マヤ諸語入門

[ミラー増補版]

Introduction to Maya languages

左:ヤシュチラン遺跡の石彫(Detail of

Lintel 26 from Yaxchilan):右:メキシコ・チアパス州のシナカンタンの若者(George E. Stuart and

National Geographic)

マヤ諸語入門

[ミラー増補版]

Introduction to Maya languages

左:ヤシュチラン遺跡の石彫(Detail of

Lintel 26 from Yaxchilan):右:メキシコ・チアパス州のシナカンタンの若者(George E. Stuart and

National Geographic)

日本語ガイド「ことばの研究―マヤ諸語の特徴(八杉佳穂)with password」

八杉佳穂編『マヤ学を学ぶ人のために』世界思想社、2004年

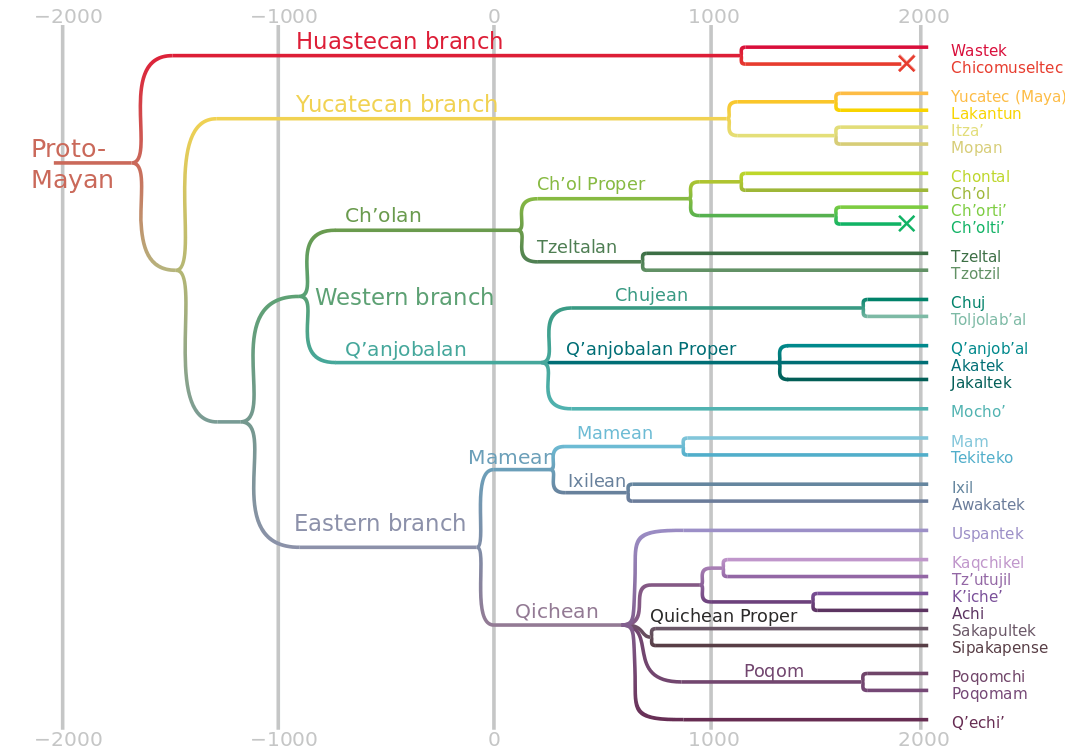

ウィキペディア(英語)の"Mayan_languages"か ら……

「マヤ語は、メソアメリカと中央アメリカ北部で話さ

れている言語ファミリーを形成している。マヤ語はグアテマラ、メキシコ、ベリーズ、エルサルバドル、ホンジュラスを中心に少なくとも600万人のマヤ人に

よって話されている。1996年、グアテマラは21のマヤ語を正式に認め、メキシコは領土内で8つのマヤ語を認めている。マヤ語族は、アメリカ大陸で最も

文書化され、最も研究されている言語のひとつである。現代のマヤ語は、少なくとも5,000年前に話されていたと考えられているプロトマヤ語の子孫であ

り、それは比較法を使用して部分的に再構築されている。原マヤ語は、ワステカン語、キチェ語、ユカテカン語、カンジョバル語、マメ語、チオラン・ツェルタ

ラン語の少なくとも6つの枝に分化した。マヤ語はメソアメリカ言語圏の一部であり、数千年にわたるメソアメリカの民族間の相互作用を通じて発展した言語収

束の地域である。すべてのマヤ語は、この言語圏の基本的な特徴を示している。たとえば、空間的な関係を示すために、前置詞の代わりに関係詞を用います。ま

た、動詞とその主語・目的語の文法的な扱いにおけるエルガティビティの使用、動詞の特殊な屈折カテゴリー、すべてのマヤ語に典型的な「位置詞」という特殊

な単語クラスなど、メソアメリカの他の言語とは異なる文法的・類型的な特徴を持っています。メソアメリカの歴史におけるコロンブス以前の時代、いくつかの

マヤ語はロゴ音節のマヤ文字で書かれていた。その使用は、マヤ文明の古典期(250-900年頃)に特に広まりった。建造物、遺跡、陶器、樹皮紙の写本に

刻まれた5,000を超えるマヤ語の碑文が現存しており、征服後にラテン文字で書かれたマヤ語の文献が豊富に残っていることから、アメリカ大陸では他に類

を見ない、コロンブス以前の歴史を現代的に理解するための基礎資料となっている。」

"The Mayan

languages[notes 1] form a language family spoken in Mesoamerica and

northern Central America. Mayan languages are spoken by at least 6

million Maya people, primarily in Guatemala, Mexico, Belize, El

Salvador and Honduras. In 1996, Guatemala formally recognized 21 Mayan

languages by name,[1][notes 2] and Mexico recognizes eight within its

territory.

The Mayan language family is one of the best-documented and most

studied in the Americas.[2] Modern Mayan languages descend from the

Proto-Mayan language, thought to have been spoken at least 5,000 years

ago; it has been partially reconstructed using the comparative method.

The proto-Mayan language diversified into at least six different

branches: the Huastecan, Quichean, Yucatecan, Qanjobalan, Mamean and

Chʼolan–Tzeltalan branches.

Mayan languages form part of the Mesoamerican language area, an area of

linguistic convergence developed throughout millennia of interaction

between the peoples of Mesoamerica. All Mayan languages display the

basic diagnostic traits of this linguistic area. For example, all use

relational nouns instead of prepositions to indicate spatial

relationships. They also possess grammatical and typological features

that set them apart from other languages of Mesoamerica, such as the

use of ergativity in the grammatical treatment of verbs and their

subjects and objects, specific inflectional categories on verbs, and a

special word class of "positionals" which is typical of all Mayan

languages.

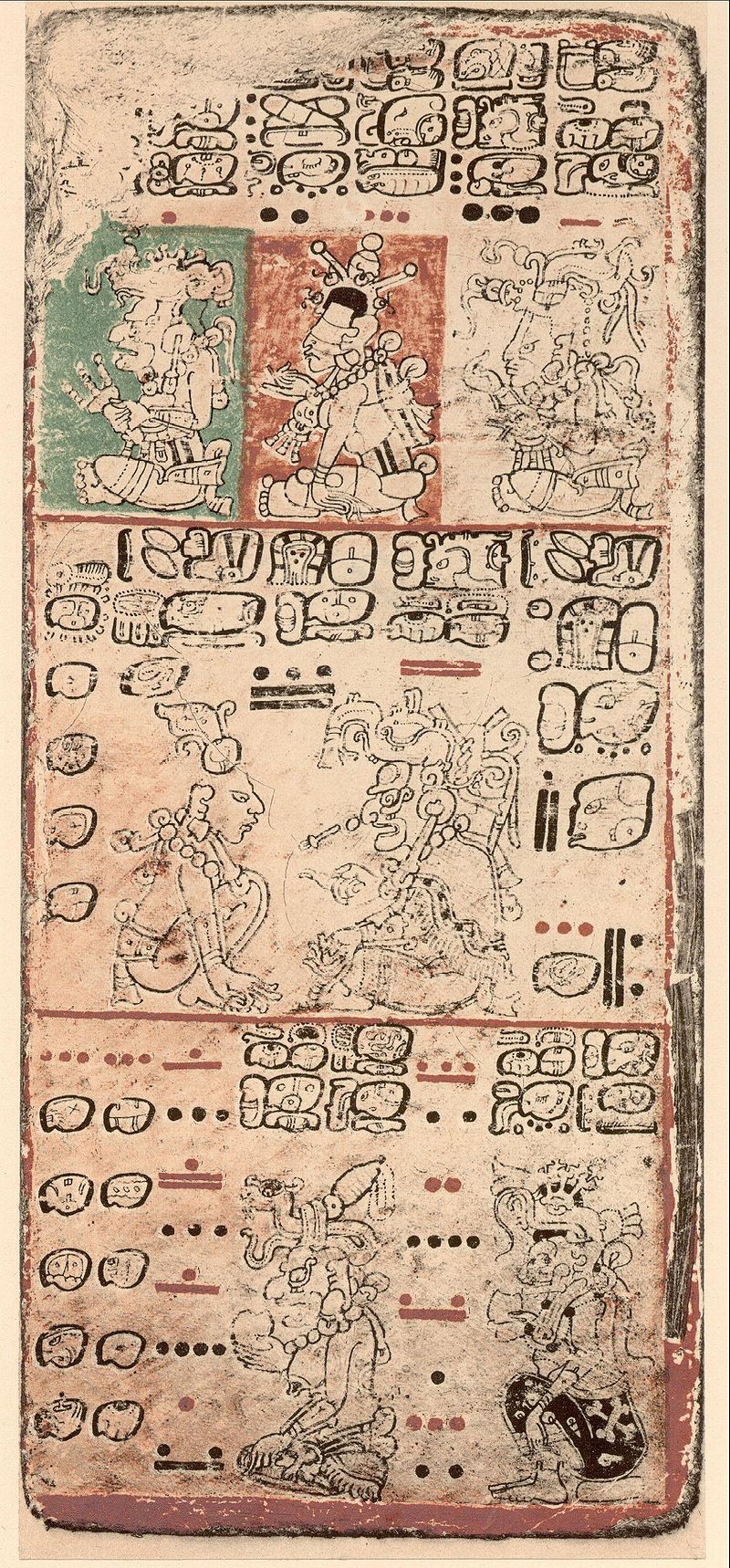

During the pre-Columbian era of Mesoamerican history, some Mayan

languages were written in the logo-syllabic Maya script. Its use was

particularly widespread during the Classic period of Maya civilization

(c. 250–900). The surviving corpus of over 5,000 known individual Maya

inscriptions on buildings, monuments, pottery and bark-paper

codices,[3] combined with the rich post-Conquest literature in Mayan

languages written in the Latin script, provides a basis for the modern

understanding of pre-Columbian history unparalleled in the Americas." -

Mayan_languages.

