氏か育ちか論争

Nature versus nurture

☆

「性」と「環境」は、生物学的および社会的な観点から、人間の遺伝的継承(性)と発育環境(環境)が人間に与える影響の相対的な重要性について、長年にわ

たって議論されてきた。英語では「nature and

nurture」という頭韻表現が少なくともエリザベス朝時代から使用されており[1]、中世フランス語にまで遡る[2]。この2つの概念の補完的な組み

合わせは古代の概念である(古代ギリシャ語:ἁπό φύσεως καὶ

εὐτροφίας)[3]。「nature」とは、人が生まれながらに備えているものと考えられており、遺伝的継承やその他の生物学的要因の影響を受け

る。育成とは一般的に、受胎後の外的要因の影響、例えば個々人が経験や学習を通じて獲得するものを指す。

この言葉は、ヴィクトリア朝の博識家であり、優生学および行動遺伝学の近代的創始者であるフランシス・ガルトンが、社会進出に対する遺伝と環境の影響につ

いて論じた際に広まった。[4][5][6]

ガルトンは、自身の異母従兄弟であり進化生物学者のチャールズ・ダーウィンが著した『種の起源』に影響を受けていた。

人間は行動特性のすべてまたはほとんどすべてを「環境」から獲得するという見解は、1690年にジョン・ロックによって「タブラ・ラーサ(白紙説、空白

説)」と名付けられた。人間の発達心理学における「白紙説」(「白紙説」とも呼ばれる)は、人間の行動特性はほぼ環境の影響のみによって発達するという考

え方であり、20世紀の大半において広く受け入れられていた。環境要因と遺伝要因の両方を認める見解と、遺伝要因の影響を否定する「白紙説」との論争は、

しばしば「生まれか育ちか」という観点で論じられてきた。

こうした人間の発達に関する2つの相反するアプローチは、20世紀後半を通じて研究計画をめぐるイデオロギー論争の中心であった。「生まれ」と「育ち」の

両方の要因が、しばしば切り離せない形で大きく影響していることが判明したため、21世紀には、人間開発の研究者の大半がこうした見方を単純または時代遅

れであると考えるようになった。[7][8][9][10][11]

このように、「生まれ」と「育ち」の強い二分法は、一部の研究分野では関連性が限定的であると主張されている。自己家畜化に見られるように、自然と環境が

絶えず影響し合うフィードバックループが存在することが分かっている。生態学や行動遺伝学では、環境が個人の性質に重要な影響を与えると考えられている。

[12][13]

同様に、他の分野でも、遺伝形質と後天的形質の境界線は、エピジェネティクス[14]や胎児発達[15]のように、不明瞭になっている。

| Nature

versus nurture is a long-standing debate in biology and society about

the relative influence on human beings of their genetic inheritance

(nature) and the environmental conditions of their development

(nurture). The alliterative expression "nature and nurture" in English

has been in use since at least the Elizabethan period[1] and goes back

to medieval French.[2] The complementary combination of the two

concepts is an ancient concept (Ancient Greek: ἁπό φύσεως καὶ

εὐτροφίας).[3] Nature is what people think of as pre-wiring and is

influenced by genetic inheritance and other biological factors. Nurture

is generally taken as the influence of external factors after

conception e.g. the product of exposure, experience and learning on an

individual. The phrase in its modern sense was popularized by the Victorian polymath Francis Galton, the modern founder of eugenics and behavioral genetics when he was discussing the influence of heredity and environment on social advancement.[4][5][6] Galton was influenced by On the Origin of Species written by his half-cousin, the evolutionary biologist Charles Darwin. The view that humans acquire all or almost all their behavioral traits from "nurture" was termed tabula rasa ('blank tablet, slate') by John Locke in 1690. A blank slate view (sometimes termed blank-slatism) in human developmental psychology, which assumes that human behavioral traits develop almost exclusively from environmental influences, was widely held during much of the 20th century. The debate between "blank-slate" denial of the influence of heritability, and the view admitting both environmental and heritable traits, has often been cast in terms of nature versus nurture. These two conflicting approaches to human development were at the core of an ideological dispute over research agendas throughout the second half of the 20th century. As both "nature" and "nurture" factors were found to contribute substantially, often in an inextricable manner, such views were seen as naive or outdated by most scholars of human development by the 21st century.[7][8][9][10][11] The strong dichotomy of nature versus nurture has thus been claimed to have limited relevance in some fields of research. Close feedback loops have been found in which nature and nurture influence one another constantly, as seen in self-domestication. In ecology and behavioral genetics, researchers think nurture has an essential influence on the nature of an individual.[12][13] Similarly in other fields, the dividing line between an inherited and an acquired trait becomes unclear, as in epigenetics[14] or fetal development.[15] |

「性」と「環境」は、生物学的および社会的な観点から、人間の遺伝的継

承(性)と発育環境(環境)が人間に与える影響の相対的な重要性について、長年にわたって議論されてきた。英語では「nature and

nurture」という頭韻表現が少なくともエリザベス朝時代から使用されており[1]、中世フランス語にまで遡る[2]。この2つの概念の補完的な組み

合わせは古代の概念である(古代ギリシャ語:ἁπό φύσεως καὶ

εὐτροφίας)[3]。「nature」とは、人が生まれながらに備えているものと考えられており、遺伝的継承やその他の生物学的要因の影響を受け

る。育成とは一般的に、受胎後の外的要因の影響、例えば個々人が経験や学習を通じて獲得するものを指す。 この言葉は、ヴィクトリア朝の博識家であり、優生学および行動遺伝学の近代的創始者であるフランシス・ガルトンが、社会進出に対する遺伝と環境の影響につ いて論じた際に広まった。[4][5][6] ガルトンは、自身の異母従兄弟であり進化生物学者のチャールズ・ダーウィンが著した『種の起源』に影響を受けていた。 人間は行動特性のすべてまたはほとんどすべてを「環境」から獲得するという見解は、1690年にジョン・ロックによって「タブラ・ラーサ(白紙説、空白 説)」と名付けられた。人間の発達心理学における「白紙説」(「白紙説」とも呼ばれる)は、人間の行動特性はほぼ環境の影響のみによって発達するという考 え方であり、20世紀の大半において広く受け入れられていた。環境要因と遺伝要因の両方を認める見解と、遺伝要因の影響を否定する「白紙説」との論争は、 しばしば「生まれか育ちか」という観点で論じられてきた。 こうした人間の発達に関する2つの相反するアプローチは、20世紀後半を通じて研究計画をめぐるイデオロギー論争の中心であった。「生まれ」と「育ち」の 両方の要因が、しばしば切り離せない形で大きく影響していることが判明したため、21世紀には、人間開発の研究者の大半がこうした見方を単純または時代遅 れであると考えるようになった。[7][8][9][10][11] このように、「生まれ」と「育ち」の強い二分法は、一部の研究分野では関連性が限定的であると主張されている。自己家畜化に見られるように、自然と環境が 絶えず影響し合うフィードバックループが存在することが分かっている。生態学や行動遺伝学では、環境が個人の性質に重要な影響を与えると考えられている。 [12][13] 同様に、他の分野でも、遺伝形質と後天的形質の境界線は、エピジェネティクス[14]や胎児発達[15]のように、不明瞭になっている。 |

