マチスモ

Machismo

The Crowning of the Virtuous Hero by Peter Paul Rubens

☆ マチズモ(/məˈtʃmːz(, mɑː-, -ˈtʃˈ; スペイン語: [maʃismo]; ポルトガル語: [maʃiʒmu]: [maʃʃismo];スペイン語のmacho「男性」と-ismoから)[1]は、「男らしい」、自立しているという感覚であり、「男性的なプライドの 強い感覚:誇張された男らしさ」と関連する概念である。 [2]マチズモとは、1930年代初頭から1940年代にかけて生まれた用語で、自分の男性性に誇りを持つことと定義するのが最も適切である。この言葉は 「家族を養い、守り、防衛する男の責任」と関連しているが[3]、マチズモは強く一貫して、支配、攻撃性、大言壮語、育てる能力の欠如と関連している。マ チズモとの相関関係は、家族の力学と文化に深く根ざしていることが判明している[4]。 マッチョという言葉は、スペイン語とポルトガル語を含め、スペインとポルトガルの両方で長い歴史を持っている。ポルトガル語とスペイン語のマッチョは、ラ テン語の「男性」を意味するmascŭlusに由来する、厳密に男性的な用語である。もともとは、特にイベリア語圏の社会や国々において、男性が地域社会 で果たすべき理想的な社会的役割に関連していた。また、ラテンアメリカの征服、戦い、絶え間ない官僚的闘争の歴史から、男性には勇敢さ、勇気、強さ、知 恵、リーダーシップを持ち、それを発揮することが期待されていた。Ser macho(文字通り「マッチョになること」)は、すべての男子の憧れだった。歴史が示すように、男性はしばしば力強く支配的な役割を担っていたため、暴 力的なマッチョマンというステレオタイプが描かれた。このように、マチズモの起源は、過去の歴史、植民地時代のラテンアメリカが直面した闘争、そして時代 によるジェンダーのステレオタイプの進化を示すものとなっている。

| Machismo

(/məˈtʃiːzmoʊ, mɑː-, -ˈtʃɪz-/; Spanish: [maˈtʃismo]; Portuguese:

[maˈʃiʒmu]; from Spanish macho 'male', and -ismo)[1] is the sense of

being "manly" and self-reliant, a concept associated with "a strong

sense of masculine pride: an exaggerated masculinity".[2] Machismo is a

term originating in the early 1930s and 1940s best defined as having

pride in one's masculinity. While the term is associated with "a man's

responsibility to provide for, protect, and defend his family",[3]

machismo is strongly and consistently associated with dominance,

aggression, grandstanding, and an inability to nurture. The correlation

to machismo is found to be deeply rooted in family dynamics and

culture.[4] The word macho has a long history both in Spain and Portugal, including the Spanish and Portuguese languages. Macho in Portuguese and Spanish is a strictly masculine term, derived from the Latin mascŭlus, which means "male". It was originally associated with the ideal societal role men were expected to play in their communities, most particularly Iberian language-speaking societies and countries. In addition, due to Latin America's history of conquest, battles and constant bureaucratic struggles, it was expected of men to possess and display bravery, courage, strength, wisdom and leadership. Ser macho (literally, "to be a macho") was an aspiration for all boys. As history shows, men were often in powerful and dominating roles thus portrayed the stereotype of a violent macho man. Thus the origin of machismo serves as an illustration of past history, the struggles that colonial Latin America faced and the evolution of gender stereotypes with time. |

マチズモ(/məˈtʃmːz(, mɑː-, -ˈtʃˈ;

スペイン語: [maʃismo]; ポルトガル語: [maʃiʒmu]:

[maʃʃismo];スペイン語のmacho「男性」と-ismoから)[1]は、「男らしい」、自立しているという感覚であり、「男性的なプライドの

強い感覚:誇張された男らしさ」と関連する概念である。

[2]マチズモとは、1930年代初頭から1940年代にかけて生まれた用語で、自分の男性性に誇りを持つことと定義するのが最も適切である。この言葉は

「家族を養い、守り、防衛する男の責任」と関連しているが[3]、マチズモは強く一貫して、支配、攻撃性、大言壮語、育てる能力の欠如と関連している。マ

チズモとの相関関係は、家族の力学と文化に深く根ざしていることが判明している[4]。 マッチョという言葉は、スペイン語とポルトガル語を含め、スペインとポルトガルの両方で長い歴史を持っている。ポルトガル語とスペイン語のマッチョは、ラ テン語の「男性」を意味するmascŭlusに由来する、厳密に男性的な用語である。もともとは、特にイベリア語圏の社会や国々において、男性が地域社会 で果たすべき理想的な社会的役割に関連していた。また、ラテンアメリカの征服、戦い、絶え間ない官僚的闘争の歴史から、男性には勇敢さ、勇気、強さ、知 恵、リーダーシップを持ち、それを発揮することが期待されていた。Ser macho(文字通り「マッチョになること」)は、すべての男子の憧れだった。歴史が示すように、男性はしばしば力強く支配的な役割を担っていたため、暴 力的なマッチョマンというステレオタイプが描かれた。このように、マチズモの起源は、過去の歴史、植民地時代のラテンアメリカが直面した闘争、そして時代 によるジェンダーのステレオタイプの進化を示すものとなっている。 |

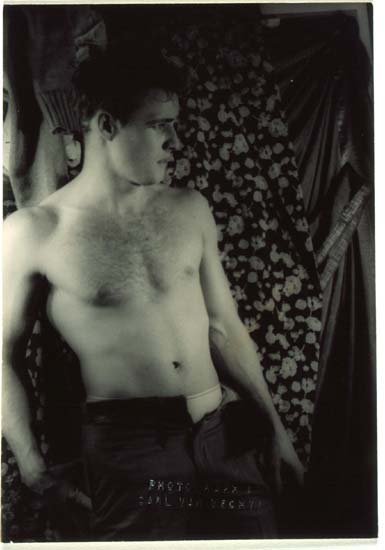

Caballerosidad Portrait of Marlon Brando as Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire "Caballerosidad" in Spanish, cavalheirismo in Portuguese, or the English mixture of both (but not a proper word in any of the previously mentioned languages), caballerismo, is the Latin American understanding of manliness that focuses more on honor and chivalry.[5] The meaning of caballero is "gentleman". This meaning is derived from the concept of being one who follows a code of honor like knights used to do, or shares certain values and ideals associated with them. These include a particular pride in honor, especially when in context of treating women kindly with especial delicacy and attention. Latin American scholars have noted that positive descriptors of machismo resemble the characteristics associated with the concept of caballerosidad.[6] Understandings of machismo in Latin American cultures are not all negative; they also involve characteristics of honor, responsibility, perseverance, and courage, related to both individual and group interaction.[6][7] Studies show that Latin American men understand masculinity to involve considerable childcare responsibilities, politeness, respect for women's autonomy, and non-violent attitudes and behaviors.[8] In this way, machismo comes to relate to both a positive and negative understanding of Latin American male identity within the immigrant context. Therefore, machismo, like all social constructions of identity, should be understood as having multiple layers.[6][9] The word caballerosidad originates from the Spanish word caballero, which is the Spanish equivalent of "a knight". Caballerosidad refers to a chivalric masculine code of behavior. (Note that the English term also stems from the Latin root caballus, through the French chevalier). Like the English chivalric code, caballerosidad developed out of a medieval socio-historical class system in which people of wealth and status owned horses and other forms of horsepower for transportation, whereas the lower classes did not. It was also associated with the class of knights in the feudal system. In Spanish, caballero referred to a land-owning colonial gentleman of high station who was master of estates and/or ranches.[6] |

キャバレロ 欲望という名の電車』のスタンリー・コワルスキー役マーロン・ブランドの肖像画 スペイン語の "Caballerosidad"、ポルトガル語の "cavalheirismo"、またはその両方が混ざった英語の "caballerismo "は、ラテンアメリカの男らしさの理解であり、名誉と騎士道に重点を置いている[5]。この意味は、かつて騎士がそうであったように、名誉の規範に従う 者、あるいは騎士に関連する特定の価値観や理想を共有する者という概念に由来する。これには、名誉に対する特別な誇り、特に女性を特別にデリケートかつ注 意深く扱うという文脈が含まれる。 ラテンアメリカの学者たちは、マチズモの肯定的な描写は、caballerosidadの概念に関連する特徴に似ていると指摘している[6]。ラテンアメ リカ文化におけるマチズモの理解は否定的なものばかりではなく、名誉、責任感、忍耐力、勇気といった、個人と集団の相互作用の両方に関連する特徴も含んで いる。 [6][7]研究によれば、ラテンアメリカの男性は男らしさについて、かなりの育児責任、礼儀正しさ、女性の自主性の尊重、非暴力的な態度や行動を伴うと 理解している[8]。このように、マチズモは移民の文脈の中で、ラテンアメリカの男性のアイデンティティに対する肯定的・否定的な理解の両方に関係するよ うになる。したがって、マチズモはアイデンティティのあらゆる社会的構築と同様に、複数の層を持つものとして理解されるべきである[6][9]。 caballerosidadという語は、スペイン語で「騎士」に相当するcaballeroに由来する。Caballerosidadは騎士道的な男性 的行動規範を指す。(英語もラテン語の語源caballusに由来し、フランス語のchevalierを経由していることに注意)。英語の騎士道規範と同 様、カバレロシダードは、中世の社会史的階級制度から発展したもので、裕福で地位のある人々は馬や移動用の馬力を所有していたが、下層階級は所有していな かった。また、封建制度における騎士階級とも関連していた。スペイン語では、カバジェロ(caballero)は、土地所有の植民地紳士で、地所や牧場の 主人である高い地位の者を指す[6]。 |

| Depictions The depictions of machismo vary, but not unlike like the gaucho, their characteristics are quite familiar. Machismo is based on biological, historical, cultural, psycho-social, and interpersonal traits or behaviors. Some of the well known traits are; Posturing: assuming a certain, often unusual or exaggerated body posture or attitude. The macho must settle all differences, verbal or physical abuse, challenges, or disagreements with violence as opposed to diplomacy. Treating their wife as a display of an aloof lord-protector: women are loving, men conquer.[10] Bravado: outrageous boasting, overconfidence. Social dominance: a socio-culturally defined dominance; macho swagger. Sexual prowess: being sexually assertive. Shyness is a collective issue for men.[11] Protecting one's honor or pride: believing in protecting the ego in spite of potential risk. A willingness to face danger.[12] From a Mexican-Chicano cultural and psychological perspective, the psycho-social traits can be summarized as; emotional invulnerability, patriarchal dominance, aggressive or controlling responses to stimuli, and ambivalence toward women.[13][14] These traits have been seen as a Mexican masculine response to the Spanish conquistador conquering of the Americas.[15] It has been noted by some scholars that machismo was adopted as a form of control for the male body.[16] |

