マシュー・アーノルド

Matthew Arnold, 1822-1888

1883年ごろのアーノルド

☆マシュー・アーノルド(Matthew Arnold、1822 年12月24日 - 1888年4月15日)は、英国の詩人、文化評論家である。ラグビー校の校長トーマス・アーノルドの息子であり、文学教授トム・アーノルドと小説家で植民 地行政官のウィリアム・デラフィールド・アーノルドの兄である。彼は、現代社会の問題について読者を戒め、教えるタイプの作家である「賢人作家」と評され ている。[1] また、35年にわたり学校の検査官を務め、国家による中等教育の規制という概念を支持していた。[2]

| Matthew Arnold (24

December 1822 – 15 April 1888) was an English poet and cultural critic.

He was the son of Thomas Arnold, the headmaster of Rugby School, and

brother to both Tom Arnold, literary professor, and William Delafield

Arnold, novelist and colonial administrator. He has been characterised

as a sage writer, a type of writer who chastises and instructs the

reader on contemporary social issues.[1] He was also an inspector of

schools for thirty-five years, and supported the concept of

state-regulated secondary education.[2] |

マ

シュー・アーノルド(Matthew Arnold、1822年12月24日 -

1888年4月15日)は、英国の詩人、文化評論家である。ラグビー校の校長トーマス・アーノルドの息子であり、文学教授トム・アーノルドと小説家で植民

地行政官のウィリアム・デラフィールド・アーノルドの兄である。彼は、現代社会の問題について読者を戒め、教えるタイプの作家である「賢人作家」と評され

ている。[1] また、35年にわたり学校の検査官を務め、国家による中等教育の規制という概念を支持していた。[2] |

| Early years He was the eldest son of Thomas Arnold and his wife Mary Penrose Arnold, born on 24 December 1822 at Laleham-on-Thames, Middlesex.[3] John Keble stood as godfather to Matthew. In 1828, Thomas Arnold was appointed Headmaster of Rugby School, where the family took up residence, that year. From 1831, Arnold was tutored by his clerical uncle, John Buckland, in Laleham. In 1834, the Arnolds occupied a holiday home, Fox How, in the Lake District. There William Wordsworth was a neighbour and close friend. In 1836, Arnold was sent to Winchester College, but in 1837 he returned to Rugby School. He moved to the sixth form in 1838 and so came under the direct tutelage of his father. He wrote verse for a family magazine, and won school prizes. His prize poem, "Alaric at Rome", was printed at Rugby. In November 1840, aged 17, Arnold matriculated at Balliol College, Oxford, where in 1841 he won an open scholarship, graduating B.A. in 1844.[3][4] During his student years at Oxford, his friendship became stronger with Arthur Hugh Clough, a Rugby pupil who had been one of his father's favourites. He attended John Henry Newman's sermons at the University Church of St Mary the Virgin but did not join the Oxford Movement. After his father's death in 1842, Fox How became the family's permanent residence. His poem Cromwell won the 1843 Newdigate prize.[5] He graduated in the following year with second class honours in Literae Humaniores. In 1845, after a short interlude of teaching at Rugby, Arnold was elected Fellow of Oriel College, Oxford. In 1847, he became Private Secretary to Lord Lansdowne, Lord President of the Council. In 1849, he published his first book of poetry, The Strayed Reveller. In 1850 Wordsworth died; Arnold published his "Memorial Verses" on the older poet in Fraser's Magazine. |

幼少期 彼はトーマス・アーノルドと妻メアリー・ペンローズ・アーノルドの長男として、1822年12月24日にミドルセックス州ラレーハム・オン・テムズで生まれた。ジョン・キーブルはマシューの代父となった。 1828年、トーマス・アーノルドはラグビー校の校長に任命され、その年に一家は同校に居を構えた。1831年より、アーノルドはラレハムで聖職者の叔父 ジョン・バックランドから家庭教師を受ける。1834年、アーノルド一家は湖水地方の別荘フォックス・ハウに滞在した。そこにはウィリアム・ワーズワース が隣人として住んでおり、親しい友人であった。 1836年、アーノルドはウィンチェスター・カレッジに送られたが、1837年にはラグビー校に戻った。1838年には6年生となり、父親の直接指導を受 けることになった。彼は家族向けの雑誌に詩を書き、学校の賞を獲得した。彼の受賞詩「ローマのアラリック」はラグビーで印刷された。 1840年11月、17歳でアーノルドはオックスフォード大学のベイリオル・カレッジに入学し、1841年には一般奨学金を獲得、1844年に文学士号を 取得した。[3][4] オックスフォード大学在学中、父の友人であったラグビー校出身のアーサー・ヒュー・クロウ(Arthur Hugh Clough)との友情が深まった。彼は、聖処女マリア教会の大学教会で行われたジョン・ヘンリー・ニューマンの説教に出席したが、オックスフォード運動 には参加しなかった。1842年に父が死去した後、フォックス・ハウは一家の恒久的な住居となった。彼の詩『クロムウェル』は1843年のニューディゲー ト賞を受賞した。[5] 彼は翌年、古典文献学で優等2等で卒業した。 1845年、ラグビーで短期間教鞭をとった後、アーノルドはオックスフォード大学オリアンカレッジのフェローに選出された。1847年には、内閣総理大臣 のランズダウン卿の個人秘書となった。1849年には最初の詩集『迷える放蕩者』を出版した。1850年には、ワーズワースが死去し、アーノルドは『フレ イザー誌』にワーズワースを追悼する詩「追悼の詩」を発表した。 |

| Marriage and career Wishing to marry but unable to support a family on the wages of a private secretary, Arnold sought the position of and was appointed in April 1851 one of Her Majesty's Inspectors of Schools. Two months later, he married Frances Lucy, daughter of Sir William Wightman, Justice of the Queen's Bench. Arnold often described his duties as a school inspector as "drudgery" although "at other times he acknowledged the benefit of regular work."[6] The inspectorship required him, at least at first, to travel constantly and across much of England. As narrated by Stefan Collini in his 1988 book on Arnold: "Initially, Arnold was responsible for inspecting Nonconformist schools across a broad swath of central England. He spent many dreary hours during the 1850s in railway waiting rooms and small-town hotels, and longer hours still listening to children reciting their lessons and parents reciting their grievances. But that also meant that he, among the first generation of the railway age, travelled across more of England than any man of letters had ever done. Although his duties were later confined to a smaller area, Arnold knew the society of provincial England better than most of the metropolitan authors and politicians of the day."[7] |

