ブーランヴィリエ伯爵夫人

Madame de Brinvilliers, 1630-1636

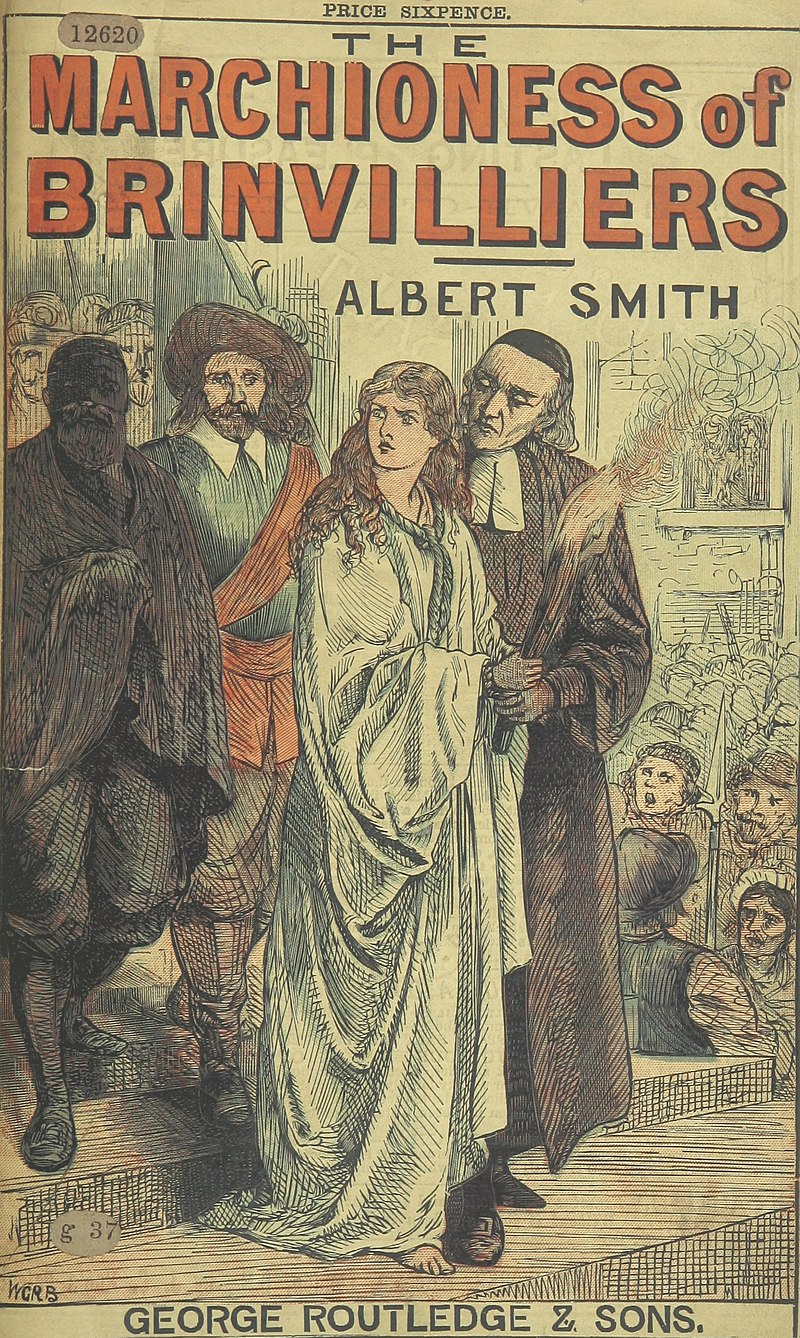

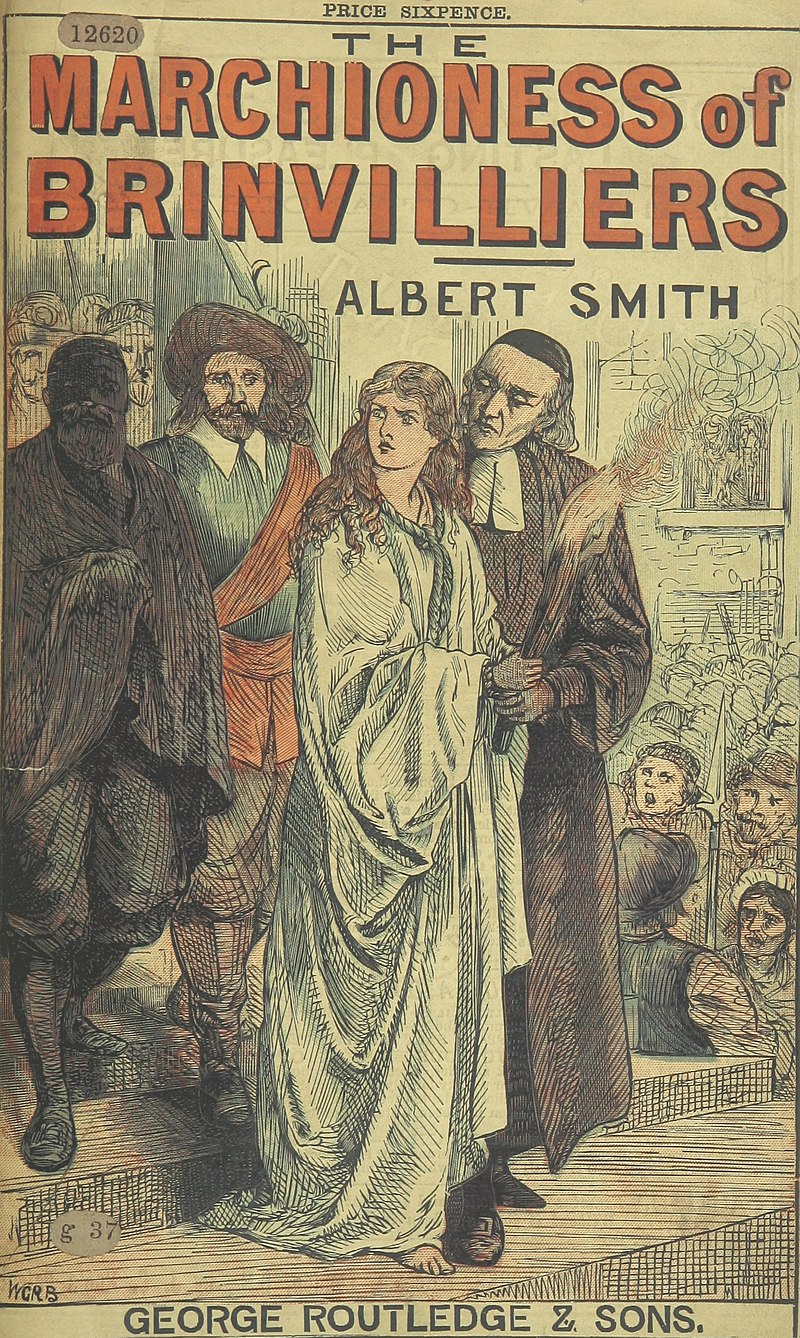

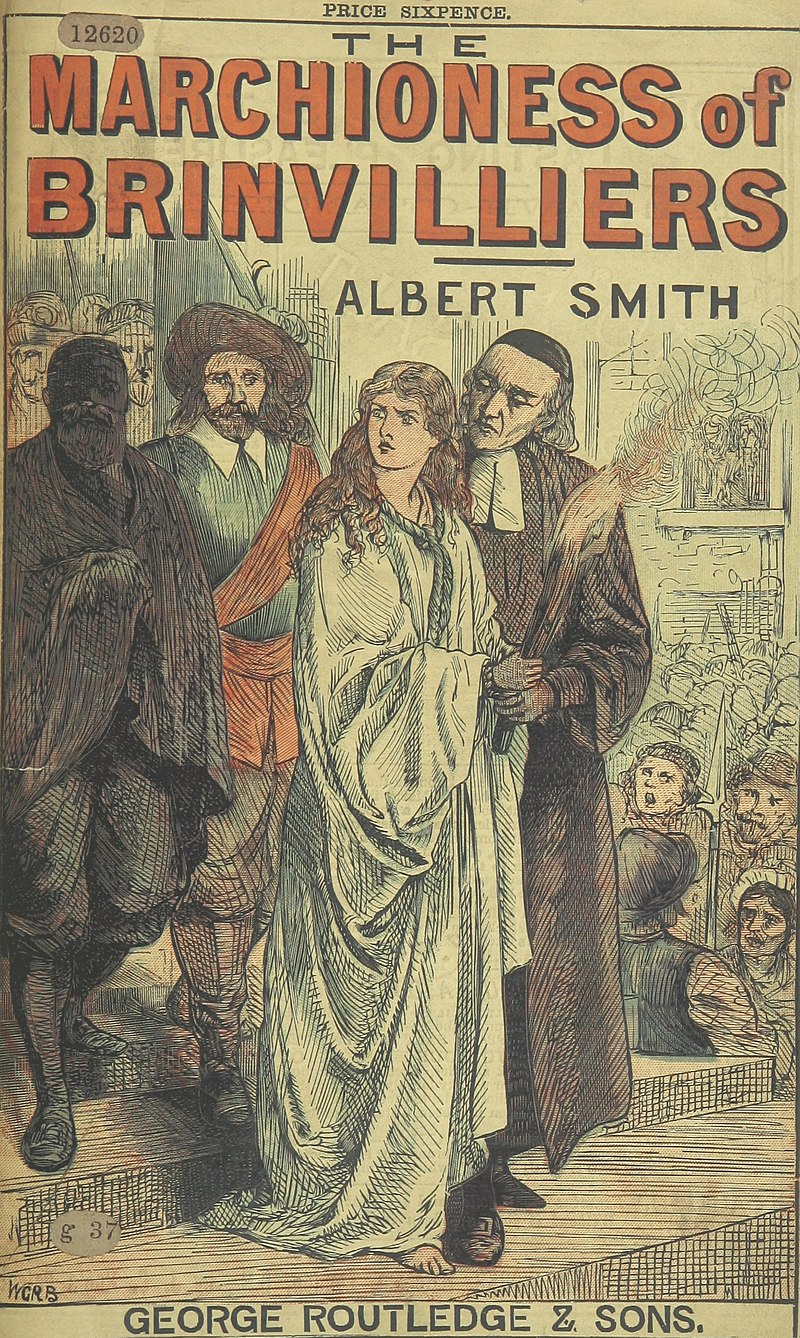