以下の情報もすべて、ウィキペディア(英語)の"Mayan_languages"に

よる

|

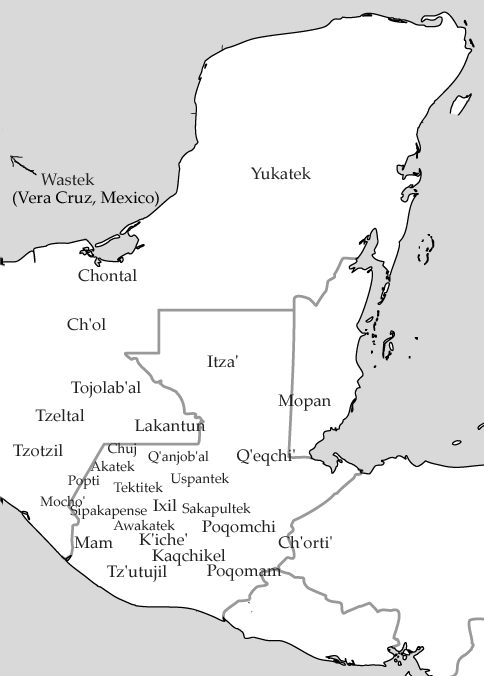

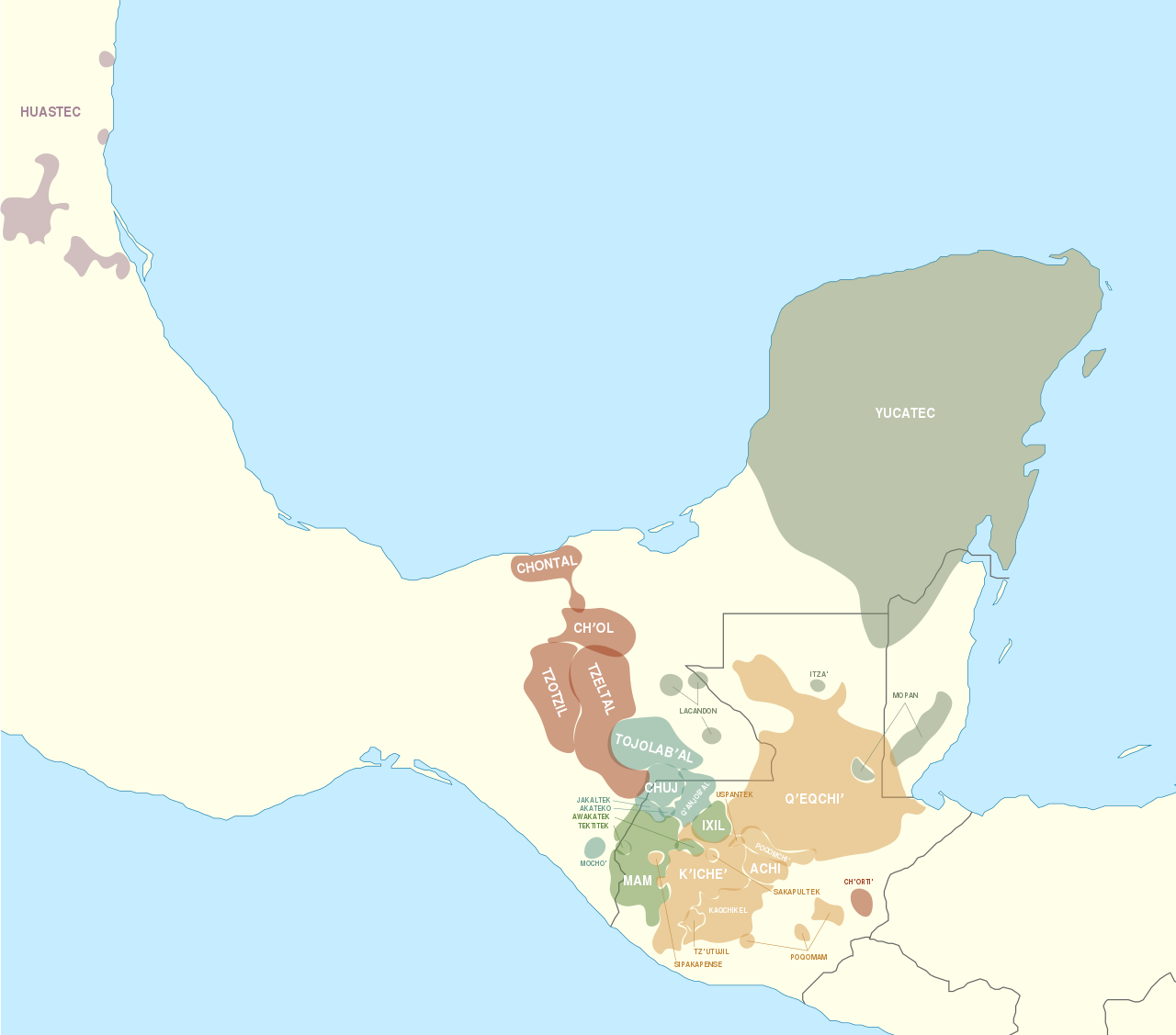

Map showing the

extent of the Maya civilization (red), compared to all other

Mesoamerica cultures (black). Within Central America and southern North

America (Mexico). This map also shows the cities and cultural

mainsteads of the Maya, who did not have an empire but rather a group

of loosely associated city-states. Map of Maya linguistic distribution +++ "In Guatemala, indigenous people of Maya descent comprise around 42% of the population.[3][20] The largest and most traditional Maya populations are in the western highlands in the departments of Baja Verapaz, Quiché, Totonicapán, Huehuetenango, Quetzaltenango, and San Marcos; their inhabitants are mostly Maya.[21] The Maya people of the Guatemala highlands include the Achi, Akatek, Chuj, Ixil, Jakaltek, Kaqchikel, Kʼicheʼ, Mam, Poqomam, Poqomchiʼ, Qʼanjobʼal, Qʼeqchiʼ, Tzʼutujil and Uspantek. The Qʼeqchiʼ live in lowland areas of Alta Vera Paz, Peten, and Western Belize. Over the course of the succeeding centuries a series of land displacements, re-settlements, persecutions and migrations resulted in a wider dispersal of Qʼeqchiʼ communities, into other regions of Guatemala (Izabal, Petén, El Quiché). They are the 2nd largest ethnic Maya group in Guatemala (after the Kʼicheʼ) and one of the largest and most widespread throughout Central America. In Guatemala, the Spanish colonial pattern of keeping the native population legally separate and subservient continued well into the 20th century.[citation needed] This resulted in many traditional customs being retained, as the only other option than traditional Maya life open to most Maya was entering the Hispanic culture at the very bottom rung. Because of this many Guatemalan Maya, especially women, continue to wear traditional clothing, that varies according to their specific local identity. The southeastern region of Guatemala (bordering with Honduras) includes groups such as the Chʼortiʼ. The northern lowland Petén region includes the Itza, whose language is near extinction but whose agroforestry practices, including use of dietary and medicinal plants may still tell us much about pre-colonial management of the Maya lowlands.[22]" →"Mayan languages" ++++ グアテマラでは、マヤ系の先住民が人口の約42%を占める。最大かつ最も伝統的なマヤの人口は、バハ・ベラパス県、キチェ県、トトニカパン県、フエウエテ ナンゴ県、ケツァルテナンゴ県、サンマルコス県の西部高地に存在する。グアテマラ高地のマヤ族には、Achi、Akatek、Chuj、Ixil、 Jakaltek、Kaqchikel、Kʼicheʼ、Mam、Poqomam、Poqomchiʼ、Qʼanjobʼal、Qʼeqchiʼ、 Tzʼutujil、Uspantekが含まれる。QʼeqchiʼはAlta Vera Paz、Peten、西ベリーズの低地に住む。その後何世紀にもわたって、土地の移動、再定住、迫害、移住が繰り返され、Qʼeqchiʼのコミュニティ はグアテマラの他の地域(Izabal、Petén、El Quiché)へと広く分散した。彼らはグアテマラでKʼicheʼ族に次いで2番目に大きなマヤ民族グループであり、中央アメリカ全体で最も大きく、最 も広く分布しているグループのひとつである。グアテマラでは、先住民を法的に分離し従属させるというスペインの植民地支配のパターンが20世紀まで続いた [要出典]。その結果、多くの伝統的な習慣が保持されることになり、ほとんどのマヤにとって伝統的なマヤの生活以外の選択肢は、最底辺のヒスパニック文化 に入ることしかなかった。このため、グアテマラ・マヤの多く、特に女性は、それぞれの地域のアイデンティティによって異なる伝統的な衣服を着続けている。 グアテマラ南東部(ホンジュラスとの国境)にはChʼortiʼのようなグループがある。ペテン北部の低地にはイツァ族がおり、彼らの言語は絶滅寸前だ が、食用植物や薬用植物の利用を含む農林業は、植民地時代以前のマヤ低地の管理について、まだ多くのことを物語っているかもしれない。 |

|

Approximate

migration routes and dates for various Mayan language families. The

region shown as Proto-Mayan is now occupied by speakers of the

Qʼanjobalan branch (light blue in other figures) Approximate

migration routes and dates for various Mayan language families. The

region shown as Proto-Mayan is now occupied by speakers of the

Qʼanjobalan branch (light blue in other figures)++++ 様々なマヤ語族のおおよその移動ルートと年代。Proto-Mayanとして示された地域は、現在Qʼanjobalan分派の話者が占めている(他の図 では水色)。 |

|

Classic period

Maya glyphs in stucco at the Museo de sitio in Palenque, Mexico メキシコ、パレンケのMuseo de sitioにある漆喰に描かれた古典時代のマヤの象形文字 |

