ナショナリティあるいは国籍

Nationality

☆

国籍とは、特定の国家に帰属する法的地位であり、一つの国に組織された人々の集団、または文化を基盤として団結した人々の集団として定義される。

国際法において、国籍とは、個人を主権国家の国民として認定する法的証明である。これにより、国家は個人に対して管轄権を行使することができ、また個人に

対しては、他の国家から国家による保護を受けることができる。[4] 国民の権利と義務は国によって異なるが、[5]

状況によっては、市民権法によって補完される場合もあり、市民権が国籍と同義となる場合もある。[6]

しかし、国籍と市民権は厳密かつ法的に異なるものであり、これは個人と国家の間の異なる法的関係である。「国民」という名詞は、市民と非市民の両方を含

む。市民権の最も一般的な区別は、市民には投票や選挙への立候補など、国家の政治生活に参加する権利があることである。しかし、ほとんどの現代国家では、

すべての国民は国家の市民であり、完全な市民は常に国家の国民である。

国際法では、「無国籍者」とは「いかなる国家によっても、その法の運用上、自国民と認められない者」である。[8]

これに対応して、世界人権宣言第15条では、「すべて人は、

国籍を有する権利を恣意的に剥奪されたり、国籍を変更する権利を否定されたりしてはならない」と定めている。ただし、国際慣習や条約により、自国民を決定

する権利は各国にあるとされている。[9]

このような決定は国籍法の一部である。国籍の決定は、場合によっては国際公法、例えば無国籍に関する条約や欧州国籍条約によっても規定される。[10]

国籍を取得するプロセスは帰化と呼ばれる。各国家は、その国籍法において、どのような条件(規定)のもとでその国民として個人を認定するか、また、どのよ

うな条件のもとでその地位が剥奪されるかを定めている。一部の国では自国民に複数の国籍を持つことを認めているが、一方で、排他的な忠誠を主張する国もあ

る。

国籍の語源から、古い文献や他の言語では、民族(共通の民族性、言語、文化、系譜、歴史などを共有する人々の集団)を指すのに「民族性」ではなく「国籍」

という語がしばしば使用される。また、個人は、より大きな主権国家に権限の一部を委譲している自治的な地位を持つ集団の国民とみなされることもある。

また、国民性という言葉は、国民アイデンティティを表す言葉としても用いられる。アイデンティティ・ポリティクスやナショナリズムの事例の中には、法的国

籍や民族性を国民アイデンティティと混同しているものもある。

| Nationality

is the legal status of belonging to a particular nation, defined as a

group of people organized in one country, under one legal jurisdiction,

or as a group of people who are united on the basis of culture.[1][2][3] In international law, nationality is a legal identification establishing the person as a subject, a national, of a sovereign state. It affords the state jurisdiction over the person and affords the person the protection of the state against other states.[4] The rights and duties of nationals vary from state to state,[5] and are often complemented by citizenship law, in some contexts to the point where citizenship is synonymous with nationality.[6] However, nationality differs technically and legally from citizenship, which is a different legal relationship between a person and a country. The noun "national" can include both citizens and non-citizens. The most common distinguishing feature of citizenship is that citizens have the right to participate in the political life of the state, such as by voting or standing for election. However, in most modern countries all nationals are citizens of the state, and full citizens are always nationals of the state.[7] In international law, a "stateless person" is someone who is "not considered as a national by any state under the operation of its law".[8] To address this, Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that "Everyone has the right to a nationality", and "No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality", even though, by international custom and conventions, it is the right of each state to determine who its nationals are.[9] Such determinations are part of nationality law. In some cases, determinations of nationality are also governed by public international law—for example, by treaties on statelessness or the European Convention on Nationality.[10] The process of acquiring nationality is called naturalization. Each state determines in its nationality law the conditions (statute) under which it will recognize persons as its nationals, and the conditions under which that status will be withdrawn. Some countries permit their nationals to have multiple nationalities, while others insist on exclusive allegiance. Due to the etymology of nationality, in older texts or other languages the word "nationality", rather than "ethnicity", is often used to refer to an ethnic group (a group of people who share a common ethnic identity, language, culture, lineage, history, and so forth). Individuals may also be considered nationals of groups with autonomous status that have ceded some power to a larger sovereign state. Nationality is also employed as a term for national identity, with some cases of identity politics and nationalism conflating the legal nationality as well as ethnicity with a national identity. |

国籍とは、特定の国家に帰属する法的地位であり、一つの国に組織された

人々の集団、または文化を基盤として団結した人々の集団として定義される。 国際法において、国籍とは、個人を主権国家の国民として認定する法的証明である。これにより、国家は個人に対して管轄権を行使することができ、また個人に 対しては、他の国家から国家による保護を受けることができる。[4] 国民の権利と義務は国によって異なるが、[5] 状況によっては、市民権法によって補完される場合もあり、市民権が国籍と同義となる場合もある。[6] しかし、国籍と市民権は厳密かつ法的に異なるものであり、これは個人と国家の間の異なる法的関係である。「国民」という名詞は、市民と非市民の両方を含 む。市民権の最も一般的な区別は、市民には投票や選挙への立候補など、国家の政治生活に参加する権利があることである。しかし、ほとんどの現代国家では、 すべての国民は国家の市民であり、完全な市民は常に国家の国民である。 国際法では、「無国籍者」とは「いかなる国家によっても、その法の運用上、自国民と認められない者」である。[8] これに対応して、世界人権宣言第15条では、「すべて人は、 国籍を有する権利を恣意的に剥奪されたり、国籍を変更する権利を否定されたりしてはならない」と定めている。ただし、国際慣習や条約により、自国民を決定 する権利は各国にあるとされている。[9] このような決定は国籍法の一部である。国籍の決定は、場合によっては国際公法、例えば無国籍に関する条約や欧州国籍条約によっても規定される。[10] 国籍を取得するプロセスは帰化と呼ばれる。各国家は、その国籍法において、どのような条件(規定)のもとでその国民として個人を認定するか、また、どのよ うな条件のもとでその地位が剥奪されるかを定めている。一部の国では自国民に複数の国籍を持つことを認めているが、一方で、排他的な忠誠を主張する国もあ る。 国籍の語源から、古い文献や他の言語では、民族(共通の民族性、言語、文化、系譜、歴史などを共有する人々の集団)を指すのに「民族性」ではなく「国籍」 という語がしばしば使用される。また、個人は、より大きな主権国家に権限の一部を委譲している自治的な地位を持つ集団の国民とみなされることもある。 また、国民性という言葉は、国民アイデンティティを表す言葉としても用いられる。アイデンティティ・ポリティクスやナショナリズムの事例の中には、法的国 籍や民族性を国民アイデンティティと混同しているものもある。 |

| International law Nationality is the status that allows a nation to grant rights to the subject and to impose obligations upon the subject.[7] In most cases, no rights or obligations are automatically attached to this status, although the status is a necessary precondition for any rights and obligations created by the state.[11] In European law, nationality is the status or relationship that gives the nation the right to protect a person from other nations.[7] Diplomatic and consular protection are dependent upon this relationship between the person and the state.[7] A person's status as being the national of a country is used to resolve the conflict of laws.[11] Within the broad limits imposed by a few treaties and international law, states may freely define who are and are not their nationals.[7] However, since the Nottebohm case, other states are only required to respect the claim(s) by a state to protect an alleged national if the nationality is based on a true social bond.[7] In the case of dual nationality, the states may determine the most effective nationality for the person, to determine which state's laws are the most relevant.[11] There are also limits on removing a person's status as a national. Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that "Everyone has the right to a nationality," and "No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality." |

