ミラーニューロンと模倣の能力

Mirror neuron and capacity of imitation

表 情を真似る新生児(新生児サル)

☆ ミラーニューロンとは、ある生物が行動するときと、その生 物が他の生物の同じ行動を観察するときの両方で発火す るニューロンのことである。したがって、このニュー ロンは、観察者自身が行動しているかのように、他の生物の 行動を「ミラー」する。この定義にしたがえば、このようなニューロンはヒトや霊長類、鳥類で直接観察されている。

| A mirror neuron

is a neuron that fires both when an organism acts and when the organism

observes the same action performed by another.[1][2][3] Thus, the

neuron "mirrors" the behavior of the other, as though the observer were

itself acting. Mirror neurons are not always physiologically distinct

from other types of neurons in the brain; their main differentiating

factor is their response patterns.[4] By this definition, such neurons

have been directly observed in humans[5] and primate species,[6] and in

birds.[7] In humans, brain activity consistent with that of mirror neurons has been found in the premotor cortex, the supplementary motor area, the primary somatosensory cortex, and the inferior parietal cortex.[8] The function of the mirror system in humans is a subject of much speculation. Birds have been shown to have imitative resonance behaviors and neurological evidence suggests the presence of some form of mirroring system.[6][9] To date, no widely accepted neural or computational models have been put forward to describe how mirror neuron activity supports cognitive functions.[10][11][12] The subject of mirror neurons continues to generate intense debate. In 2014, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B published a special issue entirely devoted to mirror neuron research.[13] Some researchers speculate that mirror systems may simulate observed actions, and thus contribute to theory of mind skills,[14][15] while others relate mirror neurons to language abilities.[16] Neuroscientists such as Marco Iacoboni have argued that mirror neuron systems in the human brain help humans understand the actions and intentions of other people. In addition, Iacoboni has argued that mirror neurons are the neural basis of the human capacity for emotions such as empathy.[17] |

ミラーニューロンとは、ある生物が行動するときと、その生

物が他の生物の同じ行動を観察するときの両方で発火す るニューロンのことである[1][2][3]。したがって、このニュー

ロンは、観察者自身が行動しているかのように、他の生物の

行動を「ミラー」する。この定義にしたがえば、このようなニューロンはヒト[5]や霊長類[6]、鳥類[7]で直接観察されている。 ヒトでは、運動前野、補足運動野、一次体性感覚皮質、下頭頂皮質において、ミラーニューロンの脳活動と一致するものが見つかっている[8]。鳥類は模倣的 共鳴行動をとることが示されており、神経学的証拠はある種のミラーリングシステムの存在を示唆している[6][9]。今日まで、ミラーニューロンの活動が 認知機能をどのようにサポートするかを説明するために、広く受け入れられている神経モデルや計算モデルは提唱されていない[10][11][12]。 ミラーニューロンの主題は激しい議論を生み続けている。2014年、Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society Bはミラーニューロン研究に特化した特集号を発行した[13]。ある研究者は、ミラーシステムが観察された行動をシミュレートすることで、心の理論スキル に貢献するのではないかと推測している[14][15]。さらにイアコボーニは、ミラーニューロンが共感など人間の感情能力の神経基盤であると主張してい る[17]。 |

| Discovery In the 1980s and 1990s, neurophysiologists Giacomo Rizzolatti, Giuseppe Di Pellegrino, Luciano Fadiga, Leonardo Fogassi, and Vittorio Gallese at the University of Parma placed electrodes in the ventral premotor cortex of the macaque monkey to study neurons specialized in the control of hand and mouth actions; for example, taking hold of an object and manipulating it. During each experiment, the researchers allowed the monkey to reach for pieces of food, and recorded from single neurons in the monkey's brain, thus measuring the neuron's response to certain movements.[18][19] They found that some neurons responded when the monkey observed a person picking up a piece of food, and also when the monkey itself picked up the food. The discovery was initially submitted to Nature, but was rejected for its "lack of general interest" before being published in a less competitive journal.[20] A few years later, the same group published another empirical paper, discussing the role of the mirror-neuron system in action recognition, and proposing that the human Broca's area was the homologue region of the monkey ventral premotor cortex.[21] While these papers reported the presence of mirror neurons responding to hand actions, a subsequent study by Pier Francesco Ferrari and colleagues[22] described the presence of mirror neurons responding to mouth actions and facial gestures. Further experiments confirmed that about 10% of neurons in the monkey inferior frontal and inferior parietal cortex have "mirror" properties and give similar responses to performed hand actions and observed actions. In 2002 Christian Keysers and colleagues reported that, in both humans and monkeys, the mirror system also responds to the sound of actions.[3][23][24] Reports on mirror neurons have been widely published[21] and confirmed[25] with mirror neurons found in both inferior frontal and inferior parietal regions of the brain. Recently, evidence from functional neuroimaging strongly suggests that humans have similar mirror neurons systems: researchers have identified brain regions which respond during both action and observation of action. Not surprisingly, these brain regions include those found in the macaque monkey.[1] However, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) can examine the entire brain at once and suggests that a much wider network of brain areas shows mirror properties in humans than previously thought. These additional areas include the somatosensory cortex and are thought to make the observer feel what it feels like to move in the observed way.[26][27] Origin Many implicitly assume that the mirrorness of mirror neurons is due primarily to heritable genetic factors and that the genetic predisposition to develop mirror neurons evolved because they facilitate action understanding.[28] In contrast, a number of theoretical accounts argue that mirror neurons could simply emerge due to learned associations, including the Hebbian Theory,[29] the Associative Learning Theory,[28] and Canalization.[30] |

発見 1980年代から1990年代にかけて、パルマ大学の神経生理学者であるジャコモ・リゾラッティ、ジュゼッペ・ディ・ペッレグリーノ、ルチアーノ・ファ ディガ、レオナルド・フォガッシ、ヴィットリオ・ガレーゼは、マカクザルの腹側運動前野に電極を設置し、手や口の動作の制御に特化したニューロンを研究し た。各実験中、研究者たちはサルに餌に手を伸ばさせて、サルの脳内の単一ニューロンから記録をとり、特定の動きに対するニューロンの反応を測定した。この 発見は当初『ネイチャー』誌に投稿されたが、競争率の低い雑誌に掲載される前に「一般的な興味に欠ける」という理由で却下された[20]。 数年後、同じグループは別の実証的論文を発表し、行動認識におけるミラーニューロンシステムの役割を論じ、ヒトのブローカ野がサルの腹側運動前野の相同領 域であると提唱した[21]。これらの論文では手の動作に反応するミラーニューロンの存在が報告されていたが、その後のピエール・フランチェスコ・フェ ラーリらによる研究[22]では、口の動作や顔のジェスチャーに反応するミラーニューロンの存在が報告された。 さらなる実験により、サルの下前頭皮質と下頭頂皮質の約10%のニューロンが「ミラー」特性を持ち、実行された手の動作と観察された動作に同様の反応を示 すことが確認された。2002年、Christian Keysersと同僚たちは、ヒトとサルの両方において、ミラーシステムが動作の音にも反応することを報告した[3][23][24]。 ミラーニューロンに関する報告は広く発表され[21]、脳の下前頭と下頭頂の両領域にミラーニューロンが存在することが確認されている[25]。最近、機 能的ニューロイメージングから得られた証拠は、ヒトにも同様のミラーニューロン・システムがあることを強く示唆している。しかし、機能的磁気共鳴画像法 (fMRI)は脳全体を一度に調べることができるため、これまで考えられていたよりもはるかに広範な脳領域のネットワークがヒトのミラー特性を示している ことが示唆されている。これらの付加的な領域には体性感覚皮質が含まれ、観察者が観察されたような動きをするとどのような感じがするかを感じさせると考え られている[26][27]。 起源 ミラーニューロンの鏡面性は主に遺伝的要因によるものであり、ミラーニューロンを発達させる遺伝的素因は、ミラーニューロンが行動の理解を容易にするため に進化したものであると暗黙のうちに仮定しているものが多い[28]。対照的に、ヘッブ理論[29]、連想学習理論[28]、カナル化[30]など、学習 された連想によってミラーニューロンが単純に出現する可能性があると主張する理論的説明も数多くある。 |

In monkeys Neonatal (newborn) macaque imitating facial expressions The first animal in which researchers have studied mirror neurons individually is the macaque monkey. In these monkeys, mirror neurons are found in the inferior frontal gyrus (region F5) and the inferior parietal lobule.[1] Mirror neurons are believed to mediate the understanding of other animals' behaviour. For example, a mirror neuron which fires when the monkey rips a piece of paper would also fire when the monkey sees a person rip paper, or hears paper ripping (without visual cues). These properties have led researchers to believe that mirror neurons encode abstract concepts of actions like 'ripping paper', whether the action is performed by the monkey or another animal.[1] The function of mirror neurons in macaques remains unknown. Adult macaques do not seem to learn by imitation. Recent experiments by Ferrari and colleagues suggest that infant macaques can imitate a human's face movements, though only as neonates and during a limited temporal window.[31] Even if it has not yet been empirically demonstrated, it has been proposed that mirror neurons cause this behaviour and other imitative phenomena.[32] Indeed, there is limited understanding of the degree to which monkeys show imitative behaviour.[10] In adult monkeys, mirror neurons may enable the monkey to understand what another monkey is doing, or to recognize the other monkey's action.[33] |

サルの場合 表情を真似る新生児(新生児サル) 研究者がミラーニューロンを個別に研究した最初の動物はマカクザルである。これらのサルでは、ミラーニューロンは下前頭回(領域F5)と下頭頂小葉に見ら れる[1]。 ミラーニューロンは、他の動物の行動の理解を媒介すると考えられている。例えば、サルが紙を破るときに発火するミラー・ニューロンは、サルが人が紙を破る のを見たり、(視覚的な手がかりなしに)紙を破る音を聞いたりしたときにも発火する。このような特性から、研究者たちは、ミラーニューロンは「紙を破る」 というような行為の抽象的な概念を、その行為がサルによって行われたものであれ、他の動物によって行われたものであれ、符号化すると考えている[1]。 マカクにおけるミラーニューロンの機能は、依然として不明である。大人のマカクは模倣によって学習することはないようである。フェラーリらによる最近の実 験によると、新生児期の限られた時間枠内ではあるが、オナガザルがヒトの顔の動きを模倣できることが示唆されている[31]。経験的にはまだ実証されてい ないものの、ミラーニューロンがこの行動やその他の模倣現象を引き起こすという説が提唱されている[32]。 成体のサルでは、ミラーニューロンによって、他のサルが何をしているかを理解したり、他のサルの行動を認識したりすることができるのかもしれない [33]。 |

| In rodents A number of studies have shown that rats and mice show signs of distress while witnessing another rodent receive footshocks.[34] The group of Christian Keysers recorded from neurons while rats experienced pain or witnessed the pain of others, and has revealed the presence of pain mirror neurons in the rat's anterior cingulate cortex, i.e. neurons that respond both while an animal experiences pain and while witnessing the pain of others.[35] Deactivating this region of the cingulate cortex led to reduced emotional contagion in the rats, so that observer rats showed reduced distress while witnessing another rat experience pain.[35] The homologous part of the anterior cingulate cortex has been associated with empathy for pain in humans,[36] suggesting a homology between the systems involved in emotional contagion in rodents and empathy/emotional contagion for pain in humans. |

