毛沢東主義

Maoism

☆ 毛沢東主義(Maoism)は、毛沢東が中華民国、そして後に中華人民共和国の農業中心の産業化前の社会で社会主義革命を実現しようとして発展させた、マル クス・レーニン主義の一派である。毛沢東主義と伝統的なマルクス・レーニン主義との違いは、産業革命以前の社会では、共産主義革命家だけではなく、階級社 会における進歩的な勢力の統一戦線が革命の先駆者となるという点だ[3]。革命の実践が第一であり、イデオロギーの正統性は二次的であるとするこの理論 は、産業革命以前の中国に適応した都市型マルクス・レーニン主義を表している。後の理論家は、毛沢東がマルクス・レーニン主義を中国の条件に適応させたと いう考えを拡大し、彼は実際にはそれを根本的に更新し、毛沢東主義は世界中で普遍的に適用可能だと主張した。この思想は、毛沢東のオリジナル思想と区別す るために、マルクス・レーニン主義・毛沢東主義と呼ばれることが多い[4][5][非一次資料が必要][6][ページ番号が必要]。 1950年代から1970年代後半の鄧小平による中国の経済改革まで、毛沢東主義は中国共産党と世界中の毛沢東主義革命運動の政治的・軍事的イデオロギー だった。[7] 1960年代の中ソ分裂後、中国共産党とソビエト連邦共産党はそれぞれ、マルクス・レーニン主義の正しい解釈と世界共産主義の思想的指導者としてのヨシ フ・スターリンの唯一の継承者・後継者であると主張した。[4]

★ 以下では、国際的な毛沢東主義(Maoism) の広がりについて解説する。それが終われば、ひきつづき、毛沢東が生きていた時代の毛沢東主義について解説する

International

influence The Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Centre) in February 2013 From 1962 onwards, the challenge to the Soviet hegemony in the world communist movement made by the CCP resulted in various divisions in communist parties around the world. At an early stage, the Albanian Party of Labour sided with the CCP.[53] So did many of the mainstream (non-splinter group) Communist parties in South-East Asia, like the Communist Party of Burma, the Communist Party of Thailand, and the Communist Party of Indonesia. Some Asian parties, like the Communist Party of Vietnam and the Workers' Party of Korea, attempted to take a middle-ground position. Cambodia's Khmer Rouge could have been considered a replica of the Maoist regime under the leadership of Angkar, however Maoists and Marxists generally contend that the CPK strongly deviated from Marxist doctrine and the few references to Maoist China in CPK propaganda were critical of the Chinese.[54][non-primary source needed] Various efforts have sought to regroup the international communist movement under Maoism since Mao's death in 1976. Many parties and organisations were formed in the West and Third World that upheld links to the CCP. Often, they took names such as Communist Party (Marxist–Leninist) or Revolutionary Communist Party to distinguish themselves from the traditional pro-Soviet communist parties. The pro-CCP movements were, in many cases, based on the wave of student radicalism that engulfed the world in the 1960s and 1970s. Only one Western classic communist party sided with the CCP, the Communist Party of New Zealand. Under the leadership of the CCP and Mao Zedong, a parallel international communist movement emerged to rival that of the Soviets, although it was never as formalised and homogeneous as the pro-Soviet tendency.  Maoist leader Prachanda speaking at a rally in Pokhara, Nepal After the death of Mao in 1976 and the resulting power struggles in China that followed, the international Maoist movement was divided into three camps. One group, composed of various ideologically nonaligned groups, gave weak support to the new Chinese leadership under Deng Xiaoping. Another camp denounced the new leadership as traitors to the cause of Marxism–Leninism–Mao Zedong Thought. The third camp sided with the Albanians in denouncing the Three Worlds Theory of the CCP (see the Sino-Albanian split).[citation needed] The pro-Albanian camp would start to function as an international group as well[55] (led by Enver Hoxha and the APL) and was also able to amalgamate many of the communist groups in Latin America, including the Communist Party of Brazil.[56] Later, Latin American Communists, such as Peru's Shining Path, also embraced the tenets of Maoism.[57] The new Chinese leadership showed little interest in the foreign groups supporting Mao's China. Many of the foreign parties that were fraternal parties aligned with the Chinese government before 1975 either disbanded, abandoned the new Chinese government entirely, or even renounced Marxism–Leninism and developed into non-communist, social democratic parties. What is today called the international Maoist movement evolved out of the second camp—the parties that opposed Deng and said they upheld the true legacy of Mao.[citation needed] |

国際的な影響 2013年2月のネパール共産党(毛沢東主義派) 1962年以降、世界共産主義運動におけるソ連のヘゲモニーに対する中国共産党の挑戦は、世界中の共産党の分裂をもたらした。初期段階では、アルバニア労 働党は中国共産党の側に立った。[53] 東南アジアの主流(分裂派ではない)共産党の多くも同様で、例えばビルマ共産党、タイ共産党、インドネシア共産党などが挙げられる。ベトナム共産党や朝鮮 労働党のようなアジアのいくつかの政党は、中間的な立場を取ろうとした。 カンボジアのクメール・ルージュは、アンカールの指導下で毛沢東主義政権の複製と見なすこともできたが、毛沢東主義者とマルクス主義者は一般的に、CPK はマルクス主義の教義から著しく逸脱しており、CPKの宣伝資料における毛沢東主義中国への言及は批判的だったと主張している。[54][非一次資料が必 要] 毛沢東の死後、1976年から国際共産主義運動を毛沢東主義の下で再結集する様々な努力が行われた。西欧と第三世界では、中国共産党とのつながりを維持す る多くの政党や組織が結成された。これら多くは、伝統的な親ソ連共産党と区別するため、「共産党(マルクス・レーニン主義)」や「革命的共産党」といった 名称を採用した。中国共産党支持の運動は、多くの場合、1960年代から1970年代にかけて世界を席巻した学生急進主義の波を基盤としていた。 西側諸国でCCPを支持した古典的な共産党は、ニュージーランド共産党のみだった。CCPと毛沢東の指導の下、ソ連に対抗する並行する国際共産主義運動が 台頭したが、これはソ連支持派ほど形式化され、均質ではなかった。  ネパールのポカラで開催された集会で演説する毛沢東主義指導者プラチャンド 1976年の毛沢東の死とその後中国で起きた権力闘争の後、国際毛沢東主義運動は3つの派閥に分裂した。1つのグループは、思想的に中立的な様々なグルー プからなり、鄧小平率いる新しい中国指導部に弱い支持を示した。もう1つの派閥は、新しい指導部をマルクス・レーニン主義・毛沢東思想の「裏切り者」と非 難した。3つ目の陣営は、アルバニア人とともに、中国共産党の「三世界理論」を非難した(中アルバニア分裂を参照)。[要出典] アルバニア支持派は、国際的なグループとしても機能し始め[55](エンヴェル・ホッジャとアルバニア労働党が指導)、ブラジル共産党を含むラテンアメリ カの多くの共産主義団体も統合することに成功した。[56] その後、ペルーの「輝ける道」など、ラテンアメリカの共産主義者も毛沢東主義の教義を受け入れた。[57] 新しい中国指導部は、毛沢東の中国を支持する外国の団体にはほとんど関心を示さなかった。1975年以前に中国政府と友好関係にあった多くの外国政党は、 解散したり、新中国政府を完全に離反したり、マルクス・レーニン主義を放棄して非共産主義の社会民主主義政党へと変貌した。現在「国際毛沢東主義運動」と 呼ばれるものは、第二陣営——鄧小平に反対し、毛沢東の真の遺産を継承すると主張した政党——から発展した[出典必要]。 |

| Afghanistan The Progressive Youth Organization was a Maoist organisation in Afghanistan. It was founded in 1965 with Akram Yari as its first leader, advocating the overthrow of the then-current order through people's war. The Communist (Maoist) Party of Afghanistan was founded in 2004 through the merger of five MLM parties.[58] Australia The Communist Party of Australia (Marxist-Leninist) is a Maoist organisation in Australia. It was founded in 1964 as a pro-Mao split from the Australian Communist Party.[59] Bangladesh The Purba Banglar Sarbahara Party is a Maoist party in Bangladesh. It was founded in 1968 with Siraj Sikder as its first leader. The party played a role in the Bangladesh Liberation War. Belgium The Sino-Soviet split had a significant influence on communism in Belgium. The pro-Soviet Communist Party of Belgium experienced a split of a Maoist wing under Jacques Grippa. The latter was a lower-ranking CPB member before the split, but Grippa rose in prominence as he formed a worthy internal Maoist opponent to the CPB leadership. His followers were sometimes referred to as Grippisten or Grippistes. When it became clear that the differences between the pro-Moscow leadership and the pro-Beijing wing were too significant, Grippa and his entourage decided to split from the CPB and formed the Communist Party of Belgium – Marxist–Leninist (PCBML). The PCBML had some influence, mainly in the heavily industrialised Borinage region of Wallonia, but never managed to gather more support than the CPB. The latter held most of its leadership and base within the pro-Soviet camp. However, the PCBML was the first European Maoist party and was recognised at its foundation as the largest and most important Maoist organisation in Europe outside of Albania.[60][61] Although the PCBML never really gained a foothold in Flanders, there was a reasonably successful Maoist movement in this region. Out of the student unions that formed in the wake of the May 1968 protests, Alle Macht Aan De Arbeiders (AMADA), or All Power To The Workers, was formed as a vanguard party under construction. This Maoist group originated primarily from students from the universities of Leuven and Ghent but did manage to gain some influence among the striking miners during the shutdowns of the Belgian stone coal mines in the late 1960s and early 1970s. This group became the Workers' Party of Belgium (PVDA-PTB) in 1979 and still exists today, although its power base has shifted somewhat from Flanders towards Wallonia. The WPB stayed loyal to the teachings of Mao for a long time, but after a general congress held in 2008, the party formally broke with its Maoist/Stalinist past.[62] |

アフガニスタン 進歩青年組織は、アフガニスタンにおける毛沢東主義の組織だった。1965年に、アクラム・ヤリを最初の指導者として設立され、人民戦争によって当時の体 制の打倒を主張していた。 アフガニスタン共産党(毛沢東主義)は、5つのマルクス・レーニン主義政党が合併して2004年に設立された。 オーストラリア オーストラリア共産党(マルクス・レーニン主義)は、オーストラリアの毛沢東主義組織だ。1964年に、オーストラリア共産党から毛沢東支持派が分裂して 設立された。[59] バングラデシュ プルバ・バングラ・サルバハラ党は、バングラデシュの毛沢東主義政党だ。1968年に、シラジ・シクダーを初代党首として設立された。この政党は、バング ラデシュ独立戦争で役割を果たした。 ベルギー 中ソ分裂は、ベルギーの共産主義に大きな影響を与えた。親ソ連のベルギー共産党は、ジャック・グリッパ率いる毛沢東主義派が分裂した。グリッパは分裂前は CPBの下級党員だったが、CPB指導部に匹敵する毛沢東主義の反対派として台頭した。彼の支持者は、グリッピスト、あるいはグリッピスト派と呼ばれた。 モスクワ派と北京派の対立が深刻化すると、グリッパとその支持者は CPB から分裂し、ベルギー共産党 - マルクス・レーニン主義者(PCBML)を結成した。PCBMLは、ワロニア地方の工業地帯であるボリナージュ地域で一定の影響力を持っていたが、CPB を超える支持を獲得することはできなかった。CPBは、指導部と支持基盤の大部分をソ連派陣営内に保持していた。しかし、PCBMLはヨーロッパ初の毛沢 東主義政党であり、設立時にアルバニアを除くヨーロッパ最大の毛沢東主義組織として認められた。[60][61] PCBML はフランダース地方では決して足場を固めることはできなかったが、この地域ではかなり成功した毛沢東主義運動があった。1968年5月の抗議運動を受けて 結成された学生組合の中から、Alle Macht Aan De Arbeiders(AMADA、労働者にすべての権力を)という先駆的な政党が結成された。この毛沢東主義グループは主にルーヴェンとゲントの大学の学 生から成り立っていたが、1960年代後半から1970年代初頭のベルギーの石炭鉱山閉鎖時にストライキに参加した鉱山労働者の間で一定の影響力を獲得し た。このグループは1979年にベルギー労働者党(PVDA-PTB)に改名し、現在も存続しているが、その勢力基盤はフランドルからワロン地方へやや 移っている。WPBは長らく毛沢東の思想に忠実だったが、2008年に開催された党大会で、毛沢東主義/スターリン主義の過去と正式に決別した。[62] |

| Ecuador The Communist Party of Ecuador – Red Sun, also known as Puka Inti, is a small Maoist guerrilla organisation in Ecuador. France See also: Communism in France In 1964, a Maoist circle formed at École Normale among students who studied with Louis Althusser.[63]: 226–227 The group initially sought to develop leadership over the French Communist Party's (PCF) student organization, but in December 1966 their own organization, the Union of Marxist-Leninist Communist Youth.[63]: 227 In 1966, PCF members dissatisfied with the party's direction formed their own movement and in 1967 they founded the Maoist-oriented French Marxist–Leninist Communist Party.[63]: 226 French Maoism grew after the Sino-Soviet split and particularly from 1966 to 1976.[63]: 225 After May 68, the cultural influence of French Maoists increased.[64]: 122 Maoists became the first group of French intellectuals to emphasize gay and lesbian rights in their publications and contributed to the nascent feminist movement in France.[64]: 122 The École Normale Maoists merged with leaders of May 68 to form Proletarian Left.[63]: 227 For six years, it was the most visible Maoist organization in France.[63]: 227 Proletarian Left worked in cities, working class suburbs, rural areas, and immigrant communities.[63]: 227 Its areas of focus included abortion rights, international leftism, and organizing in universities and among factory workers.[63]: 227 Proletarian Left included developed supporters among intellectuals, such as Jean-Paul Sartre (who nominally filled the position of editor at a Proletarian Left newspaper after its editor was arrested) and Michel Foucault (who was influential in Proletarian Left's Prison Information Group, which investigated the conditions of prisoners, including political prisoners).[63]: 227–228 Proletarian Left was radically anti-hierarchical, and ultimately failed to maintain its organization, dissolving in 1974.[63]: 228 Alain Badiou is one of the central intellectual figures in the analysis of French Maoism and its legacies.[63]: 241 |

