マックス・ヴェステンヘーファー

Max Westenhöfer, 1871-1957

☆ げんちゃんはこちら(genchan_tetsu.html) 【翻訳用】海豚ワイドモダン(00-Grid-modern.html) (★ワイドモダンgenD.png)

| Maximilian

Joseph Johann Westenhöfer (* 9. Februar 1871 in Ansbach; † 25.

September 1957 in Santiago de Chile) war ein deutscher Pathologe und

Anthropologe. Max Westenhöfer genoss als Mitarbeiter von Rudolf Virchow, als Direktor des pathologischen Museums in Berlin und vor allem aufgrund seines langjährigen Wirkens als Lehrer und Forscher in Santiago de Chile international einen herausragenden Ruf. Westenhöfer vertrat in der Abstammungsfrage des Menschen ähnlich wie der belgische Biologe Serge Frechkop, wissenschaftlich die Meinung, „daß der Mensch Mensch innerhalb der Säugetierreihe das weitestgehend urtümliche Geschöpf ist.“[1]. Diese archaische These der Entwicklung des Menschen steht scharf der klassischen Reduktionstheorie entgegen, die eine geradlinige Ableitung von Großaffen durch Reduktionen der Spezialisierungen dieser Tiere zu der unspezialisierten, mängelbehafteten Organisationsform des Menschen postulieren. Die archaische Theorie der Menschwerdung hat Westenhöfer klassisch formuliert in seinem Werk „Der Eigenweg des Menschen“. |

Maximilian Joseph Johann

Westenhöfer (* 1871年2月9日 in Ansbach; † 1957年9月25日 in Santiago de

Chile)はドイツの病理学者、人類学者である。 マックス・ヴェステンヘーファーは、ルドルフ・ヴィルヒョーの同僚として、またベルリンの病理学博物館の館長として、そして何よりもサンティアゴ・デ・チ リでの教師・研究者としての長年の仕事により、国際的に傑出した名声を得た。 ベルギーの生物学者セルジュ・フレヒコップと同様、ヴェステンヘッファーの人類の祖先に関する科学的見解は、「人間は哺乳類の中で最も原始的な生き物であ る」というものであった[1]。この古風な人間の発生に関するテーゼは、古典的な還元説とは対照的である。還元説は、類人猿の特殊性を人間の非特異的で欠 陥のある組織形態に還元することで、類人猿の直接的な派生を仮定するものである。ヴェステンヘーファーは、その著作『人間の起源』(Der Eigenweg des Menschen)の中で、古典的な人間発生論を定式化した。 |

| Max

Westenhöfer (February 9, 1871 – September 25, 1957) was a German

pathologist and biologist who contributed to the development of the

anatomic pathology and the reform of public health in Chile. Education Maximilian Joseph Johann Westenhöfer[1] was born on February 9, 1871, in Ansbach, Bavaria. His father was a school teacher called Johan Karl Westenhöffer, but the son later simplified the spelling of his surname. His mother's maiden name was Knell,[2] and in later years her name was sometimes appended to his according to the Spanish naming custom. making his name Max Westenhöfer Knell.[3] He studied at the University of Berlin where he graduated in 1894. He was a pupil of Rudolf Virchow, German physician and Professor of Pathology at the University of Berlin, known also for his interest in public health.[3] His first employment was as an army doctor, which he remained, apart from three years in Chile, until 1922.[4] |

マックス・ヴェステンヘーファー(1871年2月9日 -

1957年9月25日)はドイツの病理学者、生物学者で、チリの解剖病理学の発展と公衆衛生の改革に貢献した。 教育 マクシミリアン・ヨーゼフ・ヨハン・ヴェステンヘーファー[1]は1871年2月9日、バイエルン州アンスバッハで生まれた。父はヨハン・カール・ヴェス テンヘッファーという学校の教師であったが、息子は後に姓の綴りを簡略化した。母親の旧姓はクネルであり[2]、後年、スペインの命名の習慣に従って、母 親の名前がクネルの名前に付けられることがあり、彼の名前はマックス・ヴェステンヘッファー・ネルとなった[3]。 ベルリン大学で学び、1894年に卒業。ルドルフ・ヴィルヒョー(ドイツ人医師、ベルリン大学病理学教授)の弟子であり、公衆衛生への関心でも知られる [3]。最初の就職先は軍医で、チリでの3年間を除けば1922年まで軍医を務めた[4]。 |

