マリー・ボナパルト

Marie Bonaparte, 1882-1962

☆ マリー・ボナパルト王女(1882年7月2日 - 1962年9月21日)は、結婚後はギリシャ王女ジョージアとして知られ、フランスの作家であり、ジークムント・フロイトと親交のあった精神分析家であっ た。彼女の財産は精神分析の普及に貢献し、また、フロイトがナチス・ドイツから逃れることを可能にした。 マリー・ボナパルトは、フランス皇帝ナポレオン1世の玄孫にあたる。彼女は、カニーノおよびムジナーノの第6代王子ロラン・ナポレオン・ボナパルト (1858年 - 1924年)とマリー・フェリックス・ブランク(1859年 - 1882年)の一人娘であった。父方の祖父はピエール・ナポレオン・ボナパルト王子で、ナポレオンの反抗的な末弟であるルシアン・ボナパルト、カニーノお よびムジナーノの初代王子の息子である。このため、称号はあったものの、マリーは亡命中のフランス皇帝の王位継承権を主張するボナパルト家の王族の一員で はなかった。母方の祖父はモンテカルロの主要な不動産開発業者フランソワ・ブランであった。マリーが莫大な財産を相続したのは、この家系のほうからだっ た。

| Princess Marie

Bonaparte (2 July 1882 – 21 September 1962), known as Princess George

of Greece and Denmark upon her marriage, was a French author and

psychoanalyst, closely linked with Sigmund Freud. Her wealth

contributed to the popularity of psychoanalysis and enabled Freud's

escape from Nazi Germany. Marie Bonaparte was a great-grandniece of Emperor Napoleon I of France. She was the only child of Roland Napoléon Bonaparte, 6th Prince of Canino and Musignano (1858–1924) and Marie-Félix Blanc (1859–1882). Her paternal grandfather was Prince Pierre Napoleon Bonaparte, son of Lucien Bonaparte, 1st Prince of Canino and Musignano, Napoleon's rebellious younger brother.[1] For this reason, despite her title, Marie was not a member of the dynastic branch of the Bonapartes who claimed the French imperial throne from exile.[1] Her maternal grandfather was François Blanc, the principal real estate developer of Monte Carlo. It was from this side of her family that Marie inherited her great fortune. |

マリー・ボナパルト王女(1882年7月2日 -

1962年9月21日)は、結婚後はギリシャ王女ジョージアとして知られ、フランスの作家であり、ジークムント・フロイトと親交のあった精神分析家であっ

た。彼女の財産は精神分析の普及に貢献し、また、フロイトがナチス・ドイツから逃れることを可能にした。 マリー・ボナパルトは、フランス皇帝ナポレオン1世の玄孫にあたる。彼女は、カニーノおよびムジナーノの第6代王子ロラン・ナポレオン・ボナパルト (1858年 - 1924年)とマリー・フェリックス・ブランク(1859年 - 1882年)の一人娘であった。父方の祖父はピエール・ナポレオン・ボナパルト王子で、ナポレオンの反抗的な末弟であるルシアン・ボナパルト、カニーノお よびムジナーノの初代王子の息子である。このため、称号はあったものの、マリーは亡命中のフランス皇帝の王位継承権を主張するボナパルト家の王族の一員で はなかった。母方の祖父はモンテカルロの主要な不動産開発業者フランソワ・ブランであった。マリーが莫大な財産を相続したのは、この家系のほうからだっ た。 |

Early life The young Marie Bonaparte during the 1890s She was born at Saint-Cloud, a town in Hauts-de-Seine, Île-de-France and called Mimi within the family.[2] Her maternal grandfather, François Blanc, had left an estimated fortune of FF 88M when he died in 1877. However, his widow, born Marie Hensel, left mostly debts for her three children, including Marie's mother Marie-Félix, to pay off upon her death in July 1881. Prince Roland protected his wife's fortune by persuading her to renounce that of her late mother before the amount of her debts became known.[2] Marie-Felix died of an embolism shortly after Marie's birth, leaving half of her FF 8.4M dowry to her husband and half to her daughter.[2] Most was managed in trust during Marie's youth by her father, who had few financial resources of his own. Marie lived with her father, a published geographer and botanist, in Paris and on various family country estates where he studied, wrote and lectured, leading an active life in Parisian academic circles and on expeditions abroad, while her daily life was supervised by tutors and servants.[2] Affected by phobias and hypochondria as a youth, Marie spent much of her time in seclusion, reading literature and writing the personal journals which reveal her inquisitive spirit and early commitment to the scientific method reflected in her father's scholarship.[2] |

