音楽記号論

Music semiology

10

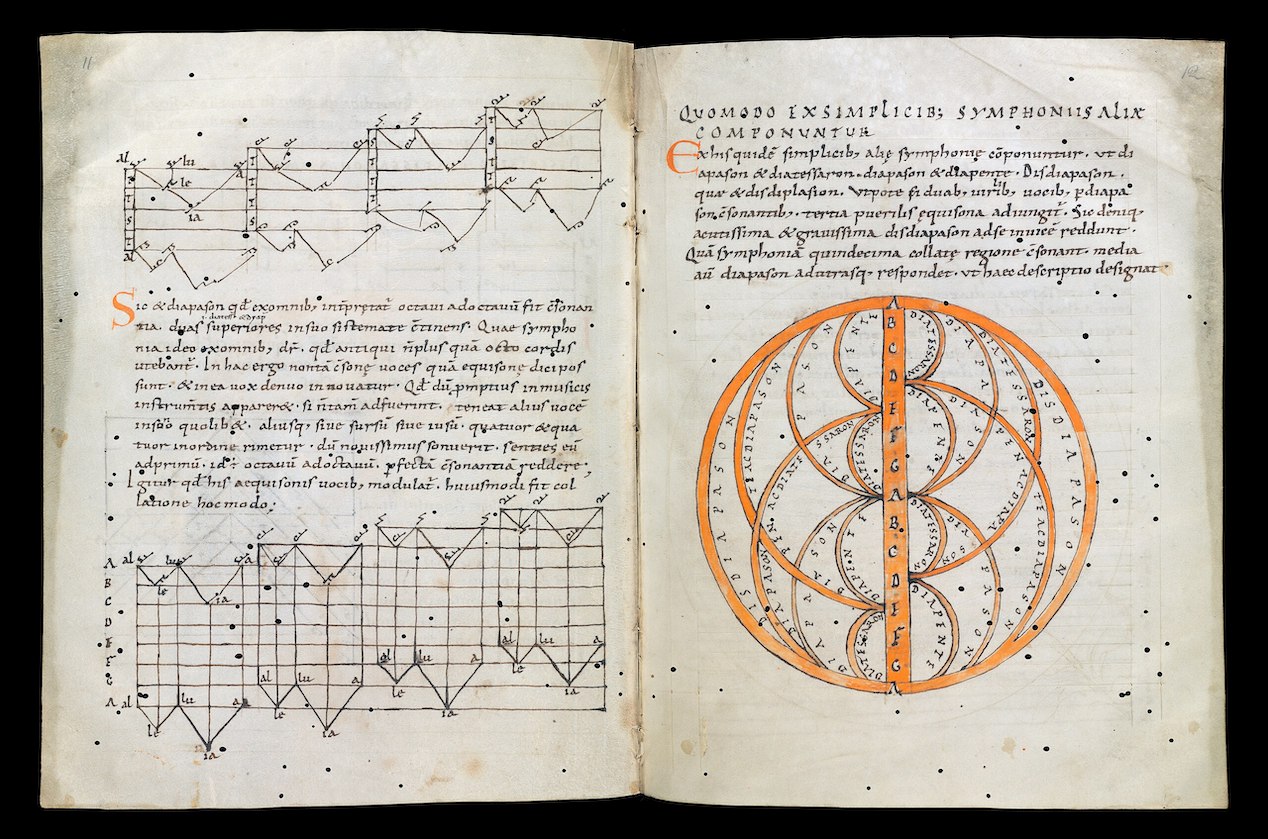

世紀の写本『Musica enchiriadis』における音域の説明

☆

音楽記号論(セミオティクス)とは、音楽の記号学の研究すなわち、様々なレベルにおいて音楽に関連する記号を研究する学問である。音楽の記号性について

は、音楽を記号化する記譜やオーディオビジュアルな記録法に関する研究アプローチと、音楽そのものを記号とみて、その受容・理解・解釈・あるいは再現に関

する人文社会的分析という解釈学的研究アプローチに大きくわかれる。

| Music semiology

(semiotics) is the study of signs as they pertain to music on a variety

of levels. |

音楽記号論(セミオティクス)とは、様々なレベルにおいて音楽に関連す

る記号を研究する学問である。 |

| Overview Following Roman Jakobson, Kofi Agawu adopts the idea of musical semiosis being introversive or extroversive—that is, musical signs within a text and without.[1] "Topics", or various musical conventions (such as horn calls, dance forms, and styles), have been treated suggestively by Agawu, among others. The notion of gesture is beginning to play a large role in musico-semiotic enquiry. There are strong arguments that music inhabits a semiological realm which, on both ontogenetic and phylogenetic levels, has developmental priority over verbal language.[non sequitur][citation needed][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9] |

概観 ロマン・ヤコブソン(Roman Jakobson)に倣い、コフィ・アガウ(Kofi Agawu) は音楽記号論の内向的・外向的という概念を採用している。つまり、音楽記号はテキスト内とテキスト外に存在するのだ[1]。「主題」、すなわち様々な音楽 的慣習(角笛の合図、舞踊形式、様式など)は、アガウをはじめとする研究者によって示唆的に扱われてきた。ジェスチャーの概念は、音楽記号論的研究におい て大きな役割を果たし始めている。 音楽は、個体発生学的および系統発生学的レベルの両方において、言語よりも発達的に優先される記号論的領域に属するという強力な主張がある。[非論理的] [出典必要][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9] |