エクアドル エクアドル共産党 – レッド・サン(Puka Inti)は、エクアドルにある小規模な毛沢東主義のゲリラ組織だ。 フランス 参照:フランスの共産主義 1964年、ルイ・アルチュセールに師事していた学生たちによって、エコール・ノルマルで毛沢東主義のサークルが結成された。[63]: 226–227 このグループは当初、フランス共産党(PCF)の学生組織の指導権を獲得しようとしたが、1966年12月に独自の組織「マルクス・レーニン主義共産主義 青年連合」を結成した。[63]: 227 1966年、党の方向性に不満を抱いた PCF 党員たちが独自の運動を結成し、1967年に毛沢東主義を志向するフランス・マルクス・レーニン主義共産党を設立した。[63]: 226 フランス毛沢東主義は、中ソ分裂後、特に 1966年から1976年にかけて成長した。[63]: 225 1968年5月以降、フランス毛沢東主義者の文化的影響力は高まった。[64]: 122 毛沢東主義者は、出版物で同性愛者の権利を強調した最初のフランス知識人グループとなり、フランスで芽生えたフェミニスト運動に貢献した。[64]: 122 エコール・ノルマル・マオイストは、1968年5月の指導者と合併してプロレタリアン・レフトを結成した。[63]: 227 6年間、フランスで最も目立つ毛沢東主義組織だった。[63]: 227 プロレタリアン・レフトは、都市、労働者階級の郊外、農村部、移民コミュニティで活動した。[63]: 227 その活動分野には、中絶の権利、国際的な左翼運動、大学や工場労働者の中での組織化が含まれていた。[63]: 227 プロレタリア左派には、ジャン=ポール・サルトル(プロレタリア左派の新聞の編集長が逮捕された後、名目上その職を務めた)やミシェル・フーコー(政治犯 を含む囚人の状況を調査したプロレタリア左派の「刑務所情報グループ」で影響力を持っていた)など、知識人層に支持者が多かった。[63]: 227–228 プロレタリア左派は、過激な反階層主義を掲げていたため、結局組織を維持できず、1974年に解散した。[63]: 228 アラン・バディウは、フランスの毛沢東主義とその遺産を分析する上で中心的な知識人の一人である。[63]: 241 |

| India Mao's ideology developed adherents among Indian communists during the 1946-1951 Telangana uprising in Andhra Pradesh and the Tebhaga Movement in Bengal (1946–1950).[65]: 118 Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong gained popularity following the 1967 Naxalbari uprising and the beginning of the Naxalite Movement.[65]: 117 The leader of the first phase of the Naxalite Movement, Charu Majumdar, placed major emphasis on the text, requiring it to be studied and to be read aloud to illiterate peasants.[65]: 117 During this phase of the Naxalite Movement, Quotations was popular among both movement participants and those who sympathized with it.[65]: 118 Contending that China's approach to revolution provided the path for revolution in India, Majumdar and others split from the Communist Party of India (Marxist) to form the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist).[65]: 120 The Communist Party of India (Maoist) is the leading Maoist organisation in India. The CPI (Maoist) is designated as a terrorist organization in India under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act.[66] Since 1967, there has been an ongoing conflict in India between the Indian government and Maoist insurgents.[67] As of 2018, there have been a total of 13,834 deaths across insurgents, security forces, and civilians.[68] Iran Main article: 1982 Amol uprising The Union of Iranian Communists (Sarbedaran) was an Iranian Maoist organisation. The UIC (S) was formed in 1976 after the alliance of Maoist groups carrying out military actions within Iran. In 1982, the UIC (S) mobilised forces in forests around Amol and launched an insurgency against the Islamist Government. The uprising was eventually a failure, and many UIC (S) leaders were shot. The party dissolved in 1982.[69] Following the dissolution of the Union of Iranian Communists, the Communist Party of Iran (Marxist–Leninist–Maoist) was formed in 2001. The party is a continuation of the Sarbedaran Movement and the Union of Iranian Communists (Sarbedaran). CPI (MLM) believes Iran is a 'semifeudal-semicolonial' country and is trying to launch a 'People's war' in Iran. Israel The 1970s group Ma'avak (an offshoot of Matzpen) was influenced by Maoism.[70] After a further split, some of its former members (including Ehud Adiv and Daud Turki) were charged with treason for meeting with Syrian intelligence officials, in a highly publicized trial.[71] Italy In Italy, the 1963 book Le Divergenze tra il compagno Togliatti e noi (Divergences between Comrade Togliatti and us) increased interest in the Chinese communist approach.[72]: 187 The text, written in China, responded to Palmiro Togliatti's criticisms of Mao for Mao's opposition to de-Stalinization.[72]: 187 Months after the publication of Le Divergenze, the first Italian party inspired by Mao's ideology was founded.[72]: 190 Shortly after, former partisan Giuseppe Regis founded the publisher Edizioni Oriente (Eastern Editions), which translated and published Maoist texts, including Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong.[72]: 190 In early 1964, Mao-oriented activists founded the newspaper Nuova Unità (New Unity), which called for Italian communists break with the stance of the Italian Communist Party and align with the socialist countries against American imperialism.[72]: 190 Numerous political factions and groupings took inspiration from Mao's theories and practice.[72]: 191–192 Among the most visible Mao-inspired group was Servire il Popolo (Serve the People), which modeled itself on the Red Guards of China.[72]: 192 Servire il Popolo practiced self-criticism and "serving and teaching the peasants" in rural Italy.[72]: 192 Violent groups which cited Mao included The Brigatte Rosse (Red Brigades) and Lotta Continua (Continuous Fight).[72]: 192 |

インド 毛沢東の思想は、1946年から1951年にかけてアンドラ・プラデシュ州で起こったテランガーナ蜂起、およびベンガル州で起こったテバガ運動(1946 年~1950年)の間に、インドの共産主義者たちの間で支持者を増やした。[65]: 118 毛沢東主席の引用は、1967年のナクサバリ蜂起とナクサライト運動の開始後に人気を博した。[65]: 117 ナクサライト運動の第1段階の指導者であるチャール・マジュムダルは、このテキストに重点を置き、その研究と、文盲の農民への朗読を義務付けた。 [65]: 117 この段階のナクサライト運動では、引用集は運動参加者だけでなく、運動に共感する人々にも人気があった。[65]: 118 中国革命のアプローチがイン ド革命の道筋を示していると主張したマジュムダルらは、インド共産党(マルクス主義)から分裂し、インド共産党(マルクス・レーニン主義)を結成した。 [65]: 120 インド共産党(毛沢東主義者)は、インドの毛沢東主義の主要組織だ。CPI(毛沢東主義者)は、違法活動(防止)法に基づき、インドでテロ組織に指定され ている。[66] 1967年以来、インドでは、インド政府と毛沢東主義の反乱軍との間で紛争が続いている。[67] 2018年現在、反乱軍、治安部隊、民間人合わせて13,834人が死亡している。[68] イラン 主な記事:1982年アモル蜂起 イラン共産党(Sarbedaran)は、イランの毛沢東主義組織だった。UIC(S)は、イラン国内で軍事行動を展開していた毛沢東主義派のグループが 連合して1976年に結成された。1982年、UIC(S)はアモルの周辺の森林に部隊を動員し、イスラム主義政権に対して反乱を起こした。この反乱は最 終的に失敗に終わり、多くのUIC(S)指導者が射殺された。同党は1982年に解散した。[69] イラン共産主義者連合の解散後、2001年にイラン共産党(マルクス・レーニン主義・毛沢東主義)が結成された。この党は、サルベダラン運動とイラン共産 主義者連合(サルベダラン)の継続組織である。CPI(MLM)は、イランは「半封建半植民地」国家であり、イランで「人民戦争」を開始しようとしている と主張している。 イスラエル 1970年代のグループ「マアヴァク」(マツペンから分裂)は毛沢東主義の影響を受けた。[70] さらに分裂した後、その元メンバーの一部(エフード・アディブとダウード・トゥルキを含む)は、シリアの諜報機関関係者との会合を理由に反逆罪で起訴さ れ、大々的に報道された裁判を受けた。[71] イタリア イタリアでは、1963年の書籍『Le Divergenze tra il compagno Togliatti e noi(同志トリアッティと我々の間の相違)』が、中国の共産主義的アプローチへの関心を高めた。[72]: 187 中国で執筆されたこのテキストは、毛沢東のスターリン主義廃止反対に対するパルミロ・トリアッティの批判に応えたものだった。[72]: 187 『Le Divergenze』の出版から数ヶ月後、毛沢東の思想に感化されたイタリア初の政党が設立された。[72]: 190 その後まもなく、元パルチザンであるジュゼッペ・レジスが、毛沢東の著作『毛沢東語録』などの毛沢東主義の文献を翻訳・出版する出版社、Edizioni Oriente(東方出版社)を設立した。[72]: 190 1964年初頭、毛沢東志向の活動家たちが新聞『Nuova Unità(新しい統一)』を創刊し、イタリアの共産主義者たちに、イタリア共産党の立場から離脱し、アメリカ帝国主義に対抗する社会主義諸国と連帯する よう呼びかけた。[72]: 190 毛沢東の理論と実践から影響を受けた政治派閥や団体は数多くあった。[72]: 191–192 最も目立った毛沢東に影響を受けたグループの一つは、中国の紅衛兵をモデルにした「Servire il Popolo(人民に奉仕する)」だった。[72]: 192 Servire il Popolo は、イタリアの農村部で自己批判と「農民への奉仕と教育」を実践した。[72]: 192 毛沢東を引用した暴力集団には、The Brigatte Rosse(赤軍派)や Lotta Continua(継続的闘争)があった。[72]: 192 |

| Mao-Spontex Mao-Spontex refers to a Maoist interpretation in western Europe that stresses the importance of the cultural revolution and overthrowing hierarchy.[73] A political movement in the Marxist and libertarian movements in Western Europe from 1968 to 1971,[74][73] Mao-Spontex came to represent an ideology promoting the ideas of Maoism with some influence from Marxism and Leninism, but rejecting the total idea of Marxism–Leninism.[73] Palestine The Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine was initially influenced by Maoism but shifted towards the Soviet Union after 1970.[75] Peru As a result of factors including the Sino-Soviet split in the early 1960s and the later development of Shining Path, Peru became the Latin American country with the largest Maoist tendency among its communist movements.[76]: 132 The Maoist-inspired group Shining Path and its leader Abimael Guzmán viewed revolution as requiring prolonged people's war.[77]: 39 According to academic Carlos Iván Degregori, Shining Path's view of violence exceeded the typical Maoist confines, with Shining Path viewing violence as a value in itself instead of a means.[77]: 141–142 In the 1980s and 1990s, it waged an insurgency against the Peruvian state that resulted in tens of thousands of deaths.[78] |

マオ・スポンテックス マオ・スポンテックスとは、文化革命と階層制度の打倒の重要性を強調する、西ヨーロッパにおける毛沢東主義の解釈を指す。[73] 1968年から1971年にかけて西ヨーロッパのマルクス主義およびリバタリアン運動の中で起こった政治運動。[74][73] マオ・スポンテックスは、マルクス主義とレーニン主義の影響を一部受けながら、マルクス・レーニン主義の全体的な思想を拒否する、毛沢東主義の思想を推進 するイデオロギーを表すようになった。 パレスチナ パレスチナ解放民主戦線は、当初は毛沢東主義の影響を受けていたが、1970年以降、ソ連に傾倒するようになった。[75] ペルー 1960年代初頭の中ソ分裂や、その後の輝ける道の発展などの要因により、ペルーは共産主義運動の中で毛沢東主義の傾向が最も強いラテンアメリカ諸国と なった[76]: 132 毛沢東主義に感化されたグループ「輝ける道」とその指導者アビマエル・グズマンは、革命には長期にわたる人民戦争が必要であると見なしていた[77]: 39 。学者カルロス・イヴァン・デグレゴリによると、輝ける道の暴力観は、典型的な毛沢東主義の枠を超え、暴力は手段ではなく、それ自体が価値であると 見なしていた。[77]: 141–142 1980年代から1990年代にかけて、ペルー政府に対して反乱を起こし、数万人の死者を出した。[78] |

| Philippines Main article: Communist Party of the Philippines The Communist Party of the Philippines is the largest communist party in the Philippines, active since December 26, 1968 (Mao's birthday). It was formed due to the First Great Rectification Movement and a split between the old Partido Komunista ng Pilipinas-1930, which the founders saw as revisionist. The CPP was formed on Maoist lines in stark contrast with the old PKP, which focused primarily on the parliamentary struggle. The CPP was founded by Jose Maria Sison and other cadres from the old party.[79] The CPP also has an armed wing that it exercises absolute control over, namely the New People's Army. It currently wages a guerrilla war against the government of the Republic of the Philippines in the countryside and is still currently active. The CPP and the NPA are part of the National Democratic Front of the Philippines, a consolidation of Maoist sectoral organisations such as Kabataang Makabayan as part of the united front strategy. The NDFP also represents the people's democratic government in peace talks.[80] |

フィリピン 主な記事:フィリピン共産党 フィリピン共産党は、1968年12月26日(毛沢東の誕生日)に結成された、フィリピン最大の共産党だ。この党は、第一次大整頓運動と、創設者たちが修 正主義的だと見なした旧フィリピン共産党(1930年)との分裂によって結成された。CPP は、主に議会闘争に重点を置いていた旧 PKP と対照的に、毛沢東主義の路線に基づいて結成された。CPP は、ホセ・マリア・シソンと旧党の幹部たちによって設立された。 CPP には、新人民軍という、CPP が絶対的な支配力を持つ武装組織もある。現在、フィリピン共和国政府に対して、農村部でゲリラ戦を展開しており、現在も活動を続けている。CPP と NPA は、統一戦線戦略の一環として、カバタアン・マカバヤンなどの毛沢東主義の部門別組織が統合して結成されたフィリピン国民民主戦線(NDFP)の一部だ。 NDFP は、和平交渉において人民民主政府も代表している[80]。 |

Portugal The flag of FP-25 Maoist movements in Portugal were very active during the 1970s, especially during the Carnation Revolution that led to the fall of the nationalist government (the Estado Novo) in 1974. Portugal's most significant Maoist movement was the Portuguese Workers' Communist Party. The party was among the most active resistance movements before the Portuguese democratic revolution of 1974, especially among the Marxist–Leninist Students' Federation in Lisbon. After the revolution, the MRPP achieved fame for its large and highly artistic mural paintings. Intensely active between 1974 and 1975, during that time, the party had members that later came to be significant in national politics. For example, a future Prime Minister of Portugal, José Manuel Durão Barroso, was active in Maoist movements in Portugal and identified as a Maoist. In the 1980s, the Forças Populares 25 de Abril was another far-left Maoist armed organisation operating in Portugal between 1980 and 1987, aiming to create socialism in post-revolutionary Portugal. Spain The Communist Party of Spain (Reconstituted) was a Spanish clandestine Maoist party. The party's armed wing was the First of October Anti-Fascist Resistance Groups. Sweden In 1968, a small extremist Maoist sect called Rebels (Swedish: Rebellerna) was established in Stockholm. Led by Francisco Sarrión, the group unsuccessfully demanded that the Chinese embassy admit them into the Chinese Communist Party. The organisation only lasted a few months.[81] Tanzania The Tanzanian socialist approach of ujamaa promoted by President Julius Nyerere drew on Maoist themes including self-reliance, mass politics, the political centrality of the peasantry.[82]: 96–97 Ujamaa also adopted Chinese historic milestones as part of its symbolism, including the Cultural Revolution and the Long March.[82]: 96 Turkey See also: Maoist insurgency in Turkey The Communist Party of Turkey/Marxist–Leninist (TKP/ML) is a Maoist organisation in Turkey currently waging a people's war against the Turkish government. It was founded in 1972 as a split from another illegal Maoist party, the Revolutionary Workers' and Peasants' Party of Turkey (TİİKP), which Doğu Perinçek founded in 1969, led by İbrahim Kaypakkaya. The party's armed wing is named the Workers' and Peasants' Liberation Army in Turkey (TİKKO). TİİKP is succeeded by the Patriotic Party, headed by Perinçek. Though Perinçek was significantly influenced by Mao, the Patriotic Party says he's not a Maoist, instead saying that he embraced "Mao's contributions to the literature of the world revolution and scientific socialism" and "adapted them to Turkey's conditions".[83] |