国際法では 国籍とは、国家がその国民に対して権利を付与し、義務を課すことができる地位である。[7] ほとんどの場合、この地位に権利や義務が自動的に付随することはないが、この地位は国家が創設するあらゆる権利や義務の前提条件である。[11] 欧州法では、国籍とは、国民を他国から保護する権利を国家に与える地位または関係である。[7] 外交的保護および領事的保護は、個人と国家の間のこの関係に依存する。[7] ある個人がある国の国民であるという地位は、抵触法の解決に用いられる。[11] 少数の条約および国際法によって課される広範な制限の範囲内で、国家は自国の国民である者、およびそうでない者を自由に定義することができる。[7] しかし、ノッテボーム事件以来、他の国家は、 国籍が真の社会的絆に基づく場合に限られる。[7]二重国籍の場合、国家は、その人物にとって最も効果的な国籍を決定し、どの国の法律が最も関連性が高い かを判断することができる。[11]また、国民としての地位を剥奪することにも制限がある。世界人権宣言第15条では、「すべて人は、国籍を有する権利を 有する」、「何人も、恣意的にその国籍を奪われ、又は国籍を変更する権利を否定されてはならない」と規定している。 |

| Determining factors Further information: Nationality law A person can be recognized or granted nationality on a number of bases. Usually, nationality based on circumstances of birth is automatic, but an application may be required. Nationality by family (jus sanguinis). If one or both of a person's parents are citizens of a given state, then the person may have the right to be a citizen of that state as well.[a] Formerly this might only have applied through the paternal line, but sex equality became common since the late twentieth century. Citizenship is granted based on ancestry or ethnicity and is related to the concept of a nation state common in Europe. Where jus sanguinis holds, a person born outside a country, one or both of whose parents are citizens of the country, is also a citizen. Some states (United Kingdom, Canada) limit the right to citizenship by descent to a certain number of generations born outside the state; others (Germany, Ireland, Switzerland[14]) grant citizenship only if each new generation is registered with the relevant foreign mission within a specified deadline; while others (Italy, for example[15]) have no limitation on the number of generations born abroad who can claim citizenship of their ancestors' country. This form of citizenship is common in civil law countries. Nationality by birth (jus soli). Some people are automatically nationals of the state in which they are born. This form of citizenship originated in England, where those who were born within the realm were subjects of the monarch (a concept pre-dating that of citizenship in England) and is common in common law countries. Most countries in the Americas grant unconditional jus soli citizenship, while it has been limited or abolished in almost all other countries. In many cases, both jus soli and jus sanguinis hold citizenship either by place or parentage (or both). Nationality by marriage (jus matrimonii). Many countries fast-track naturalization based on the marriage of a person to a citizen. Countries that are destinations for such immigration often have regulations to try to detect sham marriages, where a citizen marries a non-citizen typically for payment, without them having the intention of living together.[16] Many countries (United Kingdom, Germany, United States, Canada) allow citizenship by marriage only if the foreign spouse is a permanent resident of the country in which citizenship is sought; others (Switzerland, Luxembourg) allow foreign spouses of expatriate citizens to obtain citizenship after a certain period of marriage, and sometimes also subject to language skills and proof of cultural integration (e.g. regular visits to the spouse's country of citizenship). Naturalization. States normally grant nationality to people who have entered the country legally and been granted a permit to stay, or been granted political asylum, and also lived there for a specified period. In some countries, naturalization is subject to conditions which may include passing a test demonstrating reasonable knowledge of the language or way of life of the host country, good conduct (no serious criminal record), and moral character (such as drunkenness, or gambling, or an understanding of the nature of drunkenness, or gambling) vowing allegiance to their new state or its ruler and renouncing their prior citizenship. Some states allow dual citizenship and do not require naturalized citizens to formally renounce any other citizenship. Nationality by investment or economic citizenship. Wealthy people invest money in property or businesses, buy government bonds or simply donate cash directly, in exchange for citizenship and a passport. Whilst legitimate and usually limited in quota, the schemes are controversial. Costs for citizenship by investment range from as little as $100,000 (£74,900) to as much as €2.5m (£2.19m)[17] |

決定要因 詳細情報:国籍法 人は、いくつかの基準に基づいて国籍を認められたり付与されたりする。通常、出生時の状況に基づく国籍は自動的に付与されるが、申請が必要な場合もある。 家族による国籍(血統主義)。ある人物の両親の一方または両方が特定の国家の市民である場合、その人物もまたその国家の市民となる権利を有することがあ る。[a] 以前は父系のみに適用されていたが、20世紀後半以降は男女平等が一般的となった。国籍は先祖や民族に基づいて付与され、ヨーロッパで一般的な国民国家の 概念と関連している。 血統主義が採用されている場合、その国の国民である親の一方または両方を持ち、その国外で生まれた人もその国の国民となる。一部の国家(英国、カナダ)で は、出生地主義による市民権取得の権利を、国外で生まれた一定の世代数に限定している。また、他の国家(ドイツ、アイルランド、スイス[14])では、各 世代が指定の期限内に該当する外国公館に登録した場合にのみ市民権を付与している。さらに、他の国家(例えばイタリア[15])では、先祖の国の市民権を 主張できる国外で生まれた世代数に制限を設けていない。この形式の市民権は、民法の国々で一般的である。 出生による国籍(jus soli)。出生した国において自動的にその国の国民となる人もいる。この国籍形態はイギリスで始まり、イギリスでは、領域内で生まれた者は君主の臣民と された(これはイギリスにおける市民権の概念よりも古い)。この形態は英米法諸国で一般的である。アメリカ大陸のほとんどの国では無条件の出生地主義が採 用されているが、その他のほとんどの国では制限付きまたは廃止されている。 多くの場合、出生地主義と血統主義の両方が、出生地または血統(またはその両方)によって国籍を付与している。 婚姻による国籍取得(jus matrimonii)。多くの国では、市民との婚姻を基盤とした帰化を迅速に行っている。このような移民の受け入れ国では、市民が金銭の授受を目的とし て、同居の意思のない非市民と偽装結婚するケースを検出しようとする規制を設けていることが多い。[16] 多くの国(イギリス、ドイツ、アメリカ、カナダ)では、外国人の配偶者が その国の永住者である場合のみ、結婚による国籍取得を認めている。その他の国(スイス、ルクセンブルク)では、海外在住者の外国籍配偶者が結婚後一定期間 を経て国籍を取得できる場合があり、また、語学力や文化的な統合の証明(例えば、配偶者の国籍国の定期的な訪問)を条件としている場合もある。 帰化。通常、合法的にその国に入国し、滞在許可を得た人、あるいは政治亡命が認められ、さらに一定期間その国に居住した人には、その国が国籍を付与する。 一部の国では、帰化には、受入国の言語や生活様式に関する相応の知識を証明するテストの合格、善良な行い(重大な犯罪歴がないこと)、道徳的資質(飲酒や ギャンブル、あるいは飲酒やギャンブルの本質に対する理解など)が条件となる。また、新しい国家やその支配者への忠誠を誓い、それまでの国籍を放棄するこ とも求められる。二重国籍を認める国もあり、帰化する市民に他の国籍を正式に放棄することを要求しない国もある。 投資による国籍取得または経済的市民権。富裕層の人々は、不動産や事業に投資したり、国債を購入したり、あるいは単に現金を直接寄付したりすることで、そ の見返りとして国籍とパスポートを取得する。合法的であり、通常は定員枠が限られているものの、この制度は議論を呼んでいる。投資による国籍取得の費用 は、10万ドル(7万4900ポンド)から250万ユーロ(2190万ポンド)と幅がある[17]。 |