げっ歯類の場合 Christian Keysersのグループは、ラットが痛みを経験しているとき、または他者の痛みを目撃しているときにニューロンから記録をとり、ラットの前帯状皮質に痛 みのミラーニューロン、すなわち動物が痛みを経験しているときと他者の痛みを目撃しているときの両方に反応するニューロンが存在することを明らかにした。 [35] 帯状皮質のこの部位を不活性化すると、ラットの情動伝染が減少し、観察者であるラットが他のラットが痛みを経験しているのを目撃している間の苦痛が減少す ることがわかった。 |

In humans Diagram of the brain, showing the locations of the frontal and parietal lobes of the cerebrum, viewed from the left. The inferior frontal lobe is the lower part of the blue area, and the superior parietal lobe is the upper part of the yellow area. It is not normally possible to study single neurons in the human brain, so most evidence for mirror neurons in humans is indirect. Brain imaging experiments using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) have shown that the human inferior frontal cortex and superior parietal lobe are active when the person performs an action and also when the person sees another individual performing an action. It has been suggested that these brain regions contain mirror neurons, and they have been defined as the human mirror neuron system.[37] More recent experiments have shown that even at the level of single participants, scanned using fMRI, large areas containing multiple fMRI voxels increase their activity both during the observation and execution of actions.[26] Neuropsychological studies looking at lesion areas that cause action knowledge, pantomime interpretation, and biological motion perception deficits have pointed to a causal link between the integrity of the inferior frontal gyrus and these behaviours.[38][39][40] Transcranial magnetic stimulation studies have confirmed this as well.[41][42] These results indicate the activation in mirror neuron related areas are unlikely to be just epiphenomenal. A study published in April 2010 reports recordings from single neurons with mirror properties in the human brain.[43] Mukamel et al. (Current Biology, 2010) recorded from the brains of 21 patients who were being treated at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center for intractable epilepsy. The patients had been implanted with intracranial depth electrodes to identify seizure foci for potential surgical treatment. Electrode location was based solely on clinical criteria; the researchers, with the patients' consent, used the same electrodes to "piggyback" their research. The researchers found a small number of neurons that fired or showed their greatest activity both when the individual performed a task and when they observed a task. Other neurons had anti-mirror properties, that is, they responded when the participant performed an action but were inhibited when the participant saw that action. The mirror neurons found were located in the supplementary motor area and medial temporal cortex (other brain regions were not sampled). For purely practical reasons, these regions are not the same as those in which mirror neurons had been recorded from in the monkey: researchers in Parma were studying the ventral premotor cortex and the associated inferior parietal lobe, two regions in which epilepsy rarely occurs, and hence, single cell recordings in these regions are not usually done in humans. On the other hand, no one has to date looked for mirror neurons in the supplementary motor area or the medial temporal lobe in the monkey. Together, this therefore does not suggest that humans and monkeys have mirror neurons in different locations, but rather that they may have mirror neurons both in the ventral premotor cortex and inferior parietal lobe, where they have been recorded in the monkey, and in the supplementary motor areas and medial temporal lobe, where they have been recorded from in human – especially because detailed human fMRI analyses suggest activity compatible with the presence of mirror neurons in all these regions.[26] Another study has suggested that human beings do not necessarily have more mirror neurons than monkeys, but instead that there is a core set of mirror neurons used in action observation and execution. However, for other proposed functions of mirror neurons the mirror system may have the ability to recruit other areas of the brain when doing its auditory, somatosensory, and affective components.[44] Development Human infant data using eye-tracking measures suggest that the mirror neuron system develops before 12 months of age and that this system may help human infants understand other people's actions.[45] A critical question concerns how mirror neurons acquire mirror properties. Two closely related models postulate that mirror neurons are trained through Hebbian[46] or Associative learning[47][48][12] (see Associative Sequence Learning). However, if premotor neurons need to be trained by action in order to acquire mirror properties, it is unclear how newborn babies are able to mimic the facial gestures of another person (imitation of unseen actions), as suggested by the work of Meltzoff and Moore. One possibility is that the sight of tongue protrusion recruits an innate releasing mechanism in neonates. Careful analysis suggests that 'imitation' of this single gesture may account for almost all reports of facial mimicry by new-born infants.[49] |

人間の場合 大脳の前頭葉と頭頂葉の位置を左から見た脳の図。下前頭葉は青い部分の下部、上頭頂葉は黄色い部分の上部。 通常、ヒトの脳の単一ニューロンを研究することは不可能であるため、ヒトのミラーニューロンに関する証拠のほとんどは間接的なものである。機能的磁気共鳴 画像法(fMRI)を用いた脳画像実験によると、ヒトの下前頭皮質と上頭頂葉は、本人が行動を起こしたとき、また他の人が行動しているのを見たときに活性 化することが示されている。これらの脳領域にはミラーニューロンが存在することが示唆され、ヒトのミラーニューロン系と定義されている[37]。より最近 の実験では、fMRIを用いてスキャンした1人の被験者のレベルでも、複数のfMRIボクセルを含む広い領域が、行動の観察中と実行中の両方で活動を増加 させることが示されている[26]。 行動知識、パントマイム解釈、生物学的運動知覚障害を引き起こす病変部位を調べた神経心理学的研究では、下前頭回の完全性とこれらの行動との因果関係が指 摘されている[38][39][40]。経頭蓋磁気刺激研究でもこのことが確認されている[41][42]。これらの結果は、ミラーニューロン関連部位の 活性化が単なるエピフェノメンタルなものではなさそうであることを示している。 2010年4月に発表された研究では、ヒトの脳におけるミラー特性を持つ単一ニューロンからの記録が報告されている[43]。Mukamelら (Current Biology, 2010)は、難治性てんかんのためにロナルド・レーガンUCLA医療センターで治療を受けていた21人の患者の脳から記録を行った。患者は、外科的治療 の可能性を考慮して発作病巣を特定するために、頭蓋内に深さ電極を埋め込まれていた。電極の位置は臨床的基準のみに基づいていた。研究者たちは、患者の同 意を得て、同じ電極を用いて研究を「おんぶに抱っこ」した。研究者らは、課題を遂行したときと課題を観察したときの両方で発火または最大活動を示す少数の ニューロンを発見した。他のニューロンはアンチミラー特性、つまり、被験者がある行動をすると反応するが、被験者がその行動を見ると抑制されるという特性 を持っていた。 発見されたミラーニューロンは、補足運動野と内側側頭皮質に位置していた(他の脳領域はサンプリングされなかった)。純粋に実用的な理由から、これらの領 域はサルでミラーニューロンが記録された領域とは異なる。パルマの研究者たちは腹側運動前野とそれに関連する下頭頂葉を研究していたが、この2つの領域は てんかんがめったに起こらない領域であり、したがってこれらの領域での単一細胞の記録は通常ヒトでは行われない。一方、サルの補足運動野や内側側頭葉のミ ラーニューロンを調べた人は、今のところいない。したがって、このことは、ヒトとサルが異なる場所にミラー・ニューロンを有していることを示唆しているの ではなく、むしろ、サルでミラー・ニューロンが記録されている腹側運動前野と下頭頂葉、およびヒトでミラー・ニューロンが記録されている補足運動野と内側 側頭葉の両方にミラー・ニューロンが存在する可能性を示唆している--特に、ヒトの詳細なfMRI解析では、これらすべての領域でミラー・ニューロンの存 在に適合する活動が示唆されているためである[26]。 別の研究では、ヒトは必ずしもサルよりも多くのミラーニューロンを持っているわけではなく、行動の観察と実行に使用されるミラーニューロンの中核セットが 存在することが示唆されている。しかし、ミラーニューロンの他の機能については、ミラーシステムは聴覚、体性感覚、感情の構成要素を行う際に脳の他の領域 をリクルートする能力を持っている可能性がある[44]。 発達 視線追跡を用いたヒトの乳児のデータから、ミラーニューロンシステムは生後12ヵ月以前に発達し、このシステムはヒトの乳児が他者の行動を理解するのに役 立つ可能性が示唆されている[45]。密接に関連する2つのモデルは、ヘッブ学習[46]または連想学習[47][48][12]によってミラーニューロ ンが訓練されると仮定している(連想系列学習を参照)。しかし、もし運動前ニューロンがミラー特性を獲得するために行動によって訓練される必要があるので あれば、メルツォフとムーアの研究で示唆されたように、新生児がどのようにして他人の顔のジェスチャーを模倣(見えない行動の模倣)できるのかは不明であ る。ひとつの可能性は、新生児が舌突出を見て、生得的な放出メカニズムを呼び起こすことである。注意深く分析すると、新生児による顔面模倣のほとんどすべ ての報告が、この単一のジェスチャーの「模倣」で説明できる可能性が示唆される[49]。 |