ポルトガル FP-25 の旗 ポルトガルにおける毛沢東主義運動は、1970年代、特に1974年にナショナリスト政権(エスタド・ノヴォ)の崩壊につながったカーネーション革命の間 に非常に活発だった。 ポルトガルで最も重要な毛沢東主義運動は、ポルトガル労働者共産党だった。この党は、1974年のポルトガル民主革命以前、特にリスボンのマルクス・レー ニン主義学生連盟の中で、最も活発な抵抗運動のひとつだった。革命後、MRPP は、大規模で芸術性の高い壁画で有名になった。 1974年から1975年にかけて活発に活動し、その間、後に国の政治で重要な役割を果たすメンバーもいた。例えば、ポルトガルの元首相ジョゼ・マヌエ ル・ドゥラン・バローゾは、ポルトガルでの毛沢東主義運動に積極的に参加し、毛沢東主義者として自認していた。1980年代には、ポルトガルで1980年 から1987年まで活動した極左毛沢東主義武装組織「4月25日人民勢力」が、革命後のポルトガルに社会主義を樹立することを目的として活動した。 スペイン スペイン共産党(再建)は、スペインの秘密毛沢東主義政党だった。同党の武装部門は「10月1日反ファシスト抵抗グループ」だった。 スウェーデン 1968年、ストックホルムで「反乱軍(Rebellerna)」と呼ばれる小さな過激な毛沢東主義の宗派が設立された。フランシスコ・サリオンが率いる このグループは、中国大使館に対して、彼らを中国共産党に受け入れるよう要求したが、失敗に終わった。この組織は数ヶ月で消滅した。[81] タンザニア ジュリウス・ニエレレ大統領が推進したタンザニアの社会主義的アプローチ「ウジャマー」は、自力更生、大衆政治、農民の政治的中心性など、毛沢東主義の テーマを取り入れていた。[82]: 96–97 ウジャマーは、文化大革命や長征など、中国の歴史的節目も象徴として採用した。[82]: 96 トルコ 参照:トルコにおける毛沢東主義の反乱 トルコ共産党/マルクス・レーニン主義者(TKP/ML)は、トルコにおける毛沢東主義組織で、現在、トルコ政府に対して人民戦争を繰り広げている。 1972年に、1969年にドグウ・ペリンチェクが設立し、イブラヒム・カイパクカヤが率いた別の違法毛沢東主義政党、トルコ革命的労働者・農民党 (TİİKP)から分裂して設立された。同党の武装部門は、トルコ労働者・農民解放軍(TİKKO)と名付けられている。TİİKPは、ペリンチェクが率 いる愛国党に継承された。ペリンチェクは毛沢東に大きな影響を受けたが、愛国党は彼が毛沢東主義者ではないと主張し、代わりに「世界革命と科学的社会主義 の文献における毛沢東の貢献を擁護し、それらをトルコの状況に適応させた」と述べている。[83] |

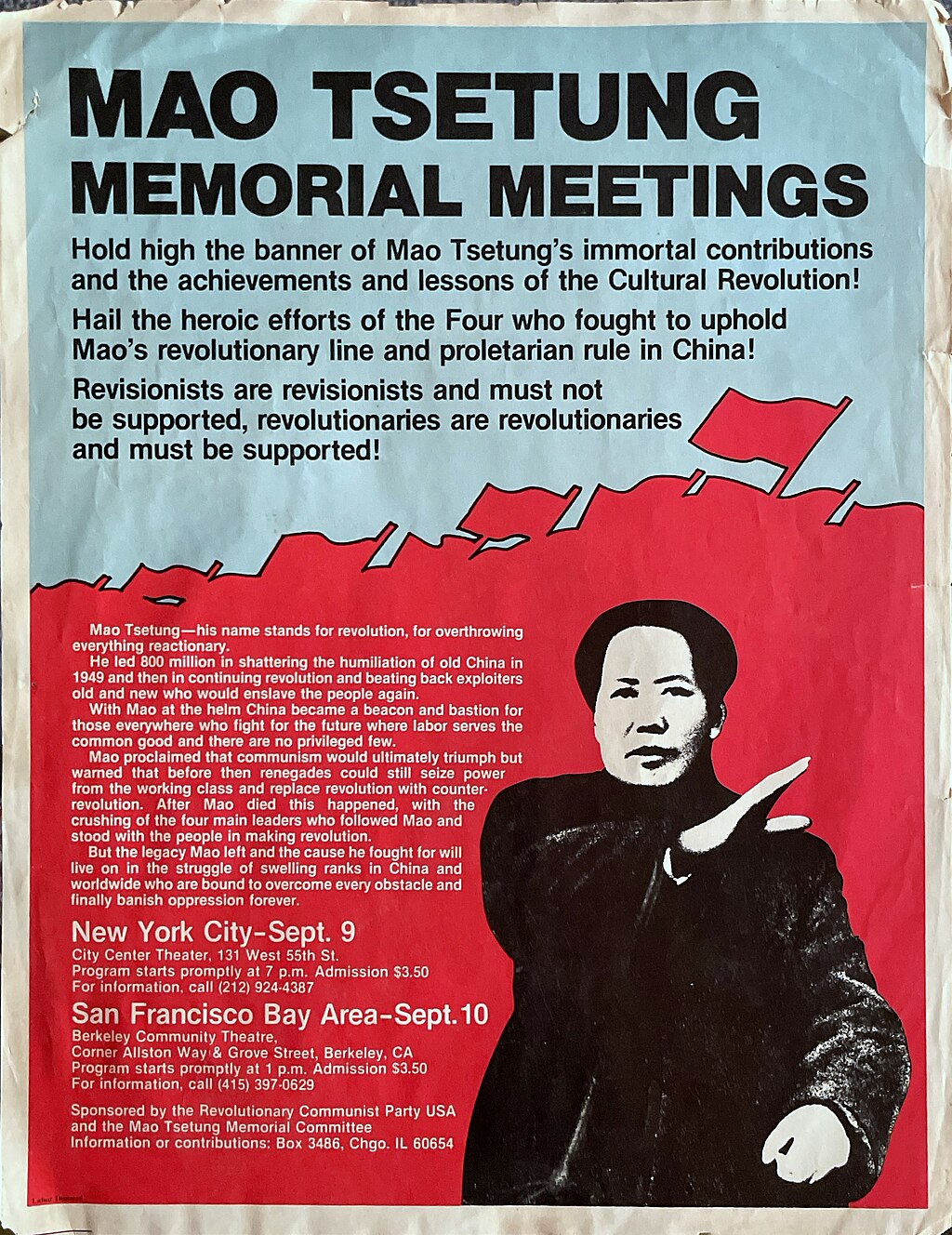

| United States After the tumultuous 1960s (particularly the events of 1968, such as the launch of the Tet Offensive, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., nationwide university protests, and the election of Richard Nixon), proponents of Maoist ideology constituted the "largest and most dynamic" branch of American socialism.[84][85] From this branch came a collection of "newspapers, journals, books, and pamphlets," each of which spoke on the unreasonability of the American system and proclaimed the need for a concerted social revolution.[84] Among the many Maoist principles, the group of aspiring American revolutionaries sympathized with the idea of a protracted people's war, which would allow citizens to address the oppressive nature of global capitalism martially.[86] Maoism was a major influence on the New Communist movement. Mounting discontent with racial oppression and socioeconomic exploitation birthed the two largest, officially-organized Maoist groups: the Revolutionary Communist Party and the October League.[87] However, these were not the only groups: a slew of organizations and movements emerged across the globe as well, including I Wor Kuen, the Black Workers Congress, the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Workers Organization, the August Twenty-Ninth Movement, the Workers Viewpoint Organization, and many others—all of which overtly supported Maoist doctrine.[84] Orchestrated by The Guardian, in the spring of 1973, an attempt to conflate the strands of American Maoism was made with a series of sponsored forums titled "What Road to Building a New Communist Party?" The forums drew 1,200 attendees to a New York City auditorium that spring.[88] The central message of the event revolved around "building an anti-revisionist, non-Trotskyist, non-anarchist party".[89] From this, other forums were held worldwide, covering topics such as "The Role of the Anti-Imperialist Forces in the Antiwar Movement" and "The Question of the Black Nation"—each forum rallying, on average, an audience of 500 activists, and serving as a "barometer of the movement's strength."[88] The Americans' burgeoning Maoist and Marxist–Leninist movements proved optimistic for a potential revolution, but "a lack of political development and rampant rightist and ultra-leftist opportunism" thwarted the advancement of the greater communist initiative.[88] In 1972, Richard Nixon made a landmark visit to the People's Republic of China to shake hands with Chairman Mao Zedong; this simple handshake marked the gradual pacification of east–west hostility and the re-formation of relations between "the most powerful and most populous" global powers: the United States and China.[90][91] Nearly a decade after the Sino-Soviet split, this newfound amiability between the two nations quieted American-based counter-capitalist rumblings and marked the steady decline of American Maoism until its unofficial cessation in the early-1980s.[92] The Black Panther Party (BPP) was another American-based, left-wing revolutionary party to oppose American global imperialism; it was a self-described Black militant organization with metropolitan chapters in Oakland, California, New York, Chicago, Seattle, and Los Angeles, and an overt sympathizer with global anti-imperialistic movements (e.g., Vietnam's resistance of American neo-colonial efforts).[93][94][95][96] In 1971, a year before Nixon's monumental visit, BPP leader Huey P. Newton landed in China, whereafter he was enthralled with the East and the achievements of the Chinese Communist Revolution.[97] After his return to the United States, Newton said that "[e]verything I saw in China demonstrated that the People's Republic is a free and liberated territory with a socialist government" and "[t]o see a classless society in operation is unforgettable".[98] He extolled the Chinese police force as one that "[served] the people" and considered the Chinese antithetical to American law enforcement, which, according to Newton, represented "one huge armed group that was opposed to the will of the people".[98] In general, Newton's first encounter with anti-capitalist society commenced a psychological liberation and embedded within him the desire to subvert the American system in favor of what the BPP called "revolutionary intercommunalism".[99] Furthermore, the BPP was founded on a similar politico-philosophical framework as that of Mao's CCP, that is, "the philosophical system of dialectical materialism" coupled with traditional Marxist theory.[97] The words of Mao, quoted liberally in BPP speeches and writings, served as a guiding light for the party's analysis and theoretical application of Marxist ideology.[100] 1978 Revolutionary Communist Party USA poster commemorating Mao's legacy. In his autobiography Revolutionary Suicide, published in 1973, Newton wrote: Chairman Mao says that death comes to all of us, but it varies in its significance: to die for the reactionary is lighter than a feather; to die for the revolution is heavier than Mount Tai. [...] When I presented my solutions to the problems of Black people, or when I expressed my philosophy, people said, "Well, isn't that socialism?" Some of them were using the socialist label to put me down, but I figured that if this was socialism, then socialism must be a correct view. So I read more of the works of the socialists and began to see a strong similarity between my beliefs and theirs. My conversion was complete when I read the four volumes of Mao Tse-tung to learn more about the Chinese Revolution.[98] |

アメリカ合衆国 激動の 1960 年代(特に、テト攻勢の開始、マーティン・ルーサー・キング・ジュニアの暗殺、全国的な大学抗議運動、リチャード・ニクソンの大統領選挙など、1968 年の出来事)の後、毛沢東主義のイデオロギーの支持者は、アメリカの社会主義の「最大かつ最もダイナミックな」一派を形成した[84][85]。この派閥 からは、「新聞、雑誌、書籍、パンフレット」などの出版物が多数発行され、そのいずれもが、アメリカ体制の不合理性を指摘し、協調的な社会革命の必要性を 唱えていました[84]。多くの毛沢東主義の原則のうち、アメリカの革命志願者たちは、市民が世界資本主義の抑圧的な性質に武力によって立ち向かうことを 可能にする、長期にわたる人民戦争の考えに共感していました。[86] 毛沢東主義は、新共産主義運動に大きな影響を与えた。 人種的抑圧と社会経済的搾取に対する不満の高まりから、公式に組織された 2 つの最大の毛沢東主義団体、革命共産党と 10 月同盟が誕生した。[87] しかし、これらは唯一のグループではなかった。世界中で数多くの組織や運動が台頭し、その中にはI Wor Kuen、ブラック・ワーカーズ・コングレス、プエルトリコ革命労働者組織、8月29日運動、ワーカーズ・ビューポイント・オーガニゼーションなど、毛沢 東主義の教義を公然と支持する団体が数多く含まれていた。[84] ガーディアン紙の主導で、1973年春、一連のスポンサー付きフォーラム「新しい共産党を構築するための道とは?」が開催され、アメリカの毛沢東主義の諸 派を統合する試みがなされた。このフォーラムには、その春、ニューヨーク市の講堂に1,200人が集まった。[88] このイベントの中心的メッセージは、「反修正主義、非トロツキスト、非アナキストの党を建設する」というものだった。[89] これをきっかけに、「反戦運動における反帝国主義勢力の役割」や「黒人国家の問題」などのテーマを扱ったフォーラムが世界中で開催され、各フォーラムには 平均 500 人の活動家が参加し、「運動の勢力のバロメーター」としての役割を果たした[88]。 アメリカで台頭する毛沢東主義とマルクス・レーニン主義の運動は、革命の可能性に楽観的な見方を示したが、「政治的発展の欠如と右派・極左派の機会主義の 蔓延」が、より広範な共産主義運動の進展を阻害した。[88] 1972年、リチャード・ニクソンは、毛沢東主席と握手するために、中華人民共和国を歴史的な訪問した。この単純な握手は、東西の敵対関係の漸進的な緩和 と、「最も強力で最も人口の多い」世界大国である米国と中国の関係の再構築を象徴するものだった。[90][91] 中ソ分裂から 10 年近く経ち、この 2 つの国民間の新たな友好関係により、アメリカを拠点とする反資本主義のうねりは静まり、アメリカの毛沢東主義は 1980 年代初頭に非公式に終焉を迎えるまで、着実に衰退していった。[92] ブラックパンサー党(BPP)は、アメリカのグローバル帝国主義に反対する、もう一つのアメリカを拠点とする左翼革命政党だった。カリフォルニア州オーク ランド、ニューヨーク、シカゴ、シアトル、ロサンゼルスに都市支部を持つ、自らを「黒人過激派組織」と表現し、グローバルな反帝国主義運動(例えば、アメ リカのネオコロニアル主義的取り組みに対するベトナムの抵抗運動)に公然と共感していた。[93][94][95][96] 1971年、ニクソン大統領の画期的な訪問の1年前、BPPのリーダーであるヒューイ・P・ニュートンは中国を訪れ、東洋と中国共産党革命の成果に魅了さ れた。[97] 米国に戻った後、ニュートンは「中国で見たものはすべて、人民共和国が社会主義政府による自由で解放された領土であることを示していた」とし、「階級なき 社会が機能しているのを見たことは忘れられない」と述べた。[98] 彼は、中国の警察を「人民に奉仕する」組織として称賛し、ニュートンによれば「人民の意志に反対する巨大な武装集団」であるアメリカの法執行機関とは正反 対のものだと考えていました。[98] 一般に、ニュートンの反資本主義社会との最初の接触は、心理的な解放をもたらし、彼の中にアメリカシステムを覆し、BPPが「革命的共同体主義」と呼ぶも のを支持する願望を植え付けた。[99] さらに、BPPは毛沢東の中国共産党(CCP)と類似した政治哲学的枠組み、すなわち「弁証法的唯物論の哲学体系」と伝統的なマルクス主義理論を組み合わ せたものに基づいて設立された。[97] BPP の演説や著作で頻繁に引用された毛沢東の言葉は、党のマルクス主義イデオロギーの分析と理論的応用における指針となった。[100]  1978 年、毛沢東の遺産を称える革命共産党 USA のポスター。 1973 年に出版された自伝『Revolutionary Suicide』の中で、ニュートンは次のように書いている。 毛沢東主席は、死は誰にでも訪れるが、その意味は人によって異なる、と述べています。反動的な者の死は羽よりも軽く、革命のために死ぬことは泰山よりも重 い、と。[...] 私が黒人の問題に対する解決策を提示したり、自分の哲学を表明したりすると、人々は「それは社会主義じゃないのか?その中には、社会主義というラベルを 使って私を貶めようとする者もいたが、もしこれが社会主義なら、社会主義は正しい見解に違いないと思った。そこで、社会主義者の著作をさらに読み、私の信 念と彼らの信念の間に強い類似点を見出した。毛沢東の四巻本を読んで中国革命についてさらに学ぶことで、私の転換は完了した。[98] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maoism |

