モルデカイ・マヌエル・ノア

Mordecai Manuel Noah, 1785-1851

モルデカイ・マヌエル・ノア

Mordecai Manuel Noah, 1785-1851

★モルデカイ・マヌエル・ノア(Mordecai Manuel Noah, 1785年7月14日、ペンシルベニア州フィラデルフィア - 1851年5月22日、ニューヨーク)は、アメリカの保安官、劇作家、外交官、ジャーナリスト、ユートピアンである。ポルトガル系セファルディ人の家系に 生まれた。19世紀初頭のニューヨークで最も重要なユダヤ人信徒指導者であり、米国の最初の言論ユダヤ人として全国的に有名になった。

| Mordecai

Manuel Noah

(July 14, 1785, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – May 22, 1851, New York)

was an American sheriff, playwright, diplomat, journalist, and utopian.

He was born in a family of Portuguese Sephardic ancestry.[1] He was the

most important Jewish lay leader in New York in the early 19th

century,[2] and the first Jew born in the United States to reach

national prominence.[3] His politically motivated reviews blasting

plays and performers "of colour" at William Brown's African Grove

Theatre led to his identification as the originator of the

stereotypical black portrayed in American minstrel shows and as "the

father of Negro minstrelsy".[4] |

モ

ルデカイ・マヌエル・ノア(Mordecai Manuel Noah, 1785年7月14日、ペンシルベニア州フィラデルフィア -

1851年5月22日、ニューヨーク)は、アメリカの保安官、劇作家、外交官、ジャーナリスト、ユートピアンである。ポルトガル系セファルディ人の家系に

生まれた。19世紀初頭のニューヨークで最も重要なユダヤ人信徒指導者であり、米国

で生まれた最初のユダヤ人として全国的に有名になった。ウィリアム・ブラウンのアフリカン・グローブ・シアターで「有色人種」の劇やパ

フォーマーを非難する政治的動機に基づく批評をしたことから、アメリカの吟遊詩人ショーに描かれるステレオタイプの黒人の元祖、「ニグロ吟遊詩人の父」と

して知られるようになった。 |

| Career Noah engaged in trade and law. After moving to Charleston, South Carolina, he dedicated himself to politics. Racial politics Noah was a vocal proponent of slavery in the United States in the mid-1800s. Noah wrote that "To emancipate the slaves would be to jeopardize the safety of the whole country." The Freedom's Journal called Noah "the black man's bitterest enemy"[5] Noah wrote a play called Fortress of Sorrento which was poorly reviewed and never staged by a white theater. However, the African Grove Theater staged and performed it. Being associated with the African-Americans whom he had dubbed eternal slaves made Noah very angry. He raided the theater, declared it illegal, and denounced black Americans as unfit to vote or hold office.[4] |

経歴 ノアは貿易と法律に従事した。サウスカロライナ州チャールストンに移住後、政治に専念する。 人種差別の政治 1800年代半ばのアメリカでは、ノアは奴隷制の推進派であった。ノア は、"奴隷を解放することは、国全体の安全を危うくすることだ "と書いている。『フリーダムズ・ジャーナル』はノアを「黒人の最も苦い敵」と呼んだ[5]。 ノアは『ソレントの要塞』という戯曲を書いたが、批評は芳しくなく、白人の劇場では上演されることはなかった。しかし、アフリカン・グローブ・シアターが それを上演し、上演された。ノアは、自分が永遠の奴隷と呼んでいたアフリカ系アメリカ人と関わりを持つことに強い怒りを覚えた。彼は劇場を襲撃し、違法と 宣言し、黒人のアメリカ人は選挙権や公職に就く資格がないと糾弾した[4]。 |