結婚とキャリア 結婚を望んでいたが、秘書の給料では家族を養うことができなかったアーノルドは、1851年4月に女王陛下の学校視察官の職を求め、任命された。 2か月後、彼は女王裁判所判事ウィリアム・ワイトマンの娘フランシス・ルーシーと結婚した。 アーノルドは学校視察官としての職務を「苦役」と表現することが多かったが、「一方で、規則正しい仕事の利点も認めていた」[6]。 視察官の職務は、少なくとも当初は、イングランドの広範囲にわたって絶えず移動することを必要とした。 ステファン・コルニーが1988年に出版したアーノルドに関する著書の中で次のように述べている。「当初、アーノルドはイングランド中部の広範囲にわたる 非国教派系の学校の視察を担当していた。1850年代には、鉄道の待合室や小さな町のホテルで多くの退屈な時間を過ごし、さらに長い時間を費やして、子供 たちが授業で暗唱した内容を聞いたり、親たちが不満を訴えたりするのを聞いた。しかし、それはまた、鉄道時代の最初の世代の一人として、文学者であれば誰 よりも多くのイングランドを旅したことを意味する。その後、彼の職務はより狭い範囲に限定されたが、アーノルドは当時の都会の作家や政治家よりも、イング ランドの地方社会をよく知っていた。 |

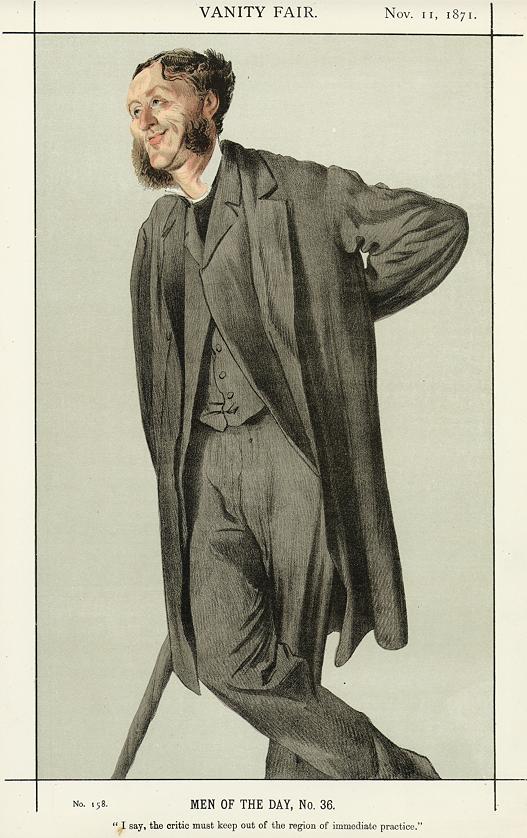

Literary career Caricature by James Tissot published in Vanity Fair in 1871 In 1852, Arnold published his second volume of poems, Empedocles on Etna, and Other Poems. In 1853, he published Poems: A New Edition, a selection from the two earlier volumes famously excluding Empedocles on Etna, but adding new poems, Sohrab and Rustum and The Scholar Gipsy. In 1854, Poems: Second Series appeared; also a selection, it included the new poem Balder Dead. Arnold was elected Professor of Poetry at Oxford in 1857, and he was the first in this position to deliver his lectures in English rather than in Latin.[8] He was re-elected in 1862. On Translating Homer (1861) and the initial thoughts that Arnold would transform into Culture and Anarchy were among the fruits of the Oxford lectures. In 1859, he conducted the first of three trips to the continent at the behest of parliament to study European educational practices. He self-published The Popular Education of France (1861), the introduction to which was later published under the title Democracy (1879).[9]  Arnold's gravestone Matthew Arnold's grave at All Saints' Church, Laleham, Surrey. In 1865, Arnold published Essays in Criticism: First Series. Essays in Criticism: Second Series would not appear until November 1888, shortly after his death. In 1866, he published Thyrsis, his elegy to Clough who had died in 1861. Culture and Anarchy, Arnold's major work in social criticism (and one of the few pieces of his prose work currently in print) was published in 1869. Literature and Dogma, Arnold's major work in religious criticism appeared in 1873. In 1883 and 1884, Arnold toured the United States and Canada[10] delivering lectures on education, democracy and Ralph Waldo Emerson. He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1883.[11] In 1886, he retired from school inspection and made another trip to America. An edition of Poems by Matthew Arnold, with an introduction by A. C. Benson and illustrations by Henry Ospovat, was published in 1900 by John Lane.[12] Death Arnold died suddenly in 1888 of heart failure whilst running to meet a tram that would have taken him to the Liverpool Landing Stage to see his daughter, who was visiting from the United States where she had moved after marrying an American. His wife died in June 1901.[13] |

文学活動 1871年に『ヴァニティ・フェア』誌に掲載されたジェームズ・ティソによる風刺画 1852年、アーノルドは詩集の第2巻『エトナのエンペドクレス、およびその他の詩』を出版した。1853年には『詩集: エトナのエンペドクレスを除くことで有名な2巻から抜粋した詩集で、新たに詩「ソラブとルスタム」と「学者ジプシー」を追加した新版である。1854年に は『詩集:第2シリーズ』が出版された。これも抜粋版で、新たに「バルダー・デッド」が追加されている。 1857年、アーノルドはオックスフォード大学の詩学教授に選出され、この職に就いた人物としては初めて、講義をラテン語ではなく英語で行った。[8] 1862年には再選された。『ホメーロス』の翻訳(1861年)や、アーノルドが『文化と無政府主義』に変貌させることになる初期の考えは、オックス フォード大学での講義の成果であった。1859年には、議会からの要請により、ヨーロッパの教育実践を研究するために、3度にわたる大陸への旅の最初の旅 を行った。彼は『フランスの大衆教育』(1861年)を自費出版し、その序文は後に『民主主義』(1879年)というタイトルで出版された。  アーノルドの墓石 マシュー・アーノルドの墓は、サリー州ラレハムのオールセインツ教会にある。 1865年、アーノルドは『批評のためのエッセイ:第1シリーズ』を出版した。『批評のためのエッセイ:第2シリーズ』は、彼の死の直後の1888年11 月まで出版されなかった。1866年には、1861年に亡くなったクロウへの挽歌『ティルシス』を出版した。社会批判に関する主要著作であり、現在でも出 版されている数少ない散文作品のひとつである『文化と無政府状態』(Culture and Anarchy)は1869年に出版された。宗教批判に関する主要著作である『文学と教義』(Literature and Dogma)は1873年に出版された。1883年と1884年には、アメリカとカナダを巡り[10]、教育、民主主義、ラルフ・ウォルドー・エマーソン に関する講演を行った。1883年には、アメリカ芸術科学アカデミーの外国人名誉会員に選出された。[11] 1886年には学校視察から引退し、再びアメリカを訪れた。マシュー・アーノルドの詩集は、A. C. ベンソンの序文とヘンリー・オスポヴァートの挿絵付きで、1900年にジョン・レーンから出版された。 死 1888年、アーノルドは、アメリカに移住した娘に会うためにリバプール・ランディング・ステージに向かう路面電車に駆け寄ろうとして、心不全により急死した。妻は1901年6月に死去した。[13] |

