呪術的思考

Magical thinking

☆ 呪術的思考(魔術的思考, Magical thinking)、または迷信的思考[1]とは、関連性のない出来事の間に妥当な因果関係が存在しないにもかかわらず、それらの出来事が因果的に 結びついていると信じることである。特に、超自然的効果の結果として結びついていると信じることである。[1][2][3] 例としては、個人の思考が何らかの行動を起こさなくても外部世界に影響を与えることができるという考え方や、 似ていたり、過去に接触したことがある場合、それらは因果関係で結ばれているに違いないという考え方である。[1][2][4] 呪術的思考は誤った思考の一種であり、無効な因果推論の一般的な原因である。[3][5] 相関関係と因果関係の混同とは異なり、呪術的思考では事象の相関関係は必要ない。[3]呪術的思考の厳密な定義は、異なる理論家によって、あるいは異なる研究分野の間で微妙に異なる場合がある。心理学では、呪術的思考とは、自分の思考だけで 世界に影響を及ぼすことができる、あるいは何かを考えればそれを実行することになるという信念である。[6] これらの信念は、特定の行為を実行したり特定の考えを持つことに対して、そうすることが脅威的な災難と相関関係にあると想定されるため、不合理な恐怖を経 験する原因となる可能性がある。 。精神医学では、呪術的思考とは、望ましくない出来事を引き起こしたり、あるいはそれを防いだりする思考、行動、あるいは言葉の能力に関する誤った信念を 指す。[7] 思考障害、統合失調型パーソナリティ障害、強迫性障害において、一般的に見られる症状である。[8][9][10]

| Magical thinking,

or superstitious thinking,[1] is the belief that unrelated events are

causally connected despite the absence of any plausible causal link

between them, particularly as a result of supernatural

effects.[1][2][3] Examples include the idea that personal thoughts can

influence the external world without acting on them, or that objects

must be causally connected if they resemble each other or have come

into contact with each other in the past.[1][2][4] Magical thinking is

a type of fallacious thinking and is a common source of invalid causal

inferences.[3][5] Unlike the confusion of correlation with causation,

magical thinking does not require the events to be correlated.[3] The precise definition of magical thinking may vary subtly when used by different theorists or among different fields of study. In psychology, magical thinking is the belief that one's thoughts by themselves can bring about effects in the world or that thinking something corresponds with doing it.[6] These beliefs can cause a person to experience an irrational fear of performing certain acts or having certain thoughts because of an assumed correlation between doing so and threatening calamities.[1] In psychiatry, magical thinking defines false beliefs about the capability of thoughts, actions or words to cause or prevent undesirable events.[7] It is a commonly observed symptom in thought disorder, schizotypal personality disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.[8][9][10] |

呪

術的思考(魔術的思考)、または迷信的思考[1]とは、関連性のない出来事の間に妥当な因果関係が存在しないにもかかわらず、それらの出来事が因果的に結

びついていると信じることである。特に、超自然的効果の結果として結びついていると信じることである。[1][2][3]

例としては、個人の思考が何らかの行動を起こさなくても外部世界に影響を与えることができるという考え方や、

似ていたり、過去に接触したことがある場合、それらは因果関係で結ばれているに違いないという考え方である。[1][2][4]

呪術的思考は誤った思考の一種であり、無効な因果推論の一般的な原因である。[3][5]

相関関係と因果関係の混同とは異なり、呪術的思考では事象の相関関係は必要ない。[3] 呪術的思考の厳密な定義は、異なる理論家によって、あるいは異なる研究分野の間で微妙に異なる場合がある。心理学では、呪術的思考とは、自分の思考だけで 世界に影響を及ぼすことができる、あるいは何かを考えればそれを実行することになるという信念である。[6] これらの信念は、特定の行為を実行したり特定の考えを持つことに対して、そうすることが脅威的な災難と相関関係にあると想定されるため、不合理な恐怖を経 験する原因となる可能性がある。 。精神医学では、呪術的思考とは、望ましくない出来事を引き起こしたり、あるいはそれを防いだりする思考、行動、あるいは言葉の能力に関する誤った信念を 指す。[7] 思考障害、統合失調型パーソナリティ障害、強迫性障害において、一般的に見られる症状である。[8][9][10] |

| Types Direct effect Bronisław Malinowski's Magic, Science and Religion (1954) discusses another type of magical thinking, in which words and sounds are thought to have the ability to directly affect the world.[11] This type of wish fulfillment thinking can result in the avoidance of talking about certain subjects ("Speak of the devil and he'll appear"), the use of euphemisms instead of certain words, or the belief that to know the "true name" of something gives one power over it; or that certain chants, prayers, or mystical phrases will bring about physical changes in the world. More generally, it is magical thinking to take a symbol to be its referent or an analogy to represent an identity.[citation needed] Sigmund Freud believed that magical thinking was produced by cognitive developmental factors. He described practitioners of magic as projecting their mental states onto the world around them, similar to a common phase in child development.[12] From toddlerhood to early school age, children will often link the outside world with their internal consciousness, e.g. "It is raining because I am sad." |