| Writers on music semiology

include Kofi Agawu (on topical theory, Schenkerian

analysis), Robert S.

Hatten (on topic, gesture), Raymond Monelle (on topic, musical

meaning), Jean-Jacques

Nattiez (on introversive taxonomic analysis and ethnomusicological

applications), Anthony Newcomb

(on narrativity), Thomas Turino

(applying the semiotics of Charles Sanders Peirce), and Eero Tarasti

(generally considered the founder of musical semiotics).[citation

needed] Roland Barthes, himself a semiotician and skilled amateur

pianist, wrote about music in some of the essays collected in Image,

Music, Text[10] and The Responsibility of Forms,[11] as well as in the

essay "Eiffel Tower",[12] though he did not consider music to be a

semiotic system.[citation needed] |

音楽記号論に関する著述家には、コフィ・アガウ(主題理論、シェンカー

分析)、 ロバート・S・ハッテン(主題、ジェスチャー)、レイモンド・モネル(主題、音楽的意味)、ジャン=ジャック・ナティエ(内

省的分類学的分析と民族音楽学的応用)、アンソニー・ニューコム(物語性)、トーマス・トゥリーノ(チャールズ・サンダース・パースの記号論の応用)、そ

してエーロ・タラステ(一般的に音楽記号論の創始者と見なされている)。[出典必要]

記号学者であり熟練したアマチュアピアニストでもあったロラン・バルトは、『イメージ、音楽、テキスト』[10]や『形態の責任』[11]に収められた

エッセイ、および「エッフェル塔」[12]というエッセイの中で音楽について論じている。ただし彼は音楽を記号体系とは見なしていなかった。[出典必要] |

| Signs,

meanings in music, happen essentially through the connotations of

sounds, and through the social construction, appropriation and

amplification of certain meanings associated with these connotations.

