ネオロジズム・新造語

Neologism

☆

言語学において、新造語(/niˈɒləˌdɒɪzəm/;

造語としても知られる)とは、大衆的または組織的な認知を獲得し、主流の言語に受け入れられつつある、新しく形成された単語、用語、またはフレーズのこと

である[1]。最も決定的なのは、単語が辞書に掲載された時点で新造語と見なされることである[2]。

新造語は語彙革新の一面であり、すなわち、新しい用語や意味がある言語の語彙に入る言語学的プロセスである。言語の変化と語形成に関する最も精密な研究

は、実際、「新語の連続体」のプロセスを特定している。非語とは、人気が高まるかどうかわからない単用語のことであり、原語とは、小さなグループの中だけ

で使用される用語のことであり、前語とは、使用されるようになりつつあるがまだ主流ではない用語のことであり、新語とは、社会制度によって受け入れられた

り認められたりするようになった用語のことである[3][4]。

新語はしばしば文化や技術の変化によって引き起こされる[5][6]。新語の一般的な例は、科学、技術、フィクション(特にSF)、映画やテレビ、商業ブ

ランディング、文学、専門用語、カント(ジャーゴン)、言語学、視覚芸術、大衆文化に見られる[要出典]。

20世紀の新語であった言葉の例としては、放射線の誘導放出による光増幅の頭字語であるlaser(1960年)、チェコの作家カレル・チャペックの戯曲

『R.U.R.』(Rossum's Universal

Robots)に登場するrobot(1921年)[7]、ロシア語の「agitatsiya」(扇動)と「propaganda」(宣伝)の合成語であ

るagitprop(1930年)などが挙げられる[8]。

| In

linguistics, a neologism (/niˈɒləˌdʒɪzəm/; also known as a coinage) is

any newly formed word, term, or phrase that has achieved popular or

institutional recognition and is becoming accepted into mainstream

language.[1] Most definitively, a word can be considered a neologism

once it is published in a dictionary.[2] Neologisms are one facet of lexical innovation, i.e., the linguistic process of new terms and meanings entering a language's lexicon. The most precise studies into language change and word formation, in fact, identify the process of a "neological continuum": a nonce word is any single-use term that may or may not grow in popularity; a protologism is such a term used exclusively within a small group; a prelogism is such a term that is gaining usage but still not mainstream; and a neologism has become accepted or recognized by social institutions.[3][4] Neologisms are often driven by changes in culture and technology.[5][6] Popular examples of neologisms can be found in science, technology, fiction (notably science fiction), films and television, commercial branding, literature, jargon, cant, linguistics, the visual arts, and popular culture.[citation needed] Examples of words that were 20th-century neologisms include laser (1960), an acronym of light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation; robot (1921) from Czech writer Karel Čapek's play R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots);[7] and agitprop (1930; a portmanteau of Russian "agitatsiya" (agitation) and "propaganda").[8] |

言語学において、新造語(/niˈɒləˌdɒɪzəm/;

造語としても知られる)とは、大衆的または組織的な認知を獲得し、主流の言語に受け入れられつつある、新しく形成された単語、用語、またはフレーズのこと

である[1]。最も決定的なのは、単語が辞書に掲載された時点で新造語と見なされることである[2]。 新造語は語彙革新の一面であり、すなわち、新しい用語や意味がある言語の語彙に入る言語学的プロセスである。言語の変化と語形成に関する最も精密な研究 は、実際、「新語の連続体」のプロセスを特定している。非語とは、人気が高まるかどうかわからない単用語のことであり、原語とは、小さなグループの中だけ で使用される用語のことであり、前語とは、使用されるようになりつつあるがまだ主流ではない用語のことであり、新語とは、社会制度によって受け入れられた り認められたりするようになった用語のことである[3][4]。 新語はしばしば文化や技術の変化によって引き起こされる[5][6]。新語の一般的な例は、科学、技術、フィクション(特にSF)、映画やテレビ、商業ブ ランディング、文学、専門用語、カント(ジャーゴン)、言語学、視覚芸術、大衆文化に見られる[要出典]。 20世紀の新語であった言葉の例としては、放射線の誘導放出による光増幅の頭字語であるlaser(1960年)、チェコの作家カレル・チャペックの戯曲 『R.U.R.』(Rossum's Universal Robots)に登場するrobot(1921年)[7]、ロシア語の「agitatsiya」(扇動)と「propaganda」(宣伝)の合成語であ るagitprop(1930年)などが挙げられる[8]。 |