| First tenure in Chile

(1908–1911): Social medicine report and expulsion In 1908 he was hired by Augusto Matte, on behalf of the government of Chile, to teach Pathology at the School of Medicine of the University of Chile. As an international expert with the role to reform and modernize the teaching of pathology in Chile, he was provided by the Chilean government with a higher salary than that of his local medical colleagues, leading to envy and resentment among some Chilean physicians.[5] In 1911 he published what has been called the Westenhöfer Report, a five-part series published in the German medical journal Berliner klinische Wochenschrift where he described in critical terms the poor health conditions and hygiene practices that he observed in certain urban areas and nursing homes in Santiago of Chile. His report led to protests from the conservative sector of the Chilean society, eventually causing the government to deport him from Chile. However, the University of Chile Student Federation (FECH) including his medical students, some unions, and leftist parties gave public support to Prof. Westenhöfer and protested his expulsion. In August 1911 there was a massive march in Santiago of Chile to protest his expulsion and make a judicial appeal to prevent it, but it did not take place until after he had left.[5] Return to Germany (1911–1929): Professor of pathology at the University of Berlin Following his departure in 1911 he returned to Germany and resumed his career with the army. During World War I, he served as a military surgeon with the rank of major (Oberstabsarzt)[6] and was awarded the Iron Cross, second class.[7] In 1922 he became Professor of Pathology at the University of Berlin.[8] At this time he was also deputy chairman of the Berlin Gesellschaft für Rassenhygiene (German Society for Racial Hygiene).[9] Second tenure in Chile (1929–1932): Reform of Chilean pathology He returned to Chile in 1929 and for three years directed the Department of Pathology at the Medical School of the University of Chile. This was his most fruitful period in furthering the development and the quality of Chilean medicine. He modernised the practice of pathology and trained Chilean colleagues. Pathology institutes were founded in the hospitals in Santiago and Valparaiso.[3] His stress on the social determinants of mortality and morbidity influenced a generation of students, including Salvador Allende, a medical student activist and later President of Chile.[10][11] While in Chile, after studying the incidence of syphilis he contributed to the ongoing controversy about the origin of this disease. Westenhöfer observed little effect of the disease in Indian carriers and the terrible effects experienced by those of European origin who were infected, leading him to propose that a corresponding STD had been present in America before the European conquest. Back to Germany (1932–1948): Publication of the Aquatic Ape Hypothesis Further information: Aquatic Ape Hypothesis He returned again to Germany where he spent the war years, living latterly in retirement in Wasserburg am Bodensee.[12] From 1923 onwards[13] he wrote several books and papers on human evolution, perhaps most fully in his 1942 book "Der Eigenweg des Menschen" (translated as "The Path Travelled by Man Alone" or "The Unique Road to Man")[14] which put forward ideas suggesting, amongst other things, that adaptation to water has played a significant part in the history of human development. That particular idea has since been developed as the controversial Aquatic ape hypothesis (AAH), but the details of Westenhöfer's theory, such as that bipedalism is primitive in mammals,[13] are not shared by most modern supporters of the AAH.[1] Final tenure in Chile (1948–1957) In 1948, at the age of 77 he returned once more to Chile under a contract with the Junta Central de Beneficencia (Central Board of Charities) to serve as a pathology adviser.[15] For his long record of contributions in Chile he was decorated by the government with the Order of Bernardo O'Higgins.[3] His legacy on the teaching of the anatomic pathology in Chile was continued by his students, especially Dr Ismael Mena at the University of Chile and Dr Roberto Barahona Silva, founder of the Department of Pathology at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile.[5] Personal life Westenhöfer was married twice. From the first marriage, to Anna Maria,[16] he had three children, Grete, who was born in Chile, and Rudolf who was educated at the German School of Santiago. Only Wolf survived the war and lived in Berlin with six children. His second marriage was to Jutta, née Windmŭller,[17] who survived him.[15] He died on September 25, 1957, in Santiago de Chile,[18] which he considered his second home. Dr. Westenhöfer was buried in the Cementerio General de Santiago. |

チリでの最初の任期(1908-1911年):