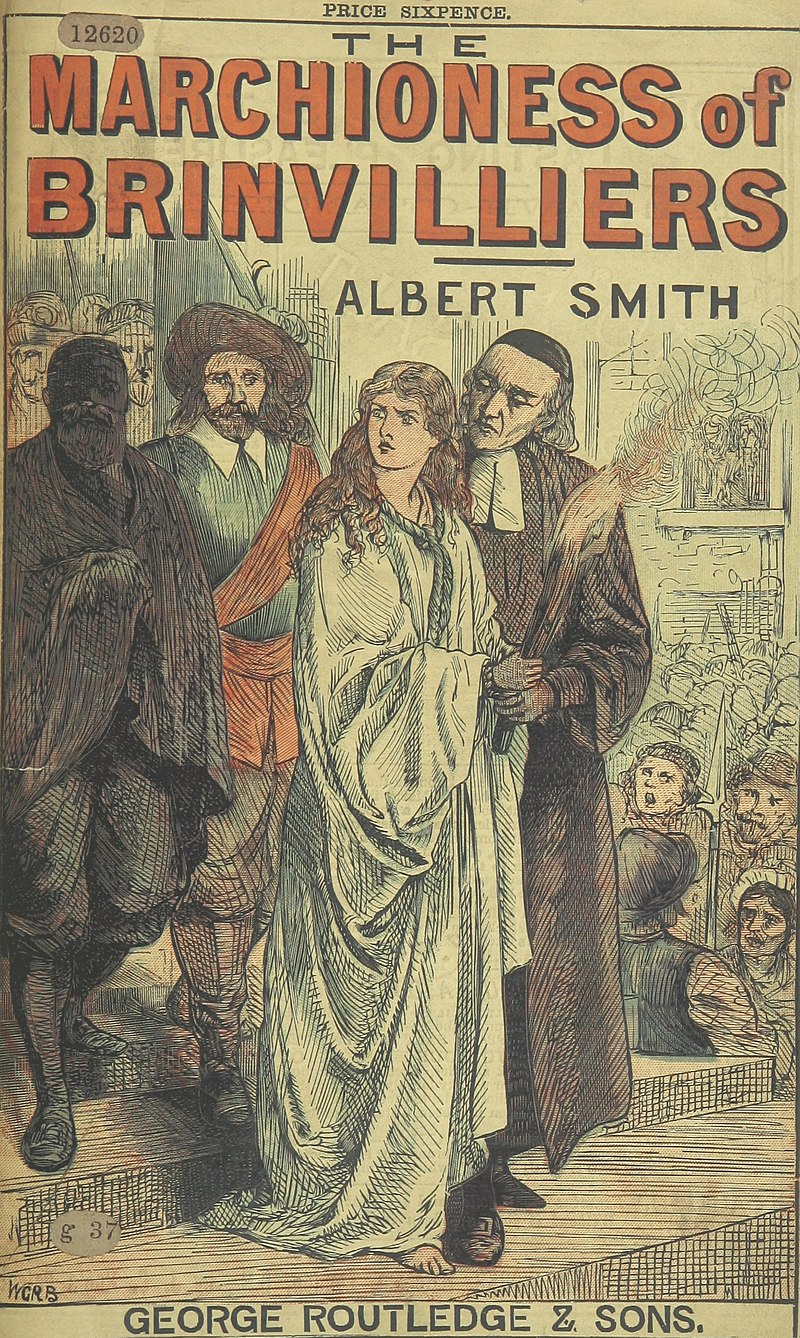

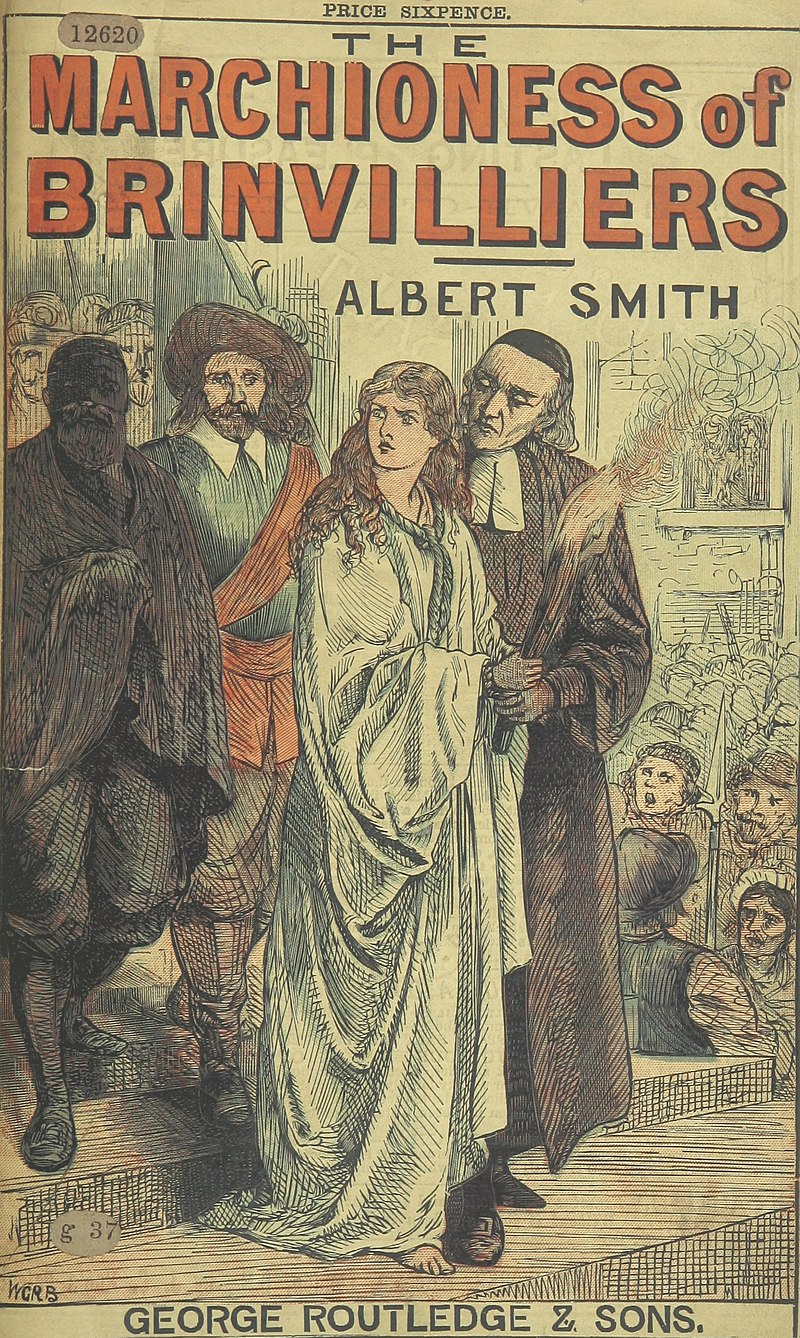

The Marchioness of

Brinvilliers: The Poisoner of the Seventeenth Century, an 1846 novel by

Albert Richard Smith (1887 edition)