|

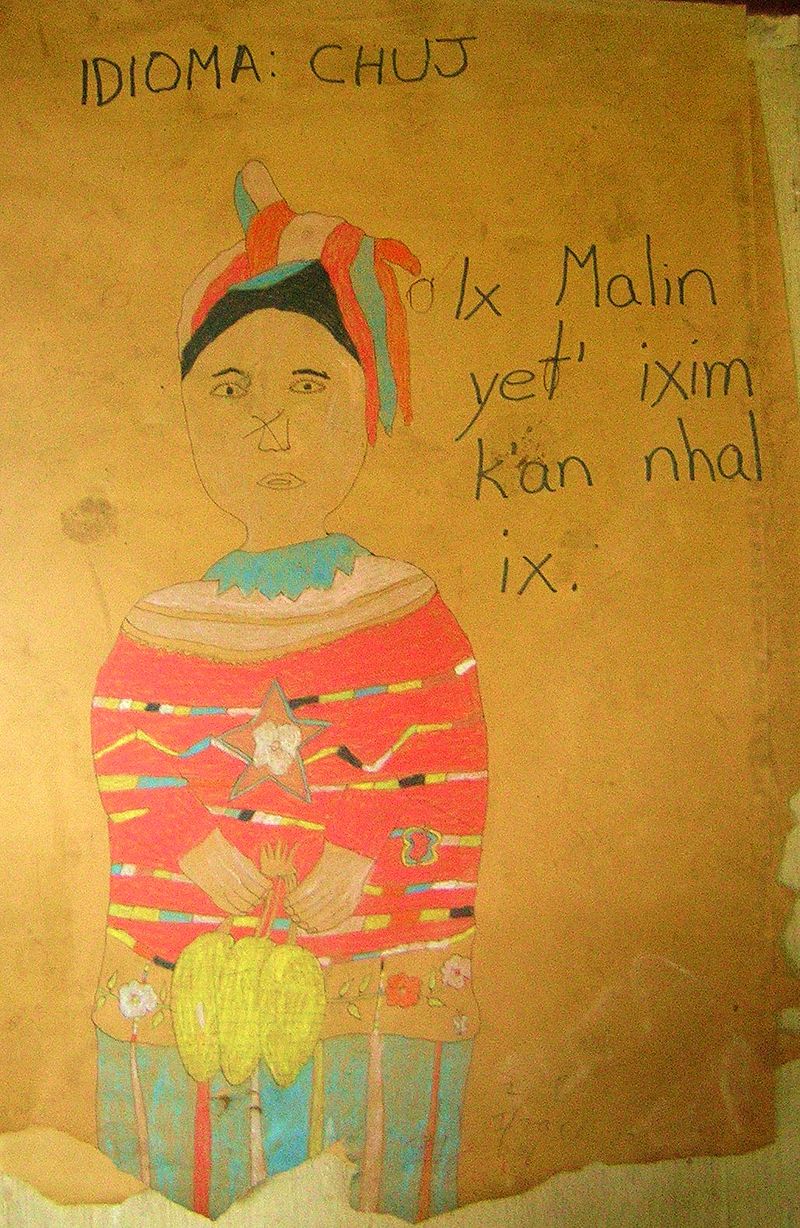

Drawing with text written in the

Chuj language from Ixcán, Guatemala. ●Western branch The Chʼolan languages were formerly widespread throughout the Maya area, but today the language with most speakers is Chʼol, spoken by 130,000 in Chiapas.[26] Its closest relative, the Chontal Maya language,[notes 10] is spoken by 55,000[27] in the state of Tabasco. Another related language, now endangered, is Chʼortiʼ, which is spoken by 30,000 in Guatemala.[28] It was previously also spoken in the extreme west of Honduras and El Salvador, but the Salvadorian variant is now extinct and the Honduran one is considered moribund. Chʼoltiʼ, a sister language of Chʼortiʼ, is also extinct.[7] Chʼolan languages are believed to be the most conservative in vocabulary and phonology, and are closely related to the language of the Classic-era inscriptions found in the Central Lowlands. They may have served as prestige languages, coexisting with other dialects in some areas. This assumption provides a plausible explanation for the geographical distance between the Chʼortiʼ zone and the areas where Chʼol and Chontal are spoken.[29] The closest relatives of the Chʼolan languages are the languages of the Tzeltalan branch, Tzotzil and Tzeltal, both spoken in Chiapas by large and stable or growing populations (265,000 for Tzotzil and 215,000 for Tzeltal).[30] Tzeltal has tens of thousands of monolingual speakers.[31] Qʼanjobʼal is spoken by 77,700 in Guatemala's Huehuetenango department,[32] with small populations elsewhere. The region of Qʼanjobalan speakers in Guatemala, due to genocidal policies during the Civil War and its close proximity to the Mexican border, was the source of a number of refugees. Thus there are now small Qʼanjobʼal, Jakaltek, and Akatek populations in various locations in Mexico, the United States (such as Tuscarawas County, Ohio[33] and Los Angeles, California[34]), and, through postwar resettlement, other parts of Guatemala.[35] Jakaltek (also known as Poptiʼ[36]) is spoken by almost 100,000 in several municipalities[37] of Huehuetenango. Another member of this branch is Akatek, with over 50,000 speakers in San Miguel Acatán and San Rafael La Independencia.[38] Chuj is spoken by 40,000 people in Huehuetenango, and by 9,500 people, primarily refugees, over the border in Mexico, in the municipality of La Trinitaria, Chiapas, and the villages of Tziscau and Cuauhtémoc. Tojolabʼal is spoken in eastern Chiapas by 36,000 people.[39] +++++ Chʼolan言語はかつてマヤ全域で話されていたが、現在最も話者が多いのはChʼolで、チアパス州で13万人が話している。最も近縁の Chontalマヤ語[注釈 10]はタバスコ州で5万5千人が話している。また、現在は絶滅の危機に瀕しているが、グアテマラで3万人が話すChʼortiʼも関連言語である。以前 はホンジュラスとエルサルバドルの最西部でも話されていたが、サルバドルのものは現在絶滅し、ホンジュラスのものは死滅したと考えられている。 Chʼortiʼの姉妹語であるChʼoltiʼも絶滅している。Chʼolan言語は語彙と音韻において最も保守的で、中央低地で発見された古典時代の 碑文の言語と密接な関係があると考えられている。中央低地で発見された古典時代の碑文の言語と密接に関連しており、一部の地域では他の方言と共存しなが ら、威信をかけた言語として機能していた可能性がある。この仮定は、Chʼortiʼ地帯とChʼolやChontalが話されている地域との地理的な距 離をもっともらしく説明するものである。Chʼolanの最も近い親戚はTzeltalanのTzotzilとTzeltalで、どちらもChiapas で話され、人口が多く安定しているか増えている(Tzotzilは265,000人、Tzeltalは215,000人)。ツェルタル語は数万人の単言語 話者がいる。QʼanjobʼalはグアテマラのHuehuetenango県で77,700人が話し、その他の地域では人口が少ない。グアテマラの Qʼanjobalan語を話す地域は、内戦中の大量虐殺政策とメキシコ国境に近いことから、多くの難民の発生源となった。そのため、現在ではメキシコ、 アメリカ(オハイオ州タスカラワス郡やカリフォルニア州ロサンゼルスなど)の各地に小さなQʼanjobʼal、Jakaltek、Akatekの集団が 存在し、戦後の再定住によってグアテマラの他の地域にも広がっている。Jakaltek(Poptiʼとしても知られる)は、Huehuetenango のいくつかの自治体で10万人近くが話す。この支部のもう一つのメンバーはアカテク語で、サン・ミゲル・アカタンとサン・ラファエル・ラ・インデペンデン シアで5万人以上が話しています。Chujはフエウエテナンゴで40,000人が話し、国境を越えてメキシコのチアパス州ラ・トリニタリア市とツィスカウ 村、クアウテモック村で難民を中心に9,500人が話している。Tojolabʼalはチアパス州東部で36,000人に話されている。 ●Eastern branch The Quichean–Mamean languages and dialects, with two sub-branches and three subfamilies, are spoken in the Guatemalan highlands. Qʼeqchiʼ (sometimes spelled Kekchi), which constitutes its own sub-branch within Quichean–Mamean, is spoken by about 800,000 people in the southern Petén, Izabal and Alta Verapaz departments of Guatemala, and also in Belize by 9,000 speakers. In El Salvador it is spoken by 12,000 as a result of recent migrations.[40] The Uspantek language, which also springs directly from the Quichean–Mamean node, is native only to the Uspantán municipio in the department of El Quiché, and has 3,000 speakers.[41] Within the Quichean sub-branch Kʼicheʼ (Quiché), the Mayan language with the largest number of speakers, is spoken by around 1,000,000 Kʼicheʼ Maya in the Guatemalan highlands, around the towns of Chichicastenango and Quetzaltenango and in the Cuchumatán mountains, as well as by urban emigrants in Guatemala City.[32] The famous Maya mythological document, Popol Vuh, is written in an antiquated Kʼicheʼ often called Classical Kʼicheʼ (or Quiché). The Kʼicheʼ culture was at its pinnacle at the time of the Spanish conquest. Qʼumarkaj, near the present-day city of Santa Cruz del Quiché, was its economic and ceremonial center.[42] Achi is spoken by 85,000 people in Cubulco and Rabinal, two municipios of Baja Verapaz. In some classifications, e.g. the one by Campbell, Achi is counted as a form of Kʼicheʼ. However, owing to a historical division between the two ethnic groups, the Achi Maya do not regard themselves as Kʼicheʼ.[notes 11] The Kaqchikel language is spoken by about 400,000 people in an area stretching from Guatemala City westward to the northern shore of Lake Atitlán.[43] Tzʼutujil has about 90,000 speakers in the vicinity of Lake Atitlán.[44] Other members of the Kʼichean branch are Sakapultek, spoken by about 15,000 people mostly in El Quiché department,[45] and Sipakapense, which is spoken by 8,000 people in Sipacapa, San Marcos.[46] The largest language in the Mamean sub-branch is Mam, spoken by 478,000 people in the departments of San Marcos and Huehuetenango. Awakatek is the language of 20,000 inhabitants of central Aguacatán, another municipality of Huehuetenango. Ixil (possibly three different languages) is spoken by 70,000 in the "Ixil Triangle" region of the department of El Quiché.[47] Tektitek (or Teko) is spoken by over 6,000 people in the municipality of Tectitán, and 1,000 refugees in Mexico. According to the Ethnologue the number of speakers of Tektitek is growing.[48] The Poqom languages are closely related to Core Quichean, with which they constitute a Poqom-Kʼichean sub-branch on the Quichean–Mamean node.[49] Poqomchiʼ is spoken by 90,000 people[50] in Purulhá, Baja Verapaz, and in the following municipalities of Alta Verapaz: Santa Cruz Verapaz, San Cristóbal Verapaz, Tactic, Tamahú and Tucurú. Poqomam is spoken by around 49,000 people in several small pockets in Guatemala.[51] ++++++ グアテマラ高地では、2つの亜分派と3つの亜科を持つキチェ語-マメ語の言語と方言が話されている。Qʼeqchiʼ(Kekchiと表記されることもあ る)は、キチェ語-マメ語の中で独自の亜分派を構成しており、グアテマラの南部ペテン県、イザバル県、アルタ・ベラパス県で約80万人が話し、ベリーズで も9,000人が話している。エルサルバドルでは、近年の移住の結果、12,000人がこの言語を話している。ウスパンテク語は、キチェ語-マメ語ノード から直接派生したもので、エル・キチェ県のウスパンテン・ミュニシピオのみが母語であり、3,000人の話者がいる。グアテマラ高地、チチカステナンゴと ケツァルテナンゴの町周辺、クチュマタン山脈の約100万人のKʼʼʼʼマヤ人によって話されている。 有名なマヤの神話文書『ポポル・ヴフ』は、しばしばClassical Kʼicheʼ(またはQuiché)と呼ばれる古代のKʼicheʼで書かれている。Kʼicheʼ文化はスペインによる征服時に頂点に達した。現在の サンタ・クルス・デル・キチェ市近郊のQʼmarkajは、その経済と儀式の中心地であった。 アチ語はバハ・ベラパスの2つの自治体、クブルコとラビナルで85,000人に話されている。Campbellによる分類などでは、アチ語は Kʼicheʼの一種として数えられている。カクチケル語はグアテマラシティからアティトラン湖北岸にかけての地域で約40万人に話されている。 Tzʼutujil語はアティトラン湖周辺で約9万人が話す。 Kʼichean支部の他のメンバーには、El Quiché県を中心に約15,000人が話すSakapultekと、San MarcosのSipacapaで8,000人が話すSipakapenseがある。 マメアン亜支部で最大の言語はマム語で、サンマルコス県とフエウエテナンゴ県で47万8,000人が話している。アワカテク語は、フエウエテナンゴのもう ひとつの自治体であるアグアカタン中央部の住民2万人が話す言語である。イシル語(おそらく3つの異なる言語)は、エル・キチェ県の「イシル・トライアン グル」地域で7万人が話す。 Tektitek(またはTeko)は、Tectitánの自治体で6,000人以上が話し、メキシコでは1,000人が難民となっている。 Ethnologueによると、テクティテクの話者数は増加傾向にある。 バハ・ベラパスのプルルハ、アルタ・ベラパスの以下の自治体で90,000人がPoqomchiʼ語を話す: サンタ・クルス・ベラパス、サン・クリストバル・ベラパス、タクティック、タマフー、トゥクルー。ポコマム語は、グアテマラのいくつかの小さな地域で約 49,000人に話されている。 |

| Yucatecan branch | Yucatec Maya (known simply as

"Maya" to its speakers) is the most commonly spoken Mayan language in

Mexico. It is currently spoken by approximately 800,000 people, the

vast majority of whom are to be found on the Yucatán Peninsula.[32][52]

It remains common in Yucatán and in the adjacent states of Quintana Roo

and Campeche.[53]

The other three Yucatecan languages are Mopan, spoken by around 10,000

speakers primarily in Belize; Itzaʼ, an extinct or moribund language

from Guatemala's Petén Basin;[54] and Lacandón or Lakantum, also

severely endangered with about 1,000 speakers in a few villages on the

outskirts of the Selva Lacandona, in Chiapas.[55] +++++++ ユカテク・マヤ語(Yucatec Maya)は、メキシコで最も一般的に話されているマヤ語である。現在、約80万人に話されており、その大部分はユカタン半島で話されている。 現在もユカタン半島と隣接するキンタナ・ロー州、カンペチェ州でよく使われています。他の3つのユカタン語は、主にベリーズで約1万人の話者が話すモパン 語、グアテマラのペテン盆地で絶滅または死滅したイツァ語、チアパスのセルバ・ラカンドナ郊外のいくつかの村で約1000人の話者が話すラカンドン語また はラカントゥム語である。 |

| Huastecan branch |

Wastek (also spelled Huastec and

Huaxtec) is spoken in the Mexican

states of Veracruz and San Luis Potosí by around 110,000 people.[56] It

is the most divergent of modern Mayan languages. Chicomuceltec was a

language related to Wastek and spoken in Chiapas that became extinct

some time before 1982.[57] +++++++ ワステク語(ワステック語、フアステック語とも表記される)は、メキシコのベラクルス州とサン・ルイス・ポトシ州で約11万人に話されている。チコムセル テックは、ワステックに近縁のチアパス州で話されていた言語で、1982年以前に絶滅した。 |