社会医学レポートと追放 1908年、彼はチリ政府を代表してAugusto Matteに雇われ、チリ大学医学部で病理学を教えることになった。チリの病理学教育を改革し近代化する役割を担う国際的な専門家として、彼はチリ政府か ら現地の同僚医師よりも高い給与を支給され、一部のチリ人医師の嫉妬と憤慨を招いた[5]。 1911年、彼はドイツの医学雑誌『Berliner klinische Wochenschrift』に5部構成で掲載されたウェステンヘーファー報告書と呼ばれるものを発表し、チリのサンティアゴの特定の都市部や老人ホーム で観察された劣悪な健康状態や衛生習慣について批判的な言葉で記述した。彼の報告はチリ社会の保守部門からの抗議を招き、最終的に政府は彼をチリから国外 追放することになった。しかし、彼の医学生を含むチリ大学学生連盟(FECH)、いくつかの労働組合、左派政党はウェステンヘファー教授を支持し、追放に 抗議した。1911年8月には、彼の追放に抗議し、追放を阻止するための大規模なデモ行進がチリのサンティアゴで行われたが、それが行われたのは彼が去っ た後であった[5]。 ドイツに戻る(1911年-1929年): ベルリン大学病理学教授 1911年の出国後、彼はドイツに戻り、陸軍でのキャリアを再開した。第一次世界大戦中、彼は軍医として少佐(Oberstabsarzt)の階級で従軍 し[6]、二等鉄十字章を授与された[7]。1922年、彼はベルリン大学の病理学教授となった[8]。 チリで2度目の在任(1929年-1932年): チリの病理学の改革 1929年にチリに戻り、3年間チリ大学医学部病理学科を指揮した。この時期が、チリ医学の発展と質の向上に最も貢献した時期であった。彼は病理学の実践 を近代化し、チリの同僚を訓練した。死亡率と罹患率の社会的決定要因に関する彼の強調は、医学生の活動家で後にチリ大統領となったサルバドール・アジェン デを含む学生世代に影響を与えた[10][11]。 チリ滞在中、梅毒の発生率を研究した後、梅毒の起源に関する現在進行中の論争に貢献した。ヴェステンヘーファーは、インディアンの保菌者には梅毒の影響は ほとんどなく、ヨーロッパ人が感染すると恐ろしい影響があることを観察し、ヨーロッパ人が征服する以前からアメリカには梅毒に対応する性病が存在していた と提唱した。 ドイツに戻る(1932-1948年): 水生類人猿仮説の発表 さらなる情報 水生類人猿仮説 1923年以降[13]、彼は人類の進化に関するいくつかの著書や論文を執筆し、特に1942年の著書 "Der Eigenweg des Menschen"(訳注:「人間だけが歩んだ道」または「人間へのユニークな道」)[14]では、水への適応が人類の発達の歴史において重要な役割を果 たしたことを示唆する考えを提示した。この特殊な考えはその後、論争の的となる水生猿仮説(AAH)として発展したが、哺乳類において二足歩行は原始的で ある[13]といったヴェステンヘーファーの理論の詳細は、AAHの現代の支持者の多くには共有されていない[1]。 チリでの最後の任期(1948年-1957年) 1948年、77歳になった彼は、中央慈善委員会(Junta Central de Beneficencia)との契約により、病理学顧問として再びチリに戻った。 [3] チリにおける解剖学的病理学の教育における彼の遺産は、彼の教え子、特にチリ大学のイスマエル・メナ博士とチリ教皇庁カトリック大学の病理学科の創設者で あるロベルト・バラホナ・シルバ博士によって受け継がれた[5]。 私生活 ヴェステンヘーファーは2度結婚した。最初の結婚ではアンナ・マリアと結婚し[16]、チリで生まれたグレーテ、サンティアゴ・ドイツ学校で教育を受けた ルドルフの3人の子供をもうけた。ヴォルフだけが戦争を生き延び、6人の子供たちとベルリンで暮らした。2度目の結婚はユッタ(旧姓ヴィントムラー) [17]で、彼女はヴォルフと死別した[15]。 1957年9月25日、第二の故郷であったチリのサンティアゴで死去[18]。ヴェステンヘーファー博士はサンティアゴのセメンテリオ・ジェネラルに埋葬 された。 |