|

★

中国における毛沢東主義

| Maoism, officially

Mao Zedong Thought,[a] is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong

developed while trying to realize a socialist revolution in the

agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of China and later

the People's Republic of China. A difference between Maoism and

traditional Marxism–Leninism is that a united front of progressive

forces in class society would lead the revolutionary vanguard in

pre-industrial societies[3] rather than communist revolutionaries

alone. This theory, in which revolutionary praxis is primary and

ideological orthodoxy is secondary, represents urban Marxism–Leninism

adapted to pre-industrial China. Later theoreticians expanded on the

idea that Mao had adapted Marxism–Leninism to Chinese conditions,

arguing that he had in fact updated it fundamentally and that Maoism

could be applied universally throughout the world. This ideology is

often referred to as Marxism–Leninism–Maoism to distinguish it from the

original ideas of Mao.[4][5][non-primary source needed][6][page needed] From the 1950s until the Chinese economic reforms of Deng Xiaoping in the late 1970s, Maoism was the political and military ideology of the Chinese Communist Party and Maoist revolutionary movements worldwide.[7] After the Sino-Soviet split of the 1960s, the Chinese Communist Party and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union each claimed to be the sole heir and successor to Joseph Stalin concerning the correct interpretation of Marxism–Leninism and the ideological leader of world communism.[4] |

毛沢東主義(Mao Zedong Thought)は、毛沢東が中華民国、そして後に中華人民共

和国の農業中心の産業化前の社会で社会主義革命を実現しようとして発展させた、マルクス・レーニン主義の一派である。毛沢東主義と伝統的なマルクス・レー

ニン主義との違いは、産業革命以前の社会では、共産主義革命家だけではなく、階級社会における進歩的な勢力の統一戦線が革命の先駆者となるという点だ

[3]。革命の実践が第一であり、イデオロギーの正統性は二次的であるとするこの理論は、産業革命以前の中国に適応した都市型マルクス・レーニン主義を表

している。後の理論家は、毛沢東がマルクス・レーニン主義を中国の条件に適応させたという考えを拡大し、彼は実際にはそれを根本的に更新し、毛沢東主義は

世界中で普遍的に適用可能だと主張した。この思想は、毛沢東のオリジナル思想と区別するために、マルクス・レーニン主義・毛沢東主義と呼ばれることが多い

[4][5][非一次資料が必要][6][ページ番号が必要]。 1950年代から1970年代後半の鄧小平による中国の経済改革まで、毛沢東主義は中国共産党と世界中の毛沢東主義革命運動の政治的・軍事的イデオロギー だった。[7] 1960年代の中ソ分裂後、中国共産党とソビエト連邦共産党はそれぞれ、マルクス・レーニン主義の正しい解釈と世界共産主義の思想的指導者としてのヨシ フ・スターリンの唯一の継承者・後継者であると主張した。[4] |

| History Chinese intellectual tradition At the turn of the 19th century, the contemporary Chinese intellectual tradition was defined by two central concepts: iconoclasm and nationalism.[8]: 12–16 Iconoclastic revolution and anti-Confucianism By the turn of the 20th century, a proportionately small yet socially significant cross-section of China's traditional elite (i.e., landlords and bureaucrats) found themselves increasingly sceptical of the efficacy and even the moral validity of Confucianism.[8]: 10 These skeptical iconoclasts formed a new segment of Chinese society, a modern intelligentsia whose arrival—or as the historian of China Maurice Meisner would label it, their defection—heralded the beginning of the destruction of the gentry as a social class in China.[8]: 11 The fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911 marked the final failure of the Confucian moral order, and it did much to make Confucianism synonymous with political and social conservatism in the minds of Chinese intellectuals. This association of conservatism and Confucianism lent to the iconoclastic nature of Chinese intellectual thought during the first decades of the 20th century.[8]: 14 Chinese iconoclasm was expressed most clearly and vociferously by Chen Duxiu during the New Culture Movement, which occurred between 1915 and 1919.[8]: 14 Proposing the "total destruction of the traditions and values of the past", the New Culture Movement, spearheaded by the New Youth, a periodical published by Chen Duxiu, profoundly influenced the young Mao Zedong, whose first published work appeared in the magazine's pages.[8]: 14 Nationalism and the appeal of Marxism Along with iconoclasm, radical anti-imperialism dominated the Chinese intellectual tradition and slowly evolved into a fierce nationalist fervor which influenced Mao's philosophy immensely and was crucial in adapting Marxism to the Chinese model.[8]: 44 Vital to understanding Chinese nationalist sentiments of the time is the Treaty of Versailles, which was signed in 1919. The Treaty aroused a wave of bitter nationalist resentment in Chinese intellectuals as lands formerly ceded to Germany in Shandong were—without consultation with the Chinese—transferred to Japanese control rather than returned to Chinese sovereignty.[8]: 17 The adverse reaction culminated in the May Fourth Movement in 1919, during which a protest began with 3,000 students in Beijing displaying their anger at the announcement of the Versailles Treaty's concessions to Japan. The protest turned violent as protesters began attacking the homes and offices of ministers who were seen as cooperating with or being in the direct pay of the Japanese.[8]: 17 The popular movement which followed "catalyzed the political awakening of a society which had long seemed inert and dormant."[8]: 17 Another international event would have a significant impact not only on Mao but also on the Chinese intelligentsia. The Russian Revolution elicited great interest among Chinese intellectuals, although the socialist revolution in China was not considered a viable option until after the 4 May Incident.[8]: 18 Afterward, "[t]o become a Marxist was one way for a Chinese intellectual to reject both the traditions of the Chinese past and Western domination of the Chinese present."[8]: 18 |

歴史 中国の知的伝統 19 世紀の変わり目に、当時の中国の知的伝統は、偶像破壊とナショナリズムという 2 つの中心的な概念によって定義されていました[8]: 12–16。 偶像破壊の革命と反儒教 20世紀の変わり目までに、中国の伝統的なエリート層(すなわち地主や官僚)のうち、その割合は小さいながらも社会的に重要な一部が、儒教の有効性、さら にはその道徳的正当性さえもますます懐疑的に見るようになった。[8]: 10 この懐疑的な偶像破壊者たちは、中国社会に新たな層を形成した。歴史家モーリス・メイザーが「脱落」と表現したように、彼らの登場は、中国における士族階 級としての破壊の始まりを告げた。[8]: 11 1911年の清朝の崩壊は、儒教の道徳秩序の最終的な崩壊を意味し、中国知識人の間で儒教が政治的・社会的保守主義と同義視されるようになった大きな要因 となった。この保守主義と儒教の関連は、20世紀初頭の中国の知識人の思想の偶像破壊的な性質に拍車をかけた。[8]: 14 中国の偶像破壊は、1915年から1919年にかけて起こった新文化運動において、陳独秀によって最も明確かつ声高に表現された。[8]: 14 「過去 の伝統と価値観の完全な破壊」を提唱した新文化運動は、陳独秀が発行した雑誌『新青年』を先導とし、毛沢東の最初の著作が同誌に掲載されたことで、若き毛 沢東に深い影響を与えた。[8]: 14 ナショナリズムとマルクス主義の魅力 偶像破壊とともに、過激な反帝国主義が中国の知的伝統を支配し、徐々に激しいナショナリズムの熱狂へと発展し、毛沢東の哲学に多大な影響を与え、マルクス 主義を中国モデルに適応させる上で重要な役割を果たした。[8]: 44 当時の中国のナショナリズムの感情を理解する上で欠かせないのが、1919年に 締結されたヴェルサイユ条約だ。この条約は、山東省でドイツに割譲されていた領土が、中国側の意見はまったく聞かれることなく、中国に返還されることなく 日本の支配下に移管されたことで、中国の知識人に激しいナショナリズムの波を引き起こした。[8]: 17 この反発は、1919年の五四運動で最高潮に達し、北京では 3,000 人の学生たちが、ヴェルサイユ条約による日本への譲歩の発表に怒りを表して抗議行動を開始した。抗議行動は、日本と協力している、あるいは日本から直接報 酬を受け取っていると思われる大臣たちの自宅や事務所を襲撃する暴徒化へと発展した。[8]: 17 この民衆運動は、「長い間、無気力で休眠状態にあるように見えた社会の政治的覚醒のきっかけとなった」[8]: 17 。 別の国際的な出来事も、毛沢東だけでなく、中国の知識層にも大きな影響を与えた。ロシア革命は中国の知識人に大きな関心を呼び起こしたが、中国における社 会主義革命は 5 月 4 日事件まで実現可能な選択肢とは考えられていなかった。[8]: 18 その後、「マルクス主義者になることは、中国の知識人が中国の伝統と、中国を支配する西洋の両方を拒絶する一つの方法となった」[8]: 18 |