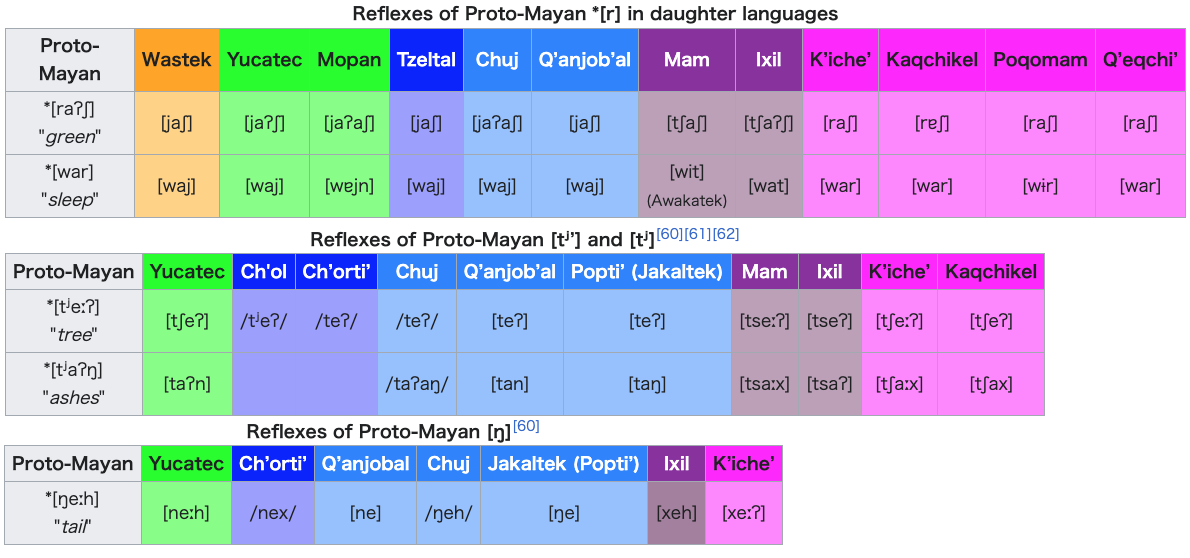

Phonology  |

Proto-Mayan

sound system/Phonological evolution of Proto-Mayan/Diphthongs(二重母音) +++++++ Proto-Mayan (the common ancestor of the Mayan languages as reconstructed using the comparative method) has a predominant CVC syllable structure, only allowing consonant clusters across syllable boundaries.[7][22][notes 12] Most Proto-Mayan roots were monosyllabic except for a few disyllabic nominal roots. Due to subsequent vowel loss many Mayan languages now show complex consonant clusters at both ends of syllables. Following the reconstruction of Lyle Campbell and Terrence Kaufman, the Proto-Mayan language had the following sounds.[22] It has been suggested that proto-Mayan was a tonal language, based on the fact that four different contemporary Mayan languages have tone (Yucatec, Uspantek, San Bartolo Tzotzil[notes 13] and Mochoʼ), but since these languages each can be shown to have innovated tone in different ways, Campbell considers this unlikely.[22] プロト=マヤ語(比較法によって復元されたマヤ諸語の共通祖先)は、音節の境界を越える子音クラスターのみを許容する CVC 音節構造が主流である。プロト=マヤ語の語根は、いくつかの二音節の名詞語根を除き、ほとんどが単音節でした。その後の母音の消失により、多くのマヤ語は 音節の両端に複雑な子音クラスターを示すようになった。ライル・キャンベルとテレンス・カウフマンの復元によれば、プロト=マヤ語には以下のような音が あった。プロト=マヤ語は調性言語であったという説があるが、これは現代のマヤ語には4つの異なる調性言語がある(ユカテク語、ウスパンテク語、サン・バ ルトロ・ツォツィル語、モチョ語)ことに基づいている。 +++++++ Phonological evolution of Proto-Mayan Main article: Proto-Mayan language. The classification of Mayan languages is based on changes shared between groups of languages. For example, languages of the western group (such as Huastecan, Yucatecan and Chʼolan) all changed the Proto-Mayan phoneme */r/ into [j], some languages of the eastern branch retained [r] (Kʼichean), and others changed it into [tʃ] or, word-finally, [t] (Mamean). The shared innovations between Huastecan, Yucatecan and Chʼolan show that they separated from the other Mayan languages before the changes found in other branches had taken place.[58] プロト=マヤ語の音韻進化 主な記事 プロト=マヤ語 マヤ語の分類は、言語グループ間で共有される変化に基づいている。例えば、西側のグループの言語(ワステカ語、ユカテカ語、チオラン語など)はすべてプロ ト=マヤ語の音素*/r/を[j]に変化させ、東側の枝のいくつかの言語は[r]を保持し(Kʼichean)、他の言語は[tʃ]または最終的に[t] に変化させた(Mamean)。Huastecan、Yucatecan、Chʼolanの間で共有されている革新は、他の分派で見られる変化が起こる前 に他のマヤ語から分離したことを示している。 +++++++ The palatalized plosives [tʲʼ] and [tʲ] are not found in most of the modern families. Instead they are reflected differently in different branches, allowing a reconstruction of these phonemes as palatalized plosives. In the eastern branch (Chujean-Qʼanjobalan and Chʼolan) they are reflected as [t] and [tʼ]. In Mamean they are reflected as [ts] and [tsʼ] and in Quichean as [tʃ] and [tʃʼ]. Yucatec stands out from other western languages in that its palatalized plosives are sometimes changed into [tʃ] and sometimes [t].[59] 口蓋化撥音[tʲʼ]と[tʲ]は、ほとんどの現代語族には見られない。その代わりに、口蓋化撥音としてこれらの音素を再構築することができるように、異 なる枝で異なるように反映される。東部支族(Chujean-QʼanjobalanとChʼolan)では、[t]と[tʼ]として反映される。 Mameanでは[ts]と[tsʼ]として、Quicheanでは[tʃ]と[tʃʼ]として反映される。ユカテク語は、口蓋化された撥音が[tʃ]や [t]に変化することがあるという点で、他の西側の言語と異なっている。 +++++++ The Proto-Mayan velar nasal *[ŋ] is reflected as [x] in the eastern branches (Quichean–Mamean), [n] in Qʼanjobalan, Chʼolan and Yucatecan, [h] in Huastecan, and only conserved as [ŋ] in Chuj and Jakaltek.[58][61][62] プロト=マヤ語のベラル鼻音 *[ŋ] は、東部分岐(Quichean-Mamean)では [x] として、Qʼanjobalan、Chʼolan、Yucatecanでは [n] として、Huastecanでは [h] として反映され、ChujとJakaltekでは [ŋ] としてのみ保存されている。 +++++++ Diphthongs Vowel quality is typically classified as having monophthongal vowels. In traditionally diphthongized contexts, Mayan languages will realize the V-V sequence by inserting a hiatus-breaking glottal stop or glide insertion between the vowels. Some Kʼichean-branch languages have exhibited developed diphthongs from historical long vowels, by breaking /e:/ and /o:/. 二重母音 母音の質は、一般的に単母音に分類される。伝統的に二重母音化された文脈では、マヤ語は母音と母音の間に、休止を破る声門停止や滑舌挿入を挿入すること で、V-Vシークエンスを実現する。K'ichean-branchの言語の中には、/e:/や/o:/を破裂させることで、歴史的な長母音から二重母音 を発達させたものもある。 |

| Grammar |

The morphology of Mayan

languages is simpler than that of other Mesoamerican languages,[notes

14] yet its morphology is still considered agglutinating and

polysynthetic.[62] Verbs are marked for aspect or tense, the person of

the subject, the person of the object (in the case of transitive

verbs), and for plurality of person. Possessed nouns are marked for

person of possessor. In Mayan languages, nouns are not marked for case

and gender is not explicitly marked. +++++++ マヤ語の形態論は、他のメソアメリカ諸語の形態論よりも単純であるが、それでもなお、その形態論は膠着性で多義的であると考えられている。動詞は、アスペ クトや時制、主語の人称、目的語の人称(他動詞の場合)、人称の複数を表す。所有名詞は、所有者の人称を表す。マヤ語では、名詞は格を表さず、性別も明示 されない。 |

| Grammar- Word order | Proto-Mayan is thought to have

had a basic verb–object–subject word order with possibilities of

switching to VSO in certain circumstances, such as complex sentences,

sentences where object and subject were of equal animacy and when the

subject was definite.[notes 15] Today Yucatecan, Tzotzil and Tojolabʼal

have a basic fixed VOS word order. Mamean, Qʼanjobʼal, Jakaltek and one

dialect of Chuj have a fixed VSO one. Only Chʼortiʼ has a basic SVO

word order. Other Mayan languages allow both VSO and VOS word

orders.[63] +++++++ プロト=マヤ語は基本的な動詞-目的語-主語の語順で、複雑な文、目的語と主語が同格の文、主語が明確な文など、特定の状況でVSOに切り替わる可能性が あったと考えられている。Mamean、Qʼanjobʼal、Jakaltek、Chujの方言はVSOの固定語順である。Chʼortiʼだけが基本 的なSVO語順を持っている。他のマヤ語ではVSOとVOSの両方の語順が認められている。 |

| Grammar- Numeral classifiers |

In many Mayan languages,

counting requires the use of numeral classifiers, which specify the

class of items being counted; the numeral cannot appear without an

accompanying classifier. Some Mayan languages, such as Kaqchikel, do

not use numeral classifiers. Class is usually assigned according to

whether the object is animate or inanimate or according to an object's

general shape.[64] Thus when counting "flat" objects, a different form

of numeral classifier is used than when counting round things, oblong

items or people. In some Mayan languages such as Chontal, classifiers

take the form of affixes attached to the numeral; in others such as

Tzeltal, they are free forms. Jakaltek has both numeral classifiers and

noun classifiers, and the noun classifiers can also be used as

pronouns.[65]

The meaning denoted by a noun may be altered significantly by changing

the accompanying classifier. In Chontal, for example, when the

classifier -tek is used with names of plants it is understood that the

objects being enumerated are whole trees. If in this expression a

different classifier, -tsʼit (for counting long, slender objects) is

substituted for -tek, this conveys the meaning that only sticks or

branches of the tree are being counted:[66] +++++++ 多くのマヤ語では、数を数えるには、数詞を使う必要がある。数詞は、数えられている項目のクラスを指定するもので、数詞を伴わずに数字を表すことはできな い。カクチケル語のように、数詞を使わないマヤ語もあります。分類は通常、その物体が生物か無生物か、または物体の一般的な形状によって割り当てられる。 したがって、「平らな」物体を数えるときには、丸いものや長方形のもの、人を数えるときとは異なる形の数詞が使われる。チョンタル語のようないくつかのマ ヤ語では、分類子は数字に付属する接辞の形をとるが、ツェルタル語のような他の言語では自由形式である。Jakaltek には、数詞の分類詞と名詞の分類詞があり、名詞の分類詞は代名詞としても使用できます。名詞が表す意味は、付随する分類詞を変えることで大きく変わること があります。たとえば、チョンタール語では、植物の名前とともに分類子 -tek が使用される場合、列挙される対象は木全体であると理解される。この表現で、-tekの代わりに別の分類子、-tsʼit(細長いものを数える)が使われ ると、木の棒や枝だけを数えるという意味になる: |

| Grammar- Possession |

The morphology of Mayan nouns is

fairly simple: they inflect for number (plural or singular), and, when

possessed, for person and number of their possessor. Pronominal

possession is expressed by a set of possessive prefixes attached to the

noun, as in Kaqchikel ru-kej "his/her horse". Nouns may furthermore

adopt a special form marking them as possessed. For nominal possessors,

the possessed noun is inflected as possessed by a third-person

possessor, and followed by the possessor noun, e.g. Kaqchikel ru-kej ri

achin "the man's horse" (literally "his horse the man").[67] This type

of formation is a main diagnostic trait of the Mesoamerican Linguistic

Area and recurs throughout Mesoamerica.[68]

Mayan languages often contrast alienable and inalienable possession by

varying the way the noun is (or is not) marked as possessed. Jakaltek,

for example, contrasts inalienably possessed wetʃel "my photo (in which

I am depicted)" with alienably possessed wetʃele "my photo (taken by

me)". The prefix we- marks the first person singular possessor in both,

but the absence of the -e possessive suffix in the first form marks

inalienable possession.[67] +++++++ マヤ語の名詞の形態は非常に単純で、数(複数形または単数形)に屈折し、所有される場 合は、所有者の人称と数に屈折します。代名詞の所有は、Kaqchikel ru-kej 「彼/彼女の馬」のように、名詞に付く所有接頭辞のセットで表します。名詞はさらに、所有されていることを示す特別な形をとることがあります。名詞的所有 格の場合、所有格の名詞は三人称の所有格に所有されているものとして屈折し、所有格の名詞が続きます。このような形成はメソアメリカ言語圏の主な特徴であ り、メソアメリカ全域で見られます。マヤの言語では、名詞が所有されている(または所有されていない)ことを示す方法を変えることで、疎外可能な所有と疎 外不可能な所有を対比させることがよくあります。たとえば、ジャカルテク語では、不可知的所有のwetʃ「(私が写っている)私の写真」と不可知的所有の wetʃele「(私が撮った)私の写真」を対比する。どちらも接頭辞we-が一人称単数の所有者を示すが、最初の形には所有接尾辞-eがないため、不可 分の所有を示す。 |

| Grammar- Relational nouns |

Mayan languages which have

prepositions at all normally have only one. To express location and

other relations between entities, use is made of a special class of

"relational nouns". This pattern is also recurrent throughout

Mesoamerica and is another diagnostic trait of the Mesoamerican

Linguistic Area. In Mayan most relational nouns are metaphorically

derived from body parts so that "on top of", for example, is expressed

by the word for head.[69] +++++++ マヤ語では、前置詞は通常 1 つしかない。位置や、エンティティ間のその他の関係を表すには、「関係名詞」という特別なクラスが使用される。このパターンはメソアメリカ全土に見られ、 メソアメリカ言語圏のもう一つの特徴である。マヤ語では、ほとんどの関係名詞が体の部位に由来するため、たとえば「on top of」は「head」という単語で表現される。 |

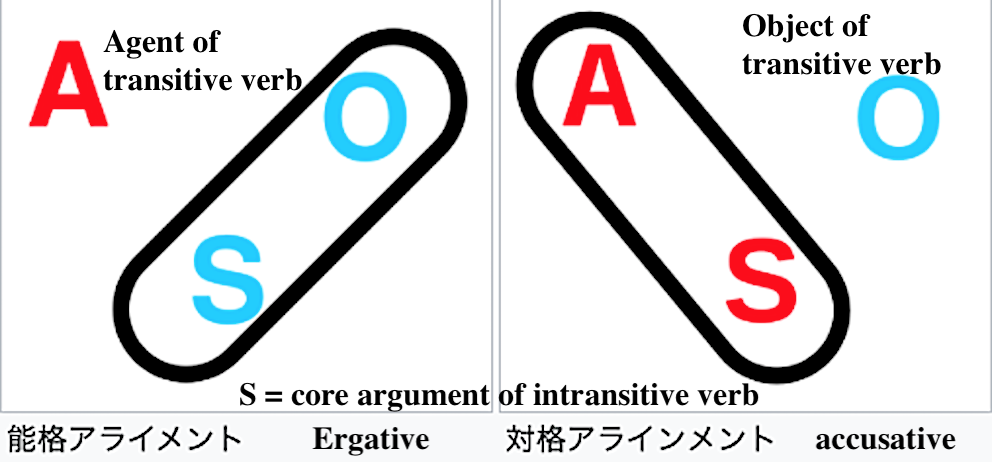

| Grammar- Subjects and objects |

Mayan languages are ergative

in

their alignment. This means that the subject of an intransitive verb is

treated similarly to the object of a transitive verb, but differently

from the subject of a transitive verb.[70]

Mayan languages have two sets of affixes that are attached to a verb to

indicate the person of its arguments. One set (often referred to in

Mayan grammars as set B) indicates the person of subjects of

intransitive verbs, and of objects of transitive verbs. They can also

be used with adjective or noun predicates to indicate the subject.[71] +++++++ マヤ語は能格言語=エルガティブ(ergative)である。つま り、自動詞の主語は他動詞の目的語と同様に扱われるが、他動詞の主語とは異なる。マヤ語には、引数の人称を表すために動詞に付ける接辞が2つあります。マ ヤ語の文法ではBセットと呼ばれることが多い)1つは自動詞の主語の人称を表し、もう1つは他動詞の目的語の人称を表す。また、形容詞や名詞の述語で主語 を表すこともあります。  マヤ語は、能格言語である。能格言語の特徴は、他動詞の目的語の活用と、自動詞の活用が同じ形態をとる。英語のような対格言語では、自動詞と他動詞の活用 は同じで区別されず、他動詞の目的語の活用は動詞の活用とは無関係にユニークである。 |

| Grammar- Verbs; Class A (Set A);

Class B (Set B) |

Tense systems in Mayan languages

are generally simple. Jakaltek, for example, contrasts only past and

non-past, while Mam has only future and non-future. Aspect systems are

normally more prominent. Mood does not normally form a separate system

in Mayan, but is instead intertwined with the tense/aspect system.[72]

Kaufman has reconstructed a tense/aspect/mood system for proto-Mayan

that includes seven aspects: incompletive, progressive,

completive/punctual, imperative, potential/future, optative, and

perfective.[73]

Mayan languages tend to have a rich set of grammatical voices.