The work of Philip Tagg

(Ten Little Tunes, Fernando the Flute, Music’s Meanings)[full citation

needed] provides one of the most complete and systematic analysis of

the relation between musical structures and connotations in western and

especially popular, television and film music. The work of Leonard B. Meyer

in Style and Music[13] theorizes the relationship between ideologies

and musical structures and the phenomena of style change, and focuses

on Romanticism as a case study. Fred Lerdahl and

Ray Jackendoff[14]

analyze how music is structured like a language with its own semiotics

and syntax. |

音

楽における記号や意味は、本質的に音の連想を通じて、またそれらの連想に関連する特定の意味の社会的構築、流用、増幅を通じて生じる。フィリップ・タグの

著作(『十の小曲』『フルートのフェルナンド』『音楽の意味』)は、西洋音楽、特に大衆音楽、テレビ音楽、映画音楽における音楽構造と連想の関係につい

て、最も完全かつ体系的な分析の一つを提供している。レナード・B・マイヤーの『様式と音楽』[13]は、イデオロギーと音楽構造の関係、様式変化の現象

を理論化し、ロマン主義を事例研究として焦点を当てている。フレッド・ラーダールとレイ・ジャッケンドフ[14]は、音楽が独自の記号論と構文を持つ言語

のように構造化されていることを分析している。 |

| Semiotics

of music videos Chromatic fourth Lament bass Musivisual language Pianto Semiology (Gregorian chant) |

ミュージックビデオの記号論 半音階的四度 哀歌の低音 音楽視覚言語 悲嘆 記号学(グレゴリオ聖歌) |

| References 1. Agawu 2008, [page needed]. 2. Middleton 1990, p. 172. 3. Nattiez 1976. 4. Nattiez 1987. 5. Nattiez 1989. 6. Stefani 1973. 7. Stefani 1976. 8. Baroni 1983. 9. Semiotica 66 1987, 1–3. 10. Barthes 1977. 11. Barthes 1985. 12. Barthes 1982, [page needed]. 13. Meyer 1989. 14. Lerdahl and Jackendoff 1983. |

参考文献 1. アガウ 2008, [ページ番号が必要]。 2. ミドルトン 1990, p. 172。 3. ナティエ 1976。 4. ナティエ 1987。 5. ナティエ 1989。 6. ステファニ 1973。 7. ステファニ 1976。 8. バローニ 1983年。 9. 『セミオティカ』66号 1987年、1–3頁。 10. バルト 1977年。 11. バルト 1985年。 12. バルト 1982年、[ページ番号不明]。 13. マイヤー 1989年。 14. ラーダールとジャッケンドフ 1983年。 |

| Sources Agawu, Kofi (2008). Music as Discourse: Semiotic Adventures in Romantic Music. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-020640-6. Baroni, Mario (1983). "The Concept of Musical Grammar", translated by Simon Maguire and William Drabkin. Music Analysis 2, no. 2:175–208. Barthes, Roland (1977). Image, Music, Text, translated by Stephen Heath. New York : Hill and Wang. ISBN 9780809057405, 9780374521363. Barthes, Roland (1982). "The Eiffel Tower". In A Barthes Reader, edited, and with an introduction, by Susan Sontag, 236–250. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 9780809028153, 9780880290159, 9780374521448. Barthes, Roland (1985). The Responsibility of Forms: Critical Essays on Music, Art, and Representation, edited by Richard Howard. Oxford: Basil Blackwell; New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 9780809080755, 9780809015221. Lerdahl, Fred, and Ray Jackendoff (1983). A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press[ISBN missing]. Meyer, Leonard B. (1989). Style and Music: Theory, History, and Ideology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226521527. Middleton, Richard (1990). Studying Popular Music. Milton Keynes and Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 9780335152766 (cloth); ISBN 9780335152759 (pbk). Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1976). Fondements d'une sémiologie de la musique. Collection Esthétique. Paris: Union générale d'éditions. ISBN 9782264000033. Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1987). Musicologie générale et sémiologie. Collection Musique /Passé/Présent. Paris: C. Bourgois. ISBN 9782267005004 Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1989). Proust as Musician, translated by Derrick Puffett. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36349-5 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-521-02802-8. Semiotica 66 (1987).[full citation needed]. Stefani, Gino (1973). "Sémiotique en musicologie". Versus 5:20–42. Stefani, Gino (1976). Introduzione alla semiotica della musica. Palermo: Sellerio editore. |