| Legal protections The following instruments address the right to a nationality: Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees[18] Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees[19] Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons[20] Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness[21] European Convention on Nationality[22] African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (art. 6) [23] American Convention on Human Rights (art. 20)[24] American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man (art. 19)[25] Arab Charter on Human Rights (art. 24)[26] Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (art. 9)[27] International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (art. 5(d)(iii))[28] Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (art. 18)[29] Convention on the Rights of the Child (arts. 7 and 8)[30] Council of Europe Convention on the Avoidance of Statelessness in Relation to State Succession[22] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (art. 24(3))[31] Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol) (art. 6(g) and (h))[32] Universal Declaration of Human Rights (art. 15)[33] |

法的保護 国籍取得の権利を定めた条約には以下のものがある。 難民の地位に関する条約[18] 難民の地位に関する議定書[19] 無国籍者の地位に関する条約[20] 無国籍の削減に関する条約[21] 国籍に関する欧州条約[22] 児童の権利および福祉に関するアフリカ憲章(第6条)[23] 米州人権条約(第20条)[24] 米州人権宣言(第19条)[25] アラブ人権憲章(第24条)[26] 女子に対するあらゆる形態の差別の撤廃に関する条約(第9条)[27] あらゆる形態の人種差別の撤廃に関する国際条約(第5条(d)(iii))[28] 障害者の権利に関する条約(第18条)[29] 児童の権利に関する条約(第7条および第8条)[30] 国家承継に関連する無国籍の回避に関する欧州評議会条約[22] 市民的及び政治的権利に関する国際規約(第24条(3))[31] アフリカにおける女性の権利に関するアフリカ人権憲章議定書(マプト議定書)(第6条(g)および(h))[32] 世界人権宣言(第15条)[33] |

| National law Nationals normally have the right to enter or return to the country they belong to. Passports are issued to nationals of a state, rather than only to citizens, because a passport is a travel document used to enter the country. However, nationals may not have the right of abode (the right to live permanently) in the countries that granted them passports. |

国民法 通常、国民は自国への入国または帰国する権利を有する。パスポートは自国民に発行されるものであり、自国民のみに発行されるものではない。なぜなら、パス ポートは自国に入国するための渡航文書だからである。しかし、パスポートを発行された国民が、そのパスポートを発行した国に居住する権利(永住する権利) を有しているとは限らない。 |

Nationality versus citizenship An immigration inspection sign at Shanghai Pudong International Airport with the English term "Chinese nationals" and the Chinese term for "Chinese citizens (中国公民)". Conceptually citizenship and nationality are different dimensions of state membership. Citizenship is focused on the internal political life of the state and nationality is the dimension of state membership in international law.[34] Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that everyone has the right to nationality.[35] As such nationality in international law can be called and understood as citizenship,[35] or more generally as subject or belonging to a sovereign state, and not as ethnicity. This notwithstanding, around 10 million people are stateless.[35] Today, the concept of full citizenship encompasses not only active political rights, but full civil rights and social rights.[7] Historically, the most significant difference between a national and a citizen is that the citizen has the right to vote for elected officials, and the right to be elected.[7] This distinction between full citizenship and other, lesser relationships goes back to antiquity. Until the 19th and 20th centuries, it was typical for only a certain percentage of people who belonged to the state to be considered as full citizens. In the past, a number of people were excluded from citizenship on the basis of sex, socioeconomic class, ethnicity, religion, and other factors. However, they held a legal relationship with their government akin to the modern concept of nationality.[7] |

国籍と市民権 上海浦東国際空港の入国審査の標識には、「Chinese nationals」という英語表記と「中国公民(Chinese citizens)」という中国語表記がある。 概念的には、市民権と国籍は国家の構成員としての異なる次元である。市民権は国家の内部政治生活に焦点を当て、国籍は国際法における国家の構成員としての 次元である。[34] 世界人権宣言第15条は、すべて人は国籍を持つ権利を有すると定めている。[35] 国際法における国籍は、市民権と呼ばれ、理解されることもある。[35] あるいは、より一般的に、主権国家の構成員または帰属者として理解されることもある。にもかかわらず、1000万人もの人々が無国籍である。 今日、完全な市民権の概念には、政治的権利だけでなく、完全な市民権と社会権が含まれる。 歴史的に見ると、国民と市民の最も重要な違いは、市民には選挙で選ばれた公職者に投票する権利と、選挙で選ばれる権利があることである。完全な市民権とそ の他の、より限定的な関係の区別は古代にまで遡る。19世紀から20世紀にかけては、国家に属する人々のうち、一定の割合の人々のみが完全な市民とみなさ れるのが一般的であった。過去においては、性別、社会経済的階級、民族、宗教、その他の要因に基づいて、多くの人々が市民権を否定されていた。しかし、彼 らは政府との間に、現代の国籍概念に類似した法的関係を有していた。[7] |

