マニ教

Manichaeism

Seal

of Mani (cleaned up). Seal with figure of Mani, possibly 3rd century

CE, possibly Irak. Cabinet des Médailles, Paris

☆

マニ教(Manichaeism)[a](/ˌmænɪˈkiːɪzəm/;[9] ペルシア語: آئین مانی, ローマ字表記: Āʾīn-ī Mānī; 中国語:

摩尼教; ピンイン:

Móníjiào)は、3世紀にパルティア[10]のイラン人[11]預言者マニ(西暦216–274年)がササン朝[12]で創設した主要な世界宗教で

あった。キリスト教の異端ともグノーシス主義運動とも様々な形で説明されるが、 [13]

マニ教はそれ自体が組織化された教義的な宗教伝統であった。[14]

それは精巧な二元論的宇宙論を教え、善なる霊的な光の世界と、悪なる物質的な闇の世界との闘争を描いた。[15]

人間史の中で進行する過程を通じて、光は物質の世界から次第に取り除かれ、神聖な世界へと還される。

マニの教えは、様々な先行する信仰や思想体系——プラトン主義、 [17][18]

キリスト教、ゾロアスター教、仏教、マルキオニズム[16]、ヘレニズム的・ラビ的ユダヤ教、グノーシス主義運動、古代ギリシャ宗教、バビロニア及びその

他のメソポタミア宗教[19]、秘儀カルト[20][21]といったものである。マニはゾロアスター、仏陀、イエスに次ぐ最後の預言者として崇敬されてい

る。マニ教の聖典には、マニに帰せられる7つの著作が含まれており、元々はシリア語で書かれた。マニ教の秘跡的儀式には、祈り、施し、断食が含まれた。共

同生活は告白と賛美歌の歌唱を中心としていた。

普遍的救済の教えと積極的な布教活動[22]を強調したマニ教は急速に成功を収め、アラム語圏[23]、地中海地域、中東全域に広がった[14]。3世紀

から7世紀にかけて隆盛を極め、最盛期には世界で最も広範な宗教の一つとなった。マニ教の教会と経典は、東は中国、西はローマ支配下のイベリア半島にまで

存在した[24]。イスラム教が広まる前、マニ教は初期キリスト教の主要な対抗勢力として一時的に台頭した。しかしローマ帝国と新興キリスト教教会による

迫害が次第に強まり、6世紀末までにローマ支配地域からほぼ消滅した。

| Manichaeism[a]

(/ˌmænɪˈkiːɪzəm/;[9] in Persian: آئین مانی, romanized: Āʾīn-ī Mānī;

Chinese: 摩尼教; pinyin: Móníjiào) was a major world religion founded in

the third century CE by the Parthian[10] Iranian[11] prophet Mani (C.E.

216–274) in the Sasanian Empire.[12] Variably described as a Christian

heresy and a Gnostic movement,[13] Manichaeism was an organized and

doctrinal religious tradition in its own right.[14] It taught an

elaborate dualistic cosmology describing the struggle between a good

spiritual world of light, and an evil material world of darkness.[15]

Through an ongoing process that takes place in human history, light is

gradually removed from the world of matter and returned to the world of

the divine. Mani's teachings were intended to integrate,[16] succeed, and surpass the "partial truths" of various prior faiths and belief systems,[14] including Platonism,[17][18] Christianity, Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Marcionism,[16] Hellenistic and Rabbinic Judaism, Gnostic movements, Ancient Greek religion, Babylonian and other Mesopotamian religions,[19] and mystery cults.[20][21] Mani is revered as the final prophet after Zoroaster, the Buddha, and Jesus. The Manichaean scriptural canon includes seven works attributed to Mani, written originally in Syriac. Manichaean sacramental rites included prayers, almsgiving, and fasting. communal life centered on confession and the singing of hymns. With its message of universal salvation and emphasis on active proselytism,[22] Manichaeism was quickly successful and spread throughout Aramaic-speaking regions,[23] the Mediterranean, and the Middle East.[14] It thrived between the third and seventh centuries, and at its height was one of the most widespread religions in the world. Manichaean churches and scriptures existed as far east as China and as far west as Roman Iberia.[24] Before the spread of Islam, Manichaeanism was briefly the main rival to early Christianity. It was increasingly persecuted both by the Roman state and the nascent Christian church, largely disappearing from Roman lands by the end of the sixth century.[25] Manichaeism continued to survive and expand in the east. It maintained its historic presence in West Asia until being repressed by the latter Abbasid rulers in the 10th century. Trade and missionary activity brought Manichaeism to Tang China in the seventh century, where it developed into its own local form. Manichaeism was the official religion of the Uyghur Khaganate until its collapse in 830; shortly thereafter, it was banned by the Tang court but experienced a resurgence under the later Mongol Yuan dynasty during the 13th and 14th centuries. Continued persecution by Chinese emperors led to Manichaeism becoming subsumed into Buddhism and Taoism before the end of the 14th century.[26] Some historic Manichaean sites still exist in China, including the temple of Cao'an in Jinjiang, Fujian, and the religion may have influenced later movements in Medieval Europe, including Paulicianism, Bogomilism, and Catharism. While most original Manichean writings have been lost, numerous translations and fragmentary texts have survived.[27] |

マニ教[a](/ˌmænɪˈkiːɪzəm/;[9]

ペルシア語: آئین مانی, ローマ字表記: Āʾīn-ī Mānī; 中国語: 摩尼教; ピンイン:

Móníjiào)は、3世紀にパルティア[10]のイラン人[11]預言者マニ(西暦216–274年)がササン朝[12]で創設した主要な世界宗教で

あった。キリスト教の異端ともグノーシス主義運動とも様々な形で説明されるが、 [13]

マニ教はそれ自体が組織化された教義的な宗教伝統であった。[14]

それは精巧な二元論的宇宙論を教え、善なる霊的な光の世界と、悪なる物質的な闇の世界との闘争を描いた。[15]

人間史の中で進行する過程を通じて、光は物質の世界から次第に取り除かれ、神聖な世界へと還される。 マニの教えは、様々な先行する信仰や思想体系——プラトン主義、 [17][18] キリスト教、ゾロアスター教、仏教、マルキオニズム[16]、ヘレニズム的・ラビ的ユダヤ教、グノーシス主義運動、古代ギリシャ宗教、バビロニア及びその 他のメソポタミア宗教[19]、秘儀カルト[20][21]といったものである。マニはゾロアスター、仏陀、イエスに次ぐ最後の預言者として崇敬されてい る。マニ教の聖典には、マニに帰せられる7つの著作が含まれており、元々はシリア語で書かれた。マニ教の秘跡的儀式には、祈り、施し、断食が含まれた。共 同生活は告白と賛美歌の歌唱を中心としていた。 普遍的救済の教えと積極的な布教活動[22]を強調したマニ教は急速に成功を収め、アラム語圏[23]、地中海地域、中東全域に広がった[14]。3世紀 から7世紀にかけて隆盛を極め、最盛期には世界で最も広範な宗教の一つとなった。マニ教の教会と経典は、東は中国、西はローマ支配下のイベリア半島にまで 存在した[24]。イスラム教が広まる前、マニ教は初期キリスト教の主要な対抗勢力として一時的に台頭した。しかしローマ帝国と新興キリスト教教会による 迫害が次第に強まり、6世紀末までにローマ支配地域からほぼ消滅した。[25] マニ教は東方において存続し拡大を続けた。西アジアでは10世紀に後期アッバース朝によって弾圧されるまで、歴史的な存在感を維持した。貿易と布教活動に より、マニ教は7世紀に唐の中国に伝わり、現地独自の形態へと発展した。マニ教は830年に滅亡するまでウイグル可汗国の国教であった。その後まもなく唐 朝廷によって禁止されたが、13~14世紀のモンゴル系元王朝下で再興を経験した。中国皇帝による継続的な迫害により、14世紀末までにマニ教は仏教と道 教に吸収された。[26] 中国には現在も曹安寺(福建省晋江市)などマニ教関連の歴史的遺跡が残っている。この宗教は中世ヨーロッパのパウリキアニズム、ボゴミル派、カタリ派など 後世の運動に影響を与えた可能性がある。マニ教の原本文献のほとんどは失われたが、多数の翻訳書や断片的なテキストが現存している。[27] |

| Terminology The spelling Manichaeism is a hypercorrection of Manichaism,[4][5][6] which derives from Koine Greek Μανιχαϊσμός[7] Manikhaïsmós via Latin Manichaismus.[8] The Greek word is built on Μανιχαῖος Manikhaîos ('Manichaeus'), one of the names of Mani in Greek sources. In English, an adherent of Manichaeism is called a Manichaean, Manichean, or Manichee.[28] |

用語 マニ教(Manichaeism)という綴りは、マニ教(Manichaism)の過剰な修正である[4][5][6]。これはコイネー・ギリシャ語の Μανιχαϊσμός(Manikhaïsmós)に由来し、ラテン語のManichaismusを経由している[8]。ギリシャ語の語は、マニのギリ シャ語資料における名の一つであるΜανιχαῖος(Manikhaîos、マニケウス)を基にしている。 英語では、マニ教の信奉者はマニ教徒(Manichaean)、マニ教信者(Manichean)、あるいはマニ教徒(Manichee)と呼ばれる[28]。 |