描写 マチズモの描写はさまざまだが、ガウチョのようなものではなく、その特徴はかなり身近なものだ。マチズモは生物学的、歴史的、文化的、心理社会的、対人的な特徴や行動に基づいている。よく知られている特徴をいくつか挙げてみよう; 姿勢:特定の、しばしば異常な、あるいは誇張された体の姿勢や態度をとる。マッチョは、すべての違い、言葉や身体による虐待、挑戦、意見の相違を、外交とは対照的に暴力で解決しなければならない。 妻を飄々とした主君=保護者のように扱う:女性は愛情深く、男性は征服する[10]。 虚勢:法外な自慢、自信過剰。 社会的優位:社会文化的に定義された優位性、マッチョな威張り方。 性的な腕前:性的な自己主張をする。内気さは男性にとって集団的な問題である[11]。 自分の名誉やプライドを守る:潜在的なリスクにもかかわらず、自我を守ることを信じる。 危険に直面することを厭わないこと[12]。 メキシコ系チカーノの文化的、心理学的観点から、精神社会的特徴は、感情的無防備、家父長的支配、刺激に対する攻撃的または支配的な反応、女性に対するア ンビバレンス[13][14]として要約することができる。これらの特徴は、スペインのアメリカ大陸征服に対するメキシコの男性的反応とみなされている [15]。 |

| Machismo in Cuba Early beginnings Machismo is a source of pride for men and they must prove their manliness by upholding their dominance in their reputation and their household. Machismo comes from the assertion of male dominance in everyday life. Examples of this would be men dominating their wives, controlling their children, and demanding the utmost respect from others in the household. Machismo has become deeply woven in Cuban society and have created barriers for women to reach full equality. The reason for this is the patriarchy that runs high in Cuban society. Cuba's patriarchal society stems from the fact that Spain has had a history of using brutal war tactics and humiliation as a means to keep and establish their power. Tomas de Torquemada, who ruled as a grand inquisitor under King Ferdinand and Queen Elizabeth of Spain, used degrading and humiliating forms of torture to get information out of prisoners. In Uva de Aragon Clavijo's, novel El Caiman Ante El Espejo, Clavijo claims that Cubans feel more power from the genital organs of past male Cuban leaders like Fidel Castro. Even though he represented a revolution, he was still a powerful and dominating man who ruled over the people. In the point of view of Clavijo, militarism and caudillismo, are what is to blame for Cuban machismo, as it established the ideology of the "leadership of the strongman" which proved to be successful in Castro becoming victorious in his revolution. Thus furthering that a male dominated political society is superior.[17] The idea of the male ego, where the male is symbolized as "hyper-masculine, virile, strong, paternalistic, sexually dominant, and the financial provider"[18] is reinforced by the teachings of the Catholic Church, the main religion practiced in Cuba and Latin America in general. According to Catholic Church teachings, the female should be a virgin but it's less important for the male to be one.[18] During colonial times, a female's chastity and demureness were linked to the family's societal standings [new], while the males were expected and sometimes pressured into proving their sexual prowess by having multiple partners.[18] There was a duality in the expression of love. Men were supposed to express between physical loves, while women were expected to only express spiritual love and romantic love. Even after marriage, carnal love was frowned upon if the woman expressed it too vigorously, instead she was more delighted by the romantic expression of the love. Cuban machismo and its effect Because of the objectification of women, domestic violence is often ignored when women decide to seek help from the police. Domestic abuse victims are given psychological counseling as a way to cope with their trauma, but little is done criminally to solve the problem.[18] Domestic Abuse cases or other violent crimes committed against women, are very rarely reported on by the media,[19] and the government does not release statistics that show the people the extent of the crimes.[20] The Cuban Revolution changed some of the ways the people of Cuba viewed women. Fidel Castro in his own words saw that the women were going through 'a revolution within the revolution, and established the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC). This organization, headed by Vilma Espin, Castro's sister in law, helped women establish themselves better into the working world and in women's right issues.[19] The FMC has continually advocated for women rights and in 1997 created the Grupo Nacional para la Prevencion y Atencion de la Violencia Familiar, a national group whose purpose is to study and find measures on how to get help for the women who fall victim to domestic violence.[19] With the help of the FMC and the Grupo Nacional para la Prevencion y Atencion de la Violencia Familiar, women can file claims against their abusers at the Office of Victim Rights. They are also now able to get access to sexual abuse therapies.[19] This by no way solves the issue of domestic abuse, but it is a turning point for the Cuban women who are now no longer feeling powerless in the fight.[19] Because Machismo is so entrenched into the very systems that keep women oppressed, women in Cuba do not hold political or monetary positions of power.[21] The role of women in revolutionary society were as subjects. Although the revolution allowed women control over their personal, professional, and reproductive lives there was a persistent view that Cuba was built by a brotherhood of men. This saw women as "revolutionary mothers" who were subalterns of the state.[22] The idea that gender equality was surface level can be shown in the Codigo de la Familia which called for men to take a more active role in the household, but was rarely enforced. Another example of this surface level equality is shown in Guevara's book, "El hombre Nuevo"(1965). Women are first and foremost depicted as wives of revolutionaries, however they also have the additional roles of militants and volunteer workers. Guevara was connecting traditional Latin American gender concepts of femininity to the socialist revolution by stating that women's commitment to the revolution was not important for the outcome of the revolution but rather for their overall desirability to men. Guevara's book continues to outline the role of women in society by dictating how they should look for men in addition to what to look for in a man.[23] The desirable Cuban man was seen as industrious and willing to serve the state when he was called upon. The Cuban man often had to participate in voluntary agricultural work to help the agricultural production of the state. This was tied to the idea that the Cuban "new man" was essential for the survival of a socialist state.[24] The depiction of women and men in Cuban media influenced gender relations in Cuban society as a whole. The outcomes of the depictions and legislations brought forth by Guevara's "New Man" are shown in the role of women in revolutionary society which saw their role in the domestic sphere mostly unchanged and pre existing notions of masculinity and femininity still being dominant in the political theatre.[25] While there are 48.9% of women in Cuban Congress, the political group that holds the most power is The Cuban Communist Party, which is made up of only 7% of women.[21] In many cases, women who do have professional jobs are often funded by the Cuban state meaning they only receive about $30 a month.[26] This means that women are employed but do not and cannot hold positions of power due to the men in power who benefit from staying in power. Machismo is mostly ingrained in domestic environments, so while 89% of women over 25 have received a secondary education,[27] if a woman is a doctor, or a lawyer even after all the work she has done during the day, at home she is still expected to cook and clean and be the primary caretaker of the children. Many feminist scholars have described this phenomenon, which takes place in other cultures, as the second shift, based on a book by Arlie Russell Hochschild by the same name.[28] Cuban males see no problem in leaving all the housework to their wives while they are allowed to go out for drinks with their friends.[29] Machismo characteristics in men have given them power over women in the home,[29] which leaves certain women more vulnerable to domestic violence committed against them. Cubans are now beginning to leave state employment, to search for jobs in tourism. These jobs produce a great deal of profit because of the wealthy tourists that visit the island and leave good tips. Cubans who were once professors and doctors are now leaving their old jobs to become bartenders and drive cabs. From the inception of machismo from both the Spanish Empire and Portuguese Empire, machismo translates to mean macho and refers to male oppression over women. Moreover, machismo is an all-encompassing term for the dominion of the elite man over 'the other'.[21] In this case 'the other' refers to women of all races and economic status, whom the macho sees as an object to protect.[21] in contrast effeminate and gay men are not seen as worthy of protection but as objects to ridicule and punish sometimes with violence. Men who do not perform their gender in the "normalized" way are referred to as maricon, (a derogatory word meaning queer or fag), because their maleness is being called into question. Many of the anti-LGBT acceptance stems from The Cuban Revolution and Fidel Castro who had strong views over masculinity and how it fit in his idea of militarism. Fidel Castro once said on homosexuality in a 1965 interview with American journalist Lee Lockwood, "A deviation of that nature clashes with the concept we have of what a militant communist should be."[30] That same year gay men in Cuba were being sent to labor camps because their sexuality made them "un-fit" to be involved in military service.[30] Machismo has not only been a tool used to control women but also to punish men who do not adhere to societal norms, should behave as well. However, in the more recent years, the establishment of CENESEX (National Centre for Sexual Education) has been established so that the population of Cuba can more readily accept sexual diversity of all kinds, especially in terms of the LGBT people. CENESEX has grown in part because of the Cuban government and with the help of Mariela Castro-Espin, daughter of Raul Castro, 16th president of Cuba, and niece to Fidel Castro. CENESEX has sought to decrease homophobia in Cuba by increasing sexual awareness by holding social gatherings like anti-homophobic rallies. Cuban machismo in the media In 1975, a new Cuban Law came onto the island: the Codigo de la Familia (Family Law). It was put into effect on 8 March 1975, 15 years after the Cuban Revolution. The new Family Law of 1975 helped a lot of women get jobs on the island and provided children with protection under the law so that child begging and homelessness amongst children was practically eradicated. The law also stated that it was required for both sexes to participate in domestic chores[31] But just because the law was passed, does not mean it was heavily reinforced, particularly in the domestic sphere.[32] One of the aspects of the new family law was not only to create equality outside of the home but inside of it as well. This new family law was not received well by many people in Cuba. And many people lashed back against the law. These grievances reflected in the media that was made in Cuba, particularly, during the "Golden Age of Cuban Cinema". In revolutionary Cuba where public political discourse was limited, films provided a platform for political discourse in Cuba by tackling controversial issues in a complex manner. Films like De Cierta Manera exemplify these shifts in Cuban society through its use of a female director and subversive plot. The film sees a relationship blossom between a low-class mulatto and a middle-class pale teacher. The plot, "exposes and subverts the traditional notion of spectator identification and thus posits a truly 'revolutionary' and potentially subversive character representation."[32] The revolutionary notions of the film can be seen through a romantic relationship sparking across racial and class lines. Subversive films like De Cierta Manera challenged the Latin American idea of Machismo. The Film Up to a Certain Point establishes a need for the abandonment of machismo in order for Cuba to be a true socialist state. Although subversive films like these were released to cement the ideal "new man" in Cuban culture, some films like Retrato de Teresa challenge the idea of Machismo, but depict the male view as dominant and instead depict the illusion of change. The abandonment of machismo is present in Cuban film although some scholars argue that it was merely surface level and represent the views of gender roles in Cuban society as a whole.[33] Women's commitment to the revolution directly influenced their desirability to men. This led to hypersexualized depictions of women who abided by the revolution while showing non-revolutionary women as undesirable to men in mass media. Cuban cartoons depict desirable Cuban women as revolutionary, sexual, and voluptuous while depicting the undesirable Cuban man as Americanized.[23] Hasta Cierto Punto Hasta Cierto Punto directed by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea is a movie that follows Oscar, an educated playwright who writes a movie on the effects of machismo in Cuban Society. In the opening scene of this movie, there is an interview with a young black man who is asked about machismo. The young man laughs and says in the movie, "Oh, they've managed to change my attitudes on that score; I'm certainly changed up to a certain point. I've probably changed up to 80% now. Maybe they can work on me and change me to 87%. But they will never, never get me up to 100%, no way!"[34] These attitudes on-screen reflect that of many men in Cuba and their attitudes towards women having more equality in everyday life. The film that Oscar was meant to write for is directed by his friend Arturo. Both are well-educated men with stable careers in their fields, wives, cars, and other luxuries. However, Arturo believes that the issue of Machismo is most directly a working class problem and that it is up to educated men such as himself and Oscar, to raise consciousness on the issue. Oscar and Arturo use working-class dock-workers to use as research for their film. This is where they meet Lina, a working-class woman who is in charge of the dock workers. At the beginning of the film she is represented to be tough on her workers and is well respected amongst all the men she works with. Oscar, the screenwriter, finds himself enamored with her tough attitudes, which are very different from those of women he has met before. However, as the movie goes on, we see Oscar increasingly find himself frustrated with Lina's free spirit and working-class "down-to-earth" personality. Oscar sees that this is not the kind of woman he is used to. Throughout the movie, although Oscar is having an affair with his wife, he finds himself being more empathetic to working-class struggles in a way that his friend Arturo is not. Arturo still believes that all working-class men are just "macho brutes"[34] The film's dynamic on working class and bourgeois machismo is very telling of Cuban society and how class reflects on the attitudes towards machismo. It also problematizes bourgeois men who believe they are intellectually above everyone else, including issues on machismo and women's equality. Lasting effects of Cuban machismo The aftermath of Guevara's "new man" ideology can be seen in the dynamics of post-revolutionary romantic relationships and society. In post-revolutionary Cuban society, men were in constant fear of infidelity as the importance of capitalism increased in Cuba. Now that monetary exchange had value in Cuba, daily necessitates were no longer provided for by the government which meant money was needed for day-to-day life. This meant that women would often leave their partner for someone who was wealthy or foreign because migration became an important part of Cuban society. Machismo is still present at this point and is embodied in men's paranoia, women were often controlled by their partners to ensure their faithfulness.[35] The impact of this shift in gender is seen in Cuban society as a whole. New class disparities emerge amongst poor Cuban men, wealthy Cuban men, and tourists. Cuban women are searching for wealthy men which in turn attracts more wealthy tourists to the island, leading to a further dominance of monetary exchange in Cuba which leads to a further class disparity between rich and poor Cubans.[36] |