種類 直接的効果 ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキの『呪術・科学・宗教』(1954年)では、言葉や音が直接的に世界に影響を与える能力を持つと考える、もうひとつの呪術的思 考が論じられている。[11] この種の願望充足的な思考は、特定の話題について口にしないこと(「 悪魔の口にでも出せば現れる」)、特定の言葉の代わりに婉曲表現を用いること、あるいは何かの「真の名前」を知ることでそのものに対する力を得られると信 じること、あるいは特定の詠唱、祈り、あるいは神秘的なフレーズが世界の物理的な変化をもたらすという信念などである。より一般的に言えば、あるシンボル をその参照対象と見なしたり、同一性を表す類推と見なしたりすることも呪術的思考である。 ジークムント・フロイトは、呪術的思考は認知発達要因によって生み出されると考えた。彼は、呪術の実践者を、自身の精神状態を周囲の世界に投影していると 表現し、それは子供の成長における一般的な段階と類似していると述べた。[12]幼児期から小学校低学年の間、子供はしばしば外の世界を自身の内的な意識 と結びつける。例えば、「私が悲しいから雨が降っている」というように。 |

| Symbolic approaches Another theory of magical thinking is the symbolic approach. Leading thinkers of this category, including Stanley J. Tambiah, believe that magic is meant to be expressive, rather than instrumental. As opposed to the direct, mimetic thinking of Frazer, Tambiah asserts that magic utilizes abstract analogies to express a desired state, along the lines of metonymy or metaphor.[13] An important question raised by this interpretation is how mere symbols could exert material effects. One possible answer lies in John L. Austin's concept of performativity, in which the act of saying something makes it true, such as in an inaugural or marital rite.[14] Other theories propose that magic is effective because symbols are able to affect internal psycho-physical states. They claim that the act of expressing a certain anxiety or desire can be reparative in itself.[15] |

象徴的アプローチ 呪術的思考のもう一つの理論は象徴的アプローチである。スタンリー・J・タンビアをはじめとするこのカテゴリーの主要な思想家たちは、呪術は道具としてよ りも表現として意図されていると信じている。フレザーの直接的で模倣的な思考とは対照的に、タンビアは、呪術は望ましい状態を表現するために、換喩や隠喩 といった抽象的な類推を用いると主張している。 この解釈から生じる重要な疑問は、単なる象徴が物質的な効果をどのようにして発揮しうるのか、という点である。その答えのひとつは、ジョン・L・オース ティンのパフォーマティビティの概念にある。この概念では、何かを口にすることでそれが真実となる、例えば就任式や婚姻儀式などである。[14] 他の理論では、象徴が内的な心理的・物理的な状態に影響を与えることができるため、呪術が効果的であると主張している。彼らは、ある不安や願望を表現する 行為自体が、それ自体で癒しとなる可能性があると主張している。[15] |

