マックス・シュティルナー

Max Stirner, 1806-1856

☆ ヨハン・カスパー・シュミット(Johann Kaspar Schmidt、1806年10月25日 - 1856年6月26日)は、マックス・シュティルナー(/ˈstɜˈrnər/; ドイツ語: [ˈstɜˈ] )として知られるドイツのポスト・ヘーゲル哲学者であり、主に社会的疎外と自己意識のヘーゲル概念を扱った。 [3]シュティルナーはしばしばニヒリズム、実存主義、精神分析理論、ポストモダニズム、個人主義的アナキズム、エゴイズムの先駆者の一人と見なされてい る[4][5]。 シュティルナーの主著である『唯一性とその性質』(ドイツ語:Der Einzige und sein Eigentum)は1844年にライプツィヒで出版され、その後多くの版や翻訳が出版されている[8][9]。

| Johann Kaspar

Schmidt (25 October 1806 – 26 June 1856), known professionally as Max

Stirner (/ˈstɜːrnər/; German: [ˈʃtɪʁnɐ]), was a German post-Hegelian

philosopher, dealing mainly with the Hegelian notion of social

alienation and self-consciousness.[3] Stirner is often seen as one of

the forerunners of nihilism, existentialism, psychoanalytic theory,

postmodernism, individualist anarchism, and egoism.[4][5] Stirner's main work, The Unique and Its Property[6][7] (German: Der Einzige und sein Eigentum), was first published in 1844 in Leipzig and has since appeared in numerous editions and translations.[8][9] |

ヨハン・カスパー・シュミット(Johann Kaspar

Schmidt、1806年10月25日 - 1856年6月26日)は、マックス・シュティルナー(/ˈstɜˈrnər/; ドイツ語:

[ˈstɜˈ] )として知られるドイツのポスト・ヘーゲル哲学者であり、主に社会的疎外と自己意識のヘーゲル概念を扱った。

[3]シュティルナーはしばしばニヒリズム、実存主義、精神分析理論、ポストモダニズム、個人主義的アナキズム、エゴイズムの先駆者の一人と見なされてい

る[4][5]。 シュティルナーの主著である『唯一性とその性質』(ドイツ語:Der Einzige und sein Eigentum)は1844年にライプツィヒで出版され、その後多くの版や翻訳が出版されている[8][9]。 |