☆ マリー=マドレーヌ・ドーブレイ、ブーランヴィリエ侯爵夫人(1630年7月22日 - 1676年7月16日)はフランスの貴族で、遺産を相続するために父親と2人の兄弟を殺害したとして告発され、有罪判決を受けた。彼女の死後、自分の毒を 試すために病院で30人以上の病人を毒殺したという憶測が流れたが、この噂は確認されなかった。彼女の犯罪が発覚したのは、恋人であり共謀者であったゴダ ン・ド・サント=クロワ大尉の死後であった。逮捕後、彼女は拷問を受け、自白を強要され、最後には処刑された。彼女の裁判と死は、ルイ14世の治世下、貴 族たちが魔術を行い、人々に毒を盛ったとして告発された一大スキャンダル「毒薬事件」の発端となった。彼女の生涯の一部は、短編小説、詩、歌など、さまざ まなメディアに翻案されている。

| Marie-Madeleine d'Aubray, Marquise de Brinvilliers

(22 July 1630 – 16 July 1676) was a French aristocrat who was accused

and convicted of murdering her father and two of her brothers in order

to inherit their estates. After her death, there was speculation that

she poisoned upwards of 30 sick people in hospitals to test out her

poisons, but these rumors were never confirmed. Her alleged crimes were

discovered after the death of her lover and co-conspirator, Captain

Godin de Sainte-Croix, who saved letters detailing dealings of

poisonings between the two. After being arrested, she was tortured,

forced to confess, and finally executed. Her trial and death spawned

the onset of the Affair of the Poisons, a major scandal during the

reign of Louis XIV accusing aristocrats of practicing witchcraft and

poisoning people. Components of her life have been adapted into various

different media including: short stories, poems, and songs to name a

few. |

マリー=マドレーヌ・ドー

ブレイ、ブーランヴィリエ侯爵夫人(1630年7月22日 -

1676年7月16日)はフランスの貴族で、遺産を相続するために父親と2人の兄弟を殺害したとして告発され、有罪判決を受けた。彼女の死後、自分の毒を

試すために病院で30人以上の病人を毒殺したという憶測が流れたが、この噂は確認されなかった。彼女の犯罪が発覚したのは、恋人であり共謀者であったゴダ

ン・ド・サント=クロワ大尉の死後であった。逮捕後、彼女は拷問を受け、自白を強要され、最後には処刑された。彼女の裁判と死は、ルイ14世の治世下、貴

族たちが魔術を行い、人々に毒を盛ったとして告発された一大スキャンダル「毒薬事件」の発端となった。彼女の生涯の一部は、短編小説、詩、歌など、さまざ

まなメディアに翻案されている。 |

| The

Marquise was born in 1630 to the relatively wealthy and influential

household of d'Aubray.[1] Her father, Antoine Dreux d'Aubray

(1600–1666), held multiple important governmental and high-ranking

positions such as the Seigneur of Offémont and Villiers, councillor of

State, Master of Requests, the Civil Lieutenant and prévôt of the city

of Paris, and Lieutenant General of the Mines of France.[2][3][4][5]

Her mother, Marie Olier (1602–1666) was the sister of Jean-Jacques

Olier, who founded the Sulpicians and helped establish the settlement

of Ville-Marie in New France, which would later be called Montreal.[1]

In her confession, the Marquise acknowledged being sexually assaulted

at the age of seven, though she did not name her assaulter.[1][5]

Further admitted in her confession is that she also had sexual

relations with her younger brother Antoine, whom she would later

poison.[1][4][5] Though the eldest of five children and loved by her father, she would not inherit his estate and was thus expected to marry into another.[3] Coming from a family of such wealth, whomever she married would inherit quite a large dowry from her, 200,000 livres, in fact.[3] At the age of 21, in 1651, she was married to Antoine Gobelin, Baron de Nourar, and Chevalier in the order of Sainte Jean of Jerusalem and later Marquis de Brinvilliers, whose estate was worth 800,000 livres.[1][3][6] His wealth came from his ancestors' famed tapestry workshops.[4] His father was the President of the Chamber of Accounts.[6] Upon marriage, the Marquise's father bestowed upon the couple a house at 12 rue Neuve St. Paul in Marais, an aristocratic district of Paris.[1][3] With the Marquis de Brinvilliers, she soon had three children, two girls and a boy.[3] She had a total of seven children, of which at least four are suspected of being illegitimate children from the Marquise's various paramours.[4] The Marquis befriended a fellow officer, Godin de Sainte-Croix, and introduced him to the Marquise; she would later have a long lasting affair with Sainte-Croix.[1][3] The Marquise's father was displeased to hear of his daughter's sexual affair with Sainte-Croix (which if became public, could damage his reputation due to his high position in French society) and was further displeased that the Marquise was in the process of separating her wealth from her husband's (who was gambling it away), which was akin to almost divorcing him, a major faux-pas in French aristocratic society.[2][3] Due to her father's position as a prévôt, granting him a large amount of power and influence, in 1663 he instigated a lettre de cachet, against her lover, Sainte-Croix, which called for his arrest and imprisonment at the Bastille.[2][7] While riding in a carriage with the Marquise de Brinvilliers, Sainte-Croix was arrested in front of her and thrown in the Bastille for a little under two months.[4][8] The Marquise later commented that perhaps if her father had not had her lover arrested, she might have never poisoned her father.[6] Many historians say that it was in his time in the Bastille where Sainte-Croix learned much about the art of poisoning.[2] He was imprisoned in the Bastille at the same time as the infamous Exili (also known as Eggidi), an Italian in the service of Queen Christina of Sweden, who was an expert on poisons.[1][4][7] Exili was imprisoned in the Bastille not because he had committed a crime, but rather because Louis XIV was suspicious of his presence in France because the courts of Sweden and France were not on the best of terms at the time.[6][1] Other historians say that it is highly possible that Sainte-Croix was already an acquaintance of Christopher Glaser, a famed Swiss pharmaceutical chemist and had attended some lectures given by him.[1][7][9] Yet, other historians doubt that Sainte-Croix came into contact with either and might have just been using their well-established names to sell his poisons for a higher price.[6] Upon his release from prison, Sainte-Croix married but remained in close-contact with the Marquise.[3] Sainte-Croix started an alchemy business to allow him to work with poisons, of which he now knew a lot about from his time in prison, by obtaining the necessary license to use certain equipment in order to distill his poisons.[1][3] It was under his tutelage that the Marquise de Brinvilliers started to experiment with poisons and concoct ideas of revenge.[7] |