| Possible functions Understanding intentions Many studies link mirror neurons to understanding goals and intentions. Fogassi et al. (2005)[25] recorded the activity of 41 mirror neurons in the inferior parietal lobe (IPL) of two rhesus macaques. The IPL has long been recognized as an association cortex that integrates sensory information. The monkeys watched an experimenter either grasp an apple and bring it to his mouth or grasp an object and place it in a cup. In total, 15 mirror neurons fired vigorously when the monkey observed the "grasp-to-eat" motion, but registered no activity while exposed to the "grasp-to-place" condition. For 4 other mirror neurons, the reverse held true: they activated in response to the experimenter eventually placing the apple in the cup but not to eating it. Only the type of action, and not the kinematic force with which models manipulated objects, determined neuron activity. It was also significant that neurons fired before the monkey observed the human model starting the second motor act (bringing the object to the mouth or placing it in a cup). Therefore, IPL neurons "code the same act (grasping) in a different way according to the final goal of the action in which the act is embedded."[25] They may furnish a neural basis for predicting another individual's subsequent actions and inferring intention.[25] Learning facilitation Another possible function of mirror neurons would be facilitation of learning. The mirror neurons code the concrete representation of the action, i.e., the representation that would be activated if the observer acted. This would allow us to simulate (to repeat internally) the observed action implicitly (in the brain) to collect our own motor programs of observed actions and to get ready to reproduce the actions later. It is implicit training. Due to this, the observer will produce the action explicitly (in his/her behavior) with agility and finesse. This happens due to associative learning processes. The more frequently a synaptic connection is activated, the stronger it becomes.[50] Empathy Stephanie Preston and Frans de Waal,[51] Jean Decety,[52][53] and Vittorio Gallese[54][55] and Christian Keysers[3] have independently argued that the mirror neuron system is involved in empathy. A large number of experiments using fMRI, electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) have shown that certain brain regions (in particular the anterior insula, anterior cingulate cortex, and inferior frontal cortex) are active when people experience an emotion (disgust, happiness, pain, etc.) and when they see another person experiencing an emotion.[56][57][58][59][60][61][62] David Freedberg and Vittorio Gallese have also put forward the idea that this function of the mirror neuron system is crucial for aesthetic experiences.[63] Nevertheless, an experiment aimed at investigating the activity of mirror neurons in empathy conducted by Soukayna Bekkali and Peter Enticott at the University of Deakin yielded a different result. After analyzing the report's data, they came up with two conclusions about motor empathy and emotional empathy. First, there is no relationship between motor empathy and the activity of mirror neurons. Second, there is only weak evidence of these neurons' activity in the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), and no evidence of emotional empathy associated with mirror neurons in key brain regions (inferior parietal lobule: IPL). In other words, there has not been an exact conclusion about the role of mirror neurons in empathy and if they are essential for human empathy.[64] However, these brain regions are not quite the same as the ones which mirror hand actions, and mirror neurons for emotional states or empathy have not yet been described in monkeys. In a recent study, done in 2022, sixteen hand actions were given for each assignment. The assignment pictured both an activity word phase and the intended word phase. The hand actions were selected in "trails" each introduced twice. One of the times was with a matching phase and the other time was with a misleading word phase. The action words were depicted in two to three words with each beginning with the word "to". For instance, "to point" (action) or "to spin" (intention). Participants were expected to answer whether the correct word phase matched the corresponding action or intention word. The word phase had to be answered within 3000 ms, with a 1000 ms black screen between each image. The black screens purpose was for an adequate amount of time in between responses. Participants pressed on the keyboard "x" or "m" to indicate their responses in a yes/no format.[65] Christian Keysers at the Social Brain Lab and colleagues have shown that people who are more empathic according to self-report questionnaires have stronger activations both in the mirror system for hand actions[66] and the mirror system for emotions,[61] providing more direct support for the idea that the mirror system is linked to empathy. Some researchers observed that the human mirror system does not passively respond to the observation of actions but is influenced by the mindset of the observer.[67] Researchers observed the link of the mirror neurons during empathetic engagement in patient care.[68] Studies in rats have shown that the anterior cingulate cortex contains mirror neurons for pain, i.e. neurons responding both during the first-hand experience of pain and while witnessing the pain of others,[35] and inhibition of this region leads to reduced emotional contagion in rats[35] and mice,[34] and reduced aversion towards harming others.[69] This provides causal evidence for a link between pain mirror neurons, and emotional contagion and prosocial behavior, two phenomena associated with empathy, in rodents. That brain activity in the homologous brain region is associated with individual variability in empathy in humans[36] suggests that a similar mechanism may be at play across mammals. Human self awareness V. S. Ramachandran has speculated that mirror neurons may provide the neurological basis of human self-awareness.[70] In an essay written for the Edge Foundation in 2009 Ramachandran gave the following explanation of his theory: "... I also speculated that these neurons can not only help simulate other people's behavior but can be turned 'inward'—as it were—to create second-order representations or meta-representations of your own earlier brain processes. This could be the neural basis of introspection, and of the reciprocity of self awareness and other awareness. There is obviously a chicken-or-egg question here as to which evolved first, but... The main point is that the two co-evolved, mutually enriching each other to create the mature representation of self that characterizes modern humans."[71] Language In humans, functional MRI studies have reported finding areas homologous to the monkey mirror neuron system in the inferior frontal cortex, close to Broca's area, one of the hypothesized language regions of the brain. This has led to suggestions that human language evolved from a gesture performance/understanding system implemented in mirror neurons. Mirror neurons have been said to have the potential to provide a mechanism for action-understanding, imitation-learning, and the simulation of other people's behaviour.[72] This hypothesis is supported by some cytoarchitectonic homologies between monkey premotor area F5 and human Broca's area.[73] Rates of vocabulary expansion link to the ability of children to vocally mirror non-words and so to acquire the new word pronunciations. Such speech repetition occurs automatically, fast[74] and separately in the brain to speech perception.[75][76] Moreover, such vocal imitation can occur without comprehension such as in speech shadowing[77] and echolalia.[78] Further evidence for this link comes from a recent study in which the brain activity of two participants was measured using fMRI while they were gesturing words to each other using hand gestures with a game of charades – a modality that some have suggested might represent the evolutionary precursor of human language. Analysis of the data using Granger Causality revealed that the mirror-neuron system of the observer indeed reflects the pattern of activity in the motor system of the sender, supporting the idea that the motor concept associated with the words is indeed transmitted from one brain to another using the mirror system[79]  The mirror neuron system seems to be inherently inadequate to play any role in syntax, given that this definitory property of human languages which is implemented in hierarchical recursive structure is flattened into linear sequences of phonemes making the recursive structure not accessible to sensory detection[80] Automatic imitation The term is commonly used to refer to cases in which an individual, having observed a body movement, unintentionally performs a similar body movement or alters the way that a body movement is performed. Automatic imitation rarely involves overt execution of matching responses. Instead the effects typically consist of reaction time, rather than accuracy, differences between compatible and incompatible trials. Research reveals that the existence of automatic imitation, which is a covert form of imitation, is distinct from spatial compatibility. It also indicates that, although automatic imitation is subject to input modulation by attentional processes, and output modulation by inhibitory processes, it is mediated by learned, long-term sensorimotor associations that cannot be altered directly by intentional processes. Many researchers believe that automatic imitation is mediated by the mirror neuron system.[81] Additionally, there are data that demonstrate that our postural control is impaired when people listen to sentences about other actions. For example, if the task is to maintain posture, people do it worse when they listen to sentences like this: "I get up, put on my slippers, go to the bathroom." This phenomenon may be due to the fact that during action perception there is similar motor cortex activation as if a human being performed the same action (mirror neurons system).[82] Motor mimicry In contrast with automatic imitation, motor mimicry is observed in (1) naturalistic social situations and (2) via measures of action frequency within a session rather than measures of speed and/or accuracy within trials.[83] The integration of research on motor mimicry and automatic imitation could reveal plausible indications that these phenomena depend on the same psychological and neural processes. Preliminary evidence however comes from studies showing that social priming has similar effects on motor mimicry.[84][85] Nevertheless, the similarities between automatic imitation, mirror effects, and motor mimicry have led some researchers to propose that automatic imitation is mediated by the mirror neuron system and that it is a tightly controlled laboratory equivalent of the motor mimicry observed in naturalistic social contexts. If true, then automatic imitation can be used as a tool to investigate how the mirror neuron system contributes to cognitive functioning and how motor mimicry promotes prosocial attitudes and behavior.[86][87] Meta-analysis of imitation studies in humans suggest that there is enough evidence of mirror system activation during imitation that mirror neuron involvement is likely, even though no published studies have recorded the activities of singular neurons. However, it is likely insufficient for motor imitation. Studies show that regions of the frontal and parietal lobes that extend beyond the classical mirror system are equally activated during imitation. This suggests that other areas, along with the mirror system are crucial to imitation behaviors.[8] Autism It has also been proposed that problems with the mirror neuron system may underlie cognitive disorders, particularly autism.[88][89] However the connection between mirror neuron dysfunction and autism is tentative and it remains to be demonstrated how mirror neurons are related to many of the important characteristics of autism.[10] Some researchers claim there is a link between mirror neuron deficiency and autism. EEG recordings from motor areas are suppressed when someone watches another person move, a signal that may relate to mirror neuron system. This suppression was less in children with autism.[88] Although these findings have been replicated by several groups,[90][91] other studies have not found evidence of a dysfunctional mirror neuron system in autism.[10] In 2008, Oberman et al. published a research paper that presented conflicting EEG evidence. Oberman and Ramachandran found typical mu-suppression for familiar stimuli, but not for unfamiliar stimuli, leading them to conclude that the mirror neuron system of children with ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder) was functional, but less sensitive than that of typical children.[92] Based on the conflicting evidence presented by mu-wave suppression experiments, Patricia Churchland has cautioned that mu-wave suppression results cannot be used as a valid index for measuring the performance of mirror neuron systems.[93] Recent research indicates that mirror neurons do not play a role in autism: ...no clear cut evidence emerges for a fundamental mirror system deficit in autism. Behavioural studies have shown that people with autism have a good understanding of action goals. Furthermore, two independent neuroimaging studies have reported that the parietal component of the mirror system is functioning typically in individuals with autism.[94] Some anatomical differences have been found in the mirror neuron related brain areas in adults with autism spectrum disorders, compared to non-autistic adults. All these cortical areas were thinner and the degree of thinning was correlated with autism symptom severity, a correlation nearly restricted to these brain regions.[95] Based on these results, some researchers claim that autism is caused by impairments in the mirror neuron system, leading to disabilities in social skills, imitation, empathy and theory of mind.[who?] Many researchers have pointed out that the "broken mirrors" theory of autism is overly simplistic, and mirror neurons alone cannot explain the differences found in individuals with autism. First of all, as noted above, none of these studies were direct measures of mirror neuron activity - in other words fMRI activity or EEG rhythm suppression do not unequivocally index mirror neurons. Dinstein and colleagues found normal mirror neuron activity in people with autism using fMRI.[96] In individuals with autism, deficits in intention understanding, action understanding and biological motion perception (the key functions of mirror neurons) are not always found,[97][98] or are task dependent.[99][100] Today, very few people believe an all-or-nothing problem with the mirror system can underlie autism. Instead, "additional research needs to be done, and more caution should be used when reaching out to the media."[101] Research from 2010[96] concluded that autistic individuals do not exhibit mirror neuron dysfunction, although the small sample size limits the extent to which these results can be generalized. A more recent review argued there was not enough neurological evidence to support this “broken-mirror theory” of autism.[102] Theory of mind In Philosophy of mind, mirror neurons have become the primary rallying call of simulation theorists concerning our "theory of mind." "Theory of mind" refers to our ability to infer another person's mental state (i.e., beliefs and desires) from experiences or their behaviour. There are several competing models which attempt to account for our theory of mind; the most notable in relation to mirror neurons is simulation theory. According to simulation theory, theory of mind is available because we subconsciously empathize with the person we're observing and, accounting for relevant differences, imagine what we would desire and believe in that scenario.[103][104] Mirror neurons have been interpreted as the mechanism by which we simulate others in order to better understand them, and therefore their discovery has been taken by some as a validation of simulation theory (which appeared a decade before the discovery of mirror neurons).[54] More recently, Theory of Mind and Simulation have been seen as complementary systems, with different developmental time courses.[105][106][107] At the neuronal-level, in a 2015 study by Keren Haroush and Ziv Williams using jointly interacting primates performing an iterated prisoner's dilemma game, the authors identified neurons in the anterior cingulate cortex that selectively predicted an opponent's yet unknown decisions or covert state of mind. These "other-predictive neurons" differentiated between self and other decisions and were uniquely sensitive to social context, but they did not encode the opponent's observed actions or receipt of reward. These cingulate cells may therefore importantly complement the function of mirror neurons by providing additional information about other social agents that is not immediately observable or known.[108] Sex differences A series of recent studies conducted by Yawei Cheng, using a variety of neurophysiological measures, including MEG,[109] spinal reflex excitability,[110] electroencephalography,[111][112] have documented the presence of a gender difference in the human mirror neuron system, with female participants exhibiting stronger motor resonance than male participants. In another study, sex-based differences among mirror neuron mechanisms was reinforced in that the data showed enhanced empathetic ability in females relative to males[citation needed]. During an emotional social interaction, females showed a greater ability in emotional perspective taking[clarification needed] than did males when interacting with another person face-to-face. However, in the study, data showed that when it came to recognizing the emotions of others, all participants' abilities were very similar and there was no key difference between the male and female subjects.[113] Sleep paralysis Baland Jalal and V. S. Ramachandran have hypothesized that the mirror neuron system is important in giving rise to the intruder hallucination and out-of-body experiences during sleep paralysis.[114] According to this theory, sleep paralysis leads to disinhibition of the mirror neuron system, paving the way for hallucinations of human-like shadowy beings. The deafferentation of sensory information during sleep paralysis is proposed as the mechanism for such mirror neuron disinhibition.[114] The authors suggest that their hypothesis on the role of the mirror neuron system could be tested: "These ideas could be explored using neuroimaging, to examine the selective activation of brain regions associated with mirror neuron activity, when the individual is hallucinating an intruder or having an out-of-body experience during sleep paralysis ."[114] Mirror neuron function, psychosis, and empathy in schizophrenia Recent research, which measured mu-wave suppression, suggests that mirror neuron activity is positively correlated with psychotic symptoms (i.e., greater mu suppression/mirror neuron activity was highest among subjects with the greater severity of psychotic symptoms). Researchers concluded that "higher mirror neuron activity may be the underpinning of schizophrenia sensory gating deficits and may contribute to sensory misattributions particularly in response to socially relevant stimuli, and be a putative mechanism for delusions and hallucinations."[115] |