| Publications M. Westenhöffer: Tabes dorsalis und Syphilis. - Berlin: C. Vogts Buchdrückerei, 1894. - 34 pages (Berlin, Medizinische Fakultät, Inaug.-Diss. von 10. Augustus 1894) Thesis on Tabes dorsalis and Syphilis M. Westenhöffer: Über die Grenzen der übertragbarkeit der Tuberculose durch Fleisch tuberculöser Rinder auf den Menschen. - Berlin : A. Hirschwald, 1904. - 48 pages "On the limits of transferability of tuberculosis through the meat of tuberculous cattle to humans" M. Westenhöffer: Über Impftuberculose - Berlin : A. Hirschwald, 1904. - 24 pages - (Sonderabdruck aus Charité-Annalen) "On vaccination tuberculosis" M. Westenhöffer: Pathologisch-anatomische Ergebnisse der oberschlesischen Genickstarreepidemie von 1905 - Jena : G. Fischer, 1906. - iv, 72 pages - (Sonderabdruck aus Klin. Jahrb.) Study of 1905 meningitis epidemic in Upper Silesia M. Westenhöffer: Atlas der pathologisch-anatomischen Sektionstechnik - Berlin : A. Hirschwald, 1908. - viii, 53 pages. Illustrated guide for the performance of autopsies. Westenhöfer, Max: Die Aufgaben der Rassenhygiene (des Nachkommenschutzes) im neuen Deutschland : Vortrag, gehalten am 27. Februar 1919 in der Berliner Gesellschaft für Rassenhygiene von Dr. Med. Westenhöfer. - Berlin : Richard Schötz, 1920. - 40 pages - (Veröffentlichungen aus dem Gebiete der Medizinalverwaltung ; 10,2 = Heft. 103) "Racial hygiene tasks (for protection of the descendants) in the new Germany" Westenhöfer, Max: Über die Erhaltung von Vorfahrenmerkmalen beim Menschen, insbesondere über eine progonische Trias und ihre praktische Bedeutung. - In: Medizinische Klinik, 1923, 37. - pages 1247–1255. "On the preservation of ancestor's characteristics in human beings, and especially on a trio of primitive features and their importance in practice" Westenhöfer, Max (October 1926). "Evidence Opposed to the Darwinian Conceptions of the Origin of Species". Journal of the American Medical Association. 87 (18): 1494–1495. doi:10.1001/jama.1926.02680180066026. Westenhöfer, Max: Über die Klettermethoden der Naturvölker und über die Stellung der grossen Zehe - Leipzig : C. Kabitzsch, 1927. - pages 361–392. - Ill. - (Aus: Archiv für Frauenkunde und Konstitutionsforschung, Band 13, 1927, Heft 5) "On the climbing methods of primitive peoples and the position of the big toe" Westenhöfer, Max (1935). Das Problem der Menschwerdung : dargestellt auf Grund morphogenetischer Betrachtungen über Gehirn und Schädel und unter Bezugnahme auf zahlreiche andere Körpergegenden. Berlin: Nornen-Verlag. - "The problem of human origin, presented through morphogenetic reflections on the brain and skull, and with reference to many other parts of the body." Westenhöfer, Max (1942). Der Eigenweg des Menschen: dargestellt auf Grund von vergleichend morphologischen Untersuchungen über die Artbildung und Menschwerdung. Berlin: Die Medizinische Welt. "The unique path of man, depicted on the basis of comparative morphological studies on the formation of species and the origin of humanity" Westenhöfer, Max (1948). Die Grundlagen meiner Theorie vom Eigenweg des Menschen: Entwicklung, Menschwerdung, Weltanschauung. Heidelberg: Winter. "The basics of my theory of man's unique path: development, human origin, worldview" |

|

| German Chileans German Chileans (Spanish: germanochilenos; German: Deutsch-Chilenen) are Chileans descended from German immigrants, about 30,000 of whom arrived in Chile between 1846 and 1914. Most of these were from Bavaria, Baden and the Rhineland, and also from Bohemia in present-day Czech Republic, which were traditionally Catholic. A smaller number of Lutherans immigrated to Chile following the failed revolutions of 1848.[2][3][4] From the middle of the 19th century to the present, they have played a significant role in the economic, political and cultural development of the Chilean nation. The 19th-century immigrants settled chiefly in Chile's Araucanía, Los Ríos and Los Lagos regions in the so-called Zona Sur of Chile, including the Chilean lake district. |

ドイツ系チリ人 ドイツ系チリ人(スペイン語: germanochilenos; ドイツ語: Deutsch-Chilenen)は、1846年から1914年の間にチリに到着した約3万人のドイツ系移民の子孫である。そのほとんどはバイエルン、 バーデン、ラインラント、そして伝統的にカトリックであった現在のチェコ共和国ボヘミアからの移民であった。1848年の革命失敗後、より少数のルター派 がチリに移住した[2][3][4]。 19世紀半ばから現在に至るまで、彼らはチリ国家の経済的、政治的、文化的発展に重要な役割を果たしてきた。19世紀の移民は主にチリのアラウカニア、ロス・リオス、ロス・ラゴス地域、いわゆるチリのゾナ・スール(チリの湖水地方を含む)に定住した。 |

