神論を導き出した人々だった。科 学と教育を促進し、普及させるべきだという点では、意見の一致が見られた。 富裕層や知識層、とりわけ経済的に成功したブルジョアジーが、啓蒙思想の担い手だった。しかし、啓蒙思想の先駆者や代表者として、多くの貴族もいた。この 運動に共感し、法的または経済的に困難な状況に陥った啓蒙思想家を支援した者もいた。マリー・ジャン・アントワーヌ・ニコラ・カリタ、コンドルセ侯爵は、 貴族の称号を放棄し、以後、ニコラ・ド・コンドルセと名乗るほどだった。[8] 18 世紀に誕生したフリーメイソンは、自由、平等、友愛、寛容、人道という基本理念で大きな重要性を獲得した。1770年、ベルリンのユダヤ人知識層の中で、 有名な哲学者モーゼス・メンデルスゾーンが、啓蒙主義の中でユダヤ人の解放と平等を目標とした団体、ハスカラーを設立した。 |

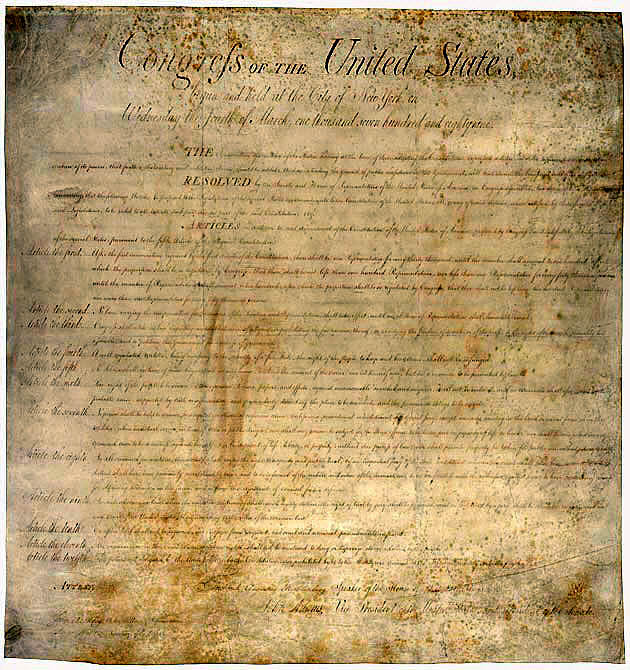

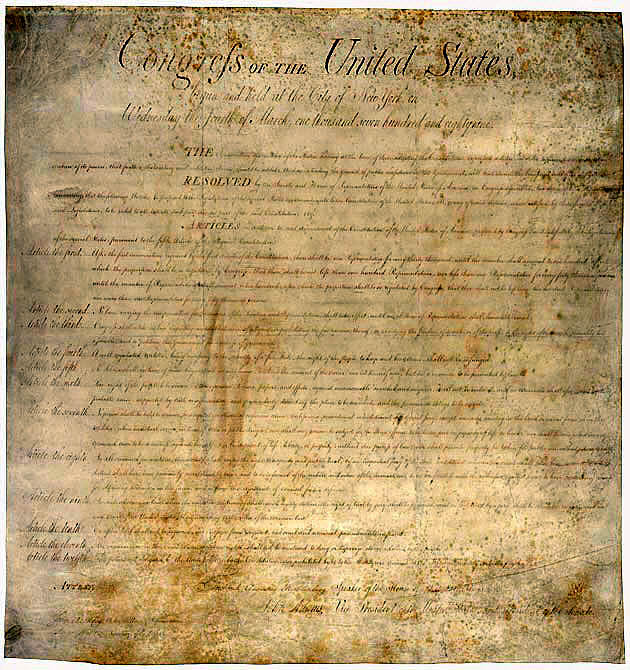

Die Bill of Rights der Vereinigten Staaten: Unveräußerliche Grundrechte Als eine der wichtigsten praktischen Errungenschaften der Aufklärung gelten die englischen Bill of Rights aus dem Jahre 1689, die die Rechte des Parlaments gegenüber dem Monarchen festlegten, und ungefähr hundert Jahre später die Verabschiedung der ersten demokratischen Verfassungen der Neuzeit. Hiermit wurde die geistige Aufklärung auf Staaten und Gesellschaften übertragen. In erster Linie Locke, Montesquieu und Rousseau formulierten die theoretischen Grundlagen. Die erste dieser Verfassungen war die Declaration of Independence (Unabhängigkeitserklärung) der 13 Gründungskolonien der USA am 4. Juli 1776 – von Thomas Jefferson verfasst, durch Benjamin Franklin und John Adams ergänzt. In ihre Präambel wurden die natürlichen von der Schöpfung her gegebenen unveräußerlichen Rechte auf Leben, Freiheit und Streben nach Glück aufgenommen. Wenig später folgte die Verfassung der Vereinigten Staaten 1787 einschließlich der Bill of Rights, als deren Vater James Madison gilt. Kurz nach dem Beginn der Französischen Revolution durch den Sturm auf die Bastille am 14. Juli 1789 verabschiedete die erste französische Nationalversammlung am 26. August 1789 die Erklärung der Menschen- und Bürgerrechte, die zur Präambel der Verfassung von 1791 wurde.[9] In Polen-Litauen wurde am 3. Mai desselben Jahres ebenfalls eine moderne Verfassung verabschiedet. Die Erklärung der Rechte der Frau und Bürgerin, verfasst von Olympe de Gouges ebenfalls im Jahr 1791 als Vorlage für die Nationalversammlung, blieb – wie nicht anders zu erwarten – folgenlos. Derweil die britischen und nordamerikanischen Aufklärer eher liberalen Zielen anhingen, setzten sich die meisten Franzosen stark für die allgemeine wirtschaftliche und soziale Wohlfahrt[10] ein, eine Tendenz, die auch heute noch von Bedeutung ist. Obgleich die Aufklärung nicht die einzige Ursache der Französischen Revolution war, hat sie diese doch in vielen Aspekten geprägt: Ihre Führer, radikale Anhänger der Aufklärung – inzwischen teilweise unduldsam geworden –, schafften den Einfluss der katholischen Kirche ab und ordneten Kalender, Uhr, Maße, Geldsystem und Gesetze anhand rein rationaler Kriterien neu. Die Französische Revolution markiert gemeinhin das Ende der Aufklärung im Sinne einer Epoche. Als Gegenströmung zum Rationalismus des späten 17. Jahrhunderts gab es seit 1720, in England und Frankreich schon 20 Jahre früher, die Empfindsamkeit als eine Variante der Aufklärung, befördert etwa durch Jean-Baptiste Dubos.[11] Sie beruhte teilweise auf den gleichen Idealen wie die vernunftorientierte Aufklärung, ein Unterschied war jedoch, dass die Tugend nicht nur über den Verstand gesucht wurde, sondern auch im Gefühl. Menschliche Gefühlsregungen waren eine wichtige Möglichkeit, ethisch zu denken und zu handeln. Einflussreich war dabei die Vorstellung, dass das reine Gefühl die Standesgrenzen überschreitet. |

アメリカ合衆国の権利章典:譲渡不可能な基本的権利 啓蒙主義の最も重要な実践的成果としては、1689年に制定された英国権利章典が挙げられる。これは、君主に対する議会の権利を定めたものであり、その約 100年後、近代初の民主的な憲法が制定された。これにより、知的啓蒙主義は国家や社会にも広まった。その理論的基礎を主に構築したのは、ロック、モンテ スキュー、ルソーだった。最初の憲法は、1776年7月4日に米国の13の植民地が発表した独立宣言だった。これはトーマス・ジェファーソンが起草し、ベ ンジャミン・フランクリンとジョン・アダムズが補足した。その前文には、創造主から与えられた、生命、自由、幸福を追求する不可侵の自然権が盛り込まれ た。その少し後、1787年に、ジェームズ・マディソンが起草した権利章典を含むアメリカ合衆国憲法が制定された。フランス革命が1789年7月14日の バスティーユ襲撃によって始まった直後、1789年8月26日に、最初のフランス国民議会が、1791年憲法の前文となった人権宣言を採択した。[9] ポーランド・リトアニアでも、同年5月3日に近代的な憲法が採択された。オリンペ・ド・グージュが1791年に国民議会の草案として起草した「女性および 市民の権利の宣言」は、当然のことながら、何の結果も生まなかった。英国の啓蒙思想家や北米の啓蒙思想家は、どちらかといえばリベラルな目標を掲げていた のに対し、ほとんどのフランス人は、一般的な経済的・社会的福祉[10] を強く支持していた。この傾向は、今日でもなお重要だ。 啓蒙主義はフランス革命の唯一の要因ではなかったが、多くの面で革命に影響を与えた。その指導者たちは、啓蒙主義の急進的な支持者たち(その一部はその後 不寛容になった)であり、カトリック教会の影響力を排除し、カレンダー、時計、測定単位、通貨制度、法律などを純粋に合理的な基準に基づいて再編成した。 フランス革命は、一般的に、一つの時代としての啓蒙主義の終焉を意味している。 17 世紀後半の合理主義に対する反動として、1720 年以降、イギリスとフランスでは 20 年も早く、ジャン=バティスト・デュボなどによって推進された、啓蒙主義の一形態である感傷主義が台頭した。[11] これは、理性中心の啓蒙主義と同じ理想に一部基づいていたが、違いは、美徳が理性だけでなく感情からも追求された点だった。人間の感情は、倫理的に考え、 行動するための重要な手段だった。純粋な感情は身分の境界を越えるという考え方が、この動きに影響を与えた。 |