| History of debate According to Records of the Grand Historian (94 BC) by Sima Qian, during Chen Sheng Wu Guang uprising in 209 B.C., Chen Sheng asked the rhetorical question as a call to war: "Are kings, generals, and ministers merely born into their kind?"[16] (Chinese: 王侯將相寧有種乎).[17] Though Chen was obviously negative to the question, the phrase has often been cited as an early quest into the nature versus nurture problem.[18] John Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) is often cited as the foundational document of the blank slate view. In the Essay, Locke specifically criticizes René Descartes's claim of an innate idea of God that is universal to humanity. Locke's view was harshly criticized in his own time. Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury, complained that by denying the possibility of any innate ideas, Locke "threw all order and virtue out of the world," leading to total moral relativism. By the 19th century, the predominant perspective was contrary to that of Locke's, tending to focus on "instinct." Leda Cosmides and John Tooby noted that William James (1842–1910) argued that humans have more instincts than animals, and that greater freedom of action is the result of having more psychological instincts, not fewer.[19] The question of "innate ideas" or "instincts" was of some importance in the discussion of free will in moral philosophy. In 18th-century philosophy, this was cast in terms of "innate ideas" establishing the presence of a universal virtue, a prerequisite for objective morals. In the 20th century, this argument was in a way inverted, since some philosophers (J. L. Mackie) now argued that the evolutionary origins of human behavioral traits forces us to concede that there is no foundation for ethics, while others (Thomas Nagel) treated ethics as a field of cognitively valid statements in complete isolation from evolutionary considerations.[20] Early to mid-20th century In the early 20th century, there was an increased interest in the role of one's environment, as a reaction to the strong focus on pure heredity in the wake of the triumphal success of Darwin's theory of evolution.[21] During this time, the social sciences developed as the project of studying the influence of culture in clean isolation from questions related to "biology. Franz Boas's The Mind of Primitive Man (1911) established a program that would dominate American anthropology for the next 15 years. In this study, he established that in any given population, biology, language, material, and symbolic culture, are autonomous; that each is an equally important dimension of human nature, but that none of these dimensions is reducible to another. Purist behaviorism John B. Watson in the 1920s and 1930s established the school of purist behaviorism that would become dominant over the following decades. Watson is often said to have been convinced of the complete dominance of cultural influence over anything that heredity might contribute. This is based on the following quote which is frequently repeated without context, as the last sentence is frequently omitted, leading to confusion about Watson's position:[22] Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I'll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select – doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief and, yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors. I am going beyond my facts and I admit it, but so have the advocates of the contrary and they have been doing it for many thousands of years. During the 1940s to 1960s, Ashley Montagu was a notable proponent of this purist form of behaviorism which allowed no contribution from heredity whatsoever:[23] Man is man because he has no instincts, because everything he is and has become he has learned, acquired, from his culture ... with the exception of the instinctoid reactions in infants to sudden withdrawals of support and to sudden loud noises, the human being is entirely instinctless. In 1951, Calvin Hall suggested that the dichotomy opposing nature to nurture is ultimately fruitless.[24] In African Genesis (1961) and The Territorial Imperative (1966), Robert Ardrey argues for innate attributes of human nature, especially concerning territoriality. Desmond Morris in The Naked Ape (1967) expresses similar views. Organised opposition to Montagu's kind of purist "blank-slatism" began to pick up in the 1970s, notably led by E. O. Wilson (On Human Nature, 1979). The tool of twin studies was developed as a research design intended to exclude all confounders based on inherited behavioral traits.[25] Such studies are designed to decompose the variability of a given trait in a given population into a genetic and an environmental component. Twin studies established that there was, in many cases, a significant heritable component. These results did not, in any way, point to overwhelming contribution of heritable factors, with heritability typically ranging around 40% to 50%, so that the controversy may not be cast in terms of purist behaviorism vs. purist nativism. Rather, it was purist behaviorism that was gradually replaced by the now-predominant view that both kinds of factors usually contribute to a given trait, anecdotally phrased by Donald Hebb as an answer to the question "which, nature or nurture, contributes more to personality?" by asking in response, "Which contributes more to the area of a rectangle, its length or its width?"[26] In a comparable avenue of research, anthropologist Donald Brown in the 1980s surveyed hundreds of anthropological studies from around the world and collected a set of cultural universals. He identified approximately 150 such features, coming to the conclusion there is indeed a "universal human nature", and that these features point to what that universal human nature is.[27] Determinism See also: Social determinism, Cultural determinism, and Biological determinism At the height of the controversy, during the 1970s to 1980s, the debate was highly ideologised. In Not in Our Genes: Biology, Ideology and Human Nature (1984), Richard Lewontin, Steven Rose and Leon Kamin criticise "genetic determinism" from a Marxist framework, arguing that "Science is the ultimate legitimator of bourgeois ideology ... If biological determinism is a weapon in the struggle between classes, then the universities are weapons factories, and their teaching and research faculties are the engineers, designers, and production workers." The debate thus shifted away from whether heritable traits exist to whether it was politically or ethically permissible to admit their existence. The authors deny this, requesting that evolutionary inclinations be discarded in ethical and political discussions regardless of whether they exist or not.[28] 1990s Heritability studies became much easier to perform, and hence much more numerous, with the advances of genetic studies during the 1990s. By the late 1990s, an overwhelming amount of evidence had accumulated that amounts to a refutation of the extreme forms of "blank-slatism" advocated by Watson or Montagu.[citation needed] This revised state of affairs was summarized in books aimed at a popular audience from the late 1990s. In The Nurture Assumption: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do (1998), Judith Rich Harris was heralded by Steven Pinker as a book that "will come to be seen as a turning point in the history of psychology."[29] However, Harris was criticized for exaggerating the point of "parental upbringing seems to matter less than previously thought" to the implication that "parents do not matter."[30] The situation as it presented itself by the end of the 20th century was summarized in The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature (2002) by Steven Pinker. The book became a best-seller, and was instrumental in bringing to the attention of a wider public the paradigm shift away from the behaviourist purism of the 1940s to 1970s that had taken place over the preceding decades.[31] Pinker portrays the adherence to pure blank-slatism as an ideological dogma linked to two other dogmas found in the dominant view of human nature in the 20th century: "noble savage," in the sense that people are born good and corrupted by bad influence; and "ghost in the machine," in the sense that there is a human soul capable of moral choices completely detached from biology. Pinker argues that all three dogmas were held onto for an extended period even in the face of evidence because they were seen as desirable in the sense that if any human trait is purely conditioned by culture, any undesired trait (such as crime or aggression) may be engineered away by purely cultural (political means). Pinker focuses on reasons he assumes were responsible for unduly repressing evidence to the contrary, notably the fear of (imagined or projected) political or ideological consequences.[32] |