キューバのマチズモ 初期の始まり マチズモは男性にとってプライドの源であり、評判や家庭での優位性を維持することで男らしさを証明しなければならない。マチズモは、日常生活における男性 の優位性の主張から生まれる。その例としては、男性が妻を支配し、子供を支配し、家庭内で他人から最大限の敬意を要求することが挙げられる。マチズモは キューバ社会に深く浸透し、女性が完全に平等になるための障壁を作り出してきた。その理由は、キューバ社会に蔓延する家父長制にある。キューバの家父長制 社会は、スペインが権力を維持・確立する手段として、残忍な戦争戦術や屈辱を用いた歴史があることに由来する。スペインのフェルディナンド王とエリザベス 女王の下で大審問官として統治したトマス・デ・トルケマーダは、囚人から情報を引き出すために卑劣で屈辱的な拷問を行った。 ウバ・デ・アラゴン・クラビホの小説『エル・カイマン・アンテ・エル・エスペホ』では、クラビホは、キューバ人はフィデル・カストロのような過去のキュー バ人男性指導者の性器から、より大きな力を感じていると主張している。彼は革命を象徴していたとはいえ、人々を支配する強力で支配的な男だった。クラヴィ ジョの視点によれば、軍国主義とコーディリズモがキューバのマチズモの原因であり、カストロが革命に勝利するために成功した「強者のリーダーシップ」のイ デオロギーを確立したからである。こうして男性優位の政治社会が優れていることがさらに証明された[17]。 男性が「超男性的で、男らしく、強く、父権的で、性的に支配的で、経済的な供給者」[18]として象徴される男性の自我の考え方は、キューバとラテンアメ リカ全般で実践されている主要な宗教であるカトリック教会の教えによって強化されている。カトリック教会の教えによれば、女性は処女であるべきだが、男性 が処女であることの重要性はそれほど高くない[18]。植民地時代、女性の貞操と慎み深さは家族の社会的地位と結びついていた[新しい]が、一方、男性は 複数のパートナーを持つことで性的能力を証明することを期待され、時には圧力をかけられていた[18]。愛の表現には二面性があった。男性は肉体的な愛だ けを表現し、女性は精神的な愛とロマンチックな愛だけを表現することになっていた。結婚後でさえ、肉欲的な愛を女性が激しく表現すると嫌われ、その代わり にロマンチックな愛の表現が喜ばれた。 キューバのマチズモとその影響 女性を客観視するあまり、女性が警察に助けを求めようとしても、家庭内暴力は無視されることが多い。家庭内暴力の被害者はトラウマに対処する方法として心 理カウンセリングを受けるが、問題を解決するために刑事的に行われることはほとんどない[18]。家庭内暴力事件や女性に対するその他の暴力犯罪がメディ アによって報道されることは非常にまれで[19]、政府は犯罪の程度を国民に示す統計を発表しない[20]。フィデル・カストロは自らの言葉で、女性たち が「革命の中の革命」を経験していることを見抜き、キューバ女性連盟(FMC)を設立した。カストロの義理の妹であるヴィルマ・エスピンが率いるこの組織 は、女性が労働の世界や女性の権利の問題によりよく身を置くことができるように支援した[19]。FMCは女性の権利を継続的に提唱し、1997年には、 家庭内暴力の犠牲になる女性のために、どのようにすれば助けを得られるかを研究し、対策を見つけることを目的とする全国的なグループであるGrupo Nacional para la Prevencion y Atencion de la Violencia Familiar(家庭内暴力の予防と対策に関する全国グループ)を設立した。 [19] FMCとGrupo Nacional para la Prevencion y Atencion de la Violencia Familiarの支援により、女性は加害者に対して被害者権利事務所に申し立てを行うことができる。また、性的虐待の治療も受けられるようになった [19]。これは決して家庭内虐待の問題を解決するものではないが、キューバの女性たちにとって、闘いにおける無力感を感じなくなる転機となった [19]。 マチズモは女性を抑圧し続けるシステムそのものに根付いているため、キューバの女性は政治的・金銭的な権力の座に就いていない[21]。革命によって女性 は個人的、職業的、生殖的な生活をコントロールできるようになったが、キューバは男性の兄弟愛によって築かれたという見方が根強かった。男女平等が表面的 なものであったという考え方は、男性が家庭でより積極的な役割を果たすことを求めた『家族法典』に見ることができるが、ほとんど施行されなかった。この表 面的な平等のもう一つの例は、ゲバラの著書『El hombre Nuevo』(1965年)に示されている。女性はまず第一に革命家の妻として描かれているが、同時に過激派やボランティア労働者という役割も担ってい る。ゲバラは、女性が革命に参加することが革命の結果にとって重要なのではなく、むしろ男性にとって魅力的であるかどうかが重要なのだと述べることで、ラ テンアメリカの伝統的な女性性の概念を社会主義革命に結びつけたのである。ゲバラの著書は、男性に何を求めるべきかということに加えて、女性が男性をどの ように探すべきかを指示することで、社会における女性の役割の輪郭を描き続けている[23]。望ましいキューバ人男性は勤勉で、要請があれば喜んで国家に 奉仕すると見られていた。キューバ人男性は、国家の農業生産を助けるために、しばしば自発的に農作業に参加しなければならなかった。これは、キューバの 「新しい男」が社会主義国家の存続に不可欠であるという考えと結びついていた[24]。キューバのメディアにおける女性と男性の描写は、キューバ社会全体 の男女関係に影響を与えた。ゲバラの「新しい男」によってもたらされた描写と法律の成果は、革命社会における女性の役割に示されており、家庭内での女性の 役割はほとんど変わらず、男性らしさと女性らしさの既存の概念が政治劇場で依然として支配的であった[25]。 9%の女性がキューバ議会にいるが、最も権力を握っている政治集団はキューバ共産党であり、女性の割合はわずか7%である[21]。多くの場合、専門職に ついている女性は、キューバ国家から資金援助を受けていることが多く、つまり月に30ドル程度しか受け取っていない[26]。これは、女性は雇用されてい るが、権力を維持することで利益を得ている権力者の男性のために、権力の座に就いておらず、就くこともできないことを意味する。25歳以上の女性の89% が中等教育を受けているにもかかわらず[27]、女性が医師や弁護士であれば、日中働いた後でも、家では料理や掃除をし、子どもの世話をすることが求めら れる。多くのフェミニスト学者は、他の文化圏でも起こっているこの現象を、アーリー・ラッセル・ホッチシルトの同名の著書に基づいて、第二のシフトと表現 している[28]。キューバ人男性は、家事をすべて妻に任せ、自分は友人と飲みに行くことを許されることに何の問題もないと考えている[29]。男性のマ チズモ的特性は、家庭内で女性に対する権力を与え[29]、その結果、特定の女性は、自分に対して行われる家庭内暴力を受けやすくなっている。キューバ人 は現在、観光業での仕事を探すために国家公務員を辞め始めている。これらの仕事は、島を訪れる裕福な観光客が良いチップを残してくれるため、大きな利益を 生む。かつては教授や医者だったキューバ人も、今ではバーテンダーやタクシーの運転手になるために以前の仕事を離れている。 スペイン帝国とポルトガル帝国の両方からマチズモが生まれたことから、マチズモはマッチョという意味に訳され、女性に対する男性の抑圧を指す。さらに、マ チズモは「他者」に対するエリート男性の支配を包括する言葉である[21]。この場合、「他者」とはあらゆる人種や経済的地位の女性を指し、マッチョはそ の女性を保護すべき対象とみなす[21]。対照的に、女々しい男性やゲイの男性は保護に値せず、嘲笑し、時には暴力で罰する対象とみなされる。正規化され た」やり方でジェンダーを演じない男性は、その男性性が問題視されるため、マリコン(クィアやホモを意味する蔑称)と呼ばれる。反LGBT受容の多くは、 キューバ革命とフィデル・カストロに起因している。カストロは、男らしさとそれが彼の考える軍国主義にどのように適合するかをめぐって強い見解を持ってい た。フィデル・カストロは、1965年のアメリカ人ジャーナリスト、リー・ロックウッドとのインタビューで、同性愛について「そのような性質の逸脱は、我 々が持つ戦闘的共産主義者がどうあるべきかという概念と衝突する」と語ったことがある[30]。同年、キューバでは、同性愛者の男性は、そのセクシュアリ ティが兵役に携わるのに「ふさわしくない」という理由で労働キャンプに送られていた[30]。しかし近年、キューバ国民があらゆる種類の性的多様性、特に LGBTの人々をより受け入れやすくなるよう、CENESEX(国立性教育センター)が設立された。CENESEXは、キューバ政府と、ラウル・カストロ (第16代キューバ大統領)の娘でフィデル・カストロの姪であるマリエラ・カストロ=エスピン氏の援助によって成長した。セネセクスは、反ホモフォビック 集会のような社会的な集まりを開催することによって性的意識を高め、キューバにおけるホモフォビアを減少させようとしてきた。 メディアにおけるキューバのマチズモ 1975年、キューバに新しい法律「家族法」が施行された。キューバ革命から15年後の1975年3月8日に施行された。1975年に施行された新しい家 族法は、多くの女性が島で仕事を得るのを助け、子どもたちに法の下での保護を提供したため、子どもたちの物乞いやホームレスは実質的に根絶された。しか し、法律が成立したからといって、それが特に家庭内で強化されたわけではなかった。この新しい家族法はキューバの多くの人々には受け入れられなかった。そ して多くの人々がこの法律に反発した。こうした不満は、キューバ、特に「キューバ映画の黄金時代」に作られたメディアに反映された。公的な政治的言説が制 限されていた革命期のキューバにおいて、映画は物議を醸す問題に複合的に取り組むことで、キューバにおける政治的言説のプラットフォームを提供した。De Cierta Manera』のような映画は、女性監督を起用し、破壊的なプロットを描くことで、キューバ社会のこうした変化を例証している。この映画では、下層階級の マルチーズと中流階級の青白い教師の間に関係が芽生える。このプロットは、「観客の同一性という伝統的な概念を暴露し、破壊することで、真に "革命的 "で潜在的に破壊的な人物表現を提起している」[32]。この映画の革命的概念は、人種や階級を越えて火花を散らす恋愛関係を通して見ることができる。 De Cierta Manera』のような破壊的な映画は、ラテンアメリカのマチズモの概念に挑戦した。映画『ある地点まで』は、キューバが真の社会主義国家となるために は、マチズモを捨てる必要があることを立証している。これらのような破壊的な映画は、キューバ文化に理想的な「新しい男」を定着させるために公開された が、『テレサの帰還』のように、マチズモの考えに挑戦しながらも、男性観が支配的であることを描き、その代わりに変化の幻想を描いている映画もある。マチ ズモの放棄はキューバ映画にも存在するが、それは表面的なものにすぎず、キューバ社会全体におけるジェンダー役割の見解を表していると主張する学者もいる [33]。そのため、革命に従順な女性の描写は性的に誇張され、非革命的な女性は男性にとって好ましくないものとしてマスメディアに登場することになっ た。キューバの漫画は、望ましいキューバ人女性を革命的で性的で豊満なものとして描く一方で、望ましくないキューバ人男性をアメリカナイズされたものとし て描いている[23]。 ハスタ・シエルト・プント トマス・グティエレス・アレア監督の『Hasta Cierto Punto』は、キューバ社会におけるマチズモの影響について映画を書く、教育を受けた劇作家オスカーを描いた映画である。この映画の冒頭シーンで、マチ ズモについて質問された黒人青年へのインタビューがある。映画の中でその青年は笑いながらこう言う。「ああ、彼らはその点では僕の態度を変えることができ た。今は80%くらいまで変わったかな。多分、彼らは私に働きかけ、私を87%まで変えることができるだろう。でも、100%には絶対にならないよ、絶対 に!」[34] スクリーン上のこうした態度は、キューバの多くの男性や、日常生活において女性がより平等であることに対する彼らの態度を反映している。オスカーが脚本を 書くことになった映画は、友人のアルトゥーロが監督した。2人とも高学歴で、それぞれの分野で安定したキャリアを持ち、妻や車など贅沢な暮らしをしてい る。しかしアルトゥーロは、マチズモの問題は最も直接的には労働者階級の問題であり、彼やオスカーのような教養ある男性がこの問題に対する意識を高めるべ きだと考えている。オスカーとアルトゥーロは、労働者階級の港湾労働者を映画のためのリサーチとして利用する。そこで彼らは、港湾労働者の責任者である労 働者階級の女性リナと出会う。映画の冒頭、彼女は労働者に厳しく、一緒に働く男たちの間で尊敬されている。脚本家のオスカーは、これまで出会った女性とは まったく異なる彼女の厳しい態度に夢中になる。しかし、映画が進むにつれ、オスカーはリナの自由な精神と労働者階級の「地に足の着いた」性格に次第に苛立 ちを覚えるようになる。オスカーは、この女性が自分の慣れ親しんだタイプの女性ではないことを知る。映画を通して、オスカーは妻と不倫関係にあるものの、 友人のアルトゥーロにはない方法で、労働者階級の苦悩に共感している自分に気づく。アルトゥーロはいまだに、労働者階級の男性はすべて「マッチョな野蛮 人」に過ぎないと信じている[34]。労働者階級とブルジョワのマチズモに関するこの映画のダイナミズムは、キューバ社会と、階級がマチズモに対する態度 にどのように反映するかを非常によく物語っている。また、マチズモと女性の平等に関する問題を含め、自分は知的に他の誰よりも優れていると信じるブルジョ ア男性を問題視している。 キューバのマチズモの永続的影響 ゲバラの「新しい男」イデオロギーの余波は、革命後の恋愛関係と社会の力学に見ることができる。革命後のキューバ社会では、キューバで資本主義の重要性が 増すにつれ、男性は常に不倫を恐れていた。キューバでは貨幣交換が価値を持つようになり、生活必需品は政府から支給されなくなった。つまり、移住がキュー バ社会の重要な一部となったため、女性はしばしば裕福な人や外国人のためにパートナーと別れることになった。マチズモはこの時点でもまだ存在し、男性のパ ラノイアに具現化されている。貧しいキューバ人男性、裕福なキューバ人男性、観光客の間に新たな階級格差が生まれる。キューバ人女性は裕福な男性を求める ようになり、その結果、より多くの裕福な観光客がキューバを訪れるようになり、キューバにおける貨幣交換の優位性がさらに高まり、富裕なキューバ人と貧困 なキューバ人との間にさらなる階級格差が生じることになる[36]。 |

