現代人の多地域起源説

Multiregional origin of modern humans

出典:「パレオアジア文化史学」https://paleoasia.jp/research_overview/

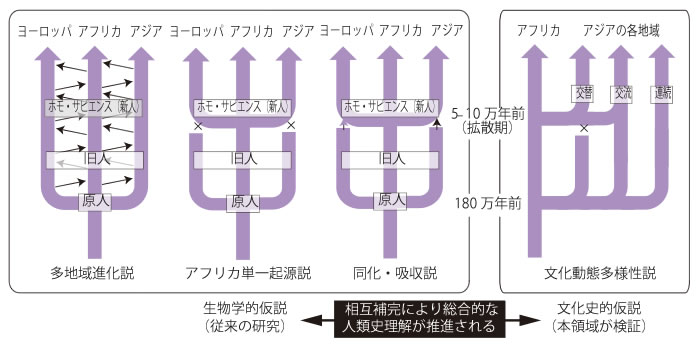

☆ 多地域仮説、多地域進化(MRE)、 または多中心仮説は、人類の進化パターンに関する単一起源説として広く受け入れられている「アフリカ単一起源説」に代わる科学的モデルである。 多地域進化説では、人類は200万年ほど前に初めて誕生し、その後の人類の進化は単一の連続した人類種の中で起こったとしている。この種は、ホモ・エレク トスやネアンデルタール人などの旧人類の形質と現代人の形質の両方を含み、解剖学的に現代人(ホモ・サピエンス)の多様な集団へと世界中で進化した。 この仮説は、「中心と周辺」のモデルによる漸進的変化のメカニズムにより、更新世を通じて遺伝的浮動、遺伝子流動、選択の間の必要なバランスが可能とな り、全体として地球規模で種としての進化が進み、一方で特定の形態的特徴については地域差が残ったと主張している[1]。多地域説の支持者は、化石やゲノ ムデータ、考古学的文化の連続性を、この仮説の根拠として挙げている。 多地域仮説は1984年に初めて提唱され、2003年に改訂された。その改訂版は、現代人はアフリカで誕生し、今日でもアフリカ起源が優勢であるとする同 化説に類似している。しかし、他の地域(旧人)のホミニン属種から地理的に異なる程度の混血も吸収している。

★ 多地域進化説は、現代人の起源に関する科学者たちの間で最も受け入れられている理論ではない。「アフリカ置換モデルは、主に現存する集団の遺伝子データ (特にミトコンドリアDNA)により、最も広く受け入れられている。このモデルは、現生人類は亜種や人種に分類できないという認識と一致しており、現生人 類のすべての集団が同じ潜在能力を共有していることを認めている」。アフリカ置換モデルは「アフリカ起源説」とも呼ばれ、現在最も広く受け入れられている モデルである。この説は、ホモ・サピエンスがアフリカで進化し、その後世界中に広がったというものである。また、「現在、主な対立する科学的仮説は、現生 人類が最近アフリカで誕生したというものである。この仮説では、現生人類は約10万~20万年前にアフリカで新種として誕生し、約5万~6万年前にアフリ カを出て、ホモ・エレクトスやネアンデルタールといった既存の人類と交配することなく置き換わったとされている。これは、多地域進化説とは異なり、多地域 進化説では、そのような移住の際に、既存の地域の人類集団との交配が予測される。

| The multiregional

hypothesis, multiregional evolution (MRE), or polycentric hypothesis,

is a scientific model that provides an alternative explanation to the

more widely accepted "out of Africa" model of monogenesis for the

pattern of human evolution. Multiregional evolution holds that the human species first arose around two million years ago and subsequent human evolution has been within a single, continuous human species. This species encompasses all archaic human forms such as Homo erectus and Neanderthals as well as modern forms, and evolved worldwide to the diverse populations of anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens). The hypothesis contends that the mechanism of clinal variation through a model of "centre and edge" allowed for the necessary balance between genetic drift, gene flow, and selection throughout the Pleistocene, as well as overall evolution as a global species, but while retaining regional differences in certain morphological features.[1] Proponents of multiregionalism point to fossil and genomic data and continuity of archaeological cultures as support for their hypothesis. The multiregional hypothesis was first proposed in 1984, and then revised in 2003. In its revised form, it is similar to the assimilation model, which holds that modern humans originated in Africa and today share a predominant recent African origin, but have also absorbed small, geographically variable, degrees of admixture from other regional (archaic) hominin species.[2] The multiregional hypothesis is not currently the most accepted theory of modern human origin among scientists. "The African replacement model has gained the widest acceptance owing mainly to genetic data (particularly mitochondrial DNA) from existing populations. This model is consistent with the realization that modern humans cannot be classified into subspecies or races, and it recognizes that all populations of present-day humans share the same potential."[3] The African replacement model is also known as the "out of Africa" theory, which is currently the most widely accepted model. It proposes that Homo sapiens evolved in Africa before migrating across the world."[4] And: "The primary competing scientific hypothesis is currently recent African origin of modern humans, which proposes that modern humans arose as a new species in Africa around 100-200,000 years ago, moving out of Africa around 50-60,000 years ago to replace existing human species such as Homo erectus and the Neanderthals without interbreeding.[5][6][7][8] This differs from the multiregional hypothesis in that the multiregional model predicts interbreeding with preexisting local human populations in any such migration."[8][9] |

多地域仮説、多地域進化(MRE)、または多中心仮説は、人類の進化パ

ターンに関する単一起源説として広く受け入れられている「アフリカ単一起源説」に代わる科学的モデルである。 多地域進化説では、人類は200万年ほど前に初めて誕生し、その後の人類の進化は単一の連続した人類種の中で起こったとしている。この種は、ホモ・エレク トスやネアンデルタール人などの旧人類の形質と現代人の形質の両方を含み、解剖学的に現代人(ホモ・サピエンス)の多様な集団へと世界中で進化した。 この仮説は、「中心と周辺」のモデルによる漸進的変化のメカニズムにより、更新世を通じて遺伝的浮動、遺伝子流動、選択の間の必要なバランスが可能とな り、全体として地球規模で種としての進化が進み、一方で特定の形態的特徴については地域差が残ったと主張している[1]。多地域説の支持者は、化石やゲノ ムデータ、考古学的文化の連続性を、この仮説の根拠として挙げている。 多地域仮説は1984年に初めて提唱され、2003年に改訂された。その改訂版は、現代人はアフリカで誕生し、今日でもアフリカ起源が優勢であるとする同 化説に類似している。しかし、他の地域(旧人)のホミニン属種から地理的に異なる程度の混血も吸収している。 多 地域進化説は、現代人の起源に関する科学者たちの間で最も受け入れられている理論ではない。「アフリカ置換モデルは、主に現存する集団の遺伝子データ(特 にミトコンドリアDNA)により、最も広く受け入れられている。このモデルは、現生人類は亜種や人種に分類できないという認識と一致しており、現生人類の すべての集団が同じ潜在能力を共有していることを認めている。」アフリカ置換モデルは「アフリカ起源説」とも呼ばれ、現在最も広く受け入れられているモデ ルである。この説は、ホモ・サピエンスがアフリカで進化し、その後世界中に広がったというものである。また、「現在、主な対立する科学的仮説は、現生人類 が最近アフリカで誕生したというものである。この仮説では、現生人類は約10万~20万年前にアフリカで新種として誕生し、約5万~6万年前にアフリカを 出て、ホモ・エレクトスやネアンデルタールといった既存の人類と交配することなく置き換わったとされている。これは、多地域進化説とは異なり、多地域進化 説では、そのような移住の際に、既存の地域の人類集団との交配が予測される。 |