幼少期 1890年代の若い頃のマリー・ボナパルト マリーは、イル・ド・フランス地域圏オー=ド=セーヌ県にあるサン・クルーで生まれ、家族内ではミミと呼ばれていた。[2] 母方の祖父フランソワ・ブランは、1877年に死去した際、推定8800万フランの財産を残していた。しかし、夫人のマリー・アンセルは、3人の子供たち に多額の負債を残し、1881年7月に亡くなった。ローラン王子は、妻の財産を守るために、妻に亡き母の財産を放棄するよう説得し、負債額が明らかになる のを防いだ。[2] マリー・フェリックスは、マリーが生まれた直後に塞栓症で亡くなり、840万フランの持参金の半分を夫に、半分を娘に残した。[2] ほとんどの財産は、自身の経済的資源がほとんどない父親によって、マリーの幼少期に管理されていた。マリーは、地理学者および植物学者として著作を残した 父親とともにパリやさまざまな田舎の屋敷で暮らし、父親はそこで研究や執筆、講義を行い、パリの学術界や海外での探検で活発な生活を送っていた。一方、マ リーの日常生活は家庭教師や使用人によって管理されていた。 2] 若い頃、恐怖症と心気症に悩まされたマリーは、多くの時間を孤独の中で過ごし、文学を読み、個人的な日記を書いていた。その日記からは、彼女の探究心と、 父親の学識に反映されている科学的手法への初期の献身がうかがえる。[2] |

| Married life Several candidates for future husband presented themselves or were considered by Prince Roland for his daughter's hand, notably a distant cousin of the princely House of Murat, Prince Hermann of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach and Louis II, Prince of Monaco. Following a Parisian luncheon Prince Roland hosted for King George I of Greece in September 1906, the king agreed to the prospect of a marriage between their children. Prince George of Greece and Denmark, second of the king's five sons, was introduced to Marie on 19 July 1907 at the Bonapartes' home in Paris.[2] Although homosexual,[3] he courted her for twenty-eight days, confiding that from 1883, he'd lived not at his father's Greek court in Athens, but at Bernstorff Palace near Copenhagen with Prince Valdemar of Denmark, his father's youngest brother. The Queen had taken the boy to Denmark to enlist him in the Danish royal navy and consigned him to the care of Valdemar, who was an admiral in the Danish fleet. Feeling abandoned by his father on this occasion, George described to his fiancée the profound attachment he developed for his uncle.[4] He admitted that, contrary to what he knew were her hopes, he could not commit to living permanently in France since he was obligated to undertake royal duties in Greece or on its behalf if summoned to do so.[2] Once his proposal of marriage was accepted, the bride's father was astonished when George waived any contractual clause guaranteeing an allowance or inheritance from Marie; she would retain and manage her own fortune (a trust yielding 800,000 francs per annum, her father leaving 60 million francs on his death in 1924) and only their future children would receive legacies.[2] On 21 November 1907 in Paris, Marie and George were married in a civil ceremony, with a subsequent Greek Orthodox ceremony on 12 December 1907, at Athens.[1] Thereafter she was known as Princess George of Greece and Denmark. By March 1908 Marie was pregnant and, as agreed, the couple returned to France to take up residence. When George brought his bride to Denmark for the first visit with his uncle, Prince Valdemar's wife, Marie d'Orléans, was at pains to explain to Marie Bonaparte the intimacy which united uncle and nephew, so deep that at the end of each of George's several yearly visits to Bernstorff he would weep, Valdemar would fall sick, and the women learned the patience not to intrude upon their husbands' private moments.[2] During the first of these visits, Marie Bonaparte and Valdemar found themselves engaging in the kind of passionate intimacies she had looked forward to with her husband who, however, only seemed to enjoy them vicariously, sitting or lying beside his wife and uncle.[2] On a later visit, Marie Bonaparte carried on a passionate flirtation with Prince Aage, Count of Rosenborg, Valdemar's eldest son. In neither case does it appear that George objected, or felt obliged to give the matter any attention.[2] Marie Bonaparte came to admire the forbearance and independence of Valdemar's wife under circumstances which caused her bewilderment and estrangement from her own husband.[2] Although Marie occasionally joined her husband in Greece or elsewhere for national holidays and dynastic ceremonies, their life together was spent mostly on her estates in the French countryside. For months at a time, George was in Athens or Copenhagen, while Marie was in Paris, Vienna or traveling with the couple's children. That pattern allowed each to pursue activities in which the other had little interest.[2] The couple had two children, Peter (1908–1980) and Eugénie (1910–1989).[1] From 1913 to early 1916, Marie carried on an intense flirtation with French prime minister Aristide Briand, but went no further because she did not want to share him with his mistress, the actress Berthe Cerny. Matters came to a head in April 1916, when Berthe Cerny broke off the relationship.[5] The affair with Briand lasted until May 1919. In 1915 Briand wrote to her that, having come to know and like Prince George, he felt guilty about their secret passion. George tried to persuade him that Greece, officially neutral during World War I but whose King was suspected of sympathy for the Central Powers, really hoped for an Allied victory: He may have influenced Briand to support the Allied expedition against the Bulgarians at Salonika.[2] When the prince and princess returned in July 1915 to France following a visit to the ailing King Constantine I in Greece, her affair with Briand had become notorious and George expressed a restrained jealousy.[2] By December 1916 the French fleet was shelling Athens and in Paris Briand was suspected, alternately, of having seduced Marie in a futile attempt to bring Greece over to the Allied side, or of having been seduced by her to oust Constantine and set George upon the Greek throne.[2] |