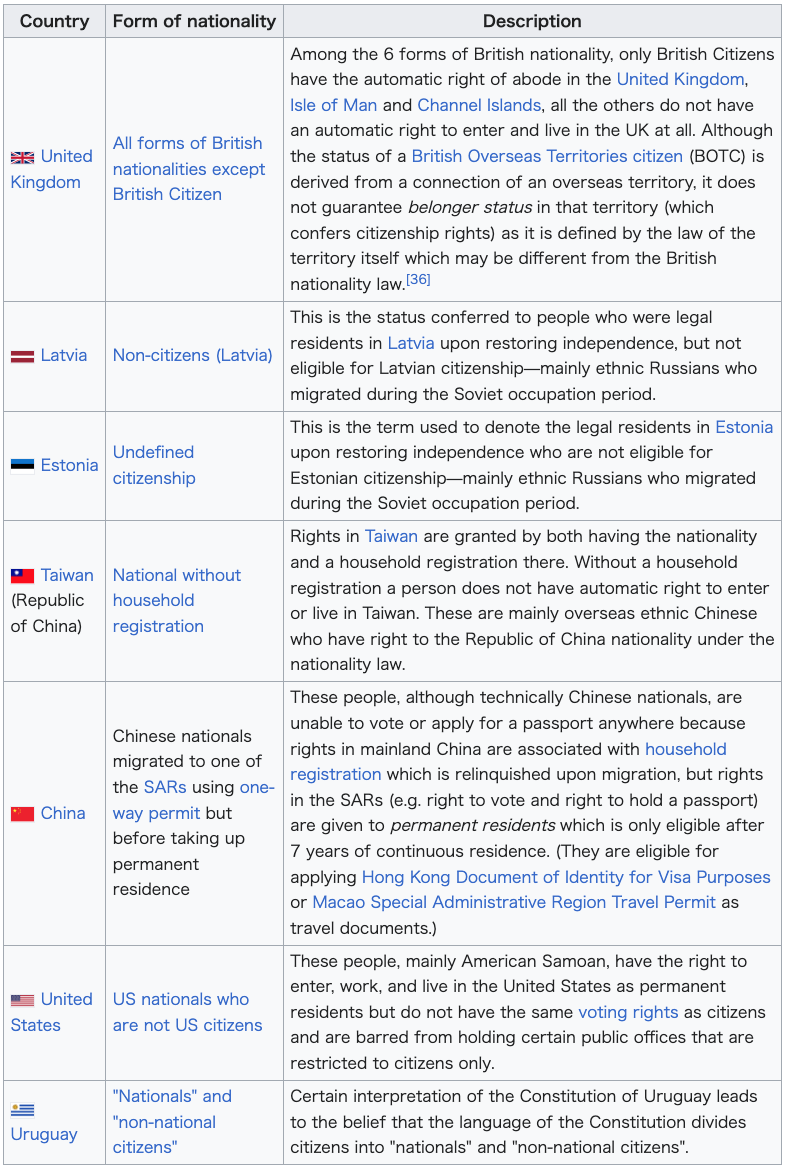

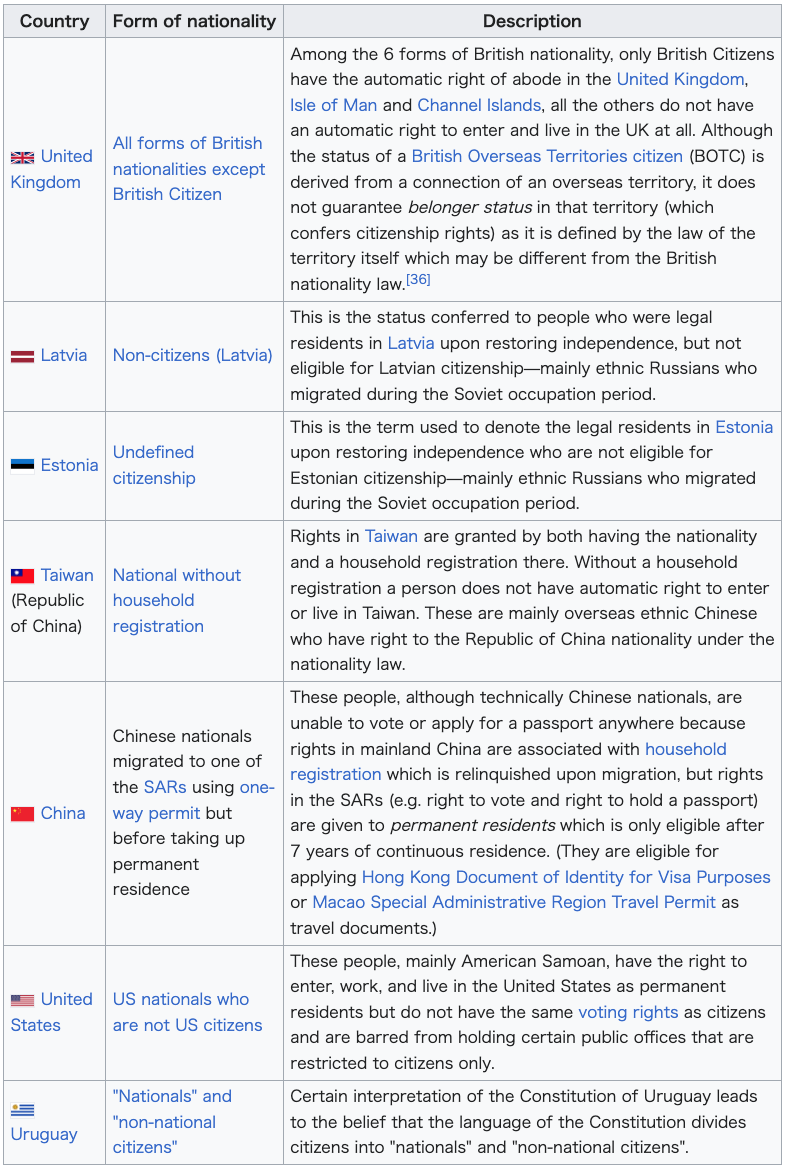

| Nationality in context United States nationality law defines some persons born in some of the US outlying possessions as US nationals but not citizens. British nationality law defines six classes of British national, among which "British citizen" is one class (having the right of abode in the United Kingdom, along with some "British subjects"). Similarly, in the Republic of China, commonly known as Taiwan, the status of national without household registration applies to people who have the Republic of China nationality, but do not have an automatic entitlement to enter or reside in the Taiwan Area, and do not qualify for civic rights and duties there. Under the nationality laws of Mexico, Colombia, and some other Latin American countries, nationals do not become citizens until they turn the age of majority. List of nationalities which do not have full citizenship rights  Even if the nationality law classifies people with the same nationality on paper (de jure), the right conferred can be different according to the place of birth or residence, creating different de facto classes of nationality, sometimes with different passports as well. For example, although Chinese nationality law operates uniformly in China, including Hong Kong and Macau SARs, with all Chinese nationals classified the same under the nationality law, in reality local laws, in mainland and also in the SARs, govern the right of Chinese nationals in their respective territories which give vastly different rights, including different passports, to Chinese nationals according to their birthplace or residence place, effectively making a distinction between Chinese national of mainland China, Hong Kong or Macau, both domestically and internationally. The United Kingdom had a similar distinction as well before 1983, where all nationals with a connection to the UK or one of the colonies were classified as Citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies, but their rights were different depending on the connection under different laws, which was formalised into different classes of nationalities under the British Nationality Act 1981. |

文脈における国籍 米国国籍法では、米国のいくつかの属領で生まれた一部の人々を米国国民ではあるが、米国市民ではないと定義している。英国国籍法では、英国国民を6つのク ラスに定義しており、そのうちの1つが「英国市民」である(「英国臣民」の一部とともに、英国に居住する権利を有する)。同様に、一般的に台湾として知ら れる中華民国では、中華民国国籍を有するが、台湾地域への入国や居住の自動的な権利を持たず、また、台湾地域における公民としての権利や義務の対象にもな らない人々に対して、戸籍のない国民という地位が適用される。メキシコ、コロンビア、およびその他のラテンアメリカ諸国の国籍法では、国民が成人に達する までは、その国民が市民権を得ることはない。 完全な市民権を持たない国籍の一覧  国籍法が、書類上(デ・ジュリ)は同じ国籍を持つ人々を分類しているとしても、出生地や居住地によって付与される権利が異なる場合があり、事実上、異なる 国籍の階級が生まれることもある。場合によっては、異なるパスポートが発行されることもある。例えば、中国の国籍法は香港とマカオ特別行政区を含めた中国 全土で統一的に運用されており、すべての中国国民は国籍法の下で同じように分類されているが、実際には、中国本土および特別行政区のそれぞれの地域では、 現地の法律が中国国民の権利を規定している 出生地や居住地によって中国国民に与えられる権利は大きく異なり、事実上、中国本土、香港、マカオの中国国民を国内および国際的に区別している。英国でも 1983年以前は同様の区別があり、英国または植民地とのつながりを持つすべての国民は「英国および植民地の国民」として分類されていたが、その権利はつ ながりの強弱によって異なる法律に基づいて異なっていた。これは1981年の英国国籍法によって、異なる国籍のクラスとして正式に制度化された。 |