| Overview The Multiregional hypothesis was proposed in 1984 by Milford H. Wolpoff, Alan Thorne and Xinzhi Wu.[10][11][1] Wolpoff credits Franz Weidenreich's "Polycentric" hypothesis of human origins as a major influence, but cautions that this should not be confused with polygenism, or Carleton Coon's model that minimized gene flow.[11][12][13] According to Wolpoff, multiregionalism was misinterpreted by William W. Howells, who confused Weidenreich's hypothesis with a polygenic "candelabra model" in his publications spanning five decades: How did Multiregional evolution get stigmatized as polygeny? We believe it comes from the confusion of Weidenreich's ideas, and ultimately of our own, with Coon's. The historic reason for linking Coon's and Weidenreich's ideas came from the mischaracterizations of Weidenreich's Polycentric model as a candelabra (Howells, 1942, 1944, 1959, 1993), that made his Polycentric model appear much more similar to Coon's than it actually was.[14] Through the influence of Howells, many other anthropologists and biologists have confused multiregionalism with polygenism i.e. separate or multiple origins for different populations. Alan Templeton for example notes that this confusion has led to the error that gene flow between different populations was added to the Multiregional hypothesis as a "special pleading in response to recent difficulties", despite the fact: "parallel evolution was never part of the multiregional model, much less its core, whereas gene flow was not a recent addition, but rather was present in the model from the very beginning"[15] (emphasis in original). Despite this, multiregionalism is still confused with polygenism, or Coon's model of racial origins, from which Wolpoff and his colleagues have distanced themselves.[16][17] Wolpoff has also defended Wiedenreich's Polycentric hypothesis from being labeled polyphyletic. Weidenreich himself in 1949 wrote: "I may run the risk of being misunderstood, namely that I believe in polyphyletic evolution of man".[18] In 1998, Wu founded a China-specific Multiregional model called "Continuity with [Incidental] Hybridization".[19][20] Wu's variant only applies the Multiregional hypothesis to the East Asian fossil record, and is popular among Chinese scientists.[21] However, James Leibold, a political historian of modern China, has argued the support for Wu's model is largely rooted in Chinese nationalism.[22] Outside of China, the Multiregional hypothesis has limited support, held only by a small number of paleoanthropologists.[23] "Classic" vs "weak" multiregionalism Chris Stringer, a leading proponent of the more mainstream recent African origin theory, debated Multiregionalists such as Wolpoff and Thorne in a series of publications throughout the late 1980s and 1990s.[24][25][26][27] Stringer describes how he considers the original Multiregional hypothesis to have been modified over time into a weaker variant that now allows a much greater role for Africa in human evolution, including anatomical modernity (and subsequently less regional continuity than was first proposed).[28] Stringer distinguishes the original or "classic" Multiregional model as having existed from 1984 (its formulation) until 2003, to a "weak" post-2003 variant that has "shifted close to that of the Assimilation Model".[29][30] Genetic studies The finding that "Mitochondrial Eve" was relatively recent and African seemed to give the upper hand to the proponents of the Out of Africa hypothesis. But in 2002, Alan Templeton published a genetic analysis involving other loci in the genome as well, and this showed that some variants that are present in modern populations existed already in Asia hundreds of thousands of years ago.[31] This meant that even if our male line (Y chromosome) and our female line (mitochondrial DNA) came out of Africa in the last 100,000 years or so, we have inherited other genes from populations that were already outside of Africa. Since this study other studies have been done using much more data (see Phylogeography). |

概要 多地域仮説は、1984年にミルフォード・H・ウォルポフ、アラン・ソーン、辛 芝によって提唱された[10][11][1]。ウォルポフは、フランツ・ヴァイデンライヒの人類起源に関する「多中心説」を大きな影響として評価している が、これを 多遺伝子説や、遺伝子流動を最小限に抑えるカールトン・クーン(Carlton Coon)のモデルと混同すべきではないと警告している[11][12][13]。ウォルポフによると、ウィリアム・W・ハウエルズ(William W. Howells)は、50年にわたる出版活動の中で、ウィーデンライヒの仮説を多遺伝子による「燭台モデル」と混同し、多地域説を誤って解釈していた。 多地域進化論がなぜ多遺伝子説として汚名を着せられることになったのか? 私たちは、ワイデンライヒの考え、ひいては私たちの考えとクーン説の混同が原因だと考えている。クーンとワイデンライヒの考え方を結びつけた歴史的な理由 は、ワイデンライヒの多中心モデルを燭台(Howells, 1942, 1944, 1959, 1993 ) ハウエルズの影響により、多くの他の人類学者や生物学者も多地域主義と多起源説(異なる集団に別々の起源、または複数の起源があるとする説)を混同してい る。例えばアラン・テンプルトンは、この混乱により、異なる集団間の遺伝子流動が「最近の困難に対する特別な弁明」として多地域仮説に付け加えられたとい う誤りが生じたと指摘している。しかし実際には、「並行進化は多地域モデルの一部でもなければ、ましてやその中核でもなかった。一方、遺伝子流動は最近付 け加えられたものではなく、当初からモデルに存在していた」[15](強調は原文のまま)。にもかかわらず、多地域説は依然として多起源説やクーンの人種 起源説と混同されており、ウォルポフと彼の同僚たちはそれらと距離を置いている[16][17]。ウォルポフは、ワイデンライヒの多中心説が多系統説と レッテルを貼られることを防いでもいる。ワイデンライヒ自身は1949年に、「私は誤解される危険を冒すかもしれない。つまり、私は人間の多系統進化論を 信じている、と」と書いている[18]。 1998年、ウーは「(付随的)雑種化による連続性」と呼ばれる中国固有の多地域モデルを提唱した[19][20]。ウーのモデルは、東アジアの化石記録 にのみ多地域仮説を適用するもので、中国の科学者の間で人気がある 科学者たちの間で人気がある[21]。しかし、現代中国の政治史家であるジェームズ・ライボルトは、ウーのモデルを支持する根拠は、主に中国のナショナリ ズムに根ざしていると主張している[22]。中国国外では、多地域起源説を支持する声は限られており、支持しているのはごく少数の古人類学者だけである [23]。 「古典的」多地域起源説と「弱」多地域起源説 アフリカ起源説の主流派であるクリス・ストリンガーは、1980年代後半から1990年代にかけて、ウォルポフやソーンなどの多地域起源説支持者と論争を 展開した 1980年代後半から1990年代にかけて、一連の出版物の中で、ウォルポフやソーンなどの多地域説支持者と論争を展開した[24][25][26] [27]。ストリンガーは、当初の多地域説が時代とともに修正され、現在では解剖学的現代性(そして当初の提案よりも地域的連続性が低い)を含む人類の進 化においてアフリカが果たす役割を大幅に認めるような、より弱い説に変化したと述べている[28]。 ストリンガーは、1984年(その定式化)から2003年まで存在していたオリジナルの「古典的」多地域モデルと、2003年以降の「弱体化」した「同化モデルに近い」変種とを区別している[29][30]。 遺伝子研究 ミトコンドリア・イブ」が比較的新しくアフリカ人であるとする発見は、アフリカ単一起源説の支持者たちに優位に働いたようである。しかし、2002年にア ラン・テンプルトンがゲノム内の他の遺伝子座も対象にした遺伝子解析を発表し、現代の人々に見られる変異の一部は、何十万年も前にすでにアジアに存在して いたことが明らかになった[31]。たとえ私たちの男性系統(Y染色体)と女性系統(ミトコンドリアDNA)が過去10万年ほどでアフリカから出てきたと しても、私たちはすでにアフリカの外にいた集団から他の遺伝子を継承していることになる。この研究以降、さらに多くのデータを用いた研究が行われている (系統地理学を参照)。 |