| Diplomat In 1811, he was appointed by President James Madison as consul at Riga, then part of Imperial Russia, but declined, and, in 1813, was nominated Consul to the Kingdom of Tunis, where he rescued American citizens kept as slaves by Moroccan slave owners. In 1815, Noah was removed from his position;[6] in the words of U.S. Secretary of State James Monroe, his religion was "an obstacle to the exercise of [his] Consular function." The incident caused outrage among Jews and non-Jews alike.[7] Noah sent many letters to the White House trying to get an answer as to why they felt his religion should be a justifiable reason for taking the office of Consul away. He had done well as consul and had even been able to accommodate the United States' request to secure the release of some hostages being held in Algiers. Noah never received a legitimate answer as to why the White House took the office of Consul away from him. The lack of a response worried Noah, as he was concerned that his removal would set a precedent that would block Jews from holding publicly elected or officially granted offices within the United States in the future.[citation needed] Noah protested and gained letters from John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison supporting church-state separation and tolerance for Jews.[8] Prominent Jewish leader Isaac Harby, a forerunner of Reform Judaism, was moved to write, in a letter to Monroe, [Jews] are by no means to be considered as a religious sect, tolerated by the government. They constitute a portion of the People. They are, in every respect, woven in and compacted with the citizens of the Republic.[9] |

外交官(Diplomat)として 1811年、ジェームズ・マディソン大統領によって当時帝政ロシアの一部であったリガの領事に任命されたが辞退し、1813 年にはチュニス王国の領事に指名され、モロッコの奴隷所有者によって奴隷として飼われていたアメリカ市民を救出した。1815年、ノアは解任された [6]。アメリカ国務長官ジェームズ・モンローの言葉を借りれば、彼の宗教は「(彼の)領事職の遂行に障害となる」ものであった。この事件はユダヤ人、非 ユダヤ人を問わず憤慨させた[7]。 ノアはホワイトハウスに多くの手紙を送り、なぜ彼の宗教が領事の職を奪う正当な理由となるのか、その答えを得ようとした。彼は領事としてよくやっていた し、アルジェで拘束されていた人質の解放を確保するために、アメリカの要求に応じることもできた。なぜ、ホワイトハウスが領事職を取り上げたのか、ノアは 正当な答えが得られなかった。ノアは、自分の解任が、将来ユダヤ人が公選または公的に認められた役職に就くことを阻む前例となることを懸念し、回答のない ことに不安を覚えた[citation needed]。 ノアは抗議し、ジョン・アダムズ、トーマス・ジェファーソン、ジェーム ズ・マディソンから、教会と国家の分離とユダヤ人に対する寛容さを支持する手紙を得た[8]。改革派ユダヤ教の先駆者である著名なユダヤ人指導者アイザッ ク・ハービーは、モンローへの手紙の中で、感動して次のように書いている。 [ユダヤ人]は決して政府によって容認されるような宗教的宗派とはみなされません。彼らは人民の一部を構成しています。彼らはあらゆる点で、共和国の市民 の中に織り込まれ、その中に組み込まれているのである[9]。 |