| Background Neologisms are often formed by combining existing words (see compound noun and adjective) or by giving words new and unique suffixes or prefixes.[9] Neologisms can also be formed by blending words, for example, "brunch" is a blend of the words "breakfast" and "lunch", or through abbreviation or acronym, by intentionally rhyming with existing words or simply through playing with sounds. A relatively rare form of neologism is when proper names are used as words (e.g., boycott, from Charles Boycott), including guy, dick, Chad, and Karen.[9] Neologisms can become popular through memetics, through mass media, the Internet, and word of mouth, including academic discourse in many fields renowned for their use of distinctive jargon, and often become accepted parts of the language. Other times, they disappear from common use just as readily as they appeared. Whether a neologism continues as part of the language depends on many factors, probably the most important of which is acceptance by the public. It is unusual for a word to gain popularity if it does not clearly resemble other words. |

背景 新造語は、既存の単語を組み合わせたり(複合名詞と形容詞を参照)、単語に新しくユニークな接尾辞や接頭辞をつけたりすることによって形成されることが多 い[9]。新造語はまた、単語をブレンドすることによって形成されることもある。例えば、「brunch」は「breakfast(朝食)」と 「lunch(昼食)」のブレンドである。新造語の比較的まれな形態は、固有名詞が単語として使われる場合である(例えば、チャールズ・ボイコットからの ボイコット)。 新造語はミメティックス、マスメディア、インターネット、口コミなどを通じて広まることがあり、独特の専門用語の使用で有名な多くの分野における学術的な 言説も含まれ、しばしば言語の一部として受け入れられるようになる。また、登場したときと同じように、すぐに一般的な使用から消えてしまうこともある。新 語が言葉の一部として使われ続けるかどうかは、多くの要因に左右されるが、おそらく最も重要なのは一般大衆に受け入れられるかどうかであろう。他の単語と 明らかに似ていない単語が人気を得るのは珍しいことである。 |

| History and meaning The term neologism is first attested in English in 1772, borrowed from French néologisme (1734).[10] The French word derives from Greek νέο- néo(="new") and λόγος /lógos, meaning "speech, utterance". In an academic sense, there is no professional neologist, because the study of such things (cultural or ethnic vernacular, for example) is interdisciplinary. Anyone such as a lexicographer or an etymologist might study neologisms, how their uses span the scope of human expression, and how, due to science and technology, they spread more rapidly than ever before in the present times.[11] The term neologism has a broader meaning which also includes "a word which has gained a new meaning".[12][13][14] Sometimes, the latter process is called semantic shifting,[12] or semantic extension.[15][16] Neologisms are distinct from a person's idiolect, one's unique patterns of vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation. Neologisms are usually introduced when it is found that a specific notion is lacking a term, or when the existing vocabulary lacks detail, or when a speaker is unaware of the existing vocabulary.[17] The law, governmental bodies, and technology have a relatively high frequency of acquiring neologisms.[18][19] Another trigger that motivates the coining of a neologism is to disambiguate a term which may be unclear due to having many meanings.[20] |

歴史と意味 新語(neologism)という用語は、フランス語のnéologisme(1734年)から借用されたもので、1772年に初めて英語で証明された [10]。フランス語の語源はギリシャ語のνέο- néo(=「新しい」)とλόγος /lógos(「発話、発声」を意味する)である。学術的な意味において、専門的な新語学者というものは存在しない。辞書学者や語源学者のような人であれ ば、新語を研究し、その用法が人間の表現の範囲にどのように広がっているのか、また科学技術のおかげで現代ではかつてないほど急速に広まっているのかを研 究することができるかもしれない[11]。 新語という用語は、「新しい意味を獲得した単語」をも含むより広い意味を持っている[12][13][14]。後者のプロセスは、意味転換[12]または 意味拡張と呼ばれることもある[15][16]。新語は、その人のイディオレクト(語彙、文法、発音の独自のパターン)とは区別される。 新語は通常、特定の概念に用語が欠けていることがわかったとき、既存の語彙に詳細が欠けているとき、または話し手が既存の語彙に気づいていないときに導入 される[17]。法律、政府機関、テクノロジーは新語を獲得する頻度が比較的高い[18][19]。 新語を作る動機となるもう1つのきっかけは、多くの意味を持つために不明確になっている用語を曖昧にすることである[20]。 |