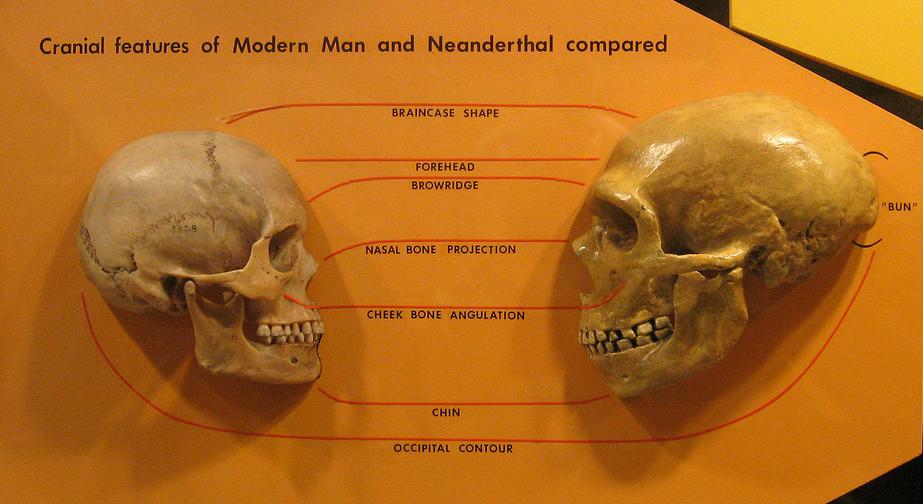

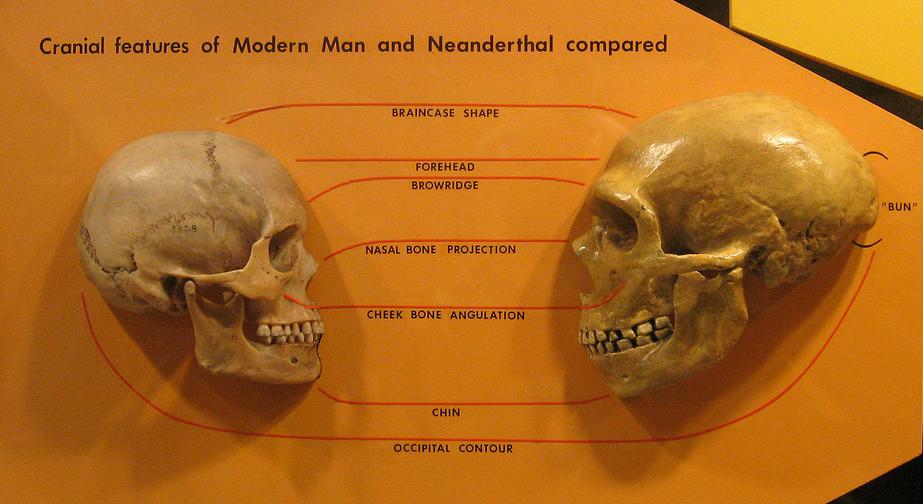

| Fossil evidence Morphological clades  Replica of Sangiran 17 Homo erectus skull from Indonesia showing obtuse face to vault angle determined by fitting of bones at brow.  Cast of anatomically modern human Kow Swamp 1 skull from Australia with a face to vault angle matching that of Sangiran 17 (Wolpoff's reconstruction). Proponents of the multiregional hypothesis see regional continuity of certain morphological traits spanning the Pleistocene in different regions across the globe as evidence against a single replacement model from Africa. In general, three major regions are recognized: Europe, China, and Indonesia (often including Australia).[32][33][34] Wolpoff cautions that the continuity in certain skeletal features in these regions should not be seen in a racial context, instead calling them morphological clades; defined as sets of traits that "uniquely characterise a geographic region".[35] According to Wolpoff and Thorne (1981): "We do not regard a morphological clade as a unique lineage, nor do we believe it necessary to imply a particular taxonomic status for it".[36] Critics of multiregionalism have pointed out that no single human trait is unique to a geographical region (i.e. confined to one population and not found in any other) but Wolpoff et al. (2000) note that regional continuity only recognizes combinations of features, not traits if individually accessed, a point they elsewhere compare to the forensic identification of a human skeleton: Regional continuity ... is not the claim that such features do not appear elsewhere; the genetic structure of the human species makes such a possibility unlikely to the extreme. There may be uniqueness in combinations of traits, but no single trait is likely to have been unique in a particular part of the world although it might appear to be so because of the incomplete sampling provided by the spotty human fossil record. Combinations of features are "unique" in the sense of being found in only one region, or more weakly limited to one region at high frequency (very rarely in another). Wolpoff stresses that regional continuity works in conjunction with genetic exchanges between populations. Long-term regional continuity in certain morphological traits is explained by Alan Thorne's "centre and edge"[37] population genetics model which resolves Weidenreich's paradox of "how did populations retain geographical distinctions and yet evolve together?". For example, in 2001 Wolpoff and colleagues published an analysis of character traits of the skulls of early modern human fossils in Australia and central Europe. They concluded that the diversity of these recent humans could not "result exclusively from a single late Pleistocene dispersal", and implied dual ancestry for each region, involving interbreeding with Africans.[38] Indonesia, Australia Thorne held that there was regional continuity in Indonesia and Australia for a morphological clade.[39][40] This sequence is said to consist of the earliest fossils from Sangiran, Java, that can be traced through Ngandong and found in prehistoric and recent Aboriginal Australians. In 1991, Andrew Kramer tested 17 proposed morphological clade features. He found that: "a plurality (eight) of the seventeen non-metric features link Sangiran to modern Australians" and that these "are suggestive of morphological continuity, which implies the presence of a genetic continuum in Australasia dating back at least one million years"[41] but Colin Groves has criticized Kramer's methodology, pointing out that the polarity of characters was not tested and that the study is actually inconclusive.[42] Phillip Habgood discovered that the characters said to be unique to the Australasian region by Thorne are plesiomorphic: ...it is evident that all of the characters proposed... to be 'clade features' linking Indonesian Homo erectus material with Australian Aboriginal crania are retained primitive features present on Homo erectus and archaic Homo sapiens crania in general. Many are also commonly found on the crania and mandibles of anatomically-modern Homo sapiens from other geographical locations, being especially prevalent on the robust Mesolithic skeletal material from North Africa."[43] Yet, regardless of these criticisms Habgood (2003) allows for limited regional continuity in Indonesia and Australia, recognizing four plesiomorphic features which do not appear in such a unique combination on fossils in any other region: a sagittally flat frontal bone, with a posterior position of minimum frontal breadth, great facial prognathism, and zygomaxillary tuberosities.[44] This combination, Habgood says, has a "certain Australianness about it". Wolpoff, initially skeptical of Thorne's claims, became convinced when reconstructing the Sangiran 17 Homo erectus skull from Indonesia, when he was surprised that the skull's face to vault angle matched that of the Australian modern human Kow Swamp 1 skull in excessive prognathism. Durband (2007) in contrast states that "features cited as showing continuity between Sangiran 17 and the Kow Swamp sample disappeared in the new, more orthognathic reconstruction of that fossil that was recently completed".[45] Baba et al. who newly restored the face of Sangiran 17 concluded: "regional continuity in Australasia is far less evident than Thorne and Wolpoff argued".[46] China  Replica of Homo erectus ("Peking man") skull from China. Xinzhi Wu has argued for a morphological clade in China spanning the Pleistocene, characterized by a combination of 10 features.[47][48] The sequence is said to start with Lantian and Peking Man, traced to Dali, to Late Pleistocene specimens (e.g. Liujiang) and recent Chinese. Habgood in 1992 criticized Wu's list, pointing out that most of the 10 features in combination appear regularly on fossils outside China.[49] He did though note that three combined: a non-depressed nasal root, non-projecting perpendicularly oriented nasal bones and facial flatness are unique to the Chinese region in the fossil record and may be evidence for limited regional continuity. However, according to Chris Stringer, Habgood's study suffered from not including enough fossil samples from North Africa, many of which exhibit the small combination he considered to be region-specific to China.[27] Facial flatness as a morphological clade feature has been rejected by many anthropologists since it is found on many early African Homo erectus fossils, and is therefore considered plesiomorphic,[50] but Wu has responded that the form of facial flatness in the Chinese fossil record appears distinct to other (i.e. primitive) forms. Toetik Koesbardiati in her PhD thesis "On the Relevance of the Regional Continuity Features of the Face in East Asia" also found that a form of facial flatness is unique to China (i.e. only appears there at high frequency, very rarely elsewhere) but cautions that this is the only available evidence for regional continuity: "Only two features appear to show a tendency as suggested by the Multiregional model: flatness at the upper face expressed by an obtuse nasio-frontal angle and flatness at the middle part of the face expressed by an obtuse zygomaxillay angle". Shovel-shaped incisors are commonly cited as evidence for regional continuity in China.[51][52] Stringer (1992) however found that shovel-shaped incisors are present on >70% of the early Holocene Wadi Halfa fossil sample from North Africa, and common elsewhere.[53] Frayer, et al. (1993) have criticized Stringer's method of scoring shovel-shaped incisor teeth. They discuss the fact that there are different degrees of "shovelled" e.g. trace (+), semi (++), and marked (+++), but that Stringer misleadingly lumped all these together: "...combining shoveling categories in this manner is biologically meaningless and misleading, as the statistic cannot be validly compared with the very high frequencies for the marked shoveling category reported for East Asians."[33] Palaeoanthropologist Fred H. Smith (2009) also emphasizes that: "It is the pattern of shoveling that identities as an East Asian regional feature, not just the occurrence of shoveling of any sort".[2] Multiregionalists argue that marked (+++) shovel-shaped incisors only appear in China at a high frequency, and have <10% occurrence elsewhere. Europe  Comparison of modern human (left) and Neanderthal (right) skulls. Since the early 1990s, David W. Frayer has described what he regards as a morphological clade in Europe.[54][55][56] The sequence starts with the earliest dated Neanderthal specimens (Krapina and Saccopastore skulls) traced through the mid-Late Pleistocene (e.g. La Ferrassie 1) to Vindija Cave, and late Upper Palaeolithic Cro-Magnons or recent Europeans. Although many anthropologists consider Neanderthals and Cro Magnons morphologically distinct,[57][58] Frayer maintains quite the opposite and points to their similarities, which he argues is evidence for regional continuity: "Contrary to Brauer's recent pronouncement that there is a large and generally recognized morphological gap between the Neanderthals and the early moderns, the actual evidence provided by the extensive fossil record of late Pleistocene Europe shows considerable continuity between Neanderthals and subsequent Europeans."[33] Frayer et al. (1993) consider there to be at least four features in combination that are unique to the European fossil record: a horizontal-oval shaped mandibular foramen, anterior mastoid tubercle, suprainiac fossa and narrowing of the nasal breadth associated with tooth-size reduction. Regarding the latter, Frayer observes a sequence of nasal narrowing in Neanderthals, following through to late Upper Palaeolithic and Holocene (Mesolithic) crania. His claims are disputed by others,[59] but have received support from Wolpoff, who regards late Neanderthal specimens to be "transitional" in nasal form between earlier Neanderthals and later Cro Magnons.[60] Based on other cranial similarities, Wolpoff et al. (2004) argue for a sizable Neanderthal contribution to modern Europeans.[61] More recent claims regarding continuity in skeletal morphology in Europe focus on fossils with both Neanderthal and modern anatomical traits, to provide evidence of interbreeding rather than replacement.[62][63][64] Examples include the Lapedo child found in Portugal[65] and the Oase 1 mandible from Peștera cu Oase, Romania,[66] though the "Lapedo child" is disputed by some.[67] |

