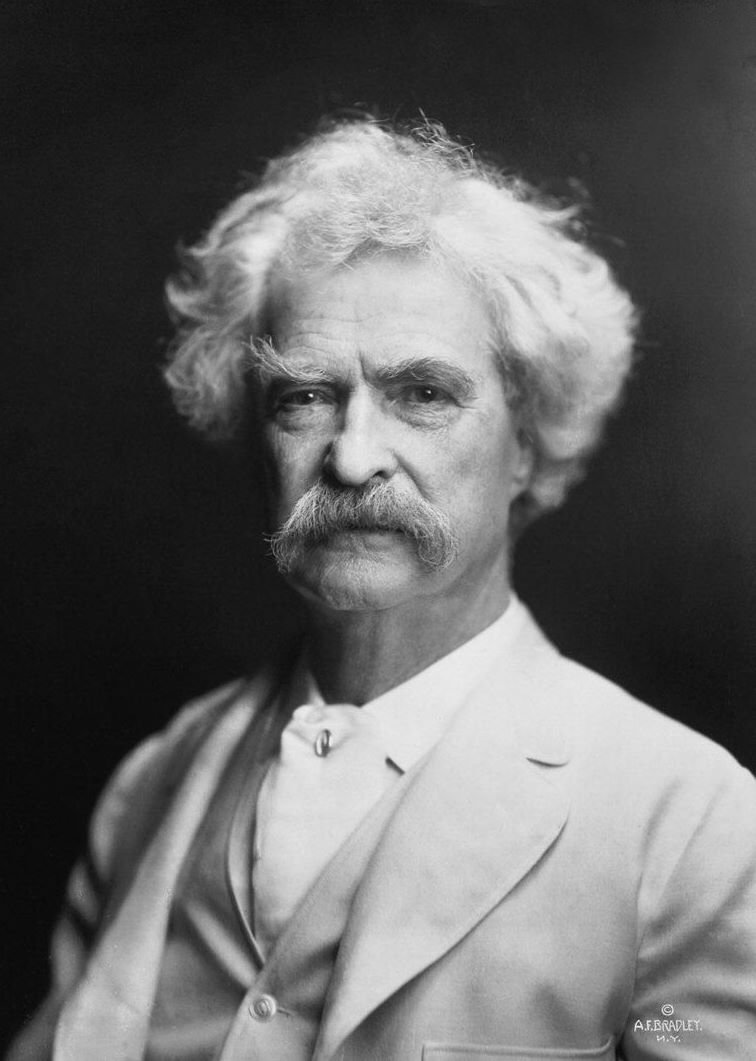

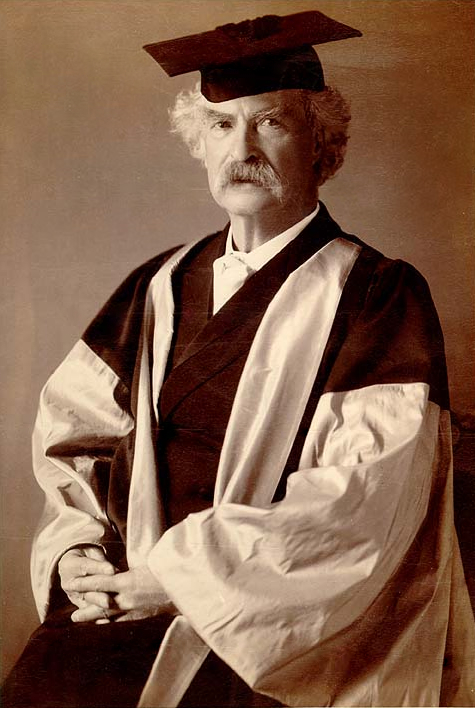

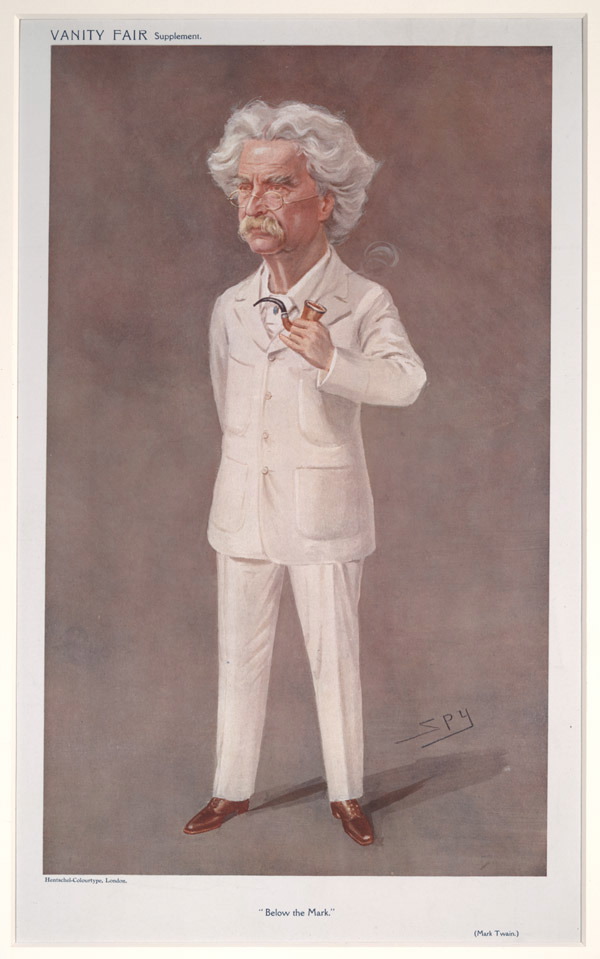

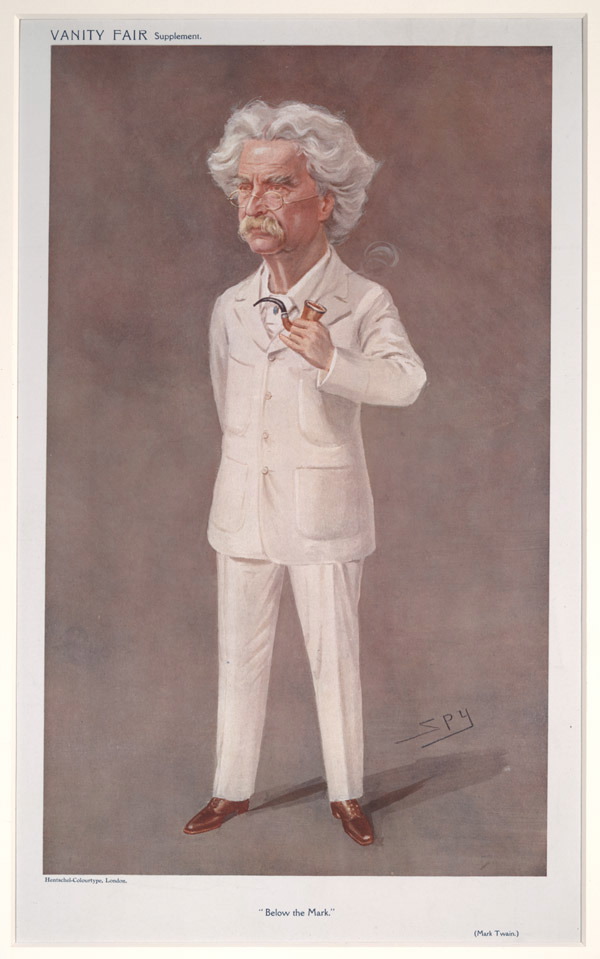

Twain in 1907

マーク・トゥエイン

Mark Twain, 1835-1910

Twain in 1907

☆ おことわり:「マーク・トゥエイン的理性」はこちらに移転していま す。「マーク・トゥエイン的理性とは、みたまま、思ったままという、ナイーブな主張を押し通すとこ ろからみえてくる認識や、道徳観のこと」であり、池田光穂による造語である(池田 2020)。

★サミュエル・ラングホーン・クレメンス(1835年11月30日-1910年4月21日)は、マーク・トウェインのペンネームで知られるアメリカの作家、 ユーモア作家、エッセイストである[1]。彼の小説には『トム・ソーヤーの冒険』(1876年)とその続編『ハックルベリー・フィンの冒険』(1884 年)があり[4]、後者はしばしば 「偉大なアメリカ小説 」と呼ばれる。トウェインはまた、『アーサー王宮廷のコネチカット・ヤンキー』(1889年)と『パッドヘッド・ウィルソン』(1894年)を書き、『金 ぴか時代』(1873年)を共著した: A Tale of Today』(1873年)をチャールズ・ダドリー・ワーナーと共著している。

| Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910),[1] known by the pen name Mark Twain,

was an American writer, humorist and essayist. He was praised as the

"greatest humorist the United States has produced,"[2] with William

Faulkner calling him "the father of American literature."[3] His novels

include The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and its sequel, Adventures

of Huckleberry Finn (1884),[4] with the latter often called the "Great

American Novel." Twain also wrote A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's

Court (1889) and Pudd'nhead Wilson (1894), and co-wrote The Gilded Age:

A Tale of Today (1873) with Charles Dudley Warner. Twain was raised in Hannibal, Missouri, which later provided the setting for both Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. He served an apprenticeship with a printer early in his career, and then worked as a typesetter, contributing articles to his older brother Orion Clemens' newspaper. Twain then became a riverboat pilot on the Mississippi River, which provided him the material for Life on the Mississippi (1883). Soon after, Twain headed west to join Orion in Nevada. He referred humorously to his lack of success at mining, turning to journalism for the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise.[5] He first achieved success as a writer with the humorous story "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County," which was published in 1865; it was based on a story that he heard at Angels Hotel in Angels Camp, California, where he had spent some time while he was working as a miner. The short story brought him international attention.[6] He wrote both fiction and non-fiction. As his fame grew, he became a much sought-after speaker. His wit and satire, both in prose and in speech, earned praise from critics and peers, and Twain was a friend to presidents, artists, industrialists, and European royalty. Although Twain initially spoke out in favor of American interests in the Hawaiian Islands, he later reversed his position,[7] going on to become vice president of the American Anti-Imperialist League from 1901 until his death in 1910, coming out strongly against the Philippine-American War and American colonialism.[8][9][10] He published a satirical pamphlet, "King Leopold's Soliloquy", in 1905 about King Leopold II of Belgium's abuses of human rights in the Congo. Twain earned a great deal of money from his writing and lectures, but invested in ventures that lost most of it, such as the Paige Compositor, a mechanical typesetter that failed because of its complexity and imprecision. He filed for bankruptcy in the wake of these financial setbacks, but in time overcame his financial troubles with the help of Standard Oil executive Henry Huttleston Rogers. Twain eventually paid all his creditors in full, even though his declaration of bankruptcy meant he was not required to do so. He was born shortly after an appearance of Halley's Comet, and predicted that his death would accompany it as well, dying a day after the comet was at its closest to Earth.[11] |

サ

ミュエル・ラングホーン・クレメンス(1835年11月30日-1910年4月21日)は、マーク・トウェインのペンネームで知られるアメリカの作家、

ユーモア作家、エッセイストである[1]。彼の小説には『トム・ソーヤーの冒険』(1876年)とその続編『ハックルベリー・フィンの冒険』(1884

年)があり[4]、後者はしばしば 「偉大なアメリカ小説

」と呼ばれる。トウェインはまた、『アーサー王宮廷のコネチカット・ヤンキー』(1889年)と『パッドヘッド・ウィルソン』(1894年)を書き、『金

ぴか時代』(1873年)を共著した: A Tale of Today』(1873年)をチャールズ・ダドリー・ワーナーと共著している。 トウェインは、後に『トム・ソーヤー』と『ハックルベリー・フィン』の舞台となるミズーリ州ハンニバルで育った。キャリアの初期に印刷工の見習いをした 後、植字工として働き、兄オリオン・クレメンズの新聞に記事を寄稿した。その後トウェインはミシシッピ川で川船の水先案内人となり、『ミシシッピ川での生 活』(1883年)の材料となった。その直後、トウェインは西に向かい、ネバダ州でオリオンと合流した。彼は採鉱で成功しなかったことをユーモラスに語 り、ヴァージニア・シティ準州のエンタープライズ紙のジャーナリズムに転向した[5]。 1865年に出版された「The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County(カラベラス郡の有名な飛び跳ねるカエル)」というユーモラスな物語で作家として初めて成功を収めた。彼はフィクションとノンフィクションの 両方を書いた。名声が高まるにつれ、彼は講演者として引っ張りだこになった。散文でもスピーチでも、彼のウィットと風刺は批評家や同業者から賞賛を浴び、 トウェインは大統領、芸術家、実業家、ヨーロッパの王族と親交を結んだ。 トウェインは当初、ハワイ諸島におけるアメリカの権益を支持する発言をしていたが、後に立場を翻し[7]、1901年から1910年に亡くなるまでアメリ カ反帝国主義連盟の副会長となり、米比戦争とアメリカの植民地主義に強く反対した[8][9][10]。1905年には、ベルギー国王レオポルド2世によ るコンゴでの人権侵害を風刺した小冊子『レオポルド王の独り言』を出版した。 トウェインは執筆活動や講演活動で巨万の富を得たが、機械植字機ペイジ・コンポジターなど、その複雑さと不正確さのために失敗した事業に投資し、その大半 を失った。このような経済的挫折をきっかけに破産を申請したが、やがてスタンダード・オイルの重役ヘンリー・ハットレストン・ロジャースの助けで財政難を 克服した。トウェインは最終的にすべての債権者に全額を支払ったが、破産宣告によってその必要はなかった。彼はハレー彗星が出現した直後に生まれ、彗星が 地球に最接近した翌日に死ぬと予言した[11]。 |