結婚生活 ローラン王子の娘の結婚相手として、複数の候補者が名乗りを上げたか、王子が検討した。特に、ムラート家の遠い親戚であるザクセン=ヴァイマル=アイゼナ ハのヘルマン王子とモナコ大公ルイ2世が候補に挙がった。1906年9月、ローラン王子がギリシャ王ゲオルギオス1世のために主催したパリの昼食会に続い て、王は二人の子供たちの結婚に同意した。ギリシャ王の5人の息子の2番目であるゲオルギオス王子は、1907年7月19日にパリのボナパルト家邸宅でマ リーに紹介された。[2] 同性愛者であったものの[3]、彼は28日間彼女に求愛し、 28日間、彼女に求愛し、1883年から父のギリシャのアテネの宮廷ではなく、コペンハーゲン近郊のベルンストルフ宮殿で、父の末弟であるデンマークの ヴァルデマール王子と暮らしていたことを打ち明けた。女王は、デンマーク王立海軍に入隊させるためにその少年をデンマークに連れて行き、デンマーク艦隊の 提督であったヴァルデマールにその少年の世話を任せていた。このとき父親に捨てられたと感じたジョージは、伯父に対する深い愛着を婚約者に語った。[4] 彼は、彼女の希望に反して、ギリシャで王族としての義務を遂行する義務があるため、フランスに永住することはできないと認めた。[2] 結婚の申し出が受け入れられると、 、マリーの父親は驚いた。ジョージは、マリーからの小遣いや相続を保証する契約条項をすべて放棄したのだ。マリーは自身の財産を保有し管理する(1924 年に父親が死去した際には6000万フランの遺産が残され、年間80万フランの信託収益があった)ことになり、将来生まれる子供たちだけが遺産を受け継ぐ ことになるのだ。 1907年11月21日、パリでマリーとジョージは民事婚を挙げ、1907年12月12日にはアテネでギリシャ正教の式を挙げた。[1] それ以降、彼女はギリシャ・デンマーク王女ジョージとして知られるようになった。 1908年3月までにマリーは妊娠し、合意通り、夫妻はフランスに戻り、住居を構えた。ジョージが新婦を連れてデンマークを初めて訪れた際、ジョージの叔 父であるヴァルデマール王子の妻マリー・ドルレアンは、ジョージとマリー・ボナパルトの絆について、その親密さを説明しようと苦心した。その絆は深く、 ジョージがベルンシュトルフを年に数回訪れるたびに、ヴァルデマールは体調を崩し、女性たちは夫たちのプライベートな時間に立ち入らない忍耐を学んだ [2] 最初の訪問の際、マリー・ボナパルトとヴァルデマールは、彼女が夫との間に期待していたような情熱的な親密さを共有していることに気づいた。しかし、夫は 傍らで座ったり横になったりしているだけで、その親密さを間接的に楽しんでいるようにしか見えなかった。[2] その後の訪問の際、マリー・ボナパルトはヴァルデマールの長男であるローゼンボー城伯のオーゲ王子と情熱的な浮気を続けた。いずれの場合も、ジョージが反 対したり、この件に注意を払う義務を感じたりした形跡はない。[2] マリー・ボナパルトは、ヴァルデマール王の妻が、自身の夫との間に困惑と疎外感を生じさせる状況下で、忍耐と自立心を示していることを称賛するようになっ た。[2] マリーは時折、夫とともにギリシャやその他の国で祝祭日や王朝の儀式に参加したが、ふたりの生活の大半はフランスの田舎にあるマリーの所有地で過ごされ た。数ヶ月間、ジョージはアテネやコペンハーゲンに滞在し、マリーはパリやウィーンに滞在したり、夫妻の子供たちと旅行したりしていた。このパターンによ り、お互いがほとんど関心を持たない活動にそれぞれが打ち込むことができた。[2] 夫妻にはピーター(1908年-1980年)とユージニー(1910年-1989年)の2人の子供がいた。[1] 1913年から1916年初頭にかけて、マリーはフランス首相のアリステド・ブリアンと熱烈な浮気をしていたが、愛人である女優ベルタ・チェルニーと彼を 共有したくないという理由で、それ以上の関係には至らなかった。1916年4月、ベルタ・チェルニーが関係を断ち切ったことで、事態は決定的となった。 [5] ブリヤンとの情事は1919年5月まで続いた。1915年、ブリヤンは彼女に手紙を書き、ジョージ王子と知り合い、彼を好きになったことで、自分たちの秘 密の情事に罪悪感を感じていると伝えた。ジョージは、第一次世界大戦中は公式に中立を保っていたものの、国王が中央同盟国への好意が疑われていたギリシャ は、同盟国の勝利を心から願っていると彼を説得しようとした。彼は、ブリアンが同盟国によるブルガリアに対するサロニカ遠征を支援するように影響を与えた のかもしれない。[2] 1915年7月、ギリシャの病弱なコンスタンティノス1世を訪問した後、夫妻がフランスに戻ったとき、彼女とブリアンとの関係は悪名高いものになってお り、ジョージは控えめな嫉妬心を表した。[2] 1916年12月までに、フランス艦隊はアテネを砲撃しており、パリでは、ブリアンがマリーを誘惑し、ギリシャを連合国側につけようとしたのではないか、 あるいは、マリーに誘惑され、コンスタンチーヌを追放してジョージをギリシャ王位につかせようとしたのではないか、と疑われていた。[2] |

