マルチン・ルター

Martin Luther, 1483-1546

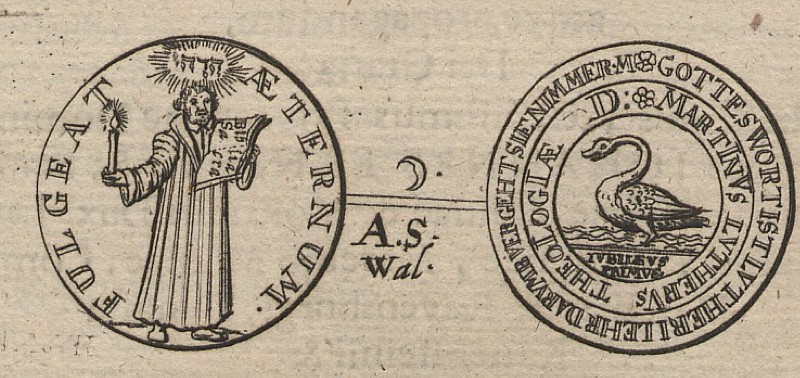

Lucas

Cranach d.Ä. - Martin Luther, 1528

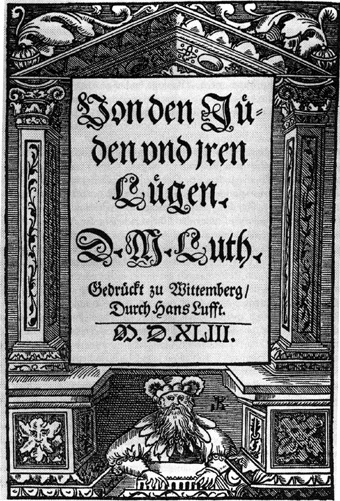

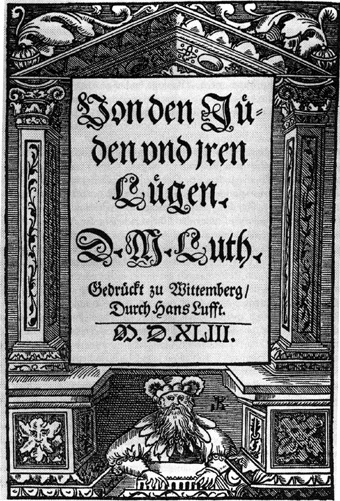

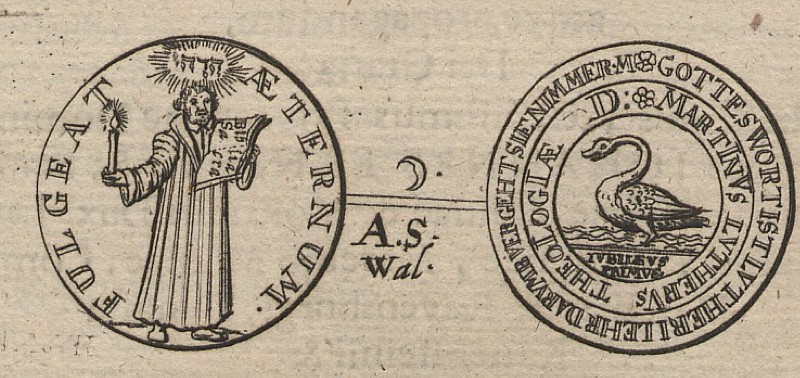

☆ マルティン・ルターOSA(1483年11月10日 - 1546年2月18日)はドイツの司祭、神学者、作家、賛美歌作者、教授、アウグスティヌス修道士。 [プロテスタント宗教改革の中心的人物であり、彼の神学的信念はルター派の基礎を形成している。 ルターは1507年に司祭に叙階された。彼はローマ・カトリック教会のいくつかの教えや慣習を否定するようになり、特に免罪符に関する見解に異論を唱え た。ルターは1517年の「95ヶ条の論題」の中で、免罪符の実践と効力について学術的な議論を提案した。1520年の教皇レオ10世と1521年のヴォ ルムス会議での神聖ローマ皇帝シャルル5世の要求に応じて、すべての著作を放棄することを拒否した結果、教皇から破門され、神聖ローマ皇帝からは無法者と して断罪された。ルターは1546年、ローマ教皇レオ10世の破門を受けたままこの世を去った。 ルターは、救い、ひいては永遠の命は善行によって得られるものではなく、むしろ、罪からの贖い主であるイエス・キリストを信じる信仰を通して、神の恵みの 無償の賜物としてのみ与えられるものだと説いた。ルターの神学は、聖書が神によって啓示された知識の唯一の源であることを教えることによって教皇の権威と 権能に異議を唱え、洗礼を受けたすべてのクリスチャンを聖なる神権であると考えることによって聖職者主義に反対した。ルターは、キリストを公 言する個人の唯一の名前として、クリスチャンまたは福音主義者(ドイツ語:evangelisch)を主張したが、これらルターの広範な教えのすべてに同 調する人々はルター派と呼ばれる。ルターが聖書をラテン語ではなくドイツ語の方言に翻訳したことで、一般の人々も聖書に親しむことができるようになった。 彼の賛美歌は、プロテスタント教会における歌唱の発展に影響を与えた。 元修道女カタリーナ・フォン・ボラとの結婚は、プロテスタントの聖職者の結婚を認め、聖職者結婚の実践のモデルとなった。 ルターは晩年の2つの著作で反ユダヤ主義的な見解を表明し、ユダヤ人の追放とシナゴーグの焼き討ちを呼びかけた。 ルターはユダヤ人の殺害を提唱していなかったにもかかわらず、彼の教えに基づき、彼のレトリックがドイツにおける反ユダ ヤ主義とナチス党の発展に大きく貢献したというのが歴史家の間での一般的な見解である。

| Martin Luther OSA

(/ˈluːθər/;[1] German: [ˈmaʁtiːn ˈlʊtɐ] ⓘ; 10 November 1483[2] – 18

February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter,

professor, and Augustinian friar.[3] He was the seminal figure of the

Protestant Reformation, and his theological beliefs form the basis of

Lutheranism. Luther was ordained to the priesthood in 1507. He came to reject several teachings and practices of the Roman Catholic Church; in particular, he disputed the view on indulgences. Luther proposed an academic discussion of the practice and efficacy of indulgences in his Ninety-five Theses of 1517. His refusal to renounce all of his writings at the demand of Pope Leo X in 1520 and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V at the Diet of Worms in 1521 resulted in his excommunication by the pope and condemnation as an outlaw by the Holy Roman Emperor. Luther died in 1546 with Pope Leo X's excommunication still in effect. Luther taught that salvation and, consequently, eternal life are not earned by good deeds; rather, they are received only as the free gift of God's grace through the believer's faith in Jesus Christ, the redeemer from sin. His theology challenged the authority and office of the pope by teaching that the Bible is the only source of divinely revealed knowledge,[4] and opposed sacerdotalism by considering all baptized Christians to be a holy priesthood.[5] Those who identify with these, and all of Luther's wider teachings, are called Lutherans, though Luther insisted on Christian or Evangelic (German: evangelisch) as the only acceptable names for individuals who professed Christ. His translation of the Bible into the German vernacular (instead of Latin) made it more accessible to the laity, an event that had a tremendous impact on both the church and German culture. It fostered the development of a standard version of the German language, added several principles to the art of translation,[6] and influenced the writing of an English translation, the Tyndale Bible.[7] His hymns influenced the development of singing in Protestant churches.[8] His marriage to Katharina von Bora, a former nun, set a model for the practice of clerical marriage, allowing Protestant clergy to marry.[9] In two of his later works, Luther expressed anti-Judaistic views, calling for the expulsion of Jews and the burning of synagogues.[10] In addition, these works also targeted Roman Catholics, Anabaptists, and nontrinitarian Christians.[11] Based upon his teachings, despite the fact that Luther did not advocate the murdering of Jews,[12][13][14] the prevailing view among historians is that his rhetoric contributed significantly to the development of antisemitism in Germany and of the Nazi Party.[15][16][17] |

マルティン・ルターOSA(1483年11月10日 -

1546年2月18日)はドイツの司祭、神学者、作家、賛美歌作者、教授、アウグスティヌス修道士。

[プロテスタント宗教改革の中心的人物であり、彼の神学的信念はルター派の基礎を形成している。 ルターは1507年に司祭に叙階された。彼はローマ・カトリック教会のいくつかの教えや慣習を否定するようになり、特に免罪符に関する見解に異論を唱え た。ルターは1517年の「95ヶ条の論題」の中で、免罪符の実践と効力について学術的な議論を提案した。1520年の教皇レオ10世と1521年のヴォ ルムス会議での神聖ローマ皇帝シャルル5世の要求に応じて、すべての著作を放棄することを拒否した結果、教皇から破門され、神聖ローマ皇帝からは無法者と して断罪された。ルターは1546年、ローマ教皇レオ10世の破門を受けたままこの世を去った。 ルターは、救い、ひいては永遠の命は善行によって得られるものではなく、むしろ、罪からの贖い主であるイエス・キリストを信じる信仰を通して、神の恵みの 無償の賜物としてのみ与えられるものだと説いた。ルターの神学は、聖書が神によって啓示された知識の唯一の源であることを教えることによって教皇の権威と 権能に異議を唱え[4]、洗礼を受けたすべてのクリスチャンを聖なる神権であると考えることによって聖職者主義に反対した[5]。ルターは、キリストを公 言する個人の唯一の名前として、クリスチャンまたは福音主義者(ドイツ語:evangelisch)を主張したが、これらルターの広範な教えのすべてに同 調する人々はルター派と呼ばれる。ルターが聖書をラテン語ではなくドイツ語の方言に翻訳したことで、一般の人々も聖書に親しむことができるようになった。 彼の賛美歌は、プロテスタント教会における歌唱の発展に影響を与えた[8]。 元修道女カタリーナ・フォン・ボラとの結婚は、プロテスタントの聖職者の結婚を認め、聖職者結婚の実践のモデルとなった[9]。 ルターは晩年の2つの著作で反ユダヤ主義的な見解を表明し、ユダヤ人の追放とシナゴーグの焼き討ちを呼びかけた[10]。 [11]ルターはユダヤ人の殺害を提唱していなかったにもかかわらず、彼の教えに基づき[12][13][14]、彼のレトリックがドイツにおける反ユダ ヤ主義とナチス党の発展に大きく貢献したというのが歴史家の間での一般的な見解である[15][16][17]。 |