侯爵夫人は1630年、比較的裕福

で影響力のあるドーブレーの家に生まれた[1]。

彼女の父アントワーヌ・ドルー・ドーブレー(1600-1666)は、オッフェモンとヴィリエの領主、国務参事官、要請の主人、パリ市の民尉兼プレヴォー

ト、フランス鉱山中将など、政府要職や高官を歴任した。

[2][3][4][5]母マリー・オリエ(1602-1666)はジャン=ジャック・オリエの妹であり、彼はスルピウス派を創設し、後にモントリオール

と呼ばれることになる新フランスのヴィル=マリー入植地の設立に貢献した。

[1]侯爵夫人は告白の中で、7歳の時に性的暴行を受けたことを認めているが、加害者の名前は挙げていない[1][5]。さらに告白の中で、後に毒殺する

ことになる弟のアントワーヌとも性的関係を持ったことを認めている[1][4][5]。 5人兄弟の長女であり、父に愛されていたが、父の遺産を相続することはなく、他の家に嫁ぐことが期待されていた[3]。 [1651年、21歳のとき、彼女はアントワーヌ・ゴブラン(ヌーラール男爵、エルサレムのサント・ジャン勲章シュヴァリエ、後のブーランヴィリエ侯爵) と結婚し、その財産は80万リーヴルに達した[1][3][6]。 [結婚すると、侯爵夫人の父は、パリの貴族街マレ地区のヌーヴ・サン・ポール通り12番地に邸宅を与えた[1][3]。 [侯爵は同僚の士官ゴダン・ド・サント=クロワと親しくなり、彼を侯爵夫人に紹介した[4]。 侯爵夫人の父親は、娘がサント=クロワと性的関係を持ったと聞いて不機嫌になり(公になれば、フランス社交界で高い地位にあったサント=クロワの評判を落 とすことになる)、さらに、侯爵夫人が自分の財産を(ギャンブルにつぎ込んでいた)夫の財産から切り離そうとしていることに不機嫌になった。 [2][3]父親がプレヴォートとして大きな権力と影響力を持っていたため、1663年、父親は彼女の恋人であるサント=クロワに対して、バスティーユで の逮捕と投獄を要求するレトル・ド・カシェを扇動した。 [2][7]ブーランヴィリエ侯爵夫人と馬車に乗っていたサント=クロワは、彼女の目の前で逮捕され、バスティーユに2ヶ月弱投獄された[4][8]。後 に侯爵夫人は、もし父が恋人を逮捕させなければ、父を毒殺することもなかったかもしれないとコメントした[6]。 多くの歴史家は、サント=クロワが毒殺の技術について多くを学んだのはバスティーユにいた時であったと言う[2]。 彼は、スウェーデンのクリスティーナ王妃に仕えていたイタリア人で、毒の専門家であった悪名高いエジリ(エギディとも呼ばれる)と同時にバスティーユに収 監された[1][4][7]。 [1][4][7] エクシリがバスティーユに収監されたのは、彼が犯罪を犯したからではなく、当時スウェーデンとフランスの宮廷は仲が悪かったため、ルイ14世が彼のフラン スでの存在を怪しんだからであった。 [6][1]他の歴史家によれば、サント=クロワはスイスの有名な製薬化学者であるクリストファー・グレーザーとすでに面識があり、彼の講義に出席してい た可能性が高いという[1][7][9]。しかし、他の歴史家はサント=クロワがどちらの人物とも接触していたのか疑っており、自分の毒薬をより高い値段 で売るために、定評のある彼らの名前を利用しただけかもしれないと述べている[6]。 出所後、サント=クロワは結婚したが、侯爵夫人とは親密な関係を保っていた[3]。サント=クロワは、獄中生活で多くの知識を得た毒を扱うために錬金術を 始め、毒を蒸留するために必要な器具の使用許可を得た[1][3]。ブーランヴィリエ侯爵夫人が毒の実験や復讐のアイデアを練り始めたのは、彼の指導の下 であった[7]。 |

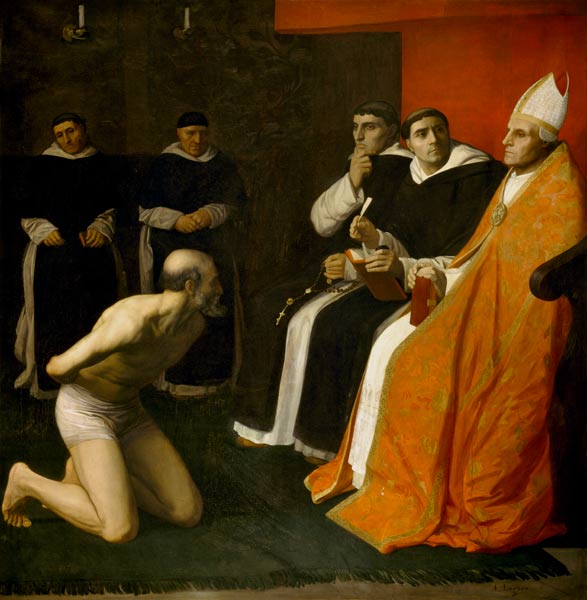

Crimes Antoine Dreux d'Aubray, poisoned by his daughter, the Marquise de Brinvilliers. Engraving by Claude Mellan It has been suggested by many researching the Marquise that before poisoning her father she tested out her poisons on unsuspecting sick hospital patients.[1][3][4] This theory comes from a report made by the lieutenant general of the Paris police, Gabriel Nicolas de La Reynie, who, in speaking of the Marquise, indicated that she, a pretty and delicate high-born woman from a respectable family, amused herself in observing how different dosages of her poisons took effect in the sick.[1][4][7] Scholars who support and acknowledge this theory do so because the era in which the Marquise lived would have enabled a woman of her rank to get away with murder quite easily.[3] Typical for the era, female members of French nobility would often visit hospitals to help care for the sick.[1][2] Because many of these patients were already ill, it provided the means for the Marquise to test out her poisons without much suspicion.[1] She tested out her poisons at the hospital, Hôtel Dieu, close to Notre Dame.[3] Furthermore, because Hôtel Dieu was not a very well managed hospital, as it was overflowing with patients, and was more concerned with saving souls than saving lives, deaths, even those under suspicious circumstances, went unnoticed.[3] She also started to experiment on her servants, giving them food tainted with her experimental poisons.[2][3] The Marquise was not tried for these crimes, however, because they were only attributed to her after her execution.[1] In 1666, the Marquise started to slowly poison her father, who would eventually die on 10 September.[8] She placed a man by the name of Gascon in her father's household to slowly administer poison to him.[3][6] In the week before his death, her father invited the Marquise and her children to stay with him.[1][7] She gave him multiple doses of "Glaser's recipe," a tried-and-true mixture of chemicals that would render him dead seemingly of natural causes.[7] Antoine Dreux d'Aubrey died with the Marquise at his side.[4] An autopsy was performed on his body which concluded that Dreux d'Aubrey died of natural causes, exacerbated by gout.[4][8] After the death of her father, the Marquise inherited some of his wealth.[6] She quickly burned through the money, and needing more, decided to poison her two brothers, hoping to get their share of her father's fortune as she was, to her knowledge, their next heir.[8] Her two brothers lived in the same household but the Marquise was not on the best of terms with either of them, making them harder to slowly poison than her father. She thus employed a man by the name of Jean Hamelin, more commonly known as La Chaussée, to work as a footman in her brothers' household.[1][9] La Chaussée went to work straight-away. Antoine d'Aubray actually suspected that he was perhaps a target of attempted poison when he noticed that his drink had a metallic taste to it.[1][3][4][6] La Chaussée's attempt at poisoning him there failed, but not long after, during an Easter feast, Antoine d'Aubray fell ill after eating a pie and never recovered, dying on 17 June 1670.[1][6] The second brother was poisoned soon after, dying in September of the same year; their subsequent autopsies would hint of poison due to the fact that their intestines were suspiciously colored but nevertheless concluded that they both died of "malignant humor".[1][2][4] Numerous individuals around the inquest of the brothers' deaths were suspicious that they were poisoned, especially because their deaths were so close to one another and in similar circumstances, but La Chaussée was never suspected; in fact, he was so well loved by the younger Dreux brother that upon his death, he bequeathed one hundred écus to La Chaussée.[6] |

犯罪 娘のブーランヴィリエ侯爵夫人に毒殺されたアントワーヌ・ドルー・ドーブレイ。クロード・メランによるエングレーヴィング この説は、パリ警察中将ガブリエル・ニコラ・ド・ラ・レイニーが侯爵夫人について語った報告書に由来しており、侯爵夫人は立派な家柄の可愛らしく繊細な高 貴な女性であり、自分の毒の異なる用量が病人にどのように作用するかを観察して楽しんでいたと指摘している[1][4][7]。 この説を支持し、認めている学者たちは、侯爵夫人が生きていた時代には、彼女のような身分の女性であれば、簡単に殺人を犯すことが可能であったからである [3]。 当時の典型的な例として、フランス貴族の女性メンバーは、しばしば病院を訪れ、病人の看護を手伝っていた[1][2]。 これらの患者の多くはすでに病気であったため、侯爵夫人にとっては、さほど疑われることなく自分の毒を試すことができる手段となった[1]。 彼女はノートルダム寺院に近いオテル・デューという病院で毒を試した。 [3]さらに、オテル・デューは患者で溢れかえっていたため、あまり管理の行き届いた病院ではなく、命を救うことよりも魂を救うことに重きを置いていたた め、不審な状況下での死でさえも気づかれることはなかった[3]。 また、彼女は使用人たちにも実験を始め、実験用の毒に汚染された食べ物を与えた[2][3]。 1666年、侯爵夫人は父をゆっくりと毒殺し始め、9月10日に死に至らしめた[8]。 父の死の1週間前、父は侯爵夫人とその子供たちを父の家に招いた[1][7]。 [7]アントワーヌ・ドルー・ドーブリーは侯爵夫人の傍らで息を引き取った[4]。彼の遺体を検死した結果、ドルー・ドーブリーの死因は痛風による自然死 であると結論づけられた[4][8]。 [彼女はすぐにその財産を使い果たし、さらに多くの財産を必要としたため、2人の兄を毒殺することにした。 二人の兄弟は同じ家に住んでいたが、侯爵夫人は二人とも仲が悪く、父親よりもゆっくりと毒を盛るのが難しかった。そこで彼女は、ジャン・ハメラン(通称 ラ・ショッセ)という男を雇い、兄たちの家で足軽として働かせることにした[1][9]。アントワーヌ・ドーブレイは、自分の飲み物が金属味を帯びている ことに気づき、自分が毒殺の標的にされたのではないかと疑った[1][3][4][6]。 ラ・ショッセの毒殺の企ては失敗に終わったが、ほどなくして、復活祭の祝宴の最中に、アントワーヌ・ドーブレイはパイを食べて体調を崩し、そのまま回復す ることなく、1670年6月17日に死亡した。 その後、2人の剖検が行われ、腸が不審な色をしていたことから毒殺が疑われたが、それでも2人とも「悪性のユーモア」によって死亡したと結論づけられた [1][2][6]。 [1][2][4]兄弟の死の検視の周辺では、特に2人の死が非常に近かったことと似たような状況であったことから、2人が毒殺されたのではないかと疑う 者が多数いたが、ラ・ショッセは疑われることはなかった。事実、彼はドリュの弟に非常に愛されており、彼の死後、彼はラ・ショッセに100エキュスを遺贈 した[6]。 |