Character Caricature from Punch, 1881: "Admit that Homer sometimes nods, That poets do write trash, Our Bard has written "Balder Dead," And also Balder-dash" "Matthew Arnold", wrote G. W. E. Russell in Portraits of the Seventies, is "a man of the world entirely free from worldliness and a man of letters without the faintest trace of pedantry".[14] Arnold was a familiar figure at the Athenaeum Club, a frequent diner-out and guest at great country houses, charming, fond of fishing (but not of shooting),[15] and a lively conversationalist, with a self-consciously cultivated air combining foppishness and Olympian grandeur. He read constantly, widely, and deeply, and in the intervals of supporting himself and his family by the quiet drudgery of school inspecting, filled notebook after notebook with meditations of an almost monastic tone. In his writings, he often baffled and sometimes annoyed his contemporaries by the apparent contradiction between his urbane, even frivolous manner in controversy, and the "high seriousness" of his critical views and the melancholy, almost plaintive note of much of his poetry. "A voice poking fun in the wilderness" was T. H. Warren's description of him.[citation needed] |

キャラクター 風刺画、1881年刊行の『パンチ』より:「ホメーロスも時にはうなずく、詩人たちがゴミのようなものを書くこともある、我らが詩人も『バルダー・デッド』や『バルダー・ダッシュ』を書いたではないか」 「マシュー・アーノルド」は、G. W. E. ラッセル著『1870年代の肖像』の中で、「俗世間から完全に自由な世界人であり、教条主義の影もない文学者」と評されている。[14] アーノルドは、アテナウム・クラブでは顔なじみの人物であり、 社交界ではよく知られた存在であり、外食や大邸宅への客として頻繁に招かれていた。魅力的で、釣り(射撃は好まなかった)を愛し、[15] 生き生きとした会話の相手となり、気取った雰囲気とオリンポスの神々のような威厳を併せ持つ、意識的に磨き上げられた風格を備えていた。彼は常に、広く、 深く読書し、自身と家族を養うために学校視察という地味な仕事に従事する合間を縫って、ノートを何冊も埋め尽くすほど、禁欲的なトーンの思索を書き留めて いた。彼の著作では、洗練された、時に軽薄な論争の態度と、彼の批判的な見解の「高い真剣さ」、そして彼の詩の多くに見られる憂鬱で、ほとんど嘆きにも似 た調子との明らかな矛盾によって、彼は同時代の人々をしばしば困惑させ、時にはいらだたせることもあった。「荒野の中で戯れる声」は、T. H. ウォーレンによる彼の描写である。[要出典] |

| Poetry Arnold's literary career — aside from two youthful prize poems — had begun in 1849 with the publication of The Strayed Reveller and Other Poems by A., which attracted little notice and was soon withdrawn. It contained what is perhaps Arnold's most purely poetical poem, "The Forsaken Merman." Empedocles on Etna and Other Poems (among them "Tristram and Iseult"), published in 1852, had a similar fate. In 1858 he published his tragedy of Merope, calculated, he wrote to a friend, "rather to inaugurate my Professorship with dignity than to move deeply the present race of humans," and chiefly remarkable for some experiments in unusual – and unsuccessful – metres. Arnold is sometimes called the third great Victorian poet, along with Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Robert Browning.[16] Harold Bloom echoes Arnold's self-characterization in his introduction (as series editor) to the Modern Critical Views volume on Arnold: "Arnold got into his poetry what Tennyson and Browning scarcely needed (but absorbed anyway), the main march of mind of his time." Of his poetry, Bloom says, Whatever his achievement as a critic of literature, society, or religion, his work as a poet may not merit the reputation it has continued to hold in the twentieth century. Arnold is, at his best, a very good but highly derivative poet. ... As with Tennyson, Hopkins, and Rossetti, Arnold's dominant precursor was Keats, but this is an unhappy puzzle, since Arnold (unlike the others) professed not to admire Keats greatly, while writing his own elegiac poems in a diction, meter, imagistic procedure, that are embarrassingly close to Keats.[17] Sir Edmund Chambers noted that "in a comparison between the best works of Matthew Arnold and that of his six greatest contemporaries ... the proportion of work which endures is greater in the case of Matthew Arnold than in any one of them."[18] Chambers judged Arnold's poetic vision by its simplicity, lucidity, and straightforwardness; its literalness ...; the sparing use of aureate words, or of far-fetched words, which are all the more effective when they come; the avoidance of inversions, and the general directness of syntax, which gives full value to the delicacies of a varied rhythm, and makes it, of all verse that I know, the easiest to read aloud.[19] His 1867 poem "Dover Beach" depicted a nightmarish world from which the old religious verities have receded. It is sometimes held up as an early, if not the first, example of the modern sensibility. In a famous preface to a selection of the poems of William Wordsworth, Arnold identified, a little ironically, as a "Wordsworthian". The influence of Wordsworth, both in ideas and in diction, is unmistakable in Arnold's best poetry. "Dover Beach" is included in Ray Bradbury's novel Fahrenheit 451, and is featured prominently in the novel Saturday by Ian McEwan. It has been quoted or alluded to in a variety of other contexts (see Dover Beach). Henry James wrote that Arnold's poetry will appeal to those who "like their pleasures rare" and who like to hear the poet "taking breath". He derived the subject matter of his narrative poems from traditional or literary sources, and much of the romantic melancholy of his earlier poems from Senancour's "Obermann". Arnold was keenly aware of his place in poetry. In an 1869 letter to his mother, he wrote: My poems represent, on the whole, the main movement of mind of the last quarter of a century, and thus they will probably have their day as people become conscious to themselves of what that movement of mind is, and interested in the literary productions which reflect it. It might be fairly urged that I have less poetical sentiment than Tennyson and less intellectual vigour and abundance than Browning; yet because I have perhaps more of a fusion of the two than either of them, and have more regularly applied that fusion to the main line of modern development, I am likely enough to have my turn as they have had theirs.[20] Stefan Collini regards this as "an exceptionally frank, but not unjust, self-assessment. ... Arnold's poetry continues to have scholarly attention lavished upon it, in part because it seems to furnish such striking evidence for several central aspects of the intellectual history of the nineteenth century, especially the corrosion of 'Faith' by 'Doubt'. No poet, presumably, would wish to be summoned by later ages merely as an historical witness, but the sheer intellectual grasp of Arnold's verse renders it peculiarly liable to this treatment."[21] |