化石証拠 形態学的系統  眉の骨の位置から、鈍角の額から頭頂角が示されている、インドネシアのサンギラン17のホモ・エレクトスの頭蓋骨のレプリカ。  オーストラリアの解剖学的に現代の人間のコウ・スワンプ1の頭蓋骨の鋳型。額から頭頂角がサンギラン17のものと同じである(Wolpoffによる復元)。 多地域仮説の支持者たちは、アフリカから単一で置き換わったというモデルを否定する証拠として、世界各地の更新世にわたる特定の形態的特徴の地域的連続性 を指摘している。一般的に、3つの主要な地域が認識されている。ヨーロッパ、中国、インドネシア(しばしばオーストラリアを含む)[32][33] [34]。ウォルポフは、これらの地域における特定の骨格の特徴の連続性を人種的な文脈で捉えるべきではないと警告し、それらは形態学的クラードと呼ぶべ きであると主張している。形態学的クラードとは、「地理的地域を唯一の特徴づける」一連の形質として定義される[35]。ウォルポフとソーン(1981) によると、 「我々は形態学的系統を独自の系統とは見なさないし、それに特定の分類学的地位を暗示する必要があると考えることもない」[36]。多地域主義の批判者た ちは、人間の特徴のどれ一つとして特定の地理的地域に固有のものはない(すなわち、ある集団にのみ存在し、他の集団には見られないものはない)と指摘して いるが、 。すなわち、ある特定の集団にのみ存在し、他の集団には見られないというわけではない)しかし、Wolpoff et al. (2000) は、地域的連続性は特徴の組み合わせを認識するだけで、個々の特徴を認識するわけではないと指摘している。彼らはこの点を、人骨鑑定と比較している。 地域的連続性とは、そのような特徴が他の場所では見られないという主張ではない。ヒトという種の遺伝的構造は、そのような可能性を極めて低いものとしてい る。特徴の組み合わせに独自性があるかもしれないが、不完全な化石記録によってそう見える可能性があるとしても、特定の地域において、単一の特徴が独自で あった可能性は低い。 特徴の組み合わせは、ある特定の地域でのみ見られるという意味で「独特」である。あるいは、ある特定の地域でのみ見られるというよりも、高い頻度で(別の 地域では非常にまれに)見られるという程度の限定的なものである。Wolpoffは、地域的な連続性は集団間の遺伝的交流と連動して機能することを強調し ている。特定の形態的特徴における長期にわたる地域的連続性は、ワイデンライヒの「集団は地理的差異を維持しながら、なぜ進化が同時進行するのか」という パラドックスを解決する、アラン・ソーンによる「中心と周辺」[37]の集団遺伝学モデルによって説明される。例えば、2001年にウォルポフと彼の同僚 たちは、オーストラリアと中央ヨーロッパの初期現代人化石の頭蓋骨の性格的特徴の分析を発表した。彼らは、これらの新人の多様性は「後期更新世の一度の拡 散のみに起因するものではない」と結論し、アフリカ人との交配を含む、各地域における二重の祖先を示唆した[38]。 インドネシア、オーストラリア ソーンは、 インドネシアとオーストラリアには形態学上の系統群の地域的連続性があるとした[39][40]。この系統は、ジャワ島のサンギランで発見された最古の化 石から成り、ングアンドンを経て、先史時代および近年のオーストラリア先住民にも見つかっているという。1991年、アンドリュー・クレイマーは、17の 提案された形態学的系統の特徴を検証した。その結果、 「17の非計量形質のうちの多数(8つ)がサンギランと現代オーストラリア人を結びつけている」こと、そして「これらは形態学的連続性を示唆しており、少 なくとも100万年前までさかのぼるオーストラリア大陸における遺伝的連続性の存在を示唆している」[41]ことがわかった。しかし、コリン・グローヴス はクレイマーの方法論を批判し、形質の極性が検証されておらず、この研究は実際には結論を出せていないと指摘した 結論は出ていない[42]。フィリップ・ハグッドは、ソーンがオーストラリア地域特有のものであるとしている形質が、実は原形質であることを発見し た。... インドネシアのホモ・エレクトゥスとオーストラリアのアボリジニの頭蓋骨をつなぐ「系統形質」であると提案された形質は、すべてホモ・エレクトゥスや初期 ホモ・サピエンスの頭蓋骨に一般的に見られる原始的な形質であることが明らかである。また、多くの特徴は、解剖学的に現代の人類であるホモ・サピエンスの 頭蓋骨や下顎にも共通して見られ、特に北アフリカの頑強な中石器時代の骨格資料に多く見られる。 しかし、これらの批判にもかかわらず、Habgood (2003) はインドネシアとオーストラリアに地域的な連続性を認め、他の地域の化石には見られない4つのプレシオモルフの特徴を認識している。 他の地域の化石ではこのような独特な組み合わせは見られない4つのプレシオモルフの特徴、すなわち、矢状面に平らな前頭骨、最小前頭幅の後方位置、大きな 顔面突出、頬骨下隆起を認める。[44] ハブグッドは、この組み合わせは「ある種のオーストラリアらしさ」を持っていると語る。 当初、ソーン氏の主張に懐疑的だったウォルポフは、インドネシアのサンギラン17号ホモ・エレクトスの頭蓋骨を復元した際に、その顔から頭蓋骨の角度が、 オーストラリアの現代人コウ・スワンプ1号の頭蓋骨と酷似し、極端な出っ歯であることを知って確信した。一方、Durband (2007) は、「サンギラン17とコウ・スワンプの標本との連続性を示すとされていた特徴は、最近完成したその化石の新しい、より正顎性の復元では消失した」と述べ ている[45]。サンギラン17の顔を新たに復元したBabaらは、「オーストラリア大陸における地域的な連続性は、ソーンとウォルポフが主張するほど明 白ではない」と結論付けている[46]。 