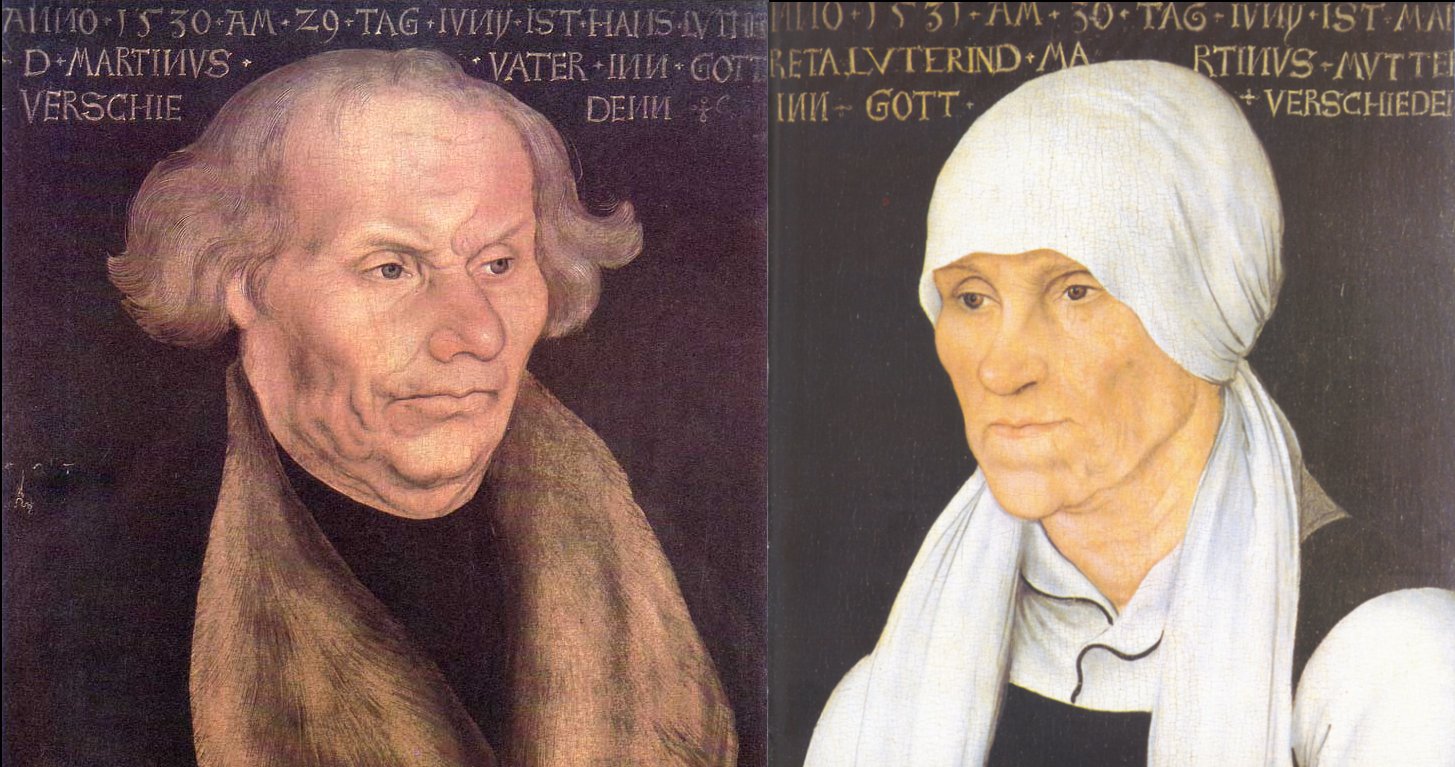

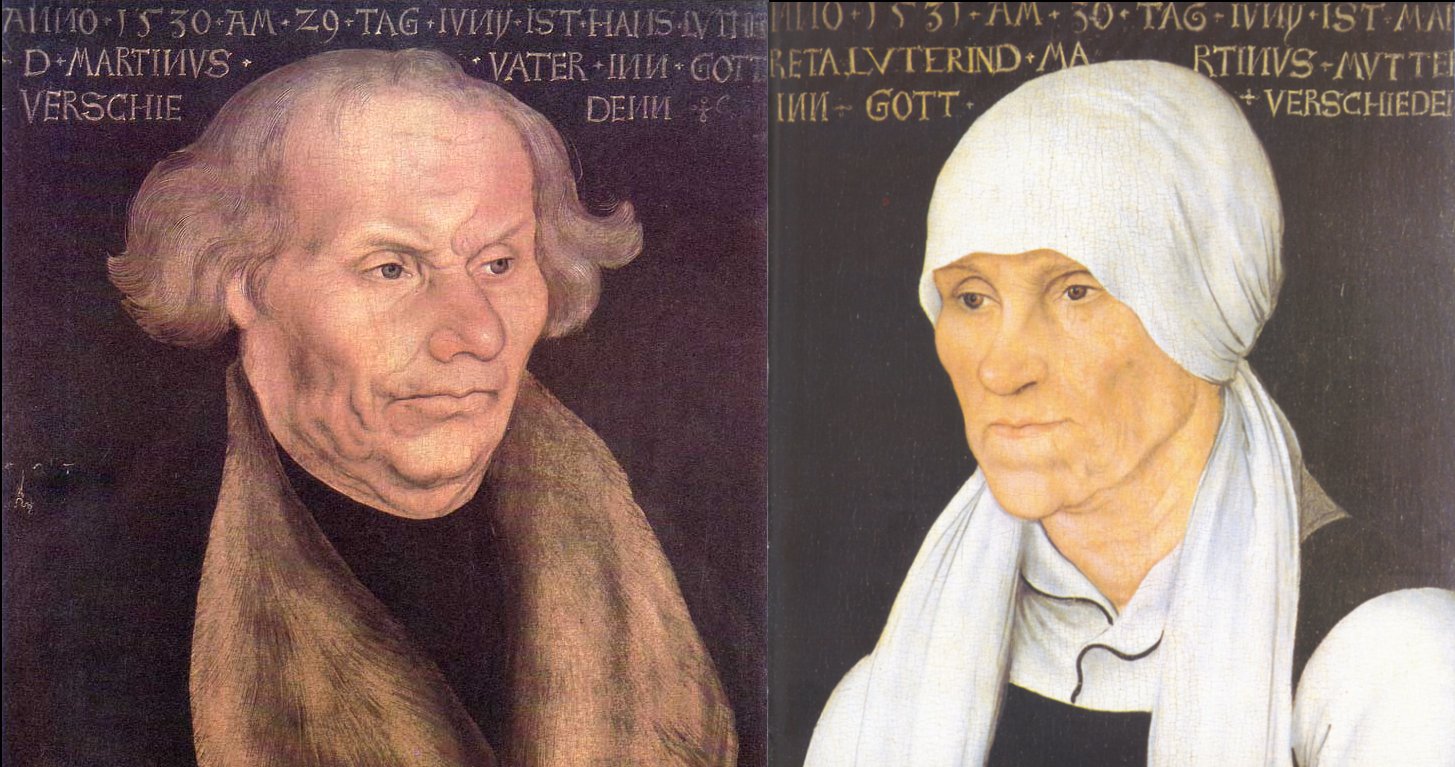

| Early life Birth and education  Portraits of Hans and Margarethe Luther by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1527  Former monks' dormitory, St Augustine's Monastery, Erfurt Martin Luther was born to Hans Luder (or Ludher, later Luther)[18] and his wife Margarethe (née Lindemann) on 10 November 1483 in Eisleben, County of Mansfeld, in the Holy Roman Empire. Luther was baptized the next morning on the feast day of St. Martin of Tours. In 1484, his family moved to Mansfeld, where his father was a leaseholder of copper mines and smelters[19] and served as one of four citizen representatives on the local council; in 1492 he was elected as a town councilor.[20][18] The religious scholar Martin Marty describes Luther's mother as a hard-working woman of "trading-class stock and middling means", contrary to Luther's enemies, who labeled her a whore and bath attendant.[18] He had several brothers and sisters and is known to have been close to one of them, Jacob.[21] Hans Luther was ambitious for himself and his family, and he was determined to see Martin, his eldest son, become a lawyer. He sent Martin to Latin schools in Mansfeld, then Magdeburg in 1497, where he attended a school operated by a lay group called the Brethren of the Common Life, and Eisenach in 1498.[22] The three schools focused on the so-called "trivium": grammar, rhetoric, and logic. Luther later compared his education there to purgatory and hell.[23] In 1501, at age 17, he entered the University of Erfurt, which he later described as a beerhouse and whorehouse.[24] He was made to wake at four every morning for what has been described as "a day of rote learning and often wearying spiritual exercises."[24] He received his master's degree in 1505.[25]  Luther as a friar, with tonsure  Luther's accommodation in Wittenberg In accordance with his father's wishes, he enrolled in law but dropped out almost immediately, believing that law represented uncertainty.[25] Luther sought assurances about life and was drawn to theology and philosophy, expressing particular interest in Aristotle, William of Ockham, and Gabriel Biel.[25] He was deeply influenced by two tutors, Bartholomaeus Arnoldi von Usingen and Jodocus Trutfetter, who taught him to be suspicious of even the greatest thinkers[25] and to test everything himself by experience.[26] Philosophy proved to be unsatisfying, offering assurance about the use of reason but none about loving God, which to Luther was more important. Reason could not lead men to God, he felt, and he thereafter developed a love-hate relationship with Aristotle over the latter's emphasis on reason.[26] For Luther, reason could be used to question men and institutions, but not God. Human beings could learn about God only through divine revelation, he believed, and Scripture therefore became increasingly important to him.[26] On 2 July 1505, while Luther was returning to university on horseback after a trip home, a lightning bolt struck near him during a thunderstorm. Later telling his father he was terrified of death and divine judgment, he cried out, "Help! Saint Anna, I will become a monk!"[27][28] He came to view his cry for help as a vow he could never break. He left university, sold his books, and entered St. Augustine's Monastery in Erfurt on 17 July 1505.[29] One friend blamed the decision on Luther's sadness over the deaths of two friends. Luther himself seemed saddened by the move. Those who attended a farewell supper walked him to the door of the Black Cloister. "This day you see me, and then, not ever again," he said.[26] His father was furious over what he saw as a waste of Luther's education.[30] Monastic life  A posthumous portrait of Luther as an Augustinian friar Luther dedicated himself to the Augustinian order, devoting himself to fasting, long hours in prayer, pilgrimage, and frequent confession.[31] Luther described this period of his life as one of deep spiritual despair. He said, "I lost touch with Christ the Savior and Comforter, and made of him the jailer and hangman of my poor soul."[32] Johann von Staupitz, his superior, concluded that Luther needed more work to distract him from excessive introspection and ordered him to pursue an academic career. On 3 April 1507, Jerome Schultz (Latin: Hieronymus Scultetus), the Bishop of Brandenburg, ordained Luther in Erfurt Cathedral. In 1508, he began teaching theology at the University of Wittenberg.[33] He received a bachelor's degree in biblical studies on 9 March 1508 and another bachelor's degree in the Sentences by Peter Lombard in 1509.[34] On 19 October 1512, he was awarded his Doctor of Theology and, on 21 October 1512, was received into the senate of the theological faculty of the University of Wittenberg,[35] having succeeded von Staupitz as chair of theology.[36] He spent the rest of his career in this position at the University of Wittenberg. He was made provincial vicar of Saxony and Thuringia by his religious order in 1515. This meant he was to visit and oversee each of eleven monasteries in his province.[37] |

生い立ち 出生と教育  ルーカス・クラナッハ(父)によるハンスとマルガレーテ・ルターの肖像画、1527年  エアフルト、聖アウグスティヌス修道院、旧修道士寮 マルティン・ルターは、1483年11月10日、神聖ローマ帝国のマンスフェルト県アイスレーベンで、ハンス・ルーダー(後のルター)とその妻マルガレー テ(旧姓リンデマン)の間に生まれた[18]。ルターは翌朝、トゥールの聖マルティヌスの祝日に洗礼を受けた。1484年、一家はマンスフェルトに移り住 み、父親は銅山と製錬所の賃貸人であり[19]、地方議会の4人の市民代表の一人を務めた。 ルターには数人の兄弟姉妹がおり、そのうちの一人であるヤコブと親しかったことが知られている[21]。 ハンス・ルターは自分自身と家族のために野心的で、長男のマルティンが弁護士になることを望んでいた。彼はマルティンをマンスフェルトのラテン語学校、 1497年にはマグデブルク、1498年にはアイゼナハのラテン語学校に通わせた。ルターは後にそこでの教育を煉獄と地獄に例えた[23]。 1501年、17歳の時にエアフルト大学に入学したルターは、後にビール小屋と娼館と形容される[24]。  修道士となったルター。  ヴィッテンベルクのルターの宿舎 父親の意向により、法学部に入学したが、法学は不確実なものであると考え、ほとんどすぐに中退した[25]。ルターは、人生についての保証を求め、神学と 哲学に惹かれ、特にアリストテレス、オッカムのウィリアム、ガブリエル・ビールに興味を示した[25]。 哲学は、理性の使用については保証を与えるが、ルターにとってより重要であった神を愛することについては保証を与えない、満足のいくものではないことが判 明した。理性は人を神へと導くことはできないと感じたルターは、その後、理性を強調するアリストテレスとの間に愛憎関係を築いた[26]。人間は神の啓示 によってのみ神について学ぶことができると彼は信じ、それゆえ聖書は彼にとってますます重要なものとなった[26]。 1505年7月2日、ルターが帰郷後、馬に乗って大学に戻る途中、雷雨の中、稲妻が彼の近くに落ちた。その後、父に死と神の裁きが怖いと告げたルターは、 「助けてください!聖アンナ、私は修道士になります!」[27][28]と叫んだ。彼は大学を去り、本を売り払い、1505年7月17日にエアフルトの聖 アウグスティヌス修道院に入った[29]。ある友人は、この決断を2人の友人の死に対するルターの悲しみのせいだと非難した。ルター自身も、この引っ越し を悲しんでいたようだ。別れの晩餐会に出席した人々は、ルターを黒い回廊の入り口まで見送った。「ルターの父親は、ルターの教育が無駄になったと激怒した [30]。 修道生活  アウグスチノ会修道士としてのルターの遺影 ルターはアウグスティヌス修道会に身を捧げ、断食、長時間の祈り、巡礼、頻繁な告解に専念した[31]。救い主であり慰め主であるキリストとの接触を失 い、キリストを私の哀れな魂の看守であり絞首刑執行人とした」[32]。 彼の上司であったヨハン・フォン・シュタウピッツは、ルターには過度の内省から気を紛らわすためにもっと仕事が必要であると結論づけ、学問の道に進むよう 命じた。1507年4月3日、ブランデンブルク司教ジェローム・シュルツ(ラテン語:Hieronymus Scultetus)は、エアフルト大聖堂でルターを聖職に就かせた。1508年、ヴィッテンベルク大学で神学を教え始める[33]。1508年3月9 日、聖書学で学士号を、1509年にはペーテル・ロンバールの文章で学士号を取得。 [34] 1512年10月19日、神学博士号を授与され、10月21日にはフォン・シュタウピッツの後任としてヴィッテンベルク大学の神学部の元老院に迎えられた [35]。 1515年、修道会からザクセンとチューリンゲンの地方牧師の任に就く。これは彼が州内の11の修道院を訪問し、それぞれを監督することを意味した [37]。 |