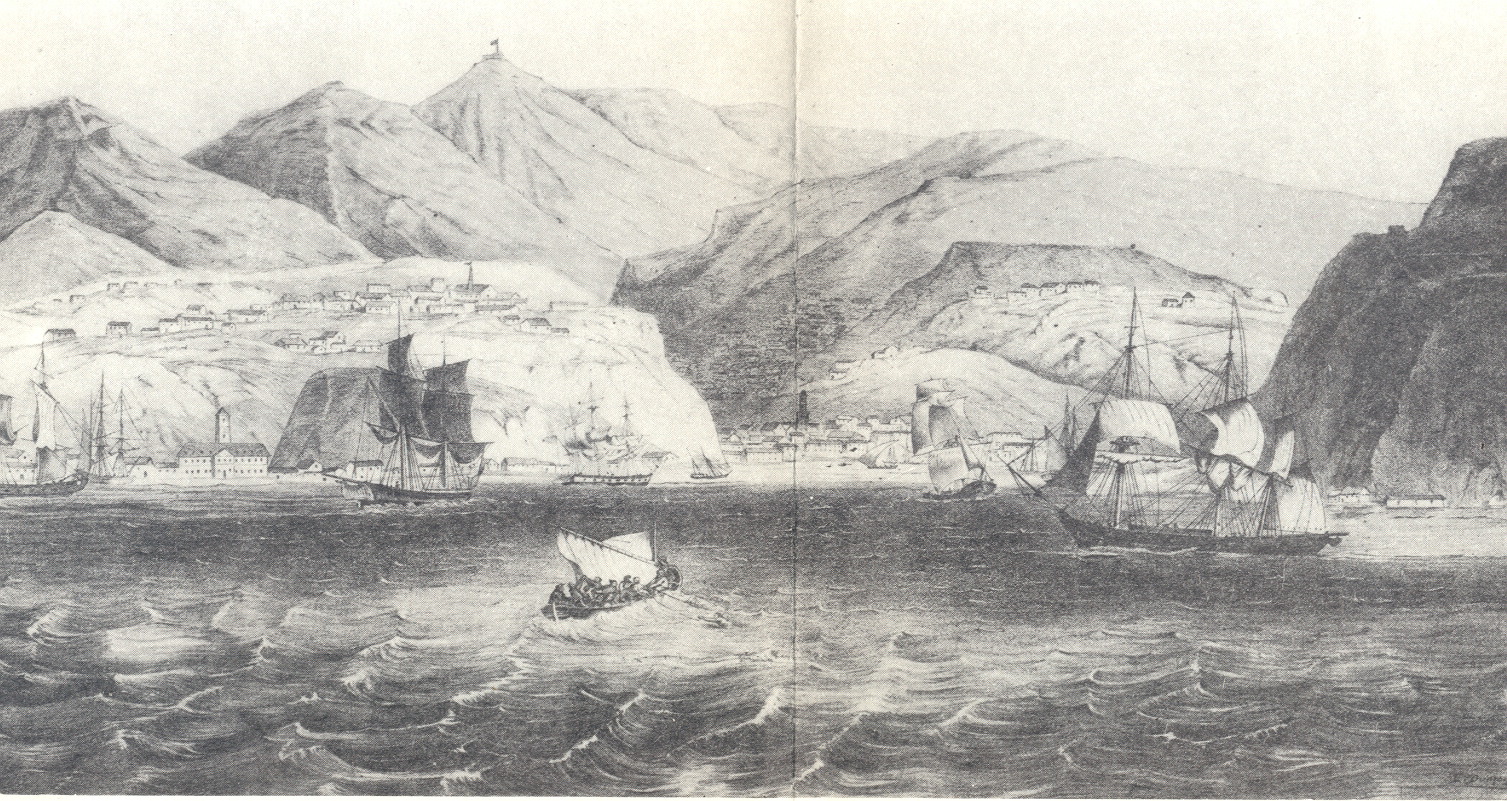

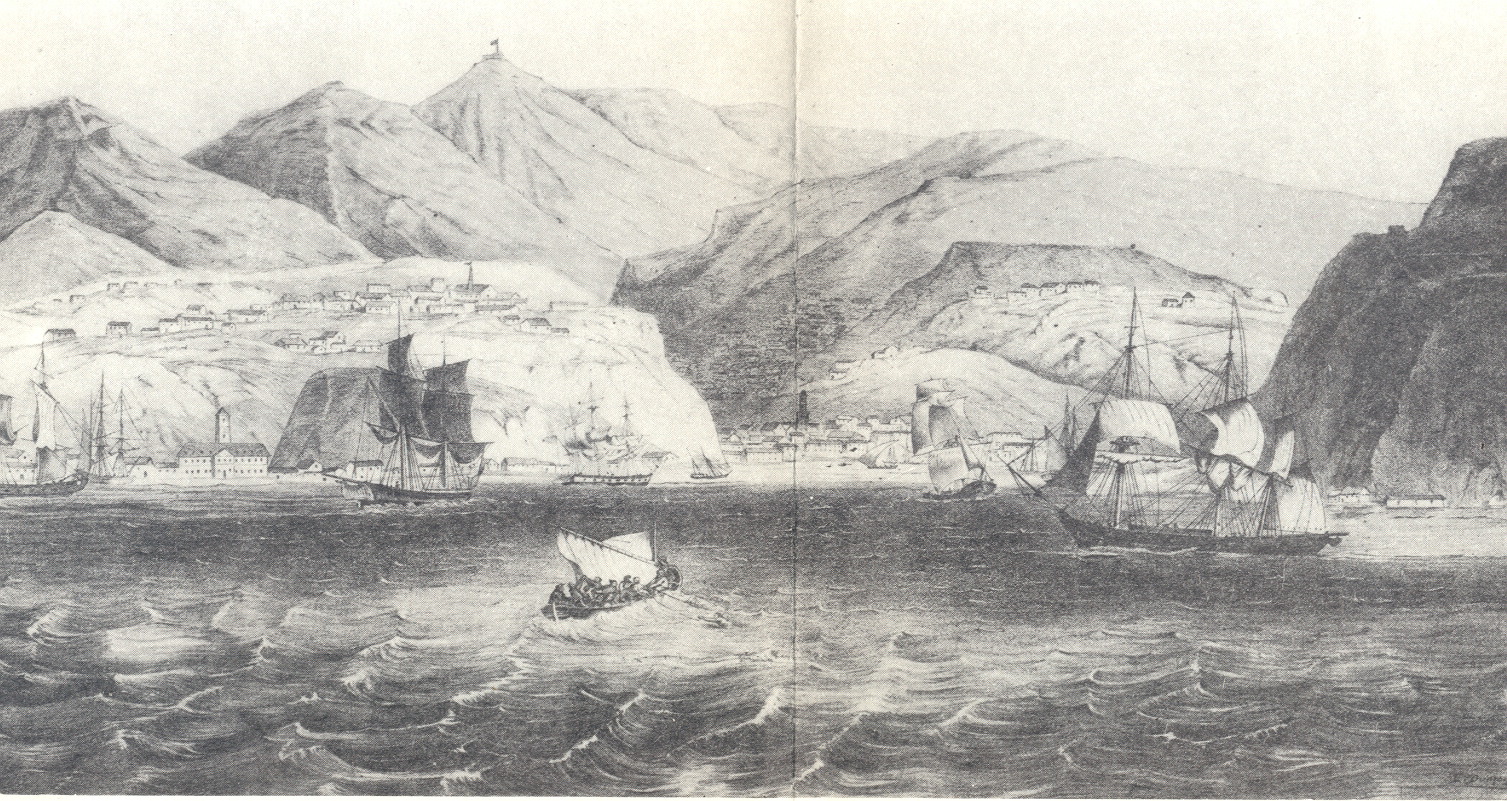

| History Germans in the Spanish colony  Incursions and settlements of the Conquistadores The first German to feature in the history of what is now Chile is Bartolomé Blumenthal (Spanish alias Bartolomé Flores) during the 16th century who accompanied Pedro de Valdivia. The latter conquistador ousted the indigenous population and founded the city of Santiago. Valdivia also arrested and took hostage the Cacique (tribal leaders and chiefs) to weaken the society of the local Mapuche people. Blumenthal took part in the defence of the Spanish settlement of Santiago when the Mapuche launched a counter-offensive on 11 September 1541 in attempt to free their caciques held hostage by the conquistadores. Later Blumenthal took part in the consolidation of the Spanish settlement that would become the Talagante Province; he was the first engineer in the remote colony. Blumenthal's son-in-law, Pedro de Lisperguer (born Peter Lisperger in Worms, Germany), was appointed as mayor of Santiago in 1572. Johann von Bohon (known in Spanish as Juan Bohón) was also part of Valdivia's expedition and was ordered to establish the city of La Serena in 1544. 19th century Hamburg and Valparaíso  Valparaíso, Chile, in 1830 In 1818 Chile became independent from Spain and began to engage in trading with more nations. The port city of Valparaíso became a major center for trade with Hamburg, with commercial travellers and merchants from Germany staying for lengthy periods of time to work in Valparaíso. Some settled there permanently. On 9 May 1838 Club Alemán de Valparaíso, the first German cultural organization was established in the city. German residents and visitors held cultural functions here. The club began to organize literary, musical and theatre productions, contributing to the cultural life of the city. Aquinas Ried, a physician, became widely known in the city for composing operas, and for writing poetry and plays. The club had its own orchestras and academic choir (singakademie) which would perform works composed by local musicians.[5] During World War I, the German Club of Valparaiso welcomed Admiral Maximilian von Spee's East Asia Squadron of the Imperial German Navy after they fought the Battle of Coronel off the Chilean coast.