詩 アーノルドの文学的キャリアは、若かりし頃に書いた2編の受賞詩を除いて、1849年に『The Strayed Reveller and Other Poems by A.』を出版したことから始まった。この詩集はほとんど注目を集めることなく、すぐに回収された。この詩集には、おそらくアーノルドの最も純粋な詩である 「The Forsaken Merman」が収められていた。1852年に出版された『エトナのエンペドクレスとその他の詩』(その中には「トリスタンとイゾルデ」も含まれる)も同 様の運命をたどった。1858年には、友人宛ての手紙で「現世の人々を深く感動させるというよりも、むしろ威厳をもって教授職に就くため」と記したとお り、悲劇『メローペ』を出版した。この作品は、主に、珍しい(そして失敗した)韻律を試みたことで注目に値する。アーノルドは、アルフレッド・テニスン卿 やロバート・ブラウニングと並んで、ビクトリア朝の3大詩人と呼ばれることもある。[16] ハロルド・ブルームは、アーノルドに関する『Modern Critical Views』の巻頭(シリーズ編集者)で、アーノルドの自己評価を引用している。「アーノルドは、テニスンやブラウニングがほとんど必要としなかった(し かし、いずれにしても吸収した)彼の時代の精神の主な流れを詩に取り入れた。」ブルームは、アーノルドの詩について、次のように述べている。 文学、社会、宗教の批評家としての彼の功績が何であれ、詩人としての彼の作品は20世紀に保ち続けた名声に値しないかもしれない。アーノルドは、最高の状 態で、非常に優れているが、非常に模倣的な詩人である。テニスン、ホプキンズ、ロセッティと同様に、アーノルドの最も影響を与えた先駆者はキーツであった が、これは不幸なパズルである。なぜなら、アーノルドは(他の詩人とは異なり)キーツを大いに賞賛しているわけではないと公言していたが、一方で、キーツ の詩作に恥ずかしくなるほど近い文体、韻律、イメージの手法で、自身の哀歌を書いていたからだ。[17] サー・エドマンド・チェンバースは、「マシュー・アーノルドの最高傑作と、彼と同時代の6人の偉大な詩人の最高傑作を比較すると、後世に残る作品の割合 は、マシュー・アーノルドの方が他の誰よりも多い」と指摘している。[18] チェンバースは、アーノルドの詩的ビジョンを、 そのシンプルさ、明晰さ、率直さ、その文字通りの表現、... 控えめな金ピカ言葉や、遠回しな言葉の使用、それらが効果を発揮する時、倒置法の回避、一般的な構文の直接性、それらが多様なリズムの繊細さを最大限に引 き出し、私が知る詩の中で最も朗読しやすいものにしている。 1867年の詩「ドーバー・ビーチ」では、古い宗教的真理が遠のいた悪夢のような世界が描かれている。これは、最初のものではないにしても、初期の近代的 な感性の例として挙げられることがある。アーノルドは、ウィリアム・ワーズワースの詩の選集の有名な序文で、少し皮肉を込めて「ワーズワース派」と名乗っ ている。ワーズワースの影響は、思想と表現の両面において、アーノルドの最も優れた詩にはっきりと見て取れる。「ドーバー・ビーチ」はレイ・ブラッドベリ の小説『華氏451』に引用されており、イアン・マキューアンの小説『土曜』でも重要な役割を果たしている。この詩は、さまざまな文脈で引用または言及さ れている(「ドーバー・ビーチ」を参照)。ヘンリー・ジェイムズは、アーノルドの詩は「めったにない快楽を好む」人々や、詩人が「息継ぎ」をするのを聞く のが好きな人々を惹きつけるだろうと書いた。彼は、物語詩の主題を伝統的または文学的な情報源から引き出し、初期の詩のロマン派的な憂鬱感の多くをセナン クール著『オベルマン』から得た。 アーノルドは、詩における自身の位置を鋭く認識していた。1869年に母親に宛てた手紙の中で、彼は次のように書いている。 私の詩は、概ね、この四半世紀における主な心の動きを表現している。そして、人々がその心の動きが何であるかに気づき、それを反映する文学作品に関心を持 つようになったとき、おそらく日の目を見るだろう。私はテニスンよりも詩情に欠け、ブラウニングよりも知的な活力と豊かさに欠けるかもしれない。しかし、 おそらく私は彼らよりもこの2つの融合を多く持ち、その融合をより規則的に近代の発展の主要な流れに適用してきたため、彼らと同じように私の時代が来る可 能性は十分にある。 ステファン・コリーニは、これを「非常に率直だが、不当ではない自己評価」とみなしている。アーノルドの詩は、19世紀の知的歴史の中心的な側面、特に 「疑い」による「信仰」の腐食について、非常に印象的な証拠を提供しているように思われるため、学術的な注目を集め続けている。おそらく、詩人であれば誰 しも、歴史の証人として後世に呼び出されることを望まないだろう。しかし、アーノルドの詩の圧倒的な知的把握力は、それをこの扱いに対して特に脆弱なもの としている。」[21] |