| Literature Neologisms may come from a word used in the narrative of fiction such as novels and short stories. Examples include "grok" (to intuitively understand) from the science fiction novel about a Martian entitled Stranger in a Strange Land by Robert A. Heinlein; "McJob" (precarious, poorly-paid employment) from Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture by Douglas Coupland; "cyberspace" (widespread, interconnected digital technology) from Neuromancer by William Gibson[21] and "quark" (Slavic slang for "rubbish"; German for a type of dairy product) from James Joyce's Finnegans Wake. The title of a book may become a neologism, for instance, Catch-22 (from the title of Joseph Heller's novel).[22] Alternatively, the author's name may give rise to the neologism, although the term is sometimes based on only one work of that author. This includes such words as "Orwellian" (from George Orwell, referring to his dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four) and "Kafkaesque" (from Franz Kafka). Names of famous characters are another source of literary neologisms. Some examples include: Quixotic, referring to a misguided romantic quest like that of the title character in Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes;[23] Scrooge, a pejorative for misers based on the avaricious main character in Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol;[24] and Pollyanna, referring to people who are unfailingly optimistic like the title character of Eleanor H. Porter's Pollyanna.[25] Scientific literature Neologisms are often introduced in technical writing, so-called Fachtexte or 'technical texts' through the process of lexical innovation. Technical subjects such as philosophy, sociology, physics, etc. are especially rich in neologisms. In philosophy, as an example, many terms became introduced into languages through processes of translation, e.g., from Ancient Greek to Latin, or from Latin to German or English, and so on. So Plato introduced the Greek term ποιότης (poiotēs), which Cicero rendered with Latin qualitas, which subsequently became our notion of 'quality' in relation to epistemology, e.g., a quality or attribute of a perceived object, as opposed to its essence. In physics, new terms were introduced sometimes via nonce formation (e.g., Murray Gell-Man's quark, taken from James Joyce) or through derivation (e.g. John von Neumann's kiloton, coined by combining the common prefix kilo- 'thousand' with the noun ton). Neologisms therefore are a vital component of scientific jargon or termini technici. |

文学 新語は、小説や短編小説などのフィクションの物語で使われる言葉から生まれることがある。例えば、ロバート・A・ハインラインの『見知らぬ土地の見知らぬ 人』という火星人を題材にしたSF小説に登場する「grok」(直感的に理解する)、『ジェネレーションX:不安定で低賃金の雇用』に登場する 「McJob」(不安定で低賃金の雇用)などがある。また、ウィリアム・ギブス[21]の『ニューロマンサー』に登場する「サイバースペース」(広まり、 相互接続されたデジタル技術)、ジェイムズ・ジョイスの『フィネガンズ・ウェイク』に登場する「クオーク」(スラブ語の俗語で「ごみ」、ドイツ語で乳製品 の一種)などがある。 本のタイトルが新語になることもあり、例えば「Catch-22」(ジョセフ・ヘラーの小説のタイトルから)はその一例である[22]。あるいは、作者の 名前から新語が生まれることもあるが、その作者の1つの作品だけに基づくこともある。これには、「Orwellian」(ジョージ・オーウェルから、彼の ディストピア小説『Nineteen Eighty-Four』を指す)や「Kafkaesque」(フランツ・カフカから)といった言葉が含まれる。 有名な登場人物の名前も、文学的新語の源である。いくつか例を挙げよう: Quixotic はミゲル・デ・セルバンテスの『ドン・キホーテ』の主人公のような見当違いのロマンチックな探求を指す[23]。Scrooge はチャールズ・ディケンズの『クリスマス・キャロル』に登場する貪欲な主人公に基づく、誤った人間に対する蔑称である[24]。 科学文献 専門的な文章、いわゆるFachtexteや「技術的な文章」では、語彙の革新の過程で新語が導入されることが多い。哲学、社会学、物理学などの専門科目 は特に新語が多い。哲学を例にとると、古代ギリシャ語からラテン語へ、ラテン語からドイツ語や英語へ、といったように、翻訳の過程を通じて多くの用語が言 語に導入された。プラトンはギリシャ語のποιότης(poiotēs)という用語を導入し、キケロはこれをラテン語のqualitas(クオリタス) で表現した。その後、この用語は認識論に関する「質」の概念となった。物理学の分野では、新しい用語は、時にはノンス形成によって(例えば、ジェイムズ・ ジョイスから取られたマレー・ゲルマンのクォーク)、あるいは派生によって(例えば、ジョン・フォン・ノイマンのキロトン(kiloton)は、一般的な 接頭辞キロ「千」と名詞トンを組み合わせた造語である)導入された。したがって、新語は科学専門用語(termini technici)の重要な構成要素である。 |