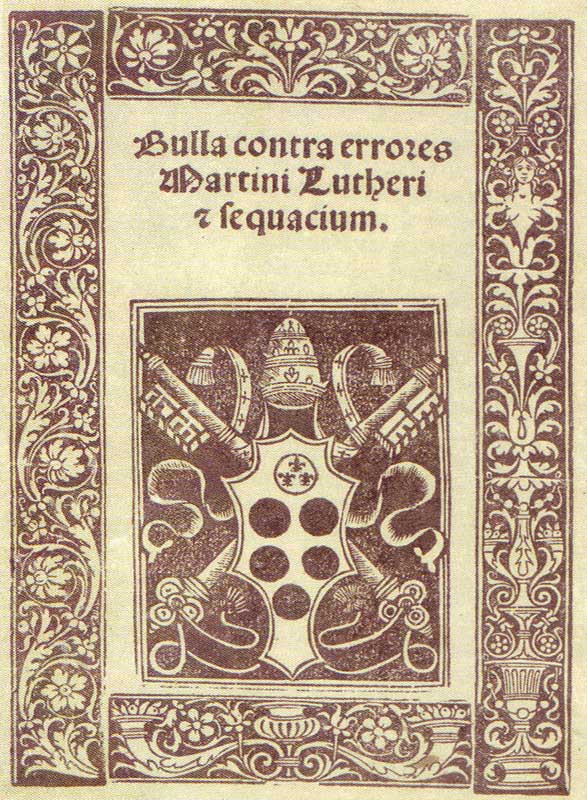

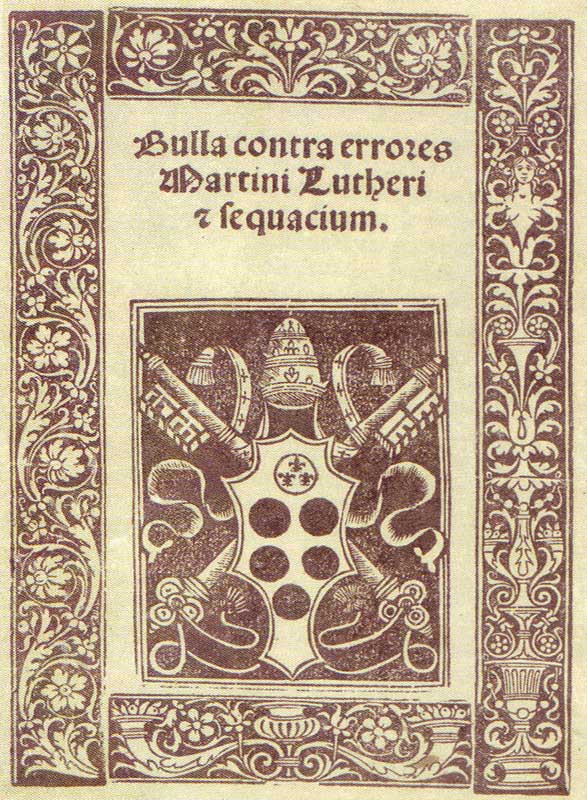

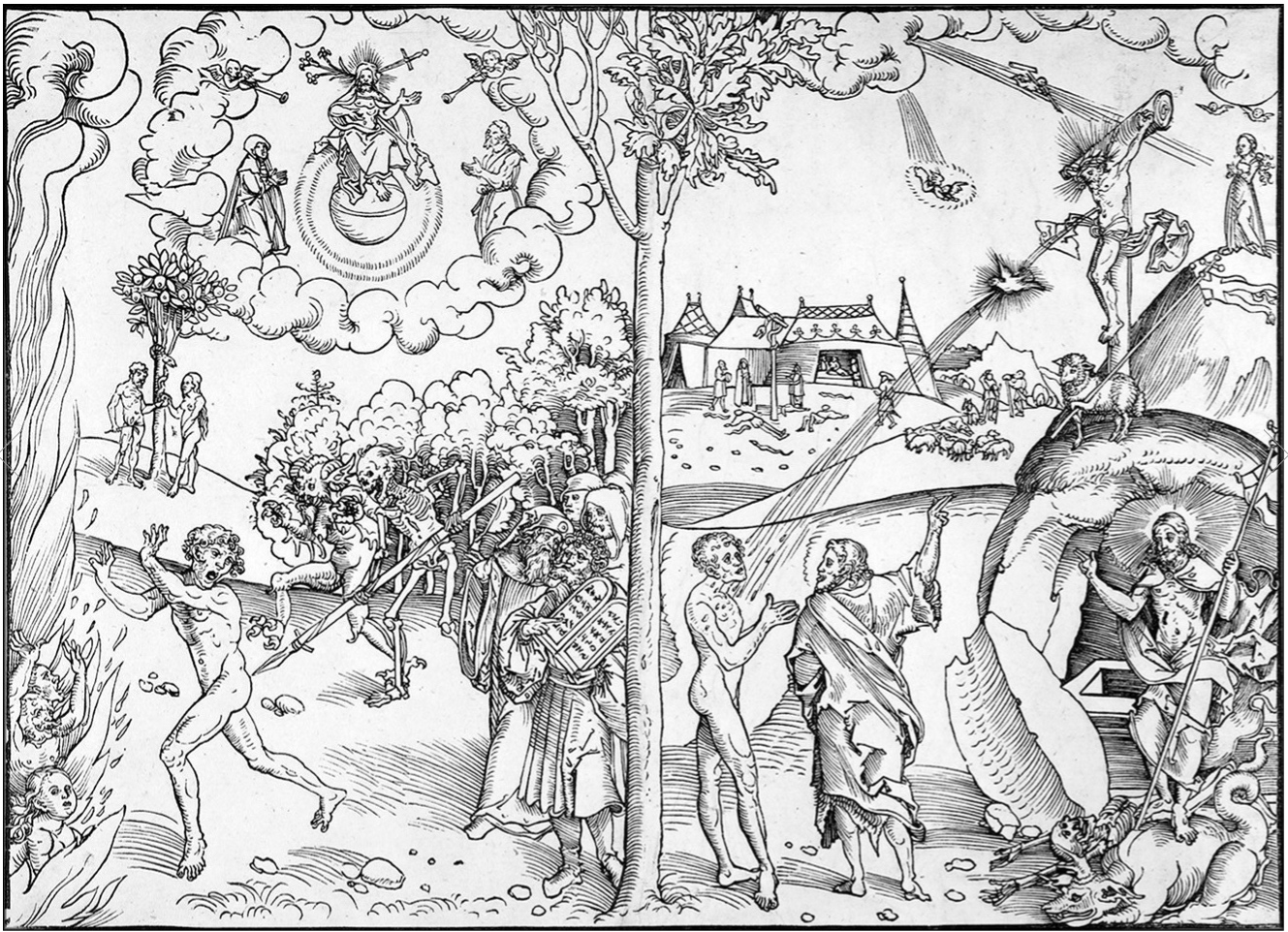

| Start of the Reformation Further information: History of Protestantism and History of Lutheranism  The Catholic sale of indulgences shown in A Question to a Mintmaker, woodcut by Jörg Breu the Elder of Augsburg, c. 1530 In 1516, Johann Tetzel, a Dominican friar, was sent to Germany by the Roman Catholic Church to sell indulgences to raise money in order to rebuild St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.[38] Tetzel's experiences as a preacher of indulgences, especially between 1503 and 1510, led to his appointment as general commissioner by Albrecht von Brandenburg, Archbishop of Mainz, who, already deeply in debt to pay for a large accumulation of benefices, had to contribute the considerable sum of ten thousand ducats[39] toward the rebuilding of the basilica. Albrecht obtained permission from Pope Leo X to conduct the sale of a special plenary indulgence (i.e., remission of the temporal punishment of sin), half of the proceeds of which Albrecht was to claim to pay the fees of his benefices. On 31 October 1517, Luther wrote to his bishop, Albrecht von Brandenburg, protesting against the sale of indulgences. He enclosed in his letter a copy of his "Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences",[a] which came to be known as the Ninety-five Theses. Hans Hillerbrand writes that Luther had no intention of confronting the church but saw his disputation as a scholarly objection to church practices, and the tone of the writing is accordingly "searching, rather than doctrinaire."[41] Hillerbrand writes that there is nevertheless an undercurrent of challenge in several of the theses, particularly in Thesis 86, which asks: "Why does the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with the money of poor believers rather than with his own money?"[41] Luther objected to a saying attributed to Tetzel that "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory (also attested as 'into heaven') springs."[42] He insisted that, since forgiveness was God's alone to grant, those who claimed that indulgences absolved buyers from all punishments and granted them salvation were in error. Christians, he said, must not slacken in following Christ on account of such false assurances.  Luther's theses are engraved into the door of All Saints' Church, Wittenberg. The Latin inscription above informs the reader that the original door was destroyed by a fire, and that in 1857, King Frederick William IV of Prussia ordered a replacement be made. According to one account, Luther nailed his Ninety-five Theses to the door of All Saints' Church in Wittenberg on 31 October 1517. Scholars Walter Krämer, Götz Trenkler, Gerhard Ritter, and Gerhard Prause contend that the story of the posting on the door, although it has become one of the pillars of history, has little foundation in truth.[43][44][45][46] The story is based on comments made by Luther's collaborator Philip Melanchthon, though it is thought that he was not in Wittenberg at the time.[47] According to Roland Bainton, on the other hand, it is true.[48] The Latin Theses were printed in several locations in Germany in 1517. In January 1518 friends of Luther translated the Ninety-five Theses from Latin into German.[49] Within two weeks, copies of the theses had spread throughout Germany. Luther's writings circulated widely, reaching France, England, and Italy as early as 1519. Students thronged to Wittenberg to hear Luther speak. He published a short commentary on Galatians and his Work on the Psalms. This early part of Luther's career was one of his most creative and productive.[50] Three of his best-known works were published in 1520: To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, and On the Freedom of a Christian. Justification by faith alone Main article: Sola fide  Luther at Erfurt, which depicts Martin Luther discovering the doctrine of sola fide (by faith alone). Painting by Joseph Noel Paton, 1861. From 1510 to 1520, Luther lectured on the Psalms, and on the books of Hebrews, Romans, and Galatians. As he studied these portions of the Bible, he came to view the use of terms such as penance and righteousness by the Catholic Church in new ways. He became convinced that the church was corrupt in its ways and had lost sight of what he saw as several of the central truths of Christianity. The most important for Luther was the doctrine of justification—God's act of declaring a sinner righteous—by faith alone through God's grace. He began to teach that salvation or redemption is a gift of God's grace, attainable only through faith in Jesus as the Messiah.[51] "This one and firm rock, which we call the doctrine of justification", he writes, "is the chief article of the whole Christian doctrine, which comprehends the understanding of all godliness."[52] Luther came to understand justification as entirely the work of God. This teaching by Luther was clearly expressed in his 1525 publication On the Bondage of the Will, which was written in response to On Free Will by Desiderius Erasmus (1524). Luther based his position on predestination on St. Paul's epistle to the Ephesians 2:8–10. Against the teaching of his day that the righteous acts of believers are performed in cooperation with God, Luther wrote that Christians receive such righteousness entirely from outside themselves; that righteousness not only comes from Christ but actually is the righteousness of Christ, imputed to Christians (rather than infused into them) through faith.[53] "That is why faith alone makes someone just and fulfills the law," he writes. "Faith is that which brings the Holy Spirit through the merits of Christ."[54] Faith, for Luther, was a gift from God; the experience of being justified by faith was "as though I had been born again." His entry into Paradise, no less, was a discovery about "the righteousness of God"—a discovery that "the just person" of whom the Bible speaks (as in Romans 1:17) lives by faith.[55] He explains his concept of "justification" in the Smalcald Articles: The first and chief article is this: Jesus Christ, our God and Lord, died for our sins and was raised again for our justification (Romans 3:24–25). He alone is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world (John 1:29), and God has laid on Him the iniquity of us all (Isaiah 53:6). All have sinned and are justified freely, without their own works and merits, by His grace, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, in His blood (Romans 3:23–25). This is necessary to believe. This cannot be otherwise acquired or grasped by any work, law, or merit. Therefore, it is clear and certain that this faith alone justifies us ... Nothing of this article can be yielded or surrendered, even though heaven and earth and everything else falls (Mark 13:31).[56] Breach with the papacy  Pope Leo X's Bull against the errors of Martin Luther, 1521, commonly known as Exsurge Domine Archbishop Albrecht did not reply to Luther's letter containing the Ninety-five Theses. He had the theses checked for heresy and in December 1517 forwarded them to Rome.[57] He needed the revenue from the indulgences to pay off a papal dispensation for his tenure of more than one bishopric. As Luther later notes, "the pope had a finger in the pie as well, because one half was to go to the building of St. Peter's Church in Rome".[58] Pope Leo X was used to reformers and heretics,[59] and he responded slowly, "with great care as is proper."[60] Over the next three years he deployed a series of papal theologians and envoys against Luther, which served only to harden the reformer's anti-papal theology. First, the Dominican theologian Sylvester Mazzolini drafted a heresy case against Luther, whom Leo then summoned to Rome. The Elector Frederick persuaded the pope to have Luther examined at Augsburg, where the Imperial Diet was held.[61] Over a three-day period in October 1518, Luther defended himself under questioning by papal legate Cardinal Cajetan. The pope's right to issue indulgences was at the centre of the dispute between the two men.[62][63] The hearings degenerated into a shouting match. More than writing his theses, Luther's confrontation with the church cast him as an enemy of the pope: "His Holiness abuses Scripture", retorted Luther. "I deny that he is above Scripture".[64][65] Cajetan's original instructions had been to arrest Luther if he failed to recant, but the legate desisted from doing so.[66] With help from the Carmelite friar Christoph Langenmantel, Luther slipped out of the city at night, unbeknownst to Cajetan.[67]  The meeting of Martin Luther (right) and Cardinal Cajetan (left, holding the book) In January 1519, at Altenburg in Saxony, the papal nuncio Karl von Miltitz adopted a more conciliatory approach. Luther made certain concessions to the Saxon, who was a relative of the Elector and promised to remain silent if his opponents did.[68] The theologian Johann Eck, however, was determined to expose Luther's doctrine in a public forum. In June and July 1519, he staged a disputation with Luther's colleague Andreas Karlstadt at Leipzig and invited Luther to speak.[69] Luther's boldest assertion in the debate was that Matthew 16:18 does not confer on popes the exclusive right to interpret scripture, and that therefore neither popes nor church councils were infallible.[70] For this, Eck branded Luther a new Jan Hus, referring to the Czech reformer and heretic burned at the stake in 1415. From that moment, he devoted himself to Luther's defeat.[71] Excommunication On 15 June 1520, the Pope warned Luther with the papal bull (edict) Exsurge Domine that he risked excommunication unless he recanted 41 sentences drawn from his writings, including the Ninety-five Theses, within 60 days. That autumn, Eck proclaimed the bull in Meissen and other towns. Von Miltitz attempted to broker a solution, but Luther, who had sent the pope a copy of On the Freedom of a Christian in October, publicly set fire to the bull and decretals in Wittenberg on 10 December 1520,[72] an act he defended in Why the Pope and his Recent Book are Burned and Assertions Concerning All Articles. Luther was excommunicated by Pope Leo X on 3 January 1521, in the bull Decet Romanum Pontificem.[73] And although the Lutheran World Federation, Methodists and the Catholic Church's Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity agreed (in 1999 and 2006, respectively) on a "common understanding of justification by God's grace through faith in Christ," the Catholic Church has never lifted the 1521 excommunication.[74][75][76] |

宗教改革の始まり さらなる情報 プロテスタンティズムの歴史とルター派の歴史  1530年頃、アウクスブルクの長老イェルク・ブリューの木版画『造幣職人への質問』に描かれたカトリックの免罪符販売。 1516年、ドミニコ会の修道士ヨハン・テッツェルは、ローマのサン・ピエトロ大聖堂を再建するための資金集めのために、免罪符を売るためにローマ・カト リック教会からドイツに派遣された。 [38]テッツェルは、特に1503年から1510年にかけて免罪符の伝道師として活躍した経験から、マインツの大司教アルブレヒト・フォン・ブランデン ブルクによって総監に任命された。アルブレヒトは、すでに多額の恩典の支払いのために多額の負債を抱えており、バシリカの再建のために1万ドゥカート [39]という大金を拠出しなければならなかった。アルブレヒトは、教皇レオ10世から、特別な免罪符(罪の仮罰の免除)の販売を行う許可を得た。 1517年10月31日、ルターは司教であるアルブレヒト・フォン・ブランデンブルクに、免罪符の販売に抗議する手紙を書いた。その手紙には、後に 「95ヶ条の論題」として知られるようになる「免罪符の効力と効力に関する論争」[a]の写しが同封されていた。ハンス・ヒラーブランドは、ルターは教会 と対立するつもりはなく、自分の論争を教会の慣行に対する学問的な異議申し立てとみなしていたと書いており、それゆえ、その文章の論調は「教義的というよ りは、むしろ探求的」であったと述べている[41]: 「今日、その富は最も裕福なクラッススの富よりも大きい教皇が、なぜサンピエトロ大聖堂を自分の金ではなく、貧しい信者の金で建てるのか」[41]。 ルターは、「棺桶の中の硬貨が鳴るとすぐに、魂は煉獄から(「天国へ」とも証言されている)湧き出る」というテッツェルの故事に異議を唱えた[42]。キ リスト者は、そのような偽りの保証のためにキリストに従うことを緩めてはならないと彼は言った。  ルターの論題は、ヴィッテンベルクの全聖徒教会の扉に刻まれている。上のラテン語の碑文によれば、オリジナルの扉は火事で焼失し、1857年にプロイセン 王フリードリヒ・ウィリアム4世が代替品の製作を命じたという。 一説によれば、ルターは1517年10月31日、ヴィッテンベルクの諸聖徒教会の扉に「95ヶ条の論題」を釘で打ち付けたという。学者であるヴァルター・ クレーマー、ゲッツ・トレンクラー、ゲルハルト・リッター、ゲルハルト・プラウゼは、扉に貼り付けられたという話は、歴史の柱の一つとなっているものの、 真実の根拠はほとんどないと主張している[43][44][45][46]。 この話は、ルターの協力者であったフィリップ・メランヒトンのコメントに基づいているが、彼は当時ヴィッテンベルクにいなかったと考えられている [47]。 ラテン語のテーゼは1517年にドイツの数カ所で印刷された。1518年1月、ルターの友人たちが「九十五箇条の論題」をラテン語からドイツ語に翻訳した [49]。2週間も経たないうちに、「九十五箇条の論題」のコピーはドイツ全土に広まった。ルターの著作は広く流布し、1519年には早くもフランス、イ ギリス、イタリアに届いた。ルターの話を聞くために、学生たちはヴィッテンベルクに押し寄せた。ルターは、ガラテヤ書の短い注解書と詩篇に関する著作を出 版した。ルターのキャリアの初期は、最も創造的で生産的な時期であった[50]: ドイツ国民のキリスト教徒貴族へ』、『教会のバビロン捕囚について』、『キリスト者の自由について』である。 信仰のみによる義認 主な記事 ソラ・フィデ  ソラ・フィデ(信仰のみによる義認)の教義を発見したマルティン・ルターを描いた『エアフルトのルター』。ジョセフ・ノエル・パトン作、1861年。 1510年から1520年にかけて、ルターは詩篇、ヘブル人への手紙、ローマ人への手紙、ガラテヤ人への手紙について講義を行った。聖書のこれらの部分を 学ぶうちに、彼はカトリック教会が懺悔や義といった用語を用いていることを新たな視点で見るようになった。ルターは、教会がそのやり方において堕落してお り、キリスト教の中心的な真理のいくつかを見失っていると確信した。ルターにとって最も重要だったのは、義認の教義-神の恵みによって信仰のみによって罪 人を義とする神の行為-であった。ルターは、救済や贖いは神の恵みの賜物であり、メシアであるイエスを信じる信仰によってのみ到達可能であると教え始めた [51]。「義認の教理と呼ぶこの一つの堅固な岩は、キリスト教の教理全体の主要な記事であり、すべての敬虔の理解を包括するものである」と彼は書いてい る[52]。 ルターは義認を完全に神の業として理解するようになった。ルターのこの教えは、デジデリウス・エラスムスの『自由意志について』(1524年)に対抗して 書かれた『意志の束縛について』(1525年)に明確に表現されている。ルターは、聖パウロのエフェソの信徒への手紙2:8-10に基づく定命についての 立場をとった。ルターは、信仰者の正しい行いは神と協力して行われるという当時の教えに対して、クリスチャンはそのような義を完全に自分自身の外から受け ると書き、その義はキリストから来るだけでなく、実際には信仰によってクリスチャンに(注入されるのではなく)付与されるキリストの義であると書いた [53]。 「だから信仰だけが人を義とし、律法を成就させるのです。「信仰はキリストの功績によって聖霊をもたらすものである」[54]。ルターにとって信仰は神か らの賜物であり、信仰によって義とされる経験は「まるで生まれ変わったかのよう」であった。彼の楽園への入城は、「神の義」についての発見であり、聖書が (ローマ1:17のように)語る「正しい人」が信仰によって生きているという発見であった: 第一条は次のとおりである: 私たちの神であり主であるイエス・キリストは、私たちの罪のために死なれ、私たちの義認のためによみがえられました(ローマ3:24-25)。彼だけが世 の罪を取り除く神の小羊であり(ヨハネ1:29)、神は私たちすべての咎を彼に負わせた(イザヤ53:6)。すべての人は罪を犯したが、キリスト・イエス の血による贖いによって、主の恵みによって、自分の行いや功績なしに、自由に義と認められる(ローマ3:23-25)。これは信じるために必要なことであ る。そうでなければ、いかなる行いや律法や功績によっても、これを獲得したり、把握したりすることはできない。したがって、この信仰だけが私たちを義とす ることは明らかであり、確かなことなのである。たとえ天と地と他のすべてのものが崩れ落ちようとも(マルコ13:31)、この信条は何一つ譲ることも明け 渡すこともできないのである[56]。 ローマ教皇庁との決裂  1521年、教皇レオ10世がマルティン・ルターの誤りに反対した勅書。 アルブレヒト大司教は、九十五ヶ条の論題を含むルターの手紙に返事を出さなかった。1517年12月、アルブレヒト大司教は、異端であるかどうかをチェッ クさせ、それをローマに送付した[57]。彼は、免罪符からの収入を、複数の司教座に在任するための教皇の免除の返済に充てる必要があった。後にルターが 述べているように、「ローマ教皇もパイに指を突っ込んでいた。 教皇レオ10世は改革者や異端者に慣れており[59]、「適切な注意を払いながら」ゆっくりと対応した[60]。その後3年間、教皇はルターに対して一連 の教皇派の神学者や使節を配置したが、それは改革者の反教皇神学を硬化させるだけであった。まず、ドミニコ会の神学者シルヴェスター・マッツォリーニがル ターに対する異端訴訟を起草し、レオはルターをローマに召喚した。選帝侯フリードリヒは教皇を説得し、帝国議会が開かれていたアウクスブルクでルターを尋 問させた[61]。 1518年10月の3日間、教皇公使カジェタン枢機卿の尋問を受け、ルターは弁明した。教皇の免罪符発行権が二人の争いの中心であった[62][63]。 ルターは、論題を書くこと以上に、教会と対立することで、教皇の敵として扱われた: 「法王は聖典を乱用している」とルターは反論した。教皇は聖典を乱用している」とルターは言い返し、「私は教皇が聖典の上にいることを否定する」[64] [65] カジェタンの当初の指示は、ルターが撤回に応じなければ逮捕するというものであったが、教皇はそれを取りやめた[66]。カルメル会の修道士クリストフ・ ランゲンマンテルの助けを借りて、ルターはカジェタンに知られることなく、夜に街を抜け出した[67]。  マルティン・ルター(右)とカジェタン枢機卿(左、本を持っている)の出会い 1519年1月、ザクセンのアルテンブルクで、ローマ教皇の枢機卿カール・フォン・ミルティッツは、より融和的なアプローチを採用した。ルターは、選帝侯 の親族であったこのザクセン人に一定の譲歩をし、反対派が黙秘するならば黙秘することを約束した[68]。しかし、神学者ヨハン・エックは、ルターの教義 を公の場で暴露することを決意した。1519年6月と7月、彼はルターの同僚アンドレアス・カールシュタットとライプツィヒで論争を行い、ルターを講演に 招いた[69]。この論争でルターが最も大胆に主張したのは、マタイによる福音書16章18節は教皇に聖典を解釈する排他的な権利を与えておらず、した がって教皇も教会公会議も無謬ではないということであった[70]。その瞬間から、彼はルターの敗北に身を捧げるようになった[71]。 破門 1520年6月15日、教皇は教皇勅令(Exsurge Domine)をもって、ルターが60日以内に「九十五箇条の論題」を含む41の文章を撤回しない限り、破門される恐れがあると警告した。その年の秋、 エックはマイセンやその他の町でこの教令を布告した。フォン・ミルティッツは解決の仲介を試みたが、10月に教皇に『キリスト者の自由について』のコピー を送っていたルターは、1520年12月10日、ヴィッテンベルクで、教皇とその最近の書物はなぜ焼かれたのか、そしてすべての記事に関する主張』の中で 弁護しているように、教皇とその最近の書物に公然と火を放った[72]。 ルターは1521年1月3日、教皇レオ10世によって、教令『Decet Romanum Pontificem』において破門された[73]。ルター派世界連盟、メソジスト派、カトリック教会の教皇庁キリスト教一致推進評議会は、「キリストへ の信仰による神の恵みによる義認の共通理解」について(それぞれ1999年と2006年に)合意したが、カトリック教会は1521年の破門を解除したこと はない[74][75][76]。 |

