ミリタリズム

Militarism

プロイセンのミリタリズム

☆ミリタリズム[Militarism]とは、政府や国民が国家は強力な軍事力を維持し、それを積極的に用いて国益や価値観を拡大すべきだと信じる、あるいは望む思想である[1]。 また、軍隊や職業軍人階級の理想を称賛すること、そして「国家の行政や政策における軍部の支配」[2]を意味する場合もある(参照:国家主義[stratocracy]、軍事政権[military junta])。

| Militarism

is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state

should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively

to expand national interests and/or values.[1] It may also imply the

glorification of the military and of the ideals of a professional

military class and the "predominance of the armed forces in the

administration or policy of the state"[2] (see also: stratocracy and

military junta). |

ミ

リタリズムとは、政府や国民が国家は強力な軍事力を維持し、それを積極的に用いて国益や価値観を拡大すべきだと信じる、あるいは望む思想である[1]。ま

た、軍隊や職業軍人階級の理想を称賛すること、そして「国家の行政や政策における軍部の支配」[2]を意味する場合もある(参照:国家主義[stratocracy]、軍事政権[military junta])。 |

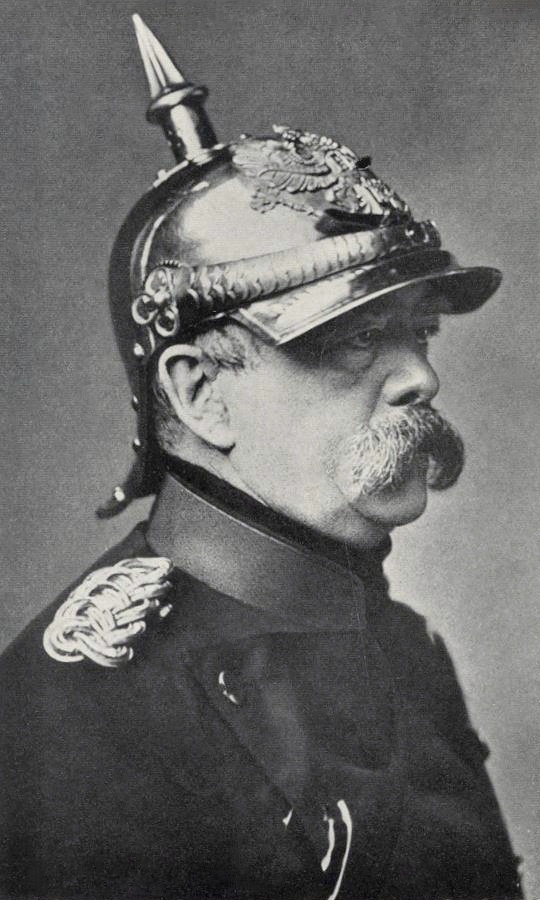

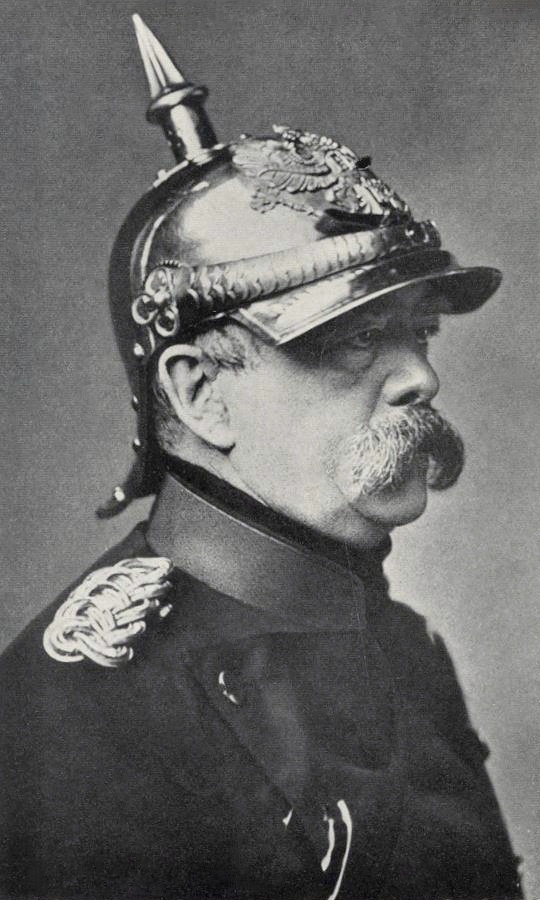

Prussian (and later German) Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, right, with General Helmuth von Moltke the Elder, left, and General Albrecht von Roon, centre. Although Bismarck was a civilian politician and not a military officer, he wore a military uniform as part of the Prussian militarist culture of the time. From a painting by Carl Steffeck. |

プロイセン(後のドイツ)首相オットー・フォン・ビスマルク(右)と、ヘルムート・フォン・モルトケ大将(左)、アルブレヒト・フォン・ルーン大将(中 央)。ビスマルクは文民政治家であり軍人ではなかったが、当時のプロイセンの軍国主義文化の一環として軍服を着用していた。カール・シュテフェックの絵画 より。 |