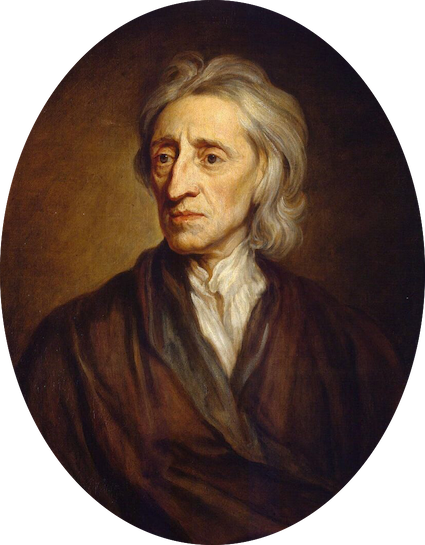

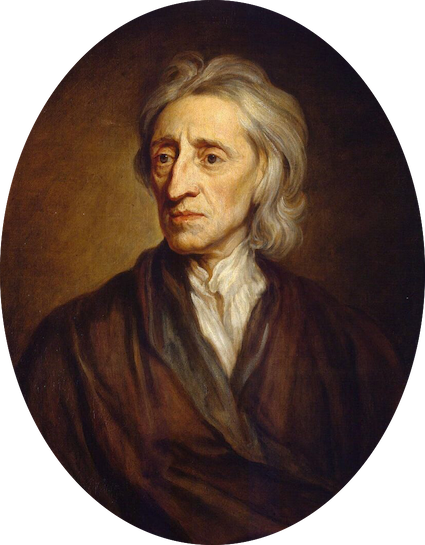

Protagonisten der

Aufklärungsgedanken John Locke (1632–1704) Der holländische rationalistische Philosoph Baruch de Spinoza vertrat in seinem Tractatus theologico-politicus von 1670 die These, Judentum und Christentum seien lediglich vergängliche Phänomene ohne absolute Gültigkeit. Samuel von Pufendorf, politischer Philosoph und früher deutscher Völkerrechtler, führte das Konzept der natürlichen säkularen Menschenwürde ein, welches später in die modernen Verfassungen aufgenommen wurde. Die Forderung nach Gedanken- und Glaubensfreiheit konnte sich unter anderem auf John Lockes Briefe über die Toleranz (1689–1692) berufen. Diese Briefe bezogen sich auf (eingeschränkte) religiöse Toleranz.[12] Seitdem wurde die Toleranzidee von verschiedenen Gelehrten und Schriftstellern verbreitet. Ungefähr 70 Jahre später, 1763, sprach sich Voltaire in seiner „Abhandlung über den Toleranzgedanken“ (Traité sur la tolérance) endlich für uneingeschränkte Glaubens- und Gewissensfreiheit aus. Nochmals mehr als ein Jahrzehnt später schrieb der deutsche Dichter Gotthold Ephraim Lessing: „An die Stelle der Religion muss die Überzeugung treten.“[13] John Toland veröffentlichte 1696 sein Erstlingswerk Christianity not Mysterious, in dem er versuchte, das Christentum mit der Vernunft in Einklang zu bringen. Er argumentierte, die Bibel beschreibe keine realen Wunder außerhalb der Naturgesetze, fast alle christlichen Glaubenssätze seien rational zu erklären. 1709 verwendete er erstmals den Begriff Pantheismus – eine Weltanschauung, deren Vertreter sich auf Spinoza bezogen. Gott sah er als Summe aller Materie. In den Literarischen Salons zuhause war der erste philosophe – ein vielseitig gebildeter Autor mit literarischen, philosophischen und unterhaltsamen naturwissenschaftlichen Veröffentlichungen – Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle. Ein weiterer herausragender französischer Frühaufklärer Pierre Bayle attackierte den Aberglauben, dass Kometen Unheil ankündigen und andere Vorurteile, setzte sich für eine Trennung von Kirche und Staat ein und verlangte vollständige Religionsfreiheit. In seinem 1695–1697 erschienenen zweibändigen Hauptwerk Dictionnaire historique et critique (Kritisch-Historisches Lexikon) belegte er kurze lexikalische Sachartikel mit unterschiedlichen ausführlich dargestellten Quellen, die häufig auf gegensätzlichen Annahmen beruhten und entwickelte damit die moderne historische Quellenkritik. Jean Meslier, der bis zu seinem Tod 1729 praktizierender katholischer Priester war, legte in seinen – wegen der Zensur und seiner Stellung nur heimlich verbreiteten, erst lange nach seinem Tod vollständig veröffentlichten – religions- und kirchenkritischen Aufzeichnungen seine materialistisch-atheistische Überzeugung dar. Um die Jahrhundertwende entwickelte der englische Moralphilosoph und Philanthrop Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3. Earl of Shaftesbury ein modernes psychologisches Menschenbild, wonach das Individuum mit seinem Verstand aufgrund von Erziehung versucht, Triebe, Leidenschaften und Gefühle, die wesentlich sind, zwischen Egoismus und Altruismus auszubalancieren. Gelingt dies harmonisch, handelt der Mensch tugendhaft als Teil und zum Wohle einer sozialen Gemeinschaft. Noch vor Francis Hutcheson sprach Shaftesbury vom „moralischen Sinn“, worunter er die Fähigkeit des Menschen versteht, den moralischen Wert seiner Handlungen zu erkennen. Politisch äußerte sich Gerhard Noodt, Rektor der Universität Leiden. In einer Rektoratsrede 1699 proklamierte er, dass dem Fürsten die Macht vom Volk genommen werden könne. 1707 befürwortete er in einer weiteren Rede die absolute Freiheit der Untertanen in Religionsfragen. Grundlegende Werke zur politischen Philosophie und zum Völkerrecht schrieben der Holländer Hugo Grotius – Wegbereiter des Souveränitätsgedankens – und sein englischer Freund, der Dichter und republikanische Staatsphilosoph John Milton, der sich auch für die Pressefreiheit starkmachte. Seine politischen Pamphlete für eine freie Republik wurden sowohl in Frankreich wie auch in England öffentlich verbrannt. Der deutsche Jurist und Philosoph Christian Thomasius wandte sich nicht nur – wie schon vor ihm der Holländer Balthasar Bekker – gegen die Hexenverfolgungen, sondern lehnte auch die Folter im Allgemeinen ab und forderte eine Humanisierung des gesamten Strafrechts. Vom Naturrecht ausgehend, erarbeitete der rationalistische Philosoph und Gelehrte Christian Wolff ein theoretisches Konzept für Justizreformen und schuf noch heute gebräuchliche Kategorien der Philosophie.[14] Dabei bezog er sich auf das leibnizsche Denken. Während die meisten Aufklärer religiöse Traditionen einer göttlichen Offenbarung ablehnten, wollte er Vernunft mit Offenbarung versöhnen. |

啓蒙思想の主人公たち ジョン・ロック(1632年~1704年) オランダの合理主義哲学者バルーク・デ・スピノザは、1670年の『神学政治論』の中で、ユダヤ教とキリスト教は、絶対的な有効性を持たない、一時的な現 象にすぎないという説を唱えた。政治哲学者であり、初期のドイツ国際法学者であるサミュエル・フォン・プフェンドルフは、自然的な世俗的人間の尊厳という 概念を導入し、それは後に現代の憲法に盛り込まれた。思想と信仰の自由を求める声は、ジョン・ロックの『寛容に関する手紙』(1689年~1692年)な どを根拠としていた。これらの手紙は(限定的な)宗教的寛容について言及していた。[12] それ以来、寛容の考えはさまざまな学者や作家によって広められた。それから約 70 年後の 1763 年、ヴォルテールは『寛容に関する論文』(Traité sur la tolérance)の中で、ついに無制限の信仰と良心の自由を主張した。さらに 10 年以上後、ドイツの詩人ゴットホルト・エフライム・レッシングは、「宗教の代わりに信念が取って代わらなければならない」と書いた[13]。 ジョン・トーランドは1696年、処女作『キリスト教は神秘ではない』を出版し、キリスト教と理性を調和させようとした。彼は、聖書は自然法則の外にある 現実の奇跡について記述しているわけではなく、キリスト教の教義のほとんどすべては合理的に説明できると主張した。1709年、彼は初めて「汎神論」とい う用語を使用した。これは、スピノザを参考にした世界観である。彼は、神をすべての物質の総体として捉えていた。文学サロンでは、文学、哲学、娯楽的な自 然科学の出版物を手掛ける、多才な教養のある作家、ベルナール・ル・ボヴィエ・ド・フォンテネルが最初の哲学者として知られていた。もう一人の傑出したフ ランス人初期啓蒙思想家、ピエール・ベイルは、彗星は災いをもたらすという迷信やその他の偏見を攻撃し、教会と国家の分離を主張し、完全な宗教の自由を要 求した。1695年から1697年に出版された2巻からなる彼の主要著作『歴史的・批判的辞典』では、短い事典的記事に、しばしば相反する仮定に基づくさ まざまな詳細な情報源を引用し、それによって現代の歴史的情報源批判を発展させた。1729年に亡くなるまでカトリックの司祭として活動したジャン・メリ エは、検閲と自身の立場のために密かに配布され、死後かなり経ってから初めて完全版が刊行された、宗教や教会を批判する記録の中で、唯物論的・無神論的な 信念を述べた。 世紀の変わり目に、イギリスの道徳哲学者であり慈善家でもあったアンソニー・アシュリー・クーパー、 シャフトズベリー伯爵は、教育によって、個人はその理性をもって、利己主義と利他主義の間で、本能、情熱、感情といった本質的な要素のバランスを取ろうと する、という現代的な人間観を打ち立てた。これが調和的に成功すれば、人間は社会共同体の一部として、その利益のために、徳のある行動をとる。フランシ ス・ハッチェソンよりも前に、シャフトズベリーは「道徳的感覚」について語っており、それは人間が自分の行動の道徳的価値を認識する能力であると理解して いた。 ライデン大学の学長、ゲルハルト・ヌートは政治について意見を述べた。1699年の学長演説で、彼は、君主は国民から権力を奪われる可能性があると宣言し た。1707年には、別の演説で、宗教問題における臣民の絶対的な自由を支持した。政治哲学と国際法に関する基礎的な著作は、主権思想の先駆者であるオラ ンダのフーゴ・グロティウスと、その友人である英国の詩人であり共和主義の政治哲学者であり、報道の自由も強く主張したジョン・ミルトンによって書かれ た。自由共和国を提唱した彼の政治パンフレットは、フランスとイギリスで公に焼却された。ドイツの法学者であり哲学者でもあるクリスティアン・トマシウス は、彼以前のオランダ人バルタザール・ベッカーと同様に、魔女狩りに反対しただけでなく、拷問全般を拒否し、刑法全体の非人道的な側面を改善するよう求め た。自然法に基づいて、合理主義の哲学者であり学者でもあるクリスティアン・ヴォルフは、司法改革のための理論的コンセプトを考案し、今日でも使用されて いる哲学のカテゴリーを創り出した[14]。その際、彼はライプニッツの思想を参照した。啓蒙思想家のほとんどが、神による啓示という宗教的伝統を否定し ていたのに対し、彼は理性と啓示の調和を図ろうとした。 |