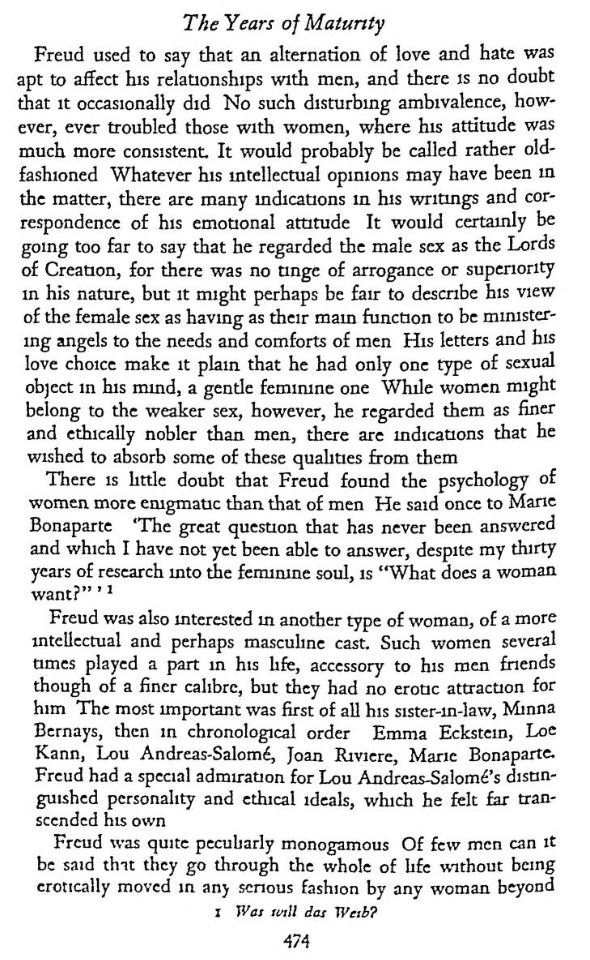

| Sexual research Despite what she described as sexual dysfunction, Marie Bonaparte conducted affairs with Sigmund Freud's disciple Rudolph Loewenstein as well as Aristide Briand, her husband's aide-de-camp Lembessiss, a prominent married French physician, and possibly others.[2] Troubled by her difficulty in achieving sexual fulfillment, Marie engaged in research.[6] In 1924, she published her results under the pseudonym A. E. Narjani and presented her theory of frigidity in the medical journal Bruxelles-Médical, having measured the distance between the vagina and the clitoral glans in 200 women.[7][8] After analyzing their sexual history she concluded that the distance between these two organs was critical for the ability to reach orgasm (volupté) during vaginal intercourse. She identified women with a short distance (the paraclitoridiennes) who reached orgasm easily during intercourse, and women with a distance of more than two and a half centimeters (the téleclitoridiennes) who had difficulties while the mesoclitoriennes were in between.[2][9] Bonaparte considered herself a téleclitorienne and approached Josef Halban to surgically move her clitoris closer to her vagina. She underwent and published the procedure as the Halban–Narjani operation.[9] When it proved unsuccessful in facilitating the sought-after outcome for Marie, the physician repeated the operation.[2][10] She modeled for the Romanian modernist sculptor Constantin Brâncuși. His sculpture of her, "Princess X", created a scandal in 1919 when he represented her or caricatured her as a large gleaming bronze phallus.[citation needed] This phallus symbolizes the model's obsession with the penis and her lifelong quest to achieve vaginal orgasm.[citation needed]  The Life and Work Of Sigmund Freud, by Ernest Jones, 1961. |