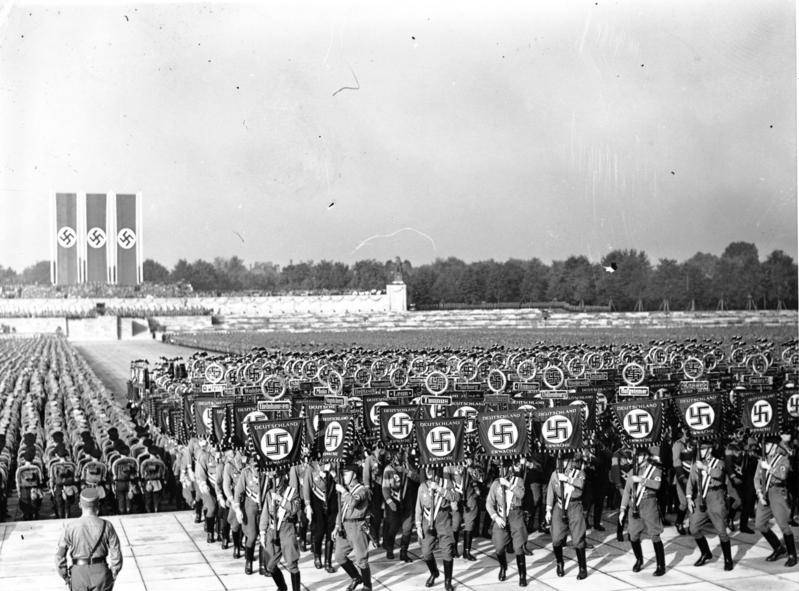

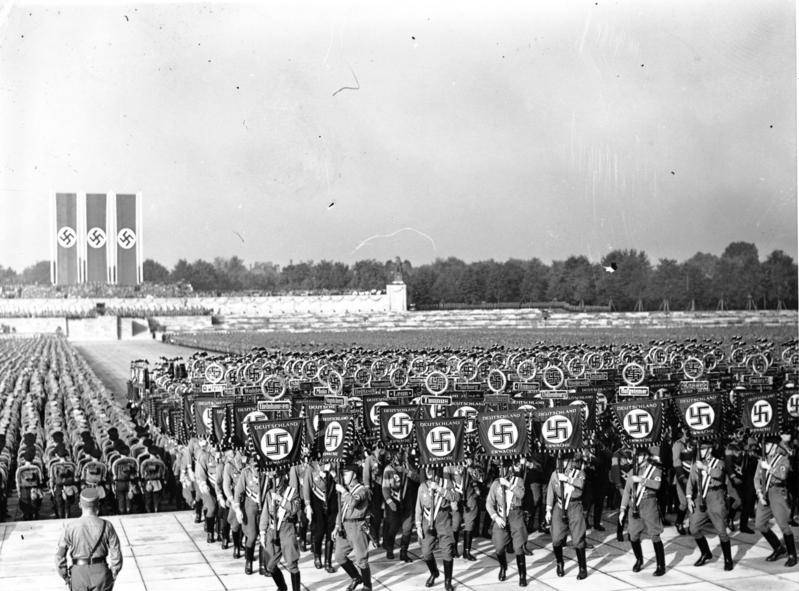

| By nation Germany Main article: German militarism See also: List of wars involving Germany and Military history of Germany  Otto von Bismarck, a civilian, wearing a cuirassier officer's metal Pickelhaube The roots of German militarism can be found in 18th- and 19th-century Prussia and the subsequent unification of Germany under Prussian leadership. However, Hans Rosenberg sees its origin already in the Teutonic Order and its colonization of Prussia during the late Middle Ages, when mercenaries from the Holy Roman Empire were granted lands by the Order and gradually formed a new landed militarist Prussian nobility, from which the Junker nobility would later evolve.[3] During the 17th-century reign of the "Great Elector" Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg, Brandenburg-Prussia increased its military to 40,000 men and began an effective military administration overseen by the General War Commissariat. In order to bolster his power both in interior and foreign matters, so-called Soldatenkönig ("soldier king") Frederick William I of Prussia started his large-scale military reforms in 1713, thus beginning the country's tradition of a high military budget by increasing the annual military spending to 73% of the entire annual budget of Prussia. By the time of his death in 1740, the Prussian Army had grown into a standing army of 83,000 men, one of the largest in Europe, at a time when the entire Prussian populace made up 2.5 million people. Prussian military writer Georg Henirich von Berenhorst would later write in hindsight that ever since the reign of the soldier king, Prussia always remained "not a country with an army, but an army with a country" (a quote often misattributed to Voltaire and Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau).[4] After Napoleon Bonaparte defeated Prussia in 1806, one of the conditions of peace was that Prussia should reduce its army to no more than 42,000 men. Since the time of Frederick The Great, however, Prussia practiced the Kruemper System, formed by dismissing a number of trained men at regular intervals and replacing them with raw recruits, thereby passing a large number of men through the ranks.[5] The officers of the army were drawn almost entirely from among the land-owning nobility. The result was that there was gradually built up a large class of professional officers on the one hand, and a much larger class, the rank and file of the army, on the other. These enlisted men had become conditioned to obey implicitly all the commands of the officers, creating a class-based culture of deference.[citation needed]  World War I propaganda of Germany This system led to several consequences. Since the officer class also furnished most of the officials for the civil administration of the country, the interests of the army came to be considered as identical to the interests of the country as a whole.[citation needed] In the 1900s militant monarchism was highly developed, garnering a fan-base in the United States of America. Wilhelm II had his palace guard dress in 37 different uniforms, including one that resampled the accessory worn by Frederick the Great. Wilhelm II appeared deluded about his physical disability, including his withered arm. He had sacked Otto von Bismarck in 1890 and obtained near absolute power but had to accept Erich Ludendorff as chief policy maker. Army general Ludendorff was appointed director of the Reich in 1917 and exercised the constitutional powers of Wilhelm II.[6] Militarism in Germany continued after World War I and the fall of the German monarchy in the German Revolution of 1918–1919, in spite of Allied attempts to crush German militarism by means of the Treaty of Versailles, as the Allies saw Prussian and German militarism as one of the major causes of the Great War. During the period of the Weimar Republic (1918–1933), the 1920 Kapp Putsch, an attempted coup d'état against the republican government, was launched by disaffected members of the armed forces. After this event, some of the more radical militarists and nationalists were submerged in grief and despair into the NSDAP party of Adolf Hitler, while more moderate elements of militarism declined and remained affiliated with the German National People's Party (DNVP) instead.[citation needed]  Militarism in Nazi Germany Throughout its entire 14-year existence, the Weimar Republic remained under threat of militaristic nationalism, as many Germans felt the Treaty of Versailles humiliated their militaristic culture. The Weimar years saw large-scale right-wing militarist and paramilitary mass organizations such as Der Stahlhelm as well as militias such as the Freikorps, which was banned in 1921.[7] In the same year, the Reichswehr set up the Black Reichswehr, a secret reserve of trained soldiers networked within its units organised as "labour battalions" (Arbeitskommandos) to circumvent the Treaty of Versailles' 100,000 man limit on the German army.;[8] it was dissolved in 1923. Many members of the Freikorps and the Black Reichswehr went on to join the Sturmabteilung (SA), the paramilitary branch of the Nazi party. All of these were responsible for the political violence of so-called Feme murders and an overall atmosphere of lingering civil war during the Weimar period. During the Weimar era, mathematician and political writer Emil Julius Gumbel published in-depth analyses of the militarist paramilitary violence characterizing German public life as well as the state's lenient to sympathetic reaction to it if the violence was committed by the political right.[citation needed] Nazi Germany was a strongly militarist state; after its defeat in 1945, militarism in German culture was dramatically reduced as a backlash against the Nazi period, and the Allied Control Council and later the Allied High Commission oversaw a program of attempted fundamental re-education of the German people at large in order to put a stop to German militarism once and for all.[citation needed] The Federal Republic of Germany today maintains a large, modern military and has one of the highest defence budgets in the world; at 1.3 percent of Germany's GDP, it is, in 2019, similar in cash terms to those of the United Kingdom, France and Japan, at around US$50bn.[9] |

国別 ドイツ 主な記事: ドイツのミリタリズム 関連項目: ドイツが関与した戦争の一覧、ドイツの軍事史  オットー・フォン・ビスマルク(文官)が騎兵将校の金属製ピッケルハウベを装着している姿 ドイツのミリタリズムの根源は、18世紀から19世紀の普魯士(プロイセン)と、その後普魯士主導で進められたドイツ統一に見出される。しかしハンス・ ローゼンベルクは、その起源を中世末期のドイツ騎士団とプロイセン植民地化に求める。当時、神聖ローマ帝国の傭兵たちは騎士団から土地を授与され、次第に 新たな土地所有軍国主義的プロイセン貴族層を形成した。この層から後にユンカー貴族が発展する。[3] 17世紀、「大選帝侯」フリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルムがブランデンブルク選帝侯として統治した時代、ブランデンブルク=プロイセンは軍隊を4万人に増強し、 総戦務局が監督する効果的な軍事行政を開始した。内政と外交の両面で権力を強化するため、いわゆる「兵士の王」フリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム1世は1713 年に大規模な軍事改革を開始した。これにより軍事費を年間予算全体の73%に増額し、プロイセンの高軍事予算の伝統が始まったのである。1740年に彼が 死去した時点で、プロイセン軍は83,000人の常備軍へと成長し、当時のプロイセン総人口250万人のうち、欧州最大規模の軍隊の一つとなっていた。プ ロイセンの軍事評論家ゲオルク・ヘニリヒ・フォン・ベレンホルストは後年、兵士の王の治世以来、プロイセンは常に「軍隊を持つ国ではなく、国を持つ軍隊」 であったと回顧している(この言葉はしばしばヴォルテールやミラボーコントオノレ・ガブリエル・リケティに誤って帰属される)。[4] ナポレオン・ボナパルトが1806年にプロイセンを破った後、和平条件の一つとしてプロイセンは軍隊を42,000人以下に削減すべきとされた。しかしフ リードリヒ大王の時代から、プロイセンはクレンパー制度を実践していた。これは定期的に訓練済みの兵士を一定数除隊させ、新兵で補充する方式で、これによ り多数の兵士が階級を経験していく仕組みだった。[5] 陸軍将校はほぼ完全に土地所有貴族から選抜されていた。その結果、一方では大規模な職業将校階級が徐々に形成され、他方ではそれよりはるかに大規模な一般 兵士階級が生まれた。これらの兵士は将校の命令を無条件に服従するよう条件付けられ、階級に基づく従属文化が形成された。[出典必要]  第一次世界大戦時のドイツの宣伝 この制度はいくつかの結果をもたらした。将校階級が国家の民政官僚の大半も供給していたため、軍の利益は国家全体の利益と同一視されるようになった。[出 典必要] 1900年代には好戦的な君主主義が高度に発達し、アメリカ合衆国でも支持層を獲得した。ヴィルヘルム2世は宮廷衛兵に37種類の異なる制服を着用させ、 その中にはフリードリヒ大王が着用した装飾品を再現したものも含まれていた。ヴィルヘルム2世は萎えた腕を含む身体的障害について、錯覚に陥っていたよう だ。1890年にオットー・フォン・ビスマルクを解任しほぼ絶対的な権力を掌握したが、政策決定の最高責任者としてエーリヒ・ルーデンドルフを受け入れざ るを得なかった。陸軍大将ルーデンドルフは1917年に帝国総統に任命され、ヴィルヘルム2世の憲法上の権限を行使した。[6] 第一次世界大戦後、1918年から1919年にかけてのドイツ革命でドイツ君主制が崩壊したにもかかわらず、ドイツのミリタリズムは継続した。連合国は ヴェルサイユ条約によってドイツミリタリズムを粉砕しようとしたが、プロイセンおよびドイツのミリタリズムを第一次世界大戦の主要な原因の一つと見なして いたのである。ワイマール共和国時代(1918年~1933年)には、1920年に軍部の不満分子による共和制政府転覆を企てたカッフのクーデターが発生 した。この事件後、より過激なミリタリズム者やナショナリストの一部は、悲嘆と絶望に沈み、アドルフ・ヒトラー率いる国家社会主義ドイツ労働者党 (NSDAP)に吸収された。一方、より穏健なミリタリズム勢力は衰退し、代わりにドイツ国民人民党(DNVP)に留まった。[出典が必要]  ナチス・ドイツにおけるミリタリズム ワイマール共和国は14年間の存続期間を通じて、軍国主義的ナショナリズムの脅威に晒され続けた。多くのドイツ人はヴェルサイユ条約が自国の軍国主義的文 化を侮辱するものと感じていたためである。ワイマール時代には、1921年に禁止された自由軍団(Freikorps)のような民兵組織に加え、鋼鉄ヘル ム(Der Stahlhelm)のような大規模な右翼軍国主義・準軍事的大衆組織が存在した。[7] 同年、ドイツ国防軍は「労働大隊」(Arbeitskommandos)として組織された部隊内にネットワーク化された訓練済み兵士の秘密予備軍「黒い国 防軍」を設置した。これはヴェルサイユ条約が定めたドイツ軍10万人制限を回避するためであった。[8] これは1923年に解散した。自由軍団と黒色帝国軍の多くのメンバーは、その後ナチ党の準軍事組織である突撃隊(SA)に加わった。これら全てが、いわゆ る「フェーム殺人」と呼ばれる政治的暴力や、ワイマール期を通じて持続した内戦状態の雰囲気の責任を負っていた。ワイマール時代、数学者であり政治評論家 でもあったエミール・ユリウス・グンベルは、ドイツの公共生活を特徴づける軍国主義的な準軍事的暴力、そしてその暴力が政治的右派によって行われた場合に 国家が寛容から同情的な反応を示すことについて、詳細な分析を発表した。 ナチス・ドイツは強硬なミリタリズム国家であった。1945年の敗戦後、ナチス時代への反動としてドイツ文化におけるミリタリズムは劇的に縮小し、連合国 管理委員会および後の連合国高等委員会は、ドイツミリタリズムを完全に根絶するため、国民全体に対する根本的な再教育プログラムを実施した。 今日のドイツ連邦共和国は、大規模で近代的な軍隊を維持し、世界でも最高水準の防衛予算を有している。2019年時点で、ドイツのGDPの1.3%に相当する約500億米ドルであり、これは現金ベースで英国、フランス、日本と同水準である。[9] |