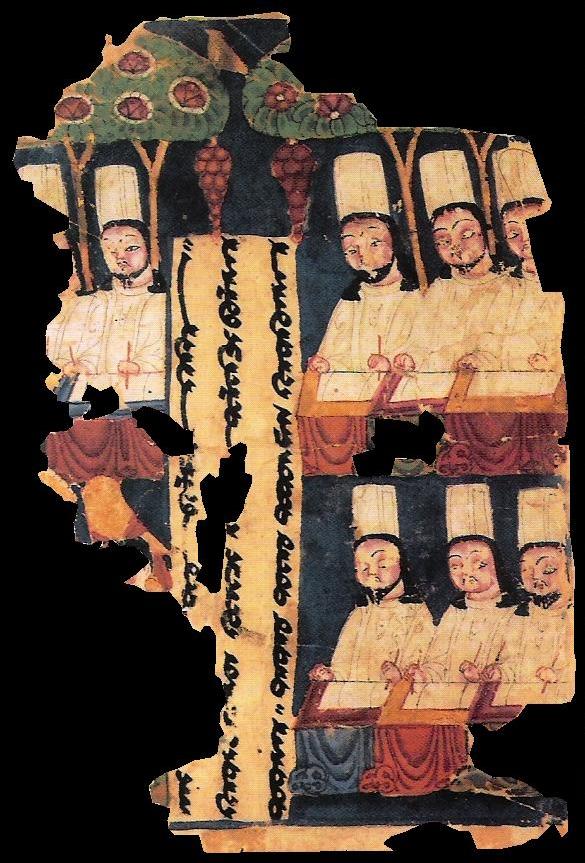

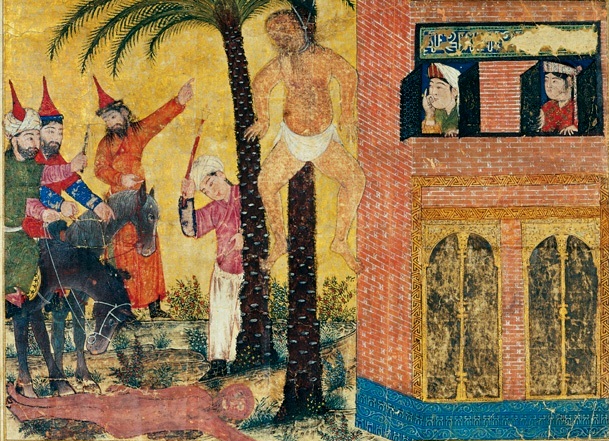

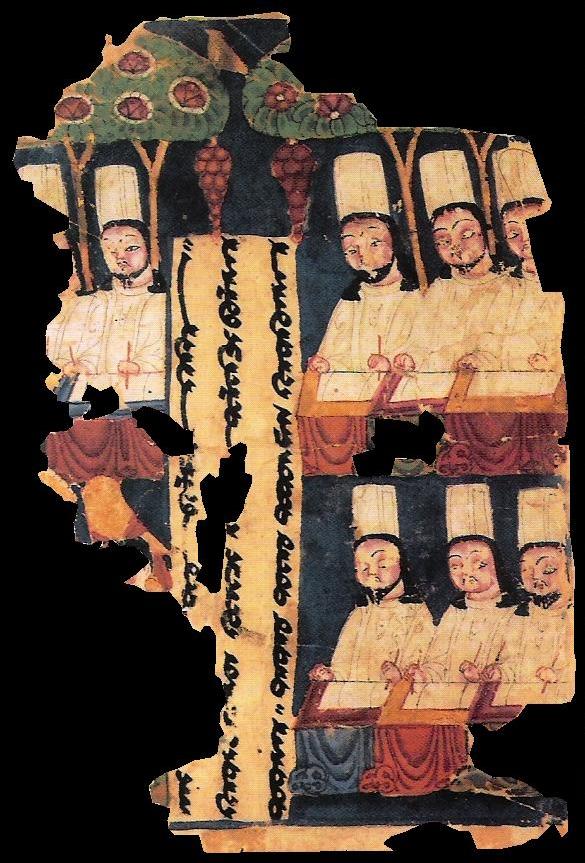

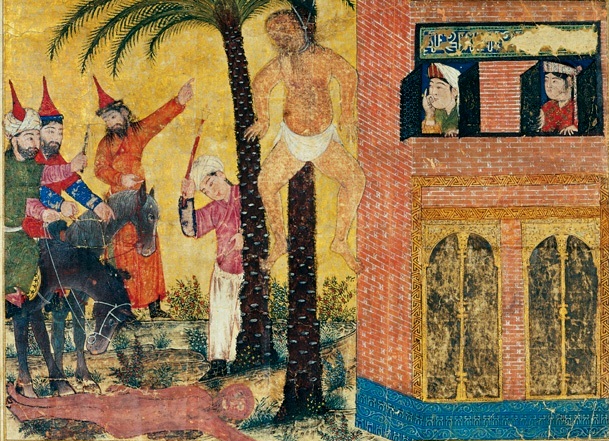

| History Life of Mani Main article: Mani (prophet)  Manichaean priests, writing at their desks. Eighth or ninth century manuscript from Gaochang, Tarim Basin, China.  Yuan Chinese silk painting Mani's Birth Mani was an Iranian[29][30][b] born in 216 CE in or near Ctesiphon (now al-Mada'in, Iraq) in the Parthian Empire. According to the Cologne Mani-Codex,[31] Mani's parents were members of the Jewish Christian Gnostic sect known as the Elcesaites.[32] Mani composed seven works, six of which were written in the late-Aramaic Syriac language. The seventh, the Shabuhragan,[33] was written by Mani in Middle Persian and presented by him to Sasanian emperor Shapur I. Although there is no proof Shapur I was a Manichaean, he tolerated the spread of Manichaeism and refrained from persecuting it within his empire's boundaries.[34] According to one tradition, Mani invented the unique version of the Syriac script known as the Manichaean alphabet[35] that was used in all of the Manichaean works written within the Sasanian Empire, whether they were in Syriac or Middle Persian, as well as most of the works written within the Uyghur Khaganate. The primary language of Babylon (and the administrative and cultural language of the Empire) at that time was Eastern Middle Aramaic, which included three main dialects: Jewish Babylonian Aramaic (the language of the Babylonian Talmud), Mandaean (the language of Mandaeism), and Syriac, which was the language of Mani as well as the Syriac Christians.[36]  A 14th-century illustration of the execution of Mani While Manichaeism was spreading, existing religions such as Zoroastrianism were still prevalent, and Christianity was gaining social and political influence. Although having fewer adherents, Manichaeism won the support of many high-ranking political figures. With the assistance of the Sasanian Empire, Mani began missionary expeditions. After failing to win the favour of the next generation of Persian royalty and incurring the disapproval of the Zoroastrian clergy, Mani is reported to have died in prison awaiting execution by the Persian emperor Bahram I. The date of his death is estimated at 276–277 CE. |

歴史 マニの生涯 主な記事: マニ(預言者)  マニ教の司祭たちが机に向かって書いている様子。8世紀または9世紀の中国・タリム盆地高昌の写本。  元代の中国絹絵マニの誕生 マニはイラン人であり、西暦216年にパルティア帝国のクテシフォン(現在のイラク、アル=マダイン)またはその近郊で生まれた。ケルン・マニ写本によれば、マニの両親はユダヤ系キリスト教グノーシス派の一派であるエルケサイ派の信徒であった。 マニは七つの著作を残した。うち六つは後期アラム語であるシリア語で書かれている。七つ目の『シャブフラガン』[33]はマニが中世ペルシア語で執筆し、 ササン朝皇帝シャプール1世に献上した。シャプール1世がマニ教徒だった証拠はないが、彼はマニ教の広がりを容認し、帝国内での迫害を控えた。[34] ある伝承によれば、マニはマニ教アルファベット[35]として知られるシリア文字の独自版を考案した。これはササン朝帝国内で書かれたマニ教の著作(シリ ア語・中世ペルシア語を問わず)や、ウイグル可汗国で書かれた著作の大半で使用された。当時のバビロンの主要言語(そして帝国の行政・文化言語)は東中世 アラム語であり、主に三つの方言を含んでいた。ユダヤ・バビロニア・アラム語(バビロニア・タルムードの言語)、マンダ教(マンダ教の言語)、そしてマニ やシリア系キリスト教徒の言語であったシリア語である[36]。  14世紀のマニ処刑図 マニ教が広まる一方で、ゾロアスター教などの既存宗教は依然として広く信仰され、キリスト教も社会的・政治的影響力を増していた。信徒数は少なかったもの の、マニ教は多くの高位の政治家の支持を得た。ササン朝帝国の支援を得て、マニは布教の旅を始めた。しかし、ペルシャ王家の次世代の支持を得られず、ゾロ アスター教聖職者の不興を買ったため、マニはペルシャ皇帝バーラム1世による処刑を待つ獄中で死亡したと伝えられている。その死は西暦276年から277 年の間と推定されている。 |

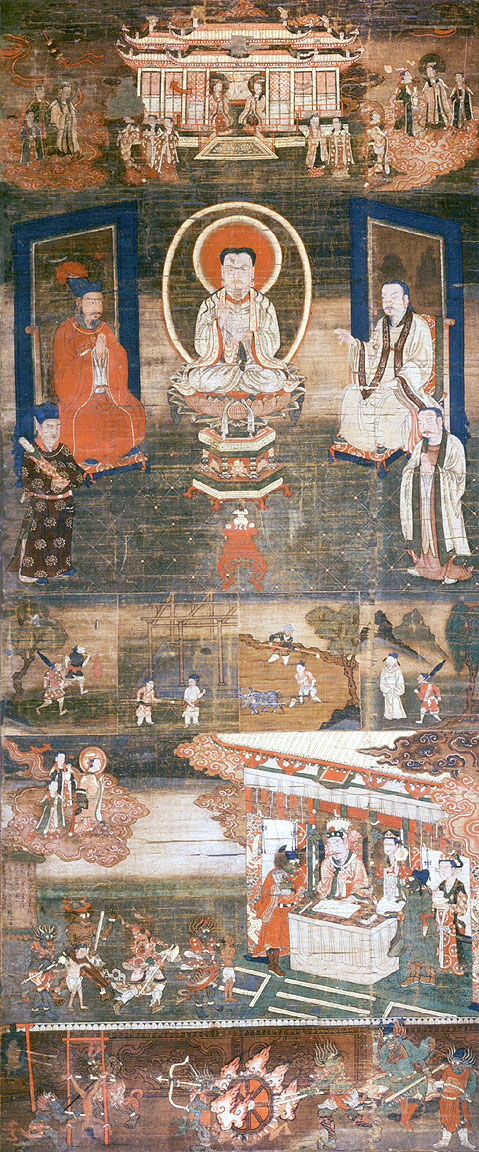

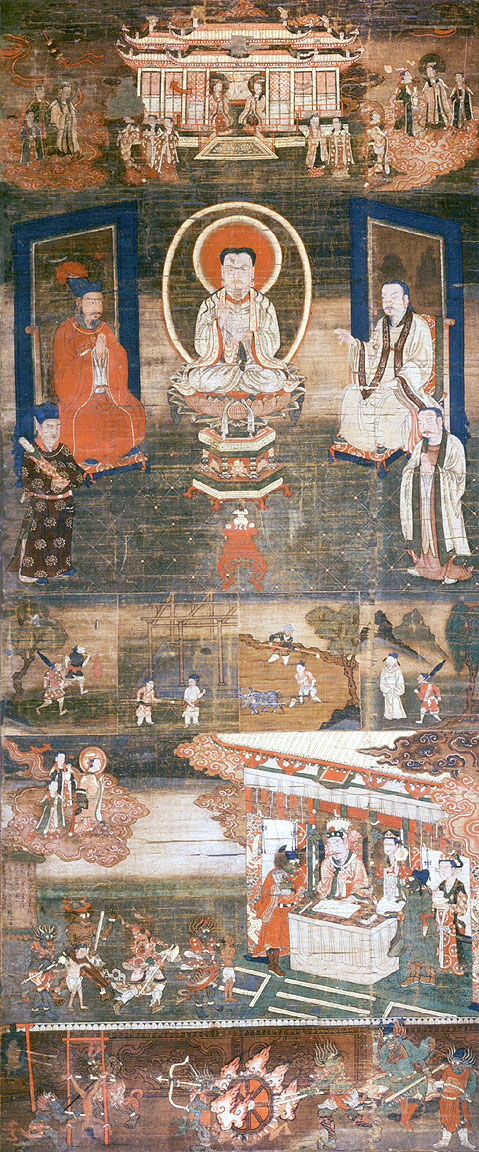

| Influences See also: Chinese Manichaeism and Docetism  Sermon on Mani's Teaching of Salvation, 13th-century Chinese Manichaean silk painting Mani believed that the teachings of Buddha, Zoroaster,[37] and Jesus were incomplete, and that his revelations were for the entire world, calling his teachings the "Religion of Light". Manichaean writings indicate that Mani received revelations when he was twelve years old and again when he was 24, and over this period, he grew dissatisfied with the Elcesaites, the Jewish Christian Gnostic sect he was born into.[38] Some researchers also point to an important Jain influence on Mani as extreme degrees of asceticism and some specific features of Jain doctrine made the influence of Mahāvīra's religious community more plausible than even the Buddha.[39] Fynes (1996) argues that various Jain influences, particularly ideas on the existence of plant souls, were transmitted from Western Kshatrapa territories to Mesopotamia and then integrated into Manichaean beliefs.[40] Mani wore colorful clothing abnormal for the time that reminded some Romans of a stereotypical Persian magus or warlord, earning him ire from the Greco-Roman world because of it.[41] Mani taught how the soul of a righteous individual returns to Paradise upon dying, but "the soul of the person who persisted in things of the flesh – fornication, procreation, possessions, cultivation, harvesting, eating of meat, drinking of wine – is condemned to rebirth in a succession of bodies."[42] Mani began preaching at an early age and was possibly influenced by contemporary Babylonian-Aramaic movements such as Mandaeism, Aramaic translations of Jewish apocalyptic works similar to those found at Qumran (e.g., the Book of Enoch literature), and by the Syriac dualist-Gnostic writer Bardaisan (who lived a generation before Mani). With the discovery of the Mani-Codex, it also became clear that he was raised in the Jewish Christian sect of the Elcasaites and possibly influenced by their writings.[citation needed] According to biographies preserved by ibn al-Nadim and the Persian polymath al-Biruni, Mani received a revelation as a youth from a spirit, whom he would later call his "Twin" (Imperial Aramaic: תאומא tɑʔwmɑ, from which is also derived the Greek name of Thomas the Apostle, Didymus; the "twin"), Syzygos (Koine Greek: σύζυγος "spouse, partner", in the Cologne Mani-Codex), "Double," "Protective Angel," or "Divine Self." This spirit taught him wisdom that he then developed into a religion. It was his "Twin" who brought Mani to self-realization. Mani claimed to be the Paraclete of the Truth promised by Jesus in the New Testament.[43]  Manichaean Painting of the Buddha Jesus depicts Jesus as a Manichaean prophet. Manichaeism's views on Jesus are described by historians: Jesus in Manichaeism possessed three separate identities: (1) Jesus the Luminous, (2) Jesus the Messiah and (3) Jesus patibilis (the suffering Jesus). (1) As Jesus the Luminous ... his primary role was as supreme revealer and guide and it was he who woke Adam from his slumber and revealed to him the divine origins of his soul and its painful captivity by the body and mixture with matter. (2) Jesus the Messiah was an historical being who was the prophet of the Jews and the forerunner of Mani. However, the Manichaeans believed he was wholly divine, and that he never experienced human birth, as the physical realities surrounding the notions of his conception and his birth filled the Manichaeans with horror. However, the Christian doctrine of virgin birth was also regarded as obscene. Since Jesus the Messiah was the light of the world, where was this light, they reasoned, when Jesus was in the womb of the Virgin? Jesus the Messiah, they believed, was truly born only at his baptism, as it was on that occasion that the Father openly acknowledged his sonship. The suffering, death and resurrection of this Jesus were in appearance only as they had no salvific value but were an exemplum of the suffering and eventual deliverance of the human soul and a prefiguration of Mani's own martyrdom. (3) The pain suffered by the imprisoned Light-Particles in the whole of the visible universe, on the other hand, was real and immanent. This was symbolized by the mystic placing of the Cross whereby the wounds of the passion of our souls are set forth. On this mystical Cross of Light was suspended the Suffering Jesus (Jesus patibilis) who was the life and salvation of Man. This mystica crucifixio was present in every tree, herb, fruit, vegetable and even stones and the soil. This constant and universal suffering of the captive soul is exquisitely expressed in one of the Coptic Manichaean psalms.[44] Augustine of Hippo also noted that Mani declared himself to be an "apostle of Jesus Christ".[45] Manichaean tradition is also noted to have claimed that Mani was the reincarnation of religious figures from previous eras such as the Buddha, Krishna, and Zoroaster in addition to Jesus himself. Academics note that much of what is known about Manichaeism comes from later 10th- and 11th-century Muslim historians like al-Biruni and ibn al-Nadim in his al-Fihrist; the latter "ascribed to Mani the claim to be the Seal of the Prophets."[46] However, given the Islamic milieu of Arabia and Persia at the time, it stands to reason that Manichaens would regularly assert in their evangelism that Mani, not Muhammad, was the "Seal of the Prophets".[47] In reality, for Mani the metaphorical expression "Seal of Prophets" is not a reference to his finality in a long succession of prophets as it is used in Islam, but rather as final to his followers (who testify or attest to his message as a "seal").[48][49] |