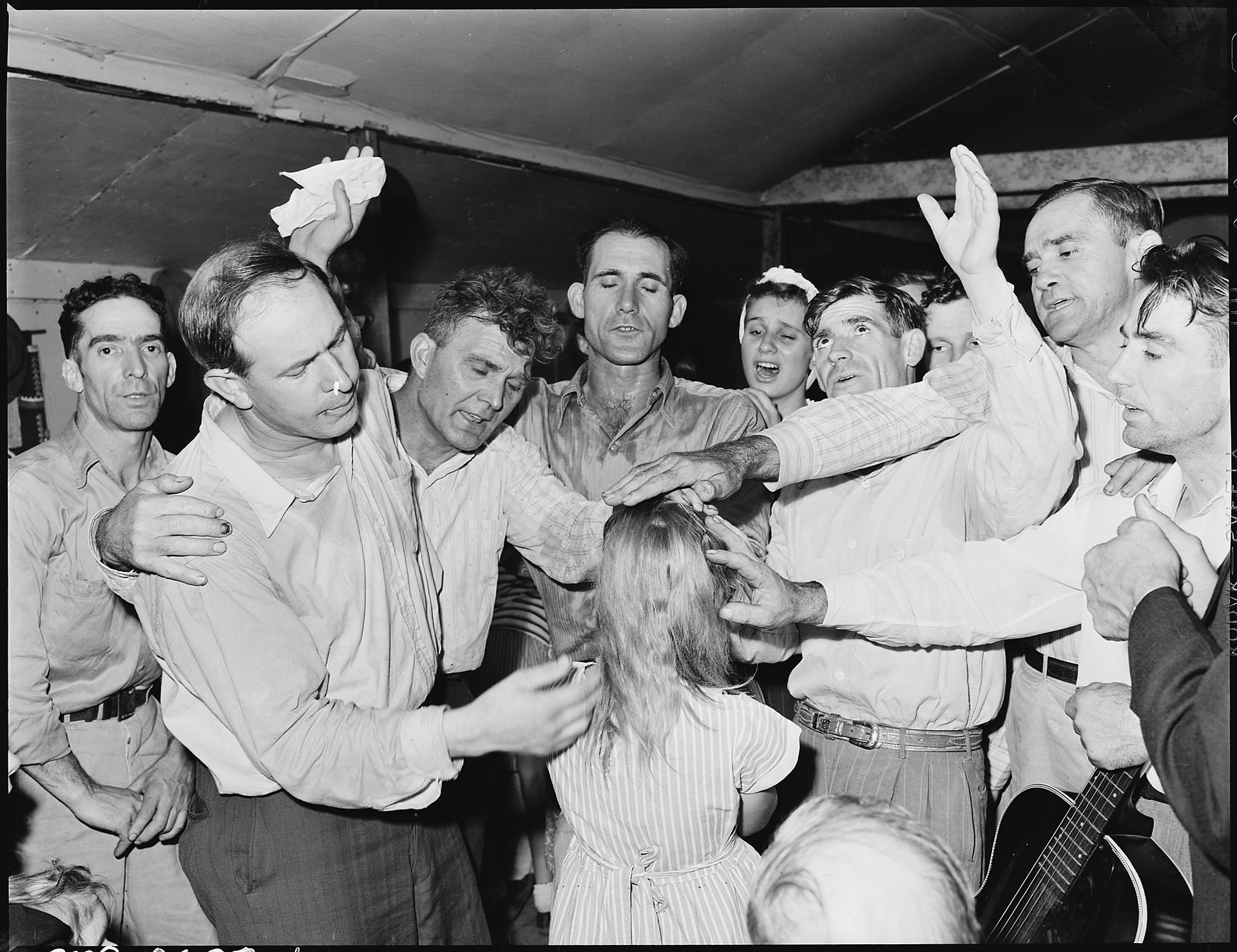

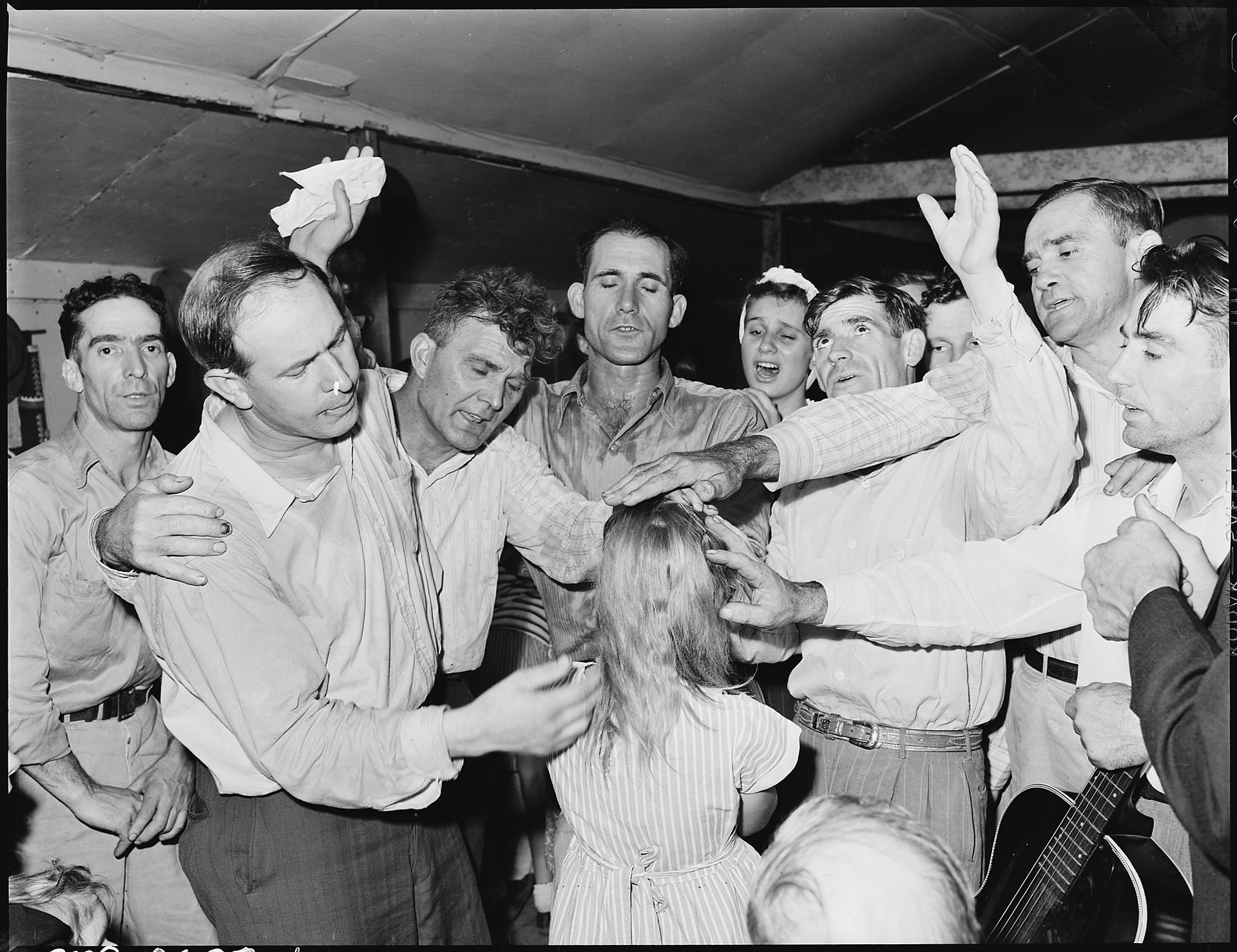

Causes A healing ritual (the laying on of hands) According to theories of anxiety relief and control, people turn to magical beliefs when there exists a sense of uncertainty and potential danger, and with little access to logical or scientific responses to such danger. Magic is used to restore a sense of control over circumstance. In support of this theory, research indicates that superstitious behavior is invoked more often in high stress situations, especially by people with a greater desire for control.[16][17] Boyer and Liénard propose that in obsessive-compulsive rituals — a possible clinical model for certain forms of magical thinking — focus shifts to the lowest level of gestures, resulting in goal demotion. For example, an obsessive-compulsive cleaning ritual may overemphasize the order, direction, and number of wipes used to clean the surface. The goal becomes less important than the actions used to achieve the goal, with the implication that magic rituals can persist without efficacy because the intent is lost within the act.