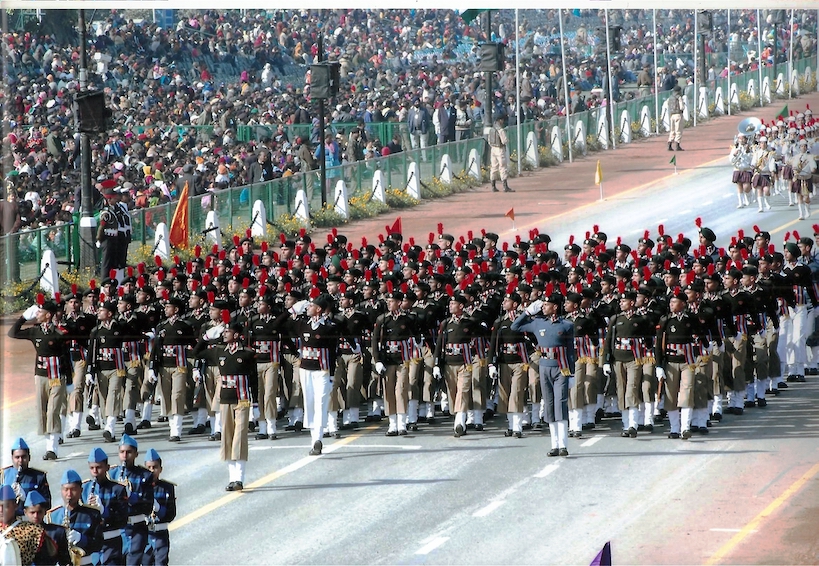

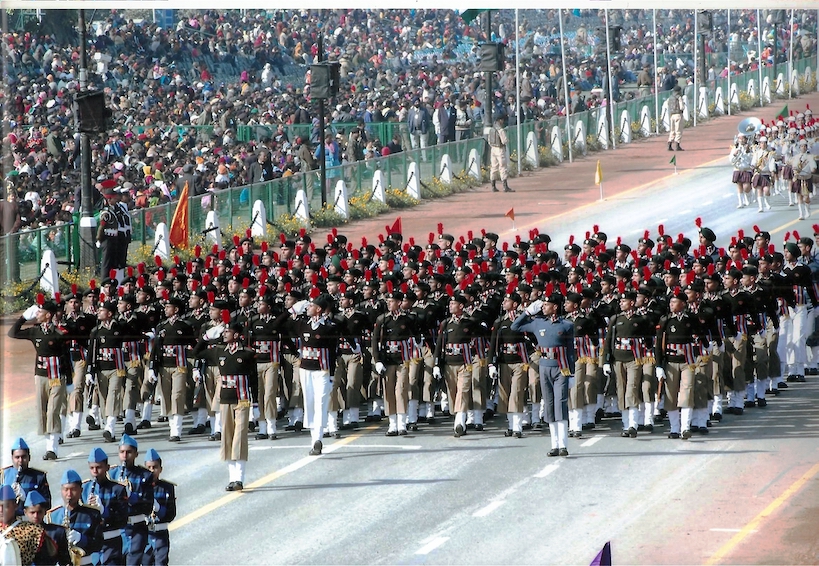

India Military parade in India The rise of militarism in India dates back to the British Raj with the establishment of several Indian independence movement organizations such as the Indian National Army led by Subhas Chandra Bose. The Indian National Army (INA) played a crucial role in pressuring the British Raj after it liberated the Andaman and Nicobar Islands with the help of Imperial Japan. After India gained independence in 1947, tensions with neighbouring Pakistan over the Kashmir dispute and other issues led the Indian government to emphasize military preparedness (see also the political integration of India). After the Sino-Indian War in 1962, India dramatically expanded its military which helped India win the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971.[10] India became the third Asian country in the world to possess nuclear weapons, culminating in the tests of 1998. The Kashmiri insurgency and recent events including the Kargil War against Pakistan, assured that the Indian government remained committed to military expansion. The disputed Jammu and Kashmir territory in India is regarded as one of the world’s most militarized places.[11] In recent years, the Indian government has increased the military expenditure of the 1.4 million-strong military across all branches and embarked on a rapid modernization program.[12][13] |

インド インドの軍事パレード インドにおけるミリタリズムの台頭は、英領インド帝国時代に遡る。スバス・チャンドラ・ボース率いるインド国民軍(INA)をはじめとする複数の独立運動 組織が結成されたのだ。インド国民軍は、日本帝国の支援を得てアンダマン・ニコバル諸島を解放した後、英領インド帝国に圧力をかける上で重要な役割を果た した。 1947年にインドが独立した後、カシミール紛争やその他の問題をめぐる隣国パキスタンとの緊張が高まり、インド政府は軍事準備を重視するようになった (インドの政治統合も参照)。1962年の中印戦争後、インドは軍隊を大幅に拡大し、これが1971年の印パ戦争での勝利に貢献した。[10] インドは1998年の核実験を頂点に、世界で3番目の核保有アジア国家となった。カシミール反乱やパキスタンとのカルギル戦争を含む近年の出来事は、イン ド政府が軍事拡大に固執し続けることを保証した。インド領内の係争地域であるジャンムー・カシミールは、世界で最もミリタリズムが顕著な地域の一つと見な されている。[11] 近年、インド政府は140万人の全軍種にわたる軍事支出を増大させ、急速な近代化計画に着手した。[12][13] |

| Japan Main articles: Japanese militarism and Japanese imperialism  Japanese march into Zhengyangmen of Beijing after capturing the city in July 1937. In parallel with 20th-century German militarism, Japanese militarism began with a series of events by which the military gained prominence in dictating Japan's affairs. This was evident in 15th-century Japan's Sengoku period or Age of Warring States, where powerful samurai warlords (daimyōs) played a significant role in Japanese politics. Japan's militarism is deeply rooted in the ancient samurai tradition, centuries before Japan's modernization. Even though a militarist philosophy was intrinsic to the shogunates, a nationalist style of militarism developed after the Meiji Restoration, which restored the Emperor to power and began the Empire of Japan. It is exemplified by the 1882 Imperial Rescript to Soldiers and Sailors, which called for all members of the armed forces to have an absolute personal loyalty to the Emperor. In the 20th century (approximately in the 1920s), two factors contributed both to the power of the military and chaos within its ranks. One was the "Military Ministers to be Active-Duty Officers Law", which required the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) and Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) to agree to the Ministry of Army position in the Cabinet. This essentially gave the military veto power over the formation of any Cabinet in the ostensibly parliamentary country. Another factor was gekokujō, or institutionalized disobedience by junior officers.[14] It was not uncommon for radical junior officers to press their goals, to the extent of assassinating their seniors. In 1936, this phenomenon resulted in the February 26 Incident, in which junior officers attempted a coup d'état and killed leading members of the Japanese government. The rebellion enraged Emperor Hirohito and he ordered its suppression, which was successfully carried out by loyal members of the military.  Elementary school students were given military drills, May 1942. In the 1930s, the Great Depression damaged Japan's economy and gave radical elements within the Japanese military the chance to realize their ambitions of conquering all of Asia. In 1931, the Kwantung Army (a Japanese military force stationed in Manchuria) staged the Mukden Incident, which sparked the Invasion of Manchuria and its transformation into the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo. Six years later, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident outside Peking sparked the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945). Japanese troops streamed into China, conquering Peking, Shanghai, and the national capital of Nanking; the last conquest was followed by the Nanking Massacre. In 1940, Japan entered into an alliance with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, two similarly militaristic states in Europe, and advanced out of China and into Southeast Asia. The following year, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor to prevent the intervention of the United States, which had banned oil sales to Japan in response to the Second Sino-Japanese War and the ensuing invasion of Indochina. In 1945, Japan surrendered to the United States, beginning the Occupation of Japan and the purging of all militarist influences from Japanese society and politics. In 1947, the new Constitution of Japan supplanted the Meiji Constitution as the fundamental law of the country, replacing the rule of the Emperor with parliamentary government. With this event, the Empire of Japan officially came to an end and the modern State of Japan was founded. |