[6] Colonization of Southern Chile Main article: German colonization of Valdivia, Osorno and Llanquihue The Chilean government encouraged German immigration in 1848, a time of revolution in Germany. Before that Bernhard Eunom Philippi recruited nine working families to emigrate from Hesse to Chile. The origin of the German immigrants in Chile began with the Law of Selective Immigration of 1845. The objective of this law was to bring people of a medium social/high cultural level to colonize the southern regions of Chile; these were between Valdivia and Puerto Montt. The process was administered by Vicente Pérez Rosales by mandate of the then-president Manuel Montt. The German immigrants revived the domestic economy, and they changed the southern zones. The leader of the first colonists, Karl Anwandter, proclaimed their goals: We shall be honest and laborious Chileans as the best of them, we shall defend our adopted country joining in the ranks of our new countrymen, against any foreign oppression and with the decision and firmness of the man that defends his country, his family and his interests. Never will have the country that adopts us as its children, reason to repent of such illustrated, human and generous proceeding,... — Carlos Anwandter The expansion and economic development of Valdivia were limited in the early 19th century. To stimulate economic development, the Chilean government initiated a highly focused immigration program under Vicente Pérez Rosales as government representative.[citation needed] Through this program, thousands of Germans settled in the area, incorporating then-modern technology and know-how to develop agriculture and industry. Some of the new immigrants stayed in Valdivia but others were given forested land, which they cleared for farms.[7] Valdivia, situated at some distance from the coast, on the Calle-calle river, is a German town. Everywhere you meet German faces, German signboards and placards alongside the Spanish. There is a large German school, a church and various Vereine, large shoe-factories, and, of course, breweries... — Carl Skottsberg For ten years after the Revolutions of 1848 in the German states, numerous liberal immigrants came from Germany, exiles of the revolutions. They settled primarily in the Llanquihue in the towns of Frutillar, Puerto Octay, Puerto Varas, Osorno and Puerto Montt. Around 1900 Valdivia prospered with industries, including the Hoffmann Gristmill and the Rudloff shoe factory. |