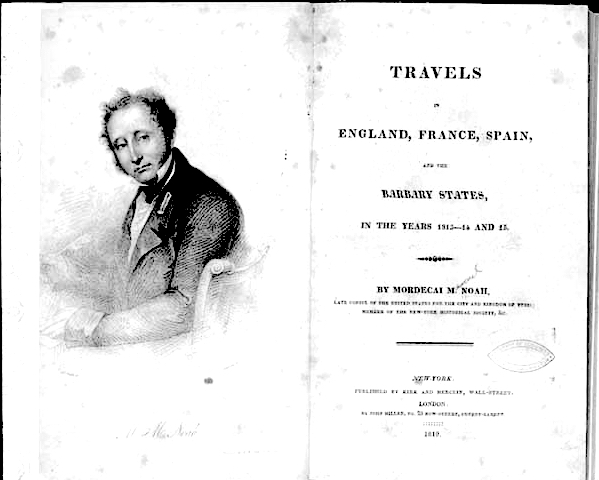

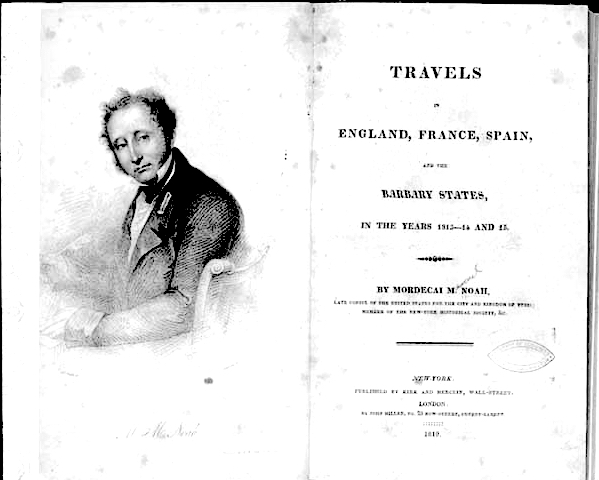

Later career Later careerNoah moved to New York, where he founded and edited The National Advocate, The New York Enquirer (later merged into the New York Courier and Enquirer), The Evening Star, and The Sunday Times newspapers. Noah was known to use his power as an editor of The National Advocate and law enforcement powers as a sheriff to personally shut down rival plays produced by black theater groups that drew attention and revenue away from his own productions, with some reports that the performers continued to recite their lines as they were dragged from the stage to their cells.[10] In 1819, Noah's most successful play, She Would Be a Soldier, was produced. That play has since established Noah as America's first important Jewish writer. She Would Be a Soldier is now included in college level anthologies.[which?] In 1825, with virtually no support from anyone — not even his fellow Jews — in a precursor to modern Zionism, he tried to found a Jewish "refuge" at Grand Island in the Niagara River, to be called "Ararat," after Mount Ararat, the Biblical resting place of Noah's Ark.[11] He purchased land on Grand Island for $4.38 per acre to build a refuge for Jews of all nations.[12] He had brought with him a cornerstone which read "Ararat, a City of Refuge for the Jews, founded by Mordecai M. Noah in the Month of Tizri, 5586 (Sept. 1825) & in the 50th Year of American Independence."[13] Noah also shared the belief, among various others, that some Native American "Indians" were from the Lost Tribes of Israel,[11] on which he wrote the Discourse on the Evidences of the American Indians being the Descendants of the Lost Tribes of Israel.[14] [15] In his Discourse on the Restoration of the Jews,[16] Noah proclaimed his faith that the Jews would return and rebuild their ancient homeland and called on America to take the lead in this endeavor.  On

September 2, 1825, soon after Noah's arrival in Buffalo from New York,

thousands of Christians and a smattering of Jews assembled for a

historic event. Noah led a large procession headed by Masons, a New

York militia company, and municipal leaders to St. Paul's Episcopal

Church.[17] Here, there was a brief ceremony — including a singing of

the psalms in Hebrew — the cornerstone was laid on the communion table,

and the new proclamation establishing the refuge was read.

"Proclamation – day ended with music, cannonade and libation. 24 guns,

recessional, masons retired to the Eagle Tavern, all with no one ever

having set foot on Grand Isle."[18] This was the beginning and the end

of Noah's venture: he lost heart and returned to New York two days

later without once having set foot on the island. The cornerstone was

taken out of the audience chamber of the church and laid against the

back of the building.[19] It is now on permanent display at the Buffalo

Historical Society in Buffalo, New York. Afterwards, despite the

failure of his project, he developed the idea of settling the Jews in

Palestine and, as such, he can be considered a forerunner of modern

Zionism.[11] On

September 2, 1825, soon after Noah's arrival in Buffalo from New York,

thousands of Christians and a smattering of Jews assembled for a

historic event. Noah led a large procession headed by Masons, a New

York militia company, and municipal leaders to St. Paul's Episcopal

Church.[17] Here, there was a brief ceremony — including a singing of

the psalms in Hebrew — the cornerstone was laid on the communion table,

and the new proclamation establishing the refuge was read.