日本 主な記事: 日本のミリタリズムと日本の帝国主義  1937年7月に北京を占領した後、日本軍が正陽門に進入する様子。 20世紀のドイツミリタリズムと並行して、日本のミリタリズムは軍部が日本の政務を主導する形で台頭する一連の出来事から始まった。これは15世紀の戦国 時代において顕著であり、有力な武将(大名)が日本政治で重要な役割を果たした。日本のミリタリズムは近代化の数世紀前から続く古代の武士道に深く根ざし ている。幕府体制にミリタリズム的理念が内在していたとはいえ、明治維新後に発展したナショナリスト的ミリタリズムは、天皇の権威を回復し大日本帝国を始 動させた。その典型が1882年の「軍艦隊誥」であり、全軍人に天皇への絶対的個人的忠誠を要求した。 20世紀(1920年代頃)、軍部の権力強化と内部混乱を招いた二つの要因があった。一つは「軍大臣は現役将校でなければならない」とする法律で、これに より陸軍省が内閣の陸軍大臣ポストを掌握することを軍部が承諾せざるを得なかった。これは名目上の議会制国家において、軍部に内閣の組閣に対する拒否権を 実質的に与えた。もう一つの要因は下級将校による組織化された不服従、いわゆる「下剋上」である[14]。過激な下級将校が目標達成のために上級将校を暗 殺する事態も珍しくなかった。1936年、この現象は二・二六事件を引き起こした。下級将校がクーデターを試み、日本政府の主要メンバーを殺害したのであ る。この反乱は昭和天皇を激怒させ、彼は鎮圧を命じた。これは軍内の忠実なメンバーによって成功裏に遂行された。  1942年5月、小学生に軍事訓練が施された。 1930年代、世界恐慌が日本経済を傷つけ、日本軍内の過激派にアジア全土征服の野望を実現する機会を与えた。1931年、満州に駐留する日本軍部隊であ る関東軍が満州事変を引き起こし、これが満州侵攻と傀儡国家・満州国樹立の契機となった。6年後、北京郊外での盧溝橋事件が日中戦争(1937-1945 年)の引き金となった。日本軍は中国に押し寄せ、北京、上海、そして国民の首都南京を制圧。最後の占領地である南京では南京大虐殺が発生した。1940 年、日本はヨーロッパの軍国主義国家であるナチス・ドイツとファシスト・イタリアと同盟を結び、中国から東南アジアへ進出した。翌年、日本は真珠湾を攻撃 した。これは日中戦争とそれに続くインドシナ侵攻への対応として、アメリカが日本への石油輸出を禁止したことに反発し、アメリカの介入を阻止するためで あった。 1945年、日本はアメリカに降伏し、日本の占領と日本社会・政治から軍国主義的影響を排除する動きが始まった。1947年、新憲法が明治憲法に代わり国 の基本法となり、天皇制から議会制政府へと移行した。この出来事を機に、大日本帝国は正式に終焉を迎え、現代国家である日本が誕生した。 |

| North Korea Main article: Songun  North Korean propaganda mural Sŏn'gun (often transliterated "songun"), North Korea's "Military First" policy, regards military power as the highest priority of the country. This has escalated so much in the DPRK that one in five people serves in the armed forces, and the military has become one of the largest in the world. Songun elevates the Korean People's Armed Forces within North Korea as an organization and as a state function, granting it the primary position in the North Korean government and society. The principle guides domestic policy and international interactions.[15] It provides the framework of the government, designating the military as the "supreme repository of power". It also facilitates the militarization of non-military sectors by emphasizing the unity of the military and the people by spreading military culture among the masses.[16] The North Korean government grants the Korean People's Army as the highest priority in the economy and in resource-allocation, and positions it as the model for society to emulate.[17] Songun is also the ideological concept behind a shift in policies (since the death of Kim Il Sung in 1994) which emphasize the people's military over all other aspects of state and the interests of the military comes first before the masses (workers). |

北朝鮮 主な記事: 先軍  北朝鮮の宣伝壁画 先軍(ソンウン)は、北朝鮮の「軍事優先」政策であり、軍事力を国家の最優先事項と位置づける。この政策は北朝鮮において過度に拡大し、国民の5人に1人が軍隊に所属し、軍隊は世界最大級の規模となった。 先軍は、組織としてまた国家機能として、朝鮮人民軍を北朝鮮国内で格上げし、北朝鮮政府と社会における主要な地位を与えている。この原則は国内政策と国際 交流を導く。[15] 政府の枠組みを提供し、軍を「権力の最高貯蔵庫」と指定する。また、大衆に軍事文化を広めることで軍と人民の統一を強調し、非軍事分野の軍事化を促進す る。[16] 北朝鮮政府は朝鮮人民軍を経済及び資源配分における最優先事項と位置付け、社会が模範とすべき存在としている[17]。先軍思想はまた、金日成の死 (1994年)以降の方針転換の背景にあるイデオロギー的概念でもあり、国家のあらゆる側面において人民軍を重視し、軍部の利益を大衆(労働者)よりも優 先させることを強調している。 |

