バニョーレスの黒人

Negro of Banyoles; Catalan: negre de

Banyoles, Spanish: negro de Banyoles or Bañola

☆ バニョレスの黒人(カタルーニャ語: negre de Banyoles、スペイン語: negro de Banyoles or Bañolas)は、バニョレス(スペイン、カタルーニャ州)のダルデル博物館の目玉であったサン族の剥製で、物議を醸した[1]。 2000年、遺骨は埋葬のためボツワナに送られた[2]。

| The

Negro of Banyoles (Catalan: negre de Banyoles, Spanish: negro de

Banyoles or Bañolas) was a controversial piece of taxidermy of a San

individual, which used to be a major attraction in the Darder Museum of

Banyoles (Catalonia, Spain).[1] In 2000, the remains of the man were

sent to Botswana for burial.[2] |

バ

ニョレスの黒人(カタルーニャ語: negre de Banyoles、スペイン語: negro de Banyoles or

Bañolas)は、バニョレス(スペイン、カタルーニャ州)のダルデル博物館の目玉であったサン族の剥製で、物議を醸した[1]。

2000年、遺骨は埋葬のためボツワナに送られた[2]。 |

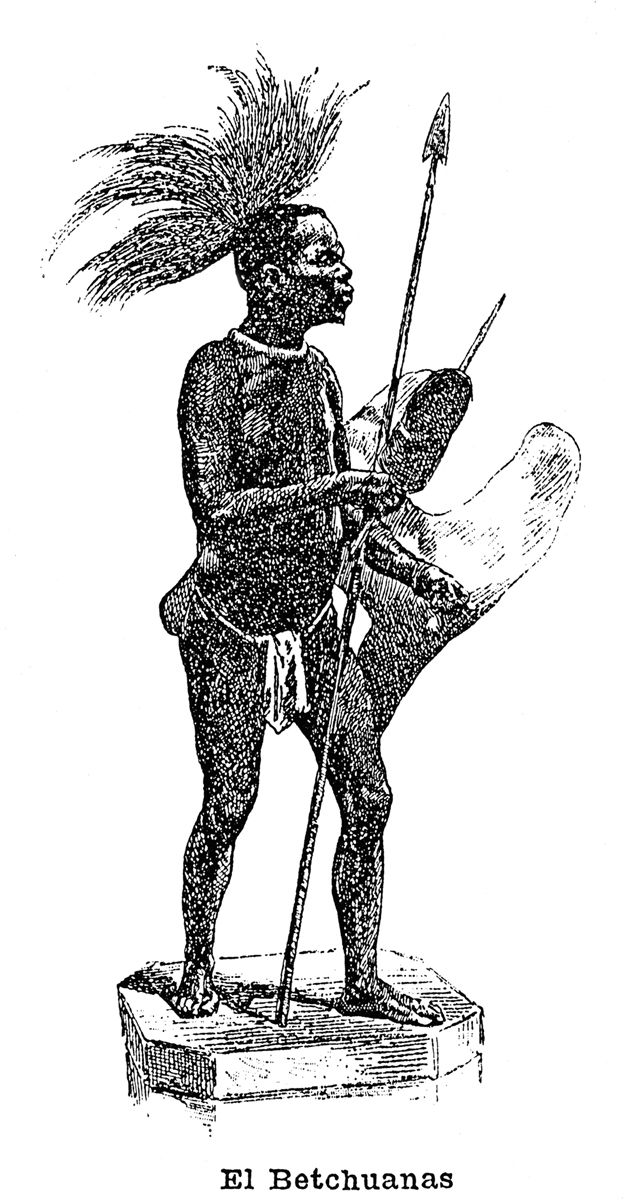

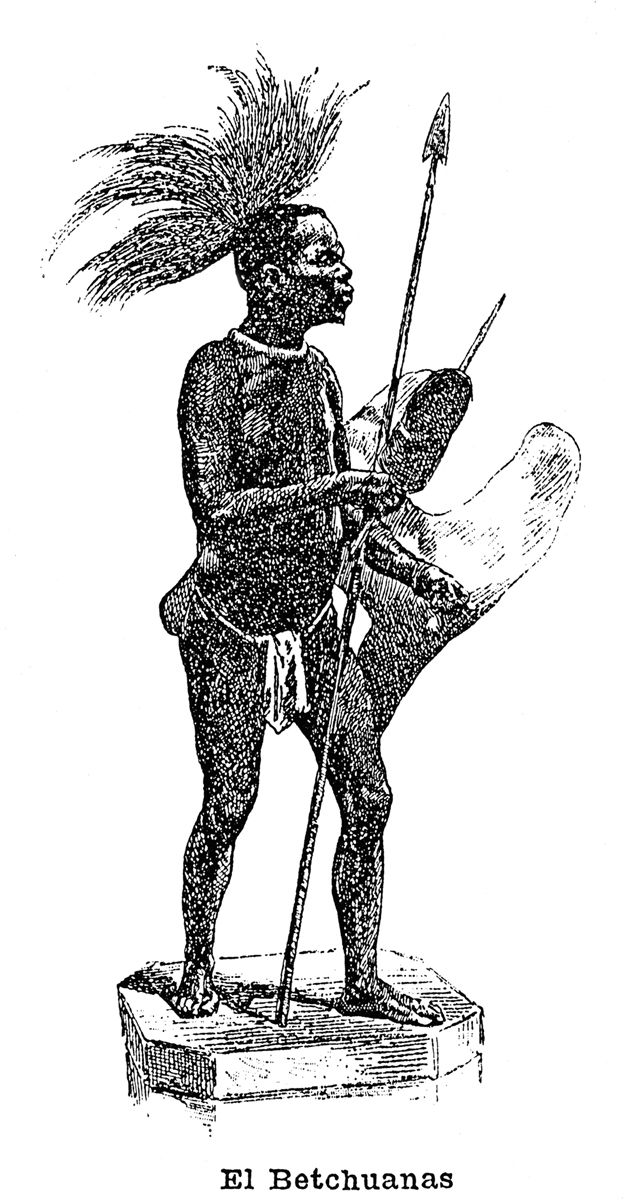

| History In 1830, the Verreaux brothers stuffed the corpse of a member of the San.[1] Analysis of the teeth shows that man was approximately 27 years old, having features typical of the African bushman.[1] In 1916, it was acquired by the Darder Museum of Banyoles.[3] The body remained in the museum without controversy until 29 October 1991. At this date Alphonse Arcelin, a doctor of Haitian origin[4] who lived in Cambrils where he was a PSC councillor,[5] wrote a letter to the mayor of Banyoles, Joan Solana, asking him to stop displaying the San's remains. This request attracted the attention of the press, which widely published the story.