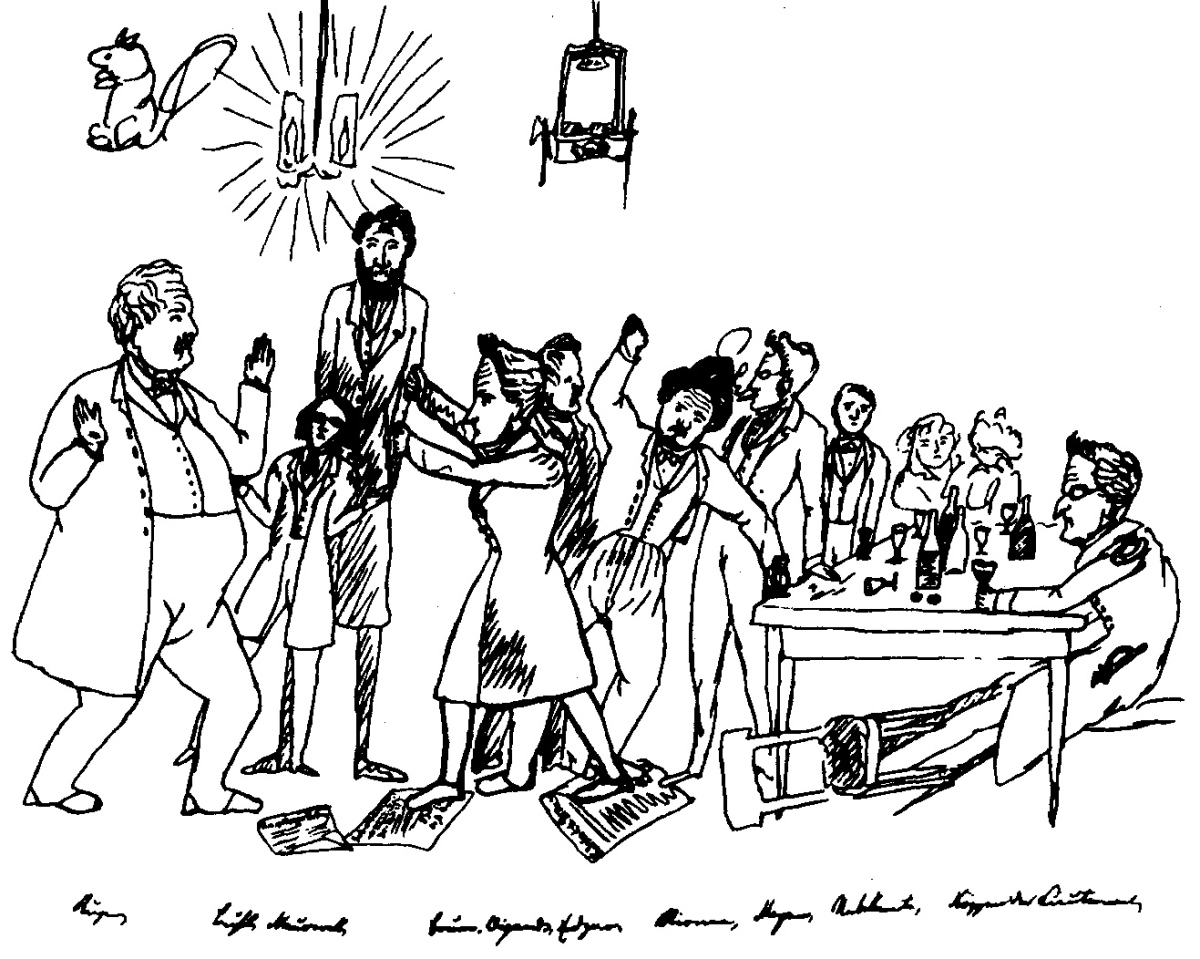

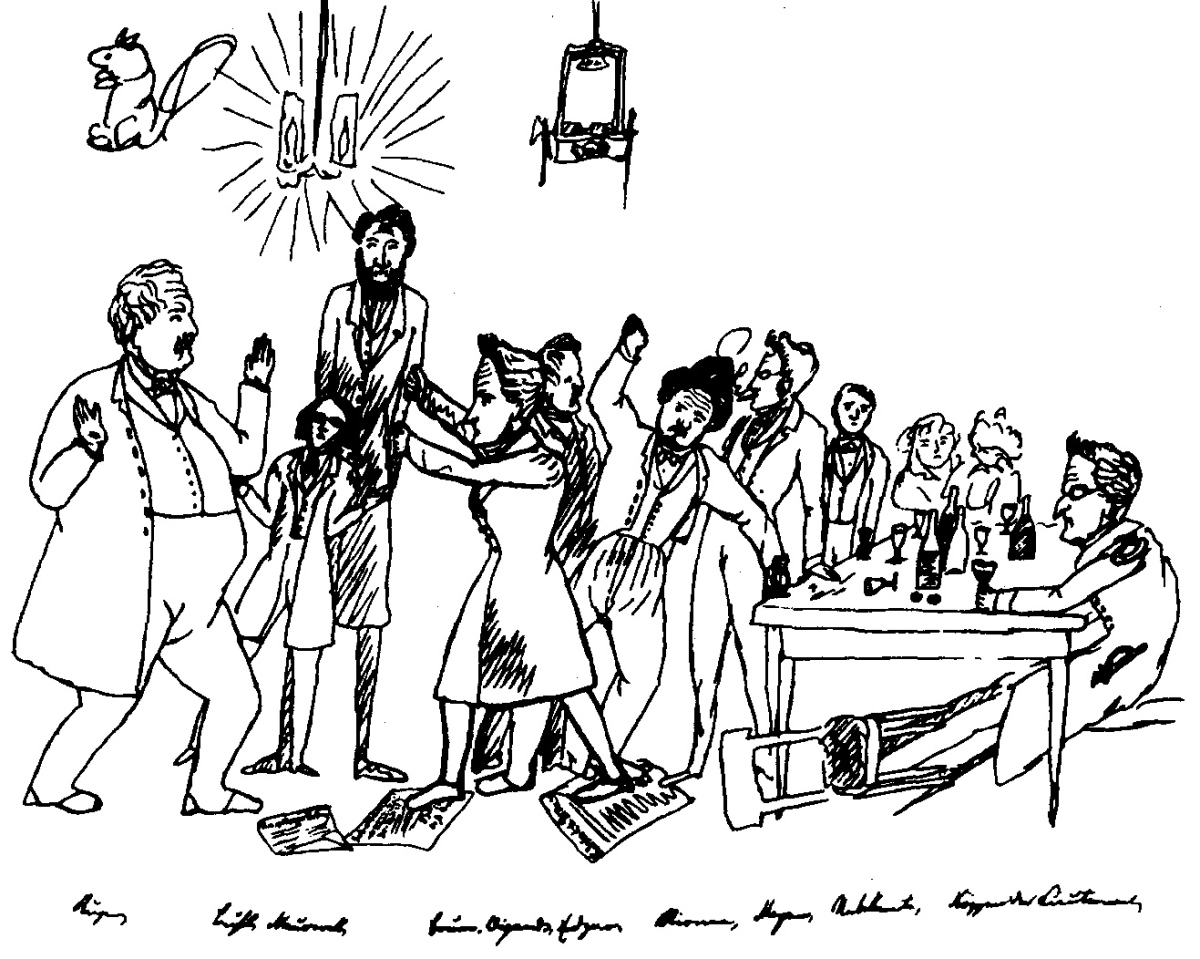

Biography Stirner's birthplace in Bayreuth Stirner was born in Bayreuth, Bavaria. What little is known of his life is mostly due to the Scottish-born German writer John Henry Mackay, who wrote a biography of Stirner (Max Stirner – sein Leben und sein Werk), published in German in 1898 (enlarged 1910, 1914) and translated into English in 2005. Stirner was the only child of Albert Christian Heinrich Schmidt (1769–1807) and Sophia Elenora Reinlein (1778–1839), who were Lutherans.[10] His father died of tuberculosis on 19 April 1807 at the age of 37.[11] In 1809, his mother remarried to Heinrich Ballerstedt (a pharmacist) and settled in West Prussian Kulm (now Chełmno, Poland). When Stirner turned 20, he attended the University of Berlin,[11] where he studied philology. He attended the lectures of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, who was to become a source of inspiration for his thinking.[12] He attended Hegel's lectures on the history of philosophy, the philosophy of religion and the subjective spirit. Stirner then moved to the University of Erlangen, which he attended at the same time as Ludwig Feuerbach.[13] Stirner returned to Berlin and obtained a teaching certificate, but he was unable to obtain a full-time teaching post from the Prussian government.[14] While in Berlin in 1841, Stirner participated in discussions with a group of young philosophers called Die Freien (The Free Ones), whom historians have subsequently categorized as the Young Hegelians. Some of the best known names in 19th-century literature and philosophy were involved with this group, including Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Bruno Bauer and Arnold Ruge. While some of the Young Hegelians were eager subscribers to Hegel's dialectical method and attempted to apply dialectical approaches to Hegel's conclusions, the left-wing members of the group broke with Hegel. Feuerbach and Bauer led this charge.  Stirner, here depicted by Engels in 1842 standing, smoking and laying a hand on a table, was a member of the short-lived Young Hegelian group known as Die Freien. Frequently the debates would take place at Hippel's, a wine bar in Friedrichstraße, attended by among others Marx and Engels, who were both adherents of Feuerbach at the time. Stirner met with Engels many times and Engels even recalled that they were "great friends,"[15] but it is still unclear whether Marx and Stirner ever met. It does not appear that Stirner contributed much to the discussions, but he was a faithful member of the club and an attentive listener.[16] The most-often reproduced portrait of Stirner is a cartoon by Engels, drawn forty years later from memory at biographer Mackay's request. It is highly likely that this and the group sketch of Die Freien at Hippel's are the only firsthand images of Stirner. Stirner worked as a teacher in a school for young girls owned by Madame Gropius[17] when he wrote his major work, The Ego and Its Own. Stirner married twice. His first wife was Agnes Burtz (1815–1838), the daughter of his landlady, whom he married on 12 December 1837. However, she died from complications with pregnancy in 1838. In 1843, he married Marie Dähnhardt, an intellectual associated with Die Freien. Their ad hoc wedding took place at Stirner's apartment, during which the participants were notably dressed casually, used copper rings as they had forgotten to buy wedding rings, and needed to search the whole neighborhood for a Bible as they did not have their own. In 1844, The Unique and Its Property was dedicated "to my sweetheart Marie Dähnhardt." Afterward, using Marie's inheritance, Stirner opened a dairy shop that handled the distribution of milk from dairy farmers into the city, but was unable to solicit the customers needed to keep the business afloat. It quickly failed and drove a wedge between him and Marie, leading to their separation in 1847.[18] Marie later converted to Catholicism and died in 1902 in London. After The Ego and Its Own, Stirner wrote Stirner's Critics and translated Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations and Jean-Baptiste Say's Traité d'economie politique into German to little financial gain. He also wrote a compilation of texts titled History of Reaction in 1852. Stirner died in 1856 in Berlin from a tumor, alleged to be due to an infected insect bite.[4] Only Bruno Bauer and Ludwig Buhl represented the Young Hegelians present at his funeral,[19] held at the Friedhof II der Sophiengemeinde Berlin. |

バイオグラフィー バイロイトのシュティルナーの生家 シュティルナーはバイエルンのバイロイトに生まれた。1898年にドイツ語で出版され(1910年、1914年に増補)、2005年に英訳されたシュティ ルナーの伝記(Max Stirner - sein Leben und sein Werk)がある。シュティルナーは、ルター派のアルベルト・クリスティアン・ハインリッヒ・シュミット(1769-1807)とソフィア・エレノーラ・ ラインライン(1778-1839)の一人っ子であった[10]。1807年4月19日、父親は37歳で結核のため死去した[11]。1809年、母親は ハインリッヒ・バレルシュテット(薬剤師)と再婚し、西プロイセンのクルム(現在のポーランドのチェルムノ)に定住した。20歳になったシュティルナーは ベルリン大学に入学し、言語学を学んだ[11]。哲学史、宗教哲学、主観的精神に関するヘーゲルの講義を聴講した[12]。その後、シュティルナーはルー トヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハと同時期に在籍していたエアランゲン大学に移る[13]。 シュティルナーはベルリンに戻り、教員免許を取得したが、プロイセン政府から専任教員のポストを得ることはできなかった[14]。1841年にベルリンに 滞在していたシュティルナーは、Die Freien(自由な者たち)と呼ばれる若い哲学者のグループとの議論に参加した。このグループには、カール・マルクス、フリードリヒ・エンゲルス、ブ ルーノ・バウアー、アーノルド・ルッゲなど、19世紀の文学・哲学界で最も有名な人々が参加していた。ヤング・ヘーゲル派の一部はヘーゲルの弁証法に熱心 に賛同し、ヘーゲルの結論に弁証法的アプローチを適用しようとしたが、グループの左翼メンバーはヘーゲルと決別した。フォイエルバッハとバウアーがその先 頭に立った。  シュティルナーは、1842年にエンゲルスによって描かれた、立ったままタバコを吸い、テーブルに手を置いている姿で、短命に終わった「フライエン」として知られる青年ヘーゲル派のメンバーであった。 当時フォイエルバッハを信奉していたマルクスとエンゲルスも参加していた。シュティルナーはエンゲルスと何度も会っており、エンゲルスは二人が「大の友 人」であったと回想している[15]。しかし、マルクスとシュティルナーが会ったことがあったかどうかはまだ不明である。シュティルナーが議論に大きく貢 献したようには見えないが、彼はクラブの忠実なメンバーであり、注意深い聞き手であった[16]。最もよく複製されるシュティルナーの肖像画は、伝記作家 マッケイの依頼で40年後に記憶に基づいて描かれたエンゲルスの漫画である。この漫画とヒッペルの『フライエンの人々』の群像画が、シュティルナーの唯一 の肉筆画である可能性が高い。シュティルナーは、代表作『自我とその所有物』を執筆した当時、グロピウス夫人[17]が所有する少女学校の教師として働い ていた。 シュティルナーは2度結婚した。最初の妻は、1837年12月12日に結婚した大家の娘、アグネス・ブルツ(1815-1838)であった。しかし、彼女 は1838年に妊娠の合併症で亡くなった。1843年、彼はディ・フライエンの知識人マリー・デンハルトと結婚した。その場限りの結婚式はシュティルナー のアパートで行われ、参加者はカジュアルな服装で、結婚指輪を買い忘れたため銅の指輪を使い、聖書を持っていなかったため近所を探し回った。1844年、 『唯一無二のものとその所有物』は、「私の恋人マリー・デンハルトに捧げられた」。その後、マリーの遺産を元手に、シュティルナーは酪農家から市内に牛乳 を卸す酪農店を開いたが、事業を維持するために必要な顧客を集めることができなかった。マリーは後にカトリックに改宗し、1902年にロンドンで死去した [18]。 『自我と自我』の後、シュティルナーは『シュティルナーの批評』を執筆し、アダム・スミスの『国富論』とジャン=バティスト・セイの『政治経済学』をドイ ツ語に翻訳したが、ナショナリズム的な利益はほとんど得られなかった。また、1852年には『反動の歴史』と題する文章集を著した。シュティルナーは 1856年にベルリンで、感染した虫刺されが原因とされる腫瘍のために死去した[4]。葬儀にはブルーノ・バウアーとルートヴィヒ・ブールのみが若きヘー ゲル派の代表として参列し、ベルリンのフリードホーフII・デア・ゾフィアンゲマインデで執り行われた[19]。 |

| Philosophy See also: Egoism and Egoist anarchism Stirner, whose main philosophical work was The Unique and Its Property, is credited as a major influence in the development of nihilism, existentialism and post-modernism as well as individualist anarchism, post-anarchism and post-left anarchy.[4][5] He also influenced illegalists, feminists, nihilists and bohemians, as well as fascists, right-libertarians and anarcho-capitalists.[20] Stirner was opposed to communism for the same reasons he opposed christianity, capitalism, humanism, liberalism, property rights and nationalism, seeing them as forms of unacceptable authority over the individual. Stirner also influenced anarcho-communists and post-left anarchists. The writers of An Anarchist FAQ report that "many in the anarchist movement in Glasgow, Scotland, took Stirner's 'Union of egoists' literally as the basis for their anarcho-syndicalist organising in the 1940s and beyond." Similarly, the noted anarchist historian Max Nettlau states that "[o]n reading Stirner, I maintain that he cannot be interpreted except in a socialist sense." Stirner was anti-capitalist and pro-labour, attacking "the division of labour resulting from private property for its deadening effects on the ego and individuality of the worker" and writing that free competition "is not 'free,' because I lack the things for competition. [...] Under the regime of the commonality the labourers always fall into the hands of the possessors of the capitalists [...]. The labourer cannot realise on his labour to the extent of the value that it has for the customer. [...] The state rests on the slavery of labour. If labour becomes free, the state is lost."[21] For Stirner, "Labor has an egoistic character; the laborer is the egoist."[22] |

哲学 こちらも参照のこと: エゴイズムとエゴイスト的アナキズム シュティルナーの主な哲学的著作は『唯一性とその性質』であり、ニヒリズム、実存主義、ポスト・モダニズム、個人主義アナキズム、ポスト・アナキズム、ポ スト・左翼アナキズムの発展に大きな影響を与えたとされている。 [シュティルナーは、キリスト教、資本主義、人文主義、自由主義、財産権、ナショナリズムに反対したのと同じ理由から共産主義に反対し、それらを個人に対 する容認しがたい権威の形態とみなした。シュティルナーはまた、アナルコミュニストやポスト左翼アナーキストにも影響を与えた。An Anarchist FAQ』の著者は、「スコットランドのグラスゴーにおけるアナーキスト運動の多くは、1940年代以降のアナーコ=シンジカリストの組織化の基礎として、 スティルナーの『エゴイストの連合』を文字通りに受け止めていた」と報告している。同様に、著名なアナキストの歴史家マックス・ネットラウは、「スティル ナーを読むと、社会主義的な意味以外では解釈できないと私は主張する」と述べている。シュティルナーは反資本主義、親労働主義者であり、「私有財産から生 じる分業は、労働者の自我や個性を死滅させる効果がある」と攻撃し、自由競争について「『自由』ではない。[中略)共同性の体制のもとでは、労働者はつね に資本家の所有者の手に落ちる。労働者は、自分の労働を、それが顧客にとってもつ価値の範囲内で実現することはできない。[国家は労働の奴隷制の上に成り 立っている。労働が自由になれば、国家は失われる」[21] スティルナーにとって、「労働はエゴイスティックな性格を持っており、労働者はエゴイストである」[22]。 |

| Egoism Stirner's egoism argues that individuals are impossible to fully comprehend, as no understanding of the self can adequately describe the fullness of experience. Stirner has been broadly understood as containing traits of both psychological egoism and rational egoism. Unlike the self-interest described by Ayn Rand, Stirner did not address individual self-interest, selfishness, or prescriptions for how one should act. He urged individuals to decide for themselves and fulfill their own egoism.[21] He believed that everyone was propelled by their own egoism and desires and that those who accepted this—as willing egoists—could freely live their individual desires, while those who did not—as unwilling egoists—will falsely believe they are fulfilling another cause while they are secretly fulfilling their own desires for happiness and security. The willing egoist would see that they could act freely, unbound from obedience to sacred but artificial truths like law, rights, morality, and religion. Power is the method of Stirner's egoism and the only justified method of gaining philosophical property. Stirner did not believe in the one-track pursuit of greed, which as only one aspect of the ego would lead to being possessed by a cause other than the full ego. He did not believe in natural rights to property and encouraged insurrection against all forms of authority, including disrespect for property.[21] |