影響 関連項目:中国のマニ教とドケティズム  『マニの救済教義に関する説教』、13世紀中国のマニ教絹絵 マニは、仏陀、ゾロアスター[37]、イエスの教えは不完全であり、自身の啓示は全世界に向けたものだと信じていた。彼は自らの教えを「光の宗教」と呼ん だ。マニ教の文献によれば、マニは12歳の時に啓示を受け、24歳の時に再び啓示を受けた。この期間に、彼は生まれ育ったユダヤ系キリスト教グノーシス派 であるエルケサイ派に不満を抱くようになった[38]。一部の研究者は、マニにジャイナ教の重要な影響があったとも指摘している。極端な禁欲主義やジャイ ナ教教義の特定の特徴から、マハーヴィーラの宗教共同体の影響が仏陀よりも説得力を持つとされたのだ[39]。ファインズ(1996)は、様々なジャイナ 教の影響、特に植物の魂の存在に関する思想が、西方のクシャトラパ領土からメソポタミアへ伝わり、マニ教の信仰に統合されたと論じている。[40] マニは当時としては異例の色彩豊かな衣服を身にまとい、一部のローマ人に典型的なペルシャの魔術師や軍閥を連想させたため、このことでギリシャ・ローマ世界から憎悪を買った。[41] マニは、正しい人格の魂は死後楽園に帰ると教えたが、「肉欲に固執した個人的な人格――淫行、生殖、所有、耕作、収穫、肉食、酒飲みに耽った個人的な人格の魂――は、次々と生まれ変わる運命にある」と説いた。[42] マニは幼い頃から説教を始め、当時のバビロニア・アラム語圏の運動、例えばマンダ教、クムランで発見されたものと類似したユダヤ終末論的著作のアラム語訳 (エノク書文学など)、そしてマニより一世代前のシリアの二元論的グノーシス主義者バルダイサンの影響を受けた可能性がある。マニ写本の発見により、彼が エルカサイ派というユダヤ系キリスト教派で育ち、その著作の影響を受けた可能性も明らかになった。[出典必要] イブン・アル=ナディムとペルシアの博学者アル=ビルーニーが伝えた伝記によれば、マニは若き日に霊から啓示を受けた。彼は後にこの霊を「双子」(帝政期 アラム語: תאומא tɑʔwmɑ、使徒トマス(ディディモス)のギリシャ名もこれに由来する)と呼んだ。「双子」)、シジゴス(コイネー・ギリシャ語: σύζυγος「配偶者、伴侶」、ケルン・マニ写本)、「二重体」、『守護天使』、「神聖なる自己」とも呼ばれた。この霊は彼に知恵を授け、マニはそれを 発展させて宗教を創始した。マニを自己実現へと導いたのは彼の「双子」であった。マニは、新約聖書でイエスが約束した「真理の助け主」であると自称した。 [43]  マニ教の仏陀絵画は、イエスをマニ教の預言者として描いている。 マニ教におけるイエスの見解は、歴史家によって次のように説明されている: マニ教におけるイエスは、三つの異なる身分を有していた: (1) 光のイエス、 (2) メシアとしてのイエス、 (3) パティビリス(苦悩のイエス)。 (1) 光のイエスとして…その主たる役割は至高の啓示者かつ導き手であり、アダムを眠りから覚まし、彼の魂の神聖な起源と、肉体による苦悩に満ちた囚われ、物質との混交を啓示した者である。 (2) メシアのイエスは歴史上の人物であり、ユダヤ人の預言者であり、マニの先駆者であった。しかしマニ教徒は、彼が完全に神聖であり、人間の出生を経験したこ とはないと信じていた。受胎と出生の概念を取り巻く物理的現実が、マニ教徒を恐怖で満たしたからである。しかしキリスト教の処女懐胎の教義もまた卑猥と見 なされた。メシアであるイエスは世界の光であったが、イエスが聖母の胎内にいた時、この光はどこにあったのか、と彼らは論じたのである。メシアであるイエ スは、洗礼の時に初めて真に生まれたと彼らは信じた。その時こそ父が公に彼の子であることを認めたからである。このイエスの苦悩、死、復活は見せかけに過 ぎず、救済的価値を持たなかった。それらは人間の魂の苦悩と最終的な解放の模範であり、マニ自身の殉教の前兆であった。 (3) 一方、可視宇宙全体に囚われた光の粒子たちが味わう苦悩は、現実的かつ内在的なものだった。これは神秘的な十字架の配置によって象徴され、そこには我々の 魂の受難の傷跡が示されている。この神秘的な光の十字架には、人類の命と救いである苦悩のイエス(イエス・パティビリウス)が懸けられていた。この神秘的 な十字架刑は、あらゆる樹木、草、果実、野菜、さらには石や土壌にも存在していた。囚われの魂のこの絶え間なく普遍的な苦悩は、コプト語のマニ教詩篇の一 つに見事に表現されている。[44] ヒッポのアウグスティヌスはまた、マニが自らを「イエス・キリストの使徒」と宣言したと記している。[45] マニ教の伝統では、マニがイエス自身に加え、仏陀、クリシュナ、ゾロアスターといった過去の宗教的人物たちの転生であると主張していたことも知られている。 学者たちは、マニ教に関する既知の情報の多くが、アル=ビルーニーやイブン・アル=ナディームの『アル=フィフルスト』といった10~11世紀のイスラム 史家による後世の記述に由来すると指摘している。後者は「マニが『預言者の封印』を自称したと記している」。[46] しかし当時のアラビアとペルシャがイスラム圏であったことを考慮すれば、マニ教徒が布教活動において「預言者の封印」はムハンマドではなくマニであると主 張していたのは当然のことである。実際、マニにとって「預言者の封印」という隠喩的表現は、イスラム教におけるような預言者たちの長い列の最終性を指すも のではなく、むしろ彼の信徒たち(彼のメッセージを「封印」として証言または立証する者たち)にとっての最終性を意味していた。[48][49] |

10th century Manichaean Electae in Gaochang (Khocho), China Other sources of Mani's scripture were the Aramaic originals of the Book of Enoch, 2 Enoch, and an otherwise unknown section of the Book of Enoch entitled The Book of Giants. Mani quoted the latter directly and expanded upon it, making it one of the six original Syriac writings of the Manichaean Church. Besides short references by non-Manichaean authors through the centuries, no original sources of The Book of Giants (which is actually part six of the Book of Enoch) were available until the 20th century.[50] Scattered fragments of both the original Aramaic Book of Giants (which were analyzed and published by Józef Milik in 1976)[51] and the Manichaean version of the same name (analyzed and published by Walter Bruno Henning in 1943)[52] were discovered along with the Dead Sea Scrolls in the Judaean desert in the 20th century and the Manichaean writings of the Uyghur Manichaean kingdom in Turpan. Henning wrote in his analysis of them: It is noteworthy that Mani, who was brought up and spent most of his life in a province of the Persian empire, and whose mother belonged to a famous Parthian family, did not make any use of the Iranian mythological tradition. There can no longer be any doubt that the Iranian names of Sām, Narīmān, etc., that appear in the Persian and Sogdian versions of the Book of the Giants, did not figure in the original edition, written by Mani in the Syriac language.[52] By comparing the cosmology of the books of Enoch to the Book of Giants, as well as the description of the Manichaean myth, scholars have observed that the Manichaean cosmology can be described as being based, in part, on the description of the cosmology developed in detail within the Enochic literature.[53] This literature describes the being that the prophets saw in their ascent to Heaven as a king who sits on a throne at the highest of the heavens. In the Manichaean description, this being, the "Great King of Honor", becomes a deity who guards the entrance to the World of Light placed at the seventh of ten heavens.[54] In the Aramaic Book of Enoch, the Qumran writings, overall, and in the original Syriac section of Manichaean scriptures quoted by Theodore bar Konai,[55] he is called malkā rabbā d-iqārā ("the Great King of Honor").[citation needed] Mani was also influenced by writings of the gnostic Bardaisan (154–222 CE), who, like Mani, wrote in Syriac and presented a dualistic interpretation of the world in terms of light and darkness in combination with elements from Christianity.[56] Mani was heavily inspired by Iranian Zoroastrian theology.[37] |

中国高昌(ガオチャン)における10世紀のマニ教選集 マニの経典の他の出典は、エノク書、第二エノク書、および『巨人書』と題されたエノク書の他に知られていない部分のアラム語原典であった。マニは後者を直 接引用し、それを拡大解釈したため、マニ教会の六つのシリア語原典の一つとなった。非マニ教徒の著者による数世紀にわたる短い言及を除けば、『巨人書』 (実際にはエノク書第六部)の原典は20世紀まで入手不可能であった[50]。 原典であるアラム語版『巨人書』(1976年にヨゼフ・ミリクが分析・出版) [51] とマニ教版同名文書(1943年にヴァルター・ブルーノ・ヘニングが分析・刊行)[52] の断片が、20世紀にユダヤ砂漠の死海文書やトルファンのウイグル・マニ教王国文書と共に発見された。ヘニングは分析の中でこう記している: 注目すべきは、マニがペルシャ帝国の属州で育ち生涯の大半を過ごし、母が名高いパルティアの家に属していたにもかかわらず、イラン神話伝統を一切利用しな かった点である。『巨人書』のペルシア語版やソグド語版に現れるサームやナリマンといったイラン系の名称が、マニがシリア語で記した原典には存在しなかっ たことは、もはや疑いの余地がない。[52] エノク書群の宇宙論と巨人書、さらにマニ教神話の記述を比較した学者たちは、マニ教の宇宙論が部分的にエノク書文学で詳細に展開された宇宙論の記述に基づ いていると指摘している。[53] この文献は、預言者たちが天界への昇天で見出した存在を、天界の最上部に玉座に座す王として描写する。マニ教の記述では、この存在「栄光の偉大なる王」 は、十の天界のうち第七天に置かれた光の世界への入口を守る神格となる。[54] アラム語の『エノク書』、クムラン文書全体、そしてテオドロス・バル・コナイが引用したマニ教経典のシリア語原典部分[55]において、この存在はマル カ・ラッバ・ディカラー(「栄光の偉大なる王」)と呼ばれている。[出典必要] マニはまた、グノーシス主義者バルダイサン(紀元154-222年)の著作の影響も受けていた。バルダイサンはマニと同様にシリア語で執筆し、キリスト教の要素と組み合わせて、光と闇という二元論的な世界解釈を提示した。[56] マニはイランのゾロアスター教神学に強く影響を受けていた。[37] |

Akshobhya in the abhirati with the Cross of Light, a symbol of Manichaeism Noting Mani's travels to the Kushan Empire (several religious paintings in Bamyan are attributed to him) at the beginning of his proselytizing career, Richard Foltz postulates Buddhist influences in Manichaeism: Buddhist influences were significant in the formation of Mani's religious thought. The transmigration of souls became a Manichaean belief, and the quadripartite structure of the Manichaean community, divided between male and female monks (the "elect") and lay followers (the "hearers") who supported them, appears to be based on that of the Buddhist sangha.[57] The Kushan monk Lokakṣema began translating Pure Land Buddhist texts into Chinese in the century prior to Mani arriving there. The Chinese texts of Manichaeism are full of uniquely Buddhist terms taken directly from these Chinese Pure Land scriptures, including the term "pure land" (Chinese: 淨土; pinyin: jìngtǔ) itself.[58] However, the central object of veneration in Pure Land Buddhism, Amitābha, the Buddha of Infinite Light, does not appear in Chinese Manichaeism and seems to have been replaced by another deity.[59] |

光十字を掲げるアブヒラティのアクショブヤ、マニ教の象徴 マニが布教活動の初期にクシャン帝国へ渡航した事実(バーミヤンの宗教画数点が彼に帰せられる)を指摘し、リチャード・フォルツはマニ教における仏教の影響を仮定する: 仏教の影響はマニの宗教思想形成において重要であった。魂の輪廻転生はマニ教の信仰となり、男性・女性僧侶(「選ばれし者」)と彼らを支える在家信徒(「聞く者」)に分かれたマニ教共同体の四部構成は、仏教の僧伽(サンガ)を基盤としているように見える。[57] クシャン僧ロカクシェマは、マニが当地に到着する1世紀前に、浄土仏教経典の漢訳を開始した。マニ教の漢訳文献には、これらの漢訳浄土経典から直接採られ た仏教特有の用語が満ちており、その中には「浄土」(中国語:淨土;ピンイン:jìngtǔ)という用語自体も含まれている。[58] しかし浄土仏教における中心的な崇拝対象である無量光仏(阿弥陀仏)は、中国のマニ教には登場せず、別の神に置き換えられたようだ。[59] |

| Spread Roman Empire  A map of the spread of Manichaeism (300–500). World History Atlas, Dorling Kindersly. Manichaeism reached Rome through the apostle Psattiq in 280, who was also in Egypt in 244 and 251. It flourished in the Faiyum in 290. Manichaean monasteries existed in Rome in 312 during the time of Pope Miltiades.[60] In 291, persecution arose in the Sasanian Empire with the murder of the apostle Sisin by Emperor Bahram II and the slaughter of many Manichaeans. Then, in 302, the first official reaction and legislation against Manichaeism from the Roman state was issued under Diocletian. In an official edict called the De Maleficiis et Manichaeis compiled in the Collatio Legum Mosaicarum et Romanarum and addressed to the proconsul of Africa, Diocletian wrote: We have heard that the Manichaeans [...] have set up new and hitherto unheard-of sects in opposition to the older creeds so that they might cast out the doctrines vouchsafed to us in the past by the divine favour for the benefit of their own depraved doctrine. They have sprung forth very recently like new and unexpected monstrosities among the race of the Persians – a nation still hostile to us – and have made their way into our empire, where they are committing many outrages, disturbing the tranquility of our people and even inflicting grave damage to the civic communities. We have cause to fear that with the passage of time they will endeavour, as usually happens, to infect the modest and tranquil of an innocent nature with the damnable customs and perverse laws of the Persians as with the poison of a malignant (serpent) ... We order that the authors and leaders of these sects be subjected to severe punishment, and, together with their abominable writings, burnt in the flames. We direct their followers, if they continue recalcitrant, shall suffer capital punishment, and their goods be forfeited to the imperial treasury. And if those who have gone over to that hitherto unheard-of, scandalous and wholly infamous creed, or to that of the Persians, are persons who hold public office, or are of any rank or of superior social status, you will see to it that their estates are confiscated and the offenders sent to the (quarry) at Phaeno or the mines at Proconnesus. And in order that this plague of iniquity shall be completely extirpated from this our most happy age, let your devotion hasten to carry out our orders and commands.[61] By 354, Hilary of Poitiers wrote that Manichaeism was a significant force in Roman Gaul. In 381, Christians requested Theodosius I to strip Manichaeans of their civil rights. Starting in 382, the emperor issued a series of edicts to suppress Manichaeism and punish its followers.[62] |