| Nationality versus ethnicity Main article: Ethnic nationalism Nationality is sometimes used simply as an alternative word for ethnicity or national origin, just as some people assume that citizenship and nationality are identical.[37] In some countries, the cognate word for nationality in local language may be understood as a synonym of ethnicity or as an identifier of cultural and family-based self-determination, rather than on relations with a state or current government. For example, some Kurds say that they have Kurdish nationality, even though there is no Kurdish sovereign state at this time in history. A Soviet birth certificate, in which the nacional'nost' of both parents (here both Jewish) was recorded. These records were subsequently used to determine the ethnicity of the child, as specified in his internal passport. In the context of former Soviet Union and former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, "nationality" is often used as translation of the Russian nacional'nost' and Serbo-Croatian narodnost, which were the terms used in those countries for ethnic groups and local affiliations within the member states of the federation. In the Soviet Union, more than 100 such groups were formally recognized. Membership in these groups was identified on Soviet internal passports, and recorded in censuses in both the USSR and Yugoslavia. In the early years of the Soviet Union's existence, ethnicity was usually determined by the person's native language, and sometimes through religion or cultural factors, such as clothing.[38] Children born after the revolution were categorized according to their parents' recorded ethnicities. Many of these ethnic groups are still recognized by modern Russia and other countries. Similarly, the term nationalities of China refers to ethnic and cultural groups in China. Spain is one nation, made up of nationalities, which are not politically recognized as nations (state), but can be considered smaller nations within the Spanish nation. Spanish law recognizes the autonomous communities of Andalusia, Aragon, Balearic Islands, Canary Islands, Catalonia, Valencia, Galicia and the Basque Country as "nationalities" (nacionalidades). In 2013, the Supreme Court of Israel unanimously affirmed the position that "citizenship" (e.g. Israeli) is separate from le'om (Hebrew: לאום; "nationality" or "ethnic affiliation"; e.g. Jewish, Arab, Druze, Circassian), and that the existence of a unique "Israeli" le'om has not been proven. Israel recognizes more than 130 le'umim in total.[39][40][41] The older ethnicity meaning of "nationality" is not defined by political borders or passport ownership and includes nations that lack an independent state (such as the Arameans, Scots, Welsh, English, Andalusians,[42] Basques, Catalans, Kurds, Punjabis, Kabyles, Baluchs, Pashtuns, Berbers, Bosniaks, Palestinians, Hmong, Inuit, Copts, Māori, Wakhis, Xhosas and Zulus, among others).[citation needed] |

国籍と民族性 詳細は「民族ナショナリズム」を参照 国籍は、民族性や出身国を意味する言葉として単に用いられることもある。一部の人は、市民権と国籍が同一のものであると想定しているが、[37] いくつかの国では、現地語で国籍を意味する同族語は、国家や現政府との関係ではなく、民族性の同義語、あるいは文化や家族に基づく自己決定の識別子として 理解されることがある。例えば、現時点でクルド人国家が存在していないにもかかわらず、クルド人の中にはクルド国籍を主張する人もいる。 両親(いずれもユダヤ人)の国籍が記載されたソビエト連邦の出生証明書。これらの記録は、その後、内部パスポートに明記された子供の民族性を決定するために使用された。 旧ソビエト連邦および旧ユーゴスラビア社会主義連邦共和国においては、「国籍」は、連邦加盟国内の民族集団や地域的帰属を表す用語として使用されていたロ シア語の「ナショナリノスト(nacional'nost)」やセルビア・クロアチア語の「ナロードノスト(narodnost)」の訳語として使用され ることが多い。ソビエト連邦では、100以上のこのような集団が正式に認められていた。これらのグループのメンバーシップはソ連国内用パスポートで識別さ れ、ソ連とユーゴスラビアの両方で実施された国勢調査にも記録されていた。ソ連成立当初は、民族は通常、その人物の母国語によって決定され、時には宗教や 服装などの文化的要因によって決定されていた。[38] 革命後に生まれた子供たちは、両親の記録された民族性によって分類された。これらの民族グループの多くは、現代のロシアやその他の国々でも依然として認め られている。 同様に、中国の「民族」という用語は、中国国内の民族や文化集団を指す。スペインは一つの国家であり、政治的には国家(国)として認められていないが、ス ペイン国民の中の小国家と見なすことができる「民族」から成り立っている。スペインの法律では、アンダルシア、アラゴン、バレアレス諸島、カナリア諸島、 カタルーニャ、バレンシア、ガリシア、バスク自治州を「民族」(nacionalidades)として認めている。 2013年、イスラエル最高裁は満場一致で、「国籍」(例えばイスラエル国籍)は「レウム」(ヘブライ語:לאום、「国籍」または「民族帰属」、例えば ユダヤ人、アラブ人、ドルーズ人、チェルケス人)とは別物であり、「イスラエル国籍」という独自のレウムの存在は証明されていないという見解を示した。イ スラエルは合計130以上のレウムを認めている。[39][40][41] 「国籍」の古い民族的な意味は、政治的な境界やパスポートの所有によって定義されるものではなく、独立国家を持たない国民(アラム人、スコットランド人、 ウェールズ人、イングランド人、アンダルシア人、バスク人、カタルーニャ人、クルド人 パンジャブ人、カビール人、バルーチ人、パシュトゥーン人、ベルベル人、ボシュニャク人、パレスチナ人、ミャオ族、イヌイット、コプト人、マオリ人、ワヒ 族、コサ人、ズールー人など)が含まれる。[要出典] |

| Nationality versus national identity National identity is person's subjective sense of belonging to one state or to one nation. A person may be a national of a state, in the sense of being its citizen, without subjectively or emotionally feeling a part of that state, for example a migrant may identify with their ancestral and/or religious background rather than with the state of which they are citizens. Conversely, a person may feel that he belongs to one state without having any legal relationship to it. For example, children who were brought to the US illegally when quite young and grew up there while having little contact with their native country and their culture often have a national identity of feeling American, despite legally being nationals of a different country. |

国籍と国民アイデンティティ 国民アイデンティティとは、ある国家、ある国民に帰属しているという個人の主観的な感覚である。ある個人は、その国の市民であるという意味ではその国の国 民であるかもしれないが、主観的あるいは感情的にはその国の一部であると感じていないかもしれない。例えば、移民は、自分が市民であるその国よりも、むし ろ先祖や宗教的背景に帰属意識を持つかもしれない。逆に、ある個人がある国に法的関係を持たないにもかかわらず、その国に帰属していると感じることもあ る。例えば、幼い頃に不法入国し、母国や母国の文化とほとんど接触することなく米国で育った子供たちは、法的には別の国の国民であるにもかかわらず、しば しば「アメリカ人」という国民としてのアイデンティティを持つ。 |

| Dual nationality Dual nationality is when a single person has a formal relationship with two separate, sovereign states.[43] This might occur, for example, if a person's parents are nationals of separate countries, and the mother's country claims all offspring of the mother's as their own nationals, but the father's country claims all offspring of the father's. Nationality, with its historical origins in allegiance to a sovereign monarch, was seen originally as a permanent, inherent, unchangeable condition, and later, when a change of allegiance was permitted, as a strictly exclusive relationship, so that becoming a national of one state required rejecting the previous state.[43] Dual nationality was considered a problem that caused a conflict between states and sometimes imposed mutually exclusive requirements on affected people, such as simultaneously serving in two countries' military forces. Through the middle of the 20th century, many international agreements were focused on reducing the possibility of dual nationality. Since then, many accords recognizing and regulating dual nationality have been formed.[43] |