"Proclamation – day ended with music, cannonade and libation. 24 guns,

recessional, masons retired to the Eagle Tavern, all with no one ever

having set foot on Grand Isle."[18] This was the beginning and the end

of Noah's venture: he lost heart and returned to New York two days

later without once having set foot on the island. The cornerstone was

taken out of the audience chamber of the church and laid against the

back of the building.[19] It is now on permanent display at the Buffalo

Historical Society in Buffalo, New York. Afterwards, despite the

failure of his project, he developed the idea of settling the Jews in

Palestine and, as such, he can be considered a forerunner of modern

Zionism.[11]From 1827 to 1828, Noah led New York City's Tammany Hall political machine. In his writings he alternately abhorred and supported southern slavery. He worried that emancipation would irreparably divide the country. MacArthur Award-winning cartoonist Ben Katchor fictionalized Noah's scheme for Grand Island in his The Jew of New York. Noah is also a minor character in Gore Vidal's 1973 novel Burr. The modern edition of Noah's writings is The Selected Writings of Mordecai Noah edited by Michael Schuldiner and Daniel Kleinfeld, and published by Greenwood Press. 1844 Discourse on the Restoration of the Jews by M.M. Noah, page 1. The page 2 shows the map of the Land of Israel. Noah's book Travels in England, France, Spain, and the Barbary States, in the Years 1813-14 and 15 |

その後の経歴 その後の経歴ノアはニューヨークに移り、『ナショナル・アドヴォケート』、『ニューヨーク・エンクワイアラー』(後に『ニューヨーク・クーリエ・アンド・エンクワイア ラー』に合併)、『イブニング・スター』、『サンデー・タイムズ』紙を創設し編集に携わった。ノアは、『ナショナル・アドヴォケート』の編集者としての権 力と保安官としての法執行力を使って、自分の作品から注目と収益を奪う黒人劇団が製作したライバル劇を自ら封殺したことで知られており、出演者は舞台から 牢屋に引きずり込まれる際にセリフを朗読し続けたという報告もある[10]。 1819年、ノアの最も成功した劇『She Would Be a Soldier』が上演された。この戯曲により、ノアはアメリカ初の重要なユダヤ人作家として確立された。She Would Be a Soldier』は現在、大学レベルのアンソロジーに収録されている[which?]。 1825年、現代のシオニズムの先駆けとして、仲間のユダヤ人ですらな く、誰からも事実上支援を受けずに、ナイアガラ川のグランドアイランドにユダヤ人の「避難所」を見つけようとし、聖書でノアの方舟が休んだアララト山にち なんで「アララト」と呼ばれるようになる。 [11] 彼はあらゆる国のユダヤ人のための避難所を建設するためにグランドアイランドの土地を1エーカーあたり4.38ドルで購入し、「アララト、ユダヤ人のため の避難所都市、モルデカイ・M・ノアによって5586年のティズリの月(1825年9月)及びアメリカ独立の50年目に設立」と書いた礎石を持ってきた[12]。 ノアはまた、様々な信念の中で、アメリカ先住民の「インディアン」の一部がイスラエ ルの失われた部族の出身であるという信念を共有しており[11]、それに基づいて『アメリカ先住民がイスラエルの失われた部族の子孫であることの証拠に関 する講話』を書いた[14] [15] ユダヤ人の復興に関する講話[16]では、ユダヤ人が帰還して古代の故郷を再建すると信じていると宣言して、アメリカにこの努力で先頭に立つよう呼び掛け た。  1825

年9月2日、ノアがニューヨークからバッファローに到着した直後、何千人ものキリスト教徒とわずかなユダヤ人が歴史的な出来事のために集合した。ノアは、

メイソン、ニューヨークの民兵隊、市の指導者たちを先頭にした大行列を率いてセント・ポール・エピスコパル教会に向かった[17]。ここで、ヘブライ語の

詩篇を歌うなどの短い式典が行われ、聖餐台の上に礎が置かれ、避難所の設立を宣言した新しい宣言が読み上げられた。「宣言-音楽、大砲、献杯で一日が終

わった。24門の大砲、退場、石工たちはEagle Tavernに退散し、誰もグランドアイルに足を踏み入れることはなかった」[18]

これがノアの冒険の始まりと終わりであった。礎石は教会の謁見の間から取り出され、建物の裏側に置かれた[19]。現在、ニューヨーク州バッファローの

バッファロー歴史協会に常設展示されている。その後、事業に失敗しながらも、パレス

チナにユダヤ人を入植させる構想を練ったことから、近代シオニズムの先駆けともいえる[11]。 1825

年9月2日、ノアがニューヨークからバッファローに到着した直後、何千人ものキリスト教徒とわずかなユダヤ人が歴史的な出来事のために集合した。ノアは、

メイソン、ニューヨークの民兵隊、市の指導者たちを先頭にした大行列を率いてセント・ポール・エピスコパル教会に向かった[17]。ここで、ヘブライ語の

詩篇を歌うなどの短い式典が行われ、聖餐台の上に礎が置かれ、避難所の設立を宣言した新しい宣言が読み上げられた。「宣言-音楽、大砲、献杯で一日が終

わった。24門の大砲、退場、石工たちはEagle Tavernに退散し、誰もグランドアイルに足を踏み入れることはなかった」[18]