マニ教の広がり ローマ帝国  マニ教の広がりを示す地図(300–500年)。『世界歴史地図帳』、ドルリング・キンダースリー社。 マニ教は280年、使徒プサッティクによってローマに伝来した。彼は244年と251年にはエジプトにも滞在していた。290年にはファイユーム地方で盛んになった。 312年、教皇ミルティアデスの時代にローマにはマニ教の修道院が存在していた[60]。 291年、ササン朝ペルシアで迫害が始まった。皇帝バーラム2世が使徒シシンを殺害し、多くのマニ教徒が虐殺されたのだ。その後、302年にディオクレ ティアヌス帝のもとで、ローマ国家によるマニ教に対する最初の公式な反応と立法が公布された。『モーセ法とローマ法の比較』に収録された「魔術とマニ教に 関する勅令」と呼ばれる公式の布告で、アフリカの総督宛てにディオクレティアヌスはこう記した: 我々はマニ教徒らが[...]古来の教義に反する新たな、かつ前代未聞の宗派を創設し、神のご加護により過去に授けられた教義を排斥し、自らの堕落した教 義を利益とするよう企てていると聞く。彼らはごく最近、我らに敵対するペルシア国民の中に新たな怪物のように現れ、我らの帝国に侵入した。そこで彼らは数 々の暴挙を働き、人民の平穏を乱し、市民共同体に甚大な損害さえ与えている。我々は、時が経つにつれ、彼らが常套手段として、善良で穏やかな性質を持つ者 たちを、悪意ある蛇の毒のように、ペルシャ人の忌むべき慣習や歪んだ法で感染しようとすることを恐れる理由がある... 我々は命ずる。これらの異端教団の創始者及び指導者らは厳罰に処され、その忌まわしき書物と共に火刑に付されること。また、その信奉者らは、もし頑なに抵 抗を続けるならば、死刑の苦悩に処され、その財産は帝国の国庫に没収されること。また、これまで聞いたこともない、不道徳で全く悪名高いその信仰、あるい はペルシャ人の信仰に改宗した者が、公職にある人格、あるいは何らかの地位や高い社会的地位にある人格であるならば、その人格の財産を没収し、罪人をファ エノの採石場あるいはプロコネススの鉱山に送るようにするのだ。この邪悪の疫病が我らが至福の時代から完全に根絶されるよう、汝らの忠誠をもって我らの命 令を速やかに実行せよ。[61] 354年までに、ポワティエのヒラリウスはマニ教がローマ属州ガリアにおいて重要な勢力であると記した。381年、キリスト教徒はテオドシウス1世に対 し、マニ教徒の市民権剥奪を要請した。382年以降、皇帝はマニ教を弾圧しその信徒を処罰するため、一連の勅令を発布した。[62] |

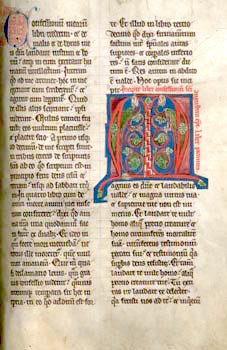

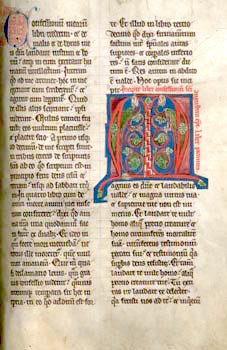

Augustine of Hippo was once a Manichaean. Augustine of Hippo (354–430) converted to Christianity from Manichaeism in the year 387. This was shortly after the Roman emperor Theodosius I issued a decree of death for all Manichaean monks in 382 and shortly before he declared Christianity the only legitimate religion for the Roman Empire in 391. Due to the heavy persecution, the religion almost disappeared from Western Europe in the fifth century and from the eastern portion of the empire in the sixth century.[63] According to his Confessions, after nine or ten years of adhering to the Manichaean faith as a member of the group of "hearers", Augustine of Hippo became a Christian and potent adversary of Manichaeism (which he expressed in writing against his Manichaean opponent Faustus of Mileve), seeing their beliefs that knowledge was the key to salvation as too passive and unable to affect any change in one's life.[64] I still thought that it is not we who sin but some other nature that sins within us. It flattered my pride to think that I incurred no guilt and, when I did wrong, not to confess it ... I preferred to excuse myself and blame this unknown thing which was in me but was not part of me. The truth, of course, was that it was all my own self, and my own impiety had divided me against myself. My sin was all the more incurable because I did not think myself a sinner.[65] Some modern scholars have suggested that Manichaean ways of thinking influenced the development of some of Augustine's ideas, such as the nature of good and evil, the idea of hell, the separation of groups into elect, hearers, and sinners, and the hostility to the flesh and sexual activity, and his dualistic theology.[66] |

ヒッポのアウグスティヌスはかつてマニ教徒であった ヒッポのアウグスティヌス(354–430)は387年にマニ教からキリスト教へ改宗した。これはローマ皇帝テオドシウス1世が382年にマニ教の僧侶全 員に死刑を宣告した直後であり、391年にキリスト教をローマ帝国の唯一の合法宗教と宣言する直前の出来事であった。激しい迫害のため、この宗教は5世紀 には西ヨーロッパから、6世紀には帝国の東部地域からほぼ消滅した[63]。 『告白録』によれば、ヒッポのアウグスティヌスはマニ教徒の「聴衆」として9~10年間信仰を続けた後、キリスト教徒となりマニ教の強力な敵対者となった (彼はマニ教徒の論敵ミレウスのファウストスに対して書面でその立場を表明している)。マニ教が「知識こそ救いの鍵」とする教えを、あまりに受動的で人生 に何の変化ももたらさないと見なしたためである。[64] 私はなおも、罪を犯すのは我々自身ではなく、我々の中に存在する別の性質だと考えていた。過ちを犯しても罪を認めず、その責任を負わないという考えは、私 の傲慢をくすぐった……私は自らを弁解し、自分の一部ではないが自分の中に存在するこの未知のものを責めることを好んだ。もちろん真実は、それが全て私自 身であり、私自身の不敬が私を分裂させていたということだ。自分が罪人だとは思っていなかったからこそ、私の罪はなおさら治癒不可能だったのだ。[65] 現代の学者の一部は、マニ教的な思考様式がアウグスティヌスの思想形成に影響を与えたと指摘している。例えば善と悪の本質、地獄の概念、選民・聴衆・罪人への集団の分化、肉欲や性行為への敵意、そして彼の二元論的神学などがそれにあたる。[66] |

A 13th-century manuscript from Augustine's book VII of Confessions criticizing Manichaeism Central Asia  Amitābha in his Western Paradise with Indians, Tibetans, and Central Asians, with two symbols of Manichaeism: Sun and Cross Some Sogdians in Central Asia believed in the religion.[67][68] Uyghur khagan Boku Tekin (759–780) converted to the religion in 763 after a three-day discussion with its preachers,[69][70] the Babylonian headquarters sent high-rank clerics to Uyghur, and Manichaeism remained the state religion for about a century before the collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate in 840.[citation needed] South Siberia After the defeat of the Uighur Khaganate by the Yenisei Kyrgyz, Manichaeism spread north to the Khakass-Minusinsk depression. Archaeological excavations in the Uybat valley revealed the existence of a Manichaean center there, which included 6 temples and 5 sanctuaries of the elements, and architecturally it was similar to the Sogdian structures in Tuva and Xinjiang. In the 1970s, a Manichaean temple that existed in the 8th-10th centuries was excavated 90 km from the Uybat center in the Puyur-sukh valley. L.R Kyzlasov interpreted these finds as evidence of the adoption of Manichaeism as an official religion in the Kyrgyz Kaganate. Few Khakass Manichaean epitaphs confirm this version; the Manichaean script also influenced the Yenisei runic script at a late stage of its development. South Siberian Manichaeism existed before the Mongol conquest. Later, it influenced the formation of the culture of the Sayano-Altai Turks (Altaians, Khakas, Tuvans), as well as the Khants, Selkups, Kets and Evenks. This influence affected the everyday beliefs of the indigenous peoples and the lexical composition of their languages.[71] |

アウグスティヌスの『告白録』第七巻から、マニ教を批判する13世紀の写本 中央アジア  西方極楽浄土のアミターバ仏と、インディアン、チベット人、中央アジア人。マニ教の二つの象徴:太陽と十字架 中央アジアのソグディアナ人の中には、この宗教を信じる者もいた。[67] [68] ウイグル可汗ボクトキン(759–780)は763年、マニ教の説教師との三日間の議論を経て改宗した[69][70]。バビロニア本部は高位の聖職者を ウイグルに派遣し、マニ教は840年にウイグル可汗国が滅亡するまでの約1世紀にわたり国教として存続した。[出典が必要] 南シベリア エニセイ・キルギスによるウイグル可汗国滅亡後、マニ教は北方のハカース・ミヌシンスク低地へ広がった。ウイバット渓谷の考古学的発掘により、6つの寺院 と5つの元素聖域を含むマニ教中心地が存在したことが判明した。その建築様式はトゥヴァや新疆のソグド式建造物と類似していた。1970年代には、ウイ バット中心地から90km離れたプユル・スク渓谷で、8~10世紀に存在したマニ教寺院が発掘された。L.R.キズラソフはこれらの発見を、キルギス可汗 国におけるマニ教の国教化を示す証拠と解釈した。ハカスのマニ教碑文がこれを裏付けている。マニ教文字はまた、エニセイ・ルーン文字の発展後期に影響を与 えた。南シベリアのマニ教はモンゴル征服以前に存在していた。その後、この思想はサヤノ・アルタイ・トルク(アルタイ人、ハカス人、トゥヴァ人)の文化形 成に影響を与えたほか、ハント人、セルクプ人、ケト人、エヴェンキ人にも及んだ。この影響は先住民の日常的な信仰や、彼らの言語の語彙構成にも及んだ。 [71] |

| China Main article: Chinese Manichaeism In the east it spread along trade routes as far as Chang'an, the capital of Tang China.[72][73] After the Tang dynasty, some Manichaean groups participated in peasant movements. Many rebel leaders used religion to mobilize followers. In Song and Yuan China, remnants of Manichaeism continued to leave a legacy contributing to sects such as the Red Turbans. During the Song dynasty, the Manichaeans were derogatorily referred by the Chinese as Chīcài shìmó (Chinese: 吃菜事魔, meaning that they "abstain from meat and worship demons").[74][75] An account in Fozu Tongji, an important historiography of Buddhism in China compiled by Buddhist scholars during 1258–1269, says that the Manichaeans worshipped the "White Buddha" and their leader wore a violet headgear, while the followers wore white costumes. Many Manichaeans took part in rebellions against the Song government and were eventually quelled. After that, all governments were suppressive against Manichaeism and its followers, and the religion was banned in Ming China in 1370.[76][75] While it had long been thought that Manichaeism arrived in China only at the end of the seventh century, a recent[when?] archaeological discovery demonstrated that it was already known there in the second half of the 6th century.[77] The nomadic Uyghur Khaganate lasted for less than a century (744–840) in the southern Siberian steppe, with the fortified city of Ordu-Baliq on the Upper Orkhon River as its capital.[78] Before the end of the year (763), Manichaeism was declared the official religion of the Uyghur state. Boku Tekin banned all the shamanistic rituals that had previously been in use. His subjects likely accepted his decision. That much results from a report that the proclamation of Manichaeism as the state religion was met with enthusiasm in Ordu-Baliq. In an inscription in which the Kaghan speaks for himself, he promised the Manichaen high priests (the "Elect") that if they gave orders, he would promptly follow them and respond to their requests. An incomplete manuscript found in the Turfan Oasis gives Boku Tekin the title of zahag-i Mani ("Emanation of Mani" or "Descendant of Mani"), a title of majestic prestige among the Manichaeans of Central Asia. Nonetheless, and despite the apparently willing conversion of the Uyghurs to Manichaeanism, traces and signs of the previous shamanistic practices persisted. For instance, in 765, only two years after the official conversion, during a military campaign in China, the Uyghur troops called forth magicians to perform a number of specific rituals. Manichaean Uyghurs continued to treat with great respect a sacred forest in Otuken.[78] The conversion to Manichaeism led to an explosion of manuscript production in the Tarim Basin and Gansu (the region between the Tibetan and the Huangtu plateaus), which lasted well into the early 11th century. In 840, the Uyghur Khaganate collapsed under the attacks of the Yenisei Kyrgyz, and the new Uyghur state of Qocho was established with a capital in the city of Qocho. Al-Jahiz (776–868 or 869) believed that the peaceful lifestyle that Manicheism brought to the Uyghurs was responsible for their later lack of military skills and eventual decline. This, however, is contradicted by the political and military consequences of the conversion. After the migration of the Uyghurs to Turfan in the ninth century, the nobility maintained Manichaean beliefs for a while before converting to Buddhism. Traces of Manicheism among the Uyghurs in Turfan may be detected in fragments of Uyghur Manichaean manuscripts. In fact, Manicheism continued to rival the influence of Buddhism among the Uyghurs until the 13th century. The Mongols gave the final blow to the Manichaeism among the Uyghurs.[78] |

