古代ギリシアの音楽

Music of ancient Greece

Ancient

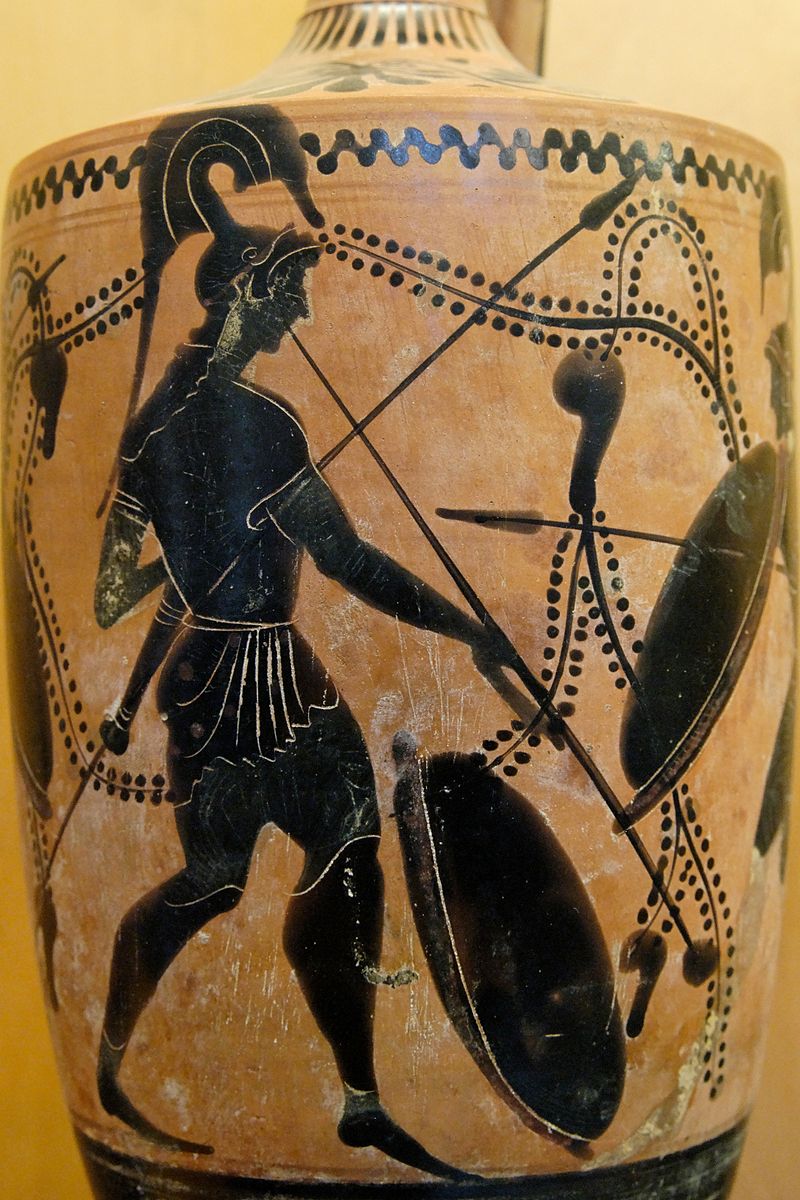

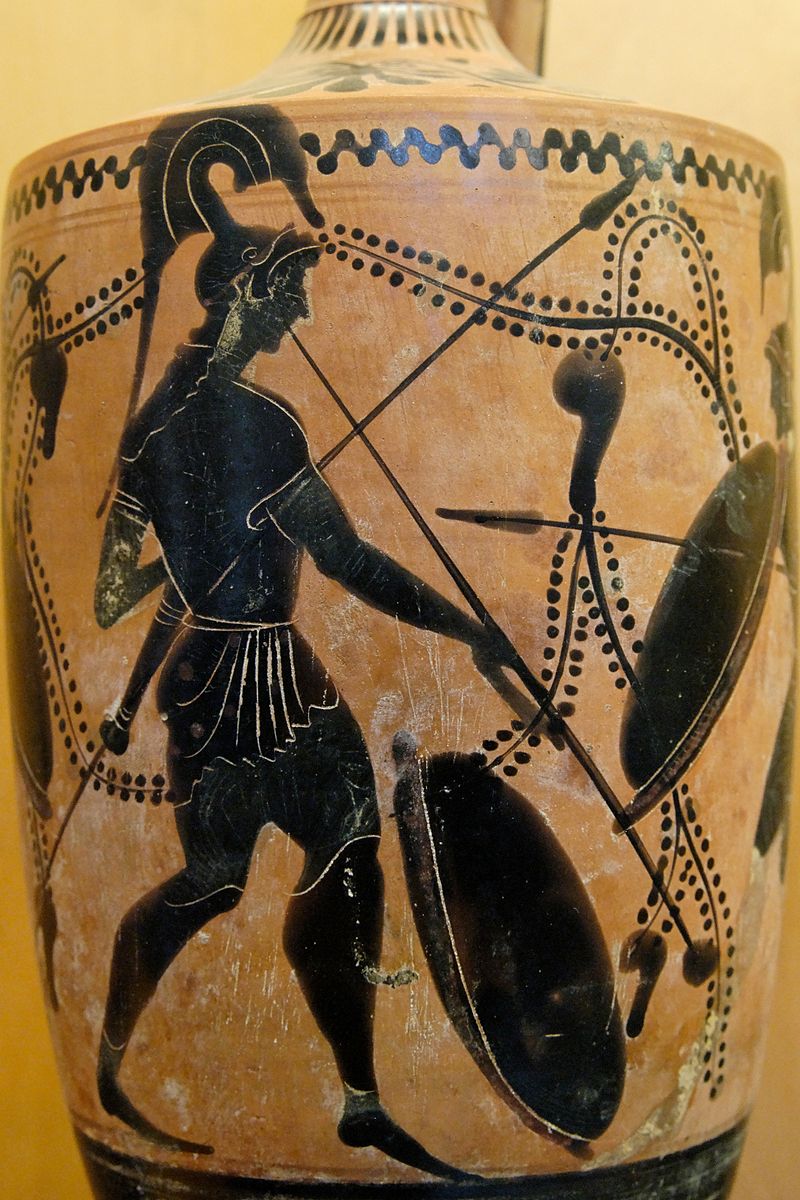

Greek warrior playing the salpinx, late 6th–early 5th century BC, Attic

black-figure (lekythos)

☆ 音楽は、冠婚葬祭や宗教儀式から演劇、民俗音楽、叙事詩のバラード的な 朗読に至るまで、古代ギリシア社会にはほとんど普遍的に存在していた。音楽は古代ギリシア人の生活に不可欠な役割を果たしていたのである。実際のギリシア 語の楽譜の断片、多くの文献、陶器に描かれた絵、関連する考古学的遺跡があり、音楽がどのように聞こえたか、社会における音楽の一般的な役 割、音楽の経済性、音楽家の職業カーストの重要性などについて、ある程度知ることができる、あるいは合理的に推測することができる。

| Music was almost

universally present in ancient Greek society, from marriages, funerals,

and religious ceremonies to theatre, folk music, and the ballad-like

reciting of epic poetry. This played an integral role in the lives of

ancient Greeks. There are some fragments of actual Greek musical

notation,[1][2] many literary references, depictions on ceramics and

relevant archaeological remains, such that some things can be known—or

reasonably surmised—about what the music sounded like, the general role

of music in society, the economics of music, the importance of a

professional caste of musicians, etc. The word music comes from the Muses, the daughters of Zeus and patron goddesses of creative and intellectual endeavours. Concerning the origin of music and musical instruments: the history of music in ancient Greece is so closely interwoven with Greek mythology and legend that it is often difficult to surmise what is historically true and what is myth. The music and music theory of ancient Greece laid the foundation for western music and western music theory, as it would go on to influence the ancient Romans, the early Christian church and the medieval composers.[3]: x Our understanding of ancient Greek music theory, musical systems, and musical ethos comes almost entirely from the surviving teachings of the Pythagoreans, Ptolemy, Philodemus, Aristoxenus, Aristides, and Plato. Some ancient Greek philosophers discussed the study of music in ancient Greece. Pythagoras in particular believed that music was subject to the same mathematical laws of harmony as the mechanics of the cosmos, evolving into an idea known as the music of the spheres.[3]: 130–131 The Pythagoreans focused on the mathematics and the acoustical science of sound and music. They developed tuning systems and harmonic principles that focused on simple integers and ratios, laying a foundation for acoustic science; however, this was not the only school of thought in ancient Greece.[3]: 132 Aristoxenus, who wrote a number of musicological treatises, for example, studied music with a more empirical tendency. Aristoxenus believed that intervals should be judged by ear instead of mathematical ratios,[4] though Aristoxenus was influenced by Pythagoras and used mathematics terminology and measurements in his research. |