Proto-Mayan had at least one passive construction as well as an

antipassive rule for downplaying the importance of the agent in

relation to the patient. Modern Kʼicheʼ has two antipassives:

one which ascribes focus to the object and another that emphasizes the

verbal action.[74] Other voice-related constructions occurring in Mayan

languages are the following: mediopassive, incorporational

(incorporating a direct object into the verb), instrumental (promoting

the instrument to object position) and referential (a kind of

applicative promoting an indirect argument such as a benefactive or

recipient to the object position).[75] +++++++ マヤ語の時制は一般的に単純である。たとえば、Jakaltek語は過去と非過去のみを対照とし、Mam語は未来と非未来のみを対照とする。アスペクト系 は通常、より顕著です。マヤ語では通常、気分は独立したシステムではなく、時制/アスペクトシステムと絡み合っています。カウフマンは、プロトマヤ語の時 制/アスペクト/ムード体系を再構築し、不完了体、進行形、完了体/接続体、命令形、潜在/未来、視唱、完了体の7つのアスペクトを含むとした。マヤの言 語には豊富な文法声部がある。原マヤ語には少なくとも1つの受動構文があり、患者に対する代理人の重要性を軽視するための反受動規則もあった。現代の Kʼicheʼには2つの反受身がある。1つは目的語に焦点を当てるもので、もう1つは動詞の動作を強調するものである。その他、マヤ語には次のような音 声関連の構文があります:媒介受動態、組込み(直接目的語を動詞に組み込む)、器械的(器械を目的語の位置に促進する)、参照的(beneffact や recipient などの間接的な引数を目的語の位置に促進する一種のアプリケーティブ)。 |

| Class A (Set A) | 他動詞の活用。他動詞を使い、目的語を主格にすると受動態表現が可能に なる。 |

| Class B (Set B) | 自動詞の活用と他動詞の目的語の活用は同じであるので、文章のなかで峻 別しなければならない。この活用のタイプだと、他動詞を使った受動態表現が可能である。それと同時に、目的語(の機能をもつ単語)をマークすることを通し て、自動詞をつかって、受動表現をおこなうことが可能になる。後者の文の変形操作を逆受動態(anti-passive)という。 |

| Grammar- Antipassive voice | The

antipassive

voice

(abbreviated antip or ap) is a type of grammatical voice that either

does not include the object or includes the object in an oblique case.

This construction is similar to the passive voice, in that it decreases

the verb's valency by one – the passive by deleting the agent and

"promoting" the object to become the subject of the passive

construction, the antipassive by deleting the object and "promoting"

the agent to become the subject of the antipassive construction. +++++++ 逆受動態(antipまたはapと略される)は、目的語 を含まないか、または斜格で目的語を含む文法的な音声の一種です。この構文は受動態と似ているが、動詞の価数を1つ減らすという点で、受動態はエージェン トを削除して目的語を受動態の主語に「昇格」させ、逆受動態は目的語を削除してエージェントを反受動態の主語に「昇格」させる。 |

| Grammar- Statives and positionals |

In Mayan languages, statives are

a class of predicative words expressing a quality or state, whose

syntactic properties fall in between those of verbs and adjectives in

Indo-European languages. Like verbs, statives can sometimes be

inflected for person but normally lack inflections for tense, aspect

and other purely verbal categories. Statives can be adjectives,

positionals or numerals.[76]

Positionals, a class of roots characteristic of, if not unique to, the

Mayan languages, form stative adjectives and verbs (usually with the

help of suffixes) with meanings related to the position or shape of an

object or person. Mayan languages have between 250 and 500 distinct

positional roots:[76] +++++++ マヤ語では、動詞と形容詞の中間に位置する構文特性を持つ、質や状態を表す述語の一種である。動詞と同様に、状態詞も人称の屈折を伴うことがありますが、 通常は時制やアスペクト、その他の純粋に動詞的なカテゴリーの屈折を伴いません。位置詞は、マヤ諸語の特徴的な根のクラスで、(通常は接尾辞の助けを借り て)形容詞や動詞を形成し、物体や人の位置や形に関連する意味を持ちます。マヤ語には、250から500の異なる位置語根があります: |

| Grammar- Word formation | Compounding of noun roots to

form new nouns is commonplace; there are also many morphological

processes to derive nouns from verbs. Verbs also admit highly

productive derivational affixes of several kinds, most of which specify

transitivity or voice.[78]

As in other Mesoamerican languages, there is widespread metaphorical

use of roots denoting body parts, particularly to form locatives and

relational nouns, such as Kaqchikel -pan ("inside" and "stomach") or

-wi ("head-hair" and "on top of").[79] +++++++ また、動詞から名詞を派生させる形態論的な過程も数多く存在する。また、動詞から名詞を派生させる形態論的な過程も数多くあります。動詞には、非常に 生産性の高い、さまざまな種類の派生接辞があります。他のメソアメリカ諸語と同様に、体の部位を表す語根の比喩的な使用が広まり、特に、カクチケル語の -pan(「内部」、「胃」)や -wi(「頭髪」、「上に」)のような、位置詞や関係詞を形成するために使用されます。 |

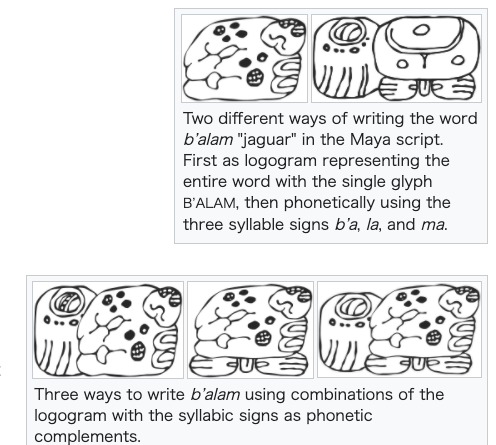

|

The complex script used to write

Mayan languages in pre-Columbian times and known today from engravings

at several Maya archaeological sites has been deciphered almost

completely. The script is a mix between a logographic and a syllabic

system.[83]

In colonial times Mayan languages came to be written in a script

derived from the Latin alphabet; orthographies were developed mostly by

missionary grammarians.[84] Not all modern Mayan languages have

standardized orthographies, but the Mayan languages of Guatemala use a

standardized, Latin-based phonemic spelling system developed by the

Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala (ALMG).[16][17] Orthographies

for the languages of Mexico are currently being developed by the

Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas (INALI).[22][85]→Glyphic

writing :The

pre-Columbian Maya civilization developed and used an intricate and

fully functional writing system, which is the only Mesoamerican script

that can be said to be almost fully deciphered. Earlier-established

civilizations to the west and north of the Maya homelands that also had

scripts recorded in surviving inscriptions include the Zapotec, Olmec,

and the Zoque-speaking peoples of the southern Veracruz and western

Chiapas area—but their scripts are as yet largely undeciphered. It is

generally agreed that the Maya writing system was adapted from one or

more of these earlier systems. A number of references identify the

undeciphered Olmec script as its most likely precursor.[86][87]

In the course of the deciphering of the Maya hieroglyphic script,

scholars have come to understand that it was a fully functioning

writing system in which it was possible to express unambiguously any

sentence of the spoken language. The system is of a type best

classified as logosyllabic, in which symbols (glyphs or graphemes) can

be used as either logograms or syllables.[83] The script has a complete

syllabary (although not all possible syllables have yet been

identified), and a Maya scribe would have been able to write anything

phonetically, syllable by syllable, using these symbols.[83]

At least two major Mayan languages have been confidently identified in

hieroglyphic texts, with at least one other language probably

identified. An archaic language variety known as Classic Maya

predominates in these texts, particularly in the Classic-era

inscriptions of the southern and central lowland areas. This language

is most closely related to the Chʼolan branch of the language family,

modern descendants of which include Chʼol, Chʼortiʼ and Chontal.

Inscriptions in an early Yucatecan language (the ancestor of the main

surviving Yucatec language) have also been recognised or proposed,

mainly in the Yucatán Peninsula region and from a later period. Three

of the four extant Maya codices are based on Yucatec. It has also been

surmised that some inscriptions found in the Chiapas highlands region

may be in a Tzeltalan language whose modern descendants are Tzeltal and

Tzotzil.[29] Other regional varieties and dialects are also presumed to

have been used, but have not yet been identified with certainty.[11]

Use and knowledge of the Maya script continued until the 16th century

Spanish conquest at least. Bishop Diego de Landa Calderón of the

Catholic Archdiocese of Yucatán prohibited the use of the written

language, effectively ending the Mesoamerican tradition of literacy in

the native script. He worked with the Spanish colonizers to destroy the

bulk of Mayan texts as part of his efforts to convert the locals to

Christianity and away from what he perceived as pagan idolatry. Later

he described the use of hieroglyphic writing in the religious practices

of Yucatecan Maya in his Relación de las cosas de Yucatán.[88] +++++++ 先コロンビア時代にマヤの言語を書くために使用され、いくつかのマヤの遺跡の彫刻から今日知られている複雑な文字は、ほぼ完全に解読されている。この文字 は、対数文字と音節文字が混在したものである。植民地時代、マヤの言語はラテンアルファベットから派生した文字で書かれるようになりました。正書法は、主 に宣教師の文法家によって開発されました。現代のすべてのマヤ諸語が標準化された正書法を持っているわけではありませんが、グアテマラのマヤ諸語は、グア テマラ言語アカデミー(ALMG)によって開発された標準化された、ラテン語ベースの音素綴りシステムを使用しています。メキシコの諸言語の正書法は現 在、国立インディオ言語研究所(INALI)が開発中である。→グリフ文字:コロンブス以前のマヤ文明は、複雑で完全に機能する文字体系を開発し、使用し ていた。マヤの故郷の西と北にある、サポテカ、オルメカ、そしてベラクルス南部とチアパス西部のゾク語を話す人々も、現存する碑文に文字が記録されている 先行文明を持っていたが、彼らの文字はまだほとんど解読されていない。一般的に、マヤの文字システムは、これらの以前のシステムの1つまたは複数から適応 されたものであると考えられています。多くの文献は、未解読のオルメカ文字がその前身である可能性が最も高いと指摘している。マヤのヒエログリフ文字が解 読される過程で、学者たちはそれが完全に機能する文字システムであり、話し言葉のあらゆる文を明確に表現することが可能であることを理解するようになっ た。この文字システムは、記号(グリフまたはグラフェム)をロゴグラムまたは音節として使用することができる、ロゴス音節として最もよく分類されるタイプ である。この文字には完全な音節があり(ただし、まだすべての音節が特定されているわけではない)、マヤの書記はこれらの記号を使って、音節ごとに音韻的 に何でも書くことができただろう。少なくとも2つの主要なマヤの言語が、ヒエログリフのテキストから確実に同定されており、少なくとも他の1つの言語も同 定されていると思われる。古典マヤとして知られる古代の言語が、特に南部と中央低地の古典時代の碑文に多く見られる。この言語はマヤ語族のChʼolan に最も近く、現代ではChʼol、Chʼortiʼ、Chontalがその子孫にあたる。初期のユカテカ語(現存する主なユカテク語の祖先)の碑文も、主 にユカタン半島地域とそれ以降の時代のものが認識または提案されている。現存する4つのマヤの写本のうち、3つはユカテク語に基づいています。また、チア パス高地地域で発見されたいくつかの碑文は、ツェルタル語やツォツィル語を現代に伝えるツェルタラン語の可能性があると推測されています。その他の地域的 な言語や方言も使用されていたと推測されているが、確実な特定には至っていない。マヤ文字の使用と知識は、少なくとも16世紀のスペイン征服まで続いた。 ユカタンカトリック大司教区のディエゴ・デ・ランダ・カルデロン司教は文字の使用を禁止し、メソアメリカの伝統であった土着の文字による識字に終止符を 打った。彼はスペインの植民者と協力し、地元の人々をキリスト教に改宗させ、異教の偶像崇拝から遠ざけようとする努力の一環として、マヤ語のテキストの大 部分を破壊した。その後、彼は『ユカタンの歴史』(Relación de las cosas de Yucatán)の中で、ユカタン・マヤの宗教的慣習における象形文字の使用について述べている。 |

| Literature |

From

the classic language to the present day, a body of literature has been

written in Mayan languages. The earliest texts to have been preserved

are largely monumental inscriptions documenting rulership, succession,

and ascension, conquest and calendrical and astronomical events. It is

likely that other kinds of literature were written in perishable media

such as codices made of bark, only four of which have survived the

ravages of time and the campaign of destruction by Spanish

missionaries.[91]

Shortly after the Spanish conquest, the Mayan languages began to be

written with Latin letters. Colonial-era literature in Mayan languages

include the famous Popol Vuh, a mythico-historical narrative written in

17th century Classical Quiché but believed to be based on an earlier

work written in the 1550s, now lost. The Título de Totonicapán and the

17th century theatrical work the Rabinal Achí are other notable early

works in Kʼicheʼ, the latter in the Achí dialect.[notes 18] The Annals

of the Cakchiquels from the late 16th century, which provides a

historical narrative of the Kaqchikel, contains elements paralleling

some of the accounts appearing in the Popol Vuh. The historical and

prophetical accounts in the several variations known collectively as

the books of Chilam Balam are primary sources of early Yucatec Maya

traditions.[notes 19] The only surviving book of early lyric poetry,

the Songs of Dzitbalche by Ah Bam, comes from this same period.[92]

In addition to these singular works, many early grammars of indigenous

languages, called "artes", were written by priests and friars.