性的研究 彼女が性的機能障害と表現したものとは裏腹に、マリー・ボナパルトはジークムント・フロイトの弟子ルドルフ・ローウェンスタインと関係を持ち、さらに夫の 副官レンベシス、著名な既婚フランス人医師アリスティード・ブリアンとも関係を持った可能性がある。[2] 性的な満足を得ることが難しいことに悩んだマリーは、研究に没頭した。[6] 1924年、彼女は A. E. Narjaniという偽名で結果を発表し、医学誌『ブリュッセル・メディカル』に、200人の女性を対象に膣とクリトリスの亀頭部分の距離を測定した結果 を発表した。[7][8] 彼女は、これらの2つの器官の距離が、膣性交中にオルガスム(絶頂感)に達する能力にとって重要であると結論づけた。彼女は、性交中に簡単にオルガスムス に達する、陰核亜属(paraclitoridiennes)と呼ばれる陰核と膣の距離が短い女性と、中間である中陰核属 (mesoclitoridiennes)と、2.5センチメートル以上の陰核遠位属(téleclitoridiennes)と呼ばれる陰核と膣の距離 が長い女性を特定した。[2][9] ボナパルトは自身を陰核遠位属と考え、ヨセフ・ハルバンにクリトリスを手術で膣に近づけるよう依頼した。彼女は手術を受け、ハルバン・ナルジャーニ手術と してその方法を発表した。[9] しかし、マリーが望んでいた結果を得るには不十分であることが判明すると、医師は手術を繰り返した。[2][10] 彼女はルーマニアのモダニズム彫刻家コンスタンティン・ブランクーシのモデルとなった。ブランクーシが彼女をモデルに制作した「プリンセスX」は、 1919年に大きな話題となった。ブランクーシは彼女を表現したのか、あるいは彼女を戯画化したのか、大きな光沢のある青銅の男根として表現したからだ。 この男根は、モデルがペニスに執着し、膣内オーガズムを達成しようと生涯をかけて探求したことを象徴している。 |

| Freud In 1925, Marie consulted Freud for treatment of what she described as her frigidity, which was later explained as a failure to have orgasms during missionary position intercourse.[11] It was to Marie Bonaparte that Freud remarked, "The great question that has never been answered and which I have not yet been able to answer, despite my thirty years of research into the feminine soul, is 'What does a woman want?'".[12]  The 4th century BC South Italian Apulian bell krater given by Marie Bonaparte to Sigmund Freud, which today contains the ashes of Freud and his wife Martha[13] Although Prince George maintained friendly relations with Freud, in 1925 he asked Marie to give up her work in psychoanalytical studies and treatment to devote herself to their family life, but she declined.[2] Robed in the diplomatic immunity of a member of a reigning European royal family and possessed of great wealth, Marie was often able to help those threatened or despoiled by World War II. When the Greek royal family were in exile or Greece was under occupation, she helped support her husband's banished relatives, including allowing the family of her husband's nephew, Prince Philip of Greece, to occupy one of her homes in Saint-Cloud and paying for their private schooling while sending her own children to public lycées. Later she paid Freud's ransom to Nazi Germany and bought the letters Freud had written to Wilhelm Fliess about his use of cocaine from Fliess's widow when he could not afford her price. Freud asked her to destroy the letters. She refused, but agreed never to read them. She was instrumental in delaying the search of Freud's apartment in Vienna by the Gestapo in early 1938, and helped him obtain an exit visa to depart Austria. She also smuggled out some of his savings in a Greek diplomatic pouch, provided him with additional funding to leave the country, and arranged for the transport to London of some of his possessions, including his analytic couch. Freud arrived himself in London on 6 June 1938.[14] In 1938, Bonaparte proposed that the United States purchase Baja California and turn it into a new Jewish state. Freud refused to take what he called her "colonial plans" seriously, but Bonaparte nonetheless authored letters to William Christian Bullitt Jr. and Franklin D. Roosevelt to advocate for the idea.[15] |

フロイト 1925年、マリーは、自分が冷感症であると説明し、フロイトに治療を求めた。これは、正常位での性交時にオーガズムに達しないことを指していた。 [11] フロイトが「女性の本質について30年研究してきたが、未だに答えが出ず、私自身も答えを見つけられていない大きな疑問は、『女性は何を求めているの か?』ということだ」と述べたのは、マリー・ボナパルトに対してであった。[12]  マリー・ボナパルトがジークムント・フロイトに贈った紀元前4世紀の南イタリアのプッリャの鐘形クラテル。現在、この中にはフロイトと妻のマルタの遺灰が収められている。[13] ジョージ王子はフロイトと友好的な関係を維持していたが、1925年にはマリーに精神分析の研究と治療の仕事を辞めて家庭生活に専念するよう求めたが、彼女はこれを断った。[2] ヨーロッパの現役の王族の一員として外交特権を持ち、莫大な財産も所有していたマリーは、第二次世界大戦によって脅威にさらされたり、財産を奪われたりし た人々をたびたび救うことができた。ギリシャ王室が亡命中であったり、ギリシャが占領下にあった際には、夫の追放された親族を支援し、夫の甥にあたるギリ シャ王太子フィリップの家族をサン・クルーの自宅に住まわせ、私立学校の学費を支払った一方で、自身の子供たちは公立のリセに通わせていた。 その後、彼女はナチス・ドイツにフロイトの身代金を支払い、フロイトがコカインを使用していることをウィルヘルム・フリエスに宛てて書いた手紙を、フロイ トがその代金を支払えないときに、フリエスの未亡人から購入した。フロイトは彼女にその手紙を破棄するよう依頼したが、彼女は拒否し、しかし決して読まな いと約束した。彼女は1938年初頭にゲシュタポがウィーンのフロイトのアパートを捜索するのを遅らせるのに尽力し、また、オーストリアを出国するための 出国ビザ取得を支援した。また、彼の貯蓄の一部をギリシャの外交用ポーチに隠して国外に持ち出し、国外脱出のための追加資金を提供し、彼の所有物の一部 (分析用ソファを含む)をロンドンに輸送する手配をした。フロイトは1938年6月6日にロンドンに到着した。 1938年、ボナパルトはアメリカ合衆国がバハ・カリフォルニアを購入し、それを新たなユダヤ人国家に変えることを提案した。フロイトは彼女の「植民地計 画」を真剣に受け止めなかったが、それでもボナパルトはウィリアム・クリスチャン・ブリット・ジュニアとフランクリン・D・ルーズベルトにそのアイデアを 支持する手紙を書いた。[15] |