| Discovery of her crimes and her escape and capture The Marquise's poisonings were not discovered initially, and in fact continued to be unknown until 1672, upon the death of her lover and conspirator, Sainte-Croix.[10] Many claim that Sainte-Croix died because an accident exposed him to his own poisons.[1][3] However, others argue that this is purely speculation and that Sainte-Croix simply died of disease.[1][6] At the time of his death, Sainte-Croix owed a great deal of money.[1][6] Among his possessions was a box containing letters between him and the Marquise, various poisons, and a note promising a sum of money to Sainte-Croix from the Marquise dated around the time her father first starting feeling ill was found, re-opening the case of foul play for her father and brothers.[1][3][5][9] These contents were instructed to be given to the Marquise upon his death, and thus were resealed and given to the Commissary Picard, until formal procedures could happen.[8] La Chaussée, hearing that Picard was in charge of Sainte-Croix's remaining affairs, went to him explaining that his former boss owed him money, and in explaining this, provided a suspiciously accurate account of Sainte-Croix's laboratory.[4][8] Picard mentioned to La Chaussée that among Sainte-Croix's possessions was the box with the incriminating letters.[8] La Chaussée, on hearing this, ran away and fled, leading to Picard to demand an inquest for La Chaussée for this suspicious behavior.[8] He was soon found, and, on interrogation, implicated not only himself, but the Marquise for crimes against her family.[1][5][10] La Chaussée was then tortured before being executed on 24 March 1673.[5] On the same day as his execution, the Marquise was condemned in absentia for her crimes and a warrant went out for her arrest.[5]  The Conciergerie, the prison where the Marquise was housed before her execution Similarly, upon news that this box had been found, the Marquise fled France to hide in England.[1][3][10] She evaded authorities for a number of years, who continued to hunt after her.[6] While in hiding, she survived off of sums of money sent to her by her sister, Marie-Thérèse.[1] Her sister died in 1674, leaving the Marquise with little money to survive on.[5] She continued to evade capture, moving from place to place every so often, including locations such as Cambrai, Valenciennes, and Antwerp.[5] It was in Belgium that the Marquise finally was caught.[5] In 1676, she rented a room in a convent in Liège where authorities there recognized her and alerted the French government who subsequently had her arrested.[1][3] Among her possessions in the convent was a letter titled "My Confessions", which as the title implies, detailed the various crimes she had committed over the years along with other personal information.[1][5] In this letter, she admits to having poisoned her father and two brothers, and that she had attempted to poison her daughter, sister and husband, although the latter three were unsuccessful.[1][6] She also confessed to having had many affairs, and that three of her children were not her husband's.[5][6] Some scholars doubt the Marquise's authenticity in her letters, but certainly the content of her confession was heavily used against her in French court. Madame de Sévigné, a contemporary French aristocrat of the Marquise's, talked about her in many of her famous letters, highlighting the gossip that spread around French nobility.[6][11] While being extradited back into France, the Marquise made various suicide attempts.[1][5][8] On her return to France, she was first interrogated at Mézières before being imprisoned in the Conciergerie, a prison located in Paris.[1][3][5][7] |

犯罪の発覚と逃亡・逮捕 侯爵夫人の毒殺は当初発見されず、実際、1672年に恋人であり共謀者であったサント=クロワが亡くなるまで不明であった[10]。サント=クロワの死因 は、事故により自らの毒に触れたためだとする説が多いが[1][3]、これは単なる憶測であり、サント=クロワは単に病死しただけだとする説もある[1] [6]。 [彼の所持品の中には、彼と侯爵夫人との間の手紙、様々な毒薬が入った箱があり、父親が最初に体調を崩し始めた頃の日付で侯爵夫人からサント=クロワに大 金を約束するメモが発見され、父親と兄弟の誣告罪が再調査された[1][3][5][9]。これらの中身は、彼の死後、侯爵夫人に渡すよう指示されていた ため、正式な手続きができるまで、再封され、ピカール委員会に渡された。 [8] ラ・ショセは、サント=クロワの残務をピカールが担当していると聞き、彼の元上司が彼に金を貸していると説明しに行き、その説明の中で、サント=クロワの 研究室について疑わしいほど正確な説明をした[4][8] ピカールはラ・ショセに、サント=クロワの所有物の中に、証拠となる手紙の入った箱があることを話した。 [8]ラ・ショセはこれを聞いて逃げ出し、ピカールはこの不審な行動に対してラ・ショセの審問を要求した[8]。 彼はすぐに発見され、尋問の結果、自分だけでなく侯爵夫人の家族に対する罪をも示唆した。[1][5][10]ラ・ショセは拷問を受けた後、1673年3 月24日に処刑された[5]。ショセの処刑と同じ日に、侯爵夫人はその罪により欠席裁判で断罪され、逮捕状が出された[5]。  侯爵夫人が処刑前に収容されていた牢獄、コンシェルジュリー 同様に、この箱が発見されたという知らせを受け、侯爵夫人はフランスを逃れてイギリスに身を隠した[1][3][10]。 何年もの間、侯爵夫人は当局の追跡を逃れ続けた[6]。[1676年、彼女はリエージュの修道院に部屋を借りたが、そこで侯爵夫人の存在を知ったフランス 政府に通報し、逮捕された[5]。 [1][3]修道院での彼女の所持品の中には「私の告白」と題された手紙があり、そのタイトルが示すように、彼女が長年にわたって犯した様々な犯罪とその 他の個人情報が詳細に記されていた[1][5]。 [1][6]また、多くの浮気をしたこと、3人の子供は夫の子ではないことも告白している[5][6]。侯爵夫人の手紙の信憑性を疑う学者もいるが、彼女 の告白の内容がフランス宮廷で不利な証拠として重用されたことは確かである。侯爵夫人と同時代のフランス貴族であったセヴィニエ夫人は、多くの有名な手紙 の中で侯爵夫人について語っており、フランス貴族の間で広まっていたゴシップを浮き彫りにしている[6][11]。 フランスに送還される間、侯爵夫人は様々な自殺未遂を繰り返した[1][5][8]。 帰国後、彼女はまずメジエールで取り調べを受けた後、パリにあるコンシェルジュリーという監獄に収監された[1][3][5][7]。 |

| Trial Madame de Sévigné, in a letter to her daughter, wrote that the Marquise's trial captured the attention of all of Paris.[5] Initially when questioned the Marquise heavily feigned ignorance, neither denying or admitting the questions raised against her but rather pretended that she was not aware of any happenings around her concerning the deaths of her family and her illicit relationship with Sainte-Croix.[8] Much of the early interrogation centered around the money trail between her, Sainte-Croix, and Pennautier, the Marquise's financier.[7] Later in the trial, the Marquise denied all crimes levied against her, placing blame on her former lover Sainte-Croix.[7] This lack of substantial evidence soon changed, however, from the testimony of another of the Marquise's former lovers, Jean-Baptiste Briancourt.[5] Briancourt alleged that not only had the Marquise admitted to him that she poisoned her brothers and fathers, but that she and Sainte-Croix had tried to murder him as well.[3][6] The Marquise dismissed all of Briancourt's accusations against her citing that he was a drunkard.[5] She was not believed, however, and after a final interrogation it was decided that she was guilty of her crimes and she was to be tortured before finally being executed by being beheaded and then having her body burned in a public spectacle.[6] |