| Cant Main article: Cant (language) Polari is a cant used by some actors, circus performers, and the gay subculture to communicate without outsiders understanding. Some Polari terms have crossed over into mainstream slang, in part through their usage in pop song lyrics and other works. Example include: acdc, barney, blag, butch, camp, khazi, cottaging, hoofer, mince, ogle, scarper, slap, strides, tod, [rough] trade (rough trade). Verlan (French pronunciation: [vɛʁlɑ̃]), (verlan is the reverse of the expression "l'envers") is a type of argot in the French language, featuring inversion of syllables in a word, and is common in slang and youth language. It rests on a long French tradition of transposing syllables of individual words to create slang words.[26]: 50 Some verlan words, such as meuf ("femme", which means "woman" roughly backwards), have become so commonplace that they have been included in the Petit Larousse.[27] Like any slang, the purpose of verlan is to create a somewhat secret language that only its speakers can understand. Words becoming mainstream is counterproductive. As a result, such newly common words are re-verlanised: reversed a second time. The common meuf became feumeu.[28][29] |

カント(ジャーゴン) 主な記事 カント(ジャーゴン言語) ポラリは、一部の俳優やサーカス団員、ゲイのサブカルチャーが部外者に理解されずにコミュニケーションを取るために使うカントである。一部のポラリ用語 は、ポップソングの歌詞やその他の作品での使用を通じて、主流のスラングにクロスオーバーしている。例えば、acdc、barney、blag、 butch、camp、khazi、cottaging、hoofer、mince、oggle、scarper、slap、strides、tod、 [rough]trade(荒っぽい取引)などがある。 ヴェルラン(フランス語発音:[vɛɑ̃])、(ヴェルランは「l'envers」の逆の表現)は、フランス語のアルゴットの一種で、単語の音節の反転を 特徴とし、スラングや若者言葉によく見られる。個々の単語の音節を入れ替えて俗語を作るというフランスの長い伝統に基づいている[26]: 50ヴェルラ ン語の中には、meuf(「femme」、「女」を大まかに逆から意味する)のように、『Petit Larousse』に収録されるほど一般的になっているものもある[27]。他のスラングと同様、ヴェルランの目的は、その話者だけが理解できる、やや秘 密めいた言語を作り出すことである。言葉が主流になることは逆効果である。その結果、そのような新しく一般的に使われるようになった単語は、再 verlan化される。一般的なmeufはfeumeuになった[28][29]。 |

| Popular culture Neologism development may be spurred, or at least spread, by popular culture. Examples of pop-culture neologisms include the American alt-Right (2010s), the Canadian portmanteau "Snowmageddon" (2009), the Russian parody "Monstration" (c. 2004), Santorum (c. 2003). Neologisms spread mainly through their exposure in mass media. The genericizing of brand names, such as "coke" for Coca-Cola, "kleenex" for Kleenex facial tissue, and "xerox" for Xerox photocopying, all spread through their popular use being enhanced by mass media.[30] However, in some limited cases, words break out of their original communities and spread through social media.[citation needed] "DoggoLingo", a term still below the threshold of a neologism according to Merriam-Webster,[31] is an example of the latter which has specifically spread primarily through Facebook group and Twitter account use.[31] The suspected origin of this way of referring to dogs stems from a Facebook group founded in 2008 and gaining popularity in 2014 in Australia. In Australian English it is common to use diminutives, often ending in –o, which could be where doggo-lingo was first used.[31] The term has grown so that Merriam-Webster has acknowledged its use but notes the term needs to be found in published, edited work for a longer period of time before it can be deemed a new word, making it the perfect example of a neologism.[31] |