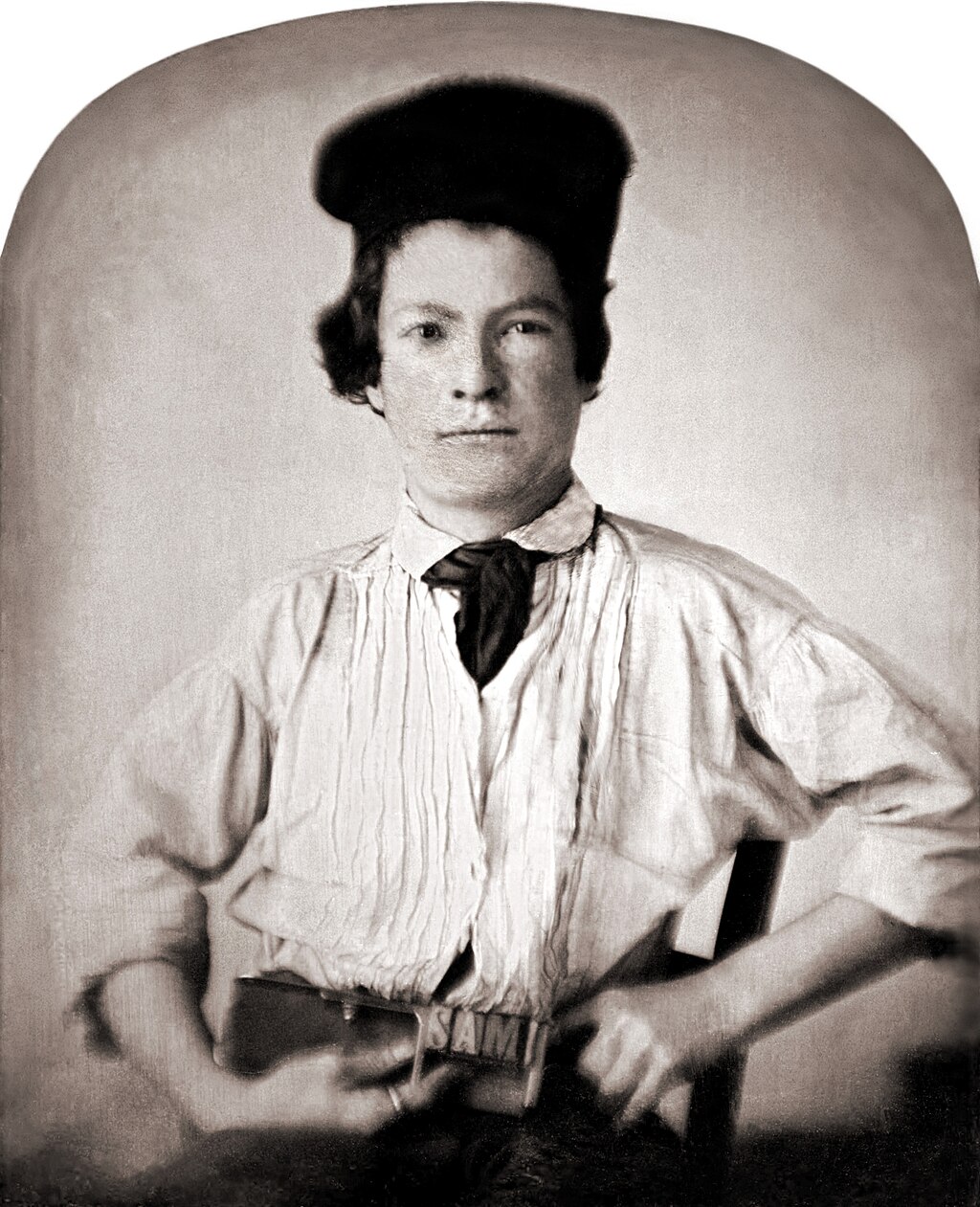

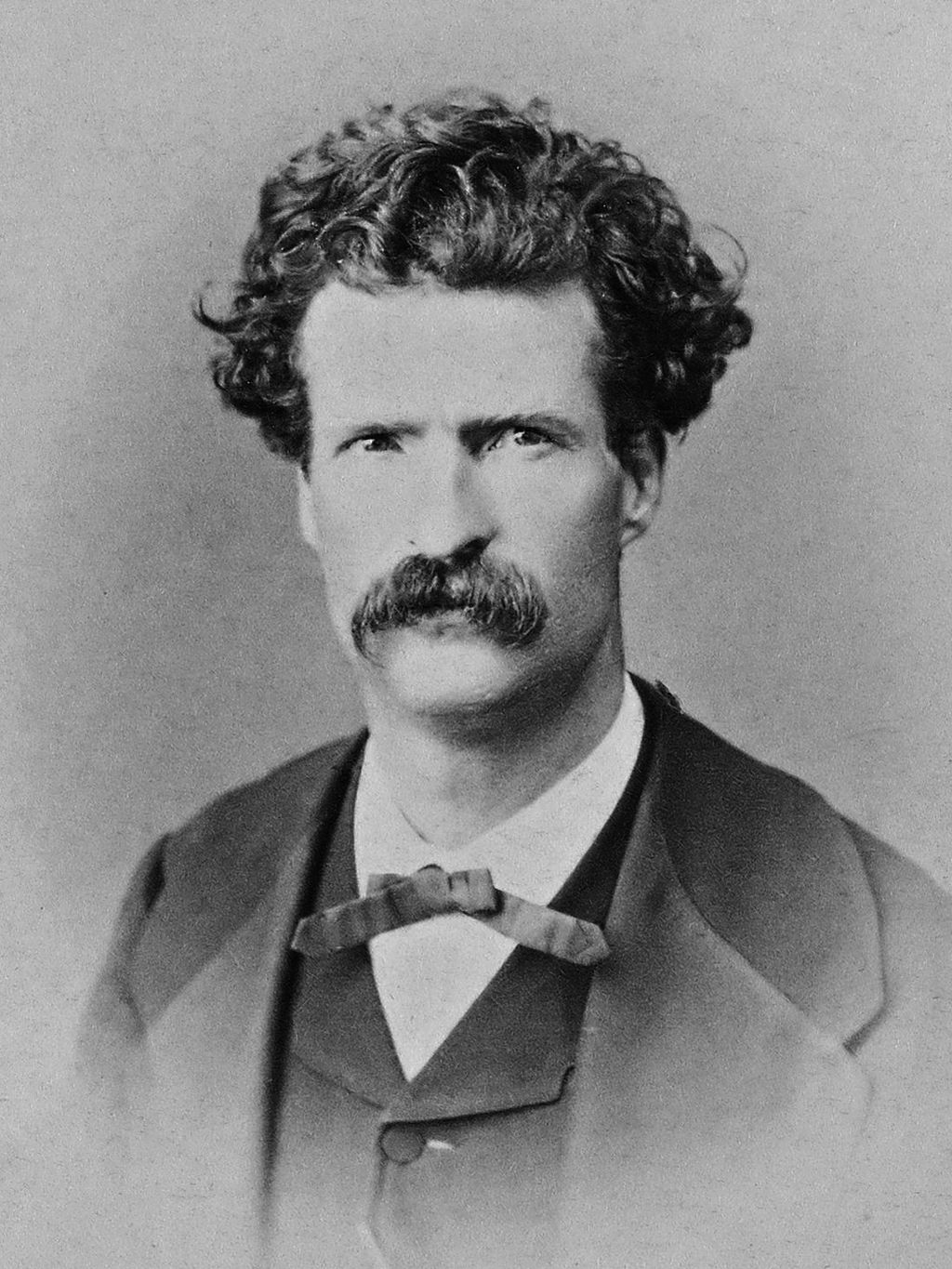

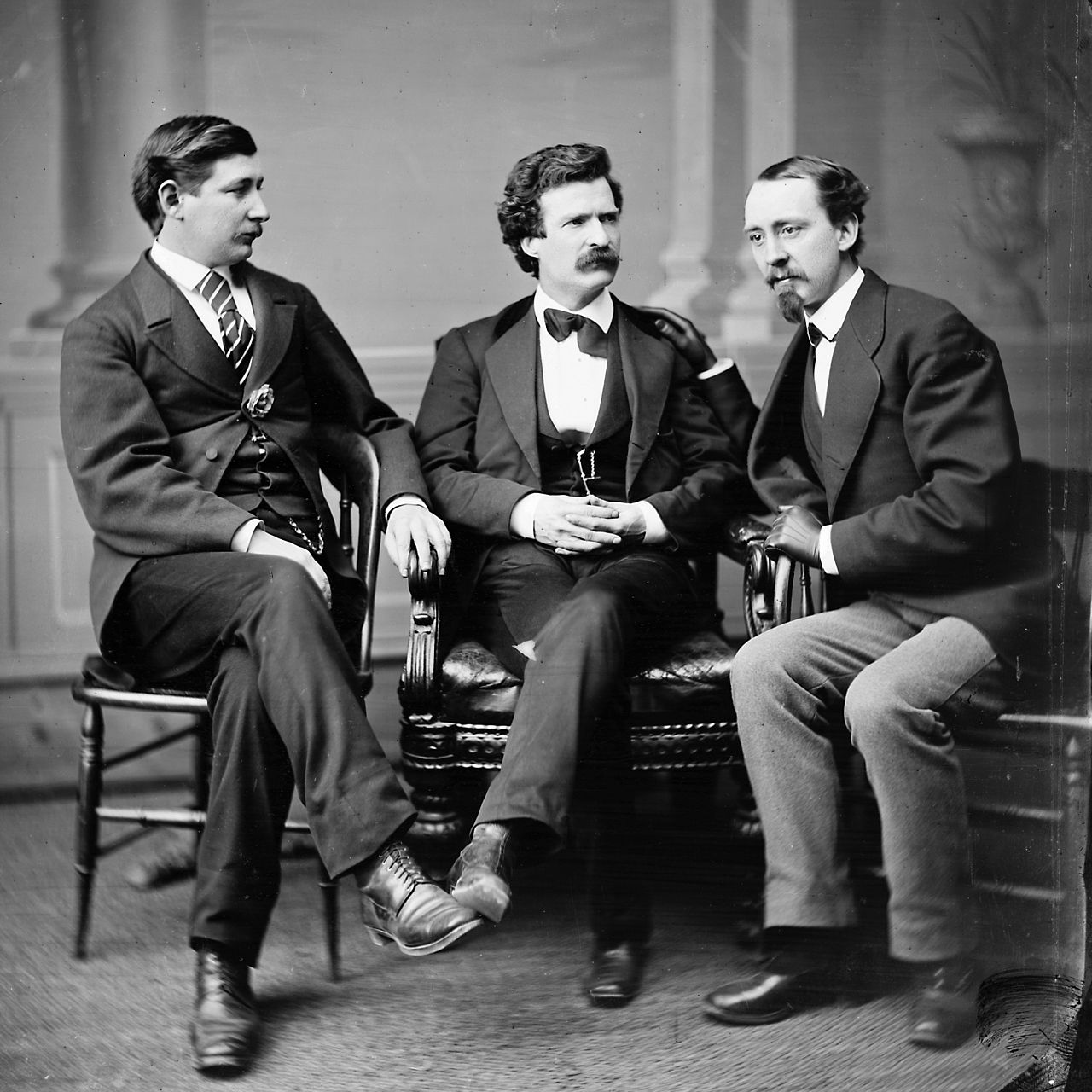

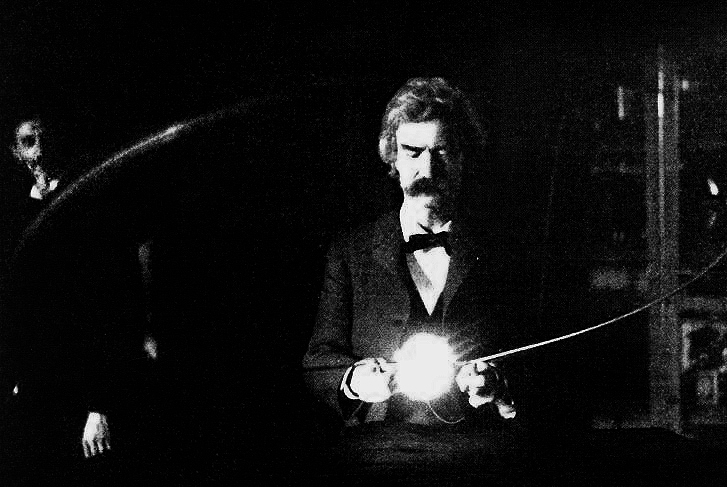

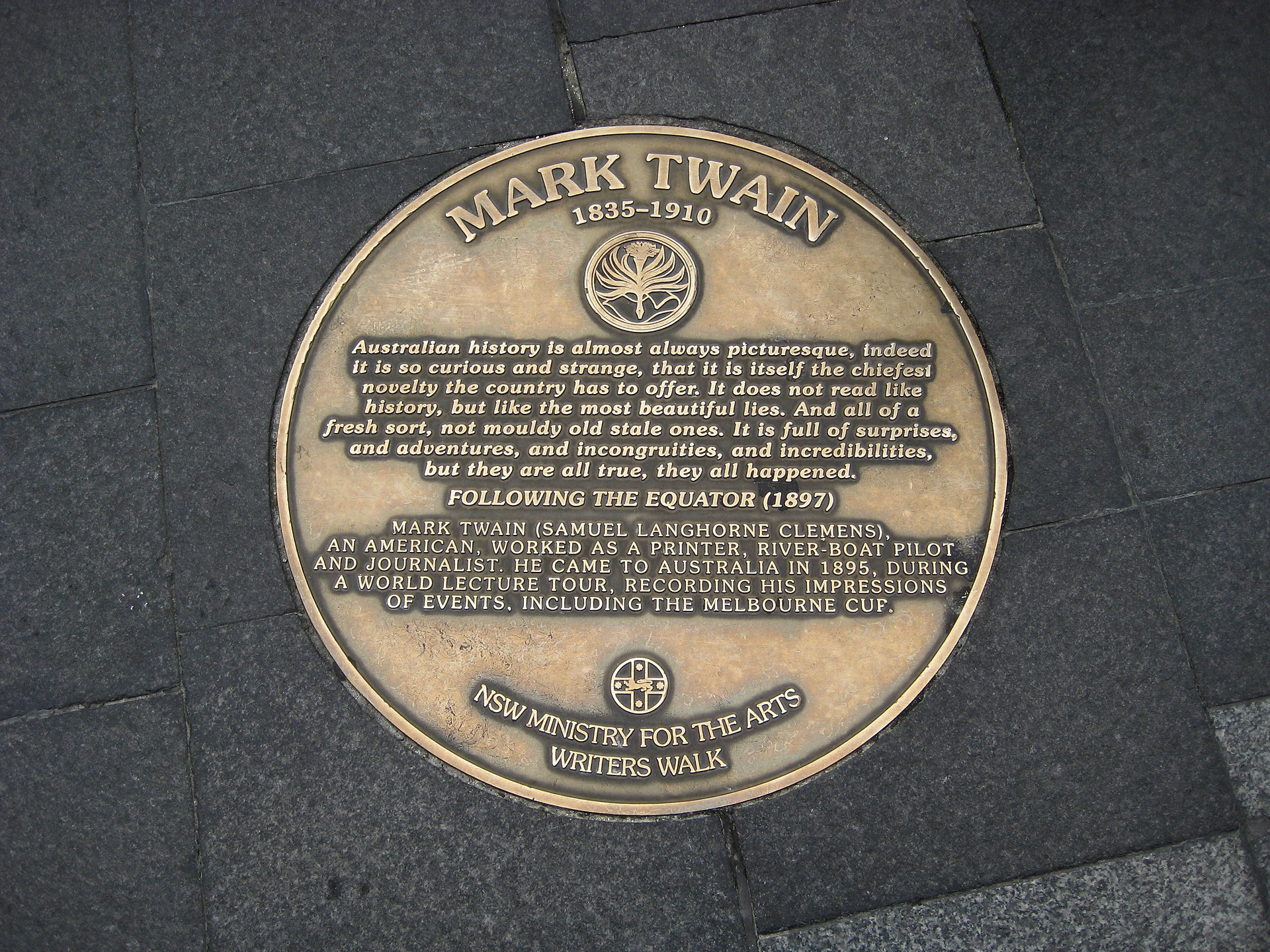

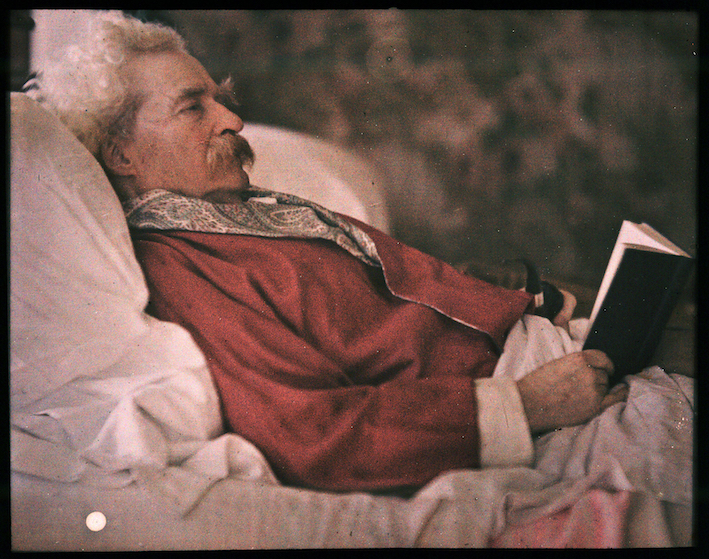

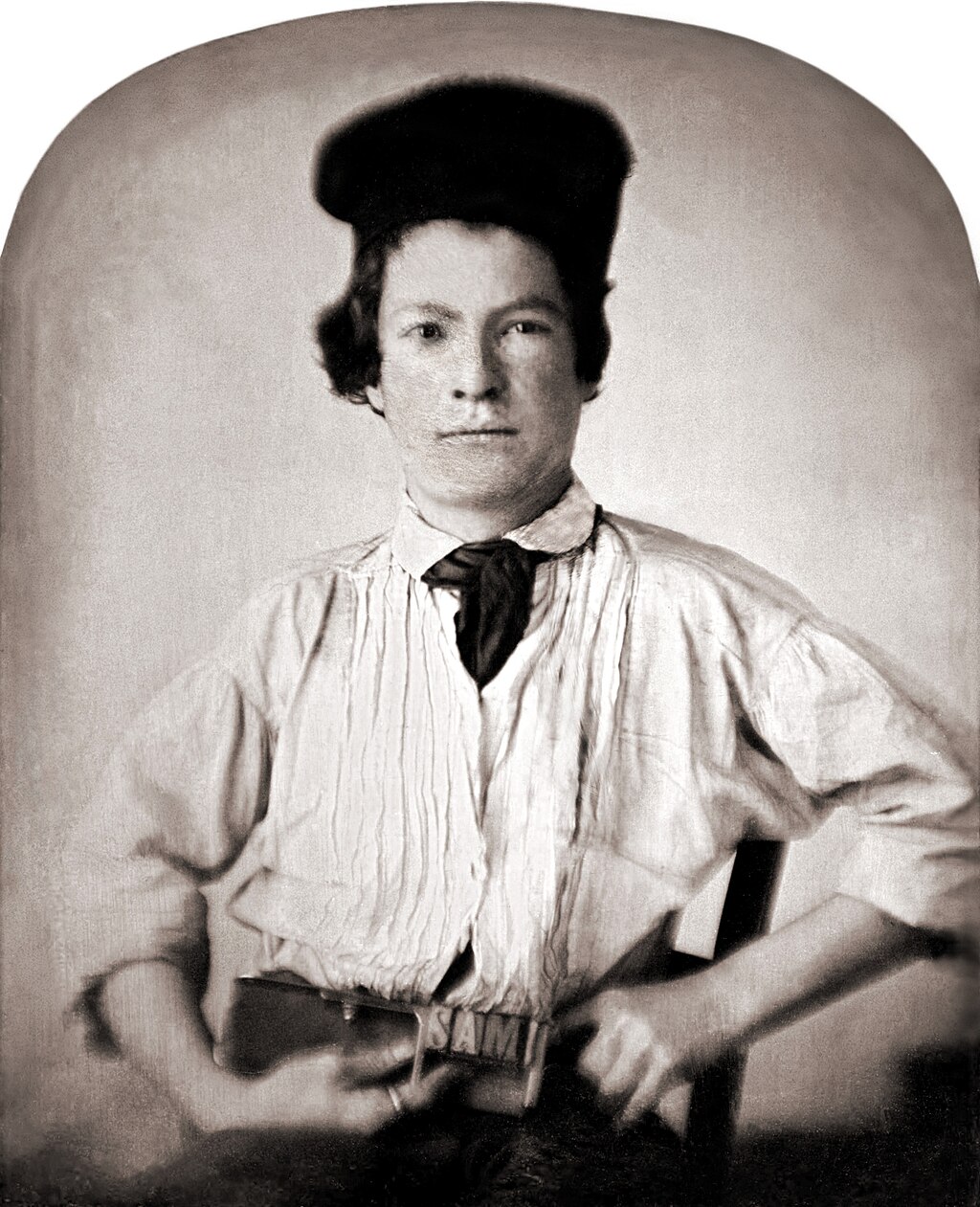

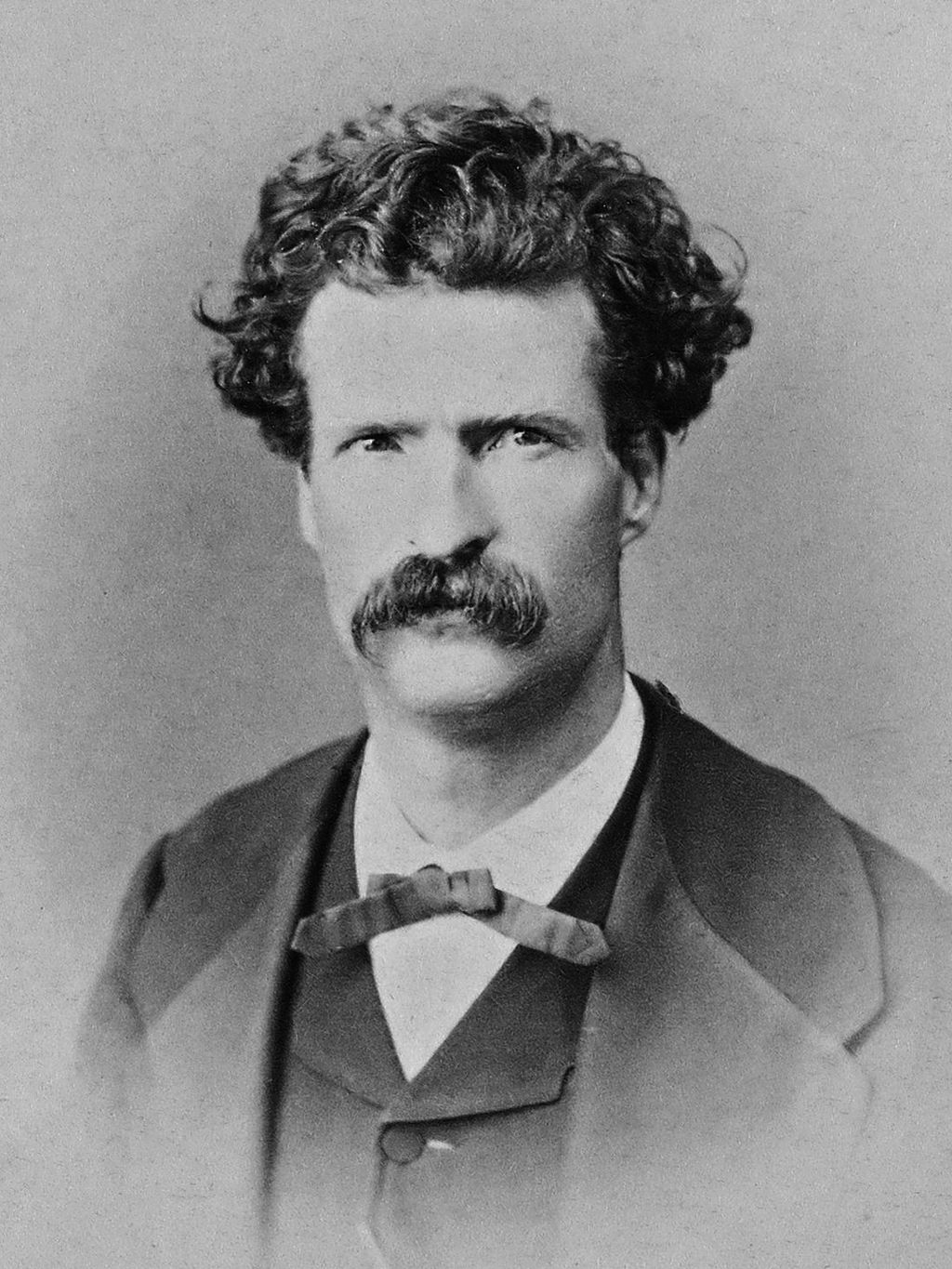

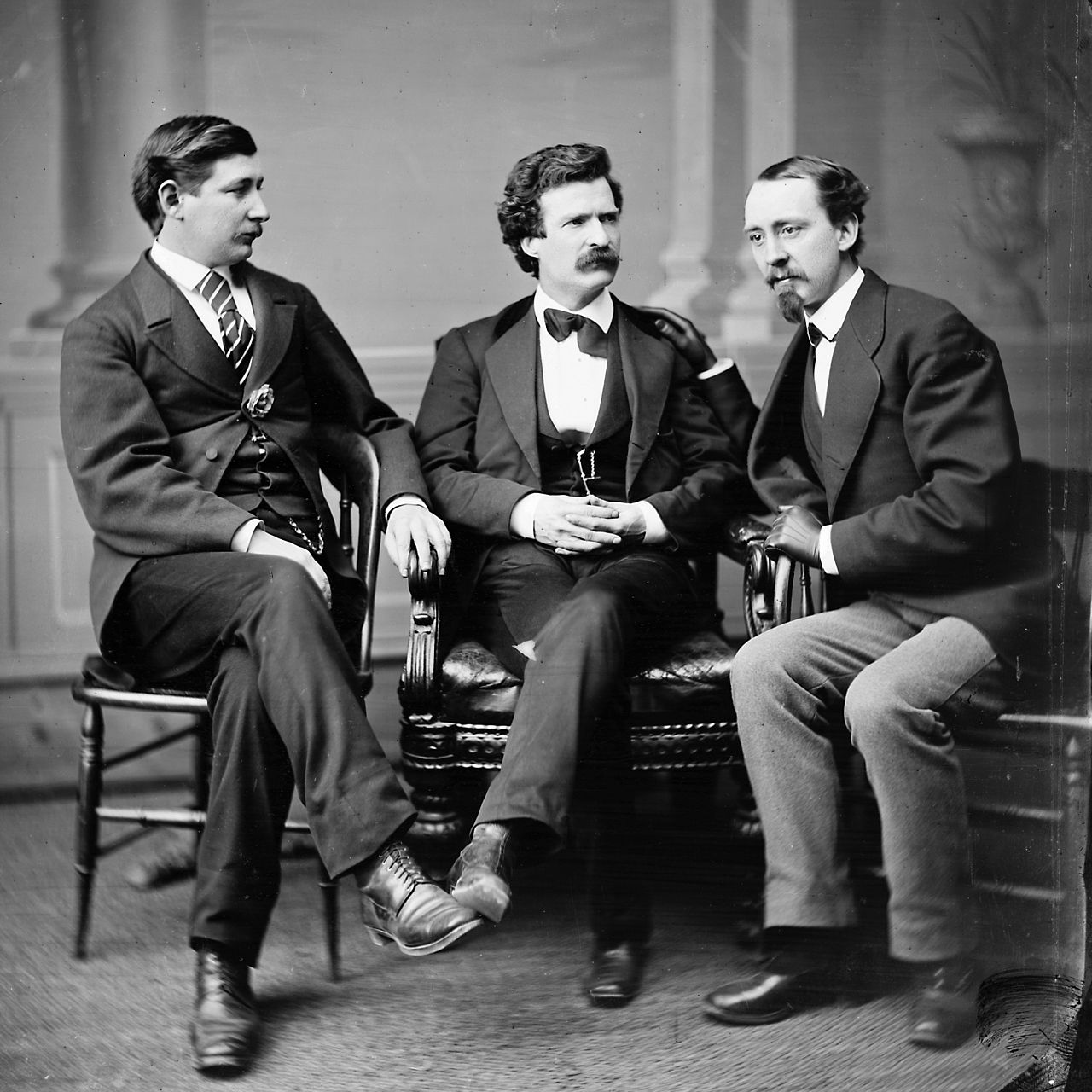

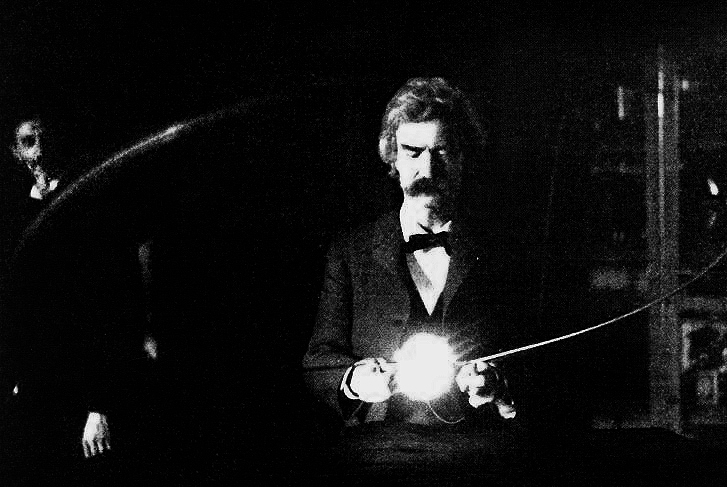

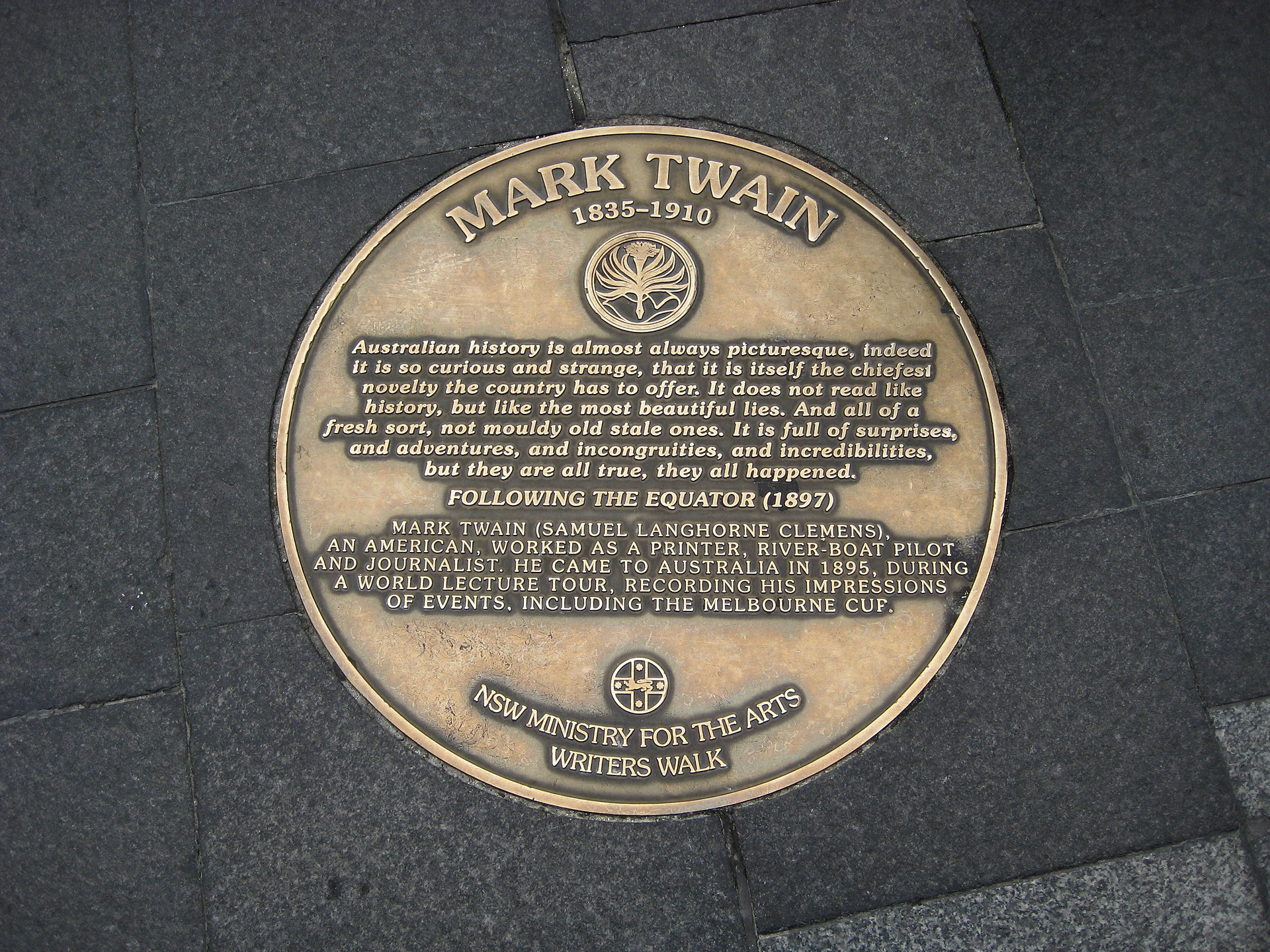

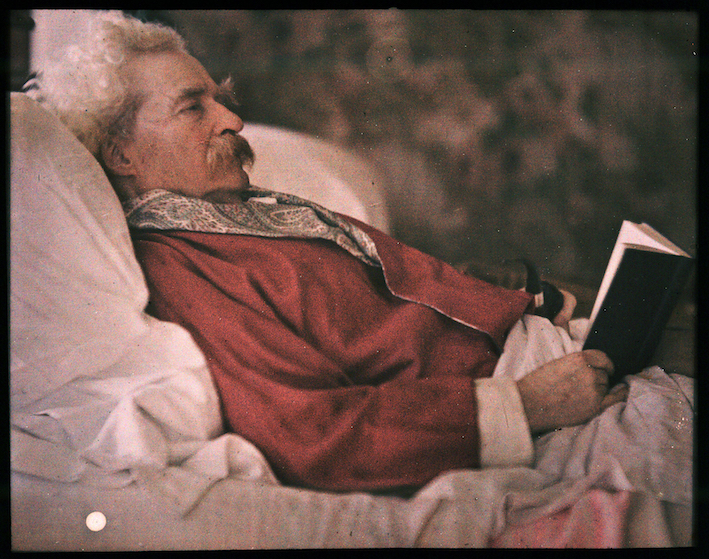

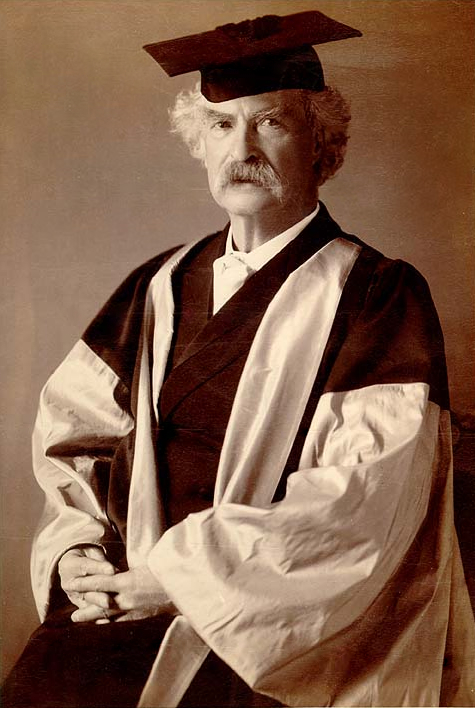

| Biography Early life  Samuel Clemens, age 15 holding metal type in a composing stick that spells out his first name. He understood that the photographic printing process reversed the contents of an image in the same way backwards moveable type was reversed in printing to give clear copy. Samuel Langhorne Clemens was born on November 30, 1835, in Florida, Missouri. He was the sixth of seven children of Jane (née Lampton; 1803–1890), a native of Kentucky, and John Marshall Clemens (1798–1847), a native of Virginia.[citation needed] His parents met when his father, a lawyer called to the bar in Kentucky, tried to help Jane's father and uncle avoid bankruptcy.[12] They were married in 1823.[13] Twain was of English and Scots-Irish descent.[14][15][16][17] Only three of his siblings lived beyond childhood: Orion (1825–1897), Pamela (1827–1904), and Henry (1838–1858). His brother Pleasant Hannibal (1828) died at three weeks of age,[18][19] his sister Margaret (1830–1839) when Twain was three, and his brother Benjamin (1832–1842) three years later.[citation needed] When he was four, Twain's family moved to Hannibal, Missouri,[20] a port town on the Mississippi River that inspired the fictional town of St. Petersburg in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.[21] Slavery was legal in Missouri at the time, and it became a theme in these writings. His father was an attorney and judge who died of pneumonia in 1847, when Twain was 11.[22] The following year, Twain left school after the fifth grade to become a printer's apprentice.[1] In 1851, he began working as a typesetter, contributing articles and humorous sketches to the Hannibal Journal, a newspaper that Orion owned. When he was 18, he left Hannibal and worked as a printer in New York City, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Cincinnati, joining the newly formed International Typographical Union, the printers trade union. He educated himself in public libraries in the evenings, finding wider information than at a conventional school.[23] Twain describes his boyhood in Life on the Mississippi, stating that "there was but one permanent ambition" among his comrades: to be a steamboatman. "Pilot was the grandest position of all. The pilot, even in those days of trivial wages, had a princely salary – from a hundred and fifty to two hundred and fifty dollars a month, and no board to pay." As Twain described it, the pilot's prestige exceeded that of the captain. The pilot had to "get up a warm personal acquaintanceship with every old snag and one-limbed cottonwood and every obscure wood pile that ornaments the banks of this river for twelve hundred miles; and more than that, must... actually know where these things are in the dark". Steamboat pilot Horace E. Bixby took Twain on as a cub pilot to teach him the river between New Orleans and St. Louis for $500 (equivalent to $18,000 in 2023), payable out of Twain's first wages after graduating. Twain studied the Mississippi, learning its landmarks, how to navigate its currents effectively, and how to read the river and its constantly shifting channels, reefs, submerged snags, and rocks that would "tear the life out of the strongest vessel that ever floated".[24] It was more than two years before he received his pilot's license. Piloting also gave him his pen name from "mark twain", the leadsman's cry for a measured river depth of two fathoms (12 feet), which was safe water for a steamboat.[25][26] As a young pilot, Clemens served on the steamer A. B. Chambers with Grant Marsh, who became famous for his exploits as a steamboat captain on the Missouri River. The two liked and admired each other, and maintained a correspondence for many years after Clemens left the river.[27] While training, Samuel convinced his younger brother Henry to work with him, and even arranged a post of mud clerk for him on the steamboat Pennsylvania. On June 13, 1858, the steamboat's boiler exploded; Henry succumbed to his wounds on June 21. Twain claimed to have foreseen this death in a dream a month earlier,[28]: 275 which inspired his interest in parapsychology; he was an early member of the Society for Psychical Research.[29] Twain was guilt-stricken and held himself responsible for the rest of his life. He continued to work on the river and was a river pilot until the Civil War broke out in 1861, when traffic was curtailed along the Mississippi River. At the start of hostilities, he enlisted briefly in a local Confederate unit. He later wrote the sketch "The Private History of a Campaign That Failed", describing how he and his friends had been Confederate volunteers for two weeks before their unit disbanded.[30] He then left for Nevada to work for his brother Orion, who was Secretary of the Nevada Territory. Twain describes the episode in his book Roughing It.[31][32]: 147 In the American West  Twain, age 31 Orion became secretary to Nevada Territory governor James W. Nye in 1861, and Twain joined him when he moved west. The brothers traveled more than two weeks on a stagecoach across the Great Plains and the Rocky Mountains, visiting the Mormon community in Salt Lake City.[33] Twain's journey ended in the silver-mining town of Virginia City, Nevada, where he became a miner on the Comstock Lode.[30] He failed as a miner and went to work at the Virginia City newspaper Territorial Enterprise,[34] working under a friend, the writer Dan DeQuille. He first used his pen name here on February 3, 1863, when he wrote a humorous travel account titled "Letter From Carson – re: Joe Goodman; party at Gov. Johnson's; music" and signed it "Mark Twain".[35][36] His experiences in the American West inspired Roughing It, written during 1870–71 and published in 1872. His experiences in Angels Camp (in Calaveras County, California) provided material for "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County" (1865).[citation needed] Twain moved to San Francisco in 1864, still as a journalist, and met writers such as Bret Harte and Artemus Ward. He may have been romantically involved with the poet Ina Coolbrith.[37] His first success as a writer came when his humorous tall tale "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County" was published on November 18, 1865, in the New York weekly The Saturday Press, bringing him national attention. A year later, he traveled to the Sandwich Islands (present-day Hawaii) as a reporter for the Sacramento Union. His letters to the Union were popular and became the basis for his first lectures.[38] In 1867, local newspapers The Alta California and New-York Tribune funded his trip to the Mediterranean aboard the Quaker City, including a tour of Europe and the Middle East. He wrote a collection of travel letters which were later compiled as The Innocents Abroad (1869). It was on this trip that he met fellow passenger Charles Langdon, who showed him a picture of his sister Olivia. Twain later claimed to have fallen in love at first sight.[39] Upon returning to the United States, Twain was offered honorary membership in Yale University's secret society Scroll and Key in 1868.