| Diet of Worms (1521) Main article: Diet of Worms  Luther Before the Diet of Worms by Anton von Werner (1843–1915) The enforcement of the ban on the Ninety-five Theses fell to the secular authorities. On 18 April 1521, Luther appeared as ordered before the Diet of Worms. This was a general assembly of the estates of the Holy Roman Empire that took place in Worms, a town on the Rhine. It was conducted from 28 January to 25 May 1521, with Emperor Charles V presiding. Prince Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, obtained a safe conduct for Luther to and from the meeting. Johann Eck, speaking on behalf of the empire as assistant of the Archbishop of Trier, presented Luther with copies of his writings laid out on a table and asked him if the books were his and whether he stood by their contents. Luther confirmed he was their author but requested time to think about the answer to the second question. He prayed, consulted friends, and gave his response the next day: Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted, and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. May God help me. Amen.[77] At the end of this speech, Luther raised his arm "in the traditional salute of a knight winning a bout." Michael Mullett considers this speech as a "world classic of epoch-making oratory."[78]  Luther Monument in Worms. His statue is surrounded by the figures of his lay protectors and earlier Church reformers including John Wycliffe, Jan Hus and Girolamo Savonarola. Eck informed Luther that he was acting like a heretic, saying, Martin, there is no one of the heresies which have torn the bosom of the church, which has not derived its origin from the various interpretation of the Scripture. The Bible itself is the arsenal whence each innovator has drawn his deceptive arguments. It was with Biblical texts that Pelagius and Arius maintained their doctrines. Arius, for instance, found the negation of the eternity of the Word—an eternity which you admit, in this verse of the New Testament—Joseph knew not his wife till she had brought forth her first-born son; and he said, in the same way that you say, that this passage enchained him. When the fathers of the Council of Constance condemned this proposition of Jan Hus—The church of Jesus Christ is only the community of the elect, they condemned an error; for the church, like a good mother, embraces within her arms all who bear the name of Christian, all who are called to enjoy the celestial beatitude.[79] Luther refused to recant his writings. He is sometimes also quoted as saying: "Here I stand. I can do no other". Recent scholars consider the evidence for these words to be unreliable since they were inserted before "May God help me" only in later versions of the speech and not recorded in witness accounts of the proceedings.[80] However, Mullett suggests that given his nature, "we are free to believe that Luther would tend to select the more dramatic form of words."[78] Over the next five days, private conferences were held to determine Luther's fate. The emperor presented the final draft of the Edict of Worms on 25 May 1521, declaring Luther an outlaw, banning his literature, and requiring his arrest: "We want him to be apprehended and punished as a notorious heretic."[81] It also made it a crime for anyone in Germany to give Luther food or shelter. It permitted anyone to kill Luther without legal consequence. |

ヴォルムスでの議論(1521年) 主な記事 ヴォルムス会議  アントン・フォン・ヴェルナー(1843-1915)作『ヴォルムス国会の前のルター』 九十五ヶ条の論題禁止令の執行は、世俗当局に委ねられた。1521年4月18日、ルターは命じられるままにヴォルムス国会に出頭した。この国会は、ライン 川沿いの町ヴォルムスで開催された神聖ローマ帝国の諸侯の総会であった。1521年1月28日から5月25日まで開催され、皇帝シャルル5世が議長を務め た。ザクセン選帝侯フリードリヒ3世は、ルターのために安全な往復の交通手段を確保した。 ヨハン・エックは、トリアー大司教の補佐官として帝国を代表し、テーブルに並べられたルターの著作のコピーをルターに差し出し、これらの書物が自分のもの であるか、またその内容を支持するかどうかを尋ねた。ルターは自分がその著作の著者であることを認めたが、2番目の質問の答えについて考える時間を求め た。ルターは祈り、友人に相談し、翌日答えを出した: 聖書の証言や明確な理性(教皇や公会議がしばしば誤りや矛盾を犯してきたことはよく知られているので、私は教皇や公会議だけを信頼することはない)によっ て確信しない限り、私は引用した聖書に拘束され、私の良心は神の言葉に囚われている。良心に逆らうことは安全でも正しいことでもないので、私は何も撤回で きないし、するつもりもない。神が私を助けてくださいますように。アーメン」[77]。 この演説の最後に、ルターは「試合に勝利した騎士の伝統的な敬礼で」腕を上げた。マイケル・マレットはこの演説を「エポックメイキングな演説の世界的古 典」とみなしている[78]。  ヴォルムスのルター記念碑。ルターの銅像の周りには、ルターを庇護した信徒や、ジョン・ウィクリフ、ヤン・フス、ジローラモ・サヴォナローラといった先代 の教会改革者たちの像が並んでいる。 エックは、ルターが異端のように振る舞っていることを告げ、こう言った、 マルタン、教会の懐を引き裂いた異端の中で、聖書のさまざまな解釈に由来しないものは一つもない。聖書そのものが、それぞれの革新者たちが欺瞞に満ちた議 論を引き出す武器なのだ。ペラギウスとアリウスが自分たちの教義を維持したのは、聖書のテキストを用いたからである。たとえばアリウスは、新約聖書のこの 一節に、みことばの永遠性--あなたがたも認めている永遠性--の否定を見出した。コンスタンツ公会議の教父たちが、ヤン・フスのこの命題を非難したと き、「イエス・キリストの教会は選民の共同体であるにすぎない。 ルターは自分の著作を撤回することを拒否した。ルターは自分の著作を撤回することを拒んだ: 「私はここに立っている。私はここに立っている。しかし、マレットは、彼の性格を考えれば、「ルターがより劇的な形式の言葉を選ぶ傾向があると信じるのは 自由である」と示唆している[78]。 その後5日間、ルターの運命を決めるための私的な会議が開かれた。1521年5月25日、皇帝はヴォルムス勅令の最終稿を提出し、ルターを無法者とし、そ の文献を禁止し、逮捕を要求した: 「我々は彼を逮捕し、悪名高い異端者として処罰することを望んでいる」[81] また、この勅令は、ドイツ国内の誰もがルターに食物や住居を与えることを犯罪とした。また、ドイツ国内の誰もがルターに食べ物や庇護を与えることを犯罪と した。 |

Wartburg Castle (1521) The Wartburg room where Luther translated the New Testament into German; an original first edition is kept in the case on the desk. Wartburg Castle in Eisenach Luther's disappearance during his return to Wittenberg was planned. Frederick III had him intercepted on his way home in the forest near Wittenberg by masked horsemen impersonating highway robbers. They escorted Luther to the security of the Wartburg Castle at Eisenach.[82] During his stay at Wartburg, which he referred to as "my Patmos",[83] Luther translated the New Testament from Greek into German and poured out doctrinal and polemical writings. These included a renewed attack on Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz, whom he shamed into halting the sale of indulgences in his episcopates,[84] and a Refutation of the Argument of Latomus, in which he expounded the principle of justification to Jacobus Latomus, an orthodox theologian from Louvain.[85] In this work, one of his most emphatic statements on faith, he argued that every good work designed to attract God's favor is a sin.[86] All humans are sinners by nature, he explained, and God's grace alone (which cannot be earned) can make them just. On 1 August 1521, Luther wrote to Melanchthon on the same theme: "Be a sinner, and let your sins be strong, but let your trust in Christ be stronger, and rejoice in Christ who is the victor over sin, death, and the world. We will commit sins while we are here, for this life is not a place where justice resides."[87] In the summer of 1521, Luther widened his target from individual pieties like indulgences and pilgrimages to doctrines at the heart of Church practice. In On the Abrogation of the Private Mass, he condemned as idolatry the idea that the mass is a sacrifice, asserting instead that it is a gift, to be received with thanksgiving by the whole congregation.[88] His essay On Confession, Whether the Pope has the Power to Require It rejected compulsory confession and encouraged private confession and absolution, since "every Christian is a confessor."[89] In November, Luther wrote The Judgement of Martin Luther on Monastic Vows. He assured monks and nuns that they could break their vows without sin, because vows were an illegitimate and vain attempt to win salvation.[90]  Luther disguised as "Junker Jörg", 1521 Luther made his pronouncements from Wartburg in the context of rapid developments at Wittenberg, of which he was kept fully informed. Andreas Karlstadt, supported by the ex-Augustinian Gabriel Zwilling, embarked on a radical programme of reform there in June 1521, exceeding anything envisaged by Luther. The reforms provoked disturbances, including a revolt by the Augustinian friars against their prior, the smashing of statues and images in churches, and denunciations of the magistracy. After secretly visiting Wittenberg in early December 1521, Luther wrote A Sincere Admonition by Martin Luther to All Christians to Guard Against Insurrection and Rebellion.[91] Wittenberg became even more volatile after Christmas when a band of visionary zealots, the so-called Zwickau prophets, arrived, preaching revolutionary doctrines such as the equality of man,[clarification needed] adult baptism, and Christ's imminent return.[92] When the town council asked Luther to return, he decided it was his duty to act.[93] |

ヴァルトブルク城(1521年) ルターが新約聖書をドイツ語に翻訳したヴァルトブルクの部屋。机の上のケースには初版の原本が保管されている。 アイゼナハのヴァルトブルク城 ヴィッテンベルクに戻ったルターの失踪は計画的だった。フリードリヒ3世は、ルターがヴィッテンベルク近郊の森に帰宅する途中、高速道路強盗になりすまし た覆面をした騎馬民族にルターを妨害させた。彼が「私のパトモス」と呼んだヴァルトブルクでの滞在中[83]、ルターは新約聖書をギリシア語からドイツ語 に翻訳し、教義的・極論的な著作を書き上げた。その中には、マインツのアルブレヒト大司教を再び攻撃し、彼の司教座における免罪符の販売を中止させたもの や[84]、ルーヴァンの正統派神学者ヤコブス・ラトムスに対して義認の原理を説いた『ラトムスの反論』などがある。 [85]信仰に関する彼の最も強調された声明のひとつであるこの著作の中で、彼は、神の好意を引き寄せるために計画されたあらゆる善行は罪であると主張し た[86]。1521年8月1日、ルターは同じテーマでメランヒトンに手紙を書いた: 「罪人であれ、罪は強くあれ、キリストへの信頼はより強くあれ、そして罪と死と世に勝利するキリストを喜びなさい。私たちはここにいる間にも罪を犯すで しょう、この世は正義が宿る場所ではないからです」[87]。 1521年の夏、ルターは、免罪符や巡礼のような個人的な信心から、教会の実践の中心にある教義へと対象を広げた。私的ミサの廃止について』では、ミサが 生け贄であるという考えを偶像崇拝として非難し、その代わりに、ミサは会衆全体が感謝をもって受ける賜物であると主張した[88]。11月には、ルターは 『修道誓願に関するマルティン・ルターの判決』を書いた。ルターは、修道士や修道女が誓願を破っても罪にはならないと断言し、誓願は救いを得ようとする非 合法で虚しい試みであるとした[90]。  1521年、"ユンカー・イェルク "に変装したルター ルターがヴァルトブルクから宣教した背景には、ヴィッテンベルクでの急速な進展があった。アンドレアス・カールシュタットは、元アウグスティヌス派のガブ リエル・ツヴィリングに支えられ、1521年6月、ルターの構想を上回る急進的な改革プログラムに着手した。この改革は、アウグスチノ会の修道士による修 道院長への反乱、教会の彫像や聖像の破壊、司政への非難などの騒乱を引き起こした。1521年12月初旬に密かにヴィッテンベルクを訪れたルターは、『マ ルティン・ルターによるすべてのキリスト教徒に対する反乱と反抗を防ぐための忠告』(A Sincere Admonition by Martin Luther to All Christians to Guard against Insurrection and Rebellion)を著した[91]。クリスマス後、ヴィッテンベルクはさらに不安定になり、いわゆるツヴィッカウの予言者たちと呼ばれる幻視狂の一団 が到着し、人間の平等、[要出典]成人の洗礼、キリストの復活といった革命的な教義を説いた[92]。 |