中国  中国出土のホモ・エレクトス(北京原人)の頭蓋骨のレプリカ。 Xinzhi Wuは、10の特徴の組み合わせを特徴とする、更新世をまたぐ中国の形態学的系統群を主張している[47][48]。この系統は、ランティアンと北京原人 から始まり、大理、後期更新世の標本(例えば、六江)、そして最近の中国人にまで遡ると言われている。1992年にハブグッドは、ウーのリストを批判し、 10の特徴の組み合わせのほとんどは、中国以外の化石にも規則的に見られることを指摘した[49]。しかし、彼は、3つの組み合わせ(陥没していない鼻 根、垂直方向に突出していない鼻骨、顔の平坦さ)は、化石記録において中国地域特有のものであり、限られた地域的連続性の証拠である可能性がある、と指摘 した。しかし、クリス・ストリンガーによると、ハブグッドの研究は北アフリカからの化石標本の数が十分でなかったため、中国特有の地域的特徴であると考え られる小さな組み合わせを示すものが多く含まれていなかったという。 形態学的系統分類の特徴としての平坦な顔は、 多くの初期アフリカのホモ・エレクトスの化石に見られるため、多くの人類学者によって形態学的分岐群の特徴として否定されてきたが、[50] ウーは、中国の化石記録における顔面の平坦な形は、他の(すなわち原始的な)形とは明らかに異なる形であると反論している。Toetik Koesbardiati は博士論文「東アジアにおける顔面の地域的連続性の特徴の関連性」の中で、顔面の平坦化の形態は中国に特有(つまり、中国でのみ高頻度で出現し、他の地域 では非常にまれ)であることを発見したが、これは地域的連続性を示す唯一の 「多地域モデルが示唆する傾向を示す特徴は2つだけである。上顎の平坦性は鈍角鼻前頭角によって、顔面の中央部の平坦性は鈍角頬顎角によって表される」 と、地域的連続性に関する唯一の証拠として注意を促している。 シャベル状の門歯は、中国における地域的連続性の証拠としてよく引用される[51][52]。しかし、ストリンガー(1992)は、シャベル状の門歯が北 アフリカの更新世ワディハルファの化石標本の70%以上に存在し、他の地域でも一般的であることを発見した[53]。フレイアーら(1993)は、ストリ ンガーのシャベル状の門歯の採点方法を批判している。彼らは、例えば「シャベル形」の度合いが、痕跡(+)、半々(++)、顕著(+++)と様々であるに もかかわらず、ストリンガーがこれらをすべてひとまとめにしてしまったという事実について論じている。「...このようにスコップのカテゴリーを分類する ことは生物学的に無意味であり、誤解を招く。なぜなら、統計値は、東アジア人に報告されているスコップのカテゴリーが顕著な非常に高い頻度と比較すること はできないからだ。」[33] 古人類学者フレッド・H・スミス(2009)も次のように強調している。「ショベルを使うパターンが東アジアの地域的特徴として認識されているだけで、単 に何らかのショベルの使用頻度が高いというわけではない」[2]。多地域論者は、顕著な(+++)ショベル状の門歯が中国で高い頻度で出現し、それ以外の 地域では<10%の頻度で出現すると主張している。 ヨーロッパ  現代人(左)とネアンデルタール人(右)の頭蓋骨の比較。 1990年代初頭以来、デビッド・W・フレイヤーは、彼がヨーロッパにおける形態学的系統群と見なすものを説明してきた[54][55][56]。この系 統は、後期更新世中期から後期にかけてのネアンデルタール人(例えばラ・フェラシー1)からヴィンディヤ洞窟、後期旧石器時代クロマニョン人や新人類へと 遡る最も古い年代が判明しているネアンデルタール人標本(クラピナ およびサッコパストール人の頭蓋骨)は、後期更新世中期から後期(例えばラ・フェラシー1)を経てヴィンジヤ洞窟まで遡ることができ、後期旧石器時代のク ロマニョン人や最近のヨーロッパ人とつながっている。多くの人類学者は、ネアンデルタール人とクロマニョン人は形態学的に異なると考えているが[57] [58]、フレイアーはまったく逆の立場をとり、両者の類似性を指摘している。 「ネアンデルタール人と初期現代人の間に、一般的に認識されているような大きな形態学的隔たりがあるとするブラウアーの最近の発表とは逆に、後期更新世の ヨーロッパの広範な化石記録が示す実際の証拠は、 後期更新世のヨーロッパの広範な化石記録が示す実際の証拠によると、ネアンデルタール人とその後のヨーロッパ人との間にはかなりの連続性がある」 [33]。 Frayer et al. (1993) は、ヨーロッパの化石記録に独特な少なくとも 4 つの特徴の組み合わせがあると考える。水平楕円形の顎孔、前乳突隆起、上顎窩、そして歯のサイズ縮小に伴う鼻幅の狭小化である。後者について、フレイヤー はネアンデルタール人の鼻の狭小化の連続を観察し、後期旧石器時代および完新世(中石器時代)の頭蓋骨にまで及んでいると指摘している。彼の主張は他の研 究者から異議を唱えられているが[59]、ウォルポフは後期ネアンデルタール人の標本を、初期ネアンデルタール人と後期クロマニョン人の鼻の形が「移行 期」にあるものとみなしており、彼の主張を支持している[60]。ウォルポフらは、他の頭蓋骨の類似点に基づいて、現代のヨーロッパ人にネアンデルタール 人の遺伝子が大きく寄与していると主張している[61]。 ヨーロッパにおける骨格形態の連続性に関するより最近の主張は ヨーロッパにおける骨格形態の連続性に関する最近の主張は、ネアンデルタール人と現代人の両方の解剖学的特徴を持つ化石に焦点を当て、交配ではなく置き換 えの証拠を提供している[62][63][64]。その例としては、ポルトガルで発見されたラペドの子供[65]や、ルーマニアのペシュテラ・ク・オアゼ で発見されたオアゼ1の下顎骨[66]が挙げられるが、「ラペドの子供」については一部で異論もある[67]。 |