[18] Alternatively, some cases of harmless "rituals" may have positive effects in bolstering intent, as may be the case with certain pre-game exercises in sports.[19] Some scholars believe that magic is effective psychologically. They cite the placebo effect and psychosomatic disease as prime examples of how our mental functions exert power over our bodies.[20] |

原因 癒しの儀式(手当て=按手療法) 不安の解消とコントロールに関する理論によると、人々は不確実性や潜在的な危険を感じ、そのような危険に対する論理的または科学的対応へのアクセスが限ら れている場合、呪術的信念に頼るようになる。呪術は、状況に対するコントロール感を取り戻すために用いられる。この理論を裏付ける研究によると、迷信的な 行動はストレスの高い状況でより頻繁に引き起こされ、特にコントロールへの欲求が強い人々によって引き起こされることが多いことが示されている。[16] [17] ボイヤーとリアナールは、強迫的儀式(呪術的思考の特定の形式における臨床モデルの可能性)では、焦点がジェスチャーの最低レベルにシフトし、結果として 目標が降格すると提案している。例えば、強迫的清掃儀式では、表面を清掃する際に使用するワイプの順序、方向、枚数を過度に強調する可能性がある。目標を 達成するための行動が目標よりも重要視されるようになり、呪術的な儀式は行為の中で意図が失われるため、効果がないにもかかわらず継続される可能性がある という意味合いを持つ。[18] あるいは、無害な「儀式」の中には、スポーツにおける試合前の準備運動のように、意図を強化する上で肯定的な効果をもたらすものもあるかもしれない。 [19] 一部の学者は、呪術は心理的に有効であると信じている。彼らは、プラシーボ効果や心身症を、精神機能が肉体に影響を及ぼす典型的な例として挙げている。[20] |