可能な機能 意図の理解 多くの研究がミラーニューロンを目標や意図の理解に関連付け ている。Fogassiら(2005)[25]は、2頭のアカゲザルの下頭頂葉(IPL)において、41個のミラーニューロンの活動を記録した。IPLは 感覚情報を統合する連合皮質として長い間認識されてきた。サルは、実験者がリンゴをつかんで口に運ぶか、物体をつかんでコップに入れるのを見た。 合計15個のミラーニューロンは、サルが「つかんで食べる」動作を観察すると活発に発火したが、「つかんで置く」条件では全く活動しなかった。 他の4つのミラー・ニューロンについては、その逆が当てはまり、実験者が最終的にリンゴをカップに入れることに反応して活性化したが、食べることには反応 しなかった。 モデルが物体を操作する運動学的な力ではなく、動作の種類だけがニューロンの活動を決定した。また、サルが人間のモデルが2番目の運動行為(物体を口に運 んだり、コップに入れたりする)を始めるのを観察する前に、ニューロンが発火したことも重要であった。したがって、IPLニュー ロンは「同じ行為(把持)を、その行為が組み込まれてい る行為の最終的な目標によって異なる方法でコード化する」[25]。 学習の促進 ミラーニューロンのもう一つの可能な機能は、学習の促進であろう。ミラーニューロンは行動の具体的表象、すなわち観察者が行動した場合に活性化されるであ ろう表象をコード化する。これによって、観察された行動を暗黙のうちに(脳内で)シミュレートし、観察された行動に関する自分の運動プログラムを収集し、 後でその行動を再現できるようにすることができる。暗黙のトレーニングである。その結果、観察者はその行動を明示的に(自分の行動の中で)敏捷かつ巧妙に 行うようになる。これは連想学習プロセスによって起こる。シナプス結合は、活性化される頻度が高いほど強くなる。 共感 ステファニー・プレストンとフランス・デ・ワール[51]、ジャン・デセティ[52][53]、ヴィットリオ・ガレーゼ[54][55]、クリスチャン・ キーザース[3]は、ミラーニューロン系が共感に関与していることを独自に主張している。fMRI、脳波(EEG)、脳磁図(MEG)を用いた多くの実験 から、人が感情(嫌悪、幸福、痛みなど)を経験したとき、また他人が感情を経験しているのを見たときに、特定の脳領域(特に前島皮質、前帯状皮質、下前頭 皮質)が活性化することが示されている[56][57]。 [56][57][58][59][60][61][62]デイヴィッド・フリードバーグとヴィットリオ・ガレーゼもまた、ミラーニューロン系のこの機能 が美的体験にとって重要であるという考えを提唱している[63]。 それにもかかわらず、ディーキン大学のソウカイナ・ベッカリとピーター・エンティコットが行った、共感におけるミラーニューロンの活動を調査することを目 的とした実験では、異なる結果が得られた。報告書のデータを分析した結果、彼らは運動共感と感情共感について2つの結論を導き出した。第一に、運動共感と ミラーニューロンの活動には関係がない。第二に、これらのニューロンが下前頭回(IFG)で活動しているという弱い証拠があるだけで、重要な脳領域(下頭 頂小葉:IPL)ではミラーニューロンと関連した情動的共感の証拠はない。言い換えれば、共感におけるミラーニューロンの役割と、それがヒトの共感に不可 欠かどうかについては、正確な結論は出ていない。[64]しかし、これらの脳領域は、手の動作をミラーリングする脳領域とはまったく同じではなく、情動状 態や共感に関するミラーニューロンは、サルではまだ報告されていない。 2022年に行われた最近の研究では、各課題に対して16の手の動作が与えられた。課題には、活動語の段階と意図した語の段階の両方が描かれていた。手の 動作は、それぞれ2回ずつ導入される「トレイル」で選択された。そのうちの1回はマッチング・フェイズ、もう1回はミスリード・ワード・フェイズである。 アクションの単語は2語から3語で描かれ、それぞれが "to "で始まる。例えば、"to point"(動作)や "to spin"(意図)である。 参加者は、正しい語相が対応する動作または意図の語と一致するかどうかを答えることが求められた。各画像の間に1000ミリ秒の黒画面を挟み、3000ミ リ秒以内に答えなければならない。黒画面は、回答間の適切な時間を確保するためのものであった。参加者はキーボードの "x "か "m "を押して、イエス/ノー形式で回答を示した[65]。 Social Brain LabのChristian Keysersとその同僚は、自己報告式の質問票によると、より共感的な人は、手の動作のミラーシステム[66]と感情のミラーシステム[61]の両方で より強い活性化を有することを示し、ミラーシステムが共感と関連しているという考えをより直接的に支持している。一部の研究者は、ヒトのミラーシステムは 行為の観察に受動 的に反応するのではなく、観察者の考え方に影響されることを 観察している[67]。 この領域の抑制は、ラット[35]およびマウス[34]における情動伝染の減少[34]、および他者を傷つけることへの嫌悪感の減少[69]につながる。 このことは、げっ歯類において、痛みのミラーニューロンと、共感と関連する2つの現象である情動伝染および向社会的行動との間に関連があることの因果関係 を示す証拠となる。相同な脳領域の脳活動がヒトにおける共感性の個人差と関連していることから[36]、哺乳類全体で同様のメカニズムが働いている可能性 が示唆される。 ヒトの自己認識 V. S.ラマチャンドランは、ミラーニューロンがヒトの自己認識の神経学的基礎を提供するかもしれないと推測している[70]。2009年にエッジ財団のため に書かれたエッセイの中で、ラマチャンドランは彼の理論について次のように説明している。これが内観の神経基盤であり、自己認識と他者認識の相互性の神経 基盤である可能性がある。どちらが先に進化したかについては、鶏が先か卵が先かという問題がある。重要なのは、現代人を特徴づける成熟した自己表象を生み 出すために、この2つが共進化し、相互に豊かになったということである」[71]。 言語 ヒトでは、機能的MRI研究によって、脳の言語領域の仮説のひとつであるブローカ野に近い下前頭皮質に、サルのミラーニューロン系と相同な領域が見つかっ たことが報告されている。このことから、ヒトの言語は、ミラーニューロンで実装されたジェスチャー演技/理解システムから進化したという指摘がなされてい る。この仮説は、サルの運動前野F5とヒトのブローカ野の細胞建築学的相同性によって支持されている。このような音声反復は、自動的に、高速で[74]、 音声知覚とは別に脳内で起こる[75][76]。さらに、このような音声模倣は、スピーチ・シャドウイング[77]やエコラリア[78]のように、理解す ることなく起こることがある。 この関連性を示すさらなる証拠は、最近の研究で、2人の参加者が手振り身振りを使って言葉をジェスチャーで伝え合いながら、fMRIを使って脳活動を測定 したことによる。このデータをグレンジャー因果性を用いて分析したところ、観察者のミラーニューロン系が、送り手の運動系の活動パターンを実際に反映して いることが明らかになり、言葉に関連する運動概念が、ミラーシステムを用いて、ある脳から別の脳へと実際に伝達されるという考えが支持された[79]。  階層的な再帰構造で実装されている人間の言語のこの定義的特性が、音素の線形シーケンスに平坦化され、再帰構造を感覚的に検出することができないことを考 えると、ミラーニューロンシステムは構文論において何らかの役割を果たすには本質的に不十分であるように思われる[80]。 自動模倣 この用語は一般的に、ある身体運動を観察した個体が、無意識のうちに同様の身体運動を行ったり、身体運動のやり方を変えたりすることを指す。自動模倣で は、一致する反応があからさまに行われることはほとんどない。その代わりに、適合する試行と適合しない試行との間に、正確さではなく反応時間の差が生じる ことが一般的である。研究の結果、自動模倣の存在は、模倣の秘密の形態であり、空間的適合性とは異なることが明らかになった。また、自動模倣は注意過程に よる入力調節と抑制過程による出力調節を受けるが、学習された長期的な感覚運動連合によって媒介されており、意図的な過程によって直接変化させることはで きないことも示されている。多くの研究者は、自動模倣はミラーニューロン系に よって媒介されていると考えている。例えば、姿勢を維持することが課題である場合、人は次のような文章を聞くと姿勢が悪くなる: "私は立ち上がり、スリッパを履き、トイレに行く" この現象は、行動認知の際に、あたかも人間が同じ行動をとったかのように、運動皮質が活性化するという事実(ミラーニューロンシステム)によるのかもしれ ない[82]。 運動模倣 自動模倣とは対照的に、運動模倣は、(1)自然な社会的状況で、(2)試行内の速度や正確さの測定ではなく、セッション内の行動頻度の測定によって観察さ れる[83]。 運動模倣と自動模倣に関する研究を統合することで、これらの現象が同じ心理的・神経的プロセスに依存しているというもっともらしい示唆が得られる可能性が ある。しかし、予備的な証拠としては、社会的プライミングが運動模倣に同様の効果をもたらすことを示す研究がある[84][85]。 それにもかかわらず、自動模倣、ミラー効果、および運動模倣の類似性から、自動模倣はミラーニューロン系によって媒介され、自然主義的な社会的文脈で観察 される運動模倣と厳密に制御された実験室で等価なものであると提唱する研究者もいる。もしそうであれば、自動模倣は、ミラーニューロン系が認知機能にどの ように寄与しているのか、また運動模倣が向社会的態度や行動をどのように促進しているのかを調査するツールとして使用できる。 ヒトにおける模倣研究のメタ分析によると、特異ニューロンの活動を記録した研究は発表されていないものの、模倣時にミラーシステムが活性化することを示す 十分な証拠があり、ミラーニューロンの関与が考えられる。しかし、運動模倣には不十分である可能性が高い。研究によると、古典的なミラーシステム以外の前 頭葉や頭頂葉の領域も、模倣時に同様に活性化される。このことは、模倣行動には、ミラーシステムとともに他の領域も重要であることを示唆している[8]。 自閉症 ミラーニューロン系の問題が認知障害、特に自閉症の根底にある可能性も提唱されている[88][89]。しかし、ミラーニューロンの機能障害と自閉症との 関連は暫定的なものであり、ミラーニューロンが自閉症の重要な特徴の多くとどのように関連しているかはまだ実証されていない[10]。 ミラーニューロンの欠乏と自閉症には関連があると主張する研究者もいる。運動野からの脳波記録は、誰かが他人の動きを見ているときに抑制される。この抑制 は自閉症の子どもでは少なかった[88]。これらの所見はいくつかのグループによって再現されているが[90][91]、他の研究では自閉症におけるミ ラーニューロンシステムの機能不全の証拠は見つかっていない[10]。2008年、Obermanらは相反する脳波の証拠を提示した研究論文を発表した。 ObermanとRamachandranは、見慣れた刺激に対しては典型的なミュー抑制を認めたが、見慣れない刺激に対しては認めなかったことから、 ASD(自閉症スペクトラム障害)の子どものミラーニューロンシステムは機能的であるが、典型的な子どもよりも感度が低いと結論づけた。 [92]ミュー波抑制実験によって示された相反する証拠に基づき、パトリシア・チャーチランドはミュー波抑制の結果をミラーニューロンシステムの性能を測 定するための有効な指標として使用することはできないと警告している[93]: ......自閉症における基本的なミラーシステムの欠損を示す明確な証拠はない。行動研究は、自閉症の人が行動目標をよく理解していることを示してい る。さらに、2つの独立した神経画像研究によって、ミラーシステムの頭頂部の構成要素は自閉症の人で典型的に機能していることが報告されている[94]。 自閉症スペクトラム障害の成人では、非自閉症の成人と比較して、ミラーニューロン関連の脳領域に解剖学的な違いがいくつか認められている。これらの皮質領 域はすべて薄くなっており、薄くなっている程度は自閉症の症状の重篤度と相関しており、その相関はほぼこれらの脳領域に限られていた[95]。これらの結 果に基づき、一部の研究者は、自閉症はミラーニューロンシステムの障害によって引き起こされ、社会的スキル、模倣、共感、心の理論の障害につながると主張 している[who?] 多くの研究者が、自閉症の「壊れた鏡」説は単純化しすぎており、ミラーニューロンだけでは自閉症の人に見られる違いを説明できないと指摘している。言い換 えれば、fMRIの活動や脳波のリズム抑制は、ミラーニューロンの明確な指標にはならない。Dinsteinたちは、fMRIを用いて自閉症者のミラー ニューロン活動が正常であることを発見した[96]。自閉症の患者では、意図理解、行動理解、生物学的運動知覚(ミラーニューロンの重要な機能)の障害が 必ずしも認められるとは限らず[97][98]、あるいは課題依存的である[99][100]。現在では、ミラーシステムに問題があれば自閉症が発症する と考える人はほとんどいない。それどころか、「さらなる研究が必要であり、メディアに働きかける際にはより注意を払うべきである」[101]。 2010年の研究[96]では、自閉症者はミラーニューロンの機能障害を示さないと結論付けられているが、サンプル数が少ないため、この結果を一般化でき る範囲には限界がある。より最近のレビューでは、自閉症のこの「ミラー破綻説」を支持する十分な神経学的証拠はないと論じている[102]。 心の理論 心の哲学において、ミラーニューロンはシミュレーション理論家の「心の理論」に関する主要な呼びかけとなっている。「心の理論」とは、経験や行動から他人 の精神状態(すなわち信念や欲求)を推測する能力のことである。 私たちの心の理論を説明しようとするモデルはいくつかあり、ミラーニューロンとの関連で最も注目されているのはシミュレーション理論である。シミュレー ション理論によると、心の理論が利用可能なのは、私たちが無意識のうちに観察している人に共感し、関連する違いを考慮した上で、そのシナリオで私たちが何 を望み、何を信じるかを想像するからである。 [103][104]。ミラー・ニューロンは、他者をよりよく理解するために他者をシミュレーショ ンするメカニズムであると解釈されてきたため、その発見はシミュレーション理論(ミラー・ニューロン発見の10年前に登場)の検証であると受け取られるこ ともあった[54]。より最近では、心の理論とシミュレーションは相補的なシステムであり、発達の時間経過が異なると考えられている[105][106] [107]。 神経細胞レベルでは、Keren HaroushとZiv Williamsによる2015年の研究で、反復囚人のジレンマゲームを行う共同的に相互作用する霊長類を使用し、著者らは前帯状皮質のニューロンを同定 した。これらの「他者予測ニューロン」は、自己と他者の意思決定を区別し、社会的文脈に特異的に敏感であったが、相手の観察された行動や報酬の受け取りを 符号化することはなかった。したがって、これらの帯状 回路は、すぐに観察できない、あるいは知られていない他の社会的主体 に関する付加的な情報を提供することによって、ミラーニューロンの機能を補 完する重要な役割を担っている可能性がある[108]。 性差 Yawei Chengが最近行った一連の研究では、MEG[109]、脊髄反射興奮性[110]、脳波[111][112]などの様々な神経生理学的測定法を用い て、ヒトのミラーニューロン系における性差の存在が記録されており、女性の参加者は男性の参加者よりも強い運動共鳴を示す。 別の研究では、ミラーニューロンのメカニズムにおける性差は、男性に比べて女性の共感能力の向上を示すデータによって補強された[要出典]。感情的な社会 的相互作用の際、女性は男性よりも感情的な視点に立つ能力が高いことが示された。しかし、この研究では、他者の感情を認識することに関しては、すべての参 加者の能力は非常に似ており、男性と女性の間に重要な違いはなかったというデータが示されている[113]。 睡眠麻痺 バランド・ジャラルとV・S・ラマチャンドランは、ミラーニューロン系が睡眠麻痺中の侵入者幻覚や体外離脱体験を生じさせるのに重要であるという仮説を立 てた[114]。この理論によると、睡眠麻痺はミラーニューロン系の抑制を解除し、人間のような影のような存在の幻覚に道を開く。このようなミラーニュー ロンの抑制解除のメカニズムとして、睡眠麻痺中の感覚情報の脱遠隔が提案されている[114]: 「睡眠麻痺中に侵入者を幻視したり、体外離脱体験をしているときに、ミラーニューロンの活動に関連する脳領域が選択的に活性化されることを調べるために、 神経画像を使ってこれらの考えを調べることができる。 統合失調症におけるミラーニューロン機能、精神病、共感性 ミュー波抑制を測定した最近の研究では、ミラーニューロンの活動が精神病症状と正の相関があることが示唆されている(すなわち、ミュー波抑制/ミラー ニューロンの活動が大きいほど、精神病症状の重症度が高い被験者で最も高かった)。研究者らは、「より高いミラーニューロン活動は、統合失調症の感覚ゲー ト欠損の基盤であり、特に社会的に関連した刺激に対する感覚の誤認識に寄与し、妄想や幻覚の仮説的メカニズムである可能性がある」と結論づけた [115]。 |