エゴイズム シュティルナーのエゴイズムは、自己を理解しても経験の全容を十分に説明することはできないため、個人を完全に理解することは不可能であると主張する。 シュティルナーは心理的エゴイズムと理性的エゴイズムの両方の特徴を含んでいると広く理解されている。アイン・ランドの言う利己主義とは異なり、シュティ ルナーは個人の利己心や利己主義、どのように行動すべきかの規定には触れなかった。彼は個人が自分で決定し、自分自身のエゴイズムを満たすように促した [21]。 彼は、誰もが自分自身のエゴイズムと欲望に突き動かされており、このことを受け入れる者-意思あるエゴイスト-は個人の欲望を自由に生きることができる が、そうでない者-意思のないエゴイスト-は、幸福と安全のために自分自身の欲望を密かに満たしている一方で、他の大義を満たしていると偽ることになると 信じていた。意欲的なエゴイストは、法律、権利、道徳、宗教といった神聖だが人為的な真理への服従に縛られることなく、自由に行動できることに気づくだろ う。権力こそが、スティルナーのエゴイズムの方法であり、哲学的財産を得るための唯一正当な方法なのである。シュティルナーは、自我の一側面として、完全 な自我以外の原因に憑依されることにつながる欲の一本調子の追求を信じなかった。彼は財産に対する自然権を信じておらず、財産の軽視を含むあらゆる形の権 威に対する反乱を奨励していた[21]。 |

Anarchism Benjamin Tucker, pioneer of individualist anarchism Stirner proposes that most commonly accepted social institutions—including the notion of state, property as a right, natural rights in general and the very notion of society—were mere illusions, "spooks" or ghosts in the mind.[23] He advocated egoism and a form of amoralism in which individuals would unite in Unions of egoists only when it was in their self-interest to do so. For him, property simply comes about through might, saying: "Whoever knows how to take and to defend the thing, to him belongs [property]. [...] What I have in my power, that is my own. So long as I assert myself as holder, I am the proprietor of the thing." He adds that "I do not step shyly back from your property, but look upon it always as my property, in which I respect nothing. Pray do the like with what you call my property!"[24] Stirner considers the world and everything in it, including other persons, available to one's taking or use without moral constraint and that rights do not exist in regard to objects and people at all. He sees no rationality in taking the interests of others into account unless doing so furthers one's self-interest, which he believes is the only legitimate reason for acting. He denies society as being an actual entity, calling society a "spook" and that "the individuals are its reality."[25] Despite being labeled as anarchist, Stirner was not necessarily one. Separation of Stirner and egoism from anarchism was first done in 1914 by Dora Marsden in her debate with Benjamin Tucker in her journals The New Freewoman and The Egoist.[26] |

アナキズム ベンジャミン・タッカー、個人主義アナキズムの先駆者 スティルナーは、国家という概念、権利としての財産、自然権全般、社会という概念など、一般的に受け入れられている社会制度のほとんどは、単なる幻想であ り、心の中の「お化け」や幽霊に過ぎないと提唱した[23]。彼は、エゴイズムと、そうすることが自己利益になる場合にのみ個人がエゴイストの連合体で団 結するという形の非道徳主義を提唱した。彼にとって、財産は単に力によってもたらされるものである: 「その物を奪い、守る術を知っている者は誰でも、その人(所有者)のものである。[......)私が自分の力で持っているもの、それは私のものである。 私が所有者であると主張する限り、私はその物の所有者である。私はあなた方の所有物から恥ずかしげもなく一歩も引かず、常に私の所有物として見ている。あ なたがたが私の所有物と呼ぶものについても、同じようにすることを祈る!」[24] スティルナーは、他の人格も含めて、世界とそこにあるすべてのものは、道徳的な制約なしに、奪ったり使ったりすることが可能であり、物や人間には権利が まったく存在しないと考えている。彼は、そうすることが自己の利益を促進しない限り、他者の利益を考慮することに合理性はないと考えている。彼は社会が実 在することを否定し、社会を「お化け」と呼び、「個人こそがその実態である」とする[25]。 アナーキストのレッテルを貼られているが、シュティルナーは必ずしもアナーキストではなかった。シュティルナーとエゴイズムをアナーキズムから分離するこ とは、1914年にドラ・マースデンが雑誌『ニュー・フリーウーマン』や『エゴイスト』でベンジャミン・タッカーと論争した際に初めて行われた[26]。 |

| Communism Stirner suggested that communism was tainted with the same idealism as Christianity and infused with superstitious ideas like morality and justice.[27] Stirner's principal critique of socialism and communism was that they ignored the individual; they aimed to hand ownership over to the abstraction society, which meant that no existing person actually owned anything.[28] The Anarchist FAQ writes that "[w]hile some may object to our attempt to place egoism and communism together, it is worth pointing out that Stirner rejected 'communism'. Stirner did not subscribe to libertarian communism, because it did not exist when he was writing and so he was directing his critique against the various forms of state communism which did. Moreover, this does not mean that anarcho-communists and others may not find his work of use to them. And Stirner would have approved, for nothing could be more foreign to his ideas than to limit what an individual considers to be in their best interest."[21] In summarizing Stirner's main arguments, the writers "indicate why social anarchists have been, and should be, interested in his ideas, saying that, John P. Clark presents a sympathetic and useful social anarchist critique of his work in Max Stirner's Egoism."[21] Daniel Guérin wrote that "Stirner accepted many of the premises of communism but with the following qualification: the profession of communist faith is a first step toward total emancipation of the victims of our society, but they will become completely 'disalienated,' and truly able to develop their individuality, only by advancing beyond communism."[29] |

共産主義 シュティルナーは、共産主義がキリスト教と同じ観念論に汚染され、道徳や正義といった迷信的な考え方に染まっていることを示唆した[27]。シュティル ナーの社会主義や共産主義に対する主な批判は、それらが個人を無視していることであった。それらは所有権を抽象化された社会に引き渡すことを目的としてお り、現存する人格が実際には何も所有していないことを意味していた[28]。 アナーキストFAQは「エゴイズムと共産主義を同列に並べようとする私たちの試みに異議を唱える人もいるかもしれないが、スティルナーが『共産主義』を拒 否したことは指摘しておく価値がある」と書いている。というのも、彼が執筆していた当時、自由主義的な共産主義は存在せず、存在したさまざまな形態の国家 共産主義に対して批判を向けていたからである。さらに、だからといって、アナーコ共産主義者やその他の人々にとって、彼の著作が役に立たないということに はならない。そして、シュティルナーも承認したであろう。なぜなら、個人が自分の最善の利益であると考えるものを制限することほど、彼の思想にとって異質 なことはないからである」[21]。シュティルナーの主要な議論を要約する中で、著者は「社会的アナーキストがなぜ彼の思想に関心を持ち、また関心を持つ べきなのかを示し、ジョン・P・クラークが『マックス・シュティルナーのエゴイズム』の中で彼の仕事に対する共感的で有用な社会的アナーキスト批判を提示 している」と述べている[21]。 ダニエル・ゲランは、「シュティルナーは共産主義の前提の多くを受け入れていたが、次のような修飾をつけていた:共産主義的な信仰の表明は、われわれの社 会の犠牲者の完全な解放に向けた第一歩であるが、彼らは共産主義を超えて前進することによってのみ、完全に『解放』され、真に個性を発展させることができ るようになる」と書いている[29]。 |

| Revolution Stirner criticizes conventional notions of revolution, arguing that social movements aimed at overturning established ideals are tacitly idealist because they are implicitly aimed at the establishment of a new ideal thereafter. "Revolution and insurrection must not be looked upon as synonymous. The former consists in an overturning of conditions, of the established condition or status, the State or society, and is accordingly a political or social act; the latter has indeed for its unavoidable consequence a transformation of circumstances, yet does not start from it but from men's discontent with themselves, is not an armed rising, but a rising of individuals, a getting up, without regard to the arrangements that spring from it. The Revolution aimed at new arrangements; insurrection leads us no longer to let ourselves be arranged, but to arrange ourselves, and sets no glittering hopes on 'institutions'. It is not a fight against the established, since, if it prospers, the established collapses of itself; it is only a working forth of me out of the established. If I leave the established, it is dead and passes into decay." |

革命 シュティルナーは従来の革命の概念を批判し、既成の理想を覆すことを目的とした社会運動は、その後の新しい理想の確立を暗黙のうちに目指しているため、暗 黙の理想主義であると主張する。「革命と暴動は同義語として捉えるべきではない。後者は、たしかに不可避の結果として状況の変容をもたらすが、しかし、そ こから出発するのではなく、人々の自分自身に対する不満から出発するのであり、武力による蜂起ではなく、個人の蜂起であり、そこから生じる取り決めとは無 関係に立ち上がるのである。革命は新たな取り決めを目指した。反乱は、もはや自分自身を取り決めさせるのではなく、自分自身を取り決めるようわれわれを導 くものであり、「制度」にきらびやかな希望を抱かせるものではない。それは既成のものに対する戦いではない。もしそれが繁栄すれば、既成のものはそれ自体 崩壊するからである。もし私が既成のものから離れれば、それは死んでしまい、腐敗の道をたどることになる」。 |

| Union of egoists Main article: Union of egoists Stirner's idea of the Union of egoists was first expounded in The Unique and Its Property. The Union is understood as a non-systematic association, which Stirner proposed in contradistinction to the state.[30] Unlike a "community" in which individuals are obliged to participate, Stirner's suggested Union would be voluntary and instrumental under which individuals would freely associate insofar as others within the Union remain useful to each constituent individual.[31] The Union relation between egoists is continually renewed by all parties' support through an act of will.[32] Some such as Svein Olav Nyberg argue that the Union requires that all parties participate out of a conscious egoism while others such as Sydney E. Parker regard the union as a "change of attitude," rejecting its previous conception as an institution.[33] |

エゴイスト連合 主な記事 エゴイストの連合 シュティルナーのエゴイスト連合という考えは、『唯一性とその性質』の中で初めて明らかにされた。個人が参加することを義務づけられた「共同体」とは異な り、シュティルナーが提案した連合は自発的かつ道具的なものであり、連合内の他者が各構成員にとって有用であり続ける限りにおいて、個人は自由に結社する ことができる[30]。 [スヴェイン・オラフ・ナイベリのように、ユニオンはすべての当事者が意識的なエゴイズムから参加することを要求していると主張する者もいれば、シド ニー・E・パーカーのように、ユニオンを「態度の変化」とみなし、制度としての以前の概念を否定する者もいる[33]。 |

Response to Hegelianism Caricature of Max Stirner taken from a sketch by Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) of the meetings of Die Freien Scholar Lawrence Stepelevich states that G. W. F. Hegel was a major influence on The Unique and Its Property. While the latter has an "un-Hegelian structure and tone" on the whole and is hostile to Hegel's conclusions about the self and the world, Stepelevich states that Stirner's work is best understood as answering Hegel's question of the role of consciousness after it has contemplated "untrue knowledge" and become "absolute knowledge." Stepelevich concludes that Stirner presents the consequences of the rediscovering one's self-consciousness after realizing self-determination.[34] Scholars such as Douglas Moggach and Widukind De Ridder have stated that Stirner was obviously a student of Hegel, like his contemporaries Ludwig Feuerbach and Bruno Bauer, but this does not necessarily make him an Hegelian. Contrary to the Young Hegelians, Stirner scorned all attempts at an immanent critique of Hegel and the Enlightenment and renounced Bauer and Feuerbach's emancipatory claims as well. Contrary to Hegel, who considered the given as an inadequate embodiment of rational, Stirner leaves the given intact by considering it a mere object, not of transformation, but of enjoyment and consumption ("His Own").[35] According to Moggach, Stirner does not go beyond Hegel, but he in fact leaves the domain of philosophy in its entirety, stating: Stirner refused to conceptualize the human self, and rendered it devoid of any reference to rationality or universal standards. The self was moreover considered a field of action, a "never-being I." The "I" had no essence to realize and life itself was a process of self-dissolution. Far from accepting, like the humanist Hegelians, a construal of subjectivity endowed with a universal and ethical mission, Stirner's notion of "the Unique" (Der Einzige) distances itself from any conceptualization whatsoever: "There is no development of the concept of the Unique. No philosophical system can be built out of it, as it can out of Being, or Thinking, or the I. Rather, with it, all development of the concept ceases. The person who views it as a principle thinks that he can treat it philosophically or theoretically and necessarily wastes his breath arguing against it."[36] |