音楽は、冠婚葬祭や宗教儀式から演劇、民俗音楽、叙事詩のバラード的な

朗読に至るまで、古代ギリシア社会にはほとんど普遍的に存在していた。音楽は古代ギリシア人の生活に不可欠な役割を果たしていたのである。実際のギリシア

語の楽譜の断片[1][2]、多くの文献、陶器に描かれた絵、関連する考古学的遺跡があり、音楽がどのように聞こえたか、社会における音楽の一般的な役

割、音楽の経済性、音楽家の職業カーストの重要性などについて、ある程度知ることができる、あるいは合理的に推測することができる。 音楽という言葉は、ゼウスの娘であり、創造的で知的な努力の守護女神であるミューズに由来する。 音楽と楽器の起源について:古代ギリシアにおける音楽の歴史は、ギリシア神話や伝説と密接に絡み合っており、何が歴史的に真実で何が神話なのかを推測する ことはしばしば困難である。古代ギリシアの音楽と音楽理論は、古代ローマ帝国、初期キリスト教会、中世の作曲家たちに影響を与えることになり、西洋音楽と 西洋音楽理論の基礎を築いた[3]: x 古代ギリシアの音楽理論、音楽体系、音楽エートスに関する我々の理解は、ほぼ完全に、現存するピタゴラス人、プトレマイオス、フィロデムス、アリストクセ ヌス、アリスティデス、プラトンの教えによるものである。 古代ギリシアの哲学者の中には、古代ギリシアにおける音楽の研究を論じた者もいた。特にピタゴラスは、音楽は宇宙の力学と同じ調和の数学的法則に従うと考 え、球体の音楽として知られる考えへと発展した[3]: 130-131 ピュタゴラス学派は、音と音楽の数学と音響学に焦点を当てた。彼らは単純な整数と比に焦点を当てた調律システムと調和原理を開発し、音響科学の基礎を築い た: 例えば、多くの音楽学理論を著した132人のアリストクセノスは、より経験的な傾向で音楽を研究していた。アリストクセノスは音程を数学的な比率で はなく耳で判断すべきであると考えていたが[4]、アリストクセノスはピタゴラスの影響を受けており、数学の用語や測定法を研究に用いていた。 |