| Prose Assessing the importance of Arnold's prose work in 1988, Stefan Collini stated, "for reasons to do with our own cultural preoccupations as much as with the merits of his writing, the best of his prose has a claim on us today that cannot be matched by his poetry."[22] "Certainly there may still be some readers who, vaguely recalling 'Dover Beach' or 'The Scholar Gipsy' from school anthologies, are surprised to find he 'also' wrote prose."[23] George Watson follows George Saintsbury in dividing Arnold's career as a prose writer into three phases: 1) early literary criticism that begins with his preface to the 1853 edition of his poems and ends with the first series of Essays in Criticism (1865); 2) a prolonged middle period (overlapping the first and third phases) characterised by social, political and religious writing (roughly 1860–1875); 3) a return to literary criticism with the selecting and editing of collections of Wordsworth's and Byron's poetry and the second series of Essays in Criticism.[24] Both Watson and Saintsbury declare their preference for Arnold's literary criticism over his social or religious criticism. More recent writers, such as Collini, have shown a greater interest in his social writing,[25] while over the years a significant second tier of criticism has focused on Arnold's religious writing.[26] His writing on education has not drawn a significant critical endeavour separable from the criticism of his social writings.[27] Selections from the Prose Work of Matthew Arnold[28] Literary criticism Arnold's work as a literary critic began with the 1853 "Preface to the Poems". In it, he attempted to explain his extreme act of self-censorship in excluding the dramatic poem "Empedocles on Etna". With its emphasis on the importance of subject in poetry, on "clearness of arrangement, rigor of development, simplicity of style" learned from the Greeks, and in the strong imprint of Goethe and Wordsworth, may be observed nearly all the essential elements in his critical theory. George Watson described the preface, written by the thirty-one-year-old Arnold, as "oddly stiff and graceless when we think of the elegance of his later prose."[29] Criticism began to take first place in Arnold's writing with his appointment in 1857 to the professorship of poetry at Oxford, which he held for two successive terms of five years. In 1861 his lectures On Translating Homer were published, to be followed in 1862 by Last Words on Translating Homer. Especially characteristic, both of his defects and his qualities, are on the one hand, Arnold's unconvincing advocacy of English hexameters and his creation of a kind of literary absolute in the "grand style," and, on the other, his keen feeling of the need for a disinterested and intelligent criticism in England.[citation needed] Although Arnold's poetry received only mixed reviews and attention during his lifetime, his forays into literary criticism were more successful. Arnold is famous for introducing a methodology of literary criticism somewhere between the historicist approach common to many critics at the time and the personal essay; he often moved quickly and easily from literary subjects to political and social issues. His Essays in Criticism (1865, 1888), remains a significant influence on critics to this day, and his prefatory essay to that collection, "The Function of Criticism at the Present Time", is one of the most influential essays written on the role of the critic in identifying and elevating literature – even while saying, "The critical power is of lower rank than the creative." Comparing himself to the French liberal essayist Ernest Renan, who sought to inculcate morality in France, Arnold saw his role as inculcating intelligence in England.[30] In one of his most famous essays on the topic, "The Study of Poetry", Arnold wrote that, "Without poetry, our science will appear incomplete; and most of what now passes with us for religion and philosophy will be replaced by poetry". He considered the most important criteria used to judge the value of a poem were "high truth" and "high seriousness". By this standard, Chaucer's Canterbury Tales did not merit Arnold's approval. Further, Arnold thought the works that had been proven to possess both "high truth" and "high seriousness", such as those of Shakespeare and Milton, could be used as a basis of comparison to determine the merit of other works of poetry. He also sought for literary criticism to remain disinterested, and said that the appreciation should be of "the object as in itself it really is."[citation needed] Social criticism He was led on from literary criticism to a more general critique of the spirit of his age. Between 1867 and 1869 he wrote Culture and Anarchy, famous for the term he popularised for the middle class of the English Victorian era population: "Philistines", a word which derives its modern cultural meaning (in English – the German-language usage was well established) from him. Culture and Anarchy is also famous for its popularisation of the phrase "sweetness and light", first coined by Jonathan Swift.[31] In Culture and Anarchy, Arnold identifies himself as a Liberal and "a believer in culture" and takes up what historian Richard Bellamy calls the "broadly Gladstonian effort to transform the Liberal Party into a vehicle of political moralism."[32][33] Arnold viewed with scepticism the plutocratic grasping in socioeconomic affairs, and engaged the questions which vexed many Victorian liberals on the nature of power and the state's role in moral guidance.[34] Arnold vigorously attacked the Nonconformists and the arrogance of "the great Philistine middle-class, the master force in our politics."[35] The Philistines were "humdrum people, slaves to routine, enemies to light" who believed that England's greatness was due to her material wealth alone and took little interest in culture.[35] Liberal education was essential, and by that Arnold meant a close reading and attachment to the cultural classics, coupled with critical reflection.[36] Arnold saw the "experience" and "reflection" of Liberalism as naturally leading to the ethical end of "renouncement," as evoking the "best self" to suppress one's "ordinary self."[33] Despite his quarrels with the Nonconformists, Arnold remained a loyal Liberal throughout his life, and in 1883, William Gladstone awarded him an annual pension of 250 pounds "as a public recognition of service to the poetry and literature of England."[37][38][39] Many subsequent critics such as Edward Alexander, Lionel Trilling, George Scialabba and Russell Jacoby have emphasised the liberal character of Arnold's thought.[40][41][42] Hugh Stuart Jones describes Arnold's work as a "liberal critique of Victorian liberalism" while Alan S. Kahan places Arnold's critique of middle-class philistinism, materialism, and mediocrity within the tradition of 'aristocratic liberalism' as exemplified by liberal thinkers such as John Stuart Mill and Alexis de Tocqueville.[43][44] Arnold's "want of logic and thoroughness of thought" as noted by John M. Robertson in Modern Humanists was an aspect of the inconsistency of which Arnold was accused.[45] Few of his ideas were his own, and he failed to reconcile the conflicting influences which moved him so strongly. "There are four people, in especial," he once wrote to Cardinal Newman, "from whom I am conscious of having learnt – a very different thing from merely receiving a strong impression – learnt habits, methods, ruling ideas, which are constantly with me; and the four are – Goethe, Wordsworth, Sainte-Beuve, and yourself." Dr. Arnold must be added; the son's fundamental likeness to the father was early pointed out by Swinburne, and was later attested by Matthew Arnold's grandson, Mr. Arnold Whitridge. Others such as Stefan Collini suggest that much of the criticism aimed at Arnold is based on "a convenient parody of what he is supposed to have stood for" rather than the genuine article.[33] Journalistic criticism In 1887, Arnold was credited with coining the phrase "New Journalism", a term that went on to define an entire genre of newspaper history, particularly Lord Northcliffe's turn-of-the-century press empire. However, at the time, the target of Arnold's irritation was not Northcliffe, but the sensational journalism of Pall Mall Gazette editor, W. T. Stead.[46] Arnold had enjoyed a long and mutually beneficial association with the Pall Mall Gazette since its inception in 1865. As an occasional contributor, he had formed a particular friendship with its first editor, Frederick Greenwood and a close acquaintance with its second, John Morley. But he strongly disapproved of the muck-raking Stead, and declared that, under Stead, "the P.M.G., whatever may be its merits, is fast ceasing to be literature."[47] He was appalled at the shamelessness of the sensationalistic new journalism of the sort he witnessed on his tour of the United States in 1886. In his account of that tour, "Civilization in the United States", he observed, "if one were searching for the best means to efface and kill in a whole nation the discipline of self-respect, the feeling for what is elevated, he could do no better than take the American newspapers."[48] Religious criticism His religious views were unusual for his time and caused sorrow to some of his best friends.[49] Scholars of Arnold's works disagree on the nature of Arnold's personal religious beliefs. Under the influence of Baruch Spinoza and his father, Dr. Thomas Arnold, he rejected the supernatural elements in religion,[50] even while retaining a fascination for church rituals. In the preface to God and the Bible, written in 1875, Arnold recounts a powerful sermon he attended discussing the "salvation by Jesus Christ", he writes: "Never let us deny to this story power and pathos, or treat with hostility ideas which have entered so deep into the life of Christendom. But the story is not true; it never really happened".[51] He continues to express his concern with the historicity of the Bible, explaining that "The personages of the Christian heaven and their conversations are no more matter of fact than the personages of the Greek Olympus and their conversations."[51] He also wrote in Literature and Dogma: "The word 'God' is used in most cases as by no means a term of science or exact knowledge, but a term of poetry and eloquence, a term thrown out, so to speak, as a not fully grasped object of the speaker's consciousness – a literary term, in short; and mankind mean different things by it as their consciousness differs."[52] He defined religion as "morality touched with emotion".[53] However, he also wrote in the same book, "to pass from a Christianity relying on its miracles to a Christianity relying on its natural truth is a great change. It can only be brought about by those whose attachment to Christianity is such, that they cannot part with it, and yet cannot but deal with it sincerely."[54] |