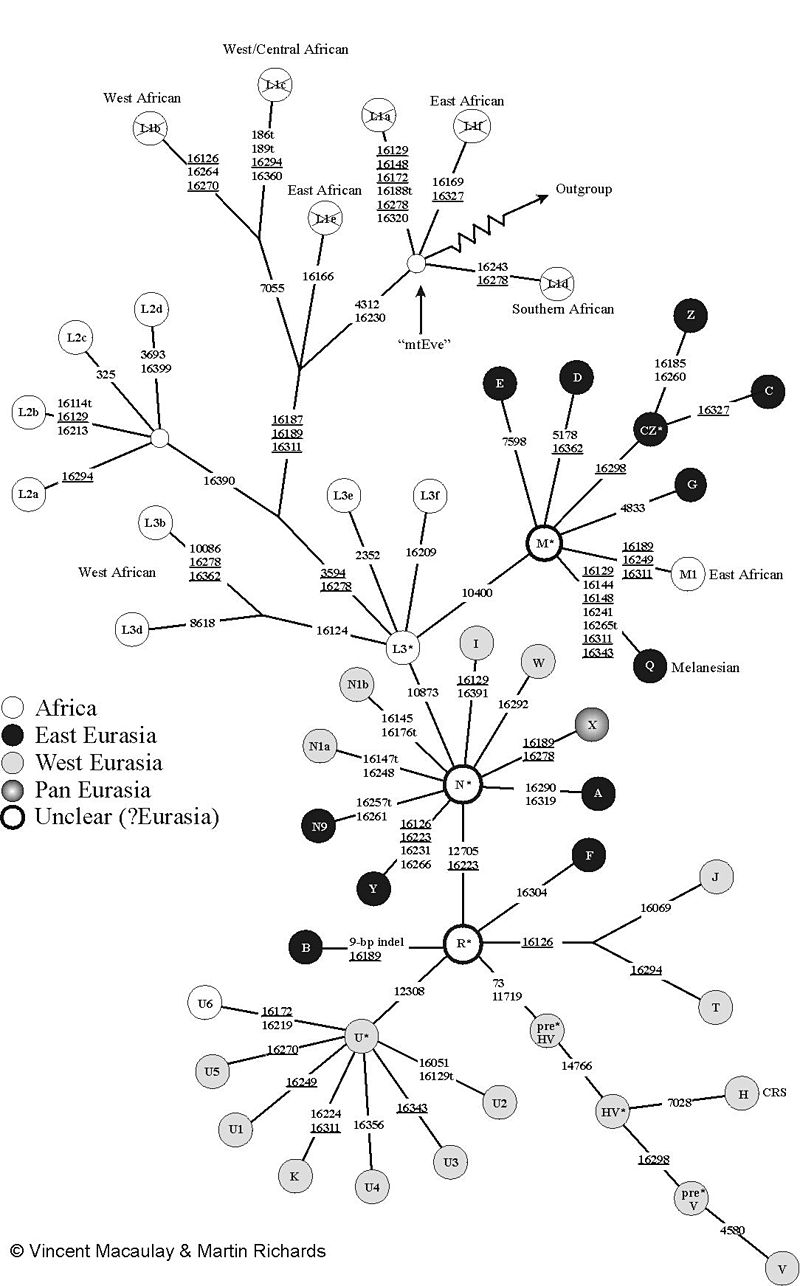

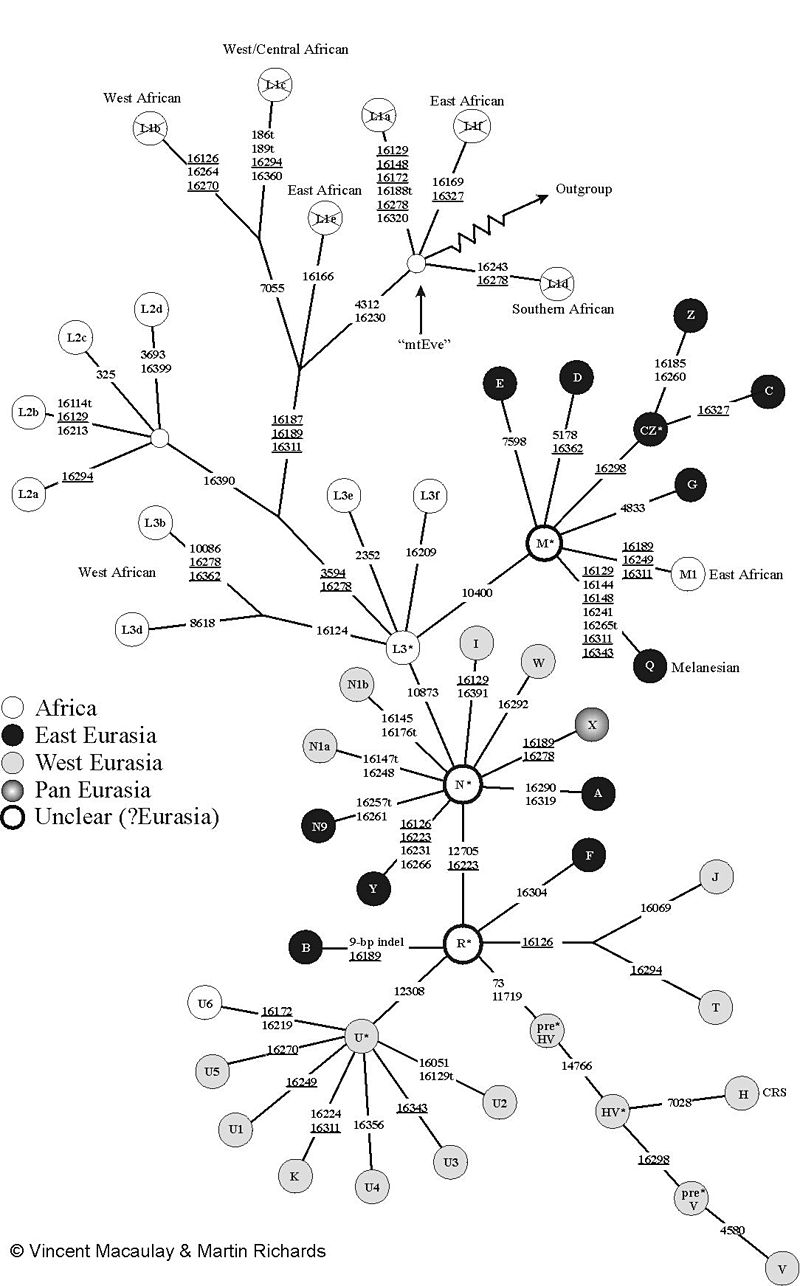

Genetic evidence Human mitochondrial DNA tree. "Mitochondrial Eve" is near the top of the diagram, next to the jagged arrow pointing to "Outgroup", and her distance from any nonafrican groups indicates that living human mitochondrial lineages coalesce in Africa. Mitochondrial Eve A 1987 analysis of mitochondrial DNA from 147 people by Cann et al. from around the world indicated that their mitochondrial lineages all coalesced in a common ancestor from Africa between 140,000 and 290,000 years ago.[68] The analysis suggested that this reflected the worldwide expansion of modern humans as a new species, replacing, rather than mixing with, local archaic humans outside of Africa. Such a recent replacement scenario is not compatible with the Multiregional hypothesis and the mtDNA results led to increased popularity for the alternative single replacement theory.[69][70][71] According to Wolpoff and colleagues:[72] When they were first published, the Mitochondrial Eve results were clearly incongruous with Multiregional evolution, and we wondered how the two could be reconciled. Multiregionalists have responded to what they see as flaws in the Eve theory,[73] and have offered contrary genetic evidences.[74][75][76] Wu and Thorne have questioned the reliability of the molecular clock used to date Eve.[77][78] Multiregionalists point out that Mitochondrial DNA alone can not rule out interbreeding between early modern and archaic humans, since archaic human mitochondrial strains from such interbreeding could have been lost due to genetic drift or a selective sweep.[79][80] Wolpoff for example states that Eve is "not the most recent common ancestor of all living people" since "Mitochondrial history is not population history".[81] Neanderthal mtDNA Neanderthal mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequences from Feldhofer and Vindija Cave are substantially different from modern human mtDNA.[82][83][84] Multiregionalists however have discussed the fact that the average difference between the Feldhofer sequence and living humans is less than that found between chimpanzee subspecies,[85][86] and therefore that while Neanderthals were different subspecies, they were still human and part of the same lineage. Nuclear DNA Initial analysis of Y chromosome DNA, which like mitochondrial DNA, is inherited from only one parent, was consistent with a recent African replacement model. However, the mitochondrial and Y chromosome data could not be explained by the same modern human expansion out of Africa; the Y chromosome expansion would have involved genetic mixing that retained regionally local mitochondrial lines. In addition, the Y chromosome data indicated a later expansion back into Africa from Asia, demonstrating that gene flow between regions was not unidirectional.[87] An early analysis of 15 noncoding sites on the X chromosome found additional inconsistencies with the recent African replacement hypothesis. The analysis found a multimodal distribution of coalescence times to the most recent common ancestor for those sites, contrary to the predictions for recent African replacement; in particular, there were more coalescence times near 2 million years ago (mya) than expected, suggesting an ancient population split around the time humans first emerged from Africa as Homo erectus, rather than more recently as suggested by the mitochondrial data. While most of these X chromosome sites showed greater diversity in Africa, consistent with African origins, a few of the sites showed greater diversity in Asia rather than Africa. For four of the 15 gene sites that did show greater diversity in Africa, the sites' varying diversity by region could not be explained by simple expansion from Africa, as would be required by the recent African replacement hypothesis.[88] Later analyses of X chromosome and autosomal DNA continued to find sites with deep coalescence times inconsistent with a single origin of modern humans,[89][90][91][92][93] diversity patterns inconsistent with a recent expansion from Africa,[94] or both.[95][96] For example, analyses of a region of RRM2P4 (ribonucleotide reductase M2 subunit pseudogene 4) showed a coalescence time of about 2 Mya, with a clear root in Asia,[97][98] while the MAPT locus at 17q21.31 is split into two deep genetic lineages, one of which is common in and largely confined to the present European population, suggesting inheritance from Neanderthals.