| Phenomenological approach Ariel Glucklich tries to understand magic from a subjective perspective, attempting to comprehend magic on a phenomenological, experientially based level. Glucklich seeks to describe the attitude that magical practitioners feel what he calls "magical consciousness" or the "magical experience". He explains that it is based upon "the awareness of the interrelatedness of all things in the world by means of simple but refined sense perception."[21] Another phenomenological model is that of Gilbert Lewis, who argues that "habit is unthinking". He believes that those practicing magic do not think of an explanatory theory behind their actions any more than the average person tries to grasp the pharmaceutical workings of aspirin.[22] When the average person takes an aspirin, he does not know how the medicine chemically functions. He takes the pill with the premise that there is proof of efficacy. Similarly, many who avail themselves of magic do so without feeling the need to understand a causal theory behind it. |

現象学的アプローチ アリエル・グラックリッチは、主観的な視点から呪術を理解しようとし、現象学的、経験に基づくレベルで呪術を理解しようとしている。グラックリッチは、呪 術の実践者が感じる態度を説明しようとしている。彼は、それを「単純だが洗練された感覚知覚によって、世界のあらゆるものの相互関連性を認識する」ことだ と説明している。 もう一つの現象学的なモデルは、ギルバート・ルイスのもので、「習慣とは思考停止である」と主張している。彼は、呪術を行う者は、アスピリンの薬理作用を 把握しようとする一般の人々以上に、自分の行動の背後にある説明理論について考えないと考えている。[22] 一般の人がアスピリンを服用する際、その薬が化学的にどのように作用するのかは知らない。効能が証明されているという前提で薬を服用している。同様に、呪 術を利用する多くの人々は、その背後にある因果理論を理解する必要性を感じることなく、そうしている。 |

| In children According to Jean Piaget's Theory of Cognitive Development,[23] magical thinking is most prominent in children between ages 2 and 7. Due to examinations of grieving children, it is said that during this age, children strongly believe that their personal thoughts have a direct effect on the rest of the world. It is posited that their minds will create a reason to feel responsible if they experience something tragic that they do not understand, e.g. a death. Jean Piaget, a developmental psychologist, came up with a theory of four developmental stages. Children between ages 2 and 7 would be classified under his preoperational stage of development. During this stage children are still developing their use of logical thinking. A child's thinking is dominated by perceptions of physical features, meaning that if the child is told that a family pet has "gone away to a farm" when it has in fact died, then the child will have difficulty comprehending the transformation of the dog not being around anymore. Magical thinking would be evident here, since the child may believe that the family pet being gone is just temporary. Their young minds in this stage do not understand the finality of death and magical thinking may bridge the gap. |

子供の場合 ジャン・ピアジェの認知発達理論によると、[23] 呪術的思考は2歳から7歳までの子供に最も顕著である。悲嘆に暮れる子供たちの調査により、この年齢の子供は、自分の個人的な思考が世界の他の部分に直接 影響を与えると強く信じていることが分かっている。例えば、死など、理解できない悲劇的な出来事を経験した場合、子供たちはその出来事に対して責任を感じ る理由を自分たちの心の中で作り出すと仮定されている。発達心理学者のジャン・ピアジェは、4つの発達段階の理論を提唱した。 2歳から7歳までの子供たちは、彼の提唱した発達段階の理論では「前操作期」に分類される。この段階では、子供たちは論理的思考の使い方をまだ学んでいる 最中である。子供の思考は、物理的な特徴の知覚によって支配されている。つまり、子供が「ペットが農場に行った」と言われた場合、実際にはペットが死んだ にもかかわらず、子供は犬がもうそこにいないという変化を理解するのが難しい。この場合、呪術的思考が明らかになる。なぜなら、子供は家族のペットがいな くなったのは一時的なことだと信じているかもしれないからだ。この段階にある幼い心は、死が最終的なものであることを理解しておらず、呪術的思考がその ギャップを埋める可能性がある。 |