二重国籍 二重国籍とは、1人の人物が2つの独立した主権国家と正式な関係を持つことを指す。[43] 例えば、両親がそれぞれ別の国の国籍を持つ場合、母親の出身国が母親の子供全員を自国の国民とみなす一方で、父親の出身国が父親の子供全員を自国の国民と みなす場合などがこれに該当する。 君主への忠誠を起源とする国籍は、当初は恒久的で本質的、かつ不変的な条件とみなされていた。その後、忠誠の変更が認められるようになると、厳密に排他的な関係とみなされるようになり、ある国家の国民となるためには、それまでの国家を拒否することが必要となった。 二重国籍は国家間の対立を引き起こす問題とみなされ、影響を受ける人々に対して、2つの国の軍隊に同時に所属するなど、時に相互に矛盾する要件を課すこと もあった。20世紀中頃までは、多くの国際協定が二重国籍の可能性を低減することに焦点が当てられていた。それ以降、二重国籍を認め、規制する多くの協定 が結ばれてきた。[43] |

| Statelessness Statelessness is the condition in which an individual has no formal or protective relationship with any state. There are various reasons why a person can become stateless. This might occur, for example, if a person's parents are nationals of separate countries, and the mother's country rejects all offspring of mothers married to foreign fathers, but the father's country rejects all offspring born to foreign mothers. People in this situation may not legally be the national of any state despite possession of an emotional national identity. Another stateless situation arises when a person holds a travel document (passport) which recognizes the bearer as having the nationality of a "state" which is not internationally recognized, has no entry into the International Organization for Standardization's country list, is not a member of the United Nations, etc. In the current era, persons native to Taiwan who hold passports of Republic of China are one example.[44][45] Some countries (like Kuwait, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia) can also remove one's citizenship; the reasons for removal can be fraud and/or security issues. There are also people who are abandoned at birth and the parents' whereabouts are not known.[46][47] |

無国籍 無国籍とは、個人と国家との間に正式な関係や保護関係が存在しない状態を指す。無国籍となる理由は様々である。例えば、両親が別々の国の国民であり、母親 の国が外国人の父親と結婚した母親の子供全員を拒否し、父親の国が外国人の母親から生まれた子供全員を拒否する場合などが挙げられる。このような状況にあ る人々は、感情的な国民としてのアイデンティティを持っていても、いかなる国家の国民であると法的に認められない可能性がある。 また、国際的に承認されていない「国家」の国籍を持つと認められる渡航文書(パスポート)を所持している場合にも、無国籍の状態が生じる。この「国家」 は、国際標準化機構の国別リストに記載されておらず、国際連合の加盟国でもない。現代では、中華民国のパスポートを所持する台湾出身者がその一例である。 一部の国(クウェート、アラブ首長国連邦、サウジアラビアなど)では、国籍を剥奪されることもある。国籍剥奪の理由は、詐欺や治安上の問題である。出生時に親に遺棄され、親の所在が不明である人もいる。[46][47] |

| De jure vs de facto statelessness This section is missing information about de jure and de facto statelessless. Please expand the section to include this information. Further details may exist on the talk page. (November 2023) Nationality law defines nationality and statelessness. Nationality is awarded based on two well-known principles: jus sanguinis and jus soli. Jus sanguinis translated from Latin means "right of blood". According to this principle, nationality is awarded if the parent(s) of the person are nationals of that country. Jus soli is referred to as "birthright citizenship". It means, anyone born in the territory of the country is awarded nationality of that country.[48] Statelessness is defined by the 1954 Statelessness Convention as "a person who is not considered a national by any State under operation of its law.”[49] A person can become stateless because of administrative reasons. For example, "A person may be at risk of statelessness if she is born in a State that applies jus sanguinis while her parents were born in a State that applies jus soli, leaving the person ineligible for citizenship in both States due to conflicting laws."[50] Moreover, there are countries in which if a person does not reside for a specified period of time, they can automatically lose their nationality.[50] To protect those individuals from being deemed "stateless", the 1961 Statelessness Convention places limitations on nationality laws.[51] |

法的な無国籍と事実上の無国籍 この節には、法的な無国籍と事実上の無国籍に関する情報が欠けている。この情報を追加するために、この節を拡張してほしい。さらに詳しい情報はノートページに存在する可能性がある。(2023年11月) 国籍法は国籍と無国籍を定義する。国籍は、よく知られた2つの原則、血統主義と出生地主義に基づいて付与される。ラテン語から翻訳された血統主義は「血統 の権利」を意味する。この原則によると、その人物の親がその国の国籍保持者である場合、その人物に国籍が付与される。出生地主義は「出生による市民権」と 呼ばれる。これは、その国の領土内で生まれた人物には、その国の国籍が付与されることを意味する。 無国籍は、1954年の無国籍条約によって「いかなる国家によっても、その法の運用により自国民と認められない者」と定義されている。[49] 行政上の理由により、人は無国籍になる可能性がある。例えば、「もし本人の両親が出生地主義を採用する国で出生し、本人が血統主義を採用する国で出生した 場合、法律の矛盾により本人は両方の国の市民権を失うことになり、無国籍となる危険性がある」[50]。さらに、 さらに、一定期間居住しなければ自動的に国籍を失う国もある。[50] 1961年の無国籍条約は、そうした人々を「無国籍」と見なされないよう保護するために、国籍法に制限を設けている。[51] |