| Doubts concerning mirror neurons Although many in the scientific community have expressed excitement about the discovery of mirror neurons, there are scientists who have expressed doubts about both the existence and role of mirror neurons in humans. According to scientists such as Hickok, Pascolo, and Dinstein, it is not clear whether mirror neurons really form a distinct class of cells (as opposed to an occasional phenomenon seen in cells that have other functions),[116] and whether mirror activity is a distinct type of response or simply an artifact of an overall facilitation of the motor system.[11] In 2008, Ilan Dinstein et al. argued that the original analyses were unconvincing because they were based on qualitative descriptions of individual cell properties, and did not take into account the small number of strongly mirror-selective neurons in motor areas.[10] Other scientists have argued that the measurements of neuron fire delay seem not to be compatible with standard reaction times,[116] and pointed out that nobody has reported that an interruption of the motor areas in F5 would produce a decrease in action recognition.[11] (Critics of this argument have replied that these authors have missed human neuropsychological and TMS studies reporting disruption of these areas do indeed cause action deficits[39][41] without affecting other kinds of perception.)[40] In 2009, Lingnau et al. carried out an experiment in which they compared motor acts that were first observed and then executed to motor acts that were first executed and then observed. They concluded that there was a significant asymmetry between the two processes that indicated that mirror neurons do not exist in humans. They stated "Crucially, we found no signs of adaptation for motor acts that were first executed and then observed. Failure to find cross-modal adaptation for executed and observed motor acts is not compatible with the core assumption of mirror neuron theory, which holds that action recognition and understanding are based on motor simulation."[117] However, in the same year, Kilner et al. showed that if goal directed actions are used as stimuli, both IPL and premotor regions show the repetition suppression between observation and execution that is predicted by mirror neurons.[118] In 2009, Greg Hickok published an extensive argument against the claim that mirror neurons are involved in action-understanding: "Eight Problems for the Mirror Neuron Theory of Action Understanding in Monkeys and Humans." He concluded that "The early hypothesis that these cells underlie action understanding is likewise an interesting and prima facie reasonable idea. However, despite its widespread acceptance, the proposal has never been adequately tested in monkeys, and in humans there is strong empirical evidence, in the form of physiological and neuropsychological (double-) dissociations, against the claim."[11] The mirror neurons can be activated only after the goal of the observed action has been attributed by other brain structures. Vladimir Kosonogov sees another contradiction. The proponents of mirror neuron theory of action understanding postulate that the mirror neurons code the goals of others' actions because they are activated if the observed action is goal-directed. However, the mirror neurons are activated only when the observed action is goal-directed (object-directed action or a communicative gesture, which certainly has a goal too). How do they "know" that the definite action is goal-directed? At what stage of their activation do they detect a goal of the movement or its absence? In his opinion, the mirror neuron system can be activated only after the goal of the observed action is attributed by some other brain structures.[50] Neurophilosophers such as Patricia Churchland have expressed both scientific and philosophical objections to the theory that mirror neurons are responsible for understanding the intentions of others. In chapter 5 of her 2011 book, Braintrust, Churchland points out that the claim that mirror neurons are involved in understanding intentions (through simulating observed actions) is based on assumptions that are clouded by unresolved philosophical issues. She makes the argument that intentions are understood (coded) at a more complex level of neural activity than that of individual neurons. Churchland states that "A neuron, though computationally complex, is just a neuron. It is not an intelligent homunculus. If a neural network represents something complex, such as an intention [to insult], it must have the right input and be in the right place in the neural circuitry to do that."[119] Cecilia Heyes has advanced the theory that mirror neurons are the byproduct of associative learning as opposed to evolutionary adaptation. She argues that mirror neurons in humans are the product of social interaction and not an evolutionary adaptation for action-understanding. In particular, Heyes rejects the theory advanced by V.S. Ramachandran that mirror neurons have been "the driving force behind the great leap forward in human evolution."[12][120] |