Denis Diderot Viele Menschen im Zeitalter der Aufklärung beflügelte der Glaube, Vernunft, Freiheit und Bildung würden die Menschheit in absehbarer Zeit von Unterdrückung, Krieg und Armut erlösen. Sie schenkten dem Diktum „Wissen ist Macht“ von Francis Bacon Vertrauen. In Frankreich entstand die berühmte Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers. Herausgegeben wurde sie von dem Schriftsteller Denis Diderot und dem Mathematiker und Physiker Jean-Baptiste le Rond d’Alembert. Als sich Letzterer zurückzog, trat der kleine Landadelige Louis de Jaucourt an seine Stelle, der mit Hilfe von eigens eingestellten Sekretären mehr als 15000 der ca. 60000 Beiträge lieferte. Berühmte französische Dichter und Gelehrte („philosophes“) wie Voltaire, Montesquieu und Rousseau schrieben Artikel für das monumentale Werk der Aufklärung. Die Enzyklopädie sollte das gesamte Wissen und Können der Menschheit gegen den Widerstand weltlicher und geistlicher Machthaber öffentlich verfügbar machen. Sie hatte insgesamt mehr als 150 Autoren, die sogenannten Enzyklopädisten. Anders als Bayle in seinem 1702 erweiterten historisch-kritischen Lexikon waren die Enzyklopädisten einer wenn auch vielfältigen Weltanschauung verpflichtet und nahmen gegensätzliche Standpunkte nicht auf. Nur den Artikel 'Pyrronienne' (Skeptizismus) übernahmen sie aus Bayles bekanntem Werk. Im britischen Königreich schrieben die Aufklärer seit 1768 an der Encyclopædia Britannica, die bis heute fortlaufend erneuert und erweitert wird. Johann Georg Sulzers Allgemeine Theorie der schönen Künste[15] war das erste deutschsprachige Werk, das wie die französische Enzyklopädie aufgebaut war. Mit seinen ca. 900 Artikeln über Literatur, Rhetorik, bildende Künste, Architektur, Tanz, Musik und Schauspielerei sollte es eine Systematisierung aller Erkenntnisse hinsichtlich der Ästhetik bieten. Der deutsche Pädagoge Johann Bernhard Basedow veröffentlichte 1774 sein neunbändiges bebildertes Elementarwerk, ein modernes Realienbuch über die Grundlagen der Erziehung, die Logik, den Aufbau und die Sozialstruktur der Gesellschaft, die Sittenlehre, Geschichte und Naturkunde aus deistisch-philanthropisch-rationalistischer Sicht. 1781 gab Ignacy Krasicki, Erzbischof und Schriftsteller, die erste polnische Enzyklopädie in zwei Bänden heraus. |

デニス・ディドロ 啓蒙時代、多くの人々は、理性、自由、教育によって、近い将来、人類は抑圧、戦争、貧困から解放されるとの信念に奮い立たされた。彼らは、フランシス・ ベーコンの「知識は力である」という格言を信じた。フランスでは、有名な『百科事典、あるいは科学、芸術、職業の合理的な辞典』が誕生した。この百科事典 は、作家デニス・ディドロと数学者・物理学者ジャン=バティスト・ル・ロンド・ダルランベールによって編集された。後者が引退すると、その地位は、小さな 貴族であるルイ・ド・ジョークールが引き継いだ。彼は、特別に雇った秘書たちの助けを借りて、約 60,000 件の寄稿のうち 15,000 件以上を提供した。ヴォルテール、モンテスキュー、ルソーなどの有名なフランスの詩人や学者(「哲学者」)たちが、啓蒙主義の記念碑的なこの著作のために 記事を執筆した。この百科事典は、世俗的および精神的権力者たちの抵抗に抗して、人類の知識と技能のすべてを公に公開することを目的としていた。この事典 には、150人以上の著者、いわゆる百科事典編纂者たちが関わった。1702 年に拡張されたベイユの歴史的・批判的辞書とは異なり、百科事典編纂者たちは、多様ではあるものの、ある世界観に忠実であり、相反する見解は掲載しなかっ た。ベイユの有名な作品から採用したのは、「Pyrronienne」(懐疑主義)に関する記事だけだった。 英国では、1768 年から啓蒙思想家たちが『ブリタニカ百科事典』の執筆に取り組み、今日までその更新と拡充が続けられている。ヨハン・ゲオルク・ズルツァーの『美の芸術の 一般理論』[15] は、フランスの百科事典と同様の構成を持つ、ドイツ語圏で最初の著作だった。文学、修辞学、美術、建築、舞踊、音楽、演劇に関する約 900 の記事で構成され、美学に関するあらゆる知見を体系化するものとなるはずだった。ドイツの教育学者ヨハン・ベルンハルト・バゼドウは、1774年に9巻か らなる図解付きの基本書、教育、論理、社会の構造と社会構造、道徳、歴史、自然科学の基礎について、神学、慈善、合理主義の観点から書かれた現代的な実科 教科書を出版した。1781年、大司教であり作家でもあったイグナツィ・クラシツキは、2巻からなるポーランド初の百科事典を出版した。 |