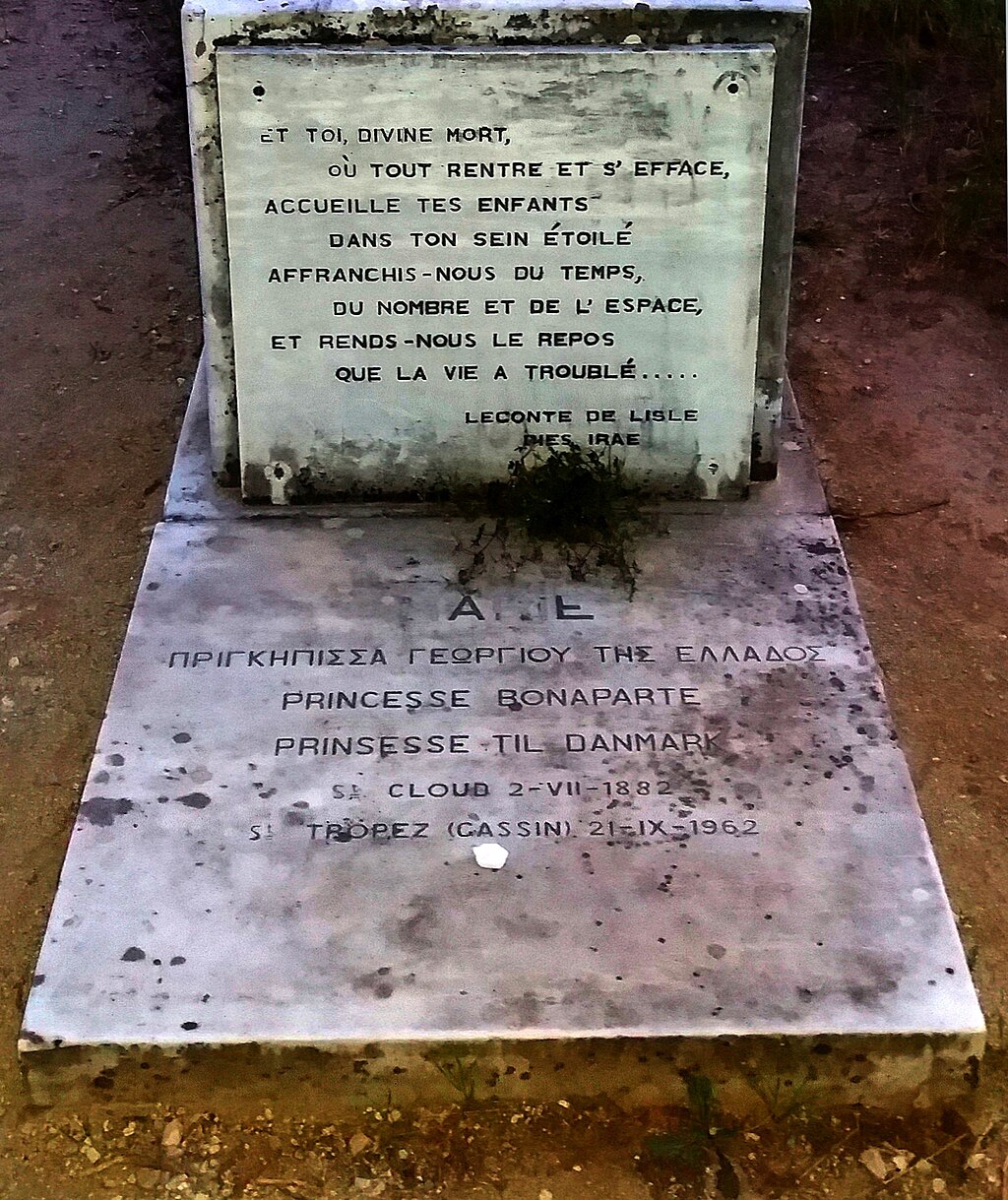

| Later life On 2 June 1953, Marie and her husband represented their nephew, King Paul of Greece, at the coronation of Elizabeth II in London. Bored with the pageantry, Marie offered a sampling of the psychoanalytic method to the gentleman seated next to her, the future French president François Mitterrand. Mitterrand obliged Marie, and the pair barely witnessed the pomp and ceremony, finding their own dialogue far more interesting.[2] She practiced as a psychoanalyst until her death in 1962, providing substantial services to the development and promotion of psychoanalysis. She authored several books on psychoanalysis,[1] translated Freud's work into French and founded the French Institute of Psychoanalysis (Société Psychoanalytique de Paris SPP) in 1926.[2] In addition to her own work and preservation of Freud's legacy, she also offered financial support for Géza Róheim's anthropological explorations. A scholar on Edgar Allan Poe, she wrote a biography and an interpretation of his work. Bonaparte's translation of a sentence in Freud's thirty-first Vorlesung ('lecture'), Wo Es war, soll Ich werden, generated some controversy. Strachey translated it into English as "Where Id was, Ego shall be".[16] Lacan, arguing that Freud used "das Es" (lit. 'the It') and "das Ich" (lit. 'the I') when he intended the meaning to be "Id" and "Ego", suggested "Wo Es war, soll Ich werden" be translated "Where It was, there shall I come to be".[17] Bonaparte translated it into French as le moi doit déloger le ça, meaning in English roughly "Ego must dislodge Id", which according to Lacan is directly contrary to Freud's intended meaning.