これがノアの冒険の始まりと終わりであった。礎石は教会の謁見の間から取り出され、建物の裏側に置かれた[19]。現在、ニューヨーク州バッファローの

バッファロー歴史協会に常設展示されている。その後、事業に失敗しながらも、パレス

チナにユダヤ人を入植させる構想を練ったことから、近代シオニズムの先駆けともいえる[11]。1827年から1828年にかけて、ノアはニューヨークの政治組織タマンニーホールを率いていた。 著作では、南部の奴隷制を忌み嫌ったり、支持したりすることを交互に繰り返していた。彼 は奴隷解放が国を取り返しのつかないほど分断することを懸念していた。 マッカーサー賞を受賞した漫画家ベン・カッチョールは、『ニューヨークのユダヤ人』の中でノアのグランドアイランド計画をフィクションとして描いている。 また、ゴア・ヴィダルが1973年に発表した小説『Burr』にもノアは脇役として登場する。 ノアの著作の現代版は、マイケル・シュルディナーとダニエル・クラインフェルドが編集したThe Selected Writings of Mordecai Noahで、グリーンウッド・プレスから出版されている。 【写真01】1844年、M.M.ノアによるユダヤ人の復興に関する講話、1ページ目。2ページ目にはイスラエルの地の地図が示されている。 【写真02】ノアの著書『1813-14年および15年のイギリス、フランス、スペイン、バーバリー諸国における旅行記』。 |

| Bibliography Noah's book Travels in England, France, Spain, and the Barbary States, in the Years 1813-14 and 15 1813 – 1814: Travels in England, France, Spain, and the Barbary States 1837 : Discourse of the Evidence of the American Indians being the descendants of the Lost Tribes of Israël 1844: Discourse on the Restoration of the Jews |

参考文献 ノア著『イングランド、フランス、スペイン、および北アフリカ諸国紀行、1813年から14年、15年 1813年から1814年:イングランド、フランス、スペイン、および北アフリカ諸国紀行 1837年:アメリカ・インディアンが失われたイスラエルの12部族の子孫であることの証拠に関する論説 1844年:ユダヤ人の復興に関する論説 |

| Sources Selig Adler & Thomas E. Connolly. From Ararat to Suburbia: the History of the Jewish Community of Buffalo (Philadelphia: the Jewish Publication Society of America, 1960, Library of Congress Number 60-15834). Mordecai Manuel Noah: Travels in England, France, Spain, and the Barbary States: In the Years 1813-14 and 15 Isaac Goldberg, Major Noah: American-Jewish Pioneer, The Jewish Publication Society of Philadelphia, 1936. Michael Schuldiner and Daniel J. Kleinfeld, The Selected Writings of Mordecai Noah, Greenwood Press, 1999. IsraIsland. Nava Semel, 2005. |

出典 セリグ・アドラー、トーマス・E・コノリー著『アララトから郊外へ:バッファローのユダヤ人コミュニティの歴史』(フィラデルフィア:アメリカ・ユダヤ人 出版協会、1960年、米国議会図書館番号60-15834)。 モルデカイ・マヌエル・ノア著『イングランド、フランス、スペイン、および北アフリカ諸国への旅:1813年から1814年、1815年』 アイザック・ゴールドバーグ著、ノア少佐:アメリカ系ユダヤ人のパイオニア、フィラデルフィアのユダヤ人出版協会、1936年。 マイケル・シュルディナーとダニエル・J・クラインフェルド著、モルデカイ・ノアの選集、グリーンウッド・プレス、1999年。 イスラ・アイランド。ナヴァ・セミエル著、2005年。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mordecai_Manuel_Noah |

|

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報