Languages covered by these early grammars include Kaqchikel, Classical

Quiché, Tzeltal, Tzotzil and Yucatec. Some of these came with

indigenous-language translations of the Catholic catechism.[84]

While Mayan peoples continued to produce a rich oral literature in the

postcolonial period (after 1821), very little written literature was

produced in this period.[93][notes 20]

Because indigenous languages were excluded from the education systems

of Mexico and Guatemala after independence, Mayan peoples remained

largely illiterate in their native languages, learning to read and

write in Spanish, if at all.[94] However, since the establishment of

the Cordemex [95] and the Guatemalan Academy of Mayan Languages (1986),

native language literacy has begun to spread and a number of indigenous

writers have started a new tradition of writing in Mayan

languages.[85][94] Notable among this new generation is the Kʼicheʼ

poet Humberto Akʼabʼal, whose works are often published in

dual-language Spanish/Kʼicheʼ editions,[96] as well as Kʼicheʼ scholar

Luis Enrique Sam Colop (1955–2011) whose translations of the Popol Vuh

into both Spanish and modern Kʼicheʼ achieved high acclaim.[97] +++++++ 古典的な言語から現代に至るまで、マヤの言語ではさまざまな文学が書かれてきた。保存されている最古のテキストは、支配権、後継者、昇位、征服、暦学的・ 天文学的出来事を記録した記念碑文が主である。他の種類の文献は、樹皮で作られた写本のような腐りやすい媒体で書かれたと思われるが、そのうちの4つだけ が、時の荒波とスペイン人宣教師による破壊作戦を生き延びた。 スペインによる征服後まもなく、マヤ語はラテン文字で書かれるようになった。植民地時代のマヤ語の文献には、有名なポポル・ヴフ(Popol Vuh)がある。これは17世紀の古典的なキチェ語で書かれた神話と歴史の物語であるが、1550年代に書かれた以前の作品に基づいていると考えられてい る。Título de Totonicapánと17世紀の演劇作品Rabinal Achíは、Kʼicheʼの他の有名な初期の作品で、後者はアチ方言である。16世紀後半に書かれた『Annals of the Cakchiquels』はカクチケルの歴史物語であり、『ポポル・ヴフ』に登場する記述と類似した要素を含んでいる。チラム・バラム(Chilam Balam)の書物として総称されるいくつかのバリエーションにある歴史的、予言的な記述は、ユカテク・マヤの初期の伝統の主要な情報源です。 現存する唯一の初期の抒情詩集であるアーバムの「ジトバルチェの歌」は、この同じ時代に書かれたものです。 このような特異な作品に加え、「アルテス」と呼ばれる多くの初期文法書が司祭や修道士によって書かれました。これらの初期の文法書の対象となった言語に は、カクチケル語、古典キチェ語、ツェルタル語、ツォツィル語、ユカテク語などがある。これらの中には、カトリックのカテキズムを先住民の言葉で翻訳した ものもあった。ポストコロニアル時代(1821年以降)、マヤの人々は豊かな口承文学を作り続けたが、文字文学はほとんど作られなかった。独立後、メキシ コとグアテマラの教育制度から先住民の言語が排除されたため、マヤの人々は母語の読み書きがほとんどできないままであり、スペイン語の読み書きを学んでい た。しかし、コルデメックスとグアテマラ・アカデミー・オブ・マヤ・ランゲージの設立(1986年)以降、母語の読み書きが普及し始め、多くの先住民の作 家がマヤ語で文章を書くという新しい伝統を始めた。この新世代の中で特筆すべきは、スペイン語とキチェ語の二言語版でしばしば作品が出版されるキチェ詩人 Humberto Akʼabʼalや、スペイン語と現代キチェの両方にポポル・ヴフを翻訳して高い評価を得たキチェ学者Luis Enrique Sam Colop(1955-2011)である。 |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Proto-Mayan_language