中国 主な記事: 中国のマニ教 東では交易路に沿って唐の都・長安まで広がった。[72][73] 唐の時代以降、一部のマニ教徒は農民運動に参加した。多くの反乱指導者は宗教を利用して支持者を動員した。宋と元の中国では、マニ教の残党が赤巾賊などの宗派に影響を与え続けた。宋代、マニ教徒は中国人に「吃菜事魔」(肉を断ち魔を祀る)と蔑称された。[74][75] 1258年から1269年にかけて仏教学者たちが編纂した中国仏教史の重要文献『仏祖通集』によれば、マニ教徒は「白仏」を崇拝し、指導者は紫色の頭巾 を、信徒は白い衣装を身に着けていた。多くのマニ教徒が宋政府に対する反乱に参加したが、最終的に鎮圧された。その後、全ての政権がマニ教とその信徒を弾 圧し、1370年には明の中国でこの宗教は禁止された。[76][75] 長らくマニ教が中国に伝来したのは7世紀末と考えられてきたが、近年の[いつ?]考古学的発見により、6世紀後半には既に中国で知られていたことが明らか になった。[77] 遊牧民によるウイグル可汗国は、南シベリア草原地帯で1世紀足らず(744-840年)存続し、オルホン川上流の要塞都市オルドゥ・バリクを首都とした。 [78] その年の終わり(763年)までに、マニ教はウイグル国家の公式宗教と宣言された。ボクトキンはそれまで行われていた全てのシャーマニズム的儀礼を禁止し た。臣民はおそらくこの決定を受け入れた。マニ教の国教宣言がオルドゥ・バリクで熱狂的に迎えられたという報告から、そのことは明らかだ。可汗自身が語っ た碑文では、マニ教の高僧(「選ばれし者」)に対し、彼らが命令を下せば即座に従い、要求には応じると約束している。トルファンオアシスで発見された不完 全な写本には、ボク・テキンが「ザーハグ・イ・マーニー」(「マーニーの化身」または「マーニーの子孫」)の称号を授けられている。これは中央アジアのマ ニ教徒の間で威厳ある称号であった。 しかしながら、ウイグル族がマニ教へ明らかに進んで改宗したにもかかわらず、以前のシャーマニズム的慣行の痕跡や兆候は残存した。例えば765年、公式改 宗からわずか2年後、中国での軍事遠征中にウイグル軍は魔術師を呼び寄せ、特定の儀礼を数多く執り行わせた。マニ教徒となったウイグル人は、オトゥケンに ある聖なる森を依然として深く敬っていた[78]。マニ教への改宗は、タリム盆地と甘粛(チベット高原と黄土高原の間の地域)における写本制作の爆発的増 加をもたらし、その勢いは11世紀初頭まで続いた。840年、ウイグル可汗国はエニセイ・キルギスの攻撃により崩壊し、新たなウイグル国家であるコチョが コチョ市を首都として成立した。 アル=ジャヒーズ(776–868または869)は、マニ教がウイグルにもたらした平和的な生活様式が、後に彼らの軍事技術の欠如と衰退の原因となったと 考えた。しかし、この見解は改宗がもたらした政治的・軍事的結果と矛盾する。9世紀にウイグルがトルファンへ移住した後、貴族階級はしばらくマニ教の信仰 を維持したが、やがて仏教へ改宗した。トルファンのウイグル人におけるマニ教の痕跡は、ウイグル語マニ教写本の断片から読み取れる。実際、マニ教は13世 紀までウイグル人社会において仏教の影響力と競合し続けた。ウイグル人社会におけるマニ教に致命的な打撃を与えたのはモンゴル人であった。[78] |

| Tibet Manichaeism spread to Tibet during the Tibetan Empire. There was a serious attempt made to introduce the religion to the Tibetans as the text Criteria of the Authentic Scriptures (a text attributed to the Tibetan Emperor Trisong Detsen) makes a great effort to attack Manichaeism by stating that Mani was a heretic who engaged in religious syncretism into a deviating and inauthentic form.[79] Iran Manichaeans in Iran tried to assimilate their religion along with Islam in the Muslim caliphates.[80] Relatively little is known about the religion during the first century of Islamic rule. During the early caliphates, Manichaeism attracted many followers. It had a significant appeal among Muslim society, especially among the elites. A part of Manichaeism that specifically appealed to the Sasanians was the Manichaean gods' names. The names Mani had assigned to the gods of his religion show identification with those of the Zoroastrian pantheon, even though some divine beings he incorporates are non-Iranian. For example, Jesus, Adam, and Eve were named Xradesahr, Gehmurd, and Murdiyanag. Because of these familiar names, Manichaeism did not feel completely foreign to the Zoroastrians.[81] Due to the appeal of its teachings, many Sasanians adopted the ideas of its theology and some even became dualists. Not only were the citizens of the Sasanian Empire intrigued by Manichaeism, but so was the ruler at the time of its introduction, Sabuhr l. As the Denkard reports, Sabuhr, the first King of Kings, was very well-known for gaining and seeking knowledge of any kind. Because of this, Mani knew that Sabuhr would lend an ear to his teachings and accept him. Mani had explicitly stated while introducing his teachings to Sabuhr, that his religion should be seen as a reform of Zarathustra's ancient teachings.[81] This was of great fascination to the king, for it perfectly fit Sabuhr's dream of creating a large empire that incorporated all people and their different creeds. Thus, Manichaeism became widespread and flourished throughout the Sasanian Empire for thirty years. An apologia for Manichaeism ascribed to ibn al-Muqaffa' defended its phantasmagorical cosmogony and attacked the fideism of Islam and other monotheistic religions. The Manichaeans had sufficient structure to have a head of their community.[82][83][84] Tolerance toward Manichaeism decreased after the death of Sabuhr I. His son, Ohrmazd, who became king, still allowed for Manichaeism in the empire, but he also greatly trusted the Zoroastrian priest, Kirdir. After Ohrmazd's short reign, his oldest brother, Wahram I, became king. Wahram I held Kirdir in high esteem, and he also had many different religious ideals than Ohrmazd and his father, Sabuhr I. Due to the influence of Kirdir, Zoroastrianism was strengthened throughout the empire, which in turn caused Manichaeism to be diminished. Wahram sentenced Mani to prison, and he died there.[81] |

チベット マニ教はチベット帝国時代にチベットへ伝播した。『正典の基準』(チベット皇帝トリソン・デツェンに帰せられる文献)がマニ教を激しく攻撃していることか ら、チベット人への宗教導入が真剣に試みられたことがわかる。同文献はマニを異端者と断じ、宗教的折衷主義によって逸脱した不純な形態を生み出したと主張 している。[79] イラン イランのマニ教徒は、イスラム教カリフ制のもとで自らの宗教を同化させようとした。[80] イスラム支配最初の1世紀におけるこの宗教については、比較的知られていることが少ない。初期カリフ制時代、マニ教は多くの信者を惹きつけた。特にエリー ト層を中心に、イスラム社会において大きな魅力を有していた。ササン朝の人々に特に訴求したマニ教の特徴は、マニ教の神々の名称であった。マニが自らの宗 教の神々に与えた名称は、ゾロアスター教の神々との同一性を示していた。彼が取り入れた神々の中には非イラン系の存在も含まれていたが、例えばイエス、ア ダム、イブはそれぞれクラーデサーフ、ゲムルド、ムルディヤーナグと名付けられた。こうした馴染み深い名称ゆえに、ゾロアスター教徒にとってマニ教は完全 に異質な宗教とは感じられなかった。[81] その教えの訴求力ゆえに、多くのササン朝民がマニ教の神学的思想を受け入れ、中には二元論者となる者さえ現れた。 ササン朝帝国の民衆がマニ教に魅了されただけでなく、その導入期に君臨したサブール1世もまた同様であった。『デンカルド』が伝えるところによれば、初代 「王の中の王」サブールは、あらゆる知識を求め得ることにおいて非常に有名であった。このためマニは、サブルが自らの教えに耳を傾け受け入れると確信して いた。マニはサブルに教えを説く際、自らの宗教はザラトゥストラの古代教義の改革と見なされるべきだと明言していた[81]。これは王にとって非常に魅力 的であった。あらゆる人民と異なる信仰を包含する大帝国を築くというサブルの理想に完璧に合致したからである。こうしてマニ教はササン朝帝国全土に広ま り、三十年にわたり栄えた。イブン・アル=ムカッファに帰せられるマニ教の弁明書は、その幻想的な宇宙生成論を擁護し、イスラム教や他の一神教の信仰主義 を攻撃した。マニ教徒は共同体の指導者を置く十分な組織構造を持っていた[82][83][84]。 サブル1世の死後、マニ教への寛容は減退した。王位を継いだ息子オルマズドは帝国内でのマニ教を依然として容認したが、ゾロアスター教司祭キルディルを大 いに信頼していた。オルマズドの短き治世の後、長兄ワフラム1世が王となった。ワラム1世はキルディルを高く評価し、またオルマズドや父サブール1世とは 異なる宗教観を持っていた。キルディルの影響により、ゾロアスター教は帝国全体で強化され、その結果マニ教は衰退した。ワラムはマニを投獄し、彼は獄中で 死んだ。[81] |

| Arab world That Manicheism went further on to the Arabian peninsula, up to the Hejaz and Mecca, where it could have possibly contributed to the formation of the doctrine of Islam, cannot be proven in pre-Islamic Arabia[85] and there was no existence of Manichaeism in the Hejaz.[86] Under the eighth-century Abbasid Caliphate, Arabic zindīq and the adjectival term zandaqa could denote many different things,[87] but it seems to have primarily—or at least initially—signified a follower of Manichaeism; however its true meaning is not known.[88] From the ninth century, it is reported that Caliph al-Ma'mun tolerated a community of Manichaeans.[89] During the early Abbasid period, the Manichaeans underwent persecution. The third Abbasid caliph, al-Mahdi, persecuted the Manichaeans, establishing an inquisition against dualists who, if found guilty of heresy, refused to renounce their beliefs, were executed. Their persecution was ended in the 780s by Harun al-Rashid.[90][91] During the reign of the Caliph al-Muqtadir, many Manichaeans fled from Mesopotamia to Khorasan in fear of persecution, and the base of the religion was later shifted to Samarkand.[63][92] Bactria The first appearance of Manichaeism in Bactria was actually during Mani's lifetime. While he never physically traveled there, he did send a disciple by the name of Mar Ammo to spread his word. Mani "called (upon) Mar Ammo, the teacher, who knew the Parthian language and script, and was well acquainted with lords and ladies and with many nobles in those places..."[93] Mar Ammo indeed did travel to the old Parthian lands of eastern Iran, which bordered Bactria. A translation of Persian texts states the following from the perspective of Mar Ammo: "They had arrived at the watch post of Kushān (Bactria), then the spirit of the border of the eastern province appeared in the shape of a girl, and he (the spirit) asked me 'Ammo what do you intend? From where have you come?' I said, 'I am a believer, a disciple of Mani, the Apostle.' That spirit said 'I do not receive you. Return from where you have come.'" Despite the initial rejection Mar Ammo faced, the text records that Mani's spirit appeared to Mar Ammo and requested he persevere and read the chapter "The Collecting of the Gates" from The Treasure of the Living. Once he did so, the spirit returned, transformed, and said, "I am Bag Ard, the frontier guard of the Eastern Province. When I receive you, then the gate of the whole East will be opened in front of you." It seemed that this "border spirit" was a reference to the local Eastern Iranian goddess Ard-oxsho, who was prevalent in Bactria.[94] |

アラブ世界 マニ教がさらにアラブ半島へ進出し、ヘジャーズやメッカに至り、そこでイスラム教の教義形成に寄与した可能性は、イスラム以前のアラビアでは証明できない [85]。またヘジャーズにはマニ教は存在しなかった。[86] 8世紀のアッバース朝カリフ制下では、アラビア語のzindīqおよび形容詞形zandaqaは異なる意味を指し得た[87]が、主に―少なくとも初期に は―マニ教の信奉者を意味していたようだ。ただしその真の意味は不明である[88]。9世紀以降、カリフ・アル=マームーンがマニ教徒の共同体を容認した と伝えられる。[89] アッバース朝初期、マニ教徒は迫害を受けた。第3代カリフ・アル=マフディーはマニ教徒を迫害し、二元論者に対する異端審問を設立した。異端の罪で有罪と され、かつ信仰を放棄することを拒んだ者は処刑された。この迫害は780年代にハルーン・アル=ラシードによって終結した。[90][91]カリフ・アル =ムクタディル治世下、多くのマニ教徒は迫害を恐れメソポタミアからホラーサーンへ逃れ、後に宗教の拠点はサマルカンドへ移された。[63][92] バクトリア バクトリアにおけるマニ教の最初の出現は、実はマニの存命中に起きた。マニ自身が実際に足を運んだことはないが、弟子であるマル・アンモを派遣して教えを 広めさせたのである。マニは「パルティア語と文字を知り、その地の貴族や貴婦人らと親交のあった教師マル・アンモを呼び寄せた…」[93] マル・アンモは確かに、バクトリアと国境を接するイラン東部の旧パルティア領へ赴いた。ペルシア語文献の翻訳によれば、マル・アンモの視点から次のように 記されている。「彼らはクシャン(バクトリア)の監視所へ到着した。すると東方の州の境界を守る精霊が少女の姿で現れ、私に問うた。『アンモよ、何の用 か?どこから来たのか?」と問うた。私は答えた。「私は信者だ。使徒マニの弟子である」。すると霊は言った。「お前を受け入れない。来た道を引き返せ」 と。」 当初の拒絶にもかかわらず、文書はマニの霊がマル・アモの前に現れ、忍耐強く『生ける者の宝』の章「門の集い」を読むよう求めたと記録している。そうする と霊は戻ってきて姿を変え、「私は東方の州の境界を守る者、バグ・アルドだ。私が君を受け入れる時、東方の全門が君の前に開かれる」と言った。この「境界 の霊」は、バクトリア地方で広く崇拝されていた東イランの女神アルド=オクショを指しているようである。[94] |