大衆文化 新語の発展は大衆文化によって促進されたり、少なくとも広まったりすることがある。大衆文化による新語の例としては、アメリカのオルト・ライト(2010 年代)、カナダのポートマント「スノーマゲドン」(2009年)、ロシアのパロディ「モンストレーション」(2004年頃)、サントラム(2003年頃) などがある。 新語は主にマスメディアへの露出を通じて広まった。コカ・コーラの「コーク」、クリネックスの「クリネックス」、ゼロックスの「ゼロックス」など、ブランド名の一般化はすべて、大衆的な使用がマスメディアによって強化されることによって広まった[30]。 しかし、限られたケースでは、単語が元のコミュニティから抜け出し、ソーシャルメディアを通じて広まることもある[要出典]。メリアム・ウェブスターによ れば、まだ新語の閾値を下回っている「DoggoLingo」[31]は、主にFacebookのグループやTwitterアカウントの使用を通じて広 まった後者の例である[31]。この犬の呼び方の起源は、2008年に設立され、2014年にオーストラリアで人気を博したFacebookグループに由 来すると考えられている。オーストラリア英語では、-oで終わることが多いdiminutivesを使用することが一般的であり、doggo-lingo が最初に使用された場所である可能性がある[31]。この用語は、Merriam-Websterがその使用を認めるほど成長したが、新語とみなされるに は、より長い期間、出版され編集された作品にこの用語が見られる必要があると指摘しており、新造語の完璧な例となっている[31]。 |