| Yan'an period between November

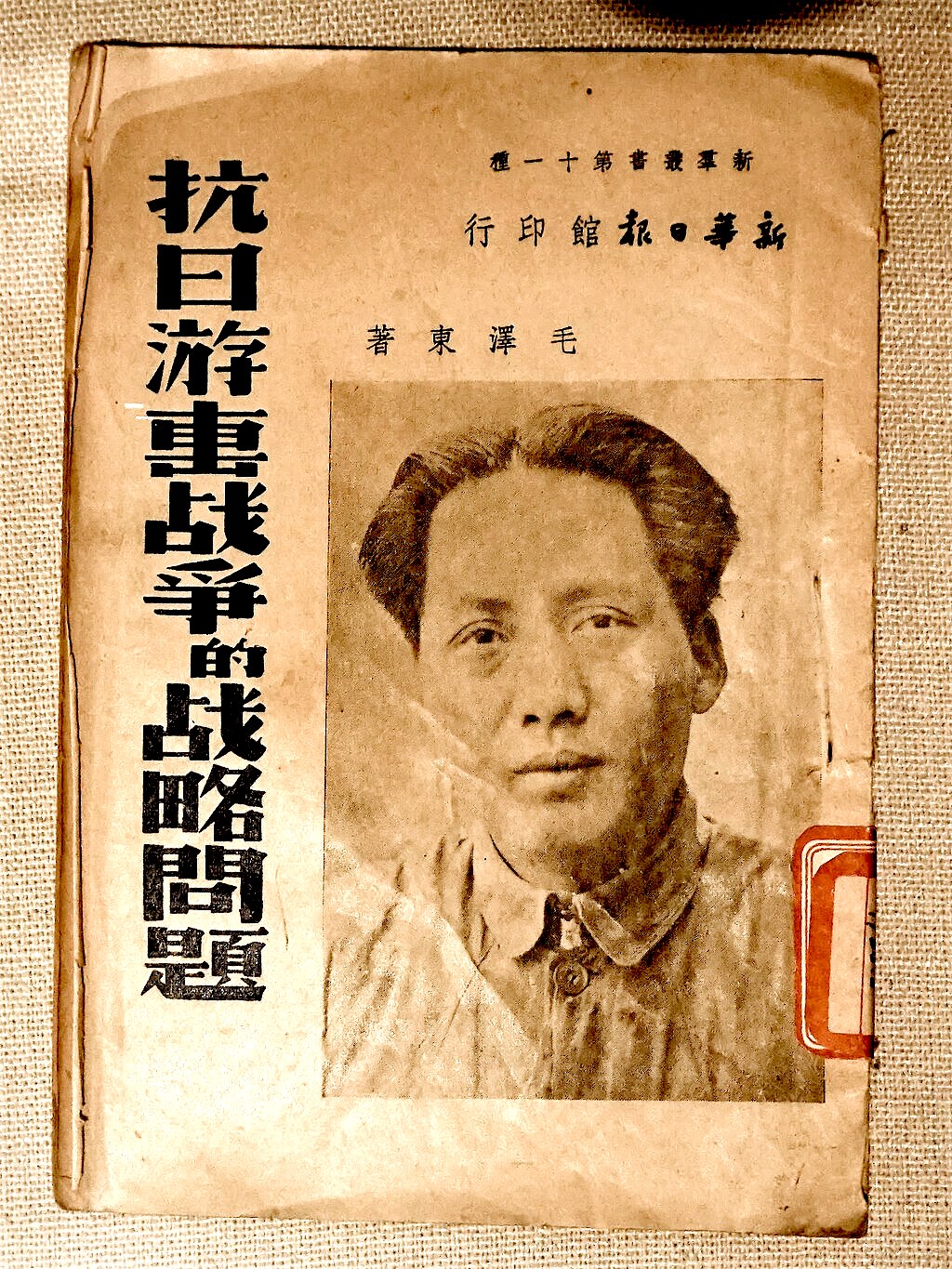

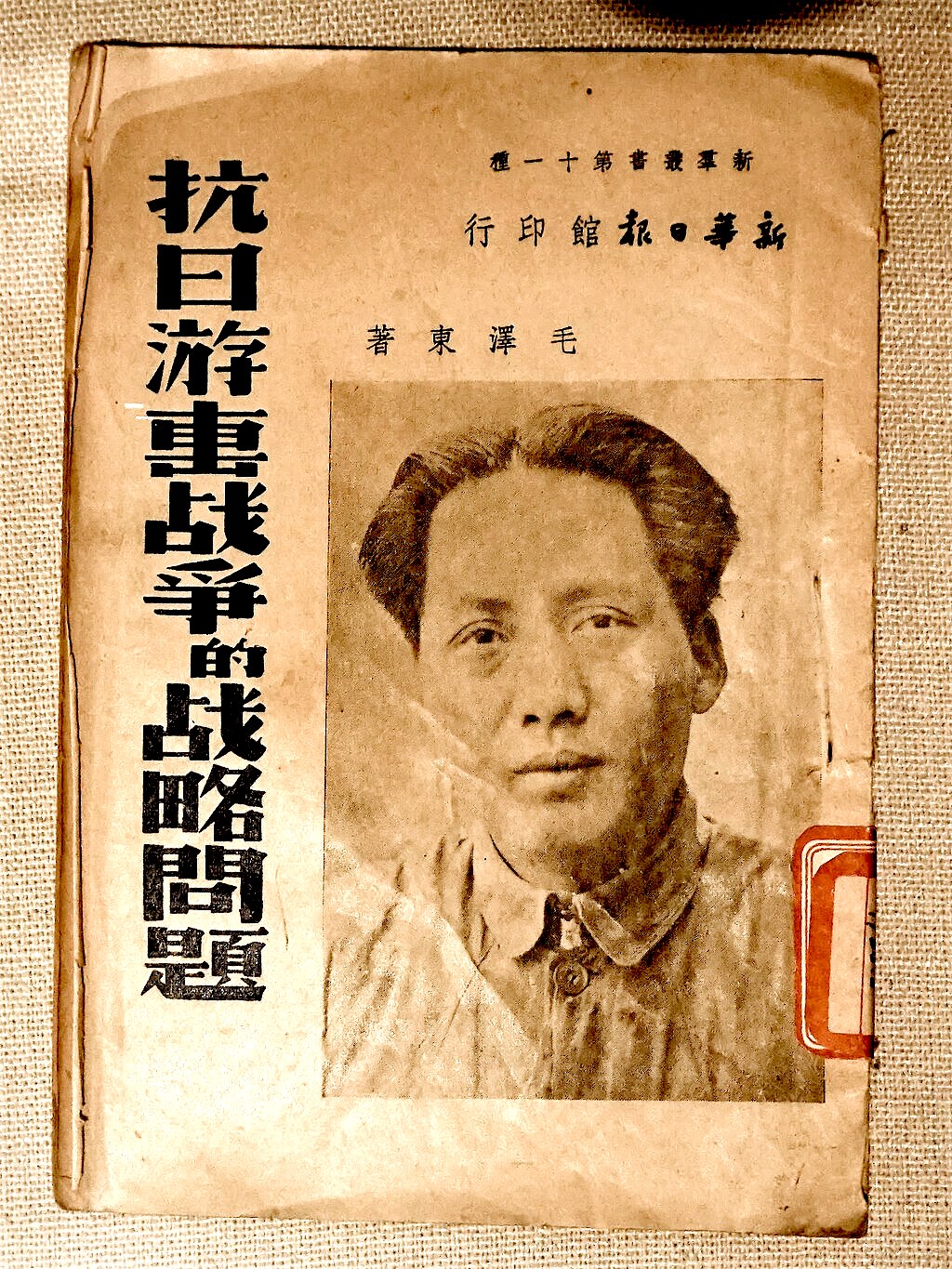

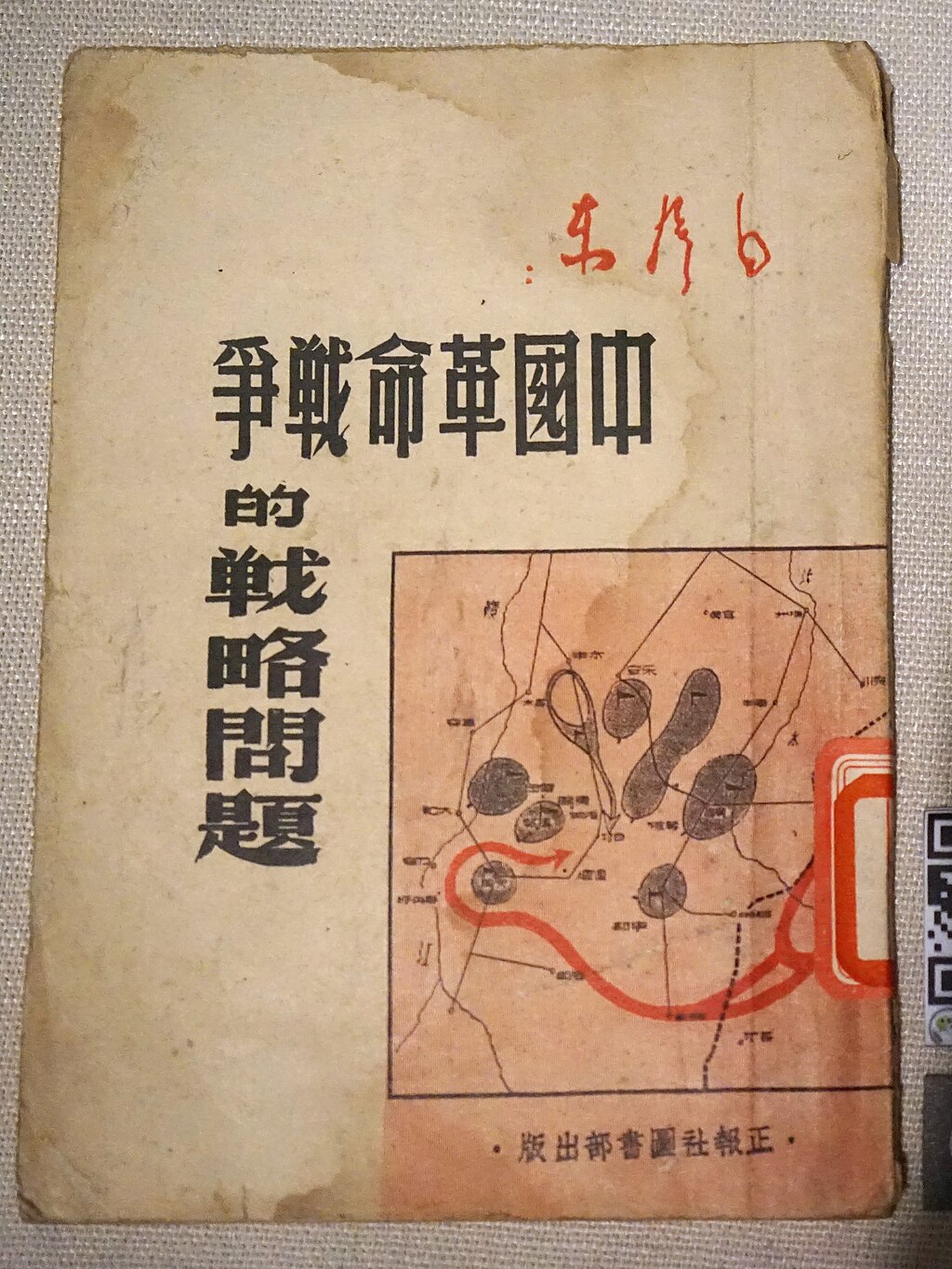

1935 and March 1947 Immediately following the Long March, Mao and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were headquartered in the Yan'an Soviet in Shaanxi. During this period, Mao established himself as a Marxist theoretician and produced most of the works that would later be canonised as the "Thought of Mao Zedong".[8]: 45 The rudimentary philosophical base of Chinese Communist ideology is laid down in Mao's numerous dialectical treatises and was conveyed to newly recruited party members. This period established ideological independence from Moscow for Mao and the CCP.[8]: 45 Although the Yan'an period did answer some of the ideological and theoretical questions raised by the Chinese Communist Revolution, it left many crucial questions unresolved, including how the Chinese Communist Party was supposed to launch a socialist revolution while wholly separated from the urban sphere.[8]: 45 Mao Zedong's intellectual development  Strategic Issues of Anti-Japanese Guerrilla War (1938) Mao's intellectual development can be divided into five significant periods, namely: the initial Marxist period from 1920 to 1926 the formative Maoist period from 1927 to 1935 the mature Maoist period from 1935 to 1940 the Civil-War period from 1940 to 1949 the post-1949 period following the revolutionary victory Initial Marxist period (1920–1926) Marxist thinking employs immanent socioeconomic explanations, whereas Mao's reasons were declarations of his enthusiasm. Mao did not believe education alone would transition from capitalism to communism for three main reasons. (1) the capitalists would not repent and turn towards communism on their own; (2) the rulers must be overthrown by the people; (3) "the proletarians are discontented, and a demand for communism has arisen and had already become a fact."[9]: 109 |

1935年11月から1947年3月までの延安時代 長征の直後、毛沢東と中国共産党(CCP)は陝西省の延安ソビエトに本部を置いた。この期間、毛沢東はマルクス主義の理論家としての地位を確立し、後に 「毛沢東思想」として正典化される作品のほとんどを執筆した。[8]: 45 中国共産党のイデオロギーの基礎となる哲学的基盤は、毛沢東の多くの弁証法的著作に確立され、新規入党した党員に伝えられた。この期間は、毛沢東と中国共 産党がモスクワからのイデオロギー的独立を確立した時期だった。[8]: 45 延安時代は、中国共産党革命が提起したイデオロギー的・理論的な問題の一部には答えを出したが、都市部から完全に隔絶された状態で中国共産党が社会主義革 命をどのように開始すべきかなど、多くの重要な問題は未解決のまま残された。[8]: 45 毛沢東の知的発展  抗日ゲリラ戦争の戦略的問題(1938年) 毛沢東の知的発展は、以下の5つの重要な時期に分けられる。 1920年から1926年までの初期マルクス主義期 1927年から1935年までの毛沢東思想形成期 1935年から1940年までの毛沢東思想成熟期 1940 年から 1949 年までの内戦期 革命勝利後の 1949 年以降の時期 初期マルクス主義期(1920 年~1926 年) マルクス主義の思想は、内在的な社会経済的な説明を採用しているが、毛沢東の理由は、彼の熱意の表明だった。毛沢東は、3つの主な理由から、教育だけでは 資本主義から共産主義への移行は不可能だと考えていました。(1) 資本家は自発的に悔い改め、共産主義に転換することはない。(2) 支配者は人民によって打倒されなければならない。(3) 「プロレタリアは不満を抱えており、共産主義の要求が生まれ、すでに事実となっている」[9]: 109 |

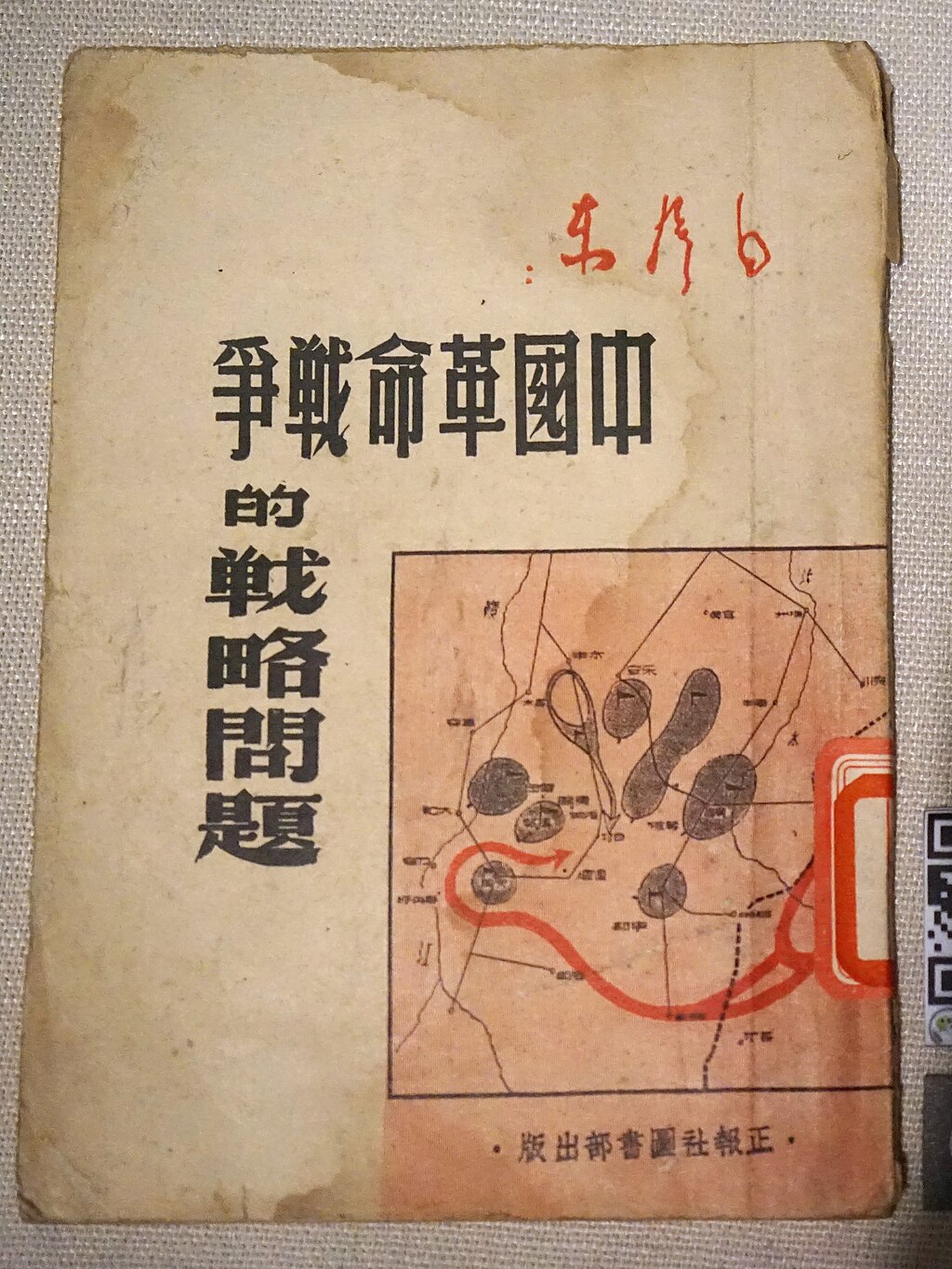

| Formative Maoist period

(1927–1935) In this period, Mao avoided all theoretical implications in his literature and employed a minimum of Marxist category thought. His writings in this period failed to elaborate on what he meant by the "Marxist method of political and class analysis".[9]: 111 Mature Maoist period (1935–1940) Intellectually, this was Mao's most fruitful time. The orientation shift was apparent in his pamphlet Strategic Problems of China's Revolutionary War (December 1936). This pamphlet tried to provide a theoretical veneer for his concern with revolutionary practice.[9]: 113 Mao started to separate from the Soviet model since it was not automatically applicable to China. China's unique set of historical circumstances demanded a correspondingly unique application of Marxist theory, an application that would have to diverge from the Soviet approach. In the late 1930s, writings and speeches by Mao and other leaders close to Mao began to emerge as the Communist Party's developing ideology.[10]: 27 This was described as the Sinicization of Marxism.[10]: 27 Mao's view was that these concepts were not a complete system of thought but were still developing.[10]: 27 As a result, he decided not to use the term "Maoism" and instead favored characterizing these ideological contributions as Mao Zedong Thought (Mao Zedong sixiang).[10]: 27 Beginning in the Yan'an period, Mao Zedong Thought became the ideological guide for developing revolutionary culture and a long-term social movement.[11]: 53  Strategic Issues in the Chinese Revolutionary War (1947) Civil War period (1940–1949) Unlike the Mature period, this period was intellectually barren. Mao focused more on revolutionary practice and paid less attention to Marxist theory. He continued to emphasise theory as practice-oriented knowledge.[9]: 117 The most crucial topic of the theory he delved into was in connection with the Cheng Feng movement of 1942. Here, Mao summarised the correlation between Marxist theory and Chinese practice: "The target is the Chinese revolution, the arrow is Marxism–Leninism. We Chinese communists seek this arrow for no other purpose than to hit the target of the Chinese revolution and the revolution of the east."[9]: 117 The only new emphasis was Mao's concern with two types of subjectivist deviation: (1) dogmatism, the excessive reliance upon abstract theory; (2) empiricism, excessive dependence on experience. In 1945, the party's first historical resolution put forward Mao Zedong Thought as the party's unified ideology.[12]: 6 It was also incorporated into the party's constitution.[13]: 23 |