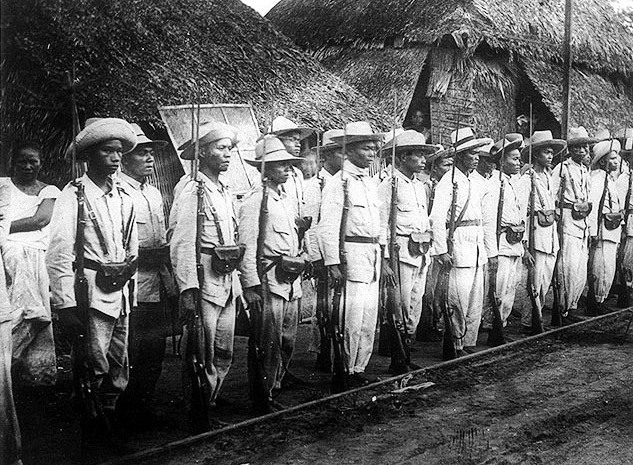

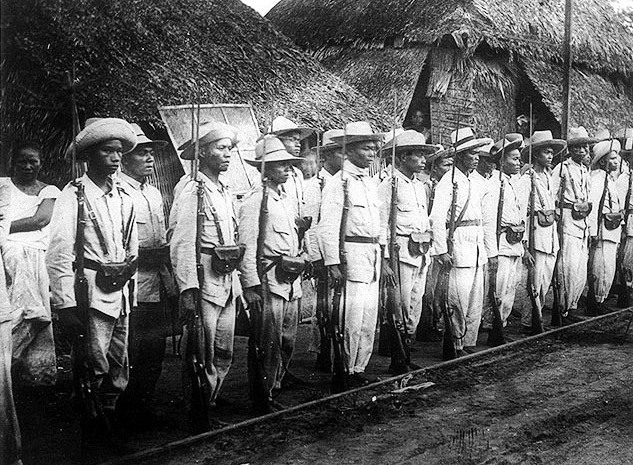

| Philippines Main article: Military history of the Philippines  Filipino soldiers at Malolos, Bulacan, c. 1899 During the pre-colonial era, the Filipino people had their own forces, divided between the islands which each had its own ruler. They were called Sandig (Guards), Kawal (Knights) these also served as the police and watchers on the land, coastlines and seas. Another notable example is the Maharlika class, that consists of free, and battle-hardened men that were expected to serve their local chieftains, and in exchange, the exemption from paying tribute, or taxes. In 1521, the Visayan king of Mactan Lapu-Lapu of Cebu, organized the first recorded military action against the Spanish colonizers, in the Battle of Mactan. During the late 19th century, Filipino militarism emerged from the struggle for independence against Spanish colonial rule. In 1892, Andrés Bonifacio and five others founded the Katipunan (KKK), a revolutionary society that sought independence through armed resistance following the failure of peaceful reform and propaganda movements such as La Liga Filipina. The revolution began with the Sigaw sa Pugad Lawin on the 23rd of August, 1896. This marked the beginning of open resistance against Spanish colonial rule in the islands. Originally, the Filipino armies organized themselves into regional armies, and sometimes miltias. Nonetheless, they achieved key victories in Kawit, Imus, Alapan, and the battles of Binakayan-Dalhican. Which demonstrated growing militarily coordination and leadership, and allowed Emilio Aguinaldo to declare independence on June 12, 1898.  Filipino soldiers marching during the inauguration of the First Philippine Republic, January, 1899. Filipino Commandant-General Antonio Luna enacted reforms within the Philippine Republican Army (PRA) reforms that attempt to combat the regionalism the army faced, and to transform the Republican Army into a formidable, disciplined, and standard fighting force for the new republic. During the Philippine-American War, Antonio Luna ordered conscription to all citizens, a mandatory form of national service (at any war) for the increase of manpower of the Philippine Army. These reforms reflected the militarism of the nascent Philippine Republic, a nation under constant war. The republic viewed military strength as essentially for the survival of the nation.[18]  Filipino soldiers standing in attention. During World War II, the Philippines was one of the participants, as a member of Allied forces, the Philippines with the U.S. forces fought the Imperial Japanese Army (1942–1945), one of the more notable battles is the Battle of Manila. Former president Ferdinand Marcos issued Proclamation Order No. 1081 (Martial law), effectively turning the Philippines into a garrison state under the Philippine Constabulary (PC) and Integrated National Police (INP) During this period, secondary and college education included mandatory military and nationalism training through programs such as Citizens Military Training (CMT) and the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC). After the 1986 constitutional change, these programs became non-compulsory, though remain a part of the basic education curriculum.[19] |

フィリピン 主な記事: フィリピンの軍事史  1899年頃、ブラカン州マロロスにおけるフィリピン人兵士 植民地時代以前、フィリピン人は独自の軍隊を持っていた。島ごとに分かれており、各島には独自の支配者がいた。彼らはサンディグ(衛兵)やカワル(騎士) と呼ばれ、警察や監視役として陸地、海岸線、海上で活動した。もう一つの顕著な例がマハルリカ階級である。これは自由で戦いに鍛えられた者たちで構成さ れ、地元の首長に仕えることが期待されていた。その見返りとして貢ぎ物や税金の支払いが免除された。1521年、ビサヤ地方のマクタン王ラプラプ(セブ 島)は、スペインの植民者に対する最初の記録された軍事行動としてマクタン島の戦いを組織した。 19世紀後半、スペイン植民地支配に対する独立闘争からフィリピンミリタリズムが台頭した。1892年、アンドレス・ボニファシオら6名はカティプナン (KKK)を創設。これはラ・リーガ・フィリピナなどの平和的改革・宣伝運動の失敗を受け、武装抵抗による独立を目指す革命組織であった。 革命は1896年8月23日のシガウ・サ・プガド・ラウィンで始まった。これは島々におけるスペイン植民地支配への公然たる抵抗の始まりを告げるものだっ た。当初、フィリピン軍は地域軍や民兵組織として編成されていた。それでもカウィット、イムス、アラパン、ビナカヤン=ダルヒカンの戦いでは重要な勝利を 収めた。これは軍事的な連携と指導力の成長を示し、エミリオ・アギナルドが1898年6月12日に独立を宣言する基盤となった。  1899年1月、第一フィリピン共和国樹立式典で行進するフィリピン兵士たち。 フィリピン共和国軍(PRA)の司令官アントニオ・ルナは、軍が直面する地域主義に対抗し、新共和国にとって強力で規律正しく標準化された戦闘部隊へと変革するため、軍内改革を実施した。 フィリピン・アメリカ戦争中、アントニオ・ルナはフィリピン軍の兵力増強のため、全市民への徴兵制を命じた。これは(あらゆる戦争における)義務的な国民 奉仕形態であった。これらの改革は、絶え間ない戦争状態にあった新生フィリピン共和国のミリタリズムを反映していた。共和国は軍事力を国民存続の根本と見 なしていた。[18]  気を付けをするフィリピン兵士たち。 第二次世界大戦中、フィリピンは連合国軍の一員として参戦した。フィリピン軍はアメリカ軍と共に日本帝国陸軍と戦った(1942年~1945年)。特に著名な戦闘の一つがマニラ攻防戦である。 フェルディナンド・マルコス前大統領は戒厳令(大統領令第1081号)を発令し、フィリピンをフィリピン憲兵隊(PC)と統合国家警察(INP)による駐 屯地国家へと変貌させた。この時期、中等教育及び高等教育では、市民軍事訓練(CMT)や予備役将校訓練課程(ROTC)といったプログラムを通じた軍事 訓練とナショナリズム教育が義務付けられていた。1986年の憲法改正後、これらのプログラムは義務教育ではなくなったが、基礎教育カリキュラムの一部と して残っている。[19] |

| Russia See also: Russian nationalism and Russian imperialism  Military parade on Red Square in Moscow  Vladimir Putin with members of the 'Yunarmiya' – or Young Army. The Young Army movement is the Kremlin's attempt to mobilize and provide basic military skills to Russian youth. Russia has also had a long history of militarism continuing on to the present day driven by its desire to protect its western frontier which has no natural buffers between potential invaders from the rest of continental Europe and her heartlands in European Russia. Ever since Peter the Great's reforms, Russia became one of Europe's great powers in terms of political and military strength. Through the Imperial era, Russia continued on her quest for territorial expansion into Siberia, Caucasus and into Eastern Europe, eventually conquering the majority of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The end of imperial rule in 1917 meant the loss of some territory following the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, but much of it was quickly reconquered by the Soviet Union later on, including events such as the partition of Poland and reconquest of the Baltic states in the late 1930s and ‘40s. Soviet influence reached its peak after WWII in the Cold War era, during which the Soviet Union occupied virtually all of Eastern Europe in a military alliance known as the Warsaw Pact, with the Soviet Army playing a key role. All this was lost with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. The Soviet Union was the most militarized large economy the world has ever seen and illustrates the dangers inherent in militarism. A climate of secrecy and control, rigid centralized allocation of resources, economic isolation from the rest of the world, and unquestioning acceptance of Communist rule were all predicated on national security. The economic and societal costs were in many cases not tracked, or were withheld from civilians. Because these costs were hidden in the Soviet system, but exposed by the transition to a market economy, many Russians blame the new system for creating these costs in the first place.[20] : 2-6 Russia was greatly weakened in what Russia's second President Vladimir Putin called the greatest geopolitical disaster of the 20th century. Nevertheless, under Putin's leadership, a resurgent modern Russia has maintained a tremendous amount of geopolitical influence in the countries spawned from the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and modern Russia remains Eastern Europe's leading, if not dominant, power. Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Russian government increased their efforts to introduce "patriotic education" into schools.[21] The Associated Press reported that some parents were shocked by the militaristic nature of the Kremlin-promoted Important Conversations lessons, with some comparing them to the "patriotic education" of the former Soviet Union.[22] By the end of 2023, Vladimir Putin planned to spend almost 40% of public expenditures on defense and security.[23] UK Chief of Defence Staff Admiral Tony Radakin said that "the last time we saw these levels was at the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union."[24] |