[40] Marriage and children  (From l. to r.)American Civil War correspondent and author George Alfred Townsend, Mark Twain and David Gray, editor of the rival Buffalo Courier[41]  Twain House in Hartford, Connecticut Twain and Olivia Langdon corresponded throughout 1868. She rejected his first marriage proposal, but he continued to court her and managed to overcome her father's initial reluctance.[42] They were married in Elmira, New York in February 1870.[38] She came from a "wealthy but liberal family"; through her, he met abolitionists, "socialists, principled atheists and activists for women's rights and social equality", including Harriet Beecher Stowe, Frederick Douglass, and utopian socialist writer William Dean Howells,[43] who became a long-time friend. The Clemenses lived in Buffalo, New York, from 1869 to 1871. He owned a stake in the Buffalo Express newspaper and worked as an editor and writer.[44][41] While they were living in Buffalo, their son Langdon died of diphtheria at the age of 19 months. They had three daughters: Susy (1872–1896), Clara (1874–1962),[45] and Jean (1880–1909). The Clemenses formed a friendship with David Gray, who worked as an editor of the rival Buffalo Courier, and his wife Martha. Twain later wrote that the Grays were "'all the solace' he and Livy had during their 'sorrowful and pathetic brief sojourn in Buffalo'", and that Gray's "delicate gift for poetry" was wasted working for a newspaper.[41] Starting in 1873, Twain moved his family to Hartford, Connecticut, where he arranged the building of a home next door to Stowe. In the 1870s and 1880s, the family summered at Quarry Farm in Elmira, the home of Olivia's sister, Susan Crane.[46][47] In 1874,[46] Susan had a study built apart from the main house so that Twain would have a quiet place in which to write. Also, he smoked cigars constantly, and Susan did not want him to do so in her house.[citation needed] Twain wrote many of his classic novels during his 17 years in Hartford (1874–1891) and over 20 summers at Quarry Farm. They include The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876), The Prince and the Pauper (1881), Life on the Mississippi (1883), Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (1889).[citation needed] The couple's marriage lasted 34 years until Olivia's death in 1904. All of the Clemens family are buried in Elmira's Woodlawn Cemetery.[citation needed] Love of science and technology  Twain in the laboratory of Nikola Tesla, early 1894 Twain was fascinated with science and scientific inquiry. He developed a close and lasting friendship with Nikola Tesla, and the two spent much time together in Tesla's laboratory.[48] Twain patented three inventions, including an "Improvement in Adjustable and Detachable Straps for Garments" (to replace suspenders) and a history trivia game.[49][50] Most commercially successful was a self-pasting scrapbook; a dried adhesive on the pages needed only to be moistened before use.[49] Over 25,000 were sold.[49] Twain was an early proponent of fingerprinting as a forensic technique, featuring it in a tall tale in Life on the Mississippi (1883) and as a central plot element in the novel Pudd'nhead Wilson (1894).[citation needed] Twain's novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (1889) features a time traveler from the contemporary U.S., using his knowledge of science to introduce modern technology to Arthurian England. This type of historical manipulation became a trope of speculative fiction as alternate histories.[citation needed] In 1909, Thomas Edison visited Twain at Stormfield, his home in Redding, Connecticut and filmed him. Part of the footage was used in The Prince and the Pauper (1909), a two-reel short film. It is the only known existing film footage of Twain.[51] Financial troubles Twain made a substantial amount of money through his writing, but he lost a great deal through investments. He invested mostly in new inventions and technology, particularly the Paige typesetting machine. It was considered a mechanical marvel that amazed viewers when it worked, but it was prone to breakdowns. Twain spent $300,000 (equivalent to $9,471,724 in 2023) on it between 1880 and 1894,[52] but before it could be perfected it was rendered obsolete by the Linotype. He lost the bulk of his book profits, as well as a substantial portion of his wife's inheritance.[53] Twain also lost money through his publishing house, Charles L. Webster and Company, which enjoyed initial success selling the memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant but failed soon afterward, losing money on a biography of Pope Leo XIII. Fewer than 200 copies were sold.[53] Twain and his family closed down their expensive Hartford home in response to the dwindling income and moved to Europe in June 1891. William M. Laffan of The New York Sun and the McClure Newspaper Syndicate offered him the publication of a series of six European letters. Twain, Olivia, and their daughter Susy were all faced with health problems, and they believed that it would be of benefit to visit European baths.[54]: 175 The family stayed mainly in France, Germany, and Italy until May 1895, with longer spells at Berlin (winter 1891–92), Florence (fall and winter 1892–93), and Paris (winters and springs 1893–94 and 1894–95). During that period, Twain returned four times to New York due to his enduring business troubles. He rented "a cheap room" in September 1893 at $1.50 per day (equivalent to $51 in 2023) at The Players Club, which he had to keep until March 1894; meanwhile, he became "the Belle of New York," in the words of biographer Albert Bigelow Paine.[54]: 176–190 Twain's writings and lectures enabled him to recover financially, combined with the help of his friend Henry Huttleston Rogers.[55] In 1893, he began a friendship with the financier, a principal of Standard Oil, that lasted the remainder of his life. Rogers first made him file for bankruptcy in April 1894, then had him transfer the copyrights on his written works to his wife to prevent creditors from gaining possession of them. Finally, Rogers took absolute charge of Twain's money until all his creditors were paid.[54]: 188 Twain accepted an offer from Robert Sparrow Smythe[56] and embarked on a year-long around-the-world lecture tour in July 1895[57] to pay off his creditors in full, although he was no longer under any legal obligation to do so.[58] It was a long, arduous journey, and he was sick much of the time, mostly from a cold and a carbuncle. The first part of the itinerary took him across northern America to British Columbia, Canada, until the second half of August. For the second part, he sailed across the Pacific Ocean. His scheduled lecture in Honolulu, Hawaii, had to be canceled due to a cholera epidemic.[54]: 188 [59] Twain went on to Fiji, Australia, New Zealand, Sri Lanka, India, Mauritius, and South Africa. His three months in India became the centerpiece of his 712-page book Following the Equator. In the second half of July 1896, he sailed back to England, completing his circumnavigation of the world begun 14 months before.[54]: 188 Twain and his family spent four more years in Europe, mainly in England and Austria (October 1897 to May 1899), with longer spells in London and Vienna. Clara had wished to study the piano under Theodor Leschetizky in Vienna.[54]: 192–211 However, Jean's health did not benefit from consulting with specialists in Vienna, the "City of Doctors".