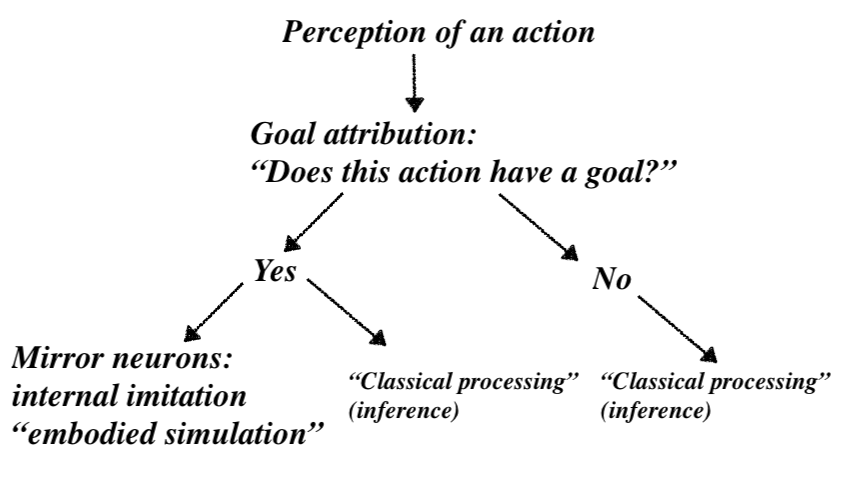

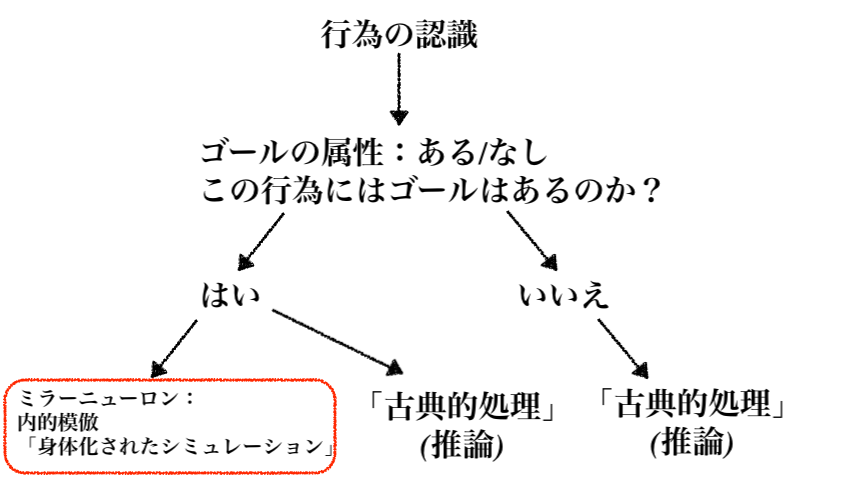

ミラーニューロンに関する疑問 科学界の多くはミラーニューロンの発見に興奮を表明しているが、ヒトにおけるミラーニューロンの存在と役割の両方について疑念を表明している科学者もい る。ヒコック、パスコロ、ディンシュタインなどの科学者によると、ミラーニューロンが(他の機能を持つ細胞で時折見られる現象とは対照的に)本当に別個の 細胞群を形成しているのかどうか[116]、ミラー活動が別個のタイプの反応なのか、それとも単に運動系の全体的な促進作用のアーチファクトなのかは明ら かでない[11]。 2008年、イラン・ディンシュタイン(Ilan Dinstein)ら は、当初の分析は個々の細胞の特性の定性的な記述に基 づいており、運動野におけるミラー選択性の強いニューロンの 数が少ないことを考慮していないため、説得力がないと主張し た[10]。 [10] 他の科学者は、ニューロンの発火遅延の測定値が標準的な 反応時間と適合していないようだと主張し[116]、F5の運動領 域の中断が行動認知の低下をもたらすことを報告した者はい ないと指摘した[11](この議論に対する批評家は、これらの著者 は、これらの領域の中断が他の種類の知覚に影響を与えずに、実 際に行動障害を引き起こすことを報告したヒトの神経心理学 的研究やTMS研究[39][41]を見逃していると反論している)[40]。 2009年、Lingnauらは、最初に観察されてから実行された運動行為と、最初に実行されてから観察された運動行為とを比較する実験を行った。その結 果、2つの過程には有意な非対称性があり、ヒトにはミラーニューロンが存在しないことが示された。そして、「決定的に重要なのは、最初に実行され、次に観 察された運動行為には適応の兆候が見られなかったことである。実行された運動行為と観察された運動行為に対するクロスモーダルな適応を見いだせなかったこ とは、行為の認識と理解は運動シミュレーションに基づいているとするミラーニューロン理論の中核的な仮定とは適合しない」[117]。しかし、同年、 Kilnerらは、目標指示行為を刺激として使用した場合、IPLと運動前野の両方が、ミラーニューロンによって予測される観察と実行の間の反復抑制を示 すことを示した[118]。 2009年、グレッグ・ヒコックは、ミラーニューロンが行動理解に関与しているという主張に対する広範な反論を発表した: 「グレッグ・ヒコックは2009年に、ミラーニューロンが行為理解に関与しているという主張に対する広範な反論を発表した。彼は、「これらの細胞が行動理 解の根底にあるという初期の仮説は、同様に興味深く、一応妥当な考えである。しかし、広く受け入れられているにもかかわらず、この仮説はサルでは十分に検 証されたことがなく、ヒトでは生理学的・神経心理学的(二重)解離という形で、この主張に対する強い経験的証拠がある」[11]。 ミラーニューロンは、観察された行動の目標が他の脳構造によって帰属された後にのみ活性化される。 ウラジーミル・コソノゴフは別の矛盾を見ている。行動理解のミラーニューロン理論の支持者は、ミラーニューロンは観察された行動が目標指向的であれば活性 化されるため、他者の行動の目標をコード化すると仮定する。しかし、ミラーニューロンが活性化されるのは、観察された行動が目標指向性(対象指向性の行 動、あるいはコミュニケーション的ジェスチャー。) ミラーニューロンはどのようにして、その明確な行動が目標指向的であることを「知る」のだろうか?作動のどの段階で、その動作の目標があるのか、あるいは ないのかを検知するのだろうか?彼の意見では、ミラーニューロンシステムは、観察された動作のゴールが他の脳構造によって帰属された後にのみ活性化するこ とができる[50]。 パトリシア・チャーチランドのような神経哲学者は、ミラーニューロンが他者の意図を理解する役割を担っているという理論に対して、科学的・哲学的な反論を 表明している。チャーチランドは2011年の著書『ブレイン・トラスト』の第5章で、ミラーニューロンが(観察された行動をシミュレートすることで)意図 の理解に関与しているという主張は、未解決の哲学的問題によって曇らされた仮定に基づいていると指摘している。彼女は、意図は個々のニューロンよりも複雑 な神経活動のレベルで理解される(コード化される)と主張する。チャーチランドは、「ニューロンは、計算上複雑ではあるが、単なるニューロンである。知的 なホムンクルスではない。神経回路網が何か複雑なもの、例えば[侮辱する]意思を表すのであれば、それには適切な入力があり、神経回路内の適切な場所にな ければならない」[119]。 セシリア・ヘイズは、ミラーニューロンは進化的適応とは対照的に、連想学習の副産物であるという説を唱えている。彼女は、ヒトのミラーニューロンは社会的 相互作用の産物であり、行動理解のための進化的適応ではないと主張している。特にヘイズは、V.S.ラマチャンドランによって提唱された、ミラーニューロ ンが「人類進化の大きな飛躍の原動力となった」という説を否定している[12][120]。 |

| Associative sequence learning Common coding theory Emotional contagion Empathy Mirror-touch synesthesia Mirroring (psychology) Motor cognition Motor theory of speech perception On Intelligence Positron emission tomography Simulation theory of empathy Speech repetition Spindle neuron |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mirror_neuron |

|

| Imitation (from Latin imitatio,

"a copying, imitation"[1]) is a behavior whereby an individual observes

and replicates another's behavior. Imitation is also a form of that

leads to the "development of traditions, and ultimately our culture. It

allows for the transfer of information (behaviors, customs, etc.)