出典 アガウ、コフィ(2008)。『音楽としての言説:ロマン派音楽における記号論的冒険』。ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-020640-6。 バローニ、マリオ(1983)。「音楽文法の概念」、サイモン・マグワイアとウィリアム・ドラブキン訳。『音楽分析』第2巻第2号:175–208頁。 バルト、ロラン(1977)。『イメージ、音楽、テクスト』、スティーブン・ヒース訳。ニューヨーク:ヒル・アンド・ワン社。ISBN 9780809057405, 9780374521363。 バルト、ロラン(1982)。「エッフェル塔」。『バルト選集』所収、スーザン・ソンタグ編・序文、236–250頁。ニューヨーク:ヒル・アンド・ワン 社。ISBN 9780809028153, 9780880290159, 9780374521448。 バルト、ロラン(1985)。『形態の責任:音楽、芸術、表象に関する批評的エッセイ』リチャード・ハワード編。オックスフォード:バジル・ブラックウェ ル;ニューヨーク:ヒル・アンド・ワン。ISBN 9780809080755, 9780809015221。 レルダール、フレッド、レイ・ジャッケンドフ(1983)。『調性音楽の生成理論』。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:MITプレス[ISBN欠落]。 マイヤー、レナード・B.(1989)。『様式と音楽:理論、歴史、イデオロギー』。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局。ISBN 9780226521527。 ミドルトン、リチャード(1990)。『ポピュラー音楽の研究』。ミルトンキーンズおよびフィラデルフィア:オープン大学出版局。ISBN 9780335152766(ハードカバー);ISBN 9780335152759(ペーパーバック)。 ナティエ、ジャン=ジャック(1976)。『音楽記号論の基礎』。コレクション・エステティック。パリ:ユニオン・ジェネラル・デディシオン。ISBN 9782264000033。 ナティエ、ジャン=ジャック(1987)。『音楽学概論と記号論』。コレクション・ミュジーク/パセ/プレザン。パリ:C. ブルゴワ。ISBN 9782267005004 ナティエ、ジャン=ジャック(1989)。『音楽家としてのプルースト』、デリック・パフェット訳。ケンブリッジおよびニューヨーク:ケンブリッジ大学出 版局。ISBN 978-0-521-36349-5(ハードカバー);ISBN 978-0-521-02802-8。 Semiotica 66 (1987).[完全な引用が必要]。 ステファニ、ジーノ (1973). 「音楽学における記号論」. Versus 5:20–42. ステファニ、ジーノ (1976). Introduzione alla semiotica della musica. パレルモ: Sellerio editore. |

| Further reading Ashby, Arved (2004). "Intention and Meaning in Modernist Music". In The Pleasure of Modernist Music, edited by Arved Ashby, [full citation needed] ISBN 1-58046-143-3. Jackendoff, Ray (1987). Consciousness and the Computational Mind. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.[ISBN missing] Martin, Serge (1978). Le Langage musical: sémiotique des systèmes. Sémiosis. Paris: Éditions Klincksieck. ISBN 2-252-02031-8. Molino, Jean (1975). "Fait musical et sémiologue de la musique". Musique en Jeu, no. 17:37–62. Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1990). Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music, translated by Carolyn Abbate from Musicologie générale et sémiologue (1987). Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02714-5. Tagg, Philip (2013). Music's Meanings. New York & Huddersfield: MMMSP, 710 pp. ISBN 978-0-9701684-5-0 (e-book); ISBN 978-0-9701684-8-1 (hard copy). |