裁判 セヴィニエ夫人は、娘に宛てた手紙の中で、侯爵夫人の裁判はパリ中の注目を集めたと記している[5]。 侯爵夫人は当初、尋問を受けると激しく無知を装い、自分に向けられた質問を否定も肯定もせず、むしろ家族の死やサント=クロワとの不正な関係に関する身の 回りの出来事を知らないふりをした[8]。 [8]初期の尋問の多くは、彼女とサント=クロワ、そして侯爵夫人の財政家であるペノーティエの間の金銭の流れを中心に行われた[7]。裁判の後半になる と、侯爵夫人は自分に対する罪をすべて否定し、元恋人のサント=クロワに責任を負わせた。 [7]しかし、侯爵夫人のもう一人の元恋人ジャン=バティスト・ブリアンクールの証言により、この実質的な証拠の欠如はすぐに変化した[5]。ブリアン クールは、侯爵夫人が兄弟や父親たちを毒殺したことを認めただけでなく、彼女とサント=クロワも彼を殺害しようとしたと主張した。 [3][6]侯爵夫人は、ブリアンクールが酒飲みであることを理由に、ブリアンクールの告発をすべて退けた[5]。 しかし、彼女は信じられず、最終的な尋問の結果、彼女の罪は有罪であり、拷問にかけられた後、斬首され、公開の見世物として遺体を焼かれることで処刑され ることが決定した[6]。 |

Torture and execution The Marquise being tortured with the water cure before her beheading (Jean-Baptiste Cariven, 1878) As France was a Catholic state at the time of her execution, a confessor was given to the Marquise in her final hours.[5] The man chosen was the abbé Edem Pirot, a theologian from the Sorbonne.[5] Despite never having ministered a criminal in their final hours, he was nonetheless chosen for the role.[8][9] He compiled a grand account of her final hours of which the original copy is housed within the Jesuit Library in Paris.[8] Within this recounting, Pirot speaks of her final hours and of her life leading up to her crimes.[12] Before her death, as part of her sentence, the Marquise was subjected to a form of torture known as the water cure where the subject was made to drink (often through a funnel) copious amounts of water in a short period of time.[5][13] In his account, Pirot noted that when faced with the prospect of torture, the Marquise said she would confess to all, however, she noted that she knew that this would not alleviate her sentence of torture.[6][10][12] She added no new information that she had not already confessed under torture except for adding that she once sold poison to a man who intended to kill his wife.[6][9] After four hours of torture she entered a final confession session with Pirot in the prison chapel.[7] She was not allowed to take communion before her death due to laws at the time forbidding condemned prisoners to take it.[8] As she left the chapel, a crowd of aristocrats gathered to see the spectacle of her death march as she and the abbé traveled to the Place de Grève for her execution.[8] The Marquise was covered in a white slip as was customary outfit for the condemned at their execution.[3] On the way to her execution, they stopped at Notre Dame so that the Marquise could perform the Amende Honorable inside of the packed Cathedral.[9][10] When they finally reached the Place de Grève the Marquise was unloaded from the cart she was in and brought up to a platform.[3] The executioner shaved her hair before pulling out a sword and chopping off her head.[3][6] The surrounding area was packed with spectators who hoped to grasp a glimpse of her execution.[5][10] Madame de Sévigné was among them, and in fact, her most well-known letter mentions the Marquise's execution.[14] After the beheading, the Marquise's body was burned of which Madame de Sévigné quotes that Brinvilliers (or, rather, her ashes) were "up in the air".[3][14] |

拷問と処刑 斬首前に水責めで拷問を受ける侯爵夫人(ジャン=バティスト・カリヴェン、1878年) 処刑当時のフランスはカトリック国家であったため、侯爵夫人の最期の時間には告解者がつけられた[5]。 ソルボンヌ大学の神学者であったエデム・ピロ修道院長が選ばれた[5]。 [8][9]彼は彼女の最期の時間について壮大な記述をまとめ、その原本はパリのイエズス会図書館に保管されている[8]。この記述の中で、ピロは彼女の 最期の時間と犯罪に至るまでの彼女の人生について語っている[12]。 侯爵夫人は生前、刑の一部として、短時間に大量の水を飲ませる(多くの場合、漏斗を通して)水責めとして知られる拷問を受けた。ピロ氏の説明では、拷問に 直面したとき、侯爵夫人はすべてを自白すると言ったが、しかし、それによって拷問が軽減されることはないと知っていたと述べている。侯爵夫人は、妻を殺そ うとした男に毒を売ったことがあると付け加えた以外には、拷問で自白していないような新しい情報は加えなかった。4時間の拷問の後、彼女は刑務所の礼拝堂 でピロとの最後の告白をおこなった。彼女が礼拝堂を出ると、大勢の貴族たちが集まり、彼女と修道院長が処刑のためにグレーヴ広場に向かう死の行進を見物し た。侯爵夫人は、死刑囚が処刑される時の習慣である白いスリップを身にまとっていた。処刑に向かう途中、ノートルダム寺院に立ち寄り、侯爵夫人は満員の大 聖堂の中でアメンド名誉刑を受けた。ようやくグレーヴ広場に到着すると、侯爵夫人は乗っていた荷車から降ろされ、壇上に上げられた。処刑人は彼女の髪を剃 り、剣を抜いて首を切り落とした。周囲は、彼女の処刑を一目見ようとする見物人で埋め尽くされた。その中にはセヴィニエ夫人も含まれており、実際、彼女の 最も有名な手紙には侯爵夫人の処刑のことが書かれている。斬首の後、侯爵夫人の遺体は焼却されたが、その際、ブーランヴィリエ(というより彼女の遺灰)は 「宙に浮いた(=空中に舞い上がった)」とセヴィニエ夫人は書き残している。 |

Ramifications Drawing of Madame de Montespan, mistress of Louis XIV who was implicated in the affair of the poisons. After the Marquise's execution, authorities, notably La Reynie and Louis XIV, were convinced that the Marquise could not have acted alone, and more individuals were involved than Sainte-Croix, La Chaussée, and Pennautier.[4][5] Because the former two persons were already dead, an investigation was launched into Pennautier. Nothing came of this investigation however, and Pennautier was cleared of all formal suspicions.[3] The inquest into the Marquise's accomplices did not stop there.[10] As La Reynie explained in a letter, because someone so highborn was involved in such a deadly scandal, it was not a far leap of thought that other members of nobility could be involved in poisonings and other suspicious manners of death.[2][5] Many people in high positions of power were arrested and tried for murder and other criminal dealings.[10] This gradually expanded until 1679 when the investigations came to their height in the resulting affair known as the Affair of the Poisons where more than a few hundred individuals were arrested.[4] Notable individuals implicated in the resulting affair include: Catherine Monvoisin, a fortune-teller better known as La Voisin, Madame de Montespan, a mistress of the king, and Olympia Mancini, the Countess of Soissons.[2][4] |

災い ルイ14世の愛妾で毒薬事件に関与したモンテスパン夫人の絵 侯爵夫人が処刑された後、ラ・レイニーやルイ14世をはじめとする権力者たちは、侯爵夫人が単独で行動したとは考えられず、サント=クロワ、ラ・ショセ、 ペンノーティエ以上の人物が関与していると確信した。前者二人はすでに死亡していたため、ペンノーティエの調査が開始された。しかし、この捜査からは何の 成果も得られず、ペンノーティエは正式な疑惑を晴らした。侯爵夫人の共犯者についての調査はこれだけにとどまらなかった。ラ・レイニーが手紙の中で説明し ているように、これほど高貴な人物がこのような致命的なスキャンダルに巻き込まれたのだから、他の貴族も毒殺やその他の不審な死に方に関わっている可能性 があるというのは、それほど飛躍した考えではなかった。多くの権力者が殺人やその他の犯罪行為で逮捕され、裁判にかけられた。1679年、数百人以上が逮 捕された「毒殺事件」で捜査が最高潮に達するまで、この事件は徐々に拡大していった。この事件に関与した有名な人物は以下の通りである: ラ・ヴォワザンの名で知られる占い師カトリーヌ・モンヴォワザン、王の愛妾モンテスパン夫人、ソワソン伯爵夫人オランピア・マンシーニなどである。 |