ヘーゲル主義への反論 フリードリヒ・エンゲルス(1820-1895)による『自由主義者たち』の会合のスケッチから引用されたマックス・シュティルナーの風刺画。 学者ローレンス・ステペレビッチは、G.W.F.ヘーゲルは『唯一性とその性質』に大きな影響を与えたと述べている。後者は全体として「非ヘーゲル的な構 造と調子」を持ち、自己と世界に関するヘーゲルの結論に敵対的であるが、シュティーレヴィッチは、シュティーナーの著作は、意識が 「真実でない知識 」を熟考し、「絶対的な知識 」となった後の意識の役割に関するヘーゲルの問いに答えるものとして最もよく理解されると述べている。シュテペレビッチは、シュティルナーは、自己決定を 実現した後に自己意識を再発見することの帰結を提示していると結論付けている[34]。 ダグラス・モッガッハやウィドゥキント・デ・リダーといった学者は、シュティルナーは同時代のルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハやブルーノ・バウアーと同様 に明らかにヘーゲルの学生であったが、だからといって必ずしもヘーゲル主義者であるとは言えないと述べている。若きヘーゲル主義者たちとは反対に、シュ ティルナーはヘーゲルと啓蒙主義に対する内在的批判の試みをすべて軽蔑し、バウアーとフォイエルバッハの解放的主張も放棄した。所与のものを合理的なもの の不十分な体現とみなしたヘーゲルとは反対に、シュティルナーは所与のものを、変容のためではなく、享受と消費のための単なる対象とみなすことによって、 そのままにしている(「彼自身」)[35]。 モッガッハによれば、シュティルナーはヘーゲルを超えているのではなく、事実、哲学の領域全体から離れているのである: シュティルナーは人間の自己を概念化することを拒否し、合理性や普遍的基準への言及を排除した。自己はさらに、行為の場であり、「決して存在しない私 」であると考えられた。私」は実現すべき本質を持たず、人生そのものが自己解体のプロセスであった。シュティルナーの「唯一者」(Der Einzige)という概念は、人文主義的なヘーゲル人のように、普遍的で倫理的な使命を与えられた主観性の解釈を受け入れるどころか、いかなる概念化か らも距離を置いている。存在」や「思考」や「私」がそうであるように、この概念から哲学体系を構築することはできない。それを原理として見る人格は、それ を哲学的あるいは理論的に扱うことができると考え、必然的にそれに対して議論して息を無駄にする」[36]。 |

| Works The False Principle of Our Education See also: Humanities In 1842, The False Principle of Our Education (Das unwahre Prinzip unserer Erziehung) was published in Rheinische Zeitung, which was edited by Marx at the time.[37] Written as a reaction to the treatise Humanism vs. Realism, written by Otto Friedrich Theodor Heinsius [de]. Stirner explains that education in either the classical humanist method or the practical realist method still lacks true value. He states that "the final goal of education can no longer be knowledge". Asserting that "only the spirit which understands itself is eternal", Stirner calls for a shift in the principle of education from making us "masters of things" to making us "free natures", naming his educational principle "personalist". Art and Religion Art and Religion (Kunst und Religion) was also published in Rheinische Zeitung on 14 June 1842. It addresses Bruno Bauer and his publication against Hegel called Hegel's Doctrine of Religion and Art Judged From the Standpoint of Faith. Bauer had inverted Hegel's relation between "Art" and "Religion" by claiming that "Art" was much more closely related to "Philosophy" than to "Religion", based on their shared determinacy and clarity, and a common ethical root. However, Stirner went beyond both Hegel and Bauer's criticism by asserting that "Art" rather created an object for "Religion" and could thus by no means be related to what Stirner considered—in opposition with Hegel and Bauer—to be "Philosophy", stating: [Philosophy] neither stands opposed to an Object, as Religion, nor makes one, as Art, but rather places its pulverizing hand upon all the business of making Objects as well as the whole of objectivity itself, and so breathes the air of freedom. Reason, the spirit of Philosophy, concerns itself only with itself, and troubles itself over no Object.[38] Stirner deliberately left "Philosophy" out of the dialectical triad (Art–Religion–Philosophy) by claiming that "Philosophy" does not "bother itself with objects" (Religion), nor does it "make an object" (Art). In Stirner's account, "Philosophy" was in fact indifferent towards both "Art" and "Religion." Stirner thus mocked and radicalised Bauer's criticism of religion.[35] The Unique and Its Property Main article: The Unique and Its Property Stirner's main work, The Unique and Its Property (Der Einzige und sein Eigentum), appeared in Leipzig in October 1844, with as year of publication mentioned 1845. In The Unique and Its Property, Stirner launches a radical anti-authoritarian and individualist critique of contemporary Prussian society and modern western society as such. He offers an approach to human existence in which he depicts himself as "the unique one", a "creative nothing", beyond the ability of language to fully express, stating that "[i]f I concern myself for myself, the unique one, then my concern rests on its transitory, mortal creator, who consumes himself, and I may say: All things are nothing to me".[39] The book proclaims that all religions and ideologies rest on empty concepts. The same holds true for society's institutions that claim authority over the individual, be it the state, legislation, the church, or the systems of education such as universities. Stirner's argument explores and extends the limits of criticism, aiming his critique especially at those of his contemporaries, particularly Ludwig Feuerbach and Bruno Bauer, also at popular ideologies, including communism, humanism (which he regarded as analogous to religion with the abstract Man or humanity as the supreme being), liberalism, and nationalism as well as capitalism, religion and statism, arguing: In the time of spirits thoughts grew till they overtopped my head, whose offspring they yet were; they hovered about me and convulsed me like fever-phantasies—an awful power. The thoughts had become corporeal on their own account, were ghosts, e. g. God, Emperor, Pope, Fatherland, etc. If I destroy their corporeity, then I take them back into mine, and say: "I alone am corporeal." And now I take the world as what it is to me, as mine, as my property; I refer all to myself.[40] |

作品紹介 私たちの教育の誤った原則 こちらも参照のこと: 人文科学 1842年、『われわれの教育の誤った原理』(Das unahre Prinzip unserer Erziehung)が、当時マルクスが編集していた『ライン新聞』(Rheinische Zeitung)に掲載された[37]。シュティルナーは、古典的な人文主義的方法と実践的な現実主義的方法のいずれにおいても、教育は依然として真の価 値を欠いていると説明する。彼は「教育の最終目標はもはや知識ではありえない」と述べる。自らを理解する精神のみが永遠である」と主張するシュティルナー は、教育の原理を「物事の主人」から「自由な本性」へと転換することを求め、その教育原理を「人格主義」と名づけた。 芸術と宗教 芸術と宗教』(Kunst und Religion)もまた、1842年6月14日にRheinische Zeitung誌に発表された。ブルーノ・バウアーがヘーゲルに対して発表した『ヘーゲルの宗教教義と信仰の立場から判断した芸術』を取り上げたものであ る。バウアーは、ヘーゲルの「芸術」と「宗教」の関係を逆転させ、「芸術」は「宗教」よりも「哲学」とはるかに密接な関係にあると主張した。しかし、シュ ティルナーは、ヘーゲルとバウアーの批判を越えて、「芸術」はむしろ「宗教」のための対象を作り出すものであり、シュティルナーがヘーゲルやバウアーと対 立して「哲学」であると考えたものとは決して関係がないと主張し、次のように述べている: [哲学は)宗教のように対象と対立するのでもなく、芸術のように対象を作るのでもなく、むしろ対象を作るすべての仕事と客観性そのものに粉砕の手を下し、 自由の空気を呼吸するのである。哲学の精神である理性は、それ自体にのみ関心を持ち、いかなる対象に対しても悩まない[38]。 シュティルナーは、「哲学」は「対象を思い煩う」こともなく(宗教)、「対象を作る」こともない(芸術)と主張することによって、弁証法的な三位一体(芸 術-宗教-哲学)から意図的に「哲学」を除外した。シュティルナーの説明では、「哲学」は「芸術」にも「宗教」にも無関心なのである。こうしてシュティル ナーはバウアーの宗教批判を嘲笑し、急進化させた[35]。 唯一性とその性質 主な記事 唯一性とその性質 シュティルナーの主著『唯一性とその性質』(Der Einzige und sein Eigentum)は1844年10月にライプツィヒで出版された。シュティルナーは『唯一性とその所有物』において、プロイセン現代社会と近代西欧社会 に対する急進的な反権威主義的・個人主義的批判を展開している。彼は人間存在へのアプローチを提示し、自分自身を「唯一無二のもの」、「創造的な無」、言 語が完全に表現する能力を超えた存在として描いている: 万物は私にとって無である」[39]。 この本は、すべての宗教やイデオロギーは空虚な概念の上に成り立っていると宣言している。国家、立法、教会、大学などの教育制度など、個人に対する権威を 主張する社会の制度についても同様である。シュティルナーの議論は、批評の限界を探り、拡張するものであり、特に同時代のイデオロギー、とりわけルート ヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハやブルーノ・バウアー、また共産主義、人本主義(彼は抽象的な人間や人類を至高の存在とする宗教に類似しているとみなした)、自 由主義、ナショナリズム、さらには資本主義、宗教、国家主義などの大衆的イデオロギーに批評の矛先を向け、論じている: 精霊の時代には、思考は私の頭の上を覆いつくすまで成長した。その思考は、神、皇帝、ローマ教皇、祖国など、それ自体で肉体を持ち、幽霊のようになってい た。もし私が彼らの身体性を破壊するなら、私は彼らを私の身体に戻し、こう言うのだ: 「私だけが肉体を持っている。そして今、私は世界を私にとってのもの、私のもの、私の所有物として捉え、すべてを私自身に言及する[40]。 |