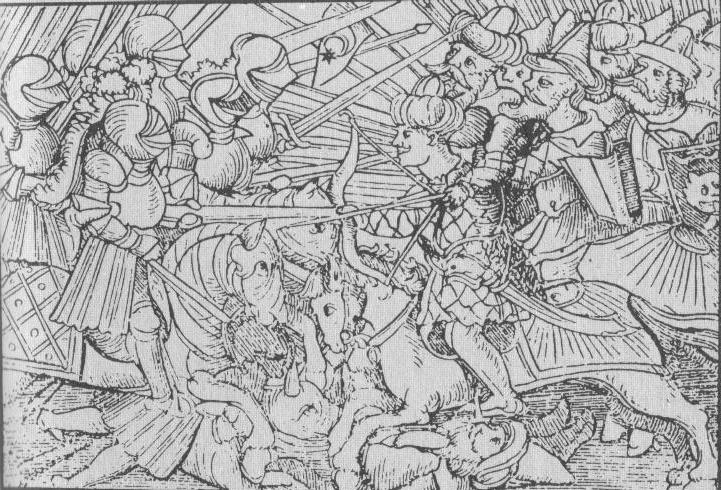

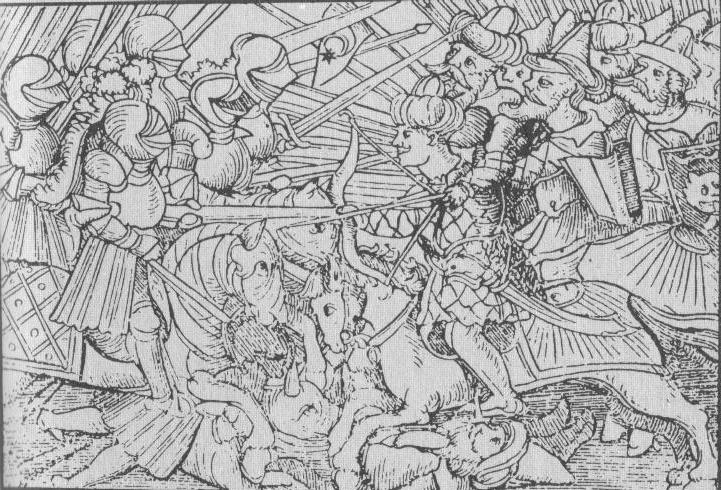

| Return to Wittenberg and

Peasants' War See also: Radical Reformation and German Peasants' War Luther secretly returned to Wittenberg on 6 March 1522. He wrote to the Elector: "During my absence, Satan has entered my sheepfold, and committed ravages which I cannot repair by writing, but only by my personal presence and living word."[94] For eight days in Lent, beginning on Invocavit Sunday, 9 March, Luther preached eight sermons, which became known as the "Invocavit Sermons". In these sermons, he hammered home the primacy of core Christian values such as love, patience, charity, and freedom, and reminded the citizens to trust God's word rather than violence to bring about necessary change.[95] Do you know what the Devil thinks when he sees men use violence to propagate the gospel? He sits with folded arms behind the fire of hell and says with malignant looks and frightful grin: "Ah, how wise these madmen are to play my game! Let them go on; I shall reap the benefit. I delight in it." But when he sees the Word running and contending alone on the battle-field, then he shudders and shakes for fear.[96] The effect of Luther's intervention was immediate. After the sixth sermon, the Wittenberg jurist Jerome Schurf wrote to the elector: "Oh, what joy has Dr. Martin's return spread among us! His words, through divine mercy, are bringing back every day misguided people into the way of the truth."[96] Luther next set about reversing or modifying the new church practices. By working alongside the authorities to restore public order, he signaled his reinvention as a conservative force within the Reformation.[97] After banishing the Zwickau prophets, he faced a battle against both the established Church and the radical reformers who threatened the new order by fomenting social unrest and violence.[98]  The Twelve Articles, 1525 Despite his victory in Wittenberg, Luther was unable to stifle radicalism further afield. Preachers such as Thomas Müntzer and Zwickau prophet Nicholas Storch found support amongst poorer townspeople and peasants between 1521 and 1525. There had been revolts by the peasantry on smaller scales since the 15th century.[99] Luther's pamphlets against the Church and the hierarchy, often worded with "liberal" phraseology, led many peasants to believe he would support an attack on the upper classes in general.[100] Revolts broke out in Franconia, Swabia, and Thuringia in 1524, even drawing support from disaffected nobles, many of whom were in debt. Gaining momentum under the leadership of radicals such as Müntzer in Thuringia, and Hipler and Lotzer in the south-west, the revolts turned into war.[101] Luther sympathised with some of the peasants' grievances, as he showed in his response to the Twelve Articles in May 1525, but he reminded the aggrieved to obey the temporal authorities.[102] During a tour of Thuringia, he became enraged at the widespread burning of convents, monasteries, bishops' palaces, and libraries. In Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants, written on his return to Wittenberg, he gave his interpretation of the Gospel teaching on wealth, condemned the violence as the devil's work, and called for the nobles to put down the rebels like mad dogs: Therefore let everyone who can, smite, slay, and stab, secretly or openly, remembering that nothing can be more poisonous, hurtful, or devilish than a rebel ... For baptism does not make men free in body and property, but in soul; and the gospel does not make goods common, except in the case of those who, of their own free will, do what the apostles and disciples did in Acts 4 [:32–37]. They did not demand, as do our insane peasants in their raging, that the goods of others—of Pilate and Herod—should be common, but only their own goods. Our peasants, however, want to make the goods of other men common, and keep their own for themselves. Fine Christians they are! I think there is not a devil left in hell; they have all gone into the peasants. Their raving has gone beyond all measure.[103] Luther justified his opposition to the rebels on three grounds. First, in choosing violence over lawful submission to the secular government, they were ignoring Christ's counsel to "Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's"; St. Paul had written in his epistle to the Romans 13:1–7 that all authorities are appointed by God and therefore should not be resisted. This reference from the Bible forms the foundation for the doctrine known as the divine right of kings, or, in the German case, the divine right of the princes. Second, the violent actions of rebelling, robbing, and plundering placed the peasants "outside the law of God and Empire", so they deserved "death in body and soul, if only as highwaymen and murderers." Lastly, Luther charged the rebels with blasphemy for calling themselves "Christian brethren" and committing their sinful acts under the banner of the Gospel.[104] Only later in life did he develop the Beerwolf concept permitting some cases of resistance against the government.[105] Without Luther's backing for the uprising, many rebels laid down their weapons; others felt betrayed. Their defeat by the Swabian League at the Battle of Frankenhausen on 15 May 1525, followed by Müntzer's execution, brought the revolutionary stage of the Reformation to a close.[106] Thereafter, radicalism found a refuge in the Anabaptist movement and other religious movements, while Luther's Reformation flourished under the wing of the secular powers.[107] In 1526 Luther wrote: "I, Martin Luther, have during the rebellion slain all the peasants, for it was I who ordered them to be struck dead."[108] |

ヴィッテンベルクへの帰還と農民戦争 こちらもご覧ください: 急進宗教改革とドイツ農民戦争 1522年3月6日、ルターは密かにヴィッテンベルクに戻った。ルターは選帝侯に手紙を書いた: 「私が不在の間に、サタンは私の羊小屋に入り込み、私が文字で書くことによっては修復できないような荒らしを行いましたが、私の個人的な存在と生きた言葉 によってのみ修復することができます」[94] 3月9日のインヴォカヴィトの日曜日に始まる四旬節の8日間、ルターは「インヴォカヴィト説教」として知られるようになった8つの説教を行った。これらの 説教の中で彼は、愛、忍耐、慈愛、自由といったキリスト教の核となる価値観の優位性を強調し、必要な変化をもたらすためには暴力ではなく神の言葉を信頼す るよう市民に呼びかけた[95]。 人が福音を広めるために暴力を用いるのを見たとき、悪魔が何を考えるかわかるだろうか。悪魔は地獄の火の後ろに腕組みをして座り、悪意に満ちた表情と恐ろ しい笑みを浮かべて言う: 「ああ、この狂人たちは、私のゲームに興じるとはなんと賢いことか!彼らに続けさせればいい。私はそれを楽しむ。しかし、みことばが戦場を独りで走り、 戦っているのを見ると、恐怖のために身震いするのである[96]。 ルターの介入の効果はすぐに現れた。6回目の説教の後、ヴィッテンベルクの法学者ジェローム・シュルフは選帝侯に手紙を書いた: 「ああ、マルチン先生の帰還は、私たちの間にどんな喜びを広げたことでしょう!彼の言葉は、神の慈悲によって、日々、誤った人々を真理の道へと連れ戻して いる」[96]。 ルターは次に、新しい教会の慣習を覆したり、修正したりすることに着手した。ツヴィッカウの預言者たちを追放した後、ルターは、既成の教会と、社会不安と 暴力を煽ることによって新しい秩序を脅かす急進的な改革派の両方との戦いに直面した[98]。  十二箇条、1525年 ヴィッテンベルクでの勝利にもかかわらず、ルターはさらなる急進主義を抑えることはできなかった。トーマス・ミュンツァーやツヴィッカウの預言者ニコラ ス・シュトルヒのような説教者たちは、1521年から1525年にかけて、より貧しい町人や農民の間に支持を見出した。ルターは、教会やヒエラルキーに反 対するパンフレットをしばしば「自由主義的」な表現で発表したため、多くの農民は、ルターが上流階級全般への攻撃を支持していると考えるようになった [100]。1524年、フランケン、シュヴァーベン、チューリンゲンで反乱が勃発し、不満を抱く貴族たちからも支持を得たが、その多くは借金を抱えてい た。テューリンゲンではミュンツァー、南西部ではヒプラーやロッツァーといった急進派の指導の下で勢いを増し、反乱は戦争へと発展した[101]。 ルターは、1525年5月の「十二箇条」への回答で示したように、農民の不満のいくつかに共感していたが、不満を抱えた人々には、現政権に従うよう念を押 した[102]。テューリンゲン地方を視察した際、修道院、修道院、司教館、図書館が広範囲にわたって焼かれたことに激怒した。ヴィッテンベルクに戻った ときに書かれた『農民の殺戮と盗賊の大群に抗して』では、富に関する福音の教えの解釈を述べ、暴力を悪魔の所業と非難し、貴族たちに狂犬のように反乱軍を 鎮圧するよう呼びかけた: それゆえ、できる者は皆、密かに、あるいは公然と、打ち、殺し、刺し、反逆者ほど毒になるもの、傷つけるもの、悪魔的なものはないことを肝に銘じ よ......。洗礼は,肉体と財産において人を自由にするのではなく,魂において人を自由にするのであり,福音は,使徒言行録4章[:32-37]で使 徒と弟子たちがしたように,自分の自由意志で行う人を除いては,財貨を一般的なものにはしない。彼らは、ピラトやヘロデのような他人の財を共有にすること を要求したのではなく、自分の財だけを共有にすることを要求したのである。ところが、私たちの農民たちは、他人の財を共有にし、自分の財は自分のものにし ようとする。彼らは立派なキリスト教徒だ!地獄には悪魔は一人も残っていないと思う。彼らの憤怒は度を越している」[103]。 ルターは、3つの理由で反乱軍への反対を正当化した。第一に、世俗的な政府への合法的な服従よりも暴力を選択することで、彼らは「カイザルのものはカイザ ルに返しなさい」というキリストの忠告を無視していた。聖パウロはローマの信徒への手紙13章1~7節で、すべての権力者は神によって任命されたものであ り、それゆえ逆らってはならない、と書いている。この聖書からの引用が、王の神聖な権利、ドイツの場合は諸侯の神聖な権利として知られる教義の基礎を形成 している。第二に、反乱、強盗、略奪という暴力的な行為によって、農民たちは「神と帝国の掟から外れた」状態に置かれたのであり、「高速道路を行き来する 者、殺人者であるにせよ、身も心も死に値する」とした。最後に、ルターは、自分たちを「キリスト教の同胞」と呼び、福音の旗印の下で罪深い行為を行ってい るとして、反乱者たちを冒涜罪で告発した[104]。 蜂起に対するルターの後ろ盾がなければ、多くの反乱軍は武器を捨て、他の反乱軍は裏切られたと感じた。1525年5月15日のフランケンハウゼンの戦いで シュヴァーベン同盟に敗れ、ミュンツァーが処刑されたことで、宗教改革の革命的段階は幕を閉じた[106]。その後、急進主義はアナバプテスト運動や他の 宗教運動に逃げ場を見つけ、ルターの宗教改革は世俗権力の下で栄えた[107]。 |

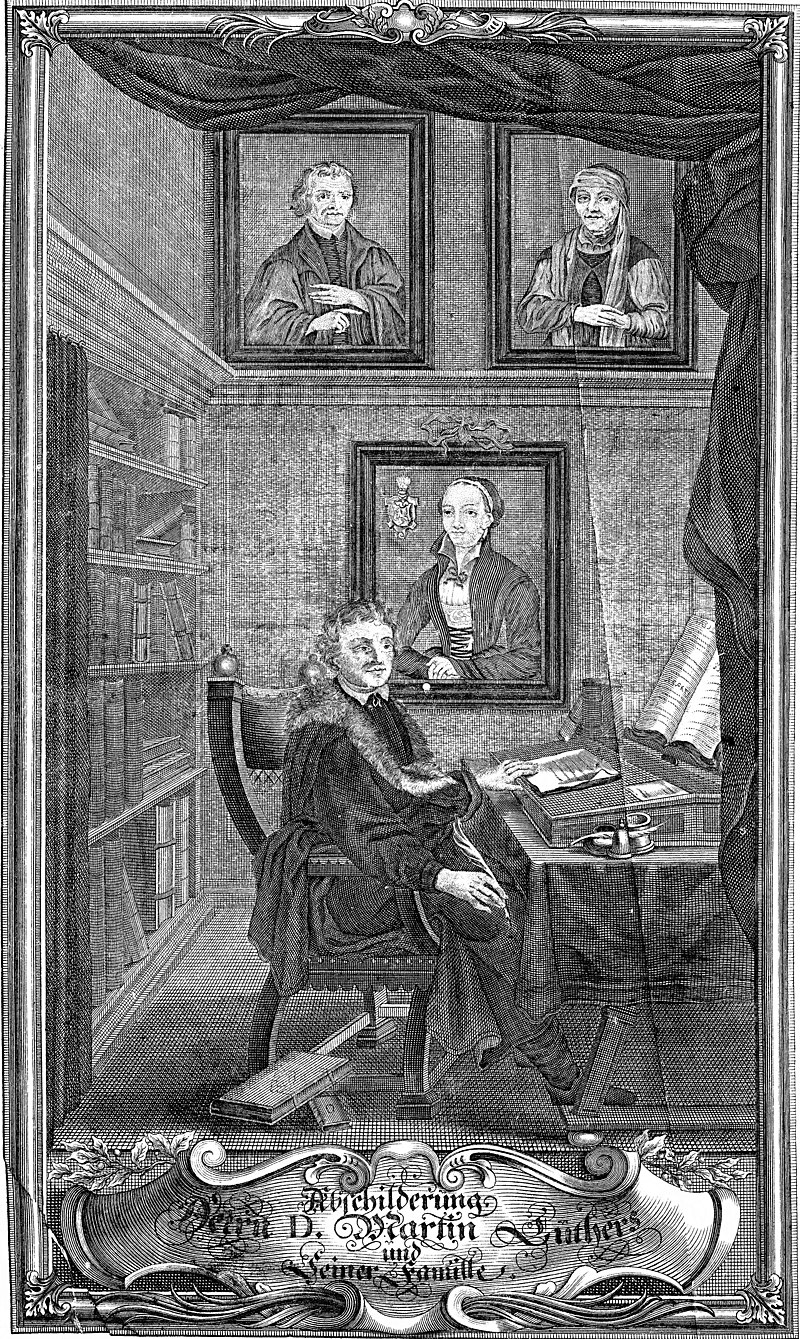

Marriage Katharina von Bora, Luther's wife, by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1526 Martin Luther married Katharina von Bora, one of 12 nuns he had helped escape from the Nimbschen Cistercian convent in April 1523, when he arranged for them to be smuggled out in herring barrels.[109] "Suddenly, and while I was occupied with far different thoughts," he wrote to Wenceslaus Link, "the Lord has plunged me into marriage."[110] At the time of their marriage, Katharina was 26 years old and Luther was 41 years old.  Martin Luther at his desk with family portraits (17th century) On 13 June 1525, the couple was engaged, with Johannes Bugenhagen, Justus Jonas, Johannes Apel, Philipp Melanchthon and Lucas Cranach the Elder and his wife as witnesses.[111] On the evening of the same day, the couple was married by Bugenhagen.[111] The ceremonial walk to the church and the wedding banquet were left out and were made up two weeks later on 27 June.[111] Some priests and former members of religious orders had already married, including Andreas Karlstadt and Justus Jonas, but Luther's wedding set the seal of approval on clerical marriage.[112] He had long condemned vows of celibacy on biblical grounds, but his decision to marry surprised many, not least Melanchthon, who called it reckless.[113] Luther had written to George Spalatin on 30 November 1524, "I shall never take a wife, as I feel at present. Not that I am insensible to my flesh or sex (for I am neither wood nor stone); but my mind is averse to wedlock because I daily expect the death of a heretic."[114] Before marrying, Luther had been living on the plainest food, and, as he admitted himself, his mildewed bed was not properly made for months at a time.[115] Luther and his wife moved into a former monastery, "The Black Cloister," a wedding present from Elector John the Steadfast. They embarked on what appears to have been a happy and successful marriage, though money was often short.[116] Katharina bore six children: Hans – June 1526; Elisabeth – 10 December 1527, who died within a few months; Magdalene – 1529, who died in Luther's arms in 1542; Martin – 1531; Paul – January 1533; and Margaret – 1534; and she helped the couple earn a living by farming and taking in boarders.[117] Luther confided to Michael Stiefel on 11 August 1526: "My Katie is in all things so obliging and pleasing to me that I would not exchange my poverty for the riches of Croesus."[118] |