[60] The family moved to London in spring 1899, following a lead by Poultney Bigelow, who had a good experience being treated by Dr. Jonas Henrik Kellgren, a Swedish osteopathic practitioner in Belgravia. They were persuaded to spend the summer at Kellgren's sanatorium by the lake in the Swedish village of Sanna. Coming back in fall, they continued the treatment in London, until Twain was convinced by lengthy inquiries in America that similar osteopathic expertise was available there.[61] In mid-1900, he was the guest of newspaper proprietor Hugh Gilzean-Reid at Dollis Hill House, located on the north side of London. Twain wrote that he had "never seen any place that was so satisfactorily situated, with its noble trees and stretch of country, and everything that went to make life delightful, and all within a biscuit's throw of the metropolis of the world."[62] He then returned to America in October 1900, having earned enough to pay off his debts. In winter 1900/01, he became his country's most prominent opponent of imperialism, raising the issue in his speeches, interviews, and writings. In January 1901, he began serving as vice-president of the Anti-Imperialist League of New York.[63][10] Speaking engagements  Plaque on Sydney Writers Walk commemorating the visit of Twain in 1895 Twain was in great demand as a featured speaker, performing solo humorous talks similar to modern stand-up comedy.[64] He gave paid talks to many men's clubs, including the Authors' Club, Beefsteak Club, Vagabonds, White Friars, and Monday Evening Club of Hartford.[citation needed] In the late 1890s, he spoke to the Savage Club in London and was elected an honorary member. He was told that only three men had been so honored, including the Prince of Wales, and he replied: "Well, it must make the Prince feel mighty fine."[54]: 197 He visited Melbourne and Sydney in 1895 as part of a world lecture tour. In 1897, he spoke to the Concordia Press Club in Vienna as a special guest, following the diplomat Charlemagne Tower, Jr. He delivered the speech "Die Schrecken der Deutschen Sprache" ("The Horrors of the German Language")—in German—to the great amusement of the audience.[32]: 50 In 1901, he was invited to speak at Princeton University's Cliosophic Literary Society, where he was made an honorary member.[65] Canadian visits In 1881, Twain was honored at a banquet in Montreal, Canada where he made reference to securing a copyright.[66] In 1883, he paid a brief visit to Ottawa,[67] and he visited Toronto twice in 1884 and 1885 on a reading tour with George Washington Cable, known as the "Twins of Genius" tour.[67][68][69] The reason for the Toronto visits was to secure Canadian and British copyrights for his upcoming book Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,[67][69] to which he had alluded in his Montreal visit. The reason for the Ottawa visit had been to secure Canadian and British copyrights for Life on the Mississippi.[67] Publishers in Toronto had printed unauthorized editions of his books at the time, before an international copyright agreement was established in 1891.[67] These were sold in the United States as well as in Canada, depriving him of royalties. He estimated that Belford Brothers' edition of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer alone had cost him $10,000 (equivalent to $340,000 in 2023).[67] He had unsuccessfully attempted to secure the rights for The Prince and the Pauper in 1881, in conjunction with his Montreal trip.[67] Eventually, he received legal advice to register a copyright in Canada (for both Canada and Britain) prior to publishing in the United States, which would restrain the Canadian publishers from printing a version when the American edition was published.[67][69] There was a requirement that a copyright be registered to a Canadian resident; he addressed this by his short visits to the country.[67][69] Later life and death The report of my death was an exaggeration. — Twain[70][71] Twain lived in his later years at 14 West 10th Street in Manhattan.[72] He passed through a period of deep depression which began in 1896 when his daughter Susy died of meningitis. Olivia's death in 1904 and Jean's on December 24, 1909, deepened his gloom.[1] On May 20, 1909, his close friend Henry Rogers died suddenly.[73] In April 1906, he heard that his friend Ina Coolbrith had lost nearly all that she owned in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, and he volunteered a few autographed portrait photographs to be sold for her benefit. To further aid Coolbrith, George Wharton James visited Twain in New York and arranged for a new portrait session. He was resistant initially, but he eventually admitted that four of the resulting images were the finest ones ever taken of him.[74] In September, Twain started publishing chapters from his autobiography in the North American Review.[75] The same year, Charlotte Teller, a writer living with her grandmother at 3 Fifth Avenue, began an acquaintanceship with him which "lasted several years and may have included romantic intentions" on his part.[76]  Twain photographed in 1908 via the Autochrome Lumiere process In 1906, Twain formed the Angel Fish and Aquarium Club, for girls whom he viewed as surrogate granddaughters. Its dozen or so members ranged in age from 10 to 16. He exchanged letters with his "Angel Fish" girls and invited them to concerts and the theatre and to play games. Twain wrote in 1908 that the club was his "life's chief delight".[32]: 28 In 1907, he met Dorothy Quick (aged 11) on a transatlantic crossing, beginning "a friendship that was to last until the very day of his death".[77]  Twain in academic regalia for acceptance of the D.Litt. degree awarded to him by Oxford University in 1907 Twain was awarded an honorary Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.) by Yale University in 1901 and a Doctor of Law by the University of Missouri in 1902. Oxford University awarded him a Doctorate of Law in 1907.[78]: 52 : 58 Twain was born two weeks after Halley's Comet's closest approach in 1835; he said in 1909:[54] I came in with Halley's Comet in 1835. It is coming again next year, and I expect to go out with it. It will be the greatest disappointment of my life if I don't go out with Halley's Comet. The Almighty has said, no doubt: "Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together". Twain's prediction was eerily accurate; he died of a heart attack on April 21, 1910, in Stormfield, one month before the comet passed Earth that year.[79]  Twain and his wife are buried side by side in Elmira's Woodlawn Cemetery. Upon hearing of Twain's death, President William Howard Taft said:[80][81] Mark Twain gave pleasure – real intellectual enjoyment – to millions, and his works will continue to give such pleasure to millions yet to come … His humor was American, but he was nearly as much appreciated by Englishmen and people of other countries as by his own countrymen. He has made an enduring part of American literature. Twain's funeral was at the Brick Presbyterian Church on Fifth Avenue, New York.[82] He is buried in his wife's family plot at Woodlawn Cemetery in Elmira, New York. The Langdon family plot is marked by a 12-foot monument (two fathoms, or "mark twain") placed there by his surviving daughter Clara.[83] There is also a smaller headstone. He expressed a preference for cremation (for example, in Life on the Mississippi), but he acknowledged that his surviving family would have the last word. Officials in Connecticut and New York estimated the value of Twain's estate at $471,000 ($11,000,000 in 2023).[84] |