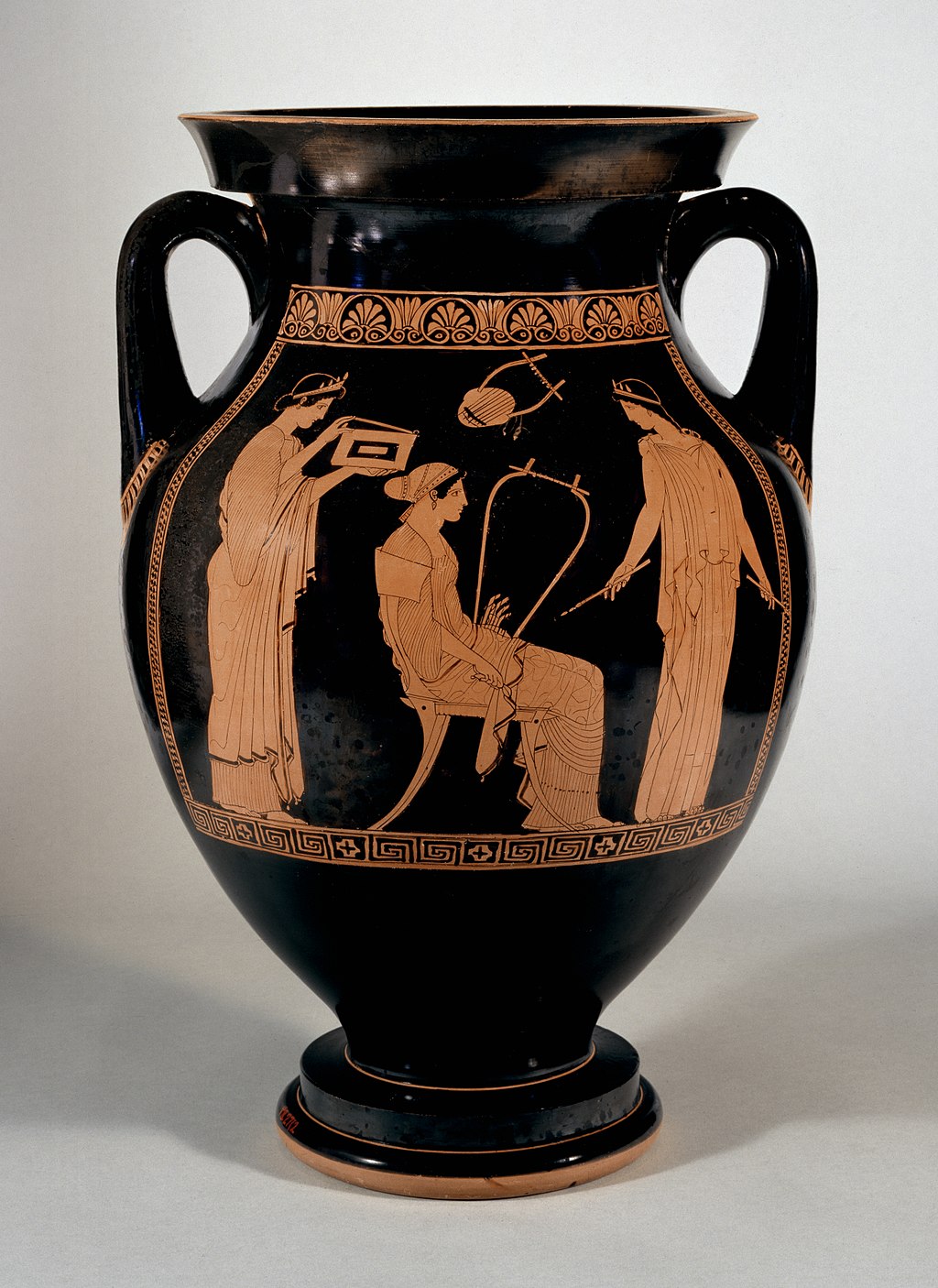

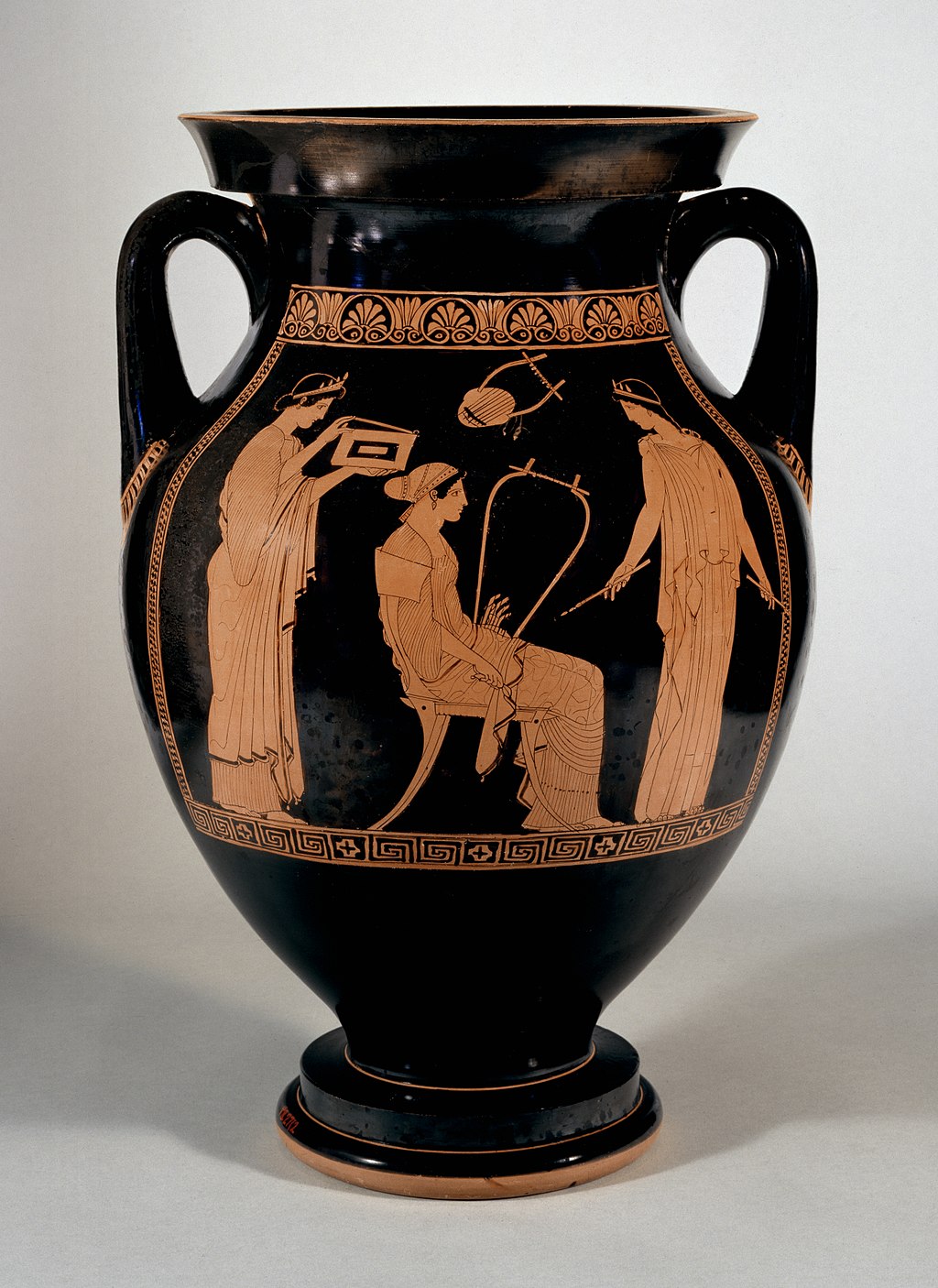

Music in society and religion Musical scene with three women painted by the Niobid painter. Side A of a red-figure amphora, Walters Art Museum Music played an integral role in ancient Greek society. Pericles' teacher Damon said, according to Plato in the Republic, "when fundamental modes of music change, the fundamental modes of the state change with them." Music and gymnastics comprised the main divisions in one's schooling. "The word 'music' expressed the entire education".[5] Instrumental music served a religious and entertaining role in ancient Greece as it would often accompany religious events, rituals, and festivals. Music was also used for entertainment when it accompanied drinking-parties or symposia. A popular type of piece to be played while drinking at these drinking parties was the skolion, a piece composed to be heard while drinking.[6] Before and after the Greek drinking parties, religious libations, or the religious the act of partaking and pouring out drink, would be made to deities, usually the Olympic gods, the heroes, and Zeus. The offering of libations were often accompanied by a special libation melody called the spondeion, which was often accompanied by an aulos player.[3]: 8 Music occupied an important role in the Greek sacrificial ceremonies. The sarcophagus of Hagia Triada shows that the aulos was present during sacrifices as early as 1300 BC.[7]: 2 Music was also present during times of initiation, worship, and religious celebration, playing very integral parts of the sacrificial cults of Apollo and Dionysus.[7]: 3 Music (along with intoxication of potions, fasting, and honey) was also integral in preparing for and catalyzing divination, as music would often induce prophets into religious ecstasy and revelation, so much so that the expression for "making music" and "prophesying" were identical in ancient Greek.[7]: 39 Instruments were also present in war time, though it may not have been considered music entirely. Specific notes of the trumpet were played to dictate commands to soldiers on the battlefield. The aulos and percussion instruments also accompanied the verbal commands given to oarsmen by the boatswain. The instruments were used mainly to help keep the oarsmen in time with one another.[3]: 8 Popular song types Hymn A hymn is a metric composition whose text addresses a god, either directly or indirectly. They are the earliest formal type in Greek music, and survive in relatively large numbers.[8]: 29–30 Paean Paeans were most commonly sung in honor or worship of Apollo as well as Athena. They usually solemnly expressed the hope for deliverance from a peril, or were sung in thanksgiving after a victory or escape.[3]: 3 Prosodion A type of hymn or processional that invoked or praised a god. Prosodions were usually sung on the road to an altar or shrine, before or after a paean.[3]: 3 Hyporchema Hyporchema was a dance-song with a marked rhythmic movement, commonly associated with the paean, and often difficult to distinguish from it. For example, the First Delphic Hymn is titled "Paean or Hyporchema".[8]: 88 Dithyrambs Usually merrily sung in celebration at festivals, performed especially in dedication to Dionysus, the god of wine. Dithyrambs featured choirs (choros) of men and boys who were accompanied by an aulos player.[3]: 4 Poetry and drama Whether or not long narrative poetry, or epic poetry like those of Homer, was sung is not entirely known. As in Plato's dialogue Ion, Socrates uses both the words "sing" and "speak" in connection with the Homeric epics,[9][page needed] however there are heavy implications that they have been at least recited unaccompanied by instruments, in a sing-song chant.[3]: 10 Music was also present in ancient Greek lyric poetry, which by definition is poetry or a song accompanied by a lyre. Lyric poetry eventually branched into two paths, monodic lyric which were performed by a singular person, and choral lyric which were sung and sometimes danced by a group of people choros. Famous lyric poets include Alkaios and Sappho from the Island of Lesbos, Sappho being one of the few women whose poetry has been preserved.[3]: 11 Music was also heavily prevalent in ancient Greek Drama. In his Poetics, Aristotle links the origins of tragic drama to dithyrambs.[10] The leaders of dithyrambs were the ones who led the song and dance moves, which would then be responded to by the group. Aristotle implies that this relationship between a single person and a group began the tragic drama, which in its earliest stages had a single actor who played all the parts through either song or speech. The single actor engaged in dialogue with the choros. The choros narrated most of the story through song and dance. In ancient Greece, the playwright was expected to not only write the script but also expected to compose the music and dance moves.[3]: 13–14 Mythology  A 17th-century representation of the Greek muses Clio, Thalia, and Euterpe playing a transverse flute, presumably the Greek photinx. The ancient Greek myths were never codified or documented into one form; what exists are several different versions from several different authors, across multiple centuries, which can lead to variations and even contradictions among authors and even the same author. According to Greek mythology, music, instruments, and the aural arts are attributed to divine origin, and the art of music was gift of the gods to men.[3]: 149 Although Apollo was prominently considered the god of music and harmony, several legendary gods and demigods were purported to have created some aspect of music as well as contributed to its development. Some gods, and especially the Muses, represented specific aspects or elements of music. The 'inventions' or 'findings' of all ancient Greek instruments were accredited to the gods as well. The performance of music was integrated into many different modes of Greek story-telling and art related to mythology, including drama, and poetry, and there are a large number of ancient Greek myths related to music and musicians.