歴史 スペイン植民地のドイツ人  コンキスタドールの侵入と入植 現在のチリの歴史に登場する最初のドイツ人は、16世紀にペドロ・デ・バルディビアに同行したバルトロメ・ブルメンタール(スペイン名バルトロメ・フロー レス)である。この征服者は先住民を追放し、サンティアゴ市を建設した。バルディビアはまた、現地のマプチェ族の社会を弱体化させるため、カチケ(部族の 指導者や首長)を逮捕し、人質に取った。1541年9月11日、マプチェ族がコンキスタドールに人質にされたカチケ族を解放するために反攻を開始したと き、ブルーメンタールはサンティアゴのスペイン人入植地の防衛に参加した。 その後ブルーメンタールは、後にタラガンテ州となるスペイン人入植地の強化に参加し、この辺境の植民地で最初のエンジニアとなった。ブルーメンタールの義 理の息子、ペドロ・デ・リスペルガー(ドイツ、ヴォルムス生まれのピーター・リスペルガー)は、1572年にサンティアゴ市長に任命された。 ヨハン・フォン・ボホン(スペイン名フアン・ボホン)もバルディビアの遠征隊の一員で、1544年にラ・セレナ市の設立を命じられた。 19世紀 ハンブルクとバルパライソ  1830年、チリのバルパライソ 1818年、チリはスペインから独立し、より多くの国々と交易を始めた。港町バルパライソはハンブルグとの貿易の主要な拠点となり、ドイツからの商業旅行者や商人がバルパライソで働くために長期滞在するようになった。定住する者もいた。 1838年5月9日、クラブ・アレマン・デ・バルパライソ(Club Alemán de Valparaíso)というドイツ初の文化団体がバルパライソに設立された。ドイツ人居住者や観光客がここで文化的な催しを行った。クラブは文学、音 楽、演劇の公演を企画し始め、街の文化的生活に貢献した。医師であったアクィナス・リートは、オペラを作曲し、詩や戯曲を書いたことで広く知られるように なった。第一次世界大戦中、バルパライソ・ドイツ・クラブは、チリ沖のコロネル海戦を戦ったドイツ海軍のマクシミリアン・フォン・シュペー提督率いる東ア ジア戦隊を歓迎した[6]。 チリ南部の植民地化 主な記事 ドイツによるバルディビア、オソルノ、ランキフエの植民地化 チリ政府は、ドイツで革命が起こった1848年にドイツ人の移民を奨励した。それ以前には、ベルンハルト・ユーノム・フィリッピ(Bernhard Eunom Philippi)がヘッセンからチリへ移住する労働者家族9組を募集した。 チリにおけるドイツ人移民の起源は、1845年に制定された選択移民法に始まる。この法律の目的は、中程度の社会的・文化的レベルの人々をチリ南部のバル ディビアとプエルト・モントの間に入植させることであった。このプロセスは、当時の大統領マヌエル・モントの委任により、ビセンテ・ペレス・ロサレスが管 理した。ドイツ人移民は国内経済を活性化させ、南部地域を変えた。最初の入植者のリーダー、カール・アンワンターは彼らの目標をこう宣言した: われわれは、誠実で勤勉なチリ人であり、最高のチリ人であり、外国からの弾圧に対抗し、自分の国、家族、利益を守る男の決断力と確固さをもって、新しい同 胞の仲間入りをし、自分たちの養子を迎えた国を守らなければならない。我々を養子として迎えてくれた国が、このような図々しく、人間的で寛大な行動を悔や む理由は決してない。 - カルロス・アンヴァンター 19世紀初頭、バルディビアの拡大と経済発展は限られていた。経済発展を刺激するため、チリ政府はビセンテ・ペレス・ロサレスを政府代表とする高度な移民 プログラムを開始した。[要出典] このプログラムを通じて、何千人ものドイツ人がこの地域に定住し、当時の近代的な技術とノウハウを取り入れて農業と工業を発展させた。新移民の一部はバル ディビアに留まったが、他の移民には森林地帯が与えられ、彼らはそれを開墾して農場を作った[7]。 海岸から少し離れたカジェカジェ川沿いに位置するバルディビアは、ドイツの町である。いたるところでドイツ人の顔を見かけ、スペイン語と並んでドイツ語の 看板やプラカードが掲げられている。大きなドイツ語学校、教会、様々な協会、大きな靴工場、そしてもちろんビール工場もある。 - カール・スコッツバーグ 1848年にドイツ諸国で革命が勃発してから10年間、革命の亡命者である多くの自由主義移民がドイツからやってきた。彼らは主にランキフエのフルティラ ル、プエルト・オクタイ、プエルト・バラス、オソルノ、プエルト・モントの町に定住した。1900年頃、バルディビアはホフマン製粉所やルドロフ靴工場な どの工業で栄えた。 |