略歴 生い立ち  サミュエル・クレメンス、15歳、自分のファーストネームを綴ったコンポジティング・スティックに金属活字を持つ。クレメンズは、写真印刷プロセスが、印刷で可動活字を反転させて鮮明なコピーを得るのと同じように、画像の内容を反転させることを理解していた。 サミュエル・ラングホーン・クレメンスは1835年11月30日、ミズーリ州フロリダに生まれた。ケンタッキー州出身のジェーン(旧姓ランプトン、 1803-1890)とヴァージニア州出身のジョン・マーシャル・クレメンス(1798-1847)の7人兄弟の6番目だった[要出典]。 両親は、ケンタッキー州で弁護士として召集されていた父親が、ジェーンの父親と叔父が破産を免れる手助けをしようとしたときに出会った[12]。 1823年に結婚[13]: オリオン(1825-1897)、パメラ(1827-1904)、ヘンリー(1838-1858)である。兄のプレザント・ハンニバル(1828)は生後 3週間で亡くなり[18][19]、妹のマーガレット(1830-1839)はトウェインが3歳のときに、弟のベンジャミン(1832-1842)はその 3年後に亡くなった[要出典]。 彼が4歳のとき、トウェインの家族はミズーリ州ハンニバルに引っ越した[20]。ミシシッピ川沿いの港町で、『トム・ソーヤーの冒険』や『ハックルベ リー・フィンの冒険』に登場する架空の町セント・ピーターズバーグに影響を与えた[21]。1851年、彼は植字工として働き始め、オリオンが所有する新 聞『ハンニバル・ジャーナル』に記事やユーモラスなスケッチを寄稿した。18歳のときハンニバルを離れ、ニューヨーク、フィラデルフィア、セントルイス、 シンシナティで印刷工として働き、新しく結成された印刷工の労働組合である国際組版組合に加入した。彼は夜間に公共図書館で独学し、従来の学校よりも幅広 い情報を得た[23]。 トウェインは『ミシシッピでの生活』の中で、彼の少年時代について、仲間たちの間には「ただひとつの永遠の野望があった」と述べている。「水先案内人は、 最も偉大な地位であった。水先案内人は、賃金の安い当時でさえ、月給が150ドルから250ドルもあり、食事代もかからなかった。トウェインの説明によれ ば、水先案内人の名声は船長のそれを上回っていた。水先案内人は、「1200マイルにわたってこの川の岸辺を飾っている、あらゆる古いスナッグや一本足の 綿の木や無名の木の山と、個人的に温かい付き合いをしなければならなかった。蒸気船の水先案内人、ホレス・E・ビグスビーは、ニューオリンズとセントルイ スの間の川を教えるため、トウェインを子水先案内人として雇い、500ドル(2023年では18,000ドルに相当)をトウェインの卒業後の最初の給料か ら支払った。トウェインはミシシッピ川を研究し、そのランドマーク、効果的な流れのナビゲート方法、川や絶えず変化する水路、岩礁、水没した杭、「これま で浮かんだ中で最も頑丈な船の命を引き裂く」ような岩の読み方を学んだ[24]。水先案内人はまた、蒸気船にとって安全な水深である2ファゾム(12 フィート)の川の深さを測定するリードマンの叫びである「マーク・トゥエイン」から彼のペンネームを得た[25][26]。 若い水先案内人だったクレメンズは、A.B.チェンバース号で、ミズーリ川での蒸気船船長としての功績で有名になったグラント・マーシュと一緒に乗船し た。クレメンズとグラント・マーシュは、ミズーリ川で蒸気船の船長として有名になった。2人は互いに好意を抱き、尊敬し合い、クレメンズがミズーリ川を 去った後も長年にわたって文通を続けた[27]。 修行中、サミュエルは弟のヘンリーに一緒に働くよう説得し、蒸気船ペンシルベニア号の泥係のポストを用意した。1858年6月13日、蒸気船のボイラーが 爆発し、ヘンリーは6月21日に負傷した。トウェインは1ヶ月前に夢でこの死を予知したと主張し[28]、超心理学に興味を持つきっかけとなった。 1861年に南北戦争が勃発し、ミシシッピ川沿いの交通が制限されるまで、彼は川での仕事を続け、水先案内人を務めた。戦争が始まると、彼は地元の南軍部 隊に短期間入隊した。後に彼はスケッチ「The Private History of a Campaign That Failed」を書き、部隊が解散するまでの2週間、彼と彼の友人たちが南軍の志願兵だったことを描写した[30]。 彼はその後、ネバダ準州の長官であった兄オリオンのもとで働くためにネバダ州に向かった。トウェインはそのエピソードを著書『Roughing It』に記している[31][32]: 147 アメリカ西部にて  トウェイン31歳 オリオンは1861年にネバダ準州知事ジェームズ・W・ナイの秘書となり、トウェインは彼が西部へ移動する際に彼と合流した。兄弟は駅馬車で2週間以上かけて大平原とロッキー山脈を横断し、ソルトレイクシティのモルモンコミュニティを訪れた[33]。 トウェインの旅はネバダ州ヴァージニアシティの銀鉱の町で終わり、コムストック・ロードで鉱夫となった[30]。鉱夫としては失敗し、ヴァージニアシティ の新聞『Territorial Enterprise』で働くことになり[34]、友人の作家ダン・デキルの下で働いた。彼が初めてペンネームを使ったのは1863年2月3日のことで、 「カーソンからの手紙-re: ジョー・グッドマン、ジョンソン州知事の家でのパーティー、音楽」と題したユーモラスな旅行記を書き、「マーク・トウェイン」と署名した[35] [36]。 アメリカ西部での経験は、1870年から71年にかけて書かれ、1872年に出版された『Roughing It』にインスピレーションを与えた。エンジェルス・キャンプ(カリフォルニア州カラベラス郡)での体験は『The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County』(1865年)の素材となった[要出典]。 1864年、トウェインはジャーナリストとしてサンフランシスコに移り住み、ブレット・ハートやアルテマス・ウォードといった作家たちと知り合った。彼は詩人のイナ・クールブリスと恋愛関係にあったかもしれない[37]。 1865年11月18日、ニューヨークの週刊誌『The Saturday Press』にユーモラスな長編小説『The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County(カラベラス郡の有名な飛び跳ねるカエル)』が掲載され、作家として最初の成功を収めた。その1年後、彼はサクラメント・ユニオン紙の記者と してサンドイッチ諸島(現在のハワイ)を訪れた。ユニオン紙への手紙は人気を博し、彼の最初の講演の基礎となった[38]。 1867年、地元紙The Alta CaliforniaとNew-York Tribuneは、ヨーロッパと中東のツアーを含むクエーカー・シティ号での地中海旅行に資金を提供した。彼は、後に『The Innocents Abroad』(1869年)として編纂された旅行書簡集を執筆した。この旅で、彼は同じ乗客のチャールズ・ラングドンと出会い、彼の妹オリヴィアの写真 を見せた。後にトウェインは一目惚れしたと主張している[39]。 アメリカに帰国したトウェインは、1868年にイェール大学の秘密結社「スクロール・アンド・キー」の名誉会員となる。 結婚と子供  (左から右へ)アメリカ南北戦争の特派員で作家のジョージ・アルフレッド・タウンゼント、マーク・トウェイン、ライバル誌『バッファロー・クーリエ』の編集者デイヴィッド・グレイ[41]。  コネチカット州ハートフォードのトウェイン邸 トウェインとオリヴィア・ラングドンは1868年を通じて文通していた。彼女は最初のプロポーズを拒絶したが、彼は彼女に求愛を続け、彼女の父親の最初の 難色をなんとか押し切った[42]。1870年2月、ふたりはニューヨーク州エルミラで結婚した[38]。彼女は「裕福だがリベラルな家庭」の出身で、彼 女を通じて、彼はハリエット・ビーチャー・ストウ、フレデリック・ダグラス、ユートピア社会主義作家のウィリアム・ディーン・ハウエルズ[43]など、奴 隷廃止論者、「社会主義者、公明正大な無神論者、女性の権利と社会的平等を求める活動家」に出会い、長年の友人となった。クレメンツ夫妻は1869年から 1871年までニューヨークのバッファローに住んでいた。彼はバッファロー・エクスプレス紙の株を所有し、編集者や作家として働いていた[44] [41]。バッファローに住んでいたとき、息子のラングドンがジフテリアで19ヶ月の若さで亡くなった。彼らには3人の娘がいた: スージー(1872-1896)、クララ(1874-1962)、ジーン(1880-1909)である[45]。クレメンツ夫妻は、ライバルの『バッファ ロー・クーリエ』紙の編集者として働いていたデイヴィッド・グレイとその妻マーサと親交を結んだ。トウェインは後に、グレイ夫妻は「彼とリヴィが『バッ ファローでの悲しく哀れな短い滞在』の間に得た『すべての慰め』」であり、グレイの「繊細な詩の才能」は新聞社で働いていたために無駄になってしまったと 書いている[41]。 1873年から、トウェインはコネチカット州ハートフォードに家族を移し、ストウの隣に家を建てる手配をした。1870年代から1880年代にかけて、一 家はオリヴィアの妹スーザン・クレインの家であるエルミラのクオリー・ファームに寄宿した[46][47]。1874年、[46]スーザンは、トウェイン が静かな場所で執筆できるように、母屋とは別に書斎を作らせた。また、彼は常に葉巻を吸っていたため、スーザンは自分の家で葉巻を吸ってほしくなかった [要出典]。 トウェインは、ハートフォードでの17年間(1874年~1891年)とクオリーファームでの20回以上の夏休みの間に、多くの名作小説を書いた。その中 には、『トム・ソーヤーの冒険』(1876年)、『王子と貧乏人』(1881年)、『ミシシッピーでの生活』(1883年)、『ハックルベリー・フィンの 冒険』(1884年)、『アーサー王宮廷のコネチカット・ヤンキー』(1889年)などが含まれる[要出典]。 夫妻の結婚生活は、1904年にオリヴィアが亡くなるまで34年間続いた。クレメンス一家は全員、エルミラのウッドローン墓地に埋葬されている[要出典]。 科学技術への愛  ニコラ・テスラの研究室でのトウェイン(1894年初頭 トウェインは科学と科学的探究に魅了されていた。ニコラ・テスラとは親密で永続的な友情を育み、2人はテスラの研究室で多くの時間を共に過ごした [48]。 トウェインは「衣服の調節可能で取り外し可能なストラップの改良」(サスペンダーの代わり)や歴史トリビアゲームなど、3つの発明の特許を取得した [49][50]。 最も商業的に成功したのは、セルフ・ペースト式のスクラップブックで、ページの乾燥した接着剤は使用前に湿らせるだけでよかった。 トウェインは法医学技術としての指紋押捺を早くから提唱しており、『ミシシッピの人生』(1883年)の長編小説や、小説『パッズヘッド・ウィルソン』(1894年)の中心的なプロット要素として指紋押捺を取り上げた[要出典]。 トウェインの小説『アーサー王宮廷のコネティカット・ヤンキー』(1889年)には、現代のアメリカからやってきたタイムトラベラーが登場し、科学の知識 を駆使してアーサー王時代のイングランドに現代の技術を導入する。このような歴史操作は、代替史として推理小説の型となった[要出典]。 1909年、トーマス・エジソンはコネチカット州レディングの自宅ストームフィールドにトウェインを訪ね、その様子を撮影した。その映像の一部は、2リー ルの短編映画『The Prince and the Pauper』(1909年)で使用された。これは現存するトウェインの唯一のフィルム映像である[51]。 金銭トラブル トウェインは執筆活動でかなりの金額を稼いだが、投資で大きな損失を出した。彼は主に新しい発明や技術、特にペイジ植字機に投資した。ペイジ活字組版機 は、動けば見る者を驚嘆させる驚異の機械だったが、故障が多かった。トウェインは1880年から1894年の間に30万ドル(2023年の947万 1724ドルに相当)を費やしたが[52]、完成する前にライノタイプによって時代遅れになってしまった。彼は書籍の利益の大部分と妻の遺産のかなりの部 分を失った[53]。 トウェインはまた、彼の出版社であるチャールズ・L・ウェブスター・アンド・カンパニーでも損失を被った。同社はユリシーズ・S・グラントの回顧録の販売 で最初の成功を収めたが、その後すぐに失敗し、ローマ教皇レオ13世の伝記で損失を被った。売れたのは200部にも満たなかった[53]。 トウェインと彼の家族は、収入の減少に対応して高価なハートフォードの家を閉鎖し、1891年6月にヨーロッパに移住した。ニューヨーク・サン紙とマク ルーア・ニュースペーパー・シンジケートのウィリアム・M・ラファンは、彼に6回にわたるヨーロッパでの手紙の連載を持ちかけた。トウェイン、オリヴィ ア、娘のスージーの3人は健康問題に直面しており、ヨーロッパの浴場を訪れることは有益だと考えていた[54]: 175 一家は1895年5月まで主にフランス、ドイツ、イタリアに滞在し、ベルリン(1891-92年冬)、フィレンツェ(1892-93年秋・冬)、パリ (1893-94年冬・春、1894-95年冬・春)に長期滞在した。この間、トウェインは仕事上のトラブルに見舞われ、ニューヨークに4度戻っている。 彼は1893年9月にプレイヤーズ・クラブで1日1.50ドル(2023年の51ドルに相当)の「安い部屋」を借り、それを1894年3月まで保たなけれ ばならなかった。その間、伝記作家アルバート・ビグロー・ペインの言葉を借りれば、彼は「ニューヨークのベル」となった[54]: 176-190 1893年、彼はスタンダード・オイルの社長であった金融業者ロジャースとの友情を始め、それは生涯続いた。ロジャースはまず1894年4月に彼に破産を 申請させ、次に債権者が彼の著作物を所有することを防ぐために、彼の著作物の著作権を妻に譲渡させた。最後に、ロジャースはすべての債権者が支払いを終え るまで、トウェインの金を絶対的に管理した[54]: 188 トウェインはロバート・スパロウ・スマイス[56]からの申し出を受け入れ、1895年7月[57]、債権者に全額返済するため、1年にわたる世界一周講 演旅行に出発した。旅程の前半は、8月後半までアメリカ北部を横断してカナダのブリティッシュコロンビア州まで行った。後半は太平洋を横断した。ハワイの ホノルルで予定されていた講演はコレラの流行により中止された[54]: 188 [59] トウェインはその後、フィジー、オーストラリア、ニュージーランド、スリランカ、インド、モーリシャス、南アフリカを訪れた。インドでの3ヵ月は、712 ページの著書『赤道をたどって』の中心となった。1896年7月後半、彼はイギリスに戻り、14ヶ月前に始めた世界一周を終えた[54]: 188 トウェインと家族はさらに4年間ヨーロッパで過ごし、主にイギリスとオーストリア(1897年10月から1899年5月まで)に滞在したが、ロンドンと ウィーンでの滞在期間も長かった。クララはウィーンでテオドール・レシェティツキーにピアノを師事することを希望していた[54]: しかし、「医者の 街」ウィーンで専門医に相談しても、ジャンの健康状態は良くならなかった[60]。1899年春、ベルグレヴィアのスウェーデン人オステオパシー医ヨナ ス・ヘンリック・ケルグレン医師の治療を受けて良い経験をしたポールトニー・ビグローの案内で、一家はロンドンに移った。彼らは、スウェーデンのサンナ村 の湖畔にあるケルグレン医師の療養所で夏を過ごすよう説得された。秋に戻ると、トウェインがアメリカで同様のオステオパシーの専門知識が得られると確信す るまで、彼らはロンドンで治療を続けた[61]。 1900年半ば、彼はロンドンの北側にあるドリス・ヒル・ハウスで新聞経営者ヒュー・ギルゼアン・リードの客となった。トウェインは「高貴な木々や広大な 田園、生活を楽しくするあらゆるものがあり、世界の大都市からビスケット一枚で行ける距離にある、これほど満足のいく場所は見たことがなかった」と書いて いる[62]。その後、1900年10月にアメリカに戻り、借金を返済するのに十分な収入を得た。1900/01年冬、彼は帝国主義に反対する自国の最も 著名な人物となり、演説、インタビュー、著作でこの問題を取り上げた。1901年1月、ニューヨークの反帝国主義者連盟の副会長を務める[63] [10]。 講演活動  1895年のトウェインの訪問を記念するシドニー・ライターズ・ウォークのプレート トウェインは、現代のスタンダップ・コメディに似たユーモラスな独演を行い、講演者として大きな需要があった[64]。 彼は、オーサーズ・クラブ、ビーフステーキ・クラブ、バガボンズ、ホワイト・フリアーズ、ハートフォードのマンデー・イブニング・クラブなど、多くの男性 クラブで有料講演を行った[要出典]。 1890年代後半にはロンドンのサベージ・クラブで講演し、名誉会員に選ばれた。彼は、名誉会員に選ばれたのはプリンス・オブ・ウェールズを含めて3人だ けだと聞かされ、こう答えた: 「と答えた[54]: 197 1895年、世界講演旅行の一環としてメルボルンとシドニーを訪れた。1897年、ウィーンのコンコルディア・プレス倶楽部で、外交官のシャルルマー ニュ・タワー・ジュニアに続いて特別ゲストとして講演。ドイツ語で「ドイツ語の恐怖(Die Schrecken der Deutschen Sprache)」というスピーチを行い、聴衆を大いに楽しませた[32]: 50 1901年、プリンストン大学のクリオソフィック文学協会に招待され、そこでスピーチを行い、名誉会員となる[65]。 カナダ訪問 1881年、トウェインはカナダのモントリオールで開かれた宴会で表彰され、そこで著作権の確保について言及した[66]。1883年にはオタワを短期間 訪問し[67]、1884年と1885年には「天才の双子」ツアーとして知られるジョージ・ワシントン・ケーブルとの朗読ツアーでトロントを2度訪れた [67][68][69]。 トロントを訪れた理由は、モントリオールを訪れた際に言及していた『ハックルベリー・フィンの冒険』[67][69]を出版するために、カナダとイギリス の著作権を確保するためであった。オタワ訪問の理由は、『ミシシッピの人生』のカナダとイギリスの著作権を確保するためであった[67]。トロントの出版 社は当時、1891年に国際著作権協定が結ばれる前に、彼の著書の無許可版を印刷していた[67]。これらはカナダだけでなくアメリカでも販売され、彼か ら印税を奪っていた。トム・ソーヤーの冒険』のベルフォード・ブラザーズ版だけでも1万ドル(2023年では34万ドルに相当)かかったと推定している [67]。1881年にはモントリオール旅行に合わせて『王子と貧民』の権利を確保しようとしたが失敗した。 [67]結局、彼はアメリカで出版する前にカナダで(カナダとイギリス両方の)著作権を登録し、アメリカ版が出版されたときにカナダの出版社が版を印刷す るのを抑制するようにという法的助言を受けた[67][69]。カナダ居住者に著作権を登録しなければならないという条件があったが、彼は短期間のカナダ 訪問によってこれに対処した[67][69]。 その後の人生と死 私が死んだという報道は誇張だった。 - トウェイン[70][71]。 トウェインは晩年、マンハッタンの西10番街14番地に住んでいた[72]。1896年に娘のスージーが髄膜炎で亡くなったことから始まる深い憂鬱の時期 を過ごした。1904年のオリヴィアの死、1909年12月24日のジーンの死は彼の憂鬱をさらに深めた[1] 。1909年5月20日、親友のヘンリー・ロジャースが急死した[73]。 1906年4月、彼は友人のイナ・クールブリスが1906年のサンフランシスコ地震で所有するほとんどすべてを失ったと聞き、彼女のためにサイン入りの ポートレート写真を数枚ボランティアで販売した。クールブリスをさらに援助するため、ジョージ・ウォートン・ジェイムズはニューヨークにトウェインを訪 ね、新しいポートレート・セッションを手配した。9月、トウェインは『ノース・アメリカン・レビュー』誌に自伝の章を掲載し始めた[75]。同年、五番街 3番地に祖母と住んでいた作家のシャーロット・テラーは、「数年続き、恋愛的な意図もあったかもしれない」彼との知人関係を始めた[76]。  1908年、オートクローム・リュミエール製法で撮影されたトウェイン 1906年、トウェインは孫娘代わりのような少女たちのために「エンジェルフィッシュ&アクアリウム・クラブ」を結成した。十数人のメンバーは10歳から 16歳までいた。彼は「エンジェルフィッシュ」の少女たちと手紙を交換し、彼女たちをコンサートや劇場、ゲームに招待した。トウェインは1908年に、こ のクラブが彼の「人生の主な楽しみ」であったと書いている[32]: 28 1907年、大西洋横断中にドロシー・クイック(11歳)と出会い、「死ぬその日まで続く友情」が始まった[77]。  1907年、オックスフォード大学から博士号を授与されたトウェイン。 トウェインは1901年にイェール大学から名誉文学博士号を、1902年にはミズーリ大学から法学博士号を授与された。オックスフォード大学からは1907年に法学博士号を授与された[78]: 52 : 58 トウェインは1835年のハレー彗星の最接近の2週間後に生まれた。彼は1909年に次のように述べている[54]。 私は1835年にハレー彗星と一緒にやってきた。来年もハレー彗星はやってくる。ハレー彗星と一緒に出なければ、人生最大の失望となるだろう。全知全能の神は間違いなくこう言った:「今ここに、この説明のつかない2つの奇怪なものがある。 トウェインの予言は不気味なほど的中した。1910年4月21日、彗星がその年に地球を通過する1ヶ月前に、彼はストームフィールドで心臓発作で亡くなった[79]。  トウェインと彼の妻は、エルミラのウッドローン墓地に並んで埋葬されている。 トウェインの死を聞いたウィリアム・ハワード・タフト大統領は次のように述べた[80][81]。 マーク・トウェインは何百万もの人々に喜びを-真の知的楽しみを-与え、彼の作品はこれからも何百万もの人々にそのような喜びを与え続けるだろう。彼はアメリカ文学の不朽の一部となった。 トウェインの葬儀はニューヨーク5番街のブリック長老教会で行われた[82]。ニューヨーク州エルミラのウッドローン墓地の妻の家族の区画に埋葬された。 ラングドン家の区画には、残された娘クララが置いた12フィートの記念碑(2ファゾム、「マーク・トゥエイン」)がある[83]。彼は火葬を希望していた が(例えば『ミシシッピの人生』)、残された家族が最後の決定権を持つことを認めていた。 コネチカット州とニューヨーク州の役人は、トウェインの遺産価値を471,000ドル(2023年には11,000,000ドル)と見積もっている[84]。 |