[99][100][101][102] In the case of the Microcephalin D allele, evidence for rapid recent expansion indicated introgression from an archaic population.[103][104][105][106] However, later analysis, including of the genomes of Neanderthals, did not find the Microcephalin D allele (in the proposed archaic species), nor evidence that it had introgressed from an archaic lineage as previously suggested.[107][108][109] In 2001, a DNA study of more than 12,000 men from 163 East Asian regions showed that all of them carry a mutation that originated in Africa about 35,000 to 89,000 years ago and these "data do not support even a minimal in situ hominid contribution in the origin of anatomically modern humans in East Asia".[110] In a 2005 review and analysis of the genetic lineages of 25 chromosomal regions, Alan Templeton found evidence of more than 34 occurrences of gene flow between Africa and Eurasia. Of these occurrences, 19 were associated with continuous restricted gene exchange through at least 1.46 million years ago; only 5 were associated with a recent expansion from Africa to Eurasia. Three were associated with the original expansion of Homo erectus out of Africa around 2 million years ago, 7 with an intermediate expansion out of Africa at a date consistent with the expansion of Acheulean tool technology, and a few others with other gene flows such as an expansion out of Eurasia and back into Africa subsequent to the most recent expansion out of Africa. Templeton rejected a hypothesis of complete recent African replacement with greater than 99% certainty (p < 10−17).[111] Ancient DNA Main article: Archaic human admixture with modern humans Recent analyses of DNA taken directly from Neanderthal specimens indicates that they or their ancestors contributed to the genome of all humans outside of Africa, indicating there was some degree of interbreeding with Neanderthals before their replacement.[112] It has also been shown that Denisova hominins contributed to the DNA of Melanesians and Australians through interbreeding.[113] By 2006, extraction of DNA directly from some archaic human samples was becoming possible. The earliest analyses were of Neanderthal DNA, and indicated that the Neanderthal contribution to modern human genetic diversity was no more than 20%, with a most likely value of 0%.[114] By 2010, however, detailed DNA sequencing of the Neanderthal specimens from Europe indicated that the contribution was nonzero, with Neanderthals sharing 1-4% more genetic variants with living non-Africans than with living humans in sub-Saharan Africa.[115][116] In late 2010, a recently discovered non-Neanderthal archaic human, the Denisova hominin from south-western Siberia, was found to share 4–6% more of its genome with living Melanesian humans than with any other living group, supporting admixture between two regions outside of Africa.[117][118] In August 2011, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles from the archaic Denisovan and Neanderthal genomes were found to show patterns in the modern human population demonstrating origins from these non-African populations; the ancestry from these archaic alleles at the HLA-A site was more than 50% for modern Europeans, 70% for Asians, and 95% for Papua New Guineans.[119] Proponents of the multiregional hypothesis believe the combination of regional continuity inside and outside of Africa and lateral gene transfer between various regions around the world supports the multiregional hypothesis. However, "Out of Africa" Theory proponents also explain this with the fact that genetic changes occur on a regional basis rather than a continental basis, and populations close to each other are likely to share certain specific regional SNPs while sharing most other genes in common.[120][121] Migration Matrix theory (A=Mt) indicates that dependent upon the potential contribution of Neanderthal ancestry, we would be able to calculate the percentage of Neanderthal mtDNA contribution to the human species. As we do not know the specific migration matrix, we are unable to input the exact data, which would answer these questions irrefutably.[85] |