| Machismo in Puerto Rico In terms of the presence of machismo in Puerto Rican society, men were to work outside the home, manage finances, and make decisions. Women were to be subordinate to their husbands and be the homemakers. Women would often have to be dependent on men for everything. Growing up, boys are taught to adhere to the machismo code, and girls are taught the marianismo code. This practice is also followed by Puerto Rican Americans outside of the island.[37] Nonetheless, this is not the only aspect to Puerto Rican machismo. Machismo can be seen in various ways in Puerto Rico from the island's colonial history to the high cases of gender based violence that occurred in 2021. Because of this, new conversations about machismo are emerging specifically the discussion of how to handle it, what ways in which the next generation can learn about it, and the effects it has on society. Colonial history and ties to machismo When evaluating Puerto Rico's machismo culture it's important to relate it to Puerto Rico's colonial status, first to Spain and then to the United States. When becoming a colony of Spain, Puerto Rico gained the machismo principles Spain instilled.[38] When Puerto Rico became a United States colony, the nation wanted to remedy the poverty Puerto Rico was in. This was done by situating poverty as the main effect of overpopulation. Thus, women's ability to reproduce was one of the ways the United States changed Puerto Rico's "culture of poverty".[39] Mid to late 20th century While Puerto Ricans may be motivated by the progressive movements of the mainland, they base their movements on their unique situation in Puerto Rico. In the 1950s, industrialization caused men's employment rates to decline while women's employment rates began to rise. Additionally, from the 1950s to the 1980s, a field of white-collar women emerged, furthering the rise in women's employment. With their new contribution to the workforce, it was still under the woman's responsibility to continue domestic tasks and now also to contribute to household finances. This caused a shift in what was deemed acceptable in households. Before women would depend greatly on a man to provide for them, but as they acquired roles that required some extent of education and provided financial aid, they were able to become more independent.[40] In the 1960s when many Puerto Ricans were moving to New York, many women were forced toward single motherhood with values that encouraged traditions like marriage. However, women still emphasized the importance of independence and final success. As an example, a mother would advise her children to marry someone who demonstrated they could be financially stable. This was something that brought a lot of tension and inner conflict with the concept of the machismo culture. In present-day society, this machismo culture is still repressed - in 2016, Puerto Rico was the only place where women made more than men, at $1.03 for every $1.[41][42][43] Scholars argue that examples like these where women move toward an independent life by being a single mother, prove that machismo and/ or marianismo cannot be concretely defined. Rather, it depends on a person's decision or circumstances in society rather than a belief they were taught and followed.[40] Rules enforced by Latin families that teach that young women should not be influenced by the dangers of the outside world, portray young women as vulnerable or in danger of being sexualized. Many times these strict rules are emphasized as some women experience pregnancy at a young age where they are said to not be ready to carry out the task of being a young mother. Young women may even lack support from their own household families and are blamed for not being properly educated. Puerto Rican families influenced by American culture may express or bend these traditional rules whether they educated their children based on the values and morals that they were taught.[44] 2021 gender-based violence rise In 2021, gender-based violence rose.[45] So much so that Governor Pedro Pierluisi declared a state of emergency on the island due to an increase in gender-based violence from 6,603 cases in 2020 to 7,876 in 2021.[46][47][45] Out of the many cases, the murders of Andrea Ruiz Costas and Keishla Rodriguez caused the public to question how gender-based violence was handled within Puerto Rico's judicial system. Andrea Ruiz Costas filed three court cases before her murder, all of them were denied.[48] The judicial system accepts that, like every institution it lacks in some instances. One of those factors is the judicial system's difficult process for filling a complaint.[48] Many times this process is difficult for the victim due the lengthy process of filling the complaint and understanding the legal implications this process entails. After the government declared a state of emergency, conversations emerged about the root of gender based violence and the need for gender perspective learning to be included in Puerto Rico's Department of Education Curriculum.[49] On 26 October 2022, the Department of Education announced a curriculum called Equity and Respect for All Human Beings which will take place every fourth Wednesday of the month during homeroom period.[50] The program intends to encourage respect and equity but supporters for gender perspective learning clarify that it lacks in acknowledging terms involving gender equity and identity.[49] LGBTQ+ tourism, discrimination, and violence In terms of tourism, Puerto Rico was seen as one of the best places to visit for LGBTQ+ tourists.[51] However, the LGBTQ+ community is also a conflicting issue to the machismo culture. Puerto Rico is known for its strong Christian community, specifically Roman Catholic and Pentecostal, along with having smaller Jewish and Muslim communities. Due to changing times and influence from the United States, the LGBTQ+ movement has been a strong force for equality, which in Puerto Rico has not always been accepted, and even harmed in the process due to difference. One of these being the murder of Alexa Negrón Luciano, a transgender woman who in 2020 was mocked and eventually shot.[52] Alexa's murder, classified as a hate crime, provoked a conversation about transphobia on the island.[52] In relation to these conversations and the hope for a more inclusive Puerto Rican society, new gender neutral identifying terms are being used in Puerto Rico like substituting the vowels (a) or (o) in Spanish (many times the (a) in a word signifies a female, the (o) a male) for the letter (e) which is considered gender neutral, though it has its own share of criticism from the locals as it promotes neocolonialism.[53] |

プエルトリコにおけるマチズモ プエルトリコ社会におけるマチズモの存在という点では、男性は家の外で働き、財政を管理し、決断を下すものであった。女性は夫に従属し、主婦であるべき だった。女性は何から何まで男性に依存しなければならないことが多い。大人になると、男の子はマチズモの掟を守るように教えられ、女の子はマリアズモの掟 を教えられる。この習慣は、島外のプエルトリコ系アメリカ人も従っている[37]。それにもかかわらず、プエルトリコのマチズモの側面はこれだけではな い。プエルトリコのマチズモは、島の植民地時代の歴史から、2021年に起こったジェンダーに基づく暴力の多発に至るまで、さまざまな形で見ることができ る。このため、マチズモに関する新たな会話が生まれつつある。具体的には、マチズモをどのように扱うか、次世代がマチズモについて学ぶにはどのような方法 があるか、マチズモが社会に及ぼす影響などについて議論されている。 植民地時代の歴史とマチズモとの関係 プエルトリコのマチズモ文化を評価する際には、プエルトリコの植民地としての地位と関連付けることが重要である。スペインの植民地になったとき、プエルト リコはスペインが植え付けたマチズモの原則を身につけた[38]。プエルトリコが米国の植民地になったとき、米国はプエルトリコの貧困を改善しようと考え た。これは、貧困を人口過剰の主な影響と位置づけることによって行われた。したがって、女性の繁殖能力は、米国がプエルトリコの「貧困文化」を変える方法 の一つであった[39]。 20世紀半ばから後半 プエルトリコ人は、本土の進歩的な運動に動かされるかもしれないが、その運動はプエルトリコ独自の状況に基づくものである。1950年代、工業化によって 男性の就業率が低下する一方で、女性の就業率が上昇し始めた。さらに、1950年代から1980年代にかけて、ホワイトカラーの女性が台頭し、女性の雇用 がさらに増加した。彼女たちが労働力として新たに貢献したことで、家事を継続することは依然として女性の責任であったが、家計にも貢献するようになった。 その結果、家庭内で許容される範囲に変化が生じた。以前の女性は、自分を養ってくれる男性に大きく依存していたが、ある程度の教育を必要とし、経済的援助 を提供する役割を獲得するにつれて、女性はより自立することができるようになった[40]。 多くのプエルトリコ人がニューヨークに移住した1960年代には、多くの女性が結婚のような伝統を奨励する価値観のもとでシングルマザーになることを余儀 なくされた。しかし、女性たちは依然として自立と最終的な成功を重要視していた。一例として、母親は子供たちに、経済的に安定した人と結婚するよう勧め る。これは、マチズモ文化の概念と多くの緊張と内的葛藤をもたらすものだった。現在の社会では、このマチズモ文化はまだ抑圧されている。2016年、プエ ルトリコは、女性が男性よりも稼いでいる唯一の場所であり、1ドルに対して1.03ドルだった[41][42][43]。 学者たちは、女性がシングルマザーになることで自立した生活へと向かうこうした例は、マチズモや/あるいはマリアニスモを具体的に定義することができない ことを証明していると主張する。むしろ、マチズモやマリアニスモは、教えられた信念に従うというよりは、その人の決断や社会における状況に左右されるもの なのである[40]。 若い女性は外界の危険に影響されるべきではないと教えるラテン系の家庭によって強制される規則は、若い女性を脆弱なものとして、あるいは性的なものにされ る危険にさらされているものとして描いている。このような厳格な規則が強調されるのは、若くして妊娠を経験し、若い母親としての仕事を遂行する準備ができ ていないと言われる女性がいるためである。若い女性は、自分の家庭の家族からのサポートがなく、適切な教育を受けていないと非難されることさえある。アメ リカ文化の影響を受けたプエルトリコの家族は、自分たちが教えられた価値観や道徳観に基づいて子どもたちを教育しているかどうか、こうした伝統的なルール を表明したり曲げたりすることがある[44]。 2021年ジェンダーに基づく暴力の増加 2021年、ジェンダーに基づく暴力が増加した[45]。ペドロ・ピエルイージ知事が、ジェンダーに基づく暴力が2020年の6,603件から2021年 には7,876件に増加したことを理由に、島に非常事態宣言を発令したほどである[46][47][45]。数ある事件の中でも、アンドレア・ルイズ・コ スタスとキーシュラ・ロドリゲスの殺人事件は、プエルトリコの司法制度においてジェンダーに基づく暴力がどのように扱われているのかを世間に問うきっかけ となった。アンドレア・ルイズ・コスタスは殺害される前に3件の裁判を起こしたが、すべて却下された[48]。司法制度は、あらゆる制度と同様に、いくつ かの点で欠けていることを受け入れる。その要因のひとつが、司法制度が苦情を申し立てるためのプロセスを困難にしていることである[48]。多くの場合、 このプロセスは、被害者にとっては、苦情を申し立てるための長いプロセスと、このプロセスが伴う法的な意味を理解することのために困難である。政府が非常 事態を宣言した後、ジェンダーに基づく暴力の根源と、プエルトリコの教育省のカリキュラムにジェンダー視点の学習が含まれる必要性についての会話が浮上し た[49]。2022年10月26日、教育省は、毎月第4水曜日のホームルームの時間に行われる「すべての人間に対する公平性と尊重」と呼ばれるカリキュ ラムを発表した[50]。このプログラムは尊重と公平性を奨励することを意図しているが、ジェンダー視点の学習の支持者は、ジェンダーの公平性とアイデン ティティに関わる用語を認識することに欠けていることを明らかにしている[49]。 LGBTQ+の観光、差別、暴力 観光の面では、プエルトリコはLGBTQ+の観光客にとって最高の場所のひとつとみなされている[51]。しかし、LGBTQ+のコミュニティは、マチズ モ文化と対立する問題でもある。プエルトリコは、特にローマ・カトリックとペンテコステ派を中心とするキリスト教コミュニティが強いことで知られており、 小規模なユダヤ教徒とイスラム教徒のコミュニティもある。時代の変化と米国からの影響により、LGBTQ+運動は平等を求める強い力となってきたが、プエ ルトリコでは必ずしも受け入れられてきたわけではなく、その過程で差異による弊害さえあった。そのひとつが、2020年に嘲笑され、最終的に射殺されたト ランスジェンダーの女性、アレクサ・ネグロン・ルシアノが殺害された事件である[52]。憎悪犯罪に分類されたアレクサの殺害事件は、島におけるトランス フォビアについての会話を引き起こした。 [52]このような会話と、より包括的なプエルトリコ社会への希望に関連して、プエルトリコでは、スペイン語の母音(a)や(o)を、新植民地主義を助長 するとして地元の人々から批判を受けているものの、ジェンダーに中立的であると考えられている文字(e)に置き換える(多くの場合、単語の(a)は女性、 (o)は男性を意味する)など、新しいジェンダーに中立的な識別用語が使用されている[53]。 |