形成期(1927年~1935年) この期間、毛沢東は著作においてあらゆる理論的含意を避け、マルクス主義のカテゴリー思考を最小限に留めた。この期間の著作では、「政治・階級分析のマル クス主義的方法」とは何を意味するのかについて詳しく説明されていない。[9]: 111 成熟期(1935年~1940年) 知的側面では、これは毛沢東の最も実り多い時期だった。方向転換は、彼の小冊子『中国の革命戦争の戦略問題』(1936年12月)に明確に表れた。この小 冊子は、彼の革命実践への関心に理論的な装いを与えようとしたものだった。[9]: 113 毛沢東は、ソ連のモデルが中国に自動的に適用できないことか ら、ソ連のモデルから離脱し始めた。中国の独特の歴史的状況には、それに応じた独特なマルクス主義理論の適用が必要であり、その適用はソビエトのアプロー チとは異なったものになるはずだった。 1930年代後半、毛沢東や毛沢東に近い指導者たちの著作や演説が、共産党の思想として台頭し始めた。[10]: 27 これは、マルクス主義の中国化として表現された。[10]: 27 毛沢東の見解では、これらの概念は完全な思想体系ではなく、まだ発展途上のものであった。[10]: 27 その結果、彼は「毛沢東主義」という用語を使用せず、これらの思想的貢献を「毛沢東思想(毛沢東思想)」と表現することを好んだ。[10]: 27 延安時代以降、毛沢東思想は、革命文化の発展と長期的な社会運動のイデオロギー的指針となった。[11]: 53  中国革命戦争の戦略的問題 (1947) 内戦期 (1940–1949) 成熟期とは異なり、この期間は知的荒廃の時代だった。毛沢東は革命実践に重点を置き、マルクス主義理論への関心を薄めた。彼は理論を実践指向の知識として 強調し続けた。[9]: 117 彼が深く探求した理論の最も重要なテーマは、1942年の「正風運動」に関連していた。ここで毛沢東は、マルクス主義理 論と中国の実践との関連性を次のように要約した:「目標は中国の革命であり、矢はマルクス・レーニン主義である。私たちは中国共産党員として、この矢を中 国革命と東洋の革命という目標に命中させるためだけに求める。」[9]: 117 唯一の新たな強調点は、毛沢東が2種類の主観主義的逸脱に懸念を示したことだった:(1) 教条主義、抽象的な理論への過度の依存;(2) 経験主義、経験への過度の依存。 1945年、党の最初の歴史的決議は、毛沢東思想を党の統一思想として提唱した。[12]: 6 また、これは党の憲法にも盛り込まれた。[13]: 23 |

| Post-Civil War period (1949–1976) To Mao, the victory of 1949 was a confirmation of theory and practice. "Optimism is the keynote to Mao's intellectual orientation in the post-1949 period."[9]: 118 Mao assertively revised the theory to relate it to the new practice of socialist construction. These revisions are apparent in the 1951 version of On Contradiction. "In the 1930s, when Mao talked about contradiction, he meant the contradiction between subjective thought and objective reality. In Dialectal Materialism of 1940, he saw idealism and materialism as two possible correlations between subjective thought and objective reality. In the 1940s, he introduced no new elements into his understanding of the subject-object contradiction. In the 1951 version of On Contradiction, he saw contradiction as a universal principle underlying all processes of development, yet with each contradiction possessed of its own particularity."[9]: 119 In 1956, Mao first fully theorized his view of continual revolution.[14]: 92 |

内戦後の時代(1949 年~1976 年) 毛沢東にとって、1949 年の勝利は理論と実践の正当性を確認するものでした。「楽観主義は、1949 年以降の毛沢東の知的指向の基調である」[9]: 118 毛沢東は、社会主義建設という新たな実践と関連付けるため、この理論を大胆に修正した。この修 正は、1951年版の『矛盾について』に顕著に表れている。「1930年代、毛沢東が矛盾について語ったとき、彼は主観的思考と客観的現実との矛盾を意味 していた。1940年の『弁証法的唯物論』では、主観的思考と客観的現実の2つの相関関係として、理想主義と唯物論を提示した。1940年代、毛沢東は主 観と客観の矛盾に関する理解に新たな要素を導入しなかった。1951年版の『矛盾について』では、矛盾はあらゆる発展過程の根底にある普遍的な原理である と同時に、それぞれの矛盾には固有の特殊性があるとの見解を示した。[9]: 119 1956年、毛沢東は、継続的な革命に関する見解を初めて完全に理論化した。[14]: 92 |

Differences from Marxism Beijing, 1978. The billboard reads, "Long Live Marxism, Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought!" Maoism and Marxism differ in how the proletariat is defined and in which political and economic conditions would start a communist revolution. For Marx, the proletariat was the urban working class, which was determined in the revolution by which the bourgeoisie overthrew feudalism.[15] For Mao Zedong, the revolutionary class was the millions of peasants he referred to as the popular masses. Mao based his revolution upon the peasantry. They possessed, according to him, two qualities: (i) they were poor and (ii) they were a political blank slate; in Mao's words, "[a] clean sheet of paper has no blotches, and so the newest and most beautiful words can be written on it."[16] For Marx, the proletarian revolution was internally fuelled by the capitalist mode of production; as capitalism developed, "a tension arises between the productive forces and the mode of production."[17] The political tension between the productive forces (the workers) and the owners of the means of production (the capitalists) would be an inevitable incentive for the proletarian revolution, resulting in a communist society. Mao did not subscribe to Marx's theory of inevitable cyclicality in the economic system. His goal was to unify the Chinese nation and so realise progressive change for China in the form of communism; hence, a revolution was needed at once. In The Great Union of the Popular Masses (1919), Mao wrote that "[t]he decadence of the state, the sufferings of humanity, and the darkness of society have all reached an extreme."[18] |

マルクス主義との相違点 1978年、北京。看板には「マルクス主義、レーニン主義、毛沢東思想万歳!」と書かれている。 毛沢東主義とマルクス主義は、プロレタリアートの定義、および共産主義革命が始まる政治的・経済的条件について相違がある。 マルクスにとって、プロレタリアートは都市の労働者階級であり、革命においてブルジョアジーが封建制を打倒することで決定された。[15] 毛沢東にとって、革命階級は彼が「人民大衆」と呼んだ数百万の農民だった。毛沢東は、革命の基盤を農民に置いた。彼らは、彼によると、二つの特徴を持って いた:(i) 貧しいこと、(ii) 政治的に白紙の状態であること。毛沢東の言葉によれば、「白紙には汚れがないため、最も新しく美しい言葉を書き込むことができる」[16]。 マルクスにとって、プロレタリア革命は資本主義的生産方式によって内部から駆動されるものでした。資本主義が発展するにつれ、「生産力と生産方式の間に緊 張が生じる」[17]。生産力(労働者)と生産手段の所有者(資本家)との間の政治的緊張は、プロレタリア革命の必然的な原動力となり、その結果、共産主 義社会が実現する。毛沢東は、経済システムにおける必然的な循環性というマルクスの理論には同意しなかった。彼の目標は、中国国民を統一し、共産主義とい う形で中国の進歩的な変化を実現することだった。そのため、革命は早急に必要だった。『大衆の団結』(1919年)の中で、毛沢東は「国家の衰退、人類の 苦悩、社会の暗黒は、すべて極限に達している」と書いている[18]。 |