The four primary prophets of Manichaeism in the Manichaean Diagram of the Universe, from left to right: Mani, Zoroaster, Buddha and Jesus Syncretism and translation Manichaeism claimed to present the complete version of teachings that were corrupted and misinterpreted by the followers of Mani's predecessors Adam, Abraham, Noah,[16] Zoroaster, the Buddha, and Jesus.[95] Accordingly, as it spread, it adapted deities from other religions into forms it could use for its scriptures. Its original Eastern Middle Aramaic texts already contained stories of Jesus. As the faith moved eastward and its scriptures were translated into Iranian languages, the names of the Manichaean deities were often transformed into the names of Zoroastrian yazatas. Thus, Abbā ḏəRabbūṯā ("The Father of Greatness"), the highest Manichaean deity of Light, in Middle Persian texts might either be translated literally as pīd ī wuzurgīh or substituted with the name of the deity Zurwān. Similarly, the Manichaean primordial figure Nāšā Qaḏmāyā ("The Original Man") was rendered Ohrmazd Bay after the Zoroastrian god Ohrmazd. This process continued in Manichaeism's meeting with Chinese Buddhism, during which, for example, the original Aramaic קריא qaryā (the "call" from the World of Light to those seeking rescue from the World of Darkness) is identified in the Chinese-language scriptures with Guanyin (觀音 or Avalokiteśvara in Sanskrit, literally, "watching/perceiving sounds [of the world]", the bodhisattva of Compassion).[citation needed] Manichaeism influenced some early texts and traditions of proto-orthodox and other forms of early Christianity, as well as doing the same for branches of Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Buddhism, and Islam.[96] |

マニ教の宇宙図における四大預言者、左から順に:マニ、ゾロアスター、ブッダ、イエス 融合と翻訳 マニ教は、マニの先駆者であるアダム、アブラハム、ノア[16]、ゾロアスター、ブッダ、イエスの信徒たちによって歪められ誤解された教えの完全版を提示 すると主張した。[95] したがって、マニ教は伝播するにつれ、他の宗教の神々を自らの経典に利用できる形へと適応させた。その原典である東方中世アラム語のテキストには、既にイ エスの物語が含まれていた。 信仰が東方へ移り、経典がイラン諸語へ翻訳される過程で、マニ教の神々の名はしばしばゾロアスター教のヤザータの名へと変容した。したがって、マニ教の最 高神である光の神アッバー・ズ・ラッブータ(「偉大なる父」)は、中世ペルシア語のテキストでは、文字通り「偉大なる父」と訳されるか、あるいは神ズール ワーンの名に置き換えられることがあった。 同様に、マニ教の始原的存在ナーシャー・カドマーヤ(「原初の人」)は、ゾロアスター教の神オームルザドに倣いオームルザド・バイと訳された。この過程は マニ教が中国仏教と接触した際にも続き、例えば 元のアラム語「קריא qaryā」(闇の世界から救いを求める者への光の世界からの「呼びかけ」)は、中国語経典において観音(観音、サンスクリット語でアヴァロキテシュヴァ ラ、文字通り「世界の音を観察・感知する者」、慈悲の菩薩)と同一視される。[出典が必要] マニ教は、初期キリスト教の正統派前身やその他の形態の初期文献・伝統に影響を与えただけでなく、ゾロアスター教、ユダヤ教、仏教、イスラム教の各分派に対しても同様の影響を及ぼした。[96] |

| Persecution and suppression See also: Manichaean schisms Manichaeism was repressed by the Sasanian Empire.[80] In 291, persecution arose in the Persian empire with the murder of the apostle Sisin by Bahram II and the slaughter of many Manichaeans. In 296, the Roman emperor Diocletian decreed all the Manichaean leaders to be burnt alive along with the Manichaean scriptures, and many Manichaeans in Europe and North Africa were killed. It was not until 372 with Valentinian I and Valens that Manichaeism was legislated against again.[97] Theodosius I issued a death decree for all Manichaean monks in 382.[98] The religion was vigorously attacked and persecuted by both the Christian Church and the Roman state, and the religion almost disappeared from western Europe in the fifth century and from the eastern portion of the empire in the sixth century.[63]  Conversion of Bögü Qaghan, third Khagan of the Uyghur Khaganate, to Manicheism in 762: detail of Bögü Qaghan in a suit of armour, kneeling to a Manichean high priest. 8th century Manichean manuscript (MIK III 4979)[99] In 732, Emperor Xuanzong of Tang banned any Chinese from converting to the religion, saying it was a heretic religion, confusing people by claiming to be Buddhism. However, the foreigners who followed the religion were allowed to practice it without punishment.[100] After the fall of the Uyghur Khaganate in 840, which was the chief patron of Manichaeism (which was also the state religion of the Khaganate) in China, all Manichaean temples in China except in the two capitals and Taiyuan were closed down and never reopened since these temples were viewed as a symbol of foreign arrogance by the Chinese (see Cao'an). Even those that were allowed to remain open did not for long.[73] The Manichaean temples were attacked by Chinese people who burned the images and idols of these temples. Manichaean priests were ordered to wear hanfu instead of traditional clothing, viewed as un-Chinese. In 843, Emperor Wuzong of Tang gave the order to kill all Manichaean clerics as part of the Huichang persecution of Buddhism, and over half died. They were made to look like Buddhists by the authorities; their heads were shaved, they were made to dress like Buddhist monks and then killed.[73] Many Manichaeans took part in rebellions against the Song dynasty. They were quelled by Song China and were suppressed and persecuted by all successive governments before the Mongol Yuan dynasty. In 1370, the religion was banned through an edict of the Ming dynasty, whose Hongwu Emperor had a personal dislike for the religion.[73][75][101] Its core teaching influences many religious sects in China, including the White Lotus movement.[102] According to Wendy Doniger, Manichaeism may have continued to exist in the Xinjiang region until the Mongol conquest in the 13th century.[103] Manicheans also suffered persecution for some time under the Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad. In 780, the third Abbasid Caliph, al-Mahdi, started a campaign of inquisition against those who were "dualist heretics" or "Manichaeans" called the zindīq. He appointed a "master of the heretics" (Arabic: صاحب الزنادقة ṣāhib al-zanādiqa), an official whose task was to pursue and investigate suspected dualists, who the Caliph then examined. Those found guilty who refused to recant their beliefs were executed.[90] This persecution continued under his successor, Caliph al-Hadi, and continued for some time during the reign of Harun al-Rashid, who finally abolished it and ended it.[90] During the reign of the 18th Abbasid Caliph al-Muqtadir, many Manichaeans fled from Mesopotamia to Khorasan from fear of persecution by him and about 500 of them assembled in Samarkand. The base of the religion was later shifted to this city, which became their new Patriarchate.[63][92] Manichaean pamphlets were still in circulation in Greek in 9th-century Byzantine Constantinople, as the patriarch Photios summarizes and discusses one that he has read by Agapius in his Bibliotheca. |

迫害と弾圧 関連項目: マニ教の分裂 マニ教はササン朝ペルシアによって弾圧された。[80] 291年、バフラム2世による使徒シシンの殺害と多くのマニ教徒の虐殺を契機に、ペルシア帝国で迫害が始まった。296年、ローマ皇帝ディオクレティアヌ スはマニ教の指導者全員をマニ教の経典と共に生きたまま焼くよう命じ、ヨーロッパと北アフリカの多くのマニ教徒が殺害された。マニ教が再び法的に禁止され たのは、372年のヴァレンティニアヌス1世とヴァレンス帝の時代になってからである。[97] テオドシウス1世は382年にマニ教の僧侶全員に対する死刑令を発した。[98] この宗教はキリスト教教会とローマ国家の両方から激しく攻撃され迫害され、5世紀には西ヨーロッパから、6世紀には帝国の東部地域からほぼ消滅した。[63]  762年、ウイグル可汗国第三代可汗・鄯善可汗の改宗:鎧をまとった鄯善可汗がマニ教の高僧に跪く場面。8世紀のマニ教写本(MIK III 4979)[99] 732年、唐の玄宗皇帝はマニ教を異端の宗教と断じ、仏教を装って人民を惑わすとして、中国人の改宗を禁止した。しかし、この宗教を信仰する外国人につい ては、処罰なしに信仰を許された. [100] 中国におけるマニ教(同教は可汗国の国教でもあった)の主要な後援者であったウイグル可汗国が840年に滅亡すると、二都と太原を除く中国国内のマニ教寺 院は全て閉鎖された。これらの寺院は中国人にとって外国の傲慢の象徴と見なされたため、再開されることはなかった(曹安を参照)。営業を許された寺院でさ え、長くは続かなかった。[73] マニ教寺院は中国人の人々による襲撃を受け、寺院内の仏像や偶像は焼かれた。マニ教の僧侶たちは、漢服を着用するよう命じられ、従来の服装は非中国的なも のと見なされた。843年、唐の武宗は仏教弾圧の一環としてマニ教の聖職者全員を処刑するよう命じ、半数以上が死亡した。当局は彼らを仏教徒に見せかける ため、頭を剃らせ、仏教僧のような服装をさせ、その後殺害した。[73] 多くのマニ教徒は宋王朝に対する反乱に参加した。彼らは宋によって鎮圧され、モンゴル系元王朝以前の全ての政権によって弾圧と迫害を受けた。1370年、 明王朝の勅令によりこの宗教は禁止された。明の洪武帝は個人的な嫌悪感を込めてこの宗教を嫌悪していた。[73] [75][101] その核心的な教えは、白蓮教を含む中国の多くの宗教宗派に影響を与えている。[102] ウェンディ・ドニガーによれば、マニ教は13世紀のモンゴル征服まで新疆地域で存続していた可能性がある。[103] マニ教徒はバグダードのアッバース朝カリフ制下でも長らく苦悩した。780年、第3代カリフ・アル=マフディーは「二元論的異端者」あるいは「マニ教徒」 と呼ばれるジンディークに対する異端審問を開始した。彼は「異端者の長」(アラビア語: صاحب الزنادقة ṣāhib al-zanādiqa)を任命した。この役人の任務は、二元論の疑いのある者を追跡・調査し、カリフが審問する手配をすることだった。有罪とされ、信仰 の撤回を拒んだ者は処刑された。[90] この迫害は後継者のハディの治世下でも続き、ハールーン・アル=ラーシードの治世中もしばらく続いたが、最終的に彼がこれを廃止し終結させた[90]。第 18代アッバース朝カリフ、ムクタディールの治世中には、多くのマニ教徒が彼による迫害を恐れてメソポタミアからホラーサーンへ逃れ、約500人がサマル カンドに集結した。この宗教の拠点は後にこの都市に移され、新たな総主教座となった。[63][92] 9世紀のビザンツ帝国コンスタンティノープルでは、マニ教のパンフレットがギリシャ語で流通していた。総主教フォティオスは自身の『書庫目録』で、アガピオスによるそのようなパンフレットを読んだことを要約し論じている。 |

| Later movements associated with Manichaeism During the Middle Ages, several movements emerged that were collectively described as "Manichaean" by the Catholic Church and persecuted as Christian heresies through the establishment of the Inquisition in 1184.[104] They included the Cathar churches of Western Europe. Other groups sometimes referred to as "neo-Manichaean" were the Paulician movement, which arose in Armenia,[105] and the Bogomils in Bulgaria and Serbia.[106] An example of this usage can be found in the published edition of the Latin Cathar text, the Liber de duobus principiis (Book of the Two Principles), which was described as "Neo-Manichaean" by its publishers.[107] As there is no presence of Manichaean mythology or church terminology in the writings of these groups, there has been some dispute among historians as to whether these groups were descendants of Manichaeism.[108] Manichaeism could have influenced the Bogomils, Paulicians, and Cathars. However, these groups left few records, and the link between them and Manichaeans is tenuous. Regardless of its accuracy, the charge of Manichaeism was leveled at them by contemporary orthodox opponents, who often tried to make contemporary heresies conform to those combatted by the church fathers.[106] Whether the dualism of the Paulicians, Bogomils, and Cathars and their belief that the world was created by a Satanic demiurge was due to influence from Manichaeism is impossible to determine. The Cathars apparently adopted the Manichaean principles of church organization. Priscillian and his followers may also have been influenced by Manichaeism. The Manichaeans preserved many apocryphal Christian works, such as the Acts of Thomas, that would otherwise have been lost.[106] Legacy in present-day Some sites are preserved in Xinjiang, Zhejiang, and Fujian in China.[109][110] The Cao'an temple is the most widely-known and best-preserved Manichaean building,[44]: 256–257 though it later became associated with Buddhism.[111] Local villagers near Cao'an still worship Mani, albeit with little distinction between Mani-as-Buddha and Gautama Buddha.[112] Other temples in China associated with Manichaeism remain standing, including the Xuanzhen Temple, noted for its stele. Some platforms on the internet and social media are trying to spread some of the teachings of Manichaeism. Some people are registered in these electronic sources, and some scholars and students in the field of religious studies and the arts continue to study Manichaeism.[113] In 2018, rituals were conducted for the Lin Deng 林瞪 (1003–1059), a Chinese Manichaean leader who lived during the Song dynasty in the three villages of Baiyang 柏洋村, Shangwan 上万村, and Tahou 塔后村 in Baiyang Township, Xiapu County, Fujian.[114] |