散文 1988年、アーノルドの散文作品の重要性を評価したステファン・コリーニは、「彼の作品の価値だけでなく、我々の文化的関心にも関係する理由から、彼の 散文の最高傑作は、 彼の詩には見られない魅力がある」と述べている。[22] 「確かに、学校の詩集で『ドーバー・ビーチ』や『学者ジプシー』を曖昧に思い出した読者の中には、彼が散文も書いていたことを知って驚く人もいるかもしれ ない」[23] ジョージ・ワトソンは、ジョージ・セインツベリーの考えに従い、散文作家としてのアーノルドのキャリアを3つの段階に分けている。1)1853年の詩集の 序文から始まり、『批評における随筆』(1865年)の最初のシリーズで終わる初期の文学批評、2)社会、政治、宗教に関する著作(おおよそ 1860年から1875年)3)ワーズワースとバイロンの詩の選集の編集と『批評エッセイ』第2シリーズの執筆による文学批評への回帰。[24] ワトソンとセインツベリーは、ともにアーノルドの社会や宗教に関する批評よりも文学批評を好んでいる。コリーニなどのより最近の作家は、彼の社会的な著作 に大きな関心を示しているが[25]、長年にわたり、アーノルドの宗教的な著作に焦点を当てた重要な第二の批評の層が存在している[26]。彼の教育に関 する著作は、彼の社会的な著作の批評から切り離された重要な批評的努力を引き出していない[27]。 マシュー・アーノルドの散文作品からの抜粋[28] 文学批評 アーノルドの文学評論家としての仕事は、1853年の「詩への序文」から始まった。この中で、彼は劇詩「エトナのエンペドクレス」を除外するという極端な 自己検閲行為を説明しようとした。詩における主題の重要性、ギリシアから学んだ「明瞭な構成、厳格な展開、簡素な文体」、そしてゲーテとワーズワースの強 い影響に重点を置いたこの序文には、彼の批評理論のほぼすべての重要な要素が観察できる。 31歳のアーノルドが書いたこの序文について、ジョージ・ワトソンは「彼の後の散文の優雅さを考えると、妙に堅苦しく、品がない」と評している。 1857年にオックスフォード大学の詩の教授職に任命されたことで、アーノルドの著作における批評が第一の主題となった。彼は5年間の任期を2期連続で務 めた。1861年には『ホメーロス翻訳論』が出版され、1862年には『ホメーロス翻訳論の最終章』が出版された。とりわけ特徴的なのは、彼の欠点と長所 である。一方では、アーノルドの説得力に欠ける英語の六歩格の擁護と「グランドスタイル」における文学的絶対の創造であり、他方では、英国における無私で 知的な批評の必要性を鋭く感じ取っていたことである。 アーノルドの詩は生前は賛否両論で注目もされなかったが、文学批評への進出は成功を収めた。アーノルドは、当時多くの批評家が用いていた歴史主義的アプ ローチと個人的なエッセイの中間にある文学批評の方法論を導入したことで有名である。彼は文学の主題から政治や社会問題へと、素早く簡単に移行することが 多かった。彼の著書『批評論集』(1865年、1888年)は、今日に至るまで批評家に多大な影響を与え続けている。また、そのコレクションの序文である 「現時点における批評の役割」は、文学を識別し高める批評家の役割について書かれた最も影響力のあるエッセイのひとつである。「批評力は創造力よりも格下 である」と述べながらも、 フランスで道徳の普及に努めた自由主義的なエッセイスト、エルネスト・レナンのような人物と自分を比較し、アーノルドは、イギリスでは知性を普及させる役 割を担うべきだと考えていた。[30] アーノルドは、このテーマに関する最も有名なエッセイのひとつ「詩の研究」の中で、「詩がなければ、科学は不完全なものに見えるだろう。そして、現在、我 々の間で宗教や哲学とされているもののほとんどが、詩によって置き換えられるだろう」と書いている。彼は詩の価値を判断する最も重要な基準として、「高い 真実性」と「高い深刻さ」を挙げていた。この基準に照らせば、チョーサーの『カンタベリー物語』はアーノルドの賛同を得るに値しない。さらに、アーノルド は「高い真実性」と「高い深刻さ」の両方を備えていることが証明されている作品、例えばシェイクスピアやミルトンの作品を、他の詩の価値を判断する基準と して比較できると考えていた。また、文学批評は利害関係のないものであり続けるべきだと考え、「対象を、それが本当にそうであるものとして評価すべきであ る」と述べた。 社会批判 彼は文学批評から、より一般的な同時代の精神の批評へと導かれた。1867年から1869年の間に、彼は『文化と無政府状態』を著した。この本は、ヴィク トリア朝時代の英国の中流階級を表す言葉として彼が広めた「フィルシタイズ(俗物)」という言葉で有名である。「フィルシタイズ (Philistines)」という言葉は、英語では現代の文化的意味を持つが(ドイツ語ではすでに定着していた)、この言葉は彼が普及させたものであ る。『文化と無政府状態』は、ジョナサン・スウィフトが最初に用いた「甘美と光明」という表現を普及させたことでも有名である。 『文化と無政府主義』において、アーノルドは自らをリベラル派であり「文化の信奉者」と位置づけ、歴史家のリチャード・ベラミーが「リベラル党を政治道徳 主義の手段に変えるためのグラッドストーン的な幅広い取り組み」と呼ぶものを引き継いだ。[32][33] アーノルドは、社会経済問題における富裕層による搾取を懐疑的に見ており、 権力の本質と道徳的指導における国家の役割について、多くのヴィクトリア朝のリベラル派を悩ませていた問題に取り組んだ。[34] アーノルドは非国教徒派と「偉大な俗物である中流階級、すなわち我々の政治の主たる勢力」の傲慢さを激しく攻撃した。[35] 俗物とは「平凡な人々、日常の奴隷、光の敵」であり、イングランドの偉大さは 物質的な富のみに起因するものであり、文化にはほとんど関心を示さなかった。[35] リベラルな教育は不可欠であり、アーノルドが意味する「リベラルな教育」とは、文化的な古典を注意深く読み、愛着を持つこと、そして批判的に考察すること を意味していた。[36] アーノルドは、リベラリズムの「経験」と「考察」は、当然ながら「放棄」という倫理的な結末につながると考えていた。それは、「最良の自己」を呼び起こ し、 「ありふれた自己」を抑制する「最良の自己」を呼び起こすのである。[33] 非国教徒派との論争にもかかわらず、アーノルドは生涯を通じて忠実な自由主義者であり続け、1883年にはウィリアム・グラッドストンから「英国の詩と文 学への貢献を公に認める」として、年金250ポンドを毎年受け取るようになった。[37][38][39] エドワード・アレクサンダー、ライオネル・トリリング、ジョージ・スカラブバ、ラッセル・ジェイコビーなど、その後の多くの批評家たちは、アーノルドの思 想のリベラルな性格を強調している。[40][41][42] ヒュー・スチュアート・ジョーンズは、アーノルドの作品を「ヴィクトリア朝のリベラリズムに対するリベラルな批判」と表現している。一方、 アラン・S・カハンは、ジョン・スチュアート・ミルやアレクシス・ド・トクヴィルといった自由主義思想家が体現する「貴族的自由主義」の伝統の中に、アー ノルドの中流階級の俗物根性、唯物論、平凡さに対する批判を位置づけている。 ジョン・M・ロバートソンが『現代のヒューマニストたち』で指摘したように、アーノルドの「論理と思想の徹底性の欠如」は、アーノルドが非難された一貫性 のなさの一側面であった。[45] 彼の考えのほとんどは彼自身の考えではなく、彼を強く動かした相反する影響を調和させることはできなかった。「特に4人の人物がいます」と、かつてニュー マン枢機卿に手紙を書いた。「彼らから学んだと自覚しているのです。それは、単に強い印象を受けたというのとはまったく違います。習慣、方法、支配的な考 え方を学びました。それらは常に私の中にあります。その4人とは、ゲーテ、ワーズワース、サント=ブーヴ、そしてあなたです。アーノルド博士を加えなけれ ばならない。息子の父親との根本的な類似性は、スウィンバーンによって早くから指摘されていたが、後にマシュー・アーノルドの孫であるアーノルド・ホイッ トリッジ氏によって証明された。ステファン・コリーニ氏など、アーノルドに対する批判の多くは、本物というよりも「彼が象徴しているとされるものの都合の 良いパロディ」に基づいていると指摘している。 ジャーナリズムの批評 1887年、アーノルドは「ニュー・ジャーナリズム」という言葉を造語したことで知られている。この言葉は、新聞史のジャンル全体を定義する言葉となり、 特にノースクリフ卿の世紀転換期の新聞帝国を定義する言葉となった。しかし、当時、アーノルドが苛立ちを覚えていたのはノースクリフではなく、パール・ モール・ガゼットの編集者W.T.ステッドの扇情的なジャーナリズムであった。[46] アーノルドは1865年の創刊以来、パール・モール・ガゼットと長く有益な関係を築いていた。時折寄稿する者として、初代編集者のフレデリック・グリーン ウッドとは特に親交を深め、2代目のジョン・モーリーとも親しい間柄であった。しかし、スティーッドの暴露記事を強く非難し、スティーッドの下では 「P.M.G.は、その長所が何であれ、急速に文学性を失いつつある」と宣言した。 彼は、1886年のアメリカ合衆国訪問中に目にしたセンセーショナルな新ジャーナリズムの恥知らずな性質に愕然とした。その訪問についての記述「アメリカ 合衆国の文明」の中で、彼は「もし、自尊心や高潔なものに対する感情を国民全体から消し去り、殺すための最善の手段を探しているなら、アメリカの新聞ほど ふさわしいものはないだろう」と述べている。 宗教批判 彼の宗教観は同時代としては異色であり、親しい友人たちを悲しませた。[49] アーノルドの作品を研究する学者の間でも、アーノルドの個人的な宗教的信念については意見が分かれている。 彼はバルーフ・スピノザと父親であるトマス・アーノルド博士の影響を受け、宗教における超自然的要素を否定したが、[50] 教会の儀式には依然として強い関心を抱いていた。1875年に書かれた『神と聖書』の序文で、アーノルドは「イエス・キリストによる救い」について語られ た力強い説教について回想し、次のように書いている。「この物語の持つ力強さや哀愁を否定してはならない。キリスト教世界の生活に深く入り込んでいる考え 方を敵対視してはならない。しかし、この物語は真実ではない。実際に起こったことではないのだ」。[51] 彼は聖書の史実性に対する懸念を表明し続け、「キリスト教の天国の人物や彼らの会話は、ギリシャ神話のオリンポスの人物や彼らの会話ほど、事実に基づくも のではない」と説明している。[51] また、『文学と教義』の中で、「『神』という言葉は、ほとんどの場合、 科学や厳密な知識の用語としてではなく、詩や雄弁の用語として、いわば話し手の意識が完全には把握できていない対象として放り出された用語、つまり文学的 な用語であり、人類は意識の相違によって、それぞれ異なる意味をそれに与えている」と述べている。[52] 彼は宗教を「感情に触れられた道徳」と定義した。[53] しかし、彼は同じ著書の中で、「奇跡に頼るキリスト教から、自然の真理に頼るキリスト教へと移行することは、大きな変化である。それは、キリスト教への愛 着が強く、キリスト教と別れることはできないが、キリスト教と真摯に向き合わなければならない人々によってのみもたらされる」とも書いている。[54] |