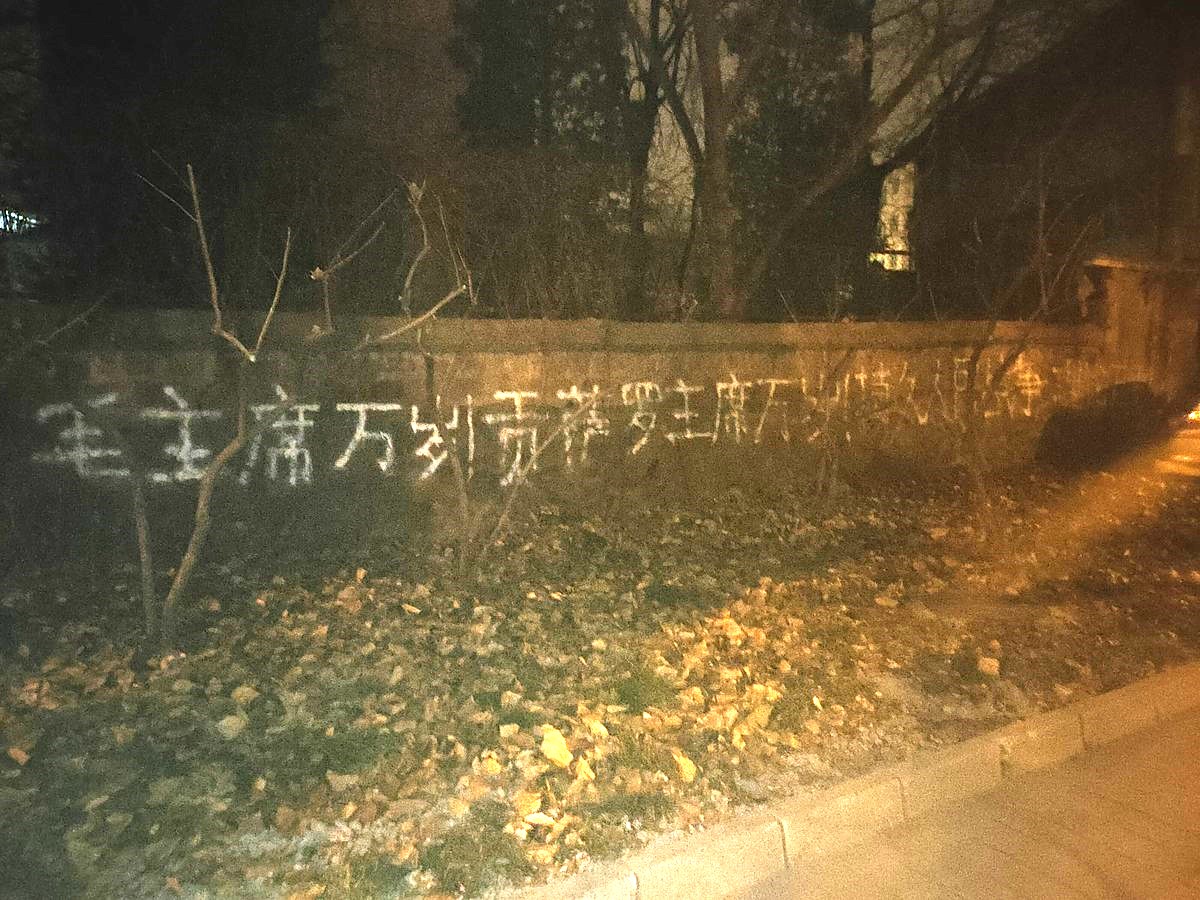

After Mao Zedong's death Deng Xiaoping The CCP's ideological framework distinguishes between political ideas described as "Thought" (as in Mao Zedong Thought) or as "Theory" (as in Deng Xiaoping Theory).[19]: 2 Thought carries more weight than Theory and conveys the greater relative importance of a leader's ideological and historical influence.[19]: 2 The process of formalizing a leader's political thinking in the Marxist tradition is important in establishing a leader's ideological legitimacy.[19]: 3 Mao Zedong Thought is frequently described as the result of collaboration between the first-generation leaders of the Party and is principally based on Mao's analysis of Marxism and Chinese history.[11]: 53 It is often also described as the adaptation of Marxism to the Chinese context.[11]: 53 Observing that concepts of both Marxism and Chinese culture were and are contested, academic Rebecca Karl writes that the development of Mao Zedong Thought is best viewed as the result of Mao's mutual interpretation of these concepts producing Mao's view of theory and revolutionary practice.[11]: 53 Mao Zedong Thought asserts that class struggle continues even if the proletariat has already overthrown the bourgeoisie and there are capitalist restorationist elements within the CCP itself. Maoism provided the CCP's first comprehensive theoretical guideline regarding how to continue the socialist revolution, the creation of a socialist society, and socialist military construction and highlights various contradictions in society to be addressed by what is termed "socialist construction". While it continues to be lauded to be the major force that defeated "imperialism and feudalism" and created a "New China" by the Chinese Communist Party, the ideology survives only in name on the Communist Party's Constitution as Deng Xiaoping abolished most Maoist practices in 1978, advancing a guiding ideology called "socialism with Chinese characteristics".[20][need quotation to verify] Shortly after Mao died in 1976, Deng Xiaoping initiated socialist market reforms in 1978, thereby beginning the radical change in Mao's ideology in the People's Republic of China (PRC).[21] Although Mao Zedong Thought nominally remains the state ideology, Deng's admonition to "seek truth from facts" means that state policies are judged on their practical consequences, and in many areas, the role of ideology in determining policy has thus been considerably reduced. Deng also separated Mao from Maoism, making it clear that Mao was fallible, and hence the truth of Maoism comes from observing social consequences rather than by using Mao's quotations dogmatically.[22] On June 27, 1981, the Communist Party's Central Committee adopted the Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the People's Republic of China.[11]: 166 The Resolution assesses the legacy of the Mao era, describing Mao as first among equals in the development of Mao Zedong Thought before 1949 and deeming Mao Zedong Thought as successful in establishing national independence, transforming China's social classes, the development of economic self-sufficiency, the expansion of education and health care, and China's leadership role in the Third World.[11]: 166–167 The Resolution describes setbacks during the period 1957 to 1964 (although it generally affirms this period) and major mistakes beginning in 1965.[11]: 167 The Resolution describes upholding the guidance of Mao Zedong Thought and Marxism-Leninism as among the Communist Party's cardinal principles.[11]: 168 Contemporary Maoists in China criticise the social inequalities created by the revisionist Communist Party. Some Maoists say that Deng's Reform and Opening economic policies that introduced market principles spelled the end of Maoism in China. However, Deng asserted that his reforms were upholding Mao Zedong Thought in accelerating the output of the country's productive forces. A recent example of a Chinese politician regarded as neo-Maoist in terms of political strategies and mass mobilisation via red songs was Bo Xilai in Chongqing.[23] Although Mao Zedong Thought is still listed as one of the Four Cardinal Principles of the People's Republic of China, its historical role has been re-assessed. The Communist Party now says that Maoism was necessary to break China free from its feudal past, but it also says that the actions of Mao led to excesses during the Cultural Revolution.[24] The official view is that China has now reached an economic and political stage, known as the primary stage of socialism, in which China faces new and different problems completely unforeseen by Mao, and as such, the solutions that Mao advocated are no longer relevant to China's current conditions. The 1981 Resolution reads: Chief responsibility for the grave 'Left' error of the 'cultural revolution,' an error comprehensive in magnitude and protracted in duration, does indeed lie with Comrade Mao Zedong [...] [and] far from making a correct analysis of many problems, he confused right and wrong and the people with the enemy [...] herein lies his tragedy.[25] Scholars outside China see this re-working of the definition of Maoism as providing an ideological justification for what they see as the restoration of the essentials of capitalism in China by Deng and his successors, who sought to "eradicate all ideological and physiological obstacles to economic reform".[26] In 1978, this led to the Sino-Albanian split when Albanian leader Enver Hoxha denounced Deng as a revisionist, stating "The events and facts are demonstrating ever more clearly that China is sinking deeper and deeper into revisionism, capitalism and imperialism"[27] and formed Hoxhaism as an anti-revisionist form of Marxism.  "Long live Chairman Mao! Long live Chairman Gonzalo! Long live the theory of protracted people's war!" (毛主席万岁!贡萨罗主席万岁!持久人民战争理论万岁!) New Leftist graffiti on a wall at Qinghua South Road, Beijing, 6 December 2021. The CCP officially regards Mao himself as a "great revolutionary leader" for his role in fighting against the Japanese fascist invasion during the Second World War and creating the People's Republic of China, but Maoism, as implemented between 1959 and 1976, is regarded by today's CCP as an economic and political disaster. In Deng's day, support of radical Maoism was regarded as a form of "left deviationism" and based on a cult of personality, although these "errors" are officially attributed to the Gang of Four rather than Mao himself.[28] Thousands of Maoists were arrested in the Hua Guofeng period after 1976. The prominent Maoists Zhang Chunqiao and Jiang Qing were sentenced to death with a two-year-reprieve, while others were sentenced to life imprisonment or imprisonment for 15 years.[citation needed] After the Tiananmen Square protests and massacre, Mao's influence continued to be weaker. Although not very influential, some radical Maoists, disgruntled by the injustices suffered by migrant workers, organized a number of protests and strikes, including the Jasic incident. In the 2020s, influenced by the growing wealth gap and the 996 working hour system, Mao's thoughts are being revived in China's generation Z, as they question authority of the CCP. The Chinese government has censored some Maoist posts.[29][30] The 2021 The Resolution on the Major Achievements and Historical Experience of the Party over the Past Century describes Mao Zedong Thought as "a summation of theories, principles, and experience on China's revolution and construction that has been proven correct through practice, and [having] put forward a series of important theories for socialist construction."[31]: 91 |

毛沢東の死後 鄧小平 中国共産党のイデオロギーの枠組みでは、政治思想は「思想」(毛沢東思想など)と「理論」(鄧小平理論など)に区別される。[19]: 2 「思想」は 「理論」よりも重要視され、指導者の思想的・歴史的影響力の相対的な重要性を示す。[19]: 2 マルクス主義の伝統において、指導者の政治思想を形式 化することは、指導者の思想的正当性を確立する上で重要だ。[19]: 3 毛沢東思想は、党の第一世代指導者たちの協力の成果としてよく説明され、主に毛沢東のマルクス主義と中国史の分析に基づいている。[11]: 53 また、マルクス主義を中国の文脈に適応させたものともよく説明される。[11]: 53 マルクス主義と中国文化の両方の概念が過去も現在も議論の的となっていることを指摘し、学者のレベッカ・カールは、毛沢東思想の発展は、毛沢東がこれらの 概念を相互に解釈し、その結果として毛沢東の理論と革命実践の観点が生まれたものと捉えるのが最も適切であると述べている。[11]: 53 毛沢東思想は、プロレタリアートがブルジョアジーを打倒した後も階級闘争は継続し、中国共産党内部にも資本主義復古派が存在すると主張している。毛沢東思 想は、社会主義革命の継続、社会主義社会の創造、社会主義軍事建設に関する中国共産党の最初の包括的な理論的指針を提供し、社会主義建設によって解決すべ き社会の様々な矛盾を強調している。中国共産党によって「帝国主義と封建主義」を打倒し、「新中国」を築いた主要な勢力として称賛され続けているが、この 思想は、鄧小平が1978年に毛沢東主義のほとんどの実践を廃止し、「中国特色の社会主義」と呼ばれる指導思想を推進したため、共産党の憲法上名目上のみ 存続している。[20][引用が必要] 1976年に毛沢東が死去した直後、1978年に鄧小平は社会主義市場改革を開始し、それによって中華人民共和国(PRC)における毛沢東のイデオロギー の急進的な変化が始まった。[21] 毛沢東思想は名目上国家のイデオロギーとして残っているが、鄧小平の「事実から真実を求める」という教訓により、国家政策は実践的な結果で判断され、多く の分野でイデオロギーが政策決定に与える役割は大幅に縮小された。また、鄧小平は毛沢東を毛沢東主義から切り離し、毛沢東にも誤りはあったことを明らかに し、毛沢東主義の真実は、毛沢東の言葉を教条的に引用することではなく、社会の結果を観察することから得られることを明らかにした。 1981年6月27日、中国共産党中央委員会は「中華人民共和国建国以来の党の歴史に関するいくつかの問題に関する決議」を採択した。[11]: 166 この決議は、毛沢東時代の遺産を評価し、毛沢東を 1949 年以前の毛沢東思想の発展において「平等者の中の第一人者」と表現し、毛沢東思想は、国家の独立の確立、中国の社会階級の変革、経済的自立の発展、教育と 保健の拡充、そして第三世界における中国の指導的役割の確立において成功したと評価している。[11]: 166–167 決議は、1957年から1964年までの期間(ただし、この期間については概ね肯定的に評価している)における挫折と、1965年から始まった重大な誤り を記述している。[11]: 167 決議は、毛沢東思想とマルクス・レーニン主義の指導を維持することを、共産党の根本原則の一つとして挙げている。[11]: 168 中国の現代毛沢東主義者は、修正主義的な共産党によって生み出された社会的不平等を批判している。一部の毛沢東主義者は、市場原理を導入した鄧小平の改革 開放政策が中国における毛沢東主義の終焉を意味したと主張している。しかし、鄧小平は自身の改革が毛沢東思想を堅持し、国の生産力を加速させるものだと主 張した。政治戦略と赤色歌謡を通じた大衆動員において新毛沢東主義者と見なされる中国の政治家として、最近の例には重慶の薄熙来が挙げられる。[23] 毛沢東思想は依然として中華人民共和国の四つの基本原則の一つとして挙げられているが、その歴史的役割は再評価されている。共産党は現在、毛沢東主義は中 国を封建的な過去から解放するために必要だったと主張しているが、毛沢東の行動は文化大革命の過激化につながったとも述べている。[24] 公式見解では、中国は現在、社会主義の第一段階と呼ばれる経済・政治の段階に達しており、毛沢東がまったく予見しなかった新たな、かつ異なる問題に直面し ているため、毛沢東が提唱した解決策は、現在の中国の状況にはもはや適用できないとされている。1981年の決議では、次のように述べられている。 文化大革命」という重大な「左」の誤りは、その規模と期間において包括的なものであり、その主な責任は毛沢東同志にある [...] [そして] 多くの問題について正しい分析を行うどころか、彼は善悪を混同し、人民を敵とみなした [...] ここに彼の悲劇がある。[25] 中国の国外の学者たちは、この毛沢東主義の定義の見直しを、経済改革の「すべてのイデオロギー的および生理学的障害を根絶する」ことを目指した鄧小平とそ の後継者たちによる、中国における資本主義の本質的な回復をイデオロギー的に正当化するものと捉えている。[26] 1978年、アルバニアの指導者エンヴェル・ホジャが鄧小平を修正主義者と非難し、「事件と事実は、中国が修正主義、資本主義、帝国主義にますます深く沈 み込んでいることをますます明確に示している」[27] と述べ、反修正主義的なマルクス主義の形態としてホジャイズムを提唱したことで、中アルバニア分裂が発生した。  「毛沢東主席万歳!ゴンサロ主席万歳!長期人民戦争理論万歳!」(毛主席万岁!贡萨罗主席万岁!持久人民战争理论万岁!) 2021年12月6日、北京の清華南路の壁に書かれた新左翼の落書き。 中国共産党は、第二次世界大戦中の日本のファシスト侵略との戦い、および中華人民共和国の創設における毛沢東の役割を「偉大な革命指導者」と公式に評価し ているが、1959年から1976年にかけて実施された毛沢東主義は、今日の中国共産党によって経済・政治上の大失敗とみなされている。鄧小平の時代、過 激な毛沢東主義の支持は「左傾化」の一形態とみなされ、個人崇拝に基づくものとされたが、これらの「誤り」は、毛沢東自身ではなく、四人組に正式に帰せら れている[28]。1976年以降の華国鋒時代には、数千人の毛沢東主義者が逮捕された。著名な毛沢東主義者である張春橋と江青は死刑判決を受け、2年間 の執行猶予が付いたが、他の者は終身刑または15年の懲役刑を宣告された。[出典が必要] 天安門事件と虐殺の後、毛沢東の影響力はさらに弱まった。あまり影響力はないものの、移民労働者が被った不正に不満を抱く一部の過激な毛沢東主義者は、 ジャシック事件をはじめとする一連の抗議行動やストライキを組織した。2020年代、富の格差の拡大と996労働時間制の影響を受けて、中国Z世代は中国 共産党の権威に疑問を抱き、毛沢東の思想が復活しつつある。中国政府は、毛沢東主義者の投稿の一部を検閲している。[29][30] 2021年の「過去100年間の党の主要な成果と歴史的経験に関する決議」は、毛沢東思想を「中国の革命と建設に関する理論、原則、経験の総括であり、実 践によってその正しさが証明され、社会主義建設に関する一連の重要な理論を提唱したもの」と表現している。[31]: 91 |

| Components New Democracy The theory of the New Democracy was known to the Chinese revolutionaries from the late 1940s. This thesis held that for most people, the "long road to socialism" could only be opened by a "national, popular, democratic, anti-feudal and anti-imperialist revolution, run by the communists".[32] People's war See also: People's war Holding that "political power grows out of the barrel of a gun",[33] Maoism emphasises the "revolutionary struggle of the vast majority of people against the exploiting classes and their state structures", which Mao termed a people's war. Mobilizing large parts of rural populations to revolt against established institutions by engaging in guerrilla warfare, Maoist Thought focuses on "surrounding the cities from the countryside". Maoism views the industrial-rural divide as a major division exploited by capitalism, identifying capitalism as involving industrial urban developed First World societies ruling over rural developing Third World societies.[34] Maoism identifies peasant insurgencies in particular national contexts as part of a context of world revolution, in which Maoism views the global countryside as overwhelming the global cities.[35] Due to this imperialism by the capitalist urban First World toward the rural Third World, Maoism has endorsed national liberation movements in the Third World.[35] Mass line Main article: Mass line Building on the theory of the vanguard party[36] by Vladimir Lenin, the theory of the mass line outlines a strategy for the revolutionary leadership of the masses, consolidation of the dictatorship of the proletariat, and strengthening of the party and the building of socialism. The mass line can be summarised as "from the masses, to the masses". It has three components or stages:[37] Gathering the diverse ideas of the masses. Processing or concentrating these ideas from the perspective of revolutionary Marxism, in light of the long-term, ultimate interests of the masses (which the masses may sometimes only dimly perceive) and in light of a scientific analysis of the objective situation. Returning these concentrated ideas to the masses in the form of a political line which will advance the mass struggle toward revolution. These three steps should be applied repeatedly, reiteratively uplifting practice and knowledge to higher and higher stages. Cultural Revolution The theory of cultural revolution - rooted in Marxism-Leninism thought[7] - states that the proletarian revolution and the dictatorship of the proletariat do not wipe out bourgeois ideology; the class struggle continues and even intensifies during socialism. Therefore, a constant struggle against bourgeois ideology, traditional cultural values, and the social roots that encourage both of them must be conducted in order to create and maintain a society in which socialism can succeed. Practical examples of this theory's application can be seen in the rapid social changes undergone by post-revolution Soviet Union in the late 1920s -1930s[38] as well as pre-revolution China in the New Culture and May Fourth movements of the 1910s-1920s.[39] Both of these sociocultural movements can be seen as shaping Maoist theory on the need for and goals of Cultural Revolution, and subsequently the mass cultural movements enacted by the CCP under Mao, which include the Great Leap Forward, the Anti-rightist movement of the 1950s, and the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution of the 1960s-1970s.[40] The social upheavals that occurred from the New Culture Movement - as well as the May Fourth Movement that followed it[41] - largely focused around the dismantling of traditional Han Chinese cultural norms in which the majority of the populace were illiterate and largely uneducated.[39][42] This consequence of this social dynamic was that political and economic power largely resided in the hands of a small group of educated elites, and Han Chinese culture formed around principles of respect and reverence for these educated and powerful authority figures. The aforementioned movements sought to combat these social norms through grassroots educational campaigns which were focused primarily around giving educational opportunities towards to people from traditionally uneducated families and normalising all people to be comfortable making challenges towards traditional figures of authority in Confucian society.[43] The cultural revolution experienced by the Soviet Union was similar to the New Culture and May Fourth movements experienced by China in that it also placed a great importance on mass education and the normalisation of challenging of traditional cultural norms in the realising of a socialist society. However, the movements occurring in the Soviet Union had a far more adversarial mindset towards proponents of traditional values, with leadership in the party taking action to censor and exile these "enemies of change" on over 200 occasions,[44] rather than exclusively putting pressure on these forces by enacting additive social changes such as education campaigns. The most prominent example of a Maoist application of cultural revolution can be seen in the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s wherein Mao claimed that "Revisionist" forces had entered society and infiltrated the government, with the goal of reinstating traditionalism and capitalism in China.[45] Leaning more on the example of the Soviet Union, which involved the silencing and subjugation of adversarial political forces to help bring about a cultural change, Mao called for his followers to speak openly and critically about revisionist forces that they were observing in society and to expel them, assuring them that their actions would be endorsed by the party and that their efforts would in no way be interfered with.[46][page needed] This warrant granted to the public ultimately lead to roughly ten years in which those seen as "Revisionist" forces - largely understood to mean landlords, rich peasants, and the so-called "bourgeoise academic"[47] - were publicly criticised and denounced in places of gathering, and in more extreme examples had physical violence inflicted on them, including being beaten, tortured, and/or killed for their perceived crimes.[48] Beginning in 1967, Mao and the PLA sought to restrain the mass organizations that had developed during the early phase of the Cultural Revolution, and began reframing the movement as one to study Mao Zedong Thought rather than using it as a guide to immediate action.[11]: 133 |