マニ教に関連する後の運動 中世において、カトリック教会によって総称して「マニ教的」とされ、1184年の異端審問所の設立を通じてキリスト教の異端として迫害されたいくつかの運 動が現れた。[104] これには西ヨーロッパのカタリ派教会が含まれる。その他、「新マニ教」と呼ばれることもある集団として、アルメニアで興ったパウリキア派運動[105]、 ブルガリアとセルビアのボゴミル派[106]がある。この用法の一例は、カタリ派のラテン語文献『二つの原理の書』(Liber de duobus principiis)の刊行版に見られる。出版者らはこれを「新マニ教的」と評した[107]。これらの集団の著作にはマニ教の神話や教会用語が全く見 られないため、彼らがマニ教の継承者であったか否かについて歴史家の間で議論がある。[108] マニ教はボゴミル派、パウリキア派、カタリ派に影響を与えた可能性がある。しかしこれらの集団は記録をほとんど残しておらず、マニ教徒との関連性は弱い。 その正確性にかかわらず、マニ教徒という非難は当時の正統派の反対者たちによって彼らに向けられた。彼らはしばしば、当時の異端を教父たちが戦った異端に 当てはめようとしたのである。[106] パウリキア派、ボゴミル派、カタリ派の二元論や、世界を悪魔的なデミウルゴスが創造したという彼らの信仰が、マニ教の影響によるものかどうかは判断できな い。カタリ派は明らかにマニ教の教会組織原理を採用した。プリスキリアヌスとその追随者たちもマニ教の影響を受けた可能性がある。マニ教徒は『トマス行 伝』など、失われていたであろう多くの外典キリスト教文献を保存した。[106] 現代における遺産 中国の新疆、浙江、福建には遺跡が保存されている。[109][110] 曹安寺は最も広く知られ、最も良好な状態で保存されたマニ教建築物である。[44]: 256–257年建造だが、後に仏教と結びついた。[111] 曹安周辺の村民は今もマニを崇拝しているが、仏陀としてのマニとゴータマ・ブッダの区別はほとんどない。[112] 中国にはマニ教に関連する他の寺院も現存しており、石碑で知られる玄真寺などが挙げられる。 インターネットやソーシャルメディア上では、マニ教の教えを広めようとする動きがある。これらの電子媒体には登録者が存在し、宗教研究や芸術分野の学者・学生もマニ教の研究を続けている[113]。 2018年には、宋代に活躍した中国のマニ教指導者・林瞪(1003–1059)の儀礼が、福建省霞浦県柏洋郷の柏洋村、上万村、塔后村の三村で執り行われた。[114] |

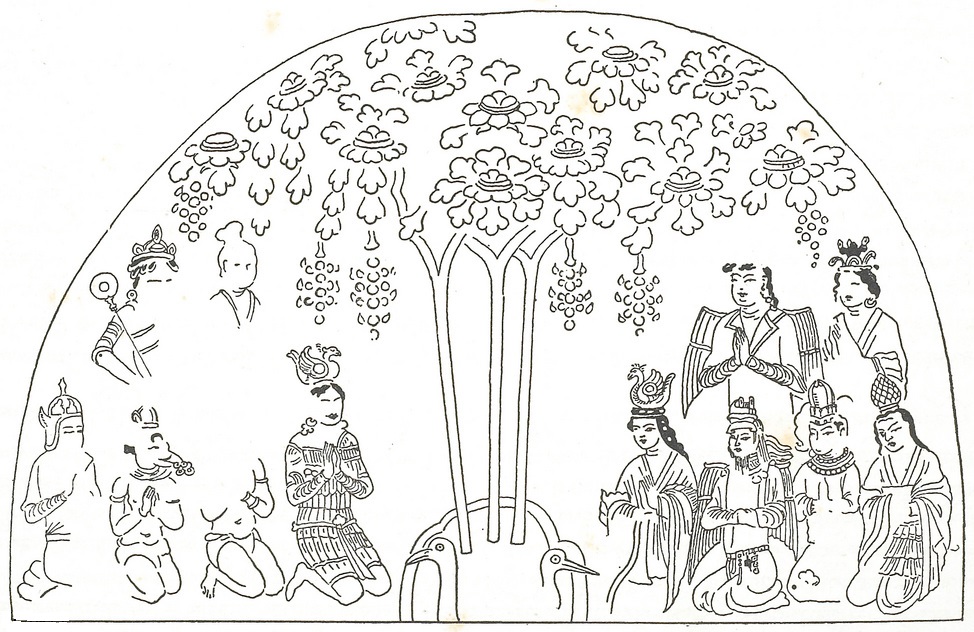

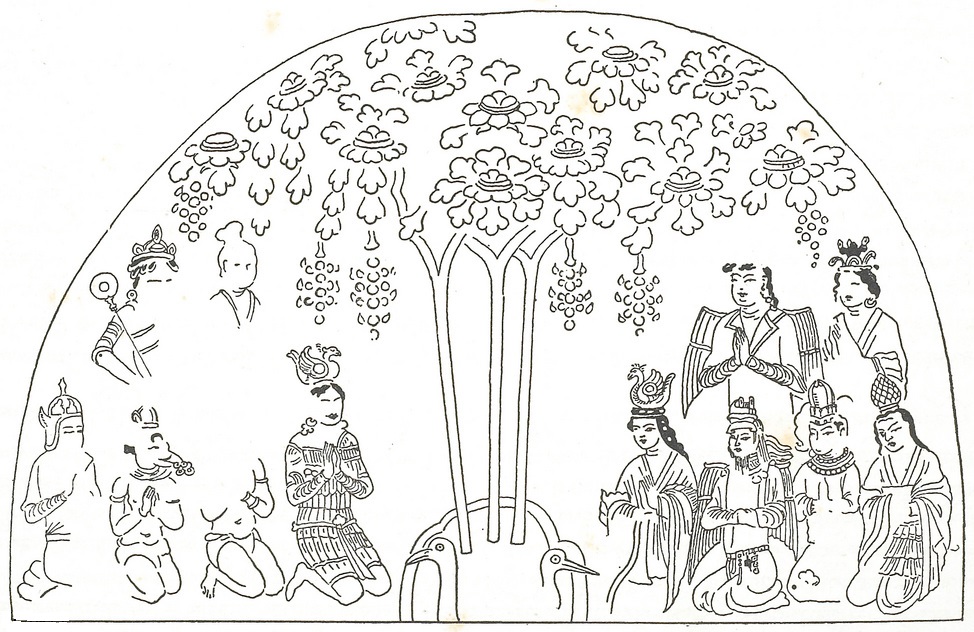

Teachings and beliefs Uyghur Manichaean clergymen, wall painting from the Khocho ruins, 10th/11th century CE. Located in the Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Humboldt Forum, Berlin.  Worship of the Tree of Life in the World of Light; a Manichaean picture from the Bezeklik Caves General Mani's teaching dealt with the origin of evil by addressing a theoretical part of the problem of evil: denying the omnipotence of God and instead postulating two opposite divine powers. Manichaean theology teaches a dualistic view of good and evil. A fundamental belief in Manichaeism is that the powerful, though not omnipotent, good power (God) was opposed by the eternal evil power (the devil). Humanity, the world, and the soul are seen as the by-product of the battle between God's proxy—Primal Man—and the devil.[115] The human person is seen as a battleground for these powers: the soul defines the person but is influenced by light and dark. This contention plays out over the world and the human body—neither the Earth nor the flesh were seen as intrinsically evil but instead possessed both light and dark portions. Natural phenomena such as rain were seen as the physical manifestation of this spiritual contention. Therefore, the Manichaean view explained the existence of evil by positing a flawed creation in the formation of which God took no part and which constituted instead the product of a battle by the devil against God.[115] |

教えと信仰 ウイグルのマニ教聖職者たち。コーチョ遺跡の壁画、10世紀/11世紀。ベルリン、フンボルト・フォーラム内アジア美術館所蔵。  光明界における生命の樹の礼拝。ベゼクリク洞窟のマニ教絵画 概説 マニの教えは、悪の起源について、悪の問題の理論的側面を扱うことで対処した。すなわち、神の全能性を否定し、代わりに二つの対立する神聖な力を仮定した のである。マニ教の神学は、善と悪の二元論的見解を教える。マニ教の基本的な信念は、強力ではあるが全能ではない善の力(神)が、永遠の悪の力(悪魔)に よって対抗されたというものである。人類、世界、魂は、神の代理人である原初の人間と悪魔との戦いの副産物と見なされる。[115] 人間の格子はこれらの力の戦場と見なされる。魂が人格を定義するが、光と闇の影響を受ける。この対立は世界と人間の身体全体に展開される。地球も肉体も本 質的に悪とは見なされず、光と闇の両面を持つとされた。雨のような自然現象は、この霊的対立の物理的現れと見なされた。したがってマニ教の視点では、悪の 存在は欠陥ある創造物として説明された。この創造には神は関与せず、代わりに悪魔が神に対して戦いを繰り広げた結果の産物であるとされたのである。 [115] |

Cosmogony Manichaean Diagram of the Universe depicts the Manichaean cosmology. Manichaeism presents an elaborate conflict between the spiritual world of light and the material world of darkness. The beings of both the world of darkness and the world of light have names. There are numerous sources for the details of the Manichaean belief[example needed]. Two portions of the scriptures are probably the closest thing to the original writings, in their original languages, that will ever be available: the Syriac quotation by the Church of the East Christian Theodore bar Konai in his 8th century Syriac scholion, known as the Ketba de-Skolion,[55] and the Middle Persian sections of Mani's Shabuhragan discovered at Turpan—a summary of Mani's teachings prepared for Shapur I.[33] From these and other sources[example needed], it is possible to derive a near-complete description of the detailed Manichaean cosmogony[116] (A complete list of Manichaean deities is outlined below). According to Mani,[citation needed]the unfolding of the universe took place in three phases: The First Creation Originally, good and evil existed in two completely separate realms: one, the World of Light (Chinese: 明界), ruled by the Father of Greatness together with his five Shekhinas (i.e., divine attributes of light), and the other, the World of Darkness, ruled by the King of Darkness. At a point in the distant past, the Kingdom of Darkness noticed the World of Light, coveted it, and attacked it. The Father of Greatness, in the first of three "calls" or "creations", called to the Mother of Life, who sent her son, Original Man (Imperial Aramaic: Nāšā Qaḏmāyā), to battle with the attacking powers of Darkness, which included the Demon of Greed. The Original Man was armed with five different shields of light (reflections of the five Shekhinas), which he lost to the forces of Darkness in the ensuing battle—described as a kind of "bait" to trick the forces of Darkness, who greedily consume as much light as they can. When the Original Man awakened, he was trapped among the forces of Darkness. The Second Creation The Father of Greatness then began the Second Creation. He called to the Living Spirit[specify], who then called to his sons and the Original Man, after which Call became a Manichaean deity proper. An answer — Answer — became another Manichaean deity, then went out from the Original Man into the World of Light. The Mother of Life, the Living Spirit, and the latter's five sons began to create the universe from the bodies of the evil beings of the World of Darkness and the light they had swallowed. Ten heavens and eight earths were created, all consisting of various mixtures of the evil material beings from the World of Darkness and the swallowed light. The sun, moon, and stars were all created from light recovered from the World of Darkness. The waxing and waning of the moon are described as the "moon filling with light", which passed to the sun, then through the Milky Way, and eventually back to the World of Light. The Third Creation/Seduction of the Archons Great demons (called archons in bar-Konai's account) were hung over the heavens, and the Father of Greatness began the Third Creation. The light was recovered from the material bodies of the evil beings and demons by causing them to become sexually aroused in greed toward beautiful images of the beings of light, such as the Third Messenger and the Virgins of Light. In Augustine of Hippo's account of Mani's writings, the Virgins of Light recovered light from the female and male archons by taking on the forms of both "beardless boys" and "beautiful virgins."[117] According to other sources, the myth included only one being (the Maiden of Light) with a transient or androgynous gender who performed the seduction, and in other versions there were multiple beings (shining warriors) which were sexless.[118][119] However, as soon as the light was expelled from their bodies and fell to the earth (sometimes in the form of abortions: the source of fallen angels in the Manichaean myth), the evil beings continued to swallow up as much of it as they could to keep the light inside themselves. The evil beings swallowed vast quantities of light, copulated, and produced Adam and Eve. The Father of Greatness then sent Jesus the Splendour to awaken Adam and enlighten him to the true source of the light trapped in his material body. Adam and Eve, however, also copulated and produced more human beings, trapping the light in the bodies of humankind throughout human history. The appearance of the Prophet Mani was another attempt by the World of Light to reveal to humanity the true source of the spiritual light imprisoned within their material bodies.[citation needed] Cosmology In the sixth century, many Manichaeans saw the earth as "a rectangular parallelepiped enclosed by walls of crystal, above which three [sky] domes" existed, with the other two being above and larger than the first one and second one, respectively.[120] These represented the "three heavens" in Chaldean religion.[120] Outline of the beings and events in the Manichaean mythology Beginning with the time of its creation by Mani, the Manichaean religion has had a detailed description of deities and events that took place within the Manichaean scheme of the universe. In every language and region that Manichaeism spread to, these same deities reappear, whether it is in the original Syriac quoted by Theodore bar Konai,[55] or the Latin terminology given by Saint Augustine from Mani's Epistola Fundamenti, or the Persian and Chinese translations found as Manichaeism spread eastward. While the original Syriac retained the original description that Mani created, the transformation of the deities through other languages and cultures produced incarnations of the gods not implied in the original Syriac writings. Chinese translations are especially syncretic, borrowing and adapting terminology common in Chinese Buddhism.[121] |