議論の歴史 司馬遷の『史記』(紀元前94年)によると、紀元前209年の嬴政の蜂起の際、嬴政は戦争への呼びかけとして次のような修辞的な質問をした。「王や将軍、 大臣は生まれながらにしてその地位にあるのか?」[16](中国語:王侯將相寧有種乎)[17] 陳は明らかにこの質問に否定的であったが、このフレーズは、生得か環境かという問題をめぐる初期の探求としてしばしば引用されている。 ジョン・ロックの『人間理解論』(1690年)は、白紙説の基礎となる文書としてしばしば引用されている。この論文の中で、ロックはルネ・デカルトが主張 した、人間に生まれつき備わっている神の観念という考え方を特に批判している。ロックの考え方は、同時代には厳しく批判された。第3代シャフツベリー伯爵 アンソニー・アシュリー=クーパーは、生まれつきの観念の可能性を否定することで、ロックは「世界からすべての秩序と美徳を投げ捨て」、完全な道徳的相対 主義に至ったと不満を述べた。19世紀になると、主流の考え方はロックのそれとは反対に、「本能」に焦点を当てる傾向が強まった。レダ・コスミデスとジョ ン・トゥービーは、ウィリアム・ジェームズ(1842年-1910年)が、人間には動物よりも多くの本能があり、より大きな行動の自由は、心理的な本能が より多く備わっていることの結果であり、本能が少ないことの結果ではないと主張したことを指摘している。 「生得観念」や「本能」の問題は、道徳哲学における自由意志の議論において、ある程度の重要性を持っていた。18世紀の哲学では、普遍的な美徳の存在を確 立する「生得観念」という観点から、客観的な道徳の前提条件として論じられた。20世紀には、この議論はある意味で逆転した。一部の哲学者(J. L. マッキー)は、人間の行動特性の進化論的起源を理由に、倫理の基盤は存在しないと主張した。一方、他の哲学者(トーマス・ナゲル)は、倫理を認知的に有効 な主張の分野として扱い、進化論的な考察とは完全に切り離して論じた。[20] 20世紀前半から中盤にかけて 20世紀初頭には、ダーウィンの進化論の勝利的な成功の余波で純粋な遺伝に強い焦点が当てられたことへの反動として、環境の役割に対する関心が高まった。 [21] この時期には、社会科学は「生物学」に関する問題から完全に切り離された文化の影響を研究するプロジェクトとして発展した。フランツ・ボアズの『原始人の 精神』(1911年)は、その後の15年間、アメリカの人類学を支配することになるプログラムを確立した。この研究において、彼は、いかなる集団において も、生物学、言語、物質、象徴文化はそれぞれ独立していること、そして、それぞれが人間性の等しく重要な側面であるが、これらの側面はどれも他の側面に還 元されるものではないことを明らかにした。 純粋行動主義 1920年代から1930年代にかけて、ジョン・B・ワトソンは、その後の数十年にわたって主流となる純粋行動主義の学派を確立した。ワトソンは、遺伝が 寄与しうるものすべてに対して文化の影響力が完全に優勢であると確信していたとされることが多い。これは、文脈を省略して繰り返し引用されることが多い以 下の引用文に基づいているが、最後の文が省略されることが多いため、ワトソンの立場について混乱が生じている。 健康で、よく形成された乳児を1ダースほど私にくれ、そして、彼らを育てるための私自身の指定した世界をくれれば、私は、彼らの中からランダムに誰かを選 び、私が選んだどんなタイプの専門家にもなるよう彼を訓練することを保証しよう。医師、弁護士、芸術家、商人、そして、そう、乞食や泥棒にもなるだろう。 彼らの才能、傾向、能力、職業、そして先祖の血統に関係なく。私は事実を越えようとしているし、それを認めているが、反対派の支持者たちも同様であり、彼 らは何千年もの間それを続けてきた。 1940年代から1960年代にかけて、アシュレイ・モンタギューは、遺伝による寄与を一切認めない、この純粋な行動主義の著名な支持者であった。 人間は本能を持たないから人間であり、人間が持つあらゆる性質や能力は、文化から学び、習得したものである。... 突然の支援の取り消しや突然の大きな騒音に対する乳幼児の反応を除いて、人間は完全に本能を持たない。 1951年、カルヴィン・ホールは、生得と獲得の二分法は最終的に無益であると示唆した。 アフリカ創世記』(1961年)と『縄張りへの衝動』(1966年)において、ロバート・アードレーは、人間の本性における生得的な属性、特に縄張り意識 について論じている。デズモンド・モリスは『裸のサル』(1967年)で同様の見解を述べている。モンタギューの純粋主義的な「空白説」に対する組織的な 反対運動は、1970年代に活発化し、特にE. O. ウィルソン(『人間の本性について』(1979年))が主導した。 遺伝的行動形質に基づくすべての交絡因子を排除することを意図した研究デザインとして、双生児研究の手法が開発された。[25] このような研究は、特定の集団における特定の形質の変動を遺伝的および環境的要素に分解するように設計されている。双生児研究により、多くの場合、有意な 遺伝的要素が存在することが証明された。これらの結果は、遺伝要因の圧倒的な寄与を指し示すものではまったくなく、遺伝率は通常40%から50%の範囲で あるため、純粋な行動主義と純粋な生得説の論争という観点で論じられるものではない。むしろ、純粋行動主義が徐々に、現在では主流となっている見解に取っ て代わられたのである。その見解では、通常、両方の種類の要因が特定の形質に寄与しているとされる。ドナルド・ヘッブは、「性格には生得と環境のどちらが より強く影響するのか?」という質問に対して、「長方形の面積には、長さと幅のどちらがより強く影響するのか?」と問い返すことで、逸話的に表現している [26]。 同様の研究分野において、1980年代に人類学者ドナルド・ブラウンは、世界中の何百もの人類学的研究を調査し、文化普遍論の体系を収集した。彼はおよそ 150のそのような特徴を特定し、確かに「普遍的人性」が存在し、これらの特徴がその普遍的人性とは何かを示しているという結論に達した。 決定論 参照:社会的決定論、文化的決定論、生物学的決定論 論争が最も激しかった1970年代から1980年代にかけて、この議論は極めてイデオロギー的なものとなっていた。リチャード・ルウォンタン、スティーブ ン・ローズ、レオン・カミンは、1984年の著書『Not in Our Genes: Biology, Ideology and Human Nature(我々の遺伝子の中にはない:生物学、イデオロギー、人間の本性)』の中で、マルクス主義の枠組みから「遺伝的決定論」を批判し、「科学はブ ルジョワイデオロギーの究極の正当化者である... 生物学的な決定論が階級間の闘争における武器であるならば、大学は武器工場であり、その教育および研究部門はエンジニア、デザイナー、生産労働者である」 と主張した。こうして、遺伝形質が存在するかどうかという議論から、その存在を認めることが政治的あるいは倫理的に許されるかどうかという議論へと移行し た。著者はこれを否定し、進化論的傾向が存在するかどうかに関わらず、倫理的および政治的議論においては進化論的傾向を捨象するよう求めている。[28] 1990年代 遺伝研究の進歩により、遺伝率研究は格段に容易になり、数も大幅に増加した。1990年代後半までに、ワトソンやモンタギューが唱えた極端な「空白主義」を否定するに足る膨大な量の証拠が蓄積された。 この修正された状況は、1990年代後半から一般読者向けに出版された書籍で要約されている。『The Nurture Assumption: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do』(1998年)において、スティーブン・ピンカーはジュディス・リッチ・ハリスを「心理学史上の転換点となる本」と評した。しかし、ハリスは「親の 育て方は以前考えられていたほど重要ではない」という主張を「親は重要ではない」という意味に拡大解釈したとして批判された。 20世紀末までに生じた状況は、スティーブン・ピンカー著『空白の白紙:人間性の現代における否定』(2002年)にまとめられている。この本はベストセ ラーとなり、1940年代から1970年代にかけての行動主義的純粋主義から離れたパラダイムシフトが、それ以前の数十年間に起こっていたことを広く一般 の人々の注目を集めるのに役立った。 ピンカーは、純粋な空白主義への固執を、20世紀における人間性に関する支配的な見解に見られる他の2つの教義と結びついたイデオロギー上の教義として描いている。 すなわち、「高潔な野蛮人」という意味で、人は生まれつき善良であるが、悪影響によって堕落するという考え方、そして 「機械の中の幽霊」という意味で、生物学とは完全に切り離された道徳的選択を行うことのできる人間の魂が存在するという考え方である。 ピンカーは、これらの3つの教義は、証拠に反して長期間にわたって信じられていたが、それは、人間の特性が純粋に文化によって形成されているのであれば、 望ましくない特性(犯罪や攻撃性など)は純粋に文化的な(政治的手段によって)操作によって取り除くことができるという意味で望ましいと見なされていたか らだと主張している。ピンカーは、特に(想像または投影された)政治的またはイデオロギー的な結果に対する恐れが、反対の証拠を不当に抑圧した原因である と想定している理由に焦点を当てている。[32] |