| Writing Overview Twain began his career writing light, humorous verse, but he became a chronicler of the vanities, hypocrisies, and murderous acts of mankind. At mid-career, he combined rich humor, sturdy narrative, and social criticism in Huckleberry Finn. He was a master of rendering colloquial speech and helped to create and popularize a distinctive American literature built on American themes and language. Many of his works have been suppressed at times for various reasons. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn has been repeatedly restricted in American high schools, not least for its frequent use of the word "nigger",[85] a slur commonly used for Black people in the nineteenth century. A complete bibliography of Twain's works is nearly impossible to compile because of the vast number of pieces he wrote (often in obscure newspapers) and his use of several different pen names. Additionally, a large portion of his speeches and lectures have been lost or were not recorded; thus, the compilation of Twain's works is an ongoing process. Researchers have rediscovered published material as recently as 1995 and 2015.[53][86] Early journalism and travelogues Twain was writing for the Virginia City newspaper the Territorial Enterprise in 1863 when he met lawyer Tom Fitch, editor of the competing newspaper Virginia Daily Union and known as the "silver-tongued orator of the Pacific".[87]: 51 He credited Fitch with giving him his "first really profitable lesson" in writing. "When I first began to lecture, and in my earlier writings," Twain later commented, "my sole idea was to make comic capital out of everything I saw and heard."[88] In 1866, he presented his lecture on the Sandwich Islands to a crowd in Washoe City, Nevada.[89][90] Afterwards, Fitch told him: Clemens, your lecture was magnificent. It was eloquent, moving, sincere. Never in my entire life have I listened to such a magnificent piece of descriptive narration. But you committed one unpardonable sin – the unpardonable sin. It is a sin you must never commit again. You closed a most eloquent description, by which you had keyed your audience up to a pitch of the intensest interest, with a piece of atrocious anti-climax which nullified all the really fine effect you had produced.[88]  Cabin where Twain wrote "Jumping Frog of Calaveras County", Jackass Hill, Tuolumne County. Click on historical marker and interior view. It was in these days that Twain became a writer of the Sagebrush School; he was known later as its most famous member.[91] His first important work was "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County," published in the New York Saturday Press on November 18, 1865. After a burst of popularity, the Sacramento Union commissioned him to write letters about his travel experiences. The first journey that he took for this job was to ride the steamer Ajax on its maiden voyage to the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii). All the while, he was writing letters to the newspaper that were meant for publishing, chronicling his experiences with humor. These letters proved to be the genesis to his work with the San Francisco Alta California newspaper, which designated him a traveling correspondent for a trip from San Francisco to New York City via the Panama isthmus. On June 8, 1867, he set sail on the pleasure cruiser Quaker City for five months, and this trip resulted in The Innocents Abroad or The New Pilgrims' Progress. In 1872, he published his second piece of travel literature, Roughing It, as an account of his journey from Missouri to Nevada, his subsequent life in the American West, and his visit to Hawaii. The book lampoons American and Western society in the same way that Innocents critiqued the various countries of Europe and the Middle East. His next work was The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today, his first attempt at writing a novel. The book, written with his neighbor Charles Dudley Warner, is also his only collaboration. Twain's next work drew on his experiences on the Mississippi River. Old Times on the Mississippi was a series of sketches published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1875 featuring his disillusionment with Romanticism.[92] Old Times eventually became the starting point for Life on the Mississippi. Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Mark Twain" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Twain's next major publication was The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, which draws on his youth in Hannibal. Tom Sawyer was modeled on Twain as a child, with traces of schoolmates John Briggs and Will Bowen.[citation needed] The book also introduces Huckleberry Finn in a supporting role, based on Twain's boyhood friend Tom Blankenship. The Prince and the Pauper was not as well received, despite a storyline that is common in film and literature today. The book tells the story of two boys born on the same day who are physically identical, acting as a social commentary as the prince and pauper switch places. Twain had started Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (which he consistently had problems completing)[93] and had completed his travel book A Tramp Abroad, which describes his travels through central and southern Europe. Twain's next major published work was the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, which confirmed him as a noteworthy American writer. Some have called it the first Great American Novel, and the book has become required reading in many schools throughout the United States. Huckleberry Finn was an offshoot from Tom Sawyer and had a more serious tone than its predecessor. Four hundred manuscript pages were written in mid-1876, right after the publication of Tom Sawyer. The last fifth of Huckleberry Finn is subject to much controversy. Some say that Twain experienced a "failure of nerve," as critic Leo Marx puts it. Ernest Hemingway once said of Huckleberry Finn: If you read it, you must stop where the Nigger Jim is stolen from the boys. That is the real end. The rest is just cheating. Hemingway also wrote in the same essay: All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn.[94] Near the completion of Huckleberry Finn, Twain wrote Life on the Mississippi, which is said to have heavily influenced the novel.[53] The travel work recounts Twain's memories and new experiences after a 22-year absence from the Mississippi River. In it, he also explains that "Mark Twain" was the call made when the boat was in safe water, indicating a depth of two (or twain) fathoms (12 feet or 3.7 metres). McDowell's cave—now known as Mark Twain Cave in Hannibal, Missouri, and frequently mentioned in Twain's book The Adventures of Tom Sawyer—has "Sam Clemens", Twain's real name, engraved on the wall by Twain himself.[95] Later writing Twain produced President Ulysses S. Grant's Memoirs through his fledgling publishing house, Charles L. Webster and Company, which he co-owned with Charles L. Webster, his nephew by marriage.[96] At this time he also wrote "The Private History of a Campaign That Failed" for The Century Magazine.[97] This piece detailed his two-week stint in a Confederate militia during the Civil War. He next focused on A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, written with the same historical fiction style as The Prince and the Pauper. A Connecticut Yankee showed the absurdities of political and social norms by setting them in the court of King Arthur. The book was started in December 1885, then shelved a few months later until the summer of 1887, and eventually finished in the spring of 1889.[citation needed] His next large-scale work was Pudd'nhead Wilson, which he wrote rapidly, as he was desperately trying to stave off bankruptcy. From November 12 to December 14, 1893, Twain wrote 60,000 words for the novel.[53] Critics[who?] have pointed to this rushed completion as the cause of the novel's rough organization and constant disruption of the plot. This novel also contains the tale of two boys born on the same day who switch positions in life, like The Prince and the Pauper. It was first published serially in Century Magazine and, when it was finally published in book form, Pudd'nhead Wilson appeared as the main title; however, the "subtitles" make the entire title read: The Tragedy of Pudd'nhead Wilson and the Comedy of The Extraordinary Twins.[53] Twain's next venture was a work of straight fiction that he called Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc and dedicated to his wife. He had long said[where?] that this was the work that he was most proud of, despite the criticism that he received for it. The book had been a dream of his since childhood, and he claimed that he had found a manuscript detailing the life of Joan of Arc when he was an adolescent.[53] This was another piece that he was convinced would save his publishing company. His financial adviser Henry Huttleston Rogers quashed that idea and got Twain out of that business altogether, but the book was published nonetheless.[citation needed] To pay the bills and keep his business projects afloat, Twain had begun to write articles and commentary furiously, with diminishing returns, but it was not enough. He filed for bankruptcy in 1894. During this time of dire financial straits, he published several literary reviews in newspapers to help make ends meet. He famously derided James Fenimore Cooper in his article detailing Cooper's "Literary Offenses". He became an extremely outspoken critic of other authors and other critics; he suggested that, before praising Cooper's work, Thomas Lounsbury, Brander Matthews, and Wilkie Collins "ought to have read some of it".[98] George Eliot, Jane Austen, and Robert Louis Stevenson also fell under Twain's attack during this time period, beginning around 1890 and continuing until his death.[99] He outlines what he considers to be "quality writing" in several letters and essays, in addition to providing a source for the "tooth and claw" style of literary criticism. He places emphasis on concision, utility of word choice, and realism; he complains, for example, that Cooper's Deerslayer purports to be realistic but has several shortcomings. Ironically, several of his own works were later criticized for lack of continuity (Adventures of Huckleberry Finn) and organization (Pudd'nhead Wilson). Twain's wife died in 1904 while the couple were staying at the Villa di Quarto in Florence. After some time had passed, he published some works that his wife, his de facto editor and censor throughout her married life, had looked down upon. The Mysterious Stranger is perhaps the best known, depicting various visits of Satan to earth. This particular work was not published in Twain's lifetime. His manuscripts included three versions, written between 1897 and 1905: the so-called Hannibal, Eseldorf, and Print Shop versions. The resulting confusion led to extensive publication of a jumbled version, and only recently have the original versions become available as Twain wrote them. Twain's last work was his autobiography, which he dictated and thought would be most entertaining if he went off on whims and tangents in non-chronological order. Some archivists and compilers have rearranged the biography into a more conventional form, thereby eliminating some of Twain's humor and the flow of the book. The first volume of the autobiography, over 736 pages, was published by the University of California in November 2010, 100 years after his death, as Twain wished.[100][101] It soon became an unexpected best-seller,[102] making Twain one of a very few authors publishing new best-selling volumes in the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries. Censorship Twain's works have been subjected to censorship efforts. According to Stuart (2013), "Leading these banning campaigns, generally, were religious organizations or individuals in positions of influence – not so much working librarians, who had been instilled with that American "library spirit" which honored intellectual freedom (within bounds of course)". In 1905, the Brooklyn Public Library banned both The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer from the children's department because of their language.[103] Publishers Mark Twain lived for two decades in a house in Hartford, Connecticut (1871–1891), and the American Publishing Company in that city published the first edition of several of his books.[104] The same can be said about a number of New York-based companies, such as Harper & Brothers and his nephew's Charles L. Webster and Company.[104] Other memorable editions were created by The Ash Ranch Press of San Diego and Barry Moser's Pennyroyal Press.[104] Views Twain's views became more radical as he grew older. In a letter to friend and fellow writer William Dean Howells in 1887, he acknowledged that his views had changed and developed over his lifetime, referring to one of his favorite works: When I finished Carlyle's French Revolution in 1871, I was a Girondin; every time I have read it since, I have read it differently – being influenced and changed, little by little, by life and environment ... and now I lay the book down once more, and recognize that I am a Sansculotte! And not a pale, characterless Sansculotte, but a Marat.[105][106] Politics Twain was a staunch supporter of technological progress and commerce. He was against welfare measures, because he believed that society in the "business age" is governed by "exact and constant" laws that should not be "interfered with for the accommodation of any individual or political or religious faction".[107] He opined that "there is no good government at all & none possible".[107] In the opinion of Washington University professor Guy A. Cardwell: By present standards Mark Twain was more conservative than liberal. He believed strongly in laissez faire, thought personal political rights secondary to property rights, admired self-made plutocrats, and advocated a leadership to be composed of men of wealth and brains. Among his attitudes now more readily recognized as liberal were a faith in progress through technology and a hostility towards monarchy, inherited aristocracy, the Roman Catholic church, and, in his later years, imperialism.[108] Labor Twain wrote glowingly about unions in the river boating industry in Life on the Mississippi, which was read in union halls decades later.[109] He supported the labor movement, especially one of the most important unions, the Knights of Labor.[43] In a speech to them, he said: Who are the oppressors? The few: the King, the capitalist, and a handful of other overseers and superintendents. Who are the oppressed? The many: the nations of the earth; the valuable personages; the workers; they that make the bread that the soft-handed and idle eat.[110] He further wrote "Why is it right that there is not a fairer division of the spoil all around? Because laws and constitutions have ordered otherwise. Then it follows that laws and constitutions should change around and say there shall be a more nearly equal division."[111] Imperialism Before 1899, Twain was largely in favor of imperialism. In the late 1860s and early 1870s, he spoke out strongly in favor of American interests in the Hawaiian Islands.[112] He said the war with Spain in 1898 was "the worthiest" war ever fought.[113] In 1899, however, he reversed course. In the New York Herald, October 16, 1900, Twain describes his transformation and political awakening, in the context of the Philippine–American War, to anti-imperialism: I wanted the American eagle to go screaming into the Pacific ... Why not spread its wings over the Philippines, I asked myself? ... I said to myself, Here are a people who have suffered for three centuries. We can make them as free as ourselves, give them a government and country of their own, put a miniature of the American Constitution afloat in the Pacific, start a brand new republic to take its place among the free nations of the world. It seemed to me a great task to which we had addressed ourselves. But I have thought some more, since then, and I have read carefully the treaty of Paris (which ended the Spanish–American War), and I have seen that we do not intend to free, but to subjugate the people of the Philippines. We have gone there to conquer, not to redeem. It should, it seems to me, be our pleasure and duty to make those people free, and let them deal with their own domestic questions in their own way. And so I am an anti-imperialist. I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land.[114][115] During the Boxer Rebellion, Twain said that "the Boxer is a patriot. He loves his country better than he does the countries of other people. I wish him success."[116] From 1901, soon after his return from Europe, until his death in 1910, Twain was vice-president of the American Anti-Imperialist League,[117] which opposed the annexation of the Philippines by the United States and had "tens of thousands of members".[43] He wrote many political pamphlets for the organization. The Incident in the Philippines, posthumously published in 1924, was in response to the Moro Crater Massacre, in which six hundred Moros were killed. He wrote "In what way was it a battle? It has no resemblance to a battle...We cleaned up our four days' work and made it complete by butchering these helpless people."[118][119] Many of his neglected and previously uncollected writings on anti-imperialism appeared for the first time in book form in 1992.[117] Twain was critical of imperialism in other countries as well. In Following the Equator, Twain expresses "hatred and condemnation of imperialism of all stripes".[43] He was highly critical of European imperialists such as Cecil Rhodes and King Leopold II of Belgium, both of whom attempted to establish colonies on the African continent during the Scramble for Africa.[43] King Leopold's Soliloquy is a political satire about the monarch's private colony, the Congo Free State. Reports of outrageous exploitation and grotesque abuses led to widespread international outcry in the early 1900s, arguably the first large-scale human rights movement. In the soliloquy, the King argues that bringing Christianity to the colony outweighs "a little starvation". The abuses against Congolese forced laborers continued until the movement forced the Belgian government to take direct control of the colony.[120][121] During the Philippine–American War, Twain wrote a short pacifist story titled The War Prayer, which makes the point that humanism and Christianity's preaching of love are incompatible with the conduct of war. It was submitted to Harper's Bazaar for publication, but on March 22, 1905, the magazine rejected the story as "not quite suited to a woman's magazine". Eight days later, Twain wrote to his friend Daniel Carter Beard, to whom he had read the story, "I don't think the prayer will be published in my time. None but the dead are permitted to tell the truth." Because he had an exclusive contract with Harper & Brothers, Twain could not publish The War Prayer elsewhere; it remained unpublished until 1916.[122] It was republished in the 1960s as campaigning material by anti-war activists.[43] Twain acknowledged that he had originally sympathized with the more moderate Girondins of the French Revolution and then shifted his sympathies to the more radical Sansculottes, indeed identifying himself as "a Marat" and writing that the Reign of Terror paled in comparison to the older terrors that preceded it.[123] Twain supported the revolutionaries in Russia against the reformists, arguing that the Tsar must be got rid of by violent means, because peaceful ones would not work.[124] He summed up his views of revolutions in the following statement: I am said to be a revolutionist in my sympathies, by birth, by breeding and by principle. I am always on the side of the revolutionists, because there never was a revolution unless there were some oppressive and intolerable conditions against which to revolute.[125] Civil rights Twain was an adamant supporter of the abolition of slavery and the emancipation of slaves, even going so far as to say, "Lincoln's Proclamation ... not only set the black slaves free, but set the white man free also".[126] He argued that non-whites did not receive justice in the United States, once saying, "I have seen Chinamen abused and maltreated in all the mean, cowardly ways possible to the invention of a degraded nature ... but I never saw a Chinaman righted in a court of justice for wrongs thus done to him".[127] He paid for at least one black person to attend Yale Law School and for another black person to attend a southern university to become a minister.[128] Twain was also a supporter of women's suffrage, as evidenced by his "Votes for Women" speech, given in 1901.[129] Helen Keller benefited from Twain's support as she pursued her college education and publishing despite her disabilities and financial limitations. The two were friends for roughly 16 years.[130] Through Twain's efforts, the Connecticut legislature voted a pension for Prudence Crandall, since 1995 Connecticut's official heroine, for her efforts towards the education of young African-American women in Connecticut. Twain also offered to purchase for her use her former house in Canterbury, home of the Canterbury Female Boarding School, but she declined.[131]: 528 At 62, he wrote in his travelogue Following the Equator (1897) that in colonized lands all over the world, "savages" have always been wronged by "whites" in the most merciless ways, such as "robbery, humiliation, and slow, slow murder, through poverty and the white man's whiskey"; his conclusion is that "there are many humorous things in this world; among them the white man's notion that he is less savage than the other savages".[132] Describing his travels, he wrote, "So far as I am able to judge nothing has been left undone, either by man or Nature, to make India the most extraordinary country that the sun visits on his rounds. Where every prospect pleases, and only man is vile."[133] Native Americans Twain's earlier writings on American Indians reflected his view of essentialized racial difference. Twain wrote in "The Noble Red Man" in 1870: His heart is a cesspool of falsehood, of treachery, and of low and devilish instincts. With him, gratitude is an unknown emotion; and when one does him a kindness, it is safest to keep the face toward him, lest the reward be an arrow in the back. To accept of a favor from him is to assume a debt which you can never repay to his satisfaction, though you bankrupt yourself trying. The scum of the earth![134] In the same tract, he advocates genocide, describing the "Noble Aborigine" as : "nothing but a poor filthy, naked scurvy vagabond, whom to exterminate were a charity to the Creator's worthier insects and reptiles which he oppresses"[135] This piece sought to undermine the sympathy felt on the "Atlantic seabord" for Native Americans.[136][137] In 1895, Twain was still ridiculing the author of Last of the Mohicans, saying in "Fenimore Cooper's Literary Offenses" that Cooper "[...] was almost always in error about his Indians. There was seldom a sane one among them."[138] Political parties Twain was a Republican for most of his life. However, in 1884 he publicly broke with his party and joined the Mugwumps to support the Democratic nominee, Grover Cleveland, over the Republican nominee, James G. Blaine, whom he considered a corrupt politician.[139] Twain spoke at rallies in favor of Cleveland. In the early 20th century, he began decrying both Democrats and Republicans as "insane" and proposed, in his 1907 book Christian Science, that while each party recognized the other's insanity, only the Mugwumps (that is, those who eschewed party loyalties in favor of voting for "the best man") could perceive the overall madness linking the two.[139] Religion See also: Twain–Ament indemnities controversy Twain was a Presbyterian.[140] He was critical of organized religion and certain elements of Christianity through his later life. He wrote, for example, "Faith is believing what you know ain't so", and "If Christ were here now there is one thing he would not be – a Christian".[141] With anti-Catholic sentiment rampant in 19th century America, Twain noted he was "educated to enmity toward everything that is Catholic".[142] As an adult, he engaged in religious discussions and attended services, his theology developing as he wrestled with the deaths of loved ones and with his own mortality.[143] Twain generally avoided publishing his most controversial[144] opinions on religion in his lifetime, and they are known from essays and stories that were published later. In the essay Three Statements of the Eighties in the 1880s, Twain stated that he believed in an almighty God, but not in any messages, revelations, holy scriptures such as the Bible, Providence, or retribution in the afterlife. He did state that "the goodness, the justice, and the mercy of God are manifested in His works", but also that "the universe is governed by strict and immutable laws", which determine "small matters", such as who dies in a pestilence.[145] At other times, he plainly professed a belief in Providence.[146] In some later writings in the 1890s, he was less optimistic about the goodness of God, observing that "if our Maker is all-powerful for good or evil, He is not in His right mind". At other times, he conjectured sardonically that perhaps God had created the world with all its tortures for some purpose of His own, but was otherwise indifferent to humanity, which was too petty and insignificant to deserve His attention anyway.[147] In 1901, Twain criticized the actions of the missionary Dr. William Scott Ament (1851–1909) because Ament and other missionaries had collected indemnities from Chinese subjects in the aftermath of the Boxer Uprising of 1900. Twain's response to hearing of Ament's methods was published in the North American Review in February 1901: To the Person Sitting in Darkness, and deals with examples of imperialism in China, South Africa, and with the U.S. occupation of the Philippines.[148] A subsequent article, "To My Missionary Critics" published in The North American Review in April 1901, unapologetically continues his attack, but with the focus shifted from Ament to his missionary superiors, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions.[149] After his death, Twain's family suppressed some of his work that was especially irreverent toward conventional religion, including Letters from the Earth, which was not published until his daughter Clara reversed her position in 1962 in response to Soviet propaganda about the withholding.[150] The anti-religious The Mysterious Stranger was published in 1916. Little Bessie, a story ridiculing Christianity, was first published in the 1972 collection Mark Twain's Fables of Man.[151] He raised money to build a Presbyterian Church in Nevada in 1864.[152] Twain created a reverent portrayal of Joan of Arc, a subject over which he had obsessed for forty years, studied for a dozen years and spent two years writing about.[153] In 1900 and again in 1908 he stated, "I like Joan of Arc best of all my books, it is the best".[153][154] Those who knew Twain well late in life recount that he dwelt on the subject of the afterlife, his daughter Clara saying: "Sometimes he believed death ended everything, but most of the time he felt sure of a life beyond."[155] Twain's frankest views on religion appeared in his final work Autobiography of Mark Twain, the publication of which started in November 2010, 100 years after his death. In it, he said:[156] There is one notable thing about our Christianity: bad, bloody, merciless, money-grabbing, and predatory as it is – in our country particularly and in all other Christian countries in a somewhat modified degree – it is still a hundred times better than the Christianity of the Bible, with its prodigious crime – the invention of Hell. Measured by our Christianity of to-day, bad as it is, hypocritical as it is, empty and hollow as it is, neither the Deity nor his Son is a Christian, nor qualified for that moderately high place. Ours is a terrible religion. The fleets of the world could swim in spacious comfort in the innocent blood it has spilled. Twain was a Freemason.[157][158] He belonged to Polar Star Lodge No. 79 A.F.&A.M., based in St. Louis. He was initiated an Entered Apprentice on May 22, 1861, passed to the degree of Fellow Craft on June 12, and raised to the degree of Master Mason on July 10. Twain visited Salt Lake City for two days and met there members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. They also gave him a Book of Mormon.[159] He later wrote in Roughing It about that book:[160][161] The book seems to be merely a prosy detail of imaginary history, with the Old Testament for a model; followed by a tedious plagiarism of the New Testament. |