宇宙生成論 マニ教の宇宙図はマニ教の宇宙観を描いている。 マニ教は、光の霊的世界と闇の物質世界との複雑な対立を提示する。闇の世界と光の世界の双方に属する存在には名前がある。マニ教の信仰の詳細については数 多くの資料が存在する[例が必要]。聖典のうち二つの部分は、おそらく原典に最も近いものと言えるだろう。それらは原語で残されており、今後も入手可能な 唯一の資料となるだろう: 東方教会キリスト教徒テオドール・バル・コナイによる8世紀のシリア語注釈書『ケトバ・デ・スコリオン』[55]、およびトルファンで発見されたマニの 『シャブフラガン』の中世ペルシア語部分——シャプール1世のために作成されたマニ教義の要約である[33]。 これら及びその他の資料[例が必要]から、マニ教の詳細な宇宙生成論[116]のほぼ完全な記述を導き出すことが可能である(マニ教の神々の完全な一覧は後述)。マニによれば[出典が必要]、宇宙の展開は三つの段階で行われた: 第一の創造 元来、善と悪は完全に分離した二つの領域に存在していた。一つは「光の界」(中国語: 明界)であり、偉大なる父とその五つのシェキナ(光の神聖な属性)が支配していた。もう一つは「闇の界」であり、闇の王が支配していた。遠い昔のある時点 で、闇の王国は光の界に気づき、それを渇望し、攻撃した。偉大なる父は三つの「呼びかけ」あるいは「創造」の最初の段階で、生命の母を呼び寄せた。生命の 母は息子である原初の男(帝王アラム語:ナーシャー・カドマーヤ)を送り込み、貪欲の悪魔を含む闇の勢力との戦いを命じた。 原初の男は五つの異なる光の盾(五つのシェキナの反映)を携えていたが、続く戦いの中で闇の勢力に奪われた。これは闇の勢力を欺く「餌」のようなものだった。闇の勢力は貪欲に光を貪り食うからだ。原初の男が目を覚ました時、彼は闇の勢力の中に閉じ込められていた。 第二の創造 偉大なる父は第二の創造を開始した。彼は生ける霊[specify]を呼び、生ける霊は息子たちと原初の人間を呼び寄せた。その後、呼びかけ(Call) はマニ教の神格となった。応答(Answer)は別のマニ教神格となり、原初の人間から光の世界へと出て行った。生命の母、生ける霊、そしてその五人の息 子たちは、闇の世界の邪悪な存在たちの肉体と、彼らが飲み込んだ光から宇宙の創造を始めた。十の天と八つの地が創造され、それらは全て闇の世界の邪悪な物 質的存在と飲み込まれた光の様々な混合物で構成されていた。太陽、月、星々は全て闇の世界から回収された光から創造された。月の満ち欠けは「月が光で満た される」と表現され、その光は太陽へ、次に天の川を通って、最終的に光の世界へ戻っていった。 第三の創造/アルコンの誘惑 大いなる悪魔(バル・コナイの記述ではアルコンと呼ばれる)が天界に吊るされ、偉大なる父は第三の創造を始めた。光は、第三の使者や光の乙女たちといった 光の存在たちの美しい姿への貪欲さによって、邪悪な存在や悪魔たちの肉体から性的興奮を引き起こすことで回収された。ヒッポのアウグスティヌスがマニの著 作を記した記述によれば、光の乙女たちは「ひげのない少年」と「美しい処女」の両方の姿を取り、雌雄のアルコンたちから光を回収した。[117] 他の資料によれば、この神話には誘惑を行う一時的あるいは両性具有の性別を持つ存在(光の乙女)が一人しか登場せず、別の版本では無性別の複数の存在(輝 く戦士たち)が登場する。[118][119] しかし光が彼らの体から排出され地上に落ちると(時には流産という形で:マニ教神話における堕天使の起源)、邪悪な存在たちは光を可能な限り飲み込み続 け、自らの内に閉じ込めようとした。邪悪な存在たちは膨大な光を飲み込み、交わり、アダムとイブを生み出した。偉大なる父はその後、輝きのイエスを遣わ し、アダムを目覚めさせ、物質的な身体に閉じ込められた光の真の出所を悟らせようとした。しかしアダムとイブもまた交わり、さらに多くの人間を生み出した ため、光は人類の歴史を通じて人間の身体に閉じ込められ続けた。預言者マニの出現は、物質的な身体に囚われた霊的な光の真の出所を人類に明らかにしようと する、光の世界によるもう一つの試みであった。[出典が必要] 宇宙論 6世紀、多くのマニ教徒は地球を「水晶の壁に囲まれた直方体」と見なし、その上に三つの天蓋が存在すると考えた。他の二つの天蓋はそれぞれ最初の天蓋と二 番目の天蓋の上方に位置し、それよりも大きかった[120]。これらはカルデア宗教における「三つの天」を表していた。[120] マニ教神話における存在と出来事の概要 マニ教はマニによって創始された当初から、マニ教の宇宙観の中で起こった神々や出来事について詳細な記述を持っていた。マニ教が伝播したあらゆる言語圏・ 地域において、これらの神々は同一の姿で再現される。テオドロス・バル・コナイが引用した原典シリア語[55]であれ、聖アウグスティヌスがマニの『基礎 書簡』から引用したラテン語用語であれ、あるいは東方に伝播した際に生まれたペルシア語・中国語訳であれ、同様である。シリア語原典はマニが創始した神々 の記述を保持していたが、他の言語や文化を通じた神々の変容は、シリア語原典には示唆されていない神々の化身を生み出した。特に中国語訳は融合的であり、 中国仏教で一般的な用語を借用し適応させている。 |

| The Manichaean Church Organization The Manichaean Church was divided into the Elect, who had taken upon themselves the vows of Manichaeism, and the Hearers, those who had not, but still participated in the Church. The Elect were forbidden to consume alcohol and meat, as well as to harvest crops or prepare food, due to Mani's claim that harvesting was a form of murder against plants. The Hearers would therefore commit the sin of preparing food, and would provide it to the Elect, who would in turn pray for the Hearers and cleanse them of these sins.[124] The terms for these divisions were already common since the days of early Christianity, however, it had a different meaning in Christianity. In Chinese writings, the Middle Persian and Parthian terms are transcribed phonetically (instead of being translated into Chinese).[125] These were recorded by Augustine of Hippo.[21] The Leader (Syriac: ܟܗܢܐ /kɑhnɑ/; Parthian: yamag; Chinese: 閻默; pinyin: yánmò), Mani's designated successor, seated as Patriarch at the head of the Church, originally in Ctesiphon, from the ninth century in Samarkand. Two notable leaders were Mār Sīsin (or Sisinnios), the first successor of Mani, and Abū Hilāl al-Dayhūri, an eighth-century leader. 12 Apostles (Latin: magistrī; Syriac: ܫܠܝܚܐ /ʃ(ə)liħe/; Middle Persian: možag; Chinese: 慕闍; pinyin: mùdū). Three of Mani's original apostles were Mār Pattī (Pattikios; Mani's father), Akouas and Mar Ammo. 72 Bishops (Latin: episcopī; Syriac: ܐܦܣܩܘܦܐ /ʔappisqoppe/; Middle Persian: aspasag, aftadan; Chinese: 薩波塞; pinyin: sàbōsāi or Chinese: 拂多誕; pinyin: fúduōdàn; see also: seventy disciples). One of Mani's original disciples who was specifically referred to as a bishop was Mār Addā. 360 Presbyters (Latin: presbyterī; Syriac: ܩܫܝܫܐ /qaʃʃiʃe/; Middle Persian: mahistan; Chinese: 默奚悉德; pinyin: mòxīxīdé) The general body of the Elect (Latin: ēlēctī; Syriac: ܡܫܡܫܢܐ /m(ə)ʃamməʃɑne/; Middle Persian: ardawan or dēnāwar; Chinese: 阿羅緩; pinyin: āluóhuǎn or Chinese: 電那勿; pinyin: diànnàwù) The Hearers (Latin: audītōrēs; Syriac: ܫܡܘܥܐ /ʃɑmoʿe/; Middle Persian: niyoshagan; Chinese: 耨沙喭; pinyin: nòushāyàn) |

マニ教教会 組織 マニ教教会は、マニ教の誓いを立てた「選ばれた者」と、誓いを立てていないが教会に参加する「聞き手」に分かれていた。選ばれた者は、マニが「収穫は植物 に対する殺害である」と主張したため、酒や肉を摂取すること、作物を収穫すること、食物を調理することを禁じられていた。従って聴衆は食物を調理するとい う罪を犯し、それを選民に提供した。選民は聴衆のために祈り、その罪を清めたのである。[124] これらの区分用語は初期キリスト教時代から既に一般的であったが、キリスト教における意味は異なるものであった。中国文献では、中世ペルシア語とパルティ ア語の用語は音訳されている(中国語に翻訳されていない)。[125] これらはヒッポのアウグスティヌスによって記録された。[21] 指導者(シリア語: ܟܗܢܐ /kɑhnɑ/; パルティア語: yamag; 中国語: 閻默; ピンイン: yánmò)は、マニが指名した後継者であり、教会の頂点に立つ総主教として、当初はクテシフォンに、9世紀以降はサマルカンドに本拠を置いた。著名な指 導者としては、マニの最初の後継者であるマル・シシン(またはシシニオス)と、8世紀の指導者アブー・ヒラール・アル=ダイフーリが挙げられる。 12使徒(ラテン語: magistrī; シリア語: ܫܠܝܚܐ /ʃ(ə)liħe/; 中世ペルシア語: možag; 中国語: 慕闍; ピンイン: mùdū)。マニの最初の使徒のうち三人は、マル・パティ(パティキオス; マニの父)、アコウアス、マル・アンモであった。 72人の司教(ラテン語: episcopī; シリア語: ܐܦܣܩܘܦܐ /ʔappisqoppe/; 中世ペルシア語: aspasag, aftadan; 中国語: 薩波塞; ピンイン: sàbōsāi または 中国語: 拂多誕; ピンイン: fúduōdàn; 参照: 七十人の弟子)。マニの最初の弟子で、特に司教と呼ばれたのはマル・アッダである。 360人の長老(ラテン語: presbyterī; シリア語: ܩܫܝܫܐ /qaʃʃiʃe/; 中世ペルシア語: mahistan; 中国語: 默奚悉德; ピンイン: mòxīxīdé) 選ばれし者たちの総称(ラテン語:ēlēctī、シリア語:ܡܫܡܫܢܐ /m(ə)ʃamməʃɑne/、中世ペルシア語:ardawan または dēnāwar、中国語:阿羅緩、ピンイン:āluóhuǎn または 電那勿、ピンイン:diànnàwù) 聴者(ラテン語: audītōrēs; シリア語: ܫܡܘܥܐ /ʃɑmoʿe/; 中世ペルシア語: niyoshagan; 中国語: 耨沙喭; ピンイン: nòushāyàn) |

| Religious practices Prayers From Manichaean sources, Manichaeans observed daily prayers: four for the hearers or seven for the elect. The sources differ about the exact time of prayer. The Fihrist by al-Nadim appoints them afternoon, mid-afternoon, just after sunset, and at nightfall. Al-Biruni places the prayers at dawn, sunrise, noon, and dusk. The elect additionally prayed at mid-afternoon, half an hour after nightfall, and midnight. Al-Nadim's account of daily prayers is probably adjusted to coincide with the public prayers for the Muslims, while Al-Biruni's report may reflect an older tradition unaffected by Islam.[126][127] When Al-Nadim's account of daily prayers was the only detailed source available, there was a concern that Muslims only adopted these practices during the Abbasid Caliphate. However, it is clear that the Arabic text provided by Al-Nadim corresponds with the descriptions of Egyptian texts from the fourth century.[128] Every prayer started with an ablution with water or, if water was not available, with other substances comparable to ablution in Islam,[129] and consisted of several blessings to the apostles and spirits. The prayer consisted of prostrating oneself to the ground and rising again twelve times during every prayer.[130] During the day, Manichaeans turned towards the Sun and during the night towards the Moon. If the Moon is not visible at night, they turned towards the north.[131] Evident from Faustus of Mileve, Celestial bodies are not the subject of worship themselves but are "ships" carrying the light particles of the world to the supreme god, who cannot be seen, since he exists beyond time and space, and also the dwelling places for emanations of the supreme deity, such as Jesus the Splendour.[131] According to the writings of Augustine of Hippo, ten prayers were performed, the first devoted to the Father of Greatness, and the following to lesser deities, spirits, and angels and finally towards the elect, to be freed from rebirth and pain and to attain peace in the realm of light.[128] Comparably, in the Uyghur confession, four prayers are directed to the supreme God (Äzrua), the God of the Sun and the Moon, and fivefold God and the buddhas.[131] |

宗教的慣行 祈り マニ教の資料によれば、マニ教徒は毎日の祈りを守っていた。聴衆向けには四回、選ばれた者向けには七回である。祈りの正確な時刻については資料によって異 なる。アル=ナディムの『フィフルスト』では午後、午後半ば、日没直後、そして夜明け前と記されている。アル=ビルーニーは夜明け、日の出、正午、そして 夕暮れと位置づけている。選ばれた者たちはさらに、午後半ば、日没後30分、真夜中に祈った。アル=ナディムの記述はイスラム教徒の公的祈祷に合わせるた め調整された可能性が高く、アル=ビルーニーの報告はイスラムの影響を受けない古い伝統を反映しているかもしれない。[126][127] アル=ナディムの記述が唯一の詳しい情報源だった時代には、ムスリムがアッバース朝時代にこれらの慣習を取り入れたとの懸念があった。しかしアル=ナディムのアラビア語テキストは、4世紀のエジプト文献の記述と一致していることが明らかである。[128] 各祈祷は水による清めから始まり、水が得られない場合はイスラム教の清めに相当する他の物質を用いた[129]。祈祷は使徒や精霊への数回の祝福から成 り、祈祷ごとに十二回、地面に伏して再び起き上がる動作を繰り返した[130]。日中は太陽の方角へ、夜間は月の方角へ向かって祈った。夜に月が見えない 場合、彼らは北を向いた。[131] ミレウスのファウストゥスから明らかなように、天体はそれ自体が崇拝の対象ではなく、世界の光粒子を最高神へ運ぶ「船」であり、またイエス・ザ・スプレン ダーのような最高神の顕現の住処でもある。最高神は時空を超越して存在するため、見ることはできない。[131] ヒッポのアウグスティヌスの記述によれば、十の祈りが捧げられた。最初の祈りは偉大なる父に捧げられ、続く祈りは下位の神々、精霊、天使たちに向けられ、 最後に選ばれし者たちへ向けられた。彼らは再生と苦痛から解放され、光の領域において平安を得るためであった。[128] 同様に、ウイグルの信仰告白では、四つの祈りが至高の神(アズルア)、太陽と月の神、五重の神、そして仏たちに向けられている。[131] |