[3]: 148 In Greek mythology: Amphion learned music from Hermes and then with a golden lyre built Thebes by moving the stones into place with the sound of his playing; Orpheus, the master-musician and lyre-player, played so magically that he could soothe wild beasts; the Orphic creation myths have Rhea "playing on a brazen drum, and compelling man's attention to the oracles of the goddess";[11]: 30 or Hermes [showing to Apollo] "... his newly-invented tortoise-shell lyre and [playing] such a ravishing tune on it with the plectrum he had also invented, at the same time singing to praise Apollo's nobility[11]: 64 that he was forgiven at once ..."; or Apollo's musical victories over Marsyas and Pan.[11]: 77 There are many such references that indicate that music was an integral part of the Greek perception of how their race had even come into existence and how their destinies continued to be watched over and controlled by the Gods. It is no wonder, then, that music was omnipresent at the Pythian Games, the Olympic Games, religious ceremonies, leisure activities, and even the beginnings of drama as an outgrowth of the dithyrambs performed in honor of Dionysus.[12] It may be that the actual sounds of the music heard at rituals, games, dramas, etc. underwent a change after the traumatic fall of Athens in 404 BC at the end of the first Peloponnesian War. Indeed, one reads of the "revolution" in Greek culture, and Plato's lament that the new music "... used high musical talent, showmanship and virtuosity ... consciously rejecting educated standards of judgement."[13] Although instrumental virtuosity was prized, this complaint included excessive attention to instrumental music such as to interfere with accompanying the human voice, and the falling away from the traditional ethos in music. Mythical origins  The Cylix of Apollo with the tortoise-shell (chelys) lyre, on a 5th century BC drinking cup (kylix) Lyre According to the Homeric Hymn to Hermes, after stealing his brother Apollo's sacred cattle, Hermes was inspired to build an instrument out of a tortoise shell; he attached horns, and gut-string, to the shell and invented the first lyre. Afterwards, Hermes gave his lyre to Apollo, who took interest in the instrument, in repayment for the stolen cattle. In other accounts, Hermes gave his newly invented lyre to Amphion, a son of Zeus and a skilled musician.[14] Aulos According to Pindar's Twelfth Pythian Ode, after Perseus beheaded Medusa, Athena 'found' or 'invented' the aulos in order to reproduce the lamentation of Medusa's sisters. Since the same Greek word is used for 'find' and 'invent', it is unclear; however, the writer Telestes in the 5th century states that Athena found the instrument in a thicket. In Plutarch's essay On the Restraint of Anger, he writes that Athena, after seeing her reflection while playing the aulos, threw the instrument away because it distorted her facial features when played, after which Marsyas a satyr, picked up her aulos and took it up as his own.[15]  Pan instructing Daphnis on the syrinx Syrinx / Pan flute According to Ovid's Metamorpheses, the original Syrinx was a Naiad, a water nymph, who ran away from Pan after he tried to woo her. While she fled, she came upon an uncrossable river and prayed to her sisters to transform her so that she may escape Pan. Her Nymph sisters transformed Syrinx into a bundle of reeds which Pan found and fashioned an instrument out of, the Pan flute or syrinx.[16] Orpheus myth Orpheus is a significant figure in the ancient Greek mythology of music. Orpheus was a legendary poet and musician, his lineage is unclear as some sources note him as the son of Apollo, the son of the Muse Calliope, or the son of mortal parents. Orpheus was the pupil and brother of Linus. Linus by some accounts is the son of Apollo and the Muse Urania; Linus was the first to be gifted the ability to sing by the Muses, which he passed to Orpheus. Other accounts state that Apollo gave Orpheus a golden lyre and taught him to play, while the muses taught Orpheus to sing. Orpheus was said to be such a skilled musician that he could charm inanimate objects.[3]: 151 According to the Argonautica, Orpheus in his adventures with Jason and the Argonauts, was able to play music more beautiful and louder than the bewitching sirens, allowing the Argonauts to travel safely without being charmed by the sirens.[17] When Orpheus' wife, Eurydice, died, he played a song so mournful that it caused the gods and all the nymphs to weep. Orpheus was then able to travel to the underworld, and with music, softened the heart of Hades enough that he was allowed to return with his wife; however, under the condition that he must not set eyes upon his wife until they finished their travel out of the underworld. Orpheus was unable to fulfill this condition and tragically, his wife vanished forever.[18][3]: 151 Marsyas myth  Apollo flaying Marsyas in Apollo and Marsyas by José de Ribera According to Pseudo-Apollodorus in Bibliotheca, Marsyas the Phrygian satyr once boasted of his skills in the aulos; a musical contest between Marsyas and Apollo was then conducted, where the victor could do "whatever they wanted" to the loser.[19] Marsyas played his aulos so wildly that everyone burst into dance, while Apollo played his lyre so beautifully that everyone cried. The muses judged the first round to be a draw. According to one account, Apollo then played his lyre upside down, which Marsyas could not do with the aulos. In another account Apollo sang beautifully, which Marsyas could not do. In another account, Marsyas played out of tune and accepted defeat. In all accounts, Apollo then flayed Marsyas alive for losing. |