追加文献(さらに読む) アッシュビー、アーヴェド (2004)。「モダニズム音楽における意図と意味」 『モダニズム音楽の喜び』 アーヴェド・アッシュビー編、[完全な引用が必要] ISBN 1-58046-143-3。 ジャッケンドフ、レイ (1987)。『意識と計算的思考』 マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:MIT Press。[ISBN 欠落] マーティン、セルジュ (1978). 『音楽言語:システムの記号論』. Sémiosis. パリ: Éditions Klincksieck. ISBN 2-252-02031-8. モリーノ、ジャン (1975). 「音楽的事実と音楽記号論者」. Musique en Jeu, no. 17:37–62. ナティエ、ジャン=ジャック(1990)。『音楽と言説:音楽記号論に向けて』、キャロリン・アバテによる『Musicologie générale et sémiologue』(1987)の翻訳。プリンストン:プリンストン大学出版局。ISBN 0-691-02714-5。 タッグ、フィリップ(2013)。『音楽の意味』ニューヨーク&ハダースフィールド:MMMSP、710頁。ISBN 978-0-9701684-5-0(電子書籍);ISBN 978-0-9701684-8-1(ハードカバー)。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_semiology |

|

| Semiotic music analysis Tagg was probably best known for his work in the field of music analysis. Using mainly pieces of popular music as analysis objects, he stresses the importance of non-notatable parameters of expression and of vernacular perception in understanding "how music communicates what to whom with what effect" in today's world. He has adapted Charles Seeger's notion of the museme to demonstrate how combinations of such units are used to create both syncritic (intensional) structures inside the extended present, and diatactical (extensional) ones over time.[23] These combinatory structures can be understood, he argues, with the help of an overall sign typology consisting of anaphones (sonic, tactile, kinetic, social), style flags (style determinants, genre synecdoches, etc.) and episodic markers.[24] The semiotic theory is basically Peircean but it draws also on Umberto Eco's theories of connotation.[25] The actual analysis method is based on both metamusical information about the analysis object (reception tests, opinions, ethnographic observation, etc.) to arrive at paramusical fields of connotation (PMFCs),[26] and on intertextuality. The latter involves identifying sounds observed in the analysis object with sounds in other music – interobjective comparison material (IOCM) – and in connecting that IOCM with its own PMFCs.[27] Tagg argues that this sort of music semiotics is musogenic, not logogenic, i.e. suited to expression in music rather than in words, and that the combination of intersubjective and interobjective procedures can, inside a given cultural context, provide reliable insights into the mediation of meaning through music. |

記号論的音楽分析 タグは音楽分析の分野での業績で最もよく知られている。主にポピュラー音楽の楽曲を分析対象とし、現代において「音楽が何を誰にどのような効果をもって伝 えるか」を理解する上で、記譜できない表現のパラメータと一般大衆の知覚の重要性を強調している。彼はチャールズ・シーガーの「ミューゼム」概念を応用 し、こうした単位の組み合わせが、拡張された現在内におけるシンクリティック(内包的)構造と、時間軸上のダイアタクティック(外延的)構造の両方を創出 する仕組みを実証した。[23] こうした組み合わせ構造は、アナフォン(音響的・触覚的・運動的・社会的)、スタイルフラグ(様式決定因子・ジャンル換喩等)、エピソードマーカーから成 る包括的記号類型論によって理解可能だと彼は論じる。[24] この記号論的理論は基本的にピアジェ的だが、ウンベルト・エコの共鳴理論も援用している。[25] 実際の分析手法は、分析対象に関するメタ音楽的情報(受容テスト、意見、エスノグラファーによる観察など)に基づく連想的パラ音楽的領域(PMFC) [26] と、相互テクスト性に基づく。後者は、分析対象で観察された音を他の音楽(対客観的比較素材:IOCM)の音と同一視し、そのIOCMを自身のPMFCs と結びつけることを含む。[27] タッグは、この種の音楽記号論はロゴジェニック(言語生成)ではなくムゾジェニック(音楽生成)であり、つまり言葉ではなく音楽による表現に適していると し、主観間的手法と客観間的手法の組み合わせが、特定の文化的文脈において、音楽を通じた意味の媒介に関する信頼できる洞察を提供し得ると論じている。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Tagg |