ロシア 関連項目:ロシアナショナリズム、ロシア帝国主義  モスクワの赤の広場で行われた軍事パレード  ウラジーミル・プーチンと「ユナルミヤ」(若き軍隊)のメンバー。若き軍隊運動は、ロシアの若者に動員と基礎的な軍事技能を提供しようとするクレムリンの試みである。 ロシアはまた、大陸ヨーロッパの他の地域からの潜在的な侵略者とロシア本土との間に自然の緩衝地帯が存在しないため、西側国境を保護したいという願望に駆 られ、今日に至るまで長いミリタリズムの歴史を持ってきた。ピョートル大帝の改革以来、ロシアは政治的・軍事的強さにおいてヨーロッパの大国の一つとなっ た。帝政時代を通じて、ロシアはシベリア、コーカサス、東ヨーロッパへの領土拡大を続け、最終的にはポーランド・リトアニア共和国連邦の大部分を征服し た。 1917年の帝政終焉はブレスト・リトフスク条約による一部領土喪失を意味したが、その多くは後にソビエト連邦によって迅速に再征服された。1930年代 末から40年代にかけてのポーランド分割やバルト諸国再征服などがその例である。ソビエトの影響力は第二次世界大戦後の冷戦時代に頂点に達し、ワルシャワ 条約機構と呼ばれる軍事同盟下でソビエト連邦は東欧ほぼ全域を占領した。ソビエト軍が中心的な役割を果たした。これら全ては1991年のソビエト連邦解体 と共に失われた。 ソビエト連邦は世界史上最も軍事化された大規模経済体であり、ミリタリズムに内在する危険性を如実に示している。秘密主義と統制の風土、硬直的な中央集権 的資源配分、世界からの経済的孤立、共産主義体制への無批判な受容は、全て国民安全保障を前提としていた。経済的・社会的コストは多くの場合、追跡されな かったか、市民から隠蔽された。ソ連体制下では隠されていたこれらのコストが、市場経済への移行によって露呈したため、多くのロシア人はそもそもこれらの コストを生み出したのは新体制のせいだと非難している。[20] : 2-6 ロシアは、同国第二代大統領ウラジーミル・プーチンが「20世紀最大の地政学的災難」と呼んだ出来事によって大きく弱体化した。しかしながら、プーチンの 指導下で復興した現代ロシアは、ソビエト連邦解体から生まれた諸国において依然として膨大な地政学的影響力を維持しており、現代ロシアは東欧における主導 的、あるいは支配的な勢力であり続けている。 ロシアのウクライナ侵攻後、ロシア政府は学校への「愛国教育」導入を強化した。[21] AP通信によれば、クレムリン推進の「重要な対話」授業の軍国主義的性質に衝撃を受けた保護者もおり、旧ソ連の「愛国教育」に例える声もあった。[22] 2023年末までに、ウラジーミル・プーチンは国防・安全保障に公的支出のほぼ40%を費やす計画だ。[23]英国統合参謀本部議長トニー・ラダキン提督は「この水準が確認されたのは冷戦終結とソ連崩壊の時以来だ」と述べた。[24] |

| United States Main article: United States militarism See also: United States involvement in regime change and Foreign interventions by the United States In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries political and military leaders reformed the US federal government to establish a stronger central government than had ever previously existed for the purpose of enabling the nation to pursue an imperial policy in the Pacific and in the Caribbean and economic militarism to support the development of the new industrial economy. This reform was the result of a conflict between Neo-Hamiltonian Republicans and Jeffersonian-Jacksonian Democrats over the proper administration of the state and direction of its foreign policy. The conflict pitted proponents of professionalism, based on business management principles, against those favoring more local control in the hands of laymen and political appointees. The outcome of this struggle, including a more professional federal civil service and a strengthened presidency and executive branch, made a more expansionist foreign policy possible.[26] After the end of the American Civil War the national army fell into disrepair. Reforms based on various European states including Britain, Germany, and Switzerland were made so that it would become responsive to control from the central government, prepared for future conflicts, and develop refined command and support structures; these reforms led to the development of professional military thinkers and cadre. During this time the ideas of social Darwinism helped propel American overseas expansion in the Pacific and Caribbean.[27][28] This required modifications for a more efficient central government due to the added administration requirements (see above). |

アメリカ合衆国 メイン記事: アメリカ合衆国のミリタリズム 関連項目: アメリカ合衆国の政権転覆への関与およびアメリカ合衆国の対外介入 19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて、政治・軍事の指導者たちは、太平洋およびカリブ海地域における帝国主義政策と、新たな産業経済の発展を支える経済 的ミリタリズムを追求するために、これまで以上に強力な中央政府を設立するため、米国連邦政府を改革した。この改革は、国民の適切な運営と外交政策の方向 性について、新ハミルトン派共和党員とジェファーソン・ジャクソン派民主党員の間で対立が生じた結果であった。この対立は、経営管理原則に基づく専門性の 支持者と、より地域的な管理を支持する素人や政治任命者との対立であった。この争いの結果、より専門的な連邦公務員制度と、大統領および行政機関の強化が 実現し、より拡張主義的な外交政策が可能となった。[26] 南北戦争終結後、国民軍は荒廃した。英国、ドイツ、スイスなど、ヨーロッパのさまざまな国家を参考にした改革が行われ、中央政府の統制に迅速に対応し、将 来の紛争に備えて、洗練された指揮系統と支援体制を構築することになった。これらの改革により、専門的な軍事思想家や幹部育成が進んだ。 この時期、社会ダーウィニズムの思想が太平洋とカリブ海におけるアメリカの海外拡張を後押しした。[27][28] これにより、追加された行政要件(前述参照)に対応するため、より効率的な中央政府への調整が必要となった。 |

Military spending, top 25 countries by % GDP, 2024[29]/ Military spending, top 25 countries by PPP, 2024[30][31] |

軍事支出、GDP比上位25カ国、2024年[29]/軍事支出、購買力平価(PPP)基準上位25カ国、2024年[30][31] |

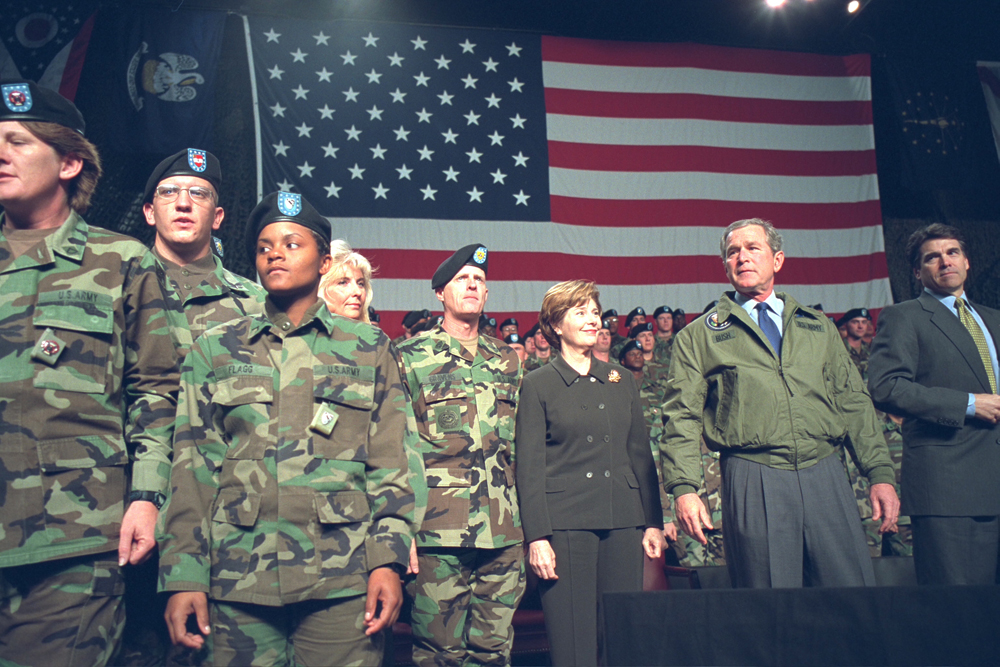

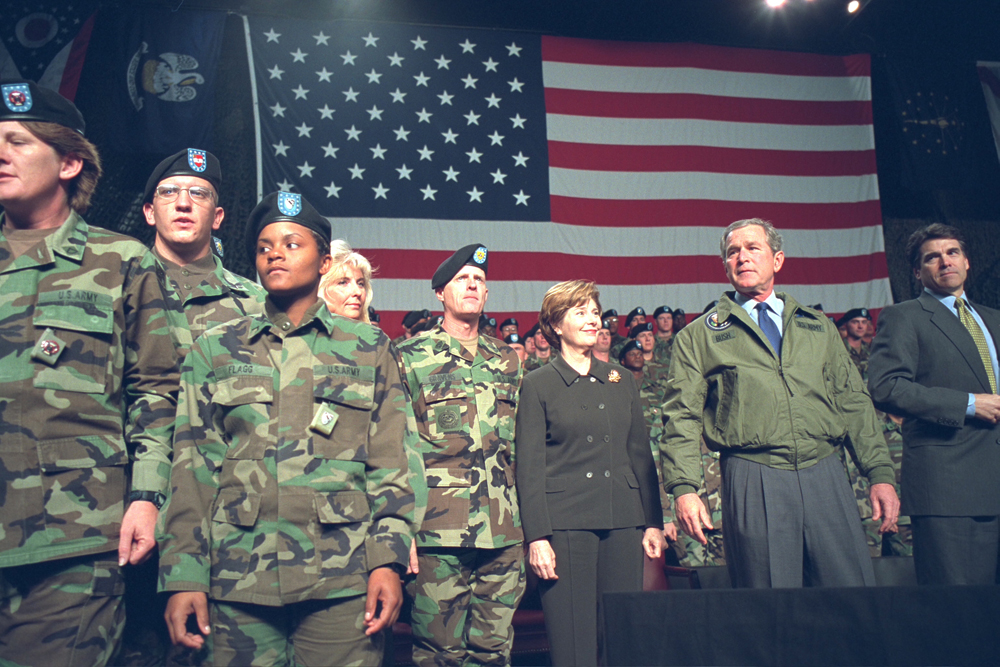

| The enlargement of the U.S. Army

for the Spanish–American War was considered essential to the occupation

and control of the new territories acquired from Spain in its defeat

(Guam, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Cuba). The previous limit by