社会と宗教における音楽 ニオビッドの画家が描いた3人の女性がいる音楽の場面。赤像アンフォラのA面、ウォルターズ美術館蔵 音楽は古代ギリシャ社会で不可欠な役割を果たした。ペリクレスの教師デイモンは、『共和国』の中でプラトンによれば、"音楽の基本的な様式が変われば、国 家の基本的な様式も変わる "と述べている。音楽と体操は、学校教育の主な部門を構成していた。「音楽という言葉は教育全体を表していた」[5]。 古代ギリシアでは、宗教的な行事や儀式、祝祭に伴奏されることが多く、器楽は宗教的かつ娯楽的な役割を果たしていた。音楽はまた、酒宴やシンポジウムに伴 う娯楽としても使われた。ギリシャの酒宴の前後には、神々(通常はオリンピックの神々、英雄、ゼウス)に捧げる宗教的な献杯、つまり酒を飲み、注ぐという 宗教的な行為が行われた。献杯にはしばしばスポンデオンと呼ばれる特別な献杯の旋律が伴われ、その旋律はしばしばアウロス奏者によって伴奏された[3]: 8。 音楽はギリシアの犠牲儀式において重要な役割を果たしていた。アギア・トリアダの石棺は、紀元前1300年頃には犠牲の際にアウロスが存在していたことを 示している[7]: 2 音楽はまた、入信、礼拝、宗教的な祝典の際にも存在し、アポロンとディオニュソスの犠牲的なカルトにおいて非常に重要な役割を果たしていた[7]:: 3 音楽は(薬物中毒、断食、蜂蜜とともに)占いの準備や触媒としても不可欠であり、音楽はしばしば預言者を宗教的エクスタシーや啓示へと誘うため、古代ギリ シア語では「音楽を奏でる」と「予言する」という表現が同一であったほどである[7]: 39 完全に音楽とは見なされなかったかもしれないが、戦時中には楽器も存在していた。トランペットの特定の音は、戦場で兵士に命令を口述するために演奏され た。また、アウロスと打楽器は、船頭が漕ぎ手に口頭で命令するときの伴奏に使われた。楽器は主に、漕ぎ手たちが互いに歩調を合わせるのを助けるために使わ れた[3]: 8。 ポピュラーな歌の種類 賛美歌 讃美歌は、直接または間接的に神に語りかける文章を持つ計量的な楽曲である。讃美歌はギリシア音楽における最も古い形式であり、比較的数多く残っている [8]: 29-30 パイアン パエーンは、アポロンとアテナを祀るために最もよく歌われた。それらは通常、危機からの救済を願う気持ちを荘厳に表現したり、勝利や脱出の後に感謝の気持 ちを込めて歌われたりした[3]: 3 プロソディオン 讃美歌や行進曲の一種で、神を召喚したり賛美したりするもの。プロソディオンは通常、祭壇や神社に向かう道すがら、賛歌の前か後に歌われた[3]: 3 ヒポケマ ハイポルケマは顕著なリズム運動を伴う舞曲であり、一般的にペーアと関連していたが、しばしばペーアとの区別が困難であった。例えば、『デルフィの讃歌』 第1番は「ペアンまたはヒポルケマ」と題されている[8]: 88。 ディティラム 通常、祝祭で陽気に歌われ、特にワインの神ディオニュソスに捧げられた。ディティランブスは、アウロス奏者を従えた男性や少年の合唱団(コロス)を特徴と していた[3]: 4 詩とドラマ 長い物語詩やホメロスのような叙事詩が歌われていたかどうかは定かではない。プラトンの対話『イオーン』のように、ソクラテスはホメロスの叙事詩に関連し て「歌う」と「語る」の両方の言葉を用いているが[9][要出典]、少なくとも楽器を伴わずに歌うように詠唱されたという意味合いが強い[3]: 10 音楽は古代ギリシアの抒情詩にも存在し、抒情詩の定義は竪琴を伴奏にした詩や歌である。抒情詩はやがて、一人で歌うモノディックな抒情詩と、集団で歌い、 時には踊るコロスによるコラールな抒情詩の2つの道に分かれた。有名な抒情詩人には、レスボス島出身のアルカイオスやサッフォーがおり、サッフォーは詩が 残っている数少ない女性の一人である[3]: 11 音楽は古代ギリシア演劇にも広く浸透していた。アリストテレスは『詩学』の中で、悲劇劇の起源をディシラムと結びつけている[10]。アリストテレスは、 このような一人の人間と集団との関係が悲劇劇の始まりであり、悲劇劇の初期の段階では、一人の俳優が歌や話し言葉によってすべての役を演じていたと示唆し ている。一人の役者はコロスたちと対話をした。コロスたちは、歌と踊りを通して物語の大部分を語った。古代ギリシアでは、劇作家は台本を書くだけでなく、 音楽や踊りを作曲することも期待されていた[3]: 13-14 神話  17世紀に描かれた、横笛を吹くギリシャのミューズ、クリオ、タリア、エウテルペ。 古代ギリシア神話は、成文化されたり、1つの形に文書化されたりすることはなかった。現存するのは、何世紀にもわたって複数の異なる作者による複数の異な るバージョンであり、作者間や同じ作者でさえも、バリエーションや矛盾につながることがある。ギリシャ神話によれば、音楽、楽器、聴覚芸術は神の起源であ り、音楽芸術は神々から人への贈り物であった[3]: 149 アポロンは音楽と調和の神として著名であったが、いくつかの伝説上の神々や半神が音楽の何らかの側面を創造し、その発展に貢献したとされている。一部の神 々、特にミューズたちは、音楽の特定の側面や要素を象徴していた。古代ギリシアのあらゆる楽器の「発明」や「発見」は、同様に神々のものとされた。音楽の 演奏は、演劇や詩を含む神話に関連するギリシャの物語や芸術の多くの異なる様式に組み込まれており、音楽や音楽家に関連する古代ギリシャ神話は数多く存在 する[3]: 148 ギリシア神話では アンフィオンはヘルメスから音楽を学び、黄金の竪琴を持って、その演奏の音で石を動かしてテーベを築いた。オルフェウスは音楽と竪琴の名手で、野獣をなだ めることができるほど魔法のように演奏した: 30; あるいはヘルメスが「...新しく発明した亀の甲羅の竪琴をアポロに見せ、...その竪琴で彼が発明した撥を使って[演奏し]、同時にアポロの気高さを賛 美するために歌った[11]: 64、彼はすぐに許された...」; あるいはアポロがマルシアスとパンに音楽で勝利した[11]: 77。 このように、音楽がギリシア人にとって、自分たちの種族がどのように存在し、どのように自分たちの運命が神々によって見守られ、支配され続けてきたかとい うことを認識する上で不可欠な要素であったことを示す文献は数多くある。ピュティウス祭、オリンピック、宗教儀式、余暇活動、さらにはディオニュソスに敬 意を表して行われたディシラムの発展としての演劇の始まりに至るまで、音楽が遍在していたとしても不思議はない[12]。 儀式、ゲーム、ドラマなどで聴かれる音楽の実際の音は、第一次ペロポネソス戦争末期の紀元前404年にアテネが陥落したトラウマの後に変化を遂げたのかも しれない。実際、ギリシャ文化における「革命」と、新しい音楽が「......高い音楽的才能、ショーマンシップ、ヴィルトゥオジティを用い...... 教養ある判断基準を意識的に拒絶している」というプラトンの嘆きを読むことができる[13]。器楽のヴィルトゥオジティは珍重されたが、この不満には、人 間の声の伴奏を妨害するような器楽への過度の注目や、音楽における伝統的なエートスからの脱却が含まれていた。 神話の起源  紀元前5世紀の酒杯(カイリックス)に描かれた、亀の甲羅の竪琴を持つアポロンのカイリックス。 竪琴 ホメロスのヘルメス讃歌によると、兄アポロンの神聖な家畜を盗んだヘルメスは、亀の甲羅で楽器を作ることを思いついた。その後、ヘルメスはその竪琴をアポ ロンに渡したが、アポロンはその楽器に興味を示し、盗まれた牛の代償として竪琴を与えたという。他の説では、ヘルメスは新しく発明した竪琴を、ゼウスの息 子で腕のいい音楽家であったアンフィオンに与えた[14]。 アウロス ピンダルの『ピュトスの頌歌』第12番によると、ペルセウスがメドゥーサの首をはねた後、アテナはメドゥーサの姉妹の嘆きを再現するためにアウロスを「発 見」または「発明」した。同じギリシア語が「発見」と「発明」に使われているため、はっきりしないが、5世紀の作家Telestesは、アテナが雑木林で 楽器を見つけたと述べている。プルタークのエッセイ『怒りの抑制』には、アウロスを演奏している自分の姿を見たアテナが、演奏すると自分の顔の形が歪むの で楽器を捨てたところ、サテュロスのマルシアスが彼女のアウロスを拾って自分のものにしたと書かれている[15]。  ダフニスにシリンクスを教えるパン シリンクス/パンの笛 オヴィッドの『メタモルフェス』によると、シリンクスの原型はナイアス(水の精)で、パンに求婚された後に逃げ出した。逃げる途中、渡れない川に出くわし た彼女は、パンを逃すために変身するよう姉妹に祈った。ニンフの姉妹はシリンクスを葦の束に変身させ、パンはそれを見つけて楽器を作り、パンの笛またはシ リンクスを作った[16]。 オルフェウス神話 オルフェウスは古代ギリシャの音楽神話において重要な人物である。オルフェウスは伝説的な詩人であり音楽家であったが、アポロンの息子、ミューズのカリオ ペの息子、あるいは死を免れない両親の息子とする資料もあり、その血筋ははっきりしない。オルフェウスはライナスの弟子であり、兄である。ライナスはアポ ロンとミューズ・ウラニアの息子であり、ライナスはミューズたちから歌う能力を最初に授かり、それをオルフェウスに伝えたとする説もある。他の説によれ ば、アポロはオルフェウスに黄金の竪琴を与えて演奏を教え、ミューズたちはオルフェウスに歌を教えたという。 オルフェウスは無生物を魅了することができるほど優れた音楽家であったと言われている[3]: 151 『アルゴナウティカ』によれば、オルフェウスはジェイソンとアルゴノートたちとの冒険の中で、妖艶なセイレーンたちよりも美しく大きな音楽を奏でることが でき、アルゴノートたちはセイレーンたちに魅了されることなく安全に旅をすることができた[17]。オルフェウスの妻エウリュディケが死んだとき、彼は神 々とすべてのニンフたちを泣かせるほど悲痛な歌を奏でた。オルフェウスは冥界に行くことができ、音楽でハデスの心を和らげ、妻を連れて戻ることを許され た。オルフェウスはこの条件を満たすことができず、悲劇的に妻は永遠に姿を消した[18][3]: 151 マルシアス神話  ホセ・デ・リベラ作『アポロンとマルシャス』におけるマルシャスの皮を剥ぐアポロン Bibliotheca』のPseudo-Apollodorusによれば、フリギアのサテュロスであるマルシャスは、かつてアウロスの腕前を自慢してい た。そのとき、マルシャスとアポロンの音楽勝負が行われ、勝った方が負けた者に「好きなように」することができた。 ミューズたちは第一ラウンドを引き分けと判断した。ある記述によると、アポロンは竪琴を逆さに弾いたが、マルシアスはアウロスを弾くことができなかった。 別の説では、アポロンは美しく歌ったが、マルシャスにはできなかった。別の説では、マルシャスは音を外して演奏し、負けを認めた。どの記述も、負けたマル シアスをアポロンは生きたまま皮を剥いだ。 |