思想的要素 新しい民主主義 新民主主義の理論は、1940年代後半から中国の革命家たちに知られていた。この理論は、大多数の人々にとって、「社会主義への長い道」は、「共産主義者 によって主導される、国民的、民主的、反封建的、反帝国主義的な革命」によってのみ開かれると主張していた。[32] 人民戦争 参照:人民戦争 「政治権力は銃の銃口から生まれる」[33] と主張する毛沢東主義は、毛沢東が「人民戦争」と呼んだ「搾取階級とその国家機構に対する大多数の人民の革命闘争」を強調している。農村部の住民の大部分 を動員して、ゲリラ戦によって既存の制度に反抗させる、毛沢東思想は「農村から都市を包囲する」ことに重点を置いている。 毛沢東主義は、産業と農村の分断を資本主義が利用している大きな分断と捉え、資本主義は、農村部の発展途上である第三世界社会を支配する、工業化が進んだ 都市部の第一世界社会であると認識している。[34] マオイズムは、特定の国の状況における農民の反乱を、世界革命の文脈の一部として捉えており、世界的な農村が世界的な都市を圧倒すると考えている。 [35] 資本主義の都市第一世界による第三世界の農村に対するこの帝国主義のため、マオイズムは第三世界の民族解放運動を支持している。[35] 大衆路線 詳細記事:大衆路線 ウラジーミル・レーニンによる先鋒党の理論[36] を基に、大衆路線は、大衆の革命的指導、プロレタリア独裁の強化、党の強化、社会主義の建設のための戦略を概説している。大衆路線は、「大衆から、大衆 へ」と要約することができる。これには3つの要素または段階がある。[37] 大衆の多様な考えを集める。 これらの思想を、革命的マルクス主義の立場から、大衆の長期的な最終的な利益(大衆が時にはぼんやりとしか認識できないもの)と、客観的状況の科学的分析 を踏まえて、整理・集中する。 これらの集中された思想を、大衆の闘争を革命へと前進させる政治的路線の形で大衆に返す。 この3つのステップは繰り返し適用され、実践と知識を繰り返し高め、より高い段階へと発展させるべきだ。 文化革命 マルクス・レーニン主義思想[7]に根ざした文化革命の理論は、プロレタリア革命とプロレタリア独裁はブルジョア思想を消滅させないとし、階級闘争は社会 主義下でも継続し、さらに激化すると主張する。したがって、社会主義が成功する社会を創造し維持するためには、ブルジョア思想、伝統的な文化価値、および それらを助長する社会的根源に対する継続的な闘争が不可欠である。 この理論の応用例は、1920年代後半から1930年代にかけての革命後のソビエト連邦[38]や、1910年代から1920年代の中国における新文化運 動と五四運動における急速な社会変化に見られる。[39] これらの社会文化運動は、毛沢東主義の文化革命の必要性と目標を形作るものとして捉えることができ、その後、毛沢東の下で中国共産党が実施した大躍進政 策、1950年代の反右派運動、1960年代から1970年代の文化大革命を含む大規模な文化運動にも反映されている。[40] 新文化運動、およびそれに続く五四運動[41] から生じた社会変動は、大部分の国民が文盲でほとんど教育を受けていなかった、伝統的な漢民族の文化規範の解体を中心に展開した[39][42]。この社 会動態の結果、政治的・経済的権力は、教育を受けた少数のエリート層の手に大きく集中し、漢民族の文化は、こうした教育を受けた権力者に対する敬意と畏敬 の念を原則として形成された。前述の運動は、主に、伝統的に教育を受けていない家庭の人々に教育機会を提供し、儒教社会における伝統的な権威者に対して、 あらゆる人々が挑戦することを当然のこととする風潮を正常化することを目的とした、草の根の教育キャンペーンを通じて、こうした社会規範と闘おうとしたも のだった。[43] ソビエト連邦が経験した文化革命は、社会主義社会の実現において、大衆教育と伝統的な文化規範への挑戦の正常化を非常に重視した点で、中国が経験した新文 化運動や五四運動と似ていた。しかし、ソビエト連邦で起こった運動は、伝統的価値観の擁護者に対してはるかに敵対的な姿勢を示し、党の指導部は「変化の 敵」とされた人々を検閲し追放する措置を200回以上も取った[44]。これは、教育キャンペーンなどの追加的な社会改革を通じてこれらの勢力に圧力をか けるだけの対応とは異なっていた。 毛沢東主義による文化革命の最も顕著な例は、1960年代から1970年代にかけての「文化大革命」で、毛沢東は「修正主義」勢力が社会に浸透し、政府に 潜入し、中国に伝統主義と資本主義を復活させようとしていると主張した。[45] ソビエト連邦の例に倣い、対立する政治勢力を黙らせ支配することで文化変革を推進したソビエト連邦の例に倣い、毛沢東は支持者に対し、社会で観察される修 正主義勢力について自由に批判的に発言し、彼らを排除するよう呼びかけた。その際、彼らの行動は党によって支持され、その努力は一切妨げられないと保証し た。[46][ページ番号必要] この公衆への権限付与は、最終的に約10年間にわたり、修正主義勢力と見なされた者たち——主に地主、富裕農民、およびいわゆる「ブルジョア知識人」 [47]——が、集会所などで公然と批判され非難され、極端な例では、彼らの「罪」とされた行為に対し、殴打、拷問、または殺害を含む身体的暴力が加えら れる事態を招いた。[48] 1967 年から、毛沢東と人民解放軍は、文化大革命の初期段階で発展した大衆組織を抑制し、この運動を、即時の行動の指針としてではなく、毛沢東思想を研究する運 動として再構築し始めた。[11]: 133 |

| Contradiction Mao drew from the writings of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Vladimir Lenin in elaborating his theory. Philosophically, his most important reflections emerge on the concept of "contradiction" (maodun). In two major essays, On Contradiction and On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People, he adopts the idea that contradiction is present in matter itself and thus also in the ideas of the brain. Matter always develops through a dialectical contradiction: "The interdependence of the contradictory aspects present in all things and the struggle between these aspects determine the life of things and push their development forward. There is nothing that does not contain contradiction; without contradiction nothing would exist".[49] Mao held that contradictions were the essential feature of society, and a wide range of contradictions dominates society, this calls for various strategies. Revolution is necessary to resolve the fully antagonistic contradictions between labour and capital. Contradictions within the revolutionary movement call for an ideological correction to prevent them from becoming antagonistic. Furthermore, each contradiction (including class struggle, the contradiction holding between relations of production and the concrete development of forces of production) expresses itself in a series of other contradictions, some dominant, others not. "There are many contradictions in the process of development of a complex thing, and one of them is necessarily the principal contradiction whose existence and development determine or influence the existence and development of the other contradictions".[50] The principal contradiction should be tackled with priority when trying to make the fundamental contradiction "solidify". Mao elaborates on this theme in the essay On Practice, "on the relation between knowledge and practice, between knowing and doing". Here, Practice connects "contradiction" with "class struggle" in the following way, claiming that inside a mode of production, there are three realms where practice functions: economic production, scientific experimentation (which also takes place in economic production and should not be radically disconnected from the former) and finally class struggle. These are the proper objects of economy, scientific knowledge, and politics.[51] These three spheres deal with matter in its various forms, socially mediated. As a result, they are the only realms where knowledge may arise (since truth and knowledge only make sense in relation to matter, according to Marxist epistemology). Mao emphasises—like Marx in trying to confront the "bourgeois idealism" of his time—that knowledge must be based on empirical evidence. Knowledge results from hypotheses verified in the contrast with a real object; this real object, despite being mediated by the subject's theoretical frame, retains its materiality and will offer resistance to those ideas that do not conform to its truth. Thus, in each of these realms (economic, scientific, and political practice), contradictions (principle and secondary) must be identified, explored, and put to function to achieve the communist goal. This involves the need to know "scientifically" how the masses produce (how they live, think and work), to obtain knowledge of how class struggle (the central contradiction that articulates a mode of production in its various realms) expresses itself.  Mao Zedong Thought is described as being Marxism–Leninism adapted to Chinese conditions, whereas its variant Marxism–Leninism–Maoism is considered universally applicable Three Worlds Theory In 1974, China announced its Three Worlds Theory at the UN.[14]: 74 Three Worlds Theory states that during the Cold War, two imperialist states formed the "first world"—the United States and the Soviet Union. The second world consisted of the other imperialist states in their spheres of influence. The third world consisted of non-imperialist countries. Both the first and the second world exploit the third world, but the first world is the most aggressive party. The first- and second-world workers are "bought up" by imperialism, preventing socialist revolution. On the other hand, the people of the third world have not even a short-sighted interest in the prevailing circumstances. Hence revolution is most likely to appear in third-world countries, which again will weaken imperialism, opening up for revolutions in other countries too.[44] Agrarian socialism Maoism departs from conventional European-inspired Marxism in that it focuses on the agrarian countryside rather than the urban industrial forces—this is known as agrarian socialism. Notably, Maoist parties in Peru, Nepal, and the Philippines have adopted equal stresses on urban and rural areas, depending on the country's focus on economic activity. Maoism broke with the framework of the Soviet Union under Nikita Khrushchev, dismissing it as state capitalist and Marxist revisionism, a pejorative term among communists referring to those who fight for capitalism in the name of socialism and who depart from historical and dialectical materialism. Although Maoism is critical of urban industrial capitalist powers, it views urban industrialisation as a prerequisite to expanding economic development and the socialist reorganisation of the countryside, with the goal being the achievement of rural industrialisation that would abolish the distinction between town and countryside.[52] |

矛盾 毛沢東は、カール・マルクス、フリードリヒ・エンゲルス、ウラジーミル・レーニンの著作から、自分の理論を精緻に構築した。哲学的には、彼の最も重要な考 察は「矛盾」(maodun)という概念に表れている。2つの主要な論文「矛盾について」と「人民の矛盾の正しい処理について」では、矛盾は物質そのもの に存在し、したがって頭脳の考えにも存在するという考えを採用している。物質は常に弁証法的矛盾を通じて発展する:「すべての物事に存在する矛盾する側面 の相互依存と、これらの側面の間の闘争が、物事の生命を決定し、その発展を推進する。矛盾を含まないものは何もなく、矛盾がなければ何も存在しない」。 [49] 毛沢東は、矛盾は社会の本質的な特徴であり、社会にはさまざまな矛盾が支配的であるため、さまざまな戦略が必要であると主張した。労働と資本との完全に敵 対的な矛盾を解決するには、革命が必要だ。革命運動内の矛盾は、敵対的なものにならないよう、イデオロギーの修正が必要だ。さらに、各矛盾(階級闘争、生 産関係と生産力の発展の具体的な発展との間の矛盾を含む)は、他の矛盾の系列として表現され、そのうちの一部は支配的であり、他はそうではない。 「複雑なものの発展過程には多くの矛盾が存在し、そのうちの1つは必然的に主要矛盾であり、その存在と発展は他の矛盾の存在と発展を決定または影響す る」。[50] 根本的な矛盾を「固める」ためには、主要な矛盾を優先的に解決しなければならない。毛沢東は、知識と実践、知と行の関係について論じた『実践について』 で、このテーマについて詳しく述べている。ここで、実践は「矛盾」と「階級闘争」を次のように結びつけ、生産様式の内側には実践が機能する三つの領域が存 在すると主張している:経済的生産、科学的実験(これは経済的生産においても行われ、前者から根本的に切り離されるべきではない)、そして最後に階級闘 争。これらは、経済、科学的知識、政治の適切な対象である。[51] この 3 つの領域は、社会的に媒介されたさまざまな形態の物質を扱っている。その結果、これらは知識が生まれる唯一の領域となる(マルクス主義の認識論によれば、 真実と知識は物質との関係においてのみ意味を持つから)。毛沢東は、当時の「ブルジョア的理想主義」に対抗しようとしたマルクスと同様に、知識は経験的証 拠に基づくものでなければならないと強調している。知識は、現実の物体との対比によって検証された仮説から生まれる。この現実の物体は、主体の理論的枠組 みによって媒介されているにもかかわらず、その物質性を保持し、その真実に適合しない考えに対して抵抗を示す。したがって、これらの領域(経済、科学、政 治の実践)のそれぞれにおいて、矛盾(原理的および二次的)を特定し、探求し、機能させて、共産主義の目標を達成しなければならない。これには、大衆がど のように生産しているか(どのように生活し、考え、働いているか)を「科学的に」知る必要があり、階級闘争(生産様式をそのさまざまな領域で表現する中心 的な矛盾)がどのように表現されているかについての知識を得る必要がある。  毛沢東思想は、中国の状況に適応したマルクス・レーニン主義と説明されているが、その変種であるマルクス・レーニン主義・毛沢東主義は、普遍的に適用可能 とみなされている。 三世界論 1974年、中国は国連で三世界論を発表した。[14]: 74 三世界論は、冷戦時代、2つの帝国主義国家、すなわち米国とソ連が「第一世界」を形成していたと主張している。第二世界は、その影響下にある他の帝国主義 国家で構成されていた。第三世界は非帝国主義諸国で構成されていた。第一世界と第二世界はともに第三世界を搾取しているが、第一世界は最も攻撃的な側だ。 第一世界と第二世界の労働者は帝国主義に「買収」されており、社会主義革命を妨げている。一方、第三世界の人々は、現在の状況について、目先の利益すら 持っていない。したがって、革命は第三世界の国々で発生する可能性が最も高く、それが再び帝国主義を弱体化させ、他の国々でも革命が起こる可能性が開ける んだ。[44] 農業社会主義 毛沢東主義は、都市の産業力よりも農業の農村部に焦点を当てている点で、従来のヨーロッパ型のマルクス主義とは一線を画している。これは農業社会主義とし て知られている。特に、ペルー、ネパール、フィリピンの毛沢東主義政党は、国の経済活動の重点に応じて、都市と農村に同等の重点を置いている。毛沢東主義 は、ニキータ・フルシチョフ下のソビエト連邦の枠組みを破棄し、それを「国家資本主義」と「マルクス主義修正主義」と非難した。後者は、共産主義者の中 で、社会主義の名の下に資本主義を擁護し、歴史的・弁証法的唯物論から逸脱した者を指す蔑称である。 毛沢東主義は都市の工業資本主義大国を批判するものの、都市の工業化を経済発展の拡大と農村の再組織化のための前提条件と捉え、町と農村の区別を廃止する 農村工業化の実現を目標としている。[52] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maoism |

|