| Machismo in Russia Aside from Latin America, machismo is often thought to be a big part of Russian culture.[54][55][56][57] The macho attitude is widely accepted by Russian society and even considered desirable.[54] Russian men often engage in masculine activities such as sports including bodybuilding, which is elevated to the state of national aspiration among many men.[58] Researchers argue that machismo in Russia can be seen when an individual exaggerated masculine pride.[59] This is something that is seen on an everyday basis in Russia, which is emphasized through magazines that promote the idealization of what a "real man" is.[60] The characteristics of a masculine man would include being heterosexual, homophobic, and having the ability to accomplish an erection. There is a strong correlation between being sexually potent and masculine as the ability to reach an orgasm is commonly used to claim the right over a woman or power over them.[60] |

ロシアにおけるマチズモ ラテンアメリカは別として、マチズモはしばしばロシア文化の大きな部分であると考えられている[54][55][56][57]。マッチョな態度はロシア 社会で広く受け入れられており、望ましいとさえ考えられている[54]。ロシアの男性はボディビルを含むスポーツなどの男性的な活動に従事することが多 く、それは多くの男性の間で国家的な憧れの状態にまで高められている[58]。 研究者たちは、ロシアにおけるマチズモは、個人が男性的な誇りを誇張したときに見られると主張している[59]。これはロシアでは日常的に見られることで あり、「本当の男」とは何かという理想化を促進する雑誌を通じて強調されている[60]。オーガズムに達する能力は、一般的に女性に対する権利や権力を主 張するために使われるため、性的に強力であることと男性的であることの間には強い相関関係がある[60]。 |