結婚 ルターの妻カタリーナ・フォン・ボラ、長老ルーカス・クラナッハ作、1526年 マルティン・ルターは、1523年4月にニンブシェン・シトー会修道院からの脱出を手助けした12人の修道女の一人、カタリーナ・フォン・ボーラと結婚し た。 家族の肖像画と机に向かうマルティン・ルター(17世紀) 1525年6月13日、ヨハネス・ブッゲンハーゲン、ユストゥス・ヨナス、ヨハネス・アペル、フィリップ・メランヒトン、長老ルーカス・クラナッハ夫妻を 証人として、ふたりは婚約した[111]。 同日夕方、ふたりはブッゲンハーゲンによって結婚式を挙げた[111]。教会への散歩と披露宴の儀式は省かれ、2週間後の6月27日に行われた [111]。 アンドレアス・カールシュタットやユストゥス・ヨナスなど、すでに結婚していた司祭や修道会の元メンバーもいたが、ルターの結婚式は聖職者の結婚を承認す るものとなった[112]。 ルターは長い間、聖書的な理由から独身を誓うことを非難していたが、結婚するという彼の決断は、無謀だと言ったメランヒトンをはじめ、多くの人々を驚かせ た[113]。私は自分の肉や性に対して鈍感なわけではないが(私は木でも石でもないからだ)、異端者の死を毎日予期しているので、私の心は結婚を嫌って いる」[114] 結婚する前、ルターは最も質素な食事で生活しており、彼自身が認めているように、カビの生えたベッドは一度に何ヶ月もきちんと作られなかった[115]。 ルターとその妻は、選帝侯ヨハネ・ザ・ステファストからの結婚祝いとして、かつての修道院「黒い回廊」に移り住んだ。カタリーナは6人の子供をもうけた [116]: ハンス(1526年6月)、エリザベート(1527年12月10日、数ヶ月で死去)、マグダレーネ(1529年、1542年にルターの腕の中で死去)、マ ルティン(1531年)、パウロ(1533年1月)、マーガレット(1534年)。ルターは1526年8月11日、ミヒャエル・シュティーフェルに、「私 のケイティは、あらゆることに恩義を感じ、私を喜ばせてくれるので、私の貧しさをクロイソスの富と引き換えにはしません」と打ち明けた[118]。 |

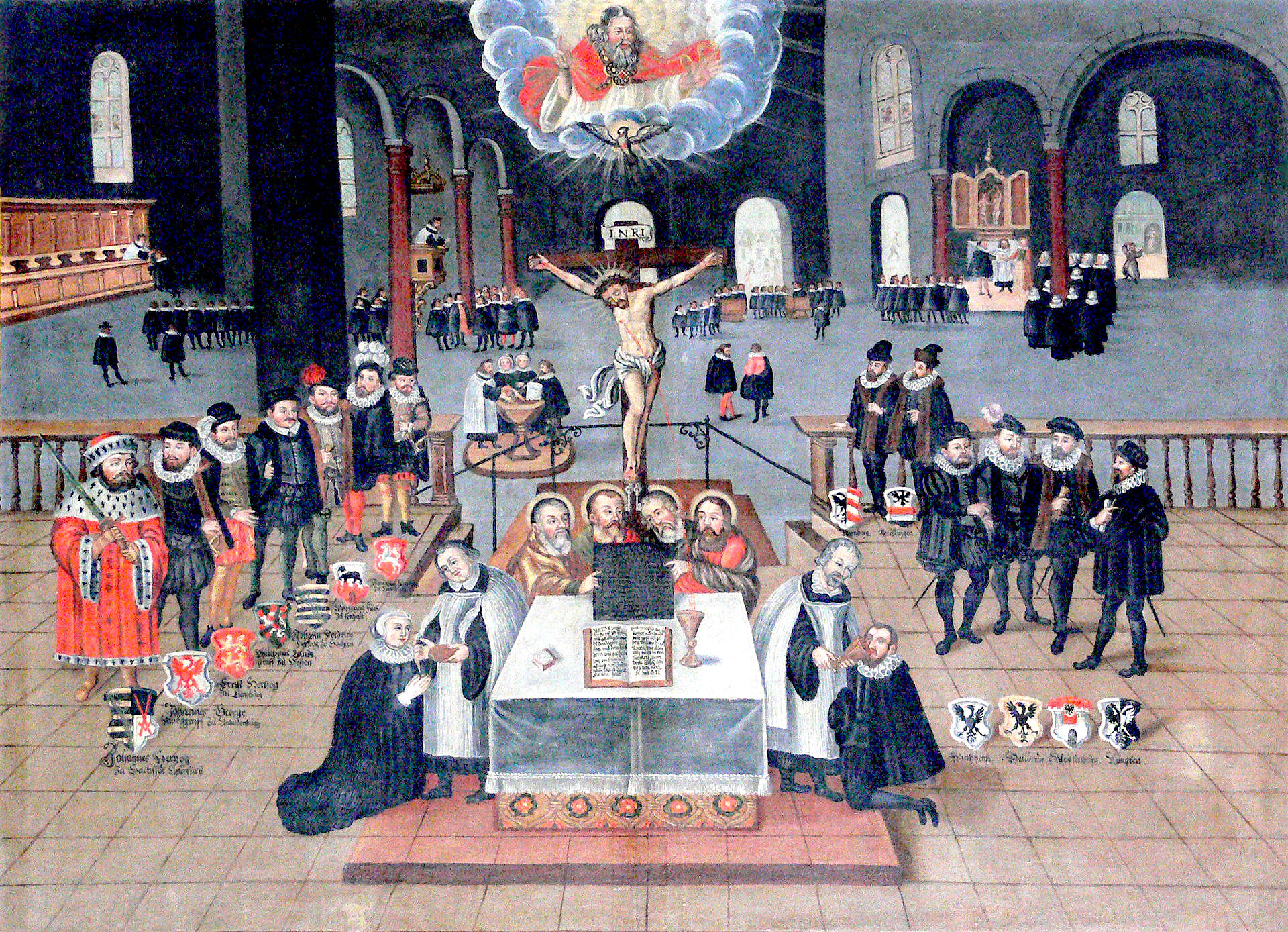

Organising the church Church orders, Mecklenburg 1650 By 1526, Luther found himself increasingly occupied in organising a new church. His biblical ideal of congregations choosing their own ministers had proved unworkable.[119] According to Bainton: "Luther's dilemma was that he wanted both a confessional church based on personal faith and experience and a territorial church including all in a given locality. If he were forced to choose, he would take his stand with the masses, and this was the direction in which he moved."[120] From 1525 to 1529, he established a supervisory church body, laid down a new form of worship service, and wrote a clear summary of the new faith in the form of two catechisms.[121] To avoid confusing or upsetting the people, Luther avoided extreme change. He also did not wish to replace one controlling system with another. He concentrated on the church in the Electorate of Saxony, acting only as an adviser to churches in new territories, many of which followed his Saxon model. He worked closely with the new elector, John the Steadfast, to whom he turned for secular leadership and funds on behalf of a church largely shorn of its assets and income after the break with Rome.[122] For Luther's biographer Martin Brecht, this partnership "was the beginning of a questionable and originally unintended development towards a church government under the temporal sovereign".[123] The elector authorised a visitation of the church, a power formerly exercised by bishops.[124] At times, Luther's practical reforms fell short of his earlier radical pronouncements. For example, the Instructions for the Visitors of Parish Pastors in Electoral Saxony (1528), drafted by Melanchthon with Luther's approval, stressed the role of repentance in the forgiveness of sins, despite Luther's position that faith alone ensures justification.[125] The Eisleben reformer Johannes Agricola challenged this compromise, and Luther condemned him for teaching that faith is separate from works.[126] The Instruction is a problematic document for those seeking a consistent evolution in Luther's thought and practice.[127]  Lutheran church liturgy and sacraments In response to demands for a German liturgy, Luther wrote a German Mass, which he published in early 1526.[128] He did not intend it as a replacement for his 1523 adaptation of the Latin Mass but as an alternative for the "simple people", a "public stimulation for people to believe and become Christians."[129] Luther based his order on the Catholic service but omitted "everything that smacks of sacrifice", and the Mass became a celebration where everyone received the wine as well as the bread.[130] He retained the elevation of the host and chalice, while trappings such as the Mass vestments, altar, and candles were made optional, allowing freedom of ceremony.[131] Some reformers, including followers of Huldrych Zwingli, considered Luther's service too papistic, and modern scholars note the conservatism of his alternative to the Catholic Mass.[132] Luther's service, however, included congregational singing of hymns and psalms in German, as well as parts of the liturgy, including Luther's unison setting of the Creed.[133] To reach the simple people and the young, Luther incorporated religious instruction into the weekday services in the form of catechism.[134] He also provided simplified versions of the baptism and marriage services.[135] Luther and his colleagues introduced the new order of worship during their visitation of the Electorate of Saxony, which began in 1527.[136] They also assessed the standard of pastoral care and Christian education in the territory. "Merciful God, what misery I have seen," Luther writes, "the common people knowing nothing at all of Christian doctrine ... and unfortunately many pastors are well-nigh unskilled and incapable of teaching."[137] Catechisms A stained glass portrayal of Luther Luther devised the catechism as a method of imparting the basics of Christianity to the congregations. In 1529, he wrote the Large Catechism, a manual for pastors and teachers, as well as a synopsis, the Small Catechism, to be memorised by the people.[138] The catechisms provided easy-to-understand instructional and devotional material on the Ten Commandments, the Apostles' Creed, The Lord's Prayer, baptism, and the Lord's Supper.[139] Luther incorporated questions and answers in the catechism so that the basics of Christian faith would not just be learned by rote, "the way monkeys do it", but understood.[140] The catechism is one of Luther's most personal works. "Regarding the plan to collect my writings in volumes," he wrote, "I am quite cool and not at all eager about it because, roused by a Saturnian hunger, I would rather see them all devoured. For I acknowledge none of them to be really a book of mine, except perhaps the Bondage of the Will and the Catechism."[141] The Small Catechism has earned a reputation as a model of clear religious teaching.[142] It remains in use today, along with Luther's hymns and his translation of the Bible. Luther's Small Catechism proved especially effective in helping parents teach their children; likewise the Large Catechism was effective for pastors.[143] Using the German vernacular, they expressed the Apostles' Creed in simpler, more personal, Trinitarian language. He rewrote each article of the Creed to express the character of the Father, the Son, or the Holy Spirit. Luther's goal was to enable the catechumens to see themselves as a personal object of the work of the three persons of the Trinity, each of which works in the catechumen's life.[144] That is, Luther depicts the Trinity not as a doctrine to be learned, but as persons to be known. The Father creates, the Son redeems, and the Spirit sanctifies, a divine unity with separate personalities. Salvation originates with the Father and draws the believer to the Father. Luther's treatment of the Apostles' Creed must be understood in the context of the Decalogue (the Ten Commandments) and The Lord's Prayer, which are also part of the Lutheran catechetical teaching.[144] |

教会の組織 メクレンブルク1650年の教会命令 1526年まで、ルターは新しい教会を組織することでますます頭がいっぱいになっていた。信徒が自ら牧師を選ぶという彼の聖書の理想は、実行不可能である ことが判明した[119]: 「ルターのジレンマは、個人的な信仰と経験に基づく告白的な教会と、与えられた地域のすべての人を含む領土的な教会の両方を望んでいたことであった。もし 選択を迫られたら、彼は大衆の側に立つだろう。 1525年から1529年にかけて、彼は監督教会組織を設立し、礼拝の新しい形式を定め、2つのカテキズムの形で新しい信仰の明確な要約を書いた [121]。人々を混乱させたり動揺させたりすることを避けるために、ルターは極端な変化を避けた。また、ある支配体制を別の支配体制に置き換えることも 望まなかった。彼はザクセン選帝侯領の教会に集中し、新しい領地の教会の顧問としてのみ活動した。ルターの伝記作者マルティン・ブレヒトにとって、この パートナーシップは「現世の君主のもとでの教会政治に向けた、疑問の多い、元来意図されなかった発展の始まり」であった[123]。 選帝侯は、以前は司教によって行使されていた教会訪問を許可した[124]。ルターの実際的な改革は、彼の以前の急進的な宣言には及ばないこともあった。 例えば、ルターの承認を得てメランヒトンが起草した『ザクセン選帝侯における教区牧師の訪問に関する指示書』(1528年)は、信仰のみが義認を保証する というルターの立場にもかかわらず、罪の赦しにおける悔い改めの役割を強調していた[125]。アイスレーベンの改革者ヨハネス・アグリコラはこの妥協に 異議を唱え、ルターは信仰が行いから切り離されたものであると教えたとして彼を非難した[126]。  ルーテル教会の典礼と秘跡 ルターは、ドイツ語の典礼を求める声に応えて、ドイツ語のミサを書き、1526年初頭に発表した[128]。ルターはこのミサを、1523年に翻案したラ テン語のミサに代わるものとして意図したのではなく、「単純な人々」のための代替物、「人々が信仰し、キリスト教徒になるための公的な刺激」として意図し た。 「129]ルターは、カトリックの礼拝を基調としながらも、「いけにえを思わせるものすべて」を省き、ミサは、誰もがパンだけでなくワインも受ける祝祭と なった[130]。 [131] フルドリヒ・ツヴィングリの信奉者を含む一部の改革者たちは、ルターの礼拝はあまりにも教皇主義的であると考え、現代の学者たちは、カトリックのミサに対 するルターの代替案の保守性を指摘している[132]。 [133]ルターは、素朴な人々や若者たちに福音を伝えるために、カテキズムの形で平日の礼拝に宗教的な教えを取り入れた[134]。 ルターとその同僚たちは、1527年に始まったザクセン選帝侯国訪問の際に、新しい礼拝の秩序を紹介した[136]。彼らはまた、領内の司牧とキリスト教 教育の水準を評価した。「庶民はキリスト教の教義をまったく知らず......残念なことに、多くの牧師はほとんど熟練しておらず、教えることができな い」[137]。 カテキズム ステンドグラスに描かれたルター ルターは、キリスト教の基本を信徒に教える方法としてカテキズムを考案した。カテキズムは、十戒、使徒信条、主の祈り、洗礼、主の晩餐について、わかりや すく説き、信心に資するものであった[138]。 [139]ルターは、キリスト教信仰の基本を「猿がやるような」暗記で学ぶのではなく、理解できるように、カテキズムに質問と回答を取り入れた [140]。 カテキズムはルターの最も個人的な著作の一つである。「私の著作を一冊の本にまとめるという計画について、彼はこう書いている。小カテキズムは、明確な宗 教的教えの模範として高い評価を得ている[142]。 小カテキズムは、ルターの賛美歌や彼の翻訳した聖書とともに、今日でも使用されている。 ルターの『小カテキズム』は、親が子供に教えるのに特に効果的であることが証明され、同様に『大カテキズム』は牧師に効果的であった[143]。彼は信条 の各条文を、父、子、聖霊の性格を表現するために書き直した。つまり、ルターは三位一体を学ぶべき教義としてではなく、知るべき者として描いたのである。 御父は創造し、御子は贖い、御霊は聖化する。救いは御父に由来し、信じる者を御父へと引き寄せる。ルターによる使徒信条の扱いは、ルター派のカテケージカ ルな教えの一部でもあるデカログ(十戒)と主の祈りの文脈の中で理解されなければならない[144]。 |