| Stirner's Critics Stirner's Critics (Recensenten Stirners) was published in September 1845 in Wigands Vierteljahrsschrift. It is a response, in which Stirner refers to himself in the third-person, to three critical reviews of The Unique and Its Property by Moses Hess in Die letzten Philosophen (The Last Philosophers), by a certain Szeliga (alias of an adherent of Bruno Bauer) in an article in the journal Norddeutsche Blätter, and by Ludwig Feuerbach anonymously in an article called On 'The Essence of Christianity' in Relation to Stirner's 'The Unique and Its Property' (Über 'Das Wesen des Christentums' in Beziehung auf Stirners 'Der Einzige und sein Eigentum') in Wigands Vierteljahrsschrift. The Philosophical Reactionaries The Philosophical Reactionaries (Die Philosophischen Reactionäre) was published in 1847 in Die Epigonen, a journal edited by Otto Wigand from Leipzig. At the time, Wigand had already published The Unique and Its Property and was about to finish the publication of Stirner's translations of Adam Smith and Jean-Baptiste Say. As the subtitle indicates, The Philosophical Reactionaries was written in response to a 1847 article by Kuno Fischer (1824–1907) entitled The Modern Sophists (Die Moderne Sophisten). The article was signed G. Edward and its authorship has been disputed ever since John Henry Mackay "cautiously" attributed it to Stirner and included it in his collection of Stirner's lesser writings. It was first translated into English in 2011 by Widukind De Ridder and the introductory note explains: Mackay based his attribution of this text to Stirner on Kuno Fischer's subsequent reply to it, in which the latter, 'with such determination', identified G. Edward as Max Stirner. The article was entitled 'Ein Apologet der Sophistik und "ein Philosophischer Reactionäre"' and was published alongside 'Die Philosophischen Reactionäre'. Moreover, it seems rather odd that Otto Wigand would have published 'Edward's' piece back-to-back with an article that falsely attributed it to one of his personal associates at the time. And, indeed, as Mackay went on to argue, Stirner never refuted this attribution. This remains, however, a slim basis on which to firmly identify Stirner as the author. This circumstantial evidence has led some scholars to cast doubts over Stirner's authorship, based on both the style and content of 'Die Philosophischen Reactionäre'. One should, however, bear in mind that it was written almost three years after Der Einzige und sein Eigentum, at a time when Young Hegelianism had withered away.[41] The majority of the text deals with Kuno Fischer's definition of sophism. With much wit, the self-contradictory nature of Fischer's criticism of sophism is exposed. Fischer had made a sharp distinction between sophism and philosophy while at the same time considering it as the "mirror image of philosophy". The sophists breathe "philosophical air" and were "dialectically inspired to a formal volubility". Stirner's answer is striking: Have you philosophers really no clue that you have been beaten with your own weapons? Only one clue. What can your common sense reply when I dissolve dialectically what you have merely posited dialectically? You have showed me with what kind of 'volubility' one can turn everything to nothing and nothing to everything, black into white and white into black. What do you have against me, when I return to you your pure art?[42] Looking back on The Unique and Its Property, Stirner claims that "Stirner himself has described his book as, in part, a clumsy expression of what he wanted to say. It is the arduous work of the best years of his life, and yet he calls it, in part, 'clumsy'. That is how hard he struggled with a language that was ruined by philosophers, abused by state-, religious- and other believers, and enabled a boundless confusion of ideas".[43] History of Reaction History of Reaction (Geschichte der Reaktion) was published in two volumes in 1851 by Allgemeine Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt and immediately banned in Austria.[11] It was written in the context of the recent 1848 revolutions in German states and is mainly a collection of the works of others selected and translated by Stirner. The introduction and some additional passages were Stirner's work. Edmund Burke and Auguste Comte are quoted to show two opposing views of revolution. |

シュティルナーの批評家たち シュティルナーの批評家たち』(Recensenten Stirners)は、1845年9月に『ヴィガンス・ヴィアテルヤールシュクリフト』誌に発表された。これは、『最後の哲学者たち』(Die letzten Philosophen)に掲載されたモーゼス・ヘス(Moses Hess)、雑誌『ノルトドイッチェ・ブレッター』(Norddeutsche Blätter)に掲載されたブルーノ・バウアーの信奉者セリーガ(Szeliga)の論文、ルートヴィヒ・フォイエルガ(Ludwig Feuertter)による『唯一性とその性質』(The Unique and Its Property)の3つの批評に対する、シュティルナーの三人称による反論である、 また、ルートヴィヒ・フォイエルバッハは匿名で、雑誌『ヴィーガンズ・ヴィアテルヤールシュクリフト』(Wigands Vierteljahrsschrift)に掲載された、シュティルナーの『独自性とその性質』(Über 'Das Wesen des Christentums' in Beziehung auf Stirners 'Der Einzige und sein Eigentum')との関連における『キリスト教の本質』(Über 'Das Wesen des Christentums' in Beziehung auf Stirners 'Der Einzige und sein Eigentum')と呼ばれる論文で述べている。 哲学的反動派 哲学的反動』(Die Philosophischen Reactionäre)は1847年、ライプツィヒのオットー・ヴィーガンドが編集する雑誌『エピゴーネン』(Die Epigonen)に掲載された。当時、ヴィーガンドはすでに『唯一とその性質』を出版しており、アダム・スミスとジャン・バティスト・セイのスティル ナー訳の出版を終えようとしていた。副題が示すように、『哲学的反動者たち』は、クノ・フィッシャー(1824-1907)が1847年に発表した『現代 のソフィストたち』(Die Moderne Sophisten)という論文に対して書かれたものである。この論文にはG.エドワードの署名があり、ジョン・ヘンリー・マッケイが「慎重に」この論文 をスティルナーのものとし、スティルナーの少ない著作集に収録して以来、その著者については論争が続いている。この本は2011年にウィドゥキンド・デ・ リダーによって初めて英訳され、序文ではこう説明されている: マッケイは、この文章をシュティルナーとした根拠を、それに対するクノ・フィッシャーの返信に求めている。この論文は「Ein Apologet der Sophistik und 「ein Philosophischer Reactionäre」」と題され、「Die Philosophischen Reactionäre」と並んで出版された。さらに、オットー・ヴィーガンドが「エドワードの作品」を、当時の彼の人格的仲間の一人の作品と偽って掲載 したのは、かなり奇妙なことである。そして実際、マッケイが続けて論じたように、スティルナーがこの帰属に反論することはなかった。しかし、これはシュ ティルナーが作者であると断定する根拠としては不十分である。このような状況証拠から、『Die Philosophischen Reactionäre』の文体と内容の両方から、シュティルナーの作者であることを疑う学者もいる。しかし、この本が書かれたのは『アインツィーゲとそ の本質』のほぼ3年後であり、若きヘーゲル主義が枯れ果てた時期であったことを念頭に置くべきである[41]。 本文の大部分は、クノ・フィッシャーによる詭弁の定義を扱っている。フィッシャーによる詭弁批判の自己矛盾が、機知に富んで露呈している。フィッシャーは 詭弁と哲学を峻別していたが、同時に詭弁を「哲学の鏡像」とみなしていた。詭弁家は「哲学的な空気」を吸っており、「弁証法的に形式的な揮発性」に触発さ れていたのである。スティルナーの答えは印象的だ: 君たち哲学者は、自分たちが自分の武器で殴られたことを本当に理解していないのだろうか?手がかりは一つしかない。あなた方が弁証法的に措定したにすぎな いものを、私が弁証法的に分解したとき、あなた方の常識は何と答えることができるだろうか?すべてを無に、無をすべてに、黒を白に、白を黒に、どのような 「揮発性」で変えることができるのか、あなたは私に示した。私があなたの純粋芸術をあなたに返すとき、あなたは私に何の恨みがあるのだろうか[42]。 シュティルナーは、『唯一とその性質』を振り返って、「シュティルナー自身、自分の著書を、部分的には、自分が言いたかったことを不器用に表現したものだ と述べている」と主張している。この本は、彼の人生の最良の年月を費やした労作であるにもかかわらず、彼はその一部を『不器用』と呼んでいる。それだけ彼 は、哲学者たちによって台無しにされ、国家や宗教、その他の信者たちによって乱用され、思想の無限の混乱を可能にする言語と格闘していたのである」 [43]。 反動の歴史 反動の歴史』(Geschichte der Reaktion)は、1851年にAllgemeine Deutsche Verlags-Anstaltから2巻で出版されたが、オーストリアでは直ちに発禁処分となった[11]。本書は、1848年にドイツ諸国で勃発したば かりの革命の文脈で書かれたもので、主にスティルナーによって選択・翻訳された他者の著作を集めたものである。序文といくつかの付加的な文章はシュティル ナーの作品である。エドマンド・バークとオーギュスト・コントが引用され、革命についての2つの対立する見解が示されている。 |

| Critical reception Stirner's work did not go unnoticed among his contemporaries. Stirner's attacks on ideology—in particular Feuerbach's humanism—forced Feuerbach into print. Moses Hess (at that time close to Marx) and Szeliga (pseudonym of Franz Zychlin von Zychlinski, an adherent of Bruno Bauer) also replied to Stirner, who answered the criticism in a German periodical in the September 1845 article Stirner's Critics (Recensenten Stirners), which clarifies several points of interest to readers of the book—especially in relation to Feuerbach. While Marx's Saint Max (Sankt Max), a large part of The German Ideology (Die Deutsche Ideologie), was not published until 1932 and thus assured The Unique and Its Property a place of curious interest among Marxist readers, Marx's ridicule of Stirner has played a significant role in the preservation of Stirner's work in popular and academic discourse despite lacking mainstream popularity.[22][44][45][46] Comments by contemporaries Twenty years after the appearance of Stirner's book, the author Friedrich Albert Lange wrote the following: Stirner went so far in his notorious work, 'Der Einzige und Sein Eigenthum' (1845), as to reject all moral ideas. Everything that in any way, whether it be external force, belief, or mere idea, places itself above the individual and his caprice, Stirner rejects as a hateful limitation of himself. What a pity that to this book—the extremest that we know anywhere—a second positive part was not added. It would have been easier than in the case of Schelling's philosophy; for out of the unlimited Ego I can again beget every kind of Idealism as my will and my idea. Stirner lays so much stress upon the will, in fact, that it appears as the root force of human nature. It may remind us of Schopenhauer.[47] Some people believe that in a sense a "second positive part" was soon to be added, though not by Stirner, but by Friedrich Nietzsche. The relationship between Nietzsche and Stirner seems to be much more complicated.[48] According to George J. Stack's Lange and Nietzsche, Nietzsche read Lange's History of Materialism "again and again" and was therefore very familiar with the passage regarding Stirner.[49] |