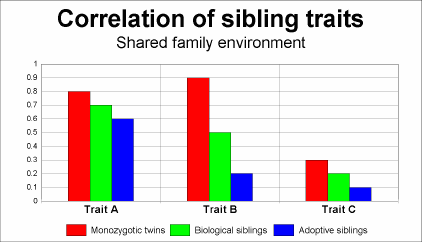

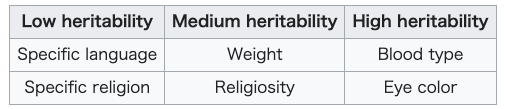

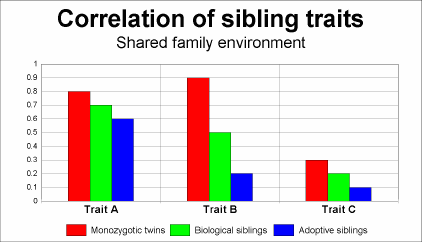

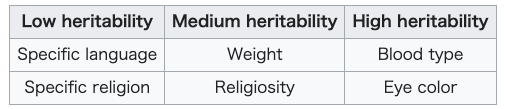

| Heritability estimates Main article: Heritability  This chart illustrates three patterns one might see when studying the influence of genes and environment on traits in individuals. Trait A shows a high sibling correlation, but little heritability (i.e. high shared environmental variance c2; low heritability h2). Trait B shows a high heritability since the correlation of trait rises sharply with the degree of genetic similarity. Trait C shows low heritability, but also low correlations generally; this means Trait C has a high nonshared environmental variance e2. In other words, the degree to which individuals display Trait C has little to do with either genes or broadly predictable environmental factors—roughly, the outcome approaches random for an individual. Notice also that even identical twins raised in a common family rarely show 100% trait correlation. The term heritability refers only to the degree of genetic variation between people on a trait. It does not refer to the degree to which a trait of a particular individual is due to environmental or genetic factors. The traits of an individual are always a complex interweaving of both.[33] For an individual, even strongly genetically influenced, or "obligate" traits, such as eye color, assume the inputs of a typical environment during ontogenetic development (e.g., certain ranges of temperatures, oxygen levels, etc.). In contrast, the "heritability index" statistically quantifies the extent to which variation between individuals on a trait is due to variation in the genes those individuals carry. In animals where breeding and environments can be controlled experimentally, heritability can be determined relatively easily. Such experiments would be unethical for human research. This problem can be overcome by finding existing populations of humans that reflect the experimental setting the researcher wishes to create. One way to determine the contribution of genes and environment to a trait is to study twins.[34] In one kind of study, identical twins reared apart are compared to randomly selected pairs of people. The twins share identical genes, but different family environments. Twins reared apart are not assigned at random to foster or adoptive parents. In another kind of twin study, identical twins reared together (who share family environment and genes) are compared to fraternal twins reared together (who also share family environment but only share half their genes). Another condition that permits the disassociation of genes and environment is adoption. In one kind of adoption study, biological siblings reared together (who share the same family environment and half their genes) are compared to adoptive siblings (who share their family environment but none of their genes). In many cases, it has been found that genes make a substantial contribution, including psychological traits such as intelligence and personality.[35] Yet heritability may differ in other circumstances, for instance environmental deprivation. Examples of low, medium, and high heritability traits include:  Twin and adoption studies have their methodological limits. For example, both are limited to the range of environments and genes which they sample. Almost all of these studies are conducted in Western countries, and therefore cannot necessarily be extrapolated globally to include non-western populations. Additionally, both types of studies depend on particular assumptions, such as the equal environments assumption in the case of twin studies, and the lack of pre-adoptive effects in the case of adoption studies. Since the definition of "nature" in this context is tied to "heritability", the definition of "nurture" has consequently become very wide, including any type of causality that is not heritable. The term has thus moved away from its original connotation of "cultural influences" to include all effects of the environment, including; indeed, a substantial source of environmental input to human nature may arise from stochastic variations in prenatal development and is thus in no sense of the term "cultural".[36][37] |

遺伝率の推定 詳細は「遺伝率」を参照  この図は、個人の形質に対する遺伝と環境の影響を研究する際に観察される可能性のある3つのパターンを示している。形質Aは高い同胞相関を示しているが、 遺伝率は低い(すなわち、高い共有環境分散c2、低い遺伝率h2)。形質Bは、形質の相関が遺伝的類似性の度合いに応じて急激に上昇しているため、高い遺 伝率を示している。形質Cは遺伝率が低いものの、相関も一般的に低い。つまり、形質Cは共有されない環境要因の分散e2が高いことを意味する。言い換えれ ば、個人が形質Cを示す程度は、遺伝子や広く予測可能な環境要因とはほとんど関係がない。つまり、結果はおおよそランダムに近づく。また、同じ家庭で育っ た一卵性双生児でも、形質相関が100%になることはほとんどない。 遺伝率という用語は、ある形質における人々の間の遺伝的変異の度合いのみを指す。特定の個人の形質が環境要因または遺伝要因のいずれに起因するのかという 度合いを指すものではない。個人の形質は常に、両者の複雑な織り交ざりである。[33] 遺伝の影響が強い、つまり「義務的」な形質(目の色など)であっても、個体発生の過程で典型的な環境からの影響を受ける(例えば、特定の範囲の温度、酸素 レベルなど)。 これに対し、「遺伝率指数」は、ある形質における個体間の差異が、その個体が持つ遺伝子の差異に起因する度合いを統計的に数値化するものである。繁殖や環 境を実験的に制御できる動物では、遺伝率は比較的容易に決定できる。しかし、人間を対象とした研究では、そのような実験は倫理的に問題がある。この問題 は、研究者が作り出したい実験設定を反映する既存の人間集団を見つけることで克服できる。 形質に対する遺伝子と環境の寄与を決定する一つの方法は、双生児の研究である。[34] ある種の研究では、離れて育てられた一卵性双生児と、無作為に選ばれた人々のペアを比較する。双生児は同一の遺伝子を共有しているが、家族環境は異なる。 離れて育てられた双生児は、里親や養親に無作為に割り当てられるわけではない。別の双子の研究では、一緒に育てられた一卵性双生児(家族環境と遺伝子を共 有)と、一緒に育てられた二卵性双生児(家族環境も共有するが、遺伝子は半分しか共有しない)を比較する。遺伝子と環境の関連性を断ち切るもう一つの条件 は養子縁組である。ある養子縁組の研究では、一緒に育てられた実のきょうだい(家族環境を共有し、遺伝子は半分しか共有しない)と、養子縁組のきょうだい (家族環境は共有するが、遺伝子は共有しない)を比較する。 多くの場合、遺伝子がかなりの影響を及ぼしていることが判明しており、知能や性格などの心理的特性も含まれる。[35] しかし、遺伝率は他の状況、例えば環境剥奪などでは異なる可能性がある。遺伝率が低い、中程度、高い特性の例としては、以下のようなものがある。  双生児研究や養子研究には、方法論的な限界がある。例えば、どちらもサンプリングする環境や遺伝子の範囲に限界がある。これらの研究のほとんどは西洋諸国 で実施されているため、西洋以外の人口を含めて世界的に外挿できるとは限らない。さらに、どちらのタイプの研究も特定の仮定に依存しており、例えば、双生 児研究の場合は環境が同等であるという仮定、養子研究の場合は養子縁組前の影響がないという仮定である。 この文脈における「性質」の定義は「遺伝性」と結びついているため、「環境」の定義は必然的に非常に広範なものとなり、遺伝性のないあらゆる種類の因果関 係を含むこととなった。この用語は、もともとの「文化的影響」という含みから離れ、環境によるあらゆる影響を含むものへと変化した。実際、人間の本性に影 響を与える環境要因の多くは、出生前の発育における確率的な変化から生じるものであり、この用語の「文化的」という意味とはまったく異なるものである。 [36][37] |