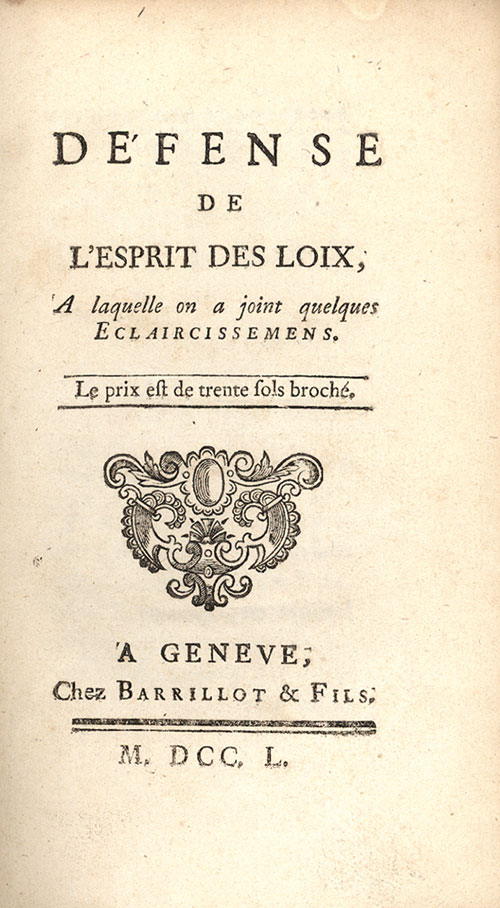

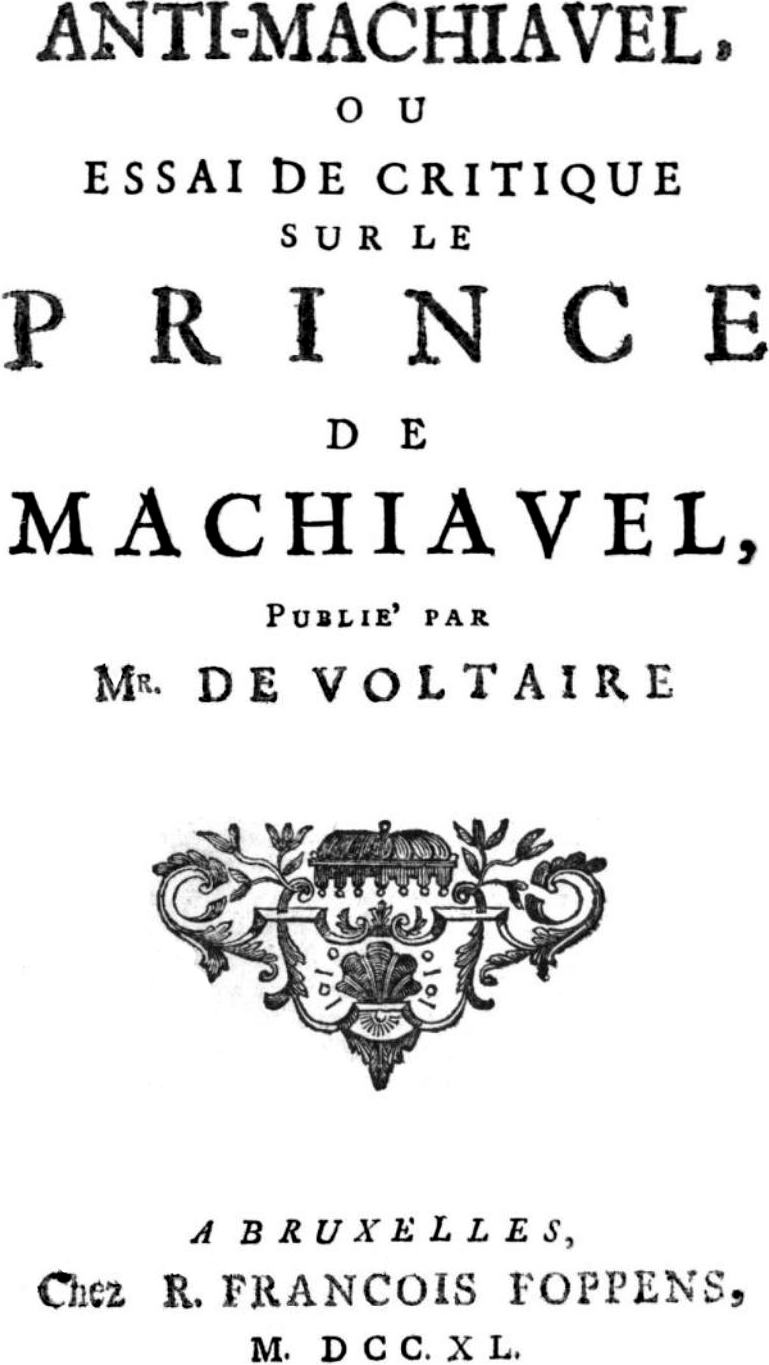

Paul Thiry d’Holbach um 1785, Ölgemälde von Alexander Roslin Diderot selbst und viele andere französische Aufklärer waren Vertreter des Materialismus, so Julien Offray de La Mettrie, Claude Adrien Helvétius und insbesondere der Radikalaufklärer Paul Thiry d’Holbach. Die Darstellung eines mechanistischen Weltbildes erschien in seiner 1770 aus Sicherheitsgründen unter Pseudonym herausgebrachten Schrift Système de la nature (System der Natur). Bereits früher und parallel dazu hatte Jean-Baptiste de Mirabaud anonym materialistisches Gedankengut verbreitet oder auch Denis Diderot in seinen Werken Pensées sur l’interprétation de la nature (1754) und Le rêve de D’Alembert (1769). Ausgehend von John Locke, entwickelte der französische Philosoph Étienne Bonnot de Condillac eine sensualistische Erkenntnistheorie mit dem Anspruch, durch Logik mehr als nur wahrscheinliche Aussagen machen zu können. Basierend auf seiner These über die Einheit von Denken und Sprache, begründete er eine handlungsorientierte Sprachtheorie. Die Seele erklärte er[16] – ohne Rückbezug auf metaphysische Annahmen – allein durch die Sinneseindrücke, welche dem Wollen und den Gefühlen zugrunde liegen. Philosophischer Antipode der französischen Materialisten war der Ire George Berkeley, ein Hauptvertreter des subjektiven Idealismus. Für Berkeley existiert keine Außenwelt, lediglich Individuen und ihre Wahrnehmungen.[17]  Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu: Verteidigung der Gewaltenteilung Das zentrale Werk des Staatstheoretikers Baron de Montesquieu aus dem Jahr 1748 De l’esprit des loix / Vom Geist der Gesetze enthält die grundlegenden Überlegungen für die Gewaltenteilung moderner Staaten, die er aufbauend auf John Lockes Legislative und Exekutive durch Judikative auf drei erweiterte. Er unterschied zwischen gemäßigten Regierungsformen (bestimmte Arten von Republiken und Monarchien) und auf Schrecken und Furcht beruhender Despotie. Nach dem Vorbild des Königreichs Britannien plädierte er für eine konstitutionelle Monarchie mit aristokratischen und demokratischen Elementen, wo begrenzt durch Gesetze und Institutionen zum Schutz der öffentlichen Ordnung am ehesten Toleranz und Freiheit zu gewährleisten seien. Montesquieu gilt als Vorläufer der modernen Milieutheorie. Der „Geist“ der Gesetze eines Staates ist bestimmt durch den „allgemeinen Geist“ („esprit général“) eines Volkes, der sich im Geschichtsprozess entwickelt. Der esprit général beruht auf geographischen und klimatischen Determinanten, die Sitten und Gebräuche beeinflussen und Gewohnheiten bilden. Dieser Prozess sollte nur behutsam beeinflusst werden. Durch Freihandel werden Vorurteile abgebaut, Sitten verändert, wird Toleranz gefördert und Wohlstand gemehrt. „Verfassungsregeln, Strafgesetze, das Zivilrecht, religiöse Vorschriften, Sitten und Gewohnheiten all das ist ineinander verwoben und beeinflusst und ergänzt sich gegenseitig. Wer da unüberlegt ändert, gefährdet seine Regierung und die Gesellschaft.“ Der italienische Rechtsphilosoph Cesare Beccaria formulierte das juristische Gebot der Verhältnismäßigkeit und lehnte die Todesstrafe ab.  Friedrich II. Anti-Machiavelli, 1740 Verfechter der Aufklärung setzten sich für eine Republik oder eine konstitutionelle Monarchie nach britischem Vorbild ein. Maria Theresia von Österreich, ihr Sohn Joseph II., die russische Zarin Katharina II. und insbesondere der preußische König Friedrich II., der selbst philosophische Schriften verfasste, waren die wichtigsten Repräsentanten des aufgeklärten Absolutismus. Die deutschen Aufklärer waren hauptsächlich Anhänger einer Konstitutionellen Monarchie. Zahlreiche Philosophen, die ihr Heimatland zeitweise verlassen mussten, fanden am Hof des Preußischen Aufklärers Zuflucht. Auf dem Gebiet der Ökonomie bewegte sich der französische Staatsmann und Aufklärer Anne Robert Jacques Turgot, der in seinem Frühwerk aus dem Jahr 1750 Tableau philosophique des progrés successifs de l’ésprit humain. (dt. Über die Fortschritte des menschlichen Geistes) den Fortschrittsglauben der Zeit begründet hatte und seit 1761 und besonders 1774 bis 1776 als Verantwortlicher für die Staatsfinanzen wichtige Reformanstrengungen im Sinne des aufgeklärten Absolutismus unternommen hatte. Mit seinem Buch Der Wohlstand der Nationen legte der schottische Philosoph Adam Smith 1776 in Abgrenzung zum vorherrschenden Merkantilismus die Grundlage für die Klassische Nationalökonomie. Er strebte einen Staat freier gebildeter Bürger mit gerechten politisch-juristischen Institutionen an. Arbeitsteilung führt Smith zufolge zu erhöhter Produktivität und ein eigennütziges Streben nach Besitzvermehrung, geregelt allein durch den Markt, zum Wohlstand in einem breiten Sinne. Einer der Gründerväter der Vereinigten Staaten, Thomas Paine, veröffentlichte während des Unabhängigkeitskrieges gegen das Königreich Großbritannien Anfang 1776 die wirkmächtige Flugschrift Common Sense (dt. Gesunder Menschenverstand), in der er das Recht auf Unabhängigkeit begründete und die Grundzüge einer Demokratie auf der Basis von Menschenrechten darlegte. Seine Ideen gingen unter anderem auf Thomas Reid zurück, der sich mit seinem Konzept des „Common Sense“, das von der Existenz einer Außenwelt ausging,[18] gegen jeden idealistischen Empirismus gewandt hatte – von Locke über Berkeley bis zu Hume.[19] Nur wenige Aufklärer, wie in Frankreich Montesquieu, Claude Adrien Helvétius und Condorcet, in Deutschland Theodor Gottlieb Hippel,[20] setzten sich für Frauenrechte ein. Condorcet wollte das allgemeine Wahlrecht auch den Frauen gewähren. Einige Aufklärer, im deutschsprachigen Raum zunächst Thomasius, später Mendelssohn, Christian Garve und andere verbreiteten die Philosophie der Aufklärung in populären allgemeinverständlichen Schriften, die sich vornehmlich an gebildete Frauen des Adels und Bürgertums wandten, teilweise als Damenphilosophie bezeichnet und von sogenannten Schulphilosophen kritisch bewertet wurden. Während in England[21] und mehr noch in Holland die Vertreter der Aufklärung relativ offen agieren konnten, waren sie in Frankreich politischen Verfolgungen ausgesetzt. Sie wurden inhaftiert, mussten vielfach zeitweise das Land verlassen, klandestin vorgehen oder ihre wahren Gedanken in Satiren bzw. Spötteleien, Fabeln und andere. literarische Formen kleiden. Ihre Werke waren nicht nur von der Zensur betroffen, sondern auch von der umgehenden Indizierung seitens der Katholischen Kirche und erschienen daher oftmals im Ausland, zum Beispiel in Genf und Amsterdam. |

1785年頃のポール・ティリー・ド・オルバック、アレクサンドル・ロスリンによる油絵 ディドロ自身や、ジュリアン・オフレイ・ド・ラ・メトリー、クロード・アドリアン・エルヴェティウス、そして特に急進的な啓蒙思想家ポール・ティリー・ド ルバックなど、多くのフランス啓蒙思想家は唯物論の支持者だった。機械論的な世界観は、1770年に安全上の理由から偽名で出版された彼の著作『自然体 系』に描かれている。それより以前、ジャン=バティスト・ド・ミラボーも匿名で唯物論的思考を広め、デニス・ディドロも『自然解釈に関する考察』 (1754年)や『ダルランベールの夢』(1769年)などの著作で唯物論的思考を広めていた。 ジョン・ロックを起点として、フランスの哲学者エティエンヌ・ボノ・ド・コンディヤックは、論理によって単なる確率的な主張以上のものを述べることができ ると主張する感覚主義的な認識論を発展させた。思考と言語の統一性に関する彼の説に基づいて、彼は行動志向の言語理論を確立した。彼は、形而上学的な仮定 に言及することなく、意志や感情の根底にある感覚的印象だけで魂を説明した。 フランスの唯物論者たちとは哲学的に正反対の立場をとったのは、主観的理想主義の主要な代表者であるアイルランド人のジョージ・バークレーだった。バーク レーにとって、外界は存在せず、個人とその知覚だけが存在する。  シャルル・ド・セコンダ、モンテスキュー男爵:三権分立の擁護 国家理論家モンテスキュー男爵の1748年の中心的な著作『法の精神』には、現代国家の三権分立に関する基本的な考察が記されている。彼はジョン・ロック の立法府と行政府に加え、司法府を加えて三権分立を三権に拡大した。彼は、穏健な政体(特定の種類の共和国や君主制)と、恐怖と威圧に基づく専制政治とを 区別した。英国をモデルとして、彼は、公の秩序を守る法律や制度によって制限された、貴族主義と民主主義の要素を備えた立憲君主制を提唱し、それが最も寛 容と自由を保証できると主張した。モンテスキューは、現代環境理論の先駆者と見なされている。国家の法律の「精神」は、歴史の過程で発展する国民全体の 「精神」(エスプリ・ジェネラル)によって決定される。エスプリ・ジェネラルは、習慣や慣習に影響を与え、習慣を形成する地理的および気候的要因に基づい ている。この過程は、慎重に影響を与えるべきだ。自由貿易によって、偏見は解消され、慣習は変化し、寛容が促進され、繁栄が増大する。「憲法、刑法、民 法、宗教的規定、慣習、習慣、これらすべてが相互に絡み合い、影響し合い、補完し合っている。軽率に変更を加える者は、その政府と社会を危険にさらすこと になる」 イタリアの法哲学者チェーザレ・ベッカリアは、比例性の法的原則を提唱し、死刑を否定した。  フリードリヒ2世『反マキャヴェッリ』、1740年 啓蒙主義の支持者たちは、英国のモデルに基づく共和国または立憲君主制の確立を目指した。オーストリアのマリア・テレジア、その息子ヨーゼフ2世、ロシア の女帝エカチェリーナ2世、そして特に、自ら哲学的著作を著したプロイセン王フリードリヒ2世は、啓蒙絶対主義の最も重要な代表者だった。 ドイツの啓蒙思想家たちは、主に立憲君主制の支持者だった。母国を一時的に離れることを余儀なくされた多くの哲学者が、プロイセンの啓蒙主義者の宮廷に避 難した。 経済分野では、フランスの政治家であり啓蒙主義者であるアンヌ・ロベール・ジャック・トゥルゴが活躍した。彼は1750年の初期作品『Tableau philosophique des progrés successifs de l’ésprit humain. (日本語訳:人間の精神の進歩について)で時代の進歩主義の信念を確立し、1761 年、特に 1774 年から 1776 年にかけて、国家財政の責任者として、啓蒙絶対主義の精神に基づく重要な改革に取り組んだ。 スコットランドの哲学者アダム・スミスは、1776年に著した『国富論』で、当時主流だった重商主義とは一線を画し、古典派経済学の基礎を築いた。彼は、 公正な政治・司法制度を備えた、自由で教養のある市民からなる国家の実現を理想としました。スミスによれば、分業は生産性の向上につながり、市場のみに よって規制される、所有物の増加という利己的な追求は、広い意味での繁栄につながる。 アメリカ合衆国の建国の父の一人であるトーマス・ペインは、1776年初めにイギリスに対する独立戦争中に、影響力のあるパンフレット『コモン・センス (常識)』を発表し、独立の権利を立証し、人権に基づく民主主義の基本原則を説明した。彼の考えは、とりわけ、外部の世界の存在を前提とした「コモン・セ ンス」の概念で、ロックからバークレー、ヒュームに至るまで、あらゆる理想主義的経験主義に反対したトーマス・リードに由来する。 フランスではモンテスキュー、クロード・アドリアン・エルヴェティウス、コンドルセ、ドイツではテオドール・ゴットリーブ・ヒッペルなど、ごく少数の啓蒙 思想家だけが女性の権利を擁護した。コンドルセは、女性にも普通選挙権を認めることを望んでいた。ドイツ語圏では、最初はトマシウス、後にメンデルスゾー ン、クリスチャン・ガルヴェなどが、啓蒙思想を、主に教養のある貴族やブルジョア階級の女性たちに向けた、広く理解できる大衆向けの著作で広めた。これ は、一部では「女性哲学」と呼ばれ、いわゆる学校哲学者に批判的に評価された。 イギリス[21]、そしてさらにオランダでは、啓蒙思想の代表者たちは比較的自由に活動できたが、フランスでは政治的迫害にさらされた。彼らは投獄され、 多くの場合、一時的に国を離れるか、秘密裏に活動するか、あるいは風刺や嘲笑、寓話、その他の文学形式を用いて自分の本当の考えを表現しなければならな かった。彼らの作品は、検閲の対象となっただけでなく、カトリック教会による差し押さえの対象にもなり、そのため、ジュネーブやアムステルダムなど、海外 で出版されることが多かった。 |