between individuals and down generations without the need for genetic

inheritance."[2] The word imitation can be applied in many contexts,

ranging from animal training to politics.[3] The term generally refers

to conscious behavior; subconscious imitation is termed mirroring.[4] |

模倣(ラテン語のimitatio「模倣、模倣」から[1])とは、個

人が他の人の行動を観察し、それを模倣する行動のことである。模倣はまた、「伝統の発展、ひいては文化の発展」につながる一形態でもある。模倣という言葉

は、動物の調教から政治に至るまで、様々な文脈で適用されることがある。 |

| Anthropology and social sciences In anthropology, some theories hold that all cultures imitate ideas from one of a few original cultures or several cultures whose influence overlaps geographically. Evolutionary diffusion theory holds that cultures influence one another, but that similar ideas can be developed in isolation. Scholars[5] as well as popular authors[6][7] have argued that the role of imitation in humans is unique among animals. However, this claim has been recently challenged by scientific research which observed social learning and imitative abilities in animals. Psychologist Kenneth Kaye showed[8][9] that the ability of infants to match the sounds or gestures of an adult depends on an interactive process of turn-taking over many successive trials, in which adults' instinctive behavior plays as great a role as that of the infant. These writers assume that evolution would have selected imitative abilities as fit because those who were good at it had a wider arsenal of learned behavior at their disposal, including tool-making and language. However, research also suggests that imitative behaviors and other social learning processes are only selected for when outnumbered or accompanied by asocial learning processes: an over-saturation of imitation and imitating individuals leads humans to collectively copy inefficient strategies and evolutionarily maladaptive behaviors, thereby reducing flexibility to new environmental contexts that require adaptation.[10] Research suggests imitative social learning hinders the acquisition of knowledge in novel environments and in situations where asocial learning is faster and more advantageous.[11][12] In the mid-20th century, social scientists began to study how and why people imitate ideas. Everett Rogers pioneered innovation diffusion studies, identifying factors in adoption and profiles of adopters of ideas.[13] Imitation mechanisms play a central role in both analytical and empirical models of collective human behavior.[14] |

人類学と社会科学 人類学では、すべての文化は数少ない原初的な文化のひとつ、あるいは地理的に影響が重なるいくつかの文化から発想を模倣しているとする理論がある。進化論 的拡散理論では、文化は互いに影響を与え合うが、似たような考え方は単独でも発展し得るとする。 学者[5]や一般的な作家[6][7]は、ヒトにおける模倣の役割は動物の中でも特殊であると主張してきた。しかしこの主張は、動物における社会的学習と 模倣能力を観察した科学的研究によって、近年覆されている。 心理学者のケネス・ケイは、乳幼児が大人の音やジェスチャーに合わせる能力は、何度も試行錯誤を繰り返す順番取りの相互作用的なプロセスに依存しており、 そこでは大人の本能的な行動が乳幼児のそれと同じくらい大きな役割を果たしていることを示した[8][9]。これらの作家は、模倣が得意な者は道具作りや 言語など、より幅広い学習行動を自由に使えるため、進化が模倣能力を選択したと仮定している。 しかし、模倣行動やその他の社会的学習過程が選択されるのは、非社会的学習過程の方が多いか、非社会的学習過程を伴っている場合だけであることも研究に よって示唆されている。模倣や模倣をする個体が過剰に飽和すると、人間は非効率的な戦略や進化的に不適応な行動を集団的に模倣するようになり、その結果、 適応を必要とする新たな環境的文脈に対する柔軟性が低下するのである[10]。研究によると、模倣的な社会的学習は、新規の環境や非社会的学習の方がより 迅速で有利な状況において、知識の獲得を妨げるとされている[11][12]。 20世紀半ば、社会科学者は人々がどのように、そしてなぜ アイデアを模倣するのかを研究し始めた。エベレット・ロジャーズはイノベーション普及研究のパイオニアであ り、アイデアの採用における要因や採用者のプロファイルを特定した[13]。 |

| Neuroscience Humans are capable of imitating movements, actions, skills, behaviors, gestures, pantomimes, mimics, vocalizations, sounds, speech, etc. and that we have particular "imitation systems" in the brain is old neurological knowledge dating back to Hugo Karl Liepmann. Liepmann's model 1908 "Das hierarchische Modell der Handlungsplanung" (the hierarchical model of action planning) is still valid. On studying the cerebral localization of function, Liepmann postulated that planned or commanded actions were prepared in the parietal lobe of the brain's dominant hemisphere, and also frontally. His most important pioneering work is when extensively studying patients with lesions in these brain areas, he discovered that the patients lost (among other things) the ability to imitate. He was the one who coined the term "apraxia" and differentiated between ideational and ideomotor apraxia. It is in this basic and wider frame of classical neurological knowledge that the discovery of the mirror neuron has to be seen. Though mirror neurons were first discovered in macaques, their discovery also relates to humans.[15] Human brain studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) revealed a network of regions in the inferior frontal cortex and inferior parietal cortex which are typically activated during imitation tasks.[16] It has been suggested that these regions contain mirror neurons similar to the mirror neurons recorded in the macaque monkey.[17] However, it is not clear if macaques spontaneously imitate each other in the wild. Neurologist V. S. Ramachandran argues that the evolution of mirror neurons were important in the human acquisition of complex skills such as language and believes the discovery of mirror neurons to be a most important advance in neuroscience.[18] However, little evidence directly supports the theory that mirror neuron activity is involved in cognitive functions such as empathy or learning by imitation.[19] Evidence is accumulating that bottlenose dolphins employ imitation to learn hunting and other skills from other dolphins.[20][21] Japanese monkeys have been seen to spontaneously begin washing potatoes after seeing humans washing them.[22] |

神経科学 人間は、動作、行為、技能、行動、ジェスチャー、パントマイム、模倣、発声、音、話し方などを模倣することができ、脳に特定の「模倣システム」があること は、フーゴー・カール・リープマンにさかのぼる古い神経学的知識である。リープマンの1908年のモデル "Das hierarchische Modell der Handlungsplanung"(行動計画の階層モデル)は今でも有効である。大脳の機能局在を研究した結果、リープマンは、計画された、あるいは命 令された行動は、脳の優位半球の頭頂葉で準備され、前頭葉でも準備されると仮定した。彼の最も重要な先駆的研究は、これらの脳領域に病変を持つ患者を広範 囲に研究したところ、患者が(とりわけ)模倣能力を失っていることを発見したことである。彼は「失行症」という言葉を作り、観念性失行症と観念運動性失行 症を区別した人物である。ミラーニューロンの発見は、このような古典的神経学の基本的かつ広範な知識の枠の中で見なければならない。ミラーニューロンはマ カクで最初に発見されたが、その発見はヒトにも関係している[15]。 機能的磁気共鳴画像法(fMRI)を用いたヒトの脳研究により、下前頭皮質と下頭頂皮質に、模倣課題中に典型的に活性化される領域のネットワークが明らか になった[16]。 神経学者のV・S・ラマチャンドランは、ミラーニューロンの進化は、人間が言語などの複雑な技能を獲得する上で重要であったと主張し、ミラーニューロンの 発見は神経科学における最も重要な進歩であると考えている[18]。しかし、ミラーニューロンの活動が共感や模倣による学習などの認知機能に関与している という説を直接裏付ける証拠はほとんどない[19]。 バンドウイルカが他のイルカから狩猟やその他の技術を学ぶために模倣を行うという証拠が蓄積されつつある[20][21]。 ニホンザルは、人間がジャガイモを洗うのを見て、自発的にジャガイモを洗い始めることが確認されている[22]。 |

| Mirror neuron system Research has been conducted to locate where in the brain specific parts and neurological systems are activated when humans imitate behaviors and actions of others, discovering a mirror neuron system. This neuron system allows a person to observe and then recreate the actions of others. Mirror neurons are premotor and parietal cells in the macaque brain that fire when the animal performs a goal directed action and when it sees others performing the same action."[23] Evidence suggests that the mirror neuron system also allows people to comprehend and understand the intentions and emotions of others.[24] Problems of the mirror neuron system may be correlated with the social inadequacies of autism. There have been many studies done showing that children with autism, compared with typically-developing children, demonstrate reduced activity in the frontal mirror neuron system area when observing or imitating facial emotional expressions. Of course, the higher the severity of the disease, the lower the activity in the mirror neuron system is.[23] |