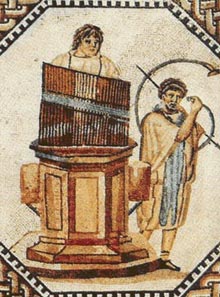

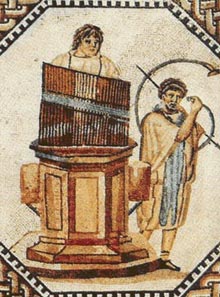

| Greek musical instruments The following were among the instruments used in the music of ancient Greece. The lyre, cithara, aulos, barbiton, hydraulis, and salpinx all found their way into the music of ancient Rome. String  A later vivid Roman representation of a woman playing the kithara, fresco painting, c. 30-40 BC Lyre A strummed and occasionally plucked string instrument, essentially a hand-held zither built on a tortoise-shell (chelys) frame, generally with seven or more strings tuned to the notes of one of the modes. The lyre was a folk-instrument, associated with the cult of Apollo. It was used to accompany others or even oneself for recitation and song, and was the conventional training-instrument for an aristocratic education. Cithara Cithara was a professional version of the lyre used by paid musicians. The kithara had a box-type frame with strings stretched from the cross-bar at the top to the sounding box at the bottom; it was held upright and played with a plectrum.[20] The strings were tunable by adjusting wooden wedges along the cross-bar. In the Politics, Aristotle describes the cithara as an "organon technikon", or an artist's instrument, requiring training.[21]  A seated woman playing the barbiton (detail), Attic red-figure amphora, c. 460 BC Barbiton A larger, bass-version of the cithara, considered to be east-Ionian, an exotic and somewhat foreign instrument. The barbiton was the primary instrument of the highly regarded ancient lyricist Sappho, as well as often associated with satyrs. Kanonaki A trapezoidal psaltery, invented by the Pythagoreans in the 6th century BC, however, may have had Mycenaean origins. The kanonaki was held on the thighs of the player, and plucked with both hands with bone pickings. Harp Harps are among the oldest known string instruments, and were in use by Sumerians and Egyptians long before they were present in Greece. The ancient version of the harp resembles a bow, with the strings connecting to the top and bottom of the arch. The strings are perpendicular to the soundbox, while the strings on a lyre are parallel.[22] Wind  A youth playing the aulon to a bearded man and his goose. Attic black-figure amphora, c. 560 BC. Aulos Usually double, consisting of two double-reed (like an oboe) pipes, not joined but generally played with a mouth-band to hold both pipes steadily between the player's lips. Modern reconstructions of the aulos indicate that they produced a low, clarinet-like sound. There is some confusion about the exact nature of the instrument; alternate descriptions indicate single-reeds instead of double reeds. It was associated with the cult of Dionysus. Syrinx or Pan flute Syrinx (σύριγξ), also known as Pan flute, is an ancient musical instrument based on the principle of the stopped pipe, consisting of a series of such pipes of gradually increasing length, tuned (by cutting) to a desired scale. Sound is produced by blowing across the top of the open pipe (like blowing across a bottle top). Hydraulis  The hydraulis. Note the presence of the curved trumpet, called the bukanē by the Greeks and, later, cornu by the Romans. A keyboard instrument, the forerunner of the modern pipe organ. As the name indicates, the hydraulis used water to supply a constant flow of pressure to the pipes. Two detailed descriptions have survived: that of Vitruvius[23] and Heron of Alexandria.[24] These descriptions deal primarily with the keyboard mechanism and with the apparatus that supplied the instrument with air.[a] Salpinx A brass trumpet used for military calls, and even contested in the Olympics. A number of sources mention this metal instrument with a bone mouthpiece. Percussion Tympanum Tympanum, also called tympanon, is a type of frame drum or tambourine. It was circular, shallow, and beaten with the palm of the hand or a stick. Crotalum The crotalum was a kind of clapper or castanet used in religious dances by groups. Koudounia The Koudounia are bell-like percussion instruments made of copper. |

ギリシャの楽器 以下、弦楽器(竪琴、キタラ、バルビトン、ハープ)、管楽器(アウロス、ハイドロリス、サルピンクス)、打楽器(ティンパナム、クロタラム、クードゥニア)が記載されている。 古代ギリシャの音楽で使われた楽器には次のようなものがある。竪琴、シタラ、アウロス、バルビトン、ハイドロリス、サルピンクスはすべて古代ローマの音楽に登場した。 弦楽器  キタラを演奏する女性を生き生きと描いた後期ローマのフレスコ画(紀元前30~40年頃 竪琴 弦楽器で、基本的には亀の甲羅(チェリス)の骨組みの上に作られた手持ちの琴で、一般に7本以上の弦があり、いずれかのモードの音に調弦される。竪琴は民 間楽器で、アポロン崇拝と結びついていた。竪琴は、他者や自分自身の伴奏として朗読や歌に使われ、貴族教育のための伝統的な訓練楽器でもあった。 キタラ キタラは、有給の音楽家が使う竪琴のプロ用バージョンである。キタラは、上部のクロスバーから下部の共鳴箱まで弦が張られた箱型のフレームを持ち、直立さ せて撥で演奏した[20]。アリストテレスは『政治学』の中で、シタラは「オルガノン・テクニコン」、すなわち芸術家の楽器であり、訓練を必要とすると述 べている[21]。  バルビトンを演奏する座った女性(詳細)、アッティカ赤像アンフォラ、紀元前460年頃 バルビトン シタラの大型低音版で、東イオニア系と考えられ、エキゾチックでやや異質な楽器。バルビトンは、高く評価されている古代の抒情詩人サッフォーの主要な楽器であり、しばしばサテュロスと関連していた。 カノナキ 紀元前6世紀にピタゴラス人によって発明された台形のプサルテリーだが、ミケーネに起源を持つ可能性がある。カノナキは奏者の太ももの上に置かれ、両手で骨を摘んで弾く。 ハープ ハープは最も古い弦楽器のひとつで、ギリシャに伝わるずっと以前からシュメール人やエジプト人によって使われていた。古代版のハープは弓に似ており、弦はアーチの上下に接続されている。竪琴の弦は平行であるのに対し、弦は響箱に対して垂直である[22]。 管楽器  髭を生やした男とガチョウの前でオーロンを演奏する青年。紀元前560年頃のアッティカ黒像アンフォラ。 アウロス オーボエのような)2本のダブルリード管で構成され、接合はされないが、一般的にはマウスバンドで両方の管を唇の間に固定して演奏する。現代のオーロスの 復元によると、クラリネットのような低い音を出す。この楽器の正確な性質については混乱があり、ダブルリードではなくシングルリードという記述もある。 ディオニュソス崇拝に関連していた。 シリンクスまたはパンフルート シリンクス(σύριγξ)は、パン・フルートとしても知られ、止め管の原理に基づく古代の楽器である。音は、開いたパイプの上部を横切るように吹く(瓶の上部を横切るように吹く)ことによって生み出される。 ハイドロリス  ハイドロリス。ギリシャではブカネ(bukanē)と呼ばれ、後にローマではコルヌ(cornu)と呼ばれる。 現代のパイプオルガンの前身である鍵盤楽器。その名が示すように、ハイドロリスはパイプに一定の圧力を供給するために水を使用した。ヴィトルヴィウスの記 述[23]とアレクサンドリアのヘロンの記述[24]の2つの詳細な記述が残っており、これらの記述は主に鍵盤機構と楽器に空気を供給する装置について述 べている[a]。 サルピンクス 軍用に使用され、オリンピックにも出場した真鍮製のトランペット。多くの資料が、骨のマウスピースを持つこの金属製の楽器について言及している。 打楽器 ティンパナム ティンパノンとも呼ばれるティンパヌムは、フレームドラムまたはタンバリンの一種。円形で浅く、手のひらや棒で叩く。 クロタラム 集団で宗教的な踊りを踊るときに使われた拍子木やカスタネットの一種。 クードゥニア 銅製の鐘のような打楽器。 |