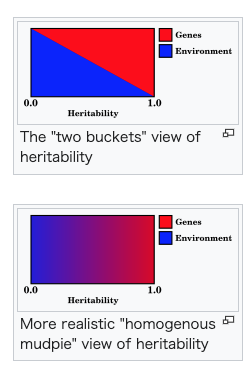

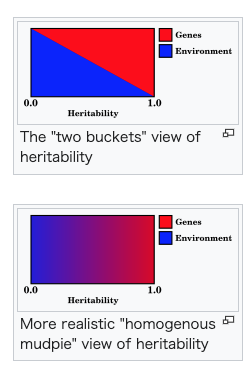

| Gene–environment interaction Main article: Gene–environment interaction Many properties of the brain are genetically organized, and don't depend on information coming in from the senses. — Steven Pinker The interactions of genes with environment, called gene–environment interactions, are another component of the nature–nurture debate. A classic example of gene–environment interaction is the ability of a diet low in the amino acid phenylalanine to partially suppress the genetic disease phenylketonuria. Yet another complication to the nature–nurture debate is the existence of gene–environment correlations. These correlations indicate that individuals with certain genotypes are more likely to find themselves in certain environments. Thus, it appears that genes can shape (the selection or creation of) environments. Even using experiments like those described above, it can be very difficult to determine convincingly the relative contribution of genes and environment. The analogy "genetics loads the gun, but environment pulls the trigger" has been attributed to Judith Stern.[38] Heritability refers to the origins of differences between people. Individual development, even of highly heritable traits, such as eye color, depends on a range of environmental factors, from the other genes in the organism, to physical variables such as temperature, oxygen levels etc. during its development or ontogenesis. The variability of trait can be meaningfully spoken of as being due in certain proportions to genetic differences ("nature"), or environments ("nurture"). For highly penetrant Mendelian genetic disorders such as Huntington's disease virtually all the incidence of the disease is due to genetic differences. Huntington's animal models live much longer or shorter lives depending on how they are cared for.[39] At the other extreme, traits such as native language are environmentally determined: linguists have found that any child (if capable of learning a language at all) can learn any human language with equal facility.[40] With virtually all biological and psychological traits, however, genes and environment work in concert, communicating back and forth to create the individual. At a molecular level, genes interact with signals from other genes and from the environment. While there are many thousands of single-gene-locus traits, so-called complex traits are due to the additive effects of many (often hundreds) of small gene effects. A good example of this is height, where variance appears to be spread across many hundreds of loci.[41] Extreme genetic or environmental conditions can predominate in rare circumstances—if a child is born mute due to a genetic mutation, it will not learn to speak any language regardless of the environment; similarly, someone who is practically certain to eventually develop Huntington's disease according to their genotype may die in an unrelated accident (an environmental event) long before the disease will manifest itself. The "two buckets" view of heritability  More realistic "homogenous mudpie" view of heritability Steven Pinker likewise described several examples:[42][43] [C]oncrete behavioral traits that patently depend on content provided by the home or culture—which language one speaks, which religion one practices, which political party one supports—are not heritable at all. But traits that reflect the underlying talents and temperaments—how proficient with language a person is, how religious, how liberal or conservative—are partially heritable. When traits are determined by a complex interaction of genotype and environment it is possible to measure the heritability of a trait within a population. However, many non-scientists who encounter a report of a trait having a certain percentage heritability imagine non-interactional, additive contributions of genes and environment to the trait. As an analogy, some laypeople may think of the degree of a trait being made up of two "buckets," genes and environment, each able to hold a certain capacity of the trait. But even for intermediate heritabilities, a trait is always shaped by both genetic dispositions and the environments in which people develop, merely with greater and lesser plasticities associated with these heritability measures. Heritability measures always refer to the degree of variation between individuals in a population. That is, as these statistics cannot be applied at the level of the individual, it would be incorrect to say that while the heritability index of personality is about 0.6, 60% of one's personality is obtained from one's parents and 40% from the environment. To help to understand this, imagine that all humans were genetic clones. The heritability index for all traits would be zero (all variability between clonal individuals must be due to environmental factors). And, contrary to erroneous interpretations of the heritability index, as societies become more egalitarian (everyone has more similar experiences) the heritability index goes up (as environments become more similar, variability between individuals is due more to genetic factors). One should also take into account the fact that the variables of heritability and environmentality are not precise and vary within a chosen population and across cultures. It would be more accurate to state that the degree of heritability and environmentality is measured in its reference to a particular phenotype in a chosen group of a population in a given period of time. The accuracy of the calculations is further hindered by the number of coefficients taken into consideration, age being one such variable. The display of the influence of heritability and environmentality differs drastically across age groups: the older the studied age is, the more noticeable the heritability factor becomes, the younger the test subjects are, the more likely it is to show signs of strong influence of the environmental factors. For example, one study found no statistically significant difference in self-reported wellbeing between middle-aged monozygotic twins separated at birth and those reared in the same household, suggesting that happiness in middle-aged adults is not based in environmental factors related to family rearing. The same result was also found among middle-aged dizygotic twins. Furthermore, there was significantly more variance in the dizygotic twins' self-reported wellbeing than there was in the monozygotic group. Genetic similarity has thus been estimated to account for around 50% of the variance in adult happiness at a given point in time, and as much as 80% of the variance in long-term happiness stability.[44] Other studies have similarly found the heritability of happiness to be around 0.35–0.50.[45][46][47][48] Some have pointed out that environmental inputs affect the expression of genes.[14] This is one explanation of how environment can influence the extent to which a genetic disposition will actually manifest.[14] Obligate vs. facultative adaptations Traits may be considered to be adaptations (such as the umbilical cord), byproducts of adaptations (the belly button) or due to random variation (convex or concave belly button shape).[49] An alternative to contrasting nature and nurture focuses on "obligate vs. facultative" adaptations.[49] Adaptations may be generally more obligate (robust in the face of typical environmental variation) or more facultative (sensitive to typical environmental variation). For example, the rewarding sweet taste of sugar and the pain of bodily injury are obligate psychological adaptations—typical environmental variability during development does not much affect their operation.[50] On the other hand, facultative adaptations are somewhat like "if-then" statements.[51] An example of a facultative psychological adaptation may be adult attachment style. The attachment style of adults, (for example, a "secure attachment style," the propensity to develop close, trusting bonds with others) is proposed to be conditional on whether an individual's early childhood caregivers could be trusted to provide reliable assistance and attention. An example of a facultative physiological adaptation is tanning of skin on exposure to sunlight (to prevent skin damage). Facultative social adaptation have also been proposed. For example, whether a society is warlike or peaceful has been proposed to be conditional on how much collective threat that society is experiencing.[52] Advanced techniques Quantitative studies of heritable traits throw light on the question. Developmental genetic analysis examines the effects of genes over the course of a human lifespan. Early studies of intelligence, which mostly examined young children, found that heritability measured 40–50%. Subsequent developmental genetic analyses found that variance attributable to additive environmental effects is less apparent in older individuals, with estimated heritability of IQ increasing in adulthood.[53][54][55] Multivariate genetic analysis examines the genetic contribution to several traits that vary together. For example, multivariate genetic analysis has demonstrated that the genetic determinants of all specific cognitive abilities (e.g., memory, spatial reasoning, processing speed) overlap greatly, such that the genes associated with any specific cognitive ability will affect all others. Similarly, multivariate genetic analysis has found that genes that affect scholastic achievement completely overlap with the genes that affect cognitive ability. Extremes analysis examines the link between normal and pathological traits. For example, it is hypothesized[by whom?] that a given behavioral disorder may represent an extreme of a continuous distribution of a normal behavior and hence an extreme of a continuous distribution of genetic and environmental variation. Depression, phobias, and reading disabilities have been examined in this context.[citation needed] For a few highly heritable traits, studies have identified loci associated with variance in that trait, for instance in some individuals with schizophrenia.[56] The budding field of epigenetics has conducted research showing that hereditable conditions like schizophrenia, which have an 80% hereditability with only 10% of those who have inherited the trait actually displaying Schizophrenic traits.[57] New research is showing that gene expression can happen in adults due to environmental stimuli. For example, people with schizophrenic gene have a genetic predisposition for this illness but the gene lays dormant in most people. However, if introduced to chronic stress or introducing some amphetamines it caused the methyl groups to stick to hippocampi histones.[58] |