| Herausragende Vertreter Jean-Jacques Rousseau  Rousseau: Abhandlung über den Ursprung und die Grundlagen der Ungleichheit unter den Menschen, Amsterdam 1755 Der Geschichts- und Kulturphilosoph, Staats- und Gesellschaftstheoretiker sowie Zivilisationskritiker Jean-Jacques Rousseau ist einer der einflussreichsten Autoren der Aufklärung. Er erarbeitete eine Systematik, mit der er in seinen Werken das jeweilige Thema historisch-kritisch erschloss. Wissen und Vernunft schätzte er allerdings gering ein. So verneinte er 1750 in seiner preisgekrönten Antwort die Frage der Akademie von Dijon, ob die Wissenschaften und Künste zum moralischen Fortschritt der Menschheit beigetragen haben, da er in der Kulturgeschichte aufgrund der Kriege, des Elends und der Unterdrückung einen sittlichen Verfall sah.[22] Rousseau formulierte seine Kultur- und Zivilisationskritik insbesondere gegen den Manierismus des Rokoko. Fast ging er in seiner Abhandlung über den Ursprung und die Grundlagen der Ungleichheit unter den Menschen 1755 so weit, das Denken (la réflexion) als widernatürlich zu bezeichnen.[23] Er konstatierte, der Mensch habe durch die Entdeckung des Privateigentums dem glücklichen Naturzustand ein Ende bereitet. Wegweisend für demokratische Gemeinwesen sind seine Begriffe Gemeinwille und Volkssouveränität in seinem politischen Hauptwerk Vom Gesellschaftsvertrag oder Prinzipien des Staatsrechtes, 1762. Dieser wird durch Abstimmungen freier Bürger ermittelt und ist anschließend für alle bindend. Eine einfache deistische Staatsreligion soll einerseits den Einzelnen auf die Nation verpflichten, andererseits durch gesicherte „Duldsamkeit“ den Rahmen für unterschiedliche Religionsausübung bieten. Seine politischen Werke beeinflussten maßgebliche Vertreter der Französischen Revolution, sein Bildungsroman Émile oder Über die Erziehung[24], ebenfalls 1762 erschienen, die Pädagogik, aber auch schon die Erziehung zeitgenössischer Kinder, insbesondere der aufgeklärten Aristokratie. Rousseau schrieb zudem „Bekenntnisse“, eine intime, sexuelle Details aber auch Verfehlungen umfassende, autobiographische Schrift,[25] die bis in die Gegenwart Autoren als Vorbild dient. |

傑出した代表者 ジャン=ジャック・ルソー  ルソー:『人間不平等起源論』、アムステルダム、1755年 歴史・文化哲学者、国家・社会理論家、文明批評家であるジャン=ジャック・ルソーは、啓蒙主義の最も影響力のある作家の一人だ。彼は、作品の中でそれぞれ のテーマを歴史的・批判的に考察するための体系を構築した。しかし、彼は知識と理性をあまり重要視していなかった。1750年、ディジョン学会の「科学と 芸術は人類の道徳的進歩に貢献してきたか」という質問に対して、彼は受賞作の中で否定的な見解を示した。それは、戦争、貧困、抑圧といった文化史上の出来 事を、道徳的衰退の証拠と捉えていたためである。[22] ルソーは、ロココ様式の様式美主義に対して、特に文化と文明に対する批判を述べた。1755年の『人間不平等起源論』では、思考(la réflexion)を不自然であるとまで言うほどだった。[23] 彼は、人間は私有財産の発見によって、幸福な自然の状態に終止符を打ったと述べた。 民主的な共同体にとって先駆的なのは、彼の主な政治著作『社会契約論、あるいは国家法の原則』(1762年)における「公共の意志」と「人民主権」の概念 だ。これは自由な市民による投票によって決定され、その後、すべての人に拘束力を持つ。単純な自然神論的な国教は、一方で個人を国家に忠誠を誓わせる一方 で、確固たる「寛容」によって、さまざまな宗教の信仰の枠組みを提供するものである。彼の政治に関する著作は、フランス革命の主要人物たちに影響を与え、 同じく1762年に出版された教育小説『エミール、あるいは教育について』は、教育学だけでなく、当時の子供たち、特に啓蒙主義的な貴族の子供たちの教育 にも影響を与えた。ルソーはさらに、性的詳細や過ちも網羅した、親密な自伝的著作『告白』[25] を執筆し、それは現在でも作家たちの手本となっている。 |

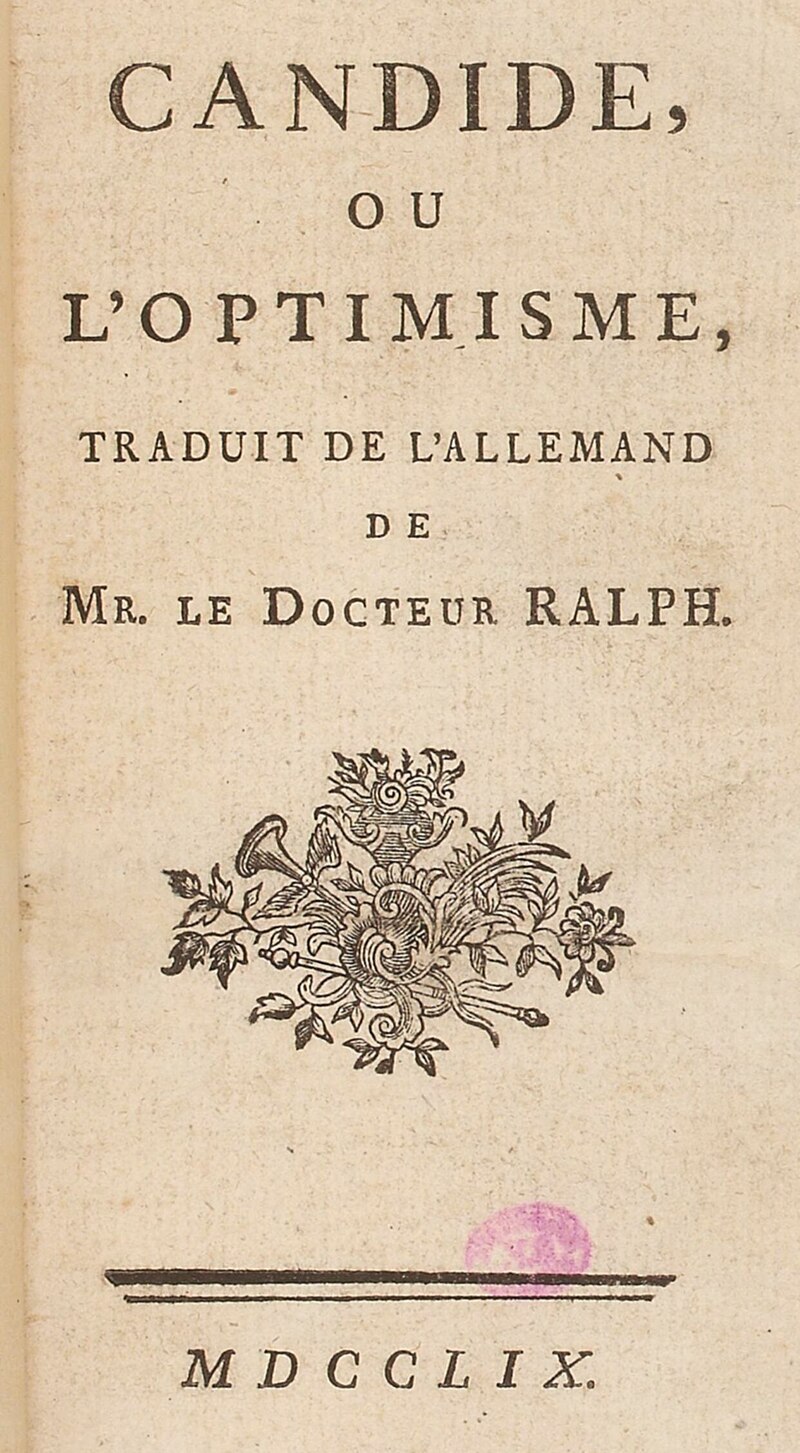

Voltaire Voltaire: Candide, Paris 1759 Sein auf den Vernunftprinzipien beharrender Kontrahent Voltaire, geboren als François Marie Arouet, ist mindestens ebenso wirksam. Der entschiedene Gegner der katholischen Kirche, des Absolutismus und des Feudalismus war ein Erneuerer der Geschichtsschreibung, die er nicht auf Ereignisse und Herrscherpersonen fokussieren wollte, sondern als Darstellung der Kultur- und Geistesgeschichte, bezogen auf die gesamte Welt, verstand. Den uneingeschränkten Glauben vieler Aufklärer an einen kontinuierlichen Fortschritt teilte er nicht. In seiner Satire Candide oder der Optimismus, die angeblich aus dem Deutschen übersetzt, in Paris 1759 anonym erschien, wandte er sich gegen Leibniz' Vorstellung von der „besten aller möglichen Welten“. Eine breite, auch nichtintellektuelle Öffentlichkeit erreichte er seit Mitte des 18. Jahrhunderts mit seinem umfangreichen, oft sarkastischen, literarisch-philosophischen Werk. Mit ca. 750 teils zunächst anonymen Veröffentlichungen ist er einer der einflussreichsten und bedeutendsten Autoren der Aufklärung. Die contes philosophiques, philosophische Erzählungen, enthalten die Hauptgedanken der Aufklärung, die hier publikumswirksam präsentiert werden. Auch die Verbreitung der naturwissenschaftlichen Erkenntnisse Newtons in Frankreich geht auf Voltaire und seine Partnerin, die Physikerin, Mathematikerin und Philosophin Émilie du Châtelet zurück. Einen großen Teil seiner Popularität verdankt Voltaire seinem erfolgreichen Kampf gegen gravierende Irrtümer bzw. willkürliche Urteile der Justiz. Außerdem propagierte er als einer der Ersten die Meinungsvielfalt. Wegbereitend für die Französische Revolution waren seine kämpferischen und gleichzeitig gut formulierten politischen Pamphlete. „Écrasez l’infâme“ (Vernichtet die Niedertracht), vor allem gegenüber der katholischen Kirche, wurde zur weitverbreiteten Losung. Der deutsche Journalist und Schriftsteller Wilhelm Ludwig Wekhrlin nahm sich Voltaire zum Vorbild, dessen Werke er auszugsweise ins Deutsche übersetzte und veröffentlichte. Er kämpfte mit ähnlichen Mitteln, zeitweise verfolgt und eingekerkert, für Bürgerrechte und Pressefreiheit. |