legislation of 24,000 men was expanded to 60,000 regulars in the new

army bill on 2 February 1901, with allowance at that time for expansion

to 80,000 regulars by presidential discretion at times of national

emergency. U.S. forces were again enlarged immensely for World War I. Officers such as George S. Patton were permanent captains at the start of the war and received temporary promotions to colonel. Between the first and second world wars, the US Marine Corps engaged in questionable activities in the Banana Wars in Latin America. Retired Major General Smedley Butler, who was at the time of his death the most decorated Marine, spoke strongly against what he considered to be trends toward fascism and militarism. Butler briefed Congress on what he described as a Business Plot for a military coup, for which he had been suggested as leader; the matter was partially corroborated, but the real threat has been disputed. The Latin American expeditions ended with Franklin D. Roosevelt's Good Neighbor policy of 1934.  President George W. Bush with troops at Fort Hood, Texas, 2003 After World War II, there were major cutbacks, such that units responding early in the Korean War under United Nations authority (e.g. Task Force Smith) were unprepared, resulting in catastrophic performance. When Harry S. Truman fired Douglas MacArthur, the tradition of civilian control held and MacArthur left without any hint of military coup. The Cold War resulted in serious permanent military buildups. Dwight D. Eisenhower, a retired top military commander elected as a civilian president, warned, as he was leaving office, of the development of a military–industrial complex.[32] In the Cold War, there emerged many civilian academics and industrial researchers, such as Henry Kissinger and Herman Kahn, who had significant input into the use of military force. The complexities of nuclear strategy and the debates surrounding them helped produce a new group of 'defense intellectuals' and think tanks, such as the Rand Corporation (where Kahn, among others, worked).[33] It has been argued that the United States has shifted to a state of neomilitarism since the end of the Vietnam War. This form of militarism is distinguished by the reliance on a relatively small number of volunteer fighters; heavy reliance on complex technologies; and the rationalization and expansion of government advertising and recruitment programs designed to promote military service.[34] President Joe Biden signed a record $886 billion defense spending bill into law on 22 December 2023.[35][36] |

米西戦争における米陸軍の増強は、敗北したスペインから獲得した新領土

(グアム、フィリピン、プエルトリコ、キューバ)の占領と統制に不可欠と見なされた。1901年2月2日の新軍法案により、従来の24,000人という法

定上限は60,000人の正規兵に拡大され、国家緊急時には大統領の裁量で80,000人まで増員できる規定が設けられた。 第一次世界大戦では米軍は再び大幅に増強された。ジョージ・S・パットンなどの将校は、戦争開始当初は常任大尉であり、大佐に一時的な昇進を受けた。 第一次世界大戦と第二次世界大戦の間の、米国海兵隊は、ラテンアメリカにおけるバナナ戦争で疑わしい活動に従事した。退役したスメドリー・バトラー少将 は、その死の時点で最も多くの勲章を受けた海兵隊員であり、彼がファシズムとミリタリズムへの傾向とみなしたものに対して強く反対した。バトラーは、軍事 クーデターのための「ビジネス陰謀」と彼が表現した事柄について議会に説明し、その指導者として彼が提案されていた。この件は部分的に裏付けられたが、実 際の脅威については議論が分かれている。ラテンアメリカ遠征は、1934年のフランクリン・D・ルーズベルトの「善隣政策」によって終結した。  2003年、テキサス州フォートフッドで軍隊を視察するジョージ・W・ブッシュ大統領 第二次世界大戦後、大幅な軍縮が行われ、朝鮮戦争の初期に国連軍として派遣された部隊(スミス機動部隊など)は準備不足で、悲惨な結果に終わった。ハ リー・S・トルーマンがダグラス・マッカーサーを解任したとき、文民統制の伝統が守られ、マッカーサーは軍事クーデターの兆候も全く見せずに去った。 冷戦は深刻な恒久的な軍事増強をもたらした。退役した最高軍事指揮官でありながら文民大統領に選出されたドワイト・D・アイゼンハワーは、退任時に軍産複 合体の発展について警告した[32]。冷戦期には、ヘンリー・キッシンジャーやハーマン・カーンといった多くの文民学者や産業研究者が台頭し、軍事力の行 使に重要な影響力を行使した。核戦略の複雑さとそれを巡る議論は、ランド社(カーンらが勤務)のような新たな「防衛知識人」やシンクタンクの誕生を促し た。[33] ベトナム戦争終結後、米国は新軍国主義状態へ移行したとの指摘がある。この形態のミリタリズムは、比較的少数の志願兵への依存、複雑な技術への重度の依 存、そして兵役促進を目的とした政府の広告・募集プログラムの合理化と拡大によって特徴づけられる。[34] ジョー・バイデン大統領は2023年12月22日、過去最高の8860億ドルの国防費支出法案に署名し、これを法律とした。[35][36] |

Venezuela Members of the Venezuelan armed forces carrying Chávez eyes flags saying, "Chávez lives, the fight continues" See also: Bolivarian Revolution and Bolivarian Continental Movement Militarism in Venezuela follows the cult and myth of Simón Bolívar, known as the liberator of Venezuela.[37] For much of the 1800s, Venezuela was ruled by powerful, militarist leaders known as caudillos.[38] Between 1892 and 1900 alone, six rebellions occurred and 437 military actions were taken to obtain control of Venezuela.[38] With the military controlling Venezuela for much of its history, the country practiced a "military ethos", with civilians today still believing that military intervention in the government is positive, especially during times of crisis, with many Venezuelans believing that the military opens democratic opportunities instead of blocking them.[38] Much of the modern political movement behind the Fifth Republic of Venezuela, ruled by the Bolivarian government established by Hugo Chávez, was built on the following of Bolívar and such militaristic ideals.[37] Syria See also: Neo-Ba'athism and Assadism  Hafez Assad visiting a military camp near Damascus, 1978 The history of Syrian militarism begins in 1963, when the army staged a military coup against the democratically elected president Nazim al-Qudsi and brought the Ba'ath Party to power, beginning a new era in Syrian history. It was after this coup that Syria turned towards militarization, and with each new internal party coup it increased. Neo-Ba'athism (whose supporters came to power in 1966) differed greatly from the standard version of Ba'athism, including the idea of strong militarization.[citation needed] Syrian Arab Army parade, 1990 In 1970 (after another coup), military General Hafez al-Assad came to power. His regime turned out to be the most stable and long-lasting. Assad also conducted an active campaign to militarize Syrian society throughout his rule to resist Israel, including alone (starting in the 80s).[39][40] This policy led to Syria becoming one of the most militarized countries in the world with a large and professional army with high number of soldiers, Air Force and tank fleets.[41][40][42] However, by December 2024, after 13 years of brutal civil war, the Syrian army had become largely degraded and weakened, due to problems such as widespread corruption, lack of fuel for armored vehicles, a ruined economy (which made it impossible for the regime to support its military spending on its own), and low morale among its soldiers. All of this led to the surprisingly rapid collapse of the Bashar Assad's regime as a result of several surprise offensives by the Syrian opposition. Iraq Like neighboring Syria, Iraq has been a highly militarized state for decades. From rule of Abd al-Karim Qasim until the Ba'athist seizure of power in 1968, the Iraqi government had followed a policy of the militarization of society. Iraqi army soldiers on the Golan Heights during October war in 1973 Abdul-Karim Qasim, who seized power in 1958, was an Iraqi nationalist and Qasimist. This brought him into conflict with his neighbors, Kuwait and Iran, whose territories he claimed (in the Iranian case, only the province of Khuzestan). To protect his ambitions, Qasim needed a competent army, which he was able to build. After coming to power in 1968, the Ba'athists continued the militarization policies begun by their predecessors. While the period from 1960 to 1980 was peaceful, expenditure on the military trebled: in 1981 it stood at US$4.3 billion and nearly equaled the national incomes of Jordan and Yemen combined.[43][44] Per capita military spending in 1981 was 370 percent higher than that for education. During the Iran–Iraq War military expenditures increased dramatically (while economic growth was shrinking) and the number of people employed in the military increased fivefold, to one million.[45] Parade of New Iraqi army, 2011 By 1990, Iraq had become the most militarized country per capita in the world, and was in the top ten on many measures.[41] However, despite the high costs of the army (in comparison with the strength of the Iraqi economy), the huge number of soldiers and all types of weapons, as well as a very good domestic military industry, its effectiveness remained questionable. In 1991 and 2003, this army was literally routed by enemy forces and suffered very heavy losses without inflicting any serious on the enemy. |