遺伝子と環境の相互作用 詳細は「遺伝子と環境の相互作用」を参照 脳の多くの特性は遺伝的に形成され、感覚から入ってくる情報に依存しない。 — スティーブン・ピンカー 遺伝子と環境の相互作用は、遺伝子-環境相互作用と呼ばれ、性質か環境かという議論のもう一つの要素である。遺伝子-環境相互作用の典型的な例は、フェニ ルケトン尿症という遺伝病を、フェニルアラニンというアミノ酸の少ない食事によって部分的に抑制できる能力である。性質か環境かという議論をさらに複雑に しているのは、遺伝子と環境の相関関係の存在である。これらの相関関係は、特定の遺伝子型を持つ個人は特定の環境に置かれる可能性が高いことを示してい る。したがって、遺伝子が環境を形成(選択または創造)できる可能性がある。上述のような実験を用いても、遺伝子と環境の相対的な寄与を説得力を持って決 定することは非常に難しい。「遺伝子が銃に弾を込めるが、環境が引き金を引く」という表現はジュディス・スターンによるものだと言われている。 遺伝率とは、人々の間の相違の起源を指す。 目の色のような遺伝率の高い形質でさえ、個々の発達は、生物の他の遺伝子から、その発達または個体発生中の温度や酸素レベルなどの物理的変数に至るまで、さまざまな環境要因に依存している。 形質の多様性は、遺伝的差異(「性質」)または環境(「育成」)に起因する特定の割合として意味のある形で説明することができる。ハンチントン病のような メンデルの法則に則った遺伝性疾患の場合、その発症のほぼすべてが遺伝的差異によるものである。ハンチントン病の動物モデルは、その世話の仕方によって寿 命が大幅に延びたり、短くなったりする。 一方、母国語などの形質は環境によって決定される。言語学者は、言語を学習する能力さえあれば、どの子供でもあらゆる人間の言語を同じように容易に習得で きることを発見している。[40] しかし、事実上、すべての生物学的および心理学的形質において、遺伝子と環境が協調して作用し、相互にコミュニケーションをとりながら、個体を形成する。 分子レベルでは、遺伝子は他の遺伝子や環境からのシグナルと相互作用する。単一遺伝子座の形質は数多く存在するが、いわゆる複雑な形質は、多くの(しばし ば数百もの)小さな遺伝的影響の累積効果によるものである。身長は、この良い例であり、そのばらつきは数百もの遺伝子座にわたって広がっているように見え る。 極端な遺伝的または環境的条件が優勢となることはまれな状況下ではあり得る。遺伝子変異により子供が生まれつき口がきけない場合、その子供はどのような環 境下でも言葉を話すことはないだろう。同様に、遺伝子型から見て最終的にハンチントン病を発症することがほぼ確実な人が、その病気が発症する前に、関係の ない事故(環境要因)で死亡することもある。 遺伝性の「2つのバケツ」という見方  より現実的な遺伝性の「均質な泥遊び」という見方 スティーブン・ピンカーも同様に、いくつかの例を挙げている。[42][43] 家庭や文化から提供される内容に明らかに依存する具体的な行動特性、すなわち、話す言語、信仰する宗教、支持する政党などは、まったく遺伝しない。しか し、言語能力の高さ、宗教性、リベラル性や保守性といった、その人の根底にある才能や気質を反映する特徴は、部分的に遺伝する。 特徴が遺伝子型と環境の複雑な相互作用によって決定される場合、集団内の特徴の遺伝率を測定することが可能である。しかし、ある割合の遺伝率を持つ特徴の 報告を目にした非科学者の多くは、特徴に対する遺伝子と環境の相互作用のない、足し算的な寄与を想像する。例えるなら、素人の中には、ある形質が「遺伝 子」と「環境」という2つの「バケツ」で構成され、それぞれがその形質を一定の容量まで保持できると考える人もいるかもしれない。しかし、中程度の遺伝率 の場合でも、形質は常に遺伝的素質と人が成長する環境の両方によって形作られる。ただ、これらの遺伝率の測定値には、より高い可塑性とより低い可塑性が関 連しているだけである。 遺伝率の測定値は、常に集団内の個体間の変動の度合いを指している。つまり、これらの統計は個体レベルでは適用できないため、性格の遺伝率指数が約0.6 である場合、性格の60%は両親から、40%は環境から得られると述べるのは正しくない。これを理解する手助けとして、すべての人間が遺伝子クローンであ ると想像してみよう。すべての形質における遺伝率指数はゼロになる(クローン個体間のすべての変動は環境要因によるものに違いない)。また、遺伝率指数の 誤った解釈とは逆に、社会が平等主義的になるにつれ(誰もがより似通った経験をする)、遺伝率指数は上昇する(環境がより似通うにつれ、個人間の変動は遺 伝要因によるものになる)。 また、遺伝率と環境性の変数は厳密ではなく、選択された集団内や文化によって異なるという事実も考慮すべきである。遺伝率と環境性の度合いは、特定の期間 における特定の集団の特定の表現型との関連性によって測定されると表現する方がより正確である。計算の正確性は、考慮される係数の数によってさらに妨げら れる。年齢もそのような変数のひとつである。遺伝性と環境性の影響の表示は、年齢層によって大きく異なる。調査対象の年齢が高くなるほど、遺伝性の要因が より顕著になり、被験者が若くなるほど、環境要因の影響が強く現れる傾向が強くなる。 例えば、ある研究では、出生時に分離された中年一卵性双生児と、同じ家庭で育てられた者との間で、自己申告による幸福感に統計的に有意な差は見られなかっ た。この結果は、中年期の幸福は、家族の養育に関連する環境要因に基づくものではないことを示唆している。同じ結果は、中年二卵性双生児の間でも見られ た。さらに、二卵性双生児の自己申告による幸福感のばらつきは、一卵性双生児のグループよりも有意に多かった。遺伝的類似性は、ある時点における成人の幸 福度のばらつきの約50%、長期的な幸福度の安定性のばらつきの80%を占めると推定されている。[44] 他の研究でも、幸福度の遺伝率は0.35~0.50程度であることが分かっている。[45][46][47][48] 環境要因が遺伝子の発現に影響を与えるという指摘もある。[14] これは、環境が遺伝的素因が実際に発現する程度に影響を与える仕組みの一つの説明である。[14] 必須適応と任意適応 形質は、適応(へその緒など)、適応の副産物(へそ)、またはランダムな変異(凸型または凹型のへそ)によるものと考えられる場合がある。[49] 自然と環境の対比に代わるものとして、「必須 vs. 任意」の適応に焦点を当てるものがある。[49] 適応は一般的に、より必須(典型的な環境の変化に強く)であるか、またはより任意(典型的な環境の変化に敏感)である。例えば、砂糖の甘い味に対する報酬 や、身体の損傷による痛みは、必須の心理的適応である。発達中の典型的な環境の変化は、それらの作用にあまり影響しない。[50] 一方、選択的適応は「もし~ならば」という条件文に似ている。[51] 選択的心理学適応の例としては、成人の愛着スタイルが挙げられる。成人の愛着スタイル(例えば、「安全な愛着スタイル」、すなわち他人と親密で信頼関係を 築く傾向)は、個人の幼少期の養育者が信頼でき、確実な支援と配慮を提供できるかどうかによって決まると考えられている。随意的な生理的適応の例として は、日光に当たることによる皮膚の褐色化(皮膚の損傷を防ぐため)が挙げられる。随意的な社会的適応も提唱されている。例えば、社会が好戦的であるか平和 的であるかは、その社会がどれほどの集団的脅威にさらされているかによって決まるということが提唱されている。 高度な技術 遺伝形質の量的研究は、この問題に光を投げかける。 発達遺伝学分析では、人間の生涯にわたる遺伝子の影響を調査する。 知能に関する初期の研究では、主に幼児を対象としていたが、遺伝率は40~50%であることが分かった。 その後の発達遺伝学分析では、加法的環境効果に起因するばらつきは高齢者ではあまり顕著ではなく、成人期におけるIQの推定遺伝率は増加することが分かっ た。 多変量遺伝分析では、同時に変化する複数の形質に対する遺伝的寄与を調査する。例えば、多変量遺伝分析では、すべての特定の認知能力(例えば、記憶力、空 間認識力、処理速度)の遺伝的決定因子が大きく重複していることが示されており、特定の認知能力に関連する遺伝子は、他のすべての能力にも影響を与えるこ とになる。同様に、多変量遺伝分析では、学業成績に影響を与える遺伝子が、認知能力に影響を与える遺伝子と完全に重複していることが分かっている。 極値分析は、正常な形質と病的な形質との間の関連性を調べる。例えば、ある行動障害は正常な行動の連続分布の極値であり、したがって遺伝的および環境的変 化の連続分布の極値である可能性があるという仮説が立てられている[誰によって?]。うつ病、恐怖症、読字障害は、この文脈で研究されている。[要出典] 遺伝性の高いいくつかの形質については、研究により、その形質における差異に関連する遺伝子座が特定されている。例えば、統合失調症患者の一部においてで ある。[56] 発達しつつあるエピジェネティクスの分野では、統合失調症のような遺伝性の疾患は、遺伝率が80%であるが、その形質を受け継いだ人のうち実際に統合失調 症の形質を示すのは10%に過ぎないことを示す研究が行われている。[57] 新しい研究では、環境刺激により成人の遺伝子発現が起こりうることを示している。例えば、統合失調症の遺伝子を持つ人は、この病気に対する遺伝的素因を 持っているが、ほとんどの人ではその遺伝子は休眠状態にある。しかし、慢性的なストレスにさらされたり、アンフェタミンを摂取したりすると、メチル基が海 馬のヒストンに付着するようになる。[58] |

| Intelligence Heritability of intelligence Main article: Heritability of IQ Cognitive functions have a significant genetic component. A 2015 meta-analysis of over 14 million twin pairs found that genetics explained 57% of the variability in cognitive functions.[59] Evidence from behavioral genetic research suggests that family environmental factors may have an effect upon childhood IQ, accounting for up to a quarter of the variance. The American Psychological Association's report "Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns" (1995) states that there is no doubt that normal child development requires a certain minimum level of responsible care. Here, environment is playing a role in what is believed to be fully genetic (intelligence) but it was found that severely deprived, neglectful, or abusive environments have highly negative effects on many aspects of children's intellect development. Beyond that minimum, however, the role of family experience is in serious dispute. On the other hand, by late adolescence this correlation disappears, such that adoptive siblings no longer have similar IQ scores.[60] Moreover, adoption studies indicate that, by adulthood, adoptive siblings are no more similar in IQ than strangers (IQ correlation near zero), while full siblings show an IQ correlation of 0.6. Twin studies reinforce this pattern: monozygotic (identical) twins raised separately are highly similar in IQ (0.74), more so than dizygotic (fraternal) twins raised together (0.6) and much more than adoptive siblings (≈0.0).[61] Recent adoption studies also found that supportive parents can have a positive effect on the development of their children.[62] Environmental role on IQ Other studies have focused on environmental factors that may affect IQ. For example, research has shown that factors such as access to education, nutrition, and social support can have a significant impact on IQ. Furthermore, research has suggested that certain experiences during early childhood, such as exposure to lead or other environmental toxins, can have a negative impact on IQ.[63] Studies have consistently shown that environmental factors can have a significant impact on IQ. Access to quality education has been found to have a positive effect on IQ, with one study indicating that access to quality preschool education had a lasting impact on IQ scores up to age 35. Malnutrition in early childhood has been linked to lower IQ scores later in life, while supplementation with certain nutrients such as iron and iodine has been shown to improve IQ scores. Social support is also an important environmental factor that positively affects IQ, with one study indicating that children who received high levels of emotional support from their mothers had higher IQ scores than those who received low levels of emotional support.[64] |