遺伝学的証拠 ヒトのミトコンドリアDNAの系統樹。 「ミトコンドリア・イブ」は、図の上部にあり、「アウトグループ」を指すギザギザの矢印の隣に位置している。アフリカ以外のグループとの距離から、現生人類ミトコンドリア系統はアフリカで融合したことがわかる。 ミトコンドリア・イブ 1987年、世界中の147人のミトコンドリアDNAを分析したCannらの研究により、彼らのミトコンドリア系統は、14万年から29万年前、アフリカ に存在した共通の祖先から分化したことが示された[68]。 000~290,000年前にアフリカで共通の祖先から分化したことが示された[68]。この分析は、アフリカ以外の地域に住む旧人類の代わりに、新種と して現代人類が世界中に広がったことを反映していると示唆している。このような最近の入れ替わりシナリオは多地域仮説と矛盾しており、mtDNAの結果 は、代替となる単一入れ替わり説の人気を高めることにつながった[69][70][71]。 Wolpoffらによると:[72] ミトコンドリア・イブの結果が最初に発表されたとき、多地域進化論とは明らかに矛盾しており、この2つをどのように調和させるか疑問に思った。 多地域進化論者は、イブ説の欠陥として受け止めていることに対して反論し、[73] 相反する遺伝的証拠を提示している[74][75][76]。WuとThorneは、イブの日付を決定するために使用された分子時計の信頼性を疑問視して いる[77][78]。多地域進化論者は、ミトコンドリアDNAだけでは、初期現代人と旧人との間の交配を否定できないと指摘している。なぜなら、そのよ うな交配によって生じた旧人類のミトコンドリア系統は、遺伝的浮動や選択的掃引によって失われた可能性があるからだ[79][80]。例えば、ウォルポフ は「ミトコンドリアの歴史は人口の歴史ではない」ため、イブは「現存するすべての人類の最も最近の共通祖先ではない」と述べている[81]。 ネアンデルタール人のmtDNA フェルドホーファーとヴィンディヤ洞窟から発見されたネアンデルタール人のミトコンドリアDNA(mtDNA)配列は、現生人類のものとは大幅に異なって いる[82][83][84]。Vindija Cave のネアンデルタール人のミトコンドリアDNA(mtDNA)配列は、現代人のmtDNAとは大幅に異なっている[82][83][84]。しかし、多地域 説の支持者たちは、Feldhoferの配列と現生人類との平均的な差異は、チンパンジー亜種間の差異よりも小さいという事実について議論しており [85][86]、したがって、ネアンデルタール人は異なる亜種ではあるが、やはり人間であり、同じ系統の一部であったとしている。 核DNA ミトコンドリアDNAと同様に、片親からのみ遺伝するY染色体のDNAの初期分析は、最近のアフリカ置換説と一致していた。しかし、ミトコンドリアDNA とY染色体のデータは、アフリカから出た現代人による拡大では説明できず、Y染色体の拡大には、地域的に局所的なミトコンドリア系統を保持する遺伝子の混 合が関わっていたと考えられる。さらに、Y染色体データは、アジアからアフリカへのより遅い拡大を示しており、地域間の遺伝子流動は一方向ではないことを 示している[87]。 X染色体上の15の非コード部位の初期分析では、最近のアフリカ置換説と矛盾するさらなる矛盾が発見された。この分析では、これらの部位の最も最近の共通 祖先までの融合時期の分布が、最近のアフリカでの置き換えの予測に反して多峰性であることがわかった。特に、200万年前(mya)付近の融合時期が予測 よりも多く、ミトコンドリアDNAのデータから示唆されるような最近ではなく、人類がホモ・エレクトスとしてアフリカから初めて出現した頃に古代の集団が 分かれたことを示唆している。これらのX染色体上のサイトのほとんどはアフリカで多様性が大きくなっており、アフリカ起源説と一致しているが、一部のサイ トではアフリカよりもアジアで多様性が大きくなっている。アフリカで多様性がより高かった15の遺伝子座のうち4つについては、地域による多様性の違い は、最近のアフリカ置換仮説[88]で必要とされるようなアフリカからの単純な拡大では説明できない。 X染色体と常染色体DNAのその後の分析では、現代人の単一起源と矛盾する深い融合時期を持つ部位[89][90][91][ 92][93]多様性のパターンはアフリカからの最近の拡大と一致しない[94]、あるいはその両方とも[95][96]。例えば、RRM2P4(リボヌ クレオチドレダクターゼM2サブユニット偽遺伝子4)領域の分析では、約200万年前からの融合時間が示され、その起源はアジアであることが明らかになっ ている[97][98]。一方、17q21.31のMAP 17q21.31 の MAPT 遺伝子座は、2つの深い遺伝系統に分かれており、そのうちの1つは現在のヨーロッパの人口に広く見られ、ネアンデルタール人から遺伝した可能性を示唆して いる[99][100][101][102]。小頭症D対立遺伝子の場合、最近の急速な拡大を示す証拠から、古来の集団からの遺伝子流入が示唆された[ 103][104][105][106]しかし、ネアンデルタール人のゲノムを含むその後の分析では、マイクロセファリンD対立遺伝子(提案されている古 種)も、以前示唆されていたように古系統から進入した証拠も見つからなかった[107][108][109]。 2001年、 2001年、東アジア163地域に住む12,000人以上の男性を対象としたDNA研究により、全員が35,000~89,000年前にアフリカで発生し た突然変異を保有していることが示され、これらの「データは、東アジアにおける解剖学的に現代的なヒトの起源において、現生人類による最小限の遺伝的寄与 さえも支持していない」[110]。 2005年にアラン・テンプルトンが25の染色体領域の遺伝系統を調査・分析したところ、アフリカとユーラシア大陸の間で34回以上遺伝子交流が起こった 形跡が見つかった。そのうち19回は少なくとも146万年前まで継続的に限定的な遺伝子交換が行われていたことが確認され、アフリカからユーラシア大陸へ の最近の拡大に関連していたのはわずか5回のみであった。3つは、約200万年前にアフリカからホモ・エレクトゥスが最初に広がったことと関連しており、 7つは、アシュレアン石器技術の発展と一致する時期にアフリカから広がったことと関連している。また、その他にも、ユーラシアからアフリカへの拡大や、ア フリカからユーラシアへの拡大など、他の遺伝子流入と関連しているものもある。テンプルトンは、アフリカが最近完全に置き換わったという仮説を、99%以 上の確実性をもって否定した(p < 10−17)。[111] 古代DNA メイン記事: 旧人類の現代人への混血 ネアンデルタール人の標本から直接採取したDNAの最近の分析によると、ネアンデルタール人またはその祖先がアフリカ以外の全人類のゲノムに貢献していた ことが示されており、ネアンデルタール人に取って代わる前にある程度の交配があったことが示唆されている[ 112] また、デニソワ人類のDNAが、交配を通じてメラネシア人やオーストラリア人のDNAにも影響を与えていることが示されている[113]。 2006年までに、いくつかの旧人類のサンプルから直接DNAを抽出することが可能になっていた。最も初期の分析はネアンデルタール人のDNAを対象に行 われたが、その結果、ネアンデルタール人が現代のヒトの遺伝的多様性に寄与した割合は20%以下であり、最も可能性が高い値は0%であることが示された [114]。しかし、2010年までにヨーロッパで発見されたネアンデルタール人の標本の詳細なDNA配列の解析により、その寄与はゼロではないことが示 された。 サハラ以南のアフリカに住む現生人類よりも、現生非アフリカ人と遺伝子の変異を共有する割合が1~4%多いことが示された[115][116]。2010 年末、最近発見されたネアンデルタール人以外の古人類であるシベリア南西部で発見されたデニソワ人(Denisova hominin)は、現生メラネシア人と他の現生人類グループよりもゲノムを共有する割合が4~6%多いことが判明し、アフリカ以外の2つの地域間の混血 の存在が裏付けられた[117][118]。 アフリカ以外の2つの地域間の混血を裏付けるものである[117][118]。2011年8月、旧人デニソワ人とネアンデルタール人のゲノムから得られた ヒト白血球抗原(HLA)対立遺伝子は、現代の人類集団にこれらのアフリカ以外の集団を起源とするパターンを示すことが判明した。HLA-A 部位におけるこれらの古風な対立遺伝子の祖先遺伝子は、現代ヨーロッパ人では 50% 以上、アジア人では 70%、パプアニューギニア人では 95% であった[119]。多地域起源説の支持者たちは、アフリカ内外における地域的な連続性と、世界中のさまざまな地域間における水平遺伝子の移動の組み合わ せが、多地域起源説を支持すると考えている。しかし、「アフリカ単一起源説」の支持者たちは、遺伝子変化は大陸単位ではなく地域単位で起こるという事実、 そして近縁の集団は特定の地域固有のSNPを共有する一方で、他のほとんどの遺伝子を共有する可能性が高いという事実をもってこれを説明している [120][121]。 移住マトリックス説(A=Mt)によると、ネアンデルタール人の祖先による潜在的な寄与率によって、ネアンデルタール人のmtDNAが人類に与えた寄与率 を計算できる。具体的な移行マトリクスがわからないため、これらの疑問に間違いなく答える正確なデータを入力することができない[85]。 |

| Archaic human admixture with modern humans Human evolution Human origins Mitochondrial Eve Phyletic gradualism Recent African origin of modern humans Y-chromosomal Adam |

現代人と古代人の混血 人間の進化 人間の起源 ミトコンドリア・イブ 系統的漸進説 現代人のアフリカ大陸起源説 Y染色体アダム |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multiregional_origin_of_modern_humans |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