批評家の評価 シュティルナーの仕事は、同時代の人々の間で注目されなかったわけではない。シュティルナーのイデオロギーに対する攻撃、特にフォイエルバッハの個別主義 に対する攻撃は、フォイエルバッハを活字にすることを余儀なくさせた。モーゼス・ヘス(当時はマルクスに近かった)とセリーガ(ブルーノ・バウアーの信奉 者フランツ・ツィクリン・フォン・ツィクリンスキーのペンネーム)もまた、シュティルナーに反論し、シュティルナーは1845年9月のドイツの定期刊行物 の記事『シュティルナーの批評家たち(Recensenten Stirners)』で批判に答えている。 マルクスの『ドイツ・イデオロギー』の大部分を占める『サンクト・マックス』は1932年まで出版されなかったため、マルクス主義者の読者の間で『唯一無 二のものとその所有物』が珍奇な関心を集める場所となったが、マルクスのシュティルナーに対する揶揄は、主流的な人気を欠いているにもかかわらず、シュ ティルナーの著作が大衆的・学術的な言説の中で保存される上で重要な役割を果たしている[22][44][45][46]。 同時代人によるコメント シュティルナーの本が登場してから20年後、作家のフリードリヒ・アルベルト・ラングは次のように書いている: シュティルナーはその悪名高い著作である『アインツィーゲとその存在』(1845年)において、あらゆる道徳観念を否定するまでに至った。外的な力であ れ、信念であれ、単なる考えであれ、個人とその気まぐれよりも上位に位置するものはすべて、スティルナーは憎むべき自己の制限として拒絶した。私たちが知 る限り最も過激なこの本に、第二の肯定的な部分が加えられなかったのは何とも残念である。無制限の自我から、あらゆる観念論を自分の意志や思想として再び 生み出すことができるからだ。事実、スティルナーは意志を非常に重視しており、それが人間性の根源的な力であるかのように見える。それはショーペンハウ アーを思い起こさせるかもしれない[47]。 ある意味で、「第二の積極的部分」が、スティルナーによってではなく、フリードリヒ・ニーチェによって、すぐに付け加えられたと考える人々もいる。ジョー ジ・J・スタックの『ランゲとニーチェ』によれば、ニーチェはランゲの『唯物史観』を「何度も何度も」読んでおり、それゆえスティルナーに関する一節を熟 知していた[49]。 |

| Influence While Der Einzige was a critical success and attracted much reaction from famous philosophers after publication, it was out of print and the notoriety that it had provoked had faded many years before Stirner's death.[50] However, since his death, it has seen a revival in publication in multiple languages.[50] Stirner had a destructive impact on left-Hegelianism, but his philosophy was a significant influence on Marx and his magnum opus became a founding text of individualist anarchism.[50] Edmund Husserl once warned a small audience about the "seducing power" of Der Einzige, but he never mentioned it in his writing.[51] As the art critic and Stirner admirer Herbert Read observed, the book has remained "stuck in the gizzard" of Western culture since it first appeared.[52] Many thinkers have read and been affected by The Unique and Its Property in their youth including Rudolf Steiner, Gustav Landauer, Victor Serge,[53] Carl Schmitt and Jürgen Habermas. Few openly admit any influence on their own thinking.[54] Ernst Jünger's book Eumeswil, had the character of the Anarch, based on Stirner's Einzige.[55] Some have tried to use Stirner’s ideas to defend capitalism while others have used them to argue for anarcho-syndicalism.[21] Several other authors, philosophers and artists have cited, quoted or otherwise referred to Max Stirner. They include Albert Camus in The Rebel (the section on Stirner is omitted from the majority of English editions including Penguin's), Benjamin Tucker, James Huneker,[56] Dora Marsden, Renzo Novatore, Emma Goldman,[57] Georg Brandes, John Cowper Powys,[58] Martin Buber,[59] Sidney Hook,[60] Robert Anton Wilson, Horst Matthai, Frank Brand, Marcel Duchamp, several writers of the Situationist International including Raoul Vaneigem[61] and Max Ernst. Oscar Wilde's The Soul of Man Under Socialism has caused some historians to speculate that Wilde (who could read German) was familiar with the book.[62] |

影響力 アインツィーゲ』は批評的には成功を収め、出版後は著名な哲学者たちから多くの反響を呼んだが、シュティルナーの死の何年も前に絶版となり、その悪評は色 あせていた[50]。 [シュティルナーは左翼ヘーゲル主義に破壊的な影響を与えたが、彼の哲学はマルクスに大きな影響を与え、彼の大著は個人主義的アナキズムの創始テキストと なった。 ルドルフ・シュタイナー、グスタフ・ランダウアー、ヴィクトル・セルジュ、カール・シュミット、ユルゲン・ハーバーマス[53]など、多くの思想家が若い 頃に『唯一とその性質』を読み、影響を受けている。エルンスト・ユンガーの著書『オイメスヴィル』には、シュティルナーの『アインツィーゲ』に基づいたア ナークのキャラクターが描かれていた[55]。シュティルナーの思想を資本主義を擁護するために利用しようとする者もいれば、アナルコ・サンディカリズム を主張するために利用する者もいた[21]。 他の作家、哲学者、芸術家の中にもマックス・シュティルナーを引用、引用、言及した者がいる。その中には、『反逆者』のアルベール・カミュ(ペンギンを含 む大半の英語版ではスティルナーの項は省略されている)、ベンジャミン・タッカー、ジェームズ・ヒューンカー、[56]ドラ・マースデン、レンゾ・ノヴァ トーレ、エマ・ゴールドマン、[57]ゲオルク・ブランデスが含まれる、 ジョン・カウパー・パウイス、[58] マルティン・ブーバー、[59] シドニー・フック、[60] ロバート・アントン・ウィルソン、ホルスト・マタイ、フランク・ブランド、マルセル・デュシャン、ラウル・ヴァニゲムを含むシチュアシオニスト・インター ナショナルの作家たち[61] 、マックス・エルンストなどである。オスカー・ワイルドの『社会主義下の人間の魂』は、(ドイツ語を読むことができた)ワイルドがこの本に精通していたと 推測する歴史家もいる[62]。 |

| Anarchist movement Main articles: Egoist anarchism and Individualist anarchism Stirner's philosophy was important in the development of modern anarchist thought, particularly individualist anarchism and egoist anarchism. Although Stirner is usually associated with individualist anarchism, he was influential to many social anarchists such as anarcha-feminists Emma Goldman and Federica Montseny. In European individualist anarchism, he influenced its major proponents after him such as Émile Armand, Han Ryner, Renzo Novatore, John Henry Mackay, Miguel Giménez Igualada and Lev Chernyi. In American individualist anarchism, he found adherence in Benjamin Tucker and his magazine Liberty while these abandoned natural rights positions for egoism.[63] Several periodicals "were undoubtedly influenced by Liberty's presentation of egoism". They included I, published by Clarence Lee Swartz and edited by William Walstein Gordak and J. William Lloyd (all associates of Liberty); and The Ego and The Egoist, both of which were edited by Edward H. Fulton. Among the egoist papers that Tucker followed, there were the German Der Eigene, edited by Adolf Brand; and The Eagle and The Serpent, issued from London. The latter, the most prominent English-language egoist journal, was published from 1898 to 1900 with the subtitle A Journal of Egoistic Philosophy and Sociology.[63] Other American egoist anarchists around the early 20th century include James L. Walker, George Schumm, John Beverley Robinson, Steven T. Byington.[63] In the United Kingdom, Herbert Read was influenced by Stirner and noted the closeness of Stirner's egoism to existentialism (see existentialist anarchism). Later in the 1960s, Daniel Guérin says in Anarchism: From Theory to Practice that Stirner "rehabilitated the individual at a time when the philosophical field was dominated by Hegelian anti-individualism and most reformers in the social field had been led by the misdeeds of bourgeois egotism to stress its opposite" and pointed to "the boldness and scope of his thought".[64] In the 1970s, an American Situationist collective called For Ourselves published a book called The Right To Be Greedy: Theses On The Practical Necessity Of Demanding Everything in which they advocate a "communist egoism" basing themselves on Stirner.[65] Later in the United States, it emerged the tendency of post-left anarchy which was influenced profoundly by Stirner in aspects such as the critique of ideology. Jason McQuinn says that "when I (and other anti-ideological anarchists) criticize ideology, it is always from a specifically critical, anarchist perspective rooted in both the skeptical, individualist-anarchist philosophy of Max Stirner".[66] Bob Black and Feral Faun/Wolfi Landstreicher strongly adhere to Stirnerist egoism. In the hybrid of post-structuralism and anarchism called post-anarchism, Saul Newman has written on Stirner and his similarities to post-structuralism. Insurrectionary anarchism also has an important relationship with Stirner as can be seen in the work of Wolfi Landstreicher and Alfredo Bonanno who has also written on him in works such as Max Stirner and Max Stirner and Anarchism.[67] Free love, homosexuals and feminists See also: Anarchism and issues related to love and sex German Stirnerist Adolf Brand produced the homosexual periodical Der Eigene in 1896. This was the first ongoing homosexual publication in the world[68] and ran until 1931. The name was taken from the writings of Stirner (who had greatly influenced the young Brand) and refers to Stirner's concept of "self-ownership" of the individual. Another early homosexual activist influenced by Stirner was John Henry Mackay. Feminists influenced by Stirner include anarchist Emma Goldman, as well as Dora Marsden who founded the journals The Freewoman, The New Freewoman, and The Egoist. Stirner also influenced free love and polyamory propagandist Émile Armand in the context of French individualist anarchism of the early 20th century which is known for "[t]he call of nudist naturism, the strong defense of birth control methods, the idea of "unions of egoists" with the sole justification of sexual practices".[69] Post-structuralism See also: Post-anarchism and Post-structuralism In his book Specters of Marx, influential French poststructuralist thinker Jacques Derrida dealt with Stirner and his relationship with Marx while also analysing Stirner's concept of "specters" or "spooks".[70] Gilles Deleuze, another key thinker associated with post-structuralism, mentions Stirner briefly in his book The Logic of Sense.[71] Saul Newman calls Stirner a proto-poststructuralist who on the one hand had essentially anticipated modern post-structuralists such as Foucault, Lacan, Deleuze and Derrida, but on the other had already transcended them, thus providing what they were unable to—i.e. a ground for a non-essentialist critique of present liberal capitalist society. This is particularly evident in Stirner's identification of the self with a "creative nothing", a thing that cannot be bound by ideology, inaccessible to representation in language. |