ヴォルテール ヴォルテール:カンディード、パリ 1759 理性主義の原則を主張する彼の対立者、ヴォルテール(本名フランソワ・マリー・アロー)も、少なくとも同等に影響力がある。カトリック教会、絶対主義、封 建制度に断固として反対した彼は、歴史記述の革新者であり、歴史を出来事や支配者に焦点を当てるのではなく、全世界に関する文化と精神の歴史の表現として 捉えていた。多くの啓蒙思想家たちが抱いていた、継続的な進歩に対する無制限の信念は、彼は共有していなかった。1759年にパリで匿名で出版された、ド イツ語から翻訳されたとされる風刺作品『カンディード、あるいは楽観主義』の中で、彼はライプニッツの「最善の世界」という概念に異議を唱えた。18世紀 半ば以降、彼は、その膨大で、しばしば皮肉に満ちた文学的・哲学的著作によって、知的ではない幅広い読者層にも影響を与えた。約 750 冊の著作(その一部は当初匿名で出版)を著した彼は、啓蒙主義の最も影響力があり、最も重要な作家の一人である。 『哲学物語』は、啓蒙主義の主な思想を、大衆にアピールする形で紹介している。また、ニュートンの自然科学の知見がフランスで広まったのも、ヴォルテール と彼のパートナーである物理学者、数学者、哲学者であるエミリー・デュ・シャトレのおかげだ。ヴォルテールは、司法の重大な誤りや恣意的な判決と闘い、勝 利を収めたことで、その人気の大部分を獲得した。さらに、彼は意見の多様性を最初に提唱した人物の一人でもある。彼の闘争的でありながら、よく練られた政 治パンフレットは、フランス革命の先駆けとなった。「Écrasez l’infâme」(卑劣なものを滅ぼせ)という、とりわけカトリック教会に対するスローガンは、広く普及した。 ドイツのジャーナリストであり作家でもあるヴィルヘルム・ルートヴィヒ・ヴェクリンは、ヴォルテールを模範とし、その著作の一部をドイツ語に翻訳して出版 した。彼は、同様の手段で、時には迫害され投獄されながらも、市民権と報道の自由のために戦った。 |

David Hume David-Hume-Denkmal in Edinburgh Ein wichtiger britischer Theoretiker der Aufklärung und Vertreter des Empirismus war – neben John Locke und George Berkeley – David Hume. Anknüpfend an Locke war er Autor einer bahnbrechenden Erkenntnistheorie. Er galt als amoralischer Atheist, so dass ihm eine universitäre Laufbahn verwehrt war. Tatsächlich verteidigte er eine auf Gefühlen beruhende deistische Religionsauffassung. In der Mitte des 18. Jahrhunderts verfasste er Eine Untersuchung über die Prinzipien der Moral, Eine Untersuchung über den menschlichen Verstand und eine Abhandlung zur Politik. Die Wurzeln der Moral liegen für Hume im Gefühl, da keine objektiven Tugenden existieren. Der Mensch lehnt ein Verbrechen aus Mitgefühl für das Opfer ab, nicht weil es für tatsächliche Ereignisse allgemein gültige Kriterien der Beurteilung gibt. Hume zufolge kann der menschliche Verstand keine Wahrheit ausdrücken, sondern immer nur eine Wahrscheinlichkeit. Als gemäßigter Skeptiker polemisierte er gegen den Wunderglauben. Mit seinem großen verfassungsgeschichtlich orientierten Werk The History of Great Britain (6 Bände, 1754–1762) – deutsche Ausgabe als Geschichte von England (vier Bände von Gaius Iulius Caesar bis zur Vereinigung mit Schottland 1707) und Geschichte von Großbritannien (zwei Bände seit 1707) – gehörte er wie Voltaire und Rousseau zu den Begründern der modernen Geschichtsschreibung. Bei den verfeindeten politischen Parteien stieß das Werk damals auf wütende Ablehnung, doch wurde es ein Bestseller. Berühmt wurde Humes Einschätzung der zivilisatorischen Leistung des Islam im frühen Mittelalter und der unterschiedlichen Rollen, die Saladin und Richard Löwenherz beim Ersten Kreuzzug spielten: Richard sei eben so tapfer gewesen wie Saladin, aber im Vergleich zu diesem doch ein intoleranter und grausamer Barbar.[26] Im deutschen Sprachbereich war es Johannes Nikolaus Tetens, der als einer der ersten Philosophen – auf der Grundlage der Wolffschen Terminologie – die Gedanken David Humes verbreitete. Sein 1777 herausgekommenes Philosophische Versuche über die menschliche Natur und ihre Entwicklung wurde von Kant rezipiert. Seinen britischen Zeitgenossen galt er als „deutscher Locke“, heute wird er im angloamerikanischen Raum eher als „deutscher Hume“ gesehen. |

デイヴィッド・ヒューム エディンバラにあるデイヴィッド・ヒュームの記念碑 ジョン・ロックやジョージ・バークレーと並んで、英国啓蒙思想の重要な理論家であり、経験主義の代表者はデイヴィッド・ヒュームだった。ロックに続き、彼 は画期的な認識論の著者となった。彼は非道徳的な無神論者と見なされていたため、大学でのキャリアは断たれた。実際には、感情に基づく有神論的な宗教観を 擁護していた。 18 世紀半ば、彼は『道徳の原理に関する考察』、『人間知性に関する考察』、そして政治に関する論文を著した。ヒュームにとって、道徳の根源は感情にある。な ぜなら、客観的な美徳は存在しないからだ。人間は、実際の出来事に対して普遍的な評価基準があるからではなく、供犠への同情から犯罪を拒絶する。ヒューム によれば、人間の知性は真実を表現することはできず、常に可能性しか表現できない。穏健な懐疑論者として、彼は奇跡の信仰に対して論争を繰り広げた。憲法 史に焦点を当てた大著『英国史 (6巻、1754年~1762年)は、ドイツ語版では『イングランドの歴史』(ガイウス・ユリウス・カエサルから1707年のスコットランドとの統合まで を4巻で扱う)および『グレートブリテン史』(1707年以降を2巻で扱う)として出版され、ヴォルテールやルソーと同様、現代の歴史学の創始者の一人と なった。当時、この著作は敵対する政党から激しい反発を受けたが、ベストセラーとなった。ヒュームは、中世初期におけるイスラムの文明的功績と、第一次十 字軍におけるサラディンとリチャード・ライオンハートの異なる役割について、有名な評価を下している。リチャードはサラディンと同じくらい勇敢であった が、サラディンと比較すると、不寛容で残酷な野蛮人であったと。[26] ドイツ語圏では、ヨハネス・ニコラウス・テテンスが、ウォルフの用語法に基づいて、デイヴィッド・ヒュームの思想を最初に広めた哲学者の一人だった。 1777年に出版された彼の著書『人間本性とその発達に関する哲学的試論』は、カントにも影響を与えた。同時代の英国人からは「ドイツのロック」と評され ていたが、今日では、英米圏では「ドイツのヒューム」とみなされている。 |

| Immanuel Kant Kant war ein bedeutender Philosoph gegen Ende des Zeitalters der Aufklärung, der in seiner Erkenntnistheorie von dem gemäßigten Skeptiker Hume beeinflusst war. Seinem Essay aus dem Jahr 1784 Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung? entstammt seine berühmte Definition der ‚Aufklärung‘ und die Aufforderung, jederzeit selbst zu denken. Damit zielt er auf den äußeren Widerstand gegen die Aufklärung, aber auch auf die innere Befreiung von Bevormundung durch „Pfaffentum“. „Aufklärung ist der Ausgang des Menschen aus seiner selbstverschuldeten Unmündigkeit. Unmündigkeit ist das Unvermögen, sich seines Verstandes ohne Leitung eines anderen zu bedienen. Selbstverschuldet ist diese Unmündigkeit, wenn die Ursache derselben nicht am Mangel des Verstandes, sondern der Entschließung und des Mutes liegt, sich seiner ohne Leitung eines anderen zu bedienen. Sapere aude! Habe Mut, dich deines eigenen Verstandes zu bedienen!“  Immanuel Kant zum 250. Geburtstag, 1974 In seinen drei Hauptwerken Kritik der reinen Vernunft (1781), Kritik der praktischen Vernunft (1788) und Kritik der Urteilskraft (1790) widmete er sich der Frage nach den Grenzen der Erkenntnis. Die vernunftorientierte Ethik Kants befasst sich mit dem Denken, dem Handeln und dem Fühlen des aufgeklärten Menschen. „Handle so, dass die Maxime deines Willens jederzeit zugleich als Prinzip einer allgemeinen Gesetzgebung gelten könne.“ Dieser berühmte Ausspruch Kants (Kategorischer Imperativ) verdeutlicht die Forderung nach einem Gesetz, das nicht den Interessen von Machthabern dient, sondern von der Einsicht und dem ethischen Handeln der Bürger ausgeht. Galt bisher als schuldhaft derjenige, der selbstherrlich dachte und handelte, ohne sich von geistlichen und weltlichen Herrschern leiten zu lassen, plädierte er für die Mündigkeit des Menschen. Trotz ihrer Grenzen sieht Kant die Vernunft als die bedeutendste Eigenschaft des Menschen, besonders in Hinblick auf die Ermöglichung eines praktischen moralischen Handelns. Gleichzeitig bezweifelt er die Möglichkeit einer schnellen, einzig vom Dritten Stand ausgehenden Erneuerung. Eine „Reform des Denkens“ könne nur langsam vonstattengehen. „Es ist für den Einzelnen schwierig, die Unmündigkeit zu überwinden, weil sie den meisten Menschen als Normalität erscheint.“ Neben einer Beschränkung der Adelswillkür ging es ihm darum, den Einfluss des Klerus auf die Politik einzuschränken. In derselben Schrift spricht Kant vom Zeitalter der Aufklärung bzw. dem Jahrhundert Friedrichs. Als Anhänger eines Verfassungsstaates verstand er sich als Weltbürger – sein Aufsatz Idee zu einer allgemeinen Geschichte in weltbürgerlicher Absicht erschien 1784. In seinem „philosophischen Entwurf“ Zum ewigen Frieden (1795) entwickelte er theoretische, auf Freiheit beruhende, antidespotische Grundbegriffe für einen vertraglich gesicherten Frieden zwischen souveränen Staaten. Sein Schüler Johann Gottfried Herder, einer der Hauptvertreter der Weimarer Klassik, grenzte sich scharf vom späten Kant ab, führte Vernunft auf Sprache zurück und postulierte einen „Nationalcharakter“ der einzelnen Völker, deren Vielfältigkeit und Eigenwertigkeit er betonte. |