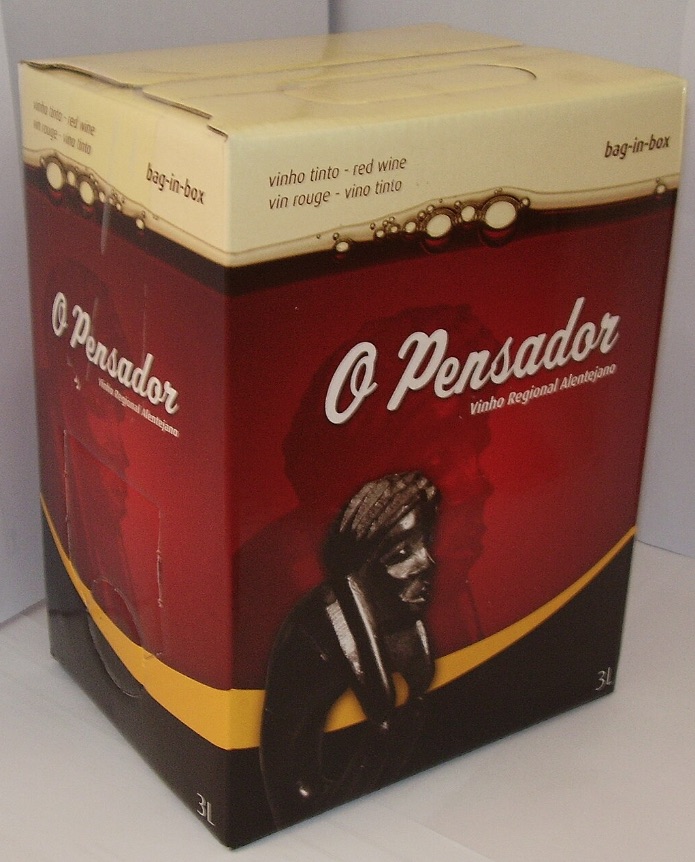

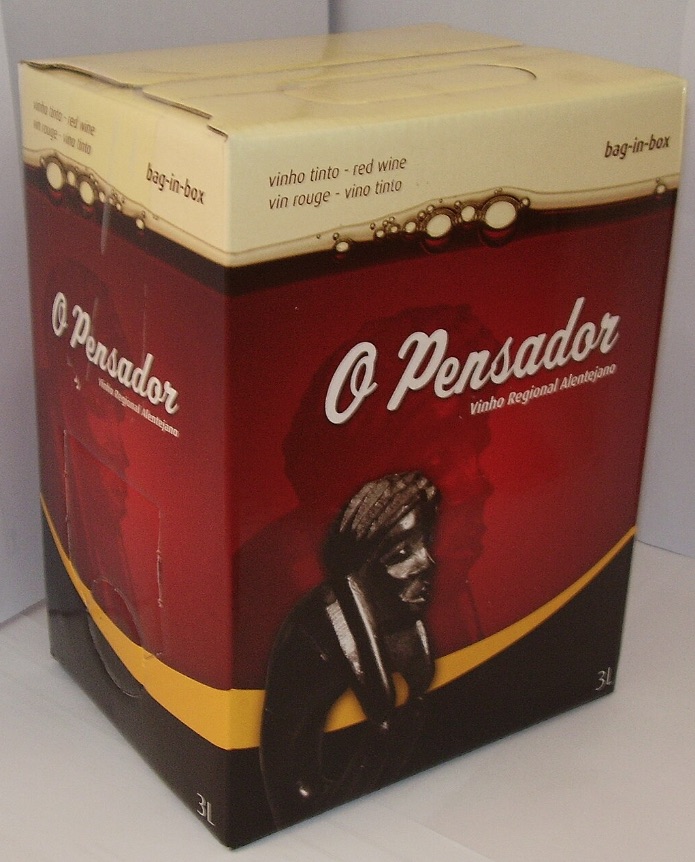

Translations In Danish a bag-in-box wine is known as papvin literally meaning "cardboard wine". This neologism was first recorded in 1982.[32] Because neologisms originate in one language, translations between languages can be difficult. In the scientific community, where English is the predominant language for published research and studies, like-sounding translations (referred to as 'naturalization') are sometimes used.[33] Alternatively, the English word is used along with a brief explanation of meaning.[33] The four translation methods are emphasized in order to translate neologisms: transliteration, transcription, the use of analogues, and loan translation.[34] When translating from English to other languages, the naturalization method is most often used.[35] The most common way that professional translators translate neologisms is through the Think aloud protocol (TAP), wherein translators find the most appropriate and natural sounding word through speech.[citation needed] As such, translators can use potential translations in sentences and test them with different structures and syntax. Correct translations from English for specific purposes into other languages is crucial in various industries and legal systems.[36][37] Inaccurate translations can lead to 'translation asymmetry' or misunderstandings and miscommunication.[37] Many technical glossaries of English translations exist to combat this issue in the medical, judicial, and technological fields.[38] |

翻訳 デンマークでは、バッグ・イン・ボックスのワインはパプヴァンと呼ばれ、文字通り「厚紙のワイン」を意味する。この新語は1982年に初めて記録された[32]。 新語はある言語から生まれたものであるため、言語間の翻訳は困難である。 科学界では、発表される研究や調査の言語は英語が主流であるため、同音異義語の翻訳(「帰化」と呼ばれる)が使用されることもある[33]。あるいは、意 味の簡単な説明とともに英語の単語が使用されることもある[33]。新語を翻訳するためには、音訳、書き下し文、類語の使用、借用翻訳の4つの翻訳方法が 重視される[34]。 プロの翻訳者が新語を翻訳する最も一般的な方法はThink aloud protocol (TAP)であり、翻訳者は発話によって最も適切で自然な響きを持つ単語を見つける[要出典]。不正確な翻訳は、「翻訳の非対称性」、すなわち誤解やミス コミュニケーションにつながる可能性がある[36][37]。医療、司法、技術の分野では、この問題に対処するために、多くの英語翻訳の技術用語集が存在 する[38]。 |

| Other uses In psychiatry and neuroscience, the term neologism is used to describe words that have meaning only to the person who uses them, independent of their common meaning.[39] This can be seen in schizophrenia, where a person may replace a word with a nonsensical one of their own invention (e.g., "I got so angry I picked up a dish and threw it at the gelsinger").[40] The use of neologisms may also be due to aphasia acquired after brain damage resulting from a stroke or head injury.[41] |

その他の用法 精神医学や神経科学では、新造語という用語は、一般的な意味とは無関係に、それを使う人にだけ意味を持つ言葉を表すのに使われる[39]。これは統合失調 症に見られることがあり、ある言葉を自分で考案した無意味な言葉に置き換えることがある(例えば、「腹が立ったので皿を拾ってゲルジンガーに投げつけ た」)[40]。新造語の使用は、脳卒中や頭部外傷による脳の損傷後に後天的に生じた失語症による場合もある[41]。 |

| Aureation Backslang Blend word Calque Language planning Mondegreen Morphology (linguistics) Nonce word Phono-semantic matching Protologism Retronym Sniglet Syllabic abbreviations Word formation |

オーレーション(華麗化・装飾化) バックスラング ブレンド語 カルケ 言語計画 モンデグリーン 形態論(言語学) ノンス・ワード フォノセマンティック・マッチング 原語論 レトロニム スニグレット 音節の省略 単語の形成 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neologism |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