知能 知能の遺伝率 詳細は「IQの遺伝率」を参照 認知機能には、遺伝的要素が大きく関わっている。2015年の1,400万組以上の双子を対象としたメタ分析では、遺伝が認知機能の変動の57%を説明す ることが分かった。[59] 行動遺伝学の研究結果によると、家族環境要因が幼少期のIQに影響を及ぼす可能性があり、その変動の最大4分の1を占めていることが示唆されている。米国 心理学会の報告書「知能:既知と未知」(1995年)では、正常な子どもの発達には、ある一定の最低限の責任あるケアが必要であることは疑いがないと述べ ている。 ここでは、環境が遺伝的要素のみであると考えられているもの(知能)に影響を与えているが、子どもがひどく疎外されたり、無視されたり、虐待されたりする 環境は、子どもの知能の発達に多くの面で非常に悪影響を与えることが分かっている。しかし、その最低限のレベルを超えた場合、家族経験の役割については深 刻な論争が続いている。 一方、青年期後半になると、この相関関係は消え、養子同士の兄弟姉妹のIQスコアはもはや似通わなくなる。[60] さらに、養子研究では、成人期までに養子同士の兄弟姉妹のIQは赤の他人と変わらなくなることが示されている(IQ相関はほぼゼロ)。一方、実の兄弟姉妹 のIQ相関は0.6である。一卵性(同一)双生児が別々に育てられた場合、IQは非常に類似している(0.74)が、一緒に育てられた二卵性(異父)双生 児(0.6)よりも、また養子兄弟(≈0.0)よりもはるかに類似している。[61] 最近の養子研究では、養子を支える親が子供の成長に良い影響を与えることも分かっている。[62] IQに対する環境の役割 他の研究では、IQに影響を与える可能性のある環境要因に焦点を当てている。例えば、教育、栄養、社会的支援へのアクセスといった要因がIQに大きな影響 を与える可能性があることが研究で示されている。さらに、鉛やその他の環境毒素への暴露など、幼少期のある種の経験がIQに悪影響を与える可能性があるこ とも研究で示唆されている。 環境要因がIQに重大な影響を与える可能性があることは、一貫して研究で示されている。質の高い教育を受ける機会はIQに良い影響を与えることが分かって おり、ある研究では質の高い就学前教育を受ける機会が35歳までのIQスコアに持続的な影響を与えることが示されている。幼児期の栄養不良は、その後の人 生におけるIQスコアの低下と関連しているが、鉄分やヨウ素などの特定の栄養素を補給することでIQスコアが改善することが分かっている。社会的支援もま た、IQにポジティブな影響を与える重要な環境要因であり、ある研究では、母親から高いレベルの情緒的支援を受けた子供は、低いレベルの情緒的支援を受け た子供よりもIQスコアが高いことが示されている。[64] |

| Personality traits Main article: Personality psychology § Genetic basis of personality Personality is a frequently cited example of a heritable trait that has been studied in twins and adoptees using behavioral genetic study designs. The most famous categorical organization of heritable personality traits were defined in the 1970s by two research teams led by Paul Costa & Robert R. McCrae and Warren Norman & Lewis Goldberg in which they had people rate their personalities on 1000+ dimensions they then narrowed these down into "The Big Five" factors of personality—openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Studies have found that extraversion has a genetic component, with estimates of heritability ranging from 30% to 50%. However, environmental factors such as parenting style, cultural values, and life experiences can also shape a person's level of extraversion. Likewise, neuroticism has a genetic component, with estimates of heritability ranging from 30% to 50%. Environmental factors such as adverse childhood experiences, chronic stress, and cultural values can also influence a person's level of neuroticism.[65] The close genetic relationship between positive personality traits and, for example, our happiness traits are the mirror images of comorbidity in psychopathology. These personality factors were consistent across cultures, and many studies have also tested the heritability of these traits. Personal agency also factors into this debate. While genetic and environmental factors can shape personality, individuals also have agency in shaping their own personality through their choices, behaviors, and attitudes. For example, one study found that college students who participated in study abroad programs scored higher on measures of openness to experience compared to those who did not participate. Another study found that individuals who lived in diverse neighborhoods were more likely to score higher on openness to experience compared to those who lived in more homogenous neighborhoods.[66] Identical twins reared apart are far more similar in personality than randomly selected pairs of people. Likewise, identical twins are more similar than fraternal twins. Also, biological siblings are more similar in personality than adoptive siblings. Each observation suggests that personality is heritable to a certain extent. A supporting article had focused on the heritability of personality (which is estimated to be around 50% for subjective well-being) in which a study was conducted using a representative sample of 973 twin pairs to test the heritable differences in subjective well-being which were found to be fully accounted for by the genetic model of the Five-Factor Model's personality domains.[67] However, these same study designs allow for the examination of environment as well as genes. Adoption studies also directly measure the strength of shared family effects. Adopted siblings share only family environment. Most adoption studies indicate that by adulthood the personalities of adopted siblings are little or no more similar than random pairs of strangers. This would mean that shared family effects on personality are zero by adulthood. In the case of personality traits, non-shared environmental effects are often found to out-weigh shared environmental effects. That is, environmental effects that are typically thought to be life-shaping (such as family life) may have less of an impact than non-shared effects, which are harder to identify. One possible source of non-shared effects is the environment of pre-natal development. Random variations in the genetic program of development may be a substantial source of non-shared environment. These results suggest that "nurture" may not be the predominant factor in "environment". Environment and our situations, do in fact impact our lives, but not the way in which we would typically react to these environmental factors. We are preset with personality traits that are the basis for how we would react to situations. An example would be how extraverted prisoners become less happy than introverted prisoners and would react to their incarceration more negatively due to their preset extraverted personality.[33]: Ch 19 Behavioral genes are somewhat proven to exist when we take a look at fraternal twins. When fraternal twins are reared apart, they show the same similarities in behavior and response as if they have been reared toget |