| Reputation Harold Bloom writes that "Whatever his achievement as a critic of literature, society or religion, his work as a poet may not merit the reputation it has continued to hold in the twentieth century. Arnold is, at his best, a very good, but highly derivative poet, unlike Tennyson, Browning, Hopkins, Swinburne and Rossetti, all of whom individualized their voices."[55] The writer John Cowper Powys, an admirer, wrote that, "with the possible exception of Merope, Matthew Arnold's poetry is arresting from cover to cover – [he] is the great amateur of English poetry [he] always has the air of an ironic and urbane scholar chatting freely, perhaps a little indiscreetly, with his not very respectful pupils."[56] Family  Frances Lucy Arnold—"Flu" to Matthew—1883 photograph The Arnolds had six children: Thomas (1852–1868); Trevenen William (1853–1872); Richard Penrose (1855–1908), an inspector of factories;[note 1] Lucy Charlotte (1858–1934), who married Frederick W. Whitridge of New York, whom she had met during Arnold's American lecture tour; Eleanore Mary Caroline (1861–1936) married (1) Hon. Armine Wodehouse (MP) in 1889, (2) William Mansfield, 1st Viscount Sandhurst, in 1909; Basil Francis (1866–1868). Reputation Harold Bloom writes that "Whatever his achievement as a critic of literature, society or religion, his work as a poet may not merit the reputation it has continued to hold in the twentieth century. Arnold is, at his best, a very good, but highly derivative poet, unlike Tennyson, Browning, Hopkins, Swinburne and Rossetti, all of whom individualized their voices."[55] The writer John Cowper Powys, an admirer, wrote that, "with the possible exception of Merope, Matthew Arnold's poetry is arresting from cover to cover – [he] is the great amateur of English poetry [he] always has the air of an ironic and urbane scholar chatting freely, perhaps a little indiscreetly, with his not very respectful pupils."[56] Family Frances Lucy Arnold—"Flu" to Matthew—1883 photograph The Arnolds had six children: Thomas (1852–1868); Trevenen William (1853–1872); Richard Penrose (1855–1908), an inspector of factories;[note 1] Lucy Charlotte (1858–1934), who married Frederick W. Whitridge of New York, whom she had met during Arnold's American lecture tour; Eleanore Mary Caroline (1861–1936) married (1) Hon. Armine Wodehouse (MP) in 1889, (2) William Mansfield, 1st Viscount Sandhurst, in 1909; Basil Francis (1866–1868). |