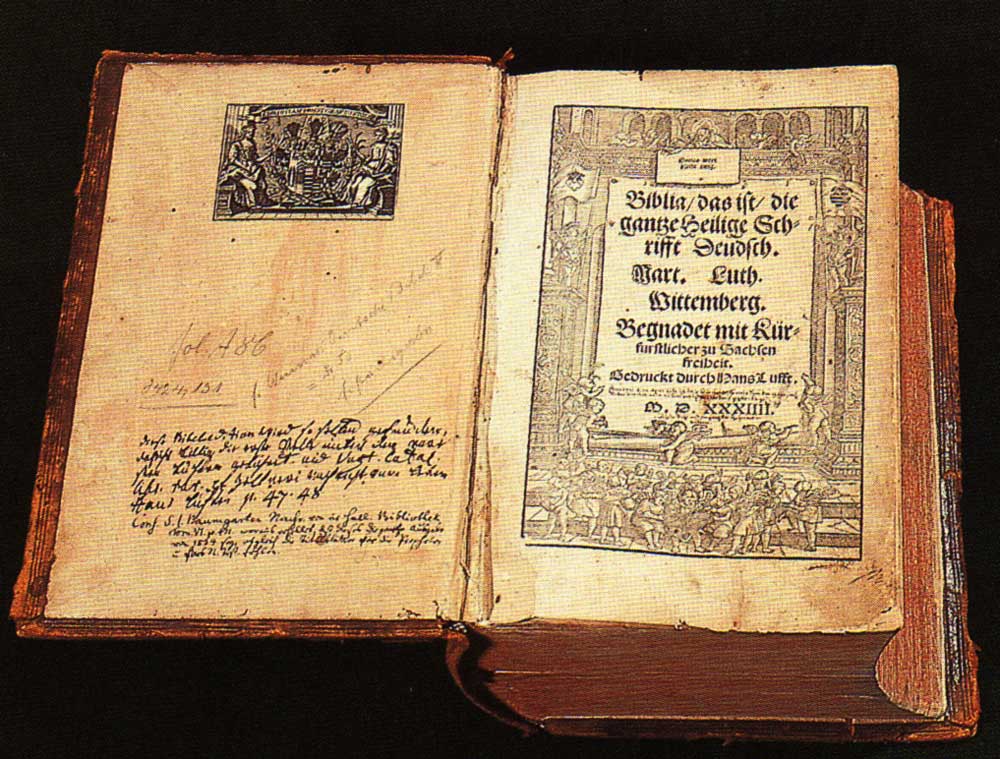

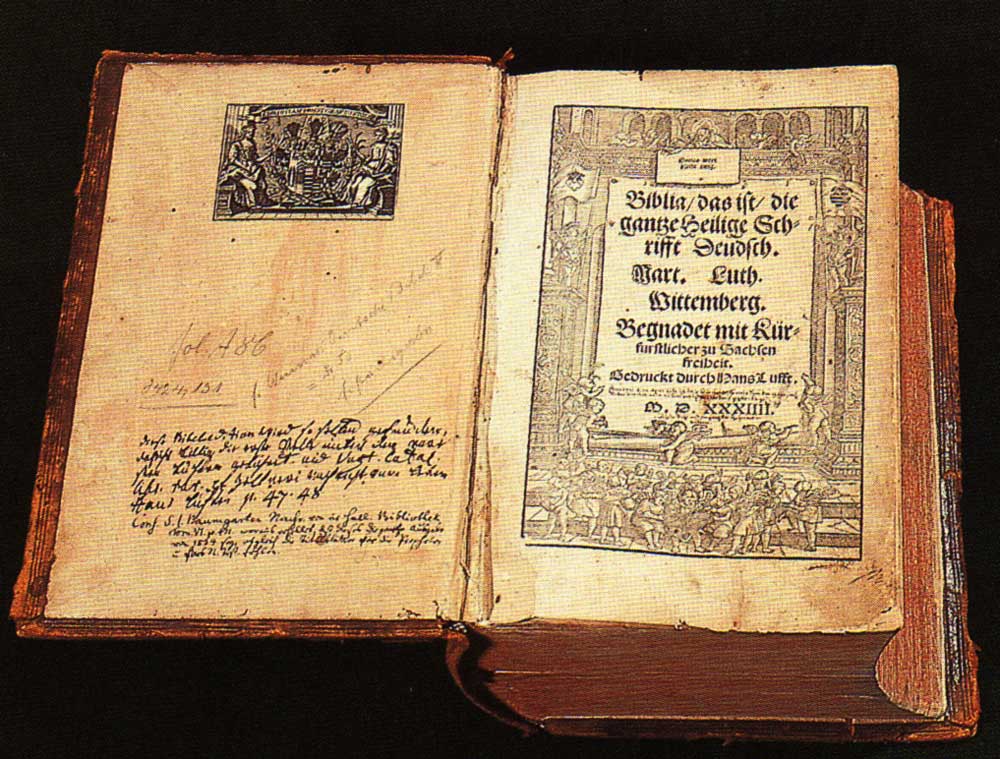

| Translation of the Bible Main article: Luther Bible  Luther's 1534 Bible Luther had published his German translation of the New Testament in 1522, and he and his collaborators completed the translation of the Old Testament in 1534, when the whole Bible was published. He continued to work on refining the translation until the end of his life.[145] Others had previously translated the Bible into German, but Luther tailored his translation to his own doctrine.[146] Two of the earlier translations were the Mentelin Bible (1456)[147] and the Koberger Bible (1484).[148] There were as many as fourteen in High German, four in Low German, four in Dutch, and various other translations in other languages before the Bible of Luther.[149] Luther's translation used the variant of German spoken at the Saxon chancellery, intelligible to both northern and southern Germans.[150] He intended his vigorous, direct language to make the Bible accessible to everyday Germans, "for we are removing impediments and difficulties so that other people may read it without hindrance."[151] Published at a time of rising demand for German-language publications, Luther's version quickly became a popular and influential Bible translation. As such, it contributed a distinct flavor to the German language and literature.[152] Furnished with notes and prefaces by Luther, and with woodcuts by Lucas Cranach that contained anti-papal imagery, it played a major role in the spread of Luther's doctrine throughout Germany.[153] The Luther Bible influenced other vernacular translations, such as the Tyndale Bible (from 1525 forward), a precursor of the King James Bible.[154] When he was criticised for inserting the word "alone" after "faith" in Romans 3:28,[155] he replied in part: "[T]he text itself and the meaning of St. Paul urgently require and demand it. For in that very passage he is dealing with the main point of Christian doctrine, namely, that we are justified by faith in Christ without any works of the Law. ... But when works are so completely cut away—and that must mean that faith alone justifies—whoever would speak plainly and clearly about this cutting away of works will have to say, 'Faith alone justifies us, and not works'."[156] Luther did not include First Epistle of John 5:7–8,[157] the Johannine Comma in his translation, rejecting it as a forgery. It was inserted into the text by other hands after Luther's death.[158][159] |

聖書の翻訳 主な記事 ルター聖書  ルターの1534年の聖書 ルターは、1522年に新約聖書のドイツ語訳を出版し、1534年に旧約聖書の翻訳を完成させ、聖書全体が出版された。ルターは晩年まで翻訳を改良し続け た[145]。以前にも他の人々が聖書をドイツ語に翻訳していたが、ルターは自分の教義に合わせて翻訳した[146]。 ルターの訳は、ザクセンの首相官邸で話されていた、北ドイツ人にも南ドイツ人にも理解できるドイツ語の変種を使用した[150]。ルターは、「他の人々が 支障なく聖書を読むことができるように、私たちは障害や困難を取り除こうとしているのです」[151]。ルターによる注釈と序文、反教皇的なイメージを含 むルーカス・クラナッハの木版画が添えられ、ルターの教義がドイツ全土に広まる上で大きな役割を果たした[153]。 ルター訳聖書は、欽定訳聖書の前身であるティンデール訳聖書(1525年以降)など、他の方言訳聖書にも影響を与えた[154]。 ローマ人への手紙3:28の「信仰」の後に「単独で」という言葉を挿入したことを批判されたとき[155]、彼は部分的に答えた: 「聖書本文そのものと聖パウロの意味は、それを緊急に要求しているのです。というのも、聖パウロはこの箇所で、キリスト教の教義の主要な点、すなわち、律 法の行いによらずにキリストを信じる信仰によって義とされるという点を扱っているからである。... しかし、業が完全に断ち切られるとき、それは信仰のみが義とされることを意味するに違いなく、業が断ち切られることについて明白かつ明確に語ろうとする者 は誰でも、『信仰のみが義とされるのであって、業が義とされるのではない』と言わなければならなくなる」[156]。このコンマはルターの死後、別の手に よってテキストに挿入された[158][159]。 |