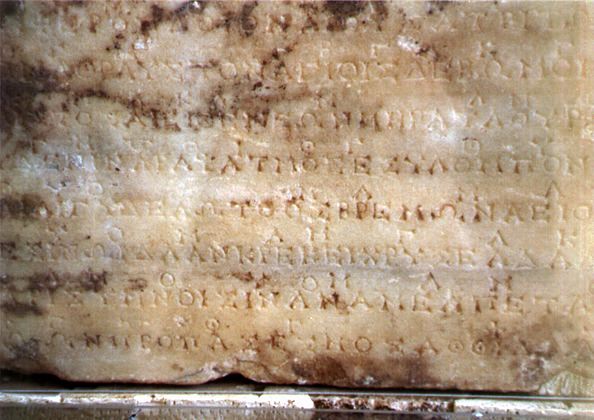

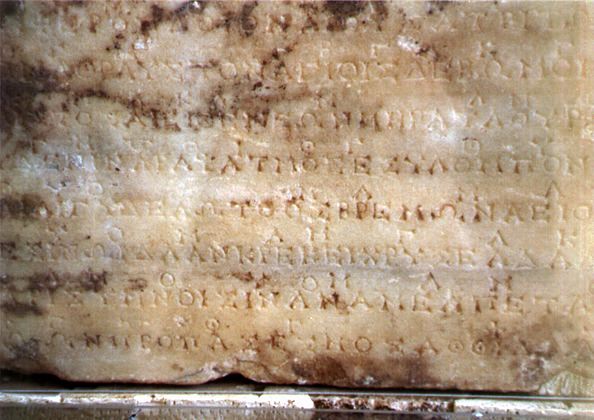

| Music and philosophy Pythagoras Main article: Pythagorean tuning The enigmatic ancient Greek figure of Pythagoras with mathematical devotion laid the foundations of our knowledge of the study of harmonics—how strings and columns of air vibrate, how they produce overtones, how the overtones are related arithmetically to one another, etc.[26] It was common to hear of the "music of the spheres" from the Pythagoreans. After studying the sound hammers made in a blacksmith's forge, Pythagoras invented the monochord, which has a movable bridge along with a string stretched over a sounding board. Using the monochord, he found the association between the vibrations and the lengths of the strings.[27] Plato At a certain point, Plato complained about the new music: Our music was once divided into its proper forms ... It was not permitted to exchange the melodic styles of these established forms and others. Knowledge and informed judgment penalized disobedience. There were no whistles, unmusical mob-noises, or clapping for applause. The rule was to listen silently and learn; boys, teachers, and the crowd were kept in order by threat of the stick. ... But later, an unmusical anarchy was led by poets who had natural talent, but were ignorant of the laws of music ... Through foolishness they deceived themselves into thinking that there was no right or wrong way in music, that it was to be judged good or bad by the pleasure it gave. By their works and their theories they infected the masses with the presumption to think themselves adequate judges. So our theatres, once silent, grew vocal, and aristocracy of music gave way to a pernicious theatrocracy ... the criterion was not music, but a reputation for promiscuous cleverness and a spirit of law-breaking.[28]  Photograph of the original stone at Delphi containing the second of the two hymns to Apollo. The music notation is the line of occasional symbols above the main, uninterrupted line of Greek lettering. From his references to "established forms" and "laws of music" we can assume that at least some of the formality of the Pythagorean system of harmonics and consonance had taken hold of Greek music, at least as it was performed by professional musicians in public, and that Plato was complaining about the falling away from such principles into a "spirit of law-breaking". Playing what "sounded good" violated the established ethos of modes that the Greeks had developed by the time of Plato: a complex system of relating certain emotional and spiritual characteristics to certain modes (scales). The names for the various modes derived from the names of Greek tribes and peoples, the temperament and emotions of which were said to be characterized by the unique sound of each mode. Thus, Dorian modes were "harsh", Phrygian modes "sensual", and so forth. In his Republic,[29] Plato talks about the proper use of various modes, the Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, etc. It is difficult for the modern listener to relate to that concept of ethos in music except by comparing our own perceptions that a minor scale is used for melancholy and a major scale for virtually everything else, from happy to heroic music. The sounds of scales vary depending on the placement of tones. Modern Western scales use the placement of whole tones, such as C to D on a modern piano keyboard, and half tones, such as C to C-sharp, but not quarter-tones ("in the cracks" on a modern keyboard) at all. This limit on tone types creates relatively few kinds of scales in modern Western music compared to that of the Greeks, who used the placement of whole-tones, half-tones, and even quarter-tones (or still smaller intervals) to develop a large repertoire of scales, each with a unique ethos. The Greek concepts of scales (including the names) found its way into later Roman music and then the European Middle Ages to the extent that one can find references to, for example, a "Lydian church mode", although name is simply a historical reference with no relationship to the original Greek sound or ethos.  Detail from Piero di Cosimo's 16th-century version of Perseus rescuing Andromeda. The instrument in the hands of the musician is an anachronism and appears to be an imaginary combination of a plucked string instrument and bassoon. From the descriptions that have come down to us through the writings of those such as Plato, Aristoxenus[30] and, later, Boethius,[31] we can say with some caution that the ancient Greeks, at least before Plato, heard music that was primarily monophonic; that is, music built on single melodies based on a system of modes / scales, themselves built on the concept that notes should be placed between consonant intervals. It is a commonplace of musicology to say that harmony, in the sense of a developed system of composition, in which many tones at once contribute to the listener's expectation of resolution, was invented in the European Middle Ages and that ancient cultures had no developed system of harmony—that is, for example, playing the third and seventh above the dominant, in order to create the expectation for the listener that the tritone will resolve to the third. Plato's Republic notes that Greek musicians sometimes played more than one note at a time, although this was apparently considered an advanced technique. The Orestes fragment of Euripides seems to clearly call for more than one note to be sounded at once.[32] Research[33] in the field of music from the ancient Mediterranean—decipherings of cuneiform music script—argue for the sounding of different pitches simultaneously and for the theoretical recognition of a "scale" many centuries before the Greeks learned to write, which they would have done before they developed their system for notating music and recorded the written evidence for simultaneous tones. All we can say from the available evidence is that, while Greek musicians clearly employed the technique of sounding more than one note at the same time, the most basic, common texture of Greek music was monophonic. That much seems evident from another passage from Plato: ... The lyre should be used together with the voices ... the player and the pupil producing note for note in unison, Heterophony and embroidery by the lyre—the strings throwing out melodic lines different from the melodia which the poet composed; crowded notes where his are sparse, quick time to his slow ... and similarly all sorts of rhythmic complications against the voices—none of this should be imposed upon pupils ...[34] Aristotle  Girls dancing with an instructress and a youth, c. 430 BC, found at Capua. British Museum Aristotle had a strong belief that music should be a part of one's education, alongside reading and writing, and gymnastics. Just as men must work hard in their duties, they must also be able to relax well. According to Aristotle, all men could agree that music was one of the most pleasurable things, so to have this as a means of leisure was only logical. Amusing oneself was not considered a viable hobby, or else we would not want to help in society. Since music combined relaxing ourselves, along with others, Aristotle claimed that learning an instrument was essential to our development.[35]: 10 Virtues is a topic that Aristotle is widely known for, and he also used them to justify why music should be involved in education. Since virtues consist of loving and rejoicing in something, then music could be pursued without issue. Music forms our character, so it should also be a part of our education. Aristotle also comments on how getting children involved in music would be a way to keep them occupied and quiet. It is important to note that since music helps in forming the character, it could cause either adverse or pleasant effects. The way in which music is taught can have a large impact on development.[35]: 16 Learning music should not interfere with the younger years, nor should it damage the body in a way that a person is unable to fulfill duties in the military. Those that have learned music in education should not be at the same level as a professional, but they should have a greater knowledge than the slaves and other commoners.[35]: 15 Aristotle was specific in what instruments should be learned. The harp and flute should not be taught in school, as they are too complicated. Additionally, only certain melodies have benefits in an educational setting. Ethical melodies should be taught, but melodies of passion and melodies of action should be for performances.[35]: 16 |