ミラーニューロンシステム 人間が他人の行動や行為を模倣する際に、脳のどの部分や神経系が活性化されるかを特定する研究が行われ、ミラーニューロンシステムが発見された。この ニューロンシステムによって、人は他人の行動を観察し、それを再現することができる。ミラーニューロンは、サルの脳にある運動前野と頭頂の細胞で、その動 物が目標に向けた行動をするときや、他者が同じ行動をするのを見たときに発火する。自閉症の子どもは、定型発達の子どもと比較して、顔の感情表現を観察し たり模倣したりする際に、前頭部のミラーニューロン系領域の活動が低下していることを示す研究が数多く行われている。もちろん、病気の重症度が高ければ高 いほど、ミラーニューロン系の活動は低下する[23]。 |

| Animal behavior Scientists debate whether animals can consciously imitate the unconscious incitement from sentinel animals, whether imitation is uniquely human, or whether humans do a complex version of what other animals do.[25][26] The current controversy is partly definitional. Thorndike uses "learning to do an act from seeing it done."[27] It has two major shortcomings: first, by using "seeing" it restricts imitation to the visual domain and excludes, e.g., vocal imitation and, second, it would also include mechanisms such as priming, contagious behavior and social facilitation,[28] which most scientist distinguish as separate forms of observational learning. Thorpe suggested defining imitation as "the copying of a novel or otherwise improbable act or utterance, or some act for which there is clearly no instinctive tendency."[29] This definition is favored by many scholars, though questions have been raised how strictly the term "novel" has to be interpreted and how exactly a performed act has to match the demonstration to count as a copy. Hayes and Hayes (1952) used the "do-as-I-do" procedure to demonstrate the imitative abilities of their trained chimpanzee "Viki."[30] Their study was repeatedly criticized for its subjective interpretations of their subjects' responses. Replications of this study[31] found much lower matching degrees between subjects and models. However, imitation research focusing on the copying fidelity got new momentum from a study by Voelkl and Huber.[32] They analyzed the motion trajectories of both model and observer monkeys and found a high matching degree in their movement patterns. Paralleling these studies, comparative psychologists provided tools or apparatuses that could be handled in different ways. Heyes[33][34] and co-workers reported evidence for imitation in rats that pushed a lever in the same direction as their models, though later on they withdrew their claims due to methodological problems in their original setup.[35] By trying to design a testing paradigm that is less arbitrary than pushing a lever to the left or to the right, Custance and co-workers[36] introduced the "artificial fruit" paradigm, where a small object could be opened in different ways to retrieve food placed inside—not unlike a hard-shelled fruit. Using this paradigm, scientists reported evidence for imitation in monkeys[37][38] and apes.[39][40][41] There remains a problem with such tool (or apparatus) use studies: what animals might learn in such studies need not be the actual behavior patterns (i.e., the actions) that were observed. Instead they might learn about some effects in the environment (i.e., how the tool moves, or how the apparatus works).[42] This type of observational learning, which focuses on results, not actions, has been dubbed emulation (see Emulation (observational learning)). In an article written by Carl Zimmer, he looked into a study being done by Derek Lyons, focusing on human evolution, in which he studied a chimpanzee. He first started with showing the chimpanzee how to retrieve food from a box. The chimpanzee soon caught on and did exactly what the scientist just did. They wanted to see if the chimpanzee's brain functioned just like a human brain, so they replicated the experiment using 16 children, following the same procedure; once the children saw how it was done, they followed the same exact steps.[43] Imitation in animals BLACKBIRD-Mimicking Police Siren Imitation in animals is a study in the field of social learning where learning behavior is observed in animals specifically how animals learn and adapt through imitation. Ethologists can classify imitation in animals by the learning of certain behaviors from conspecifics.[44] More specifically, these behaviors are usually unique to the species and can be complex in nature and can benefit the individual's survival.[44] Some scientists believe true imitation is only produced by humans, arguing that simple learning though sight is not enough to sustain as a being who can truly imitate.[45] Thorpe defines true imitation as "the copying of a novel or otherwise improbable act or utterance, or some act for which there is clearly no instinctive tendency," which is highly debated for its portrayal of imitation as a mindless repeating act.[45] True imitation is produced when behavioral, visual and vocal imitation is achieved, not just the simple reproduction of exclusive behaviors.[45] Imitation is not a simple reproduction of what one sees; rather it incorporates intention and purpose.[45] Animal imitation can range from survival purpose; imitating as a function of surviving or adapting, to unknown possible curiosity, which vary between different animals and produce different results depending on the measured intelligence of the animal.[45] There is considerable evidence to support true imitation in animals.[46] Experiments performed on apes, birds and more specifically the Japanese quail have provided positive results to imitating behavior, demonstrating imitation of opaque behavior.[46] However the problem that lies is in the discrepancies between what is considered true imitation in behavior.[46] Birds have demonstrated visual imitation, where the animal simply does as it sees.[46] Studies on apes however have proven more advanced results in imitation, being able to remember and learn from what they imitate.[46] Studies have demonstrated far more positive results with behavioral imitation in primates and birds than any other type of animal.[46] Imitation in non-primate mammals and other animals have been proven difficult to conclude solid positive results for and poses a difficult question to scientists on why that is so.[46] Theories There are two types of theories of imitation, transformational and associative. Transformational theories suggest that the information that is required to display certain behavior is created internally through cognitive processes and observing these behaviors provides incentive to duplicate them.[47] Meaning we already have the codes to recreate any behavior and observing it results in its replication. Albert Bandura's "social cognitive theory" is one example of a transformational theory.[48] Associative, or sometimes referred to as "contiguity",[49] theories suggest that the information required to display certain behaviors does not come from within ourselves but solely from our surroundings and experiences.[47] These theories have not yet provided testable predictions in the field of social learning in animals and have yet to conclude strong results.[47] New developments There have been three major developments in the field of animal imitation. The first, behavioral ecologists and experimental psychologists found there to be adaptive patterns in behaviors in different vertebrate species in biologically important situations.[50] The second, primatologists and comparative psychologists have found imperative evidence that suggest true learning through imitation in animals.[50] The third, population biologists and behavioral ecologists created experiments that demand animals to depend on social learning in certain manipulated environments.[50] |

動物行動 科学者たちは、動物が無意識のうちにセンチネルアニマルからの扇動を意識的に模倣することができるのか、模倣は人間特有のものなのか、あるいは人間は他の 動物が行うことの複雑なバージョンを行っているのかについて議論している[25][26]。ソーンダイクは「ある行為が行われるのを見てそれを行うことを 学習する」[27]と定義しているが、これには2つの大きな欠点がある。第1に、「見る」ことを用いることによって、模倣を視覚的領域に限定し、例えば声 による模倣を除外していること、第2に、プライミング、伝染行動、社会的促進[28]などのメカニズムも含まれることになり、多くの科学者はこれらを観察 学習の別形態として区別している。ソープは模倣を「新奇な、あるいはあり得ない行為や発話、あるいは明らかに本能的な傾向がない行為を模倣すること」と定 義することを提案した[29]。この定義は多くの学者に支持されているが、「新奇な」という用語をどの程度厳密に解釈しなければならないか、また模倣とし てカウントするために実演された行為がどの程度正確に実演と一致しなければならないかという疑問が提起されている。 HayesとHayes(1952)は、訓練されたチンパンジー「Viki」の模倣能力を実証するために「Do-as-I-Do」手順を使用した [30]。この研究の複製[31]では、被験者とモデルのマッチング度ははるかに低いことが判明している。しかし、模倣の忠実性に焦点を当てた模倣研究 は、VoelklとHuberによる研究[32]から新たな勢いを得た。彼らはモデルと観察者両方のサルの運動軌跡を分析し、その運動パターンに高い一致 度を見出した。 これらの研究と並行して、比較心理学者は様々な方法で扱える道具や装置を提供した。Hees[33][34]らは、モデルと同じ方向にレバーを押すラッ トにおける模倣の証拠を報告したが、後に当初の設定に方法論 的な問題があったため、その主張を撤回した[35]。このパラダイムを用いて、科学者たちはサル[37][38]や類人猿における模倣の証拠を報告した [39][40][41]。このような道具(または器具)使用研究には問題が残っている:このような研究で動物が学ぶかもしれないことは、観察された実際 の行動パターン(すなわち行動)である必要はない。このような観察学習はエミュレーションと呼ばれている(エミュレーション(観察学習)参照)。 カール・ジマーが書いた記事の中で、彼はチンパンジーを研究しているデレク・ライオンズが行っているヒトの進化に焦点を当てた研究を調べた。彼はまず、箱 から餌を取り出す方法をチンパンジーに見せることから始めた。チンパンジーはすぐに理解し、科学者が今やったことと同じことをした。彼らはチンパンジーの 脳が人間の脳と同じように機能するかどうかを確かめたかったので、16人の子供を使って同じ手順で実験を再現した。 動物における模倣 BLACKBIRD-Mimicking Police Siren 動物における模倣とは、社会学習の分野における研究であり、動物における学習行動を観察するものである。倫理学者は、動物における模倣を、同種の動物から 特定の行動を学習することによって分類することができる。 一部の科学者は真の模倣は人間によってのみ生み出されると考えており、視覚による単純な学習だけでは真に模倣できる存在として維持するには不十分であると 主張している[45]。ソープは真の模倣を「斬新な、あるいはそうでなければありえない行為や発話、あるいは明らかに本能的な傾向がない何らかの行為を模 倣すること」と定義しているが、これは模倣を無心な反復行為として描写しているとして大いに議論されている。 [真の模倣とは、行動模倣、視覚模倣、音声模倣が達成されたときに生じるものであり、排他的な行動の単純な再現を意味するものではない[45]。 動物における真の模倣を裏付ける証拠はかなりある[46]。類人猿、鳥類、より具体的にはニホンウズラを用いた実験では、模倣行動に対して肯定的な結果が 得られており、不透明な行動の模倣が実証されている[46]。しかし問題は、行動における真の模倣と見なされるものの食い違いにある。 [しかし類人猿の研究では、模倣したものを記憶し、そこから学ぶことができるという、模倣においてより高度な結果が証明されている。霊長類や鳥類における 行動模倣は、他のどの種類の動物よりもはるかに肯定的な結果が証明されている。霊長類以外の哺乳類やその他の動物における模倣は、肯定的な結果をしっかり と結論づけることが難しいことが証明されており、なぜそうなのかという難しい問題を科学者に投げかけている[46]。 理論 模倣には、形質転換説と連想説の2種類がある。変容理論では、ある行動を示すために必要な情報は、認知プロセスを通じて内部で作成され、これらの行動を観 察することで、それを複製するインセンティブが得られると示唆する。アルバート・バンデューラの「社会的認知理論」は変容的理論の一例である[48]。連 想的理論、または「連続性」[49]と呼ばれることもある理論は、特定の行動を示すために必要な情報は、私たち自身の内部からではなく、もっぱら私たちの 周囲や経験からもたらされることを示唆している[47]。これらの理論は、動物の社会的学習の分野ではまだ検証可能な予測を提供しておらず、強力な結果を 結論づけるには至っていない[47]。 新たな発展 動物の模倣の分野では、3つの大きな発展があった。1つ目は、行動生態学者と実験心理学者が、生物学的に重要な状況において、異なる脊椎動物の種における 行動に適応的なパターンが存在することを発見したことである[50]。2つ目は、霊長類学者と比較心理学者が、動物における模倣による真の学習を示唆する 不完全な証拠を発見したことである[50]。3つ目は、集団生物学者と行動生態学者が、特定の操作された環境において、動物に社会的学習に依存することを 要求する実験を作成したことである[50]。 |