| Implications Generational cycle Some people identify that machismo is perpetuated through the pressure to raise children a certain way and instill social constructions of gender throughout a child's development.[61] This is complemented by the distant father-son relationship in which intimacy and affection are typically avoided. These aspects set up the environment through which the ideology perpetuates itself.[61] It creates a sense of inferiority that drives boys to reach an unattainable level of masculinity, a pursuit often validated by the aggressive and apathetic behavior they observe in the men around them and ultimately leading them to continue the cycle.[61] Mental health There is accumulating evidence that supports the relation between the way men are traditionally socialized to be masculine and its harmful mental and physical health consequences.[62] Respectively, machismo, is sociocultural term associated with male and female socialization in Latin American cultures; it is a set of values, attitudes and beliefs about masculinity.[63] Although the construct of machismo holds both positive and negative aspects of masculinity, emerging research suggests the gender role conceptualization of machismo has associations with negative cognitive-emotional factors (i.e., depression symptoms; trait anxiety and anger; cynical hostility) among Latin American populations.[63] Similarly, a well-documented disparity notes Latino adolescents reporting higher levels of depression than other ethnic backgrounds. Research suggests this may be associated to adolescent perceived gender role discrepancies which challenge the traditional perceptions of gender role (i.e., machismo).[64] Enhanced understanding on associations between the gender role conceptualizations of machismo with negative cognitive-emotional factors may prove invaluable to mental health professionals.[63] According to Fragoso and Kashubeck, "if a therapist notes that a client seems to endorse high levels of machismo, that therapist might explore whether the client is experiencing high levels of stress and depression".[62] Therefore, "conducting a gender role assessment would help a therapist assess a client's level of machismo and whether aspects of gender role conflict are present".[62] Many counseling psychologists are interested in further studies for comprehending the connection between counseling for males and topics such as sex-role conflicts and male socialization.[65] This high demand stems from such psychologists' abilities to make patients aware how some inflexible and pre-established ideals regarding sex-roles may be detrimental to people's way of regarding new changes in societal expectancies, fostering relationships, and physical and mental health.[65] Professionals such as Thomas Skovholt, psychology professor at the University of Minnesota, claim that more research needs to be done in order to have efficient mediation for men through counseling.[65] Several elements of machismo are considered psychologically harmful for men.[66] Competition is a widely talked about subject in this area, as studies show that there are both positive and negative connotations to it.[66] Many benefits arise from healthy competition such as team-building abilities, active engagement, pressure handling, critical thinking, and the strive to excel.[67] As these qualities and traits are highly valued by many, they are widely taught to children from a young age both at school and at home.[67] Scholars also argue that men could be mentally harmed from competition, such as the one experienced by many at their job, as their impetus to rise above their peers and fulfill the breadwinner concept in many societies can cause stress, jealousy, and psychological strain.[66] Negative implications Violence "Machismo as a cultural factor is substantially associated with crime, violence, and lawlessness independently of the structural control variables"[68] (26-27). One key aspect of Machismo's association to violence is its influence in a man's behavior towards proving his strength[61] (57). While strength and fortitude are recognized as key components to the stereotype of machismo, demonstrations of violence and aggressive actions have become almost expected of men and have been justified as desirable products of being tough and macho. It can be implied that "if you are violent, you are strong and thus more of a man than those who back down or do not fight".[69] Violent encounters can stem from the desire to protect his family, friends, and particularly his female relatives that are vulnerable to the machismo actions of other men,[61] (59). However, through jealousy, competitiveness, and pride, violent encounters are also often pursued to demonstrate his strength to others. A man's insecurities can be fueled by a number of pressures. These range from societal pressures to "be a man" to internal pressures of overcoming an inferiority complex,[61] (59). This can translate into actions that devalue feminine characteristics and overemphasize the characteristics of strength and superiority attributed to masculinity,[61] (59). Domestic and sexual violence In many cases, a man's position of superiority over a female partner can lead him to gain control over different aspects of her life.[70] Since women are viewed as subservient to men in many cultures, men often have power to decide whether his wife can work, study, socialize, participate in the community, or even leave the house. With little opportunity for attaining an income, minimal means to get an education, and the few people they have as a support system, many women become dependent on their husbands financially and emotionally.[70] This leaves many women particularly vulnerable to domestic violence both because it is justified through this belief that men are superior and thus are free to express that superiority and because women cannot leave such an abusive relationship since they rely on their husbands to live.[70] Gender roles The power difference in the relationship between a man and a woman not only creates the social norm of machismo, but by consequence also creates the social concept of marianismo.[71] which is the idea that women are meant to be pure and wholesome. Marianismo derives its origins from Spanish Colonization, as many social constructs from Latin America do. It emphasizes the perfect femininity of a woman and her virginity. One could argue that in the similar manner of Patriarchy, the man is the head of the household while the "fragile" woman is submissive and tends to remain behind the scenes. This brings to focus the idea that women are inferior and are thus dependent on their husbands. As a result, they not only rely on their husbands for financial support, but in the social realm are put at the same level as "children under age 12, mentally ill persons, and spendthrifts"[71] (265). By way of tradition, not only are women given limited opportunities in what they are able to do and to be, but they are also viewed as people that cannot even take care of themselves. Getting married provides a woman with security under her husband's success, but also entails a lifelong commitment towards serving her husband and her children.[71] Machismo has negative impacts when it is used to emphasize a man’s power and dominance in relation to the submission of the women in their lives.[72] This dominance can be used to justify abuse, which is seen in the high rates of violence against women, and Femicide in Latin America.[72] The power of machismo in shaping gender roles can not only make these issues more robust to address, but also change the nature with which they must be addressed, requiring a shift from a legal focus to a focus on changing the gender norms regarding machismo in Latin America.[72] While social pressures and expectations play huge roles in the perpetuation of the marianismo construct, this ideology is also taught to girls as they grow up.[71] They learn the importance of performing domestic labor and household chores, such as cooking and cleaning, because this will be the role they will play in their future families. They are taught that these must be done well so that they can adequately serve their families and avoid punishment and discipline by their authoritative husbands.[71] Men exercise their authority with their demand for respect and power in the house. Thus, it could culturally be a norm to follow the rules of the man. As generations continue, the idea of machismo may diminish but will still be, to some extent, present. Further, research suggests that still in today's society, men continue to take roles that often leave women without a voice to express themselves or the power to portray. Some experts hypothesize, since there is a lack of empirical research on gender-role conflicts, that men might suffer from such conflicts because of their fear of femininity.[66] Professionals from several universities in the United States developed a model around this hypothesis with six behavioral patterns:[66] Restrictive emotionality: restraining oneself from expressing feelings or not allowing others to express their feelings.[66] Homophobia: the fear of homosexuals or the fear of being a homosexual, not limited to all the stereotypes associated with that.[66] Socialized control, power, and competition: The desire for the authority of being in charge of the situation, commanding others, and to excel above others.[66] Restrictive sexual and affectional behavior: Showing little to no affection or sexuality to others.[66] Obsession with achievement and success: having an ongoing complex that accomplishment, work, and illustriousness constitutes one's value.[66] Health problems: unhealthy diet, stress levels, and lifestyle.[66] The model was developed around the idea that these six patterns are all influenced by men's fear of femininity.[66] This theory was then partially supported by a study done by five professionals.[66] Some tools already created to measure gender-role attitudes include the Personal Attributes Questionnaire, the Bem Sex-Role Inventory, the Attitudes Toward Women Scale, and the Attitudes Toward the Male's Role Scale.[66] Evidence suggests that gender-roles conflicts inflicted by machismo can lead males who were raised with this mentality and or live in a society in which machismo is prevalent to suffer high levels of anxiety and low self-esteem.[73] Additionally, studies found that many males facing such conflicts are subject to experience anger, depression, and substance abuse.[74] Sexually-transmitted infections One implication of the Machismo concept is the pressure for a man to be sexually experienced.[70] Male infidelity is of common practice in many cultures, as men are not as expected to hold nearly the same level of chastity as women are. Meanwhile, girls are oftentimes brought up to tolerate an unfaithful partner, since it is a part of the machismo culture.[70] As such, this puts populations at risk for transmitting STIs as men seek out multiple sexual partners with little interference from their wives or from society. The risk is further heightened by the lack of condom use by men who are both miseducated about the effectiveness of a condom's protection against STIs and the belief that this would not happen to them.[70] This mentality also deters men from getting themselves tested to know if they are HIV-positive, which leads them to even spread STIs without even knowing it.[70] Sexuality and sexual orientation For men in many Latin American countries, their perceived level of masculinity determines the amount of respect they receive in society.[75] Because homosexual men are associated with feminine attributes, they are perceived with lower level of masculinity, and as a result, they receive less respect than heterosexual men in society. This, in turn, can limit their "ability to achieve upward social mobility, to be taken seriously, or to hold positions of power".[75] Also, because homosexuality is seen as taboo or even sinful in many Christian denominations, homosexual men tend to lack a support system, leaving many unable to express their true sexuality. To deal with such oppression, they must make the choice either to conform to heteronormativity and repress their homosexual identity, to assimilate towards masculine ideals and practices while maintaining their homosexual identity in private, or to openly express their homosexuality and suffer ostracization from society.[75] This creates a hierarchy of homosexuality corresponding to how much "respect, power, and social standing" a homosexual man can expect to receive. The more a man acts in accordance with the stereotypical heterosexual hegemonic masculinity, the higher on the social hierarchy they are.[75] On the lower end of the hierarchy are the locas or maricones.[75] These men are those that are deemed as effeminate because they do not live by the social construct of hegemonic masculinity and also publicize their homosexuality. As such, they receive little respect both in society in general and among the LGBT community. Many homosexual men resist being associated with the "loca" stereotype by either demonstrating overt masculinity or by ridiculing and distancing themselves from other "loca" men.[75] A common Puerto Rican saying demonstrates this resistance: "mejor un drogadicto que un pato" (better a drug addict than a faggot).[75] Homosexuality is perceived as negative or weak within the machista ideal. It does not fit into the masculine attributes that machismo extols. This often leads homosexual or bisexual men living in machista communities to be reluctant about being open about their sexuality because of the negative connotation associated with it. Familismo, which is an idea in Latin cultures that ties an individual with a commitment to his or her family, and homophobia can sometimes cause in homosexual individuals the repression of sexual identity, family separation, and to hide their sexuality. Such situations may hinder personal shame and secret sexual actions that increases HIV and STI risk in Latino homosexuals. Regularly experiencing homophobia and low self-esteem have a connection with sexual risk. A survey conducted by the Virginia Commonwealth University found that men who had high machismo values or characteristics were more than five times more probable to participate in activities or behave in a way to put them at risk for contracting HIV or an STI.[76] Because of the negative connotations that come with identifying as homosexual, the definition of homosexuality has become ambiguous. By genderizing sexual practices, only men who are sexually penetrated during sex, locas are considered homosexual while men who are the sexual penetrators during sex can maintain their heterosexual identity.[75] Also, in many Latin American countries, the media portrayal of homosexual men often play into the stereotype of an effeminate, flamboyant male role. As a result, the idea of a masculine homosexual man remains almost unheard of and privatized by the community and by society, which allows this stereotype of homosexual men as locas to persist.[75] Positive implications Altruism Machismo can also pressure a man to defend the well-being of his loved ones, his community, and his country.[77] It allows them to perform altruistic acts in order to provide protection to others. In the past, and even in many current societies where people rely on subsistence agriculture and economy to survive, machismo helped provide men with the courage to drive off potential threats to protect his land and his crop.[78] Today, this contributes to the substantial gender gap in the makeup of military and armed forces around the world, even considering growing female representation in the military today.[77] Beyond the realm of the armed forces, however, the machismo ideology can also drive a man to work towards service because he is in a "superior" position, which enables him to demonstrate his success by offering his own strengths to help others. Their dependence on him can validate his ego and help maintain this difference in power.[77] Another approach to machismo is that of the "caballerismo" ideology,[79] that because a man is the head of the household, he is responsible for the well-being of the members of his family. This describes the call for a man to be chivalrous, nurturing, and protective of his loved ones.[79] It translates to the belief that a true man would never act violent towards his wife or children, but would instead ensure that no harm come to them. Machismo, seen through this approach, inspires men to create "harmonious interpersonal relationships through respect for self and others".[80] This allows fathers to maintain positive, intimate relationships with their children and share a more egalitarian relationship with their wives. Men and work In many cultures in the world, there is a long-standing tradition that the man is the head of the household and is responsible for providing for the family.[81] In some cases, this may mean he is the only parent working in paid-work while in other conditions this may mean both parents are working but the man is expected to be the primary income contributor. In either case, part of the masculine identity and his self-respect is defined by his ability to provide for his family. If he is unable to do so, or if he brings home less money than that of his wife, his position as head of the family is challenged.[81] In some cultures, this may mean ultimate shame for him if he cannot fulfill this role: "that being unable to find work meant that 'there is no recognition even to [his] humanity ... Those who do not work are like dead people'"[81] (212). Beyond providing economic support for his family, a man engaging in paid-work is seen as honorable because he is sacrificing time and energy that he could be spending with his family. These are costs that cannot be repaid and thus are a priceless investment on his part towards the well-being of his family unit.[81] Ancient history Although culture may present homophobia, misogyny and masculinity as innately bundled together, history presents different models of masculinity.[82] Masculinity was part of homosexuality in ancient Greece. Neither was it all misogyny. Goddesses were worshiped in temples, and the female poet Sappho wrote of Lesbian love. In ancient times, women too had their share of machismo-like vices, and virtues. The lore of the Amazons, which tells of women heroically fighting as defenders in the Trojan War, and according to National Geographic, "Archaeology shows that these fierce women also smoked pot, got tattoos, killed and loved men."[83] Homosexual-machismo helped thwart Sparta's power hold over ancient Greek city-states: In 371 BC the Sacred Band of Thebes was an elite fighting unit composed of 150 homosexual male pairs. They were credited with helping remove Sparta's military domination, and their actions were linked to the spread of Western culture: Theban General Epaminondas taught Philip II of Macedon military tactics and diplomacy used to reunify the Greeks under Macedonia. His son Alexander the Great was credited with the Hellenization of Persia, Egypt and Jerusalem in 332 BC. The Greeks had the Hebrew scriptures translated into the Septuagint, fostering the spread of Judaism throughout the region. Alexander and Hephaestion had been heavily influenced by Homer's Iliad, particularly the masculine love between Achilles and Patroclus. They paired themselves as their modern incarnation, nearly a millennium after the Trojan War. Later, the Roman Empire shared a degree of homosexuality alongside the virtues of masculinity. In 19BC, Virgil's epic poem Aeneid contributed to the folklore of Rome, while depicting the love of fellow warriors Nisus and Euryalus. In 128 AD, Antonious the love of Emperor Hadrian, was celebrated in the public. In Hebrew culture circa 1006 BC,[84] the covenant between David and Jonathan was recorded in the Books of Samuel.[85] Gradually, the Septuagint would be expanded with new Greek books, eventually forming Christian Bibles, the earliest extant versions being the Codex Vaticanus and Codex Sinaiticus from 300 AD-360 AD. Tradeoffs Machismo changes some dynamics of life in a way have both positive and negative effects. For example, machismo grants women authority in the home but at the expense of a man's relationship to his children and work related stress having worked long hours. Female respect and responsibility In the traditional household, the man is expected to work and provide for his family while his wife stays home to care for the children.[86] As such, fathers are seen as a distant authority figure to his children while mothers assume the majority of responsibility in this domestic realm and thus gain agency and the ultimate respect of her children.[86] With the rise of female power, decisions in the household can take on a more egalitarian approach, where mothers can have equal say in the household. Meanwhile, the machismo mentality in men as a provider and protector of the family can inspire him to persevere through challenges introduced by work.[86] "Within each of our memories there is the image of a father who worked long hours, suffered to keep his family alive, united, and who struggled to maintain his dignity. Such a man had little time for concern over his "masculinity". Certainly he did not have ten children because of his machismo, but because he was a human being, poor, and without "access" to birth control."[87] "Machismo ideology is as beneficial to women in that it encourages their husbands to provide for and protect them and their children. Further, by subordinating their needs to those of their family, women earn a lifetime of support from their husbands and children and in this way gain some control in the family".[88] Because fathers are typically more invested in paid labor, mothers typically spend more time with the children and thus gain credibility in important decisions such as a child's schooling or a child's health care. Nevertheless, in these machist households the fathers will have the last word whenever they choose to, as they are the breadwinners, and all the family ultimately depends on them for survival. In case of a separation or divorce, it is typically the mothers who suffer the most, since they did not invest their time in their career, and will probably still have to provide and care for the children. |