執筆 概要 トウェインは、軽妙でユーモラスな詩を書くことからキャリアをスタートさせたが、やがて人間の虚栄心、偽善、殺人行為の記録者となった。キャリア半ばで、 彼は『ハックルベリー・フィン』の中で豊かなユーモア、骨太な物語、社会批判を組み合わせた。口語表現の名手であり、アメリカ的なテーマと言語を土台とし た独特のアメリカ文学の創造と普及に貢献した。 彼の作品の多くは、様々な理由から時に弾圧されてきた。ハックルベリー・フィンの冒険』は、19世紀に黒人に対してよく使われた蔑称である「ニガー」[85]という言葉が頻繁に使われていることなどが理由で、アメリカの高校で繰り返し制限されてきた。 トウェインの著作の完全な書誌を作成することは、彼が書いた膨大な数の作品(しばしば無名の新聞に掲載された)と複数の異なるペンネームを使用していたた め、ほぼ不可能である。さらに、彼の演説や講演の大部分は失われているか、記録されていない。したがって、トウェインの著作の編纂は現在進行中である。研 究者たちは1995年と2015年の時点で出版された資料を再発見している[53][86]。 初期のジャーナリズムと旅行記 1863年、ヴァージニア・シティの新聞『テリトリアル・エンタープライズ』に寄稿していたトウェインは、競合する新聞『ヴァージニア・デイリー・ユニオ ン』の編集者で「太平洋の銀舌の演説家」として知られる弁護士のトム・フィッチと出会った[87]: 51 彼はフィッチから「初めて本当に有益な教え」を受けたと信じている。「1866年、彼はネバダ州ワショー・シティの観衆を前に、サンドイッチ諸島について の講演を行った[89][90]。 その後、フィッチは彼にこう言った: クレメンス、君の講演は素晴らしかった。雄弁で、感動的で、誠実だった。私の生涯で、これほど見事な叙述を聴いたことはない。しかし、あなたは一つの許さ れざる罪を犯した。それは二度と犯してはならない罪だ。あなたは、最も雄弁な描写によって聴衆を最も強い関心の高さへと導いていたのに、非道なアンチクラ イマックスでそれを閉じてしまった。  トウェインが 「Jumping Frog of Calaveras County 」を書いた小屋、トゥオルミ郡ジャッカス・ヒル。歴史的なマーカーをクリックすると内部を見ることができる。 トウェインがサゲブラシ派の作家となったのはこの頃で、後に最も有名なメンバーとして知られるようになる[91]。彼の最初の重要な作品は、1865年 11月18日にNew York Saturday Pressに掲載された 「The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County 」である。人気が爆発した後、サクラメント・ユニオンは彼に旅行体験についての手紙を書くよう依頼した。この仕事のために彼が最初にした旅は、サンド ウィッチ諸島(ハワイ)への処女航海で蒸気船エイジャックスに乗ることだった。その間、彼はユーモアを交えて自分の体験を記した出版用の手紙を新聞社に書 き続けた。これらの手紙は、サンフランシスコ・アルタ・カリフォルニア紙での仕事の発端となり、同紙は彼をサンフランシスコからパナマ地峡を経由して ニューヨークへ向かう旅の特派員に任命した。 1867年6月8日、彼は遊覧船クエーカー・シティ号で5ヶ月間航海し、この旅から『イノセント・アブロード』または『新・巡礼の道程』が生まれた。 1872年には、ミズーリ州からネバダ州への旅、その後のアメリカ西部での生活、ハワイ訪問の記録として、2作目の旅行文学『Roughing It』を出版した。この本は、『イノセント』がヨーロッパや中東の国々を批評したのと同じように、アメリカや西欧社会を揶揄している。次の作品は『金ぴか 時代』である: A Tale of Today』で、小説の執筆に初めて挑戦した。隣人のチャールズ・ダドリー・ワーナーと書いたこの本は、彼の唯一の共作でもある。 トウェインの次の作品は、ミシシッピ川での体験をもとにしたものだった。オールド・タイムズ・オン・ザ・ミシシッピ』は、1875年に『アトランティック・マンスリー』誌に掲載されたスケッチのシリーズで、ロマン主義への幻滅が描かれている[92]。 トム・ソーヤーとハックルベリー・フィン このセクションは検証のために追加の引用が必要である。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力いただきたい。ソースのないものは異議申し立てがなされ、削除されることがある。 出典を探す 「Mark Twain」 - news - newspapers - books - scholar - JSTOR (March 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) トウェインの次の主な出版物は、ハンニバルでの少年時代を描いた『トム・ソーヤーの冒険』である。トム・ソーヤーは、学友ジョン・ブリッグスやウィル・ ボーエンの面影を残しながら、幼い頃のトウェインをモデルにしている[要出典]。この本には、トウェインの少年時代の友人トム・ブランケンシップをモデル にした、脇役のハックルベリー・フィンも登場する。 王子と貧乏人』は、今日の映画や文学でよく見られるストーリーにもかかわらず、評判はそれほど良くなかった。この本は、同じ日に生まれた身体的に同じ2人 の少年の物語であり、王子と貧民が入れ替わることで社会的な批評として機能している。トウェインは『ハックルベリー・フィンの冒険』を書き始め[93]、 中南欧の旅を描いた旅行記『A Tramp Abroad』を完成させていた。 トウェインの次に出版された主要な作品は『ハックルベリー・フィンの冒険』であり、これによって彼は注目すべきアメリカ人作家であることが確認された。こ の作品を最初の偉大なアメリカ小説と呼ぶ人もおり、この本は全米の多くの学校で必読書となっている。ハックルベリー・フィンはトム・ソーヤーから派生した 作品で、前作よりも深刻なトーンだった。400ページの原稿は、『トム・ソーヤー』出版直後の1876年半ばに書かれた。ハックルベリー・フィンの最後の 5分の1は、多くの論争にさらされている。批評家のレオ・マルクスが言うように、トウェインは「神経衰弱」に陥ったと言う人もいる。アーネスト・ヘミング ウェイはかつてハックルベリー・フィンについてこう言った: 読むなら、ニガー・ジムが少年たちから奪われるところで止めなければならない。それが本当の結末だ。残りはただのごまかしだ。 ヘミングウェイは同じエッセイでこうも書いている: 現代のアメリカ文学はすべて、マーク・トウェインの『ハックルベリー・フィン』という一冊の本から来ている」[94]。 ハックルベリー・フィン』の完成間近に、トウェインは『ミシシッピ川での生活』を書き、この小説に大きな影響を与えたと言われている[53]。その中で彼 はまた、「マーク・トウェイン」とは、ボートが安全な水深2ファゾン(12フィートまたは3.7メートル)にあることを示す呼びかけだと説明している。 マクダウェルの洞窟-現在はミズーリ州ハンニバルにあるマーク・トウェイン洞窟として知られ、トウェインの著書『トム・ソーヤーの冒険』にも頻繁に登場する-には、トウェインの本名である「サム・クレメンス」がトウェイン自身によって壁に刻まれている[95]。 後の執筆活動 トウェインは、結婚して甥となったチャールズ・L・ウェブスターと共同経営していた設立間もない出版社チャールズ・L・ウェブスター・アンド・カンパニーを通じて、ユリシーズ・S・グラント大統領の回想録を制作した[96]。 この頃、彼は『The Century Magazine』誌に『The Private History of a Campaign That Failed』も執筆している[97]。この作品では、南北戦争中に南軍の民兵として2週間活動したことを詳述している。彼は次に『アーサー王宮廷のコネ ティカット・ヤンキー』に焦点を当て、『王子と貧乏人』と同じ歴史小説のスタイルで書いた。A Connecticut Yankee』は、アーサー王の宮廷を舞台に、政治的・社会的規範の不条理を描いた。この本は1885年12月に書き始められ、数カ月後に1887年夏ま で棚上げされ、最終的に1889年春に完成した[要出典]。 次の大作は『Pudd'nhead Wilson』で、彼は破産を食い止めようと必死だったため、急速に執筆を進めた。1893年11月12日から12月14日にかけて、トウェインはこの小 説のために6万語を書き上げた[53]。批評家[誰?]は、この小説の粗雑な構成とプロットの絶え間ない混乱の原因として、この急ぎの完成を指摘してい る。この小説には、『王子と貧乏人』のように、同じ日に生まれた二人の少年が人生の中で立場を入れ替える物語も含まれている。センチュリー』誌に連載さ れ、単行本化されたときには『パッド・ヘッド・ウィルソン』がメイン・タイトルとして掲載された: しかし、「サブタイトル 」をつけると、タイトル全体は次のようになる:The Tragedy of Pudd'nhead Wilson and the Comedy of The Extraordinary Twins [53]. トウェインの次の冒険は、『ジョーン・オブ・アークの個人的回想』と名付け、妻に捧げたストレート・フィクションの作品であった。彼は長い間[どこ で?]、この作品は批判を受けながらも、最も誇りに思っている作品だと語っていた。この本は彼の子供の頃からの夢であり、彼は思春期の頃にジョーン・オ ブ・アークの生涯を詳述した原稿を見つけたと主張していた[53]。彼の財務アドバイザーであったヘンリー・ハットルストン・ロジャースはその考えを打ち 砕き、トウェインをその事業から完全に撤退させたが、それでもこの本は出版された[要出典]。 請求書を支払い、事業計画を維持するために、トウェインは猛烈に記事や解説を書き始めたが、その見返りは減っていった。彼は1894年に破産を申請した。 経済的に困窮していたこの時期、彼は生活費を稼ぐために新聞にいくつかの文芸評論を発表した。クーパーの「文学的犯罪」を詳述した記事の中で、ジェーム ズ・フェニモア・クーパーを揶揄したことは有名である。彼は他の作家や他の批評家に対して非常に率直な批評家となり、クーパーの作品を賞賛する前に、トマ ス・ラウンスベリー、ブランダー・マシューズ、ウィルキー・コリンズが「少しは読むべきだった」と示唆した[98]。 ジョージ・エリオット、ジェーン・オースティン、ロバート・ルイス・スティーヴンソンもまた、1890年頃から亡くなるまで、この時期にトウェインの攻撃 を受けた[99]。例えば、クーパーの『鹿殺し』は写実的であるように装っているが、いくつかの欠点があると苦言を呈している。皮肉なことに、彼自身の作 品のいくつかは、連続性の欠如(『ハックルベリー・フィンの冒険』)や構成力の欠如(『パッズヘッド・ウィルソン』)で後に批判された。 トウェインの妻は1904年、夫妻がフィレンツェのクアルト荘に滞在中に亡くなった。しばらく時間が経った後、結婚生活を通じて事実上の編集者であり検閲 者であった妻が見下していたいくつかの作品を出版した。謎めいた見知らぬ男』はおそらく最もよく知られた作品で、サタンの地上への様々な訪問を描いてい る。この作品はトウェインの存命中には出版されなかった。彼の原稿には、1897年から1905年の間に書かれた3つのバージョン、いわゆるハンニバル 版、エセルドルフ版、プリントショップ版が含まれていた。その結果、混乱が生じ、ごちゃごちゃした版が広範囲にわたって出版されることになったが、最近に なってようやく、トウェインが書いたままのオリジナル版が入手できるようになった。 トウェインの最後の仕事は自伝で、彼は口述筆記で、時系列に並べずに気まぐれに脱線していくのが一番面白いだろうと考えた。一部の記録保管者や編纂者は、 自伝をよりオーソドックスな形に並べ替え、それによってトウェインのユーモアの一部と本の流れをなくしてしまった。736ページを超える自伝の第1巻は、 トウェインの希望通り、死後100年を経た2010年11月にカリフォルニア大学から出版された[100][101]。すぐに予想外のベストセラーとなり [102]、トウェインは19世紀、20世紀、21世紀において新たにベストセラーを出版した数少ない作家の一人となった。 検閲 トウェインの作品は検閲の対象となってきた。スチュアート(2013)によれば、「こうした禁止キャンペーンを主導したのは、概して宗教団体や影響力のあ る立場にある個人であり、(もちろんその範囲内で)知的自由を尊ぶアメリカの「図書館精神」を叩き込まれた現役の図書館員ではなかった」。1905年、ブ ルックリン公共図書館は、『ハックルベリー・フィンの冒険』と『トム・ソーヤーの冒険』の両方を、その言語を理由に児童書部門から追放した[103]。 出版社 マーク・トウェインはコネチカット州ハートフォードの家に20年間住み(1871年~1891年)、同市のアメリカン・パブリッシング・カンパニーが彼の 著作の初版を出版した[104]。 ハーパー&ブラザーズや彼の甥のチャールズ・L・ウェブスター&カンパニーなど、ニューヨークを拠点とする数多くの会社についても同じことが言える [104]。その他、サンディエゴのアッシュ・ランチ・プレスやバリー・モーザーのペニーロイヤル・プレスが記念すべき版を出版した[104]。 見解 トウェインの見解は、年をとるにつれて過激になっていった。1887年に友人で作家仲間のウィリアム・ディーン・ハウエルズに宛てた手紙の中で、彼は自分の見解が生涯を通じて変化し、発展してきたことを認め、お気に入りの作品のひとつに言及している: 1871年にカーライルの『フランス革命』を読み終えたとき、私はジロンダンだった。それ以来、この本を読むたびに、私は違った読み方をしてきた!そして、青白く無個性なサンスクロットではなく、マラットなのだ[105][106]。 政治 トウェインは技術の進歩と商業の支持者であった。彼は、「ビジネス時代」の社会は「正確で不変の」法律によって支配されており、それは「いかなる個人、政 治的、宗教的派閥の便宜のためにも干渉されるべきではない」と考えていたため、福祉施策には反対だった[107]。彼は、「善良な政府などまったく存在し ないし、存在し得ない」[107]という見解を示した: 現在の基準では、マーク・トウェインはリベラルというより保守的だった。