| Grief It was discovered that children often feel that they are responsible for an event or events occurring or are capable of reversing an event simply by thinking about it and wishing for a change: namely, "magical thinking".[24] Make-believe and fantasy are an integral part of life at this age and are often used to explain the inexplicable.[25][26] According to Piaget, children within this age group are often "egocentric", believing that what they feel and experience is the same as everyone else's feelings and experiences.[27] Also at this age, there is often a lack of ability to understand that there may be other explanations for events outside of the realm of things they have already comprehended. What happens outside their understanding needs to be explained using what they already know, because of an inability to fully comprehend abstract concepts.[27] Magical thinking is found particularly in children's explanations of experiences about death, whether the death of a family member or pet, or their own illness or impending death. These experiences are often new for a young child, who at that point has no experience to give understanding of the ramifications of the event.[28] A child may feel that they are responsible for what has happened, simply because they were upset with the person who died, or perhaps played with the pet too roughly. There may also be the idea that if the child wishes it hard enough, or performs just the right act, the person or pet may choose to come back, and not be dead any longer.[29] When considering their own illness or impending death, some children may feel that they are being punished for doing something wrong, or not doing something they should have, and therefore have become ill.[30] If a child's ideas about an event are incorrect because of their magical thinking, there is a possibility that the conclusions the child makes could result in long-term beliefs and behaviours that create difficulty for the child as they mature.[31] |

悲しみ 子供たちはしばしば、起こった出来事に対して自分にも責任があると感じたり、あるいは、ただ考えたり、変化を望むだけで出来事を覆すことができると感じた りすることがあることが分かっている。すなわち、「呪術的思考」である。[24] ごっこ遊びや空想は、この年齢の子供たちの生活に欠かせないものであり、しばしば説明のつかないことを説明するために使われる。[25][26] ピアジェによると、この年齢の子供たちはしばしば「自己中心的」であり、自分が感じたり経験したりしていることは、他の人たちの感情や経験と同じであると 信じている。[27] また、この年齢では、すでに理解していることの範囲外の出来事については、他の説明があるかもしれないということを理解できないことが多い。理解できない ことについては、すでに知っていることを使って説明する必要がある。なぜなら、抽象的な概念を完全に理解できないからだ。 呪術的思考は、特に家族やペットの死、あるいは自身の病気や死の危機といった死に関する経験を説明する子供たちの説明に見られる。 こうした経験は幼い子供にとっては新しい経験であることが多く、その時点ではその出来事がもたらす影響を理解する経験がない。[28] 子供は、亡くなった人と喧嘩していた、あるいはペットを乱暴に扱っていたという理由だけで、起こった出来事に対して自分が責任があると感じるかもしれな い。また、子供が強く望めば、あるいはちょうど良い行いをすれば、その人物やペットが戻ってくることを選び、もはや死んでいないかもしれないという考えも あるかもしれない。 自身の病気や迫り来る死について考えたとき、子供たちは、何か悪いことをした、あるいは何かすべきことをしなかったために罰せられ、病気になったと感じる ことがある。[30] 子供が呪術的思考によって出来事について間違った考えを持つ場合、その結論が長期的な信念や行動となり、子供が成長する上で困難を生じさせる可能性があ る。[31] |

| Related terms "Quasi-magical thinking" describes "cases in which people act as if they erroneously believe that their action influences the outcome, even though they do not really hold that belief".[32] People may realize that a superstitious intuition is logically false, but act as if it were true because they do not exert an effort to correct the intuition.[33] |

関連用語 「準呪術的思考」とは、「人々が、実際にはそう考えていないにもかかわらず、あたかも自分の行動が結果に影響を与えると誤って信じているかのように行動す るケース」を指す。[32] 人々は、迷信的な直感が論理的に誤りであると気づいていても、その直感を修正する努力をしないため、あたかもそれが真実であるかのように行動する。 [33] |

| Cognitive bias Faith Illusion of control Law of attraction (New Thought) Mythopoeic thought Psychology of religion Psychological theories of magic Schizotypal personality disorder Synchronicity Tinkerbell effect The Year of Magical Thinking, an account of how mourning the death of a spouse led to magical thinking |

認知バイアス 信仰 幻想のコントロール 引き寄せの法則(ニューソート) 神話的思考 宗教心理学 呪術の心理学理論 統合失調型パーソナリティ障害 シンクロニシティ ティンカー・ベル効果 『マジカル・シンキングの年』、配偶者の死を悼むことが呪術的思考につながった経緯についての記述 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magical_thinking |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