ベネズエラ ベネズエラ軍隊の兵士たちがチャベスの肖像画を掲げ、「チャベスは生きている、闘いは続く」と書かれた旗を掲げている 関連項目:ボリバル革命、ボリバル大陸運動 ベネズエラのミリタリズムは、解放者シモン・ボリバルの神話と崇拝に根ざしている[37]。19世紀の大半、ベネズエラは軍閥指導者(カウディージョ)と 呼ばれる強権的な軍事指導者たちによって支配された[38]。1892年から1900年にかけてだけでも、6回の反乱が発生し、ベネズエラの支配権獲得の ために437件の軍事行動が取られた。[38] ベネズエラは歴史の大半を軍部が支配してきたため、「軍国主義的気風」が根付いている。今日でも民間人の多くは、特に危機的状況下では政府への軍部の介入 が有益だと信じている。多くのベネズエラ人は、軍部が民主主義の機会を阻害するのではなく、むしろ開くと考えているのだ。[38] ウーゴ・チャベスによって樹立されたボリバル政府が統治するベネズエラ第五共和国の現代的政治運動の多くは、ボリバルの思想とこうした軍国主義的理念の追随に基づいて構築された。[37] シリア 関連項目: 新バアス主義とアサド主義  1978年、ダマスカス近郊の軍事キャンプを視察するハフェズ・アサド シリアのミリタリズムの歴史は1963年に始まる。この年、軍が民主的に選出されたナジム・アル=クドシー大統領に対して軍事クーデターを起こし、バアス 党を政権に就かせたことで、シリアの歴史に新たな時代が幕を開けた。このクーデター以降、シリアは軍事化へと向かい、党内での新たなクーデターが起きるた びにその傾向は強まっていった。新バース主義(その支持者が1966年に権力を掌握)は、強固なミリタリズムという思想を含め、標準的なバース主義とは大 きく異なる。[出典が必要] シリア・アラブ軍パレード、1990年 1970年(別のクーデター後)、軍将校ハフェズ・アル=アサドが権力を掌握した。彼の政権は最も安定し長期にわたるものとなった。アサドはまた、イスラ エルに対抗するため(80年代から単独でも)、統治期間を通じてシリア社会の軍事化を積極的に推進した。[39][40] この政策により、シリアは兵員数、空軍、戦車部隊の規模が大きな専門的な軍隊を擁する、世界で最も軍事化された国の一つとなった。[41][40] [42] しかし2024年12月までに、13年に及ぶ残忍な内戦を経て、シリア軍は広範な汚職、装甲車両用燃料の不足、経済の崩壊(政権が単独で軍事支出を支えら れなくなった)、兵士の士気低下などの問題により、大きく衰退し弱体化していた。こうした状況が重なり、シリア反体制派による数回の奇襲攻撃の結果、バ シャール・アサド政権は驚くほど急速に崩壊したのである。 イラク 隣国シリアと同様、イラクも数十年にわたり高度にミリタリズム化された国家であった。アブド・アル=カリーム・カーシム政権から1968年のバース党による政権掌握まで、イラク政府は社会の軍事化政策を推進していた。 1973年10月戦争時のゴラン高原におけるイラク軍兵士 1958年に権力を掌握したアブドル・カリム・カセムは、イラクナショナリストかつカセミストであった。この立場から、彼は隣国であるクウェートやイラン (イランの場合はフゼスタン州のみ)と領土問題で対立した。自らの野望を守るため、カセムは有能な軍隊を必要としていた。そして彼はそれを築き上げたので ある。 1968年に政権を掌握したバアス党は、前政権が始めたミリタリズム政策を継続した。1960年から1980年までは平和な時期だったが、軍事費は3倍に 膨れ上がった。1981年には43億米ドルに達し、ヨルダンとイエメンの国民を合わせた額にほぼ匹敵した[43][44]。1981年の一人当たり軍事支 出は教育費の370%を上回っていた。イラン・イラク戦争中、軍事支出は急増した(一方で経済成長は縮小していた)。軍に従事する人員は5倍に増え、 100万人に達した。[45] 2011年、新イラク軍のパレード 1990年までに、イラクは一人当たり軍事費が世界で最も高い国となり、多くの指標で上位10位以内に入った。[41] しかし、イラク経済の規模と比較して軍隊の維持費が膨大であったこと、膨大な兵員数とあらゆる種類の兵器、そして非常に優れた国内軍事産業を有していたに もかかわらず、その実戦効果は疑問視され続けた。1991年と2003年、この軍隊は文字通り敵軍に壊滅的な敗北を喫し、敵に深刻な損害を与えることなく 甚大な損害を被った。 |

| Economic militarism Jingoism Militarization of police Military-industrial complex Stratocracy |

経済的ミリタリズム 国粋主義 警察の軍事化 軍産複合体 国家主義 |

| References |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Militarism |

|

| Further reading Bacevich, Andrew J. The New American Militarism. Oxford: University Press, 2005. Barr, Ronald J. "The Progressive Army: US Army Command and Administration 1870–1914." St. Martin's Press, Inc. 1998. ISBN 0-312-21467-7. Barzilai, Gad. Wars, Internal Conflicts and Political Order. Albany: State University of New York Press. 1996. Bond, Brian. War and Society in Europe, 1870–1970. McGill-Queen's University Press. 1985 ISBN 0-7735-1763-4 Conversi, Daniele 2007 'Homogenisation, nationalism and war’, Nations and Nationalism, Vol. 13, no 3, 2007, pp. 1–24 Ensign, Tod. America's Military Today. The New Press. 2005. ISBN 1-56584-883-7. Fink, Christina. Living Silence: Burma Under Military Rule. White Lotus Press. 2001. ISBN 1-85649-925-1. Freedman, Lawrence, Command: The Politics of Military Operations from Korea to Ukraine, Allen Lane, September 2022, 574 pp., ISBN 978 0 241 45699 6 Frevert, Ute. A Nation in Barracks: Modern Germany, Military Conscription and Civil Society. Berg, 2004. ISBN 1-85973-886-9 Huntington, Samuel P.. Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1981. Ito, Tomohide: Militarismus des Zivilen in Japan 1937–1940: Diskurse und ihre Auswirkungen auf politische Entscheidungsprozesse (Reihe zur Geschichte Asiens; Bd. 19). Iudicium Verlag, München 2019. ISBN 978-3862052202 Ritter, Gerhard. The Sword and the Scepter; the Problem of Militarism in Germany, translated from the German by Heinz Norden, Coral Gables, Fla., University of Miami Press 1969–73. Vagts, Alfred. A History of Militarism. Meridian Books, 1959. Western, Jon. Selling Intervention and War. Johns Hopkins University . 2005. ISBN 0-8018-8108-0 |

追加文献(さらに読む) Bacevich, Andrew J. 『新しいアメリカのミリタリズム』 オックスフォード:大学出版局、2005年。 Barr, Ronald J. 『進歩的な軍隊:1870年から1914年の米陸軍司令部と行政』 セント・マーティンズ・プレス社、1998年。ISBN 0-312-21467-7。 バルジライ、ガド。『戦争、内戦、政治秩序』。オールバニ:ニューヨーク州立大学出版局。1996年。 ボンド、ブライアン。『1870年から1970年のヨーロッパにおける戦争と社会』。マギル・クイーンズ大学出版局。1985年 ISBN 0-7735-1763-4 コンヴェルシ、ダニエレ 2007年「均質化、ナショナリズム、戦争」『国民とナショナリズム』第13巻第3号、2007年、pp.1-24 エンサイン、トッド『今日のアメリカ軍』ザ・ニュー・プレス、2005年 ISBN 1-56584-883-7 フィンク、クリスティーナ『沈黙の生活:軍事政権下のビルマ』ホワイト・ロータス・プレス、2001年。ISBN 1-85649-925-1。 フリードマン、ローレンス『指揮:朝鮮からウクライナまでの軍事作戦の政治学』アレン・レーン、2022年9月、574頁、ISBN 978 0 241 45699 6 フリーヴァート、ウテ。『兵営の中の国民:現代ドイツ、徴兵制と市民社会』。ベルグ、2004年。ISBN 1-85973-886-9 ハンティントン、サミュエル・P。『兵士と国家:文民統制の理論と政治』。ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局ベルナップ・プレス、1981年。 伊藤知英『日本の市民的軍国主義 1937-1940:言説と政治的意思決定過程への影響』(アジア史叢書第19巻)。ユディキウム出版社、ミュンヘン、2019年。ISBN 978-3862052202 リッター、ゲルハルト。『剣と笏:ドイツにおけるミリタリズムの問題』 ドイツ語からハインツ・ノルデンが翻訳、コーラルゲーブルズ、フロリダ、マイアミ大学出版、1969-73年。 ヴァグツ、アルフレッド。『ミリタリズムの歴史』 メリディアン・ブックス、1959年。 ウェスタン、ジョン。『介入と戦争の売り込み』。ジョンズ・ホプキンズ大学。2005年。ISBN 0-8018-8108-0 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099