[18] Death  Grave of Princess Marie (née Bonaparte) at her husband's tomb Bonaparte died of leukemia in Saint-Tropez on 21 September 1962. She was cremated in Marseille, and her ashes were interred adjacent to Prince George's tomb at Tatoï, near Athens.[2] Legacy The story of her relationship with Sigmund Freud, including assisting his family's escape into exile, was made into a television film in 2004 as Princesse Marie [fr], directed by Benoît Jacquot, starring Catherine Deneuve as Princess Marie Bonaparte and Heinz Bennent as Freud. |

晩年 1953年6月2日、マリーと夫は甥であるギリシャ王パウロスを代理し、ロンドンで行われたエリザベス2世の戴冠式に出席した。儀式に退屈したマリーは、 隣に座っていた紳士(後のフランス大統領フランソワ・ミッテラン)に精神分析の手法を試してみた。ミッテランはマリーの申し出を受け入れ、2人は式典を辛 うじて目にしたが、自分たちの対話の方がはるかに興味深いと感じていた。 彼女は1962年に亡くなるまで精神分析家として活動し、精神分析の発展と普及に多大な貢献をした。彼女は精神分析に関する複数の著書を執筆し、[1] フロイトの著作をフランス語に翻訳し、1926年にはフランス精神分析協会(Société Psychoanalytique de Paris SPP)を設立した。[2] 自身の研究やフロイトの遺産の保存に加え、彼女はゲザ・ローハイムの人類学的探求にも財政的支援を行った。エドガー・アラン・ポーの研究者でもあった彼女 は、ポーの伝記と作品の解釈を著した。 フロイトの講義第31回『我はどこにあり、我となるべきか』の一節をボナパルトが翻訳したことは、論争を巻き起こした。ストラチェイはこれを「Where Id was, Ego shall be」と英訳した。[16] ラカンは、フロイトが「das Es」(直訳すると「それ」)と「das Ich」(直訳すると「私」)という語を使用した際には、本来「Id」と「Ego」という意味を意図していたと主張し、「Wo Es war, soll Ich werden"を「Where It was, there shall I come to be」と訳した。[17] ボナパルトはこれをle moi doit déloger le çaとフランス語に訳し、英語では「エゴはイドを追い出さなければならない」という意味になるが、ラカンによると、これはフロイトの意図した意味とは正反 対である。[18] 死  マリー・ボナパルト王女(旧姓)の夫の墓にある墓碑 ボナパルトは1962年9月21日にサン=トロペで白血病により死去した。彼女はマルセイユで火葬され、遺灰はアテネ近郊のタトイにあるジョージ王子の墓の隣に埋葬された。 遺産 彼女とジークムント・フロイトの関係、および彼の家族の亡命を手助けしたことなどを題材にしたテレビ映画『プリンセス・マリー』(原題: Princesse Marie)が2004年に制作された。監督はブノワ・ジャコ、マリー・ボナパルト王女役をカトリーヌ・ドヌーヴ、フロイト役をハインツ・ベネントが演じ た。 |