イマヌエル・カント カントは、啓蒙主義の終わりに活躍した重要な哲学者で、その認識論は穏健な懐疑論者ヒュームの影響を受けていた。1784年のエッセイ「啓蒙とは何か」の 中で、彼は「啓蒙」の有名な定義と、常に自分で考えるよう呼びかけている。これは、啓蒙に対する外部の抵抗だけでなく、「聖職者による支配」からの内面の 解放も指している。 「啓蒙とは、人間が自らの責任による未熟から脱却することである。未熟とは、他人の指導なしに自分の理性を活用することができない状態である。この未熟さ は、その原因が知性の欠如ではなく、他人の指導なしに自分の知性を使う決断力と勇気の欠如にある場合、自らが招いたものである。Sapere aude!自分の知性を使う勇気を持て!」  イマヌエル・カント生誕 250 周年、1974 年 彼の3つの主要著作『純粋理性批判』(1781年)、『実践理性批判』(1788年)、『判断力批判』(1790年)では、認識の限界について考察してい る。カントの理性主義的な倫理観は、啓蒙された人間の思考、行動、感情を扱っている。 「あなたの意志の格律が、いつでも普遍的な立法の原則として通用するような行動をとれ」。カントのこの有名な言葉(定言命法)は、権力者の利益に奉仕する 法律ではなく、市民の洞察力と倫理的な行動に基づく法律の必要性を明らかにしている。これまで、精神的、世俗的な支配者に導かれることなく、独断的に考 え、行動する者は有罪とされてきたが、カントは人間の成熟を主張した。 その限界にもかかわらず、カントは、特に実践的な道徳的行動を可能にするという点で、理性は人間の最も重要な特性であると考えている。同時に、第三階級だ けによる迅速な刷新の可能性については疑問を抱いている。「思考の改革」は、ゆっくりとしか進まないだろう。「個人にとって、未熟さを克服することは難し い。なぜなら、それはほとんどの人にとって当然のことのように思えるからだ」。貴族の専制を制限することに加え、彼は聖職者の政治への影響力を制限するこ とにも関心を持っていた。同じ著作の中で、カントは啓蒙時代、すなわちフリードリヒの世紀について述べている。 憲法国家の支持者として、彼は自らを世界市民と認識していた。彼の論文「世界市民的意図による普遍的歴史の構想」は1784年に発表された。彼の「哲学的 構想」である『永遠の平和について』(1795年)では、主権国家間の契約によって保証される平和のために、自由に基づく反専制的な基本概念を理論的に展 開した。 彼の弟子であるヨハン・ゴットフリート・ヘルダーは、ワイマール古典主義の主要人物の一人であり、後期カントとは一線を画し、理性を言語に帰し、個々の民 族の「国民性」を提唱し、その多様性と独自性を強調した。 |

| Literatur Eva Stollreiter, Elisabeth Conradi (Herausgeber): Philosophie. Ideen, Denker und Begriffe. Brockhaus, München / Leipzig 2004, ISBN 978-3-7653-0571-9. Ernst Cassirer: Die Philosophie der Aufklärung. (1932), Meiner, Hamburg 1998, ISBN 3-7873-1362-1. Matthias Vogt (Herausgeber): Dumonts Handbuch Philosophie. Dumont, Köln 2003, ISBN 3-8320-8778-8, S. 162–187. Manfred Geier: Aufklärung. Das europäische Projekt. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2012, ISBN 978-3-498-02518-2. Wolfgang Hardtwig (Hrsg.): Die Aufklärung und ihre Weltwirkung (= Geschichte und Gesellschaft, Sonderheft 23), Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2010, ISBN 978-3-525-36423-9. Frank Kelleter: Amerikanische Aufklärung. Sprachen der Rationalität im Zeitalter der Revolution. Schöningh, Paderborn 2002, ISBN 3-506-74416-X. Panajotis Kondylis: Die Aufklärung im Rahmen des neuzeitlichen Rationalismus. Meiner, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-7873-1613-2. Werner Krauss: Studien zur deutschen und französischen Aufklärung (= Neue Beiträge zur Literaturwissenschaft, Band 16). Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1963, DNB 452573750. Peter Pütz: Die deutsche Aufklärung. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1991, ISBN 3-534-06092-X. Helmut Reinalter (Hrsg.): Die Aufklärung in Österreich. Ignaz von Born und seine Zeit (= Demokratische Bewegungen in Mitteleuropa 1770–1850; Band 4). Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1991, ISBN 3-631-43379-4. Jochen Schmidt (Hrsg.): Aufklärung und Gegenaufklärung in der europäischen Literatur, Philosophie und Politik von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1989, ISBN 3-534-10251-7. Werner Schneiders (Hrsg.): Lexikon der Aufklärung, Deutschland und Europa. Beck, München 2005, ISBN 3-406-47571-X. Winfried Schröder (Hrsg.): Französische Aufklärung. Bürgerliche Emanzipation, Literatur und Bewußtseinsbildung. Reclam, Leipzig 1979, Ost. Jürgen Stenzel (Hrsg.): Das Zeitalter der Aufklärung (= Deutsche Schriftsteller im Porträt, Band 2), Beck, München 1980, ISBN 3-406-06020-X. Hans Joachim Störig: Weltgeschichte der Philosophie. 1950, überarbeitete und erweiterte Neuauflagen als Kleine Weltgeschichte der Philosophie. 17. Auflage. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-17-016070-2, S. 313–437. Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger: Europa im Jahrhundert der Aufklärung. Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-15-017025-7, S. 313–437. (Rezension). Fritz Wagner: Europa im Zeitalter des Absolutismus und der Aufklärung (= Handbuch der europäischen Geschichte, hrsg. von Theodor Schieder, Band 4), Union, Stuttgart 1968, 3. Auflage: Klett, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-12-907560-7. |

参考文献 Eva Stollreiter、Elisabeth Conradi(編集):哲学。思想、思想家、概念。Brockhaus、ミュンヘン/ライプツィヒ、2004年、ISBN 978-3-7653-0571-9。 Ernst Cassirer:啓蒙主義の哲学。(1932年)、マイナー、ハンブルク 1998年、ISBN 3-7873-1362-1。 マティアス・フォクト(編集):デュモンの哲学ハンドブック。デュモン、ケルン 2003年、ISBN 3-8320-8778-8、162-187 ページ。 マンフレート・ガイアー:啓蒙主義。ヨーロッパのプロジェクト。Rowohlt、ラインベック・バイ・ハンブルク 2012、ISBN 978-3-498-02518-2。 ヴォルフガング・ハルトヴィグ(編集):啓蒙主義とその世界への影響(= 歴史と社会、特別号 23)、Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht、ゲッティンゲン 2010、 ISBN 978-3-525-36423-9。 フランク・ケレター:アメリカの啓蒙主義。革命時代の合理性の言語。シェーニング、パーダーボルン、2002年、ISBN 3-506-74416-X。 パナヨティス・コンディリス:近代合理主義の枠組みにおける啓蒙主義。マイナー、ハンブルク、2002年、ISBN 3-7873-1613-2。 ヴェルナー・クラウス:ドイツとフランスの啓蒙に関する研究(= 新しい文学研究、第16巻)。リュッテン&ローニング、ベルリン、1963年、DNB 452573750。 Peter Pütz:ドイツ啓蒙主義。Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft、ダルムシュタット、1991年、ISBN 3-534-06092-X。 Helmut Reinalter(編):オーストリアにおける啓蒙主義。イグナツ・フォン・ボーンとその時代(= 中欧における民主主義運動 1770–1850; 第 4 巻)。ラング、フランクフルト・アム・マイン、1991 年、ISBN 3-631-43379-4。 ヨッヘン・シュミット(編):古代から現代までのヨーロッパ文学、哲学、政治における啓蒙主義と反啓蒙主義。科学書籍協会、ダルムシュタット、1989 年、ISBN 3-534-10251-7。 ヴェルナー・シュナイダーズ(編):啓蒙、ドイツ、ヨーロッパの事典。ベック、ミュンヘン、2005年、ISBN 3-406-47571-X。 ウィンフリード・シュレーダー(編):フランス啓蒙。市民的解放、文学、意識形成。レクラム、ライプツィヒ、1979年、東。 ユルゲン・ステンツェル(編):啓蒙の時代(= ドイツ作家ポートレート、第 2 巻)、ベック、ミュンヘン、1980 年、ISBN 3-406-06020-X。 ハンス・ヨアヒム・シュテリグ:世界哲学史。1950 年、改訂・増補新版として『世界哲学小史』として出版。第 17 版。コールハンマー、シュトゥットガルト、1999 年、ISBN 3-17-016070-2、313-437 ページ。 バーバラ・シュトルベルク=リリンガー:啓蒙の世紀のヨーロッパ。シュトゥットガルト、2000 年、ISBN 3-15-017025-7、313-437 ページ。(書評)。 フリッツ・ワグナー:絶対主義と啓蒙主義の時代のヨーロッパ(= ヨーロッパ史ハンドブック、テオドール・シーダー編、第 4 巻)、ユニオン、シュトゥットガルト、1968 年、第 3 版:クレット、シュトゥットガルト、1996 年、ISBN 3-12-907560-7。 |