意味 世代サイクル マチズモは、子どもを特定の方法で育て、子どもの成長を通じてジェンダーの社会的解釈を植え付けるという圧力によって永続していると指摘する人もいる [61]。これは、親密さや愛情が一般的に避けられる遠い親子関係によって補完される。これらの側面は、イデオロギーがそれ自体を永続させる環境を設定す る[61]。劣等感を生み出し、男児を達成不可能なレベルの男らしさに到達させる。 メンタルヘルス マチズモ(machismo)とは、ラテンアメリカの文化圏にお ける男性と女性の社会化に関連する社会文化用語であり、男らしさ に関する一連の価値観、態度、信念である[63]、 ラテンアメリカの人々の間では、うつ症状;特性不安と怒り;冷笑的敵意)があることが示唆されている[63]。 同様に、ラテンアメリカの青少年が他の民族的背景よりも高いレベルのうつ病を報告していることは、よく知られた格差として指摘されている。これは、伝統的 な性別役割分担の認識(すなわち、マチズモ)に挑戦する思春期の認識された性別役割の不一致と関連している可能性があることが研究により示唆されている [64]。 FragosoとKashubeckによると、「セラピストが、クライエントが高レベルのマチズモを支持しているようだと指摘した場合、そのセラピスト は、クライエントが高レベルのストレスや抑うつを経験しているかどうかを探るかもしれない」[62]。 したがって、「ジェンダー役割アセスメントを実施することは、セラピストがクライエントのマチズモのレベルを評価し、ジェンダー役割の葛藤の側面が存在す るかどうかを評価するのに役立つ」[62]。 多くのカウンセリング心理士は、男性に対するカウンセリングと性役割の葛藤や男性の社会化といったトピックとの関連性を理解するためのさらなる研究に関心 を持っている[65]。 このような高い需要は、性役割に関するいくつかの柔軟性がなく、あらかじめ確立された理想が、社会的期待の新たな変化、人間関係の育成、心身の健康に対す る人々のあり方にとっていかに有害であるかを患者に認識させる、そのような心理士の能力から生じている。 [65] ミネソタ大学の心理学教授であるトーマス・スコフホルトのような専門家は、カウンセリングを通じて男性のための効率的な調停を行うためには、より多くの研 究が必要であると主張している[65]。 マチズモのいくつかの要素は、男性にとって心理的に有害であると考えられている[66]。競争には肯定的な意味合いと否定的な意味合いの両方があることが 研究によって示されているため、この分野では競争は広く語られているテーマである[66]。 [これらの資質や特性は多くの人に高く評価されているため、学校や家庭で幼い頃から広く子どもたちに教えられている[67]。学者たちはまた、多くの社会 で仲間よりも上に立ち、稼ぎ手の概念を満たそうとする衝動がストレス、嫉妬、心理的緊張を引き起こす可能性があるため、多くの人が仕事で経験しているよう な競争から、男性は精神的に害を受ける可能性があると主張している[66]。 否定的な意味合い 暴力 「文化的要因としてのマチズモは、構造的統制変数とは無関係に、犯罪、暴力、無法と実質的に関連している」[68](26-27)。マチズモと暴力との関 連性の重要な側面のひとつは、自分の強さを証明するための男の行動における影響である[61](57)。強さと不屈の精神はマチズモのステレオタイプに とって重要な要素であると認識されているが、暴力や攻撃的な行動は男性にほとんど期待されるようになり、タフでマッチョであることの望ましい産物として正 当化されてきた。暴力的であれば強いので、引き下がったり戦わなかったりする人よりも男らしい」と暗示されることもある[69]。 暴力的な出会いは、自分の家族、友人、特に他の男性のマチズモ的行動に弱い女性の親族を守りたいという欲求から生じることがある[61](59)。しか し、嫉妬、競争心、プライドを通して、暴力的な出会いは、しばしば自分の強さを他人に示すためにも追求される。男の不安は多くの圧力によって煽られる。男 らしくあれ」という社会的圧力から、劣等コンプレックスを克服しなければならないという内的圧力[61](59)まで様々である。これは、女性的な特徴を 軽んじ、男性性に起因する強さと優越性の特徴を過度に強調する行動[61](59)につながる可能性がある。 家庭内暴力と性的暴力 多くの場合、男性が女性パートナーよりも優位な立場にあることで、男性が女性の生活のさまざまな側面を支配するようになることがある[70]。多くの文化 において女性は男性に従属するものとみなされているため、男性はしばしば、妻が働くかどうか、勉強するかどうか、社交的になるかどうか、地域社会に参加す るかどうか、あるいは家を出るかどうかさえも決定する権力を持つ。収入を得る機会はほとんどなく、教育を受ける手段も最小限であり、支援システムとして 持っている人は数少ないため、多くの女性は経済的にも精神的にも夫に依存するようになる[70]。このことは、男性は優れているため、その優越性を表現す る自由があるというこの信念によって正当化されるため、また、女性は生きるために夫に依存しているため、そのような虐待的な関係から離れることができない ため、多くの女性を特に家庭内暴力にさらされやすい状態にする[70]。 ジェンダー的役割 男女の関係における力の差は、マチズモという社会規範を生み出すだけでなく、結果として、マリアニスモという社会概念も生み出す[71]。マリアニスモ は、ラテンアメリカの多くの社会構成がそうであるように、スペイン植民地化に起源を持つ。女性の完璧な女性性と処女性を強調する。家父長制と同じように、 男性は家庭の長であり、"か弱い "女性は従順で、舞台裏に留まる傾向があると言える。このことは、女性は劣っており、したがって夫に依存しているという考えに焦点を当てる。その結果、経 済的に夫に依存するだけでなく、社会的な領域では「12歳未満の子供、精神病患者、浪費家」[71](265)と同じレベルに置かれる。伝統によって、女 性にはできることやなる機会が制限されているだけでなく、自分の世話すらできない人間として見られている。結婚することで、女性は夫の成功のもと安泰を得 るが、同時に夫と子どもたちに生涯尽くすことを約束することになる[71]。 ラテンアメリカにおける女性に対する暴力やフェミサイドの高い発生率に見られるように、この優位性は虐待を正当化するために使われることがある[72]。 ジェンダーの役割を形成するマチズモの力は、これらの問題に取り組むことをより強固なものにするだけでなく、取り組むべき性質を変える可能性がある。 社会的圧力と期待がマリアニスモの構図の永続化に大きな役割を果たす一方で、このイデオロギーは少女たちが成長するにつれて教え込まれる[71]。彼女た ちは、家族に十分な奉仕をし、権威ある夫からの罰やしつけを避けるために、これらをうまくこなさなければならないと教えられる[71]。男性は、家の中で の尊敬と権力を要求することで、権威を行使する。したがって、男性のルールに従うことは文化的に規範となりうる。世代が進むにつれて、マチズモという考え 方は減っていくかもしれないが、それでもある程度は存在するだろう。さらに、調査によれば、現代社会では依然として、男性が役割を担い続けているために、 女性が自分を表現する声や描写する力を失っていることが多いという。 ジェンダーと役割の葛藤に関する実証的な研究が不足しているため、男性は女性らしさを恐れているためにそのような葛藤に苦しんでいるのではないかという仮説を立てる専門家もいる[66]。 米国のいくつかの大学の専門家は、この仮説に基づき、以下の6つの行動パターンからなるモデルを開発した[66]。 制限的感情性:感情を表現することを自制したり、他者が感情を表現することを許さない[66]。 同性愛嫌悪:同性愛者に対する恐怖、または同性愛者であることへの恐怖であり、それに関連するすべてのステレオタイプに限定されない[66]。 社会化された支配、権力、競争: 自分がその場の責任者であるという権威を求め、他者に命令し、他者よりも優位に立ちたいという欲求である[66]。 性的・愛情的行動の制限: 他人に対して愛情や性欲をほとんど示さない[66]。 達成と成功への執着:達成、仕事、輝かしいことが自分の価値を構成するというコンプレックスを持ち続ける[66]。 健康問題:不健康な食事、ストレスレベル、ライフスタイル[66]。 このモデルは、これら6つのパターンがすべて男性の女性性への恐怖に影響されているという考えに基づいて開発された[66]。この理論は、その後5人の専 門家によって行われた研究によって部分的に支持された[66]。ジェンダーロール態度を測定するためにすでに作成されたツールには、個人属性質問票、ベ ム・セックスロール目録、女性に対する態度尺度、男性の役割に対する態度尺度などがある。 [66] マチズモによって引き起こされる性別役割の葛藤は、このようなメンタリティで育てられた男性やマチズモが蔓延する社会に住む男性を、高いレベルの不安や低 い自尊心に苦しめる可能性があることを証拠が示唆している[73]。さらに、このような葛藤に直面する多くの男性が、怒り、抑うつ、薬物乱用を経験するこ とが研究で明らかにされている[74]。 性感染症 マチズモの概念が意味することのひとつに、男性が性的に経験豊富でなければならないという圧力がある[70]。男性の不倫は多くの文化で一般的な慣行であ り、男性は女性ほど貞操を守ることを期待されていない。一方、女子はマチズモ文化の一部であるため、浮気相手を許容するように育てられることが多い [70]。このように、男性は妻や社会からの干渉をほとんど受けずに複数の性的パートナーを求めるため、集団はSTI感染のリスクにさらされる。このリス クは、コンドームによるSTI防御の有効性と、自分には起こらないという信念の両方について不勉強な男性がコンドームを使用しないことによってさらに高ま る[70]。このようなメンタリティはまた、自分がHIV陽性であるかどうかを知るために検査を受けることを躊躇させ、その結果、知らないうちにSTIを 広めてしまうことさえある[70]。 セクシュアリティと性的指向 多くのラテンアメリカ諸国の男性にとって、認知される男らしさのレベルが社会で受ける尊敬の度合いを決定する[75]。同性愛の男性は女性的な属性を連想 させるため、男らしさのレベルが低いと認識され、その結果、社会で異性愛者の男性よりも尊敬を受けることが少なくなる。また、多くのキリスト教の宗派では 同性愛はタブー視され、罪深いとさえみなされているため、同性愛の男性はサポートシステムを欠く傾向があり、多くの人が自分の本当のセクシュアリティを表 現できないままになっている。このような抑圧に対処するために、彼らはヘテロ規範に順応して同性愛者であることを抑圧するか、同性愛者であることを内密に 保ちながら男性的な理想と実践に同化するか、同性愛者であることを公然と表明して社会から追放される苦しみを味わうかの選択を迫られる[75]。このこと は、同性愛男性がどれだけの「尊敬、権力、社会的地位」を期待できるかに対応する同性愛のヒエラルキーを生み出す。ステレオタイプな異性愛者の覇権主義的 男らしさに従って行動すればするほど、社会的ヒエラルキーの上位に位置することになる[75]。 ヒエラルキーの下位に位置するのは、ロカやマリコネスである[75]。これらの男性は、覇権的男性性の社会的構成に従って生きておらず、また同性愛である ことを公表しているため、女々しいとみなされる。そのため、社会一般でもLGBTコミュニティの間でも、彼らはほとんど尊敬されていない。多くの同性愛男 性は、あからさまな男らしさを示すか、他の「ロカ」男性たちを嘲笑し距離を置くことによって、「ロカ」ステレオタイプに結び付けられることに抵抗する [75]: 「mejor un drogadicto que un pato"(ホモより麻薬中毒者の方がいい)[75]。 ホモセクシュアリティは、マチスタの理想の中では否定的、あるいは弱いものとして認識されている。それはマチズモが称賛する男性的な属性になじまない。こ のため、マチスタのコミュニティに住む同性愛者やバイセクシュアルの男性は、否定的な意味合いを持つことから、自分のセクシュアリティをオープンにするこ とに消極的になることが多い。ファミリズモ(家族主義)とは、ラテン文化における、個人を家族へのコミットメントで結びつける考え方であり、同性愛嫌悪 は、時に同性愛者に性的アイデンティティの抑圧、家族離散、セクシュアリティの隠蔽を引き起こすことがある。このような状況は、個人的な羞恥心や秘密の性 行為を妨げ、ラテン系同性愛者のHIVやSTIリスクを高める可能性がある。常日頃から同性愛嫌悪や低い自尊心を経験していることは、性的リスクと関係が ある。ヴァージニア・コモンウェルス大学が実施した調査によると、マチズモ的価値観や特徴が高い男性は、HIVやSTIに感染するリスクのある活動や行動 に参加する確率が5倍以上であった[76]。 同性愛者であると認識することに否定的な意味合いがあるため、同性愛の定義は曖昧になっている。性行為を性別化することで、性行為の際に性的に挿入される ロカの男性のみが同性愛者とみなされ、性行為の際に性的に挿入される側の男性は異性愛者としてのアイデンティティを維持することができる。その結果、男性 的な同性愛男性という考えはほとんど聞かれないままであり、コミュニティや社会によって私物化されているため、ロカとしての同性愛男性のこのようなステレ オタイプが存続しているのである[75]。 肯定的な意味合い 利他主義 マチズモはまた、愛する人々、地域社会、国の幸福を守るよう男性に圧力をかけることができる[77]。過去において、そして現在でも、人々が生き残るため に自給自足の農業と経済に依存している多くの社会においてさえ、マチズモは、自分の土地と作物を守るために潜在的な脅威を追い払う勇気を男性に与えるのに 役立っている[78]。今日、軍隊における女性の割合が増加していることを考慮しても、これは世界中の軍隊と軍隊の構成における実質的な男女格差の一因と なっている。 [77]しかし、軍隊の領域を超えて、マチズモのイデオロギーは、自分が「優れた」立場にあるため、他人を助けるために自分の長所を提供することで自分の 成功を示すことができるという理由で、男性を奉仕に向かわせることもある。彼への依存は彼のエゴを正当化し、この力の差を維持する助けとなる[77]。 マチズモに対するもう一つのアプローチは「カバレリズモ」イデオロギーであり[79]、男は家庭の長であるため、家族のメンバーの幸福に責任があるという ものである。これは、男は騎士道を重んじ、養い、愛する者を守るものであるべきだという呼びかけを表している[79]。真の男は妻や子供に暴力を振るうこ とはなく、その代わりに彼らに危害が及ばないようにするという信念に通じている。このようなアプローチを通して見られるマチズモは、男性に「自己と他者を 尊重することによって、調和のとれた対人関係」を築くよう促す[80]。これによって父親は、子供と前向きで親密な関係を維持し、妻とはより平等主義的な 関係を共有することができる。 男性と仕事 世界の多くの文化では、男性が家庭の長であり、家族を養う責任があるという長年の伝統がある[81]。ある場合には、男性が唯一の親として有給労働に従事 することを意味する場合もあれば、両親が共働きであるが、男性が主な収入貢献者であることが期待されている場合もある。いずれにせよ、男性的アイデンティ ティと自尊心の一部は、家族を養う能力によって定義される。もしそれができなかったり、妻よりも少ない収入しか得られなかったりすると、一家の長としての 彼の地位が問われることになる[81]。文化によっては、この役割を果たせないことは彼にとって究極の恥を意味することもある。働かない者は死人のような ものだ』[81](212)」。家族を経済的に支えるだけでなく、有給労働に従事する男性は、家族と過ごすことのできる時間とエネルギーを犠牲にしている ため、名誉なことだと見なされる。これらは返済不可能なコストであり、したがって家族単位の幸福のための貴重な投資なのである[81]。 古代の歴史 文化は同性愛嫌悪、女性嫌悪、男らしさを生まれながらにして一体化したものとして示すかもしれないが、歴史は男らしさの異なるモデルを示している [82]。古代ギリシャでは男らしさは同性愛の一部であった。女性嫌悪ばかりではなかった。女神は神殿で崇拝され、女性詩人サッフォーはレズビアンの愛に ついて書いている。古代では、女性にもマチズモ的な悪徳や美徳があった。ナショナルジオグラフィック誌によれば、「考古学によれば、これらの獰猛な女性た ちもまた、マリファナを吸い、タトゥーを入れ、男性を殺し、愛していた」[83]: 紀元前371年、テーベの聖なる一団は、150組の同性愛男性からなる精鋭戦闘部隊だった。彼らはスパルタの軍事的支配を排除するのに貢献したとされ、彼 らの行動は西洋文化の普及につながった: テーベの将軍エパミノンダスは、マケドニアのフィリップ2世に軍事戦術と外交術を教え、マケドニアの下にギリシアを再統一した。彼の息子アレクサンダー大 王は、紀元前332年にペルシャ、エジプト、エルサレムのヘレニズム化に貢献したとされている。ギリシャ人はヘブライ語の聖典をセプトゥアギンタに翻訳さ せ、ユダヤ教をこの地域に広めた。 アレクサンダーとヘファエスティオンは、ホメロスの『イーリアス』、特にアキレスとパトロクロスの男性的な愛に大きな影響を受けていた。彼らはトロイ戦争 からほぼ千年後に、現代の姿としてペアを組んだ。その後、ローマ帝国では、男性性の美徳とともに、ある程度の同性愛が共有された。紀元前19年、ヴァージ ルの叙事詩『アエネーイス』は、仲間の戦士ニススとエウリュアロスの愛を描きながら、ローマの民間伝承に貢献した。西暦128年、ハドリアヌス帝のアント ニウスの恋は、世間で祝福された。紀元前1006年頃のヘブライ文化[84]では、ダビデとヨナタンの間の聖約が『サムエル記』に記録されている [85]。徐々に、セプトゥアギンタは新しいギリシャ語の書物によって拡張され、最終的にキリスト教の聖書が形成される。 トレードオフ マチズモは、生活の力学にプラスとマイナスの両方の変化をもたらす。例えば、マチズモは女性に家庭での権威を与えるが、その代償として男性の子供との関係や長時間労働による仕事上のストレスが生じる。 女性の尊敬と責任 伝統的な家庭では、男性は働いて家族を養い、妻は家にいて子どもの世話をすることが期待されている[86]。そのため、父親は子どもにとって遠い権威者と みなされる一方で、母親はこの家庭内の領域で責任の大部分を引き受け、その結果、主体性と子どもからの最終的な尊敬を得ることになる[86]。女性の力が 高まるにつれて、家庭内の決定はより平等主義的なアプローチをとるようになり、母親が家庭内で同等の発言権を持つことができるようになる。一方、家族を養 い、守る者としての男性のマチズモ精神は、仕事によってもたらされる困難を辛抱強く乗り越えるよう、男性を鼓舞することができる[86]。 「私たちの記憶の中には、長時間働き、家族を生かし、団結させるために苦しみ、尊厳を保つために奮闘する父親の姿がある。そのような男には、自分の「男ら しさ」を気にしている暇はほとんどなかった。確かに彼が10人の子どもを産んだのは、マチズモのせいではなく、人間であり、貧しく、避妊具を "入手 "できなかったからである」[87]。 「マチズモのイデオロギーは、夫が自分と子どもを養い守るよう促すという点で、女性にとっても有益である。さらに、自分の欲求を家族の欲求に従属させるこ とで、女性は夫や子どもたちから生涯の扶養を得ることができ、そうすることで家族の中である程度の支配力を得ることができる」[88]。父親は一般的に有 給労働により多くの時間を費やすため、母親は一般的に子どもと過ごす時間が長くなり、その結果、子どもの就学や子どもの健康管理といった重要な決定におい て信頼を得ることができる。とはいえ、このような機械主義的な家庭では、父親が稼ぎ手であり、家族全員が最終的に父親にかかっているため、父親がいつでも 最後の決定権を持つ。別居や離婚の場合、一般的に最も苦しむのは母親である。なぜなら、母親は自分の時間をキャリアに投資しなかったからであり、おそらく 依然として子どもたちを養い、世話をしなければならないからである。 |