| MAYAN LANGUAGES: BIBLIOGRAPHY I Basic Source Materials Bibliography of Mayan Languages and Linguistics, 1978, Lyle Campell et al., (eds.). PM 396l, B 524, LAC (excellent bibliography through l976). Handbook of Middle American Indians, 1967, 1969, R. Wauchope (series ed.). Vol 7 (ethnographic sketches of Mayan groups), Volume 5 (linguistic sketches and other useful materials). F 1434, H 3, LAC (ref). Supplement to the Handbook of Middle American Indians, (V.R. Bricker (series ed.), Volume 2 (sketches of Cholti and Huastec), Volume 3 (articles on Yucatecan, Tzotzil, Quiche, and Chorti literature). Languages of Guatemala, l966, Marvin K. Mayers (Ed.) (contains ethnographic and grammatical sketches of Mayan languages in Guatemala, along with illustrative texts and a 2OO word comparative word list). PM 3361, M 3, 1966 LAC. Estudios de Cultura Maya published periodically by the Centro de Estudios Mayas, U.N.A.M. de Mexico. (contains many fine articles dealing with all aspects of Mayan cultures. G 972.O15, Es 87. Journal of Mayan Linguistics, 1978-, PM 3961, A 36, LAC (journal is preceded by 3 separately published earlier attempts at a journal: l) Marlys McClaran (ed.) l976, Mayan Linguistics (U.C.L.A., Latin American Studies Center) PM 3961, A 44. 2) Nora England (ed.), l978, Papers in Mayan Linguistics (U. Of Missouri, Misc. Pubs. in Anthropology No. 6). 3) Laura Martin (ed.), l979, Papers in Mayan Linguistics. Columbia, Mo., LucasBrothers Pubs. Annual Review of Anthropology. 1985. has overview article and helpful bibliography by Lyle Campbell and Terrence Kaufman, "Mayan Linguistics: Where are We Now?". Annual Review of Anthropology. 1995?. has overview article and helpful bibliography on Maya Hieroglyphic Writing by Victoria Bricker. II Maya Culture and Civilization: Background Introductions Elizabeth P. Benson, l977, The Maya World. (pb) F l435, B 47, l977 LAC. Peter Canby, The Heart of the Sky. M.D. Coe, l966, The Maya (pb); revised edition l98O (pb) G 972.Ol5, C 65m, l966. Freidel, David, Schele, Linda, and Joy Parker. 1993. Maya Cosmos. (uses ethnographic data to inform studies of Classic Maya worldview) Menchú, Rigoberta. I Rigoberta Menchú. F1465.2, Q5, M3813, 1984 LAC Sharer, Robert (& S.G. Morley, G.W. Brainerd) 1994. The Ancient Maya. (fifth edition) G 972.Ol5, M 827a, l956, l983, 1994. (most comprehensive account, well illustrated) Schele, Linda and Mary Ellen Miller 1986. The Blood of Kings. (most up to date materials on Maya kingship, iconography, and hieroglyphic writing) Schele, Linda and David Freidel. 1990. A Forest of Kings. (The first real history of the Classic Maya) George and Gene Stuart, l977, The Mysterious Maya. F l435, S 89, LAC T. Patrick Culbert, l974, The Lost Civilization: The Story of the Classic Maya. F L435, C82, LAC J.E.S. Thompson, l966, The Rise and Fall of Maya Civilization. G 972.Ol5, T 374r. Carter Wilson, 1965. Crazy February. G 8l3, W 692 C PCL, LAC & 813, W69l8 C III Ethnographic: Mayan Societies Today CAKCHIQUEL F. McBryde, l934, "Solola: A Guatemalan Town and Cakchiquel Market Center." Middle American Research Institute Pub. 5, Tulane U. G 9l3.728, T 82, no. 5. CHORTI C. Wisdom, l94O, The Chorti Indians Of Guatemala. G 97O.3, W 753c. HUASTEC J. Alcorn, l984 Huastec Mayan Ethnobotany. F1221, H8A42, 1984 (LAC), GN 476.43, A42, 1984. IXIL B.N. Colby and P. van den Berghe, l969, Ixil Country. G 3O9.l728l, C 672i. B.N. Colby and Lore Colby, l981, The Daykeeper. F1465.2, I95 C64, LAC JACALTEC O. LaFarge and D. Byers, l93l, The Year Bearers People. G 9l3.728, T 82, no. 3. KANJOBAL O. LaFarge, l947, Santa Eulalia. G 972.8l, L l32s. Gaspar Pedro González, A Mayan Life. (La Otra Cara) Yaxte' Press KEKCHI R. Wilson. 1998. Maya Resurgence in Guatemala. LACANDON A.M. Tozzer, 19O7, A Comparative Study of the Mayas and the Lacandones (F l435, T699 LAC) Bruce, Robert 1976. Lacandon Dream Symbolism. Mexico. MAM M. Oakes, l95l, The Two Crosses of Todos Santos. G 972.8l, Oa 4t. MOCHO P. Petrich, 1985. La Alimentacion Mochó: Acto y Palabra. Centro de Estudios Indigenas, Universidad Autonoma de Chiapas. MOPAN J.E.S. Thompson, l93O, Ethnology of the Mayas of Southern and Central British Honduras. GN 2, F 4, v. l7, no. 2, LAC. POCOMAM R.E. Reina, l966, The Law Of The Saints. G 97O.3, P 756r. QUICHE R. Bunzel, l952, Chichicastenango. G 9l7.28l, B 887c. R.M. Carmack, l98l, The Quiché Mayas of Utatlán. F1465.2, Q5 C267, PCL B. Tedlock, l982, Time and the Highland Maya (2nd Ed.). F1465.2, Q5 T43, 1982 TOJOLABAL M. Ruz (ed.) Los Tojolabales (3 volumes). TZELTAL June Nash, l97O, In the Eyes of the Ancestors. G 3O9.17274, N l74i. Hermitte, M. Esther 197O. Poder Sobrenatural y Control Social: en un Pueblo Maya Contemporaneo. Ediciones Expeciales, 57. Mexico: Instituto Indigenista Interamericano (Rev. AA 76:92O-1) Ruz, Mario 1985. Copanaguastla en un Espejo. Serie Monografias 1, Centro de Estudios Indigenas, Universidad Autonoma de Chiapas. TZOTZIL E.Z. Vogt, l969. Zinacantán. G 97O.497274, v 868zi. Kazuyasu, Ochiai 1985. Cuando Los Santos Vienen Marchando. Rituales Publicos Intercomunitarios Tzotziles. Serie Monografias 3, Centro de Estudios Indigenas, Univ. Auton. de Chiapas. TZUTUJIL J. Sexton 1981. Son of Tecun Uman. YUCATEC R. Redfield and A. Villa Rojas, l934, Chan Kom: A Maya Village. (also l962 abridged pb. edition). qF1435.1, C47 R3 or F1435.1, C47 R3, 1962. T. Rugely 2001. Maya Wars: Ethnographic Accounts from Nineteenth-Century Yucatan. IV Folklore/Oral Literature Annals of the Cakchiquels. (Cakchiquel - trans. by Recinos G 972.81, An 72m, 1967 LAC) Sarah Blaffer, l972, The Black Man of Zinacantán (Tzotzil). F 1221, T 9, B 55, LAC. Roberto Bruce, 1974, El Libro de chan K'in (Lacandon cosmological folklore). F 1221, L2, C 45, LAC-Z, non-circ. Allen Burns 1982, An Epoch of MIracles: Oral Literature of hte Yucatec Maya. The Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel. (Yucatec - trans. by Roys qG 972.O15, C 435cE, l967; Edmonson). The Book of Chilam Balam of Tizimín (Yucatec - trans. by Makemson, Edmonson) Louanna Furbee (-Losee) (ed.), l976, l979, l98O, Mayan Texts I, II, & III. (Nos. l, 3, & 5 of the International Journal of American Linguistics, Native American Texts Series of monographs) PM 3968.8, M 39, LAC. Gary Gossen, l974, Chamulas in the World of the Sun. (Tzotzil oral literature). F 1221, T 9, G 677, LAC. C.A. Castro, l965, Narraciones Tzeltales de Chiapas. G 97O.3, kT996C, LAC John Fought, 1972, Chorti Texts I. PM 3661, Z 73, F 6, LAC. Charles Andrew Hofling, 1991, Itzá Maya Texts (has a grammatical overview) Eva Hunt, l977, The Transformation of the Hummingbird. (Tzotzil). F 1221, T 9, H 86, LAC. Robert Laughlin, l977, Of Cabbages and Kings. (Tzotzil folklore). GN 1,S 54, no. 23, LAC. Robert Laughlin, l98O, Of Shoes and Ships and Sealing Wax. (Tzotzil texts) Montejo, Victor, 1991. The Bird Who Cleans the World: and other Mayan Fables. Marvin Mayers, l958, Pocomchí Texts. 497.4, M453p or MCFICHE 1983, LAC Montejo, Victor, 1991. The Bird Who Cleans the World: and other Mayan Fables. Peñalosa, Fernando, 1995. Tales and Legend of the Q'anjob'al Maya. Yaxte' Press. Peñalosa, Fernando (ed.) 1992. Cuentos de Don Pedro Miguel Say. Yaxte' Press. (Kanjobal / Q'anjob'al texts) Popol Vuh (Quiche - best translations are by Recinos (GZ, G913.7281, P 814S, 1947), Edmonson (F 1421, T 95, no. 35 LAC) , D. Tedlock, 1985). Also see F 1465, P 828, 1961, LAC. G 913.7281, P 814S, 1964, l969. Mary Shaw (ed.), l97l, According to our Ancestors. (S.I.L. texts and translations from ACH, AGU, CAK, CHJ, IXL, JAC, KEK, MOP, PCM, PCH., QUI, TZU, USP). F 1465.3, F 6, S 48, LAC. Brian Stross, l977, Love in the Armpit: Tzeltal Tales. F 1221, T 8, L 683, PCL Brian Stross, 1978, Demons and Monsters: Tzeltal Tales. F 1221, T 8, S 87, LAC Paul Townsend, 198O, Ritual Rhetoric From Cotzál (Ixil texts) Paul Townsend l975, Ixil Texts, With Spanish Translation. (S.I.L. microfiche). A. Whittaker and V. Warkentin, l965, Chol Texts of the Supernatural. PM 3649, W 5, LAC. R.L. Roys, ed. and trans., 1965, Ritual of the Bacabs. (Yucatec) G 972.O15, R518 TE, LAC E.R. Craine and R.C. Reindorp, l979, The Codex Perez and the Book of chilam Balam of Mani. F 1435.3, C14, C62 LAC. M. & R. Ulrich, 1986. Historias de lo Sagrado, Lo Serio, Lo Sensacional, Y lo Sencillo. (SIL) V Mayan Vocabularies HUA R. Larsen, l955, Vocabulario Huasteco (S.I.L.) FILM 8391 LAC CHC G. Zimmermann, l955, "Das Cotoque: die Maya-Sprache von Chicomucelo." (in Zeitschrift fur Ethnologie l955:59-87) L572.O5, Z37 PCL ITZ C. Hoffling, 1993, Itzá Maya Texts With a Grammatical Overview. O. Schumann, l97l, Descripción Estructural Del Maya Itzá del Peten. (U.N.A.M.) PM 3969, S3 LAC YUC C. Alvarez, l98O, Diccionario Etnolingüistico Del Idioma Maya Yucateco Colonial. (U.N.A.M.) (2 volumes; I Mundo Fisico, II Aprovechamiento de los Recursos Naturales) PM 3969, A48, LAC J. Martinez Hernandez (ed.), l929, Diccionario de Motul. G 497, C 498d J. Pio Perez, l866-77, Diccionario de la Lengua Maya. GZ 497.22O3, P 415 Z LAC O. Michelon (ed.), Diccionario de San Francisco (Yucatán). A. Barrera Vasquez et al, l98O, Diccionario Maya Cordemex. LAC ref. (rev. IJAL 49:2O8) 497.O5, IN 8, PCL. G. Bevington, 1995, Maya For Travelers and Students LAC R. Bruce, l978, Lacandón Dream Symbolism, Vol. II (dictionary, index, plus). F 1221, L2, B 78, LAC MOP M. & R. Ulrich, l976, Diccionario Bilinguie. ITZ C. Hofling, 1997. Itzá Dictionary TOJ C. Mendenhall & J. Supple, l949, "Tojolabal Texts and Dictionary." (MCMCA 26 - in LAC. Microfilm collection. C. Lenkersdorf, l979, l98l, B'omak'umal Tojol Ab'al-Kastiya 1. Vol 1, & 2. Vol 2. (rev. IJAL 49:214) 497.O5, IN 8, PCL L. Furbee, l98l, Tojolabal Maya-English dictionary. TZE M. Slocum and F. Gerdel, l965, Vocabulario Tzeltal De Bachajón. (S.I.L.) PM 4461, S563, LAC C. Robles Uribe, 1966, La Dialectología Tzeltal y El Diccionario Compacto. G 497.4, R 571d M. Ruz (ed.) 1986. Vocabulario de Lengua Tzeltal Segun el Orden de Copanabastla. Fr. Domingo de Ara. Mexico: U.N.A.M. TZO R. Laughlin, l975, The Great Tzotzil Dictionary of San Lorenzo Zinacantán. qPM 4466, Z5, L 38, LAC R. Laughlin, 1987, The Great Tzotzil Dictionry Of Santo Domingo Zinacantán. A. Hurley de Delgaty y A. Ruiz Sanchez, l978, Diccionario Tzotzil de San Andres con Variaciones Dialectales. (S.I.L.). PM 4466, Z 5, H 8, LAC. CHL H.W. & E.W. Aulie, l978, Diccionario Ch'ol (S.I.L.) PM 3649, Z5A9, LAC O. Schumann, 1973, La Lengua Chol de Tila (Chiapas). CHN S.M. Knowles 1984, A Descriptive Grammar of Chontal Maya (Appendix V, Lexicon) (Ph.D. Diss. Tulane) O. Smailus, 1975, El Maya-Chontal de Acalan. PM3651, S6318, LAC CHR C. Wisdom, l949, "Materials on the Chorti Language." (MCMCA 28- in LAC microfilm collection) Film, G 8O3, no. 28. CHLT P. Moran, l935, Arte y Diccionario en Lengua Cholti. The Maya Society, Baltimore. O. Schumann, l973, La Lengua Chol, de Tila (Chiapas). (U.N.A.M.) CHJ N. Hopkins, l967, Chuj-Dictionary (m.s.) J. Maxwell, 1993, Chuj Dictionary (m.s.) M. Felipe Diego. 1998. Diccionario Chuj (PLFM) JAC C. Day, n.d. Un Diccionario de Jacalteco (ms. U. of Rochester) A. F. Méndez Cruz. 1997. Diccionario Popti' QUI M.S. Edmonson, l956, Quiché-English Dictionary. (M.A.R.I. no. 3O) F1421, T 95, no. 3O, LAC A. Garcia H. & S. Yac Sam & D.H. Pontious, n.d. Diccionario Quiché. J. de Leon 19 , Diccionario Quiché-Español PM 4231, D476, LAC Proyecto Lingüistico Francisco Marroquin 1996, Diccionario Del Idioma K'iche' C.N. Teletor, l959, Diccionario Castellano-Quiché y Voces Castellano- Pocomam. G497.4, T236D, LAC CAK C. Saenz de Santa Maria, l94O, Diccionario Cakchiquel-Español. G 497, Sa Hed. R. Blair et al. l981, Diccionario Español-Cakchiquel-Ingles PCM Déborah Ruyán Canú, Jo Ann Munson L. and Rafael Coyote Tum. 1991. Diccionario Cakchiquel Central y Español. Guatemala: S.I.L. N. Cojti Macario, M. Chacach Cutzal, & M. Armando Cali. 1998. Diccionario Kaqchikel. (PLFM) PCH M. Mayers, l956, Vocabulario Pocomchi. (S.I.L.) (microfiche) KEK G. Sedat, l955, Nuevo Diccionario de las Lenguas K'ekchí y Española. PM 3913, Z 5, S 37, LAC. MAM F.D. de Reynoso/A. Maria Carreno, l9l6, Vocabulario de la lengua Mame. G 497, R 276v, l9l6. J. Maldonado A., J. Ordónez D, and J. Ortiz D., 1986. Diccionario Mam Filiberto Lopez Gabriel and Wes Collins. 1991 Diccionario de Verbos Mames U'j Te Pujb'il Yol, Noq Te Ipb'il. Guatemala: S.I.L. TEC T. Kaufman, l969, "Teco-a New Mayan Language." IJAL 35:154-74. 497.O5, IN 8, PCL IXL T. Kaufman, l974, Ixil dicionary. (computer printout, U.C., Irvine) L. Asicona Ramírez, D. Méndez Rivera & R.D. Xinic Bop. 1998. Diccionario Ixil de San Gaspar Chajul. (PLFM) MOT T. Kaufman, l967, Preliminary Mochó Vocabulary (W.P. no. 5, LBRL - U.Cal. Berkeley.) VI Mayan Grammars YUC A.M. Tozzer, l92l, A Maya Grammar (also a Dover pb., l977) G497.4, T669M, LAC. or PM 3963, T6, 1977, LAC R. Blair, l965, Yucatec Maya Noun and Verb Morpho-syntax (l97l Ph.D. diss., Indiana U. - also MCMCA lO9) PM 3963, B 563, LAC. LAC R. Bruce, l968, Gramatica Lacandón. G 497.4, B 83g, l968. ITZ O. Schumann G., l97l, Descripción Estructural del Del Maya Itzá Del Peten, Guatemala, C.A. PM 3969, S3, LAC Charles Andrew Hofling, 1982. Itzá Maya Morphosyntax From a Discourse Perspective. (Ph.D. diss., Washington Univ., 377pp) CHR J. Fought, l967, Chortí (Mayan): Phonology, Morphophonemics and Morphology. (l967 Ph.D. diss., Yale). Film, G 29O5. CHL J.J. Attinasi, l973, Lak T'an: A Grammar of the Chol (Mayan) Word. (Ph.D. diss., Chicago). V. Warkentin & R. Scott, l98O, Gramatica Ch'ol. (S.I.L.) PM 3649, W3 CHN Susan M. Knowles, 1984, A Descriptive Grammar of Chontal Maya (San Carlos Dialect). (unpub. doctoral dissertation, Tulane University) TZE T. Kaufman, l97l, Tzeltal Phonology and Morphology. Diaz Olivares, Jorge 198O. Manual del Tseltal. Univ. Auton. de Chiapas. Tuxtla Gutierrez. (338 pp. Mimiographed) TZO M. Cowan, l969, Tzotzil Grammar. (S.I.L.). G 498, C 838t H. Sarles, l966, A Descriptive Grammar of the Tzotzil Language. (l966 Ph.D. diss., U. of Chicago) PM, 4466, S 275, LAC. J. Aissen, 1987, Tzotzil Clause Structure.. Reidel Publishers. J. Haviland, 1981. El Tzotzil de San Lorenzo Zinacantán. Centro de Estudios Mayas. U.N.A.M. Mexico. TOJ L. Furbee-Losee, l976, The Correct Language, Tojolabal. PM 36OL, F 8, L976, LAC. Mary Jill Brody, 1982. Discourse Processes of Highlighting in Tojolabal Maya Morphosyntax (Mexico). (Ph.D. diss., Washington U. 317 pp) CHJ N.A. Hopkins, l967, The Chuj Language (Ph.D. diss., Chicago). Laura Ellen Martin, 1977. Positional Roots in Kanjobal (Mayan). (PhD. diss., U. of Florida, 464pp) JAC C. Day, l973, The Jacaltec Language. PM 3889, D 3, LAC. C. Craig, l977, The Structure of Jacaltec. PM 3889, C 7, LAC. Margaret J. Dickeman Datz, 198O. Jacaltec Syntactic Structures and The Demands of Discourse. (Ph.D. diss. U. of Colorado at Boulder 470 + pp) QUI James L. Mondloch, l978, Basic Quiché Grammar. (IMS-SUNY Albany, 2). PM 4231, M 66, LAC. Mondloch, James Lorin 198O. Voice in Quiché-Maya. (Ph.D. diss. S.U.N.Y., Albany, 359pp) SAC John W. DuBois, 1981. The Sacapultec Language. (PhD. diss.,U.C. Berkeley, 315 pp) TZU Jon Philip Dayley, l985, Tzutujil Grammar. UCPL Vol. 107 PM 4471, D39, 1985, PCL. KEK S. Pinkerton (ed.), l976, Studies in K'ekchi. (PH.D. DISS., U.T. AUSTIN). R. Freeze, l97O, Case in a Grammar of K'ekchi. (Ph.D. diss., U.T. Austin) TC 197O, F879, PCL Reserves. E. Haeserijn V., l966, Ensayo de la Gramatica del K'ekch'i'. G 497.4, H ll9e. A. Berinstein, 1985. Evidence for Multiattachment in K'ekchi Mayan.. Garland Publishers. J. Alberto Tzul & A Tzimaj Cacao. 