|

| Contribution to musical cognition Jackendoff, together with Fred Lerdahl, has been interested in the human capacity for music and its relationship to the human capacity for language. In particular, music has structure as well as a "grammar" (a means by which sounds are combined into structures). When a listener hears music in an idiom he or she is familiar with, the music is not merely heard as a stream of sounds; rather, the listener constructs an unconscious understanding of the music and is able to understand pieces of music never heard previously. Jackendoff is interested in what cognitive structures or "mental representations" this understanding consists of in the listener's mind, how a listener comes to acquire the musical grammar necessary to understand a particular musical idiom, what innate resources in the human mind make this acquisition possible and, finally, what parts of the human music capacity are governed by general cognitive functions and what parts result from specialized functions geared specifically for music (Jackendoff & Lerdahl, 1983; Lerdahl, 2001). Similar questions have also been raised regarding human language, although there are differences. For instance, it is more likely that humans evolved a specialized language module than having evolved one for music, since even the specialized aspects of music comprehension are tied to more general cognitive functions.[1] |

音楽認知への貢献 ジャッケンドフは、フレッド・ラーダールと共に、人間の音楽能力とその言語能力との関係に関心を寄せてきた。特に音楽には構造と「文法」(音を構造に組み 立てる手段)が存在する。聴き手が慣れ親しんだ様式の音楽を聴くとき、それは単なる音の流れとして聴かれるのではなく、聴き手は無意識のうちに音楽を理解 する構造を構築し、これまで聴いたことのない楽曲さえも理解できるようになる。ジャッケンドフは、この理解が聴取者の心の中でどのような認知構造や「心的 表象」を構成するのか、特定の音楽的イディオムを理解するために必要な音楽的文法をどのように習得するのか、この習得を可能にする人間の心の中の生来の資 源は何か、そして最終的に、人間の音楽能力のどの部分が一般的な認知機能によって支配され、どの部分が音楽に特化した機能の結果であるのかに関心を持って いる(Jackendoff & ラーダール、1983年;ラーダール、2001年)。同様の疑問は人間の言語についても提起されているが、相違点も存在する。例えば、音楽理解の特殊な側 面でさえより一般的な認知機能と結びついていることから、人間が音楽専用のモジュールを進化させたよりも、言語専用のモジュールを進化させた可能性の方が 高いと考えられる。[1] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ray_Jackendoff |

★

| Musical semiotics |

(音楽理論のなかの)音楽記号論 |

Further information: Music

semiology and Jean-Jacques Nattiez Semiotician Roman Jakobson Music semiology (semiotics) is the study of signs as they pertain to music on a variety of levels. Following Roman Jakobson, Kofi Agawu adopts the idea of musical semiosis being introversive or extroversive—that is, musical signs within a text and without.[citation needed] "Topics", or various musical conventions (such as horn calls, dance forms, and styles), have been treated suggestively by Agawu, among others.[citation needed] The notion of gesture is beginning to play a large role in musico-semiotic enquiry.[citation needed] "There are strong arguments that music inhabits a semiological realm which, on both ontogenetic and phylogenetic levels, has developmental priority over verbal language."[96][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][incomplete short citation][clarification needed] |

補足情報:音楽記号論とジャン=ジャック・ナティエ 記号論者ロマン・ヤコブソン 音楽記号論(セミオティクス)とは、様々なレベルで音楽に関連する記号を研究する学問である。ロマン・ヤコブソンに倣い、コフィ・アガウは音楽的記号作用 が内向的または外向的であるという概念を採用している。つまり、テキスト内とテキスト外の音楽的記号を指す。[出典必要] 「トピック」、すなわち様々な音楽的慣習(角笛の合図、舞踊形式、様式など)は、アガウらによって示唆的に扱われてきた。[出典必要] ジェスチャーの概念は、音楽記号論的研究において大きな役割を果たし始めている。[出典が必要] 「音楽は、個体発生学的・系統発生学的両レベルにおいて言語より発達的に優先される記号論的領域に存在する」という強い主張がある。[96][97] [98][99][100][101][102][103][不完全な短引用][説明が必要] |