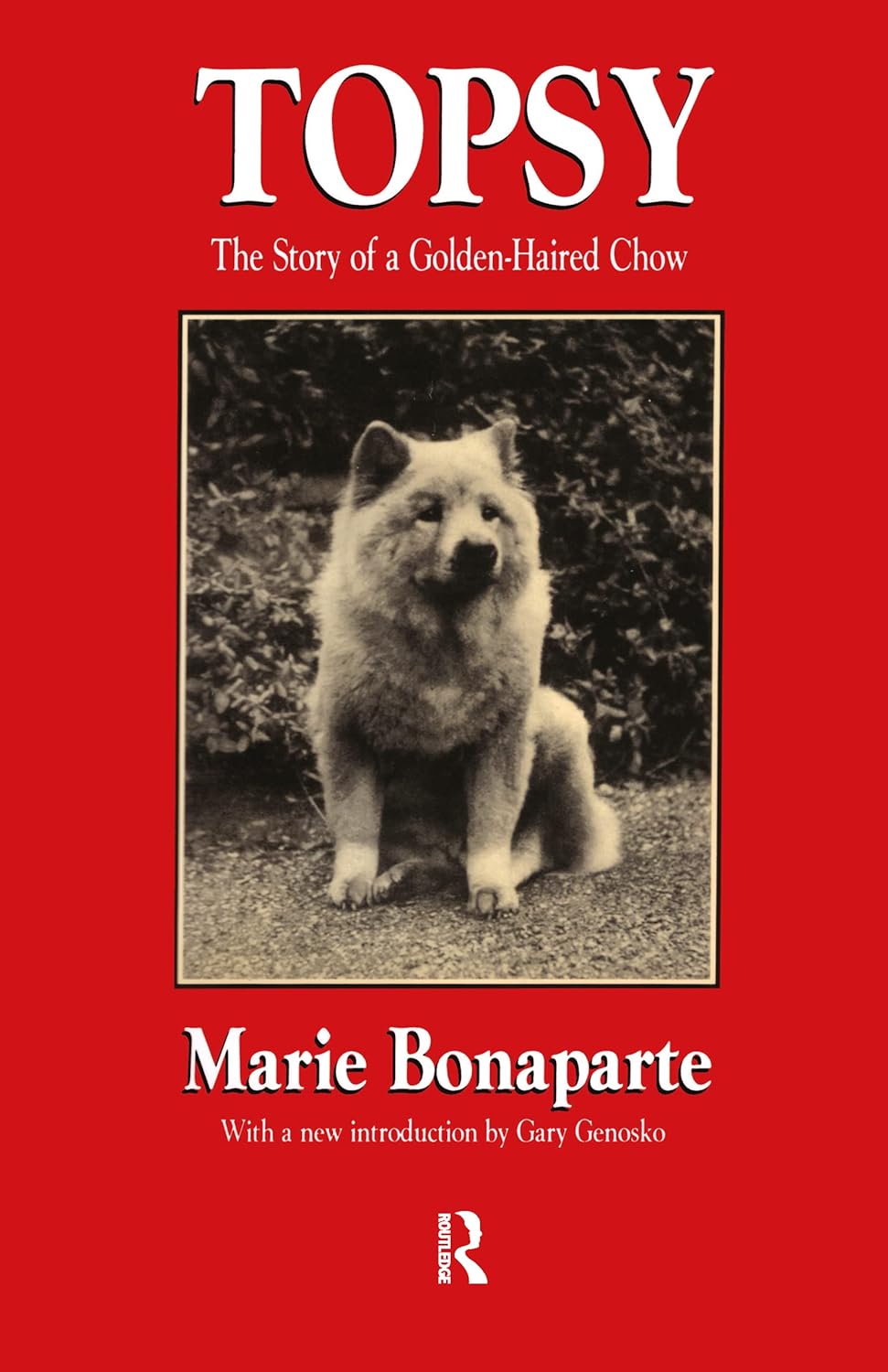

| "Le Printemps sur mon Jardin." Paris: Flammarion, 1924. "Topsy, chow-chow, au poil d'or." Paris: Denoel et steele, 1937. The Life and Works of Edgar Allan Poe: A Psycho-Analytic Interpretation with a foreword by Sigmund Freud – 1934 (translated into English, 1937) Topsy – 1940 – a love story about her dog "La Mer et le Rivage." Paris: for the author, 1940. "Monologues Devant la Vie et la Mort." London: Imago Publishing Co., 1951. "De la Sexualite de la Femme." Paris: Press Universitaires de France, 1951. "Psychanalyse et Anthropologie." Paris: Press Universitaires de France, 1952. "Chronos, Eros, Thanatos." London: Imago Publishing Co., 1952. "Psychanalyse et Biologique." Paris: Press Universitaires de France, 1952. Five Copy Books – 1952 Female Sexuality – 1953 "A La Mémoire Des Disparus" London: Chorley & Pickersgill Ltd., 1953 |

「庭のプランタン」 パリ: Flammarion, 1924. 「トプシー、チャウチャウ、ポワルドール」 パリ: Denoel et steele, 1937. The Life and Works of Edgar Allan Poe: A Psycho-Analytic Interpretation with a foreword by Sigmund Freud(エドガー・アラン・ポーの生涯と作品:ジークムント・フロイトによる序文付き精神分析的解釈) - 1934年(英訳、1937年 Topsy - 1940 - 愛犬をめぐる愛の物語 「ラ・メールとリヴァージュ」 パリ:1940年、著者のために 「Monologues Devant la Vie et la Mort.」. ロンドン:イマーゴ出版社、1951年。 「De la Sexualite de la Femme.」. Paris: フランス大学出版会, 1951. 「精神分析と人間学」. パリ: フランス大学出版会, 1952. 「クロノス、エロス、タナトス」. London: Imago Publishing Co., 1952. 「精神分析と生物学」. パリ: フランス大学出版会、1952年。 コピー本5冊(1952年 女性の性 - 1953年 「不和の記憶" ロンドン チョーリー&ピッカースギル社、1953年 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marie_Bonaparte |  |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