音楽と哲学 ピタゴラス 主な記事 ピタゴラス音律 ピタゴラスという謎めいた古代ギリシアの人物は、数学に傾倒し、弦や空気の柱がどのように振動するのか、どのように倍音を発生させるのか、倍音は互いにど のように算術的に関連しているのかなど、倍音学の知識の基礎を築いた[26]。鍛冶屋の鍛冶場でハンマーの音を研究した後、ピタゴラスは、響板に張られた 弦と可動式のブリッジを持つモノコードを発明した。モノコードを使って、彼は振動と弦の長さの関連性を発見した[27]。 プラトン ある時、プラトンは新しい音楽について苦言を呈した: われわれの音楽はかつて適切な形に分割されていた。われわれの音楽は、かつてその適切な形式に分けられた......そして、これらの確立された形式と他 の形式の旋律様式を交換することは許されなかった。知識と情報に基づいた判断が、不服従を罰したのだ。口笛も、音楽的でない群衆のノイズも、拍手のための 手拍子もなかった。少年たち、教師たち、そして群衆は、棒で脅すことによって秩序を保っていた。しかしその後、天賦の才能を持ちながら音楽の法則を知らな い詩人たちによって、音楽とは無縁の無政府状態が生まれた。彼らは愚かさによって、音楽には正しい道も間違った道もなく、それが与える快楽によって良し悪 しが判断されるものだと自分たちを欺いた。自分たちの作品や理論によって、大衆は自分たちが適切な判断者だと思い込むようになった。こうして、かつては沈 黙していたわが国の劇場は声高になり、音楽の貴族主義は悪質な劇場主義へと道を譲った......その基準は音楽ではなく、乱雑な巧みさの評判と掟破りの 精神であった[28]。  アポロンへの2つの賛歌のうちの2番を含むデルフィの原石の写真。楽譜は、ギリシャ文字の途切れることのない主要な線の上に、時折記号が並んでいる。 確立された形式」と「音楽の法則」についての彼の言及から、少なくともピタゴラスの倍音と協和音の体系の形式的な部分が、少なくともプロの音楽家が公の場 で演奏するようなギリシア音楽に定着していたこと、そしてプラトンは、そのような原則から「掟破りの精神」へと堕落していくことに苦言を呈していたことが 推測できる。 いい音」で演奏することは、プラトンの時代までにギリシア人が確立していたモードの倫理観に反するものだった。様々なモードの名前は、ギリシャの部族や民 族の名前に由来しており、その気質や感情は、それぞれのモードの独特な響きによって特徴付けられると言われていた。したがって、ドリアン・モードは「辛 辣」、フリギア・モードは「官能的」といった具合である。プラトンは『共和国』[29]の中で、ドリアン、フリギア、リディアンなど、さまざまなモードの 適切な使い方について語っている。現代の聴き手が、音楽におけるエトスという概念に共感するのは、哀愁には短調の音階が使われ、幸福な音楽から英雄的な音 楽まで、それ以外のほとんどすべての音楽には長調の音階が使われるという私たち自身の認識と比較する以外には難しい。 音階の響きは、音の配置によって異なる。現代の西洋音階では、CからDといった全音や、Cから嬰Cといった半音は使われるが、4分音符(現代の鍵盤では 「割れ目」)はまったく使われない。ギリシア人は全音、半音、さらには4分音符(あるいはさらに小さな音程)の配置を駆使して、それぞれ独自のエスプリを 持つ音階のレパートリーを大量に開発していました。ギリシアの音階の概念(名前も含めて)は、後のローマ音楽、そしてヨーロッパ中世へと伝わり、例えば 「リディアン・チャーチ・モード」という呼称が見られるようになった。  ピエロ・ディ・コジモが16世紀に描いた「アンドロメダを助けるペルセウス」の細部。手に持っている楽器は時代錯誤のもので、撥弦楽器とファゴットを組み合わせた想像上のものと思われる。 プラトン、アリストクセノス[30]、後にボエティウス[31]などの著作を通じて私たちに伝わってきた記述から、少なくともプラトン以前の古代ギリシア 人が聴いていた音楽は主に単旋律であった。和声とは、一度に多くの音が聴き手の解決への期待に貢献するような、発展した作曲のシステムという意味で、ヨー ロッパの中世に発明されたものであり、古代文化には発展した和声のシステムはなかったというのが音楽学の通説である。 プラトンの『共和国』には、ギリシアの音楽家が一度に複数の音を演奏することがあったと記されているが、これは高度な技術と考えられていたようだ。古代地 中海の音楽分野の研究[33]-楔形文字の解読-は、ギリシア人が文字を学ぶ何世紀も前に、異なる音程を同時に鳴らすこと、そして「音階」を理論的に認識 していたことを論じている。入手可能な証拠から言えることは、ギリシアの音楽家たちは明らかに複数の音を同時に鳴らすテクニックを採用していたが、ギリシ ア音楽の最も基本的で一般的なテクスチャーは単旋律であったということだ。 そのことは、プラトンの別の一節からも明らかなようだ: ... 竪琴は声楽と一緒に使われるべきである......奏者と生徒がユニゾンで音符と音符を作り出すこと、ヘテロフォニーと竪琴による刺繍......弦楽器 は詩人が作曲したメロディアとは異なる旋律線を投げかける......彼の音符がまばらであるところでは混雑した音符、彼の遅い音符には速い時 間......そして同様に、声楽に対するあらゆる種類のリズムの複雑さ......このどれも生徒に課すべきではない.....[34]。 アリストテレス  女教師と若者と踊る少女たち、紀元前430年頃、カプアで発見。大英博物館 アリストテレスは、読み書きや体操と並んで、音楽も教育の一部であるべきだという強い信念を持っていた。男性は職務に励まなければならないのと同様に、リ ラックスもできなければならない。アリストテレスによれば、音楽が最も楽しいもののひとつであることは誰もが認めるところであり、これを余暇の手段として 持つことは理に適っていた。自分自身を楽しませることは、趣味として成立しないと考えられていた。音楽は他者とともに自分自身をリラックスさせるものであ るため、アリストテレスは楽器を学ぶことは人間の成長に不可欠であると主張した[35]: 10 美徳は、アリストテレスが広く知られているトピックであり、彼はまた、音楽が教育に関与すべきである理由を正当化するためにそれらを使用しました。美徳と は何かを愛し、喜ぶことであるから、音楽は問題なく追求できる。音楽は私たちの人格を形成するのだから、教育の一部であるべきだ。アリストテレスはまた、 子供を音楽に参加させることが、いかに子供を退屈させず、静かにさせる方法であるかについても述べている。音楽は人格形成に役立つので、悪影響も快影響も 引き起こす可能性があることに注意することが重要である。音楽の教え方は、発達に大きな影響を与える可能性がある[35]: 16 音楽を学ぶことは、若い時期を妨げるものであってはならないし、軍隊での職務を果たせないような形で身体にダメージを与えるものであってはならない。教育 において音楽を学んだ者は、専門家と同じレベルであってはならないが、奴隷や他の平民よりも大きな知識を持つべきである[35]: 15 アリストテレスは、どのような楽器を学ぶべきかについて具体的に述べている。ハープとフルートは複雑すぎるので、学校では教えるべきではない。さらに、教 育の場では特定のメロディーのみが有益である。倫理的な旋律は教えるべきだが、情熱の旋律や行動の旋律は演奏のために使うべきだ: 16 |

| Surviving music Classical Period Eleusis inv. 907 (trumpet signal) Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Comp. 63 f. Euripides, Orestes, Papyrus Vienna G 2315 Papyrus Leiden inv. P. 510 (Euripides, Iphigenia in Aulis) Hellenistic Period Papyrus Ashm. inv. 89B/31, 33 Papyrus Ashm. inv. 89B/29-32 (citharodic nomes) Papyrus Hibeh 231 Papyrus Zeno 59533 Papyrus Vienna G 29825 a/b recto Papyrus Vienna G 29825 a/b verso Papyrus Vienna G 29825 c Papyrus Vienna G 29825 d-f Papyrus Vienna G 13763/1494 Papyrus Berlin 6870 Epidaurus, SEG 30. 390 (Hymn to Asclepius) Roman imperial period Delphic Hymns Seikilos epitaph Hymns of Mesomedes |

|

| Nomos (music) Oxyrhynchus hymn Ancient Roman music For a technical discussion, Musical system of ancient Greece or Ancient Greek Musical Notation |

ノモス オキシルヒンクス賛歌 古代ローマ音楽 専門的な議論は、古代ギリシアの音楽体系または古代ギリシア楽譜を参照。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_of_ancient_Greece |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