評価 ハロルド・ブルームは、「文学、社会、宗教の批評家としての彼の功績がどのようなものであれ、詩人としての彼の作品は、20世紀を通じて保ち続けてきた評 価に値するものではないかもしれない。アーノルドは、最高の状態で、非常に優れた詩人であるが、テニスン、ブラウニング、ホプキンズ、スウィンバーン、ロ セッティといった、独自のスタイルを確立した詩人たちとは異なり、非常に模倣的な詩人である」と書いている。[55] マシュー・アーノルドの詩は、メロペを除いては、最初から最後まで目を引く。彼は英国詩の偉大なアマチュアであり、常に皮肉で洗練された学者のような雰囲気を漂わせ、おそらくは少し無遠慮に、あまり敬意を払っていない生徒たちと自由に雑談している。 家族  フランシス・ルーシー・アーノルド(マシューの愛称は「フルー」)1883年の写真 アーノルド夫妻には6人の子供がいた。 トーマス(1852年~1868年) トレヴェネン・ウィリアム(1853年~1872年) リチャード・ペンローズ(1855年~1908年)は工場検査官であった。[注1] ルーシー・シャーロット(1858年 - 1934年)は、アーノルドのアメリカ講演ツアー中に知り合ったニューヨークのフレデリック・W・ホイットリッジと結婚した。 エレノア・メアリー・キャロライン(1861年 - 1936年)は、1889年にアルマイン・ウォドハウス(国会議員)と、1909年にウィリアム・マンチェスター(初代サンドハースト子爵)と結婚した。 バジル・フランシス(1866年 - 1868年)。 評価 ハロルド・ブルームは、「文学、社会、宗教の批評家としての彼の功績がどのようなものであれ、詩人としての彼の作品は、20世紀を通じて保ち続けてきた名 声に値するものではないかもしれない。アーノルドは、最高の状態で、非常に優れた詩人ではあるが、テニスン、ブラウニング、ホプキンズ、スウィンバーン、 ロセッティとは異なり、彼らの声は個性的であった」と書いている。 アーノルドの熱烈な支持者であった作家ジョン・カウパー・パウイスは、「メロペを除いては、マシュー・アーノルドの詩は最初から最後まで人を惹きつけてや まない。彼は英国詩の偉大なアマチュアであり、常に皮肉で洗練された学者の雰囲気を漂わせ、おそらくは少し無遠慮に、あまり敬意を払っていない生徒たちと 自由に雑談している」と書いている。[56] 家族 フランシス・ルーシー・アーノルド(マシューの呼び名は「フルー」)1883年の写真 アーノルド夫妻には6人の子供がいた。 トーマス(1852年~1868年)、 トレヴェネン・ウィリアム(1853年~1872年)、 リチャード・ペンローズ(1855年~1908年)は工場検査官であった。[注1] ルーシー・シャーロット(1858年~1934年)は、アーノルドのアメリカ講演ツアー中に知り合ったニューヨークのフレデリック・W・ホイットリッジと結婚した。 エレノア・メアリー・キャロライン(1861年 - 1936年)は、1889年にアルマイン・ウォドハウス(国会議員)と、1909年に初代サンドハースト子爵ウィリアム・マンチェスターと結婚した。 バジル・フランシス(1866年 - 1868年)。 |

| Selected bibliography Poetry Stanzas in Memory of the Author of "Obermann" (1849) The Strayed Reveller, and Other Poems (1849) Empedocles on Etna, and Other Poems (1852) Sohrab and Rustum (1853) The Scholar-Gipsy (1853) Stanzas from the Grande Chartreuse (1855) Memorial Verses to Wordsworth Rugby Chapel (1867) Thyrsis (1865) Prose Essays in Criticism (1865, 1888) Culture and Anarchy (1869) Friendship's Garland (1871) Literature and Dogma (1873) God and the Bible (1875) The Study Of Poetry(1880) |

参考文献 詩 『オベルマン』の著者追悼のスタンザ(1849年) 迷える放蕩者、およびその他の詩(1849年) エトナのエンペドクレス、およびその他の詩(1852年) ソラブとルスタム(1853年) 学者ジプシー(1853年) グランド・シャルトルーズからのスタンザ(1855年) ワーズワース追悼の詩 ラグビー・チャペル(1867年 ティルシス(1865年 散文 評論集(1865年、1888年 文化と無政府状態(1869年 友情の花冠(1871年 文学と教義(1873年 神と聖書(1875年 詩の研究(1880年 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matthew_Arnold |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