| Writers on music semiology

include Kofi Agawu (on topical theory),[104] Heinrich

Schenker,[105][106] Robert Hatten (on topic, gesture)[citation needed],

Raymond Monelle (on topic, musical meaning)[107], Jean-Jacques Nattiez

(on introversive taxonomic analysis and ethnomusicological

applications)[citation needed], Anthony Newcomb (on

narrativity)[citation needed], and Eero Tarasti[citation needed]. Roland Barthes, himself a semiotician and skilled amateur pianist, wrote about music in Image Music Text,[108] The Responsibility of Forms,[109] and The Eiffel Tower,[110] though he did not consider music to be a semiotic system.[111] |

音楽記号論に関する著述家には、トピック理論に関するコフィ・アガウ

[104]、ハインリヒ・シェンカー[105]、

[106]ロバート・ハッテン(主題、ジェスチャーについて)[出典必要]、レイモンド・モネル(主題、音楽的意味について)[107]、ジャン=ジャッ

ク・ナティエ(内省的分類学的分析と民族音楽学的応用について)[出典必要]、アンソニー・ニューコム(物語性について)[出典必要]、エーロ・タラス

ティ[出典必要]などが挙げられる。 ローラン・バルトは、自身も記号論者であり熟練したアマチュアピアニストであったが、『イメージ・音楽・テクスト』[108]、『形態の責任』 [109]、『エッフェル塔』[110]において音楽について論じた。ただし彼は音楽を記号論的体系とは見なしていなかった[111]。 |

| Signs, meanings in music, happen

essentially through the connotations of sounds, and through the social

construction, appropriation and amplification of certain meanings

associated with these connotations. The work of Philip Tagg (Ten Little

Tunes,[full citation needed] Fernando the Flute,[full citation needed]

Music's Meanings[full citation needed]) provides one of the most

complete and systematic analysis of the relation between musical

structures and connotations in western and especially popular,

television and film music. The work of Leonard B. Meyer in Style and

Music[full citation needed] theorizes the relationship between

ideologies and musical structures and the phenomena of style change,

and focuses on romanticism as a case study. |

音楽における記号や意味は、本質的に音の連想を通じて、またそれらの連

想に関連する特定の意味の社会的構築、流用、増幅を通じて生じる。フィリップ・タグの研究(『十の小曲』 [出典必要]

フルートのフェルナンド[出典必要]

音楽の意味[出典必要])は、西洋音楽、特に大衆音楽、テレビ音楽、映画音楽における音楽構造と連想の意味の関係について、最も包括的かつ体系的な分析の

一つを提供している。レナード・B・マイヤーの『様式と音楽』[出典必要]

は、イデオロギーと音楽構造の関係、様式変化の現象を理論化し、ロマン主義を事例研究として焦点を当てている。 |

| 96. Middleton 1990, 172.

Middleton, Richard (1990). Studying Popular Music. Milton Keynes and

Philadelphia: Open University Press. 97. Nattiez 1976. Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1976). Fondements d'une sémiologie de la musique. Collection Esthétique. Paris: Union générale d'éditions. 98. Nattiez 1990. Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1990). Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music, translated by Carolyn Abbate of Musicologie generale et semiologie. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 99. Nattiez1989. Nattiez, Jean-Jacques(1989). Proust as Musician, translated by Derrick Puffett. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. 100. Stefani 1973. Stefani, Gino (1973). "Sémiotique en musicologie". Versus 5:20–42. 101. Stefani 1976. Stefani, Gino (1976). Introduzione alla semiotica della musica. Palermo: Sellerio editore. 102. Baroni 1983. Baroni, Mario (1983). "The Concept of Musical Grammar", translated by Simon Maguire and William Drabkin. Music Analysis 2, no. 2:175–208. 103. Semiotica 1987, 66:1–3. 104. Kofi Agawu, Music as Discourse. Semiotic Adventures in Romantic Music, Oxford University Press, 2009, pp. 41-50 and passim. 105. Dunsby & Stopford 1981, 49–53. 106. Meeùs 2017, 81–96. 107. Raymond Monelle, Linguistics and Semiotics in Music, Chur, Harwood, 1992, pp. 229-232, etc. 108. Roland Barthes, Image Music Text. Essays selected and translated by St. Heath. London, Fontana Press, 1977. 109. Roland Barthes, The Responsibility of Forms. Critical Essays on Music, Art, and Representation. R. Howard transl. New York, Hill and Wang, 1985. 110. Roland Barthes, The Eiffel Tower and other Mythologies. R. Howard transl. University of California Press, 1997. 111. Roland Barthes, "Éléments de sémiologie", Communications 4 (1964), republished with Le degré zéro de l'écriture, Paris, Gonthier, 1965, 80: "There is no meaning but named, and the world of signified is that of language." |