[2] The first step towards the return of the "negre" to Botswana was made in 1991, when the then-secretary of UNESCO, Federico Mayor Zaragoza, held the meeting with Joan Solana. Later, when Kofi Annan became Secretary-General of the United Nations, he expressed interest in the issue and spoke with Solana.[2] By that time, the "negre" had become so notorious that it was quite usual to hear references made to the displayed San in diplomatic communications. Some African governments showed their support for Arcelín, who had sent several letters to the press and various heads of government. The issue worried many international museum associations because it made them fear that human remains kept in museums might have to be returned to their place of origin.[2] In 1997, the issue was repeatedly discussed by both the UN and the Organisation of African Unity.[2] Later, in March of that year, the body was removed from the Darder Museum.[6] It was described in El Mundo as a relic of colonialism.[7] Many people in Banyoles and the surrounding area were unhappy with the removal because the San was seen as "a member of the community".[3] Return to Botswana Botswana's government offered to aid the OAU bury the man, once all of his remains were returned to the country.[2] In 2000, after the loincloth, feathered head-dress and spear he had worn in Banyoles were removed, the body was sent to the National Museum of Anthropology in Madrid where artificial parts including a wooden spine, eyes, hair, and genitals were removed. The skull and remaining bones were then sent to Botswana in a box[8] and they arrived on 4 October. He was buried on 5 October[2] in Tsholofelo Park, in Gaborone;[9] his gravesite was declared a national monument.[9] |