1997. Gramatica del Idioma Q'eqchi' (PLFM) PCM J.F. Santos Nicolas, A de J. Cervantes Lopez, M. M. Gomez, & J. G Benito P. 1997. Gramatica Del Idioma Poqomam. (PLFM) MAM N. England l983, A Grammar of Mam, A Mayan Language. (based on her diss. which is in Film, l4.384, LAC) IXL Glenn Thompson Ayres, 198O. Un Bosquejo Gramatical del Idioma Ixil. (Ph.D. diss, U.C. Berkeley) VII Mayan Reconstructions Fisher, William, 1973.Towards The Reconstruction of Proto-Yucatec. (Ph.D. diss., Chicago (l973) FILM 8465, LAC) T. Kaufman, l964, "Materiales linguisticos para el estudio de las relaciones internas y externas de la familia de idiomas mayanos." (pp. 8l-l36) in E. Vogt and A. Ruz (eds.), l964, Desarrollo Cultural De Los Mayas. G 972.O15, C76 T. Kaufman, l969, "Teco--a new Mayan language." IJAL 35:l54-l74. 497.O5, IN 8, PCL T.C. Smith Stark, l976, "Some hypotheses on syntactic and morphological aspects of Proto-Mayan." in M. McClaran (ed.) Mayan Linguistics I. PM 3961, A319, V 1, LAC. J.A. Fox, l978, Proto-Mayan Accent, Morpheme Structure Conditions and Velar Innovations.. (Ph.D. diss., Chicago). J.S. Robertson, l977, "A phonological reconstruction of the ergative third-person singular pronoun in common Mayan." IJAL 43:2O1-lO. 497.O5 IN 8, PCL J.S. Robertson, 1986. "A reconstruction and evolutionary statement of the Mayan numerals from twenty to four hundred." IJAL 52:227-241. L. Campbell, l977, Quichean Linguistic Prehistory. PM 4232, C 35, LAC T. Kaufman, l972, El Proto-Tzeltal-Tzotzil: Fonología Comparada y Diccionario Reconstruido (CdeEM Cuaderno 5, UNAM, Mexico). PM 4461, K 297, LAC. Stross, B. l973, Reconstructed humor in a Tzeltal ritual formula, International Journal of American Linguistics, 39:32-4l (497.O5, IN 8, PCL); Stross, B. Oppositional pairing in Mesoamerican divinatory day names. Anthropological Linguistics 25:273 (4O5, AN 89, PCL); M. Swadesh, l96O, "Interrelaciones de las lenguas Mayas." Anales del INAH l3:23l-67. qF 1219, M 6O5, LAC Z non circ. T. Kaufman, l976, "Archaeological and linguistic correlations in Mayaland and associated areas of Mesoamerica." World Archaeology. 8(l):lOl-ll. (PCL) 913.O5, W 893. L. Campbell and T. Kaufman, l976, "A linguistic look at the Olmecs." American Antiquity. 4l(l):8O-89. (PCL) E 51, A 51. T. Kaufman, l98O, "Pre-Columbian borrowing involving Huastec." in K. Klar et al (eds.), American Indian and Indoeuropean Studies: Papers in Honor of Madison S. Beeler. C. Brown and S. Witkowski, l979, "Aspects of the phonological history of Mayan-Zoquean. IJAL 45:34-47. (this and the following 3 articles should be read together). (UGL microfilm), 497.O5, IN 8, PCL S. Witkowski and C. Brown, l98l, "Mesoamerican historical linguistics and distant genetic relationship. American Anthropologist. 83:9O5-9ll. (PCL) 572.O5, AM 35. L. Campbell and T. Kaufman, l98O, "On Mesoamerican linguistics." AA 82:85O-857. L. Campbell and T. Kaufman, l983, "Mesoamerican historical linguistics and distant genetic relationship: getting it straight." AA 85:362-372. T.S. Kaufman and W.M. Norman "An outline of proto-Cholan phonology, morphology, and vocabulary." in Justeson and Campbell (eds.), Phoneticism in Maya Hieroglyphic Writing. VIII Maya Hieroglyphic Writing V. R. Bricker, 1986, A Grammar of Mayan Hieroglyphs. M.D. Coe 1999 Breaking the Maya Code M.D. Coe and M. Van Stone 2001. Reading the Maya Glyphs D. Freidel, L. Schele, and J. Parker. 1993. Maya Cosmos. S. Houston, O. Chinchilla M., and D Stuart (eds.) 2002. The Decipherment of Ancient Maya Writing. J. Justeson, W.M. Norman, L. Campbell, T. Kaufman 1985. The Foreign Impact on Lowland Mayan Language and Script. F 1421, T95,No. 53, LAC J. Justeson and L. Campbell 1984. Phoneticism in Mayan Hieroglyphic Writing. D. Kelley, l976, Deciphering the Maya Script. qF l435.3, P 6, K 44, LAC. (dated but still useful, and well illustrated) B. MacLeod, 1986, An Epigrapher's Annotated Index to Cholan and Yucatecan Verb Morphology.. S. Martin and N. Grube 2000 Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens. M.G. Robertson, ed., l974, Primera Mesa Redonda de Palenque. (This and subsequent Mesa Redonda proceedings are very important for Maya glyph studies). F 1435, P2 M43, 1973, LAC L. Schele, l982, Maya Glyphs: The Verbs. F 1435.3, P6 S27, LAC (or UGL) L. Schele, l983, Notebook for the Maya Hieroglyphic Writing Workshop at Texas. F 1435.3, P6 N673 '78-'86 LAC Z L. Schele and M.E. Miller, 1986. The Blood of Kings. L. Schele and D. Freidel, 1990. A Forest of Kings. L. Schele and Peter Matthews, 1998. The Code of Kings J.E.S. Thompson, l97l, Maya Hieroglyphic Writing. (3rd ed.) F 1435.3, P 6, T 48, l97l, LAC. (dated, but still useful) J.E.S. Thompson, l962, A Catalog of Maya Hieroglyphs.. G 497.4, T 374c. IX Some Useful Books on Mayans R.E.W. Adams, 1977, The Origins of Maya Civilization. F 1435, O75, LAC B. Berlin, l968, Tzeltal Numeral Classifiers. PM 4461, B 4, l968. B. Berlin, D. Breedlove, & P. Raven, l974, Principles of Tzeltal Plant Classification. F 1221, T 8, B 47, LAC. V.R. Bricker, 1973, Ritual Humor in Highland Chiapas. F 1221, T 9, B 74, LAC. P. Brown 1979. Language, Interaction, and Sex Roles in a Mayan Community: A Study of Politeness and the Position of Women. (unpub. Ph.D. dissertation, U.C. Berkeley) (treats the Tenejapa Tzeltal) Dienhart, John M. 1989. The Mayan Languges: a Comparative Vocabulary. (3 Volumes). Odense: Odense University Press. ((See his website database and annotated bibliography)) M.S. Edmonson (ed.), l973, Meaning in Mayan Languages. PM 3969, M 4, l973, LAC. N.C. England. 1992. Autonomía De Los Idiomas Mayas: Historia e Identidad. (Editorial Cholsamaj) N.C England (ed.) 1993. Los Idiomas Mayas de Guatemala. (Editorial Cholsamaj) E.F. Fischer and R. McKenna Brown (eds.) 1996. Maya Cultural Acivism in Guatemala. U.T. Press Susan Garzon, R. McKenna Brown, Julia Becker Richards, and Wuqu' Ajpub' (eds.) 1998. The Life of the Kaqchikel Lanaguage: Maintenance, Shift and Revitalization. U.T. Press. E.S. Hunn, l977, Tzeltal Folk Zoology. F 1221, T 8, H 86, LAC. Friar Diego de Landa, (Gates' ed. & trans.), l978, Yucatan Before and After the Conquest. (dover pb.)(not as detailed as the Tozzer volume). F 1376, L24613, 1978, LAC M. López Raquec. 1989. Acerca de los Idiomas Mayas de Guatemala. (PLFM). H.L. Neuenswander & D.E. Arnold (eds.), l977, Cognitive Studies of Southern Mesoamerica. (S.I.L.). John S. Robertson, 198O, The Structure of Pronoun Incorporation in the Mayan Verb complex. Garland Publishing Co. John S. Robertson, 1992. The History of Tense/Aspect/Mood/Voice in the Mayan Verbal complex. U.T. Press. R.L. Roys, l93l, The Ethnobotany of the Maya. (ISHI reprint, l976S). G 9l3.728, T 82, no. 2. Tedlock, Dennis. 1993. Breath on the Mirror: Mythic Voices & Visions of the Living Maya. (Harper Collins Paperback, edition 1994) J.E.S. Thompson, l97O, Maya History and Religion. G 972.Ol5, T 374 may. A.M. Tozzer (ed.), l94l, Landa's Relación de las Cosas de Yucatan.(vital early colonial report on the Yucatecs, includes a glyphic syllabary. G 972.64, L 23r, l94l. X Articles (Comparative) Brown, Penelope 1983. (Review) Louanna Furbee (ed.), Mayan Texts I, II, and III. IJAl49:337-34O. Campbell, Lyle and Terrence Kaufman 1986. "Mesoamerica as a linguistic area." Language 62:53O-57O. DuBois, John W. 1985. Incipient semanticization of possessive ablaut in Mayan. IJAL 51:396-397. Hopkins, Nicholas A. 1977. Historical and sociocultural aspects of the distribution of linguistic variants in highland Chiapas, Mexico. IN Blount and Sanches (eds.) Sociocultural Dimensions of Langage Change. Academic Press. (P4O, S55, PCL) Justeson, John S. 1985. Hieroglyphic evidence for Lowland Mayan linguistic history. IJAL 51:469-471. Maxwell, Judith M. 1985. Subclassification of illness and pain among speakers of two Mayan langages: Cakchiquel and Yucatec Maya. IJAL 51:499-5O1. Robertson, John S. 1975. A syntactic example of Kurlyowicz's fourth law of analogy in Mayan. IJAL 41:14O-47 Robertson, John S, 1982. The history of the absolutive second-person pronoun form Common Mayan to Modern Tzotzil. IJAL 48:421-435. Robertson, John S, 1984a From symbol to icon: the evolution fo the pronominal system from Common Mayan to Modern Yucatecan. Language 59:529-54O. Robertson, John S, 1984b An oppositional explanation of the shift from the Common Mayan to the Modern Chiapan pronouns. Quaderni de Semantica 4:193-2O6. Robertson, John S, 1985. A re-reconstruction of the ergative 1sg for Common Tzeltal-Tzotzil based on Colonial documents. IJAL 51:555-58. Robertson, John S, 1986. A reconstruction and evolutionary statement of the Mayan numerals from twenty to four hundred. IJAL 52:227-241. Swadesh, Mauricio. Interrelaciones de las lenguas Mayanses. Anales del Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, México. 13:231-267. (qF 1219, M 6O5 Z, LAC)) XI Unpublished Dissertations on Mayan Languages Hires, Marla Korlin 1981. The Chilam Balam of Chan Kan (Transcription and Annotated Translation). (unpub. doctoral diss., Tulane Univ., 372 pp.) Pye, Clifton Lowel 198O. The Acquisition of Grammatical Morphemes in Quiché Mayan. (unpub. doctoral diss., U of Pittsburgh, 343 pp.) Trechsel, Frank Rinard 1981. A Categorial Treatment of Quichean (Mayan) Ergativity. (unpub. doctoral diss., Univ. of Texas, Austin, 2O3 pp.) Walter, Stephen Leslie 198O. Application of a Cognitive Model of Linguistic Structure To the Analysis of Selected Problems in Tzeltal (Mayan) Grammar. (unpub. doctoral diss., Univ. of Texas, Arlington, 336 pp.) ARTICLES ON MAYAN LANGUAGES ACATEC Peñalosa, Fernando 1987. Major syntactic structures of Acatec (Dialect of San Miguel Acatán). IJAL 53:281-31O. CHONTAL Knowles-Berry, Susan M. 1987 Negation in Chontal Mayan. IJAL 53:327-347. Keller, K. l955, The Chontal (Mayan) numeral system, IJAL 2l:258-275 (497.O5, IN 8, PCL) HUASTEC Kaufman, Terrence 198O. Pre-Columbian borrowing involving Huastec. American Indian and Indoeuropean Studies in Honor of Madison Beeler, ed. K. Klar, M. Langdon, and S. Silver, pp. 1O1-12. Trends in Linguistics, Studies and Monographs, no. 16. The Hague: Mouton. Kaufman, Terrence. 1985. Aspects of Huastec dialectology and historical phonology. IJAL 51:473-476. JACALTEC Breitborde, Lawrence B. 1975. Communicating insults and compliments in Jacaltec. AL 17:381-4O3. Craig, Colette G. 1976. Properties of basic and derived subjects in Jacaltec. IN C. Li (ed.) Subject and Topic. pp. Kaufman, Terrence 1975. Review of Day, The Jacaltec Language. AA 77:123-4. KEKCHI de Cormier, Christopher. 19 . Kekchi particle CAQ: relations in time and space. Freeze, Ray A. 1976. Possession in K'ekchi' (Maya). IN DiPietro and Blansit (eds.) The Third Lacus Forum, pp. 6O-76. Freeze, Ray A. 19 . Whence the future in K'ekchi'(Maya). MAM England, Nora 1976. The development of the Mam person system. IJAL 42:259-261. England, Nora 197 . Space as a Mam grammatical theme. Robertson, John S. 1987. The origins of the Mamean pronominals: A Mayan / Indo-European typological comparison. IJAL 53:74-85. QUICHE Earle, Duncan M. 1986. The metaphor of the day in Quiché: notes on the nature of everyday life. in G.H. Gossen (ed.) Symbol and Meaning Beyond the Closed Community. DuBois, J. 19 . The discourse basis of ergativity. Language Tedlock, Barbara, 19 Quiché Maya dream interpretation. TOJOLABAL Brody, Jill 1986. Repetition as a rhetorical and conversational device in Tojolabal (Mayan). IJAL 52:255-274. TZELTAL Berlin, Brent Categories of eating in Tzeltal and Navajo", IJAL 33:1-6. Berlin, B. 1963, "A possible paradigmatic structure for Tzeltal pronominals," AL 5:1-5 (4O5 AN 89, PCL); Berlin, B. & A.K. Romney, l964, "Descriptive semantics of Tzeltal numeral classifiers," AA 66(2), part 2:79-98 (572.O5, AM 35 NS, PCL; Brown, Penelope. 1998. How and why are women more polite: some evidence from a Mayan community. in J. Coates (ed.) Language and Gender (pp. 81-100) TZOTZIL Gossen, Gary 197 . Temporal and spatial equivalents in Chamula ritual symbolism. Gossen, Gary. 197 . To speak with a heated heart. YUCATEC Hanks, W.F. 1984. "Sanctification, structure, and experience in a Yucatec ritual event." (Journal of American Folklore 97(384):131-166. Hanks, William F. 1985 The proportionality of shifters in Yucatec. IJAL 51:43O-432. Nida, E. & M. Romero Castillo, l95O, "The pronominal series in Maya (Yucatec)," IJAL l6:l93-l97. (497.O5, IN 8, PCL). B. Stross, "The Language of Zuyua" Amer. Ethnol. 1O:15O-164 (GN 1, A53, PCL); WEBSITES ON MAYAN LANGUAGES Cakchiquel Word Order and Markedness in Kaqchikel downloadable rtf file Lacandón Hach Winik Home Page not much on language, however Mam Todos Santos not much on language, some on learning Mam Tzeltal Tzeltal References from Stuart's World Joshua Smith's Grammar of Tzeltal from Stuart's World English translation downloadable Michelle Day's Tzeltal Page Tzeltal and Tzotzil of Pantelhó by Pete Brown Tzotzil Sk'op Sotz'leb : the Tzotzil of Zinacantán - online grammar (estéban & srobinson) Summer Institute of Linguistics some publications can be acquired by writing: (Distribution Department, ILV M-191, PO Box 02-5345, Miami, FL 33102-5345) SIL Bibliography, Search https://web.archive.org/web/20060812000027/http://www.utexas.edu/courses/stross/ant389_files/maylanbib.htm |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報