アナキズム運動 主な記事 エゴイスト的アナキズムと個人主義的アナキズム シュティルナーの哲学は、近代アナキズム思想、特に個人主義アナキズムとエゴイスト・アナキズムの発展において重要であった。シュティルナーは通常、個人 主義的アナキズムと結びつけられているが、アナーカ・フェミニストのエマ・ゴールドマンやフェデリカ・モンセニーなど多くの社会的アナキストに影響を与え た。ヨーロッパの個人主義アナーキズムでは、エミール・アルマン、ハン・ライナー、レンゾ・ノヴァトーレ、ジョン・ヘンリー・マッケイ、ミゲル・ギメネ ス・イグアラダ、レフ・チェルニイなど、彼以降の主な支持者に影響を与えた。 アメリカの個人主義アナーキズムでは、ベンジャミン・タッカーと彼の雑誌『リバティ』に信奉者を見出したが、その一方で、これらは自然権の立場を放棄して エゴイズムの立場をとった[63]。いくつかの定期刊行物は「間違いなくリバティのエゴイズムの提示に影響を受けていた」。その中には、クラレンス・ リー・スワーツが発行し、ウィリアム・ウォルスタイン・ゴルダックとJ・ウィリアム・ロイド(いずれもリバティの仲間)が編集した『I』や、エドワード・ H・フルトンが編集した『エゴ』と『エゴイスト』が含まれていた。タッカーの後に続いたエゴイストの新聞には、アドルフ・ブランドが編集したドイツの『デ ア・アイゲン』、ロンドンから発行された『イーグル』と『サーペント』がある。後者は最も著名な英語のエゴイスト雑誌であり、1898年から1900年に かけて『A Journal of Egoistic Philosophy and Sociology』という副題で発行されていた[63]。20世紀初頭の他のアメリカのエゴイスト・アナキストには、ジェームス・L・ウォーカー、 ジョージ・シュム、ジョン・ビヴァリー・ロビンソン、スティーヴン・T・バイントンなどがいる[63]。 イギリスでは、ハーバート・リードがスターナーの影響を受けており、スターナーのエゴイズムが実存主義に近いことを指摘していた(実存主義アナーキズムを 参照)。1960年代後半、ダニエル・ゲランは『アナキズム』の中で次のように述べている: 哲学の分野がヘーゲル的な反個人主義によって支配され、社会分野の改革者のほとんどがブルジョア的エゴイズムの悪行によってその反対を強調するように導か れていた時期に、個人を回復させた」とダニエル・ゲランは『From Theory to Practice』の中で述べており、「彼の思想の大胆さと広さ」を指摘している[64]。1970年代には、For Ourselvesと呼ばれるアメリカのシチュアシオニスト集団が『The Right To Be Greedy(貪欲である権利)』という本を出版した: Theses On The Practical Necessity Of Demanding Everything』という本を出版し、その中で彼らはスティルナーに基づいた「共産主義的エゴイズム」を提唱していた[65]。 その後、アメリカでは、イデオロギー批判などの側面でスティルナーから多大な影響を受けたポスト・レフト無政府主義の傾向が現れた。ジェイソン・マクウィ ンは、「私(や他の反イデオロギー的アナキスト)がイデオロギーを批判するとき、それは常にマックス・シュティルナーの懐疑的で個人主義的なアナキスト哲 学の両方に根ざした、特に批判的なアナキストの視点からである」と述べている[66]。 ボブ・ブラックとフェラル・ファウン/ウォルフィ・ランドシュトライヒャーは、シュティルナー主義のエゴイズムを強く支持している。ポスト・アナーキズム と呼ばれるポスト構造主義とアナーキズムのハイブリッドにおいて、ソウル・ニューマンはスティルナーとポスト構造主義との類似性について書いている。ま た、『マックス・シュティルナー』や『マックス・シュティルナーとアナーキズム』などの著作でシュティルナーについて書いているウォルフィ・ランドシュト ライヒャーやアルフレード・ボナーノの作品に見られるように、反乱主義的アナーキズムもシュティルナーと重要な関係にある[67]。 自由恋愛、同性愛者、フェミニスト こちらも参照のこと: アナキズムと愛と性に関する問題 ドイツのスティルナー主義者アドルフ・ブランドは、1896年に同性愛定期刊行物『Der Eigene』を創刊した。これは世界初の継続的な同性愛雑誌であり[68]、1931年まで発行された。この名前は、(若いブランドに大きな影響を与え た)スティルナーの著作から取られたもので、スティルナーの個人の「自己所有」の概念を指している。また、スティルナーの影響を受けた初期の同性愛活動家 にジョン・ヘンリー・マッケイがいる。スターナーの影響を受けたフェミニストには、アナーキストのエマ・ゴールドマンや、雑誌『フリーウーマン』 『ニュー・フリーウーマン』『エゴイスト』を創刊したドラ・マースデンがいる。スティルナーはまた、20世紀初頭のフランスの個人主義的アナーキズムの文 脈で、自由恋愛とポリアモリーの宣伝者エミール・アルマンにも影響を与えた。このアナーキズムは、「ヌーディスト・ナチュリズムの呼びかけ、避妊法の強力 な擁護、性行為を唯一正当化する「エゴイストの組合」の思想」で知られている[69]。 ポスト構造主義 以下も参照: ポスト・アナーキズムとポスト構造主義 フランスの有力なポスト構造主義の思想家であるジャック・デリダは、その著書『マルクスの亡霊』の中で、スティルナーと彼のマルクスとの関係を扱い、同時 にスティルナーの「亡霊」や「お化け」の概念についても分析している[70]。ポスト構造主義に関連するもう一人の重要な思想家であるジル・ドゥルーズ は、その著書『感覚の論理』の中でスティルナーについて少し触れている。 [ソウル・ニューマンはスティルナーをポスト構造主義の原型と呼び、一方ではフーコー、ラカン、ドゥルーズ、デリダといった現代のポスト構造主義者を本質 的に先取りしていたが、他方ではすでにそれらを超越していたため、彼らがなしえなかったこと、すなわち現在の自由資本主義社会に対する非本質的な批判の根 拠を提供していた。このことは、スティルナーが自己を「創造的な無」と同一視していること、すなわちイデオロギーに束縛されることのないもの、言語による 表現にアクセスできないものと同一視していることに個別主義的に表れている。 |

| Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels Friedrich Engels commented on Stirner in poetry at the time of Die Freien: Look at Stirner, look at him, the peaceful enemy of all constraint. For the moment, he is still drinking beer, Soon he will be drinking blood as though it were water. When others cry savagely "down with the kings" Stirner immediately supplements "down with the laws also." Stirner full of dignity proclaims; You bend your willpower and you dare to call yourselves free. You become accustomed to slavery Down with dogmatism, down with law.[72] Engels once even recalled at how they were "great friends" (Duzbrüder).[15] In November 1844, Engels wrote a letter to Karl Marx in which he first reported a visit to Moses Hess in Cologne and then went on to note that during this visit Hess had given him a press copy of a new book by Stirner, The Unique and Its Property. In his letter to Marx, Engels promised to send a copy of the book to him, for it certainly deserved their attention as Stirner "had obviously, among the 'Free Ones', the most talent, independence and diligence."[15] To begin with, Engels was enthusiastic about the book and expressed his opinions freely in letters to Marx: But what is true in his principle, we, too, must accept. And what is true is that before we can be active in any cause we must make it our own, egoistic cause—and that in this sense, quite aside from any material expectations, we are communists in virtue of our egoism, that out of egoism we want to be human beings and not merely individuals.[73] Later, Marx and Engels wrote a major criticism of Stirner's work. The number of pages Marx and Engels devote to attacking Stirner in the unexpurgated text of The German Ideology exceeds the total of Stirner's written works.[74] In the book Stirner is derided as Sankt Max (Saint Max) and as Sancho (a reference to Cervantes' Sancho Panza). As Isaiah Berlin has described it, Stirner "is pursued through five hundred pages of heavy-handed mockery and insult."[75] The book was written in 1845–1846, but it was not published until 1932. Marx's lengthy ferocious polemic against Stirner has since been considered an important turning point in Marx's intellectual development from idealism to materialism. It has been argued that historical materialism was Marx's method of reconciling communism with a Stirnerite rejection of morality.[44][45][46] |

カール・マルクスとフリードリヒ・エンゲルス フリードリヒ・エンゲルスは、『ディ・フライエン』執筆当時、詩の中でシュティルナーについてこう評している: シュティルナーを見よ、彼を見よ、あらゆる束縛の平和的な敵だ。 今のところ、彼はまだビールを飲んでいる、 やがて彼は血を水のように飲むだろう。 他人が野蛮に 「王を倒せ 」と叫ぶと、シュティルナーは即座に 「王を倒せ 」と補足する。 スティルナーは即座に、「法律も倒せ 」と補足する。 威厳に満ちたスティルナーはこう宣言する; 自分の意志を曲げ、あえて自由を名乗る。 隷属に慣れきっている。 教条主義を捨てよ、法を捨てよ」[72]。 1844年11月、エンゲルスはカール・マルクスに宛てて手紙を書き、その中でまずケルンのモーゼス・ヘスを訪問したことを報告し、その訪問の際にヘスが シュティルナーの新刊書『唯一とその所有物』のプレス・コピーを彼に渡したことを記した[15]。マルクスへの手紙の中で、エンゲルスは、この本のコピー をマルクスに送ることを約束した。なぜなら、スティルナーは「『自由人』の中で、明らかに、最も才能があり、独立心があり、勤勉であった」[15]ので、 この本は彼らの注目に値するものであったからである: しかし、彼の原則の中で真実であることは、我々も受け入れなければならない。そして、何が真実であるかというと、われわれが何らかの大義に積極的になる前 に、われわれはそれを自分自身の、エゴイスティックな大義にしなければならないということであり、この意味において、物質的な期待とはまったく別に、われ われはエゴイズムのゆえに共産主義者であり、エゴイズムのゆえに、われわれは単なる個人ではなく、人間でありたいと願っているのである[73]。 その後、マルクスとエンゲルスはスティルナーの著作に対する主要な批判を書いた。マルクスとエンゲルスが『ドイツ・イデオロギー』の未抄訳テキストの中で スティルナーを攻撃するために割いたページ数は、スティルナーの著作の総数を超えている[74]。この本の中でスティルナーは、サンクト・マックス(聖人 マックス)、サンチョ(セルバンテスのサンチョ・パンサへの言及)と揶揄されている。アイザイア・バーリンが表現したように、シュティルナーは「500 ページにも及ぶ強引な嘲笑と侮辱に追いかけられる」[75]。この本は1845年から1846年にかけて書かれたが、出版されたのは1932年であった。 マルクスのスティルナーに対する長い猛烈な極論は、それ以来、マルクスの観念論から唯物論への知的発展における重要な転換点とみなされている。史的唯物論 はマルクスが共産主義とスティルナー的な道徳の拒絶を調和させるための方法であったと論じられている[44][45][46]。 |

| Possible influence on Friedrich Nietzsche Main article: Relationship between Friedrich Nietzsche and Max Stirner The ideas of Stirner and Friedrich Nietzsche have often been compared and many authors have discussed apparent similarities in their writings, sometimes raising the question of influence.[76] During the early years of Nietzsche's emergence as a well-known figure in Germany, the only thinker discussed in connection with his ideas more often than Stirner was Arthur Schopenhauer.[77] It is certain that Nietzsche read about The Unique and Its Property, which was mentioned in Friedrich Albert Lange's History of Materialism and Karl Robert Eduard von Hartmann's Philosophy of the Unconscious, both of which Nietzsche knew well.[78] However, there is no indication that he actually read it as no mention of Stirner is known to exist anywhere in Nietzsche's publications, papers or correspondence.[79] In 2002, a biographical discovery revealed it is probable that Nietzsche had encountered Stirner's ideas before he read Hartmann and Lange in October 1865, when he met with Eduard Mushacke, an old friend of Stirner's during the 1840s.[80] As soon as Nietzsche's work began to reach a wider audience, the question of whether he owed a debt of influence to Stirner was raised. As early as 1891 when Nietzsche was still alive, though incapacitated by mental illness, Hartmann went so far as to suggest that he had plagiarized Stirner.[81] By the turn of the century, the belief that Nietzsche had been influenced by Stirner was so widespread that it became something of a commonplace at least in Germany, prompting one observer to note in 1907 that "Stirner's influence in modern Germany has assumed astonishing proportions, and moves in general parallel with that of Nietzsche. The two thinkers are regarded as exponents of essentially the same philosophy."[82] From the beginning of what was characterized as "great debate"[83] regarding Stirner's possible positive influence on Nietzsche, serious problems with the idea were nonetheless noted.[84] By the middle of the 20th century, if Stirner was mentioned at all in works on Nietzsche, the idea of influence was often dismissed outright or abandoned as unanswerable.[85] However, the idea that Nietzsche was influenced in some way by Stirner continues to attract a significant minority, perhaps because it seems necessary to explain the oft-noted (though arguably superficial) similarities in their writings.[86] In any case, the most significant problems with the theory of possible Stirner influence on Nietzsche are not limited to the difficulty in establishing whether the one man knew of or read the other. They also consist in determining if Stirner in particular might have been a meaningful influence on a man as widely read as Nietzsche.[87] |