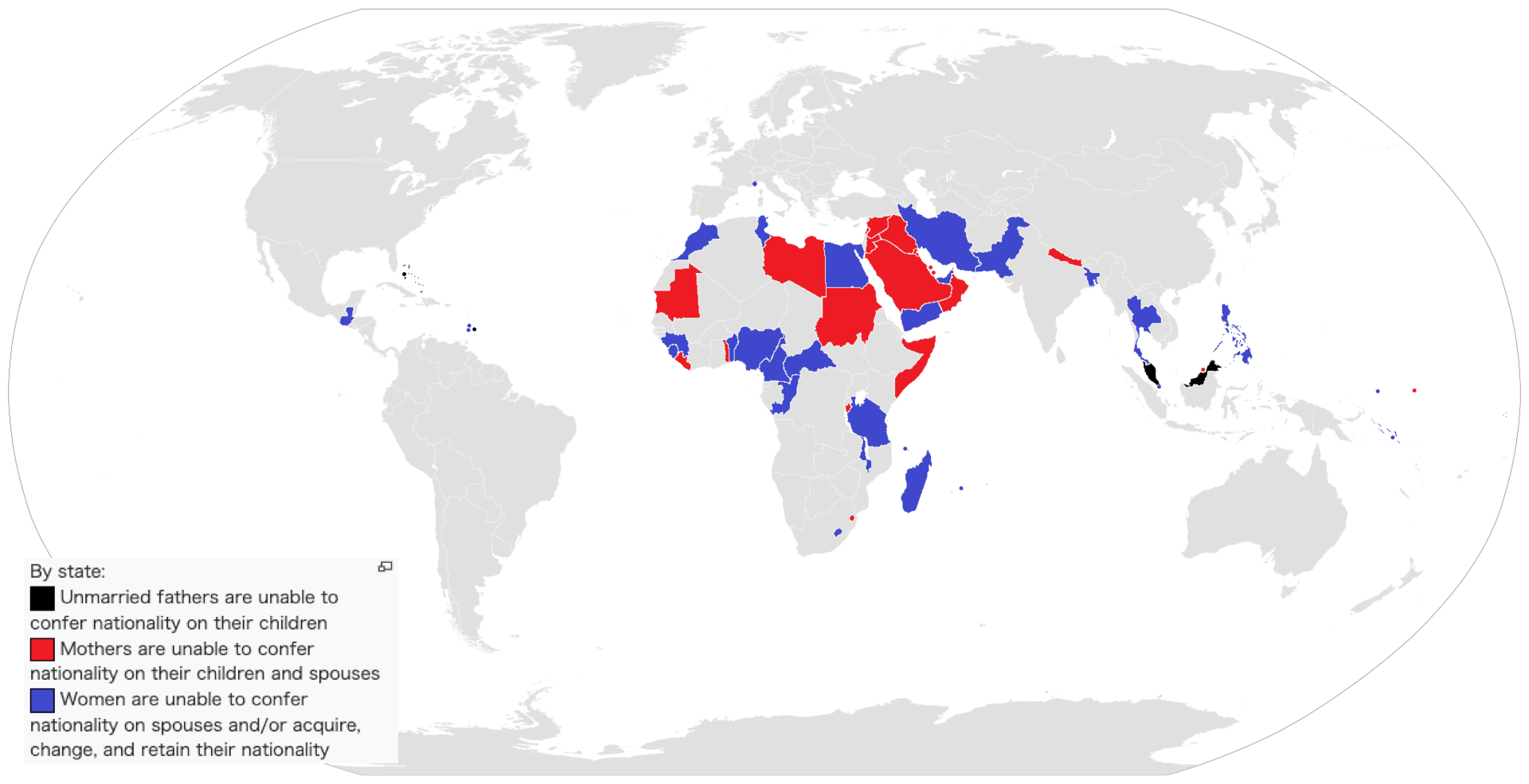

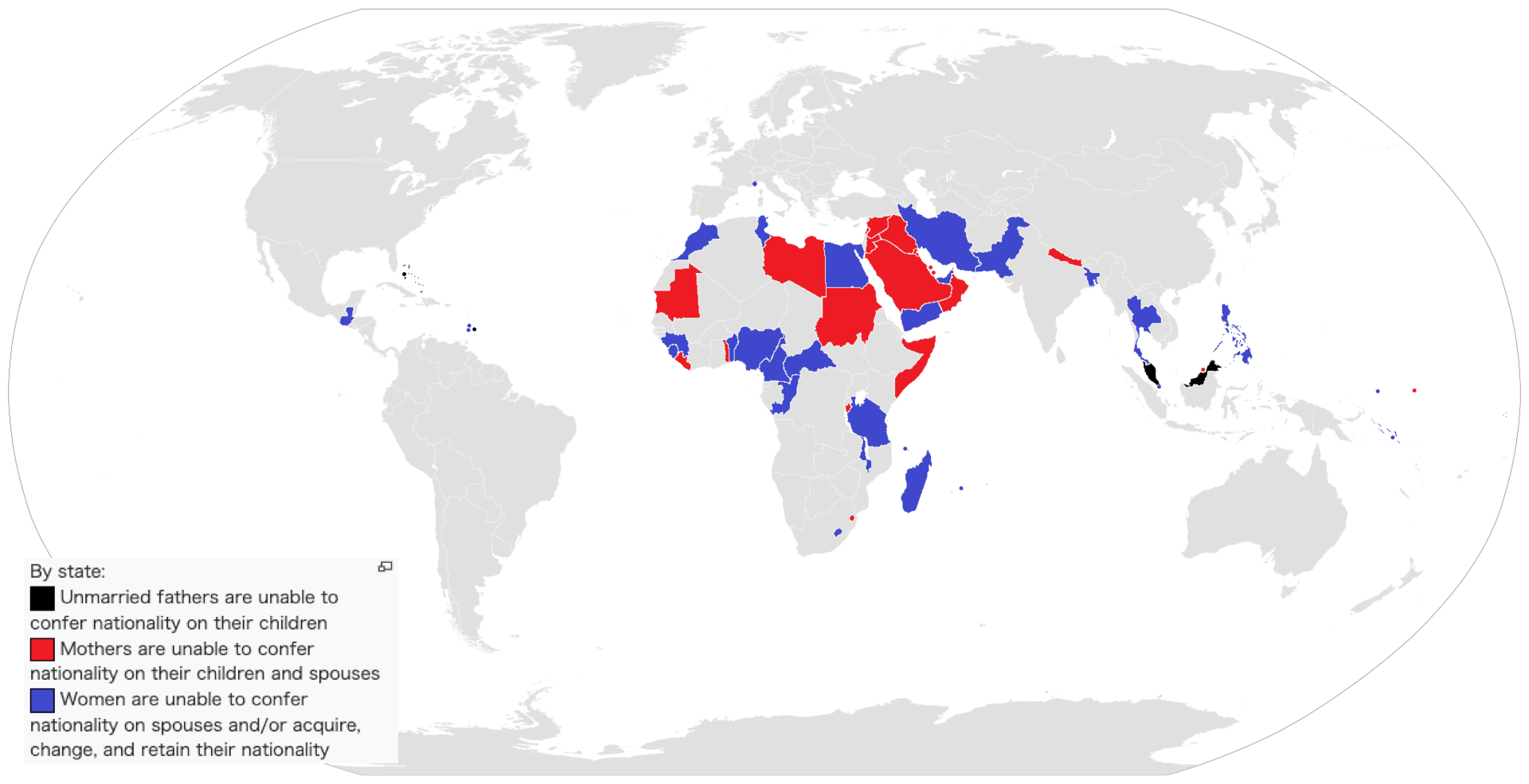

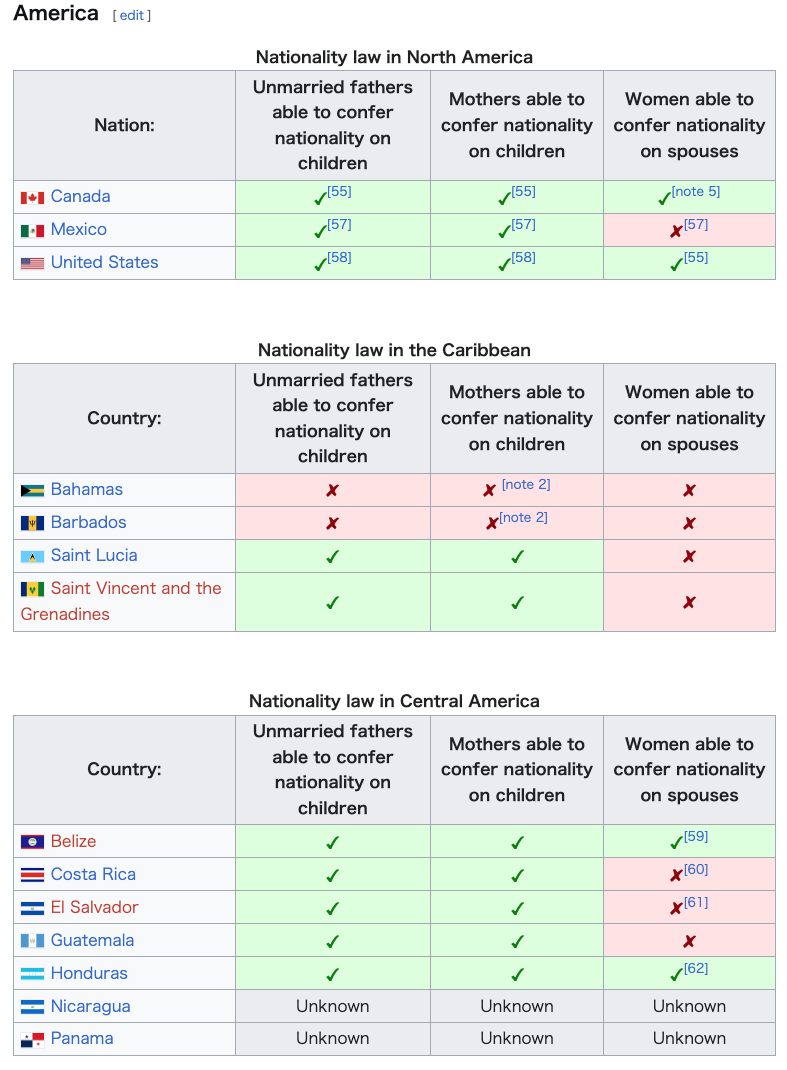

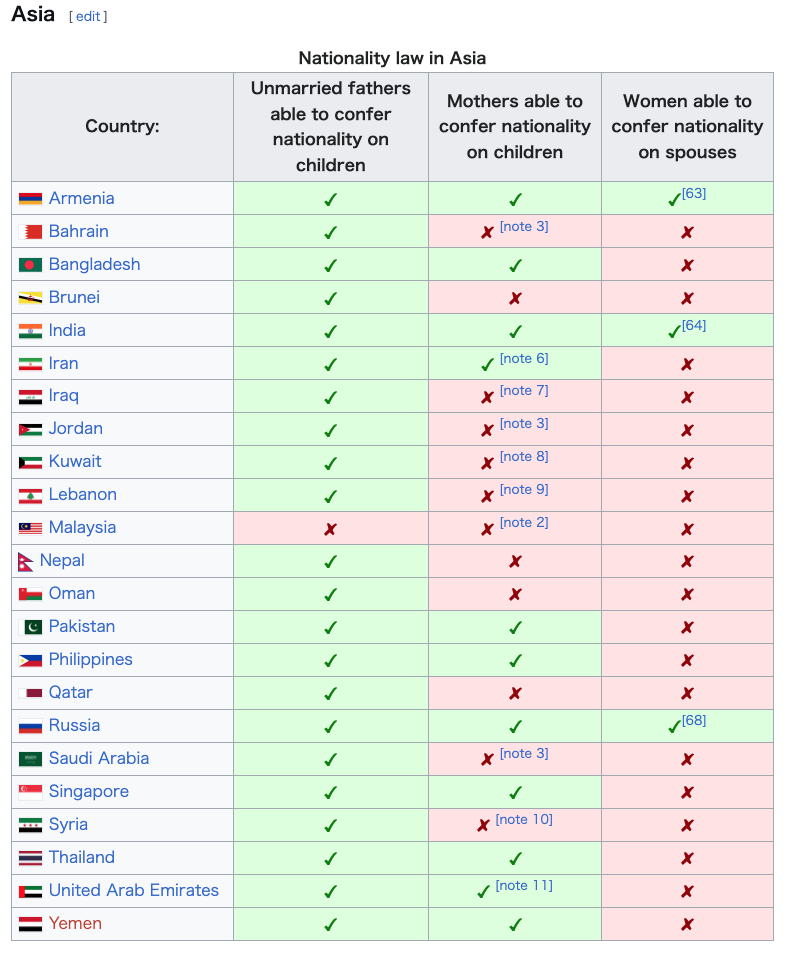

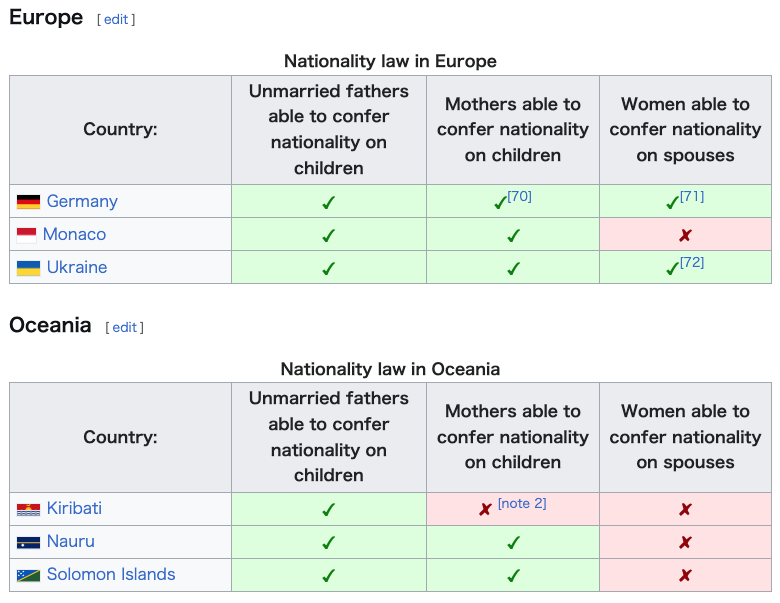

| Conferment of nationality By state: Unmarried fathers are unable to confer nationality on their children Mothers are unable to confer nationality on their children and spouses Women are unable to confer nationality on spouses and/or acquire, change, and retain their nationality The following list includes states in which parents are able to confer nationality on their children or spouses.[52][53]  |

国籍の付与 州別: 未婚の父親は、子供に国籍を付与できない 母親は、子供および配偶者に国籍を付与できない 女性は、配偶者に国籍を付与できない、または自身の国籍を取得、変更、保持できない 以下のリストには、両親が子供または配偶者に国籍を付与できる州が含まれている。[52][53]  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Blood quantum laws Demonym Imagined communities Intersectionality jus sanguinis jus soli List of adjectival and demonymic forms for countries and nations Nottebohm (Liechtenstein v. Guatemala), a 1955 case that is cited for its definitions of nationality Second-class citizen People Volk |

血統主義 デモイニム 想像の共同体 重層的 血統主義 出生地主義 国名および国民の形容詞形およびデモイニムの一覧 国籍の定義について言及されている1955年のノッテボーム事件(リヒテンシュタイン対グアテマラ) 二級市民 人民 民族 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nationality |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