96. ミドルトン

1990、172。ミドルトン、リチャード(1990)。『ポピュラー音楽の研究』。ミルトン・キーンズおよびフィラデルフィア:オープン大学出版局。 97. ナティエ 1976。ナティエ、ジャン=ジャック(1976)。『音楽記号論の基礎』。コレクション・エステティック。パリ:ユニオン・ジェネラル・デディシオン。 98. ナティエ 1990。ナティエ、ジャン=ジャック(1990)。『音楽と談話:音楽記号論に向けて』、キャロリン・アバテ訳、Musicologie generale et semiologie。プリンストン:プリンストン大学出版局。 99. ナティエ 1989。ナティエ、ジャン=ジャック(1989)。『音楽家としてのプルースト』、デリック・パフェット訳。ケンブリッジおよびニューヨーク:ケンブ リッジ大学出版局。 100. ステファニ 1973。ステファニ、ジーノ(1973)。「音楽学における記号論」。Versus 5:20–42。 101. ステファニ 1976。ステファニ、ジーノ(1976)。音楽記号論入門。パレルモ:セッレリオ出版社。 102. バローニ 1983. バローニ、マリオ(1983)。「音楽文法の概念」、サイモン・マグワイア、ウィリアム・ドラブキン訳。音楽分析 2、第 2 号:175–208。 103. Semiotica 1987, 66:1–3. 104. Kofi Agawu, Music as Discourse. Semiotic Adventures in Romantic Music, Oxford University Press, 2009, pp. 41-50 and passim. 105. Dunsby & Stopford 1981, 49–53. 106. Meeùs 2017、81–96。 107. Raymond Monelle、Linguistics and Semiotics in Music、Chur、Harwood、1992、229-232 ページなど。 108. Roland Barthes、Image Music Text。St. Heath によるエッセイの選択および翻訳。ロンドン、Fontana Press、1977。 109. Roland Barthes, The Responsibility of Forms. Critical Essays on Music, Art, and Representation. R. Howard transl. New York, Hill and Wang, 1985. 110. Roland Barthes, The Eiffel Tower and other Mythologies. R. Howard transl. University of California Press, 1997. 111. ロラン・バルト『記号論の基礎』Communications 4 (1964)、Le degré zéro de l'écriture(1965年、パリ、ゴンティエ社)に再掲載、80ページ:「意味は名付けられて初めて存在し、意味の世界は言語の世界である」。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Music_theory |

★ミュー ジック・アズ・ソーシャルライフ : 歌い踊ることをめぐる政治 / トマス・トゥリノ著 ; 野澤豊一, 西島千尋訳, 東京 : 水声社 , 2015.8

世 界音楽(ワールド・ミュージック)への招待—音楽家であり、大学で民族学を講ずる教育者としても名高い著者が、ペルー、ジンバブエ、アメリカでのフィール ドワークで得た経験をもとに、チャールズ・S・パースやグレゴリー・ベイトソンの理論などを用いながら分類・分析した、音楽民族学(→実質的に音楽記号論 [引用者])の理論的入門書。

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099