性格特性 詳細は「性格心理学 § 性格の遺伝的基礎」を参照 性格は、行動遺伝学的研究デザインを用いて双生児や養子について研究されてきた、遺伝形質の頻繁に引用される例である。遺伝する性格特性の最も有名なカテ ゴリー別分類は、ポール・コスタとロバート・R・マクレア、ウォーレン・ノーマンとルイス・ゴールドバーグの2つの研究チームによって1970年代に定義 されたもので、1000以上の次元で人々に自分の性格を評価させ、それを「ビッグ・ファイブ」と呼ばれる性格要因、すなわち開放性、誠実さ、外向性、協調 性、神経症傾向に絞り込んだ。研究により、外向性には遺伝的要素があり、遺伝率は30%から50%と推定されていることが分かっている。しかし、子育ての スタイル、文化的価値観、人生経験などの環境要因も、その人の外向性の度合いを形作る可能性がある。同様に、神経症傾向にも遺伝的要素があり、遺伝率は 30%から50%と推定されている。幼少期の逆境体験、慢性的ストレス、文化的価値観などの環境要因も、その人の神経症傾向に影響を与える可能性がある。 [65] ポジティブな性格特性と、例えば幸福の特性との間の密接な遺伝的関係は、精神病理学における併存症の鏡像である。これらの性格要因は文化を越えて一貫して おり、多くの研究がこれらの特性の遺伝可能性についても検証している。この議論には個人の行動も影響する。遺伝的および環境的要因が性格を形成する一方 で、個人は自身の選択、行動、および態度を通じて、自身の性格を形成する自由も有している。例えば、ある研究では、海外留学プログラムに参加した大学生 は、参加しなかった大学生と比較して、経験への開放性を測る尺度でより高いスコアを記録したことが分かっている。また、別の研究では、多様な地域社会で暮 らす人々は、同質的な地域社会で暮らす人々と比較して、経験への開放性を測る尺度でより高いスコアを記録する可能性が高いことが分かっている。 離れて育てられた一卵性双生児は、ランダムに選ばれた2人組よりもはるかに性格が似ている。同様に、一卵性双生児は二卵性双生児よりも性格が似ている。ま た、実の兄弟姉妹は養子同士よりも性格が似ている。これらの観察結果は、性格はある程度遺伝する可能性を示唆している。性格の遺伝性(主観的な幸福度につ いては約50%と推定されている)に焦点を当てた研究では、973組の双子ペアの代表サンプルを使用して研究が行われ、 主観的な幸福度の遺伝的差異をテストするために、973組の双子の代表サンプルを使用した研究が行われた。その結果、5因子モデルの性格特性領域の遺伝モ デルによって、主観的な幸福度の遺伝的差異が完全に説明できることが判明した。[67] しかし、これらの研究デザインでは、遺伝子だけでなく環境についても調査が可能である。 養子縁組に関する研究では、家族環境の共有による影響の強さを直接測定している。養子となった兄弟姉妹は家族環境のみを共有している。ほとんどの養子縁組 に関する研究では、成人期までに養子となった兄弟姉妹の性格は、ランダムに選んだ見知らぬ他人同士とほとんど変わらないか、あるいはまったく変わらなくな ることを示している。これは、成人期までに性格に対する家族環境の共有の影響はゼロになることを意味する。 性格特性の場合、共有されない環境効果の方が、共有される環境効果よりも大きいことがしばしば見られる。つまり、一般的に人生を形成すると考えられている 環境効果(家族生活など)は、特定が難しい共有されない効果よりも影響が少ない可能性がある。共有されない効果の可能性のある原因のひとつは、出生前の発 育環境である。発育の遺伝的プログラムにおけるランダムな変化は、共有されない環境の主な要因である可能性がある。これらの結果は、「環境」において「育 成」が主要な要因ではない可能性を示唆している。環境や状況は、実際には私たちの生活に影響を与えるが、私たちが通常これらの環境要因に反応する方法では ない。私たちは、状況にどのように反応するかの基礎となる性格特性をあらかじめ備えている。例えば、外向的な囚人が内向的な囚人よりも幸福度が低くなり、 投獄に対してより否定的な反応を示すのは、生まれつき外向的な性格であることが原因である。[33]: 19章 行動遺伝子は、二卵性双生児を調べると、その存在がいくらか証明されている。二卵性双生児が別々に育てられた場合、まるで一緒に育てられたかのように、行 動や反応に同じような類似性が現れる。 |

| Genetics The relationship between personality and people's own well-being is influenced and mediated by genes.[67] There has been found to be a stable set point for happiness that is characteristic of the individual (largely determined by the individual's genes). Happiness fluctuates around that setpoint (again, genetically determined) based on whether good things or bad things are happening to us ("nurture"), but only fluctuates in small magnitude in a normal human. The midpoint of these fluctuations is determined by the "great genetic lottery" that people are born with, which leads them[who?] to conclude that how happy they may feel at the moment or over time is simply due to the luck of the draw, or gene. This fluctuation was also not due to educational attainment, which only accounted for less than 2% of the variance in well-being for women, and less than 1% of the variance for men.[44] They[who?] consider that the individualities measured together with personality tests remain steady throughout an individual's lifespan. They further believe that human beings may refine their forms or personality but can never change them entirely. Darwin's Theory of Evolution steered naturalists such as George Williams and William Hamilton to the concept of personality evolution. They suggested that physical organs and also personality is a product of natural selection.[69] With the advent of gene sequencing, it has become possible to search for and identify specific gene polymorphisms that affect traits such as IQ and personality. These techniques work by tracking the association of differences in a trait of interest with differences in specific molecular markers or functional variants. An example of a visible human trait for which the precise genetic basis of differences are relatively well known is eye color. In contrast to views developed in 1960s that gender identity is primarily learned (which led to a protocol of surgical sex changes in male infants with injured or malformed genitals, such as David Reimer), genomics has provided solid evidence that both sex and gender identities are primarily influenced by genes: It is now clear that genes are vastly more influential than virtually any other force in shaping sex identity and gender identity ... The growing consensus in medicine is that ... children should be assigned to their chromosomal (i.e., genetic) sex regardless of anatomical variations and differences—with the option of switching, if desired, later in life. — Siddhartha Mukherjee, The Gene: An Intimate History, 2016 |

遺伝学 性格と個人の幸福の関係は、遺伝子によって影響を受け、媒介される。[67] 個人の特徴である幸福の安定したセットポイント(主に個人の遺伝子によって決定される)が存在することが分かっている。幸福は、良いことが起こっているか 悪いことが起こっているか(「環境」)によって、そのセットポイント(やはり遺伝的に決定される)の周りで変動するが、通常の人間では変動の幅は小さい。 これらの変動の中間点は、人が生まれながらに持つ「偉大な遺伝的くじ引き」によって決定され、それによって、人は、今、あるいは将来に感じるかもしれない 幸福は、単に運、あるいは遺伝によるものだと結論づける。この変動は、教育達成度によるものでもなかった。教育達成度は、女性の幸福度の変動の2%以下、 男性の変動の1%以下にしか相当しなかった。 彼ら(誰のことか?)は、性格テストで測定された個性は、個人の生涯を通じて安定していると考えている。さらに、人間は自身の形や性格を磨くことはできて も、それを完全に変えることはできないと信じている。ダーウィンの進化論は、ジョージ・ウィリアムズやウィリアム・ハミルトンといった博物学者たちを性格 進化の概念へと導いた。彼らは、身体器官や性格も自然淘汰の産物であると示唆した。 遺伝子配列決定技術の出現により、IQや性格などの形質に影響を与える特定の遺伝的多型を探索し、特定することが可能になった。これらの技術は、関心のあ る形質における差異と、特定の分子マーカーや機能的変異における差異との関連を追跡することで機能する。差異の正確な遺伝的基礎が比較的よく知られている 目に見える人間の形質の例としては、目の色が挙げられる。 1960年代に唱えられた「性同一性は主に学習によるもの」という見解(これは、性器が損傷または奇形を負った男児に対して外科的性転換手術を行うという プロトコルにつながった)とは対照的に、ゲノム科学は、性別と性同一性の双方が主に遺伝子によって影響を受けるという確固たる証拠を提供している。 性同一性およびジェンダー・アイデンティティの形成において、遺伝子が他のほぼあらゆる要因よりもはるかに大きな影響力を持っていることは明らかである。 医学界では、解剖学的な相違や差異に関わらず、子供たちを染色体(すなわち遺伝子)上の性別に分類すべきであるという意見が主流になりつつある。ただし、 望むのであれば、人生の後半で変更するオプションも用意されている。 — シッダールタ・ムカジー著『ザ・ジーン:ア・インティメート・ヒストリー』2016年 |

| Behavioral epigenetics – Study of epigenetics' influencing behavior Dual inheritance theory – Theory of human behavior Interactionism (nature versus nurture) – Perspective that human behavior is caused by interaction of genetic and environmental factors Nature–culture divide – Theoretical foundation of anthropology Niche picking – Psychological theory Science wars – 1990s dispute in philosophy of science Sociobiology – Subdiscipline of biology regarding social behavior Structure and agency – Debate in social sciences Identical Strangers – 2007 memoir by reunited identical twins Three Identical Strangers – 2018 documentary film directed by Tim Wardle |

行動エピジェネティクス – エピジェネティクスが行動に影響を与えることの研究 二重相続理論 – 人間の行動に関する理論 相互作用説(生得対環境) – 人間の行動は遺伝的要因と環境的要因の相互作用によって引き起こされるという見解 自然-文化の断絶 – 人類学の理論的基礎 ニッチ・ピッキング – 心理学的理論 科学戦争 – 1990年代の科学哲学における論争 社会生物学 – 社会行動に関する生物学のサブディシプリン 構造と作用 – 社会科学における議論 同一の他人 – 2007年の再会した一卵性双生児による回顧録 三人の同一の他人 – 2018年のティム・ウォードル監督によるドキュメンタリー映画 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nature_versus_nurture |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