彼は自由放任主義を強く信じ、個人の政治的権利は財産権にとって二の次だと考え、 自力で築いた富豪を賞賛し、富と頭脳の持ち主で構成される指導部を提唱した。現在ではリベラルと認識されやすい彼の態度のなかには、技術による進歩への信 頼と、君主制、世襲貴族制、ローマ・カトリック教会、そして晩年には帝国主義への敵意があった[108]。 労働 トウェインは『ミシシッピの人生』の中で、川船業界の組合について熱烈に書いており、それは数十年後に組合会館で読まれるようになった[109]。 彼は労働運動、特に最も重要な組合のひとつである労働騎士団を支持した[43]。 彼らに向けた演説の中で、彼はこう言った: 抑圧者は誰か。国王、資本家、そして一握りの監督者、管理者である。抑圧されているのは誰か?多くの人々:地上の国々、貴重な人物、労働者、軟弱で怠惰な人々が食べるパンを作っている人々である」[110]。 彼はさらにこう書いている。「なぜ戦利品の公平な分配が行われないのが正しいのか。法律と憲法がそうでないように命じているからである。それならば、法律や憲法は一転して、よりほぼ平等な分配を行うべきだと言うべきだ」[111]。 帝国主義 1899年以前、トウェインは帝国主義を支持していた。1860年代後半から1870年代前半にかけて、彼はハワイ諸島におけるアメリカの権益を強く支持 していた[112]。 1898年のスペインとの戦争は「最も価値ある」戦争であったと述べている[113]。1900年10月16日付の『ニューヨーク・ヘラルド』紙で、ト ウェインはフィリピン・アメリカ戦争を背景に、反帝国主義への変貌と政治的覚醒を述べている: 私はアメリカの鷲が太平洋に雄叫びを上げながら飛び立つのを望んでいた。なぜフィリピンに翼を広げないのかと私は自問した。... ここに3世紀にわたって苦しんできた人々がいる。彼らを自分たちと同じように自由にし、自分たちだけの政府と国を与え、アメリカ憲法のミニチュアを太平洋 に浮かべ、世界の自由な国々の仲間入りをするために、真新しい共和国を始めることができる。それは、私たちが自らに課した偉大な使命のように思えた。 しかし、それ以来、私はさらに考え、(米西戦争を終結させた)パリ条約を注意深く読み、私たちはフィリピンの人々を解放するつもりはなく、服従させるつもりであることを知った。我々はフィリピンに征服しに行ったのであって、救済しに行ったのではない。 フィリピンの人々を自由にし、彼ら自身の国内問題は彼ら自身のやり方で処理させることが、私たちの喜びであり義務であるように思える。だから私は反帝国主義者だ。ワシが他の土地に爪を立てることには反対である[114][115]。 義和団の乱のとき、トウェインは「義和団は愛国者だ。彼は他国民の国よりも自分の国を愛している。彼の成功を祈っている」[116]。 ヨーロッパから帰国した直後の1901年から1910年に亡くなるまで、トウェインはアメリカによるフィリピン併合に反対し、「数万人の会員」を擁したア メリカ反帝国主義同盟の副会長を務めていた[117]。死後1924年に出版された『フィリピン事件』は、600人のモロ人が殺されたモロ・クレーター虐 殺事件に対するものであった。彼はこう書いている。我々は4日間の仕事を片付け、この無力な人々を虐殺することで完全なものにした」[118][119] 反帝国主義について、これまで顧みられることのなかった彼の著作の多くが、1992年に初めて書籍化された[117]。 トウェインは他国の帝国主義にも批判的だった。赤道をたどって』の中で、トウェインは「あらゆる帝国主義に対する憎悪と非難」を表明している[43]。彼 は、セシル・ローズやベルギーのレオポルド2世といったヨーロッパの帝国主義者を強く批判していた。レオポルド王の独白』は、君主の私的植民地であるコン ゴ自由国についての政治風刺である。とんでもない搾取とグロテスクな虐待の報告は、1900年代初頭に広く国際的な反発を招き、間違いなく最初の大規模な 人権運動となった。独り言の中で国王は、植民地にキリスト教をもたらすことは「少しの飢え」を凌駕すると主張している。コンゴ人強制労働者に対する虐待 は、この運動によってベルギー政府が植民地を直接管理するようになるまで続いた[120][121]。 アメリカ・フィリピン戦争中、トウェインは『戦争の祈り』という平和主義的な短編小説を書いた。この作品はハーパース・バザー誌に投稿されたが、1905 年3月22日、同誌は「女性誌にはふさわしくない」として却下した。その8日後、トウェインはこの物語を読んだ友人ダニエル・カーター・ビアードにこう書 いた。死者以外は真実を語ることを許されない」。トウェインはハーパー&ブラザーズと専属契約を結んでいたため、『戦争の祈り』を他で出版することはでき ず、1916年まで未発表のままだった[122]。 トウェインはもともとフランス革命のより穏健なジロンダンに同調していたことを認めており、その後より急進的なサンスキュロット派に同調するようになり、 実際に自らを「一人のマラ」と認め、テロールの治世はそれに先立つ古い恐怖に比べれば淡いものであったと書いている[123]。 トウェインは改革派に対抗するロシアの革命派を支持し、平和的な手段ではうまくいかないので暴力的な手段でツァーを排除しなければならないと主張した [124]: 私は、生まれつき、血筋から、そして主義から、革命家であると言われている。というのも、革命するための抑圧的で耐え難い状況がなければ、革命は起こらなかったからである[125]。 公民権 トウェインは奴隷制廃止と奴隷解放の断固とした支持者であり、「リンカーンの宣言は......黒人奴隷を自由にしただけでなく、白人も自由にした」とま で言っている[126]。 彼は非白人がアメリカでは正義を受けていないと主張し、「私は中国人が卑劣で卑怯な方法で虐待され、虐待されるのを見てきた。 しかし、こうして彼になされた過ちに対して、正義の法廷で正されたシナ人を見たことはない」[127]。彼は少なくとも一人の黒人がイェール大学ロース クールに通うための学費を支払い、もう一人の黒人が牧師になるために南部の大学に通うための学費を支払った[128]。 トウェインはまた、1901年に行われた「女性のための投票権」の演説に見られるように、女性参政権の支持者でもあった[129]。 ヘレン・ケラーは、障害や経済的な制約があったにもかかわらず、大学での教育を受け、出版を目指したため、トウェインの支援の恩恵を受けた。二人はおよそ16年間友人であった[130]。 トウェインの努力によって、コネチカット州議会は1995年以来コネチカット州の公式ヒロインであるプルーデンス・クランダルに、コネチカット州の若いア フリカ系アメリカ人女性の教育に対する彼女の努力に対して年金を支給することを議決した。トウェインはまた、カンタベリー女子寄宿学校の本拠地であるカン タベリーの旧家を彼女のために購入することを申し出たが、彼女は辞退した[131]: 528 62歳のとき、彼は旅行記『赤道をたどって』(1897年)の中で、世界中の植民地化された土地では、「野蛮人」は常に「白人」によって、「強盗、屈辱、 そして貧困と白人のウィスキーによるゆっくりとした殺人」など、最も無慈悲な方法で不当な扱いを受けてきたと書いている。彼の結論は、「この世にはユーモ ラスなことがたくさんある。 [132]彼は旅についてこう書いている。「私が判断する限り、インドを太陽が巡回する中で最も驚異的な国にするために、人為的にも自然的にもやり残した ことは何もない。そこではあらゆる展望が楽しめ、人間だけが下劣である」[133]。 アメリカ先住民 アメリカ・インディアンに関するトウェインの初期の著作は、本質化された人種的差異に対する彼の見方を反映していた。トウェインは1870年の「高貴な赤い人」でこう書いている: 彼の心は偽り、裏切り、卑しく悪魔的な本能の巣窟である。彼にとっては、感謝は未知の感情であり、人が彼に親切をするときは、その報酬が背中に矢とならな いように、彼に顔を向けておくのが最も安全である。彼からの好意を受け入れることは、自分が破産しようとも、彼が満足するような返済は決してできない負債 を背負うことなのだ。地球のクズだ![134]」と述べている。 同じトラクトの中で、彼は大量虐殺を提唱し、「高貴なアボリジニ」をこう表現している: 「哀れな不潔で裸の壊血病の浮浪者にすぎず、彼らを絶滅させることは、創造主が抑圧しているもっと価値のある昆虫や爬虫類への施しである」[135]。こ の作品は「大西洋沿岸」でネイティブ・アメリカンに抱かれていた同情を弱めようとするものであった。 [136][137]1895年、トウェインはまだ『ラスト・オブ・モヒカン』の作者を嘲笑しており、「フェニモア・クーパーの文学的犯罪」の中でクー パーは「[...]彼のインディアンについてはほとんどいつも間違っていた。彼らの中にまともな者はめったにいなかった」[138]。 政党 トウェインは生涯のほとんどを共和党員だった。しかし、1884年には党を公然と離党し、マグワンプに加わり、腐敗した政治家だと考えていた共和党候補の ジェームズ・G・ブレインではなく、民主党候補のグローヴァー・クリーヴランドを支持した[139]。20世紀初頭、彼は民主党と共和党の両方を「正気で はない」と批判し始め、1907年の著書『クリスチャン・サイエンス』の中で、それぞれの政党が相手の狂気を認識している一方で、マグワンプ(つまり「最 高の男」に投票することを優先して政党への忠誠心を捨てた人々)だけが両者を結びつける全体的な狂気を認識することができると提唱した[139]。 宗教 以下も参照のこと: トウェイン-エーメント補償論争 トウェインは長老派であった[140]。彼は晩年を通じて、組織化された宗教やキリスト教の特定の要素に批判的であった。19世紀のアメリカでは反カト リック感情が蔓延していたため、トウェインは「カトリック的なものすべてを敵視するように教育された」と述べている[142]。大人になってからは宗教的 な議論に参加したり礼拝に出席したりし、愛する人の死や自分自身の死と格闘しながら神学を発展させていった[143]。 トウェインは一般的に、宗教に関する最も物議を醸す[144]意見を生前に発表することを避けており、それらは後に発表されたエッセイや物語から知られて いる。1880年代に発表されたエッセイ『80年代の3つの発言』の中で、トウェインは全能の神を信じるが、メッセージや啓示、聖書のような聖典、摂理、 死後の世界での報いなどは信じていないと述べている。彼は「神の善意、正義、慈悲は神の御業に現れている」と述べているが、「宇宙は厳格で不変の法則に よって支配されている」とも述べており、その法則は疫病で誰が死ぬかといった「小さな事柄」を決定するものであるとも述べている[145]。 [1890年代後半の著作では、彼は神の善良さについてあまり楽観的ではなく、「もしわれわれの創造主が善悪にかかわらず万能であるならば、彼は正気では ない」と述べている[146]。またあるときは、おそらく神はご自身の何らかの目的のために、あらゆる拷問を伴う世界を創造されたのだろうが、そうでなけ れば、神の注意に値するにはあまりにもちっぽけで取るに足らない人間性には無関心なのだろうと、冷淡に推測していた[147]。 1901年、トウェインは宣教師ウィリアム・スコット・エーメント博士(1851-1909)の行動を批判した。エーメントと他の宣教師たちは、1900 年の義和団蜂起の余波で中国人から賠償金を徴収していたからである。アメントのやり方を聞いたトウェインの反応は、1901年2月の『ノース・アメリカ ン・レビュー』に掲載された: 続いて1901年4月に『ノース・アメリカン・レビュー』誌に発表された「私の宣教師批判者たちへ」という論文は、彼の攻撃を堂々と続けているが、焦点は アメントから彼の宣教師の上司であるアメリカ対外伝道委員会に移されている[149]。 彼の死後、トウェインの家族は、『大地からの手紙』を含む、従来の宗教に対して特に不遜な彼の作品のいくつかを抑圧した。この作品は、抑圧に関するソビエ トのプロパガンダに対抗して、1962年に娘のクララが立場を翻すまで出版されなかった[150]。キリスト教を揶揄した『リトル・ベッシー』は、 1972年に出版された『マーク・トウェインの人間寓話集』で初公開された[151]。 彼は1864年にネバダに長老派教会を建てるために資金を集めた[152]。 トウェインはジョーン・オブ・アークを敬虔に描いたが、それは彼が40年間執着し、12年間研究し、2年間かけて書いたテーマであった[153]。 晩年のトウェインをよく知る人たちは、彼が死後の世界についてくよくよ考えていたことを語り、娘のクララはこう言っている: 「時々彼は死がすべてを終わらせると信じていたが、ほとんどの場合、彼はあの世での人生を確信していた」[155]。 トウェインの宗教に対する最も率直な見解は、彼の死後100年を経た2010年11月に出版が開始された最後の著作『マーク・トウェイン自伝』に現れている。その中で彼は次のように述べている[156]。 われわれのキリスト教について特筆すべきことがひとつある。それは、われわれの国では特にそうであり、他のすべてのキリスト教国でも多少は修正されている が、それでも、地獄の発明というとてつもない犯罪を犯した聖書のキリスト教よりは100倍ましだということだ。今日のキリスト教は、それが悪いものである にせよ、偽善的であるにせよ、空虚で中途半端なものであるにせよ、神もその子もキリスト教徒ではないし、そのような中程度の高い地位につく資格もない。私 たちの宗教は恐ろしいものだ。世界の艦隊は、この宗教が流した罪のない血の中を悠々と泳ぐことができるだろう。 トウェインはフリーメーソンであった[157][158]。彼はセントルイスを拠点とするポーラー・スター・ロッジ第79A.F.&A.M.に所 属していた。1861年5月22日に入門見習いとして入門し、6月12日にフェロー・クラフトに合格、7月10日にマスター・メーソンに昇格した。 トウェインはソルトレイクシティを2日間訪れ、そこで末日聖徒イエス・キリスト教会の会員に会った。彼らはまた彼にモルモン書を与えた[159]。後に彼はその本についてRoughing Itの中で次のように書いている[160][161]。 この本は、旧約聖書を手本にした、想像上の歴史を稚拙に詳述したものにすぎず、その後に新約聖書の退屈な剽窃が続くように思われる。 |