Popular culture The Marchioness of Brinvilliers: The Poisoner of the Seventeenth Century, an 1846 novel by Albert Richard Smith (1887 edition) Fictional accounts of her life include The Leather Funnel by Arthur Conan Doyle, The Marquise de Brinvilliers by Alexandre Dumas, père, The Devil's Marchioness by William Fifield, Intrigues of a Poisoner by Émile Gaboriau,[15] and The Marchioness of Brinvilliers: The Poisoner of the Seventeenth Century, by Albert Richard Smith. In her 1836 poem, "A Supper of Madame de Brinvilliers", Letitia Elizabeth Landon envisages the poisoning of a discarded lover. Robert Browning's 1846 poem "The Laboratory" imagines an incident in her life. Her capture and burning is mentioned in The Oracle Glass by Judith Merkle Riley, also the poisoning of the poor is echoed by the main character, Genevieve's, mother. The plot of the novel The Burning Court by John Dickson Carr concerns a murder that appears to be the work of the ghost of Marie d'Aubray Brinvilliers.[16] There have been two musical treatments of her life. An opera titled La marquise de Brinvilliers with music by nine composers—Daniel Auber, Désiré-Alexandre Batton, Henri Montan Berton, Giuseppe Marco Maria Felice Blangini, François-Adrien Boieldieu, Michele Carafa, Luigi Cherubini, Ferdinand Hérold, and Ferdinando Paer—premiered at the Paris Opéra-Comique in 1831.[17] A musical comedy called Mimi – A Poisoner's Comedy written by Allen Cole, Melody A. Johnson, and Rick Roberts premiered in Toronto, Canada in September 2009.[18] The radio docu-drama Crime Classics featured her story in 1954. The 2009 French television film The Marquise of Darkness (French: La Marquise des Ombres) starred Anne Parillaud as de Brinvilliers.[19] |

大衆文化 ブーランヴィリエ侯爵夫人: アルバート・リチャード・スミスによる1846年の小説『17世紀の毒殺者』(1887年版) 彼女の生涯を描いたフィクションには、アーサー・コナン・ドイルの『革の漏斗』、アレクサンドル・デュマ(父)の『ブーランヴィリエ侯爵夫人』、ウィリア ム・フィフィールの『悪魔の侯爵夫人』、エミール・ガボリオーの『ある毒殺者の陰謀』[15]、『ブーランヴィリエ侯爵夫人』などがある: アルバート・リチャード・スミス著『17世紀の毒殺者』。レティシア・エリザベス・ランドンは1836年の詩「ブーランヴィリエ夫人の晩餐」で、捨てられ た恋人の毒殺を想定している。ロバート・ブラウニングの1846年の詩 "The Laboratory "は、彼女の人生におけるある出来事を想像している。ジュディス・マークル・ライリーの『オラクル・グラス』では、彼女の捕獲と火刑が言及されており、主 人公ジュヌヴィエーヴの母親もまた、貧しい人々の毒殺を描いている。ジョン・ディクソン・カーの小説『The Burning Court』のプロットは、マリー・ドーブレイ・ブランヴィリエの亡霊の仕業と思われる殺人事件に関係している[16]。 彼女の生涯を扱った音楽は2つある。ダニエル・オーベール、デジレ=アレクサンドル・バットン、アンリ・モンタン・ベルトン、ジュゼッペ・マルコ・マリ ア・フェリーチェ・ブランジーニ、フランソワ=アドリアン・ボワルデュー、ミケーレ・カラファ、ルイジ・ケルビーニ、フェルディナンド・エロルド、フェル ディナンド・ペールの9人の作曲家による『ブランヴィリエ侯爵夫人』というタイトルのオペラが1831年にパリのオペラ・コミックで初演された。 [17] アレン・コール、メロディ・A・ジョンソン、リック・ロバーツによって書かれたミュージカル・コメディ『Mimi - A Poisoner's Comedy』が2009年9月にカナダのトロントで初演された[18]。 ラジオドラマ『Crime Classics』は1954年に彼女の物語を取り上げた。2009年のフランスのテレビ映画『闇の侯爵夫人』(仏:La Marquise des Ombres)では、アンヌ・パリローがド・ブランヴィリエを演じた[19]。 |

| Amende honorable was

originally a mode of punishment in France which required the offender,

barefoot and stripped to his shirt, and led into a church or auditory

with a torch in his hand and a rope round his neck held by the public

executioner, to beg pardon on his knees of his God, his king, and his

country. By acknowledging their guilt, the offender made it clear, implicitly or explicitly, that they would refrain from future misconduct and would not seek revenge. Often used as a political punishment, and sometimes as an alternative to execution,[1] it would sometimes serve as an acknowledgement of defeat and an instrument to restore peace. The term is now used to denote a satisfactory apology or reparation.[2] |

アメンド名誉刑とは、もともとはフランスで行われた刑罰の一種で、犯罪者は裸足でシャツ一枚になり、松明を手に教会や聴衆席に導かれ、公開処刑人に首に縄をかけられ、神と王と国に膝をついて許しを請うというものであった。 罪を認めることで、加害者は暗黙のうちに、あるいは明示的に、今後の非行を慎み、復讐を求めないことを明らかにした。政治的な罰として用いられることも多 く、処刑に代わるものとして用いられることもあったが[1]、敗北を認め、平和を回復するための手段として用いられることもあった。 現在では、満足のいく謝罪や賠償を意味する言葉として使われている[2]。 |

| Origins Despite its name, the Amende honorable is a ritual of public humiliation, which origins can be traced back to the Roman ritual of deditio or receptio in fidem.[1] From the 9th to the 14th century, a punishment called Harmiscara in Latin (Harmschar in German, Haschiée in French), consisting in carrying a dog or a saddle, was used to punish members of the nobility who had outraged the monarch or the church. Such a punishment was imposed, for example, in 1155 by Frederick Barbarossa to punish those who have troubled the peace in the Holy Roman Empire.[3] In a similar fashion, In 1347, the Burghers of Calais presented themselves in shirt and rope around their necks to beg the forgiveness of King Edward III, offended by the city's refusal to submit to him - a ritual that may have biblical origins.[4] The term "Amende honorable" seems to spread during the 14th and 15th centuries - historian Jean-Marie Moeglin notes that Enguerrand de Monstrelet used it in the context of the reparations requested by the Duchess of Orleans after the assassination of her husband, Duke Louis of Orleans. It appeared in the acts of Parliament at roughly the same time, in an agreement of 1401. During the 15th century, the Amende honorable seems a rather common form of punishment administered by ecclesiastical courts. Studying the forms of punishment pronounced by the judicial vicar of Cambray, Véronique Beaulande-Barraud finds the Amende honorable to be among the most common of sentences, rarer than fines in wax but as common as prison terms and excommunications.[5] However, the Amende honorable rarely constitutes the full sanction, but generally a complement to other forms of punishment, such as banishment, pilgrimages, jail or even death sentences. Nicole Gothier notes: The Amende honorable is addressed to those who have suffered the insult or damage, [and] it takes place on the "place of wrongdoing" as specified in the style of the Parliament. But such a ceremony, which puts the convicted person's self-esteem to the test, since it makes no mystery of the indignity of the crime, is rarely sufficient in itself. To punish the misdeed, once the culprit has publicly confessed their darkness and acknowledged their guilt, another penalty feels needed. In the best of cases it is only a banishment, [but] usually a corporal punishment, or even a death sentence. Thus, the Amende honorable is close to a confession and penance, made with the prospect of facing the tribunal of God.[6] Amende honorable by John the Fearless (1408) The first widely known example of Amende honorable is the one made by Duke of Burgundy John the Fearless, after the murder of Duke Louis of Orleans in 1408: In order to make reparation for his crime, the Duke of Burgundy had to make Amende honorable: in the presence of the entire royal court, he had to confess his crime publicly and ask forgiveness from the victims, that is the Duchess of Orleans and her son, while wearing a girdle or a chaperone, kneeling on the ground.[1] Amable Guillaume Prosper Brugière, baron de Barante thus describes the ordeal: The Duke of Burgundy was to be brought to the Louvre or to whatever place the king liked. There, in the presence of the king, or of the Duke of Aquitaine, of all those of royal blood, and of the council, before the people, the said Duke of Burgundy, without hood or belt, kneeling before Madame d'Orléans and her children, accompanied by as many people as they would like, was to say and confess, publicly and loudly, that, maliciously and by ambush, he had murdered the Duke of Orleans out of hatred, envy, covetousness and not for any other cause, notwithstanding the things he had claimed on the subject. For each and every one of his offenses, he repented and asked Madame d'Orléans and her children to forgive him, humbly begging them to forgive him; that he knew of nothing ill against the good and honor of the Duke d'Orléans. He was then to be taken to the courtyard of the palace and to the Hôtel Saint-Paul where, on the scaffolding erected for this purpose, he would repeat the same words; he would remain there on his knees until the priests present had recited the seven psalms of penance, the litanies, and prayers for the repose of the soul of the Duke d'Orléans. Then, he would kiss the ground and ask for forgiveness. An account of this Amend would be made in the royal letters addressed to all the good cities, in order to be shouted and published to the sound of the trumpets.[7] Grande Rebeyne revolt (1529) After the failed Grande Rebeyne revolt in Lyon, several rebels were sentenced to an Amende honorable in the streets of the city: Several rebels had to make Amende honorable: it is said that they had to hold a burning torch in their fist, and to put a rope around their necks, escorted by sergeants and criers, who loudly and clearly announced the identity of the accused and his crimes. The undignified appearance comes to reinforce the public statement in two parts: confession and request for forgiveness for one's faults.[6] Amende honorable as part of the execution of Robert-François Damiens (1757) The amende honorable was sometimes incorporated into a larger ritual of capital punishment (specifically the French version of drawing and quartering) for parricides and regicides; this is described in the 1975 book Discipline and Punish by Michel Foucault, notably in reference to Robert-François Damiens who was condemned to make the amende honorable before the main door of the Church of Paris in 1757. |