| 20th century By the mid-1930s, most of the farming land around the towns of Valdivia and Osorno had been claimed. Some German immigrants moved further south to places such as Puyuhuapi in the Aysén region (settled by Sudeten Germans from present-day Czech Republic);[8] Sudeten German settlers from Broumov (called Braunau in German and located in present-day Czech Republic) also stayed and lived in Puerto Varas, wherein the village was called Nueva Braunau.[9]  German settlers in Aysén Region in the 1930s. Subsequently, a new wave of German immigrants arrived in Chile, with many settling in Temuco, and Santiago. Many founded businesses; for example, Horst Paulmann's small store in the capital of the Araucanía Region grew into Cencosud, one of the largest businesses in the region.  German settlers in Aysén Region in 1951. See also: Nazism in Chile Even before the Nazi takeover of Germany in 1933, a German Chilean youth organization was established with strong Nazi influence. Nazi Germany pursued a policy of Nazification of the German Chilean community.[10] These communities and their organizations were considered a cornerstone to extend the Nazi ideology across the world by Nazi Germany. Most German Chileans were passive supporters of Nazi Germany. Nazism was widespread among the German Lutheran Church hierarchy in Chile. A local chapter of the Nazi Party was started in Chile.[10] During World War II, many German Jews fled to Chile before and during the Holocaust. For example, the families of Mario Kreutzberger and Tomás Hirsch came to Chile during this time. Shortly after World War II, former members of Nazi Germany tried to take refuge in South America, including Chile, fleeing trials against them in Europe and elsewhere. Among these was SS Standartenführer and war criminal Walter Rauff. Paul Schäfer, a former army medic, founded Colonia Dignidad, a German enclave in the Maule Region, in which abuses against human rights were allegedly carried out. The precise number of Nazi refugees hidden in Chile after WWII remains unknown. |

20世紀 1930年代半ばまでに、バルディビアとオソルノの町周辺の農地はほとんど所有権を獲得した。一部のドイツ系移民はさらに南下し、アイセン地方のプユワピ (現在のチェコ共和国出身のスデーテン系ドイツ人が入植)などに移り住んだ[8]。ブルモフ(ドイツ語でブラウナウと呼ばれ、現在のチェコ共和国に位置す る)出身のスデーテン系ドイツ人入植者もプエルト・バラスに滞在し、村はヌエバ・ブラウナウと呼ばれた[9]。  1930年代のアイセン地方のドイツ人入植者。 その後、ドイツ系移民の新しい波がチリに押し寄せ、多くのドイツ系移民がテムコとサンティアゴに定住した。例えば、アラウカニア州の州都にあったホルス ト・パウルマン(Horst Paulmann)の小さな商店は、同州最大の企業の一つであるセンコスード(Cencosud)に成長した。  1951年、アイセン州のドイツ人入植者たち。 こちらも参照: チリにおけるナチズム 1933年にナチスがドイツを占領する以前から、ナチスの強い影響力を持つチリのドイツ人青年組織が設立されていた。ナチス・ドイツはチリ系ドイツ人コ ミュニティのナチス化政策を進めた[10]。これらのコミュニティとその組織は、ナチス・ドイツによってナチス・イデオロギーを世界に広げるための礎石と 見なされた。ほとんどのチリ系ドイツ人はナチス・ドイツの消極的な支持者であった。ナチズムはチリのドイツ・ルーテル教会階層の間に広まっていた。ナチ党 の地方支部がチリで発足した[10]。 第二次世界大戦中、多くのドイツ系ユダヤ人がホロコーストの前後にチリに逃れた。例えば、マリオ・クロイツベルガー(Mario Kreutzberger)とトマス・ヒルシュ(Tomás Hirsch)の家族はこの時期にチリに渡った。 第二次世界大戦後まもなく、ナチス・ドイツの元メンバーたちは、ヨーロッパなどでの裁判から逃れて、チリを含む南米に避難しようとした。その中には、SS 親衛隊長で戦争犯罪人のヴァルター・ラウフも含まれていた。元陸軍衛生兵のポール・シェーファーは、マウレ地方にドイツの飛び地コロニア・ディグニダード を設立し、そこで人権侵害が行われたとされている。第二次世界大戦後、チリに潜伏したナチス難民の正確な数はいまだに不明である。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