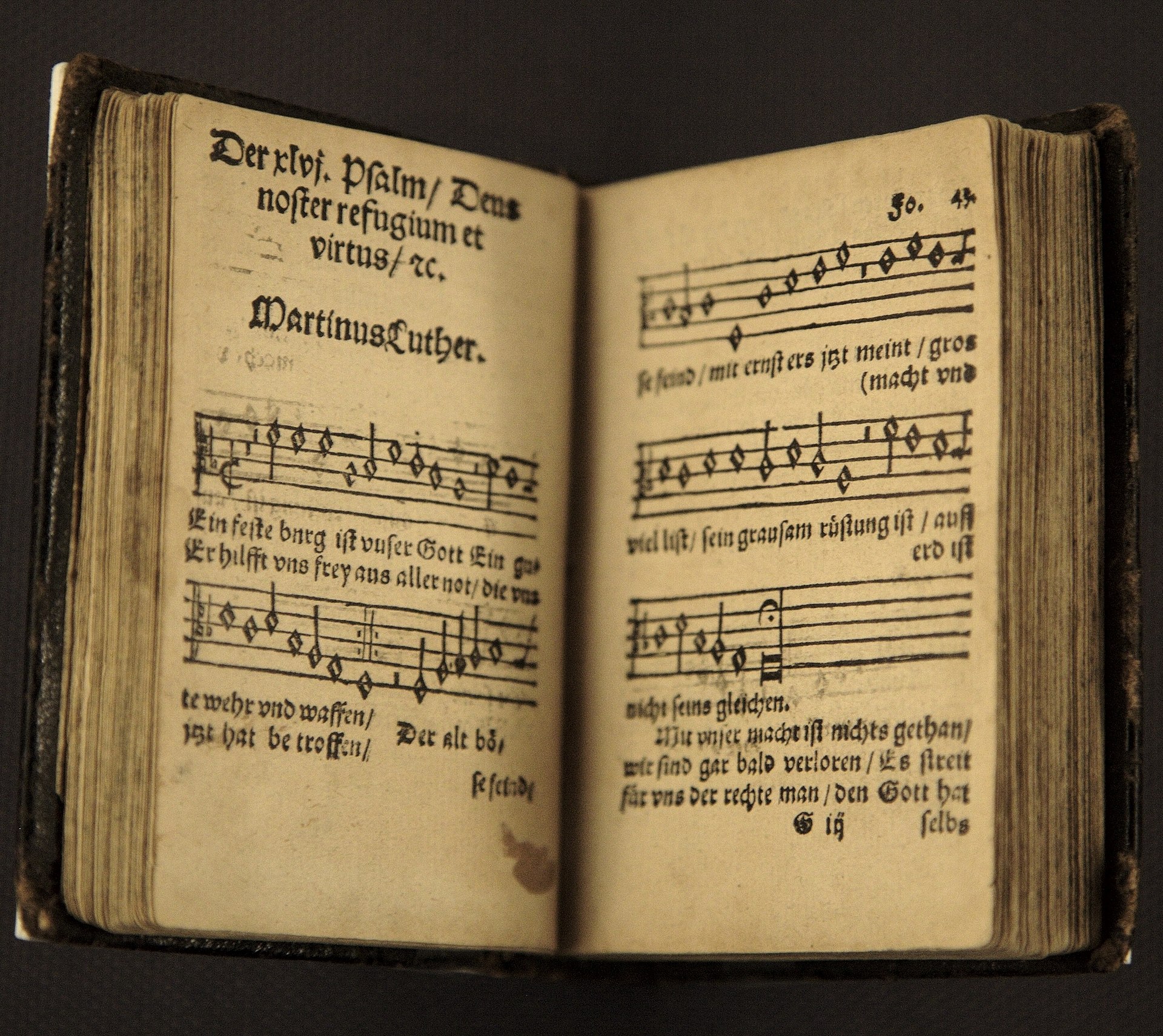

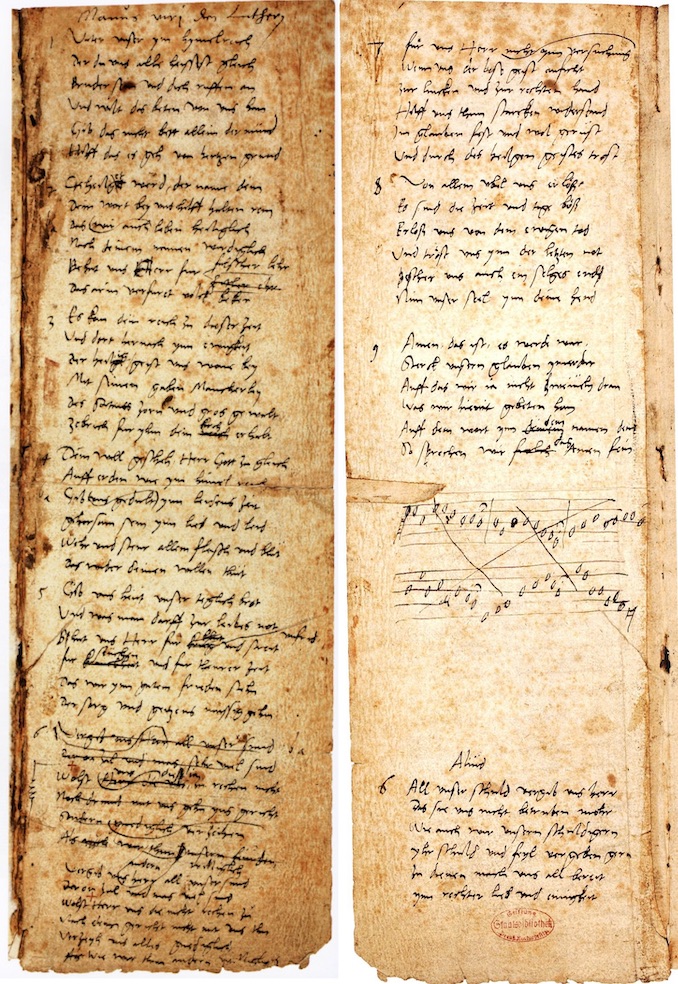

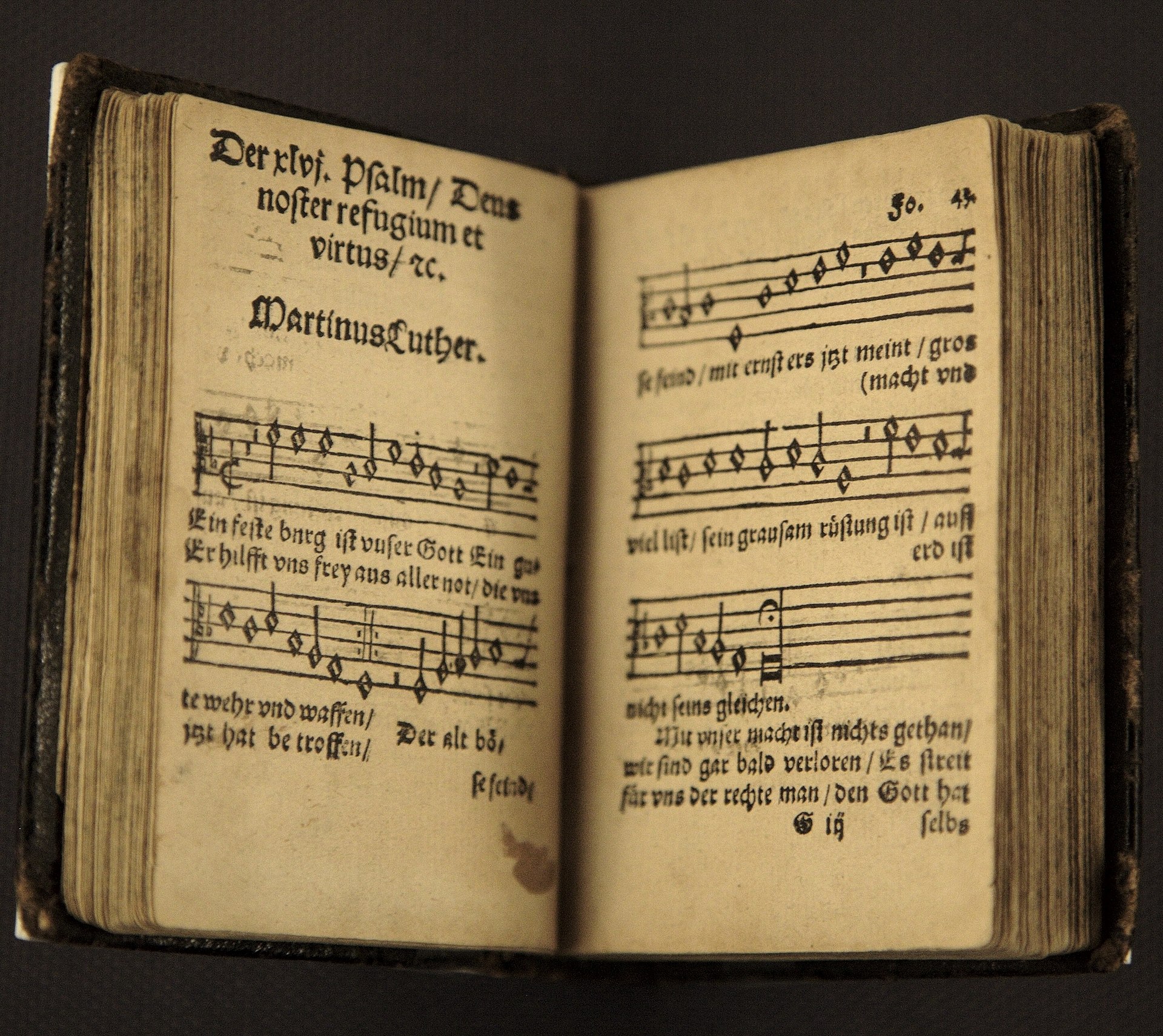

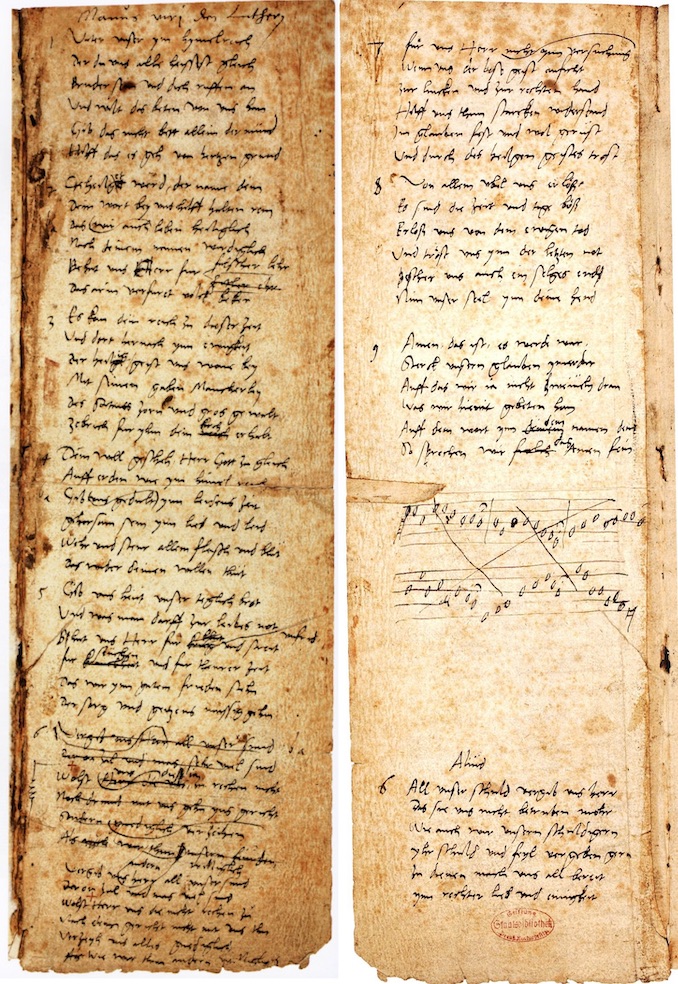

| Hymnodist

(Luther's musical heritage) Main article: List of hymns by Martin Luther  An early printing of Luther's hymn "Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott" Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott [German church song][+English translation] Problems playing this file? See media help. Luther was a prolific hymnodist, authoring hymns such as "Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott" ("A Mighty Fortress Is Our God"), based on Psalm 46, and "Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her" ("From Heaven Above to Earth I Come"), based on Luke 2:11–12.[160] Luther connected high art and folk music, also all classes, clergy and laity, men, women and children. His tool of choice for this connection was the singing of German hymns in connection with worship, school, home, and the public arena.[161] He often accompanied the sung hymns with a lute, later recreated as the waldzither that became a national instrument of Germany in the 20th century.[162] Luther's hymns were frequently evoked by particular events in his life and the unfolding Reformation. This behavior started with his learning of the execution of Jan van Essen and Hendrik Vos, the first individuals to be martyred by the Roman Catholic Church for Lutheran views, prompting Luther to write the hymn "Ein neues Lied wir heben an" ("A New Song We Raise"), which is generally known in English by John C. Messenger's translation by the title and first line "Flung to the Heedless Winds" and sung to the tune Ibstone composed in 1875 by Maria C. Tiddeman.[163] Luther's 1524 creedal hymn "Wir glauben all an einen Gott" ("We All Believe in One True God") is a three-stanza confession of faith prefiguring Luther's 1529 three-part explanation of the Apostles' Creed in the Small Catechism. Luther's hymn, adapted and expanded from an earlier German creedal hymn, gained widespread use in vernacular Lutheran liturgies as early as 1525. Sixteenth-century Lutheran hymnals also included "Wir glauben all" among the catechetical hymns, although 18th-century hymnals tended to label the hymn as Trinitarian rather than catechetical, and 20th-century Lutherans rarely used the hymn because of the perceived difficulty of its tune.[161]  Autograph of "Vater unser im Himmelreich", with the only notes extant in Luther's handwriting Luther's 1538 hymnic version of the Lord's Prayer, "Vater unser im Himmelreich", corresponds exactly to Luther's explanation of the prayer in the Small Catechism, with one stanza for each of the seven prayer petitions, plus opening and closing stanzas. The hymn functions both as a liturgical setting of the Lord's Prayer and as a means of examining candidates on specific catechism questions. The extant manuscript shows multiple revisions, demonstrating Luther's concern to clarify and strengthen the text and to provide an appropriately prayerful tune. Other 16th- and 20th-century versifications of the Lord's Prayer have adopted Luther's tune, although modern texts are considerably shorter.[164] Luther wrote "Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir" ("From depths of woe I cry to You") in 1523 as a hymnic version of Psalm 130 and sent it as a sample to encourage his colleagues to write psalm-hymns for use in German worship. In a collaboration with Paul Speratus, this and seven other hymns were published in the Achtliederbuch, the first Lutheran hymnal. In 1524 Luther developed his original four-stanza psalm paraphrase into a five-stanza Reformation hymn that developed the theme of "grace alone" more fully. Because it expressed essential Reformation doctrine, this expanded version of "Aus tiefer Not" was designated as a regular component of several regional Lutheran liturgies and was widely used at funerals, including Luther's own. Along with Erhart Hegenwalt's hymnic version of Psalm 51, Luther's expanded hymn was also adopted for use with the fifth part of Luther's catechism, concerning confession.[165] Luther wrote "Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein" ("Oh God, look down from heaven"). "Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland" (Now come, Savior of the gentiles), based on Veni redemptor gentium, became the main hymn (Hauptlied) for Advent. He transformed A solus ortus cardine to "Christum wir sollen loben schon" ("We should now praise Christ") and Veni Creator Spiritus to "Komm, Gott Schöpfer, Heiliger Geist" ("Come, Holy Spirit, Lord God").[166] He wrote two hymns on the Ten Commandments, "Dies sind die heilgen Zehn Gebot" and "Mensch, willst du leben seliglich". His "Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ" ("Praise be to You, Jesus Christ") became the main hymn for Christmas. He wrote for Pentecost "Nun bitten wir den Heiligen Geist", and adopted for Easter "Christ ist erstanden" (Christ is risen), based on Victimae paschali laudes. "Mit Fried und Freud ich fahr dahin", a paraphrase of Nunc dimittis, was intended for Purification, but became also a funeral hymn. He paraphrased the Te Deum as "Herr Gott, dich loben wir" with a simplified form of the melody. It became known as the German Te Deum. Luther's 1541 hymn "Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam" ("To Jordan came the Christ our Lord") reflects the structure and substance of his questions and answers concerning baptism in the Small Catechism. Luther adopted a preexisting Johann Walter tune associated with a hymnic setting of Psalm 67's prayer for grace; Wolf Heintz's four-part setting of the hymn was used to introduce the Lutheran Reformation in Halle in 1541. Preachers and composers of the 18th century, including J.S. Bach, used this rich hymn as a subject for their own work, although its objective baptismal theology was displaced by more subjective hymns under the influence of late-19th-century Lutheran pietism.[161] Luther's hymns were included in early Lutheran hymnals and spread the ideas of the Reformation. He supplied four of eight songs of the First Lutheran hymnal Achtliederbuch, 18 of 26 songs of the Erfurt Enchiridion, and 24 of the 32 songs in the first choral hymnal with settings by Johann Walter, Eyn geystlich Gesangk Buchleyn, all published in 1524. Luther's hymns inspired composers to write music. Johann Sebastian Bach included several verses as chorales in his cantatas and based chorale cantatas entirely on them, namely Christ lag in Todes Banden, BWV 4, as early as possibly 1707, in his second annual cycle (1724 to 1725) Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein, BWV 2, Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam, BWV 7, Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 62, Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ, BWV 91, and Aus tiefer Not schrei ich zu dir, BWV 38, later Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott, BWV 80, and in 1735 Wär Gott nicht mit uns diese Zeit, BWV 14. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin_Luther#Hymnodist ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++  The reformer Martin Luther, a prolific hymnodist, regarded music and especially hymns in German as important means for the development of faith. Luther wrote songs for occasions of the liturgical year (Advent, Christmas, Purification, Epiphany, Easter, Pentecost, Trinity), hymns on topics of the catechism (Ten Commandments, Lord's Prayer, creed, baptism, confession, Eucharist), paraphrases of psalms, and other songs. Whenever Luther went out from pre-existing texts, here listed as "text source" (bible, Latin and German hymns), he widely expanded, transformed and personally interpreted them.[1][2] Luther worked on the tunes, sometimes modifying older tunes, in collaboration with Johann Walter. Hymns were published in the Achtliederbuch, in Walter's choral hymnal Eyn geystlich Gesangk Buchleyn (Wittenberg) and the Erfurt Enchiridion (Erfurt) in 1524, and in the Klugsches Gesangbuch, among others. For more information, see Martin Luther § Hymnodist. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_hymns_by_Martin_Luther +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Luther's canon is the biblical canon attributed to Martin Luther, which has influenced Protestants since the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. While the Lutheran Confessions specifically did not define a biblical canon, it is widely regarded as the canon of the Lutheran Church. It differs from the 1546 Roman Catholic canon of the Council of Trent in that it rejects the deuterocanonical books and questions the seven New Testament books, called "Luther's Antilegomena",[1] four of which are still ordered last in German-language Luther Bibles to this day.[2][3] Despite Luther's personal commentary on certain books of the Bible, the actual books included in the Luther Bible that came to be used by the Lutheran Churches do not differ greatly from those in the Catholic Bible, though the Luther Bible places what Catholics view as the deuterocanonical books in an intertestamental section, between the Old Testament and New Testament, terming these as Apocrypha.[4][5][6] The books of the Apocrypha, in the Lutheran tradition, are non-canonical, but "worthy of reverence," thus being included in Lutheran lectionaries used during the Divine Service; the Luther Bible is widely used by Anabaptist Christians, such as the Amish, as well.[7][8] Old Testament apocrypha Main articles: Deuterocanonical books and Biblical apocrypha Luther included the deuterocanonical books in his translation of the German Bible, but he did relocate them to after the Old Testament, calling them "Apocrypha, that are books which are not considered equal to the Holy Scriptures, but are useful and good to read."[9] New Testament "disputed books": Hebrews, James, Jude, and Revelation Main article: Antilegomena In the 4th century the Council of Rome had outlined the 27 New Testament books which now appear in the Catholic canon.[10] Luther considered Hebrews, James, Jude, and the Revelation to be "disputed books", which he included in his translation but placed separately at the end in his New Testament published in 1522; these books needed to be interpreted subject to the undisputed books, which are called the "canon within a canon."[11] This group of books begins with the book of Hebrews, and in its preface Luther states, "Up to this point we have had to do with the true and certain chief books of the New Testament. The four which follow have from ancient times had a different reputation." According to some scholars such as Johann Michael Reu, but controversial,[11] Luther did not personally regard these books as canonical:[12] in the September Testament he included them but did not add numbers to them, and in the 1534 Bible he treated them the same as the Old Testament Aprocrypha. In the Preface to James of the 1522 September Testament, Luther explicitly stated it was not "apostolic" (which for Luther did not mean being written by the Apostles, but "whatever preaches Christ"):[12]: 28 "I think highly of the epistle of James, and regard it as valuable although it was rejected in early days. It does not expound human doctrines, but lays much emphasis on God's law. […] I do not hold it to be of apostolic authorship."[13] Luther goes on to say that it contradicts St Paul and cannot be defended: it teaches "works-righteousness" and does not mention "the Passion, the Resurrection or the Spirit of Christ." In Luther's preface to the New Testament, Luther ascribed to several books of the New Testament different degrees of doctrinal value: St. John's Gospel and his first Epistle, St. Paul's Epistles, especially those to the Romans, Galatians, Ephesians, and St. Peter's Epistle—these are the books which show to thee Christ, and teach everything that is necessary and blessed for thee to know, even if you were never to see or hear any other book of doctrine. Therefore, St. James' Epistle is a perfect straw-epistle compared with them, for it has in it nothing of an evangelic kind."[14] However, in the view of theologian Charles Caldwell Ryrie Luther was comparing (in his opinion) doctrinal value, not canonical validity.[15] Luther's private antipathy to James continued into the 1530s and 1540s: he added a note to James 2:12 "O this chaos";[12]: 26 in 1540 "Some day I will use James to fire my stove;"[17] in 1542 "The Epistle of James we have thrown out from this school (Wittenberg) because it has no value...I hold it is written by some Jew" (not a Christian.)[19] Theologian Jason Lane has noted "the general perception that Luther could not understand James because the letter failed to fit his conception of Pauline theology."[11] In response to doubts such as Luther's, the Catholic Church's Council of Trent on April 8, 1546 dogmatically defined the contents of the biblical canon and thus settled the matter for Catholics.[20][21][22][23][24][25] This affirmed the canonicity of Hebrews, James, Jude and Revelation, as well as various Deuterocanonical books of the Old Testament. Sola fide doctrine Main article: Sola fide In The Protestant Spirit of Luther’s Version, Philip Schaff asserts that: The most important example of dogmatic influence in Luther’s version is the famous interpolation of the word alone in Rom. 3:28 (allein durch den Glauben), by which he intended to emphasize his solifidian doctrine of justification, on the plea that the German idiom required the insertion for the sake of clearness. But he thereby brought Paul into direct verbal conflict with James, who says (James 2:24), "by works a man is justified, and not only by faith" ("nicht durch den Glauben allein"). It is well known that Luther deemed it impossible to harmonize the two apostles in this article, and characterized the Epistle of James as an "epistle of straw," because it had no evangelical character ("keine evangelische Art").[26] Martin Luther's description of the Epistle of James changes. In some cases, Luther argues that it was not written by an apostle; but in other cases, he describes James as the work of an apostle.[27][verification needed] He even cites it as authoritative teaching from God[28] and describes James as "a good book, because it sets up no doctrines of men but vigorously promulgates the law of God."[29] Lutherans hold that the Epistle is rightly part of the New Testament, citing its authority in the Book of Concord.[30] Lutheran teachings resolve James' and Paul's verbal conflict regarding faith and works in alternate ways from the Catholics and E. Orthodox: Paul was dealing with one kind of error while James was dealing with a different error. The errorists Paul was dealing with were people who said that works of the law were needed to be added to faith in order to help earn God's favor. Paul countered this error by pointing out that salvation was by faith alone apart from deeds of the law (Galatians 2:16; Romans 3:21-22). Paul also taught that saving faith is not dead but alive, showing thanks to God in deeds of love (Galatians 5:6 ['...since in Christ Jesus it is not being circumcised or being uncircumcised that can effect anything - only faith working through love.']). James was dealing with errorists who said that if they had faith they didn't need to show love by a life of faith (James 2:14-17). James countered this error by teaching that faith is alive, showing itself to be so by deeds of love (James 2:18,26). James and Paul both teach that salvation is by faith alone and also that faith is never alone but shows itself to be alive by deeds of love that express a believer's thanks to God for the free gift of salvation by faith in Jesus.[31] Similar canons at the time In his book Canon of the New Testament, Bruce Metzger notes that in 1596 Jacob Lucius published a Bible at Hamburg which labeled as Apocrypha Luther's four Antilegomena: Hebrews, James, Jude and Revelation; Lucius explained this category of "Apocrypha" as "That is, books that are not held equal to the other holy Scripture". David Wolder, the pastor of Hamburg's Church of St. Peter, published in the same year a triglot Bible which labeled those books as "non canonical". J. Vogt published a Bible at Goslar in 1614 similar to Lucius'. In Sweden, Gustavus Adolphus published in 1618 the Gustavus Adolphus Bible with those four books labeled as "Apocr(yphal) New Testament." Metzger considers those decisions a "startling deviation among Lutheran editions of the Scriptures".[32] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luther%27s_canon |