起源 その名前とは裏腹に、名誉のアメンドは公の場で恥をかかせる儀式であり、その起源はローマ時代の献体またはレセシオ・イン・フィデムの儀式にまで遡ることができる[1]。 9世紀から14世紀にかけて、ラテン語でハルミスカラ(ドイツ語でHarmschar、フランス語でHaschiée)と呼ばれる、犬や鞍を背負う刑罰 が、君主や教会を侮辱した貴族を罰するために用いられた。このような刑罰は、例えば1155年にフリードリヒ・バルバロッサが神聖ローマ帝国の平和を乱し た者を罰するために課した[3]。 似たような例として、1347年には、カレーの准囚たちが、エドワード3世に服従を拒まれたことに腹を立てたエドワード3世に許しを請うために、シャツと首に縄を巻いた姿で出頭した--これは聖書に起源を持つ儀式かもしれない[4]。 歴史家のジャン=マリー・モーグランは、夫であるオルレアン公ルイが暗殺された後、オルレアン公爵夫人が要求した賠償金の文脈でこの言葉を使ったと述べている。この言葉は、ほぼ同時期、1401年の協定で議会法に登場した。 15世紀には、アメンド名誉刑は、教会裁判所で行われる刑罰の形式としてはかなり一般的なものであったようだ。ヴェロニク・ボーラン=バローは、カンブ レーの司法司祭が宣告した刑罰の形式を研究し、アメンド名誉刑が最も一般的な刑の一つであり、蝋の罰金よりは稀であるが、懲役刑や破門刑と同じくらい一般 的であることを発見した[5]。 しかし、アメンド名誉刑が完全な制裁となることは稀で、追放、巡礼、牢獄、あるいは死刑といった他の刑罰の補完的な意味合いを持つことが一般的である。ニコール・ゴティエはこう指摘する: 名誉の儀式(Amene honorable)は、侮辱や損害を被った人々に向けて行われ、国会の様式で定められた「不義を行った場所」で行われる。しかし、このような儀式は、犯 罪の屈辱を全く感じさせないため、有罪判決を受けた人の自尊心が試されるものであり、それだけで十分であることはほとんどない。悪行を罰するためには、犯 人が公にその闇を告白し、罪を認めれば、別の罰則が必要になる。最良の場合、それは追放に過ぎないが、通常は体罰、あるいは死刑である。このように、名誉 あるアメンドは、神の法廷に直面することを予期して行われる、告白と懺悔に近いものである[6]。 大胆不敵なヨハネによる名誉あるアメンド(1408年) アメンド名誉の最初の例として広く知られているのは、1408年にオルレアン公ルイが殺害された後、ブルゴーニュ公ジョン・ザ・フィアレスが行ったものである: 自分の犯した罪を償うために、ブルゴーニュ公爵は名誉あるアメンドを行わなければならなかった。それは、王宮全体の面前で、自分の罪を公に告白し、被害者であるオルレアン公爵夫人とその息子に許しを請うことであった。 バランテ男爵アマブル・ギョーム・プロスペール・ブルギエールはこの試練をこう描写している: ブルゴーニュ公爵はルーブル美術館か王の好きな場所に連れて行かれた。 そこで、国王、アキテーヌ公爵、王家の血を引く者すべて、評議会、民衆の面前で、ブルゴーニュ公爵は頭巾も帯も着けず、オルレアン夫人とその子供たちの前 にひざまずき、望むだけの民衆に付き添われた、 ブルゴーニュ公爵は、悪意と待ち伏せによって、オルレアン公爵を憎悪と嫉妬と貪欲のために殺害したのであって、それ以外の理由によるものではないことを、 公然と大声で告白することになった。自分の犯した罪のひとつひとつについて、彼は悔い改め、オルレアン夫人とその子供たちに自分を許してくれるよう、謙虚 に懇願した。 その後、オルレアン公は宮殿の中庭とオテル・サン=ポールに連れて行かれ、このために建てられた足場の上で同じ言葉を繰り返し、その場にいた司祭たちが7 つの懺悔の詩篇、典礼、オルレアン公の冥福を祈る祈りを唱えるまで、ひざまずいたままそこに留まる。その後、地面に接吻し、許しを請うた。このアマンダム の記録は、ラッパの音に合わせて叫び、公表されるために、すべての善良な都市に宛てた勅書に記載された[7]。 グラン・ルベーヌの反乱(1529年) リヨンで起こったグラン・ルベーヌの反乱の失敗の後、何人かの反乱者は街の通りで名誉のアメンドを言い渡された: 何人かの反逆者は、名誉のアメンドを言い渡された。燃える松明を拳に持ち、首に縄をかけられ、軍曹や運び屋に付き添われ、被告人の身元と罪を大声ではっき りと告げられたと言われている。威厳のない姿は、懺悔と自分の過ちに対する赦しの要請という2つの部分からなる公的な声明を強化するものである[6]。 ロベール=フランソワ・ダミアンの処刑における名誉のアメンド(1757年) これはミシェル・フーコーによる1975年の著書『規律と処罰』(Discipline and Punish)に記述されており、特に1757年にパリ教会の正門の前で名誉のアメンドを行うよう宣告されたロベール=フランソワ・ダミアンスについて言及されている。 |

In the arts Alphonse Legros, Une amende honorable, musée d'Orsay. In Victor Hugo's The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, the death sentence imposed on Esmeralda includes an amende honorable: The clerk then began to write, and presently handed a long scroll of parchment to the President; after which the poor girl heard the people stirring, and an icy voice say: “Bohemian girl, on such a day as it shall please our lord the King to appoint, at the hour of noon, you shall be taken in a tumbrel, in your shift, barefoot, a rope round your neck, before the great door of Notre Dame, there to do penance with a wax candle of two pounds’ weight in your hands; and from there you shall be taken to the Place-de-Grève, where you will be hanged and strangled on the town gibbet, and your goat likewise; and shall pay to the Office three lion-pieces of gold in reparation of the crimes, by you committed and confessed, of sorcery, magic, prostitution, and murder against the person of the Sieur Phœbus de Châteaupers. And God have mercy on your soul!”[8] L'Amende Honorable is the name of an 1831 painting by Eugène Delacroix - it depicts an imaginary scene, taking place in the 16th century in the Palace of Justice in Rouen, in which a monk is dragged before the Bishop of Madrid for rebelling against his orders.[9] Alphonse Legros also painted an Amende Honorable (around 1868), depicting a religious court at the time of the Inquisition.[10] |

芸術の世界 アルフォンス・レグロ《名誉の償い》、オルセー美術館。 ヴィクトル・ユーゴーの『ノートルダムのせむし男』では、エスメラルダに下された死刑判決に名誉の賛辞が含まれている: 書記官が書き始め、やがて羊皮紙の長い巻物を大統領に手渡した: 「ボヘミアン娘よ、国王がお決めになる日、正午に、お前は、着の身着のまま、裸足で、首に縄をかけられ、ノートルダム寺院の大扉の前に連れて行かれ、そこ で2ポンドの重さの蝋燭を手に懺悔するのだ; そこからグレーヴ広場に連れて行かれ、町の絞首台で絞首刑に処される。神よ、あなたの魂に慈悲を!」[8]。 L'Amende Honorable」はウジェーヌ・ドラクロワが1831年に描いた絵画の名前であり、16世紀にルーアンの司法宮殿で起こった架空の場面を描いている。この場面では、修道士が命令に反抗した罪でマドリード司教の前に引きずり出される[9]。 アルフォンス・レグロもまた、異端審問の時代の宗教法廷を描いた『Amende Honorable』(1868年頃)を描いている[10]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amende_honorable |

|

The Marquise being tortured with the water cure before her beheading (Jean-Baptiste Cariven, 1878)/ The Marchioness of Brinvilliers: The Poisoner of the Seventeenth Century, an 1846 novel by Albert Richard Smith (1887 edition)

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099