フリードリヒ・ニーチェへの影響の可能性 主な記事 フリードリヒ・ニーチェとマックス・シュティルナーの関係 シュティルナーとフリードリヒ・ニーチェの思想はしばしば比較され、多くの著者が彼らの著作における明らかな類似点を論じており、時には影響についての疑 問を提起することもあった[76]。ニーチェがドイツで有名な人物として台頭してきた初期において、シュティルナーよりも彼の思想との関連で頻繁に論じら れていた唯一の思想家はアルトゥール・ショーペンハウアーであった[77]。 [ニーチェがフリードリヒ・アルベルト・ラングの『唯物論史』とカール・ロベルト・エドゥアルト・フォン・ハルトマンの『無意識の哲学』で言及されている 『唯一性とその性質』について読んだことは確かである。 [しかし、ニーチェの出版物、論文、書簡のどこにもシュティルナーに関する言及が存在しないことから、彼が実際にそれを読んだことを示すものはない [79]。2002年、ある伝記的発見によって、ニーチェは1865年10月にハルトマンとラングを読む前に、1840年代にシュティルナーの旧友であっ たエドゥアルド・ムシャッケと会ったときにシュティルナーの思想に出会っていた可能性が高いことが明らかになった[80]。 ニーチェの著作がより多くの読者に届くようになるとすぐに、ニーチェがスティルナーに影響を受けた借りがあるかどうかという疑問が持ち上がった。世紀が変 わる頃には、ニーチェがシュティルナーの影響を受けているという考え方は非常に広まり、少なくともドイツでは当たり前のこととなった。二人の思想家は本質 的に同じ哲学の代表者とみなされている」[82]。 ニーチェに対するシュティルナーの肯定的な影響の可能性に関して「大論争」[83]と特徴づけられるものが始まった当初から、それにもかかわらず、この考 え方の深刻な問題が指摘されていた[84]。 20世紀半ばまでに、ニーチェに関する著作の中でシュティルナーについて言及されることがあったとしても、影響に関する考え方はしばしば真っ向から否定さ れるか、答えのないものとして放棄された。 [しかし、ニーチェがスティルナーから何らかの影響を受けたという考え方は、おそらく彼らの著作におけるよく指摘される(間違いなく表面的な)類似性を説 明するために必要だと思われるためか、かなりの少数派を惹きつけ続けている[86]。いずれにせよ、ニーチェに対するスティルナーの影響の可能性に関する 理論における最も重大な問題は、一方の人物が他方の人物を知っていたか、読んでいたかを立証することの難しさに限定されるものではない。それらはまた、特 にシュティルナーがニーチェのように広く読まれている人物に有意義な影響を与えたかどうかを判断することにある[87]。 |

| Rudolf Steiner The individualist anarchist orientation of Rudolf Steiner's early philosophy—before he turned to theosophy around 1900—has strong parallels to and was admittedly influenced by Stirner's conception of the ego, for which Steiner claimed to have provided a philosophical foundation.[88] |

ルドルフ・シュタイナー 1900年頃に神智学に傾倒する以前のルドルフ・シュタイナーの初期の哲学における個人主義的な無政府主義的志向は、シュタイナーが哲学的基礎を提供したと主張するシュティルナーの自我の概念と強い類似性を持ち、その影響を受けていたことが認められている[88]。 |

| Alterity Anarchism in Germany Antihumanism Contemporary anarchism Difference (philosophy) Différance Egoist anarchism Enlightened self-interest Ethical solipsism Hauntology Individualist anarchism Individualist anarchism in Europe Other (philosophy) |

アルタリティ ドイツのアナキズム 反ヒューマニズム 現代のアナキズム 差異(哲学) 差延 エゴイスト的アナキズム 啓蒙的利己主義 倫理的独我論 ハウントロジー=憑在論 個人主義的アナキズム ヨーロッパにおける個人主義アナキズム その他(哲学) |

| References Stirner, Max: Der Einzige und sein Eigentum (1845 [October 1844]). Stuttgart: Reclam-Verlag, 1972ff; English translation The Ego and Its Own (1907), ed. David Leopold, Cambridge/ New York: CUP 1995. Stirner, Max: "Recensenten Stirners" (September 1845). In: Parerga, Kritiken, Repliken, Bernd A. Laska, ed., Nürnberg: LSR-Verlag, 1986; English translation Stirner's Critics (abridged), see below. Max Stirner, Political Liberalism (1845). Further reading Max Stirner's 'Der Einzige und sein Eigentum' im Spiegel der zeitgenössischen deutschen Kritik. Eine Textauswahl (1844–1856). Hg. Kurt W. Fleming. Leipzig: Verlag Max-Stirner-Archiv 2001 (Stirneriana). Arena, Leonardo V., Note ai margini del nulla, ebook, 2013. Arvon, Henri, Aux Sources de l'existentialisme, Paris: P.U.F. 1954. Essbach, Wolfgang, Gegenzüge. Der Materialismus des Selbst. Eine Studie über die Kontroverse zwischen Max Stirner und Karl Marx. Frankfurt: Materialis 1982. Feiten, Elmo (2013). "Would the Real Max Stirner Please Stand Up?". Anarchist Developments in Cultural Studies (1). ISSN 1923-5615. Helms, Hans G, Die Ideologie der anonymen Gesellschaft. Max Stirner 'Einziger' und der Fortschritt des demokratischen Selbstbewusstseins vom Vormärz bis zur Bundesrepublik, Köln: Du Mont Schauberg, 1966. Koch, Andrew M., "Max Stirner: The Last Hegelian or the First Poststructuralist". In: Anarchist Studies, vol. 5 (1997) pp. 95–108. Laska, Bernd A., Ein dauerhafter Dissident. Eine Wirkungsgeschichte des Einzigen, Nürnberg: LSR-Verlag 1996 (TOC, index). Laska, Bernd A., Ein heimlicher Hit. Editionsgeschichte des "Einzigen". Nürnberg: LSR-Verlag 1994 (abstract). Marshall, Peter H. "Max Stirner" in "Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism "(London: HarperCollins, 1992). Moggach, Douglas; De Ridder, Widukind, "Hegelianism in Restoration Prussia, 1841–1848: Freedom, Humanism and 'Anti-Humanism' in Young Hegelian Thought". In: Herzog, Lisa (ed.): Hegel's Thought in Europe: Currents, Crosscurrents and Undercurrents. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, pp. 71–92 (Google Books). Newman, Saul (ed.), Max Stirner (Critical Explorations in Contemporary Political Thought), Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011 (full book). Newman, Saul, Power and Politics in Poststructural Thought. London and New York: Routledge 2005. Parvulescu, C. "The Individualist Anarchist Discourse of Early Interwar Germany". Cluj University Press, 2018 (full book). Paterson, R. W. K., The Nihilistic Egoist: Max Stirner, Oxford: Oxford University Press 1971. Spiessens, Jeff. The Radicalism of Departure. A Reassessment of Max Stirner's Hegelianism, Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, 2018. Stepelevich, Lawrence S. (1985a). "Max Stirner as Hegelian". Journal of the History of Ideas. 46 (4): 597–614. doi:10.2307/2709548. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 2709548. Stepelevich, Lawrence S., Ein Menschenleben. Hegel and Stirner". In: Moggach, Douglas (ed.): The New Hegelians. Philosophy and Politics in the Hegelian School. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp. 166–176. Welsh, John F. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. Wilkinson, Will (2008). "Stirner, Max (1806–1856)". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. pp. 493–494. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n300. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024. Di Mascio, Carlo, Stirner Giuspositivista. Rileggendo l'Unico e la sua proprietà, 2 ed., Edizioni Del Faro, Trento, 2015, p. 253, ISBN 978-88-6537-378-1. |

参考文献 Stirner, Max: Der Einzige und sein Eigentum (1845 [October 1844]). Stuttgart: Stuttgart: Reclam-Verlag, 1972ff; 英語訳 The Ego and Its Own (1907). David Leopold, Cambridge/ New York: CUP 1995. Stirner, Max: 「Recensenten Stirners」 (September 1845). In: Parerga, Kritiken, Repliken, Bernd A. Laska, ed., Nürnberg: 英語訳Stirner's Critics(抄訳)、下記参照。 Max Stirner, Political Liberalism (1845). さらに読む Max Stirner's 'Der Einzige und sein Eigentum' im Spiegel der Zeitgenössischen deutschen Kritik. Eine Textauswahl (1844-1856). Hg. Kurt W. Fleming. Leipzig: Verlag Max-Stirner-Archiv 2001 (Stirneriana). Arena, Leonardo V., Note ai margini del nulla, ebook, 2013. Arvon, Henri, Aux Sources de l'existentialisme, Paris: P.U.F. 1954. Essbach, Wolfgang, Gegenzüge. Der Materialismus des Selbst. マックス・シュティルナーとカール・マルクスの間の対立に関する研究。Frankfurt: Materialis 1982. Feiten, Elmo (2013). 「Would the Real Max Stirner Please Stand Up?」. Anarchist Developments in Cultural Studies (1). issn 1923-5615. Helms, Hans G, Die Ideologie der anonymen Gesellschaft. Max Stirner 'Einziger' und der Fortschritt des demokratischen Selbstbewusstseins vom Vormärz bisur Bundesrepublik, Köln: Du Mont Schauberg, 1966. Koch, Andrew M., "Max Stirner: Max Stirner: The Last Hegelian or the First Poststructuralist」. In: Anarchist Studies, vol.5 (1997) pp. 95-108. Laska, Bernd A., Ein dauerhafter Dissident. Eine Wirkungsgeschichte des Einzigen, Nürnberg: Laska, Bernd A., Ein dauerhafterissident. Laska, Bernd A., Ein heimlicher Hit. Editionsgeschichte des 「Einzigen」. Nürnberg: LSR-Verlag 1994(抄録)。 Marshall, Peter H. 「Max Stirner」 in "Demanding the Impossible: A History of Anarchism "(London: HarperCollins, 1992). Moggach, Douglas; De Ridder, Widukind, "Hegelianism in Restoration Prussia, 1841-1848: 若きヘーゲル思想における自由、ヒューマニズム、『反ヒューマニズム』」。In: Herzog, Lisa (ed.): Hegel's Thought in Europe: ヨーロッパにおけるヘーゲル思想:潮流、クロスカレント、アンダーカレント」。Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, pp.71-92 (Google Books). Newman, Saul (ed.), Max Stirner (Critical Explorations in Contemporary Political Thought), Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011 (full book)。 Newman, Saul, Power and Politics in Poststructural Thought. London and New York: Routledge 2005. Parvulescu, C. 「The Individualist Anarchist Discourse of Early Interwar Germany」. Cluj University Press, 2018(全著書)。 Paterson, R. W. K., The Nihilistic Egoist: Max Stirner, Oxford: Oxford University Press 1971. Spiessens, Jeff. The Radicalism of Departure. A Reassessment of Max Stirner's Hegelianism, Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, 2018. Stepelevich, Lawrence S. (1985a). 「Max Stirner as Hegelian」. Journal of the History of Ideas. 46 (4): doi:10.2307/2709548. issn 0022-5037. JSTOR 2709548. Stepelevich, Lawrence S., Ein Menschenleben. Hegel and Stirner」. In: ヘーゲルとシュティルナー」: The New Hegelians. ヘーゲル学派における哲学と政治。Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp.166-176. Max Stirner's Dialectical Egoism: A New Interpretation. Lexington Books. 2010. Wilkinson, Will (2008). 「Stirner, Max (1806-1856)」. In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. 493–494. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n300. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024. Di Mascio, Carlo, Stirner Giuspositivista. Rileggendo l'Unico e la sua proprietà, 2 ed., Edizioni Del Faro, Trento, 2015, p. 253, ISBN 978-88-6537-378-1. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max_Stirner |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