| Prevalence and acculturation in the 21st century Despite machismo's documented history in Iberian and Latin American communities, research throughout the years has shown a shift in prevalence among younger generations. In Brazil, researchers found that while the majority of young men interviewed held traditional attitudes on gender roles and machismo, there was a small sample of men that did not agree with these views.[12] Macho attitudes still prevail, the values place women into a lower standard. Acculturation and education have been proposed to be a factor in how machismo is passed down through Iberian and Latin American generations in the United States.[89] According to researchers who measured self-reported levels of machismo among 72 university students, 37 whom identified as Latino, the "somewhat unique population of college-educated students who have been heavily influence[d] by egalitarian attitudes, values, and norms" may explain why ethnicity did not directly predict machismo attitudes in two studies.[89] Because education and acculturation of American values in Latino individuals may result in the development of attitudes supporting gender-equality, this demonstrates how machismo may gradually decline over time in the United States. Moreover, researchers analyzed a large cross-sectional survey among 36 countries, including 6 Latin American countries, from 2009 and discovered countries with less gender inequality had adolescents that supported attitudes of gender-equality, though females were more likely to support LGBT and non-traditional genders than males.[90] While the mean score of gender-equality attitudes was 49.83, with lower scores indicating less gender equality attitudes, Latin American countries scored the following: Chile (51.554), Colombia (49.416), Dominican Republic (43.586), Guatemala (48.890), Mexico (45.596), Paraguay (48.370).[90] Machismo is associated with gender inequality. Therefore, this study suggests that Latino individuals living in their native countries may support more machismo attitudes than Latino immigrants adopting U.S. values of gender equality. Masuda also studied self-reported measures of sexual relationship power among 40 recently immigrated Latino couples found data against machismo attitudes since women perceived themselves to have greater control and decision-making roles in their relationships.[91] This serves as a stark contrast because machismo traditionally creates a relationship dynamic that relegates women to submissive roles and men to dominant roles. Again, acculturation may play a role in this dynamic shift because the couples averaged about 8 years since immigrating to the United States.[91] Acculturation has not only been associated with a decline in machismo, it has appeared to affect how it manifests and how it is transferred through generations. Recently, Mexican American adolescents in romantic relationships demonstrated "adaptive machismo", which consist of the positive qualities of machismo, such as "emotional availability, demonstrations of affection, desire to financially care for a female partner, responsibility in child-rearing, and/or to the community or friends", during conflict resolution scenarios.[92] Furthermore, while Mexican American adolescent males were found to have certain values and attitudes, such as caballerismo, passed down by their families, machismo was not one of them.[93] Because families are not teaching machismo, this implies that it may be learned from sources separate from the family unit, such as peers and the media.[94] Ultimately, these findings suggest that machismo is changing in terms of its prevalence, manifestation, and socialization. |

21世紀における流行と文化化 イベリアやラテンアメリカのコミュニティにおけるマチズモの歴史は記録されているにもかかわらず、長年にわたる調査によって、若い世代における普及率の変 化が示されてきた。ブラジルの研究者たちは、インタビューした若い男性の大多数が、ジェンダーの役割とマチズモに関する伝統的な態度を保持している一方 で、これらの見解に同意しない男性のサンプルが少数存在することを発見した[12]。マッチョな態度は依然として優勢であり、価値観は女性をより低い基準 に置いている。 ラテンアメリカ系とイベリア系の世代を通じて、マチズモが米国でどのように受け継がれているかについては、文化化と教育が要因であると提唱されている [89]。ラテンアメリカ系であると認識している37人の大学生72人を対象に、マチズモの自己申告レベルを測定した研究者によると、「平等主義的な態 度、価値観、規範から大きな影響を受けている大学教育を受けた学生というやや特殊な集団」が、2つの研究で民族性がマチズモ態度を直接予測しなかった理由 を説明している可能性がある。 [ラテンアメリカ人における教育やアメリカ的価値観の定着は、男女平等を支持する態度の発達につながる可能性があるため、このことは、アメリカにおいてマ チズモが時間の経過とともに徐々に減少していく可能性を示している。 さらに研究者たちは、2009年に行われたラテンアメリカ6カ国を含む36カ国を対象とした大規模な横断調査を分析し、男女不平等が少ない国では、 LGBTや非伝統的なジェンダーを支持する傾向が男性よりも女性の方が強いが、男女平等の態度を支持する青年がいることを発見した[90]。男女平等の態 度の平均スコアは49.83点で、スコアが低いほど男女平等の態度が低いことを示すが、ラテンアメリカ諸国のスコアは以下の通りであった: チリ(51.554)、コロンビア(49.416)、ドミニカ共和国(43.586)、グアテマラ(48.890)、メキシコ(45.596)、パラグア イ(48.370)であった[90]。したがって、この研究は、母国で生活するラテン系個人は、米国の男女平等の価値観を採用するラテン系移民よりもマチ ズモ態度を支持する可能性があることを示唆している。 増田はまた、最近移民してきた40組のラテン系カップルを対象に、自己申告による性的関係力の測定値を調査したところ、女性が自分たちの関係においてより 大きな支配力と意思決定の役割を担っていると認識していることから、マチズモ意識に反するデータを発見した[91]。マチズモは伝統的に女性を従順な役割 に、男性を支配的な役割に追いやる関係力学を生み出すため、これは対照的な結果となる。カップルは米国に移住してから平均約8年であったため、ここでもま た、文化化がこのダイナミックな変化に一役買っている可能性がある[91]。 文化化はマチズモの衰退と関連しているだけでなく、マチズモがどのように現れ、どのように世代を超えて受け継がれていくのかにも影響を及ぼしているようで ある。最近、恋愛関係にあるメキシコ系アメリカ人の青少年は、葛藤解決のシナリオにおいて、「感情的な利用可能性、愛情表現、女性パートナーを経済的に世 話する願望、子育てにおける責任、および/またはコミュニティや友人に対する責任」といったマチズモの肯定的な資質からなる「適応的マチズモ」を示した。 [92]さらに、メキシコ系アメリカ人の思春期の男性は、キャバレリスモのような特定の価値観や態度を家族から受け継いでいることがわかったが、マチズモ はそのうちのひとつではなかった[93]。家族がマチズモを教えているわけではないので、これはマチズモが仲間やメディアといった家族単位とは別の情報源 から学ばれている可能性を示唆している[94]。結局のところ、これらの調査結果は、マチズモがその普及、顕在化、社会化という点で変化していることを示 唆している。 |