歴史 1830年、ヴェロー兄弟がサン族の一人の死体を剥製にした[1]。歯の分析によると、その男はおよそ27歳で、アフリカのブッシュマンに典型的な特徴を 持っていた[1]。1916年、その死体はバニョレスのダルデル博物館に収蔵された[3]。1991年10月29日まで、その死体は論争もなく博物館に保 管されていた。この日、カンブリスに住むハイチ出身の医師アルフォンス・アルセリン(Alphonse Arcelin)[4]がPSC評議員[5]として、バニョレス市長のジョアン・ソラナ(Joan Solana)に手紙を書き、サンの遺体の展示を中止するよう求めた。この要請はマスコミの注目を集め、マスコミはこの記事を大きく掲載した[2]。 1991年、当時のユネスコ事務局長であったフェデリコ・マヨール・サラゴサがジョアン・ソラナと会談を行い、「ネグレ」のボツワナ返還に向けた第一歩が 踏み出された。その後、コフィ・アナンが国連事務総長に就任すると、彼はこの問題に関心を示し、ソラナと話をした[2]。 そのころには、「ネグレ」は非常に悪名高くなり、外交上のやり取りで、表示されたサンについて言及されるのはごく普通のことだった。いくつかのアフリカの 政府はアルセリンを支持する姿勢を示し、アルセリンはマスコミや様々な政府首脳に何通もの手紙を送っていた。この問題は多くの国際的な博物館協会を悩ま せ、博物館に保管されている人骨が元の場所に戻されなければならなくなるかもしれないという不安を抱かせたからである[2]。 1997年、この問題は国連とアフリカ統一機構の両方で繰り返し議論された[2]。その後、同年3月、遺体はダルダー博物館から撤去された[6]。 El Mundo』紙に植民地主義の遺物として紹介された[7]。バニョレスとその周辺地域の多くの人々は、サンが「コミュニティの一員」とみなされていたた め、撤去に不満を抱いていた[3]。 ボツワナへの帰還 ボツワナ政府は、遺骨がすべてボツワナに返還されれば、OAUがサンを埋葬するのを援助すると申し出た[2]。2000年、バニョレスで身に着けていたふ んどし、羽毛の頭飾り、槍が取り除かれた後、遺体はマドリードの国立人類学博物館に送られ、木製の背骨、目、髪、生殖器などの人工的な部品が取り除かれ た。頭蓋骨と残りの骨は箱に入れられてボツワナに送られ[8]、10月4日に到着した。彼は10月5日にハボローネのツォロフェロ公園に埋葬された [2]。 |

| Legacy The Darder Museum currently avoids any references to the controversy of the "negre of Banyoles". The only record of the San in the museum is a silent video with black and white images on a small plasma screen. The video allows people to see the San as he was displayed until his removal.[6] Several books have dealt with the "el negre" controversy, most notably El Negro en ik (El Negro and me) by Frank Westerman, which shows that naturalist Georges Cuvier knew about the man.[1] |

遺産 ダルデル博物館は現在、「バニョレスのネグレ 」論争への言及を避けている。博物館にあるサンの唯一の記録は、小さなプラズマスクリーンに映し出される白黒映像の無声ビデオである。このビデオでは、撤去されるまで展示されていたサンを見ることができる[6]。 エル・ネグレ」論争を扱った書籍はいくつかあるが、中でもフランク・ウェスターマン著『El Negro en ik(エル・ネグロと私)』は、博物学者ジョルジュ・キュヴィエがサンについて知っていたことを示している[1]。 |

| Human zoo Julia Pastrana, a sideshow performer preserved via taxidermy Ota Benga Repatriation of human remains Saartjie Baartman Scientific racism |

人間動物園 フリア・パストラーナ、剥製で保存された余興パフォーマー オタ・ベンガ 遺体・遺骨の返還 サーティ・バートマン(サラ・バートマン) 科学的人種差別 |

| Davies, Caitlin: The Return of El Negro. Johannesburg: Penguin Books 2003. Fock, Stefanie: »Un individu de raça negroide«. El Negro und die Wunderkammern des Rassismus. In: Entfremdete Körper. Rassismus als Leichenschändung, ed. Wulf D. Hund. Bielefeld: transcript 2009, pp. 165 – 204. Westermann, Frank: El Negro en ik. Amsterdam: Atlas 2004. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negro_of_Banyoles | |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