| Anmerkungen 1. Lichtenberg schrieb seine Gedanken ab 1764 in Hefte („Sudelbücher“), in Teilen erstmals 1800 veröffentlicht. 2. Discours préliminaire (Einleitung) zur Encyclopédie 3. Der Begriff «Aufklärung des Verstandes» taucht erstmals 1691 auf. Manfred Geier: Aufklärung.Das europäische Projekt. Reinbek bei Hamburg 2012, S. 9 (Geier 2012) 4. L' Ingenu. (Der Freimütige). 1748, siehe Liste der Werke Voltaires 5. der Salon befand sich seit 1772 in der rue d’Auteuil Nr. 59 6. 1689 veröffentlichte Locke sein Werk Zwei Abhandlungen über die Regierung (engl.: Two Treatises of Government) anonym. Er enthüllte erst in seinem Testament die öffentlich vermutete Urheberschaft. 7. In seinen Persischen Briefen formulierte 1721 auch Montesquieu ein solches Recht auf Widerstand gegen absolutistische Fürsten, die die Freiheit unterdrückten und das Streben nach Glück behinderten. 8. Das französische „de“ entspricht dem deutschen „von“. 9. Die republikanisch-demokratische Französische Verfassung von 1793 sah erstmals ein uneingeschränktes allgemeines Wahlrecht (für Männer) vor, trat aber – trotz Konventbeschluss und Volksabstimmung – nie in Kraft. 10. Der Begriff Wohlfahrtsstaat hat seinen Ursprung im aufgeklärten Absolutismus Friedrichs. 11. Réflexions critiques sur la poésie et sur la peinture, 1719, (Kritische Betrachtungen über die Poesie und Malerei). 12. Der erste Brief erschien zunächst aus Sicherheitsgründen anonym auf Lateinisch. 13. In: Nathan der Weise, 1779 veröffentlicht, Uraufführung 1783. Auch in seiner religionsphilosophischen Schrift Die Erziehung des Menschengeschlechts (1777) plädierte er für religiöse Toleranz. 14. In seinem Werk Philosophia rationalis, sive logica (1728) prägte er zum Beispiel den Begriff Teleologie. 15. verfasst seit 1753, veröffentlicht in zwei Bänden 1771 und 1774 16. 1754 in seinem Werk Traité des sensations 17. Treatise Concerning the Principles of Human Knowledge. Erstauflage, Dublin 1710, (Abhandlung über die Prinzipien der menschlichen Erkenntnis). 18. Ried, der Begründer der Schottischen Schule der Philosophie, sah den Ursprung des „Common Sense“ in Gottes Schöpfung 19. Hume kam erkenntnistheoretisch vollkommen ohne Gottesbezug aus. 20. in seiner Schrift Über die bürgerliche Verbesserung der Weiber (1792) und in der überarbeiteten Auflage von 1793 seines mehrmals veränderten Werkes Über die Ehe. 21. Die Werke der Deisten konnten allerdings bis weit in das 18. Jahrhundert hinein nicht frei erscheinen, die Autoren wurden juristisch belangt. Einige Vergehen mit religiösem Hintergrund konnten die Todesstrafe oder eine Verbrennung des Buches nachsichziehen. 22. Discours sur les sciences et les arts, 1750 23. “...j’ose presque assurer que l’état de réflexion est un état contre nature, et que l’homme qui médite est un animal dépravé.” 24. Darin schildert er die Erziehung eines Knaben, der durch weitgehende Abschirmung von der verderblichen Zivilisation mit unmerklicher Unterstützung, seine natürlichen Anlagen entfalten kann. 25. Les Confessions (Die Bekenntnisse), posthum erschienen 1782 26. David Hume: The History of Great Britain, Band 1, Kap. 6. |

注釈 1. リヒテンベルクは1764年から自分の考えをノート(「スデルブッフ」)に書き留め、その一部は1800年に初めて出版された。 2. 『百科事典』の序文(Discours préliminaire) 3. 「知性の啓蒙」という用語は1691年に初めて登場した。マンフレート・ガイアー『啓蒙。ヨーロッパのプロジェクト』 ラインベック(ハンブルク近郊)2012年、9ページ(ガイアー 2012) 4. L' Ingenu(率直な男)。1748年、ヴォルテールの作品リストを参照 5. サロンは1772年以来、オートゥイユ通り59番地にあった 6. 1689年、ロックは『二つの政府論』を匿名で出版した。彼は遺言で、公に推測されていたその著作の作者であることを明らかにした。 7. 1721年、モンテスキューも『ペルシャの書簡』の中で、自由を抑圧し、幸福の追求を妨げる絶対主義的な君主に対する抵抗の権利について述べている。 8. フランス語の「de」は、ドイツ語の「von」に相当する。 9. 1793年の共和民主主義的なフランス憲法は、初めて無制限の普通選挙権(男性)を規定したが、国民議会での決議と国民投票にもかかわらず、決して施行さ れることはなかった。 10. 福祉国家という概念は、フリードリヒの啓蒙的絶対主義に起源がある。 11. Réflexions critiques sur la poésie et sur la peinture(詩と絵画に関する批判的考察)、1719年。 12. 最初の書簡は、安全上の理由から、ラテン語で匿名で発表された。 13. 『賢者ナタン』に掲載、1779年出版、1783年初演。宗教哲学の著作『人類の教育』(1777年)でも、宗教的寛容を主張した。 14. 著作『Philosophia rationalis, sive logica』(1728年)で、例えば「目的論」という概念を提唱した。 15. 1753 年から執筆、1771 年と 1774 年に 2 巻で出版。 16. 1754 年、彼の著作『感覚に関する論文』で。 17. 『人間の知識の原理に関する論文』。初版、ダブリン、1710 年。 18. スコットランド哲学の創始者であるリードは、「常識」の起源を神の創造に見出していた。 19. ヒュームは、認識論において、神をまったく参照することなく論じている。 20. 彼の著作『女性の市民的改良について』(1792年)および、何度か改訂された著作『結婚について』の1793年の改訂版で述べている。 21. しかし、18世紀のかなり後まで、自然神論者の著作は自由に発表することができず、著者は法的に訴追された。宗教的な背景のある犯罪の中には、死刑や書籍 の焼却につながるものもあった。 22. 『科学と芸術に関する論考』1750年 23. 「...私は、熟考の状態は不自然な状態であり、熟考する人間は堕落した動物であるとほぼ断言できる。」 24. この作品では、有害な文明からほぼ完全に隔離され、目立たない支援を受けながら、その生来の才能を開花させる少年教育について描かれている。 25. 『告白録』 (Les Confessions)、1782年に死後出版 26. デヴィッド・ヒューム『英国史』第1巻、第6章。 |

| Aufklärer |

カテゴリー:啓蒙思想家、世界観による人物、活動による近世の人物 |

| Kategorie:Aufklärer |

Kategorien: AufklärungPerson

nach WeltanschauungPerson der Frühen Neuzeit nach Tätigkeit |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vordenker_der_Aufkl%C3%A4rung |

★啓蒙哲学(Enlightenment philosophy)——下の啓蒙の部分と重なるために冒頭の表題のみ記す

| Enlightenment philosophy[a]

was the philosophy produced during the Age of Enlightenment (late 17th

and 18th centuries), originating in France, then western Europe and

spreading throughout the rest of Europe. The Enlightenment philosophers

included (among others) Baruch Spinoza, David Hume, John Locke, Edward

Gibbon, Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Denis Diderot, Pierre Bayle,

and Isaac Newton. Enlightenment philosophy was influenced by the

Scientific Revolution in southern Europe, arising directly from the

Italian Renaissance with people like Galileo Galilei. Many Enlightenment philosophers viewed themselves as part of a progressive intellectual élite and opposed religious and political persecution, criticizing what they regarded as irrationality, arbitrariness, obscurantism, and superstition in earlier periods. They redefined the study of knowledge to fit the ethics and aesthetics of their time. Their works had great influence at the end of the 18th century, in the American Declaration of Independence and the French Revolution.[3] This intellectual and cultural renewal by the Enlightenment movement was, in its strictest sense, limited to Europe. These ideas were well understood in Europe, but beyond France the idea of "enlightenment" had generally meant a light from outside, whereas in France it meant a light coming from knowledge one gained. In the most general terms, in science and philosophy, the Enlightenment aimed for the triumph of reason over faith and belief; in politics and economics, the increasing political influence of the bourgeoisie relative to the nobility and clergy. | 啓

蒙思想[a]とは、啓蒙時代(17世紀後半から18世紀)に生まれた哲学である。フランスで始まり、西ヨーロッパに広がり、やがてヨーロッパ全域に普及し

た。啓蒙思想家には(とりわけ)バルーフ・スピノザ、デイヴィッド・ヒューム、ジョン・ロック、エドワード・ギボン、ヴォルテール、ジャン=ジャック・ル

ソー、デニス・ディドロ、ピエール・ベイル、アイザック・ニュートンらが含まれる。啓蒙思想は南ヨーロッパにおける科学革命の影響を受け、ガリレオ・ガリ

レイらに代表されるイタリア・ルネサンスに直接起因する。 多くの啓蒙思想家は自らを進歩的な知的エリートの一員と見なし、宗教的・政治的迫害に反対した。彼らは過去の時代に存在したとされる非合理性、恣意性、蒙 昧主義、迷信を批判したのである。彼らは当時の倫理観や美意識に適合するよう知識の研究を再定義した。彼らの著作は18世紀末、アメリカ独立宣言やフラン ス革命において大きな影響力を持った。[3] 啓蒙運動によるこの知的・文化的刷新は、厳密な意味ではヨーロッパに限定されていた。これらの思想はヨーロッパでは広く理解されていたが、フランス以外で は「啓蒙」という言葉は一般的に外部からの光を意味していたのに対し、フランスでは自ら得た知識から生まれる光を意味していた。 最も一般的な意味で、啓蒙主義は科学と哲学において、信仰や信念に対する理性の勝利を目指した。政治と経済においては、貴族や聖職者に対するブルジョワジーの政治的影響力の増大を目指した。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enlightenment_philosophy |

☆啓蒙(ウィキペディア英語版)

★ Kehinde Andrews, The New Age of Empire: How Racism and Colonialism Still Rule the World, 2022.

The

Enlightenment was essential in providing the intellectual basis for

Western imperialism, justifying White supremacy through scientific

rationality. - Kehinde Andrews.

啓蒙主義は西洋帝国主義の知的基盤を提供する上で不可欠であり、科学的合理性を通じて白人至上主義を正当化した(カヒンデ・アンドリュース)

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